資本主義批判

Criticism of capitalism

★資本主義は、生産手段の私的所有を基盤とする経済システムである。これは一般的に、利益の道徳 的許容性、自由貿易、資本の蓄積、自発的な交換、賃金労働な どを含むものと解釈されている。現代の資本主義は、16世紀から18世紀にかけてイギリスで農業社会から発展し、ヨーロッパ各地で重商主義的実践を経て形 成された。18世紀の産業革命は、工場と複雑な分業を特徴とする資本主義を主要な生産方法として確立した。その出現、進化、普及は、広範な研究と議論の対 象となっている(→「資本主義」)。

☆資本主義に対する批判(Criticism of

capitalism)

は、資本主義の特定の側面や結果に対する反対意見から、資本主義システムの原則そのものを全面的に否定するものまで多岐にわたる。批判は、アナキスト、社

会主義者、宗教的、ナショナリストの立場を含む多様な政治的・哲学的アプローチから提起されている。一部の人々は、資本主義は革命を通じてのみ克服できる

と主張する一方、他の人々[誰?]は、政治改革を通じて徐々に構造改革が実現可能だと考えている。一部の批判者は、資本主義には長所があると認めつつ、政

府規制(例:社会市場主義)を通じた何らかの社会的なコントロールでバランスを取るべきだと主張している。

資本主義に対する批判の中でも特に目立つのは、資本主義は本質的に搾取的、疎外的、不安定、持続不可能であり、大規模な経済的不平等を生み出し、人民を商

品化し、反民主的であり、人権と国民主権の侵食を招きながら帝国主義的拡大と戦争を促進し、少数派の利益を多数派の犠牲の上に築くという指摘だ。環境科学

者や活動家、左派、デグロース[脱成長]派など[誰?]からは、資源の枯渇、気候変動、生物多様性の喪失、表土の喪失、富栄養化、大量の汚染物質と廃棄物の発生を引き起こすとの批判もある。

| Criticism of

capitalism typically ranges from expressing disagreement with

particular aspects or outcomes of capitalism to rejecting the

principles of the capitalist system in its entirety.[1] Criticism comes

from various political and philosophical approaches, including

anarchist, socialist, religious, and nationalist viewpoints. Some

believe that capitalism can only be overcome through revolution while

others[who?] believe that structural change can come slowly through

political reforms. Some critics believe there are merits in capitalism

and wish to balance it with some form of social control, typically

through government regulation (e.g. the social market movement). Prominent among critiques of capitalism are accusations that capitalism is inherently exploitative, alienating, unstable, unsustainable, and creates massive economic inequality, commodifies people, is anti-democratic, leads to an erosion of human rights and national sovereignty while it incentivises imperialist expansion and war, and that it benefits a small minority at the expense of the majority of the population. There are also criticisms from environmental scientists and activists, leftists, degrowthers and others[who?], that it depletes resources, causes climate change, biodiversity loss, topsoil loss, eutrophication, and generates massive amounts of pollution and waste. |

資本主義に対する批判は、資本主義の特定の側面や結果に対する反対意見

から、資本主義システムの原則そのものを全面的に否定するものまで多岐にわたる。批判は、アナキスト、社会主義者、宗教的、ナショナリストの立場を含む多

様な政治的・哲学的アプローチから提起されている。一部の人々は、資本主義は革命を通じてのみ克服できると主張する一方、他の人々[誰?]は、政治改革を

通じて徐々に構造改革が実現可能だと考えている。一部の批判者は、資本主義には長所があると認めつつ、政府規制(例:社会市場主義)を通じた何らかの社会

的なコントロールでバランスを取るべきだと主張している。 資本主義に対する批判の中でも特に目立つのは、資本主義は本質的に搾取的、疎外的、不安定、持続不可能であり、大規模な経済的不平等を生み出し、人民を商 品化し、反民主的であり、人権と国民主権の侵食を招きながら帝国主義的拡大と戦争を促進し、少数派の利益を多数派の犠牲の上に築くという指摘だ。環境科学 者や活動家、左派、デグロース[脱成長]派など[誰?]からは、資源の枯渇、気候変動、生物多様性の喪失、表土の喪失、富栄養化、大量の汚染物質と廃棄物の発生を引 き起こすとの批判もある。 |

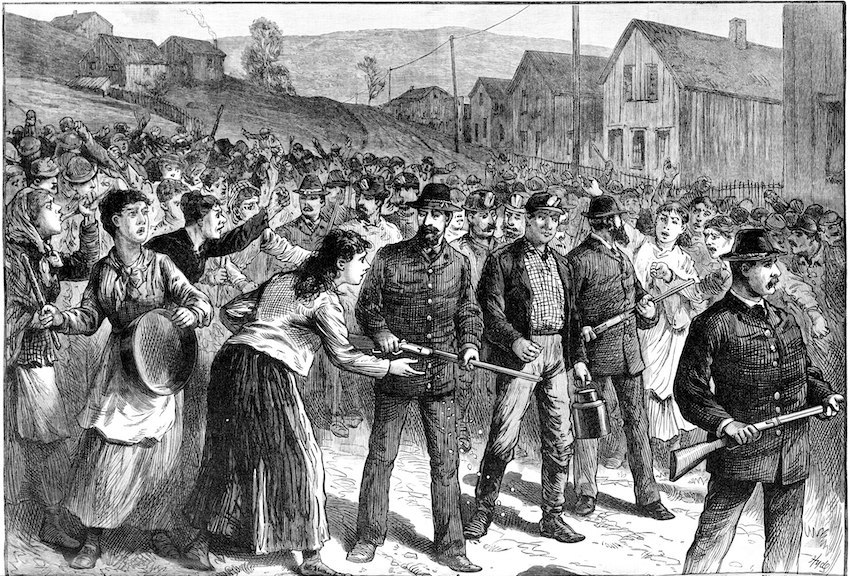

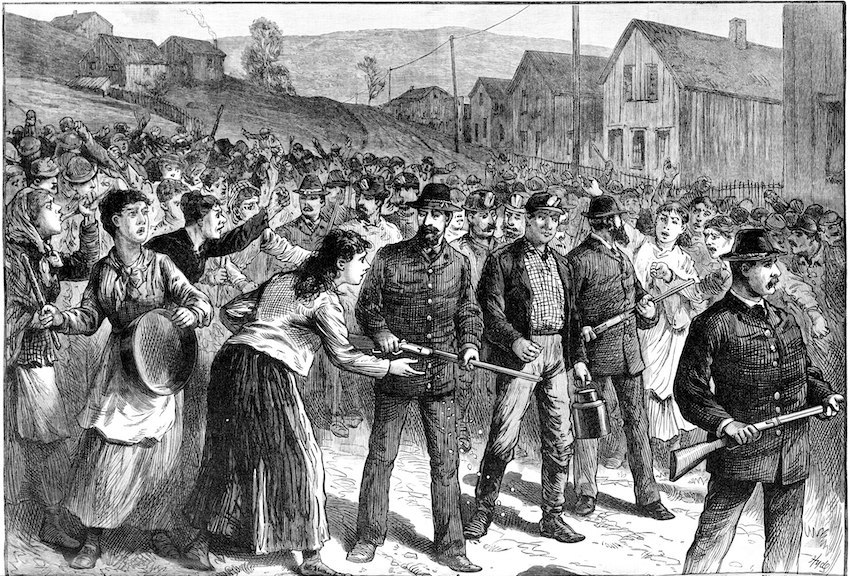

| History Early critics of capitalism, such as Friedrich Engels, claim that rapid industrialization in Europe created working conditions viewed as unfair, including 14-hour work days, child labor and shanty towns.[2] Some modern economists argue that average living standards did not improve, or only very slowly improved, before 1840.[3] |

歴史 フリードリヒ・エンゲルスなどの資本主義の初期批判者は、ヨーロッパにおける急速な工業化により、14時間の労働時間、児童労働、スラム街など、不公正と みなされる労働条件が生まれたと主張している[2]。一部の現代経済学者たちは、1840年以前は平均的な生活水準は向上しなかった、あるいはごくゆっく りとしか向上しなかったと主張している[3]。 |

| Criticism by different schools of thought Anarchism See also: Anarchism and Libertarian socialism French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon opposed government privilege that protects capitalist, banking and land interests and the accumulation or acquisition of property (and any form of coercion that led to it) which he believed hampers competition and keeps wealth in the hands of the few. The Spanish individualist anarchist Miguel Giménez Igualada sees "capitalism is an effect of government; the disappearance of government means capitalism falls from its pedestal vertiginously ... That which we call capitalism is not something else but a product of the State, within which the only thing that is being pushed forward is profit, good or badly acquired. And so to fight against capitalism is a pointless task, since be it State capitalism or Enterprise capitalism, as long as Government exists, exploiting capital will exist. The fight, but of consciousness, is against the State".[4] Within anarchism, there emerged a critique of wage slavery which refers to a situation perceived as quasi-voluntary slavery,[citation needed] where a person's livelihood depends on wages, especially when the dependence is total and immediate.[5][6] It is a negatively connoted term used to draw an analogy between slavery and wage labor by focusing on similarities between owning and renting a person. The term "wage slavery" has been used to criticize economic exploitation and social stratification, with the former seen primarily as unequal bargaining power between labor and capital (particularly when workers are paid comparatively low wages, e.g. in sweatshops)[7] and the latter as a lack of workers' self-management, fulfilling job choices and leisure in an economy.[8][9] Libertarian socialists believe if freedom is valued, then society must work towards a system in which individuals have the power to decide economic issues along with political issues. Libertarian socialists seek to replace unjustified authority with direct democracy, voluntary federation and popular autonomy in all aspects of life,[10] including physical communities and economic enterprises. With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, thinkers such as Proudhon and Marx elaborated the comparison between wage labor and slavery in the context of a critique of societal property not intended for active personal use,[11] Luddites emphasized the dehumanization brought about by machines while later Emma Goldman famously denounced wage slavery by saying: "The only difference is that you are hired slaves instead of block slaves".[12] American anarchist Emma Goldman believed that the economic system of capitalism was incompatible with human liberty. "The only demand that property recognizes", she wrote in Anarchism and Other Essays, "is its own gluttonous appetite for greater wealth, because wealth means power; the power to subdue, to crush, to exploit, the power to enslave, to outrage, to degrade".[13] She also argued that capitalism dehumanized workers, "turning the producer into a mere particle of a machine, with less will and decision than his master of steel and iron".[13] Noam Chomsky contends that there is little moral difference between chattel slavery and renting one's self to an owner or "wage slavery". He feels that it is an attack on personal integrity that undermines individual freedom. He holds that workers should own and control their workplace.[8] Many libertarian socialists argue that large-scale voluntary associations should manage industrial manufacture while workers retain rights to the individual products of their labor.[14] As such, they see a distinction between the concepts of "private property" and "personal possession". Whereas "private property" grants an individual exclusive control over a thing whether it is in use or not and regardless of its productive capacity, "possession" grants no rights to things that are not in use.[15] In addition to anarchist Benjamin Tucker's "big four" monopolies (land, money, tariffs and patents) that have emerged under capitalism, neo-mutualist economist Kevin Carson argues that the state has also transferred wealth to the wealthy by subsidizing organizational centralization in the form of transportation and communication subsidies. He believes that Tucker overlooked this issue due to Tucker's focus on individual market transactions, whereas Carson also focuses on organizational issues. The theoretical sections of Studies in Mutualist Political Economy are presented as an attempt to integrate marginalist critiques into the labor theory of value.[16] Carson has also been highly critical of intellectual property.[17] The primary focus of his most recent work has been decentralized manufacturing and the informal and household economies.[18] Carson holds that "[c]apitalism, arising as a new class society directly from the old class society of the Middle Ages, was founded on an act of robbery as massive as the earlier feudal conquest of the land. It has been sustained to the present by continual state intervention to protect its system of privilege without which its survival is unimaginable".[19] Carson coined the pejorative term "vulgar libertarianism", a phrase that describes the use of a free market rhetoric in defense of corporate capitalism and economic inequality. According to Carson, the term is derived from the phrase "vulgar political economy", which Karl Marx described as an economic order that "deliberately becomes increasingly apologetic and makes strenuous attempts to talk out of existence the ideas which contain the contradictions [existing in economic life]".[20] |

異なる思想による批判 アナキズム 関連項目:アナキズム、リバタリアン社会主義 フランスのアナキスト、ピエール・ジョゼフ・プルードンは、資本家、銀行、土地の利益、および財産の蓄積や取得(およびそれに至るあらゆる形態の強制)を 保護する政府の特権に反対し、それが競争を阻害し、富を少数の手に集中させる要因だと考えていました。スペインの個人主義的アナキスト、ミゲル・ヒメネ ス・イグアラダは、「資本主義は政府の効果である。政府が消滅すれば、資本主義は台座から急落する……私たちが資本主義と呼ぶものは、国家の産物に他なら ず、その中で推進されているのは、正当か不正かに関わらず、利益のみである」と述べた。したがって、資本主義と戦うことは無意味な任務だ。国家資本主義で あれ企業資本主義であれ、政府が存在するかぎり、搾取的な資本は存在し続けるからだ。戦うべきは、意識の戦いであり、国家に対してだ」。[4] アナキズムの中には、賃金奴隷制に対する批判が生まれた。これは、特にその依存が完全かつ直接的な場合、人格の生計が賃金に依存している状況を、準自発的 な奴隷制とみなすものである[要出典]。これは、人格を所有することと人格を借りることの類似点に焦点を当て、奴隷制と賃金労働を類推するために使用され る、否定的な意味合いの用語だ。「賃金奴隷制」という用語は、経済的搾取と社会的階層化を批判するために用いられてきた。前者は主に労働者と資本の間の不 平等な交渉力(特に労働者が比較的に低い賃金で支払われる場合、例えば sweat shops など)[7]、後者は労働者の自己管理、職業選択の自由、余暇の充足を欠く経済システムを指す。[9] リバタリアン社会主義者は、自由が重視されるならば、社会は、個人が政治問題とともに経済問題も決定する権限を持つシステムに向けて努力しなければならな いと信じている。リバタリアン社会主義者は、物理的なコミュニティや経済企業を含む生活のあらゆる側面において、不当な権威を直接民主主義、自発的な連邦 制、および民衆の自治に置き換えることを目指している[10]。産業革命の到来と共に、プロウドンやマルクスは、人格的な使用を目的としない社会的財産に 対する批判の文脈で、賃金労働と奴隷制の比較を詳細に論じた[11]。ラッド派は機械による人間性の喪失を強調し、のちにエマ・ゴールドマンは賃金奴隷制 を次のように非難した:「異なる点は、あなたが雇われた奴隷であるか、ブロック奴隷であるかだ」[12] アメリカのアナキスト、エマ・ゴールドマンは、資本主義の経済システムは人間の自由と相容れないと信じていた。「財産が認める唯一の要求は」、彼女は『ア ナキズムとその他のエッセイ』で書いた。「より大きな富への貪欲な欲望だ。なぜなら富は力だからだ。抑圧し、破壊し、搾取する力、奴隷化し、冒涜し、堕落 させる力だ」。[13] 彼女はまた、資本主義は労働者を非人間化し、「生産者を機械の単なる部品に変え、鋼鉄の主人よりも意志や判断力が少ない存在にする」と主張した。[13] ノーム・チョムスキーは、奴隷制と、所有者に自分自身を貸す「賃金奴隷制」との間に道徳的な違いはほとんど異なる、と主張している。彼は、これは個人の自 由を損なう、人格に対する攻撃であると感じている。彼は、労働者は自分の職場を所有し、管理すべきだと主張している。[8] 多くのリバタリアン社会主義者は、大規模な自主的な団体が工業生産を管理し、労働者は自分の労働の成果に対する権利を保持すべきだと主張している。 [14] そのため、彼らは「私有財産」と「人格所有」の概念に区別を見出している。「私有財産」は、物が使用中か否か、生産能力の有無にかかわらず、人格に排他的 支配権を付与するが、「所有」は使用されていない物に対しては権利を付与しない。[15] 資本主義下で台頭したアナキストのベンジャミン・タッカーの「四大独占」(土地、貨幣、関税、特許)に加え、新相互主義経済学者のケビン・カーソンは、国 家が交通や通信の補助金を通じて組織の集中化を補助することで、富を富裕層に移転してきたと主張している。カーソンは、タッカーが個人間の市場取引に焦点 を当てたためこの問題を見落としたと指摘し、自身は組織の問題にも焦点を当てていると述べている。『相互主義的政治経済学の研究』の理論的章は、限界主義 的批判を労働価値説に統合しようとする試みとして提示されている。[16] カーソンは知的財産権に対しても強く批判的だ。[17] 彼の最近の研究の主な焦点は、分散型製造と非公式経済・家庭経済にある。[18] カーソンは、「資本主義は、中世の旧階級社会から直接生まれた新しい階級社会として、土地の封建的征服に匹敵する大規模な略奪行為に基づいて成立した。そ の特権制度を保護するための継続的な国家介入によって現在まで維持されてきた。その特権制度がなければ、資本主義の存続は想像できない」と主張している。 [19] カーソンは、企業資本主義と経済的不平等を擁護するために自由市場論を悪用することを指す蔑称「下品な自由主義」という用語を考案した。カーソンによる と、この用語はカール・マルクスが「経済秩序が、経済生活に存在する矛盾を含む思想を否定するために、意図的にますます弁解的になり、その存在を否定しよ うとする激しい努力を重ねる」と説明した「俗流政治経済学」という表現から派生した。 |

