スペイン初期近代

Early modern Spain

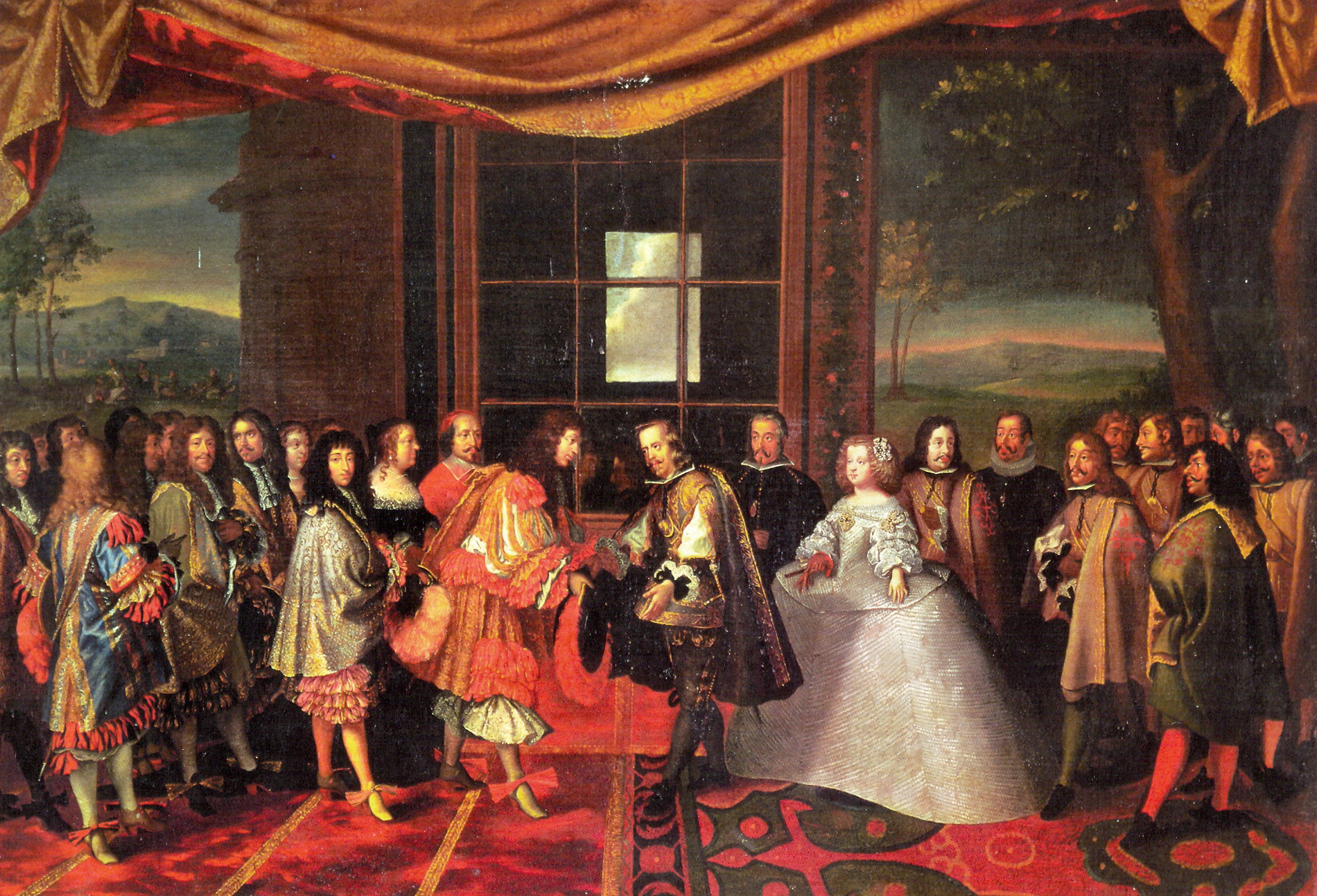

Wedding

portrait of the Catholic Monarchs

☆こ

こでは、スペイン初期近代からブルボン朝時代までの期間(1474-1715)のスペインの歴史について解説する。

| Early modern Spain Main articles: Contemporary history of Spain, Habsburg Spain, Spanish Golden Age, Spain in the 17th century, History of Spain (1700–1810), and Enlightenment in Spain Dynastic union of the Catholic Monarchs  Wedding portrait of the Catholic Monarchs In the 15th century, the most important among all of the Christian kingdoms that made up the old Hispania were the Kingdom of Castile, the Kingdom of Aragon, and the Kingdom of Portugal. The rulers of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon were allied with dynastic families in Portugal, France, and other neighboring kingdoms. The death of King Henry IV of Castile in 1474 set off a struggle for power called the War of the Castilian Succession (1475–1479). Contenders for the throne of Castile were Henry's one-time heir Joanna la Beltraneja, supported by Portugal and France, and Henry's half-sister Queen Isabella I of Castile, supported by the Kingdom of Aragon and by the Castilian nobility. Isabella retained the throne and ruled jointly with her husband, King Ferdinand II. Isabella and Ferdinand had married in 1469.[72] Their marriage united both crowns and set the stage for the creation of the Kingdom of Spain, at the dawn of the modern era. That union, however, was a union in title only, as each region retained its own political and judicial structure. Pursuant to an agreement signed by Isabella and Ferdinand on January 15, 1474,[73] Isabella held more authority over the newly unified Spain than her husband, although their rule was shared.[73] Together, Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon were known as the "Catholic Monarchs" (Spanish: los Reyes Católicos), a title bestowed on them by Pope Alexander VI. |

初期近代スペイン 主な記事:スペイン現代史、ハプスブルク朝スペイン、スペイン黄金時代、17世紀のスペイン、スペインの歴史(1700年-1810年)、スペイン啓蒙 カトリック両王の王朝同盟  カトリック両王の結婚肖像画 15世紀、かつてのヒスパニアを構成していたキリスト教王国の中で最も重要なのは、カスティーリャ王国、アラゴン王国、ポルトガル王国であった。カスティーリャ王国とアラゴン王国の支配者は、ポルトガル、フランス、その他の近隣諸国の王族と同盟関係にあった。 1474年にカスティーリャ王ヘンリー4世が死去すると、カスティーリャ継承戦争(1475年~1479年)と呼ばれる権力闘争が勃発した。カスティー リャ王位継承権を主張したのは、ポルトガルとフランスが支援したヘンリーの元婚約者であるジョアンナ・ラ・ベルトラーニャと、アラゴン王国とカスティー リャ貴族が支援したヘンリーの異母姉であるカスティーリャ女王イサベル1世であった。 イザベラは王位を維持し、夫であるフェルナンド2世と共同統治した。イザベラとフェルナンドは1469年に結婚した。[72] 彼らの結婚は両国の王冠を結びつけ、近代の幕開けとともにスペイン王国の誕生への道筋をつけた。しかし、この統一は名目上のものに過ぎず、各地方は独自の 政治・司法機構を維持していた。1474年1月15日にイザベラとフェルディナンドが署名した協定に従い、[73] 統治は共同で行われたものの、イザベラは夫よりも新しく統一されたスペインに対して大きな権限を持っていた。カスティーリャのイザベラとアラゴンのフェル ディナンドは、共に「カトリック両王」(スペイン語:ロス・レイエス・カトリコス)として知られ、この称号はアレクサンデル6世によって与えられたもので ある。 |

| Conclusion of the Reconquista and expulsions of Jews and Muslims Further information: Reconquista, Spanish Inquisition, and Black legend (Spain) The monarchs oversaw the final stages of the Reconquista of Iberian territory from the Moors with the conquest of Granada, conquered the Canary Islands, and expelled the Jews from Spain under the Alhambra Decree. Although until the 13th century religious minorities (Jews and Muslims) had enjoyed considerable tolerance in Castile and Aragon – the only Christian kingdoms where Jews were not restricted from any professional occupation – the situation of the Jews collapsed over the 14th century, reaching a climax in 1391 with large scale massacres in every major city except Ávila. The Catholic Monarchs ordered the remaining Jews to convert or face expulsion from Spain in 1492, and extended the expulsion decrees to their territories on the Italian peninsula, including Sicily (1493), Naples (1542), and Milan (1597).[74] Over the following decades, Muslims faced the same fate; and about 60 years after the Jews, they were also compelled to convert ("Moriscos") or be expelled. In the early 17th century, the converts were also expelled. Isabella ensured long-term political stability in Spain by arranging strategic marriages for her five children. Her firstborn, Isabella, married Afonso of Portugal, forging important ties between these two neighboring countries and hopefully ensuring future alliance, but the younger Isabella soon died before giving birth to an heir. Juana, Isabella's second daughter, married into the Habsburg dynasty when she wed Philip the Fair, the son of Maximilian I, King of Bohemia (Austria) and likely heir to the crown of the Holy Roman Emperor. This ensured an alliance with the Habsburgs and the Holy Roman Empire, a powerful, far-reaching territory that assured Spain's future political security. Isabella's only son, Juan, married Margaret of Austria, further strengthening ties with the Habsburg dynasty. Isabella's fourth child, Maria, married Manuel I of Portugal, strengthening the link forged by her older sister's marriage. Her fifth child, Catherine, married King Henry VIII of England and was mother to Queen Mary I of England. |

