ダニングとクルーガーの効果

Dunning–Kruger effect

☆ ダニングとクルーガー効果(Dunning–Kruger effect)とは、特定の領域で能力が限られている人が自分の能力を過大評価する認知バイアスのことである。1999年にジャスティン・ク ルーガーとデビッド・ダニングによって初めて報告された。研究者の中には、高い業績を上げている人が自分の能力を過小評価する傾向があるという逆の効果も 含んでいる。ポピュラーカルチャー(大衆文化)では、ダニングとクルーガー効果は、特定の課題に不得手な人の特定の過信ではなく、知能の低い人の一般的な過信に関する主張とし て誤解されることが多いが、本来意味は逆。

| The Dunning–Kruger effect

is a cognitive bias in which people with limited competence in a

particular domain overestimate their abilities. It was first described

by Justin Kruger and David Dunning in 1999. Some researchers also

include the opposite effect for high performers: their tendency to

underestimate their skills. In popular culture, the Dunning–Kruger

effect is often misunderstood as a claim about general overconfidence

of people with low intelligence instead of specific overconfidence of

people unskilled at a particular task. Numerous similar studies have been done. The Dunning–Kruger effect is usually measured by comparing self-assessment with objective performance. For example, participants may take a quiz and estimate their performance afterward, which is then compared to their actual results. The original study focused on logical reasoning, grammar, and social skills. Other studies have been conducted across a wide range of tasks. They include skills from fields such as business, politics, medicine, driving, aviation, spatial memory, examinations in school, and literacy. There is disagreement about the causes of the Dunning–Kruger effect. According to the metacognitive explanation, poor performers misjudge their abilities because they fail to recognize the qualitative difference between their performances and the performances of others. The statistical model explains the empirical findings as a statistical effect in combination with the general tendency to think that one is better than average. Some proponents of this view hold that the Dunning–Kruger effect is mostly a statistical artifact. The rational model holds that overly positive prior beliefs about one's skills are the source of false self-assessment. Another explanation claims that self-assessment is more difficult and error-prone for low performers because many of them have very similar skill levels. There is also disagreement about where the effect applies and about how strong it is, as well as about its practical consequences. Inaccurate self-assessment could potentially lead people to making bad decisions, such as choosing a career for which they are unfit, or engaging in dangerous behavior. It may also inhibit people from addressing their shortcomings to improve themselves. Critics argue that such an effect would have much more dire consequences than what is observed. |

ダ

ニングとクルーガーの効果とは、特定の領域で能力が限られている人が自分の能力を過大評価する認知バイアスのことである。1999年にジャスティン・ク

ルーガーとデビッド・ダニングによって初めて報告された。研究者の中には、高い業績を上げている人が自分の能力を過小評価する傾向があるという逆の効果も

含んでいる。ポピュラーカルチャー(大衆文化)では、ダニングとクルーガーの効果は、特定の課題に不得手な人の特定の過信ではなく、知能の低い人の一般的

な過信に関する主張として誤解されることが多い。 同様の研究は数多く行われている。ダニングとクルーガーの効果は通常、自己評価と客観的パフォーマンスを比較することで測定される。例えば、参加者が小テ ストを受け、その後に自分の成績を推定し、それを実際の成績と比較する。当初の研究では、論理的推論、文法、社会的スキルに焦点が当てられていた。他の研 究は、幅広いタスクにわたって実施されている。その中には、ビジネス、政治、医学、運転、航空、空間記憶、学校での試験、読み書きといった分野のスキルも 含まれている。 ダニングとクルーガーの効果の原因については意見が分かれている。メタ認知的な説明によれば、成績不振者は自分のパフォーマンスと他者のパフォーマンスの 質的な違いを認識できないため、自分の能力を誤って判断してしまう。統計的モデルでは、自分は平均より優れていると考える一般的傾向と組み合わさった統計 的効果として経験的所見を説明する。この見解の支持者の中には、ダニングとクルーガーの効果はほとんど統計的な人工物であるとする者もいる。合理的なモデ ルでは、自分の技能について過度に肯定的な事前信念が、誤った自己評価の原因であるとする。別の説明では、低業績者の多くは非常に似たようなスキルレベル であるため、自己評価はより難しく、誤りを犯しやすいと主張する。 また、この効果が適用される場所や、どの程度強いのか、さらにその実際的な影響についても意見が分かれている。不正確な自己評価は、自分にふさわしくない 職業を選んだり、危険な行動に走ったりするなど、誤った決断をさせる可能性がある。また、自分を向上させるために自分の欠点に取り組むことを阻害する可能 性もある。批評家たちは、そのような効果は、観察されているものよりもはるかに悲惨な結果をもたらすだろうと主張している。 |

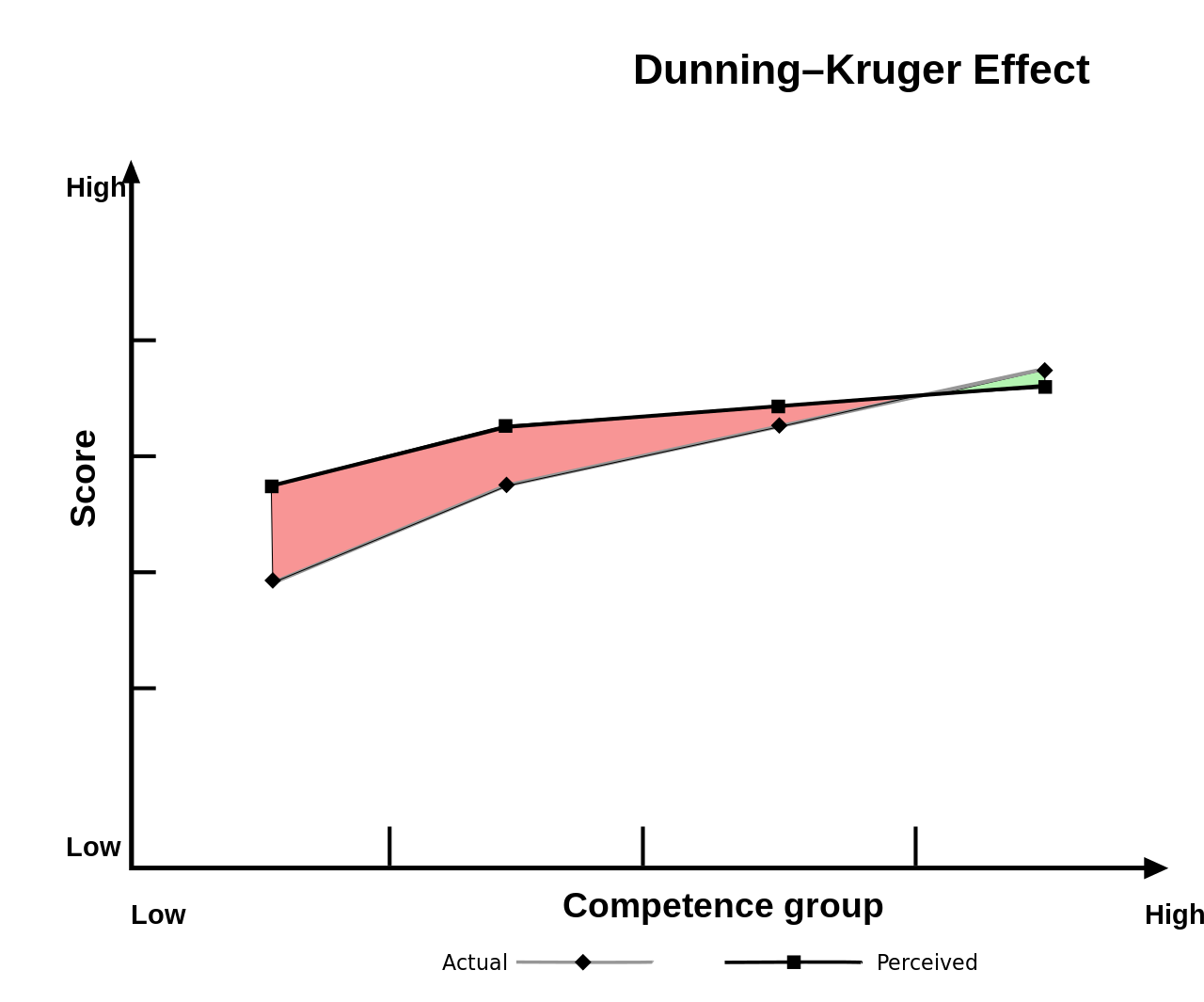

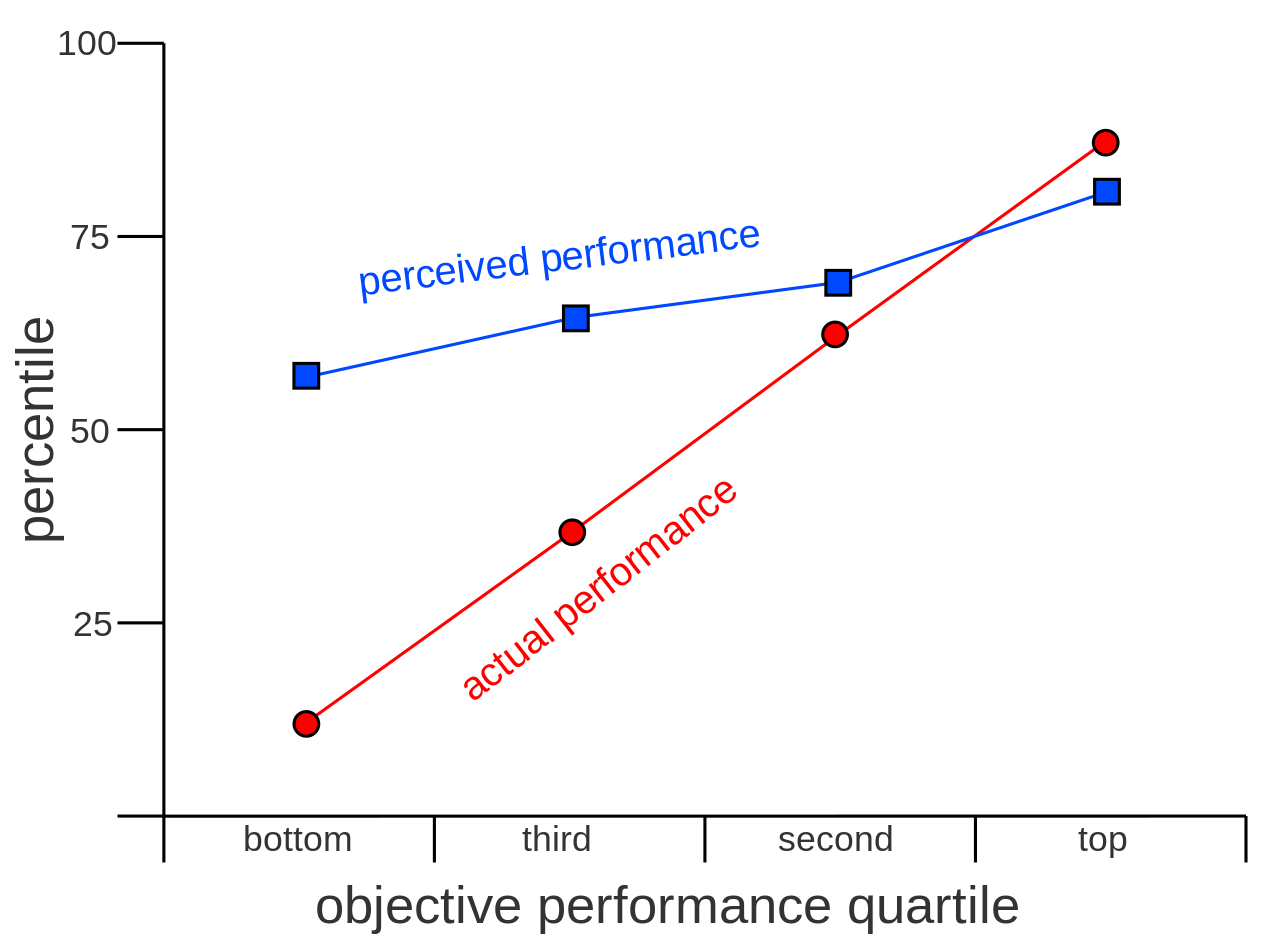

Relation

between average self-perceived performance and average actual

performance on a college exam.[1] The red area shows the tendency of

low performers to overestimate their abilities. Nevertheless, low

performers' self-assessment is lower than that of high performers. Relation

between average self-perceived performance and average actual

performance on a college exam.[1] The red area shows the tendency of

low performers to overestimate their abilities. Nevertheless, low

performers' self-assessment is lower than that of high performers. |

大学受験における平均的な自己認識能力と平均的な実技能力の関係[1] 赤い部分は、成績下位者が自分の能力を過大評価する傾向を示している。それにもかかわらず、成績下位者の自己評価は成績上位者のそれよりも低い。 大学受験における平均的な自己認識能力と平均的な実技能力の関係[1] 赤い部分は、成績下位者が自分の能力を過大評価する傾向を示している。それにもかかわらず、成績下位者の自己評価は成績上位者のそれよりも低い。 |

