大日本帝国憲法あるいは明治憲法

The Constitution of the Empire of

Japan, 1890.

1945 National Geographic map of Korea, showing Japanese placenames and provincial boundaries

大日本帝国憲法あるいは明治憲法

The Constitution of the Empire of

Japan, 1890.

1945 National Geographic map of Korea, showing Japanese placenames and provincial boundaries

★大日本帝国憲法(だいにっぽんていこくけんぽう、英: Dai-Nippon Teikoku Kenpō)は、2月11日に公布された大日本帝国憲法。明治憲法(めいじけんぽう)は、1889年2月11日に公布され、1890年11月29日から 1947年5月2日まで施行された大日本帝国憲法である。比較憲法論の観点からは、立憲君主制と絶対君主制が混在していると指摘されるが、統帥権干犯問題 (1930年)にみられるように、憲法の上の規定では、絶対君主制のもとでの立憲政治が可能というタイプの憲法であり、「 第3条天皇ハ神聖ニシテ侵スヘカラス」や、天皇機関説論争で天皇機関説(=主権は国家にあって天皇にはなく天皇は国家を代表する最高の機関そのものである という美濃部達吉らの学説)が戦前の軍部が弾圧したように、明治憲法下における立憲君主制の要素を見つけることはやや困難であると言えよう。

| The Constitution of

the Empire of Japan (Kyūjitai: 大日本帝國憲法; Shinjitai: 大日本帝国憲法, romanized:

Dai-Nippon Teikoku Kenpō), known informally as the Meiji Constitution

(明治憲法, Meiji Kenpō), was the constitution of the Empire of Japan which

was proclaimed on February 11, 1889, and remained in force between

November 29, 1890 and May 2, 1947.[1] Enacted after the Meiji

Restoration in 1868, it provided for a form of mixed constitutional and

absolute monarchy, based jointly on the German and British models.[2]

In theory, the Emperor of Japan was the supreme leader, and the

Cabinet, whose Prime Minister would be elected by a Privy Council, were

his followers; in practice, the Emperor was head of state but the Prime

Minister was the actual head of government. Under the Meiji

Constitution, the Prime Minister and his Cabinet were not necessarily

chosen from the elected members of parliament. During the American Occupation of Japan the Meiji Constitution was replaced with the "Postwar Constitution" on November 3, 1946; the latter document has been in force since May 3, 1947. In order to maintain legal continuity, the Postwar Constitution was enacted as an amendment to the Meiji Constitution. |

大日本帝国憲法(だいにっぽんていこくけんぽう、英:

Dai-Nippon Teikoku

Kenpō)は、2月11日に公布された大日本帝国憲法。明治憲法(めいじけんぽう)は、1889年2月11日に公布され、1890年11月29日から

1947年5月2日まで施行された大日本帝国憲法である[1]。

[1868年の明治維新後に制定され、ドイツとイギリスを手本とした立憲君主制と絶対君主制の混合形態を規定した[2]。理論上は天皇が最高指導者で、枢

密院で選ばれる内閣総理大臣がその従者であるが、実際には天皇が元首で内閣総理大臣が政府の実質的なトップであった。明治憲法では、内閣総理大臣と内閣は

必ずしも選挙で選ばれた国会議員の中から選ばれたわけではなかった。 アメリカの占領下、1946年11月3日に明治憲法は「戦後憲法」に改められ、1947年5月3日から戦後憲法すなわち「日本国憲法」が施行されている。戦後憲法は、法律の連続 性を保つために、明治憲法を改正して制定された。 |

| Outline The Meiji Restoration in 1868 provided Japan a form of constitutional monarchy based on the Prusso-German model, in which the Emperor of Japan was an active ruler and wielded considerable political power over foreign policy and diplomacy which was shared with an elected Imperial Diet.[3] The Diet primarily dictated domestic policy matters. After the Meiji Restoration, which restored direct political power to the emperor for the first time in over a millennium, Japan underwent a period of sweeping political and social reform and westernization aimed at strengthening Japan to the level of the nations of the Western world. The immediate consequence of the Constitution was the opening of the first Parliamentary government in Asia.[4] The Meiji Constitution established clear limits on the power of the executive branch and the Emperor. It also created an independent judiciary. Civil rights and civil liberties were allowed, though they were freely subject to limitation by law.[5] Free speech, freedom of association and freedom of religion were all limited by laws.[5] The leaders of the government and the political parties were left with the task of interpretation as to whether the Meiji Constitution could be used to justify authoritarian or liberal-democratic rule. It was the struggle between these tendencies that dominated the government of the Empire of Japan. Franchise was limited, with only 1.1% of the population eligible to vote for the Diet.[5] Universal manhood suffrage was not established (under law) until the General Election Law, which gave every male aged 25 and over a voting right, was enacted in 1925. The Meiji Constitution was used as a model for the 1931 Constitution of Ethiopia by the Ethiopian intellectual Tekle Hawariat Tekle Mariyam. This was one of the reasons why the progressive Ethiopian intelligentsia associated with Tekle Hawariat were known as "Japanizers".[6] By the surrender in the World War II on 2 September 1945, the Empire of Japan was deprived of sovereignty by the Allies, and the Meiji Constitution was suspended. During the Occupation of Japan, the Meiji Constitution was replaced by a new document, the postwar Constitution of Japan. This document replaced imperial rule with a form of Western-style liberal democracy. To preserve legal continuity, these changes were enacted as a constitutional amendment per Article 73 of the Meiji Constitution. After garnering the required two-thirds majority in both chambers, it received imperial assent on 3 November 1946 and took effect on 3 May 1947. |

