コリード

Corrido

Corrido

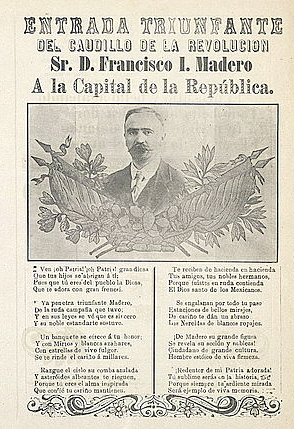

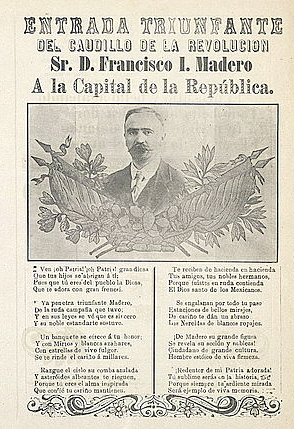

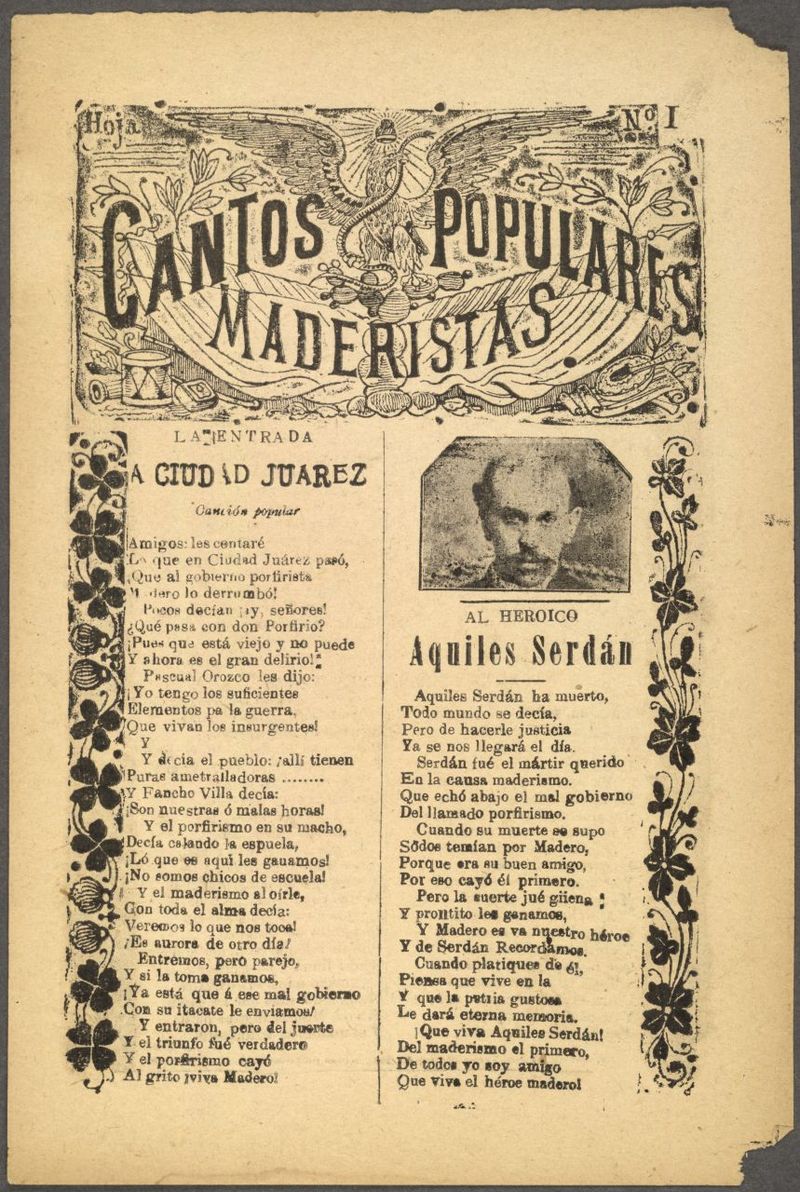

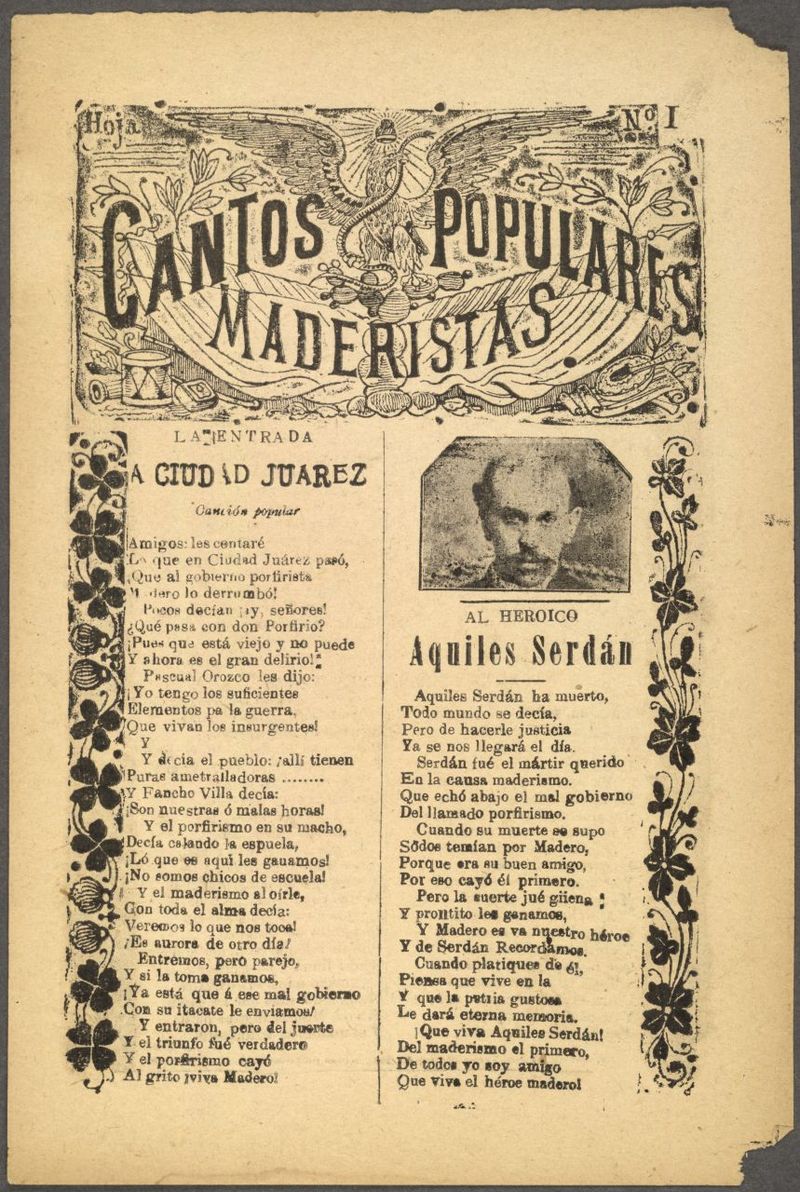

broadside celebrating the entry of Francisco I. Madero into Mexico City

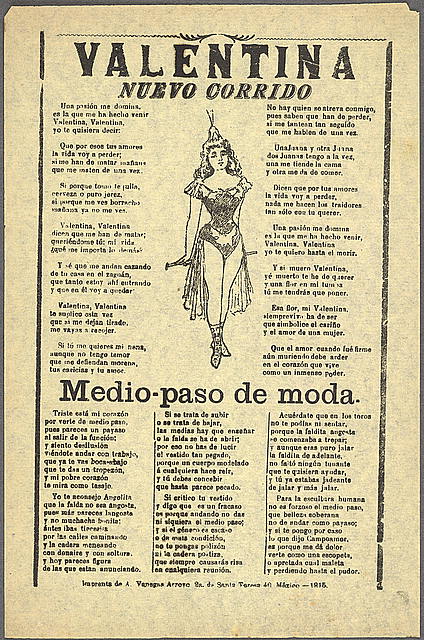

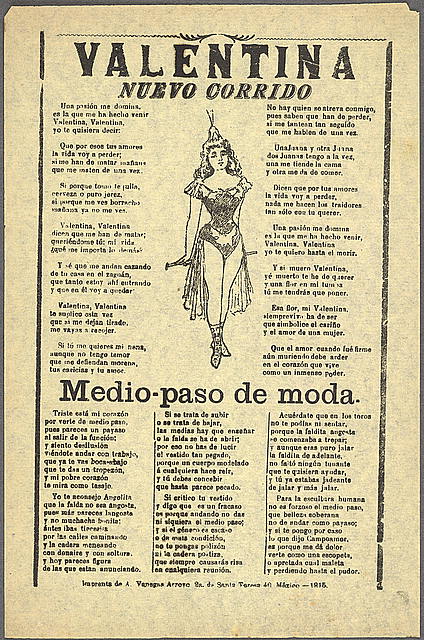

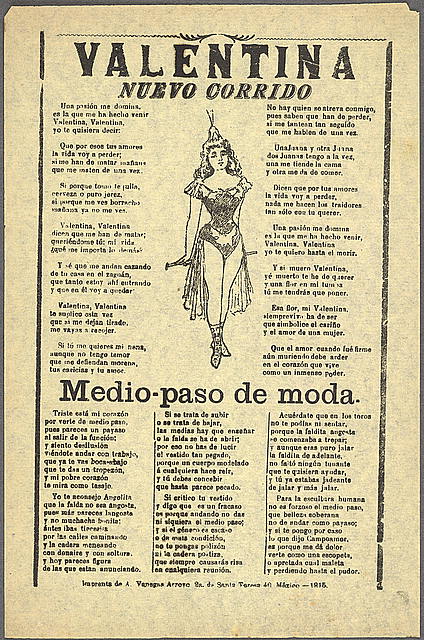

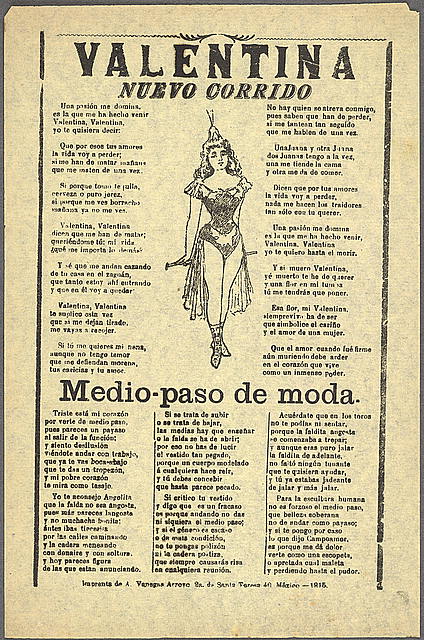

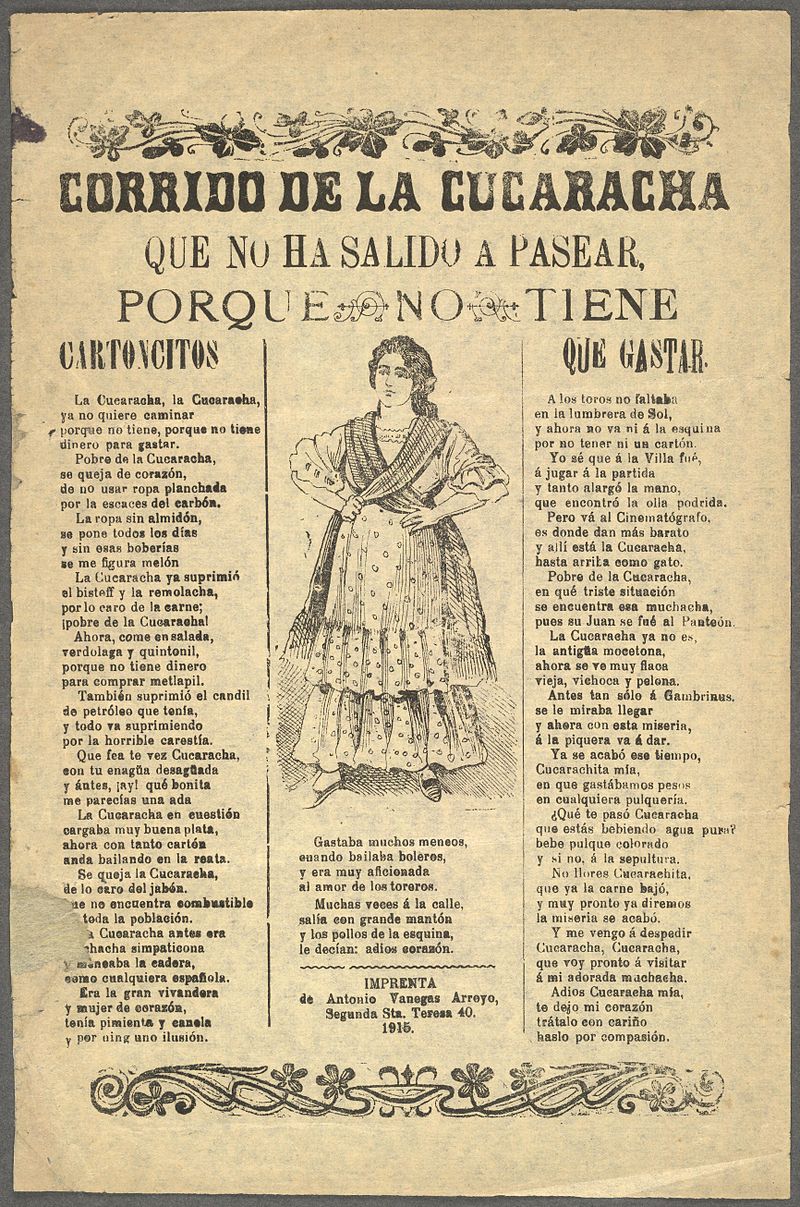

in 1911./ a corrido song sheet or sheet music, this one from 1915 at

the height of the Mexican Revolution.

