ダニエル・ゴールドハーゲン

Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, b.1959

ダニエル・ゴールドハーゲン

Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, b.1959

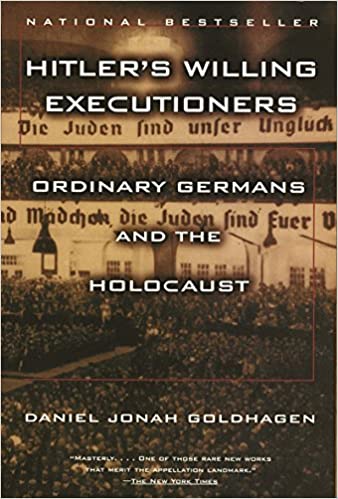

ダニエル・ジョナ・ゴールドハーゲン(1959年6月30日生まれ)[1]は、アメリカの作 家であり、ハーバード大学の元政府・社会学准教授である。ホロコーストについて論議を呼んだ2冊の本の著者として、国際的に注目され、幅広い批判を浴び た。ヒトラーの意志ある処刑者たち』(1996年)、『道徳的再認識』(2002年)の2冊のホロコーストに関する著書で国際的に注目され、幅広い批判を 浴びた。また、ジェノサイド現象を考察したWorse Than War(2009年)、世界的な反ユダヤ主義の悪質な台頭を追跡したThe Devil That Never Dies(2013年)の著者でもある[2][3]。

| Daniel

Jonah Goldhagen (born June 30, 1959)[1] is an American author, and

former associate professor of government and social studies at Harvard

University. Goldhagen reached international attention and broad

criticism as the author of two controversial books about the Holocaust:

Hitler's Willing Executioners (1996), and A Moral Reckoning (2002). He

is also the author of Worse Than War (2009), which examines the

phenomenon of genocide, and The Devil That Never Dies (2013), in which

he traces a worldwide rise in virulent antisemitism.[2][3] |

ダ

ニエル・ジョナ・ゴールドハーゲン(1959年6月30日生まれ)[1]は、アメリカの作家であり、ハーバード大学の元政府・社会学准教授である。ホロ

コーストについて論議を呼んだ2冊の本の著者として、国際的に注目され、幅広い批判を浴びた。ヒトラーの意志ある処刑者たち』(1996年)、『道徳的再

認識』(2002年)の2冊のホロコーストに関する著書で国際的に注目され、幅広い批判を浴びた。また、ジェノサイド現象を考察したWorse

Than War(2009年)、世界的な反ユダヤ主義の悪質な台頭を追跡したThe Devil That Never

Dies(2013年)の著者でもある[2][3]。 |

| Biography Daniel Goldhagen was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to Erich and Norma Goldhagen. He grew up in nearby Newton.[4] His wife Sarah (née Williams) is an architectural historian, and critic for The New Republic magazine.[5] Daniel Goldhagen's father is Erich Goldhagen, a retired Harvard professor. Erich is a Holocaust survivor who, with his family, was interned in a Jewish ghetto in Czernowitz (present-day Ukraine).[4][needs update] Daniel credits his father for being a "model of intellectual sobriety and probity".[6] Goldhagen has written that his "understanding of Nazism and of the Holocaust is firmly indebted" to his father's influence.[6] In 1977, Goldhagen entered Harvard, and remained there for some twenty years - first as an undergraduate and graduate student, then as an assistant professor in the Government and Social Studies Department.[7][8] During early graduate studies, he attended a lecture by Saul Friedländer, in which he had what he describes as a "lightbulb moment": The functionalism versus intentionalism debate did not address the question, "When Hitler ordered the annihilation of the Jews, why did people execute the order?". Goldhagen wanted to investigate who the German men and women who killed the Jews were, and their reasons for killing.[4] |

バイオグラフィー マサチューセッツ州ボストンでエリック・ゴールドハーゲンとノーマ・ゴールドハーゲンの間に生まれた[4]。妻のサラ(旧姓ウィリアムズ)は建築史家であり、『ニュー・リパブリック』誌の批評家である[5]。 ダニエル・ゴールドハーゲンの父親は、ハーバード大学を退職したエーリッヒ・ゴールドハーゲンである。エーリッヒはホロコーストの生存者で、家族とともに ツェルノヴィッツ(現在のウクライナ)のユダヤ人ゲットーに収容された[4][要更新]。ダニエルは父親を「知的節制と高潔さのモデル」であったと信じて いる[6]。 [1977年、ゴールドハーゲンはハーバード大学に入学し、学部生と大学院生、そして政府・社会学部の助教授として約20年間在籍した[7][8]。 大学院の初期にソール・フリードランダーの講義を受け、そこで彼は「光明を得る瞬間」と表現している。機能主義〈対〉意図主義の議論では、「ヒトラーがユダヤ人殲滅を命じたとき、なぜ人々はその命令を実行したのか」という問いは扱われなかった。ゴールドハーゲンは、ユダヤ人を殺したドイツ人の男女は誰で、なぜ殺したのかを調べようとしたのである[4]。 |

| Academic and literary career As a graduate student, Goldhagen undertook research in the German archives.[4][9] The thesis of Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust proposes that, during the Holocaust, many killers were ordinary Germans, who killed for having been raised in a profoundly antisemitic culture, and thus were acculturated — "ready and willing" — to execute the Nazi government's genocidal plans. Goldhagen's first notable work was a book review titled "False Witness" published by The New Republic magazine on April 17, 1989. It was one in a series of hostile reviews of the 1988 book Why Did the Heavens Not Darken? by an American-Jewish professor of Princeton University born in Luxembourg, Arno J. Mayer.[10] Goldhagen wrote that "Mayer's enormous intellectual error" was in ascribing the cause of the Holocaust to anti-Communism, rather than to antisemitism,[11] and criticized Prof. Mayer's saying that most massacres of Jews in the USSR, during the first weeks of Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941 were committed by local peoples (see the Lviv pogroms for more historical background), with little Wehrmacht participation.[11] Goldhagen accused him also of misrepresenting the facts about the Wannsee Conference (1942), which was meant for plotting the genocide of European Jews, not (as Mayer said) merely the resettlement of the Jews.[11] Goldhagen further accused Mayer of obscurantism, of suppressing historical fact, and of being an apologist for Nazi Germany, like Ernst Nolte, for attempting to "de-demonize" National Socialism.[11] Also in 1989, historian Lucy Dawidowicz reviewed Why Did the Heavens Not Darken? in Commentary magazine, and praised Goldhagen's "False Witness" review, identifying him as a rising Holocaust historian who formally rebutted "Mayer's falsification" of history.[10][12] In 2003, Goldhagen resigned from Harvard to focus on writing. His work synthesizes four historical elements, kept distinct for analysis; as presented in the books A Moral Reckoning: the Role of the Catholic Church in the Holocaust and its Unfulfilled Duty of Repair (2002) and Worse Than War (2009): (i) description (what happens), (ii) explanation (why it happens), (iii) moral evaluation (judgment), and (iv) prescription (what is to be done?).[13][14] According to Goldhagen, his Holocaust studies address questions about the political, social, and cultural particulars behind other genocides: "Who did the killing?" "What, despite temporal and cultural differences, do mass killings have in common?", which yielded Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity, about the global nature of genocide, and averting such crimes against humanity.[15] |

学問と文学のキャリア 大学院生時代、ゴールドハーゲンはドイツの公文書館で研究を行った[4][9]。その結果、ナチス政府の大量虐殺計画を実行するための文化的適応、すなわち「準備ができていて、喜んで」殺人を行ったのだ、と提唱している[10]。 ゴールドハーゲンの最初の注目すべき仕事は、1989年4月17日に『ニュー・リパブリック』誌に掲載された「偽りの証人」と題する書評であった。この書 評は、ルクセンブルク生まれのアメリカ系ユダヤ人であるプリンストン大学のアルノ・J・メイヤー教授の1988年の著書『なぜ天は暗くならないのか』に対 する一連の敵対的書評の一つだった[10]。ゴールドハーゲンは、ホロコーストの原因を反セミティズムではなく、反共産主義だとしたことに「メイヤーの大 きな知的誤りがある」としており[11]、教授を批判している。メイヤー教授は、1941年夏のバルバロッサ作戦の最初の数週間の間にソ連で行われたユダ ヤ人虐殺のほとんどは地元の人々によって行われ(より歴史的背景についてはリヴィウのポグロムを参照)、国防軍はほとんど参加しなかったと述べている [11]。 11] ゴールドハーゲンは、ヴァンゼー会議(1942年)についても、(メイヤーが言うように)単なるユダヤ人の再定住ではなく、ヨーロッパユダヤ人の大量虐殺 を企てるためのものだったという事実を誤って伝えていると非難した[11] ゴールドハーゲンはさらに、メイヤーが曖昧主義、史実を抑制し、国家社会主義の「脱悪霊」化を試みるエルンスト・ノルテ同様ナチスドイツの弁証者であると 非難した[10]。 [11] また、1989年には、歴史家のルーシー・ダウィドウィッツが『コメンタリー』誌で『なぜ天は暗くならないのか』を評し、ゴールドハーゲンの「偽りの証 人」評を賞賛し、彼を、歴史に対する「メイヤーの改竄」に正式に反駁した新進のホロコースト歴史学者と認定している[10][12]。 2003年、ゴールドハーゲンはハーバード大学を辞職し、執筆活動に専念する。彼の仕事は、4つの歴史的要素を統合し、分析のために区別しておくことで、 『A Moral Reckoning: the Role of the Catholic Church in the Holocaust and its Unfulfilled Duty of Repair』(2002)、『Worse Than War』(2009)の中で紹介している。(ゴールドハーゲンによれば、彼のホロコースト研究は、他の大量虐殺の背後にある政治的、社会的、文化的な特殊 性についての疑問を扱っている[13][14]。「誰が殺人を行ったのか?時間的・文化的差異にもかかわらず、大量殺戮に共通するものは何か?"という問いを提起し、大量殺戮のグローバルな性質とそのような人道に対する罪を回避することについて、『戦争よりひどい:ジェノサイド、排除主義、そして人類への継続的な攻撃』を生み出している[15]。 |

| Hitler's Willing Executioners Hitler's Willing Executioners (1996) posits that the vast majority of ordinary Germans were "willing executioners" in the Holocaust because of a unique and virulent "eliminationist antisemitism" in German identity that had developed in the preceding centuries. Goldhagen argued that this form of antisemitism was widespread in Germany, that it was unique to Germany, and that because of it, ordinary Germans willingly killed Jews. Goldhagen asserted that this mentality grew out of medieval attitudes with a religious basis, but was eventually secularized.[16] Goldhagen's book was meant to be a "thick description" in the manner of Clifford Geertz.[17] As such, to prove his thesis Goldhagen focused on the behavior of ordinary Germans who killed Jews, especially the behavior of the men of Order Police (Orpo) Reserve Battalion 101 in occupied Poland in 1942 to argue ordinary Germans possessed by "eliminationist anti-Semitism" chose to willingly murder Jews in cruel and sadistic ways.[18] In this, Goldhagen was essentially rehashing much of what had been published before, adding his touch of intentionalist prose to already covered ground. Scholars such as Yehuda Bauer, Otto Kulka, Israel Gutman, among others, asserted long before Goldhagen, the primacy of ideology, radical anti-Semitism, and the corollary of an inimitability exclusive to Germany.[19] The book, which began as a doctoral dissertation, was written largely as a response to Christopher Browning's Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (1992).[20] Much of Goldhagen's book was concerned with the same Order Police battalion, but with very different conclusions.[21] On April 8, 1996, Browning and Goldhagen discussed their differences during a symposium hosted by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.[22] Browning's book recognizes the impact of the unending campaign of antisemitic propaganda, but it takes other factors into account, such as fear of breaking ranks, desire for career advancement, a concern not to be viewed as weak, the effect of state bureaucracy,[23] battlefield conditions and peer-bonding.[21][24] Goldhagen does not acknowledge the influence of these variables. Goldhagen's book went on to win the American Political Science Association's 1994 Gabriel A. Almond Award in comparative politics and the Democracy Prize of the Journal for German and International Politics.[25] Time magazine reported that it was one of the two most important books of 1996,[26] and The New York Times called it "one of those rare, new works that merit the appellation 'landmark'".[27] The book sparked controversy in the press and academic circles. Several historians characterized its reception as an extension of the Historikerstreit, the German historiographical debate of the 1980s that sought to explain Nazi history.[28] The book was a "publishing phenomenon",[29] achieving fame in both the United States and Germany despite being criticized by some historians,[30][31][32][33][34] who called it ahistorical and,[35] according to Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg, "totally wrong about everything" and "worthless".[36][37] Due to its alleged "generalizing hypothesis" about Germans, it has been characterized as anti-German.[38][39][40] The Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer claims that "Goldhagen stumbles badly", "Goldhagen's thesis does not work",[41] and charges "... that the anti-German bias of his book, almost a racist bias (however much he may deny it), leads nowhere".[42] The American historian Fritz Stern denounced the book as unscholarly and full of racist Germanophobia.[43] Hilberg summarised the debates, "by the end of 1996, it was clear that in sharp distinction from lay readers, much of the academic world had wiped Goldhagen off the map".[44] |