| Conservatism and traditionalism See also: Conservatism and Traditionalist conservatism In Conservatives Against Capitalism, Peter Kolozi relies on Norberto Bobbio's definition of right and left, dividing the two camps according to their preference for equality or hierarchy. Kolozi argued that capitalism has faced persistent criticism from the right since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Such critics, while heterogeneous, are united in the belief “that laissez-faire capitalism has undermined an established social hierarchy governed by the virtuous or excellent".[21] In September 2018, Murtaza Hussain wrote in The Intercept about "Conservatives Against Capitalism", stating: For all their differences, there is one key aspect of the intellectual history charted in "Conservatives Against Capitalism" that deals with an issue of shared concern on both the left and the right: the need for community. One of the grim consequences of the Social Darwinian pressures unleashed by free-market capitalism has been the destruction of networks of community, family, and professional associations in developed societies. ... These so-called intermediate institutions have historically played a vital role giving ordinary people a sense of meaning and protecting them from the structural violence of the state and the market. Their loss has led to the creation of a huge class of atomized and lonely people, cut adrift from traditional sources of support and left alone to contend with the power of impersonal economic forces.[22] In June 2023, Bridget Ryder wrote in The European Conservative about the degrowth movement, stating:[23] The capitalist-critical conservative, however, sees possibilities for technological progress and personal freedoms that lie beyond market-driven economics, finding inspiration in European traditions that have been supplanted by industrialisation. Despite the gains in efficiency made within capitalism, many conservatives remain sceptical of the possibility of endless economic growth, particularly given that God is infinite and his creatures, including petroleum and other minerals, are not. |

保守主義と伝統主義 関連項目:保守主義、伝統主義的保守主義 『Conservatives Against Capitalism』の中で、ピーター・コロジは、ノルベルト・ボッビオの「右」と「左」の定義に基づき、平等主義と階層主義のどちらを好むかによって 2 つの陣営を分類している。コロジは、資本主義は産業革命以来、右派から絶え間ない批判にさらされてきたと主張している。こうした批判者は、その構成は多様 であるものの、「自由放任主義の資本主義は、高潔または優れた者によって支配される確立された社会階層を損なった」という信念で結束している。[21] 2018年9月、ムルタザ・フセインは『The Intercept』誌に「資本主義に反対する保守派」という記事を掲載し、次のように述べている。 さまざまな異なる点はあるものの、「資本主義に反対する保守派」で描かれている知的歴史には、左派と右派が共通して関心を持つ問題、すなわちコミュニティ の必要性という重要な側面がある。自由市場資本主義によって解き放たれた社会ダーウィニズムの圧力による悲惨な結果のひとつは、先進社会におけるコミュニ ティ、家族、職業団体などのネットワークの破壊だ。... これらのいわゆる中間機関は、歴史的に、一般の人民に意味を与え、国家や市場の構造的暴力から彼らを守る上で重要な役割を果たしてきた。これらの喪失は、 伝統的な支援源から切り離され、非人間的な経済力の力に対峙するしかなくなった、孤立した孤独な人民の巨大な階級の誕生につながった。[22] 2023年6月、ブリジット・ライダーは『The European Conservative』誌で、脱成長運動について次のように述べている。[23] しかし、資本主義を批判する保守派は、市場主導の経済を超えた技術進歩と人格の自由の可能性を見出し、工業化によって置き換えられたヨーロッパの伝統から インスピレーションを得ている。資本主義の中で効率が向上したにもかかわらず、多くの保守派は、神は無限であり、石油やその他の鉱物を含む神の創造物は無 限ではないことを考えると、経済が無限に成長し続ける可能性に懐疑的だ。 |

| Fascism See also: Economics of fascism, Fascism, and Fascism and ideology Fascists opposed both international socialism and free-market capitalism, arguing that their views represented a Third Position[24] and claiming to provide a realistic economic alternative that was neither laissez-faire capitalism nor communism.[25] They favored corporatism and class collaboration, believing that the existence of inequality and social hierarchy was natural (contrary to the views of socialists)[26][27] while also arguing that the state had a role in mediating relations between classes (contrary to the views of economic liberals).[28] Liberalism See also: History of liberalism and Liberalism During the Age of Enlightenment, some proponents of liberalism were critics of wage slavery.[29][30] However, classical liberalism itself was very much an ideology of capitalism, supporting the free market and laissez-faire. |

ファシズム 関連項目:ファシズムの経済学、ファシズム、ファシズムとイデオロギー ファシストたちは、国際社会主義と自由市場資本主義の両方に反対し、自分たちの見解は「第三の立場」[24] を代表するものであり、自由放任主義の資本主義でも共産主義でもない現実的な経済代替案を提供すると主張した。[25] 彼らはコーポラティズムと階級協調を支持し、不平等や社会階層の存在は自然なものだと考えていた(社会主義者の見解とは対照的)[26][27]。同時 に、国家は階級間の関係を仲介する役割があるとも主張した(経済自由主義者の見解とは対照的)。[28] 自由主義 参照:自由主義の歴史、自由主義 啓蒙時代、自由主義の支持者の中には、賃金奴隷制を批判する者もいた[29][30]。しかし、古典的自由主義自体は、自由市場と自由放任主義を支持する、まさに資本主義のイデオロギーだった。 |

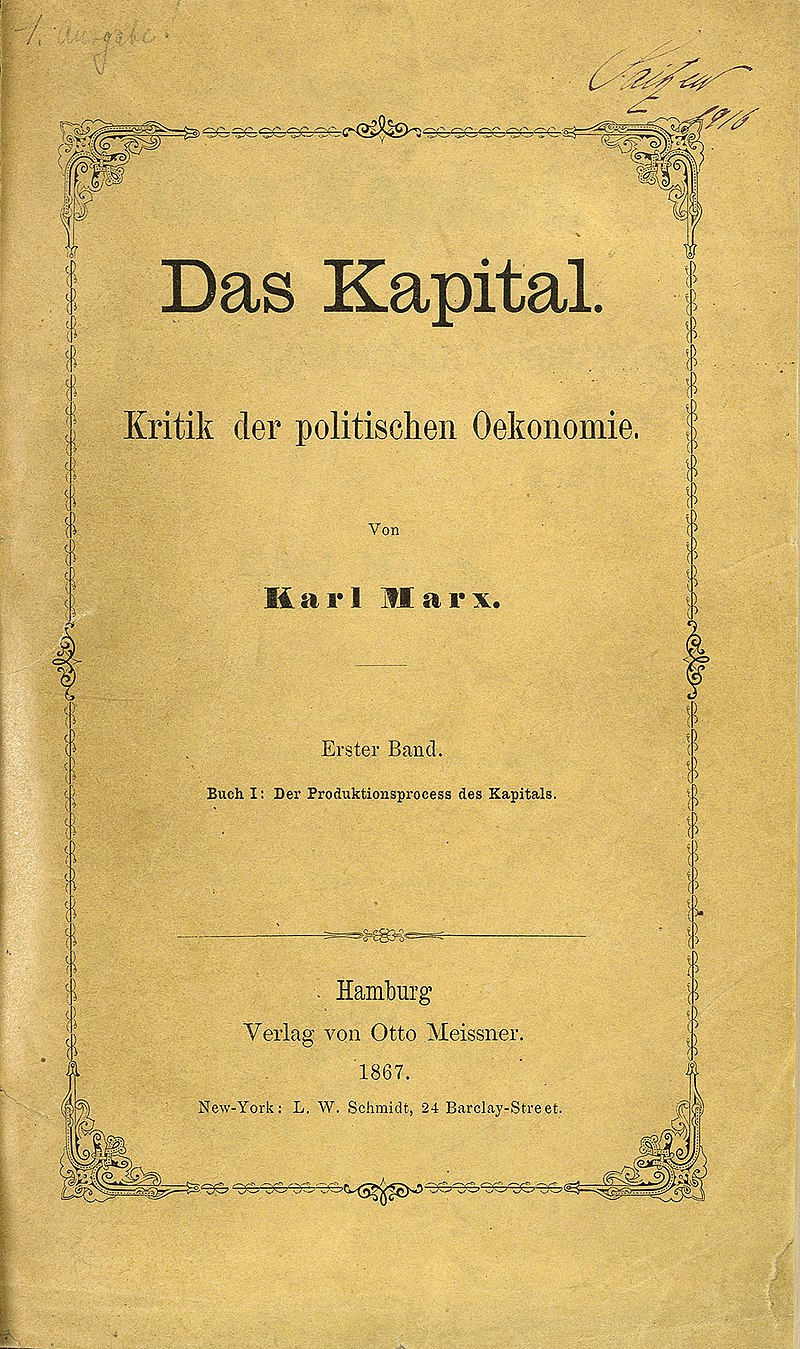

| Marxism Main articles: Critique of political economy § Marx's critique of political economy, and Marxian economics Karl Marx considered capitalism to be a historically specific mode of production (the way in which the productive property is owned and controlled, combined with the corresponding social relations between individuals based on their connection with the process of production).[citation needed] The "capitalistic era" according to Marx dates from 16th-century merchants and small urban workshops.[31] Marx knew that wage labour existed on a modest scale for centuries before capitalist industry. For Marx, the capitalist stage of development or "bourgeois society" represented the most advanced form of social organization to date, but he also thought that the working classes would come to power in a worldwide socialist or communist transformation of human society as the end of the series of first aristocratic, then capitalist and finally working class rule was reached.[32][33] Following Adam Smith, Marx distinguished the use value of commodities from their exchange value in the market. According to Marx, capital is created with the purchase of commodities for the purpose of creating new commodities with an exchange value higher than the sum of the original purchases. For Marx, the use of labor power had itself become a commodity under capitalism and the exchange value of labor power, as reflected in the wage, is less than the value it produces for the capitalist. This difference in values, he argues, constitutes surplus value, which the capitalists extract and accumulate. In his book Capital, Marx argues that the capitalist mode of production is distinguished by how the owners of capital extract this surplus from workers—all prior class societies had extracted surplus labor, but capitalism was new in doing so via the sale-value of produced commodities.[34] He argues that a core requirement of a capitalist society is that a large portion of the population must not possess sources of self-sustenance that would allow them to be independent and are instead forced to sell their labor for a wage.[35][36][37] In conjunction with his criticism of capitalism was Marx's belief that the working class, due to its relationship to the means of production and numerical superiority under capitalism, would be the driving force behind the socialist revolution.[38] In Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916), Vladimir Lenin further developed Marxist theory and argued that capitalism necessarily led to monopoly capitalism and the export of capital—which he also called "imperialism"—to find new markets and resources, representing the last and highest stage of capitalism.[39] Some 20th-century Marxian economists consider capitalism to be a social formation where capitalist class processes dominate, but are not exclusive.[40] To these thinkers, capitalist class processes are simply those in which surplus labor takes the form of surplus value, usable as capital; other tendencies for utilization of labor nonetheless exist simultaneously in existing societies where capitalist processes predominate. However, other late Marxian thinkers argue that a social formation as a whole may be classed as capitalist if capitalism is the mode by which a surplus is extracted, even if this surplus is not produced by capitalist activity as when an absolute majority of the population is engaged in non-capitalist economic activity.[41] In Limits to Capital (1982), David Harvey outlines an overdetermined, "spatially restless" capitalism coupled with the spatiality of crisis formation and resolution.[42] Harvey used Marx's theory of crisis to aid his argument that capitalism must have its "fixes", but that we cannot predetermine what fixes will be implemented, nor in what form they will be. His work on contractions of capital accumulation and international movements of capitalist modes of production and money flows has been influential.[43] According to Harvey, capitalism creates the conditions for volatile and geographically uneven development.[44] Sociologists such as Ulrich Beck envisioned the society of risk as a new cultural value which saw risk as a commodity to be exchanged in globalized economies. This theory suggested that disasters and capitalist economy were inevitably entwined. Disasters allow the introduction of economic programs which otherwise would be rejected as well as decentralizing the class structure in production.[45] |

