Leon Festinger's Cognitive dissonance, 1953

フェスティンガーの「認知的不協和」論

Leon Festinger's Cognitive dissonance, 1953

かいせつ:池田光穂

認知的不協和 (cognitive

dissonance)

とは、ある集団や個人が、その外部からやってくる情報や事実に直面する時に、自分が考えているそれらと「矛盾する認知」を同時に得た状態、あるいは、その

不快感やストレスのことをさす。

In the field of psychology, cognitive dissonance is the perception of contradictory information and the mental toll of it. Relevant items of information include a person's actions, feelings, ideas, beliefs, values, and things in the environment. Cognitive dissonance is typically experienced as psychological stress when persons participate in an action that goes against one or more of those things. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_dissonance.

心理学の分野では、認知的不協和とは、矛

盾する情報の知覚とそれに対する精神的負担のことである。それらに関連する情報には、人の行動、感情、

考え、信念、価値観、環境にあるものなどが含まれる。認知的不協和は一般的に、人がそれらの1つまたは複数に反する行動に参加するときに、心理的ストレス

として経験される。

Festinger, Leon and Daniel Katz, ed. Resarch Methods in the Behavioral Sciences. New York: Dryden, 1953.

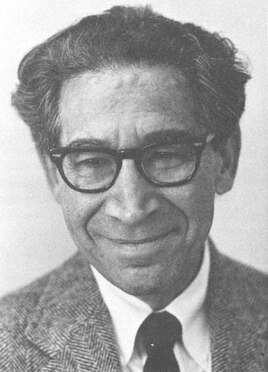

●Leon Festinger (1919-1989), experimental social psychologist

★

|

『認知的不協和の理論』(1957) 1. An Introduction to the Theory of Dissonance 2. The Consequences of Decisions: Theory 3. The Consequences of Decisions: Data 4. The Effects of Forced Compliance: Theory 5. The Effects of Forced Compliance: Data 6. Voluntary and Involuntary Exposure to Information: Theory 7. Voluntary and Involuntary Exposure to Information: Data 8. The Role of Social Support: Theory 9. The Role of Social Support: Data on Influence Process 10. The Role of Social Support: Data on Mass Phenomena 11. Recapitulation and Further Suggestions |

認知的不協和理論 1. 不協和理論への導入 2. 決断の帰結 理論編 3. 意思決定の結果 データ 4. 強制的な服従の効果 理論編 5. 強制遵守の効果 データ 6. 情報への自発的・非自発的な露出。理論編 7. 情報への自発的・非自発的なアクセス:理論編 データ 8. ソーシャルサポートの役割 理論編 9. ソーシャルサポートの役割 影響過程のデータ 10. ソーシャル・サポートの役割 集団現象に関するデータ 11. まとめと今後の提案 |

★

| Festinger's seminal

1957 work integrated existing research literature on influence and

social communication under his theory of cognitive dissonance.[56] The

theory was motivated by a study of rumors immediately following a

severe earthquake in India in 1934. Among people who felt the shock but

sustained no damage from the earthquake, rumors were widely circulated

and accepted about even worse disasters to come. Although seemingly

counter-intuitive that people would choose to believe "fear-provoking"

rumors, Festinger reasoned that these rumors were actually

"fear-justifying."[57] The rumors functioned to reduce the

inconsistency of people's feelings of fear despite not directly

experiencing the effects of the earthquake by giving people a reason to

be fearful. Festinger described the basic hypotheses of cognitive dissonance as follows: 1. The existence of dissonance [or inconsistency], being psychologically uncomfortable, will motivate the person to try to reduce the dissonance and achieve consonance [or consistency]. 2. When dissonance is present, in addition to trying to reduce it, the person will actively avoid situations and information which would likely increase the dissonance.[58] Dissonance reduction can be achieved by changing cognition by changing actions,[59] or selectively acquiring new information or opinions. To use Festinger's example of a smoker who has knowledge that smoking is bad for his health, the smoker may reduce dissonance by choosing to quit smoking, by changing his thoughts about the effects of smoking (e.g., smoking is not as bad for your health as others claim), or by acquiring knowledge pointing to the positive effects of smoking (e.g., smoking prevents weight gain).[60] Festinger and James M. Carlsmith published their classic cognitive dissonance experiment in 1959.[61] In the experiment, subjects were asked to perform an hour of boring and monotonous tasks (i.e., repeatedly filling and emptying a tray with 12 spools and turning 48 square pegs in a board clockwise). Some subjects, who were led to believe that their participation in the experiment had concluded, were then asked to perform a favor for the experimenter by telling the next participant, who was actually a confederate, that the task was extremely enjoyable. Dissonance was created for the subjects performing the favor, as the task was in fact boring. Half of the paid subjects were given $1 for the favor, while those of the other half received $20. As predicted by Festinger and Carlsmith, those paid $1 reported the task to be more enjoyable than those paid $20. Those paid $1 were forced to reduce dissonance by changing their opinions of the task to produce consonance with their behavior of reporting that the task was enjoyable. The subjects paid $20 experienced less dissonance, as the large payment provided consonance with their behavior; they therefore rated the task as less enjoyable and their ratings were similar to those who were not asked to perform the dissonance-causing favor. |

フェスティンガーの1957年の代表的な著作は、影響力と社会的コミュ

ニケーションに関する既存の研究文献を彼の認知的不協和の理論のもとに統合した[56]

。この理論は、1934年にインドで起きた大地震の直後の噂の研究によって動機づけされた。衝撃を感じたが地震による被害を受けなかった人々の間では、今

後さらに悪い災害が起こるという噂が広く流布され、受け入れられていた。人々が「恐怖を引き起こす」噂を信じることを選択することは一見直感に反している

が、フェスティンガーはこれらの噂が実際には「恐怖の正当化」であると推論した[57]。噂は人々に恐怖である理由を与えることによって、地震の影響を直

接経験していないにもかかわらず人々が感じる恐怖の矛盾を軽減する機能を有していたのだ。 フェスティンガーは認知的不協和の基本的な仮説を次のように説明している。 1. 不協和[または矛盾]の存在は、心理的に不快であるため、不協和を軽減し、協和[または一貫性]を達成しようとする動機となる。 2. 不協和が存在する場合、それを低減しようとすることに加えて、人は不協和を増大させる可能性のある状況や情報を積極的に回避することになる[58]。 不協和の解消は行動を変えることで認知を変化させるか[59]、新しい情報や意見を選択的に獲得することで達成することができる。喫煙が健康に悪いという 知識を持つ喫煙者のフェスティンガーの例を使うと、喫煙者は禁煙を選択したり、喫煙の影響についての考えを変えたり(例:喫煙は他の人が主張するほど健康 に悪くない)、喫煙のプラス効果を指摘する知識を得たり(例:喫煙は体重増加を防ぐ)して不協和を低減することができる[60]。 フェスティンガーとジェームズ・M・カールスミスは1959年に古典的な認知的不協和実験を発表した[61]。実験では、被験者は退屈で単調な作業を1時 間行うよう求められた(例:12個のスプールが付いたトレイを入れたり出したりを繰り返す、盤の48個の角くぎを時計回りに回転させるなど)。実験への参 加が終了したと思い込まされた被験者の中には、次の被験者(実は共犯者)に「この作業は非常に楽しかった」と言うことで、実験者のために好意を示すように 頼まれた人もいた。このとき、被験者の好意は、実際には退屈なタスクであるため、不協和が生じる。半数の被験者には1ドル、残りの半数の被験者には20ド ルの報酬が支払われた。フェスティンガーとカールスミスの予想通り、1ドルの報酬を受けた被験者は、20ドルの報酬を受けた被験者よりも、その課題が楽し いと報告した。1ドル支払われた被験者は、課題に対する意見を変えることで不協和を解消し、課題が楽しいと報告する行動との協和を図ることを余儀なくされ た。20ドル支払われた被験者は、多額の支払いが自分の行動との協和をもたらすため、不協和をより少なく経験した。したがって、彼らは課題をより楽しくな いと評価し、その評価は不協和の原因となる好意を求められなかった被験者と同様であった。 |

| Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leon_Festinger#Cognitive_dissonance | https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

Leon

Festinger (8 May 1919 – 11 February 1989) was an American social

psychologist who originated the theory of cognitive dissonance and

social comparison theory. The rejection of the previously dominant

behaviorist view of social psychology by demonstrating the inadequacy

of stimulus-response conditioning accounts of human behavior is largely

attributed to his theories and research.[1] Festinger is also credited

with advancing the use of laboratory experimentation in social

psychology,[2] although he simultaneously stressed the importance of

studying real-life situations,[3] a principle he practiced when

personally infiltrating a doomsday cult. He is also known in social

network theory for the proximity effect (or propinquity).[4] Leon

Festinger (8 May 1919 – 11 February 1989) was an American social

psychologist who originated the theory of cognitive dissonance and

social comparison theory. The rejection of the previously dominant

behaviorist view of social psychology by demonstrating the inadequacy

of stimulus-response conditioning accounts of human behavior is largely

attributed to his theories and research.[1] Festinger is also credited

with advancing the use of laboratory experimentation in social

psychology,[2] although he simultaneously stressed the importance of

studying real-life situations,[3] a principle he practiced when

personally infiltrating a doomsday cult. He is also known in social

network theory for the proximity effect (or propinquity).[4]Festinger studied psychology under Kurt Lewin, an important figure in modern social psychology, at the University of Iowa, graduating in 1941;[5] however, he did not develop an interest in social psychology until after joining the faculty at Lewin's Research Center for Group Dynamics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1945.[6] Despite his preeminence in social psychology, Festinger turned to visual perception research in 1964 and then archaeology, history, and the human evolutionary sciences in 1979 until his death in 1989.[7] Following B. F. Skinner, Jean Piaget, Sigmund Freud, and Albert Bandura, Festinger was the fifth most cited psychologist of the 20th century.[8] |

