アダム・スミス

Adam Smith, 1723-1790

☆ アダム・スミス(Adam Smith FRS FRSE FRSA、1723年6月16日[西暦6月5日]洗礼[1] - 1790年7月17日)はスコットランドの経済学者・哲学者で、政治経済学の先駆者であり、スコットランド啓蒙時代の重要人物である。 [経済学の父」、「資本主義の父」とも呼ばれ、『道徳感情論』(1759年)と『国富の本質と原因に関する探究』(1776年)という2つの古典的著作を 残した。後者はしばしば『国富論』と略され、彼の最高傑作とされ、経済学を包括的な体系として、また学問分野として扱った最初の近代的著作である。スミス は富と権力の分配を神の意志で説明することを拒否し、その代わりに自然的、政治的、社会的、経済的、法的、環境的、技術的要因とそれらの相互作用に訴え た。他の経済理論の中でも、この著作はスミスの絶対優位の考え方を紹介した。 スミスはグラスゴー大学とオックスフォード大学のバリオール・カレッジで社会哲学を学び、同じスコットランド人のジョン・スネルが設立した奨学金の恩恵を 受けた最初の学生の一人であった。卒業後、エディンバラ大学で公開講義を行い成功を収め、スコットランド啓蒙時代のデイヴィッド・ヒュームとの共同研究に つながった。スミスはグラスゴーで教授職を得、道徳哲学を教え、その間に『道徳感情論』を執筆・出版した。晩年は家庭教師の職を得てヨーロッパ各地を旅行 し、当時の知的指導者たちと知り合った。 輸入を最小化し、輸出を最大化することで、国内市場と商人を保護する一般的な政策、いわゆる重商主義への反動として、スミスは古典的な自由市場経済理論の 基礎を築いた。国富論』は、経済学という近代的な学問分野の先駆けとなった。この著作やその他の著作の中で、彼は分業の概念を発展させ、合理的な利己心と 競争がいかに経済的繁栄をもたらすかを説いた。スミスは当時物議を醸し、彼の一般的なアプローチや文体は、ホレス・ウォルポールなどの作家によってしばし ば風刺された。

| Adam Smith FRS

FRSE FRSA (baptised 16 June [O.S. 5 June] 1723[1] – 17 July 1790) was a

Scottish[a] economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking

of political economy and key figure during the Scottish

Enlightenment.[3] Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"[4] or "The

Father of Capitalism",[5] he wrote two classic works, The Theory of

Moral Sentiments (1759) and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of

the Wealth of Nations (1776). The latter, often abbreviated as The

Wealth of Nations, is considered his magnum opus and the first modern

work that treats economics as a comprehensive system and as an academic

discipline. Smith refuses to explain the distribution of wealth and

power in terms of God's will and instead appeals to natural, political,

social, economic, legal, environmental and technological factors and

the interactions among them. Among other economic theories, the work

introduced Smith's idea of absolute advantage.[6] Smith studied social philosophy at the University of Glasgow and at Balliol College, Oxford, where he was one of the first students to benefit from scholarships set up by fellow Scot John Snell. After graduating, he delivered a successful series of public lectures at the University of Edinburgh,[7] leading him to collaborate with David Hume during the Scottish Enlightenment. Smith obtained a professorship at Glasgow, teaching moral philosophy and during this time, wrote and published The Theory of Moral Sentiments. In his later life, he took a tutoring position that allowed him to travel throughout Europe, where he met other intellectual leaders of his day. As a reaction to the common policy of protecting national markets and merchants through minimizing imports and maximizing exports, what came to be known as mercantilism, Smith laid the foundations of classical free market economic theory. The Wealth of Nations was a precursor to the modern academic discipline of economics. In this and other works, he developed the concept of division of labour and expounded upon how rational self-interest and competition can lead to economic prosperity. Smith was controversial in his own day and his general approach and writing style were often satirised by writers such as Horace Walpole.[8] |

アダム・スミス(Adam Smith FRS

FRSE FRSA、1723年6月16日[西暦6月5日]洗礼[1] -

1790年7月17日)はスコットランド[a]の経済学者・哲学者で、政治経済学の先駆者であり、スコットランド啓蒙時代の重要人物である。

[経済学の父」[4]、「資本主義の父」[5]とも呼ばれ、『道徳感情論』(1759年)と『国富の本質と原因に関する探究』(1776年)という2つの

古典的著作を残した。)

後者はしばしば『国富論』と略され、彼の最高傑作とされ、経済学を包括的な体系として、また学問分野として扱った最初の近代的著作である。スミスは富と権

力の分配を神の意志で説明することを拒否し、その代わりに自然的、政治的、社会的、経済的、法的、環境的、技術的要因とそれらの相互作用に訴えた。他の経

済理論の中でも、この著作はスミスの絶対優位の考え方を紹介した[6]。 スミスはグラスゴー大学とオックスフォード大学のバリオール・カレッジで社会哲学を学び、同じスコットランド人のジョン・スネルが設立した奨学金の恩恵を 受けた最初の学生の一人であった。卒業後、エディンバラ大学で公開講義を行い成功を収め[7]、スコットランド啓蒙時代のデイヴィッド・ヒュームとの共同 研究につながった。スミスはグラスゴーで教授職を得、道徳哲学を教え、その間に『道徳感情論』を執筆・出版した。晩年は家庭教師の職を得てヨーロッパ各地 を旅行し、当時の知的指導者たちと知り合った。 輸入を最小化し、輸出を最大化することで、国内市場と商人を保護する一般的な政策、いわゆる重商主義への反動として、スミスは古典的な自由市場経済理論の 基礎を築いた。国富論』は、経済学という近代的な学問分野の先駆けとなった。この著作やその他の著作の中で、彼は分業の概念を発展させ、合理的な利己心と 競争がいかに経済的繁栄をもたらすかを説いた。スミスは当時物議を醸し、彼の一般的なアプローチや文体は、ホレス・ウォルポールなどの作家によってしばし ば風刺された[8]。 |

