マヤ・デレン「ディヴァイン・ホースメン」

Divine Horsemen, by Maya Deren

Divine

Horsemen The Living Gods of Haiti by Maya Deren

☆ マヤ・デレン(/ˈdɛˈ; Eleonora Derenkovskaya; ウクライナ語: Елеоно́ра Деренко́вська; May 12 [O.S. April 29] 1917[1] - 1961年10月13日)は、ウクライナ生まれのアメリカ人実験映画作家であり、1940年代から1950年代にかけて前衛芸術の重要な一翼を担った。振 付家、ダンサー、映画理論家、詩人、講師、作家、写真家でもあった。 ダンスと振付、民族誌、アフリカの精霊信仰であるハイチ・ヴードゥー(1947-1951年撮影)、象徴主義詩、ゲシュタルト心理学(クルト・コフカの生徒として)の専門知識を、知覚 的なモノクロ短編映画のシリーズに融合させた。編集、多重露光、ジャンプ・カット、重ね合わせ、スローモーション、その他のカメラ・テクニックを駆使し て、デレンは物理的な空間と時間の既成概念を捨て去り、特定の概念的な目的をもって入念に計画された映画によって革新をもたらした[3][4]。 当時夫であったアレクサンダー・ハミッドとの共作である『午後のメッシュ』(1943年)は、アメリカ映画史において最も影響力のある実験映画のひとつで ある。デレンはその後、『At Land』(1944年)、『A Study in Choreography for Camera』(1945年)、『Ritual in Transfigured Time』(1946年)など、脚本、製作、監督、編集、撮影を、カメラマンのヘラ・ヘイマンただ一人の人格の助けを借りながら行った。

Divine horsemen : Voodoo gods of Haiti / Maya Deren ; preface, Joseph Campbell, Chelsea House , 1970 [国立民族学博物館]

1. 三位一体:屍体、ミステリー、マラサたち

2. 従者たち

3. 神聖なホースメン

4. フンガン(ホーガン)、ヒエラルキー、フントゥ(ドラムの霊)

5. 儀礼

6.ドラム(太鼓)とダンス

7. 白い暗闇

+++

| Haiti and Vodou When Maya Deren decided to make an ethnographic film in Haiti, she was criticized for abandoning avant-garde film where she had made her name, but she was ready to expand to a new level as an artist.[43][44] She had studied ethnographic footage by Gregory Bateson in Bali in 1947, and was interested in including it in her next film.[3] In September, she divorced Hammid and left for a nine-month stay in Haiti. The Guggenheim Fellowship grant in 1946 enabled Deren to finance her travel and film footage for what would posthumously become Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. She went on three additional trips through 1954 to document and record the rituals of Haitian Vodou. A source of inspiration for ritual dance was Katherine Dunham who wrote her master's thesis on Haitian dances in 1939, which Deren edited. While working as Dunham's assistant, Deren was given access to Dunham's archive which included 16mm documents on the dances in Trinidad and Haiti. Exposure to these documents led her to write her 1942 essay titled, "Religious Possession in Dancing."[45] Afterwards, Deren wrote several articles on religious possession in dancing before her first trip to Haiti.[46] Deren filmed, recorded and photographed many hours of Vodou ritual, but she also participated in the ceremonies. She documented her knowledge and experience of Vodou in Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti (New York: Vanguard Press, 1953), edited by Joseph Campbell, which is considered a definitive source on the subject. She described her attraction to Vodou possession ceremonies, transformation, dance, play, games and especially ritual came from her strong feeling on the need to decenter our thoughts of self, ego and personality.[8] In her book An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form, and Film she wrote: The ritualistic form treats the human being not as the source of the dramatic action, but as a somewhat depersonalized element in a dramatic whole. The intent of such depersonalization is not the destruction of the individual; on the contrary, it enlarges him beyond the personal dimension and frees him from the specializations and confines of personality. He becomes part of a dynamic whole which, like all such creative relationships, in turn, endow its parts with a measure of its larger meaning.[2] |

ハイチとヴードゥー 1947年、彼女はグレゴリー・ベイトソンの民族誌的映像をバリ島で学び、次回作に取り入れたいと考えていた[3] 。1946年にグッゲンハイム・フェローシップの助成金を得たことで、デレンは旅費と、死後に『ディヴァイン・ホースメン』となる作品の撮影資金を得るこ とができた: The Living Gods of Haiti』となる。彼女は1954年までさらに3回、ハイチ・ヴォドゥーの儀式を記録するために旅に出た。 儀式舞踊のインスピレーションの源は、1939年にハイチの舞踊について修士論文を書いたキャサリン・ダナムであり、デレンはその論文を編集した。ダンハ ムのアシスタントとして働いていたデレンは、トリニダードとハイチのダンスに関する16ミリフィルムを含むダンハムのアーカイブにアクセスする機会を与え られた。これらの資料に触れたことが、1942年に「ダンスにおける宗教的憑依」と題するエッセイを書くきっかけとなった[45]。その後、デレンは初め てハイチを訪れる前に、ダンスにおける宗教的憑依についていくつかの記事を書いた[46]。彼女はヴォドゥーに関する知識と経験を『ディヴァイン・ホース メン』に記録している: The Living Gods of Haiti (New York: Vanguard Press, 1953)』(ジョセフ・キャンベル編)に自分のヴォドゥーに関する知識と経験を記録している。彼女は、ヴードゥー憑依の儀式、変容、ダンス、遊び、ゲー ム、そして特に儀式に惹かれるのは、自己、エゴ、人格という思考を分離する必要性を強く感じているからだと述べている[8]: 儀式的な形式は、人間をドラマティックな行為の源としてではなく、ドラマティックな全体におけるいくぶん非人格化された要素として扱う。このような非人格 化の意図は、個人の破壊ではない。それどころか、個人的な次元を超えて人間を拡大し、人格の特殊化や束縛から解放する。彼はダイナミックな全体の一部とな り、そのような創造的な関係はすべてそうであるように、その部分により大きな意味の尺度を与えるのである[2]。 |

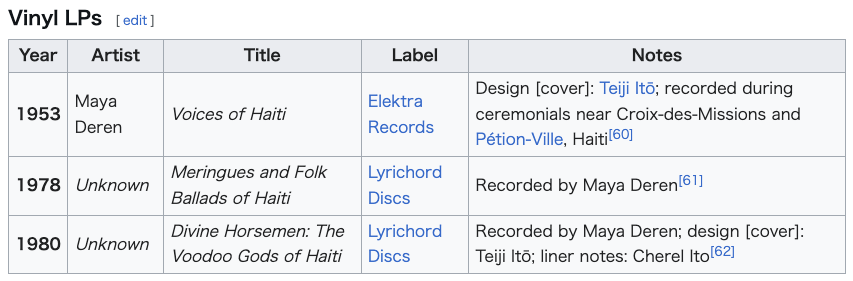

| Deren filmed 18,000 feet of

Vodou rituals and people she met in Haiti on her Bolex camera.[47] The

footage was incorporated into a posthumous documentary film Divine

Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti, edited and produced in 1977 (with

funding from Deren's friend James Merrill) by her ex-husband, Teiji Itō

(1935–1982), and his wife Cherel Winett Itō (1947–1999).[48][49][50]

