資本主義と奴隷制

Capitalism and Slavery

★「ニ

グロはニグロだ。ある状況下では、彼は奴隷になる。ラバは綿を紡ぐ機械だ。特定の状況下で初めて資本となる。これらの状況外では、それは金がお金として本

質的に価値を持つように、または砂糖が砂糖の価格であるように、資本ではない。資本は生産の社会的関係である。それは生産の歴史的関係である」——カー

ル・マルクス『労働と資本』N. Rh. Z.第266号1849年4月7日.

☆『資 本主義と奴隷制』は、1962年にトリニダード・トバゴの初代首相となったエリック・ウィリアムズの博士論文の出版のタイトルである。18世紀後半か らの奴隷制、特に大西洋奴隷貿易とイギリス領西インド諸島における奴隷制の衰退に経済的要因が与えた影響について、多くの論文を展開している。また、当時 の大英帝国の歴史学に対する批判も行っている。特に、1833年に制定された奴隷制廃止法を一種の道徳的な枢軸として用いていることについて、また、帝国 憲政史を立法による絶え間ない前進とみなす歴史学派に対する批判も行っている。経済学的な議論、特にいわゆるラガッツ=ウィリアムズの衰退理論の適用可能 性は、それがアメリカ独立戦争前後の時期に用いられる場合、今日に至るまで歴史 家の間で論争となっている。他方、奴隷制がイギリス経済に与えた影響、特に奴隷制廃止の余波や大西洋貿易の商業的後背地に関する詳細な経済学的調査は、盛 んな研究分野である。大英帝国の歴史学は、いまだに広く論争を呼んでいる。Oxford Dictionary of National Biographyに寄稿しているケネス・モーガンは、『Capitalism and Slavery』を「おそらく奴隷制の歴史に関して20世紀に書かれた本の中で最も影響力のある本」と評価している。この本は1944年にアメリカで出版 されたが、1833年にイギリスで制定された奴隷制度廃止法の人道主義的動機を損なうなどの理由から、大手出版社はイ ギリスでの出版を拒否した。1964年にアンドレ・ドイッチュが英国で出版し、1991年まで何度も再版され、2022年にペンギン・モダン・クラ シックスから英国初の大衆版として出版され、ベストセラーとなった。

| Capitalism and

Slavery is the published version of the doctoral dissertation of Eric

Williams, who was the first Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago in

1962. It advances a number of theses on the impact of economic factors

on the decline of slavery, specifically the Atlantic slave trade and

slavery in the British West Indies, from the second half of the 18th

century. It also makes criticisms of the historiography of the British

Empire of the period: in particular on the use of the Slavery Abolition

Act of 1833 as a sort of moral pivot; but also directed against a

historical school that saw the imperial constitutional history as a

constant advance through legislation. It uses polemical asides for some

personal attacks, notably on the Oxford historian Reginald Coupland.

Seymour Drescher, a prominent critic among historians of some of the

theses put forward in Capitalism and Slavery by Williams, wrote in

1987: "If one criterion of a classic is its ability to reorient our

most basic way of viewing an object or a concept, Eric Williams's study

supremely passes that test."[1] The applicability of the economic arguments, and specially in the form of so-called Ragatz–Williams decline theory, is a contentious matter to this day for historians, when it is used for the period around the American Revolutionary War. On the other hand detailed economic investigations of the effects of slavery on the British economy, in particular, the aftermath of abolition, and the commercial hinterland of the Atlantic trade, are a thriving research area. The historiography of the British Empire is still widely contested. Kenneth Morgan writing in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography evaluates Capitalism and Slavery as "perhaps the most influential book written in the twentieth century on the history of slavery".[2] It was published in the United States in 1944, but major publishers refused to have it published in Britain, on grounds including that it undermined the humanitarian motivation for Britain's Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. In 1964 André Deutsch published it in Britain; it went through numerous reprintings to 1991,[3] and was published in the first UK mass-market edition by Penguin Modern Classics in 2022,[4] becoming a best-seller.[5] |

『資本主義と奴隷制』は、1962年にトリニダード・トバゴの初代首相

となったエリック・ウィリアムズの博士論文の出版のタイトルである。18世紀後半からの奴隷制、特に大西洋奴隷貿易とイギリス領西インド諸島における奴隷

制の衰退に経済的要因が与えた影響について、多くの論文を展開している。また、当時の大英帝国の歴史学に対する批判も行っている。特に、1833年に制定

された奴隷制廃止法を一種の道徳的な枢軸として用いていることについて、また、帝国憲政史を立法による絶え間ない前進とみなす歴史学派に対する批判も行っ

ている。特にオックスフォードの歴史家レジナルド・クープランドに対する個人攻撃には、極論的な余談が使われている。ウィリアムズが『資本主義と奴隷制』

で提唱したいくつかの論点を歴史家の間で著名に批判していたシーモア・ドレシャーは、1987年に次のように書いている。「古典の一つの基準が、ある対象

や概念に対する我々の最も基本的な見方を方向づける能力であるとすれば、エリック・ウィリアムズの研究はそのテストに見事に合格している」[1]。 経済学的な議論、特にいわゆるラガッツ=ウィリアムズの衰退理論の適用可能性は、それがアメリカ独立戦争前後の時期に用いられる場合、今日に至るまで歴史 家の間で論争となっている。他方、奴隷制がイギリス経済に与えた影響、特に奴隷制廃止の余波や大西洋貿易の商業的後背地に関する詳細な経済学的調査は、盛 んな研究分野である。大英帝国の歴史学は、いまだに広く論争を呼んでいる。Oxford Dictionary of National Biographyに寄稿しているケネス・モーガンは、『Capitalism and Slavery』を「おそらく奴隷制の歴史に関して20世紀に書かれた本の中で最も影響力のある本」と評価している[2]。 この本は1944年にアメリカで出版されたが、1833年にイギリスで制定された奴隷制度廃止法の人道主義的動機を損なうなどの理由から、大手出版社はイ ギリスでの出版を拒否した。1964年にアンドレ・ドイッチュが英国で出版し、1991年まで何度も再版され[3]、2022年にペンギン・モダン・クラ シックスから英国初の大衆版として出版され[4]、ベストセラーとなった[5]。 |

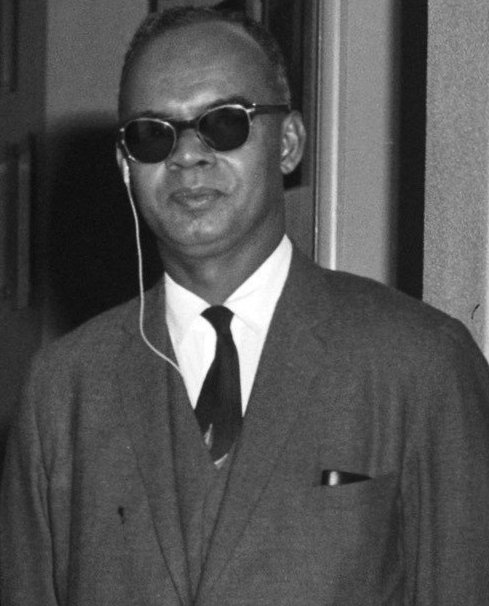

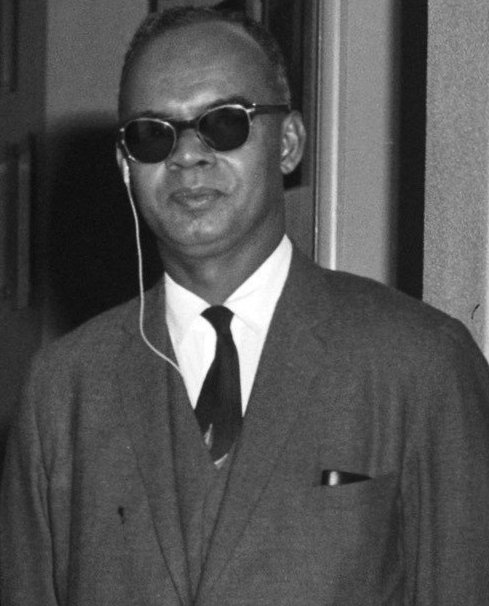

| Williams as an Oxford

undergraduate In 1931 Williams came to the University of Oxford from Trinidad on an Island Scholarship. He joined St Catherine's Society, not then a college (until that year the Delegacy for Non-Collegiate Students).[2][6] He obtained a first-class degree in Modern History, but found social life largely unfriendly. He made a friend of a Thai student, interacted with his tutors, and attended the Indian Majlis, a student club.[7] |

オックスフォード大学時代のウィリアムズ 1931年、ウィリアムズは島(アイランド)奨学金を得てトリニダードからオックスフォード大学に入学。当時はまだカレッジではなかったセント・キャサリンズ・ソサエ ティ(その年までは非大学生のための代議員会)に入った[2][6]。彼はタイ人の学生と友達になり、チューターと交流し、学生クラブであるインド・マ ジュリスに出席した[7]。 |

|

The Economic Aspect of the Abolition of the West Indian Slave Trade and

Slavery Williams wrote his Oxford D.Phil. dissertation under Vincent Harlow, on a topic suggested by C. L. R. James. The tone of the dissertation is judged "deferential", in comparison with the 1944 published version.[8][9] One of the D.Phil. examiners was Reginald Coupland, from 1920 second holder of the Beit Chair at Oxford for "colonial history", founded in 1905.[10][11] An emphasis on constitutional history led at Oxford, as Behm puts it, to "enthusiasm for social and moral reform [...] in an atmosphere already permeated by 'constitutional progress' as shorthand for centuries of world-historical advance".[12] Alfred Beit, the founder, was a friend of Cecil Rhodes and Alfred Milner, and the Chair came under the influence of the Round Table movement that forwarded Milner's ideas, and to which Coupland belonged.[10][13] In his later work British Historians and the West Indies (1966), Williams attacked the generality of Oxford historians who had dealt with the topic. He excepted Sydney Olivier.[14] Williams had been made aware of the potential importance of Coupland to his academic career by Joseph Oliver Cutteridge, the ex-British Army officer who was director of education in Trinidad and Tobago. This was at the point in 1936 when Williams was given funding for his doctoral work; Cutteridge had contacted Coupland on his behalf, to use influence with Claud Hollis, the Governor. Cutteridge had then advised "caution".[15] The original dissertation was published in 2014.[16] Its argument has the same basic structure of a "decline" thesis, and the negation of good intentions of abolitionists as a historical factor. Ryden identifies the three faces of decline in the first half of the 19th century as: "falling sugar planting profits"; "decline of the relative importance of the West Indian trade" in the British economy; and "a rising anti-mercantilist tide".[17] |