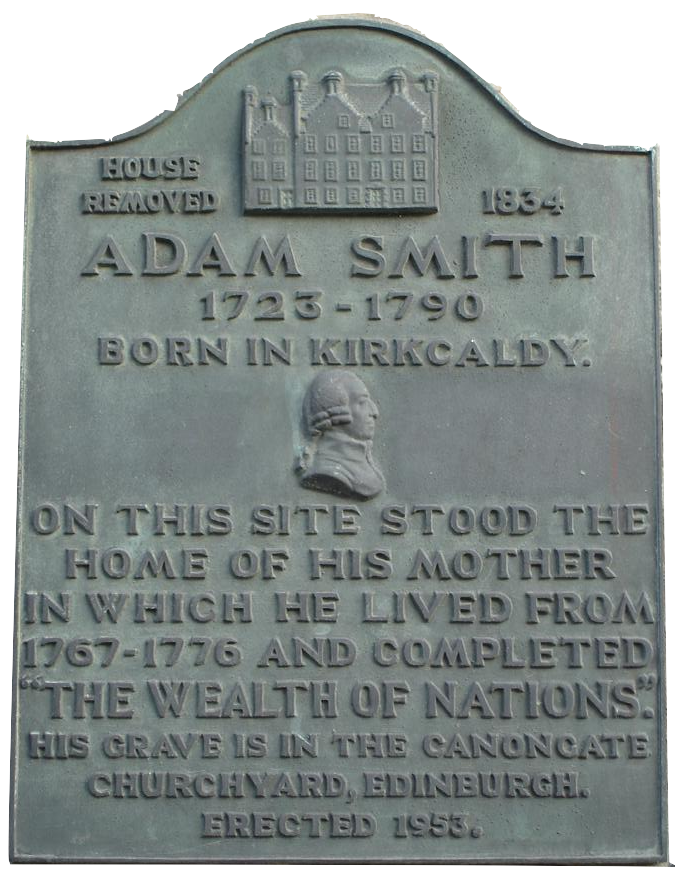

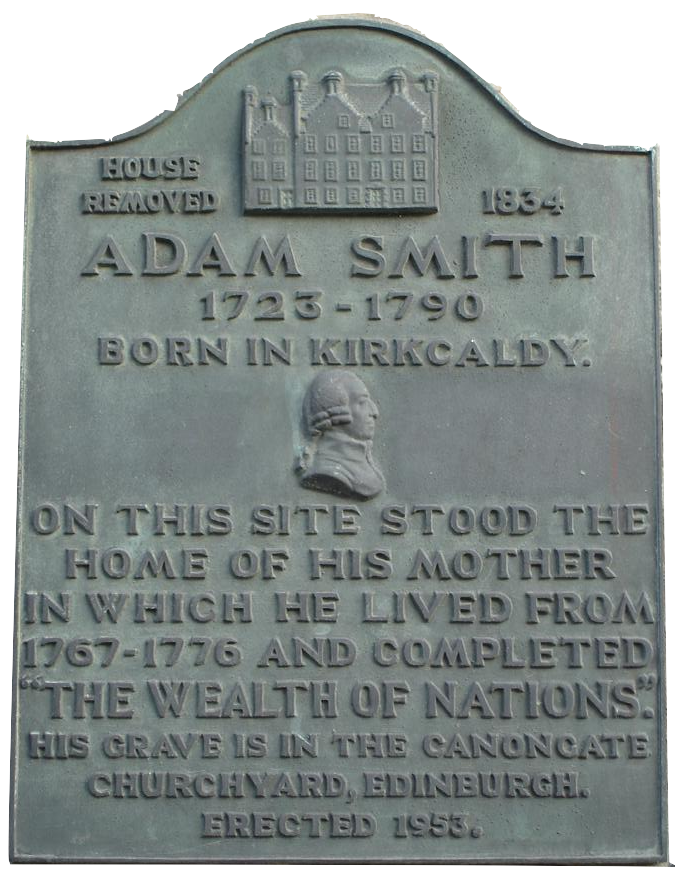

| Biography Early life Smith was born in Kirkcaldy, in Fife, Scotland. His father, Adam Smith senior, was a Scottish Writer to the Signet (senior solicitor), advocate and prosecutor (judge advocate) and also served as comptroller of the customs in Kirkcaldy.[9] Smith's mother was born Margaret Douglas, daughter of the landed Robert Douglas of Strathendry, also in Fife; she married Smith's father in 1720. Two months before Smith was born, his father died, leaving his mother a widow.[10] The date of Smith's baptism into the Church of Scotland at Kirkcaldy was 5 June 1723[11] and this has often been treated as if it were also his date of birth,[9] which is unknown. Although few events in Smith's early childhood are known, the Scottish journalist John Rae, Smith's biographer, recorded that Smith was abducted by Romani at the age of three and released when others went to rescue him.[b][13] Smith was close to his mother, who probably encouraged him to pursue his scholarly ambitions.[14] He attended the Burgh School of Kirkcaldy—characterised by Rae as "one of the best secondary schools of Scotland at that period"[12]—from 1729 to 1737, he learned Latin, mathematics, history, and writing.[14] Formal education Smith entered the University of Glasgow at age 14 and studied moral philosophy under Francis Hutcheson.[14] Here he developed his passion for the philosophical concepts of reason, civilian liberties, and free speech. In 1740, he was the graduate scholar presented to undertake postgraduate studies at Balliol College, Oxford, under the Snell Exhibition.[15] Smith considered the teaching at Glasgow to be far superior to that at Oxford, which he found intellectually stifling.[16] In Book V, Chapter II of The Wealth of Nations, he wrote: "In the University of Oxford, the greater part of the public professors have, for these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching." Smith is also reported to have complained to friends that Oxford officials once discovered him reading a copy of David Hume's A Treatise of Human Nature, and they subsequently confiscated his book and punished him severely for reading it.[12][17][18] According to William Robert Scott, "The Oxford of [Smith's] time gave little if any help towards what was to be his lifework."[19] Nevertheless, he took the opportunity while at Oxford to teach himself several subjects by reading many books from the shelves of the large Bodleian Library.[20] When Smith was not studying on his own, his time at Oxford was not a happy one, according to his letters.[21] Near the end of his time there, he began suffering from shaking fits, probably the symptoms of a nervous breakdown.[22] He left Oxford University in 1746, before his scholarship ended.[22][23] In Book V of The Wealth of Nations, Smith comments on the low quality of instruction and the meager intellectual activity at English universities, when compared to their Scottish counterparts. He attributes this both to the rich endowments of the colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, which made the income of professors independent of their ability to attract students, and to the fact that distinguished men of letters could make an even more comfortable living as ministers of the Church of England.[18] Smith's discontent at Oxford might be in part due to the absence of his beloved teacher in Glasgow, Francis Hutcheson, who was well regarded as one of the most prominent lecturers at the University of Glasgow in his day and earned the approbation of students, colleagues, and even ordinary residents with the fervor and earnestness of his orations (which he sometimes opened to the public). His lectures endeavoured not merely to teach philosophy, but also to make his students embody that philosophy in their lives, appropriately acquiring the epithet, the preacher of philosophy. Unlike Smith, Hutcheson was not a system builder; rather, his magnetic personality and method of lecturing so influenced his students and caused the greatest of those to reverentially refer to him as "the never to be forgotten Hutcheson"—a title that Smith in all his correspondence used to describe only two people, his good friend David Hume and influential mentor Francis Hutcheson.[24]  Portrait of Smith's mother, Margaret Douglas Teaching career Smith began delivering public lectures in 1748 at the University of Edinburgh,[25] sponsored by the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh under the patronage of Lord Kames.[26] His lecture topics included rhetoric and belles-lettres,[27] and later the subject of "the progress of opulence". On this latter topic, he first expounded his economic philosophy of "the obvious and simple system of natural liberty". While Smith was not adept at public speaking, his lectures met with success.[28] In 1750, Smith met the philosopher David Hume, who was his senior by more than a decade. In their writings covering history, politics, philosophy, economics, and religion, Smith and Hume shared closer intellectual and personal bonds than with other important figures of the Scottish Enlightenment.[29] In 1751, Smith earned a professorship at Glasgow University teaching logic courses, and in 1752, he was elected a member of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh, having been introduced to the society by Lord Kames. When the head of Moral Philosophy in Glasgow died the next year, Smith took over the position.[28] He worked as an academic for the next 13 years, which he characterised as "by far the most useful and therefore by far the happiest and most honorable period [of his life]".[30] Smith published The Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759, embodying some of his Glasgow lectures. This work was concerned with how human morality depends on sympathy between agent and spectator, or the individual and other members of society. Smith defined "mutual sympathy" as the basis of moral sentiments. He based his explanation, not on a special "moral sense" as the Third Lord Shaftesbury and Hutcheson had done, nor on utility as Hume did, but on mutual sympathy, a term best captured in modern parlance by the 20th-century concept of empathy, the capacity to recognise feelings that are being experienced by another being.  A drawing of a man sitting down François Quesnay, one of the leaders of the physiocratic school of thought Following the publication of The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith became so popular that many wealthy students left their schools in other countries to enroll at Glasgow to learn under Smith.[31] At this time, Smith began to give more attention to jurisprudence and economics in his lectures and less to his theories of morals.[32] For example, Smith lectured that the cause of increase in national wealth is labour, rather than the nation's quantity of gold or silver, which is the basis for mercantilism, the economic theory that dominated Western European economic policies at the time.[33] In 1762, the University of Glasgow conferred on Smith the title of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.).[34] At the end of 1763, he obtained an offer from British chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend—who had been introduced to Smith by David Hume—to tutor his stepson, Henry Scott, the young Duke of Buccleuch as preparation for a career in international politics. Smith resigned from his professorship in 1764 to take the tutoring position. He subsequently attempted to return the fees he had collected from his students because he had resigned partway through the term, but his students refused.[35] Tutoring, travels, European intellectuals Smith's tutoring job entailed touring Europe with Scott, during which time he educated Scott on a variety of subjects. He was paid £300 per year (plus expenses) along with a £300 per year pension; roughly twice his former income as a teacher.[35] Smith first travelled as a tutor to Toulouse, France, where he stayed for a year and a half. According to his own account, he found Toulouse to be somewhat boring, having written to Hume that he "had begun to write a book to pass away the time".[35] After touring the south of France, the group moved to Geneva, where Smith met with the philosopher Voltaire.[36]  Philosopher David Hume, painting David Hume was a friend and contemporary of Smith's. From Geneva, the party moved to Paris. Here, Smith met American publisher and diplomat Benjamin Franklin, who a few years later would lead the opposition in the American colonies against four British resolutions from Charles Townshend (in history known as the Townshend Acts), which threatened American colonial self-government and imposed revenue duties on a number of items necessary to the colonies. Smith discovered the Physiocracy school founded by François Quesnay and discussed with their intellectuals.[37] Physiocrats were opposed to mercantilism, the dominating economic theory of the time, illustrated in their motto Laissez faire et laissez passer, le monde va de lui même! (Let do and let pass, the world goes on by itself!). The wealth of France had been virtually depleted by Louis XIV[c] and Louis XV in ruinous wars,[d] and was further exhausted in aiding the American revolutionary soldiers, against the British. Given that the British economy of the day yielded an income distribution that stood in contrast to that which existed in France, Smith concluded that "with all its imperfections, [the Physiocratic school] is perhaps the nearest approximation to the truth that has yet been published upon the subject of political economy."[38] The distinction between productive versus unproductive labour—the physiocratic classe steril—was a predominant issue in the development and understanding of what would become classical economic theory. Later years In 1766, Henry Scott's younger brother died in Paris, and Smith's tour as a tutor ended shortly thereafter.[39] Smith returned home that year to Kirkcaldy, and he devoted much of the next decade to writing his magnum opus.[40] There, he befriended Henry Moyes, a young blind man who showed precocious aptitude. Smith secured the patronage of David Hume and Thomas Reid in the young man's education.[41] In May 1767, Smith was elected fellow of the Royal Society of London,[42][43] and was elected a member of the Literary Club in 1775. The Wealth of Nations was published in 1776 and was an instant success, selling out its first edition in only six months.[44] In 1778, Smith was appointed to a post as commissioner of customs in Scotland and went to live with his mother (who died in 1784)[45] in Panmure House in Edinburgh's Canongate.[46] Five years later, as a member of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh when it received its royal charter, he automatically became one of the founding members of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.[47] From 1787 to 1789, he occupied the honorary position of Lord Rector of the University of Glasgow.[48] Death  A plaque of Smith A commemorative plaque for Smith is located in Smith's home town of Kirkcaldy. Smith died in the northern wing of Panmure House in Edinburgh on 17 July 1790 after a painful illness. His body was buried in the Canongate Kirkyard.[49] On his deathbed, Smith expressed disappointment that he had not achieved more.[50] Smith's literary executors were two friends from the Scottish academic world: the physicist and chemist Joseph Black and the pioneering geologist James Hutton.[51] Smith left behind many notes and some unpublished material, but gave instructions to destroy anything that was not fit for publication.[52] He mentioned an early unpublished History of Astronomy as probably suitable, and it duly appeared in 1795, along with other material such as Essays on Philosophical Subjects.[51] Smith's library went by his will to David Douglas, Lord Reston (son of his cousin Colonel Robert Douglas of Strathendry, Fife), who lived with Smith.[53] It was eventually divided between his two surviving children, Cecilia Margaret (Mrs. Cunningham) and David Anne (Mrs. Bannerman). On the death in 1878 of her husband, the Reverend W. B. Cunningham of Prestonpans, Mrs. Cunningham sold some of the books. The remainder passed to her son, Professor Robert Oliver Cunningham of Queen's College, Belfast, who presented a part to the library of Queen's College. After his death, the remaining books were sold. On the death of Mrs. Bannerman in 1879, her portion of the library went intact to the New College (of the Free Church) in Edinburgh and the collection was transferred to the University of Edinburgh Main Library in 1972. |

