Capitalism

資本主義

Capitalism

池田光穂

★資本主義は[我々の欲望に直接訴えてくる分だけ]我々の想像以上にタフでレジリエントである——垂水源之介(1998)

★資本主義(英語ウィキペディア)は、生産手段の私的所有を基盤とする経済システムである。これは一般的に、利益の道徳的許容性、自由貿易、資本の蓄積、自発的な交換、賃金労働な どを含むものと解釈されている。現代の資本主義は、16世紀から18世紀にかけてイギリスで農業社会から発展し、ヨーロッパ各地で重商主義的実践を経て形 成された。18世紀の産業革命は、工場と複雑な分業を特徴とする資本主義を主要な生産方法として確立した。その出現、進化、普及は、広範な研究と議論の対 象となっている。多少、日本語ウィキペディアでは「資本主義または資本制は、 貿易と産業が、国政よりも営利目的の個人的所有者たちによって制御されている経済的・政治的システム。特に近現代の資本主義の根幹は、自由資本主義・リベ ラルキャピタリズムと呼ばれており、資本主義を肯定・擁護・推進する思想や主張は、普通は自由主義とされる。資本主義に基づく社会は「資本主義社会」「市 民社会」「近代社会」「ブルジョア社会」などと呼ばれる」とある。

★ここでいう資本主義は産業資本主義(Industrial capitalism)を考える

|

産業資本(さ んぎょうしほん、industrial capital、ドイツ語: industrielles Kapital)とは、18世紀後半から19世紀前半にかけての産業革命の結果成立した資本主義的生産の基軸となる資本形態のことであり、主たる資産が産 業設備である資本のこと、また、産業とくに工業を基盤とする営利企業のことをいう[1]。製造業や鉱業、物流業などにおける資本がそれにあたり、その流通 過程より利潤を獲得する。産業資本は、近代に独自の資本形態である[2]。 18 世紀末に紡績機械の改良をきっかけとして、イギリスでは新興の木綿工業が飛躍的に発展した[3]。これが産業革命のはじまりである。産業資本は、この産業 革命により登場した資本形態であり、それに先立つ商業資本や高利貸資本とは異なり、生産過程をその内部にもつ[2]。産業資本成立のためには、農民から土 地を収奪し、彼らを生産手段をもたない労働者階級に転化する「資本の本源的蓄積」のプロセスが歴史的に先行しなければならない。産業資本が近代に独自の資 本形態とされるのは、そのためである[2]。イギリスでは、1830年前後には、蒸気機関や紡績機、綿布機械などが発明・改良されて工場制度の下に大生産 がおこなわれ、資本家が多数の労働者を雇用して一定の規律のもとに労働させるシステム(資本制的生産様式、あるいは単に資本主義)が形成されていった [3]。 G - W ... P ... W' - G' マ ルクス経済学の説明では、生産資本の活動は、まず貨幣形態(G)で投下され、それによって生産手段(産業設備、土地など)と労働力商品(商品としての労働 力)が購入され、賃金によって労働者を働かせ、機械等の産業設備を稼動させる(生産過程Pを進行させる)ことによって剰余価値を内包する商品(W')を生 産し、それを流通させ、最終的に販売することによって利潤を上げる[2]。すなわち、価値はこの過程で増殖するのであり、利潤の源泉は商品生産過程におい て生じた剰余価値ということになる。こうして、賃労働と資本の結合によって生まれた利潤は、さらに新たな生産手段の獲得のために再投資され、生産活動と利 潤の拡張を自己目的として、これら全体の営為が繰り返される[2]。産業革命当初に形成された産業資本は、初期投資の額が比較的軽微ですむ繊維工業などの 軽工業分野の資本であった。それがやがて、製鉄業、機械工業、鉱業、鉄道建設などに拡大されるにつれ、それぞれの分野において産業資本が生まれた。 歴 史的にみれば、先行して成立した商業資本(G―W―G')や高利貸資本(G…G')は、産業資本の成立とともに、これに従属し、以後は産業資本の部分的機 能を代行するのみの従属的な役割を果たすだけになった[2]。産業資本はまた、先行するギルド組織が商工業者の自治理念に発しながら自己の組織・利害を守 ること自体を目的としたのに対し、それが資本制的システムの自由な展開にとって障害となってきたところから、「営業の自由(freedom of trade)」を主張した[1][注釈 1]。それが、アダム・スミスの『諸国民の富』(国富論)で主張されるところの「経済における自由放任主義」(自由主義経済)である。スミスの唱えた経済 学は自由競争時代の産業資本家の利益を代弁するものであった。そしてまた、「営業の自由(freedom of trade)」は、やがて「自由貿易(free trade)」の主張となっていく[1][注釈 2]。 産業資本が成長し、規模の拡大や多業種への活動拡大に金融資本が関与するようになると、資本主義は独占資本が一国のほとんど全産業を支配する独占資本主義の段階へと移り、国際政治のうえでは、列強によって帝国主義の政策が採られるようになった(→「産業資本」)。 |

☆呼称の起源

資本主義(capitalism)という用語は誰が 使い始めたのか? カール・マルクス(Karl Marx, 1818-1883)か?どうも、マルクスやその盟友フリードリヒ・エンゲルス(Friedrich Engels, 1820-1895)ではないようだ。『資本論(Das Capital)』も第1巻は1867年にマルクスの生前に発刊されたが、この書物のもともとのタイトルは『経済学批判(1857-1858; 1858-1859)』であり、その表題は副題として残っている。第2巻は、マルクスの死後2年後の1885年に、第3巻はエンゲルスがなくなる1年前の 1894年に刊行された。実質的に2巻以降は、マルクスとエンゲルスの共著であるといってもよい。第4巻は資本論のタイトルがなく、それをまとめたカー ル・カウツキーらにより『剰余価値学説史』(1905-1910)となって20世紀になってようやく完成をみた(→「資本主義批判」)。

マルクスらが依拠したり、また批判して論敵とした、 ルイ・ブラン(Louis Blanc, 1811-1882)が資本主義を 「ある者が他者を締め出す事による、資本の占有」の状態を1850年にその ように呼んだようだ。フランス語では資本主義は1753年には商品を所有する人の意味ですでに使われていたそうだ。ピエール・ジョゼフ・プルードン(Pierre Joseph Proudhon, 1809-1865)は、フェルナン・ブローデルの説によると資本主義の体制のもとでは労働する者は資本を持たないと説明している。『資本論』の中では、 資本家のシステムないしは、本家の生産様式などと表現されていて、彼らが批判してやまない制度を資本主義とは呼ばなかったようだ。『資本論』第2巻では、 資本主義はわずか1度だけしかでてこない(ドイツ語のウィキペディアKapitalismusよ り)。日本語のウィキペディアも、資本主義とマルクスらの関係については曖昧なままの説明に終わっている。

20世紀になると、ヴェルナー・ゾンバルトがDer moderne Kapitalismus (1902) を、マックス・ウェーバーがDie protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus (1904).を書名のタイトルに採用してから、資本主義は人口に膾炙するようになるとみてもよいので資本論からはほぼ30年ちかくの歳月がかかっている ことになる。

では資本主義とはなにか?マルクス主義が思想界を席 巻した1970−80年代に書かれたと思われるコトバンクだとこう説明されている;「生産手段を資本として私有する資本家が、自己の労働力以外に売るもの を持たない労働者から労働力を商品として買い、それを上回る価値を持つ商品を生産して利潤を得る経済構造」。ここで「上回る価値を持つ商品を生産」という ところが、マルクスやエンゲルスのいうところの剰余価値労働によって、上前を刎ねられて「搾取」されているお馴染みの図式が想定されている。だがはっきり 言おう、これは資本主義のメカニズム分析に立ち入ってかつ不正確な説明である。そのため、資本主義のミニマックスの定義が必要である。つまり、資本主義と は「(リアルやヴァーチャルを問わず)会社や商店が労働者を働かせて利潤のあげ、そ れ(=労働の結果や成果)を給料という対価を支払い、それで回っている世の中のしくみ」 ということだ。市場や「自由」の概念というものは、そのような世の中のしくみ、からうまれてくる必然あるいは「改良されて一定の均衡安定を得たもの」とい うことがある。その意味で、市場が国家をコントロールし、市民が享受すべき自由などなくても資本主義を回せるという中国共産党の改革開放政策以降の中華人 民共和国も、資本主義国なのである。

| Capitalism

is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of

production and their operation for profit.[1][2][3][4][5] Central

characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive

markets, price systems, private property, property rights recognition,

economic freedom, profit motive, commodification, voluntary exchange,

wage labor and the production of commodities.[6][7][8][9] In a market

economy, decision-making and investments are determined by owners of

wealth, property, or ability to maneuver capital or production ability

in capital and financial markets—whereas prices and the distribution of

goods and services are mainly determined by competition in goods and

services markets.[10] Economists, historians, political economists, and sociologists have adopted different perspectives in their analyses of capitalism and have recognized various forms of it in practice. These include laissez-faire or free-market capitalism, anarcho-capitalism, state capitalism, and welfare capitalism. Different forms of capitalism feature varying degrees of free markets, public ownership,[11] obstacles to free competition, and state-sanctioned social policies. The degree of competition in markets and the role of intervention and regulation, as well as the scope of state ownership, vary across different models of capitalism.[12][13] The extent to which different markets are free and the rules defining private property are matters of politics and policy. Most of the existing capitalist economies are mixed economies that combine elements of free markets with state intervention and in some cases economic planning.[14] Capitalism in its modern form emerged from agrarianism in England, as well as mercantilist practices by European countries between the 16th and 18th centuries. The Industrial Revolution of the 18th century established capitalism as a dominant mode of production, characterized by factory work and a complex division of labor. Through the process of globalization, capitalism spread across the world in the 19th and 20th centuries, especially before World War I and after the end of the Cold War. During the 19th century, capitalism was largely unregulated by the state, but became more regulated in the post–World War II period through Keynesianism, followed by a return of more unregulated capitalism starting in the 1980s through neoliberalism. Market economies have existed under many forms of government and in many different times, places, and cultures. Modern industrial capitalist societies developed in Western Europe in a process that led to the Industrial Revolution. Capitalist economies promote economic growth through accumulation of capital, however a business cycle of economic growth followed by recession is a common characteristic of such economies.[15] |

資本主義(しほんしゅぎ、英:

Capitalism)とは、生産手段の私有と営利を目的としたその運用に基づく経済体制である[1][2][3][4][5]。資本主義の中心的な特徴

として、資本蓄積、競争市場、価格システム、私有財産、財産権の承認、経済的自由、利潤動機、商品化、自発的交換、賃金労働、商品生産などが挙げられる。

[6][7][8][9]市場経済においては、意思決定と投資は、富、財産、または資本市場や金融市場における資本や生産能力を操縦する能力の所有者に

よって決定され、一方、財やサービスの価格と分配は、主に財やサービス市場における競争によって決定される[10]。 経済学者、歴史家、政治経済学者、社会学者は、資本主義の分析において異なる視点を採用し、実際において資本主義の様々な形態を認めてきた。これらには、 自由放任または自由市場資本主義、無政府資本主義、国家資本主義、福祉資本主義が含まれる。資本主義のさまざまな形態の特徴は、自由市場、公的所有権、 [11]自由競争に対する障害、国家公認の社会政策の程度が異なることである。市場における競争の程度、介入と規制の役割、国家所有の範囲は、資本主義の 異なるモデルによって異なる[12][13]。現存する資本主義経済のほとんどは、自由市場の要素と国家の介入、場合によっては経済計画の要素を組み合わ せた混合経済である[14]。 近代的な形態の資本主義は、16世紀から18世紀にかけてのヨーロッパ諸国による重商主義の実践と同様に、イギリスにおける農耕主義から生まれた。18世 紀の産業革命は、工場労働と複雑な分業を特徴とする、支配的な生産様式としての資本主義を確立した。グローバリゼーションの過程を通じて、資本主義は19 世紀から20世紀にかけて、特に第一次世界大戦前と冷戦終結後に世界中に広がった。19世紀には、資本主義は国家による規制をほとんど受けなかったが、第 二次世界大戦後のケインズ主義によって規制が強化され、その後、1980年代から新自由主義によって規制のない資本主義が復活した。 市場経済は様々な形態の政府の下で、様々な時代、場所、文化の中で存在してきた。近代産業資本主義社会は、産業革命に至る過程で西ヨーロッパで発展した。 資本主義経済は資本の蓄積を通じて経済成長を促進するが、経済成長の後に不況が訪れるという景気循環は、このような経済に共通する特徴である[15]。 |

| Etymology Other terms sometimes used for capitalism: Capitalist mode of production[16] Economic liberalism[17] Free enterprise[18][page needed] Free enterprise economy[19] Free market[18][page needed] Free market economy[19] Laissez-faire[20] Market economy[21] Profits system[22][page needed] Self-regulating market[18][page needed] The term "capitalist", meaning an owner of capital, appears earlier than the term "capitalism" and dates to the mid-17th century. "Capitalism" is derived from capital, which evolved from capitale, a late Latin word based on caput, meaning "head"—which is also the origin of "chattel" and "cattle" in the sense of movable property (only much later to refer only to livestock). Capitale emerged in the 12th to 13th centuries to refer to funds, stock of merchandise, sum of money or money carrying interest.[23]: 232 [24] By 1283, it was used in the sense of the capital assets of a trading firm and was often interchanged with other words—wealth, money, funds, goods, assets, property and so on.[23]: 233 The Hollantse (German: holländische) Mercurius uses "capitalists" in 1633 and 1654 to refer to owners of capital.[23]: 234 In French, Étienne Clavier referred to capitalistes in 1788,[25] four years before its first recorded English usage by Arthur Young in his work Travels in France (1792).[24][26] In his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), David Ricardo referred to "the capitalist" many times.[27] English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge used "capitalist" in his work Table Talk (1823).[28] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon used the term in his first work, What is Property? (1840), to refer to the owners of capital. Benjamin Disraeli used the term in his 1845 work Sybil.[24] Alexander Hamilton used "capitalist" in his Report of Manufactures presented to the United States Congress in 1791. The initial use of the term "capitalism" in its modern sense is attributed to Louis Blanc in 1850 ("What I call 'capitalism' that is to say the appropriation of capital by some to the exclusion of others") and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in 1861 ("Economic and social regime in which capital, the source of income, does not generally belong to those who make it work through their labor").[23]: 237 Karl Marx frequently referred to the "capital" and to the "capitalist mode of production" in Das Kapital (1867).[29][30] Marx did not use the form capitalism but instead used capital, capitalist and capitalist mode of production, which appear frequently.[30][31] Due to the word being coined by socialist critics of capitalism, economist and historian Robert Hessen stated that the term "capitalism" itself is a term of disparagement and a misnomer for economic individualism.[32] Bernard Harcourt agrees with the statement that the term is a misnomer, adding that it misleadingly suggests that there is such a thing as "capital" that inherently functions in certain ways and is governed by stable economic laws of its own.[33] In the English language, the term "capitalism" first appears, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), in 1854, in the novel The Newcomes by novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, where the word meant "having ownership of capital".[34] Also according to the OED, Carl Adolph Douai, a German American socialist and abolitionist, used the term "private capitalism" in 1863. |