レ

オン・フェスティンガー(Leon Festinger、1919年5月8日 -

1989年2月11日)はアメリカの社会心理学者で、認知的不協和の理論と社会的比較理論を創始した。フェスティンガーはまた、社会心理学における実験室

での実験の利用を推進したことでも知られているが[2]、同時に彼は現実の状況を研究することの重要性を強調しており[3]、この原則は彼が個人的に終末

論カルトに潜入した際に実践したものである。彼はまた、社会的ネットワーク理論において近接効果(または親近性)でも知られている[4]。 レ

オン・フェスティンガー(Leon Festinger、1919年5月8日 -

1989年2月11日)はアメリカの社会心理学者で、認知的不協和の理論と社会的比較理論を創始した。フェスティンガーはまた、社会心理学における実験室

での実験の利用を推進したことでも知られているが[2]、同時に彼は現実の状況を研究することの重要性を強調しており[3]、この原則は彼が個人的に終末

論カルトに潜入した際に実践したものである。彼はまた、社会的ネットワーク理論において近接効果(または親近性)でも知られている[4]。フェスティンガーはアイオワ大学で現代社会心理学の重要人物であるクルト・ルーウィンの下で心理学を学び、1941年に卒業した[5]が、1945年にマ サチューセッツ工科大学でルーウィンの集団力学研究センターの教員になるまで社会心理学に興味を持つことはなかった。 [社会心理学で卓越していたにもかかわらず、フェスティンガーは1964年に視覚知覚研究に転向し、1979年には考古学、歴史学、人類進化科学に転向 し、1989年に亡くなるまで活躍した[7]。B・F・スキナー、ジャン・ピアジェ、ジークムント・フロイト、アルバート・バンデューラに続き、フェス ティンガーは20世紀で5番目に引用された心理学者である[8]。 |

| Life Early life and education Festinger was born in Brooklyn New York on May 8, 1919 to Russian-Jewish immigrants Alex Festinger and Sara Solomon Festinger. His father, an embroidery manufacturer, had "left Russia a radical and atheist and remained faithful to these views throughout his life."[9] Festinger attended Boys' High School in Brooklyn, and received his BS degree in psychology from the City College of New York in 1939.[10] He proceeded to study under Kurt Lewin at the University of Iowa, where Festinger received his MA in 1940 and PhD in 1942 in the field of child behavior.[11] By his own admission, he was not interested in social psychology when he arrived at Iowa, and did not take a single course in social psychology during his entire time there; instead, he was interested in Lewin's earlier work on tension systems, but Lewin's focus had shifted to social psychology by the time Festinger arrived at Iowa.[12] However, Festinger continued to pursue his original interests, studying level of aspiration,[13] working on statistics,[14][15] developing a quantitative model of decision making,[16] and even publishing a laboratory study on rats.[17] Explaining his lack of interest in social psychology at the time, Festinger stated, "The looser methodology of the social psychology studies, and the vagueness of relation of the data to Lewinian concepts and theories, all seemed unappealing to me in my youthful penchant for rigor."[18] Festinger considered himself to be a freethinker and an atheist.[19] After graduating, Festinger worked as a research associate at Iowa from 1941 to 1943, and then as a statistician for the Committee on Selection and Training of Aircraft Pilots at the University of Rochester from 1943 to 1945 during World War II. In 1943, Festinger married Mary Oliver Ballou, a pianist,[20] with whom he had three children, Catherine, Richard, and Kurt.[21] Festinger and Ballou were later divorced, and Festinger married Trudy Bradley, currently a professor of social work emeritus at New York University,[22] in 1968.[23] Career In 1945, Festinger joined Lewin's newly formed Research Center for Group Dynamics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as an assistant professor. It was at MIT that Festinger, in his own words, "became, by fiat, a social psychologist, and immersed myself in the field with all its difficulties, vaguenesses, and challenges."[24] It was also at MIT that Festinger began his foray into social communication and pressures in groups that marked a turning point in his own research. As Festinger himself recalls, "the years at M.I.T. [sic] seemed to us all to be momentous, ground breaking, the new beginning of something important."[25] Indeed, Stanley Schachter, Festinger's student and research assistant at the time, states, "I was lucky enough to work with Festinger at this time, and I think of it as one of the high points of my scientific life."[26] Yet, this endeavor "started as almost an accident"[27] while Festinger was conducting a study on the impact of architectural and ecological factors on student housing satisfaction for the university. Although the proximity effect (or propinquity) was an important direct finding from the study, Festinger and his collaborators also noticed correlations between the degree of friendship within a group of residents and the similarity of opinions within the group,[28] thus raising unexpected questions regarding communication within social groups and the development of group standards of attitudes and behaviors.[29] Indeed, Festinger's seminal 1950 paper on informal social communication as a function of pressures toward attitude uniformity within a group cites findings from this seemingly unrelated housing satisfaction study multiple times.[30] After Lewin's death in 1947, Festinger moved with the research center to the University of Michigan in 1948. He then moved to the University of Minnesota in 1951, and then on to Stanford University in 1955. During this time, Festinger published his highly influential paper on social comparison theory, extending his prior theory regarding the evaluation of attitudes in social groups to the evaluation of abilities in social groups.[31] Following this, in 1957, Festinger published his theory of cognitive dissonance, arguably his most famous and influential contribution to the field of social psychology.[32] Some also view this as an extension of Festinger's prior work on group pressures toward resolving discrepancies in attitudes and abilities within social groups to how the individual resolves discrepancies at the cognitive level.[33] Festinger also received considerable recognition during this time for his work, both from within the field, being awarded the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award by the American Psychological Association in 1959,[34] and outside of the field, being named as one of America's ten most promising scientists by Fortune magazine shortly after publishing social comparison theory.[35] Despite such recognition, Festinger left the field of social psychology in 1964, attributing his decision to "a conviction that had been growing in me at the time that I, personally, was in a rut and needed an injection of intellectual stimulation from new sources to continue to be productive."[36] He turned his attention to the visual system, focusing on human eye movement and color perception. In 1968, Festinger returned to his native New York City, continuing his perception research at The New School, then known as the New School for Social Research. In 1979, he closed his laboratory, citing dissatisfaction with working "on narrower and narrower technical problems."[37] Later life Writing in 1983, four years after closing his laboratory, Festinger expressed a sense of disappointment with what he and his field had accomplished: Forty years in my own life seems like a long time to me and while some things have been learned about human beings and human behavior during this time, progress has not been rapid enough; nor has the new knowledge been impressive enough. And even worse, from a broader point of view we do not seem to have been working on many of the important problems.[38] Festinger subsequently began exploring prehistoric archaeological data, meeting with Stephen Jay Gould to discuss ideas and visiting archaeological sites to investigate primitive toolmaking firsthand.[39] His efforts eventually culminated in the book, The Human Legacy, which examined how humans evolved and developed complex societies.[40] Although seemingly the product of a disillusioned, wholesale abandonment of the field of psychology, Festinger considered this research as a return to the fundamental concerns of psychology. He described the goal of his new research interests as "see[ing] what can be inferred from different vantage points, from different data realms, about the nature, the characteristics, of this species we call human,"[41] and felt bemused when fellow psychologists asked him how his new research interests were related to psychology.[42] Festinger's next and final enterprise was to understand why an idea is accepted or rejected by a culture, and he decided that examining why new technology was adopted quickly in the West but not in the Eastern Byzantine Empire would illuminate the issue.[43] However, Festinger was diagnosed with cancer before he was able to publish this material. He decided not to pursue treatment, and died on February 11, 1989.[44] |

生涯 生い立ちと教育 フェスティンガーは1919年5月8日、ニューヨークのブルックリンでロシア系ユダヤ人のアレックス・フェスティンガーとサラ・ソロモン・フェスティン ガーの間に生まれた。彼の父親は刺繍メーカーであったが、「急進的で無神論者であったロシアを去り、生涯を通じてその考えに忠実であった」[9]。 彼はアイオワ大学でクルト・ルウィンに師事し、1940年に修士号を、1942年に博士号を児童行動学の分野で取得した[11]。彼自身の告白によれば、 アイオワに到着したとき、彼は社会心理学に興味がなく、アイオワでの全期間中、社会心理学の講義は一度も履修しなかった。 [12]しかし、フェスティンガーは当初の関心を追求し続け、向上心のレベルを研究し[13]、統計学に取り組み[14][15]、意思決定の定量的モデ ルを開発し[16]、さらにはラットの実験室研究を発表した。 [17]当時、社会心理学に興味がなかったことを説明するために、フェスティンガーは「社会心理学研究の緩い方法論、レヴィニアンの概念や理論とのデータ の関係の曖昧さは、厳密さを求める若かりし頃の私にはすべて魅力的に思えなかった」と述べている[18]。 卒業後、フェスティンガーは1941年から1943年までアイオワ大学で研究員として働き、第二次世界大戦中の1943年から1945年までロチェスター 大学で航空機パイロットの選抜と訓練に関する委員会の統計学者として働いた。1943年、フェスティンガーはピアニストのメアリー・オリヴァー・バルーと 結婚し[20]、彼女との間にキャサリン、リチャード、クルトの3人の子供をもうけた[21]。フェスティンガーとバルーは後に離婚し、フェスティンガー は1968年にトゥルーディ・ブラッドリー(現ニューヨーク大学ソーシャルワーク名誉教授)と結婚した[22]。 キャリア 1945年、フェスティンガーはマサチューセッツ工科大学に新しく設立されたルウィンの集団力学研究センターに助教授として加わった。彼自身の言葉を借り れば、フェスティンガーはマサチューセッツ工科大学で「社会心理学者となり、その困難さ、曖昧さ、挑戦のすべてを伴うこの分野に没頭した」[24]。フェ スティンガー自身が回想しているように、「M.I.T.での数年間は、私たち全員にとって記念すべきもの、画期的なもの、重要なものの新たな始まりのよう に思えた」[25]。実際、当時フェスティンガーの学生であり研究助手であったスタンリー・シャクターは、「この時期にフェスティンガーと仕事ができたこ とは幸運であり、私の科学者人生の最高潮の一つであったと思う」と述べている[26]。 とはいえ、この試みは、フェスティンガーが大学のために学生寮の満足度に与える建築的・生態学的要因の影響に関する研究を行っていたときに、「ほとんど偶 然に始まった」[27]。近接効果(または親近性)はこの研究から得られた重要な直接的知見であったが、フェスティンガーと彼の共同研究者たちは、居住者 グループ内の友好度とグループ内の意見の類似性との間の相関関係にも気づいており[28]、その結果、社会的グループ内のコミュニケーションや態度や行動 に関するグループ標準の発展に関する予期せぬ疑問を提起している[29]。実際、グループ内の態度の統一に向けた圧力の関数としての非公式な社会的コミュ ニケーションに関するフェスティンガーの1950年の代表的な論文では、一見無関係に見えるこの住宅満足度研究から得られた知見が何度も引用されている [30]。 1947年のルーウィンの死後、フェスティンガーは1948年に研究センターとともにミシガン大学に移った。その後、1951年にミネソタ大学に移り、 1955年にはスタンフォード大学に移った。この間、フェスティンガーは社会的比較理論に関する非常に影響力のある論文を発表し、社会的集団における態度 の評価に関する先行理論を社会的集団における能力の評価に拡張した[31]。これに続いて1957年、フェスティンガーは認知的不協和に関する理論を発表 したが、これは間違いなく社会心理学の分野における彼の最も有名で影響力のある貢献である。 [また、これは社会集団内の態度や能力の不一致を解決するための集団の圧力に関するフェスティンガーの先行研究を、個人が認知レベルでどのように不一致を 解決するのかに拡張したものとみなす者もいる[33]。フェスティンガーはまた、1959年にアメリカ心理学会から特別科学貢献賞を授与されるなど、この 分野の内部から[34]、また社会的比較理論を発表した直後にフォーチュン誌によってアメリカで最も有望な10人の科学者の一人に選ばれるなど、この分野 の外部からも、この時期に彼の研究に対してかなりの評価を受けた[35]。 このような評価にもかかわらず、フェスティンガーは1964年に社会心理学の分野を離れ、その決断の理由を「当時、私個人はマンネリ化しており、生産的で あり続けるためには新しい情報源からの知的刺激の注入が必要であるという確信が芽生えていた」[36]と述べている。1968年、フェスティンガーは生ま れ故郷のニューヨークに戻り、ニュースクール(当時はニュースクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチとして知られていた)で知覚の研究を続けた。1979 年、彼は「ますます狭い技術的問題に取り組む」ことへの不満を理由に研究室を閉鎖した[37]。 その後の人生 研究室を閉鎖してから4年後の1983年、フェスティンガーは、自分と自分の研究分野が達成したことへの失望感を表明している: 私自身の人生における40年は、私にとっては長い時間のように思えるし、この間に人間と人間の行動についていくつかのことが学ばれたが、進歩は十分に速く はなかったし、新しい知識は十分に印象的でもなかった。さらに悪いことに、より広い観点から見ると、私たちは重要な問題の多くに取り組んでこなかったよう に思われる[38]。 フェスティンガーはその後、先史時代の考古学的データの探求を始め、スティーヴン・ジェイ・グールドと会ってアイデアについて議論し、原始的な道具作りを 直接調査するために遺跡を訪れた。彼は自分の新たな研究関心の目標を「人間と呼ばれるこの種の性質や特徴について、異なる視点、異なるデータ領域から何が 推測されうるかを見ること」[41]であると説明し、同僚の心理学者たちから自分の新たな研究関心が心理学とどのように関連しているのかと質問されたこと に困惑を感じていた[42]。 フェスティンガーの次の、そして最終的な事業は、ある考えがなぜある文化に受け入れられ、あるいは拒絶されるのかを理解することであり、彼はなぜ新しい技 術が西洋ではすぐに採用されたが、東ビザンティン帝国では採用されなかったのかを調べることが、その問題を明らかにすることになると考えた[43]。フェ スティンガーは治療を続けることを断念し、1989年2月11日に死去した[44]。 |