マルクス主義 主な記事:政治経済批判 § マルクスの政治経済批判、およびマルクス経済学カール・マルクスは、資本主義を歴史的に特定の生産様式(生産財の所有と支配の方法、および生産過程との関連に基づく個人間の対応する社会関係)とみなした。[要出典] マルクスによると、「資本主義時代」は 16 世紀の商人や小規模な都市の工房から始まった。[31] マルクスは、資本主義産業が登場する何世紀も前から、小規模ながら賃金労働が存在していたことを知っていた。マルクスにとって、資本主義の発展段階または 「ブルジョア社会」は、当時までに到達した最も高度な社会組織形態だったが、彼はまた、貴族支配、資本主義支配、そして最終的に労働者階級支配の連鎖が終 焉を迎えた際に、労働者階級が世界的な社会主義または共産主義への変革を通じて権力を掌握すると考えていた。[32][33] アダム・スミスに倣い、マルクスは商品の使用価値と市場における交換価値を区別した。マルクスによると、資本は、元の購入額の合計を超える交換価値を持つ 新たな商品を生み出す目的で商品を購入することで創造される。マルクスにとって、労働力の使用そのものが資本主義下で商品となり、賃金に反映される労働力 の交換価値は、資本家が生産する価値よりも低い。 この価値の差は、剰余価値を構成すると彼は主張する。資本家はこれを搾取し蓄積するとされる。マルクスは『資本論』において、資本主義的生産方式は、資本 の所有者が労働者からこの剰余を搾取する方法によって特徴付けられると論じている。すべての以前の階級社会は剰余労働を搾取してきたが、資本主義は生産さ れた商品の販売価値を通じてこれを行う点で新しかった。[34] 彼は、資本主義社会の基本的な要件として、人口の大部分が自己維持の手段を所有せず、独立して生活できず、賃金で労働力を売ることを余儀なくされる状態が 必須であると主張している。[35][36][37] 資本主義に対する批判と関連して、マルクスは、生産手段との関係と資本主義下での数的な優位性から、労働者階級が社会主義革命の原動力になると信じていた。[38] 『資本主義の最高段階としての帝国主義』(1916年)において、ウラジーミル・レーニンはマルクス主義理論をさらに発展させ、資本主義は必然的に独占資 本主義と資本の輸出(彼も「帝国主義」と呼んだ)へと至り、新たな市場と資源を求めることで、資本主義の最終的かつ最高段階を表すと主張した。[39] 20 世紀のマルクス主義経済学者の中には、資本主義を、資本主義階級プロセスが支配的ではあるが、排他的ではない社会形成とみなす者もいる。[40] これらの思想家たちにとって、資本主義階級プロセスとは、余剰労働が資本として利用できる余剰価値の形をとるプロセスにすぎない。しかし、資本主義プロセ スが支配的な既存の社会には、労働力を利用するための他の傾向も同時に存在している。しかし、他の後期のマルクス主義思想家は、社会形成全体が資本主義と 分類されるのは、資本主義が剰余を抽出する方式である場合であり、たとえその剰余が資本主義的活動によって生産されていない場合でも、例えば人口の絶対的 多数が非資本主義的経済活動に従事している場合でも、と主張している。[41] 『資本の限界』(1982年)で、デビッド・ハーヴェイは、危機の形成と解決の空間性とともに、過度に決定された「空間的に不安定な」資本主義の概要を述 べている。[42] ハーヴェイはマルクスの危機理論を用いて、資本主義には「修正」が必要だが、その修正がどのような形で実施されるかは事前に決定できないと主張した。彼の 資本蓄積の収縮と資本主義的生産様式および資金の流れの国際的移動に関する研究は影響力がある。[43] ハーヴェイによると、資本主義は変動的で地理的に不均衡な発展の条件を生み出す。[44] ウルリッヒ・ベックなどの社会学者たちは、リスクをグローバル化した経済の中で交換される商品と捉える、リスク社会を新しい文化的価値として構想した。こ の理論は、災害と資本主義経済は必然的に絡み合っていることを示唆している。災害は、そうでなければ拒否されるような経済政策の導入を可能にし、生産にお ける階級構造を分散化させる。[45] |

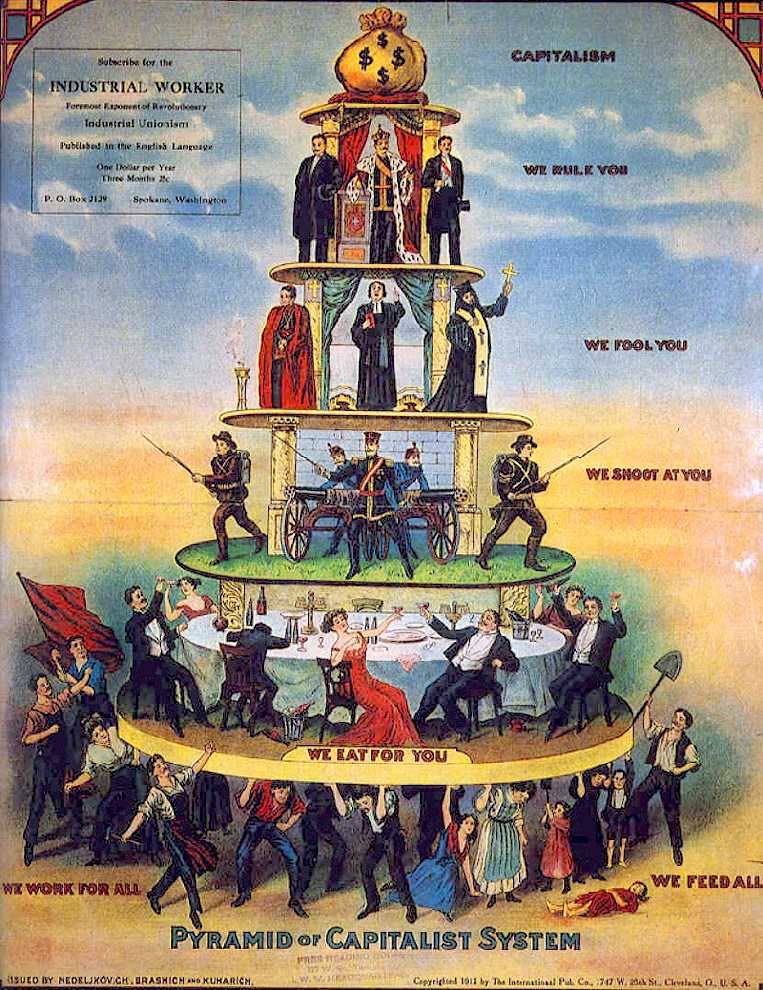

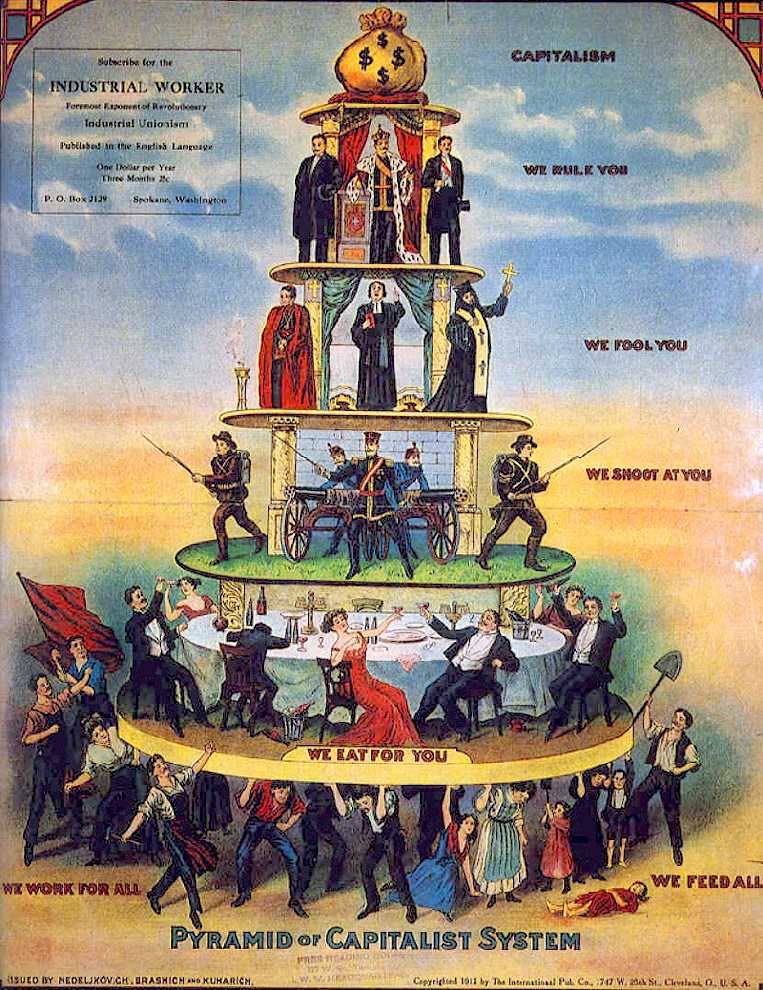

The "Pyramid of Capitalist System" cartoon made by the Industrial Workers of the World (1911) is an example of a socialist critique of capitalism and of social stratification. |

世界産業労働者組合(1911年)が制作した「資本主義システムのピラミッド」という漫画は、資本主義と社会階層に対する社会主義的な批判の例です。 |

| Religion See also: Christian communism, Christian left, Christian socialism, Islamic socialism, Jewish left, Liberation theology, Religious communism, and Social Gospel Many organized religions have criticized or opposed specific elements of capitalism. Traditional Judaism, Christianity, and Islam forbid lending money at interest,[46][47] although alternative methods of banking have been developed. Some Christians have criticized capitalism for its materialist aspects and its inability to account for the wellbeing of all people.[48] Many of Jesus' parables deal with economic concerns: farming, shepherding, being in debt, doing hard labor, being excluded from banquets and the houses of the rich and have implications for wealth and power distribution.[49][50] Catholic scholars and clergy have often criticized capitalism because of its disenfranchisement of the poor, often promoting distributism as an alternative. In his 84-page apostolic exhortation Evangelii gaudium, Catholic Pope Francis described unfettered capitalism as "a new tyranny" and called on world leaders to fight rising poverty and inequality, stating:[51] Some people continue to defend trickle-down theories which assume that economic growth, encouraged by a free market, will inevitably succeed in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness in the world. This opinion, which has never been confirmed by the facts, expresses a crude and naive trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power and in the sacralized workings of the prevailing economic system. Meanwhile, the excluded are still waiting.[52] The Catholic Church forbids usury.[53][54][55] As established by papal encyclicals Rerum Novarum and Quadragesimo Anno, Catholic social teaching does not support unrestricted capitalism, primarily because it is considered part of liberalism and secondly by its nature, which goes against social justice. In 2013, Pope Francis said that more restrictions on the free market were required because the "dictatorship" of the global financial system and the "cult of money" were making people miserable.[56] In his encyclical Laudato si', Pope Francis denounced the role of capitalism in furthering climate change.[57] Islam forbids lending money at interest (riba), the mode of operation of capitalist finance.[58][59] |

宗教 関連項目:キリスト教共産主義、キリスト教左派、キリスト教社会主義、イスラム社会主義、ユダヤ教左派、解放の神学、宗教共産主義、社会福音 多くの組織化された宗教は、資本主義の特定の要素を批判したり反対したりしてきた。伝統的なユダヤ教、キリスト教、イスラム教は、利息付きの金銭の貸し付 けを禁じている[46][47]が、代替的な銀行業務の方法が開発されている。一部のキリスト教徒は、資本主義の物質主義的な側面と、すべての人民の幸福 を説明できない点を批判している。[48] イエスの多くのたとえ話は、農業、牧畜、借金、過酷な労働、宴会や富裕層の自宅からの排除など、経済的な問題を取り上げており、富と権力の分配に関する示 唆を含んでいる。[49][50] カトリックの学者や聖職者は、資本主義が貧しい人々を排除する点で批判し、代替案として分配主義を提唱してきた。カトリック教皇フランシスコは、84ペー ジの使徒的勧告『Evangelii gaudium』で、規制のない資本主義を「新しい独裁」と形容し、世界指導者に貧困と不平等拡大との闘いを呼びかけた。[51] 一部の人々は、自由市場によって促進される経済成長は、必然的に世界により大きな正義と包摂性をもたらすというトリクルダウン理論を依然として擁護してい る。この見解は、事実によって確認されたことはなく、経済権力を持つ者たちの善い意志と、支配的な経済システムの神聖化された働きに対する粗雑でナイーブ な信頼を表している。その間、排除された人々は依然として待ち続けている。[52] カトリック教会は高利貸しを禁じています。[53][54][55] 教皇回勅「レラム・ノヴァラム」および「クアドラゲジモ・アンノ」で確立されているように、カトリックの社会教説は、主にそれが自由主義の一部であるとみ なされることから、そして第二に、その性質が社会正義に反するからです。2013年、フランシスコ教皇は、グローバルな金融システムの「独裁」と「金銭崇 拝」が人々を不幸にしているとして、自由市場に対するさらなる規制が必要だと述べた。[56] 教皇フランシスコは回勅『ラウダート・シ』で、気候変動を助長する資本主義の役割を非難した。[57] イスラム教は、資本主義金融の運営方式である利子付き融資(リバ)を禁じています。[58][59] |

