アダム・スミス『諸国民の富』ノート

On Adam Smith's "An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of

the Wealth of Nations"

このページは「マイケル・ムーア vs. アダム・スミス」の授業 の資料編です。この資料の出典は、堂目卓生『アダム・スミス:『道徳感情論』と『国富論』の世界』中公新書(No.1936)、東京:中央公論新社、 2008年、とくに第4〜8章、 Pp.143-267.からとりました。ここで触れられる項目は下記のとおりです。(授業ポータル:暴力について考える(2010年))『国富論』は『諸国民の富』とも言われます。

こ のページを作ったあとに、大阪大学大学院経済学研究科長の堂目卓生さんと出会いました。堂目先生におかれましては、私のページのいくつかの内 容をご存知で、このページの趣旨についても、学生・院生諸氏が、上掲の本や、それに関連する書物を紐解き(繙き)、アダム・スミスへの思索を深めるための ものだと、モラルサポートしていただけることを念じております。なお、堂目先生のご著作からのOCR読み取りなので、誤変換が含まれています。自分で原著 ——どこの図書館が書店でも簡単に手に入るものですので——と対照してチェックをおねがいします。私のサイトは、みなさんの自習と学習の意欲を促すサイト で、これだけで勉強できるサイトではありません!

■ 豊かさとはどういうことか? ■分業 ■分業の効果 ■資本蓄積 ■経済発展 ■経済理論:重商主義 ■財政 ■交換性向 ■互恵市場 ■交換社会 ■市場の条件——「見えざる手」 ■労働者階級 ■労働者の限界 ■個人の浪費 ■地主の怠惰 ■土地・地代・借地人 ■商人 ■戦費という無駄 ■政府の浪費 ■土地に対する愛着 ■労働集約度および付加率 ■エコノミック・ヒストリー ■大変革は意図せざるところにある ■植民地統治 ■植民地政策の誤り ■重商主義の欠陥 ■国債による国家の弱体化 ■自由競争 ■規制緩和

■豊かさとはどういうことか?

「すべての国民の年間の労働は、その国民が年聞に消費するすべての生活の必需品や便益品を供給する原資であって、消費される必需品や便益品 は、つねに、国民の労働の直接の生産物であるか、あるいはその生産物で他の諸国民から購入されるものである。/したがってこの生産物、またはこの生産物で 購入されるものと、それを消費する人びとの数との割合が大きいか小さいかに応じて、その国民が必要とする必需品と便益品が十分に供給されているといえるか どうかが決まる。/この割合は、どの国民にあっても二つの異なる事情によって規定される。すなわち、第一には、その国民の労働が一般に使用される際の熟 練、技量、および判断力によって、そして第二には、有用な労働に従事する人びとの数と、そうでない人びとの数との割合によって規定される。国の土壌や気候 や国土の広さがいかなるものであろうとも、そうした特定の状況の中で、その国民が受ける必需品と便益品の年間の供給が豊かであるか乏しいかは、それら二つ の事情に依存する」(堂目 2008:143-144)。

■分業

「必需品と便益品の供給が豊かであるか否かは、それら二つの事情[労働生産性と生産的労働・不生産的労働の比率]のうち、後者よりも前者に よるところが大きいように思われる。猟師や漁夫からなる未開民族においては、働くことのできる個人は、すべて、多かれ少なかれ有用労働に従事し、自分自身 を養うとともに、自分の家族または種族のうち、狩猟や漁獲に出かけるには高齢すぎたり、若すぎたり、病弱にすぎたりすることに努める。しかしながら、その ような民族は極度に貧しいために、幼児や高齢者や長びく病気にかかっている者を、ときには直接に殺害するか、ときには放置して飢え死にさせるか、野獣に食 われるままにしなければならないことがしばしばある。少なくとも彼らは、そう考えている。/これに反し、文明化し繁栄している民族の間では、多数の人びと は全然労働しないのに、働く人びとの大部分よりも十倍、しばしば百倍もの労働の生産物を消費する。しかし、その社会の労働全体の生産物はきわめて多いの で、すべての人が十分な供給を受けるし、最低最貧の労働者ですら、倹約かつ勤勉であれば、未開人が獲得しうるよりも大きな割合の生活必需品や便益品を享受 することができる。労働の生産力のこの増大の原因、および労働の生産物が社会のさまざまな階級や状態の人びとの聞に自然に分配される法則が、本書の第一編 の主題をなす」(堂目 2008:146-147)。

■分業の効果

「文明国においては、最下層の人でさえ、何千人もの人びとの助力と協力を通じて、[中略]彼が普通に使う生活設備の供給を受けている。たし かに、地位の高い人びとのもっと法外な奢侈に比べれば、最下層の人の生活設備は実に単純で容易に見えるにちがいない。しかし、ヨーロッパの王侯の生活設備 が勤勉で質素な農夫のそれよりも優っている程度は、後者の生活設備が、何万もの裸の未開人の生命と自由の絶対的支配者であるアフリカの国王のそれよりも 優っている程度には必ずしも及ばないであろう。(『国富論』一編一章)」(堂目 2008:157)。

「多くの利益を生み出すこの分業は、もともとは、それが生み出す一般的富裕を予見し意図するという人間の英知の結果ではない。それは、その ような広範な有用性をめざすわけではない人間本性の中のひとつの性向、すなわち、ある物を他の物と取引し、交換し、交易する性向の、きわめて緩慢で漸次的 ではあるが、必然的な結果なのである。この性向が人間の本性の中にある、それ以上は説明できないような本源的な原理のひとつであるのかどうか、それとも、 この方がもっともらしく思われるが、推理したり話したりする人間の能力の必然的な結果であるのかどうか、そのことは、本書の研究主題にはならない。(『国 富論』一編ニ章)」(堂目 2008:158)。

■資本蓄積

「どの国民でも、労働が用いられる際の熟練、技量、判断力の実際の状態がいかなるものであれ、その状態が変わらなければ、年間の供給が豊富 であるか稀少であるかは、有用労働に従事する人びとの数と、従事しない人びとの数との割合による。後に明らかにするように、有用かつ生産的な労働者の数 は、どこでも、彼らを働かせる資本の量と、資本が用いられる方法とに比例する。それゆえ、第二編は、資本の性質、資本がしだいに蓄積されていく仕方、そし て資本の用いられ方に応じて資本が作動させる労働量の相違を扱う」(堂目 2008:148-149)。

「資本の蓄積は、ものごとの性質上、分業に先立っていなければならない。資本の蓄積先行して進むことに応じてのみ、分業の進展が可能になる のである。分業が進むに同数の人びとが加工する原材料の総量は大幅に増加する。また、各人の作業が徐々に単純化されていくとともに、それらの作業を容易に し、短縮するために、さまざまな新しい機械が発明される。したがって、分業が進む中で、同数の職人に雇用を与え続けるためには、以前と同量の食料のストッ クとともに、分業が進んでいなかったときに必要とされた量よりも多量の原材料と道具のストックが、前もって蓄積されていなければならない(『国富「論』二 編序論)」(堂目 2008:178-179)。

■経済発展

「労働が用いられる上での熟練、技量、判断力に関してかなり進歩した諸国民は、労働を全体として向かわせる方向に関して、きわめて異なる計 画にしたがってきた。それらの計画は必ずしもすべて生産物の増大に等しく有利であったわけではない。ある国の政策は農村の産業に特別な奨励を与えてきた し、別の国の政策は都市の産業に与えてきた。ほとんどどの国も、すべての種類の産業を平等かつ公平に扱ってはこなかった。ローマ帝国の没落以来、ヨーロッ パの政策は、農村の産業である農業よりも、都市の産業である工芸、製造業、商業を優遇してきた。この政策を導入し確立したと思われる事情は第3編で説明さ れる」(堂目 2008:150)。

■経済理論:

重商主義 「さまざまな計画は、おそらく、最初は特定層の人びとの私利や偏見によって、社会全体の福利に及ぼす影響についての配慮や予見もなしに導入されたのであっ た。しかし、それらの計画はきわめて多様な経済理論を生んだ。それらの中の、あるものは都市で行なわれる産業の重要さを強調し、別のものは農村で行なわれ る産業の重要さを強調した。それらの理論は、学識者の意見だけでなく、主権者や国家の政治方針に対しても大きな影響を与えた。私は第四編で、それらの理論 と、それらがさまざまな時代や国民に与えた主要な影響を、できるかぎり十分かつ明確に説明することに努めた」(堂目 2008:150)。

■財政

「最初の四編の目的は、国民の収入は何によるものなのか、あるいは、さまざまな時代と国において国民の年間の消費を満たす原資がどのような 性質のものであったのかを説明することである。これに対して、最後の第五編は、主権者または国家の収入を扱う。この編で私が示そうと努めたのは、第一に、 主権者または国家にとっての必要な費用は何であるのか、またそうした費用のうちのどれが社会全体の一般的納付金によって支払われるべきか、またそのうちの どれが社会のある特定部分だけの、つまりある特定の成員たちの納付金によって支払われるべきか、第二に、社会全体が負担すべき費用の支払いを社会全体が負 担するのにどのような方法があるのか、そうした方法のそれぞれがもっ主な利点や欠点はどのようなものであるのか、第三に、そして最後に、近代のほとんどす べての政府が、税収のある部分を担保に借金をするに至った理由や原因、つまり国債を発行するに至った理由や原因は何であるのか、また国債が、真の富、すな わち社会の土地と労働による年生産物に対してどのような影響を与えてきたのかということである」(堂目 2008:153)

■交換性向

「交換性向の本当の基礎は、人間本性の中であのように支配的な説得性向なのである。説得するための何かの議論が提起されるときには、それが 適切な効果をもつことが、つねに期待される。ある人が月について、真実とはかぎらないことを何か主張するとき、彼は反論されるかもしれないことに不安を感 じるであろう。そして、もしも説得しようとしている人が彼と同じ考え方をしていることがわかれば、彼は非常に喜ぶだろう。したがって、われわれは大いに説 得能力を養成すべきであり、実際に、われわれは意図しないでそうしているのである。人間の全生涯が説得能力の訓練に費やされるのだから、その結果、物を交 換するために必要な方法が取得されるにちがいない」(堂目 2008:160)。

■互恵市場

「人間社会のすべての構成員は、相互の援助を必要としているし、同様に相互の侵害にさらされている。必要な援助が、愛情から、感謝から、そ して友情と尊敬から、相互に提供される場合は、その社会は繁栄し、そして幸福である。[中略]しかし、必要な援助が、そのように寛容で私心のない動機から 提供されることがないとしても、また、その社会構成員の間に相互の愛情や愛着がないとしても、その社会は、幸福さと快適さにおいてるとはいえ、必然的に解 体することはないであろう。/社会は、さまざまな人びとの間でーーさまざまな商人の間でそうであるように——相互の愛情や愛着がなくても、社会は有用であ るという感覚によって存立する。そして、社会は、その中の誰も他人に対して責務や感謝を感じなくても、人びとが、ある一致した評のもとで損得勘定にもとづ いた世話を交換することによって、いぜんとして維持されるのである。(『道徳感情論』二部二編三章)」(堂目 2008:161-162)。

「われわれが食事ができると思うのは、肉屋や酒屋やパン屋の慈悲心に期待するからではなく、彼ら自身の利益に対する彼らの関心に期待するか らである。われわれが呼びかけるのは、彼らの人間愛に対してではなく、自愛心に対してであり、われわれが彼らに語りかけるのは、われわれ自身の必要につい てではなく、彼らの利益についてである。(『国富論』一編二章)」(堂目 2008:163)。

■交換社会

「分業が完全に確立してしまうと、人が自分自身の労働の生産物のうちのきわめてわずかな部分にすぎなくなる。人が欲求の圧倒的大部分を充足 するのは、自分の労働の生産物のうちで、自身による消費を超える余剰部分をのうちで自分が必要とする部分と交換することによってである。こう交換すること によって生活するようになり、言いかえれば、ある程社会そのものが商業社会と呼ぶのが適当なものになる(『国富論』一編4章)」(堂目 2008:166)。

■市場の条件——「見えざる手」

「どの個人も、できるだけ自分の資本を国内の労働を支えることに用いるよう努め、その生産物が最大の価値をもつように労働を方向づけること にも努めるのであるから、必然的に社会の年間の収入をできるだけ大きくしようと努めることになる。たしかに個人は、一般に公共の利益を推進しようと意図し てもいないし、どれほど推進しているかを知っているわけでもない。[中略]個人はこの場合にも、他の多くの場合と同様に、見えざる手に導かれて、自分の意 図の中にはまったくなかった目的を推進するのである。それが個人の意図にまったくなかったということは、必ずしも社会にとって悪いわけではない。自分自身 の利益を追求することによって、個人はしばしば、社会の利益を、実際にそれを促進しようと意図する場合よりも効果的に推進するのである。(『国富論』四編 二章)」(堂目 2008:170-171)。