概要 1868年の明治維新により、日本はプロイセン・ドイツ型の立憲君主制を導入した。この立憲君主制では、天皇は積極的な支配者であり、外交や政策に関して 大きな政治力を行使し、選挙で選ばれた帝国議会と共有した。 3] 議会は主に国内の政策事項を決定した。 明治維新によって千年ぶりに天皇に直接の政治的権力が与えられた後、日本は西洋諸国と同じレベルまで強化することを目的とした大規模な政治的、社会的改革 と西洋化の時期を経た。憲法がもたらした直接的な影響は、アジアで最初の議会制政府の発足であった[4]。 明治憲法は、行政府と天皇の権力に明確な制限を設けた。また、独立した司法機関も設立された。言論の自由、結社の自由、信教の自由はすべて法律によって制 限されていた[5]。 政府と政党の指導者は、明治憲法が権威主義と自由民主主義のどちらの支配を正当化するために使われるかについての解釈の仕事を任された。大日本帝国の政治 を支配したのは、これらの傾向の間の闘いであった。1925年に25歳以上のすべての男性に選挙権を与える「普通選挙法」が制定されるまで、男子普通選挙 権は(法律上)確立されていなかった。 明治憲法は、エチオピアの知識人であるテクレ・ハワリアット・テクレ・マリヤムによって1931年のエチオピア憲法のモデルとして使われた。これが、テク レ・ハワリアートと関連する進歩的なエチオピアの知識人が「ジャパナイザー」と呼ばれるようになった理由の1つである[6]。 1945年9月2日の第二次世界大戦における降伏によって、大日本帝国は連合国によって主権を奪われ、明治憲法は停止された。占領下において、明治憲法は 戦後日本国憲法という新たな文書に置き換えられた。この憲法は、天皇制から西洋の自由民主主義に置き換わった。法律の連続性を保つため、この改正は明治憲 法第73条による憲法改正として制定された。1946年11月3日、両議院で3分の2以上の賛成を得た後、1947年5月3日に施行された。 |

| Background Prior to the adoption of the Meiji Constitution, Japan had in practice no written constitution. Originally, a Chinese-inspired legal system and constitution known as ritsuryō was enacted in the 6th century (in the late Asuka period and early Nara period); it described a government based on an elaborate and theoretically rational meritocratic bureaucracy, serving under the ultimate authority of the emperor and organised following Chinese models. In theory the last ritsuryō code, the Yōrō Code enacted in 752, was still in force at the time of the Meiji Restoration. However, in practice the ritsuryō system of government had become largely an empty formality as early as in the middle of the Heian period in the 10th and 11th centuries, a development which was completed by the establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate in 1185. The high positions in the ritsuryō system remained as sinecures, and the emperor was de-powered and set aside as a symbolic figure who "reigned, but did not rule" (on the theory that the living god should not have to defile himself with matters of earthly government). The Charter Oath was promulgated on 6 April 1868, which outlined the fundamental policies of the government and demanded the establishment of deliberative assemblies, but it did not determine the details. The idea of a written constitution had been a subject of heated debate within and without the government since the beginnings of the Meiji government.[8] The conservative Meiji oligarchy viewed anything resembling democracy or republicanism with suspicion and trepidation, and favored a gradualist approach. The Freedom and People's Rights Movement demanded the immediate establishment of an elected national assembly, and the promulgation of a constitution. |

背景 明治憲法が制定される以前、日本には憲法が存在しなかった。元々、6世紀(飛鳥時代末から奈良時代初期)には、中国に影響を受けた律令制と憲法が制定され ていた。それは、精巧で理論的に合理的な能力主義の官僚制に基づき、皇帝の最終権限のもとに、中国のモデルに従って組織された政府を説明するものだった。 理論的には、752年に制定された最後の律令である「養老律令」は、明治維新の際にも有効であった。 しかし、実際には、平安時代中期の10〜11世紀には、律令制はすでに空文化しており、1185年の鎌倉幕府の成立によって、律令制は完成したのである。 律令制の高い地位は副葬品として残され、天皇は「君臨すれども統治せず」(生ける神が地上の政治に関わることで自分を汚してはいけないという理屈)の象徴 的な人物として力を失い、脇に置かれることになった。 1868 年4月6日に公布された「憲章の誓い」は、政府の基本方針を示し、審議会の設置を求めたが、その内容は決定していない。明文憲法の制定は、明治政府の発足 以来、政府内外で激しい議論が交わされてきた。[8]。明治の保守的な寡頭政治家は、民主主義や共和制のようなものを疑心暗鬼にとらえ、漸進主義的なアプ ローチをとることをよしとした。自由民権運動は、選挙で選ばれた国民議会の即時設置と憲法の発布を要求した。 |

| Drafting On October 21, 1881, Itō Hirobumi was appointed to chair a government bureau to research various forms of constitutional government, and in 1882, Itō led an overseas mission to observe and study various systems first-hand.[9] The United States Constitution was rejected as too liberal. The French and Spanish models were rejected as tending toward despotism. The Reichstag and legal structures of the German Empire, particularly that of Prussia, proved to be of the most interest to the Constitutional Study Mission. Influence was also drawn from the British Westminster system, although it was considered as being unwieldy and granting too much power to Parliament. He also rejected some notions as unfit for Japan, as they stemmed from European constitutional practice and Christianity.[10] He therefore added references to the kokutai or "national polity" as the justification of the emperor's authority through his divine descent and the unbroken line of emperors, and the unique relationship between subject and sovereign.[11] The Council of State was replaced in 1885 with a cabinet headed by Itō as Prime Minister.[12] The positions of Chancellor, Minister of the Left, and Minister of the Right, which had existed since the seventh century, were abolished. In their place, the Privy Council was established in 1888 to evaluate the forthcoming constitution, and to advise Emperor Meiji. The draft committee included Inoue Kowashi, Kaneko Kentarō, Itō Miyoji and Iwakura Tomomi, along with a number of foreign advisors, in particular the German legal scholars Rudolf von Gneist and Lorenz von Stein. The central issue was the balance between sovereignty vested in the person of the Emperor, and an elected representative legislature with powers that would limit or restrict the power of the sovereign.[citation needed] After numerous drafts from 1886–1888, the final version was submitted to Emperor Meiji in April 1888. The Meiji Constitution was drafted in secret by the committee, without public debate.[citation needed] |