ヒトラーの喜んで参加した処刑者たち Hitler's Willing Executioners (1996) は、大多数の普通のドイツ人がホロコーストにおいて「喜んで処刑された」のは、それ以前の数世紀に発展した、ドイツのアイデンティティにおける独特で悪質 な「排除主義的反ユダヤ主義」によるものだと仮定している。ゴールドハーゲンは、このような形の反ユダヤ主義がドイツに広く存在し、それがドイツに特有の ものであり、それゆえに、普通のドイツ人が進んでユダヤ人を殺したのだと主張した。ゴールドハーゲンの著書は、クリフォード・ギアツのような「厚い記述」 を意図したものであった[16]。 [このように、ゴールドハーゲンは自分の論文を証明するために、ユダヤ人を殺した普通のドイツ人の行動、特に1942年の占領下のポーランドにおける教導 警察(オルポ)予備隊101大隊の隊員の行動に注目し、「排除主義の反ユダヤ主義」に憑かれた普通のドイツ人が残酷でサディスティックな方法でユダヤ人を 進んで殺害することを選択したと主張している[18] この点において、ゴールドハーゲンは本質的に以前に出版されていたものの多くを焼き直し、すでにカバーされている地面に意図論的散文のタッチを取り入れて いたのだった。イェフダ・バウアー、オットー・クルカ、イスラエル・グートマンといった学者たちは、ゴールドハーゲンよりもずっと前に、イデオロギーの優 位性、急進的な反ユダヤ主義、そしてドイツだけの無窮性の付帯を主張していたのである[19]。 この本は、博士論文として始まり、クリストファー・ブラウニングの 『Ordinary Men』への応答として書かれたものである。ゴールドハーゲンの本の多くは、同じ教導隊大隊に関するものであったが、結論は大きく異なっていた[21]。 1996年4月8日、ブラウニングとゴールドハーゲンは、アメリカ合衆国ホロコースト記念館主催のシンポジウムで、その相違点について議論している [22]。 [ブラウニングの本は、反ユダヤ的プロパガンダの終わりのないキャンペーンの影響を認めているが、階級を破ることへの恐れ、出世欲、弱者と見なされたくな いという懸念、国家の官僚主義の影響、戦場の状況、仲間の絆といった他の要因も考慮している[21][24]。 ゴールドハーゲンはこれらの変数の影響を認めていない[25]。ゴールドハーゲンの本は、比較政治学におけるアメリカ政治学会1994年ガブリエル・A・アーモンド賞とドイツ国際政治ジャーナルの民主主義賞を受賞した[25]。 タイム誌は、それが1996年の最も重要な2冊の本のうちの1つであると報告し[26]、ニューヨークタイムズはそれを「『ランドマーク』の称号に値する稀で新しい作品のうちの一つ」と呼んでいる[27]。 この本はマスコミと学界で論争を巻き起こした。何人かの歴史家は、この本の受容を、ナチスの歴史を説明しようとした1980年代のドイツの歴史学的議論で ある「ヒストリカーシュトライト」の延長線上にあるものと特徴づけた[28]。 [28] この本は「出版現象」[29]であり、一部の歴史家によって批判されたにもかかわらずアメリカとドイツの両方で名声を得た[30][31][32] [33][34]。ホロコースト史家のラウル・ヒルバーグはこれを非歴史性と呼び [35] 「すべてにおいて完全に間違っており」「価値のない」ものとしている [36][37] そのドイツ人の「一般化仮説」であると主張したことから反独として特徴づけられてきた。 38][39][40] イスラエルの歴史家イェフダ・バウアーは「ゴールドハーゲンはひどくつまずき」「ゴールドハーゲンの論文は機能しない」と主張し[41]、「...彼の本 の反ドイツの偏見、ほとんど人種差別の偏見(彼がどんなにそれを否定しようとも)はどこにも導かないと告発する」[42]。 [アメリカの歴史家フリッツ・スターンは、この本を学問的でなく、人種差別的なドイツ恐怖症に満ちていると非難した[43]。 ヒルバーグは、「1996年の終わりには、一般読者と区別して、学界の多くがゴールドハーゲンを地図から消し去ったことは明らかだった」と議論を総括している[44]。 |

| A Moral Reckoning In 2002, Goldhagen published A Moral Reckoning: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Holocaust and Its Unfulfilled Duty of Repair, his account of the role of the Catholic Church before, during and after World War II. In the book, Goldhagen acknowledges that individual bishops and priests hid and saved a large number of Jews,[45] but also asserts that others promoted or accepted antisemitism before[46] and during the war,[47] and some played a direct role in the persecution of Jews in Europe during the Holocaust.[48] David Dalin and Joseph Bottum of The Weekly Standard criticized the book, calling it a "misuse of the Holocaust to advance [an] anti-Catholic agenda", and poor scholarship.[49] Goldhagen noted in an interview with The Atlantic, as well as in the book's introduction, that the title and the first page of the book reveal its purpose as a moral, rather than historical analysis, asserting that he has invited European Church representatives to present their own historical account in discussing morality and reparation.[50] |

道徳的な再会 2002年、ゴールドハーゲンは「A Moral Reckoning(道徳的な再会)」を出版した。この本は、第二次世界大戦の前、中、後のカトリック教会の役割について述べたものである。この本の中 で、ゴールドハーゲンは、個々の司教や司祭が多くのユダヤ人をかくまい、救ったことを認めているが[45]、戦前[46]、戦中に反ユダヤ主義を推進、容認した者もおり、ホロコースト中のヨーロッパにおけるユダヤ人迫害に直接的役割を演じた者もいると主張している[47]。 『ウィークリー・スタンダード』のデヴィッド・ダリンとジョセフ・ボッタムは、この本を「反カトリックの議題を推進するためのホロコーストの誤用」であ り、学問的にもお粗末であると批判した[49]。 ゴールドハーゲンは『アトランティック』とのインタビューや本の紹介で、タイトルと最初のページがこの本の目的が歴史的分析というよりもむしろ道徳的分析 として明らかにしていると述べ、道徳と賠償について話し合う中でヨーロッパの教会代表に彼ら自身の歴史記述を発表するように求めている、と主張している [50]。 |

| Worse Than War In Worse than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity (2009), Goldhagen described Nazism and the Holocaust as "eliminationist assaults". He worked on the book intermittently for a decade, interviewing atrocity perpetrators and victims in Rwanda, Guatemala, Cambodia, Kenya, and the USSR, and politicians, government officers, and private humanitarian organization officers. Goldhagen states that his aim is to help "craft institutions and politics that will save countless lives and also lift the lethal threat under which so many people live". He concludes that eliminationist assaults are preventable because "the world's non-mass-murdering countries are wealthy and powerful, having prodigious military capabilities (and they can band together)", whereas the perpetrator countries "are overwhelmingly poor and weak".[51][52] The book was cinematically adapted, and the documentary film of Worse Than War was first presented in the U.S. in Aspen, Colorado, on August 6, 2009 – the sixty-fourth anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945.[53] In Germany, the documentary was first broadcast by the ARD television network October 18, 2009,[54] and was to be nationally broadcast by PBS in 2010.[55] Uğur Ümit Üngör criticized the title of the book, stating "Worse than war? What does that mean? If I write a book about the enormous destruction and deaths of innocent people brought about by war, could I call it Better than Genocide?"[56] David Rieff, characterizing Goldhagen as a "pro-Israel polemicist and amateur historian", writes that the subtext of what Goldhagen deems "eliminationism" may be his own view of contemporary Islam. Rieff writes that Goldhagen's website states that the author "speaks nationally ... about Political Islam's Offensive, the threat to Israel, Hitler's Willing Executioners, the Globalization of Anti-Semitism, and more".[52] Rieff questions Goldhagen's equating the "culture of death" of Nazism with that of "political Islam", as well as Goldhagen's conclusion that, in order to prevent "eliminationism", the United Nations should be remade into an interventionist entity focusing on "a devoted international push for democratizing more countries".[52] Adam Jones, who praised this book for its fluid style and commendable passion, concludes however, that the book is undermined by a casual approach to basic research, and by the author's tendency to overreach and overstate his case.[57] The British historian David Elstein accused Goldhagen of manipulating his sources to make a false accusation of genocide against the British during the Mau Mau Uprising of the 1950s in Kenya.[58] Elstein wrote in his view that the chapter on Kenya left Goldhagen open "...to the charge that he is the kind of scholar who is either unaware of the facts or prefers to exclude those which do not fit his thesis".[58] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Goldhagen |

戦争よりひどい Worse than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity (2009) の中で、ゴールドハーゲンはナチズムとホロコーストを「排除主義の攻撃」であると述べている。ルワンダ、グアテマラ、カンボジア、ケニア、ソ連の残虐行為 の加害者や被害者、政治家、政府職員、民間人道団体の役員にインタビューを行い、10年間断続的にこの本の執筆に取り組んだ。ゴールドハーゲンは、その目 的を「無数の命を救い、多くの人々が生きている致命的な脅威を取り除くための制度と政治を作る」ことにあると述べている。彼は、「世界の大量殺戮を行わな い国々は裕福で強力であり、天才的な軍事力を持っている(そして彼らは団結できる)」のに対し、加害国は「圧倒的に貧しく弱い」ため、排除主義の攻撃は防 ぐことができると結論づけている[51][52]。 この本は映画化され、『Worse Than War』のドキュメンタリー映画は、1945年の広島への原爆投下から64年目にあたる2009年8月6日にコロラド州アスペンで初めて上映された [53]。ドイツでは、このドキュメンタリーはARDテレビネットワークによって2009年10月18日に初めて放送され[54]、2010年にPBSに よって全国放送される予定だった。[55] ウーレット・ウンジョルからは本のタイトルを批判し「Worse than war? どういう意味だ?もし私が戦争によってもたらされた膨大な破壊と罪のない人々の死についての本を書いたら、それをジェノサイドよりましと呼ぶことができる だろうか」[56]。 デヴィッド・リーフはゴールドハーゲンを「親イスラエル極論家、アマ チュア歴史家」と特徴づけて、ゴールドハーゲンが「排除主義」とみなすもののサブテキストは彼自身の現代イスラムに対する見方かもしれないと書いている。 リーフは、ゴールドハーゲンのウェブサイトに、著者が「政治的イスラームの攻勢、イスラエルへの脅威、ヒトラーの意志ある処刑者、反ユダヤ主義のグローバ ル化などについて...全国的に講演している」と書いている。 また、ゴールドハーゲンは、「排除主義」を防ぐために、国連を「より多くの国々の民主化のための献身的な国際的推進」に焦点を当てた介入主義的な存在に作 り変えるべきだという結論にも疑問を投げかけている[52]。 52] アダム・ジョーンズは、その流動的なスタイルと称賛に値する情熱によって本書を賞賛しているが、しかし、本書は基礎研究に対するカジュアルなアプローチ と、著者の過剰な主張と誇張の傾向によって損なわれていると結論づけている[57]。 [57] イギリスの歴史家デイヴィッド・エルスタインは、ゴールドハーゲンが1950年代のケニアにおけるマウマウ蜂起の際のイギリス人に対する大量虐殺について 誤った告発をするために情報源を操作していると非難した[58] エルスタインは、ケニアに関する章はゴールドハーゲンに「・・・彼が事実を知らないか、自分の論文に合わないものを排除したがるタイプの学者だという告発 にさらされる」見解を記している[58]。 https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust is a 1996 book by American writer Daniel Goldhagen, in which he argues collective guilt, that the vast majority of ordinary Germans were "willing executioners" in the Holocaust because of a unique and virulent "eliminationist antisemitism" in German political culture which had developed in the preceding centuries. Goldhagen argues that eliminationist antisemitism was the cornerstone of German national identity, was unique to Germany, and because of it ordinary German conscripts killed Jews willingly. Goldhagen asserts that this mentality grew out of medieval attitudes rooted in religion and was later secularized. The book challenges several common ideas about the Holocaust that Goldhagen believes to be myths. These "myths" include the idea that most Germans did not know about the Holocaust; that only the SS, and not average members of the Wehrmacht, participated in murdering Jews; and that genocidal antisemitism was a uniquely Nazi ideology without historical antecedents. The book, which began as a Harvard doctoral dissertation, was written largely as an answer to Christopher Browning's 1992 book Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. Much of Goldhagen's book is concerned with the actions of the same Reserve Battalion 101 of the Nazi German Ordnungspolizei and his narrative challenges numerous aspects of Browning's book. Goldhagen had already indicated his opposition to Browning's thesis in a review of Ordinary Men in the July 13, 1992, edition of The New Republic titled "The Evil of Banality". His doctoral dissertation, The Nazi Executioners: A Study of Their Behavior and the Causation of Genocide, won the American Political Science Association's 1994 Gabriel A. Almond Award for the best dissertation in the field of comparative politics.[1] Goldhagen's book stoked controversy and debate in Germany and the United States. Some historians have characterized its reception as an extension of the Historikerstreit, the German historiographical debate of the 1980s that sought to explain Nazi history. The book was a "publishing phenomenon",[2] achieving fame in both the United States and Germany, despite its "mostly scathing" reception among historians,[3] who were unusually vocal in condemning it as ahistorical and, in the words of Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg, "totally wrong about everything" and "worthless".[4][5] Hitler's Willing Executioners won the Democracy Prize of the Journal for German and International Politics. The Harvard Gazette asserted that the selection was the result of Goldhagen's book having "helped sharpen public understanding about the past during a period of radical change in Germany".[6] |