| Definition The Dunning–Kruger effect is defined as the tendency of people with low ability in a specific area to give overly positive assessments of this ability.[2][3][4] This is often seen as a cognitive bias, i.e. as a systematic tendency to engage in erroneous forms of thinking and judging.[5][6][7] In the case of the Dunning–Kruger effect, this applies mainly to people with low skill in a specific area trying to evaluate their competence within this area. The systematic error concerns their tendency to greatly overestimate their competence, i.e. to see themselves as more skilled than they are.[5] The Dunning–Kruger effect is usually defined specifically for the self-assessments of people with a low level of competence.[8][5][9] But some theorists do not restrict it to the bias of people with low skill, also discussing the reverse effect, i.e., the tendency of highly skilled people to underestimate their abilities relative to the abilities of others.[2][4][9] In this case, the source of the error may not be the self-assessment of one's skills, but an overly positive assessment of the skills of others.[2] This phenomenon can be understood as a form of the false-consensus effect, i.e., the tendency to "overestimate the extent to which other people share one's beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours".[10][2][9] Not knowing the scope of your own ignorance is part of the human condition. The problem with it is we see it in other people, and we don't see it in ourselves. The first rule of the Dunning–Kruger club is you don't know you're a member of the Dunning–Kruger club.-- David Dunning[11] Some researchers include a metacognitive component in their definition. In this view, the Dunning–Kruger effect is the thesis that those who are incompetent in a given area tend to be ignorant of their incompetence, i.e., they lack the metacognitive ability to become aware of their incompetence. This definition lends itself to a simple explanation of the effect: incompetence often includes being unable to tell the difference between competence and incompetence. For this reason, it is difficult for the incompetent to recognize their incompetence.[12][5] This is sometimes termed the "dual-burden" account, since low performers are affected by two burdens: they lack a skill and they are unaware of this deficiency.[9] Other definitions focus on the tendency to overestimate one's ability and see the relation to metacognition as a possible explanation that is not part of the definition.[5][9][13] This contrast is relevant since the metacognitive explanation is controversial. Many criticisms of the Dunning–Kruger effect target this explanation but accept the empirical findings that low performers tend to overestimate their skills.[8][9][13] Among laypeople, the Dunning–Kruger effect is often misunderstood as the claim that people with low intelligence are more confident in their knowledge and skills than people with high intelligence.[14] According to psychologist Robert D. McIntosh and his colleagues, it is sometimes understood in popular culture as the claim that "stupid people are too stupid to know they are stupid".[15] But the Dunning–Kruger effect applies not to intelligence in general but to skills in specific tasks. Nor does it claim that people lacking a given skill are as confident as high performers. Rather, low performers overestimate themselves but their confidence level is still below that of high performers.[14][1][7] |

定義 ダニングとクルーガーの効果とは、特定の分野において能力が低い人が、その能力に対して過度に肯定的な評価を下す傾向として定義される[2][3] [4]。これはしばしば認知バイアス、すなわち誤った思考や判断を行う系統的な傾向として見られる。系統的誤りは、自分の能力を大幅に過大評価する、つま り自分自身を実際よりも熟練していると見なす傾向に関するものである[5]。 ダニングとクルーガーの効果は通常、能力の低い人の自己評価に特化して定義されている[8][5][9]が、理論家の中には、能力の低い人のバイアスに限 定せず、逆の効果、すなわち この場合、誤りの原因は自分のスキルに対する自己評価ではなく、他者のスキルに対する過剰な肯定的評価である可能性がある[2]。この現象は偽合意効果、 すなわち「他の人々が自分の信念、態度、行動を共有する程度を過大評価する」傾向の一形態として理解することができる[10][2][9]。 自分の無知の範囲を知らないことは、人間の条件の一部である。問題なのは、私たちは他人の無知に気づき、自分の無知に気づかないことである。ダニング・クルーガー・クラブの最初のルールは、自分がダニング・クルーガー・クラブのメンバーであることに気づかないことだ。——デイヴィッド・ダニング[11] 定義にメタ認知的要素を含める研究者もいる。この見解では、ダニングとクルーガーの効果とは、ある領域で無能な人は自分の無能さに気づかない傾向がある、 つまり自分の無能さを自覚するメタ認知能力が欠如しているというテーゼである。この定義は、この効果を簡単に説明するのに適している。無能とは、しばしば 有能と無能の区別がつかないことを含むのである。他の定義では、自分の能力を過大評価する傾向 に焦点を当て、メタ認知との関連は定義に含まれない可能 性のある説明であるとしている[5][9][13]。ダニング-クルーガー効果に対する多くの批判はこの説明を対象としているが、成績の低い者は自分のス キルを過大評価する傾向があるという経験的知見は受け入れている[8][9][13]。 心理学者のロバート・D・マッキントッシュとその同僚によると、ダニン グ=クルーガー効果は大衆文化の中で「バカな人はバカすぎて自分がバカで あることを知らない」という主張として理解されることがある[15]。ダニングとクルーガーの効果は、あるスキルに欠けている人が、高い成果を上げている 人と同じくらい自信があると主張するものでもない。むしろ、低業績者は自分自身を過大評価しているが、その自信のレベルは依然として高業績者のそれを下 回っている[14][1][7]。 |

