Gregory Bateson, 1904-1980

グレゴリー・ベイトソン

Gregory Bateson, 1904-1980

1904 5月9日。英国グランチェスターに生まれる。父ウィリアム・ベイトソンは遺伝学者。祖父はケンブリッジのセント・ジョーンズ・カレッジ学長経験者のウィ リアム・ヘンリー・ベイトソン

1922 ケンブリッジ大学のセント・ジョーンズ・カレッジに入学

1925 学士号(自然科学)

1926 父との連名で、鳥の羽の対称性を扱う論文を公刊

1927 大学院に入学人類学を専攻。ニューブリテンおよびニューギニアでフィールドワーク

1929 フィールドワークから帰国

1930 人類学で修士号を取得

1930 セント・ジョーンズ・カレッジ研究員(〜1937)。ニューギニア・イアトムル集落でフィールドワーク(〜1933)

1935 渡米、コロンビア大学、シカゴ大学で講演

1936 マーガレット・ミード(1901-1978)と結婚(ミードは3度目の結婚)。バ リでのフィールドワークの開始(〜1938)

1936 『ナヴェン(Naven)』公刊:"Naven: A Study of the Problems Suggested by a Composite Picture of the Culture of a New Guinea Tribe Drawn from Three Points of View", (Stanford University Press, 1936, 2nd ed., 1958).

1938 -1939 ニューギニアでフィールドワーク

1939 2万5千枚の写真と2万2千フィートの16ミリフィルムを米国へ。ミード、キャサリン・ベイトソンを出産。

1941 ニューヨーク近代美術館で映画を分析

1941

ジョシュア・メイシー・ジュニア財団主催で会議がはじまる、後年メイシー会議(Macy conferences)

と言われる。この会議はサイバネティクス会議を含み、1960年まで続く。

1942

『バリ人の性格』(ベイトソンとの共著)/Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis, with

Margaret Mead, (The New York Academy of Science,

1942).=外山昇訳『バリ島人の性格——写真による分析』(国文社, 2001年)を出版(同年フ

ランツ・ボアズ死亡)

1942 OSS(戦略情報部; Office of Strategic Services)Office of Strategic Services、から派遣されて、セイロン、インド、ビルマ、中華民国へ、心理作戦要員として、日本軍の宣伝放送の かく乱に従事(〜1945)

1946 ハーバード大学講師(契約は1年で終わる)

1946 第1回サイバネティクス会議(Cybernetics Conferences)First Cybernetics Conference, March 21–22, 1946、開催(→Macy conferences). Second Cybernetics Conference, October 17–18, 1946。Warren Sturgis McCullochらと知りあう。

1947 Third Cybernetics Conference, March 13–14, 1947/Fourth Cybernetics Conference, October 23–24, 1947

1948 Fifth Cybernetics Conference, March 18–19, 1948

1949 Sixth Cybernetics Conference, March 24–25, 1949

1950 Seventh Cybernetics Conference, March 23–24, 1950

1951 Eighth Cybernetics Conference, March 15–16, 1951

1951

Communication: the Social Matrix of Psychiatry, with Jurgen Ruesch,

(Norton, 1951)./佐藤悦子, ロバート・ボスバーグ訳『コミュニケーション——精神医学の社会的マトリックス』(思索社,

1989年)=改題『精神のコミュニケーション』(新思索社, 1995年)

1952 Ninth Cybernetics Conference, March 20–21, 1952

1953

Tenth Cybernetics Conference, April 22–24, 1953

1960 全米学術基金(NSF)にタコのコミュニケーション研究助成を申請し却下される。サンフランシスコ・カリフォルニア美術学校非常勤講師

1961 統合失調症(精神分裂病)研究に対して、フリーダ・フロム=ライヒマン賞受賞。(編著)Perceval's Narrative: A Patient's Account of his Psychosis, 1830-1832, (Stanford University Press, 1961).

1961 ロイス・キャマックと結婚。自宅でタコを飼い始める。

1972 Steps to an Ecology of Mind, (Ballantine Book, 1972)./佐藤良明訳『精神の生態学』(思索社, 1990年/改訂第2版, 新思索社 2000年)

1979

Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity, (Wildwood House,

1979)./佐藤良明訳『精神と自然——生きた世界の認識論』(思索社, 1982年/改訂版, 新思索社 2001年/普及版, 新思索社

2006年)

1980 7月4日死去

1987

Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred, with Mary

Catherine Bateson, (Macmillan,

1987)./星川淳・吉福伸逸訳『天使のおそれ——聖なるもののエピステモロジー』(メアリー・キャサリン・ベイトソンとの共著、青土社,

1988年/新版, 1992年)

1991 A Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind, edited by Rodney E. Donaldson, (Cornelia & Michael Bessie Book, 1991).

+++

| Gregory Bateson

(9 May 1904 – 4 July 1980) was an English anthropologist, social

scientist, linguist, visual anthropologist, semiotician, and

cyberneticist whose work intersected that of many other fields. His

writings include Steps to an Ecology of Mind (1972) and Mind and Nature

(1979). In Palo Alto, California, Bateson and colleagues developed the double-bind theory of schizophrenia. Bateson's interest in systems theory forms a thread running through his work. He was one of the original members of the core group of the Macy conferences in Cybernetics (1941–1960), and the later set on Group Processes (1954–1960), where he represented the social and behavioral sciences. He was interested in the relationship of these fields to epistemology. His association with the editor and author Stewart Brand helped widen his influence. |

グレゴリー・ベイトソン(1904年5月9日 -

1980年7月4日)は、イギリスの人類学者、社会科学者、言語学者、視覚人類学者、記号学者、サイバネティシスト。著書に『Steps to an

Ecology of Mind』(1972年)、『Mind and Nature』(1979年)など。 カリフォルニア州パロアルトで、ベイトソンと同僚たちは精神分裂病のダブルバインド理論を開発した。 ベイトソンのシステム理論への関心は、彼の仕事を貫く糸となっている。彼は、サイバネティクスのメイシー会議(1941-1960)、および後のグルー プ・プロセスに関する会議(1954-1960)のコア・グループのオリジナル・メンバーの一人であり、社会科学と行動科学を代表した。彼は、これらの分 野と認識論との関係に関心を寄せていた。編集者であり作家でもあるスチュワート・ブランドとの交友は、彼の影響力を広げるのに役立った。 |