西インド奴隷貿易と奴隷制廃止の経済的側面 ウィリアムズは、C.L.R.ジェイムズが提案したテーマについて、ヴィンセント・ハーロウの下でオックスフォード博士論文を執筆した。この論文の論調 は、1944年に出版されたものと比べて「遜色ない」と評価されている[8][9]。 ベームが言うように、オックスフォードでは憲法史が重視され、「何世紀にもわたる世界史的進歩の略語としての『憲法の進歩』がすでに浸透していた雰囲気の 中で、社会的・道徳的改革への熱意が高まっていた」。 [創設者のアルフレッド・ベイトはセシル・ローズとアルフレッド・ミルナーの友人であり、同委員会はミルナーの思想を推し進め、クープランドも所属してい た円卓会議の影響下にあった[10][13]。ウィリアムズは後年の著作『British Historians and the West Indies』(1966年)の中で、このテーマを扱ったオックスフォードの歴史家の一般性を攻撃している。彼はシドニー・オリヴィエを除いていた [14]。 ウィリアムズは、トリニダード・トバゴの教育局長であった元イギリス陸軍将校のジョセフ・オリヴァー・カッタリッジによって、彼の学問的キャリアにとって クープランドが潜在的に重要であることを認識させられていた。カッタリッジはウィリアムズに代わってクープランドに接触し、総督のクラウド・ホリスに影響 力を行使した。カッタリッジはそのとき「注意」するよう忠告していた[15]。 論文の原文は2014年に出版された[16]。その論旨は「衰退」論文と同じ基本構造を持っており、歴史的要因として奴隷廃止論者の善意を否定している。 ライデンは、19世紀前半における衰退の3つの顔を挙げている: 「砂糖栽培の利益の低下」、イギリス経済における「西インド貿易の相対的重要性の低下」、「反重商主義の潮流の高まり」である[17]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capitalism_and_Slavery | |

| Howard University, and

publication Williams left the United Kingdom for the United States in 1939. After a period of unsuccessful job applications, he had been appointed assistant professor at Howard University, an historically black college, in Washington D.C.[2] A close colleague there, who wrote a foreword to Williams's The Negro in the Caribbean (1942), was Alain LeRoy Locke. Others on the faculty were Ralph Bunche, E. Franklin Frazier, and Charles S. Johnson.[18] Williams was brought to Howard by Locke, supported by Bunche and Abram Lincoln Harris, and took on a teaching load in the Political Science department.[19] Excerpts of his thesis were published in 1939 by The Keys, the journal of the London-based League of Coloured Peoples.[20] An attempt by Williams to have his dissertation published in the United Kingdom through Fredric Warburg failed: the undermining of the humanitarian motivation for the Abolition Act 1833 was found unacceptable, culturally speaking.[7] Publication of Capitalism and Slavery happened finally in the United States, in 1944. It appeared in a British edition in 1964, with an introduction by Denis William Brogan, summarising Williams's thesis in a phrase on abolition as a cutting of losses, and illustration of the workings of self-interest. Brogan had reviewed Capitalism and Slavery in the Times Literary Supplement, and accepted its general argument on the predominance of economic forces.[21][22] |

ハワード大学と出版 ウィリアムズは1939年に英国から米国に渡った。就職活動に失敗した後、彼はワシントンD.C.にある歴史的黒人大学であるハワード大学の助教授に任命 された[2]。ウィリアムズの『カリブ海の黒人』(The Negro in the Caribbean、1942年)に序文を書いた親しい同僚がアラン・ルロイ・ロック(Alain LeRoy Locke)であった。ウィリアムズはロックによってハワード大学に引き抜かれ、バンチェとエイブラム・リンカーン・ハリスの支援を受け、政治学部で教鞭 をとることになった[19]。 彼の論文の抜粋は、1939年にロンドンを拠点とする有色人種連盟の機関誌『ザ・キーズ』によって出版された[20]。ウィリアムズがフレドリック・ウォ ルバーグを通じて彼の論文をイギリスで出版しようとした試みは失敗に終わった。この本は1964年に英国版として出版され、デニス・ウィリアム・ブローガ ンの序文が添えられ、ウィリアムズの論文を、損切りとしての奴隷廃止、利己主義の働きの例示という言葉で要約している。ブローガンは『資本主義と奴隷制』 を『タイムズ・リテラリー・サプリメント』誌で書評し、経済的な力の優位性に関するその一般的な主張を受け入れていた[21][22]。 |

|

Arguments and sources of Capitalism and Slavery Capitalism and Slavery covers the economic history of sugar and slavery into the 19th century and discusses the decline of Caribbean sugar plantations from 1823 until the emancipation of the slaves in the 1830s. It also notes the British government's use of the equalisation of the sugar duties Acts in the 1840s, to reduce protectionism for sugar from the British West Indian colonies, and promote free trade in sugar from Cuba and Brazil, where it was cheaper.[23] The work relied on economic reasoning going back to Lowell Joseph Ragatz, to whom it was dedicated.[24][25][26] The secondary sources bibliography, after commending works by Ragatz, mentioned The Development of the British West Indies, 1700–1763 (1917) by the American historian Frank Wesley Pitman. In two 1918 reviews of Pitman's book, Hugh Edward Egerton, the first holder of the Beit Chair at Oxford, picked out the baseline 1763—when the Seven Years' War ended in the Peace of Paris, and Great Britain returned to France the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe while keeping Canada—as (in Pitman's argument) the start of manipulation of the sugar trade and its regulation, by British producers, for profit. In other words artificial scarcity was created by the West India Interest, an example of client politics.[27][28] In the American context, it had been argued by William Babcock Weeden (1834–1912), and in 1942 by Lorenzo Greene, that the slave trade was integral to the economic development of New England.[29] Williams argued that slavery played a major role in developing the British economy; the high profits from slavery, he wrote, helped finance the Industrial Revolution. British capital was gained from unpaid work.[30] The bibliography also cites The Black Jacobins by C. L. R. James for its priority in giving in 1938 a statement (in English) of the major thesis of Capitalism and Slavery; and a master's dissertation from that year by Wilson Williams at Howard University. Wilson Williams and Abram Harris are taken to be the sources of the work's interest in the commercial writer Malachy Postlethwayt.[31] |

『資本主義と奴隷制』の論拠と出典 『資本主義と奴隷制』は19世紀までの砂糖と奴隷制の経済史を扱っており、1823年から1830年代の奴隷解放までのカリブ海の砂糖プランテーションの衰 退について論じている。また、イギリス政府が1840年代に砂糖関税均等法を利用し、イギリス西インド植民地からの砂糖に対する保護主義を弱め、より安価 なキューバやブラジルからの砂糖の自由貿易を促進したことにも言及している[23]。 この著作は、ローウェル・ジョセフ・ラガッツにさかのぼる経済的推論に依拠しており、ラガッツに捧げられていた[24][25][26]。二次資料の書誌 は、ラガッツの著作を称賛した後に、アメリカの歴史家フランク・ウェズリー・ピットマンの『The Development of the British West Indies, 1700-1763』(1917年)に言及していた。ピットマンの著書に対する1918年の2つの書評の中で、オックスフォード大学のベイト・チェアの初 代ホルダーであるヒュー・エドワード・エガートンは、(ピットマンの主張では)七年戦争がパリの和約で終結し、イギリスがカナダを維持したままカリブ海の グアドループ島をフランスに返還した1763年というベースラインを、イギリス人生産者による砂糖貿易の操作とその規制が利益のために開始された時期とし て取り上げている。言い換えれば、人為的な欠乏は西インド利権によって作り出されたものであり、クライアント・ポリティクスの一例であった[27] [28]。 アメリカの文脈では、ウィリアム・バブコック・ウィーデン(1834年-1912年)によって、また1942年にはロレンゾ・グリーンによって、奴隷貿易 がニューイングランドの経済発展に不可欠であったことが主張されていた[29]。この書誌はまた、1938年にC・L・R・ジェイムズによる『黒いジャコ バン』(The Black Jacobins)を引用し、資本主義と奴隷制の主要なテーゼを(英語で)述べている。ウィルソン・ウィリアムズとアブラム・ハリスは、商業作家マラ シー・ポストレスウェイトに対するこの作品の関心の源であるとされている[31]。 |

|

The book, besides dealing with a passage of economic history, was

furthermore a frontal attack on the idea that moral and humanitarian

motives were key in the victory of British abolitionism. It was also a

critique of the idea common in the 1930s, and in particular advocated

by Reginald Coupland, that the British Empire was essentially propelled

by benevolent impulses. The centenary celebration of the 1833 Act that

took place in the United Kingdom in 1933, in Kingston upon Hull, where

William Wilberforce was born, was a public event in which Coupland made

these ideas explicit, supported in The Times by G. M. Trevelyan.[32]

Williams made a number of pointed critical remarks in this direction,

including: "Professor Coupland contends that behind the legal judgement lay the moral judgement, and that the Somersett case was the beginning of the end of slavery throughout the British Empire. This is merely poetic sentimentality translated into modern history."[33] From the "Conclusion": "But historians, writing a hundred years after, have no excuse for continuing to wrap the real interests in confusion." Footnoted as: "Of this deplorable tendency Professor Coupland of Oxford University is a notable example."[34] Williams rejected moralised explanation and argued that abolition was driven by diminishing returns, after a century of sugarcane raising had exhausted the soil of the islands.[30] Beyond this aspect of the decline thesis, he argued that the slave-based Atlantic economy of the 18th century generated new pro-free trade and anti-slavery political interests. These interacted with the rise of evangelical antislavery and with the self-emancipation of slave rebels, from the Haitian Revolution of 1792–1804 to the Jamaica Christmas Rebellion of 1831, to bring the end of slavery in the 1830s.[35] |