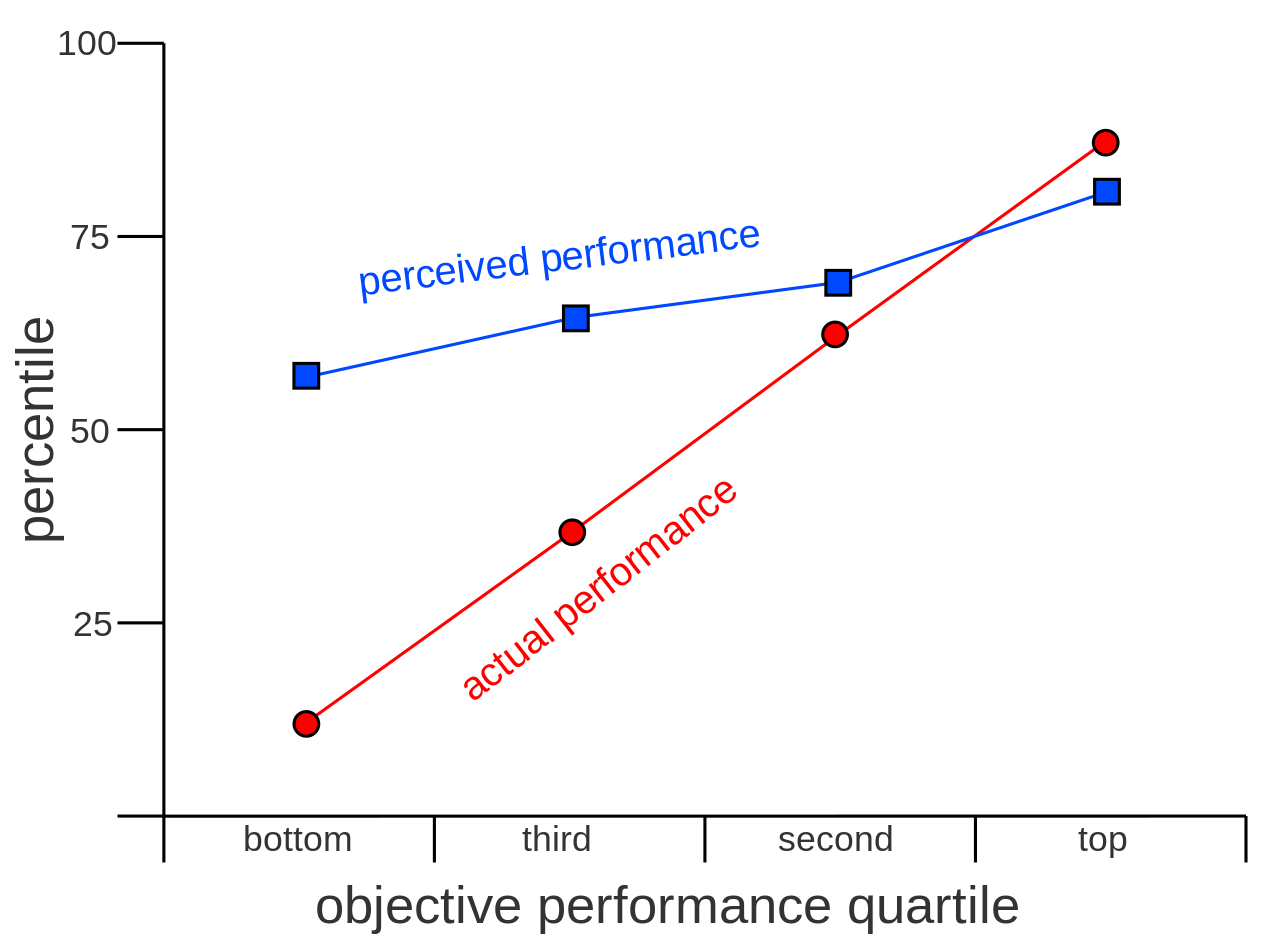

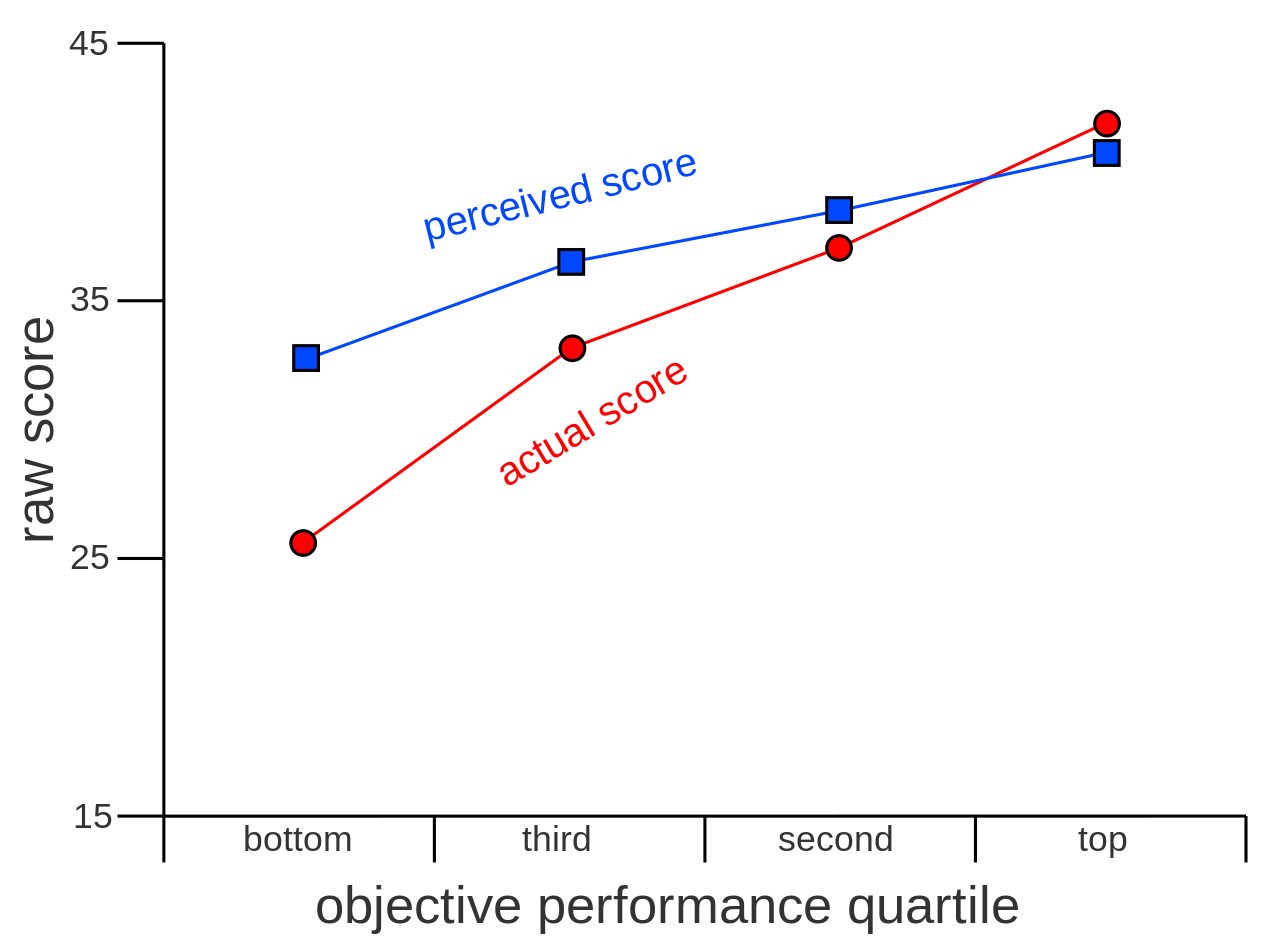

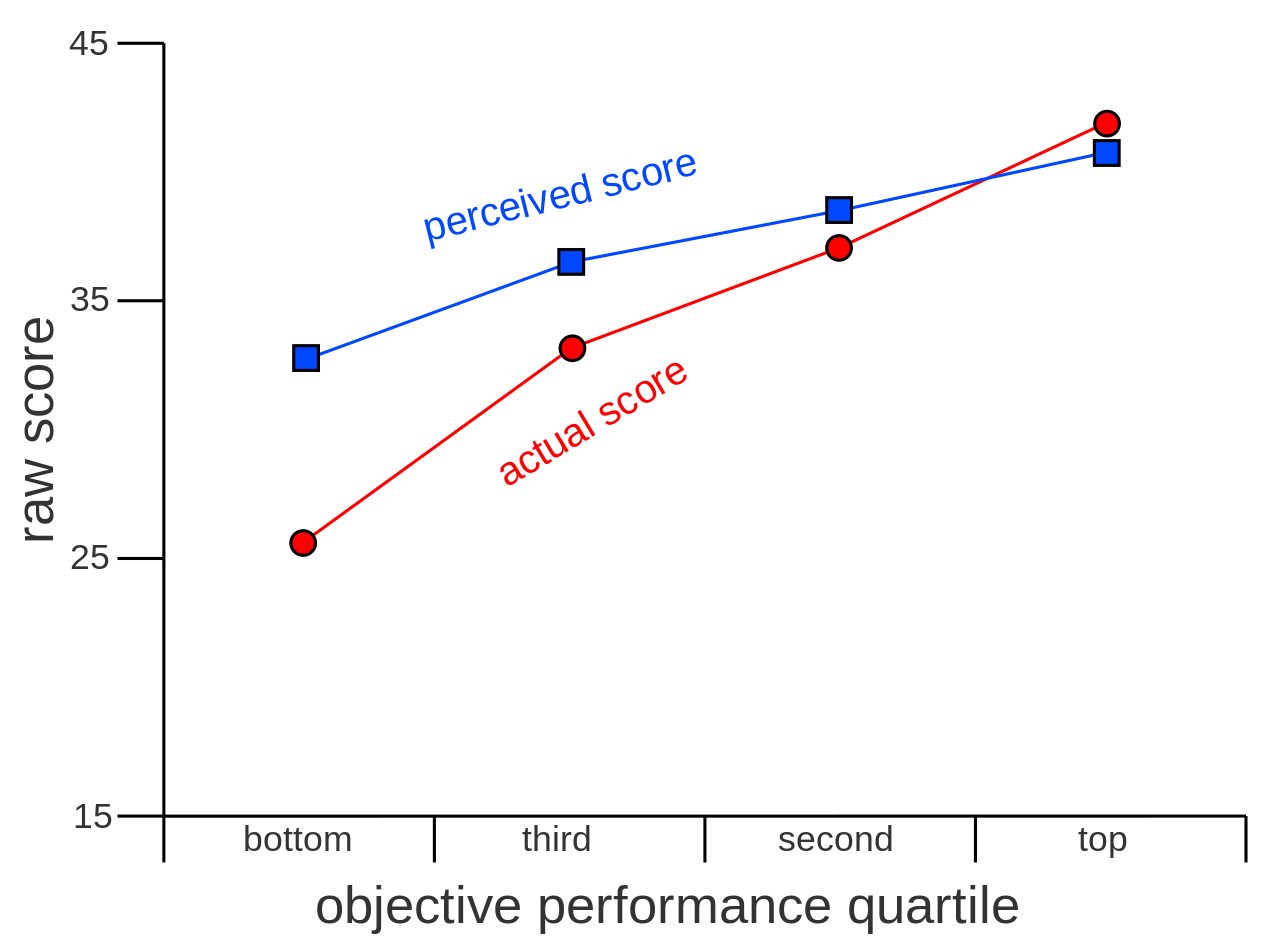

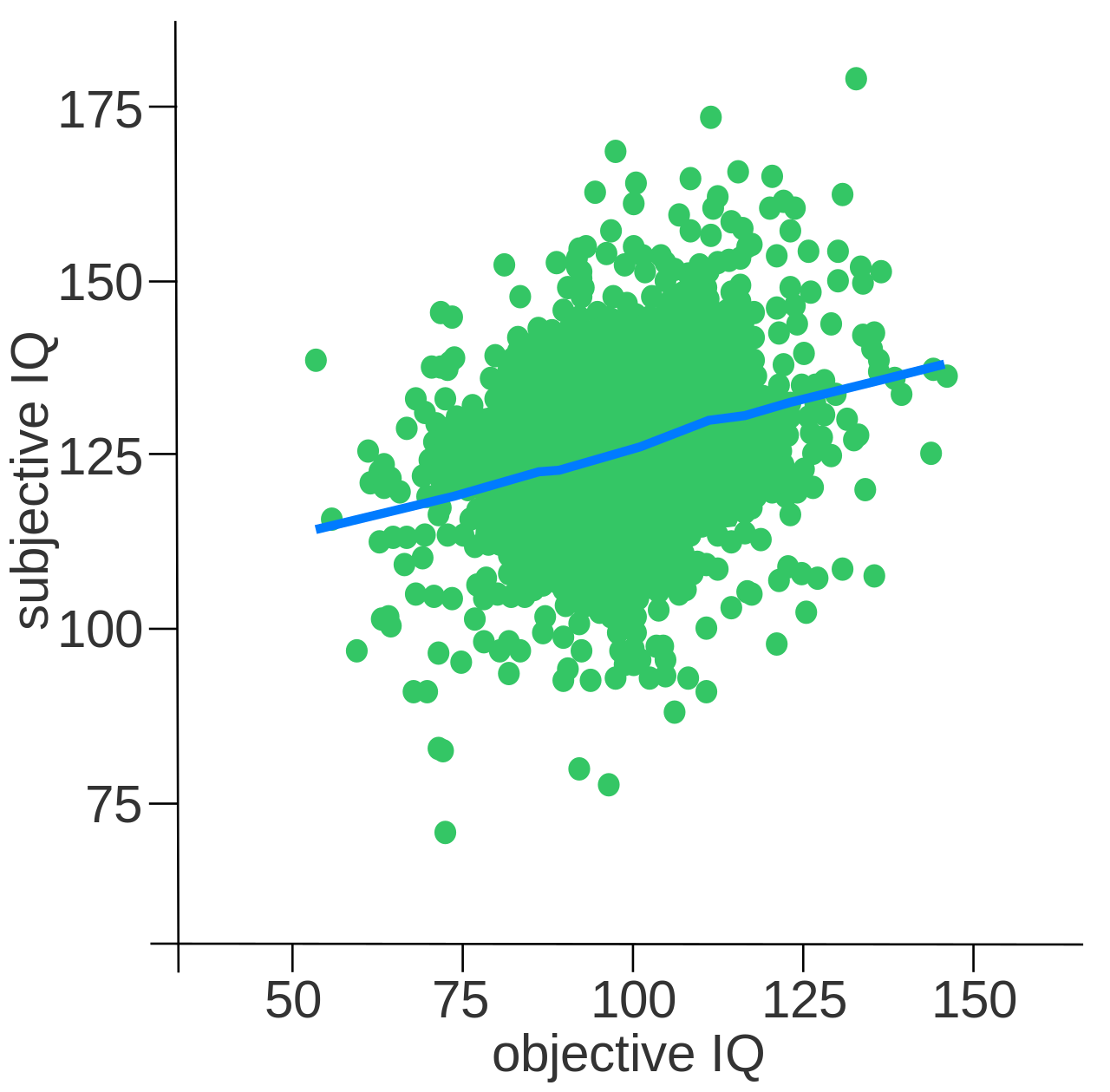

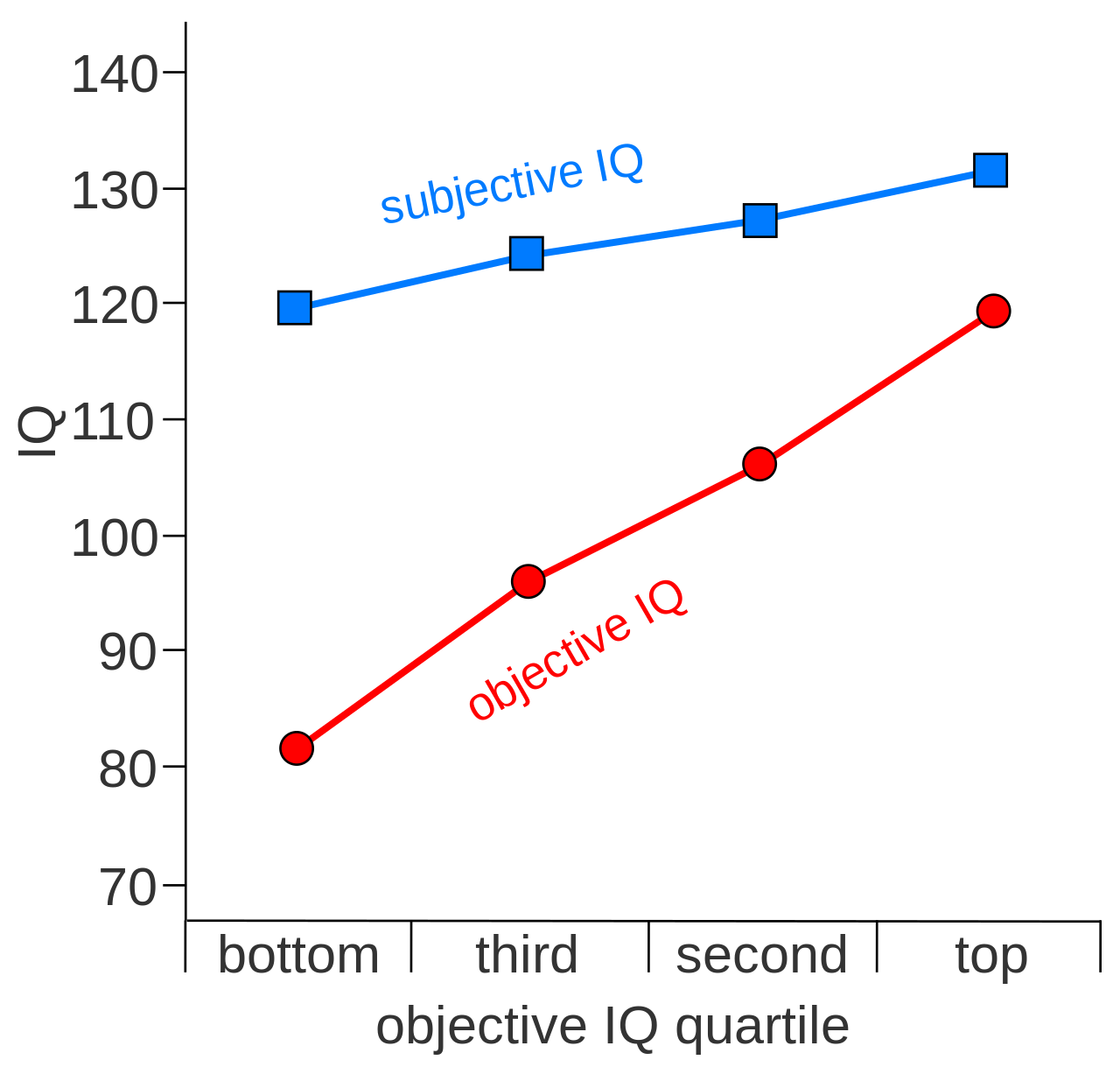

| Measurement, analysis, and investigated tasks Performance in relation to peer group  Performance in relation to number of correct responses  Performance at an exam with 45 questions, measured first in relation to the peer group (top) and then in relation to the number of questions answered correctly (bottom). The diagram shows the average performance of the groups corresponding to each quartile.[16] The most common approach to measuring the Dunning–Kruger effect is to compare self-assessment with objective performance. The self-assessment is sometimes called subjective ability in contrast to the objective ability corresponding to the actual performance.[7] The self-assessment may be done before or after the performance.[9] If done afterward, the participants receive no independent clues during the performance as to how well they did. Thus, if the activity involves answering quiz questions, no feedback is given as to whether a given answer was correct.[13] The measurement of the subjective and the objective abilities can be in absolute or relative terms. When done in absolute terms, self-assessment and performance are measured according to objective standards, e.g. concerning how many quiz questions were answered correctly. When done in relative terms, the results are compared with a peer group. In this case, participants are asked to assess their performances in relation to the other participants, for example in the form of estimating the percentage of peers they outperformed.[17][13][2] The Dunning–Kruger effect is present in both cases, but tends to be significantly more pronounced when done in relative terms. This means that people are usually more accurate when predicting their raw score than when assessing how well they did relative to their peer group.[18] The main point of interest for researchers is usually the correlation between subjective and objective ability.[7] To provide a simplified form of analysis of the measurements, objective performances are often divided into four groups. They start from the bottom quartile of low performers and proceed to the top quartile of high performers.[2][7] The strongest effect is seen for the participants in the bottom quartile, who tend to see themselves as being part of the top two quartiles when measured in relative terms.