薬物の自由化

Drug liberalization

A

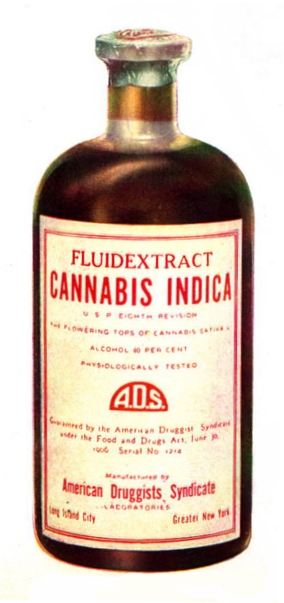

sign for a cannabis shop in Portland, Oregon. Cannabis has been

gradually legalized for recreational use in some U.S. states since 2012.

☆薬物自由化(Drug

liberalization)

とは、禁止薬物の生産、所持、販売、使用を禁止する法律を廃止、合法化、または撤廃する薬物政策のプロセスである。薬物自由化には、薬物の合法化、薬物の

再合法化、薬物の非犯罪化などのバリエーションがある。薬物自由化の推進派は、現在違法とされている薬物の一部またはすべてについて、アルコール、カフェ

イン、タバコと同様の方法で生産、販売、流通を規制する体制を支持する場合がある。

薬物自由化の推進派は、薬物の合法化によって違法薬物市場を根絶し、法執行コストと投獄率を削減できると主張している。彼らは、大麻、オピオイド、コカイ

ン、アンフェタミン、幻覚剤などの娯楽用薬物の禁止は効果的ではなく、かえって逆効果であると主張することが多い。薬物の使用については、ハームリダク

ションの実践を実施し、依存症治療の利用可能性を高めることで対応する方が望ましい。さらに、薬物の規制においては相対的な害も考慮すべきであると主張す

る。例えば、アルコール、タバコ、カフェインなどの習慣性または依存性のある物質は、何世紀にもわたって多くの文化で伝統的に使用されてきたものであり、

ほとんどの国では合法であるが、アルコール、カフェイン、タバコよりも害の少ない他の薬物は全面的に禁止されており、所持しただけで厳しい刑事罰が科せら

れる、と主張するかもしれない。

薬物の自由化に反対する人々は、薬物の使用者が増え、犯罪が増え、家庭が破壊され、薬物使用者の身体に悪影響が及ぶと主張している。

| Drug

liberalization is a drug policy process of decriminalizing,

legalizing, or repealing laws that prohibit the production, possession,

sale, or use of prohibited drugs. Variations of drug liberalization

include drug legalization, drug relegalization, and drug

decriminalization.[1] Proponents of drug liberalization may favor a

regulatory regime for the production, marketing, and distribution of

some or all currently illegal drugs in a manner analogous to that for

alcohol, caffeine and tobacco. Proponents of drug liberalization argue that the legalization of drugs would eradicate the illegal drug market and reduce the law enforcement costs and incarceration rates.[2] They frequently argue that prohibition of recreational drugs—such as cannabis, opioids, cocaine, amphetamines and hallucinogens—has been ineffective and counterproductive and that substance use is better responded to by implementing practices for harm reduction and increasing the availability of addiction treatment. Additionally, they argue that relative harm should be taken into account in the regulation of drugs. For instance, they may argue that addictive or dependence-forming substances such as alcohol, tobacco and caffeine have been a traditional part of many cultures for centuries and remain legal in most countries, although other drugs which cause less harm than alcohol, caffeine or tobacco are entirely prohibited, with possession punishable with severe criminal penalties.[3][4][5] Opponents of drug liberalization argue that it would increase the amount of drug users, increase crime, destroy families, and increase the amount of adverse physical effects among drug users.[6] |

薬物自由化とは、禁止薬物の生産、所持、販売、使用を禁止する法律を廃

止、合法化、または撤廃する薬物政策のプロセスである。薬物自由化には、薬物の合法化、薬物の再合法化、薬物の非犯罪化などのバリエーションがある。

[1]

薬物自由化の推進派は、現在違法とされている薬物の一部またはすべてについて、アルコール、カフェイン、タバコと同様の方法で生産、販売、流通を規制する

体制を支持する場合がある。 薬物自由化の推進派は、薬物の合法化によって違法薬物市場を根絶し、法執行コストと投獄率を削減できると主張している。[2] 彼らは、大麻、オピオイド、コカイン、アンフェタミン、幻覚剤などの娯楽用薬物の禁止は効果的ではなく、かえって逆効果であると主張することが多い。薬物 の使用については、ハームリダクションの実践を実施し、依存症治療の利用可能性を高めることで対応する方が望ましい。さらに、薬物の規制においては相対的 な害も考慮すべきであると主張する。例えば、アルコール、タバコ、カフェインなどの習慣性または依存性のある物質は、何世紀にもわたって多くの文化で伝統 的に使用されてきたものであり、ほとんどの国では合法であるが、アルコール、カフェイン、タバコよりも害の少ない他の薬物は全面的に禁止されており、所持 しただけで厳しい刑事罰が科せられる、と主張するかもしれない。[3][4][5] 薬物の自由化に反対する人々は、薬物の使用者が増え、犯罪が増え、家庭が破壊され、薬物使用者の身体に悪影響が及ぶと主張している。[6] |

A sign for a cannabis shop in Portland, Oregon. Cannabis has been gradually legalized for recreational use in some U.S. states since 2012. |

オレゴン州ポートランドのマリファナ販売店の看板。2012年以降、米国の一部の州では、娯楽用マリファナが徐々に合法化されている。 |

| Policies The 1988 United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances made it mandatory for the signatory countries to "adopt such measures as may be necessary to establish as criminal offences under its domestic law" (art. 3, § 1) all the activities related to the production, sale, transport, distribution, etc. of the substances included in the most restricted lists of the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs and 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances. Criminalization also applies to the "cultivation of opium poppy, coca bush or cannabis plants for the purpose of the production of narcotic drugs". The Convention distinguishes between the intent to traffic and personal consumption, stating that the latter should also be considered a criminal offence, but "subject to the constitutional principles and the basic concepts of [the state's] legal system" (art. 3, § 2).[7] Drug liberalization proponents hold differing reasons to support liberalization, and have differing policy proposals. The two most common positions are drug legalization (or re-legalization), and drug decriminalization. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) defines decriminalization as the removal of a conduct or activity from the sphere of criminal law; depenalisation signifying merely a relaxation of the penal sanction exacted by law. Decriminalization usually applies to offences related to drug consumption and may include either the imposition of sanctions of a different kind (administrative) or the abolition of all sanctions; other (noncriminal) laws then regulate the conduct or activity that has been decriminalized. Depenalisation usually consists of personal consumption as well as small-scale trading and generally signifies the elimination or reduction of custodial penalties, while the conduct or activity still remains a criminal offence. The term legalization refers to the removal of all drug-related offences from criminal law, such as use, possession, cultivation, production, and trading.[7][8] Harm reduction refers to a range of public health policies designed to reduce the harmful consequences associated with recreational drug use and other high risk activities. Harm reduction is put forward as a useful perspective alongside the more conventional approaches of demand and supply reduction.[9] Many advocates argue that prohibitionist laws criminalize people for suffering from a disease and cause harm, for example by obliging drug addicts to obtain drugs of unknown purity from unreliable criminal sources at high prices, increasing the risk of overdose and death.[10] Its critics are concerned that tolerating risky or illegal behaviour sends a message to the community that these behaviours are acceptable.[11][12] |

政策 1988年の国連麻薬及び向精神薬不正取引条約は、締約国に対して「国内法の下で刑事犯罪として定めるために必要な措置を講じる」ことを義務付けている (第3条、 1961年の麻薬に関する単一条約および1971年の向精神薬に関する条約で最も厳しく規制されているリストに含まれる物質の生産、販売、輸送、流通な ど、すべての活動について、国内法で刑事犯罪として定めるために必要な措置を講じることを締約国に義務付けている。また、麻薬の製造を目的としたケシ、コ カの木、大麻植物の栽培も犯罪化の対象となる。条約では、密売目的と個人使用目的を区別しており、後者も犯罪行為とみなされるべきであるが、「憲法の原則 および(国家の)法制度の基本概念に従う」べきであるとしている(第3条、第2項)。[7] 薬物の自由化を推進する人々は、自由化を支持する理由や政策提案がそれぞれ異なる。最も一般的な立場は、薬物の合法化(または再合法化)と薬物の非犯罪化 である。欧州麻薬薬物監視センター(EMCDDA)は、非犯罪化を「行為や活動を刑法の適用範囲から除外すること」と定義している。一方、脱犯罪化は、法 律によって課される刑罰の緩和を意味する。非犯罪化は通常、薬物の消費に関連する犯罪に適用され、異なる種類の制裁(行政処分)の適用、またはすべての制 裁の廃止のいずれかを含む。その他の(非犯罪化された)法律は、非犯罪化された行為や活動を規制する。非犯罪化は通常、個人使用や小規模取引を含み、一般 的に拘禁刑の廃止または軽減を意味するが、その行為や活動は依然として犯罪行為である。合法化という用語は、使用、所持、栽培、生産、取引など、薬物関連 の犯罪を刑法から削除することを指す。[7][8] ハームリダクションとは、娯楽目的の薬物使用やその他の危険性の高い行為に伴う有害な結果を軽減することを目的とした、一連の公衆衛生政策を指す。ハーム リダクションは、需要と供給の削減という従来のアプローチと並ぶ有益な視点として提唱されている。[9] 多くの擁護派は、禁止主義の法律は、例えば薬物中毒患者に 純度の不明な薬物を、信頼性の低い犯罪組織から高額で入手することを強制し、過剰摂取や死亡のリスクを高めることにつながる、と主張している。[10] その批判派は、危険な行為や違法行為を容認することは、そのような行為が容認されるというメッセージを社会に発信することにつながると懸念している。 [11][12] |

| The Controlled Substance Act

(United States) The Controlled Substance Act (CSA) categorizes all substances in need of regulation into one of the five schedules under the federal law. The categorization of these substances is determined by the potential for abuse and how safe it is to consume. In addition, a big determinant of this is the way in which the substance can be consumed or used medically.[13] In its earliest stages, the CSA was created to combine the needs of two international treaties. These treaties were known as the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961 and the Convention of Psychotropic Substances of 1971. Both treaties allowed public health authorities to work with the medical and scientific communities to create a classification system. The Schedule I substances were described as those that have no medical use whatsoever; meaning there is no prescription written for such substance. Schedule II substances are those that can be easily abused and lead to dependence. These substances can only be accessed through a written or electronic prescription from a physician. The schedule III substances are classified as those which have less potential for abuse than Schedule I and II but can still cause the individual to develop a mild dependence. Schedule IV substances are those with the least likeliness for abuse, therefore its medical use is common in the United States. Lastly, the Schedule V substances are those with little to no likelihood of abuse, along with very minimal dependence development.[14] |