☆ コリード(スペイン語発音:[koˈriðo])は、バラードを形成する有名な物語的叙事詩である。コリードはメキシコ革命期やアメリカ 南西部の 開拓時代に広く流行し、後に西部劇音楽に影響を与えたテハーノや ニューメキシコ音楽の発展の一端を担った。 コリドは主にロマンスに由来し、最もよく知られた形式では、歌い手の挨拶、物語のプロローグ、物語そのもの、歌い手の道徳と別れから成る。メキシコでは、 今日でも人気のあるジャンルである。 メキシコ以外では、チリの フィエスタス・パトリアスの祝祭でコリドスが人気である。

| The corrido (Spanish

pronunciation: [koˈriðo]) is a famous narrative metrical tale and

poetry that forms a ballad. The songs are often about oppression,

history, daily life for criminals, the vaquero lifestyle, and other

socially relevant topics.[1] Corridos were widely popular during the

Mexican Revolution and in the Southwestern American frontier as it was

also a part of the development of Tejano and New Mexico music, which

later influenced Western music. The corrido derives mainly from the romance and, in its most known form, consists of a salutation from the singer, a prologue to the story, the story itself, and a moral and farewell from the singer. In Mexico, it is still a popular genre today. Outside Mexico, corridos are popular in Chilean national celebrations of Fiestas Patrias.[2][3] |

コリード(スペイン語発音:

[koˈriðo])は、バラードを形成する有名な物語的叙事詩である。コリードはメキシコ革命期やアメリカ 南西部の

開拓時代に広く流行し、後に西部劇音楽に影響を与えたテハーノや ニューメキシコ音楽の発展の一端を担った。 コリドは主にロマンスに由来し、最もよく知られた形式では、歌い手の挨拶、物語のプロローグ、物語そのもの、歌い手の道徳と別れから成る。メキシコでは、 今日でも人気のあるジャンルである。 メキシコ以外では、チリの フィエスタス・パトリアスの祝祭でコリドスが人気である[2][3]。 |

