フッサール『ヨーロッパ諸学の危機と超越論的現象学』

Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie, 1936-1938

フッサール『ヨーロッパ諸学の危機と超越論的現象学』

Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie, 1936-1938

★『ヨーロッパ諸科学の危機と超越論的現象学:現象学的哲学への序説』(原題:Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie: Eine Einleitung in die phänomenologische Philosophie)は、ドイツの哲学者エドムント・フッサールが1936年に執筆した未完の著作である。この著作は影響力があり、フッサールの思想 の集大成と見なされているが、彼の初期の著作からの転換点とも見なされてきた。

| La Crise des sciences européennes et la phénoménologie transcendantale

est un texte d'Edmund Husserl issu du volume VI des Husserliana publié

en 1954, soit seize ans après la mort du philosophe. Le manuscrit de

départ remonte aux années 1935-1936. Ce texte est composé de deux

écrits d'importance inégale, le texte principal et des textes

complémentaires. Le traducteur français Gérard Granel y voit une

troisième étape dans l'évolution de la pensée du philosophe et son

véritable testament[1]. Le présent article emploie le diminutif « Krisis » pour désigner cette œuvre (tiré du titre allemand : Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendantale Phänomenologie). |

『ヨーロッパ科学の危機と超越論的現象学』は、哲学者エドムント・フッ

サールの死後16年経った1954年に出版された『フッサリアナ』第6巻に掲載された文章だ。原稿は1935年から1936年にさかのぼる。この文章は、

主文と補足文という、重要度が異なる2つの文章で構成されている。フランス語訳者のジェラール・グラネルは、この著作を哲学者の思想の進化における第三段

階、そして彼の真の遺言とみなしている[1]。 本稿では、この著作を「Krisis」という略称で呼ぶ(ドイツ語のタイトル「Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendantale Phänomenologie」から引用)。 |

| Composition générale de l'ouvrage L'Encyclopædia Universalis[2] donne le résumé suivant : « les deux premières parties du « texte principal » ont d'abord paru dans la revue Philosophia (1936) : « La Crise des sciences comme expression de la crise radicale de la vie dans l'humanité européenne » (paragraphes 1 à 7) ; « Élucidation de l'origine de l'opposition moderne entre l'objectivisme physiciste et le subjectivisme transcendantal » (paragraphes 8 à 27). La troisième partie : « Clarification du problème transcendantal. La fonction qui dans ce contexte revient à la psychologie » (paragraphes 28 à 73), plus composite, provient des manuscrits. L'ouvrage comprend aussi de très importants compléments, dont une conférence prononcée à Vienne en 1935 : La crise de l'humanité européenne et la philosophie et, parmi les appendices, L'origine de la géométrie ». Dans la première partie du texte, l'auteur confère une importance décisive à l'articulation entre la philosophie et les sciences qu'il définit comme un rapport de fondation. Une partie importante de sa réflexion est ensuite consacrée à la différenciation de la science entre « science de la nature » et « science de l'esprit », question qui réapparaît vers la fin de l'œuvre. Les paragraphes 9 à 27 sont consacrés aux traits particuliers des Temps modernes, que l'on peut regrouper sous quatre thèmes principaux : la rupture galiléenne, l'origine et le renforcement du dualisme, les limites de l'époché cartésienne, à laquelle Husserl reproche de ne pas être assez radicale et la nécessité de cheminer avec Kant dans la voie de la « phénoménologie transcendantale », dans l'espoir de dévoiler le fondement ultime de tous les phénomènes du monde. Parcourant ce nouveau chemin, les paragraphes 28 à 73 sont consacrés au développement du concept de « monde de la vie », au phénomène de l'« a priori correlationnel » et l'analyse sur plusieurs paragraphes du paradoxe de la subjectivité humaine, à la fois sujet et objet du monde. « Avec la Krisis, ainsi que les autres œuvres qui jalonnent cette période de sa philosophie, Husserl explicite radicalement son tournant ontologique au sein de la phénoménologie. il tente de faire du « monde de la vie » un objet de science au même titre que tout objet de science (qu'elle soit naturelle, humaine ou historique). Toutefois, il faut garder à l'esprit que cet objet est un « a priori universel de corrélation », au sens où il ne possède pas les mêmes caractères « empiriques » que l'objet étudié par les autres sciences », écrit Mario Charland[3]. |

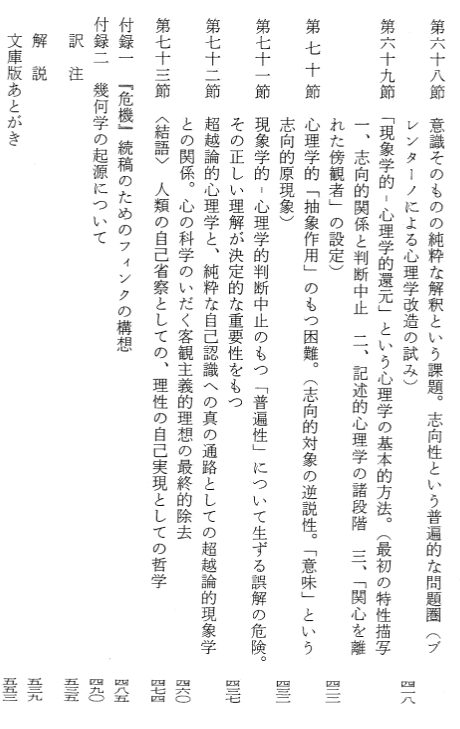

著作の全体構成 Encyclopædia Universalis[2] は、次のように要約している。「『本文』の最初の 2 つの部分は、雑誌 Philosophia (1936) に最初に掲載されたものである。 「ヨーロッパの人類における生命の根本的な危機としての科学の危機」 (1 段落から 7 段落) 「物理学的客観主義と超越的観念論の現代的対立の起源の解明」(第8項から第27項)。第3部「超越的問題の解明。この文脈における心理学の機能」(第 28項から第73項)は、より複合的な内容で、原稿から引用されている。この著作には、1935年にウィーンで発表された講演「ヨーロッパの人類の危機と 哲学」や、付録の「幾何学の起源」など、非常に重要な補足も含まれている。本文の最初の部分では、著者は哲学と科学の関連性を決定的に重要視し、それを基 礎的な関係と定義している。そして、その考察の大部分は、「自然科学」と「精神科学」という科学の区別に費やされており、この問題は、この著作の終わり近 くでも再び取り上げられている。 第9項から第27項は、近代の特徴について論じている。その特徴は、主に4つのテーマにまとめることができる。ガリレオの革新、二元論の起源と強化、カン トの「エポケー」の限界(フッサールは、その過激さが不十分であると批判している)、そして、世界のあらゆる現象の究極の基盤を明らかにするために、カン トとともに「超越論的現象学」の道を歩む必要性である。 この新しい道を歩む中で、28項から73項は「生活世界」の概念の発展、「相関的先験性」の現象、そして世界の主観であり客観でもある人間の主観性のパラ ドックスに関する数項にわたる分析に捧げられている。『危機』や、この時期の彼の哲学の他の著作で、フッサールは現象学における存在論的転換を徹底的に明 らかにしている。彼は「生活世界」を、他のあらゆる科学の対象(自然科学、人文科学、歴史科学を問わず)と同様に、科学の対象としようとしている。しか し、この対象は「普遍的な相関の先験的条件」であり、他の科学が研究する対象と同じ「経験的」特徴を持たないことを念頭に置いておく必要がある」とマリ オ・シャルランドは書いている[3]。 |