規制物質法(米国) 規制物質法(CSA)は、規制の必要なすべての物質を連邦法のもとで5つのスケジュールに分類している。これらの物質の分類は、乱用の可能性と摂取の安全 性によって決定される。さらに、この分類の大きな決定要因となるのは、その物質がどのように摂取されるか、または医療用に使用されるかである。[13] CSAは、当初、2つの国際条約の必要性を統合するために策定された。これらの条約は、1961年の麻薬に関する単一条約(Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961)と1971年の向精神薬に関する条約(Convention of Psychotropic Substances of 1971)として知られている。 両条約では、保健当局が医療および科学界と協力して分類システムを作成することが認められていた。 スケジュールIの物質は、医療用途が一切ないものと定義されており、つまり、そのような物質については処方箋が発行されないことを意味する。 スケジュールIIの物質は、乱用が容易で依存症を引き起こす可能性があるものとして分類されている。これらの物質は、医師による書面または電子処方箋がな ければ入手できない。スケジュールIIIの物質は、スケジュールIおよびIIよりも乱用の可能性は低いものの、軽度の依存症を引き起こす可能性があるもの として分類されている。スケジュールIVの物質は、最も乱用の可能性が低いとされるため、米国では医療用として一般的に使用されている。最後に、スケ ジュールVの物質は、乱用の可能性がほとんどないか、まったくないもので、依存症を引き起こす可能性も極めて低い。[14] |

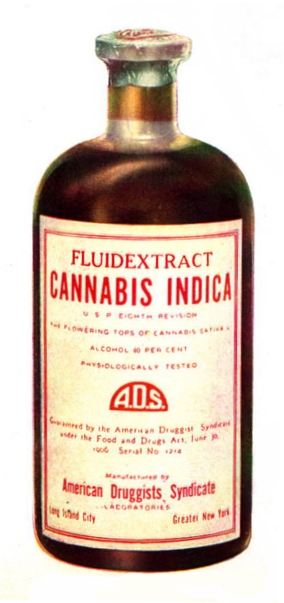

| Drug legalization (United States) Drug legalization calls for a return to pre–1906 Pure Food and Drug Act attitudes when almost all drugs were legal. This would require ending government-enforced prohibition on the distribution or sale and personal use of specified (or all) currently banned drugs. Proposed ideas range from full legalization which would completely remove all forms of government control, to various forms of regulated legalization, where drugs would be legally available, but under a system of government control which might mean for instance:[15] Mandated labels with dosage and medical warnings. Restrictions on advertising. Age limitations. Restrictions on amount purchased at one time. Requirements on the form in which certain drugs would be supplied. Ban on sale to intoxicated persons. Special user licenses to purchase particular drugs. A possible clinical setting for the consumption of some intravenous drugs or supervised consumption. The regulated legalization system would probably have a range of restrictions for different drugs, depending on their perceived risk, so while some drugs would be sold over the counter in pharmacies or other licensed establishments, drugs with greater risks of harm might only be available for sale on licensed premises where use could be monitored and emergency medical care made available. Examples of drugs with different levels of regulated distribution in most countries include: caffeine (coffee, tea), nicotine (tobacco),[16] and ethyl alcohol (beer, wine, spirits). Since each country has its own regulations and most distinguish between different classes of drugs, there can be difficulties when it come to regulating which should be more readily accessible, since a particular drug criminalized in one area might be completely acceptable elsewhere. Full legalization is often proposed by groups, such as libertarians, who object to drug laws on moral grounds, while regulated legalization is suggested by groups like Law Enforcement Against Prohibition who object to the drug laws on the grounds that they fail to achieve their stated aims and instead they say greatly worsen the problems associated with use of prohibited drugs but acknowledge that there are harms associated with currently prohibited drugs which need to be minimized. Not all proponents of drug re-legalization necessarily share a common ethical framework, and people may adopt this viewpoint for a variety of reasons. In particular, favoring drug legalization does not imply approval of drug use.[17][18][19] |

薬物の合法化(米国) 薬物の合法化は、ほぼ全ての薬物が合法であった1906年以前の純粋食品および薬品法の考え方への回帰を求めるものである。これは、現在禁止されている薬 物のうち特定のもの(または全て)の流通や販売、および人格使用に対する政府による強制的な禁止を廃止することを意味する。提案されているアイデアは、政 府によるあらゆる管理を完全に撤廃する完全合法化から、薬物が合法的に入手可能となるが、政府管理のシステム下に置かれるという、さまざまな形態の規制付 き合法化まで、多岐にわたっている。例えば、以下のような内容が考えられる。[15] 用量と医療上の警告を記載したラベルの義務付け。 広告の制限。 年齢制限。 一度の購入量に対する制限。 特定の薬物の供給形態に関する要件。 酩酊状態にある人物への販売禁止。 特定の薬物を購入するための特別な利用者ライセンス。 一部の静脈注射薬の使用や管理下での使用を認める臨床環境。 規制された合法化システムでは、おそらく薬物のリスクの認識に応じて、異なる薬物に対してさまざまな制限が設けられることになるだろう。そのため、薬局や その他の認可された施設では一部の薬物が店頭販売される一方で、より深刻な被害のリスクがある薬物は、使用状況を監視でき、緊急医療ケアが利用可能な認可 された施設でのみ販売されることになる可能性もある。ほとんどの国々で異なるレベルの規制下で流通している薬物の例としては、カフェイン(コーヒー、紅 茶)、ニコチン(タバコ)、[16] エチルアルコール(ビール、ワイン、蒸留酒)などがある。各国が独自の規制を定めており、ほとんどの国が薬物の異なる分類を区別しているため、どの薬物が より容易に利用可能であるべきかを規制するにあたっては困難が生じる可能性がある。ある地域で犯罪化されている特定の薬物が、他の地域では完全に容認され ている可能性があるからだ。薬物に関する法律を道徳的な観点から反対するリバタリアンなどのグループは、全面的な合法化を提案することが多い。一方、法執 行禁止派(Law Enforcement Against Prohibition)などのグループは、薬物に関する法律が掲げる目的を達成できていないばかりか、禁止薬物の使用に伴う問題を悪化させていると主張 し、現行の禁止薬物には害があることを認めながらも、その害を最小限に抑える必要があると主張している。薬物の再合法化を主張する人々が必ずしも共通の倫 理観を持っているわけではなく、人々はさまざまな理由からこの見解を採用している。特に、薬物の合法化を支持することは、薬物の使用を承認することを意味 するわけではない。[17][18][19] |

| Drug decriminalization Drug decriminalization calls for reduced or eliminated control or penalties compared to existing laws. There are proponents of drug decriminalization that support a system whereby those who use and possess drugs for personal use are not penalized. While others support the use of fines or other punishments to replace prison terms, and often propose systems whereby illegal drug users who are caught would be fined, but would not receive a permanent criminal record as a result. A central feature of drug decriminalization is the concept of harm reduction. Drug decriminalization is in some ways an intermediate between prohibition and legalization, and has been criticized by Peter Lilley as being "the worst of both worlds", in that drug sales would still be illegal, thus perpetuating the problems associated with leaving production and distribution of drugs to the criminal underworld, while also failing to discourage illegal drug use by removing the criminal penalties that might otherwise cause some people to choose not to use drugs.[20] In 2001, Portugal began treating use and possession of small quantities of drugs as a public health issue.[21] Rather than incarcerating those in possession, they are referred to a treatment program by a regional panel composed of social workers, medical professionals, and drug experts.[22] This also decreases the amount of money the government spends fighting a war on drugs and money spent keeping drug users incarcerated. HIV infection rates also have dropped from 104.2 new cases per million in 2000 to 4.2 cases per million in 2015. Anyone caught with any type of drug in Portugal, if it is for personal consumption, will not be imprisoned. Portugal is the first country that has decriminalized the possession of small amounts of drugs, to positive results.[23] As noted by the EMCDDA, across Europe in the last decades, there has been a movement toward "an approach that distinguishes between the drug trafficker, who is viewed as a criminal, and the drug user, who is seen more as a sick person who is in need of treatment" (EMCDDA 2008, 22). A number of Latin American countries have similarly moved to reduce the penalties associated with drug use and personal possession" (Laqueur, 2015, p. 748). Mexico City has decriminalized certain drugs and Greece has just announced that it is going to do so. Spain has also followed the Portugal model. Italy after waiting 10 years to see the result of the Portugal model, which Portugal deemed a success, has since recently followed suit. In May 2014, the Criminal Chamber of the Italian Supreme Court upheld a previous decision in 2013 by Italy's Constitutional Court, to reduce the penalties for the convictions for sale of soft drugs.[24][25] Some other countries have virtual decriminalization for marijuana only, including in three U.S. states, such as Colorado,[26] Washington, and Oregon, the Australian State of South Australia, and across the Netherlands, where there are legal marijuana cafes. In the Netherlands these cafes are called "coffeeshops".[27] |

薬物の非犯罪化 薬物の非犯罪化とは、現行法と比較して規制や処罰を軽減または撤廃することを指す。薬物の非犯罪化を支持する人々の中には、個人的な使用目的で薬物を所持 または使用する人々を処罰しない制度を支持する者もいる。一方、刑務所での服役に代わる罰金やその他の処罰を支持する者もおり、違法薬物使用者を発見した 場合に罰金を科す制度を提案することも多いが、その場合、犯罪歴は永久に残らない。薬物の非犯罪化の中心となる特徴は、ハームリダクションの概念である。 薬物の非犯罪化は、ある意味では禁止と合法化の中間的なものであり、ピーター・リリーは「両方の世界の最悪な部分」であると批判している。薬物の販売は依 然として違法であるため、犯罪組織による薬物の生産と流通に関連する問題が継続し、また、刑事罰を廃止することで違法薬物の使用を思いとどまらせる可能性 がなくなるため、違法薬物の使用を抑制できないという点である。 2001年、ポルトガルは少量の薬物の使用および所持を公衆衛生上の問題として扱うようになった。[21] 薬物を所持している人々を投獄するのではなく、ソーシャルワーカー、医療専門家、薬物専門家で構成される地域委員会が、彼らを治療プログラムに紹介する。 [22] これにより、政府が麻薬撲滅戦争に費やす費用と、麻薬使用者を投獄するために費やす費用も削減される。HIV感染率も、2000年の100万人あたり 104.2件から、2015年には100万人あたり4.2件に減少した。ポルトガルで薬物を所持しているところを発見された場合、それが個人使用目的であ れば、投獄されることはない。ポルトガルは、少量の薬物所持を非犯罪化した最初の国であり、成果を上げている。 EMCDDAが指摘しているように、ここ数十年の間、ヨーロッパでは「犯罪者と見なされる麻薬密売者と、治療を必要とする病人と見なされる麻薬使用者の区 別を明確にするアプローチ」への動きが見られる(EMCDDA 2008, 22)。ラテンアメリカ諸国の多くも同様に、薬物使用や個人所持に関連する刑罰の軽減に動いている」(Laqueur, 2015, p. 748)。メキシコシティは特定の薬物を非犯罪化し、ギリシャも非犯罪化を発表したばかりである。スペインもポルトガルモデルを採用している。イタリアは ポルトガルが成功とみなしたポルトガルモデルの結果を10年間待った後、最近になって追随した。2014年5月、イタリア最高裁刑事部は、イタリア憲法裁 判所が2013年に下した、ソフトドラッグの販売に対する有罪判決の刑罰を軽減するという決定を支持した。[24][25] その他 マリファナのみ事実上の非犯罪化を行っている国もある。米国ではコロラド州、ワシントン州、オレゴン州の3州、オーストラリアでは南オーストラリア州、そ してマリファナ合法カフェが存在するオランダ全土がこれに該当する。オランダでは、これらのカフェは「コーヒーショップ」と呼ばれている。[27] |