「同業組合の排他的特権と、徒弟法、および特定の職業での競争を、それがなければ参入によって増えるかもしれない数よりも少人数に限定する すべての法律は、程度は劣るにしても独占と同じ傾向をもっている。それらは一種の拡大された独占であり、しばしば何世代にもわたって、またすべての種類の 職業で、特定商品の市場価格を自然価格以上に保ち、そこで用いられる労働の賃金と資本の利潤とを自然率よりもいくらか高くする。市場が自然価格を上回る状 態は、それを生んだ行政上の規制があるかぎり続くであろう(『国富論』一編七章)」(堂目 2008:172)。

■労働者階級

「労働者階級のうち、上層で育った人たちは、本来の職業では仕事を見つけることができないため、最下層の仕事を求めるようになるだろう。し かし、最下層の仕事も、もともとの働き手だけでなく、他のすべての階層からあふれてきた働き手が過剰となっているため雇用を求める競争は激しくなり、労働 の賃金を、労働者の最も惨めで乏しい生計の水準で引き下げるだろう。多くの人びとは、こうした厳しい条件でさえ雇用を見つけることもできず、飢えるか、あ るいは物乞いをするなり、極悪非道を犯すなりして、生計を求めることになるだろう。(『国富論』一編八章)」(堂目 2008:181-182)。

■労働者の限界

「労働者の利害は社会の利害と緊密に結びついているとはいえ、労働者は社会の利害を理解することも、社会の利害と自分の利害との結びつきを 理解することもできない。労働者の生活状態は、必要な情報を受け取るための時聞を彼に与えないし、たとえ十分な情報を得たとしても、教育と習慣のせいで適 切な判断を下すことができないのが普通である。したがって、公共の審議において、労働者の声は、特定の場合には、雇い主によって、労働者の利益のためでは なく雇い主の利益のために、鼓舞され、扇動され、支持されることがある。しかし、その場合を除けば、労働者の声は、ほとんど聞いてもらえないし、尊重もさ れない」(『国富論』一編十一章)」(堂目 2008:203)。

■個人の浪費

「浪費についていうなら、支出に駆り立てる性向は、現在の享楽を求める情念である。この情念は、ときには激しくて、きわめて抑制しがたいこ ともあるが、一般には瞬間的で、たまにしか起きない。これに対し、貯蓄に駆り立てる原理は、自分の状態を改善しようとする欲求である。この欲求は、一般に は平静で非激情的ではあるが、胎内からわれわれとともに生まれ、われわれが墓に入るまで決して離れることがない。[中略]ほとんどの人は、支出性向にとき どき支配され、また、人によっては、ほとんどの場合に支配されるのであるが、大部分の人びとにおいては、生涯の平均をとれば、支出性向よりも倹約性向の方 が優位を占め、その優位さは著しいように思われる。(『国富論』2編3章)(堂目 2008:190)。

■地主の怠惰

「[地主階級・資本家階級・労働者階級の]三つの階級の中で、地主階級だけは、収入が労働も気苦労もなしに、いわばひとりでに、彼ら自身の 企図とは無関係に入ってくる。境遇が安楽で安定していることの自然な結果として、地主は怠惰になり、そのため、彼らは単に無知であるだけでなく、公的に定 める規則の結果を予測し理解するために必要とされる知性の活用もできないことが多い。(『国富論』一編十一章)」(堂目 2008:192)。

■土地・地代・借地人

「大土地所有者は、土地改良の現状が提供しうる水準を上回る地代を借地人に要求した。借地人たちは、これに同意する条件として、土地を改良 するためにどれだけ資本を投入しても、それが利潤とともに回収されるだけの期間、土地の保有を保障されるという条件を提示した。地主は、虚栄心から、この 条件を喜んで受けいれたが、それは高くつくことになった。長期借地契約の起源はここにある。(『国富論』三編四章)」」(堂目 2008:211)。

■商人

「商人や親方製造業者は、しばしば郷土の寛大さにつけこみ、郷土の利害ではなく自分たちの利害が公共の利害と一致するのだという、まことに 単純ではあるが正直な信念から、郷土を説得して彼の利益をも公共の利益をも放棄させてきた。しかしながら、商業や製業のどの部門でも、業者たちの利害は、 つねに何らかの点で公共の利害とは異なるし、それに対立することもある。市場を拡大し、競争を制限することは、つねに業者たちの利となる。市場を拡大する ことは、しばしば公共の利益と十分一致するであろう。しかし、競争を制限することは、つねに公共の利益に反するにちがいない。競争の制限によって、業者た ちは利潤を自然な水準以上に引き上げることができ、自分たちの利益のために、他のすべての同胞市民たちに、ばかげた税を課すことができる。商業上たは規制 について、この階級から提案されるものには、つねに多大けるべきであり、最も周到な注意だけでなく、最も疑り深い注意を払っ慎重に検討した上でなければ、 決して彼らの提案を採用しれ川害が公共の利害と一致しない階級の人びと、一般に公共を欺くこと、とする階級の人びと、そして、実際、これまで多くの場合に 公共を欺き級の人びとから出されている提案なのである。(『国富論』1編11章)」(堂目 2008:194)。

■戦費という無駄

「四回にわたる対仏戦争の過程で、イギリス国民は、戦争によって毎年生じる臨時費の他に、一億四五OO万ポンド以上の債務を背負うことに なったのだから、戦費の総額はどう計算してみても二億ポンドを下回ることはない。名誉革命以来、さまざまな場合に、この国の土地と労働の年間生産物のこれ ほどの大きな部分が、異常な数の不生産的な人びとを維持するために使用されてきた。もしそれらの戦争が、これほど多額の資本を、不生な方向に向かわせな かったならば、その大部分は、自然に、生産的な人びとの維持に使用されただろうし、彼らの労働は、自分たちの消費の全価値を利潤とともに回収したであろ う。[中略]その場合、今日までに国の真の富と収入がどれほど速く増大しえたか像することさえ容易ではないであろう。(『国富論』二編3章)」(堂目 2008:194-195)。

■政府の浪費

「政府の浪費は、富と改良に向けてのイングランドの自然の進歩を遅らせたには違いないが、それを停止することはできなかった。[中略]政府 が重税を取り立てる中で、諸個人の倹約や品行方正によって、つまり自分自身の状態をよりよくしようとする一般的で継続的な努力によって、資本は、黙々と、 そして徐々に蓄積されてきたのである。[中略〕したがって、国王や大臣たちが奢侈禁止法や外国産奢侈品の禁止禁止によって、個人の家計を監視し、その支出 を抑制するような素振りをするのは、非礼僭越のきわみである。国王や大臣こそつねに、また、何の例外もなしに、社会の最大の浪費家なのだ、彼らは自分たち 自身の支出をよく監視するがいい。そして、個人の支出は安心して個人にまかせておけばいい。もし国王や大臣の浪費が国を滅ぼすことがないならば、国民の浪 費が国を滅ぼすことは決してないであろう。(『国富論』2編3章)」(堂目 2008:196)。

■土地に対する愛着

「農村の美しき、田園生活の楽しさ、それが約束する心の平静、そして不当な法律によってじゃまされないかぎり与えられる独立心、これらは多 かれ少なかれ万人を引きつける魅力をもっている。そして、土地を耕作することこそ人間の本来の運命であったのだから、人類の歴史のあらゆる段階において、 人間は、この原初の仕事への愛着をもち続けているように思われる。(『国富論』三編一章」(堂目 2008:199)。

■労働集約度および付加率

「ある国の資本が以上三つ[農業・製造業・貿易]の目的のすべてには十分でない場合には、資本のうちで農業に使用される部分が大きいのに比 例して、それが国内で活動させる生産的労働の量も大きいだろうし、この資本の使用がその社会の土地と労働の年間生産物につけ加える価値も大きいであろう。 農業の次には、製造業に使用される資本が最大の量の生産労働を活動させ、年生産物に最大の価値をつけ加える。輸出貿易に使用される資本は、これらの三つの うちで最小の効果しかもたない」(『国富論』二編五章)」(堂目 2008:204)。

■エコノミック・ヒストリー

「ゲルマン民族とスキタイ民族がローマ帝国西部の諸州を侵略した後、何世紀もの問、激変によって引き起こされた混乱が続いた。蛮族が先住民 に対して行なった略奪と暴行は、町と農村の聞の商業を途絶させてしまった。町は見捨てられ、農村は耕作されずに放置され、ローマ帝国のもとでかなり繁栄し ていたヨーロッパの西部地域は、極度の貧困と野蛮に落ち込んだ。混乱が続くなか、蛮族の首長や主要な指導者たちは、地方の土地を獲得または強奪した。土地 の大部分は耕作されていなかったが、耕作されていようといまいと所有者なしに残された土地はまったくなかった。土地はすべて占拠され、しかも、その半は少 数の大土地所有者によって占拠されたのだった。(『国富論』三編二章)」(堂目 2008:206)。

■大変革は意図せざるところにある

「このようにして、社会の幸福にとって最大の重要さをもっ変革が、社会に奉仕しようとする意図をまったくもたない二つの階層の人びとによっ てもたらされた。唯一の動機は、子どもじみた虚栄心を満足させることであった。商人や手工業者も、滑稽さの点では、大土地所有者とくらべてはるかにましで あるにしても、自分たちの利益だけを考えて、一ペニーでも手に入る所なら一ペニーでも運用しようという行商人的性格にしたがって行動したにすぎない。両者 とも、一方の愚行と他方の勤労がしだいに実現しつつあった大変革を知ってはいなかったし、予見もしていなかった。(『国富論』三編四章)」(堂目 2008:212)。

■植民地統治

「ヨーロッパの政策は、アメリカ植民地の最初の建設においても、また植民地の統治に関するかぎり、その後の繁栄においても、誇るべきものは ほとんどない。植民地建設の最初の計画を支配し指導した原理は、愚行と不正であった。すなわち、金や銀の鉱山を探し求めた愚行と、無害な先住民の土地を奪 い取った不正である。先住民たちは、最初に到着した国冒険家たちに危害を加えるどころか、あらゆる親切と歓待をもって彼らを迎った。その後、植民地を建設 した官険家たちは、金銀鉱山の発見という妄想的な計画よりも、もっとまともな、もっと称賛すべき他の動機をつけ加えたが、そうした動機でさえ、ヨーロッパ の政策の名誉になるようなものはほとんどない。(『国富論』四編七章二節)」(堂目 2008:216)。

「植民地が完成し、本国の関心を引くほど重要なものになったとき、植民地に対して本国が行なった最初の規制は、つねに、植民地貿易を本国が 独占すること、植民地の市場を制限して、その犠牲の上に本国の市場を拡大すること、したがって植民地の繁栄を速め、促進するよりは、むしろ遅らせ、阻止す ることをめざすものであった。ヨーロッパ諸国の植民地政策における最も本質的な違いのひとつは、独占の仕方にある。それらの中で最良のもの、すなわちイン グランドの独占の仕方にしても、反自由主義的で抑圧的な程度が、他国よりも幾分ましであったにすぎない。(『国富論』四編七章二節)(堂目 2008:217-218)。

■植民地政策の誤り

「アメリカ大陸と喜望峰経由の東インド航路が発見されたとき、たまたまヨーロッパ人の武力が先住民の武力を圧倒していたため、ヨーロッパ人 は、遠方の園で、あらゆる種類の不正を行なっても処罰されないでいることができた。おそらく、これからは、これらの国の住民はより強くなり、一方、ヨー ロッパ人はより弱くなり、世界のあらゆる地域の住民が勇気と力において対等になるだろう。そうなれば、諸国民は、相互に畏敬の念をもつようになるので、不 正を抑制し、相互の権利を尊重し合うようになるだろう。しかし、すべての国と国の間の広範な貿易が、自然に、あるいは必然的に促進する、知識とあらゆる種 類の改良の相互交流ほど、力の平等を確立するものはないように思われる。(『国富論』編七章三節)」(堂目 2008:223-224)。

■重商主義の欠陥

「諸国民は、自国の利益はすべての隣国を貧乏にしてしまうことであると教えられてきた。各国の国民は、自国と貿易するすべての国民の繁栄を 怒りの目で見て、彼らの利益は自国の損失だと考えるようになった。諸個人の聞の商業と同様、諸国民の聞の貿易は、本来は連合と友情の絆であるはずなのに、 不和と敵意の源泉となっている。[中略]この教義を考案したのも拡げたのも、もとは独占精神であったことに疑いの余地はない。(『国富論』四編三章二 節)」(堂目 2008:228)。

