色のない緑色の考えは猛烈に眠る

Colorless green ideas sleep furiously

☆ ノーム・チョムスキーは、1957年の著書『Syntactic Structures』の中で、文法上は正しいが意味のない文の例として、「無色透明な緑色の考えは猛烈に眠る」という文章を書いた。この文章は、 1955年の論文『言語理論の論理構造』と1956年の論文「言語の記述のための3つのモデル」で初めて使用された。[1]:116 この文章からは明白な理解可能な意味を導き出すことはできず、これは構文と意味の区別を示しており、構文的に正しい文章が意味的にも正しいとは限らないと いう考え方を示している。カテゴリーミスの例として、ある種の確率論的モデルの不十分さと、より構造化されたモデルの必要性を示すことが意図されていた。

| Colorless green ideas sleep furiously

was composed by Noam Chomsky in his 1957 book Syntactic Structures as

an example of a sentence that is grammatically well-formed, but

semantically nonsensical. The sentence was originally used in his 1955

thesis The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory and in his 1956 paper

"Three Models for the Description of Language".[1]: 116 There is no

obvious understandable meaning that can be derived from it, which

demonstrates the distinction between syntax and semantics, and the idea

that a syntactically well-formed sentence is not guaranteed to also be

semantically well-formed. As an example of a category mistake, it was

intended to show the inadequacy of certain probabilistic models of

grammar, and the need for more structured models. |

ノー ム・チョムスキーは、1957年の著書『Syntactic Structures』の中で、文法上は正しいが意味のない文の例として、「無色透明な緑色の考えは猛烈に眠る」という文章を書いた。この文章は、 1955年の論文『言語理論の論理構造』と1956年の論文「言語の記述のための3つのモデル」で初めて使用された。[1]:116 この文章からは明白な理解可能な意味を導き出すことはできず、これは構文と意味の区別を示しており、構文的に正しい文章が意味的にも正しいとは限らないと いう考え方を示している。カテゴリー・ミステイクの例として、ある種の確率論的モデルの不十分さと、より構造化されたモデルの必要性を示すことが意図されていた。 |

