文化戦争

Culture

war

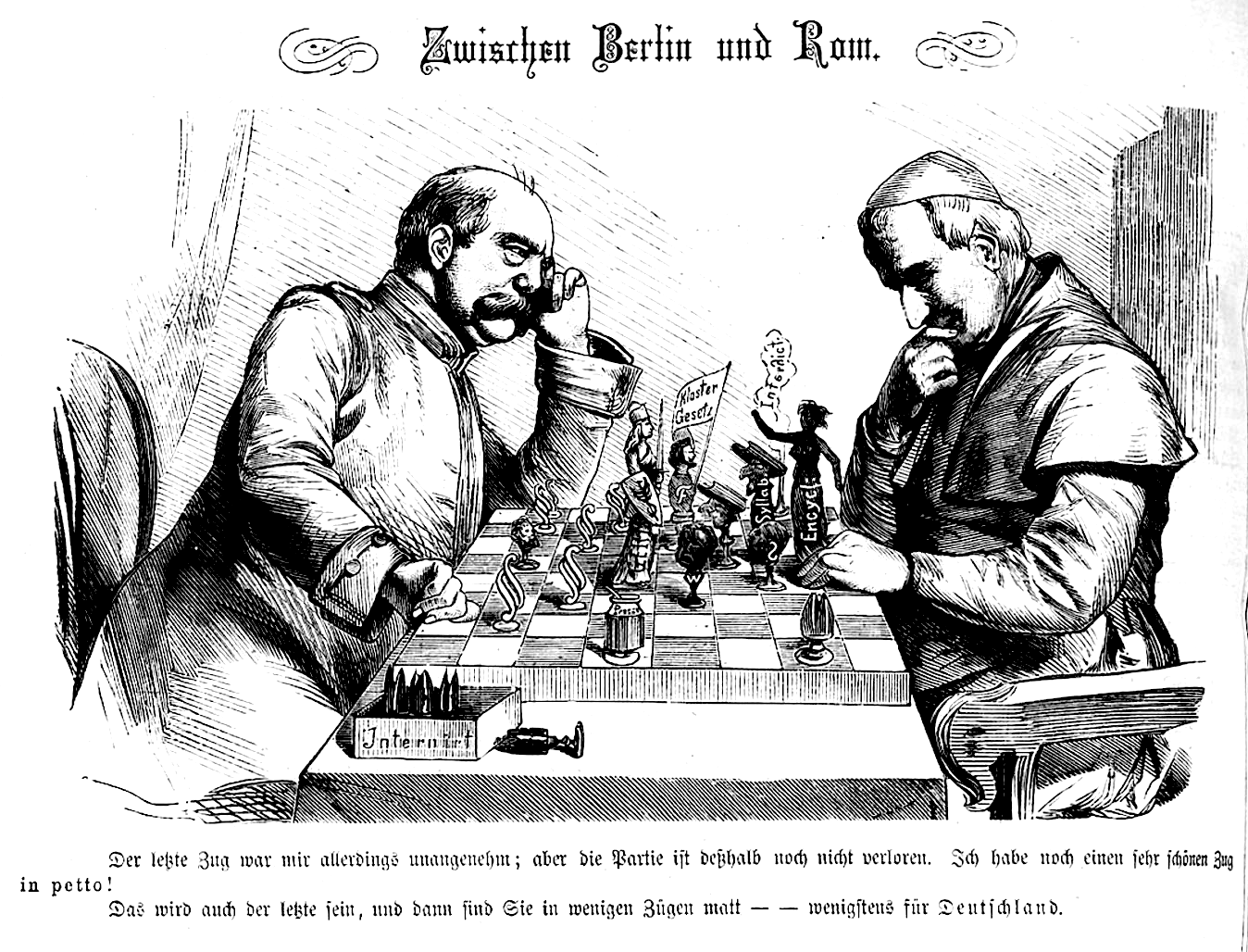

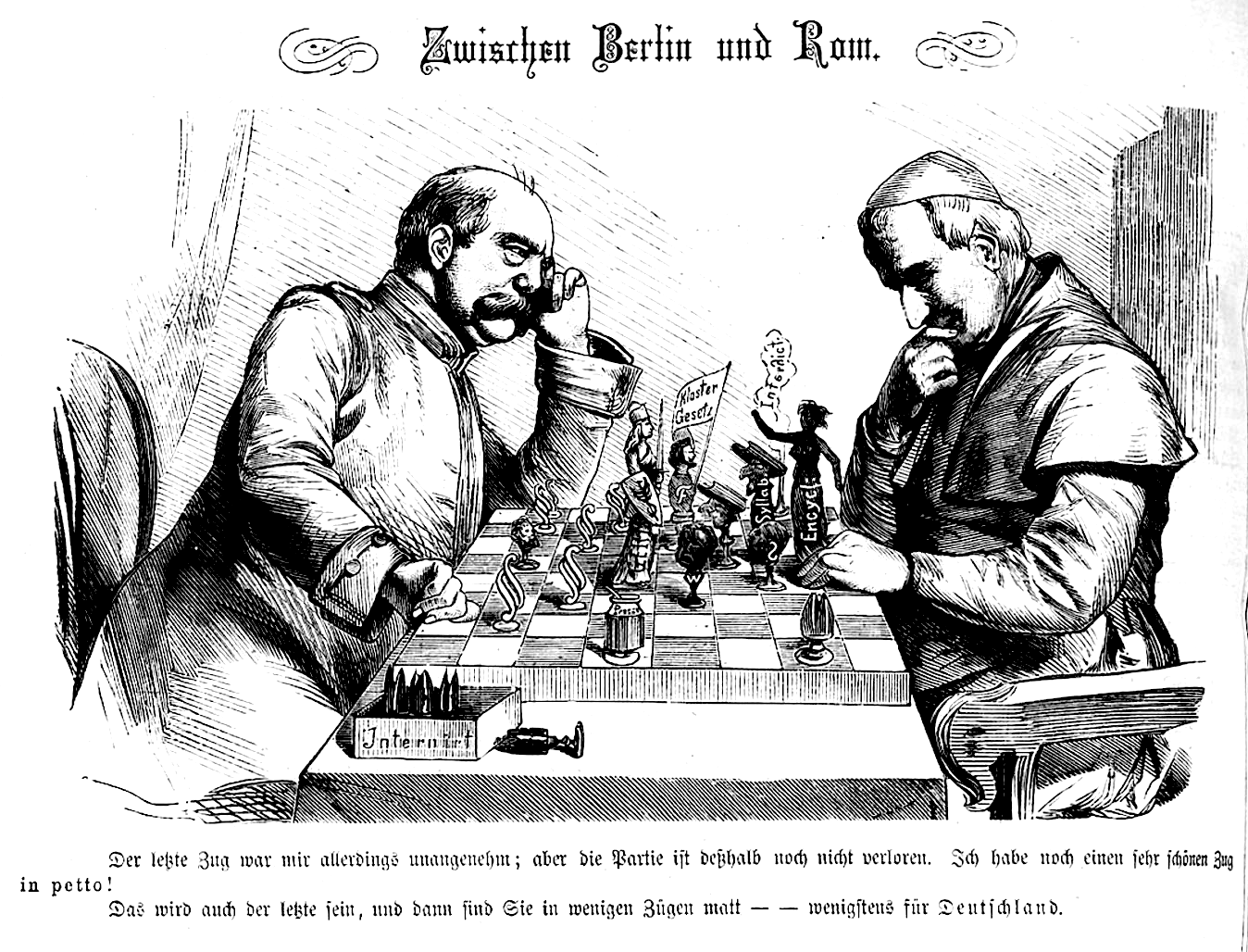

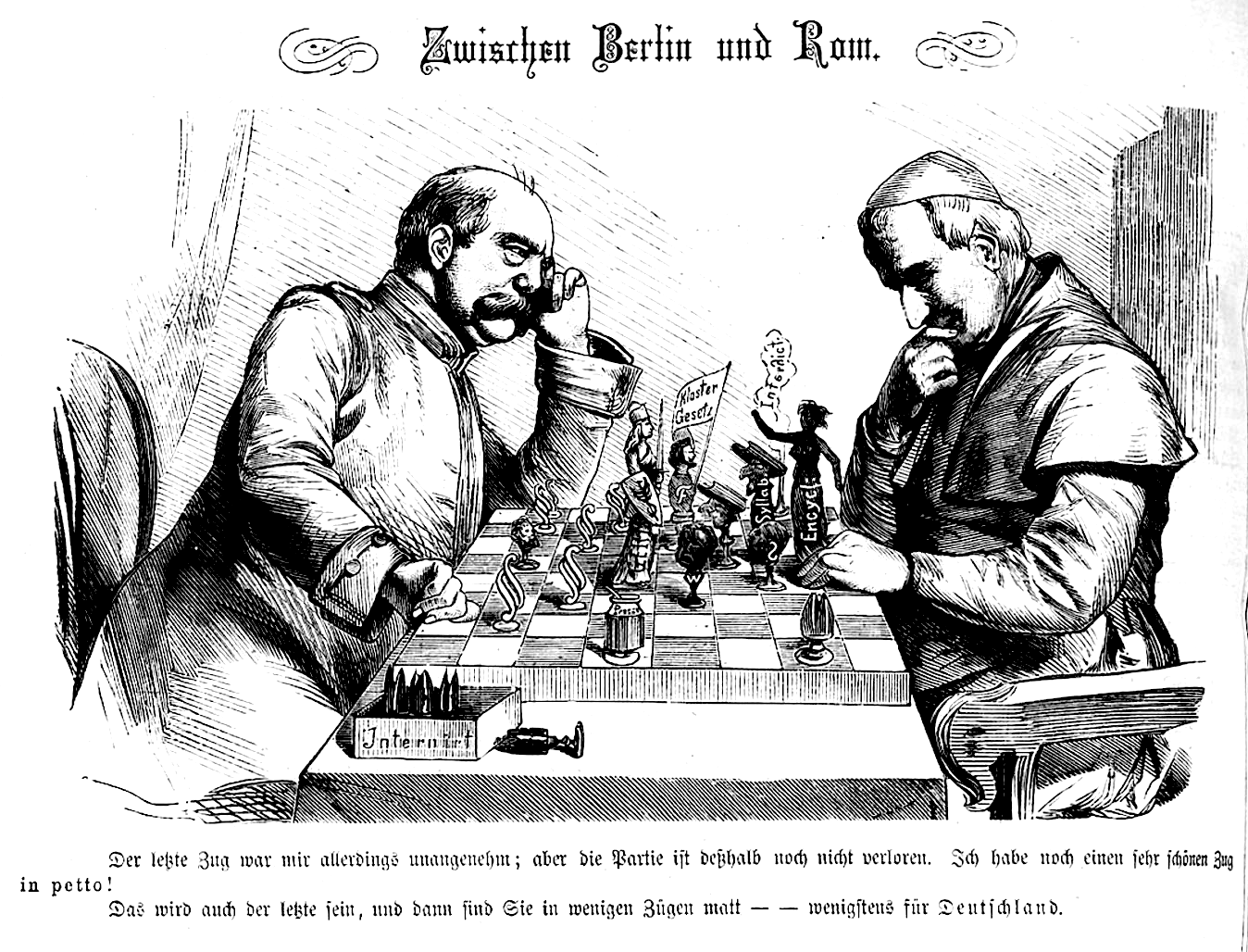

Bismarck

(left) and Pope Pius IX (right), from the German satirical magazine

Kladderadatsch, 1875

☆文 化戦争(ぶんかせんそう; culture war)とは、社会集団間の文化的対立であり、それぞれの価値観、信念、慣習の優劣をめぐる争いである。一般的には、社会的価値観における一般的な 社会的意見の相違や二極化が見られるテーマを指す。アメリカでの用法では、「文化戦争」は伝統主義的または保守的とされる価値観と進歩的またはリベラルと される価値観の対立を意味することがある。

★ 「政治学において文化戦争とは、自分たちのイデオロギー(信念、美徳、慣行)を社会に政治的に押し付けようともがく異なる社会集団間の文化的対立の一種で ある。政治的な用法では、文化戦争という用語は、価値観やイデオロギーに関する「話題の」政治の比喩であり、公共政策や消費に関する経済的な問題をめぐっ て、社会の主流の間で政治的分極を引き起こすことを意図した、意図的に敵対的な社会的物語によって実現される。実践的な政治として、カルチャー・ウォーと は、多文化社会における政治的分断を引き起こすことを意図した、価値観、道徳観、ライフスタイルに関する抽象的な議論に基づく社会政策のくさび問題のこと である。」- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_war

| In political science, a culture war

is a type of cultural conflict between different social groups who

struggle to politically impose their own ideology (beliefs, virtues,

practices) upon their society.[1][2] In political usage, the term

culture war is a metaphor for "hot-button" politics about values and

ideologies, realized with intentionally adversarial social narratives

meant to provoke political polarization among the mainstream of society

over economic matters of [3][4] public policy[5] and of consumption.[1]

As practical politics, a culture war is about social policy wedge

issues that are based on abstract arguments about values, morality, and

lifestyle meant to provoke political cleavage in a multicultural

society.[2] |

政治科学において文化戦争とは、自分たちのイデオロギー(信条、美徳、慣行)を社会に政治的に押し付けようともがく異なる社会集団間の文化的対立の一種である[1][2]。政治的な用法では、文化戦争という用語は、[3][4]公共政策[5]や消費の経済的な問題をめぐって社会の主流派の間に政治的分極を引き起こすことを意図した意図的に敵対的な社会的物語で実現される、価値観やイデオロギーに関する「話題の」政治の比喩である。 [1]実践的な政治として、文化戦争とは、多文化社会における政治的分断を引き起こすことを意図した、価値観、道徳観、ライフスタイルに関する抽象的な議論に基づく社会政策のくさび問題に関するものである[2]。 |