[19][7][20] The initial study by David Dunning and Justin Kruger examined the performance and self-assessment of undergraduate students in inductive, deductive, and abductive logical reasoning; English grammar; and appreciation of humor. Across four studies, the research indicates that the participants who scored in the bottom quartile overestimated their test performance and their abilities. Their test scores placed them in the 12th percentile, but they ranked themselves in the 62nd percentile.[21][22][5] Other studies focus on how a person's self-view causes inaccurate self-assessments.[23] Some studies indicate that the extent of the inaccuracy depends on the type of task and can be improved by becoming a better performer.[24][25][21] Overall, the Dunning–Kruger effect has been studied across a wide range of tasks, in aviation, business, debating, chess, driving, literacy, medicine, politics, spatial memory, and other fields.[5][9][26] Many studies focus on students—for example, how they assess their performance after an exam. In some cases, these studies gather and compare data from different countries.[27][28] Studies are often done in laboratories; the effect has also been examined in other settings. Examples include assessing hunters' knowledge of firearms and large Internet surveys.[19][13] |

測定、分析、調査課題 仲間との関係における成績  正答数に対する成績  45問の試験での成績。まず同級生グループとの関係で測定し(上)、次に正解した問題数との関係で測定した(下)。この図は、各四分位群に対応するグループの平均成績を示す[16]。 ダニングとクルーガーの効果を測定する最も一般的なアプローチは、自己評価と客観的パフォーマンスを比較することです。自己評 価は、実際のパフォーマンスに対応する客観的能力と対比 して、主観的能力と呼ばれることがある[7]。自己評 価は、パフォーマンスの前または後に行われる[9]。したがって、クイズに答える活動であれば、与えられた答えが 正しかったかどうかについてのフィードバックは与えられない[13]。絶対的な用語で行われる場合、自己評価とパフォーマンスは客観的な基準に従って測定 される。相対的な観点で行われる場合、結果は同僚グループと比較される。この場 合、参加者は他の参加者との関係において自分のパフ ォーマンスを評価するよう求められる。つまり、人は通常、仲間グループとの相対的な比較でどれだけうまくいったかを評価するときよりも、自分の生のスコア を予測するときの方がより正確だということです[18]。 研究者の主な関心事は、通常、主観的能力と客観的能力の相関関係である[7]。測定値の簡略化された分析形式を提供するために、客観的成績はしばしば4つ のグループに分けられる。最も強い効果が見られるのは、下位4分の1の参加者であ り、相対的に測定された場合、上位2つの4分の1に属していると見な す傾向がある[19][7][20]。 デビッド・ダニングとジャスティン・クルーガーによる最初の研究では、帰納的、演繹的、および帰納的論理的推論、英文法、およびユーモアの鑑賞における学 部生のパフォーマンスと自己評価が調査された。4つの研究を通して、下位4分の1の得点の参加者は、テストの成績と自分の能力を過大評価していることがわ かった。21][22][5]他の研究では、人の自己観がどのように不正確な自己評 価を引き起こすかに焦点が当てられている[23]。いくつかの研 究では、不正確さの程度は課題のタイプに依存し、より良いパフォーマ ンになることで改善できることが示されている[24][25][21]。 全体として、ダニングとクルーガーの効果は、航空、ビジネス、ディベート、チェス、運転、読み書き、医学、政治、空間記憶、その他の分野など、幅広いタス クで研究されている[5][9][26]。このような研究では、異なる国のデータを収集し、比較する場合もある[27][28]。研究は多くの場合研究室 で行われるが、他の環境でも効果が検討されている。例えば、狩猟者の銃器に関する知識の評価や大規模なインターネット調査などがある[19][13]。 |