All of the original wire recordings, photographs and notes are held in

the Maya Deren Collection at the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research

Center at Boston University. The film footage is housed at Anthology

Film Archives in New York City. An LP of some of Deren's wire recordings was published by the newly formed Elektra Records in 1953 entitled Voices of Haiti. The cover art for the album was by Teiji Itō.[51] Anthropologists Melville Herkovitz and Harold Courlander acknowledged the importance of Divine Horsemen, and in contemporary studies it is often cited as an authoritative voice, where Deren's methodology has been especially praised because "Vodou has resisted all orthodoxies, never mistaking surface representations for inner realities."[52] In her book of the same name[53] Deren uses the spelling Voudoun, explaining: "Voudoun terminology, titles and ceremonies still make use of the original African words and in this book they have been spelled out according to usual English phonetics and so as to render, as closely as possible, the Haitian pronunciation. Most of the songs, sayings and even some of the religious terms, however, are in Creole, which is primarily French in derivation (although it also contains African, Spanish and Indian words). Where the Creole word retains its French meaning, it has been written out so as to indicate both the original French word and the distinctive Creole pronunciation." In her Glossary of Creole Words, Deren includes 'Voudoun' while the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary[54] draws attention to the similar French word, Vaudoux. |

デレンは、ハイチで出会ったヴードゥーの儀式や人々を18,000

フィート(約12,000メートル)のボレックス・カメラで撮影した[47]。その映像は、彼女の遺作となったドキュメンタリー映画『ディヴァイン・ホー

スメン』に盛り込まれた:

デレンの元夫である伊藤悌二(1935-1982)とその妻チェレル・ウィネット伊藤(1947-1999)によって1977年に編集・制作された(デレ

ンの友人であるジェームズ・メリルの資金援助による)。[48][49][50]

オリジナルのワイヤー・レコーディング、写真、メモはすべて、ボストン大学のハワード・ゴットリーブ・アーカイバル・リサーチ・センターのマヤ・デレン・

コレクションに所蔵されている。フィルム映像はニューヨークのアンソロジー・フィルム・アーカイヴに所蔵されている。 1953年、デレンのワイヤ・レコーディングの一部を収録したLP『Voices of Haiti』が、設立されたばかりのエレクトラ・レコードから出版された。このアルバムのジャケット・アートは伊藤悌二によるものだった[51]。 人類学者のメルヴィル・ハルコヴィッツとハロルド・クールランダーは『ディヴァイン・ホースメン』の重要性を認めており、現代の研究においても権威ある声 としてしばしば引用されている。特にデレンの方法論は「ヴードゥーはあらゆる正統性に抵抗しており、表面的な表象を内面的な現実と取り違えることはなかっ た」という理由で賞賛されている[52]。 同名の著書[53]において、デレンはVoudounという綴りを使い、こう説明している: ヴードゥーンの専門用語、称号、儀式はいまだにオリジナルのアフリカ語を用いており、本書ではそれらを通常の英語音声学にしたがって綴り、可能な限りハイ チ語の発音に近づけるようにした」と説明している。しかし、歌や格言、宗教用語のほとんどはクレオール語であり、主にフランス語に由来する(アフリカ語、 スペイン語、インディアン語も含まれるが)。クレオール語の意味がフランス語のまま残っている場合は、元のフランス語とクレオール語独特の発音の両方を示 すように書き分けられている」。デレンの『クレオール語用語集』には「Voudoun」が収録されているが、『オックスフォード英英辞典』[54]では似 たようなフランス語の「Vaudoux」に注目している。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maya_Deren |

Still

from the experimental 1943 short film Meshes of the Afternoon by Maya

Deren. The still shows Deren looking out of a window.

| Maya Deren

(/ˈdɛrən/; born Eleonora Derenkovskaya; Ukrainian: Елеоно́ра

Деренко́вська; May 12 [O.S. April 29] 1917[1] – October 13, 1961) was a

Ukrainian-born American experimental filmmaker and important part of

the avant-garde in the 1940s and 1950s. Deren was also a choreographer,

dancer, film theorist, poet, lecturer, writer, and photographer. The function of film, Deren believed, was to create an experience.[2] She combined her expertise in dance and choreography, ethnography, the African spirit religion of Haitian Vodou, symbolist poetry and gestalt psychology (as a student of Kurt Koffka) in a series of perceptual, black-and-white short films. Using editing, multiple exposures, jump-cutting, superimposition, slow-motion, and other camera techniques to her advantage, Deren abandoned established notions of physical space and time, innovating through carefully planned films with specific conceptual aims.[3][4] Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), her collaboration with her husband at the time, Alexander Hammid, has been one of the most influential experimental films in American cinema history. Deren went on to make several more films, including but not limited to At Land (1944), A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945), and Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946), writing, producing, directing, editing, and photographing them with help from only one other person, Hella Heyman, her camerawoman. |

マヤ・デレン(/ˈdɛˈ; Eleonora

Derenkovskaya; ウクライナ語: Елеоно́ра Деренко́вська; May 12 [O.S. April 29]

1917[1] -

1961年10月13日)は、ウクライナ生まれのアメリカ人実験映画作家であり、1940年代から1950年代にかけて前衛芸術の重要な一翼を担った。振

付家、ダンサー、映画理論家、詩人、講師、作家、写真家でもあった。 ダンスと振付、民族誌、アフリカの精霊信仰であるハイチ・ヴードゥー、象徴主義詩、ゲシュタルト心理学(クルト・コフカの生徒として)の専門知識を、知覚 的なモノクロ短編映画のシリーズに融合させた。編集、多重露光、ジャンプ・カット、重ね合わせ、スローモーション、その他のカメラ・テクニックを駆使し て、デレンは物理的な空間と時間の既成概念を捨て去り、特定の概念的な目的をもって入念に計画された映画によって革新をもたらした[3][4]。 当時夫であったアレクサンダー・ハミッドとの共作である『午後のメッシュ』(1943年)は、アメリカ映画史において最も影響力のある実験映画のひとつで ある。デレンはその後、『At Land』(1944年)、『A Study in Choreography for Camera』(1945年)、『Ritual in Transfigured Time』(1946年)など、脚本、製作、監督、編集、撮影を、カメラマンのヘラ・ヘイマンただ一人の人格の助けを借りながら行った。 |