| Career In 1928, Bateson lectured in linguistics at the University of Sydney. From 1931 to 1937, he was a Fellow of St. John's College, Cambridge. He spent the years before World War II in the South Pacific in New Guinea and Bali doing anthropology. In the 1940s, he helped extend systems theory and cybernetics to the social and behavioral sciences. Although initially reluctant to join the intelligence services, Bateson served in OSS during World War II along with dozens of other anthropologists.[4] He was stationed in the same offices as Julia Child (then Julia McWilliams), Paul Cushing Child, and others.[5] He spent much of the war designing 'black propaganda' radio broadcasts. He was deployed on covert operations in Burma and Thailand, and worked in China, India, and Ceylon as well. Bateson used his theory of schismogenesis to help foster discord among enemy fighters. He was upset by his wartime experience and disagreed with his wife over whether science should be applied to social planning or used only to foster understanding rather than action.[4] In Palo Alto, California, Bateson developed the double-bind theory, together with his colleagues Donald Jackson, Jay Haley and John H. Weakland, also known as the Bateson Project (1953–1963).[6] In 1956, he became a naturalised citizen of the United States. Bateson was one of the original members of the core group of the Macy conferences in cybernetics (1941–1960), and the later set on Group Processes (1954–1960), where he represented the social and behavioral sciences. In the 1970s, he taught at the Humanistic Psychology Institute in San Francisco, renamed the Saybrook University,[7] and in 1972 joined the faculty of Kresge College at the University of California, Santa Cruz.[8] In 1976, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[9] California Governor Jerry Brown appointed him to the Regents of the University of California,[10] a position he held until his death, although he resigned from the Special Research Projects committee in 1979 in opposition to the university's work on nuclear weapons. Bateson spent the last decade of his life developing a "meta-science" of epistemology to bring together the various early forms of systems theory developing in different fields of science.[11] |

経歴 1928年、シドニー大学で言語学の講師を務める。1931年から1937年までケンブリッジ大学セント・ジョンズ・カレッジのフェロー。第二次世界大戦 前の数年間は、南太平洋のニューギニアとバリ島で人類学の研究に従事。 1940年代には、システム理論とサイバネティクスを社会科学と行動科 学に拡張することに貢献した。当初は諜報機関への参加に消極的であったが、ベイトソンは第二次世界大戦中、数十人の人類学者とともにOSSに所属した [4]。 彼はジュリア・チャイルド(当時はジュリア・マクウィリアムズ)、ポール・クッシング・チャイルドらと同じ事務所に配属された[5]。彼は戦争の大半を 「ブラック・プロパガンダ」ラジオ放送の設計に費やした。彼はビルマとタイで秘密作戦に投入され、中国、インド、セイロンでも働いた。ベイトソンは、敵の 戦闘員の間に不和を助長するために、彼の分裂発生理論を利用した。彼は戦時中の経験に動揺し、科学が社会計画に適用されるべきか、それとも行動ではなく理 解を促進するためだけに使用されるべきかで妻と意見が対立した[4]。 Price, David H. (Dr.). "Gregory Bateson and the OSS: World War II and Bateson's Assessment of Applied Anthropology." Human Organization Vol. 57, No. 4 (WINTER 1998), pp. 379-384 (6 pages) →「OSS(戦略情報部; Office of Strategic Services)資料集」 カリフォルニア州パロアルトで、ベイトソンは同僚のドナルド・ジャクソン、ジェイ・ヘイリー、ジョン・H・ウィークランドとともに、ベイトソン・プロジェ クト(1953-1963)としても知られるダブルバインド理論を開発した[6]。 1956年、米国に帰化。 ベイトソンは、サイバネティクスのメイシー会議(1941年-1960年)、および後の集団過程に関する会議(1954年-1960年)の中心メンバーの 一人であり、社会科学と行動科学を代表した。 1970年代には、サンフランシスコの人間性心理学研究所(セイブルック大学と改名)で教鞭をとり[7]、1972年にはカリフォルニア大学サンタクルー ズ校のクレスゲ・カレッジの教授陣に加わった[8]。 1976年にはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出され[9]、カリフォルニア州知事のジェリー・ブラウンからカリフォルニア大学の摂政に任命さ れ[10]、亡くなるまでその職を務めたが、1979年には同大学の核兵器に関する研究に反対して特別研究プロジェクト委員会を辞任した。 ベイトソンは人生の最後の10年間を、科学のさまざまな分野で発展しているシステム理論のさまざまな初期の形態をまとめるために、認識論の「メタ科学」を 発展させることに費やした[11]。 |

| Personal life From 1936 until 1950, he was married to American cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead.[12] He applied his knowledge to the war effort before moving to the United States.[13] Bateson and Mead had a daughter, Mary Catherine Bateson (1939–2021), who also became an anthropologist.[14] Bateson separated from Mead in 1947, and they were divorced in 1950.[15] In 1951, he married Elizabeth "Betty" Sumner, the daughter of the Episcopalian Bishop of Oregon, Walter Taylor Sumner. They had a son, John Sumner Bateson (1951–2015), as well as twins who died shortly after birth in 1953. Bateson and Sumner were divorced in 1957, after which Bateson was married a third time, to therapist and social worker Lois Cammack (born 1928), in 1961. They had one daughter, Nora Bateson (born 1969).[15] Bateson was a lifelong atheist, as his family had been for several generations.[16] He was a member of William Irwin Thompson's esoteric Lindisfarne Association. Bateson died on July 4, 1980, at age 76, in the guest house of the San Francisco Zen Center.[17] The 2014 novel Euphoria by Lily King is a fictionalized account of Bateson's relationships with Mead and Reo Fortune in pre-WWII New Guinea.[18] Philosophy Where others might see a set of inexplicable details, Bateson perceived simple relationships.[19] In "From Versailles to Cybernetics," Bateson argues that the history of the twentieth century can be perceived as the history of a malfunctioning relationship. In his view, the Treaty of Versailles exemplifies a whole pattern of human relationships based on betrayal and hate. He therefore claims that the treaty of Versailles and the development of cybernetics—which for him represented the possibility of improved relationships—are the only two anthropologically important events of the twentieth century.[20] |

私生活 1936年から1950年まで、彼はアメリカの文化人類学者マーガレット・ミードと結婚していた[12]。ベイトソンとミードの間には、同じく人類学者と なった娘メアリー・キャサリン・ベイトソン(Mary Catherine Bateson, 1939-2021)がいた[14]。 [ベイトソンは1947年にミードと別れ、1950年に離婚した[15]。1951年、オレゴン州のエピスコパリアン司教ウォルター・テイラー・サムナー の娘エリザベス・"ベティ"・サムナーと結婚。二人の間には息子ジョン・サムナー・ベイトソン(1951-2015)と、1953年に生後まもなく亡く なった双子がいた。ベイトソンとサムナーは1957年に離婚し、ベイトソンは1961年にセラピストでソーシャルワーカーのロイス・キャマック(1928 年生まれ)と3度目の結婚をした。二人の間にはノラ・ベイトソン(1969年生まれ)という娘がいた[15]。 ベイトソンは、彼の家族が数世代にわたってそうであったように、生涯無神論者であった[16]。 彼はウィリアム・アーウィン・トンプソンの秘教的なリンディスファーン協会のメンバーであった。 ベイトソンは1980年7月4日、サンフランシスコ禅センターのゲストハウスで76歳で死去した[17]。リリー・キングによる2014年の小説『ユー フォリア』は、第二次世界大戦前のニューギニアにおけるベイトソンとミードやレオ・フォーチュンとの関係をフィクションとして描いたものである[18]。 哲学 ベイトソンは、「ベルサイユからサイバネティクスへ」の中で、20世紀の歴史は機能不全に陥った関係の歴史として捉えることができると論じている。彼の見 解では、ヴェルサイユ条約は裏切りと憎悪に基づく人間関係の全パターンを例証している。それゆえ彼は、ヴェルサイユ条約とサイバネティクスの発展-彼に とっては人間関係を改善する可能性を象徴するもの-が20世紀の人類学的に重要な唯一の出来事であると主張している[20]。 |