略歴 生い立ち スミスはスコットランドのファイフ州カークカルディで生まれた。父親のアダム・スミス・シニアはスコットランドのシグネット(上級事務弁護士)、弁護人、 検察官(判事の弁護人)であり、カークカルディの税関長も務めた[9]。スミスが生まれる2ヶ月前に父親が亡くなり、母親は未亡人となった[10]。スミ スがカークカルディでスコットランド国教会の洗礼を受けた日は1723年6月5日であり[11]、しばしばこの日がスミスの生年月日であるかのように扱わ れてきたが[9]、それは不明である。 スミスの幼少期の出来事はほとんど知られていないが、スミスの伝記作家であるスコットランドのジャーナリスト、ジョン・ライは、スミスが3歳の時にロマニ に誘拐され、他の者が助けに行くと解放されたと記録している[13]。 [1729年から1737年までカークカルディのバーグ・スクールに通い、ラテン語、数学、歴史、文章を学んだ[14]。 正式な教育 スミスは14歳でグラスゴー大学に入学し、フランシス・ハッチェソンの下で道徳哲学を学んだ[14]。ここで彼は理性、市民の自由、言論の自由という哲学 的概念への情熱を育んだ。1740年、彼はスネル展のもとオックスフォードのバリオール・カレッジで大学院の研究を行うために贈られた大学院生奨学生と なった[15]。 スミスは、グラスゴーの教育が、知的息苦しさを感じるオックスフォードの教育よりもはるかに優れていると考えていた[16]。『国富論』の第五巻第二章で は、「オックスフォード大学では、公の教授の大部分は、ここ何年もの間、教えるふりさえも完全に放棄している」と書いている。スミスはまた、オックス フォード大学の職員にデイヴィッド・ヒュームの『人間本性論』を読んでいるところを発見され、その後、本を没収され、それを読んだことで厳しく罰せられた と友人に愚痴をこぼしたと伝えられている[12][17][18]。 ウィリアム・ロバート・スコットによれば、「(スミスの)当時のオックスフォード大学は、彼のライフワークとなるべきものに対して、助けは与えたとして も、ほとんど与えてくれなかった。 「それにもかかわらず、彼はオックスフォード在学中に、大きなボドリアン図書館の書棚から多くの本を読むことによって、いくつかの科目を独学する機会を得 た[20]。 スミスが独学していないとき、彼の手紙によれば、オックスフォードでの時間は幸福なものではなかった[21]。 在学期間の終わり近くに、彼はおそらく神経衰弱の症状であろう震え発作に悩まされるようになった[22]。 彼は奨学金が終わる前の1746年にオックスフォード大学を去った[22][23]。 スミスは『国富論』第五巻で、スコットランドの大学と比較した場合、イギリスの大学における教育の質の低さと知的活動の貧弱さについてコメントしている。 スミスは、これはオックスフォードとケンブリッジのカレッジの寄付金が豊かで、教授たちの収入が学生を集める能力に左右されなかったことと、著名な文人た ちがイングランド国教会の牧師としてさらに安楽な生活を送ることができたことの両方が原因であるとしている[18]。 彼は当時のグラスゴー大学で最も著名な講師の一人として高く評価されており、その熱意と真摯な講義(彼は時に一般にも公開した)で学生や同僚、さらには一 般住民の賛同を得ていた。彼の講義は、単に哲学を教えるだけでなく、その哲学を生徒たちの生活の中で体現させることに努め、哲学の伝道師という蔑称を得る にふさわしいものであった。スミスとは異なり、ハッチェソンはシステムを構築する人ではなかった。むしろ、彼の魅力的な人格と講義の方法が生徒たちに大き な影響を与え、最も偉大な生徒たちが彼を「決して忘れ去られることのないハッチェソン」と敬愛するようになった。  スミスの母マーガレット・ダグラスの肖像画 教職に就く スミスは1748年にエジンバラ大学で公開講義を始めた[25]。ケイムズ卿の後援のもと、エジンバラ哲学協会が主催していた[26]。この後者のテーマ について、彼はまず「自然的自由の明白で単純なシステム」という経済哲学を説いた。スミスは人前で話すことは得意ではなかったが、彼の講義は成功を収めた [28]。 1750年、スミスは10年以上先輩の哲学者デイヴィッド・ヒュームと出会う。歴史、政治、哲学、経済学、宗教を網羅した著作の中で、スミスとヒューム は、スコットランド啓蒙主義の他の重要人物よりも緊密な知的・個人的結びつきを共有していた[29]。 1751年、スミスはグラスゴー大学で論理学の講義を教える教授職に就き、1752年にはケイムズ卿の紹介でエジンバラ哲学協会の会員に選ばれた。翌年、 グラスゴーの道徳哲学の責任者が亡くなると、スミスはその職を引き継いだ[28]。その後13年間は学者として働いたが、その期間を彼は「(人生の中で) 圧倒的に有益であり、それゆえに圧倒的に幸福で名誉ある期間であった」と評している[30]。 スミスは、グラスゴーでの講義の一部を具体化した『道徳感情論』を1759年に出版した。この著作は、人間の道徳が、行為者と見物人、あるいは個人と社会 の他の構成員との間の共感によってどのように左右されるかに関心を寄せていた。スミスは「相互の共感」を道徳的感情の基礎と定義した。彼は、第三卿シャフ ツベリーやハッチェソンのような特別な「道徳的感覚」ではなく、ヒュームのような実用性でもなく、「相互共感」に基づいて説明したのである。  座っている男の絵 フランソワ・ケスネ、フィジオクラテス(重農)学派の指導者の一人 『道徳感情論』の出版後、スミスは非常に人気を博し、多くの裕福な学生が他国の学校を離れ、スミスの下で学ぶためにグラスゴーに入学した[31]。 [32]例えば、スミスは、国富の増加の原因は、国家の金や銀の量よりもむしろ労働であると講義し、これは当時西欧の経済政策を支配していた経済理論であ る重商主義の基礎となっている[33]。 1762年、グラスゴー大学はスミスに法学博士(LL.D.)の称号を授与した[34]。1763年末、デイヴィッド・ヒュームからスミスを紹介された チャールズ・タウンゼント英国大蔵大臣から、国際政治家としてのキャリアを築く準備として、彼の連れ子である若きバクルーク公ヘンリー・スコットの家庭教 師を依頼された。スミスは1764年に教授の職を辞し、家庭教師の職に就いた。その後、学期の途中で辞職したため、学生から徴収した学費を返還しようとし たが、学生はこれを拒否した[35]。 家庭教師、旅行、ヨーロッパの知識人 スミスの家庭教師の仕事はスコットとヨーロッパを旅行することであり、その間、彼はスコットに様々なテーマについて教育した。スミスは家庭教師として最初 にフランスのトゥールーズを訪れ、1年半滞在した。彼自身の記述によれば、彼はトゥールーズがやや退屈であることに気づき、「時間をつぶすために本を書き 始めた」とヒュームに書き送っている[35]。南フランスを観光した後、一行はジュネーヴに移動し、そこでスミスは哲学者ヴォルテールと出会った [36]。  哲学者デイヴィッド・ヒューム、絵画 デイヴィッド・ヒュームはスミスと同時代の友人であった。 一行はジュネーブからパリに移動した。彼は数年後、アメリカの植民地の自治を脅かし、植民地に必要な多くの品目に歳入関税を課したチャールズ・タウンシェ ントの4つのイギリス決議(歴史上タウンシェント法として知られる)に反対するアメリカ植民地の反対運動の先頭に立つことになる。スミスはフランソワ・ケ スネーによって創設されたフィジオクラシー学派を発見し、その知識人たちと議論した[37]。フィジオクラシー学派は当時の主流であった経済理論である重 商主義に反対しており、彼らのモットーであるLaissez faire et laissez passer, le monde va de lui même!(世界は自ら進む!)。 フランスの富は、ルイ14世[c]とルイ15世によって破滅的な戦争で事実上枯渇し[d]、さらに、イギリスに対するアメリカ革命の兵士を助けるために疲 弊していた。当時のイギリス経済がフランスとは対照的な所得分配を生み出していたことを考えると、スミスは「その不完全さはあるにせよ、(フィジオクラテ ス学派は)おそらく政治経済学の主題に関してまだ発表されている中で最も真理に近いものであろう」[38]と結論づけた。 後年 1766年、ヘンリー・スコットの弟がパリで亡くなり、スミスの家庭教師としてのツアーはその直後に終了した[39]。スミスはその年にカークカルディに 帰国し、その後の10年の大半を大著の執筆に費やした[40]。1767年5月、スミスはロンドン王立協会のフェローに選出され[42][43]、 1775年には文学クラブの会員に選出された。1776年に出版された『国富論』は瞬く間に成功を収め、初版はわずか6ヶ月で完売した[44]。 1778年、スミスはスコットランドの税関総監に任命され、エディンバラのキャノンゲートにあるパンミュア・ハウスに母親(1784年に死去)[45]と 住むようになった[46]。5年後、エディンバラ哲学協会が王室御用達となった際にその会員となったスミスは、自動的にエディンバラ王立協会の創設メン バーの一人となった[47]。 死去  スミスの記念プレート スミスの故郷カークカルディには、スミスの記念プレートがある。 スミスは1790年7月17日、エディンバラのパンミュア・ハウスの北棟で苦しい闘病生活の末に死去した。彼の遺体はカノンゲート・カークヤードに埋葬さ れた[49]。死の床でスミスは、自分がもっと多くのことを成し遂げられなかったことに失望を表明した[50]。 スミスの文学的遺言執行者は、物理学者で化学者のジョセフ・ブラックと先駆的な地質学者のジェームズ・ハットンというスコットランドの学界の2人の友人で あった[51]。スミスは多くのメモといくつかの未発表の資料を残したが、出版に適さないものは破棄するように指示を与えた[52]。 スミスの蔵書は遺言により、スミスと同居していたレストン卿デイヴィッド・ダグラス(ファイフ州ストラセンドリーの従兄弟ロバート・ダグラス大佐の息子) に譲渡された[53]。最終的には、彼の2人の遺児、セシリア・マーガレット(カニンガム夫人)とデイヴィッド・アン(バナーマン夫人)に分割された。 1878年に夫であるプレストンパンズの牧師W.B.カニンガムが亡くなると、カニンガム夫人は本の一部を売却した。残りは息子のロバート・オリヴァー・ カニンガム教授(クイーンズ・カレッジ、ベルファスト)に受け継がれ、彼はその一部をクイーンズ・カレッジの図書館に寄贈した。彼の死後、残りの蔵書は売 却された。1879年のバナーマン夫人の死後、彼女の蔵書の一部はそのままエディンバラのニュー・カレッジ(自由教会)に渡り、コレクションは1972年 にエディンバラ大学図書館本館に移された。 |

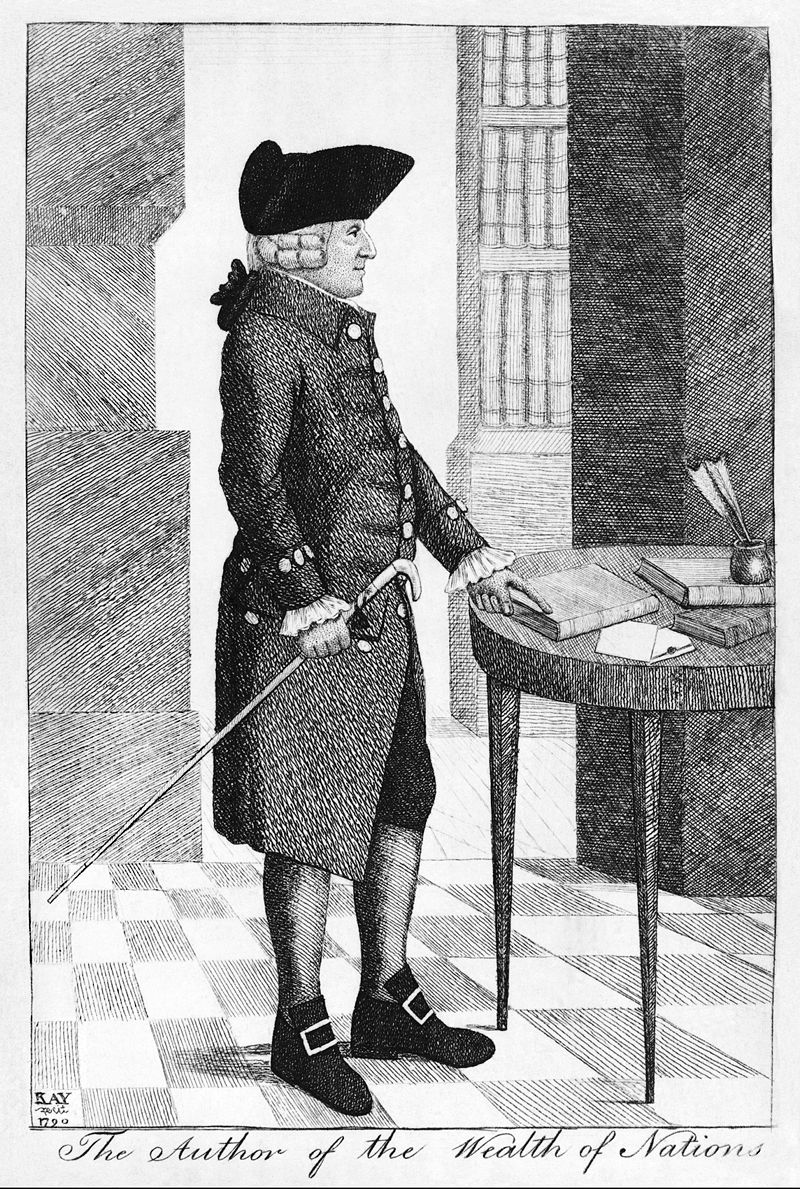

| Personality and beliefs Character  A drawing of a man standing up, with one hand holding a cane and the other pointing at a book Portrait of Smith by John Kay, 1790 Not much is known about Smith's personal views beyond what can be deduced from his published articles. His personal papers were destroyed after his death, per his request.[52] He never married,[54] and seems to have maintained a close relationship with his mother, with whom he lived after his return from France and who died six years before him.[55] Smith was described by several of his contemporaries and biographers as comically absent-minded, with peculiar habits of speech and gait, and a smile of "inexpressible benignity".[56] He was known to talk to himself,[50] a habit that began during his childhood when he would smile in rapt conversation with invisible companions.[57] He also had occasional spells of imaginary illness,[50] and he is reported to have had books and papers placed in tall stacks in his study.[57] According to one story, Smith took Charles Townshend on a tour of a tanning factory, and while discussing free trade, Smith walked into a huge tanning pit from which he needed help to escape.[58] He is also said to have put bread and butter into a teapot, drunk the concoction, and declared it to be the worst cup of tea he had ever had. According to another account, Smith distractedly went out walking in his nightgown and ended up 15 miles (24 km) outside of town, before nearby church bells brought him back to reality.[57][58] James Boswell, who was a student of Smith's at Glasgow University, and later knew him at the Literary Club, says that Smith thought that speaking about his ideas in conversation might reduce the sale of his books, so his conversation was unimpressive. According to Boswell, he once told Sir Joshua Reynolds, that "he made it a rule when in company never to talk of what he understood".[59] Smith has been alternatively described as someone who "had a large nose, bulging eyes, a protruding lower lip, a nervous twitch, and a speech impediment" and one whose "countenance was manly and agreeable".[18][60] Smith is said to have acknowledged his looks at one point, saying, "I am a beau in nothing but my books."[18] Smith rarely sat for portraits,[61] so almost all depictions of him created during his lifetime were drawn from memory. The best-known portraits of Smith are the profile by James Tassie and two etchings by John Kay.[62] The line engravings produced for the covers of 19th-century reprints of The Wealth of Nations were based largely on Tassie's medallion.[63] Religious views Considerable scholarly debate has occurred about the nature of Smith's religious views. His father had shown a strong interest in Christianity and belonged to the moderate wing of the Church of Scotland,[64] and the fact he received the Snell Exhibition suggests that he may have gone to Oxford with the intention of pursuing a career in the Church of England.[65] Anglo-American economist Ronald Coase has challenged the view that Smith was a deist, based on the fact that Smith's writings never explicitly invoke God as an explanation of the harmonies of the natural or the human worlds.[66] According to Coase, though Smith does sometimes refer to the "Great Architect of the Universe", later scholars such as Jacob Viner have "very much exaggerated the extent to which Adam Smith was committed to a belief in a personal God",[67] a belief for which Coase finds little evidence in passages such as the one in the Wealth of Nations in which Smith writes that the curiosity of mankind about the "great phenomena of nature", such as "the generation, the life, growth, and dissolution of plants and animals", has led men to "enquire into their causes", and that "superstition first attempted to satisfy this curiosity, by referring all those wonderful appearances to the immediate agency of the gods. Philosophy afterwards endeavoured to account for them, from more familiar causes, or from such as mankind were better acquainted with than the agency of the gods".[67] Some authors argue that Smith's social and economic philosophy is inherently theological and that his entire model of social order is logically dependent on the notion of God's action in nature.[68] Brendan Long argues that Smith was a theist,[69] whereas according to professor Gavin Kennedy, Smith was "in some sense" a Christian.[70] Smith was also a close friend of David Hume, who, despite debate about his religious views in modern scholarship, was commonly characterised in his own time as an atheist.[71] The publication in 1777 of Smith's letter to William Strahan, in which he described Hume's courage in the face of death in spite of his irreligiosity, attracted considerable controversy.[72] |