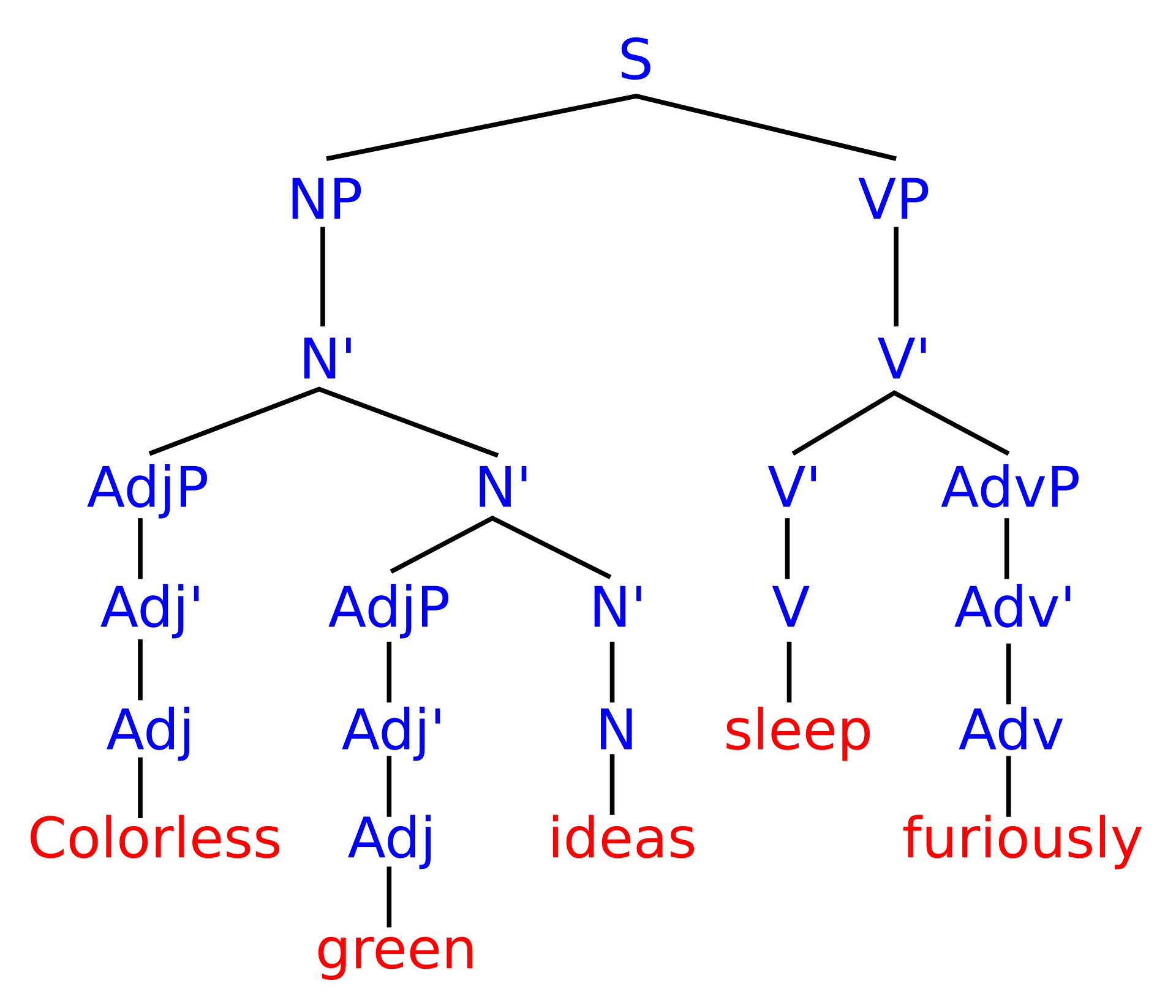

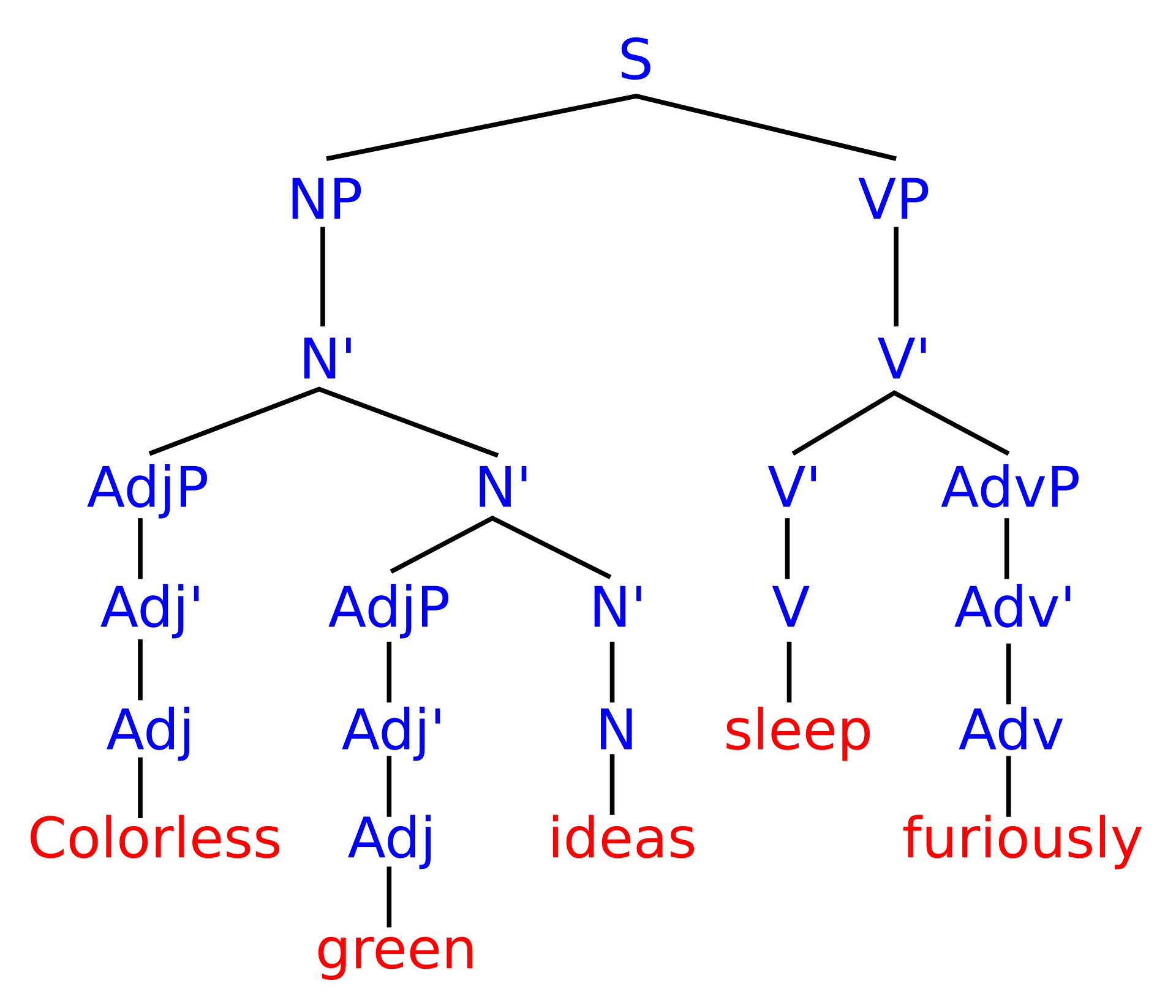

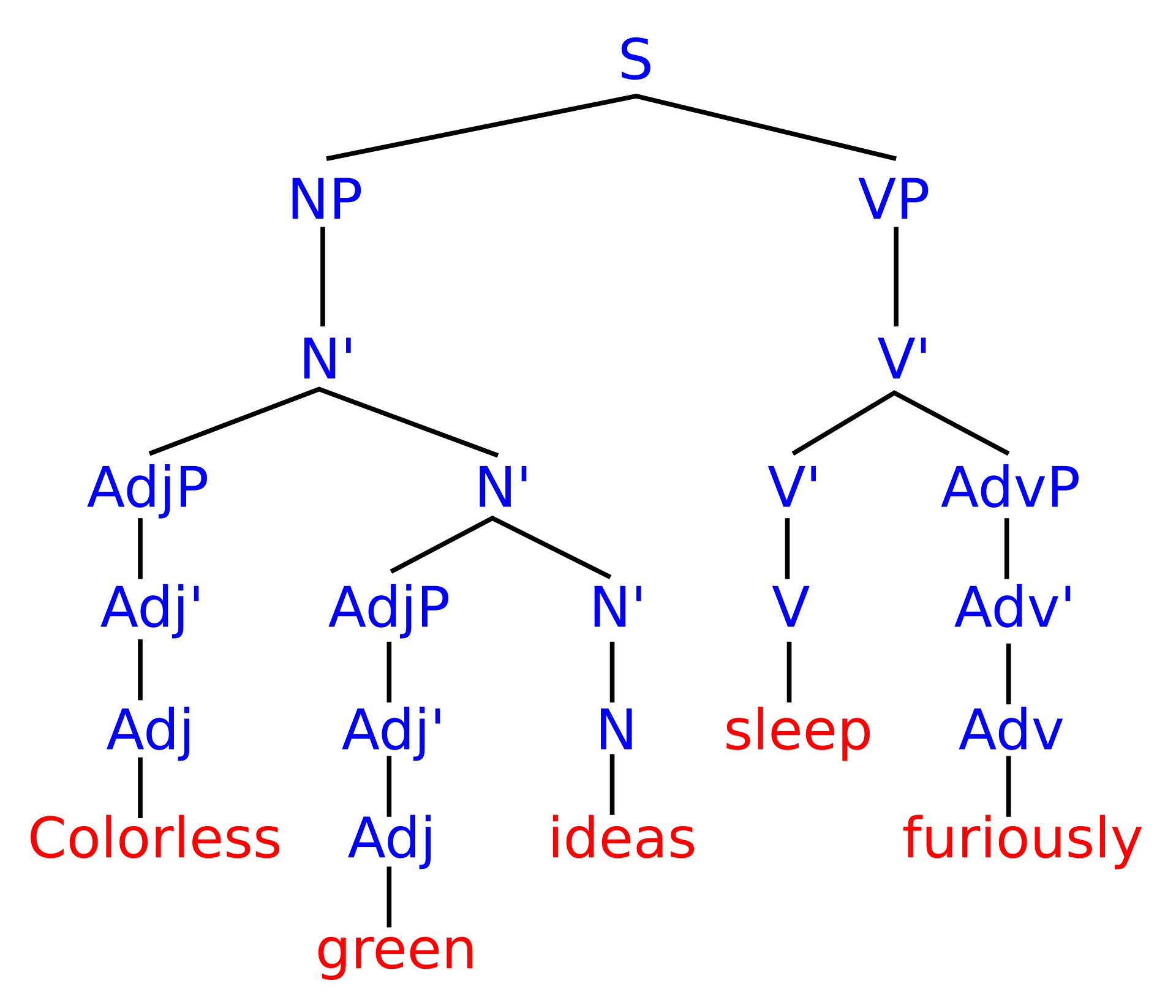

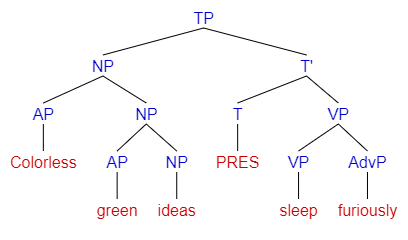

Approximate X-bar representation of Colorless green ideas sleep furiously. See phrase structure rules. |

Colorless green ideas sleep furiously. のX-bar表記の概略。phrasestructure rules. |

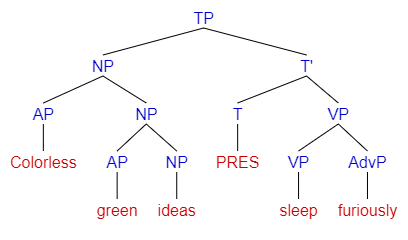

| Senseless but grammatical Chomsky wrote in his 1957 book Syntactic Structures: Colorless green ideas sleep furiously. *Furiously sleep ideas green colorless.[a] It is fair to assume that neither sentence (1) nor (2) had ever previously occurred in an English discourse. Hence, in any statistical model that accounts for grammaticality, these sentences will be ruled out on identical grounds as equally "remote" from English. Yet (1), though nonsensical, is grammatical, while (2) is not grammatical.[2][1]  Approximate representation of Colorless green ideas sleep furiously Approximate representation of "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously". See Minimalist Program. Colorless green ideas – which functions as the subject of the sentence – is an anomalous string for at least two reasons: The adjective colorless can be understood as dull, uninteresting, or lacking in color, and so when it combines with the adjective green, this is nonsensical: an object cannot simultaneously lack color and have the color of green. In the phrase colorless green ideas the abstract noun idea is described as being colorless and green. However, due to its abstract nature, an idea cannot have or lack color. Sleep furiously – which functions as the predicate of the sentence – is structurally well-formed; in other words, it is grammatical. However, the meaning that it expresses is peculiar, as the activity of sleeping is not generally taken