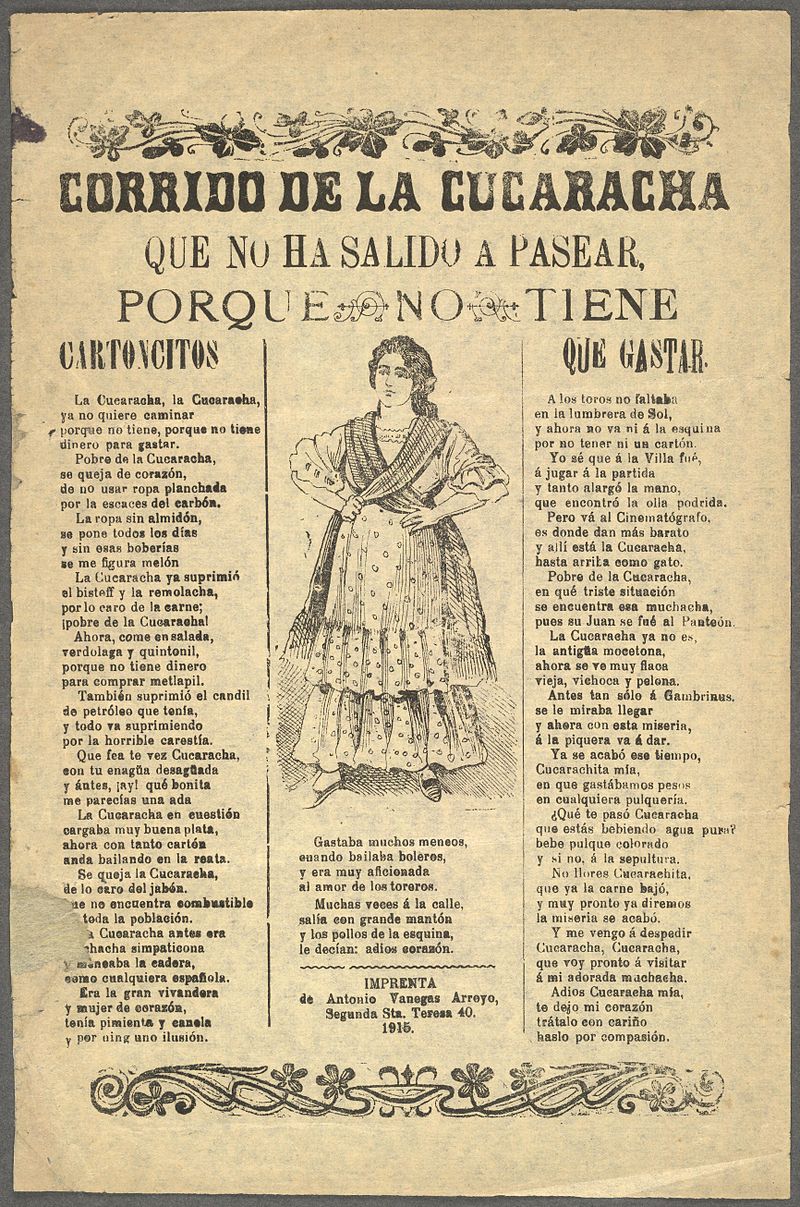

History An example of a corrido song sheet or sheet music, this one from 1915 at the height of the Mexican Revolution. Corridos play an essential part in Mexican and Mexican American culture. The name comes from the Spanish word correr ("to run"). A typical corrido's formula is eight quatrains with four to six lines containing eight syllables.[4] Corridos have a long history in Mexico, starting from the Mexican War of Independence in 1810 and throughout the Mexican Revolution.[5] Until the arrival and success of electronic mass media (mid-20th century), the corrido served in Mexico as the leading informational and educational outlet, even with subversive purposes, due to an apparent linguistic and musical simplicity that lent itself to oral transmission. After the spread of radio and television, the genre evolved into a new stage and is still in maturation. Some scholars, however, consider the corrido dead or moribund in more recent times (see, e.g. Vicente T. Mendoza, El corrido mexicano, 1954). In more rural areas where Spanish and Mexican cultures have been preserved because of isolation, the romance has also taken on other forms related to the corrido. In New Mexico, for example, a story-song emerged during the colonial period known as an Indita, which loosely follows the format of a corrido, but is chanted rather than sung, similar to a Native American chant, hence the name Indita. The earliest living specimens of corrido are adapted versions of Spanish romances or European tales, mainly about disgraced or idealized love or religious topics. These, which include (among others) "La Martina" (an adaptation of the romance "La Esposa Infiel") and "La Delgadina", show the same basic stylistic features of the later mainstream corridos (1/2 or 3/4 tempo and verso menor lyric composing, meaning verses of eight or less phonetic syllables, grouped in strophes of six or fewer verses). Soy Zapatista Del Estado De Morelos - Corrido Zapatista Soy zapatista del Edo. de Morelos (I'm a Zapatista from the State of Morelos), an example of a southern corrido written during the Mexican Revolution about the war, written by Marciano Silva [es]. Beginning with the Mexican War of Independence (1810–1821) and culminating during the Mexican Revolution (1910–1921), the genre flourished and acquired its "epic" tones, along with the three-step narrative structure as described above.  A contemporary corrido song sheet of "La cucaracha" issued during the Mexican Revolution. Note the original lyrics and the reference to cartoncitos, a scrip issued as pay. Some corridos are love stories. These are not exclusively male; there are also corridos about women, such as La Venganza de Maria, Laurita Garza, El Corrido de Rosita Alvirez and La Adelita, or couples, such as La Fama de la Pareja sung by Los Tigres del Norte. Some even employ fictional stories invented by their composers. Before the widespread use of radio, popular corridos were passed around as an oral tradition, often to spread the news of events (for example, La cárcel de Cananea) and famous heroes and humour to the population, many of whom were illiterate before the post-Revolution improvements to the educational system. The academic study of corridos written during the Revolution shows that they were used to communicate news throughout Mexico as a response to the propaganda being spread in the newspapers, which the corrupt government of Porfirio Díaz owned. Sheet music of popular corridos was sold or included in publications. Other corrido sheets were passed out free as a form of propaganda to eulogize leaders, armies, and political movements or, in some cases, to mock the opposition. The best-known Revolutionary corrido is "La Cucaracha", an old song rephrased to celebrate the exploits of Pancho Villa's army and poke fun at his nemesis Victoriano Huerta. With the consolidation of "Presidencialismo" (the political era following the Mexican Revolution) and the success of electronic mass media, the corrido lost its primacy as a mass communication form, becoming part of a folklorist cult in one branch and, in another, the voice of the new subversives: oppressed workers, drug growers or traffickers, leftist activists and emigrated farm workers (mainly to the United States). Scholars designate this as the "decaying" stage of the genre, which tends to erase the stylistic or structural characteristics of "revolutionary" or traditional corrido without a clear and unified understanding of its evolution. This is mainly signified by the "narcocorrido", many of which are egocentric ballads paid for by drug smugglers to anonymous and almost illiterate composers, but with others coming from the most popular norteño and banda artists and written by some of the most successful and influential ranchera composers. 