デジタル・デバイド

Digital divide

デジタル・デバイドの英語(えいご)はつぎのように書きます

デジタル = digital

デバイド = divide

デジタル・デバイト、とはデジタル化され た情報が生みだす社会的——とくに経済的——不平等(デバイドには隔離や分別という意味もありま す)のこと。

"A digital divide is any uneven distribution in the access to, use of, or impact of information and communications technologies (ICT) between any number of distinct groups, which can be defined based on social, geographical, or geopolitical criteria, or otherwise.[U.S. Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) 1995] The term digital divide was first coined by Lloyd Morrisett, when he was president of the Markle Foundation (Hoffman, et al., 2001). Traditionally considered to be a question of having or not having access, with a global mobile phone penetration of over 95%[2000-2003] it is becoming a relative inequality between those who have more and less bandwidth[4] and more or fewer skills."- Digital divide.

「情報格差(じょうほうかくさ)またはデジタル・ディバイド

(英: digital divide)とは、インターネット等の情報通信技術

(ICT)を利用できる者と利用できない者との間にもたらされる格差の

こと[1]。国内の都市と地方などの地域間の格差を指す地域間デジタル・ディバイド[1]、身体的・社会的条件から情報通信技術(ICT)

を使いこなせる者と使いこなせない者の間に生じる格差を指す個人間・集団間デジタル・ディバイド[1]、インターネット等の利用可能性から国際間に生じる

国際間デジタル・ディバイド[1]がある。特に情報技術を使えていない、あるいは取り入れられる情報量が少ない人々または放送・通信のサービスを(都市部

と同水準で)受けられない地域・集団を指して情報弱者と呼ぶ場合もある」情報格差)

この概念の歴史的経緯である。アメリカ合 衆国商務省(U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE)が1995年に報告書を書いて、情報ハイウエー構想を打ち出し、かつ推進していた合衆国の情報化戦略のネガティブな面をさらけだしたも のである。もっとも、プラグマティスト的伝統の中で、そのような情報化の差異が収入の差異に反映する事実を明らかにし、よりよい情報化を引き続き推進すべ きであるという彼/彼女らの趣旨に大きな変更はない。(→関連リンク)

■ デジタル・デバイド問題(オリジナル 文献)

デジタル・デバイド問題を取り上げると、 もともと金持ちだからコンピュータをもちインターネットにアクセスできる、貧乏人はそうではない、 という「経済的格差が、入手したり、操作できる情報の格差につながる」経済階層による情報格差の反映論を思いつくが、その言わんとしているところはそうで はない。いち早く情報を入手し、操作できる能力が、経済的成功のチャンス生み、それがまた情報収集に投下する経済資本を増やし、それがまた利潤の向上に結 びつく、ということを問題にしているというのがユニークな指摘なのだ。

まあ、このような情報錬金術が本当なら事態は深刻ではある。しかし、実態とし ては、現代の情報化社会にそのような傾向はあるものの、それが一義的に決定要因を形成しているというものでもないらしい。

ただし、大学生・大学院生の就職戦線につ いて多少なりとも指導したことのある教師なら、企業のウェブサイトにアクセスして、エントリーシー トを書いたり、面接の予約をとることは当たり前、また、企業から送られてくるメールにいち早く返事を書くこと(もちろんメールにおける応答の適切さが チェックされる)によって内定が左右されるということぐらいは、常識になりつつある。もし、そんなチャンスを活かした学生が、就職後も高い職位についた り、もっとよい職場にハントされ、収入が増加する傾向が本当なら(それ以外の集団の収入に有意な差があるとすれば)この問題は、かなり深刻なものになろ う。

デジタル・デバイト問題は、情報のグロー バル化にともなう普遍的かつ一般的な側面と、その社会の情報化の進展パターンに応じて特有な変化を とげる側面があるようだ。

☆

| The digital divide

refers to unequal access to and effective use of digital technology,

encompassing four interrelated dimensions: motivational, material,

skills, and usage access.[1] The digital divide worsens inequality

around access to information and resources. In the Information Age,

people without access to the Internet and other technology are at a

disadvantage, for they are unable or less able to connect with others,

find and apply for jobs, shop, and learn.[2][3][4][5] People living in poverty, in insecure housing or homeless, elderly people, and those living in rural communities may have limited access to the Internet; in contrast, urban middle class people have easy access to the Internet. Another divide is between producers and consumers of Internet content,[6][7] which could be a result of educational disparities.[8] While social media use varies across age groups, a US 2010 study reported no racial divide.[9] |

デジタルデバイドとは、デジタル技術へのアクセスと効果的な利用におけ

る不平等を指し、相互に関連する四つの側面を含む:動機付け、物質的要因、スキル、利用機会である。[1]

デジタルデバイドは、情報や資源へのアクセスにおける不平等を悪化させる。情報化時代において、インターネットやその他の技術を利用できない人々はおろ

か、不利な立場にある。なぜなら、他者と繋がったり、仕事を探して応募したり、買い物や学習を行ったりすることができない、あるいは困難だからだ。[2]

[3][4][5] 貧困層、不安定な住居環境やホームレス状態にある人々、高齢者、農村地域住民はインターネットへのアクセスが制限される可能性がある。対照的に、都市部の 中産階級は容易にインターネットを利用できる。別の格差はインターネットコンテンツの生産者と消費者の間にある[6][7]。これは教育格差の結果である 可能性がある[8]。ソーシャルメディアの利用は年齢層によって異なるが、2010年の米国調査では人種間の格差は報告されていない[9]。 |

| History The historical roots of the digital divide in America refer to the increasing gap that occurred during the early modern period between those who could and could not access the real time forms of calculation, decision-making, and visualization offered via written and printed media.[10] "Over time, focus has shifted from binary access to differentiated use, where quality and purpose of engagement vary across socio-economic groups."[11] Within this context, ethical discussions regarding the relationship between education and the free distribution of information were raised by thinkers such as Immanuel Kant, Jean Jacques Rousseau, and Mary Wollstonecraft (1712–1778). The latter advocated that governments should intervene to ensure that any society's economic benefits should be fairly and meaningfully distributed. Amid the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain, Rousseau's idea helped to justify poor laws that created a safety net for those who were harmed by new forms of production. Later when telegraph and postal systems evolved, many used Rousseau's ideas to argue for full access to those services, even if it meant subsidizing hard-to-serve citizens. Thus, "universal services"[12] referred to innovations in regulation and taxation that would allow phone services such as AT&T in the United States to serve hard-to-serve rural users. In 1996, as telecommunications companies merged with Internet companies, the Federal Communications Commission adopted Telecommunications Services Act of 1996 to consider regulatory strategies and taxation policies to close the digital divide. Though the term "digital divide" was coined among consumer groups that sought to tax and regulate information and communications technology (ICeT) companies to close the digital divide, the topic soon moved onto a global stage. The focus was the World Trade Organization which passed a Telecommunications Services Act, which resisted regulation of ICT companies so that they would be required to serve hard to serve individuals and communities. In 1999, to assuage anti-globalization forces, the WTO hosted the "Financial Solutions to Digital Divide" in Seattle, US, co-organized by Craig Warren Smith of Digital Divide Institute and Bill Gates Sr. the chairman of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It catalyzed a full-scale global movement to close the digital divide, which quickly spread to all sectors of the global economy.[13] In 2000, US president Bill Clinton mentioned the term in the State of the Union Address. |

歴史 アメリカにおけるデジタルデバイドの歴史的根源は、近代初期に生じた格差を指す。すなわち、書物や印刷媒体を通じて提供されるリアルタイムの計算・意思決 定・視覚化手段にアクセスできる者とできない者との間の隔たりである。[10] 「時が経つにつれ、焦点は二元的なアクセスから差別化された利用へと移行した。つまり、関与の質と目的が社会経済的グループによって異なる状態である。」 この文脈において、教育と情報の自由な流通の関係に関する倫理的議論が、イマヌエル・カント、ジャン=ジャック・ルソー、メアリー・ウルストンクラフト (1712–1778)といった思想家たちによって提起された。後者は、あらゆる社会の経済的利益が公平かつ有意義に分配されるよう、政府が介入すべきだ と主張した。英国産業革命期において、ルソーの思想は新たな生産形態の被害者に対する安全網となる救貧法を正当化する一助となった。その後、電信や郵便シ ステムが発展すると、多くの者がルソーの思想を引用し、サービス提供が困難な市民への補助を伴う場合でも、これらのサービスへの完全なアクセスを主張し た。こうして「ユニバーサルサービス」[12]とは、米国におけるAT&Tのような電話サービスが、サービス提供が困難な地方のユーザーにサービ スを提供できるようにする規制と課税の革新を指すようになった。1996年、通信企業とインターネット企業の合併が進む中、連邦通信委員会はデジタル格差 解消に向けた規制戦略と課税政策を検討するため「1996年電気通信サービス法」を採択した。「デジタル格差」という用語は、情報通信技術(ICT)企業 への課税と規制を通じて格差解消を目指す消費者団体によって提唱されたが、この問題はすぐに国際的な舞台へと移った。焦点となったのは世界貿易機関 (WTO)であり、同機関は「電気通信サービス法」を可決した。この法律はICT企業への規制に抵抗し、サービス提供が困難な個人やコミュニティへのサー ビス提供を義務付けることを拒否した。1999年、反グローバリゼーション勢力を鎮めるため、WTOは米国シアトルで「デジタルデバイドの金融的解決策」 会議を主催した。この会議はデジタルデバイド研究所のクレイグ・ウォーレン・スミスとビル&メリンダ・ゲイツ財団会長のビル・ゲイツ・シニアが共同で企画 したものである。この会議はデジタルデバイド解消に向けた本格的な世界的な運動の触媒となり、瞬く間に世界経済のあらゆる分野に広がった[13]。 2000年には、米国のビル・クリントン大統領が一般教書演説でこの用語に言及した。 |

| During the COVID-19 pandemic At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments worldwide issued stay-at-home orders that established lockdowns, quarantines, restrictions, and closures. The resulting interruptions to schooling, public services, and business operations drove nearly half of the world's population into seeking alternative methods to live while in isolation.[14] These methods included telemedicine, virtual classrooms, online shopping, technology-based social interactions and working remotely, all of which require access to high-speed or broadband internet access and digital technologies. A Pew Research Centre study reports that 90% of Americans describe the use of the Internet as "essential" during the pandemic.[15] The accelerated use of digital technologies creates a landscape where the ability, or lack thereof, to access digital spaces becomes a crucial factor in everyday life.[16] According to the Pew Research Center, 59% of children from lower-income families were likely to face digital obstacles in completing school assignments.[15] These obstacles included the use of a cellphone to complete homework, having to use public Wi-Fi because of unreliable internet service in the home and lack of access to a computer in the home. This difficulty, titled the homework gap, affects more than 30% of K-12 students living below the poverty threshold, and disproportionally affects American Indian/Alaska Native, Black, and Hispanic students.[17][18] These types of interruptions or privilege gaps in education exemplify problems in the systemic marginalization of historically oppressed individuals in primary education. The pandemic exposed inequity causing discrepancies in learning.[19] "Large-scale events such as COVID-19 intensify both access and skills gaps, underlining the need for resilient digital inclusion policies.[20] Studies during COVID-19 reveal first-level (access) and second-level (skills) divides, with underserved students struggling with reliable internet, devices, and platform navigation [21]” A lack of "tech readiness", that is, confident and independent use of devices, was reported among the US elderly population; with more than 50% reporting an inadequate knowledge of devices and more than one-third reporting a lack of confidence.[15][22] "Older adults often face skills and confidence barriers, illustrating later-stage divides in van Dijk’s model."[23] Moreover, according to a UN research paper, similar results can be found across various Asian countries, with those above the age of 74 reporting a lower and more confused usage of digital devices.[24] This aspect of the digital divide and the elderly occurred during the pandemic as healthcare providers increasingly relied upon telemedicine to manage chronic and acute health conditions.[25] |

COVID-19パンデミックの間 COVID-19パンデミックの初期段階において、世界各国の政府は外出禁止令を発令し、ロックダウン、隔離、制限、閉鎖を実施した。その結果、学校教 育、公共サービス、事業運営が中断され、世界人口のほぼ半数が隔離生活を送るための代替手段を模索せざるを得なくなった。[14] これらの手段には、遠隔医療、仮想教室、オンラインショッピング、技術に基づく社会的交流、リモートワークが含まれ、いずれも高速またはブロードバンドイ ンターネットへのアクセスとデジタル技術が必要である。ピュー・リサーチ・センターの調査によれば、アメリカ人の90%がパンデミック期間中のインター ネット利用を「不可欠」と表現している。[15] デジタル技術の急速な普及は、デジタル空間へのアクセス能力の有無が日常生活における決定的要因となる状況を生み出した。[16] ピュー・リサーチ・センターによれば、低所得世帯の子どもの59%が、学校の課題を完了する際にデジタル上の障壁に直面する可能性が高いとされている。 [15] これらの障壁には、宿題を完了するために携帯電話を使用すること、自宅のインターネットサービスが不安定なため公共Wi-Fiを利用せざるを得ないこと、 自宅にコンピューターがないことなどが含まれる。この「宿題格差」と呼ばれる問題は、貧困線以下の生活を送る小中高生の30%以上に影響を及ぼし、特にア メリカインドの・アラスカインドの、黒人、ヒスパニック系の生徒に不均衡な影響を与えている[17][18]。こうした教育における中断や特権格差は、初 等教育において歴史的に抑圧されてきた人々が体系的に周縁化される問題の典型例だ。パンデミックは学習格差を生む不平等を露呈した[19]。「COVID -19のような大規模事象はアクセス格差とスキル格差を深刻化させ、強靭なデジタル包摂政策の必要性を浮き彫りにする[20]。COVID-19期間中の 研究は、第一段階(アクセス)と第二段階(スキル)の分断を明らかにしており、支援不足の生徒は信頼性の高いインターネット、端末、プラットフォーム操作 に苦戦している[21]」 米国の高齢者層では「技術的準備不足」、すなわちデバイスを自信を持って自立的に使用できない状態が報告されている。50%以上がデバイス知識の不足を、 3分の1以上が自信の欠如を認めている[15][22]。「高齢者はしばしばスキルと自信の障壁に直面し、ヴァン・ダイクモデルの後半段階における分断を 実証している」 [23] さらに国連研究論文によれば、同様の結果はアジア諸国でも確認され、74歳以上の層ではデジタル機器の使用頻度が低く、操作に混乱が見られた[24]。こ のデジタル格差と高齢者の問題はパンデミック下で顕在化した。医療提供者が慢性・急性疾患の管理に遠隔医療を依存する度合いが高まったためである [25]。 |

