1833年の奴隷廃止法

Slavery Abolition Act 1833

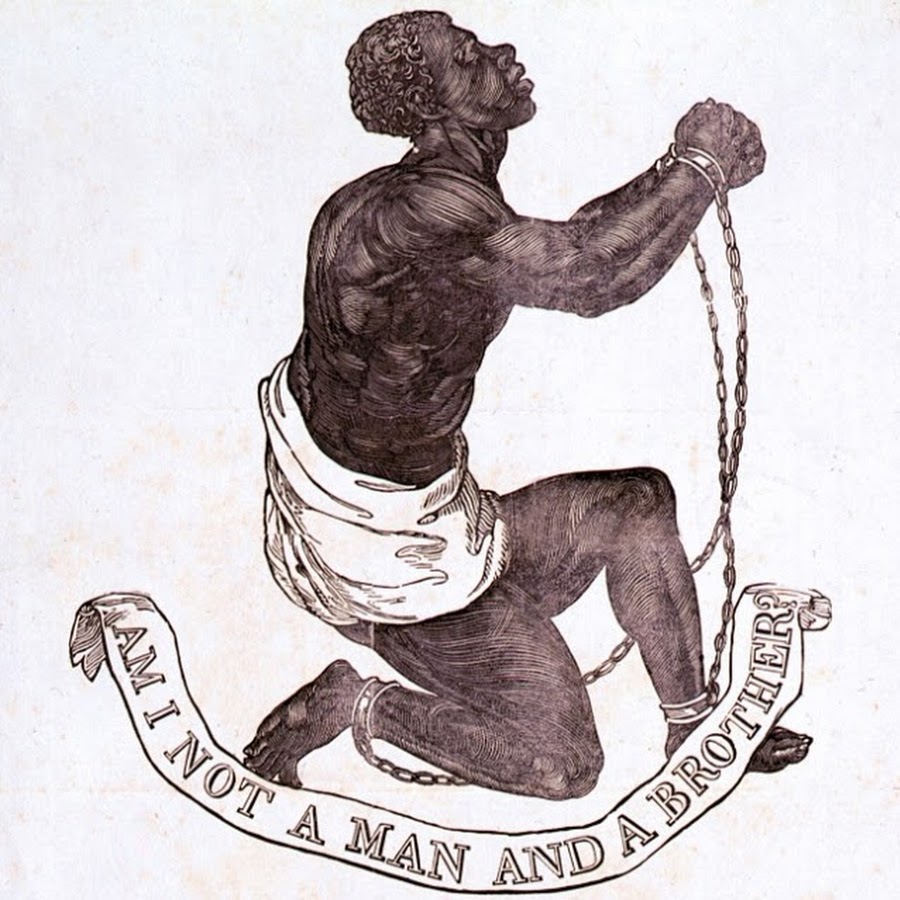

The Wedgwood anti-slavery medallion created as part of anti-slavery campaign by Josiah Wedgwood, 1787

☆ 奴隷制度廃止法(Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. 4. c. 73))は、大英帝国の大部分における奴隷制度の段階的廃止を定めたイギリス議会の法律である。グレイ伯の改革政権によって可決されたこの法律は、 1807年の奴隷貿易法の管轄権を拡大し、英領内では奴隷の購入や所有を違法としたが、「東インド会社が領有する地域」、セイロン(現スリランカ)、セン トヘレナは例外とされた。この法律は1834年8月1日に施行され、1998年に英国の制定法の合理化の一環として廃止されたが、その後の奴隷制度廃止法 は現在も有効である。

| The Slavery Abolition Act 1833

(3 & 4 Will. 4. c. 73) was an Act of the Parliament of the United

Kingdom which provided for the gradual abolition of slavery in most

parts of the British Empire. Passed by Earl Grey's reforming

administration, it expanded the jurisdiction of the Slave Trade Act

1807 and made the purchase or ownership of slaves illegal within the

British Empire, with the exception of "the Territories in the

Possession of the East India Company", Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and

Saint Helena. The Act came into force on 1 August 1834, and was

repealed in 1998 as a part of wider rationalisation of English statute

law; however, later anti-slavery legislation remains in force. |

奴

隷制度廃止法(Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. 4. c.

73))は、大英帝国の大部分における奴隷制度の段階的廃止を定めたイギリス議会の法律である。グレイ伯の改革政権によって可決されたこの法律は、

1807年の奴隷貿易法の管轄権を拡大し、英領内では奴隷の購入や所有を違法としたが、「東インド会社が領有する地域」、セイロン(現スリランカ)、セン

トヘレナは例外とされた。この法律は1834年8月1日に施行され、1998年に英国の制定法の合理化の一環として廃止されたが、その後の奴隷制度廃止法

は現在も有効である。 |

| Background In May 1772, Lord Mansfield's judgment in the Somerset case emancipated a slave who had been brought to England from Boston in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and thus helped launch the movement to abolish slavery throughout the British Empire.[2][3] The case ruled that slavery had no legal status in England as it had no common law or statutory law basis, and as such someone could not legally be a slave in England.[4] However, many campaigners, including Granville Sharp, took the view that the ratio decidendi of the Somerset case meant that slavery was unsupported by law within England and that no ownership could be exercised on slaves entering English or Scottish soil.[5][6] Ignatius Sancho, who in 1774 became the first known person of African descent to vote in a British general election, wrote a letter in 1778 that opens in praise of Britain for its "freedom – and for the many blessings I enjoy in it", before criticizing the actions towards his black brethren in parts of the Empire such as the West Indies.[7][8] In 1785, English poet William Cowper wrote: We have no slaves at home – Then why abroad? Slaves cannot breathe in England; if their lungs Receive our air, that moment they are free. They touch our country, and their shackles fall. That's noble, and bespeaks a nation proud. And jealous of the blessing. Spread it then, And let it circulate through every vein.[9] |