草案作成 1881年10月21日、伊藤博文が憲政調査会会長に任命され、1882年には海外視察団を率いて諸制度を実地に調査した[9]。フランスやスペインの憲 法は専制主義的であるとして否定された。ドイツ帝国、特にプロイセンの帝国議会と法体系は、憲法調査団にとって最も興味深いものであった。また、イギリス のウェストミンスター制度にも影響を受けたが、これは扱いにくく、議会に大きな権限を与えすぎるとされた。 そのため、天皇の権威を正当化するものとして、天皇の神統と連綿と続く天皇の家系、臣民と君主の独特な関係である国体への言及が加えられた[11]。 1885年に国務院は伊藤を首相とする内閣に変わり[12]、7世紀以来存在した大蔵大臣、左大臣、右大臣の地位は廃止された。その代わりに、1888年に枢密院が設置され、来るべき憲法を評価し、明治天皇に助言することになった。 井上馨、金子堅太郎、伊藤美齢、岩倉具視らのほか、ドイツの法学者ルドルフ・フォン・グナイストやローレンツ・フォン・シュタインら外国人顧問も多数参加 した。1886年から1888年にかけて何度も草案が作られた後、1888年4月に最終版が明治天皇に提出された[citation needed]。明治憲法は委員会によって秘密裏に起草され、公開討論は行われなかった[citation needed]。 |

| Promulgation Itō Hirobumi and Emperor Meiji (Servet-i Fünun 25 October 1894 front page) The new constitution was promulgated by Emperor Meiji on of the Meiji State : Outline|website=National Diet Library. Japan.|url=https://www.ndl.te=September 4, 2020}}</ref> The first National Diet of Japan, a new representative assembly, convened on the day the Meiji Constitution came into force.[4] The organizational structure of the Diet reflected both Prussian and British influences, most notably in the inclusion of the House of Representatives as the lower house (existing currently, under the Article 42 of the post-war Japanese Constitution based on bicameralism) and the House of Peers as the upper house, (which resembled the Prussian Herrenhaus and the British House of Lords, now the House of Councillors of Japan under the Article 42 of the post-war Japanese Constitution based on bicameralism), and in the formal Speech from the Throne delivered by the Emperor on Opening Day (existing currently, under the Article 7 of the post-war Japanese Constitution). The second chapter of the constitution, detailing the rights of citizens, bore a resemblance to similar articles in both European and North American constitutions of the day. |

公布 伊藤博文と明治天皇(『サーベト・イ・フニュン』1894年10月25日号一面) 明治天皇の発布した新憲法は、明治国家の誕生と同時に発布された。概要|website=国立国会図書館. Japan.|url=https://www.ndl.te=September, 2020}}</ref> 明治憲法が施行された日に、新しい代表制議会である第1回国会が召集された。 [4] 国会の組織構造はプロイセンおよびイギリスの影響を反映しており、特に衆議院(現在、二院制に基づく戦後日本国憲法第42条の下に存在)と参議院である貴 族院を含んでいることが特徴である。(戦後日本国憲法第42条のもとで、プロイセン王国ヘレンハウスやイギリス貴族院に相当する参議院となった)、そし て、天皇陛下が開会日に行う玉音放送(戦後日本国憲法第7条のもとで、現存する)であった。第2章の国民の権利は、当時の欧米の憲法に類似している。 |

| Structure The Meiji Constitution consists of 76 articles in seven chapters, together amounting to around 2,500 words. It is also usually reproduced with its Preamble, the Imperial Oath Sworn in the Sanctuary in the Imperial Palace, and the Imperial Rescript on the Promulgation of the Constitution, which together come to nearly another 1,000 words.[13] The seven chapters are: I. The Emperor (1–17) II. Rights and Duties of Subjects (18–32) III. The Imperial Diet (33–54) IV. The Ministers of State and the Privy Council (55–56) V. The Judicature (57–61) VI. Finance (62–72) VII. Supplementary Rules (73–76) |

構造 明治憲法は、7章76条、約2,500字で構成されている。また、通常、前文、皇居内の聖域で宣誓した勅語、憲法公布の詔書と合わせて、さらに1,000字近い文章で再現される[13]。 I. 天皇(1-17) 二.臣民の権利と義務(18~32歳) 三.帝国議会(33-54) IV. 国務大臣と枢密院 (55-56) V. 司法(57-61) 六.財政(62-72) VII. 附則 (73-76) |

| Imperial sovereignty See also: Lèse-majesté in Japan Unlike its modern successor, the Meiji Constitution was founded on the principle that sovereignty resided in person of the Emperor, by virtue of his divine ancestry "unbroken for ages eternal", rather than in the people. Article 4 states that the "Emperor is the head of the Empire, combining in himself the rights of sovereignty". The Emperor, nominally at least, united within himself all three branches (executive, legislative and judiciary) of government, although legislation (article 5) and the budget (article 64) were subject to the "consent of the Imperial Diet". Laws were issued and justice administered by the courts "in the name of the Emperor". Rules on the succession of the imperial throne and on the Imperial household were left outside the Constitution; instead, a separate Act on the Imperial household (koshitu tenpan) was adopted.[5] This Act was not publicly promulgated, because it was seen as a private Act of the Imperial household rather than a public law.[5] Separate provisions of the Constitution are contradictory as to whether the Constitution or the Emperor is supreme. Article 3 declares him to be "sacred and inviolable", a formula which was construed by hard-line monarchists to mean that he retained the right to withdraw the constitution, or to ignore its provisions. Article 4 binds the Emperor to exercise his powers "according to the provisions of the present Constitution". Article 11 declares that the Emperor commands the army and navy. The heads of these services interpreted this to mean "The army and navy obey only the Emperor, and do not have to obey the cabinet and diet", which caused political controversy. Article 55, however, confirmed that the Emperor’s commands (including Imperial Ordinance, Edicts, Rescripts, etc.) had no legal force within themselves, but required the signature of a "Minister of State". On the other hand, these "Ministers of State" were appointed by (and could be dismissed by), the Emperor alone, and not by the Prime Minister or the Diet |

