Can you analyze people's "personalities" from their photos?

写真からの人々の「性格」を分析できるのか?

Can you analyze people's "personalities" from their photos?

●

| Trance and Dance in

Bali is a short documentary film shot by the anthropologists Margaret

Mead and Gregory Bateson during their research on Bali in the 1930s. It

shows female dancers with sharp kris daggers dancing in trance,

eventually stabbing themselves without injury. The film was not

released until 1951. It has attracted praise from later anthropologists

for its pioneering achievement, and criticism for its focus on the

performance, omitting relevant details such as the conversation of the

dancers. |

バリのトランスとダンス』は、人類学者のマーガレット・ミードとグレゴ

リー・ベイトソンが1930年代にバリ島を調査した際に撮影した短編ドキュメンタリー映画である。鋭利なクリス短剣を持った女性ダンサーたちがトランス状

態で踊り、最終的には怪我をすることなく自らを刺す様子を映し出している。この映画が公開されたのは1951年のことである。後世の人類学者たちからは、

その先駆的な業績に対する賞賛と、パフォーマンスだけに焦点を当て、踊り子たちの会話など関連する詳細が省略されているという批判を集めている。 |

| History The anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson visited Bali for two years of research in the 1930s, shooting some 22,000 feet of 16-millimetre film and 25,000 photographs, and completing seven films, of which Trance and Dance in Bali is one. They were married in 1936. Their output of visual materials has been described as unrivalled in anthropology.[1][2] This was driven by their method of participant observation, which was intended to be recorded in copious systematic field notes so as to grasp the subject's point of view.[3] They paid careful attention to photographic technique, using both still and motion-picture cameras. During their stay, Bateson sent home for additional bulk film, a larger developing tank, and a rapid winder to allow photographs to be taken "in very rapid succession".[3] The dance for Trance and Dance in Bali was specially arranged during daylight hours, as no lighting equipment was available; the dance was, according to Mead, "ordinarily performed only late at night".[3] Mead later noted that "The man who made the arrangements decided to substitute young beautiful women for the withered old women who performed at night, and we could record how women who had never before been in trance flawlessly replicated the customary behavior they had watched all their lives".[3] In this way, Mead justified the changes as part of their anthropological inquiry.[3] The film, like Bateson and Mead's other works, initially received a puzzled welcome. The films became classics, launched the field of visual anthropology, and have "landmark status" with little to compare them to. Most of the footage of Trance and Dance in Bali was shot on 16 December 1937 in a performance that they commissioned (on Mead's birthday). They referenced their payment for the performance to Balinese cultural patronage. The trance ritual that they filmed was, according to the anthropologist Ira Jacknis, "not an ancient form, but had been created during the period of their fieldwork", as a Balinese group had in 1936 "combined the Rangda or Witch play (Tjalonarang) with the Barong and kris-dance play, which was then popularized with tourists through the efforts of [the painter] Walter Spies and his friends."[4] |

歴史 人類学者のマーガレット・ミードとグレゴリー・ベイトソンは、1930年代に2年間バリ島を訪れ、約22,000フィートの16ミリフィルムと 25,000枚の写真を撮影し、7本の映画を完成させた。ふたりは1936年に結婚した。彼らの映像資料の生産量は、人類学において比類なきものと評され ている[1][2]。 その原動力となったのは、被験者の視点を把握するために、膨大な量の体系的フィールドノートに記録することを意図した参加者観察の手法であった[3]。滞 在中、ベイトソンは追加のバルクフィルム、より大きな現像タンク、写真を「非常に素早く連続して」撮影できるようにするためのラピッドワインダーを自宅に 送った[3]。 バリの恍惚と舞踏』のための舞踏は、照明機材がなかったため、特別に昼間の時間帯にアレンジされた。ミードによれば、舞踏は「通常は深夜にのみ演じられ る」ものだった。 [3]ミードは後に、「手配をした男は、夜に演じる枯れ果てた老女たちの代わりに若い美しい女性たちに代えることにした。 この映画は、ベイトソンとミードの他の作品と同様、当初は戸惑いながらも歓迎された。映画は古典となり、映像人類学の分野を立ち上げ、比較対象がほとんど ないまま「画期的な地位」を獲得した。トランス&ダンス・イン・バリ』の映像のほとんどは、1937年12月16日、彼らが依頼したパフォーマンス(ミー ドの誕生日)で撮影されたものだ。彼らは、このパフォーマンスに対する支払いをバリの文化的後援に言及した。人類学者のアイラ・ジャックニスによれば、彼 らが撮影したトランス儀式は「古代の形式ではなく、彼らのフィールドワークの期間に創作されたもの」であり、1936年にバリのあるグループが「ランダ (Tjalonarang)や魔女劇(Tjalonarang)とバロン(Barong)やクリス・ダンス(kris-dance)を組み合わせたもの で、(画家の)ウォルター・スピースとその友人たちの努力によって観光客に普及した」ものであった[4]。 |