本書は、経済史の一節を扱っただけでなく、さらに、道徳的・人道的動機がイギリスの奴隷廃止主義の勝利の鍵であったという考えに対する正面からの攻撃で

あった。また、1930年代に一般的だった、特にレジナルド・クープランドが提唱した、大英帝国は本質的に博愛的な衝動によって推進されたという考えに対

する批判でもあった。ウィリアム・ウィルバーフォースの出身地であるキングストン・アポン・ハルで1933年にイギリスで行われた1833年法の100周

年記念式典は、クープランドがこうした考えを明確にした公的なイベントであり、G.M.トレヴェリアンによって『タイムズ』紙で支持された[32]: 「クープランド教授は、法的判断の背後には道徳的判断があり、サマセット事件は大英帝国全体の奴隷制の終わりの始まりであったと主張している。これは現代 史に翻訳された詩的感傷にすぎない」[33]。 結論」より: "しかし、100年後に書く歴史家は、現実の利益を混乱に包み続ける言い訳はできない。" と脚注されている: 「この嘆かわしい傾向については、オックスフォード大学のクープランド教授が顕著な例である」[34]。 ウィリアムズは道徳化された説明を否定し、100年にわたるサトウキビ 栽培が島の土壌を疲弊させた後、収穫逓増によって奴隷廃止が推進されたと主張した[30]。これらは福音主義的な反奴隷制の台頭や、1792年から 1804年にかけてのハイチ革命から1831年のジャマイカのクリスマスの反乱に至る奴隷解放運動と相互作用し、1830年代に奴隷制の終焉をもたらした [35]。 |

| Periodisation of Capitalism and

Slavery The points raised required periodisation, by calibration to a timeline. The D.Phil. dissertation limited itself to the period 1780–1833.[36] In Chapter 4 of the book, "The West India Interest", an outline of a timeline is given, reflecting the difference of interests of planters and the sugar merchants: 1739: Planters and merchants find their interests conflicting, on the issue of free trade with continental Europe (p. 92). 1764: The West India Interest in its "heyday" (p. 97). c.1780: The American Revolution disrupts the existing system of British commerce (p. 96). At this point the interests of planters and merchants had become aligned (p. 92). 1832: The Reform Parliament at Westminster represents the Lancashire manufacturing interest, rather than the West India Interest (p. 97). Chapter 5, "British Industry and the Triangular Trade", in other words on the Atlantic slave trade as part of the triangular trade completed by sugar, begins on p. 98 with "Britain was accumulating great wealth from the triangular trade." It ends with a few pages of overview, arguing that the economic development already visible by 1783 was outgrowing the system dubbed mercantilism. The 1807 prohibition of the international slave trade, Williams argued, prevented French expansion of sugar plantations on other islands. British investment turned to Asia, where labour was plentiful and slavery was unnecessary.[30] Dividing up the period c.1780 to 1832, by the end of the triangular trade in 1807, Williams wrote that "The abolitionists for a long time eschewed and repeatedly disowned any idea of emancipation."[37] He also presented economic data to show that the triangular trade alone had generated only minor profits compared to the sugar plantations. Then from 1823 the British Caribbean sugar industry went into terminal decline, and the British parliament no longer felt they needed to protect the economic interests of the West Indian sugar planters.[38] |

資本主義と奴隷制の時代区分 指摘された論点は、年表に照らし合わせることで時代区分する必要があった。博士論文は1780年から1833年という期間に限定していた[36]。 本書の第4章「西インド利権」では、プランターと砂糖商人の利害の相違を反映した年表の概要が示されている: 1739年:ヨーロッパ大陸との自由貿易の問題で、プランターと商人の利害が対立する(p.92)。 1764: 全盛期」の西インド利権(p.97)。 c.1780: アメリカ独立戦争がイギリス商業の既存システムを崩壊させる(p. 96)。この時点で、プランターと商人の利害は一致していた(p. 92)。 1832: ウェストミンスターで改革議会が開かれ、西インド利権よりもむしろランカシャーの製造業利権が代表される(p.97)。 第5章「イギリスの産業と三角貿易」、つまり砂糖によって完成された三角貿易の一部としての大西洋奴隷貿易については、p.98の "イギリスは三角貿易から巨万の富を蓄積していた "で始まる。1783年までにすでに目に見えていた経済発展は、重商主義と呼ばれたシステムを凌駕しつつあった、と論じた数ページの概説で終わる。 1807年の国際奴隷貿易の禁止は、フランスによる他の島々での砂糖プランテーションの拡大を妨げたとウィリアムズは論じた。イギリスの投資は、労働力が 豊富で奴隷制度が不要であったアジアへと向かった[30]。 ウィリアムズは、1780年頃から1832年頃までの期間を1807年の三角貿易の終了によって分割し、「奴隷廃止論者は長い間、奴隷解放の考えを避け、 繰り返し否定していた」と書いている[37]。また、三角貿易だけでは砂糖プランテーションと比較してわずかな利益しか生んでいなかったことを示す経済 データを提示している。そして1823年以降、イギリス領カリブ海の砂糖産業は衰退の一途をたどり、イギリス議会は西インド諸島の砂糖プランターの経済的 利益を保護する必要性を感じなくなった[38]。 |

| Reception The book was published in the United States in 1944. Early American reviews by historians ranged from enthusiasm, with Henry Steele Commager, to expressed reservations from Elizabeth Donnan and Frank Tannenbaum.[22] Ryden, writing in 2012 and relying on some citation analysis, spoke of three waves of interest in Capitalism and Slavery over the previous four decades and more, the first being associated with a largely critical review article of 1968 by Roger Anstey. The background was of consistent growth in attention.[39] Writing in 1994 in A Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century World History, Tadman stated that: "A revised version of the Williams thesis (of economic and class self-interest leading to abolition) seems to have much explanatory power. Rising urban interests perceived slavery as unprofitable, backward, and a threat to liberal (and middle-class) values."[40] Hilary Beckles wrote in 2004 of "the fundamental academic respect that Capitalism and Slavery enjoys within the Caribbean", after noting the "persistent and penetrative criticisms".[41] Supporters cited were Sydney H. H. Carrington (1937–2018), an advocate of the decline thesis as originally stated, and Gordon Kenneth Lewis (1919–1991), whose view was that "it is testimony to the essential correctness of that thesis that the attempt of a later scholarship to impugn it has been unsuccessful."[42] Billy Strachan, a leading Black civil rights activist and communist in Britain, credited the book with heavily influencing his world outlook.[43] No major British publisher published the book until forty years after Williams's death, although he had sought to have it published; it had been refused on grounds including that it undermined the humanitarian motivation for Britain's Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. Publisher Fredric Warburg, who published several provocative books in 1930s Britain, considered that suggesting that the slave trade and slavery were abolished for economic and not humanitarian reasons was "contrary to the British tradition—I would never publish such a book". In 1964 André Deutsch published it in Britain, it went through numerous reprintings to 1991,[3] and was published in the first UK mass-market edition by Penguin Modern Classics in 2022,[4] becoming a best-seller.[5] |

評価と受容 本書は1944年に米国で出版された。歴史家たちによるアメリカ初期の批評は、ヘンリー・スティール・コメジャーによる熱狂的なものから、エリザベス・ド ナンやフランク・タネンバウムによる留保を表明したものまで様々であった[22]。ライデンは2012年に執筆し、いくつかの引用分析に依拠しているが、 それまでの40年以上にわたる『資本主義と奴隷制』への関心の3つの波について語っている。その背景には、一貫して関心が高まっていることがあった [39]。 1994年に『A Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century World History』の中でタッドマンは次のように述べている: 「ウィリアムズのテーゼの改訂版(経済的・階級的利己心が奴隷制廃止につながったというもの)は、多くの説明力をもっていると思われる。台頭する都市の利 害関係者は、奴隷制を不採算で後進的なものであり、リベラルな(そして中流階級の)価値観に対する脅威であると認識していた」[40]。 ヒラリー・ベックルズは2004年に、「持続的かつ浸透的な批判」を指摘した上で、「カリブ海諸国において『資本主義と奴隷制』が享受している基本的な学 問的敬意」について書いている[41]。キャリントン(Sydney H. H. Carrington、1937-2018)、衰退論の擁護者、ゴードン・ケネス・ルイス(Gordon Kenneth Lewis、1919-1991)であり、彼の見解は、「後世の学者がこの論文を非難する試みが成功しなかったことは、この論文の本質的な正しさを証明す るものである」というものであった[42]。 イギリスの代表的な黒人公民権運動家であり共産主義者であったビリー・ストラチャンは、この本が彼の世界観に大きな影響を与えたと信じている[43]。 ウィリアムズはこの本の出版を求めていたが、1833年に制定されたイギリスの奴隷制廃止法の人道主義的動機を損なうものであるなどの理由で拒否されてい た。1930年代の英国でいくつかの挑発的な本を出版していた出版社のフレデリック・ウォルバーグは、奴隷貿易と奴隷制が人道的な理由ではなく経済的な理 由で廃止されたと示唆することは「英国の伝統に反する。1964年にアンドレ・ドイッチュが英国で出版し、1991年まで何度も再版され[3]、2022 年にペンギン・モダン・クラシックスから初の英国大衆版として出版され[4]、ベストセラーとなった[5]。 |

|

Economic factors Richard Pares, in an article written before Williams's book, had dismissed the influence of wealth generated from the West Indian plantations on the financing of the Industrial Revolution, stating that whatever substantial flow of investment from West Indian profits into industry there was had occurred after emancipation, not before.[44] Heuman states: In Capitalism and Slavery, Eric Williams argued that the declining economies of the British West Indies led to the abolition of the slave trade and of slavery. More recent research has rejected this conclusion; it is now clear that the colonies of the British Caribbean profited considerably during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.[45] Stanley Engerman finds that even without subtracting the associated costs of the slave trade or reinvestment of profits, the total profits from the slave trade and of West Indian plantations amounted to less than 5% of the British economy during any year of the Industrial Revolution.[46] In support of the Williams thesis, Ryden (2009) presented evidence to show that by the early 19th century there was an emerging crisis of profitability.[47] Richardson (1998) finds Williams's claims regarding the Industrial Revolution are exaggerated, for profits from the slave trade amounted to less than 1% of domestic investment in Britain. He finds also that the "terms of trade" (how much the ship owners paid for the slave cargo) moved heavily in favour of the Africans after about 1750.[48] Ward has argued that slavery remained profitable in the 1830s, because of innovations in agriculture.[49] |