帝国主権 こちらもご覧ください。日本における不敬事件 明治憲法は、その後継憲法とは異なり、主権は国民にではなく、「不磨の大典」である天皇にあるという原則のもとに制定された。第4条では、「天皇は、帝国 の元首であつて、君主の権利を一身に集め」るとある。天皇は、少なくとも名目上、行政、立法、司法の三権を一身に集めたが、立法(第5条)と予算(第64 条)は「帝国議会の同意」を必要とした。法律は、「天皇の名において」公布され、司法は裁判所が行う。 皇位継承や皇室に関する規定は憲法の外に置かれ、皇室典範という法律が制定された[5]。この法律は、公法ではなく皇室の私法と見なされ、公布されなかった[5]。 憲法の別の規定は、憲法と天皇のどちらが最高かについて矛盾している。 第3条は、天皇は「神聖にして侵すことのできない」存在であると宣言しているが、この表現は、強硬な君主主義者によって、憲法を撤回したり、その条項を無視したりする権利を保持していると解釈された。 第4条は、天皇が「この憲法の定めるところにより」その権能を行使することを拘束する。 第11条は、天皇が陸海軍を指揮することを宣言している。これを「陸海軍は天皇にのみ従い、内閣や議会に従う必要はない」と解釈し、政治的論争を引き起こした。 しかし第55条は、天皇の命令(勅令、詔書などを含む)は、それ自体では法的効力を持たず、「国務大臣」の署名を必要とすることを確認した。一方、この「太政大臣」は、内閣総理大臣や国会ではなく、天皇が単独で任命(解任も可能)するものであった |

| Rights and duties of subjects Duties: The constitution asserts the duty of Japanese subjects to uphold the constitution (preamble), pay taxes (Article 21) and serve in the armed forces if conscripted (Article 20). Qualified rights: The constitution provides for a number of rights that subjects may enjoy where the law does not provide otherwise. These included the right to: Freedom of movement (Article 22). Not have one's house searched or entered (Article 25). Privacy of correspondence (Article 26). Private property (Article 27). Freedom of speech, assembly and association (Article 29). Less conditional rights Right to "be appointed to civil or military or any other public offices equally" (Article 19). 'Procedural' due process (Article 23). Right to trial before a judge (Article 24). Freedom of religion (Guaranteed by Article 28 "within limits not prejudicial to peace and order, and not antagonistic to their duties as subjects"). Right to petition government (Article 30). |

国民主体の権利と義務 義務 憲法は、日本国民の義務として、憲法を擁護し(前文)、税金を納め(第21条)、徴兵された場合は軍隊に服する(第20条)ことを主張している。 資格のある権利 憲法は、法律で規定されていない場合に、臣民が享受できるいくつかの権利を定めている。その中には以下のような権利が含まれる。 移動の自由(第22条)。 自宅を捜索されたり、立ち入られたりしない(第25条)。 通信のプライバシー(第26条)。 私有財産(第27条)。 言論、集会、結社の自由(第29条)。 条件付きではない権利 文官、軍人、その他の公職に等しく任命される」権利(第19条)。 手続き上の」デュープロセス(第23条)。 裁判官の前で裁判を受ける権利(24条)。 信教の自由(第28条で「平和と秩序を害しない範囲内で、かつ、臣民としての義務に反しない範囲内で」保障されている)。 政府に請願する権利(第30条)。 |

| Organs of government Main article: Government of Meiji Japan The Emperor of Japan had the right to exercise executive authority, and to appoint and dismiss all government officials. The Emperor also had the sole rights to declare war, make peace, conclude treaties, dissolve the lower house of Diet, and issue Imperial ordinances in place of laws when the Diet was not in session. Most importantly, command over the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy was directly held by the Emperor, and not the Diet. The Meiji Constitution provided for a cabinet consisting of Ministers of State who answered to the Emperor rather than the Diet, and to the establishment of the Privy Council. Not mentioned in the Constitution were the genrō, an inner circle of advisors to the Emperor, who wielded considerable influence. Under the Meiji Constitution, a legislature, the Diet, was established with two houses. The Upper House, or House of Peers consisted of members of the Imperial Family, hereditary peerage and members appointed by the Emperor. The Lower House, or House of Representatives was directly elected by all males who paid at least 15 yen in property taxes, effectively limiting the suffrage to 1.1 percent of the population. These qualifications were loosened in 1900 and 1919 with universal adult male suffrage introduced in 1925.[14] The Emperor shared legislative authority with the Diet, and no measure could become law without the agreement of the Emperor and the Diet. On the other hand, the Diet was given the authority to initiate legislation, approve all laws, and approve the budget. |

政府機関 主な記事 明治日本の政府 明治天皇は行政権を行使し、すべての官吏を任免する権能を有していた。また、宣戦布告、講和、条約締結、衆議院の解散、国会が開かれていないときの法律に 代わる勅令の発布も天皇が単独で行う権能を有していた。最も重要なことは、日本陸軍と日本海軍の指揮権は、国会ではなく、天皇が直接握っていたことであ る。明治憲法は、国会ではなく天皇に答える国務大臣からなる内閣と、枢密院の設置を規定した。明治憲法には、天皇の側近で大きな影響力を持つ元老の名前は ない。 明治憲法では、立法府として国会が設置され、2院からなる。参議院は、皇族、世襲の貴族、天皇の任命する議員で構成された。衆議院は、固定資産税15円以 上を納めているすべての男性から直接選ばれ、事実上、参政権は人口の1.1%に制限されていた。天皇は国会と立法権を共有し、天皇と国会の同意がなければ 法律は成立しなかった[14]。一方、国会には立法発議権、すべての法律の承認権、予算承認権が与えられていた。 |

| Amendments Amendments to the constitution were provided for by Article 73. This stipulated that, to become law, a proposed amendment had to be submitted first to the Diet by the Emperor through an imperial order or rescript. To be approved by the Diet, an amendment had to be adopted in both chambers by a two-thirds majority of the total number of members of each (rather than merely two-thirds of the total number of votes cast). Once it had been approved by the Diet, an amendment was then promulgated into law by the Emperor, who had an absolute right of veto. No amendment to the constitution was permitted during the time of a regency. Despite these provisions, no amendments were made to the imperial constitution from the time it was adopted until its demise in 1947. The present constitution is legally reckoned as an amendment to the Meiji Constitution; this was done to preserve legal continuity even though it is a completely new document. However, according to Article 73 of the Meiji Constitution, the amendment should be authorized by the Emperor. Indeed, the 1947 Constitution was authorized by the Emperor (as was declared in the letter of promulgation), which is in apparent conflict of the 1947 Constitution, according to which that constitution was made and authorized by the nation ("the principle of popular sovereignty"). To dissipate such inconsistencies, some peculiar doctrine of "August Revolution" was proposed by Toshiyoshi Miyazawa of the University of Tokyo, but without much persuasiveness. |