性格と信念 性格  片方の手で杖を持ち、もう片方の手で本を指しながら立っている男の肖像画。 ジョン・ケイによるスミスの肖像画、1790年 スミスの個人的な見解については、出版された論文から推測される以上のことはあまり知られていない。スミスは結婚することなく[54]、フランスからの帰 国後に一緒に暮らし、6年前に亡くなった母親と親密な関係を保っていたようである[55]。 スミスは、同時代人や伝記作家の何人かに、滑稽なほど無心で、話し方や歩き方に独特の癖があり、「言い表せないほど温和」な微笑みを浮かべていたと評され ている[56]。 彼は独り言を言うことで知られており[50]、その癖は幼少期に、目に見えない仲間と夢中になって会話をして微笑んでいたことから始まった[57]。 [57]ある話によると、スミスはチャールズ・タウンゼントを連れて皮なめし工場を見学し、自由貿易について議論している最中に、スミスは巨大な皮なめし の穴に入ってしまい、そこから脱出するのに助けを必要とした[58]。別の証言によれば、スミスは気が散って寝間着のまま散歩に出かけ、町から15マイル (24キロ)離れたところまで行ってしまったが、近くの教会の鐘が彼を現実に引き戻したという[57][58]。 グラスゴー大学でスミスの教え子であり、後に文学クラブで彼を知ったジェームズ・ボスウェルは、スミスは会話の中で自分の考えを話すと本の売れ行きが落ち るかもしれないと考えていたため、彼の会話は印象的ではなかったと述べている。ボズウェルによれば、彼はかつてジョシュア・レイノルズ卿に、「彼は社内に いるときは、自分が理解していることを決して話さないことをルールにしていた」と語っている[59]。 スミスは「大きな鼻、膨らんだ目、突き出た下唇、神経質な痙攣、言語障害」を持つ人物とも、「表情は男らしく、好感が持てる」人物とも表現されている [18][60]。 スミスはあるとき自分の容姿を認め、「私は本以外には何もない美男だ」と言ったと言われている[18]。最もよく知られているスミスの肖像画は、ジェーム ズ・タッシーによる横顔とジョン・ケイによる2枚の銅版画である[62]。19世紀に出版された『国富論』の再版の表紙のために制作された線刻画は、主に タッシーのメダリオンに基づいている[63]。 宗教的見解 スミスの宗教観については、学者間でかなりの議論が交わされてきた。彼の父親はキリスト教に強い関心を示しており、スコットランド国教会の穏健派に属して いた[64]。彼がスネル展を受賞した事実は、彼が英国国教会のキャリアを追求する意図を持ってオックスフォード大学に進学した可能性を示唆している [65]。 英米の経済学者ロナルド・コースは、スミスの著作が自然界や人間界の調和を説明するものとして神を明確に引用していないという事実に基づいて、スミスが神 学者であったという見解に異議を唱えている。 [66]コースによれば、スミスは「宇宙の偉大な建築家」に言及することはあるが、ジェイコブ・ヴィナーのような後の学者は「アダム・スミスが個人的な神 への信仰に傾倒していた程度を非常に誇張している」[67]、 スミスは、「動植物の生成、生命、成長、溶解」といった「自然の大いなる現象」に対する人類の好奇心が、「その原因を探究」するようになった、と書いてい る。哲学はその後、より身近な原因、あるいは神々の働きよりも人類がよく知っている原因から、それらを説明しようと努めた」[67]。スミスの社会・経済 哲学は本質的に神学的であり、彼の社会秩序モデル全体が、自然における神の働きという概念に論理的に依存していると主張する著者もいる[68]。ブレンダ ン・ロングはスミスは神学者であったと主張し[69]、ギャビン・ケネディ教授によれば、スミスは「ある意味で」クリスチャンであった[70]。 スミスはまたデイヴィッド・ヒュームとも親交があった。デイヴィッド・ヒュームは、近代的な学問の世界では彼の宗教観について議論されていたにもかかわら ず、同時代においては一般的に無神論者であるとされていた[71]。1777年にスミスがウィリアム・ストラハンに宛てた書簡が出版されたが、その中で彼 は、無宗教であるにもかかわらず死に直面したヒュームの勇気について述べており、大きな議論を呼んだ[72]。 |

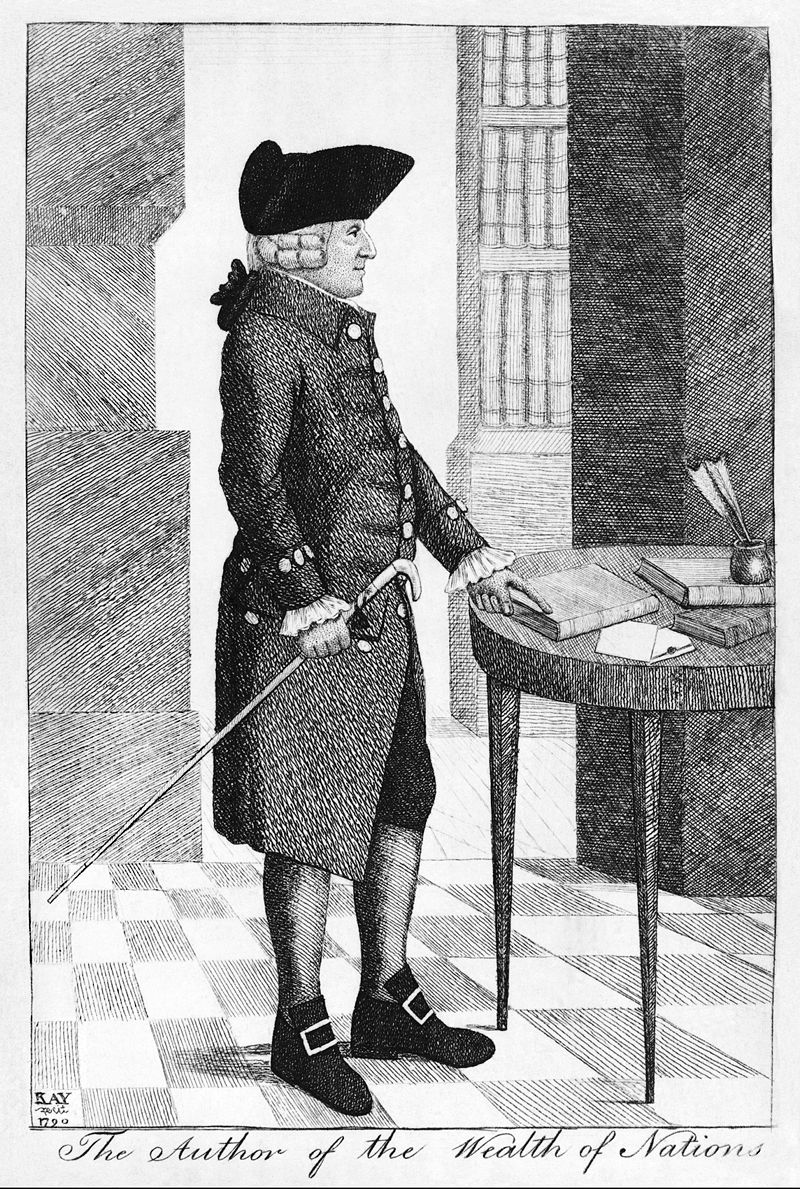

| Published works The Theory of Moral Sentiments Main article: The Theory of Moral Sentiments In 1759, Smith published his first work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, sold by co-publishers Andrew Millar of London and Alexander Kincaid of Edinburgh.[73] Smith continued making extensive revisions to the book until his death.[e] Although The Wealth of Nations is widely regarded as Smith's most influential work, Smith himself is believed to have considered The Theory of Moral Sentiments to be a superior work.[75] In the work, Smith critically examines the moral thinking of his time, and suggests that conscience arises from dynamic and interactive social relationships through which people seek "mutual sympathy of sentiments."[76] His goal in writing the work was to explain the source of mankind's ability to form moral judgment, given that people begin life with no moral sentiments at all. Smith proposes a theory of sympathy, in which the act of observing others and seeing the judgments they form of both others and oneself makes people aware of themselves and how others perceive their behaviour. The feedback received by an individual from perceiving (or imagining) others' judgment creates an incentive to achieve "mutual sympathy of sentiments" with them and leads people to develop habits, and then principles, of behaviour, which come to constitute one's conscience.[77] Some scholars have perceived a conflict between The Theory of Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations; the former emphasises sympathy for others, while the latter focuses on the role of self-interest.[78] In recent years, however, some scholars[79][80][81] of Smith's work have argued that no contradiction exists. They contend that in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith develops a theory of psychology in which individuals seek the approval of the "impartial spectator" as a result of a natural desire to have outside observers sympathise with their sentiments. Rather than viewing The Theory of Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations as presenting incompatible views of human nature, some Smith scholars regard the works as emphasising different aspects of human nature that vary depending on the situation. In the first part – The Theory of Moral Sentiments – he laid down the foundation of his vision of humanity and society. In the second – The Wealth of Nations – he elaborated on the virtue of prudence, which for him meant the relations between people in the private sphere of the economy. It was his plan to further elaborate on the virtue of justice in the third book.[82] Otteson argues that both books are Newtonian in their methodology and deploy a similar "market model" for explaining the creation and development of large-scale human social orders, including morality, economics, as well as language.[83] Ekelund and Hebert offer a differing view, observing that self-interest is present in both works and that "in the former, sympathy is the moral faculty that holds self-interest in check, whereas in the latter, competition is the economic faculty that restrains self-interest."[84] The Wealth of Nations Main article: The Wealth of Nations Disagreement exists between classical and neoclassical economists about the central message of Smith's most influential work: An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). Neoclassical economists emphasise Smith's invisible hand,[85] a concept mentioned in the middle of his work – Book IV, Chapter II – and classical economists believe that Smith stated his programme for promoting the "wealth of nations" in the first sentences, which attributes the growth of wealth and prosperity to the division of labour. He elaborated on the virtue of prudence, which for him meant the relations between people in the private sphere of the economy. It was his plan to further elaborate on the virtue of justice in the third book.[82] Smith used the term "the invisible hand" in "History of Astronomy"[86] referring to "the invisible hand of Jupiter", and once in each of his The Theory of Moral Sentiments[87] (1759) and The Wealth of Nations[88] (1776). This last statement about "an invisible hand" has been interpreted in numerous ways.  A brown building Later building on the site where Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good. It is an affectation, indeed, not very common among merchants, and very few words need be employed in dissuading them from it. Those who regard that statement as Smith's central message also quote frequently Smith's dictum:[89] It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages. However, in The Theory of Moral Sentiments he had a more sceptical approach to self-interest as driver of behaviour: How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.  The first page of a book The first page of The Wealth of Nations, 1776 London edition In relation to Mandeville's contention that "Private Vices ... may be turned into Public Benefits",[90] Smith's belief that when an individual pursues his self-interest under conditions of justice, he unintentionally promotes the good of society. Self-interested competition in the free market, he argued, would tend to benefit society as a whole by keeping prices low, while still building in an incentive for a wide variety of goods and services. Nevertheless, he was wary of businessmen and warned of their "conspiracy against the public or in some other contrivance to raise prices."[91] Again and again, Smith warned of the collusive nature of business interests, which may form cabals or monopolies, fixing the highest price "which can be squeezed out of the buyers."[92] Smith also warned that a business-dominated political system would allow a conspiracy of businesses and industry against consumers, with the former scheming to influence politics and legislation. Smith states that the interest of manufacturers and merchants "in any particular branch of trade or manufactures, is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public ... The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order, ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention."[93] Thus Smith's chief worry seems to be when business is given special protections or privileges from government; by contrast, in the absence of such special political favours, he believed that business activities were generally beneficial to the whole society: It is the great multiplication of the production of all the different arts, in consequence of the division of labour, which occasions, in a well-governed society, that universal opulence which extends itself to the lowest ranks of the people. Every workman has a great quantity of his own work to dispose of beyond what he himself has occasion for; and every other workman being exactly in the same situation, he is enabled to exchange a great quantity of his own goods for a great quantity, or, what comes to the same thing, for the price of a great quantity of theirs. He supplies them abundantly with what they have occasion for, and they accommodate him as amply with what he has occasion for, and a general plenty diffuses itself through all the different ranks of society. (The Wealth of Nations, I.i.10) The neoclassical interest in Smith's statement about "an invisible hand" originates in the possibility of seeing it as a precursor of neoclassical economics and its concept of general equilibrium; Samuelson's "Economics" refers six times to Smith's "invisible hand". To emphasise this connection, Samuelson[94] quotes Smith's "invisible hand" statement substituting "general interest" for "public interest". Samuelson[95] concludes: "Smith was unable to prove the essence of his invisible-hand doctrine. Indeed, until the 1940s, no one knew how to prove, even to state properly, the kernel of truth in this proposition about perfectly competitive market."  1922 printing of An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, edited by Edwin Cannan Conversely, classical economists see in Smith's first sentences his programme to promote "The Wealth of Nations". Using the physiocratical concept of the economy as a circular process, to secure growth the inputs of Period 2 must exceed the inputs of Period 1. Therefore, those outputs of Period 1 which are not used or usable as inputs of Period 2 are regarded as unproductive labour, as they do not contribute to growth. This is what Smith had heard in France from, among others, François Quesnay, whose ideas Smith was so impressed by that he might have dedicated The Wealth of Nations to him had he not died beforehand.[96][97] To this French insight that unproductive labour should be reduced to use labour more productively, Smith added his own proposal, that productive labour should be made even more productive by deepening the division of labour.[98] Smith argued that deepening the division of labour under competition leads to greater productivity, which leads to lower prices and thus an increasing standard of living—"general plenty" and "universal opulence"—for all. Extended markets and increased production lead to the continuous reorganisation of production and the invention of new ways of producing, which in turn lead to further increased production, lower prices, and improved standards of living. Smith's central message is, therefore, that under dynamic competition, a growth machine secures "The Wealth of Nations". Smith's argument predicted Britain's evolution as the workshop of the world, underselling and outproducing all its competitors. The opening sentences of the "Wealth of Nations" summarise this policy: The annual labour of every nation is the fund which originally supplies it with all the necessaries and conveniences of life which it annually consumes ... . [T]his produce ... bears a greater or smaller proportion to the number of those who are to consume it ... .[B]ut this proportion must in every nation be regulated by two different circumstances; first, by the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which its labour is generally applied; and, secondly, by the proportion between the number of those who are employed in useful labour, and that of those who are not so employed [emphasis added].[99] However, Smith added that the "abundance or scantiness of this supply too seems to depend more upon the former of those two circumstances than upon the latter."[100] Other works A burial  Smith's burial place in Canongate Kirkyard Shortly before his death, Smith had nearly all his manuscripts destroyed. In his last years, he seemed to have been planning two major treatises, one on the theory and history of law and one on the sciences and arts. The posthumously published Essays on Philosophical Subjects, a history of astronomy down to Smith's own era, plus some thoughts on ancient physics and metaphysics, probably contain parts of what would have been the latter treatise. Lectures on Jurisprudence were notes taken from Smith's early lectures, plus an early draft of The Wealth of Nations, published as part of the 1976 Glasgow Edition of the works and correspondence of Smith. Other works, including some published posthumously, include Lectures on Justice, Police, Revenue, and Arms (1763) (first published in 1896); and Essays on Philosophical Subjects (1795).[101] |