経済的要因 リチャード・パレスはウィリアムズの本より前に書かれた論文で、産業革命の資金調達に西インド諸島のプランテーションから生み出された富が影響したことを 否定し、西インド諸島の利益から産業への実質的な投資の流れがあったとしても、それは奴隷解放の前ではなく、奴隷解放の後に起こったことだと述べていた [44]: 資本主義と奴隷制』の中で、エリック・ウィリアムズは、イギリス領西インド諸島の経済が衰退したことが奴隷貿易と奴隷制の廃止につながったと主張した。よ り最近の研究ではこの結論は否定されており、イギリス領カリブ海の植民地が革命戦争とナポレオン戦争でかなりの利益を得ていたことが明らかになっている [45]。 スタンリー・エンガーマンは、奴隷貿易の関連費用や利益の再投資を差し引かなくても、奴隷貿易と西インド諸島のプランテーションからの利益の総額は、産業 革命のどの年においても、イギリス経済の5%未満であったとしている[46]。 [リチャードソン(1998)は、産業革命に関するウィリアムズの主張は誇張されており、奴隷貿易からの利益はイギリスの国内投資の1%未満であったとし ている。彼はまた、「交易条件」(船主が奴隷の積荷に対していくら支払ったか)が1750年頃以降、アフリカ人に大きく有利に動いたことを発見している [48]。ウォードは、農業における革新のために、奴隷制度は1830年代においても利益を上げていたと主張している[49]。 |

|

Abolitionist sentiment In a major attack on the propositions brought forward by Williams, Seymour Drescher in Econocide (1977) argued that the United Kingdom's abolition of the slave trade in 1807 resulted not from the diminishing value of slavery for the nation, but instead from the moral outrage of the British public which could vote.[50] Geggus in 1981 gave details of the sugar industry of the British West Indies in the 1780s, casting some doubt on the method used by Drescher for capital valuation.[51] Carrington in a reply from 1984 advocated for two "main theses" stated in Capitalism and Slavery, and subsequently attacked by "historians from the metropolises": "the rise of industrial capitalism in Britain led to the destruction of the slave trade and slavery itself", and "the slave trade and the sugar industry based on slavery led to the formation of capital in England which helped in financing the Industrial Revolution".[52] On the detail of Drescher's periodisation in arguing against the first of those theses, Carrington then says that Drescher is agreeing with what Ragatz had argued in 1928, namely that decline set in at peak prosperity for the planters, but was misplacing that peak by systematic neglect of the effects of the American Revolutionary War, and the slow subsequent recovery from those.[53] |

廃止論者の感情 ウィリアムズが提唱した命題に対する主要な攻撃として、シーモア・ドレシャーは『エコノサイド』(1977年)の中で、1807年にイギリスが奴隷貿易を 廃止したのは、国家にとっての奴隷制の価値が低下したためではなく、投票権を持つイギリス国民の道徳的憤慨からであると主張していた[50]。 キャリントンは1984年からの返信の中で、『資本主義と奴隷制』の中で述べられ、その後「大都市の歴史家たち」によって攻撃された2つの「主要なテー ゼ」を提唱していた: 「イギリスにおける産業資本主義の台頭は、奴隷貿易と奴隷制度そのものの破壊につながった」、そして「奴隷貿易と奴隷制度に基づく砂糖産業は、イギリスに おける資本の形成につながり、産業革命の資金調達に役立った」。 [キャリントンは、これらのテーゼのうち最初のものに対して反論しているドレシャーの時代区分の詳細について、ドレシャーは1928年にラガッツが主張し ていたこと、すなわち、農民の繁栄がピークに達したときに衰退が始まったということに同意しているが、アメリカ独立戦争の影響とそれからの回復の遅れを体 系的に無視することによって、そのピークを見誤っていると述べている[53]。 |

|

Later developments Robin Blackburn in The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, 1776–1848 (1988) summarised the thesis of Capitalism and Slavery in the terms that it took slavery to be a part of colonial mercantilism, that was then overtaken by the colonial expansion and domestic wage labour of the rising European powers. Noting that Williams provided both argument and illustration, while ignoring slavery in the United States, he considers the schematic ultimately "mechanical and unsatisfactory". He finds David Brion Davis fuller on abolitionist thought, and Eugene Genovese better on the resistance ideas of the enslaved people.[54] Catherine Hall and the other authors of Legacies of British Slave-Ownership: Colonial Slavery and the Formation of Victorian Britain (2014) identified four key arguments of Capitalism and Slavery, and wrote of a schism between Anglo-American historians and those from the Caribbean on their status. The context is a series of projects run by University College London, with Web presence at www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs. The stated arguments are:[55] |

その後の展開 ロビン・ブラックバーンはThe Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, 1776-1848 (1988)において、『資本主義と奴隷制』のテーゼを、奴隷制は植民地重商主義の一部であり、それが勃興するヨーロッパ列強の植民地拡大と国内賃金労働 に追い越されたとする言葉で要約している。ウィリアムズがアメリカにおける奴隷制を無視しながら、論証と説明の両方を提供したことを指摘し、この図式は結 局のところ「機械的で満足のいくものではない」と考えている。彼は、デイヴィッド・ブリオン・デイヴィスが奴隷廃止論者の思想についてより充実しており、 ユージン・ジェノヴェーゼが奴隷にされた人々の抵抗思想についてより優れていると見なしている[54]。 キャサリン・ホールと『Legacies of British Slave-Ownership: Colonial Slavery and the Formation of Victorian Britain』(2014年)は、『資本主義と奴隷制』の4つの主要な論点を特定し、その地位について英米の歴史家とカリブ海諸国の歴史家の間に分裂が あると書いている。その背景には、ユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンが運営する一連のプロジェクトがあり、ウェブでは www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs。その主張は以下の通りである[55]。 |

|

Slavery as key to the Industrial Revolution. Slave-produced wealth as integral to the British economy in the 18th century. Economic decline by 1783, or even 1763. The role of the West Indian planters changed from the leading economic edge, to behind the times. These are all recognised as somewhat contentious, with #1 and #3 particularly so. All four are considered fundamental to the project work, and capable of being illuminated by the gathering of further data.[55] Gareth Austin writing in the Cambridge History of Capitalism vol. II (2014) describes the rejection of Williams's thesis about the economic impact of slavery on the Industrial Revolution as revisionist interpretation. He goes on to describe a challenge to that interpretation by Joseph E. Inikori, based on whole-Atlantic trade and (for example) the hinterland trade of British cloth destined for West Africa. He footnotes a comment "One should distinguish the issue of causality of the industrial revolution from the fact that various specific industrial investments were indeed made with profits from slave ships or slave estates, as Williams documented."[56] |

産業革命の鍵としての奴隷制度。 奴隷が生産した富は18世紀のイギリス経済に不可欠であった。 1783年、あるいは1763年までの経済衰退。 西インド諸島のプランターの役割は、経済の最先端から時代遅れへと変化した。 これらはすべて多少議論の余地があるものとして認識されており、特に1番と3番がそうである。4つともプロジェクト作業の基本であり、さらなるデータ収集 によって明らかにすることができると考えられている[55]。 Cambridge History of Capitalism vol.II』(2014年)で執筆しているガレス・オースティンは、産業革命における奴隷制の経済的影響に関するウィリアムズのテーゼの否定を修正主義 的解釈として記述している。彼はさらに、ジョセフ・E・イニコリによる、大西洋貿易全体と(例えば)西アフリカ向けの英国布の内陸貿易に基づく、この解釈 への挑戦について述べている。彼は、「産業革命の因果関係の問題は、ウィリアムズが文書化しているように、奴隷船や奴隷地からの利益によって様々な特定の 産業投資が実際に行われたという事実とは区別すべきである」というコメントを脚注している[56]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capitalism_and_Slavery | |

