エドムント・フッサール

Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl, 1859-1938

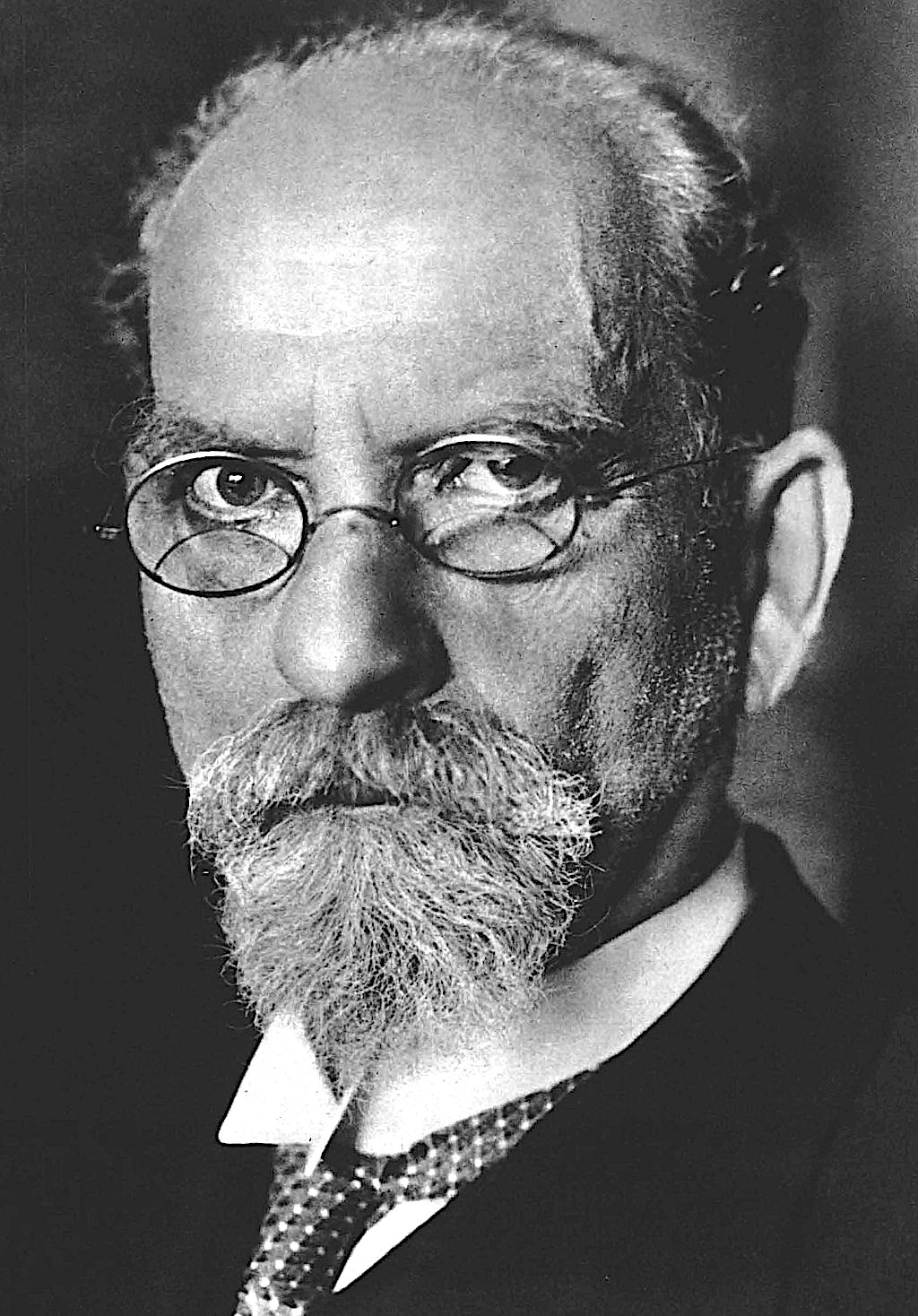

☆ エドムント・グスタフ・アルベルト・フッサール(/ˈhʊsɜːrl/ HUUSS-url;[14] 米国では /ˈhʊsərəl/ HUUSS-ər-əl,[15] ドイツ語: [ˈɛtm 1859年4月8日 - 1938年4月27日[17])は、現象学派を創始したオーストリア系ドイツ人の哲学者、数学者である。 初期の著作では、志向性の分析を基盤として、歴史主義と心理主義の論理に対する批判を詳細に論じている。円熟した作品では、いわゆる現象学的還元に基づく 体系的な基礎科学の構築を目指した。超越論的意識がすべての可能な知識の限界を定めるという主張に基づき、フッサールは現象学を超越論的観念論哲学として 再定義した。フッサールの思想は20世紀の哲学に多大な影響を与え、現代哲学を超えて、今なお著名な人物である。 フッサールは、カール・ワイエルシュトラスとレオ・ケーニヒスベルガーから数学を、フランツ・ブレンターノとカール・シュトゥンプから哲学を学んだ。 [18] 1887年からハレで、その後1901年からゲッティンゲンで、さらに1916年からフライブルクで教授として哲学を教え、1928年に引退するまで教鞭 をとり、その後も非常に生産的な活動を続けた。1933年、ナチス党の人種法により、ユダヤ人としての家系を理由にフッサールはフライブルク大学の図書館 から追放され、数か月後にはドイツ学術アカデミーも退会した。病気療養の後、1938年にフライブルクで死去した。[19]

| Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl

[ˈhʊsɐl] (* 8. April 1859 in Proßnitz in Mähren, Kaisertum Österreich;

† 27. April 1938 in Freiburg im Breisgau, Deutsches Reich)[1] war ein

österreichisch-deutscher Philosoph und Mathematiker und Begründer der

philosophischen Strömung der Phänomenologie. Er gilt als einer der

einflussreichsten Denker des 20. Jahrhunderts. Husserl studierte an der Universität Leipzig Mathematik bei Karl Weierstraß und Leo Koenigsberger sowie Philosophie bei Franz Brentano und Carl Stumpf.[2] Ab 1887 unterrichtete er an der Universität Halle Philosophie als Privatdozent. Von 1901 an lehrte er zunächst an der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, später als Professor an der Universität Freiburg. 1928 wurde er emeritiert, was seinem philosophischen Schaffen jedoch keinen Abbruch tat. 1938 erkrankte er und starb im selben Jahr in Freiburg. Während seine frühen Schriften eine psychologische Grundlegung der Mathematik anstrebten, legte Husserl mit seinen 1900 und 1901 erschienenen Logischen Untersuchungen eine umfassende Kritik des zu dieser Zeit vorherrschenden Psychologismus vor, der die Gesetze der Logik als Ausdruck bloßer psychischer Gegebenheiten sah. Er stellte darüber hinaus weitreichende Betrachtungen zur reinen Logik vor. Um 1907 stellte Husserl die von ihm entwickelte Methode der „phänomenologischen Reduktion“ vor. Diese würde fortan nicht nur sein weiteres Schaffen maßgeblich beeinflussen, sondern in seinen folgenden Werken zum philosophischen Ansatz eines transzendentalen Idealismus führen. Husserls Denken prägte die Philosophie des 20. Jahrhunderts besonders in Deutschland und Frankreich und ist bis in die Gegenwart von großer Wirkung. Zu Husserls Schülern zählen Martin Heidegger, Oskar Becker, Ludwig Ferdinand Clauß, Eugen Fink, Edith Stein und Günther Anders. Max Scheler, Alfred Schütz, Jean-Paul Sartre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Emmanuel Levinas und viele mehr wurden von seinem Denken maßgeblich beeinflusst. |

エドムント・グスタフ・アルベルト・フッサール(ドイツ語発音:

[ˈhuːsɐl]、1859年4月8日 -

1938年4月27日)は、現象学の分野における業績で最もよく知られるオーストリア=ドイツの哲学者、数学者である。20世紀で最も影響力のある思想家

の一人とみなされている。 フッサールはライプツィヒ大学でカール・ワイエルシュトラスとレオ・ケーニヒスベルガーのもとで数学を、フランツ・ブレンターノとカール・シュトゥンプの もとで哲学を学んだ。1887年よりハレ大学で哲学の非常勤講師を務めた。1901年からはゲッティンゲン大学のゲオルク・アウグスト大学で教鞭をとり、 その後フライブルク大学の教授に就任した。1928年に退職したが、哲学的な研究には影響を与えなかった。1938年に病気になり、同年にフライブルクで 死去した。 初期の著作では数学の心理学的基礎を確立しようとしていたが、1900年と1901年に発表された『論理的研究』では、当時主流であった心理学的アプロー チを包括的に批判し、論理法則を単なる精神現象の表現とみなす考え方を否定した。また、純粋論理に関する広範囲にわたる考察も提示した。1907年頃、 フッサールは彼が開発した「現象学的還元」の方法を提示した。それ以降、この方法は彼のその後の研究に決定的な影響を与えただけでなく、その後の研究では 超越論的観念論の哲学的アプローチにつながった。 フッサールの思想は、特にドイツとフランスにおいて20世紀の哲学に大きな影響を与え、今日に至るまで多大な影響を与え続けている。フッサールの弟子に は、マルティン・ハイデッガー、オスカー・ベッカー、ルートヴィヒ・フェルディナント・クラウス、オイゲン・フィンク、エディト・シュタイン、ギュン ター・アンダースなどがいる。また、マックス・シェーラー、アルフレッド・シュッツ、ジャン=ポール・サルトル、モーリス・メルロ=ポンティ、エマニュエ ル・レヴィナスなど、多くの人々がフッサールの思想に大きな影響を受けた。 |

| Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Leben 1.1 Jugend und Bildung 1.2 Akademische Forschung und Lehre 1.3 Letzte Jahre 2 Grundlagen der Philosophie Husserls 2.1 Frühe Philosophie 2.2 Psychologismuskritik 2.3 Intentionalität 2.4 Phänomenologische Reduktion und Epoché 3 Philosophie als strenge Wissenschaft 4 Das Spätwerk: Krisis der Wissenschaften 5 Ontologie und Metaphysik 6 Intersubjektivität 6.1 Hua XIII 6.2 Hua XIV 6.3 Hua XV 7 Phänomenologie des Raumes und der Bewegung (Hua XVI) 8 Ethik 9 Psychologie und Psychiatrie 10 Husserls Nachlass 11 Schriften Husserls 11.1 Husserliana 11.2 Zu Husserls Lebzeiten erschienene Schriften 11.3 Weitere Ausgaben 12 Literatur 12.1 Zu Husserl 12.2 Weiterführendes 12.3 Rezeption 13 Weblinks |

目次 1 生涯 1.1 青年期と教育 1.2 学術研究と教育 1.3 晩年 2 フッサール哲学の基礎 2.1 初期の哲学 2.2 心理主義への批判 2.3 志向性 2.4 現象学的還元とエポケー 3 厳密科学としての哲学 4 晩年の仕事:科学の危機 5 存在論と形而上学 6 間主観性 6.1 13 Hua 6.2 14 Hua 6.3 15 Hua 7 空間と運動の現象学(16 Hua) 8 倫理学 9 心理学と精神医学 10 フッサールの遺産 11 フッサールの著作 11.1 フッサール関連 11.2 フッサール存命中に出版された著作 11.3 その他の版 12 文献 12.1 フッサールについて 12.2 その他の参考文献 12.3 反響 13 外部リンク |