改正 憲法の改正は、第73条によって規定された。これは、法律として成立させるためには、まず天皇が勅令または詔勅によって改正案を国会に提出しなければなら ないことを定めたものである。国会で承認されるには、両院の議員総数の3分の2以上(単に投票総数の3分の2以上ではない)の賛成が必要であった。改正案 は国会で承認された後、天皇が法律として公布した。摂政の間は憲法を改正することはできない。このような規定があるにもかかわらず、帝国憲法は制定されて から1947年に廃止されるまで、一度も改正されることがなかった。現行憲法は、法的には明治憲法の改正とされ、全く新しい憲法であるにもかかわらず、法 的連続性を保つために、このような措置がとられた。 しかし、明治憲法第73条によれば、改正は天皇の許可を得なければならない。実際、1947年憲法は天皇の承認を受けており(公布文で宣言されている)、 1947年憲法が国民によって作られ承認されたとする(「国民主権の原則」)ことと明らかに矛盾しているのである。このような矛盾を解消するために、東京 大学の宮沢俊義が「八月革命」という独特の学説を提唱したが、あまり説得力がなかった。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meiji_Constitution |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

|

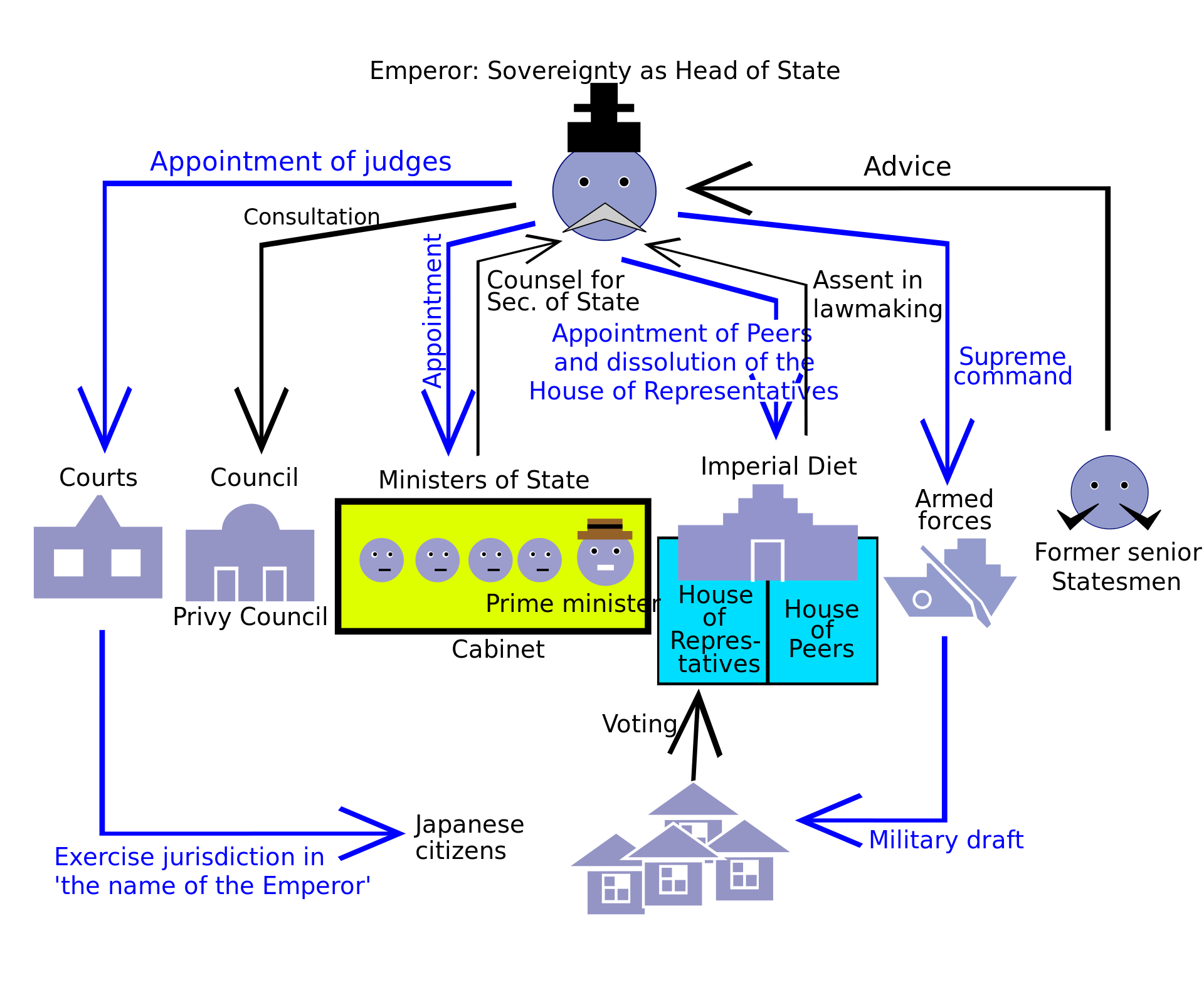

Schematic overview of the government structure under the Constitution |

| 大日本帝国憲法 目次 第1章 天皇(第1条-第17条) 第2章 臣民権利義務(第18条-第32条) 第3章 帝国議会(第33条-第54条) 第4章 国務大臣及枢密顧問(第55条-第56条) 第5章 司法(第57条-第61条) 第6章 会計(第62条-第72条) 第7章 補則(第73条-第76条) 告文 皇朕レ謹ミ畏ミ 皇祖 皇宗ノ神霊ニ誥ケ白サク皇朕レ天壌無窮ノ宏謨ニ循ヒ惟神ノ宝祚ヲ承継シ旧図ヲ保持シテ敢テ失墜スルコト無シ顧ミルニ世局ノ進運ニ膺リ人文ノ発達ニ随ヒ宜ク 皇祖 皇宗ノ遺訓ヲ明徴ニシ典憲ヲ成立シ条章ヲ昭示シ内ハ以テ子孫ノ率由スル所ト為シ外ハ以テ臣民翼賛ノ道ヲ広メ永遠ニ遵行セシメ益々国家ノ丕基ヲ鞏固ニシ八洲民生ノ慶福ヲ増進スヘシ茲ニ皇室典範及憲法ヲ制定ス惟フニ此レ皆 皇祖 皇宗ノ後裔ニ貽シタマヘル統治ノ洪範ヲ紹述スルニ外ナラス而シテ朕カ躬ニ逮テ時ト倶ニ挙行スルコトヲ得ルハ洵ニ 皇祖 皇宗及我カ 皇考ノ威霊ニ倚藉スルニ由ラサルハ無シ皇朕レ仰テ 皇祖 皇宗及 皇考ノ神祐ヲ祷リ併セテ朕カ現在及将来ニ臣民ニ率先シ此ノ憲章ヲ履行シテ愆ラサラムコトヲ誓フ庶幾クハ 神霊此レヲ鑒ミタマヘ 憲法発布勅語 朕国家ノ隆昌ト臣民ノ慶福トヲ以テ中心ノ欣栄トシ朕カ祖宗ニ承クルノ大権ニ依リ現在及将来ノ臣民ニ対シ此ノ不磨ノ大典ヲ宣布ス 惟フニ我カ祖我カ宗ハ我カ臣民祖先ノ協力輔翼ニ倚リ我カ帝国ヲ肇造シ以テ無窮ニ垂レタリ此レ我カ神聖ナル祖宗ノ威徳ト並ニ臣民ノ忠実勇武ニシテ国ヲ愛シ公 ニ殉ヒ以テ此ノ光輝アル国史ノ成跡ヲ貽シタルナリ朕我カ臣民ハ即チ祖宗ノ忠良ナル臣民ノ子孫ナルヲ回想シ其ノ朕カ意ヲ奉体シ朕カ事ヲ奨順シ相与ニ和衷協同 