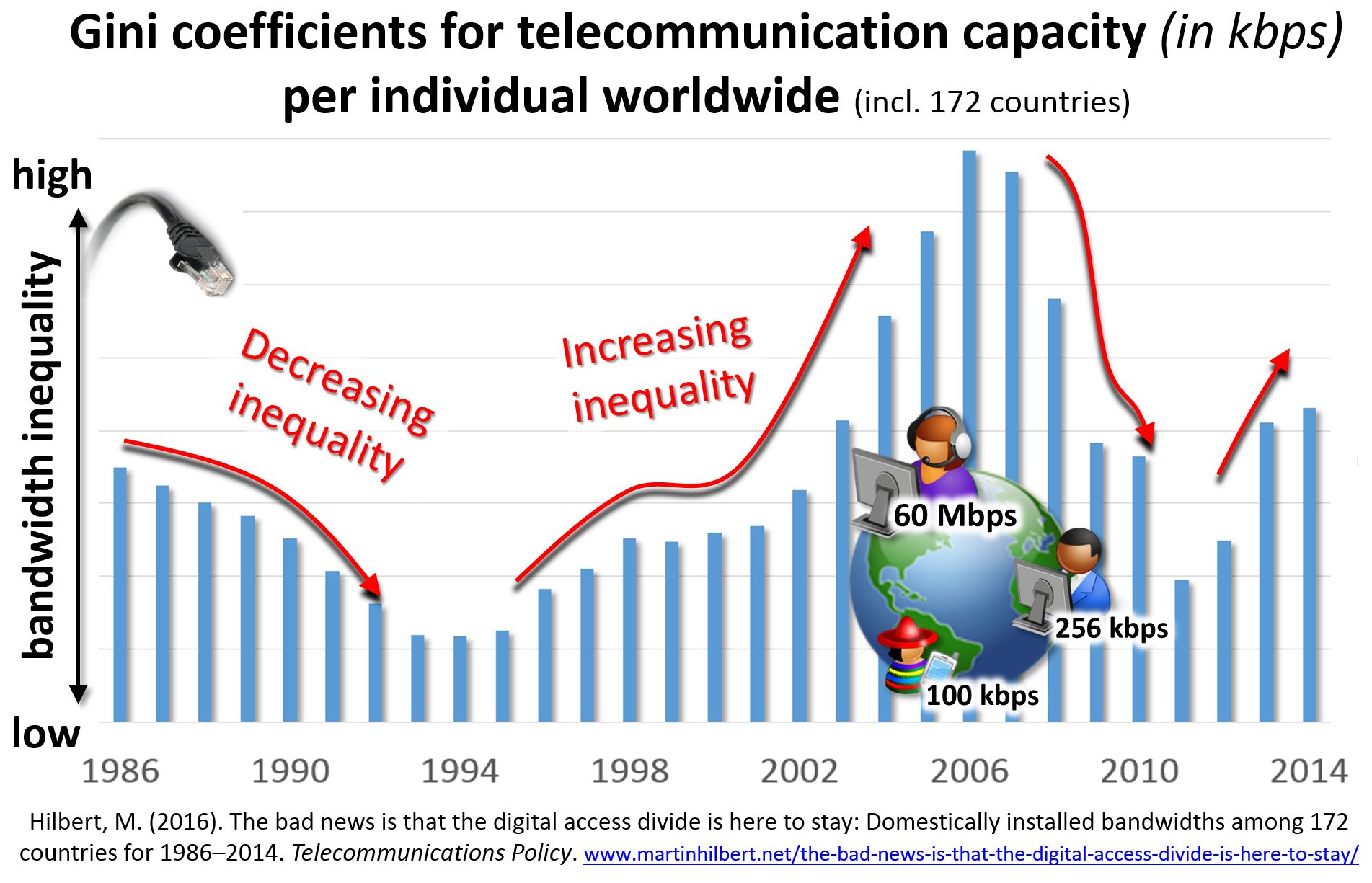

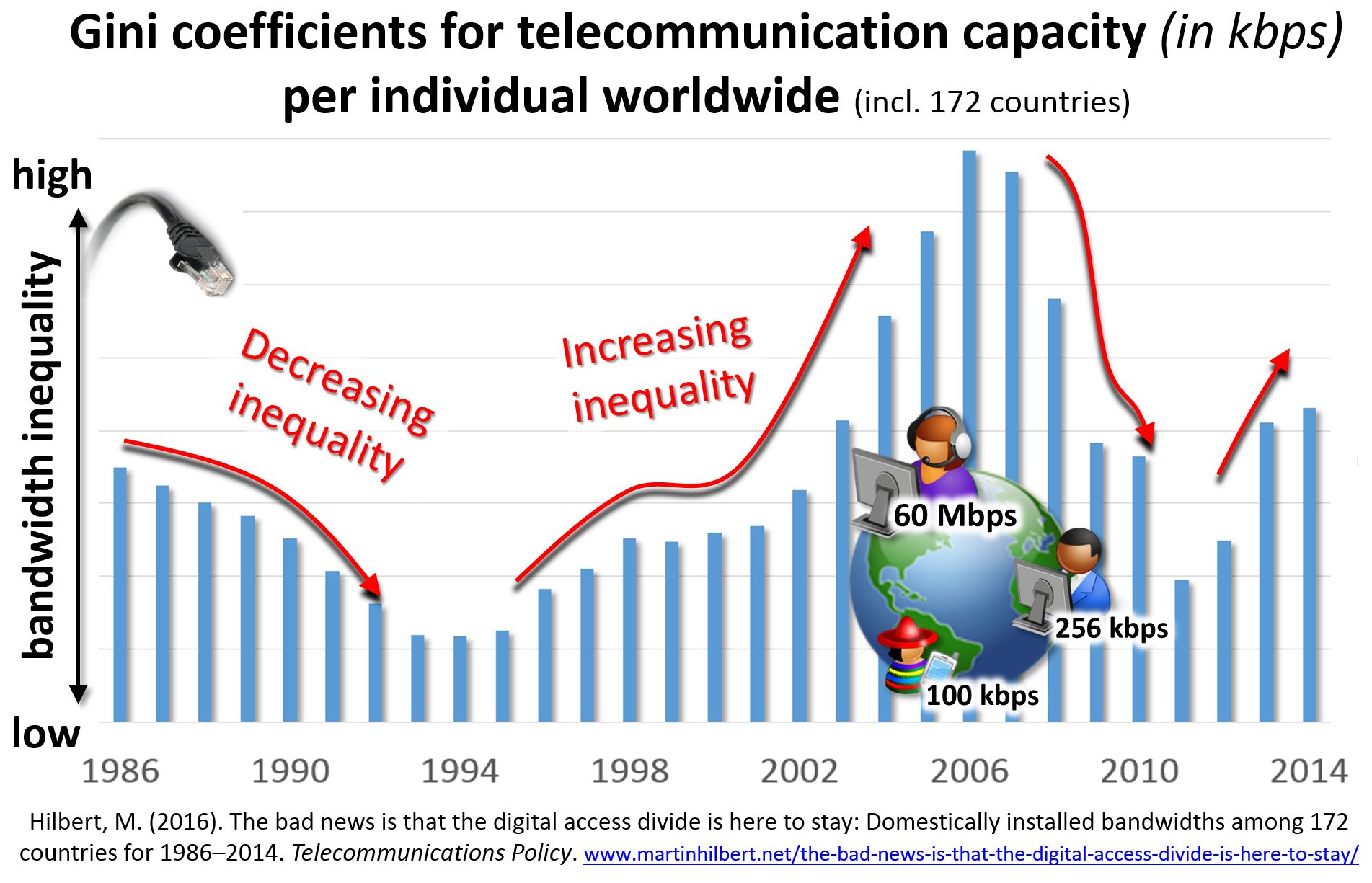

| Aspects There are various definitions of the digital divide, all with slightly different emphasis, which is evidenced by related concepts like digital inclusion,[26] digital participation,[27] digital skills,[28] media literacy,[29] and digital accessibility.[30]“Van Dijk’s model identifies sequential barriers—motivational, material, skills, and usage—that must be addressed to bridge the divide.”[23] Infrastructure The infrastructure by which individuals, households, businesses, and communities connect to the Internet address the physical mediums that people use to connect to the Internet such as desktop computers, laptops, basic mobile phones or smartphones, iPods or other MP3 players, gaming consoles such as Xbox or PlayStation, electronic book readers, and tablets such as iPads.[31]  The digital divide measured in terms of bandwidth is not closing, but fluctuating up and down. Gini coefficients for telecommunication capacity (in kbit/s) among individuals worldwide[32] Traditionally, the nature of the divide has been measured in terms of the existing numbers of subscriptions and digital devices. Given the increasing number of such devices, some have concluded that the digital divide among individuals has increasingly been closing as the result of a natural and almost automatic process.[33][34] Others point to persistent lower levels of connectivity among women, racial and ethnic minorities, people with lower incomes, rural residents, and less educated people as evidence that addressing inequalities in access to and use of the medium will require much more than the passing of time.[35][36] Recent studies have measured the digital divide not in terms of technological devices, but in terms of the existing bandwidth per individual (in kbit/s per capita).:[37][32] “Contemporary measures also assess affordability, network reliability, and quality of service as critical indicators of the divide [38]” As shown in the Figure on the side, the digital divide in kbit/s is not monotonically decreasing but re-opens up with each new innovation. For example, "the massive diffusion of narrow-band Internet and mobile phones during the late 1990s" increased digital inequality, as well as "the initial introduction of broadband DSL and cable modems during 2003–2004 increased levels of inequality".[37] During the mid-2000s, communication capacity was more unequally distributed than during the late 1980s, when only fixed-line phones existed. The most recent increase in digital equality stems from the massive diffusion of the latest digital innovations (i.e. fixed and mobile broadband infrastructures, e.g. 5G and fiber optics FTTH).[39] Measurement methodologies of the digital divide, and more specifically an Integrated Iterative Approach General Framework (Integrated Contextual Iterative Approach – ICI) and the digital divide modeling theory under measurement model DDG (Digital Divide Gap) are used to analyze the gap existing between developed and developing countries, and the gap among the 27 members-states of the European Union.[40][41] The Good Things Foundation, a UK non-profit organisation, collates data on the extent and impact of the digital divide in the UK[42] and lobbies the government to fix digital exclusion[43] |

側面 デジタルデバイドには様々な定義があり、それぞれに若干の重点の違いがある。これはデジタルインクルージョン[26]、デジタル参加[27]、デジタルス キル[28]、メディアリテラシー[29]、デジタルアクセシビリティ[30]といった関連概念からも明らかだ。「ヴァン・ダイクのモデルは、デバイドを 埋めるために克服すべき段階的な障壁——動機付け、物質的要因、スキル、利用——を特定している」[23]。 インフラ 個人、世帯、企業、コミュニティがインターネットに接続するためのインフラとは、デスクトップコンピュータ、ノートパソコン、基本機能の携帯電話やスマー トフォン、iPodやその他のMP3プレイヤー、XboxやPlayStationなどのゲーム機、電子書籍リーダー、iPadなどのタブレット端末な ど、人民がインターネット接続に使用する物理的な媒体を指す。[31]  帯域幅で測られるデジタルデバイドは縮小しておらず、上下に変動している。世界各国の個人間における通信容量(kbit/s)のジニ係数[32] 従来、この格差の性質は既存の契約数やデジタル機器の数で測られてきた。こうした機器の増加を踏まえ、個人の間のデジタル格差は自然かつほぼ自動的な過程 の結果として縮小しつつあると結論づける者もいる[33][34]。一方で、女性、人種的・民族的マイノリティ、低所得の人民、農村の人民、教育水準の低 い人民における接続性の持続的な低さを指摘し、メディアへのアクセスと利用における不平等に対処するには時間の経過だけでは不十分だと主張する者もいる。 [35][36] 最近の研究では、デジタルデバイドを技術的デバイスではなく、個人当たりの既存帯域幅(kbit/s/人)で測定している。[37][32] 「現代的な測定法では、手頃な価格、ネットワークの信頼性、サービス品質もデバイドの重要な指標として評価される[38]」 図が示す通り、kbit/s単位のデジタル格差は単調に縮小せず、新たな技術革新ごとに拡大を繰り返す。例えば「1990年代後半の狭帯域インターネット と携帯電話の普及」がデジタル格差を拡大させたのと同様に、「2003~2004年のブロードバンドDSL・ケーブルモデム導入初期段階でも格差は拡大し た」。[37] 2000年代半ばには、固定電話のみが存在した1980年代後半よりも通信容量の不平等な分配が顕著だった。デジタル平等性の最近の向上は、最新のデジタ ル技術革新(固定・移動体ブロードバンド基盤、例えば5Gや光ファイバーFTTHなど)の大規模普及に起因する。[39] デジタルデバイドの測定手法、具体的には統合反復アプローチ総合枠組み(Integrated Contextual Iterative Approach – ICI)と測定モデルDDG(Digital Divide Gap)に基づくデジタルデバイドモデリング理論を用いて、先進国と発展途上国の間、および欧州連合27加盟国間の格差を分析している。[40][41] 英国の非営利団体グッドシングス財団は、英国におけるデジタルデバイドの規模と影響に関するデータを収集している[42]。また政府に対し、デジタル排除 の解消を働きかけている[43]。 |