Etymology Bismarck (left) and Pope Pius IX (right), from the German satirical magazine Kladderadatsch, 1875 Kulturkampf This section is an excerpt from Kulturkampf.[edit] In the history of Germany, the Kulturkampf (Cultural Struggle) was the seven-year political conflict (1871–1878) occurred between the Catholic Church in Germany, led by Pope Pius IX, and the Kingdom of Prussia, led by chancellor Otto von Bismarck. The Prussian church-and-state political conflict was about the Church's direct control of both education and ecclesiastical appointments in the Prussian kingdom as a Roman Catholic nation and country. Moreover, when compared to other church-and-state conflicts about political culture, the German Kulturkampf of Prussia also featured anti-Polish bigotry fueled by "racist anxieties" in Germany "about the Polish portions of the Prussian East."[6] In modern political usage, the German term Kulturkampf describes any conflict (political, ideological, social) between the secular government and the religious authorities of a society. The term also describes the great and small culture wars among political factions who hold deeply opposing values and beliefs within a nation, a community, and a cultural group.[7] In the English language, the term culture war is a calque of the German word Kulturkampf (culture struggle), which refers to an historical event in Germany. The term appears as the title of an 1875 British book review of a German pamphlet.[8] |

語源 ビスマルク(左)と教皇ピウス9世(右)、ドイツの風刺雑誌『Kladderadatsch』より、1875年 文化闘争 このセクションは『Kulturkampf』からの抜粋である[編集]。 ドイツの歴史において、文化闘争(Kulturkampf)は、教皇ピウス9世率いるドイツのカトリック教会とオットー・フォン・ビスマルク首相率いるプ ロイセン王国との間で起こった7年間の政治的対立(1871年~1878年)である。プロイセンの政教対立は、ローマ・カトリックの国であるプロイセン王 国において、教育も教会任命も教会が直接管理するというものであった。さらに、政治文化に関する他の政教対立と比較すると、プロイセンのドイツ文化闘争 は、「プロイセン東部のポーランド部分に関する」ドイツ国内の「人種差別的な不安」に煽られた反ポーランド的な偏見も特徴としていた[6]。 現代の政治的用法では、ドイツ語のKulturkampfという用語は、ある社会の世俗的な政府と宗教的な権威との間のあらゆる対立(政治的、イデオロ ギー的、社会的)を表す。この用語はまた、国家、地域社会、文化集団の中で深く対立する価値観や信念を保持する政治的な派閥間の大小の文化戦争を表現して いる[7]。 英語では、文化戦争という用語はドイツ語のKulturkampf(文化闘争)をもじったものであり、ドイツにおける歴史的な出来事を指している。この言葉は1875年にイギリスで出版されたドイツのパンフレットの書評のタイトルとして登場する[8]。 |