| Work Proximity effect Festinger, Stanley Schachter, and Kurt Back examined the choice of friends among college students living in married student housing at MIT. The team showed that the formation of ties was predicted by propinquity, the physical proximity between where students lived, and not just by similar tastes or beliefs as conventional wisdom assumed. In other words, people simply tend to befriend their neighbors. They also found that functional distance predicted social ties as well. For example, in a two-storey apartment building, people living on the lower floor next to a stairway are functionally closer to upper-floor residents than are others living on the same lower floor. The lower-floor residents near the stairs are more likely than their lower-floor neighbors to befriend those living on the upper floor. Festinger and his collaborators viewed these findings as evidence that friendships often develop based on passive contacts (e.g., brief meetings made as a result of going to and from home within the student housing community) and that such passive contacts are more likely to occur given closer physical and functional distance between people.[45] Informal social communication In his 1950 paper, Festinger postulated that one of the major pressures to communicate arises from uniformity within a group, which in turn arises from two sources: social reality and group locomotion.[46] Festinger argued that people depend on social reality to determine the subjective validity of their attitudes and opinions, and that they look to their reference group to establish social reality; an opinion or attitude is therefore valid to the extent that it is similar to that of the reference group. He further argued that pressures to communicate arise when discrepancies in opinions or attitudes exist among members of a group, and laid out a series hypotheses regarding determinants of when group members communicate, whom they communicate with, and how recipients of communication react, citing existing experimental evidence to support his arguments. Festinger labeled communications arising from such pressures toward uniformity as "instrumental communication" in that the communication is not an end in itself but a means to reduce discrepancies between the communicator and others in the group. Instrumental communication is contrasted with "consummatory communication" where communication is the end, such as emotional expression.[47] Social comparison theory Festinger's influential social comparison theory (1954) can be viewed as an extension of his prior theory related to the reliance on social reality for evaluating attitudes and opinions to the realm of abilities. Starting with the premise that humans have an innate drive to accurately evaluate their opinions and abilities, Festinger postulated that people will seek to evaluate their opinions and abilities by comparing them with those of others. Specifically, people will seek out others who are close to one's own opinions and abilities for comparison because accurate comparisons are difficult when others are too divergent from those of oneself. To use Festinger's example, a chess novice does not compare his chess abilities to those of recognized chess masters,[48] nor does a college student compare his intellectual abilities to those of a toddler. People will, moreover, take action to reduce discrepancies in attitudes, whether by changing others to bring them closer to oneself or by changing one's own attitudes to bring them closer to others. They will likewise take action to reduce discrepancies in abilities, for which there is an upward drive to improve one's abilities. Thus Festinger suggested that the "social influence processes and some kinds of competitive behavior are both manifestations of the same socio-psychological process...[namely,] the drive for self evaluation and the necessity for such evaluation being based on comparison with other persons."[49] Festinger also discussed implications of social comparison theory for society, hypothesizing that the tendency for people to move into groups that hold opinions which agree with their own and abilities that are near their own results in the segmentation of society into groups which are relatively alike. In his 1954 paper, Festinger again systematically set forth a series of hypotheses, corollaries, and derivations, and he cited existing experimental evidence where available. He stated his main set of hypotheses as follows: 1. There exists, in the human organism, a drive to evaluate his opinion and abilities. 2. To the extent that objective, nonsocial means are available, people evaluate their opinions and abilities by comparison respectively with the opinions and abilities of others. 3. The tendency to compare oneself with some other specific person decreases as the difference between his opinion or ability and one's own increases. 4. There is a unidirectional drive upward in the case of abilities which is largely absent in opinions. 5. There are nonsocial restraints which make it difficult or even impossible to change one's ability. These nonsocial restraints are largely absent for opinions. 6. The cessation of comparison with others is accompanied by hostility or derogation to the extent that continued comparison with those persons implies unpleasant consequences. 7. Any factors which increase the importance of some particular group as a comparison group for some particular opinion or ability will increase the pressure toward uniformity concerning that ability or opinion within that group. 8. If persons who are very divergent from one's own opinion or ability are perceived as different from oneself on attributes consistent with the divergence, the tendency to narrow the range of comparability becomes stronger. 9. When there is a range of opinion or ability in a group, the relative strength of the three manifestations of pressures toward uniformity will be different for those who are close to the mode of the group than those who are distant from the mode. Specifically, those close to the mode of the group will have stronger tendencies to change the positions of others, relatively weaker tendencies to narrow the range of comparison, and much weaker tendencies to change their position compared to those who are distant from the mode of the group.[50] When Prophecy Fails Main article: When Prophecy Fails Festinger and his collaborators, Henry Riecken and Stanley Schachter, examined conditions under which disconfirmation of beliefs leads to increased conviction in such beliefs in the 1956 book When Prophecy Fails. The group studied a small apocalyptic cult led by Dorothy Martin (under the pseudonym Marian Keech in the book), a suburban housewife.[51][52] Martin claimed to have received messages from "the Guardians," a group of superior beings from another planet called 'Clarion.' The messages purportedly said that a flood spreading to form an inland sea stretching from the Arctic Circle to the Gulf of Mexico would destroy the world on December 21, 1954. The three psychologists and several more assistants joined the group. The team observed the group firsthand for months before and after the predicted apocalypse. Many of the group members quit their jobs and disposed of their possessions in preparation for the apocalypse. When doomsday came and went, Martin claimed that the world had been spared because of the "force of Good and light"[53] that the group members had spread. Rather than abandoning their discredited beliefs, group members adhered to them even more strongly and began proselytizing with fervor. Festinger and his co-authors concluded that the following conditions lead to increased conviction in beliefs following disconfirmation: 1. The belief must be held with deep conviction and be relevant to the believer's actions or behavior. 2. The belief must have produced actions that are arguably difficult to undo. 3. The belief must be sufficiently specific and concerned with the real world such that it can be clearly disconfirmed. 4. The disconfirmatory evidence must be recognized by the believer. 5. The believer must have social support from other believers.[54] Festinger also later described the increased conviction and proselytizing by cult members after disconfirmation as a specific instantiation of cognitive dissonance (i.e., increased proselytizing reduced dissonance by producing the knowledge that others also accepted their beliefs) and its application to understanding complex, mass phenomena.[55] The observations reported in When Prophecy Fails were the first experimental evidence for belief perseverance.[citation needed] Cognitive dissonance Main article: Cognitive dissonance Festinger's seminal 1957 work integrated existing research literature on influence and social communication under his theory of cognitive dissonance.[56] The theory was motivated by a study of rumors immediately following a severe earthquake in India in 1934. Among people who felt the shock but sustained no damage from the earthquake, rumors were widely circulated and accepted about even worse disasters to come. Although seemingly counter-intuitive that people would choose to believe "fear-provoking" rumors, Festinger reasoned that these rumors were actually "fear-justifying."[57] The rumors functioned to reduce the inconsistency of people's feelings of fear despite not directly experiencing the effects of the earthquake by giving people a reason to be fearful. Festinger described the basic hypotheses of cognitive dissonance as follows: 1. The existence of dissonance [or inconsistency], being psychologically uncomfortable, will motivate the person to try to reduce the dissonance and achieve consonance [or consistency]. 2. When dissonance is present, in addition to trying to reduce it, the person will actively avoid situations and information which would likely increase the dissonance.[58] Dissonance reduction can be achieved by changing cognition by changing actions,[59] or selectively acquiring new information or opinions. To use Festinger's example of a smoker who has knowledge that smoking is bad for his health, the smoker may reduce dissonance by choosing to quit smoking, by changing his thoughts about the effects of smoking (e.g., smoking is not as bad for your health as others claim), or by acquiring knowledge pointing to the positive effects of smoking (e.g., smoking prevents weight gain).[60] Festinger and James M. Carlsmith published their classic cognitive dissonance experiment in 1959.[61] In the experiment, subjects were asked to perform an hour of boring and monotonous tasks (i.e., repeatedly filling and emptying a tray with 12 spools and turning 48 square pegs in a board clockwise). Some subjects, who were led to believe that their participation in the experiment had concluded, were then asked to perform a favor for the experimenter by telling the next participant, who was actually a confederate, that the task was extremely enjoyable. Dissonance was created for the subjects performing the favor, as the task was in fact boring. Half of the paid subjects were given $1 for the favor, while those of the other half received $20. As predicted by Festinger and Carlsmith, those paid $1 reported the task to be more enjoyable than those paid $20. Those paid $1 were forced to reduce dissonance by changing their opinions of the task to produce consonance with their behavior of reporting that the task was enjoyable. The subjects paid $20 experienced less dissonance, as the large payment provided consonance with their behavior; they therefore rated the task as less enjoyable and their ratings were similar to those who were not asked to perform the dissonance-causing favor. |