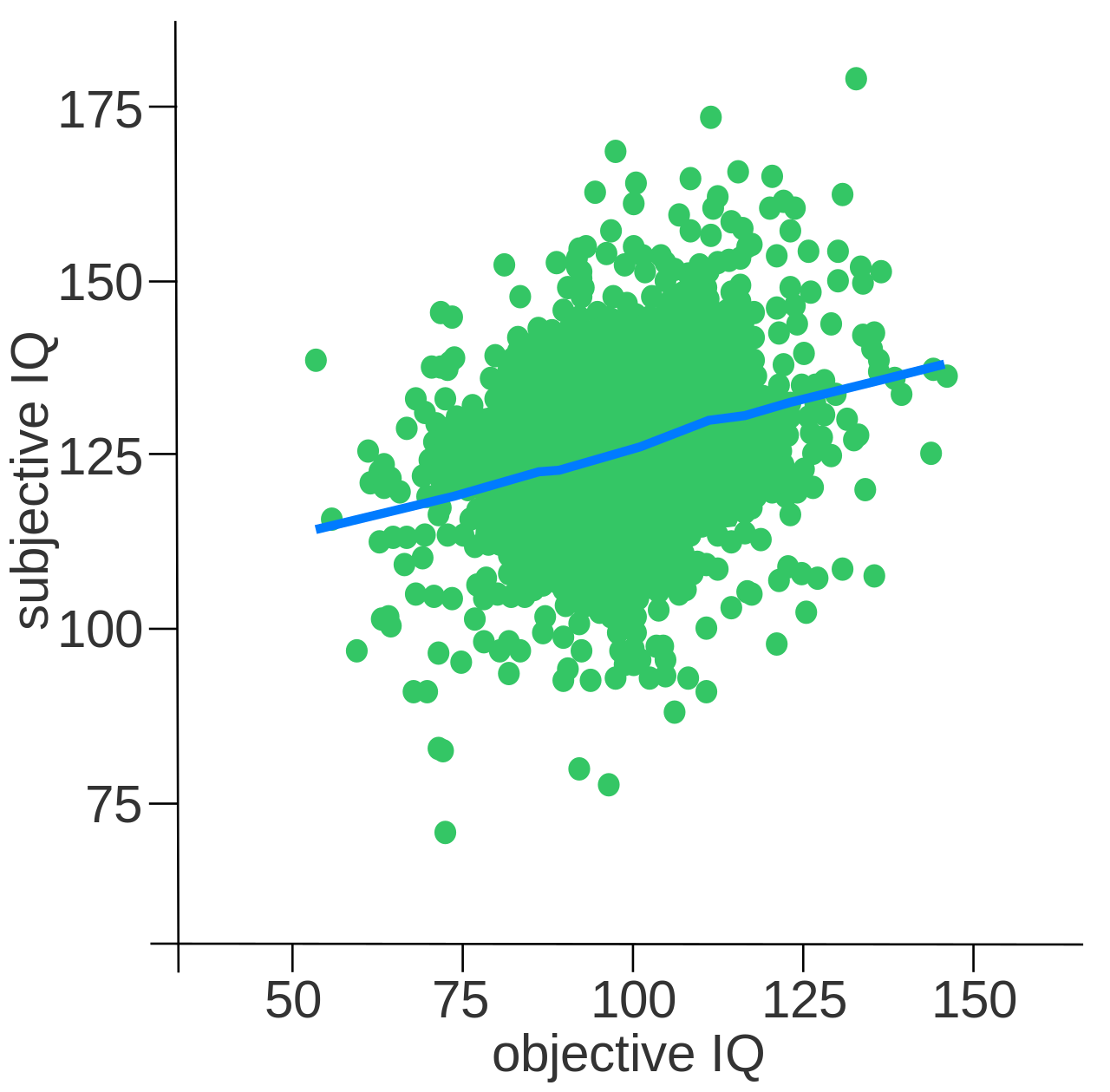

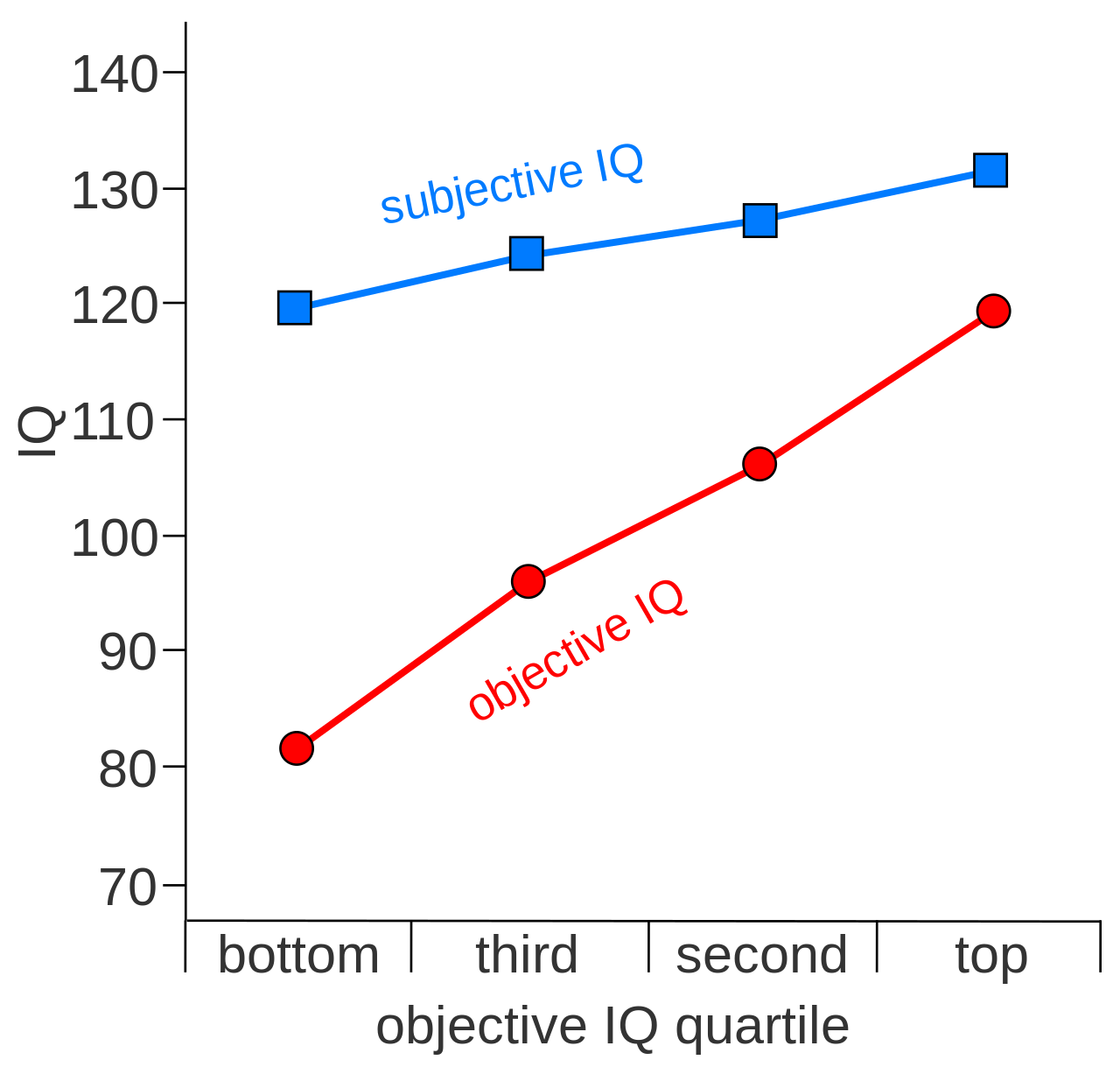

| Explanations Various theorists have tried to provide models to explain the Dunning–Kruger effect's underlying causes.[13][20][9] The original explanation by Dunning and Kruger holds that a lack of metacognitive abilities is responsible. This interpretation is not universally accepted, and many alternative explanations are discussed in the academic literature. Some of them focus only on one specific factor, while others see a combination of various factors as the cause.[29][13][5] Metacognitive The metacognitive explanation rests on the idea that part of acquiring a skill consists in learning to distinguish between good and bad performances of the skill. It assumes that people of low skill level are unable to properly assess their performance because they have not yet acquired the discriminatory ability to do so. This leads them to believe that they are better than they actually are because they do not see the qualitative difference between their performance and that of others. In this regard, they lack the metacognitive ability to recognize their incompetence.[5][7][30] This model has also been called the "dual-burden account" or the "double-burden of incompetence", since the burden of regular incompetence is paired with the burden of metacognitive incompetence.[9][13][15] The metacognitive lack may hinder some people from becoming better by hiding their flaws from them.[31] This can then be used to explain how self-confidence is sometimes higher for unskilled people than for people with an average skill: only the latter are aware of their flaws.[32][33] Some attempts have been made to measure metacognitive abilities directly to examine this hypothesis. Some findings suggest that poor performers have reduced metacognitive sensitivity, but it is not clear that its extent is sufficient to explain the Dunning–Kruger effect.[9] Another study concluded that unskilled people lack information but that their metacognitive processes have the same quality as those of skilled people.[15] An indirect argument for the metacognitive model is based on the observation that training people in logical reasoning helps them make more accurate self-assessments.[2] Many criticisms of the metacognitive model hold that it has insufficient empirical evidence and that alternative models offer a better explanation.[20][9][13] Statistical and better-than-average effect Individual data points  Group averages  Simulated data of the relation between subjective (self-assessed) and objective IQ. The upper diagram shows the individual data points and the lower one shows the averages of the different IQ groups. This simulation is based only on the statistical effect known as the regression toward the mean together with the better-than-average effect. Proponents of the statistical explanation use it to support their claim that these two factors are sufficient to explain the Dunning–Kruger effect.[7] A different interpretation is further removed from the psychological level and sees the Dunning–Kruger effect as mainly a statistical artifact.[7][34][30] It is based on the idea that the statistical effect known as regression toward the mean explains the empirical findings. This effect happens when two variables are not perfectly correlated: if one picks a sample that has an extreme value for one variable, it tends to show a less extreme value for the other variable. For the Dunning–Kruger effect, the two variables are actual performance and self-assessed performance. If a person with low actual performance is selected, their self-assessed performance tends to be higher.[13][7][30] Most researchers acknowledge that regression toward the mean is a relevant statistical effect that must be taken into account when interpreting the empirical findings. This can be achieved by various methods.[35][9] Some theorists, like Gilles Gignac and Marcin Zajenkowski, go further and argue that regression toward the mean in combination with other cognitive biases, like the better-than-average effect, can explain most of the empirical findings.[2][7][9] This type of explanation is sometimes called "noise plus bias".[15] According to the better-than-average effect, people generally tend to rate their abilities, attributes, and personality traits as better than average.[36][37] For example, the average IQ is 100, but people on average think their IQ is 115.[7] The better-than-average effect differs from the Dunning–Kruger effect since it does not track how the overly positive outlook relates to skill. The Dunning–Kruger effect, on the other hand, focuses on how this type of misjudgment happens for poor performers.[38][2][4] When the better-than-average effect is paired with regression toward the mean, it shows a similar tendency. This way, it can explain both that unskilled people greatly overestimate their competence and that the reverse effect for highly skilled people is much less pronounced.[7][9][30] This can be shown using simulated experiments that have almost the same correlation between objective and self-assessed ability as actual experiments.[7] Some critics of this model have argued that it can explain the Dunning–Kruger effect only when assessing one's ability relative to one's peer group. But it may not be able to explain self-assessment relative to an objective standard.[39][9] A further objection claims that seeing the Dunning–Kruger effect as a regression toward the mean is only a form of relabeling the problem and does not explain what mechanism causes the regression.[40][41] Based on statistical considerations, Nuhfer et al. arrive at the conclusion that there is no strong tendency to overly positive self-assessment and that the label "unskilled and unaware of it" applies only to few people.[42][43]; Dunning has defended his findings.[44] At least one researcher makes the case that this effect is the only one shown in the original and subsequent papers.[45] Rational The rational model of the Dunning–Kruger effect explains the observed regression toward the mean not as a statistical artifact but as the result of prior beliefs.[13][30][20] If low performers expect to perform well, this can cause them to give an overly positive self-assessment. This model uses a psychological interpretation that differs from the metacognitive explanation. It holds that the error is caused by overly positive prior beliefs and not by the inability to correctly assess oneself.[30] For example, after answering a ten-question quiz, a low performer with only four correct answers may believe they got two questions right and five questions wrong, while they are unsure about the remaining three. Because of their positive prior beliefs, they will automatically assume that they got these three remaining questions right and thereby overestimate their performance.[13] Distribution of high and low performers Another model sees the way high and low performers are distributed as the source of erroneous self-assessment.[46][20] It is based on the assumption that many low performers' skill levels are very similar, i.e., that "many people [are] piled up at the bottom rungs of skill level".[2] This would make it much more difficult for them to accurately assess their skills in relation to their peers.[9][46] According to this model, the reason for the increased tendency to give false self-assessments is not a lack of metacognitive ability but a more challenging situation in which this ability is applied.[46][2][9] One criticism of this interpretation is directed against the assumption that this type of distribution of skill levels can always be used as an explanation. While it can be found in various fields where the Dunning–Kruger effect has been researched, it is not present in all of them. Another criticism holds that this model can explain the Dunning–Kruger effect only when the self-assessment is measured relative to one's peer group. But it may fail when it is measured relative to absolute standards.[2] Lack of incentive A further explanation, sometimes given by theorists with an economic background, focuses on the fact that participants in the corresponding studies lack incentive to give accurate self-assessments.[47][48] In such cases, intellectual laziness or a desire to look good to the experimenter may motivate participants to give overly positive self-assessments. For this reason, some studies were conducted with additional incentives to be accurate. One study gave participants a monetary reward based on how accurate their self-assessments were. These studies failed to show any significant increase in accuracy for the incentive group in contrast to the control group.[47] Practical significance There are disagreements about the Dunning–Kruger effect's magnitude and practical consequences as compared to other psychological effects. Claims about its significance often focus on how it causes affected people to make decisions that have bad outcomes for them or others. For example, according to Gilles E. Gignac and Marcin Zajenkowski, it can have long-term consequences by leading poor performers into careers for which they are unfit. High performers underestimating their skills, though, may forgo viable career opportunities matching their skills in favor of less promising ones that are below their skill level. In other cases, the wrong decisions can also have short-term effects. For example, Pavel et al. hold that overconfidence can lead pilots to operate a new aircraft for which they lack adequate training or to engage in flight maneuvers that exceed their proficiency.[4][7][8] Emergency medicine is another area where the correct assessment of one's skills and the risks of treatment matters. According to Lisa TenEyck, the tendencies of physicians in training to be overconfident must be considered to ensure the appropriate degree of supervision and feedback.[33] Schlösser et al. hold that the Dunning–Kruger effect can also negatively affect economic activities. This is the case, for example, when the price of a good, such as a used car, is lowered by the buyers' uncertainty about its quality. An overconfident buyer unaware of their lack of knowledge may be willing to pay a much higher price because they do not take into account all the potential flaws and risks relevant to the price.[2] Another implication concerns fields in which researchers rely on people's self-assessments to evaluate their skills. This is common, for example, in vocational counseling or to estimate students' and professionals' information literacy skills.[3][7] According to Khalid Mahmood, the Dunning–Kruger effect indicates that such self-assessments often do not correspond to the underlying skills. It implies that they are unreliable as a method for gathering this type of data.[3] Regardless of the field in question, the metacognitive ignorance often linked to the Dunning–Kruger effect may inhibit low performers from improving themselves. Since they are unaware of many of their flaws, they may have little motivation to address and overcome them.[49][50] Not all accounts of the Dunning–Kruger effect focus on its negative sides. Some also concentrate on its positive sides, e.g. that ignorance is sometimes bliss. In this sense, optimism can lead people to experience their situation more positively, and overconfidence may help them achieve even unrealistic goals.[51] To distinguish the negative from the positive sides, two important phases have been suggested to be relevant for realizing a goal: preparatory planning and the execution of the plan. According to Dunning, overconfidence may be beneficial in the execution phase by increasing motivation and energy. However it can be detrimental in the planning phase since the agent may ignore bad odds, take unnecessary risks, or fail to prepare for contingencies. For example, being overconfident may be advantageous for a general on the day of battle because of the additional inspiration passed on to his troops. But it can be disadvantageous in the weeks before by ignoring the need for reserve troops or additional protective gear.[52] In 2000, Kruger and Dunning were awarded the satirical Ig Nobel Prize in recognition of the scientific work recorded in "their modest report".[53] |