■国債による国家の弱体化

「長期国債によって資金調達を行なう方法をとった国は、すべて、しだいに弱体化していった。最初にそれを始めたのはイタリアの諸共和国だっ たようである。ジェノヴァとヴェネツィアは、それらのうちで、今なお独立国と称しうるただ二つの国であるが、ともに、国債のために弱体化してしまった。ス ペインは、国債による資金調達の方法をイタリアの諸共和国から学んだようであるが、税制が、イタリア諸共和国よりも思慮に欠けたものであったため、本来の 国力の割には、イタリア諸共和国よりもさらに弱体化した。[中略]フランスは、その自然資源の豊かさにもかかわらず、同種の重い財政負担のもとにあえいで いる。オランダ共和国は、国債のために、ジェノヴァやヴェネツィアと同じくらい衰弱している。他のどの国をも弱体化させた資金調達の方法が、グレート・プ リテンにおいてだけ、まったく無害だということがありうるだろうか。(『国富論』五編三章)」(堂目 2008:232-233)。

■自由競争

「優先と抑制の体系がすべて除去されれば、単純かつ明快な自然的自由の体系が自然に確立される。そこでは、正義の諸法を犯さないかぎり、す べての人が自分のやり方で利益を追求することができ、自分の労働と資本を使って、どの人、またはどの階層の人とも自由に競争することができる。主権者は、 遂行しようとすれば必ず無数の迷妄に惑わされ、また、人間のどんな知恵や知識をもってしでも適切に遂行できない義務から、すなわち個人の勤労を監督し、そ れを社会の利益に最も適った用途に向かわせるという義務から完全に解放される。(『国富論』四編九章)」(堂目 2008:237)。

■規制緩和

「グレート・ブリテンに植民地貿易の独占権を与えている法律を、少しずつかつ徐々に緩和し、やがてほとんど自由にしてしまうことは、暴動や 無秩序の危険からグレート・ブリテンを永久に解放する唯一の方策である。それは、資本の一部を過度に成長した事業から引き上げ、保護された産業よりも利潤 の低い他の産業にふり向けることを可能にし、そうせざるをえなくする唯一の方策である。そして、それは、保護された産業部門を徐々に縮小させ、他の産業部 門を徐々に拡張させることによって、すべての産業部門を、完全な自由が必然的に確立し、また完全な自由だけが維持しうる自然で健全で適正な均衡に向かって て、しだいに復帰させることができる唯一の方策だと思われる。(『国富論』4編7章3節)(堂目 2008:239-240)

■アメリカの植民地

「アメリカの指導者たちの社会的な地位を維持し、彼らの野心を満足させる方法としては、本国議会に議席を用意すること以上に明快なものはな いと思われるが、いずれにせよ、何らかの方法を取らないかぎり、彼らが自発的に服従することはありそうにない。われわれは、彼らを武力で服従させようとす る場合に流される血の一滴一滴が、われわれの同胞の血か、あるいは同胞にしたいと思う人びとの血であるということを忘れるべきではない。事態がここまで進 んでしまっているのに、植民地を武力だけで簡単に征服することができると自惚れている人は、非常に愚鈍な人である。/現在、大陸議会と呼んでいるものの決 議を取り仕切っている人びとは、ヨーロッパの偉大な大臣たちでさえ感じることができないほどの社会的重要性を自分の中に感じているであろう。彼らは、商店 主、小商人、弁護士から政治家や立法者となり、今や、広大な帝国のための新しい政治形態を作り出すことに携わっている。そして、彼らは、この帝国が、かつ て世界に存在したことのない偉大で恐るべき帝国になるだろうと自負し、事実そうなる見込みもきわめて大きいのである。(『国富論』四編七章三節)」(堂目 2008:255)。

「アメリカで生まれた人びとは、アメリカが帝国の政治の中心から遠く離れていることは、それほど長く続かないだろうと考えるかもしれない し、その考えには、もっともな理由がある。アメリカにおける富と人口と改良のこれまでの進歩は非常に急速であり、おそらく一世紀もたてば、アメリカの納税 額がプリテンの納税額を超えるであろう。そうなれば、帝国の首都は、帝国全体の防衛と維持に最も貢献する地方へと自然に移動することになるであろう。 (『国富論』四編七章三節)」(堂目 2008:257)。

「私は、この統合が容易に実現できるとか、実施にあたって、困難を、しかも大きな困難をともなわないとか言うつもりはない。もっとも、私は 克服できそうもない困難があるという話をこれまで聞いたことはない。おそらく、主な困難は、事柄の本質からではなく、大西洋をはさむ両岸の人びとの偏見や 世論から生ずるのであろう。(『国富論』四編七章三節)」(堂目 2008:258)。

■経済的意味からみたアメリカの独立

「もし分離案が採用されるのなら、グレー ト・プリテンは、平時の植民地防衛の年間経費からただちに解放されるばかりでなく、自由貿易を効果 的に保障する通商条約を植民地との間に締結することができるだろう。自由貿易協定は、現在グレート・ブリテンが保有している独占貿易よりも、商人にとって は不利だが、大多数の国民にとっては有利なものである。このようにして良友と別れることになれば、近年の不和がほとんど消滅させてしまった本国に対する植 民地の自然な愛情は急速に復活するだろう。そうなれば、彼らは、分離するときに結んだ通商条約をい今までも尊重するだろうし、貿易だけでなく戦争において も、われわれを支持し、現在のような不穏で党派的な臣民であるかわりに、最も誠実で好意的で寛容な同盟者になってくれるだろう。こうして、古代ギリシャの 植民地と母都市との間に存在したのと同種の、一方の側の親としての愛情と他方の側の子としての尊敬が、グレート・プリテンとその植民地との間に復活するだ ろう。(『国富論』四編七章三)」(堂目 2008:260)。

「グレート・ブリテンは自発的に植民地に 対するすべての権限を放棄すべきであり、植民地が自分たち自身の為政者を選ぴ、自分たち自身の法律 を制定し、自分たちが適切と考えるとおりに和戦を決めるのを放任すべきだと提案することは、これまで世界のどの国によっても採用されたことのない、また今 後も決して採用されることがない方策を提案することになるだろう。植民地を統治することがどれほど厄介で、必要な経費に比べて植民地が提供する収入がどれ ほど小さくとも、植民地に対する支配権を自発的に放棄した国は、いまだかつてない。植民地の放棄は、しばしば国民の利益に合致するとしても、つねに国民の 誇りを傷つけ、さらに重要なことには、支配階層の私的な利害に反するであろう。[中略]最も夢想的な熱狂家でも、そのような方策を、少なくともいつかは採 用されるであろうという、真剣な期待をいくらかでももって提案することは、ほとんどできないであろう。(『国富論』四編七章三節)」(堂目 2008:262)。

「ブリテンの支配者たちは、過去一世紀以 上の問、大西洋の西側に大きな帝国をもっているという想像で国民を楽しませてきた。しかしながら、 この帝国は、これまで、想像の中にしか存在しなかった。これまでのところ、それは帝国ではなく、帝国に関する計画であり、金鉱山ではなく、金鉱山に関する 計画であった。それは、何の利益ももたらさないのに巨大な経費がかかってきたし、現在もかかり続けている。また、今までどおりのやり方で追求されるなら ば、すでに示したように、植民地貿易の独占の結果は、国民の大多数にとって、利益ではなく、単なる損失だからである。/今こそ、われわれの支配者たちが ——そして、おそらく国民も——ふけってきた、この黄金の夢を実現するか、さもなければ、その夢から目覚め、また国民を目覚めさせるよう努めるべきときで ある。もしこの計画を実現できないのであれば、計画を断念すべきである。もし帝国のどの植民地も帝国全体の財政を支えることに貢献させられないのであれ ば、今こそ、グレート・ブリテンが、戦時にそれらの領域を防衛する費用、平時にその民事的・軍事的施設を維持する費用から自らを解放し、将来の展望と計画 を、自の丈に合ったものにするよう努めるべきときである。(『国富論』五編三章)」(堂目 2008:263-264)。

★The Wealth of Nations, 1776

| An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations,

usually referred to by its shortened title The Wealth of Nations, is a

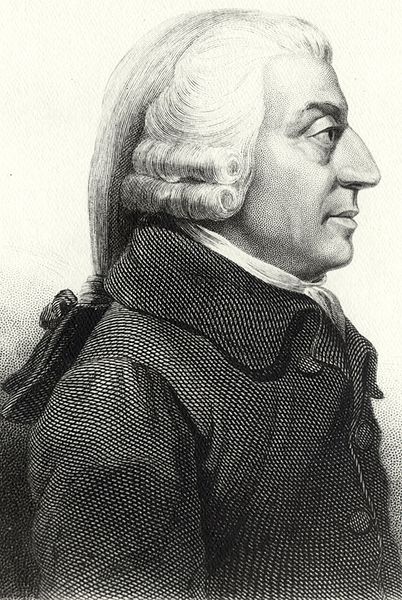

book by the Scottish economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith;

published on 9 March 1776, it offers one of the first accounts of what

builds nations' wealth. It has become a fundamental work in classical

economics, and been described as "the first formulation of a

comprehensive system of political economy".[1] Reflecting upon

economics at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, Smith

introduced key concepts such as the division of labour, productivity,

free markets and the role prices play in resource allocation.[2][3] The book fundamentally shaped the field of economics and provided a theoretical foundation for free market capitalism and economic policies that prevailed in the 19th century. A product of the Scottish Enlightenment and the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, the treatise offered a critical examination of the mercantilist policies of the day and advocated the implementation of free trade and effective tax policies to drive economic progress. It represented a clear paradigm shift from previous economic thought by proposing that self-interest and the forces of supply and demand, rather than regulation, should determine economic activity. Smith laid out a system of political economy with the famous metaphor of the "invisible hand" regulating the marketplace through individual self-interest. He provided a comprehensive analysis of different economic aspects – the accumulation of stock, price determination, and the flow of labor, capital, and rent. The book contained Smith's critique of mercantilism, high taxes on luxury goods, the slave trade, and monopolies, advocating for free competition and open markets. Over revised editions during his lifetime, the work evolved and gained widespread recognition, shaping economic philosophies, government policies, and the intellectual discourse on trade, taxation, and economic growth in the coming centuries. |

国富の本質と原因に関する探究』(An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations)は、スコットランドの経済学者であり道徳哲学者でもあったアダム・スミスの著書である。産業革命初期の経済学を振り返り、スミスは分業、生産性、自由市場、資源配分において価格が果たす役割といった重要な概念を紹介した[2][3]。 この本は経済学の分野を根本的に形成し、19世紀に広まった自由市場資本主義と経済政策の理論的基礎を提供した。スコットランドの啓蒙思想と産業革命の黎 明期の産物であるこの論文は、当時の重商主義政策を批判的に検討し、経済進歩を推進するための自由貿易と効果的な税制の導入を提唱した。規制ではなく、私 利私欲と需要と供給の力が経済活動を決定すべきであると提唱し、それまでの経済思想からの明確なパラダイム・シフトを示した。 スミスは、個人の利己心によって市場を規制する「見えざる手」という有名な隠喩とともに、政治経済学の体系を打ち立てた。彼は、ストックの蓄積、価格の決 定、労働、資本、家賃の流れといった異なる経済的側面を包括的に分析した。この本には、スミスの重商主義、贅沢品への高い税金、奴隷貿易、独占に対する批 判が含まれており、自由競争と開かれた市場を提唱した。スミスが存命中に改訂版を重ねながら、この著作は進化を遂げ、広く認知されるようになり、経済哲 学、政府政策、貿易、税制、経済成長に関する知的言説を今後数世紀にわたって形成していった。 |

| History The Wealth of Nations was published in two volumes on 9 March 1776 (with books I–III included in the first volume and books IV and V included in the second),[4] during the Scottish Enlightenment and the Scottish Agricultural Revolution.[5] It influenced several authors and economists, such as Karl Marx, as well as governments and organizations, setting the terms for economic debate and discussion for the next century and a half.[6] For example, Alexander Hamilton was influenced in part by The Wealth of Nations to write his Report on Manufactures, in which he argued against many of Smith's policies. Hamilton based much of this report on the ideas of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, and it was, in part, Colbert's ideas that Smith responded to, and criticised, with The Wealth of Nations.[7] The Wealth of Nations was the product of seventeen years of notes and earlier studies, as well as an observation of conversation among economists of the time (like Nicholas Magens) concerning economic and societal conditions during the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, and it took Smith some ten years to produce.[8] The result was a treatise which sought to offer a practical application for reformed economic theory to replace the mercantilist and physiocratic economic theories that were becoming less relevant in the time of industrial progress and innovation.[9] It provided the foundation for economists, politicians, mathematicians, and thinkers of all fields to build upon. Irrespective of historical influence, The Wealth of Nations represented a clear paradigm shift in the field of economics,[10] comparable to what Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason was for philosophy.  Bust of Smith in the Adam Smith Theatre, Kirkcaldy Five editions of The Wealth of Nations were published during Smith's lifetime: in 1776, 1778,[11] 1784, 1786 and 1789.[12] Numerous editions appeared after Smith's death in 1790. To better understand the evolution of the work under Smith's hand, a team led by Edwin Cannan collated the first five editions. The differences were published along with an edited sixth edition in 1904.[13] They found minor but numerous differences (including the addition of many footnotes) between the first and the second editions; the differences between the second and third editions are major.[14] In 1784, Smith annexed these first two editions with the publication of Additions and Corrections to the First and Second Editions of Dr. Adam Smith's Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, and he also had published the three-volume third edition of the Wealth of Nations, which incorporated Additions and Corrections and, for the first time, an index. Among other things, the Additions and Corrections included entirely new sections, particularly to book 4, chapters 4 and 5, and to book 5, chapter 1, as well as an additional chapter (8), "Conclusion of the Mercantile System", in book 4.[14] The fourth edition, published in 1786, had only slight differences from the third edition, and Smith himself says in the Advertisement at the beginning of the book, "I have made no alterations of any kind."[15] Finally, Cannan notes only trivial differences between the fourth and fifth editions—a set of misprints being removed from the fourth and a different set of misprints being introduced. |