| Research Criticism and evaluation Since the time that James Davison Hunter first applied the concept of culture wars to American life, the idea has been subject to questions about whether "culture wars" names a real phenomenon, and if so, whether the phenomenon it describes is a cause of, or merely a result of, membership in groups like political parties and religions. Culture wars have also been subject to the criticism of being artificial, imposed, or asymmetric conflicts, rather than a result of authentic differences between cultures. Researchers have differed about the scientific validity of the notion of culture war. Some claim it does not describe real behavior, or that it describes only the behavior of a small political elite. Others claim culture war is real and widespread, and even that it is fundamental to explaining Americans' political behavior and beliefs. A 2023 study on the circulation of conspiracy theories on social media noted that disinformation actors insert polarizing claims in culture wars by taking one side or the other, thus making the adherents circulate and parrot disinformation as a rhetorical ammunition against their perceived opponents.[1] Political scientist Alan Wolfe participated in a series of scholarly debates in the 1990s and 2000s against Hunter, claiming that Hunter's concept of culture wars did not accurately describe the opinions or behavior of Americans, which Wolfe claimed were more united than polarized.[9] A meta-analysis of opinion data from 1992 to 2012 published in the American Political Science Review concluded that, in contrast to a common belief that political party and religious membership shape opinion on culture war topics, instead opinions on culture war topics lead people to revise their political party and religious orientations. The researchers view culture war attitudes as "foundational elements in the political and religious belief systems of ordinary citizens."[10] Artificiality or asymmetry Some writers and scholars have said that culture wars are created or perpetuated by political special interest groups, by reactionary social movements, by party dynamics, or by electoral politics as a whole. These authors view culture war not as an unavoidable result of widespread cultural differences, but as a technique used to create in-groups and out-groups for a political purpose. Political commentator E. J. Dionne has written that culture war is an electoral technique to exploit differences and grievances, remarking that the real cultural division is "between those who want to have a culture war and those who don't."[11] Sociologist Scott Melzer says that culture wars are created by conservative, reactive organizations and movements. Members of these movements possess a "sense of victimization at the hands of a liberal culture run amok. In their eyes, immigrants, gays, women, the poor, and other groups are (undeservedly) granted special rights and privileges." Melzer writes about the example of the National Rifle Association of America, which he says intentionally created a culture war in order to unite conservative groups, particularly groups of white men, against a common perceived threat.[12] Similarly, religion scholar Susan B. Ridgely has written that culture wars were made possible by Focus on the Family. This organization produced conservative Christian "alternative news" that began to bifurcate American media consumption, promoting a particular "traditional family" archetype to one part of the population, particularly conservative religious women. Ridgely says that this tradition was depicted as under liberal attack, seeming to necessitate a culture war to defend the tradition.[13] Political scientists Matt Grossmann and David A. Hopkins have written about an asymmetry between the US's two major political parties, saying the Republican party should be understood as an ideological movement built to wage political conflict, and the Democratic party as a coalition of social groups with less ability to impose ideological discipline on members.[14] This encourages Republicans to perpetuate and to draw new issues into culture wars, because Republicans are well equipped to fight such wars.[15] According to The Guardian, "many on the left have argued that such [culture war] battles [a]re 'distractions' from the real fight over class and economic issues."[16] Internet manipulation This section is an excerpt from Internet manipulation.[edit] Internet manipulation refers to the co-optation of online digital technologies, including algorithms, social bots, and automated scripts, for commercial, social, military, or political purposes.[17] Internet and social media manipulation are the prime vehicles for spreading disinformation due to the importance of digital platforms for media consumption and everyday communication.[18] When employed for political purposes, internet manipulation may be used to steer public opinion,[19] polarise citizens,[20] circulate conspiracy theories,[21] and silence political dissidents. Internet manipulation can also be done for profit, for instance, to harm corporate or political adversaries and improve brand reputation.[22] Internet manipulation is sometimes also used to describe the selective enforcement of Internet censorship[23][24] or selective violations of net neutrality.[25] |

研究 批判と評価 ジェームズ・デイヴィソン・ハンターが初めてカルチャー・ウォーズという概念をアメリカ生活に適用して以来、この考え方は、「カルチャー・ウォーズ」が現 実の現象なのか、もしそうだとすれば、その現象は政党や宗教のような集団に属することが原因なのか、それとも単にその結果なのかという疑問の対象になって きた。カルチャー・ウォーズはまた、文化間の真の違いの結果ではなく、人為的、押し付け的、非対称的な対立であるという批判にもさらされてきた。 文化戦争という概念の科学的妥当性については、研究者の間でも意見が分かれている。ある者は、文化戦争は現実の行動を表していない、あるいは一部の政治的 エリートの行動を表しているに過ぎないと主張する。また、文化戦争は現実のものであり、広く浸透しており、アメリカ人の政治的行動や信条を説明する上で基 本的なものだと主張する研究者もいる。 ソーシャルメディアにおける陰謀論の流通に関する2023年の研究では、偽情報の発信者はどちらか一方の側に立つことで、文化戦争における偏向的な主張を 挿入し、その結果、信奉者は偽情報を流通させ、認識された相手に対する修辞的な弾薬としてオウム返しをさせると指摘している[1]。 政治学者のアラン・ウルフは1990年代から2000年代にかけてハンターに対して一連の学術論争に参加し、ハンターのカルチャー・ウォーズの概念はアメリカ人の意見や行動を正確に描写していないと主張した。 American Political Science Review誌に掲載された1992年から2012年までの世論データのメタ分析によれば、カルチャー・ウォーのトピックに関する意見は政党や宗教によっ て形成されるという一般的な考えとは対照的に、カルチャー・ウォーのトピックに関する意見は政党や宗教の方向性を修正させるという結論に達している。研究 者たちは、文化戦争の態度を「一般市民の政治的・宗教的信念体系における基礎的な要素」と捉えている[10]。 人為性または非対称性 一部の作家や学者は、文化戦争は政治的な特別利益団体、反動的な社会運動、政党の力学、あるいは選挙政治全体によって生み出され、あるいは永続していると 述べている。これらの著者は、文化戦争は広範な文化的相違の不可避な結果ではなく、政治的目的のために内集団と外集団を作り出すために使われる手法である と見ている。 政治評論家のE.J.ディオンヌは、文化戦争は違いや不満を利用するための選挙テクニックであると書いており、本当の文化的分裂は「文化戦争をしたい人とそうでない人の間にある」と述べている[11]。 社会学者のスコット・メルザーは、文化戦争は保守的で反応的な組織や運動によって生み出されると言う。こうした運動のメンバーは、「リベラルな文化の暴走 による被害者意識」を持っている。彼らの目には、移民、同性愛者、女性、貧困層、その他のグループが(不当に)特別な権利や特権を与えられているように映 る」。メルツァーは全米ライフル協会の例について書いているが、彼は保守的なグループ、特に白人男性のグループを、共通の脅威と認識されるものに対して団 結させるために、意図的に文化戦争を作り出したと言う[12]。 同様に、宗教学者のスーザン・B・リッジリーは、文化戦争はフォーカス・オン・ザ・ファミリーによって可能になったと書いている。この組織は保守的なキリ スト教の「オルタナティブ・ニュース」を制作し、アメリカのメディア消費を二分し始め、人口の一部、特に保守的な宗教女性に特定の「伝統的家族」の典型を 宣伝した。リッジリーによれば、この伝統はリベラル派の攻撃を受けているように描かれ、伝統を守るために文化戦争が必要であるかのように見えたという [13]。 政治学者のマット・グロスマンとデビッド・A・ホプキンスは、アメリカの二大政党間の非対称性について書いている。共和党は政治的対立を行うために作られ たイデオロギー運動として理解されるべきであり、民主党はメンバーにイデオロギー的規律を課す能力が低い社会集団の連合体として理解されるべきであると述 べている[14]。共和党はこのような戦争を戦うのに十分な能力を持っているため、このことは共和党が文化戦争を永続させ、新たな問題を文化戦争に引き込 むことを促している[15]。 ガーディアン紙によれば、「左派の多くは、このような(文化戦争の)戦いは、階級や経済問題をめぐる真の戦いからの『気晴らし』であると主張している」[16]。 インターネット操作 このセクションはインターネット操作からの抜粋である[編集]。 インターネット操作とは、商業的、社会的、軍事的、政治的な目的のために、アルゴリズム、ソーシャルボット、自動化されたスクリプトを含むオンライン・デ ジタル・テクノロジーを共同利用することを指す[17]。メディア消費と日常的なコミュニケーションにおけるデジタル・プラットフォームの重要性から、イ ンターネットとソーシャルメディア操作は偽情報を広めるための主要な手段である[18]。政治的な目的のために使われる場合、インターネット操作は世論を 誘導し[19]、市民を偏向させ[20]、陰謀論を流布させ[21]、政治的反体制派を黙らせるために使われることがある。インターネット操作はまた、例 えば企業や政治的敵対者に危害を加えたり、ブランドの評判を向上させたりするために、営利目的で行われることもある[22]。インターネット操作はまた、 インターネット検閲の選択的実施[23][24]や、ネット中立性の選択的侵害[25]を表現するために使われることもある。 |