| Skills and digital literacy Research from 2001 showed that the digital divide is more than just an access issue and cannot be alleviated merely by providing the necessary equipment. There are at least three factors at play: information accessibility, information utilization, and information receptiveness. More than just accessibility, the digital divide consists of society's lack of knowledge on how to make use of the information and communication tools once they exist within a community.[44] Information professionals have the ability to help bridge the gap by providing reference and information services to help individuals learn and utilize the technologies to which they do have access, regardless of the economic status of the individual seeking help.[45] Location One can connect to the internet in a variety of locations, such as homes, offices, schools, libraries, public spaces, and Internet cafes. Levels of connectivity often vary between rural, suburban, and urban areas.[46][47] In 2017, the Wireless Broadband Alliance published the white paper The Urban Unconnected, which highlighted that in the eight countries with the world's highest GNP about 1.75 billion people had no internet connection, and one third of them lived in the major urban centers. Delhi (5.3 millions, 9% of the total population), São Paulo (4.3 millions, 36%), New York (1.6 mln, 19%), and Moscow (2.1 mln, 17%) registered the highest percentages of citizens who had no internet access of any type.[48] “As of 2023, 67% of the global population uses the Internet, leaving 2.6 billion people offline, primarily in least developed countries and rural areas. ”[38] Also, the governments of different countries have different policies about privacy, data governance, speech freedoms and many other factors. Government restrictions make it challenging for technology companies to provide services in certain countries. This disproportionately impacts the different regions of the world; Europe has the highest percentage of the population online while Africa has the lowest. From 2010 to 2014 Europe went from 67% to 75% and in the same time span Africa went from 10% to 19%.[49]“Internet penetration in 2023 ranges from 89% in Europe to 37% in Africa, highlighting persistent global disparities .”[38] Network speeds play a large role in the quality of an internet connection. Large cities and towns may have better access to high speed internet than rural areas, which may have limited or no service.[50] Households can be locked into a specific service provider, since it may be the only carrier that even offers service to the area. This applies to regions that have developed networks, like the United States, but also applies to developing countries, so that very large areas have virtually no coverage.[51] In those areas there are very limited actions that a consumer could take, since the issue is mainly infrastructure. Technologies that provide an internet connection through satellite are becoming more common, like Starlink, but they are still not available in many regions.[52] Based on location, a connection may be so slow as to be virtually unusable, solely because a network provider has limited infrastructure in the area. For example, to download 5 GB of data in Taiwan it might take about 8 minutes, while the same download might take 30 hours in Yemen.[53] From 2020 to 2022, average download speeds in the EU climbed from 70 Mbps to more than 120 Mbps, owing mostly to the demand for digital services during the pandemic.[54] There is still a large rural-urban disparity in internet speeds, with metropolitan areas in France and Denmark reaching rates of more than 150 Mbps, while many rural areas in Greece, Croatia, and Cyprus have speeds of less than 60 Mbps.[54][55] The EU aspires for complete gigabit coverage by 2030, however as of 2022, only over 60% of Europe has high-speed internet infrastructure, signalling the need for more enhancements.[54][56] Applications Common Sense Media, a nonprofit group based in San Francisco, surveyed almost 1,400 parents and reported in 2011 that 47 percent of families with incomes more than $75,000 had downloaded apps for their children, while only 14 percent of families earning less than $30,000 had done so.[57] |

スキルとデジタルリテラシー 2001年の研究によれば、デジタルデバイドは単なるアクセス問題ではなく、必要な機器を提供するだけでは解消できない。少なくとも三つの要因が作用して いる:情報へのアクセス可能性、情報の活用、情報受容性である。デジタルデバイドは単なるアクセスの問題ではなく、コミュニティ内に情報通信ツールが存在 しても、それを活用する方法に関する社会の知識不足から成り立っている。[44] 情報専門家は、支援を求める個人の経済状況に関わらず、アクセス可能な技術を学び活用するための参考資料や情報サービスを提供することで、この格差を埋め る手助けができる。[45] 場所 インターネットには、自宅、職場、学校、図書館、公共スペース、インターネットカフェなど様々な場所で接続できる。接続レベルは、地方、郊外、都市部でしばしば異なる。[46] [47] 2017年、ワイヤレス・ブロードバンド・アライアンスは白書『都市部の未接続層』を発表した。これによれば、世界最高GNPを誇る8カ国において約17 億5000万人がインターネット接続を持っておらず、その3分の1が主要都市部に居住している。デリー(530万人、総人口の9%)、サンパウロ(430 万人、36%)、ニューヨーク(160万人、19%)、モスクワ(210万人、17%)では、あらゆる形態のインターネットアクセスを持たない市民の割合 が最も高かった。[48] 「2023年現在、世界人口の67%がインターネットを利用しており、26億人がオフライン状態にある。主に後発開発途上国と農村地域に集中している。」 [38] また、各国政府はプライバシー、データ管理、言論の自由など様々な要素について異なる政策を有している。政府の規制により、テクノロジー企業が特定国で サービスを提供することは困難だ。これは世界の各地域に不均衡な影響を与える。欧州は人口のオンライン比率が最も高く、アフリカは最も低い。2010年か ら2014年にかけて欧州は67%から75%に上昇したのに対し、同期間のアフリカは10%から19%に留まった。[49]「2023年のインターネット 普及率は欧州89%からアフリカ37%まで幅があり、持続的な世界的格差を浮き彫りにしている。」[38] ネットワーク速度はインターネット接続の品質に大きく影響する。大都市や町では高速インターネットへのアクセスが良好な一方、地方ではサービスが限定的あ るいは全く利用できない場合がある。[50] 地域によってはサービスを提供する事業者が唯一の存在であるため、世帯は特定のサービスプロバイダーに縛られることもある。これは米国のようなネットワー クが整備された地域にも当てはまるが、発展途上国にも同様に適用されるため、広大な地域が事実上カバーされていない状態だ。[51] こうした地域では、問題が主にインフラにあるため、消費者が取れる手段は非常に限られている。スターリンクのような衛星経由でインターネット接続を提供す る技術は普及しつつあるが、依然として多くの地域では利用できない。[52] 地域によっては、ネットワーク事業者のインフラが限られているという理由だけで、接続速度が極端に遅くなり、実質的に使用不能になることがある。例えば、 台湾で5GBのデータをダウンロードするのに約8分かかるのに対し、イエメンでは同じダウンロードに30時間かかる可能性がある。[53] 2020年から2022年にかけて、EU域内の平均ダウンロード速度は70Mbpsから120Mbps以上に上昇した。これは主にパンデミック下でのデジ タルサービス需要の増加によるものである。[54] インターネット速度には依然として都市部と地方の格差が大きく、フランスやデンマークの都市部では150Mbpsを超える速度を達成している一方、ギリ シャ、クロアチア、キプロスの多くの地方では60Mbps未満の速度に留まっている。[54] [55] EUは2030年までに全土のギガビット網整備を目標としているが、2022年時点で欧州の60%超にしか高速インターネット基盤が整備されておらず、さらなる拡充が必要だ。[54] [56] アプリケーション サンフランシスコに拠点を置く非営利団体コモンセンスメディアは、約1,400人の親を対象に調査を実施し、2011年に報告した。それによると、年収 75,000ドル以上の世帯の47%が子供向けにアプリをダウンロードしていたのに対し、年収30,000ドル未満の世帯ではわずか14%だった。 [57] |

| Reasons and correlating variables As of 2014, the gap in a digital divide was known to exist for a number of reasons. Obtaining access to ICTs and using them actively has been linked to demographic and socio-economic characteristics including income, education, race, gender, geographic location (urban-rural), age, skills, awareness, political, cultural and psychological attitudes.[58][59][60][61][62][63][64] Multiple regression analysis across countries has shown that income levels and educational attainment are identified as providing the most powerful explanatory variables for ICT access and usage.[65] Evidence was found that Caucasians are much more likely than non-Caucasians to own a computer as well as have access to the Internet in their homes.[citation needed][66][67] As for geographic location, people living in urban centers have more access and show more usage of computer services than those in rural areas. In developing countries, a digital divide between women and men is apparent in tech usage, with men more likely to be competent tech users. Controlled statistical analysis has shown that income, education and employment act as confounding variables and that women with the same level of income, education and employment actually embrace ICT more than men (see Women and ICT4D), this argues against any suggestion that women are "naturally" more technophobic or less tech-savvy.[68] However, each nation has its own set of causes or the digital divide. For example, the digital divide in Germany is unique because it is not largely due to difference in quality of infrastructure.[69] The correlation between income and internet use suggests that the digital divide persists at least in part due to income disparities.[70] Most commonly, a digital divide stems from poverty and the economic barriers that limit resources and prevent people from obtaining or otherwise using newer technologies. In research, while each explanation is examined, others must be controlled to eliminate interaction effects or mediating variables,[58] but these explanations are meant to stand as general trends, not direct causes. Measurements for the intensity of usages, such as incidence and frequency, vary by study. Some report usage as access to Internet and ICTs while others report usage as having previously connected to the Internet. Some studies focus on specific technologies, others on a combination (such as Infostate, proposed by Orbicom-UNESCO, the Digital Opportunity Index, or ITU's ICT Development Index). |

理由と関連変数 2014年時点で、デジタルデバイドの格差が存在する理由は複数知られていた。ICTへのアクセス獲得と積極的な利用は、所得、教育、人種、性別、地理的 場所(都市部・農村部)、年齢、スキル、認知度、政治的・文化的・心理的態度といった人口統計学的・社会経済的特性と関連している。[58][59] [60][61] [62][63][64] 複数国を対象とした多重回帰分析では、所得水準と教育達成度がICTへのアクセスと利用を説明する最も強力な変数として特定されている。[65] 白人系住民は非白人系住民に比べ、自宅にコンピューターを所有しインターネットにアクセスできる可能性がはるかに高いという証拠が確認されている。[出典 必要][66] [67] 地理的立地に関しては、都市部に居住する人民は農村地域の人々よりもコンピューターサービスへのアクセス機会が多く、利用頻度も高い。 発展途上国では、技術利用において男女間のデジタル格差が顕著であり、男性の方が技術に習熟している傾向がある。しかし統制された統計分析によれば、所 得・教育・雇用は交絡変数として作用し、同水準の所得・教育・雇用を持つ女性の方が実際には男性よりICTを活用している(詳細は「女性とICT4D」参 照)。これは「女性は本質的に技術恐怖症である」あるいは「技術に疎い」という主張を否定するものである。[68] ただし、各国民にはデジタルデバイドの固有要因が存在する。例えばドイツのデジタルデバイドは、インフラ品質の差が主な原因ではない点で特異である。 [69] 所得とインターネット利用の相関関係は、デジタルデバイドが少なくとも部分的には所得格差によって持続していることを示唆している。[70] デジタルデバイドは、貧困や資源を制限し、人民が新しい技術を入手したり利用したりすることを妨げる経済的障壁に起因する場合が最も多い。 研究においては、各説明要因を検証する一方で、相互作用効果や媒介変数を排除するために他の要因を制御する必要がある。[58] ただし、これらの説明は直接的な原因ではなく、一般的な傾向として提示されるものである。利用頻度や利用率といった使用強度の測定方法は研究によって異な る。インターネットやICTへのアクセスを「利用」と報告する研究もあれば、過去にインターネットに接続した経験があることを「利用」と報告する研究もあ る。特定の技術に焦点を当てる研究もあれば、複数の技術を組み合わせた指標(オービコム-ユネスコが提案したインフォステート、デジタル機会指数、ITU のICT開発指数など)を用いる研究もある。 |

| Economic gap in the United States During the mid-1990s, the United States Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications & Information Administration (NTIA) began publishing reports about the Internet and access to and usage of the resource. The first of three reports is titled "Falling Through the Net: A Survey of the "Have Nots" in Rural and Urban America" (1995),[71] the second is "Falling Through the Net II: New Data on the Digital Divide" (1998),[72] and the final report "Falling Through the Net: Defining the Digital Divide" (1999).[73] The NTIA's final report attempted clearly to define the term digital divide as "the divide between those with access to new technologies and those without".[73] Since the introduction of the NTIA reports, much of the early, relevant literature began to reference the NTIA's digital divide definition. The digital divide is commonly defined as being between the "haves" and "have-nots".[73][71] The U.S. Federal Communications Commission's (FCC) 2019 Broadband Deployment Report indicated that 21.3 million Americans do not have access to wired or wireless broadband internet.[74] "Actual broadband unavailability and affordability issues may be underestimated in federal reports; independent and local studies suggest higher gaps.[38][75] As of 2020, BroadbandNow, an independent research company studying access to internet technologies, estimated that the actual number of United States Americans without high-speed internet is twice that number.[76] According to a 2021 Pew Research Center report, smartphone ownership and internet use has increased for all Americans, however, a significant gap still exists between those with lower incomes and those with higher incomes:[77] U.S. households earning $100K or more are twice as likely to own multiple devices and have home internet service as those making $30K or more, and three times as likely as those earning less than $30K per year.[77] The same research indicated that 13% of the lowest income households had no access to internet or digital devices at home compared to only 1% of the highest income households.[77] According to a Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults executed from January 25 to February 8, 2021, the digital lives of Americans with high and low incomes are varied. Conversely, the proportion of Americans that use home internet or cell phones has maintained constant between 2019 and 2021. "Multiple devices enable more diverse and productive online engagement, affecting economic and educational outcomes."[78] A quarter of those with yearly average earnings under $30,000 (24%) says they don't own smartphones. Four out of every ten low-income people (43%) do not have home internet access or a computer (43%). Furthermore, the more significant part of lower-income Americans does not own a tablet device.[77] On the other hand, every technology is practically universal among people earning $100,000 or higher per year. Americans with larger family incomes are also more likely to buy a variety of internet-connected products. Wi-Fi at home, a smartphone, a computer, and a tablet are used by around six out of ten families making $100,000 or more per year, compared to 23 percent in the lesser household.[77] |