『ヒトラーの喜んで加担する死刑執行人:普通のドイツ人とホロコースト』 『ヒトラーの喜んで加担する死刑執行人:普通のドイツ人とホロコースト』は、1996年にアメリカの作家ダニエル・ゴールドハーゲンが著した本である。こ の本の中で、彼は集団的罪責を主張し、何世紀にもわたって発展してきたドイツの政治文化における独特で悪質な「根絶的アンチセミティズム」のために、普通 のドイツ人の大半がホロコーストにおける「喜んで加担する死刑執行人」であったと論じている。ゴールドハーゲンは、根絶的ユダヤ人排斥主義がドイツ国民と してのアイデンティティの礎であり、ドイツ特有のものであり、そのためドイツの一般兵士たちは進んでユダヤ人を殺害したと主張している。ゴールドハーゲン は、この考え方は宗教に根ざした中世の考え方から生まれ、後に世俗化されたと主張している。 この本は、ゴールドハーゲンが神話であると考えるホロコーストに関するいくつかの一般的な考え方に異議を唱えている。これらの「神話」には、ほとんどのド イツ人はホロコーストについて知らなかったという考え方、ユダヤ人殺害に参加したのは国防軍の一般兵士ではなく親衛隊だけだったという考え方、そして、大 量虐殺的な反ユダヤ主義は歴史的な前例のないナチス独自のイデオロギーであったという考え方などがある。 ハーバード大学の博士論文として書き始められたこの本は、1992年に出版されたクリストファー・ブラウニング著『Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland(邦題『普通の男たち:ナチス親衛隊予備警察大隊101とポーランドの最終解決』)』への反論として書かれた部分が大きい。ゴールドハーゲン の著書の大部分は、ナチス・ドイツの秩序警察予備大隊101の行動を取り上げており、彼の主張はブラウニングの本の多くの側面を否定するものである。ゴー ルドハーゲンは、1992年7月13日付の『ザ・ニュー・リパブリック』誌に掲載された「平凡さの悪」と題された『Ordinary Men』の書評で、ブラウニングの論文に対する反対意見をすでに表明していた。彼の博士論文『ナチスの処刑人:彼らの行動と大量虐殺の原因に関する研究』 は、比較政治学分野における最優秀論文に贈られるアメリカ政治学会の1994年ガブリエル・A・アーモンド賞を受賞した。 ゴールドハーゲンの著書は、ドイツとアメリカで論争と議論を巻き起こした。一部の歴史家は、この著書の受け止め方を、ナチスの歴史を説明しようとした 1980年代のドイツの歴史叙述論争である「Historikerstreit」の延長と位置づけている。この本は「出版界の現象」であり、[2] 歴史家たちからは「概ね酷評」されたにもかかわらず、アメリカとドイツの両国で名声を博した。[3] 歴史家たちは異例とも言えるほど声を荒げて、この本を歴史に即していないと非難し、ホロコーストの歴史家ラウル・ヒルバーグの言葉を借りれば、「すべてに おいて完全に間違っており」「価値のない」ものだと述べた。[4][5] 『ヒトラーの喜んで従う死刑執行人』は、ドイツおよび国際政治ジャーナルの民主主義賞を受賞した。ハーバード・ガゼットは、ゴールドハーゲン著の書籍が 「ドイツにおける急激な変化の時期に、過去に関する人々の理解を深めるのに役立った」結果として、同書が選ばれたと主張した。[6] |

| The Evil of Banality In 1992, the American historian Christopher Browning published a book titled Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland about the Reserve Police Battalion 101, which had been used in 1942 to massacre and round up Jews for deportation to the Nazi death camps in German-occupied Poland. The conclusion of the book, which was much influenced by the Milgram experiment on obedience, was that the men of Unit 101 were not demons or Nazi fanatics but ordinary middle-aged men of working-class background from Hamburg, who had been drafted but found unfit for military duty. In the course of the murderous Operation Reinhard, these men were ordered to round up Jews, and if there was not enough room for them on the trains, to shoot them. In other, more chilling cases, they were ordered simply to kill a specified number of Jews in a given town or area. In one instance, the commander of the unit gave his men the choice of opting out of this duty if they found it too unpleasant; the majority chose not to exercise that option, resulting in fewer than 15 men out of a battalion of 500 opting out. Browning argued that the men of Unit 101 agreed willingly to participate in massacres out of a basic obedience to authority and peer pressure, not bloodlust or primal hatred.[7] In his review of Ordinary Men published in July 1992,[8] Goldhagen expressed agreement with several of Browning's findings, namely, that the killings were not, as many people believe, done entirely by SS men, but also by Trawnikis; that the men of Unit 101 had the option not to kill, and – a point Goldhagen emphasizes – that no German was ever punished in any serious way for refusing to kill Jews.[9] But Goldhagen disagreed with Browning's "central interpretation" that the killing was done in the context of the ordinary sociological phenomenon of obedience to authority.[9] Goldhagen instead contended that "for the vast majority of the perpetrators a monocausal explanation does suffice".[10] They were not ordinary men as we usually understand men to be, but "ordinary members of extraordinary political culture, the culture of Nazi Germany, which was possessed of a hallucinatory, lethal view of the Jews. That view was the mainspring of what was, in essence, voluntary barbarism."[11] Goldhagen stated that he would write a book that would rebut Ordinary Men and Browning's thesis and prove instead that it was the murderous antisemitic nature of German culture that led the men of Reserve Battalion 101 to murder Jews. |

陳腐な悪 1992年、米国の歴史家クリストファー・ブラウニングは、1942年にドイツ占領下のポーランドでナチスの強制収容所への移送のためにユダヤ人の虐殺と 一斉検挙に利用された予備警察大隊101について、『Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland(邦題『普通の男たち:ナチス親衛隊予備警察大隊101とポーランドの最終解決』)』を出版した。ミルグラムの服従実験に強く影響を受けたこ の本の結論は、101部隊の隊員たちは悪魔でもナチ狂信者でもなく、ハンブルク出身の労働者階級の平凡な中年男性であり、徴兵されたものの軍務には不適格 とされた人々であった。殺戮作戦ラインハルト作戦の過程で、これらの隊員たちはユダヤ人の一斉検挙を命じられ、列車に十分なスペースがない場合はユダヤ人 を射殺するよう命じられた。もっとぞっとするようなケースでは、特定の町や地域で指定された数のユダヤ人を殺害するよう命じられただけだった。あるケース では、部隊の指揮官が、あまりにも不快な任務であれば、その任務から外れる選択肢を部下たちに与えた。しかし、大半の者はその選択肢を行使せず、500人 の大隊のうち、任務から外れたのは15人以下だった。ブラウニングは、101部隊の隊員たちは、権力への服従や同調圧力から、進んで虐殺に参加したのであ り、血に飢えていたり、根源的な憎悪を抱いていたわけではないと主張した。 1992年7月に出版された『Ordinary Men』の書評で、ゴールドハーゲンはブラウニングのいくつかの調査結果に同意を示した。すなわち、殺人は多くの人が信じているように、すべてがSS隊員 によって行われたのではなく、トラウニキたちによっても行われたこと、101部隊の隊員たちは殺害を行わないという選択肢もあったこと、そして、ゴールド ハーゲンが強調しているように、ユダヤ人の殺害を拒否したために深刻な処罰を受けたドイツ人は一人もいなかったことである。ゴールドハーゲンは、ブラウニ ングの「中心的解釈」である「殺人は権威への服従という通常の社会学的な現象の文脈で行われた」という説には反対であった。[9] ゴールドハーゲンは代わりに、「加害者の大半にとっては単一の原因による説明で十分である」と主張した。[10] 彼らは、我々が通常理解しているような普通の人間ではなく、「並外れた政治文化、すなわちユダヤ人に対する幻覚的で致命的な見解を持っていたナチス・ドイ ツの文化の普通の構成員であった。その考えこそが、本質的には自発的な野蛮主義の原動力であった」[11] ゴールドハーゲンは、ブラウニングの論文と『普通の人々』に反論し、代わりにドイツ文化の殺人的な反ユダヤ主義の性質が予備大隊101の兵士たちにユダヤ 人殺害をさせたのだということを証明する本を書くつもりだと述べた。 |

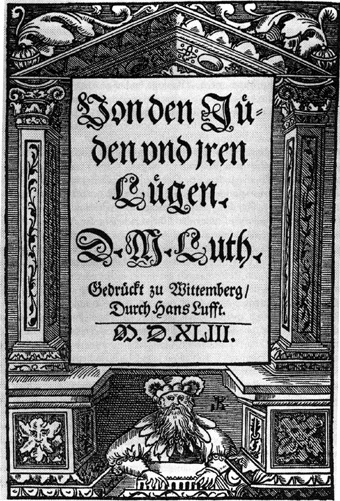

| Goldhagen's thesis In Hitler's Willing Executioners Goldhagen argued that Germans possessed a unique form of antisemitism, which he called "eliminationist antisemitism," a virulent ideology stretching back through centuries of German history. Under its influence, the vast majority of Germans wanted to eliminate Jews from German society, and the perpetrators of the Holocaust did what they did because they thought it was "right and necessary." For Goldhagen the Holocaust, in which so many Germans participated, must be explained as a result of the specifically German brand of antisemitism.[12]  Map listing (in German) the presence of Judensau images on churches of central Europe; the ones that were removed marked in red Goldhagen charged that every other book written on the Holocaust was flawed by the fact that historians had treated Germans in the Third Reich as "more or less like us," wrongly believing that "their sensibilities had remotely approximated our own."[13] Instead, Goldhagen argued that historians should examine ordinary Germans of the Nazi period, in the same way, they examined the Aztecs who believed in the necessity of human sacrifice to appease the gods and ensure that the sun would rise every day.[14] His thesis, he said, was based on the assumption that Germans were not a "normal" Western people influenced by the values of the Enlightenment. His approach would be anthropological, treating Germans the same way that an anthropologist would describe preindustrial people who believed in absurd things such as trees having magical powers.[15] Goldhagen's book was meant to be an anthropological "thick description" in the manner of Clifford Geertz.[16] The violent antisemitic "cultural axiom" held by Martin Luther in the 16th century and expressed in his 1543 book On the Jews and Their Lies, according to Goldhagen, were the same as those held by Adolf Hitler in the 20th century.[17] He argued that such was the ferocity of German "eliminationist antisemitism" that the situation in Germany had been "pregnant with murder" regarding the Jews since the mid-19th century and that all Hitler did was merely to unleash the deeply rooted murderous "eliminationist antisemitism" that had been brooding within the German people since at least Luther's time, if not earlier.[18]  Title page of Martin Luther's On the Jews and Their Lies. Wittenberg, 1543. Goldhagen used Luther's book to argue for the deep-rooted unique "eliminationist" antisemitism of German culture. Hitler's Willing Executioners marked a revisionist challenge to the prevailing orthodoxy surrounding the question of German public opinion and the Final Solution.[19] The British historian Sir Ian Kershaw, a leading expert in the social history of the Third Reich, wrote, "The road to Auschwitz was built by hate, but paved with indifference,"[20][21] that is, that the progress leading up to Auschwitz was motivated by a vicious form of antisemitism on the part of the Nazi elite, but that it took place in a context where the majority of German public opinion was indifferent to what was happening.[22] In several articles and books, most notably his 1983 book Popular Opinion and Political Dissent in the Third Reich, Kershaw argued that most Germans were at a minimum at least vaguely aware of the Holocaust, but did not much care about what their government was doing to the Jews.[23] Other historians, such as the Israeli historian Otto Dov Kulka, the Israeli historian David Bankier, and the American historian Aron Rodrigue, while differing from Kershaw over many details about German public opinion, arguing that the term "passive complicity" is a better description than "indifference", have largely agreed with Kershaw that there was a chasm of opinion about the Jews between the Nazi "true believers" and the wider German public, whose views towards Jews seemed to have expressed more of a dislike than a hatred.[22] Goldhagen, in contrast, declared the term "indifference" to be unacceptable, contending that the vast majority of Germans were active antisemites who wanted to kill Jews in the most "pitiless" and "callous" manner possible.[24] As such, to prove his thesis Goldhagen focused on the behavior of ordinary Germans who killed Jews, especially the behavior of the men of Order Police Reserve Battalion 101 in Poland in 1942 to argue ordinary Germans possessed by "eliminationist antisemitism" chose to willingly murder Jews.[25] The 450 or so men of Battalion 101 were mostly middle-aged, working-class men from Hamburg who showed little interest in National Socialism and who had no special training to prepare them for genocide.[26] Despite their very different interpretations of Battalion 101, both Browning and Goldhagen have argued that the men of the unit were a cross-sample of ordinary Germans.[26] Using Geertz's anthropological methods, Goldhagen argued by studying the men of Battalion 101 one could engage in a "thick description" of the German "eliminationist antisemitic" culture.[27] Contra Browning, Goldhagen argued that the men of Battalion 101 were not reluctant killers, but instead willingly murdered Polish Jews in the cruelest and sadistic manner possible, that "brutality and cruelty" were central to the ethos of Battalion 101.[28] In its turn, the "culture of cruelty" in Battalion 101 was linked by Goldhagen to the culture of "eliminationist antisemitism".[29] Goldhagen noted that the officers in charge of Battalion 101 led by Major Wilhem Trapp allowed the men to excuse themselves from killing if they found it too unpleasant, and Goldhagen used the fact that the vast majority of the men of Battalion 101 did not excuse themselves to argue that this proved the murderous antisemitic nature of German culture.[30] Goldhagen argued for the specific antisemitic nature of Battalion 101's violence by noting that in 1942 the battalion was ordered to shoot 200 Gentile Poles, and instead shot 78 Polish Catholics while shooting 180 Polish Jews later that same day.[31] Goldhagen used this incident to argue the men of Battalion 101 were reluctant to kill Polish Catholics, but only too willing to murder Polish Jews.[31] Goldhagen wrote the men of Battalion 101 felt "joy and triumph" after torturing and murdering Jews.[32] Goldhagen used antisemitic statements by Cardinal Adolf Bertram as typical of what he called the Roman Catholic Church's support for genocide.[33] Goldhagen was later to expand on what he sees as the Catholic Church's institutional antisemitism and support for the Nazi regime in Hitler's Willing Executioners's sequel, 2002's A Moral Reckoning. Goldhagen argued that it "strains credibility" to imagine that "ordinary Danes or Italians" could have acted as he claimed ordinary Germans did during the Holocaust to prove that "eliminationist" anti-Semitism was uniquely German.[34] |

