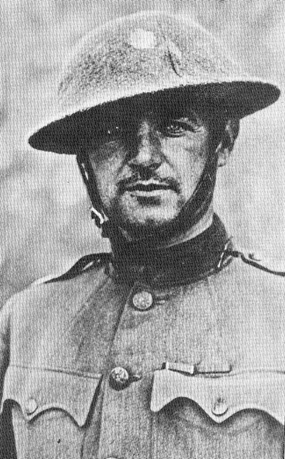

William

Joseph "Wild Bill" Donovan in 1918

「学

者なら誰でも知っているように、出版することと読者に受け入れられることは全く別のことであり(OSSの)支部で作成された報告書、分析、予測が軍事的、

外交的な政策決定に決定的な影響を与えたという証拠はほとんどないのである」(バリー・カッツ 1989:196).

●OSS(戦略サービ ス局; Office of Strategic Services)に関する用語集(→これは「ナチス・ハン ティングとインテリジェンス」「ナチス医学関係者との戦争犯罪と戦後の科 学研究」にあった同名のセクションを拡充するものである)

☆前駆組織としての情報調整官事務所 COI あるいはOCOI, Office of the Coordinator of Information

| The Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI)

was an intelligence and propaganda agency of the United States

Government, founded on July 11, 1941, by President Franklin D.

Roosevelt, prior to U.S. involvement in the Second World War. It was

intended to overcome the lack of coordination between existing agencies

which, in part, it did by duplicating some of their functions. Roosevelt was persuaded to create the office several months before the United States entered the war by prominent New York lawyer William J. Donovan, who had been dispatched to London by the president to assess the ability of the British to continue fighting after the French capitulation to German aggression, and by American playwright Robert Sherwood, who served as Roosevelt's primary speechwriter on foreign affairs.[1] British officials, including John Godfrey of the British Naval Intelligence Division and William Stephenson, head of British Security Co-ordination in New York, also encouraged Roosevelt to create the agency. British-Australian MI6 intelligence officer Dick Ellis has been credited with writing the blueprint for Donovan. Donovan's primary interests were military intelligence and covert operations. Sherwood handled the dissemination of domestic information and foreign propaganda. He recruited the noted radio producer John Houseman, who because of his Romanian birth at the time was technically an enemy alien,[2] to develop an overseas radio program for broadcast to the Axis powers and the populations of the territories they had conquered, which became known as the Voice of America. The first broadcast, called in German Stimmen aus Amerika ("Voices from America") aired on Feb. 1, 1942, and included the pledge: "Today, and every day from now on, we will be with you from America to talk about the war. ... The news may be good or bad for us – We will always tell you the truth."[3] Donovan's desire to use propaganda for tactical military purposes and Sherwood's emphasis on what later became known as public diplomacy were a continuing source of conflict between the two men.[4] On June 13, 1942, Roosevelt split the functions and created two new agencies: the Office of Strategic Services, a predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Office of War Information, a predecessor of the United States Information Agency. Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI) |

情報調整官事務所(Office

of the Coordinator of

Information:COI)は、第二次世界大戦に参戦する前の1941年7月11日、フランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領によって設立されたアメ

リカ政府の情報・宣伝機関である。この機関は、既存の機関間の調整の欠如を克服することを意図しており、機能の一部を重複させることでそれを実現した。 ルーズベルトは米国が参戦する数カ月前に、ドイツの侵略にフランスが降伏した後のイギリスの戦闘継続能力を評価するために大統領によってロンドンに派遣さ れていた著名なニューヨークの弁護士ウィリアム・J・ドノヴァンと、ルーズベルトの外交問題についての主要なスピーチライターを務めていたアメリカの劇作 家ロバート・シャーウッドによって、このオフィスの設立を説得された[1]。 イギリス海軍情報部のジョン・ゴッドフリーやニューヨークのイギリス安全保障調整部長のウィリアム・スティーブンソンなどのイギリス政府高官も、ルーズベ ルトに情報機関の設立を勧めた。イギリス系オーストラリア人のMI6諜報部員ディック・エリスは、ドノヴァンの青写真を書いたと言われている。 ドノヴァンの主な関心は軍事情報と秘密工作だった。シャーウッドは国内情報と対外プロパガンダの普及を担当した。彼は、当時ルーマニア人であったために厳 密には敵性外国人であった著名なラジオプロデューサー、ジョン・ハウスマンをスカウトし[2]、枢軸国および彼らが征服した地域の住民に放送する海外ラジ オ番組を開発させた。最初の放送は、ドイツ語で「アメリカからの声(Stimmen aus Amerika)」と呼ばれ、1942年2月1日に放送された: 「今日、そしてこれから毎日、私たちはアメリカから皆さんと一緒に戦争について語ります。... ニュースは私たちにとって良いものであれ悪いものであれ、私たちは常に真実をお伝えします」[3]。 1942年6月13日、ルーズベルトは機能を分割し、中央情報局の前身である戦略局と合衆国情報局の前身である戦争情報局という2つの新しい機関を創設した。 |

| 情報調整局あるいは情報調整官事務所(

Office of the Coordinator of

Information、OCOI)は、かつて存在したアメリカ合衆国の情報機関。中央情報局(CIA)の前身となった組織の1つ[1][2][3]。第

二次世界大戦期の1941年7月11日、それまで国務省、陸軍省、海軍省などが別々に重複して行っていた情報活動の調整を担当する情報調整官

(Coordinator of

Information、COI)の部局として、時の大統領フランクリン・ルーズベルトが設置した諜報・プロパガンダ機関である。後に戦略情報局

(OSS)に改編し、戦後曲折を経てCIAに変遷した。 |

1. “O.S.S.-State Department Intelligence and Research Reports”. 国立国会図書館憲政資料室 (2018年2月9日). 2020年6月13日閲覧。 2. “Records of the Office of Strategic Services, Washington Director's Office Administrative Files, 1941-1945”. 国立国会図書館憲政資料室 (2018年8月9日). 2020年6月13日閲覧。 3. 長南政義. “トーチ作戦とインテリジェンス(19)”. 「トーチ作戦とインテリジェンス」メールマガジン. 2020年6月13日閲覧。 |

| 歴史 フランクリン・ルーズベルト大統領はニューヨークの弁護士ウィリアム・ドノバンや劇作家・映画脚本家でルーズベルト大統領のスピーチライターであったロ バート・シャーウッド(英語版)からの説得でOCOIの設立を決定した[4]。イギリス海軍情報部部長ジョン・ヘンリー・ゴドフリーやニューヨークのイギ リス秘密情報部直属のイギリス安全保障調整局(英語版)(BSC)のウィリアム・S・スティーブンソン(英語版)らも大統領に設立を促していた。 ドノバンは軍事的インテリジェンスと秘密作戦を担当し、シャーウッドは米国内の情報宣伝と外国でのプロパガンダを担当した。設立に伴い、海外情報サービス (FIS)が運用され、国際ラジオ放送(VOAの前身)が開始され、1941年12月の日本の真珠湾攻撃以後は日本に向けた戦争のプロパガンダの手段とし て利用された[5]。シャーウッドは、ラジオプロデューサーでルーマニア出身のジョン・ハウスマンを雇い、枢軸国側に向けたプロパガンダ放送局ボイス・オ ブ・アメリカを運営した[6]。ナチス・ドイツに向けた最初の放送は1942年2月1日に放送され、「わたしたちはこれから真実を放送する」と告げた [7]。 ドノバンの構想では、プロパガンダ(広報)を軍事戦略として用い、シャーウッドはのちにパブリックディプロマシー(政府と民間が連携して広報や文化交流を 通じて外国の国民や世論に直接働きかける外交活動[8])として知られる手法を主張し、両者はしばしば方針をめぐって対立した[9]。 1942年6月13日、ルーズベルトは情報調整局を、戦略情報局(OSS、後の中央情報局〈CIA〉)と戦時情報局(OWI、のち国務省隷下となりアメリカ合衆国情報庁〈USIA〉)に分割した。 OSS、OWIはともに戦時下におけるプロパガンダ組織だが、前者は諜報活動のような、非合法な手段によって公衆に不信・混乱・恐怖を与えることを目指す 「黒いプロパガンダ」を担当し、後者は放送のような、情報を明瞭な事実として公衆に理解させることを目指した「白いプロパガンダ」を担当した[5]。 VOAは戦時中に、OWIに所属する米国広報庁(USIS)のもとで拡大され、1953年にアメリカ合衆国情報局(USIA)が設立されるとさらに拡大・ 整備されていった[5]。なおUSIAは1999年に、テレビ部門が放送理事会(英語版)(BBG)、それ以外の機能がアメリカ合衆国国務次官(公共外 交・広報担当)に移行した。 |

4. Houseman, John, Front & Center, 1979, New York: Simon and Schuster, pp. 45-46. 5. a b c 冷戦期のアメリカの対日外交政策と日本への技術導入 : 読売新聞グループと日本のテレビジョン放送及び原子力導入 : 1945年〜1956年第1章 アメリカの心理戦とテレビジョン放送 奥田謙造、東京工業大学、2007/03/26 6. Houseman, John (1979), op. cit., p. 23. 7. Kern, Chris. “A Belated Correction: The Real First Broadcast of the Voice of America”. 2014年4月19日閲覧。. 8. よくある質問集 外務省 9. Houseman, John (1979), op. cit., pp. 25-28. |

| Houseman, John, Front & Center, 1979, New York: Simon and Schuster. |

|

| https://x.gd/m2wQe |

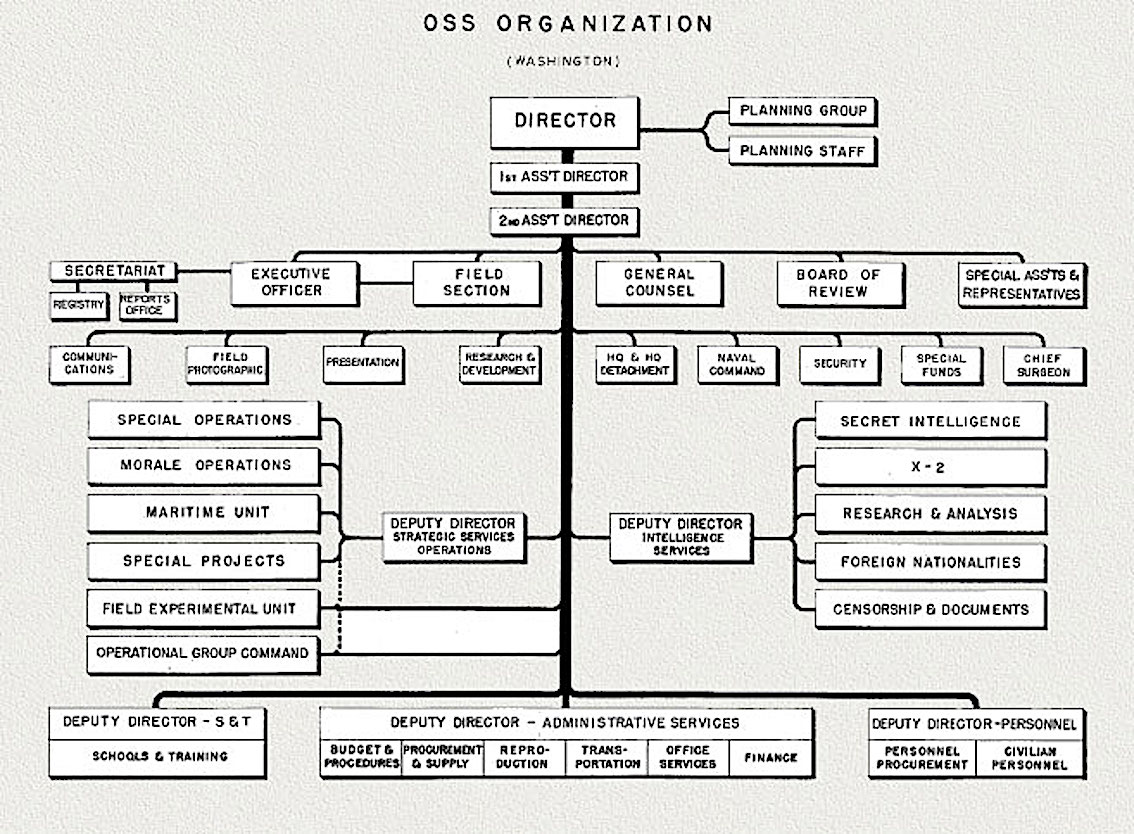

●OSS入門

| The Office of

Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United

States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the

Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS)[3] to coordinate espionage activities

behind enemy lines for all branches of the United States Armed Forces.