| La tâche de la Krisis Diagnostic de la crise La crise à laquelle il s'agit de répondre est issue de l'objectivisme. « Il ne s'agit pas à proprement parler de la crise de la théorie physique, mais de la crise atteignant la signification des sciences pour la vie elle-même » écrit Jean-François Lyotard [4]. L'œuvre intervient dans le contexte politique des années 1935-1936, moment le plus crucial pour l'Europe où l'on peut percevoir « comme une espèce de basculement d'un Monde, qui se prenait pour le Monde », écrit Gérard Granel[5]. « La baisse de la foi en une raison absolue entraîne une baisse de la foi en un sens de l'histoire, du monde, de l'humanité, et de l'homme lui-même [...] Nous sommes devant le plus grand danger : un naufrage sceptique » écrit l'auteur anonyme de l'article sur la Krisis [6],[N 1]. « Une des tâches de la Krisis est de soumettre la philosophie moderne à l'examen critique de sa dépendance à l'égard du modèle galiléen et de l'idée absolutisée de la nature qu'il impose » écrit Pierre Guenancia[7]. Husserl se propose d'analyser les causes de cette crise (qui est en réalité une crise de la raison) en remontant aux origines de l'Europe dont il va chercher à montrer qu'elles déterminent, à la manière d'une « entéléchie » son destin. Ce que Husserl reproche aux sciences modernes c'est d'avoir creusé un fossé infranchissable entre elles (le monde de la science) et le monde de la vie, le monde environnant (de la vie) (Lebenswelt, Lebens-umwelt)[8]. Gérard Granel résume ainsi le projet explicite de la Krisis « réveiller sous la forme de la « philosophie transcendantale » [...] l'immanence de la raison dans l'homme, qui définit son humanité »[9]. « Le symptôme de la crise des sciences européennes est l'oubli ou la mésinterprétation du sol ou de l'origine de la pensée scientifique moderne [...] C'est cette substitution d'un monde spatio-temporel au monde concret et quotidien, au monde de la vie, que Husserl entreprend longuement de rendre présente aux esprits élevés dans l'évidence de l'idée galiléenne de la nature »[10],[N 2]. « La science moderne ne peut pas guérir la conscience européenne, car elle est elle-même l'une des causes de cette crise (elle est d'ailleurs elle-même en crise, faute de s'être interrogée sur son essence : elle n'est pas un ensemble de faits, mais une émanation de l'esprit humain - comme le montrent les incertitudes de la physique quantique). La science est incapable de guérir la conscience européenne, elle n'a rien à nous dire concernant les problèmes fondamentaux de l'existence et loin d'être neutre, elle peut être, dans ses applications techniques, un puissant auxiliaire de la barbarie »[8]. |

クリシス(危機)の任務 危機の診断 対応すべき危機は客観主義から生じている。「厳密に言えば、物理理論の危機ではなく、生命そのものに対する科学の意味の危機である」とジャン=フランソ ワ・リオタールは記している[4]。この作品は、1935年から1936年にかけての政治的な状況の中で生まれた。この時期は、ヨーロッパにとって最も重 要な時期であり、ジェラール・グラネルは「世界そのものを世界だと思い込んでいた世界が、ある種の転換点を迎えた」と書いている[5]。「絶対的な理性へ の信頼の低下は、歴史、世界、人類、そして人間そのものの意味への信頼の低下をもたらす [...] 私たちは最大の危険、すなわち懐疑主義の沈没に直面している」と、Krisisに関する記事の匿名著者は書いている[6]、[N 1]。「クリシス誌の任務の一つは、現代哲学を、ガリレオのモデルと、それが押し付ける絶対化された自然観への依存について批判的に検証することだ」とピ エール・グエンシアは書いている[7]。フッサールは、この危機(実際には理性の危機)の原因を、ヨーロッパの起源にまで遡って分析しようとしている。彼 は、ヨーロッパの起源が「エンテレキー」のようにその運命を決定づけていることを示そうとしているのだ。フッサールが現代科学を非難しているのは、科学の 世界と生活の世界、つまり周囲の世界(Lebenswelt、Lebens-umwelt)との間に越えられない溝を掘ったことだ。ジェラール・グラネル は、クリシス(Krisis)の明確な目的を「『超越論的哲学』という形で、人間の人間性を定義する、人間における理性の内在性を目覚めさせること」と要 約している[9]。 「ヨーロッパの科学の危機の兆候は、現代科学思想の基盤や起源の忘却、あるいは誤解にある [...] フッサールは、ガリレオの自然観の明白さの中で、具体的な日常の世界、生活の世界に代わって空間的・時間的な世界が提示されるようになったことを、高い知 性を持つ人々に理解させるべく、長年にわたり取り組んできた」 [10]、[N 2]。「現代科学は、ヨーロッパの意識を癒すことはできない。なぜなら、科学自体が、この危機の原因の一つであるからだ(さらに言えば、科学は、その本質 について自問することを怠った結果、自らも危機に陥っている。科学は、一連の事実の集合体ではなく、量子物理学の不確実性が示すように、人間の精神から発 せられるものである)。科学はヨーロッパの意識を癒すことはできず、存在の根本的な問題について何も教えてくれず、中立とはほど遠い、技術的な応用におい ては野蛮の強力な補助手段となりうる」[8]。 |

| Origine de la crise Selon Husserl, la « méthode scientifique » repose sur un fondement subjectif caché et oublié[11]. Husserl reconnaît en Descartes, « l'initiateur des temps modernes » ; avec lui, « la philosophie porte en elle l'idée directrice d'une fondation de toutes les sciences. Comme science universelle, la philosophie doit fonder la scientificité de toutes les sciences », écrit Emmanuel Housset[12]. Le philosophe, face à la crise actuelle sur le fondement ultime des sciences, s'interroge sur le « motif originel » « qui donne son sens depuis Descartes à toutes les philosophies modernes [...] [motif originel] que l'on ne peut obtenir que si l'on s'enfonce dans l'unité de l'historicité de la philosophie moderne dans son ensemble, [...] [à savoir la question] de l'ultime source de toutes les formations de connaissance, c'est l'auto-méditation du sujet connaissant sur soi-même et sur sa vie de connaissance, dans laquelle toutes les formations scientifiques qui valent pour lui ont lieu « téléologiquement », sont conservées comme un acquis et sont devenues librement disponibles », écrit Husserl[13]« Ce qui constitue finalement le sens d'unité téléologique qui traverse toutes les tentatives de système de l'histoire de la philosophie dans son ensemble, n'est-ce pas de laisser percer cette vue théorique, selon laquelle la science n'est en général possible que comme philosophie universelle, celle-ci demeurant une unique science à travers toutes les sciences [...] que toutes les connaissances reposeraient sur un seul et unique fondement ? »[14]. Husserl évoque une « théorie téléologique de l'histoire »[15]. |

