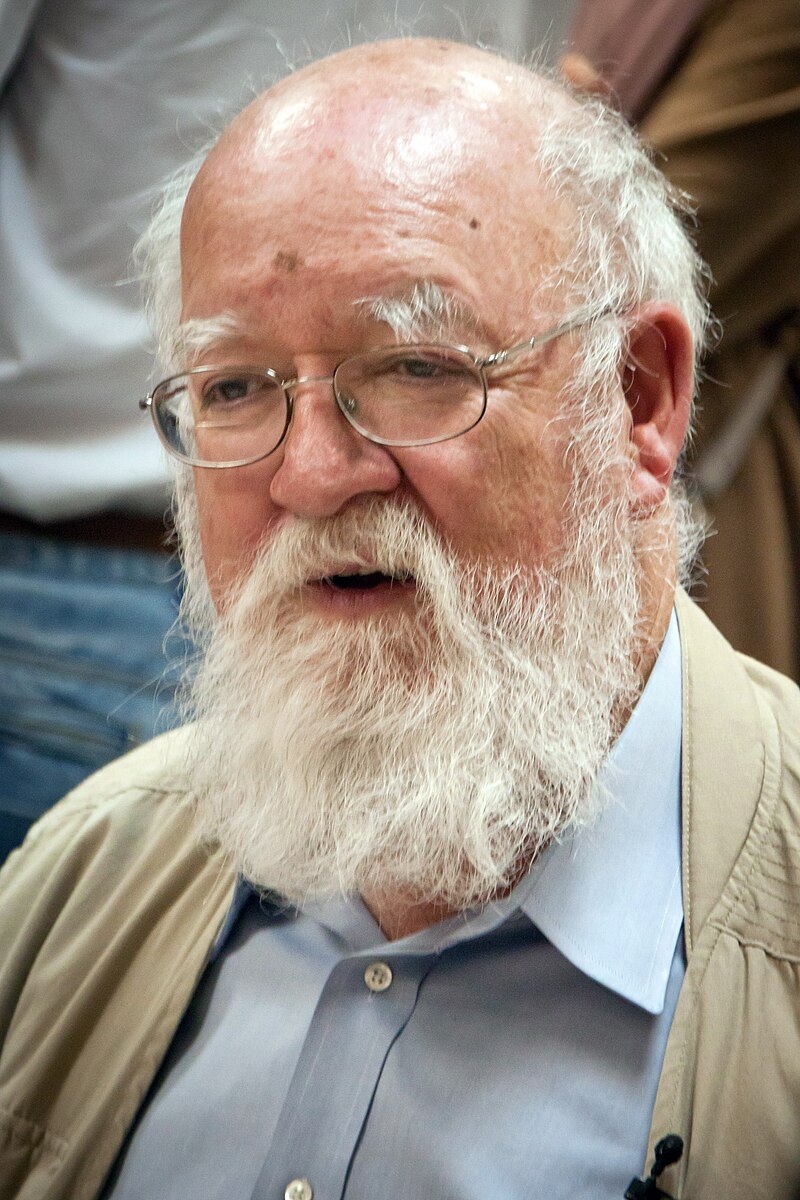

ダニエル・デネット

Daniel Clement Dennett III, 1942-2024

☆ ダニエル・クレメント・デネット3世(1942年3月28日 - 2024年4月19日)は、アメリカの哲学者、認知科学者である。彼の研究は、心の哲学、科学哲学、生物学の哲学を中心に、特にそれらの分野が進化生物学 や認知科学と関連しているものだった。 デネットはマサチューセッツ州のタフツ大学で認知研究センターの共同ディレクターおよびオースティン・B・フレッチャー哲学教授を務めた。[10] デネットは『ラザフォード・ジャーナル』の編集委員であり[11]、また『聖職者プロジェクト』の共同創設者でもある。[12] 著名な無神論者であり世俗主義者であるデネットは、「最も広く読まれ、議論されているアメリカの哲学者の一人」と評されている。[13] 彼は、リチャード・ドーキンス、サム・ハリス、クリストファー・ヒッチェンズとともに、「ニューエイティズムの4騎士」の一人と呼ばれていた。

| Daniel Clement

Dennett III (March 28, 1942 – April 19, 2024) was an American

philosopher and cognitive scientist. His research centered on the

philosophy of mind, the philosophy of science, and the philosophy of

biology, particularly as those fields relate to evolutionary biology

and cognitive science.[9] Dennett was the co-director of the Center for Cognitive Studies and the Austin B. Fletcher Professor of Philosophy at Tufts University in Massachusetts.[10] Dennett was a member of the editorial board for The Rutherford Journal[11] and a co-founder of The Clergy Project.[12] A vocal atheist and secularist, Dennett has been described as "one of the most widely read and debated American philosophers".[13] He was referred to as one of the "Four Horsemen" of New Atheism, along with Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Christopher Hitchens. |

ダニエル・クレメント・デネット3世(1942年3月28日 -

2024年4月19日)は、アメリカの哲学者、認知科学者である。彼の研究は、心の哲学、科学哲学、生物学の哲学を中心に、特にそれらの分野が進化生物学

や認知科学と関連しているものだった。 デネットはマサチューセッツ州のタフツ大学で認知研究センターの共同ディレクターおよびオースティン・B・フレッチャー哲学教授を務めた。[10] デネットは『ラザフォード・ジャーナル』の編集委員であり[11]、また『聖職者プロジェクト』の共同創設者でもある。[12] 著名な無神論者であり世俗主義者であるデネットは、「最も広く読まれ、議論されているアメリカの哲学者の一人」と評されている。[13] 彼は、リチャード・ドーキンス、サム・ハリス、クリストファー・ヒッチェンズとともに、「ニューエイティズムの4騎士」の一人と呼ばれていた。 |

| Early life and education Daniel Clement Dennett III was born on March 28, 1942, in Boston, Massachusetts,[14] the son of Ruth Marjorie (née Leck; 1903–1971) and Daniel Clement Dennett Jr. (1910–1947).[15][16][17] Dennett spent part of his childhood in Lebanon,[10] where, during World War II, his father, who had a PhD in Islamic studies from Harvard University, was a covert counter-intelligence agent with the Office of Strategic Services posing as a cultural attaché to the American Embassy in Beirut. His mother, an English major at Carleton College, went for a master's degree at the University of Minnesota before becoming an English teacher at the American Community School in Beirut.[18] In 1947, his father was killed in a plane crash in Ethiopia.[19] Shortly after, his mother took him back to Massachusetts.[20] Dennett's sister is the investigative journalist Charlotte Dennett.[18] Dennett said that he was first introduced to the notion of philosophy while attending Camp Mowglis in Hebron, New Hampshire, at age 11, when a camp counselor said to him, "You know what you are, Daniel? You're a philosopher."[21] Dennett graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy in 1959, and spent one year at Wesleyan University before receiving his BA degree in philosophy at Harvard University in 1963.[10] There, he was a student of Willard Van Orman Quine.[10] He had decided to transfer to Harvard after reading Quine's From a Logical Point of View and, thinking that Quine was wrong about some things, decided, as he said "as only a freshman could, that I had to go to Harvard and confront this man with my corrections to his errors!"[22][23] |