背景 1772年5月、マンスフィールド卿がサマセット訴訟で下した判決により、マサチューセッツ湾植民地ボストンからイングランドに連れてこられた奴隷が解放 され、これにより大英帝国全体での奴隷制度廃止運動が開始されることとなった。[2][3] この訴訟では、イングランドにはコモン・ローも制定法も存在しないため、奴隷制度は法的地位を持たないと裁定され、 イングランドでは、誰かを合法的に奴隷とすることはできないと裁定した。[4] しかし、グランヴィル・シャープを含む多くの活動家は、サマセット訴訟の判決理由から、イングランド国内では奴隷制は法律で認められておらず、イングラン ドまたはスコットランドの領土に入った奴隷に対して所有権を行使することはできないという見解を示した。[5][6] 1774年に 1774年に英国の総選挙で投票したアフリカ系の人として初めて知られるようになったイグナティウス・サンチョは、1778年に英国を賞賛する手紙を書 き、その手紙では「自由、そして私が享受する多くの恩恵」について述べた後、西インド諸島などの帝国の一部における黒人同胞に対する行動を批判した。 [7][8] 1785年には、英国の詩人ウィリアム・カウパーが次のように書いた。 我が家には奴隷はいない。ではなぜ外国にいるのか? 奴隷はイングランドでは息ができない。もし彼らの肺が 我々の空気を吸うことができれば、その瞬間、彼らは自由になる。 彼らは我々の国に触れ、彼らの束縛は解かれる。 それは崇高であり、誇り高い国民の証である。 そして、その祝福を羨む。それを広め、 すべての血管に循環させよう。[9] |

| Campaigns See also: Abolitionism in the United Kingdom The Wedgwood anti-slavery medallion created as part of anti-slavery campaign by Josiah Wedgwood, 1787 By 1783, an anti-slavery movement to abolish the slave trade throughout the Empire had begun among the British public,[10] with the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade being established in 1787.[11] The Wedgwood anti-slavery medallion by Josiah Wedgwood, was, according to the BBC, "the most famous image of a black person in all of 18th-century art".[12] Fellow abolitionist Thomas Clarkson wrote: "Of the ladies several wore them in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in an ornamental manner as pins for their hair. At length, the taste for wearing them became general; and thus fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless things, was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom."[13] Spurred by an incident involving Chloe Cooley, a slave woman brought to Canada by an American loyalist, the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, John Graves Simcoe, tabled the Act Against Slavery in 1793. Passed by the local Legislative Assembly, it was the first legislation to outlaw the slave trade in a part of the British Empire.[10] By the late 18th century, Britain was simultaneously the largest slave trader and centre of the largest abolitionist movement.[14] William Wilberforce had written in his diary in 1787 that his great purpose in life was to suppress the slave trade before waging a 20-year fight on the industry.[15] Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act 1807, which outlawed the international slave trade, but not slavery itself. The legislation was timed to coincide with the expected Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves by the United States, Britain's chief rival in maritime commerce. This legislation imposed fines that did little to deter slave trade participants. Abolitionist Henry Brougham realised that trading had continued, and as a new MP successfully introduced the Slave Trade Felony Act 1811 which at last made the overseas slave trade a felony throughout the empire. The Royal Navy established the West Africa Squadron to suppress the Atlantic slave trade by patrolling the coast of West Africa. It did suppress the slave trade, but did not stop it entirely. Between 1808 and 1860, the West Africa Squadron captured 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans.[16] They resettled many in Jamaica and the Bahamas.[17][18] Britain also used its influence to coerce other countries to agree to treaties to end their slave trade and allow the Royal Navy to seize their slave ships.[19][20] |

キャンペーン 関連項目:イギリスの奴隷制度廃止運動 ジョサイア・ウェッジウッドによる奴隷制度廃止運動の一環として制作されたウェッジウッドの奴隷制度廃止メダル、1787年 1783年までに、大英帝国全体で奴隷貿易を廃止する奴隷制度廃止運動が英国民の間で始まり、1787年には奴隷貿易廃止協会が設立された。ジョサイア・ ウェッジウッドによる奴隷制度廃止メダルは、 BBCによると、ジョサイア・ウェッジウッドによる奴隷制度廃止運動のメダイヨンは、「18世紀の芸術作品の中で最も有名な黒人の肖像」である。[12] 同じく奴隷制度廃止運動家のトマス・クラークソンは次のように書いている。「女性たちのうち何人かはそれをブレスレットとして身につけ、また他の人々はそ れを髪留めとして装飾的に身につけていた。やがて、それらを身に付けることが一般的になり、通常は価値のないものに限定されるファッションが、正義、人 道、自由の促進という名誉ある任務に一度だけ見られるようになった。」[13] アメリカ合衆国の忠誠者によってカナダに連れてこられた奴隷の女性、クロエ・クーリーの事件をきっかけに、アッパー・カナダの副総督ジョン・グレイブス・ シムコーは1793年に奴隷制度廃止法を提出した。地元の立法議会で可決されたこの法律は、大英帝国の一部における奴隷貿易を違法とする初の立法であっ た。[10] 18世紀後半には、英国は最大の奴隷貿易国であると同時に、最大の 廃止運動の中心地でもあった。[14] ウィリアム・ウィルバーフォースは1787年に、奴隷貿易を廃止することが人生における最大の目的であり、そのために20年にわたる闘争を繰り広げるつも りだと日記に記している。 議会は1807年に奴隷貿易法を可決し、国際的な奴隷貿易を違法としたが、奴隷制度自体は違法とはしなかった。この法律は、海上貿易における英国の最大の ライバルであった米国による奴隷輸入禁止法の成立に合わせるようにタイミングを計って可決された。この法律は罰金を課しただけで、奴隷貿易の参加者たちを 阻止するにはほとんど効果はなかった。奴隷制度廃止論者ヘンリー・ブラウフムは、貿易が継続していることに気づき、新しく選出された国会議員として、つい に海外での奴隷貿易を帝国全域で重罪とする奴隷貿易重罪法(1811年)を成立させた。英国海軍は西アフリカ沿岸をパトロールして大西洋での奴隷貿易を抑 制するために西アフリカ艦隊を設立した。奴隷貿易は抑制されたが、完全に阻止することはできなかった。1808年から1860年の間に、西アフリカ艦隊は 1,600隻の奴隷船を拿捕し、150,000人のアフリカ人を解放した。[16] 彼らは多くの人々をジャマイカとバハマに移住させた。[17][18] 英国はまた、自国の影響力を利用して、他の国々に対して奴隷貿易を廃止する条約に同意させ、英国海軍が奴隷船を拿捕することを認めるよう強制した。 [19][20] |