to be something that can be done in a furious fashion. Nevertheless, sleep furiously is both grammatical and interpretable, though its interpretation is unusual. Combining Colorless green ideas with sleep furiously creates a sentence that some believe to be nonsensical. On the one hand, an abstract noun like idea is taken to not have the ability to engage in an activity like sleeping. On the other hand, some think it possible for an idea to sleep.[3][4] Linguists account for the unusual nature of this sentence by distinguishing two types of selection: semantic selection (s-selection) and categorical selection (c-selection). Relative to s-selection, the sentence is semantically anomalous – senseless – for three reasons: The s-selection of the adjective colorless is violated because it can only describe objects that lack color. The s-selection of the adverb furiously is violated because it can only describe activity that is compatible with angry action, and such meanings are generally incompatible with the activity of sleeping. The s-selection of the verb sleep is violated because it can occur only with subjects that can engage in sleep. However, relative to c-selection, the sentence is structurally well-formed: The c-selection of the adverb furiously is satisfied, as it combines with the verb sleep, satisfying the requirement that an adverb modifies a verb. The c-selection of the adjectives colorless and green are satisfied as they combine with noun idea, satisfying the requirement that an adjective modifies a noun. The c-selection of the intransitive verb sleep is satisfied as it combines with the subject colorless green ideas, satisfying the requirement that an intransitive verb combines with a subject. This leads to the conclusion that although meaningless, the structural integrity of this sentence is high. |