幼少期と教育 ダニエル・クレメント・デネット3世は1942年3月28日、マサチューセッツ州ボストンで、ルース・マージョリー(旧姓レック、1903年 - 1971年)とダニエル・クレメント・デネット・ジュニア(1910年 - 1947年)の間に生まれた。 デネットは幼少期の一部をレバノンで過ごした。[10] 第二次世界大戦中、ハーバード大学でイスラム学の博士号を取得した父親は、戦略事務局の秘密諜報員として、ベイルートのアメリカ大使館の文化担当官を装っ ていた。母親はカールトン・カレッジで英文学を専攻し、ミネソタ大学で修士号を取得した後、ベイルートのアメリカン・コミュニティ・スクールで英語教師と なった。[18] 1947年、父親はエチオピアで飛行機事故により死亡した。[19] その後まもなく、母親は彼をマサチューセッツ州に連れ戻した。[20] デネットの姉は調査ジャーナリストのシャーロット・デネットである。[18] デネットは、11歳の時にニューハンプシャー州ヘブロンにあるキャンプ・モーグリに参加した際に、キャンプカウンセラーから「自分が何者か知っているかい、ダニエル?君は哲学者だよ」と言われたことが、哲学という概念に初めて触れたきっかけだったと語っている。 デネットは1959年にフィリップス・エクセター・アカデミーを卒業し、ウェスリアン大学で1年間を過ごした後、1963年にハーバード大学で哲学の学士 号を取得した。 [10] そこで彼はウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインの教え子であった。[10] クワインの著書『論理的な観点から』を読んでハーバード大学への編入を決意した彼は、クワインがいくつかの点で間違っていると考え、「新入生らしい考え方 だが、私はハーバード大学に行って、この男の誤りを正さなければならない!」と決意したという。[22][23] |

| Academic career In 1965, Dennett received his DPhil in philosophy at the University of Oxford, where he studied under Gilbert Ryle and was a member of Hertford College.[24][10] His doctoral dissertation was entitled The Mind and the Brain: Introspective Description in the Light of Neurological Findings; Intentionality.[25] From 1965 to 1971, Dennett taught at the University of California, Irvine, before moving to Tufts University where he taught for many decades.[13][10] He also spent periods visiting at Harvard University and several other universities.[26] Dennett described himself as "an autodidact—or, more properly, the beneficiary of hundreds of hours of informal tutorials on all the fields that interest me, from some of the world's leading scientists".[27] Throughout his career, he was an interdisciplinarian who argued for "breaking the silos of knowledge", and he collaborated widely with computer scientists, cognitive scientists, and biologists.[23] Dennett was the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship and two Guggenheim Fellowships. |

学術経歴 1965年、デネットはオックスフォード大学で哲学の博士号を取得した。同大学ではギルバート・ライルの下で学び、ハートフォード・カレッジのメンバーで もあった。[24][10] 博士論文のタイトルは『心と脳:神経学的知見に照らした内省的な記述;意図性』であった。[25] 1965年から1971年にかけて、デネットはカリフォルニア大学アーバイン校で教鞭をとり、その後タフツ大学に移り、そこで何十年にもわたって教鞭を とった。[13][10] また、ハーバード大学やその他のいくつかの大学でも教鞭をとった。 [26] デネットは自らを「独学者、あるいはより正確に言えば、世界をリードする科学者たちから、関心のあるあらゆる分野について何百時間にもわたる非公式な個人 指導を受けた受益者」と表現している。[27] キャリアを通じて、彼は「知識のサイロを壊す」ことを主張する学際的研究家であり、コンピュータ科学者、認知科学者、生物学者と幅広く共同研究を行ってきた。[23] デネットはフルブライト奨学金と2つのグッゲンハイム奨学金の受賞者である。 |

| Philosophical views Free will vs Determinism While he was a confirmed compatibilist on free will, in "On Giving Libertarians What They Say They Want"—chapter 15 of his 1978 book Brainstorms[28]—Dennett articulated the case for a two-stage model of decision making in contrast to libertarian views. The model of decision making I am proposing has the following feature: when we are faced with an important decision, a consideration-generator whose output is to some degree undetermined, produces a series of considerations, some of which may of course be immediately rejected as irrelevant by the agent (consciously or unconsciously). Those considerations that are selected by the agent as having a more than negligible bearing on the decision then figure in a reasoning process, and if the agent is in the main reasonable, those considerations ultimately serve as predictors and explicators of the agent's final decision.[29] While other philosophers have developed two-stage models, including William James, Henri Poincaré, Arthur Compton, and Henry Margenau, Dennett defended this model for the following reasons: First ... The intelligent selection, rejection, and weighing of the considerations that do occur to the subject is a matter of intelligence making the difference. Second, I think it installs indeterminism in the right place for the libertarian, if there is a right place at all. Third ... from the point of view of biological engineering, it is just more efficient and in the end more rational that decision making should occur in this way. A fourth observation in favor of the model is that it permits moral education to make a difference, without making all of the difference. Fifth—and I think this is perhaps the most important thing to be said in favor of this model—it provides some account of our important intuition that we are the authors of our moral decisions. Finally, the model I propose points to the multiplicity of decisions that encircle our moral decisions and suggests that in many cases our ultimate decision as to which way to act is less important phenomenologically as a contributor to our sense of free will than the prior decisions affecting our deliberation process itself: the decision, for instance, not to consider any further, to terminate deliberation; or the decision to ignore certain lines of inquiry. These prior and subsidiary decisions contribute, I think, to our sense of ourselves as responsible free agents, roughly in the following way: I am faced with an important decision to make, and after a certain amount of deliberation, I say to myself: "That's enough. I've considered this matter enough and now I'm going to act," in the full knowledge that I could have considered further, in the full knowledge that the eventualities may prove that I decided in error, but with the acceptance of responsibility in any case.[30] Leading libertarian philosophers such as Robert Kane have rejected Dennett's model, specifically that random chance is directly involved in a decision, on the basis that they believe this eliminates the agent's motives and reasons, character and values, and feelings and desires. They claim that, if chance is the primary cause of decisions, then agents cannot be liable for resultant actions. Kane says: [As Dennett admits,] a causal indeterminist view of this deliberative kind does not give us everything libertarians have wanted from free will. For [the agent] does not have complete control over what chance images and other thoughts enter his mind or influence his deliberation. They simply come as they please. [The agent] does have some control after the chance considerations have occurred. But then there is no more chance involved. What happens from then on, how he reacts, is determined by desires and beliefs he already has. So it appears that he does not have control in the libertarian sense of what happens after the chance considerations occur as well. Libertarians require more than this for full responsibility and free will.[31] |