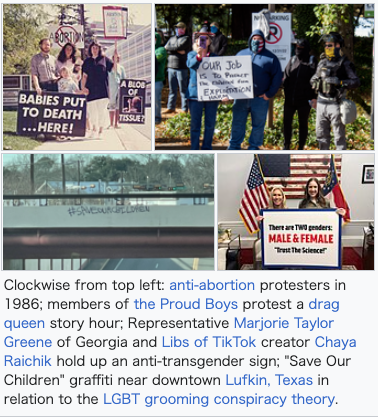

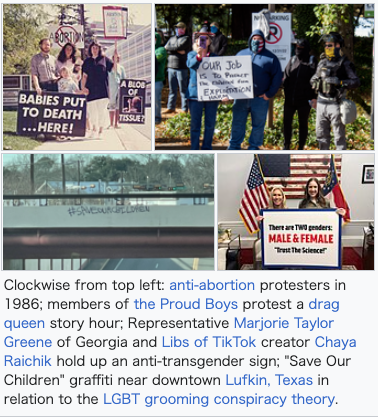

| Culture wars by country United States This section is an excerpt from Ethnocultural politics in the United States.[edit] Ethnocultural politics in the United States (or ethnoreligious politics) refers to the pattern of certain cultural or religious groups to vote heavily for one party. Groups can be based on ethnicity (such as Hispanics, Irish, Germans), race (Whites, Blacks, Asian Americans) or religion (Protestant [and later, Evangelical] or Catholic) or on overlapping categories (Irish Catholics). In the South, race was the determining factor. Each of the two major parties was a coalition of ethnoreligious groups in the Second Party System (1830s to 1850s) as well as the Third Party System (1850s to 1890s). 1920s–1991: Origins [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2021) In American usage, "culture war" may imply a conflict between those values considered traditionalist or conservative and those considered progressive or liberal. This usage originated in the 1920s when urban and rural American values came into closer conflict.[26] This followed several decades of immigration to the States by people who earlier European immigrants considered 'alien'. It was also a result of the cultural shifts and modernizing trends of the Roaring '20s, culminating in the presidential campaign of Al Smith in 1928.[27] In subsequent decades during the 20th century, the term was published occasionally in American newspapers.[28][29] 1991–2001: Rise in prominence James Davison Hunter, a sociologist at the University of Virginia, introduced the expression again in his 1991 publication, Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America. Hunter described what he saw as a dramatic realignment and polarization that had transformed American politics and culture. He argued that on an increasing number of "hot-button" defining issues—abortion, gun politics, separation of church and state, privacy, recreational drug use, homosexuality, censorship—there existed two definable polarities. Furthermore, not only were there a number of divisive issues, but society had divided along essentially the same lines on these issues, so as to constitute two warring groups, defined primarily not by nominal religion, ethnicity, social class, or even political affiliation, but rather by ideological world-views. Hunter characterized this polarity as stemming from opposite impulses, toward what he referred to as Progressivism and as Orthodoxy. Others have adopted the dichotomy with varying labels. For example, Bill O'Reilly, a conservative political commentator and former host of the Fox News Channel talk show The O'Reilly Factor, emphasizes differences between "Secular-Progressives" and "Traditionalists" in his 2006 book Culture Warrior.[30][31] Historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez attributes the 1990s emergence of culture wars to the end of the Cold War in 1991. She writes that Evangelical Christians viewed a particular Christian masculine gender role as the only defense of America against the threat of communism. When this threat ended upon the close of the Cold War, Evangelical leaders transferred the perceived source of threat from foreign communism to domestic changes in gender roles and sexuality.[32] During the 1992 presidential election, commentator Pat Buchanan mounted a campaign for the Republican nomination for president against incumbent George H. W. Bush. In a prime-time slot at the 1992 Republican National Convention, Buchanan gave his speech on the culture war.[33] He argued: "There is a religious war going on in our country for the soul of America. It is a cultural war, as critical to the kind of nation we will one day be as was the Cold War itself."[34] In addition to criticizing environmentalists and feminism, he portrayed public morality as a defining issue: The agenda [Bill] Clinton and [Hillary] Clinton would impose on America—abortion on demand, a litmus test for the Supreme Court, homosexual rights, discrimination against religious schools, women in combat units—that's change, all right. But it is not the kind of change America wants. It is not the kind of change America needs. And it is not the kind of change we can tolerate in a nation that we still call God's country.[34] A month later, Buchanan characterized the conflict as about power over society's definition of right and wrong. He named abortion, sexual orientation and popular culture as major fronts—and mentioned other controversies, including clashes over the Confederate flag, Christmas, and taxpayer-funded art. He also said that the negative attention his "culture war" speech received was itself evidence of America's polarization.[35] The culture war had significant impact on national politics in the 1990s.[4] The rhetoric of the Christian Coalition of America may have weakened president George H. W. Bush's chances for re-election in 1992 and helped his successor, Bill Clinton, win reelection in 1996.[36] On the other hand, the rhetoric of conservative cultural warriors helped Republicans gain control of Congress in 1994.[37] The culture wars influenced the debate over state-school history curricula in the United States in the 1990s. In particular, debates over the development of national educational standards in 1994 revolved around whether the study of American history should be a "celebratory" or "critical" undertaking and involved such prominent public figures as Lynne Cheney, Rush Limbaugh, and historian Gary Nash.[38][39] 2001–2012: Post-9/11 era  (from right to left) 43rd President George W. Bush, Donald Rumsfeld, and Paul Wolfowitz were prominent neoconservatives of the 2000s. A political view called neoconservatism shifted the terms of the debate in the early 2000s. Neoconservatives differed from their opponents in that they interpreted problems facing the nation as moral issues rather than economic or political ones. For example, neoconservatives saw the decline of the traditional family structure as well as the decline of religion in American society as spiritual crises that required a spiritual response. Critics accused neoconservatives of confusing cause and effect.[40] During the 2000s, voting for Republicans began to correlate heavily with traditionalist or orthodox religious belief across diverse religious sects. Voting for Democrats became more correlated to liberal or modernist religious belief, and to being nonreligious.[11] Belief in scientific conclusions, such as climate change, also became tightly coupled to political party affiliation in this era, causing climate scholar Andrew Hoffman to observe that climate change had "become enmeshed in the so-called culture wars."[41]  Rally for Proposition 8, an item on the 2008 California ballot to ban same-sex marriage Topics traditionally associated with culture war were not prominent in media coverage of the 2008 election season, with the exception of coverage of vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin,[42] who drew attention to her conservative religion and created a performative climate change denialism brand for herself.[43] Palin's defeat in the election and subsequent resignation as governor of Alaska caused the Center for American Progress to predict "the coming end of the culture wars," which they attributed to demographic change, particularly high rates of acceptance of same-sex marriage among millennials.[44] 2012–present: Broadening of the culture war See also: List of monuments and memorials removed during the George Floyd protests, List of changes made due to the George Floyd protests, and List of name changes due to the George Floyd protests While traditional culture war issues, like abortion, continue to be a focal point,[45] the issues identified with the culture war broadened and intensified in the mid-late 2010s. Jonathan Haidt, author of The Coddling of the American Mind, identified a rise in cancel culture via social media among young progressives since 2012, which he believes had "transformative effects on university life and later on politics and culture throughout the English-speaking world," in what Haidt[46] and other commentators[47][48] have called the "Great Awokening". Journalist Michael Grunwald says that "President Donald Trump has pioneered a new politics of perpetual culture war" and lists Black Lives Matter, U.S. national anthem protests, climate change, education policy, healthcare policy including Obamacare, and infrastructure policy as culture war issues in 2018.[49] The rights of transgender people and the role of religion in lawmaking were identified as "new fronts in the culture war" by political scientist Jeremiah Castle, as the polarization of public opinion on these two topics resembles that of previous culture war issues.[50] In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, North Dakota governor Doug Burgum described opposition to wearing face masks as a "senseless" culture war issue that jeopardizes human safety.[51]  Clockwise from top left: anti-abortion protesters in 1986; members of the Proud Boys protest a drag queen story hour; Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia and Libs of TikTok creator Chaya Raichik hold up an anti-transgender sign; "Save Our Children" graffiti near downtown Lufkin, Texas in relation to the LGBT grooming conspiracy theory. This broader understanding of culture war issues in the mid-late 2010s and 2020s is associated with a political strategy called "owning the libs." Conservative media figures employing this strategy, emphasize and expand upon culture war issues with the goal of upsetting liberal people. According to Nicole Hemmer of Columbia University, this strategy is a substitute for the cohesive conservative ideology that existed during the Cold War. It holds a conservative voting bloc together in the absence of shared policy preferences among the bloc's members.[52]  The Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in August 2017, an alt-right event regarded as a battle of the culture wars[53] A number of conflicts about diversity in popular culture occurring in the 2010s, such as the Gamergate controversy, Comicsgate and the Sad Puppies science fiction voting campaign, were identified in the media as being examples of the culture war.[54] Journalist Caitlin Dewey described Gamergate as a "proxy war" for a larger culture war between those who want greater inclusion of women and minorities in cultural institutions versus anti-feminists and traditionalists who do not.[55] The perception that culture war conflict had been demoted from electoral politics to popular culture led writer Jack Meserve to call popular movies, games, and writing the "last front in the culture war" in 2015.[56] These conflicts about representation in popular culture re-emerged into electoral politics via the alt-right and alt-lite movements.[57] According to media scholar Whitney Phillips, Gamergate "prototyped" strategies of harassment and controversy-stoking that proved useful in political strategy. For example, Republican political strategist Steve Bannon publicized pop-culture conflicts during the 2016 presidential campaign of Donald Trump, encouraging a young audience to "come in through Gamergate or whatever and then get turned onto politics and Trump."