1. La Cucaracha  Song about the battle of Ciudad Juarez title Toma de Ciudad Juárez In the Mestizo-Mexican cultural area, the three variants of corrido (romance, revolutionary and modern) are both alive and sung, along with popular sister narrative genres, such as the "valona" of Michoacán state, the "son arribeño" of the Sierra Gorda (Guanajuato, Hidalgo and Querétaro states) and others. Its vitality and flexibility allow original corrido lyrics to be built on non-Mexican musical genres, such as blues and ska, or with non-Spanish lyrics, like the famous song El Paso by Marty Robbins, and corridos composed or translated by Mexican indigenous communities or by the "Chicano" people in the United States, in English or "Spanglish". The corrido was, for example, a favourite device employed by the Teatro Campesino led by Luis Valdez in mobilizing predominantly Mexican and Mexican-American farmworkers in California during the 1960s. Corridos have seen a renaissance in the 21st century. Contemporary corridos feature contemporary themes such as drug trafficking (narcocorridos), immigration, migrant labour and even the chupacabra.[6] |

歴史[編集] 1915年、メキシコ革命の真っ只中に作られたコリドの楽譜の一例。 コリードはメキシコおよびメキシコ系アメリカ人の文化において重要な役割を担っている。その名前はスペイン語のcorrer(「走る」)に由来する。典型 的なコリードの公式は、8つの音節を含む4~6行からなる8つの四分音符である[4]。メキシコにおけるコリードの歴史は古く、1810年のメキシコ独立 戦争から始まり、メキシコ革命の間ずっと続いた[5]。電子マスメディアの登場と成功(20世紀半ば)までは、コリードはメキシコにおいて、破壊的な目的 を持っていたとしても、口承伝達に適した明白な言語的・音楽的単純さによって、主要な情報発信・教育手段として機能していた。ラジオとテレビの普及後、こ のジャンルは新たな段階へと進化し、現在もなお成熟の途上にある。しかし、近年では、コリドは死語、あるいは衰退したと考える学者もいる(例えば、 Vicente T. Mendoza,El corrido mexicano, 1954を参照)。スペインとメキシコの文化が孤立して保存されている地方では、ロマンスはコリドに関連する他の形態も取っている。例えば、ニューメキシ コでは、植民地時代にインディタと呼ばれる物語歌が生まれた。これは、コリドの形式を大まかに踏襲しているが、ネイティブ・アメリカンの詠唱に似ているた め、歌うのではなく、詠唱される。 コリードの最も古い現存する見本は、スペインのロマンスやヨーロッパの物語を脚色したもので、主に不名誉な恋や理想化された恋、宗教的なテーマが題材と なっている。ラ・マルティーナ」(ロマンス「ラ・エスポサ・インフィエル」の翻案)や「ラ・デルガディーナ」などがその例で、後に主流となるコリードの基 本的な様式(1/2または3/4テンポ、ヴェルソ・メノール作詞、つまり8音節以下の節を6節以下のストローフにまとめたもの)と同じ特徴を示している。 Soy Zapatista Del Estado De Morelos - Corrido Zapatista Soy zapatista del Edo. de Morelos(私は モレロス 州の サパティスタ)」は、メキシコ革命時に書かれた南部のコリドの一例で、戦争について書かれたもので、マルシアーノ・シルバ[es]によって書かれた。 メキシコ独立戦争(1810年~1821年)に始まり、メキシコ革命(1910年~1921年)に至るまで、このジャンルは繁栄し、上記のような3段階の 物語構造とともに、「叙事詩」の色合いを獲得した。  メキシコ革命時に発行された "La cucaracha "のコリード歌譜。オリジナルの歌詞と、カルトンシトス(給与として発行される小切手)への言及に注目。 コリードの中にはラブストーリーもある。ラ・ヴェンガンサ・デ・マリア」、「ラウリータ・ガルサ」、「エル・コリド・デ・ロシータ・アルビレス」、「ラ・ アデリータ」のような女性についてのコリドや、ロス・ティグレス・デル・ノルテが歌う「ラ・ファマ・デ・ラ・パレハ」のようなカップルについてのコリドも ある。中には、作曲者が創作した架空の物語を使ったものさえある。 ラジオが普及する以前は、ポピュラーなコリードは口承として語り継がれ、革命後に教育制度が改善されるまでは読み書きのできない人々が多かった国民に、事 件(例えば、La cárcel de Cananea)や有名な英雄やユーモアのニュースを広めるために使われることが多かった。革命時に書かれたコリードスの学術的研究によると、コリードス は、腐敗したポルフィリオ・ディアス政権が所有していた新聞に流されたプロパガンダに対抗して、メキシコ全土にニュースを伝えるために使われた。ポピュ ラーなコリドの楽譜は販売されたり、出版物に掲載されたりした。その他のコリードの楽譜は、指導者、軍隊、政治運動を賛美するプロパガンダとして、あるい は場合によっては反対派をあざ笑うために、無料で配られた。最も有名な革命コリドは「ラ・クカラチャ」で、パンチョ・ビジャの軍隊の功績を讃え、宿敵ビク トリアーノ・ウエルタをからかうために古い歌を言い換えたものである。 プレジデンシアリスモ」(メキシコ革命後の政治的時代)の定着と電子マスメディアの成功によって、コリドはマス・コミュニケーションとしての優位性を失 い、ある分野では民俗学的カルトの一部となり、また別の分野では、新しい破壊活動家たち(抑圧された労働者、麻薬栽培者や密売人、左翼活動家、(主にアメ リカに)移住した農民労働者)の代弁者となった。学者たちは、これをこのジャンルの「衰退」段階と呼び、その進化を明確かつ統一的に理解することなく、 「革命的」あるいは伝統的なコリドの様式的あるいは構造的特徴を消し去る傾向にある。これは主に"ナルココリド"に象徴されるもので、その多くは麻薬密輸 業者から無名のほとんど文盲の作曲家に支払われたエゴセントリックなバラードだが、最も人気のあるノルテーニョや バンダのアーティストから生まれたものや、最も成功し影響力のあるランチェーラの作曲家によって書かれたものもある。 1. ラ・クカラチャ  シウダー・フアレスの戦いについての歌 タイトルToma de Ciudad Juárez メスティーソ=メキシコ文化圏では、ミチョアカン州の"バローナ"、シエラゴルダ(グアナファト州、イダルゴ州、ケレタロ州)の"ソンアリベーニョ"など のポピュラーな姉妹物語ジャンルと共に、コリードの3つのバリエーション(ロマンス、革命、現代)が生きて歌われている。その活力と柔軟性により、ブルー スや スカのような非メキシコ音楽ジャンルや、マーティー・ロビンスの有名な歌「エル・パソ」のような非スペイン語歌詞、メキシコ先住民コミュニティや米国の 「チカーノ」たちが英語または「スパングリッシュ」で作曲または翻訳したコリドのオリジナル歌詞を作ることができる。例えば、コリドは、1960年代、ル イス・バルデス率いるテアトロ・カンペシーノが、主にメキシコ系、メキシコ系アメリカ人の農民を動員するために、カリフォルニアで好んで使用された。 コリドスは21世紀にルネッサンスを迎えた。現代のコリドスは、麻薬密売(ナルココリドス)、移民、移民労働、さらにはチュパカブラといった現代的なテー マを特徴としている[6]。 |