レコンキスタの完了とユダヤ教徒およびイスラム教徒の追放 さらに詳しい情報:レコンキスタ、スペイン異端審問、黒い伝説(スペイン). 両王は、グラナダ征服によりムーア人からイベリア半島を奪還するレコンキスタの最終段階を監督し、カナリア諸島を征服し、アルハンブラ勅令によりスペイン からユダヤ教徒を追放した。13世紀までは、カスティーリャとアラゴンでは宗教的少数派(ユダヤ教徒とイスラム教徒)がかなりの寛容さをもって受け入れら れていたが、これはキリスト教国の中で唯一、ユダヤ教徒が職業を制限されていなかった国である。しかし、14世紀にはユダヤ教徒の状況は崩壊し、1391 年にはアビラを除く主要都市で大規模な虐殺事件が起こり、その状況は頂点に達した。 カトリック両王は、1492年に残っていたユダヤ教徒に改宗するかスペインからの追放を受けるかを命じ、追放令をシチリア(1493年)、ナポリ(1542年)、ミラノ(1597年)を含むイタリア半島全域に拡大した。[74] その後数十年にわたって、イスラム教徒も同じ運命をたどることになり、ユダヤ人から約60年遅れて、改宗(「モリスコス」)するか追放されることを余儀なくされた。17世紀初頭には、改宗者も追放された。 イサベルは、5人の子供たちに戦略的な結婚相手を見つけることで、スペインの長期にわたる政治的安定を確保した。長女イザベラはポルトガルのアフォンソと 結婚し、隣国同士の重要な結びつきを築き、将来の同盟を確かなものにしようとしたが、イザベラは跡継ぎを産むことなく早世した。イザベラの次女フアナは、 神聖ローマ皇帝の王位継承者である可能性が高かったマクシミリアン1世(ボヘミア王、オーストリア大公)の息子、フィリップ善良王と結婚し、ハプスブルク 家に嫁いだ。 これにより、ハプスブルク家および神聖ローマ帝国との同盟が確実なものとなり、強力な広大な領土がスペインの将来の政治的安全を保証した。イザベラの唯一 の息子フアンは、オーストリアのマルガリータと結婚し、ハプスブルク家との結びつきをさらに強固なものにした。イザベラの4番目の子供であるマリアは、ポ ルトガルのマヌエル1世と結婚し、姉の結婚によって築かれた絆をさらに強固なものにした。5番目の子供であるカタリナは、イングランド王ヘンリー8世と結 婚し、イングランド女王メアリー1世の母親となった。 |

| Conquest of the Canary Islands, Columbian expeditions to the New World, and African expansion See also: Conquest of the Canary Islands, Kingdom of the Canary Islands, and Voyages of Christopher Columbus  Christopher Columbus leads expedition to the New World, 1492, sponsored by Spanish crown- John Vanderlyn (1775-1852)  Taking of Oran by Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros in 1509. The Castilian conquest of the Canary Islands, inhabited by Guanche people, took place between 1402 (with the conquest of Lanzarote) and 1496 (with the conquest of Tenerife). Two periods can be distinguished in this process: the noble conquest, carried out by the nobility in exchange for a pact of vassalage, and the royal conquest, carried out directly by the Crown, during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs.[75] By 1520, European military technology combined with the devastating epidemics such as bubonic plague and pneumonia brought by the Castilians and enslavement and deportation of natives led to the extinction of the Guanches. Isabella and Ferdinand authorized the 1492 expedition of Christopher Columbus, who became the first known European to reach the New World since Leif Ericson. This and subsequent expeditions led to an influx of wealth into Spain, supplementing income from within Castile for the state that was a dominant power in Europe for the next two centuries. Spain established colonies in North Africa that ranged from the Atlantic Moroccan coast to Tripoli in Libya. Melilla was occupied in 1497, Oran in 1509, Larache in 1610, and Ceuta was annexed from the Portuguese in 1668. Today, both Ceuta and Melilla still remain under Spanish control, together with smaller islets known as the presidios menores (Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera, las Islas de Alhucemas, las Islas de Chafarinas). |

カナリア諸島の征服、コロンブスの新大陸探検、アフリカの拡大 関連項目:カナリア諸島の征服、カナリア諸島王国、クリストファー・コロンブスの航海  1492年、スペイン王冠の援助により、クリストファー・コロンブスが新大陸への遠征を指揮- John Vanderlyn (1775-1852)  1509年、フランシスコ・ヒメネス・デ・シスネロスによるオランの占領。 グアンチェ族が居住していたカナリア諸島へのカスティーリャ征服は、1402年(ランサローテ征服)から1496年(テネリフェ征服)にかけて行われた。 この過程では、2つの時期に区別できる。貴族による征服は、臣従の誓約と引き換えに貴族によって行われた。王による征服は、カトリック両王の治世下で王権 が直接行ったものである 。1520年までに、ヨーロッパの軍事技術と、カスティーリャ人が持ち込んだペストや肺炎などの壊滅的な疫病、そして先住民の奴隷化と追放が組み合わさ り、グアンチェ族は絶滅した。イザベラとフェルディナンドは、1492年のクリストファー・コロンブスの遠征を承認した。コロンブスは、レイフ・エリクソ ン以来、新大陸に到達した最初のヨーロッパ人として知られている。この遠征とそれに続く遠征により、スペインに富が流入し、カスティーリャ国内からの収入 を補い、その後2世紀にわたってヨーロッパの覇権を握る国家となった。 スペインは、モロッコの海岸からリビアのトリポリに至る北アフリカに植民地を建設した。メリリャは1497年に、オランは1509年に、ララシェは 1610年に占領され、1668年にはポルトガルからセウタが併合された。現在、セウタとメリリャはともにスペインの統治下にあり、さらに、プレシディ オ・メノル(ペニョン・デ・ベレス・デ・ラ・ゴメラ、ラス・イスラス・デ・アルフセマス、ラス・イスラス・デ・チャファリナス)として知られる小さな島々 もスペイン領となっている。 |