アメリカ合衆国の経済格差 1990年代半ば、アメリカ合衆国商務省傘下の国家電気通信情報局(NTIA)は、インターネットと、その資源へのアクセス及び利用に関する報告書の発刊 を開始した。3つの報告書のうち最初のものは「ネットの隙間からこぼれ落ちる人々:米国農村部と都市部の『持たざる者』に関する調査」(1995年) [71]、2つ目は「ネットの隙間からこぼれ落ちる人々II:デジタルデバイドに関する新たなデータ」(1998年)[72]、最終報告書は「ネットの隙 間からこぼれ落ちる人々:デジタルデバイドの定義」(1999年)[73]である。(1999年)である。[73] NTIAの最終報告書は「デジタル・ディバイド」という用語を「新技術へのアクセスを持つ者と持たない者との隔たり」と明確に定義しようとした。[73] NTIA報告書発表以降、関連する初期文献の多くがNTIAの定義を参照し始めた。デジタル・ディバイドは一般に「持つ者と持たざる者」の間の隔たりと定 義される。[73][71] 米国連邦通信委員会(FCC)の2019年ブロードバンド展開報告書によれば、2130万人のアメリカ人が有線・無線ブロードバンドインターネットを利用 できない状態にある。[74] 「実際のブロードバンド利用不可と手頃な価格の問題は連邦報告書で過小評価されている可能性があり、独立した地域調査ではより大きな格差が示唆されてい る。[38] [75] 2020年時点で、インターネット技術へのアクセスを研究する独立調査会社BroadbandNowは、高速インターネットを利用できない米国人の実数は この数値の2倍と推定した。[76] 2021年のピュー・リサーチ・センター報告書によれば、全米民のスマートフォン所有率とインターネット利用率は上昇したものの、低所得層と高所得層の間 には依然として顕著な格差が存在する。[77] 年収10万ドル以上の世帯は、3万ドル以上の世帯と比べ複数端末所有と家庭内インターネットサービスの利用率が2倍、3万ドル未満の世帯と比べ3倍高い。 [77] 同調査では、最貧困層世帯の13%が家庭でインターネットやデジタル端末を利用できないのに対し、最高所得層世帯ではわずか1%だった。[77] ピュー・リサーチ・センターが2021年1月25日から2月8日にかけて実施した米国成人調査によれば、高所得層と低所得層のデジタル生活には差異が見ら れる。一方で、家庭用インターネットや携帯電話を利用する米国人の割合は2019年から2021年にかけて横ばい状態だ。「複数のデバイスはオンライン活 動における多様性と生産性を高め、経済的・教育的成果に影響を与える」[78] 年収3万ドル未満の世帯の4分の1(24%)はスマートフォンを所有していないと回答している。低所得層の10人中4人(43%)は自宅インターネット接 続やコンピューターを所有していない。さらに、低所得層の大部分はタブレット端末を所有していない。[77] 一方、年収10万ドル以上の層では、あらゆる技術がほぼ普遍的に普及している。世帯収入が高いアメリカ人は、インターネット接続製品を複数購入する傾向も 強い。年収10万ドル以上の世帯では約6割が自宅Wi-Fi・スマートフォン・コンピューター・タブレットを利用しているが、低所得世帯では23%に留ま る。[77] |