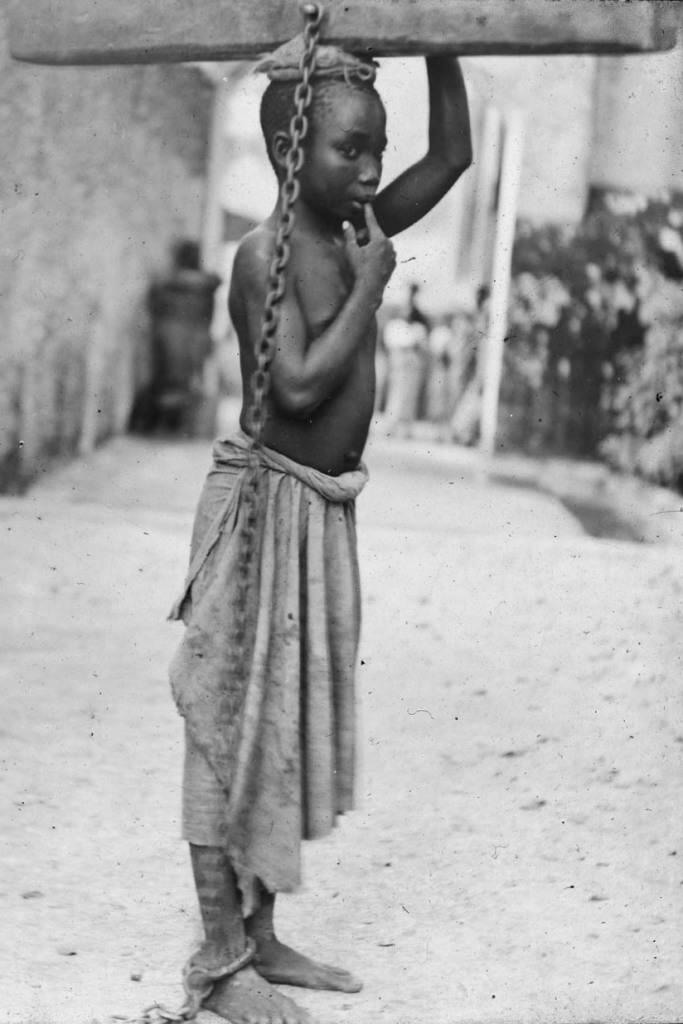

Synopsis Film still showing women dancers bending and writhing The women dance ecstatically, stabbing themselves with their razor-sharp kris daggers, and coming to no harm. The film describes and illustrates a single performance of the Kris Dance, a ritual dance on the Indonesian island of Bali. The dance portrays the struggle of good, in the shape of dragons, against evil, in the shape of masked Tjalonarang witches. The dancers are young women. They hold kris daggers. They are seen to enter trance, one at a time, and are revived from it. While in trance, they dance ecstatically and stab themselves with their daggers, remaining unharmed. The film opens and closes with displayed blocks of text, summarizing the dance's story.[3] No sounds were recorded at the time of filming. The film's soundtrack consists of narration by Mead, and Balinese music recorded elsewhere, possibly by Bateson and Mead's collaborators, the Canadian musicologist Colin McPhee, and the scholar of Balinese dance Katherane Mershon.[3] |

あらすじ 曲げたり悶えたりする女性ダンサーのスチール写真。 女性たちは恍惚とした表情で踊り、鋭いクリス・ダガーで身を刺す。 この映画は、インドネシアのバリ島に伝わる儀式舞踊、クリス・ダンスの一場面を描写したものである。このダンスは、龍の姿をした善と、仮面をかぶったジャ ロナランの魔女の姿をした悪との闘いを描いている。踊り手は若い女性だ。彼らはクリスの短剣を持っている。一人ずつトランス状態に入り、そこから復活す る。トランス状態の間、彼女たちは恍惚とした踊りを踊り、短剣で自分自身を刺す。映画の冒頭と最後には、ダンスのストーリーを要約したテキストが表示され る[3]。 撮影時に音は録音されていない。映画のサウンドトラックは、ミードによるナレーションと、ベイトソンとミードの共同研究者であるカナダの音楽学者コリン・ マクフィーとバリ舞踊研究家キャサリン・マーションが別の場所で録音したバリ音楽で構成されている[3]。 |

| Publication Trance and Dance in Bali was filmed in the 1930s, most of it in 1937,[4] and released in 1951. It is written and narrated by Mead, with cinematography by Bateson, and co-directed by Bateson and Mead. The short film is now available for free download.[5] |