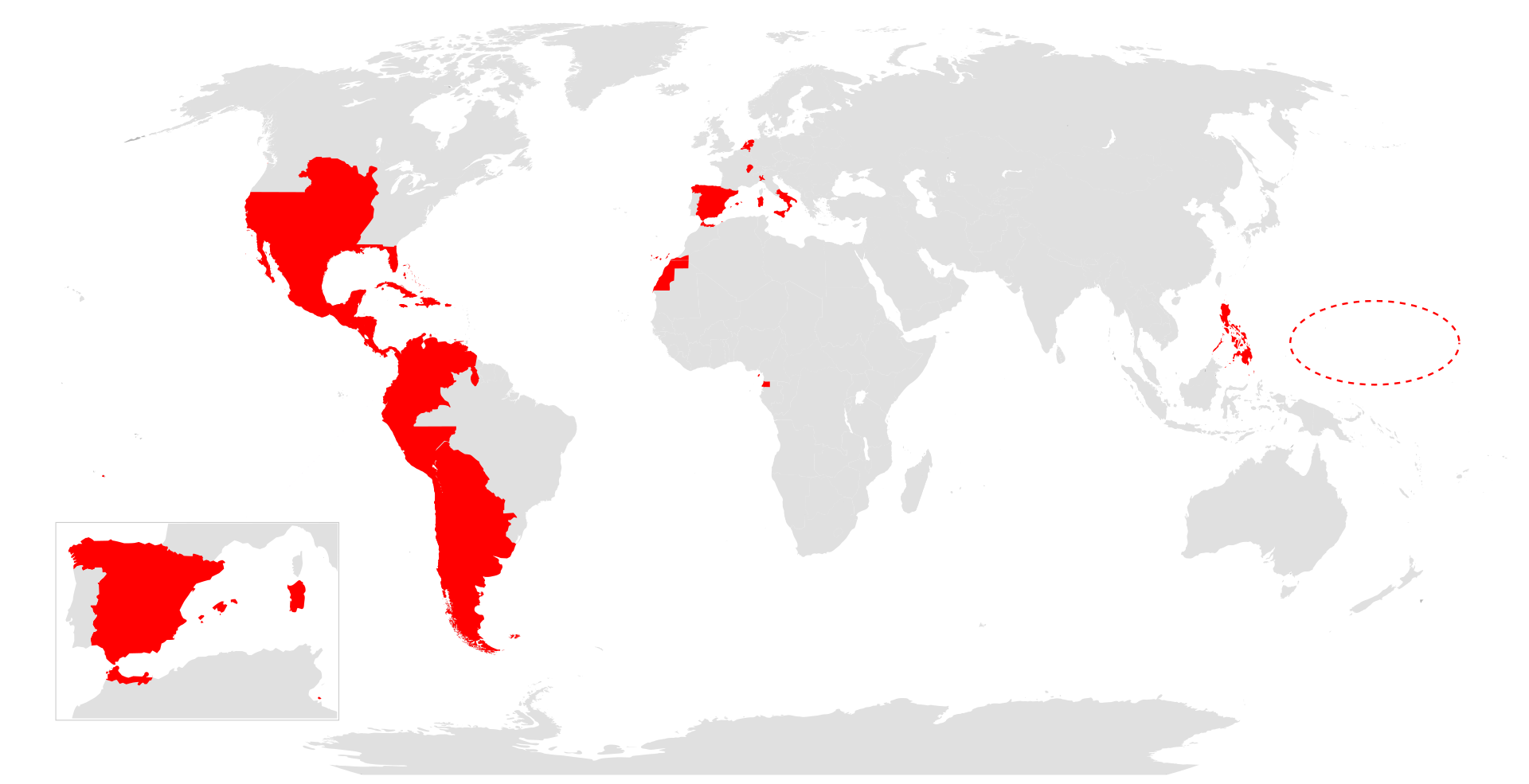

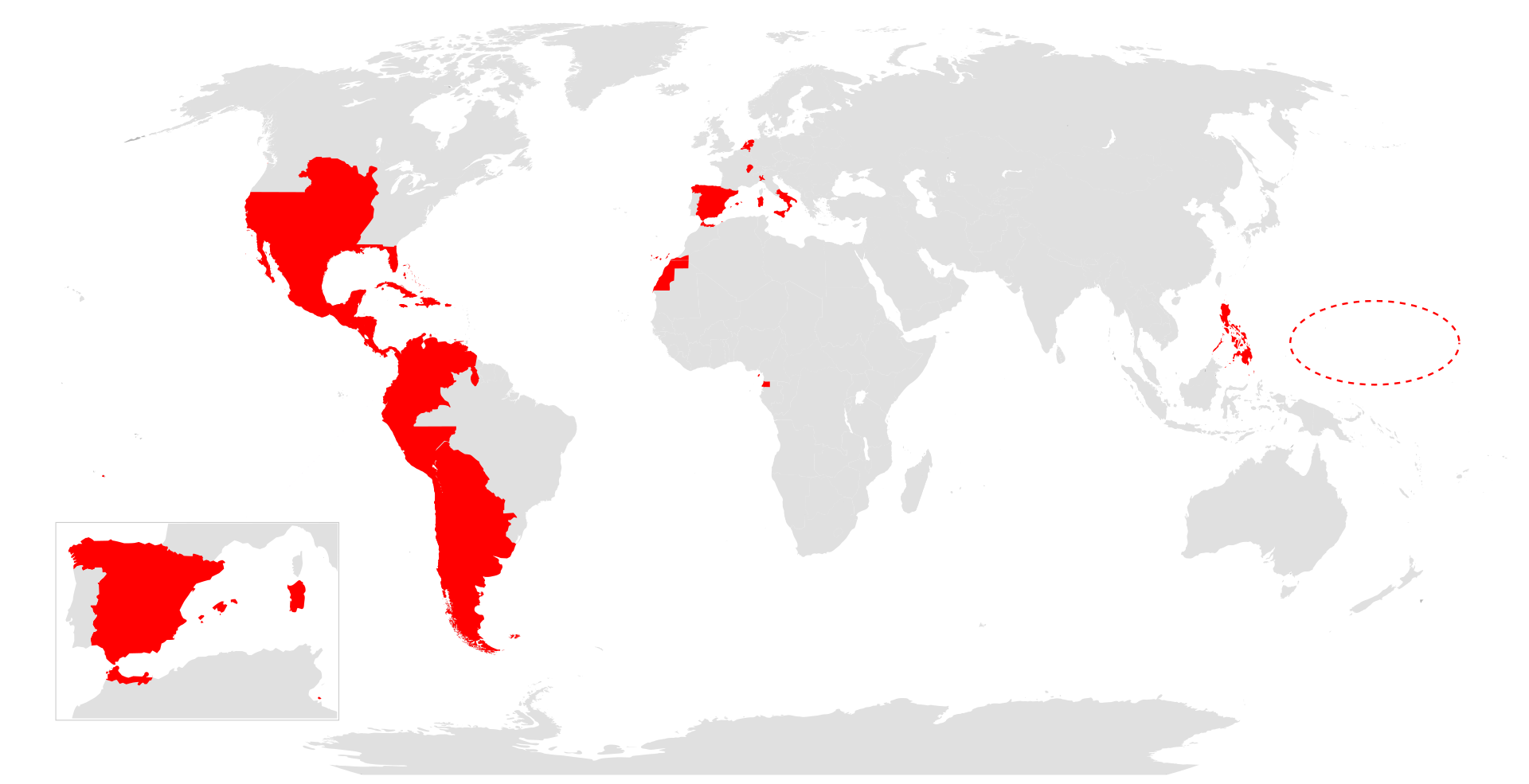

| Spanish empire Main article: Spanish Empire See also: Habsburg Spain  Map of territories that were once part of the Spanish Empire The Spanish Empire was one of the first global empires. It was also one of the largest empires in world history. In the 16th century, Spain and Portugal were in the vanguard of European global exploration and colonial expansion. The two kingdoms on the conquest and Iberian Peninsula competed with each other in opening of trade routes across the oceans. Spanish imperial conquest and colonization began with the Canary Islands in 1312 and 1402.[76] which began the Castilian conquest of the Canary Islands, completed in 1495.  The Conquest of Tenochtitlán In the 15th and 16th centuries, trade flourished across the Atlantic between Spain and the Americas and across the Pacific between East Asia and Mexico via the Philippines. Spanish Conquistadors, operating privately, deposed the Aztec, Inca and Maya governments with extensive help from local factions and took control of vast stretches of land.[77] In the Philippines, the Spanish, using Mexican Conquistadors like Juan de Salcedo, conquered the kingdoms and sultanates of the islands by pitting Pagans and Muslims against each other, employing the principle of "Divide and Conquer".[78] They considered their war against the Muslims of the Southeast Asia an extension of the Spanish Reconquista.[79] This New World empire was at first a disappointment, as the natives had little to trade. Diseases such as smallpox and measles that arrived with the colonizers devastated the native populations, especially in the densely populated regions of the Aztec, Maya and Inca civilizations, and this reduced their economic potential. Estimates of the pre-Columbian population of the Americas vary but possibly stood at 100 million—one fifth of humanity in 1492. Between 1500 and 1600 the population of the Americas was halved. In Mexico alone, it has been estimated that the pre-conquest population of around 25 million was reduced within 80 years to about 1.3 million. In the 1520s, large-scale extraction of silver from the rich deposits of Mexico's Guanajuato began to be greatly augmented by the silver mines in Mexico's Zacatecas and Bolivia's Potosí from 1546. These silver shipments re-oriented the Spanish economy, leading to the importation of luxuries and grain. The resource-rich colonies of Spain thus caused large cash inflows.[80] They also became indispensable in financing the military capability of Habsburg Spain in its long series of European and North African wars.  The Port of Seville in the late 16th century. Seville became one of the most populous and cosmopolitan European cities after the expeditions to the New World.[81] Spain enjoyed a cultural golden age in the 16th and 17th centuries. For a time, the Spanish Empire dominated the oceans with its experienced navy and ruled the European battlefield with its well trained infantry, the tercios. The financial burden within the peninsula was on the backs of the peasant class while the nobility enjoyed an increasingly lavish lifestyle. From the incorporation of the Portuguese Empire in 1580 (lost in 1640) until the loss of its American colonies in the 19th century, Spain maintained one of the largest empires in the world even though it suffered military and economic misfortunes from the 1640s. The thought that Spain could bring Christianity to the New World and protect Catholicism in Europe played a strong role in the expansion of Spain's empire.[82] |