説明 様々な理論家がダニングとクルーガーの効果の根底にある原因を説明するモデルを提供しようとしてきた。ダニングとクルーガーによるオリジナルの説明は、メ タ認知能力の欠如が原因であるとするものである。この解釈は普遍的に受け入れられているわけではなく、多くの代替的な説明が学術文献で議論されている。そ の中には、ある特定の要因のみに焦点を当てたものもあれば、様々な要因の組み合わせが原因であるとするものもある[29][13][5]。 メタ認知的 メタ認知的な説明は、技能習得の一部は、技能の良いパフォーマンスと悪いパフォーマンスを区別することを学ぶことにあるという考えに基づいている。スキル レベルが低い人は、自分のパフォーマンスを適切に評価することができない。そのため、自分のパフォーマンスと他人のパフォーマンスの質的な違いが分から ず、自分は実際よりも優れていると思い込んでしまう。この点で、彼らは自分の無能さを認識するメタ認知能力を欠いている。[5][7][30] このモデルは、通常の無能さの負担とメタ認知的無能さの負担が対になっていることから、「二重の負担の説明」または「無能さの二重の負担」とも呼ばれてい る。 [9][13][15]メタ認知の欠如は、ある人々が自分の欠点を隠 すことによって、より良くなることを妨げるかもしれない[31]。 この仮説を検証するためにメタ認知能力を直接測定する試みがいくつかなされている。しかし、その程度がダニング-クルーガー効 果を説明するのに十分であるかどうかは明らかではない。 [メタ認知モデルに対する間接的な論拠は、論理的推論を訓練することで、より正確な自己評価ができるようになるという観察に基づいている[2]。メタ認知 モデルに対する多くの批判は、メタ認知モデルには十分な経験的証拠がなく、代替モデルの方がより良い説明ができるとしている[20][9][13]。 統計的効果と平均以上の効果 個々のデータ点  グループ平均  主観的(自己評価)IQと客観的IQの関係のシミュレーションデータ。上の図は個々のデータポイントを示し、下の図は異なるIQグループの平均を示す。こ のシミュレーションは、平均への回帰として知られる統計的効果と、平均より良い効果のみに基づいている。統計的説明の支持者は、ダニングとクルーガーの効 果を説明するにはこの2つの要因で十分だという主張を支持するためにこのシミュレーションを使用している[7]。 異なる解釈は、心理学的なレベルからさらに離れており、ダニングとクルーガーの効果を主に統計的な人工物であると見なしている。この効果は、2つの変数が 完全に相関していないときに起こります:1つの変数について極端な値を持つサンプルを選ぶと、もう1つの変数については極端でない値を示す傾向がありま す。ダニングとクルーガーの効果では、2つの変数とは実際の成績と自己評価による成績である。実際のパフォーマンスが低い人が選ばれた場合、その人の自己 評価パフォーマンスは高くなる傾向がある[13][7][30]。 ほとんどの研究者は、平均への回帰が経験的知見を解釈する際に考慮しなければならない関連した統計的効果であることを認めている。これは様々な方法によっ て達成することができる[35][9]。ジル・ジニャックやマーシン・ザジェンコフスキのような一部の理論家は、さらに進んで、平均への回帰が better-than-average効果のような他の認知バイアスと組み合わさって、経験的知見のほとんどを説明することができると主張している [2][7][9]。このタイプの説明は、「ノイズ+バイアス」と呼ばれることがある[15]。 平均より優れている効果によると、人々は一般的に自分の能力、属性、性格特性を平均より優れていると評価する傾向がある[36][37]。例えば、平均 IQは100であるが、人々は平均的に自分のIQは115であると考えている。一方、ダニングとクルーガーの効果は、この種の誤判 断が成績不振者にどのように起こるかに焦点を当てている[38][2][4]。ベター・ ザン・アベレージ効果を平均への回帰と対にすると、同様の傾向を示す。この方法では、熟練していない人が自分の能力を大幅に過大評価することと、熟練した 人の逆効果がはるかに顕著でないことの両方を説明することができる[7][9][30]。このことは、客観的能力と自己評価能力の間に実際の実験とほぼ同 じ相関がある模擬実験を使って示すことができる[7]。 このモデルを批判する人の中には、このモデルがダニングとクルーガーの効果を説明できるのは、自分の能力を仲間グループと相対的に評価する場合だけだと主 張する人もいる。さらなる反論は、ダニングとクルーガーの効果を平均への回帰と見ることは問題を再ラベル化する形に過ぎず、どのようなメカニズムが回帰を 引き起こすのかを説明していないと主張している[40][41]。 統計的考察に基づき、Nuhferらは、過度に肯定的な自己評価には強い傾向はなく、「スキルがなくそれに気づいていない」というレッテルは少数の人にしか当てはまらないという結論に達している[42][43]。 合理的 ダニングとクルーガーの効果の合理的モデルは、観察された平均への回帰を統計的な人工物ではなく、事前の信念の結果として説明する[13][30] [20] 。このモデルは、メタ認知的説明とは異なる心理学的解釈を用 いている。例えば、10問の小テストに答えた後、4問しか正答できな かった成績下位者は、2問は正解し、5問は間違ったが、残りの 3問については自信がないと考えるかもしれない。事前信念が肯定的であるため、残りの3問は 正解したと自動的に思い込み、それによって自分のパフォーマ ンスを過大評価することになる[13]。 成績上位者と下位者の分布 別のモデルでは、高成績者と低成績者の分布方法が誤った自己評 価の原因であると見ている[46][20]。このモデルは、低成績者の多く のスキルレベルは非常に似ているという仮定に基づいてい る、 このモデルによれば、誤った自己評価をする傾向が高まる理由は、メタ認知能力の欠如ではなく、この能力が適用されるより困難な状況にある。ダニングとク ルーガーの効果が研究されている様々な分野で見られるが、すべての分野で見られるわけではない。もう一つの批判は、このモデルがダニングとクルーガーの効 果を説明できるのは、自己評価が同輩グループとの相対評価で測られた場合だけだというものである。しかし、絶対的な基準に対して相対的に測定した場合には 失敗する可能性がある[2]。 インセンティブの欠如 このような場合、知的怠慢や実験者に良く見られたいという欲求が、参加者が過度に肯定的な自己評価をする動機となる可能性がある[47][48]。このた め、いくつかの研究では、正確であるための追加的な動機づけが実施された。ある研究では、自己評価の正確さに応じて参加者に金銭的報酬を与えた。これらの 研究では、対照群とは対照的に、インセンティブ群では精度の有意な増加は示されなかった[47]。 実際的意義 ダニングとクルーガーの効果の大きさや他の心理学的効果と比較した場合の実際的な結果については意見が分かれている。ダニングとクルーガーの効果の重要性 についての主張は、影響を受けた人々が自分または他人にとって悪い結果をもたらす意思決定をどのように行うかということに焦点が当てられることが多い。例 えば、ジル・E・ジニャックとマーシン・ザジェンコフスキーによれば、この効果は、成績不振者を適性のないキャリアに導くことによって、長期的な結果をも たらす可能性がある。しかし、自分のスキルを過小評価しているハイパフォーマーは、自分のスキルに見合った有望なキャリアの機会を見送り、自分のスキルレ ベルよりも低い有望なキャリアを選ぶかもしれない。また、誤った決断が短期的な影響を及ぼす場合もある。例えば、Pavelらは、パイロットが過信するこ とによって、十分な訓練を受けていない新しい航空機を操縦したり、熟練度を超える飛行操作を行ったりする可能性があるとしている[4][7][8]。 救急医療もまた、自分の技能と治療のリスクを正しく評価することが重要な分野である。リサ・テネイクによると、適切な監督とフィードバックの程度を確保す るためには、研修中の医師が過信する傾向を考慮しなければならない[33]。シュレッサーらは、ダニングとクルーガーの効果は経済活動にも悪影響を及ぼす 可能性があるとしている。例えば、中古車のような財の価格が、その品質に対する買い手の不確実性によって引き下げられる場合がそうである。自分の知識不足 に気づいていない自信過剰な買い手は、価格に関連する潜在的な欠陥やリスクをすべて考慮していないため、はるかに高い価格を支払うことを望むかもしれない [2]。 もう1つの意味合いは、研究者が人々のスキルを評価するために自己評価に依存している分野に関係する。これは、例えば職業カウンセリングや学生や専門家の 情報リテラシー・スキルを推定する際に一般的である[3][7]。Khalid Mahmoodによると、ダニングとクルーガーの効果は、このような自己評価がしばしば根本的なスキルと一致しないことを示している。問題の分野に関係な く、ダニングとクルーガーの効果にしばしば関連するメタ認知的無知は、低業績者の自己改善を阻害する可能性がある。自分の欠点の多くに気づいていないた め、その欠点に対処し克服しようという意欲が乏しいのかもしれない[49][50]。 ダニングとクルーガーの効果に関する説明のすべてが、その負の側面に焦点を当てているわけではない。例えば、無知は時に至福であるといった肯定的な側面に 焦点を当てるものもある。この意味で、楽観主義は人々が自分の状況をより前 向きに経験するように導く可能性があり、自信過剰は非現実 的な目標でさえ達成するのに役立つ可能性がある。ダニングによると、過信は、モチベーションとエネルギーを高めることで、実行段階では有益である可能性が ある。しかし、計画段階では、エージェントが不利な状況を無視したり、不必要なリスクを冒したり、不測の事態への準備を怠ったりする可能性があるため、不 利になる可能性がある。例えば、自信過剰であることは、戦いの日、部隊にさらなるインスピレーションを与えるため、将軍にとっては有利かもしれない。しか し、予備兵力や追加防具の必要性を無視することで、数週間前に不利になることもある[52]。 2000年、クルーガーとダニングは、「彼らのささやかな報告書」に記録された科学的研究が認められ、風刺的なイグ・ノーベル賞を受賞した[53]。 |

| Curse of knowledge – Cognitive bias of failing to disregard information only available to oneself Four stages of competence – Psychological states when gaining a skill Grandiose delusions – Subtype of delusion Hubris – Extreme pride or overconfidence, often in combination with arrogance I know that I know nothing – Famous saying by Socrates Illusion of explanatory depth – Form of cognitive bias Illusory superiority – Overestimating one's abilities and qualifications; a cognitive bias Impostor syndrome – Psychological pattern of doubting one's accomplishments and fearing exposure Narcissism – Excessive preoccupation with oneself Overconfidence effect – Personal cognitive bias Pygmalion effect – Phenomenon in psychology Self-deception – Practice of feigning to be what one is not or to believe what one does not Self-serving bias – Distortion to enhance self-esteem, or to see oneself overly favorably Superiority complex – Psychological defense mechanism articulated by Alfred Adler Ultracrepidarianism – Warning to avoid passing judgement beyond one's expertise – Passing judgment beyond one's expertise |