無意味だが文法的 チョムスキーは1957年の著書『Syntactic Structures』で次のように書いた。 Colorless green ideas sleep furiously. *Furiously sleep ideas green colorless.[a] 文(1)も(2)も、英語の文章ではこれまで一度も使われたことがないと考えてよい。したがって、文法性を説明する統計モデルでは、これらの文は同じ理由 で英語から「かけ離れている」として除外される。しかし、(1)は無意味ではあるが文法的であり、(2)は文法的ではない。[2][1]  「無色で緑色の考えは猛烈に眠る」の近似表現 「無色で緑色の考えは猛烈に眠る」の近似表現。ミニマリスト・プログラムを参照。 「無色で緑色の考え」は、少なくとも2つの理由から、文の主語として機能する異常な語列である。 形容詞の「colorless」は「退屈な、面白くない、色のない」と解釈できるため、形容詞の「green」と組み合わせると、これは無意味になる。つまり、物体は同時に色がなく、かつ緑色であることはありえない。 「colorless green ideas」というフレーズでは、抽象名詞の「idea」が「色のない」かつ「緑色」であると表現されている。しかし、その抽象性により、「idea」は色を持つことも、色を持たないこともありえない。 文の述語として機能する「猛烈に眠る」は、構造的には正しく、つまり文法的である。しかし、眠るという行為は一般的に猛烈に行うことができるものとは考えられていないため、この表現が示す意味は独特である。しかし、「猛烈に眠る」は文法的であり、解釈も可能である。 無色緑色のアイデアと猛烈に眠るを組み合わせると、意味不明の文章になる。一方、アイデアのような抽象名詞は、眠るような活動を行う能力を持たないとみなされる。他方、アイデアが眠る可能性を認める考え方もある。 言語学者は、この文の特異性を説明するために、2つのタイプの選択、すなわち意味的選択(s-選択)と範疇的選択(c-選択)を区別している。この文は、以下の3つの理由により、s-選択との関連において、意味的に異常である、つまり無意味である。 形容詞の「colorless」のS選択は、色のない物体のみを描写できるため、違反している。 副詞の「furiously」のS選択は、怒りの感情にふさわしい行動のみを描写できるため、違反している。また、そのような意味は一般的に、眠るという行動とは相容れない。 動詞 sleep の s-選択は、睡眠をとることができる主語としか組み合わせることができないため、違反している。 しかし、c-選択と比較すると、この文は構造的には正しく形成されている。 副詞 furiously の c-選択は、動詞 sleep と組み合わせることで、副詞が動詞を修飾するという要件を満たしている。 形容詞のcolorlessとgreenのc-selectionは、名詞ideaと結合し、形容詞が名詞を修飾するという要件を満たしているため、満たされている。 自動詞sleepのc-selectionは、主語colorless green ideasと結合し、自動詞が主語と結合するという要件を満たしているため、満たされている。 この結論から、この文は意味をなさないが、構造的には完全であるということがわかる。 |

| Attempts at meaningful interpretations Polysemy The mechanism of polysemy – where a word has multiple meanings – can be used to create an interpretation for an otherwise non-sensical sentence. For example, the adjectives green and colorless both have figurative meanings. Green has a wide range of figurative meanings, including "immature", "pertaining to environmental consciousness", "newly formed", and "naive". And colorless can be interpreted as "nondescript". Likewise the verb sleep can have the figurative meaning of "being in dormant state", and the adverb furiously can have the figurative meaning "to do an action violently or quickly". figurative meanings of colorless: nondescript, unseen, drab figurative meanings of green: immature, pertaining to environmental consciousness, newly formed, naive, jealous figurative meanings of sleep: be in a dormant state figurative meanings of furiously: to do an action quickly, vigorously, intensely, energetically or violently When these figurative meanings are taken into account the sentence Colorless green ideas sleep furiously can have legitimate meaning, with less oblique semantics, and so is compatible with the following interpretations: Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.= "Nondescript immature ideas have violent nightmares." Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.= "Naive ideas which have not yet attained their full scope can cause a mind to race even while it attempts to rest" Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.= "Suppressed envious ideas lie dormant, though the negative feelings intensify" |