ゴールドハーゲンの論文 『ヒトラーの快楽の処刑者たち』において、ゴールドハーゲンはドイツ人が「根絶的アンチセミティズム」と呼ばれる独特な反ユダヤ主義を抱いていたと主張し た。この思想は、ドイツの歴史の数世紀にわたって広がった悪質なイデオロギーである。その影響により、大多数のドイツ人がユダヤ人をドイツ社会から排除す ることを望み、ホロコーストの加害者たちは「正しいこと、必要なこと」として行動した。ゴールドハーゲンにとって、多くのドイツ人が関与したホロコースト は、ドイツ特有の反ユダヤ主義の結果として説明されなければならない。  中央ヨーロッパの教会にユダヤの像が存在したことを示す地図(ドイツ語)。撤去されたものは赤でマークされている ゴールドハーゲンは、ホロコーストに関する他のすべての書籍は、第三帝国のドイツ人を「我々と多少なりとも似た存在」として扱い、「彼らの感性は我々の感 性と遠からず近似している」と誤って信じていたという事実によって欠陥があると主張した。[13] その代わりに、ゴールドハーゲンは、歴史家はナチス時代のドイツ人の一般市民を、 神々をなだめ、毎日太陽が昇るようにするために人身御供が必要だと信じていたアステカ人について研究したのと同じ方法で、ナチス時代のドイツ人についても 研究すべきだと主張した。[14] 彼の主張は、ドイツ人は啓蒙主義の価値観に影響された「普通の」西洋人ではないという仮定に基づいていると彼は述べた。彼の手法は人類学的なもので、木々 に魔力があると信じていたような前工業化時代の民を人類学者が描写するのと同じように、ドイツ人を扱うというものだった。 ゴールドハーゲンの著書は、Clifford Geertzの「厚い記述」という人類学の手法を意図したものであった。[16] ゴールドハーゲンによると、16世紀のマルティン・ルターが1543年の著書『ユダヤ人と彼らの嘘について』で表明した暴力的な反ユダヤ主義の「文化的公 理」は、20世紀のアドルフ・ヒトラーのそれと同じであった。[17] 彼は、ドイツの「根絶的ユダヤ人排斥主義」の激しさは、19世紀半ば以降、ドイツ国内のユダヤ人に対する状況が「殺意に満ちた」ものだったほどであり、ヒ トラーがやったことは、少なくともルターの時代、あるいはそれ以前からドイツ国民の間にくすぶっていた根深い殺意に満ちた「根絶的ユダヤ人排斥主義」を解 き放ったに過ぎない、と主張した。  マルティン・ルター著『ユダヤ人と彼らの嘘について』のタイトルページ。ヴィッテンベルク、1543年。ゴールドハーゲンはルターの著書を引き合いに出し、ドイツ文化に深く根付いた独特の「根絶主義的」反ユダヤ主義を主張した。 ヒトラーの喜んで加担する処刑人』は、ドイツ世論と最終的解決に関する支配的な正統派の見解に対する修正主義的な挑戦であった。[19] 第三帝国の社会史の第一人者であるイギリスの歴史家イアン・カーショー卿は、「アウシュビッツへの道は憎悪によって築かれたが、無関心によって舗装され た」と述べている。[20][21] つまり、アウシュビッツに至るまでの経過は、 ナチス・エリート層による悪質な反ユダヤ主義が動機ではあったが、ドイツ世論の大多数がその出来事に無関心であった状況下で起こったことであると主張して いる。[22] カーショウは、いくつかの論文や著書、特に1983年の著書『Popular Opinion and Political Dissent in the Third Reich』の中で、ほとんどのドイツ人は少なくとも漠然とホロコーストについて知っていたが、 自国の政府がユダヤ人に対して行っていることについて、あまり関心を抱いていなかったと主張している。[23] イスラエルの歴史家オットー・ドヴ・クルカ、イスラエルの歴史家デヴィッド・バンキエール、アメリカの歴史家アロン・ロドリゲといった他の歴史家たちは、 ドイツの世論に関する多くの詳細についてカーショウと意見を異にしているものの、「無関心」よりも「受動的加担」という表現の方が適切であると主張し、 ナチスの「狂信者」とより広範なドイツ国民の間には、ユダヤ人に対する意見の隔たりがあり、その意見は憎悪というよりも嫌悪を表明しているように見えた。 [22] これに対し、ゴールドハーゲンは「無関心」という表現は受け入れられないと主張し、大多数のドイツ人は、ユダヤ人を可能な限り「無慈悲」かつ「冷淡」な方 法で殺害しようとする積極的反ユダヤ主義者であったと論じた。[24] そのため、ゴールドハゲンは自説を証明するために、ユダヤ人を殺害した一般ドイツ人の行動、特に1942年のポーランドにおける親衛警察予備大隊101の 男性たちの行動に焦点を当て、一般ドイツ人が「根絶的反ユダヤ主義」に取りつかれてユダヤ人の殺害を自ら進んで選択したと主張した。101大隊の隊員は、 ハンブルクの中年労働者階級の男性がほとんどで、国家社会主義にはほとんど関心がなく、大量虐殺に備えた特別な訓練も受けていなかった。[26] 101大隊に対する解釈は大きく異なっていたが、ブラウニングとゴールドハーゲンはともに、この部隊の隊員は一般ドイツ人の典型的なサンプルであると主張 した。[26] ゴールドハーゲンは、ゲーツの文化人類学的手法を用いて、第101大隊の兵士たちを研究することで、ドイツの「根絶的ユダヤ人排斥」文化の「厚みのある描 写」が可能であると主張した。[27] ブラウニングとは対照的に、ゴールドハーゲンは、第101大隊の兵士たちは消極的な殺人者ではなく、むしろ、可能な限り残酷でサディスティックな方法で ポーランド系ユダヤ人を喜んで殺害したと主張した。「 残虐性と残酷さ」が第101大隊の精神の中心であったと主張した。[28] また、ゴールドハーゲンは、第101大隊の「残虐の文化」を「根絶的ユダヤ人排斥主義」の文化と結びつけた。[29] ゴールドハーゲンは、ヴィルヘルム・トラップ少佐が率いる第101大隊の指揮官たちは、兵士たちが殺人を忌まわしいと感じた場合には殺人を免除することを 認めていたと指摘し、 あまりにも不快であると感じた場合、殺害を免除することを許可していたと指摘し、ゴールドハーゲンは、第101大隊の兵士の大多数が殺害免除を申請しな かったという事実を、ドイツ文化の殺人的な反ユダヤ主義的本質を証明するものとして論じた。[30] ゴールドハーゲンは、1942年に第101大隊が200人の異教徒ポーランド人の射殺を命じられたが、 この事件を挙げ、ゴールドハーゲンは101大隊の兵士たちはポーランド人カトリック教徒を殺すことを嫌がったが、ポーランド人ユダヤ人の殺害には喜んで従 事したと主張した。[31] ゴールドハーゲンは、101大隊の兵士たちはユダヤ人を拷問し殺害した後、「喜びと勝利感」を感じたと書いた 。ゴールドハーゲンは、アドルフ・バートラム枢機卿による反ユダヤ主義的な発言を、ローマ・カトリック教会による大量虐殺の支援の典型例として引用した。 ゴールドハーゲンは、「根絶主義」反ユダヤ主義がドイツ独特のものであることを証明するために、ホロコースト時にドイツ人が行ったとされる行為を「普通の デンマーク人やイタリア人」が行ったと想像するのは「信憑性を欠く」と主張した。[34] |