| Subcategories Narcocorridos Main article: Narcocorrido Modern artists have created a modern twist to the historical corridos. This new type of corridos is called narcocorridos ("drug ballads").[7] The earliest form of corridos emerged in the Mexican Revolution and told stories of revolutionary leaders and battles. Narcocorridos typically use accurate dates and places to tell mainly stories of drug smuggling, including violence, murder, poverty, corruption, and crime.[8] The border zone of Rio Grande has been credited with being the birthplace of narcocorridos. This began in the 1960s with the fast growth of drug empires in the border states of Mexico and the United States.[9] As drug lords grew in influence, people idolized them and began to show their respect and admiration through narcocorridos.[9] There are two main types of narcocorridos: commercial corridos and private corridos. Commercial narcocorridos are recorded by famous artists who idolize a specific drug dealer and release a song about him, while the drug dealer usually commissions private narcocorridos.[10] While commercial corridos are available to the public, private narcocorridos are restricted to nightclubs that are frequently attended by drug dealers or through CDs bought on the street. Drug lords often pay singers to write songs about them to send a message to rivals. These songs are found to be most popular on YouTube; many have a banner "Approved by the cartel". These types of corridos are changing from the formula historical and typical corridos would usually take. A first-person voice is now being sung instead of the historic third-person point of view.[11] The Mexican government has tried to ban narcocorridos because of their explicit and controversial lyrics. Most of the Mexican public argues that crimes and violence are to blame for narcocorridos.[12] However, despite the efforts of the Mexican government to ban narcocorridos, the northern states of Mexico can still get access to these songs through US radio stations whose signal still reaches the conditions of the north of Mexico. Narcocorridos are also widely available on websites like YouTube and iHeartRadio. Today, narcocorridos are popular in Latin American countries like Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, Guatemala and Honduras.[13] Narcocorridos has grown in popularity in the United States, and the American public has targeted them. More recent narcocorridos are even targeted towards the American people; some are even written in English. Like many artists, narcocorrido singers have chosen American cities to perform concerts because the American public can buy concert tickets for a higher price than the average Mexican citizen.[14] Corridos tumbados "Corridos tumbados" or "trap corridos" are corrido ballads influenced by hip hop and Latin trap. Largely popularized by Natanael Cano, the idea to fuse the two genres was proposed by Dan Sanchez, who wrote Natanael's first corrido tumbado, "Soy El Diablo", which later saw a remix featuring popular reggaeton and trap rapper Bad Bunny. Other prominent artists include Peso Pluma, Fuerza Regida and Junior H. Many corrido tumbado artists cite Ariel Camacho as one of their main influences.[15] Since 2023, this subgenre of corridos saw a major boom on the mainstream scene all around the world, with popular artists appearing on songs. These artists include Eladio Carrión, Myke Towers and Argentinian producer Bizarrap, who released a music session with Peso Pluma, which became a major hit. As corridos tumbados became popular around the world, major artists from the American hip-hop scene like Drake, Travis Scott and Lil Baby have been seen with acts from corridos tumbados. In Mexico, the genre has been controversial for some lyrics pertaining to "violent themes" including drug criminals.[16] |