意味のある解釈の試み 多義性 単語が複数の意味を持つ多義性のメカニズムは、そうでなければ意味のない文章に解釈を与えるために利用することができる。例えば、形容詞の「緑」と「無 色」はどちらも比喩的な意味を持つ。「緑」には「未熟」、「環境意識に関する」、「新しく形成された」、「素朴」など、幅広い比喩的な意味がある。また、 無色は「特徴のない」という意味にも解釈できる。同様に、動詞の「眠る」には「休眠状態にある」という比喩的な意味があり、副詞の「猛烈に」には「激し く、または素早く行動する」という比喩的な意味がある。 無色:特徴のない、目立たない、地味な 緑の比喩的な意味:未熟、環境意識に関する、新たに形成された、ナイーブ、嫉妬深い 眠りの比喩的な意味:休眠状態にある 猛烈に:素早く、精力的に、激しく、エネルギッシュに、または激しく行動する これらの比喩的な意味を考慮すると、文「無色透明な緑のアイデアが猛烈に眠る」は、斜めの意味論が少なく、正当な意味を持つ可能性があり、以下の解釈と一致する。 「無色透明の青い考えは猛烈に眠る」=「特徴のない未熟な考えは激しい悪夢を見る」 「無色透明の青い考えは猛烈に眠る」=「まだ完全な形になっていない素朴な考えは、休息しようとしても心が落ち着かなくなる」 「無色透明の青い考えは猛烈に眠る」=「抑圧された羨望の念は眠ったままになっているが、否定的な感情は強まっている」 |

| In popular culture Chomsky's "colorless green" inspired written works, which all try to create meaning from the semantically meaningless utterance through added context. In 1958, linguist and anthropologist Dell Hymes presented his work to show that nonsense words can develop into something meaningful when in the right sequence.[5][6] Hued ideas mock the brain, Notions of color not yet color, Of pure, touchless, branching pallor Of invading, essential Green — Dell Hymes, 1958 Russian-American linguist and literary theorist Roman Jakobson (1959)[7] interpreted "colorless green" as a pale green, and "sleep furiously" as the wildness of "a state-like sleep, as that of inertness, torpidity, numbness." Jakobson gave the example that if "[someone's] hatred never slept, why then, cannot someone's ideas fall into sleep?" John Hollander, an American poet and literary critic, argued that the sentence operates in a vacuum as it is without context. He went on to write a poem based on that idea, entitled Coiled Alizarine that was included in his book, The Night Mirror (1971).[8] Curiously deep, the slumber of crimson thoughts: While breathless, in stodgy viridian Colorless green ideas sleep furiously. — John Hollander, 1971 Years later, Hollander contacted Chomsky about whether the color choice of 'green' was intentional; however, Chomsky denied any intentions or influences, especially the hypothesized influence from Andrew Marvell's lines from "The Garden" (1681). "Annihilating all that's made / To a green thought in a green shade" One of the first writers to have attempted to provide the sentence meaning through context is Chinese linguist Yuen Ren Chao (1997).[9] Chao's poem, entitled Making Sense Out of Nonsense: The Story of My Friend Whose "Colorless Green Ideas Sleep Furiously" (after Noam Chomsky) was published in 1971. This poem attempts to explain what "colorless green ideas" are and how they are able to "sleep furiously". Chao interprets "colorless" as plain, "green" as unripened, and "sleep furiously" as putting the ideas to rest; sleeping on them overnight whilst having internal conflict with these ideas.[10] I have a friend who is always full of ideas, good ideas and bad ideas, fine ideas and crude ideas, old ideas and new ideas. Before putting his new ideas into practice, he usually sleeps over them to let them mature and ripen. However, when he is in a hurry, he sometimes puts his ideas into practice before they are quite ripe, in other words, while they are still green. Some of his green ideas are quite lively and colorful, but not always, some being quite plain and colorless. When he remembers that some of his colorless ideas are still too green to use, he will sleep over them, or let them sleep, as he puts it. But some of those ideas may be mutually conflicting and contradictory and when they sleep together in the same night they get into furious fights and turn the sleep into a nightmare. Thus my friend often complains that his colorless green ideas sleep furiously. British linguist Angus McIntosh was unable to accept that Chomsky's utterance was entirely meaningless because to him, "colorless green ideas may well sleep furiously". As if to prove that the sentences are in fact meaningful, McIntosh wrote two poems influenced by Chomsky's utterance, one of which was entitled Nightmare I.[11] Tortured my mind's eye at its small peephole sees through the virid glass the endless ghostly oscillographic stream Furiously sleep ideas green colorless Madly awake am I at my small window — Angus McIntosh, 1961 |