History Prior to prohibition, cannabis was available freely in a variety of forms. The cultivation, use and trade of psychoactive and other drugs has occurred since the dawn of civilization. Motivations claimed by supporters of drug prohibition laws across various societies and eras have included religious observance, allegations of violence by racial minorities, and public health concerns. Those who are proponents of drug legislation characterize these motivations as religious intolerance, racism, and public healthism. The British had gone to war with China in the 19th century in what became known as the First and Second Opium Wars to protect their valuable trade in narcotics. It was only in the 20th century that Britain and the United States outlawed cannabis. The campaign against alcohol prohibition culminated in the Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution repealing prohibition on 5 December 1933, as well as liberalization in Canada, and some but not all of the other countries that enforced prohibition. Despite this, many laws controlling the use of alcohol continue to exist even in these countries. In the mid-20th century, the United States government led a major renewed surge in drug prohibition called the war on drugs.[28] Initial attempts to change the punitive drug laws which were introduced all over the world from the late 1800s onwards were primarily based around recreational use. Timothy Leary was one of the most prominent campaigners for the legal and recreational use of LSD. In 1967, a "Legalise pot" rally was held in Britain.[29] As death toll from the drug war rose, other organisations began to form to campaign on a more political and humanitarian basis. Drug Policy Foundation formed in America and Release, a charity which gives free legal advice to drugs users and currently campaigns for drug decriminalization, also incorporated in the 1970s. Into the 21st century, the focus of the world's drug policy reform organisations is on the promotion of harm reduction in the Western World, and attempting to prevent the catastrophic loss of human life in developing countries where much of the world's supply of heroin, cocaine, and marijuana are produced. Drug policy reform advocates point to failed efforts, such as the Mexican Drug War, as signs that a new approach to drug policy is needed. According to some observers, the Mexican Drug War has claimed as many as 80,000 lives.[30] In 2014, a European Citizens' Initiative called "Weed Like to Talk" was launched within the European Union, with the aim of starting a debate in Europe about the legalization of the production, sale and use of marijuana in the European Union and finding a common policy for all EU member states.[31][32] As of June 30, 2014, the initiative has collected 100,000 signatures from citizens in European member states. Should they reach 1 million signatures, from nationals of at least one quarter of the member states, the European Commission will be required to initiate a legislative proposal and a debate on the issue.[33] |

歴史 禁止される前は、大麻はさまざまな形態で自由に手に入った。 精神作用薬やその他の薬物の栽培、使用、取引は、文明の始まりから行われてきた。 さまざまな社会や時代において薬物禁止法を支持する人々が主張する動機には、宗教的遵守、人種的少数派による暴力の申し立て、公衆衛生上の懸念などがあ る。 薬物関連法の推進派は、これらの動機を宗教的偏狭、人種主義、公衆衛生主義などと特徴づけている。19世紀、英国はアヘン貿易の利益を守るために中国と戦 争し、これが第一次・第二次アヘン戦争として知られるようになった。イギリスとアメリカ合衆国が大麻を違法とするのは20世紀に入ってからである。アル コール禁止に対するキャンペーンは、1933年12月5日にアメリカ合衆国憲法修正第21条によって禁酒法が廃止されたことで頂点に達した。また、カナダ や、禁酒法を実施していた他の国々でも一部では自由化された。しかし、これらの国々でもアルコールの使用を規制する法律は数多く存在し続けている。20世 紀半ば、アメリカ合衆国政府は「麻薬との戦い」と呼ばれる麻薬禁止の新たな大きな高まりを主導した。 1800年代後半以降、世界中で導入された処罰的な麻薬取締法を改正しようとする最初の試みは、主に娯楽的使用を目的としたものであった。ティモシー・リ アリーは、LSDの合法化と娯楽的使用を求める運動の最も著名な活動家の一人であった。1967年には、英国で「大麻合法化」集会が開催された。[29] 麻薬戦争による死者数が増加するにつれ、より政治的・人道的な立場からキャンペーンを行う他の組織が結成され始めた。アメリカで設立されたDrug Policy Foundationや、薬物使用者に対して無料の法的アドバイスを提供し、現在では薬物の非犯罪化を求めるキャンペーンを行っている慈善団体 Releaseも、1970年代に設立された。21世紀に入ると、世界の薬物政策改革団体の焦点は、欧米諸国におけるハームリダクションの推進と、ヘロイ ン、コカイン、マリファナの世界供給の大部分が生産されている発展途上国における人命の壊滅的な損失を防ぐことに置かれている。薬物政策改革の提唱者たち は、メキシコ麻薬戦争のような失敗した取り組みを、薬物政策に対する新たなアプローチが必要であることの兆候として指摘している。一部の観察者によると、 メキシコ麻薬戦争では8万人もの命が失われたという。[30] 2014年には、欧州連合(EU)内で「Weed Like to Talk」と呼ばれる欧州市民イニシアティブが発足した。このイニシアティブは、欧州連合(EU)内でのマリファナの生産、販売、使用の合法化について欧 州で議論を開始し、 。2014年6月30日現在、このイニシアティブは欧州連合加盟国の国民から10万人の署名を集めている。加盟国の少なくとも4分の1の国民から100万 人の署名が集まれば、欧州委員会は立法提案とこの問題に関する討論を開始することが義務付けられる。[33] |

| Economics There are numerous economic and social impacts of the criminalization of drugs. According to economist Mark Thornton, prohibition increases the prices of drugs, political corruption, and criminal activity. It also produces more dangerous and addictive drugs.[34] In many developing countries the production of drugs offers a way to escape poverty. Milton Friedman estimated that over 10,000 deaths a year in the US are caused by the criminalization of drugs, and if drugs were to be made legal innocent victims such as those shot down in drive by shootings, would cease or decrease.[35][36] The economic inefficiency and ineffectiveness of such government intervention in preventing drug trade has been fiercely criticised by drug-liberty advocates. The war on drugs of the United States, that provoked legislation within several other Western governments, has also garnered criticism for these reasons. The legalization of drugs would affect the supply and demand that is present today with these illegal substances. The price of production would increase due to the costs that come with the transportation and distribution of these substances.[37] It has been noted that the prohibition of drugs has led to a decrease in the consumer surplus. The decrease in consumption is due to the price increase of these drugs. In a clear example of the way in which the supply and demand is affected, individuals have responded to the price increase from high levels, rather than responding to the prices which started off low.[38] |

経済 薬物の犯罪化には、数多くの経済的および社会的影響がある。経済学者マーク・ソーントンによると、禁止は薬物の価格、政治腐敗、犯罪活動を増加させる。ま た、より危険で中毒性の高い薬物を生み出す。[34] 多くの発展途上国では、薬物の生産が貧困からの脱出の手段となっている。ミルトン・フリードマンは、米国では薬物の非合法化によって年間1万人以上が死亡 していると推定しており、薬物が合法化されれば、ドライブバイ・シューティングの犠牲者など罪のない被害者はなくなるか、減少するだろうと述べている。 麻薬取引の防止を目的とした政府の介入は経済的に非効率であり、また効果的でもないという主張は、薬物の自由化を支持する人々から激しい批判を受けてい る。米国の麻薬戦争は、他のいくつかの西側諸国の政府による法制定を促したが、それらの理由からも批判を集めている。麻薬の合法化は、現在これらの違法薬 物に対して存在する需要と供給に影響を与えるだろう。これらの物質の輸送や流通に伴うコストにより、生産コストが上昇するだろう。[37] 薬物の禁止が消費者余剰の減少につながっていることが指摘されている。消費の減少は、薬物の価格上昇によるものである。需要と供給が影響を受ける典型的な 例として、個人は、低価格から始まった価格上昇ではなく、高水準からの価格上昇に反応している。[38] |

| Prices and consumption Much of the debate surrounding the economics of drug legalization centers on the shape of the demand curve for illegal drugs and the sensitivity of consumers to changes in the prices of illegal drugs.[39] Proponents of drug legalization often assume that the quantity of addictive drugs consumed is unresponsive to changes in price; however, studies into addictive but legal substances like alcohol and cigarettes have shown that consumption can be quite responsive to changes in prices.[40] In the same study, economists Michael Grossman and Frank J. Chaloupka estimated that a 10% reduction in the price of cocaine would lead to a 14% increase in the frequency of cocaine use.[40]: 459 This increase indicates that consumers are responsive to price changes in the cocaine market. There is also evidence that in the long run, consumers are much more responsive to price changes than in the short run,[40]: 454 but other studies have led to a wide range of conclusions.[41]: 2043 Considering that legalization would likely lead to an increase in the supply of drugs, the standard economic model predicts that the quantity of drugs consumed would rise and the prices would fall.[40]: 428 Andrew E. Clark, an economist who has studied the effects of drug legalization, suggests that a specific tax, or sin tax, would counteract the increase in consumption.[39]: 3 Additionally, the legalization of it would reduce the cost of having to mass incarcerate marginalized communities, which are those who are disproportionately affected. Of those arrested for drug possession or drug related crimes, the majority of those individuals arrested are Black or Hispanic.[42] |

価格と消費 薬物合法化の経済性に関する議論の多くは、違法薬物の需要曲線の形状と、違法薬物の価格変動に対する消費者の感度に集中している。[39] 薬物合法化の推進派は、中毒性薬物の消費量は価格の変動に反応しないと想定することが多いが、アルコールやタバコのような中毒性がありながらも合法な物質 に関する研究では、 価格の変化にかなり敏感に反応することが示されている。[40] 同じ研究において、経済学者のマイケル・グロスマンとフランク・J・チャルプカは、コカインの価格が10%下がれば、コカイン使用の頻度は14%増加する と推定している。[40]: 459 この増加は、コカイン市場における消費者が価格の変化に敏感に反応していることを示している。また、長期的には、消費者は短期的よりも価格変動に敏感に反 応するという証拠もあるが[40]:454、他の研究では幅広い結論が導き出されている。[41]:2043 合法化によって薬物の供給量が増える可能性が高いことを考慮すると、標準的な経済モデルでは、消費される薬物の量が増加し、価格が下落すると予測される。 [40]: 428 薬物の合法化の影響を研究している経済学者のアンドリュー・E・クラークは、 特定の税金、つまり「悪税」を課すことで、消費量の増加を抑制できると提案している。[39]: 3 さらに、薬物の合法化は、不均衡な影響を受ける疎外されたコミュニティを大規模に投獄する必要性を減らすことにもなる。薬物所持や薬物関連犯罪で逮捕され た者の大半は、黒人またはヒスパニック系である。[42] |

| Associated costs Proponents of drug prohibition argue that many negative externalities, or third party costs, are associated with the consumption of illegal drugs.[41]: 2043 [43]: 183 Externalities like violence, environmental effects on neighborhoods, increased health risks, and increased healthcare costs are often associated with the illegal drug market.[39]: 3 Opponents of prohibition argue that many of those externalities are created by current drug policies. They believe that much of the violence associated with drug trade is due to the illegal nature of drug trade, where there is no mediating authority to solve disputes peacefully and legally.[39]: 3 [43]: 177 The illegal nature of the market also affects the health of consumers by making it difficult to acquire syringes, which often leads to needle sharing.[43]: 180–181 Prominent economist Milton Friedman argues that prohibition of drugs creates many negative externalities like increased incarceration rates, the undertreatment of chronic pain, corruption, disproportional imprisonment of African Americans, compounding harm to users, the destruction of inner cities and harm to foreign countries.[44] Proponents of legalization also argue that prohibition decrease the quality of the drugs made, which often leads to more physical harm, like accidental overdoses and poisoning, to the drug users.[43]: 179 Steven D. Levitt and Ilyana Kuziemko point to the over crowding of prisons as another negative side effect of the war on drugs. They believe that by sending such a large number of drug offenders to prison, the war on drugs has reduced the prison space available for other offenders. This increased incarceration rate not only costs tax payers more to maintain, it could possibly increase crime by crowding violent offenders out of prison cells and replacing them with drug offenders.[41]: 2043 |