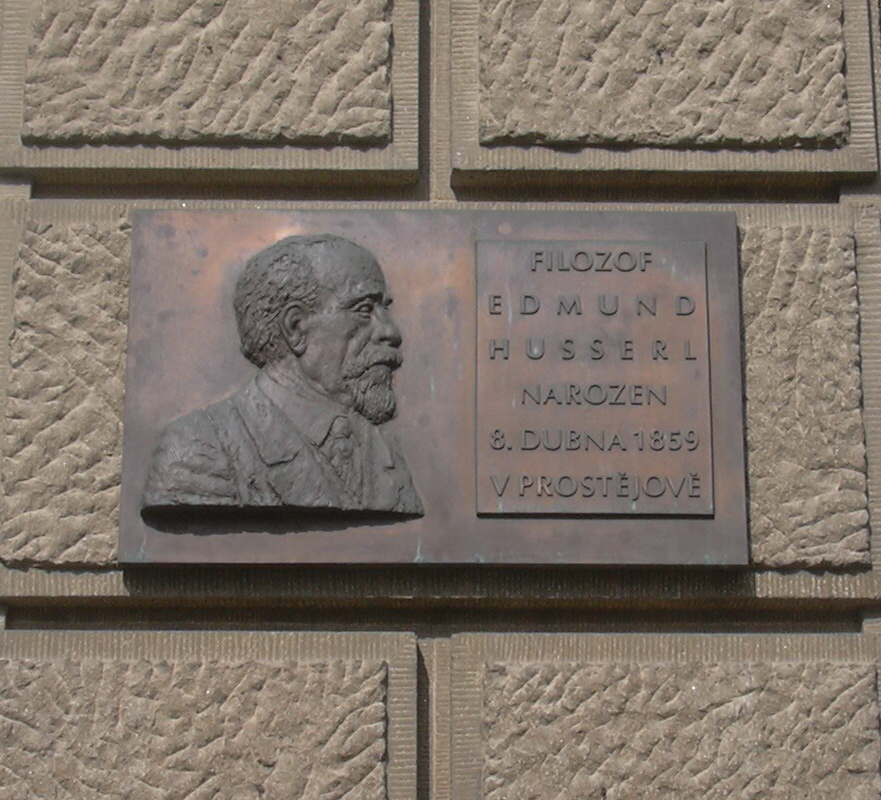

| Leben Jugend und Bildung  Gedenktafel in Prostějov Als zweiter Sohn einer der deutschsprachigen Mittelschicht angehörigen jüdischen Tuchhändler-Familie wurde Husserl 1859 in Prostějov (deutsch Proßnitz) in Mähren im Kaisertum Österreich geboren. Er besuchte das Gymnasium in Olmütz, an dem er 1876 die Hochschulreife erlangte. An der Universität Leipzig (1876–1878) studierte er Mathematik und Physik sowie Astronomie und besuchte die Vorlesungen des Philosophen Wilhelm Wundt, eines der Begründer der modernen, naturwissenschaftlich orientierten Psychologie. Wundt vertrat einen holistischen Wissenschaftsansatz, in dem natur- und geisteswissenschaftliche Perspektiven verbunden waren. Die Philosophie blieb jedoch zunächst nur eine Nebenbeschäftigung Husserls. An der Universität Leipzig lernte er Tomáš G. Masaryk kennen, der ebenfalls aus Mähren kam und als Privatlehrer seinen Lebensunterhalt verdiente. Masaryk wurde später Abgeordneter im österreichischen Reichsrat, setzte sich während des Ersten Weltkrieges an die Spitze der tschechischen Unabhängigkeitsbewegung und wurde im Jahr 1918 (nach dem Zusammenbruch der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie) erster Präsident der Tschechoslowakei. Auch wenn sich beide nach drei Semestern in Leipzig aus den Augen verloren, hatte die Begegnung Folgen für Husserls weitere Entwicklung. Masaryk unterstützte nicht nur die Konvertierung Husserls zum evangelisch-lutherischen Glauben, er empfahl ihm auch seinen Doktorvater, den Philosophen Franz Brentano, als philosophischen Lehrer und Mentor. Zunächst zog Husserl 1878 nach Berlin, um an der Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität (heute: Humboldt-Universität) sein Mathematikstudium unter Leopold Kronecker und Karl Weierstraß fortzusetzen. Dort besuchte er die Philosophie-Vorlesungen von Friedrich Paulsen. Im Jahr 1881 wechselte er an die Universität Wien, um sein Mathematikstudium unter der Leitung eines ehemaligen Schülers von Karl Weierstraß, Leo Königsberger, abzuschließen. Bei diesem wurde er 1883 mit seiner mathematischen Arbeit Beiträge zur Theorie der Variationsrechnung promoviert.[3] Promoviert kehrte er nach Berlin zurück, um dort als Assistent von Karl Weierstraß zu arbeiten. Als dieser erkrankte, zog Husserl abermals nach Wien und leistete dort seinen Militärdienst. 1884 besuchte er an der Universität Wien die Vorlesung Franz Brentanos über Philosophie und philosophische Psychologie. Brentano gilt als Begründer der Aktpsychologie und lehrte Psychologie vom empirischen Standpunkt (1874), wie der Titel seines Hauptwerkes lautet. Er führte Husserl in die Werke von Bernard Bolzano, Hermann Lotze, John Stuart Mill und David Hume ein. Husserl war so beeindruckt von Brentanos Schaffen, dass er entschied, sein Leben der Philosophie zu widmen. Somit wird Franz Brentano oft als wichtigster Einflussgeber Husserls angesehen. Da Brentano als Privatdozent Husserl nicht habilitieren konnte, folgte dieser 1886 Carl Stumpf, einem ehemaligen Studenten Brentanos, der – wie Wundt – ein Vorreiter der modernen Psychologie war, an die Universität Halle/Saale, wo er sich unter seiner Leitung 1887 mit der Arbeit Über den Begriff der Zahl[4] habilitierte. Diese zwischen Psychologie und Mathematik angesiedelte Abhandlung sollte später als Grundlage für seine erste einflussreiche Schrift Philosophie der Arithmetik (1891) dienen. Im Jahr 1887 heiratete Husserl Malvine Steinschneider und ließ sich aus diesem Anlass evangelisch taufen und trauen. 1892 wurde ihre Tochter Elizabeth geboren, 1893 ihr Sohn Gerhart, 1894 ihr Sohn Wolfgang, der im Ersten Weltkrieg fiel. Gerhart Husserl wurde Rechtsphilosoph, der zum Thema vergleichendes Recht forschte und zuerst in den USA und nach dem Krieg in Deutschland lehrte. |

人生 若さと教育  プロスチェヨフの記念プレート ユダヤ人の布商人一家の次男として、ドイツ語話者の中流階級に属する家庭に生まれたフッサールは、1859年にオーストリア帝国領モラヴィアのプロスチェ ヨフ(ドイツ語名:プロスニッツ)で生まれた。彼はオロモウツのグラマースクールに通い、1876年に大学入学資格を取得した。彼はライプツィヒ大学で数 学と物理学、天文学を学び(1876年~1878年)、近代科学心理学の創始者の一人である哲学者ヴィルヘルム・ヴントの講義を受講した。ヴントは自然科 学と人文科学の視点を組み合わせた科学への全体論的アプローチを提唱した。しかし、当初は哲学はフッサールにとってあくまで副業にすぎなかった。ライプ ツィヒ大学で、同じくモラヴィア出身で家庭教師として生計を立てていたトマーシュ・マサリクと出会った。マサリクは後にオーストリア帝国の帝国議会である オーストリア帝国議会の議員となり、第一次世界大戦中はチェコ独立運動の指導的役割を担った。オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国の崩壊後、1918年にチェコ スロバキアの初代大統領に就任した。ライプツィヒでの3学期を終えた後、2人は互いの消息を失ったが、この出会いはフッサールにとってさらなる発展につな がるものとなった。マサリクはフッサールの福音ルーテル派への改宗を支援しただけでなく、フッサールに哲学の師として指導者となるよう、博士課程の指導教 官であった哲学者フランツ・ブレンターノを推薦した。 当初、フッサールは1878年にベルリンに移り、フリードリヒ・ウィルヘルム大学(現フンボルト大学)でレオポルト・クロネッカーとカール・ワイエルシュ トラスのもとで数学の研究を続けた。そこでフリードリヒ・パウルゼンの哲学講義を受講した。1881年、ウィーン大学に移り、カール・ワイエルシュトラス の元学生であるレオ・ケーニヒスベルガーの指導の下で数学の研究を続けた。1883年、数学論文「変分学の理論への貢献」により、彼とともに博士号を取得 した。 卒業後、ベルリンに戻り、カール・ワイエルシュトラスの助手として働く。ワイエルシュトラスが病に倒れると、フッサールは再びウィーンに移り、そこで兵役 についた。1884年、ウィーン大学でフランツ・ブレンターノの哲学と哲学心理学の講義を受講した。ブレンターノは行為心理学の創始者とみなされており、 経験的観点からの心理学(1874年)という主著のタイトルにもなっている。彼はフッサールにベルンハルト・ボルツァーノ、ヘルマン・ロッツェ、ジョン・ スチュアート・ミル、デイヴィッド・ヒュームの著作を紹介した。フッサールはブレンターノの著作に感銘を受け、哲学に生涯を捧げることを決意した。そのた め、フランツ・ブレンターノはしばしばフッサールに最も大きな影響を与えた人物とみなされている。ブレンターノは個人講師としてフッサールをハビリテー ション(大学教授資格)させることができなかったため、フッサールは1886年にヴントと同様に近代心理学のパイオニアであったブレンターノの元教え子 カール・シュムンプトに師事し、1887年にシュムンプトの指導の下、ハレ大学で「数の概念について」という論文でハビリテーションした。心理学と数学の 中間に位置するこの論文は、後に彼の最初の影響力のある著作『算術哲学』(1891年)の基礎となった。 1887年、フッサールはマルバイン・シュタインシュナイダーと結婚し、この機会に自らプロテスタントの洗礼を受け、結婚した。1892年には娘のエリザ ベスが、1893年には息子のゲルハルトが、そして1894年には息子のヴォルフガングが誕生したが、ヴォルフガングは第一次世界大戦で命を落とした。ゲ ルハルト・フッサールは比較法学を研究する法哲学者となり、まずアメリカで、そして戦後はドイツで教鞭をとった。 |

| Akademische Forschung und Lehre Im Anschluss an seine Habilitation begann Husserl im Jahr 1887 seine Universitätskarriere als unbesoldeter Privatdozent an der Universität Halle/Saale. Mit seiner Schrift Philosophie der Arithmetik (1891),[5] die sich auf seine früheren Arbeiten über die Mathematik und die Philosophie beruft und einen psychologischen Rahmen als Basis der Mathematik vorschlägt, erregte Husserl die kritische Aufmerksamkeit des Logikers Gottlob Frege. Mit Rücksicht auf dessen Psychologismuskritik stellte er bis zur Jahrhundertwende umfangreiche Logische Untersuchungen an, die zu seinem ersten Hauptwerk heranwuchsen und dem Zweiundvierzigjährigen 1901 einen Ruf nach Göttingen einbrachten, wo er vierzehn Jahre lang, zunächst als außerordentlicher, ab 1906 ordentlicher Professor, lehrte. Der erste Band der Logischen Untersuchungen enthält Reflexionen über eine „reine Logik“, die eine Zurückweisung des „Psychologismus“[6] darstellen. Das Werk wurde positiv aufgenommen und unter anderem Thema eines Seminars von Wilhelm Dilthey. Persönlich bekannt wurde er in der Göttinger Zeit unter anderen mit David Hilbert, Leonard Nelson, Wilhelm Dilthey, Max Scheler, Alexandre Koyré und Karl Jaspers sowie dem Dichter Hugo von Hofmannsthal.  Das Wohnhaus Husserls in Göttingen bis 1916 (Hermann-Föge-Weg 7, mit Göttinger Gedenktafel[7]) Husserl besuchte 1908 seinen ehemaligen Lehrer Franz Brentano in Italien. 1910 wurde er Mitherausgeber der Zeitschrift Logos. Während dieser Zeit hielt er Vorlesungen über das innere Zeitbewusstsein, die mehr als zehn Jahre später von seinem ehemaligen Studenten Martin Heidegger für die Veröffentlichung bearbeitet wurden.[8] 1912 gründete Husserl mit den Anhängern seiner Philosophie das Jahrbuch für Philosophie und Phänomenologische Forschung, das von 1913 bis 1930 Artikel der neuen philosophischen Richtung veröffentlichte – so etwa in der ersten Ausgabe des Jahrbuchs Husserls einflussreiche Arbeit Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie.[9] Im Oktober 1914 wurden beide Söhne Husserls eingezogen und mussten an der Westfront des Ersten Weltkriegs kämpfen. Im darauffolgenden Jahr wurde Wolfgang Husserl schwer verwundet. Am 8. März 1916 starb er auf dem Schlachtfeld von Verdun. Im nächsten Jahr wurde auch sein anderer Sohn Gerhart Husserl im Gefecht verletzt, überlebte jedoch. Husserls Mutter Julia starb im selben Jahr. Im November 1917 fiel Adolf Reinach, einer von Husserls bemerkenswertesten Studenten und selbst Rechtsphilosoph, in Flandern.  Das Wohnhaus Husserls in Freiburg von 1916 bis 1937 Husserl folgte 1916 einem Ruf an die Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg (im Breisgau), wo er als ordentlicher Professor den Lehrstuhl des Neukantianers Heinrich Rickert übernahm und seine philosophischen Forschungen vorantrieb. Zu dieser Zeit hatte sich Husserl – trotz der prekären Lage Deutschlands nach dem verlorenen Ersten Weltkrieg – zu einem der führenden deutschsprachigen Philosophen entwickelt, der einen großen Schülerkreis um sich hatte und sowohl im Inland wie im Ausland Anerkennung erfuhr. Als seine persönliche Assistentin arbeitete in diesen ersten Jahren Edith Stein; von 1920 bis 1923 übernahm Martin Heidegger diese Stelle. Im Jahr 1922 hielt Husserl vier Vorlesungen über die phänomenologische Methode am University College London. Die Universität von Berlin bot ihm im Jahr 1923 eine Stelle an, die er allerdings ablehnte. Er erhielt Ehrendoktorwürden der Universitäten London, Paris, Prag und Boston und wurde zum Mitglied der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften, der American Academy of Arts and Sciences und der British Academy[10] gewählt. Im Jahr 1927 widmete Heidegger Husserl sein Buch Sein und Zeit „in dankbarer Verehrung und Freundschaft“.[11] Husserl blieb Professor in Freiburg, bis er darum bat, in den Ruhestand gehen zu dürfen; seine letzte Vorlesung hielt er am 25. Juli 1928. Eine Festschrift als Geschenk zu seinem siebzigsten Geburtstag wurde ihm am 8. April 1929 überreicht. Zu seinen Schülern gehörten neben Edith Stein und Martin Heidegger, der die Nachfolge des Freiburger Lehrstuhls übernahm, der Technikphilosoph Günther Stern (Anders), der Rassen- und Völkerpsychologe Ludwig Ferdinand Clauß sowie unter anderem die Philosophen Eugen Fink, Dietrich von Hildebrand und Ludwig Landgrebe. Letzte Jahre  Grab Husserls auf dem Friedhof in Freiburg Günterstal Trotz seiner Emeritierung hielt Husserl noch weitere bedeutende Vorlesungen: Die Pariser Vorlesungen aus dem Jahr 1929 führten zu den Cartesianischen Meditationen (Paris 1931).[12] Seine Vorlesungen in Prag 1935[13][14] und in Wien im Jahr 1936 (nach anderen Quellen 1935[15][16]) mündeten in Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie (Belgrad 1936).[17] Die letzten Schriften tragen die Früchte seines akademischen Lebens. Nach seinem Rücktritt aus dem universitären Betrieb arbeitete Husserl mit großer Intensität und vollendete mehrere größere Arbeiten. Im April 1933 wurde Husserl – obwohl bereits emeritiert – durch einen Sondererlass des Landes Baden zum Reichsgesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums, das es erlaubte, sowohl politische Gegner der Nationalsozialisten wie auch jüdische Beamte zu entlassen, beurlaubt, womit ihm jegliche Lehrtätigkeit untersagt wurde. Aufgrund der Widersinnigkeit dieses Beschlusses und der Tatsache, dass Husserl, da sein Sohn an der Front gefallen war, unter das Frontkämpferprivileg fiel, wurde der Beschluss im Juli 1933 revidiert. Allerdings wurde ihm 1936, nach Verschärfung der rassischen Verfolgung mit der Einführung der Nürnberger Rassengesetze, endgültig die Lehrbefugnis entzogen. Sein Kollege Heidegger übernahm am 21. April 1933 den Posten des Rektors an der Universität Freiburg und wurde am 1. Mai 1933 Mitglied der NSDAP. Husserl dagegen trat aus der Deutschen Akademie aus. Nach einem Sturz im Herbst 1937 erkrankte Husserl an einer Brustfellentzündung. Er starb am 27. April 1938 in Freiburg, kurz nach seinem 79. Geburtstag. Seine Frau Malvine überlebte ihn. Eugen Fink, sein wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter, hielt seine Grabrede. Als einziger Vertreter der Universität Freiburg besuchte Gerhard Ritter das Begräbnis. Husserl wechselte zu Lebzeiten nicht nur zwischen verschiedenen Studienorten und wissenschaftlichen Disziplinen, sondern auch seine Staatsangehörigkeit und Konfession. Letztere hatte er 1887, kurz vor seiner Eheschließung in Wien, gewechselt. Er ließ sich evangelisch-lutherisch taufen, schloss sich also nicht dem vor Ort dominierenden Katholizismus an, sondern dem als fortschrittlicher geltenden Protestantismus. Damit gehört er zu einer Minderheit der jüdischen Staatsbürger, die zum Christentum übertraten. Wenn ihm auch der Übertritt die wissenschaftliche Karriere erleichterte, konvertierte er doch nicht aus Opportunismus, sondern aus Überzeugung. Vor weiterer Verfolgung durch die Nationalsozialisten bewahrte ihn schließlich sein Tod. Husserl nahm 1896, nachdem er bereits sechzehn Jahre im Deutschen Reich gelebt hatte, die preußische Staatsbürgerschaft an. |