語源 資本主義について使われることがある他の用語 資本主義的生産様式[16] 経済自由主義[17] 自由企業主義[18][要ページ]。 自由企業経済[19] 自由市場[18][ページが必要]。 自由市場経済[19] 自由放任主義[20] 市場経済[21] プロフィット・システム[22][ページが必要]。 自主規制市場[18][ページが必要]。 資本の所有者を意味する 「capitalist 」という用語は、「capitalism 」という用語よりも古く、17世紀半ばに登場する。「資本主義」は、「頭」を意味するcaputに基づく後期ラテン語であるcapitaleから発展した capitaleが語源であり、動産という意味での「chattel」や「cattle」の語源でもある(家畜のみを指すようになったのはずっと後のこと である)。Capitaleは12世紀から13世紀にかけて、資金、商品在庫、金銭の総額、利子を伴う金銭を指すようになった[23]: 232 [24] 1283年までには、商社の資本資産の意味で使われるようになり、しばしば他の単語-富、金銭、資金、商品、資産、財産など-と交換された[23]: 233。 フランス語では、エティエンヌ・クラヴィエが1788年にcapitalistesに言及している[25]。 [24][26]デイヴィッド・リカルドは『政治経済学および課税の原理』(1817年)の中で「資本家」に何度も言及している[27]。 イギリスの詩人サミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジは『テーブル・トーク』(1823年)の中で「資本家」を使用している[28]。 ピエール=ジョゼフ・プルードンは処女作『財産とは何か』(1840年)の中で資本の所有者を指す言葉としてこの言葉を使用している。ベンジャミン・ディ ズレーリは1845年の著作『シビル』の中でこの用語を使用している[24]。アレクサンダー・ハミルトンは1791年にアメリカ合衆国議会に提出した 『製造業報告書』の中で「資本家」を使用している。 現代的な意味での「資本主義」という用語の最初の使用は、1850年のルイ・ブラン(「私が『資本主義』と呼ぶもの、すなわち、他者を排除した一部による 資本の充当」)と1861年のピエール=ジョゼフ・プルードン(「所得の源泉である資本が、労働を通じてそれを働かせる人々に一般的に帰属しない経済社会 体制」)に起因している[23]。 [29][30]マルクスは資本主義という形式を使わず、代わりに資本、資本家、資本主義的生産様式を使用したが、これらは頻繁に登場する[30] [31]。この言葉は資本主義に対する社会主義的批判者によって作られたものであるため、経済学者であり歴史家でもあるロバート・ヘッセンは、「資本主 義」という言葉自体が蔑称であり、経済的個人主義に対する誤用であると述べている。 [32]バーナード・ハーコートは、この用語が誤用であるという声明に同意し、この用語は、本質的に特定の方法で機能し、それ自体の安定した経済法則に よって支配される「資本」のようなものが存在することを誤解を招くように示唆していると付け加えている[33]。 英語では、オックスフォード英語辞典(OED)によれば、「資本主義」という用語は1854年に小説家ウィリアム・メイクピース・サッカレイの小説 『The Newcomes』の中で初めて登場し、この単語は「資本の所有権を持つこと」を意味していた[34]。 またOEDによれば、ドイツ系アメリカ人の社会主義者で奴隷廃止論者であったカール・アドルフ・ドゥーアイは、1863年に「私的資本主義」という用語を 使っていた。 |

| Definition There is no universally agreed upon definition of capitalism; it is unclear whether or not capitalism characterizes an entire society, a specific type of social order, or crucial components or elements of a society.[35] Societies officially founded in opposition to capitalism (such as the Soviet Union) have sometimes been argued to actually exhibit characteristics of capitalism.[36] Nancy Fraser describes usage of the term "capitalism" by many authors as "mainly rhetorical, functioning less as an actual concept than as a gesture toward the need for a concept".[8] Scholars who are uncritical of capitalism rarely actually use the term "capitalism".[37] Some doubt that the term "capitalism" possesses valid scientific dignity,[35] and it is generally not discussed in mainstream economics,[8] with economist Daron Acemoglu suggesting that the term "capitalism" should be abandoned entirely.[38] Consequently, understanding of the concept of capitalism tends to be heavily influenced by opponents of capitalism and by the followers and critics of Karl Marx.[37] |

定義 資本主義が社会全体を特徴づけるのか、特定のタイプの社会秩序を特徴づけるのか、あるいは社会の重要な構成要素や要素を特徴づけるのかは不明である [35]。資本主義に反対して公式に設立された社会(ソビエト連邦など)は、資本主義の特徴を実際に示していると主張されることもある[36]。ナン シー・フレイザーは、多くの著者による「資本主義」という用語の用法を「主に修辞的なものであり、概念の必要性に対するジェスチャーというよりも実際の概 念として機能している」と述べている[8]。 [資本主義に批判的でない学者は、「資本主義」という用語を実際に使用することはほとんどない[37]。 資本主義」という用語が有効な科学的品位を有していることを疑う者もおり[35]、主流派の経済学では一般的に議論されておらず[8]、経済学者のダロ ン・アセモグルは「資本主義」という用語を完全に放棄するべきだと提言している[38]。 その結果、資本主義の概念に対する理解は、資本主義の反対者やカール・マルクスの信奉者や批判者によって大きな影響を受ける傾向にある[37]。 |

| History of

capitalism |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capitalism |

★資本主義の歴史(History of Capitalism)

| Capitalism

is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of

production. This is generally taken to imply the moral permissibility

of profit, free trade, capital accumulation, voluntary exchange, wage

labor, etc. Modern capitalism evolved from agrarianism in England and

mercantilist practices across Europe between the 16th and 18th

centuries. The 18th-century Industrial Revolution cemented capitalism

as the primary method of production, characterized by factories and a

complex division of labor. Its emergence, evolution, and spread are the

subjects of extensive research and debate. The term "capitalism" in its modern sense emerged in the mid-19th century, with thinkers like Louis Blanc and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon coining the term to describe an economic and social order where capital is owned by some and not others who labor. Karl Marx discussed "capital" and the "capitalist mode of production" extensively in Das Kapital (1867). Some historians argue that the roots of modern capitalism lie in the "crisis of the Late Middle Ages," a period of conflict between the aristocracy and agricultural workers. This system differs from earlier forms of trade by focusing on surplus value from production rather than simply "buying cheap and selling dear." Conceptions of capitalism have evolved significantly over time, influenced by various political and analytical viewpoints. Debates sometimes focus on how to bring substantive historical data to bear on key questions.[1] Key parameters of debate include: the extent to which capitalism is natural, versus the extent to which it arises from specific historical circumstances; whether its origins lie in towns and trade or in rural property relations; the role of class conflict; the role of the state; the extent to which capitalism is a distinctively European innovation; its relationship with European imperialism; whether technological change is a driver or merely a secondary byproduct of capitalism; and whether or not it is the most beneficial way to organize human societies.[2] |

資本主義は、生産手段の私的所有を基盤とする経済システムである。これ

は一般的に、利益の道徳的許容性、自由貿易、資本の蓄積、自発的な交換、賃金労働などを含むものと解釈されている。現代の資本主義は、16世紀から18世

紀にかけてイギリスで農業社会から発展し、ヨーロッパ各地で重商主義的実践を経て形成された。18世紀の産業革命は、工場と複雑な分業を特徴とする資本主

義を主要な生産方法として確立した。その出現、進化、普及は、広範な研究と議論の対象となっている。 「資本主義」という用語は、19世紀半ばにルイ・ブランやピエール=ジョゼフ・プルードンといった思想家によって、資本が一部の者によって所有され、労働 する他の者には所有されない経済的・社会的秩序を形容するために造語された。カール・マルクスは『資本論』(1867年)で「資本」と「資本主義的生産方 式」を詳細に論じた。 一部の歴史家は、現代資本主義の根源は「中世後期の危機」にあると主張しています。これは、貴族と農業労働者との間の対立の時代です。このシステムは、生 産からの剰余価値に焦点を当てる点で、単に「安く買って高く売る」という以前の貿易形態と異なります。資本主義の概念は、時間とともに大きく進化してきま した。これは、多様な政治的・分析的視点に影響を受けています。議論は、重要な問題に実質的な歴史的データをどう適用するかに焦点を当てることもありま す。[1] 議論の主要なパラメーターには、次のようなものがある:資本主義が自然なものか、それとも特定の歴史的状況から生じたものか;その起源が都市と貿易にある のか、それとも農村部の財産関係にあるのか; 階級闘争の役割;国家の役割;資本主義がヨーロッパ特有の革新である程度;ヨーロッパ帝国主義との関係;技術的変化が資本主義の駆動要因か、単なる二次的 な副産物か;そして、それが人類社会を組織する最も有益な方法であるかどうか。[2] |

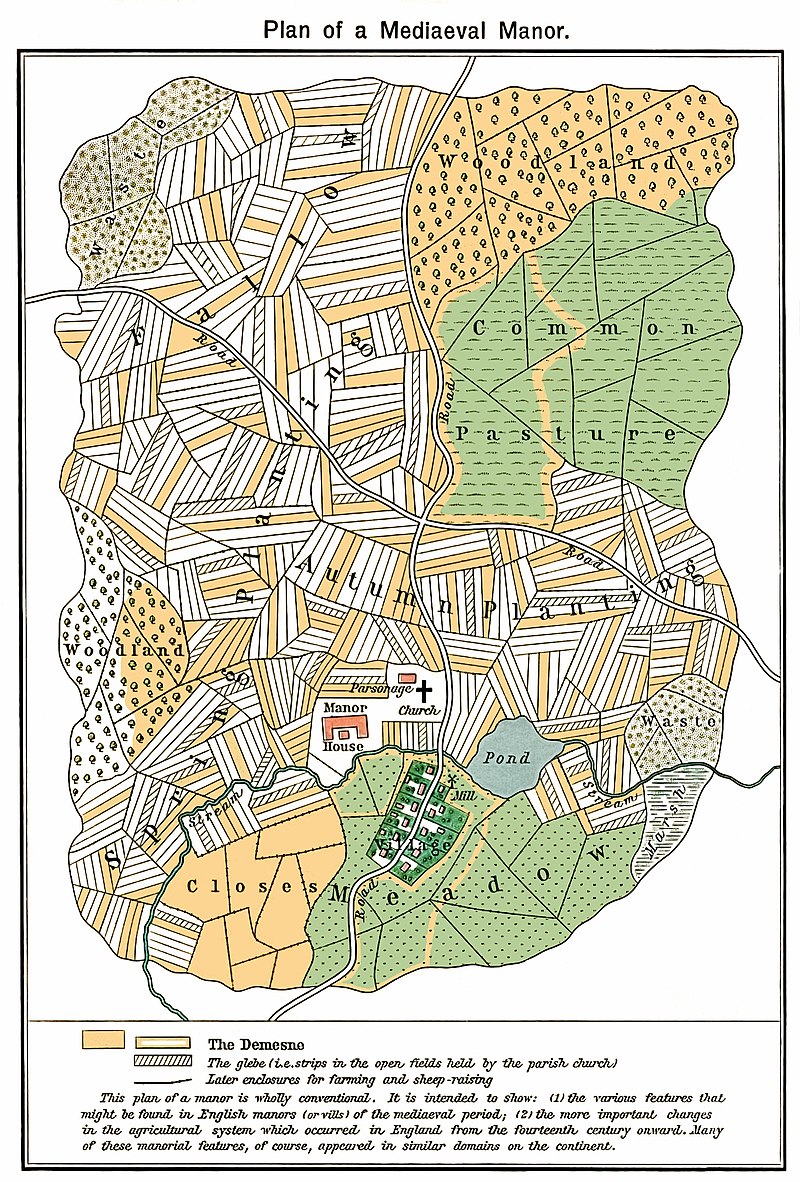

| Agrarian capitalism Crisis of the 14th century  Map of a medieval manor. Notice the large commons area and the division of land into small strips. The mustard-colored areas are part of the demesne, the hatched areas part of the glebe. William R. Shepherd, Historical Atlas, 01923 According to some historians,[3] the modern capitalist system originated in the "crisis of the Late Middle Ages", a conflict between the land-owning aristocracy and the agricultural producers, or serfs. Manorial arrangements inhibited the development of capitalism in a number of ways. Serfs had obligations to produce for lords and to sustain their own families. The lords who owned the land[citation needed] relied on force to guarantee that they received sufficient food. Because lords expanded their power and wealth through military means, they spent their wealth on military equipment or on conspicuous consumption that helped foster alliances with other lords.[4] The demographic crisis of the 14th century upset this arrangement. This crisis had several causes: agricultural productivity reached its technological limitations and stopped growing, bad weather led to the Great Famine of 1315–1317, and the Black Death of 1348–1350 led to a population crash. These factors led to a decline in agricultural production. In response, feudal lords sought to expand agricultural production by extending their domains through warfare; therefore they demanded more tribute from their serfs to pay for military expenses. In England, many serfs rebelled. Some moved to towns, some bought land, and some entered into favorable contracts to rent lands from lords who needed to repopulate their estates.[5] In effect, feudalism began to lay some of the foundations necessary for the development of mercantilism, a precursor of capitalism. Feudalism lasted from the medieval period through the 16th century. Feudal manors were almost entirely self-sufficient, and therefore limited the role of the market. This stifled any incipient tendency towards capitalism. However, the relatively sudden emergence of new technologies and discoveries, particularly in agriculture[6] and exploration, facilitated the growth of capitalism. The most important development at the end of feudalism[citation needed] was the emergence of what Robert Degan calls "the dichotomy between wage earners and capitalist merchants".[7] The competitive nature meant there are always winners and losers, and this became clear as feudalism evolved into mercantilism, an economic system characterized by the private or corporate ownership of capital goods, investments determined by private decisions, and by prices, production, and the distribution of goods determined mainly by competition in a free market.[citation needed] |