仕事 近接効果 フェスティンガー、スタンリー・シャクター、カート・バックの3人は、マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)の学生寮に住む大学生の友人選びを調査した。研 究チームは、絆の形成は、学生が住んでいる場所の物理的な近さである親近性によって予測されるのであって、従来の常識が想定していたような趣味や信条の類 似によって予測されるのではないことを示した。つまり、人は単に隣人と親しくなる傾向があるのだ。また、機能的距離も社会的つながりを予測することがわ かった。たとえば、2階建てのアパートでは、階段に隣接する下層階に住む人は、同じ下層階に住む人よりも上層階に住む人と機能的に近い。階段に近い低層階 の住人は、低層階の隣人よりも高層階の住人と親しくなる可能性が高い。フェスティンガーと彼の共同研究者たちは、これらの知見を、友人関係は受動的接触 (例えば、学生寮コミュニティ内での行き帰りの結果として生じる短い出会い)に基づいて発展することが多く、そのような受動的接触は、人々の間の物理的・ 機能的距離が近いほど生じやすいという証拠であるとみなしている[45]。 インフォーマルな社会的コミュニケーション フェスティンガーは1950年の論文で、コミュニケーションへの主要な圧力の1つは集団内の均一性から生じ、それは2つの源、すなわち社会的現実と集団運 動から生じると仮定している。さらに彼は、集団のメンバーの間に意見や態度の不一致が存在する場合、コミュニケーションへの圧力が生じると主張し、集団の メンバーがいつコミュニケーションをとるのか、誰とコミュニケーションをとるのか、コミュニケーションの受け手がどのように反応するのかの決定要因に関す る一連の仮説を、既存の実験的証拠を引用しながら提示した。 フェスティンガーは、このような画一性への圧力から生じるコミュニケーションを、コミュニケーションそれ自体が目的ではなく、コミュニケーターとグループ 内の他者との間の齟齬を減らすための手段であるという意味で、「道具的コミュニケーション」と名付けた。道具的コミュニケーションは、感情表現のようにコ ミュニケーションが目的である「消費的コミュニケーション」と対比される[47]。 社会比較理論 フェスティンガーの影響力のある社会的比較理論(1954年)は、態度や意見を評価するために社会的現実に依存することに関する彼の先行理論を能力の領域 まで拡張したものとみなすことができる。フェスティンガーは、人間には自分の意見や能力を正確に評価しようとする生得的な欲求があるという前提から出発 し、人は自分の意見や能力を他者のそれと比較することによって評価しようとすると仮定した。具体的には、自分の意見や能力とあまりにかけ離れた他者と比較 すると、正確な比較が難しくなるため、自分の意見や能力に近い他者を比較対象として求めるようになる。フェスティンガーの例で言えば、チェス初心者は自分 のチェス能力をチェス名人と比較しないし[48]、大学生は自分の知的能力を幼児と比較しない。 さらに人は、他人を変えて自分に近づけるか、自分の態度を変えて他人に近づけるかにかかわらず、態度の不一致を減らすために行動を起こす。同様に、自分の 能力を向上させようとする上昇志向があり、能力の不一致を減らすために行動を起こす。このようにフェスティンガーは、「社会的影響過程とある種の競争行動 は、どちらも同じ社会心理学的過程の現れである...すなわち、自己評価の原動力と、そのような評価が他の人物との比較に基づく必要性である」と示唆した [49]。フェスティンガーはまた、社会比較理論の社会に対する含意について議論し、人々が自分の意見に同意する意見や自分の能力に近い能力を保持する集 団に移動する傾向が、社会を相対的に似た集団に細分化するという仮説を立てた。 1954年の論文で、フェスティンガーは再び一連の仮説、傍証、導出を体系的に示し、利用可能な場合には既存の実験的証拠を引用した。彼は主な仮説のセッ トを次のように述べた: 1. 人間には、自分の意見や能力を評価しようとする衝動が存在する。 2. 2.客観的で非社会的な手段が利用できる限り、人は自分の意見や能力を他人の意見や能力とそれぞれ比較することによって評価する。 3. ある特定の他人と自分を比較する傾向は、その人の意見や能力と自分の意見との差が大きくなるにつれて減少する。 4. 意見の場合はほとんどないが、能力の場合は上方への一方向的なドライブがある。 5. 自分の能力を変えることを困難にする、あるいは不可能にする非社会的拘束がある。こうした非社会的拘束は意見にはほとんどない。 6. 他者との比較の停止は、その人との比較を続けることが不快な結果を意味する程度まで、敵意や軽蔑を伴う。 7. ある特定の意見や能力について、比較対象集団としてのある特定の集団の重要性を高めるような要因があれば、その集団内でその能力や意見に関する統一を求め る圧力が高まる。 8. 自分の意見や能力と大きく乖離した人物が、その乖離と一致する属性において自分とは異なると認識された場合、比較可能な範囲を狭めようとする傾向が強くな る。 9. ある集団の中に意見や能力の幅がある場合、その集団の最頻値に近い者と遠い者とでは、画一性への圧力の3つの現れ方の相対的な強さが異なってくる。具体的 には、集団のモードに近い人は、集団のモードから遠い人に比べて、他者の立場を変えようとする傾向がより強く、比較の範囲を狭めようとする傾向が相対的に 弱く、自分の立場を変えようとする傾向がかなり弱くなる[50]。 予言が失敗するとき 主な記事 予言が失敗するとき フェスティンガーと彼の共同研究者であるヘンリー・リーケンとスタンリー・シャクターは、1956年に出版された『予言が失敗するとき(When Prophecy Fails)』という本の中で、信念の不確認がそのような信念の確信の増大につながる条件を調べた。このグループは、郊外の主婦であるドロシー・マーティ ン(この本ではマリアン・キーチというペンネームで登場する)が率いる小さな終末論的カルト教団を研究した[51][52]。マーティンは、「クラリオ ン」と呼ばれる別の惑星から来た優れた存在である「ガーディアン」からメッセージを受け取ったと主張した。そのメッセージは、北極圏からメキシコ湾まで広 がる内海を形成するように広がる洪水が1954年12月21日に世界を破壊すると伝えていた。人の心理学者と数人のアシスタントがそのグループに加わっ た。チームは予言された黙示録の前後数ヶ月間、グループを直接観察した。グループのメンバーの多くは、黙示録に備えて仕事を辞め、持ち物を処分した。終末 の日が来たとき、マーティンは、グループのメンバーが広めた「善と光の力」[53]のおかげで世界は助かったと主張した。グループのメンバーは、信用を 失った信念を捨てるどころか、さらに強く信奉し、熱心に布教を始めた。 フェスティンガーとその共著者たちは、次のような条件が、不確認の後 に信念の確信を強めることにつながると結論づけた: 1. その信念は深い確信を持っていて、信者の行動や言動と関連性があ ること。 2. その信念が、間違いなく取り消すのが困難な行動を生み出していること。 3. その信念は十分に具体的で、現実の世界と関係があり、明確に否定でき るものでなければならない。 4. その否認の証拠は、信者が認めるものでなければならない。 5. 信者は他の信者から社会的な支持を得ていなければならない。 フェスティンガーはまた、後に認知的不協和の具体的なインスタンスと して、不確認の後にカルト教団員による確信と布教が増加すること(すなわ ち、布教の増加は、他の人々も自分の信念を受け入れているという知識を生 み出すことによって不協和を減少させる)と、複雑な大衆現象を理解するため のその応用について述べている[55]。 予言が失敗するとき』で報告された観察は、信念の持続に関する最初の実験的証拠であった[要出典]。 認知的不協和 主な記事 認知的不協和 フェスティンガーの1957年の代表的な著作は、影響力と社会的コミュニケーションに関する既存の研究文献を認知的不協和の理論の下に統合したものであ る。衝撃は感じたが地震による被害は受けなかった人々の間で、今後さらに大きな災害が起こるという噂が広く流布し、受け入れられていた。人々が「恐怖を誘 発する」噂を信じるということは一見直感に反し ているように見えるが、フェスティンガーはこれらの噂が実際には「恐怖を 正当化する」ものであると推論した[57]。 フェスティンガーは、認知的不協和の基本的仮説を以下のように説明した: 1. 不協和[または矛盾]の存在は、心理的に不快であるため、不協和を軽減し、協和[または一貫性]を達成しようとする動機となる。 2. 不協和が存在する場合、それを軽減しようとすることに加えて、人は不協和を増大させる可能性の高い状況や情報を積極的に避けるようになる[58]。 不協和の低減は、行動を変えることによって認知を変化させたり[59]、選択的に新しい情報や意見を獲得することによって達成することができる。喫煙が健 康に悪いという知識を持つ喫煙者の例を用いると、喫煙者は禁煙を選択したり、喫煙の影響についての考えを変えたり(例えば、喫煙は他人が主張するほど健康 に悪くない)、喫煙のプラスの効果を指摘する知識を得たり(例えば、喫煙は体重増加を防ぐ)することによって、不協和を軽減することができる[60]。 フェスティンガーとジェームズ・M・カールスミスは、1959年に古典的な認知的不協和実験を発表した[61]。この実験では、被験者は退屈で単調な作業 を1時間行うよう求められた(すなわち、12個のスプールが入ったトレイを入れたり空けたりすることを繰り返したり、48個の四角い釘を入れた板を時計回 りに回したりすること)。実験への参加は終わったと思い込まされた被験者の中には、次に実験者のために、実は共犯者である次の参加者に、このタスクは非常 に楽しかったと話すよう頼まれた者もいた。実際には退屈な課題であったため、好意を受けた被験者には不協和が生じた。報酬を得た被験者の半数には好意に対 して1ドルが与えられ、残りの半数には20ドルが与えられた。フェスティンガーとカールスミスの予想通り、1ドルもらった被験者は20ドルもらった被験者 より、その課題が楽しかったと報告した。1ドル支払われた被験者は、課題に対する意見を変えることによって不協和を減少させ、課題が楽しいと報告する行動 との協和を生み出すことを余儀なくされた。20ドル支払われた被験者は、多額の支払いが自分の行動との協和をもたらしたため、不協和をより少なく経験し た。そのため、彼らは課題をより楽しくないと評価し、その評価は不協和を引き起こす好意を行うよう要求されなかった被験者と同様であった。 |