学術研究と教育 1887年、ハビリタチオン(大学での研究・教育能力認定)を経て、フッサールはハレ大学の無給の非常勤講師として大学でのキャリアをスタートさせた。数 学と哲学に関するそれ以前の著作を基に、数学の基礎として心理学的な枠組みを提案した著書『算術の哲学』(1891年)[5]により、フッサールは論理学 者ゴットロープ・フレーゲの批判的な注目を集めた。フロゲの心理主義批判に応える形で、彼は広範な論理的な調査に着手し、それは彼の最初の主要な研究へと 発展し、1901年、42歳のときにゲッティンゲン大学の教授職を得ることとなった。『論理的研究』の第1巻には、「心理主義」を否定する「純粋論理」に 関する考察が含まれている。[6] この著作は好評を博し、とりわけヴィルヘルム・ディルタイのセミナーのテーマとなった。ゲッティンゲン在住中、彼はデイヴィッド・ヒルベルト、レオナル ド・ネルソン、ヴィルヘルム・ディルタイ、マックス・シェーラー、アレクサンドル・コイレ、カール・ヤスパース、そして詩人のフーゴ・フォン・ホフマンス タールなどと個人的に親交を深めた。  ゲッティンゲンのフッサール邸宅(1916年まで) (ヘルマン・フェーゲ通り7番地、ゲッティンゲン記念プレート付き[7]) 1908年、フッサールはかつての師フランツ・ブレンターノをイタリアに訪ねた。1910年には学術誌『ロゴス』の共同編集者となった。この時期、彼は内 的時間意識に関する講義を行い、その講義は10年以上経ってから、かつての教え子であったマルティン・ハイデッガーによって編集され出版された。 1912年、フッサールとその哲学の信奉者たちは『哲学・現象学的研究年報』を創刊し、1913年から1930年にかけて、新しい哲学の方向性を示す論文 を掲載した。例えば、年報の創刊号には、フッサールの影響力のある著作『純粋現象学のためのアイデア』と『現象学的哲学』が掲載されている。 1914年10月、フッサールの息子2人とも徴兵され、第一次世界大戦の西部戦線で戦うことになった。翌年、ヴォルフガング・フッサールは重傷を負った。 1916年3月8日、彼はベルダンの戦場で死亡した。翌年、もう一人の息子ゲルハルト・フッサールも戦場で負傷したが、一命を取り留めた。フッサールの母 ユリアは、その同じ年に死亡した。1917年11月、フッサールの最も優れた学生の一人であり、法哲学者でもあったアドルフ・ライナッハがフランダースで 戦死した。  1916年から1937年までフライブルクにあったフッサール邸宅 1916年、フッサールはフライブルク(ブライスガウ)のアルバート・ルートヴィヒ大学の教授職を引き受け、新カント派のハインリヒ・リッケルトの教授職 を引き継ぎ、哲学研究を続けた。この頃には、ドイツが第一次世界大戦に敗れて不安定な状況にあったにもかかわらず、フッサールはドイツ語圏を代表する哲学 者の一人となり、国内外で多くの学生たちに師事され、その名を知られるようになっていた。エディト・シュタインは、この初期の時期にフッサールの個人秘書 を務めていた。1920年から1923年までは、マルティン・ハイデッガーがその役職を引き継いだ。1922年、フッサールはロンドン大学で現象学的方法 に関する4回の講義を行った。1923年、ベルリン大学から教授職のオファーを受けたが、辞退した。ロンドン、パリ、プラハ、ボストンの大学から名誉博士 号を授与され、ハイデルベルク科学アカデミー、アメリカ芸術科学アカデミー、英国学士院の会員に選出された。1927年、ハイデッガーは著書『存在と時 間』を「感謝と尊敬の念を込めて」フッサールに捧げた。[11] フッサールは定年退職を許されるまでフライブルク大学の教授職にとどまり、1928年7月25日に最後の講義を行った。70歳の誕生日に贈られた記念論文 集は1929年4月8日に手渡された。彼の教え子には、エディト・シュタインや、フライブルクの教授職を引き継いだマルティン・ハイデッガー、技術哲学の ギュンター・シュテルン(アンダース)、人種学・民族学心理学者のルートヴィヒ・フェルディナント・クラウス、そして、哲学者のオイゲン・フィンク、 ディートリヒ・フォン・ヒルデブラント、ルートヴィヒ・ランドグレーベなどがいた。 晩年  フライブルク・ギュンターシュタールの墓地にあるフッサールの墓 引退後も、フッサールは重要な講義をいくつか行った。1929年からのパリ講義は、『デカルト的省察』(パリ、1931年)につながった。 1935年のプラハでの講義[13][14]、および1936年のウィーンでの講義(他の情報源によると1935年[15][16])は、『ヨーロッパ科 学の危機と超越論的現象学』(1936年、ベオグラード)へとつながった。[17] 彼の学術的な人生の成果が最後の著作に結実した。大学での職務から退いた後、フッサールは非常に熱心に研究に取り組み、いくつかの主要な著作を完成させ た。 1933年4月、フッサールはバーデン州の特別法令により、ナチス政権の専門公務員復権法により休職処分となった。この法令は、ナチス政権の政治的反対者 とユダヤ人公務員の解雇を認めるもので、フッサールは教職を禁じられた。この決定の不合理性と、フッサールが前線で息子を亡くしていたため前線で戦う兵士 の特権の対象となったという事実により、1933年7月にこの決定は撤回された。しかし、1936年、ニュルンベルク法の導入による人種迫害の激化によ り、ついに教授資格を剥奪された。同僚のハイデッガーは1933年4月21日にフライブルク大学の学長に就任し、1933年5月1日にはナチス党員となっ た。一方、フッサールはドイツ学士院を辞職した。 1937年秋に転倒したフッサールは、胸膜炎を患った。1938年4月27日、79回目の誕生日を迎えて間もなく、フライブルクで死去した。妻のマル ヴィーネが遺された。研究助手のオイゲン・フィンクが弔辞を述べた。フライブルク大学を代表して葬儀に参列したのはゲルハルト・リッターのみであった。 生涯において、フッサールは研究の場や科学分野を転々としただけでなく、国籍や信仰も変えている。1887年、ウィーンで結婚する直前に、彼は信仰を変え た。プロテスタントのルーテル派に洗礼を受け、地元で主流であったカトリックではなく、より進歩的と考えられていたプロテスタントに改宗した。ユダヤ人市 民の中でキリスト教に改宗した少数派の一人であった。改宗は彼の学術的なキャリアを後押ししたが、日和見主義からではなく、信念から改宗した。結局、ナチ スによるさらなる迫害から彼を救ったのは彼の死であった。1896年、ドイツ帝国に16年間住んだ後、フッサールはプロイセンの市民権を取得した。 |

| Grundlagen der Philosophie Husserls Frühe Philosophie In seinen frühen Arbeiten versucht Husserl, Mathematik, Psychologie und Philosophie zu verbinden mit dem Ziel, eine Grundlegung der Mathematik auszuarbeiten. Er analysiert den psychischen Prozess, der nötig ist, um den Begriff der Zahl zu bilden; daran anknüpfend versucht er, eine systematische Theorie zu entwerfen. Auf diesem Weg greift er auf unterschiedliche Methoden und Konzepte seiner Lehrer zurück. So übernimmt er beispielsweise von Weierstraß die Idee, dass wir den Begriff der Zahl erwerben, indem wir eine bestimmte Sammlung von Objekten zählen. Von Brentano und Stumpf übernimmt er die Unterscheidung zwischen „konkreten“ und „unkonkreten“ Vorstellungen. Husserls Beispiel dafür ist: wenn man vor einem Haus steht, dann hat man eine „konkrete“, „direkte“ Vorstellung dieses Hauses, sucht man es jedoch und fragt nach einer Wegbeschreibung, dann stellt die Wegbeschreibung (z. B. das Haus an der Ecke dieser und jener Straße) eine „unkonkrete“, „indirekte“ Vorstellung dar. Anders gesagt, hat man eine „konkrete“ Vorstellung eines Objektes, wenn es unmittelbar präsent ist, und eine „unkonkrete“ (oder „symbolische“, wie Husserl es auch nennt) Vorstellung, wenn man das Objekt durch Zeichen, Symbole etc. darstellt. Logik ist eine formale Theorie des Urteilens, die die formalen a priori Relationen von Urteilen mit Hilfe von Bedeutungskategorien untersucht. Mathematik ist ihrerseits formale Ontologie. Somit sind die Untersuchungsgegenstände einer Philosophie der Logik und der Mathematik nicht sinnliche Gegenstände, sondern die unterschiedlichen formalen Kategorien der Logik und der Mathematik. Das Problem der psychologischen Herangehensweise an Mathematik und Logik ist, dass sie der Tatsache, dass es um formale Kategorien und nicht einfach um Abstraktionen des Empfindungsvermögens geht, nicht Rechnung trägt. Der Grund, warum wir nicht einfach mit sinnlichen Dingen in der Mathematik arbeiten, ist die „kategoriale Abstraktion“, eine andere Ebene des Verstehens. Auf dieser Ebene können wir sinnliche Komponenten des Urteilens beiseitelassen und uns auf die formalen Kategorien selbst konzentrieren. Husserl kritisiert die Logiker seiner Zeit dafür, diesen Zusammenhang in ihren psychologischen Grundlegungen außer Acht zu lassen. |