農業資本主義 14世紀の危機  中世の荘園の地図。広大な共有地と、土地が細長い区画に分割されていることに注目して。マスタード色の部分は領主の所有地(デムズン)、斜線部分は小作人の耕作地(グリーブ)だ。 ウィリアム・R・シェパード『歴史地図帳』、1923年 一部の歴史家によると[3]、現代の資本主義システムは「中世後期の危機」と呼ばれる、土地所有貴族と農業生産者(農奴)との対立から生まれた。荘園制度 は資本主義の発展を複数の面で阻害した。農奴は領主への生産義務と自身の家族を養う義務を負っていた。土地を所有する領主[出典必要]は、十分な食料を確 保するために武力に依存していた。領主は軍事手段を通じて権力と富を拡大したため、その富を軍事装備や他の領主との同盟関係を強化する目立つ消費に費やし た。[4] 14 世紀の人口危機は、この体制を崩壊させた。この危機にはいくつかの原因があった。農業の生産性が技術的な限界に達して成長が止まったこと、悪天候によって 1315 年から 1317 年にかけて大飢饉が発生したこと、1348 年から 1350 年にかけてペストが流行して人口が激減したことなどだ。これらの要因により、農業生産は低迷した。これに対応して、封建領主は戦争を通じて領土を拡大し農 業生産を拡大しようとした。そのため、軍事費を賄うために農奴からより多くの貢物を要求した。イングランドでは多くの農奴が反乱を起こした。一部は町に移 住し、一部は土地を購入し、一部は領主から土地を借りる有利な契約を結んだ。[5] 事実上、封建制度は、資本主義の前身である重商主義の発展に必要な基礎の一部を築き始めた。封建制度は、中世から 16 世紀まで続いた。封建領地はほぼ完全に自給自足であり、そのため市場の役割は限定的だった。これにより、資本主義への初期的な傾向は抑制された。しかし、 特に農業[6] や探検分野における新しい技術や発見の比較的突然の出現が、資本主義の成長を促進した。封建制度末期の最も重要な発展[要出典] は、ロバート・デガンが「賃金労働者と資本主義商人との二分化」と呼ぶものの出現だった。[7] 競争の性質上、勝者と敗者が必ず出現することになり、これは、封建制度が、資本財の個人または企業による所有、個人の決定による投資、そして主に自由市場 での競争によって決定される価格、生産、および商品の流通を特徴とする経済システムである重商主義へと発展するにつれて明らかになった。 |

| Enclosure Main article: Enclosure  Decaying hedges mark the lines of the straight field boundaries created by an inclosure act. England in the 16th century was already a centralized state, in which much of the feudal order of Medieval Europe had been swept away. This centralization was strengthened by a good system of roads and a disproportionately large capital city, London.[8] The capital acted as a central market for the entire country, creating a large internal market for goods, in contrast to the fragmented feudal holdings that prevailed in most parts of the Continent. The economic foundations of the agricultural system were also beginning to diverge substantially; the manorial system had broken down by this time, and land began to be concentrated in the hands of fewer landlords with increasingly large estates. The system put pressure on both the landlords and the tenants to increase agricultural productivity to create profit. The weakened coercive power of the aristocracy to extract peasant surpluses encouraged them to try out better methods. The tenants also had an incentive to improve their methods to succeed in an increasingly competitive labour market. Land rents had moved away from the previous stagnant system of custom and feudal obligation, and were becoming directly subject to economic market forces. An important aspect of this process of change was the enclosure[9] of the common land previously held in the open field system where peasants had traditional rights, such as mowing meadows for hay and grazing livestock. Once enclosed, these uses of the land became restricted to the owner, and it ceased to be land for commons. The process of enclosure began to be a widespread feature of the English agricultural landscape during the 16th century. By the 19th century, unenclosed commons had become largely restricted to rough pasture in mountainous areas and to relatively small parts of the lowlands. Marxist and neo-Marxist historians argue that rich landowners used their control of state processes to appropriate public land for their private benefit. This created a landless working class that provided the labour required in the new industries developing in the north of England. For example: "In agriculture the years between 1760 and 1820 are the years of wholesale enclosure in which, in village after village, common rights are lost".[10] "Enclosure (when all the sophistications are allowed for) was a plain enough case of class robbery".[11] Anthropologist Jason Hickel notes that this process of enclosure led to myriad peasant revolts, among them Kett's Rebellion and the Midland Revolt, which culminated in violent repression and executions.[12] Other scholars[13] argue that the better-off members of the European peasantry encouraged and participated actively in enclosure, seeking to end the perpetual poverty of subsistence farming. "We should be careful not to ascribe to [enclosure] developments that were the consequence of a much broader and more complex process of historical change."[14] "[T]he impact of eighteenth and nineteenth century enclosure has been grossly exaggerated...."[15] |

囲い込み 主な記事:囲い込み  腐朽した生垣が、囲い込み法によって作られたまっすぐな畑の境界線を示している。 16世紀のイギリスは、中世ヨーロッパの封建制度が大部分が消滅した、すでに中央集権的な国家だった。この中央集権化は、優れた道路網と、不釣り合いに大 きな首都ロンドンによって強化された。[8] 首都は全国の中央市場として機能し、大陸の大部分で支配的だった分断された封建領地とは対照的に、大規模な国内市場を形成した。農業システムの経済的基盤 も著しく分岐し始めていた。この頃には荘園制度が崩壊し、土地はますます大規模な領地を所有する少数の地主の手に集中し始めた。このシステムは、地主と小 作人双方に農業生産性を向上させて利益を創出する圧力をかけた。貴族の強制力が弱まり、農民の余剰生産物を徴収する能力が低下したため、彼らはより良い方 法を試すようになった。小作人も、ますます競争が激化する労働市場で成功するため、方法の改善に意欲を示した。地代は、以前の慣習と封建的義務に基づく停 滞したシステムから離れ、経済的市場原理に直接左右されるようになっていった。 この変化のプロセスにおける重要な側面の一つは、農民が伝統的な権利(例えば、牧草地を刈り取って干し草を採取したり、家畜を放牧したりする権利)を持っ ていたオープンフィールドシステムで管理されていた共有地の囲い込み[9]だった。囲い込みが完了すると、これらの土地の利用は所有者に限定され、共有地 としての性格を失った。囲い込みのプロセスは、16世紀にイングランドの農業景観の広範な特徴となるようになった。19世紀までに、囲い込みが行われてい ない共有地は、山岳地帯の荒れた牧草地や低地の比較的狭い地域にほとんど限定されるようになった。 マルクス主義や新マルクス主義の歴史家は、富裕な土地所有者が国家の過程を支配して、公共の土地を私的な利益のために収奪したと主張している。これによ り、イングランド北部で発展した新しい産業に必要な労働力を提供する、土地を持たない労働者階級が生まれた。例えば:「農業において、1760年から 1820年までの期間は、村から村へと共同利用権が失われていく大規模な囲い込みの時代だった」。[10] 「囲い込み(あらゆる複雑な要素を考慮しても)は、明白な階級略奪のケースだった」。[11] 人類学者のジェイソン・ヒッケルは、この囲い込みのプロセスが、ケッツの反乱やミッドランド反乱を含む数多くの農民反乱を引き起こし、暴力的な弾圧と処刑 で終結したと指摘している。[12] 他の学者たち[13] は、ヨーロッパの農民のうち比較的裕福な層が、自給自足の農業による永久的な貧困を終わらせるため、囲い込みを奨励し、積極的に参加したと主張している。 「囲い込みに、より広範で複雑な歴史的変化の結果として生じた発展を帰属させてはならない」[14]。「18世紀と19世紀の囲い込みの影響は過大評価さ れている」[15]。 |

| Merchant capitalism and mercantilism Main articles: Merchant capitalism and Mercantilism Precedents  The city of Genoa, one of the birthplaces of capitalism While trade has existed since early in human history, it was not capitalism.[16] The earliest recorded activity of long-distance profit-seeking merchants can be traced to the old Assyrian merchants active in Mesopotamia the 2nd millennium BCE.[17] The Roman Empire developed more advanced forms of commerce, and similarly widespread networks existed in Islamic nations. However, capitalism took shape in Europe in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. An early emergence of commerce occurred on monastic estates in Italy and France, but in particular in the independent Italian city-states during the late Middle Ages, such as Florence, Genoa and Venice. Those states pioneered innovative financial instruments such as bills of exchange and banking practices that facilitated long-distance trade. The competitive nature of these city-states fostered a spirit of innovation and risk-taking, laying the groundwork for capitalism's core principles of private ownership, market competition, and profit-seeking behavior. The economic prowess of the Italian city-states during this time not only fueled its own prosperity but also contributed significantly to the spread of capitalist ideas and practices throughout Europe and beyond.[18][19] |

商人資本主義と重商主義 主な記事:商人資本主義と重商主義 先例  資本主義の発祥地のひとつであるジェノヴァ市 貿易は人類の歴史の初期から存在していたが、それは資本主義ではなかった。[16] 最古の記録に残る長距離貿易を行う利益追求型の商人の活動は、紀元前2千年紀のメソポタミアで活動していた古代アッシリアの商人まで遡ることができる。 [17] ローマ帝国はより高度な商業形態を発展させ、イスラム国民にも同様の広範なネットワークが存在した。しかし、資本主義は中世後期とルネサンス期にヨーロッ パで形を成した。 商業の早期の出現は、イタリアとフランスの修道院領で起こったが、特に中世後期の独立したイタリアの都市国家、フィレンツェ、ジェノヴァ、ヴェネツィアな どで顕著だった。これらの都市国家は、為替手形や銀行業務などの革新的な金融手段を考案し、長距離貿易を促進した。これらの都市国家の競争的な性質は、革 新とリスクテイクの精神を育み、資本主義の核心的な原則である私有財産、市場競争、利益追求行動の基盤を築いた。この時代のイタリアの都市国家の経済的優 位性は、自らの繁栄を促進するだけでなく、資本主義の思想と実践がヨーロッパ全土およびその先へ広がることに大きく貢献した。[18][19] |

| Emergence Modern capitalism resembles some elements of mercantilism in the early modern period between the 16th and 18th centuries.[20][21] Early evidence for mercantilist practices appears in early modern Venice, Genoa, and Pisa over the Mediterranean trade in bullion. The region of mercantilism's real birth, however, was the Atlantic Ocean.[22]  Sir Josiah Child, an influential proponent of mercantilism. Painting attributed to John Riley. England began a large-scale and integrative approach to mercantilism during the Elizabethan Era. An early statement on national balance of trade appeared in Discourse of the Common Weal of this Realm of England, 1549: "We must always take heed that we buy no more from strangers than we sell them, for so should we impoverish ourselves and enrich them."[23][full citation needed] The period featured various but often disjointed efforts by the court of Queen Elizabeth to develop a naval and merchant fleet capable of challenging the Spanish stranglehold on trade and of expanding the growth of bullion at home. Elizabeth promoted the Trade and Navigation Acts in Parliament and issued orders to her navy for the protection and promotion of English shipping. These efforts organized national resources sufficiently in the defense of England against the far larger and more powerful Spanish Empire, and in turn paved the foundation for establishing a global empire in the 19th century.[citation needed] The authors noted most for establishing the English mercantilist system include Gerard de Malynes and Thomas Mun, who first articulated the Elizabethan System. The latter's England's Treasure by Forraign Trade, or the Balance of our Forraign Trade is The Rule of Our Treasure gave a systematic and coherent explanation of the concept of balance of trade. It was written in the 1620s and published in 1664.[24] Mercantile doctrines were further developed by Josiah Child. Numerous French authors helped to cement French policy around mercantilism in the 17th century. French mercantilism was best articulated by Jean-Baptiste Colbert (in office, 1665–1683), although his policies were greatly liberalised under Napoleon. |

出現 現代資本主義は、16 世紀から 18 世紀にかけての近世初期の重商主義の一部の要素と類似している。[20][21] 重商主義の慣行の初期の証拠は、地中海における貴金属の取引において、近世初期のヴェネツィア、ジェノヴァ、ピサで見られる。しかし、重商主義が実際に誕 生したのは大西洋地域だった。[22]  重商主義の有力な支持者であったジョサイア・チャイルド卿。ジョン・ライリーによる絵画。 イングランドは、エリザベス朝時代に、大規模かつ統合的な重商主義政策を開始した。貿易収支に関する初期の声明は、1549年の『イングランド王国の公共 の福祉に関する言説』に掲載されている。「私たちは、他国から購入する量よりも販売する量が多くなることがないように常に注意しなければならない。そうし なければ、私たちは自らを貧しくし、他国を豊かにすることになるからだ。」[23][出典必要] この時代、エリザベス女王の宮廷は、スペインの貿易支配に挑戦し、国内の貴金属の成長を拡大するための海軍と商船隊の整備に、多様なものの断片的な努力を 重ねた。エリザベスは議会で貿易と航海に関する法律を推進し、海軍に対して英国の船舶の保護と促進を命じた。 これらの努力は、はるかに大規模で強力なスペイン帝国に対するイングランドの防衛のために国民資源を十分に組織化し、その結果、19世紀に世界帝国を確立 するための基盤を築いた。[出典必要] イングランドの重商主義システムを確立した主要な人物として、ジェラード・デ・マリンズとトーマス・ムンが挙げられる。後者の『イングランドの財宝は外国 貿易により、または外国貿易の均衡により、すなわち財宝の規則により』は、貿易収支の概念を体系的かつ一貫した形で説明した。この著作は1620年代に執 筆され、1664年に出版された。[24] 商業主義の教義はジョサイア・チャイルドによってさらに発展した。17世紀には、多くのフランス人著者がフランス政策を商業主義に固めるのに貢献した。フ ランス商業主義はジャン=バティスト・コルベール(在任1665–1683)によって最も明確に表現されたが、彼の政策はナポレオンの下で大幅に自由化さ れた。 |

| Doctrines Under mercantilism, European merchants, backed by state controls, subsidies, and monopolies, made most of their profits from buying and selling goods. In the words of Francis Bacon, the purpose of mercantilism was "the opening and well-balancing of trade; the cherishing of manufacturers; the banishing of idleness; the repressing of waste and excess by sumptuary laws; the improvement and husbanding of the soil; the regulation of prices..."[25] Similar practices of economic regimentation had begun earlier in medieval towns. However, under mercantilism, given the contemporaneous rise of absolutism, the state superseded the local guilds as the regulator of the economy.  The Anglo-Dutch Wars were fought between the English and the Dutch for control over the seas and trade routes. Among the major tenets of mercantilist theory was bullionism, a doctrine stressing the importance of accumulating precious metals. Mercantilists argued that a state should export more goods than it imported so that foreigners would have to pay the difference in precious metals. Mercantilists asserted that only raw materials that could not be extracted at home should be imported. They promoted the idea that government subsidies, such as granting monopolies and protective tariffs, were necessary to encourage home production of manufactured goods. Proponents of mercantilism emphasized state power and overseas conquest as the principal aim of economic policy. If a state could not supply its own raw materials, according to the mercantilists, it should acquire colonies from which they could be extracted. Colonies constituted not only sources of raw materials but also markets for finished products. Because it was not in the interests of the state to allow competition, to help the mercantilists, colonies should be prevented from engaging in manufacturing and trading with foreign powers. Mercantilism was a system of trade for profit, although commodities were still largely produced by non-capitalist production methods.[26] Noting the various pre-capitalist features of mercantilism, Karl Polanyi argued that "mercantilism, with all its tendency toward commercialization, never attacked the safeguards which protected [the] two basic elements of production – labor and land – from becoming the elements of commerce." Thus mercantilist regulation was more akin to feudalism than capitalism. According to Polanyi, "not until 1834 was a competitive labor market established in England, hence industrial capitalism as a social system cannot be said to have existed before that date."[27] |

教義 重商主義の下では、国家の規制、補助金、独占の支援を受けたヨーロッパの商人は、商品の売買によってほとんどの利益を得ていた。フランシス・ベーコンの言 葉を借りれば、重商主義の目的は「貿易の開放と均衡の維持、製造業の育成、怠惰の排除、奢侈禁止法による浪費と過剰の抑制、土地の改良と管理、価格の規 制……」だった[25]。同様の経済統制の慣行は、中世の都市でより早くから始まっていた。しかし、重商主義の下では、同時期に絶対主義が台頭したため、 経済を規制する役割は、地元のギルドから国家に移った。  英蘭戦争は、海と貿易ルートの支配権を争う、イギリスとオランダの間で戦われた戦争だ。 重商主義の主要な教義の一つは、貴金属の蓄積の重要性を強調する貴金属主義だった。重商主義者は、国家は輸入よりも多くの商品を輸出し、その差額を外国に 貴金属で支払わせるべきだと主張した。重商主義者は、国内で採掘できない原材料のみ輸入すべきだと主張した。彼らは、製造品の国内生産を促進するために、 独占権の付与や保護関税などの政府補助金が不可欠であると主張した。 重商主義の支持者は、経済政策の主な目的として国家の権力と海外征服を強調した。重商主義者によると、国家が自国の原材料を供給できない場合、それらを採 掘できる植民地を獲得すべきだとしました。植民地は原材料の供給源だけでなく、完成品の市場としても機能しました。国家の利益に反するため、重商主義者を 支援するために、植民地は製造業や外国との貿易を禁止されるべきだとされました。 重商主義は利益を目的とした貿易システムだったが、商品の大部分は依然として非資本主義的な生産方法によって生産されていた。[26] 重商主義の様々な前資本主義的特徴を指摘し、カール・ポラニーは「重商主義は、商業化への傾向にもかかわらず、生産の二つの基本要素である労働と土地が商 業の要素となることを防ぐ安全装置を攻撃しなかった」と主張した。したがって、重商主義の規制は資本主義よりも封建制に近かった。ポラニーによると、 「1834年までイギリスに競争的な労働市場が確立されなかったため、産業資本主義として社会システムが存在したとは、その日付以前には言えない」 [27]。 |