危機の起源 フッサールによれば、「科学的方法」は、隠され、忘れ去られた主観的な基盤の上に成り立っている[11]。フッサールは、デカルトを「近代の創始者」と認 め、彼とともに、「哲学は、すべての科学の基盤となる指導的理念をその中に抱いている」と述べている。普遍的な科学として、哲学はすべての科学の科学性を 基礎づけなければならない」とエマニュエル・ウセットは書いている[12]。 哲学者は、科学の究極的な基礎に関する現在の危機に直面し、「デカルト以来、すべての近代哲学に意味を与えてきた「原初的な動機」について疑問を抱いてい る。[...] [原初的な動機] は、近代哲学全体の歴史性の統一に深く入り込むことによってのみ得ることができる。[...] すなわち、あらゆる知識形成の究極の源は、認識主体が自分自身と自らの認識の営みについて自己内省することであり、そこにおいて、その主体にとって価値の あるあらゆる科学的形成が「目的論的に」行われ、獲得物として保存され、自由に利用可能になるのだ」とフッサールは書いている[13]。結局のところ、哲 学の歴史全体におけるあらゆる体系化の試みに通底する目的論的統一性の意味は、科学は一般的に普遍的な哲学としてのみ可能であり、哲学はすべての科学を通 じて唯一の科学であり続けるという理論的見解、すなわちすべての知識は単一の基盤の上に成り立っているという見解を垣間見せることではないだろうか?」と 述べている[14]。フッサールは「目的論的歴史理論」[15]について言及している。 |

| La réponse à la crise Face à des sciences que le philosophe juge sans fondement indubitable, Husserl cherche à construire une philosophie, appelée transcendantale qui aura pour ambition de « régresser vers la subjectivité connaissante comme vers le lieu originel de toute formation objective et de toute validité d'être »[16]. Pour mettre à jour le fondement caché et oublié de la méthode scientifique, Husserl procède dans la Krisis selon un double mouvement : le premier mouvement consiste à déconstruire l'histoire de la philosophie jusqu'à Kant, pour déceler le « refoulé et l'oublié » qui commandent toute cette histoire, pour dans un deuxième temps extraire ce qu'il appelle le « monde de la vie » pour faire apparaître sa part de « constitué » avec sa constitution dans l'« égologie absolue »[1]. Dans cette œuvre, Husserl s'emploie à frayer, par la réduction phénoménologique, une autre voie que celle trop cartésienne des Ideen, « une nouvelle voie vers la phénoménologie transcendantale qui s’appuierait sur une prise en vue thématique du monde de la vie , la Lebenswelt, comme sol pré-scientifique ainsi que sur ses modes de donation propres » (monde pré-scientifique, soit monde tel qu'il se donne par opposition au monde exact construit par les sciences modernes de la nature)[N 3]. Comme le remarque Julien Farges, de nombreux paragraphes de la Krisis comportent cette expression de « monde de la vie » étudié sous divers angles, par exemple vis-à-vis des sciences, dans l'œuvre de Kant, face à l'attitude naïve, de la nécessité d'une ontologie du « monde de la vie »[17]. Le chemin poursuivi jusqu'ici, notamment dans les Ideen, qui partait de problèmes logiques ou des questions perceptives, conduisait à l'« ego absolu ». Avec la Krisis, l'historicité est réintroduite et le philosophe prend conscience de sa situation de ce que nous sommes actuellement avec nos préjugés qui résultent en réalité « des sédimentations de l'histoire ». |

危機への対応 哲学者によって確固たる根拠がないと判断された科学に直面し、フッサールは「あらゆる客観的形成と存在の妥当性の原点である、認識する主観性へと回帰する こと」[16]を目的とする、超越論的哲学の構築を試みた。科学的方法の隠され、忘れ去られた基礎を明らかにするために、フッサールは『危機』の中で二重 の動きを進めている。最初の動きは、カントまでの哲学の歴史を解体し、その歴史全体を支配する「抑圧され、忘れられたもの」を発見することである。次に、 彼が「生活世界」と呼ぶものを抽出し、その「構成された」部分と、「絶対的エゴロジー」におけるその構成を明らかにすることである[1]。 この著作の中で、フッサールは現象学的還元によって、『観念論』のあまりにもデカルト的な道とは別の道を切り開こうとしている。「生活世界、すなわち Lebensweltを、前科学的な基盤として、またその固有の与えられ方として、主題的に捉えることに基づく、超越論的現象学への新たな道」[N 3]を開こうとしている。ジュリアン・ファルジュが指摘しているように、『危機』の多くの段落には、例えば科学との関係、カントの著作、素朴な態度、そし て「生活世界」のオントロジーの必要性など、さまざまな角度から考察された「生活世界」という表現が含まれている[17]。 これまで、特に『アイデア』で追求されてきた、論理的問題や知覚の問題から出発した道筋は、「絶対的自我」へと至っていた。『危機』では、歴史性が再導入され、哲学者は、現実には「歴史の堆積物」である偏見を持つ、現在の我々の状況について認識する。 |

| L'ambition de la Krisis « Une des tâches de la Krisis est de soumettre la philosophie moderne à l'examen critique de sa dépendance à l'égard du modèle galiléen et de l'idée absolutisée de la nature qu'il impose » écrit Pierre Guenancia[7]. L’idée de science universelle qui guidait les Méditations cartésiennes et qui était le rêve de toute la phénoménologie, se retrouve mise en question. [...] La tradition antique qui préjuge tacitement qu’il y a une vérité ultime, un être-en-soi ultimement valable, absolu (...) un monde vrai est rejetée[18]. « Les questions qu’aborde la Krisis sont les questions qui portent sur le sens ou sur l’absence de sens de toute existence humaine »[19]. Retrouver du sens c'est lutter contre le nihilisme ambiant pour qui « les questions qu’aborde la Krisis sont les questions qui portent sur le sens ou sur l’absence de sens de toute cette existence humaine [...] l’événement historique n’est rien d’autre qu’un enchaînement incessant d’élans illusoires et d’amères déceptions »[20]. Pour cela « il s’agit très clairement pour Husserl de renouveler l’intérêt du thème si souvent traité de la crise européenne en développant l’idée historico-philosophique (ou encore le sens téléologique) de l’humanité européenne ». Par sens téléologique, il faut entendre la téléologie de la raison. L’histoire de l’Europe est la téléologie de la raison[21]. Husserl se positionne quant à cette crise et tente de la résoudre par le biais de la phénoménologie transcendantale. Le monde perd de son évidence : « ce que j’avais là autrefois devant les yeux comme le monde étant et valant pour moi, cela est devenu un simple phénomène »[22]. |

クリシスの野望 「クリシスの任務の一つは、現代哲学を、ガリレオのモデルと、それが押し付ける絶対化された自然観への依存について批判的に検証することだ」とピエール・ グエンシアは書いている[7]。デカルトの『省察』を導き、現象学全体の夢であった普遍的な科学という概念は、疑問視されるようになった。[...] 究極の真実、究極的に有効な絶対的な存在、つまり真実の世界があるということを暗黙のうちに前提とする古代の伝統は、否定される[18]。「クリシスが扱 う問題は、あらゆる人間の存在の意味、あるいは無意味さに関する問題だ」[19]。意味を見出すことは、周囲のニヒリズムと闘うことである。ニヒリズム は、「クリシスが扱う問題は、人間存在全体の意味、あるいは無意味に関する問題である [...] 歴史的出来事は、幻想的な衝動と苦い失望の絶え間ない連鎖に他ならない」[20] と考える。そのため、「フッサールにとっては、ヨーロッパの危機という、これまで何度も扱われてきたテーマへの関心を、ヨーロッパの人類に関する歴史哲学 的(あるいは目的論的)な考えを発展させることによって、明らかに新たにすることである」。目的論的意味とは、理性の目的論を意味する。ヨーロッパの歴史 は、理性の目的論である[21]。フッサールはこの危機に対して立場を明確にし、超越現象学によってその解決を試みている。世界は、その自明性を失いつつ ある。「かつて私の目の前に、私にとって存在し、価値のある世界としてあったものは、単なる現象となった」[22]。 |