| Reception What some commentators termed "The Goldhagen Affair"[35] began in late 1996, when Goldhagen visited Berlin to participate in the debate on television and in lecture halls before capacity crowds, on a book tour.[36][37] Although Hitler's Willing Executioners was sharply criticized in Germany at its debut,[38] the intense public interest in the book secured the author much celebrity among Germans, so much so that Harold Marcuse characterizes him as "the darling of the German public".[39] Many media commentators observed that, while the book launched a passionate national discussion about the Holocaust,[40] this discussion was carried out civilly and respectfully. Goldhagen's book tour became, in the opinion of some in the German media, "a triumphant march", as "the open-mindedness that Goldhagen encountered in the land of the perpetrators" was "gratifying" and something of which Germans ought to be proud, even in the context of a book which sought, according to some critics, to "erase the distinction between Germans and Nazis".[35] Goldhagen was awarded the Democracy Prize in 1997 by the German Journal for German and International Politics, which asserted that "because of the penetrating quality and the moral power of his presentation, Daniel Goldhagen has greatly stirred the consciousness of the German public." The laudatio, awarded for the first time since 1990, was given by Jürgen Habermas and Jan Philipp Reemtsma.[37][41] Elie Wiesel praised the work as something every German schoolchild should read.[42] Debate about Goldhagen's theory has been intense.[43] Detractors have contended that the book is "profoundly flawed"[44] or "bad history".[45] Some historians have criticized or simply dismissed the text, citing among other deficiencies Goldhagen's "neglect of decades of research in favour of his own preconceptions", which he proceeds to articulate in an "intemperate, emotional, and accusatory tone".[46] In 1997, the German historian Hans Mommsen gave an interview in which he said that Goldhagen had a poor understanding of the diversities of German antisemitism, that he construed "a unilinear continuity of German anti-semitism from the medieval period onwards" with Hitler as its end result, whereas, said Mommsen, it is obvious that Hitler's antisemitic propaganda had no significant impact on the election campaigns between September 1930 and November 1932 and on his coming to power, a crucial phenomenon ignored by Goldhagen. Goldhagen's one-dimensional view of German antisemitism also ignores the specific impact of the völkisch antisemitism as proclaimed by Houston Stuart Chamberlain and the Richard Wagner movement which directly influenced Hitler as well as the Nazi party. Finally, Mommsen criticizes Goldhagen for errors in his understanding of the internal structure of the Third Reich.[47] In the interview, Mommsen distinguished three varieties of German antisemitism. "Cultural antisemitism," directed primarily against the Eastern Jews, was part of the "cultural code" of German conservatives, who were mainly found in the German officer corps and the high civil administration. It stifled protests by conservatives against persecutions of the Jews, as well as Hitler's proclamation of a "racial annihilation war" against the Soviet Union. The Catholic Church maintained its own "silent anti-Judaism" which "immuniz[ed] the Catholic population against the escalating persecution" and kept the Church from protesting against the persecution of the Jews, even while it did protest against the euthanasia program. Third was the so-called völkisch antisemitism or racism, the most vitriolic form, the foremost advocate of using violence.[47] Christopher Browning wrote in response to Goldhagen's criticism of him in the 1998 "Afterword" to Ordinary Men published by HarperCollins: Goldhagen must prove not only that Germans treated Jewish and non-Jewish victims differently (on which virtually all historians agree), but also that the different treatment is to be explained fundamentally by the antisemitic motivation of the vast majority of the perpetrators and not by other possible motivations, such as compliance with different government policies for different victim groups. The second and third case studies of Hitler's Willing Executioners are aimed at meeting the burden of proof on these two points. Goldhagen argues that the case of the Lipowa and Flughafen Jewish labor camps in Lublin demonstrates that in contrast to other victims, only Jewish labor was treated murderously by the Germans without regard for and indeed counter to economic rationality. And the Helmbrechts death march case, he argues, demonstrates that Jews were killed even when orders have been given to keep them alive, and hence the driving motive for the killing was not compliance to government policy or obedience to orders, but the deep personal hatred of the perpetrators for their Jewish victims that had been inculcated by German culture.[48] About Goldhagen's claims that the men of Order Police Reserve Battalion 101 were reluctant to kill Polish Catholics while being eager to kill Polish Jews, Browning accused Goldhagen of having double standards with the historical evidence.[49] Browning wrote: Goldhagen cites numerous instances of gratuitous and voluntaristic killing of Jews as relevant to assessing the attitudes of the killers. But he omits a similar case of gratuitous, voluntaristic killing by Reserve Police Battalion 101 when the victims were Poles. A German police official was reported killed in the village of Niezdów, whereupon policemen about to visit the cinema in Opole were sent to carry out a reprisal action. Only elderly Poles, mostly women, remained in the village, as the younger Poles had all fled. Word came, moreover, that the ambushed German policeman had been only wounded, not killed. Nonetheless, the men of Reserve Police Battalion 101 shot all the elderly Poles and set the village on fire before returning to the cinema for an evening of casual and relaxing entertainment. There is not much evidence of "obvious distaste and reluctance" to kill Poles to be seen in this episode. Would Goldhagen have omitted this incident if the victims had been Jews and an anti-Semitic motivation could have easily been inferred?[50] About the long-term origins of the Holocaust, Browning argued that by the end of the 19th century, antisemitism was widely accepted by most German conservatives and that virtually all German conservatives supported the Nazi regime's antisemitic laws of 1933–34 (and the few who did object like President Hindenburg only objected to the inclusion of Jewish war veterans in the antisemitic laws that they otherwise supported) but that left to their own devices, would not have gone further and that for all their fierce anti-Semitism, German conservatives would not have engaged in genocide.[51] Browning also contended that the antisemitism of German conservative elites in the military and the bureaucracy long prior to 1933 meant that they made few objections, moral or otherwise to the Nazi/völkisch antisemitism.[51] Browning was echoing the conclusions of the German conservative historian Andreas Hillgruber who once presented at a historians' conference in 1984 a counter-factual scenario whereby, had it been a coalition of the German National People's Party and Der Stahlhelm that took power in 1933 without the NSDAP, all the antisemitic laws in Germany that were passed between 1933 and 1938 would still have occurred but there would have been no Holocaust.[52] The Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer wrote that Goldhagen's thesis about a murderous antisemitic culture applied better to Romania than to Germany and murderous anti-Semitism was not confined to Germany as Goldhagen had claimed.[53] Bauer wrote of the main parties of the Weimar Coalition that dominated German politics until 1930, the leftist SPD and the liberal DDP were opposed to anti-Semitism while the right-of-the-centre Catholic Zentrum was "moderately" antisemitic.[54] Bauer wrote of the major pre-1930 political parties, the only party that could be described as radically antisemitic was the conservative German National People's Party, who Bauer called "the party of the traditional, often radical anti-Semitic elites" who were "a definite minority" while the NSDAP won only 2.6% of the vote in the Reichstag elections in May 1928.[54] Bauer charged that it was the Great Depression, not an alleged culture of murderous anti-Semitism that allowed the NSDAP to make its electoral breakthrough in the Reichstag elections of September 1930.[54] Formally, at least, the Jews had been fully emancipated with the establishment of the German Empire, although they were kept out of certain influential occupations, enjoyed extraordinary prosperity ... Germans intermarried with Jews: in the 1930s some 50,000 Jews were living in mixed German-Jewish marriages, so at least 50,000 Germans, and presumably parts of their families, had familial contact with the Jews. Goldhagen himself mentions that a large proportion of the Jewish upper classes in Germany converted to Christianity in the nineteenth century. In a society where eliminationist norms were universal and in which Jews were rejected even after they had converted, or so he argues, the rise of this extreme form of assimilation of Jews would hardly have been possible.[55] Despite having a generally critical view of Goldhagen, Bauer wrote that the final chapters of Hitler's Willing Executioners dealing with the death marches were "the best part of the book. Little is new in the overall description, but the details and the way he analyzes the attitude of the murderers is powerful and convincing".[56] Finally Bauer charged "that the anti-German bias of his book, almost a racist bias (however much he may deny it) leads nowhere".[56] Concerning Order Police Reserve Battalion 101, the Australian historian Inga Clendinnen wrote that Goldhagen's picture of Major Trapp, the unit's commander as an antisemitic fanatic was "far-fetched" and "there is no indication, on that first day or later that he found the murdering of Jewish civilians a congenial task".[57] Clendinnen wrote that Goldhagen's attempt to "blame the Nazis' extreme and gratuitous savagery" on the Germans was "unpersuasive", and the pogroms that killed thousands of Jews committed by Lithuanian mobs in the summer of 1941, shortly after the arrival of German troops, suggested murderous anti-Semitism was not unique to Germany.[58] Clendinnen ended her essay by stating she found Browning's account of Battalion 101 to be the more believable.[59] The Israeli historian Omer Bartov wrote that to accept Goldhagen's thesis would also have to mean accepting that the entire German Jewish community was "downright stupid" from the mid-19th century onwards because it is otherwise impossible to explain why they chose to remain in Germany, if the people were so murderously hostile or why so many German Jews wanted to assimilate into an "eliminationist anti-Semitic" culture.[60] In a 1996 review in First Things, the American Catholic priest Father Richard John Neuhaus took issue with Goldhagen's claim that the Catholic and Lutheran churches in Germany were genocidal towards the Jews, arguing that there was a difference between Christian and Nazi anti-Semitism.[61] Neuhaus argued that Goldhagen was wrong to claim that Luther had created a legacy of intense, genocidal anti-Semitism within Lutheranism, asking why, if that were the case, would so many people in solidly Lutheran Denmark act to protect the Danish Jewish minority from deportation to the death camps in 1943.[61] The Canadian historian Peter Hoffmann accused Goldhagen of maligning Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, arguing that Goldhagen had taken wildly out of context the list of Jewish doctors forbidden to practice that Goerdeler as Lord Mayor of Leipzig had issued in April 1935. Hoffmann contended that what happened was that on April 9, 1935, the Deputy Mayor of Leipzig, the National Socialist Rudolf Haake, banned all Jewish doctors from participating in public health insurance and advised all municipal employees not to consult Jewish doctors, going beyond the existing antisemitic laws then in place.[62] In response, the Landesverband Mitteldeutschland des Centralvereins deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens e. V (Middle German Regional Association of the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith) complained to Goerdeler about Haake's actions and asked him to enforce the existing antisemitic laws, which at least allowed some Jewish doctors to practice.[62] On 11 April 1935, Goerdeler ordered the end of Haake's boycott, and provided a list of "non-Aryan" physicians permitted to operate under the existing laws and those who were excluded.[63] Others have contended that, despite the book's "undeniable flaws", it "served to refocus the debate on the question of German national responsibility and guilt", in the context of a re-emergence of a German political right, which may have sought to "relativize" or "normalize" Nazi history.[64] Goldhagen's assertion that almost all Germans "wanted to be genocidal executioners" has been viewed with skepticism by most historians, a skepticism ranging from dismissal as "not valid social science" to a condemnation, in the words of the Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer, as "patent nonsense".[2][65][66] Common complaints suggest that Goldhagen's primary hypothesis is either "oversimplified",[67] or represents "a bizarre inversion of the Nazi view of the Jews" turned back upon the Germans.[3] One German commentator suggested that Goldhagen's book "pushes us again and again headfirst into the nasty anti-Semitic mud. This is his revenge."[68] Eberhard Jäckel wrote a very hostile book review in the Die Zeit newspaper in May 1996 that called Hitler's Willing Executioners "simply a bad book".[69] The British historian Sir Ian Kershaw wrote that he fully agreed with Jäckel on the merits of Hitler's Willing Executioners".