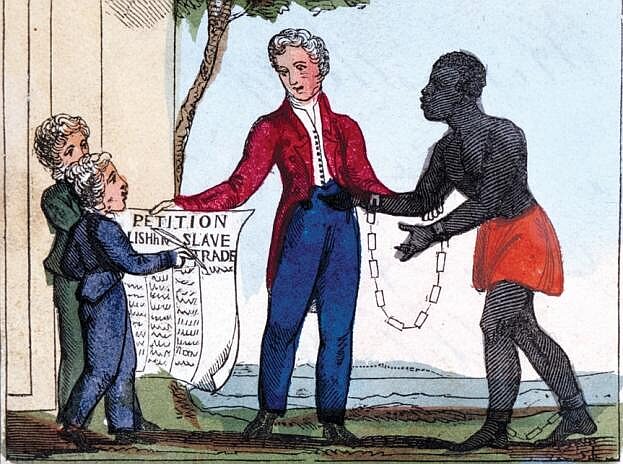

Illustration from the book The Black Man's Lament, or, how to make sugar by Amelia Opie. (London, 1826) Between 1807 and 1823, abolitionists showed little interest in abolishing slavery itself. Eric Williams presented economic data in Capitalism and Slavery to show that the slave trade itself generated only small profits compared to the much more lucrative sugar plantations of the Caribbean, and therefore slavery continued to thrive on those estates. However, from 1823 the British Caribbean sugar industry went into terminal decline, and the British parliament no longer felt they needed to protect the economic interests of the West Indian sugar planters.[21] In 1823, the Anti-Slavery Society was founded in London. Members included Joseph Sturge, Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce, Henry Brougham, Thomas Fowell Buxton, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd, Jane Smeal, Elizabeth Pease, and Anne Knight.[22] Jamaican mixed-race campaigners such as Louis Celeste Lecesne and Richard Hill were also members of the Anti-Slavery Society.  Protector of Slaves Office (Trinidad), Richard Bridgens, 1838 During the Christmas holiday of 1831, a large-scale slave revolt in Jamaica, known as the Baptist War, broke out. It was organised originally as a peaceful strike by the Baptist minister Samuel Sharpe. The rebellion was suppressed by the militia of the Jamaican plantocracy and the British garrison ten days later in early 1832. Because of the loss of property and life in the 1831 rebellion, the British Parliament held two inquiries. The results of these inquiries contributed greatly to the abolition of slavery with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.[23][24] Up until then, sugar planters from rich British islands such as the Colony of Jamaica and Barbados were able to buy rotten and pocket boroughs, and they were able to form a body of resistance to moves to abolish slavery itself. This West India Lobby, which later evolved into the West India Committee, purchased enough seats to be able to resist the overtures of abolitionists. However, the Reform Act 1832 swept away their rotten borough seats, clearing the way for a majority of members of the House of Commons to push through a law to abolish slavery itself throughout the British Empire.[25] |

アメリア・オーピー著『黒人の嘆き、あるいは砂糖の作り方』より挿絵。(ロンドン、1826年) 1807年から1823年の間、奴隷制度廃止論者たちは奴隷制度そのものを廃止することにはほとんど関心を示さなかった。エリック・ウィリアムズは著書 『資本主義と奴隷制』で経済データを示し、奴隷貿易自体はカリブ海の砂糖プランテーションに比べると利益が少ないことを明らかにし、そのため奴隷制はプラ ンテーションで繁栄し続けた。しかし、1823年以降、英国のカリブ海の砂糖産業は衰退の一途をたどり、英国議会は西インド諸島の砂糖プランテーションの 経済的利益を守る必要がなくなった。 1823年には、ロンドンで反奴隷制度協会が設立された。会員には、ジョセフ・スタージ、トーマス・クラークソン、ウィリアム・ウィルバーフォース、ヘン リー・ブルーム、トーマス・フォーウェル・バクストン、エリザベス・ヘイリック、メアリー・ロイド、ジェーン・スミール、エリザベス・ピース、アン・ナイ トなどがいた。[22] ジャマイカ出身の混血活動家であるルイス・セレステ・レセズネやリチャード・ヒルも反奴隷制度協会の会員であった。  トリニダードの奴隷保護官、リチャード・ブリッジンス、1838年 1831年のクリスマス休暇中、ジャマイカで大規模な奴隷反乱(バプテスト戦争)が勃発した。この反乱は、バプテスト派の牧師サミュエル・シャープが平和 的なストライキとして組織したものだった。反乱は、1832年初頭の10日後にジャマイカのプランテーションの民兵とイギリス軍によって鎮圧された。 1831年の反乱による財産と人命の損失により、英国議会は2つの調査を行った。これらの調査結果は、1833年の奴隷制度廃止法による奴隷制度廃止に大 きく貢献した。 それまで、ジャマイカやバルバドスなどのイギリス植民地の富裕な砂糖農園主たちは、腐敗した買収可能な選挙区を購入することができ、奴隷制度そのものの廃 止の動きに抵抗する団体を形成することができた。この西インド諸島ロビー(後に西インド諸島委員会へと発展)は、奴隷制度廃止論者の申し入れに抵抗できる だけの議席を購入した。しかし、1832年の改革法により腐敗した選挙区の議席は廃止され、英帝国全体における奴隷制度の廃止を推進する議員が多数派とな る道が開かれた。[25] |

