ポスト真実の政治状況

ポスト真実の政治状況、あるいは「ポスト 真理の政治(post-truth politics)」——類似語として「ポスト事実の政治」「ポスト現実の政治」——とは、政策の実際の詳細や、それまでの客観的な事実よりも、それらが背景化され、個人の信条や感情 (思い)が主題化(=重要視)され る政治状況あるいは政治文化のことである。具体的に は、第45代アメリカ合衆国大統領ドナルド・ジョン・トランプ(Donald John Trump, 1946- ) 氏による、2016年時の選挙キャンペーンと、当選、就任後の、アメリカの政治文化は、典型的な「真理の後の政治状況」あるいは「ポスト真実の政治」と 言っても良いだろう。マイナーな事件ではあるが、同じ2016年のDeNAによる、ネットに虚偽情報を拡散させ、サーキュレーション閉鎖に追い込まれた事 件も「ポスト真実の政治」性が示唆される現象である。

さて、西欧リベラリズムの歴史的淵源は破

壊と暴力に裏付けられていた(→「リ

ヴァイアサン・テーゼ」)。それゆえ、現代人が希求するように、リ

ベラリズムを主張した啓蒙主義者たちからそれらの冷酷さと残忍性を除いたら単なる幼稚園の「よい子の約束」になってしまう。それゆえに、啓蒙主義者たちの

著作にある毒に痺れることがなくなる.これがポスト真理論者の免疫力のなさ原因だ。

ウィキペディア(英語)では、これが現在では世界的な現象であるよ うで、次のように説明されている。

"Post-truth politics (also

called post-factual politics[1]

and post-reality politics)[2]

is a political culture in which debate is framed largely by appeals

to emotion disconnected from the details of policy, and by the repeated

assertion of talking points to which factual rebuttals are ignored.

Post-truth differs from traditional contesting and falsifying of facts

by relegating facts and expert opinions to be of secondary importance

relative to appeal to emotion. While this has been described as a

contemporary problem, some observers have described it as a

long-standing part of political life that was less notable before the

advent of the Internet and related social changes./ As of 2018,

political commentators have identified post-truth politics as ascendant

in many nations, notably Brazil, Russia, India, the United Kingdom and

the United States, among others. As with other areas of debate, this is

being driven by a combination of the 24-hour news cycle, false balance

in news reporting, and the increasing ubiquity of social media and fake

news websites.[3][4][5][6][7][8] In 2016, post-truth was chosen as the

Oxford Dictionaries' Word of the Year[9] due to its prevalence in the

context of that year's Brexit referendum and media coverage of the US

presidential election.[10][11]" - Post-truth

politics.

「ポスト真実政治(ポスト事実政治、ポス

ト現実政治とも呼ばれる)とは、政策の詳細から切り離された感情への訴えや、事実に基づく反論が無視される論点の繰り返し主張によって、議論が大きく組み

立てられる政治文化のことである。ポスト・トゥルースは、事実や専門家の意見を感情への訴えに比べて二の次にすることで、従来の事実の論争や改竄とは異な

る。これは現代の問題として語られているが、インターネットや関連する社会的変化の出現以前にはあまり注目されていなかった政治生活の長年の一部であると

評する観察者もいる。2018年現在、政治評論家たちは、特にブラジル、ロシア、インド、イギリス、アメリカなど、多くの国でポスト真実政治が台頭してい

ると指摘している。他の議論分野と同様、これは24時間ニュースサイクル、ニュース報道における誤ったバランス、ソーシャルメディアとフェイクニュースサ

イトのユビキタス化の組み合わせによって推進されている。2016年、「ポスト・トゥルース」は、同年のブレグジット国民投票やアメリカ大統領選挙のメ

ディア報道を背景に広まったため、オックスフォード辞書の「今年の言葉」に選ばれた。」(→後述)

これに関連する現代用語を列挙してみよ う。

● 著 者たち(シンガーとブルッキング 2019:39-41, 414-415)の認識:「現代のインターネットは単なるネットワークではなく、40億に近い人びとのエコシステムで、その一人一人が独自の思想と望みを もち、広大なデジタルの広場に自身の小さな一部を刻むことができる」(シンガーとブルッキング 2019:41)。

| 大きな嘘 (Big lie) |

チェリー・ピッキ

ング (cherry picking) |

サーキュラー・レ

ポーティン

グ(Circular reporting) |

欺瞞 (Deception) |

ダブルスピーク (Doublespeak) |

| エコーチェンバー (Echo chamber in media) |

ユーフェミス

ティック・ミス

スピーキング(Euphemistic

misspeaking) |

ユーロミス=EU

の神話 (Euromyth) |

偽旗作戦 (false flag) |

ファクトイド (factoid) |

| 誤謬 (Fallacy) |

虚偽報道/フェイクニュース (Fake news) |

フィルターバブル (Filter bubble) |

ガスライティング (gaslighting) |

半分真実 (Half-truth) |

| [イデオロギー]フレーミング(Framing

- social sciences) |

ネット操作 (Internet manipulation) |

情報操作 (Media manipulation) |

プロパガンダ (Propaganda) |

文脈から外れた引

用 (Quoting out of context) |

| 科学での捏造(Fabrication

in science) |

ソーシャルボット

(Social bot) |

スピン(Spin in

propaganda) |

ハイブリッド戦争(Hybrid warfare) |

‘Gerasimov

Doctrine, 2014- ’ [Valery Gerasimov,

1955- ] |

| フェイスブックド

リル

(ウォールバンキング)26 |

サイバーバング、

サイバータ

グ 26 |

ネプチューン・ス

ピア作戦

90 |

オープンソース・

インテリ

ジェンス (Open-source intelligence, OSINT)125 |

Human

intelligence, HUMINT |

| Signals

intelligence, SIGINT |

ソックパペット

(偽名ユー

ザー)179 |

インフルエンサー

183 |

ヘイトメッセージ |

いかに異様であっ

ても「馴染

みやすい情報は拡散しやすい」 |

| ボット |

「テロリズムは劇

場である」

ブライアン・ジェンキンス 239 |

バイラル・マーケティング (Viral marketing) |

感情の操作

257 Emotional manipulation |

信憑性 264 |

| マイクロターゲ

ティング |

ナラティブ (→ナラティブ・ターン) |

「三戦」(心

理戦・法律戦・世論戦)中国人民解放軍 293 |

アテンション・エ

コノミー (Attention economy) |

ソーシャルメディ

アの兵器化

(NATO)294 |

| ミー

ム (meme) 301 |

ミーム学(Memetics)303 |

「カメラが私の銃」314 |

ハクティビスト(Hacktivist) | ハ クティビズム(Hacktivism) |

| ソーシャル・エンジニアリング [社会科学] Social engineering (political science) |

ソーシャル・エンジニアリング [不正技術] Social engineering (security) |

敵

対生成ネットワーク (Generative adversarial network, GAN)406 |

Joint Readiness Training

Center

(JRTC), a U.S. Army

training center at Fort Polk, Louisiana |

Social Media

Environment

and Internet Replication, SMEIR |

| デンジャラス・スピーチ 422 |

情報における公衆衛生 (Public Health in Information) |

ファクト・チェッキング (Fact-checking) 検証行為 |

側面思考 (Lateral thinking) |

プラトンの洞窟→洞窟の寓意 (Allegory of the Cave) |

| 陰謀

論・陰謀理

論 |

で

たらめを見破る方法 |

感情 |

コミュニティ |

情報氾濫 |

| サ

イボーグ |

戦争 |

構造的暴力 |

テ

ロリズム |

ク

リティカル・シンキング |

| インフォデミック |

もう一つの事実

(alternative fact) |

反撃すること

(fighting back) |

ファクトチェッキング |

政治的変態たちの生態研究 |

上掲の数字は、(シンガーとブルッキング

2019)による。

●

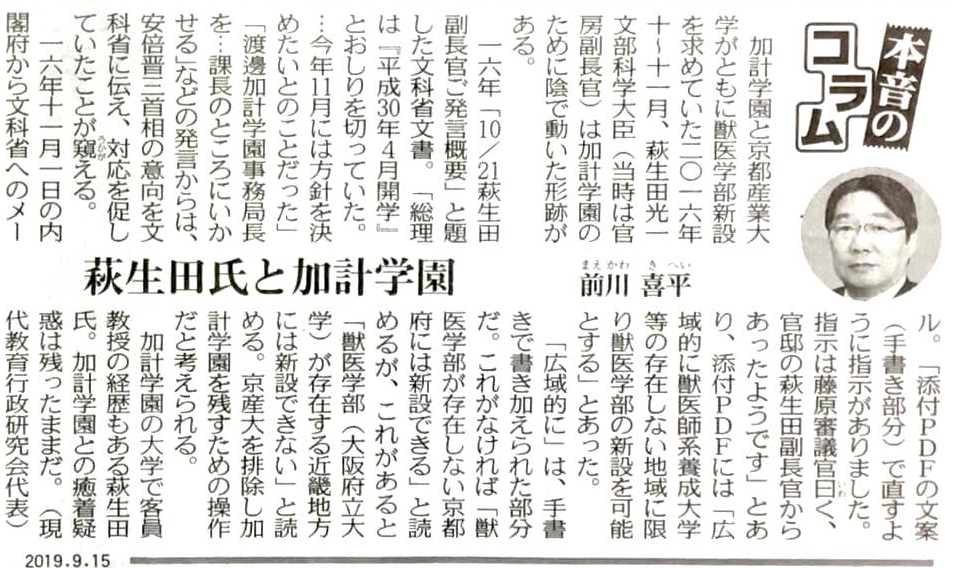

日本におけるポスト真理の政治状況(前川喜平さんのコラム)——ポスト真理の舞台を裏側から支えていた元官僚の暴露趣味的解説

出典:前川喜平「萩生田氏と加計学園」『東京新聞』2019年9月15日

● もっと冷静な分析も必要かもしれない

Anthony Downsの実質的デビュー作An Economic Theory of Democracy,

1957に二大政党制はイデオロギー的マンネリズムに陥りトランプのような新党が簡単にイ

デオロギーの配分を変えると予言しているよ。1957年にだ

ぜ!! 1980年に邦訳されている→民主主義の経済理論 / アンソニー・ダウンズ著 ; 古田精司監訳, 東京 : 成文堂, 1980年(→「民主主義の経済理論」)

● ポスト真実に関する審問(Lee McIntyre 2018 による)

| 1. ポスト真実ってなんだろうか? |

| 2. ポスト真実を理解するためのロードマップとしての科学拒否 |

| 3. 認知的バイアスの起源 |

| 4. 伝統的メディアの衰退 |

| 5. ソーシャル・メディアの隆盛とフェイクニュースの問題 |

| 6. ポストモダニズムははたしてポスト真理を生み出したのか? |

| 7. ポスト真実(の政治的状況)と戦うには? |

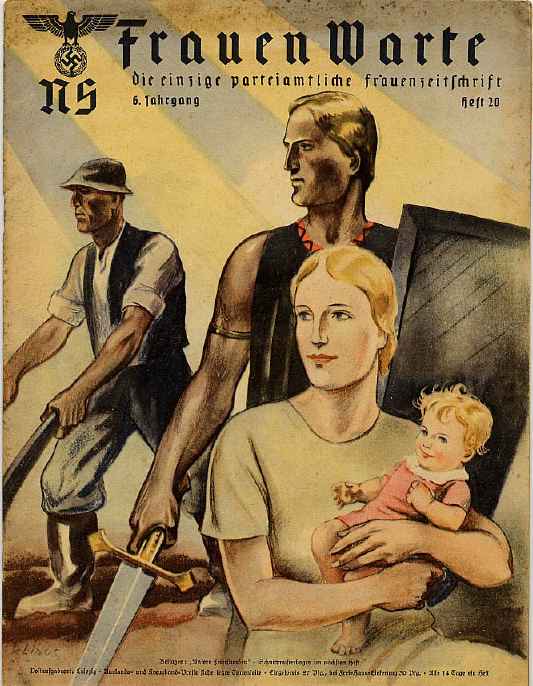

● フェイスブックならびにその運用会社であるMetaに送った異議申立書(2022.07.01)

タイトル「画像を検閲して一方的に禁止す るのではなくメインのタイムラインをみて総合的に判断してください」。

これは、ナチスが発行していた『国家社会 主義女性モニター(NS-Frauen-Warte)』誌の表紙映像です。画像そのものは、ハイデルベ ルグ大学でデジタル公開化されており、コモンズ化されており、著作権保護のないものです。私の投稿が禁止された理由はFBの側がきちんとアナウンスしない ために不詳ですが、画像の中にある、ナチス党のシンボルマークあるいは鉤十字が、親ナチと判断したようですが、ナチスのプロパガンダによるものでありませ ん。それは、そのメインのスレッドにおける文言から、ナチスの女性意識や優生政策との関連を批判的に紹介したものであることが、人間ならきちんとわかるは ずです。そのため、この禁止措置はネット上における「言論の自由」に抵触し、反ナチズムの啓蒙ためにナチの資料も公開されて広く論議されるべきという原則 を検閲により制限するという「言論の弾圧」をフェイスブックならびにその運用会社であるMetaは容認していると判断せざるをえません。この措置が人為的 なものなのか、AIによるものかは、私(=異議申立人)にはわかりませんが、安易な検閲手段が、重大な人権の侵害につながるものとして、フェイスブックな らびにその運用会社であるMetaは猛省していただきたいと思い、この抗議文を認めるものです。なお、この投稿には文字がありませんが、私は追加情報を記 載する時に、1)画像情報を投稿する、2)画像がアップされた時点で、さらに出典情報を追記する、という手順で、投稿記事をさらに加工することを常態的に おこなっていますが、フェイスブックならびにその運用会社であるMetaは、画像入力の投稿直後に検閲措置を講じたために、修正や抗弁する機会を一切与え ずに24時間の利用制限をかけ、またそれ以外の機能の制限をかけたままです。そのために、投稿者の良心ならびに精神衛生において多大な損害を生じせしめま した。このような事故がおこったのは、フェイスブックならびにその運用会社であるMetaの管理上の責任でもあり、事前の約款においてすでに通告済であっ たとしても、きわめて利用者の利便性と快適性を損なうものであります。以上、誠実に申し上げます。