| Early life Deren was born May 12 [O.S. April 29] 1917 in Kiev, into a Jewish family,[5] to psychologist Solomon Derenkowsky and Gitel-Malka (Marie) Fiedler,[1] who supposedly named their daughter after Italian actress Eleonora Duse.[6][7] In 1922, the family fled the Ukrainian SSR because of antisemitic pogroms perpetrated by the White Volunteer Army and moved to Syracuse, New York. Her father shortened the family name from Derenkovskaya to "Deren" shortly after they arrived in New York.[8][9] He became the staff psychiatrist at the State Institute for the Feeble-Minded in Syracuse.[10] Deren's mother was a musician and dancer who had studied these arts in Kiev.[9] In 1928, Deren's parents became naturalized citizens of the United States.[5] Deren was highly intelligent, starting fifth grade at only eight years old.[9] She attended the League of Nations International School of Geneva, Switzerland for high school from 1930 to 1933.[11] Her mother moved to Paris, France to be nearer to her while she studied. Deren learned to speak French while she was abroad.[12] Deren enrolled at Syracuse University at sixteen, where she began studying journalism and political science.[13][9] Deren became a highly active socialist activist during the Trotskyist movement in her late teens.[3] She served as National Student Secretary in the National Student office of the Young People's Socialist League and was a member of the Social Problems Club at Syracuse University. At age eighteen in June 1935, she married Gregory Bardacke, a socialist activist whom she met through the Social Problems Club.[3] After his graduation in 1935, she moved to New York City. She finished school at New York University with a Bachelor's degree in literature in June 1936, and returned to Syracuse that fall.[8] She and Bardacke became active in various socialist causes in New York City; and it was during this time that they separated and eventually divorced three years later.[14] In 1938, Deren attended the New School for Social Research, and received a master's degree in English literature at Smith College.[15] Her Master's thesis was titled The Influence of the French Symbolist School on Anglo-American Poetry (1939).[16] This included works of Pound, Eliot, and the Imagists. By the age of 21, Deren had earned two degrees in literature.[12] |

生い立ち デレンは1917年5月12日[西暦4月29日]、キエフのユダヤ人家庭に、心理学者のソロモン・デレンコフスキーとギテル=マルカ(マリー)・フィード ラーの間に生まれた[5]。 1922年、一家は白人義勇軍による反ユダヤ主義のポグロムを理由にウクライナSSRを逃れ、ニューヨーク州シラキュースに移り住んだ。父親はニューヨー クに着いて間もなく、デレンコフスカヤという姓を「デレン」と略した[8][9]。父親はシラキュースにある国立精神薄弱者研究所のスタッフ精神科医と なった[10]。 1930年から1933年まで、高校はスイスのジュネーブにある国民連盟国際学校に通った[11]。デレンは留学中にフランス語を話せるようになった [12]。 デレンは16歳でシラキュース大学に入学し、ジャーナリズムと政治学を学び始めた[13][9]。 デレンは10代後半のトロツキスト運動で非常に活発な社会主義活動家となった[3]。 1935年6月、18歳のとき、社会問題クラブを通じて知り合った社会主義活動家のグレゴリー・バーダッケと結婚した[3]。1936年6月にニューヨー ク大学の文学部を卒業し、その年の秋にシラキュースに戻った[8]。 1938年、デレンはニュー・スクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチに通い、スミス・カレッジで英文学の修士号を取得した[15]。彼女の修士論文のタ イトルは『The Influence of the French Symbolist School on Anglo-American Poetry』(1939年)で、パウンド、エリオット、イマジストの作品が含まれていた[16]。21歳までにデレンは文学の学位を2つ取得した [12]。 |

| Early career After graduation from Smith, Deren returned to New York's Greenwich Village, where she joined the European émigré art scene.[17] She supported herself from 1937 to 1939 by freelance writing for radio shows and foreign-language newspapers. During that time she also worked as an editorial assistant to famous American writers Eda Lou Walton, Max Eastman, and then William Seabrook.[3] She wrote poetry and short fiction, tried her hand at writing a commercial novel, and also translated a work by Victor Serge which was never published.[9] She became known for her European-style handmade clothes, wild red curly hair and fierce convictions.[8][18] In 1940, Deren moved to Los Angeles to focus on her poetry and freelance photography. In 1941, Deren wrote to Katherine Dunham—an African American dancer, choreographer, and anthropologist of Caribbean culture and dance—suggesting a children's book on dance and applying for a managerial job for her and her dance troupe; she later became Dunham's assistant and publicist. Deren travelled with the troupe for a year, learning greater appreciation for dance, as well as interest and appreciation for Haitian culture.[9] Dunham's fieldwork influenced Deren's studies of Haitian culture and Vodou mythology.[19][18] At the end of touring a new musical Cabin in the Sky, the Dunham dance company stopped in Los Angeles for several months to work in Hollywood. It was there that Deren met Alexandr Hackenschmied (who later changed his name to Alexander Hammid), a celebrated Czech-born photographer and cameraman who would become Deren's second husband in 1942. Hackenschmied had fled from Czechoslovakia in 1938 after the Sudetenland crisis. Deren and Hammid lived together in Laurel Canyon, where he helped her with her still photography which focused on local fruit pickers in Los Angeles.[3] Of two still photography magazine assignments of 1943 to depict artists active in New York City, including Ossip Zadkine, her photographs appeared in the Vogue magazine article.[20] The other article intended for Mademoiselle magazine was not published,[21] but three signed enlargements of photographs intended for this article, all depicting Deren's friend New York ceramist Carol Janeway, are preserved in the MoMA[22] and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[23][24] All prints were from Janeway's estate.[25] |

初期のキャリア スミスを卒業後、デレンはニューヨークのグリニッジ・ヴィレッジに戻り、ヨーロッパの移民アートシーンに加わった[17]。1937年から1939年ま で、ラジオ番組や外国語新聞のフリーライターとして自活していた。その間、彼女は有名なアメリカ人作家のイーダ・ルー・ウォルトン、マックス・イーストマ ン、そしてウィリアム・シーブルックの編集アシスタントとしても働いていた[3]。彼女は詩や短編小説を書き、商業小説の執筆にも挑戦し、出版されなかっ たヴィクトール・セルジュの作品の翻訳も手がけた[9]。 1940年、デレンはロサンゼルスに移り住み、詩作とフリーランスの写真撮影に専念する。1941年、アフリカ系アメリカ人のダンサー、振付師、カリブ海 文化とダンスの人類学者であるキャサリン・ダナムに手紙を書き、ダンスに関する児童書の出版を提案し、彼女と彼女の舞踊団のマネージャーの仕事に応募し た。ダンハムのフィールドワークは、ダンハムのハイチ文化とヴォドゥー神話の研究に影響を与えた[19][18]。新作ミュージカル『キャビン・イン・ ザ・スカイ』のツアーの終わりに、ダンハム・ダンス・カンパニーはハリウッドで仕事をするためにロサンゼルスに数カ月滞在した。そこでデレンは、1942 年にデレンの2番目の夫となるチェコ生まれの著名な写真家兼カメラマン、アレクサンドル・ハッケンシュミード(後にアレクサンダー・ハミードと改名)と出 会う。ハッケンシュミードは1938年のスデーテンランド危機の後、チェコスロバキアから逃れてきた。 デレンとハミッドはローレル・キャニオンで同棲し、彼はロサンゼルスの果物狩りの人々に焦点を当てた彼女のスチール写真を手伝った[3]。1943年にオ シップ・ザドキンを含むニューヨークで活躍するアーティストを撮影する2つのスチール写真雑誌の仕事のうち、彼女の写真は『ヴォーグ』誌の記事に掲載され た[20]。 [20]マドモアゼル誌に掲載される予定だったもう1つの記事は掲載されなかったが[21]、この記事に掲載される予定だった、デレンの友人であるニュー ヨークの陶芸家キャロル・ジェインウェイを撮影した3枚の写真の拡大写真がサイン入りでMoMA[22]とフィラデルフィア美術館に保存されている [23][24]。 |