| Les chemins vers la phénoménologie transcendantale Le monde de la vie Article détaillé : Monde de la vie. Julien Farges[23] relève dans son article des Études germaniques que la troisième section de la Krisis est consacrée à « la prise en vue thématique de la Lebenswelt comme sol pré-scientifique ainsi que sur ses modes de donation propres ». Une dizaine de paragraphes font explicitement référence, dans cette section au « monde de la vie ». Husserl juge au § 28 que la problématique kantienne d'une critique de la raison présuppose l'existence d'un monde de la vie, in-interrogé, de vérités acceptées d'avance comme une évidence. Ce monde exercerait une domination cachée. « Toute pensée scientifique et toute problématique philosophique comportent des évidences préalables : que le monde est, qu'il est toujours d'avance là, que toute expérience présuppose déjà le monde dans son être »[24]. Ce long paragraphe expose les liens de l'espace et de la chair. Emmanuel Housset[25], résume « l'apparition de la chose physique et l'appréhension de ma chair sont indissociables l'une de l'autre et c'est une telle corrélation qui est à l'origine de l'espace ». Au § 29, Husserl aborde des phénomènes que l'on appelle couramment subjectifs mais qui sont « des processus d'esprit , qui s'acquittent par une nécessité d'essence de la fonction de constituer des formations de sens ». Du § 30 au 32, Husserl dénonce l'absence de radicalité de la méthode kantienne et la confusion qui découle de l'usage de la science psychologique tout en reconnaissant « la possibilité d'une vérité cachée dans la « philosophie transcendantale » de Kant »[26]. Le § 33 réintroduit la subjectivité et l'historicité du savant dans un monde de la vie qui sert de sol intangibles aux théories scientifiques. Ce monde est essentiellement éprouvé et donné dans l’intuition, déterminé par les intérêts pratiques de la vie quotidienne[27]. |

超越論的現象学への道 生活世界 詳細記事:生活世界。 ジュリアン・ファルジュ[23]は、ドイツ学研究誌の記事の中で、『危機』の第3章は「前科学的基盤としての生活世界、およびその固有の与えられ方につい て、主題的に考察したもの」であると指摘している。このセクションでは、10ほどの段落が「生活世界」について明示的に言及している。 フッサールは、§ 28 で、カントの理性批判の問題は、生活世界の存在、つまり、疑問視されることなく、あらかじめ当然のこととして受け入れられている真実の存在を前提としてい ると評価している。この世界は、隠れた支配力を行使している。「あらゆる科学的思考と哲学的問題は、あらかじめ明らかなことを含んでいる。世界は存在し、 それは常にあらかじめそこにあり、あらゆる経験はすでにその存在において世界を前提としている」[24]。この長い段落は、空間と肉体の関連性を述べてい る。エマニュエル・ウセット[25]は、「物理的なものの出現と私の肉体の認識は、互いに切り離せないものであり、そのような相関関係が空間の起源であ る」と要約している。 § 29 で、フッサールは、一般に主観的と呼ばれる現象について論じているが、それらは「本質的な必然性によって意味の形成を構成する機能を果たす精神のプロセス」である。 第30項から第32項にかけて、フッサールはカントの方法の急進性の欠如と、心理学の利用から生じる混乱を非難しつつ、「カントの『超越論的哲学』に隠された真実の可能性」を認めている。 § 33 では、科学理論の基盤となる生活世界において、学者の主観性と歴史性が再導入されている。この世界は、本質的に経験され、直観によって与えられ、日常生活の実践的な関心によって決定されるものである[27]。 |

| L'a priori corrélationnel Article détaillé : A priori corrélationnel (Husserl). Ce que découvre Husserl, selon l'intitulé même du § 48, c'est que « tout étant quel qu'en soit le sens [...] est l'index d'un système subjectif de corrélation »[28], et que cette corrélation forme ce qu'il appelle un a priori universel, écrit Renaud Barbaras[29]. Au § 36 de la Krisis, Husserl note « nous autres qui sommes depuis l’école prisonniers de la métaphysique traditionnelle objectiviste n’avons tout d’abord aucun accès à l’idée d’un « a priori universel » relevant purement du monde de la vie » souligné par Jean Vioulac[30]. Le premier objet correspondant à l'« a priori universel » va être le monde de la vie lui-même. |

相関的先験性 詳細記事:相関的先験性(フッサール)。 フッサールが発見したのは、§ 48 の題名にもある通り、「あらゆる存在は、その意味が何であれ、主観的な相関システムの指標である」[28] ということ、そしてこの相関が、彼が普遍的先験と呼ぶものを形成している、とルノー・バルバラスは書いている[29]。 『危機』の第36項で、フッサールは「学校以来、伝統的な客観主義的形而上学の囚人である我々は、まず第一に、純粋に生活世界に関連する「普遍的先験」の 概念にアクセスすることすらできない」と記している(ジャン・ヴィウラックによる強調[30])。「普遍的先験的」に対応する最初の対象は、生活世界その ものである。 |

| L'énigme de subjectivité humaine À partir du § 53, Husserl s'intéresse, selon l'intitulé de ce paragraphe, au « paradoxe de la subjectivité humaine : être sujet pour le monde, et en même temps être objet dans le monde »[31]. La résolution du paradoxe passe par la possibilité d'accéder à la philosophie transcendantale en partant d'une psychologie rénovée, c'est-à-dire débarrassée du préjugé dualiste (paragraphes 58 à 67). Au § 68 Husserl, étudie ce qu'il appelle la problématique universelle de l'intentionnalité comme quoi dans la vie de conscience on ne trouve pas des « data-de-couleur », (des faits), des « data-de-son », des « data-de-sensation », mais on trouve ce que déjà Descartes découvrait, le cogito, avec ses cogitata, autrement dit l'intentionnalité, je vois un arbre, j'entends le bruissement des feuilles, c'est-à-dire, non un objet dans une conscience mais une « conscience de »[32]. |

人間の主観性の謎 第53項以降、フッサールは、この項のタイトルにあるように、「人間の主観性のパラドックス、すなわち、世界にとっての主体であると同時に、世界における 対象でもあるというパラドックス」[31]に関心を寄せている。このパラドックスを解決するには、二元論的な偏見を取り除いた、刷新された心理学から出発 して、超越哲学に到達することが必要だ(§58~67)。 68項でフッサールは、意識の生活では「色のデータ」(事実)や「音のデータ」、「感覚のデータ」は見出せないが、 デカルトがすでに発見したコギト、すなわちコギタタ、つまり意図性、つまり、私は木を見て、葉のざわめきを聞く、つまり、意識の中の物体ではなく、「意 識」[32]を見つける。 |

| Références 1. Krisis, quatrième de couverture. 2. Encyclopédie Universalis 2017. 3. Mario Charland 1999, p. 160. 4. Jean-François Lyotard 2011, p. 40. 5. Gerard Granel 1959, p. IV préface. 6. Les Philosophes 2017, p. 3. 7. Pierre Guenancia 1989, p. 78. 8. Robin Guilloux 2016. 9. Gerard Granel 1959, p. préface. 10. Pierre Guenancia 1989, p. 77. 11. Krisis, p. 11. 12. Emmanuel Housset 2000, p. 31. 13. Krisis, p. 113. 14. Krisis, p. 128. 15. Krisis, p. 84. 16. Krisis, p. 115. 17. Julien Farges 2006, p. 1-7. 18. Jean Vioulac 2005, § 8. 19. Jean Vioulac 2005, § 4. 20. Jean Vioulac 2005, § 4 et 5. 21. Jean Vioulac 2005, § 7. 22. Jean Vioulac 2005, § 10. 23. Julien Farges 2006, § 4. 24. Krisis, p. 126. 25. Emmanuel Housset 2000, p. 200. 26. Krisis, p. 130-134. 27. Julien Farges 2006, § 50. 28. Krisis, p. 187. 29. Renaud Barbaras 2008, p. 11. 30. Jean Vioulac 2005, § 13. 31. Krisis, p. 203. 32. Krisis, p. 262. |