★注意書き「この記事の主要な投稿 者は、 その主題と密接なつながりがあるようだ。ウィキペディアのコンテンツポリシー、特に中立的な視点に従うために、クリーンアップが必要かもしれない。トーク ページでさらに議論してほしい。」

| Post-truth politics Post-truth politics, also described as post-factual politics[1] or post-reality politics,[2] amidst varying academic and dictionary definitions of the term, refer to a recent historical period where political culture is marked by public anxiety about what claims can be publicly accepted facts.[3][4][5] It suggests that the public (not scientific or philosophical) distinction between truth and falsity—as well as honesty and lying—have become a focal concern of public life, and are viewed by popular commentators and academic researchers alike as having a consequential role in how politics operates in the early 21st century. It is regarded as especially being influenced by the arrival of new communication and media technologies.[6][4][7] Popularized as a term in news media and a dictionary definition, post-truth has developed from a short-hand label for the abundance and influence of misleading or false political claims into a concept empirically studied and theorized by academic research. Oxford Dictionaries declared that its international word of the year in 2016 was "post-truth", citing a 20-fold increase in usage compared to 2015, and noted that it was commonly associated with the noun "post-truth politics".[8] Since post-truth politics are primarily known through public truth statements in specific media contexts (such as commentary on major broadcasting networks, podcasts, YouTube videos, and social media), it is especially studied as a media and communication studies phenomenon with particular forms of truth-telling, including intentional rumors, lies, conspiracy theories, and fake news.[4][7][9][6] In the context of media and politics, it often involves the manipulation of information or the spread of misinformation to shape public perceptions and advance political agendas. Deceptive communication, "[d]isinformation, rumor bombs, and fake news have mass communication era antecedents in both war and security (gray propaganda) and commercial communication (advertising and public relations). All can be said to be forms of strategic communication and not mere accidental or innocent misstatements of facts." Deceptive political communication is timeless.[10] However, distrust in major social institutions, political parties, government, news media, and social media, along with the fact that anyone today can create and circulate content that has generic characteristics of news (fake news) creates the conditions for post-truth politics.[11][12][13][14] Distrust is also politically polarized, where those identifying with one political party dislike and don't trust those of another. Distrust becomes the bearer of post-truth politics, since citizens cannot first-hand verify claims about things happening in the world and don't usually have expert knowledge about subjects being reported factually; they are faced with the choice of trusting news providers and other public truth-tellers. For this reason, some scholars have argued that post-truth does not at all refer to a sense that facts are irrelevant but to a public anxiety about the status of publicly accepted facts on which democracy can function.[15][3] As of 2018, political commentators and academic researchers have identified post-truth politics as ascendant in many nations, notably Australia, Brazil, India, Ghana, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, among others. In Ghana, Coker and Afriyie delved into the prevalence of post-truth politics in the Ghanaian context, with a specific focus on publications in print newspapers affiliated with the country's major political parties, the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the National Democratic Congress (NDC). The authors highlighted that post-truth practices have become ingrained in the fabric of election campaigns and political discourse in sub-Saharan Africa, including Ghana. Their research aimed to dissect the post-truth strategies employed by Ghanaian politicians affiliated with these two prominent parties, as manifested in their respective politically aligned newspapers, namely, The Daily Statesman and The Enquirer. Coker and Afriyie identified three distinct strategies within this context, which they labeled as kairos, disinformation/misinformation, and the deliberate transmission of strategic falsehoods. These strategies were found to be actively shaping political narratives and public perceptions. |

ポスト真理の政治 ポスト真理の政治は、ポスト事実政治[1]あるいはポスト現実政治[2] とも表現され、学術的な定義や辞書的な定義は様々であるが、政治文化が、どのような主張が公に認められる事実となりうるかについての大衆の不安によって特 徴づけられる最近の歴史的な時期を指す[3][4][5]。 この用語は、真実と 虚偽の間の(科学的または哲学的ではない)公的な区別が、正直さと嘘と 同様に、公的生活の焦点となる関心事となっていることを示唆しており、21世紀初頭において政治がどのように運営されるかに結果的な役割を持つものとし て、一般的なコメンテーターや学術研究者によって同様にみなされている。ポスト・トゥルースは、ニュースメディアの用語や辞書の定義として広まり、誤解を 招いたり虚偽の政治的主張の多さや影響力を表す略語的なラベルから、学術研究によって実証的に研究され理論化された概念へと発展した。オックスフォード・ ディクショナリーズは、2016年の国際的な流行語大賞を「ポスト・トゥルース」とし、2015年と比較して使用量が20倍増加したと発表し、「ポスト・ トゥルース・ポリティクス」という名詞と一般的に関連付けられていると指摘した[8]。 ポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクスは主に特定のメディア文脈(主要な放送ネットワークでのコメント、ポッドキャスト、YouTubeの動画、ソーシャルメ ディアなど)における公的な真実の表明を通じて知られるため、意図的な噂、嘘、陰謀論、フェイクニュースなど、真実を語る特定の形式を伴うメディア・コ ミュニケーション研究の現象として特に研究されている[4][7][9][6]。メディアと政治の文脈では、大衆の認識を形成し政治的アジェンダを推進す るための情報操作や誤った情報の拡散を伴うことが多い。欺瞞的コミュニケーション、「情報操作、風評爆弾、フェイクニュースには、戦争と安全保障(灰色の プロパガンダ)と商業コミュニケーション(広告と広報)の両方において、マス・コミュニケーション時代の先例がある。すべて戦略的コミュニケーションの一 形態であり、単なる偶然や無実の事実誤認ではないと言える。" しかし、主要な社会制度、政党、政府、ニュースメディア、ソーシャルメディアに対する不信と、今日誰でもニュースの一般的な特徴を持つコンテンツ(フェイ クニュース)を作成し流通させることができるという事実が、ポスト真実政治の条件を作り出している[11][12][13][14]。不信はまた政治的に 二極化しており、ある政党に所属する人々は別の政党の人々を嫌い、信用しない。市民は世の中で起きていることについての主張を直接確認することができず、 事実として報道される対象についての専門的な知識も通常は持っていないため、不信感はポスト真実政治の担い手となる。このため、一部の学者は、ポスト・ トゥルースとは、事実が無関係であるという感覚を指すのではなく、民主主義が機能しうる公に認められた事実の地位に対する国民の不安を指すのだと主張して いる[15][3]。 2018年現在、政治評論家や学術研究者は、オーストラリア、ブラジル、インド、ガーナ、ロシア、イギリス、アメリカなど、多くの国でポスト・トゥルース 政治が台頭していると指摘している。ガーナでは、CokerとAfriyieが、ガーナの主要政党である新愛国党(NPP)と国民民主会議(NDC)系の 新聞に掲載された記事を中心に、ガーナの文脈におけるポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクスの普及を調査した。著者らは、ガーナを含むサハラ以南のアフリカで は、選挙キャンペーンや政治的言説にポスト・トゥルースの慣行が根付いていることを強調した。彼らの研究は、この2つの著名な政党に所属するガーナの政治 家たちが、政治的に連携しているそれぞれの新聞、すなわちデイリー・ステーツマン紙とエンクワイアラー紙に現れているポスト・トゥルース戦略を分析するこ とを目的としている。コーカーとアフリイエは、この文脈の中で3つの異なる戦略を特定し、それを「カイロス」「ディスインフォメーション/ミスインフォ メーション」「戦略的虚偽の意図的伝達」と名づけた。これらの戦略は、政治的ナラティブと大衆の認識を積極的に形成していることがわかった。 |

| History of terminology The term post-truth politics appears to have developed from other adjectival uses of "post-truth", such as "post-truth political environment", "post-truth world", "post-truth era", "post-truth society", and very close cousins, such as "post-fact society" and "post-truth presidency". According to Oxford Dictionaries, the Serbian-American playwright Steve Tesich may have been the first to use the term post-truth in a 1992 essay in The Nation. Tesich writes that following the shameful truth of Watergate (1972–1974), more assuaging coverage of the Iran–Contra scandal (1985–1987)[16] and Persian Gulf War (1990–1991) demonstrates that "we, as a free people, have freely decided that we want to live in some post-truth world."[17][18] However, as Harsin (2018) notes, the term was in academic circulation in the 1990s. The media studies scholar John Hartley used the term "post-truth as the title of a chapter, "Journalism in a Post-truth Society", in his 1992 book The Politics of Pictures.[4][19] In 2004 Ralph Keyes used the term "post-truth era" in his book by that title.[20] In it he argued that deception is becoming more prevalent in the current media-driven world. According to Keyes, lies stopped being treated as something inexcusable and started being viewed as something acceptable in certain situations, which supposedly led to the beginning of the post-truth era. The same year American journalist Eric Alterman spoke of a "post-truth political environment" and coined the term "the post-truth presidency" in his analysis of the misleading statements made by the Bush administration after 9/11 in 2001.[21] More specifically, the American academic Moustafa Bayoumi argued that it was the 2003 "Iraq War that ushered in the post-truth era and that the United States is to blame". Bayoumi believes that there existed differences compared to the times, for example, of the Spanish–American War and of the Gulf of Tonkin incident. Starting from 2002-2003, through the formation of the Office of Special Plans and supported by the neocons' noble lie ideology, the greatest difference from previous time periods of all existed and "the apparatus of lying became institutionalized".[22] In his 2004 book Post-democracy, Colin Crouch used the term post-democracy to mean a model of politics where "elections certainly exist and can change governments", but "public electoral debate is a tightly controlled spectacle, managed by rival teams of professionals expert in the techniques of persuasion, and considering a small range of issues selected by those teams". Crouch directly attributes the "advertising industry model" of political communication to the crisis of trust and accusations of dishonesty that a few years later others have associated with post-truth politics.[23] More recently, scholars have followed Crouch in demonstrating the role of professional political communication's contribution to distrust and wrong beliefs, where strategic use of emotion is becoming key to gaining trust for truth statements.[24] The term "post-truth politics" may have originally been coined by the blogger David Roberts in a blog post for Grist on 1 April 2010. Roberts defined it as "a political culture in which politics (public opinion and media narratives) have become almost entirely disconnected from policy (the substance of legislation)".[25][26] Post truth was used by philosopher Joseph Heath to describe the 2014 Ontario election.[27] The term became widespread during the campaigns for the 2016 presidential election in the United States and for the 2016 "Brexit" referendum on membership in the European Union in the United Kingdom.[28][29][30] |

用語の歴史[編集] ポスト・トゥルース政治という用語は、「ポスト・トゥルース政治環境」、「ポスト・トゥルース世界」、「ポスト・トゥルース時代」、「ポスト・トゥルース 社会」といった「ポスト・トゥルース」の他の形容詞的用法や、「ポスト・ファクト社会」、「ポスト・トゥルース大統領制」といった非常に近い従兄弟から発 展したようだ。オックスフォード・ディクショナリーズによれば、ポスト・トゥルースという言葉を最初に使ったのは、セルビア系アメリカ人の劇作家スティー ブ・テシッチであろう。テシッチは、ウォーターゲート事件(1972~1974年)の恥ずべき真実に続いて、イラン・コントラ疑惑(1985~1987 年)[16]やペルシャ湾戦争(1990~1991年)の報道が、「われわれは自由な国民として、ある種のポスト・トゥルースの世界に生きたいと自由に決 めた」ことを示していると書いている[17][18]。メディア研究の研究者であるジョン・ハートリーは、1992年の著書『The Politics of Pictures』の中で、「ポスト真実社会におけるジャーナリズム」という章のタイトルとして「ポスト真実」という言葉を使っている[4][19]。 2004年、ラルフ・キーズはそのタイトルの本の中で「ポスト真実の時代」という言葉を使った[20]。 その中で彼は、現在のメディア主導の世界では欺瞞が蔓延しつつあると主張した。キーズによれば、嘘は許されないものとして扱われなくなり、ある状況下では 許容されるものと見なされるようになり、それがポスト・トゥルース時代の始まりにつながったとされている。同じ年、アメリカのジャーナリスト、エリック・ アルターマンは「ポスト・トゥルースの政治環境」について語り、2001年の9.11後にブッシュ政権が行った誤解を招くような発言を分析する中で、「ポ スト・トゥルース大統領制」という言葉を生み出した[21]。バヤウミは、たとえば米西戦争や トンキン湾事件の時代とは異なる点が存在すると考えている。2002年から2003年にかけて、特別計画室が設立され、ネオコンの 高貴な嘘イデオロギーに支えられて、それまでの時代との最大の違いが存在し、「嘘の装置が制度化された」。 [22] コリン・クラウチは2004年の著書『ポスト・デモクラシー』の中で、ポスト・デモクラシーという言葉を、「選挙は確かに存在し、政権を交代させることが できる」が、「公選の討論は厳しく管理された見世物であり、説得の技術に精通した専門家からなるライバルチームによって管理され、そのチームによって選ば れた小さな範囲の問題を検討する」という政治モデルを意味する言葉として使っている。クラウチは、政治的コミュニケーションの「広告産業モデル」が、数年 後に他の人たちがポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクスと関連づけた信頼の危機と不誠実さへの非難につながったと直接的に指摘している[23]。最近になっ て、学者たちはクラウチにならって、専門的な政治的コミュニケーションが不信と間違った信念に果たす役割を実証しており、そこでは感情を戦略的に利用する ことが、真実の主張に対する信頼を得るための鍵となりつつある[24]。 ポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクス(ポスト真実政治)」という用語は、もともとはブロガーのデビッド・ロバーツが2010年4月1日にGristに投稿し たブログの中で作り出したものかもしれない。ロバーツはこれを「政治(世論やメディアの語り)が政策(立法の中身)からほぼ完全に切り離された政治文化」 と定義した[25][26]。 ポスト真実は哲学者のジョセフ・ヒースによって 2014年のオンタリオ州選挙を説明するために使われた[27]。 この言葉は2016年のアメリカ大統領選挙や2016年のイギリスのEU加盟を問う国民投票「ブレグジット」のキャンペーン中に広まった[28][29] [30]。 |