[69] Kershaw wrote in 2000 that Goldhagen's book would "occupy only a limited place in the unfolding, vast historiography of such a crucially important topic-probably at best as a challenge to historians to qualify or counter his 'broad-brush' generalisations".[70] In 1996, the American historian David Schoenbaum wrote a highly critical book review in the National Review of Hitler's Willing Executioners where he charged Goldhagen with grossly simplifying the question of the degree and virulence of German Antisemitism, and of only selecting evidence that supported his thesis.[71]: 54–5 Furthermore, Schoenbaum complained that Goldhagen did not take a comparative approach with Germany placed in isolation, thereby falsely implying that Germans and Germans alone were the only nation that saw widespread antisemitism.[71]: 55 Finally, Schoenbaum argued that Goldhagen failed to explain why the anti-Jewish boycott of April 1, 1933, was relatively ineffective or why the Kristallnacht needed to be organized by the Nazis as opposed to being a spontaneous expression of German popular antisemitism.[71]: 56 Using an example from his family history, Schoenbaum wrote that his mother in law, a Polish Jew who lived in Germany between 1928–47, never considered the National Socialists and the Germans synonymous, and expressed regret that Goldhagen could not see the same.[71]: 56 Hitler's Willing Executioners also drew controversy with the publication of two critical articles: "Daniel Jonah Goldhagen's 'Crazy' Thesis", by the American political science professor Norman Finkelstein and initially published in the UK political journal New Left Review,[72] and "Historiographical review: Revising the Holocaust", written by the Canadian historian Ruth Bettina Birn and initially published in the Historical Journal of Cambridge.[3] These articles were later published as the book A Nation on Trial: The Goldhagen Thesis and Historical Truth.[3] In response to their book, Goldhagen sought a retraction and apology from Birn, threatening at one point to sue her for libel and according to Salon declaring Finkelstein "a supporter of Hamas".[3] The force of the counterattacks against Birn and Finkelstein from Goldhagen's supporters was described by Israeli journalist Tom Segev as "bordering on cultural terrorism ... The Jewish establishment has embraced Goldhagen as if he were Mr Holocaust himself ... All this is absurd, because the criticism of Goldhagen is backed up so well."[73] The Austrian-born American historian Raul Hilberg has stated that Goldhagen is "totally wrong about everything. Totally wrong. Exceptionally wrong."[4] Hilberg also wrote in an open letter on the eve of the book launch at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum that "The book is advertised as something that will change our thinking. It can do nothing of the sort. To me it is worthless, all the hype by the publisher notwithstanding".[5] Yehuda Bauer was similarly condemnatory, questioning how an institute such as Harvard could award a doctorate for a work which so "slipped through the filter of critical scholarly assessment".[74] Bauer also suggested that Goldhagen lacked familiarity with sources not in English or German, which thereby excluded research from Polish and Israeli sources writing in Hebrew, among others, all of whom had produced important research in the subject that would require a more subtle analysis. Bauer also argued that these linguistic limitations substantially impaired Goldhagen from undertaking broader comparative research into European antisemitism, which would have demanded further refinements to his analysis. Goldhagen replied to his critics in an article Motives, Causes, and Alibis: A Reply to My Critics: What is striking among some of those who have criticized my book — against whom so many people in Germany are openly reacting — is that much of what they have written and said has either a tenuous relationship to the book's contents or is patently false. Some of the outright falsehoods include: that little is new in the book; that it puts forward a monocausal and deterministic explanation of the Holocaust, holding it to have been the inevitable outcome of German history; that its argument is ahistorical; and that it makes an "essentialist," "racist" or ethnic argument about Germans. None of these is true.[75] Ruth Bettina Birn and Volker Riess recognised the need to examine the primary sources (the Police Battalion investigation records) Goldhagen had cited and determine if Goldhagen had applied the historical method in his research. Their task was complicated by the way that "Goldhagen's book [had] neither a bibliography nor a listing of archival sources".[76] Their conclusions were that Goldhagen's analysis of the records: seems to follow no stringent methodological approach whatsoever. This is the problem. He prefers instead to use parts of the statements selectively, to re-interpret them according to his own point of view, or to take them out of context and make them fit into his own interpretative framework. [...] Using Goldhagen's method of handling evidence, one could easily find enough citations from the Ludwigsburg material to prove the exact opposite of what Goldhagen maintains. [...] Goldhagen's book is not driven by sources, be they primary or secondary ones. He does not allow the witness statements he uses to speak for themselves. He uses material as an underpinning for his pre-conceived theory.[77] Historian Richard J. Evans was highly critical, saying of Goldhagen's work: ...a book which argued in a crude and dogmatic fashion that virtually all Germans had been murderous antisemites since the middle ages, had been longing to exterminate the Jews for decades before Hitler came to power, and actively enjoyed participating in the extermination when it began. The book has since been exposed as a tissue of misrepresentation and misinterpretation, written in shocking ignorance of the huge historical literature on the topic and making numerous elementary mistakes in its interpretation of the documents.[78] Accusations of racism Several critics, including David North,[3][79] have characterized Goldhagen's text as adopting Nazi concepts of identity and utilizing them to slur Germans. Hilberg, to whom Browning dedicated his monograph, wrote that "Goldhagen has left us with the image of a medieval-like incubus, a demon latent in the German mind ... waiting for the opportunity for the chance to strike out".[80] The American columnist D.D. Guttenplan, author of The Holocaust on Trial (about the David Irving libel case), also dedicated to Hilberg, wrote that the only difference between Goldhagen's claims of an eliminationist culture and those of Meir Kahane was that Goldhagen's targets were the Germans, whereas Kahane's targets were the Arabs.[80] Guttenplan charged that Goldhagen's remarks about the deaths of three million Soviet POWs in German custody in World War II as "incidental" to the Holocaust were factually wrong, stating that the first people gassed at Auschwitz in August 1941 were Soviet POWs.[81] Influenced by the thesis about the Jews and Soviets as equal victims of the Holocaust presented in the American historian Arno J. Mayer's 1988 book Why Did the Heavens Not Darken? Guttenplan argued that the Nazi theories about "Judo-Bolshevism" made for a more complex explanation for the Holocaust than the Goldhagen thesis about an "eliminationist anti-Semitic" culture.[81] Goldhagen has said that there is no racist or ethnic argument about Germans in his text. Some of his critics have agreed with him that his thesis is "not intrinsically racist or otherwise illegitimate", including Ruth Bettina Birn and Norman Finkelstein (A Nation on Trial).[82] Popular response When the English edition of Hitler's Willing Executioners was published in March 1996, numerous German reviews ensued. In April 1996, before the book had appeared in German translation, Der Spiegel ran a cover story on Hitler's Willing Executioners under the title "Ein Volk von Dämonen?".[83] The phrase ein Volk von Dämonen (translated "a people/nation of demons") was often used by the Nazis to describe Jews, and the title of the cover story was meant by Rudolf Augstein and the editors of Der Spiegel to suggest a moral equivalence between the Nazi view of Jews and Goldhagen's view of Germans.[83] The most widely read German weekly newspaper Die Zeit published an eight-part series of opinions of the book before its German publication in August 1996. Goldhagen arrived in Germany in September 1996 for a book tour, and appeared on several television talk shows, as well as a number of sold-out panel discussions.[65][84] The book had a "mostly scathing" reception among historians,[3][85][86][87] who were vocal in condemning it as ahistorical.[88] "[W]hy does this book, so lacking in factual content and logical rigour, demand so much attention?" Raul Hilberg wondered.[89] The pre-eminent Jewish-American historian Fritz Stern denounced the book as unscholarly and full of racist Germanophobia.[86] Hilberg summarised the debates: "by the end of 1996, it was clear that in sharp distinction from lay readers, much of the academic world had wiped Goldhagen off the map."[90] Steve Crawshaw writes that although the German readership was keenly aware of certain "professional failings" in Goldhagen's book, [T]hese perceived professional failings proved almost irrelevant. Instead, Goldhagen became a bellwether of German readiness to confront the past. The accuracy of his work was, in this context, of secondary importance. Millions of Germans who wished to acknowledge the (undeniable and well-documented) fact that ordinary Germans participated in the Holocaust welcomed his work; his suggestion that Germans were predestined killers was accepted as part of the uncomfortable package. Goldhagen's book was treated as a way of ensuring that Germany came to terms with its past.[2] Crawshaw further asserts that the book's critics were partly historians "weary" of Goldhagen's "methodological flaws", but also those who were reluctant to concede that ordinary Germans bore responsibility for the crimes of Nazi Germany.[2] In Germany, the leftist general public's insistence on further penitence prevailed, according to most observers.[67] American historian Gordon A. Craig and Der Spiegel have argued that whatever the book's flaws, it should be welcomed because it will reinvigorate the debate on the Holocaust and stimulate new scholarship.[86]: 287 Journalism In May 1996, Goldhagen was interviewed about Hitler's Willing Executioners by the American journalist Ron Rosenbaum. When Rosenbaum asked Goldhagen about scholarly literature that contends that Austrian anti-Semitism was far more virulent and violent than German anti-Semitism, and if the fact that Hitler was an Austrian had any effect on his thesis, Goldhagen replied: There were regional variations in anti-Semitism even within Germany. But Hitler's exemplified and brought to an apotheosis the particular form of eliminationist anti-Semitism that came to the fore in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Whatever the variations, I think Austrian and German anti-Semitism can be seen of a piece, where there was a central model of Jews and a view that they needed to be eliminated.[91] Rosenbaum inquired about Goldhagen's "pregnant with murder" metaphor, which suggested that the Shoah was something inevitable that would have happened without Hitler and Milton Himmelfarb's famous formulation "No Hitler, no Holocaust".[92] Rosenbaum asked "So you would agree with Himmelfarb's argument?"[92] Goldhagen replied: "If the Nazis had never taken power, there would not have been a Hitler. Had there not been a depression in Germany, then in all likelihood the Nazis wouldn't have come to power. The anti-Semitism would have remained a potential, in the sense of the killing form. It required a state."[92] Rosenbaum asked Goldhagen about Richard Levy's 1975 book The Downfall of the Anti-Semitic Political Parties in Imperial Germany which traced the decline of the völkisch parties in the early 20th century until they were all but wiped out in the 1912 Reichstag election. Goldhagen replied that voting for or against the wildly antisemitic völkisch parties had nothing to do with antisemitic feeling, and that people could still hate Jews without voting for the völkisch parties.[93] In 2006, Jewish American conservative columnist Jonah Goldberg argued that "Goldhagen's thesis was overstated but fundamentally accurate. There was something unique to Germany that made its fascism genocidal. Around the globe, there have been dozens of self-declared fascist movements (and a good deal more that go by different labels), and few of them have embraced Nazi-style genocide. Indeed, fascist Spain was a haven for Jews during the Holocaust" he said.[94] Goldberg went on to state that Goldhagen was mistaken in believing that "eliminationist antisemitism" was unique to Germany, and Goldberg charged "eliminationist antisemitism" was just as much a feature of modern Palestinian culture as it was of 19th-20th-century German culture, and that in all essentials Hamas today was just as genocidal as the NSDAP had been.[94] In 2011, in an apparent reference to Hitler's Willing Executioners, the American columnist Jeffrey Goldberg wrote the leaders of the Islamic Republic of Iran were all "eliminationist anti-Semites".[95] From a different angle, the American political scientist Norman Finkelstein charged that the book was Zionist propaganda meant to promote the image of a Gentile world forever committed to the destruction of the Jews, thus justifying the existence of Israel, and as such, Goldhagen's book was more concerned with the politics of the Near East and excusing what Finkelstein claimed was Israel's poor human rights record rather than European history.[96] In turn during a review of A Nation On Trial, the American journalist Max Frankel wrote that Finkelstein's anti-Zionist politics had led him to "get so far afield from the Goldhagen thesis that it is a relief to reach the critique by Ruth Bettina Birn".[97] |