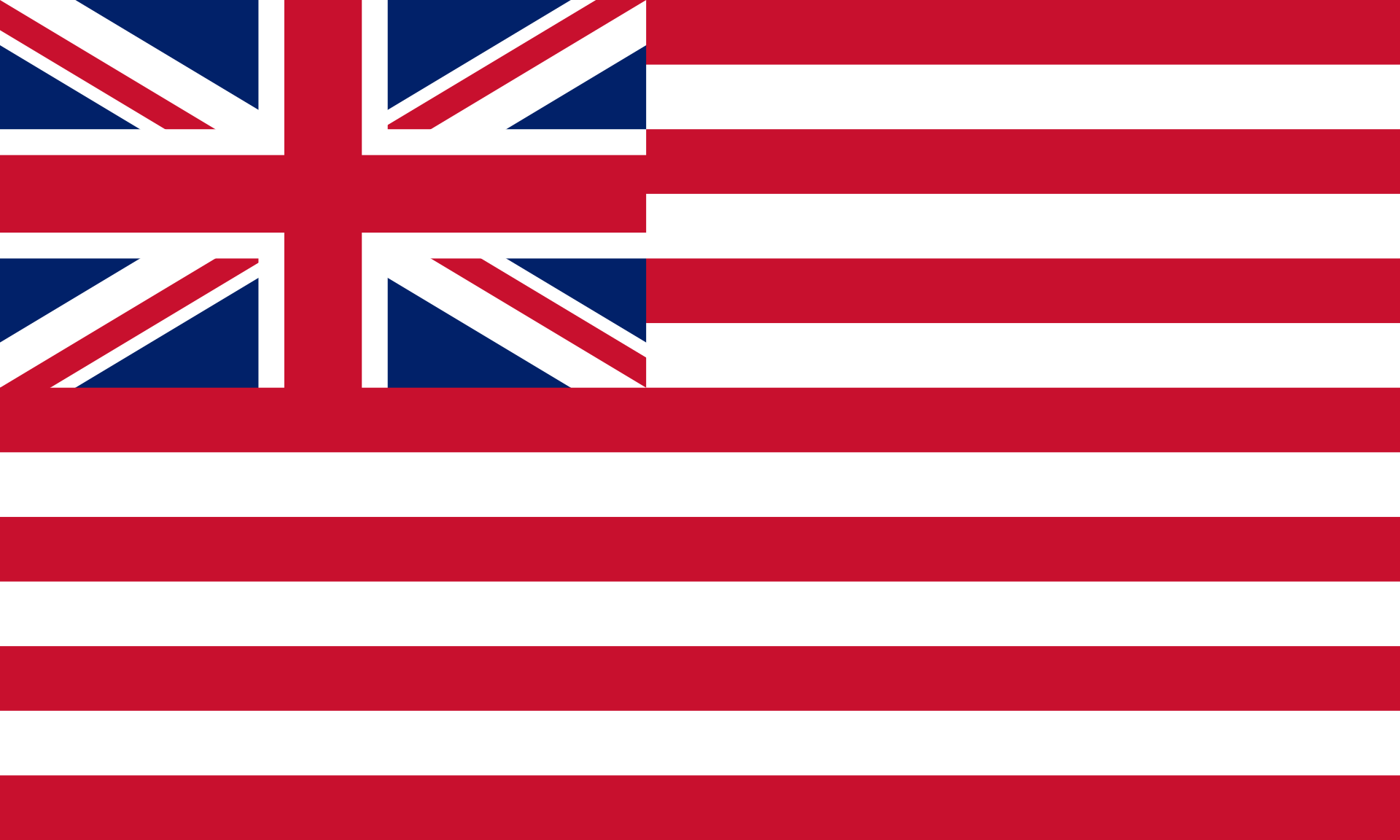

Chartered trading companies British East India Company 1801 The Muscovy Company was the first major chartered joint stock English trading company. It was established in 1555 with a monopoly on trade between England and Muscovy. It was an offshoot of the earlier Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands, founded in 1551 by Richard Chancellor, Sebastian Cabot and Sir Hugh Willoughby to locate the Northeast Passage to China to allow trade. This was the precursor to a type of business that would soon flourish in England, the Dutch Republic and elsewhere. The British East India Company (1600) and the Dutch East India Company (1602) launched an era of large state chartered trading companies.[28][29] These companies were characterized by their monopoly on trade, granted by letters patent provided by the state. Recognized as chartered joint-stock companies by the state, these companies enjoyed lawmaking, military, and treaty-making privileges.[30] Characterized by its colonial and expansionary powers by states, powerful nation-states sought to accumulate precious metals, and military conflicts arose.[28] During this era, merchants, who had previously traded on their own, invested capital in the East India Companies and other colonies, seeking a return on investment. |

特許貿易会社 イギリス東インド会社 1801 ムスコヴィ会社は、最初の主要な特許合資会社であるイギリスの貿易会社だった。1555年に設立され、イギリスとムスコヴィ間の貿易の独占権を持ってい た。これは、1551年にリチャード・チャネル、セバスチャン・カボット、サー・ヒュー・ウィロビーによって設立された「新大陸への商人冒険者会社」の分 派で、中国への東北航路の発見を目的として設立された。これは、イギリス、オランダ共和国、その他の地域で繁栄する新たなビジネス形態の先駆けとなった。 イギリス東インド会社(1600年)とオランダ東インド会社(1602年)は、国家が特許状を付与した大規模な貿易会社の時代を築いた。[28][29] これらの会社は、国家から付与された特許状により貿易の独占権を保持していたことが特徴だった。国家から特許状を付与された合資会社として認められたこれ らの会社は、立法権、軍事権、条約締結権などの特権を享受した。[30] 国家の植民地化と拡張政策により、強力な国民は貴金属の蓄積を追求し、軍事衝突が発生した。[28] この時代、従来は個人で貿易を行っていた商人たちは、東インド会社や他の植民地に資本を投資し、投資利益を追求した。 |

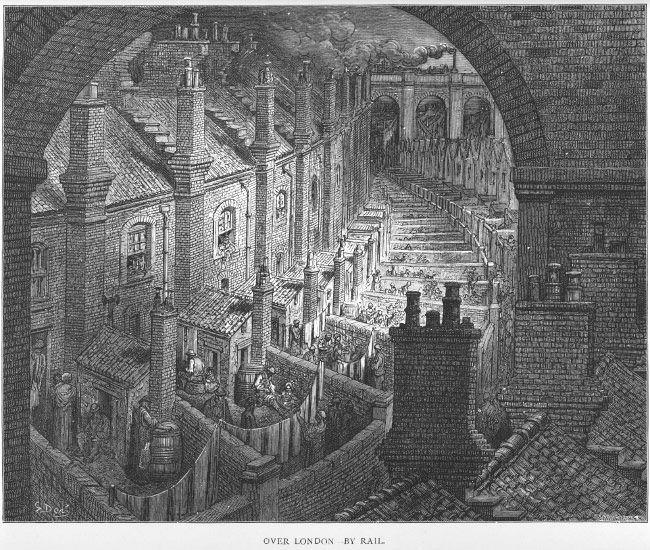

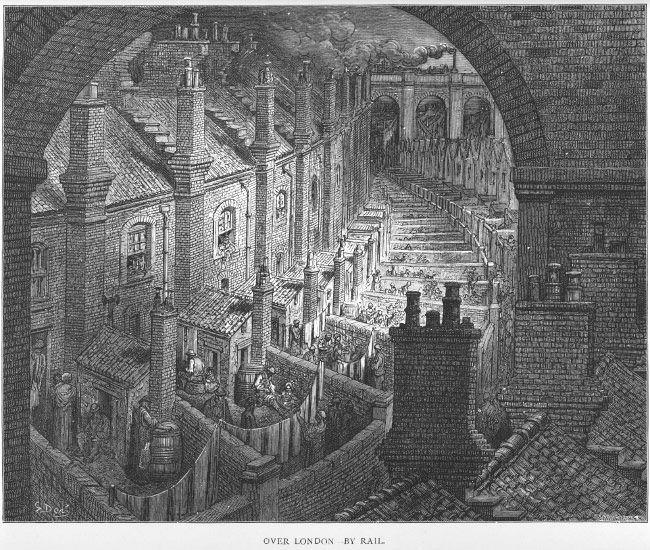

Industrial capitalism Gustave Doré's 19th-century engraving depicted the dirty, overcrowded slums where the industrial workers of London lived. Mercantilism declined in Great Britain in the mid-18th century, when a new group of economic theorists, led by Adam Smith, challenged fundamental mercantilist doctrines, such as that the world's wealth remained constant and that a state could increase its wealth only at the expense of another state. However, mercantilism continued in less developed economies, such as Prussia and Russia, with their much younger manufacturing bases. The mid-18th century gave rise to industrial capitalism, made possible by (1) the accumulation of vast amounts of capital under the merchant phase of capitalism and its investment in machinery, and (2) the fact that the enclosures meant that Britain had a large population of people with no access to subsistence agriculture, who needed to buy basic commodities via the market, ensuring a mass consumer market.[31] Industrial capitalism, which Marx dated from the last third of the 18th century, marked the development of the factory system of manufacturing, characterized by a complex division of labor between and within work processes and the routinization of work tasks. Industrial capitalism finally established the global domination of the capitalist mode of production.[20] During the resulting Industrial Revolution, the industrialist replaced the merchant as a dominant actor in the capitalist system, which led to the decline of the traditional handicraft skills of artisans, guilds, and journeymen. Also during this period, capitalism transformed relations between the British landowning gentry and peasants, giving rise to the production of cash crops for the market rather than for subsistence on a feudal manor. The surplus generated by the rise of commercial agriculture encouraged increased mechanization of agriculture. There is an active debate on the role of the Atlantic slavery in the emergence of industrial capitalism.[32] Eric Williams (1944) argued on Capitalism and Slavery about the crucial role of plantation slavery in the growth of industrial capitalism, since both happened in similar time periods. Harvey (2019) wrote that "A flagship of the industrial revolution, the Lancashire mills and their 465,000 textile workers, was entirely reliant [in the 1860s] on the labour of three million cotton slaves in the American Deep South."[33] |

産業資本主義 ギュスターヴ・ドレの19世紀の版画は、ロンドンの産業労働者が住んでいた汚く過密なスラム街を描いたものだよ(そうか?!ありがとう)。 18世紀半ば、アダム・スミスをリーダーとする新しい経済理論家たちが、世界の富は一定であり、国家は他の国家の犠牲によってのみ富を増やすことができる という、重商主義の基本教義に異議を唱えたことで、イギリスでは重商主義が衰退した。しかし、プロイセンやロシアなど、製造業の基盤がまだ未熟な後進国で は、重商主義が継続した。 18世紀半ばには、産業資本主義が台頭した。これは、(1) 資本主義の商人段階における莫大な資本の蓄積とその機械への投資、および (2) 囲い込みによりイギリスに自給自足農業にアクセスできない大規模な人々(すなわち、イギリスにおける消費者の大部分を占める人々)が生まれ、彼らが市場を 通じて基本商品を購入する必要が生じたため、大規模な消費者市場が確保されたこと、の2つの要因により可能となった。[31] マルクスが18世紀後半に起源を置く産業資本主義は、製造における工場制度の発展を特徴とし、作業プロセス間およびプロセス内の複雑な分業と作業のルー ティン化が特徴だった。産業資本主義は最終的に資本主義的生産方式のグローバルな支配を確立した。[20] その結果生じた産業革命において、資本主義システムにおける支配的な役割は商人から実業家に移り、職人の伝統的な手工業の技能、ギルド、見習い制度は衰退 した。また、この期間、資本主義はイギリスの土地所有貴族と農民の関係を変革し、封建的な荘園での自給自足ではなく、市場向けの換金作物の生産が盛んに なった。商業農業の台頭によって生じた余剰は、農業の機械化の進展を促した。 大西洋奴隷貿易が産業資本主義の台頭において果たした役割については、活発な議論がある[32]。エリック・ウィリアムズ(1944)は、『資本主義と奴 隷制』の中で、産業資本主義の成長と奴隷制は同時期に起こったことから、プランテーション奴隷制が産業資本主義の成長に重要な役割を果たしたと主張した。 ハーヴェイ(2019)は、「産業革命の象徴であるランカシャーの工場と46万5,000人の紡績労働者は、1860年代にはアメリカ南部の300万人の 綿花奴隷の労働力に完全に依存していた」と書いている。[33] |