| Concepts Information disorder has been proposed as an umbrella term for the wide variety of poor or false information being used for political purposes in post-truth politics.[31] Post-truth Scholars and popular commentators disagree about whether post-truth is a label that is newly generated but can be applied to phenomena such as lying in any historical period; or whether it is historically specific, with empirically more recent observable causes (especially new social and political relations enabled by new digital communication technologies) and is only simplistically reduced to the age-old phenomenon of political lying. Scholars and popular commentators also disagree about the degree to which emotion should be emphasized in theories of post-truth, despite the emphasis on emotion in the Oxford Dictionary's original definition of the word.[4] While the term "post-truth" had no dictionary entry before Oxford Dictionaries' entry in 2016, the Oxford entry[30] was inspired by the outcomes of the Brexit referendum and the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign; it was thus already implicitly referring to politics. Further, in the original Oxford Dictionaries' entry's (even today, more of a press release than traditional dictionary entry) justification for their choice, they say that it is often used in noun form of "post-truth politics". Thus, post-truth is often used interchangeably with post-truth politics.[30] Post-truth politics is a subset of the broader term post-truth, whose use precedes the recent focus on political events. While Oxford Dictionaries influentially named post-truth its 2016 word-of-the-year, current academic development of post-truth as a concept does not entirely reflect their original emphasis on "circumstances" where appeals to "objective facts" fail to influence as much as "appeals to emotion and personal belief" (see "Drivers" section below).[32] The use of post-truth communication as a major tool in political campaigns such as the Brexit debate in the UK and the Trump campaign in the United States resulted in intense scholarly and journalistic interest in it as an aspect of politics.[33][34] The existence of "post-truth politics" as a concept that makes sense and as a problem in the political life of liberal democracies is sometimes denied by critics.[35][34] Some uses of the concept are more general, referring not to historical conditions of widely empirically documented distrust or a context of promotional capitalism, easily accessible and hard-to-control amateur mass communication of social media, but to the presence of lying and distrust in politics and bias in journalism (and commentators' opinions that people of the day were distrustful or that political lying was common). Reducing the concept of post-truth to dishonest political communication and different styles thereof, some scholars argue that what one identifies as post-truth politics today is really a return of previous periods of politics. Some argue that what is being called "post-truth" is a return to 18th- and 19th-century political and media practices in the United States, followed by a period in the 20th century where the media was relatively balanced and political rhetoric was toned down.[36] Such a view nonetheless also conflicts with those in other countries at other times. For example, in 1957 scientist Kathleen Lonsdale remarked in the British context that "for many people truthfulness in politics has now become a mockery.... Anyone who listens to the radio in a mixed company of thinking people knows how deep-seated is this cynicism."[37] Similarly, New Scientist characterised the pamphlet wars that arose with the growth of printing and literacy, beginning in the 1600s, as an early form of post-truth politics. Slanderous and vitriolic pamphlets were cheaply printed and widely disseminated, and the dissent that they fomented contributed to starting wars and revolutions such as the English Civil War (1642–1652) and (much later) the American Revolution (1765–1791).[38] Drivers Communication and media scholars and philosophers tend to view the definition, origins, and causes of post-truth slightly differently. Media and communication scholars emphasize the historical revolution in communication technologies, which has fundamentally altered social life, including ways of knowing socially (social epistemology), shared authorities, and trust in institutions. Some also do not see post-truth as primarily a problem of knowledge, but rather of confusion, disorientation, and distrust. Philosophers tend to cite media and communications changes but claim that academic movements themselves, such as postmodernism, have influenced society, resulting in a situation where feeling and belief create an epistemic crisis for politics.[34] Scholars in the field of science and technology studies (STS) have studied post-truth as part of the evolution of knowledge society, and as shifts to long-standing roles of scientific truth-telling in public and political arenas.[39] The "circumstances" surrounding post-truth (politics) noted by the original Oxford Dictionaries' definition have been expanded to denote a historical period, defined by the convergence of numerous empirically documented shifts. As opposed to early commentators who described it as a long-standing part of political life that was less notable before the advent of the Internet and related social changes, several scholars point to a host of empirical changes that are contemporary and are the core of the concept. For these scholars, post-truth differs from traditional contesting and falsifying of facts in public life by pointing to a cultural and historical convergence of several developments: An abundance of competing truth claims, partly due to accessible technologies of communication production, personal websites, videos, micro-blogging, and chat groups; A lack of shared authorities for adjudicating truth claims, especially with the demise of traditional journalism as a gatekeeper of issues and public truth claims; A fragmented public space, facilitated by algorithms, where truth claims appear unchallenged or unexamined by a larger public in attendance to them, sometimes associated with false knowledge effects of echo chambers and filter bubbles; A well-resourced influence or persuasive industry in public relations, marketing, advertising, and big data analytics, whose goals are especially to influence, not inform or educate; A cultural backdrop of "promotional culture", characterized by self-promoting, self-branding, user-generated content, about image as much as truth; A resorting to emotion and cognitive bias as a means to practically deal with the competition and confusion; A far-reaching context of social distrust to which post-truth political communication contribute and are affected by; Communication technologies corresponding to a culture of acceleration, distraction, and "hot cognition; and, perhaps, changing historical ethics about how much misleading or "spin" is acceptable.[4][6][7][40][41][42][43][44] Before "post-truth" entered the Oxford Dictionary, in 2015, "regime of post-truth" entered the academic conceptual vocabulary.[9] "Regime of post-truth" instead of merely "post-truth politics" refers to a way of governing, with professional pan-partisan political communication manipulating the communication competitively in a context where institutions and discourses (such as science and news media) were formerly interdependent on one another to stabilize the public circulation of truth.[45] The concept refers to a convergent set of historical developments that have created the conditions of post-truth society and its politics: the political communication informed by cognitive science, which aims at managing perception and belief of segmented populations through techniques like microtargeting, which includes the strategic use of rumors and falsehoods;[46][47] the fragmentation of modern, more centralized mass news media gatekeepers, which have largely repeated one another's scoops and their reports;[48][49] the attention economy marked by information overload and acceleration, user-generated content and fewer society-wide common trusted authorities to distinguish between truth and lies, accurate and inaccurate;[50][51] the algorithms which govern what appears in social media and search engine rankings, based on what users want (per algorithm) and not on what is factual; and news[52] media which have been marred by scandals of plagiarism, hoaxes, propaganda, and changing news values. These developments have occurred on the background of economic crises, downsizing and favoring trends toward more traditional tabloid stories and styles of reporting, known as tabloidization[53] and infotainment.[54] In this view, post-truth cannot be understood without regard for the revolution in communication technologies and social life, their effects on cognition (the way people are disposed to think online),[55][43] in a backdrop of social acceleration.[56] In terms of entertainment, some scholars argue that citizens' orientations towards politics are dispositions formed first as audiences in relation to entertainment forms such as reality television, which can be shown to be transposable to their evaluation of political communication.[52][57][58] The concept of regime of post-truth has been expanded by other scholars to a geo-political level, analyzing political communication cases in the non-Western as well as Western world.[7] While some of these phenomena (such as a more tabloidesque press) may suggest a return to the past, the effect of the convergences is a socio-political phenomenon which exceeds earlier forms of journalism in deliberate distortion, error, and cultural confusion. Fact-checking and rumor-busting sites abound, but they are unable to reunite a fragmented set of audiences (attention-wise) and their respective trustful-/distrustfulness. Other scholars, such as the philosopher Lee McIntyre (2018), who focuses on "post-truth" generally and not politics specifically, argue that rising social distrust of scientific expertise and postmodern academic discourse, allegedly promoting a devaluing of or disregard for truth, have combined with cognitive biases to produce conditions where feeling triumphs over facts. While several of these scholars cite distrust as an agent of post-truth social and political effects, the origin of the distrust is less clear. McIntyre sees public relations efforts to undermine scientific truths, on, for example, the effects of tobacco, as important factors (in addition to the alleged influence of academic postmodernism on conservative politics, though this link is not empirically established). As another specific example of corporate interests undermining truths for which there exists scientific consensus, McIntyre cites previous donations of BP to organizations which deny climate change.[34] However, public relations is just one part of a larger culture of promotionalism (consumer capitalism),[59] where truth has long been the last concern in strategies to influence people to feel positively or negatively towards brands as businesses, countries, products, parties, and politicians. Furthermore, the scandals in journalism around plagiarism and "cheerleading" for the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq,[60][61][22] combine with promotional culture, ethically questionable professional strategic political communication, potential viral mediascapes, algorithmically customized presentation of information, among other factors to reproduce various forms of specific and generalized distrust—trust being crucial for recognition of legitimate public truth-tellers.[47][57] While many popular treatments of post-truth (sometimes used interchangeably with fake news) claim or imply a growth in political lying, several scholars see lying as only one feature of post-truth (which cannot historically distinguish it as new), instead focusing on problems of distinguishing true and false (common authorities for inducing belief being scarcer), or on disorientation, confusion, misperception, and distraction. Here post-truth is not synonymous with lying, fake news or other deception but is about a public anxiety that there is no confident way to secure publicly accepted facts in political culture.[62][3] The appeals to scientific expertise (though minority views in their fields), as with anti-vaccine supporters, demonstrates that across the board, people do in fact respect scientific experts, or the idea thereof. But science and expertise have been politicized, making it harder for the unknowing to identify legitimate authorities (all of whom may hold advanced degrees).[4][58] Furthermore, it may not be so much that post-truth is manifest trust in one's emotions before truth claims as one's identification of emotional truth-tellers as authentic, honest, and therefore trustworthy.[58] Misinformation Misinformation is inadvertently false or misleading information used in political discourse. The term is also used as an umbrella term for any type of misinformation, disinformation, or fake news.[63] Disinformation Disinformation is purposely and intentionally misleading information, for example, in propaganda.[63] Fake news Fake news is "fabricated information that mimics news media content in form but not in organizational process or intent."[64][63] Conspiracy theories Conspiracy theories are elaborate packages of interconnected assertions with respect to powerful conspirators which are typically characterized by improbability; however, actual political conspiracies such as the Watergate breakin and coverup do exist.[63] Rumor bombs Across an interdisciplinary body of research, the core of rumor definitions is a statement that is not verifiably true or false.[65] The militaristic metaphor "rumor bomb," refers to a rumor that is strategically "dropped" to cause confusion, doubt, or dis-, mis-, belief.[66][67][68] Vulnerability There are two aspects of vulnerability to misinformation: gullibility with respect to poorer information, and distrust and skepticism with respect to better information that might correct it.[63] Manufactured controversy Political operatives in the post-truth space may fabricate controversies for economic or political advantage or, as in gaslighting, to disorient and confuse the public. |