| Legacy Social comparison theory and cognitive dissonance have been described by other psychologists as "the two most fruitful theories in social psychology."[62] Cognitive dissonance has been variously described as "social psychology's most notable achievement,"[63] "the most important development in social psychology to date,"[64] and a theory without which "social psychology would not be what it is today."[65] Cognitive dissonance spawned decades of related research, from studies focused on further theoretical refinement and development[66] to domains as varied as decision making, the socialization of children, and color preference.[67] In addition, Festinger is credited with the ascendancy of laboratory experimentation in social psychology as one who "converted the experiment into a powerful scientific instrument with a central role in the search for knowledge."[68] An obituary published by the American Psychologist stated that it was "doubtful that experimental psychology would exist at all" without Festinger.[69] Yet it seems that Festinger was wary about burdensome demands for greater empirical precision. Warning against the dangers of such demands when theoretical concepts are not yet fully developed, Festinger stated, "Research can increasingly address itself to minor unclarities in prior research rather than to larger issues; people can lose sight of the basic problems because the field becomes defined by the ongoing research."[70] He also stressed that laboratory experimentation "cannot exist by itself," but that "there should be an active interrelation between laboratory experimentation and the study of real-life situations."[71] Also, while Festinger is praised for his theoretical rigor and experimental approach to social psychology, he is regarded as having contributed to "the estrangement between basic and applied social psychology in the United States."[72] He "became a symbol of the tough-minded, theory-oriented, pure experimental scientist," while Ron Lippitt, a fellow faculty member at Lewin's Research Center for Group Dynamics with whom Festinger often clashed, "became a symbol of the fuzzy-minded, do-gooder, practitioner of applied social psychology."[73] One of the greatest impacts of Festinger's studies lies in their "depict[ion] of social behavior as the responses of a thinking organism continually acting to bring order into his world, rather than as the blind impulses of a creature of emotion and habit," as cited in his Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award.[74] Behaviorism, which had dominated psychology until that time, characterized man as a creature of habit conditioned by stimulus-response reinforcement processes. Behaviorists focused only on the observable, i.e., behavior and external rewards, with no reference to cognitive or emotional processes.[75] Theories like cognitive dissonance could not be explained in behaviorist terms. For example, liking was simply a function of reward according to behaviorism, so greater reward would produce greater liking; Festinger and Carlsmith's experiment clearly demonstrated greater liking with lower reward, a result that required the acknowledgement of cognitive processes.[76] With Festinger's theories and the research that they generated, "the monolithic grip that reinforcement theory had held on social psychology was effectively and permanently broken."[77] |

遺産 社会的比較理論と認知的不協和は、他の心理学者によって「社会心理学における最も実りある2つの理論」[62]と評されている。認知的不協和は、「社会心 理学の最も注目すべき業績」[63]、「今日までの社会心理学における最も重要な発展」[64]、「社会心理学が今日のようなものでなかっただろう理論」 [65]と様々に評されている。 「認知的不協和は、さらなる理論的洗練と発展[66]に焦点を当てた研究から、意思決定、子どもの社会化、色彩嗜好など多様な領域まで、数十年に及ぶ関連 研究を生み出した[67]。 加えて、フェスティンガーは「実験を知識の探求において中心的な役割を果たす強力な科学的道具に変えた」人物として、社会心理学における実験室での実験が 台頭するきっかけを作ったと評価されている[68]。American Psychologist誌が発表した追悼記事には、フェスティンガーがいなければ「実験心理学が存在していたかどうかは疑わしい」と記されている [69]。理論的概念がまだ十分に開発されていないときにそのような要求がなされることの危険性を警告するために、フェスティンガーは「研究はより大きな 問題よりもむしろ先行研究の些細な不明点に取り組むことが多くなる。 「また、フェスティンガーは、その理論的厳密さと社会心理学への実験的アプローチが賞賛される一方で、「アメリカにおける基礎社会心理学と応用社会心理学 の疎遠化」に貢献したとみなされている[72]。彼は「強気で理論志向の純粋な実験科学者の象徴となった」一方で、フェスティンガーがしばしば衝突した ルーウィンの集団力学研究センターの同僚教員であるロン・リピットは「ファジーマインドで善良な応用社会心理学の実践者の象徴となった」[73]。 フェスティンガーの研究の最大の影響の1つは、彼の特別科学貢献賞に引用されているように、「感情や習慣の生き物の盲目的な衝動としてではなく、自分の世 界に秩序をもたらすために絶えず行動している思考する生物の反応として、社会的行動を描いた」ことにある[74]。 それまで心理学を支配していた行動主義は、刺激と反応の強化過程によって条件づけられた習慣の生き物として人間を特徴づけていた。行動主義者は観察可能な もの、すなわち行動と外的報酬にのみ注目し、認知や感情のプロセスには全く言及しなかった。認知的不協和のような理論は行動主義の用語では説明できなかっ た。例えば、行動主義によれば、好意は単純に報酬の関数であり、より大きな報酬がより大きな好意を生み出す。フェスティンガーとカールスミスの実験は、よ り低い報酬でより大きな好意を明らかに示したが、これは認知過程を認める必要がある結果であった[76]。フェスティンガーの理論とそれらが生み出した研 究によって、「強化理論が社会心理学に保持していた一枚岩のグリップは効果的かつ永久に破られた」[77]。 |

| Works Allyn, J., & Festinger, L. (1961). Effectiveness of Unanticipated Persuasive Communications. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62(1), 35–40. Back, K., Festinger, L., Hymovitch, B., Kelley, H., Schachter, S., & Thibaut, J. (1950). The methodology of studying rumor transmission. Human Relations, 3(3), 307–312. Brehm, J., & Festinger, L. (1957). Pressures toward uniformity of performance in groups. Human Relations, 10(1), 85–91. Cartwright, D., & Festinger, L. (1943). A quantitative theory of decision. Psychological Review, 50, 595–621. Coren, S., & Festinger, L. (1967). Alternative view of the "Gibson normalization effect". Perception & Psychophysics, 2(12), 621–626. Festinger, L. (1942a). A theoretical interpretation of shifts in level of aspiration. Psychological Review, 49, 235–250. Festinger, L. (1942b). Wish, expectation, and group standards as factors influencing level of aspiration. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 37, 184–200. Festinger, L. (1943a). Development of differential appetite in the rat. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32(3), 226–234. Festinger, L. (1943b). An exact test of significance for means of samples drawn from populations with an exponential frequency distribution. Psychometrika, 8, 153–160. Festinger, L. (1943c). A statistical test for means of samples from skew populations. Psychometrika, 8, 205–210. Festinger, L. (1943d). Studies in decision: I. Decision-time, relative frequency of judgment and subjective confidence as related to physical stimulus difference. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32(4), 291–306. Festinger, L. (1943e). Studies in decision: II. An empirical test of a quantitative theory of decision. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32(5), 411–423. Festinger, L. (1946). The significance of difference between means without reference to the frequency distribution function. Psychometrika, 11(2), 97–105. Festinger, L. (1947a). The role of group belongingness in a voting situation. Human Relations, 1(2), 154–180. Festinger, L. (1947b). The treatment of qualitative data by scale analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 44(2), 149–161. Festinger, L. (1949). The analysis of sociograms using matrix algebra. Human Relations, 2(2), 153–158. Festinger, L. (1950). Informal social communication. Psychological Review, 57(5), 271–282. Festinger, L. (1950b). Psychological Statistics. Psychometrika, 15(2), 209–213. Festinger, L. (1951). Architecture and group membership. Journal of Social Issues, 7(1–2), 152–163. Festinger, L. (1952). Some consequences of de-individuation in a group. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 47(2), 382–389. Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140. Festinger, L. (1955a). Handbook of social psychology, vol 1, Theory and method, vol 2, Special fields and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 39(5), 384–385. Festinger, L. (1955b). Social psychology and group processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 6, 187–216. Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Festinger, L. (1959a). Sampling and related problems in research methodology. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 64(2), 358–369. Festinger, L. (1959b). Some attitudinal consequences of forced decisions. Acta Psychologica, 15, 389–390. Festinger, L. (1961). The psychological effects of insufficient rewards. American Psychologist, 16(1), 1–11. Festinger, L. (1962). Cognitive dissonance. Scientific American, 207(4), 93–107. Festinger, L. (1964). Behavioral support for opinion change. Public Opinion Quarterly, 28(3), 404–417. Festinger, L. (Ed.). (1980). Retrospections on Social Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Festinger, L. (1983). The Human Legacy. New York: Columbia University Press. Festinger, L. (1981). Human nature and human competence. Social Research, 48(2), 306–321. Festinger, L., & Canon, L. K. (1965). Information about spatial location based on knowledge about efference. Psychological Review, 72(5), 373–384. Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58(2), 203–210. Festinger, L., Cartwright, D., Barber, K., Fleischl, J., Gottsdanker, J., Keysen, A., & Leavitt, G. (1948). A study of rumor transition: Its origin and spread. Human Relations, 1(4), 464–486. Festinger, L., Gerard, H., Hymovitch, B., Kelley, H. H., & Raven, B. (1952). The influence process in the presence of extreme deviates. Human Relations, 5(4), 327–346. Festinger, L., & Holtzman, J. D. (1978). Retinal image smear as a source of information about magnitude of eye-movement. Journal of Experimental Psychology-Human Perception and Performance, 4(4), 573–585. Festinger, L., & Hutte, H. A. (1954). An experimental investigation of the effect of unstable interpersonal relations in a group. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 49(4), 513–522. Festinger, L., & Katz, D. (Eds.). (1953). Research methods in the behavioral sciences. New York, NY: Dryden. Festinger, L., & Maccoby, N. (1964). On resistance to persuasive communications. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 68(4), 359–366. Festinger, L., Riecken, H. W., & Schachter, S. (1956). When Prophecy Fails. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Festinger, L., Schachter, S., & Back, K. (1950). Social Pressures in Informal Groups: A Study of Human Factors in Housing. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Festinger, L., Sedgwick, H. A., & Holtzman, J. D. (1976). Visual-perception during smooth pursuit eye-movements. Vision Research, 16(12), 1377–1386. Festinger, L., & Thibaut, J. (1951). Interpersonal communication in small groups. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 46(1), 92–99. Festinger, L., Torrey, J., & Willerman, B. (1954). Self-evaluation as a function of attraction to the group. Human Relations, 7(2), 161–174. Hertzman, M., & Festinger, L. (1940). Shifts in explicit goals in a level of aspiration experiment. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 27(4), 439–452. Hochberg, J., & Festinger, L. (1979). Is there curvature adaptation not attributable to purely intravisual phenomena. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2(1), 71–71. Hoffman, P. J., Festinger, L., & Lawrence, D. H. (1954). Tendencies toward group comparability in competitive bargaining. Human Relations, 7(2), 141–159. Holtzman, J. D., Sedgwick, H. A., & Festinger, L. (1978). Interaction of perceptually monitored and unmonitored efferent commands for smooth pursuit eye movements. Vision Research, 18(11), 1545–1555. Komoda, M. K., Festinger, L., & Sherry, J. (1977). The accuracy of two-dimensional saccades in the absence of continuing retinal stimulation. Vision Research, 17(10), 1231–1232. Miller, J., & Festinger, L. (1977). Impact of oculomotor retraining on visual-perception of curvature. Journal of Experimental Psychology-Human Perception and Performance, 3(2), 187–200. Schachter, S., Festinger, L., Willerman, B., & Hyman, R. (1961). Emotional disruption and industrial productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 45(4), 201–213. |