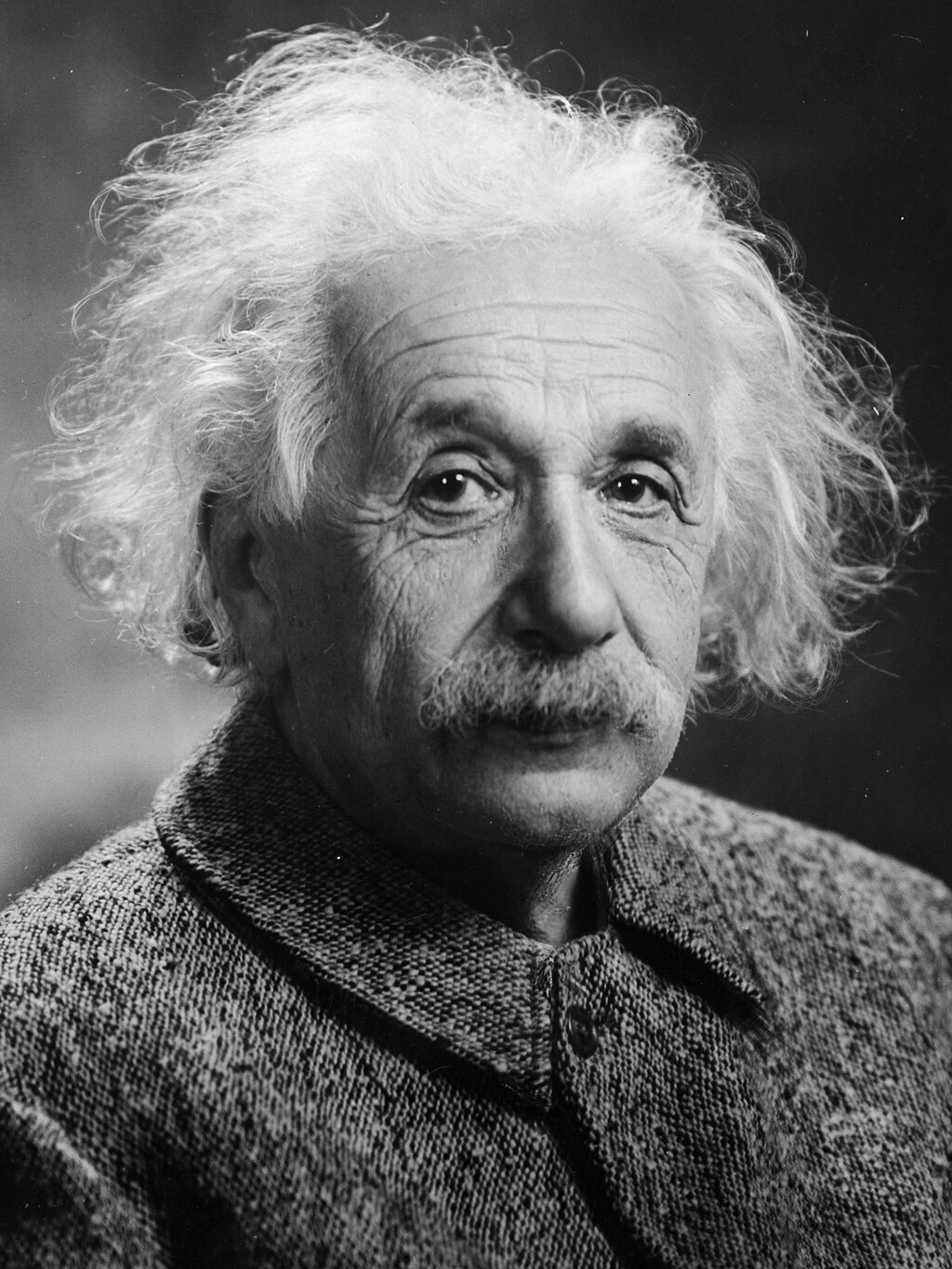

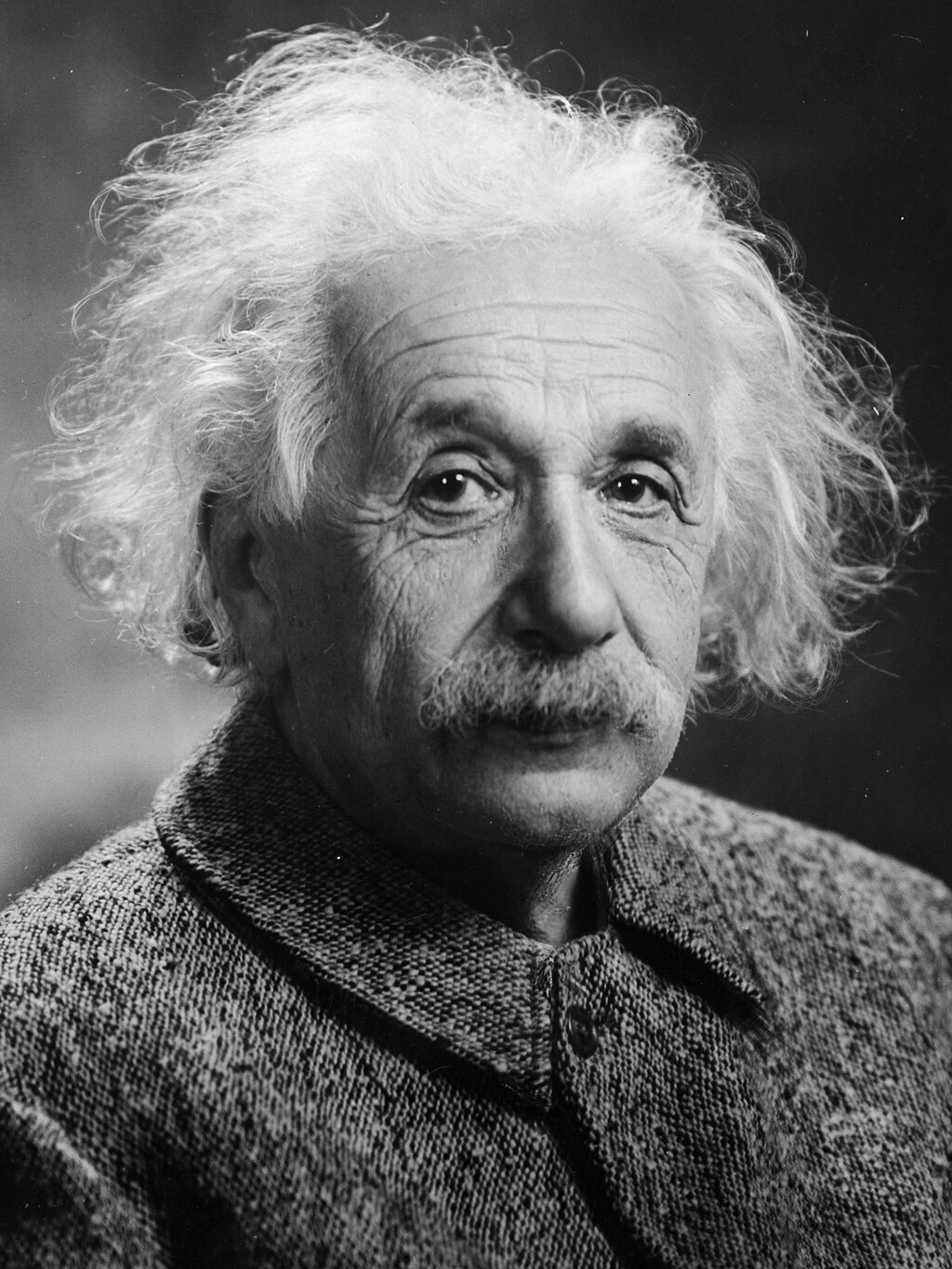

| Socialism Socialists argue that the accumulation of capital generates waste through externalities that require costly corrective regulatory measures. They also point out that this process generates wasteful industries and practices that exist only to generate sufficient demand for products to be sold at a profit (such as high-pressure advertisement), thereby creating rather than satisfying economic demand.[60][61] Socialists argue that capitalism consists of irrational activity, such as the purchasing of commodities only to sell at a later time when their price appreciates (known as speculation), rather than for consumption. Therefore, a crucial criticism often made by socialists is that making money, or accumulation of capital, does not correspond to the satisfaction of demand (the production of use-values).[62] The fundamental criterion for economic activity in capitalism is the accumulation of capital for reinvestment in production. This spurs the development of new, non-productive industries that do not produce use-value and only exist to keep the accumulation process afloat. An example of a non-productive industry is the financial industry, which contributes to the formation of economic bubbles.[63] Socialists view private property relations as limiting the potential of productive forces in the economy. According to socialists, private property becomes obsolete when it concentrates into centralized, socialized institutions based on private appropriation of revenue (but based on cooperative work and internal planning in allocation of inputs) until the role of the capitalist becomes redundant.[64] With no need for capital accumulation and a class of owners, private property of the means of production is perceived as being an outdated form of economic organization that should be replaced by a free association of individuals based on public or common ownership of these socialized assets.[65][66] Private ownership imposes constraints on planning, leading to uncoordinated economic decisions that result in business fluctuations, unemployment and a tremendous waste of material resources during crisis of overproduction.[67] Excessive disparities in income distribution lead to social instability and require costly corrective measures in the form of redistributive taxation. This incurs heavy administrative costs while weakening the incentive to work, inviting dishonesty and increasing the likelihood of tax evasion (the corrective measures) while reducing the overall efficiency of the market economy.[68] These corrective policies limit the market's incentive system by providing things such as minimum wages, unemployment insurance, taxing profits and reducing the reserve army of labor, resulting in reduced incentives for capitalists to invest in more production. In essence, social welfare policies cripple capitalism's incentive system and are thus unsustainable in the long-run.[69] Marxists argue that the establishment of a socialist mode of production is the only way to overcome these deficiencies. Socialists and specifically Marxian socialists, argue that the inherent conflict of interests between the working class and capital prevent optimal use of available human resources and leads to contradictory interest groups (labor and business) striving to influence the state to intervene in the economy at the expense of overall economic efficiency. Early socialists (utopian socialists and Ricardian socialists) criticized capitalism for concentrating power and wealth within a small segment of society[70] who do not utilize available technology and resources to their maximum potential in the interests of the public.[66]  Albert Einstein advocated for a socialist planned economy with his 1949 article "Why Socialism?" In the May 1949 issue of the Monthly Review titled "Why Socialism?", Albert Einstein wrote:[71] I am convinced there is only one way to eliminate (the) grave evils (of capitalism), namely through the establishment of a socialist economy, accompanied by an educational system which would be oriented toward social goals. In such an economy, the means of production are owned by society itself and are utilized in a planned fashion. A planned economy, which adjusts production to the needs of the community, would distribute the work to be done among all those able to work and would guarantee a livelihood to every man, woman, and child. The education of the individual, in addition to promoting his own innate abilities, would attempt to develop in him a sense of responsibility for his fellow-men in place of the glorification of power and success in our present society. |

社会主義 社会主義者は、資本の蓄積は外部性を通じて無駄を生み出し、高額な是正規制措置を必要とするとしている。また、このプロセスは、製品を利益を得るために十 分な需要を生み出すためだけに存在する無駄な産業や慣行(例えば、高圧的な広告)を生み出し、経済需要を満足させるのではなく、むしろ創造していると指摘 している。[60][61] 社会主義者は、資本主義は、消費のためではなく、価格が上昇した時点で売却するために商品を購入する(投機と呼ばれる)などの非合理的な活動で構成されて いると主張している。したがって、社会主義者がしばしば行う重要な批判は、金儲け、すなわち資本の蓄積は、需要の満足(使用価値の生産)には対応していな いというものである。[62] 資本主義における経済活動の根本的な基準は、生産への再投資のための資本の蓄積だ。これは、使用価値を生産せず、蓄積プロセスを維持するためだけに存在す る新しい非生産的産業の発展を促す。非生産的産業の例として、経済バブルの形成に寄与する金融産業が挙げられる。[63] 社会主義者は、私有財産関係は経済における生産力の可能性を制限するものと見なしている。社会主義者によると、私有財産は、資本家の役割が不要になるま で、収益の私的収奪(ただし、投入の配分に関しては協力的な労働と内部計画に基づく)に基づく、中央集権化された社会主義的機関に集中すると、時代遅れに なる。[64] 資本蓄積や所有者階級が不要となった場合、生産手段の私有は、これらの社会化された資産を公共または共有財産とする、個人の自由な連合に取って代わられる べき、時代遅れの経済組織形態であると認識される。[65][66] 私有は計画に制約を課し、経済的な意思決定の連携の乱れを引き起こし、その結果、景気変動、失業、そして過剰生産の危機における膨大な物質的資源の浪費に つながる。[67] 所得分配の過度の格差は、社会不安を引き起こし、再分配的な課税という形で多額の是正措置を必要とする。これは、行政コストを重くする一方で、労働意欲を 低下させ、不正行為を招き、脱税の可能性を高め(是正措置)、市場経済の全体的な効率性を低下させる。[68] これらの是正政策は、最低賃金、失業保険、利益課税、労働予備軍の削減などにより市場のインセンティブシステムを制限し、資本家がより多くの生産に投資す るインセンティブを低下させる。本質的に、社会福祉政策は資本主義のインセンティブシステムを弱体化させ、したがって長期的に持続不可能だ。[69] マルクス主義者は、社会主義的な生産方式の確立が、これらの欠陥を克服する唯一の方法であると主張している。社会主義者、特にマルクス主義社会主義者は、 労働者階級と資本家の間の本質的な利益の対立が、利用可能な人的資源の最適な活用を妨げ、矛盾した利益団体(労働者と企業)が、経済全体の効率を犠牲にし て国家に経済への介入を働きかける結果になると主張している。 初期の社会主義者(ユートピア社会主義者とリカード社会主義者)は、資本主義が権力と富を社会の少数派に集中させ[70]、公共の利益のために利用可能な技術と資源を最大限に活用していないと批判した。[66]  アルバート・アインシュタインは、1949年の記事「なぜ社会主義なのか」で、社会主義の計画経済を提唱した。 1949年5月号の『Monthly Review』誌に掲載された「なぜ社会主義なのか」という記事の中で、アルバート・アインシュタインは次のように書いている。[71] 私は、(資本主義の)深刻な悪を消去法による排除する唯一の方法は、社会目標志向の教育制度を伴う社会主義経済の確立にあると確信している。そのような経 済では、生産手段は社会自体が所有し、計画的に活用される。コミュニティの需要に合わせて生産を調整する計画経済は、働く能力のあるすべての人に仕事を分 配し、すべての男性、女性、子供に生活を保障する。個人の教育は、その個人の先天的な能力の育成を促進するだけでなく、現在の社会における権力と成功の glorification に代わって、他者に対する責任感を育むことを目指す。 |