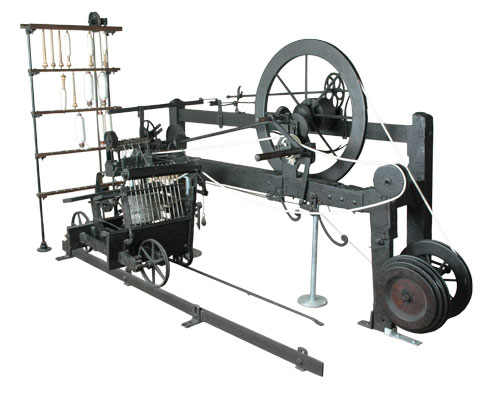

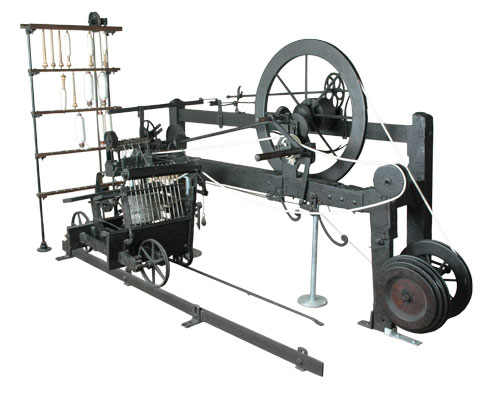

| Industrial Revolution Main article: Industrial Revolution The productivity gains of capitalist production began a sustained and unprecedented increase at the turn of the 19th century, in a process commonly referred to as the Industrial Revolution. Starting in about 1760 in England, there was a steady transition to new manufacturing processes in a variety of industries, including going from hand production methods to machine production, new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes, improved efficiency of water power, the increasing use of steam power and the development of machine tools. It also included the change from wood and other bio-fuels to coal.  The Spinning mule, built by the inventor Samuel Crompton In textile manufacturing, mechanized cotton spinning powered by steam or water increased the output of a worker by a factor of about 1000, due to the application of James Hargreaves' spinning jenny, Richard Arkwright's water frame, Samuel Crompton's Spinning Mule and other inventions. The power loom increased the output of a worker by a factor of over 40.[34] The cotton gin increased the productivity of removing seed from cotton by a factor of 50. Large gains in productivity also occurred in spinning and weaving wool and linen, although they were not as great as in cotton. Finance  The Rothschild family revolutionised international finance. The Frankfurt terminus of the Taunus Railway was financed by the Rothschilds and opened in 1840 as one of Germany's first railways. The growth of Britain's industry stimulated a concomitant growth in its system of finance and credit. In the 18th century, services offered by banks increased. Clearing facilities, security investments, cheques and overdraft protections were introduced. Cheques had been invented in the 17th century in England, and banks settled payments by direct courier to the issuing bank. Around 1770, they began meeting in a central location, and by the 19th century a dedicated space was established, known as a bankers' clearing house. The London clearing house used a method where each bank paid cash to and then was paid cash by an inspector at the end of each day. The first overdraft facility was set up in 1728 by The Royal Bank of Scotland. The end of the Napoleonic War and the subsequent rebound in trade led to an expansion in the bullion reserves held by the Bank of England, from a low of under 4 million pounds in 1821 to 14 million pounds by late 1824. Older innovations became routine parts of financial life during the 19th century. The Bank of England first issued bank notes during the 17th century, but the notes were hand written and few in number. After 1725, they were partially printed, but cashiers still had to sign each note and make them payable to a named person. In 1844, parliament passed the Bank Charter Act tying these notes to gold reserves, effectively creating the institution of central banking and monetary policy. The notes became fully printed and widely available from 1855.[citation needed] Growing international trade increased the number of banks, especially in London. These new "merchant banks" facilitated trade growth, profiting from England's emerging dominance in seaborne shipping. Two immigrant families, Rothschild and Baring, established merchant banking firms in London in the late 18th century and came to dominate world banking in the next century. The tremendous wealth amassed by these banking firms soon attracted much attention. The poet George Gordon Byron wrote in 1823: "Who makes politics run glibber all?/ The shade of Bonaparte's noble daring?/ Jew Rothschild and his fellow-Christian, Baring." The operation of banks also shifted. At the beginning of the century, banking was still an elite preoccupation of a handful of very wealthy families. Within a few decades, however, a new sort of banking had emerged, owned by anonymous stockholders, run by professional managers, and the recipient of the deposits of a growing body of small middle-class savers. Although this breed of banks was newly prominent, it was not new – the Quaker family Barclays had been banking in this way since 1690. |

産業革命 主な記事:産業革命 資本主義生産の生産性の向上は、19 世紀の変わり目に、産業革命と一般に呼ばれる過程で、持続的かつ前例のない増加を始めました。1760年頃、イギリスで始まったこの変化は、手作業による 生産から機械生産への移行、新しい化学製造や鉄の製造プロセス、水力の効率向上、蒸気力の利用拡大、工作機械の開発など、さまざまな産業で新しい製造プロ セスへの着実な移行をもたらした。また、木材やその他のバイオ燃料から石炭への燃料の転換も含まれた。  発明家サミュエル・クロンプトンによって製作された紡績機「スピニング・ミュール」 紡績産業では、蒸気や水力で駆動される機械化された綿紡績が、ジェームズ・ハーグリーブズの「スピンニング・ジェニー」、リチャード・アークロフトの 「ウォーター・フレーム」、サミュエル・クロンプトンの「スピンニング・ミュール」などの発明により、労働者の生産性を約1000倍に増加させた。パ ワー・ロームは、労働者の生産性を40倍以上増加させた。[34] 綿繰り機は、綿から種を取り除く生産性を50倍に増加させた。羊毛や麻の紡績と織物においても生産性の大幅な向上が見られたが、綿ほどではなかった。 金融  ロスチャイルド家は国際金融に革命をもたらした。タウヌス鉄道のフランクフルト終着駅はロスチャイルド家によって資金提供され、1840年にドイツ初の鉄道の一つとして開業した。 イギリスの産業の成長は、その金融と信用システムの発展を同時に促進した。18世紀には、銀行が提供するサービスが増加した。決済施設、証券投資、小切 手、当座貸越保護が導入された。小切手は17世紀にイギリスで発明され、銀行は発行銀行への直接の宅配便で支払いを清算していた。1770年ごろ、銀行は 中央の場所で集まり始め、19世紀には専用のスペースが設けられ、銀行清算所と呼ばれるようになった。ロンドン清算所では、各銀行が1日の終わりに検査官 に現金で支払い、その後検査官から現金で支払われる方法が採用されていた。最初の当座貸越制度は1728年にロイヤル・バンク・オブ・スコットランドに よって設立された。 ナポレオン戦争の終結とそれに続く貿易の回復により、イングランド銀行が保有する金塊準備高は、1821年の400万ポンド未満から、1824年末には1,400万ポンドまで増加した。 19世紀には、古い革新技術が金融生活の日常的な一部となった。イングランド銀行は17世紀に初めて銀行券を発行したが、手書きで枚数も少なかった。 1725年以降、一部が印刷されるようになったが、出納係は各券に署名し、特定の人格宛てに支払いを指定する必要があった。1844年、議会は銀行憲章法 (Bank Charter Act)を可決し、これらの銀行券を金準備に連動させることで、中央銀行制度と貨幣政策の機関を実質的に創設した。紙幣は1855年から完全に印刷され、 広く流通するようになった。 国際貿易の拡大に伴い、特にロンドンで銀行の数が増加した。これらの新しい「商社銀行」は、英国の海上輸送における優位性の拡大から利益を得て、貿易の成 長を促進した。18世紀後半、ロスチャイルド家とベアリング家の2つの移民家族がロンドンに商社銀行を設立し、翌世紀には世界銀行業界を支配するに至っ た。これらの銀行が蓄積した莫大な富は、すぐに大きな注目を集めた。詩人のジョージ・ゴードン・バイロンは1823年に次のように書いている。「政治を円 滑に動かすのは誰だ?/ ナポレオンの勇敢な影か?/ ユダヤ人のロスチャイルドと彼のキリスト教徒の仲間、ベアリングか?」 銀行の業務も変化した。世紀の初め、銀行業務はごく少数の富裕層の家族によるエリートの専売特許だった。しかし、数十年後には、匿名の株主が所有し、専門 の経営者が運営し、増加する中産階級の小規模貯蓄者からの預金を受け入れる、新しいタイプの銀行が登場した。この種の銀行は新たに台頭したものだったが、 決して新しいものではなかった。クエーカー教徒のバークレー家は、1690年からこの方式で銀行業を営んでいた。 |

| Free trade and globalization At the height of the First French Empire, Napoleon sought to introduce a "continental system" that would render Europe economically autonomous, thereby emasculating British trade and commerce. It involved such stratagems as the use of beet sugar in preference to the cane sugar that had to be imported from the tropics. Although this caused businessmen in England to agitate for peace, Britain persevered, in part because it was well into the Industrial Revolution. The war had the opposite effect – it stimulated the growth of certain industries, such as pig-iron production which increased from 68,000 tons in 1788 to 244,000 by 1806.[citation needed]  19th-century Great Britain become the first global economic superpower, because of superior manufacturing technology and improved global communications such as steamships and railroads. In 1817, David Ricardo, James Mill and Robert Torrens, in the famous theory of comparative advantage, argued that free trade would benefit the industrially weak as well as the strong. In Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Ricardo advanced the doctrine still considered the most counterintuitive in economics: When an inefficient producer sends the merchandise it produces best to a country able to produce it more efficiently, both countries benefit. By the mid 19th century, Britain was firmly wedded to the notion of free trade, and the first era of globalization began.[20] In the 1840s, the Corn Laws and the Navigation Acts were repealed, ushering in a new age of free trade. In line with the teachings of the classical political economists, led by Adam Smith and David Ricardo, Britain embraced liberalism, encouraging competition and the development of a market economy. Industrialization allowed cheap production of household items using economies of scale,[citation needed] while rapid population growth created sustained demand for commodities. Nineteenth-century imperialism decisively shaped globalization in this period. After the First and Second Opium Wars by Britain and France and the completion of the British conquest of India by 1858, the French conquest of Africa, Polynesia and Indochina by 1887, vast populations of these regions became ready consumers of European exports. During this period, areas of sub-Saharan Africa and the Pacific islands were incorporated into the world system, especially by the British and French. Meanwhile, the European conquest of new parts of the globe, notably Africa by Britain and France, yielded valuable natural resources such as rubber, diamonds and coal and helped fuel trade and investment between the European imperial powers, their colonies, and the United States.[35] |

自由貿易とグローバル化 第一フランス帝国の最盛期、ナポレオンは、ヨーロッパを経済的に自立させ、それによってイギリスの貿易と商業を弱体化させる「大陸封鎖令」の導入を目指し た。この政策には、熱帯地方から輸入しなければならなかったサトウキビの砂糖に代わって、テンサイの砂糖を使用するという策略も含まれていた。この政策に より、イギリスの実業家たちは平和を訴えたが、イギリスは産業革命がすでにかなり進んでいたこともあり、この政策を堅持した。戦争は逆効果となり、 1788年に68,000トンだった銑鉄の生産量は1806年には244,000トンへと増加するなど、特定の産業の成長を促進した。  19世紀、英国は、優れた製造技術と蒸気船や鉄道などの世界的な通信手段の改善により、世界初の経済大国となった。 1817年、デヴィッド・リカード、ジェームズ・ミル、ロバート・トレンズは、有名な比較優位理論において、自由貿易は産業の弱い国にも強い国にも利益を もたらす、と主張した。『政治経済と課税の原理』の中で、リカードは、今でも経済学において最も直感に反する教義とみなされている、次のような教義を提唱 した。 非効率な生産者が、自分が最も生産効率の高い商品を、より効率的に生産できる国に輸出すると、両国ともに利益を得る。 19 世紀半ばまでに、英国は自由貿易の概念を固く信奉し、グローバル化の最初の時代が始まった[20]。1840 年代、穀物法と航海法が廃止され、自由貿易の新時代が幕を開けた。アダム・スミスやデビッド・リカードに代表される古典派経済学者たちの教えに沿って、英 国は自由主義を採用し、競争と市場経済の発展を奨励した。 工業化により、規模の経済を活かした家庭用品の低コスト生産が可能になり[出典必要]、急速な人口増加が商品への持続的な需要を生み出した。19世紀の帝 国主義は、この時代のグローバル化を決定的に形作った。イギリスとフランスの第一次・第二次アヘン戦争と、1858年までのイギリスのインド征服、 1887年までのフランスのアフリカ、ポリネシア、インドシナ征服により、これらの地域の広大な人口がヨーロッパの輸出品の主要な消費者となった。この期 間中、サハラ以南のアフリカと太平洋の島々は、特にイギリスとフランスによって世界システムに組み込まれました。一方、ヨーロッパの新たな地域(特にイギ リスとフランスによるアフリカ)の征服は、ゴム、ダイヤモンド、石炭などの貴重な天然資源をもたらし、ヨーロッパの帝国主義諸国、その植民地、およびアメ リカ合衆国間の貿易と投資を促進しました。[35] |

The gold standard formed the financial basis of the international economy from 1870 to 1914. The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea, the various products of the whole earth, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep. Militarism and imperialism of racial and cultural rivalries were little more than the amusements of his daily newspaper. What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man was that age which came to an end in August 1914. The global financial system was mainly tied to the gold standard during this period. The United Kingdom first formally adopted this standard in 1821. Soon to follow was Canada in 1853, Newfoundland in 1865, and the United States and Germany (de jure) in 1873. New technologies, such as the telegraph, the transatlantic cable, the Radiotelephone, the steamship, and the railway allowed goods and information to move around the world at an unprecedented degree.[36] The eruption of civil war in the United States in 1861 and the blockade of its ports to international commerce meant that the main supply of cotton for the Lancashire looms was cut off. The textile industries shifted to reliance upon cotton from Africa and Asia during the course of the U.S. civil war, and this created pressure for an Anglo-French controlled canal through the Suez peninsula. The Suez canal opened in 1869, the same year in which the Central Pacific Railroad that spanned the North American continent was completed. Capitalism and the engine of profit were making the globe a smaller place. |

金本位制は、1870年から1914年まで国際経済の金融基盤を形成していた。 ロンドンの住民は、朝の紅茶を飲みながら、電話で世界中のさまざまな商品を注文し、その商品が自分の玄関先に早く届くことを当然のように期待することがで きた。人種や文化の対立による軍国主義や帝国主義は、彼の毎日の新聞の娯楽にすぎなかった。1914年8月に終焉を迎えたその時代は、人類の経済発展にお いて、まさに驚異的な時代だった。 この期間、世界の金融システムは主に金本位制に縛られていた。イギリスが1821年にこの制度を正式に採用し、その後、1853年にカナダ、1865年に ニューファンドランド、1873年にアメリカとドイツ(法的に)がそれに続いた。電信、大西洋横断ケーブル、無線電話、蒸気船、鉄道などの新技術により、 商品や情報が前例のないほど世界中に流通するようになった。[36] 1861年にアメリカ合衆国で内戦が勃発し、その港が国際貿易に封鎖されたことで、ランカシャーの織機用の綿の主な供給源が断たれた。アメリカ内戦の間、 紡績産業はアフリカとアジアからの綿花に依存するようになり、これを受けて、スエズ半島を通る英仏共同管理の運河建設の圧力が高まった。スエズ運河は 1869年に開通し、同年に北米大陸を横断する中央太平洋鉄道が完成した。資本主義と利益追求のエンジンは、世界をますます小さな場所に変えていった。 |