Other OSS functions included the use of propaganda, subversion, and

post-war planning. The OSS was dissolved a month after the end of the war. Intelligence tasks were shortly later resumed and carried over by its successors, the Department of State's Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) and the independent Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). On December 14, 2016, the organization was collectively honored with a Congressional Gold Medal.[4] |

戦略サービス局(OSS)は、第二次世界大戦中のアメリカの諜報機関で

ある。OSSは統合参謀本部(JCS)の一機関として設立され[3]、アメリカ軍の全兵科のために敵陣後方でのスパイ活動を調整した。その他のOSSの機

能には、プロパガンダの利用、破壊工作、戦後計画などがあった。 OSSは終戦の1ヵ月後に解散した。インテリジェンス業務はまもなく再開され、後継の国務省情報調査局(INR)と独立した中央情報局(CIA)に引き継 がれた。 2016年12月14日、同組織はまとめて米議会ゴールドメダルを授与された[4]。 |

| Origin Prior to the formation of the OSS, the various departments of the executive branch, including the State, Treasury, Navy, and War Departments conducted American intelligence activities on an ad hoc basis, with no overall direction, coordination, or control. The US Army and US Navy had separate code-breaking departments: Signal Intelligence Service and OP-20-G. (A previous code-breaking operation of the State Department, the MI-8, run by Herbert Yardley, had been shut down in 1929 by Secretary of State Henry Stimson, deeming it an inappropriate function for the diplomatic arm, because "gentlemen don't read each other's mail."[5]) The FBI was responsible for domestic security and anti-espionage operations. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was concerned about American intelligence deficiencies. On the suggestion of William Stephenson, the senior British intelligence officer in the western hemisphere, Roosevelt requested that William J. Donovan draft a plan for an intelligence service based on the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) and Special Operations Executive (SOE). Donovan envisioned a single agency responsible for foreign intelligence and special operations involving commandos, disinformation, partisan and guerrilla activities.[6] After submitting his work, "Memorandum of Establishment of Service of Strategic Information", he was appointed "coordinator of information" on July 11, 1941, heading the new organization known as the office of the Coordinator of Information (COI).  William J. Donovan Thereafter the organization was developed with British assistance; Donovan had responsibilities but no actual powers and the existing US agencies were skeptical if not hostile. Until some months after Pearl Harbor, the bulk of OSS intelligence came from the UK. British Security Co-ordination (BSC) trained the first OSS agents in Canada, until training stations were set up in the US with guidance from BSC instructors, who also provided information on how the SOE was arranged and managed. The British immediately made available their short-wave broadcasting capabilities to Europe, Africa, and the Far East and provided equipment for agents until American production was established.[7] The Office of Strategic Services was established by a Presidential military order issued by President Roosevelt on June 13, 1942, to collect and analyze strategic information required by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and to conduct special operations not assigned to other agencies. During the war, the OSS supplied policymakers with facts and estimates, but the OSS never had jurisdiction over all foreign intelligence activities. The FBI was left responsible for intelligence work in Latin America, and the Army and Navy continued to develop and rely on their own sources of intelligence. |

起源 OSSが結成される以前は、国務省、財務省、海軍省、陸軍省など、行政府のさまざまな部局が、全体的な指示、調整、統制を受けることなく、その場限りのア メリカ情報活動を行っていた。米陸軍と米海軍はそれぞれ別の暗号解読部門を持っていた: 信号情報局とOP-20-Gである。(国務省の以前の暗号解読部門であるMI-8はハーバート・ヤードリーによって運営されていたが、1929年にヘン リー・スティムソン国務長官によって閉鎖された。 フランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領は、アメリカの情報不足を懸念していた。ルーズベルトは、西半球の英国情報部幹部ウィリアム・スティーブンソンの提 案により、ウィリアム・J・ドノヴァンに、英国秘密情報部(MI6)と特殊作戦局(SOE)を基礎とする情報機関の計画案を作成するよう要請した。ドノ ヴァンは、対外諜報と、コマンドー、偽情報、パルチザン、ゲリラ活動を含む特殊作戦を担当する単一の機関を構想していた[6]。ドノヴァンは、「戦略情報 サービス設立に関する覚書」を提出した後、1941年7月11日に「情報調整官」に任命され、情報調整官室(COI)——後述——として知られる新組織を率いた。  ウィリアム・J・ドノバン ドノバンには責任はあったが実権はなく、既存の米国機関は敵対的でないにしても懐疑的であった。真珠湾攻撃の数カ月後まで、OSS情報の大部分は英国から もたらされた。英国安全保障調整局(BSC)はカナダで最初のOSS諜報員を訓練し、その後、BSCの教官の指導のもとに訓練所が米国に設置され、SOE がどのように配置され管理されているかについての情報も提供した。イギリスは直ちにヨーロッパ、アフリカ、極東への短波放送能力を利用できるようにし、ア メリカでの生産が確立されるまで諜報員に機材を提供した[7]。 戦略サービス局は、1942年6月13日にルーズベルト大統領が発した大統領軍事命令によって設立され、統合参謀本部が必要とする戦略情報の収集と分析を 行い、他の機関に割り当てられていない特殊作戦を実施した。戦時中、OSSは政策立案者に事実と推定を提供したが、すべての対外情報活動を管轄することは なかった。ラテンアメリカでの情報活動はFBIに任され、陸海軍は独自の情報源を開発し、それに依存し続けた。 |

| Activities General William J. Donovan reviews Operational Group members in Bethesda, Maryland, prior to their departure for China in 1945. OSS missions and bases in East Asia OSS proved especially useful in providing a worldwide overview of the German war effort, its strengths and weaknesses. In direct operations it was successful in supporting Operation Torch in French North Africa in 1942, where it identified pro-Allied potential supporters and located landing sites. OSS operations in neutral countries, especially Stockholm, Sweden, provided in-depth information on German advanced technology. The Madrid station set up agent networks in France that supported the Allied invasion of southern France in 1944. Most famous were the operations in Switzerland run by Allen Dulles that provided extensive information on German strength, air defenses, submarine production, and the V-1 and V-2 weapons. It revealed some of the secret German efforts in chemical and biological warfare. Switzerland's station also supported resistance fighters in France, Austria and Italy, and helped with the surrender of German forces in Italy in 1945.[8] For the duration of World War II, the Office of Strategic Services was conducting multiple activities and missions, including collecting intelligence by spying, performing acts of sabotage, waging propaganda war, organizing and coordinating anti-Nazi resistance groups in Europe, and providing military training for anti-Japanese guerrilla movements in Asia, among other things.[9] At the height of its influence during World War II, the OSS employed almost 24,000 people.[10] From 1943–1945, the OSS played a major role in training Kuomintang troops in China and Burma, and recruited Kachin and other indigenous irregular forces for sabotage as well as guides for Allied forces in Burma fighting the Japanese Army. Among other activities, the OSS helped arm, train, and supply resistance movements in areas occupied by the Axis powers during World War II, including Mao Zedong's Red Army in China (known as the Dixie Mission) and the Viet Minh in French Indochina. OSS officer Archimedes Patti played a central role in OSS operations in French Indochina and met frequently with Ho Chi Minh in 1945.[11] One of the greatest accomplishments of the OSS during World War II was its penetration of Nazi Germany by OSS operatives. The OSS was responsible for training German and Austrian individuals for missions inside Germany. Some of these agents included exiled communists and Socialist party members, labor activists, anti-Nazi prisoners-of-war, and German and Jewish refugees. The OSS also recruited and ran one of the war's most important spies, the German diplomat Fritz Kolbe. From 1943 the OSS was in contact with the Austrian resistance group around Kaplan Heinrich Maier. As a result, plans and production facilities for V-2 rockets, Tiger tanks and aircraft (Messerschmitt Bf 109, Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet, etc.) were passed on to Allied general staffs in order to enable Allied bombers to get accurate air strikes. The Maier group informed very early about the mass murder of Jews through its contacts with the Semperit factory near Auschwitz. The group was gradually dismantled by the German authorities because of a double agent who worked for both the OSS and the Gestapo. This uncovered a transfer of money from the Americans to Vienna via Istanbul and Budapest, and most of the members were executed after a People's Court hearing.[12][13] OSS 1st Lieutenant George Musulin behind enemy lines in German-occupied Serbia, as a Chetnik, during his first mission in November 1943. His second mission was Operation Halyard. In 1943, the Office of Strategic Services set up operations in Istanbul.[14] Turkey, as a neutral country during the Second World War, was a place where both the Axis and Allied powers had spy networks. The railroads connecting central Asia with Europe, as well as Turkey's close proximity to the Balkan states, placed it at a crossroads of intelligence gathering. The goal of the OSS Istanbul operation called Project Net-1 was to infiltrate and extenuate subversive action in the old Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires.[14] The head of operations at OSS Istanbul was a banker from Chicago named Lanning "Packy" Macfarland, who maintained a cover story as a banker for the American lend-lease program.[15] Macfarland hired Alfred Schwarz,[16] an Austrian businessman (* 25. April 1904 in Prostějov, Austria-Hungary; † 13. August 1988 in Lucerne, Switzerland) who came to be known as "Dogwood" and ended up establishing the Dogwood information chain.[17] Dogwood in turn hired a personal assistant named Walter Arndt and established himself as an employee of the Istanbul Western Electrik Kompani.[17] Through Schwarz and Arndt the OSS was able to infiltrate anti-fascist groups in Austria, Hungary, and Germany. Schwarz was able to convince Romanian, Bulgarian, Hungarian, and Swiss diplomatic couriers to smuggle American intelligence information into these territories and establish contact with elements antagonistic to the Nazis and their collaborators.[18] Couriers and agents memorized information and produced analytical reports; when they were not able to memorize effectively they recorded information on microfilm and hid it in their shoes or hollowed pencils.[19] Through this process information about the Nazi regime made its way to Macfarland and the OSS in Istanbul and eventually to Washington. While the OSS "Dogwood-chain" produced a lot of information, its reliability was increasingly questioned by British intelligence. By May 1944, through collaboration between the OSS, British intelligence, Cairo, and Washington, the entire Dogwood-chain was found to be unreliable and dangerous.[19] Planting phony information into the OSS was intended to misdirect the resources of the Allies. Schwarz's Dogwood-chain, which was the largest American intelligence gathering tool in occupied territory, was shortly thereafter shut down.[20] The OSS purchased Soviet code and cipher material (or Finnish information on them) from émigré Finnish army officers in late 1944. Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, Jr., protested that this violated an agreement President Roosevelt made with the Soviet Union not to interfere with Soviet cipher traffic from the United States. General Donovan might have copied the papers before returning them the following January, but there is no record of Arlington Hall receiving them, and CIA and NSA archives have no surviving copies. This codebook was in fact used as part of the Venona decryption effort, which helped uncover large-scale Soviet espionage in North America.[21] RYPE was the codename of the airborne unit who was dropped in the Norwegian mountains of Snåsa on March 24, 1945 to carry out sabotage actions behind enemy lines. From the base at the Gjefsjøen mountain farm, the group conducted successful railroad sabotages, with the intention of preventing the withdrawal of German forces from northern Norway. Operasjon Rype was the only U.S. operation on German-occupied Norwegian soil during WW2. The group consisted mainly of Norwegian Americans recruited from the 99th Infantry Battalion. Operasjon Rype was led by William Colby.[22] The OSS sent four teams of two under Captain Stephen Vinciguerra (codename Algonquin, teams Alsace, Poissy, S&S and Student), with Operation Varsity in March 1945 to infiltrate and report from behind enemy lines, but none succeeded. Team S&S had two agents in Wehrmacht uniforms and a captured Kϋbelwagon; to report by radio. But the Kϋbelwagon was put out of action while in the glider; three tires and the long-range radio were shot up (German gunners were told to attack the gliders not the tow planes).[23] |

活動内容 1945年、中国への出発前にメリーランド州ベセスダで作戦グループのメンバーを確認するウィリアム・J・ドノバン将軍。 東アジアにおけるOSSの任務と拠点 OSSは、ドイツの戦争努力、その長所と短所を世界的に概観する上で特に有用であることがわかった。直接作戦では、1942年のフランス領北アフリカでの トーチ作戦を支援することに成功し、親連合国の潜在的支援者を特定し、上陸地点の特定を行った。中立国、特にスウェーデンのストックホルムでのOSS活動 は、ドイツの先端技術に関する詳細な情報を提供した。マドリード支局はフランスで諜報員ネットワークを構築し、1944年の連合軍の南フランス侵攻を支援 した。最も有名なのは、アレン・ダレスがスイスで行った作戦で、ドイツの戦力、防空、潜水艦の生産、V-1とV-2兵器に関する広範な情報を提供した。化 学兵器や生物兵器におけるドイツの秘密工作の一端も明らかになった。スイスの支局はまた、フランス、オーストリア、イタリアのレジスタンスを支援し、 1945年にイタリアでドイツ軍の降伏を助けた[8]。 第二次世界大戦の期間中、戦略局は、スパイによる情報収集、破壊工作の実行、プロパガンダ戦争の遂行、ヨーロッパにおける反ナチ抵抗勢力の組織化と調整、 アジアにおける抗日ゲリラ運動への軍事訓練の提供など、複数の活動と任務を遂行していた[9]。 第二次世界大戦中、その影響力の最盛期には、OSSはほぼ24,000人を雇用していた[10]。 1943年から1945年にかけて、OSSは中国とビルマで国民党軍の訓練に主要な役割を果たし、カチン族やその他の土着の非正規部隊を破壊工作のために リクルートし、日本軍と戦うビルマの連合軍の案内役を務めた。その他の活動として、OSSは第二次世界大戦中、枢軸国に占領された地域の抵抗運動の武装、 訓練、補給を支援した。その中には、中国の毛沢東の赤軍(ディキシー・ミッションとして知られる)やフランス領インドシナのベトミンが含まれる。OSS将 校のアルキメデス・パティはフランス領インドシナにおけるOSSの作戦で中心的な役割を果たし、1945年にはホーチミンと頻繁に会談した[11]。 第二次世界大戦中のOSSの最大の功績のひとつは、OSSの工作員によるナチス・ドイツへの浸透であった。OSSはドイツ国内での任務のためにドイツ人と オーストリア人を訓練する役割を担っていた。これらの工作員の中には、亡命共産主義者や社会党員、労働運動家、反ナチス捕虜、ドイツ人やユダヤ人難民など が含まれていた。OSSはまた、戦争で最も重要なスパイの一人であるドイツ人外交官フリッツ・コルベをリクルートし、運営していた。 1943年以降、OSSはカプラン・ハインリッヒ・マイヤーを中心とするオーストリアのレジスタンス組織と接触した。その結果、連合軍の爆撃機が正確な空 爆を行えるようにするため、V-2ロケット、タイガー戦車、航空機(メッサーシュミットBf109、メッサーシュミットMe163コメットなど)の計画や 生産設備が連合軍参謀本部に伝えられた。マイヤーグループは、アウシュビッツ近郊のゼンペリット工場との接触を通じて、ユダヤ人の大量殺戮について非常に 早い時期から情報を得ていた。このグループは、OSSとゲシュタポの両方のために働いていた二重スパイがいたため、ドイツ当局によって徐々に解体されて いった。これによってアメリカからイスタンブール、ブダペストを経由してウィーンへの送金が発覚し、人民裁判所の審問の後にメンバーのほとんどが処刑され た[12][13]。 1943年11月、最初の任務でチェトニクとしてドイツ占領下のセルビアで敵陣の背後にいたOSSのジョージ・ムスリン1尉。2回目の任務はハリヤード作 戦。 1943年、戦略局はイスタンブールで作戦を開始した[14]。第二次世界大戦中、中立国であったトルコは、枢軸国も連合国もスパイ網を持つ場所であっ た。中央アジアとヨーロッパを結ぶ鉄道とバルカン諸国に近接するトルコは、情報収集の十字路に位置していた。プロジェクト・ネット-1と呼ばれたOSSイ スタンブールの作戦の目的は、旧オスマン帝国とオーストリア=ハンガリー帝国に潜入し、破壊活動を宥めることだった[14]。 OSSイスタンブールの作戦責任者はシカゴ出身の銀行家ラニング・"パッキー"・マクファーランドで、彼はアメリカのレンドリース・プログラムの銀行家と して偽装工作を続けていた[15]。 マクファーランドはオーストリアの実業家アルフレッド・シュヴァルツ[16]を雇った(* 25. 1904年4月 Prostějov, Austria-Hungary; † 13. シュヴァルツとアルントを通じて、OSSはオーストリア、ハンガリー、ドイツの反ファシストグループに潜入することができた。シュヴァルツはルーマニア、 ブルガリア、ハンガリー、スイスの外交使節に、アメリカの諜報情報をこれらの地域に密輸し、ナチスと敵対する勢力やその協力者と接触するよう説得すること ができた[18]。 OSSの「ドッグウッド・チェーン」は多くの情報を生み出したが、その信頼性はイギリス情報部によって次第に疑問視されるようになった。1944年5月ま でに、OSS、イギリス情報部、カイロ、ワシントンの協力により、ドッグウッドチェーン全体が信頼性に欠け危険であることが判明した[19]。OSSにニ セの情報を仕込むことは、連合国のリソースを誤らせることを目的としていた。シュワルツのドッグウッドチェーンは、占領地におけるアメリカ最大の情報収集 ツールであったが、その後まもなく閉鎖された[20]。 OSSは1944年後半、移住してきたフィンランド陸軍将校からソ連の暗号資料(またはそれらに関するフィンランドの情報)を購入した。エドワード・ス テッティニウス・ジュニア国務長官は、これはルーズベルト大統領がソ連と交わした、アメリカからのソ連の暗号通信を妨害しないという合意に違反すると抗議 した。ドノバン将軍は翌年1月に返却する前にコピーしたかもしれないが、アーリントン・ホールが受け取ったという記録はなく、CIAとNSAの公文書館に も現存するコピーはない。このコードブックは実際にヴェノナの解読作業の一部として使用され、北米におけるソ連の大規模なスパイ活動の摘発に貢献した [21]。 RYPEは、1945年3月24日に敵陣の背後で破壊工作を行うためにノルウェーのスノーサの山中に投下された空挺部隊のコードネームである。ギェフ シェーエン山麓を拠点に、ノルウェー北部からのドイツ軍の撤退を阻止する目的で、鉄道破壊工作を成功させた。オペラスヨン・ライプは、第2次世界大戦中、 ドイツ占領下のノルウェーで行われた唯一の米軍作戦だった。グループは主に第99歩兵大隊から採用されたノルウェー系アメリカ人で構成されていた。オペラ シオン・ライプはウィリアム・コルビーによって率いられた[22]。 OSSは1945年3月、スティーブン・ヴィンチグエラ大尉(コードネーム:アルゴンキン、チーム:アルザス、ポワシー、S&S、スチューデン ト)率いる2人1組の4チームをバーシティ作戦で派遣し、敵陣後方から潜入して報告させたが、いずれも成功しなかった。チームS&Sは、ドイツ国 防軍の制服を着た2人の諜報員と、捕獲したKϋワゴンを持っていた。しかし、Kϋワゴンはグライダーに乗っている間に行動不能になり、3つのタイヤと長距 離無線機が撃ち落とされた(ドイツ軍の砲手は曳航機ではなくグライダーを攻撃するように指示されていた)[23]。 |