出版物 道徳感情論 主な記事 道徳感情論 1759年、スミスは最初の著作である『道徳感情論』を出版し、ロンドンのアンドリュー・ミラーとエディンバラのアレクサンダー・キンケイドの共同出版社 から売り出された[73]。 この著作の中でスミスは、当時の道徳的思考を批判的に検討し、良心が、人々が「感情の相互共感」[76]を求めるダイナミックで相互作用的な社会関係から 生まれることを示唆している。スミスは、他者を観察し、他者が他者と自分自身の両方に対して下す判断を見るという行為が、人々に自分自身と他者が自分の行 動をどのように受け止めているかを認識させるという共感理論を提唱している。他者の判断を知覚すること(あるいは想像すること)から個人が受け取るフィー ドバックは、他者との「感情の相互共感」を達成しようとする動機を生み出し、人々を行動の習慣、ひいては原則へと導き、それが自分の良心を構成するように なる[77]。 前者は他者への共感を強調し、後者は利己心の役割に焦点を当てている[78]。しかし近年、スミスの著作を研究する学者[79][80][81]の中に は、矛盾は存在しないと主張する者もいる。彼らの主張によれば、『道徳感情論』においてスミスは、外部の観察者に自分の感情に共感してもらいたいという自 然な欲求の結果として、個人が「公平な観衆」の承認を求めるという心理学の理論を展開している。スミス研究者の中には、『道徳感情論』と『国富論』を相容 れない人間観の提示とみなすのではなく、状況によって異なる人間性の側面を強調しているとみなす者もいる。第1部『道徳感情論』では、スミスは人間観と社 会観の基礎を築いた。第二部『国富論』では、慎重の徳について詳しく述べた。これは彼にとって、経済の私的領域における人間関係を意味した。オッテソン は、両書はその方法論においてニュートン的であり、道徳、経済、言語を含む大規模な人間の社会秩序の創造と発展を説明するために、同様の「市場モデル」を 展開していると論じている[82]。 [83]エーケルンドとヘベールは異なる見解を提示しており、どちらの著作にも利己心が存在し、「前者では共感が利己心を抑制する道徳的能力であるのに対 し、後者では競争が利己心を抑制する経済的能力である」と述べている[84]。 国富論 主な記事 国富論 スミスの最も影響力のある著作の中心的なメッセージについては、古典派経済学者と新古典派経済学者の間に意見の相違が存在する: An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776)』である。新古典派経済学者はスミスの見えざる手[85]を強調し、古典派経済学者はスミスが「国富」を促進するためのプログラムを最初の文 章で述べていると考えている。彼は慎重の徳について詳しく説明したが、それは彼にとって、経済の私的領域における人々の関係を意味していた。第3巻では正 義の徳についてさらに詳しく説明する予定であった[82]。 スミスは『天文学史』[86]において「木星の見えざる手」に言及し、『道徳感情論』[87](1759年)と『国富論』[88](1776年)のそれぞ れにおいて一度ずつ「見えざる手」という用語を使用している。この最後の「見えざる手」についての記述は、さまざまに解釈されている。  茶色の建物 スミスが『国富論』を執筆した場所にある後の建物 それゆえ、すべての個人が、自分の資本を国内産業の扶助にできるかぎり使用するように努め、またその生産物が最大の価値をもつようにその産業を指導するよ うに努めるように、すべての個人は必然的に、社会の年間収入をできるかぎり大きくするように努める。一般に、彼は公共の利益を促進するつもりもなければ、 自分がどれほど促進しているかも知らない。外国の産業よりも国内の産業を支援することを好むのは、自分の安全だけを意図しているからであり、その生産物が 最大の価値を持つようにその産業を導くのは、自分の利益だけを意図しているからである。また、それが社会にとって悪いことだとは限らない。自分の利益を追 求することで、社会の利益を本当に促進しようとする場合よりも効果的に促進することがよくある。私は、公共の利益のために商売をするような人たちが、あま り良いことをしているのを知らない。このような気取りは、商人の間では実に一般的ではなく、このような気取りを思いとどまらせるのに必要な言葉はほとんど ない。 この発言をスミスの中心的なメッセージとみなす人々は、スミスの次の独言も頻繁に引用している[89]。 われわれが夕食を期待するのは、肉屋や醸造業者やパン屋の善意からではなく、彼ら自身の利益に対する配慮からである。われわれは、彼らの人間性ではなく自 己愛に訴え、彼らに自分の必要を語るのではなく、彼らの利点を語るのである。 しかし、『道徳感情論』では、行動の原動力としての利己心に対して、より懐疑的なアプローチをとっている: 人間がいかに利己的であろうと、その本性には、他人の幸福に関心を持ち、その幸福を見る喜び以外には何も得られないにもかかわらず、その幸福を自分にとっ て必要なものとする原理があることは明らかである。  本の最初のページ 『国富論』の最初のページ(1776年ロンドン版) マンデヴィルの「私的な悪徳は......公的な利益に転化されるかもしれない」という主張[90]に関連して、スミスは、個人が正義の条件のもとで私利 私欲を追求するとき、彼は意図せずして社会の利益を促進するという信念を持っている。自由市場における利己的な競争は、価格を低く抑えることによって社会 全体に利益をもたらし、同時に多種多様な財やサービスに対するインセンティブを生み出すと彼は主張した。それにもかかわらず、彼は実業家を警戒し、彼らの 「公衆に対する陰謀、あるいは価格を吊り上げるための他の策略」[91]を警告した。スミスは何度も何度も、陰謀団や独占を形成し、「買い手から搾り取る ことができる」最高価格を決定する可能性のある、実業界の利害の癒着性について警告した。スミスは、製造業者や商人の利害は「貿易や製造のいかなる特定の 分野においても、一般大衆の利害とは常にいくつかの点で異なっており、正反対でさえある」と述べている。したがって、スミスの最大の懸念は、ビジネスが政 府から特別な保護や特権を与えられることにあるようだ。対照的に、そのような特別な政治的恩恵がない場合には、ビジネス活動は一般的に社会全体にとって有 益であると彼は考えていた: 分業の結果、あらゆる芸術の生産が増大し、よく統治された社会では、民衆の最下層にまで及ぶ普遍的な豊かさがもたらされる。そして、他の労働者もまったく 同じ状況にあるため、自分の商品を大量に、あるいはそれと同じように、彼らの商品を大量に交換することができる。彼は、彼らが必要とするものを彼らに豊富 に供給し、彼らもまた、彼が必要とするものを彼に十分に供給する。(国富論』I.i.10)。 見えざる手」に関するスミスの記述に対する新古典派的関心は、それを新古典派経済学とその一般均衡概念の先駆とみなす可能性に由来する。この関連性を強調 するために、サミュエルソン[94]はスミスの「見えざる手」の記述を引用し、「一般の利益」を「公共の利益」に置き換えている。サミュエルソン[95] は次のように結論付けている: 「スミスは彼の見えざる手の教義の本質を証明することができなかった。実際、1940年代まで、完全競争市場に関するこの命題の真理の核心を証明する方法 を、適切に述べることさえ、誰も知らなかった。」  エドウィン・カナン編『国富の本質と原因に関する探究』1922年刊 逆に、古典派経済学者たちは、スミスの最初の文章に、『国富論』を推進するための彼のプログラムを見る。循環過程としての経済という生理学的概念を用いる と、成長を確保するためには、第2期の投入が第1期の投入を上回らなければならない。したがって、第1期の生産物のうち、第2期の投入物として使用されな かったり、使用できなかったりするものは、成長に寄与しないため、非生産的労働とみなされる。これは、スミスがフランスで、とりわけフランソワ・ケスネか ら聞いたものであり、スミスは彼の考え方に感銘を受け、彼が事前に亡くなっていなければ『国富論』を彼に捧げていたかもしれないほどであった[96] [97]。労働をより生産的に使用するために非生産的労働を削減すべきであるというこのフランス人の洞察に、スミスは、分業を深めることによって生産的労 働をさらに生産的にすべきであるという彼自身の提案を加えた[98]。 [スミスは、競争のもとでの分業の深化が生産性の向上につながり、それが価格の低下、ひいてはすべての人の生活水準の向上、すなわち「一般的な豊かさ」と 「普遍的な豊かさ」につながると主張した。市場の拡大と生産の増加は、生産の継続的な再編成と新しい生産方法の発明につながり、それがさらなる生産の増 加、価格の低下、生活水準の向上につながる。したがって、スミスの中心的なメッセージは、ダイナミックな競争のもとでは、成長マシンが「国富」を確保する ということである。スミスの主張は、イギリスが世界の工房として、すべての競争相手を凌駕し、凌ぎを削って進化していくことを予言していた。国富論』の冒 頭の文章は、この方針を要約している: あらゆる国の年間労働は、その国が毎年消費するすべての生活必需品と便益を、元来供給する資金である。[この生産物は......それを消費しようとする 人々の数に大なり小なり比例する......しかし、この比例は、どの国においても、二つの異なる状況によって調節されなければならない; 第一に、その労働が一般に適用される技術、器用さ、判断力によって、である、 第二に、有用な労働に従事する者の数と、そうでない者の数との間の割合である[強調は追加]。 しかし、スミスは、「この供給が豊かであるか乏しいかは、後者よりもこれら2つの状況のうち前者に依存するように思われる」と付け加えている[100]。 その他の作品 埋葬  カノンゲート・カークヤードにあるスミスの埋葬場所 死の直前、スミスはほとんどすべての原稿を破棄した。晩年、彼は2つの主要な論説を計画していたようである。1つは法の理論と歴史に関するもの、もう1つ は科学と芸術に関するものであった。死後に出版された『Essays on Philosophical Subjects』は、スミス自身の時代に至るまでの天文学の歴史と、古代の物理学と形而上学に関する考察をまとめたもので、おそらく後者の論文の一部を 含んでいるのだろう。法学講義』は、スミスの初期の講義から取られたメモと『国富論』の初期草稿で、1976年のグラスゴー版『スミスの著作と書簡』の一 部として出版された。その他の著作には、死後に出版されたものも含めて、Lectures on Justice, Police, Revenue, and Arms (1763)(初版は1896年)、Essays on Philosophical Subjects (1795)などがある[101]。 |