| Personal life In 1943, she moved to a bungalow on Kings Road in Hollywood[3] and adopted the name Maya, a pet name her second husband Hammid coined. Maya is the name of the mother of the historical Buddha as well as the dharmic concept of the illusory nature of reality. In Greek myth, Maia is the mother of Hermes and a goddess of mountains and fields. In 1944, back in New York City, her social circle included Marcel Duchamp, André Breton, John Cage, and Anaïs Nin.[26] In 1944, Deren filmed The Witch's Cradle in Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century gallery with Duchamp featured in the film. In the December 1946 issue of Esquire magazine, a caption for her photograph teased that she "experiments with motion pictures of the subconscious, but here is finite evidence that the lady herself is infinitely photogenic."[27] Her third husband, Teiji Itō, said: "Maya was always a Russian. In Haiti she was a Russian. She was always dressed up, talking, speaking many languages and being a Russian."[27] |

私生活 1943年、彼女はハリウッドのキングス・ロードにあるバンガローに移り住み[3]、2番目の夫ハミッドが作ったペットネーム「マヤ」を名乗った。マヤは 歴史上の仏陀の母親の名前であり、現実の幻想的な性質というダルマの概念でもある。ギリシャ神話では、マイアはヘルメスの母であり、山と野原の女神であ る。 1944年、ニューヨークに戻ったデレンの社交界には、マルセル・デュシャン、アンドレ・ブルトン、ジョン・ケージ、アナイス・ニンらがいた[26]。 1944年、デレンはペギー・グッゲンハイムのアート・オブ・ザ・センチュリーのギャラリーで『呪術師のゆりかご』を撮影し、デュシャンが映画に登場し た。 1946年12月号の『エスクァイア』誌に掲載された彼女の写真のキャプションには、「潜在意識の動画で実験しているが、彼女自身が限りなくフォトジェ ニックであるという有限の証拠がここにある」とからかわれている[27]: 「マヤはいつもロシア人だった。ハイチでも彼女はロシア人だった。彼女はいつも着飾り、話し、多くの言語を話し、ロシア人であった」[27]。 |

| Film career Deren defined cinema as an art, provided an intellectual context for film viewing, and filled a theoretical gap for the kinds of independent films that film societies were featuring.[28] As Sarah Keller states, “Maya Deren lays claim to the honor of being one of the most important pioneers of the American film avant-garde with a scant seventy-five or so minutes of finished films to her credit.”[29] Deren began to screen and distribute her films in the United States, Canada, and Cuba, lecturing and writing on avant-garde film theory, and additionally on Vodou. In February 1946 she booked the Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village for a major public exhibition, titled Three Abandoned Films, in which she showed Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), At Land (1944) and A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945).[14] The event was completely sold out, inspiring Amos Vogel's formation of Cinema 16, the most successful film society of the 1950s.[30] In 1946, she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for "Creative Work in the Field of Motion Pictures", and in 1947, won the Grand Prix International for avant-garde film at the Cannes Film Festival for Meshes of the Afternoon. She then created a scholarship for experimental filmmakers, the Creative Film Foundation.[31] Between 1952 and 1955, Deren collaborated with the Metropolitan Opera Ballet School and Antony Tudor to create The Very Eye of Night. Deren's background and interest in dance appears in her work, most notably in the short film A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945). This combination of dance and film has often been referred to as "choreocinema", a term first coined by American dance critic John Martin.[32] In her work, she often focused on the unconscious experience, such as in Meshes of the Afternoon. This is thought to be inspired by her father who was a student of psychiatrist Vladimir Bekhterev who explored trance and hypnosis as neurological states.[33] She also regularly explored themes of gender identity, incorporating elements of introspection and mythology. Despite her feminist subtext, she was mostly unrecognized by feminist writers at the time, even influential writers Claire Johnston and Laura Mulvey ignored Deren at the time,[34] though Mulvey later would give Deren this recognition, since their works were often in conversation with each other.[35] |

映画のキャリア デレンは映画を芸術として定義し、映画鑑賞に知的文脈を提供し、映画協会が特集していた種類のインディペンデント映画に対する理論的ギャップを埋めた [28]。サラ・ケラーが言うように、「マヤ・デレンは、75分ほどのわずかな完成映画で、アメリカ映画アヴァンギャルドの最も重要な先駆者の一人である という名誉を主張する」[29]。 デレンはアメリカ、カナダ、キューバで彼女の映画を上映、配給し始め、前衛映画理論、さらにヴードゥーについて講義や執筆を行った。1946年2月、彼女 はグリニッジ・ヴィレッジのプロヴィンスタウン・プレイハウスを予約し、『3つの放棄された映画』と題した大規模な一般公開を行った。 1946年、彼女は「映画の分野における創造的な仕事」に対してグッゲンハイム・フェローシップを授与され、1947年には『午後のメッシュ』でカンヌ国 際映画祭の前衛映画グランプリを受賞した。その後、実験映画製作者のための奨学金、クリエイティブ・フィルム財団を設立した[31]。 1952年から1955年にかけて、デレンはメトロポリタン・オペラ・バレエ学校とアントニー・テューダーと共同で『The Very Eye of Night』を制作した。 デレンのダンスへの関心と経歴は、短編映画『A Study in Choreography for Camera』(1945年)を筆頭に、彼女の作品に現れている。このダンスと映画の組み合わせはしばしば「コレオシネマ」と呼ばれ、アメリカのダンス批 評家ジョン・マーティンが最初に作った言葉である[32]。 彼女の作品では、『Meshes of the Afternoon』のように、無意識の体験に焦点を当てることが多い。これは、神経学的な状態としてのトランスと催眠を探求した精神科医ウラジーミル・ ベクテレフの弟子であった彼女の父に触発されたと考えられている[33]。また、内省と神話の要素を取り入れながら、ジェンダー・アイデンティティのテー マも定期的に探求している。彼女のフェミニスト的なサブテキストにもかかわらず、当時のフェミニスト作家たちからはほとんど認知されておらず、影響力のあ る作家であるクレア・ジョンストンとローラ・マルヴェイでさえ、当時はデレンを無視していた[34]。 |