Eric Eustace Williams TC CH (25 September 1911 – 29 March 1981) was a Trinidad and Tobago politician.[6] He has been described as the "Father of the Nation",[1][2][3][4][5] having led the then British Colony of Trinidad and Tobago to majority rule on 28 October 1956, to independence on 31 August 1962, and republic status on 1 August 1976, leading an unbroken string of general elections victories with his political party, the People's National Movement, until his death in 1981. He was the first Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago and also a Caribbean historian, especially for his book entitled Capitalism and Slavery.[7] Early life Williams was born on 25 September in 1911. His father Thomas Henry Williams was a minor civil servant and devout Roman Catholic, and his mother Eliza Frances Boissiere (13 April 1888 – 1969) was a descendant of the mixed French Creole Mulatto elite and had African and French ancestry. She was a descendant of the notable de Boissière family in Trinidad. Eliza's paternal grandfather was John Boissiere, a married upper-middle class Frenchman who had an intimate relationship with an African slave named Ma Zu Zule. From the union, Jules Arnold Boissiere, father of Eliza, was born.[8] He saw his first school years at Tranquillity Boys' Intermediate Government School and he was later educated at Queen's Royal College in Port of Spain, where he excelled at academics and football. A football injury at QRC led to a hearing problem which he wore a hearing aid to correct. He won an island scholarship in 1932, which allowed him to attend St. Catherine's Society, Oxford (later renamed St. Catherine's College). In 1935, he received a first class honours degree, and ranked first among history graduates that year. He also represented the university at football. In 1938, he went on to obtain his doctorate (see section below). In Inward Hunger, his autobiography, he described his experience of studying at Oxford, including his frustrations with rampant racial discrimination at the institution, and his travels in Germany after the Nazis' seizure of power. Scholarly career In Inward Hunger, Williams recounts that in the period following his graduation, He was "severely handicapped in my research by my lack of money ... I was turned down everywhere I tried ... and could not ignore the racial factor involved". However, in 1936, thanks to a recommendation made by Sir Alfred Claud Hollis (Governor of Trinidad and Tobago, 1930–36), the Leathersellers' Company awarded him a £50 grant to continue his advanced research in history at Oxford.[9] He completed the D.Phil in 1938 under the supervision of Vincent Harlow. His doctoral thesis was titled The Economic Aspects of the Abolition of the Slave Trade and West Indian Slavery, and was published as Capitalism and Slavery in 1944,[10] although excerpts of his thesis were published in 1939 by The Keys, the journal of the League of Coloured Peoples. According to Williams, Fredric Warburg – a publisher of Marxist literature, who Williams asked to publish his thesis – refused to publish, saying that "such a book... would be contrary to the British tradition".[11] His thesis was both a direct attack on the idea that moral and humanitarian motives were the key facts in the success of the British abolitionist movement, and a covert critique of the established British historiography on the West Indies (as exemplified by, in Williams' view, the works of Oxford professor Reginald Coupland) as supportive of continued British colonial rule. Williams's argument owed much to the influence of C. L. R. James, whose The Black Jacobins, also completed in 1938, also offered an economic and geostrategic explanation for the rise of abolitionism in the Western world.[12] Gad Heuman states: In Capitalism and Slavery, Eric Williams argued that the declining economies of the British West Indies led to the abolition of the slave trade and of slavery. More recent research has rejected this conclusion; it is now clear that the colonies of the British Caribbean profited considerably during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.[13] However, Capitalism and Slavery covers the economic history of sugar and slavery beyond just the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, and discusses the decline of sugar plantations from 1823 until the emancipation of the slaves in the 1830s. It also discusses the British government's use of the equalisation of the sugar duties Acts in the 1840s to sever their responsibilities to buy sugar from the British West Indian colonies, and to buy sugar on the open market from Cuba and Brazil, where it was cheaper.[14] In support of the Williams thesis, David Ryden presented evidence to show that by the early nineteenth century there was an emerging crisis of profitability.[15] Williams's argument about abolitionism went far beyond this decline thesis. What he argued was that the new economic and social interest created in the 18th century by the slave-based Atlantic economy generated new pro-free trade and anti-slavery political interests. These interacted with the rise of evangelical antislavery and with the self-emancipation of slave rebels, from the Haitian Revolution of 1792–1804 to the Jamaica Christmas Rebellion of 1831, to bring the end of Slavery in the 1830s.[16] In 1939, Williams joined the Political Science department at Howard University.[12] In 1943, Williams organized a conference about the "economic future of the Caribbean."[17] He argued that small islands of the West Indies would be vulnerable to domination by the former colonial powers in the event that these islands became independent states; Williams advocated for a West Indian Federation as a solution to post-colonial dependence.[17] Shift to public life In 1944, Williams was appointed to the Anglo-American Caribbean Commission. In 1948 he returned to Trinidad as the Commission's deputy chairman of the Caribbean Research Council. In Trinidad, he delivered an acclaimed series of educational lectures. In 1955, after disagreements between Williams and the Commission, the Commission elected not to renew his contract. In a speech at Woodford Square in Port of Spain, he declared that he had decided to "put down his bucket" in the land of his birth. He rechristened that enclosed park, which stood in front of the Trinidad courts and legislature, "The University of Woodford Square", and proceeded to give a series of public lectures on world history, Greek democracy and philosophy, the history of slavery, and the history of the Caribbean to large audiences drawn from every social class.[citation needed] Entry into nationalist politics in Trinidad and Tobago From that public platform on 15 January 1956, Williams inaugurated his own political party, the People's National Movement (PNM), which would take Trinidad and Tobago into independence in 1962, and dominate its post-colonial politics. Until this time his lectures had been carried out under the auspices of the Political Movement, a branch of the Teachers Education and Cultural Association, a group that had been founded in the 1940s as an alternative to the official teachers' union. The PNM's first document was its constitution. Unlike the other political parties of the time, the PNM was a highly organized, hierarchical body. Its second document was The People's Charter, in which the party strove to separate itself from the transitory political assemblages which had thus far been the norm in Trinidadian politics. In elections held eight months later, on 24 September the Peoples National Movement won 13 of the 24 elected seats in the Legislative Council, defeating 6 of the 16 incumbents running for re-election. Although the PNM did not secure a majority in the 31-member Legislative Council, he was able to convince the Secretary of State for the Colonies to allow him to name the five appointed members of the council (despite the opposition of the Governor, Sir Edward Betham Beetham). This gave him a clear majority in the Legislative Council. Williams was thus elected Chief Minister and was also able to get all seven of his ministers elected. Federation and independence After the Second World War, the Colonial Office had preferred that British colonies move towards political independence in the kind of federal systems which had appeared to succeed since the Canadian confederation, which created Canada, in the 19th century. In the British West Indies, this goal coincided with the political aims of the nationalist movements which had emerged in all the colonies of the region during the 1930s. The Montego Bay conference of 1948 had declared the common aim to be the achievement by the West Indies of "Dominion Status" (which meant constitutional independence from the British government) as a Federation. In 1958, a West Indies Federation emerged from the British Caribbean, which with British Guiana (now Guyana) and British Honduras (now Belize) choosing to opt out of the Federation, leaving Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago as the dominant players. Most political parties in the various territories aligned themselves into one of two Federal political parties – the West Indies Federal Labour Party (led by Grantley Adams of Barbados and Norman Manley of Jamaica) and the Democratic Labour Party (DLP) led by Manley's cousin, Sir Alexander Bustamante. The PNM affiliated with the former, while several opposition parties (the People's Democratic Party, the Trinidad Labour Party and the Party of Political Progress Groups) aligned themselves with the DLP, and soon merged to form the Democratic Labour Party of Trinidad and Tobago. The DLP victory in the 1958 Federal Elections and subsequent poor showing by the PNM in the 1959 County Council Elections soured Williams on the Federation. Lord Hailes (Governor-General of the Federation) also overruled two PNM nominations to the Federal Senate in order to balance a disproportionately WIFLP-dominated Senate. When Bustamante withdrew Jamaica from the Federation, this left Trinidad and Tobago in the untenable position of having to provide 75% of the Federal budget while having less than half the seats in the Federal government. In a speech, Williams declared that "one from ten leaves nought". Following the adoption of a resolution to that effect by the PNM General Council on 15 January 1962, Williams withdrew Trinidad and Tobago from the West Indies Federation. This action led the British government to dissolve the Federation. In 1961 the PNM had introduced the Representation of the People Bill. This Bill was designed to modernise the electoral system by instituting permanent registration of voters, identification cards, voting machines and revised electoral boundaries. These changes were seen by the DLP as an attempt to disenfranchise illiterate rural voters through intimidation, to rig the elections through the use of voting machines, to allow Afro-Caribbean immigrants from other islands to vote, and to gerrymander the boundaries to ensure victory by the PNM. Opponents of the PNM saw "proof" of these allegations when A. N. R. Robinson was declared winner of the Tobago seat in 1961 with more votes than there were registered voters, and in the fact that the PNM was able to win every subsequent election until the 1980 Tobago House of Assembly Elections. The 1961 elections gave the PNM 57% of the votes and 20 of the 30 seats. This two-thirds majority allowed them to draft the Independence Constitution without input from the DLP. Although supported by the Colonial Office, independence was blocked by the DLP, until Williams was able to make a deal with DLP leader Rudranath Capildeo that strengthened the rights of the minority party and expanded the number of Opposition Senators. With Capildeo's assent, Trinidad and Tobago became independent on 31 August 1962, 25 days after Jamaica. In addition to primeministership, Williams was also Minister of Finance from 1957 to 1961 and from 1966 to 1971.