哲学的な見解 自由意志 vs 決定論 彼は自由意志に関する確立された共存説の支持者であったが、1978年の著書『Brainstorms』の第15章「リバタリアンが望むものを与えること」において、デネットはリバタリアンの見解とは対照的な意思決定の2段階モデルを明確に示した。 私が提案する意思決定モデルには、次のような特徴がある。重要な意思決定に直面した際、ある程度未確定なアウトプットを生成する考察生成器が、一連の考察 を生成する。そのうちのいくつかは、もちろん、エージェントによって即座に無関係として却下される可能性もある(意識的または無意識的に)。そして、その 選択された考慮事項が意思決定に無視できない影響を与えるものである場合、その考慮事項は推論プロセスに組み込まれる。そして、その主体が概ね理性的であ る場合、それらの考慮事項は最終的に、その主体の最終的な意思決定の予測因子および説明因子となる。[29] ウィリアム・ジェームズ、アンリ・ポアンカレ、アーサー・コンプトン、ヘンリー・マーゲンハウスのような他の哲学者たちが2段階モデルを展開している一方で、デネットは以下の理由からこのモデルを擁護している。 第一に... 対象者が思い浮かべる考察の選択、拒絶、評価は、知性の違いによるものである。 第二に、自由意志論者にとって正しい場所に不確定性が存在するとすれば、このモデルは正しい場所に不確定性を取り入れるものである。 第三に... 生物工学の観点から見ると、意思決定がこの方法で行われることは、より効率的であり、最終的にはより合理的である。 このモデルを支持する4つ目の指摘は、道徳教育がすべてを変えるわけではないが、違いを生み出すことはできる、という点である。 5つ目、そしてこれがこのモデルを支持する上で最も重要なことだと思うが、このモデルは、私たちが道徳的な決断を下す主体であるという、私たちの重要な直観について、ある説明を提供している。 最後に、私が提案するモデルは、私たちの道徳的判断をとりまく多くの決定について指摘しており、多くの場合、行動の方向性に関する私たちの最終的な決定 は、自由意志の感覚に影響を与える先行する決定よりも現象学上は重要ではないことを示唆している。例えば、それ以上考えないという決定、熟考を打ち切ると いう決定、あるいは特定の調査を無視するという決定などである。 こうした先行する補助的な決定は、おそらく次のような形で、責任ある自由な存在としての自己意識に貢献していると思う。重要な決定を迫られ、ある程度の熟 考の後、私は自分自身にこう言う。「もう十分だ。この問題については十分に考えたので、今から行動に移そう」と、さらに考え続けることも可能だったし、最 終的に私が誤った判断をしたことが判明する可能性もあることを十分に理解した上で、しかし、いずれにしても責任を引き受けるという姿勢で、そう言うのだ。 リバタリアン哲学の第一人者であるロバート・ケインなどは、特に、決定にランダムな偶然が直接関与するというデネットのモデルを否定している。彼らは、こ れが主体の動機や理由、性格や価値観、感情や欲求を排除するものであると信じているからだ。彼らは、もし偶然が決定の主な原因であるならば、主体は結果と しての行動に責任を負うことはできないと主張している。ケインは言う。 デネットが認めているように、この熟考に関する因果的不定論の見解は、自由意志に求めるリバタリアンの望むすべてを私たちに与えてくれるわけではない。な ぜなら、[意思決定者]は、偶然のイメージやその他の思考が心に入り込み、熟考に影響を与えることを完全に制御することはできないからだ。それらは単に、 思いのままにやってくる。[意思決定者]は、偶然の考慮事項が発生した後、ある程度の制御を行うことができる。 しかし、その場合はもはや偶然は関与していない。その後の出来事、つまり彼がどう反応するかは、彼がすでに持っている願望や信念によって決定される。つま り、偶然の考慮が起こった後の出来事についても、リバタリアン的な意味での制御はできないということのようだ。リバタリアンは、完全な責任と自由意志を主 張する以上、これ以上のことを要求している。[31] |