| Topics of criticism Democracy and freedom Further information: Criticism of the free market Economist Branko Horvat stated that "[I]t is now well known that capitalist development leads to the concentration of capital, employment and power. It is somewhat less known that it leads to the almost complete destruction of economic freedom".[72] Critics argue that capitalism is in fact not a democracy, but a plutocracy, because in capitalism there is a lack of political, democratic and economic power for the vast majority of the population. They say that this is because in capitalism the means of production are owned privately by a minority of the population, with the vast majority of the population having no control of the economy. Critics argue that capitalism creates large concentrations of money and property in the hands of the elite, leading to vast wealth and income inequalities between the elite and the majority of the population.[73] Evidence for the fact that capitalism is plutocratic can be seen in policies that benefit capitalists at the expense of workers, such as policies where taxes are raised on workers and reduced for capitalists, and the retirement age being increased despite it being against the will of the people. "Corporate capitalism" and "inverted totalitarianism" are terms used by the aforementioned activists and critics of capitalism to describe a capitalist marketplace—and society—characterized by the dominance of hierarchical, bureaucratic, large corporations, which are legally required to pursue profit without concern for social welfare. Corporate capitalism has been criticized for the amount of power and influence corporations and large business interest groups have over government policy, including the policies of regulatory agencies and influencing political campaigns. Many social scientists have criticized corporations for failing to act in the interests of the people; they claim the existence of large corporations seems to circumvent the principles of democracy, which assumes equal power relations between all individuals in a society.[74] As part of the political left, activists against corporate power and influence work towards a decreased income gap and improved economical equity.[citation needed] "Capitalism is the astounding belief that the most wickedest of men will do the most wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone". — John Maynard Keynes[75] The rise of giant multinational corporations has been a topic of concern among the aforementioned scholars, intellectuals and activists, who see the large corporation as leading to deep, structural erosion of such basic human rights and civil rights as equitable wealth and income distribution, equitable democratic political and socio-economic power representation and many other human rights and needs. They have pointed out that in their view large corporations create false needs in consumers and—they contend—have had a long history of interference in and distortion of the policies of sovereign nation states through high-priced legal lobbying and other almost always legal, powerful forms of influence peddling. In their view, evidence supporting this belief includes invasive advertising (such as billboards, television ads, adware, spam, telemarketing, child-targeted advertising and guerrilla marketing), massive open or secret corporate political campaign contributions in so-called "democratic" elections, corporatocracy, the revolving door between government and corporations, regulatory capture, "too big to fail" (also known as "too big to jail"), massive taxpayer-provided corporate bailouts, socialism/communism for the very rich and brutal, vicious, Darwinian capitalism for everyone else, and—they claim—seemingly endless global news stories about corporate corruption (Martha Stewart and Enron, among other examples).[citation needed] Anti-corporate-activists express the view that large corporations answer only to large shareholders, giving human rights issues, social justice issues, environmental issues and other issues of high significance to the bottom 99% of the global human population virtually no consideration.[74][76] American political philosopher Jodi Dean says that contemporary economic and financial calamities have dispelled the notion that capitalism is a viable economic system, adding that "the fantasy that democracy exerts a force for economic justice has dissolved as the US government funnels trillions of dollars to banks and European central banks rig national governments and cut social programs to keep themselves afloat."[77] According to Quinn Slobodian, one way capitalism undermines democracy is by "punching holes in the territory of the nation state" to create special economic zones, of which there are 5,400 around the globe, ranging from tax havens to "sites for low-wage production . . . often ringed by barbed wire," that he describes as "zones of exception with different laws and often no democratic oversight."[78][79] David Schweickart wrote: "Ordinary people [in capitalist societies] are deemed competent enough to select their political leaders-but not their bosses. Contemporary capitalism celebrates democracy, yet denies us our democratic rights at precisely the point where they might be utilized most immediately and concretely: at the place where we spend most of the active and alert hours of our adult lives".[80] Thomas Jefferson, one of the founders of the United States, said "I hope we shall crush ... in its birth the aristocracy of our moneyed corporations, which dare already to challenge our government to a trial of strength and bid defiance to the laws of our country".[81] In a 29 April 1938 message to the U. S. Congress, Franklin D. Roosevelt warned that the growth of private power could lead to fascism, arguing that "the liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerate the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than their democratic state itself. That, in its essence, is fascism—ownership of government by an individual, by a group, or by any other controlling private power.[82][83][84] Statistics of the Bureau of Internal Revenue reveal the following figures for 1935: "Ownership of corporate assets: Of all corporations reporting from every part of the Nation, one-tenth of 1 percent of them owned 52 percent of the assets of all of them".[82][84] U. S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower criticized the notion of the confluence of corporate power and de facto fascism[85] and in his 1961 Farewell Address to the Nation brought attention to the "conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry" in the United States[86] and stressed "the need to maintain balance in and among national programs—balance between the private and the public economy, balance between cost and hoped for advantage".[86] In a 1986 debate on Socialism vs Capitalism with John Judis vs Harry Binswanger and John Ridpath, intellectual Christopher Hitchens said: capitalism as a system has coexisted with and in on occasion sponsored feudalism, monarchy, fascism, slavery, apartheid, and under development. It has also been the great engine of progress, development and innovation in a certain few heartland countries. This means that it must be a system studied as a system and not as an idea. Its claims to be the sponsor of freedom are purely contingent. It's good propaganda but it's not very good political science[87] |

批判のテーマ 民主主義と自由 詳細情報:自由市場に対する批判 経済学者ブランコ・ホルヴァットは、「資本主義の発展は、資本、雇用、権力の集中につながることは今ではよく知られている。しかし、それが経済の自由のほぼ完全な破壊につながることは、あまり知られていない」と述べている。[72] 資本主義は、実際には民主主義ではなく、金権政治であるとの批判がある。なぜなら、資本主義では、大多数の国民が政治的、民主的、経済的な権力を持ってい ないからだ。これは、資本主義では、生産手段が少数の国民によって私的に所有されており、大多数の国民は経済を支配できないためだと彼らは言う。資本主義 は、エリート層に莫大な富と財産が集中し、エリート層と大多数の国民の間で巨大な富と所得の格差を生むと批判されている。[73] 資本主義がプラウトクラシーである証拠は、労働者に税金を課し資本家への税金を減らす政策や、国民の意思に反して定年を延長する政策など、資本家を優遇し 労働者を犠牲にする政策に見られる。「企業資本主義」と「逆転した全体主義」は、前述の活動家や資本主義の批判者が、階層的で官僚的な大企業が支配し、社 会福祉を無視して利益追求を法的に義務付けられた資本主義市場と社会を形容するために用いる用語だ。企業資本主義は、企業や大企業利益団体が政府政策、特 に規制機関の政策や政治キャンペーンへの影響力において持つ権力と影響力の大きさが批判されている。多くの社会科学者は、企業が人々(国民)の利益のため に行動していないと批判している。彼らは、大企業の存在が、社会におけるすべての個人間の平等な力関係を前提とする民主主義の原則を回避しているように見 えると主張している。[74] 政治的左派の一員として、企業権力と影響力に反対する活動家は、所得格差の縮小と経済的公平性の向上を目指している。[出典が必要] 「資本主義とは、最も邪悪な人間が、すべての人々の最大の利益のために、最も邪悪なことを行うという驚くべき信念だ」 — ジョン・メイナード・ケインズ[75] 巨大多国籍企業の台頭は、前述の学者、知識人、活動家たちの間で懸念の的となっている。彼らは、大企業が、公平な富と所得の分配、公平な民主的政治的・社 会経済的権力代表、その他多くの基本的人権とニーズを含む、基本的な人権と市民権の深刻な構造的侵食を引き起こしていると見ている。彼らは、大企業が消費 者に偽の需要を創出していると指摘し、さらに、高価な法的ロビイングや、ほとんど常に合法的だが強力な影響力行使を通じて、主権国民の政策に干渉し歪めて きた長い歴史があると主張している。彼らの見解では、この信念を裏付ける証拠には、侵入的な広告(看板、テレビ広告、アドウェア、スパム、テレマーケティ ング、子供向け広告、ゲリラマーケティングなど)、いわゆる「民主的」選挙における大規模な公開または秘密の企業政治献金、コーポラトクラシー、政府と企 業の間での人材の流動性、規制の捕獲、「大きすぎて倒産できない」(「大きすぎて刑務所に入れられない」とも呼ばれる)、 大規模な納税者負担の企業救済、超富裕層のための社会主義/共産主義、残酷で残忍なダーウィニズム的資本主義、そして——彼らが主張するように——企業腐 敗に関する終わりのないグローバルなニュース報道(マーサ・スチュワートやエンロンなど)が含まれる。[出典必要] 反企業活動家は、大企業は大きな株主のみに責任を負い、人権問題、社会正義問題、環境問題、および世界人口の99%を占める下層階級にとって重要な他の問 題にほとんど考慮を払っていないと主張している。[74][76] アメリカの政治哲学者ジョディ・ディーンは、現代の経済的・金融的危機が資本主義が持続可能な経済システムであるという考えを打ち砕いたと指摘し、「民主 主義が経済的正義の力として機能するという幻想は、米国政府が銀行に数兆ドルを注入し、欧州中央銀行が国民政府を操作し、社会プログラムを削減して自分た ちの存続を図る中で消え去った」と述べている。[77] クイン・スロボディアンによると、資本主義が民主主義を弱体化させる一つの方法は、「国民の領土に穴を開ける」ことで、世界中に5,400カ所存在する特 別経済区を創設することだ。これらの特別経済区は、租税回避地から「低賃金生産の拠点……しばしば有刺鉄線で囲まれた場所」まで多岐にわたり、スロボディ アンはこれらを「異なる法律が適用され、民主的な監視がない例外区域」と形容している。[78][79] デビッド・シュワイカートは、「(資本主義社会における)一般の人民は、政治指導者を選ぶ能力は十分にあるとみなされているが、上司を選ぶ能力はないとみ なされている。現代の資本主義は民主主義を称賛しているが、その民主的権利が最も直接かつ具体的に活用できる場、すなわち、私たちが成人として活動的で意 識の高い時間を最も多く過ごす場で、その権利を私たちから奪っている」と書いている。[80] アメリカ合衆国の建国の父の一人であるトーマス・ジェファーソンは、「私は、すでに私たちの政府に力比べを挑み、私たちの国の法律に反抗している、金持ち 企業による貴族主義を、その誕生の段階で打ち砕くことを願っている」と述べた。[81] 1938年4月29日、フランクリン・D・ルーズベルトは米国議会へのメッセージで、私的権力の拡大はファシズムにつながる可能性があると警告し、「民主 主義の自由は、人民が私的権力の拡大を、民主主義国家そのものを凌ぐほどまで容認すれば、安全ではなくなる」と主張した。それは本質的に、個人、集団、あ るいはその他の支配的な私的権力による政府の所有、すなわちファシズムである。[82][83][84] 内国歳入庁の統計によると、1935年の数字は次のとおりだ。「企業資産の所有:国民のすべての企業のうち、10 分の 1 未満の企業が、全企業の資産の 52% を所有していた」。[82][84] ドワイト・D・アイゼンハワー米国大統領は、企業権力と事実上のファシズムの融合という概念を批判し[85]、1961年の国民への別れの演説で、米国に おける「巨大な軍事組織と大規模な軍需産業の結合」に注目を集めた。[86] さらに、「国民プログラム内およびプログラム間のバランスを維持する必要性——民間経済と公共経済のバランス、コストと期待される利益のバランス」を強調 した。[86] 1986年、ジョン・ジュディスとハリー・ビンズワンガー、ジョン・リドパスによる「社会主義対資本主義」に関する討論で、知識人のクリストファー・ヒッチェンズは次のように述べた。 資本主義は、封建制度、君主制、ファシズム、奴隷制度、アパルトヘイト、開発遅滞と共存し、時にはそれらを支援してきた制度だ。また、特定のいくつかの中 心国では、進歩、発展、革新の偉大な原動力ともなってきました。これは、資本主義はシステムとして研究すべきであり、思想として研究すべきではないことを 意味する。自由の支援者であるという主張は、純粋に偶然的なものだ。それは良いプロパガンダだが、政治学としてはあまり良いものではない[87]。 |

| Exploitation of workers See also: Wage slavery and Sweatshop  "Of usury", from Sebastian Brant's Stultifera Navis (the Ship of Fools; woodcut attributed to Albrecht Dürer) Critics of capitalism view the system as inherently exploitative. In an economic sense, exploitation is often related to the expropriation of labor for profit and based on Karl Marx's version of the labor theory of value. The labor theory of value was supported by classical economists like David Ricardo and Adam Smith who believed that "the value of a commodity depends on the relative quantity of labor which is necessary for its production".[88] "In capitalism, workers are separated from the means of production, implying that they must compete in labour markets to sell their labour power to capitalists in order to earn a living." —Thomas Wiedmann, lead author of "Scientists’ warning on affluence"[89] In Das Kapital, Marx identified the commodity as the basic unit of capitalist organization. Marx described a "common denominator" between commodities, in particular that commodities are the product of labor and are related to each other by an exchange value (i.e. price).[90] By using the labor theory of value, Marxists see a connection between labor and exchange value, in that commodities are exchanged depending on the socially necessary labor time needed to produce them.[91] However, due to the productive forces of industrial organization, laborers are seen as creating more exchange value during the course of the working day than the cost of their survival (food, shelter, clothing and so on).[92] Marxists argue that capitalists are thus able to pay for this cost of survival while expropriating the excess labor (i.e. surplus value).[91] Marxists further argue that due to economic inequality, the purchase of labor cannot occur under "free" conditions. Since capitalists control the means of production (e.g. factories, businesses, machinery and so on) and workers control only their labor, the worker is naturally coerced into allowing their labor to be exploited.[93] Critics argue that exploitation occurs even if the exploited consents, since the definition of exploitation is independent of consent. In essence, workers must allow their labor to be exploited or face starvation. Since some degree of unemployment is typical in modern economies, Marxists argue that wages are naturally driven down in free market systems. Hence, even if a worker contests their wages, capitalists are able to find someone from the reserve army of labor who is more desperate.[94] The act (or threat) of striking has historically been an organized action to withhold labor from capitalists, without fear of individual retaliation.[95] Some critics of capitalism, while acknowledging the necessity of trade unionism, believe that trade unions simply reform an already exploitative system, leaving the system of exploitation intact.[96][11] Lysander Spooner argued that "almost all fortunes are made out of the capital and labour of other men than those who realize them. Indeed, large fortunes could rarely be made at all by one individual, except by his sponging capital and labour from others".[97] Some labor historians and scholars have argued that unfree labor—by slaves, indentured servants, prisoners, or other coerced persons—is compatible with capitalist relations. Tom Brass argued that unfree labor is acceptable to capital.[98][99] Historian Greg Grandin argues that capitalism has its origins in slavery, saying that "[w]hen historians talk about the Atlantic market revolution, they are talking about capitalism. And when they are talking about capitalism, they are talking about slavery."[100] Some scholars, including Edward E. Baptist, Sven Beckert and Matthew Desmond, assert that slavery was an integral component in the violent development of American and global capitalism.[101][102][103] The Slovenian continental philosopher Slavoj Žižek posits that the new era of global capitalism has ushered in new forms of contemporary slavery, including migrant workers deprived of basic civil rights on the Arabian Peninsula, the total control of workers in Asian sweatshops and the use of forced labor in the exploitation of natural resources in Central Africa.[104] Academics such as the developmental psychologist Howard Gardner have proposed the adoption of upper limits in individual wealth as "a solution that would make the world a better place".[105] Marxian economist Richard D. Wolff postulates that capitalist economies prioritize profits and capital accumulation over the social needs of communities, and that capitalist enterprises rarely include the workers in the basic decisions of the enterprise.[106] Political economist Clara E. Mattei of the New School for Social Research demonstrates that the imposition of fiscal, monetary and industrial austerity policies meant to discipline labor by reinforcing hierarchal wage relations and therefore protect the capitalist system through wage repression and the weakening of collective bargaining power by workers can increase their exploitation while boosting the profits of the ownership class, which she says is one of the primary drivers of the "global inequality trend". As an example, Mattei shows that over the last four decades in the United States the profit share of national output increased while labor's share plummeted, demonstrating a symmetrical relationship between owner profit and worker loss, where the former was taking from the latter. She adds that “an increase in exploitation was also evident, with real wages grossly lagging behind labor productivity.”[107] |