[58] Canada Main articles: Political culture of Canada and Monuments and memorials in Canada removed in 2020–2022 Some observers in Canada have used the term "culture war" to refer to differing values between Western versus Eastern Canada, urban versus rural Canada, as well as conservatism versus liberalism and progressivism.[59] The phrase has also been used to describe the Harper government's attitude towards the arts community. Andrew Coyne termed this negative policy towards the arts community as "class warfare."[60] Australia Main article: History wars During the tenure of the Liberal–National Coalition government of 1996 to 2007, interpretations of Aboriginal history became a part of a wider political debate regarding Australian national pride and symbolism occasionally called the "culture wars", more often the "history wars".[61] This debate extended into a controversy over the presentation of history in the National Museum of Australia and in high-school history curricula.[62][63] It also migrated into the general Australian media, with major broadsheets such as The Australian, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age regularly publishing opinion pieces on the topic. Marcia Langton has referred to much of this wider debate as "war porn"[64] and as an "intellectual dead end".[65] Two Australian Prime Ministers, Paul Keating (in office 1991–1996) and John Howard (in office 1996–2007), became major participants in the "wars". According to Mark McKenna's analysis for the Australian Parliamentary Library,[66] John Howard believed that Paul Keating portrayed Australia pre-Whitlam (Prime Minister from 1972 to 1975) in an unduly negative light; while Keating sought to distance the modern Labor movement from its historical support for the monarchy and for the White Australia policy by arguing that it was the conservative Australian parties which had been barriers to national progress. He accused Britain of having abandoned Australia during the Second World War. Keating staunchly supported a symbolic apology to Australian Aboriginals for their mistreatment at the hands of previous administrations, and outlined his view of the origins and potential solutions to contemporary Aboriginal disadvantage in his Redfern Park Speech of 10 December 1992 (drafted with the assistance of historian Don Watson). In 1999, following the release of the 1998 Bringing Them Home Report, Howard passed a Parliamentary Motion of Reconciliation describing treatment of Aborigines as the "most blemished chapter" in Australian history, but he refused to issue an official apology.[67] Howard saw an apology as inappropriate as it would imply "intergeneration guilt"; he said that "practical" measures were a better response to contemporary Aboriginal disadvantage. Keating has argued for the eradication of remaining symbols linked to colonial origins: including deference for ANZAC Day,[68] for the Australian flag and for the monarchy in Australia, while Howard supported these institutions. Unlike fellow Labor leaders and contemporaries, Bob Hawke (Prime Minister 1983–1991) and Kim Beazley (Labor Party leader 2005–2006), Keating never traveled to Gallipoli for ANZAC Day ceremonies. In 2008 he described those who gathered there as "misguided".[69] In 2006 John Howard said in a speech to mark the 50th anniversary of Quadrant that "Political Correctness" was dead in Australia but: "we should not underestimate the degree to which the soft-left still holds sway, even dominance, especially in Australia's universities".[citation needed] Also in 2006, Sydney Morning Herald political editor Peter Hartcher reported that Opposition foreign-affairs spokesman Kevin Rudd was entering the philosophical debate by arguing in response that "John Howard, is guilty of perpetrating 'a fraud' in his so-called culture wars ... designed not to make real change but to mask the damage inflicted by the Government's economic policies".[70] The defeat of the Howard government in the Australian Federal election of 2007 and its replacement by the Rudd Labor government altered the dynamic of the debate. Rudd made an official apology to the Aboriginal Stolen Generation[71] with bi-partisan support.[72] Like Keating, Rudd supported an Australian republic, but in contrast to Keating, Rudd declared support for the Australian flag and supported the commemoration of ANZAC Day; he also expressed admiration for Liberal Party founder Robert Menzies.[73][74] Subsequent to the 2007 change of government, and prior to the passage, with support from all parties, of the Parliamentary apology to indigenous Australians, Professor of Australian Studies Richard Nile argued: "the culture and history wars are over and with them should also go the adversarial nature of intellectual debate",[75] a view contested by others, including conservative commentator Janet Albrechtsen.[76] Climate change in Australia is also considered a highly divisive or politically controversial topic, to the point it is sometimes called a "culture war".[77][78] African Continent According to political scientist Constance G. Anthony, American culture war perspectives on human sexuality were exported to Africa as a form of neocolonialism. In his view, this began during the AIDS epidemic in Africa, with the United States government first tying HIV/AIDS assistance money to evangelical leadership and the Christian right during the Bush administration, then to LGBTQ tolerance during the administration of Barack Obama. This stoked a culture war that resulted in (among others) the Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Act of 2014.[79] Zambian scholar Kapya Kaoma notes that because "the demographic center of Christianity is shifting from the global North to the global South" Africa's influence on Christianity worldwide is increasing. American conservatives export their culture wars to Africa, Kaoma says, particularly when they realize they may be losing the battle back home. US Christians have framed their anti-LGBT initiatives in Africa as standing in opposition to a "Western gay agenda", a framing which Kaoma finds ironic.[80] North American and European conspiracy theories have become widespread in West Africa via social media, according to 2021 survey by First Draft News. COVID-19 misinformation, New World Order conspiracy thinking, QAnon and other conspiracy theories associated with culture war topics are spread by American, Pro-Russian, French-language, and local disinformation websites and social media accounts, including prominent politicians in Nigeria. This has contributed to vaccine hesitancy in West Africa, with 60 percent of survey respondents saying they were unlikely to try to get vaccinated, and an erosion of trust in institutions in the region.[81] United Kingdom See also: Actions against memorials in Great Britain during the George Floyd protests A 2021 report from King's College London argued that many people's views on cultural issues in Britain had become tied up with the side of the Brexit debate with which they identify, while the public party-political identities, although not as strong, show similar alignments and that around half the country held relatively strong views on "culture war" issues such as debates on Britain's colonial history or Black Lives Matter. However, the report concluded Britain's cultural and political divide was not as stark as the Republican–Democratic divide in the US and that a sizeable section of the public can be categorised as having either moderate views or as being disengaged from social debates. It also found that The Guardian, as opposed to the centre-right newspapers, was more likely to talk about the culture wars.[82] The Conservative Party have been described as attempting to ignite culture wars in regard to "conservative values" under the tenure of Prime Minister Boris Johnson. However, others argue that it is the left who are engaging in "culture wars", particularly against liberal values, accepted words and British institutions.[83][84][85][86] Observers such as Johns Hopkins University professor Yascha Mounk and journalist and author Louise Perry have argued that the collapse in support for the Labour Party during the 2019 United Kingdom general election came as a result of both a media-induced public perception and a deliberate strategy of Labour of pursuing messages and policy ideas based on cultural issues that resonated with more university educated grassroots activists on the left of the party but alienated Labour's traditional working class voters.[87][88] An April 2022 survey found evidence that Britons are less divided on "culture war" issues than has often been portrayed in the media. The greatest predictor of opinion was how people voted in the UK's referendum on membership of the European Union, Brexit, yet even among those who voted 'Leave', 75% agreed "it is important to be attentive to issues of race and social justice". Similarly, even among Remainers and those who last voted for the Labour Party, there was moderately strong support for several socially conservative positions.[89][90] Europe See also: "Polish death camp" controversy, Language policy in Ukraine, and LGBT ideology-free zone Poland's Law and Justice party,[91] Hungary's Viktor Orbán, Serbia's Aleksandar Vučić, and Slovenia's Janez Janša[92] have each been accused of fomenting culture wars in their respective countries by encouraging dissent, resistance to LGBT rights, and restrictions on abortion. One facet of the controversy in Poland is the removal of Soviet War Memorials which is divisive because some Poles viewed the memorials positively as commemorations of their ancestors who died during World War II while others felt negatively due to the oppression that some Poles experienced under the Soviet-backed Polish People's Republic[93][94] Culture war in Turkey is alleged by Kim Scheppele to be a disguise for democratic backsliding by Viktor Orbán.[95] Ukraine, meanwhile, has experienced a decades-long culture war pitting the eastern, predominately Russian-speaking, regions against the western Ukrainian-speaking areas of the country.[96] LGBT rights are controversial in Poland, as exemplified by President Andrzej Duda vow in 2020 to oppose both same-sex marriage and LGBT adoption.[97][98] Different interpretations of bitter events during World War II have become especially contentious in Poland since 2015, shortly after the start of the Russo-Ukrainian War.[99] One disputed issue is whether Poland bears any responsibility for the Holocaust, or whether Poland was entirely a victim of Nazi Germany. This dispute is embodied by the "Polish death camp" controversy (involving concentration camps that had been built by Nazi Germany during World War II on German-occupied Polish soil) and an attempt to address that controversy with a now partly repealed law[100] A second issue, also addressed by the partly repealed law, revolves around Poland–Ukraine relations Poland is not alone[101] in the region in passing a law to criminalize negative interpretations of the country's collaborationist nationalist movements during WWII and Poland–Ukraine relations have suffered as a result of a similar law in Ukraine that was criticized in Poland for deflecting blame away from the Ukrainian Insurgent Army and their massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.[102] |