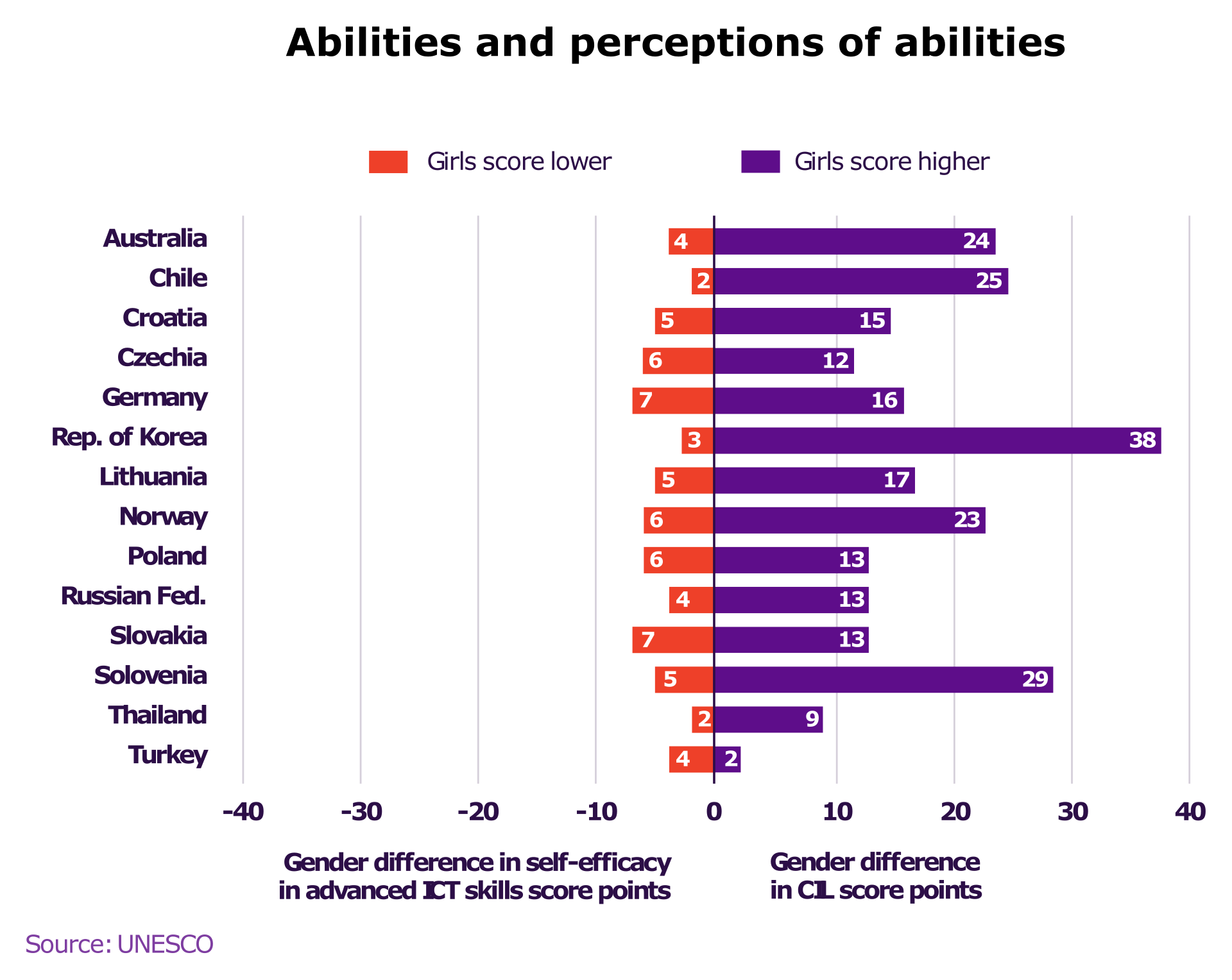

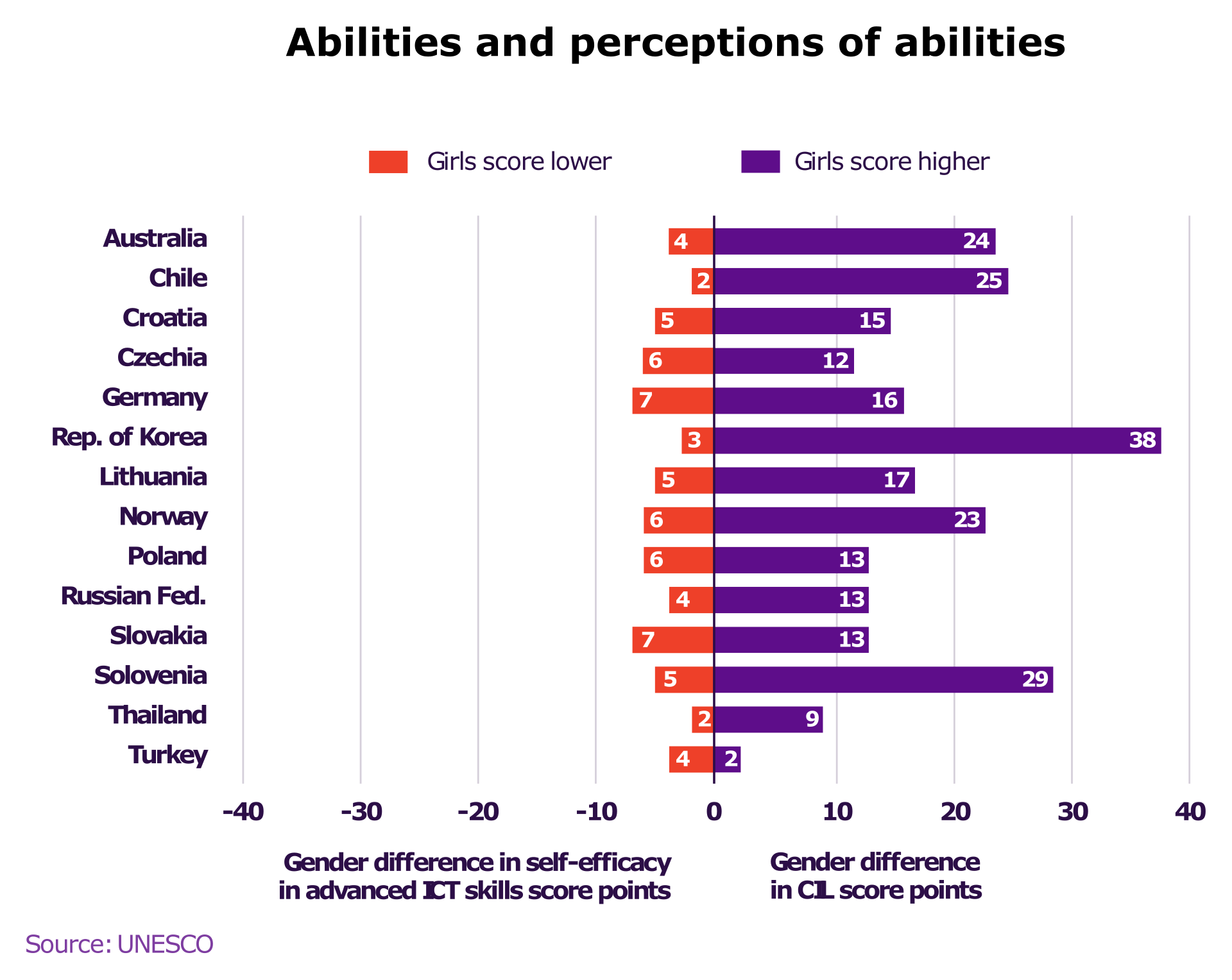

| Racial gap in the United States Although many groups in society are affected by a lack of access to computers or the Internet, communities of color are specifically observed to be negatively affected by the digital divide.[79] "Urban areas also exhibit neighborhood-level divides due to affordability, infrastructure quality, and localized socio-economic differences."[75] Pew research shows that as of 2021, home broadband rates are 81% for White households, 71% for Black households and 65% for Hispanic households.[80] While 63% of adults find the lack of broadband to be a disadvantage, only 49% of White adults do.[79] Smartphone and tablet ownership remains consistent with about 8 out of 10 Black, White, and Hispanic individuals reporting owning a smartphone and half owning a tablet.[79] A 2021 survey found that a quarter of Hispanics rely on their smartphone and do not have access to broadband.[79] Physical and mental disability gap Inequities in access to information technologies are present among individuals living with a physical disability in comparison to those who are not living with a disability. In 2011, according to the Pew Research Center, 54% of households with a person who had a disability had home Internet access, compared to 81% of households that did not have a person who has a disability.[81] The type of disability an individual has can prevent them from interacting with computer screens and smartphone screens, such as having a quadriplegia disability or having a disability in the hands. However, there is still a lack of access to technology and home Internet access among those who have a cognitive and auditory disability as well. There is a concern of whether or not the increase in the use of information technologies will increase equality through offering opportunities for individuals living with disabilities or whether it will only add to the present inequalities and lead to individuals living with disabilities being left behind in society.[82] Issues such as the perception of disabilities in society, national and regional government policy, corporate policy, mainstream computing technologies, and real-time online communication have been found to contribute to the impact of the digital divide on individuals with disabilities. In 2022, a survey of people in the UK with severe mental illness found that 42% lacked basic digital skills, such as changing passwords or connecting to Wi-Fi.[83][84] People with disabilities are also the targets of online abuse. Online disability hate crimes have increased by 33% across the UK between 2016–17 and 2017–18 according to a report published by Leonard Cheshire, a health and welfare charity.[85] Accounts of online hate abuse towards people with disabilities were shared during an incident in 2019 when model Katie Price's son was the target of online abuse that was attributed to him having a disability. In response to the abuse, a campaign was launched by Price to ensure that Britain's MPs held accountable those who perpetuate online abuse towards those with disabilities.[86] Online abuse towards individuals with disabilities is a factor that can discourage people from engaging online which could prevent people from learning information that could improve their lives. Many individuals living with disabilities face online abuse in the form of accusations of benefit fraud and "faking" their disability for financial gain, which in some cases leads to unnecessary investigations. Gender gap Main article: Gender digital divide Due to the rapidly declining price of connectivity and hardware, skills deficits have eclipsed barriers of access as the primary contributor to the gender digital divide. “OECD recommends policies including targeted digital skills training for women, promoting female participation in ICT careers, and designing relevant online content to close the gender divide.” [87][88] Studies show that women are less likely to know how to leverage devices and Internet access to their full potential, even when they do use digital technologies.[89] In rural India, for example, a study found that the majority of women who owned mobile phones only knew how to answer calls. They could not dial numbers or read messages without assistance from their husbands, due to a lack of literacy and numeracy skills.[90] A survey of 3,000 respondents across 25 countries found that adolescent boys with mobile phones used them for a wider range of activities, such as playing games and accessing financial services online. Adolescent girls in the same study tended to use just the basic functionalities of their phone, such as making calls and using the calculator.[91] Similar trends can be seen even in areas where Internet access is near-universal. A survey of women in nine cities around the world revealed that although 97% of women were using social media, only 48% of them were expanding their networks, and only 21% of Internet-connected women had searched online for information related to health, legal rights or transport.[91] In some cities, less than one quarter of connected women had used the Internet to look for a job.[89] "Inclusion policies must address exploitative conditions of participation in digital platforms, not just physical access."[92]  Abilities and perceptions of abilities Studies show that despite strong performance in computer and information literacy (CIL), girls do not have confidence in their ICT abilities. According to the International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS) assessment girls' self-efficacy scores (their perceived as opposed to their actual abilities) for advanced ICT tasks were lower than boys'.[93][89] A paper published by J. Cooper from Princeton University points out that learning technology is designed to be receptive to men instead of women. Overall, the study presents the problem of various perspectives in society that are a result of gendered socialization patterns that believe that computers are a part of the male experience since computers have traditionally presented as a toy for boys when they are children.[94] This divide is followed as children grow older and young girls are not encouraged as much to pursue degrees in IT and computer science. In 1990, the percentage of women in computing jobs was 36%, however in 2016, this number had fallen to 25%. This can be seen in the under representation of women in IT hubs such as Silicon Valley.[95] There has also been the presence of algorithmic bias that has been shown in machine learning algorithms that are implemented by major companies.[clarification needed] In 2015, Amazon had to abandon a recruiting algorithm that showed a difference between ratings that candidates received for software developer jobs as well as other technical jobs. As a result, it was revealed that Amazon's machine algorithm was biased against women and favored male resumes over female resumes. This was due to the fact that Amazon's computer models were trained to vet patterns in resumes over a 10-year period. During this ten-year period, the majority of the resumes belong to male individuals, which is a reflection of male dominance across the tech industry.[96] |

米国における人種格差 社会における多くの集団がコンピューターやインターネットへのアクセス不足の影響を受けているが、特に有色人種コミュニティはデジタルデバイドによって悪 影響を受けていることが確認されている。[79]「都市部では、手頃な価格、インフラの質、地域ごとの社会経済的差異により、地域レベルでの格差も生じて いる。」 [75] ピュー研究所の調査によれば、2021年時点で家庭用ブロードバンド普及率は白人世帯が81%、黒人世帯が71%、ヒスパニック世帯が65%である。 [80] 成人の63%がブロードバンド不足を不利と認識しているが、白人成人では49%に留まる。[79] スマートフォンとタブレットの所有率はほぼ同水準で、黒人・白人・ヒスパニックの約10人中8人がスマートフォンを所有し、半数がタブレットを所有してい る。[79] 2021年の調査では、ヒスパニックの4分の1がスマートフォンに依存し、ブロードバンドを利用できない状況にある。[79] 身体障害・精神障害による格差 身体障害を持つ個人とそうでない個人では、情報技術へのアクセスに不平等が存在する。ピュー・リサーチ・センターによれば、2011年時点で障害を持つ人 格がいる世帯の54%が家庭用インターネットを利用していたのに対し、障害者がいない人格では81%が利用していた。[81] 四肢麻痺や手足の障害など、障害の種類によってはコンピューター画面やスマートフォン画面との操作が困難な場合がある。しかし認知障害や聴覚障害を持つ人 々においても、技術へのアクセスや家庭内インターネット接続の不足は依然として存在する。情報技術の利用拡大が、障害を持つ個人に機会を提供することで平 等を促進するのか、それとも既存の不平等を助長し、障害を持つ個人が社会に取り残される結果となるのかが懸念されている。[82] 障害に対する社会の認識、国民や地域の政府政策、企業方針、主流のコンピューティング技術、リアルタイムのオンラインコミュニケーションといった問題が、 デジタルデバイドが障害者に与える影響に寄与していることが判明している。2022年に英国で重度の精神疾患を持つ人々を対象に行った調査では、42%が パスワード変更やWi-Fi接続といった基本的なデジタルスキルを欠いていることが明らかになった。[83] [84] 障害者はオンライン上の虐待の標的にもなる。健康福祉慈善団体レナード・チェシャーの報告書によれば、英国全体で2016-17年から2017-18年に かけてオンライン上の障害者差別犯罪は33%増加した。[85] 2019年には、モデルであるケイティ・プライスの息子が障害を理由にネットいじめの標的となった事件が発生した際、障害者へのオンライン憎悪虐待の実態 が共有された。これを受けプライスは、障害者を標的としたネットいじめを助長する者に対し、英国国会議員が責任を追及するよう求める運動を開始した。 [86] 障害者へのオンライン虐待は、人民のネット利用意欲を削ぐ要因となり、生活改善につながる情報取得を阻害する可能性がある。多くの障害者は、福祉給付の不 正受給や金銭目的の「障害詐称」といった非難という形でオンライン虐待に直面しており、場合によっては不要な調査を招くこともある。 ジェンダー格差 詳細記事: ジェンダー・デジタル・ディバイド 接続環境とハードウェアの価格が急速に低下した結果、ジェンダー・デジタル・ディバイドの主な要因はアクセス障壁からスキル不足へと移行した。「OECD は、女性向けデジタルスキル研修の実施、ICT分野での女性のキャリア参加促進、ジェンダー格差解消のための関連オンラインコンテンツ設計を含む政策を推 奨している。」 [87][88] 研究によれば、女性はデジタル技術を利用する場合でも、デバイスやインターネット接続を最大限に活用する方法を知らない傾向が強い。[89] 例えばインドの農村部では、携帯電話を所有する女性の大半が通話応答しかできないことが判明した。読み書きや計算能力の不足から、夫の助けなしでは番号を ダイヤルしたりメッセージを読んだりできなかったのである。[90] 25カ国3,000人を対象とした調査では、携帯電話を持つ少年はゲームやオンライン金融サービスなど多様な用途で利用していた。一方、同調査の少女は通 話や電卓機能といった基本機能のみに留まる傾向があった。[91] インターネット普及率がほぼ100%の地域でも同様の傾向が見られる。世界の9都市の女性を対象とした調査では、97%の女性がソーシャルメディアを利用 しているものの、ネットワークを拡大しているのは48%のみであり、インターネット接続環境のある女性の21%しか健康・法的権利・交通機関に関する情報 をオンラインで検索したことがなかった。[91] 一部の都市では、インターネット接続のある女性の4分の1未満しか求職活動にインターネットを利用していなかった。[89] 「インクルージョン政策は、物理的なアクセスだけでなく、デジタルプラットフォーム参加における搾取的な条件に対処しなければならない。」[92]  能力と能力に対する認識 研究によると、コンピュータおよび情報リテラシー(CIL)の成績は優れているにもかかわらず、女子は自分の ICT 能力に自信を持っていない。国際コンピュータ・情報リテラシー調査(ICILS)の評価によると、高度な ICT タスクに対する女子の自己効力感スコア(実際の能力ではなく、自分が認識している能力)は男子よりも低かった。[93] [89] プリンストン大学の J. クーパーが発表した論文は、学習技術は女性ではなく男性を受け入れるように設計されていると指摘している。全体として、この研究は、コンピュータが子供の 頃から男の子のおもちゃとして提示されてきたため、コンピュータは男性体験の一部であると考える、性別による社会化のパターンに起因する、社会におけるさ まざまな視点の問題を提示している。[94] この格差は、子供たちが成長するにつれて続き、少女たちは IT やコンピュータサイエンスの学位の取得をあまり奨励されない。1990 年、コンピュータ関連の仕事に就く女性の割合は 36% だったが、2016 年にはこの数字は 25% にまで低下した。これは、シリコンバレーなどの IT 拠点における女性の過小評価にも見られる。[95] また、大手企業が導入する機械学習アルゴリズムにはアルゴリズムバイアスが存在することが明らかになっている。2015年、アマゾンはソフトウェア開発職 や技術職の候補者評価に差を生む採用アルゴリズムの使用を中止せざるを得なかった。その結果、アマゾンの機械アルゴリズムが女性に対して偏見を持ち、男性 の履歴書を女性の履歴書よりも優先していたことが明らかになった。これは、アマゾンのコンピューターモデルが10年間にわたる履歴書のパターンを審査する ように訓練されていたためである。この10年間、履歴書の大半は男性のものであり、これはテクノロジー業界全体における男性の優位性を反映している。 [96] |

| Age gap The age gap contributes to the digital divide due to the fact that people born before 1983 did not grow up with the internet. "Even among 'digital natives,' skills vary widely based on socio-economic status, race, and parental education.[97] According to Marc Prensky, people who fall into this age range are classified as "digital immigrants."[98] A digital immigrant is defined as "a person born or brought up before the widespread use of digital technology."[99] The internet became officially available for public use on January 1, 1983; anyone born before then has had to adapt to the new age of technology.[100] On the contrary, people born after 1983 are considered "digital natives". Digital natives are defined as people born or brought up during the age of digital technology.:[99] “Generational divides are nuanced; even among youth, socio-economic background significantly shapes skills and usage patterns.[101] Across the globe, there is a 10% difference in internet usage between people aged 15–24 years old and people aged 25 years or older. According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 75% of people aged 15–24 used the internet in 2022 compared to 65% of people aged 25 years or older.[102] The highest amount of digital divide between generations occurs in Africa with 55% of the younger age group using the internet compared to 36% of people aged 25 years or older. The lowest amount of divide occurs between the Commonwealth of Independent States with 91% of the younger age group using the internet compared to 83% of people aged 25 years or older. In addition to being less connected with the internet, older generations are less likely to use financial technology, also known as fintech. Fintech is any way of managing money via digital devices.[103] Some examples of fintech include digital payment apps such as Venmo and Apple Pay, tax services such as TurboTax, or applying for a mortgage digitally. In data from World Bank Findex, 40% of people younger than 40 years old utilized fintech compared to less than 25% of people aged 60 years or older.[104] Global level Main article: Global digital divide See also: World Summit on the Information Society and Digital divide by country The divide between differing countries or regions of the world is referred to as the global digital divide, which examines the technological gap between developing and developed countries.[105] The divide within countries (such as the digital divide in the United States) may refer to inequalities between individuals, households, businesses, or geographic areas, usually at different socioeconomic levels or other demographic categories. In contrast, the global digital divide describes disparities in access to computing and information resources, and the opportunities derived from such access.[106] ITU’s Facts and Figures 2024 reports persistent global gaps in internet connectivity, underscoring disparities by region and income level.[107] As the internet rapidly expands it is difficult for developing countries to keep up with the constant changes. In 2014 only three countries (China, US, Japan) host 50% of the globally installed bandwidth potential.[32] This concentration is not new, as historically only ten countries have hosted 70–75% of the global telecommunication capacity (see Figure). The U.S. lost its global leadership in terms of installed bandwidth in 2011, replaced by China, who hosted more than twice as much national bandwidth potential in 2014 (29% versus 13% of the global total).[32] Some zero-rating programs such as Facebook Zero offer free/subsidized data access to certain websites. Critics object that this is an anti-competitive program that undermines net neutrality and creates a "walled garden".[108] A 2015 study reported that 65% of Nigerians, 61% of Indonesians, and 58% of Indians agree with the statement that "Facebook is the Internet" compared with only 5% in the US.[109] |