参考文献 1. Krisis、裏表紙。 2. Encyclopédie Universalis 2017。 3. Mario Charland 1999、160ページ。 4. Jean-François Lyotard 2011、40ページ。 5. Gerard Granel 1959、IVページ序文。 6. Les Philosophes 2017、3ページ。 7. Pierre Guenancia 1989、78ページ。 8. Robin Guilloux 2016。 9. Gerard Granel 1959、序文。 10. Pierre Guenancia 1989、77ページ。 11. Krisis、11ページ。 12. エマニュエル・ウセット 2000、31ページ。 13. クリシス、113ページ。 14. クリシス、128ページ。 15. クリシス、84ページ。 16. クリシス、115ページ。 17. ジュリアン・ファルジュ 2006、1-7ページ。 18. ジャン・ヴィウラック 2005、§ 8。 19. ジャン・ヴィウラック 2005、§ 4。 20. ジャン・ヴィウラック 2005、§ 4 および 5。 21. ジャン・ヴィウラック 2005、§ 7。 22. ジャン・ヴィウラック 2005、§ 10。 23. ジュリアン・ファルジュ 2006、§ 4。 24. クリシス、126 ページ。 25. エマニュエル・ウセット 2000、200 ページ。 26. クリシス、130-134 ページ。 27. ジュリアン・ファルジュ 2006、§ 50。 28. クリシス、187 ページ。 29. ルノー・バルバラス 2008、11 ページ。 30. ジャン・ヴィウラック 2005、§ 13。 31. クリシス、203 ページ。 32. クリシス、262 ページ。 |

| Notes 1. Jean Vioulac dans son article des Études philosophiques accentue ce thème « Le problème le plus constant auquel Husserl s’est confronté, depuis ses premières recherches sur la validité des idéalités mathématiques, est celui du scepticisme, du relativisme et du positivisme, menaces permanentes qui pèsent sur l’idéal de la science, auxquelles il tente de répondre par une refondation du sens. Son itinéraire le conduit alors à élargir sans cesse le domaine de cette crise du sens, pour finalement, dans les années 1930, l’aborder comme une crise de la civilisation européenne dans sa totalité, saisie en son fond comme « une crise radicale de la vie ». Cette catastrophe du sens »-Jean Vioulac 2005, § 4. 2. La critique de Husserl porte sur l'abstraction de la science galiléenne mais aussi sur la philosophie qui aurait « intériorisé le modèle de l'objectivité c'est-à-dire d'un monde où les corps sont reliés les uns aux autres par une causalité universelle, déterminable avec exactitude [...] L'époché ou réduction transcendantale est pour Husserl la véritable solution pour sortir des crises engendrées par des philosophies restées aveugles face à leur thème propre, unique et commun, la science de la subjectivité pure »-Pierre Guenancia 1989, p. 78. 3. « La radicalisation de la réduction transcendantale a expressément pour fonction de réduire non plus seulement le monde objectif à l’ego constituant, mais de réduire cet ego à la vie qui le fonde. Husserl reprend alors au § 43 les analyses de 1924 et thématise « un nouveau chemin vers la réduction » distinct du « chemin cartésien », dont le « gros désavantage » est de donner un ego transcendantal « vide de contenu » »-Jean Vioulac 2005, § 14. |

注 1. ジャン・ヴィウラックは、哲学研究誌の記事の中で、このテーマを強調している。「フッサールが、数学的観念の妥当性に関する初期の研究以来、最も絶えず直 面してきた問題は、懐疑主義、相対主義、実証主義、すなわち科学の理想を常に脅かす脅威であり、彼は意味の再構築によってこれに対応しようとしている。彼 の歩みは、この意味の危機の領域を絶えず拡大し、最終的には1930年代に、ヨーロッパ文明全体の危機として、その根底にある「生命の根本的な危機」とし て捉えるに至った。この意味の破滅」-ジャン・ヴィウラック 2005年、§ 4。 2. フッサールの批判は、ガリレオの科学の抽象性だけでなく、「客観性のモデル、すなわち、物体が普遍的な因果関係によって互いに結びつき、正確に決定できる 世界というモデルを内面化した」哲学にも向けられている。エポケー、すなわち超越的還元は、フッサールにとって、自らの主題、つまり純粋主観性の科学とい う唯一かつ共通の主題に対して盲目であり続けた哲学によって引き起こされた危機から脱する真の解決策である」―ピエール・グアナンシア 1989年、p. 78。 3. 「超越的還元を徹底化することは、客観的世界を構成する自我に還元するだけでなく、その自我を、それを基礎とする生命に還元することを明確に目的としてい る。フッサールは、§ 43 で 1924 年の分析を再び取り上げ、「デカルトの道」とは別の「還元への新たな道」を主題としている。デカルトの道の「大きな欠点」は、「内容のない」超越的自我を 与えることにある」―ジャン・ヴィウラック 2005、§ 14。 |

| Lexique de phénoménologie Idées directrices pour une phénoménologie et une philosophie phénoménologique pures Leçons pour une phénoménologie de la conscience intime du temps Monde de la vie Méditations cartésiennes Monde de la vie A priori corrélationnel (Husserl) Réduction phénoménologique Intentionnalité De la phénoménologie |

現象学用語集 純粋な現象学および現象学的哲学のための指針 時間の内面的意識の現象学のための教訓 生活世界 デカルト的瞑想 生活世界 相関的先験性(フッサール) 現象学的還元 意図性 現象学について |

| Bibliographie Edmund Husserl (trad. Gérard Granel), La crise des sciences européennes et la phénoménologie transcendantale, Paris, Gallimard, coll. « Tel », 1989, 589 p. (ISBN 2-07-071719-4). Renaud Barbaras, Introduction à la philosophie de Husserl, Chatou, Les Éditions de la transparence, coll. « Philosophie », 2008, 158 p. (ISBN 978-2-35051-041-5). Jean-François Lyotard, La phénoménologie, Paris, PUF, coll. « Quadrige », 2011, 133 p. (ISBN 978-2-13-058815-3). Emmanuel Housset, Husserl et l’énigme du monde, Seuil, coll. « Points », 2000, 263 p. (ISBN 978-2-02-033812-7). Jean-François Lyotard, La phénoménologie, Paris, PUF, coll. « Quadrige », 2011, 133 p. (ISBN 978-2-13-058815-3). Pierre Guenancia, « Espace et communauté », dans Edmund Husserl, Les éditions de minuit, 1989 (ISBN 2-7073-1274-6), chap. 21. |