| Weapons and gadgets OSS T13 Beano Grenade and compass hidden in a button, CIA Museum The OSS espionage and sabotage operations produced a steady demand for highly specialized equipment.[9] General Donovan invited experts, organized workshops, and funded labs that later formed the core of the Research & Development Branch. Boston chemist Stanley P. Lovell became its first head, and Donovan humorously called him his "Professor Moriarty".[24]: 101 Throughout the war years, the OSS Research & Development successfully adapted Allied weapons and espionage equipment, and produced its own line of novel spy tools and gadgets, including silenced pistols, lightweight sub-machine guns, "Beano" grenades that exploded upon impact, explosives disguised as lumps of coal ("Black Joe") or bags of Chinese flour ("Aunt Jemima"), acetone time delay fuses for limpet mines, compasses hidden in uniform buttons, playing cards that concealed maps, a 16mm Kodak camera in the shape of a matchbox, tasteless poison tablets ("K" and "L" pills), and cigarettes laced with tetrahydrocannabinol acetate (an extract of Indian hemp) to induce uncontrollable chattiness.[24][25][26] The OSS also developed innovative communication equipment such as wiretap gadgets, electronic beacons for locating agents, and the "Joan-Eleanor" portable radio system that made it possible for operatives on the ground to establish secure contact with a plane that was preparing to land or drop cargo. The OSS Research & Development also printed fake German and Japanese-issued identification cards, and various passes, ration cards, and counterfeit money.[27] On August 28, 1943, Stanley Lovell was asked to make a presentation in front of a hostile Joint Chiefs of Staff, who were skeptical of OSS plans beyond collecting military intelligence and were ready to split the OSS between the Army and the Navy.[28]: 5–7 While explaining the purpose and mission of his department and introducing various gadgets and tools, he reportedly casually dropped into a waste basket a Hedy, a panic-inducing explosive device in the shape of a firecracker, which shortly produced a loud shrieking sound followed by a deafening boom. The presentation was interrupted and did not resume since everyone in the room fled. In reality, the Hedy, jokingly named after Hollywood movie star Hedy Lamarr for her ability to distract men, later saved the lives of some trapped OSS operatives.[29]: 184–185 Not all projects worked. Some ideas were odd, such as a failed attempt to use insects to spread anthrax in Spain.[30]: 150–151 Stanley Lovell was later quoted saying, "It was my policy to consider any method whatever that might aid the war, however unorthodox or untried".[31] In 1939, a young physician named Christian J. Lambertsen developed an oxygen rebreather set (the Lambertsen Amphibious Respiratory Unit) and demonstrated it to the OSS—after already being rejected by the U.S. Navy—in a pool at the Shoreham Hotel in Washington D.C., in 1942.[32][33] The OSS not only bought into the concept, they hired Lambertsen to lead the program and build up the dive element for the organization.[33] His responsibilities included training and developing methods of combining self-contained diving and swimmer delivery including the Lambertsen Amphibious Respiratory Unit for the OSS "Operational Swimmer Group".[32][34] Growing involvement of the OSS with coastal infiltration and water-based sabotage eventually led to creation of the OSS Maritime Unit. |

武器とガジェット ボタンに隠されたOSS T13 Beano手榴弾とコンパス、CIA博物館 ドノバン将軍は専門家を招き、ワークショップを開催し、後に研究開発部門の中核となる研究所に資金を提供した。ボストンの化学者スタンリー・P・ラヴェル がその初代責任者となり、ドノバンはユーモアたっぷりに彼を「モリアーティ教授」と呼んだ[24]: 101 戦時中を通じて、OSS研究開発部門は連合軍の武器やスパイ用装備の適合に成功し、サイレンサー付きピストル、軽量サブマシンガン、衝撃で爆発する「ビー ノ」手榴弾、石炭の塊(「ブラック・ジョー」)や中国産小麦粉の袋(「ジェミマおばさん」)に偽装した爆薬など、独自の斬新なスパイ用具や小道具を製造し た、 リムペット地雷用のアセトン時間遅延信管、制服のボタンに隠されたコンパス、地図を隠したトランプ、マッチ箱の形をした16mmコダックカメラ、無味の毒 錠剤(「K」と「L」の錠剤)、制御不能のおしゃべりを誘発するために酢酸テトラヒドロカンナビノール(インド麻の抽出物)を混入したタバコなど。 [24][25][26] OSSはまた、盗聴ガジェット、諜報員の居場所を特定するための電子ビーコン、地上の諜報員が着陸や貨物投下の準備をしている飛行機と安全な連絡を確立す ることを可能にした「ジョーン・エレノア」携帯無線システムなどの革新的な通信機器も開発した。OSS研究開発はまた、ドイツと日本が発行した偽の身分証 明書、さまざまなパス、配給カード、偽札を印刷した[27]。 1943年8月28日、スタンリー・ラヴェルは敵対する統合参謀本部の前でプレゼンテーションを行うよう求められた。彼らは軍事情報を収集する以上の OSSの計画に懐疑的であり、陸軍と海軍の間でOSSを分割する用意があった[28]: 5-7 部署の目的と使命を説明し、さまざまな小道具や道具を紹介する中で、彼は何気なくヘディ(爆竹の形をしたパニックを誘発する爆発物)をゴミ箱に落としたと 伝えられている。プレゼンテーションは中断され、会場にいた全員が逃げ出したため、再開されることはなかった。実際には、ハリウッドの映画スターであるヘ ディ・ラマーにちなんで、男性の注意をそらす能力があることから冗談で名付けられたヘディは、その後、窮地に陥った何人かのOSS工作員の命を救った [29]: 184-185 すべてのプロジェクトがうまくいったわけではない。スペインで炭疽菌を撒くために昆虫を使おうとして失敗するなど、奇妙なアイデアもあった[30]: ス タンリー・ラヴェルは後に、「戦争に役立つ可能性のある方法であれば、どんなに異端であろうと、未試行であろうと、どんな方法であろうと検討するのが私の 方針であった」と語っている[31]。 1939年、クリスチャン・J・ランバートセンという若い医師は酸素再呼吸装置(ランバートセン水陸両用呼吸装置)を開発し、すでにアメリカ海軍に拒否さ れた後、ワシントンD.C.のショアハムホテルのプールでOSSに実演した、 1942年[32][33]、OSSはそのコンセプトを受け入れただけでなく、ランバートセンを雇ってプログラムを指揮させ、組織のための潜水要素を構築 させた[33]。彼の責任には、OSS「作戦水泳部隊」のためのランバートセン水陸両用呼吸ユニットを含む、自己完結型の潜水と水泳を組み合わせた方法の 訓練と開発が含まれていた[32][34]。 |

| Facilities At Camp X, near Whitby, Ontario, an "assassination and elimination" training program was operated by the British Special Operations Executive, assigning exceptional masters in the art of knife-wielding combat, such as William E. Fairbairn and Eric A. Sykes, to instruct trainees. Many members of the Office of Strategic Services also were trained there. It was dubbed "the school of mayhem and murder" by George Hunter White who trained at the facility in the 1950s.[citation needed] From these incipient beginnings, the Office of Strategic Services opened camps in the United States, and finally abroad. Prince William Forest Park (then known as Chopawamsic Recreational Demonstration Area) was the site of an OSS training camp that operated from 1942 to 1945. Area "C", consisting of approximately 6,000 acres (24 km2), was used extensively for communications training, whereas Area "A" was used for training some of the OGs (Operational Groups).[35] Catoctin Mountain Park, now the location of Camp David, was the site of OSS training Area "B" where the first Special Operations, or SO, were trained.[36] Special Operations was modeled after Great Britain's Special Operations Executive, which included parachute, sabotage, self-defense, weapons, and leadership training to support guerrilla or partisan resistance.[37] Considered most mysterious of all was the "cloak and dagger" Secret Intelligence, or SI branch.[38] Secret Intelligence employed "country estates as schools for introducing recruits into the murky world of espionage. Thus, it established Training Areas E and RTU-11 ("the Farm") in spacious manor houses with surrounding horse farms."[39] Morale Operations training included psychological warfare and propaganda.[40] The Congressional Country Club (Area F) in Bethesda, Maryland, was the primary OSS training facility. The Facilities of the Catalina Island Marine Institute at Toyon Bay on Santa Catalina Island, Calif., are composed (in part) of a former OSS survival training camp. The National Park Service commissioned a study of OSS National Park training facilities by Professor John Chambers of Rutgers University.[41] The main OSS training camps abroad were located initially in Great Britain, French Algeria, and Egypt; later as the Allies advanced, a school was established in southern Italy. In the Far East, OSS training facilities were established in India, Ceylon, and then China. The London branch of the OSS, its first overseas facility, was at 70 Grosvenor Street, W1. In addition to training local agents, the overseas OSS schools also provided advanced training and field exercises for graduates of the training camps in the United States and for Americans who enlisted in the OSS in the war zones. The most famous of the latter was Virginia Hall in France.[41] The OSS's Mediterranean training center in Cairo, Egypt, known to many as the Spy School, was a lavish palace belonging to King Farouk's brother-in-law, called Ras el Kanayas.[42][43][self-published source?] It was modeled after the SOE's training facility STS 102 in Haifa, Palestine.[44][self-published source?] Americans whose heritage stemmed from Italy, Yugoslavia, and Greece were trained at the "Spy School"[45] and also sent for parachute, weapons, and commando training, and Morse code and encryption lessons at STS 102.[46][47][48] After completion of their spy training, these agents were sent back on missions to the Balkans and Italy where their accents would not pose a problem for their assimilation.[49][50] |