スペイン帝国 詳細は「スペイン帝国」を参照 ハプスブルク家のスペインも参照  かつてスペイン帝国の一部であった領土の地図 スペイン帝国は、世界史上初のグローバル帝国の一つであり、世界史上最大の帝国の一つでもあった。16世紀、スペインとポルトガルはヨーロッパによる世界 的な探検と植民地拡大の先鋒を切っていた。イベリア半島征服を巡って、両王国は海洋を越えた貿易ルートの開拓で互いに競い合った。スペイン帝国の征服と植 民地化は、1312年と1402年のカナリア諸島から始まった。  テノチティトラン征服(画1650年) 15世紀から16世紀にかけて、大西洋を挟んだスペインとアメリカ大陸、太平洋を挟んだフィリピン経由の東アジアとメキシコの間で貿易が盛んに行われた。 スペインのコンキスタドールたちは、現地の派閥から広範な支援を受け、アステカ、インカ、マヤの政府を倒し、広大な土地を支配下に置いた。フィリピンで は、スペインはフアン・デ・サルセードのようなメキシコのコンキスタドールたちを使い、 異教徒とイスラム教徒を対立させることで「分断して征服する」という原則を適用し、島の王国とスルタン国を征服した。[78] 彼らは東南アジアのイスラム教徒との戦争をスペインのレコンキスタの延長線上にあるものと考えた。[79] この新世界帝国は当初、期待外れであった。先住民には交易するものがほとんどなかったからだ。天然痘や麻疹などの病気が入植者とともに持ち込まれ、先住民 の人口を激減させた。特にアステカ、マヤ、インカ文明の人口密集地域ではその傾向が顕著で、経済的潜在能力が低下した。コロンブス到来以前のアメリカ大陸 の人口は諸説あるが、おそらく1億人、すなわち1492年当時の世界の人口の5分の1であったと考えられる。1500年から1600年の間に、アメリカ大 陸の人口は半減した。メキシコだけでも、征服前の人口約2500万人が80年後には130万人にまで減少したと推定されている。 1520年代には、メキシコのグアナフアトの豊富な銀鉱床から大規模な銀の採掘が始まり、1546年からはメキシコのサカテカスとボリビアのポトシの銀鉱 山によって、その採掘量は大幅に増加した。これらの銀の輸送はスペイン経済の方向性を変え、贅沢品や穀物の輸入につながった。このように、資源に恵まれた スペインの植民地は、多額の現金流入をもたらした。[80] また、ハプスブルク家のスペインがヨーロッパや北アフリカで繰り広げた一連の戦争において、軍事力を維持する上でも不可欠となった。  16世紀後半のセビリア港。セビリアは、新世界への探検の後、ヨーロッパで最も人口が多く国際的な都市の一つとなった。[81] スペインは16世紀から17世紀にかけて文化の黄金時代を謳歌した。スペイン帝国は、経験豊富な海軍により一時的に海洋を支配し、よく訓練された歩兵隊であるテルシオによりヨーロッパの戦場を支配した。 半島内の財政負担は農民階級が負う一方で、貴族階級はますます贅沢な生活を享受した。1580年のポルトガル帝国の併合(1640年に失う)から19世紀 のアメリカ植民地の喪失まで、スペインは1640年代に軍事的・経済的な不幸に見舞われたにもかかわらず、世界最大規模の帝国を維持していた。スペインが 新世界にキリスト教をもたらし、ヨーロッパのカトリック教徒を守ることができるという考えは、スペインの帝国拡大に大きな役割を果たした。[82] |

| Spanish Kingdoms under the 'Great' Habsburgs (16th century) Charles I, Holy Emperor  Charles I of Spain (better known in the English-speaking world as the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V) was the most powerful European monarch of his day.[83] Spain's world empire reached its greatest territorial extent in the late 18th century but it was under the Habsburg dynasty in the 16th and 17th centuries it reached the peak of its power and declined. The Iberian Union with Portugal meant that the monarch of Castile was also the monarch of Portugal, but they were ruled as separate entities both on the peninsula and in Spanish America and Brazil. In 1640, the House of Braganza revolted against Spanish rule and reasserted Portugal's independence.[84] When Spain's first Habsburg ruler Charles I became king of Spain in 1516 (with his mother and co-monarch Queen Juana I effectively powerless and kept imprisoned till her death in 1555), Spain became central to the dynastic struggles of Europe. Charles also became Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and because of his widely scattered domains was not often in Spain. In 1556 Charles abdicated, giving his Spanish empire to his only surviving son, Philip II of Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire to his brother, Ferdinand. Philip treated Castile as the foundation of his empire, but the population of Castile (about a third of France's) was never large enough to provide the soldiers needed. His marriage to Mary Tudor allied England with Spain. |

ハプスブルク家の「偉大なる」スペイン王国(16世紀) 神聖ローマ皇帝カール1世  スペイン王カルロス1世(英語圏では神聖ローマ皇帝カール5世としての方がよく知られている)は、当時ヨーロッパで最も権力を持った君主であった。 スペインの世界帝国は18世紀後半に領土が最大となったが、16世紀と17世紀のハプスブルク家の時代に最盛期を迎え、衰退した。ポルトガルとのイベリア 連合により、カスティーリャの君主はポルトガルの君主でもあったが、イベリア半島とスペイン領アメリカおよびブラジルではそれぞれ別個の国家として統治さ れていた。1640年、ブラガンサ家がスペインの支配に反旗を翻し、ポルトガルの独立を再主張した。 スペインの最初のハプスブルク家支配者であるカルロス1世が1516年にスペイン王となったとき(母親であり共同君主であった女王フアナ1世は事実上無力 であり、1555年に死去するまで投獄されていた)、スペインはヨーロッパの王位継承を巡る闘争の中心となった。カルロスは神聖ローマ皇帝カール5世とも なり、領土が広く分散していたため、スペインにはあまりいなかった。 1556年、カルロスは退位し、スペイン帝国を唯一の存命の息子であるスペイン王フェリペ2世に、神聖ローマ帝国を弟のフェルディナントに譲った。フェリ ペはカスティーリャを帝国の基盤として扱ったが、カスティーリャの人口(フランスの約3分の1)では必要な兵士を確保するには十分ではなかった。メア リー・チューダーとの結婚により、イングランドはスペインと同盟を結んだ。 |