大衆文化において、 チョムスキーの「色のない緑」は、文脈を追加することで意味論的に意味のない発話を意味のあるものにしようとする文学作品にインスピレーションを与えた。 1958年、言語学者であり人類学者でもあるデル・ハイムズは、無意味な言葉が正しい順序で並べられることで意味のあるものへと発展しうることを示す研究 を発表した。 色づけされた考えは脳をあざ笑う。 色という概念はまだ色ではない。 純粋で、触れることのできない、枝分かれした青白さの 侵略的で、本質的な緑の —デル・ハイムズ、1958年 ロシア系アメリカ人の言語学者であり文学理論家であるローマン・ヤコブソン(1959年)[7]は、「色のない緑」を淡い緑色、「猛烈に眠る」を「無気 力、無気力、無感覚のような、国家のような眠りの荒々しさ」と解釈した。ヤコブソンは、「もし[誰かの]憎悪が眠らないのであれば、なぜ[誰かの]考えが 眠りに落ちることができないのか?」という例を挙げた。アメリカの詩人であり文芸評論家でもあるジョン・ホランダーは、文脈を伴わないこの文章は真空の中 で機能していると主張した。彼はその考えに基づいて詩を書き、その詩は『The Night Mirror』(1971年)という著書に収録された『Coiled Alizarine』という題名が付けられた。[8] 不思議なほど深い、深紅の思考の眠り: 息も絶え絶えに、どっしりとしたビリジアン色の中で 無色透明の緑色のアイデアが猛烈に眠っている。 —ジョン・ホランダー、1971年 何年も経ってから、ホランダーは「緑」という色の選択が意図的なものだったのかどうかについてチョムスキーに問い合わせたが、チョムスキーは意図や影響を 否定し、特にアンドリュー・マーヴェルの「The Garden」(1681年)からの引用が影響しているという仮説を否定した。 「すべてを破壊しつくす/緑の陰で緑の思考に」 文脈からその意味を説明しようとした最初の作家の一人は、中国の言語学者ユエン・レン・チャオ(1997年)である。[9] チャオの詩『無意味から意味を創り出す:私の友人の物語。「無色緑色のアイデアが猛烈に眠る」(ノーム・チョムスキーの作品にちなんで)』は1971年に 出版された。この詩は、「色なき緑の思想」とは何か、そしてそれがどのようにして「猛烈に眠る」ことができるのかを説明しようとしている。チャオは、「色 なき」を「平凡な」、「緑の」を「未熟な」と解釈し、「猛烈に眠る」とは、その考えをいったん休ませることを意味すると解釈している。つまり、その考えに ついて一晩じっくり考えをめぐらせ、熟考することである。 私の友人に、いつもアイデアに満ち溢れている人がいる。良いアイデアも悪いアイデアも、素晴らしいアイデアも粗野なアイデアも、古いアイデアも新しいアイ デアもある。彼は新しいアイデアを実践に移す前に、熟成させるために一晩寝かせるのが常だ。しかし、急いでいるときは、熟しきっていない、つまり、まだ青 いアイデアを実践に移すこともある。彼の青いアイデアの中には、非常に生き生きとしていてカラフルなものもあるが、そうでないものもある。無色透明のアイ デアの中には、まだ青すぎて使えないものもあることを思い出すと、彼はそれらを寝かせる、つまり眠らせる。しかし、それらのアイデアの中には、互いに矛盾 し、相反するものもあり、同じ夜に一緒に眠ると、激しい喧嘩になり、悪夢のような眠りになってしまう。そのため、私の友人は、彼の「色のない緑色のアイデ ア」が猛烈に眠っているとよく不満を漏らす。 イギリスの言語学者アンガス・マッキントッシュは、チョムスキーの発言がまったく意味をなさないと受け入れることができなかった。なぜなら、彼にとって 「色のない緑色のアイデア」は「猛烈に眠る」可能性があるからだ。この文章が実際には意味があることを証明するかのように、マッキントッシュはチョムス キーの発言に影響を受けて2つの詩を書いた。そのうちの1つは『悪夢 I』というタイトルだった。 心の目で小さな覗き穴を拷問し、 緑色のガラス越しに 無限の幽霊のようなオシログラフのストリームを 見る。無色で緑色のアイデアが猛烈に眠っている。 私は小さな窓の前で狂気のように目覚めている — アンガス・マッキントッシュ、1961年 |

| Stanford 1985 competition In 1985, a literary competition was held at Stanford University in which the contestants were invited to make Chomsky's sentence meaningful using not more than 100 words of prose or 14 lines of verse.[12] An example entry from the competition, by C. M. Street, is: It can only be the thought of verdure to come, which prompts us in the autumn to buy these dormant white lumps of vegetable matter covered by a brown papery skin, and lovingly to plant them and care for them. It is a marvel to me that under this cover they are labouring unseen at such a rate within to give us the sudden awesome beauty of spring flowering bulbs. While winter reigns the earth reposes but these colourless green ideas sleep furiously. |

1985年のスタンフォード大学でのコンテスト 1985年、スタンフォード大学で文学コンテストが開催され、参加者はチョムスキーの文章を、散文100語以内、詩14行以内で意味のあるものにするよう求められた。[12] コンテスト参加者のC. M. Streetによる作品の一例は次の通りである。 それは、来るべき緑の季節を思う気持ちにほかならない。秋になると、私たちはこの休眠状態にある白い塊の野菜を、茶色の紙のような皮に覆われた状態で買い 求め、愛情を込めて植え、世話をしたくなるのだ。この皮の下で、目に見えないところで、これほどまでに懸命に働いて、春に咲く球根の突然の畏敬の念を起こ させるような美しさを私たちに与えてくれるのは、私にとって驚嘆に値することである。冬が支配する間、地球は休んでいるが、これらの無色透明の緑のアイデ アは猛烈に眠っている。 |

| Experimental usage Research has been done by implementing this into conversations on text.[13] Research led by Bruno Galantucci at Yeshiva University has implemented the meaningless sentence into real conversations to test reactions.[14] They ran 30 conversations with 1 male and 1 female slipping "colorless green ideas sleep furiously" eight minutes into the conversation during silence. After the conversation, the experimenters did a post-conversation questionnaire, mainly asking if they thought the conversation was unusual. Galantucci concluded that there was a trend of insensitivity to conversational coherence. There are two general theories that were garnered from this experiment. The first theory is that people tend to ignore the inconsistency of speech to protect the quality of the conversation. In particular, face-to-face conversation has a 33.33% lower detection rate of nonsensical sentences than online messaging. The authors further explain how humans often disregard some contents of every conversation. The second theory the authors deduced is that effective communication may be subconsciously undermined when dealing with conversational coherence. These conclusions support the idea that phatic communication plays a key role in social life. |