国別文化戦争 米国 このセクションは、米国のエスノカルチュラル・ポリティクス[編集]からの抜粋です。 米国におけるエスノカルチュラル・ポリティクス(またはエスノレリジュー・ポリティクス)とは、特定の文化的または宗教的集団がある政党に多く投票するパ ターンを指す。集団は民族(ヒスパニック系、アイルランド系、ドイツ系など)、人種(白人、黒人、アジア系アメリカ人)、宗教(プロテスタント(後に福音 派)、カトリック)、あるいは重複するカテゴリー(アイルランド系カトリック)に基づくことがある。南部では人種が決定要因だった。二大政党はそれぞれ、 第二党制(1830年代から1850年代)と第三党制(1850年代から1890年代)における民族宗教グループの連合体であった。 1920s-1991: 起源 [アイコン] このセクションは拡張が必要です。追加することで貢献できます。(2021年12月) アメリカでの用法では、「文化戦争」は伝統主義的または保守的とされる価値観と進歩的またはリベラルとされる価値観の対立を意味することがある。この用法 は、アメリカの都市部と農村部の価値観がより緊密に対立するようになった1920年代に生まれた[26]。これは、それ以前のヨーロッパからの移民が「異 質なもの」とみなしていた人々が、数十年にわたってアメリカに移民してきたことに続くものであった。また、1928年のアル・スミスの大統領選挙を頂点と する、20年代の爛熟期の文化的転換と近代化の傾向の結果でもあった[27]。その後20世紀の数十年間、この言葉はアメリカの新聞に時折掲載された [28][29]。 1991-2001: 台頭 ヴァージニア大学の社会学者であるジェームズ・デイヴィソン・ハンターは、1991年に出版した『Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America』でこの表現を再び紹介した。ハンターは、アメリカの政治と文化を一変させた劇的な再編成と分極化について述べた。 妊娠中絶、銃社会、政教分離、プライバシー、嗜好品としての薬物使用、同性愛、検閲など、"ホット・バトン "と呼ばれる定義づけをめぐる問題には、明確な二極性が存在する。さらに、多くの分断的な問題が存在するだけでなく、社会はこれらの問題に関して本質的に 同じ路線で分裂しており、主に名目的な宗教、民族、社会階級、さらには政治的所属によってではなく、むしろイデオロギー的な世界観によって定義される2つ の抗争集団を構成していた。 ハンターはこの両極性を、進歩主義と正統主義と呼ばれる正反対の衝動に由来するものとして特徴づけた。また、この二項対立をさまざまなレッテルで表現して いる人々もいる。例えば、保守派の政治コメンテーターであり、Fox News Channelのトーク番組「The O'Reilly Factor」の元司会者であるビル・オライリーは、2006年に出版した著書「Culture Warrior」の中で、「世俗的進歩主義者」と「伝統主義者」の違いを強調している[30][31]。 歴史家のクリスティン・コベス・デュ・メズは、1990年代に文化戦争が勃興したのは1991年の冷戦の終結が原因であるとしている。彼女は、福音派のキ リスト教徒は、共産主義の脅威からアメリカを守る唯一の防衛手段として、特定のキリスト教徒的な男性的性別役割を見ていたと書いている。冷戦の終結によっ てこの脅威がなくなると、福音派の指導者たちは脅威の原因を外国の共産主義から国内のジェンダー役割とセクシュアリティの変化に移した[32]。 1992年の大統領選挙で、コメンテーターのパット・ブキャナン(Pat Buchanan) は、現職のジョージ・H・W・ブッシュに対抗して、共和党の大統領候補指名キャンペーンを行った。1992年の共和党全国大会のプライムタイム枠で、ブ キャナンは文化戦争についての演説を行った[33]: 「アメリカの魂をめぐって、宗教戦争が起こっている。それは文化戦争であり、冷戦そのものであったように、われわれがいつかどのような国家になるかにとっ て極めて重要である」[34]と主張し、環境保護主義者やフェミニズムを批判するとともに、公衆道徳を決定的な問題として描いた: ビル・クリントンとヒラリー・クリントンがアメリカに押し付けるであろうアジェンダは、オンデマンドの人工妊娠中絶、最高裁判所のリトマス試験紙、同性愛 の権利、宗教学校への差別、戦闘部隊への女性の参加などである。しかし、それはアメリカが望む変化ではない。アメリカが必要としている変化でもない。そし て、私たちがいまだに神の国と呼んでいる国で容認できるような変化でもない[34]。 その1ヵ月後、ブキャナンはこの対立を、社会の善悪の定義をめぐる権力に関するものだと位置づけた。彼は中絶、性的指向、大衆文化を主要な前線として挙 げ、南軍旗、クリスマス、税金で賄われる芸術をめぐる衝突など、他の論争についても言及した。彼はまた、彼の「文化戦争」演説が否定的な注目を浴びたこと 自体が、アメリカの二極化の証拠であるとも述べた[35]。 文化戦争は1990年代の国政に大きな影響を与えた[4]。 アメリカキリスト教連合のレトリックは、1992年のジョージ・H・W・ブッシュ大統領の再選の可能性を弱め、彼の後継者であるビル・クリントンの1996年の再選を助けたかもしれない[36]。 文化戦争は、1990年代のアメリカにおける州立学校の歴史カリキュラムをめぐる議論に影響を与えた。特に1994年の全国的な教育基準の策定をめぐる議 論は、アメリカ史の学習が「祝賀的」なものであるべきか「批判的」なものであるべきかをめぐって展開され、リン・チェイニー、ラッシュ・リンボー、歴史家 ゲイリー・ナッシュといった著名人が関与していた[38][39]。 2001-2012: ポスト9.11時代  (右から)第43代大統領ジョージ・W・ブッシュ、ドナルド・ラムズフェルド、ポール・ウォルフォウィッツは2000年代の著名な新保守主義者。 新保守主義と呼ばれる政治的見解は、2000年代初頭に議論の条件をシフトさせた。新保守主義者は、国家が直面する問題を経済的、政治的な問題ではなく、 道徳的な問題として解釈するという点で、反対派とは異なっていた。たとえば、新保守主義者たちは、伝統的な家族構造の衰退やアメリカ社会における宗教の衰 退を、精神的な対応を必要とする精神的危機とみなした。批評家たちは新保守主義者たちが原因と結果を混同していると非難した[40]。 2000年代には、共和党への投票は、多様な宗教宗派にまたがる伝統主義的あるいは正統的な宗教的信念と大きく相関し始めた。気候変動のような科学的結論 の信奉も、この時代には所属政党と密接に結びつくようになり、気候変動学者のアンドリュー・ホフマンは、気候変動は「いわゆる文化戦争に巻き込まれた」と 観察している[41]。  2008年カリフォルニア州投票の同性婚禁止を求める提案8号への集会 伝統的に文化戦争に関連するトピックは、2008年の選挙シーズンのメディア報道では目立たなかったが、保守的な宗教に注目を集め、自身のためにパフォー マティブな気候変動否定主義のブランドを作り上げたサラ・ペイリン副大統領候補[42]の報道は例外だった[43]。ペイリンの選挙での敗北とその後のア ラスカ州知事辞任によって、アメリカ進歩センターは「文化戦争の終わりが来る」と予測し、その原因は人口動態の変化、特にミレニアル世代における同性婚の 高い受容率にあるとした[44]。 2012年-現在: 文化戦争の拡大 以下も参照: ジョージ・フロイドの抗議行動で撤去されたモニュメントと記念碑のリスト、ジョージ・フロイドの抗議行動による変更のリスト、ジョージ・フロイドの抗議行動による名称変更のリスト 中絶のような伝統的な文化戦争の問題は引き続き焦点となっているが[45]、文化戦争と特定される問題は2010年代半ばから後半にかけて拡大し、激化し た。The Coddling of the American Mind』の著者であるジョナサン・ヘイトは、2012年以降、若い進歩主義者たちの間でソーシャルメディアを通じてキャンセル文化が台頭していることを 指摘し、それが「大学生活、そしてその後の英語圏全体の政治や文化に変革的な影響を与えた」と考えている。ジャーナリストのマイケル・グルンワルドは、 「ドナルド・トランプ大統領は永続的な文化戦争の新しい政治を開拓した」とし、2018年の文化戦争問題として、黒人差別問題、米国国歌斉唱抗議、気候変 動、教育政策、オバマケアを含む医療政策、インフラ政策を挙げている。 [49]トランスジェンダーの権利と法律制定における宗教の役割は、政治学者のジェレマイア・キャッスルによって「文化戦争の新たな前線」とされ、この2 つのトピックに関する世論の二極化は以前の文化戦争の問題と類似しているためである[50]。 2020年、COVID-19のパンデミックの際、ノースダコタ州知事のダグ・バーガムは、フェイスマスク着用への反対を、人間の安全を脅かす「無意味 な」文化戦争の問題であると述べた[51]。  左上から時計回りに:1986年の中絶反対デモ参加者、ドラァグクイーンのお話会に抗議するプラウドボーイズのメンバー、反トランスジェンダーの看板を掲 げるジョージア州のマージョリー・テイラー・グリーン下院議員とLibs of TikTokのクリエイターであるチャヤ・ライチク、LGBTグルーミング陰謀論に関連するテキサス州ラフキンのダウンタウン付近の「Save Our Children」の落書き。 2010年代半ばから2020年代にかけての文化戦争問題に対するこのような幅広い理解は、"ownning the libs "と呼ばれる政治戦略に関連している。この戦略を採用する保守派のメディア関係者は、リベラル派を動揺させる目的で、文化戦争の問題を強調し、拡大解釈す る。コロンビア大学のニコール・ヘマーによれば、この戦略は冷戦時代に存在した結束力のある保守イデオロギーの代用品だという。ブロックのメンバー間で政 策的な好みが共有されていない中で、保守的な投票ブロックをまとめているのである[52]。  2017年8月にヴァージニア州シャーロッツヴィルで開催されたユナイト・ザ・ライトの集会は、文化戦争の戦いとみなされたオルト・ライトのイベント[53]。 ゲームゲート論争、コミックスゲート、サッド・パピーズのSF投票キャンペーンなど、2010年代に発生した大衆文化の多様性に関する多くの対立は、メ ディアにおいて文化戦争の例であると認識されていた。 [54] ジャーナリストのケイトリン・デューイは、ゲームゲートを、文化機関における女性やマイノリティのインクルージョンの拡大を望む人々と、そうでないアンチ フェミニストや伝統主義者との間の、より大きな文化戦争の「代理戦争」であると表現した[55]。文化戦争の対立が選挙政治から大衆文化へと降格したとい う認識から、作家のジャック・メザーヴは2015年に大衆映画、ゲーム、文章を「文化戦争の最後の前線」と呼んだ[56]。 大衆文化における表現に関するこうした対立は、オルト・ライト運動やオルト・ライト運動を通じて選挙政治に再登場した[57]。メディア研究者のホイット ニー・フィリップスによれば、ゲームゲートは政治戦略に有用であることが証明された嫌がらせや論争を煽る戦略の「プロトタイプ」であった。例えば、共和党 の政治戦略家であるスティーブ・バノンは、ドナルド・トランプの2016年の大統領選挙キャンペーン中にポップカルチャーの対立を公表し、若い聴衆に 「ゲームゲートや何かを通して入ってきて、政治やトランプに目を向けるように」促していた[58]。 