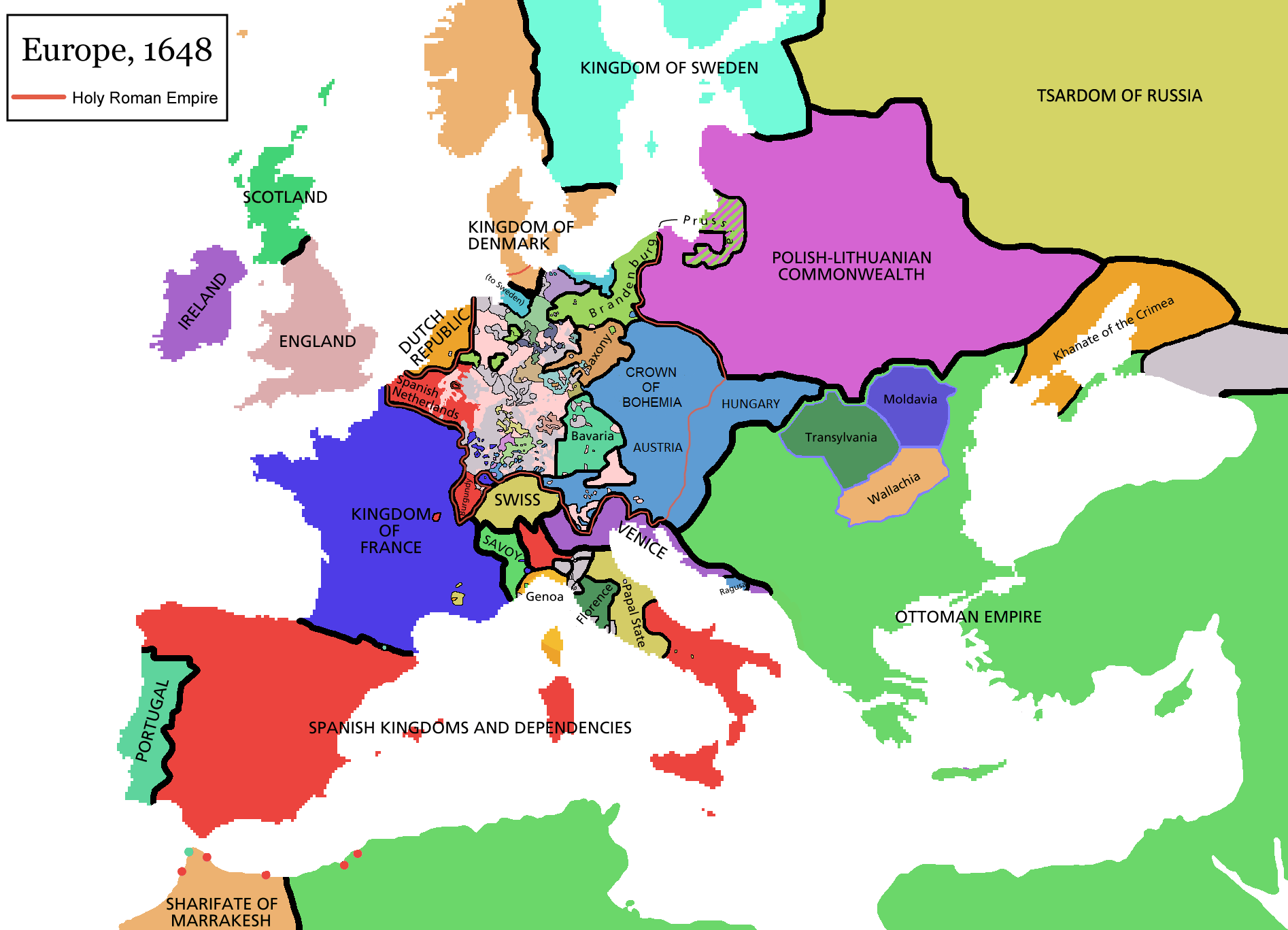

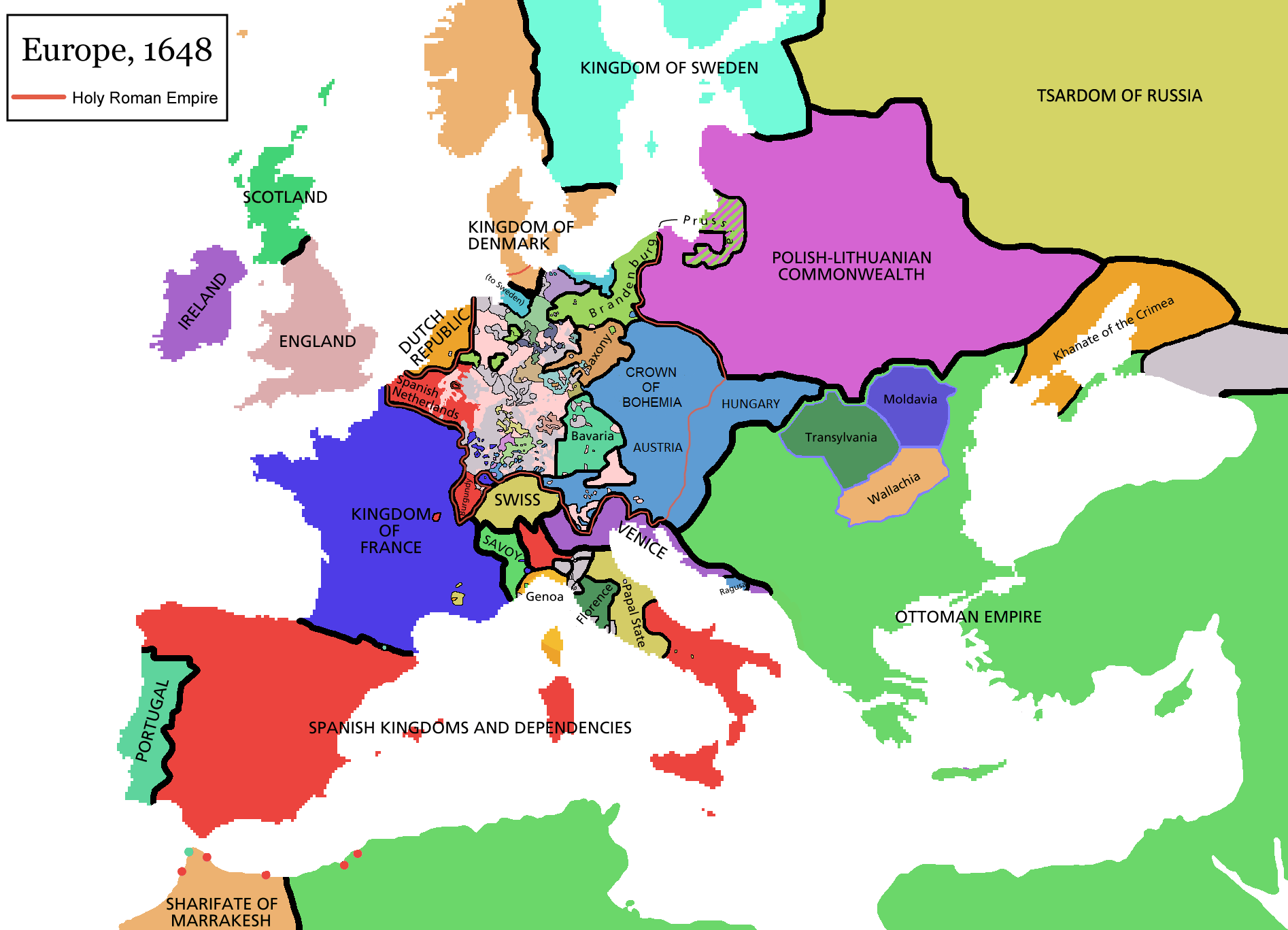

Philip II and the wars of religion Battle of St. Quentin In the 1560s, plans to consolidate control of the Netherlands led to unrest, which gradually led to the Calvinist leadership of the revolt and the Eighty Years' War. The Dutch armies waged a war of maneuver and siege, successfully avoiding pitched battle. This conflict consumed much Spanish expenditure during the later 16th century. Other extremely expensive failures included an attempt to invade Protestant England in 1588 that produced the worst military disaster in Spanish history when the Spanish Armada—costing 10 million ducats—was scattered by a storm. Economic and administrative problems multiplied in Castile, and the weakness of the native economy became evident in the following century. Rising inflation, financially draining wars in Europe, the ongoing aftermath of the expulsion of the Jews and Moors from Spain, and Spain's growing dependency on the silver imports, combined to cause several bankruptcies that caused economic crisis in the country, especially in heavily burdened Castile. The great plague of 1596–1602 killed 600,000 to 700,000, or about 10% of the population. Altogether more than 1,250,000 deaths resulted from the extreme incidence of plague in 17th-century Spain.[85] Economically, the plague destroyed the labor force as well as creating a psychological blow.[86]  A map of Europe in 1648, after the Peace of Westphalia |