労働者の搾取 関連項目:賃金奴隷制、スウェットショップ  「高利貸しについて」、セバスティアン・ブラントの『愚者の船』(アルブレヒト・デューラーによる木版画)より 資本主義の批判者は、このシステムを本質的に搾取的だと見なしている。経済的な意味では、搾取はしばしば利益のための労働の収奪に関連し、カール・マルク スの労働価値説に基づいている。労働価値説は、デビッド・リカードやアダム・スミスなどの古典派経済学者によって支持され、彼らは「商品の価値は、その生 産に必要な労働の相対的な量に依存する」と信じていた。[88] 「資本主義では、労働者は生産手段から切り離されており、生計を立てるためには労働市場で資本家に労働力を売り、競争しなければならないことを意味する。」 —トーマス・ヴィードマン、「科学者による豊かさに関する警告」の筆頭著者[89] 『資本論』において、マルクスは商品(commodity)を資本主義組織の基本単位と特定した。マルクスは商品に共通する「共通分母」を説明し、特に商 品が労働の産物であり、交換価値(すなわち価格)によって互いに関連している点を指摘した。[90] 労働価値説を用いるマルクス主義者は、商品が生産に要する社会的必要労働時間に応じて交換される点において、労働と交換価値の関連性を指摘している。 [91] しかし、産業組織の生産力により、労働者は労働日中に生存コスト(食料、住居、衣類など)を超える交換価値を創造していると見なされる。[92] マルクス主義者は、資本家が生存コストを支払いつつ、余剰労働(すなわち剰余価値)を搾取できると主張する。[91] マルクス主義者はさらに、経済的不平等により、労働力の購入は「自由」な条件下では起こらないと主張する。資本家が生産手段(工場、企業、機械など)を支 配し、労働者は労働力のみを支配するため、労働者は必然的に労働力を搾取されることを許さざるを得ない。[93] 批判者は、搾取は被搾取者が同意しても発生すると主張する。なぜなら、搾取の定義は同意に依存しないからである。本質的に、労働者は労働力を搾取されるこ とを許さなければ飢えに直面する。現代経済では一定程度の失業が典型的であるため、マルクス主義者は、自由市場システムでは賃金が自然に低下すると主張す る。したがって、労働者が賃金を争っても、資本家は労働予備軍からより絶望的な労働者を見つけることができる。[94] ストライキ(またはその脅威)は、歴史的に、資本家からの報復を恐れることなく、労働力を差し控えるための組織的な行動だった。[95] 資本主義の批判者の一部は、労働組合の必要性を認めつつも、労働組合は既に搾取的なシステムを改革するだけで、搾取のシステムそのものを残したままだと主 張している。[96][11] ライサンダー・スプーナーは、「ほとんどすべての富は、それを実現した者以外の他人の資本と労働から作られている。実際、一人の個人によって大きな富を築 くことは、他人の資本と労働を搾取しない限り、ほとんど不可能だ」と主張した。[97] 一部の労働史家や学者は、奴隷、年季奉公人、囚人、その他の強制された人格による不自由な労働は、資本主義関係と両立すると主張している。トム・ブラス は、不自由な労働は資本にとって容認できると主張している。[98][99] 歴史家のグレッグ・グランディンは、資本主義は奴隷制に起源があると主張し、「歴史家が大西洋市場革命について語る場合、彼らは資本主義について語ってい るのだ」と述べている。そして、彼らが資本主義について話すとき、彼らは奴隷制について話している」と述べている。[100] エドワード・E・バプティスト、スベン・ベッカー、マシュー・デズモンドを含む一部の学者たちは、奴隷制がアメリカと世界の資本主義の暴力的な発展におけ る不可欠な要素であったと主張している。[101][102][103] スロベニアの大陸哲学者スラヴォイ・ジジェクは、グローバル資本主義の新時代が、アラビア半島で基本的人権を剥奪された移民労働者、アジアの過酷な工場で の労働者の完全な支配、中央アフリカでの自然資源の搾取における強制労働など、現代の奴隷制の新形態をもたらしたと主張している。[104] 発達心理学者ハワード・ガードナーなどの学者は、「世界をより良い場所にする解決策」として、個人の富の上限を採用することを提案している。[105] マルクス主義経済学者リチャード・D・ウォルフは、資本主義経済は、コミュニティの社会的ニーズよりも利益と資本蓄積を優先し、資本主義企業は、企業の基 本的な決定に労働者をほとんど関与させていないと主張している。[106] 政治経済学者のクララ・E・マッテイ(ニュー・スクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチ)は、労働者を規律し資本主義システムを保護するため、階層的な賃 金関係を強化する財政・金融・産業緊縮政策が、賃金抑制と労働者の団体交渉力の弱体化を通じて、労働者の搾取を増加させつつ所有者階級の利益を増加させる ことを示している。彼女は、これが「グローバルな不平等傾向」の主要な要因の一つだと指摘している。例として、マッテイは、過去40年間で米国において、 国民総生産に占める利益の割合が増加した一方で、労働者のシェアは急落し、所有者の利益と労働者の損失が対称的な関係にあることを示している。彼女はさら に、「搾取の増加も明らかであり、実質賃金は労働生産性に大幅に遅れを取っている」と付け加えている。[107] |

| Imperialism, political oppression, and genocide Near the start of the 20th century, Vladimir Lenin wrote that state use of military power to defend capitalist interests abroad was an inevitable corollary of monopoly capitalism.[39] He argued that capitalism needs imperialism to survive.[108] According to Lenin, the export of financial capital superseded the export of commodities; banking and industrial capital merged to form large financial cartels and trusts in which production and distribution are highly centralized; and monopoly capitalists influenced state policy to carve up the world into spheres of interest. These trends led states to defend their capitalist interests abroad through military power. According to economic anthropologist Jason Hickel, capitalism requires the accumulation of excess wealth in the hands of economic elites for the purpose of large scale investment, continuous growth and expansion, and enormous amounts of cheap labor. As such, there was never and could never have been a gradual or peaceful transition to capitalism, and that "organized violence, mass impoverishment, and the destruction of self-sufficient subsistence economies" ushered in the capitalist era. Its emergence was fueled by immiseration and extreme violence that accompanied enclosure and colonization, with colonized peoples becoming enslaved workers producing products that were then processed by European peasants, dispossessed by enclosure, who filled the factories in desperation as exploited cheap labor. Hickel adds that there was fierce resistance to these developments, as that the period 1500 to the 1800s, "right into the Industrial Revolution, was among the bloodiest, most tumultuous times in world history."[109][110] Sociologist David Nibert argues that while capitalism "turned out to be every bit as violent and oppressive as the social systems dominated by the old aristocrats", it also included "an additional and pernicious peril—the necessity for continuous growth and expansion". As an example of this, Nibert points to the mass killing of millions of buffalo on the Great Plains and the subjugation and expulsion of the indigenous population by the U.S. military in the 19th century for the purpose of expanding ranching operations, and rearing livestock for the purpose of profit.[111] Capitalism and capitalist governments have also been criticized by socialists as oligarchic in nature,[112][113] due to the inevitable inequality.[114][115] The military–industrial complex, mentioned in Dwight D. Eisenhower's presidential farewell address, appears to play a significant role in the American capitalist system. It may be one of the driving forces of American militarism and intervention abroad.[116] The United States has used military force and has encouraged and facilitated state terrorism and mass violence to entrench neoliberal capitalism in the Global South, protect the interests of U.S. economic elites, and to crush any possible resistance to this entrenchment, especially during the Cold War,[117][118][119] with significant cases being Brazil, Chile and Indonesia.[118][120][121][122] |

帝国主義、政治的抑圧、およびジェノサイド 20世紀初頭、ウラジーミル・レーニンは、資本主義の利益を守るために国家が軍事力を行使することは、独占資本主義の必然的な結果であると述べた [39]。彼は、資本主義は生き残るために帝国主義を必要としていると主張した。[108] レニンによると、金融資本の輸出は商品輸出に取って代わり、銀行資本と産業資本が合併して大規模な金融カルテルやトラストを形成し、生産と流通が高度に集 中化。独占資本家は国家政策に影響を及ぼし、世界を利害関係圏に分割した。これらの傾向は、国家が軍事力を用いて海外の資本主義的利益を防衛する結果を招 いた。 経済人類学者のジェイソン・ヒッケルによると、資本主義は、大規模な投資、継続的な成長と拡大、そして莫大な量の安価な労働力を確保するために、経済エ リートの手に過剰な富を蓄積する必要がある。そのため、資本主義への段階的または平和的な移行は決して存在せず、また存在し得なかった。そして、「組織的 な暴力、大規模な貧困化、自給自足経済の破壊」が資本主義時代をもたらした。その出現は、囲い込みと植民地化に伴う貧困化と極度の暴力によって促進され、 植民地化された人民は奴隷労働者として製品を生産し、囲い込みによって土地を奪われたヨーロッパの農民が、絶望から工場に詰め込まれ、搾取される安価な労 働力として働かされた。ヒッケルは、これらの動向に対して激しい抵抗があったと付け加え、1500年から1800年代、つまり「産業革命に至るまで」は 「世界史上で最も血なまぐさい、最も混乱した時代の一つ」だったと指摘している。[109][110] 社会学者デビッド・ニバートは、資本主義は「旧貴族が支配していた社会システムと同じくらい暴力的で抑圧的」であった一方で、「継続的な成長と拡大の必要 性」という追加的で有害な危険性を伴っていたと主張している。この例として、ニバートは、19世紀にアメリカ軍が牧場経営の拡大と利益目的の畜産のため、 グレートプレーンズで数百万頭のバッファローを大量殺戮し、先住民を支配・追放した事例を挙げている。[111] 資本主義と資本主義政府は、不可避的な不平等から、社会主義者たちによって寡頭制的であると批判されてきた。[112][113] ドワイト・D・アイゼンハワー大統領の退任演説で言及された軍事産業複合体は、アメリカの資本主義システムにおいて重要な役割を果たしているようだ。これ は、アメリカの軍国主義と海外介入の原動力の一つであるかもしれない。[116] アメリカ合衆国は、新自由主義的資本主義をグローバル・サウスに定着させ、アメリカ経済エリートの利益を保護し、この定着に対するあらゆる抵抗を弾圧する ために、軍事力を使用し、国家テロリズムと大量暴力の促進と支援を行ってきた。特に冷戦期には、ブラジル、チリ、インドネシアなどが顕著な事例である。 [117][118][119][121][122] |

| Inefficiency, irrationality, and unpredictability Some opponents criticize capitalism's inefficiency. They note a shift from pre-industrial reuse and thriftiness before capitalism to a consumer-based economy that pushes "ready-made" materials.[123] It is argued that a sanitation industry arose under capitalism that deemed trash valueless—a significant break from the past when much "waste" was used and reused almost indefinitely.[123] In the process, critics say, capitalism has created a profit driven system based on selling as many products as possible.[124] Critics relate the "ready-made" trend to a growing garbage problem in which, as of 2008, 4.5 pounds of trash are generated per person each day (compared to 2.7 pounds in 1960).[125] Anti-capitalist groups with an emphasis on conservation include eco-socialists and social ecologists. Planned obsolescence has been criticized as a wasteful practice under capitalism. By designing products to wear out faster than need be, new consumption is generated.[123] This would benefit corporations by increasing sales while at the same time generating excessive waste. A well-known example is the charge that Apple designed its iPod to fail after 18 months.[126] Critics view planned obsolescence as wasteful and an inefficient use of resources.[127] Other authors such as Naomi Klein have criticized brand-based marketing for putting more emphasis on the company's name-brand than on manufacturing products.[128] Some economists, most notably Marxian economists, argue that the system of perpetual capital accumulation leads to irrational outcomes and a mis-allocation of resources as industries and jobs are created for the sake of making money as opposed to satisfying actual demands and needs.[129] Market failure Market failure is a term used by economists to describe the condition where the allocation of goods and services by a market is not efficient. Keynesian economist Paul Krugman views this scenario in which individuals' pursuit of self-interest leads to bad results for society as a whole.[130] John Maynard Keynes preferred economic interventionism by government to free markets.[131] Some believe that the lack of perfect information and perfect competition in a free market is grounds for government intervention. Others perceive certain unique problems with a free market including: monopolies, monopsonies, insider trading and price gouging.[132] |

非効率性、非合理性、予測不可能性 一部の反対派は、資本主義の非効率性を批判している。彼らは、資本主義以前の産業革命前の再利用と倹約の文化から、「既製品」を推し進める消費主義経済へ の移行を指摘している。[123] 資本主義の下で、ゴミを価値のないものと見なす衛生産業が台頭し、多くの「廃棄物」がほぼ無限に再利用されていた過去からの大きな断絶が生じたと主張され ている。[123] 批判者は、この過程で資本主義が、可能な限り多くの製品を販売する利益追求型システムを生み出したと指摘している。[124] 批判者は、「既製品」の傾向を、2008年時点で1人格あたり1日4.5ポンドのゴミが排出される(1960年は2.7ポンド)というゴミ問題の拡大と関 連付けている。[125] 環境保護を重視する反資本主義団体には、エコ社会主義者や社会生態学者などがいる。 計画的陳腐化は、資本主義の下での無駄の多い慣行として批判されている。必要以上に早く摩耗するように製品を設計することで、新たな消費が生み出される。 [123] これは、売上を増加させると同時に過剰な廃棄物を発生させるため、企業にとって利益となる。有名な例として、アップルがiPodを18ヶ月で故障するよう に設計したとの指摘がある。[126] 批判者は計画的陳腐化を無駄で資源の非効率的な利用と見なしている。[127] ナオミ・クラインのような他の著者たちは、製品の製造よりも企業のブランド名に重点を置くブランドベースのマーケティングを批判している。[128] 一部の経済学者、特にマルクス経済学者たちは、永続的な資本蓄積のシステムは、実際の需要やニーズを満たすためではなく、お金を稼ぐために産業や雇用が創出されるため、非合理的な結果や資源の誤配分につながる、と主張している。[129] 市場の失敗 市場の失敗とは、経済学者たちが、市場による商品やサービスの配分が効率的ではない状態を表現するために用いる用語だ。ケインズ経済学者ポール・クルーグ マンは、個人が自己の利益を追求することが社会全体にとって悪い結果をもたらすというこのシナリオを、市場の失敗と捉えている。[130] ジョン・メイナード・ケインズは、自由市場よりも政府による経済介入主義を好んだ。[131] 自由市場における完全な情報と完全な競争の欠如が、政府の介入の根拠であると考える人もいる。他方、自由市場には、独占、独占的買手市場、インサイダー取 引、価格操作など、特有の問題があるとの見方もある。[132] |