出版 トランス&ダンス・イン・バリ』は1930年代、その大部分は1937年に撮影され[4]、1951年に公開された。脚本とナレーションはミード、撮影は ベイトソン、監督はベイトソンとミードの共同。この短編映画は現在、無料でダウンロードできる[5]。 |

| Historical significance 21:41 Trance and Dance in Bali (22 minutes) In 1999 the film was deemed "culturally significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[5] The film was "very influential for its time", according to the anthropologist Jordan Katherine Weynand. She states that it records Balinese people "dancing while going through violent trances, stabbing themselves with daggers without injury. They are then restored to consciousness with holy water and incense."[6] The Indonesian American anthropologist Fatimah Tobing Rony argues that the "photogenic" violence and trance are untranslatable: anthropology can look at trance but never really penetrates its mystery. In her view, "the naughty voices of the girls and the vain chuckles of the old women, transcribed by the secretary, are never heard in the voiceover or soundtrack: the women become undifferentiated exotic trancers. And the spiritual depths of the older women are not considered."[7] As for objectivity, Rony remarks that "The photogenic Trance and Dance in Bali is representative of a kind of anthropological imperialist blindness, ironic considering that these scientists believed [in] and promoted the idea of their own superior vision".[7] The anthropologist Hildred Geertz calls the film pioneering, writing that Bateson and Mead are more than pathbreakers: their films "remain in certain crucial respects exemplary achievements."[8] In her view, their films are sophisticated "even by today's standards in that they use film not as ethnographic illustration but as a powerful tool in systematic cultural research."[8] Geertz argues that Trance and Dance in Bali sets out a hypothesis about the interconnectedness of cultural experiences of childhood, ritual, and folk drama. The film is a "minute" sample of Mead's "incredibly large corpus of visual materials", now all archived and annotated. Geertz notes, too, that the film is "a highly dramatic and moving presentation of Balinese culture" that words alone could not achieve, even if the Witch-and-Dragon ritual dance had to be shot in daylight "rather than catching it in all its terrifying mystery" at night.[8] The visual anthropologist Beverly Seckinger notes that the film created a visual record of one performance of the Kris Dance, with the minimum of written and voiced-over narration. She comments that the film was pioneering in focusing on one ritual, rather than attempting to show a whole "culture" (her quotation marks) in one film; and in limiting the amount of narration.[3] She quotes Geertz's conclusion that "the film remains an evocative and striking presentation of the way in which multiple meanings are condensed within a centrally significant cultural form".[8] Seckinger remarks that all the same the film is "a product of its time", with not attempt to have the participants speak for themselves; she notes that without audio equipment, this would have been difficult. Further, the film treats the dancers as typical of Balinese culture, not as individuals, and there is no Balinese voice or quoted Balinese text. Instead, Mead's narration "inevitably takes on the character of 'scientific' authority".[3] The hypnotherapists Jay Haley and Madeleine Richeport-Haley describe the film as "a masterpiece of historical importance". They visited Bali around 50 years after Bateson and Mead, met some of the same people, and created a film with the title Dance and Trance of Balinese Children, combining new footage with clips from Trance and Dance in Bali.[1] The scholar of film Trevor Ponech writes that by altering the customary conditions of performance, Bateson and Mead's objectivity is open to question, perhaps influenced by their "ethically questionable, lifeworld-distorting desires".[9] |