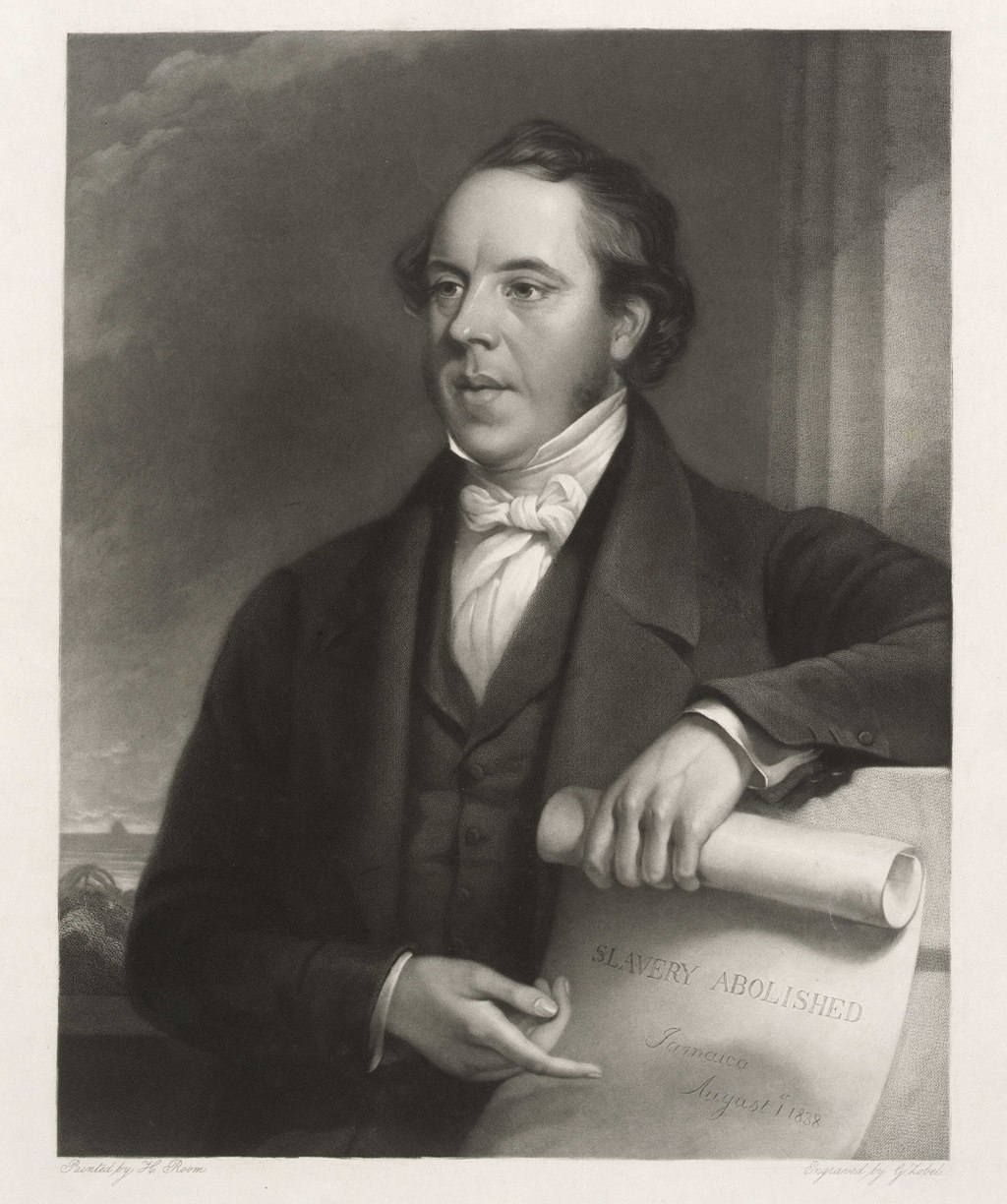

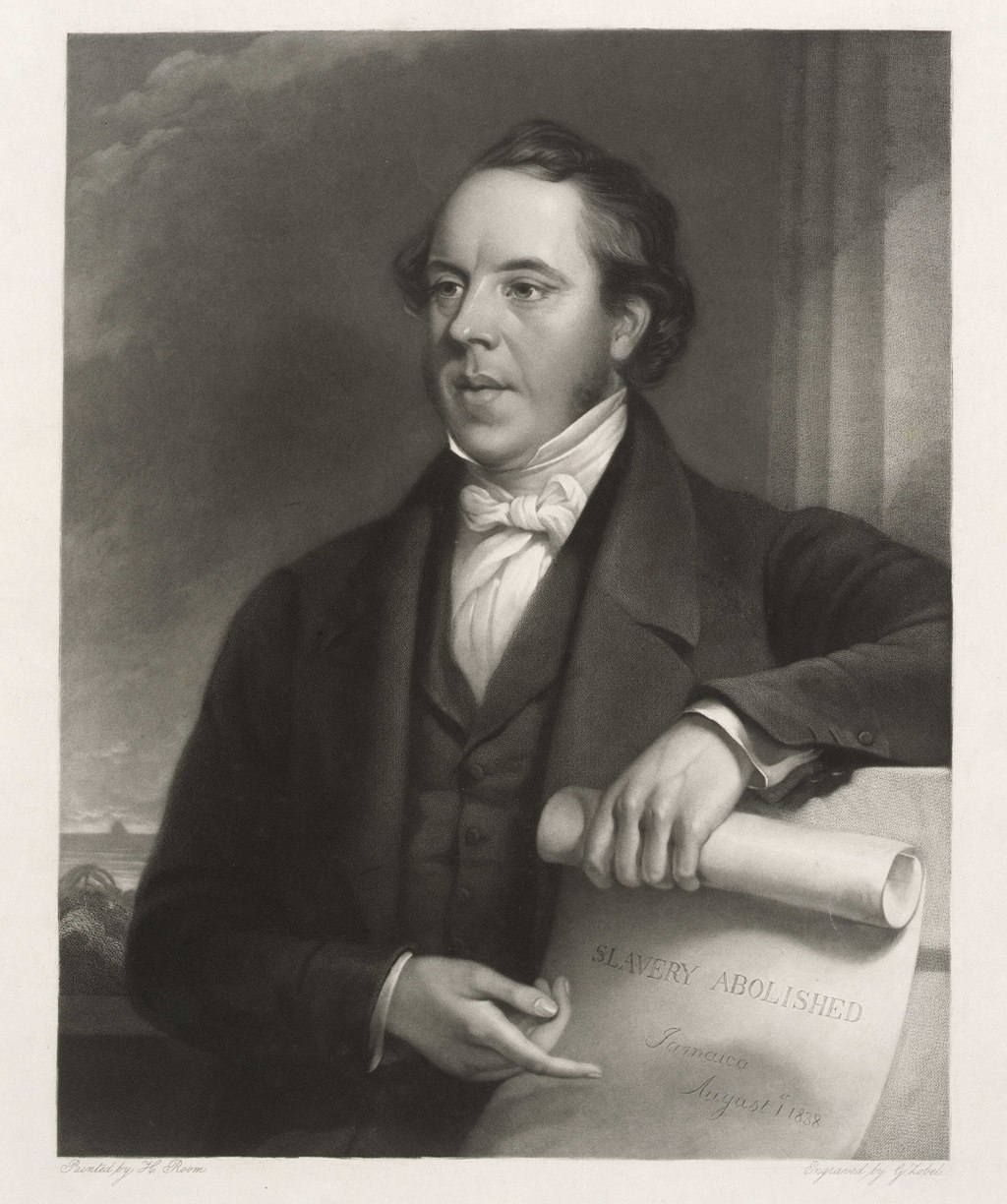

The act Portrait of abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, circa 1840, after Henry Room; on the scroll is "Slavery abolished; Jamaica; August 1st 1838", the date the apprenticeships ended The act passed its second reading in the House of Commons unopposed on 22 July 1833, just a week before William Wilberforce died.[26] It received royal assent a month later, on 28 August, and came into force the following year, on 1 August 1834. In practical terms, only slaves below the age of six were freed in the colonies. Former slaves over the age of six were redesignated as "apprentices", and their servitude was gradually abolished in two stages: the first set of apprenticeships came to an end on 1 August 1838, while the final apprenticeships were scheduled to cease on 1 August 1840. The act specifically excluded "the Territories in the Possession of the East India Company, or to the Island of Ceylon, or to the Island of Saint Helena."[27] The exceptions were eliminated in 1843 with the Indian Slavery Act, 1843.[28][29] |

その法律 奴隷制度廃止論者トーマス・クラークソンの肖像画、1840年頃、ヘンリー・ルームの後に、巻物には「奴隷制度廃止、ジャマイカ、1838年8月1日」と書かれている。これは徒弟制度が終了した日付である この法案は、1833年7月22日にウィリアム・ウィルバーフォースが亡くなるわずか1週間前に、下院で反対意見なしのまま2回目の読会を通過した。 [26] 1か月後の8月28日に国王の承認を受け、翌年の1834年8月1日に施行された。実際には、植民地では6歳未満の奴隷のみが解放された。6歳以上の元奴 隷は「見習い」と再分類され、彼らの隷属は2段階で徐々に廃止された。最初の「見習い」は1838年8月1日に終了し、最後の「見習い」は1840年8月 1日に終了する予定であった。この法律では、「東インド会社が領有する地域、セイロン島、セントヘレナ島」は明確に除外されていた。[27] 例外は、1843年のインディアン奴隷法によって廃止された。[28][29] |

| Payments to slave owners Main articles: Slave Compensation Act 1837 and London Society of West India Planters and Merchants The act provided for compensation to slave-owners, but not to slaves. The amount of money to be spent on the payments was set at "the Sum of Twenty Million Pounds Sterling".[30] Under the terms of the act, the British government raised £20 million[31] to pay out for the loss of the slaves as business assets to the registered owners of the freed slaves. In 1833, £20 million amounted to 40% of the Treasury's annual income[32] or approximately 5% of British GDP at the time.[33] To finance the payments, the British government took on a £15 million loan, finalised on 3 August 1835, with banker Nathan Mayer Rothschild and his brother-in-law Moses Montefiore; £5 million was paid out directly in government stock, worth £1.5 billion in present day.[34] There have been claims the money was not paid back by the British taxpayers until 2015,[35] however this claim is based on a technicality as to how the British Government financed their debt though undated gilts. According to the Treasury the 1837 slave debts were subsumed into a consolidated 4% loan issued in 1927 (maturing in 1957 or after).