フィリップ2世と宗教戦争 サン・カンタンでの戦い 1560年代、オランダの支配を強化する計画が不安定な状況を招き、それが徐々にカルヴァン派の指導による反乱と80年戦争へとつながっていった。オラン ダ軍は機動戦と包囲戦を展開し、激しい戦闘を回避することに成功した。この紛争により、16世紀後半のスペインの支出は大幅に増加した。その他にも、 1588年のプロテスタントのイングランド侵攻の試みは、1000万ダカットを費やしたスペイン無敵艦隊が嵐で散り散りになるというスペイン史上最大の軍 事的惨事を招き、非常に高価な失敗となった。 カスティーリャでは経済と行政の問題が深刻化し、その後の世紀には国内経済の脆弱性が明らかになった。インフレの進行、ヨーロッパでの財政を圧迫する戦 争、スペインからのユダヤ人とムーア人の追放の余波、銀の輸入へのスペインの依存の高まりなどが相まって、スペイン国内、特に重い負担を強いられていたカ スティーリャで経済危機を引き起こすいくつかの破産を引き起こした。1596年から1602年にかけての大ペストでは、人口の約10%にあたる60万から 70万人が死亡した。17世紀のスペインではペストの流行が極度に激しく、合計125万人以上が死亡した。[85] 経済的には、ペストは労働力を破壊するとともに、心理的な打撃を与えた。[86]  1648年のヨーロッパの地図。ウェストファリア条約締結後。 |

| Cultural Golden Age (Siglo de Oro) Main article: Spanish Golden Age  View of Toledo by El Greco, between 1596 and 1600 The Spanish Golden Age (Siglo de Oro) was a period of flourishing arts and letters in the Spanish Empire (now Spain and the Spanish-speaking countries of Latin America), coinciding with the political decline and fall of the Habsburgs. Arts flourished despite the decline of the empire in the 17th century. The last great writer of the age, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, died in New Spain in 1695.[87] The Habsburgs were great patrons of art in their countries. El Escorial, the great royal monastery built by King Philip II, invited the attention of some of Europe's greatest architects and painters. Diego Velázquez, regarded as one of the most influential painters of European history and a greatly respected artist in his own time, cultivated a relationship with King Philip IV and his chief minister, the Count-Duke of Olivares, leaving several portraits that demonstrate his style and skill. El Greco, a respected Greek artist from the period, settled in Spain, and infused Spanish art with the styles of the Italian renaissance and helped create a uniquely Spanish style of painting. Some of Spain's greatest music is regarded as having been written in the period. Such composers as Tomás Luis de Victoria, Luis de Milán and Alonso Lobo helped to shape Renaissance music and the styles of counterpoint and polychoral music, and their influence lasted into the Baroque period. Spanish literature blossomed as well, most famously demonstrated in the work of Miguel de Cervantes, the author of Don Quixote. Spain's most prolific playwright, Lope de Vega, wrote possibly as many as one thousand plays over his lifetime, over four hundred of which survive. |

文化の黄金時代(シグロ・デ・オロ) 詳細は「スペイン黄金時代」を参照  エル・グレコによるトレドの眺め、1596年から1600年の間 スペイン黄金時代(シグロ・デ・オロ)は、スペイン帝国(現在のスペインおよびラテンアメリカにおけるスペイン語圏の国々)における芸術と文学が栄えた時 代であり、ハプスブルク家の政治的衰退と崩壊と時を同じくしていた。17世紀に帝国が衰退したにもかかわらず、芸術は栄えた。この時代の最後の偉大な作家 であるソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルスは、1695年にヌエバ・エスパーニャで死去した。 ハプスブルク家は自国の芸術の偉大な後援者であった。フェリペ2世が建てた壮大な王立修道院であるエル・エスコリアルは、ヨーロッパの偉大な建築家や画家 たちの注目を集めた。ヨーロッパ史上最も影響力のある画家の一人であり、同時代にも非常に尊敬されていたディエゴ・ベラスケスは、フェリペ4世王と宰相オ リヴァレス公と親交を結び、そのスタイルと技術を示す肖像画を数点残している。同時代に活躍したギリシャ人画家のエル・グレコはスペインに定住し、イタリ ア・ルネサンスのスタイルをスペイン美術に吹き込み、スペイン独特の絵画スタイルの創出に貢献した。 スペインの偉大な音楽のいくつかは、この時代に書かれたと考えられている。トマス・ルイス・デ・ビクトリア、ルイス・デ・ミラン、アロンソ・ロボなどの作曲家は、ルネサンス音楽と対位法や多声部音楽のスタイルを形作るのに貢献し、その影響力はバロック時代まで続いた。 スペイン文学もまた花開き、そのことは何よりもミゲル・デ・セルバンテス(ドン・キホーテの作者)の作品に顕著に示されている。スペインで最も多作な劇作家であるロペ・デ・ベガは、生涯に1,000もの劇を書き、そのうち400以上が現存している。 |