概念 情報無秩序は、ポスト・トゥルース政治において政治的な目的のために利用されている多種多様な貧弱な情報や虚偽の情報の包括的な用語として提案されている [31]。 ポスト・トゥルース ポスト・トゥルースとは新しく生み出されたレッテルであるが、どのような歴史的時代においても嘘のような現象に適用することができるのか、それとも歴史的 に特異なものであり、経験的に最近の観察可能な原因(特に新しいデジタル・コミュニケーション技術によって可能になった新しい社会的・政治的関係)を持 ち、古くからある政治的嘘の現象に単純化されるだけなのかについて、学者や一般的な論者は意見を異にしている。ポスト・トゥルース」という用語は、 2016年にオックスフォード・ディクショナリーズが登録する以前には辞書に登録されていなかったが、オックスフォード・ディクショナリーズの登録 [30]は、ブレグジットの国民投票と2016年のアメリカ大統領選挙の結果に触発されたものであり、すでに暗黙のうちに政治に言及していた。さらに、 オックスフォード辞書のオリジナルの項目(現在でも、従来の辞書の項目というよりはプレスリリースのようなものである)の選択理由では、「ポスト・トゥ ルース・ポリティクス」という名詞の形で使われることが多いとしている。したがって、ポスト・トゥルースはしばしばポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクスと互 換的に使われる[30]。 ポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクスは、より広範な用語であるポスト・トゥルースのサブセットであり、その使用は最近の政治的出来事への注目よりも先行して いる。オックスフォード・ディクショナリーズはポスト・トゥルースを2016年の流行語大賞に選んだが、ポスト・トゥルースの概念としての現在の学術的発 展は、「客観的事実」への訴えが「感情や個人的信念への訴え」ほど影響力を与えられない「状況」(以下の「推進力」の項を参照)に重点を置いた彼らの当初 の主張を完全に反映しているわけではない。 [32]英国のBrexit議論や米国のトランプ・キャンペーンなどの政治キャンペーンにおいて主要なツールとしてポスト・トゥルース・コミュニケーショ ンが使用された結果、政治の一側面としてのポスト・トゥルース・コミュニケーションに学者やジャーナリズムが強い関心を抱くようになった[33] [34]。自由民主主義国家の政治生活において意味のある概念として、また問題としての「ポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクス」の存在は、批判者によって否 定されることもある[35][34]。 この概念のいくつかの用法はより一般的であり、広く経験的に文書化された不信の歴史的状況や、宣伝資本主義、容易にアクセス可能でコントロールが難しい ソーシャルメディアのアマチュア・マス・コミュニケーションの文脈ではなく、政治における嘘や不信、ジャーナリズムにおける偏向の存在(そして当時の人々 が不信感を抱いていた、あるいは政治的な嘘が一般的であったというコメンテーターの意見)に言及している。ポスト・トゥルースという概念を不誠実な政治的 コミュニケーションとそのさまざまなスタイルに還元すると、今日ポスト・トゥルース政治と認識されているものは、実際には以前の政治時代の再来であると主 張する学者もいる。ポスト・トゥルース」と呼ばれているものは、18~19世紀のアメリカにおける政治的・メディア的慣行への回帰であり、その後20世紀 にはメディアが比較的均衡を保ち、政治的レトリックがトーンダウンした時期があったと主張する者もいる[36]。こうした見方は、それにもかかわらず、他 の時代の他の国々における見方とも対立する。たとえば、1957年に科学者のキャスリーン・ロンスデールは、イギリスの文脈で、「多くの人々にとって、政 治における真実性は今や嘲笑の対象となっている。同様に、『ニューサイエンテ ィスト』誌は、1600年代に始まる印刷と識字率の向上とともに生じたパンフレッ ト戦争を、ポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクスの初期形態として特徴づけている。誹謗中傷に満ちた激しいパンフレットは安価に印刷され、広く流布し、それら が煽った反対意見は、イギリス内戦(1642-1652)や(ずっと後の)アメリカ独立戦争(1765-1791)のような戦争や革命を引き起こす一因と なった[38]。 推進者 コミュニケーションやメディアの学者や哲学者は、ポスト・トゥルースの定義、起源、原因について少し異なった見方をする傾向がある。メディアとコミュニ ケーションの学者は、社会的に知る方法(社会認識論)、共有される権威、制度への信頼など、社会生活を根本的に変化させたコミュニケーション技術の歴史的 革命を強調している。また、ポスト・トゥルースを、主として知識の問題ではなく、むしろ混乱、見当識障害、不信の問題として捉える者もいる。哲学者たちは メディアやコミュニケーションの変化を挙げる傾向にあるが、ポストモダニズムのような学問的な動き自体が社会に影響を与えており、その結果、感情や信念が 政治にとっての認識論的危機を生み出す状況になっていると主張している[34]。科学技術研究(STS)の分野の学者たちは、ポスト・トゥルースを知識社 会の進化の一部として、また公共的・政治的な場における科学的な真実告知の長年の役割に対する転換として研究している[39]。 最初のオックスフォード辞典の定義によって指摘されたポスト・トゥルース(政治)を取り巻く「状況」は、経験的に文書化された数多くのシフトの収束によっ て定義された歴史的な期間を示すものへと拡大された。初期の論者たちが、ポスト・トゥルースとは政治生活の長年にわたる一部であり、インターネットや関連 する社会的変化の出現以前にはあまり注目されていなかったと述べていたのとは対照的に、何人かの学者たちは、現代における経験的な変化の数々がこの概念の 核心であると指摘している。これらの学者にとって、ポスト・トゥルースは、いくつかの進展の文化的・歴史的な収束を指摘することによって、公共生活におけ る伝統的な事実の争いや改竄とは異なる: 競合する真実の主張が氾濫している。その一因は、アクセス可能なコミュニケーション生産技術、個人のウェブサイト、ビデオ、マイクロブログ、チャットグ ループによるものである; 特に伝統的なジャーナリズムが、問題や公的な真実の主張のゲートキーパーとしての役割を終えたことで、真実の主張を裁く権威が共有されていない; アルゴリズムによって断片化された公共空間が促進され、真実の主張が反論されなかったり、より多くの大衆によって検証されなかったりして、エコーチェン バーや フィルターバブルによる誤った知識効果につながることがある; 広報、マーケティング、広告、ビッグデータ分析など、影響力や説得力のある業界は、特に影響力を与えることを目的としており、情報や教育を与えることを目 的としていない; 自己宣伝、セルフブランディング、ユーザー生成コンテンツを特徴とする「宣伝文化」の文化的背景; 競争や混乱に現実的に対処する手段として、感情や認知バイアスに頼ること; ポスト真実の政治的コミュニケーションが貢献し、影響を受ける、社会不信の広範な文脈; 加速、注意散漫、「ホットな認知」の文化に対応するコミュニケーション技術、そしておそらくは、どの程度のミスリードや「スピン」が許容されるかについて の歴史的倫理の変化[4][6][7][40][41][42][43][44]。 ポスト・トゥルース」がオックスフォード辞典に入る前の2015年には、「レジーム・オブ・ポスト・トゥルース」が学術的な概念語彙に入った[9]。「レ ジーム・オブ・ポスト・トゥルース」とは、単に「ポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクス」ではなく、「レジー ム・オブ・ポスト・トゥルース」とは、以前は(科学やニュースメディアなどの)制度や言説が互いに依存しあって真実の公共的な流通を安定させていた状況に おいて、プロの汎党派的な政治的コミュニケーションが競争的にコミュニケーションを操作する統治方法を指す。 [45]この概念は、ポスト真実社会とその政治の条件を作り出した一連の歴史的展開を指す: 噂や虚偽の戦略的利用を含むマイクロ・ターゲティングのような手法を通じて、セグメント化された集団の認識や信念を管理することを目的とした、認知科学に よって知られる政治的コミュニケーション[46][47]; [48][49] 情報過多と加速化、ユーザー生成コンテンツ、そして真実と嘘、正確なものと不正確なものを区別する社会全体で共通に信頼される権威の減少によって特徴づけ られる注目経済、[50][51]何が事実に基づいているかではなく、(アルゴリズムごとに)ユーザーが望むものに基づいて、ソーシャルメディアや検索エ ンジンのランキングに表示されるものを支配するアルゴリズム、そして盗作、デマ、プロパガンダ、ニュースの価値観の変化といったスキャンダルによって傷つ けられたニュース[52]メディア。こうした動きは、タブロイド化[53]やインフォテインメント[54 ]として知られる、より伝統的なタブロイド紙のストーリーや報道スタイルに向かう経済危機、縮小、好意的な傾向を背景に生じている。この見解では、ポス ト・トゥルースは、社会的加速を背景に、コミュニケーション・テクノロジーや社会生活における革命、認知(人々がオンラインで考えるようになる方法)への 影響[55][43]を無視して理解することはできない。 [56]エンターテインメントの観点からは、市民の政治に対する志向性は、リアリティ・テレビのようなエンタテインメントの形態に関連して観客として最初 に形成された気質であり、それは政治的コミュニケーションに対する評価にも転嫁可能であることが示されると主張する学者もいる[52][57][58]ポ スト・トゥルースのレジームという概念は、他の学者によって地理政治的なレベルまで拡大され、西欧世界だけでなく非西欧世界における政治的コミュニケー ションの事例を分析している[7]。 これらの現象の一部(よりタブロイド的な報道など)は、過去への回帰を示唆するかもしれないが、収束の効果は、意図的な歪曲、誤り、文化的混乱において、 以前のジャーナリズムの形態を凌駕する社会政治的現象である。ファクトチェックやデマ潰しのサイトは氾濫しているが、(注目度的に)分断された聴衆の集合 と、それぞれの信頼性/不信性を再統一することはできない。 哲学者のリー・マッキンタイア(2018年)のように、政治に特化せず一般的に「ポスト・トゥルース」に注目する他の学者は、科学的専門性に対する社会的 不信の高まりや、真実の軽視や軽視を促すとされるポストモダンの学問的言説が、認知バイアスと組み合わさって、事実よりも感情が勝利する状況を生み出して いると主張している。これらの学者の何人かは、ポスト真実の社会的・政治的影響の要因として不信を挙げているが、不信の起源はそれほど明確ではない。マッ キンタイアは、例えばタバコの影響などに関する科学的真実を弱体化させようとする広報活動が重要な要因であると見ている(この関連性は実証的に確立されて いないが、保守政治に対するアカデミックなポストモダニズムの影響という疑惑もある)。マッキンタイアは、科学的コンセンサスが存在する真実を損なう企業 利益のもう一つの具体例として、気候変動を否定する団体へのBPの過去の寄付を挙げている[34]。しかし、パブリック・リレーションズは、より大きな宣 伝主義(消費資本主義)の文化の一部分に過ぎず[59]、そこでは、真実は、企業、国、製品、政党、政治家などのブランドに対して肯定的または否定的な感 情を抱くように人々に影響を与える戦略において、長い間、最後の関心事となってきた。さらに、剽窃や2003年のアメリカのイラク侵攻への「チアリーディ ング」をめぐるジャーナリズムのスキャンダル[60][61][22]は、プロモーション文化、倫理的に疑問のある専門的な戦略的政治コミュニケーショ ン、潜在的なバイラルメディアスケープ、アルゴリズムによってカスタマイズされた情報の提示などと組み合わさって、様々な形の具体的で一般化された不信を 再生産している。 ポスト・トゥルース(フェイク・ニュースと同じ意味で使われることもある)についての一般的な扱いの多くは、政治的な嘘の増加を主張したり示唆したりして いるが、何人かの学者は、嘘はポスト・トゥルースの特徴のひとつにすぎず(歴史的に新しいものとして区別することはできない)、その代わりに、真偽の区別 の問題(信念を誘導するための一般的な権威が乏しくなっている)や、見当識障害、混乱、誤認、注意散漫に焦点を当てている。ここでいうポスト・トゥルース とは、嘘やフェイクニュース、その他の欺瞞と同義ではなく、政治文化において公に受け入れられた事実を確保する確信の持てる方法がないという一般大衆の不 安に関するものである[62][3]。反ワクチン支持者と同様に、科学的専門知識(その分野では少数意見ではあるが)への訴えは、全体として、人々が実際 に科学的専門家やその考えを尊重していることを示している。しかし、科学と専門知識は政治化されており、知らない人が正当な権威(全員が高度な学位を持っ ているかもしれない)を識別することを難しくしている[4][58]。さらに、ポスト・トゥルースとは、真実の主張の前に自分の感情を信頼することではな く、感情的な真実の語り手を本物であり、正直であり、したがって信頼できると識別することなのかもしれない[58]。 誤報 誤報とは、政治的言説の中で使用される、不注意による虚偽または誤解を招く情報のことである。この用語はあらゆる種類の誤報、偽情報、フェイクニュースの 総称としても使われる[63]。 偽情報 偽情報とは、例えばプロパガンダにおいて意図的かつ意図的に誤解を招くような情報のことである[63]。 フェイクニュース フェイクニュースとは「形式的にはニュースメディアのコンテンツを模倣しているが、組織的なプロセスや意図は模倣していない捏造された情報」のことである [64][63]。 陰謀論 陰謀論は、一般的にありえないことを特徴とする、強力な陰謀家に関する相互に結びついた主張の精巧なパッケージである。しかし、ウォーターゲート事件の脱 獄と隠蔽のような実際の政治的陰謀は存在する[63]。 噂爆弾 学際的な一連の研究において、噂の定義の核心は、検証可能な真実でも虚偽でもない声明である[65]。軍事的な比喩である「噂爆弾」は、混乱、疑念、ある いは不信、誤信を引き起こすために戦略的に「投下」される噂を指す[66][67][68]。 脆弱性 誤報に対する脆弱性には2つの側面がある:劣悪な情報に対する騙されやすさと、誤報を修正するかもしれないより良い情報に対する不信と 懐疑である[63]。 捏造された論争 ポスト・トゥルース空間における政治工作員は、経済的または政治的な利点を得るために、あるいはガスライティングのように、大衆を混乱させ混乱させるため に、論争をでっち上げることがある。 |