サブカテゴリー[編集] ナルココリドス[編集] 主な記事 ナルココリド 現代のアーティストたちは、歴史的なコリドスに現代的なひねりを加えている。この新しいタイプのコリドスはナルココリドス(「麻薬バラード」)と呼ばれる [7]。コリドスの最も初期の形態はメキシコ革命で生まれ、革命指導者や戦いの物語を語っていた。ナルココリドスは通常、正確な日付と場所を用いて、暴 力、殺人、貧困、汚職、犯罪など、主に麻薬密輸の物語を語る[8]。 リオグランデの 国境地帯は、ナルココリド発祥の地とされている。これは1960年代にメキシコとアメリカの国境州で麻薬帝国が急成長したことに始まる[9]。麻薬王が影 響力を増すにつれて、人々は彼らを偶像化し、ナルココリドスを通じて敬意と賞賛を示すようになった[9]。 ナルココリドスには大きく分けて商業的なコリドスと私的なコリドスの2種類がある。商業的なナルココリドスは、特定の麻薬ディーラーを偶像化し、彼につい ての歌をリリースする有名なアーティストによって録音され、麻薬ディーラーは通常、私的なナルココリドスを依頼する[10]。商業的なコリドスが一般に入 手可能であるのに対し、私的なナルココリドスは、麻薬ディーラーが頻繁に通うナイトクラブに限定されるか、路上で購入したCDを通じて入手される。麻薬王 はしばしば、ライバルにメッセージを送るため、歌手に金を払って自分たちのことを歌にする。これらの曲はユーチューブで最も人気があり、その多くには「カルテル公認」というバナーがついている。このようなタイプのコリードは、歴史的で典型的なコリードの定型から変わりつつある。歴史的な三人称視点ではなく、一人称の声が歌われるようになっている[11]。 メキシコ政府は、その露骨で物議を醸す歌詞のために、ナルココリドスを禁止しようとしてきた。メキシコ国民の大半は、犯罪と暴力がナルココリドのせいだと 主張している[12]。しかし、メキシコ政府がナルココリドスを禁止しようと努力しているにもかかわらず、メキシコ北部の州は、メキシコ北部の状況にまだ 電波が届いているアメリカのラジオ局を通じて、これらの歌を聴くことができる。ナルココリドはYouTubeやiHeartRadioのようなウェブサイ トでも広く聴くことができる。今日、ナルココリドスはボリビア、コロンビア、ペルー、グアテマラ、ホンジュラスといったラテンアメリカ諸国で人気がある [13]。 ナルココリドスはアメリカでも人気が高まっており、アメリカ国民はナルココリドスをターゲットにしている。最近のナルココリドは、アメリカ国民をターゲッ トにしたものさえあり、英語で書かれたものさえある。多くのアーティストがそうであるように、ナルコドリド歌手もアメリカの都市を選んでコンサートを開い ている。 コリドス・トゥンバドス[編集] 「コリドス・トゥンバドス」または「トラップ・コリドス」は、ヒップホップや ラテン・トラップの影響を受けたコリド・バラードである。この2つのジャンルを融合させるというアイデアは、ナタネル・カノによって大々的に広められた が、ナタネルの最初のコリドス・トゥンバド「Soy El Diablo」を書いたダン・サンチェスによって提案された。他の著名なアーティストには、Peso Pluma、Fuerza Regida、Junior Hなどがいる。多くのコリド・トゥンバド・アーティストは、アリエル・カマーチョを主な影響を受けたアーティストの一人として挙げている[15]。 2023年以降、このコリドのサブジャンルは世界中のメインストリームで大ブームを巻き起こし、人気アーティストが楽曲に登場するようになった。これらの アーティストには、エラディオ・カリオン、マイケ・タワーズ、アルゼンチン人プロデューサーのビザラップが含まれ、彼はペソ・プルマとの音楽セッションを リリースし、大ヒットとなった。コリドス・トゥンバドスが世界中で人気を博すにつれ、ドレイク、トラヴィス・スコット、リル・ベイビーといったアメリカ ン・ヒップホップ・シーンの主要アーティストがコリドス・トゥンバドスのアーティストと共演するようになった。メキシコでは、このジャンルは麻薬犯罪者を 含む「暴力的なテーマ」に関わる歌詞があるとして物議を醸している[16]。 |

| Gregorio Cortez Gregorio Cortez was a Mexican man born on a ranch near Matamoros, Mexico, in 1875, as the "seventh child to a family of eight."[17] Cortez, his parents, and his eight siblings moved to Manor, Texas, in 1887. In 1889, Cortez joined his older brother, Ronaldo, in Karnes County, near Gonzales, Texas. They both worked for farmers as ranch hands and farmhands. They even worked as vaqueros. In 1900, Gregorio and Romaldo went to settle down and married. They were "inseparable". On June 12, 1901, sheriff W.T. Morris came to Cortez and Román to investigate a horse theft. Even though Cortez and Román were innocent, they spoke Spanish, and the Sheriff did not. Sheriff Morris relied on poor Spanish translations from his fellow Texas Rangers. Cortez and Romaldo got confused and played along. The Sheriff was looking for a horse thief and asked if they traded a horse. Gregorio said "no" and told the Sheriff he had a mare.[18] After a while, Sheriff Morris assumed Gregorio and Romaldo were lying and framed them for a crime they did not commit. However, when the Sheriff tried to arrest the brothers, Gregorio stood up to him, saying "You can't arrest me for nothing". The Sheriff did not understand his Spanish and thought he said, "No white man can arrest me". The Sherriff got out his pistol and shot Ronaldo, wounding him. Gregorio shot the Sheriff in retaliation. However, Gregorio left the scene and headed straight towards the Austin-Gonzales vicinity.[19] Cortez walked eighty miles daily through rugged terrain to get to the border. All the while, Texas Rangers were following him, and he even killed the Gonzales sheriff Robert M. Glover, who led the charge. Gregorio walked 100 miles to meet a friend, Ceferino Flores, who gave him a saddle. Cortez eventually got a horse to ride 400 miles to the border. Gregorio landed at the Abran de la Garza sheep camp on June 22, 1901, where he started to talk with a man named Jesús González. González, however, led the rangers to find Cortez, and the rangers arrested him.[20] Many Tejanos would brand González a traitor, and he would eventually be known as El Teco.[21] Cortez was later put on trial. A formal letter was written and signed by the Mexicans of Mexico City and the president of Mexico, who gave him money to help fund his claim. Subsequently, Gregorio was sentenced to life imprisonment for murder and the supposed theft of a horse. However, he was freed after a year. This verdict was a "victory" for Mexican Americans and the unfair treatment of Mexican Americans. His name became immortalized, and his story became a corrido, where Cortez was portrayed as a hero. Ballad The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez is a corrido that is well known by Mexican Americans who live near the Rio Grande border between the United States and Mexico. It tells the story of a Mexican man named Gregorio Cortez, who takes up a pistol to defend his rights against 33 Texas Rangers from June 12 to June 22, 1901. The story of Gregorio Cortez was made into a corrido, and he would become a folk hero among people on the Texas-Mexico Border. Cortez, a Mexican man with a kind heart and a diligent work ethic, was described as "a man who never raised his voice to the parent or elder brother and never disobeyed."[22] Most of the story is no different from his real life, but the report calls him a sharpshooter, and his brother Romaldo was renamed Román. Sheriff Morris had Román and Cortez questioned about the horses. Instead of Romaldo being wounded, his counterpart Román was shot dead trying to protect his brother and collapsed on the ground. However, Gregorio got a gun and shot the sheriff to avenge his brother. The story fantasizes Gregorio as being a non-disabled man who ran across the country with the Texas Rangers on his tail. The story tells that Gregorio walked 100 miles and rode more than 400 miles. Gregorio walked and walked until he reached the Rio Grande. However, as Gregorio arrived in Goliad, Texas, he met with his friend named "El Teco". However, El Teco betrayed him and turned him in to the police. The police arrested Gregorio and put him on trial, and Gregorio was sentenced to "ninety-nine years and a day" in federal prison for horse theft, despite never stealing a horse.[23] Impact The story of Gregorio Cortez is a testament to the culture of Mexican-Americans who live in the southwest United States and Mexican American culture in general. His tale was later made into a corrido and passed on from person to person. Cortez ended up becoming a folk hero, and it helped inspire stories of heroism and told the "spirit of the border strife." Many people called Cortez a hero because his biography and the corrido both involved him running away from the rinches, or Texas Rangers. He kept evading them until his capture. This gave Mexican-Americans a Hispanic hero who defended his rights from American "outsiders".[24] Both the story and the corrido tell how Gregorio Cortez was strong because he stood up to a legal system that did not favour Mexican Americans and became a hero to people of Mexican descent in Texas.[25] The corrido has been adapted to other media as well. In 1958, Américo Paredes wrote the book With His Pistol in His Hand: A Border Ballad and Its Hero. This book details the corrido and the story of Gregorio Cortes in detail. It has become a "classic of Mexican-American prose." In 1982, a film titled The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez was created, and Edward James Olmos starred as Gregorio Cortez.[26] |