| Major films Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) Main article: Meshes of the Afternoon  Deren in Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) In 1943, Deren purchased a used 16mm Bolex camera with some of the inheritance money after her father's death from a heart attack. This camera was used to make her first and best-known film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), made in collaboration with Hammid in their Los Angeles home on a budget of $250.[4] Meshes of the Afternoon is recognized as a seminal American avant-garde film. Critics have seen autobiographical elements in the film, as well as thoughts about woman as subject rather than as object. Originally a silent film with no dialogue, music for the film was composed, long after its initial screenings, by Deren's third husband Teiji Itō in 1952. The film can be described as an expressionistic "trance film", full of dramatic angles and innovative editing. It investigates the ephemeral ways in which the protagonist's unconscious mind works and makes connections between objects and situations. A woman, played by Maya Deren, walks up to a house in Los Angeles, falls asleep and seems to have a dream. The sequence of walking up to the gate on the partially shaded road restarts numerous times, resisting conventional narrative expectations, and ends in various situations inside the house. Movement from the wind, shadows and the music sustain the heartbeat of the dream. Recurring symbols include a cloaked figure, mirrors, a key, and a knife. The loose repetition and rhythm cut short any expectation of a conventional narrative, heightening the dream-like qualities. The camera initially does not show her face, which precludes identification with a particular woman, which creates a universalizing, totalizing effect- as it is easier to relate to an unknown, faceless woman. Multiple selves appear, shifting between the first and third person, suggesting that the super-ego is at play, which is in line with the psychoanalytic Freudian staircase and flower motifs. This kind of Freudian interpretation, which she disagreed with, led Deren to add sound, composed by Teiji Itō, to the film. Another interpretation is that each film is an example of a "personal film". Her first film, Meshes of the Afternoon, explores a woman's subjectivity and relation to the external world. Georges Sadoul said Deren may have been "the most important figure in the post-war development of the personal, independent film in the U.S.A."[36] In featuring the filmmaker as the woman whose subjectivity in the domestic space is explored, the feminist dictum "the personal is political" is foregrounded. As with her other films on self-representation, Deren navigates conflicting tendencies of the self and the "other", through doubling, multiplication and merging of the woman in the film. Following a dreamlike quest with allegorical complexity, Meshes of the Afternoon has an enigmatic structure and a loose affinity with both film noir and domestic melodrama.[8] The film is famous for how it resonated with Deren's own life and anxieties. According to a review in The Moving Image, "this film emerges from a set of concerns and passionate commitments that are native to Deren's life and her trajectory. The first of these trajectories is Deren's interest in socialism during her youth and university years".[37] Director's notes There is no concrete information about the conception of Meshes of the Afternoon beyond that Deren offered the poetic ideas and Hammid was able to turn them into visuals, as she envisioned them. Deren's initial concept began on the terms of a subjective camera, one that would show the point of view of herself without the aid of mirrors and would move as her eyes through spaces. According to the earliest program note, she describes Meshes of the Afternoon as follows: This film is concerned with the interior experiences of an individual. It does not record an event which could be witnessed by other persons. Rather, it reproduces the way in which the subconscious of an individual will develop, interpret, and elaborate an apparently simple and casual incident into a critical emotional experience. |

主な作品 午後の網目 (1943) 主な作品 午後のメッシュ  『昼下がりの網目』(1943)におけるデレン 1943年、デレンは父親を心臓発作で亡くした後の遺産で、中古の16mmボレックスカメラを購入した。このカメラは、ロサンゼルスの自宅でハミッドと共 同で、予算250ドルで製作された、彼女の最初の、そして最もよく知られた映画『昼下がりのメッシュ』(1943)の製作に使われた[4]。『昼下がりの メッシュ』は、アメリカの前衛映画の代表作として知られている。批評家たちは、この映画に自伝的な要素や、対象としてではなく主体としての女性についての 考えを見出した。当初はセリフのないサイレント映画だったが、初上映から長い年月を経て、1952年にデレンの3番目の夫である伊藤悌二が音楽を担当し た。ドラマチックなアングルと斬新な編集に満ちた、表現主義的な「トランス映画」と言える。主人公の無意識がどのように働き、物や状況を結びつけるのか、 その刹那的な方法を探っている。マヤ・デレン扮する女性が、ロサンゼルスの家まで歩いて行き、眠りに落ちて夢を見るようだ。部分的に日陰になった道を門ま で歩いていくシークエンスは、従来の物語の予想に反して何度もリスタートし、家の中のさまざまな状況で終わる。風の動き、影、音楽が夢の鼓動を支えてい る。繰り返されるシンボルには、マントをかぶった人物、鏡、鍵、ナイフなどがある。 緩やかな反復とリズムは、型にはまった物語への期待を削ぎ、夢のような特質を高めている。カメラは最初、彼女の顔を映さない。これは、特定の女性との同一 主義を排除し、普遍化、全体化の効果を生み出す。一人称と三人称の間を行き来する複数の自己が登場し、超自我が働いていることを示唆するが、これは精神分 析学的なフロイトの階段や花のモチーフと一致している。このようなフロイト的な解釈は、デレンにとっては同意しがたいものであったため、デレンは伊藤てい じが作曲した音響を作品に加えることになった。 もうひとつの解釈は、各作品が「人格映画」の一例であるというものだ。彼女の最初の作品『昼下がりの網目』は、女性の主観性と外界との関係を探求してい る。ジョルジュ・サドゥールは、デレンは「戦後、アメリカにおける個人的なインディペンデント映画の発展において、最も重要な人物」であったかもしれない と述べている[36]。国内空間における主観性を探求する女性として映画監督をフィーチャーすることで、「個人的なものは政治的である」というフェミニズ ムの教義が前景化している。自己表象に関する彼女の他の作品と同様に、デレンは、映画の中の女性の二重化、増殖、融合を通して、自己と「他者」の相反する 傾向をナビゲートする。寓話的な複雑さを伴う夢のような探求に続く『昼下がりの網目』は、謎めいた構造を持ち、フィルム・ノワールと家庭内メロドラマの両 方と緩やかな親和性を持っている[8]。この映画は、デレン自身の人生と不安といかに共鳴していたかで有名である。ムービング・イメージ』誌の批評によれ ば、「この映画は、デレンの人生とその軌跡に固有な一連の懸念と情熱的なコミットメントから生まれた」。これらの軌跡の第一は、デレンが青年期と大学時代 に社会主義に関心を持ったことである」[37]。 監督ノート 『午後のメッシュ』の構想については、デレンが詩的なアイデアを提供し、ハミッドがそれを彼女の構想通りに映像化したという以上の具体的な情報はない。デ レンの最初の構想は、主観的なカメラ、つまり鏡の助けを借りずに自分自身の視点を映し出し、彼女の目として空間を移動するカメラという条件から始まった。 最古のプログラム・ノートによれば、彼女は『午後のメッシュ』について次のように語っている: この映画は個人の内面的な体験に関係している。他の人格が目撃できるような出来事を記録しているのではない。そうではなく、個人の潜在意識が、一見単純で 何気ない出来事を、重大な感情体験へと発展させ、解釈し、練り上げる方法を再現している。 |