[36] It was only when the British government modernised the gilt portfolio in 2015 by redeeming all remaining undated gilts was there complete certainty that the debt was extinguished. The long gap between this money being borrowed and certainty of repayment was due to the type of financial instrument that was used, rather than the amount of money borrowed.[37] Regardless, this does not contradict the fact that, in practical terms, taxpayer's money serviced the debt originated from the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.[38] Half of the money went to slave-owning families in the Caribbean and Africa, while the other half went to absentee owners living in Britain.[31] The names listed in the returns for slave owner payments show that ownership was spread over many hundreds of British families,[39] many of them (though not all[40]) of high social standing. For example, Henry Phillpotts (then the Bishop of Exeter), with three others (as trustees and executors of the will of John Ward, 1st Earl of Dudley), was paid £12,700 for 665 slaves in the West Indies,[41] whilst Henry Lascelles, 2nd Earl of Harewood received £26,309 for 2,554 slaves on six plantations.[42] The majority of men and women who were paid under the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 are listed in a Parliamentary Return, entitled Slavery Abolition Act, which is an account of all moneys awarded by the Commissioners of Slave Compensation in the Parliamentary Papers 1837–8 (215) vol. 48.[43] |

奴隷所有者への支払い 主な記事:1837年の奴隷賠償法、西インド諸島プランターおよび商人ロンドン協会 この法律は奴隷所有者に補償金を支払うことを定めたが、奴隷には支払われなかった。支払いに充てられる金額は「2000万ポンドの総額」と定められた。 [30] この法律の条項に基づき、英国政府は2000万ポンドを調達し[31]、事業資産として登録された奴隷所有者に解放された奴隷の損失分として支払った。 1833年には、2000万ポンドは財務省の年間収入の40%に相当し[32]、当時の英国のGDPの約5%に相当した[33]。支払いの資金調達のた め、英国政府は 1835年8月3日に最終合意された、銀行家ネイサン・メイヤー・ロスチャイルドとその義理の兄弟モーゼス・モンテフィオーリとの1500万ポンドの融資 契約である。500万ポンドは、現在の価値で15億ポンド相当の政府株式として直接支払われた。 この資金は2015年まで英国の納税者によって返済されなかったという主張もあるが[35]、この主張は、英国政府が日付のない国債によって負債をどのよ うに賄ったかという点に関する形式的な問題に基づいている。財務省によると、1837年の奴隷債務は1927年に発行された統合4%ローン(1957年以 降に満期)に組み込まれた。[36] 英国政府が2015年に残存する永久国債をすべて償還して国債ポートフォリオを近代化したときに初めて、債務が消滅したという確信が完全に得られた。この 資金が借り入れられ、返済が確実になるまでの長い期間は、借り入れられた金額というよりも、使用された金融商品の種類によるものである。[37] しかし、このことは、実質的には、1833年の奴隷制度廃止法に由来する債務が納税者の資金で賄われたという事実と矛盾するものではない。[38] その資金の半分はカリブ海とアフリカの奴隷所有者の家族に、残りの半分は英国在住の不在者所有者に支払われた。[31] 奴隷所有者への支払いに関する申告書に記載された名前から、所有権は数百に及ぶ英国の家族に分散していたことが明らかになっている。[39] その多く(ただし、すべてではない。[40])は社会的地位の高い家族であった。例えば、ヘンリー・フィリポッツ(当時エクセター主教)は、ジョン・ ウォード初代ダドリー伯爵の遺言執行者および受託者として、西インド諸島の奴隷665人に対して12,700ポンドを受け取っていた[41]。一方、ヘン リー・ラスセルズ、ハーウッド伯爵(第2代)は、6つの農園の奴隷2,554人に対して26,309ポンドを受け取っていた[42]。 6つの農園で2,554人の奴隷に対して支払われた。[42] 1833年の奴隷制度廃止法に基づき支払われた男女の大半は、議会文書1837-8(215)第48巻に収められた「奴隷制度廃止法」と題された議会報告 書に記載されている。[43] |