カナダ 主な記事 カナダの政治文化、2020年から2022年にかけて撤去されたカナダの記念碑と記念碑 カナダの一部のオブザーバーは、「文化戦争」という言葉を、カナダ西部対東部、カナダ都市部対農村部、保守主義対リベラリズム、進歩主義といった価値観の 違いを指す言葉として使っている[59]。この言葉は、芸術コミュニティに対するハーパー政権の態度を表す言葉としても使われている。アンドリュー・コイ ンは、芸術コミュニティに対するこの否定的な政策を「階級闘争」と呼んだ[60]。 オーストラリア 主な記事 歴史戦争 1996年から2007年の自由党・国民連合政権在任中、アボリジニの歴史解釈は、オーストラリアの国家としての誇りと象徴性に関するより広範な政治的議 論の一部となり、「文化戦争」と呼ばれることもあったが、「歴史戦争」と呼ばれることのほうが多かった。 [この論争は、オーストラリア国立博物館や高校の歴史教育課程における歴史の記述をめぐる論争にまで発展した[62][63]。この論争はオーストラリア の一般メディアにも波及し、オーストラリアン紙、シドニー・モーニング・ヘラルド紙、エイジ紙などの主要紙が定期的にこの問題に関する意見記事を掲載し た。マーシャ・ラングトンは、こうした広範な議論の多くを「戦争ポルノ」[64]、「知的行き詰まり」と呼んでいる[65]。 オーストラリアの二人の首相、ポール・キーティング(1991-1996年在任)とジョン・ハワード(1996-2007年在任)は、「戦争」の主要な参 加者となった。オーストラリア国会図書館のためのマーク・マッケンナの分析によると[66]、ジョン・ハワードは、ポール・キーティングがホワイトラム以 前のオーストラリア(1972年から1975年まで首相)を不当に否定的に描いていると考えていた。彼は、イギリスが第二次世界大戦中にオーストラリアを 見捨てたと非難した。キーティングは、オーストラリアのアボリジニが以前の政権によって虐待を受けたことに対する象徴的な謝罪を支持し、1992年12月 10日のレッドファーン公園での演説(歴史学者ドン・ワトソンの協力を得て起草)で、現代のアボリジニの不遇の起源と潜在的な解決策についての見解を示し た。1999年、ハワードは1998年の「Bringing Them Home報告書」の発表を受けて、アボリジニーの扱いをオーストラリアの歴史における「最も汚点の多い章」とする和解動議を議会で可決したが、公式な謝罪 は拒否した[67]。ハワードは、謝罪は「世代間の罪」を意味するため不適切であると考え、現代のアボリジニーの不利な状況に対しては「実際的」な対策が より良い対応策であると述べた。キーティングは、アンザック・デー、オーストラリア国旗[68]、オーストラリアにおける君主制への敬意など、植民地起源 に関連する残存するシンボルの根絶を主張したが、ハワードはこれらの制度を支持した。同じ労働党の指導者であり、同世代のボブ・ホーク (1983~1991年首相)やキム・ビーズリー(2005~2006年労働党党首)とは異なり、キーティングはアンザックデーの式典のためにガリポリを 訪れることはなかった。2008年、彼はガリポリに集まった人々を「見当違い」と評した[69]。 2006年、ジョン・ハワードはクオドラント50周年を記念する演説で、「ポリティカル・コレクトネス(政治的正しさ)」はオーストラリアでは死んだと述 べたが、「我々は過小評価すべきではない: 2006年、シドニー・モーニング・ヘラルドの政治編集者ピーター・ハートチャーは、野党のケヴィン・ラッド外交部報道官が「ジョン・ハワードは、いわゆ る文化戦争において『詐欺』を働いた罪を犯している......真の変化をもたらすためではなく、政府の経済政策によってもたらされた損害を覆い隠すため に設計された」と反論し、哲学論争に参入していると報じた[70]。 2007年のオーストラリア連邦選挙でハワード政権が敗北し、ラッド労働党政権に交代したことで、この議論の流れは変わった。ラッドは超党派の支持を得 て、アボリジニの「盗まれた世代」[71]に公式謝罪を行った[72]。キーティングと同様、ラッドはオーストラリア共和国を支持したが、キーティングと は対照的に、ラッドはオーストラリア国旗の支持を表明し、アンザックデーの記念を支持した。 2007年の政権交代後、全政党の支持を得てオーストラリア先住民への議会謝罪が可決される前に、オーストラリア研究のリチャード・ナイル教授は次のよう に主張した: 「文化と歴史の戦争は終わり、それとともに知的な議論の敵対的な性質も終わるべきだ」と主張し[75]、保守派の論客であるジャネット・アルブレヒツェン をはじめとする他の論客はこの意見に異論を唱えている[76]。 オーストラリアにおける気候変動もまた、「文化戦争」と呼ばれることもあるほど、非常に分裂的、あるいは政治的に議論の多いテーマと考えられている[77][78]。 アフリカ大陸 政治学者のコンスタンス・G・アンソニーによれば、人間のセクシュアリティに関するアメリカの文化戦争の視点は、新植民地主義の一形態としてアフリカに輸 出された。彼の見解によれば、これはアフリカでのエイズ流行の際に始まったもので、アメリカ政府はまず、ブッシュ政権時代にHIV/エイズ支援資金を福音 派の指導者やキリスト教右派と結びつけ、次いでバラク・オバマ政権時代にLGBTQ寛容と結びつけた。これにより文化戦争が煽られ、2014年のウガンダ 反同性愛法(Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Act of 2014)が制定された[79]。 ザンビアの学者であるカピヤ・カオマは、「キリスト教の人口的中心が世界の北から南へとシフトしている」ため、世界のキリスト教に対するアフリカの影響力 が増大していると指摘している。アメリカの保守派は、特に自国での戦いに敗れそうなときに、文化戦争をアフリカに輸出するのだとカオマは言う。アメリカの キリスト教徒は、アフリカにおける反LGBTの取り組みを「西側のゲイのアジェンダ」に反対するものとしているが、これはカオマにとって皮肉なことである [80]。 First Draft Newsによる2021年の調査によれば、北米とヨーロッパの陰謀論はソーシャルメディアを通じて西アフリカで広まっている。COVID-19の誤報、新 世界秩序の陰謀思想、QAnon、その他文化戦争のトピックに関連する陰謀論は、ナイジェリアの著名な政治家を含め、アメリカ、親ロシア、フランス語、現 地の偽情報サイトやソーシャルメディアアカウントによって広まっている。このことは、西アフリカにおけるワクチン接種のためらいを助長し、調査回答者の 60%がワクチン接種を受けようとする可能性は低いと答えており、この地域の制度に対する信頼も失われている[81]。 イギリス こちらも参照: ジョージ・フロイド事件における英国内の追悼施設に対する行動 キングス・カレッジ・ロンドンの2021年の報告書によれば、英国の文化的問題に対する多くの人々の見解は、ブレグジット論争のどちらを支持するかという ことと結びついており、政党と政治的アイデンティティも、それほど強くはないものの、同様の傾向を示している。しかし、報告書は、英国の文化的・政治的分 裂は、米国の共和党と民主党の分裂ほど激しくなく、国民のかなりの部分は、穏健な意見を持っているか、社会的議論に無関心であるかのどちらかに分類できる と結論づけた。また、中道右派の新聞とは対照的に、『ガーディアン』はカルチャー・ウォーズについて語る傾向が強いこともわかった[82]。保守党は、ボ リス・ジョンソン首相の在任中、「保守的価値観」に関してカルチャー・ウォーズを引き起こそうとしていると言われてきた。 しかし、「文化戦争」、特にリベラルな価値観や受容された言葉、イギリスの制度に対して関与しているのは左派であると主張する者もいる[83][84] [85]。 [83][84][85][86]ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学のヤッシャ・モーンク教授やジャーナリストで作家のルイーズ・ペリーなどのオブザーバーは、 2019年のイギリス総選挙における労働党の支持率の崩壊は、メディアによって誘発された一般大衆の認識と、党の左派にいるより大学教育を受けた草の根活 動家には共鳴するものの、労働党の伝統的な労働者階級の有権者を疎外する文化的な問題に基づいたメッセージや政策アイデアを追求する労働党の意図的な戦略 の両方の結果として生じたと主張している[87][88]。 2022年4月の調査では、メディアでしばしば描かれてきたほどには、イギリス人が「文化戦争」の問題で分裂していないという証拠が見つかった。意見の最 大の予測要因は、EU加盟を問う英国の国民投票「ブレグジット」で人々がどのように投票したかだったが、「離脱」に投票した人々の間でも、75%が「人種 や社会正義の問題に配慮することは重要だ」と同意していた。同様に、残留派や最後に労働党に投票した人々の間でも、いくつかの社会的に保守的な立場への支 持が中程度に強かった[89][90]。 ヨーロッパ 以下も参照: 「ポーランドの死の収容所」論争、ウクライナにおける言語政策、LGBTイデオロギーフリーゾーン ポーランドの法と正義党[91]、ハンガリーのヴィクトール・オルバン、セルビアのアレクサンダル・ヴチッチ、スロベニアのヤネス・ヤンシャ[92]はそ れぞれ、反対意見やLGBTの権利に対する抵抗、中絶の制限を奨励することによって、それぞれの国で文化戦争を煽っていると非難されている。ポーランドに おける論争の一面は、ソビエト戦争記念碑の撤去であり、第二次世界大戦中に亡くなった先祖を記念するものとして肯定的にとらえるポーランド人もいれば、ソ ビエトに支援されたポーランド人民共和国[93][94]のもとで一部のポーランド人が経験した抑圧のために否定的に感じるポーランド人もいるため、分裂 を招いている。 [一方、ウクライナでは、ロシア語を主に話す東部地域とウクライナ語を話す西部地域が数十年にわたる文化戦争を経験している[96]。ポーランドでは、ア ンドレイ・ドゥダ大統領が2020年に同性婚とLGBTの養子縁組の両方に反対すると宣言したことに代表されるように、LGBTの権利が物議を醸している [97][98]。 第二次世界大戦中の苦い出来事に対する解釈の違いは、露・ウクライナ戦争が始まった直後の2015年以降、ポーランドで特に論争となっている[99]。争 点のひとつは、ポーランドがホロコーストの責任を負うのか、それともポーランドは完全にナチス・ドイツの犠牲者だったのか、というものである。この論争 は、「ポーランドの死の収容所」論争(第二次世界大戦中、ナチス・ドイツがドイツ占領下のポーランド国内に建設した強制収容所に関する論争)と、現在では 一部廃止された法律でこの論争に対処しようとした試み[100]によって具体化されている。 ポーランドは、第二次世界大戦中の自国の協力主義的な民族主義運動に対する否定的な解釈を犯罪とする法律を通過させたこの地域で唯一の国ではなく [101]、ポーランド・ウクライナ関係は、ウクライナ反乱軍とヴォルヒニアと東ガリシアにおけるポーランド人の虐殺から非難をそらすとしてポーランドで 批判されたウクライナの同様の法律の結果として苦しんできた[102]。 |