作品 Allyn, J., & Festinger, L. (1961). 予期せぬ説得的コミュニケーションの効果。Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62(1), 35-40. Back, K., Festinger, L., Hymovitch, B., Kelley, H., Schachter, S., & Thibaut, J. (1950). 噂の伝達を研究する方法論。人間関係, 3(3), 307-312. Brehm, J., & Festinger, L. (1957). 集団におけるパフォーマンスの均一性への圧力。人間関係, 10(1), 85-91. Cartwright, D., & Festinger, L. (1943). 意思決定の量的理論。Psychological Review, 50, 595-621. Coren, S., & Festinger, L. (1967). ギブソン正規化効果」の代替見解。知覚と心理物理学, 2(12), 621-626. Festinger, L. (1942a). 願望水準のシフトの理論的解釈。Psychological Review, 49, 235-250. Festinger, L. (1942b). 願望水準に影響を及ぼす要因としての願望、期待、集団基準。異常心理学・社会心理学雑誌, 37, 184-200. Festinger, L. (1943a). ラットにおける食欲の差の発達。実験心理学雑誌, 32(3), 226-234. Festinger, L. (1943b). 指数度数分布を持つ集団から抽出された標本の平均の有意性の正確検定。Psychometrika, 8, 153-160. Festinger, L. (1943c). 歪んだ母集団からの標本の平均に対する統計的検定. Psychometrika, 8, 205-210. Festinger, L. (1943d). 意思決定に関する研究: 判断時間,判断の相対頻度および主観的確信と物理的刺激差との関係.実験心理学雑誌, 32(4), 291-306. フェスティンガー, L. (1943e). 意思決定に関する研究: 意思決定の研究:II. 意思決定の量的理論の実証的検証。実験心理学雑誌, 32(5), 411-423. Festinger, L. (1946). 度数分布関数によらない平均間の差の有意性。Psychometrika, 11(2), 97-105. Festinger, L. (1947a). 投票場面における集団帰属意識の役割。人間関係, 1(2), 154-180. Festinger, L. (1947b). 尺度分析による質的データの取り扱い。心理学紀要, 44(2), 149-161. Festinger, L. (1949). 行列代数を用いたソシオグラムの分析。人間関係, 2(2), 153-158. Festinger, L. (1950). インフォーマルな社会的コミュニケーション。心理学評論, 57(5), 271-282. Festinger, L. (1950b). 心理統計学。Psychometrika, 15(2), 209-213. Festinger, L. (1951). 建築とグループ・メンバーシップ。社会問題研究, 7(1-2), 152-163. Festinger, L. (1952). 集団における非分離のいくつかの結果。Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 47(2), 382-389. フェスティンガー L. (1954). 社会的比較過程の理論。人間関係, 7, 117-140. Festinger, L. (1955a). 社会心理学ハンドブック、第1巻、理論と方法、第2巻、特殊分野と応用。応用心理学雑誌, 39(5), 384-385. Festinger, L. (1955b). 社会心理学と集団過程。心理学年報, 6, 187-216. Festinger, L. (1957). 認知的不協和の理論. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Festinger, L. (1959a). 研究方法論におけるサンプリングと関連する問題。American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 64(2), 358-369. Festinger, L. (1959b). 強制された決定のいくつかの態度的帰結。Acta Psychologica, 15, 389-390. Festinger, L. (1961). 不十分な報酬の心理的効果。American Psychologist, 16(1), 1-11. フェスティンガー, L. (1962). 認知的不協和。Scientific American, 207(4), 93-107. フェスティンガー, L. (1964). 世論変化に対する行動的支持。Public Opinion Quarterly, 28(3), 404-417. フェスティンガー, L. (Ed.). (1980). 社会心理学の回顧. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局。 Festinger, L. (1983). 人間の遺産. ニューヨーク: コロンビア大学出版局。 Festinger, L. (1981). 人間の本性と人間の能力。Social Research, 48(2), 306-321. フェスティンガー, L. & キャノン, L. K. (1965). 効果に関する知識に基づく空間的位置に関する情報。心理学評論, 72(5), 373-384. フェスティンガー, L. & カールスミス, J. M. (1959). 強制遵守の認知的帰結。The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58(2), 203-210. フェスティンガー, L., カートライト, D., バーバー, K., フライシュル, J., ゴッツダンカー, J., キーセン, A., & リービット, G. (1948). 噂の変遷に関する研究: その起源と広がり。人間関係, 1(4), 464-486. フェスティンガー、L.、ジェラード、H.、ハイモビッチ、B.、ケリー、H.H.、レイヴン、B.(1952)。極端な逸脱者の存在下における影響過 程。人間関係, 5(4), 327-346. Festinger, L., & Holtzman, J. D. (1978). 眼球運動の大きさに関する情報源としての網膜像の汚れ。実験心理学-人間の知覚とパフォーマンス, 4(4), 573-585. フェスティンガー, L. & ヒュッテ, H. A. (1954). 集団における不安定な対人関係の影響に関する実験的研究。Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 49(4), 513-522. フェスティンガー, L. & カッツ, D. (Eds.). (1953). 行動科学における研究方法。ニューヨーク州ニューヨーク: ドライデン。 Festinger, L., & Maccoby, N. (1964). 説得的コミュニケーションに対する抵抗について。Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 68(4), 359-366. Festinger, L., Riecken, H. W., & Schachter, S. (1956). 予言が失敗するとき。ミネアポリス、ミネソタ: ミネソタ大学出版局。 Festinger, L., Schachter, S., & Back, K. (1950). 非公式集団における社会的圧力: A Study of Human Factors in Housing. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Festinger, L., Sedgwick, H. A., & Holtzman, J. D. (1976). 滑らかな追跡眼球運動中の視覚知覚。視覚研究, 16(12), 1377-1386. Festinger, L., & Thibaut, J. (1951). 小集団における対人コミュニケーション。Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 46(1), 92-99. Festinger, L., Torrey, J., & Willerman, B. (1954). 集団への魅力の関数としての自己評価。人間関係, 7(2), 161-174. Hertzman, M., & Festinger, L. (1940). 願望水準実験における明示的目標の変化。実験心理学雑誌, 27(4), 439-452. Hochberg, J., & Festinger, L. (1979). 純粋な視覚内現象に起因しない曲率順応は存在するか?行動と脳科学, 2(1), 71-71. Hoffman, P. J., Festinger, L., & Lawrence, D. H. (1954). 競争的交渉における集団比較可能性への傾向。人間関係, 7(2), 141-159. Holtzman, J. D., Sedgwick, H. A., & Festinger, L. (1978). 知覚的に監視された眼球運動と監視されていない眼球運動の相互作用。視覚研究, 18(11), 1545-1555. 菰田真一、フェスティンガー、L.、シェリー、J. (1977). 網膜刺激が継続しない場合の2次元サッケードの正確さ。視覚研究, 17(10), 1231-1232. Miller, J., & Festinger, L. (1977). 眼球運動再教育が視覚的曲率知覚に及ぼす影響。実験心理学-人間の知覚とパフォーマティビティ, 3(2), 187-200. Schachter, S., Festinger, L., Willerman, B., & Hyman, R. (1961). 感情の混乱と工業生産性。応用心理学雑誌, 45(4), 201-213. |

| Belief perseverance Cognitive dissonance Elliot Aronson Kurt Lewin Propinquity Social comparison theory Social psychology Stanley Schachter The Great Disappointment When Prophecy Fails |

信念の忍耐 認知的不協和 エリオット・アロンソン クルト・ルーイン プロパンシー 社会比較理論 社会心理学 スタンリー・シャクター 大いなる失望 予言が失敗するとき |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leon_Festinger |

▲▲▲▲

| Belief perseverance

(also known as conceptual conservatism[1]) is maintaining a belief

despite new information that firmly contradicts it.[2] Since rationality involves conceptual flexibility,[3][4] belief perseverance is consistent with the view that human beings act at times in an irrational manner. Philosopher F.C.S. Schiller holds that belief perseverance "deserves to rank among the fundamental 'laws' of nature".[5] If beliefs are strengthened after others attempt to present evidence debunking them, this is known as a backfire effect.[6] There are psychological mechanisms by which backfire effects could potentially occur, but the evidence on this topic is mixed, and backfire effects are very rare in practice.[7][8][9] A 2020 review of the scientific literature on backfire effects found that there have been widespread failures to replicate their existence, even under conditions that would be theoretically favorable to observing them.[8] Due to the lack of reproducibility, as of 2020 most researchers believe that backfire effects are either unlikely to occur on the broader population level, or they only occur in very specific circumstances, or they do not exist.[8] For most people, corrections and fact-checking are very unlikely to have a negative impact, and there is no specific group of people in which backfire effects have been consistently observed.[8] |