| Exceptions and continuations As a notable exception to the rest of the British Empire, the act did not extend to any of the territories administered by the East India Company, including the islands of Ceylon and Saint Helena,[27] in which the company had been independently regulating, and in part prohibiting the slave trade since 1774; with regulations prohibiting the enslavement, the sale without a written deed, and the transport of slaves into company territory prohibited over the period.[44] The Indian Slavery Act, 1843 went on to prohibit company employees from owning, or dealing in slaves, along with granting limited protection under the law, that included the ability for a slave to own, transfer or inherit property, notionally benefitting the 8 to 10 million that were estimated to exist in company territory, to quote Rev. Howard Malcom: The number of slaves in the Carnatic, Mysore, and Malabar, is said to be greater than in most other parts of India, and embraces nearly the whole of the Punchum Bundam caste. The whole number in British India has never been ascertained, but is supposed, by the best informed persons I was able to consult, to be, on an average, at least one in eight, that is about ten millions. Many consider them twice as numerous.[45] A successor organisation to the Anti-Slavery Society was formed in London in 1839, the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which worked to outlaw slavery worldwide.[46] The world's oldest international human rights organisation, it continues today as Anti-Slavery International.[47] Clandestine slave trading still continued within the British Empire despite its illegality. In 1854, Nathaniel Isaacs, owner of the island of Matakong off the coast of Sierra Leone, was accused of slave trading by the governor of Sierra Leone, Sir Arthur Kennedy. Papers relating to the charges were lost when the Forerunner was wrecked off Madeira in October 1854. Due to the absence of the papers, the English courts refused to proceed with the prosecution.[48] The Act also did not outlaw other forms of forced labour like indentured servitude and blackbirding. Protests against apprenticeships On 1 August 1834, an unarmed group of mainly elderly people being addressed by the governor at Government House in Port of Spain, Trinidad, about the new laws, began chanting: "Pas de six ans. Point de six ans" ("Not six years. No six years"), drowning out the voice of the governor. Peaceful protests continued until a resolution to abolish apprenticeship was passed and de facto freedom was achieved. Full emancipation for all was legally granted ahead of schedule on 1 August 1838.[49] |

例外と継続 大英帝国の他の地域に対する顕著な例外として、この法律は東インド会社が統治する領土には適用されず、セイロン島やセントヘレナ島も含まれていた。 [27] これらの島々では、1774年以来、東インド会社が独自に奴隷貿易を規制し、一部では禁止していた。奴隷化、証書のない売買、会社領土への奴隷の移送を禁 止する規制が 。1843年のインディアン奴隷法は、会社領土内に存在すると推定された800万から1000万人の奴隷に、財産の所有、譲渡、相続の権利を与えるなど、 限定的な保護を法律で認める一方で、会社従業員による奴隷の所有や取引を禁止した。ハワード・マルコム牧師の言葉を引用すると、 カルナータカ、マイソール、マラバルの奴隷の数は、インドの他のほとんどの地域よりも多いと言われており、パンチュム・ブンダムのカーストのほぼすべてを 包含している。英領インドにおける奴隷の総数はこれまで一度も正確に把握されたことはないが、私が相談した最も情報通の人々によれば、平均して少なくとも 8人に1人、つまり約1,000万人であると考えられている。多くの人々は、その数は2倍であると考えている。[45] 1839年にはロンドンで奴隷制度廃止協会の後継団体である「英国および外国の奴隷制度廃止協会」が結成され、世界中で奴隷制度を違法とするよう活動し た。[46] 世界最古の国際的人権団体であるこの協会は、現在も「奴隷制度廃止国際協会」として活動を続けている。[47] 奴隷密売は、違法とされていたにもかかわらず、大英帝国の内部でも依然として行われていた。1854年、シエラレオネ沖のマタコン島(Matakong) の所有者であったナサニエル・アイザックス(Nathaniel Isaacs)は、シエラレオネ総督のサー・アーサー・ケネディ(Sir Arthur Kennedy)から奴隷貿易の容疑をかけられた。 1854年10月にマデイラ沖で難破したフォアランナー号(Forerunner)の関係書類が失われたため、書類が存在しないことを理由に、英国の裁判 所は起訴手続きを進めることを拒否した。 この法律は、契約奴隷やブラックバーディングのような他の形態の強制労働を違法とするものではなかった。 徒弟制度に対する抗議 1834年8月1日、トリニダードのポートオブスペインにある総督邸で、主に高齢者からなる非武装のグループが総督から新法について説明を受けた後、「6 年ではない。6年ではない」と唱え始め、 「6年ではない。6年はない」と叫び、知事の声を掻き消した。見習い制度廃止の決議が可決され、事実上の自由が達成されるまで、平和的な抗議は続いた。 1838年8月1日、予定より早く、すべての完全な解放が法律で認められた。[49] |