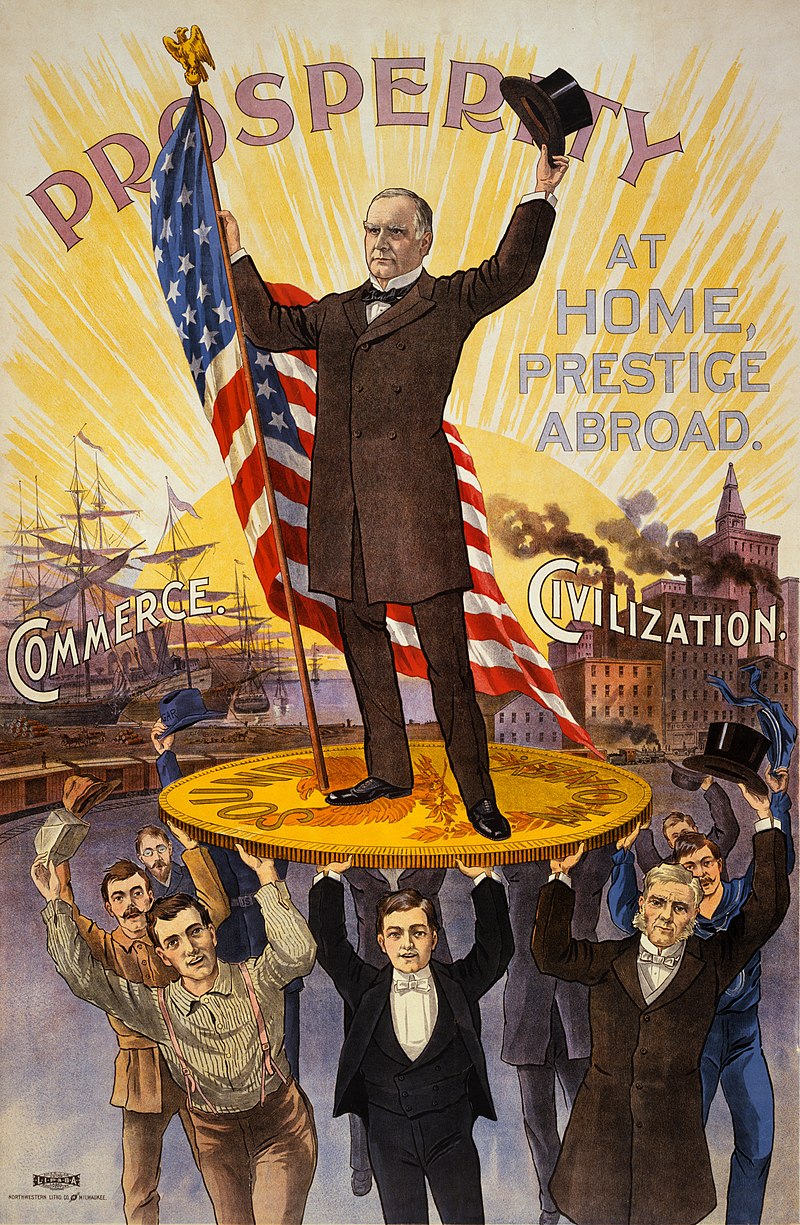

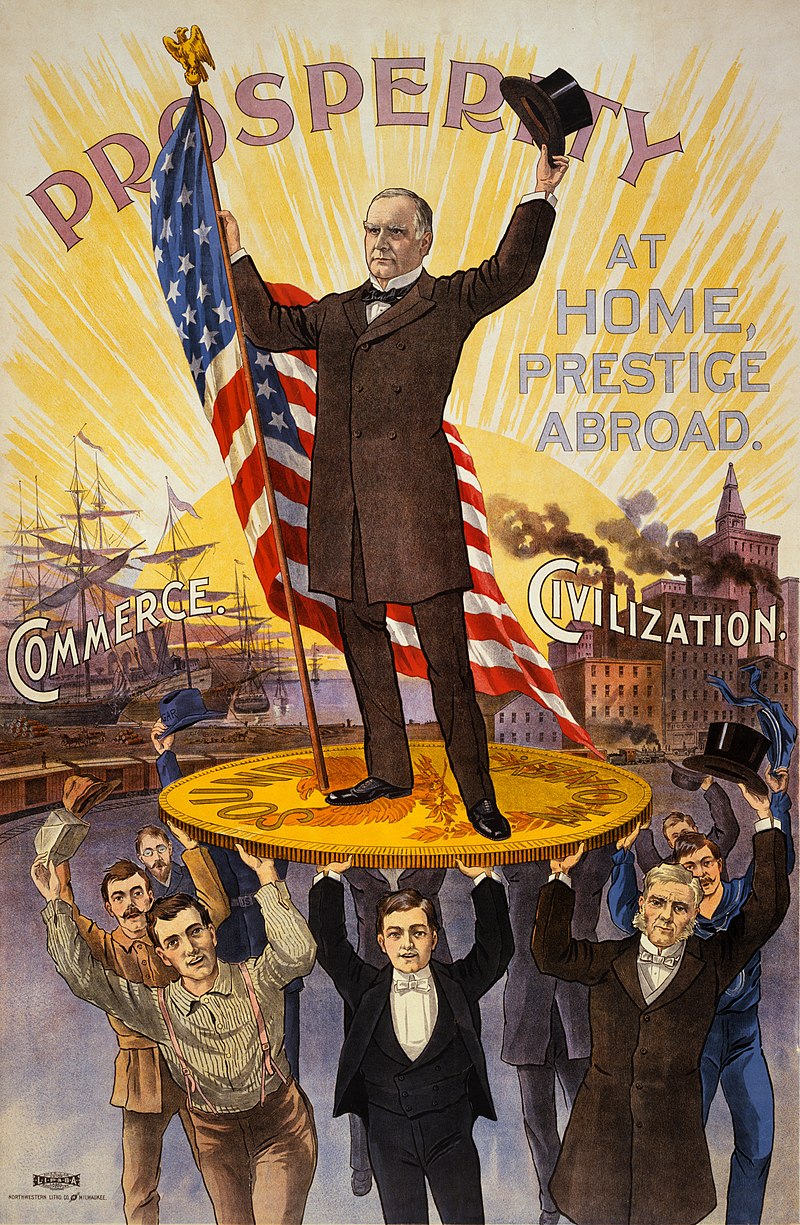

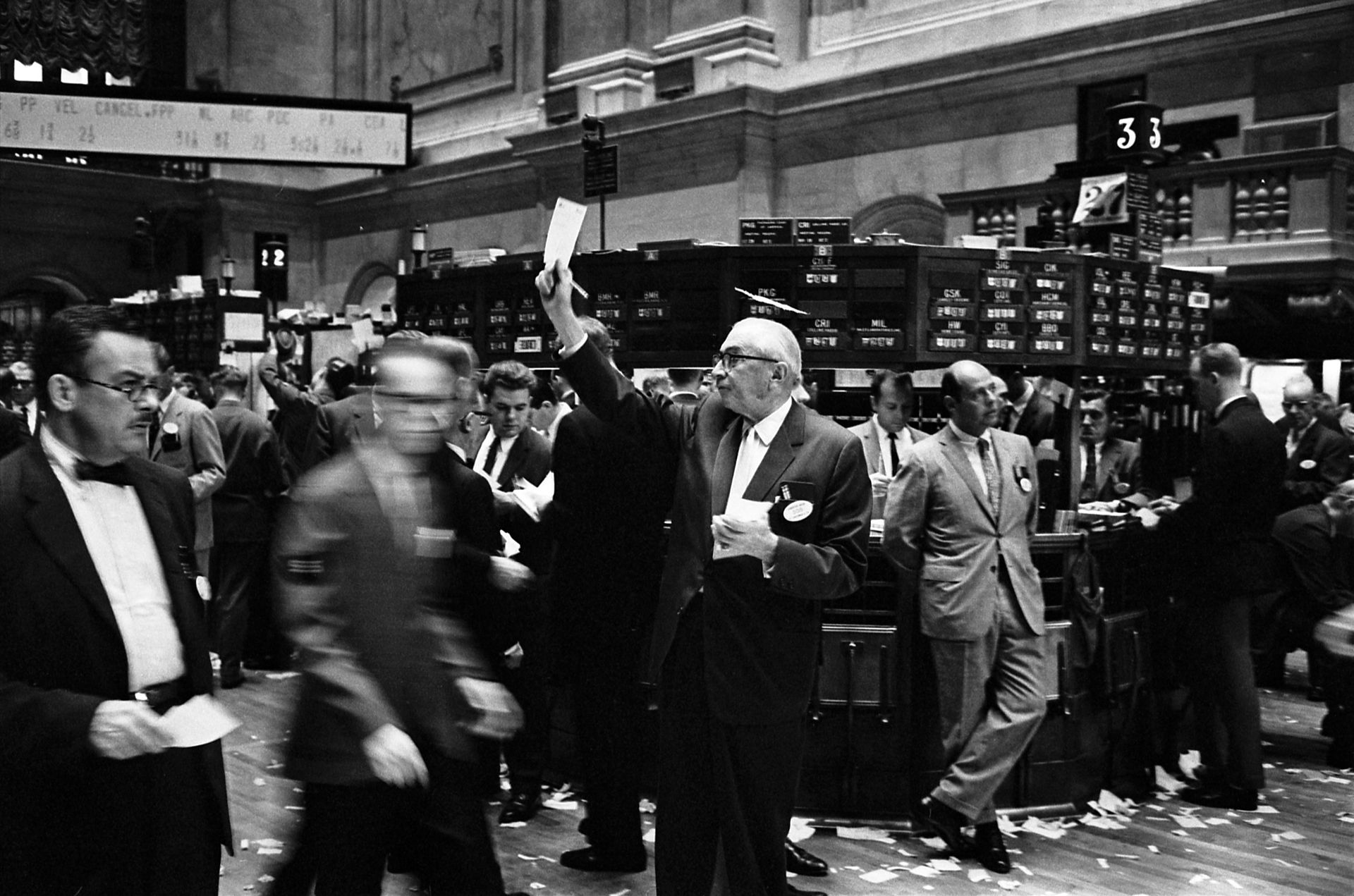

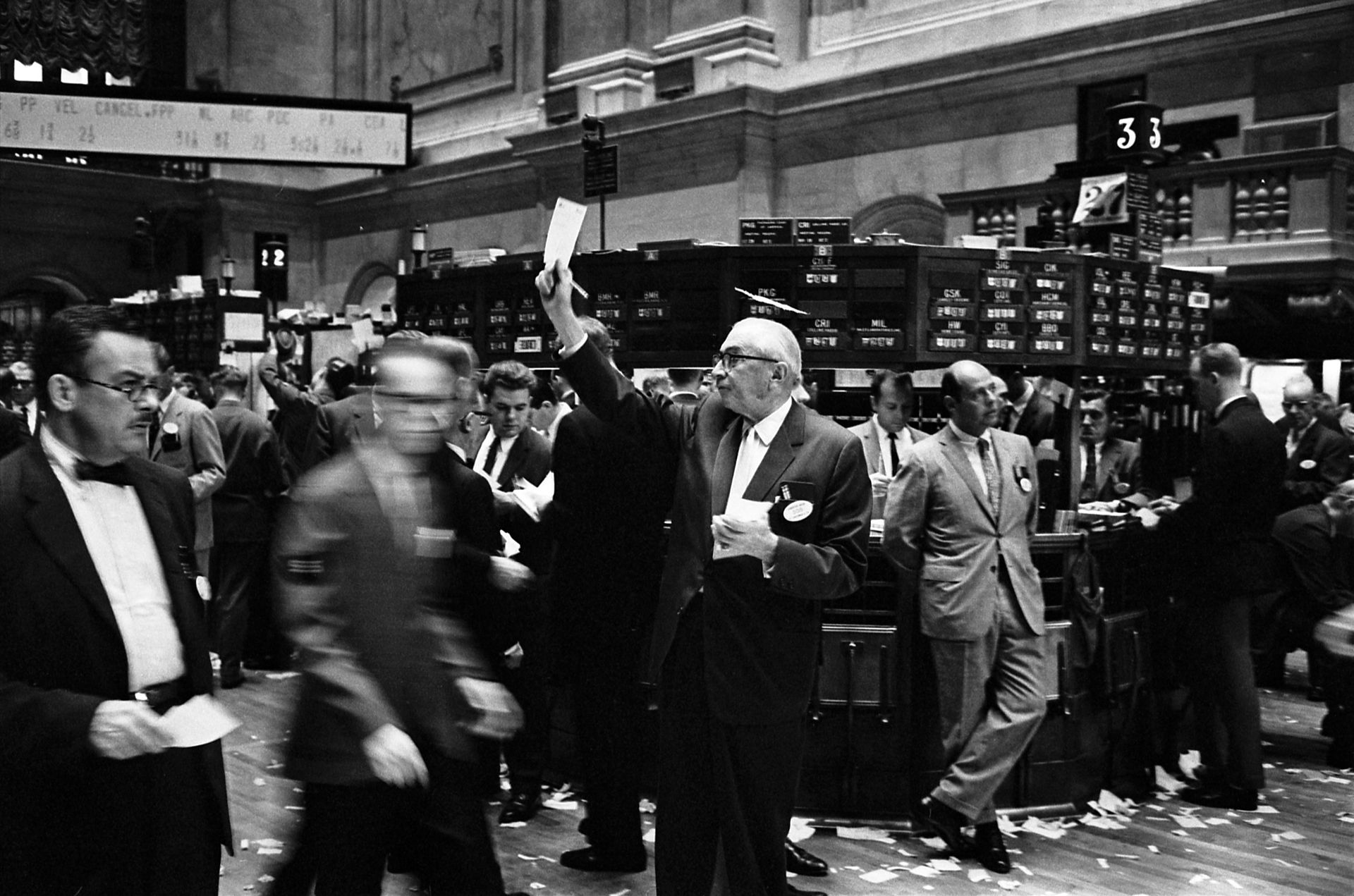

| 20th century Several major challenges to capitalism appeared in the early part of the 20th century. The Russian revolution in 1917 established the first state with a ruling communist party in the world; a decade later, the Great Depression triggered increasing criticism of the existing capitalist system. One response to this crisis was a turn to fascism, an ideology that advocated state capitalism.[37] Another response was to reject capitalism altogether in favour of communist or democratic socialist ideologies. Keynesianism and free markets Main articles: Keynesian economics and Neoliberalism  The New York stock exchange traders' floor (1963) The economic recovery of the world's leading capitalist economies in the period following the end of the Great Depression and the Second World War—a period of unusually rapid growth by historical standards—eased discussion of capitalism's eventual decline or demise.[38] The state began to play an increasingly prominent role to moderate and regulate the capitalistic system throughout much of the world. Keynesian economics became a widely accepted method of government regulation and countries such as the United Kingdom experimented with mixed economies in which the state owned and operated certain major industries. The state also expanded in the US; in 1929, total government expenditures amounted to less than one-tenth of GNP; from the 1970s they amounted to around one-third.[21] Similar increases were seen in all industrialised capitalist economies, some of which, such as France, have reached even higher ratios of government expenditures to GNP than the United States. A broad array of new analytical tools in the social sciences were developed to explain the social and economic trends of the period, including the concepts of post-industrial society and the welfare state.[20] The long post-war boom ended in the 1970s, amid the economic crises experienced following the 1973 oil crisis.[39] The "stagflation" of the 1970s led many economic commentators and politicians to embrace market-oriented policy prescriptions inspired by the laissez-faire capitalism and classical liberalism of the nineteenth century, particularly under the influence of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. The theoretical alternative to Keynesianism was more compatible with laissez-faire and emphasised individual rights and absence of government intervention. Market-oriented solutions gained increasing support in the Western world, especially under the leadership of Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the UK in the 1980s. Public and political interest began shifting away from the so-called collectivist concerns of Keynes's managed capitalism to a focus on individual choice, called "remarketized capitalism".[40] The three booming decades that followed the Second World War, according to political economist Clara E. Mattei, were an anomaly in the history of contemporary capitalism. She writes that austerity did not originate with the emergence of the neoliberal era starting in the 1970s, but "has been the mainstay of capitalism."[41] |