シ益々我カ帝国ノ光栄ヲ中外ニ宣揚シ祖宗ノ遺業ヲ永久ニ鞏固ナラシムルノ希望ヲ同クシ此ノ負担ヲ分ツニ堪フルコトヲ疑ハサルナリ 大日本帝国憲法 朕祖宗ノ遺烈ヲ承ケ万世一系ノ帝位ヲ践ミ朕カ親愛スル所ノ臣民ハ即チ朕カ祖宗ノ恵撫慈養シタマヒシ所ノ臣民ナルヲ念ヒ其ノ康福ヲ増進シ其ノ懿徳良能ヲ発達 セシメムコトヲ願ヒ又其ノ翼賛ニ依リ与ニ倶ニ国家ノ進運ヲ扶持セムコトヲ望ミ乃チ明治十四年十月十二日ノ詔命ヲ履践シ茲ニ大憲ヲ制定シ朕カ率由スル所ヲ示 シ朕カ後嗣及臣民及臣民ノ子孫タル者ヲシテ永遠ニ循行スル所ヲ知ラシム 国家統治ノ大権ハ朕カ之ヲ祖宗ニ承ケテ之ヲ子孫ニ伝フル所ナリ朕及朕カ子孫ハ将来此ノ憲法ノ条章ニ循ヒ之ヲ行フコトヲ愆ラサルヘシ 朕ハ我カ臣民ノ権利及財産ノ安全ヲ貴重シ及之ヲ保護シ此ノ憲法及法律ノ範囲内ニ於テ其ノ享有ヲ完全ナラシムヘキコトヲ宣言ス 帝国議会ハ明治二十三年ヲ以テ之ヲ召集シ議会開会ノ時ヲ以テ此ノ憲法ヲシテ有効ナラシムルノ期トスヘシ 将来若此ノ憲法ノ或ル条章ヲ改定スルノ必要ナル時宜ヲ見ルニ至ラハ朕及朕カ継統ノ子孫ハ発議ノ権ヲ執リ之ヲ議会ニ付シ議会ハ此ノ憲法ニ定メタル要件ニ依リ之ヲ議決スルノ外朕カ子孫及臣民ハ敢テ之カ紛更ヲ試ミルコトヲ得サルヘシ 朕カ在廷ノ大臣ハ朕カ為ニ此ノ憲法ヲ施行スルノ責ニ任スヘク朕カ現在及将来ノ臣民ハ此ノ憲法ニ対シ永遠ニ従順ノ義務ヲ負フヘシ 御名御璽 明治二十二年二月十一日 内閣総理大臣 伯爵 黒田清隆 枢密院議長 伯爵 伊藤博文 外務大臣 伯爵 大隈重信 海軍大臣 伯爵 西郷従道 農商務大臣 伯爵 井上 馨 司法大臣 伯爵 山田顕義 大蔵大臣兼内務大臣 伯爵 松方正義 陸軍大臣 伯爵 大山 巌 文部大臣 子爵 森 有礼 逓信大臣 子爵 榎本武揚 大日本帝国憲法 第1章 天皇 第1条大日本帝国ハ万世一系ノ天皇之ヲ統治ス 第2条皇位ハ皇室典範ノ定ムル所ニ依リ皇男子孫之ヲ継承ス 第3条天皇ハ神聖ニシテ侵スヘカラス 第4条天皇ハ国ノ元首ニシテ統治権ヲ総攬シ此ノ憲法ノ条規ニ依リ之ヲ行フ 第5条天皇ハ帝国議会ノ協賛ヲ以テ立法権ヲ行フ 第6条天皇ハ法律ヲ裁可シ其ノ公布及執行ヲ命ス 第7条天皇ハ帝国議会ヲ召集シ其ノ開会閉会停会及衆議院ノ解散ヲ命ス 第8条天皇ハ公共ノ安全ヲ保持シ又ハ其ノ災厄ヲ避クル為緊急ノ必要ニ由リ帝国議会閉会ノ場合ニ於テ法律ニ代ルヘキ勅令ヲ発ス 2 此ノ勅令ハ次ノ会期ニ於テ帝国議会ニ提出スヘシ若議会ニ於テ承諾セサルトキハ政府ハ将来ニ向テ其ノ効力ヲ失フコトヲ公布スヘシ 第9条天皇ハ法律ヲ執行スル為ニ又ハ公共ノ安寧秩序ヲ保持シ及臣民ノ幸福ヲ増進スル為ニ必要ナル命令ヲ発シ又ハ発セシム但シ命令ヲ以テ法律ヲ変更スルコトヲ得ス 第10条天皇ハ行政各部ノ官制及文武官ノ俸給ヲ定メ及文武官ヲ任免ス但シ此ノ憲法又ハ他ノ法律ニ特例ヲ掲ケタルモノハ各々其ノ条項ニ依ル 第11条天皇ハ陸海軍ヲ統帥ス 第12条天皇ハ陸海軍ノ編制及常備兵額ヲ定ム 第13条天皇ハ戦ヲ宣シ和ヲ講シ及諸般ノ条約ヲ締結ス 第14条天皇ハ戒厳ヲ宣告ス 2 戒厳ノ要件及効力ハ法律ヲ以テ之ヲ定ム 第15条天皇ハ爵位勲章及其ノ他ノ栄典ヲ授与ス 第16条天皇ハ大赦特赦減刑及復権ヲ命ス 第17条摂政ヲ置クハ皇室典範ノ定ムル所ニ依ル 2 摂政ハ天皇ノ名ニ於テ大権ヲ行フ 第2章 臣民権利義務 第18条日本臣民タル要件ハ法律ノ定ムル所ニ依ル 第19条日本臣民ハ法律命令ノ定ムル所ノ資格ニ応シ均ク文武官ニ任セラレ及其ノ他ノ公務ニ就クコトヲ得 第20条日本臣民ハ法律ノ定ムル所ニ従ヒ兵役ノ義務ヲ有ス 