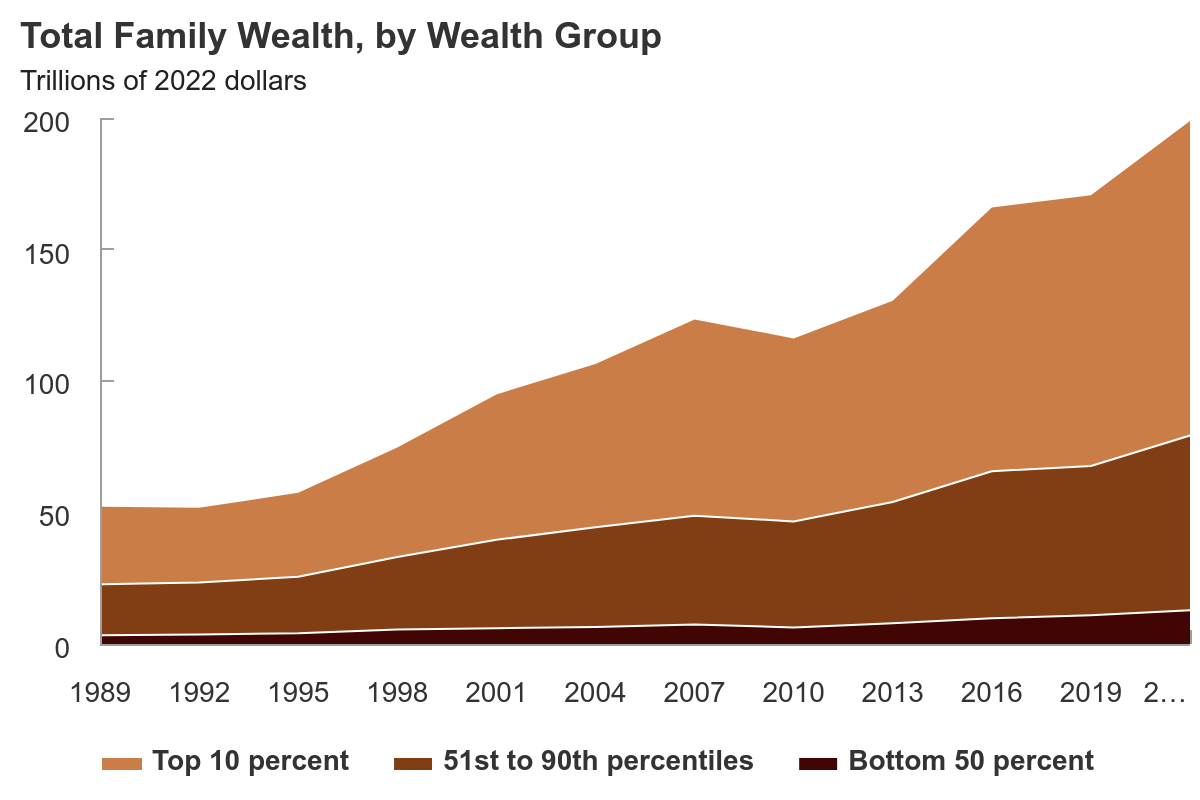

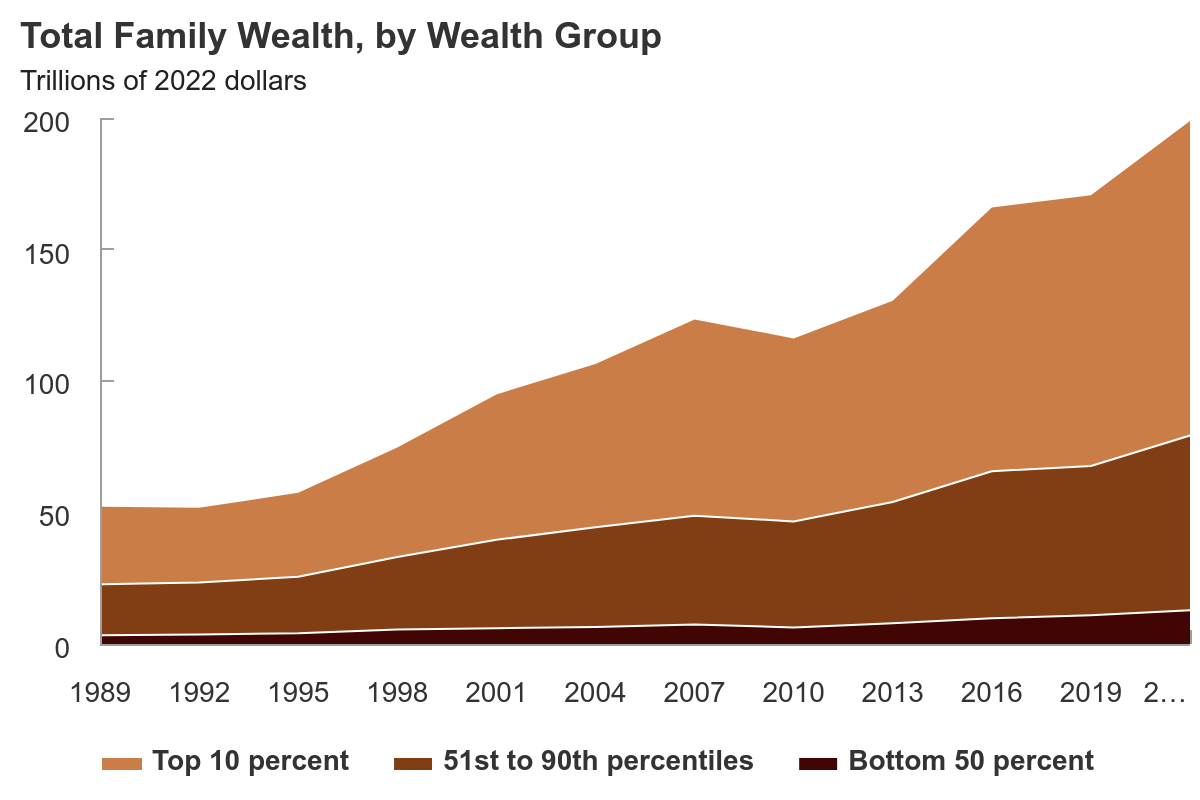

| Inequality See also: Economic inequality and Social inequality  A man at the protest event Occupy Wall Street Critics argue that capitalism is associated with the unfair distribution of wealth and power; a tendency toward market monopoly or oligopoly (and government by oligarchy); imperialism, counter-revolutionary wars and various forms of economic and cultural exploitation; repression of workers and trade unionists and phenomena such as social alienation, economic inequality, unemployment and economic instability. Critics have argued that there is an inherent tendency toward oligopolistic structures when laissez-faire is combined with capitalist private property. Capitalism is regarded by many socialists to be irrational in that production and the direction of the economy are unplanned, creating many inconsistencies and internal contradictions and thus should be controlled through public policy.[133] In the early 20th century, Vladimir Lenin argued that state use of military power to defend capitalist interests abroad was an inevitable corollary of monopoly capitalism.[39] In 2019, Marxian Economist Richard D. Wolff argued that Capitalism is unstable, Capitalism is unequal, and fundamentally Undemocratic.[134] In a 1965 letter to Carlos Quijano, editor of Marcha, a weekly newspaper published in Montevideo, Uruguay, Che Guevara wrote: The laws of capitalism, which are blind and are invisible to ordinary people, act upon the individual without he or she being aware of it. One sees only the vastness of a seemingly infinite horizon ahead. That is how it is painted by capitalist propagandists who purport to draw a lesson from the example of Rockefeller—whether or not it is true—about the possibilities of individual success. The amount of poverty and suffering required for a Rockefeller to emerge, and the amount of depravity entailed in the accumulation of a fortune of such magnitude, are left out of the picture, and it is not always possible for the popular forces to expose this clearly. ... It is a contest among wolves. One can win only at the cost of the failure of others.[135]  Wealth inequality in the United States increased from 1989 to 2013.[136] |

不平等 関連項目:経済的不平等、社会的不平等  抗議イベント「オキュパイ・ウォールストリート」に参加する男性 資本主義は、富と権力の不公正な分配、市場独占や寡占(および寡頭政治)への傾向、帝国主義、反革命戦争、さまざまな形態の経済的・文化的搾取、労働者や 労働組合員の抑圧、社会的疎外、経済的不平等、失業、経済不安などの現象と関連していると批判されている。批判者は、自由放任主義と資本主義的私有財産が 組み合わさると、寡占的構造への内在的な傾向が生じると主張している。多くの社会主義者は、生産と経済の方向性が計画されていないため、多くの不一致と内 部矛盾を生み出し、したがって公共政策を通じて制御されるべきであるとして、資本主義を非合理的なものとしている。[133] 20世紀初頭、ウラジーミル・レーニンは、資本主義の利益を海外で守るための国家の軍事力行使は、独占資本主義の不可避的な派生物であると主張した。[39] 2019年、マルクス主義経済学者リチャード・D・ウォルフは、資本主義は不安定で、不平等であり、根本的に非民主的であると主張した。[134] 1965年、ウルグアイのモンテビデオで発行されていた週刊新聞『マルチャ』の編集者カルロス・キハノ宛ての手紙の中で、チェ・ゲバラは次のように書いている。 資本主義の法則は盲目であり、一般の人民には見えないが、個人に気づかれることなく作用している。人は、目の前に広がる無限に広がる地平線の広大さしか見 ることができない。これが、ロックフェラーの例から教訓を導き出そうとする資本主義の宣伝家たちが描く姿だ——それが真実かどうかは別として——個人の成 功の可能性について。ロックフェラーのような人物が現れるために必要な貧困と苦悩の量、そしてそのような莫大な財産の蓄積に伴う堕落の程度は、この絵から 省略されており、民衆の力がこれを明確に暴露することは常に可能ではない。... これは狼同士の争いだ。他者の失敗を代償にしか勝利は得られない。[135]  アメリカ合衆国の富の格差は、1989年から2013年にかけて拡大した。[136] |

| A modern critic of capitalism is

Ravi Batra, who focuses on inequality as a source of immiserization but

also of system failure. Batra popularised the concept "share of wealth

held by richest 1%" as an indicator of inequality and an important

determinant of depressions in his best-selling books in the

1980s.[137][138] The scholars Kristen Ghodsee and Mitchell A. Orenstein

suggest that left to its own devices, capitalism will result in a small

group of economic elites capturing the majority of wealth and power in

society.[139] Dylan Sullivan and Jason Hickel argue that poverty

continues to exist in the contemporary global capitalist system in

spite of it being highly productive because it is undemocratic and has

maintained conditions of extreme inequality where masses of working

people, who have no ownership or control over the means of production,

have their labor power "appropriated by a ruling class or an external

imperial power," and are cut off from common land and resources.[140]

They further contend that capitalism needs significant levels of

inequality as capital accumulation requires access to cheap labor, and

lots of it, as without it the system would be crippled.[141] "Since value is produced only by workers, capitalists can extract, appropriate and accumulate the surplus part of this value only through exploitation. And exploitation, by definition, negates equality." — Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler.[142] In the United States, the shares of earnings and wealth of the households in the top 1 percent of the corresponding distributions are 21 percent (in 2006) and 37 percent (in 2009), respectively.[143] Critics, such as Ravi Batra, argue that the capitalist system has inherent biases favoring those who already possess greater resources. The inequality may be propagated through inheritance and economic policy. Rich people are in a position to give their children a better education and inherited wealth and that this can create or increase large differences in wealth between people who do not differ in ability or effort. One study shows that in the United States 43.35% of the people in the Forbes magazine "400 richest individuals" list were already rich enough at birth to qualify.[144] Another study indicated that in the United States wealth, race and schooling are important to the inheritance of economic status, but that IQ is not a major contributor and the genetic transmission of IQ is even less important.[145] Batra has argued that the tax and benefit legislation in the United States since the Reagan presidency has contributed greatly to the inequalities and economic problems and should be repealed.[146] |

資本主義の現代的な批判者には、不平等が貧困化だけでなくシステム崩壊

の原因でもあると指摘するラヴィ・バトラがいる。バトラは、1980年代にベストセラーとなった著書で、不平等と不況の重要な決定要因として「最富裕層

1%が保有する富の割合」という概念を普及させた[137][138]。学者であるクリステン・ゴドシーとミッチェル・A・オレンスタインは、資本主義を

そのまますべてに任せておけば、社会の大半の富と権力を少数の経済エリートが独占することになると指摘している。[139]

ディラン・サリバンとジェイソン・ヒッケルは、現代の世界資本主義システムは生産性は高いにもかかわらず、非民主的であり、生産手段を所有も支配もできな

い大衆の労働力が「支配階級や外部の帝国主義勢力によって奪われ」、共有地や資源から切り離されているという極端な不平等状態を維持しているため、貧困が

依然として存在していると主張している。[140]

さらに、資本主義は、資本の蓄積には安価な労働力、それも大量の労働力が必要であり、それなしではシステムが機能しなくなるため、かなりの不平等が必要で

あると主張している。[141] 「価値は労働者によってのみ生産されるため、資本家は搾取によってのみ、この価値の余剰部分を抽出、収奪、蓄積することができる。そして、搾取は、その定義上、平等を否定するものである。」 — ジョナサン・ニッツァンとシムション・ビッチラー。[142] 米国では、所得と資産の分配の上位 1% の世帯のシェアは、それぞれ 21% (2006 年) と 37% (2009 年) だ。[143] ラヴィ・バトラなどの批判者は、資本主義システムには、すでに多くの資源を所有する者を優遇する本質的な偏りがあると主張している。不平等は相続や経済政 策を通じて拡大される可能性がある。富裕層は子供により良い教育や相続財産を与えることができ、これが能力や努力に異なる人々之间に大きな資産格差を生み 出したり拡大したりする可能性がある。ある研究によると、アメリカ合衆国ではフォーブス誌の「400大富豪」リストに載る人々の43.35%は、出生時に 既に十分な資産を保有していた。[144] 別の研究では、アメリカでは、富、人種、教育が経済的地位の相続に重要だが、IQは主要な要因ではなく、IQの遺伝的伝達はさらに重要ではないと示されて いる。[145] バトラは、レーガン政権以降のアメリカの税制と福祉政策が不平等と経済問題に大きく寄与しており、廃止すべきだと主張している。[146] |