| At Land (1944) Main article: At Land  Deren in a still from the film At Land (1944) Deren filmed At Land in Port Jefferson and Amagansett, New York in the summer of 1944. Taking on more of an environmental psychologist's perspective, Deren "externalizes the hidden dynamic of the external world...as if I had moved from a concern with the life of the fish, to a concern with the sea which accounts for the character of the fish and its life."[36] Maya Deren washes up on the shore of the beach, and climbs up a piece of driftwood that leads to a room lit by chandeliers, and one long table filled with men and women smoking. She seems to be invisible to the people as she crawls across the table, uninhibited; her body continues seamlessly again onto a new frame, crawling through foliage; following the flowing pattern of water on rocks; following a man across a farm, to a sick man in bed, through a series of doors, and finally popping up outside on a cliff. She shrinks in the wide frame as she walks farther away from the camera, up and down sand dunes, then frantically collecting rocks back on the shore. Her expression seems confused when she sees two women playing chess in the sand. She runs back through the entire sequence, and because of the jump-cuts, it seems as though she is a double or "doppelganger", where her earlier self sees her other self running through the scene. Some of her movements are controlled, suggesting a theatrical, dancer-like quality, while some have an almost animalistic sensibility as she crawls through the seemingly foreign environments. This is one of Deren's films in which the focus is on the character's exploration of her own subjectivity in her physical environment, inside as well as outside her subconscious, although it has a similar amorphous quality compared to her other films. |

陸にて(1944年) 主な記事 陸にて  映画『At Land』(1944年)のスチール写真でのデレン デレンは1944年夏、ニューヨークのポート・ジェファーソンとアマガンセットで『At Land』を撮影した。マヤ・デレンは浜辺の岸辺に漂着し、流木をよじ登り、シャンデリアに照らされた部屋と、喫煙する男女でいっぱいの長いテーブルにた どり着く。テーブルの上を奔放に横切る彼女の姿は、人々の目には見えないようだ。彼女の身体はまた新しいフレームへとシームレスに続き、葉の間を這い、岩 の上を流れる水のパターンを追い、牧場を横切る男の後を追い、ベッドに横たわる病人のところへ行き、いくつものドアをくぐり抜け、最後は外の崖の上に飛び 出す。彼女はカメラから遠く離れて歩き、砂丘を上り下りし、必死で石を集めて海岸に戻ると、広いフレームの中で縮こまる。砂浜でチェスをしている2人の女 性を見て、彼女の表情は混乱しているように見える。彼女は全シークエンスを走って戻ってくるが、ジャンプカットがあるため、彼女は二重人格、あるいは 「ドッペルゲンガー」であるかのように見える。彼女の動きには、演劇的でダンサーのような質感を示唆するコントロールされたものもあれば、一見異質な環境 の中を這い回るような、ほとんど動物的な感性を持ったものもある。この作品は、デレンの他の作品と比べると、同じような非定形的な質を持っているが、物理 的な環境、潜在意識の内と外における彼女自身の主観性の探求に焦点が当てられている。 |

| A Study in Choreography for

Camera (1945) Main article: A Study in Choreography for Camera Still from A Study in Choreography for Camera In the spring of 1945 she made A Study in Choreography for Camera, which Deren said was "an effort to isolate and celebrate the principle of the power of movement."[36] The compositions and varying speeds of movement within the frame inform and interact with Deren's meticulous edits and varying film speeds and motions to create a dance that Deren said could only exist on film. Excited by the way the dynamic of movement is greater than anything else within the film, Maya established a completely new sense of the word "geography" as the movement of the dancer transcends and manipulates the ideas of both time and space.[36] "For Deren, no transition is needed between a place outside (such as a forest, or a park, or the beach) and an interior room. One action can be performed across different physical spaces, as in A Study in Choreography For Camera (1945), and in this way sews together layers of reality, thereby suggesting continuity between different levels of consciousness."[38] At just under 3 minutes long, A Study in Choreography for Camera is a fragment depicting a carefully constructed exploration of a man who dances in a forest, and then seems to teleport to the inside of a house because of how continuous his movements are from one place to the next. The edit is broken, choppy, showing different angles and compositions, and even with parts in slow-motion, Deren is able to keep the quality of the leap smooth and seemingly uninterrupted. The choreography is perfectly synched as he seamlessly appears in an outdoor courtyard and then returns to an open, natural space. It shows a progression from nature to the confines of society, and back to nature. The figure belongs to dancer and choreographer Talley Beatty, whose last movement is a leap across the screen back to the natural world. Deren and Beatty met through Katherine Dunham, while Deren was her assistant and Beatty was a dancer in her company.[39] It is worth noting that Beatty collaborated heavily with Deren in the creation of this film, hence why he is credited alongside Deren in the film's credit sequence.[33] The film is also subtitled 'Pas de Deux', a dance term referring to a dance between two people, or in this case, a collaboration between Deren and Beatty.[33] A Study in Choreography for Camera was one of the first experimental dance films to be featured in the New York Times as well as Dance Magazine.[33] |

カメラのための振付の研究 (1945) 主な記事 カメラのための振付の研究 カメラのための振付の研究』のスチール写真 1945年の春、彼女は『カメラのための振付の研究』を制作した。この作品についてデレンは、「動きの力の原理を分離し、賛美する努力」であったと語って いる[36]。フレーム内の構図と動きのさまざまな速度は、デレンの綿密な編集、さまざまなフィルムの速度と動きと相互に影響し合い、デレンがフィルム上 にしか存在し得ないと語ったダンスを創り出した。動きのダイナミックさが映画内の他の何よりも大きいことに興奮したマヤは、ダンサーの動きが時間と空間の 両方の概念を超越し、操作することで、「地理」という言葉のまったく新しい感覚を確立した[36]。 「デレンにとって、外の場所(森、公園、海辺など)と室内の間の移動は必要ない。ひとつの行為は、『カメラのための振付の研究』(1945)のように、異 なる物理的空間をまたいで行うことができ、このようにして現実の層を縫い合わせることで、異なる意識レベルの間の連続性を示唆している」[38]。 長さ3分弱の『カメラのための振付の研究』は、森の中で踊る男の入念に構成された探検を描いた断片であり、彼の動きがある場所から次の場所へと連続的であ るため、家の中にテレポートしているように見える。編集は途切れ途切れで、さまざまなアングルや構図を見せ、スローモーションの部分もあるが、デレンはス ムーズで途切れることのない跳躍の質を保つことができている。彼が屋外の中庭にシームレスに現れ、開放的な自然空間に戻る振り付けは完璧にシンクロしてい る。それは、自然から社会の枠内へ、そして自然へと戻っていく過程を示している。この人物はダンサーであり振付師でもあるタリー・ビーティのもので、最後 の動きはスクリーンを跳躍して自然界に戻るものだ。デレンとビーティは、キャサリン・ダナムを通じて知り合い、デレンは彼女のアシスタント、ビーティは彼 女のカンパニーのダンサーであった[39]。ビーティが本作の制作においてデレンと深く協力していることは注目に値する。 A Study in Choreography for Camera』は、『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙や『ダンス・マガジン』誌で特集された最初の実験的ダンス映画のひとつである[33]。 |