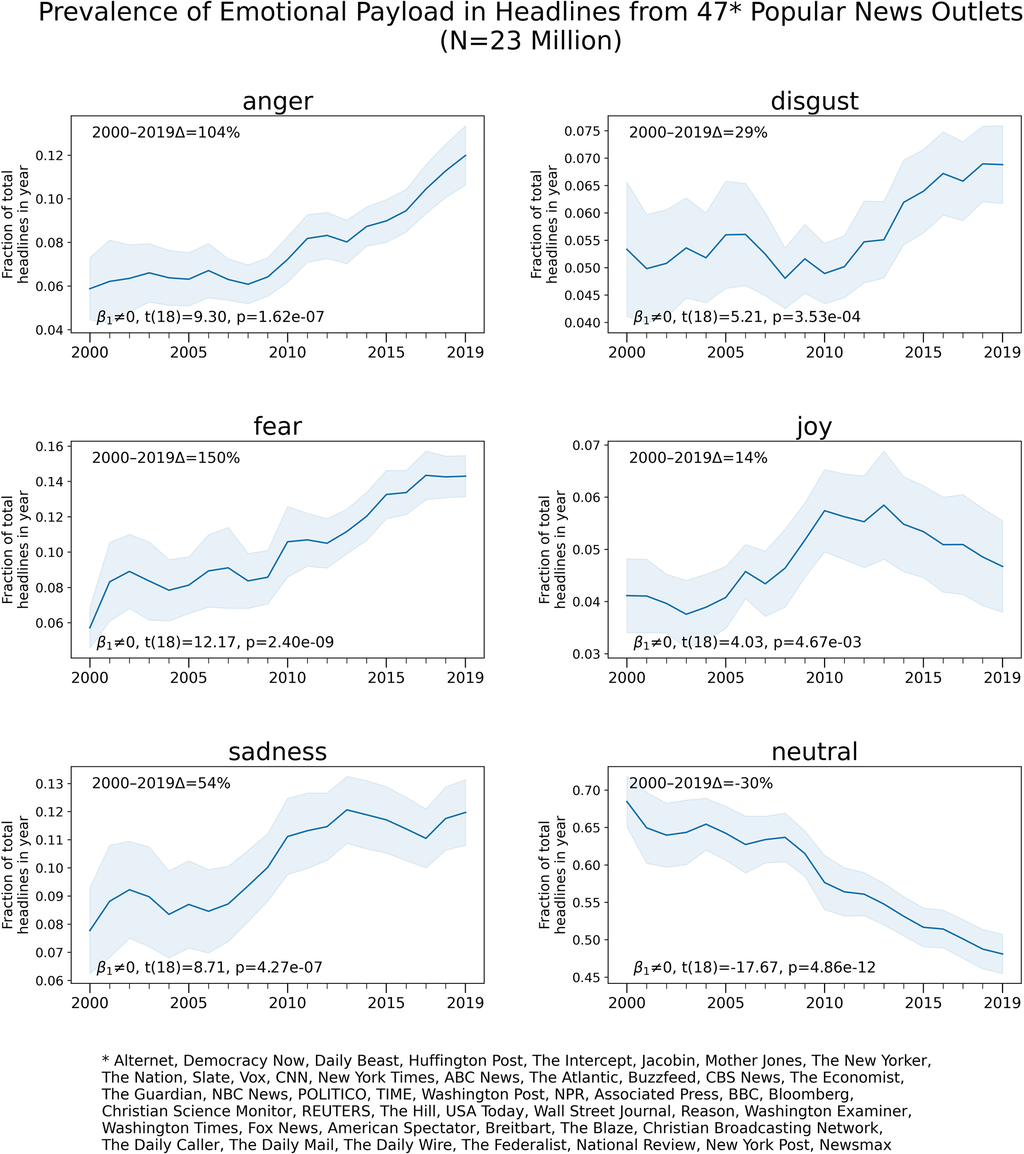

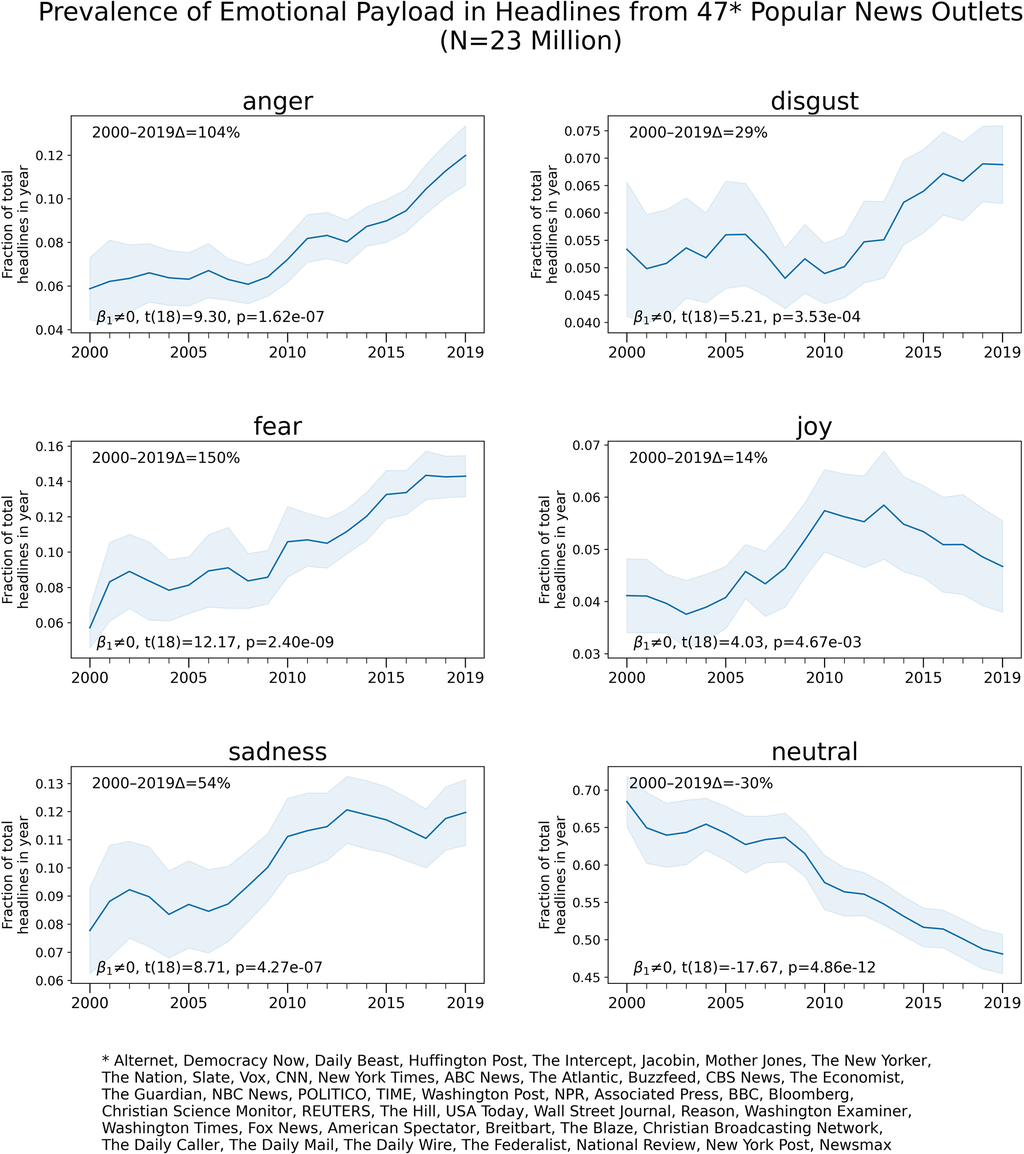

| Description This section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. (February 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  A Vote Leave poster with a contested claim about the EU membership fee, cited as an example of post-truth politics[69] In modern professionalization of political communication (tied to marketing and advertising research), a defining trait of post-truth politics is that campaigners continue to repeat their talking points, even when media outlets, experts in the field in question, and others provide proof that contradicts these talking points.[70][71] For example, during campaigning for the British EU referendum campaign, Vote Leave made repeated use of the claim that EU membership cost £350 million a week, although later began to use the figure as a net amount of money sent directly to the EU. This figure, which ignored the UK rebate and other factors, was described as "potentially misleading" by the UK Statistics Authority, as "not sensible" by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, and was rejected in fact checks by BBC News, Channel 4 News and Full Fact.[72][73][74] Vote Leave nevertheless continued to use the figure as a centrepiece of their campaign until the day of the referendum, after which point they downplayed the pledge as having been an "example", pointing out that it was only ever suggested as a possible alternative use of the net funds sent to the EU.[75] Tory MP and Leave campaigner Sarah Wollaston, who left the group in protest during its campaign, criticised its "post-truth politics".[69] The justice secretary Michael Gove controversially claimed in an interview that the British people "Had had enough of experts".[76] Michael Deacon, parliamentary sketchwriter for The Daily Telegraph, summarised the core message of post-truth politics as "Facts are negative. Facts are pessimistic. Facts are unpatriotic." He added that post-truth politics can also include a claimed rejection of partisanship and negative campaigning.[77] In this context, campaigners can push a utopian "positive campaign" to which rebuttals can be dismissed as smears and scaremongering and opposition as partisan.[26][77] In its most extreme mode, post-truth politics can make use of conspiracism.[78][79] In this form of post-truth politics, false rumors (such as the "birther" or "Muslim" conspiracy theories about Barack Obama) become major news topics.[80] In the case of the "pizzagate" conspiracy, this resulted in a man entering the Comet Ping Pong pizzeria and firing an AR-15 rifle.[81] In contrast to simply telling untruths, writers such as Jack Holmes of Esquire describe the process as something different, with Holmes putting it as: "So, if you don't know what's true, you can say whatever you want and it's not a lie".[2] Finally, scholars have argued that post-truth is not simply about clear cut true/false statements and people's failure to distinguish between them but about strategically ambiguous statements that may be true in some ways, from some perspectives and interpretations, and false in others. This was the case around the disinformation campaigns of the UK and US in promoting the US invasion of Iraq (Saddam Hussein/Al Qaeda "ties" or "links" and Weapons of Mass Destruction), which have been described as watershed moments of the post-truth era.[82][47][21] Major news outlets  Decline of neutrality and rise in emotionality in large U.S. media news articles headlines since 2000[83] Several trends in the media landscape have been blamed for the perceived rise of post-truth politics. One contributing factor has been the proliferation of state-funded news agencies like CCTV News and RT, and Voice of America in the US which allow states to influence Western audiences. According to Peter Pomerantsev, a British-Russian journalist who worked for TNT in Moscow, one of their prime objectives has been to de-legitimize Western institutions, including the structures of government, democracy, and human rights.[citation needed] As of 2016, trust in the mainstream media in the US had reached historical lows.[29] It has been suggested that under these conditions, fact checking by news outlets struggles to gain traction among the wider public[29][84] and that politicians resort to increasingly drastic messaging.[85] Many news outlets desire to appear to be, or have a policy of being, impartial. Many writers have noted that in some cases, this leads to false balance, the practice of giving equal emphasis to unsupported or discredited claims without challenging their factual basis.[86] The 24-hour news cycle also means that news channels repeatedly draw on the same public figures, which benefits PR-savvy politicians and means that presentation and personality can have a larger impact on the audience than facts,[87] while the process of claim and counter-claim can provide grist for days of news coverage at the expense of deeper analysis of the case.[88] Social media and the Internet General availability of vast amounts of information on the internet bypassed established media that were generally reliable due to editorial process and professional journalistic and academic discipline which acted as gatekeepers which filtered out misinformation. Now misinformation that might have been filtered out is often published in popular globally accessible forums which enter the marketplace of ideas liberal democracies depend on for informing their electorate.[63] Social media adds an additional dimension, as user networks can become echo chambers possibly emphasised by the filter bubble where one political viewpoint dominates and scrutiny of claims fails,[88][38][89] allowing a parallel media ecosystem of websites, publishers and news channels to develop, which can repeat post-truth claims without rebuttal.[90] In this environment, post-truth campaigns can ignore fact checks or dismiss them as being motivated by bias.[79] The Guardian editor-in-chief Katherine Viner laid some of the blame on the rise of clickbait, articles of dubious factual content with a misleading headline and which are designed to be widely shared, saying that "chasing down cheap clicks at the expense of accuracy and veracity" undermines the value of journalism and truth.[91] In 2016, David Mikkelson, co-founder of the fact checking and debunking site Snopes.com, described the introduction of social media and fake news sites as a turning point, saying "I'm not sure I'd call it a post-truth age but ... there's been an opening of the sluice-gate and everything is pouring through. The bilge keeps coming faster than you can pump."[92] The digital culture allows anybody with a computer and access to the internet to post their opinions online and mark them as fact which may become legitimized through echo-chambers and other users validating one another. Content may be judged based on how many views a post gets, creating an atmosphere that appeals to emotion, audience biases, or headline appeal instead of researched fact. Content which gets more views is continually filtered around different internet circles[clarification needed], regardless of its legitimacy. Some also argue that the abundance of fact available at any time on the internet leads to an attitude focused on knowing basic claims to information instead of an underlying truth or formulating carefully thought-out opinions.[93] The Internet allows people to choose where they get their information, often facilitating them to reinforce their own opinions.[94] Researchers have developed prototypical falsity scores for over 800 contemporary elites on Twitter and associated exposure scores. Various similar countermeasures that are largely based on technical changes or extensions to common platforms and software have been proposed (see below).[95][96] In 2017, a rise in national protests sparked against the 2016 United States presidential election and the victory of Donald Trump attributed to the fake news stories posted and shared by millions of users on Facebook. Following this incident, the spread of misinformation was given the word "post-truth", a term coined from Oxford Dictionaries as the "word of the year".[97] Polarized political culture The rise of post-truth politics coincides with polarized political beliefs.[98] A Pew Research Center study of American adults found that "those with the most consistent ideological views on the left and right have information streams that are distinct from those of individuals with more mixed political views—and very distinct from each other".[99] Data is becoming increasingly accessible as new technologies are introduced to the everyday lives of citizens. An obsession for data and statistics also filters into the political scene, and political debates and speeches become filled with snippets of information that may be misconstrued, false, or not contain the whole picture. Sensationalized television news emphasizes grand statements and further publicizes politicians. This shaping from the media influences how the public views political issues and candidates.[94] |