信念の持続(概念的保守主義[1]とも呼ばれる)とは、信念と矛盾する

新たな情報にもかかわらず、信念を維持することである[2]。 合理性には概念の柔軟性が含まれるため[3][4]、信念の持続は、人間は時に非合理的な行動をとるという見解と一致する。哲学者のF.C.S.シラー は、信念の持続性は「自然の基本的な『法則』の中に位置づけ られるに値する」と考えている[5]。 他人がそれを否定する証拠を提示しようとした後に信念が強 まる場合、これはバックファイア効果として知られている[6]。バックファイア 効果が起こりうる心理的メカニズムがあるが、このトピックに関す る証拠はまちまちであり、バックファイア効果は実際には非常に稀であ る[7][8][9]。バックファイア効果に関する科学文献を2020年にレビューし たところ、理論的にはバックファイア効果を観察するのに好都合な条件下 でさえ、その存在を再現することに広く失敗していることがわかった。 [8]再現性がないため、2020年現在、ほとんどの研究者は、バックファイア効果はより広い集団レベルでは起こりにくいか、非常に特殊な状況でのみ起こ るか、存在しないかのいずれかであると考えている[8]。ほとんどの人にとって、訂正や事実確認が悪影響を及ぼす可能性は非常に低く、バックファイア効果 が一貫して観察されている特定の集団は存在しない[8]。 |

| Evidence from experimental

psychology According to Lee Ross and Craig A. Anderson, "beliefs are remarkably resilient in the face of empirical challenges that seem logically devastating".[10] The first study of belief perseverance was carried out by Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter.[11] These psychiatrists spent time with members of a doomsday cult who believed the world would end on December 21, 1954.[11] Despite the failure of the forecast, most believers continued to adhere to their faith.[11][12][13] In When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group That Predicted the Destruction of the World (1956) and A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957), Festinger proposed that human beings strive for internal psychological consistency to function mentally in the real world.[11] A person who experiences internal inconsistency tends to become psychologically uncomfortable and is motivated to reduce the cognitive dissonance.[11][12][14] They tend to make changes to justify the stressful behavior, either by adding new parts to the cognition causing the psychological dissonance (rationalization) or by avoiding circumstances and contradictory information likely to increase the magnitude of the cognitive dissonance (confirmation bias).[11][12][14] When asked to reappraise probability estimates in light of new information, subjects displayed a marked tendency to give insufficient weight to the new evidence. They refused to acknowledge the inaccurate prediction as a reflection of the overall validity of their faith. In some cases, subjects reported having a stronger faith in their religion than before.[15] In a separate study, mathematically capable teenagers and adults were given seven arithmetical problems and asked to estimate approximate solutions using manual estimating. Then, using a calculator rigged to provide increasingly erroneous figures, they were asked for accurate answers (e.g., yielding 252 × 1.2 = 452.4, when it is actually 302.4). About half of the participants went through all seven tasks while commenting on their estimating abilities or tactics, never letting go of the belief that calculators are infallible. They simply refused to admit that their previous assumptions about calculators could have been incorrect.[16] Lee Ross and Craig A. Anderson led some subjects to the false belief that there existed a positive correlation between a firefighter's stated preference for taking risks and their occupational performance. Other subjects were told that the correlation was negative. The participants were then thoroughly debriefed and informed that there was no link between risk taking and performance. These authors found that post-debriefing interviews pointed to significant levels of belief perseverance.[17] In another study, subjects spent about four hours following instructions of a hands-on instructional manual. At a certain point, the manual introduced a formula which led them to believe that spheres were 50 percent larger than they are. Subjects were then given an actual sphere and asked to determine its volume; first by using the formula, and then by filling the sphere with water, transferring the water to a box, and directly measuring the volume of the water in the box. In the last experiment in this series, all 19 subjects held a Ph.D. degree in a natural science, were employed as researchers or professors at two major universities, and carried out the comparison between the two volume measurements a second time with a larger sphere. All but one of these scientists clung to the spurious formula despite their empirical observations.[18] Even when we deal with ideologically neutral conceptions of reality, when these conceptions have been recently acquired, when they came to us from unfamiliar sources, when they were assimilated for spurious reasons, when their abandonment entails little tangible risks or costs, and when they are sharply contradicted by subsequent events, we are, at least for a time, disinclined to doubt such conceptions on the verbal level and unlikely to let go of them in practice. –Moti Nissani[1] |

実験心理学からの証拠 リー・ロスとクレイグ・A・アンダーソンによると、「信念は、論理的に壊滅 的と思われるような経験的挑戦に直面しても、驚くほど回復力がある」 [10]。 この精神科医たちは、1954年12月21日に世界が終わると信じていた終末教団のメンバーとともに過ごした[11]。予言が外れたにもかかわらず、ほと んどの信者は信仰を守り続けた[11][12][13]: フェスティンガーは『予言が失敗するとき:世界の滅亡を予言した現代集団の社会的・心理学的研究』(1956年)と『認知的不協和の理論』(1957年) において、人間は現実世界で精神的に機能するために心理学的な内的整合性を取ろうと努力すると提唱している[11]。 [11][12][14]心理的不協和を引き起こしている認知に新たな部分を追加する(合理化)か、認知的不協和の大きさを増大させる可能性が高い状況や 矛盾する情報を回避する(確証バイアス)ことによって、ストレスの多い行動を正当化するために変更を加える傾向がある[11][12][14]。 新しい情報に照らして確率の推定を再評価するよう求められたとき、被験者は新しい証拠に十分な重みを与えない顕著な傾向を示した。彼らは、不正確な予測を 自分の信仰の全体的な妥当性の反映と認めることを拒否した。場合によっては、被験者は自分の宗教に対する信仰が以前よりも強くなったと報告した[15]。 別の研究では、数学的能力のあるティーンエイジャーと成人に7つの算術問題を与え、手作業による推定を使って近似解を推定するよう求めた。次に、だんだん 誤った数字を出すように仕組まれた電卓を使って、正確な答えを求めた(例えば、実際には302.4であるのに、252×1.2=452.4と出すなど)。 参加者の約半数は、自分の見積もり能力や戦術についてコメントしながら、7つのタスクのすべてをこなした。彼らは、電卓に関する以前の仮定が誤っていた可 能性があることを単純に認めようとしなかった[16]。 リー・ロスとクレイグ・A・アンダーソンは、何人かの被験者に、消防士が危険を冒すことを好むと述べたことと、彼らの職業上のパフォーマンスとの間に正の 相関関係が存在するという誤った信念を抱かせた。他の被験者には、相関関係は否定的であると告げられた。その後、被験者に徹底的なデブリーフィングを行 い、リスクテイクとパフォーマンスには関連性がないことを伝えた。これらの著者らは、デブリーフィング後の面接で、有意なレベルの信念の忍耐が指摘された ことを発見した[17]。 別の研究では、被験者は実地指導マニュアルの指示に従って約4時間を過ごした。ある時点で、マニュアルは被験者に球体は実際より50%大きいと信じさせる 公式を紹介した。まず公式を使い、次に球体に水を入れて箱に移し、箱の中の水の体積を直接測定した。このシリーズの最後の実験では、19人全員が自然科学 の博士号を持ち、2つの主要大学の研究者または教授として働いており、2つの体積測定の比較を、より大きな球体で2回目に行った。これらの科学者のうち1 人を除いて全員が、経験的観察にもかかわらず偽の公式を信奉した[18]。 イデオロギー的に中立的な現実の概念を扱っているときでも、その概念が最近獲得されたものであったり、なじみのない情報源からもたらされたものであった り、偽りの理由で同化されたものであったり、その概念の放棄がほとんど具体的なリスクやコストを伴わないものであったり、その後の出来事によって大きく矛 盾するものであったりするとき、私たちは少なくともしばらくの間、そのような概念を言葉のレベルでは疑う気になれず、実践の場では手放すことはないだろ う。 -モティ・ニッサーニ[1]。 |

| Backfire effects If beliefs are strengthened after others attempt to present evidence debunking them, this is known as a backfire effect (compare boomerang effect).[6] For example, this would apply if providing information on the safety of vaccinations resulted in increased vaccination hesitancy.[19][20] Types of backfire effects include: Familiarity Backfire Effect (from making myths more familiar), Overkill Backfire Effect (from providing too many arguments), and Worldview Backfire Effect (from providing evidence that threatens someone's worldview).[8] There are a number of techniques to debunk misinformation, such as emphasizing the core facts and not the myth, or providing explicit warnings that the upcoming information is false, and providing alternative explanations to fill the gaps left by debunking the misinformation.[21] However, more recent studies provided evidence that the backfire effects are not as likely as once thought.[22] There are psychological mechanisms by which backfire effects could potentially occur, but the evidence on this topic is mixed, and backfire effects are very rare in practice.[7][8][9] A 2020 review of the scientific literature on backfire effects found that there have been widespread failures to replicate their existence, even under conditions that would be theoretically favorable to observing them.[8] Due to the lack of reproducibility, as of 2020 most researchers believe that backfire effects are either unlikely to occur on the broader population level, or they only occur in very specific circumstances, or they do not exist.[8] Brendan Nyhan, one of the researchers who initially proposed the occurrence of backfire effects, wrote in 2021 that the persistence of misinformation is most likely due to other factors.[9] For most people, corrections and fact-checking are very unlikely to have a negative impact, and there is no specific group of people in which backfire effects have been consistently observed.[8] Presenting people with factual corrections has been demonstrated to have a positive effect in many circumstances.[8][23][24] For example, this has been studied in the case of informing believers in 9/11 conspiracy theories about statements by actual experts and witnesses.[23] One possibility is that criticism is most likely to backfire if it challenges someone's worldview or identity. This suggests that an effective approach may be to provide criticism while avoiding such challenges.[24] In many cases, when backfire effects have been discussed by the media or by bloggers, they have been over-generalized from studies on specific subgroups to incorrectly conclude that backfire effects apply to the entire population and to all attempts at correction.[8][9] |

バックファイア効果 例えば、予防接種の安全性に関する情報を提供した結果、 予防接種をためらう人が増えた場合などがこれに該当する[19][20]: 親近感による逆効果(神話をより身近なものにすることによる)、過剰な逆効果(論拠を提供しすぎることによる)、世界観による逆効果(誰かの世界観を脅か す証拠を提供することによる)などがある。 [神話ではなく核となる事実を強調したり、今度の情報は誤りであるという明確な警告を提供したり、誤った情報を否定することによって残されたギャップを埋 めるために代替説明を提供したりするなど、誤った情報を否定するためのテクニックは数多くある[21]。しかし、最近の研究では、バックファイア効果はか つて考えられていたほど可能性が高くないという証拠が示されている[22]。 バックファイア効果が起こりうる心理学的メカニズムはあるが、このトピックに関する証拠はまちまちであり、バックファイア効果は実際には非常にまれである [7][8][9]。2020年のバックファイア効果に関する科学文献のレビューでは、理論的にはバックファイア効果を観察するのに有利な条件下であって も、バックファイア効果の存在を再現することに広く失敗していることがわかった。 [8]再現性の欠如のため、2020年現在、ほとんどの研究者は、バックファイア効果はより広範な集団レベルでは起こりにくいか、非常に特殊な状況でのみ 起こるか、存在しないかのいずれかであると考えている[8]。 ほとんどの人々にとって、訂正やファクトチェックがマイナ スの影響を与える可能性は非常に低く、バックファイア効果が一貫 して観察されている特定の集団は存在しない[8]。このことは、そのような挑戦を避けながら批判を提供することが効果的なアプローチである可能性を示唆し ている[24]。 多くの場合、メディアやブロガーによって逆効果が議論されるとき、特定のサブグループに関する研究から過剰に一般化され、逆効果が母集団全体や訂正の試み すべてに適用されると誤って結論付けられている[8][9]。 |

| In cultural innovations Physicist Max Planck wrote that "the new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it".[25] For example, the heliocentric theory of the great Greek astronomer, Aristarchus of Samos, had to be rediscovered about 1,800 years later, and even then undergo a major struggle before astronomers took its veracity for granted.[26] Belief persistence is frequently accompanied by intrapersonal cognitive processes. "When the decisive facts did at length obtrude themselves upon my notice," wrote the chemist Joseph Priestley, "it was very slowly, and with great hesitation, that I yielded to the evidence of my senses."[27] In education Students often "cling to ideas that form part of their world view even when confronted by information that does not coincide with this view."[28] For example, students may spend months studying the solar system and do well on related tests, but still believe that moon phases are produced by Earth's shadow. What they learned was not able to intrude on the beliefs they held prior to that knowledge.[29] Causes The causes of belief perseverance remain unclear. Experiments in the 2010s suggest that neurochemical processes in the brain underlie the strong attentional bias of reward learning. Similar processes could underlie belief perseverance.[30] Peter Marris suggests that the process of abandoning a conviction is similar to the working out of grief. "The impulse to defend the predictability of life is a fundamental and universal principle of human psychology." Human beings possess "a deep-rooted and insistent need for continuity".[31] Philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn points to the resemblance between conceptual change and Gestalt perceptual shifts (e.g., the difficulty encountered in seeing the hag as a young lady). Hence, the difficulty of switching from one conviction to another could be traced to the difficulty of rearranging one's perceptual or cognitive field.[32] |