歴史 国富論』は、スコットランド啓蒙主義とスコットランド農業革命の最中の1776年3月9日に2巻で出版された(第1巻には第1巻から第3巻までが、第2巻 には第4巻と第5巻が収録されている)[4]。[例えば、アレクサンダー・ハミルトンは『国富論』に影響を受け、スミスの政策の多くに反対する『製造業報 告書』を書いた。ハミルトンはこの報告書の多くをジャン=バティスト・コルベールの考えに基づいており、スミスが『国富論』で反論し批判したのは、部分的 にはコルベールの考えであった[7]。 国富論』は、17年間にわたるメモや先行研究の成果であり、当時の経済学者(ニコラス・マゲンスなど)の産業革命初期の経済的・社会的状況に関する会話の 観察から生まれたものであり、スミスはその制作に約10年を費やした。[8]その結果、産業の進歩と革新の時代に適切でなくなりつつあった重商主義的経済 理論やフィジオクラテス的経済理論に代わる、改革された経済理論の実践的な応用を提供しようとする論考が生まれた[9]。この論考は、経済学者、政治家、 数学者、あらゆる分野の思想家が土台とする基礎を提供した。歴史的な影響力とは関係なく、『国富論』は経済学の分野における明確なパラダイムシフトを象徴 しており[10]、イマヌエル・カントの『純粋理性批判』が哲学にとってそうであったことに匹敵する。  カークカルディのアダム・スミス劇場にあるスミスの胸像 国富論』は、スミスの存命中に1776年、1778年、[11] 1784年、1786年、1789年の5版が出版された[12]。スミスの手による作品の変遷をよりよく理解するために、エドウィン・カナン率いるチーム が最初の5つの版を照合した。その相違は、1904年に編集された第6版とともに出版された[13]。彼らは、第1版と第2版の間に、わずかではあるが多 くの相違点(多くの脚注の追加を含む)を発見した。[1784年、スミスは『アダム・スミス博士の国富の本質と原因に関する探究』(アダム・スミス著)の 第一版と第二版への加筆と訂正を発表し、これら第一版と第二版を併合し、さらに加筆と訂正と初めて索引を取り入れた『国富論』全三巻の第三版を発表した。 とりわけ、追加と訂正には、特に第4巻の第4章と第5章、第5巻の第1章にまったく新しい部分が含まれており、また第4巻に「商業制度の結論」という章 (第8章)が追加されていた[14]。 1786年に出版された第4版は、第3版とはわずかな違いしかなく、スミス自身も巻頭の広告で「私はいかなる変更も加えていない」と述べている[15]。 最後にカンナンは、第4版と第5版の間には、第4版から誤植が削除され、異なる誤植が導入されたという些細な違いしかないと指摘している。 |

| Synopsis Book I: Of the Causes of Improvement in the productive Powers of Labour Of the Division of Labour: Division of labour has caused a greater increase in production than any other factor. This diversification is greatest for nations with more industry and improvement, and is responsible for "universal opulence" in those countries. This is in part due to increased quality of production, but more importantly because of increased efficiency of production, leading to a higher nominal output of units produced per time unit.[16] Agriculture is less amenable than manufacturing to division of labour; hence, rich nations are not so far ahead of poor nations in agriculture as in manufacturing. Of the Principle which gives Occasion to the Division of Labour: Division of labour arises not from innate wisdom, but from humans' propensity to barter. That the Division of Labour is Limited by the Extent of the Market: Limited opportunity for exchange discourages division of labour. Because "water-carriage" (i.e. transportation) extends the market, division of labour, with its improvements, comes earliest to cities near waterways. Civilization began around the highly navigable Mediterranean Sea. Of the Origin and Use of Money: With division of labour, the produce of one's own labour can fill only a small part of one's needs. Different commodities have served as a common medium of exchange, but all nations have finally settled on metals, which are durable and divisible, for this purpose. Before coinage, people had to weigh and assay with each exchange, or risk "the grossest frauds and impositions." Thus nations began stamping metal, on one side only, to ascertain purity, or on all sides, to stipulate purity and amount. The quantity of real metal in coins has diminished, due to the "avarice and injustice of princes and sovereign states," enabling them to pay their debts in appearance only, and to the defraudment of creditors. Of the Wages of Labour: In this section, Smith describes how the wages of labour are dictated primarily by the competition among labourers and masters. When labourers bid against one another for limited employment opportunities, the wages of labour collectively fall, whereas when employers compete against one another for limited supplies of labour, the wages of labour collectively rise. However, this process of competition is often circumvented by combinations among labourers and among masters. When labourers combine and no longer bid against one another, their wages rise, whereas when masters combine, wages fall. In Smith's day, organised labour was dealt with very harshly by the law. Smith himself wrote about the "severity" of such laws against worker actions, and made a point to contrast the "clamour" of the "masters" against workers' associations, while associations and collusions of the masters "are never heard by the people" though such actions are "always" and "everywhere" taking place: We rarely hear, it has been said, of the combinations of masters, though frequently of those of workmen. But whoever imagines, upon this account, that masters rarely combine, is as ignorant of the world as of the subject. Masters are always and everywhere in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform, combination, not to raise the wages of labour above their actual rate [...] Masters, too, sometimes enter into particular combinations to sink the wages of labour even below this rate. These are always conducted with the utmost silence and secrecy till the moment of execution; and when the workmen yield, as they sometimes do without resistance, though severely felt by them, they are never heard of by other people". In contrast, when workers combine, "the masters [...] never cease to call aloud for the assistance of the civil magistrate, and the rigorous execution of those laws which have been enacted with so much severity against the combination of servants, labourers, and journeymen.[17] In societies where the amount of labour exceeds the amount of revenue available for waged labour, competition among workers is greater than the competition among employers, and wages fall. Conversely, where revenue is abundant, labour wages rise. Smith argues that, therefore, labour wages only rise as a result of greater revenue disposed to pay for labour. Smith thought of labour as being like any other commodity in this respect: the demand for men, like that for any other commodity, necessarily regulates the production of men; quickens it when it goes on too slowly, and stops it when it advances too fast. It is this demand which regulates and determines the state of propagation in all the different countries of the world, in North America, in Europe, and in China; which renders it rapidly progressive in the first, slow and gradual in the second, and altogether stationary in the last.[18] However, the amount of revenue must increase constantly in proportion to the amount of labour for wages to remain high. Smith illustrates this by juxtaposing England with the North American colonies. In England, there is more revenue than in the colonies, but wages are lower, because more workers flock to new employment opportunities caused by the large amount of revenue – so workers eventually compete against each other as much as they did before. By contrast, as capital continues to flow to the colonial economies at least at the same rate that population increases to "fill out" this excess capital, wages there stay higher than in England. Smith was highly concerned about the problems of poverty. He writes: poverty, though it does not prevent the generation, is extremely unfavourable to the rearing of children [...] It is not uncommon [...] in the Highlands of Scotland for a mother who has borne twenty children not to have two alive [...] In some places one half the children born die before they are four years of age; in many places before they are seven; and in almost all places before they are nine or ten. This great mortality, however, will every where be found chiefly among the children of the common people, who cannot afford to tend them with the same care as those of better station.[18] The only way to determine whether a man is rich or poor is to examine the amount of labour he can afford to purchase. "Labour is the real exchange for commodities". Smith also describes the relation of cheap years and the production of manufactures versus the production in dear years. He argues that while some examples, such as the linen production in France, show a correlation, another example in Scotland shows the opposite. He concludes that there are too many variables to make any statement about this. Of the Profits of Stock: In this chapter, Smith uses interest rates as an indicator of the profits of stock. This is because interest can only be paid with the profits of stock, and so creditors will be able to raise rates in proportion to the increase or decrease of the profits of their debtors. Smith argues that the profits of stock are inversely proportional to the wages of labour, because as more money is spent compensating labour, there is less remaining for personal profit. It follows that, in societies where competition among labourers is greatest relative to competition among employers, profits will be much higher. Smith illustrates this by comparing interest rates in England and Scotland. In England, government laws against usury had kept maximum interest rates very low, but even the maximum rate was believed to be higher than the rate at which money was usually loaned. In Scotland, however, interest rates are much higher. This is the result of a greater proportion of capitalists in England, which offsets some competition among labourers and raises wages. However, Smith notes that, curiously, interest rates in the colonies are also remarkably high (recall that, in the previous chapter, Smith described how wages in the colonies are higher than in England). Smith attributes this to the fact that, when an empire takes control of a colony, prices for a huge abundance of land and resources are extremely cheap. This allows capitalists to increase their profits, but simultaneously draws many capitalists to the colonies, increasing the wages of labour. As this is done, however, the profits of stock in the mother country rise (or at least cease to fall), as much of it has already flocked offshore. Of Wages and Profit in the Different Employments of Labour and Stock: Smith repeatedly attacks groups of politically aligned individuals who attempt to use their collective influence to manipulate the government into doing their bidding. At the time, these were referred to as "factions", but are now more commonly called "special interests," a term that can comprise international bankers, corporate conglomerations, outright oligopolies, trade unions and other groups. Indeed, Smith had a particular distrust of the tradesman class. He felt that the members of this class, especially acting together within the guilds they want to form, could constitute a power block and manipulate the state into regulating for special interests against the general interest: People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices. It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice. But though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies; much less to render them necessary. Smith also argues against government subsidies of certain trades, because this will draw many more people to the trade than what would otherwise be normal, collectively lowering their wages. Of the Rent of the Land: Chapter 10, part ii, motivates an understanding of the idea of feudalism. Rent, considered as the price paid for the use of land, is naturally the highest the tenant can afford in the actual circumstances of the land. In adjusting lease terms, the landlord endeavours to leave him no greater share of the produce than what is sufficient to keep up the stock from which he furnishes the seed, pays the labour, and purchases and maintains the cattle and other instruments of husbandry, together with the ordinary profits of farming stock in the neighbourhood. This is evidently the smallest share with which the tenant can content himself without being a loser, and the landlord seldom means to leave him any more. Whatever part of the produce, or, what is the same thing, whatever part of its price, is over and above this share, he naturally endeavours to reserve to himself as the rent of his land, which is evidently the highest the tenant can afford to pay in the actual circumstances of the land. Sometimes, indeed, the liberality, more frequently the ignorance, of the landlord, makes him accept of somewhat less than this portion; and sometimes too, though more rarely, the ignorance of the tenant makes him undertake to pay somewhat more, or to content himself with somewhat less, than the ordinary profits of farming stock in the neighbourhood. This portion, however, may still be considered as the natural rent of land, or the rent for which it is naturally meant that land should for the most part be let. |