説明 このセクションには 、 本題に明確に言及していない 、あるいは 本題に関連して いない 資料の統合が 含まれている可能性が ある。関連する議論はトークページで見られるかもしれない。(2017年2月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)  ポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクス[69]の一例として引用された、EU加盟金に関する主張が争点となった離脱票のポスター。 マーケティングや広告リサーチと結びついた)政治的コミュニケーションの現代的な専門化において、ポスト真実政治の決定的な特徴は、メディアや当該分野の 専門家などがこれらのトーキング・ポイントと矛盾する証拠を提供しても、選挙運動家がトーキング・ポイントを繰り返し続けることである[70][71]。 例えば、英国のEU国民投票キャンペーンのキャンペーン中、離脱票はEU加盟に週3億5,000万ポンドかかるという主張を繰り返し使用したが、後にこの 数字をEUに直接送られる純額として使用し始めた。英国のリベートやその他の要因を無視したこの数字は、英国統計局によって「誤解を招く可能性がある」と され、財政問題研究所によって「賢明ではない」とされ、BBCニュース、チャンネル4ニュース、フルファクトによるファクトチェックで否定された。 [72][73][74]それにもかかわらず、離脱票は国民投票当日までキャンペーンの目玉としてこの数字を使い続けたが、それ以降は「一例」としてこの 公約を軽視し、EUに送られる純資金の代替的な使い道として提案されたにすぎないと指摘した。 [75]トリーの議員で離脱運動家のサラ・ウォラストンは、キャンペーン中に抗議のためにグループを脱退し、その「ポスト真実政治」を批判した[69]。 マイケル・ゴーヴ司法長官はインタビューで、イギリス国民は「専門家にうんざりしていた」と主張し、物議を醸した[76]。 デイリー・テレグラフ紙の議会スケッチライターであるマイケル・ディーコンは、ポスト真実政治の核心的メッセージを「事実は否定的である。事実は悲観的で ある。事実は非国民である。彼はさらに、ポスト真実政治には、党派性やネガティブキャンペーンを否定する主張も含まれると付け加えた[77]。この文脈で は、運動家はユートピア的な「ポジティブキャンペーン」を推し進めることができ、それに対する反論は中傷や 脅しとして、反対は党派的なものとして退けることができる[26][77]。 ポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクスの最も極端なモードでは、陰謀論が利用されることがある[78][79]。ポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクスのこの形態 では、(バラク・オバマに関する「樺太人」や「イスラム教徒」の陰謀論などの)虚偽の噂が主要なニューストピックとなる[80]。"ピザゲート"の陰謀の 場合、この結果、コメット・ピンポン・ピザ屋に男が入り込み、AR-15ライフルを発砲した[81]。 単に真実でないことを話すのとは対照的に、『エスクァイア』のジャック・ホームズなどの作家は、このプロセスを何か違うものとして表現しており、ホームズ は次のように表現している: 「つまり、何が真実かわからなければ、何を言ってもいいし、それは嘘ではないということだ」[2]最後に、学者たちは、ポスト・トゥルースとは、単純に真 実か嘘かをはっきりさせた発言や、人々がそれを区別できないことではなく、戦略的にあいまいな発言をすることであり、ある観点や解釈からは真実であって も、ある観点や解釈からは嘘であるということだと主張している。これは、アメリカのイラク侵攻を促進するためのイギリスとアメリカの偽情報キャンペーン (サダム・フセインとアルカイダの「つながり」や「つながり」、大量破壊兵器)をめぐるケースであり、ポスト・トゥルース時代の分水嶺と言われている [82][47][21]。 主要な報道機関[編集]  2000年以降の米国大手メディアのニュース記事の見出しにおける中立性の低下と感情性の上昇[83]。 ポスト・トゥルース政治が台頭してきたとされる背景には、メディアをめぐるいくつかの傾向がある。その要因のひとつは、CCTVニュースや RT、アメリカのボイス・オブ・アメリカなど、国家が資金を提供する通信社が急増したことである。モスクワのTNTに勤務していたイギリス系ロシア人の ジャーナリストであるピーター・ポメランツェフによると、彼らの主要な目的のひとつは、政府の構造、民主主義、人権を含む西側の制度を非正統化することで ある[要出典]。2016年の時点で、アメリカの主流メディアに対する信頼は歴史的な低水準に達していた[29]。このような状況下では、報道機関による 事実確認は、より広範な人々の間で支持を得るのに苦労し[29][84]、政治家はますます思い切ったメッセージングに頼るようになると示唆されている [85]。 多くの報道機関は、公平であるように見せたい、あるいは公平であることをポリシーとしている。多くのライターは、場合によってはこれが偽りのバランス、つ まり事実の根拠に異議を唱えることなく、裏付けのない、あるいは信用できない主張に等しく重点を置く慣行につながることを指摘している[86]。24時間 のニュースサイクルはまた、ニュースチャンネルが同じ公人を繰り返し起用することを意味し、これはPRに精通した政治家に利益をもたらし、プレゼンテー ションや個性が事実よりも視聴者に大きな影響を与えることを意味する[87]。 ソーシャルメディアとインターネット インターネット上の膨大な情報の一般的な利用可能性は、編集プロセスや専門的なジャーナリズムや 学術的な規律によって一般的に信頼できる既存メディアを迂回し、誤った情報を濾過するゲートキーパーの役割を果たした。現在では、フィルターにかけられた かもしれない誤った情報が、世界的にアクセス可能な人気のあるフォーラムで発表されることも多く、自由民主主義国家が有権者に情報を提供するために依存し ている思想市場に入り込んでいる[63]。 ソーシャル・メディアは、ユーザー・ネットワークがエコーチェンバー(反響室)になる可能性があり、ひとつの政治的視点が支配的で主張の精査がうまくいか ないフィルター・バブルによって強調され[88][38][89]、反論なしにポスト・トゥルースの主張を繰り返すことができるウェブサイト、出版社、 ニュース・チャンネルからなるパラレル・メディア・エコシステムが発展することを可能にするからである[90]。このような環境では、ポスト・トゥルー ス・キャンペーンはファクト・チェックを無視したり、バイアスに動かされているとしてそれを退けることができる。 79] ガーディアン紙の キャサリン・ヴィナー編集長は、クリックベイト(誤解を招くような見出しをつけた、事実かどうか疑わしい内容の記事で、広く共有されるように設計されたも の)の台頭に責任の一端を負わせ、「正確さと真実性を犠牲にして安価なクリック数を追い求める」ことは、ジャーナリズムと真実の価値を損なうと述べた [91]。 [91]2016年、ファクトチェックと デバンキングサイト Snopes.comの共同創設者であるデイヴィッド・マイケルソンは、ソーシャルメディアとフェイクニュースサイトの導入を転換点として説明し、「ポス ト・トゥルースの時代と呼ぶかどうかはわからないが、......水門が開き、あらゆるものが流れ込んでいる。ポンプで汲み上げるよりも速いスピードでビ ルジが押し寄せてくる」[92]。 デジタル文化は、コンピュータとインターネットへのアクセスさえあれば、誰でも自分の意見をオンラインに投稿し、それを事実としてマークすることを可能に する。コンテンツは、投稿の閲覧数に基づいて判断され、調査された事実ではなく、感情や視聴者の偏見、見出しに訴えるような雰囲気を作り出す。より多くの ビューを獲得したコンテンツは、その正当性に関係なく、さまざまなインターネットサークル[要解説]で継続的にフィルタリングされる。また、インターネッ ト上でいつでも入手可能な豊富な事実が、根本的な真実や注意深く考え抜かれた意見を形成する代わりに、情報に対する基本的な主張を知ることに焦点を当てた 姿勢につながると主張する人もいる[93]。インターネットは、人々がどこで情報を得るかを選択することを可能にし、しばしば自分の意見を強化することを 容易にする[94]。 研究者たちは、ツイッター上の800人以上の現代エリートのプロトタイプ的な虚偽性スコアと、関連する暴露スコアを開発した。主に一般的なプラットフォー ムやソフトウェアの技術的な変更や拡張に基づく様々な同様の対策が提案されている(下記参照 )[95][96]。 2017年、2016年のアメリカ合衆国大統領選挙と ドナルド・トランプの勝利に対して巻き起こった全国的な抗議の高まりは、フェイスブック上で何百万人ものユーザーによって投稿され共有されたフェイク ニュースの記事に起因していた。この事件後、誤った情報の拡散は「ポスト・トゥルース」という言葉を与えられ、オックスフォード・ディクショナリーズが 「今年の言葉」として造語した[97]。 政治文化の分極化 ポスト・トゥルース政治の台頭は、政治信条の二極化と一致している[98]。ピュー・リサーチ・センターがアメリカの成人を対象に行った調査によると、 「左右で最も一貫したイデオロギー的見解を持つ人々は、より複雑な政治的見解を持つ個人とは異なる、そして互いに非常に異なる情報の流れを持っている」 [99]。データや統計への執着は政治シーンにも入り込み、政治討論や演説は、誤解や虚偽、あるいは全体像を含んでいない可能性のある情報の断片で埋め尽 くされるようになる。センセーショナルなテレビニュースは、大言壮語を強調し、政治家をさらに宣伝する。メディアによるこのような形成は、一般大衆が政治 問題や候補者をどのように見るかに影響を与える[94]。 |

| Origin Post-truth politics has its origins in the reaction of sectors of the public to widespread adoption of neoliberalism and other proposed global solutions to problems such as climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic[100] by global economic and political elites.[101][102][103][98] In Six Faces of Globalization: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why It Matters, a book by Anthea Roberts and Nicolas Lamp, two Australian scholars, the establishment neoliberal narrative and major reactions to it such as the "left-wing populist narrative", the "corporate power narrative", the "right-wing populist narrative", the "geoeconomic narrative" and a number of "global threats narratives" are compared and contrasted.[104] The establishment narrative supported by consensus of democratic political parties and institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) is based on international negotiation of agreements allowing the economic principles of competition and comparative advantage to operate, maximizing gross domestic product (GDP) in each country. The principles employed are well established and work, producing expanded global economic production, but also result in gains for some sectors of the international economy and losses for others.[104] |

起源 ポスト真実政治は、新自由主義や、気候変動や COVID-19パンデミック[100]のような問題に対するグローバルな解決策をグローバルな経済的・政治的エリートが広く採用したことに対する大衆の 反応に端を発している[101][102][103][98]。 グローバリゼーションの6つの顔』のなかで: 2人のオーストラリア人学者であるアンシア・ロバーツとニコラス・ランプによる著書『Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why It Matters』では、既成のネオリベラルの物語と、それに対する主な反応である「左翼ポピュリストの物語」、「企業権力の物語」、「右翼ポピュリストの 物語」、「地球経済の物語」、そして数多くの「地球規模の脅威の物語」が比較対照されている[104]。 民主主義政党のコンセンサスと、世界銀行、国際通貨基金(IMF)、世界貿易機関(WTO)などの機関によって支えられている既成の物語は、競争と 比較優位の経済原則を機能させ、各国の国内総生産(GDP)を最大化することを可能にする協定の国際交渉に基づいている。採用されている原則は十分に確立 されたものであり、世界的な経済生産の拡大を生み出し、機能しているが、国際経済のある部門にとっては利益となり、他の部門にとっては損失となる結果にも なっている[104]。 |