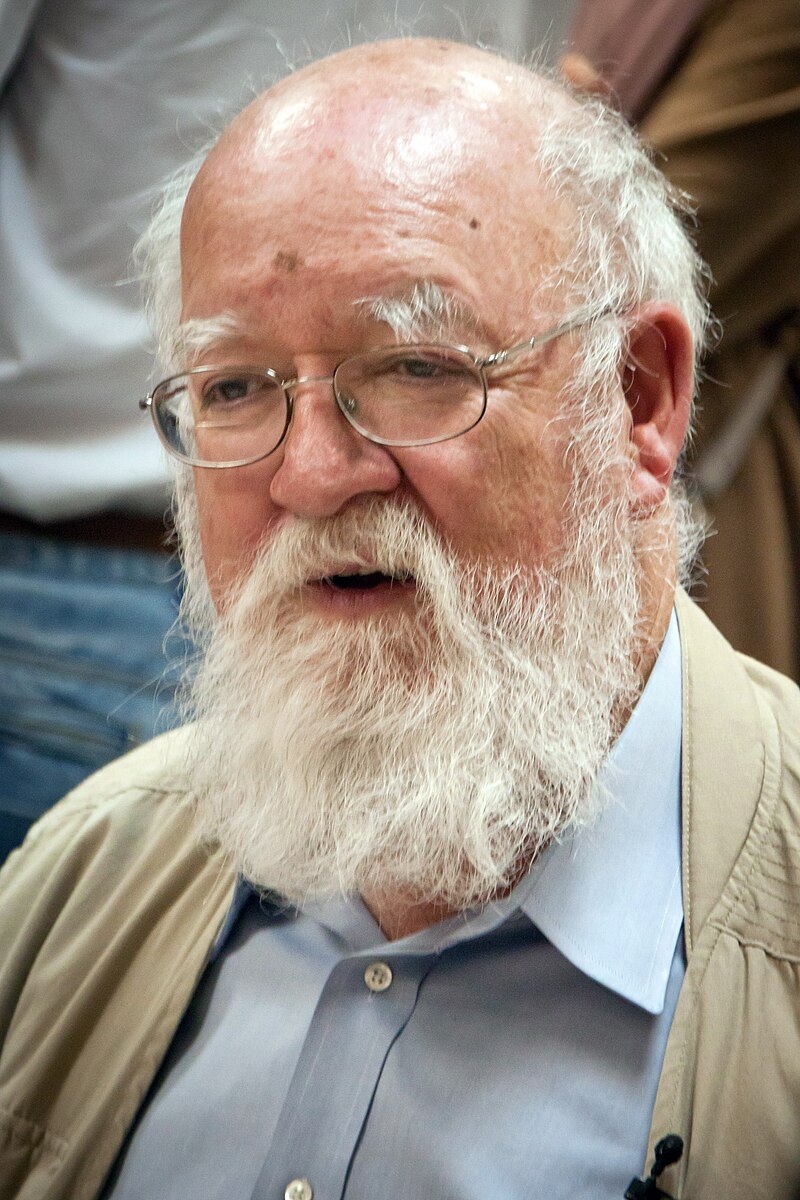

| Mind Dennett in 2008 Dennett is a proponent of materialism in the philosophy of mind. He argues that mental states, including consciousness, are entirely the result of physical processes in the brain. In his book Consciousness Explained (1991), Dennett presents his arguments for a materialist understanding of consciousness, rejecting Cartesian dualism in favor of a physicalist perspective.[32] Dennett remarked in several places (such as "Self-portrait", in Brainchildren) that his overall philosophical project remained largely the same from his time at Oxford onwards. He was primarily concerned with providing a philosophy of mind that is grounded in empirical research. In his original dissertation, Content and Consciousness, he broke up the problem of explaining the mind into the need for a theory of content and for a theory of consciousness. His approach to this project also stayed true to this distinction. Just as Content and Consciousness has a bipartite structure, he similarly divided Brainstorms into two sections. He would later collect several essays on content in The Intentional Stance and synthesize his views on consciousness into a unified theory in Consciousness Explained. These volumes respectively form the most extensive development of his views.[33] In chapter 5 of Consciousness Explained, Dennett described his multiple drafts model of consciousness. He stated that, "all varieties of perception—indeed all varieties of thought or mental activity—are accomplished in the brain by parallel, multitrack processes of interpretation and elaboration of sensory inputs. Information entering the nervous system is under continuous 'editorial revision.'" (p. 111). Later he asserts, "These yield, over the course of time, something rather like a narrative stream or sequence, which can be thought of as subject to continual editing by many processes distributed around the brain, ..." (p. 135, emphasis in the original). In this work, Dennett's interest in the ability of evolution to explain some of the content-producing features of consciousness is already apparent, and this later became an integral part of his program. He stated his view is materialist and scientific, and he presents an argument against qualia; he argued that the concept of qualia is so confused that it cannot be put to any use or understood in any non-contradictory way, and therefore does not constitute a valid refutation of physicalism. This view is rejected by neuroscientists Gerald Edelman, Antonio Damasio, Vilayanur Ramachandran, Giulio Tononi, and Rodolfo Llinás, all of whom state that qualia exist and that the desire to eliminate them is based on an erroneous interpretation on the part of some philosophers regarding what constitutes science.[34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42] Dennett's strategy mirrored his teacher Ryle's approach of redefining first-person phenomena in third-person terms, and denying the coherence of the concepts which this approach struggles with. Dennett self-identified with a few terms: [Others] note that my "avoidance of the standard philosophical terminology for discussing such matters" often creates problems for me; philosophers have a hard time figuring out what I am saying and what I am denying. My refusal to play ball with my colleagues is deliberate, of course, since I view the standard philosophical terminology as worse than useless—a major obstacle to progress since it consists of so many errors.[43] In Consciousness Explained, he affirmed "I am a sort of 'teleofunctionalist', of course, perhaps the original teleofunctionalist". He went on to say, "I am ready to come out of the closet as some sort of verificationist." (pp. 460–61). Dennett was credited[44] with inspiring false belief tasks used in developmental psychology. He noted that when four-year-olds watch the Punch and Judy puppet show, they laugh because they know that they know more about what's going on than one of the characters does:[45] Very young children watching a Punch and Judy show squeal in anticipatory delight as Punch prepares to throw the box over the cliff. Why? Because they know Punch thinks Judy is still in the box. They know better; they saw Judy escape while Punch's back was turned. We take the children's excitement as overwhelmingly good evidence that they understand the situation--they understand that Punch is acting on a mistaken belief (although they are not sophisticated enough to put it that way). |

マインド・ デネット(2008年) デネットは心の哲学における唯物論の提唱者である。彼は意識を含む精神状態は、すべて脳内の物理的プロセスによる結果であると主張している。著書『意識の 説明』(1991年)の中で、デネットは意識の唯物論的理解を主張し、デカルト主義的二元論を否定し、物理主義的観点に賛成している。 デネットは、いくつかの箇所(『Brainchildren』の「自画像」など)で、自身の哲学プロジェクト全体はオックスフォード大学在籍時からほとん ど変わっていないと述べている。彼は主に、経験的研究に基づく心の哲学の提供に重点を置いていた。彼の最初の論文『Content and Consciousness』では、心を説明するという問題を、内容の理論と意識の理論の必要性に分けていた。このプロジェクトに対する彼の取り組みも、 この区別を忠実に守っていた。『コンテンツと意識』が二部構成であるように、『ブレインストーミング』も同様に2つのセクションに分けられている。彼は後 に『意図的スタンス』でコンテンツに関するいくつかの論文をまとめ、『意識の説明』で意識に関する自身の考えを統一理論に統合した。これらの著作はそれぞ れ、彼の考えを最も広範に展開したものである。 『意識の説明』の第5章で、デネットは意識に関する彼の複数の草稿モデルを説明している。彼は、「知覚のあらゆる種類、すなわち思考や精神活動のあらゆる 種類は、感覚入力の解釈と精緻化の並列多重トラックプロセスによって脳内で達成される。神経系に入力される情報は、継続的な『編集改訂』を受けている」と 述べている(p. 111)。その後、彼は「これらは、時間の経過とともに、物語の流れや連続のようなものをもたらす。これは、脳の至る所に分散する多くのプロセスによって 継続的に編集されるものとして考えることができる」と主張している(p. 135、強調は原文のまま)。 この著作において、デネットは進化が意識のコンテンツ生成機能の一部を説明できるという能力に興味を持っていることがすでに明らかであり、これは後に彼の プログラムの不可欠な一部となった。彼は自身の見解は唯物論的かつ科学的であり、クオリアに対する反論を提示していると述べている。彼はクオリアの概念は あまりにも混乱しており、何らかの用途に利用したり、矛盾のない方法で理解することはできないと主張し、したがって物理主義に対する有効な反論とはならな いと論じた。 この見解は神経科学者のジェラルド・エデルマン、アントニオ・ダマシオ、ヴィラヤヌール・ラマチャンドラン、ジュリオ・トノーニ、ロドルフォ・リナスに よって否定されており、彼らは皆クオリアは存在し、それを排除しようとする試みは科学を構成するものに関する一部の哲学者の誤った解釈に基づいていると主 張している。[34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42] デネットの戦略は、彼の師であるライルの一人称の現象を三人称の用語で再定義するというアプローチを反映しており、このアプローチが抱える概念の一貫性を否定するものであった。 デネットは、いくつかの用語を自己同一視していた。 「このような問題を論じるための標準的な哲学用語を避ける」ことが、しばしば私にとって問題を引き起こす、と指摘する人もいる。哲学者たちは、私が何を 言っているのか、何を否定しているのかを理解するのに苦労している。同業者たちと歩調を合わせないという私の姿勢は、もちろん意図的なものである。標準的 な哲学用語は、役に立たないどころか有害であると私は考えているからだ。なぜなら、それは多くの誤りを含んでいるため、進歩の大きな障害となっているから だ。[43] 著書『意識の説明』の中で、彼は「私はもちろん、おそらくは元祖テレオファンクショナリストである『テレオファンクショナリスト』の一種だ」と断言してい る。さらに、「私はある種の検証論者として、カミングアウトする準備ができている」とも述べている(460-61ページ)。 デネットは、発達心理学で用いられる誤った信念課題に影響を与えたことで評価されている[44]。彼は、4歳児がパンチとジュディの人形劇を見ると笑うのは、登場人物の1人よりも自分の方が状況をよく理解していることを知っているからだと指摘している[45]。 パンチとジュディのショーを見ている幼い子供たちは、パンチが箱を崖から投げ落とそうとすると、期待に胸を躍らせて声を上げる。なぜだろうか?パンチが ジュディがまだ箱の中に入っていると思っていることを子供たちは知っているからだ。パンチが背を向けている間にジュディが逃げ出したのを目撃しているから だ。子供たちが興奮しているのは、状況を理解しているという圧倒的な証拠である。子供たちは、パンチが誤った信念に基づいて行動していることを理解してい る(とはいえ、それを言葉で表現するほど洗練されているわけではない)。 |