| Work New Guinea Bateson's beginning years as an anthropologist were spent floundering, lost without a specific objective in mind. He began in 1927 with a trip to New Guinea, spurred by mentor A. C. Haddon.[21] His goal, as suggested by Haddon, was to explore the effects of contact between the Sepik natives and whites. Unfortunately for Bateson, his time spent with the Baining of New Guinea was halted and difficult. The Baining were not particularly accommodating of his research, and he missed out on many communal activities. They were also not inclined to share their religious practices with him.[21] He left the Baining frustrated. Next, he set out to study the Sulka, belonging to another native population of New Guinea. Although the Sulka were very different from the Baining and their culture more easily observed, he felt their culture was dying, which left him dispirited and discouraged.[21] He experienced more success with the Iatmul people, an indigenous people living along New Guinea's Sepik River. The observations he made among the Iatmul people allowed him to develop his concept of schismogenesis. In his 1936 book Naven he defined the term, based on his Iatmul fieldwork, as "a process of differentiation in the norms of individual behaviour resulting from cumulative interaction between individuals" (p. 175). The book was named after the 'naven' rite, an honorific ceremony among the Iatmul, still continued today, that celebrates first-time cultural achievements. The ceremony entails behaviours that are otherwise forbidden during everyday social life. For example, men and women reverse and exaggerate gender roles; men dress in women's skirts, and women dress in men's attire and ornaments.[21] Additionally, some women smear mud in the faces of other relatives, beat them with sticks, and hurl bawdy insults. Mothers may drop to the ground so their celebrated 'child' walks over them. And during a male rite, a mother's brother may slide his buttocks down the leg of his honoured sister's son, a complex gesture of masculine birthing, pride, and insult, rarely performed before women, that brings the honoured sister's son to tears.[22] Bateson suggested the influence of a circular system of causation, and proposed that: Women watched for the spectacular performances of the men, and there can be no reasonable doubt that the presence of an audience is a very important factor in shaping the men's behavior. In fact, it is probable that the men are more exhibitionistic because the women admire their performances. Conversely, there can be no doubt that the spectacular behavior is a stimulus which summons the audience together, promoting in the women the appropriate behavior.[21][page needed] In short, the behaviour of person X affects person Y, and the reaction of person Y to person X's behaviour will then affect person X's behaviour, which in turn will affect person Y, and so on. Bateson called this the "vicious circle."[21] He then discerned two models of schismogenesis: symmetrical and complementary.[21] Symmetrical relationships are those in which the two parties are equals, competitors, such as in sports. Complementary relationships feature an unequal balance, such as dominance-submission (parent-child), or exhibitionism-spectatorship (performer-audience). Bateson's experiences with the Iatmul led him to publish a book in 1936 titled Naven: A Survey of the Problems suggested by a Composite Picture of the Culture of a New Guinea Tribe drawn from Three Points of View (Cambridge University Press). The book proved to be a watershed in anthropology and modern social science.[23] Until Bateson published Naven, most anthropologists assumed a realist approach to studying culture, in which one simply described social reality. Bateson's book argued that this approach was naive, since an anthropologist's account of a culture was always and fundamentally shaped by whatever theory the anthropologist employed to define and analyse the data. To think otherwise, stated Bateson, was to be guilty of what Alfred North Whitehead called the "fallacy of misplaced concreteness." There was no singular or self-evident way to understand the Iatmul naven rite. Instead, Bateson analysed the rite from three unique points of view: sociological, ethological, and eidological. The book, then, was not a presentation of anthropological analysis but an epistemological account that explored the nature of anthropological analysis itself. The sociological point of view sought to identify how the ritual helped bring about social integration. In the 1930s, most anthropologists understood marriage rules to regularly ensure that social groups renewed their alliances. But Iatmul, argued Bateson, had contradictory marriage rules. Marriage, in other words, could not guarantee that a marriage between two clans would at some definite point in the future recur. Instead, Bateson continued, the naven rite filled this function by regularly ensuring exchanges of food, valuables, and sentiment between mothers' brothers and their sisters' children, or between separate lineages. Naven, from this angle, held together the different social groups of each village into a unified whole. The ethological point of view interpreted the ritual in terms of the conventional emotions associated with normative male and female behaviour, which Bateson called ethos. In Iatmul culture, observed Bateson, men and women lived different emotional lives. For example, women were rather submissive and took delight in the achievement of others; men fiercely competitive and flamboyant. During the ritual, however, men celebrated the achievement of their nieces and nephews while women were given ritual license to act raucously. In effect, naven allowed men and women to experience momentarily the emotional lives of each other, and thereby to achieve a level of psychological integration. The third and final point of view, the eidological, was the least successful. Here Bateson endeavoured to correlate the organisation structure of the naven ceremony with the habitual patterns of Iatmul thought. Much later, Bateson would harness the very same idea to the development of the double-bind theory of schizophrenia. In the Epilogue to the book, Bateson was clear: "The writing of this book has been an experiment, or rather a series of experiments, in methods of thinking about anthropological material." That is to say, his overall point was not to describe Iatmul culture of the naven ceremony but to explore how different modes of analysis, using different premises and analytic frameworks, could lead to different explanations of the same sociocultural phenomenon. Not only did Bateson's approach re-shape fundamentally the anthropological approach to culture, but the naven rite itself has remained a locus classicus in the discipline. In fact, the meaning of the ritual continues to inspire anthropological analysis.[24] |