あらすじ 第1巻 労働生産力向上の原因について 分業について 分業は、他のどの要素よりも大きな生産量の増加をもたらした。この多様化は、より多くの産業と改良を有する国民にとって最大であり、それらの国々における 「普遍的な豊かさ」の原因となっている。これは、生産の質の向上によるところもあるが、より重要なのは、生産効率の向上によるものであり、単位時間当たり の生産単位である名目生産高の向上につながるものである[16]。農業は製造業よりも分業になじみにくいため、豊かな国民は、農業においては製造業ほど貧 しい国民に先行していない。 分業を生み出す原理について: 分業は生来の知恵からではなく、人間の物々交換の性質から生じる。 分業は市場の広がりによって制限される: 交換の機会が限られていると、分業は阻害される。水運」(すなわち交通手段)は市場を拡大するため、分業はその改善とともに水路に近い都市に最も早くもたらされる。文明は、航行性の高い地中海周辺で始まった。 貨幣の起源と使用 分業によって、自分の労働生産物は自分の必要量のほんの一部しか満たすことができなくなった。異なる商品が共通の交換媒体として機能してきたが、最終的に すべての国民が、耐久性があり、分割可能な金属に落ち着いた。硬貨が発行される以前は、人民は交換のたびに重量を量り、その値を測定しなければならなかっ た。こうしてナショナリズムは、純度を確認するために片面だけに、あるいは純度と量を規定するために全面に金属を刻印するようになった。貨幣に含まれる本 物の金属の量が減少したのは、「君主や主権国家の貪欲と不正」によって、見かけだけの債務を支払うことができるようになり、債権者を欺くようになったから である。 労働の賃金について:この節でスミスは、労働の賃金が主として労働者と主人の間の競争によって決定されることを述べている。労働者が限られた雇用機会をめ ぐって互いに競い合うと、労働賃金は集団的に下落し、一方、使用者が限られた労働力の供給をめぐって互いに競い合うと、労働賃金は集団的に上昇する。しか し、この競争過程は、労働者間や主人間の組み合わせによって回避されることが多い。労働者が結合して互いに競り合うことがなくなれば賃金は上昇し、一方、 親方が結合すれば賃金は下落する。スミスの時代には、組織化された労働は法律によって非常に厳しく扱われていた。 スミス自身、労働者の行動に対するこのような法律の「厳しさ」について書いており、労働者の団体に対する「主人たち」の「喧騒」と、主人たちの団体や結託が「常に」「いたるところで」行われているにもかかわらず「人民の耳に入ることはない」と対比している: 労働者の結社はよく耳にするが、親方の結社はめったに耳にしない。しかし、このような理由で、親方がめったに結合しないと想像する者は、この話題について 無知であるのと同様に、この世界についても無知である。親方たちは、労働賃金を実際の賃率よりも上げないために、常に、どこでも、一種の暗黙の、しかし恒 常的で均一な結合を結んでいる[...]親方たちもまた、労働賃金をこの賃率よりもさらに下げるために、個別主義的な結合を結ぶことがある。これらは、実 行の瞬間まで、常に最大限の沈黙と秘密をもって行われる。労働者が屈服したとき、彼らには厳しく感じられるが、抵抗することなく屈服することがあるよう に、人民の耳に入ることはない」。対照的に、労働者が結合すると、「主人たちは[......]市民司法の援助と、使用人、労働者、職工の結合に対して非 常に厳しく制定された法律の厳格な執行を声高に求めてやまない」[17]。 労働量が賃労働に利用可能な収入量を上回る社会では、労働者間の競争は使用者間の競争よりも大きくなり、賃金は低下する。逆に、歳入が豊富な社会では、労 働賃金は上昇する。したがって、労働賃金が上昇するのは、労働の対価として支出される歳入が増加した結果である、とスミスは主張する。この点で、スミスは 労働を他の商品と同様に考えた: 人間に対する需要は、他のあらゆる商品に対する需要と同様に、必然的に人間の生産を調整する。北米でもヨーロッパでも中国でも、世界のすべての異なる国々 における伝播の状態を規制し、決定しているのはこの需要であり、この需要によって、前者では急速に進行し、後者ではゆっくりと徐々に進行し、後者では完全 に静止している[18]。 しかし、賃金が高止まりするためには、労働量に比例して収入量が絶えず増加しなければならない。スミスはこのことを、イングランドと北米植民地とを並べる ことによって説明している。イングランドでは、植民地よりも歳入が多いが、賃金は低い。なぜなら、歳入の多さによって生じる新たな雇用機会に、より多くの 労働者が群がるからである--したがって、労働者は結局、以前と同じように互いに競争することになる。これとは対照的に、植民地経済には、少なくともこの 余剰資本を「埋める」ために人口が増加するのと同じ割合で資本が流入し続けるため、そこでの賃金はイギリスよりも高く維持される。 スミスは貧困問題を強く懸念していた。彼はこう書いている: スコットランドのハイランド地方では、20人の子どもを産んだ母親が2人も生きていないことは珍しくない。しかし、このような死亡率の高さは、どこの地域でも、主として、より良い身分の人と同じように世話をする余裕のない、庶民の子どもたちに見られるものである[18]。 人が金持ちか貧乏かを判断する唯一の方法は、その人が購入できる労働力の量を調べることである。「労働は商品との真の交換である」。 スミスはまた、安価な年の生産と高価な年の生産との関係についても述べている。彼は、フランスのリネン生産のようないくつかの例は相関関係を示している が、スコットランドの別の例はその逆を示していると論じている。そして、これについては変数が多すぎて何とも言えないと結論づけている。 株の利益について この章では、スミスは金利を株式の利益の指標として用いている。というのも、金利は株式の利益によってのみ支払われるため、債権者は債務者の利益の増減に比例して金利を引き上げることができるからである。 スミスは、株式の利益は労働賃金に反比例すると主張する。なぜなら、労働の対価としてより多くの資金が費やされれば、人格的利益のために残る資金は少なく なるからである。労働者間の競争が雇用者間の競争に比して最も大きい社会では、利潤ははるかに高くなるということになる。スミスは、イングランドとスコッ トランドの金利を比較して、このことを説明している。イングランドでは、政府の高利貸し禁止法によって最高金利は非常に低く抑えられていたが、最高金利で さえも、通常お金を貸すときの金利よりも高いと信じられていた。しかしスコットランドでは、金利ははるかに高い。これは、イングランドでは資本家の比率が 高いため、労働者間の競争が相殺され、賃金が上昇した結果である。 しかしスミスは、不思議なことに植民地の金利も著しく高いことに注目している(前章でスミスは、植民地の賃金がイングランドより高いことを説明したことを 思い出してほしい)。スミスは、帝国が植民地を支配すると、膨大な土地と資源の価格が極端に安くなるからだとしている。これによって資本家は利潤を増やす ことができるが、同時に多くの資本家が植民地に集まり、労働賃金が上昇する。しかし、このようなことが行われると、すでに多くの資本家が海外に流出してい るため、母国にある株式の利益は上昇する(あるいは、少なくとも下落しなくなる)。 労働とストックの異なる使用における賃金と利益について: スミスは、政治的に連携した個人の集団を繰り返し攻撃し、その集団的影響力を利用して政府を自分たちの言いなりに操ろうとしている。当時、これらのグルー プは「派閥」と呼ばれていたが、現在ではより一般的に「特別利益」と呼ばれ、国際的な銀行家、企業複合体、完全な寡占企業、労働組合、その他のグループか らなる用語である。実際、スミスは商人階級に個別主義的な不信感を抱いていた。彼は、この階級の構成員が、特に彼らが結成を望むギルドの中で一緒に行動す ることで、権力ブロックを構成し、国家を操作して、一般の利益に反して特別な利益のために規制することができると考えた: 同じ商売をする人民が一堂に会することはめったになく、たとえ歓談や気晴らしのためであっても、その会話は一般大衆に対する陰謀や、価格をつり上げるため の策略に終始する。自由と正義に合致し、実行可能な法律によって、このような集会を妨げることは確かに不可能である。しかし、法律は同じ商売をする人民が 集まることを妨げることはできないが、そのような集会を容易にするようなことはすべきではない。 スミスはまた、政府が特定の業種に補助金を出すことに反対している。なぜなら、補助金を出すと、通常よりも多くの人民がその業種に集まり、その人民の賃金が低下するからである。 土地の賃貸料について 第10章第2部は、封建制の考え方を理解する動機となる。土地の使用料として支払われる家賃は、当然ながら、土地の実際の状況において借地人が支払い可能 な最高額である。借地条件を調整する際、地主は、種子を供給し、労働力を支払い、牛やその他の畜産用具を購入し、維持するのに十分な家畜と、近隣の畜産用 具の通常の利益とを維持するのに十分な家畜以上に、生産物の取り分を残さないように努める。 これが、借地人が損をすることなく満足できる最小の取り分であることは明らかであり、地主がこれ以上の取り分を残そうとすることはめったにない。この分け 前を超える農産物の一部、あるいは同じ意味で農産物の価格の一部であろうと、地主は当然、土地の賃料として自分のものにしようとする。また、まれにではあ るが、借地人の無知が、近隣の農作物の通常の利益よりもいくらか多く支払うか、あるいはいくらか少なくても満足させることもある。しかし、この部分は、依 然として土地の自然賃料、あるいは、土地の大部分を貸すことが自然に意図されている賃料とみなすことができる。 |

| Book II: Of the Nature, Accumulation, and Employment of Stock Of the Division of Stock: When the stock which a man possesses is no more than sufficient to maintain him for a few days or a few weeks, he seldom thinks of deriving any revenue from it. He consumes it as sparingly as he can, and endeavours by his labour to acquire something which may supply its place before it be consumed altogether. His revenue is, in this case, derived from his labour only. This is the state of the greater part of the labouring poor in all countries. But when he possesses stock sufficient to maintain him for months or years, he naturally endeavours to derive a revenue from the greater part of it; reserving only so much for his immediate consumption as may maintain him till this revenue begins to come in. His whole stock, therefore, is distinguished into two parts. That part which, he expects, is to afford him this revenue, is called his capital.[18] Of Money Considered as a particular Branch of the General Stock of the Society: From references of the first book, that the price of the greater part of commodities resolves itself into three parts, of which one pays the wages of the labour, another the profits of the stock, and a third the rent of the land which had been employed in producing and bringing them to market: that there are, indeed, some commodities of which the price is made up of two of those parts only, the wages of labour, and the profits of stock: and a very few in which it consists altogether in one, the wages of labour: but that the price of every commodity necessarily resolves itself into some one, or other, or all of these three parts; every part of it which goes neither to rent nor to wages, being necessarily profit to somebody. Of the Accumulation of Capital, or of Productive and Unproductive Labour: One sort of labour adds to the value of the subject upon which it is bestowed: there is another which has no such effect. The former, as it produces a value, may be called productive; the latter, unproductive labour. Thus the labour of a manufacturer adds, generally, to the value of the materials which he works upon, that of his own maintenance, and of his master's profit. The labour of a menial servant, on the contrary, adds to the value of nothing. Of Stock Lent at Interest: The stock which is lent at interest is always considered as a capital by the lender. He expects that in due time it is to be restored to him, and that in the meantime the borrower is to pay him a certain annual rent for the use of it. The borrower may use it either as a capital, or as a stock reserved for immediate consumption. If he uses it as a capital, he employs it in the maintenance of productive labourers, who reproduce the value with a profit. He can, in this case, both restore the capital and pay the interest without alienating or encroaching upon any other source of revenue. If he uses it as a stock reserved for immediate consumption, he acts the part of a prodigal, and dissipates in the maintenance of the idle what was destined for the support of the industrious. He can, in this case, neither restore the capital nor pay the interest without either alienating or encroaching upon some other source of revenue, such as the property or the rent of land. The stock which is lent at interest is, no doubt, occasionally employed in both these ways, but in the former much more frequently than in the latter. Of the different employment of Capital: A capital may be employed in four different ways; either, first, in procuring the rude produce annually required for the use and consumption of the society; or, secondly, in manufacturing and preparing that rude produce for immediate use and consumption; or, thirdly in transporting either the rude or manufactured produce from the places where they abound to those where they are wanted; or, lastly, in dividing particular portions of either into such small parcels as suit the occasional demands of those who want them. |