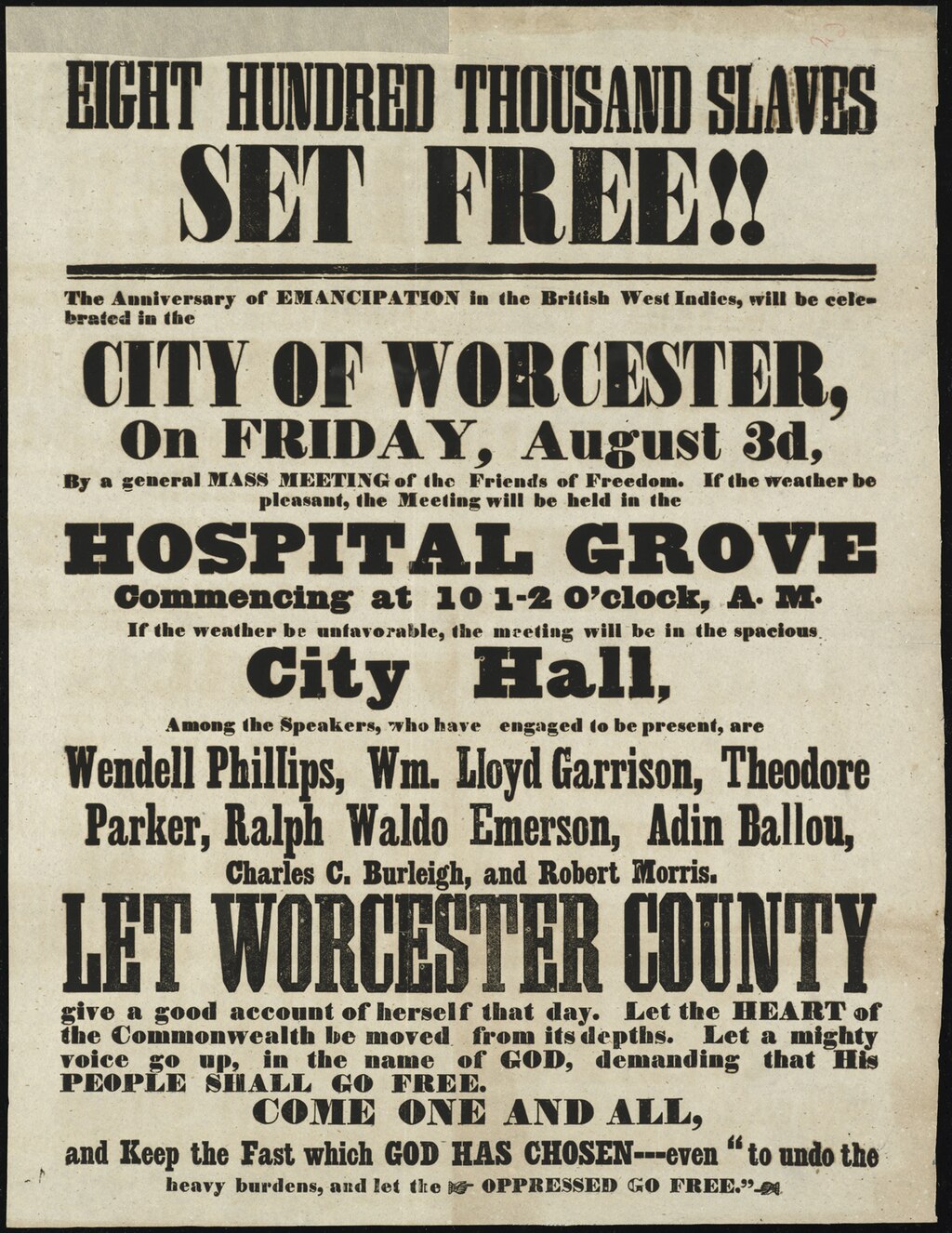

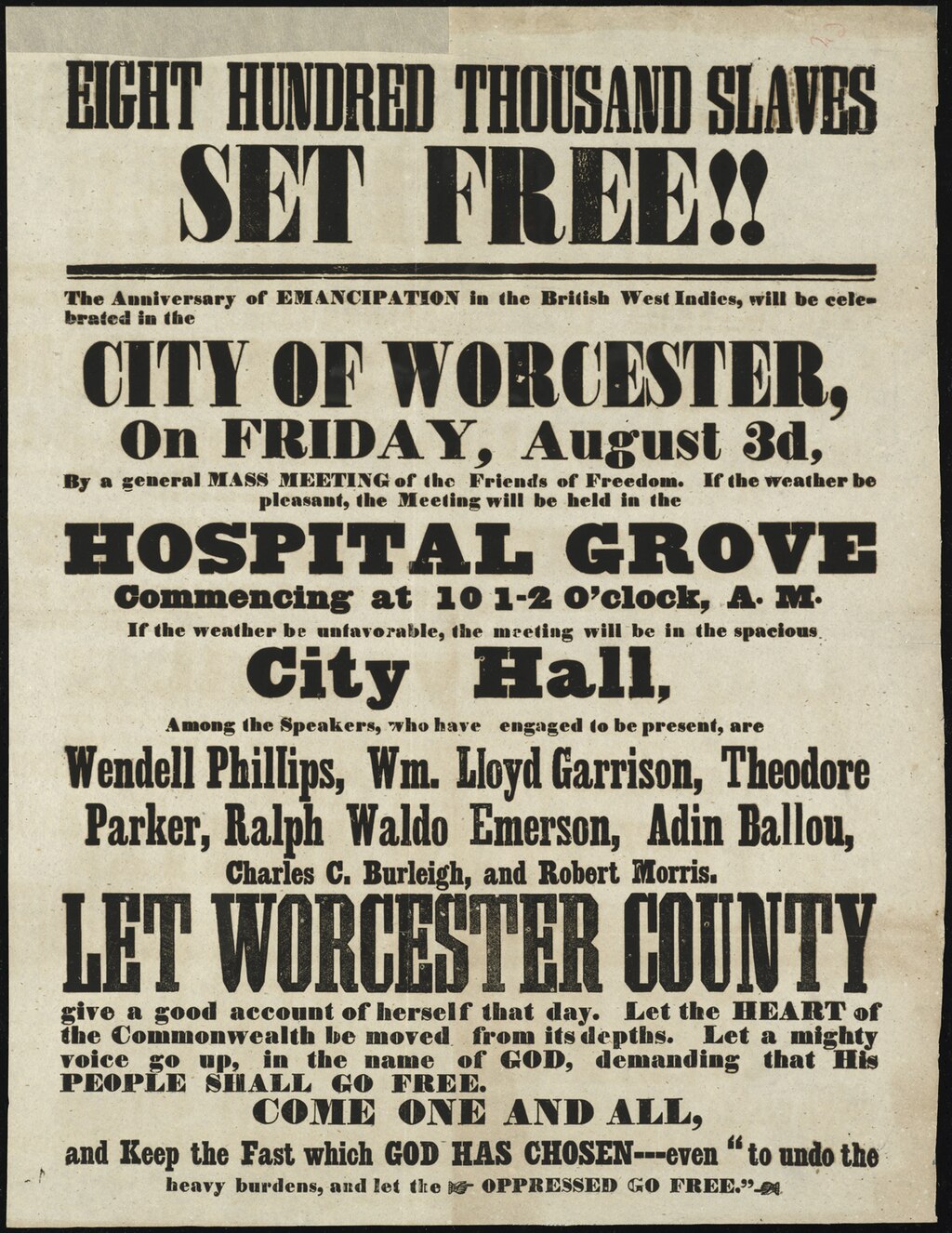

Repeal Poster for an event in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1849, commemorating the end of slavery in the British West Indies The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 was repealed in its entirety by the Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1998.[50][51] The repeal has not made slavery legal again, sections of the Slave Trade Act 1824, Slave Trade Act 1843 and Slave Trade Act 1873 continuing in force. In its place the Human Rights Act 1998 incorporates into British Law Article 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights which prohibits the holding of persons as slaves.[52][53][54][55] |