仕事 ニューギニア ベイトソンの人類学者としての最初の数年間は、具体的な目標が定まらないまま、迷いながらバタバタと過ごしていた。1927年、彼は師であるA.C.ハド ンの勧めで、ニューギニアへの旅に出発した[21]。ハドンが示唆した彼の目的は、セピック原住民と白人との接触の影響を探ることであった。ベイトソンに とって不運だったのは、ニューギニアのバイニング族と過ごした時間が中途半端で、困難なものだったことである。ベイニング族は特に彼の研究に協力的ではな く、彼は多くの共同活動に参加できなかった。彼らはまた、自分たちの宗教的慣習を彼と共有する気もなかった[21]。次に彼は、ニューギニアの別の先住民 であるスルカ族の研究に着手した。スルカ族はバイニン族とは大きく異なり、彼らの文化を観察することは容易であったが、彼は彼らの文化が滅びつつあると感 じ、意気消沈し落胆した[21]。 彼は、ニューギニアのセピック川沿いに住む先住民であるイアトムル族で、より多くの成功を経験した。イアトムル族の観察によって、彼は分裂生成の概念を発 展させることができた。1936年の著書『ナヴェン』の中で、彼はイアトムルのフィールドワークに基づき、この言葉を「個人間の累積的な相互作用から生じ る、個人の行動規範における分化のプロセス」(p.175)と定義した。本書は、イアトムル族の儀式である「ナヴェン」にちなんで命名された。ナヴェンと は、イアトムル族が初めて文化的功績を達成したことを祝う儀式で、現在も続いている。この儀式では、日常の社会生活では禁じられている行為が行われる。例 えば、男性は女性のスカートを履き、女性は男性の服装や装飾品を身につけるなど、男女の性役割分担を逆転させ、誇張する[21]。さらに、一部の女性は他 の親族の顔に泥を塗り、棒で殴り、下品な侮辱を浴びせる。母親は、祝われた「子供」が自分の上を歩くように地面に伏せることもある。これは男性的な出産、 誇り、侮辱の複雑なジェスチャーであり、女性の前ではめったに行われない: 女性たちは男性たちの華やかな演技に注目しており、観客の存在が男性たちの行動を形成する上で非常に重要な要素であることに合理的な疑いはない。実際、女 性たちが彼らの演技を賞賛するからこそ、男性たちはより見せびらかすようになるのだろう。逆に、派手な行動が観客を呼び寄せる刺激となり、女性たちに適切 な行動を促すことは疑いない[21][要ページ]。 要するに、Xという人物の行動はYという人物に影響を与え、Xという人物の行動に対するYという人物の反応がXという人物の行動に影響を与え、それがまた Yという人物に影響を与えるというように、Xという人物の行動はYという人物の行動に影響を与えるのである。ベイトソンはこれを「悪循環」[21]と呼 び、分裂生成の2つのモデル、すなわち対称的関係と相補的関係を明らかにした。相補的な関係とは、支配と服従(親と子)や、展示主義と観客主義(パフォー マーと観客)のように、不平等なバランスを特徴とする関係である。ベイトソンはイアトムルとの経験から、1936年に『ナヴェン』という本を出版した: A Survey of the Problems suggested by a Composite Picture of a New Guinea Tribe Cultural drawn from Three Points of View』(ケンブリッジ大学出版局)という本を出版した。この本は人類学と現代社会科学の分水嶺となることを証明した[23]。 ベイトソンが『ナヴェン』を出版するまで、ほとんどの人類学者は文化を 研究するために、単に社会的現実を記述するという現実主義的なアプローチを想定していた。ベイトソンの著書は、文化に関する人類学者の説明は、データを定 義し分析するために人類学者が採用した理論によって常に、そして基本的に形成されていたため、このアプローチは素朴であると主張した。そうでないと考える ことは、アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドが言うところの "見当違いの具体性の誤謬 "を犯すことになるとベイトソンは述べた。イアトムル・ナヴェンの儀式を理解する唯一の、あるいは自明な方法など存在しない。その代わりにベイトソンは、 社会学的、エソロジー的(動物行動学)、エイドス的(形相的)という3つのユニークな視点から儀式を分析した。つまり、本書は人類学的分析の提示ではな く、人類学的分析そのものの本質を探る認識論的説明であった。 社会学的な視点は、儀式がどのように社会的統合をもたらすのに役立っているかを明らかにしようとするものであった。1930年代、ほとんどの人類学者は、 結婚の規則は社会集団が定期的に同盟を更新するためのものだと理解していた。しかしベイトソンは、イアトムルには矛盾した結婚規則があると主張した。つま り、婚姻は2つの氏族間の婚姻が将来のある明確な時点で再発することを保証するものではなかった。その代わりに、母親の兄弟とその姉妹の子供、あるいは別 々の血統の間で、食べ物や貴重品、情緒の交換を定期的に保証することによって、ナヴェンという儀式がこの機能を果たしていた、とベイトソンは続けた。ナ ヴェンは、このような角度から見ると、それぞれの村の異なる社会集団を統合した全体としてまとめていたのである。 エソロジー的(動物行動学)な視点は、ベイトソンがエー トスと呼んだ規範的な男女の行動に関連する慣習的な感情の観点から儀式を解釈した。ベイトソンによれば、イアトムル文化では、男性と女性は異なる感情生活 を送っていた。たとえば、女性はどちらかといえば従順で、他人の功績を喜び、男性は激しく競争し、派手だった。しかし、儀式の間、男性は姪や甥の功績を称 え、女性には騒々しく振舞う儀式の許可が与えられた。事実上、ナベンによって男女は互いの感情的な生活を瞬間的に体験し、それによって心理的な統合を達成 することができたのである。 最後の第三の視点であるエイドス的(形相的)つまり環境学的視点は、 最も成功しなかった。ベイトソンはここで、ナヴェンの儀式の組織構造とイアトムルの習慣的な思考パターンを関連付けようとした。ずっと後になって、ベイト ソンはまったく同じアイデアを統合失調症のダブルバインド理論の展開に利用することになる。 本書のエピローグで、ベイトソンは次のように明言している。"本書の執筆は、人類学的な素材について考える方法についての実験、いや、むしろ一連の実験で あった"。つまり、彼の全体的な目的は、イアトムルのナヴェン儀式文化を記述することではなく、異なる前提や分析枠組みを用いた異なる分析様式が、同じ社 会文化的現象についていかに異なる説明を導きうるかを探求することだった。ベイトソンのアプローチは、文化に対する人類学的アプローチを根本から塗り替え ただけでなく、ナヴェンの儀式そのものが、この学問分野における古典的な位置づけであり続けている。事実、儀式の意味は人類学的分析を刺激し続けている [24]。 |

| Bali Bateson next[when?] travelled to Bali with his new wife Margaret Mead to study the people of the village Bajoeng Gede. Here, Lipset states, "in the short history of ethnographic fieldwork, film was used both on a large scale and as the primary research tool."[21] Bateson took 25,000 photographs of their Balinese subjects.[25] He discovered that the people of Bajoeng Gede raised their children very unlike children raised in Western societies. Instead of attention being paid to a child who was displaying a climax of emotion (love or anger), Balinese mothers would ignore them. Bateson notes, "The child responds to [a mother's] advances with either affection or temper, but the response falls into a vacuum. In Western cultures, such sequences lead to small climaxes of love or anger, but not so in Bali. At the moment when a child throws its arms around the mother's neck or bursts into tears, the mother's attention wanders".[21] This model of stimulation and refusal was also seen in other areas of the culture. Bateson later described the style of Balinese relations as stasis instead of schismogenesis. Their interactions were "muted" and did not follow the schismogenetic process because they did not often escalate competition, dominance, or submission.[21] |