[18] Black Power Main article: Black Power Revolution Between 1968 and 1970 the Black Power movement gained strength in Trinidad and Tobago. The leadership of the movement developed within the Guild of Undergraduates at the St. Augustine Campus of the University of the West Indies. Led by Geddes Granger, the National Joint Action Committee joined up with trade unionists led by George Weekes of the Oilfields Workers' Trade Union and Basdeo Panday, then a young trade-union lawyer and activist. The Black Power Revolution started during the 1970 Carnival. In response to the challenge, Williams countered with a broadcast entitled "I am for Black Power". He introduced a 5% levy to fund unemployment reduction and established the first locally owned commercial bank. However, this intervention had little impact on the protests. On 3 April 1970, a protester was killed by the police. This was followed on 13 April by the resignation of A. N. R. Robinson, Member of Parliament for Tobago East. On 18 April sugar workers went on strike, and there was the talk of a general strike. In response to this, Williams proclaimed a State of Emergency on 21 April and arrested 15 Black Power leaders. In response to this, a portion of the Trinidad and Tobago Defence Force, led by Raffique Shah and Rex Lassalle, mutinied and took hostages at the army barracks at Teteron. Through the action of the Trinidad and Tobago Coast Guard the mutiny was contained and the mutineers surrendered on 25 April. Williams made three additional speeches in which he sought to identify himself with the aims of the Black Power movement. He reshuffled his cabinet and removed three ministers (including two White members) and three senators. He also proposed a Public Order Bill which would have curtailed civil liberties in an effort to control protest marches. After public opposition, led by A. N. R. Robinson and his newly created Action Committee of Democratic Citizens (which later became the Democratic Action Congress), the Bill was withdrawn. Attorney General Karl Hudson-Phillips offered to resign over the failure of the Bill, but Williams refused his resignation. Death Prime Minister Eric Eustace Williams of Trinidad and Tobago, died on 29 March 1981 due to throat cancer at his official house in St. Anne, a Port of Spain neighborhood in Trinidad and Tobago. He was 69 years old at the time of his death.[19][20] Personal life Eric Williams had married Elsie Ribeiro, a music studies student born to a mother from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and a Portuguese Trinidadian father, on 30 January 1937, while he was a postgraduate student at Oxford University. He had known Ribeiro from Trinidad before he left for the United Kingdom and she was the sister of his roommate in England. The ceremony was private out of fear that the terms of his scholarship could have prohibited marriage and he did not want it to be terminated. After he graduated, they moved to Washington, D.C. in the United States where he obtained a position at Howard University. They had a son, Alistair Williams, in 1943 and a daughter, Elsie Pamela Williams, in 1947. However, Williams questioned the paternity of Elsie Pamela, thus leading to problems in the marriage. In May 1948, Williams left Washington, D.C. to go back to Trinidad, abandoning his wife and children. His reason for not financially supporting them after leaving was because Ribeiro refused to send their children to Oxford University in the future.[21][22] After returning to Trinidad in 1948, he met Evelyn Siulan Soy Moyou, a typist 13 years his junior of Chinese descent on her father's side and Chinese, African, and Portuguese descent on her mother's side, and she was a niece of Solomon Hochoy, the future Governor and Governor-General of Trinidad and Tobago during Williams's premiership. She worked at the Caribbean Commission where Williams had taken up a position. They began a relationship and he initiated divorce proceedings from Ribeiro in January 1950 on a Caribbean Commission trip to the U.S. Virgin Islands.[21][22] Ribeiro responded with an injunction restraining him from proceeding with his petition. After dropping the proceedings, in a letter of April 1950 submitted to the jurisdiction of the District of Columbia court, he agreed to abide by its decision and be bound by an order regarding alimony. However, a few months later while on a research holiday in the United States he reinitiated divorce proceedings in Reno, Nevada, known for its quick divorces, due to the fact that Moyou was pregnant with his child. However, Ribeiro obtained an injunction preventing Williams from making any attempt at divorce, on the grounds that he had earlier subjected himself to the jurisdiction of the District of Columbia court. Williams filed formal proceedings for a divorce on 24 November 1950. On 13 December 1950, Williams was ordered to appear in court, most likely because he had filed for a divorce in Reno, even though he had earlier submitted himself to the jurisdiction of the District of Columbia. Even though a lawyer had been assigned to him, he did not appear and on 22 December 1950 he was ordered to be taken into custody by a US Marshal. His lawyer in Reno pointed out that his divorce had been granted, though a search of the court records showed no entry for a final decree. Williams eventually met the six-week residential requirement to obtain a Nevada divorce and on 2 January 1951, he married Moyou in Reno, in a ceremony performed by The Rev. Munroe Warner of First Christian Church. Their daughter, Erica Williams, was born on 12 February 1951, in Reno. After his second marriage, Ribeiro obtained a divorce from him on 20 January 1951, on grounds of desertion. It was made effective on 21 July 1951 and he was ordered to pay a monthly alimony of US$250 for the maintenance of his first wife and two children. On 26 May 1953, Mayou died from Tuberculosis.[21][22] He later married Mayleen Mook Sang, his daughter's dentist.[23] She was of Chinese Guyanese origin.[24] They were married on Caledonia Island on 13 November 1957 by Rev. Andrew McKean, of Greyfriars Presbyterian Church on Frederick Street in Port of Spain.[25] However, the couple never lived together and the marriage was kept hidden by Williams. The marriage was exposed 18 months later when Mook Sang sent a copy of their marriage certificate to the Chronicle newspaper following rumors of Williams having an affair with a local beauty queen. They remained married till his death. After his death she filed to receive Willaims's benefits and pension from his premiership, however it was given to his daughter, Erica, who was named his heir in his will.[26] Legacy Academic contributions Williams specialised in the study of slavery. Many Western academics focused on his chapter on the abolition of the slave trade, but that is just a small part of his work. In his 1944 book, Capitalism and Slavery, Williams argued that the British government's passage of the Slave Trade Act in 1807 was motivated primarily by economic concerns rather than by humanitarian ones. Williams also argued that by extension, so was the emancipation of the slaves and the blockade of Africa, and that as industrial capitalism and wage labour began to expand, eliminating the competition from wage-free slavery became economically advantageous. Williams' impact on that field of study has proved of lasting significance. As Barbara Solow and Stanley Engerman put it in the preface to a compilation of essays on Williams that was based on a commemorative symposium held in Italy in 1984, Williams "defined the study of Caribbean history, and its writing affected the course of Caribbean history.... Scholars may disagree on his ideas, but they remain the starting point of discussion.... Any conference on British capitalism and Caribbean slavery is a conference on Eric Williams." In an open letter to Solow, Yale Professor of History David Brion Davis refers to Williams' thesis of the declining economic viability of slave labor as "undermined by a vast mountain of empirical evidence and has been repudiated by the world’s leading authorities on New World slavery, the transatlantic slave trade, and the British abolition movement".[27] A major work which was written to refute Eric Williams' thesis was Seymour Drescher's Econocide, which argued that when the slave trade was abolished in 1807, Britain's sugar economy was thriving. However, other historians have noted that Drescher ended his study of the economic history of the British West Indies in 1822, and did not address the decline of the British sugar industry (something which was highlighted by Williams) which began in the mid-1820s, and continued until the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.[28] The majority of Eric William's thesis, which addressed the decline of the sugar industry in the 1820s, the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833, and the sugar equalisation acts of the 1840s, has continued to influence the historiography of the 19th-century West Indies and it's connection to the wider Atlantic world as a whole.[29][30] In addition to Capitalism and Slavery, Williams produced a number of other scholarly works focused on the Caribbean. Of particular significance are two published long after he had abandoned his academic career for public life: British Historians and the West Indies and From Columbus to Castro. The former, based on research done in the 1940s and initially presented at a symposium at Clark Atlanta University, sought to challenge established British historiography on the West Indies. Williams was particularly scathing in his criticism of the work of Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle. The latter work is a general history of the Caribbean from the 15th to the mid-20th centuries. The work appeared at the same time as a similarly titled book (De Cristóbal Colón a Fidel Castro) by another Caribbean scholar-statesman, Juan Bosch of the Dominican Republic. Williams sent one of 73 Apollo 11 Goodwill Messages to NASA for the historic first lunar landing in 1969. The message still rests on the lunar surface today. He wrote, in part: "It is our earnest hope for mankind that while we gain the moon, we shall not lose the world."[31] The Eric Williams Memorial Collection Main article: Eric Williams Memorial Collection The Eric Williams Memorial Collection (EWMC) at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago was inaugurated in 1998 by former US Secretary of State Colin Powell. In 1999, it was named to UNESCO's prestigious Memory of the World Register. Secretary Powell heralded Williams as a tireless warrior in the battle against colonialism, and for his many other achievements as a scholar, politician and international statesman. The Collection consists of the late Dr. Williams' Library and Archives. Available for consultation by researchers, the Collection amply reflects its owner's eclectic interests, comprising some 7,000 volumes, as well as correspondence, speeches, manuscripts, historical writings, research notes, conference documents and a miscellany of reports. The Museum contains a wealth of emotive memorabilia of the period and copies of the seven translations of Williams' major work, Capitalism and Slavery (into Russian, Chinese and Japanese [1968, 2004] among them, and a Korean translation was released in 2006). Photographs depicting various aspects of his life and contribution to the development of Trinidad and Tobago complete this extraordinarily rich archive, as does a three-dimensional re-creation of Williams' study. Dr Colin Palmer, Dodge Professor of History at Princeton University, has said: "as a model for similar archival collections in the Caribbean...I remain very impressed by its breadth.... [It] is a national treasure." Palmer's biography of Williams up to 1970, Eric Williams and the Making of the Modern Caribbean (University of North Carolina Press, 2008), is dedicated to the Collection. Film In 2011, to mark the centenary of Williams' birth, Mariel Brown directed the documentary film Inward Hunger: the Story of Eric Williams, scripted by Alake Pilgrim.[32] Selected bibliography Capitalism and Slavery, 1944. Documents of West Indian History: 1492–1655 from the Spanish discovery to the British conquest of Jamaica, Volume 1, 1963. History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago, 1964. British Historians and the West Indies, 1964. The Negro In The Caribbean, 1970. Inward Hunger: The Education of a Prime Minister, 1971. From Columbus to Castro: The History of the Caribbean 1492–1969, 1971. Forged from the Love of Liberty: Selected Speeches of Dr. Eric Williams, 1981. |