施設 オンタリオ州ウィットビー近郊のキャンプXでは、ウィリアム・E・フェアバーンやエリック・A・サイクスといった、ナイフを振り回す戦闘術の卓越した達人 が訓練生を指導する「暗殺・抹殺」訓練プログラムが、英国特殊作戦局によって運営されていた。戦略局の多くのメンバーもそこで訓練を受けた。1950年代 にこの施設で訓練を受けたジョージ・ハンター・ホワイトは「騒乱と殺人の学校」と呼んだ[要出典]。 このような萌芽的な始まりから、戦略局は米国内にキャンプを開設し、最終的には海外にもキャンプを開設した。プリンス・ウィリアム森林公園(当時はチョパ ワムシック・レクリエーション・デモンストレーション・エリアとして知られていた)は、1942年から1945年まで運営されたOSS訓練キャンプの場所 であった。およそ6,000エーカー(24km2)からなるエリア「C」は通信訓練に広範囲に使用され、エリア「A」はOG(作戦グループ)の一部の訓練 に使用された[35]。現在キャンプ・デイビッドのあるカトクティン・マウンテン・パークはOSS訓練エリア「B」の場所で、最初の特殊作戦(SO)が訓 練された。 [36]特殊作戦はイギリスの特殊作戦実行部をモデルにしており、ゲリラやパルチザンの抵抗を支援するためのパラシュート、破壊工作、自己防衛、武器、 リーダーシップの訓練が含まれていた[37]。メリーランド州ベセスダのコングレッショナル・カントリー・クラブ(エリアF)はOSSの主要な訓練施設で あった。カリフォルニア州サンタ・カタリナ島のトヨン湾にあるカタリナ島海洋研究所の施設は、かつてのOSSサバイバル訓練キャンプで(部分的に)構成さ れている。国立公園局は、ラトガース大学のジョン・チェンバーズ教授にOSS国立公園訓練施設の調査を依頼した[41]。 海外におけるOSSの主な訓練キャンプは、当初イギリス、フランス領アルジェリア、エジプトにあり、後に連合国が前進するにつれて、南イタリアに学校が設 立された。極東では、インド、セイロン、そして中国にOSS訓練施設が設立された。OSSの最初の海外施設であるロンドン支部は、W1のグロブナー通り 70番地にあった。現地の諜報員を訓練するだけでなく、海外のOSS学校は、アメリカ国内の訓練キャンプの卒業生や、戦地でOSSに入隊したアメリカ人に 上級訓練や実地演習を提供した。後者で最も有名なのはフランスのヴァージニア・ホールであった[41]。 エジプトのカイロにあるOSSの地中海訓練センターは、スパイ学校として多くの人に知られていたが、ラス・エル・カナヤスと呼ばれるファルーク国王の義兄 の所有する豪華な宮殿であった[42][43][自費出版?] それはパレスチナのハイファにあるSOEの訓練施設STS102をモデルにしていた[44][自費出版? イタリア、ユーゴスラビア、ギリシャの血を引くアメリカ人は「スパイ学校」で訓練を受け[45]、STS102ではパラシュート、武器、コマンドーの訓 練、モールス信号や暗号のレッスンにも派遣された[46][47][48]。スパイ訓練終了後、これらの諜報員は彼らの訛りが同化に問題とならないバルカ ン半島やイタリアへのミッションに再び派遣された[49][50]。 |

| Personnel The names of all 13,000 OSS personnel and documents of their OSS service, previously a closely guarded secret, were released by the US National Archives on August 14, 2008. Among the 24,000 names were those of Sterling Hayden, Carl C. Cable, Julia Child, Ralph Bunche, Arthur Goldberg, Saul K. Padover, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Bruce Sundlun, William Colby, René Joyeuse, and John Ford.[51][10][52] The 750,000 pages in the 35,000 personnel files include applications of people who were not recruited or hired, as well as the service records of those who served.[53] OSS soldiers were primarily inducted from the United States Armed Forces. Other members included foreign nationals including displaced individuals from the former czarist Russia, an example being Prince Serge Obolensky. Donovan sought independent thinkers, and in order to bring together those many intelligent, quick-witted individuals who could think out-of-the box, he chose them from all walks of life, backgrounds, without distinction to culture or religion. Donovan was quoted as saying, "I'd rather have a young lieutenant with enough guts to disobey a direct order than a colonel too regimented to think for himself." In a matter of a few short months, he formed an organization which equalled and then rivalled Great Britain's Secret Intelligence Service and its Special Operations Executive. Donovan, inspired by Britain's SOE, assembled an outstanding group of clinical psychologists to carry out evaluations of potential OSS candidates at a variety of sites, primary among these was Station S in Northern Virginia near where Dulles International Airport now stands.[54] Recent research from remaining records from the OSS Station S program describes how those characteristics (independent thought, effective intelligence, interpersonal skills) were found among OSS candidates [55] Major league baseball player Moe Berg of the Boston Red Sox was an OSS agent. One such agent was Ivy League polyglot and Jewish American baseball catcher Moe Berg, who played 15 seasons in the major leagues. As a Secret Intelligence agent, he was dispatched to seek information on German physicist Werner Heisenberg and his knowledge on the atomic bomb.[56] One of the most highly decorated and flamboyant OSS soldiers was US Marine Colonel Peter Ortiz. Enlisting early in the war, as a French Foreign Legionnaire, he went on to join the OSS and to be the most highly decorated US Marine in the OSS during World War II.[57] Col. Peter Ortiz, USMC Julia Child, who later authored cookbooks, worked directly under Donovan.[58] René Joyeuse M.D., MS, FACS was a Swiss, French and American soldier, physician and researcher, who distinguished himself as an agent of Allied intelligence in German-occupied France during World War II. He received the US Army Distinguished Service Cross for his actions with the OSS, after the war he became a Physician, Researcher and was a co-founder of The American Trauma Society.[59][60] "Jumping Joe" Savoldi (code name Sampson) was recruited by the OSS in 1942 because of his hand-to-hand combat and language skills as well as his deep knowledge of the Italian geography and Benito Mussolini's compound. He was assigned to the Special Operations branch and took part in missions in North Africa, Italy, and France during 1943–1945.[61][62][63] OSS created this false ID for Joe Savoldi - posing as Giuseppe De Leo while infiltrating the black market in Naples. One of the forefathers of today's commandos was Navy Lieutenant Jack Taylor. He was sequestered by the OSS early in the war and had a long career behind enemy lines.[64] Taro and Mitsu Yashima, both Japanese political dissidents who were imprisoned in Japan for protesting its militarist regime, worked for the OSS in psychological warfare against the Japanese Empire.[65][66] Nisei linguists In late 1943, a representative from OSS visited the 442nd Infantry Regiment looking to recruit volunteers willing to undertake "extremely hazardous assignment."[67] All selected were Nisei. The recruits were assigned to OSS Detachments 101 and 202, in the China-Burma-India Theater. "Once deployed, they were to interrogate prisoners, translate documents, monitor radio communications, and conduct covert operations... Detachment 101 and 102's clandestine operations were extremely successful."[67] |

人員 米国国立公文書館は2008年8月14日、これまで極秘扱いだったOSS要員13,000人全員の氏名とOSS勤務に関する文書を公開した。24,000 名の中には、スターリング・ヘイデン、カール・C・ケーブル、ジュリア・チャイルド、ラルフ・バンチ、アーサー・ゴールドバーグ、ソウル・K・パド ヴァー、アーサー・シュレジンジャー・ジュニア、ブルース・サンドラン、ウィリアム・コルビー、ルネ・ジョワイユーズ、ジョン・フォードの名前が含まれて いる[51][10][52] 35,000の人事ファイルの750,000ページには、リクルートも採用もされなかった人々の申請書や、従軍した人々の従軍記録も含まれている [53]。 OSSの兵士は主にアメリカ軍から入隊した。その他のメンバーには、セルジュ・オボレンスキー皇太子のような旧帝国主義ロシアからの離散者を含む外国人も 含まれていた。 ドノヴァンは独立した思想家を求め、既成概念にとらわれない発想ができる知的で機転の利く人材を多く集めるために、文化や宗教の区別なく、あらゆる階層、 背景から彼らを選んだ。ドノヴァンは、"規則正しすぎて自分の頭で考えることができない大佐よりも、直接の命令に背くだけの度胸のある若い中尉の方がいい "と言ったと引用されている。わずか数ヶ月の間に、ドノヴァンはイギリスの秘密情報部や特殊作戦実行部隊に匹敵する組織を作り上げた。イギリスのSOEに 触発されたドノヴァンは、さまざまな場所でOSS候補者の評価を実施するために、優れた臨床心理学者たちを集めた。その中でも主なものは、現在ダレス国際 空港がある場所の近くにあるバージニア州北部のステーションSであった[54]。OSSステーションSプログラムの残された記録から得られた最近の研究で は、OSS候補者の中にどのような特徴(独立した思考、効果的な知性、対人能力)が見られたかが述べられている[55]。 ボストン・レッドソックスのメジャーリーガー、モー・バーグはOSSのエージェントであった。 そのような諜報員の一人が、メジャーリーグで15シーズンプレーしたアイビーリーグの多趣味でユダヤ系アメリカ人の野球捕手モー・バーグであった。彼は秘 密諜報員として、ドイツの物理学者ヴェルナー・ハイゼンベルクと彼の原子爆弾に関する知識に関する情報を求めるために派遣された[56]。最も高い勲章を 授与された華やかなOSS兵士の一人は、アメリカ海兵隊のピーター・オルティス大佐だった。戦争初期にフランス外人部隊員として入隊した彼は、OSSに参 加し、第二次世界大戦中にOSSで最も高い勲章を受けたアメリカ海兵隊員となった[57]。 ピーター・オルティス米海兵隊大佐 後に料理本を著すジュリア・チャイルドは、ドノヴァンの下で直接働いていた[58]。 ルネ・ジョワイユーズM.D.、MS、FACSはスイス、フランス、アメリカの軍人、医師、研究者で、第二次世界大戦中、ドイツ占領下のフランスで連合国 の諜報員として活躍した。戦後は医師、研究者となり、アメリカ外傷学会の共同設立者でもあった[59][60]。 "ジャンピング・ジョー "サヴォルディ(コードネームはサンプソン)は、その白兵戦と語学力、イタリアの地理とベニート・ムッソリーニの屋敷に関する深い知識を買われ、1942 年にOSSにスカウトされた。彼は特殊作戦支部に配属され、1943年から1945年にかけて北アフリカ、イタリア、フランスでの任務に参加した[61] [62][63]。 OSSはジョー・サヴォルディのためにこの偽のIDを作った-ナポリの闇市場に潜入している間、ジュゼッペ・デ・レオを装っていた。 今日のコマンドーの祖先の一人は、ジャック・テイラー海軍中尉である。彼は戦争初期にOSSに隔離され、敵陣の背後で長いキャリアを積んだ[64]。 軍国主義体制に抗議して日本で投獄された日本の政治的反体制者である八島太郎と八島みつは、OSSの下で日本帝国に対する心理戦に従事した[65] [66]。 二世言語学者 1943年後半、OSSの代表が442歩兵連隊を訪れ、「極めて危険な任務」を引き受ける志願者を募集した[67]。新兵たちは、中国-ビルマ-インド劇 場のOSS分遣隊101と202に配属された。「配属後、彼らは捕虜の尋問、文書の翻訳、無線通信の監視、秘密工作を行うことになった。第101分遣隊と 第102分遣隊の秘密作戦は非常に成功した」[67]。 |

| Dissolution into other agencies On September 20, 1945, President Truman signed Executive Order 9621, terminating the OSS.[68] The State Department took over the Research and Analysis Branch; it became the Bureau of Intelligence and Research, The War Department took over the Secret Intelligence (SI) and Counter-Espionage (X-2) Branches, which were then housed in the new Strategic Services Unit (SSU). Brigadier General John Magruder (formerly Donovan's Deputy Director for Intelligence in OSS) became the new SSU director. He oversaw the liquidation of the OSS and managed the institutional preservation of its clandestine intelligence capability.[69] In January 1946, President Truman created the Central Intelligence Group (CIG),[70] which was the direct precursor to the CIA. SSU assets, which now constituted a streamlined "nucleus" of clandestine intelligence, were transferred to the CIG in mid-1946 and reconstituted as the Office of Special Operations (OSO). The National Security Act of 1947 established the Central Intelligence Agency, which then took up some OSS functions. The direct descendant of the paramilitary component of the OSS is the CIA Special Activities Division.[71] Today, the joint-branch United States Special Operations Command, founded in 1987, uses the same spearhead design on its insignia, as homage to its indirect lineage. The Defense Intelligence Agency currently manages the OSS' mandate to provide strategic military intelligence to the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Secretary of Defense and to coordinate human espionage activities across the United States Armed Forces (through the Defense Clandestine Service) and was awarded status as an OSS Heritage organization by the OSS Society. |

他の機関への解散 1945年9月20日、トルーマン大統領は大統領令9621号に署名し、OSSを終了させた[68]。国務省は調査分析部門を引き継ぎ、情報調査局とな り、陸軍省は秘密情報(SI)部門と対スパイ活動(X-2)部門を引き継ぎ、これらは新しい戦略サービスユニット(SSU)に収容された。ジョン・マグ ルーダー准将(元OSSドノバン情報部副部長)が新しいSSU部長に就任した。彼はOSSの清算を監督し、その秘密情報能力の制度的維持を管理した [69]。 1946年1月、トルーマン大統領はCIAの直接の前身である中央情報部(CIG)を創設した[70]。現在では秘密諜報活動の合理化された「核」を構成 するSSUの資産は、1946年半ばにCIGに移管され、特殊作戦室(OSO)として再編成された。1947年の国家安全保障法によって中央情報局が設立 され、OSSの機能の一部が引き継がれた。OSSの準軍事部門の直接の子孫がCIA特別活動部である[71]。 今日、1987年に設立された合同支部の合衆国特殊作戦司令部は、その間接的な系譜へのオマージュとして、その記章に同じ先鋒のデザインを使用している。 国防情報局は現在、統合参謀本部と国防長官に戦略的軍事情報を提供し、米軍全体の人的スパイ活動を調整するというOSSの任務を管理しており(国防秘密情 報部を通じて)、OSS協会からOSS遺産組織としての地位を与えられている。 |