年齢差 年齢差はデジタルデバイドの一因となる。1983年以前に生まれた人民はインターネットと共に成長しなかったからだ。「デジタルネイティブ」と呼ばれる人 民の中ですら、社会経済的地位、人種、親の教育水準によってスキルには大きな差がある[97]。マーク・プレンスキーによれば、この年齢層に属する人々は 「デジタル移民」と分類される[98]。デジタル移民とは「デジタル技術が普及する前に生まれ育った人格」と定義される[99]。インターネットが公的に 利用可能になったのは1983年1月1日であり、それ以前に生まれた者は新たな技術時代に適応せざるを得なかった[100]。対照的に、1983年以降に 生まれた者は「デジタルネイティブ」と見なされる。デジタルネイティブとは、デジタル技術の時代に生まれ育った人々を指す。[99]「世代間の隔たりは複 雑だ。若者の中でも、社会経済的背景がスキルや利用パターンを大きく左右する。」[101] 世界的に見て、15~24歳と25歳以上のインターネット利用率には10%の差がある。国際電気通信連合(ITU)によれば、2022年時点で15~24 歳の75%の人民がインターネットを利用していたのに対し、25歳以上では65%の人民だった。[102] 世代間のデジタル格差が最も大きいのはアフリカで、若年層のインターネット利用率は55%であるのに対し、25歳以上では36%の人民である。最も格差が 小さいのは独立国家共同体(CIS)で、若年層のインターネット利用率は91%であるのに対し、25歳以上では83%である。 インターネット接続率が低いことに加え、高齢世代は金融技術(フィンテック)の利用率も低い。フィンテックとはデジタル機器を用いたあらゆる資金管理手法 を指す。[103] フィンテックの例としては、VenmoやApple Payのようなデジタル決済アプリ、TurboTaxのような税務サービス、あるいはデジタルでの住宅ローン申請などが挙げられる。世界銀行フィンデック スのデータによれば、40歳未満の40%の人民がフィンテックを利用しているのに対し、60歳以上の利用率は25%未満である。[104] グローバルレベル 主な記事: グローバルデジタルデバイド 関連項目:世界情報社会サミット、国別デジタルデバイド 世界各国の地域間における格差は「グローバルデジタルデバイド」と呼ばれ、発展途上国と先進国の技術格差を分析する。[105] 一方、国内における格差(例:米国のデジタルデバイド)は、個人・世帯・企業・地域間の不平等を指し、通常は異なる社会経済レベルやその他の人口統計学的 カテゴリーに基づく。対照的に、グローバルなデジタルデバイドは、コンピューティングや情報資源へのアクセス、およびそのアクセスから得られる機会の格差 を説明するものである。[106] ITUの『Facts and Figures 2024』は、インターネット接続性における持続的な世界的格差を報告し、地域や所得水準による不均衡を強調している。[107] インターネットが急速に拡大する中、発展途上国が絶え間ない変化についていくのは困難である。2014年時点で、世界の設置済み帯域幅ポテンシャルの 50%をわずか3カ国(中国、米国、日本)が占めていた[32]。この集中は新たな現象ではなく、歴史的に見ても世界の通信容量の70~75%を10カ国 が占めてきた(図参照)。米国は2011年に設置帯域幅における世界首位を失い、中国に取って代わられた。2014年時点で中国は国民帯域幅潜在量の2倍 以上を保有(世界総量の29%対13%)していた。[32] Facebook Zeroのようなゼロレーティングプログラムは、特定ウェブサイトへの無料/補助付きデータアクセスを提供する。批判派は、これが競争阻害的なプログラム であり、ネット中立性を損ない「囲い込み型サービス」を生み出すと反論している。[108] 2015年の調査では、ナイジェリア人の65%、インドネシア人の61%、インドの58%が「Facebookはインターネットそのものだ」という主張に 同意しているのに対し、米国ではわずか5%だった。[109] |

| Implications Social capital Once an individual is connected, Internet connectivity and ICTs can enhance his or her future social and cultural capital. Social capital is acquired through repeated interactions with other individuals or groups of individuals.: “Capital-enhancing uses (education, employment) generate more benefits than purely recreational uses, influencing social capital accumulation [78]” Connecting to the Internet creates another set of means by which to achieve repeated interactions. ICTs and Internet connectivity enable repeated interactions through access to social networks, chat rooms, and gaming sites. Once an individual has access to connectivity, obtains infrastructure by which to connect, and can understand and use the information that ICTs and connectivity provide, that individual is capable of becoming a "digital citizen."[58] Economic disparity In the United States, the research provided by Unguarded Availability Services notes a direct correlation between a company's access to technological advancements and its overall success in bolstering the economy.[110]“In many Global South contexts, digital inclusion can occur under exploitative conditions—‘adverse digital incorporation’—that deepen inequality [92]” The study, which includes over 2,000 IT executives and staff officers, indicates that 69 percent of employees feel they do not have access to sufficient technology to make their jobs easier, while 63 percent of them believe the lack of technological mechanisms hinders their ability to develop new work skills.[110] Additional analysis provides more evidence to show how the digital divide also affects the economy in places all over the world. A BEG report suggests that in countries like Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.K., the digital connection among communities is made easier, allowing for their populations to obtain a much larger share of the economies via digital business.[111] In fact, in these places, populations hold shares approximately 2.5 percentage points higher.[111] During a meeting with the United Nations a Bangladesh representative expressed his concern that poor and undeveloped countries would be left behind due to a lack of funds to bridge the digital gap.[112] Education The digital divide impacts children's ability to learn and grow in low-income school districts. Without Internet access, students are unable to cultivate necessary technological skills to understand today's dynamic economy.[113]“Even with access, disparities in device quality, internet reliability, and digital literacy influence educational outcomes, especially for low-income and minority students [114][115]” The need for the internet starts while children are in school – necessary for matters such as school portal access, homework submission, and assignment research.[116] The Federal Communications Commission's Broadband Task Force created a report showing that about 70% of teachers give students homework that demand access to broadband.[117] Approximately 65% of young scholars use the Internet at home to complete assignments as well as connect with teachers and other students via discussion boards and shared files.[117] A recent study indicates that approximately 50% of students say that they are unable to finish their homework due to an inability to either connect to the Internet or in some cases, find a computer.[117] Additionally, The Public Policy Institute of California reported in 2023 that 27% of the state’s school children lack the necessary broadband to attend school remotely, and 16% have no internet connection at all.[118] This has led to a new revelation: 42% of students say they received a lower grade because of this disadvantage.[117] According to research conducted by the Center for American Progress, "if the United States were able to close the educational achievement gaps between native-born white children and black and Hispanic children, the U.S. economy would be 5.8 percent—or nearly $2.3 trillion—larger in 2050".[119] In a reverse of this idea, well-off families, especially the tech-savvy parents in Silicon Valley, carefully limit their own children's screen time. The children of wealthy families attend play-based preschool programs that emphasize social interaction instead of time spent in front of computers or other digital devices, and they pay to send their children to schools that limit screen time.[120] American families that cannot afford high-quality childcare options are more likely to use tablet computers filled with apps for children as a cheap replacement for a babysitter, and their government-run schools encourage screen time during school. Students in school are also learning about the digital divide.[120] To reduce the impact of the digital divide and increase digital literacy in young people at an early age, governments have begun to develop and focus policy on embedding digital literacies in both student and educator programs, for instance, in Initial Teacher Training programs in Scotland.[121] The National Framework for Digital Literacies in Initial Teacher Education was developed by representatives from Higher Education institutions that offer Initial Teacher Education (ITE) programs in conjunction with the Scottish Council of Deans of Education (SCDE) with the support of Scottish Government [121] This policy driven approach aims to establish an academic grounding in the exploration of learning and teaching digital literacies and their impact on pedagogy as well as ensuring educators are equipped to teach in the rapidly evolving digital environment and continue their own professional development. Demographic differences Factors such as nationality, gender, and income contribute to the digital divide across the globe. Depending on what someone identifies as, their access to the internet can potentially decrease. According to a study conducted by the ITU in 2022, Africa has the fewest people on the internet at a 40% rate; the next lowest internet population is the Asia-Pacific region at 64%. Internet access remains a problem in Least Developing Countries and Landlocked Developing Countries. They both have 36% of people using the internet compared to a 66% average around the world.[102] "Persistent gender gaps stem from affordability barriers, socio-cultural norms, lower confidence, and limited relevance of digital content for women."[87][122] The gender parity score across the globe is 0.92. A gender parity score is calculated by the percentage of women who use the internet divided by the percentage of men who use the internet. Ideally, countries want to have gender parity scores between 0.98 and 1.02. The region with the least gender parity is Africa with a score of 0.75. The next lowest gender parity score belongs to the Arab States at 0.87. Americans, Commonwealth of Independent States, and Europe all have the highest gender parity scores with scores that do not go below 0.98 or higher than 1. Gender parity scores are often impacted by class. Low income regions have a score of 0.65 while upper-middle income and high income regions have a score of 0.99.[102] The difference between economic classes has been a prevalent issue with the digital divide up to this point. People who are considered to earn low income use the internet at a 26% rate followed by lower-middle income at 56%, upper-middle income at 79%, and high income at 92%. The staggering difference between low income individuals and high income individuals can be traced to the affordability of mobile products. Products are becoming more affordable as the years pass; according to the ITU, “the global median price of mobile-broadband services dropped from 1.9 percent to 1.5 percent of average gross national income (GNI) per capita.” There is still plenty of work to be done, as there is a 66% difference between low income individuals and high income individuals' access to the internet.[102] Facebook divide The Facebook divide,[123][124][125][126] a concept derived from the "digital divide", is the phenomenon with regard to access to, use of, and impact of Facebook on society. It was coined at the International Conference on Management Practices for the New Economy (ICMAPRANE-17) on February 10–11, 2017.[127] "Differences in platform use—between social, economic, and civic purposes—parallel broader usage divides in urban populations."[75] Additional concepts of Facebook Native and Facebook Immigrants were suggested at the conference. Facebook divide, Facebook native, Facebook immigrants, and Facebook left-behind are concepts for social and business management research. Facebook immigrants utilize Facebook for their accumulation of both bonding and bridging social capital. Facebook natives, Facebook immigrants, and Facebook left-behind induced the situation of Facebook inequality. In February 2018, the Facebook Divide Index was introduced at the ICMAPRANE conference in Noida, India, to illustrate the Facebook divide phenomenon.[128] |