関連費用 薬物の禁止を主張する人々は、違法薬物の消費には多くの負の外部性、すなわち第三者の費用が伴うと主張している。[41]: 2043 [43]: 183 暴力、近隣への環境影響、保健リスクの増大、医療費の増大などの外部性は、違法薬物市場と関連していることが多い。[39]: 3 禁止に反対する人々は、これらの外部性の多くは現在の薬物政策によって生み出されていると主張している。麻薬取引に関連する暴力の多くは、麻薬取引の非合 法性によるものであり、紛争を平和的かつ合法的に解決する仲介機関が存在しないことが原因であると彼らは考えている。[39]: 3 [43]: 177 市場の非合法性は、注射器の入手を困難にし、それがしばしば注射針の共用につながることで、消費者の保健にも影響を及ぼしている。[43]: 180–181 針の共用につながることも多い。[43]: 180–181 著名な経済学者ミルトン・フリードマンは、麻薬の禁止は、投獄率の上昇、慢性的な痛みの治療不足、汚職、アフリカ系アメリカ人の不均衡な投獄、使用者への 複合的な害、都心部の荒廃、外国への害など、多くの負の外部性を生み出すと主張している。[44] 合法化の支持者たちは、また、禁止によって製造される薬物の質が低下し、薬物使用者に事故による過剰摂取や中毒などのより深刻な身体的被害をもたらすこと が多いと主張している。[43]:179 スティーブン・D・レヴィットとイリヤナ・クジエムコは、刑務所の過剰収容を薬物戦争の別の負の副作用として指摘している。彼らは、これほど多数の薬物犯 罪者を刑務所に送ったことで、薬物戦争が他の犯罪者用の刑務所スペースを減少させてしまったと考えている。この収監率の増加は、維持費の増大という税負担 を強いるだけでなく、暴力的犯罪者を刑務所から追い出して薬物犯罪者に置き換えることで、犯罪を増加させる可能性もある。[41]: 2043 |

| Direct costs A Harvard economist, Jeffrey Miron, estimated that ending the war on drugs would inject 76.8 billion dollars into the US economy in 2010 alone.[45] He estimates that the government would save $41.3 billion for law enforcement and the government would gain up to $46.7 billion in tax revenue.[46] Since the war on drugs began under the administration of President Richard Nixon, the federal drug-fighting budget has increased from $100 million in 1970 to $15.1 billion in 2010, with a total cost estimated near 1 trillion dollars over 40 years. In the same time period an estimated 37 million nonviolent drug offenders have been incarcerated. $121 billion was spent to arrest these offenders and $450 billion to incarcerate them.[47] |

直接費用 ハーバード大学の経済学者ジェフリー・ミロンは、麻薬撲滅戦争を終結させることで、2010年だけでも768億ドルが米国経済に注入されると推定してい る。[45] 彼は、法執行に要する費用が413億ドル節約され、政府は最大467億ドルの税収増を得られると推定している [46] リチャード・ニクソン大統領の政権下で麻薬撲滅戦争が始まって以来、連邦政府の麻薬対策予算は1970年の1億ドルから2010年には151億ドルに増加 しており、40年間の総費用は1兆ドル近くに上ると推定されている。同じ期間に、非暴力的な麻薬犯罪者とされる3700万人が投獄された。これらの犯罪者 を逮捕するために1210億ドル、収監するために4500億ドルが費やされた。[47] |

| Size of the illegal drug market According to 2013 data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and European crime-fighting agency Europol, the annual global drugs trade is worth around $435 billion a year, with the annual cocaine trade worth $84 billion of that amount.[48][49] |

違法薬物市場の規模 国連薬物犯罪事務所(UNODC)と欧州犯罪対策機関ユーロポール(Europol)の2013年のデータによると、世界の麻薬取引の年間総額は約 4350億ドルで、コカインの年間取引額は840億ドルである。[48][49] |

| Policies by country Asia Philippines Senator Bato dela Rosa, despite having the reputation of leading the deadly war on drugs during the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte as chief of the Philippine National Police, filed a bill in the senate in November 2022 proposing the decriminalization of illegal drug use. This bid was an attempt to deal with prison overcrowding and underutilization of drug rehabilitation centers. While the proposal do not include drug trafficking and manufacturing, the bill was met with opposition from law enforcement agencies who believes it would send a "wrong signal" and encourage drug abuse. The Department of Health has supported the proposal.[50] |

国別政策 アジア フィリピン バト・デラ・ロサ上院議員は、フィリピン国家警察長官としてロドリゴ・ドゥテルテ大統領の時代に「麻薬撲滅戦争」を主導したことで知られているが、 2022年11月、上院に違法薬物使用の非犯罪化を提案する法案を提出した。この法案は、刑務所の過剰収容と薬物リハビリセンターの利用率の低さに対処す るための試みであった。この提案には麻薬の密売や製造は含まれていないが、この法案は「間違ったメッセージ」を送り、麻薬乱用を助長するとして、法執行機 関から反対を受けた。保健省はこの提案を支持している。[50] |

| Thailand "A committee tasked with controlling illegal drugs has won a majority vote to have cannabis and hemp reclassified as narcotics, and the listing will take effect on" 1 January 2024, according to media.[51] Although Thailand has a strict drug policy, in May 2018, the Cabinet approved draft legislation that allows for more research into the effects of marijuana on people. Thus, the Government Pharmaceutical Organization (GPO) will soon begin clinical trials of marijuana as a preliminary step in the production of drugs from this plant. These medical studies are considered exciting, new landmarks in the history of Thailand, because the manufacture, storage, and use of marijuana has been completely outlawed in Thailand since 1979.[52] On 9 November 2018, the National Assembly of Thailand officially proposed to allow licensed medical use of marijuana, thereby legalizing what was previously considered a dangerous drug. The National Assembly on Friday submitted its amendments to the Ministry of Health, which would place marijuana and vegetable kratom in the category allowing their licensed possession and distribution in regulated conditions. The ministry reviewed the amendments before sending them to the cabinet, which returned it to the National Assembly for a final vote. This process was completed on 25 December 2018.[53] Thus, Thailand became the first Asian country to legalize medical cannabis.[54] These changes did not allow recreational use of drugs. These actions were taken because of the growing interest in the use of marijuana and its components for the treatment of certain diseases. Cannabis became decriminalized in Thailand on 9 June 2022, making recreational use also legal, although smoking in public can still incur penalties due to being considered a public nuisance.[55][56] Supporters of legalization argue that the legal market for marijuana in Thailand could increase to $5 billion by 2024.[57] |

タイ 「違法薬物の取締りを担当する委員会は、大麻と麻を麻薬として再分類するよう多数決で可決し、そのリストは2024年1月1日に発効する」とメディアは報 じている。[51] タイは厳格な薬物政策をとっているが、2018年5月には、マリファナが人体に及ぼす影響についてより多くの研究を認める法案が閣議で承認された。そのた め、政府医薬品機構(GPO)は、この植物から医薬品を製造する準備段階として、まもなく大麻の臨床試験を開始する。これらの医学研究は、タイの歴史上、 新たな画期的な出来事として期待されている。なぜなら、1979年以来、タイでは大麻の製造、保管、使用は完全に違法とされているからだ。 2018年11月9日、タイの国民議会は、医療用大麻の使用を正式に許可するよう提案し、それによって、これまで危険薬物とされていたものを合法化するこ ととなった。金曜日、国民議会は、大麻と植物のクラトンを規制された条件下で認可された所持と流通を許可するカテゴリーに分類する改正案を保健省に提出し た。保健省は、改正案を閣議に送る前に検討し、最終投票のために国民議会に差し戻した。このプロセスは2018年12月25日に完了した。[53] こうしてタイは医療用大麻を合法化したアジア初の国となった。[54] これらの変更は、薬物の娯楽的使用を認めるものではなかった。これらの措置は、特定の疾患の治療における大麻およびその成分の利用に対する関心の高まりを 受けて取られた。2022年6月9日、タイでは大麻が非犯罪化され、娯楽目的の使用も合法化されたが、公共の場での喫煙は依然として迷惑行為とみなされ、 罰則の対象となる可能性がある。[55][56]合法化の支持者たちは、タイにおける大麻の合法市場は2024年までに50億ドルに達する可能性があると 主張している。[57] |

| Europe Czech Republic In the Czech Republic, until 31 December 1998 only drug possession "for other person" (i.e. intent to sell) was criminal (apart from production, importation, exportation, offering or mediation, which was and remains criminal) while possession for personal use remained legal.[58] On 1 January 1999, an amendment of the Criminal Code, which was necessitated in order to align the Czech drug rules with the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, became effective, criminalizing possession of "amount larger than small" also for personal use (Art. 187a of the Criminal Code) while possession of small amounts for personal use became a misdemeanor.[58] The judicial practice came to the conclusion that the "amount larger than small" must be five to ten times larger (depending on drug) than a usual single dose of an average consumer.[59] On 14 December 2009, the Government of the Czech Republic adopted Regulation No. 467/2009 Coll., that took effect on 1 January 2010, and specified what "amount larger than small" under the Criminal Code meant, effectively taking over the amounts that were already established by the previous judicial practice. According to the regulation, a person could possess up to 15 grams of marijuana or 1.5 grams of heroin without facing criminal charges. These amounts were higher (often many times) than in any other European country, possibly making the Czech Republic the most liberal country in the European Union when it comes to drug liberalization, apart from Portugal.[60] Under the Regulation No. 467/2009 Coll, possession of the following amounts or less of illicit drugs was to be considered smaller than large for the purposes of the Criminal Code and was to be treated as a misdemeanor subject to a fine equal to a parking ticket:[61] Marijuana 15 grams (or five plants) Hashish 5 grams Magic mushrooms 40 pieces Peyote 5 plants LSD 5 tablets Ecstasy 4 tablets Amphetamine 2 grams Methamphetamine 2 grams Heroin 1.5 grams Coca 5 plants Cocaine 1 gram In 2013, a District Court in Liberec was deciding a case of a person that was accused of criminal possession for having 3.25 grams of methamphetamine (1.9 grams of straight methamphetamine base), well over the Regulation's limit of 2 grams. The court considered that basing a decision on mere Regulation would be unconstitutional and in breach of Article 39 of the Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms which states that "only a law may designate which acts constitute a crime and what penalties, or other detriments to rights or property, may be imposed for committing them" and proposed to the Constitutional Court to abolish the Regulation. In line with the District Courts' argument, the Constitutional Court abolished the Regulation effective from 23 August 2013, noting that the "amount larger than small" within the meaning of the Criminal Code may be designated only by the means of an Act of Parliament, and not a Governmental Regulation. Moreover, the Constitutional Court further noted that the Regulation merely took over already existing judicial practice of interpretation of what constitutes "amount larger than small" and thus its abolishment will not really change the criminality of drug possession in the country.[62] Thus, the above-mentioned amounts from the now-not-effective Regulation remain as the base for consideration of police and prosecutors, while courts are not bound by the precise grammage. Sale of any amount (not purchase) remains a criminal act. Possession of "amount larger than a small" of marijuana can result in a jail sentence of up to one year. For other illicit drugs, the sentence is up to two years. Trafficking as well as production (apart from growing up to five plants of marijuana) offenses carry stiffer sentences.[63] Medical use of cannabis on prescription has been legal and regulated since 1 April 2013.[64][65] |