参考文献 エドムント・フッサール(ジェラール・グラネル訳)、『ヨーロッパ科学の危機と超越論的現象学』、パリ、ガリマール社、「テル」シリーズ、1989年、589ページ(ISBN 2-07-071719-4)。 ルノー・バルバラ『フッサール哲学入門』、シャトゥー、レ・エディシオン・ド・ラ・トランスペランス社、「哲学」シリーズ、2008年、158ページ(ISBN 978-2-35051-041-5)。 ジャン=フランソワ・リオタール『現象学』PUF社「Quadrige」シリーズ、2011年、133ページ(ISBN 978-2-13-058815-3)。 エマニュエル・ウセット、『フッサールと世界の謎』、Seuil、coll. 「Points」、2000年、263ページ。(ISBN 978-2-02-033812-7)。 ジャン=フランソワ・リオタール、『現象学』、パリ、PUF、coll. 「Quadrige」、 2011年、133ページ(ISBN 978-2-13-058815-3)。 ピエール・グエンシア、「空間と共同体」、エドムント・フッサール著、レ・エディシオン・ド・ミニュイ、1989年(ISBN 2-7073-1274-6)、第21章。 |

| https://x.gd/iXo21 |

★英語版「ヨーロッパ諸学の危機と超越論的現象学」(著者フッサールの紹介つき)

| "Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl ( 8 April 1859 – 27 April 1938[23]) was a German[24][25] philosopher who established the school of phenomenology. In his early work, he elaborated critiques of historicism and of psychologism in logic based on analyses of intentionality. In his mature work, he sought to develop a systematic foundational science based on the so-called phenomenological reduction. Arguing that transcendental consciousness sets the limits of all possible knowledge, Husserl redefined phenomenology as a transcendental-idealist philosophy. Husserl's thought profoundly influenced 20th-century philosophy, and he remains a notable figure in contemporary philosophy and beyond. Husserl studied mathematics, taught by Karl Weierstrass and Leo Königsberger, and philosophy taught by Franz Brentano and Carl Stumpf.[26] He taught philosophy as a Privatdozent at Halle from 1887, then as professor, first at Göttingen from 1901, then at Freiburg from 1916 until he retired in 1928, after which he remained highly productive. In 1933, due to racial laws, having been born to a Jewish family, he was expelled from the library of the University of Freiburg, and months later resigned from the Deutsche Akademie. Following an illness, he died in Freiburg in 1938.[27]....Husserl was born in 1859 in Prostějov, a town in the Margraviate of Moravia, which was then in the Austrian Empire, and which today is Prostějov in the Czech Republic. He was born into a Jewish family, the second of four children. His father was a milliner. His childhood was spent in Prostějov, where he attended the secular elementary school. Then Husserl traveled to Vienna to study at the Realgymnasium there, followed next by the Staatsgymnasium in Olomouc (Ger.: Olmütz)." | 「エドムント・グスタフ・アルベルト・フッサール(Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl、1859年4月8日 - 1938年4月27日[23])は、現象学派を創始したドイツの哲学者である。初期の著作では、意図性の分析を基に、歴史主義と論理における心理主義に対 する詳細な批判を展開した。円熟した著作では、いわゆる現象学的還元に基づく体系的な基礎科学の構築を目指した。超越論的意識がすべての可能な知識の限界 を定めるという主張に基づき、フッサールは現象学を超越論的観念論哲学として再定義した。フッサールの思想は20世紀の哲学に多大な影響を与え、現代哲学 を超えて、今なお著名な人物である。フッサールは、カール・ワイエルシュトラスとレオ・ケーニヒスベルガーから数学を、フランツ・ブレンターノとカール・ シュトゥンプから哲学を学んだ。[26] 1887年からハレで、その後1901年からゲッティンゲンで、さらに1916年からフライブルクで教授として哲学を教え、1928年に引退するまで教鞭 をとり、その後も非常に生産的な活動を続けた。1933年、人種法により、ユダヤ人家庭に生まれたためフライブルク大学の図書館から追放され、数か月後に はドイツ学術アカデミーを辞任した。病気療養ののち、1938年にフライブルクで死去した。[27]...フッサールは1859年、当時オーストリア帝国 領であったモラヴィア辺境伯領の都市プロスチェヨフ(現在のチェコ共和国プロスチェヨフ)で生まれた。ユダヤ人家庭に4人兄弟の2番目として生まれた。父 親は帽子屋であった。幼少期はプロスチェヨフで過ごし、世俗的な小学校に通った。その後、フッサールはウィーンのギムナジウムで学び、次いでオロモウツ (独:オルミュッツ)のギムナジウムで学んだ。」 |

| On "The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology," 1936-1938 | |

The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology is Husserl's most influential work;[5] according to the philosopher Ante Pažanin (1930-2015), it was also the most influential philosophical work of its time.[6] Husserl's discussion of Galileo is famous.[7] The work is considered the culmination of Husserl's thought.[7][8] It has been compared to Hegel's The Phenomenology of Spirit by the philosophers Maurice Natanson and Michael Inwood,[9][10] and described as a "great work".[11][10] Natanson argued that Husserl's views can be compared to those of the novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky, despite the differences between Husserl and Dostoevsky.[9] Inwood argued that in The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology Husserl adopted a philosophical approach that differed from that he had adopted in earlier works such as Ideas (1913) and Cartesian Meditations (1931). In his view, the work brought into question Husserl's attempt to found a rigorous science that would be free from all preconceptions. He noted that some philosophers, including Maurice Merleau-Ponty, considered it a significant departure from Husserl's earlier work.[10]/ Carr described the work as important,[12] while R. Philip Buckley maintained that its themes continue to be relevant to contemporary philosophy. Buckley credited Husserl with providing a powerful "critique of the development of modern science". However, he suggested that the book's history makes it clear that Husserl found it a struggle to "give clearer expression to his ideas and to unify them into a coherent whole" while working on it. He noted that Husserl was dissatisfied with Part III of the work and wanted to revise it. He also argued that the work left some problems unresolved, including the question of how the decay of philosophy and science has made the existence of that decay apparent.[7] Dan R. Stiver maintained that because The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology is unfinished, its interpretation is "notoriously difficult." He maintained that in it, Husserl adopted views that placed his belief in the possibility of basing philosophy on the "direct givenness to intuition of what is experienced" under severe strain. He argued that while one of Husserl's comments has been seen as expressing his awareness of the failure of phenomenology, it was more likely that Husserl wanted to recognize that "what had been a burgeoning program attracting many disciples had fallen to the wayside with its founder, having been overtaken by other philosophical movements."[13] |

「『ヨーロッパ科学の危機と超越論的現象学』は、フッサールのもっとも影響力のある著作であ る。[5] 哲学者のアンテ・パジャニン(1930年 - 2015年)によると、同書は同時代におけるもっとも影響力のある哲学書でもあった。[6] フッサールのガリレオに関する議論は有名である。[7] この著作はフッサールの思想の集大成とみなされている。 [7][8] モーリス・ナタンソンとマイケル・インウッドの哲学者によって、ヘーゲルの『精神現象学』と比較されており[9][10]、「偉大な作品」と評されてい る。[11][10] ナタンソンは、フッサールとドストエフスキーの間に相違点があるにもかかわらず、フッサールの見解は小説家フョードル・ドストエフスキーのそれと比較でき ると主張した。 [9] インウッドは『ヨーロッパ科学の危機と超越論的現象学』において、フッサールは『イデーン』(1913年)や『デカルト的瞑想』(1931年)などの初期 の著作で採用したアプローチとは異なる哲学的アプローチを採用したと論じた。同著は、先入観を一切排除した厳密な科学の創設を試みたフッサールの試みを疑 問視するものだと彼は考えた。彼は、モーリス・メルロ=ポンティを含む一部の哲学者が、この著作をフッサールのそれ以前の著作から大きく逸脱したものとみ なしていることを指摘している。[10] カーはこの著作を重要であると評し、[12] 一方、R.フィリップ・バックリーは、そのテーマは現代の哲学にも依然として関連していると主張している。Buckleyは、フッサールが「近代科学の発 展に対する批判」を力強く提示したと評価した。しかし、同書はフッサールが執筆中に「自身の考えをより明確に表現し、首尾一貫した全体へと統合する」こと に苦労していたことが明らかであると示唆している。また、フッサールは同書の第3部には満足しておらず、改訂を望んでいたと指摘している。また、この著作 には、哲学と科学の衰退がその衰退の存在を明らかにしてきたという問題を含め、いくつかの問題が未解決のまま残されていると論じた。[7] ダン・R・スティバーは、『ヨーロッパ諸科学の危機と超越論的現象学』が未完であるため、その解釈は「非常に難しい」と主張した。彼は、その中でフッサー ルは、哲学を「経験されたものが直観に直接与えられているもの」に基づいて構築できるという自身の信念を、深刻な危機にさらすような見解を採用したと主張 した。彼は、フッサールのコメントの1つは現象学の失敗に対する自覚を表明していると見られているが、むしろフッサールは「多くの弟子たちを惹きつけてい た活気のあるプログラムが、その創始者とともに道半ばで挫折し、他の哲学運動に追い越された」ことを認識したかったのではないか、と主張した。」 |

| The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology: An Introduction to Phenomenological Philosophy