| Drugs Drug decriminalization Harm reduction Legal drinking age War on Drugs Education and parenting Corporal punishment and child discipline, most notably spanking Creation–evolution controversy Family values Homeschooling and educational choice Sexual education and abstinence only education Environment and energy Global warming controversy[41] Gender and sexuality Anti-gender movement Age of consent Circumcision controversies Feminism LGBT rights and same-sex marriage Polyamory Sex work Sexual revolution Law and government Crypto wars Gun rights Immigration reform Law and order Red state vs. blue state divide Life issues Anti-war movement Capital punishment Reproductive rights including birth control (and its coverage by insurance) Right to die movement and euthanasia Stem-cell research Universal healthcare Society and culture Animal rights Call-out culture Christmas controversy Counterculture Cultural conflict Cultural Marxism conspiracy theory Expurgation – Form of censorship of artistic or other media works Geographical renaming History wars Media bias in the U.S. Moral absolutism vs. moral relativism Multiculturalism Negationism Owning the libs Permissive society Race, affirmative action Secularism and secularization Social justice warrior Theory wars Woke |

薬物 薬物の非犯罪化 薬害削減 飲酒適齢期 薬物との戦い 教育と子育て 体罰と子供のしつけ(特にスパンキング 創造と進化の論争 家族の価値観 ホームスクーリングと教育の選択 性教育と禁欲教育 環境とエネルギー 地球温暖化論争[41] ジェンダーとセクシュアリティ 反ジェンダー運動 同意年齢 割礼論争 フェミニズム LGBTの権利と同性婚 ポリアモリー セックスワーク 性革命 法と政府 暗号戦争 銃の権利 移民制度改革 法と秩序 レッドステート対ブルーステートの対立 生活問題 反戦運動 死刑制度 避妊を含む生殖の権利(および保険適用) 死ぬ権利運動と安楽死 幹細胞研究 国民皆保険 社会と文化 動物の権利 コールアウト文化 クリスマス論争 カウンターカルチャー 文化的対立 文化的マルクス主義陰謀論 釈明 - 芸術作品やその他のメディア作品の検閲の一形態 地理的名称変更 歴史戦争 アメリカにおけるメディアの偏向 道徳絶対主義対道徳相対主義 多文化主義 否定主義 リブの支配 寛容な社会 人種、アファーマティブ・アクション 世俗主義と世俗化 社会正義の戦士 理論戦争 目覚め |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_war |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099