バリ島 ベイトソンは次に[いつ?]、新妻マーガレット・ミードとともにバリ島を訪れ、バジョアン・グデ村の人々を調査した。ここでリプセットは、「民族誌的 フィールドワークの短い歴史の中で、フィルムは大規模かつ主要な調査ツールとして使われた」と述べている[21]。 彼は、バジョエン・グデの人々が西洋社会で育つ子どもたちとはまったく違って子育てをしていることを発見した。感情の絶頂(愛情や怒り)を示す子供に注意 を払う代わりに、バリの母親はその子供を無視した。ベイトソンは、「子どもは(母親の)誘いかけに愛情か気性のどちらかで反応するが、その反応は空白に陥 る」と指摘する。西洋文化では、このような連続は愛や怒りの小さなクライマックスにつながるが、バリではそうではない。子どもが母親の首に腕を回したり、 涙をこぼしたりする瞬間、母親の注意はさまよう」[21]。この刺激と拒絶のモデルは、文化の他の地域でも見られた。ベイトソンは後に、バリの人間関係の 様式を分裂生成ではなく静止と表現した。彼らの相互作用は「穏やか」であり、競争や支配、服従をエスカレートさせることがあまりなかったため、分裂生成過 程には従わなかった[21]。 |

New Guinea, 1938 In

1938, Bateson and Mead returned to the Sepik River, and settled into

the village of Tambunum, where Bateson had spent three days in the

1920s. They aimed to replicate the Balinese project on the relationship

between childraising and temperament, and between conventions of the

body – such as pose, grimace, holding infants, facial expressions, etc.

– reflected wider cultural themes and values. Bateson snapped some

10,000 black and white photographs, and Mead typed thousands of pages

of fieldnotes. But Bateson and Mead never published anything

substantial from this research.[26] In

1938, Bateson and Mead returned to the Sepik River, and settled into

the village of Tambunum, where Bateson had spent three days in the

1920s. They aimed to replicate the Balinese project on the relationship

between childraising and temperament, and between conventions of the

body – such as pose, grimace, holding infants, facial expressions, etc.

– reflected wider cultural themes and values. Bateson snapped some

10,000 black and white photographs, and Mead typed thousands of pages

of fieldnotes. But Bateson and Mead never published anything

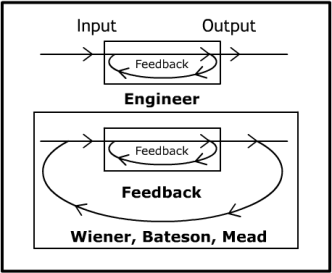

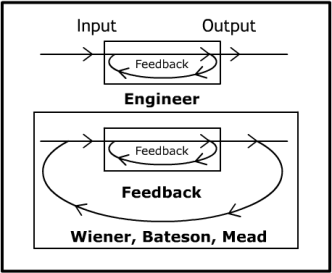

substantial from this research.[26]Bateson and Margaret Mead contrasted first and second-order cybernetics with this diagram in an interview in 1973.[27] Bateson's encounter with Mead on the Sepik river (Chapter 16) and their life together in Bali (Chapter 17) is described in Mead's autobiography Blackberry Winter: My Earlier Years (Angus and Robertson. London. 1973). Their daughter Catherine's birth in New York on 8 December 1939 is recounted in Chapter 18. |

ニューギニア、1938年 1938

年、ベイトソンとミードはセピック川に戻り、1920年代にベイトソンが3日間滞在したタンブヌム村に落ち着いた。彼らは、子育てと気質との関係や、ポー

ズ、しかめっ面、乳幼児の抱き方、顔の表情など、身体の慣習がより広い文化的テーマや価値観に反映されることについてのバリ人のプロジェクトを再現するこ

とを目指した。-

それは、より広い文化的テーマや価値観を反映したものだった。ベイトソンは約10,000枚の白黒写真を撮影し、ミードは何千ページものフィールドノート

をタイプした。しかし、ベイトソンとミードはこの調査から実質的なものを発表することはなかった[26]。 1938

年、ベイトソンとミードはセピック川に戻り、1920年代にベイトソンが3日間滞在したタンブヌム村に落ち着いた。彼らは、子育てと気質との関係や、ポー

ズ、しかめっ面、乳幼児の抱き方、顔の表情など、身体の慣習がより広い文化的テーマや価値観に反映されることについてのバリ人のプロジェクトを再現するこ

とを目指した。-

それは、より広い文化的テーマや価値観を反映したものだった。ベイトソンは約10,000枚の白黒写真を撮影し、ミードは何千ページものフィールドノート

をタイプした。しかし、ベイトソンとミードはこの調査から実質的なものを発表することはなかった[26]。ベイトソンとマーガレット・ミードは1973年のインタヴューで、一次と二次のサイバネティクスをこの図で対比している[27]。 セピック川でのベイトソンとミードとの出会い(第16章)とバリでの共同生活(第17章)は、ミードの自伝『Blackberry Winter: My Earlier Years (Angus and Robertson. London. 1973)に書かれている。1939年12月8日のニューヨークでの娘キャサリンの誕生は第18章に記されている。 |

| Double bind theory of

schizophrenia Main article: Double bind In 1956 in Palo Alto, Bateson and his colleagues Donald Jackson, Jay Haley, and John Weakland[6] articulated a related theory of schizophrenia as stemming from double bind situations. The double bind refers to a communication paradox described first in families with a schizophrenic member. The first place where double binds were described (though not named as such) was according to Bateson, in Samuel Butler's The Way of All Flesh (a semi-autobiographical novel about Victorian hypocrisy and cover-up).[28] Full double bind requires several conditions to be met: 1. The victim of double bind receives contradictory injunctions or emotional messages on different levels of communication (for example, love is expressed by words, and hate or detachment by nonverbal behaviour; or a child is encouraged to speak freely, but criticised or silenced whenever he or she actually does so). 2. No metacommunication is possible – for example, asking which of the two messages is valid or describing the communication as making no sense. 3. The victim cannot leave the communication field. 4. Failing to fulfill the contradictory injunctions is punished (for example, by withdrawal of love). The strange behaviour and speech of schizophrenics was explained by Bateson et al. as an expression of this paradoxical situation, and were seen in fact as an adaptive response, which should be valued as a cathartic and transformative experience. The double bind was originally presented (probably mainly under the influence of Bateson's psychiatric co-workers) as an explanation of part of the etiology of schizophrenia. Currently, it is considered to be more important as an example of Bateson's approach to the complexities of communication which is what he understood it to be.[citation needed] |

