談話分析

Discourse analysis, DA, だんわぶんせき

| Discourse analysis

(DA), or discourse studies, is an approach to the analysis of written,

vocal, or sign language use, or any significant semiotic event. The objects of discourse analysis (discourse, writing, conversation, communicative event) are variously defined in terms of coherent sequences of sentences, propositions, speech, or turns-at-talk. Contrary to much of traditional linguistics, discourse analysts not only study language use 'beyond the sentence boundary' but also prefer to analyze 'naturally occurring' language use, not invented examples.[1] Text linguistics is a closely related field. The essential difference between discourse analysis and text linguistics is that discourse analysis aims at revealing socio-psychological characteristics of a person/persons rather than text structure.[2] Discourse analysis has been taken up in a variety of disciplines in the humanities and social sciences, including linguistics, education, sociology, anthropology, social work, cognitive psychology, social psychology, area studies, cultural studies, international relations, human geography, environmental science, communication studies, biblical studies, public relations, argumentation studies, and translation studies, each of which is subject to its own assumptions, dimensions of analysis, and methodologies. |

談話分析=言説分析(DA)、または談話学は、書き言葉、話し言葉、手

話、またはあらゆる重要な記号論的事象を分析するアプローチである。 談話分析の対象(談話、文章、会話、コミュニケーション・イベント) は、文章、命題、スピーチ、ターン・アット・トークの一貫した一連の流れなど、さまざまに定義される。伝統的な言語学の多くとは異なり、談 話分析家は「文の境界を超えた」言語使用を研究するだけでなく、作り出された例ではなく「自然に発生する」言語使用を分析することを好む[1]。談話分析 とテキスト言語学の本質的な違いは、談話分析がテキストの構造よりもむしろ、人/人物の社会心理学的特徴を明らかにすることを目的としていることである [2]。 談話分析は、言語学、教育学、社会学、人類学、ソーシャルワーク、認知心理学、社会心理学、地域研究、文化研究、国際関係学、人文地理学、環境科学、コ ミュニケーション学、聖書学、パブリック・リレーションズ、議論学、翻訳学など、人文科学や社会科学のさまざまな分野で取り上げられており、それぞれが独 自の前提、分析の次元、方法論を持っている。 |

| History Early use of the term The ancient Greeks (among others) had much to say on discourse; however, there is ongoing discussion about whether Austria-born Leo Spitzer's Stilstudien (Style Studies) of 1928 is the earliest example of discourse analysis (DA). Michel Foucault translated it into French.[3] However, the term first came into general use following the publication of a series of papers by Zellig Harris from 1952[citation needed] reporting on work from which he developed transformational grammar in the late 1930s. Formal equivalence relations among the sentences of a coherent discourse are made explicit by using sentence transformations to put the text in a canonical form. Words and sentences with equivalent information then appear in the same column of an array. This work progressed over the next four decades (see references) into a science of sublanguage analysis (Kittredge & Lehrberger 1982), culminating in a demonstration of the informational structures in texts of a sublanguage of science, that of Immunology, (Harris et al. 1989)[4] and a fully articulated theory of linguistic informational content (Harris 1991).[5] During this time, however, most linguists ignored such developments in favor of a succession of elaborate theories of sentence-level syntax and semantics.[6] In January 1953, a linguist working for the American Bible Society, James A. Lauriault/Loriot, needed to find answers to some fundamental errors in translating Quechua, in the Cuzco area of Peru. Following Harris's 1952 publications, he worked over the meaning and placement of each word in a collection of Quechua legends with a native speaker of Quechua and was able to formulate discourse rules that transcended the simple sentence structure. He then applied the process to Shipibo, another language of Eastern Peru. He taught the theory at the [7] Summer Institute of Linguistics in Norman, Oklahoma, in the summers of 1956 and 1957 and entered the [8] University of Pennsylvania to study with Harris in the interim year. He tried to publish a paper [9]Shipibo Paragraph Structure, but it was delayed until 1970 (Loriot & Hollenbach 1970).[citation needed] In the meantime, Kenneth Lee Pike, a professor at University of Michigan,[10] Ann Arbor, taught the theory, and one of his students, Robert E. Longacre developed it in his writings. Harris's methodology disclosing the correlation of form with meaning was developed into a system for the computer-aided analysis of natural language by a team led by Naomi Sager at NYU, which has been applied to a number of sublanguage domains, most notably to medical informatics. The software for the Medical Language Processor is publicly available on SourceForge. |