フッサール哲学の基礎 初期の哲学 初期の著作において、フッサールは数学の基礎を築くことを目的として、数学、心理学、哲学を統合しようとした。彼は数の概念が形成される精神過程を分析 し、それを基盤として体系的な理論を展開しようとした。その際、彼は師から学んださまざまな方法や概念を活用した。例えば、ワイエルシュトラスの「私たち は特定の物体の集合を数えることで数の概念を習得する」という考え方を採用した。 また、ブレンターノとシュトゥンプからは、「具体的」な観念と「非具体的」な観念の区別を取り入れた。フッサールの例を挙げると、ある家を前にして立って いるときには、その家について「具体的」で「直接的な」考えを持つが、その家を探していて道を尋ねているときには、道順(例えば、○○通りの角にある家) は「非具体的」で「間接的な」考えを表す。言い換えれば、対象が即座に存在している場合には「具体的な」考え方であり、対象を記号やシンボルなどを通して 表現する場合には「非具体的な」(あるいはフッサールが「象徴的」とも呼ぶ)考え方である。 論理学は、意味のカテゴリーを援用して判断の形式的な先験的関係を調査する形式的な判断理論である。数学は形式存在論である。したがって、論理学と数学の 哲学の研究対象は、感覚的な対象ではなく、論理学と数学の異なる形式カテゴリーである。数学と論理学に対する心理学的なアプローチの問題点は、形式カテゴ リーを扱っているのであって、感覚の抽象化を扱っているのではないという事実を考慮に入れていないことである。数学において感覚物自体を扱わない理由は、 「範疇的抽象」という異なるレベルの理解にある。このレベルでは、判断の感覚的要素を脇に置いて、形式的なカテゴリー自体に焦点を当てる。フッサールは、 当時の論理学者たちが心理学的な基礎においてこれを無視していると批判している。 |

| Psychologismuskritik Nachdem Husserl in Mathematik promoviert worden war, analysierte er die Grundlagen der Mathematik von einem psychologischen Standpunkt aus. In seiner Habilitationsschrift Über den Begriff der Zahl (1886) und in seiner Philosophie der Arithmetik (1891) versucht er in Anwendung von Brentanos deskriptiver Psychologie, die natürlichen Zahlen auf eine Art und Weise zu definieren, die die Methoden und Techniken von Karl Weierstraß, Richard Dedekind, Georg Cantor, Gottlob Frege und anderen fortschreibt. Im ersten Teil seiner Logischen Untersuchungen, den Prolegomena der reinen Logik, attackiert Husserl dann jedoch den psychologischen Standpunkt in der Logik und der Mathematik. Folgt man dem Psychologismus, so wäre laut Husserl Logik keine autonome Disziplin, sondern ein Zweig der Psychologie: entweder eine präskriptive und praktische „Art und Weise“ des richtigen Urteilens (eine Position, die Brentano und einige seiner orthodoxeren Studierenden vertraten) oder eine Beschreibung der faktischen Prozesse des menschlichen Denkens. Den Grund dafür, dass die Gegner des Psychologismus den Psychologismus nicht überwinden konnten, sieht Husserl in deren Versäumnis, zwischen der theoretischen, fundamentalen Seite der Logik und der angewandten, praktischen Seite derselben zu unterscheiden. Reine Logik befasse sich überhaupt nicht mit „Gedanken“ oder „Urteilen“ als geistigen Episoden, vielmehr gehe es ihr um Gesetze und Bedingungen a priori jeglicher Theorie und jeglichen Urteils. Anhänger des Psychologismus scheiterten daran, zu zeigen, wie wir die Gewissheit logischer Prinzipien, etwa des Prinzips der Identität und des ausgeschlossenen Widerspruchs, von einem psychologischen Standpunkt aus gewährleisten können. Es sei deshalb sinnlos, logische Gesetze und Grundsätze auf unsichere Prozesse des empirischen Bewusstseins zu stützen. Diese Kritik am Psychologismus, die Unterscheidung zwischen psychischen Akten und intentionalen Objekten und die Differenz zwischen der normativen Seite der Logik und ihrer theoretischen, wird von einer idealen Konzeption der Logik abgeleitet. Das bedeutet, dass logische und mathematische Gesetze unabhängig vom empirischen menschlichen Bewusstsein gelten. |

心理主義への批判 数学の博士号を取得した後、フッサールは心理学的な観点から数学の基礎を分析した。ハビリテーション論文『数の概念について』(1886年)および『算術 哲学』(1891年)において、彼はカール・ワイエルシュトラス、リヒャルト・デデキント、ゲオルク・カントール、ゴットロープ・フレーゲなどの方法と技 術を継承し、ブレンターノの記述心理学を適用して自然数を定義しようと試みた。 『論理的研究』の第一部『純粋論理学のプロレゴメナ』において、フッサールは次に、論理学と数学における心理学的観点に攻撃を仕掛ける。フッサールによれ ば、心理主義に従うのであれば、論理学は自律的な学問ではなく、心理学の一分野となる。すなわち、正しく判断するための規範的かつ実践的な「方法」である (ブレンターノや彼の正統派の弟子たちもこの立場をとっていた)か、あるいは人間の思考の事実上のプロセスを記述するものとなる。フッサールは、心理主義 の反対派が心理主義を克服できなかった理由を、論理の理論的・基礎的な側面と、同じく応用的・実践的な側面とを区別できなかったことにあると見ている。純 粋な論理は、精神のエピソードとしての「思考」や「判断」とはまったく関係がない。むしろ、あらゆる理論や判断に先験的に備わる法則や条件に関係してい る。心理主義の信奉者は、同一律や非矛盾律といった論理原則の確実性を、心理学的観点からどのように保証できるかを示せなかった。したがって、論理法則や 原理を不確かな経験的意識のプロセスに基づいて論じるのは無意味である。 この心理主義批判、心的作用と対象の区別、論理の規範的側面と理論的側面の相違は、論理の理想的な概念から導かれる。つまり、論理的・数学的法則は、経験的な人間の意識とは無関係に成り立つ。 |

| Intentionalität Von Brentano übernimmt Husserl das Konzept der Intentionalität. Intentionalität bedeutet, dass das Bewusstsein sich dadurch auszeichnet, dass es immer auf etwas bezogen ist. Häufig vereinfacht als „Bewusstsein von etwas“ zusammengefasst oder die Beziehung zwischen einem Bewusstseinsakt und der äußeren Welt, definiert Brentano es als Hauptcharakteristikum von geistigen Phänomenen, wodurch er diese von physikalischen Phänomenen unterscheidet. Jeder psychische Akt besitzt einen Inhalt, bezieht sich auf ein Objekt (das intentionale Objekt). Jeder Glaube, Wunsch etc. besitzt ein Objekt, auf das er sich bezieht: das Geglaubte, das Gewünschte. Husserl selbst arbeitet den Begriff erstmals in seiner fünften Logischen Untersuchung in systematischer Art und Weise aus. „Erkenntnis“ ist zwar an psychische und physiologische Prozesse gebunden, sie ist aber nicht mit diesen identisch. Aus einem empirisch psychologischen Satz kann niemals eine logische Norm abgeleitet werden. Empirische Sätze sind bloß wahrscheinlich und können falsifiziert werden. Logik hingegen unterliegt nicht wie die Empirie der Kausalität. Philosophie als Wissenschaft kann sich daher nicht an den Naturalismus binden. Philosophie, Erkenntnistheorie, Logik und reine Mathematik sind Idealwissenschaften, deren Gesetze ideale Wahrheiten a priori ausdrücken. Phänomenologie als „Wesensschau des Gegebenen“ soll die voraussetzungslose Grundlage allen Wissens sein. |

志向性 フッサールはブレンターノから志向性の概念を採用した。志向性とは、意識が常に何かに関連しているという特徴を持つことを意味する。しばしば「何かの意 識」または意識の作用と外部世界との関係として単純化されるが、ブレンターノはそれを精神現象の主な特徴として定義し、それによって精神現象を物理現象と 区別した。あらゆる精神作用には内容があり、対象(志向対象)を指し示す。信念、欲望など、あらゆるものは、それらが指し示す対象、すなわち、信念の対 象、欲望の対象を持っている。フッサール自身がこの概念を初めて体系的に展開したのは、彼の『第五の論理的研究』においてである。 「認識」は心理学的および生理学的プロセスと結びついているが、それらと同一ではない。論理的な規範は、経験的な心理学的命題から導かれることは決してな い。経験的な命題は単に可能性があるだけであり、誤りである可能性もある。一方、論理は経験論のような因果関係の影響を受けない。科学としての哲学は、自 然主義に縛られることはできない。哲学、認識論、論理学、純粋数学は、その法則が理想的な真理を先験的に表現する理想科学である。「与えられたものの本質 の見方」としての現象学は、あらゆる知識の無条件の基礎となるべきものである。 |

| Phänomenologische Reduktion und Epoché Einige Jahre nach der Publikation der Logischen Untersuchungen im Jahr 1900–1901 entwickelte Husserl einige entscheidende begriffliche Differenzierungen. Er war zu der Auffassung gelangt, dass zur Untersuchung der Struktur des Bewusstseins zwischen einem „Akt des Bewusstseins“ und einem „Phänomen, auf welches es sich richtet“ (das Objekt, auf das man sich intentional bezieht) zu unterscheiden sei. Das Wissen um das Wesen wäre durch die „Einklammerung“ aller Vorurteile über die Existenz einer Außenwelt möglich. Das entsprechende methodische Verfahren nennt Husserl Epoché (ἐποχή). Diese neue Auffassung führte zur Publikation der Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie im Jahr 1913 sowie den Plänen für eine zweite Auflage der Logischen Untersuchungen. Seit der Veröffentlichung seiner Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie konzentrierte sich Husserl auf die idealen, wesentlichen Strukturen des Bewusstseins. Dabei war das metaphysische Problem der vom wahrnehmenden Subjekt unabhängigen Wirklichkeit der Gegenstände für ihn von keinem besonderen Interesse, obwohl er einen transzendentalen Idealismus vertrat. Er bezeichnete die Weise, mit der wir als „Menschen des natürlichen Lebens“[18] die natürliche Welt und die uns umgebenden Dinge wahrnehmen, als natürliche Einstellung. Diese sei durch die Annahme gekennzeichnet, dass Objekte außerhalb des wahrnehmenden Subjekts existierten und Eigenschaften besäßen, die wir wahrnehmen: „Ich finde beständig vorhanden als meine Gegenüber die eine räumlich-zeitliche Wirklichkeit, der ich selbst zugehöre, wie alle anderen in ihr vorfindlichen und auf sie in gleicher Weise bezogenen Menschen. Die ‚Wirklichkeit‘, das sagt schon das Wort, finde ich als daseiende vor und nehme sie, wie sie sich mir gibt, auch als daseiende hin. Alle Bezweiflung und Verwerfung von Gegebenheiten der natürlichen Welt ändert nichts an der Generalthesis der natürlichen Einstellung.“[19] Gegenüber der natürlichen Einstellung vollzieht die Phänomenologie nun eine Änderung: Sie schaltet die natürliche Einstellung aus, indem sie „eine gewisse Urteilsenthaltung“[20] übt und die natürliche Welt einklammert. Der Blick richtet sich so auf das transzendentale Ich – und auf seine Bewusstseinsinhalte –, das in vielerlei Hinsicht intentional auf die Objekte gerichtet ist und sie dadurch „konstituiert“.[21] Vom phänomenologischen Standpunkt aus existiert dabei das Objekt nicht einfach „außerhalb“ und gibt auch nicht selbst Hinweise dafür, was es ist, sondern wird zu einem Bündel von wahrnehmbaren und funktionalen Aspekten, die sich gegenseitig unter der Idee eines bestimmten Objekts oder „Typs“ implizieren. Die Realität der Objekte wird von der Phänomenologie nicht abgelehnt, sondern „eingeklammert“ – als eine Weise, wie wir Objekte betrachten, anstelle einer Eigenschaft, die dem Wesen des Objekts innewohnt. Um die Welt der Erscheinungen und der Dinge besser zu verstehen, zielt die Phänomenologie darauf, die invarianten Strukturen unserer Wahrnehmungsweisen zu identifizieren und liefert so Erkenntnis über das leistende Bewusstsein und die Strukturen dieser Leistungen. |