グレゴリオ・コルテス[編集] グレゴリオ・コルテスは1875年、メキシコのマタモロス近郊の牧場で「8人家族の7番目の子供」として生まれたメキシコ人男性であった[17]。 1887年、コルテスは両親と8人の兄弟とともにテキサス州マナーに移り住んだ。1889年、コルテスはテキサス州ゴンザレス近郊のカルネス郡で兄のロナ ウドと一緒になった。ふたりは牧場労働者や農場労働者として農家で働いた。2人はバケロスとしても働いた。1900年、グレゴリオとロマルドは定住し、結 婚した。二人は「切っても切れない」関係だった。 1901年6月12日、保安官W.T.モリスが馬の盗難事件の捜査のためにコルテスとロマンのもとを訪れた。コルテスとロマンは無実であったにもかかわら ず、彼らはスペイン語を話し、保安官はスペイン語を話さなかった。モリス保安官は、仲間のテキサス・レンジャーの下手なスペイン語翻訳に頼っていた。コル テスとロマンは混乱し、その場しのぎをした。保安官は馬泥棒を探していて、馬を取引したのかと尋ねた。しばらくして、モリス保安官はグレゴリオとロマルド が嘘をついていると思い込み、やってもいない犯罪の濡れ衣を着せた[18]。 しかし、保安官が兄弟を逮捕しようとしたとき、グレゴリオは彼に立ち向かい、「何もしないで逮捕することはできない」と言った。保安官は彼のスペイン語が 理解できず、彼が「白人は私を逮捕できない」と言ったのだと思った。保安官はピストルを取り出し、ロナウドを撃って負傷させた。グレゴリオは報復として保 安官を撃った。しかし、グレゴリオはその場を去り、そのままオースティン・ゴンザレス近辺に向かった[19]。 コルテスは険しい地形を毎日80マイル歩いて国境に向かった。その間、テキサスレンジャーが彼を尾行し、突撃を指揮したゴンザレス保安官ロバート・M・グ ローバーさえ殺害した。グレゴリオは100マイル歩いて友人のセフェリーノ・フローレスに会い、彼から鞍をもらった。コルテスはやがて馬を手に入れ、国境 まで400マイルを走った。1901年6月22日、グレゴリオはアブラン・デ・ラ・ガルサの羊キャンプに上陸し、そこでヘスス・ゴンサレスという男と話を 始めた。しかしゴンサレスはレンジャーにコルテスを発見させ、レンジャーは彼を逮捕した[20]。多くのテハノ人はゴンサレスを裏切り者と決めつけ、彼は やがてエル・テコとして知られるようになる[21]。 コルテスは後に裁判にかけられた。正式な手紙が書かれ、メキシコ・シティのメキシコ人とメキシコ大統領によって署名され、メキシコ大統領は彼の主張のため の資金を彼に与えた。その後、グレゴリオは殺人と馬の窃盗の罪で終身刑を言い渡された。しかし、1年後に釈放された。この判決は、メキシコ系アメリカ人に 対する不当な扱いに対する「勝利」であった。彼の名前は不朽のものとなり、彼の物語はコルテスが英雄として描かれるコリドとなった。 バラード[編集] グレゴリオ・コルテスのバラード(The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez)は、米国と メキシコのリオ・グランデ国境付近に住むメキシコ系アメリカ人によく知られているコリドである。1901年6月12日から6月22日まで、33人のテキサ ス・レンジャーから自分の権利を守るためにピストルを手にしたグレゴリオ・コルテスというメキシコ人男性の物語である。 グレゴリオ・コルテスの物語はコリドになり、彼はテキサスとメキシコの国境の人々の間でフォーク・ヒーローとなる。 心優しく勤勉なメキシコ人であるコルテスは、「親や兄に声を荒げることなく、決して逆らわない男」と評された[22]。物語のほとんどは彼の実生活と変わらないが、報告書では彼を狙撃手と呼び、弟のロマルドはロマンと改名された。 モリス保安官はロマンとコルテスに馬について尋問させた。ロマルドが負傷したのではなく、相方のロマンが弟を守ろうとして射殺され、地面に倒れたのだ。し かしグレゴリオは銃を手にし、兄の仇を討つために保安官を射殺した。物語は、グレゴリオがテキサスレンジャーに追われながら国を横断した、障害を持たない 男であると空想する。物語は、グレゴリオは100マイル歩き、400マイル以上走ったと語る。グレゴリオはリオ・グランデに着くまで歩き続けた。しかし、 テキサス州ゴリアッドに到着したグレゴリオは、「エル・テコ」という名の友人と出会った。しかし、エル・テコは彼を裏切り、警察に突き出した。警察はグレ ゴリオを逮捕して裁判にかけ、グレゴリオは馬を盗んだことがないにもかかわらず、馬の窃盗の罪で連邦刑務所に「99年と1日」の刑を言い渡された [23]。 影響[編集] グレゴリオ・コルテスの物語は、アメリカ南西部に住むメキシコ系アメリカ人の文化、そしてメキシコ系アメリカ人の文化全般を物語るものである。彼の物語は 後にコリドとなり、人から人へと語り継がれた。コルテスは結局、民衆の英雄となり、英雄譚を鼓舞し、"国境闘争の精神 "を語るのに役立った。多くの人々がコルテスを英雄と呼んだのは、彼の伝記とコリドがともにリンチ(テキサス・レンジャー)から逃げ回るという内容だった からだ。コルテスは捕まるまでレンジャーから逃げ続けた。これによってメキシコ系アメリカ人は、アメリカ人の「よそ者」から自分の権利を守るヒスパニック 系のヒーローを得た[24]。 この物語とコリードは、メキシコ系アメリカ人を優遇しない法制度に立ち向かったグレゴリオ・コルテスがいかに強く、テキサスのメキシコ系アメリカ人のヒーローとなったかを語っている[25]。 コリードは他のメディアにも転用されている。1958年、アメリコ・パレデスは『With His Pistol in His Hand』という本を書いた: A Border Ballad and Its Hero』という本を書いた。この本には、コリードの詳細とグレゴリオ・コルテスの物語が詳しく書かれている。この本は "メキシコ系アメリカ人の散文の古典 "となった。1982年には『The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez』というタイトルの映画が制作され、エドワード・ジェームズ・オルモスがグレゴリオ・コルテス役で主演した[26]。 |

| Form Corridos, like rancheras, have introductory instrumental music and adornos (ornamentations), accommodating the stanzas of the lyrics. Like rancheras, corridos can be played in virtually all regional Mexican styles. Also, like rancheras, corridos are usually played in polka, waltz, or mazurka mode.[citation needed] Films 2006 - Al Otro Lado (To the Other Side). Directed by Natalia Almada.[clarification needed] 2007 - El Violin (The Violin) Directed by Francisco Vargas. 2008 - El chrysler 300: Chuy y Mauricio Directed by Enrique Murillo. 2009 - El Katch (The Katch) Directed by Oscar Lopez. |