(German: Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die

transzendentale Phänomenologie: Eine Einleitung in die

phänomenologische Philosophie) is an unfinished 1936 book by the German

philosopher Edmund Husserl. The work was influential and is considered the culmination of Husserl's thought, though it has been seen as a departure from Husserl's earlier work. |

『ヨーロッパ諸科学の危機と超越論的現象学:現象学的哲学への序説』

(原題:Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale

Phänomenologie: Eine Einleitung in die phänomenologische

Philosophie)は、ドイツの哲学者エドムント・フッサールが1936年に執筆した未完の著作である。 この著作は影響力があり、フッサールの思想の集大成と見なされているが、彼の初期の著作からの転換点とも見なされてきた。 |

| The work is divided into three

main sections: "Part I: The Crisis of the Sciences as Expression of the

Radical Life-Crisis of European Humanity", "Part II: Clarification of

the Origin of the Modern Opposition between Physicalistic Objectivism

and Transcendental Subjectivism", and "Part III: The Clarification of

the Transcendental Problem and the Related Function of Psychology".[1] In Part I, Husserl discusses what he considers a crisis of science, while in Part II he discusses the astronomer Galileo Galilei and introduces the concept of the lifeworld.[2] |

本書は三つの主要な部分に分かれている。「第一部:ヨーロッパ人類の根本的な生活危機の表れとしての科学の危機」、「第二部:物理主義的客観性と超越的主観主義という近代的対立の起源の解明」、そして「第三部:超越論的問題の解明と心理学の関連機能」である。[1] 第一部ではフッサールは科学の危機と彼が考えるものを論じ、第二部では天文学者ガリレオ・ガリレイを取り上げ、生活世界という概念を導入する。[2] |

| Publication history The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology was published by Martinus Nijhoff Publishers in 1954. A second printing followed in 1962. An English translation by David Carr was published by Northwestern University Press in 1970.[3][4] |

出版の歴史 『ヨーロッパ科学の危機と超越論的現象学』は、1954年にマーティヌス・ナイホフ出版社から出版された。1962年に第2刷が発行された。デビッド・カーによる英訳版は、1970年にノースウェスタン大学出版局から出版された。 |

| Reception The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology is Husserl's most influential work;[5] according to the philosopher Ante Pažanin, it was also the most influential philosophical work of its time.[6] Husserl's discussion of Galileo is famous.[7] The work is considered the culmination of Husserl's thought.[7][8] It has been compared to Hegel's The Phenomenology of Spirit by the philosophers Maurice Natanson and Michael Inwood,[9][10] and described as a "great work".[11][10] Natanson argued that Husserl's views can be compared to those of the novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky, despite the differences between the two.[9] Inwood argued that in The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology Husserl adopted a philosophical approach that differed from the one he had employed in earlier works such as Ideas (1913) and Cartesian Meditations (1931). In his view, the work brought into question Husserl's attempt to found a rigorous science that would be free from all preconceptions. He noted that some philosophers, including Maurice Merleau-Ponty, considered it a significant departure from Husserl's earlier work.[10] Carr described the work as important,[12] while R. Philip Buckley maintained that its themes continue to be relevant to contemporary philosophy. Buckley credited Husserl with providing a powerful "critique of the development of modern science". However, he suggested that the book's history makes it clear that Husserl found it a struggle to "give clearer expression to his ideas and to unify them into a coherent whole" while working on it. He noted that Husserl was dissatisfied with Part III of the work and wanted to revise it. He also argued that the work left some problems unresolved, including the question of how the decay of philosophy and science has made the existence of that decay apparent.[7] Dan R. Stiver maintained that because The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology is unfinished, its interpretation is "notoriously difficult." He maintained that in it, Husserl adopted views that placed his belief in the possibility of basing philosophy on the "direct givenness to intuition of what is experienced" under severe strain. He argued that while one of Husserl's comments has been seen as expressing his awareness of the failure of phenomenology, it was more likely that Husserl wanted to recognize that "what had been a burgeoning program attracting many disciples had fallen to the wayside with its founder, having been overtaken by other philosophical movements."[13] The philosopher Richard Velkley considered Husserl's reflections on the lifeworld to be among the "most striking and fundamental" of the new concerns that Husserl developed in response to his awareness of a contemporary moral and political crisis. However, he considered details of Husserl's account of science open to question.[11] The philosopher Roger Scruton used Husserl's concept of the lifeworld to explore the nature of human sexuality. He maintained that Husserl correctly recognized that the lifeworld is given intersubjectively, but that the "transcendental psychology" Husserl adopted in association with the idea of its intersubjectivity is flawed.[14] The economist Peter Galbács wrote that some researches utilized the work to show how other disciplines, such as mainstream economics, shared the crisis of modern sciences.[15] |

受容 『ヨーロッパ科学の危機と超越論的現象学』はフッサールの最も影響力のある著作である[5]。哲学者アンテ・パザニンによれば、これは当時最も影響力のあ る哲学著作でもあった[6]。フッサールのガリレオに関する議論は有名である[7]。この著作はフッサール思想の集大成と見なされている[7]。[8] 哲学者モーリス・ナタンソンとマイケル・インウッドは、この著作をヘーゲルの『精神現象学』と比較している[9][10]。また「偉大な著作」と評されて いる[11][10]。ナタンソンは、両者が異なる点はあるものの、フッサールの見解は小説家フョードル・ドストエフスキーのそれと比較可能だと論じた。 [9] インウッドは『ヨーロッパ科学の危機と超越論的現象学』において、フッサールが『観念論』(1913年)や『デカルト的省察』(1931年)といった初期 著作で用いた哲学的アプローチとは異なる手法を採用したと論じた。彼の見解では、この著作はあらゆる先入観から解放された厳密な科学を確立しようとする フッサールの試みに疑問を投げかけたのである。彼はモーリス・メルロ=ポンティを含む一部の哲学者が、この著作をフッサールの初期作品からの重要な転換点 と見なしていることを指摘した。[10] カーはこの著作を重要と評した[12]。一方R・フィリップ・バックリーは、その主題が現代哲学にとって依然として関連性を持つと主張した。バックリーは フッサールが「近代科学の発展に対する強力な批判」を提供したと評価した。しかし彼は、本書の成立経緯から、フッサールが執筆中に「自らの思想をより明確 に表現し、それらを首尾一貫した全体へと統合する」ことに苦闘していたことが明らかだと示唆した。フッサールが本書の第3部に不満を持ち、改訂を望んでい た点も指摘している。さらに彼は、哲学と科学の衰退が、その衰退の存在をいかに明らかにしたかという問題を含む、いくつかの課題が未解決のまま残されてい ると論じた。[7] ダン・R・スティバーは、『ヨーロッパ諸科学の危機と超越論的現象学』が未完であるため、その解釈は「著しく困難」だと主張した。彼は、この著作において フッサールが採った見解は、「経験されるものの直観への直接的与えられ」を哲学の基盤とする可能性への自身の信念を深刻な危機に陥れるものだったと主張し た。彼は、フッサールの発言の一つが現象学の失敗を自覚したものと解釈されてきたが、むしろフッサールは「多くの弟子を惹きつけた急成長中の計画が、他の 哲学的潮流に追い越され、創始者と共に廃れ去った」ことを認めたかった可能性が高いと論じた。[13] 哲学者リチャード・ヴェルクリーは、フッサールが現代の道徳的・政治的危機への認識から発展させた新たな関心事の中で、生活世界に関する考察が「最も顕著 かつ根本的」な部類に属すると考えた。しかし彼は、フッサールの科学論の詳細については疑問の余地があると見なした。[11] 哲学者ロジャー・スクルートンは、フッサールの生活世界概念を用いて人間の性の本質を探求した。彼は、フッサールが生活世界が相互主観的に与えられること を正しく認識していたと主張したが、その相互主観性の概念と結びつけてフッサールが採用した「超越的心理学」には欠陥があると述べた。[14] 経済学者ピーター・ガルバチは、この著作を用いて主流派経済学など他分野が現代科学の危機を共有していることを示す研究が存在すると記した。[15] |