第21条日本臣民ハ法律ノ定ムル所ニ従ヒ納税ノ義務ヲ有ス 第22条日本臣民ハ法律ノ範囲内ニ於テ居住及移転ノ自由ヲ有ス 第23条日本臣民ハ法律ニ依ルニ非スシテ逮捕監禁審問処罰ヲ受クルコトナシ 第24条日本臣民ハ法律ニ定メタル裁判官ノ裁判ヲ受クルノ権ヲ奪ハルヽコトナシ 第25条日本臣民ハ法律ニ定メタル場合ヲ除ク外其ノ許諾ナクシテ住所ニ侵入セラレ及捜索セラルヽコトナシ 第26条日本臣民ハ法律ニ定メタル場合ヲ除ク外信書ノ秘密ヲ侵サルヽコトナシ 第27条日本臣民ハ其ノ所有権ヲ侵サルヽコトナシ 2 公益ノ為必要ナル処分ハ法律ノ定ムル所ニ依ル 第28条日本臣民ハ安寧秩序ヲ妨ケス及臣民タルノ義務ニ背カサル限ニ於テ信教ノ自由ヲ有ス 第29条日本臣民ハ法律ノ範囲内ニ於テ言論著作印行集会及結社ノ自由ヲ有ス 第30条日本臣民ハ相当ノ敬礼ヲ守リ別ニ定ムル所ノ規程ニ従ヒ請願ヲ為スコトヲ得 第31条本章ニ掲ケタル条規ハ戦時又ハ国家事変ノ場合ニ於テ天皇大権ノ施行ヲ妨クルコトナシ 第32条本章ニ掲ケタル条規ハ陸海軍ノ法令又ハ紀律ニ牴触セサルモノニ限リ軍人ニ準行ス 第3章 帝国議会 第33条帝国議会ハ貴族院衆議院ノ両院ヲ以テ成立ス 第34条貴族院ハ貴族院令ノ定ムル所ニ依リ皇族華族及勅任セラレタル議員ヲ以テ組織ス 第35条衆議院ハ選挙法ノ定ムル所ニ依リ公選セラレタル議員ヲ以テ組織ス 第36条何人モ同時ニ両議院ノ議員タルコトヲ得ス 第37条凡テ法律ハ帝国議会ノ協賛ヲ経ルヲ要ス 第38条両議院ハ政府ノ提出スル法律案ヲ議決シ及各々法律案ヲ提出スルコトヲ得 第39条両議院ノ一ニ於テ否決シタル法律案ハ同会期中ニ於テ再ヒ提出スルコトヲ得ス 第40条両議院ハ法律又ハ其ノ他ノ事件ニ付キ各々其ノ意見ヲ政府ニ建議スルコトヲ得但シ其ノ採納ヲ得サルモノハ同会期中ニ於テ再ヒ建議スルコトヲ得ス 第41条帝国議会ハ毎年之ヲ召集ス 第42条帝国議会ハ三箇月ヲ以テ会期トス必要アル場合ニ於テハ勅命ヲ以テ之ヲ延長スルコトアルヘシ 第43条臨時緊急ノ必要アル場合ニ於テ常会ノ外臨時会ヲ召集スヘシ 2 臨時会ノ会期ヲ定ムルハ勅命ニ依ル 第44条帝国議会ノ開会閉会会期ノ延長及停会ハ両院同時ニ之ヲ行フヘシ 2 衆議院解散ヲ命セラレタルトキハ貴族院ハ同時ニ停会セラルヘシ 第45条衆議院解散ヲ命セラレタルトキハ勅令ヲ以テ新ニ議員ヲ選挙セシメ解散ノ日ヨリ五箇月以内ニ之ヲ召集スヘシ 第46条両議院ハ各々其ノ総議員三分ノ一以上出席スルニ非サレハ議事ヲ開キ議決ヲ為ス事ヲ得ス 第47条両議院ノ議事ハ過半数ヲ以テ決ス可否同数ナルトキハ議長ノ決スル所ニ依ル 第48条両議院ノ会議ハ公開ス但シ政府ノ要求又ハ其ノ院ノ決議ニ依リ秘密会ト為スコトヲ得 第49条両議院ハ各々天皇ニ上奏スルコトヲ得 第50条両議院ハ臣民ヨリ呈出スル請願書ヲ受クルコトヲ得 第51条両議院ハ此ノ憲法及議院法ニ掲クルモノヽ外内部ノ整理ニ必要ナル諸規則ヲ定ムルコトヲ得 第52条両議院ノ議員ハ議院ニ於テ発言シタル意見及表決ニ付院外ニ於テ責ヲ負フコトナシ但シ議員自ラ其ノ言論ヲ演説刊行筆記又ハ其ノ他ノ方法ヲ以テ公布シタルトキハ一般ノ法律ニ依リ処分セラルヘシ 第53条両議院ノ議員ハ現行犯罪又ハ内乱外患ニ関ル罪ヲ除ク外会期中其ノ院ノ許諾ナクシテ逮捕セラルヽコトナシ 第54条国務大臣及政府委員ハ何時タリトモ各議院ニ出席シ及発言スルコトヲ得 第4章 国務大臣及枢密顧問 第55条国務各大臣ハ天皇ヲ輔弼シ其ノ責ニ任ス 2 凡テ法律勅令其ノ他国務ニ関ル詔勅ハ国務大臣ノ副署ヲ要ス 