知識の呪い - 自分にしかない情報を無視できないという認知バイアス 能力の4段階 - 技能を習得するときの心理状態 誇大妄想 - 妄想のサブタイプ 傲慢(ごうまん) - 過度の自尊心や自信過剰。 私は何も知らないことを知っている - ソクラテスの有名な言葉 説明の深さの錯覚 - 認知バイアスの一種 錯覚的優越感 - 自分の能力や資質を過大評価すること。 偽者症候群 - 自分の業績を疑い、暴露されることを恐れる心理的パターン。 ナルシシズム (Narcissism) - 自分自身への過度な偏愛。 過信効果 - 個人的な認知バイアス ピグマリオン効果 - 心理学における現象 自己欺瞞(じこぎまん) - 自分がそうでないように見せかけたり、そうでないことを信じたりすること Self-serving bias(利己的バイアス) - 自尊心を高めるため、または自分を過度に好意的に見るための歪曲。 優越コンプレックス - アルフレッド・アドラーが提唱した心理的防衛機制。 Ultracrepidarianism(ウルトラクレピダリアニズム) - 自分の専門以上の判断を下すことを避けるための警告 - 自分の専門以上の判断を下すこと |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunning%E2%80%93Kruger_effect |

|

| Impostor syndrome,

also known as impostor phenomenon or impostorism, is a psychological

occurrence. Those who have it may doubt their skills, talents, or

accomplishments. They may have a persistent internalized fear of being

exposed as frauds.[1] Despite external evidence of their competence,

those experiencing this phenomenon do not believe they deserve their

success or luck. They may think that they are deceiving others because

they feel as if they are not as intelligent as they outwardly portray

themselves to be.[2] Impostor syndrome can stem from and result in

strained personal relationships and can hinder people from achieving

their full potential in their fields of interest.[3] The term

"impostorization" shifts the source of the phenomenon away from the

supposed impostor to institutions whose policies, practices, or

workplace cultures "either make or intend to make individuals question

their intelligence, competence, and sense of belonging."[4] History The term impostor phenomenon was introduced in an article published in 1978, titled "The Impostor Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention" by Pauline R. Clance and Suzanne A. Imes. Clance and Imes defined impostor phenomenon as "an internal experience of intellectual phoniness" and initially focused their research on women in higher education and professional industries.[5] The researchers surveyed over 100 women, approximately one-third of whom were involved in psychotherapy for reasons besides impostor syndrome and two-thirds of whom they knew from their own lectures and therapy groups. All of the participants had been formally recognized for their professional excellence by colleagues and displayed academic achievement through educational degrees and standardized testing scores. Despite the consistent external validation these women received, they lacked internal acknowledgement of their accomplishments. When asked about their success, some participants attributed it to luck, while some believed that people had overestimated their capabilities. Clance and Imes believed that this mental framework of impostor phenomenon developed from factors such as gender stereotypes, familial problems, cultural norms, and attribution style. They discovered that the women in the study experienced symptoms of "generalized anxiety, lack of self-confidence, depression, and frustration related to inability to meet self-imposed standards of achievement."[6] Psychopathology People with impostor syndrome may see themselves as less ill (less depressed, less anxious) than their peers or other mentally ill people, citing their lack of severe symptoms as the indication of the absence of or a minor underlying issue. People with this mindset often do not seek help for their issues because they see their problems as not worthy of psychiatric attention.[7][8] Impostor phenomenon is studied as a reaction to particular stimuli and events. It is an experience that a person has, not a mental disorder.[9] Impostor phenomenon is not recognized in the DSM or ICD, although both of these classification systems recognize low self-esteem and sense of failure as associated symptoms of depression.[10] |

イ

ンポスター症候群は、インポスター現象またはインポストリズムとも呼ばれ、心理的な出来事である。この症候群にかかった人は、自分の技能、才能、業績を疑

うことがある。自分が有能であるという外的証拠があるにもかかわらず、この現象を経験している人は、自分が成功や幸運に値するとは思っていない。偽者=イ

ンポスター症候群は、個人的な人間関係の緊張に起因し、その結果、人々が関心のある分野で潜在能力を十分に発揮することを妨げる可能性がある[3]。

「偽者化」という用語は、この現象の原因を、偽者=インポスターとされる人物から、「個人の知性、能力、帰属意識に疑問を抱かせるか、抱かせることを意図

している」政策、慣行、または職場文化を持つ機関に移すものである[4]。 歴史 インポスター現象という言葉は、1978年に発表された論文「The Impostor Phenomenon in High Achieving Women」で紹介された: Pauline R. ClanceとSuzanne A. Imesによる "The Impostor Phomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention "という論文で紹介されました。ClanceとImesは、インポスター現象を「知的インチキの内的経験」と定義し、当初は高等教育や専門的な業界で働く 女性に焦点を当てて研究を行っていた[5]。 研究者たちは100人以上の女性を調査し、そのうちの約3分の1はインポスター症候群以外の理由で心理療法を受けており、3分の2は自分たちの講義やセラ ピー・グループで知り合った人たちであった。参加者は全員、同僚から仕事上の卓越性を正式に認められており、学位や標準化テストの成績によって学問的成果 を示していた。彼女たちは一貫して外面的な評価を受けていたにもかかわらず、内面的には自分の業績を認めてもらえなかった。自分の成功について尋ねると、 運が良かったからだと答える参加者もいれば、自分の能力を過大評価されたと考える参加者もいた。クランスとイムズは、このような偽者現象の精神的枠組み は、ジェンダーの固定観念、家族問題、文化的規範、帰属スタイルなどの要因から発展すると考えた。彼らは、研究の女性たちが「全般的な不安、自信の欠如、 抑うつ、自己に課した達成基準を満たせないことに関連する欲求不満」の症状を経験していることを発見した[6]。 精神病理学 偽者症候群の人は、同世代の人や他の精神疾患者よりも自分の方が病気ではない(抑うつ状態や不安感が少ない)と考えることがあり、重い症状がないのは根本 的な問題がないか、あっても軽微であることの表れであるとしている。このような考え方をする人は、自分の問題は精神医学的な注意を払うに値しないと考える ため、しばしば自分の問題に対する助けを求めない[7][8]。 偽者現象は、特定の刺激や出来事に対する反応として研究されている。DSMやICDでは、偽者現象は認められていないが、これらの分類体系では、自尊心の低下や挫折感はうつ病の関連症状として認められている[10]。 |

| The

first scale designated to measure characteristics of impostor

phenomenon was designed by Clance in 1985, called the Clance Impostor

Phenomenon Scale (CIPS). The scale can be used to determine if

characteristics of fear are present in the person, and to what extent.

The aspects of fear include: "fear of evaluation, fear of not

continuing success and fear of not being as capable as others."[11]

Characteristics of impostor syndrome such as a person's self-esteem and

their perspective of how they achieve success are measured by the CIPS.

A sample of 1271 engineering college students were studied by Brian F.

French, Sarah C. Ullrich-French, and Deborah Follman to examine the

psychometric properties of the CIPS. They found that scores of the

scales' individual components were not entirely reliable or consistent

and suggested that these should not be used to make significant

decisions about people with the syndrome.[12] In her 1985 paper, Clance explained that impostor phenomenon can be distinguished by the following six characteristics, of which a person who has impostorism must experience at least two: [2] The impostor cycle The need to be special or the best Characteristics of superman/superwoman Fear of failure Denial of ability and discounting praise Feeling fear and guilt about success Occurrence It has been estimated that nearly 70% of people will experience signs and symptoms of impostor phenomenon at least once in their life.[13] Research shows that impostor phenomenon is not uncommon for students who enter a new academic environment. Feelings of insecurity can come as a result of an unknown, new environment. This can lead to lower self-confidence and belief in their own abilities.[11] Gender differences When impostor syndrome was first conceptualised, it was viewed as a phenomenon that was common among high-achieving women. Further research has shown that it affects both men and women; the proportion affected are more or less equally distributed among the genders.[1][14] People with impostor syndrome often have corresponding mental health issues, which may be treated with psychological interventions, though the phenomenon is not a formal mental disorder.[15] Clance and Imes stated in their 1978 article that, based on their clinical experience, impostor phenomenon was less prevalent in men.[16] However, more recent research has mostly found that impostor phenomenon is spread equally among men and women.[1][17] Research has shown that women commonly face impostor phenomenon in regard to performance. The perception of ability and power is evidenced in out-performing others. For men, impostor phenomenon is often driven by the fear of being unsuccessful, or not good enough.[17] Settings Impostor phenomenon can occur in other various settings. Some examples include a new environment,[2] academic settings,[16] in the workplace,[16] social interactions,[11] and relationships (platonic or romantic).[11] In relationships, people with impostorism often feel they do not live up to the expectations of their friends or loved ones. It is common for the person with impostorism to think that they must have somehow tricked others into liking them and wanting to spend time with them. They experience feelings of being unworthy, or of not deserving the beneficial relationships they possess.[11] There is empirical evidence that demonstrates the harmful effects of impostor phenomenon in students. Studies have shown that when a student's academic self-concept increases, the symptoms of impostor phenomenon decrease, and vice versa.[17] The worry and emotions the students held, had a direct impact of their performance in the program. Common facets of impostor phenomenon experienced by students include not feeling prepared academically (especially when comparing themselves to classmates),[2] questioning the grounds on which they were accepted into the program,[11] and perceiving that positive recognition, awards, and good grades stemmed from external factors rather than personal ability or intelligence.[11] Cokley et al. investigated the impact impostor phenomenon has on students, specifically ethnic minority students. They found that the feelings the students had of being fraudulent resulted in psychological distress. Ethnic minority students often questioned the grounds on which they were accepted into the program. They held the false assumption that they only received their acceptance due to affirmative action—rather than an extraordinary application and qualities they had to offer.[18] Tigranyan et al. (2021) examined the way impostor phenomenon relates to psychology doctoral students. The purpose of the study was to investigate the IP's relationship to perfectionistic cognitions, depression, anxiety, achievement motives, self-efficacy, self-compassion, and self-esteem in clinical and counseling psychology doctoral students. Furthermore, this study sought to investigate how IP interferes with academic, practicum, and internship performance of these students and how IP manifests throughout a psychology doctoral program. Included were 84 clinical and counseling psychology doctoral students and they were instructed to respond to an online survey. The data was analyzed using a Pearson's product-moment correlation and a multiple linear regression. Eighty-eight percent of the students in the study reported at least moderate feelings of IP characteristics. This study also found significant positive correlations between the IP and perfectionistic cognitions, depression, anxiety, and self-compassion. This study indicates that clinical faculty and supervisors should take a supportive approach to assist students to help decrease feelings of IP, in hopes of increasing feelings of competence and confidence.[19] Connections Research has shown that there is a relationship between impostor phenomenon and the following factors: Family expectations[11] Overprotective parent(s) or legal guardian(s)[13] Graduate-level coursework[11] Racial identities[11] Attribution style[17] Anxiety[17] Depression[17] Low trait self-esteem[17] Perfectionism[16] Excessive self-monitoring, with an emphasis on self-worth[2] The aspects listed are not mutually exclusive. These components are often found to correlate among people with impostor phenomenon. It is incorrect to infer that the correlational relationship between these aspects cause the impostor experience.[11] In people with impostor phenomenon, feelings of guilt often result in a fear of success. The following are examples of common notions that lead to feelings of guilt and reinforce the phenomenon.[20] The good education they were able to receive Being acknowledged by others for success Belief that it is not right or fair to be in a better situation than a friend or loved one Being referred to as:[11] "The smart one" "The talented one" "The responsible one" "The sensitive one" "The good one" "Our favorite" Depression Impostor syndrome occurs when a person is incapable of believing they deserve to be successful or when they feel their success does not stem from their own abilities. Rather, the things they accomplish are due to “pure luck”. A study conducted by McGregor, Gee, and Posey (2008) at Lyon College in Batesville, AR suggests that individuals who experience feelings of being an impostor might also struggle with feelings of depression.[21] This research study consisted of 71 men and 115 women who agreed to fill out a packet during an intro-level college course. This packet contained the Impostor Phenomenon Test and the Beck Depression Inventory, taking roughly 30 minutes to complete. The results generated a positive connection between the IP scores and BDI-II scores, placing emphasis on the fact that women are more likely to experience Imposter Syndrome than men. The individuals that conducted this study believe that a relation between Impostor Phenomenon and depression exists due to the negative thoughts and self-doubt associated with Impostor Phenomenon being similar to the negative thoughts and self-doubt experienced by individuals with depression. The research also concluded that impostors constantly evaluate their performance to begin with and they tend to be tough critics on themselves, making it more difficult for impostors to recognize that their thoughts might mask symptoms of depression. This study gives individuals a further understanding of Impostor Phenomenon from a new angle, showcasing the toll Impostor Syndrome can have on those who suffer from it. Management In their 1978 paper, Clance and Imes proposed a therapeutic approach they used for their participants or clients with impostor phenomenon. This technique includes a group setting where people meet others who are also living with this experience. The researchers explained that group meetings made a significant impact on their participants. They proposed that this impact was a result of the realization that they were not the only ones who experienced these feelings. The participants were required to complete various homework assignments as well. In one assignment, participants recalled all of the people they believed they had fooled or tricked in the past. In another take-home task, people wrote down the positive feedback they had received. Later, they would have to recall why they received this feedback and what about it made them perceive it in a negative light. In the group sessions, the researchers also had the participants re-frame common thoughts and ideas about performance. An example would be to change: "I might fail this exam" to "I will do well on this exam".[16] The researchers concluded that simply extracting the self-doubt before an event occurs helps eliminate feelings of impostorism.[16] It was recommended that people struggling with this experience seek support from friends and family. Although impostor phenomenon is not a pathological condition, it is a distorted system of belief about oneself that can have a powerful negative impact on a person's valuation of their own worth.[13] Impostor syndrome is not a recognized psychiatric disorder and is not featured in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual nor is it listed as a diagnosis in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). However, outside the academic literature, impostor syndrome has become widely discussed, especially in the context of achievement in the workplace. Perhaps because it is not an officially recognized clinical diagnosis, despite the large peer review and lay literature, although there has been a qualitative review, there has never been a published systematic review of the literature on impostor syndrome. Thus, clinicians lack evidence on the prevalence, comorbidities, and best practices for diagnosing and treating impostor syndrome.[22] Other research on therapeutic approaches for impostorism emphasizes the importance of self-worth. People who live with impostor phenomenon commonly relate self-esteem and self-worth to others. A major aspect of other therapeutic approaches for impostor phenomenon focus on separating the two into completely separate entities.[17] In a study in 2013, researcher Queena Hoang proposed that intrinsic motivation can decrease the feelings of being a fraud that are common in impostor phenomenon.[11] Hoang also suggested that implementing a mentor program for new or entering students will minimize students' feelings of self-doubt. Having a mentor who has been in the program will help the new students feel supported. This allows for a much smoother and less overwhelming transition. Impostor experience can be addressed with many kinds of psychotherapy.[23][24][25] Group psychotherapy is an especially common and effective way of alleviating the impostor experience.[26][27] |