統合失調症のダブルバインド理論 主な記事 ダブルバインド 1956年にパロアルトで、ベイトソンと彼の同僚であるドナルド・ジャクソン、ジェイ・ヘイリー、ジョン・ウィークランド[6]は、精神分裂病がダブルバ インド(二重拘束)の状況に由来するという関連理論を発表した。ダブルバインドとは、精神分裂病患者のいる家庭で最初に報告されたコミュニケーションのパ ラドックスのことである。ベイトソンによれば、ダブルバインドが最初に記述されたのは、サミュエル・バトラーの『The Way of All Flesh』(ヴィクトリア朝の偽善と隠蔽を描いた半自伝的小説)であった[28]。 完全なダブルバインドにはいくつかの条件が満たされる必要がある: 1. ダブルバインドの犠牲者は、異なるレベルのコミュニケーションにおいて、矛盾した命令や感情的メッセージを受け取る(例えば、愛は言葉によって表現され、 憎しみや離反は非言語的行動によって表現される。) 2. メタコミュニケーションはできない;例えば、2つのメッセージのうちどちらが正しいかを尋ねたり、コミュニケーションが意味をなさないと表現したりする。 3. 被害者はコミュニケーションの場から離れることはできない。 4. 矛盾した命令を履行しないと罰せられる(例えば、愛の撤回)。 精神分裂病患者の奇妙な行動や言動は、ベイトソンらによってこの逆説的な状況の表現として説明され、実際には適応的な反応であり、カタルシスや変容をもた らす経験として評価されるべきものであると見なされた。 ダブルバインドはもともと(おそらく主にベイトソンの精神医学の共同研究者の影響下で)、精神分裂病の病因の一部を説明するものとして発表された。現在で は、ベイトソンが理解した複雑なコミュニケーションへのアプローチの一例として、より重要視されている[要出典]。 |

| The role of somatic change in

evolution Bateson writes about how the actual physical changes in the body occur within evolutionary processes.[29] He describes this through the introduction of the concept of "economics of flexibility".[29] In his conclusion he makes seven statements or theoretical positions which may be supported by his ideology. The first is the idea that although environmental stresses have theoretically been believed to guide or dictate the changes in the soma (physical body), the introduction of new stresses do not automatically result in the physical changes necessary for survival as suggested by original evolutionary theory.[29] In fact the introduction of these stresses can greatly weaken the organism. An example that he gives is the sheltering of a sick person from the weather or the fact that someone who works in an office would have a hard time working as a rock climber and vice versa. The second position states that though "the economics of flexibility has a logical structure-each successive demand upon flexibility fractioning the set of available possibilities".[29] This means that theoretically speaking each demand or variable creates a new set of possibilities. Bateson's third conclusion is "that the genotypic change commonly makes demand upon the adjustive ability of the soma".[29] This, he states, is the commonly held belief among biologists although there is no evidence to support the claim. Added demands are made on the soma by sequential genotypic modifications is the fourth position. Through this he suggests the following three expectations:[29] The idea that organisms that have been through recent modifications will be delicate. The belief that these organisms will become progressively harmful or dangerous. That over time these new "breeds" will become more resistant to the stresses of the environment and change in genetic traits. The fifth theoretical position which Bateson believes is supported by his data is that characteristics within an organism that have been modified due to environmental stresses may coincide with genetically determined attributes.[29] His sixth position is that it takes less economic flexibility to create somatic change than it does to cause a genotypic modification. The seventh and final theory he believes to be supported is the idea that in rare occasions there will be populations whose changes will not be in accordance with the thesis presented within this paper. According to Bateson, none of these positions (at the time) could be tested but he called for the creation of a test which could possibly prove or disprove the theoretical positions suggested within.[29] |

進化における身体的変化の役割 ベイトソンは、身体における実際の身体的変化が進化のプロセスの中でどのように起こるかについて書いている。 彼は「柔軟性の経済学」という概念の導入を通じてこのことを説明している。 1つ目は、環境ストレスは理論的にはソーマ(肉体)の変化を導く、あるいは指示すると信じられてきたが、新たなストレスの導入は、本来の進化論が示唆する ような生存に必要な肉体的変化を自動的にもたらすわけではないという考えである。その例として、病人を天候から守ることや、オフィスで働く人がロッククラ イマーとして働くことが難しいこと、あるいはその逆が挙げられる。第二の立場は、「柔軟性の経済学には論理的構造がある-柔軟性に対する要求が連続するご とに、利用可能な可能性の集合が分画される」[29]と述べている。これは、理論的に言えば、各要求や変数が新たな可能性の集合を生み出すということであ る。ベイトソンの第三の結論は、「遺伝子型の変化は一般に体躯の調整能力に対して要求を行う」というものである。付加的な要求は、遺伝子型の逐次的な変化 によって身体に対してなされるというのが第4の立場である。これを通じて、彼は以下の3つの予想を提案している。 最近の改変を経た生物はデリケートになるという考え。 これらの生物は次第に有害または危険なものになるという考え。 時間の経過とともに、これらの新しい「品種」は環境のストレスや遺伝的形質の変化に対してより耐性を持つようになるだろうということ。 ベイトソンが彼のデータによって支持されていると考えている5つ目の理論的立場は、環境ストレスによって変化した生物体内の特徴は、遺伝的に決定された属 性と一致する可能性があるというものである[29]。ベイトソンが支持すると考える7つ目の最後の理論は、まれにこの論文で提示されたテーゼに沿わない変 化をする個体群が存在するという考えである。ベイトソンによれば、(当時は)これらの立場のどれも検証することはできなかったが、彼はその中で示唆された 理論的立場を証明したり反証したりすることができる可能性のあるテストを作成することを求めた[29]。 |