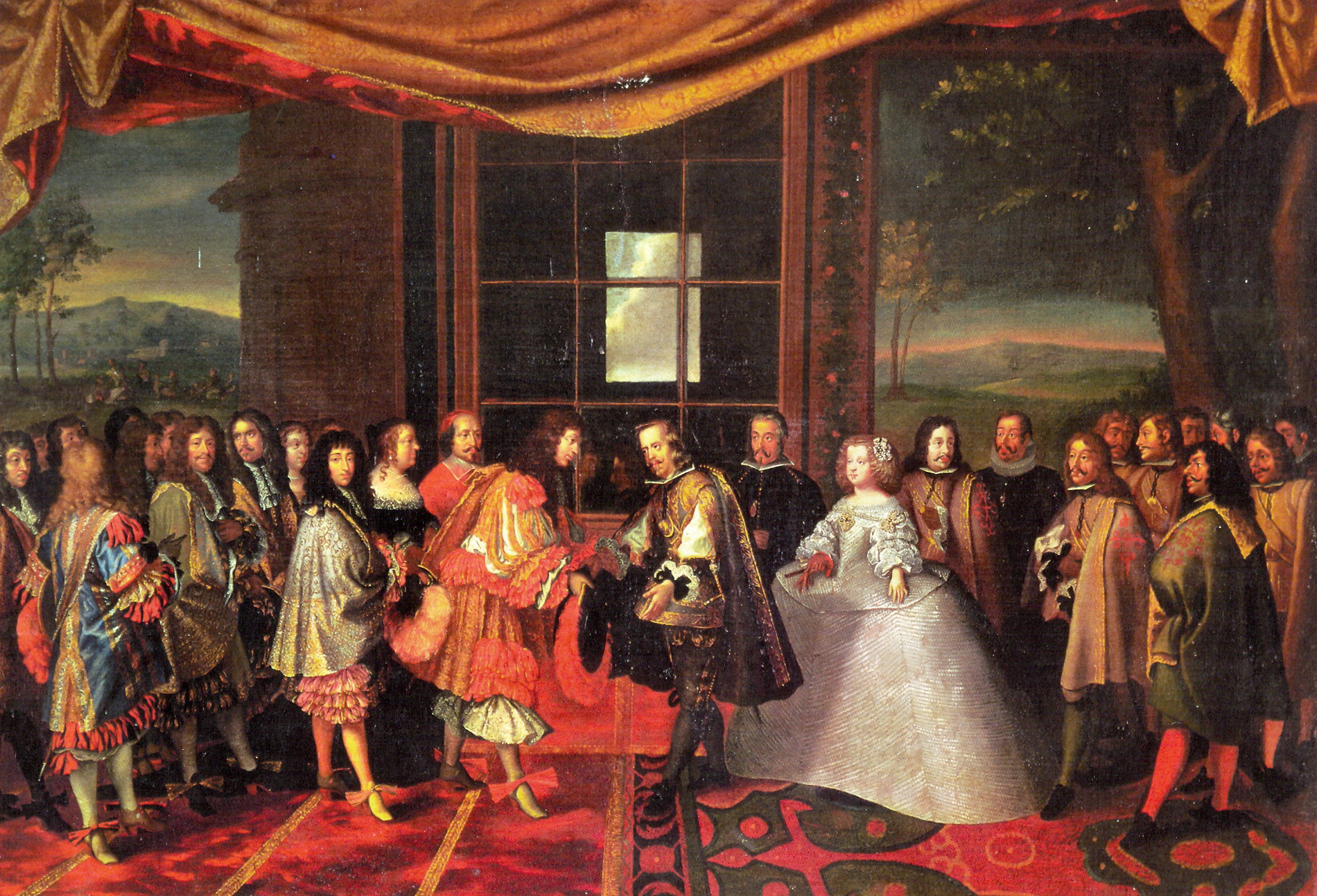

| Decline under the 'Minor' Habsburgs (17th century) See also: Decline of Spain Spain's severe financial difficulties began in the middle 16th century, and continued for the remainder of Habsburg rule. Despite the successes of Spanish armies, the period was marked by monetary inflation, mercantilism, and a variety of government monopolies and interventions. Spanish kings were forced to declare sovereign defaults nine times between 1557 and 1666.[88] Philip II died in 1598, and was succeeded by his son Philip III. In his reign (1598–1621) a ten-year truce with the Dutch was overshadowed in 1618 by Spain's involvement in the European-wide Thirty Years' War. Philip III was succeeded in 1621 by his son Philip IV of Spain (reigned 1621–65). Much of the policy was conducted by the Count-Duke of Olivares, the inept prime minister from 1621 to 1643. He over-exerted Spain in foreign affairs and unsuccessfully attempted domestic reform. His policy of committing Spain to recapture Holland led to a renewal of the Eighty Years' War while Spain was also embroiled in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). His attempts to centralise power and increase wartime taxation led to revolts in Catalonia and in Portugal, which brought about his downfall.[89] During the Thirty Years' War, in which various Protestant forces battled Imperial armies, France provided subsidies to Habsburg enemies, especially Sweden. Sweden lost and France's First Minister, Cardinal Richelieu, in 1635 declared war on Spain. The open war with Spain started with a victory for the French at Les Avins in 1635. The following year Spanish forces based in the Southern Netherlands hit back with devastating lightning campaigns in northern France that left the economy of the region in tatters. After 1636, however, Olivares, fearful of provoking another bankruptcy, stopped the advance. In 1640, both Portugal and Catalonia rebelled. Portugal was lost for good; in northern Italy and most of Catalonia, French forces were expelled and Catalonia's independence was suppressed. In 1643, the French defeated one of Spain's best armies at Rocroi, northern France.[90] Main article: Spain in the 17th century  Louis XIV of France and Philip IV of Spain at the Meeting on the Isle of Pheasants in June 1660, part of the process to put an end to the Franco-Spanish War (1635–59). The Spanish "Golden Age" politically ends no later than 1659, with the Treaty of the Pyrenees, ratified between France and Habsburg Spain. During the long regency for Charles II, the last of the Spanish Habsburgs, favouritism milked Spain's treasury, and Spain's government operated principally as a dispenser of patronage. Plague, famine, floods, drought, and renewed war with France wasted the country. The Peace of the Pyrenees (1659) had ended fifty years of warfare with France, whose king, Louis XIV, found the temptation to exploit a weakened Spain too great. Louis instigated the War of Devolution (1667–68) to acquire the Spanish Netherlands. By the 17th century, the Catholic Church and Spain had a close bond, attesting to the fact that Spain was virtually free of Protestantism during the 16th century. In 1620, there were 100,000 Spaniards in the clergy; by 1660 the number had grown to about 200,000, and the Church owned 20% of all the land in Spain. The Spanish bureaucracy in this period was highly centralized, and totally reliant on the king for its efficient functioning. Under Charles II, the councils became the sinecures of wealthy aristocrats despite attempts at reform. Political commentators in Spain, known as arbitristas, proposed a number of measures to reverse the decline of the Spanish economy, with limited success. In rural areas, heavy taxation of peasants reduced agricultural output as peasants migrated to the cities. The influx of silver from the Americas has been cited as the cause of inflation, although only the quinto real (royal fifth) actually went to Spain. A prominent internal factor was the Spanish economy's dependence on the export of luxurious Merino wool, which had its markets in northern Europe reduced by war and growing competition from cheaper textiles. The once proud Spanish army was falling far behind its foes. It did badly at Bergen op Zoom in 1622. The Dutch won very easily at 's-Hertogenbosch and Wesel in 1629. In 1632 the Dutch captured the strategic fortress town of Maastricht, repulsing three relief armies and dooming the Spanish to defeat.[91] While Spain built a rich American Empire that exported a silver treasure fleet every year, it was unable to focus its financial, military, and diplomatic power on building up its Spanish base. The Crown's dedication to destroying Protestantism through almost constant warfare created a cultural ethos among Spanish leaders that undermined the opportunity for economic modernization or industrialization. When Philip II died in 1598, his treasury spent most of its income on funding the huge deficit, which continued to grow. In peninsular Spain, the productive forces were undermined by steady inflation, heavy taxation, immigration of ambitious youth to the colonies, and by depopulation. Industry went into reverse – Seville in 1621 operated 400 looms, where it had 16,000 a century before. Religiosity led by saints and mystics, missionaries and crusaders, theologians and friars dominated Spanish culture, with the psychology of a reward in the next world. Palmer and Colton argue: the generations of crusading against infidels, even, heathens and heretics had produced an exceptionally large number of minor aristocrats, chevaliers, dons, and hidalgos, who as a class were contemptuous of work and who were numerous enough and close enough to the common people to impress their haughty indifference upon the country as a whole.[92] Elliott cites the achievements of Castille in many areas, especially high culture. He finds:[93] A certain paradox in the fact that the achievement of the two most outstanding creative artists of Castile – Cervantes and Velázquez – was shot through with a deep sense of disillusionment and failure; but the paradox was itself a faithful reflection of the paradox of sixteenth-and seventeenth-century Castile. For here was a country which had climbed to the heights and sunk to the depths; which had achieved everything and lost everything; which had conquered the world only to be vanquished itself. The Spanish achievement of the sixteenth century was essentially the work of Castile, but so also was the Spanish disaster of the seventeenth; and it was Ortega y Gasset who expressed the paradox most clearly when he wrote what may serve as an epitaph on the Spain of the House of Austria: ‘Castile has made Spain, and Castile has destroyed it.’ The Habsburg dynasty became extinct in Spain with Charles II's death in 1700, and the War of the Spanish Succession ensued in which the other European powers tried to assume control of the Spanish monarchy. King Louis XIV of France eventually lost the War of the Spanish Succession. The victors were Britain, the Dutch Republic and Austria. They allowed the crown of Spain to pass to the Bourbon dynasty, provided that Spain and France never merged.[94] After the War of the Spanish Succession, the assimilation of the Crown of Aragon by the Castilian Crown, through the Nueva Planta Decrees, was the first step in the creation of the Spanish nation state. And like other European nation-states in formation,[95] it was not on a uniform ethnic basis, but by imposing the political and cultural characteristics of the dominant ethnic group, in this case the Castilian, on those of the other ethnic groups, so they become national minorities to be assimilated.[96][97] Nationalist policies, sometimes very aggressive,[98][99][100][101] and still in force,[102][103][104] have been and are the seeds of repeated territorial conflicts within the state. |