20世紀 20世紀初頭、資本主義はいくつかの大きな課題に直面した。1917年のロシア革命により、世界初の共産党が政権を握る国家が誕生し、その10年後、大恐 慌により、既存の資本主義体制に対する批判が高まった。この危機に対する反応の一つは、国家資本主義を主張するファシズムへの転換だった[37]。もう一 つの反応は、資本主義を完全に拒否し、共産主義や民主社会主義のイデオロギーを採用することだった。 ケインズ主義と自由市場 主な記事:ケインズ経済学と新自由主義  ニューヨーク証券取引所のトレーダーフロア(1963年) 大恐慌と第二次世界大戦後の期間、世界の主要資本主義経済が歴史的に見ても異例の急速な成長を遂げたことで、資本主義の最終的な衰退や崩壊に関する議論は 沈静化した。[38] 国家は、世界の大部分で資本主義システムを調整・規制する役割をますます重要視するようになった。 ケインズ経済学は政府の規制方法として広く受け入れられ、イギリスなどの国々は、国家が主要産業の一部を所有・運営する混血の経済を実験した。 アメリカでも国家は拡大した。1929年には政府支出の総額は国内総生産(GNP)の10%未満だったが、1970年代には約30%に達した。[21] 同様の増加はすべての工業化資本主義経済でみられ、フランスなど一部の国では、政府支出のGNP比率はアメリカを上回る水準に達した。 この時代の社会・経済動向を説明するために、社会科学の分野で多様な新たな分析ツールが開発された。その中には、ポスト産業社会や福祉国家といった概念が含まれる。[20] 戦後の長期好景気は、1973年の石油危機に続く経済危機の中で、1970年代に終焉を迎えた。[39] 1970年代の「スタグフレーション」は、多くの経済評論家や政治家が、19世紀の自由放任資本主義と古典的自由主義にインスパイアされた市場指向の政策 処方箋を採用するきっかけとなった。特にフリードリヒ・ハイエクとミルトン・フリードマンの影響下で、ケインズ主義の理論的代替案は自由放任とより相容 れ、個人の権利と政府の介入の不在を強調した。市場指向の解決策は、特に1980年代のアメリカ合衆国のロナルド・レーガンとイギリスのマーガレット・ サッチャーの指導下で、西欧世界においてますます支持を集めた。公共の関心と政治的関心は、ケインズの管理資本主義のいわゆる集団主義的な懸念から、個人 選択に焦点を当てた「再市場化資本主義」へと移行し始めた。[40] 政治経済学者クララ・E・マッテイによると、第二次世界大戦後の30年間の好景気は、現代資本主義の歴史において異常な現象だった。彼女は、緊縮政策は 1970年代に始まった新自由主義時代の出現によって始まったものではなく、「資本主義の柱であった」と書いている。[41] |

Globalization The New York Stock Exchange Although overseas trade has been associated with the development of capitalism for over five hundred years, some thinkers argue that a number of trends associated with globalisation have acted to increase the mobility of people and capital since the last quarter of the twentieth century, combining to circumscribe the room to manoeuvre of states in choosing non-capitalist models of development. Today, these trends have bolstered the argument that capitalism should now be viewed as a truly world system (Burnham). However, other thinkers argue that globalisation, even in its quantitative degree, is no greater now than during earlier periods of capitalist trade.[42] After the abandonment of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, and the strict state control of foreign exchange rates, the total value of transactions in foreign exchange was estimated to be at least twenty times greater than that of all foreign movements of goods and services (EB). The internationalisation of finance, which some see as beyond the reach of state control, combined with the growing ease with which large corporations have been able to relocate their operations to low-wage states, has posed the question of the 'eclipse' of state sovereignty, arising from the growing 'globalization' of capital.[43] While economists generally agree about the size of global income inequality, there is a general disagreement about the recent direction of change of it.[44] In cases such as China, where income inequality is clearly growing[45] it is also evident that overall economic growth has rapidly increased with capitalist reforms.[46] Indur M. Goklany's book The Improving State of the World, published by the libertarian think tank Cato Institute, argues that economic growth since the Industrial Revolution has been very strong and that factors such as adequate nutrition, life expectancy, infant mortality, literacy, prevalence of child labor, education, and available free time have improved greatly.[47] Some scholars, including Stephen Hawking[48] and researchers for the International Monetary Fund,[49][50] contend that globalization and neoliberal economic policies are not ameliorating inequality and poverty but exacerbating it,[51][52][53] and are creating new forms of contemporary slavery.[54][55] Such policies are also expanding populations of the displaced, the unemployed and the imprisoned[56][57] along with accelerating the destruction of the environment[51] and species extinction.[58][59] In 2017, the IMF warned that inequality within nations, in spite of global inequality falling in recent decades, has risen so sharply that it threatens economic growth and could result in further political polarization.[60] Surging economic inequality following the economic crisis and the anger associated with it have resulted in a resurgence of socialist and nationalist ideas throughout the Western world, which has some economic elites from places including Silicon Valley, Davos and Harvard Business School concerned about the future of capitalism.[61] According to the scholars Gary Gerstle and Fritz Bartel, with the end of the Cold War and the emergence of neoliberal financialized capitalism as the dominant system, capitalism has become a truly global order in a way not seen since 1914.[62][63] Economist Radhika Desai, while concurring that 1914 was the peak of the capitalist system, argues that the neoliberal reforms that were intended to restore capitalism to its primacy have instead bequeathed to the world increased inequalities, divided societies, economic crises and misery and a lack of meaningful politics, along with sluggish growth which demonstrates that, according to Desai, the system is "losing ground in terms of economic weight and world influence" with "the balance of international power . . . tilting markedly away from capitalism."[64] Gerstle argues that in the twilight of the neoliberal period "political disorder and dysfunction reign" and posits that the most important question for the United States and the world is what comes next.[62] |

グローバル化 ニューヨーク証券取引所 海外貿易は 500 年以上にわたり資本主義の発展と関連付けられてきたが、一部の思想家は、20 世紀の最後の 25 年間に、グローバル化に伴ういくつかの傾向が、人と資本の流動性を高め、非資本主義的な開発モデルを選択する国家の行動の余地を制限する要因となったと主 張している。現在、これらの傾向は、資本主義を真に世界システムとして捉えるべきだという主張を強化している(バーナム)。しかし、他の思想家は、グロー バル化は、その量的程度においてさえ、資本主義貿易の以前の時期よりも現在の方がより進んでいるわけではないと主張している。[42] 1971年にブレトン・ウッズ体制が放棄され、為替レートの厳格な国家管理が廃止された後、外国為替取引の総額は、すべての外国間の商品およびサービスの 移動額の少なくとも 20 倍に達したと推定されている(EB)。国家の統制の及ばない領域と見なされる金融の国際化と、大企業が低賃金国への事業移転を容易に行えるようになったこ とが、資本の「グローバル化」の進展から生じる「国家主権の衰退」という問題を提起している。[43] 経済学者たちは、世界的な所得格差の大きさについては概ね一致しているが、その最近の変化の方向性については意見が分かれている[44]。中国のように、 所得格差が明らかに拡大しているケース[45]では、資本主義改革に伴い、経済成長が急速に進んだことも明らかだ。[46] リバタリアン系シンクタンクのCato Instituteから出版されたIndur M. Goklanyの著書『The Improving State of the World』は、産業革命以降の経済成長は非常に強く、栄養状態、平均寿命、乳児死亡率、識字率、児童労働の普及率、教育、余暇の確保など、多くの指標が 大幅に改善されたと主張している。[47] スティーブン・ホーキング[48]や国際通貨基金(IMF)の研究者たち[49][50]を含む一部の学者たちは、グローバル化と新自由主義的経済政策は 不平等と貧困を緩和するのではなく、むしろ悪化させている[51][52][53]と主張し、現代の新たな形態の奴隷制を生み出していると指摘している。 [54][55] これらの政策は、環境破壊[51]と種の絶滅[58][59]を加速させる一方で、避難民、失業者、収監者の人口を拡大している[56][57]。 2017年、IMFは、近年グローバルな不平等が減少しているにもかかわらず、国内の不平等が急激に拡大し、経済成長を脅かし、政治的分極化をさらに招く 可能性があると警告した。[60] 経済危機後の経済的不平等拡大とそれに伴う怒りは、西欧世界全体で社会主義やナショナリストの思想の復活を招き、シリコンバレー、ダボス、ハーバード・ビ ジネス・スクールなどの経済エリートの一部は資本主義の未来に懸念を抱いている。[61] 学者ゲイリー・ガースルとフリッツ・バーテルによると、冷戦の終結と、新自由主義的な金融資本主義が支配的なシステムとして台頭したことで、資本主義は 1914年以来見られなかったような、真にグローバルな秩序となった。[62][63] 経済学者のラディカ・デサイは、1914年が資本主義システムの頂点だった点には同意しつつも、資本主義の優位性を回復する目的で実施された新自由主義改 革が、世界にもたらしたのは、格差の拡大、社会の分断、経済危機、貧困、意味のある政治の欠如、そして成長の鈍化であり、 デサイによると、このシステムは「経済的重量と世界影響力において後退している」と指摘し、「国際的な力のバランスは資本主義から著しく離反している」と 述べています。[64] ゲルストルは、新自由主義時代の黄昏期に「政治的混乱と機能不全が支配している」と指摘し、アメリカ合衆国と世界にとって最も重要な問題は「次に何が起こ るか」だと主張しています。[62] |

| 21st century By the beginning of the twenty-first century, mixed economies with capitalist elements had become the pervasive economic systems worldwide. The collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1991 significantly reduced the influence of socialism as an alternative economic system. Leftist movements continue to be influential in some parts of the world, most notably Latin-American Bolivarianism, with some having ties to more traditional anti-capitalist movements, such as Bolivarian Venezuela's ties to Cuba. In many emerging markets, the influence of banking and financial capital have come to increasingly shape national developmental strategies, leading some to argue we are in a new phase of financial capitalism.[65] State intervention in global capital markets following the 2008 financial crisis was perceived by some as signalling a crisis for free-market capitalism. Serious turmoil in the banking system and financial markets due in part to the subprime mortgage crisis reached a critical stage during September 2008, characterised by severely contracted liquidity in the global credit markets posed an existential threat to investment banks and other institutions.[66][67] |

21世紀 21世紀初頭までに、資本主義的要素を含む混合の経済が世界的に普及した経済システムとなった。1991年のソ連圏の崩壊により、代替経済システムとして の社会主義の影響力は大幅に低下した。左翼運動は、世界の一部の地域、特にラテンアメリカのボリバル主義において引き続き影響力を持っており、その一部 は、ボリバル主義のベネズエラとキューバの関係など、より伝統的な反資本主義運動と結びついている。 多くの新興市場では、銀行や金融資本の影響力が国民の開発戦略をますます形作っているため、私たちは金融資本主義の新たな段階にあるとの見方もある。[65] 2008年の金融危機後の世界的な資本市場への国家の介入は、自由市場資本主義の危機を告げるものとの見方もある。サブプライム住宅ローン危機も一因と なった銀行システムと金融市場の深刻な混乱は、2008年9月に危機的な段階に達し、世界的な信用市場の流動性が著しく収縮し、投資銀行やその他の金融機 関の存続を脅かす事態となった。[66][67] |

| Future According to Michio Kaku,[68] the transition to the information society involves abandoning some parts of capitalism, as the "capital" required to produce and process information becomes available to the masses and difficult to control, and is closely related to the controversial issues of intellectual property. Some[68] have further speculated that the development of mature nanotechnology, particularly of universal assemblers, may make capitalism obsolete, with capital ceasing to be an important factor in the economic life of humanity. Various thinkers have also explored what kind of economic system might replace capitalism, such as Bob Avakian, Jason Hickel, Paul Mason, Richard D. Wolff and contributors to the "Scientists' warning on affluence".[69] |

未来 ミチオ・カクによると[68]、情報社会への移行は、情報生産と処理に必要な「資本」が一般大衆が利用可能になり、管理が困難になるため、資本主義の一部 を放棄することと密接に関連しており、知的財産権に関する議論とも深く関わっている。一部[68]では、成熟したナノテクノロジー、特にユニバーサルアセ ンブラーの開発が資本主義を陳腐化させ、資本が人類の経済生活における重要な要因でなくなる可能性がさらに推測されている。ボブ・アヴァキアン、ジェイソ ン・ヒッケル、ポール・メイソン、リチャード・D・ウォルフ、および「豊かさの警告」に寄稿した研究者たち[69]など、さまざまな思想家が、資本主義に 代わる経済システムがどのようなものになるかを探求している。 |

| Role of women Women's historians have debated the impact of capitalism on the status of women.[70][71] Alice Clark argued that, when capitalism arrived in 17th-century England, it negatively impacted the status of women, who lost much of their economic importance. Clark argued that, in 16th-century England, women were engaged in many aspects of industry and agriculture. The home was a central unit of production, and women played a vital role in running farms and in some trades and landed estates. Their useful economic roles gave them a sort of equality with their husbands. However, Clark argued, as capitalism expanded in the 17th century, there was more and more division of labor, with the husband taking paid labor jobs outside the home, and the wife reduced to unpaid household work. Middle-class women were confined to an idle domestic existence, supervising servants; lower-class women were forced to take poorly paid jobs. Capitalism, therefore, had a negative effect on women.[72] By contrast, Ivy Pinchbeck argued that capitalism created the conditions for women's emancipation.[73] Tilly and Scott have emphasized the continuity and the status of women, finding three stages in European history. In the preindustrial era, production was mostly for home use, and women produced many household needs. The second stage was the "family wage economy" of early industrialization. During this stage, the entire family depended on the collective wages of its members, including husband, wife, and older children. The third, or modern, stage is the "family consumer economy", in which the family is the site of consumption, and women are employed in large numbers in retail and clerical jobs to support rising standards of consumption.[74] |

女性の役割 女性史研究者は、資本主義が女性の地位に与えた影響について議論してきた[70][71]。アリス・クラークは、17 世紀に資本主義がイギリスに伝わったことで、経済的に重要な役割の多くを失った女性たちの地位が低下したと主張している。クラークは、16 世紀のイギリスでは、女性は産業や農業のさまざまな分野で活躍していたと主張している。家庭は生産の中心的単位であり、女性は農場の運営や一部の職業、土 地所有地において重要な役割を果たしていた。その経済的な役割は、彼女たちに夫との一種の平等をもたらした。しかし、クラークは、17世紀に資本主義が拡 大するにつれ、労働分業がますます進み、夫は家庭外で有給の労働に従事し、妻は無給の家事労働に追いやられたと主張した。中流階級の女性は、使用人を監督 する怠惰な家庭生活に閉じ込められ、下層階級の女性は低賃金の仕事に就かざるを得なかった。したがって、資本主義は女性に対して否定的な影響を与えた。 [72] これに対し、アイヴィ・ピンチベックは、資本主義が女性の解放の条件を創出したと主張した。[73] ティリーとスコットは、女性の地位の継続性を強調し、ヨーロッパの歴史に3つの段階を見出した。産業革命前の時代には、生産は主に家庭用であり、女性は多 くの家庭用品を生産していた。第二段階は、初期工業化期の「家族賃金経済」だ。この段階では、家族全体が夫、妻、成人した子供を含む家族の総賃金に依存し ていた。第三段階、または現代の段階は「家族消費経済」で、家族が消費の場所となり、女性は小売業や事務職に大量に雇用され、消費水準の向上を支えてい る。[74] |

| 2008 financial crisis Brenner debate Capitalism and Islam Capitalist mode of production Enclosure and British Agricultural Revolution Fernand Braudel History of capitalist theory History of globalization History of private equity and venture capital Primitive accumulation of capital Protestant work ethic Simple commodity production |