含意 社会資本 個人が接続されると、インターネット接続とICTは将来の社会的・文化的資本を高める。社会資本は他者や集団との反復的な交流を通じて獲得される。「資本 増強的利用(教育、雇用)は純粋な娯楽利用より多くの利益を生み、社会資本の蓄積に影響する[78]」。インターネット接続は反復的交流を達成する新たな 手段を提供する。ICTとインターネット接続は、ソーシャルネットワーク、チャットルーム、ゲームサイトへのアクセスを通じて反復的な交流を可能にする。 個人が接続手段を獲得し、接続のためのインフラを整え、ICTと接続が提供する情報を理解・活用できる状態になれば、その個人は「デジタル市民」となり得 る[58]。 経済格差 米国におけるUnguarded Availability Servicesの研究は、企業の技術進歩へのアクセスと経済強化における総合的成功の間に直接的な相関関係があることを指摘している[110]。「多く のグローバルサウス(南半球諸国)の文脈では、デジタルインクルージョンは搾取的な条件下——『不利なデジタル組み込み』——で発生し、不平等を深化させ る[92]」 2,000人以上のIT幹部・スタッフを対象とした調査では、従業員の69%が業務効率化に必要な技術にアクセスできていないと感じ、63%が技術的仕組 みの不足が新たな業務スキル習得の妨げになっていると回答している[110]。追加分析は、デジタル格差が世界中の経済に与える影響をさらに裏付ける証拠 を提供している。BEGの報告書によれば、スウェーデン、スイス、英国などの国々では、地域間のデジタル接続が容易化されており、住民がデジタルビジネス を通じて経済のより大きなシェアを獲得できるという。[111] 実際、これらの地域では住民のシェアが約2.5パーセントポイント高い。[111] 国連会議でバングラデシュ代表は、貧しい発展途上国がデジタル格差を埋める資金不足により取り残される懸念を表明した。[112] 教育 デジタル格差は低所得地域の児童生徒の学習・成長能力に影響する。インターネットアクセスがなければ、生徒は現代のダイナミックな経済を理解する上で必要 な技術的スキルを育めない。[113]「アクセスがあっても、端末の品質、インターネットの信頼性、デジタルリテラシーの格差が教育成果に影響する。特に 低所得層や少数派の生徒において顕著だ[114][115]」インターネットの必要性は、子供が学校に通っている段階から始まる。学校ポータルへのアクセ ス、宿題の提出、課題調査などに不可欠だからだ。[116]連邦通信委員会(FCC)のブロードバンド対策チームが作成した報告書によれば、教師の約 70%が生徒にブロードバンド接続を必要とする宿題を出している。[117]若年層の学習者の約65%が、家庭でインターネットを利用して課題を完了し、 ディスカッションボードや共有ファイルを通じて教師や他の生徒と交流している。[117] 最近の調査によれば、約50%の生徒が「インターネット接続ができない」「場合によってはコンピューターが見つからない」ことを理由に宿題を完了できない と回答している。[117] さらにカリフォルニア公共政策研究所は2023年、州内の学童の27%が遠隔授業に必要なブロードバンド環境を欠き、16%がインターネット接続を全く持 たないと報告した。[118] これにより新たな事実が明らかになった。生徒の42%が、この不利な状況により成績が下がったと述べているのだ[117]。アメリカ進歩センターの研究に よれば、「米国が白人系米国生まれの子供と黒人・ヒスパニック系児童の学力格差を解消できれば、2050年までに米国経済は5.8%(約2.3兆ドル)拡 大する」とされている。[119] この考えとは逆に、裕福な家庭、特にシリコンバレーの技術に精通した親たちは、自らの子供のスクリーンタイムを厳しく制限している。富裕層の子供たちは、 コンピューターやデジタル機器の前で過ごす時間ではなく、社会的交流を重視する遊び中心の就学前プログラムに通い、スクリーンタイムを制限する学校に子供 を通わせるために費用を払っている。[120] 高品質な保育サービスを利用できないアメリカの家庭では、ベビーシッターの代わりに子供向けアプリを搭載したタブレット端末を安価な代替手段として使う傾 向が強い。また政府運営の学校では授業中のスクリーンタイムを推奨している。生徒たちは学校でデジタルデバイドについても学んでいる。[120] デジタルデバイドの影響を軽減し、若年層のデジタルリテラシーを早期に高めるため、政府は学生と教育者双方のプログラムにデジタルリテラシーを組み込む政 策の開発と重点化を開始している。例えばスコットランドの教員養成初期プログラム(Initial Teacher Training)がそれにあたる。[121] スコットランド政府の支援のもと、教員養成プログラムを提供する高等教育機関の代表者とスコットランド教育学部長会議(SCDE)が共同で「教員養成にお けるデジタルリテラシー国家枠組み」を策定した。[121] この政策主導型アプローチは、デジタルリテラシーの学習・教授法の探求と教育学への影響に関する学術的基盤を確立するとともに、教育者が急速に進化するデ ジタル環境で教える能力を備え、自身の専門的成長を継続できるようにすることを目的としている。 人口統計学的差異 国籍、性別、所得などの要因が、世界的なデジタル格差に寄与している。個人の属性によって、インターネットへのアクセス可能性は低下する可能性がある。 ITUが2022年に実施した調査によれば、アフリカはインターネット利用者率が40%と最も低く、次いで低いのはアジア太平洋地域の64%である。後発 開発途上国と内陸開発途上国では、インターネットアクセスが依然として問題となっている。両地域のインターネット利用率は36%であり、世界の平均66% を大きく下回っている。[102] 「持続的なジェンダー格差は、経済的障壁、社会文化的規範、自信の欠如、女性にとってのデジタルコンテンツの関連性の低さから生じている。」 [87][122] 世界のジェンダー・パリティ指数は0.92である。この指数はインターネット利用女性の割合を男性の割合で割って算出される。理想的には0.98から 1.02の範囲が望ましい。最も低いのはアフリカの0.75である。次に低いのはアラブ諸国で0.87である。アメリカ、独立国家共同体(CIS)、ヨー ロッパは全て0.98を下回らず、1を超える最高水準のスコアを示している。ジェンダー・パリティ・スコアは階級の影響を強く受ける。低所得地域では 0.65であるのに対し、上位中所得地域と高所得地域では0.99を記録している。[102] 経済階層間の格差は、これまでのデジタルデバイドにおける主要な問題だ。低所得層のインターネット利用率は26%、次いで中低所得層が56%、中高所得層 が79%、高所得層が92%である。低所得者と高所得者の間の著しい差は、モバイル製品の価格差に起因する。製品は年々手頃な価格になりつつある。ITU によれば「モバイルブロードバンドサービスの世界的な価格中央値は、国民総所得(GNI)一人当たり平均の1.9%から1.5%に低下した」と報告されて いる。低所得者と高所得者のインターネットアクセス格差は66%も存在するため、まだ多くの課題が残されている。[102] フェイスブック格差 「フェイスブック格差」[123][124][125][126]は、「デジタル格差」から派生した概念であり、フェイスブックへのアクセス、利用、およ び社会への影響に関する現象を指す。この概念は2017年2月10~11日に開催された「新経済経営実践国際会議(ICMAPRANE-17)」で提唱さ れた[127]。「プラットフォーム利用の差異——社会的・経済的・市民的目的間の違い——は、都市人口におけるより広範な利用格差と並行している」 [75]。 同会議では「フェイスブック・ネイティブ」と「フェイスブック移民」という追加概念も提案された。フェイスブック格差、フェイスブックネイティブ、フェイ スブック移民、フェイスブック取り残された者らは、社会・経営管理研究における概念である。フェイスブック移民は、結束的・橋渡し的社会的資本の蓄積のた めにフェイスブックを利用する。フェイスブックネイティブ、フェイスブック移民、フェイスブック取り残された者らが、フェイスブック格差の状況を招いた。 2018年2月、インド・ノイダで開催されたICMAPRANE会議において、フェイスブック格差現象を可視化するため「フェイスブック格差指数」が導入 された[128]。 |

| Solutions In the year 2000, the United Nations Volunteers (UNV) program launched its Online Volunteering service,[129] which uses ICT as a vehicle for and in support of volunteering. It constitutes an example of a volunteering initiative that effectively contributes to bridge the digital divide. ICT-enabled volunteering has a clear added value for development. If more people collaborate online with more development institutions and initiatives, this will imply an increase in person-hours dedicated to development cooperation at essentially no additional cost. This is the most visible effect of online volunteering for human development.[130] Since May 17, 2006, the United Nations has raised awareness of the divide by way of the World Information Society Day.[131] In 2001, it set up the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Task Force.[132] Later UN initiatives in this area are the World Summit on the Information Society since 2003, and the Internet Governance Forum, set up in 2006. As of 2009, the borderline between ICT as a necessity good and ICT as a luxury good was roughly around US$10 per person per month, or US$120 per year,[65] which means that people consider ICT expenditure of US$120 per year as a basic necessity. Since more than 40% of the world population lives on less than US$2 per day, and around 20% live on less than US$1 per day (or less than US$365 per year), these income segments would have to spend one third of their income on ICT (120/365 = 33%). The global average of ICT spending is at a mere 3% of income.[65] Potential solutions include driving down the costs of ICT, which includes low-cost technologies and shared access through Telecentres.[133][134] In 2022, the US Federal Communications Commission started a proceeding "to prevent and eliminate digital discrimination and ensure that all people of the United States benefit from equal access to broadband internet access service, consistent with Congress's direction in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.[135] Social media websites serve as both manifestations of and means by which to combat the digital divide. The former describes phenomena such as the divided users' demographics that make up sites such as Facebook, WordPress and Instagram. Each of these sites hosts communities that engage with otherwise marginalized populations. Libraries  A laptop lending kiosk at Texas A&M University–Commerce's Gee Library In 2010, an "online indigenous digital library as part of public library services" was created in Durban, South Africa to narrow the digital divide by not only giving the people of the Durban area access to this digital resource, but also by incorporating the community members into the process of creating it.[136] In 2002, the Gates Foundation started the Gates Library Initiative which provides training assistance and guidance in libraries.[137] "Structural reforms in digital policy, equitable platform design, and affordable connectivity are necessary alongside community initiatives.[138][92] In Kenya, lack of funding, language, and technology illiteracy contributed to an overall lack of computer skills and educational advancement. This slowly began to change when foreign investment began.[139][140] In the early 2000s, the Carnegie Foundation funded a revitalization project through the Kenya National Library Service. Those resources enabled public libraries to provide information and communication technologies to their patrons. In 2012, public libraries in the Busia and Kiberia communities introduced technology resources to supplement curriculum for primary schools. By 2013, the program expanded into ten schools.[141] Effective use Even though individuals might be capable of accessing the Internet, many are opposed by barriers to entry, such as a lack of means to infrastructure or the inability to comprehend or limit the information that the Internet provides. Some individuals can connect, but they do not have the knowledge to use what information ICTs and Internet technologies provide them. This leads to a focus on capabilities and skills, as well as awareness to move from mere access to effective usage of ICT.[142] Community informatics (CI) focuses on issues of "use" rather than "access". CI is concerned with ensuring the opportunity not only for ICT access at the community level but also, according to Michael Gurstein, that the means for the "effective use" of ICTs for community betterment and empowerment are available.[143] Gurstein has also extended the discussion of the digital divide to include issues around access to and the use of "open data" and coined the term "data divide" to refer to this issue area.[144] Criticism Knowledge divide Since gender, age, race, income, and educational digital divides have lessened compared to the past, some researchers suggest that the digital divide is shifting from a gap in access and connectivity to ICTs to a knowledge divide.[145] A knowledge divide concerning technology presents the possibility that the gap has moved beyond the access and having the resources to connect to ICTs to interpreting and understanding information presented once connected.[146] However, research on the digital divide in internet access in the United States has not found that greater equality of internet access has reduced knowledge divides or educational inequality.[153]: “Skills, autonomy of use, and purpose of engagement shape the benefits users derive, reinforcing broader social inequalities .”[78] Second-level digital divide The second-level digital divide, also referred to as the production gap, describes the gap that separates the consumers of content on the Internet from the producers of content.[154] As the technological digital divide is decreasing between those with access to the Internet and those without, the meaning of the term digital divide is evolving.[145] Previously, digital divide research was focused on accessibility to the Internet and Internet consumption. However, with an increasing number of the population gaining access to the Internet, researchers are examining how people use the Internet to create content and what impact socioeconomics are having on user behavior.[155] New applications have made it possible for anyone with a computer and an Internet connection to be a creator of content, yet the majority of user-generated content available widely on the Internet, like public blogs, is created by a small portion of the Internet-using population. Web 2.0 technologies like Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Blogs enable users to participate online and create content without having to understand how the technology actually works, leading to an ever-increasing digital divide between those who have the skills and understanding to interact more fully with the technology and those who are passive consumers of it.[154] Some of the reasons for this production gap include material factors like the type of Internet connection one has and the frequency of access to the Internet. The more frequently a person has access to the Internet and the faster the connection, the more opportunities they have to gain the technology skills and the more time they have to be creative.[156] Other reasons include cultural factors often associated with class and socioeconomic status. Users of lower socioeconomic status are less likely to participate in content creation due to disadvantages in education and lack of the necessary free time for the work involved in blog or website creation and maintenance.[156] Additionally, there is evidence to support the existence of the second-level digital divide at the K-12 level based on how educators' use technology for instruction.[157] Schools' economic factors have been found to explain variation in how teachers use technology to promote higher-order thinking skills.[157] |

解決策 2000年、国連ボランティア計画(UNV)はオンライン・ボランティアサービスを開始した[129]。これはICTをボランティア活動の手段かつ支援と して活用するものである。デジタルデバイドの解消に効果的に寄与するボランティア活動の事例と言える。ICTを活用したボランティア活動は、開発にとって 明らかな付加価値を持つ。より多くの人々がオンラインでより多くの開発機関やイニシアチブと協力すれば、実質的に追加コストをかけずに開発協力に充てられ る人時が増加する。これが人間開発におけるオンライン・ボランティアの最も顕著な効果である[130]。 2006年5月17日以降、国連は「世界情報社会デー」を通じてこの格差への認識を高めてきた[131]。2001年には情報通信技術(ICT)タスク フォースを設置した[132]。その後、この分野における国連の取り組みとして、2003年以降開催されている「世界情報社会サミット」と、2006年に 設立された「インターネットガバナンスフォーラム」がある。 2009年時点で、ICTが必需品となる境界線と贅沢品となる境界線は、おおよそ1人格あたり月額10米ドル、年間120米ドルであった[65]。これ は、年間120米ドルのICT支出が基本的な必要経費と見なされることを意味する。世界人口の40%以上が1日2ドル未満で生活し、約20%が1日1ドル 未満(年間365ドル未満)で生活していることから、これらの所得層は収入の3分の1をICTに費やす必要がある(120/365 = 33%)。世界のICT支出平均は収入のわずか3%である。[65] 解決策としては、低コスト技術の導入やテレセンターを通じた共有アクセスなど、ICTコストの削減が挙げられる。[133][134] 2022年、米国連邦通信委員会は「デジタル格差を防止・解消し、インフラ投資雇用法における議会の指示に沿って、全米の人々がブロードバンドインターネットサービスへの平等なアクセスを享受できるよう確保する」手続きを開始した。[135] ソーシャルメディアサイトは、デジタルデバイドの現れであると同時に、それを解消する手段でもある。前者は、Facebook、WordPress、 Instagramなどのサイトを構成するユーザー層の分断といった現象を指す。これらのサイトはそれぞれ、他の場では疎外されがちな人々と交流するコ ミュニティをホストしている。 図書館  テキサスA&M大学コマース校ジー図書館のノートパソコン貸出キオスク 2010年、南アフリカ・ダーバンでは「公共図書館サービスの一環としてのオンライン先住民デジタル図書館」が創設された。これはダーバン地域住民にデジ タル資源へのアクセスを提供するだけでなく、コミュニティメンバーをその構築プロセスに組み込むことでデジタル格差の解消を目指したものである。 [136] 2002年、ゲイツ財団は図書館向け研修支援・指導を提供する「ゲイツ図書館イニシアチブ」を開始した[137]。「デジタル政策の構造改革、公平なプラットフォーム設計、手頃な価格の接続環境は、地域イニシアチブと並行して必要である」[138][92] ケニアでは、資金不足、言語障壁、技術リテラシーの欠如が、コンピュータースキルと教育進歩の全体的な不足を招いていた。この状況は、外国投資が始まると 徐々に変化し始めた。[139][140] 2000年代初頭、カーネギー財団はケニア国立図書館サービスを通じた活性化プロジェクトに資金を提供した。これらの資源により、公共図書館は利用者に対 して情報通信技術を提供できるようになった。2012年には、ブシアとキベリア地域の公共図書館が、小学校のカリキュラムを補完する技術資源を導入した。 2013年までに、このプログラムは10校に拡大した。[141] 効果的な利用 個人がインターネットにアクセスできる能力を持っていても、インフラへの手段の不足や、インターネットが提供する情報を理解・制限できないといった参入障 壁に阻まれる場合が多い。接続はできても、ICTやインターネット技術が提供する情報を活用する知識を持たない個人もいる。このため、単なるアクセスから ICTの効果的な利用へ移行するには、能力やスキル、そして意識の向上が焦点となる。[142] コミュニティ情報学(CI)は「アクセス」よりも「利用」の問題に焦点を当てる。CIは、コミュニティレベルでのICTアクセス機会を確保することだけで なく、マイケル・ガーシュタインによれば、コミュニティの改善とエンパワーメントのためのICTの「効果的な活用」手段が利用可能であることも重視する。 [143] ガーシュタインはまた、デジタルデバイドの議論を「オープンデータ」へのアクセスと利用に関する問題にまで拡大し、この問題領域を指すために「データデバ イド」という用語を提唱した。[144] 批判 知識格差 性別、年齢、人種、所得、教育水準によるデジタル格差は過去に比べ縮小しているため、一部の研究者はデジタル格差がICTへのアクセス・接続性の差から知 識格差へと移行しつつあると指摘する[145]。技術に関する知識格差は、格差がICTへのアクセスや接続資源の有無を超え、接続後に提示される情報の解 釈・理解能力へと移行した可能性を示唆している。[146] しかし、米国におけるインターネットアクセスに関するデジタル格差の研究では、インターネットアクセスの平等化が進んでも知識格差や教育格差が縮小した証 拠は見つかっていない。[153]:「スキル、利用の自律性、関与の目的がユーザーが得る利益を形作り、より広範な社会的不平等を強化している。」 [78] 第二段階のデジタルデバイド 第二段階のデジタルデバイド(生産格差とも呼ばれる)は、インターネット上のコンテンツ消費者と生産者を分断する格差を指す。[154] インターネットへのアクセス有無による技術的デジタルデバイドが縮小する中、デジタルデバイドの概念は変化しつつある。[145] 従来、デジタルデバイド研究はインターネットへのアクセス可能性と消費に焦点が当てられていた。しかし、インターネットにアクセスできる人口が増えるにつ れ、研究者は人民がインターネットをどのように利用してコンテンツを創造しているか、また社会経済的要因がユーザーの行動にどのような影響を与えているか を検証している。[155] 新しいアプリケーションにより、コンピューターとインターネット接続さえあれば誰でもコンテンツの創造者になれるようになった。しかし、公開ブログのよう にインターネット上で広く利用可能なユーザー生成コンテンツの大部分は、インターネット利用人口のごく一部によって作成されている。Facebook、 YouTube、Twitter、ブログといったWeb 2.0技術は、ユーザーが技術の仕組みを理解せずともオンライン参加やコンテンツ作成を可能にし、技術とより深く関わるスキルや理解を持つ者と、受動的な 消費者との間のデジタルデバイドを拡大させている。[154] この生産格差が生じる理由には、インターネット接続の種類やアクセス頻度といった物質的要因が含まれる。インターネットへのアクセス頻度が高く、接続速度が速いほど、人格が技術スキルを習得する機会が増え、創造的な活動に充てる時間も増える。[156] その他の理由には、階級や社会経済的地位と関連する文化的要因が含まれる。社会経済的地位が低いユーザーは、教育面での不利や、ブログやウェブサイトの作 成・維持に必要な作業に充てる自由時間の不足から、コンテンツ制作に参加する可能性が低い。[156]さらに、教育者が指導に技術を活用する方法に基づけ ば、K-12レベル(小学校から高校まで)における第二段階のデジタルデバイドの存在を裏付ける証拠がある。[157] 学校の経済的要因が、教師が技術を活用して高次思考スキルを促進する方法の差異を説明することが判明している。[157] |