| Ritual in Transfigured Time

(1946) Main article: Ritual in Transfigured Time By her fourth film, Deren discussed in An Anagram that she felt special attention should be given to unique possibilities of time and that the form should be ritualistic as a whole. Ritual in Transfigured Time began in August and was completed in 1946. It explored the fear of rejection and the freedom of expression in abandoning ritual, looking at the details as well as the bigger ideas of the nature and process of change. The main roles were played by Deren herself and the dancers Rita Christiani and Frank Westbrook.[40] |

変容した時間の中の儀式(1946年) 主な記事 変容した時間における儀式 4作目まで、デレンは『アナグラム』の中で、時間のユニークな可能性に特別な注意を払うべきであり、形式は全体として儀式的であるべきだと感じていると論 じていた。Ritual in Transfigured Time』は8月に始まり、1946年に完成した。拒否されることへの恐れと、儀式を放棄することによる表現の自由を探求し、細部だけでなく、変化の本質 とプロセスという大きなアイデアにも目を向けた。主役はデレン自身とダンサーのリタ・クリスチャニとフランク・ウェストブルックが演じた[40]。 |

| Meditation on Violence (1948) Main article: Meditation on Violence Deren's Meditation on Violence was made in 1948. Chao-Li Chi's performance obscures the distinction between violence and beauty. It was an attempt to "abstract the principle of ongoing metamorphosis", found in Ritual in Transfigured Time, though Deren felt it was not as successful in the clarity of that idea, brought down by its philosophical weight.[36] Halfway through the film, the sequence is rewound, producing a film loop. |

暴力への瞑想 (1948) 主な記事 暴力への瞑想 デレンの『暴力の瞑想』は1948年に制作された。チャオリー・チーのパフォーマンスは、暴力と美の区別を曖昧にしている。この作品は、『変容した時間の 中の儀式』に見られる「継続的な変容の原理を抽象化する」試みであったが、デレンはその哲学的な重さによって、そのアイデアの明確さにおいて成功していな いと感じていた。 |

| Criticism of Hollywood Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Deren attacked Hollywood for its artistic, political and economic monopoly over American cinema. She stated, "I make my pictures for what Hollywood spends on lipstick," criticizing the amount of money spent on production. She also observed that Hollywood "has been a major obstacle to the definition and development of motion pictures as a creative fine-art form." She set herself in opposition to the Hollywood film industry's standards and practices.[41] Deren talks about the freedoms of independent cinema: Artistic freedom means that the amateur filmmaker is never forced to sacrifice visual drama and beauty to a stream of words...to the relentless activity and explanations of a plot...nor is the amateur production expected to return profit on a huge investment by holding the attention of a massive and motley audience for 90 minutes...Instead of trying to invent a plot that moves, use the movement of wind, or water, children, people, elevators, balls, etc. as a poem might celebrate these. And use your freedom to experiment with visual ideas; your mistakes will not get you fired.[42] |

ハリウッド批判 1940年代から1950年代にかけて、デレンはアメリカ映画を芸術的、政治的、経済的に独占しているハリウッドを攻撃した。彼女は「ハリウッドが口紅に 費やす金額で私は映画を作る」と述べ、製作に費やされる金額を批判した。彼女はまた、「ハリウッドは、創造的なファインアートとしての映画の定義と発展を 大きく妨げてきた」とも述べている。彼女は、ハリウッドの映画産業の基準や慣行と対立することを自らに課した[41]。デレンは、インディペンデント映画 の自由について語る: 芸術的自由とは、アマチュアの映画作家が、言葉の流れのために......筋書きの執拗な活動や説明のために......視覚的なドラマや美しさを犠牲に することを決して強いられないということである。そして、自由な発想で視覚的なアイデアを試してみよう。失敗してもクビにはならない[42]。 |

| Haiti and Vodou | ハイチとヴードゥー(このページの冒頭にあり) |

| Death Deren died in 1961, at the age of 44 from a brain hemorrhage, which has been attributed to a combination of malnutrition and drug use.[55] Her condition may have also been weakened by her long-term dependence on amphetamines and sleeping pills prescribed by Max Jacobson, a doctor and member of the arts scene, notorious for his liberal prescription of drugs,[8] who later became famous as one of President John F. Kennedy's physicians. |

死因 デレンは1961年、44歳の若さで脳出血のため死去したが、その原因は栄養失調と薬物使用の複合によるものとされている[55]。 彼女の病状は、医師であり、芸術シーンのメンバーであり、薬物を自由に処方することで悪名高く、後にジョン・F・ケネディ大統領の主治医の一人として有名 になったマックス・ジェイコブソン[8]によって処方されたアンフェタミンと睡眠薬に長期間依存していたことでも弱っていた可能性がある。 |

| Legacy Deren was an inspiration to such up-and-coming avant-garde filmmakers as Curtis Harrington, Stan Brakhage, and Kenneth Anger, who emulated her independent, entrepreneurial spirit. Her influence can also be seen in films by Carolee Schneemann, Barbara Hammer, and Su Friedrich.[19] In his review for renowned experimental filmmaker David Lynch's Inland Empire, writer Jim Emerson compares the work to Meshes of the Afternoon, apparently a favorite of Lynch's.[56] Deren was a key figure in the creation of a New American Cinema, highlighting personal, experimental, underground film. In 1986, the American Film Institute created the Maya Deren Award to honor independent filmmakers. The Legend of Maya Deren, Vol. 1 Part 2 consists of hundreds of documents, interviews, oral histories, letters, and autobiographical memoirs.[8] Works about Deren and her works have been produced in various media: Deren appears as a character in the long narrative poem The Changing Light at Sandover (1976-1980) by her friend James Merrill. In 1987, Jo Ann Kaplan directed a biographical documentary about Deren, titled Invocation: Maya Deren (65 min) In 1994, the UK-based Horse and Bamboo Theatre created and toured Dance of White Darkness throughout Europe—the story of Deren's visits to Haiti. In 2002, Martina Kudláček [de] directed a feature-length documentary about Deren, titled In the Mirror of Maya Deren (Im Spiegel der Maya Deren), which featured music by John Zorn. Deren's films have also been shown with newly written alternative soundtracks: In 2004, the British rock group Subterraneans produced new soundtracks for six of Deren's short films as part of a commission from Queen's University Belfast's annual film festival. At Land won the festival prize for sound design. In 2008, the Portuguese rock group Mão Morta produced new soundtracks for four of Deren's short films as part of a commission from Curtas Vila do Conde's annual film festival. |