| Legacy In economics and moral philosophy The Wealth of Nations was a precursor to the modern academic discipline of economics. In this and other works, Smith expounded how rational self-interest and competition can lead to economic prosperity. Smith was controversial in his own day and his general approach and writing style were often satirised by Tory writers in the moralising tradition of Hogarth and Swift, as a discussion at the University of Winchester suggests.[102] In 2005, The Wealth of Nations was named among the 100 Best Scottish Books of all time.[103] In light of the arguments put forward by Smith and other economic theorists in Britain, academic belief in mercantilism began to decline in Britain in the late 18th century. During the Industrial Revolution, Britain embraced free trade and Smith's laissez-faire economics, and via the British Empire, used its power to spread a broadly liberal economic model around the world, characterised by open markets, and relatively barrier-free domestic and international trade.[104] George Stigler attributes to Smith "the most important substantive proposition in all of economics". It is that, under competition, owners of resources (for example labour, land, and capital) will use them most profitably, resulting in an equal rate of return in equilibrium for all uses, adjusted for apparent differences arising from such factors as training, trust, hardship, and unemployment.[105] Paul Samuelson finds in Smith's pluralist use of supply and demand as applied to wages, rents, and profit a valid and valuable anticipation of the general equilibrium modelling of Walras a century later. Smith's allowance for wage increases in the short and intermediate term from capital accumulation and invention contrasted with Malthus, Ricardo, and Karl Marx in their propounding a rigid subsistence–wage theory of labour supply.[106] Joseph Schumpeter criticised Smith for a lack of technical rigour, yet he argued that this enabled Smith's writings to appeal to wider audiences: "His very limitation made for success. Had he been more brilliant, he would not have been taken so seriously. Had he dug more deeply, had he unearthed more recondite truth, had he used more difficult and ingenious methods, he would not have been understood. But he had no such ambitions; in fact he disliked whatever went beyond plain common sense. He never moved above the heads of even the dullest readers. He led them on gently, encouraging them by trivialities and homely observations, making them feel comfortable all along."[107] Classical economists presented competing theories to those of Smith, termed the "labour theory of value". Later Marxian economics descending from classical economics also use Smith's labour theories, in part. The first volume of Karl Marx's major work, Das Kapital, was published in German in 1867. In it, Marx focused on the labour theory of value and what he considered to be the exploitation of labour by capital.[108][109] The labour theory of value held that the value of a thing was determined by the labour that went into its production. This contrasts with the modern contention of neoclassical economics, that the value of a thing is determined by what one is willing to give up to obtain the thing.  A brown building The Adam Smith Theatre in Kirkcaldy The body of theory later termed "neoclassical economics" or "marginalism" formed from about 1870 to 1910. The term "economics" was popularised by such neoclassical economists as Alfred Marshall as a concise synonym for "economic science" and a substitute for the earlier, broader term "political economy" used by Smith.[110][111] This corresponded to the influence on the subject of mathematical methods used in the natural sciences.[112] Neoclassical economics systematised supply and demand as joint determinants of price and quantity in market equilibrium, affecting both the allocation of output and the distribution of income. It dispensed with the labour theory of value of which Smith was most famously identified with in classical economics, in favour of a marginal utility theory of value on the demand side and a more general theory of costs on the supply side.[113] The bicentennial anniversary of the publication of The Wealth of Nations was celebrated in 1976, resulting in increased interest for The Theory of Moral Sentiments and his other works throughout academia. After 1976, Smith was more likely to be represented as the author of both The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, and thereby as the founder of a moral philosophy and the science of economics. His homo economicus or "economic man" was also more often represented as a moral person. Additionally, economists David Levy and Sandra Peart in "The Secret History of the Dismal Science" point to his opposition to hierarchy and beliefs in inequality, including racial inequality, and provide additional support for those who point to Smith's opposition to slavery, colonialism, and empire. Emphasised also are Smith's statements of the need for high wages for the poor, and the efforts to keep wages low. In The "Vanity of the Philosopher: From Equality to Hierarchy in Postclassical Economics", Peart and Levy also cite Smith's view that a common street porter was not intellectually inferior to a philosopher,[114] and point to the need for greater appreciation of the public views in discussions of science and other subjects now considered to be technical. They also cite Smith's opposition to the often expressed view that science is superior to common sense.[115] Smith also explained the relationship between growth of private property and civil government: Men may live together in society with some tolerable degree of security, though there is no civil magistrate to protect them from the injustice of those passions. But avarice and ambition in the rich, in the poor the hatred of labour and the love of present ease and enjoyment, are the passions which prompt to invade property, passions much more steady in their operation, and much more universal in their influence. Wherever there is great property there is great inequality. For one very rich man there must be at least five hundred poor, and the affluence of the few supposes the indigence of the many. The affluence of the rich excites the indignation of the poor, who are often both driven by want, and prompted by envy, to invade his possessions. It is only under the shelter of the civil magistrate that the owner of that valuable property, which is acquired by the labour of many years, or perhaps of many successive generations, can sleep a single night in security. He is at all times surrounded by unknown enemies, whom, though he never provoked, he can never appease, and from whose injustice he can be protected only by the powerful arm of the civil magistrate continually held up to chastise it. The acquisition of valuable and extensive property, therefore, necessarily requires the establishment of civil government. Where there is no property, or at least none that exceeds the value of two or three days' labour, civil government is not so necessary. Civil government supposes a certain subordination. But as the necessity of civil government gradually grows up with the acquisition of valuable property, so the principal causes which naturally introduce subordination gradually grow up with the growth of that valuable property. (...) Men of inferior wealth combine to defend those of superior wealth in the possession of their property, in order that men of superior wealth may combine to defend them in the possession of theirs. All the inferior shepherds and herdsmen feel that the security of their own herds and flocks depends upon the security of those of the great shepherd or herdsman; that the maintenance of their lesser authority depends upon that of his greater authority, and that upon their subordination to him depends his power of keeping their inferiors in subordination to them. They constitute a sort of little nobility, who feel themselves interested to defend the property and to support the authority of their own little sovereign in order that he may be able to defend their property and to support their authority. Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defence of the rich against the poor, or of those who have some property against those who have none at all.[116] In British imperial debates Smith opposed empire. He challenged ideas that colonies were key to British prosperity and power. He rejected that other cultures, such as China and India, were culturally and developmentally inferior to Europe. While he favoured "commercial society", he did not support radical social change and the imposition of commercial society on other societies. He proposed that colonies be given independence or that full political rights be extended to colonial subjects.[117] Smith's chapter on colonies, in turn, would help shape British imperial debates from the mid-19th century onward. The Wealth of Nations would become an ambiguous text regarding the imperial question. In his chapter on colonies, Smith pondered how to solve the crisis developing across the Atlantic among the empire's 13 American colonies. He offered two different proposals for easing tensions. The first proposal called for giving the colonies their independence, and by thus parting on a friendly basis, Britain would be able to develop and maintain a free-trade relationship with them, and possibly even an informal military alliance. Smith's second proposal called for a theoretical imperial federation that would bring the colonies and the metropole closer together through an imperial parliamentary system and imperial free trade.[118] Smith's most prominent disciple in 19th-century Britain, peace advocate Richard Cobden, preferred the first proposal. Cobden would lead the Anti-Corn Law League in overturning the Corn Laws in 1846, shifting Britain to a policy of free trade and empire "on the cheap" for decades to come. This hands-off approach toward the British Empire would become known as Cobdenism or the Manchester School.[119] By the turn of the century, however, advocates of Smith's second proposal such as Joseph Shield Nicholson would become ever more vocal in opposing Cobdenism, calling instead for imperial federation.[120] As Marc-William Palen notes: "On the one hand, Adam Smith's late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Cobdenite adherents used his theories to argue for gradual imperial devolution and empire 'on the cheap'. On the other, various proponents of imperial federation throughout the British World sought to use Smith's theories to overturn the predominant Cobdenite hands-off imperial approach and instead, with a firm grip, bring the empire closer than ever before."[121] Smith's ideas thus played an important part in subsequent debates over the British Empire. Portraits, monuments, and banknotes  A statue of Smith in Edinburgh's High Street, erected through private donations organised by the Adam Smith Institute Smith has been commemorated in the UK on banknotes printed by two different banks; his portrait has appeared since 1981 on the £50 notes issued by the Clydesdale Bank in Scotland,[122][123] and in March 2007 Smith's image also appeared on the new series of £20 notes issued by the Bank of England, making him the first Scotsman to feature on an English banknote.[124]  Statue of Smith built in 1867–1870 at the old headquarters of the University of London, 6 Burlington Gardens A large-scale memorial of Smith by Alexander Stoddart was unveiled on 4 July 2008 in Edinburgh. It is a 10-foot (3.0 m)-tall bronze sculpture and it stands above the Royal Mile outside St Giles' Cathedral in Parliament Square, near the Mercat cross.[125] 20th-century sculptor Jim Sanborn (best known for the Kryptos sculpture at the United States Central Intelligence Agency) has created multiple pieces which feature Smith's work. At Central Connecticut State University is Circulating Capital, a tall cylinder which features an extract from The Wealth of Nations on the lower half, and on the upper half, some of the same text, but represented in binary code.[126] At the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, outside the Belk College of Business Administration, is Adam Smith's Spinning Top.[127][128] Another Smith sculpture is at Cleveland State University.[129] He also appears as the narrator in the 2013 play The Low Road, centred on a proponent on laissez-faire economics in the late 18th century, but dealing obliquely with the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the recession which followed; in the premiere production, he was portrayed by Bill Paterson. A bust of Smith is in the Hall of Heroes of the National Wallace Monument in Stirling. Five paving stones, displaying quotations from Smith's works, were unveiled in December 2023 in the High Street, Glasgow. The stones were commissioned by the University of Glasgow to mark the 300th anniversary of Smith's birth.[130] Panmure House Adam Smith resided at Panmure House from 1778 to 1790. In 2008, the house was purchased by the Edinburgh Business School at Heriot-Watt University and funds were raised for its restoration.[131][132] In 2018 it was formally opened as a study centre in Smith's honour.[133] As a symbol of free-market economics Smith has been celebrated by advocates of free-market policies as the founder of free-market economics, a view reflected in the naming of bodies such as the Adam Smith Institute in London, multiple entities known as the "Adam Smith Society", including an historical Italian organisation,[134] and the U.S.-based Adam Smith Society,[135][136] and the Australian Adam Smith Club,[137] and in terms such as the Adam Smith necktie.[138] Former US Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan argues that, while Smith did not coin the term laissez-faire, "it was left to Adam Smith to identify the more-general set of principles that brought conceptual clarity to the seeming chaos of market transactions." Greenspan continues that The Wealth of Nations was "one of the great achievements in human intellectual history."[139] P.J. O'Rourke describes Smith as the "founder of free market economics."[140] Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman believed in 1976, 200 years after the publishing of The Wealth of Nations, that the work of Adam Smith was, "...far more immediately relevant today than he was at the Centennial of The Wealth of Nations in 1876."[141] Other writers have argued that Smith's support for laissez-faire (which in French means leave alone) has been overstated. Herbert Stein wrote that the people who "wear an Adam Smith necktie" do it to "make a statement of their devotion to the idea of free markets and limited government", and that this misrepresents Smith's ideas. Stein writes that Smith "was not pure or doctrinaire about this idea. He viewed government intervention in the market with great skepticism...yet he was prepared to accept or propose qualifications to that policy in the specific cases where he judged that their net effect would be beneficial and would not undermine the basically free character of the system. He did not wear the Adam Smith necktie." In Stein's reading, The Wealth of Nations could justify the Food and Drug Administration, the Consumer Product Safety Commission, mandatory employer health benefits, environmentalism, and "discriminatory taxation to deter improper or luxurious behavior".[142] Similarly, Vivienne Brown stated in The Economic Journal that in the 20th-century United States, Reaganomics supporters, The Wall Street Journal, and other similar sources have spread among the general public a partial and misleading vision of Smith, portraying him as an "extreme dogmatic defender of laissez-faire capitalism and supply-side economics".[143] In fact, The Wealth of Nations includes the following statement on the payment of taxes: The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state.[144] Some commentators have argued that Smith's works show support for a progressive, not flat, income tax and that he specifically named taxes that he thought should be required by the state, among them luxury-goods taxes and tax on rent.[145] Yet Smith argued for the "impossibility of taxing the people, in proportion to their economic revenue, by any capitation".[146] Smith argued that taxes should principally go toward protecting "justice" and "certain publick institutions" that were necessary for the benefit of all of society, but that could not be provided by private enterprise.[147] Additionally, Smith outlined the proper expenses of the government in The Wealth of Nations, Book V, Ch. I. Included in his requirements of a government is to enforce contracts and provide justice system, grant patents and copy rights, provide public goods such as infrastructure, provide national defence, and regulate banking. The role of the government was to provide goods "of such a nature that the profit could never repay the expense to any individual" such as roads, bridges, canals, and harbours. He also encouraged invention and new ideas through his patent enforcement and support of infant industry monopolies. He supported partial public subsidies for elementary education, and he believed that competition among religious institutions would provide general benefit to the society. In such cases, however, Smith argued for local rather than centralised control: "Even those publick works which are of such a nature that they cannot afford any revenue for maintaining themselves ... are always better maintained by a local or provincial revenue, under the management of a local and provincial administration, than by the general revenue of the state" (Wealth of Nations, V.i.d.18). Finally, he outlined how the government should support the dignity of the monarch or chief magistrate, such that they are equal or above the public in fashion. He even states that monarchs should be provided for in a greater fashion than magistrates of a republic because "we naturally expect more splendor in the court of a king than in the mansion-house of a doge".[148] In addition, he allowed that in some specific circumstances, retaliatory tariffs may be beneficial: The recovery of a great foreign market will generally more than compensate the transitory inconvenience of paying dearer during a short time for some sorts of goods.[149] However, he added that in general, a retaliatory tariff "seems a bad method of compensating the injury done to certain classes of our people, to do another injury ourselves, not only to those classes, but to almost all the other classes of them".[150] Economic historians such as Jacob Viner regard Smith as a strong advocate of free markets and limited government (what Smith called "natural liberty"), but not as a dogmatic supporter of laissez-faire.[151] Economist Daniel Klein believes using the term "free-market economics" or "free-market economist" to identify the ideas of Smith is too general and slightly misleading. Klein offers six characteristics central to the identity of Smith's economic thought and argues that a new name is needed to give a more accurate depiction of the "Smithian" identity.[152][153] Economist David Ricardo set straight some of the misunderstandings about Smith's thoughts on free market. Many continue to fall victim to the thinking that Smith was a free-market economist without exception, though he was not. Ricardo pointed out that Smith was in support of helping infant industries. Smith believed that the government should subsidise newly formed industry, but he did fear that when the infant industry grew into adulthood, it would be unwilling to surrender the government help.[154] Smith also supported tariffs on imported goods to counteract an internal tax on the same good. Smith also fell to pressure in supporting some tariffs in support for national defence.[154] Some have also claimed, Emma Rothschild among them, that Smith would have supported a minimum wage,[155] although no direct textual evidence supports the claim. Indeed, Smith wrote: The price of labour, it must be observed, cannot be ascertained very accurately anywhere, different prices being often paid at the same place and for the same sort of labour, not only according to the different abilities of the workmen, but according to the easiness or hardness of the masters. Where wages are not regulated by law, all that we can pretend to determine is what are the most usual; and experience seems to show that law can never regulate them properly, though it has often pretended to do so. (The Wealth of Nations, Book 1, Chapter 8) However, Smith also noted, to the contrary, the existence of an imbalanced, inequality of bargaining power:[156] A landlord, a farmer, a master manufacturer, a merchant, though they did not employ a single workman, could generally live a year or two upon the stocks which they have already acquired. Many workmen could not subsist a week, few could subsist a month, and scarce any a year without employment. In the long run, the workman may be as necessary to his master as his master is to him, but the necessity is not so immediate. |