| Ecological anthropology and

cybernetics In his book Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Bateson applied cybernetics to the field of ecological anthropology and the concept of homeostasis.[30] He saw the world as a series of systems containing those of individuals, societies and ecosystems. Within each system is found competition and dependency. Each of these systems has adaptive changes which depend upon feedback loops to control balance by changing multiple variables. Bateson believed that these self-correcting systems were conservative by controlling exponential slippage. He saw the natural ecological system as innately good as long as it was allowed to maintain homeostasis[30] and that the key unit of survival in evolution was an organism and its environment.[30] Bateson also viewed that all three systems of the individual, society and ecosystem were all together a part of one supreme cybernetic system that controls everything instead of just interacting systems.[30] This supreme cybernetic system is beyond the self of the individual and could be equated to what many people refer to as God, though Bateson referred to it as Mind.[30] While Mind is a cybernetic system, it can only be distinguished as a whole and not parts. Bateson felt Mind was immanent in the messages and pathways of the supreme cybernetic system. He saw the root of system collapses as a result of Occidental or Western epistemology. According to Bateson, consciousness is the bridge between the cybernetic networks of individual, society and ecology and the mismatch between the systems due to improper understanding will result in the degradation of the entire supreme cybernetic system or Mind. Bateson thought that consciousness as developed through Occidental epistemology was at direct odds with Mind.[30] At the heart of the matter is scientific hubris. Bateson argues that Occidental epistemology perpetuates a system of understanding which is purpose or means-to-an-end driven.[30] Purpose controls attention and narrows perception, thus limiting what comes into consciousness and therefore limiting the amount of wisdom that can be generated from the perception. Additionally Occidental epistemology propagates the false notion that man exists outside Mind and this leads man to believe in what Bateson calls the philosophy of control based upon false knowledge.[30] Bateson presents Occidental epistemology as a method of thinking that leads to a mindset in which man exerts an autocratic rule over all cybernetic systems.[30] In exerting his autocratic rule man changes the environment to suit him and in doing so he unbalances the natural cybernetic system of controlled competition and mutual dependency. The purpose-driven accumulation of knowledge ignores the supreme cybernetic system and leads to the eventual breakdown of the entire system. Bateson claims that man will never be able to control the whole system because it does not operate in a linear fashion and if man creates his own rules for the system, he opens himself up to becoming a slave to the self-made system due to the non-linear nature of cybernetics. Lastly, man's technological prowess combined with his scientific hubris gives him the potential to irrevocably damage and destroy the supreme cybernetic system, instead of just disrupting the system temporally until the system can self-correct.[30] Bateson argues for a position of humility and acceptance of the natural cybernetic system instead of scientific arrogance as a solution.[30] He believes that humility can come about by abandoning the view of operating through consciousness alone. Consciousness is only one way in which to obtain knowledge and without complete knowledge of the entire cybernetic system disaster is inevitable. The limited conscious must be combined with the unconscious in complete synthesis. Only when thought and emotion are combined in whole is man able to obtain complete knowledge. He believed that religion and art are some of the few areas in which a man is acting as a whole individual in complete consciousness. By acting with this greater wisdom of the supreme cybernetic system as a whole man can change his relationship to Mind from one of schism, in which he is endlessly tied up in constant competition, to one of complementarity. Bateson argues for a culture that promotes the most general wisdom and is able to flexibly change within the supreme cybernetic system.[30] |

生態人類学とサイバネティクス ベイトソンは著書『Steps to an Ecology of Mind』の中で、サイバネティクスを生態人類学の分野とホメオスタシスの概念に応用した[30]。それぞれのシステムの中には、競争と依存が存在する。 これらのシステムはそれぞれ、複数の変数を変化させることでバランスを制御するフィードバック・ループに依存する適応的な変化を持っている。ベイトソン は、これらの自己修正システムは指数関数的な滑りを制御することによって保守的であると考えた。彼は自然の生態系はホメオスタシス[30]を維持すること が許されている限り生来的に良いものであり、進化における生存の重要な単位は生物とその環境であると考えた[30]。 ベイトソンはまた、個人、社会、生態系の3つのシステムはすべて一緒になって、相互作用するシステムだけでなく、すべてを制御する1つの至高のサイバネ ティックシステムの一部であると見ていた[30]。この至高のサイバネティックシステムは個人の自己を超えたものであり、多くの人々が神と呼ぶものと同一 視することができるが、ベイトソンはそれをマインドと呼んでいた[30]。ベイトソンはマインドが至高のサイバネティック・システムのメッセージと経路に 内在していると感じていた。彼は、システム崩壊の根源は西洋的な認識論の結果であると考えた。ベイトソンによれば、意識は個人、社会、エコロジーのサイバ ネティック・ネットワークの架け橋であり、不適切な理解によるシステム間のミスマッチは、至高のサイバネティック・システム全体、あるいはマインドの劣化 をもたらす。ベイトソンは、西洋の認識論によって発展した意識はマインドと真っ向から対立していると考えていた[30]。 問題の核心は科学的傲慢さである。ベイトソンは、西洋の認識論は、目的または手段から目的へと駆り立てられる理解のシステムを永続させていると主張してい る。さらに西洋の認識論は、人間はマインドの外側に存在するという誤った概念を広めることで、ベイトソンが「誤った知識に基づく支配の哲学」と呼ぶものを 人間が信じるように仕向ける[30]。 ベイトソンは西洋思想の認識論を、人間がすべてのサイバネティック・システムに対して独裁的な支配を及ぼす考え方をもたらす思考法として提示している [30]。目的主導の知識の蓄積は、至高のサイバネティック・システムを無視し、最終的にはシステム全体の崩壊につながる。ベイトソンは、人間はシステム 全体をコントロールすることは決してできないと主張する。なぜなら、システムは直線的に作動しないからであり、もし人間がシステムのために独自のルールを 作れば、サイバネティックスの非直線的な性質のために、人間は自ら作ったシステムの奴隷になることを自ら開くことになるからである。最後に、人間の科学的 傲慢と組み合わさった技術力は、システムが自己修正できるまで一時的にシステムを混乱させるだけでなく、至高のサイバネティック・システムに取り返しのつ かないダメージを与え、破壊する可能性を与える[30]。 ベイトソンは解決策として、科学的な傲慢さの代わりに、自然なサイバネティック・システムを謙虚に受け入れる立場を主張している[30]。意識は知識を得 るためのひとつの方法に過ぎず、サイバネティック・システム全体に関する完全な知識がなければ、災害は避けられない。限られた意識は無意識と組み合わさ れ、完全に統合されなければならない。思考と感情が全体として組み合わされて初めて、人間は完全な知識を得ることができる。彼は、宗教と芸術は、人間が完 全な意識の中で個人全体として行動している数少ない分野であると考えた。この至高のサイバネティック・システムという大いなる叡智をもって全体として行動 することで、人間はマインドとの関係を、絶え間ない競争に際限なく縛られる分裂の関係から、相補性の関係に変えることができる。ベイトソンは、最も一般的 な知恵を促進し、至高のサイバネティック・システムの中で柔軟に変化することができる文化を主張している[30]。 |