| Evolutionary debate Much of Dennett's work from the 1990s onwards was concerned with fleshing out his previous ideas by addressing the same topics from an evolutionary standpoint, from what distinguishes human minds from animal minds (Kinds of Minds),[10] to how free will is compatible with a naturalist view of the world (Freedom Evolves).[citation needed] Dennett saw evolution by natural selection as an algorithmic process (though he spelt out that algorithms as simple as long division often incorporate a significant degree of randomness).[46] This idea is in conflict with the evolutionary philosophy of paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, who preferred to stress the "pluralism" of evolution (i.e., its dependence on many crucial factors, of which natural selection is only one).[citation needed] Dennett's views on evolution are identified as being strongly adaptationist, in line with his theory of the intentional stance, and the evolutionary views of biologist Richard Dawkins. In Darwin's Dangerous Idea, Dennett showed himself even more willing than Dawkins to defend adaptationism in print, devoting an entire chapter to a criticism of the ideas of Gould. This stems from Gould's long-running public debate with E. O. Wilson and other evolutionary biologists over human sociobiology and its descendant evolutionary psychology, which Gould and Richard Lewontin opposed, but which Dennett advocated, together with Dawkins and Steven Pinker.[47] Gould argued that Dennett overstated his claims and misrepresented Gould's, to reinforce what Gould describes as Dennett's "Darwinian fundamentalism".[48] Dennett's theories have had a significant influence on the work of evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey Miller.[citation needed] |

進化論に関する議論 1990年代以降のデネットの研究の多くは、進化論の観点から、人間と動物の精神の違い(『心の種』)から、自由意志が自然主義的世界観とどのように両立 するのか(『自由は進化する』)まで、同じテーマを取り上げながら、それまでの自身の考えをさらに掘り下げることに重点が置かれていた。 デネットは自然淘汰による進化をアルゴリズム的なプロセスと捉えている(ただし、彼は、簡単なアルゴリズムである割り算にもしばしばかなりのランダム性が 組み込まれていることを指摘している)。[46] この考え方は、進化論の哲学者である古生物学者スティーブン・ジェイ・グールドの進化論の「多元論」(すなわち、進化は多くの重要な要因に依存しており、 自然淘汰はそのうちの1つに過ぎないという考え方)を強調する立場と対立している。[要出典] デネットの進化論に関する見解は、彼の意図主義の理論に沿った強い適応論的立場であり、生物学者リチャード・ドーキンスの進化論的見解と一致している。著 書『ダーウィンの危険な思想』の中で、デネットはドーキンス以上に適応論を擁護する姿勢を示し、グールドの考えに対する批判に一章を割いている。これは、 グールドがE. O. ウィルソンや他の進化生物学者と、人間の社会生物学とその子孫である進化心理学について長期間にわたって公の場で論争を繰り広げていたことに起因する。 グールドとリチャード・ルウォンタンはこれに反対したが、デネットはドーキンスやスティーヴン・ピンカーとともにこれを支持した。[47] グールドは、デネットが主張を誇張し、グールドの主張を誤って伝えていると主張し、グールドが「デネットのダーウィン原理主義」と表現したものを強化し た。[48] デネットの理論は、進化心理学者ジェフリー・ミラーの研究に大きな影響を与えている。[要出典] |

| Religion and morality Dennett was a vocal atheist and secularist, a member of the Secular Coalition for America advisory board,[49] and a member of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, as well as an outspoken supporter of the Brights movement. Dennett was referred to as one of the "Four Horsemen of New Atheism", along with Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and the late Christopher Hitchens.[50] Dennett sends a solidarity message to ex-Muslims convening in London in July 2017. In Darwin's Dangerous Idea, Dennett wrote that evolution can account for the origin of morality. He rejected the idea that morality being natural to us implies that we should take a skeptical position regarding ethics, noting that what is fallacious in the naturalistic fallacy is not to support values per se, but rather to rush from facts to values.[citation needed] In his 2006 book, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon, Dennett attempted to account for religious belief naturalistically, explaining possible evolutionary reasons for the phenomenon of religious adherence. In this book he declared himself to be "a bright", and defended the term.[citation needed] He did research into clerics who are secretly atheists and how they rationalize their works. He found what he called a "don't ask, don't tell" conspiracy because believers did not want to hear of loss of faith. This made unbelieving preachers feel isolated, but they did not want to lose their jobs and church-supplied lodgings. Generally, they consoled themselves with the belief that they were doing good in their pastoral roles by providing comfort and required ritual.[51] The research, with Linda LaScola, was further extended to include other denominations and non-Christian clerics.[52] The research and stories Dennett and LaScola accumulated during this project were published in their 2013 co-authored book, Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind.[53] |