実験的使用 テキスト上の会話にこれを導入して研究が行われた。[13] イエシーバー大学のブルーノ・ガランツッチ氏による研究では、実際の会話に無意味な文章を導入し、反応をテストした。[14] 1人の男性と1人の女性が参加し、会話の8分目に「colorless green ideas sleep furiously」という文章を沈黙中に挿入した30回の会話が行われた。会話終了後、実験者は主に会話が異常だったと思うかどうかを尋ねる会話後のア ンケートを実施した。Galantucciは会話の一貫性に対する鈍感さの傾向があると結論づけた。 この実験から得られた一般的な理論は2つある。1つ目の理論は、人々は会話の質を守るために発言の矛盾を無視する傾向にあるというものである。特に、対面 での会話では、オンラインメッセージングよりも無意味な文章の検出率が33.33%も低い。著者はさらに、人間はあらゆる会話において、その内容の一部を 無視することが多いと説明している。著者が導き出した2つ目の理論は、会話の一貫性を保とうとすると、効果的なコミュニケーションが潜在意識下で損なわれ る可能性があるというものである。これらの結論は、情緒的コミュニケーションが社会生活において重要な役割を果たしているという考え方を裏付けるものであ る。 |

| Statistical challenges Since the 1950s, the field has used techniques more in line with Chomsky's approach. However, this all changed in the mid-1980s, when researchers started to experiment with statistical models, convincing over 90% of the researchers in the field to switch to statistical approaches.[15] In 2000, Fernando Pereira of the University of Pennsylvania fitted a simple statistical Markov model to a body of newspaper text, and showed that under this model, Furiously sleep ideas green colorless is about 200,000 times less probable than Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.[16] This statistical model defines a similarity metric, whereby sentences which are more like those within a corpus in certain respects are assigned higher values than sentences less alike. Pereira's model assigns an ungrammatical version of the same sentence a lower probability than the syntactically well-formed structure demonstrating that statistical models can identify variations in grammaticality with minimal linguistic assumptions. However, it is not clear that the model assigns every ungrammatical sentence a lower probability than every grammatical sentence. That is, colorless green ideas sleep furiously may still be statistically more "remote" from English than some ungrammatical sentences. To this, it may be argued that no current theory of grammar is capable of distinguishing all grammatical English sentences from ungrammatical ones.[17] |

統計上の課題 1950年代以降、この分野ではチョムスキーのアプローチにより近い手法が用いられてきた。しかし、1980年代半ばに研究者が統計モデルの実験を開始し、この分野の研究者の90%以上が統計的アプローチに切り替えるよう説得したことで、すべてが変わった。 2000年には、ペンシルベニア大学のフェルナンド・ペレイラが、新聞記事のテキストにシンプルな統計的マルコフモデルを当てはめ、このモデルでは 「Furiously sleep ideas green colorless」は「Colorless green ideas sleep furiously」よりも約20万分の1の確率であることを示した。 この統計モデルは類似度を定義し、コーパス内の文章と特定の点で類似している文章には、類似度が低い文章よりも高い値が割り当てられる。ペレイラのモデル では、文法的に正しくない同じ文章には、統語的に正しく形成された構造よりも低い確率が割り当てられ、統計モデルが最小限の言語的仮定で文法性のバリエー ションを特定できることを示している。しかし、このモデルが文法的に正しくないすべての文に対して、文法的に正しいすべての文よりも低い確率を割り当てる かどうかは明らかではない。つまり、「colorless green ideas sleep furiously」は、文法的に正しくない文の中には、英語から統計的に見て「より離れた」位置にある可能性がある。これに対しては、現在の文法理論で は、文法的に正しい英語の文と文法的に正しくない英語の文をすべて区別することはできないという反論があるかもしれない。[17] |

| Related and similar examples This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) In other languages The French syntactician Lucien Tesnière came up with the French language sentence "Le silence vertébral indispose la voile licite" ("The vertebral silence indisposes the licit sail"). In Russian schools of linguistics, the glokaya kuzdra example has similar characteristics. In games The game of exquisite corpse is a method for generating nonsense sentences. It was named after the first sentence generated in the game in 1925: Le cadavre exquis boira le vin nouveau (the exquisite corpse will drink the new wine). In the popular game of "Mad Libs", a chosen player asks each other player to provide parts of speech without providing any contextual information (e.g., "Give me a proper noun", or "Give me an adjective"), and these words are inserted into pre-composed sentences with a correct grammatical structure, but in which certain words have been omitted. The humor of the game is in the generation of sentences which are grammatical but which are meaningless or have absurd or ambiguous meanings (such as 'loud sharks'). The game also tends to generate humorous double entendres. |