現象学的還元とエポケー 『論理的研究』の出版から数年後の1900年から1901年にかけて、フッサールはいくつかの重要な概念上の区別を展開した。彼は、意識の構造を調査する ためには、「意識の行為」と「それが向けられる現象」(意図的に参照する対象)を区別しなければならないという結論に達した。外部世界の存在に関するあら ゆる偏見を「括弧に入れる」ことで、本質に関する知識が可能になる。フッサールは、この対応する方法論的プロセスをエポケー(ἐποχή)と呼ぶ。この新 しい概念は、1913年の『イデーン:純粋現象学への一般序説』の出版、および『論理的研究』の第2版の計画につながった。 『イデーン:純粋現象学への一般序説』の出版以来、フッサールは意識の理想的な本質的構造に集中した。超越論的観念論を唱えてはいたが、知覚する主体から 独立した対象の実在という形而上学的な問題には、彼は特に興味を示さなかった。彼は、我々「自然生活者」[18]が自然界や身の回りの物自体を自然な態度 で知覚する方法を説明した。これは、対象が知覚する主体の外側に存在し、知覚される性質を持つという前提によって特徴づけられる。 「私は常に、私自身もそこに属し、他の人々と同じようにそこに存在し、それと関連しているひとつの時空の現実を、私の対極として存在しているのを見出す。 私は「現実」という言葉をその意味の通り、存在するものとして見出し、また、存在するものとして私に示されるままにそれを受け入れる。自然界の事実に対す る疑いや拒絶は、自然態の一般的な命題を変えることはない。」[19] 自然態とは対照的に、現象学は今、変化をもたらす。それは「ある種の判断からの棄却」[20]を実践し、自然界を括弧で囲むことによって自然態を排除す る。 焦点は超越論的自我、そしてその意識の内容に置かれる。それは意図的にさまざまな方法で対象に向けられ、それによって「構成」される。 現象学的な観点から見ると、対象は「外側」に単に存在しているわけではなく、それ自体が何であるかについてのヒントを与えるわけでもないが、特定の対象ま たは「タイプ」という概念の下で、相互に暗示し合う知覚可能な機能的側面の束となる。現象学は、物自体の現実性を否定するのではなく、それを「括弧」に入 れる。つまり、物自体の本質に内在する性質ではなく、物を見る方法として捉えるのである。現象学は、現象や物自体の世界をよりよく理解するために、私たち の知覚の不変の構造を特定することを目的としている。それにより、心やその成果の構造に対する洞察が得られる。 |

| Philosophie als strenge Wissenschaft Husserl antwortete auf Diltheys 1911 erschienene Weltanschauungsphilosophie noch im selben Jahr mit dem Aufsatz Philosophie als strenge Wissenschaft.[22] Husserl weist dort zunächst den Naturalismus zurück, da dieser sich nicht selbst über seine erkenntnistheoretischen Voraussetzungen Klarheit verschaffen kann.[23] Dies kann nur eine „wissenschaftliche Wesenserkenntnis des Bewußtseins“ leisten[24] und diese ist die Phänomenologie. Sie ermittelt das, was allen individuellen Bewusstseinsakten gemeinsam ist, nämlich Bewusstsein von… zu sein, d. h., sie meinen ein Gegenständliches.[25] Im Absehen von dem im von… gemeinten ergibt sich das Wesen der Bewusstseinsakte, es lässt sich als „objektive Einheit fixieren“.[26] Die Feststellung objektiv gültiger Tatsachen ist möglich, weil, auch wenn diese historisch Gewordene sind, sie trotzdem absolut gültig sein können – die Genesis beeinträchtigt nicht die Geltung.[27] Als Beispiel eines Systems notwendiger Sätze nennt Husserl die Mathematik, welche für die Beurteilung der Wahrheit ihrer Theorien sich überhaupt nicht an der Historie orientieren kann.[28] „Die ‚Idee‘ der Wissenschaft […] ist eine überzeitliche, […] durch keine Relation auf den Geist einer Zeit begrenzt.“[29] Husserl proklamiert daher gegen die Weltanschauungsphilosophie den „Wille[n] zu strenger Wissenschaft“.[30] |

厳密な科学としての哲学 フッサールは、1911年に発表されたディルタイの世界観の哲学に、同年発表の論文『厳密な科学としての哲学』で応えた。22] その中で、フッサールはまず、自然主義が自身の認識論的前提条件について明確な説明を提供できないとして、それを否定した。 [23] これは「意識の本質に関する科学的知識」によってのみ達成可能であり[24]、これが現象学である。それは、個々の意識の作用に共通するものを決定する。 すなわち、意識の...、すなわち、それらは対象を意味する。[25] ...において意味されるものが存在しない場合、意識の作用の本質が生じ、「客観的な単位として固定」される。[26] 客観的に妥当な事実の決定は可能である。なぜなら、それらが歴史的なものになったとしても、それらは依然として絶対的に妥当であり得るからである。起源は 妥当性に影響を与えない。 必要命題の体系の例として、フッサールは数学を挙げている。数学は、その理論の真偽を評価する上で、歴史をまったく基盤とすることができない。 [28] 「科学の『理念』は[...]超時間的なものであり、[...]時代の精神との関係によって制限されるものではない」[29] したがって、フッサールは世界観の哲学に対して「厳格な科学への意志」を宣言する。[30] |

Das Spätwerk: Krisis der Wissenschaften Das Wohnhaus Husserls in Freiburg von Juli 1937 bis zu seinem Tod am 27. April 1938 In seinem Spätwerk kritisierte Husserl, dass die modernen Wissenschaften mit ihrem Anspruch, die Welt objektivistisch zu erfassen, die Fragen der Menschen nach dem Sinn des Lebens nicht mehr beantworten. Er forderte daher die Wissenschaften auf, sich darauf zu besinnen, dass sie selbst ihre Entstehung der menschlichen Lebenswelt verdanken. Die Lebenswelt, als zentraler Begriff, ist für Husserl die vortheoretische und noch unhinterfragte Welt der natürlichen Einstellung: die Welt, in der wir leben, denken, wirken und schaffen.[31] Husserls transzendentale Phänomenologie versucht, die entstandene Entfremdung zwischen den Menschen und der Welt zu vermindern. |

晩年の作品:科学の危機 1937年7月から1938年4月27日の死まで過ごしたフライブルクのフッサール邸 彼の晩年の著作において、フッサールは、客観的に世界を把握するという主張によって、もはや人々の人生の意味に関する問いに答えられなくなったと近代科学 を批判した。 それゆえ、科学が人間的生活世界にその起源を負っていることを忘れないよう、彼は科学に呼びかけた。フッサールにとって、生活世界 (Lebenswelt)は中心概念であり、自然な態度という理論以前の、未だ疑われることのない世界である。すなわち、私たちが生活し、考え、働き、創 造する世界である。31] フッサールの超越論的現象学は、人と世界との間に生じた疎外を解消しようとするものである。 |

| Ontologie und Metaphysik Husserls Phänomenologie versteht sich zwar als eine Zurückweisung „metaphysische[r] Abenteuer“,[32] keineswegs jedoch als Zurückweisung jeglicher Metaphysik überhaupt.[33] Husserls Auseinandersetzung mit Ontologie und Metaphysik kann in drei Phasen unterteilt werden. In den Logischen Untersuchungen findet sich zunächst eine Neutralität in Hinblick auf die metaphysische Frage, die Husserl hier als „[d]ie Frage nach der Existenz und Natur der ‚Außenwelt‘“.[34] versteht. Er konzentriert sich in diesem Werk allein auf die „Erkenntnistheorie, als allgemeine Aufklärung über das ideale Wesen und über den gültigen Sinn des erkennenden Denkens“.[34] Jene Erkenntnistheorie, die er auch als apriorische Theorie der Gegenstände als solcher begreift, bezeichnet Husserl später rückblickend mit dem „alten Ausdruck Ontologie“.[35] Die zweite Phase findet sich in den Ideen I. Im Ausgang von der Epoché strebt Husserl nun eine Phänomenologie als eidetische und transzendentale Wissenschaft an. Sie umfasst eine universale formale Ontologie sowie regionale, materiale Ontologien. Diese liegen als Wesenswissenschaften sämtlichen Erfahrungs- bzw. Tatsachenwissenschaften zugrunde[36] und stellen eine „unabläßliche Vorbedingung […] für jede Metaphysik und sonstige Philosophie – ‚die als Wissenschaft wird auftreten können‘“,[37] dar. Husserl vertieft dieses neue Verständnis von Ontologie und Metaphysik vor allem in der Vorlesung Erste Philosophie: Als „Erste Philosophie“ gehe voran „eine Wissenschaft von der Totalität der reinen (apriorischen) Prinzipien aller möglichen Erkenntnisse und der Gesamtheit der in diesen systematisch beschlossenen, also rein aus ihnen deduktibeln apriorischen Wahrheiten“[38] deren „Anwendung“ auf „die Gesamtheit der ‚echten‘, d. i. der in rationaler Methode ‚erklärenden‘ Tatsachenwissenschaften“[39] zu einer „‚Zweiten Philosophie‘“[39] hinführe, die Husserl auch als „‚metaphysische‘ Interpretation des ‚Weltall[s]‘“ (letzteres als „das universale Thema der positiven Wissenschaften“) versteht.[40] Die dritte Phase enthält eine Umkehrung des Verhältnisses von ontologischer Möglichkeit und metaphysischer Wirklichkeit: „Aber das Eidos transzendentales Ich ist undenkbar ohne transzendentales Ich als faktisches“.[41] „Alle Wesensnotwendigkeiten sind Momente seines Faktums“.[42] Und allgemeiner: „Wir kommen auf letzte ‚Tatsachen‘ – Urtatsachen, auf letzte Notwendigkeiten, die Urnotwendigkeiten“.[41] Eine Metaphysik der Urtatsachen liegt jetzt einer phänomenologischen Wesenswissenschaft und Ontologie zugrunde, die wiederum die Bestimmungen a priori für die Tatsachenwissenschaften liefert. Im Zuge der Rückbesinnung auf Aristoteles seit Trendelenburg, Brentano und Meinong sowie im Umkreis derjenigen frühen Schüler Husserls, die seiner Hinwendung zum Idealismus kritisch gegenüberstanden, entwickelten sich schon früh Ansätze zu Ontologie und Metaphysik, die realistische, in jedem Falle anti-idealistische Züge tragen. Dies gilt etwa für Adolf Reinach, Hedwig Conrad-Martius, Moritz Geiger, Roman Ingarden, aber auch für Nicolai Hartmann. Husserls Assistenten Ludwig Landgrebe und Eugen Fink arbeiteten wiederum auf je eigene Weise an einer Behandlung metaphysischer Fragen im Ausgang von der Husserl’schen Phänomenologie. In der zeitgenössischen Phänomenologie können Weiterführungen bei László Tengelyi, Alexander Schnell, Jocelyn Benoist, Jean-François Lavigne und Dominique Pradelle gefunden werden. |

存在論と形而上学 フッサールの現象学は「形而上学的冒険」の拒絶として理解されているが[32]、決して形而上学のすべてを完全に拒絶するものではない[33]。フッサールの存在論と形而上学への取り組みは3つの段階に分けられる。 『論理的研究』では、まず第一に、形而上学的な問いに関しての中立性が示されている。ここでフッサールは「『外界』の存在と本質に関する問い」としてこれ を理解している。[34] この著作では、彼は「認識論、すなわち、認識思考の理想的な本質と妥当な意味の一般的な解明」にのみ集中している。[34] フッサールは後に、この認識論について言及し、それを「古い用語の存在論」を振り返りながら、物自体のアプリオリな理論として理解している。[35] 第二段階は『アイデア I』に見られる。エポケーから出発したフッサールは、今や現象学をイデア的かつ超越論的科学として目指している。それは普遍的な形式存在論と地域的、物質 的な存在論を包含している。「本質の科学」として、これらはすべての経験的または事実に基づく科学[36]の基礎となり、「いかなる形而上学やその他の哲 学にも不可欠な前提条件」[37]となる。フッサールは、この存在論と形而上学に関する新たな理解を、主に講義『第一哲学』の中で深めていく。「第一哲 学」は「あらゆる知識の純粋な(先験的)原理の全体性と、それらに体系的に帰結される先験的真理の全体性、つまり、それらから純粋に演繹可能なもの」 [38]に先行するものであるため、この「第一哲学」の「応用」は、「『真正な』全体性、つまり、合理的メソッドにおける『説明』」に 事実科学」[39]を「第二哲学」[39]に適用する。フッサールは、この「第二哲学」を「『世界』の『形而上学的』解釈(後者は『実証科学』の普遍的 テーマ)」と理解している。[40] 第三段階では、存在論的可能性と形而上学的現実の関係が逆転する。「しかし、形而上学的超越的自我は、事実としての超越的自我なしには考えられない」 [41] 「すべての本質的な必要条件は、その事実の瞬間である」[42] さらに一般的に言えば、「究極の『事実』、すなわち究極の必要条件、原初の必要条件に到達する」[41] 本質と存在論の現象学的な科学の根底には、今や、原初的な事実の形而上学が存在し、それが事実の科学に対して先験的な決定を提供する。 トレンデルブルク、ブレンターノ、マイノンの時代以降のアリストテレスへの回帰の過程において、また、フッサールの初期の学生たちで、彼の観念論への転向 に批判的だった人々の間でも、現実的で、いずれにしても反観念論的な特徴を持つ存在論や形而上学へのアプローチが早くから発展していた。これは例えばアド ルフ・ラインハック、ヘドウィグ・コンラート=マルティウス、モーリッツ・ガイガー、ロマン・インガルデン、そしてニコライ・ハルトマンにも当てはまる。 一方、フッサールの助手であったルートヴィヒ・ランドグレーベとオイゲン・フィンクは、それぞれ独自の方法でフッサールの現象学に基づく形而上学的な問題 の考察に取り組んだ。現代現象学においては、ラースロー・テンゲリー、アレクサンダー・シュネル、ジョスリン・ベノワ、ジャン=フランソワ・ラヴィニュ、 ドミニク・プラデルらの研究にさらなる発展が見られる。 |