歴史的意義 21:41 バリでのトランスとダンス(22分) 1999年、この映画はアメリカ議会図書館によって「文化的に重要」とみなされ、ナショナル・フィルム・レジストリに保存されることになった[5]。 人類学者のジョーダン・キャサリン・ウェイナンドによれば、この映画は「当時としては非常に影響力があった」。彼女は、この映画にはバリの人々が「暴力的 な恍惚状態に陥りながら踊り、怪我をすることなく短剣で自分自身を刺す」様子が記録されていると述べている。その後、聖水とお香で意識を取り戻す」 [6]。 インドネシアのアメリカ人人類学者ファティマ・トビン・ロニーは、「フォトジェニック」な暴力とトランスは翻訳不可能だと主張する。彼女の見解によれば、 「秘書によって書き起こされた少女たちのいたずらな声や老女たちのむなしい笑い声は、ナレーションやサウンドトラックでは決して聞かれない。そして、年配 の女性たちの精神的な深みは考慮されていない」[7]。客観性に関しては、ロニーは「写真的な『バリの恍惚と舞踏』は、人類学的な帝国主義的盲目の代表の ようなものであり、科学者たちが自分たちの優れたヴィジョンを信じ、それを宣伝していたことを考えると皮肉である」と述べている[7]。 人類学者のヒルドレッド・ギアーツはこの映画を先駆的なものと呼び、ベイトソンとミードは道を切り開いた以上の存在であり、彼らの映画は「ある重要な点に おいて模範的な業績であり続けている」[8]と書いている。彼女の見解によれば、彼らの映画は「民族誌的な図解としてではなく、体系的な文化調査における 強力な道具として映画を使っているという点で、今日の基準から見ても洗練されている」[8]。この映画は、ミードの「信じられないほど膨大な映像資料群」 の「ごくわずかな」サンプルであり、現在はすべてアーカイブ化され、注釈がつけられている。たとえ魔女とドラゴンの儀式舞踏が「その恐ろしい謎のすべてを 捉えるのではなく」夜間に昼間に撮影されなければならなかったとしても、この映画は言葉だけでは達成できない「バリの文化を非常に劇的かつ感動的に表現」 している[8]とギアーツは指摘している。 映像人類学者のビヴァリー・セッキンカーは、この映画が、文字と音声によるナレーションを最小限に抑え、クリス・ダンスの1つのパフォーマンスの映像記録 を作り上げたと指摘する。彼女は、1本の映画で「文化」(彼女の引用符)全体を見せようとするのではなく、1つの儀式に焦点を当てた点、ナレーションの量 を制限した点で、この映画は先駆的であったとコメントしている。 [8]セッキンカーは、同じようにこの映画は「時代の産物」であり、参加者自身に語らせようとはしていないと指摘する。さらに、この映画はダンサーを個人 としてではなく、バリ文化の典型として扱っており、バリの声や引用されたバリの文章はない。その代わり、ミードのナレーションは「必然的に『科学的』権威 の性格を帯びている」[3]。 催眠療法士のジェイ・ヘイリーとマドレーヌ・リシュポート・ヘイリーは、この映画を「歴史的に重要な傑作」と評している。彼らはベイトソンとミードから約 50年後にバリを訪れ、同じ人々に何人か会い、新しい映像と『バリでのトランスとダンス』のクリップを組み合わせた『バリの子供たちのダンスとトランス』 というタイトルの映画を制作した[1]。 映画学者のトレヴァー・ポネックは、パフォーマンスの慣習的な条件を変えることで、ベイトソンとミードの客観性が疑われるようになり、おそらく彼らの「倫 理的に問題があり、生命世界を歪める欲望」に影響されたのだろうと書いている[9]。 |

| Haley,

Jay; Richeport-Haley, Madeleine (2015). "Autohypnosis and Trance Dance

in Bali". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis.

64 (4): 455–468. doi:10.1080/00207144.2015.1062701. PMID 26305133.

S2CID 41658040. "Margaret Mead: Human Nature and the Power of Culture". Library of Congress. 30 November 2001. Retrieved 7 January 2022. Seckinger, Beverly (1991). "Filming Culture: Interpretation and Representation in Thence and Dance in Bali (1951), A Balinese Trance Seance (1980), and I t o on Jew: A Balinese Trance SeanceObserved (198" (PDF). CVA Review (Commission on Visual Anthropology) (Spring 1991): 27–33. Jacknis, Ira (May 1988). "Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson in Bali: Their Use of Photography and Film". Cultural Anthropology. 3 (2): 60–177. doi:10.1525/can.1988.3.2.02a00030. JSTOR 656349. "Trance and Dance in Bali". Library of Congress. Retrieved 17 October 2018. Weynand, Jordan Katherine (8 September 2016). "Margaret Mead & Gregory Bateson". Emory University. Retrieved 17 October 2018. Rony, Fatimah Tobing (2006). "The Photogenic Cannot Be Tamed: Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson's Trance and Dance in Bali". Discourse. 28 (1): 5–27. doi:10.1353/dis.2008.0006. JSTOR 41389738. S2CID 143757682. Geertz, Hildred (1976). "Trance and Dance in Bali. Gregory Bateson, Margaret Mead. ; Bathing Babies in Three Cultures. Gregory Bateson, Margaret Mead. ; Karba's First Years. Gregory Bateson, Margaret Mead". American Anthropologist. 78 (3): 725–726. doi:10.1525/aa.1976.78.3.02a01160. Ponech, Trevor (2021). What is Non-Fiction Cinema? On the Very Idea of Motion Picture Communication. London: Routledge. pp. 11–14. doi:10.4324/9780429267499. ISBN 978-0-367-21341-1. OCLC 1285688409. |

Belo, Jane (1960). Trance in Bali. Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/belo94442. ISBN 978-0231944427. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trance_and_Dance_in_Bali |

史上最低/最高の文化人類学の授業とはなにか?(ポータルペー ジ)

リンク

文献

その他の情報