エ リック・ユースタス・ウィリアムズ TC CH(1911年9月25日 - 1981年3月29日)はトリニダード・トバゴの政治家である。[6] 彼は「国家の父」と評されており、[1][2][3][4][5] 1956年10月28日に多数派支配、1962年8月31日に独立、1976年8月1日に共和制へと導き、1981年に死去するまで、自身の政党である人 民国民運動とともに、総選挙での勝利を途切れることなく続けた。彼はトリニダード・トバゴの初代首相であり、またカリブ海地域の歴史家でもあり、特に著書 『資本主義と奴隷制』で知られている。 幼少期 ウィリアムズは1911年9月25日に生まれた。父親のトーマス・ヘンリー・ウィリアムズは下級公務員で敬虔なローマ・カトリック信者であり、母親のイラ イザ・フランシス・ボワシエ(1888年4月13日 - 1969年)はフランス系混血エリートの子孫で、アフリカとフランスの血筋を引いていた。彼女はトリニダードの著名なド・ボワシエール家の末裔であった。 イライザの父方の祖父はジョン・ボワシエールで、既婚の上流中流階級のフランス人であり、マ・ズー・ズーレという名の奴隷の女性と親密な関係にあった。こ の関係から、イライザの父ジュールズ・アーノルド・ボワシエールが生まれた。 彼はトランキリティ・ボーイズ・インターミディエイト・ガバメント・スクールで最初の学校生活を送り、その後ポート・オブ・スペインのクイーンズ・ロイヤル・カレッジで学んだ。QRCでサッカーの負傷を機に聴力障害を患い、補聴器を着用して聴力を補っていた。 1932年には島嶼奨学金を獲得し、オックスフォードのセント・キャサリン・ソサエティ(後にセント・キャサリン・カレッジと改称)に入学した。1935 年には優等学位を取得し、その年の歴史学部の卒業生の中で第1位となった。また、サッカーでは大学代表選手として活躍した。1938年には博士号を取得し た(下記参照)。自伝『Inward Hunger』では、オックスフォード大学での経験について、大学内での人種差別の横行に対するフラストレーションや、ナチスが政権を握った後のドイツで の旅行などを含めて記述している。 学術的な経歴 ウィリアムズは『Inward Hunger』の中で、卒業後の時期について次のように述べている。「私は金銭的な問題で研究に著しく支障をきたしていた。どこに行っても断られ、人種的 な要因を無視することはできなかった」と述懐しています。しかし、1936年には、アルフレッド・クロード・ホリス卿(1930年から1936年までトリ ニダード・トバゴ総督)の推薦により、オックスフォード大学で歴史学の高度な研究を継続するための助成金50ポンドがレザーセラーズ・カンパニーから授与 されました。 彼はヴィンセント・ハーロウの指導の下、1938年に博士号を取得した。彼の博士論文のタイトルは『奴隷貿易廃止と西インド諸島における奴隷制の経済的側 面』であり、1944年に『資本主義と奴隷制』として出版されたが、論文の抜粋は1939年に有色人種連盟の機関誌『ザ・キーズ』に掲載されていた。ウィ リアムズによると、マルクス主義の文献の出版者であるフレデリック・ウォーバーグは、ウィリアムズが自身の論文の出版を依頼した人物であるが、彼は「その ような本は...英国の伝統に反する」として出版を拒否したという。[11] 彼 の論文は、道徳的および また、英国の奴隷制度廃止運動の成功の鍵となる要因は道徳的・人道的な動機であるという考えに対する直接的な攻撃であり、また、英国の西インド諸島に関す る定説の歴史学(ウィリアムズの見解では、オックスフォード大学のレジナルド・クープランド教授の著作に代表される)が英国の植民地支配の継続を支持して いるという隠れた批判でもあった。ウィリアムズの主張は、C. L. R. ジェームズの影響を強く受けており、ジェームズの著書『黒人ジャコバン人』(1938年完成)もまた、西洋世界における奴隷制度廃止論の高まりを経済的お よび地政学的に説明している。 ガッド・ヒューマンは次のように述べている。 『資本主義と奴隷制』において、エリック・ウィリア ムズは、イギリス領西インド諸島の経済衰退が奴隷貿易と奴隷制度の廃止につながったと主張した。より最近の研究では、この結論は否定されている。英領カリ ブ海の植民地が、アメリカ独立戦争およびナポレオン戦争の間に多大な利益を得ていたことは明らかである。 しかし、『資本主義と奴隷制』は、アメリカ独立戦争およびナポレオン戦争の時代を超えて砂糖と奴隷の経済史をカバーしており、1823年から1830年代の奴隷解放までの砂糖プランテーションの衰退についても論じている。また、1840年代に英国政府が砂糖関税均等化法を利用して、西インド諸島植民地から砂糖を買う責任を放棄し、より安価なキューバやブラジルから市場で砂糖を買うようになったことについても論じている。[14] ウィリアムズの論文を裏付けるものとして、デイヴィッド・ライデンは19世紀初頭には収益性の危機が迫っていたことを示す証拠を提示した。[15] ウィリアムズの(奴隷)廃止論に関する主張は、この(経済)衰退論をはるかに超えるものであった。彼が主張したことは、18世紀に奴隷制に基づく大西洋経済によって生み出された新しい経済的・社会的利益が、自由貿易推進派と奴隷制廃止派という新しい政治的利益を生み出したということである。これらは、1792年から1804年のハイチ革命から1831年のジャマイカのクリスマス蜂起までの、福音主義的奴隷廃止運動の高まりや、奴隷反乱者の自己解放と相互作用し、1830年代に奴隷制度の終焉をもたらした。[16] 1939年、ウィリアムズはハワード大学の政治学部に入学した。[12] 1943年、ウィリアムズは「カリブ海地域の経済的未来」に関する会議を主催した。[17] 彼は、西インド諸島が独立国家となった場合、これらの島々はかつての宗主国による支配を受けやすいと主張した。ウィリアムズは、植民地独立後の依存関係の 解決策として西インド諸島連邦を提唱した。[17] 公的生活への転身 1944年、ウィリアムズは英米カリブ委員会に任命された。1948年、カリブ研究協議会の副議長としてトリニダードに戻った。トリニダードでは、彼は教 育的な講演シリーズを行い、高い評価を得た。1955年、ウィリアムズと委員会との意見の相違により、委員会は彼の契約を更新しないことを決定した。ポー ト・オブ・スペインのウッドフォード・スクエアでの演説で、彼は「生まれ故郷の地に身を置く」ことを決意したと宣言した。トリニダードの裁判所と立法府の 前にあった囲い込み公園を「ウッドフォード・スクエア大学」と改名し、世界史、ギリシャの民主主義と哲学、奴隷制の歴史、カリブ海の歴史などについて、あ らゆる階層から集まった大勢の聴衆を対象に一連の公開講座を開講した。 トリニダード・トバゴのナショナリスト政治への参入 1956年1月15日、ウィリアムズは、その公の演説の壇上から、自身の政党である人民国民運動(People's National Movement、PNM)を結成した。この政党は、1962年にトリニダード・トバゴを独立に導き、その後の植民地後の政治を支配することになる。それ までは、彼の講義は政治運動(Political Movement)の後援の下で行われていた。政治運動は、1940年代に公式の教員組合の代替組織として設立された教員教育文化協会(Teachers Education and Cultural Association)の一部門である。 PNMの最初の文書は党の憲法であった。当時の他の政党とは異なり、PNMは高度に組織化された階層的な組織であった。その第二の文書は『人民憲章』であ り、この党はそれまでのトリニダードの政治の常識であった一過性の政治結集から自らを切り離そうと努力した。 その8か月後の9月24日に行われた選挙では、人民国民運動は立法議会の24議席中13議席を獲得し、再選を目指した現職議員16名のうち6名を破った。 PNMは31議席からなる立法議会の過半数を占めることはできなかったが、植民地大臣を説得して、任命された5人の議員を指名することを認めさせた(総督 のエドワード・ベサム・ビータム卿の反対にもかかわらず)。これにより、立法議会でPNMは明確な多数派となった。ウィリアムズはこうして首席大臣に選出 され、7人の閣僚全員を当選させることもできた。 連邦化と独立 第二次世界大戦後、イギリス植民地省は、19世紀にカナダを建国したカナダ連邦以来、成功を収めていると思われた連邦制のような政治的独立に向けて、イギ リス植民地が歩み寄ることを望んでいた。イギリス領西インド諸島では、この目標は1930年代にこの地域のすべての植民地で勃興した民族主義運動の政治的 目標と一致していた。1948年のモンテゴベイ会議では、西インド諸島が連邦として「ドミニオン・ステータス」(英国政府からの憲法上の独立を意味する) を達成することが共通の目標として宣言された。1958年、ジャマイカとトリニダード・トバゴが主導権を握る中、西インド諸島連邦が英国領カリブ地域から 誕生した。このとき、英領ガイアナ(現ガイアナ)と英領ホンジュラス(現ベリーズ)は連邦からの離脱を選択した。各領内のほとんどの政党は、西インド諸島 連邦労働党(バルバドスのグラントリー・アダムスとジャマイカのノーマン・マンリーが指導)と、マンリーの従兄弟であるアレクサンダー・バスタマンテ卿が 指導する民主労働党(DLP)の2つの連邦政党のどちらかに合流した。PNMは前者の政党と提携し、複数の野党(人民民主党、トリニダード労働党、政治進 歩グループ党)はDLPと提携し、その後まもなく合併してトリニダード・トバゴ民主労働党を結成した。 1958年の連邦議会選挙でのDLPの勝利と、それに続く1959年のカウンティ議会選挙でのPNMの不振により、ウィリアムズは連邦に幻滅した。また、 ヘイルズ卿(連邦総督)は、WIFLPが過半数を占める上院のバランスを取るために、PNMが指名した上院議員2名を却下した。 ブスタマンテがジャマイカを連邦から脱退させたことで、トリニダード・トバゴは連邦予算の75%を負担しなければならない立場に置かれながら、連邦政府の 議席数は半分以下という、耐え難い立場に置かれることとなった。 ウィリアムズは演説で「10人中1人が去っても、残りはゼロにはならない」と宣言した。1962年1月15日にPNMの一般評議会が同様の決議を採択した ことを受け、ウィリアムズはトリニダード・トバゴを西インド諸島連邦から脱退させた。この行動により、英国政府は連邦を解散した。 1961年、PNMは人民代表法案を提出した。この法案は、有権者の恒久的な登録、身分証明書、投票機、選挙区の境界の見直しなどを導入することで、選挙 制度を近代化することを目的としていた。これらの変更は、DLP(人民党)から、脅迫によって文盲の農村部の有権者の選挙権を剥奪し、投票機を使用して選 挙を不正に操作し、他の島々からのアフリカ系カリブ移民に投票を認め、PNM(トリニダードトバゴ労働党)の勝利を確実にするために選挙区の境界を細工す る試みであると見なされた。PNMの反対派は、1961年にA. N. R. ロビンソンがトバゴの議席で、有権者登録者数よりも多い票を獲得して当選したこと、および1980年のトバゴ議会選挙までPNMがその後のすべての選挙で 勝利を収めたという事実を、これらの主張の「証拠」と見なした。 1961年の選挙では、PNMは57%の票を獲得し、30議席中20議席を獲得した。この3分の2の多数派により、DLPの意見を聞かずに独立憲法を起草 することが可能となった。植民地省の支援を受けていたものの、独立はDLPによって阻止されていたが、ウィリアムズがDLP党首のルドラナート・カピル ディオと取引を成立させ、少数派の政党の権利を強化し、野党の上院議員の数を増やすことで、独立は実現した。カピルデオの同意を得て、トリニダード・トバ ゴはジャマイカから25日遅れの1962年8月31日に独立した。ウィリアムズは1957年から1961年、および1966年から1971年まで、首相職 に加えて財務大臣も務めた。 ブラックパワー 詳細は「ブラックパワー革命」を参照 1968年から1970年にかけて、トリニダード・トバゴではブラックパワー運動が勢いを増した。この運動の指導部は、西インド諸島大学セントオーガス ティン・キャンパスの学部生組合内で形成された。ゲデス・グランジャーが率いる全国合同行動委員会は、石油労働者組合のジョージ・ウィークスや、当時若手 の労働組合弁護士兼活動家であったバスディオ・パンデイが率いる労働組合主義者たちと合流した。1970年のカーニバルの期間中にブラックパワー革命が始 まった。