宗教と道徳 デネットは、声高な無神論者であり世俗主義者であり、アメリカ世俗連合の諮問委員会のメンバーであり[49]、懐疑的調査委員会のメンバーであり、またブ ライト運動の公然たる支持者でもあった。デネットは、リチャード・ドーキンス、サム・ハリス、故クリストファー・ヒッチェンズとともに、「ニューエイティ ズムの4騎士」の一人と呼ばれていた。 デネットは2017年7月にロンドンに集まった元イスラム教徒たちに連帯のメッセージを送った。 著書『ダーウィンの危険な思想』の中で、デネットは進化論が道徳の起源を説明できると書いた。彼は、道徳が人間にとって自然なものであるという考えは、倫 理に対して懐疑的な立場を取るべきであることを意味するという考えを否定し、自然主義的誤謬における誤りは価値観自体を支持しないことではなく、むしろ事 実から価値観へと急ぐことであると指摘した。 2006年の著書『Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon』で、デネットは宗教的信念を自然主義的に説明しようとし、宗教的帰依という現象の進化論的な理由を説明した。この本の中で、彼は自 らを「聡明な人間」であると宣言し、その表現を擁護した。 彼は、秘密裏に無神論者である聖職者たちについて研究し、彼らがどのようにして自らの活動を合理化しているかを調査した。彼は、信者たちが信仰の喪失につ いて耳にしたくないために、「聞くな、言うな」という陰謀が存在していると主張した。このため、信仰を持たない説教師たちは孤立感を覚えたが、職や教会が 提供する宿舎を失いたくないという思いから、 一般的に、彼らは牧師としての役割において、慰めや必要な儀式を提供することで善行をなしているという信念で自らを慰めていた。[51] リンダ・ラスコーラとの共同研究はさらに拡大し、他の宗派やキリスト教以外の聖職者も対象に加わった。[52] このプロジェクトでデネットとラスコーラが収集した研究結果やエピソードは、2013年に共著で出版された『説教壇に捕らわれて: 信念を捨て去る」[53] |

| Memetics, postmodernism and deepity Dennett wrote about and advocated the notion of memetics as a philosophically useful tool, his last work on this topic being his "Brains, Computers, and Minds", a three-part presentation through Harvard's MBB 2009 Distinguished Lecture Series.[citation needed] Dennett was critical of postmodernism, having said: Postmodernism, the school of "thought" that proclaimed "There are no truths, only interpretations" has largely played itself out in absurdity, but it has left behind a generation of academics in the humanities disabled by their distrust of the very idea of truth and their disrespect for evidence, settling for "conversations" in which nobody is wrong and nothing can be confirmed, only asserted with whatever style you can muster.[54] Dennett adopted and somewhat redefined the term "deepity", originally coined by Miriam Weizenbaum.[55] Dennett used "deepity" for a statement that is apparently profound, but is actually trivial on one level and meaningless on another. Generally, a deepity has two (or more) meanings: one that is true but trivial, and another that sounds profound and would be important if true, but is actually false or meaningless. Examples are "Que será será!", "Beauty is only skin deep!", "The power of intention can transform your life."[56] The term has been cited many times. |

ミーム論、ポストモダニズム、そして「ディープイティ」 デネットは、ミーム論を哲学的に有用なツールとして提唱し、このテーマに関する最後の著作は、ハーバード大学のMBB 2009 Distinguished Lecture Series(著名な講演シリーズ)における3部構成のプレゼンテーション「Brains, Computers, and Minds(脳、コンピュータ、心)」である。 デネットはポストモダニズムに対して批判的であり、次のように述べている。 ポストモダニズムは、「真理など存在せず、あるのは解釈だけだ」と主張する「思想」の学派であるが、その主張はほとんどが不条理である。しかし、ポストモ ダニズムは、人文科学の学者たちに、真理という概念に対する不信感と証拠に対する軽視を植え付け、誰もが間違っておらず、何も確認できない「会話」に落ち 着くように仕向けた。 デネットは、ミリアム・ワイゼンバウムが最初に作った造語である「ディープティ」という用語を採用し、若干再定義した。[55] デネットは、「ディープティ」という用語を、一見すると深遠なようだが、実際にはある側面では些細で、別の側面では意味のない主張に対して用いた。一般的 に、ディープティには2つ(またはそれ以上)の意味がある。1つは、真実ではあるが些細なものであり、もう1つは、深遠に聞こえ、真実であれば重要である が、実際には偽りまたは無意味であるものである。例としては、「なるようになるさ!」「美しさは外見だけ!」「意図の力で人生を変えることができる」 [56] などがある。この用語は何度も引用されている。 |

| Artificial intelligence While approving of the increase in efficiency that humans reap by using resources such as expert systems in medicine or GPS in navigation, Dennett saw a danger in machines performing an ever-increasing proportion of basic tasks in perception, memory, and algorithmic computation because people may tend to anthropomorphize such systems and attribute intellectual powers to them that they do not possess.[57] He believed the relevant danger from artificial intelligence (AI) is that people will misunderstand the nature of basically "parasitic" AI systems, rather than employing them constructively to challenge and develop the human user's powers of comprehension.[58] In the 1990s, Dennett collaborated with a group of computer scientists at MIT to attempt to develop a humanoid, conscious robot, named "Cog".[59][23] The project did not produce a conscious robot, but Dennett argued that in principle it could have.[59] As given in his penultimate book, From Bacteria to Bach and Back, Dennett's views were contrary to those of Nick Bostrom.[60] Although acknowledging that it is "possible in principle" to create AI with human-like comprehension and agency, Dennett maintained that the difficulties of any such "strong AI" project would be orders of magnitude greater than those raising concerns have realized.[61] Dennett believed, as of the book's publication in 2017, that the prospect of superintelligence (AI massively exceeding the cognitive performance of humans in all domains) was at least 50 years away, and of far less pressing significance than other problems the world faces.[62] |