偽

者現象の特徴を測定するために指定された最初の尺度は、1985年にクランスによって考案されたもので、クランス偽者現象尺度(CIPS)と呼ばれてい

る。この尺度は、恐怖の特徴がその人に存在するかどうか、またその程度を判定するために用いることができる。恐怖の側面には以下のようなものがある:

「評価への恐れ、成功が続かないことへの恐れ、他人と同程度の能力がないことへの恐れ」[11]などの偽者症候群の特徴が、CIPSによって測定される。

Brian F. French、Sarah C. Ullrich-French、Deborah

Follmanは、CIPSの心理測定学的特性を検討するために、1271人の工学系大学生のサンプルを調査した。彼らは、尺度の個々の構成要素の得点が

完全に信頼できるものでも一貫性のあるものでもないことを発見し、症候群のある人について重要な決定を下すためにこれらを使用すべきではないことを示唆し

た[12]。 1985年の論文でクランスは、インポスター現象は以下の6つの特徴によって区別することができ、そのうち少なくとも2つを経験しなければならないと説明している[2]。 偽者サイクル 特別でありたい、最高でありたいという欲求 スーパーマン/スーパーウーマンの特徴 失敗を恐れる 能力の否定と賞賛の軽視 成功に対する恐れと罪悪感 発生 インポスター現象の兆候や症状は、70%近くの人が一生に一度は経験すると推定されている[13]。研究によると、インポスター現象は、新しい学問環境に 入った学生にとって珍しいことではない。未知の新しい環境の結果、不安感が生じることがある。その結果、自信や自分の能力に対する信念が低下する可能性が ある[11]。 性差 インポスター症候群が最初に概念化されたとき、それは成績優秀な女性によく見られる現象とみなされていた。さらなる研究により、インポスター症候群は男女 ともに罹患することが示されており、罹患する割合は男女間で多かれ少なかれ等しく分布している[1][14]。インポスター症候群の人は、しばしば対応す る精神衛生上の問題を抱えており、心理的介入によって治療されることがあるが、この現象は正式な精神障害ではない[15]。 クランスとアイムスは1978年の論文で、彼らの臨床経験に基づくと、インポスター現象は男性にはあまり見られないと述べている[16]が、より最近の研 究では、インポスター現象は男女に等しく広がっていることがほとんどである[1][17]。能力や力の認識は、他人を出し抜くことで証明される。男性の場 合、インポスター現象はしばしば、自分が成功しない、あるいは十分でないという恐れによって引き起こされる[17]。 設定 インポスター現象は他にも様々な場面で起こりうる。いくつかの例としては、新しい環境、[2]学問的環境、[16]職場、[16]社会的相互作用、[11]人間関係(プラトニックまたはロマンチック)などがある[11]。 人間関係では、偽者主義の人はしばしば、自分が友人や恋人の期待に応えられていないと感じる。偽者主義の人は、自分が何らかの方法で他人を騙して自分を好 きにさせ、一緒に過ごしたいと思わせたに違いないと考えるのが一般的である。自分には価値がない、あるいは自分が持っている有益な人間関係に値しないとい う感情を経験する[11]。 学生における偽者現象の有害な影響を示す経験的証拠がある。研究によると、生徒の学問的自己概念が高まると、インポスター現象の症状は減少し、その逆もま た然りである[17]。生徒が抱く心配や感情は、プログラムでの成績に直接影響を与えた。学生が経験する偽者現象の一般的な側面には、学問的な準備ができ ていないと感じること(特にクラスメートと自分を比較したとき)[2]、プログラムに受け入れられた根拠を疑うこと[11]、肯定的な評価や賞、良い成績 は個人の能力や知性ではなく外的要因に由来すると認識すること[11]などが含まれる。 Cokleyらは、偽者現象が学生、特に少数民族の学生に与える影響を調査した。彼らは、学生たちが詐称しているという感情を抱くことで、心理的苦痛が生 じることを発見した。エスニック・マイノリティの学生は、自分がプログラムに受け入れられた根拠を疑うことが多かった。彼らは、アファーマティブ・アク ションのおかげで合格したのであり、むしろ並外れた願書や資質があったから合格したのだという誤った思い込みを抱いていた[18]。 Tigranyanら(2021年)は、インポスター現象が心理学博士課程の学生にどのように関係しているかを調査した。研究の目的は、臨床心理学とカウ ンセリング心理学の博士課程の学生において、完璧主義的認知、抑うつ、不安、達成動機、自己効力感、自己理解、自尊心とIPの関係を調査することであっ た。さらに本研究では、IPがこれらの学生の学業、実習、インターンシップの成績にどのような支障をきたすか、また心理学博士課程を通してIPがどのよう に現れるかを調査しようとした。対象は84名の臨床心理学およびカウンセリング心理学の博士課程の学生で、オンライン調査に回答するよう指示された。デー タはピアソンの積率相関と重回帰を用いて分析された。研究対象の学生の88%が、IP特性について少なくとも中程度の感情を抱いていると報告した。また本 研究では、IPと完璧主義的認知、抑うつ、不安、セルフ・コンパッションとの間に有意な正の相関があることがわかった。この研究は、臨床の教授陣と指導者 が、学生の能力感と自信を高めることを期待して、IPの感情を減少させるのを助けるために、学生を支援するアプローチをとるべきであることを示している [19]。 つながり 研究では、インポスター現象と以下の要因との間に関係があることが示されている: 家族の期待[11]。 過保護な親または法的保護者[13]。 大学院レベルのコースワーク[11] 人種的アイデンティティ[11] 帰属スタイル[17] 不安[17] 抑うつ[17] 低い特性自尊心[17] 完璧主義[16] 自己価値[2]に重点を置いた過剰な自己監視 列挙した側面は相互に排他的なものではない。これらの構成要素は、偽者現象に罹患している人々の間で相関していることがしばしば見出される。これらの側面の相関関係がインポスター体験を引き起こすと推論するのは正しくない[11]。 インポスター現象のある人の場合、罪悪感の感情が成功への恐れにつながることが多い。以下は罪悪感をもたらし、現象を強化する一般的な観念の例である[20]。 自分が受けることができた良い教育 他人から成功を認められたこと 友人や愛する人よりも良い状況にあるのは正しくない、公平ではないという信念 次のように呼ばれること[11]。 "賢い人" 「才能のある人 「責任感のある人 「繊細な人 "良い子" "私たちのお気に入り" うつ病 偽者症候群は、自分が成功するに値すると信じることができなかったり、自分の成功が自分の能力によるものではないと感じたりする場合に起こる。むしろ、彼 らが成し遂げたことは「純粋な運」によるものなのだ。McGregor、Gee、Posey(2008)がAR州BatesvilleにあるLyon Collegeで実施した研究によると、偽者であるという感情を経験した人は、うつ病の感情とも闘っている可能性があることが示唆されている[21]。こ の小冊子には、偽者現象テストとベックうつ病目録が含まれており、およそ30分で完了した。その結果、IPの得点とBDI-IIの得点の間に正の相関が見 られ、男性よりも女性の方がインポスター症候群を経験しやすいことが強調された。この研究を行った研究者たちは、インポスター現象とうつ病の間には、イン ポスター現象に伴う否定的な考えや自信喪失が、うつ病患者が経験する否定的な考えや自信喪失と類似しているため、関係があると考えている。また、そもそも 詐欺師は常に自分のパフォーマンスを評価しており、自分自身に対して厳しい批評家になる傾向があるため、詐欺師が自分の思考がうつ病の症状を隠している可 能性があることを認識するのがより困難であるとも結論づけている。この研究は、新しい角度からインポスター現象をさらに理解させ、インポスター・シンド ロームが苦しむ人々に与える影響を示している。 マネジメント 1978年の論文で、クランスとアイムスは、インポスター現象の参加者やクライエントに用いた治療的アプローチを提案した。この手法には、人々が同じよう にこの体験とともに生きている人々と出会うグループ設定が含まれている。研究者たちは、グループミーティングが参加者に大きな影響を与えたと説明した。こ の影響は、このような感情を経験しているのは自分たちだけではないことを実感した結果であると提案した。参加者は、さまざまな宿題もこなさなければならな かった。ある課題では、参加者は過去に騙した、あるいは騙されたと思われる人をすべて思い出すというものだった。別の宿題では、自分が受けた肯定的な フィードバックを書き留めた。後で、なぜそのフィードバックを受けたのか、そのフィードバックのどこを否定的に受け止めたのかを思い出さなければならな い。グループ・セッションでは、研究者たちは参加者たちに、パフォーマンスに関する一般的な考えやアイディアを再構成させた。例えば 例えば、「私はこの試験に落ちるかもしれない」を「私はこの試験でうまくいくだろう」に変更することである[16]。 研究者たちは、出来事が起こる前に自責の念を抽出するだけで、インポストリズムの感情をなくすことができると結論づけた[16]。このような経験で苦しん でいる人は、友人や家族のサポートを求めることが推奨された。インポスター現象は病的な状態ではないが、自分自身に関する歪んだ信念体系であり、その人の 自分の価値評価に強力な悪影響を及ぼす可能性がある[13]。 インポスター症候群は認知された精神疾患ではなく、アメリカ精神医学会の診断統計マニュアルにも、国際疾病分類第10改訂版(ICD-10)にも診断名と して記載されていない。しかし、学術的な文献以外では、偽者症候群は、特に職場における達成感の文脈で広く議論されるようになっている。おそらく、公式に 認められた臨床診断ではないため、大規模な査読や一般向けの文献があるにもかかわらず、質的レビューはあっても、インポスター症候群に関する文献の体系的 レビューは発表されていない。したがって、臨床家はインポスター症候群の有病率、併存疾患、診断と治療のベストプラクティスに関する証拠を欠いている。 インポスター症候群の治療アプローチに関する他の研究では、自己価値の重要性が強調されている。偽者現象とともに生きる人々は、一般的に自尊心と自己価値 を他者と関連づけている。偽者現象に対する他の治療的アプローチの主要な側面は、両者を完全に別個の存在に分離することに焦点を当てている[17]。 2013年の研究で、研究者のQueena Hoangは、内発的動機づけが、インポスター現象によく見られる詐欺師であるという感情を減少させることができると提案している[11]。Hoangは また、新入生や入学生にメンタープログラムを実施することで、学生の自信喪失の感情を最小限に抑えることができると提案している。プログラムに参加したこ とのあるメンターがいれば、新入生はサポートされていると感じることができる。これにより、移行がよりスムーズになり、圧倒されることも少なくなる。 インポスター体験は、多くの種類の心理療法で対処することができる[23][24][25]。集団心理療法は、インポスター体験を緩和する特に一般的で効果的な方法である[26][27]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impostor_syndrome |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