歴史 用語の初期の使用 しかし、オーストリア生まれのレオ・スピッツァーが1928年に発表した『スタイル研究』(Stilstudien)が談話分析(DA)の最も古い例であるかどうかについては議論が続いている。ミ シェル・フーコーがこれをフランス語に翻訳した[3]。しかし、この用語が最初に一般的に使われるようになったのは、ゼリグ・ハリスが1930年代後半に変形文法を開発した研究を報告する一連の論文を1952年に発表 した後である[要出典]。首尾一貫した談話の文の間の形式的な等価関係は、文の変換を使用してテキストを正規形にすることによって明示され る。等価な情報を持つ単語と文は、配列の同じ列に表示される。 この研究はその後40年にわたり(参考文献を参照)、下位言語分析の科学へと発展し(Kittredge & Lehrberger 1982)、最終的には科学の下位言語である免疫学のテキストにおける情報構造の実証(Harris et al. 1953年1月、アメリカ聖書協会で働く言語学者ジェームズ・A・ローリエ(James A. Lauriault/Loriot)は、ペルーのクスコ地域でケチュア語を翻訳する際の根本的な誤りに対する答えを見つける必要があった。ハリスが1952年に発表した論文に従って、彼はケチュア語のネイティブ・スピーカーとケチュ ア語の伝説集の各単語の意味と配置を検討し、単純な文構造を超越した談話規則を定式化することができた。そして、そのプロセスをペルー東部 のもうひとつの言語であるシピボ語に適用した。彼は1956年と 1957年の夏にオクラホマ州ノーマンの言語学夏季研究所 [7] でこの理論を教え、その中間年にペンシルバニア大学に入学したハリスは 彼に師事した。彼(ハリス?)は論文[9]Shipibo Paragraph Structureを発表しようとしたが、それは1970年まで延期された(Loriot & Hollenbach 1970)[要出典]。その間にミシガン大学アナーバー校の教授であったケネス・ リー・パイク[10]がこの理論を教え、彼の教え子の一人であるロバート・E・ロングエーカーは著作の中でこの理論を発展させた。形と意味 の相関関係を明らかにしたハリスの方法論は、ニューヨーク大学のナオミ・セイガー率いるチームによって、自然言語のコンピュータ支援分析システムとして開 発され、多くのサブ言語領域、特に医療情報学に応用された。Medical Language ProcessorのソフトウェアはSourceForgeで公開されている。 |

| In the humanities In the late 1960s and 1970s, and without reference to this prior work, a variety of other approaches to a new cross-discipline of DA began to develop in most of the humanities and social sciences concurrently with, and related to, other disciplines. These include semiotics, psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics, and pragmatics. Many of these approaches, especially those influenced by the social sciences, favor a more dynamic study of oral talk-in-interaction. An example is [11]"conversational analysis", which was influenced by the Sociologist Harold Garfinkel,[12] the founder of Ethnomethodology. |

人文科学において 1960年代後半から1970年代にかけて、このような先行研究を参照することなく、人文科学や社会科学の大部分において、他の学問分野と同時並行的に、 また他の学問分野と関連しながら、新しい分野横断的なDAへの様々なアプローチが展開され始めた。記号論、心理言語学、社会言語学、語用論などである。こ れらのアプローチ、特に社会科学の影響を受けたアプローチの多くは、口頭での会話-相互作用のよりダイナミックな研究を支持している。例えば、[11] 「会話分析」は、エスノメソドロジーの創始者である社会学者ハロルド・ガーフィンケル[12]の影響を受けている。 |

| Foucault In Europe, Michel Foucault became one of the key theorists of the subject, especially of discourse, and wrote The Archaeology of Knowledge. In this context, the term 'discourse' no longer refers to formal linguistic aspects, but to institutionalized patterns of knowledge that become manifest in disciplinary structures and operate by the connection of knowledge and power. Since the 1970s, Foucault's works have had an increasing impact especially on discourse analysis in the field of social sciences. Thus, in modern European social sciences, one can find a wide range of different approaches working with Foucault's definition of discourse and his theoretical concepts. Apart from the original context in France, there is, since 2005, a broad discussion on socio-scientific discourse analysis in Germany. Here, for example, the sociologist Reiner Keller developed his widely recognized 'Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse (SKAD)'.[13] Following the sociology of knowledge by Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, Keller argues that our sense of reality in everyday life and thus the meaning of every object, action and event is the product of a permanent, routinized interaction. In this context, SKAD has been developed as a scientific perspective that is able to understand the processes of 'The Social Construction of Reality' on all levels of social life by combining the prementioned Michel Foucault's theories of discourse and power while also introducing the theory of knowledge by Berger/Luckmann. Whereas the latter primarily focus on the constitution and stabilization of knowledge on the level of interaction, Foucault's perspective concentrates on institutional contexts of the production and integration of knowledge, where the subject mainly appears to be determined by knowledge and power. Therefore, the 'Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse' can also be seen as an approach to deal with the vividly discussed micro–macro problem in sociology.[citation needed] |