| Other terms used by Bateson Abduction. Used by Bateson to refer to a third scientific methodology (along with induction and deduction) which was central to his own holistic and qualitative approach. Refers to a method of comparing patterns of relationship, and their symmetry or asymmetry (as in, for example, comparative anatomy), especially in complex organic (or mental) systems. The term was originally coined by American Philosopher/Logician Charles Sanders Peirce, who used it to refer to the process by which scientific hypotheses are generated. Criteria of Mind (from Mind and Nature A Necessary Unity):[30] Mind is an aggregate of interacting parts or components. The interaction between parts of mind is triggered by difference. Mental process requires collateral energy. Mental process requires circular (or more complex) chains of determination. In mental process the effects of difference are to be regarded as transforms (that is, coded versions) of the difference which preceded them. The description and classification of these processes of transformation discloses a hierarchy of logical types immanent in the phenomena. Creatura and Pleroma. Borrowed from Carl Jung who applied these gnostic terms in his "Seven Sermons To the Dead".[31] Like the Hindu term maya, the basic idea captured in this distinction is that meaning and organisation are projected onto the world. Pleroma refers to the non-living world that is undifferentiated by subjectivity; Creatura for the living world, subject to perceptual difference, distinction, and information. Deuterolearning. A term he coined in the 1940s referring to the organisation of learning, or learning to learn:[32] Schismogenesis – the emergence of divisions within social groups. Information – Bateson defined information as "a difference which makes a difference." This definition, however, is taken out of its context and lacks Bateson's reference to the requirement of energy to make a difference, and his definition of a difference as a matter that can be abstract also.[33][34] For Bateson, information in fact mediated Alfred Korzybski's map–territory relation, and thereby resolved, according to Bateson, the mind-body problem.[35][36][37] Continuing extensions of his work In 1984, his daughter Mary Catherine Bateson published a joint biography of her parents (Bateson and Margaret Mead).[38] His other daughter the filmmaker Nora Bateson released An Ecology of Mind, a documentary that premiered at the Vancouver International Film Festival.[39] This film was selected as the audience favourite with the Morton Marcus Documentary Feature Award at the 2011 Santa Cruz Film Festival,[40] and honoured with the 2011 John Culkin Award for Outstanding Praxis in the Field of Media Ecology by the Media Ecology Association.[41] The Bateson Idea Group (BIG) initiated a web presence in October 2010. The group collaborated with the American Society for Cybernetics for a joint meeting in July 2012 at the Asilomar Conference Grounds in California. The modern view of artificial intelligence based on social machines has deep links to Bateson's ecological perspectives of intelligence.[42] |

ベイトソンが使用した他の用語 アブダクション。ベイトソンが、(帰納法、演繹法と並ぶ)第三の科学的方法論を指すのに使用。特に複雑な有機的(または精神的)システムにおいて、関係の パターンやその対称性・非対称性を(例えば比較解剖学のように)比較する方法を指す。この用語はもともとアメリカの哲学者/論理学者チャールズ・サンダー ス・パイアースによって作られたもので、彼は科学的仮説が生成されるプロセスを指すのにこの用語を使用した。 心の基準(『心と自然 A Necessary Unity』より):[30]。 心とは相互作用する部分または構成要素の集合体である。 心の部分間の相互作用は差異によって引き起こされる。 精神的プロセスは付随的エネルギーを必要とする。 精神的プロセスは決定の循環的な(あるいはより複雑な)連鎖を必要とする。 心的過程では、差異がもたらす影響は、それに先立つ差異の変換(つまりコード化されたバージョン)とみなされる。 これらの変換の過程の記述と分類は、現象に内在する論理的タイプの階層を開示する。 CreaturaとPleroma。カール・ユングが『死者への7つの説教』の中でこれらのグノーシス的な用語を適用したことから借用した[31]。ヒン ドゥー教の用語マヤと同様に、この区別に捉えられた基本的な考え方は、意味と組織が世界に投影されるということである。プレローマは主観性によって未分化 な非生命世界を指し、クリエートゥーラは知覚的差異、区別、情報の対象となる生命世界を指す。 デューテロラーニング。1940年代に彼が作った造語で、学習の組織化、あるいは学習するための学習を指す[32]。 分裂発生-社会集団内の分裂の出現。 情報 - ベイトソンは情報を「違いを生み出す違い」と定義した。しかしこの定義は文脈から取り出されたものであり、差異を生み出すためのエネルギーの要件に対する ベイトソンの言及や、抽象的であることも可能な物質としての差異の定義が欠落している[33][34]。ベイトソンにとって情報は実際にはアルフレッド・ コージブスキーの地図-領域関係を媒介するものであり、それによってベイトソンによれば心身問題を解決するものであった[35][36][37]。 彼の仕事の継続的な拡張 1984年、娘のメアリー・キャサリン・ベイトソンは両親(ベイトソンとマーガレット・ミード)の共同伝記を出版した[38]。 もう一人の娘で映画監督のノラ・ベイトソンは、バンクーバー国際映画祭でプレミア上映されたドキュメンタリー映画『An Ecology of Mind』を発表した[39]。この映画は、2011年のサンタクルーズ映画祭でモートン・マーカス・ドキュメンタリー長編賞の観客賞として選ばれ [40]、メディアエコロジー協会からメディアエコロジーの分野における卓越した実践に対して2011年ジョン・カルキン賞を授与された[41]。 2010年10月、ベイトソン・アイディア・グループ(BIG)がウェブでの活動を開始。同グループは、2012年7月にカリフォルニアのアシロマー会議 場で開催されたアメリカサイバネティックス学会との合同会議に協力した。 社会的機械に基づく人工知能の現代的見解は、ベイトソンの知性の生態学的観点と深いつながりがある[42]。 |

| Books Bateson, G. (1965) [First published 1936]. Naven: A Survey of the Problems suggested by a Composite Picture of the Culture of a New Guinea Tribe drawn from Three Points of View. Stanford University Press. Bateson, G. (2000) [First published 1972]. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226039053. Bateson, G. (2002) [First published 1979]. Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity. Hampton Press. ISBN 9781572734340. Bateson, G. (2005) [First published 1991]. Donaldson, Rodney E. (ed.). A Sacred Unity: Further Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Hampton Press. ISBN 9781572736252. Bateson, G.; Bateson, M.C. (2005) [First published 1987]. Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred. Hampton Press. ISBN 9781572735941. Bateson, G.; Mead, M. (1985) [First published 1942]. Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis. Special Publications of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 2. New York Academy of Sciences. ISBN 9780890727805. Hall, Robert A.; Bateson, G.; Mead, Margaret; Kaberry, Phyllis M.; Reed, Stephen W.; Whiting, John W.M. (1943). Melanesian Pidgin English: Grammar, Texts, Vocabulary. Special Publications of the Linguistic Society of America. Linguistic Society of America at the Waverly Press, Inc. Hall, Robert A.; Bateson, G.; Whiting, John W.M.; Linguistic Society of America; United States Armed Forces Institute (1943). Melanesian Pidgin English, Short Grammar and Vocabulary: With Grammatical Introduction. Special Publications of the Linguistic Society of America. Linguistic Society of America at the Waverly Press, Inc. Perceval, John (1974) [First published 1961]. Bateson, G. (ed.). Perceval's Narrative: A Patient's Account of His Psychosis, 1830-1832. Stanford University Press. Ruesch, Jurgen; Bateson, G. (2008) [First published 1951]. Pinsker, Eve C.; Combs, Gene (eds.). Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315080932. ISBN 9781351527590. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregory_Bateson |

次 の写真は、マーガレット・ミードとグレゴリー・ベイトソンの『バリ人の性格』という写真による民族誌の古典からの引用(実際は『フィール ドからの手紙』)である。

リンク(サイト内でベイトソン言及したもの)

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