ヨーロッパ チェコ共和国 チェコ共和国では、1998年12月31日までは、薬物の所持は「他者への提供」のみ(すなわち販売目的)が犯罪とされていた(製造、輸入、輸出、提供、 仲介は犯罪であり、現在も犯罪である)。一方、個人使用目的の所持は合法であった。[58] 1999年1月1日、チェコの薬物規定を「麻薬に関する単一条約」に整合させるために必要とされた刑法の改正が施行され、 個人使用目的であっても「少量を超える量」の所持を犯罪化する刑法改正が施行された(刑法第187a条)。一方、個人使用目的の少量所持は軽犯罪となっ た。[58] 司法の慣行では、「少量を超える量」とは、平均的な消費者の通常の1回分の量よりも5~10倍(薬物によって異なる)多い量でなければならないという結論 に達した。[59] 2009年12月14日、チェコ共和国政府は2010年1月1日に施行された規則第467/2009号を採択し、刑法における「少量を超える量」が何を意 味するかを明確にした。これにより、従来の司法慣行で既に確立されていた量は事実上、引き継がれた。この規定によると、大麻15グラム、ヘロイン1.5グ ラムまでは刑事責任を問われない。これらの量は他のヨーロッパ諸国よりも多く(多くの場合、数倍も多い)、ポルトガルを除けば、チェコ共和国は薬物自由化 に関して欧州連合で最も自由主義的な国である可能性がある。[60] 2009年コルレギュレーション第467号では、 2009年コル法により、以下の量の違法薬物所持は刑法上は少量と見なされ、駐車違反切符と同等の罰金刑が科される軽犯罪として扱われることになった。 マリファナ 15グラム(または5株) ハシシ 5グラム 呪術的キノコ 40個 ペヨーテ 5株 LSD 5錠 エクスタシー 4錠 アンフェタミン 2グラム メタンフェタミン 2グラム ヘロイン 1.5グラム コカ 5株 コカイン 1グラム 2013年、リベレツの地方裁判所は、規制の限度である2グラムを大幅に超える3.25グラムのメタンフェタミン(純粋なメタンフェタミン塩基1.9グラ ム)を所持していたとして刑事上の所持で起訴されたある人格の事件を裁いていた。裁判所は、単なる規制を根拠に決定を下すことは違憲であり、チェコ基本権 および自由憲章第39条に違反すると考えた。同条項は、「犯罪を構成する行為およびそれらの行為に対する刑罰、または権利や財産に対するその他の不利益を 規定できるのは法律のみである」と定めている。裁判所は、憲法裁判所に規制の廃止を提案した。地方裁判所の主張に沿って、憲法裁判所は2013年8月23 日より効力のある規則を廃止した。刑法の「少額を超える額」という意味は、政府規則ではなく、議会の法律によってのみ指定される可能性があると指摘した。 さらに、憲法裁判所は、この規則は「少量を超える量」を構成するものの解釈に関する既存の司法慣行を単に引き継いだものであり、したがって、その廃止は国 内における薬物所持の犯罪性を実際に変えるものではないと指摘した。[62] したがって、現在効力を有していないこの規則に記載されていた上記の金額は、警察や検察官の検討の基準として残っているが、裁判所は厳密な文言に拘束され ることはない。 購入ではなく)いかなる量でも販売することは依然として犯罪行為である。マリファナの「少量を超える量」の所持は、最高1年の実刑判決につながる可能性が ある。その他の違法薬物については、刑期は最長2年である。密売や製造(大麻の栽培は5株まで)は、より厳しい刑期が科せられる。[63] 2013年4月1日より、処方による医療用大麻の使用は合法化され、規制されている。[64][65] |

| France Following a contentious debate France opened its first supervised injection centre on 11 October 2016. Marisol Touraine, the Minister of Health, declared that the centre, located near the Gare du Nord in Paris, was "a strong political response, for a pragmatic and responsible policy that brings high-risk people back towards the health system rather than stigmatizing them."[66] |

フランス 激しい議論の末、フランスは2016年10月11日に同国初の管理下注射センターを開設した。マリソル・トゥーレーヌ保健大臣は、パリ北駅近くに開設され たこのセンターについて、「高リスクの人々を社会から排除するのではなく、医療制度に再び取り込むという現実的かつ責任ある政策への政治的な強い意思表示 である」と述べた。[66] |

| Germany See also: Drug policy of Germany and Cannabis in Germany In 1994, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that drug addiction was not a crime, nor was the possession of small amounts of drugs for personal use. In 2000, the German narcotic law (BtmG) was changed to allow for supervised drug injection rooms. In 2002, a pilot study was started in seven German cities to evaluate the effects of heroin-assisted treatment on addicts, compared to methadone-assisted treatment. The positive results of the study led to the inclusion of heroin-assisted treatment into the services of the mandatory health insurance in 2009. On 4 May 2016, the Cabinet of Germany decided to approve the measure for legal cannabis for seriously ill patients who have consulted with a doctor and "have no therapeutic alternative". German Health Minister, Hermann Gröhe, presented the legal draft on the legalization of medical cannabis to the cabinet which was expected to take effect early 2017.[needs update][67][68][69][70][71] |

ドイツ 関連情報:ドイツの薬物政策、ドイツにおける大麻 1994年、連邦憲法裁判所は薬物中毒は犯罪ではなく、また少量の薬物を個人使用の目的で所持することも犯罪ではないとの判決を下した。2000年には、 ドイツ麻薬法(BtmG)が改正され、管理下での薬物注射ルームの設置が認められるようになった。2002年には、ヘロインを用いた治療が中毒患者に与え る影響を、メサドンを用いた治療と比較評価するパイロット研究がドイツの7都市で開始された。この研究の良好な結果を受けて、2009年にはヘロインを用 いた治療が強制加入の健康保険のサービスに組み入れられることになった。2016年5月4日、ドイツ政府は、医師の診察を受け、「治療法が他にない」重病 の患者に対して医療用大麻を合法化する措置を承認することを決定した。ドイツ保健大臣ヘルマン・グロエは、2017年初頭に施行される見込みの医療用大麻 合法化の法案を閣議に提出した。[更新が必要][67][68][69][70][71] |

| Ireland On 2 November 2015, Aodhán Ó Ríordáin, the minister in charge of the National Drugs Strategy, announced that Ireland planned to introduce supervised injection rooms. The minister also referenced that possession of controlled substances will be decriminalized although supply and production will remain criminalized.[72] On 12 July 2017, the Health Committee of the Irish government rejected a bill that would have legalized medical cannabis.[73] |

アイルランド 2015年11月2日、アオハン・オ・リードナン(Aodhán Ó Ríordáin)国家麻薬対策担当大臣は、アイルランドが管理下の注射室を導入する計画であると発表した。同大臣はまた、規制薬物の所持は非犯罪化され るが、供給と生産は引き続き犯罪化されると述べた。[72] 2017年7月12日、アイルランド政府の保健委員会は医療用大麻を合法化する法案を否決した。[73] |

| Netherlands See also: Drug policy of the Netherlands The drug policy of the Netherlands is based on two principles: (1) drug use is a public health issue, not a criminal matter, and (2) a distinction between hard and soft drugs exists. Additionally, a policy of non-enforcement has led to a situation where reliance upon non-enforcement has become common; because of this, the courts have ruled against the government when individual cases were prosecuted. Cannabis remains a controlled substance in the Netherlands and both possession and production for personal use are still misdemeanors, punishable by fine. Cannabis coffee shops are also illegal according to the statutes.[74] |

オランダ 関連情報:オランダの薬物政策 オランダの薬物政策は、次の2つの原則に基づいている。(1)薬物使用は刑事事件ではなく、公衆衛生の問題である。(2)ハードドラッグとソフトドラッグ を区別する。さらに、非取締政策により、取締を行わないことが一般的になっている。そのため、個々の事件が起訴された場合、裁判所は政府に不利な判決を下 している。オランダでは大麻は依然として規制薬物であり、個人使用目的の所持および生産はいずれも軽犯罪であり、罰金刑に処せられる。大麻コーヒーショッ プも法律上は違法である。[74] |

| Norway On 14 June 2010, the Stoltenberg commission recommended implementing heroin assisted treatment and expanding harm reduction measures.[75] On 18 June 2010, Knut Storberget, Minister of Justice and the Police, announced that the ministry was working on new drug policy involving decriminalization by the Portugal model, which was to be introduced to parliament before the next general election.[76] Storberget later changed his statements, saying the decriminalization debate is "for academics", instead calling for coerced treatment.[77] In early March 2013, minister of health and care services Jonas Gahr Støre proposed to decriminalize the inhalation of heroin by 2014 as a measure to decrease drug overdoses.[78] In 2011, there were 294 fatal overdoses, in comparison to only 170 traffic related deaths.[78] The country was preparing a massive policy change in terms of how to deal with drug use and drug possession for personal use. The reform titled "From punishment to help" was approved by the Norwegian government in 2017 and was in the final phase of approval by the parliament. Changes were expected to be implemented by early 2021.[needs update] The new reform policy emphasizes that criminalizing drug use has no significant effect on rates of drug consumption and that drug addiction is better dealt with by health care services, hence the slogan "from punishment to help". Instead of fines or prison time, a person caught with a drug quantity for personal use will now be met with an independent panel consisting of social and health care workers that will discuss administrative sanctions or addiction treatment methods. This will hopefully encourage problematic users to seek help rather than fear of prosecution. There is also hope that this will improve the relationship between drug users and law enforcement officers. Opponents of the reform, including the police force and the Progress Party, fear that drug use will increase once a person is no longer at risk of facing criminal charges.[79] As of 21 July 2022, drug decriminalisation has not materialised in Norway. As of this date, only those who have substance use disorders may go unpunished if the amount of illegal drugs they have meets the criteria of what is deemed an amount for personal use.[80] |

ノルウェー 2010年6月14日、ストルテンベルグ委員会はヘロイン補助療法の実施とハームリダクション対策の拡大を勧告した。[75] 2010年6月18日、クヌート・ストルベルゲット法務警察大臣は、ポルトガルモデルによる非犯罪化を含む新たな薬物政策に取り組んでいることを発表した ポルトガルモデルによる非犯罪化を含む新たな薬物政策に取り組んでいると発表し、次期総選挙前に議会に提出する予定であると述べた。[76] その後、ストーベルゲート大臣は、非犯罪化の議論は「学術的なもの」であり、強制的な治療を求めるべきだと発言を変更した。[77] 2013年3月初旬、保健・介護サービス大臣のヨナス・ 薬物の過剰摂取を減らすための対策として、2014年までにヘロイン吸引の非犯罪化を提案した。[78] 2011年には、薬物の過剰摂取による死亡者数は294人であったのに対し、交通事故による死亡者数はわずか170人であった。[78] 同国は、薬物使用や個人使用目的の薬物所持への対処方法について、大規模な政策変更を準備していた。「処罰から支援へ」と題されたこの改革は2017年に ノルウェー政府によって承認され、議会による承認の最終段階に入っていた。変更は2021年初頭までに実施される見込みであった。[更新が必要] 新しい改革政策では、薬物使用を犯罪化しても薬物消費率に大きな影響はないこと、薬物中毒は医療サービスによって対処する方が効果的であることが強調され ており、これが「処罰から支援へ」というスローガンに反映されている。 個人使用目的の薬物量で捕まった人格には、罰金や禁固刑ではなく、社会福祉や医療従事者で構成される独立した委員会が行政制裁や中毒治療方法を話し合うこ とになる。これにより、問題を抱える使用者が起訴を恐れるよりも、助けを求めるようになることが期待される。また、薬物使用者と法執行官の関係が改善され ることも期待されている。警察や進歩党など、この改革に反対する人々は、刑事責任を問われる恐れがなくなれば、薬物使用が増えることを懸念している。 2022年7月21日現在、ノルウェーでは薬物の非犯罪化は実現していない。この日付現在、違法薬物の量が個人使用とみなされる量に達している場合、物質 使用障害を持つ人だけが処罰されない可能性がある。[80] |

| Portugal See also: Drug policy of Portugal In 2001, Portugal became the first European country to abolish all criminal penalties for personal drug possession, under Law 30/2000.[81] In addition, drug users were to be provided with therapy rather than prison sentences. Research commissioned by the Cato Institute and led by Glenn Greenwald found that in the five years after the start of decriminalization, illegal drug use by teenagers had declined, the rate of HIV infections among drug users had dropped, deaths related to heroin and similar drugs had been cut by more than half, and the number of people seeking treatment for drug addiction had doubled.[82] Peter Reuter, a professor of criminology and public policy at the University of Maryland, College Park, suggested that the heroin usage rates and related deaths may have been due to the cyclical nature of drug epidemics. In 2009, he stated that "decriminalization in Portugal has met its central goal. Drug use did not rise."[23] In 2023, drug use had increased by 7,8 percent, compared to 2001 when the policies had been implemented.[83] |