第56条枢密顧問ハ枢密院官制ノ定ムル所ニ依リ天皇ノ諮詢ニ応ヘ重要ノ国務ヲ審議ス 第5章 司法 第57条司法権ハ天皇ノ名ニ於テ法律ニ依リ裁判所之ヲ行フ 2 裁判所ノ構成ハ法律ヲ以テ之ヲ定ム 第58条裁判官ハ法律ニ定メタル資格ヲ具フル者ヲ以テ之ニ任ス 2 裁判官ハ刑法ノ宣告又ハ懲戒ノ処分ニ由ルノ外其ノ職ヲ免セラルヽコトナシ 3 懲戒ノ条規ハ法律ヲ以テ之ヲ定ム 第59条裁判ノ対審判決ハ之ヲ公開ス但シ安寧秩序又ハ風俗ヲ害スルノ虞アルトキハ法律ニ依リ又ハ裁判所ノ決議ヲ以テ対審ノ公開ヲ停ムルコトヲ得 第60条特別裁判所ノ管轄ニ属スヘキモノハ別ニ法律ヲ以テ之ヲ定ム 第61条行政官庁ノ違法処分ニ由リ権利ヲ傷害セラレタリトスルノ訴訟ニシテ別ニ法律ヲ以テ定メタル行政裁判所ノ裁判ニ属スヘキモノハ司法裁判所ニ於テ受理スルノ限ニ在ラス 第6章 会計 第62条新ニ租税ヲ課シ及税率ヲ変更スルハ法律ヲ以テ之ヲ定ムヘシ 2 但シ報償ニ属スル行政上ノ手数料及其ノ他ノ収納金ハ前項ノ限ニ在ラス 3 国債ヲ起シ及予算ニ定メタルモノヲ除ク外国庫ノ負担トナルヘキ契約ヲ為スハ帝国議会ノ協賛ヲ経ヘシ 第63条現行ノ租税ハ更ニ法律ヲ以テ之ヲ改メサル限ハ旧ニ依リ之ヲ徴収ス 第64条国家ノ歳出歳入ハ毎年予算ヲ以テ帝国議会ノ協賛ヲ経ヘシ 2 予算ノ款項ニ超過シ又ハ予算ノ外ニ生シタル支出アルトキハ後日帝国議会ノ承諾ヲ求ムルヲ要ス 第65条予算ハ前ニ衆議院ニ提出スヘシ 第66条皇室経費ハ現在ノ定額ニ依リ毎年国庫ヨリ之ヲ支出シ将来増額ヲ要スル場合ヲ除ク外帝国議会ノ協賛ヲ要セス 第67条憲法上ノ大権ニ基ツケル既定ノ歳出及法律ノ結果ニ由リ又ハ法律上政府ノ義務ニ属スル歳出ハ政府ノ同意ナクシテ帝国議会之ヲ廃除シ又ハ削減スルコトヲ得ス 第68条特別ノ須要ニ因リ政府ハ予メ年限ヲ定メ継続費トシテ帝国議会ノ協賛ヲ求ムルコトヲ得 第69条避クヘカラサル予算ノ不足ヲ補フ為ニ又ハ予算ノ外ニ生シタル必要ノ費用ニ充ツル為ニ予備費ヲ設クヘシ 第70条公共ノ安全ヲ保持スル為緊急ノ需用アル場合ニ於テ内外ノ情形ニ因リ政府ハ帝国議会ヲ召集スルコト能ハサルトキハ勅令ニ依リ財政上必要ノ処分ヲ為スコトヲ得 2 前項ノ場合ニ於テハ次ノ会期ニ於テ帝国議会ニ提出シ其ノ承諾ヲ求ムルヲ要ス 第71条帝国議会ニ於テ予算ヲ議定セス又ハ予算成立ニ至ラサルトキハ政府ハ前年度ノ予算ヲ施行スヘシ 第72条国家ノ歳出歳入ノ決算ハ会計検査院之ヲ検査確定シ政府ハ其ノ検査報告ト倶ニ之ヲ帝国議会ニ提出スヘシ 2 会計検査院ノ組織及職権ハ法律ヲ以テ之ヲ定ム 第7章 補則 第73条将来此ノ憲法ノ条項ヲ改正スルノ必要アルトキハ勅命ヲ以テ議案ヲ帝国議会ノ議ニ付スヘシ 2 此ノ場合ニ於テ両議院ハ各々其ノ総員三分ノニ以上出席スルニ非サレハ議事ヲ開クコトヲ得ス出席議員三分ノ二以上ノ多数ヲ得ルニ非サレハ改正ノ議決ヲ為スコトヲ得ス 第74条皇室典範ノ改正ハ帝国議会ノ議ヲ経ルヲ要セス 2 皇室典範ヲ以テ此ノ憲法ノ条規ヲ変更スルコトヲ得ス 第75条憲法及皇室典範ハ摂政ヲ置クノ間之ヲ変更スルコトヲ得ス 第76条法律規則命令又ハ何等ノ名称ヲ用ヰタルニ拘ラス此ノ憲法ニ矛盾セサル現行ノ法令ハ総テ遵由ノ効力ヲ有ス 2 歳出上政府ノ義務ニ係ル現在ノ契約又ハ命令ハ総テ第六十七条ノ例ニ依ル |

|

| https://www.ndl.go.jp/constitution/etc/j02.html |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報