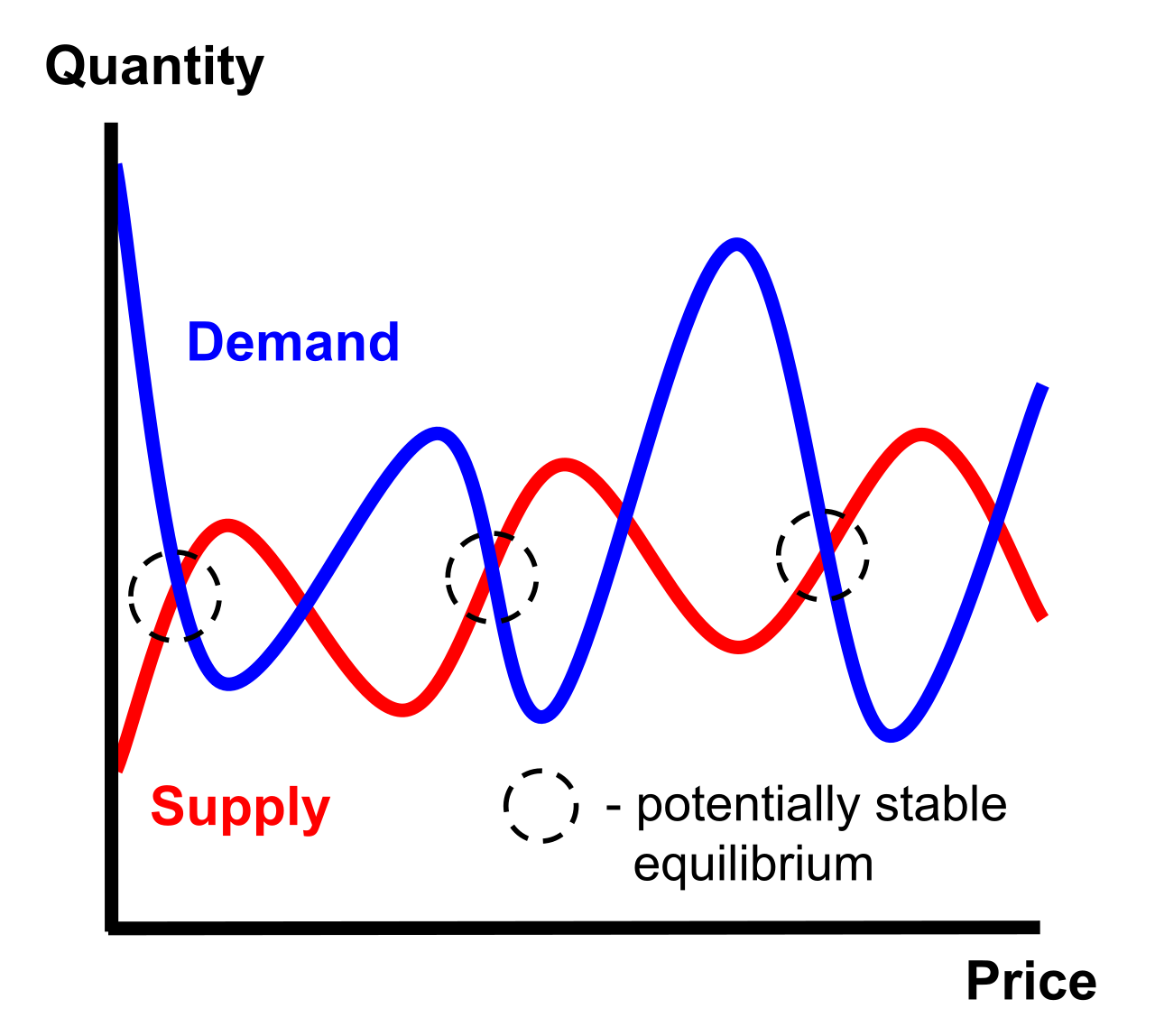

| Market instability Critics of capitalism, particularly Marxists, identify market instability as a permanent feature of capitalist economy.[147][148] Marx believed that the unplanned and explosive growth of capitalism does not occur in a smooth manner, but is interrupted by periods of overproduction in which stagnation or decline occur (i.e. recessions).[149] In the view of Marxists, several contradictions in the capitalist mode of production are present, particularly the internal contradiction between anarchy in the sphere of capital (i.e. free market) and socialised production in the sphere of labor (i.e. industrialism).[150] In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels highlighted what they saw as a uniquely capitalist juxtaposition of overabundance and poverty: "Society suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarism. And why? Because there is too much civilization, too much means of subsistence, too much industry, too much commerce".[149] Some scholars blame the 2008 financial crisis on the neoliberal capitalist model.[157] Following the banking crisis of 2007, economist and former Chair of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan told the United States Congress on 23 October 2008 that "[t]his modern risk-management paradigm held sway for decades. The whole intellectual edifice, however, collapsed in the summer of last year",[158] and that "I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interests of organizations, specifically banks and others, were such that they were best capable of protecting their own shareholders and their equity in firms ... I was shocked".[159] |

市場の不安定性 資本主義の批判者、特にマルクス主義者は、市場の不安定性を資本主義経済の恒久的な特徴であると指摘している。[147][148] マルクスは、資本主義の計画的ではない爆発的な成長は円滑には進まず、停滞や衰退(すなわち不況)を伴う過剰生産の期間によって中断されると考えていた。 [149] マルクス主義者の見解では、資本主義的生産方式にはいくつかの矛盾が存在し、特に資本の領域(すなわち自由市場)における無政府状態と、労働の領域(すな わち産業主義)における社会化された生産との間の内部矛盾が挙げられる。[150] 『共産党宣言』で、マルクスとエンゲルスは、資本主義に特有の過剰と貧困の対立を次のように指摘した:「社会は突然、一時的な野蛮状態に戻される。なぜな のか?文明が過剰であり、生活手段が過剰であり、産業が過剰であり、商業が過剰だからだ」。[149] 一部の学者は、2008年の金融危機を新自由主義的資本主義モデルに起因すると指摘している。[157] 2007年の銀行危機を受けて、経済学者で元連邦準備制度理事会(FRB)議長のアラン・グリーンスパンは、2008年10月23日に米国議会で、「この 現代的なリスク管理パラダイムは、何十年にもわたって支配的だった。しかし、この知的枠組みは昨年夏に崩壊した」と述べ、さらに「私は、組織、特に銀行や 他の組織の自己利益が、自社の株主や企業の株式を最も適切に保護できると仮定した点で誤っていた。私は驚いた」と述べた。[159] |

| Property Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Friedrich Engels argue that the free market is not necessarily free, but weighted towards those who already own private property.[94][160] They view capitalist regulations, including the enforcement of private property on land and exclusive rights to natural resources, as unjustly enclosing upon what should be owned by all, forcing those without private property to sell their labor to capitalists and landlords in a market favorable to the latter, thus forcing workers to accept low wages to survive.[161] In his criticism of capitalism, Proudhon believed that the emphasis on private property is the problem. He argued that property is theft, arguing that private property leads to despotism: "Now, property necessarily engenders despotism—the government of caprice, the reign of libidinous pleasure. That is so clearly the essence of property that, to be convinced of it, one need but remember what it is, and observe what happens around him. Property is the right to use and abuse".[160] Many left-wing anarchists, such as anarchist communists, believe in replacing capitalist private property with a system where people can lay claim to things based on personal use and claim that "[private] property is the domination of an individual, or a coalition of individuals, over things; it is not the claim of any person or persons to the use of things" and "this is, usufruct, a very different matter. Property means the monopoly of wealth, the right to prevent others using it, whether the owner needs it or not".[162] Mutualists and some anarchists support markets and private property, but not in their present form.[163] They argue that particular aspects of modern capitalism violate the ability of individuals to trade in the absence of coercion. Mutualists support markets and private property in the product of labor, but only when these markets guarantee that workers will realize for themselves the value of their labor.[160] In recent times, most economies have extended private property rights to include such things as patents and copyrights. Critics see these so-called intellectual property laws as coercive against those with few prior resources. They argue that such regulations discourage the sharing of ideas and encourage nonproductive rent seeking behavior, both of which enact a deadweight loss on the economy, erecting a prohibitive barrier to entry into the market.[164] Not all pro-capitalists support the concept of copyrights, but those who do argue that compensation to the creator is necessary as an incentive.[164] |

財産 ピエール・ジョゼフ・プルードンとフリードリヒ・エンゲルスは、自由市場とは必ずしも自由ではなく、すでに私有財産を所有している者に有利に偏っている、 と主張している[94]。[160] 彼らは、土地の私有権の強制や自然資源の独占的権利を含む資本主義の規制を、すべての人々が所有すべきものを不当に囲い込むものとして見なし、私有財産を 持たない人々を資本家や地主に対して有利な市場で労働力を売り渡すことを強制し、その結果、労働者が生存するために低賃金を甘受せざるを得ない状況を生み 出していると指摘している。[161] プロウドンは資本主義批判において、私有財産の強調が問題だと考えていた。彼は、財産は盗みであり、私有財産は専制政治をもたらすと主張した:「財産は必 然的に専制政治を生む——恣意の支配、欲望の快楽の支配。これが財産の真髄であることは、それを思い出せば、周囲で起こっていることを観察すれば、明白 だ。財産とは、使用と濫用の権利だ」。[160] 多くの左派アナキスト、例えばアナキスト共産主義者は、資本主義の私有財産を、個人使用に基づいて物に権利を主張できるシステムに置き換えるべきだと主張 し、「[私有]財産は、個人または個人の連合が物に対する支配権を主張することであり、いかなる人格または個人の集団も物を使用する権利を主張するもので はない」と述べ、「これは、使用権とは全く異なる問題だ」と主張している。財産とは、富の独占、所有者が必要とするかどうかに関わらず、他者がそれを使用 することを妨げる権利だ」と主張している。[162] 相互主義者や一部のアナキストは、市場と私有財産を支持しているが、現在の形では支持していない。[163] 彼らは、現代資本主義の特定の側面は、強制のない状態で個人が取引を行う能力を侵害していると主張している。相互主義者は、労働の産物における市場と私有 財産を支持するが、これらの市場が労働者が自らの労働の価値を自ら実現することを保証する場合に限る。[160] 最近では、ほとんどの経済は、特許や著作権などのものを私有財産権の対象に拡大している。批判者は、これらのいわゆる知的財産権法を、事前の資源が少ない 者に対する強制的なものと見なしている。彼らは、このような規制がアイデアの共有を妨げ、非生産的なレントシーキング行動を助長し、どちらも経済に死重損 失をもたらし、市場への参入を阻む障壁を築くと主張している。[164] すべての資本主義支持者が著作権の概念を支持しているわけではないが、支持する者は、創作者への補償がインセンティブとして必要だと主張している。 [164] |

| Environmental sustainability See also: Degrowth and Steady-state economy  Gullfaks oil field in the North Sea. As petroleum is a non-renewable natural resource the industry is faced with an inevitable eventual depletion of the world's oil supply. Many aspects of capitalism have come under attack from the anti-globalization movement, which is primarily opposed to corporate capitalism. Environmentalists and scholars have argued that capitalism requires continual economic growth and that it will inevitably deplete the finite natural resources of Earth and cause mass extinctions of animal and plant life.[165][166][167][168] Such critics argue that while neoliberalism, the ideological backbone of contemporary globalized capitalism, has indeed increased global trade, it has also destroyed traditional ways of life, exacerbated inequality, increased global poverty, and that environmental indicators indicate massive environmental degradation since the late 1970s.[169][170][171][172]  Placard saying "capitalism equals climate crisis" at a demonstration. A placard criticising capitalism held by a climate change protester in Australia Some scholars argue that the capitalist approach to environmental economics does not take into consideration the preservation of natural resources[173] and that capitalism creates three ecological problems: growth, technology, and consumption.[174] The growth problem results from the nature of capitalism, as it focuses around the pursuit of limitless economic growth and the accumulation of capital.[174][175] The innovation of new technologies has an impact on the environmental future as they serve as a capitalist tool in which environmental technologies can result in the expansion of the system.[176] Consumption is focused around the capital accumulation of commodities and neglects the use-value of production.[174] Professor Radhika Desai, director of the Geopolitical Economy Research Group at the University of Manitoba, contends that ecological crises such as climate change, pollution and biodiversity loss occur when "capitalist firms compete to appropriate and plunder the free resources of nature and when this very appropriation and plunder forces working people to overexploit their ever-shrinking share of these resources."[177] One of the main modern criticism to the sustainability of capitalism is related to the so-called commodity chains, or production/consumption chains.[178][179] These terms refer to the network of transfers of materials and commodities that is currently part of the functioning of the global capitalist system. Examples include high tech commodities produced in countries with low average wages by multinational firms and then being sold in distant high income countries; materials and resources being extracted in some countries, turned into finished products in some others and sold as commodities in further ones; and countries exchanging with each other the same kind of commodities for the sake of consumers' choice (e.g. Europe both exporting and importing cars to and from the United States). According to critics, such processes, all of which produce pollution and waste of resources, are an integral part of the functioning of capitalism (i.e. its "metabolism").[180] Critics note that the statistical methods used in calculating ecological footprint have been criticized and some find the whole concept of counting how much land is used to be flawed, arguing that there is nothing intrinsically negative about using more land to improve living standards (rejection of the intrinsic value of nature).[181][182] Under what anti-capitalists such as Murray Bookchin call the "grow or die" imperative of capitalism, they say there is little reason to expect hazardous consumption and production practices to change in a timely manner. They also claim that markets and states invariably drag their feet on substantive environmental reform and are notoriously slow to adopt viable sustainable technologies.[183][184] Immanuel Wallerstein, referring to the externalization of costs as the "dirty secret" of capitalism, claims that there are built-in limits to ecological reform and that the costs of doing business in the world capitalist economy are ratcheting upward because of deruralization and democratization.[185] A team of Finnish scientists hired by the UN Secretary-General to aid the 2019 Global Sustainable Development Report assert that capitalism as we know it is moribund, primarily because it focuses on short term profits and fails to look after the long term needs of people and the environment which is being subjected to unsustainable exploitation. Their report goes on to link many seemingly disparate contemporary crises to this system, including environmental factors such as global warming and accelerated species extinctions and also societal factors such as rising economic inequality, unemployment, sluggish economic growth, rising debt levels, and impuissant governments unable to deal with these problems. The scientists say a new economic model, one which focuses on sustainability and efficiency and not profit and growth, will be needed as decades of robust economic growth driven by abundant resources and cheap energy is rapidly coming to a close.[186][187] Another group of scientists contributing to the 2020 "Scientists warning on affluence" argue that a shift away from paradigms fixating on economic growth and the "profit-driven mechanism of prevailing economic systems" will be necessary to mitigate human impacts on the environment, and suggest a range of ideas from the reformist to the radical, with the latter consisting of degrowth, eco-socialism and eco-anarchism.[89] Some scientists contend that the rise of capitalism, which itself developed out of European imperialism and colonialism of the 15th and 16th centuries, marks the emergence of the Anthropocene epoch, in which human beings started to have significant and mostly negative impacts on the earth system.[188] Others have warned that contemporary global capitalism "requires fundamental changes" to mitigate the worst environmental impacts, including the "abolition of perpetual economic growth, properly pricing externalities, a rapid exit from fossil-fuel use, strict regulation of markets and property acquisition, reining in corporate lobbying, and the empowerment of women".[189][190] Jason Hickel writes that capitalism creates pressures for population growth: "more people means more labour, cheaper labour, and more consumers." He argues that continued population growth makes the challenge of sustainability even more difficult, but adds that even if the population leveled off, capitalism will simply get already existing consumers to increase their consumption, as consumption rates have always outpaced population growth rates.[191] In 2024 a group of experts including Michael E. Mann and Naomi Oreskes published "An urgent call to end the age of destruction and forge a just and sustainable future". They made an extensive review of existing scientific literature about the issue. They put the blame for the ecological crisis on "imperialism, extractive capitalism, and a surging population" and proposed a paradigm shift that replaces it with a socio-economic model prioritizing sustainability, resilience, justice, kinship with nature, communal well-being. They described many ways in which the transition can be achieved.[192] |