この挑戦を受けて、ウィリアムズ首相は「私はブラックパワーを支持する」と題する放送で反論した。失業率の低下を目的とした5%の課税を導入し、 初の地元資本による商業銀行を設立した。しかし、この介入は抗議活動にほとんど影響を及ぼさなかった。 1970年4月3日、抗議活動家が警察に射殺された。これを受けて、4月13日にはトバゴ東地区選出の国会議員A. N. R. ロビンソンが辞任した。4月18日には砂糖労働者がストライキに入り、ゼネストの噂も流れた。これを受けて、ウィリアムズは4月21日に非常事態を宣言 し、ブラックパワーの指導者15名を逮捕した。これに対して、ラフィーク・シャーとレックス・ラサールが率いるトリニダード・トバゴ防衛軍の一部が反乱を 起こし、テテロンにある軍の兵舎で人質をとった。トリニダード・トバゴ沿岸警備隊の活動により、反乱は鎮圧され、反乱軍は4月25日に降伏した。 ウィリアムズはさらに3度演説を行い、ブラックパワー運動の目標に自らを同調させようとした。彼は内閣を改造し、3人の大臣(うち2人は白人)と3人の上 院議員を解任した。また、デモ行進を規制するために市民の自由を制限する公共秩序法案を提出した。A. N. R. ロビンソンと彼が新たに結成した民主市民行動委員会(後に民主行動会議となる)が主導した世論の反対を受け、この法案は撤回された。法案の失敗の責任を取 り、カール・ハドソン=フィリップス司法長官は辞任を申し出たが、ウィリアムズ首相は辞任を拒否した。 死 トリニダード・トバゴの首相エリック・ユースタス・ウィリアムズは、1981年3月29日、ポート・オブ・スペイン近郊のセント・アンにある公邸で、喉頭癌のため死去した。享年69歳であった。[19][20] 私生活 エリック・ウィリアムズは、セントビンセント・グレナディーン出身の母親とトリニダード・トバゴ出身のポルトガル人の父親を持つ音楽専攻の学生、エル シー・リベイロと1937年1月30日に結婚した。彼は英国に留学する前からトリニダードでリベイロと知り合っており、彼女は英国での彼のルームメイトの 姉妹であった。奨学金の規定が結婚を禁じており、それを理由に奨学金を打ち切られることを望まなかったため、式は内輪で執り行われた。卒業後、2人はワシ ントンD.C.に移り、そこでウィリアムズはハワード大学で職を得た。1943年に息子のアリスター・ウィリアムズ、1947年に娘のエルシー・パメラ・ ウィリアムズが誕生した。しかし、ウィリアムズはエルシー・パメラの父親が自分であるかどうか疑い、それが結婚生活に問題を引き起こした。1948年5 月、ウィリアムズは妻と子供たちを捨ててワシントンD.C.を離れ、トリニダードに戻った。彼が家族を経済的に支援しなかった理由は、リベイロが将来子供 たちをオックスフォード大学に入学させないことを拒否したためだった。 1948年にトリニダードに戻った後、彼は13歳年下のタイピスト、イヴリン・シウラン・ソイ・モイヨと出会った。彼女は父親が中国人、母親が中国人、ア フリカ人、ポルトガル人の混血であり、ウィリアムズが首相在任中にトリニダード・トバゴの総督および総督となったソロモン・ホチョイの姪であった。彼女 は、ウィリアムズが職を得たカリブ共同体で働いていた。2人は関係を持ち、1950年1月、カリブ共同体による米領ヴァージン諸島への出張中に、ウィリア ムズはリベイロとの離婚手続きを開始した。[21][22] リベイロは、彼が離婚の申し立てを進めることを差し止める命令を出した。訴訟を取り下げた後、1950年4月にコロンビア特別区裁判所に提出した書簡で、 彼はその判決に従うこと、扶養料に関する命令に従うことに同意した。しかし、数ヵ月後、休暇で米国に滞在中に、モユーが彼の子供を身籠もっていたことを理 由に、離婚手続きを迅速な離婚で知られるネバダ州リノで再開した。しかし、リベイロは、以前コロンビア特別区裁判所の管轄権に自らを服従させたことを理由 に、ウィリアムズが離婚を試みることを禁じる命令を得た。ウィリアムズは1950年11月24日に正式に離婚手続きを行った。1950年12月13日、 ウィリアムズは裁判所への出頭を命じられた。おそらく、それ以前にコロンビア特別区の管轄権に身を委ねていたにもかかわらず、リノで離婚を申請したことが 原因だったと思われる。弁護士が割り当てられたにもかかわらず、彼は出頭せず、1950年12月22日、連邦保安官によって身柄を拘束されるよう命じられ た。リノの弁護士は、離婚が成立したと指摘したが、裁判記録の検索では最終判決の記載は見つからなかった。最終的に、ウィリアムズはネバダ州での離婚に必 要な6週間の居住要件を満たし、1951年1月2日、リノでモヨと結婚した。結婚式は、ファースト・クリスチャン教会のモンロー・ワーナー牧師によって執 り行われた。二人の娘、エリカ・ウィリアムズは、1951年2月12日にリノで生まれた。二度目の結婚後、リベイロは1951年1月20日に彼から離婚を 言い渡された。理由は「遺棄」であった。1951年7月21日に成立し、彼は最初の妻と2人の子供たちの生活費として毎月250ドルの扶養料を支払うよう 命じられた。1953年5月26日、マヨウは結核により死亡した。[21][22] その後、娘の歯科医であるメイリーン・ムック・サンと結婚した。彼女は中国系ガイアナ人であった。[24] 1957年11月13日、ポート・オブ・スペインのフレデリック・ストリートにあるグレイフライアーズ・プレズビテリアン教会の牧師アンドリュー・マッ キーンによって、カリドニア島で結婚式を挙げた。[25] しかし、夫婦は同居することはなく、ウィリアムズは結婚を隠し続けた。結婚が暴露されたのは、それから18ヶ月後、ウィリアムズが地元のミスコン優勝者と 不倫関係にあるという噂が流れた後、ムック・サンが結婚証明書のコピーを新聞『クロニクル』に送ったときだった。 2人はウィリアムズの死まで結婚生活を続けた。 彼の死後、彼女はウィリアムズの首相としての給付金と年金を受け取るよう申請したが、それは彼の遺言で後継者に指名された娘のエリカに与えられた。 遺産 学術的貢献 ウィリアムズは奴隷制の研究を専門としていた。多くの西洋の学者は奴隷貿易廃止に関する彼の章に注目したが、それは彼の研究のごく一部に過ぎない。 1944年に出版された著書『資本主義と奴隷制』の中で、ウィリアムズは1807年に英国政府が奴隷貿易法を可決した動機は、人道的なものではなく、主に 経済的な懸念であったと主張した。また、ウィリアムズは、奴隷解放やアフリカの封鎖も同様であり、産業資本主義と賃金労働が拡大し始めると、賃金が発生し ない奴隷制による競争を排除することが経済的に有利になるとも主張した。 ウィリアムズの研究分野への影響は、今なお重要な意味を持ち続けている。1984年にイタリアで開催された記念シンポジウムに基づくウィリアムズの論文集 の序文で、バーバラ・ソローとスタンリー・エンゲルマンは次のように述べている。「ウィリアムズはカリブ海地域の歴史研究を定義づけ、その著作はカリブ海 地域の歴史の流れに影響を与えた。学者たちは彼の考えに反対するかもしれないが、議論の出発点には変わりない。英国資本主義とカリブ海奴隷制に関する会議 は、すべてエリック・ウィリアムズに関する会議である」 ソロー教授宛ての公開書簡で、イェール大学の歴史学教授デビッド・ブライアン・デイビスは、奴隷労働の経済的持続可能性の低下に関するウィリアムズの論文 を「膨大な量の経験的証拠によって損なわれ、新世界における奴隷制、大西洋奴隷貿易、英国の奴隷廃止運動の分野における世界的な権威者たちによって否定さ れた」と述べている 大西洋奴隷貿易、および英国の奴隷廃止運動に関する世界的な権威者たちによって否定されている」と述べている。[27] エリック・ウィリアムズの論文に反論するために書かれた主要な著作に、シーモア・ドレシャーの『エコノサイド』がある。同書は、1807年に奴隷貿易が廃 止されたとき、英国の砂糖経済は繁栄していたと主張している。しかし、他の歴史家は、ドレシャーが1822年に英領西インド諸島の経済史の研究を終えてお り、1820年代半ばに始まり、1833年の奴隷制度廃止法成立まで続いた英領西インド諸島の砂糖産業の衰退(これはウィリアムズが強調した点である)に ついては取り上げていないことを指摘している。[28] エリック・ウィリアムズの 1820年代の砂糖産業の衰退、1833年の奴隷制度廃止法の成立、1840年代の砂糖平価法について論じたウィリアムズの論文の大半は、19世紀の西イ ンド諸島の歴史学に影響を与え続け、大西洋世界全体とのつながりにも影響を与えている。 資本主義と奴隷制』に加え、ウィリアムズはカリブ海地域に焦点を当てた学術的な著作を数多く発表した。特に重要なのは、学術的なキャリアを捨てて公人とし ての生活を始めた後に発表された2つの著作、『イギリスの歴史家と西インド諸島』と『コロンブスからカストロまで』である。前者は1940年代の研究を基 にしており、当初はクラーク・アトランタ大学でのシンポジウムで発表された。この著作は、西インド諸島に関するイギリスの定説的な歴史学に異議を唱えるこ とを目的としていた。ウィリアムズは特にスコットランドの歴史家トーマス・カーライルの業績に対する批判を痛烈に展開した。後者の著作は15世紀から20 世紀半ばまでのカリブ海地域の通史である。この著作は、同じカリブ海地域の学者であり政治家であるドミニカ共和国のフアン・ボッシュによる同タイトルの著 作(『クリストバル・コロンからフィデル・カストロへ』)と同時期に発表された。 ウィリアムズは、1969年の人類初の月面着陸を記念してNASAに送られた73通の「アポロ11号親善メッセージ」のうちの1通を書いた。そのメッセー ジは今もなお月の表面に残っている。彼は次のように書いた。「月を手に入れる一方で、世界を失わないことが人類にとっての切なる願いである」[31]。 エリック・ウィリアムズ記念コレクション 詳細は「エリック・ウィリアムズ記念コレクション」を参照 トリニダード・トバゴの西インド諸島大学にあるエリック・ウィリアムズ記念コレクション(EWMC)は、1998年にコリン・パウエル元米国務長官によっ て設立された。1999年には、ユネスコの世界記憶遺産に登録された。パウエル長官は、ウィリアムズを植民地主義との戦いにおける不屈の戦士であり、学 者、政治家、国際政治家として数々の功績を残した人物と称賛した。 コレクションは、故ウィリアムズ博士の図書館と文書館から構成されている。研究者の閲覧に供されているコレクションは、その所有者の幅広い関心を十分に反 映しており、7,000冊の書籍、書簡、スピーチ原稿、歴史的文献、研究ノート、会議資料、各種報告書などから構成されている。この博物館には、当時の感 動的な記念品や、ウィリアムズの主要著作『資本主義と奴隷制』の7言語(ロシア語、中国語、日本語[1968年、2004年]、2006年には韓国語版も 出版)への翻訳版が収められている。 彼の生涯とトリニダード・トバゴの発展への貢献をさまざまな側面から描いた写真や、ウィリアムズの書斎を再現した3D模型も、この非常に貴重なアーカイブ を完成させている。 プリンストン大学の歴史学教授であるコリン・パーマー博士は、「カリブ海地域における同様のアーカイブコレクションの模範として...私はその広さに非常 に感銘を受けている。...これは国の宝である」と述べている。パーマーの著書『1970年までのエリック・ウィリアムズと近代カリブ海地域の形成』 (University of North Carolina Press、2008年)は、このコレクションに捧げられている。 映画 2011年、ウィリアムズ生誕100周年を記念して、マリエル・ブラウンが監督したドキュメンタリー映画『Inward Hunger: the Story of Eric Williams』が公開された。脚本はアラケ・ピルグリムが担当した。 主な著書 資本主義と奴隷制、1944年。 西インド諸島史の資料:1492年~1655年、スペインによる発見からイギリスによるジャマイカ征服まで、第1巻、1963年。 トリニダード・トバゴの人々の歴史、1964年。 イギリスの歴史家と西インド諸島、1964年。 カリブ海の黒人、1970年。 内なる飢え:首相の教育、1971年。 コロンブスからカストロまで:カリブ海の歴史1492年~1969年、1971年。 自由への愛から鍛えられた:エリック・ウィリアムズ博士の講演集、1981年。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099