遺産 デレンは、カーティス・ハリントン、スタン・ブラッケージ、ケネス・アンガーといった新進気鋭の前衛映画作家たちにインスピレーションを与え、彼らは彼女 の独立心、起業家精神を見習った。彼女の影響は、キャロリー・シュニーマン、バーバラ・ハマー、スー・フリードリッヒの映画にも見られる[19]。著名な 実験映画監督デヴィッド・リンチの『インランド・エンパイア』の批評で、作家のジム・エマーソンは、この作品をリンチのお気に入りだったらしい『午後の メッシュ』と比較している[56]。 デレンは、人格的、実験的、アンダーグラウンドな映画を強調するニュー・アメリカン・シネマの創設において重要な人物であった。1986年、アメリカン・ フィルム・インスティテュートは、インディペンデント映画製作者を称えるマヤ・デレン賞を創設した。 The Legend of Maya Deren, Vol.1 Part 2』は、何百もの文書、インタビュー、オーラル・ヒストリー、手紙、自伝的回想録で構成されている[8]。 デレンと彼女の作品に関する作品は、様々なメディアで制作されている: デレンは、友人のジェームズ・メリルによる長編物語詩『The Changing Light at Sandover』(1976~1980年)の登場人物として登場する。 1987年には、ジョー・アン・カプランがデレンの伝記的ドキュメンタリー『Invocation』を監督した: 65分 1994年、英国を拠点とするホース・アンド・バンブー・シアターは、デレンがハイチを訪れた際の物語『Dance of White Darkness』を創作し、ヨーロッパ全土で上演した。 2002年には、マルティナ・クドラーチェク(Martina Kudláček [de])がデレンの長編ドキュメンタリー『In the Mirror of Maya Deren(Im Spiegel der Maya Deren)』を監督し、ジョン・ゾーンの音楽をフィーチャーした。 デレンの映画は、新たに書き下ろされたオルタナティブ・サウンドトラックでも上映されている: 2004年、イギリスのロックグループSubterraneansは、クイーンズ大学ベルファストの年次映画祭の依頼で、デレンの短編映画6本のために新 しいサウンドトラックを制作した。At Land』は映画祭のサウンドデザイン賞を受賞した。 2008年には、ポルトガルのロックグループMão Mortaが、Curtas Vila do Condeの年次映画祭からの依頼で、デレンの短編映画4本のサウンドトラックを新たに制作した。 |

| Awards and honors Guggenheim Fellowship 1946 Grand Prix International for Avant-garde Film at the Cannes Film Festival (1947)[57] Creative Work in Motion Pictures (1947) |

受賞歴 グッゲンハイム・フェローシップ(1946年 カンヌ国際映画祭前衛映画グランプリ(1947年)[57]。 映画創作賞(1947) |

Filmography |

|

Discography |

|

| Written works Deren was also an important film theorist. Her most widely read essay on film theory is probably An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film, Deren's seminal treatise that laid the groundwork for many of her ideas on film as an art form (Yonkers, NY: Alicat Book Shop Press, 1946). Her collected essays were published[63] in 2005 and arranged in three sections: Film Poetics, including: Amateur versus Professional, Cinema as an Art Form, An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film, Cinematography: The Creative Use of Reality Film Production, including: Creating Movies with a New Dimension: Time, Creative Cutting, Planning by Eye, Adventures in Creative Film-Making Film in Medias Res, including: A Letter, Magic is New, New Directions in Film Art, Choreography for the Camera, Ritual in Transfigured Time, Meditation on Violence, The Very Eye of Night. Divine Horsemen: Living Gods of Haiti was published in 1953 by Vanguard Press (New York City) and Thames & Hudson (London), republished under the title of The Voodoo Gods by Paladin in 1975, and again under its original title by McPherson & Company in 1998. |

著作 デレンは重要な映画理論家でもあった。 彼女の映画理論に関するエッセイで最も広く読まれているのは、芸術形態としての映画に関する多くのアイデアの基礎を築いたデレンの代表的な論考 『Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film』(ニューヨーク州ヨンカーズ:Alicat Book Shop Press、1946年)だろう。 彼女のエッセイ集は2005年に出版され[63]、3つのセクションで構成されている: 『映画詩学』である: アマチュア対プロフェッショナル」、「芸術形態としての映画」、「芸術、形態、映画に関するアナグラム」、「シネマトグラフィ」である: 現実の創造的利用 映画制作: 新しい次元で映画を作る: 時間」、「創造的なカット割り」、「目によるプランニング」、「創造的な映画作りの冒険」など。 メディアス・レスにおける映画 手紙』、『呪術は新しい』、『映画芸術の新たな方向性』、『カメラのための振付』、『変容した時間における儀式』、『暴力への瞑想』、『まさに夜の眼』な ど。 ディヴァイン・ホースメン 1953年にVanguard Press(ニューヨーク)とThames & Hudson(ロンドン)から出版され、1975年にPaladin社から『The Voodoo Gods』というタイトルで再出版され、1998年にMcPherson & Company社から再び原題で出版された。 |

| Brody, Richard (November 16,

2022). "How Maya Deren Became the Symbol and Champion of American

Experimental Film". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 21, 2023. Deren, Maya. Edited by Bruce R. McPherson. New York: McPherson & Company, 2005. Keller, Sarah. "Frustrated Climaxes: On Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon and Witch’s Cradle." Cinema Journal 52, no. 3 (Spring 2013): 75-98. Nichols, Bill, ed. Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 2001. Soussloff, Catherine M. (2001). "Maya Deren Herself". In Nichols, Bill (ed.). Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde. University of California Press. ISBN 0520227328. Retrieved February 29, 2020. |

Brody, Richard (November 16,

2022). 「マヤ・デレンはいかにしてアメリカ実験映画の象徴となり、チャンピオンとなったか」. The New Yorker.

2023年3月21日取得。 デレン、マヤ。ブルース・R・マクファーソン編集。ニューヨーク: McPherson & Company, 2005. Keller, Sarah. 「Frustrated Climaxes: マヤ・デレンの『昼下がりのメッシュ』と『呪術師のゆりかご』について」. Cinema Journal 52, no. 3 (Spring 2013): 75-98. Nichols, Bill, ed. Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 2001. Soussloff, Catherine M. (2001). 「Maya Deren Herself」. Nichols, Bill (ed.). Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde. University of California Press. ISBN 0520227328. 2020年2月29日取得。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maya_Deren |

Divine Horsemen - Baton Twirlers.(約4分)

REAL

Voodoo Rituals(50分)

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