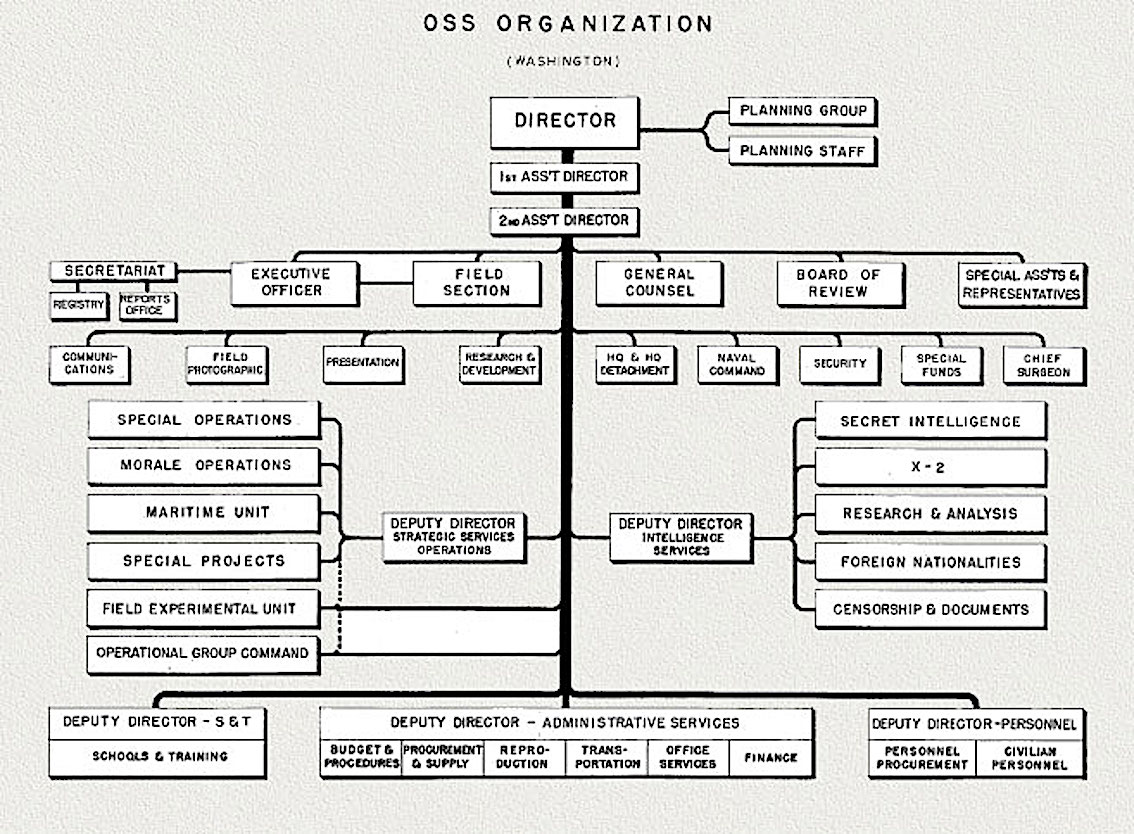

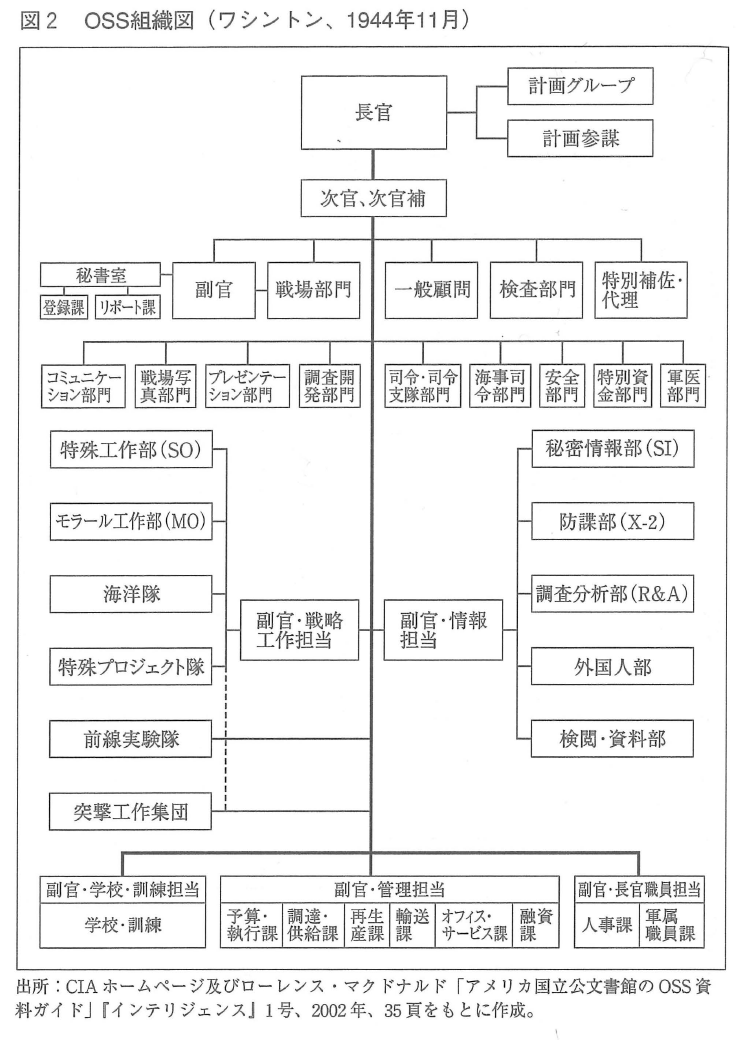

| Censorship and Documents Field Experimental Unit Foreign Nationalities Maritime Unit Morale Operations Branch Operational Group Command Research & Analysis Secret Intelligence[72] Security Special Operations Special Projects X-2 (counterespionage) |

|

| Detachments OSS Deer Team: Vietnam OSS Detachment 101: Burma OSS Detachment 202: China OSS Detachment 303: New Delhi, India OSS Detachment 404: attached to British South East Asia Command in Kandy, Ceylon OSS Detachment 505: Calcutta, India US Army units attached to the OSS 2671st Special Reconnaissance Battalion 2677th Office of Strategic Services Regiment |

|

| Charles Douglas Jackson Operation Jedburgh Operation Paperclip Paramarines Special Forces (United States Army) X-2 Counter Espionage Branch History of espionage Art Looting Investigation Unit (ALIU) |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Office_of_Strategic_Services |

|

| Office

of the Coordinator of Information, COI について |

|

| The

Office of the Coordinator of Information was an intelligence and

propaganda agency of the United States Government, founded on July 11,

1941, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, prior to U.S. involvement in

the Second World War. It was intended to overcome the lack of

coordination between existing agencies which, in part, it did by

duplicating some of their functions. Roosevelt was persuaded to create the office several months before the United States entered the war by prominent New York lawyer William J. Donovan, who had been dispatched to London by the president to assess the ability of the British to continue fighting after the French capitulation to German aggression, and by American playwright Robert Sherwood, who served as Roosevelt's primary speechwriter on foreign affairs.[1] British officials, including John Godfrey of the British Naval Intelligence Division and William Stephenson, head of British Security Co-ordination in New York, also encouraged Roosevelt to create the agency. Donovan's primary interests were military intelligence and covert operations. Sherwood handled the dissemination of domestic information and foreign propaganda. He recruited the noted radio producer John Houseman, who because of his Romanian birth at the time was technically an enemy alien,[2] to develop an overseas radio program for broadcast to the Axis powers and the populations of the territories they had conquered, which became known as the Voice of America. The first broadcast, called in German Stimmen aus Amerika ("Voices from America") aired on Feb. 1, 1942, and included the pledge: "Today, and every day from now on, we will be with you from America to talk about the war. . . . The news may be good or bad for us -- We will always tell you the truth."[3] Donovan's desire to use propaganda for tactical military purposes and Sherwood's emphasis on what later became known as public diplomacy were a continuing source of conflict between the two men.[4] On June 13, 1942, Roosevelt split the functions and created two new agencies: the Office of Strategic Services, a predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Office of War Information, a predecessor of the United States Information Agency. |

情

報調整局(Office of the Coordinator of

Information)は、第二次世界大戦にアメリカが参戦する前の1941年7月11日、フランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領によって設立されたア

メリカ政府の情報・宣伝機関である。この機関は、既存の機関間の調整不足を克服することを意図しており、機能の一部を重複させることでそれを実現した。 ルーズベルトは米国が参戦する数カ月前、著名なニューヨークの弁護士ウィリアム・J・ドノヴァンに説得され、この事務所を設立した。ドノヴァンは、ドイツ の侵略にフランスが降伏した後、英国が戦闘を継続する能力を評価するために大統領からロンドンに派遣されていた人物であり、また、ルーズベルトの外交問題 に関する主要なスピーチライターを務めていた米国の劇作家ロバート・シャーウッドによって説得された。 [1] イギリス海軍情報部のジョン・ゴッドフリーやニューヨークのイギリス安全保障調整部長ウィリアム・スティーブンソンなどのイギリス政府高官も、ルーズベル トに機関の設立を勧めた。 ドノヴァンの主な関心は軍事情報と秘密工作であった。シャーウッドは国内情報と対外宣伝の普及を担当した。彼は著名なラジオプロデューサー、ジョン・ハウ スマンを採用したが、彼は当時ルーマニア生まれであったため、厳密には敵性外国人であった[2]。最初の放送は、ドイツ語で「アメリカからの声」 (Stimmen aus Amerika)と呼ばれ、1942年2月1日に放送された: 「今日、そしてこれから毎日、私たちはアメリカから皆さんと一緒に戦争について語ります。. . . ニュースは私たちにとって良いものであれ、悪いものであれ--私たちは常に真実をお伝えします」[3]。 ルーズベルトは1942年6月13日、中央情報局(Central Intelligence Agency)の前身である戦略サービス局(Office of Strategic Services)と米国情報局(United States Information Agency)の前身である戦争情報局(Office of War Information)の機能を分割し、2つの新しい機関を創設した。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Office_of_the_Coordinator_of_Information |

|

●第二次大戦中のOSS

ナチハンティングに関しては、OSS(戦略情報部; Office of Strategic Services, 1942-1945)に関する隠語を含む用語と活動について知り尽くすことが重要である。出典の元になったのは、ペルシコ、ジョーゼフ『ナチ・ドイツの心 臓を狙え』宇田道夫・芳地昌三訳、サンケイ出版、1981年(Joseph E. Persico, 1997. Piercing the Reich: the Penetration of Nazi Germany By American Secret Agents During World War II. Barnes & Noble Books.)である。

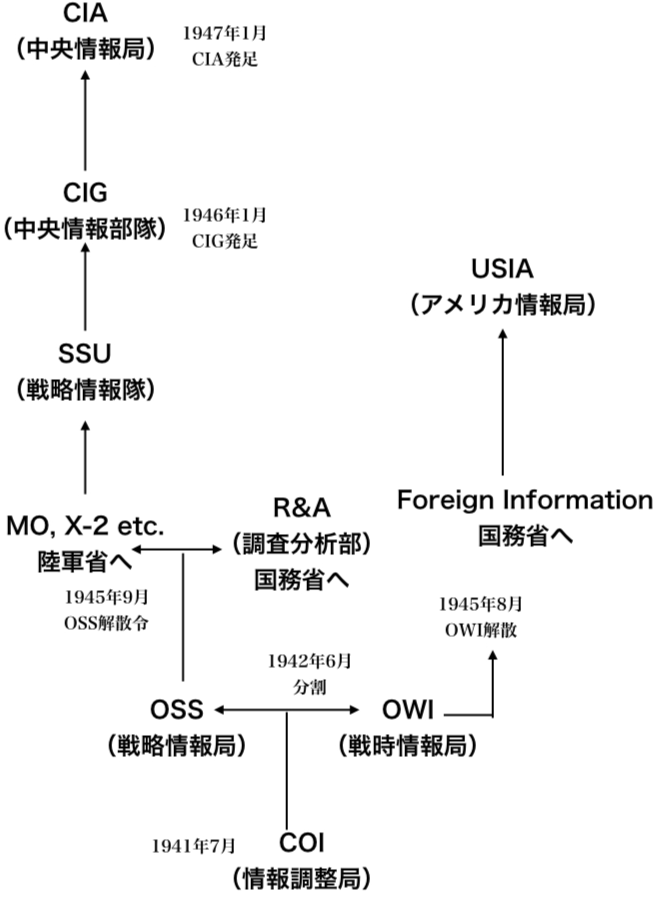

OSSは、それまであった情報調整局(COI, Office of the Coordinator of Information, 1941年6月18日〜1942年6月)が改組して、1942年6月13日にできたものである。Office of Strategic Services(戦略情報部)という。OSS(1942年6月13日に発足し)は1945年9月20日には解散して、陸軍省の所管の部局(MO, X-2など)と国務省所轄の部局(R&A=調査分析部)に別れるので、OSSが存在していた期間は、およそ3年3ヶ月ほどである。

下記は、連合国側のナチスへの対応の他に、対日戦争 にならびに戦後の対応に関する組織について書いている。

| A-2 |

Air Force

intelligence service [American] |

|

| AGAS |

Air Ground Aid

Service [American] |

|

| AGFRTS |

Air and Ground

Forces Resources Technical Staff, an OSS offspring in China under the

14th Air Force [American] |

|

| APPLE |

Chinese

Communists-proposed intelligence plan with OSS |

|

| AVG |

American

Volunteers' Group, the Flying Tigers under Claire Lee Chennault

[Chinese, American] |

|

| BAAG |

British Air Aid

Group, London's secret intelligence organization in wartime China under

the protection of the U.S. AGAS |

|

| BEW |

Board of Economic Warfare under

Henry Wallace [American] |

|

| BIS |

Bureau of Investigation and

Statistics under the National Military Council [Chinese] |

|

| CBI |

China-Burma-India theater |

|

| CCP |

Chinese Communist Party |

|

| CCS |

Combined Chiefs of Staff

[Anglo-American] |

|

| CIC |

Counter Intelligence Corps of

the U.S. Army |

|

| CIG |

Central Intelligence Group

[American] |

|

| CNAC |

China National Aviation

Corporation |

|

| COI |

Coordinator of Information

[American] |

|

| COMMO |

Communications, OSS |

|

| CT |

China theater |

|

| FEA |

Foreign Economic Administration

[American] |

|

| FEB |

Far Eastern Bureau of the

Ministry of Information [British] |

|

| FP |

field photographic branch of OSS |

|

| G-2 |

Army intelligence [American] |

|

| GBT |

Gordon-Bernard-Tam intelligence

network in Japanese-occupied French Indochina |

|

| GRU |

Soviet military intelligence

agency |

|

| IDC |

Interdepartmental Committee for

the Acquisition of Foreign Periodicals [American] |

|

| JCS |

Joint Chiefs of Staff [American] |

|

| JICA |

Joint Intelligence Collection

Agency [American] |

|

| JPWC |

Joint Psychological Warfare

Committee [American] |

|

| Jun Tong |

same as BIS [Chinese] |

|

| KMT |

Kuomintang, the Chinese

Nationalist Party |

|

| MA |

military attache |

|

| MAGIC |

American code name for decoded

Japanese diplomatic messages |

|

| MID |

Military Intelligence Division,

or G-2 [American] |

|

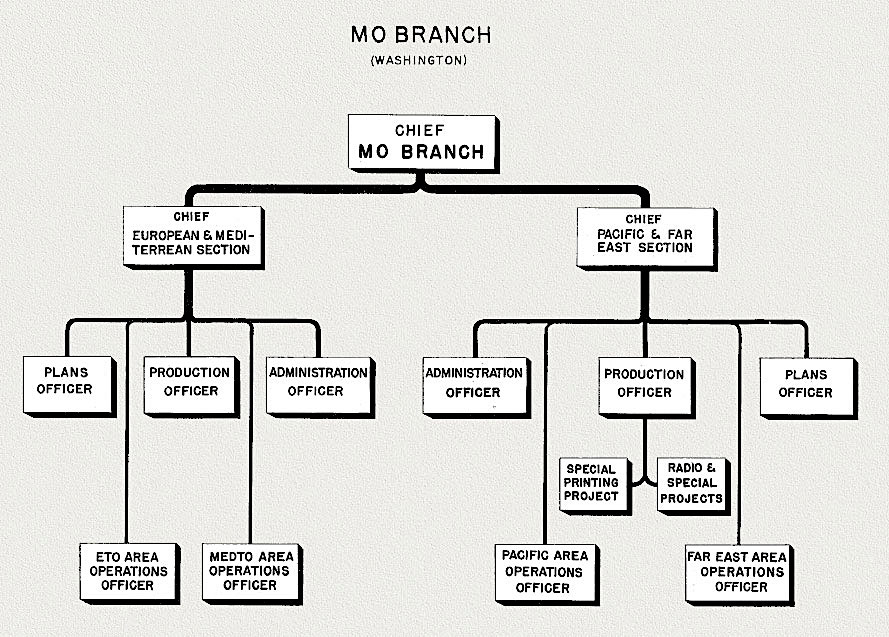

| MO |

morale operations branch of OSS |

|

| MOI |

Ministry of Information [British] |

|

| NA |

naval attache [American] |

|

| NKVD |

predecessor of the KGB [Soviet] |

|

| OG |

operations group of OSS |

|

| OMS |

Department of Overseas

Relations, the Communist International (Comintern) |

|

| ONI |

Office of Naval Intelligence

[American] |

|

| OPD |

operations division, War

Department [American] |

|

| OSS |

Office of Strategic Services |

|

| OWI |

Office of War Information

[American] |

|

| P Division |

intelligence umbrella agency

under Mountbatten in SEAC [British] |

|

| R&A |

research and analysis branch of

OSS |

|

| S&T |

school and training branch of OSS |

|

| SACO |

Sino-American Special Technical

Cooperative Organization [Sino-American] |

|

| SAD |

Social Affairs Department

[Chinese Communist] |

|

| SEAC |

Southeast Asia Command under

Mountbatten |

|

| SEPM |

Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury |

|

| SI |

secret intelligence branch of OSS |

|

| SO |

special operations branch of OSS |

|

| SOE |

Special Operations Executive

[British] |

|

| SSU |

Strategic Services Unit

[American] |

|

| X-2 |

counterespionage branch of OSS |

|

| YENSIG |

OSS signal intelligence project

with the Chinese Communists |

|

| Zhong Tong |

Bureau of Investigation and

Statistics under the Organization Department of the Chinese Nationalist

Party (KMT) |

出典:OSS

in China : prelude to Cold War / Maochun Yu, Annapolis, Md. :