2008年の金融危機(リーマン・ブラザーズ倒産) ブレナー論争 資本主義とイスラム教 資本主義的生産方式 囲い込みと英国の農業革命 フェルナン・ブローデル 資本主義理論の歴史 グローバル化の歴史 プライベート・エクイティとベンチャーキャピタルの歴史 資本の原始的蓄積 プロテスタントの労働倫理 単純商品生産 |

| Further reading Appleby, Joyce (2011). The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism. "Italy and the Origins of Capitalism". Business History Review. 94 (1). Spring 2020. Braudel, Fernand (1979), "The Wheels of Commerce", Civilization and Capitalism 15th–18th Century Cheta, Omar Youssef (April 2018). "The economy by other means: The historiography of capitalism in the modern Middle East". History Compass. 16 (4). doi:10.1111/hic3.12444. Comninel, George C. (2000). "English feudalism and the origins of capitalism". Journal of Peasant Studies. 27 (4): 1–53. doi:10.1080/03066150008438748. Hilton, Rodney H., ed. (1976). The Transition from Feudalism to Capitalism. "Blog on the Dobb-Sweezy debate". Leftspot.com. Duplessis, Robert S. (1997). Transitions to Capitalism in Early Modern Europe. Friedman, Walter A. (2017). "Recent trends in business history research: Capitalism, democracy, and innovation". Enterprise & Society. 18 (4): 748–771. Giddens, Anthony (1971). Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber. Greene, Julie (April 2020). "Bookends to a Gentler Capitalism: Complicating the Notion of First and Second Gilded Ages". The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. 19 (2). Cambridge University Press: 197–205. doi:10.1017/S1537781419000628. Hilt, Eric (June 2017). "Economic History, Historical Analysis, and the 'New History of Capitalism'" (PDF). Journal of Economic History. 77 (2): 511–536. Kocka, Jürgen (2016). Capitalism: A Short History. McCarraher, Eugene (2022). The Enchantments of Mammon: How Capitalism Became the Religion of Modernity. Marx, Karl (1867). Das Kapital. Morton, Adam David (2005). "The Age of Absolutism: capitalism, the modern states-system and international relations". Review of International Studies. 31. Cambridge University Press: 495–517. doi:10.1017/S0260210505006601. Neal, Larry; Williamson, Jeffrey G., eds. (2016). The Cambridge History of Capitalism. Vol. 1–2. Olmstead, Alan L.; Rhode, Paul W. (2018). "Cotton, slavery, and the new history of capitalism" (PDF). Explorations in Economic History. 67: 1–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-03-08. O'Sullivan, Mary (2018). "The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Capitalism" (PDF). Enterprise & Society. 19 (4): 751–802. Nolan, Peter (2009). Crossroads: The End of Wild Capitalism. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-462-09968-2. Patriquin, Larry (2004). "The Agrarian Origins of the Industrial Revolution in England". Review of Radical Political Economics. 36 (2): 196–216. doi:10.1177/0486613404264190. Perelman, Michael (2000). The Invention of Capitalism: Classical Political Economy and the Secret History of Primitive Accumulation. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2491-1. Prak, Maarten; Zanden, Jan Luiten van (2022). Pioneers of Capitalism: The Netherlands 1000–1800. Princeton University Press. Schuessler, Jennifer (6 April 2013). "In History Departments, It's Up With Capitalism". The New York Times. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1978). Can Capitalism Survive?. Steuart, James Denham (1767). An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy. Vol. 3. Weber, Max (2002). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Zmolek, Mike (2000). "The case for Agrarian capitalism: A response to Albritton". Journal of Peasant Studies. 27 (4): 138–59. Zmolek, Mike (October 2001). "DEBATE – Further Thoughts on Agrarian Capitalism: A Reply to Albritton". The Journal of Peasant Studies. 29 (1): 129–154. "Debating Agrarian Capitalism: A Rejoinder to Albritton". Journal of Peasant Studies. 31 (2): 276. "Research in Political Economy, Volume 22". CompuServe. "The Roots of Merchant Capitalism". SmallBusinessPages.org. McCraw, Thomas K. (August 2011). "The Current Crisis and the Essence of Capitalism". The Montreal Review. Łapniewska, Zofia (2014). "History of Capitalism" (PDF). Museum des Kapitalismus. Berlin. |

さらに読む アップルビー、ジョイス(2011)。『容赦なき革命:資本主義の歴史』。 「イタリアと資本主義の起源」。ビジネス・ヒストリー・レビュー。94 (1)。2020年春。 ブラデル、フェルナン(1979)、「商業の車輪」、文明と資本主義 15〜18 世紀 チェタ、オマル・ユセフ(2018年4月)。「他の手段による経済:現代中東における資本主義の歴史学」。History Compass. 16 (4). doi:10.1111/hic3.12444. コムニネル、ジョージ・C.(2000)。「英国の封建制度と資本主義の起源」。Journal of Peasant Studies. 27 (4): 1–53. doi:10.1080/03066150008438748. Hilton, Rodney H., ed. (1976). The Transition from Feudalism to Capitalism. 「ドブ・スウィージー論争に関するブログ」。Leftspot.com。 デュプレシス、ロバート S. (1997)。『近世ヨーロッパの資本主義への移行』。 フリードマン、ウォルター A. (2017)。「ビジネス史研究における最近の傾向:資本主義、民主主義、そしてイノベーション」。『エンタープライズ&ソサエティ』。18 (4): 748–771。 ギデンズ、アンソニー (1971)。資本主義と現代社会理論:マルクス、デュルケーム、マックス・ヴェーバーの著作の分析。 グリーン、ジュリー(2020年4月)。「より穏やかな資本主義へのブックエンド:第一と第二の黄金時代の概念の複雑化」。The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era(黄金時代と進歩主義時代ジャーナル)。19 (2)。ケンブリッジ大学出版局:197–205。doi:10.1017/S1537781419000628。 Hilt, Eric (2017年6月). 「経済史、歴史分析、そして『資本主義の新しい歴史』」 (PDF). Journal of Economic History. 77 (2): 511–536. コッカ、ユルゲン (2016)。資本主義:その短い歴史。 マッカラハー、ユージーン (2022)。マモンの魅力:資本主義が現代性の宗教となった理由。 マルクス、カール (1867)。資本論。 モートン、アダム・デイヴィッド (2005)。「絶対主義の時代:資本主義、近代国家体制、国際関係」。国際研究レビュー。31。ケンブリッジ大学出版局:495–517。doi:10.1017/S0260210505006601。 ニール、ラリー、ウィリアムソン、ジェフリー G.、編(2016)。The Cambridge History of Capitalism. Vol. 1–2. オルムステッド、アラン L.; ロード、ポール W. (2018). 「綿、奴隷制、そして資本主義の新しい歴史」 (PDF). 経済史の探求. 67: 1–17. 2021年3月8日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ。 オサリバン、メアリー (2018). 「資本主義の賢い女性のためのガイド」 (PDF). エンタープライズ&ソサエティ. 19 (4): 751–802. ノーラン、ピーター (2009). 岐路:野生の資本主義の終焉. マーシャル・キャベンディッシュ. ISBN 978-0-462-09968-2。 パトリキン、ラリー (2004). 「イギリス産業革命の農業的起源」. Review of Radical Political Economics. 36 (2): 196–216. doi:10.1177/0486613404264190. ペレルマン、マイケル(2000)。『資本主義の発明:古典政治経済学と原始的蓄積の秘密の歴史』。デューク大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8223-2491-1。 プラク、マーテン;ザンデン、ヤン・ルイテン・ファン(2022)。『資本主義のパイオニア:オランダ 1000–1800』。プリンストン大学出版局。 シュレスラー、ジェニファー (2013年4月6日)。「歴史学部では、資本主義が台頭している」。ニューヨーク・タイムズ。 シュンペーター、ジョセフ・A. (1978)。資本主義は生き残ることができるか? スチュアート、ジェームズ・デナム (1767)。政治経済学の原理に関する考察。第 3 巻。 ヴェーバー、マックス (2002)。『プロテスタントの倫理と資本主義の精神』。 Zmolek, Mike (2000). 「農業資本主義の主張:アルブリットンへの反論」 『Journal of Peasant Studies』 27 (4): 138–59. Zmolek, Mike (2001年10月). 「討論 – 農業資本主義に関するさらなる考察:アルブリットンへの反論」。農民研究ジャーナル。29 (1): 129–154. 「農業資本主義に関する討論:アルブリットンへの反論」。農民研究ジャーナル。31 (2): 276. 「政治経済学の研究、第 22 巻」。CompuServe. 「商人資本主義のルーツ」。SmallBusinessPages.org。 マックロー、トーマス・K.(2011年8月)。「現在の危機と資本主義の本質」。モントリオール・レビュー。 Łapniewska、ゾフィア(2014)。「資本主義の歴史」(PDF)。資本主義博物館。ベルリン。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_capitalism |

リンク

●マルクス『資本論』

カール・マルクス(フリードリヒ・エンゲルス

補筆等)『資本論』

|

Capital: A Critique of Political

Economy. A Critique of Political Economy, Book One: The Process of

Production of Capital Prefaces and Afterwords Part I: Commodities and Money Ch. 1: Commodities Ch. 1 as per First German Edition Ch. 2: Exchange Ch. 3: Money, or the Circulation of Commodities Part II: The Transformation of Money into Capital Ch. 4: The General Formula for Capital Ch. 5: Contradictions in the General Formula of Capital Ch. 6: The Buying and Selling of Labour-Power Part III: The Production of Absolute Surplus-Value Ch. 7: The Labour-Process and the Process of Producing Surplus-Value Ch. 8: Constant Capital and Variable Capital Ch. 9: The Rate of Surplus-Value Ch. 10: The Working-Day Ch. 11: Rate and Mass of Surplus-Value Part IV: Production of Relative Surplus Value Ch. 12: The Concept of Relative Surplus-Value Ch. 13: Co-operation Ch. 14: Division of Labour and Manufacture Ch. 15: Machinery and Modern Industry Part V: The Production of Absolute and of Relative Surplus-Value Ch. 16: Absolute and Relative Surplus-Value Ch. 17: Changes of Magnitude in the Price of Labour-Power and in Surplus-Value Ch. 18: Various Formula for the Rate of Surplus-Value Part VI: Wages Ch. 19: The Transformation of the Value (and Respective Price) of Labour-Power into Wages Ch. 20: Time-Wages Ch. 21: Piece-Wages Ch. 22: National Differences of Wages Part VII: The Accumulation of Capital Ch. 23: Simple Reproduction Ch. 24: Conversion of Surplus-Value into Capital Ch. 25: The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation Part VIII: Primitive Accumulation Ch. 26: The Secret of Primitive Accumulation Ch. 27: Expropriation of the Agricultural Population from the Land Ch. 28: Bloody Legislation against the Expropriated, from the End of the 15th Century. Forcing down of Wages by Acts of Parliament Ch. 29: Genesis of the Capitalist Farmer Ch. 30: Reaction of the Agricultural Revolution on Industry. Creation of the Home-Market for Industrial Capital Ch. 31: Genesis of the Industrial Capitalist Ch. 32: Historical Tendency of Capitalist Accumulation Ch. 33: The Modern Theory of Colonisation Appendix to the First German Edition: The Value-Form |

|

●ロバート・ライシュ『最後の資本主義』雨宮寛・今 井章子訳、東洋経済新聞社、2016年/ Saving capitalism : for the many, not the few / Robert Reich. Icon Books , 2017

第1部 自由市場

第2部 労働と価値

第3部 拮抗勢力

★ハージュン・チャン(Ha-Joon Chang)の

テーゼ;23

Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalismより

| 嘘 |

事実(真実) |

| 1.市場は自由でないといけな

い |

1.自由市場なんて存在しない |

| 2.株主の利益を第1に考えて

企業経営せよ |

2.株式の利益を最優先する企

業は発展しない |

| 3.市場経済では誰もが能力に

みあう賃金をもらえる |

3.富裕国の人々の大半は賃金

をもらいすぎている |

| 4.インターネットは世界を根

本的に変えた |

4.洗たく機はインターネット

よりも世界をかえた |

| 5.市場がうまく働くのは人間

が最悪(利己的)だからだ |

5.人間を最悪と考えれば、最

悪の結果しか得られない |

| 6.インフレを抑えれば経済は

安定し、成長する |

6.マクロ経済が安定しても世

界経済は安定しなかった |

| 7.途上国は自由市場・自由貿

易によって富み栄える |

7.自由市場政策によって貧し

い国が富むことはめったにない |

| 8.資本にはもはや国境はない |

8.資本にはいまなお国境があ

る |

| 9.世界は脱工業化時代に突入

した |

9.脱工業化時代は神話であり

幻想にすぎない |

| 10.ア メリカの生活水準は世界一である | 10.アメリカよりも生活水準

が高い国はいくつもある |

| 11.アフリカは発展できない

宿命にある |

11.アフリカは政策を変えさ

えすれば発展できる |

| 12.政府が勝たせようと企業

や産業は敗北する |

12.政府は企業や産業を勝利

に導ける |

| 13.富者をさらに富ませれば

他の者たちも潤う |

13.富は貧者にまではしたた

り落ちない |

| 14.経営者への高額報酬は必

要であり正当でもある |

14.アメリカの経営者の報酬

はあきれるほど高額すぎる |

| 15.貧しい国が発展できない

のは企業家精神の欠如だ |

15.貧しい国の人びとは富裕

国の人びとよりも起業家精神に富む |

| 16.すべて市場に任せるべき

だ |

16.わたくしたちは市場任せ

にできるほど利口じゃない |

| 17.教育こそ繁栄の鍵だ |

17.教育の向上そのものが国

を富ませることはない |

| 18.企業に自由にやらせるの

が国全体の経済にもよい |

18.企業の自由を制限するの

が経済にも企業にも良い場合がある |

| 19.共産主義の崩壊とともに

計画経済も消滅した |

19.わたくしたちは今なお計

画経済の世界に生きている |

| 20.今や努力すれば誰でも成

功できる |

20.機会均等だからフェアと

は限らない |

| 21.経済を発展させるには小

さな政府のほうがよい |

21.大きな政府こそ経済を活

性化できる |

| 22.金融市場の効率化こそが

国に繁栄をもたらす |

22.金融市場の効率化は良く

するのではなく悪くしなければならない |

| 23.良い経済政策の導入には

経済に関する深い知識が必要である。 |

23.経済を成功させるのに優

秀なエコノミストなど必要なし! |

| 【池田による加筆】資本主義は合理的である |

行動経済学によるとホモ・エコノミクスは幻想であり、資本主義は宗教で

あるという論者の歴史は辿れば1世紀以上の間に多数でてきた。 |

もともとのクレジットは「資本主義について彼らが言 わない23のこと」でした。

| Ha-Joon Chang

(/tʃæŋ/; Korean: 장하준; born 7 October 1963) is a South Korean economist

and academic. Chang specialises in institutional economics and

development, and has been lecturing in economics at the University of

Cambridge from 1990-2021, before becoming professor of economics at the

School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in 2022.[2][3] Chang is

the author of several bestselling books on economics and development

policy, most notably Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in

Historical Perspective (2002).[4][5][6] In 2013, Prospect magazine

ranked Chang as one of the top 20 World Thinkers.[7] Chang has served as a consultant to the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the European Investment Bank, as well as to Oxfam[8] and various United Nations agencies.[9] He is also a fellow at the Center for Economic and Policy Research[10] in Washington, D.C. In addition, Chang serves on the advisory board of Academics Stand Against Poverty (ASAP). |

チャン・ハジュン(/tʃ, 韓国語:

장하준、1963年10月7日生まれ)は韓国の経済学者、学者。専門は制度経済学と開発で、1990年から2021年までケンブリッジ大学で経済学の講師

を務めた後、2022年に東洋アフリカ研究学院(SOAS)の経済学教授に就任した[2][3]。経済学と開発政策に関するベストセラーを数冊執筆してお

り、特に『Kicking Away the Ladder:

4][5][6]2013年、『プロスペクト』誌はチャンを世界の思想家トップ20にランクインさせた[7]。 チャンは世界銀行、アジア開発銀行、欧州投資銀行、オックスファム[8]、様々な国連機関[9]のコンサルタントを務めており、ワシントンD.C.にある 経済政策研究センター[10]のフェローでもある。 |