関連する類似の例 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分である。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の無い内容は、異議申し立てにより削除される場合があります。 他の言語では フランスの文法学者ルシアン・テニエールは、フランス語の文章「Le silence vertébral indispose la voile licite」(「脊椎の静寂は合法的な帆を不快にする」)を考案した。 ロシアの言語学では、glokaya kuzdraの例も同様の特徴を持つ。 ゲームでは エクスキーズ・コーパスのゲームは、ナンセンスな文章を生成する方法である。このゲームは1925年に生成された最初の文章「Le cadavre exquis boira le vin nouveau(エクスキーズ・コーパスは新酒を飲む)」にちなんで名付けられた。 人気のゲーム「マッド・リブ」では、選ばれたプレイヤーが他のプレイヤーに文法上の情報を一切提供せずに品詞を指定する(例えば、「固有名詞を言って」や 「形容詞を言って」など)。これらの単語は、正しい文法構造を持つが、特定の単語が省略された、すでに構成された文章に挿入される。このゲームの面白さ は、文法的に正しいが意味のない、あるいは不条理な、あるいは曖昧な意味を持つ文章が生成されることにある(「loud sharks」など)。また、このゲームはユーモアのある二重の意味を生み出す傾向もある。 |

| In philosophy There are likely earlier examples of such sentences, possibly from the philosophy of language literature, but not necessarily uncontroversial ones, given that the focus has been mostly on borderline cases. For example, followers of logical positivism hold that "metaphysical" (i.e. not empirically verifiable) statements are simply meaningless; e.g. Rudolf Carnap wrote an article in which he argued that almost every sentence from Heidegger was grammatically well-formed, yet meaningless.[18] The philosopher Bertrand Russell used the sentence "Quadruplicity drinks procrastination" in his "An Inquiry into Meaning and Truth" from 1940, to make a similar point;[19] W.V. Quine took issue with him on the grounds that for a sentence to be false is nothing more than for it not to be true; and since quadruplicity does not drink anything, the sentence is simply false, not meaningless.[20] Other arguably "meaningless" utterances are ones that make sense, are grammatical, but have no reference to the present state of the world, such as Russell's "The present King of France is bald" (France does not presently have a king) from "On Denoting"[21] (also see definite description). |

哲学においては、 言語哲学の文献から、このような文のより早い例が存在する可能性が高いが、論争の的にならないものとは限らない。なぜなら、焦点はほとんどが境界線上の ケースに当てられてきたからだ。例えば、論理実証主義の信奉者は、「形而上学的」(すなわち、経験的に検証できない)な文は単に意味をなさないと主張して いる。例えば、ルドルフ・カナルプは、ハイデガーのほとんどの文は文法的に正しくても意味をなさないと主張する論文を書いた。 哲学者のバートランド・ラッセルは、1940年の著書『意味と真実についての探究』の中で、「Quadruplicity drinks procrastination」という文章を用いて同様の主張を行っている。[19] W.V. クワインは、文章が偽であるということは、その文章が真実ではないということに他ならないという理由でラッセルに異議を唱えた。また、 quadruplicityは何も飲まないため、その文章は単に偽であり、無意味ではない。[20] 他の「無意味」な発話は、意味があり、文法的に正しいが、世界の現在の状態をまったく参照していないものである。例えば、ラッセルの「現在のフランス王は ハゲている」(フランスには現在王がいない)という「On Denoting」からの引用がある[21](明確な記述も参照)。 |

| In literature and entertainment Another approach is to create a syntactically-well-formed, easily parsable sentence using nonsense words; a famous such example is "The gostak distims the doshes". Lewis Carroll's Jabberwocky is also famous for using this technique, although in this case for literary purposes; similar sentences used in neuroscience experiments are called Jabberwocky sentences. In a sketch about linguistics, British comedy duo Fry and Laurie used the nonsensical sentence "Hold the newsreader's nose squarely, waiter, or friendly milk will countermand my trousers."[22] The Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Darmok" features a race that communicates entirely by referencing folklore and stories. While the vessel's universal translator correctly translates the characters and places from these stories, it fails to decipher the intended meaning, leaving Captain Picard unable to understand the alien. |

文学やエンターテイメントでは、 ナンセンスな単語を使用して、文法的に正しく、簡単に解析できる文を作成するという別の方法もある。有名な例としては、「The gostak distims the doshes」がある。ルイス・キャロルの『ジャバウォーキー』も、このテクニックを使用した例として有名であるが、この場合は文学的な目的で使用されて いる。神経科学の実験で使用される同様の文は、ジャバウォーキー文と呼ばれる。 英国のコメディアン、フライとローリーは、言語学に関するスケッチの中で、「ニュースキャスターの鼻をしっかりと押さえろ、ウェイター、さもないと、優しい牛乳が私のズボンを台無しにしてしまうだろう」という意味不明の文章を使用した。 スタートレック:ネクストジェネレーションのエピソード「ダモク」では、民話や物語を引用してコミュニケーションを取る種族が登場する。宇宙船の翻訳機 は、これらの物語に登場する人物や場所を正しく翻訳するが、意図された意味を解読できず、ピカード艦長は異星人の言葉を理解できない。 |

| List of linguistic example sentences Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo James while John had had had had had had had had had had had a better effect on the teacher Pseudoword Syntax‐semantics interface Comparative illusion, also known as Escher sentences |

言語例文一覧 バッファロー・バッファロー・バッファロー・バッファロー・バッファロー・バッファロー ジェームズは、ジョンが教師によりよい影響を与えた一方で、持っていた。 擬似単語 統語論と意味論のインターフェース 比較錯視、別名エッシャー文 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colorless_green_ideas_sleep_furiously |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