フーコー派による言説分析 ヨーロッパでは、ミシェル・フーコーが主体、特に言説の重要な理論家の一人となり、『知の考古学』を著した。この文脈では、「言説」という用語はもはや形 式的な言語的側面(すなわち談話分析(DA)の対象)を指すのではなく、学問的構造の中で顕在化し、知識と権力の結びつきによって作用する、制度化された 知識のパターンを指す。1970年代以降、フーコーの著作は、特に社会科学の分野における言説分析に大きな影響を与えるようになった。そのため、現代の ヨーロッパの社会科学では、フーコーの言説の定義や理論的概念を用いたさまざまなアプローチが見られる。フランスにおける当初の文脈とは別に、2005年 以降、ドイツでは社会科学的な言説分析に関する幅広い議論が行われている。例えば、社会学者のライナー・ケラーは、広く認知された「言説への知識社会学的 アプローチ(SKAD)」を開発した[13]。ケラーは、ピーター・L・バーガーとトーマス・ルックマンによる知識社会学に倣い、日常生活におけるわれわ れの現実感、ひいてはあらゆる対象、行為、出来事の意味は、永続的で日常化された相互作用の産物であると主張している。この文脈においてSKADは、前述 のミシェル・フーコーの言説論と権力論を組み合わせつつ、バーガーとルックマンの知識論を導入することで、社会生活のあらゆるレベルにおける「現実の社会 的構築」のプロセスを理解できる科学的な視点として発展してきた。後者が主に相互作用のレベルでの知識の構成と安定化に焦点を当てるのに対し、フーコーの 視点は知識の生産と統合の制度的文脈に集中し、そこでは主体が主に知識と権力によって決定されるように見える。したがって、「言説への知識社会学的アプ ローチ」は、社会学において鮮明に議論されているミクロ-マクロ問題に対処するためのアプローチとしても見ることができる[要出典]。 |

| Perspectives The following are some of the specific theoretical perspectives and analytical approaches used in linguistic discourse analysis: Applied linguistics, an interdisciplinary perspective on linguistic analysis[14] Cognitive neuroscience of discourse comprehension[15][16] Cognitive psychology, studying the production and comprehension of discourse. Conversation analysis Critical discourse analysis Discursive psychology Emergent grammar Ethnography of communication Functional grammar Interactional sociolinguistics Mediated Stylistics Pragmatics Response based therapy (counselling) Rhetoric Stylistics (linguistics) Sublanguage analysis Tagmemics Text linguistics Variation analysis Although these approaches emphasize different aspects of language use, they all view language as social interaction and are concerned with the social contexts in which discourse is embedded. Often a distinction is made between 'local' structures of discourse (such as relations among sentences, propositions, and turns) and 'global' structures, such as overall topics and the schematic organization of discourses and conversations. For instance, many types of discourse begin with some kind of global 'summary', in titles, headlines, leads, abstracts, and so on. A problem for the discourse analyst is to decide when a particular feature is relevant to the specification required. A question many linguists ask is: "Are there general principles which will determine the relevance or nature of the specification?[17]"[citation needed] |

|

| Topics of interest Topics of discourse analysis include:[18] The various levels or dimensions of discourse, such as sounds (intonation, etc.), gestures, syntax, the lexicon, style, rhetoric, meanings, speech acts, moves, strategies, turns, and other aspects of interaction Genres of discourse (various types of discourse in politics, the media, education, science, business, etc.) The relations between discourse and the emergence of syntactic structure The relations between text (discourse) and context The relations between discourse and power[19] The relations between discourse and interaction The relations between discourse and cognition and memory |

|

| Prominent academics Marc Angenot Johannes Angermuller Mikhail Bakhtin Roland Barthes Émile Benveniste Jean-Paul Benzécri Jan Blommaert Georges Canguilhem Teun van Dijk Oswald Ducrot Norman Fairclough Michel Foucault Heidi E. Hamilton Roman Jakobson Barbara Johnstone Dominique Maingueneau Sinfree Makoni Damon Mayaffre Michel Pêcheux Jonathan Potter Paul Ricœur Georges-Elia Sarfati Ferdinand de Saussure Deborah Schiffrin Deborah Tannen Margaret Wetherell Ruth Wodak |

|

| Political discourse Political discourse is the text and talk of professional politicians or political institutions, such as presidents and prime ministers and other members of government, parliament or political parties, both at the local, national and international levels, includes both the speaker and the audience.[20] Political discourse analysis is a field of discourse analysis which focuses on discourse in political forums (such as debates, speeches, and hearings) as the phenomenon of interest. Policy analysis requires discourse analysis to be effective from the post-positivist perspective.[21][22] Political discourse is the formal exchange of reasoned views as to which of several alternative courses of action should be taken to solve a societal problem.[23][24] |

|

| Corporate discourse Corporate discourse can be broadly defined as the language used by corporations. It encompasses a set of messages that a corporation sends out to the world (the general public, the customers and other corporations) and the messages it uses to communicate within its own structures (the employees and other stakeholders).[25] |

|

| See also Actor (policy debate) Critical discourse analysis Dialogical analysis Discourse representation theory Frame analysis Communicative action Essex School of discourse analysis Ethnolinguistics Foucauldian discourse analysis Interpersonal communication Linguistic anthropology Narrative analysis Pragmatics Rhetoric Sociolinguistics Statement analysis Stylistics (linguistics) Worldview |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discourse_analysis |