人工知能 医療におけるエキスパートシステムやナビゲーションにおけるGPSなどのリソースを使用することで人間が享受する効率性の向上を認める一方で、デネット は、知覚、記憶、アルゴリズム計算などの基本的な作業の割合がますます増大するにつれ、人間がそうしたシステムを擬人化し、システムが本来持たない知的能 力をシステムに帰属させる傾向にあるため、機械に危険性があると考えた。[57] 彼は、人工知能(AI)に関連する危険性は、基本的に「寄生」的なAIシステムの性質を人々が誤解することであり、 AIシステムの本質を誤解し、むしろ、人間の理解力を試したり、それを発展させるために建設的にそれらを利用するのではなく、 1990年代、デネットはマサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)のコンピュータ科学者グループと協力し、ヒューマノイドで意識を持つロボット「Cog」の開 発を試みた。[59][23] このプロジェクトでは意識を持つロボットは開発されなかったが、デネットは原理的には可能であると主張した。[59] デネットの考えは、彼が最後に出版した著書『バクテリアからバッハへ、そしてまたバッハへ』で示されているが、ニック・ボストロームの見解とは対立するも のである。[60] 人間のような理解力と行動力を備えたAIを創り出すことは「原理的には可能」であると認めながらも、デネットは、そのような「強いAI」プロジェクトの困 難さは、懸念を表明している人々が認識しているよりも桁違いに大きいと主張している。 [61] デネットは、2017年の本出版時点では、超知能(あらゆる領域で人間の認知能力を大幅に上回るAI)の実現は少なくとも50年先であり、世界が直面する 他の問題よりも緊急性は低いと考えていた。[62] |

| Realism Dennett was known for his nuanced stance on realism. While he supported scientific realism, advocating that entities and phenomena posited by scientific theories exist independently of our perceptions, he leant towards instrumentalism concerning certain theoretical entities, valuing their explanatory and predictive utility, as showing in his discussion of real patterns.[63] Dennett's pragmatic realism underlines the entanglement of language, consciousness, and reality. He posited that our discourse about reality is mediated by our cognitive and linguistic capacities, marking a departure from Naïve realism.[64] |

リアリズム デネットはリアリズムに対する微妙な立場を取っていたことで知られていた。彼は科学的リアリズムを支持し、科学的理論によって仮定された実体や現象は、人 間の知覚とは独立して存在すると主張していたが、特定の理論上の実体に関しては、その説明力や予測力を重視する道具主義に傾倒していた。これは、彼の実在 パターンに関する議論にも表れている。[63] デネットの実用主義的リアリズムは、言語、意識、現実の絡み合いを強調している。彼は、現実についての我々の議論は、我々の認知能力と言語能力によって媒 介されていると主張し、素朴実在論からの脱却を明確にした。[64] |

| Realism and instrumentalism Dennett's philosophical stance on realism was intricately connected to his views on instrumentalism and the theory of real patterns.[63] He drew a distinction between illata, which are genuine theoretical entities like electrons, and abstracta, which are "calculation bound entities or logical constructs" such as centers of gravity and the equator, placing beliefs and the like among the latter. One of Dennett's principal arguments was an instrumentalistic construal of intentional attributions, asserting that such attributions are environment-relative.[65] In discussing intentional states, Dennett posited that they should not be thought of as resembling theoretical entities, but rather as logical constructs, avoiding the pitfalls of intentional realism without lapsing into pure instrumentalism or even eliminativism.[66] His instrumentalism and anti-realism were crucial aspects of his view on intentionality, emphasizing the centrality and indispensability of the intentional stance to our conceptual scheme.[67] |

実在論と道具主義 デネットの実在論に関する哲学的立場は、道具主義と実在パターン理論に関する見解と複雑に絡み合っていた。[63] 彼は、電子のような真正の理論的実体であるイラータと、重心や赤道のような「計算に束縛された実体または論理構成」であるアブストラクタを区別し、信念な どは後者に分類した。デネットの主な主張のひとつは、意図的帰属を道具主義的に解釈することであり、そのような帰属は環境相対的であると主張した。 意図の状態について論じる中で、デネットは、それを理論上の実体と考えるのではなく、むしろ論理的な構成として考えるべきであると主張した。これにより、 純粋な道具主義や排除主義に陥ることなく、意図的実在論の落とし穴を回避できる。[66] 彼の道具主義と反実在論は、意図性に関する彼の考え方の重要な側面であり、意図的な姿勢が我々の概念体系にとって中心的なものであり、不可欠であることを 強調している。[67] |

| Recognition Dennett was the recipient of a Fellowship at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences.[68] He was a Fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry and a Humanist Laureate of the International Academy of Humanism.[69] He was named 2004 Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association.[70][10] In 2006, Dennett received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[71] He became a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2009.[10] In February 2010, he was named to the Freedom From Religion Foundation's Honorary Board of distinguished achievers.[72] In 2012, he was awarded the Erasmus Prize, an annual award for a person who has made an exceptional contribution to European culture, society or social science, "for his ability to translate the cultural significance of science and technology to a broad audience".[73][10] In 2018, he was awarded an honorary doctorate (Dr.h.c.) by the Radboud University in Nijmegen, Netherlands, for his contributions to and influence on cross-disciplinary science.[74] |

認知 デネットは、行動科学高等研究所のフェローシップの受賞者であった。[68] 彼は懐疑的調査委員会のフェローであり、国際ヒューマニズムアカデミーのヒューマニスト・ローレイトであった。[69] 彼はアメリカヒューマニスト協会から2004年のヒューマニスト・オブ・ザ・イヤーに選ばれた。 [70][10] 2006年には、デネットはアメリカン・アカデミー・オブ・アチーブメントのゴールデン・プレート賞を受賞した。[71] 2009年にはアメリカ科学振興協会のフェローとなった。[10] 2010年2月には、フリーダム・フロム・リリジョン・ファンデーションの名誉理事に選出された。[72] 2012年には、科学技術の文化的意義を幅広い聴衆に伝える能力を理由に、ヨーロッパ文化、社会、社会科学に顕著な貢献をした人格に贈られるエラスムス賞 を授与された。 [73][10] 2018年には、学際的な科学への貢献と影響が評価され、オランダのナイメーヘンにあるラドバウド大学から名誉博士号(Dr.h.c.)を授与された。 [74] |

| Personal life In 1962, Dennett married Susan Bell.[75] They lived in North Andover, Massachusetts, and had a daughter, a son, and six grandchildren.[13][76] He was an avid sailor[77] who loved sailing Xanthippe, his 13-meter sailboat. He also played many musical instruments and sang at glee clubs.[23] Dennett died of interstitial lung disease at Maine Medical Center on April 19, 2024, at the age of 82.[13][78] |