遺産 経済学と道徳哲学において 国富論』は、経済学という近代的な学問分野の先駆けとなった。スミスはこの著作や他の著作の中で、合理的な利己心と競争がいかに経済的繁栄をもたらすかを 説いた。ウィンチェスター大学での議論が示唆するように、スミスは当時物議を醸し、彼の一般的なアプローチや文体は、ホガースやスウィフトの道徳的な伝統 を受け継ぐトーリー派の作家たちによってしばしば風刺された[102]。2005年、『国富論』は「スコットランドの本ベスト100」に選ばれた [103]。 スミスをはじめとするイギリスの経済理論家たちが提唱した議論に照らし合わせると、18世紀後半、イギリスでは重商主義に対する学術的な信仰が衰退し始め た。産業革命の間、イギリスは自由貿易とスミスの自由放任経済学を受け入れ、大英帝国を通じて、開かれた市場と比較的障壁のない国内外貿易を特徴とする、 広く自由主義的な経済モデルを世界中に広めるために権力を行使した[104]。 ジョージ・スティグラーは、「経済学の中で最も重要な実質的命題」をスミスに与えたとしている。それは、競争のもとでは、資源(例えば労働、土地、資本) の所有者はそれらを最も有益に使用し、その結果、訓練、信頼、苦難、失業などの要因から生じる見かけ上の差異を調整した上で、すべての使用について均衡に おいて等しい収益率をもたらすというものである[105]。 ポール・サミュエルソンは、賃金、レント、利潤に適用されるスミスの需要と供給の多元的な使用に、1世紀後のウォルラスの一般均衡モデリングの有効かつ貴 重な先取りを見出す。スミスは、資本蓄積と発明による短期的・中期的な賃金の上昇を許容しており、マルサス、リカルド、カール・マルクスが労働供給の硬直 的な自給理論を提唱していたのとは対照的であった[106]。 ジョセフ・シュンペーターはスミスを技術的な厳密さに欠けると批判していたが、そのおかげでスミスの著作はより多くの読者にアピールすることができたと主 張していた: 「彼の限界が成功をもたらした。もし彼がもっと優秀であったなら、これほど真剣に受け取られることはなかっただろう。もし彼がもっと深く掘り下げていた ら、もっと奥深い真理を発掘していたら、もっと難解で独創的な方法を用いていたら、理解されることはなかっただろう。しかし、彼にはそのような野心はな かった。事実、彼は常識の範囲を超えることを嫌っていた。彼は、どんなに鈍い読者でも、決して頭上から動かなかった。彼は読者を優しく導き、些細なことや 家庭的な観察によって読者を励まし、読者を終始心地よくさせた」[107]。 古典派経済学者たちは、「労働価値説」と呼ばれるスミスの理論に対抗する理論を提示した。古典派経済学の流れを汲む後のマルクス経済学も、部分的にはスミ スの労働理論を利用している。カール・マルクスの主要著作『資本論』の第1巻は、1867年にドイツ語で出版された。その中でマルクスは、価値の労働理論 と、彼が資本による労働の搾取であると考えたものに焦点を当てた[108][109]。価値の労働理論は、物の価値はその生産に費やされた労働によって決 定されるとした。これは、モノの価値はそのモノを手に入れるために人が何をあきらめるかによって決まるという、新古典派経済学の現代的な主張とは対照的で ある。  茶色の建物 カークカルディにあるアダム・スミス劇場 後に「新古典派経済学」あるいは「限界主義」と呼ばれる理論群は、1870年頃から1910年頃にかけて形成された。経済学」という用語は、アルフレッ ド・マーシャルなどの新古典派経済学者によって、「経済科学」の簡潔な同義語として、またスミスが使用した以前のより広範な用語である「政治経済学」の代 用として広められた[110][111]。これは、自然科学で使用される数学的手法がこのテーマに与えた影響に対応していた[112]。新古典派経済学 は、古典派経済学においてスミスが最も有名であった労働価値説を排除し、需要側では価値の限界効用説を、供給側ではより一般的な費用説を支持した [113]。 1976年に『国富論』出版200周年が祝われ、その結果、『道徳感情論』やスミスの他の著作に対する関心が学界全体で高まった。1976年以降、スミス は『国富論』と『道徳感情論』の著者として、ひいては道徳哲学と経済学の創始者として扱われるようになった。彼のホモ・エコノミクス(経済人)もまた、道 徳的な人間として表現されることが多かった。さらに、経済学者のデイヴィッド・レヴィとサンドラ・パートは、「The Secret History of the Dismal Science 」の中で、スミスがヒエラルキーに反対し、人種的不平等を含む不平等を信じたことを指摘し、スミスが奴隷制度、植民地主義、帝国に反対したことを指摘する 人々にさらなる支持を与えている。また、スミスが貧しい人々のために高い賃金を必要とし、賃金を低く抑えようとしたことも強調されている。哲学者の虚栄 心』の中で: ポスト古典派経済学における平等からヒエラルキーへ」において、ピートとレヴィはまた、一般の街頭ポーターが哲学者よりも知的に劣っているわけではないと いうスミスの見解を引用し[114]、科学や現在では専門的であると考えられている他の主題についての議論において、一般大衆の見解をより高く評価する必 要性を指摘している。彼らはまた、科学は常識よりも優れているというしばしば表明される見解に対するスミスの反対意見も挙げている[115]。 スミスはまた、私有財産の増大と市民政府との関係についても説明している: 人間は社会である程度は安全に共に暮らすことができるが、そのような情念の不正から彼らを守る民政官は存在しない。しかし、富める者には貪欲と野心が、貧 しい者には労働を憎み、現在の安楽と享楽を愛する感情が、財産を侵害することを促す。大きな財産があるところには、大きな不平等がある。一人の大金持ちに は少なくとも500人の貧乏人がいるはずであり、少数の豊かさは多数の貧しさを前提としている。金持ちの豊かさは貧乏人の怒りを買い、貧乏人はしばしば貧 しさに駆られ、妬みに駆られて金持ちの財産を侵害する。長年の、あるいはおそらくは何世代にもわたる労働によって手に入れた貴重な財産の所有者が、一晩安 心して眠ることができるのは、民政官の庇護の下においてのみである。彼は常に未知の敵に取り囲まれており、彼らを挑発したことはないが、なだめることはで きない。そして、その不正から彼を守ることができるのは、それを懲らしめるために常に差し伸べられる市民司法の強力な腕だけである。したがって、価値ある 広範な財産の獲得には、必然的に民政の確立が必要となる。財産がない場合、あるいは少なくとも2、3日の労働の価値を超える財産がない場合には、民政はそ れほど必要ではない。民政は一定の従属を前提としている。しかし、民政の必要性が価値ある財産の獲得とともに次第に高まるように、従属を自然にもたらす主 要な原因も、価値ある財産の成長とともに次第に高まる。(中略)劣った富を持つ人々は、優れた富を持つ人々の財産の所有権を守るために団結するが、それ は、優れた富を持つ人々が、彼らの財産の所有権を守るために団結するためである。劣等な羊飼いや牧夫たちはみな、自分たちの群れや羊の群れの安全が、偉大 な羊飼いや牧夫の群れの安全にかかっていること、自分たちより劣った権威の維持が、偉大な権威の維持にかかっていること、そして自分たちが彼に従属するこ とが、劣等な者たちを自分たちに従属させておく力にかかっていることを感じている。彼らは一種の小貴族を構成し、自分たちの小君主が自分たちの財産を守 り、権威を支えることができるようにするために、その小君主の財産を守り、権威を支えることに関心を感じている。民政は、それが財産の保障のために制定さ れている限りにおいて、実際には、貧乏人に対する金持ちの防衛のため、あるいはまったく財産を持たない者に対する多少の財産を持つ者の防衛のために制定さ れているのである[116]。 イギリスの帝国論議において スミスは帝国に反対していた。彼は植民地がイギリスの繁栄と権力の鍵であるという考えに異議を唱えた。彼は中国やインドのような他の文化がヨーロッパより も文化的にも発展的にも劣っているという考えを否定した。彼は「商業社会」を支持したが、急進的な社会変革や他の社会への商業社会の押し付けは支持しな かった。彼は植民地に独立を与えるか、植民地の臣民に完全な政治的権利を拡大することを提案した[117]。 スミスの植民地に関する章は、19世紀半ば以降のイギリスの帝国論議を形成する助けとなった。国富論』は帝国問題に関して曖昧なテキストとなった。植民地 に関する章において、スミスは大西洋を挟んで帝国の13のアメリカ植民地の間で生じている危機をどのように解決するかについて思案した。彼は緊張を和らげ るために2つの異なる案を提示した。第一の案は、植民地に独立を認め、友好的な形で別れることで、イギリスは植民地と自由貿易関係を築き、維持することが できる。スミスの第二の提案は、帝国議会制度と帝国自由貿易を通じて植民地とメトロポールとをより緊密に結びつける理論的な帝国連合を求めた[118]。 19世紀のイギリスにおけるスミスの最も著名な弟子であった平和論者のリチャード・コブデンは第一の提案を好んだ。コブデンは1846年に反コーン法同盟 を率いてコーン法を覆し、イギリスを自由貿易と「安価な」帝国という政策に移行させることになる。このような大英帝国に対する手放しのアプローチは、コブ デン主義またはマンチェスター学派として知られるようになる[119]。しかし、今世紀に入ると、ジョセフ・シールド・ニコルソンのようなスミスの第二の 提案の擁護者たちは、コブデン主義に反対し、代わりに帝国連邦を主張するようになる[120]。 マルク=ウィリアム・パレンが指摘しているように: 一方では、アダム・スミスの19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてのコブデン派の信奉者たちは、彼の理論を用いて、漸進的な帝国の委譲と「安価な」帝国を 主張した。他方で、イギリス世界全体の帝国連邦のさまざまな支持者たちは、スミスの理論を用いて、優勢なコブデン派の手をかけない帝国主義的アプローチを 覆し、その代わりに、しっかりとした握力で帝国をこれまで以上に緊密なものにしようとした」[121]。スミスの思想はこのように、その後の大英帝国をめ ぐる議論において重要な役割を果たした。 肖像画、記念碑、紙幣  エジンバラのハイ・ストリートにあるスミスの銅像は、アダム・スミス研究所が組織した個人の寄付によって建てられた。 スミスの肖像は1981年からスコットランドのクライズデール銀行が発行する50ポンド紙幣に描かれており[122][123]、2007年3月にはイン グランド銀行が発行する新シリーズの20ポンド紙幣にも描かれ、イギリスの紙幣に描かれた初のスコットランド人となった[124]。  