レセプション 一部の評論家が「ゴールドハーゲン事件」と呼んだ論争は[35]、1996年の終わりにゴールドハーゲンがベルリンを訪れ、本の宣伝のための講演会やテレ ビ討論会で満員の聴衆を前に講演したときに始まった。[36][37] 『ヒトラーの愉快な執行者たち』はドイツで出版された当初は激しい批判にさらされたが[3 8] しかし、この本に対する強い関心は著者にドイツ国民の間で多くの名声をもたらし、ハロルド・マルクーゼは著者を「ドイツ国民の寵児」と評したほどであっ た。[39] 多くのメディア解説者は、この本がホロコーストに関する熱のこもった国民的議論を巻き起こした一方で、[40] この議論は礼節をわきまえたものであったと指摘した。ゴールドハーゲンの本の宣伝ツアーは、ドイツのメディアの一部の意見によると、「凱旋行進」となっ た。「加害者の国でゴールドハーゲンが遭遇した寛容さ」は「満足のいく」ものであり、一部の批評家によると「ドイツ人とナチスを区別する線を消し去ろう」 とした本の内容に関わらず、ドイツ人が誇りに思うべきことである。 ゴールドハーゲンは1997年に『ドイツおよび国際政治ジャーナル』誌から民主主義賞を授与された。同誌は「ゴールドハーゲンの著作の洞察力と道徳的影響 力により、ドイツ国民の意識は大きく揺り動かされた」と主張した。1990年以来初めて授与されたこの賞賛の言葉は、ユルゲン・ハーバーマスとヤン・フィ リップ・リーメンシュマによって贈られた。[37][41] エリ・ヴィーゼルは、この著作をドイツのすべての小学生が読むべきものだと賞賛した。[42] ゴールドハーゲンの理論に関する議論は激しいものとなっている。[43] 批判者たちは、この本は「深刻な欠陥がある」[44] あるいは「質の悪い歴史書」であると主張している。[45] 一部の歴史家は、ゴールドハーゲンの「自身の先入観を支持する代わりに数十年にわたる研究を無視したこと」を挙げ、この本を批判したり、あるいは単に否定 したりしている。 。彼は「節度を欠き、感情的で、非難的な口調」でそれを明確に述べている。[46] 1997年、ドイツの歴史家ハンス・モムゼンは、ゴールドハーゲンがドイツの反ユダヤ主義の多様性を十分に理解していないと述べたインタビューを行った。 彼は「 中世以降のドイツの反ユダヤ主義の単線的な継続」を、その最終結果としてヒトラーを位置づけたと述べた。一方、モムゼンによれば、ヒトラーの反ユダヤ主義 的プロパガンダが、1930年9月から1932年11月までの選挙運動や、彼が政権を握ることに、重要な影響を与えたことは明らかである。これはゴールド ハーゲンが無視した重要な現象である。また、ゴールドハーゲンが描くドイツの反ユダヤ主義の単一的な見解は、ヒトラーやナチス党に直接的な影響を与えた ヒューストン・スチュアート・チェンバレンやリヒャルト・ワーグナーの民族主義的反ユダヤ主義の持つ特別な影響力も無視している。最後に、モムゼンは第三 帝国の内部構造に対するゴールドハーゲンの理解の誤りを批判している。[47] インタビューの中で、モムゼンはドイツの反ユダヤ主義を3つの種類に分類している。「文化的反ユダヤ主義」は主に東ヨーロッパのユダヤ人に対して向けられ たもので、ドイツの保守派の「文化的規範」の一部であった。保守派は主にドイツ軍将校や高級文官に多く見られた。この規範は、ユダヤ人迫害に対する保守派 の抗議の声を封じ込め、ヒトラーによるソ連に対する「人種絶滅戦争」の宣言をも封じ込めた。カトリック教会は独自の「沈黙の反ユダヤ主義」を維持し、それ は「カトリック信者を迫害の拡大から守る免疫」となり、教会が安楽死計画に抗議する一方で、ユダヤ人迫害に抗議しない理由となった。第三は、最も辛辣な形 態であり、暴力の行使を最も強く主張する、いわゆる民族主義的反ユダヤ主義または人種差別主義であった。 クリストファー・ブラウニングは、1998年にハーパーコリンズ社から出版された『Ordinary Men』の「あとがき」でゴールドハーゲンから批判されたことに対して、次のように反論している。 ゴールドハーゲンは、ドイツ人がユダヤ人と非ユダヤ人の犠牲者を異なっ た方法で扱ったことを証明するだけでなく(この点については、事実上すべての歴史家が同意している)、その異なった扱いは、加害者の大多数の反ユダヤ主義 的な動機によって根本的に説明されるべきであり、異なる犠牲者グループに対する異なる政府方針に従うことなど、他の可能性のある動機によって説明されるべ きではないことを証明しなければならない。『ヒトラーの意志を継ぐ者たち』の2番目と3番目の事例研究は、この2つの点に関する立証責任を果たすことを目 的としている。ゴールドハーゲンは、ルブリンのリポワとフラウエンシュタットのユダヤ人強制労働収容所の事例が、他の犠牲者とは対照的に、ユダヤ人労働者 だけが経済合理性など考慮されることもなく、それどころか経済合理性を無視してドイツ人によって殺人的に扱われたことを示していると論じている。ヘルムブ レヒトの死の行進の事例は、ユダヤ人の命を維持するよう命令が出されていた場合でも、ユダヤ人が殺害されていたことを示している。したがって、殺害の主な 動機は、政府の方針に従うことでも、命令に従うことでもなく、加害者たちのユダヤ人に対する深い個人的な憎悪であり、それはドイツ文化によって植え付けら れたものだった。[48] ゴールドハーゲンが、親衛隊予備大隊101の隊員たちはポーランド系ユダヤ人の殺害には熱心だったが、ポーランド系カトリック教徒の殺害には消極的だったと主張したことについて、ブラウニングは、ゴールドハーゲンが歴史的証拠に対して二重基準を用いていると非難した。 ゴールドハーゲンは、ユダヤ人の無償かつ自発的な殺害の事例を多数挙げ、殺人者の態度を評価するのに関連していると主張している。しかし、犠牲者がポーラ ンド人であった場合の予備警察大隊101による同様の無償かつ自発的な殺害の事例は省略している。ドイツの警察官がNiezdów村で死亡したとの報告を 受け、オポーレの映画館に向かおうとしていた警官たちが報復行動に出動した。若いポーランド人は全員逃げ出していたため、村には高齢のポーランド人、ほと んどが女性だけが残されていた。さらに、待ち伏せしていたドイツ人警官は殺されず、負傷しただけだったという情報も入った。それでも、予備警察大隊101 の隊員たちは、高齢のポーランド人全員を射殺し、村に火を放ってから、映画館に戻って、気楽でリラックスした娯楽の夜を過ごした。このエピソードには、 ポーランド人を殺すことに対する「明白な嫌悪感と不本意」を示す証拠はあまり見られない。もし犠牲者がユダヤ人であり、反ユダヤ主義的な動機が容易に推測 できたとしたら、ゴールドハーゲンは、この事件を省略しただろうか?[50] ホロコーストの長期にわたる起源について、ブラウニングは、19世紀末には反ユダヤ主義はドイツの保守派のほとんどに広く受け入れられており、事実上すべ てのドイツの保守派が1933年から34年のナチス政権の反ユダヤ法を支持していた(ヒンデンブルク大統領のように異議を唱えた少数派は、反ユダヤ法にユ ダヤ人退役軍人が含まれていることだけを異議としており、それ以外は支持していた)と主張した。しかし、 彼ら自身のやりたいようにさせておけば、それ以上は進まなかっただろうし、彼らの激しい反ユダヤ主義にもかかわらず、ドイツの保守派は大量虐殺には踏み切 らなかっただろうと主張している。[51] また、ブラウニングは、軍や官僚組織におけるドイツの保守派エリートが1933年よりずっと以前から反ユダヤ主義であったことは、彼らがナチスや民族社会 主義者の反ユダヤ主義に対して道徳的あるいはその他の異議をほとんど唱えなかったことを意味すると主張している。[51] ブラウニングは、ドイツの保守派の歴史家であるアンドレアス・ヒルグルーバーの結論を引用している。 1984年に歴史家会議で、もし1933年に国家社会主義ドイツ労働者党(NSDAP)抜きでドイツ国民人民党とシュタールヘルムの連立政権が誕生してい たならば、1933年から1938年の間にドイツで成立した反ユダヤ法はすべて成立していたであろうが、ホロコーストは起こらなかったであろうという反事 実的シナリオを発表した。 イスラエルの歴史家イェフーダ・バウアーは、ゴールドハーゲンが主張した殺人反ユダヤ的文化に関する論文は、ドイツよりもルーマニアに当てはまるものであ り、殺人反ユダヤ主義はゴールドハーゲンが主張したようにドイツに限られたものではなかったと書いている。[53] バウアーは、1930年までドイツの政治を支配していたワイマール連立政権の主要政党について、左派のSPDと自由主義のDDPは反ユダヤ主義に反対して いたが、 。一方、中道右派のカトリック政党であるドイツ中央党は「穏健な」反ユダヤ主義であったと述べている。[54] バウアーは1930年以前の主要政党について、急進的な反ユダヤ主義政党として唯一挙げられるのは保守政党のドイツ国民人民党であると述べている。バウ アーは、この政党を「伝統的で、しばしば急進的な反ユダヤ主義エリート」の政党と呼び、 「明確な少数派」であった一方で、1928年5月の帝国議会選挙ではNSDAPは2.6%の票しか獲得できなかった。[54] バウアーは、1930年9月の帝国議会選挙でNSDAPが躍進できたのは、殺人反ユダヤ主義の文化があったからではなく、世界大恐慌があったからだと主張 した。[54] 少なくとも形式上は、ドイツ帝国の成立によりユダヤ人は完全に解放されていたが、彼らは特定の有力な職業から締め出されていたものの、異常なほどの繁栄を 享受していた。ドイツ人とユダヤ人の間では異人種間の結婚が行われていた。1930年代には、約5万人のユダヤ人がドイツ人とユダヤ人の混血結婚で暮らし ており、少なくとも5万人のドイツ人と、おそらくその家族の一部がユダヤ人と家族ぐるみの付き合いをしていた。ゴールドハーゲン自身も、19世紀にはドイ ツのユダヤ人上流階級の多くがキリスト教に改宗したと述べている。排除主義的な規範が一般的であり、ユダヤ人が改宗してもなお拒絶された社会では、このよ うな極端な同化現象は起こり得なかったと彼は主張している。 ゴールドハーゲンに対して概ね批判的な見解を持つバウアーは、それでも『ヒトラーの快楽の処刑者たち』の最終章で扱われている死の行進については、「この 本の最も優れた部分」と書いた。全体的な記述には目新しいものはほとんどないが、細部や殺人者の態度を分析する方法は力強く、説得力がある」と述べた。 [56] そして最後にバウアーは、「(著者がいくら否定しようとも)彼の著書には反ドイツ的バイアス、つまり人種差別的バイアスが感じられ、それは何処にも導かな い」と非難した。[56] オーストラリアの歴史家インガ・クレンディネンは、『警察予備大隊101』について、同部隊の指揮官トラップ少佐を反ユダヤ狂信者として描いたゴールド ハーゲンの記述は「無理がある」とし、「ユダヤ人市民の殺害を快い任務と感じていたことを示す兆候は、その最初の日にも、それ以降にも見られない」と述べ た。[57] クレンディネンは、ゴールドハーゲンが「 極端で無意味な残虐性」をドイツ人のせいにしようとする試みは「説得力がない」とし、ドイツ軍が到着した直後の1941年夏にリトアニア人の暴徒によって 数千人のユダヤ人が殺されたポグロムは、殺人的な反ユダヤ主義がドイツ特有のものではないことを示唆していると述べた。[58] クレディネンは、ブラウニングによる第101大隊の記述の方がより信憑性が高いと結論づけている。[59] イスラエルの歴史家オマー・バルトは、ゴールドハーゲン説を受け入れるということは、19世紀半ば以降のドイツのユダヤ人社会全体が「徹底的に愚か」で あったと認めることにもなる、と述べている。なぜなら、もし彼らがそれほどまでに殺意を抱くほど敵対的な人々であったならば、なぜドイツに残ることを選ん だのか、また、なぜこれほど多くのドイツのユダヤ人が「根絶的」な反ユダヤ主義文化に同化しようとしたのかを説明できないからだ。1996年の『ファース ト・シングス』誌のレビューで、アメリカのカトリック司祭リチャード・ジョン・ノイハウス神父は、ドイツのカトリック教会とルーテル教会がユダヤ人に対し てジェノサイドを行っていたというゴールドハーゲンの主張に異議を唱え、キリスト教の反ユダヤ主義とナチスの反ユダヤ主義には違いがあると論じた。 [61] ノイハウスは、ルーテル教会内に激しいジェノサイド的な反ユダヤ主義の遺産を残したと主張したゴールドハーゲンは間違っていると論じ、 もしそうであれば、なぜ1943年に、ルター派が根強いデンマークで、多くの人々がデンマークのユダヤ人少数派を強制収容所への移送から守るために行動し たのか、と問いかけた。[61] カナダの歴史家ピーター・ホフマンは、ゴールドハーゲンがカール・フリードリヒ・ゲルデラーを中傷したと非難し、ゲルデラーが1935年4月にライプツィ ヒ市長として発布したユダヤ人医師の業務禁止リストを、ゴールドハーゲンが文脈を無視して不当に引用したと主張した。ホフマンは、1935年4月9日にラ イプツィヒの副市長で国家社会主義者のルドルフ・ハーケが、当時施行されていた反ユダヤ法を逸脱して、すべてのユダヤ人医師を公的健康保険から排除し、す べての市職員にユダヤ人医師の診察を受けないよう勧告したと主張した。[62] これに対して、中央協会ドイツ国民ユダヤ教信仰中央協会ミッテルドイツ地域協会(Landesverband Mitteldeutschland des Centralvereins deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens e.V)は、ハーケの行動についてゲルデラーに苦情を申し立て、少なくとも一部のユダヤ人医師に診療を許可していた反ユダヤ法の施行を求めた。[62] 4月11日、 ゲルデラーにハーケの行動を訴え、少なくとも一部のユダヤ人医師に開業を許可していた既存の反ユダヤ法の施行を求めた。[62] 1935年4月11日、ゲルデラーはハーケのボイコットの終了を命じ、既存の法律の下で開業が許可された「非アーリア人」医師と除外された医師のリストを 提供した。[63] 他の人々は、この本には「否定できない欠陥」があるものの、ドイツの政治的右派が再び台頭する中で、「ドイツ国民の責任と罪悪感に関する議論を再燃させる のに役立った」と主張している。ナチスの歴史を「相対化」または「正常化」しようとした可能性があるという文脈においてである。 ゴールドハーゲンの主張、すなわち、ほとんどすべてのドイツ人が「大量虐殺の実行者になりたかった」という主張は、ほとんどの歴史家から懐疑的に見られて いる。その懐疑的な見方は、「有効な社会科学ではない」という否定から、イスラエルの歴史家イェフーダ・バウアーの言葉によれば「明白なナンセンス」とい う非難まで、幅広いものである。[2][65][66] よくある ゴールドハーゲンの主要な仮説は「単純化しすぎている」[67]、あるいは「ナチスによるユダヤ人観の奇妙な逆転」であり、ドイツ人に向けられたものだ [3]という批判が一般的である。ドイツのあるコメンテーターは、ゴールドハーゲンの著書は「我々を反ユダヤ主義の泥沼に何度も何度も突き落とす。これは 彼の復讐である」と述べた。[68] エバーハルト・イェッケルは1996年5月に『ディー・ツァイト』紙に非常に敵対的な書評を書き、ヒトラーの快楽殺人者たちを「単に駄作」と呼んだ。 [69] イギリスの歴史家イアン・カーショー卿は、ヒトラーの快楽殺人者たちについて、その価値においてイェッケルに完全に同意すると述べた。 。[69] カーショウは2000年に、ゴルダヘン著の書物は「おそらく、歴史家たちに彼の『大雑把な』一般化を修正するか、反論するよう促すという意味において、こ のような極めて重要なテーマに関する広範な歴史学の展開において限られた位置を占めるだけだろう」と書いている。[70] 1996年、アメリカの歴史家デビッド・ショーンバウムは、ナショナル・レビュー誌に『ヒトラーの喜んで処刑人となる者たち』という非常に批判的な書評を 寄稿し、ゴールドハーゲンがドイツの反ユダヤ主義の度合いと悪質さの問題を著しく単純化し、自説を裏付ける証拠だけを選んでいると非難した。[71]: 54–5 さらに、ショーンバウムは、ゴールドハーゲンが ドイツを孤立させた比較アプローチを取らず、ドイツ人とドイツ人だけが広範な反ユダヤ主義を抱く国民であるかのように誤って暗示していると不満を述べた。 [71]: 55 最後に、ショーンバウムは、1933年4月1日の反ユダヤ的ボイコットがなぜ比較的効果的でなかったのか、あるいは、なぜナチスがクリスタル・ナハトを組 織する必要があったのか、ドイツ国民の反ユダヤ主義の自然発生的な表現ではなく、 ドイツ国民の反ユダヤ主義の自然発生的な表現であると主張した。[71]: 56 自身の家族の歴史を例に挙げ、ショーンバウムは、1928年から1947年の間ドイツに住んでいた義理の母であるポーランド系ユダヤ人は、ナチスとドイツ 人を同義語として考えたことは一度もなく、ゴールドハーゲンが同じように考えられないことを残念に思っていると書いた。