ポルトガル 関連情報:ポルトガルの薬物政策 2001年、ポルトガルは法律30/2000に基づき、個人による薬物所持に対するすべての刑事罰を廃止した最初のヨーロッパの国となった。[81] さらに、薬物使用者は刑務所ではなく治療を受けることになった。ケイトー研究所の委託でグレン・グリーンウォルドが主導した調査によると、非犯罪化開始後 の5年間で、ティーンエイジャーによる違法薬物の使用は減少し、薬物使用者のHIV感染率は低下し、ヘロインや類似薬物に関連する死亡数は半分以下に減少 した。薬物中毒の治療を求める人の数は2倍に増加した。[82] メリーランド大学カレッジパーク校の犯罪学および公共政策学教授であるピーター・ロイターは、ヘロインの使用率と関連死は薬物の流行が周期的な性質を持つ ことによるものかもしれないと示唆した。2009年には、「ポルトガルにおける非犯罪化は、その主要な目標を達成した。薬物の使用は増加していない」と述 べている。[23] 2023年には、政策が実施された2001年と比較して、薬物の使用は7.8%増加した。[83] |

| Ukraine The use of marijuana in Ukraine is not prohibited, but the manufacture, storage, transportation and sale of cannabis and its derivatives are under administrative and criminal liability.[84] Speaking on the legalization of soft drugs in Ukraine has been going on for a long time. In June 2016, the Parliament received a bill on the legalization of marijuana for medical purposes. It dealt with changes to the current act "On narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances and precursors" and was registered number 4533.[85] The document must examine the relevant committee, and then submit it to the government. It was expected that this would happen in the fall of 2016, but the bill was not considered. In October 2018, a petition appeared on the website of electronic appeals to the President of Ukraine asking for the legalization of marijuana.[86] In October 2018, the State Service of Ukraine on Drugs and Drug Control issued the first license for the import and re-export of raw materials and products derived from cannabis. The corresponding licenses were obtained by the USA company C21. The company is also in the process of applying for additional licenses, including the cultivation of cannabis.[87] |

ウクライナ ウクライナではマリファナの使用は禁止されていないが、大麻およびその派生物の製造、貯蔵、輸送、販売は行政および刑事責任の対象となる。[84] ウクライナにおけるソフトドラッグの合法化については、長い間議論が続けられている。2016年6月、議会は医療目的の大麻合法化に関する法案を受理し た。これは、現行の「麻薬、向精神薬および前駆物質に関する法律」の改正を扱うもので、第4533号として登録された。[85] この文書は関連委員会で審査され、政府に提出されなければならない。 2016年秋にこれが実現する見込みであったが、法案は審議されなかった。2018年10月、ウクライナ大統領への電子請願のウェブサイトに、マリファナ の合法化を求める請願書が現れた。[86] 2018年10月、ウクライナ麻薬・麻薬管理庁は、大麻由来の原材料および製品の輸入・再輸出に関する最初のライセンスを発行した。 対応するライセンスは、米国企業C21が取得した。この会社は、大麻の栽培を含む追加のライセンスの申請も進めている。[87] |

| Latin America Main article: Latin American drug legalization In the late 2000s and early 2010s, advocacy for drug legalization has increased in Latin America. Spearheading the movement Uruguayan government announced in 2012 plans to legalize state-controlled sales of marijuana in order to fight drug-related crimes. Some countries in this region have already advanced towards depenalization of personal consumption. |

ラテンアメリカ 詳細は「ラテンアメリカにおける麻薬合法化」を参照 2000年代後半から2010年代前半にかけて、ラテンアメリカでは麻薬合法化を求める声が高まっている。この運動の先頭に立っているウルグアイ政府は、 2012年に麻薬関連犯罪と戦うために大麻の国家管理下での販売を合法化する計画を発表した。この地域の一部の国では、すでに個人使用の非犯罪化に向けて 前進している。 |

| Argentina In August 2009, the Supreme Court of Argentina declared in a landmark ruling that it was unconstitutional to prosecute citizens for having drugs for their personal use – "adults should be free to make lifestyle decisions without the intervention of the state".[88] The decision affected the second paragraph of Article 14 of the country's drug control legislation (Law Number 23,737) that punishes the possession of drugs for personal consumption with prison sentences ranging from one month to two years (although education or treatment measures can be substitute penalties). The unconstitutionality of the article concerns cases of drug possession for personal consumption that does not affect others.[89][90] |

アルゼンチン 2009年8月、アルゼンチンの最高裁は画期的な判決を下し、個人使用目的の麻薬所持で市民を起訴することは違憲であると宣言した。「成人は、国家の介入 なしにライフスタイルを自由に決定する権利を持つべきである」[88] この判決は、 個人使用目的の薬物の所持を1ヶ月から2年の禁固刑で処罰する同国の薬物取締法(第23,737号)第14条の第2項に影響を与えた(ただし、教育や治療 措置を代替刑罰とすることも可能)。この条項の違憲性は、他人に影響を与えない個人使用目的の薬物所持のケースに関するものである。[89][90] |

| Brazil In 2002 and 2006, Brazil went through legislative changes, resulting in a partial decriminalization of possession for personal use. Prison sentences no longer applied and were replaced by educational measures and community services;[91] however, the 2006 law does not provide objective means to distinguish between users or traffickers. A disparity exists between the decriminalization of drug use and the increased penalization of selling drugs, punishable with a maximum prison sentences of 5 years for the sale of very minor quantities of drugs. Most of those incarcerated for drug trafficking are offenders caught selling small quantities of drugs, among them drug users who sell drugs to finance their drug habits. Since 2006, there has been a long debate whether the anti-drug law goes against the Constitution and principle of personal freedom. In 2009,[92] the Supreme Federal Court re-opened to vote if the law is Constitutional, or if it goes against the Constitution specifically against personal Freedom of choice. Since each Minister inside the tribunal can take a personal time to evaluate the law, the voting can take years. In fact, the voting was re-opened in 2015, 3 ministers voted in favor, and then the law was again paused by another minister.[93] |

ブラジル 2002年と2006年にブラジルでは法改正が行われ、個人使用目的の所持が部分的に非犯罪化された。 実刑判決は適用されなくなり、教育措置や社会奉仕活動に置き換えられたが[91]、2006年の法律では使用者と密売人の区別を客観的に判断する手段が規 定されていない。薬物使用の非犯罪化と、ごく少量の薬物の販売に対する最高5年の実刑判決という、販売に対する厳罰化との間に矛盾が生じている。薬物売買 で投獄される者の大半は、少量の薬物を販売した罪で捕まった者であり、その中には薬物常習者が薬物を買う資金を稼ぐために販売している者もいる。2006 年以降、薬物取締法が憲法や個人の自由の原則に反するかどうかについて、長い間議論が続いている。2009年、連邦最高裁判所は、この法律が憲法に適合し ているか、あるいは特に個人の選択の自由を侵害しているとして、投票による再審理を行った。裁判所内の各大臣が法律を評価するために個人的な時間を割くこ とができるため、投票には何年もかかる可能性がある。実際、投票は2015年に再開され、3人の大臣が賛成票を投じたが、その後、別の大臣によって法律は 再び保留となった。 |

| Colombia Guatemalan President Otto Pérez Molina and Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos proposed the legalization of drugs in an effort to counter the failure of the war on drugs, which was said to have yielded poor results at a huge cost.[94] On 25 May 2016, the Colombian congress approved the legalization of marijuana for medical usage.[95] |

コロンビア グアテマラのオットー・ペレス・モリーナ大統領とコロンビアのフアン・マヌエル・サントス大統領は、多大な費用をかけても成果が上がっていないとされる麻 薬戦争の失敗に対抗する試みとして、麻薬の合法化を提案した。[94] 2016年5月25日、コロンビア議会は医療用大麻の合法化を承認した。[95] |

| Costa Rica Costa Rica has decriminalized drugs for personal consumption. Manufacturing or selling drugs is still a jailable offense. |

コスタリカ コスタリカでは、個人使用目的の麻薬は非犯罪化されている。麻薬の製造や販売は依然として禁固刑に値する犯罪である。 |

| Ecuador According to the 2008 Constitution of Ecuador, in its Article 364, the Ecuadorian state does not see drug consumption as a crime but only as a health concern.[96] Since June 2013, the state drugs regulatory office CONSEP has published a table which establishes maximum quantities carried by persons so as to be considered in legal possession and that person as not a seller of drugs.[96][97][98] The "CONSEP established, at their latest general meeting, that the following quantities be considered the maximum consumer amounts: 10 grams of marijuana or hash, 4 grams of opiates, 100 milligrams of heroin, 5 grams of cocaine, 0.020 milligrams of LSD, and 80 milligrams of methamphetamine or MDMA".[99] |

エクアドル 2008年のエクアドル憲法第364条によると、エクアドル国家は薬物の使用を犯罪とは見なさず、保健上の問題としてのみ扱う。[96] 2013年6月以来、国家麻薬規制局(CONSEP)は、 合法的な所持と見なされるために個人が携帯できる最大量と、その人物が麻薬の売人ではないと見なされるための表を公表している。[96][97][98] 「CONSEPは最新の総会で、以下の量が最大消費量と見なされることを決定した。マリファナまたはハシシ10グラム、アヘン4グラム、ヘロイン100ミ リグラム、コカイン5グラム、LSD0.020ミリグラム、メタンフェタミンまたはMDMA80ミリグラム」と定めた。[99] |

| Honduras On 22 February 2008, Honduras President Manuel Zelaya called on the United States to legalize drugs in order to prevent the majority of violent murders occurring in Honduras. Honduras is used by cocaine smugglers as a transiting point between Colombia and the US. Honduras, with a population of 7 million affected people an average of 8–10 murders a day, with an estimated 70% being as a result of this international drug trade. According to Zelaya, the same problem is occurring in Guatemala, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Mexico.[100] |