第II巻 在庫の性質、蓄積および使用について 株式の分割について 人間が所有する在庫が、数日あるいは数週間を維持するのに十分な程度しかないとき、そこから収入を得ようと考えることはめったにない。彼はそれをできるだ け控えめに消費し、それが完全に消費される前に、その代わりとなる何かを労働によって手に入れようと努力する。この場合、彼の収入は彼の労働からのみ得ら れる。これが、あらゆる国の労働貧困層の大部分である。しかし、数カ月あるいは数年間を維持するのに十分な在庫を所有している場合には、当然ながら、その 大部分から収入を得ようとする。したがって、彼の全財産は2つの部分に区別される。この収入が彼にもたらされると期待される部分は、彼の資本と呼ばれる [18]。 貨幣は、社会の一般的な在庫の個別主義的な部分であると考えられる: 第1巻の文献によれば、商品の価格の大部分は3つの部分に分解され、そのうちの1つは労働の賃金を支払い、もう1つは在庫の利益を支払い、3つ目はそれら を生産し市場に出すために使用された土地の賃貸料を支払う: しかし、すべての商品の価格は、必然的に、これら3つの部分のいずれか、あるいは他の部分、あるいはすべてに分解される。 資本の蓄積について、あるいは生産的労働と非生産的労働について: ある種の労働は、それが与えられる対象の価値を増大させる。前者は価値を生み出すので生産的労働と呼ばれ、後者は非生産的労働と呼ばれる。このように、製 造業者の労働は、一般に、彼が作業する材料の価値に、彼自身の維持と主人の利益の価値を加える。反対に、下働きの労働は何の価値も生まない。 金利で貸与される株式について 利息付きで貸し出される株式は、貸し手にとっては常に資本とみなされる。貸し手は、やがてそれが自分の手元に戻ることを期待し、その間に借り手はその使用 料として一定の年利を支払うことを期待している。借り手は、それを資本として使うこともできるし、すぐに消費するために蓄えておくストックとして使うこと もできる。資本として使用する場合は、生産的な労働者を維持するために使用し、その労働者は利潤を得て価値を再生産する。この場合、他の収入源を疎外した り侵害したりすることなく、資本を回復し、利子を支払うことができる。もしそれを、すぐに消費するための蓄えとして使うなら、彼は放蕩者の役割を果たし、 勤勉な労働者の扶養のために予定されていたものを、怠け者の維持のために散財することになる。この場合、財産や土地の賃貸料といった他の収入源を侵害しな い限り、資本を回復することも利息を支払うこともできない。利息付きで貸し出された株式は、間違いなく、この両方の方法で使用されることがあるが、前者の 方が後者よりもはるかに頻繁に使用される。 資本の異なる使用について 第一に、社会の使用と消費のために毎年必要とされる無骨な農産物を調達すること、第二に、その無骨な農産物を製造し、即時の使用と消費のために準備するこ と、第三に、無骨な農産物または製造された農産物のいずれかを、それらが豊富にある場所から、それらが必要とされる場所まで輸送すること、最後に、どちら かの個別主義を、それらを必要とする人々の時々の需要に合うような小分けにすることである。 |

| Book III: Of the different Progress of Opulence in different Nations Long-term economic growth Adam Smith uses this example to address long-term economic growth. Smith states, "As subsistence is, in the nature of things, prior to conveniency and luxury, so the industry which procures the former, must necessarily be prior to that which ministers to the latter".[19] In order for industrial success, subsistence is required first from the countryside. Industry and trade occur in cities while agriculture occurs in the countryside. Agricultural jobs Agricultural work is a more desirable situation than industrial work because the owner is in complete control. Smith states that: In our North American colonies, where uncultivated land is still to be had upon easy terms, no manufactures for distant sale have ever yet been established in any of their towns. When an artificer has acquired a little more stock than is necessary for carrying on his own business in supplying the neighbouring country, he does not, in North America, attempt to establish with it a manufacture for more distant sale, but employs it in the purchase and improvement of uncultivated land. From artificer he becomes planter, and neither the large wages nor the easy subsistence which that country affords to artificers, can bribe him rather to work for other people than for himself. He feels that an artificer is the servant of his customers, from whom he derives his subsistence; but that a planter who cultivates his own land, and derives his necessary subsistence from the labour of his own family, is really a master, and independent of all the world.[19] Where there is open countryside agriculture is much preferable to industrial occupations and ownership. Adam Smith goes on to say "According to the natural course of things, therefore, the greater part of the capital of every growing society is, first, directed to agriculture, afterwards to manufactures, and last of all to foreign commerce".[19] This sequence leads to growth, and therefore opulence. The great commerce of every civilised society is that carried on between the inhabitants of the town and those of the country. It consists in the exchange of crude for manufactured produce, either immediately, or by the intervention of money, or of some sort of paper which represents money. The country supplies the town with the means of subsistence and the materials of manufacture. The town repays this supply by sending back a part of the manufactured produce to the inhabitants of the country. The town, in which there neither is nor can be any reproduction of substances, may very properly be said to gain its whole wealth and subsistence from the country. We must not, however, upon this account, imagine that the gain of the town is the loss of the country. The gains of both are mutual and reciprocal, and the division of labour is in this, as in all other cases, advantageous to all the different persons employed in the various occupations into which it is subdivided. Of the Discouragement of Agriculture: Chapter 2's long title is "Of the Discouragement of Agriculture in the Ancient State of Europe after the Fall of the Roman Empire". When the German and Scythian nations overran the western provinces of the Roman empire, the confusions which followed so great a revolution lasted for several centuries. The rapine and violence which the barbarians exercised against the ancient inhabitants interrupted the commerce between the towns and the country. The towns were deserted, and the country was left uncultivated, and the western provinces of Europe, which had enjoyed a considerable degree of opulence under the Roman empire, sunk into the lowest state of poverty and barbarism. During the continuance of those confusions, the chiefs and principal leaders of those nations acquired or usurped to themselves the greater part of the lands of those countries. A great part of them was uncultivated; but no part of them, whether cultivated or uncultivated, was left without a proprietor. All of them were engrossed, and the greater part by a few great proprietors. This original engrossing of uncultivated lands, though a great, might have been but a transitory evil. They might soon have been divided again, and broke into small parcels either by succession or by alienation. The law of primogeniture hindered them from being divided by succession: the introduction of entails prevented their being broke into small parcels by alienation. Of the Rise and Progress of Cities and Towns, after the Fall of the Roman Empire: The inhabitants of cities and towns were, after the fall of the Roman empire, not more favoured than those of the country. They consisted, indeed, of a very different order of people from the first inhabitants of the ancient republics of Greece and Italy. These last were composed chiefly of the proprietors of lands, among whom the public territory was originally divided, and who found it convenient to build their houses in the neighbourhood of one another, and to surround them with a wall, for the sake of common defence. After the fall of the Roman empire, on the contrary, the proprietors of land seem generally to have lived in fortified castles on their own estates, and in the midst of their own tenants and dependants. The towns were chiefly inhabited by tradesmen and mechanics, who seem in those days to have been of servile, or very nearly of servile condition. The privileges which we find granted by ancient charters to the inhabitants of some of the principal towns in Europe sufficiently show what they were before those grants. The people to whom it is granted as a privilege that they might give away their own daughters in marriage without the consent of their lord, that upon their death their own children, and not their lord, should succeed to their goods, and that they might dispose of their own effects by will, must, before those grants, have been either altogether or very nearly in the same state of villanage with the occupiers of land in the country. How the Commerce of the Towns Contributed to the Improvement of the Country: Smith often harshly criticised those who act purely out of self-interest and greed, and warns that, ...[a]ll for ourselves, and nothing for other people, seems, in every age of the world, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind.[20] |

第III巻 国民の豊かさの異なる進歩について 長期的な経済成長 アダム・スミスはこの例を使って長期的な経済成長を論じている。スミスは「物事の本質において、生計が便利さや贅沢さに先立つように、前者を調達する産業は、必然的に後者に奉仕する産業に先立つに違いない」と述べている。工業と貿易は都市で行われ、農業は田舎で行われる。 農業の仕事 農業労働は、所有者が完全に支配しているため、工業労働よりも望ましい状況である。スミスは次のように述べている: 北米の植民地では、耕作されていない土地はまだ容易な条件で手に入るが、遠方で販売するための製造業はまだどの町にも設立されていない。ある職人が、隣国 への供給という自分の仕事を遂行するのに必要な以上の在庫を手に入れたとき、北アメリカでは、それを使ってより遠くへ販売するための製造業を確立しようと はせず、未耕地の購入と改良に使う。そして、その国が職人に与えてくれる多額の賃金も簡単な生活費も、自分のためよりもむしろ人民のために働くよう、彼を 買収することはできない。しかし、自分の土地を耕し、自分の家族の労働から必要な生活費を得ているプランターは、本当に主人であり、すべての世界から独立 している[19]。 田園が開けているところでは、農業は工業的な職業や所有よりもはるかに好ましい。 アダム・スミスはさらに、「物事の自然な成り行きによれば、成長する社会の資本の大部分は、まず農業に向けられ、次に製造業に向けられ、最後に外国貿易に向けられる」[19]と述べている。 あらゆる文明社会における大商取引は、町の住民と田舎の住民の間で行われるものである。それは、即座に、あるいは貨幣や貨幣を象徴する何らかの紙を介在さ せることによって、粗製品と生産された農産物を交換することである。国から町へは、生活手段と製造材料が供給される。町はこの供給に対して、製造された生 産物の一部を国の住民に送り返す。物質の再生産が存在せず、また存在しえない町は、その富と生活のすべてを国から得ていると言って差し支えないだろう。し かし、このことを理由に、町の利益が国の損失だと考えてはならない。労働の分割は、他のすべての場合と同様に、分割されたさまざまな職業に従事するすべて の異なる人格にとって有益である。 農業の奨励について 第2章の長いタイトルは「ローマ帝国滅亡後のヨーロッパの古代国家における農業の落胆について」である。 ドイツとスキタイの国民がローマ帝国の西方諸州を制圧したとき、この大革命に続くナショナリズムは数世紀にわたって続いた。蛮族が古くからの住民に対して 行った強姦と暴力は、町と田舎の間の商業を中断させた。町は荒れ果て、田舎は耕作されないまま放置され、ローマ帝国のもとでかなりの豊かさを享受していた ヨーロッパの西部諸州は、貧困と野蛮の最低の状態に沈んだ。こうした混乱が続く間に、ナショナリズムの首長や主要指導者たちは、これらの国々の土地の大部 分を手に入れたり、自分たちのものにしたりした。しかし、耕作地であれ未耕作地であれ、所有者のいない土地はなかった。しかし、耕作地であろうと未耕作地 であろうと、所有者のいない土地はなかった。耕作されていない土地のこのような占有は、大きなものではあったが、一過性の弊害に過ぎなかったかもしれな い。土地はすぐにまた分割され、相続や疎開によって小区画に分割されたかもしれない。原始相続の法律は、世襲によって分割されることを妨げたし、エンテー ルの導入は、疎外によって小区画に分割されることを妨げた。 ローマ帝国滅亡後の都市と町の勃興と進歩について ローマ帝国滅亡後の都市や町の住民は、田舎の住民よりも恵まれていたわけではない。古代ギリシャ共和国やイタリア共和国の最初の住民とは、実に異なる人民 で構成されていた。彼らは、もともと公共の領土が分割されていた土地の所有者であり、共同防衛のために、互いに隣接した場所に家を建て、城壁で囲むことが 便利であると考えたのである。ローマ帝国が滅亡した後、土地の所有者たちは一般的に、自分の土地に城を築き、借地人や扶養家族の中に住んでいたようだ。町 には主に商人や機械工が住んでいたが、彼らは当時、隷属的、あるいはほとんど隷属的な状態にあったと思われる。ヨーロッパの主要な町の住民に古代の勅許状 によって与えられた特権を見れば、勅許状が交付される以前の町の様子がよくわかる。領主の同意なしに自分の娘を嫁がせることができること、自分の死後は領 主ではなく自分の子供が財産を継ぐこと、善い意志によって自分の持ち物を処分することができることなどが特権として認められている人民は、そのような特権 が与えられる以前は、田舎の土地の占有者とまったく同じか、あるいはほとんど同じような隷属状態にあったに違いない。 町の商業はどのように国の改善に貢献したか スミスは、純粋に私利私欲や貪欲さから行動する人々をしばしば厳しく批判し、次のように警告している、 ......すべては自分のために、人民のためには何もしない、というのは、世界のどの時代においても、人類の支配者たちの下劣な格律であったように思われる[20]。 |