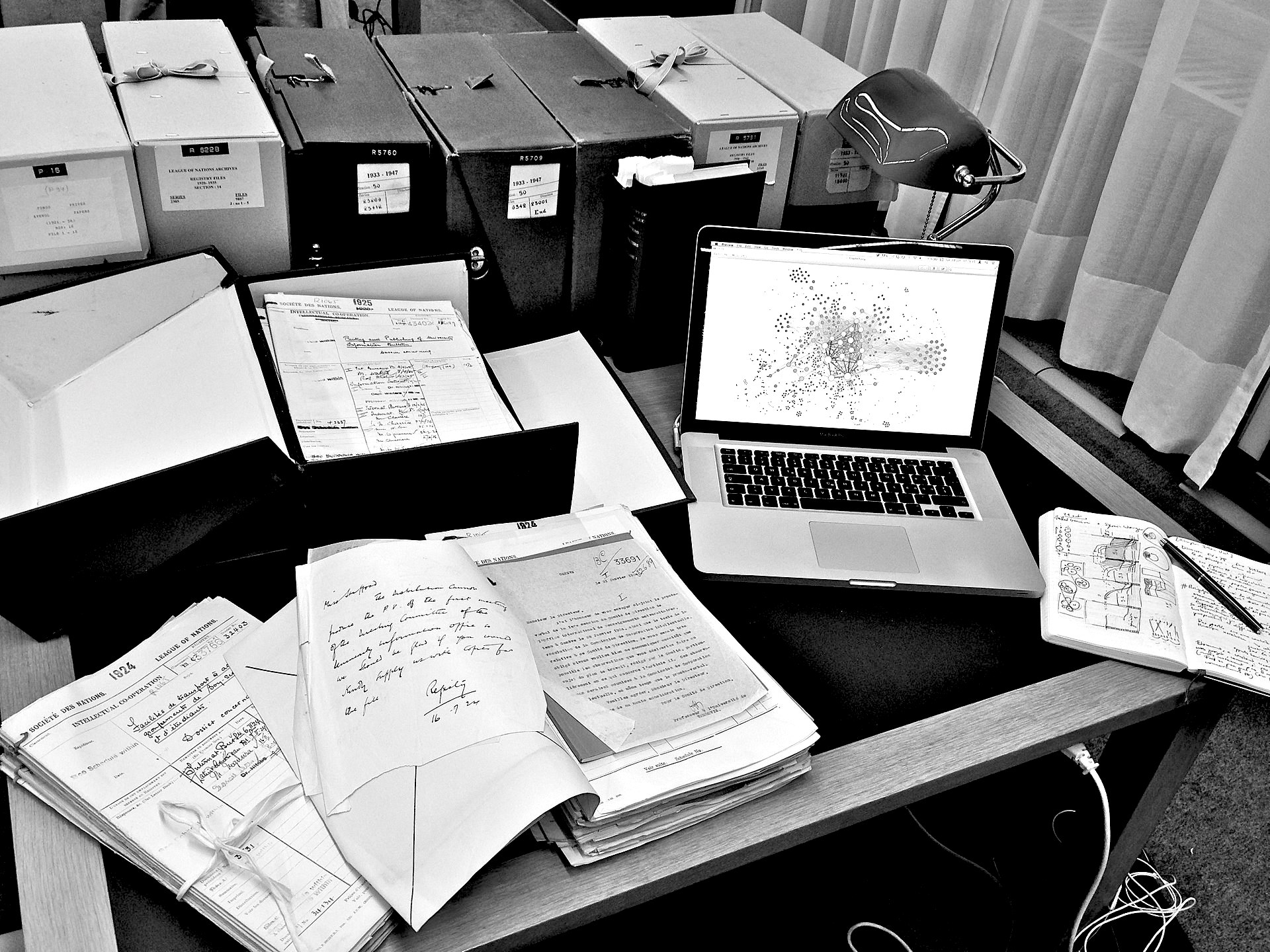

Illustration

of the epistemologic changes of the 'digital humanities': archives

organized with network visualization and analysis. League of Nations

Archives (UN Geneva). GRANDJEAN Martin, The Networks of Intellectual

Cooperation. The League of Nations as an Actor of the Scientific and

Cultural Exchanges in the Inter-War Period, University of Lausanne,

2018, 600 p. (PDF)

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099