| Achievement gap Civic opportunity gap Computer technology for developing areas Digital divide by country Digital divide in Canada Digital divide in China Digital divide in South Africa Digital divide in Thailand Digital rights in the Caribbean Digital inclusion Digital rights Global Internet usage Government by algorithm Information society International communication Internet geography Internet governance List of countries by Internet connection speeds Light-weight Linux distribution Literacy National broadband plans from around the world NetDay Net neutrality Rural Internet Satellite internet Starlink Groups devoted to digital divide issues Center for Digital Inclusion Digital Textbook a South Korean Project that intends to distribute tablet notebooks to elementary school students. Inveneo Michelson 20MM Foundation TechChange United Nations Information and Communication Technologies Task Force |

学力格差 市民参加の機会格差 発展途上地域向けコンピューター技術 国別のデジタルデバイド カナダのデジタルデバイド 中国のデジタルデバイド 南アフリカのデジタルデバイド タイのデジタルデバイド カリブ海のデジタル権利 デジタルインクルージョン デジタル権利 世界のインターネット利用状況 アルゴリズムによる統治 情報社会 国際通信 インターネット地理学 インターネットガバナンス インターネット接続速度別国一覧 軽量Linuxディストリビューション 識字率 世界各国の国家ブロードバンド計画 ネットデイ ネット中立性 地方インターネット 衛星インターネット スターリンク デジタルデバイド問題に取り組む団体 デジタルインクルージョンセンター デジタル教科書:韓国が小学生にタブレット端末を配布する計画。 インベネオ ミシェルソン20MM財団 テックチェンジ 国連情報通信技術タスクフォース |

| Sources This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from I'd blush if I could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education, UNESCO, EQUALS Skills Coalition, UNESCO. UNESCO. Citations The British Museum. "Our Earliest Technology?" Smarthistory. Accessed October 12, 2022. Our earliest technology? – Smarthistory. What Is The Digital Divide and How Is It Being Bridged? Wise, Jason. "How Many People Own Televisions in 2022? (Ownership Stats)." EarthWeb, September 6, 2022. How Many People Own Televisions in 2022? (Ownership Stats) – EarthWeb. Published by Statista Research Department, and Sep 20. "Internet and Social Media Users in the World 2022." Statista, September 20, 2022. Internet and social media users in the world 2022. Bibliography Borland, J. (April 13, 1998). "Move Over Megamalls, Cyberspace Is the Great Retailing Equalizer". Knight Ridder/Tribune Business News. Brynjolfsson, Erik; Smith, Michael D. (October 2001). "The great equalizer? : consumer choice behavior at Internet shopbots". Sloan Working Papers. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.198.8755. hdl:1721.1/48027. James, J. (2004). Information Technology and Development: A new paradigm for delivering the Internet to rural areas in developing countries. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32632-X (print). ISBN 0-203-32550-8 (e-book). Southwell, B. G. (2013). Social networks and popular understanding of science and health: sharing disparities. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-1324-2 (book). World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS), 2005. "What's the state of ICT access around the world?" Retrieved July 17, 2009. World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS), 2008. "ICTs in Africa: Digital Divide to Digital Opportunity". Retrieved July 17, 2009. |

出典 本記事はフリーコンテンツ作品からのテキストを組み込んでいる。CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO ライセンス下。テキストは「教育を通じてデジタルスキルにおけるジェンダー格差を解消する:もし赤面できるなら恥ずかしい」より引用。ユネスコ、 EQUALSスキル連合、ユネスコ。ユネスコ。 引用 大英博物館。「最古の技術とは?」Smarthistory。2022年10月12日閲覧。最古の技術か? – Smarthistory. デジタルデバイドとは何か?そしてそれはどう埋められるのか? ワイズ、ジェイソン。「2022年にテレビを所有する人は何人か?(所有統計)」EarthWeb、2022年9月6日。2022年にテレビを所有する人は何人か?(所有統計) – EarthWeb. Statistaリサーチ部門、2022年9月20日発行。「世界のインターネット・ソーシャルメディア利用者数 2022年」。Statista、2022年9月20日。世界のインターネット・ソーシャルメディア利用者数 2022年。 参考文献 Borland, J. (1998年4月13日). 「巨大ショッピングモールよ、退け。サイバースペースこそが小売業界の平等化装置だ」. Knight Ridder/Tribune Business News. Brynjolfsson, Erik; Smith, Michael D. (2001年10月). 「平等化装置か?:インターネット・ショップボットにおける消費者の選択行動」. Sloan Working Papers. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.198.8755. hdl:1721.1/48027. James, J. (2004). 『情報技術と開発:途上国農村地域へのインターネット普及に向けた新たなパラダイム』. ニューヨーク: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32632-X (印刷版). ISBN 0-203-32550-8 (電子書籍)。 サウスウェル、B. G. (2013)。ソーシャルネットワークと科学および健康に関する大衆の理解:格差の共有。メリーランド州ボルチモア:ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学出版局。ISBN 978-1-4214-1324-2 (書籍)。 世界情報社会サミット(WSIS)、2005年。「世界におけるICTアクセスの現状は?」 2009年7月17日取得。 世界情報社会サミット(WSIS)、2008年。「アフリカのICT:デジタルデバイドからデジタルチャンスへ」 2009年7月17日取得。 |

| Further reading "Falling Through the Net: Defining the Digital Divide" (PDF Archived 2011-06-09 at the Wayback Machine), NTIS, U.S. Department of Commerce, July 1999. DiMaggio, P. & Hargittai, E. (2001). "From the "Digital Divide" to 'Digital Inequality': Studying Internet Use as Penetration Increases", Working Paper No. 15, Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies, Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University. Retrieved May 31, 2009. Foulger, D. (2001). "Seven bridges over the global digital divide" Archived May 9, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. IAMCR & ICA Symposium on Digital Divide, November 2001. Retrieved July 17, 2009. Rogers, Everett M. (2001). "The Digital Divide". Convergence. 7 (4): 96–111. doi:10.1177/135485650100700406. Chen, W.; Wellman, B. (2004). "The global digital divide within and between countries" (PDF). IT & Society. 1 (7): 39–45. Council of Economic Advisors (2015). Mapping the Digital Divide. "A Nation Online: Entering the Broadband Age", NTIS, U.S. Department of Commerce, September 2004. James, J (2005). "The global digital divide in the Internet: developed countries constructs and Third World realities". Journal of Information Science. 31 (2): 114–23. doi:10.1177/0165551505050788. S2CID 42678504. Rumiany, D. (2007). "Reducing the Global Digital Divide in Sub-Saharan Africa" Archived October 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Posted on Global Envision with permission from Development Gateway, January 8, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2009. "Telecom use at the Bottom of the Pyramid 2 (use of telecom services and ICTs in emerging Asia)", LIRNEasia, 2007. "Telecom use at the Bottom of the Pyramid 3 (Mobile2.0 applications, migrant workers in emerging Asia)", LIRNEasia, 2008–09. "São Paulo Special: Bridging Brazil's digital divide", Digital Planet, BBC World Service, October 2, 2008. Graham, M. (2009). "Global Placemark Intensity: The Digital Divide Within Web 2.0 Data", Floatingsheep Blog. Graham, M (2011). "Time Machines and Virtual Portals: The Spatialities of the Digital Divide". Progress in Development Studies. 11 (3): 211–227. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.659.9379. doi:10.1177/146499341001100303. S2CID 17281619. Yfantis, V. (2017). Disadvantaged Populations And Technology In Music. ISBN 978-1-4927-2862-7 Lythreatis, Sophie; Singh, Sanjay Kumar; El-Kassar, Abdul-Nasser (2022). "The digital divide: A review and future research agenda". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 175 121359. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121359. |

参考文献 「ネットの隙間から落ちる:デジタルデバイドの定義」(PDF 2011年6月9日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ)、NTIS、米国商務省、1999年7月。 DiMaggio, P. & Hargittai, E. (2001). 「『デジタルデバイド』から『デジタル不平等』へ:普及率の増加に伴うインターネット利用の研究」, ワーキングペーパー No. 15, 芸術文化政策研究センター, ウッドロー・ウィルソン・スクール, プリンストン大学. 2009年5月31日取得. Foulger, D. (2001). 「グローバルなデジタルデバイドを乗り越える 7 つの橋」 2021年5月9日、ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ。IAMCR & ICA デジタルデバイドに関するシンポジウム、2001年11月。2009年7月17日取得。 ロジャース、エベレット M. (2001). 「デジタルデバイド」. コンバージェンス. 7 (4): 96–111. doi:10.1177/135485650100700406. チェン、W.; ウェルマン、B. (2004). 「国内および国家間のグローバルなデジタルデバイド」 (PDF). IT & Society. 1 (7): 39–45. 経済諮問委員会 (2015). デジタルデバイドの地図化. 「オンライン国民:ブロードバンド時代への突入」, NTIS, 米国商務省, 2004年9月. James, J (2005). 「インターネットにおける世界的なデジタルデバイド:先進国の構築と第三世界の現実」. Journal of Information Science. 31 (2): 114–23. doi:10.1177/0165551505050788. S2CID 42678504. ルミャニ、D.(2007)。「サハラ以南アフリカにおけるグローバルなデジタルデバイドの縮小」Archived October 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine。Development Gatewayの許可を得てGlobal Envisionに掲載、2007年1月8日。2009年7月17日取得。 「ピラミッド底辺層における通信利用2(新興アジアにおける通信サービスとICTの利用)」、LIRNEasia、2007年。 「ピラミッド底辺層における通信利用3(モバイル2.0アプリケーション、新興アジアの移民労働者)」、LIRNEasia、2008-09年。 「サンパウロ特集:ブラジルのデジタル格差を埋める」『デジタル・プラネット』BBCワールドサービス、2008年10月2日。 Graham, M. (2009). 「グローバルな場所情報の密度:Web 2.0データ内のデジタル格差」『Floatingsheep Blog』。 Graham, M (2011). 「タイムマシンと仮想ポータル:デジタルデバイドの空間性」. 開発研究の進歩. 11 (3): 211–227. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.659.9379. doi:10.1177/146499341001100303. S2CID 17281619. イファンティス, V. (2017). 『音楽における恵まれない層と技術』. ISBN 978-1-4927-2862-7 Lythreatis, Sophie; Singh, Sanjay Kumar; El-Kassar, Abdul-Nasser (2022). 「デジタル・ディバイド:レビューと将来の研究課題」. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 175 121359. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121359. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_divide |

☆

リンク

▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099