ホンジュラス 2008年2月22日、ホンジュラス大統領マヌエル・セラヤ氏は、ホンジュラスで発生している大半の凶悪殺人事件を防ぐために、米国に麻薬の合法化を呼び かけた。ホンジュラスはコカインの密輸業者によって、コロンビアと米国を結ぶ中継地点として利用されている。人口700万人のホンジュラスでは、1日平均 8~10件の殺人事件が発生しており、そのうちの70%は、この国際的な麻薬取引が原因であると推定されている。 セラーヤ大統領によると、同様の問題はグアテマラ、エルサルバドル、コスタリカ、メキシコでも発生しているという。[100] |

| Mexico In April 2009, the Mexican Congress approved changes in the General Health Law that decriminalized the possession of illegal drugs for immediate consumption and personal use allowing a person to possess up to 5 g of marijuana or 500 mg of cocaine. The only restriction is that people in possession of drugs should not be within a 300-meter radius of schools, police departments, or correctional facilities. Opium, heroin, LSD, and other synthetic drugs were also decriminalized, it will not be considered as a crime as long as the dose does not exceed the limit established in the General Health Law.[101] Many question this, as cocaine is as much synthesised as heroin, both are produced as extracts from plants. The law establishes very low amount thresholds and strictly defines personal dosage. For those arrested with more than the threshold allowed by the law this can result in heavy prison sentences, as they will be assumed to be small traffickers even if there are no other indications that the amount was meant for selling.[102] |

メキシコ 2009年4月、メキシコ議会は、即時消費および個人使用のための違法薬物の所持を非犯罪化する一般保健法の改正を承認した。これにより、マリファナ5グ ラムまたはコカイン500ミリグラムまでの所持が人格に認められることとなった。唯一の制限は、薬物を所持する人物が学校、警察署、または矯正施設の半径 300メートル以内にいないことである。アヘン、ヘロイン、LSD、その他の合成麻薬も非犯罪化され、一般保健法で定められた限度を超えない限り、犯罪と は見なされない。[101] コカインはヘロインと同様に合成されたものであり、どちらも植物から抽出された物質であるため、これに疑問を呈する声も多い。この法律では、非常に低い量 の閾値が定められ、個人の服用量が厳密に定義されている。法律で認められた基準値以上のコカインを所持して逮捕された場合、販売目的で所持していたという 証拠が他にない場合でも、小規模な密売人であると見なされ、重い実刑判決が下される可能性がある。[102] |

| Uruguay See also: Legality of cannabis in Uruguay Uruguay is one of few countries that never criminalized the possession of drugs for personal use. Since 1974, the law establishes no quantity limits, leaving it to the judge's discretion to determine whether the intent was personal use. Once it is determined by the judge that the amount in possession was meant for personal use, there are no sanctions.[103] In June 2012, the Uruguayan government announced plans to legalize state-controlled sales of marijuana in order to fight drug-related crimes. The government also stated that they will ask global leaders to do the same.[104] On 31 July 2013, the Uruguayan House of Representatives approved a bill to legalize the production, distribution, sale, and consumption of marijuana by a vote of 50 to 46. The bill then passed the Senate, where the left-leaning majority coalition, the Broad Front, held a comfortable majority. The bill was approved by the Senate by 16 to 13 on 10-December-2013.[105] The bill was presented to the President José Mujica, also of the Broad Front coalition, who has supported legalization since June 2012. Relating this vote to the 2012 legalization of marijuana by the U.S. states Colorado and Washington, John Walsh, drug policy expert of the Washington Office on Latin America, stated that "Uruguay's timing is right. Because of last year's Colorado and Washington State votes to legalize, the U.S. government is in no position to browbeat Uruguay or others who may follow."[106] In July 2014, government officials announced that part of the implementation of the law (the sale of cannabis through pharmacies) is postponed to 2015, as "there are practical difficulties". Authorities will grow all the cannabis that can be sold legal. Concentration of THC shall be 15% or lower.[107] In August 2014, an opposition presidential candidate, who was not elected in the November 2014 presidential elections, claimed that the new law was never going to be applied, as it was not workable.[108] By the end of 2016 the government announced that the sale through pharmacies will be fully implemented during 2017.[109] |

ウルグアイ 参照:ウルグアイにおける大麻の合法性 ウルグアイは、個人使用目的の薬物所持を犯罪化していない数少ない国のひとつである。1974年以来、法律では所持量に制限を設けておらず、所持の意図が 個人使用目的であったかどうかは裁判官の裁量に委ねられている。所持量が個人使用目的であると裁判官が判断すれば、処罰はない。[103] 2012年6月、ウルグアイ政府は薬物関連犯罪に対処するため、国が管理する大麻販売を合法化する計画を発表した。政府はまた、世界の指導者たちにも同様 の措置を講じるよう要請するとも述べた。[104] 2013年7月31日、ウルグアイ下院は、マリファナの生産、流通、販売、消費を合法化する法案を賛成50、反対46で可決した。この法案は、左派寄りの 多数派連合であるブロード・フロントが安定多数を占める上院でも可決された。2013年12月10日、上院で16対13の賛成多数で可決された。 [105] この法案は、ブロード・フロント連合のホセ・ムヒカ大統領にも提出された。ムヒカ大統領も2012年6月以来、合法化を支持している。この投票を2012 年に米国のコロラド州とワシントン州で大麻が合法化されたことに関連して、ワシントン・ラテンアメリカ研究所の薬物政策専門家ジョン・ウォルシュ氏は、 「ウルグアイのタイミングは適切だ。昨年、コロラド州とワシントン州で合法化されたため、米国政府はウルグアイや、後に続く可能性のある他の国々を威圧す る立場にはない」と述べた。[106] 2014年7月、政府当局者は「実際的な困難がある」として、法律の一部施行(薬局を通じた大麻の販売)を2015年に延期すると発表した。当局は合法的 に販売できる大麻をすべて栽培する。THCの濃度は15%以下とする。[107] 2014年8月、2014年11月の大統領選挙で落選した野党の大統領候補は、この新法は それは実行不可能であるため、適用されることは決してないだろうと主張した。[108] 2016年末までに、政府は2017年中に薬局での販売を全面的に実施すると発表した。[109] |

| North America Canada  A cannabis shop in Montreal See also: Drug policy of Canada and Cannabis in Canada The cultivation of cannabis is currently legal in Canada, except in Manitoba and Quebec. Citizens outside those provinces may grow up to four plants per residence for personal use, and recreational use of cannabis by the general public is legal with restrictions on smoking in public locations that vary by jurisdiction. The sale of marijuana seeds is also legal.[110] In 2001, The Globe and Mail reported that a poll found 47% of Canadians agreed with the statement, "The use of marijuana should be legalized" in 2000, compared to 26% in 1975.[111] A more recent poll found that more than half of Canadians supported legalization. In 2007, Prime Minister Stephen Harper's government tabled Bill C-26 to amend the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, 1996 to bring forth a more restrictive law with higher minimum penalties for drug crimes.[112][113] Bill-26 died in committee after the dissolution of the 39th Canadian Parliament in September 2008, but the Bill was subsequently resurrected by the government twice. In 2015, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the Liberal Party of Canada campaigned on a promise to legalize marijuana. The Cannabis Act was passed on 19 June 2018, which made marijuana legal across Canada on 17 October 2018.[114][115][116] Since legalization, the country has set up an online framework to allow consumers to purchase a wide variety of merchandise ranging from herbs, extract, oil capsules, and paraphernalia. Most provinces also provide a venue for purchase through physical brick and mortar stores. In 2021, the city councils of Vancouver and Toronto voted to decriminalize the simple possession of all drugs; and submitted proposals requesting special exemption from the federal Health Minister to do so, citing numerous scientific, psychological, medical, and socio-economic benefits.[117] In early 2022, the Province of British Columbia submitted its own request for exemption, closely following the Vancouver model. By April of that year, the Edmonton City Council had also passed a motion to request exemption from federal drug enforcement laws in order decriminalize "simple personal possession" of illegal drugs, voting in favour 11–2.[117][118] On 31 May 2022, the federal government of Canada approved British Columbia's proposal to decriminalize all "hard drugs", such as heroin, fentanyl, cocaine, and methamphetamine. As of 1 January 2023, British Columbians aged 18 years or older are allowed to carry up to a cumulative total of 2.5 grams of these substances without the risk of arrest or criminal charges. Police are not to confiscate the drugs, and there is no requirement that people found to be in possession seek treatment; however, the production, trafficking, and exportation of these drugs remain illegal.[119] |

北アメリカ カナダ  モントリオールにあるマリファナ販売店 参照: カナダの薬物政策、カナダの大麻 マリファナの栽培は、マニトバ州とケベック州を除いて、現在カナダでは合法である。それらの州以外の市民は、個人使用のために1軒あたり最大4株まで栽培 することができ、一般市民による娯楽目的のマリファナ使用は、管轄区域によって異なる公共の場所での喫煙に関する制限付きで合法である。マリファナの種子 の販売も合法である。 2001年、グローブ・アンド・メール紙は、2000年の世論調査で「マリファナの使用は合法化されるべきである」という意見に賛成するカナダ人が47% に上ったことを報じた。これは1975年の26%と比較すると高い割合である。[111] さらに最近の世論調査では、カナダ人の半数以上が合法化を支持していることが分かった。2007年、スティーブン・ハーパー首相の政府は、薬物犯罪に対す る最低刑をより厳しくした、より制限的な法律を制定するために、1996年の規制薬物及び規制物質法を改正する法案C-26を提出した。[112] [113] 2008年9月の第39回カナダ議会解散により、法案C-26は委員会で廃案となったが、その後、政府によって2度復活した。 2015年、ジャスティン・トルドー首相とカナダ自由党は、マリファナを合法化するという公約を掲げて選挙戦を戦った。2018年6月19日に大麻法が可 決され、2018年10月17日にカナダ全土で大麻が合法化された。[114][115][116] 合法化以来、この国では、ハーブ、抽出物、オイルカプセル、器具に至るまで、幅広い商品を消費者が購入できるオンラインの枠組みが構築されている。ほとん どの州では、実店舗での購入も可能となっている。 2021年、バンクーバー市議会とトロント市議会は、すべての薬物の単純所持を非犯罪化するよう投票で決定し、そのために連邦保健大臣に特別な免除を求め る提案を提出した。その際、多数の科学的、心理学的、医学的、社会経済的利益を挙げた。[117] 2022年初頭、ブリティッシュコロンビア州は、バンクーバーのモデルを厳密に踏襲した独自の免除申請を提出した。同年4月までに、エドモントン市議会も 違法薬物の「単純な個人所持」を非犯罪化するために、連邦麻薬取締法の適用除外を求める動議を可決し、賛成11、反対2で採択された。[117][1 18] 2022年5月31日、カナダ連邦政府はヘロイン、フェンタニル、コカイン、メタンフェタミンなどの「ハードドラッグ」のすべてを非犯罪化するというブリ ティッシュコロンビア州の提案を承認した。2023年1月1日より、ブリティッシュコロンビア州在住の18歳以上の者は、これらの物質を合計2.5グラム まで所持することが認められ、逮捕や刑事告発のリスクなしに所持できる。警察はこれらの薬物を没収することはできず、所持が発覚した者が治療を受ける必要 もないが、これらの薬物の製造、密売、輸出は依然として違法である。[119] |