私生活 1962年、デネットはスーザン・ベルと結婚した。[75] 夫妻はマサチューセッツ州ノースアンドーバーに住み、娘と息子、6人の孫がいた。[13][76] 彼は熱心なヨット愛好家であり、13メートルのヨット「ザンティッペ」を操っていた。また、多くの楽器を演奏し、グリークラブで歌っていた。[23] デネットは2024年4月19日、間質性肺疾患によりメイン医療センターで死去した。享年82歳であった。[13][78] |

| Selected works Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology (MIT Press 1981) (ISBN 0-262-54037-1) Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting (MIT Press 1984) – on free will and determinism (ISBN 0-262-04077-8) Content and Consciousness (Routledge & Kegan Paul Books Ltd; 2nd ed. 1986) (ISBN 0-7102-0846-4) The Intentional Stance (6th printing), Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1996, ISBN 0-262-54053-3 (First published 1987) Consciousness Explained. Back Bay Books. 1992. ISBN 0-316-18066-1. Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life (Simon & Schuster; reprint edition 1996) (ISBN 0-684-82471-X) Kinds of Minds: Towards an Understanding of Consciousness (Basic Books 1997) (ISBN 0-465-07351-4) Brainchildren: Essays on Designing Minds (Representation and Mind) (MIT Press 1998) (ISBN 0-262-04166-9) – A Collection of Essays 1984–1996 Hofstadter, Douglas R.; Dennett, Daniel C. (January 17, 2001). The Mind's I: Fantasies And Reflections On Self & Soul. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03091-0. Freedom Evolves (Viking Press 2003) (ISBN 0-670-03186-0) Sweet Dreams: Philosophical Obstacles to a Science of Consciousness (MIT Press 2005) (ISBN 0-262-04225-8) Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (Penguin Group 2006) (ISBN 0-670-03472-X). Neuroscience and Philosophy: Brain, Mind, and Language (Columbia University Press 2007) (ISBN 978-0-231-14044-7), co-authored with Max Bennett, Peter Hacker, and John Searle Science and Religion: Are They Compatible? (Oxford University Press 2010) (ISBN 0-199-73842-4), co-authored with Alvin Plantinga Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking (W. W. Norton & Company 2013) (ISBN 0-393-08206-7) Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind (Pitchstone Publishing – 2013) (ISBN 978-1634310208) co-authored with Linda LaScola Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind (MIT Press – 2011) (ISBN 978-0-262-01582-0), co-authored with Matthew M. Hurley and Reginald B. Adams Jr. From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds (W. W. Norton & Company – 2017) (ISBN 978-0-393-24207-2) I've Been Thinking (Allen Lane 2023) (ISBN 978-0-393-86805-0) |

主な著作 Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology (MIT Press 1981) (ISBN 0-262-54037-1) Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting (MIT Press 1984) – 自由意志と決定論について (ISBN 0-262-04077-8) 『内容と意識』(Routledge & Kegan Paul Books Ltd; 第2版、1986年)(ISBN 0-7102-0846-4) 『意図的スタンス』(6刷)、マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MIT Press、1996年、ISBN 0-262-54053-3(初版1987年) 『意識の説明』。Back Bay Books。1992年。ISBN 0-316-18066-1。 『ダーウィンの危険な思想:進化と生命の意味』(Simon & Schuster、1996年再版版)(ISBN 0-684-82471-X) 『心の種類:意識の理解に向けて』(Basic Books 1997年)(ISBN 0-465-07351-4) 『脳の創造物:心の設計に関するエッセイ』(Representation and Mind)(MIT Press 1998年)(ISBN 0-262-04166-9) - 1984年から1996年のエッセイ集 ホフスタッター、ダグラス・R.; デネット、ダニエル・C. (2001年1月17日). 心の私:自己と魂についての空想と考察. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03091-0. 自由の進化 (Viking Press 2003) (ISBN 0-670-03186-0) 『Sweet Dreams: Philosophical Obstacles to a Science of Consciousness』(MIT Press 2005年)(ISBN 0-262-04225-8) 『Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon』(Penguin Group 2006年)(ISBN 0-670-03472-X) 『神経科学と哲学:脳、心、言語』(コロンビア大学出版 2007年)(ISBN 978-0-231-14044-7)マックス・ベネット、ピーター・ハッカー、ジョン・サールとの共著 『科学と宗教:両立し得るか?』(オックスフォード大学出版局 2010年)(ISBN 0-199-73842-4)アルビン・プランティンガとの共著 『直観ポンプ:思考のためのその他のツール』(W. W. Norton & Company 2013年)(ISBN 0-393-08206-7) Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind (Pitchstone Publishing – 2013) (ISBN 978-1634310208) リンダ・ラスコーラとの共著 『Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind』(マサチューセッツ工科大学出版局、2011年)(ISBN 978-0-262-01582-0)マシュー・M・ハーレー、レジナルド・B・アダムス・ジュニアとの共著 バクテリアからバッハ、そしてまたバクテリアへ:心の進化(W. W. Norton & Company – 2017年)(ISBN 978-0-393-24207-2) I've Been Thinking(Allen Lane 2023年)(ISBN 978-0-393-86805-0) |

| The Atheism Tapes Cartesian materialism Cognitive biology Evolutionary psychology of religion Jean Nicod Prize |

『無神論テープ』 デカルト主義唯物論 認知生物学 宗教の進化心理学 ジャン・ニコ賞 |

| Further reading Brockman, John (1995). The Third Culture. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80359-3 (Discusses Dennett and others) Brook, Andrew and Don Ross (eds.) (2000). Daniel Dennett. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00864-6 Dennett, Daniel C. (1997). "True Believers: The Intentional Strategy and Why it Works" in John Haugeland, Mind Design II: Philosophy, Psychology, Artificial Intelligence. Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ISBN 0-262-08259-4 (reprint of 1981 publication). Elton, Matthew (2003). Dennett: Reconciling Science and Our Self-Conception. Cambridge, UK Polity Press. ISBN 0-7456-2117-1 Hacker, P. M. S. and M. R. Bennett (2003). Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience. Oxford, and Malden, Mass: Blackwell ISBN 1-4051-0855-X (Has an appendix devoted to a strong critique of Dennett's philosophy of mind) Ross, Don, Andrew Brook and David Thompson (eds.) (2000). Dennett's Philosophy: A Comprehensive Assessment Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-18200-9 Symons, John (2000). On Dennett. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 0-534-57632-X |

さらに読む Brockman, John (1995). The Third Culture. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80359-3 (デネットと他の人物について論じている) Brook, Andrew and Don Ross (eds.) (2000). Daniel Dennett. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00864-6 デネット、ダニエル C. (1997年). 「真の信奉者たち:意図主義とその理由」ジョン・ホーゲランド著『マインド・デザインII:哲学、心理学、人工知能』マサチューセッツ工科大学出版局、マ サチューセッツ州、ISBN 0-262-08259-4(1981年出版の再版)。 Elton, Matthew (2003). Dennett: Reconciling Science and Our Self-Conception. Cambridge, UK Polity Press. ISBN 0-7456-2117-1 Hacker, P. M. S. and M. R. Bennett (2003). 『神経科学の哲学的基礎』. オックスフォード、マサチューセッツ州マルデン: Blackwell ISBN 1-4051-0855-X (デネットの心に関する哲学に対する強力な批判をまとめた付録あり) ロス、ドン、アンドリュー・ブルック、デビッド・トンプソン(編)(2000年)。 デネットの哲学:包括的評価。 マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MITプレス。 ISBN 0-262-18200-9 サイモンズ、ジョン(2000年)。 デネットについて。 カリフォルニア州ベルモント:ワズワース。 ISBN 0-534-57632-X |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Dennett |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