廃止 1849年にマサチューセッツ州ウースターで行われた、イギリス領西インド諸島における奴隷制の廃止を記念するイベントのポスター。 1833年に制定された奴隷制廃止法は、1998年に制定された法令法(廃止法)により全廃された[50][51]。この廃止により奴隷制が再び合法化さ れたわけではなく、1824年に制定された奴隷貿易法、1843年に制定された奴隷貿易法、1873年に制定された奴隷貿易法の各条項は引き続き有効であ る。その代わりに1998年人権法は、人を奴隷として拘束することを禁止する欧州人権条約第4条を英国法に組み込んだ[52][53][54][55]。 |

| In popular culture Ava DuVernay was commissioned by the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture to create a film which debuted at the museum's opening on 24 September 2016. This film, 28 August: A Day in the Life of a People, tells of six significant events in African-American history that happened on the same date, 28 August. Events depicted include (among others) William IV's royal assent to the Slavery Abolition Act.[56] Amazing Grace is a 2006 British-American biographical drama film directed by Michael Apted, about the campaign against the slave trade in the British Empire, led by William Wilberforce, who was responsible for steering anti-slave trade legislation through the British parliament. The title is a reference to the 1772 hymn "Amazing Grace". The film also recounts the experiences of John Newton as a crewman on a slave ship and subsequent religious conversion, which inspired his writing of the poem later used in the hymn. Newton is portrayed as a major influence on Wilberforce and the abolition movement.[citation needed] The Act is referenced in the 2010 novel The Long Song by British author Andrea Levy and in the 2018 BBC television adaptation of the same name. The novel and television series tell the story of a slave in colonial Jamaica who lives through the period of slavery abolition in the British West Indies. |

大衆文化において エヴァ・デュヴァーネイは、スミソニアン国立アフリカ系アメリカ人歴史文化博物館の依頼で映画を制作し、2016年9月24日の同博物館のオープニングで 初公開された。この映画『8月28日』である: A Day in the Life of a People』は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の歴史において、同じ8月28日に起こった6つの重要な出来事を描いている。描かれている出来事には、(とりわ け)ウィリアム4世の奴隷制度廃止法への王室同意が含まれる[56]。 アメイジング・グレイス』(Amazing Grace)は、マイケル・アプテッドが監督した2006年のイギリス系アメリカ人の伝記ドラマ映画で、イギリス議会で奴隷貿易禁止法の制定に舵を切った ウィリアム・ウィルバーフォース率いる大英帝国の奴隷貿易反対運動を描いている。タイトルは1772年の賛美歌「アメイジング・グレイス」にちなんでい る。この映画はまた、ジョン・ニュートンが奴隷船の乗組員として体験したこと、その後の宗教的改宗、そして後に賛美歌に使われる詩を書くきっかけとなった ことを描いている。ニュートンは、ウィルバーフォースと奴隷廃止運動に大きな影響を与えた人物として描かれている[要出典]。 この法律は、イギリスの作家アンドレア・レヴィによる2010年の小説『The Long Song』や、2018年のBBCによる同名のテレビドラマで言及されている。この小説とテレビシリーズは、植民地時代のジャマイカで、イギリス領西イン ド諸島の奴隷制度廃止の時代を生きた奴隷の物語である。 |

| 1926 Slavery Convention – from which an international treaty resulted Act Against Slavery – an act in Upper Canada that banned the importation of slaves there in 1793 Blockade of Africa Brussels Conference Act of 1890 – an early abolitionist treaty Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery Compensated emancipation Indian Slavery Act, 1843 Slave Trade Acts Slavery in Britain Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution – which prohibited slavery in the United States in 1865 Timeline of abolition of slavery and serfdom |

1926年 奴隷条約 - 国際条約が結ばれた 奴隷禁止法 - アッパーカナダで1793年に奴隷の輸入を禁止した法律 アフリカ封鎖 1890年ブリュッセル会議法-初期の奴隷廃止条約 英国奴隷制度遺産研究センター 補償付き奴隷解放 インディアン奴隷法(1843年 奴隷貿易法 イギリスの奴隷制度 アメリカ合衆国憲法修正第13条 - 1865年にアメリカ合衆国で奴隷制が禁止された 奴隷制と農奴制廃止の年表 |

| Drescher, Seymour. Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery (2009) Hinks, Peter, and John McKivigan, eds. Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition (2 vol. 2006) Huzzey, Richard. Freedom Burning: Anti-Slavery and Empire in Victorian Britain. (Cornell University Press, 2012) 303pp. Washington, Jon-Michael. "Ending the Slave Trade and Slavery in the British Empire: An Explanatory Case Study Utilizing Qualitative Methodology and Stratification and Class Theories." (2012 NCUR) (2013). online Archived 4 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine Williams, Eric (1987) [1964]. Capitalism and Slavery. London: Andre Deutsch. |

ドレッシャー、シーモア Abolition: 奴隷制と反奴隷制の歴史 (2009) Hinks, Peter, and John McKivigan, eds. Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition(反奴隷制と奴隷制廃止の百科事典) (2 vol. 2006) Huzzey, Richard. Freedom Burning: Freedom burning: Anti-Slavery and Empire in Victorian Britain. (Cornell University Press, 2012) 303pp. Washington, Jon-Michael. 「大英帝国における奴隷貿易と奴隷制の終焉: An Explanatory Case Study Utilizing Qualitative Methodology and Stratification and Class Theories」. (2012 NCUR) (2013). オンライン Archived 4 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine Williams, Eric (1987) [1964]. Capitalism and Slavery. London: Andre Deutsch. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavery_Abolition_Act_1833 |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