| Book IV: Of Systems of political Economy Smith vigorously attacked the antiquated government restrictions he thought hindered industrial expansion. In fact, he attacked most forms of government interference in the economic process, including tariffs, arguing that this creates inefficiency and high prices in the long run. It is believed that this theory influenced government legislation in later years, especially during the 19th century. Smith advocated a government that was active in sectors other than the economy. He advocated public education for poor adults, a judiciary, and a standing army—institutional systems not directly profitable for private industries. Of the Principle of the Commercial or Mercantile System: The book has sometimes been described as a critique of mercantilism and a synthesis of the emerging economic thinking of Smith's time. Specifically, The Wealth of Nations attacks, inter alia, two major tenets of mercantilism: The idea that protectionist tariffs serve the economic interests of a nation (or indeed any purpose whatsoever) and The idea that large reserves of gold bullion or other precious metals are necessary for a country's economic success. This critique of mercantilism was later used by David Ricardo when he laid out his Theory of Comparative Advantage. Of Restraints upon the Importation: Chapter 2's full title is "Of Restraints upon the Importation from Foreign Countries of such Goods as can be Produced at Home". The "invisible hand" is a frequently referenced theme from the book, although it is specifically mentioned only once. As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. (Book 4, Chapter 2) The metaphor of the "invisible hand" has been widely used out of context. In the passage above Smith is referring to "the support of domestic industry" and contrasting that support with the importation of goods. Neoclassical economic theory has expanded the metaphor beyond the domestic/foreign manufacture argument to encompass nearly all aspects of economics.[21] Of the extraordinary Restraints: Chapter 3's long title is "Of the extraordinary Restraints upon the Importation of Goods of almost all Kinds, from those Countries with which the Balance is supposed to be Disadvantageous". Of Drawbacks: Merchants and manufacturers are not contented with the monopoly of the home market, but desire likewise the most extensive foreign sale for their goods. Their country has no jurisdiction in foreign nations, and therefore can seldom procure them any monopoly there. They are generally obliged, therefore, to content themselves with petitioning for certain encouragements to exportation. Of these encouragements what are called Drawbacks seem to be the most reasonable. To allow the merchant to draw back upon exportation, either the whole or a part of whatever excise or inland duty is imposed upon domestic industry, can never occasion the exportation of a greater quantity of goods than what would have been exported had no duty been imposed. Such encouragements do not tend to turn towards any particular employment a greater share of the capital of the country than what would go to that employment of its own accord, but only to hinder the duty from driving away any part of that shares to other employments. Of Bounties: Bounties upon exportation are, in Great Britain, frequently petitioned for, and sometimes granted to the produce of particular branches of domestic industry. By means of them our merchants and manufacturers, it is pretended, will be enabled to sell their goods as cheap, or cheaper than their rivals in the foreign market. A greater quantity, it is said, will thus be exported, and the balance of trade consequently turned more in favour of our own country. We cannot give our workmen a monopoly in the foreign as we have done in the home market. We cannot force foreigners to buy their goods as we have done our own countrymen. The next best expedient, it has been thought, therefore, is to pay them for buying. It is in this manner that the mercantile system proposes to enrich the whole country, and to put money into all our pockets by means of the balance of trade. Of Treaties of Commerce: When a nation binds itself by treaty either to permit the entry of certain goods from one foreign country which it prohibits from all others, or to exempt the goods of one country from duties to which it subjects those of all others, the country, or at least the merchants and manufacturers of the country, whose commerce is so favoured, must necessarily derive great advantage from the treaty. Those merchants and manufacturers enjoy a sort of monopoly in the country which is so indulgent to them. That country becomes a market both more extensive and more advantageous for their goods: more extensive, because the goods of other nations being either excluded or subjected to heavier duties, it takes off a greater quantity of theirs: more advantageous, because the merchants of the favoured country, enjoying a sort of monopoly there, will often sell their goods for a better price than if exposed to the free competition of all other nations. Such treaties, however, though they may be advantageous to the merchants and manufacturers of the favoured, are necessarily disadvantageous to those of the favouring country. A monopoly is thus granted against them to a foreign nation; and they must frequently buy the foreign goods they have occasion for dearer than if the free competition of other nations was admitted. Of Colonies: Of the Motives for establishing new Colonies: The interest which occasioned the first settlement of the different European colonies in America and the West Indies was not altogether so plain and distinct as that which directed the establishment of those of ancient Greece and Rome. All the different states of ancient Greece possessed, each of them, but a very small territory, and when the people in any one of them multiplied beyond what that territory could easily maintain, a part of them were sent in quest of a new habitation in some remote and distant part of the world; warlike neighbours surrounded them on all sides, rendering it difficult for any of them to enlarge their territory at home. The colonies of the Dorians resorted chiefly to Italy and Sicily, which, in the times preceding the foundation of Rome, were inhabited by barbarous and uncivilised nations: those of the Ionians and Eolians, the two other great tribes of the Greeks, to Asia Minor and the islands of the Egean Sea, of which the inhabitants seem at that time to have been pretty much in the same state as those of Sicily and Italy. The mother city, though she considered the colony as a child, at all times entitled to great favour and assistance, and owing in return much gratitude and respect, yet considered it as an emancipated child over whom she pretended to claim no direct authority or jurisdiction. The colony settled its own form of government, enacted its own laws, elected its own magistrates, and made peace or war with its neighbours as an independent state, which had no occasion to wait for the approbation or consent of the mother city. Nothing can be more plain and distinct than the interest which directed every such establishment. Causes of Prosperity of new Colonies: The colony of a civilised nation which takes possession either of a waste country, or of one so thinly inhabited that the natives easily give place to the new settlers, advances more rapidly to wealth and greatness than any other human society. The colonists carry out with them a knowledge of agriculture and of other useful arts superior to what can grow up of its own accord in the course of many centuries among savage and barbarous nations. They carry out with them, too, the habit of subordination, some notion of the regular government which takes place in their own country, of the system of laws which supports it, and of a regular administration of justice; and they naturally establish something of the same kind in the new settlement. Of the Advantages which Europe has derived from the Discovery of America, and from that of a Passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good Hope: Such are the advantages which the colonies of America have derived from the policy of Europe. What are those which Europe has derived from the discovery and colonisation of America? Those advantages may be divided, first, into the general advantages which Europe, considered as one great country, has derived from those great events; and, secondly, into the particular advantages which each colonising country has derived from the colonies which particularly belong to it, in consequence of the authority or dominion which it exercises over them.: The general advantages which Europe, considered as one great country, has derived from the discovery and colonisation of America, consist, first, in the increase of its enjoyments; and, secondly, in the augmentation of its industry. The surplus produce of America, imported into Europe, furnishes the inhabitants of this great continent with a variety of commodities which they could not otherwise have possessed; some for conveniency and use, some for pleasure, and some for ornament, and thereby contributes to increase their enjoyments. Conclusion of the Mercantile System: Smith's argument about the international political economy opposed the idea of mercantilism. While the Mercantile System encouraged each country to hoard gold, while trying to grasp hegemony, Smith argued that free trade eventually makes all actors better off. This argument is the modern 'Free Trade' argument. Of the Agricultural Systems: Chapter 9's long title is "Of the Agricultural Systems, or of those Systems of Political Economy, which Represent the Produce of Land, as either the Sole or the Principal, Source of the Revenue and Wealth of Every Country". That system which represents the produce of land as the sole source of the revenue and wealth of every country has, so far as by that time, never been adopted by any nation, and it at present exists only in the speculations of a few men of great learning and ingenuity in France. It would not, surely, be worthwhile to examine at great length the errors of a system which never has done, and probably never will do, any harm in any part of the world. |

第4巻 政治経済学の体系 スミスは、産業拡大を妨げると考えた時代遅れの政府の規制を激しく攻撃した。実際、彼は関税を含む経済プロセスへの政府の干渉のほとんどの形態を攻撃し、 これが長期的には非効率と高価格を生み出すと主張した。この理論が後年、特に19世紀の政府立法に影響を与えたと考えられている。 スミスは、経済以外の分野に積極的に関与する政府を提唱した。彼は、貧しい成人に対する公教育、司法、常備軍など、民間産業にとって直接利益をもたらさない制度的システムを提唱した。 本書は、「商業または商業制度の原理について」である: 本書は時に、重商主義に対する批判であり、スミス当時の経済思想の新潮流を統合したものであると評される。具体的には、『国富論』は特に重商主義の2つの主要な信条を攻撃している: 保護主義的関税が国民の経済的利益に資するという考え方(あるいは、実際にはいかなる目的にも資するという考え方)。 国の経済的成功のためには、金塊やその他の貴金属の大量備蓄が必要であるという考え方。この重商主義批判は、後にデービッド・リカルドが比較優位論を打ち立てた際に用いられた。 輸入制限について 第2章の正式なタイトルは「自国で生産可能な財の外国からの輸入の制限について」である。見えざる手」は本書で頻繁に言及されるテーマであるが、具体的に言及されているのは一度だけである。 したがって、すべての個人は、自分の資本を国内産業の扶助にできるだけ使い、その生産物が最大の価値を持つように、その産業を指導するように努めるよう に、すべての個人は必然的に、社会の年間収入をできるだけ大きくするように努力する。一般に、彼は公共の利益を促進するつもりもなければ、自分がどれほど 促進しているかも知らない。外国の産業よりも国内の産業を支援することを好むのは、自分の安全だけを意図しているからであり、その生産物が最大の価値を持 つようにその産業を指導するのは、自分の利益だけを意図しているからである。この場合も、他の多くの場合と同様に、見えない手によって、自分の意図とは無 関係な目的を促進するように導かれている。また、それが社会にとって悪いことだとは限らない。自分の利益を追求することで、社会の利益を本当に促進するつ もりであったときよりも、より効果的に促進することがよくある。(第4巻第2章) 見えざる手」の隠喩は、文脈から外れて広く使われてきた。上記の一節でスミスは「国内産業の支援」に言及し、その支援と商品の輸入を対比している。新古典 派経済理論は、この比喩を国内製造/国外製造の議論にとどまらず、経済学のほぼすべての側面を包含するまでに拡大した[21]。 異常な抑制の 第3章の長いタイトルは「均衡が不利であると思われる国々からの、ほとんどあらゆる種類の物品の輸入に対する異常な抑制について」である。 欠点について: 商人や製造業者は、自国市場の独占に満足することなく、自分たちの商品の最も広範な海外販売を望んでいる。自国は外国に管轄権を持たないため、外国での独占権を得ることはほとんどできない。そのため、輸出を奨励するよう嘆願することで満足せざるを得ない。 このような奨励のうち、ドローバックと呼ばれるものが最も合理的であるように思われる。商人が輸出に際して、国内産業に課される物品税や内陸税の全額また は一部を引き戻すことを認めることは、関税が課されなかった場合に輸出されたであろう量よりも、より多くの量の商品の輸出をもたらすことはあり得ない。こ のような奨励は、国の資本のうち、自発的にその雇用に向かうであろう割合よりも大きな割合を、特定の雇用に向かわせる傾向にはなく、関税がその資本の一部 を他の雇用に向かわせるのを妨げるだけである。 報奨金について 英国では、輸出に対する報奨金が頻繁に請求され、国内産業の個別分野の生産物に対して交付されることもある。これを利用することで、わが国の商人や製造業 者は、外国市場でライバルと同等かそれよりも安く商品を売ることができるようになるとされる。こうして輸出量が増え、貿易収支が自国に有利になると言われ ている。自国市場で行ってきたように、外国市場で自国の労働者を独占させることはできない。自国民にしてきたように、外国人に自国の商品を買わせることも できない。従って、次善の策は、外国人にお金を払って買ってもらうことだと考えられてきた。このようにして、商人制度は国全体を豊かにし、貿易収支によっ て我々の懐を潤すことを提案しているのである。 通商条約について ある国民が条約によって、ある外国からの特定の商品の持ち込みを許可し、他のすべての外国からの持ち込みを禁止するか、またはある国の商品を免除し、他の すべての国の商品を関税の対象とする場合、その国、少なくともその国の商人や製造業者は、その条約によって大きな利益を必ず得なければならない。それらの 商人や製造業者は、自分たちに好意的な国において、一種の独占を享受することになる。その国は、彼らの商品にとって、より広範で有利な市場となる。より広 範な市場となるのは、他国の商品が排除されるか、より重い関税が課されるため、彼らの商品がより大量に引き取られるからであり、より有利な市場となるの は、好意的な国の商人が、そこで一種の独占を享受しているため、他のすべての国の自由競争にさらされるよりも、より良い価格で商品を販売することが多いか らである。しかし、このような条約は、有利な国の商人や製造業者にとっては有利であっても、有利な国の商人や製造業者にとっては必ず不利になる。こうして 外国に独占が認められ、外国はしばしば、他国との自由競争が認められた場合よりも高い値段で外国製品を買わなければならなくなる。 植民地について 新しい植民地を設立する動機について: アメリカや西インド諸島に異なるヨーロッパの植民地を最初に設立した動機は、古代ギリシアやローマの植民地設立を方向づけた動機ほど単純明快なものではな かった。古代ギリシアの異なる国家は、それぞれ非常に小さな領土しか持たなかった。いずれかの国家の人民が、その領土が維持できる限度を超えて増加する と、その一部は世界の遠く離れた場所に新たな居住地を求めて送られた。ドーリア人の植民地は主にイタリアとシチリア島であったが、ローマ建国以前の時代に は野蛮で未開の国民が住んでいた。母都市は植民地を子供のように考えており、常に大きな恩恵と援助を受ける権利があり、その見返りとして多くの感謝と尊敬 を払っていたが、植民地を解放された子供のように考え、直接的な権限や管轄権を主張しないふりをしていた。植民地は独自の統治形態を定め、独自の法律を制 定し、独自の行政官を選出し、独立国家として近隣諸国と和平や戦争を行った。このような設立を指示した利害関係ほど明白で明確なものはない。 新植民地の繁栄の原因 文明化した国民の植民地は、荒れ果てた国や、ナショナリズムが新しい入植者に容易に場所を譲ることができるほど人の住まない国を手に入れると、他のどのよ うな人間社会よりも急速に富と偉大さを獲得する。ナショナリズムの入植者たちは、未開の野蛮な国民が何世紀もかけて自力で育んできたものよりも優れた、農 業やその他の有用な技術に関する知識を持ち帰る。彼らはまた、従属の習慣や、自国で行われている規則正しい政治、それを支える法体系、規則正しい司法運営 についての考え方も持ち出す。 アメリカ大陸の発見と、喜望峰による東インド諸島への航路の発見から、ヨーロッパが得た利点について: アメリカの植民地がヨーロッパの政策から得た利点はこのようなものである。アメリカの発見と植民地化によってヨーロッパが得た利点とは何だろうか。これら の利点は、第一に、ヨーロッパを一つの大国とみなして、これらの大きな出来事から得た一般的な利点と、第二に、各植民地国が、自国に特に属する植民地に対 して行使している権威や支配権の結果として、それらの植民地から得た個別主義的な利点とに分けることができる: ヨーロッパがアメリカの発見と植民地化から得た一般的な利点は、第一にその享楽の増大、第二にその産業の増大である。 ヨーロッパに輸入されたアメリカの余剰生産物は、この偉大な大陸の住民に、そうでなければ手に入れることができなかったさまざまな商品を提供する。 商業システムの結論 国際政治経済に関するスミスの主張は、重商主義の考え方に反対するものであった。重商主義が各国に金を蓄えさせ、覇権を握ろうとするのに対して、スミスは 自由貿易が最終的にすべての行為者をより良くすると主張した。この主張が現代の「自由貿易論」である。 農業システムの 第9章の長いタイトルは「農業制度について、あるいは、土地の生産物をすべての国の歳入と富の唯一の、あるいは主要な源泉として代表する政治経済学の制度について」である。 土地の生産物をすべての国の歳入と富の唯一の源泉とする制度は、当時までのところ、どの国民にも採用されたことはなく、現在では、フランスの学識と独創性 に富む数人の人物の思索の中にしか存在しない。世界のどの地域でも害を及ぼしたことはなく、おそらく今後も害を及ぼすことはないであろうこの制度の誤り を、長々と検討する価値はないだろう。 |