ハプスブルク家の「マイナー」家系による衰退(17世紀) 関連項目:スペインの衰退 スペインの深刻な財政難は16世紀半ばに始まり、ハプスブルク家の支配が続く間、続いた。スペイン軍の成功にもかかわらず、この時代は通貨のインフレ、重 商主義、さまざまな政府による独占や介入によって特徴づけられた。スペイン王は1557年から1666年の間に9回、国家債務不履行を宣言せざるを得な かった。 1598年にフェリペ2世が死去し、その息子フェリペ3世が王位を継承した。フェリペ3世の治世(1598年~1621年)では、1618年にスペインが ヨーロッパ全土に及んだ三十年戦争に介入したことで、オランダとの10年間の休戦協定が影を潜めた。フェリペ3世は1621年に息子のフェリペ4世(在位 1621年~1665年)に王位を譲った。政策の多くは、1621年から1643年まで無能な首相として君臨したオリヴァレス伯が主導した。彼はスペイン を外交問題に過度に介入させ、国内改革を試みたが失敗した。スペインをオランダ奪還に専念させるという政策は、スペインが三十年戦争(1618年 ~1648年)に巻き込まれている最中に、八十年戦争の再燃を招くこととなった。権力を集中させ、戦時増税を試みたことで、カタルーニャとポルトガルで反 乱が起こり、それが彼の失脚につながった。 三十年戦争では、プロテスタント諸国が帝国軍と戦ったが、フランスはハプスブルク家の敵国、特にスウェーデンに資金援助を行った。スウェーデンは敗北し、 1635年、フランスの宰相リシュリュー枢機卿はスペインに宣戦布告した。スペインとの全面戦争は、1635年のレザヴァンでのフランスの勝利で始まっ た。翌年、南ネーデルラントを拠点とするスペイン軍は、フランス北部で電撃的なキャンペーンを展開し、同地域の経済を荒廃させた。しかし、1636年以 降、オリヴァレスは再び破産を招くことを恐れ、進撃を停止した。1640年には、ポルトガルとカタルーニャが反乱を起こした。ポルトガルは完全に失墜し、 イタリア北部とカタルーニャの大部分ではフランス軍が追い出され、カタルーニャの独立は抑圧された。1643年、フランス軍はフランス北部のロクロワでス ペイン最強の軍隊を打ち負かした。 詳細は「17世紀のスペイン」を参照  1660年6月、キジ島会談におけるフランス王ルイ14世とスペイン王フェリペ4世。これは、フランス・スペイン戦争(1635年-1659年)を終結させるためのプロセスの一部である。 スペインの「黄金時代」は、フランスとハプスブルク家のスペインとの間で批准されたピレネー条約により、1659年を最後に政治的には終わった。 スペイン・ハプスブルク家の最後の王カルロス2世の長い摂政期間中、寵愛主義によりスペインの国庫は枯渇し、スペイン政府は主に恩恵の分配者として運営さ れていた。ペスト、飢饉、洪水、干ばつ、そしてフランスとの新たな戦争により、スペインは疲弊した。ピレネー条約(1659年)により、スペインとフラン スの50年にわたる戦争は終結したが、フランス王ルイ14世は弱体化したスペインを搾取する誘惑に駆られた。ルイはスペイン領ネーデルラントを手に入れる ために、返還戦争(1667年~1668年)を仕掛けた。 17世紀には、カトリック教会とスペインの結びつきは強固なものとなり、16世紀のスペインには事実上プロテスタントが存在しなかったことを証明してい る。1620年には聖職者の10万人がスペイン人であったが、1660年にはその数は20万人にまで増加し、教会はスペイン全土の土地の20%を所有して いた。この時代のスペインの官僚機構は極めて中央集権的であり、その効率的な機能は完全に国王に依存していた。カルロス2世の治世下では、改革の試みにも かかわらず、評議会は富裕な貴族たちの特権となっていた。スペインの政治評論家たちは、スペイン経済の衰退を食い止めるためのさまざまな政策を提案した が、その成果は限定的であった。農村部では、農民への重税により農業生産量が減少し、農民たちは都市部へと移住した。アメリカ大陸から流入した銀がインフ レの原因であると指摘されているが、実際にスペインに送られたのはクイント・レアル(王の5分の1)のみであった。スペイン経済が贅沢品であるメリノ種の 羊毛の輸出に依存していたことも、国内の要因として挙げられる。この羊毛の市場は戦争と安価な織物との競争激化により、北欧で縮小していた。 かつては誇り高かったスペイン軍は、敵に大きく遅れをとっていた。1622年のベルヘン・オプ・ゾームでは大敗を喫した。1629年のスヘルトーヘンボス とヴェセルでは、オランダ軍が簡単に勝利した。1632年には、オランダ軍は戦略的要塞都市マーストリヒトを占領し、3つの救援軍を撃退し、スペインの敗 北を決定づけた。 スペインは毎年銀財宝艦隊を輸出する豊かなアメリカ帝国を築き上げたが、その財政力、軍事力、外交力をスペイン本国を強化するために集中させることはでき なかった。 王権がほぼ絶え間なく戦争を続けることでプロテスタントを根絶することに専念したため、スペインの指導者たちの間には経済の近代化や工業化の機会を損なう ような文化的風潮が生まれた。1598年にフェリペ2世が死去した際には、その財政は巨額の赤字を埋めるために収入のほとんどを費やしており、赤字はさら に拡大していた。イベリア半島では、生産力は着実なインフレ、重税、野心に満ちた若者たちの植民地への移住、そして人口減少によって弱体化していた。産業 は衰退し、1621年のセビリアでは100年前には16,000台あった織機が400台しか稼働していなかった。聖人や神秘主義者、宣教師や十字軍の戦 士、神学者や修道士に導かれた宗教性がスペイン文化を支配し、来世での報いという心理が支配的であった。PalmerとColtonは次のように主張して いる。 異教徒、異教徒、異端者に対する十字軍の世代が、非常に多くの小貴族、シュヴァリエ、ドン、イダルゴを生み出した。彼らは階級として労働を軽蔑し、その数 は十分で、かつ一般市民に近かったため、その傲慢な無関心を国全体に印象づけるほどであった。[92] エリオットは、カスティーリャの多くの分野、特に高度な文化における功績を挙げている。彼は次のように述べている。[93] カスティーリャの最も優れた2人の芸術家、セルバンテスとベラスケスの業績が、深い幻滅と挫折感に貫かれているという事実には、ある種の逆説がある。しか し、この逆説自体が、16世紀と17世紀のカスティーリャの逆説を忠実に反映している。この国は、頂点にまで登りつめ、奈落の底まで落ちた。あらゆるもの を達成し、あらゆるものを失った。世界を征服したかと思えば、今度は征服される側になった。16世紀のスペインの功績は、本質的にはカスティーリャの功績 であったが、17世紀のスペインの災厄も同様であった。そして、この矛盾を最も明確に表現したのは、オルテガ・イ・ガセットであり、彼は、ハプスブルク家 のスペインの墓碑銘ともいえる言葉を残している。「カスティーリャがスペインを作り、カスティーリャがそれを破壊した」 ハプスブルク家は1700年のカルロス2世の死によってスペインで断絶し、スペイン継承戦争が勃発した。この戦争では、他のヨーロッパ諸国がスペイン王家 の支配権を握ろうとした。最終的にスペイン継承戦争に勝利したのはフランス王ルイ14世であった。勝利者となったのはイギリス、オランダ共和国、オースト リアであった。彼らはスペイン王冠がブルボン朝に渡ることを認め、スペインとフランスが統合されることはないという条件を提示した。 スペイン継承戦争の後、ヌエバ・プランタ勅令によるアラゴン王冠のカスティーリャ王冠への同化は、スペイン国民国家の形成における第一歩となった。そし て、形成途上にある他のヨーロッパの国民国家と同様に、[95] それは均一な民族を基盤としたものではなく、この場合ではカスティーリャ人の政治的・文化的特性を他の民族集団に押し付けることで、それらの民族が同化さ れるべき少数民族となるようにしたのである 。[96][97] 時には非常に攻撃的な[98][99][100][101]民族主義的政策は、現在も施行されており[102][103][104]、国家内部で繰り返さ れる領土紛争の種となっている。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099