| United States This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (November 2020) Further information: Legality of cannabis by U.S. jurisdiction, Legalization of non-medical cannabis in the United States, Medical cannabis in the United States, and Psilocybin decriminalization in the United States As of 2024, prior to November elections, 38 states, Washington, D.C., and certain U.S. territories allow medical use of cannabis. Of those 38 states, 24 also allow recreational use, as does Washington, D.C. Voters in North and South Dakota and Florida will decide on recreational use in November, and Nebraskans will vote on cannabis use for medical reasons.[120] Legalization in states created significant legal and policy tensions between federal and state governments and sometimes between states. [citation needed] State laws in conflict with federal law about cannabis remain valid, and prevent state level prosecution, despite cannabis being illegal under federal law, as determined in Gonzales v. Raich (2005). Throughout the United States, various people and groups have been pushing for the legalization of marijuana for medical reasons. Organizations such as NORML and the Marijuana Policy Project work to decriminalize and legalize possession, use, cultivation, and sale of marijuana by adults.[121] In 1996, 56% of California voters voted for California Proposition 215, legalizing the growing and use of marijuana for medical purposes and making California both the first state to outlaw marijuana, in 1913,[122] and the first state to legalize medical marijuana.[123] On 6 November 2012, the states of Washington and Colorado legalized possession of small amounts of marijuana for private recreational use and created a process for writing rules for legal growing and commercial distribution of marijuana within each state, after having legalized medical cannabis in 1998 and 2000, respectively.[124] In 2014, voters in Oregon, Alaska, and Washington, D.C. voted to legalize marijuana for recreational use, as did California in 2016, with the passage of California Proposition 64,[125][126] and Michigan in 2018.[127] In 2019, Illinois passed the Illinois Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act, making Illinois the first state to legalize recreational use by an act of the state legislature, which took effect 1 January 2020. In 2020, Oregon decriminalized the possession of all drugs in Measure 110,[128] but in 2024, the Oregon State Senate passed a bill to reverse the decriminalization of hard drugs such as heroin after there was public backlash to the impacts of the measure.[129][130][131] In 2021, New York legalized adult-use cannabis when it passed the Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act (MRTA).[132] The movement to decriminalize psilocybin in the United States began in 2019 with Denver, Colorado, becoming the first city to decriminalize psilocybin in May of that year. The cities of Oakland and Santa Cruz, California, decriminalized psilocybin in June 2019 and January 2020, respectively. Washington, D.C., followed soon in November 2020, as did Somerville, Massachusetts, in January 2021, and then the neighboring Cambridge and Northampton in February 2021 and March 2021, respectively. Seattle, Washington, became the largest U.S. city on the growing list in October 2021. Detroit, Michigan, followed in November 2021. Oregon voters passed a 2020 ballot measure making it the first state to both decriminalize psilocybin and also legalize its supervised use.[133][134] Colorado followed with a similar measure in 2022.[135] The use, sale, and possession of psilocybin in the United States is illegal under federal law. |

アメリカ この節は更新が必要である。最近の出来事や新たに利用可能となった情報を反映させるため、この記事の更新にご協力ください。 (2020年11月) 追加情報:米国の管轄区域による大麻の合法性、米国における非医療用大麻の合法化、米国における医療用大麻、米国におけるシロシビン脱犯罪化 2024年現在、11月の選挙に先立ち、38の州、ワシントンD.C.、および特定の米国領土では医療用大麻の使用が認められている。この38州のうち 24州では娯楽用も合法化されており、ワシントンD.C.でも合法である。ノースダコタ、サウスダコタ、フロリダの有権者は11月に娯楽用大麻の使用につ いて決定を下し、ネブラスカでは医療用大麻の使用について投票が行われる予定である。[120] 州での合法化は、連邦政府と州政府の間、また時には州間で、重大な法的・政策的な緊張関係を生み出した。[要出典] 連邦法と矛盾する州法は有効であり、ゴンザレス対ライチ(2005年)で決定されたように、連邦法では大麻が違法であるにもかかわらず、州レベルでの起訴 を妨げている。 アメリカ合衆国全土で、さまざまな人々や団体が医療目的の大麻合法化を推進している。NORMLやマリファナ政策プロジェクトなどの団体は、成人による大 麻の所持、使用、栽培、販売の非犯罪化と合法化に取り組んでいる。1996年には、カリフォルニア州の有権者の56%がカリフォルニア州提案 医療目的の大麻の栽培と使用を合法化するカリフォルニア州提案215号に賛成票を投じた。これにより、カリフォルニア州は1913年に大麻を非合法化した 最初の州となり、また医療用大麻を合法化した最初の州ともなった。 2012年11月6日、ワシントン州とコロラド州は、娯楽目的の個人使用のための少量のマリファナ所持を合法化し、各州内での合法的な栽培と商業流通のた めの規則制定のプロセスを創設した。1998年と2000年にそれぞれ医療用大麻を合法化していたが、[124] 2014年にはオレゴン州、アラスカ州、ワシントンD.C.の有権者が 娯楽用マリファナの合法化を可決した。2016年にはカリフォルニア州でもカリフォルニア州提案64号が可決され、[125][126] 2018年にはミシガン州でも合法化された。[127] 2019年にはイリノイ州がイリノイ州大麻規制・課税法を可決し、州議会による立法行為によって娯楽用マリファナを合法化した最初の州となった。この法律 は2020年1月1日に施行された。2020年、オレゴン州はMeasure 110によりすべての薬物の所持を非犯罪化したが[128]、2024年、オレゴン州議会は、 この措置の影響に対する市民の反発があったためである。[129][130][131] 2021年、ニューヨーク州はマリファナ規制・課税法(MRTA)を可決し、成人による大麻使用を合法化した。[132] アメリカ合衆国におけるサイロシビンの非犯罪化の動きは、2019年にコロラド州デンバーが同年5月にサイロシビンを非犯罪化した最初の都市となったこと から始まった。カリフォルニア州オークランド市とサンタクルーズ市は、それぞれ2019年6月と2020年1月にサイロシビンを非犯罪化した。ワシントン D.C.は2020年11月に、マサチューセッツ州サマービルは2021年1月に、それぞれそれに続いた。さらに、近隣のケンブリッジとノーサンプトン は、それぞれ2021年2月と3月に続いた。ワシントン州シアトルは、2021年10月に、この拡大するリストの中で最大の米国都市となった。ミシガン州 デトロイトは2021年11月に続いた。 オレゴン州の有権者は2020年の投票で法案を可決し、サイロシビンを非犯罪化すると同時に、その監督下での使用を合法化する初の州となった。[133] [134] コロラド州は2022年に同様の法案を可決した。[135] アメリカ合衆国では、サイロシビンの使用、販売、所持は連邦法の下では違法である。 |

| Oceania Australia Further information: Cannabis in Australia and Illicit drug use in Australia In 2016, Australia legalised medicinal cannabis on a federal level. Since 1985, the Federal Government has run a declared war on drugs and while initially Australia led the world in 'harm-minimization' approach, they have since lagged. Australia has a number of political parties that focus on cannabis reform, The (HEMP) Help End Marijuana Prohibition Party was founded in 1993 and registered by the Australian Electoral Commission in 2000. The Legalise Cannabis Queensland Party was established in 2020. A number of Australian and international groups have promoted reform in regard to 21st-century Australian drug policy. Organisations such as Australian Parliamentary Group on Drug Law Reform, Responsible Choice, the Australian Drug Law Reform Foundation, Norml Australia, Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP) Australia and Drug Law Reform Australia advocate for drug law reform without the benefit of government funding. The membership of some of these organisations is diverse and consists of the general public, social workers, lawyers and doctors, and the Global Commission on Drug Policy has been a formative influence on a number of these organisations. In 1994, the Australian National Task Force on Cannabis formed under the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy noted that the social harm of cannabis prohibition is greater than the harm from cannabis itself,[136] total prohibition policies have been unsuccessful in reducing drug use and have caused significant social harm, as well as higher law enforcement costs, the use of cannabis is widespread in Australia and that its adverse health effects are modest and only affect a minority of users.[137] In 2012, the think tank Australia 21, released a report on the decriminalization of drugs in Australia.[138] It noted that "by defining the personal use and possession of certain psychoactive drugs as criminal acts, governments have also avoided any responsibility to regulate and control the quality of substances that are in widespread use."[139] Prohibition has fostered the development of a criminal industry that is corrupting civil society and government and killing our children."[139] The report also highlighted the fact that, just as alcohol and tobacco are regulated for quality assurance, distribution, marketing and taxation, so should currently, unregulated, illicit drugs.[139] There has been a number of enquires in Australia relating to cannabis and other illicit drugs, in 2019 the Queensland government instructed the Queensland Productivity Commission to conduct an enquiry into imprisonment and recidivism in QLD; the final report was sent to the Queensland Government on 1 August 2019 and publicly released on 31 January 2020. The commission found that "all available evidence shows the war on drugs fails to restrict usage or supply" and that "decriminalisation would improve the lives of drug users without increasing the rate of drug use"[140] with the commission ultimately recommending that the Queensland government legalise cannabis.[141] The QPC said the system had also fuelled an illegal market, particularly for methamphetamine. Although the Palaszczuk Queensland Labor Party led state government rejected the recommendations of its own commission and said it had no plans to alter any laws around cannabis,[142] a decision that received heavy scrutiny from supporters of decriminalization, legalisation, progressive and non progressive drug policy advocates alike.[143] In 2019, The Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) and St. Vincent's Health Australia called on the NSW Government to publicly release the findings of the Special Commission of Inquiry into the Drug 'Ice, saying there was "no excuse" for the delay.[144] The report was the culmination of months of evidence from health and judicial experts, as well as families and communities affected by amphetamine-type substances across NSW. The report made 109 recommendations aimed to strengthen the NSW Governments response regarding amphetamine-based drugs such as crystal meth or ice. Major recommendations included more supervised drug use rooms, a prison needle and syringe exchange program, state-wide clinically supervised substance testing, including mobile pill testing at festivals, decriminalisation of drugs for personal use, a cease to the use of drug detection dogs at music festivals and to limit the use of strip searches. The report, also called for the NSW Government to adopt a comprehensive Drug and Alcohol policy, with the last drug and Alcohol policy expiring over a decade ago. The reports commissioner said the state's approach to drug use was profoundly flawed and said reform would require "political leadership and courage" and "Criminalising use and possession encourages us to stigmatise people who use drugs as the authors of their own misfortunate". Mr Howard said current laws "allow us tacit permission to turn a blind eye to the factors driving most problematic drug use" including childhood abuse, domestic violence and mental illness.[145] The NSW government rejected the reports key recommendations, saying it would consider the other remaining recommendations. Director of the Drug Policy Modelling Program (DPMP) at UNSW Sydney's Social Policy Research Centre said the NSW Government has missed an opportunity to reform the state's response to drugs based on evidence.[146] The NSW Government is yet to officially respond to the inquiry as of November 2020, a statement was released from the government citing intention to respond by the end of 2020.[147] In the Australian Capital Territory, after a bill was passed on 25 September 2019, new laws came into effect on 31 January 2020. While personal possession and growth of small amounts of cannabis remains prohibited non-medicinal purposes in every other jurisdiction in Australia, it allowed for possession of up to 50 grams of dry material, 150 grams of wet material, and cultivation of 2 plants per individual up to 4 plants per household, effectively legalising the possession and growing of cannabis in the ACT; however the sale and supply of cannabis and cannabis seeds is still illegal, so the effects of the laws are limited and the laws also contradict federal laws. It is also still illegal to smoke or use cannabis in a public place, expose a child or young person to cannabis smoke, store cannabis where children can reach it, grow cannabis using hydroponics or artificial cultivation, grow plants where they can be accessed by the public, share or give cannabis as a gift to another person, to drive with any cannabis in your system, or for people aged under 18 to grow, possess, or use cannabis.[148] |