文化的革新の中で 物理学者マックス・プランクは、「新しい科学的真理は、反対者を説得し、彼らに光を見出させることによって勝利するのではなく、むしろ反対者がやがて死 に、それをよく知る新しい世代が育つからである」と書いている[25]。例えば、ギリシャの偉大な天文学者であるサモスのアリスタルコスの天動説は、約 1800年後に再発見されなければならず、天文学者がその真実性を当然と考えるようになるまでには、大きな闘争を経なければならなかった[26]。 信念の持続には、しばしば個人内認知プロセスが伴う。「化学者ジョセフ・プリーストリーは、「決定的な事実が、ついに私の目に飛び込んできたとき、私は非 常にゆっくりと、そして非常にためらいながら、自分の感覚の証拠に屈服した」と書いている[27]。 教育において 生徒たちはしばしば、「自分の世界観の一部となっている考え方に固執し、その世界観と一致しない情報に直面しても、その考え方に固執する」[28]。例え ば、生徒たちは太陽系について何ヶ月もかけて勉強し、関連するテストでは好成績を収めても、月の満ち欠けは地球の影によって生じると信じていることがあ る。彼らが学んだことは、その知識を得る前に抱いていた信念を侵すことはできなかったのである[29]。 原因 信念の持続の原因は、依然として不明である。2010年代の実験によると、脳内の神経化学的プロセスが、報酬学習 の強い注意バイアスの根底にあることが示唆されている。同様の過程が信念の持続の根底にあ る可能性がある[30]。 ピーター・マリスは、信念を放棄する過程は悲しみの解消に似てい ると示唆している。「人生の予測可能性を守ろうとする衝動は、人間心理の基本的 かつ普遍的な原理である。人間は「継続性に対する根深く執拗な欲求」を持っている[31]。 科学哲学者のトーマス・クーンは、概念的な変化とゲシュタルト的な知覚の変化(例えば、ババアを若い女性として見ることの難しさ)との類似性を指摘してい る。したがって、ある確信から別の確信に切り替えることの難しさは、自分の知覚や認識の場を再配置することの難しさにまで遡ることができる[32]。 |

| Asch conformity experiments –

Study of if and how individuals yielded to or defied a majority group Cognitive dissonance – Stress from contradiction between beliefs and actions Cognitive inertia – Lack of motivation to mentally tackle a problem or issue Confirmation bias – Bias confirming existing attitudes Conservatism (belief revision) – Cognitive bias Denialism – Person's choice to deny psychologically uncomfortable truth Idée fixe – Personal fixation Paradigm shift – Fundamental change in ideas and practices within a scientific discipline Stanley Milgram – American social psychologist Semmelweis reflex – Cognitive bias Status quo bias – Cognitive bias True-believer syndrome – Continued belief in a debunked theory Anussava - Do not go upon what has been acquired by repeated hearing. |

アッシュの適合性実験 -

個人が多数派集団に屈服するか、反抗するかを研究する。 認知的不協和 - 信念と行動の矛盾からくるストレス 認知的惰性 - 問題や課題に精神的に取り組む意欲の欠如。 確証バイアス - 既存の態度を確認するバイアス 保守主義(信念の修正) - 認知バイアス 否定主義 - 心理的に不快な真実を否定することを選択する。 固定観念 - 個人的な固定観念 パラダイムシフト - 科学分野内の考え方や実践の根本的な変化 スタンレー・ミルグラム - アメリカの社会心理学者 ゼンメルワイス反射 - 認知バイアス 現状維持バイアス - 認知バイアス トゥルービリーバー症候群 - 論破された理論を信じ続ける。 アヌサヴァ - 繰り返し聞くことで身についたことをそのまま信じてはならない。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belief_perseverance |

++++++++++++++++

リンク

After performing

dissonant behavior (lying) a person might find external, consonant

elements. Therefore, a snake oil

salesman might find a psychological self-justification (great profit)

for promoting medical falsehoods, but, otherwise, might need to change

his beliefs about the falsehoods.

不協和な行動(嘘をつくこと)をした後、人は外的な、協和的な要素を見つけるかもしれない。したがって、偽薬のセールスマンは、医学的な虚偽を宣伝することに心理的な自己正当化(大きな利益)を見出

すかもしれないが、そうでなければ、虚偽についての信念を変える必要(→それでも満足してこの薬の効用を本当に信じる人がいたり、本当に「治る」可能だっ

てゼロじゃない、と正当化する)があるかもしれない。

●Visualization of Cognitive dissonance

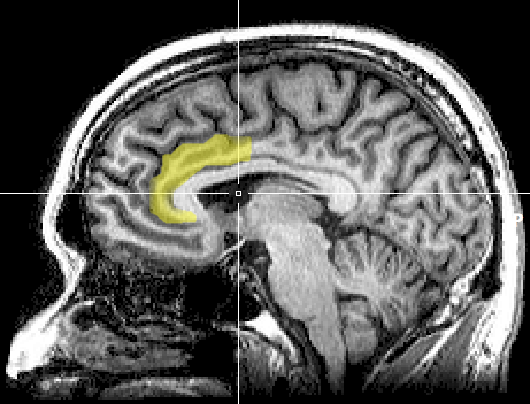

| The study Neural

Activity Predicts Attitude Change in Cognitive Dissonance[108] (Van

Veen, Krug, etc., 2009) identified the neural bases of cognitive

dissonance with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI); the

neural scans of the participants replicated the basic findings of the

induced-compliance paradigm. When in the fMRI scanner, some of the

study participants argued that the uncomfortable, mechanical

environment of the MRI machine nevertheless was a pleasant experience

for them; some participants, from an experimental group, said they

enjoyed the mechanical environment of the fMRI scanner more than did

the control-group participants (paid actors) who argued about the

uncomfortable experimental environment.[108] The results of the neural scan experiment support the original theory of Cognitive Dissonance proposed by Festinger in 1957; and also support the psychological conflict theory, whereby the anterior cingulate functions, in counter-attitudinal response, to activate the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insular cortex; the degree of activation of said regions of the brain is predicted by the degree of change in the psychological attitude of the person.[108] As an application of the free-choice paradigm, the study How Choice Reveals and Shapes Expected Hedonic Outcome (2009) indicates that after making a choice, neural activity in the striatum changes to reflect the person's new evaluation of the choice-object; neural activity increased if the object was chosen, neural activity decreased if the object was rejected.[109] Moreover, studies such as The Neural Basis of Rationalization: Cognitive Dissonance Reduction During Decision-making (2010)[35] and How Choice Modifies Preference: Neural Correlates of Choice Justification (2011) confirm the neural bases of the psychology of cognitive dissonance.[96][110] The Neural Basis of Rationalization: Cognitive Dissonance Reduction During Decision-making[35] (Jarcho, Berkman, Lieberman, 2010) applied the free-choice paradigm to fMRI examination of the brain's decision-making process whilst the study participant actively tried to reduce cognitive dissonance. The results indicated that the active reduction of psychological dissonance increased neural activity in the right-inferior frontal gyrus, in the medial fronto-parietal region, and in the ventral striatum, and that neural activity decreased in the anterior insula.[35] That the neural activities of rationalization occur in seconds, without conscious deliberation on the part of the person; and that the brain engages in emotional responses whilst effecting decisions.[35] |

Neural Activity Predicts

Attitude Change in Cognitive Dissonance[108] (Van Veen, Krug, etc.,

2009)という研究では、機能的磁気共鳴画像法(fMRI)を用いて認知的不協和の神経基盤を同定した。fMRIスキャナーにいるとき、研究参加者の一

部は、MRI装置の不快で機械的な環境は、それにもかかわらず、自分にとって心地よい経験であると主張した。実験グループの参加者の中には、不快な実験環

境について主張した対照グループの参加者(有料の俳優)よりも、fMRIスキャナーの機械的な環境をより楽しんでいると答えた者もいた[108]。 神経スキャン実験の結果は、1957年にフェスティンガーによって提唱された認知的不協和の原理論を支持しており、また心理的葛藤理論も支持している。前 帯状皮質は、態度反応に対抗して、背側前帯状皮質と前部島皮質を活性化するように機能し、脳の当該領域の活性化の程度は、人の心理的態度の変化の程度に よって予測される[108]。 自由選択のパラダイムの応用として、How Choice Reveals and Shapes Expected Hedonic Outcome(2009年)という研究では、選択を行った後、線条体の神経活動が変化し、選択対象に対する人の新しい評価を反映することが示されてい る: 意思決定過程における認知的不協和の低減(2010年)[35]や「選択はどのように選好を変容させるか(How Choice Modifies Preference)」などの研究がある: Neural Correlates of Choice Justification (2011)は認知的不協和の心理学の神経基盤を確認している[96][110]。 合理化の神経基盤: Cognitive Dissonance Reduction During Decision-making[35] (Jarcho, Berkman, Lieberman, 2010)は、研究参加者が認知的不協和を積極的に減少させようとする間、脳の意思決定プロセスのfMRI検査に自由選択パラダイムを適用した。その結 果、心理的不協和を能動的に減少させることで、右下前頭回、内側前頭-頭頂領域、腹側線条体の神経活動が増加し、前部島皮質では神経活動が減少することが 示された[35]。合理化の神経活動は、人が意識的に熟考することなく、数秒で起こること、脳は意思決定を行いながら感情的反応を行うことが示された [35]。 |

The biomechanics of cognitive dissonance: MRI evidence indicates that the greater the psychological conflict signalled by the anterior cingulate cortex, the greater the magnitude of the cognitive dissonance experienced by the person. |

認知的不協和のバイオメカニクス:

MRIの証拠は、前帯状皮質によって示される心理的葛藤が大きければ大きいほど、その人が経験する認知的不協和の大きさが大きくなることを示している。 |

| Visualization of Cognitive dissonance |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099