[71]: 56 また、『ヒトラーの喜んで従う処刑人』は、2つの批判的な論文の発表によっても論争を巻き起こした。1つは、アメリカの政治学教授ノーマン・フィンケル シュタインによる「ダニエル・ヨナ・ゴールドハゲンの『狂気』のテーゼ」で、当初は英国の政治誌『ニュー・レフト・レビュー』に掲載された[72]。もう 1つは、 ホロコーストの見直し」は、カナダの歴史家ルース・ベッティーナ・バームが執筆し、当初はケンブリッジの『歴史ジャーナル』誌に掲載された。[3] これらの記事は後に書籍『国民を裁く: ゴールドハーゲン・テーゼと歴史的真実』として出版された。[3] この本に対して、ゴールドハーゲンはバーンに撤回と謝罪を求め、名誉棄損で訴えると脅迫した。また、サロン誌によると、フィンケルシュタインを「ハマスの 支持者」と宣言した。[3] ゴールドハーゲンの支持者によるバーンとフィンケルシュタインに対する反撃の勢いは、イスラエルのジャーナリスト、トム・セゲブによって「文化テロに等し い... ユダヤのエスタブリッシュメントは、ゴールドハゲンをあたかもホロコーストの生き証人のように受け入れている。ゴールドハゲンの批判は十分に裏付けられて いるのだから、こうしたことはすべて馬鹿げている。」[73] オーストリア生まれの米国の歴史家ラウル・ヒルバーグは、ゴールドハーゲンは「すべてにおいて完全に間違っている。完全に間違っている。例外的に間違って いる」と述べている。[4] ヒルバーグはまた、米国ホロコースト記念博物館での出版記念会の前夜に公開書簡を書き、「この本は、私たちの考え方を変えるものとして宣伝されている。し かし、そのようなことはできない。出版社の宣伝文句はともかく、私には価値のない本だ」と述べている。[5] ユダ・バウアーも同様に批判的であり、ハーバード大学のような研究機関が、これほど「学術的な批判的評価のフィルターを通過していない」作品に対して博士 号を授与することに疑問を呈した。[ 74] バウアーはまた、ゴールドハーゲンが英語やドイツ語以外の資料に精通していないことを指摘し、それによってポーランド語やヘブライ語で書かれたイスラエル 人の資料など、より繊細な分析を必要とするこのテーマの重要な研究を排除していると主張した。バウアーはさらに、これらの言語上の制約がゴールドハーゲン がヨーロッパの反ユダヤ主義に関するより広範な比較研究を行うことを著しく妨げ、それには彼の分析をさらに洗練させる必要があったと主張した。 ゴールドハーゲンは、論文「動機、原因、そしてアリバイ:批判者たちへの反論」で、批判者たちに反論した。 私の著書を批判した人々の中には、ドイツでは多くの人々が公然と反応しているが、彼らの書いたことや発言の多くは、この本の内容とほとんど関係がないか、 明らかな誤りである。明白な誤りには、本書には目新しいものはほとんどない、ホロコーストを単一の原因と決定論的な説明で説明し、ドイツの歴史の必然的な 帰結であるとしている、本書の論点は歴史的ではない、本書はドイツ人について「本質論的」、「人種差別的」、あるいは民族的な主張をしている、などがあ る。これらはすべて事実ではない。[75] ルース・ベッティーナ・バーンとフォルカー・リースは、ゴールドハゲンが引用した一次資料(警察大隊の調査記録)を検証し、ゴールドハゲンが研究に歴史的 アプローチを適用したかどうかを判断する必要性を認識していた。彼らの任務は、「ゴールドハゲンの著書には参考文献も、記録資料の一覧も記載されていな い」という事実によって複雑化していた。[76] 彼らの結論は、ゴールドハゲンによる記録の分析は 厳格な方法論的アプローチを一切踏襲していないように見える。これが問題なのだ。彼は、証言の一部を恣意的に選択し、それを自身の視点で再解釈したり、文 脈を無視して自身の解釈の枠組みに当てはめたりすることを好む。... ゴールドハーゲンが証拠を扱う方法を用いれば、ゴールドハーゲンの主張の正反対を証明するのに十分なルートヴィヒスブルクの資料からの引用を簡単に発見で きるだろう。... ゴールドハーゲンの著書は一次資料であれ二次資料であれ、資料に導かれているわけではない。彼は、使用する証言をそれ自体で語らせることはしない。彼は、 あらかじめ考えた理論を裏付けるものとして資料を使用しているのだ。[77] 歴史家のリチャード・J・エヴァンズはゴールドハーゲンの著作を厳しく批判し、次のように述べた。... この本は、中世以来、事実上すべてのドイツ人が殺人鬼的な反ユダヤ主義者であり、ヒトラーが政権を握る何十年も前からユダヤ人の絶滅を熱望し、絶滅が始ま ると積極的にその参加を楽しんだと、粗野で独断的な論調で主張している。この本は、このテーマに関する膨大な歴史文献をまったく知らずに書かれたものであ り、文書解釈においても初歩的な誤りが数多くあることが明らかになっている。[78] 人種差別主義者という非難 デビッド・ノース(David North)を含む複数の批評家は、ゴールドハーゲンの著作がナチスのアイデンティティ概念を採用し、ドイツ人を中傷するためにそれを利用していると評し ている。ブラウニングがその単行本を捧げたヒルバーグは、「ゴールドハーゲンは、中世の悪夢のような、ドイツ人の心に潜む悪魔のイメージを我々に残し た。... 攻撃する機会を狙っている」と書いた。[80] デビッド・アーヴィングの名誉棄損訴訟に関する著書『ホロコーストを裁く』の著者であるアメリカのコラムニスト、D.D.グットンプランもまた、 ヒルバーグに献辞を捧げたコラムニストのD.D.グットンプランは、ゴールドハゲンの主張する「絶滅文化」と、マイヤー・カーハネの主張する「アラブ文 化」との唯一の違いは、ゴールドハゲンの標的がドイツ人であるのに対し、カーハネの標的はアラブ人であるという点であると書いた。[80] グットンプランは、第二次世界大戦中にドイツ軍の捕虜となったソ連軍兵士300万人の死を、ゴールドハゲンがホロコーストの「 事実誤認であると主張し、1941年8月にアウシュビッツで初めてガス室に送られたのはソ連軍捕虜であったと述べた。[81] アメリカの歴史家アルノ・J・メイヤーが1988年に著した『天はなぜ暗くならなかったのか』で提示された、ユダヤ人とソ連人がホロコーストの同等の犠牲 者であるという論文に影響を受けたグットンプランは、 グットゲンは、ナチスの「ユダヤ・ボルシェビズム」理論は、ゴールドハーゲンによる「排除的反ユダヤ主義」文化に関するホロコーストの説明よりも、より複 雑な説明であると主張した。 ゴールドハーゲンは、自著にはドイツ人に関する人種差別的あるいは民族的な議論は一切ないとしている。彼の批判者の一部は、彼の論文は「本質的に人種差別 的でも、あるいはその他の点で非合法でもない」という彼の意見に同意している。これにはルース・ベッティーナ・バームやノーマン・フィンケルシュタイン (『裁判にかけられた国民』)などが含まれる。[82] 一般的な反応 『ヒトラーの自発的執行者たち』の英語版が1996年3月に出版されると、ドイツでは多くの論評が巻き起こった。1996年4月、ドイツ語訳が出版される 前に、『シュピーゲル』誌は「悪魔の国民?」というタイトルで『ヒトラーの自発的処刑者たち』に関する記事を一面に掲載した。[83] 「悪魔の国民」という表現(「悪魔のような国民」と訳される)は、ナチスがユダヤ人を表現する際に頻繁に使用していたものであり、 、表紙記事のタイトルは、ルドルフ・アウグストと『シュピーゲル』誌の編集者たちが、ナチスによるユダヤ人観とゴールドハゲンによるドイツ人観の間に道徳 的な同等性があることを示唆する意図で付けたものである。[83] 最も広く読まれているドイツの週刊新聞『ディー・ツァイト』は、1996年8月のドイツでの出版に先立ち、この本の意見を8回にわたって連載した。ゴール ドハーゲンは1996年9月にドイツに到着し、本の宣伝ツアーを行い、いくつかのテレビのトークショーや、完売となったパネルディスカッションに多数出演 した。 この本は歴史家たちの間では「概ね酷評」されたが、歴史家たちはこの本を歴史に即していないと強く非難した。「なぜこの本は、事実内容や論理的厳密さに欠 けているにもかかわらず、これほど注目を集めるのか?」 ラウル・ヒルバーグは疑問を呈した。[89] 著名なユダヤ系アメリカ人歴史家のフリッツ・スターンは、この本を学術的ではなく、人種差別的なドイツ嫌いに満ちたものとして非難した。[86] ヒルバーグは論争を次のように要約した。「1996年末までに、一般読者とは対照的に、学術界の多くはゴールドハーゲンを地図から消し去ったことは明らか だった。」[90] スティーブ・クロウショーは、ドイツの読者はゴールドハーゲンの著書における「専門家の欠陥」を鋭く認識していたものの、 [T] これらの認識された専門家の欠陥はほとんど無関係であることが証明されたと書いている。むしろ、ゴールドハーゲンはドイツ人が過去と向き合う準備ができて いることを示す先導者となった。この文脈において、彼の研究の正確性は二次的な重要性であった。否定しようのない、詳細に記録された)事実として、一般ド イツ人がホロコーストに加担していたことを認めたいと願う何百万人ものドイツ人が、彼の著作を歓迎した。ドイツ人が生まれながらの殺人者であるという彼の 主張は、受け入れがたいものの、その一部として受け入れられた。ゴールドハーゲンの著書は、ドイツが過去と向き合うことを確実にするための手段として扱わ れた。 クロウショーはさらに、この本の批判者の一部は、ゴールドハーゲンの「方法論上の欠陥」に「うんざり」した歴史家であったが、ナチス・ドイツの犯罪に対す る責任を一般ドイツ人が負うことを認めたくない人々もいたと主張している。[2] ドイツでは、左派の一般市民が さらに悔い改めるべきだという主張が優勢であったと、ほとんどの観察者は述べている。[67] アメリカの歴史学者ゴードン・A・クレイグや『シュピーゲル』誌は、この本の欠点が何であれ、ホロコーストに関する議論を再び活気づけ、新たな研究を刺激 するものであるため、歓迎されるべきだと主張している。[86]:287 ジャーナリズム 1996年5月、ゴールドハーゲンは、アメリカのジャーナリスト、ロン・ローゼンバウムのインタビューを受け、ヒトラーの快楽殺人者たちについて語った。 ローゼンバウムが、オーストリアの反ユダヤ主義はドイツの反ユダヤ主義よりもはるかに悪質で暴力的であったとする学術文献についてゴールドハーゲンに尋 ね、また、ヒトラーがオーストリア人であったことが彼の論文に影響を与えたかどうかを尋ねたところ、ゴールドハーゲンは次のように答えた。 ドイツ国内でも反ユダヤ主義には地域的な違いがあった。しかし、ヒトラーは19世紀後半に台頭した、特定の排除主義的ユダヤ人排斥主義を体現し、それを神 格化した。どのような違いがあったにせよ、ユダヤ人に対する中心的なモデルと、彼らを排除する必要性という見解があったという点で、オーストリアとドイツ の反ユダヤ主義は一体のものとして捉えることができると思う。 ローゼンバウムは、ホロコーストはヒトラーが存在しなくても起こったであろう不可避的なものだったというゴールドハーゲンの「殺意を孕む」という比喩表現 について尋ねた。また、ミルトン・ヒムラーファブの有名な「ヒトラーがいなければホロコーストもなかった」という定式化についても尋ねた。[92] ローゼンバウムは「では、あなたはヒムラーファブの主張に同意するのですか?」と尋ねた。[92] ゴールドハーゲンは次のように答えた。「もしナチスが政権を握っていなければ、ヒトラーは存在しなかったでしょう。もしドイツに大恐慌が起こっていなけれ ば、おそらくナチスは政権を握ることはなかったでしょう。反ユダヤ主義は、殺戮の形態という意味では潜在的なものにとどまっていたでしょう。国家が必要 だったのだ」[92] ローゼンバウムはゴールドハーゲンに、リチャード・レヴィが1975年に著した『帝政ドイツにおける反ユダヤ主義政党の衰退』について尋ねた。この本は、 20世紀初頭の民族主義政党の衰退を、1912年の帝国議会選挙でほぼ全滅するまでたどったものである。ゴールドハーゲンは、反ユダヤ主義的な民族主義政 党に投票したか否かは、反ユダヤ感情とは何の関係もないと反論し、民族主義政党に投票しなくても、人々はユダヤ人を憎むことは可能であると主張した。 [93] 2006年、米国在住のユダヤ人保守派コラムニスト、ジョナ・ゴールドバーグは、「ゴールドハーゲンの主張は誇張されているが、基本的には正確である。ド イツには、そのファシズムをジェノサイドへと駆り立てた独特の何かがあった。世界を見渡せば、自らをファシストと称する運動は数十存在する(さらに多くの 運動が異なる名称で呼ばれている)。そして、そのうちナチス式のジェノサイドを採用したものはほとんどない。実際、ファシストのスペインはホロコーストの 時代にユダヤ人の避難場所であった」と彼は述べた。[94] ゴールドバーグはさらに、ゴールドハーゲンが「根絶的アンチセミティズム」がドイツに特有のものであると信じているのは誤りであると述べ、ゴールドバーグ は「根絶的アンチセミティズム」は19世紀から20世紀のドイツ文化と同様に、現代のパレスチナ文化の特徴であると主張し、 世紀のドイツ文化の特徴であり、本質的には現在のハマスもナチス同様に大量虐殺を行っていると主張した。[94] 2011年、アメリカのコラムニスト、ジェフリー・ゴールドバーグは、ヒトラーの『進んで処刑する者たち』を明らかに参照しながら、イラン・イスラム共和 国の指導者たちは全員「根絶主義的反ユダヤ主義者」であると書いた。[95 。別の観点から、アメリカの政治学者ノーマン・フィンケルシュタインは、この著書はユダヤ人の絶滅に永遠に献身する異教徒の世界のイメージを宣伝し、それ によってイスラエルの存在を正当化しようとするシオニストのプロパガンダであり、したがってゴールドハゲンの著書は、ヨーロッパの歴史よりもむしろ中東の 政治に関心があり、フィンケルシュタインが主張するイスラエルの ヨーロッパの歴史よりも、イスラエルの人権記録の悪さを正当化することに重点を置いていた。[96] また、アメリカ人ジャーナリストのマックス・フランケルは、『裁かれる国民』の書評の中で、フィンケルシュタインの反シオニストの政治的立場が「ゴールド ハゲン説からあまりにもかけ離れたものになってしまったため、ルース・ベッティーナ・バーンによる批判にたどり着いてほっとした」と書いている。[97] |

| Collective guilt Sonderweg |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hitler%27s_Willing_Executioners |

|

| A Moral Reckoning: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Holocaust and Its Unfulfilled Duty of Repair A Moral Reckoning: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Holocaust and Its Unfulfilled Duty of Repair is a 2003 book by the political scientist Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, previously the author of Hitler's Willing Executioners (1996). Goldhagen examines the Roman Catholic Church's role in the Holocaust and offers a review of scholarship in English addressing what he argues is antisemitism throughout the history of the Church, which he claims contributed substantially to the persecution of the Jews during World War II. Goldhagen recommends several significant steps that might be taken by the Church to make reparation for its alleged role. A Moral Reckoning received mixed reviews and was the subject of considerable controversy regarding allegations of inaccuracies and anti-Catholic bigotry.[1][2] |