| Dissenting views Unlike some academic treatments of post-truth that see it as historically specific and closely associated with shifts in journalism, social trust, and new media and communication technologies, several popular commentators (pundits and journalists), equating post-truth with lying or sensational news, have proposed that post-truth is an imprecise or misleading term and/or should be abandoned. In an editorial, New Scientist suggested "a cynic might wonder if politicians are actually any more dishonest than they used to be", and hypothesized that "fibs once whispered into select ears are now overheard by everyone".[38] David Helfand argues, following Edward M. Harris, that "public prevarication is nothing new" and that it is the "knowledge of the audience" and the "limits of plausibility" within a technology-saturated environment that have changed. We are, rather, in an age of misinformation where such limits of plausibility have vanished and where everyone feels equally qualified to make claims that are easily shared and propagated.[105] The writer George Gillett has suggested that the term "post-truth" mistakenly conflates empirical and ethical judgements, writing that the supposedly "post-truth" movement is in fact a rebellion against "expert economic opinion becoming a surrogate for values-based political judgements".[106] Toby Young, writing for The Spectator, called the term a "cliché" used selectively primarily by left-wing commentators to attack what are actually universal ideological biases, contending that "[w]e are all post-truthers and probably always have been".[107] The Economist has called this argument "complacent", however, identifying a qualitative difference between political scandals of previous generations, such as those surrounding the Suez Crisis and the Iran–Contra affair (which involved attempting to cover-up the truth) and contemporary ones in which public facts are simply ignored.[108] Similarly, Alexios Mantzarlis of the Poynter Institute said that political lies were not new and identified several political campaigns in history which would now be described as "post-truth". For Mantzarlis, the "post-truth" label was—to some extent—a "coping mechanism for commentators reacting to attacks on not just any facts, but on those central to their belief system", but also noted that 2016 had been "an acrimonious year for politics on both sides of the Atlantic".[109] Mantzarlis also noted that interest in fact checking had never been higher, suggesting that at least some reject "post-truth" politics.[109][110] In addition, The Guardian's Kathryn Viner notes that while false news and propaganda are rampant, social media is a double-edged sword. While it has helped some untruths to spread, it has also restrained others; as an example, she said The Sun's false "The Truth" story following the Hillsborough disaster, and the associated police cover-up, would be hard to imagine in the social media age.[91] By country Post-truth politics has been applied as a political buzzword to a wide range of political cultures; one article in The Economist identified post-truth politics in Austria, Germany, North Korea, Poland, Russia, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[108] Australia The repeal of carbon pricing by the government of Tony Abbott was described as "the nadir of post-truth politics" by The Age.[111] Germany In December 2016 "postfaktisch" (post-factual) was named word of the year by the Gesellschaft für deutsche Sprache (German language society), also in connection with a rise of right-wing populism[112] from 2015 on. Since the 1990s, "post-democracy" was used in sociology more and more. India Amulya Gopalakrishnan, columnist for The Times of India, identified similarities between the Trump and Brexit campaigns on the one hand, and hot-button issues in India such as the Ishrat Jahan case and the ongoing case against Teesta Setalvad on the other, where accusations of forged evidence and historical revisionism have resulted in an "ideological impasse".[88] Indonesia Post-truth politics have been discussed in Indonesia since at least 2016. In September 2016, the incumbent governor of Jakarta Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, during a speech to citizens of Thousand Islands, said that some citizens were being "deceived using Verse 51 of Al Maidah and other things", referring to a verse of the Quran used by his political opponents.[113] The video was later edited to omit a single word, misrepresenting his statement and instigating a political scandal that resulted in a blasphemy charge and two-year imprisonment.[114] Since this event, post-truth politics have played a more significant role in political campaigns, as well as interactions between Indonesian voters. Yoseph Wihartono, researcher in crimonology at the University of Indonesia, identified social media outlets and "internet mobbing" as sources of post-truth dynamics that have potentially "opened wide" the opportunity for religious populism to expand.[115] South Africa Health care and education in South Africa was substantially compromised during the presidency of Thabo Mbeki due to his HIV/AIDS denialism.[116] United Kingdom An early use of the phrase in British politics was in March 2012 by Scottish Labour MSP Iain Gray in criticising the difference between Scottish National Party's claims and official statistics.[117] Scottish Labour leader Jim Murphy also described an undercurrent of post-truth politics in which people "cheerfully shot the messenger" when presented with facts that did not support their viewpoint, seeing it among pro-independence campaigners in the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, and Leave campaigners in the then-upcoming EU membership referendum.[118] Post-truth politics has been retroactively identified in the lead-up to the Iraq War,[119] particularly after the Chilcot Report, published in July 2016, concluded that Tony Blair misrepresented military intelligence to support his view that Iraq's chemical weapons program was advanced.[120][121] The phrase became widely used during the 2016 UK EU membership referendum to describe the Leave campaign.[28][29][119][69][122] Faisal Islam, political editor for Sky News, said that Michael Gove used "post-fact politics" that were imported from the Trump campaign; in particular, Gove's comment in an interview that "I think people in this country have had enough of experts..." was singled out as illustrative of a post-truth trend, although this is only part of a longer statement.[29][122][123] Similarly, Arron Banks, the founder of the unofficial Leave.EU campaign, said that "facts don't work ... You've got to connect with people emotionally. It's the Trump success."[77] Andrea Leadsom—a prominent campaigner for Leave in the EU referendum and one of the two final candidates in the Conservative leadership election—has been singled out as a post-truth politician,[77] especially after she denied having disparaged rival Theresa May's childlessness in an interview with The Times in spite of transcript evidence.[91] United States Further information: Trumpism and Alternative facts In conjunction with the rise of new media and communication technologies (especially the Internet and blogging) and the professionalization of political communication (political consulting), scholars have viewed the periods following 9/11 and the George W. Bush administration's strategic communication as a seminal moment in the emergence of what has subsequently been called post-truth politics, before the term and concept exploded in public visibility in 2016. The Bush administration's talking points about "links" or "ties" between Saddam Hussein and Al Qaeda (repeated in parallel by the Tony Blair government), and Hussein's alleged possession of Weapons of Mass Destruction (both highly contested by experts at the time or later disproven and shown to be misleading) were viewed by some scholars[124][47][125] as part of a historical shift. Despite age-old precedents of political and government lying (such as the systematic lying by the U.S. government documented in The Pentagon Papers), these propaganda efforts were seen as more sophisticated in their organization and execution in a new media age, part of a complicated new public communication culture (between a wide number of cable and satellite TV, online, and legacy news media sources). In the U.S., the distrust and deception identified with strategic communication of Karl Rove, George W. Bush, and Donald Rumsfeld, among others, were a close historical precedent to controversies around truth (as accuracy and/or honesty) that entered the media agenda of U.S. public life, drawing significant news and new media attention and producing measurable confusion and false belief.[22] The most spectacular examples studied by scholars include the presidential candidacy of John Kerry in 2004 (accusations by the Republican consultant-directed "Swift boat Veterans for Truth" that he lied about his war record) and then, several years later (prior to the 2008 U.S. presidential campaign), that then candidate Barack Obama was a Muslim, despite his declaration that he was Christian, and was using a fake birth certificate (allegedly born in Kenya).[126][127][128] In its original formulation, the phrase "post-truth politics" was used to describe the paradoxical situation in the United States where the Republican Party, which enforced stricter party discipline than the Democratic Party, was nevertheless able to present itself as more bipartisan, since individual Democrats were more likely to support Republican policies than vice versa.[26] The term was used by Paul Krugman in The New York Times to describe Mitt Romney's 2012 presidential campaign in which certain claims—such as that Barack Obama had cut defense spending and that he had embarked on an "apology tour"—continued to be repeated long after they had been debunked.[129] Other forms of scientific denialism in modern US politics include the anti-vaxxer movement, and the belief that existing genetically modified foods are harmful[130] despite a strong scientific consensus that no currently marketed GMO foods have any negative health effects.[131] The health freedom movement in the US resulted in the passage of the bipartisan Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, which allows the sale of dietary supplements without any evidence that they are safe or effective for the purposes consumers expect, though the FDA has begun regulation of homeopathic products. In a review for the Harvard Gazette, Christopher Robichaud—a lecturer in ethics and public policy at Harvard Kennedy School—described conspiracy theories about the legitimacy of elections and politicians, such as the "birther" idea that Barack Obama is not a natural-born US citizen, as one side-effect of post-truth politics. Robichaud also contrasted the behavior of the candidates with that following the contested result of the 2000 election, in which Al Gore conceded and encouraged his supporters to accept the result of Bush v. Gore.[36] Similarly, Rob Boston, writing for The Humanist saw a rise in conspiracy theories across US public life, including Birtherism, climate change denialism, and rejecting evolution, which he identified as a result of post-truth politics, noting that the existence of extensive and widely available evidence against these conspiracy theories had not slowed their growth.[90] In 2016, the "post-truth" label was especially widely used to describe the presidential campaign of Donald Trump, including by Professor Daniel W. Drezner in The Washington Post,[29] Jonathan Freedland in The Guardian,[28] Chris Cillizza in The Independent,[79] Jeet Heer in The New Republic,[132] and James Kirchick in the Los Angeles Times,[133] and by several professors of government and history at Harvard.[36] In 2017, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and others, began to point out lies or falsehoods in Trump's statements after the election.[134][135][136][137] Former president Barack Obama stated that the new media ecosystem "means everything is true and nothing is true".[138] Political "facts" Newt Gingrich, a prominent American politician and Trump supporter, in an interview with CNN reporter Alisyn Camerota aired July 22, 2016, explained that facts based on the feelings of the electorate were more important in a political campaign than the statistics collected by a reliable government agency are: "CAMEROTA: They feel it, yes, but the facts don't support it. GINGRICH: As a political candidate, I'll go with how people feel and I'll let you go with the theoreticians."[139][140][34] Supporters of those who are publishing or asserting things that are not true do not necessarily believe them, but have accepted that that is how the game is played.[141][142][143] Environmental politics Although the consensus among scientists is that human activities contribute to global warming, several political parties around the world have made climate change denial a basis of their policies. These parties have been accused of using post-truth techniques to attack environmental measures meant to combat climate changes to benefit industry donors.[144] In the wake of the 2016 election, the United States saw numerous climate change deniers rise to power, such as new Environmental Protection Agency head Scott Pruitt replacing Barack Obama's appointee Gina McCarthy. |