| 1. Husserl 1989, pp. ix–xiv. 2. Husserl 1989, pp. 3, 23–59, 103–189. 3. Husserl 1989, pp. viii. 4. Carr 1989, pp. xv–xliii. 5. Stiver 1992, pp. 425–427; Buckley 1994, pp. 245–251; Pažanin 2010, pp. 11–29; Carr 1989, pp. xv. 6. Pažanin 2010, pp. 11–29. 7. Buckley 1994, pp. 245–251. 8. Welton 1999, p. ix. 9. Natanson 1996, pp. 167, 169. 10. Inwood 2005, p. 410. 11. Velkley 1987, pp. 881, 884–885. 12. Carr 1989, p. xv. 13. Stiver 1992, pp. 425–427. 14. Scruton 1994, pp. 8–13, 394. 15. Galbács 2015, pp. 1–52. |

1. フッサール 1989、ix–xiv ページ。 2. フッサール 1989、3、23–59、103–189 ページ。 3. フッサール 1989、viii ページ。 4. カー 1989、xv–xliii ページ。 5. Stiver 1992、425-427 ページ、Buckley 1994、245-251 ページ、Pažanin 2010、11-29 ページ、Carr 1989、xv ページ。 6. Pažanin 2010、11-29 ページ。 7. バックリー 1994、245-251 ページ。 8. ウェルトン 1999、ix ページ。 9. ナタンソン 1996、167、169 ページ。 10. インウッド 2005、p. 410。 11. ヴェルクリー 1987、pp. 881、884–885。 12. Carr 1989、p. xv。 13. Stiver 1992、pp. 425–427。 14. Scruton 1994、pp. 8–13、394。 15. Galbács 2015、pp. 1–52。 |

| Bibliography Books Carr, David (1989). "Translator's Introduction". The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology: An Introduction to Phenomenological Philosophy. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-8101-0458-X. Galbács, Peter (2015). The Theory of New Classical Macroeconomics: A Positive Critique. Contributions to Economics. Heidelberg/New York/Dordrecht/London: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-17578-2. ISBN 978-3-319-17578-2. Husserl, Edmund (1989). The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology: An Introduction to Phenomenological Philosophy. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-8101-0458-X. Inwood, M. J. (2005). "Husserl, Edmund". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, Second Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7. Natanson, Maurice (1996). Edmund Husserl: Philosopher of Infinite Tasks. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University. ISBN 0-8101-0456-3. Scruton, Roger (1994). Sexual Desire: A Philosophical Investigation. London: Phoenix Books. ISBN 1-85799-100-1. Stiver, Dan R. (1992). "Edmund Husserl". In McGreal, Ian P. (ed.). Great Thinkers of the Western World. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-270026-X. Velkley, Richard (1987). "Edmund Husserl". In Strauss, Leo; Cropsey, Joseph (eds.). History of Political Philosophy, Third Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-77710-3. Welton, Donn (1999). "Introduction: The Development of Husserl's Phenomenology". In Welton, Donn (ed.). The Essential Husserl. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21273-1. Journals Buckley, R. Philip (1994). "Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie (Book Review)". Research in Phenomenology. 24 (1). doi:10.1163/156916494X00159. – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required) Pažanin, Ante (2010). "Phenomenology of late Husserl as practical philosophy". Politicka Misao: Croatian Political Science Review. 47 (3). – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required) |

参考文献 書籍 カー、デイヴィッド (1989). 「翻訳者による序文」. 『ヨーロッパ科学の危機と超越的現象学:現象学的哲学入門』. エヴァンストン:ノースウェスタン大学出版局. ISBN 0-8101-0458-X. ガルバックス、ピーター(2015)。『新古典派マクロ経済学の理論:肯定的批判』。経済学への貢献。ハイデルベルク/ニューヨーク/ドルドレヒト/ロン ドン:スプリンガー。doi:10.1007/978-3-319-17578-2。ISBN 978-3-319-17578-2。 フッサール、エドムント(1989)。『ヨーロッパの科学の危機と超越論的現象学:現象学的哲学入門』。エヴァンストン:ノースウェスタン大学出版局。ISBN 0-8101-0458-X。 インウッド、M. J. (2005)。「フッサール、エドムント」。Honderich, Ted (ed.) 編. 『オックスフォード哲学事典』第 2 版. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7. Natanson, Maurice (1996). 『エドムント・フッサール:無限の課題の哲学者』. イリノイ州エバンストン: ノースウェスタン大学. ISBN 0-8101-0456-3. スクルートン、ロジャー(1994)。『性的欲求:哲学探究』。ロンドン:フェニックスブックス。ISBN 1-85799-100-1。 スティバー、ダン R.(1992)。「エドムント・フッサール」。マクグレアル、イアン P.(編)。『西洋世界の偉大な思想家たち』。ニューヨーク:ハーパーコリンズ出版社。ISBN 0-06-270026-X。 ヴェルクリー、リチャード(1987)。「エドムント・フッサール」。ストラウス、レオ、クロプシー、ジョセフ(編)。『政治哲学の歴史、第 3 版』。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 0-226-77710-3。 ウェルトン、ドン (1999). 「序論:フッサールの現象学の発展」. ウェルトン、ドン (編). 『フッサールの本質』. ブルーミントンおよびインディアナポリス: インディアナ大学出版局. ISBN 0-253-21273-1. 学術誌 バックリー, R. フィリップ (1994). 「ヨーロッパの科学の危機と超越論的現象学 (書評)」. 『現象学研究』. 24 (1). doi:10.1163/156916494X00159. – EBSCO's Academic Search Complete経由 (購読が必要) パザニン、アンテ (2010). 「実践哲学としての後期フッサールの現象学」. 『政治思想:クロアチア政治学レビュー』. 47 (3). – EBSCOのAcademic Search Complete経由 (購読が必要) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Crisis_of_European_Sciences_and_Transcendental_Phenomenology |

★

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