1867年から1870年にかけてロンドン大学旧本部(バーリントン・ガーデンズ6番地)に建てられたスミス像 2008年7月4日、アレクサンダー・ストッダートによるスミスの大規模な記念碑がエディンバラで除幕された。高さ10フィート(3.0メートル)のブロ ンズ像で、パーラメント・スクエアのセント・ジャイルズ大聖堂の外、ロイヤル・マイルの上、メルカットの十字架の近くに立っている[125]。20世紀の 彫刻家ジム・サンボーン(アメリカ中央情報局にあるクリプトスの彫刻で有名)は、スミスの作品をモチーフにした複数の作品を制作している。セントラル・コ ネティカット州立大学には、『国富論』からの抜粋を下半分に、同じ文章の一部をバイナリコードで表現した背の高い円筒形の「Circulating Capital」がある[126]。ノースカロライナ大学シャーロット校のベルク経営学部の外には、アダム・スミスの「Spinning Top」がある。 [127][128]クリーブランド州立大学にもスミスの彫刻がある[129]。2013年に上演された舞台『The Low Road』では、18世紀後半の自由放任経済学の提唱者を中心に、2007年から2008年にかけての金融危機とそれに続く不況を斜めに扱った語り手とし ても登場する。 スミスの胸像は、スターリングの国立ウォレス記念碑の英雄の館にある。 2023年12月、グラスゴーのハイ・ストリートにスミスの作品からの引用を記した5つの敷石が除幕された。この石は、スミスの生誕300年を記念してグ ラスゴー大学が依頼したものである[130]。 パンミュア・ハウス アダム・スミスは1778年から1790年までパンミュア・ハウスに住んでいた。2008年、この邸宅はヘリオット・ワット大学のエジンバラ・ビジネスス クールが購入し、修復のための資金が集められた[131][132]。2018年、スミスに敬意を表し、研究センターとして正式にオープンした [133]。 自由市場経済学の象徴として スミスは自由市場経済学の創始者として自由市場政策の擁護者たちから称えられ、その見解はロンドンのアダム・スミス研究所、歴史的なイタリアの組織を含む 「アダム・スミス協会」として知られる複数の組織[134]、米国を拠点とするアダム・スミス協会[135][136]、オーストラリアのアダム・スミ ス・クラブ[137]といった組織の名称や、アダム・スミス・ネクタイといった用語に反映されている[138]。 元米連邦準備制度理事会(FRB)議長のアラン・グリーンスパンは、スミスは自由放任という言葉を造語したわけではないが、「市場取引という一見混沌とし た状況に概念的な明瞭さをもたらす、より一般的な一連の原則を特定することはアダム・スミスに任された」と主張している。グリーンスパンは、『国富論』は 「人類の知的歴史における偉大な業績のひとつ」であると続けている[139]。P.J.オルークは、スミスを「自由市場経済学の創始者」と評している [140]。 ノーベル経済学賞受賞者のミルトン・フリードマンは、『国富論』出版から200年後の1976年に、アダム・スミスの業績は「...1876年の『国富 論』100周年記念のときよりも、今日の方がはるかに即座に適切である」と考えていた[141]。 他の作家は、スミスの自由放任(フランス語で放任を意味する)支持は誇張されすぎていると主張している。ハーバート・スタインは、「アダム・スミスのネク タイを締める」のは「自由市場と限定政府という思想への献身を表明するため」であり、これはスミスの思想を誤って表現していると書いている。スタインは、 スミスは「この考えについて純粋でも教条主義的でもなかった。政府による市場への介入を非常に懐疑的に見ていた......しかし、その正味の効果が有益 であり、システムの基本的な自由な性格を損なわないと判断した具体的な場合には、その政策を受け入れたり、そのような政策に対する制限を提案したりする用 意があった。彼はアダム・スミスのネクタイを締めなかった」。スタインの読みでは、『国富論』は、食品医薬品局、消費者製品安全委員会、雇用者の健康手当 の義務化、環境保護主義、「不適切な行動や贅沢な行動を抑止するための差別的課税」を正当化することができる[142]。 同様に、ヴィヴィアン・ブラウンは『エコノミック・ジャーナル』誌で、20世紀のアメリカでは、レーガノミクス支持者、『ウォールストリート・ジャーナ ル』紙、その他同様の情報源が、スミスを「自由放任資本主義とサプライサイド経済学の極端な独断的擁護者」として描き、一般大衆の間にスミスの部分的で誤 解を招くようなビジョンを広めてきたと述べている[143]。 事実、『国富論』には納税に関する次のような記述がある: すべての国家の臣民は、政府の扶養のために、それぞれの能力にできるだけ比例して、つまり国家の保護のもとでそれぞれ享受する収入に比例して、拠出すべき である」[144]。 一部の論者は、スミスの著作は、所得税は一律ではなく累進課税を支持しており、彼は国家が要求すべきと考える税金、とりわけ贅沢品税と家賃課税を具体的に 挙げていると論じている[145]。 [145]しかし、スミスは「人民の経済的収入に比例して、いかなる人頭賦課によっても課税することは不可能である」と主張した[146]。スミスは、税 金は主として「正義」と、社会全体の利益のために必要であるが私企業では提供することができない「特定の公的制度」を保護するために使われるべきであると 主張した[147]。 さらに、スミスは『国富論』第5巻第1章において、政府の適切な経費について概説している。政府の要件には、契約の執行と司法制度の提供、特許権や複製権 の付与、インフラストラクチャーなどの公共財の提供、国防の提供、銀行の規制などが含まれている。政府の役割は、道路、橋、運河、港湾など、「いかなる個 人に対しても、その利益を返済することができないような性質の」財を提供することであった。彼はまた、特許権の行使や幼児産業独占の支援を通じて、発明や 新しいアイデアを奨励した。彼は初等教育への部分的な公的補助を支持し、宗教団体間の競争は社会に一般的な利益をもたらすと考えていた。しかしこのような 場合、スミスは中央集権的な統制よりもむしろ地方的な統制を主張した: 維持するための収入を得られないような性質の公共事業であっても......国家の一般収入によって維持するよりも、地方や州の行政機関の管理の下で、地 方や州の収入によって維持する方が常によい」(『国富論』V.i.d.18)。最後に彼は、政府が君主や首長の威厳をどのように支えるべきかを概説した。 彼は、「我々は当然、王の宮廷にはドージェの邸宅よりも華麗なものを期待する」[148]から、君主には共和制の君主よりも格別の待遇を与えるべきである とさえ述べている。 さらに彼は、特定の状況においては、報復関税が有益である場合もあることを認めている: 大きな海外市場の回復は、一般的に、ある種の商品について短期間により安く支払うという一過性の不便さを補う以上のものであろう」[149]。 しかし、一般的には、報復関税は「わが国民の特定の階級に加えられた損害を補償するための悪い方法であり、それらの階級だけでなく、ほとんどすべての他の 階級に別の損害を与えるものである」と付け加えた[150]。 ジェイコブ・ヴィナーなどの経済史家は、スミスを自由市場と制限された政府(スミスは「自然的自由」と呼んだ)の強力な擁護者であるとみなしているが、自 由放任の独断的な支持者ではないとみなしている[151]。 経済学者のダニエル・クラインは、スミスの思想を特定するために「自由市場経済学」や「自由市場経済学者」という言葉を使うのは一般的すぎるし、少し誤解 を招くと考えている。クラインはスミスの経済思想のアイデンティティの中心となる6つの特徴を提示しており、「スミス的」アイデンティティをより正確に描 写するためには新しい名称が必要であると主張している[152][153]。経済学者のデイヴィッド・リカルドは、自由市場に関するスミスの思想について の誤解を正した。多くの人々が、スミスは例外なく自由市場経済主義者であったという考え方に陥り続けている。リカルドは、スミスが乳幼児産業を援助するこ とを支持していたことを指摘した。スミスは、政府は新しく形成された産業に補助金を出すべきだと考えていたが、彼は、幼児産業が成人に成長したとき、政府 の援助を放棄することを嫌がるようになることを恐れていた[154]。スミスはまた、同じ商品に対する内税に対抗するために、輸入品に対する関税を支持し ていた。スミスはまた、国防のためにいくつかの関税を支持するという圧力にも屈した[154]。 また、エマ・ロスチャイルドのように、スミスは最低賃金を支持していたと主張する者もいるが[155]、その主張を裏付ける直接的なテキスト上の証拠はな い。実際、スミスはこう書いている: 労働の価格は、どこでも非常に正確に把握することはできない。同じ場所で、同じ種類の労働に対して、労働者の能力の違いだけでなく、主人の容易さや困難さ によっても、異なる価格が支払われることがよくある。法律で賃金が規制されていない場合、われわれが決定できるのは、最も一般的な賃金を決めるふりをする ことだけである。(国富論』第1巻第8章)。 しかし、スミスはそれとは逆に、不均衡で不平等な交渉力の存在も指摘している[156]。 地主、農民、製造業者、商人は、労働者を一人も雇っていないにもかかわらず、一般に、すでに手に入れた在庫によって1、2年は生活することができた。多く の労働者は1週間も生活できず、1カ月も生活できる者はほとんどいない。長い目で見れば、労働者は主人にとって必要であるのと同様に、主人にとっても必要 であるかもしれない。 |

| Critique of political economy Organizational capital List of abolitionist forerunners List of Fellows of the Royal Society of Arts People on Scottish banknotes Adam Smith's America |

政治経済学批判 組織資本 廃止論者の先駆者リスト 王立芸術協会フェローのリスト スコットランド紙幣の人物 アダム・スミスのアメリカ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adam_Smith |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