Naval Institute Press , 2011, c1996.

| 用語・略語・人名など |

言語 |

日本語あるいは解説 | 補注、資料、出典など |

| OSS |

Office

of Strategic Services |

戦

略諜報局、戦略情報部:「OSSは、それまであった情報調整局(COI, Office of the Coordinator of

Information, 1941年6月18日〜1942年6月)が改組して、1942年6月13日にできたものである。Office of

Strategic

Services(戦略情報部)という。OSS(1942年6月13日に発足し)は1945年9月20日には解散して、陸軍省の所管の部局(MO,

X-2など)と国務省所轄の部局(R&A=調査分析部)に別れるので、OSSが存在していた期間は、およそ3年3ヶ月ほどである。」 戦

略諜報局、戦略情報部:「OSSは、それまであった情報調整局(COI, Office of the Coordinator of

Information, 1941年6月18日〜1942年6月)が改組して、1942年6月13日にできたものである。Office of

Strategic

Services(戦略情報部)という。OSS(1942年6月13日に発足し)は1945年9月20日には解散して、陸軍省の所管の部局(MO,

X-2など)と国務省所轄の部局(R&A=調査分析部)に別れるので、OSSが存在していた期間は、およそ3年3ヶ月ほどである。」作図は加藤哲郎『象徴天皇制の起源』平凡社、2005年。p.53,p.55など。 |

|

| Abwehr | the German

military intelligence service for the Reichswehr and Wehrmacht. |

アプヴェーア(1921-1944)。ド

イツ国防軍情報部(陸軍参謀本部所属) Amt Ausland/Abwehr im Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (1938-1945) |

ペルシコ、ジョーゼフ『ナチ・ドイツの心 臓を狙え』宇田道夫・芳地昌三訳、サンケイ出版、1981年(Joseph E. Persico, 1997. Piercing the Reich: the Penetration of Nazi Germany By American Secret Agents During World War II. Barnes & Noble Books.)The Abwehr. |

| BACH |

バッハ部、OSSロンドンの経歴・文書偽

造部門 |

(Persico, 1997)邦訳,

Pp.39- |

|

| COI |

Coordinator

of Information |

情報調査部、OSSの前身、後のCIA |

Office

of Strategic Services. |

| DGER |

Direction

générale des études et recherches. |

フランスの情報機関, ancien

organe du renseignement français, créé juste après la Libération et qui

précéda le SDECE (Service

de documentation extérieure et de contre-espionnage). |

|

| DIP |

情報処理部。OSS・ロンドンのドイツ浸

透作戦担当部門、労働部を吸収。 |

||

| ETO |

European

Theater of Operations |

ヨーロッパ作戦戦域(The European Theater of

Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA)) |

作戦戦域(A theater of

operations)と言う語は、アメリカ軍の軍事マニュアルでは、「侵攻を受けたもしくは、防御する陸及び海の地域、これは軍事作戦に付随する戦略的

な活動を行なう地域も含む」と定義している(チャート12)(ETOUSA)。 |

| Gestapo |

The Geheime

Staatspolizei (Secret State Police), abbreviated Gestapo |

秘密国家警察。親衛隊所属のナチス政治警

察 |

|

| G-2 |

General-Staff 2,

Army Intelligence Staff. |

アメリカ陸軍部隊の作戦情報担当部局 |

|

| ISK |

国際社会主義闘争連盟。ドイツ社会党の分

派 |

||

| ITWF |

国際貿易業者連合。 |

||

| Maquis |

マキ。フランス左翼レジンタンス団体:

The Maquis (French pronunciation: [maˈki]) were rural guerrilla bands

of French Resistance fighters, called maquisards, during the Nazi

occupation of France in World War II. |

||

| MI-5 |

domestic

intelligence agency. |

イギリス国内諜報機関 |

|

| MI-6 |

Secret

Intelligence Service. |

イギリス秘密情報部 |

|

| MO |

Morale

Operations Branch, OSS. |

心理作戦部。OSSの宣伝担当部門 |

|

| O5 |

オーストリアの軍隊内抵抗組織 |

||

| OWI |

United

States Office of War Information. |

戦時情報部。アメリカの宣伝作戦の統制機

関 |

OWI operated from

June 1942 until September 1945. Through radio broadcasts, newspapers,

posters, photographs, films and other forms of media, the OWI was the

connection between the battlefront and civilian communities. The office

also established several overseas branches, which launched a

large-scale information and propaganda campaign abroad. |

| POEN |

暫定オーストリア全国委員会。オーストリ

アの抵抗組織 |

||

| R and A, R&A |

Research

and Analysis Branch, Office of Strategic Services |

OSSの研究分析部 OSSの研究分析部 |

O.S.S./State

Department Intelligence and Research Reports (戦略諜報局情報研究報告):

「1941年7月ルーズベルト大統領は、諜報活動が国務、陸軍、海軍各省でそれぞれ別個に調整なく重複して行われた現状を改めるため、情報調整官

(Coordinator Information, COI)をホワイトハウスに付設し、民間人(弁護士)のドノヴァン(William Joseph

Donovan)を任命した。情報調整局(Office of the Coordinator of Information,

OCOI)の職務は、安全保障にかかわるあらゆる情報を収集・分析し、大統領や大統領の指定する政府機関・職員に提供することであった。ドノヴァンは、図

書館や政府機関等にある公開資料を専門家が詳細に分析すれば、枢軸国の戦力・経済力といった諜報上重要な問題についても解答が得られるという考えから、研

究分析部(Research

and Analysis Branch, R&A)を設置した。1942年6月13日に、対外情報局(Foreign

Information Service, FIS)を除く、COI局の部局は戦略諜報局(Office of Strategic

Services, OSS)に改組され、研究分析部もOSSの1部局となった」出典:上掲リンク) |

| RSHA (Reich

Main Security Office) |

Reichssicherheitshauptamt

or RSHA |

国家保安本部。ゲシュタポとSDを統括するナチスの全国保安機関 |

|

| SA |

Sturmabteilung |

突撃隊。ナチスの暴力組織; the Nazi Party's

original paramilitary wing. |

|

| SD, Security Service |

Sicherheitsdienst |

SS保安部。親衛隊の情報・防諜部門 |

|

| SHAEF |

Supreme

Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force |

ヨーロッパ派遣連合軍最高司令部 |

|

| SI |

Secret

Intelligence Branch |

秘密情報部。OSS所属 |

|

| SIS |

Secret

Intelligence Service |

イギリス秘密情報部。MI-6の別名。 |

|

| SO |

Special Operation |

秘密作戦部。特殊工作部(加藤哲郎訳)、

OSS所属 |

|

| SOE |

Special

Operations Executive (SOE). |

特殊作戦実施部。特殊工作本部(加藤

訳)。レジスタンスの組織・育

成を担当するイギリス機関 |

|

| SS, Protection Squadron | Schutzstaffel | 親衛隊。ナチ党の軍事、政治、警察組織。 |

|

| X-2 |

X-2

Counter Espionage Branch |

対敵情報部。OSS所属 |

|

| XX |

MI-5の二重スパイ部門 |

||

| FIS | Foreign Information Service | 対外情報部(COI) |

|

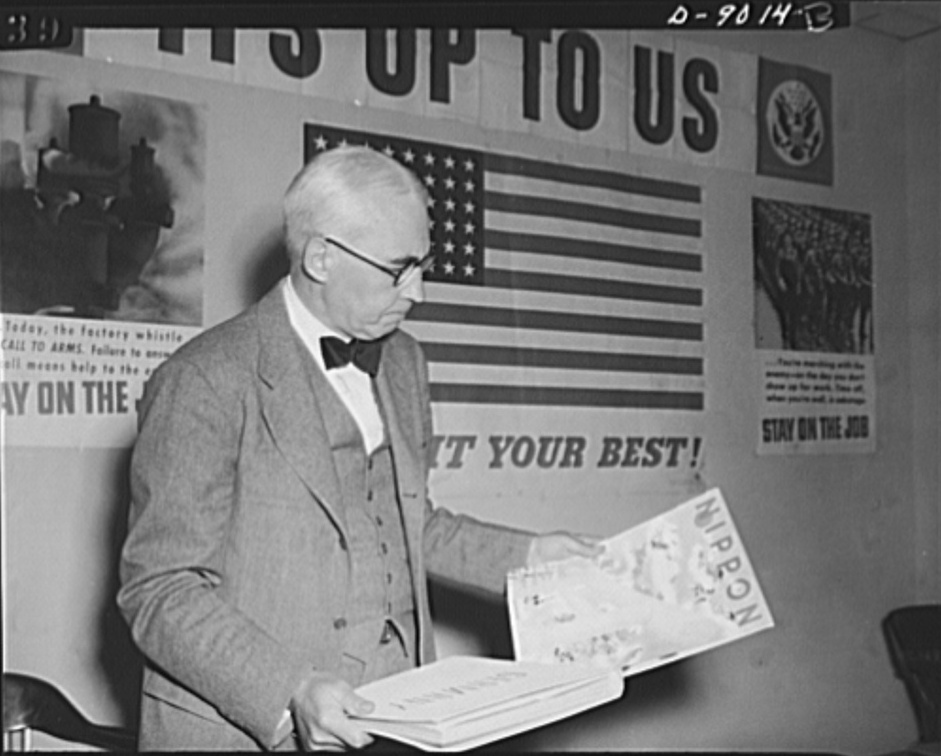

| William Joseph

"Wild Bill" Donovan, 1883-1959 |

ウィリアム・ドノバン |

戦略諜報局(OSS)の創設者。「アメリ

カ情報機関の父」(Father of American Intelligence)、「CIAの父」(Father of Central

Intelligence) |

|

| CIA |

Central

Intelligence Agency |

中央情報局 |

The

Central Intelligence Agency

(CIA; /siaɪˈeɪ/), known informally as "The Agency" and "The

Company",[6][7] is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the

federal government of the United States, officially tasked with

gathering, processing, and analyzing national security information from

around the world, primarily through the use of human intelligence

(HUMINT). As a principal member of the United States Intelligence

Community (IC), the CIA reports to the Director of National

Intelligence and is primarily focused on providing intelligence for the

President and Cabinet of the United States. (→CIAの誕生について) |

| OWI |

Office of War

Information |

1941年6月18日(7月11日)に設 置されたCOI(情報調整局)が42年6月13日に分割されてOSSが誕生するときに生まれた別の双子組織がOWI(戦時情報局) |  こ

れらの組織を統括していたのが、緊急事態管理局 (Office for Emergency Management ,OEM)

である。任務はそれまでのプロパガンダのほかに、海外のニュースやレポート、そして国内外のプロパガンダを分析するという新しい任務も負い、CBS

Newsのエルマー・ディヴィス(Elmer Davis)をディレクターに、アメリカ有数の学者たちが雇われた。 こ

れらの組織を統括していたのが、緊急事態管理局 (Office for Emergency Management ,OEM)

である。任務はそれまでのプロパガンダのほかに、海外のニュースやレポート、そして国内外のプロパガンダを分析するという新しい任務も負い、CBS

Newsのエルマー・ディヴィス(Elmer Davis)をディレクターに、アメリカ有数の学者たちが雇われた。 |

| Elmer Davis,

1890-1958 |

Elmer Davis,

Director of the Office of War Information, エルマー・ディビス |

|

|

| ACLS |

American Council of Learned Societies |

全米学術団体協議会 |

|

| CFR |

Council on Foreign Relations |

外交問題評議会 |

外交問題評議会(Council on Foreign

Relations,

略称はCFR)は、アメリカ合衆国のシンクタンクを含む超党派組織。1921年に設立され、外交問題・世界情勢を分析・研究する非営利の会員制組織であ

り、アメリカの対外政策決定に対して著しい影響力を持つと言われている。超党派の組織であり、外交誌『フォーリン・アフェアーズ』の刊行などで知られる。

本部所在地はニューヨーク。会員はアメリカ政府関係者、公的機関、議会、国際金融機関、大企業、大学、コンサルティング・ファーム等に多数存在する。 |

| Jewish Virtual

Library |

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ | ||

| COI |

Office of the Coordinator of Information | 情報調整局 | |

| FBI |

Fedearal Bureau of Investigation |

連邦捜査局 |

|

| FRUS |

Foreign Relation of the United

States |

米国国防省外交資料集() |

The Foreign

Relations of the United States (FRUS) series presents the official

documentary historical record of major U.S. foreign policy decisions

and significant diplomatic activity. |

| GHQ |

General Headquartes |

連

合国軍総司令部. |

1945年10月〜1952年4月 |

| IPR |

Institute of Pacific Relations |

太

平洋問題調査会. |

The Institute of Pacific

Relations (IPR) was an international NGO established in 1925 to provide

a forum for discussion of problems and relations between nations of the

Pacific Rim. 1925-1961.日本は、1925-1936年まで参加。 |

| JPWC |

Joint Psychological Warfare

Committee |

心理戦共同委員会 |

Psychological

operations (United States); |

| LC |

Library of

Congress |

米

国議会図書館 |

|

| MIS |

Military

Intelligence Service |

陸

軍省軍事情報部 |

1941-1945. |

| MO |

Morale

Operation Branch |

モラール工作部(OSS) |

Morale Operations was a branch

of the Office of Strategic Services during World War II. It utilized

psychological warfare, particularly propaganda, to produce specific

psychological reactions in both the general population and military

forces of the Axis powers in support of larger Allied political and

military objectives. |

| NARA |

National Archives and Records

Administration, (Wiki) |

米国国立公文書館(wiki アメリカ国立公文書記録管理局) |

|

| ONI |

Office of Naval Intelligence (wiki) |

海軍情報部 |

|

| PWE |

Political

Warfare Excutive |

政治戦争本部(英国) |

|

| SSRC |

The

social science research council (wiki) |

全米社会科学協議会 |

1923- present. |

| SSU |

Strategic

Services Unit |

陸軍戦略情報隊 |

The Strategic

Services Unit was an intelligence agency of the United States

government that existed in the immediate post–World War II period. It

was created from the Secret Intelligence and Counter-Espionage branches

of the wartime Office of Strategic

Services.

Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy was instrumental in

preserving the two branches of the OSS as a going-concern with a view

to forming a permanent peace-time intelligence agency. The unit was

established on October 1, 1945 through Executive Order 9621, which

simultaneously abolished the OSS.[1] The SSU was headed by General John

Magruder.[2][3][4]

In January 1946, a new National Intelligence Authority was established

along with a small Central Intelligence Group. On April 2, 1946 the

Strategic Services Unit was transferred to the new group as the Office

of Special Operations and a transfer of personnel began immediately.

In 1947, the Central Intelligence Agency was established under the 1947

National Security Act, incorporating the Central Intelligence Group. In

August 1952, the Office of Special Operations was combined with the

Office of Policy Coordination to form the Directorate of Plans. |

| OSSの組織史(R&A) |

加藤哲郎『象徴天皇制の起源』平凡社、2005年 |

R&Aは1945年8月の時点で2,000名のアナリストを擁

したとされる。リクルートは次の三段階。 1)学会の大御所、外交問題評議会(CFR)、ホワイトハウスに影響力をもつ長老研究者がドノバンのもとにあつまる(加藤 2005:64-65)——COIの時期 2)若手研究者の組織化(加藤 2005:66)——COIからOSSへ 3)連合軍の勝利がみえてきた、1943年春以降、亡命ユダヤ人、ドイツ人、日系アメリカ人などが加わる(加藤 2005:69)。ただし、アジア人は基本的に手足として使われる。 |

|

| Barry M. Katz | Barry

M. Katz is Professor of Industrial and Interaction Design at California

College of the Arts, Consulting Professor in the Design Group at

Stanford University, and Fellow at IDEO, Inc. He is coauthor of Change

by Design, with Tim Brown, and NONOBJECT, with Branko Lukić (MIT Press). |

Foreign intelligence : research and analysis in the Office of Strategic Services, 1942-1945 / Barry M. Katz, Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press , 1989 | Preface 1. Military Disciplines Academic Recruitment The Epistemology of Intelligence The Organization of Research and Analysis 2. The Frankfurt School Goes to War Hegel, Marx, and the Criticism of Arms Political and Psychological Warfare: 1943 Military Occupation and Denazification: 1944 War Crimes: 1945 War and Peace 3. Historians Making History The German Catastrophe R&A/Washington: 1943 R&A/London: 1944 R&A/Germany: 1945 Beyond History 4. The Political Economy of Intelligence Economic Autarky The Economists'War Operation OCTOPUS From D-Day to V-Day The History and Value of Economics 5, Social Science m One Country: The USSR Division What Is To Be Done TheFirst Five-Year Plan Peaceful Coexistence The Dictatorship of the Professoriate 6. The Critique of Modenity The Decline of the West The Transvaluation of Values The Disenchantment of the World The Return of the Repressed Conclusion: Intellect and Intelligence Note on Sources Notes Charts index |

文献:ペルシコ、ジョーゼフ『ナチ・ドイツの心臓を 狙え』宇田道夫・芳地昌三訳、サンケイ出版、1981年(Joseph E. Persico, 1997. Piercing the Reich: the Penetration of Nazi Germany By American Secret Agents During World War II. Barnes & Noble Books.

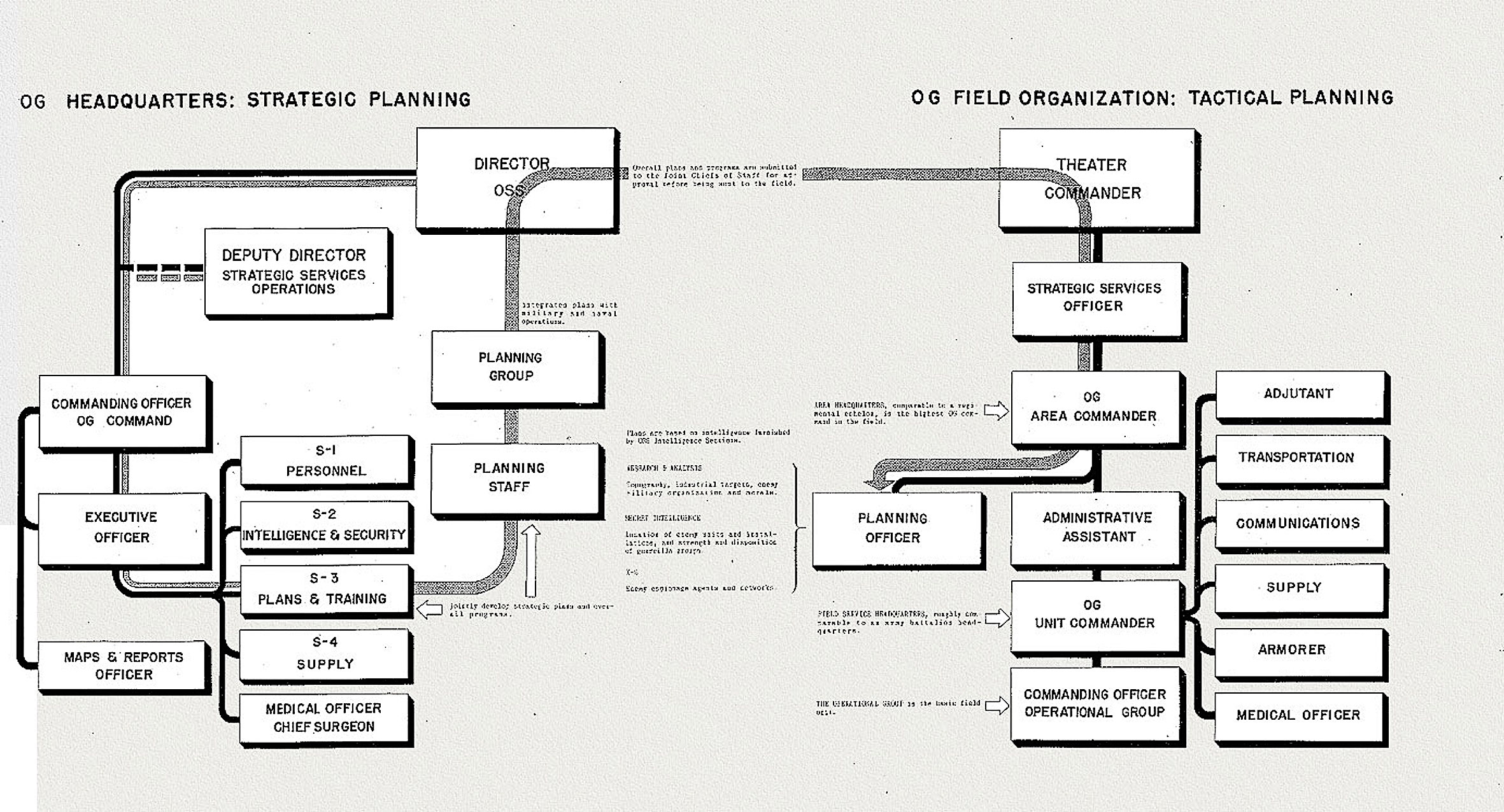

作戦行動の流れ(戦略計画から戦術計画へ)Office of Strategic Services(OSS), Organization and Functions, より(→「戦略的情報」も参照せよ)

●OSSの沿革

●Foreign intelligence : research and analysis in the Office of Strategic Services, 1942-1945 / Barry M. Katz, Harvard University Press , 1989, Pp.196-198.

| Google translator

bundle を基礎に |

DeepL を基礎に(https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator) |

|

| It has recently

been argued that "every historical narrative has as its latent or

manifest purpose the desire to moralize the events of which it

treats." The foregoing study of academic scholarship in the

Office of Strategic Services would seem to lend special credence to

this claim, for I have conceived it from the beginning in moral terms.

The Research and Analysis Branch mobilized a formidable battalion of

progressive scholars whose vocation was to manipulate ideas, who

understood the war in political terms, and who wanted to help. Wartime

Washington was not Periclean Athens, Florence under the Medici, or

Goethe's Weimar, but there remains something inspiring about it, even

if the motives of particular individuals were often more pragmatic:

transfers to OSS were known in the army as "cellophane commissions"-you

could see right through them, but they protected you from the draft. |

最近、「すべての歴史的物語は、その潜在

的または明白な目的として、それが扱う出来事を道徳的にしたいという願望を持っている」と主張されています。戦略情報局での学術研究に関する前述の研究

は、私が最初から道徳的な観点から考えてきたので、この主張に特別な信憑性を与えるように思われます。研究分析部門は、アイデアを操作することを使命と

し、政治的な観点から戦争を理解し、支援したいと考えていた進歩的な学者の手ごわい大隊を動員しました。戦時中のワシントンは、ペリクリーンアテネ、メ

ディチ家の下のフィレンツェ、ゲーテのワイマールではありませんでしたが、特定の個人の動機がより実用的であったとしても、それについて何か刺激的なもの

が残っています。OSSへの移籍は軍では「セロハン委員会」として知られていました。 |

近、「すべての歴史物語には、それが扱う

出来事を道徳的に表現したいという潜在的または顕在的な目的がある」と論じられています1。

前述した戦略サービス局の学術研究についての研究は、この主張に特別な信憑性を与えているように思えるが、私は最初から道徳的な観点から考えていた。調査

分析部は、思想を操ることを天職とし、戦争を政治的観点から理解し、助けたいと願う進歩的な学者たちの強力な大隊を動員していた。戦時中のワシントンは、

ペリクレス時代のアテネでも、メディチ家時代のフィレンツェでも、ゲーテのワイマールでもありませんでしたが、特定の個人の動機がより現実的なものであっ

たとしても、そこには何か刺激的なものがありました。 |

| If my desire to

moralize does not necessarily derive from the purity of individuals'

motivations, neither is it prompted by the decisive role played by the

Research and Analysis Branch in winning the war. The work these

scholars produced was, as a general rule, of exceptionally high

quality, the more so given the duress of wartime conditions and the

need to forge wholly new tools of analysis and research. As any scholar

knows, however, it is one thing to publish and quite another to find a

receptive readership, and there is precious little evidence that the

reports, analyses, and forecasts churned out in the Branch figured

decisively in the determination of military or diplomatic policy. The

failure of the government to utilize this unique resource to the

maximum was, in my opinion, a tragic waste. |

私の道徳的欲求が必ずしも個人の動機の純

粋さに由来するわけではない場合、それは戦争に勝つために研究分析部門が果たした決定的な役割によっても促されません。これらの学者が生み出した作品は、

原則として、非常に質の高いものであり、戦時中の厳しい状況と、まったく新しい分析と研究のツールを構築する必要性を考えると、さらにそうです。しかし、

どの学者も知っているように、出版することと受容的な読者を見つけることはまったく別のことであり、支部で発表されたレポート、分析、および予測が軍事的

または外交的決定において決定的に理解されたという貴重な証拠はほとんどありません。ポリシー。政府がこのユニークな資源を最大限に活用できなかったこと

は、私の意見では、悲劇的な浪費でした。 |

私が道徳的になりたいと思うのは、必ずし

も個人の動機が純粋であるからではなく、研究分析部門が戦争に勝つために決定的な役割を果たしたからでもない。戦時下の過酷な状況下で、全く新しい分析・

研究手段を構築しなければならなかったのだから、彼らの研究成果は、概して非常に質の高いものであった。しかし、学者なら誰でも知っているように、出版することと読者に受け入れられることは全く別のことであ