| Book V: Of the Revenue of the Sovereign or Commonwealth Smith postulated four "maxims" of taxation: proportionality, transparency, convenience, and efficiency. Some economists interpret Smith's opposition to taxes on transfers of money, such as the Stamp Act, as opposition to capital gains taxes, which did not exist in the 18th century.[22] Other economists credit Smith as one of the first to advocate a progressive tax.[23][24] Smith wrote, "The necessaries of life occasion the great expense of the poor. They find it difficult to get food, and the greater part of their little revenue is spent in getting it. The luxuries and vanities of life occasion the principal expense of the rich, and a magnificent house embellishes and sets off to the best advantage all the other luxuries and vanities which they possess. A tax upon house-rents, therefore, would in general fall heaviest upon the rich; and in this sort of inequality there would not, perhaps, be anything very unreasonable. It is not very unreasonable that the rich should contribute to the public expense, not only in proportion to their revenue, but something more than in that proportion." Smith believed that an even "more proper" source of progressive taxation than property taxes was ground rent. Smith wrote that "nothing [could] be more reasonable" than a land value tax. Of the Expenses of the Sovereign or Commonwealth: Smith uses this chapter to comment on the concept of taxation and expenditure by the state. On taxation, Smith wrote, The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state. The expense of government to the individuals of a great nation is like the expense of management to the joint tenants of a great estate, who are all obliged to contribute in proportion to their respective interests in the estate. In the observation or neglect of this maxim consists what is called the equality or inequality of taxation. Smith advocates a tax naturally attached to the "abilities" and habits of each echelon of society. For the lower echelon, Smith recognised the intellectually erosive effect that the otherwise beneficial division of labour can have on workers, what Marx, though he mainly opposes Smith, later named "alienation"; therefore, Smith warns of the consequence of government failing to fulfill its proper role, which is to preserve against the innate tendency of human society to fall apart. ..."the understandings of the greater part of men are necessarily formed by their ordinary employments. The man whose whole life is spent in performing a few simple operations, of which the effects are perhaps always the same, or very nearly the same, has no occasion to exert his understanding or to exercise his invention in finding out expedients for removing difficulties which never occur. He naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become. The torpor of his mind renders him not only incapable of relishing or bearing a part in any rational conversation, but of conceiving any generous, noble, or tender sentiment, and consequently of forming any just judgment concerning many even of the ordinary duties of private life... But in every improved and civilized society this is the state into which the labouring poor, that is, the great body of the people, must necessarily fall, unless government takes some pains to prevent it."[25] Under Smith's model, government involvement in any area other than those stated above negatively impacts economic growth. This is because economic growth is determined by the needs of a free market and the entrepreneurial nature of private persons. A shortage of a product makes its price rise, and so stimulates producers to produce more and attracts new people to that line of production. An excess supply of a product (more of the product than people are willing to buy) drives prices down, and producers refocus energy and money to other areas where there is a need.[26] Of the Sources of the General or Public Revenue of the Society: In his discussion of taxes in Book Five, Smith wrote: The necessaries of life occasion the great expense of the poor. They find it difficult to get food, and the greater part of their little revenue is spent in getting it. The luxuries and vanities of life occasion the principal expense of the rich, and a magnificent house embellishes and sets off to the best advantage all the other luxuries and vanities which they possess. A tax upon house-rents, therefore, would in general fall heaviest upon the rich; and in this sort of inequality there would not, perhaps, be anything very unreasonable. It is not very unreasonable that the rich should contribute to the public expense, not only in proportion to their revenue, but something more than in that proportion.[27] He also introduced the distinction between a direct tax, and by implication an indirect tax (although he did not use the word "indirect"): Capitation taxes, so far as they are levied upon the lower ranks of people, are direct taxes upon the wages of labour, and are attended with all the inconveniences of such taxes.[28] And further: It is thus that a tax upon the necessaries of life operates exactly in the same manner as a direct tax upon the wages of labour. This term was later used in United States, Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution, and James Madison, who wrote much of the Constitution, is known to have read Smith's book. Of War and Public Debts: ...when war comes [politicians] are both unwilling and unable to increase their [tax] revenue in proportion to the increase of their expense. They are unwilling for fear of offending the people, who, by so great and so sudden an increase of taxes, would soon be disgusted with the war [...] The facility of borrowing delivers them from the embarrassment [...] By means of borrowing they are enabled, with a very moderate increase of taxes, to raise, from year to year, money sufficient for carrying on the war, and by the practice of perpetually funding they are enabled, with the smallest possible increase of taxes [to pay the interest on the debt], to raise annually the largest possible sum of money [to fund the war]. ...The return of peace, indeed, seldom relieves them from the greater part of the taxes imposed during the war. These are mortgaged for the interest of the debt contracted in order to carry it on.[29] Smith then goes on to say that even if money was set aside from future revenues to pay for the debts of war, it seldom actually gets used to pay down the debt. Politicians are inclined to spend the money on some other scheme that will win the favour of their constituents. Hence, interest payments rise and war debts continue to grow larger, well beyond the end of the war. Summing up, if governments can borrow without check, then they are more likely to wage war without check, and the costs of the war spending will burden future generations, since war debts are almost never repaid by the generations that incurred them. |

第5巻:君主または連邦の収入について 比例性、透明性、利便性、効率性である。経済学者の中には、スミスが印紙税のような金銭の移動に対する課税に反対したのは、18世紀には存在しなかった キャピタルゲイン税に反対したためであると解釈する者もいる[22]。 他の経済学者は、スミスが累進課税を最初に提唱した一人であると評価している[23][24]。彼らは食物を手に入れることが困難であり、わずかな収入の 大部分はそれを手に入れるために費やされる。生活の贅沢品や虚栄品は、金持ちの主な出費の原因であり、立派な家は、彼らが所有する他のすべての贅沢品や虚 栄品を最もよく飾り、引き立たせる。したがって、家屋家賃にかかる税金は、一般に富裕層に最も重くのしかかる。このような不平等には、おそらくそれほど不 合理な点はないだろう。富裕層がその収入に比例するだけでなく、それ以上に公費を拠出することは、それほど不合理なことではない」。スミスは、財産税より もさらに「適切な」累進課税の源泉は地代家賃であると考えていた。スミスは、地価税ほど「合理的なものはない」と書いている。 君主または連邦の経費について スミスはこの章において、国家による課税と支出の概念について述べている。課税について、スミスはこう書いている、 各州の臣民は、できる限りそれぞれの能力に比例して、つまり、国家の保護の下で各自が享受する収入に比例して、政府を支えるために貢献すべきである。大国 民の個人にとっての政府の経費は、大領地の共同借家人にとっての管理経費のようなものである。この格律を守るか無視するかで、課税の平等・不平等と呼ばれ るものが決まる。 スミスは、社会の各階層の「能力」と「習慣」に自然に付随する税を提唱している。 それゆえ、スミスは、政府がその本来の役割(人間社会が生まれながらにして持っている崩壊の傾向から身を守ること)を果たさないことの結果について警告している。 ......「人間の大部分の理解は、必然的に通常の仕事によって形成される。人生のすべてを、おそらくいつも同じか、ほとんど同じであろう単純な作業を いくつかこなすことに費やしている人間には、理解力を発揮する機会も、決して起こらない困難を取り除くための方便を見つけるために発明を働かせる機会もな い。そのため、そのような努力をする習慣は自然に失われ、一般に、人間という生き物がなりうるのと同じくらい愚かで無知になる。心の疲弊は、理性的な会話 を楽しんだり、その一翼を担ったりすることができないばかりか、寛大で、気高く、優しい感情を思い浮かべることもできず、その結果、私生活における普通の 義務の多くについてさえ、正当な判断を下すことができなくなる...。しかし、改善され文明化された社会では、政府が何らかの苦心をしてこれを防止しない 限り、労働力のある貧困層、すなわち人民の大多数が必ず陥る状態である」[25]。 スミスのモデルの下では、上記以外の分野への政府の関与は経済成長にマイナスの影響を与える。なぜなら、経済成長は自由市場のニーズと私人の起業家精神に よって決定されるからである。製品が不足すると価格が上昇するため、生産者はより多く生産するように刺激され、その生産ラインに新しい人民が集まる。製品 の過剰供給(人民が買いたいと思う以上の製品の供給)は価格を下落させ、生産者はエネルギーと資金をニーズのある他の分野に集中させる[26]。 社会の一般的または公的な収入源について 第5巻の税についての議論の中で、スミスはこう書いている: 生活必需品は貧しい人々に大きな出費を強いている。彼らは食物を得ることが困難であり、わずかな収入の大部分はそれを得るために費やされる。生活に必要な 贅沢品や虚栄品は、金持ちの主な出費の原因であり、立派な家は、彼らが所有する他のすべての贅沢品や虚栄品を最もよく飾り、引き立たせる。したがって、家 屋家賃にかかる税金は、一般に富裕層に最も重くのしかかる。このような不平等には、おそらく不合理な点はないだろう。富裕層がその収入に比例してだけでな く、それ以上に公費を拠出することは、それほど不合理なことではない。 彼はまた、直接税と間接税(「間接」という言葉は使わなかったが)との区別を導入した: 人頭税は、下層の人民に対して課される限り、労働の賃金に対する直接税であり、そのような税のすべての不都合を伴うものである」[28]。 さらにこうも言う: このように、生活必需品に対する税は、労働賃金に対する直接税とまったく同じように作用するのである。 この用語は後に合衆国憲法第1条第2節第3節で使われるようになり、憲法の多くを書いたジェームズ・マディソンはスミスの著書を読んでいたことが知られている。 戦争と公債について ...戦争が起こると、[政治家たちは]出費の増加に比例して[税収]を増やそうとしないし、増やすこともできない。人民の機嫌を損ねることを恐れて不本 意なのである。人民は、あまりに急激な増税によって、すぐに戦争に嫌悪感を抱くだろう。借金をすることによって、非常に緩やかな増税で、戦争を継続するの に十分な資金を毎年調達することができ、恒久的に資金を調達することによって、(借金の利子を支払うための)可能な限り小さな増税で、(戦争資金を調達す るための)可能な限り大きな金額を毎年調達することができる。] ...実際、平和が戻ってきても、戦争中に課された税金の大部分から解放されることはめったにない。これらの税金は、戦争を継続するために契約した負債の 利子のために抵当に入れられるのである[29]。 さらにスミスは、戦争による債務を支払うために将来の収入から資金を積み立てたとしても、それが実際に債務の返済に充てられることはめったにないと言う。 政治家たちは、有権者の支持を得られるような他の計画に資金を使いたがる。それゆえ、利払いは増え、戦争の借金は戦争が終わっても増え続ける。 要約すると、もし政府がチェックなしに借金をすることができるなら、チェックなしに戦争をする可能性が高くなる。戦争費用は将来の世代に負担を強いることになる。 |