反対意見 ポスト真実を歴史的に特異なものであり、ジャーナリズム、社会的信頼、新しいメディアや通信技術の変化と密接に関連していると捉える一部の学術的な研究と は異なり、ポスト真実を嘘やセンセーショナルなニュースと同義とみなす一部の人気コメンテーター(専門家やジャーナリスト)は、ポスト真実は不正確または 誤解を招く用語であり、かつ/または放棄すべきであると提言している。ニューサイエンティスト誌は社説で、「皮肉屋は、政治家が以前よりも不誠実になった のかと疑問に思うかもしれない」と提案し、「かつては選ばれた人々の耳元でささやかれていた嘘が、今では誰にでも聞かれてしまう」と仮説を立てた。 [38] デビッド・H・ エドワード・M・ハリスに続いて、「公の場でのごまかしは何も目新しいことではない」と主張し、テクノロジーが浸透した環境下で「聴衆の知識」と「信憑性 の限界」が変化したと述べている。むしろ、私たちは、信憑性の限界が消え失せた誤報の時代にあり、誰もが等しく、簡単に共有・拡散される主張を行う資格が あると感じている時代にある。[105] 作家のジョージ・ギレットは、 「ポスト真実」という用語は、経験的判断と倫理的判断を誤って混同していると指摘し、この「ポスト真実」とされる運動は、実際には「価値に基づく政治的判 断の代理となる専門家の経済的意見」に対する反発であると書いている。[106] ザ・スペクテイター誌に寄稿したトビー・ヤングは、この用語を主に左派の論説家たちが、実際には普遍的なイデオロギー的偏見を攻撃するために選択的に使用 する「陳腐な表現」と呼び、「我々は皆ポストトゥルース論者であり、おそらく常にそうであった」と主張している。[107] しかし、エコノミスト誌は、この主張を「自己満足的」と呼び、 スエズ動乱やイラン・コントラ事件(真実を隠蔽しようとした事件)など、過去の政治スキャンダルと、単に公の事実が無視される現代のスキャンダルとの間に は質的な違いがあると指摘している。[108] 同様に、ポインター研究所のアレクシオス・マンザリス氏は、政治的な嘘は新しいものではなく、現在では「ポスト真実」と表現されるであろう歴史上の政治 キャンペーンをいくつか挙げている。マンザリスにとって、「ポスト真実」というレッテルは、ある程度は「事実に対する攻撃だけでなく、信念体系の中心に対 する攻撃に反応するコメンテーターの対処法」であったが、2016年は「 大西洋の両側で政治が険悪になった年」であったと指摘している。[109] また、マンツァリスは、ファクトチェックへの関心がかつてないほど高まっていることを指摘し、少なくとも一部の人々が「ポスト真実」の政治を拒絶している ことを示唆している。[109][110] さらに、ガーディアンのキャサリン・ヴァイナーは、偽ニュースやプロパガンダが横行する一方で、ソーシャルメディアは諸刃の剣であると指摘している。ソー シャルメディアは一部の虚偽の拡散を助長する一方で、他の拡散を抑制する効果もある。その一例として、ヴァイナーは、ヒルズバラの悲劇の後にザ・サン紙が 掲載した虚偽の「真実」記事と、それに関連する警察の隠蔽工作について挙げ、ソーシャルメディア時代にはこのようなことは考えられないと述べている。 国別 ポスト真実政治は、幅広い政治文化に政治的な流行語として適用されている。エコノミスト誌のある記事では、オーストリア、ドイツ、北朝鮮、ポーランド、ロ シア、トルコ、英国、米国におけるポスト真実政治を特定している。[108] オーストラリア トニー・アボット政権による炭素価格設定の廃止は、ザ・エイジ紙によって「ポスト真実政治のどん底」と表現された。[111] ドイツ 2016年12月、「ポストファクト(事実に反する)」がドイツ語協会(Gesellschaft für deutsche Sprache)により今年の単語に選ばれたが、これも2015年以降の右派ポピュリズムの台頭との関連でである[112]。1990年代以降、「ポスト 民主主義」という言葉は社会学でますます使われるようになった。 インド Amulya Gopalakrishnan氏は、英紙『タイムズ・オブ・インディア』のコラムニストであり、トランプ大統領とブレグジットのキャンペーンの類似点と、 インドにおけるイシュラット・ジャハン事件や、現在係争中のテスタ・セタルヴァドに対する事件などのホットイシュー(社会的に大きな影響を持つ問題)との 類似点を指摘している。偽造証拠や歴史修正主義の告発が「イデオロギー的な行き詰まり」をもたらしたというのだ。[88] インドネシア ポスト真実政治は、少なくとも2016年からインドネシアで議論されている。2016年9月、現職のジャカルタ知事バスキ・チャハジャ・プルナマは、千の 島々の市民への演説の中で、一部の市民は「アル・メイダ第51節やその他のものを使って欺かれている」と述べた。これは、彼の政治的反対派が使用したコー ランの一節を指している。 。この動画は後に編集され、彼の発言を歪めて伝え、冒涜罪で2年の実刑判決を受けるという政治スキャンダルを引き起こす結果となった。インドネシア大学の 犯罪学研究者であるヨセフ・ウィハルトノは、ポスト真実の力学の源としてソーシャルメディアと「ネット上の集団暴行」を挙げ、それが宗教的ポピュリズムの 拡大の機会を「大きく開いた」可能性があると指摘している。[115] 南アフリカ 南アフリカの医療と教育は、タボ・ムベキ大統領の任期中、同大統領のHIV/AIDS否定論により、大幅に損なわれた。[116] イギリス イギリス政治におけるこのフレーズの初期の使用例は、2012年3月にスコットランド労働党のイアン・グレイ議員が、スコットランド国民党の主張と公式統 計の相違を批判したものである。[117] スコットランド労働党のジム・マーフィー党首も、 人々が自分たちの見解を裏付ける事実を提示された際に「メッセンジャーを快く攻撃する」というポスト真実政治の潮流を、2014年のスコットランド独立の 是非を問う住民投票における独立推進派のキャンペーンや、当時間近に迫っていたEU残留の是非を問う国民投票における残留推進派のキャンペーンに見られる と述べた。 ポスト真実政治は、イラク戦争の準備段階で遡及的に特定されてきたが[119]、特に2016年7月に発表されたチルコット報告書が、トニー・ブレアがイ ラクの化学兵器開発が進んでいるという自身の考えを支持するために軍事情報を偽って伝えたと結論づけた後、その傾向が強まった[120][121]。 このフレーズは、2016年の英国のEU残留・離脱を問う国民投票の際には、離脱キャンペーンを表現する際に広く使用された。[28][29][119] [69][122] スカイニュースの政治担当編集者であるファイサル・イスラムは、マイケル・ゴーブがトランプ陣営から輸入した「ポストファクト政治」を使用したと述べた。 特に、 インタビューで「この国の国民は専門家にはもううんざりしていると思う」と発言したことが、ポスト真実の傾向を示すものとして取り上げられたが、これはよ り長い発言の一部に過ぎない[29][122][123]。同様に、非公式のEU離脱キャンペーン「Leave.EU」の創設者であるアロン・バンクス は、「事実ではうまくいかない... 人々の感情に訴えかけなければならない。それがトランプの成功だ」と述べた。[77] 国民投票でEU離脱派の有力なキャンペーン担当者であり、保守党党首選の最終候補者2人のうちの1人であるアンドレア・リーダスは、ポスト真実の政治家と して取り上げられている。特に、彼女が『タイムズ』紙とのインタビューで、テレサ・メイのライバルが子供を持たないことをけなしたことを否定したことが、 その理由である。 アメリカ合衆国 詳細情報:トランプ主義とオルタナティブ・ファクト 新しいメディアや通信技術(特にインターネットやブログ)の台頭と政治コミュニケーション(政治コンサルティング)の専門化に伴い、学者たちは、2016 年にこの用語や概念が一般に広く知られるようになる以前に、9.11同時多発テロ事件とジョージ・W・ブッシュ政権の戦略的コミュニケーションの時代を、 後にポスト真実政治と呼ばれるものの出現における画期的な瞬間と捉えていた。ブッシュ政権による、サダム・フセインとアルカイダの「つながり」や「関連 性」に関する主張(トニー・ブレア政権も同様の主張を繰り返した)、およびフセインが大量破壊兵器を保有しているという主張(いずれも当時、または後に専 門家によって強く否定され、誤解を招くものであることが判明した)は、一部の学者[124][47][125] からは歴史的な変化の一部と見なされた。政治や政府による嘘は昔からあることではあるが(例えば、ペンタゴン・ペーパーズに記録されているような米国政府 による組織的な嘘)、これらのプロパガンダ活動は、新しいメディア時代における組織化と実行の面でより洗練されたものとして見られており、複雑な新しい公 共コミュニケーション文化(多数のケーブルテレビや衛星テレビ、オンライン、従来のニュースメディアソースの間で)の一部である。米国では、カール・ロー ブ、ジョージ・W・ブッシュ、ドナルド・ラムズフェルドらによる戦略的コミュニケーションにまつわる不信と欺瞞は、真実(正確性および/または誠実さ)を めぐる論争が米国の公共生活のメディアの議題に入り込み、ニュースやニューメディアの注目を集め、測定可能な混乱と誤信を生み出したという、歴史的な先例 に近いものだった。[22] 学者たちが研究した最も見事な例としては、2004年のジョン・ケリー大統領候補 (共和党のコンサルタントが指揮する「真実のためのベトナム帰還兵協会」による、彼の戦争経験に関する虚偽の主張)や、それから数年後(2008年の米国 大統領選挙キャンペーン前)に、当時候補者であったバラク・オバマ氏がキリスト教徒であると宣言していたにもかかわらず、イスラム教徒であり、偽の出生証 明書(ケニア生まれとされる)を使用していたという主張である。[126][127][128] 「ポスト真実政治」という表現は、当初は、民主党よりも厳しい党内規律を課している共和党が、民主党議員の方が共和党の政策を支持する傾向が強いため、よ り両党寄りであるかのように見せかけることができるという、米国の逆説的な状況を説明するのに使われていた。ポール・クルーグマンがニューヨーク・タイム ズ紙で、バラク・オバマが国防費を削減したことや「謝罪ツアー」に出たことなど、すでに否定された主張が2012年のミット・ロムニーの大統領選挙キャン ペーンで繰り返されたことを指して用いた言葉である。[129] 現代の米国政治における科学否定論の他の形態には、ワクチン反対運動や、 現在販売されている遺伝子組み換え食品には健康への悪影響はないという強い科学的コンセンサスがあるにもかかわらず、遺伝子組み換え食品は有害であるとい う信念である。[131] 米国の健康自由運動は、超党派による1994年の栄養補助食品健康教育法の可決につながった。この法律は、消費者が期待する目的に対して安全または有効で あるという証拠がなくても、栄養補助食品の販売を許可するものである。 ハーバード・ガゼット誌のレビューで、ハーバード・ケネディ・スクールの倫理・公共政策講師であるクリストファー・ロビショーは、選挙や政治家の正当性に 関する陰謀論、例えばバラク・オバマが米国の生まれながらの市民ではないという「birther」の考え方などをポスト真実政治の副作用のひとつとして説 明している。ロビショーはまた、2000年の選挙で争われた結果を受けて、アル・ゴアが降参し、支持者たちにブッシュ対ゴアの結果を受け入れるよう促した ことと、今回の候補者たちの行動を対比させた。[36] 同様に、ヒューマニスト誌に寄稿したロブ・ボストンは、 米国の公共生活における陰謀論の台頭を指摘し、その例として、birtherism(出生地主義)、気候変動否定論、進化論否定論などを挙げ、それらはポ スト真実政治の結果であると指摘し、これらの陰謀論に反する広範かつ入手可能な証拠が数多く存在しているにもかかわらず、陰謀論の勢いは衰えていないと述 べている。 2016年には、「ポスト真実」というレッテルは特にドナルド・トランプの大統領選挙キャンペーンを表現するために広く使用され、ワシントン・ポスト紙の ダニエル・W・ドレズナー教授[29]、ガーディアン紙のジョナサン・フリードランド[28]、インディペンデント紙のクリス・チリッツァ[79]、 ニュー・リパブリック誌のジート・ヒア[132]、ロサンゼルス・タイムズ紙のジェームズ・カーチク[133]、 ハーバード大学の政治学や歴史学の教授数名も指摘している。[36] 2017年には、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙やワシントン・ポスト紙などが、選挙後にトランプ大統領の発言の嘘や虚偽を指摘し始めた。[134][135] [136][137] オバマ前大統領は、新しいメディアの生態系について「すべてが真実であり、何も真実ではない」と述べた。[138] 政治的な「事実」 著名なアメリカ人政治家でトランプ氏の支持者でもあるニュート・ギングリッチ氏は、2016年7月22日に放映されたCNNの記者アリシン・カモロタ氏と のインタビューで、選挙民の感情に基づく事実の方が、信頼できる政府機関が収集した統計よりも政治キャンペーンでは重要であると説明した。 「CAMEROTA:彼らはそう感じている。しかし、事実はそれを裏付けていない。 ギングリッチ:私は政治候補者として、人々がどう感じるかという点に重点を置く。理論家には君に任せよう」[139][140][34] 真実ではないことを公表したり主張したりする人々の支持者たちは、必ずしもそれらを信じているわけではないが、それがゲームのやり方であることを受け入れ ている。[141][142][143] 環境政策 科学者の間では、人間の活動が地球温暖化の原因となっているという見解で一致しているが、世界ではいくつかの政党が気候変動否定論を政策の根拠としてい る。これらの政党は、気候変動対策を攻撃して産業界の寄付者に利益をもたらそうとするポスト真実のテクニックを使用していると非難されている。[144] 2016年の選挙後、米国では多数の気候変動否定論者が権力を握るようになった。例えば、バラク・オバマ大統領が任命したジーナ・マッカーシー氏に代わっ て、スコット・プルイット氏が環境保護庁の新長官に就任した。 |

| Solutions See also: Misinformation § Countermeasures Political scientists Alfred Moore (University of York), Carlo Invernizzi-Accetti (City University of New York), Elizabeth Markovits (Mount Holyoke College), and Zeynep Pamuk (St John's College), evaluated American historian Sophia A. Rosenfeld's book, Democracy and Truth: A Short History (2019) and its potential solutions for dealing with post-truth politics, in what Invernizzi-Accetti calls "remedies for the growing split between populism and technocracy in contemporary democratic regimes".[145] Rosenfeld highlights seven potential solutions to the problem of post-truth politics: an ethical commitment to truth-telling and fact-checking in public; a proscription against reopening settled debates; a crackdown on disinformation by social media companies; a shift away from free-speech absolutism; protecting the integrity of political institutions; improving information literacy with education; and the support of nonviolent protest against lying and corruption.[146] Invernizzi-Accetti criticizes Rosenfeld's solutions, as he does not see the value of truth in politics. "Truth functions politically as a justification of authority", writes Invernizzi-Accetti, "whereas self-government is predicated on its exclusion from the political domain – it follows that any attempt to construe democracy as a 'regime of truth' is ultimately bound to contradict itself."[145] In response, Rosenfeld writes, "truth is bound always to be a problematic intrusion into any democracy", and that "skepticism is indeed intrinsic to democracy."[145] Alfred Moore responds to Rosenfeld's proposal noting that "solutions will not come from the better organization and communication of knowledge, whether popular or expert, nor from institutions and practices of competition and interaction between them, but from the generation of substantive relations of common interest and mutual commitment".[145] |

解決策 以下も参照のこと: 誤報§対策 政治学者のアルフレッド・ムーア(ヨーク大学)、カルロ・インヴェルニッツィ=アクセッティ(ニューヨーク市立大学)、エリザベス・マーコヴィッツ(マウ ント・ホリヨーク・カレッジ)、ゼイネプ・パムク(セント・ジョンズ・カレッジ)は、アメリカの歴史家ソフィア・A・ローゼンフェルドの著書 『Democracy and Truth: A Short History』(2019年)と、ポスト真実政治に対処するための潜在的な解決策を、インヴェルニッツィ=アクセッティが「現代の民主主義体制における ポピュリズムと テクノクラシーの分裂の拡大に対する救済策」と呼ぶものとして評価している。 [145]ローゼンフェルドは、ポスト・トゥルース・ポリティクスの問題に対する潜在的な解決策として、公の場での真実告知とファクトチェックへの倫理的 コミットメント、決着済みの議論のやり直しの禁止、ソーシャルメディア企業による偽情報の取り締まり、言論の自由絶対主義からの脱却、政治制度の完全性の 保護、教育による情報リテラシーの向上、嘘と腐敗に対する非暴力的抗議の支援という7つを挙げている[146]。インヴェルニッツィ=アチェッティは、政 治における真実の価値を見いだせないとして、ローゼンフェルドの解決策を批判している。「真理は権威を正当化するものとして政治的に機能する」とインヴェ ルニッツィ=アクセッティは書き、「一方、自治は政治的領域から排除されることを前提としている-民主主義を『真理の体制』として解釈しようとする試み は、最終的にそれ自体に矛盾をきたすことになる」と述べている[145]。 「145]アルフレッド・ムーアはローゼンフェルドの提案に対して、「解決策は、大衆的であれ専門家であれ、知識の組織化や伝達の改善からもたらされるも のではなく、また競争や相互作用の制度や実践からもたらされるものでもなく、共通の関心と相互コミットメントの実質的な関係の生成からもたらされるもので ある」と指摘している[145]。 |

| Agnotology – Study

of culturally induced ignorance or doubt Alternative facts – Expression associated with political misinformation established in 2017 Antiscience – Attitudes that reject science and the scientific method "Art, Truth and Politics" (Nobel lecture) Big lie – Propaganda technique Dark Enlightenment – Anti-democratic, reactionary philosophy founded by Curtis Yarvin in 2007 Doublespeak Award – Ironic award given to deceptive public speakers Fact checking – Process of verifying information in non-fictional text Fake news website – Website that deliberately publishes hoaxes and disinformation Firehosing – Propaganda technique Half-truth – Deceptive statement Hyperreality – Term for cultural process of shifting ideas of reality On Bullshit – Philosophical essay by Harry Frankfurt Orwellian – Pertaining to a dystopia like in George Orwell's fiction Politics and the English Language – 1946 essay by George Orwell Post-truth – Concept regarding objective facts Pro-Truth Pledge – Promotion to encourage truth and rational thinking Reactionary modernism – Political ideology characterized by embrace of technology and anti-Enlightenment thought Reality-based community – Derisive term for certain people Swiftboating – Political jargon for a particular form of character assassination as a smear tactic Truthiness – Quality of preferring concepts or facts one wishes to be true, rather than actual truth Trumpism – American political movement Truth sandwich – Technique in journalism Why Leaders Lie (book) |

アグノトロジー- 文化的に誘導された無知や疑念の研究 Alternative facts- 2017年に確立された政治的誤報に関連する表現 反科学- 科学と科学的方法を否定する態度 「芸術、真実、政治」(ノーベル賞講演) 大嘘- プロパガンダの手法 ダーク・エンライトメント- 2007年にカーティス・ヤービンによって創設された反民主的、反動的な哲学。 ダブルスピーク賞- 人を欺く演説者に贈られる皮肉な賞 ファクトチェック- ノンフィクションの文章の情報を検証するプロセス。 フェイクニュースサイト- デマや偽情報を意図的に掲載するウェブサイト。 Firehosing- プロパガンダ手法 ハーフ・トゥルース- 欺瞞的な発言 ハイパーリアリティ- 現実の観念が変化する文化的プロセスを指す言葉 デタラメについて- ハリー・フランクフルトによる哲学的エッセイ。 Orwellian- ジョージ・オーウェルの小説のようなディストピアを指す。 政治と英語- ジョージ・オーウェルによる1946年のエッセイ ポスト真実- 客観的事実に関する概念 プロ・トゥルース誓約- 真実と合理的思考を奨励するプロモーション 反動的モダニズム- テクノロジーの受容と反啓蒙思想を特徴とする政治イデオロギー Reality-basedcommunity - 特定の人々を揶揄する言葉。 Swiftboating(スウィフトボーティング) - 中傷戦術としての特定の人格攻撃の政治専門用語。 真実性- 実際の真実よりも、真実であってほしいと願う概念や事実を好む性質。 トランプ主義- アメリカの政治運動 真実のサンドイッチ- ジャーナリズムにおけるテクニック なぜリーダーは嘘をつくのか (単行本) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-truth_politics |

★ポスト真理状況を分析する人類学の可能性

| Jan