り、支部で作成された報告書、分析、予測が軍事的、外交的な政策決定に決定的な影響を与えたという証拠はほとんどないのである。政府がこの

ユニークな資源を最大限に活用できなかったことは、悲劇的な無駄であったと私は考えている。 |

| The Office of

Strategic Services 9620, signed by President Truman on September 20,

1945, and effective ten days later. The teams of Special Operations,

Secret Intelligence, and Counter-Intelligence agents were mostly

disbanded and dispersed throughout the Strategic Services Unit of the

War Department, but exceptional efforts were made to preserve the

Research and Analysis Branch intact.2 Long before the war was over,

General Donovan had begun to anticipate America's peacetime

intelligence needs and so advised the President: "We have now in the

Government the trained and specialized men needed for the task," he

wrote referring specifically to R&A. "This talent should not be

dispersed." |

1945年9月20日にトルーマン大統領

によって署名された戦略サービス局9620は、10日後に発効します。特殊作戦、シークレットインテリジェンス、およびカウンターインテリジェンスのエー

ジェントのチームは、ほとんどが解散し、陸軍省の戦略サービスユニット全体に分散しましたが、研究分析部門を無傷に保つために並外れた努力が払われまし

た。2戦争が終わるずっと前に、ドノバン将軍はアメリカの平時の諜報機関の必要性を予測し始めていたので、大統領に次のように助言した。「この才能は分散

されるべきではありません。」 |

1945年9月20日にトルーマン大統領

が署名し、その10日後に発効した「戦略サービス局9620」である。特殊作戦、秘密情報、防諜のエージェントチームはほとんど解散し、陸軍省の戦略サー

ビス部門に分散されたが、研究分析部門をそのまま残すために特別な努力が払われた2。戦争が終わるずっと前から、ドノバン将軍はアメリカの平時の情報ニー

ズを予測し始め、大統領に助言していた。「ドノバン将軍は、平時におけるアメリカの諜報活動の必要性を予測し、大統領に次のように助言していた。「我々は

現在、任務に必要な訓練を受けた専門的な人材を政府内に有している。「この才能を分散させてはならない」と。 |

| The combined

recalcitrance of the government and the community of scholars sabotaged

the hopes of Donovan, Langer, and other OSS administrators that their

organization would be permitted to evolve into a peacetime intelligence

agency. Scholars who had been prepared to lend their academic skills to

the war against Hitler found that with the destruction of Nazism the

danger no longer seemed to be so clear and present. Some allowed

themselves to be transferred to desks in the Interim Research and

Intelligence Service in the State Department, others circulated

proposals to channel promising graduate students into intelligence work

or to induce professors to use sabbatical leaves for

intelligence-gathering activities abroad, and a very few remained long

enough to join Langer and Sherman Kent on the CIA's Board of National

Estimates in 1950.4 From the South-East Asia Command the anthropologist

Gregory Bateson noted that even as the atomic blasts over Japan

foretold the end of conventional warfare among the great powers,

"already even the best personnel in O.S.S. are beginning to think that

their job is finished, and powerful forces in government are already

aligned to get rid of the agencies concerned with clandestine

operations, psychological warfare, international economic controls, and

the collecting and analysis of intelligence. "5 The great majority felt

that even in R&A they had been exiled to a foreign land, forced to

speak and write in a foreign tongue and to think with a foreign

intelligence. In droves they shed their uniforms and returned to

unfinished manuscripts and doctoral dissertations, and it cannot be

gainsaid that their departure from Washington was viewed with some

relief. Even William Langer conceded that "the academic is all too apt

to lack elasticity. He is generally an individualist, and when he

thinks he is right he is all too prone to be impatient with the

difficulties."6 But the judgment of one astute journalist may be

closest to the mark: "Too many professors." |

政府と学者のコミュニティの複合的な抵抗

は、彼らの組織が平時の諜報機関に進化することを許可されるというドノヴァン、ランガー、および他のOSS管理者の希望を妨害しました。ヒトラーとの戦争

に学力を貸す準備ができていた学者たちは、ナチズムの破壊により、危険はもはやそれほど明確で存在していないように思われることに気づきました。国務省の

暫定研究情報局のデスクに異動することを許可した人もいれば、有望な大学院生を諜報活動に導くか、教授に海外の諜報収集活動にサバティカルの葉を使用する

ように促す提案を回覧した人もいました。

1950年にCIAの国家推定委員会でランガーとシャーマンケントに加わるのに十分な長さを保ちました。4南東アジア司令部から、人類学者のグレゴリー・

ベイトソンは、日本を襲った原子爆風が大国間の通常戦争の終結を予告したとしても、「すでにOSSの最高の職員でさえ彼らの仕事が終わったと考え始めてい

る。政府の強力な勢力は、秘密作戦、心理戦、国際経済統制、情報収集と分析に関係する機関を排除するためにすでに調整されています。」5大多数は、R&A

においてさえ彼らが追放されたと感じました。外国の土地、外国の言語で話したり書いたりすることを余儀なくされ、外国の知性で考えることを余儀なくされま

した。彼らは大勢で制服を脱ぎ、未完成の原稿と博士論文に戻った。そして、彼らのワシントンからの出発がいくらか安心して見られたとは言えません。ウィリ

アム・ランガーでさえ、「学者は弾力性に欠ける傾向があります。彼は一般的に個人主義者であり、彼が正しいと思うとき、彼は困難に焦りがちです。」6しか

し、ある鋭敏なジャーナリストの判断マークに最も近いかもしれません:「教授が多すぎます。」 |

政府と学者の不一致が重なって、ドノバ

ン、ランガーらOSSの管理者は、平時の情報機関としての発展を期待していたが、その期待は裏切られた。対ヒトラー戦争に自分の学術的能力を提供する準備

をしていた学者たちは、ナチズムが壊滅したことで、危険性がそれほど明確ではなくなったと感じた。国務省の暫定調査情報局のデスクに転属する者、有望な大

学院生を諜報活動に参加させたり、教授にサバティカル休暇を利用して海外での情報収集活動をさせたりする提案を行う者、1950年にランガーとシャーマ

ン・ケントがCIAの国家推計委員会に参加するまでに残った者など、ごく少数ではあったが、このような活動を行っていた。

東南アジア司令部からは、人類学者のグレゴリー・ベイトソンが、日本での原爆投下が大国間の通常戦争の終わりを予感させるものであったにもかかわらず、

「すでにO.S.S.の優秀な人材でさえ、自分たちの仕事は終わったと考え始めており、政府内の強力な勢力が、秘密工作、心理戦、国際的な経済統制、情報

の収集と分析に関わる機関を排除しようとすでに連携している」と指摘した5。「5

大多数の人々は、R&Aにおいても、自分たちは異国の地に追放され、異国の言葉で話したり書いたり、異国の知性で考えることを強いられていると感

じていた。彼らは次々と軍服を脱ぎ捨て、書きかけの原稿や博士論文に戻っていったが、彼らがワシントンを離れることに安堵感があったことは間違いない。

ウィリアム・ランガーも、「学者というのは弾力性に欠ける傾向がある」と認めている。彼は一般的に個人主義者であり、自分が正しいと思ったときには、困難

に耐えられなくなる傾向があります」6 しかし、ある鋭いジャーナリストの判断が最も的を射ているかもしれない。"教授の数が多すぎる" |

| For the continuity

of the Research and Analysis Branch we must look not to the State

Department or the CIA but to that ultimate decentralized intelligence

agency, the American academic establishment. From around the country,

two generations of American and European scholars had converged upon

Washington, bringing with them techniques of statistical evaluation,

familiarity with the European trade union movement, fluency in regional

dialects, the philosopher's grasp of ideological structures, the

sociologist's expertise in content analysis. The war hardened and

sharpened these skills, called forth new ones, and imparted to a

community of humanist and social scientific scholars a concrete sense

of the embeddedness of their ideas-and themselves-in history, which

they brought back with them to their universities. |

研究分析部門の継続性のために、私たちは

国務省やCIAではなく、その究極の分散型諜報機関であるアメリカの学術機関に目を向ける必要があります。全国から、2世代のアメリカ人とヨーロッパ人の

学者がワシントンに集まり、統計的評価の技術、ヨーロッパの労働組合運動に精通していること、地域の方言に精通していること、哲学者の思想構造の把握、社

会学者の内容に関する専門知識をもたらしました分析。戦争はこれらのスキルを強化し、研ぎ澄まし、新しいスキルを呼び起こし、ヒューマニストと社会科学の

学者のコミュニティに、彼らのアイデアと彼ら自身が歴史に埋め込まれているという具体的な感覚を与え、彼らはそれを大学に持ち帰りました。 |

調査分析部の存続のためには、国務省や

CIAではなく、究極の分散型情報機関であるアメリカの学界に目を向けなければならない。彼らは、統計的評価の技術、ヨーロッパの労働組合運動の知識、地

方の方言、哲学者のイデオロギー構造の把握、社会学者の内容分析の専門知識などを持ち込んだ。戦争は、これらの技術を硬化させ、研ぎ澄まし、新たな技術を

呼び起こし、ヒューマニストや社会科学者のコミュニティに、自分の考えや自分自身が歴史の中に埋め込まれているという具体的な感覚を与え、彼らはそれを大

学に持ち帰った。 |

| Even in academic

life, however, the legacy of the Research and Analysis Branch has been

attenuated over time. Shortly after the war, the anthropologist Cora

DuBois told an audience at Smith College that the collaborative

experience of the war, while not yet abstractly formulated, had already

greatly accelerated interdisciplinary thinking: "The walls separating

the social sciences are crumbling with increasing rapidity," she

observed. "People are beginning to think, as well as feel, about the

kind of world in which they wish to live."7 This notice, it would seem,

was premature. The blasts of war had indeed battered down the

fortifications behind which the disciplines had sequestered themselves,

but they have been rebuilt with a surprising sense of urgency. I think

this is unfortunate, because scholarship as a whole benefits-as the

epistemology of intelligence suggests-when the greatest diversity of

minds, methods, and morals are thrown together, free from the

surveillance of what Aby Warburg once called "the Grenzpolizewi ho

patrol the borders of the disciplines." |

しかし、学術的な生活の中でさえ、研究分

析部門の遺産は時間とともに弱められてきました。戦争の直後、人類学者のコーラ・デュボアはスミス大学の聴衆に、戦争の共同体験はまだ抽象的に定式化され

ていないものの、学際的思考をすでに大幅に加速させたと語った。彼女は観察した。「人々は、自分たちが住みたいと思う世界の種類について考え始め、感じ始

めています。」この通知は、時期尚早だったように思われます。戦争の爆発は確かに、規律が彼ら自身を隔離した背後にある要塞を打ち砕きました、しかし、彼

らは驚くべき切迫感で再建されました。これは残念なことだと思いますが、 |

しかし、アカデミックな世界

でも、調査分析部門の遺産は時とともに弱まっている。戦後間もない頃、人類学者の

コーラ・デュボアは、スミス・カレッジの聴衆に向かって、戦争の共同体験は、まだ抽象的な形にはなっていないものの、すでに学際的な思考を大きく加速させ

ていると語った。

「社会科学を隔てる壁は、ますます急速に崩れている」と彼女は観察した。社会科学を隔てる壁は、ますます急速に崩れています」「人々は、自分たちが生きた

いと思う世界のあり方について、感じるだけでなく、考え始めています」。戦争の爆風は、確かに学問の世界が閉じこもっていた砦を打ち崩しましたが、驚くほ

どの緊迫感を持って再建されたのです。というのも、インテリジェンスの認識論が示唆するように、学問全体が恩恵を受けるのは、アビー・ウォーバーグがかつ

て「学問の境界を巡回する国境警備隊(Grenzpolizewi)」と呼んだ監視から解放されたときだからである。 ※Cora DuBois, Social Forces in Southeast Asia (University of Minnesota Press,1949), pp. 10-11 。 |

| The historian's

"desire to moralize," to which I have so readily abandoned myself in

these chapters, is no longer (or not yet) widely respected by

historians. It seems to me an emblem, however, of the desire to escape

the parochialism of the academic consciousness, to chart an

intersection with the world beyond the narrow protocols of the

disciplines and even of the university. This effort was called forth in

the Research and Analysis Branch by the exigencies of war. It has been

difficult to sustain under the exigencies of peace. |

私がこれらの章ですぐに自分自身を放棄し

た歴史家の「道徳的欲求」は、もはや歴史家によって広く尊敬されていません(またはまだ)。しかし、私には、学問意識の地方主義から逃れ、学問分野や大学

の狭いプロトコルを超えて世界との交差点を図示したいという願望の象徴のように思えます。この努力は、戦争の緊急事態によって研究分析部門で呼び出されま

した。平和の緊急事態の下で維持することは困難でした。 |

これらの章で私がいとも簡単に身を任せた

歴史家の「道徳化の欲求」は、もはや(あるいはまだ)歴史家の間では広く尊重されていない。しかし、私には、学問的な意識の偏狭さから逃れたい、分野や大

学の狭いプロトコルを超えて世界との交わりを描きたいという願望の象徴のように思えます。この努力は、戦争の必要性から調査分析部門に求められたものであ

る。しかし、平和な時代になっても、それを維持するのは難しい。 |

●OSS入門

記事リンク

- ︎Why Did Israel Let Mengele

Go?,

New York Times▶︎Contention;

or, My Disputes with Irving Howe, Yiddish Academia, and Holocaust

Memorials, RUTH

R. WISSE▶石井部隊とランダム化比較試験︎︎▶アイヒマン問題(Karl Adolf Eichmann's

Problem on the Cause of System of the Holocaust)︎▶︎︎ヨーゼフ・メンゲレ(Josef Mengele,

1911-1979)▶ペーパークリップ作戦︎▶アーネンエアベ協会︎︎▶ナ

チス医学関係者との戦争犯罪と戦後の科学研究の継続性と断続性︎▶︎︎戦略的情報▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

リンク

- Nazi Hunting, by New York Times

- CIA ポータル

- Directorate of Military Intelligence (United Kingdom)

- Joseph E. Persico, 1930-2014.

- Japanese

military strategies in 1942, Wiki

文献

- ナチ・ハンターズ = The Nazi hunters, チャールズ・アッシュマン, ロバート・J・ワグマン著 ; 大田民雄訳, 時事通信社, 1992.2

- アニー・ジェイコブセン『ナチ科学者を獲得せよ』太田出版(2015)/Jacobsen, Annie, Operation paperclip : the secret intelligence program that brought nazi scientists to America. NY: Little, Brown and Company. 2014

- ナ チ犯罪人を追う : S.ヴィーゼンタール回顧録 / ジーモン・ヴィーゼンタール著 ; 下村由一, 山本達夫訳、時事通信社 , 1998.

- 希 望の帆 : コロンブスの夢、ユダヤ人の夢 / S. ヴィーゼンタール著 ; 徳永恂, 宮田敦子訳、新曜社 , 1992.

- ヒ トラー政権と科学者たち / A.D.バイエルヘン著 ; 常石敬一訳、岩波書店 , 1980.1 . - (岩波現代選書 ; NS 513)

- ヒ トラーと物理学者たち : 科学が国家に仕えるとき / フィリップ・ボール [著] ; 池内了, 小畑史哉訳、岩波書店 , 2016

- ペルシコ、ジョーゼフ『ナチ・ドイツの心 臓を狙え』宇田道夫・芳地昌三訳、サンケイ出版、1981年(Joseph E. Persico, 1997. Piercing the Reich: the Penetration of Nazi Germany By American Secret Agents During World War II. Barnes & Noble Books.)

- 福井七子「ルー

ス・ベネディクト、ジェフリー・ゴーラー、ヘレン・ミアーズの日本人論・日本文化論を総括する (pdf without

password)」『関西大学外国語学部紀要』7:81-109, 2012年

Bibliography

- Kōgun : the Japanese army in the Pacific War / Saburo Hayashi in collabo.with Alvin D.Coox, Westport : Greenwood Press , 1978

- Foreign intelligence : research and analysis in the Office of

Strategic Services, 1942-1945 / Barry M. Katz, Harvard University

Press , 1989

その他の情報