| Intersubjektivität Den besten Aufschluss über Husserls Phänomenologie der Intersubjektivität geben die Bände 13–15 der Husserliana (Hua).[43] Diese Editionen zeichnen sich formal dadurch aus, dass sie mit wenigen Ausnahmen auf den sogenannten „Forschungsmanuskripten“ beruhen, die Husserl monologisch nur für sich selbst schrieb, und in denen er nicht Problemlösungen einem Publikum vorlegt, sondern nach solchen sucht. Der erste Band[44] umfasst Haupttexte zur Phänomenologie der Intersubjektivität von 1905 bis 1920, der zweite[45] solche von 1921 bis 1928, und der dritte[46] solche von 1929 bis 1935. Die Aufteilung in drei verschiedene Bände entspricht drei verschiedenen großen Arbeitsphasen von Husserls Ringen um die Konzeption und Darstellung seiner phänomenologischen Philosophie. Hua XIII Der früheste Text,[47] der zum Problem der Intersubjektivität im Nachlass gefunden werden konnte, stammt aus dem Sommer 1905, trägt den von Husserl stammenden Titel „Individualität von Ich und Erlebnissen“ und ist dem Unterschied der erlebenden Individuen gewidmet. Er stammt aus dem Beginn der Zeit, in der Husserl die Idee der phänomenologischen Reduktion als „prinzipiellste aller Methoden“ erarbeitete, und die 1910/11 mit den Vorlesungen „Grundprobleme der Phänomenologie“[48] einen Höhepunkt erreichte. Der Hauptpunkt dieser Vorlesungen bestand in der Überwindung des phänomenologischen Solipsismus, in dem Husserl mit seiner Konzeption der phänomenologischen Reduktion in seinen Vorlesungen „Einführung in die Erkenntnistheorie“ von 1906/07[49] und in der Einleitung seiner Vorlesung „Hauptstücke aus der Phänomenologie und Kritik der Vernunft“ von 1907[50] noch befangen war, durch die Ausdehnung der phänomenologischen Reduktion auf die Intersubjektivität. Konkreter gesprochen bestand er darin, dass er die in der Einfühlung (Fremderfahrung) vergegenwärtigten anderen (fremden) intentionalen Bewusstseinssubjekte mit in das phänomenologische Forschungsfeld einbezog. Begreiflicherweise begann Husserl in den Jahren zwischen 1905 und 1910/11, sich auch mit den damals bekanntesten Theorien der Erkenntnis von fremden Ich auseinanderzusetzen: mit Benno Erdmanns Theorie des Analogieschlusses auf das fremde Ich sowie Theodor Lipps’ Kritik derselben und dessen eigener Theorie der in seiner Ästhetik wurzelnden Lehre der unmittelbaren Einfühlung von Erlebnissen in wahrgenommene äußere Leiber. Beide Theorien hielt Husserl für falsch.[51] Von Lipps übernahm Husserl für die Fremderfahrung das Wort Einfühlung, obschon er dessen Theorie der Einfühlung immer ablehnte und der Auffassung war, dass für die Erfahrung fremder Erlebnisse „Einfühlung ein falscher Ausdruck ist“, da diese Erfahrung durch Vergegenwärtigung sich fremder Erlebnisse bewusst ist und in ihr daher nicht aktuelle eigene eingefühlt (introjiziert) sein können.[52] Doch erst in den Jahren 1914/15 hat Husserl sich mit der Analyse der Einfühlung intensiv beschäftigt und diese Problematik in einer Weise gestaltet, die auch für seine spätere Auseinandersetzung mit ihr während der zwanziger und dreißiger Jahre grundlegend war. Die entsprechende Textgruppe[53] handelt zwar nicht ausschließlich von der Einfühlung (Fremderfahrung), sondern auch von verschiedenen anderen Arten (Weisen) von Vergegenwärtigungen; die Einfühlung ist aber ein durchgängiges Problem. Der dritte dieses sechs Texte trägt den Titel: „Studien über anschauliche Vergegenwärtigungen, [d. h. über] Erinnerungen, Phantasien, Bildvergegenwärtigungen mit besonderer Rücksicht auf die Frage des darin vergegenwärtigten Ich und die Möglichkeit, sich Ich’s vorstellig zu machen“, und Husserl bemerkt in einer späteren Fußnote dazu: „Der Zweck dieser Studien war, für die besondere Weise der Vergegenwärtigung, die Einfühlung heisst, etwas zu lernen.“[54] Dieser Kontext zeigt, dass Husserl das Problem der Erfahrung (Einfühlung) des Anderen (d. h. eines anderen Ich und seiner Erlebnisse) als eine Art von Vergegenwärtigung wie etwa die Erinnerung an eigene Erlebnisse anging, die als eine andere Art von Vergegenwärtigung auch ein Ich und seine Erlebnisse vergegenwärtigt, die nicht unmittelbar gegenwärtig sind. Während aber die in der Erinnerung erinnerten eigenen Erlebnisse vergangene sind und das erinnerte Ich dasselbe ist wie das sich erinnernde, können die in der Einfühlung vergegenwärtigten Erlebnisse zeitlich gegenwärtig sein, und es besteht keine Identität zwischen einfühlendem und eingefühltem Ich. Im ersten Text dieser Gruppe[55] stellt Husserl die Frage: „Wie findet diese Interpretation [eines Körpers außer mir als fremder Mensch] statt?“[56] und antwortet schließlich, nachdem er den, aber ab 1920/21 nicht mehr befriedigenden Ansatz versucht hat, die Möglichkeit eines fremden Ich vor seiner wirklichen Erfahrung zu denken, mit dem für ihn nun immer geltenden Satz: „Hätte ich keinen Leib, wäre mir nicht mein Leib, mein empirisches Ich […] gegeben, so könnte ich also keinen anderen Leib, keinen anderen Menschen ‚sehen’ […] Fremden Leib kann ich nur erfassen in der Interpretation eines dem meinen ähnlichen Leibkörpers als Leibes und damit als Trägers eines Ich (eines dem meinen ähnlichen).“[57] Dieser Satz ist die Grundlage der „Paarung [zwischen fremden Leibkörper und eigenem Leib] als assoziativ konstituierende Komponente der Fremderfahrung“ im § 51 in der fünften der Cartesianischen Meditationen von 1931. Husserl denkt in der Textgruppe von 1914/15 das andere Ich als Analogon des eigenen Ich im Dort, d. h. als Gesichtspunkt auf die Welt, die ich hätte, wenn ich nicht hier, sondern dort wäre.[58] Im Text Nr. 14 aus der Zeit zwischen 1914 und 1917 geht Husserl dem durch die psychophysische Konditionalität bedingten Relativismus der Normalität der Erfahrung nach und erörtert Bedingungen der Möglichkeit der intersubjektiven Objektivität der Natur bis hin zur logisch-mathematischen Objektivität. Er äußert in diesem Zusammenhang wohl zum ersten Mal den Gedanken der Intersubjektivität der Erscheinungen („Aspekte“, Anblicke),[59] die er in der ersten Fassung der Ideen II noch als dem einzelnen Subjekt – der einzelnen Monade – zugehörig betrachtete. Im Text Nr. 15 aus dem September 1918 entwickelt er die Unterscheidung zwischen „gerader Einfühlung“, in welcher der Einfühlende auf die dem eingefühlten Ich erscheinende Umwelt gerichtet ist, und „obliquer Einfühlung“, in welcher der Einfühlende auf die intentionalen Erlebnisse des eingefühlten Ich reflektiert. Im Zentrum des letzten, im Sommer 1920 entstandenen Textes[60] von Hua XIII steht der Unterschied zwischen „uneigentlicher (unanschaulicher) Einfühlung“, die der naturwissenschaftlichen Psychologie, und der „eigentlichen (anschaulichen Einfühlung)“ als „absolut einfühlender Kenntnisnahme“, die den Geisteswissenschaften zugrunde liegt.[61] |

相互主観性 フッサールにおけるintersubjectivity(間主観性)の現象学に関する最も優れた洞察は、HuaのHusserliana(フッサリアナ) 第13巻から第15巻によって提供されている。[43] これらの版は、いくつかの例外を除いて、いわゆる「研究原稿」に基づいており、フッサールが自分自身に対してのみモノローグ形式で書いたものであり、聴衆 に対する問題の解決策を提示するのではなく、その問題を探索しているという点で、形式的に区別されている。第1巻[44]には1905年から1920年ま での間における主観性の現象学に関する主要なテキストが、第2巻[45]には1921年から1928年までの間における主観性の現象学に関する主要なテキ ストが、第3巻[46]には1929年から1935年までの間における主観性の現象学に関する主要なテキストがそれぞれ収録されている。3つの異なる巻に 分かれているのは、フッサールが自身の 現象学哲学の構想と提示に関する彼の研究における3つの主要な段階に対応している。 Hua XIII(フッサリアーナ 13巻) 主観性の問題に関する最も初期のテキスト[47]は、1905年の夏に書かれたもので、タイトルは「私と経験の個別性」(ドイツ語では 「Individualität von Ich und Erlebnissen」)であり、フッサールが選んだもので、経験する個人の間の差異に捧げられている。この論文は、フッサールが「あらゆる方法のなか でも最も根本的なもの」として現象学的還元の考え方を発展させた時期の初期のものであり、1910年から1911年にかけて行われた「現象学の根本問題」 [48]と題された講義で頂点に達した。これらの講義の主な目的は、現象学的還元の概念に依然として囚われていたフッサールが、1906年から1907年 の講義「知識論序説」[49]や、1907年の講義「理性の現象学と批判の主要部分」の序説で 現象学的還元を相互主観性へと拡張することで、1907年の『理性の現象学と批判の主要部分』[50]の序文でも同様の現象学的還元を行った。より具体的 には、共感(他者の経験)によって想起される他者(他者)の意図的意識の主題を、現象学的研究の分野に含めた。当然のことながら、フッサールは1905年 から1910年/11年の間、当時最もよく知られていた他者自我の知識に関する理論の研究を始めた。ベノ・エルドマンの他者自我に関する類推的結論の理 論、そしてテオドール・リップスの それに対する批判、そして自身の美学に根ざした、知覚された他者の身体における直接的な経験の共感の教義に関する自身の理論を探究し始めた。 フッサールによると、両理論とも誤りであった。 [51] リップスから、フッサールは他者の経験を表す「Einfühlung」という語を採用したが、彼は常に「Einfühlung」の理論を否定しており、 「Einfühlung」は他者の経験を表す「不正確な表現」であるという意見を持っていた。なぜなら、この経験は視覚化を通じて他者の経験を認識するも のであり、したがって、現在存在していない自身の経験が「Einfühlt」(内面化)される可能性があるからだ。 しかし、フッサールが共感の分析に集中的に取り組んだのは1914年から1915年にかけてであり、この問題を1920年代と1930年代に彼がそれにつ いて後に行なった調査にも根本的な形で定式化した。対応するテキスト群[53]は、共感(他者の経験)のみに焦点を当てているのではなく、さまざまな他の タイプ(方法)の視覚化についても論じている。しかし、共感は一貫した問題である。これら6つのテキストのうち3つ目のタイトルは、 「絵画的表象についての研究、すなわち、記憶、空想、そこに表現されている自我の問題と自我の存在の可能性を特に考慮した絵画的表象」と題されており、 フッサールは後の脚注で次のように述べている。「これらの研究の目的は、共感と呼ばれる特別な表象の方法について何かを学ぶことだった。」 [54] この文脈から、フッサールが他者(すなわち、もう一つの自我とその経験)を経験(感情移入)するという問題を、自身の経験の記憶のような一種の心的表象と して捉えていたことがわかる。記憶もまた、別の種類の心的表象として、現在に即してはいない自我とその経験を表象する。しかし、記憶の中で想起される経験 は過去の経験であり、想起される自己は想起する自己と同じであるが、共感の中で視覚化される経験は一時的に存在する可能性があり、共感する自己と共感され る自己の間には同一性はない。 このグループの最初の文章[55]で、フッサールは「この解釈(私以外の身体を他者としての人間として解釈すること)はどのようにして行われるのか?」 [56]という問いを投げかけ、最終的に、1920/21年以降はもはや満足のいくものではなくなった、他者としての自己の現実的な経験の前にその可能性 について考えるというアプローチを試みた後、次のような文章で答えを出した。「もし私が身体を持たなければ、私の身体、私の経験的自我は私に与えられない だろうから、私は他の身体、他の人間を『見る』ことはできないだろう。私は、私と似た身体を身体として、そして自我の担い手として(私と似たものとして) 解釈することによってのみ、異物をつかむことができるのだ。」 [57] この文章は、1931年の『デカルト的省察』第5部の§51における「異物に対する経験の連想的に構成的な要素としての結合」の基礎となっている。 1914/15年の文章群において、フッサールは他者の自我を、そこにいる自分の自我の類似体として考えている。つまり、 つまり、私がここにいなくてあそこにいるとしたら持つであろう世界の見方としてである。 1914年から1917年の間に書かれたテキスト第14号において、フッサールは心理物理的条件性によって条件付けられる経験の正常性の相対主義を調査 し、論理数学的客観性までの自然の相互主観的客観性の可能性の条件について論じている。この文脈において、おそらく彼は現象(「側面」、「見解」)の相互 主観性という考えを初めて表現した。この考えは、彼が『イデーン』第2巻の最初のバージョンでは依然として個々の主題、すなわち個々のモナドに属するもの として考えていたものである。1918年9月のテキスト第15号では、共感する人物が共感される自我に見える環境に向かう「ストレートな共感」と、共感す る人物が共感される自我の意図的な経験を振り返る「斜めの共感」の区別を展開している。1920年の夏に書かれた最後の文章の焦点は、科学心理学の基礎で ある「非現実的(非例示的)共感」と、人文科学の基礎である「絶対的共感的知識」としての「現実的(例示的共感)」との違いである。 |