形式[編集] コリードスは、ランチェーラと同様に、序奏的な器楽曲と、歌詞のスタンザに対応したアドルノ(装飾)がある。ランチェーラと同様、コリードスも メキシコのほぼすべての地域のスタイルで演奏することができる。また、ランチェーラと同様に、コリードは通常ポルカ、ワルツ、マズルカ・モードで演奏され る[要出典]。 映画[編集] 2006年 - 『アル・オトロ・ラド』(To the Other Side)。監督はナタリア・アルマダ[要出典]。 2007 -El Violinフランシスコ・バルガス監督作品。 2008 -El chrysler 300: Chuy y Mauricio監督:エンリケ・ムリージョ。 2009 -エル・カッチ(The Katch) 監督:オスカー・ロペス |

| Tambora Sinaloense Duranguense |

タンボラ・シナロエンセ デュラングェンセ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corrido |

|

| Ranchera

(pronounced [ranˈtʃeɾa]) or canción ranchera is a genre of traditional

music of Mexico. It dates to before the years of the Mexican

Revolution. Rancheras today are played in the vast majority of regional

Mexican music styles. Drawing on rural traditional folk music, the

ranchera developed as a symbol of a new national consciousness in

reaction to the aristocratic tastes of the period.[citation needed] |

ラ

ンチェラ(Ranchera、発音[ranˈtɾa])またはカンシオン・ランチェラは、メキシコの伝統音楽のジャンルである。その起源はメキシコ革命以

前に遡る。今日、ランチェーラはメキシコの地方音楽の大半で演奏されている。ランチェーラは、農村の伝統的な民族音楽を基にして、当時の貴族の嗜好に反発

する新しい国民意識の象徴として発展した[要出典]。 |

| Definitions José Alfredo Jiménez' tomb in Dolores Hidalgo, Guanajuato, attracts visitors from around the world. The word ranchera was derived from the word rancho because the songs originated on the ranches and in the countryside of rural Mexico. Lola Beltrán and Aida Cuevas 1976 Traditional themes in rancheras are about love, heartbreak, patriotism or nature. Rhythms can have a meter in 2 4 (in slow tempo: ranchera lenta and faster tempo: ranchera marcha), 3 4 (ranchera vals), or 4 4 (bolero ranchero).[citation needed] Songs are usually in a major key, and consist of an instrumental introduction, verse and refrain, instrumental section repeating the verse, and another verse and refrain, with a tag ending. Rancheras are also noted for the grito mexicano, a yell that is done at musical interludes within a song, either by the musicians and/or the listening audience.[citation needed] Miguel Aceves Mejía The normal musical pattern of rancheras is a–b–a–b. Rancheras usually begin with an instrumental introduction (a). The first lyrical portion then begins (b), with instrumental adornments interrupting the lines in between. The instruments then repeat the theme again, and then the lyrics may either be repeated or begin a new set of words. One also finds the form a–b–a–b–c–b used, in which the intro (a) is played, followed by the verse (b). This form is repeated, and then a refrain (c) is added, ending with the verse.[citation needed] The most popular ranchera composers include Lucha Reyes, Cuco Sánchez, Antonio Aguilar, Juan Gabriel and José Alfredo Jiménez, who composed many of the best-known rancheras, with compositions totaling more than 1,000 songs, making him one of the most prolific songwriters in the history of western music.[citation needed] Another closely related style of music is the corrido, which is often played by the same ensembles that regularly play rancheras. The corrido, however, is apt to be an epic story about heroes and villains, or the narrator's lifestyle.[citation needed] |

定義[編集] グアナファト州ドローレス・イダルゴにあるホセ・アルフレド・ヒメネスの墓には、世界中から観光客が訪れる。 ランチェラの語源は、メキシコの牧場や田園地帯で生まれた歌であることから、ランチョと呼ばれるようになった。 ロラ・ベルトランと アイーダ・クエバス1976年 ランチェーラの伝統的なテーマは、愛、失恋、愛国心、自然などである。 リズムは2 4(遅いテンポ:ランチェラ・レンタ、速いテンポ:ランチェラ・マルカ)、3 4(ランチェラ・バルス)、または4 4(ボレロ・ランチェロ)である[要出典]。 曲は通常、長調で、楽器の序奏、詩とリフレイン、詩を繰り返す楽器の部分、別の詩とリフレインで構成され、タグで終わる。また、ランチェーラは、グリト・ メヒカーノ(grito mexicano)と呼ばれる、ミュージシャンや聴衆が曲の間奏で行う雄叫びでも知られている[要出典]。 ミゲル・アセベス・メヒア ランチェーラの通常の音楽パターンはa-b-a-bである。通常、ランチェーラは楽器のイントロ(a)で始まる。その後、最初の叙情的な部分が始まり (b)、その間に楽器の装飾が挿入される。その後、楽器が再び主題を繰り返し、歌詞が繰り返されるか、新しい言葉が始まる。また、a-b-a-b-c-b という形式もあり、イントロ(a)が演奏され、その後に詩(b)が続く。この形式が繰り返された後、リフレイン(c)が追加され、詩で終わる[要出典]。 最も人気のあるランチェーラの作曲家には、ルチャ・レイエス、クコ・サンチェス、アントニオ・アギラール、フアン・ガブリエル、ホセ・アルフレッド・ヒメ ネスなどがいる。彼は最も有名なランチェーラの多くを作曲し、作曲した曲の総数は1,000曲を超え、西部音楽の歴史の中で最も多作な作曲家の一人となっ た[要出典]。 もう1つの密接に関連した音楽スタイルにコリドがあり、これはランチェラを定期的に演奏するのと同じアンサンブルによって演奏されることが多い。しかし、コリードは英雄と悪人、あるいは語り手のライフスタイルについての壮大な物語になりがちである[要出典]。 |

| Rocío Dúrcal La Prieta Linda Vicente Fernández |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ranchera |

★

JOSÉ ALFREDO JIMÉNEZ ÉXITOS SUS MEJORES RANCHERAS - 30 GRANDES ÉXITOS ROMANTICOS.

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