| Hua XIV Aus den zahlreichen Texten, die in Zur Phänomenologie der Intersubjektivität, Zweiter Teil: 1921–1928 veröffentlicht wurden, seien hier nur vier Themen aus Texten oder Textgruppen hervorgehoben. Im ersten der Texte aus dem Zusammenhang der Vorbereitungen eines „grossen systematischen Werkes“ (1921/22) bringen ihn seine phänomenologischen Analysen zum ersten Mal zur Anerkennung des eingefühlten Ich als radikale Transzendenz gegenüber dem eigenen Ich, obschon es zum transzendental-phänomenologischen Bereich gehört: „Die Einfühlung schafft die erste wahre Transzendenz […] Hier ist ein zweiter Bewusstseinsstrom mitgesetzt, nicht [wie die physischen Dinge] als Sinnbildung meines Stromes, sondern als durch seine Sinnbildung [Konstitution] und Rechtgebung nur indiziert […].“[62] Besondere Beachtung verdienen innerhalb der Textgruppe von 1921/22 die Texte Nr. 9 und 10 und ihre Beilagen, die Husserl unter den Titel „Gemeingeist“ stellte. Diesen Begriff übernimmt Husserl vom Begründer der deutschen Soziologie, Ferdinand Tönnies (1855–1936). Mit ihm wird im Deutschen seit Herder der gemeinsame Geist einer Gemeinschaft bezeichnet. Husserl hat diesen Begriff in dem von ihm mit „Personale Einheiten höherer Ordnung und ihre Wirkungskorrelate“ überschriebenen Text Nr. 10 übernommen; in Text Nr. 9 bezieht er sich namentlich auf Tönnies und sein Werk Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft.[63] In Text Nr. 10 heißt es: „Es ist also keine blosse Analogie, kein blosses Bild, wenn wir von einem Gemeingeist […] sprechen, ebenso wenig als wenn wir korrelativ von einem Gebilde wie der Sprache sprechen oder der Sitte usw. Eine Fakultät hat Überzeugungen, Wünsche, Willensentschlüsse, sie vollzieht Handlungen, ebenso ein Verein, ein Volk, ein Staat. Und auch von Vermögen, von Charakter, von Gesinnung usw. können wir im strengen, aber entsprechend höherstufigen Sinn reden.“[64] Ebenso wichtig und für Text Nr. 10 grundlegend ist Text Nr. 9, dem Husserl auch den Titel „Gemeingeist“ gab. Hier geht es um die „sozialen Akte“, die Husserl vom bloßen Einfühlen und Verstehen unterscheidet und die er in diesem Text, nur andeutungsweise gesprochen, in Akte des sich an Andere Wendens, ihnen etwas Zeigens, des in der Ich-Du-Beziehung miteinander Sprechens, des miteinander gemeinsam etwas Wollens, etwas Verrichtens, einander Liebens in dessen verschiedenen Weisen (von der sexuellen Liebe bis zur Nächstenliebe) differenziert. In keinen anderen Texten hat Husserl so differenziert von solchen sozialen Akten und entsprechenden Gemeinschaften gesprochen wie in diesen beiden und ihren Beilagen. Im Text Nr. 19 (zwischen 1925 und 1928) wird der Begriff der „Originalität“, der schon in Text Nr. 11 (um 1921) zur Sprache kam, genauer analysiert. Husserl versucht zuerst, auch die Erfahrung von Anderen als originale Erfahrung zu bestimmen, verwirft dann aber diesen Ansatz und unterscheidet schließlich drei verschiedene Begriffe der originalen Erfahrung: 1. die Sphäre der „primordinalen Originalität (Uroriginalität)“,[65] „die originale Erfahrung, die keine Einfühlungsbestände, keine Bestände des fremden Subjekts […] gelten lässt“,[66] 2. die Sphäre der „sekundären Originalität [erste Originarität]“, „die eines jeden Anderen originale Erfahrungssphäre in sich schliesst“,[67] 3. meine „tertiäre originale Erfahrung [= zweite Originarität]“, die mir „Kulturobjekte gibt, die ihrerseits ihre Sinngebung ursprünglich den kultivierenden [fremden] Subjekten verdanken“.[68] In dieser Differenzierung tritt zum ersten Mal der Begriff der „primordinalen Originalität (Uroriginalität)“ auf, den Husserl in seinem Begriff der Primordinalspähre oder Eigenheitsspäre in der fünften Cartesianischen Meditation (Hua I) übernimmt und der grundlegend ist für seinen Begriff der Monade: Die Monade ist nach Husserl identisch mit der Sphäre der primordinalen Originalität oder der Eigenheit. Die Texte (Nr. 20–37) aus dem Zusammenhang des zweiten Teils der Vorlesungen „Einführung in die Phänomenologie“ des WS 1926/27 enthalten die genauesten Reflexionen und phänomenologischen Analysen zum Problem der Fremderfahrung, der „Wahrnehmung eines Menschen“, seit der Textgruppe von 1914/15 in Hua XIII. Die größte Leistung dieser Reflexionen ist ihr Erweis, dass das für die Einfühlung grundlegende unmittelbare Wahrnehmen der Entsprechung zwischen dem mir im äußeren Raum erscheinenden sich bewegenden (sich verhaltenden) fremden und dem mir erscheinenden eigenen Leib, trotz der prinzipiellen Verschiedenheit ihrer visuellen Erscheinungsweisen, durch die konstitutive Rückbeziehung jeder räumlichen Bewegung und Ortsveränderung auf das eigene subjektive „kinästhetische“ Bewegen und Bewegenkönnen ohne Analogisierung „ohne weiteres“[69] verständlich wird.[70] Dieses bloß sinnliche, gegenwärtigende Sehen ist zwar noch kein vergegenwärtigendes „in der Phantasie“ sich Versetzen auf den Gesichtspunkt dieses sich zu seiner räumlichen Umgebung verhaltenden lebendigen Wesens und damit noch kein Verstehen eines anderen Ich, aber dessen notwendige Grundlage. Hua XV Der dritte Teil von Zur Phänomenologie der Intersubjektivität, Dritter Teil: 1929–1935.[71] umfasst 670 Seiten. Der Text Nr. 35 und seine Beilage XLVIII aus dem September 1933 widmen sich gegenüber den beiden vorangehenden Bänden einem ganz neuen, durch die Problematik der Lebenswelt bedingten sehr reichhaltigen Thema: dem Verhältnis von Heimwelt und fremder Welt, der Zueignung von fremden Welten („Verheimatlichen von Fremde“[72]), dem einander Verstehen als Menschen mit einem Sinneskern von Welt als einem verstandenen „Kern der Unverstandenheiten, die Menschentum und Welt erst konkret machen in ihrer natürlichen Relativität“.[72] Die Beilage endet mit den Sätzen „Wir leben normalerweise […] in einer Umwelt, die für uns […] wirklich vertraute Welt ist […]. Im mittelbaren Horizont sind die fremdartigen Menschheiten und Kulturen; die gehören dazu als fremde und fremdartige, aber Fremdheit besagt Zugänglichkeit in der eigentlichen Unzugänglichkeit im Modus der Unverständlichkeit.“[73] |

Hua XIV(フッサリアーナ 14巻) 『相互主観性の現象学』第2部(1921年~1928年)で発表された多数のテクストの中から、ここでは4つのトピックに絞って取り上げる。 最初のテキストは、「大規模な体系的な作品」の準備(1921/22年)の文脈から抜粋されたもので、彼の現象学的分析は、超越論的現象学の領域に属する ものであるが、共感する自己を初めて根本的な自己超越として認識するに至った。「共感は最初の真の超越を生み出す。[...] ここで、第二の意識の流れが仮定される。それは、[物理的な物自体のように] 私の流れの意味の形成としてではなく、意味の形成[構成]と立法によって示されるものとしてである。[...]」[62] 1921/22年のテクスト群の中で、番号9と10のテクストとそれらの封入物については、フッサールが「ゲマインゲイスト」(共通精神)というタイトル を付けているため、特に注目に値する。フッサールは、この用語をドイツ社会学の創始者であるフェルディナント・トニース(1855-1936)から借用し ている。ドイツ語では、ヘルダー以来、この用語は共同体に共通する精神を表現するために使われてきた。フッサールは「高次個人単位とその相関効果」(テキ スト第10号)と題したテキストでこの用語を採用し、テキスト第9号では、トニースと彼の著書『共同体と社会』(Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft)に言及している。[63] テキスト第10号には次のように書かれている。「したがって、共通の精神について語る場合、それは単なる類推でも単なるイメージでもない。言語や習慣など の現象について相関的に語る場合と同様である。能力には信念、欲望、意志の決定があり、団体や国民、国家が行うように行動を行う。そして、能力、性格、態 度などについても、厳密ではあるが、より高度な意味で語ることができる。」[64] テキスト第10番にとって同様に重要かつ基本的なテキスト第9番は、フッサールも「共通精神」というタイトルを付けた。 ここでフッサールは、単なる共感や理解から「社会的行為」を区別し、このテキストでは、 ほのめかしているにすぎず、他者に向かう行為、何かを見せる行為、I-Thou関係において互いに語り合う行為、共に何かを望む行為、共に何かを行う行 為、様々な方法で互いに愛し合う行為(性的な愛から隣人愛まで)に区別している。フッサールが、この2つのテクストとその補遺において、これほどまでに多 様な社会的行為やそれに対応する共同体について、これほどまでに詳細に語ったことはない。 テクスト第19号(1925年から1928年の間に執筆)では、テクスト第11号(1921年頃)ですでに登場していた「オリジナリティ」の概念 がさらに 詳しく分析されている。フッサールはまず他者の経験を「原初的オリジナル体験」として定義しようとするが、このアプローチを拒否し、最終的に3つの異なる 「オリジナル体験」の概念を区別する。1.「原初的オリジナル体験(原初的オリジナル体験)」の領域[65]、「共感の蓄え、他者の主題の蓄えを一切許さ ないオリジナル体験」[ [66] 2. 「二次的独創性(第一のオリジナリティ)」の領域。「あらゆる他者の原体験を内包する」[67] 3. 私の「三次的独創性(第二のオリジナリティ)」。「私に文化的対象を与える。それらの文化的対象は、元来、育成する(他者)の主題にその意味を負う」 [68] [68] この区別において、「原初的独創性(原初的独創)」という概念が初めて登場する。これは、フッサールが第五のデカルト的省察( Hua I )における原初的領域または特異性の領域の概念で採用したものであり、彼のモナドの概念の基礎となっている。フッサールによれば、モナドは原初的独創また は特異性の領域と同一である。 1926/27年冬学期の講義「現象学入門」の第二部の文脈におけるテキスト(第20-37番)は、1914/15年のテキスト群(『Hua XIII』)以来、「他者の経験」の問題、すなわち「人間の知覚」に関する最も正確な考察と現象学的分析を含んでいる。これらの考察の最大の功績は、外部 空間において私に見える動く(振る舞う)他者と、私に見える私自身の身体との間の対応関係を直接知覚することが、共感の基礎となるものであり、視覚的な外 見に根本的な違いがあるにもかかわらず、「さらなる説明なしに」理解できることを証明したことである[69]。あらゆる空間的な動きと位置の変化を、自身 の主観的な「 類推の必要もなく、さらなる説明もなしに、自分の主観的な「運動感覚」の動きと移動能力へと帰着する。」[69] この感覚的な表象的な視覚は、空間環境と関わるこの生き物の視点に「想像上」に自分を置く視覚化ではなく、したがって、他者の自我の理解ではなく、しか し、その理解の必要条件である。 Hua XV(フッサリアーナ 15巻) 『相互主観性の現象学』第3部:1929年~1935年[71]の第3部は670ページからなる。これまでの2巻と比較すると、1933年9月のテキスト 第35号とその補遺第48号は、生活世界の諸問題に条件づけられた、まったく新しい広範なテーマに捧げられている。すなわち、内界と外界の関係、他界の獲 得(「他界を内界とする」[72])、 「人間性と世界を自然な相対性の中で具体化する不可解さの核心」として理解される世界観を核として、人間としてお互いを理解することである。[72] 補遺は「私たちは通常、[...]私たちにとって本当に馴染みのある世界である[...]環境の中で暮らしている」という文章で締めくくられている。間接 的な地平線上には、異質な人文科学や文化がある。それらは、異質で異質なものとしてそこに属しているが、異質性は、理解不能という様式において、まさにア クセス不能性の中にアクセス可能性を暗示している。」[73] |

| Phänomenologie des Raumes und der Bewegung (Hua XVI) Husserl hat sich zeitlebens mit der Analyse der Wahrnehmung von räumlichen Gegenständen beschäftigt. Von besonderer Bedeutung ist dabei eine im Sommersemester 1907 gehaltene Vorlesung, die 1973 unter dem Titel Ding und Raum als Band XVI der Husserliana publiziert wurde. Dem Grundgedanken der phänomenologischen Intentionalanalyse entsprechend, steht in Husserls Wahrnehmungsanalysen die „Korrelation von Wahrnehmung und wahrgenommener Dinglichkeit“[74] im Zentrum. Dabei zeigt sich, dass im Bewusstsein des Wahrnehmenden das wahrgenommene Ding immer nur einseitig gegeben ist. Diese „wesentliche Inadäquation jeder vereinzelten äußeren Wahrnehmung“ zeichnet die „Wahrnehmung räumlicher Dinge“ aus.[75] Ihr entspricht die notwendige Verwiesenheit auf weitere mit- und untereinander verbundene Wahrnehmungsmöglichkeiten von demselben Ding. Wahrnehmungsdinge können daher nicht in isolierten Akten des Wahrnehmens erfasst werden, sondern nur in Wahrnehmungsprozessen, die in „Synthesen der Identifikation übergehen“.[76] Husserl vertieft seine Wahrnehmungsanalysen, indem er die Abhängigkeit der Konstitution des Wahrnehmungsgegenstandes von leiblichen Bewegungsphänomenen thematisiert und den Zusammenhang zwischen den Bewegungsempfindungen, den sog. Kinästhesen, und den mit ihnen jeweils verbundenen Erscheinungsabwandlungen untersucht. Die besondere Leistung der Kinästhesen besteht zum einen in der Konstitution identischer, körperlich-voluminöser Gegenstände. Zum anderen konstituiert sich gemäß Husserl (anders als für Kant) in und durch die Erscheinungen der wahrgenommenen Dinge zugleich der Raum unserer Wahrnehmungserfahrung. Auch der Raum wird daher letztlich in den kinästhetischen Wahrnehmungssystemen konstituiert.[77] Im Einzelnen arbeitet Husserl die verschiedenen, für die Konstitution des Dinges und des Raumes notwendigen kinästhetischen Leistungen und Erfahrungen heraus, indem er vom einäugigen zum zweiäugigen Sehen, vom starren Blick zur Augen-, Kopf- und Oberkörperbewegung und schließlich zur freien leiblichen Bewegung des Wahrnehmenden übergeht. Dabei äußert er sich hinsichtlich der Frage, welche Kinästhesen letztlich die Erfahrung der dreidimensionalen körperlich-räumlichen Welt zu Stande bringen, schwankend. Während er im Rahmen von Ding und Raum erwogen hat, dass der Übergang vom einäugigen zum zweiäugigen Sehen bereits mit der Erfahrung räumlicher Tiefe verbunden ist,[78] hat er in späteren Arbeiten die Konstitution räumlicher Tiefe als Leistung des taktuellen Feldes verstanden.[79] In sachlicher Hinsicht dürfte es allerdings wenig sinnvoll sein, die konstitutiven Leistungen der visuellen oder taktuellen Wahrnehmung und der ihnen entsprechenden Kinästhesen gegeneinander auszuspielen. Vielmehr sind das visuelle und das taktuelle Feld nach Husserl eng miteinander verflochten.[80] |

空間と運動の現象学(Hua XVI) フッサールは生涯を通じて、空間的な物体の知覚の分析に懸命に取り組んでいた。この点において特に重要なのは、1907年の夏学期に開かれた講義で、 1973年に『Ding und Raum(物自体と空間)』というタイトルで『フッサリアナ』第16巻として出版された。現象学的志向分析の基本的な考え方に沿って、フッサールの知覚分 析の焦点は「知覚と知覚された物自体の相関関係」にある。[74] それによれば、知覚者の意識において、知覚された物は常に一方的にしか与えられない。この「孤立した外部知覚のすべての本質的な不十分さ」は、「空間的な 物自体の知覚」の特徴である。[75] これは、同じ物自体をさらに相互に連結し、相互に関連する可能性として知覚する際に必要な参照に対応する。したがって知覚されるものは、孤立した知覚行為 では把握できず、「同一化の総合へと融合する」知覚のプロセスにおいてのみ把握できるのである。[76] フッサールは、知覚の対象の構成が身体の運動現象に依存していることを指摘し、運動感覚、いわゆる運動感覚知覚と、それに関連する外観のそれぞれの変化と の関係を検証することで、知覚の分析を深めている。一方、運動感覚知覚の特別な功績は、同一の物理的な容積を持つ物体の構成にある。一方、フッサールによ れば(カントとは異なり)、知覚経験の空間は知覚された物自体の様相によって構成される。したがって、空間も最終的には運動感覚知覚システムによって構成 される。 具体的には、フッサールは、物自体と空間自体の構成に必要なさまざまな運動感覚の達成と経験を、単眼視から両眼視へ、固定した視線から目、頭、上半身の運 動へと移行し、最終的には知覚者の自由な身体運動へと移行することで明らかにする。そうすることで、最終的にどの運動感覚が三次元の物理的空間世界の経験 をもたらすのかという問題に対する不確実性を表現している。彼は『物自体と空間』の文脈において、単眼視から両眼視への移行がすでに空間的奥行きの経験と 結びついているとみなしていたが[78]、後の著作では空間的奥行きの構成を触覚領域の達成として理解していた。 しかし、事実に基づいた観点から見ると、視覚や触覚の知覚の構成上の成果と、それに対応する運動感覚を互いに相殺し合うことはほとんど意味がない。むし ろ、フッサールによれば、視覚と触覚の領域は密接に絡み合っている。 |

| Ethik Husserls ethische Überlegungen lassen sich in drei Phasen einteilen: die frühe Phase einer kognitivistisch orientierten Wertethik, die mittlere Phase einer rationalistischen Willensethik und die Spätphase einer affektiven Liebesethik. Alle diese Phasen sind von den phänomenologischen Begriffen des Wertes und der Person durchzogen. Husserls Ziel in der Ethik ist es, mithilfe seiner phänomenologischen Methode einen Mittelweg zwischen Gefühlsmoral und Verstandesmoral zu ebnen. Dabei soll die Herausarbeitung einer formalen und materialen Rationalität der Gemütsakte des Wertens und Wollens den Subjektivismus und Relativismus der Gefühlsmoral zurückweisen. Gleichzeitig hält Husserl gegen die rationalistische Ignoranz der Rolle der Gefühle an der These fest, dass uns Ethisches letztlich nur in Gemütsakten, d. h. in Akten des Wertens und Wollens zugänglich ist und auch nur darin gründen kann. In den Vorlesungen über Ethik und Wertlehre[81] von 1914 vertritt Husserl einen strengen Parallelismus zwischen Logik und Ethik und spricht gemäß seiner antipsychologistischen Auffassung ethischen Sachverhalten eine Eigenrealität zu. Obwohl er in seinem an Brentano angelehnten kategorischen Imperativ „Tue das Beste unter dem Erreichbaren!“ die Situation des handelnden Subjekts mitberücksichtigt, tut er dies unter der Prämisse, dass es in jeder Situation ein formales und materiales Apriori gibt, das eidetisch zu ermitteln wäre. Diese Haltung, dass jedes beliebige Subjekt „nachrechnen“[82] könnte, was für es zu tun eidetisch richtig wäre, gibt Husserl in seiner späten Ethik auf. Dabei ist es aber nicht so, dass er seine axiologische Theorie und seine Überlegungen zu Vorzugsgesetzen des Wollens als falsch verwerfen würde. Er hält sie bloß nicht mehr für eine Zugangsweise, die der ethischen Erfahrung angemessen wäre. Entscheidend hierfür ist Moritz Geigers Einwand, dass „es lächerlich wäre, an eine Mutter die Forderung zu stellen, sie solle erst erwägen, ob die Förderung ihres Kindes das Beste in ihrem praktischen Bereich sei“.[83] Das Bemühen, die Objektivität von Werten und die Rationalität des Gefühls phänomenologisch auszuweisen, weicht damit der Einsicht, dass eine rein theoretische bzw. metaethische Betrachtung der ethischen Getroffenheit durch einen Ruf nicht gerecht wird und führt zu einer Fokussierung auf das personale und individualisierende Angerufen-Sein durch „Liebeswerte“. Dies prägt die zweite und dritte Phase von Husserls Ethik ab 1918, wobei diese Phasen teilweise ineinandergreifen. Einerseits weisen die „Fünf Aufsätze über Erneuerung“[84] aus 1922–1924 deutliche rationalistische und perfektionistische Züge auf: Die Antwort auf den Anruf ist hier ein sich über das ganze Leben erstreckender Willensentschluss, in ständiger Erneuerung auf das Ziel ethischer Vervollkommnung und „wahrer Menschwerdung“ hinzustreben. Andererseits finden sich in Husserls Nachlass[85] die Motive einer Betonung der Affektivität und Passivität des Gerufen-Seins im „absoluten Sollen“ und die Antwort darauf in der aktiven Liebe („Liebeswert“ und „Liebesgemeinschaft“), sowie neben theologisch-teleologischen auch dunklere Motive wie Schicksal, Tod, Opfer und Entscheidung.[86] |

倫理 フッサールの倫理的考察は、3つの段階に分けることができる。すなわち、認識論的価値倫理の初期段階、合理主義的意志倫理の中間段階、情動的愛の倫理の後 期段階である。これらのすべての段階は、価値と人格に関する現象学の概念によって貫かれている。フッサールの倫理学の目的は、現象学的方法を用いて感情的 な道徳と理性的な道徳の間の中道を切り開くことである。 その際、価値づけと意志づけの感情的な行為の形式的かつ物質的な合理性の精緻化は、感情的な道徳の主観主義と相対主義を拒絶することを目的としている。同 時に、感情の役割に対する合理主義者の無知を前にして、フッサールは、倫理的な問題は最終的には感情の行為、すなわち価値づけと意志づけの行為においての み私たちにアクセス可能であり、それらにのみ根拠づけることができるという命題に固執している。 1914年の倫理学と価値論に関する講義において、フッサールは論理と倫理の厳密な平行性を主張し、反心理主義的な見解に沿って、倫理的諸事実に本質的な 現実性を帰属させた。彼は、ブレンターノによる[カント]「定言命法」の解釈において、行為主体の状況を考慮しているが、それはあらゆる状況において、エ イドス的に決定できる形式的な先験的要素と物質的な先験的要素が存在するという前提に基づいている。彼の倫理に関する後年の著作では、フッサールは、あら ゆる主体が「再計算」[82] できるというこの態度を放棄している。すなわち、主体にとってエイドティックに正しいとされる行為を「再計算」できるというものである。しかし、彼は価値 論的理論や、意志の選択の法則に関する考察を誤りであるとして捨て去ることはしなかった。彼は単に、それらを倫理的経験にふさわしいアプローチとは考えな くなっただけである。この点で重要なのは、モーリッツ・ガイガーが「母親に対して、自分の子どもを育てるのが自分の現実的な領域で最善の行動かどうかをま ず考えるように要求するのは馬鹿げている」と異議を唱えていることである。 83] 価値の客観性と現象学的な感情の合理性を示す努力は、呼びかけの倫理的影響を純粋に理論的または形而上学的考察によって正当に評価することはできないとい う洞察に道を譲り、「愛の価値」によって呼びかけられるという個人的かつ個別化された側面に焦点を当てることになる。これは、1918年以降のフッサール の倫理学の第二段階と第三段階の特徴であるが、これらの段階は部分的に重複している。一方、1922年から1924年にかけて書かれた『刷新についての5 つのエッセイ』[84]には、明確な合理主義的・完璧主義的な特徴が表れている。呼びかけに対する答えは、人生全体にわたる意志の決定であり、倫理的な完 璧さや「真の人間化」という目標に向かって絶え間なく刷新を続ける努力である。一方、フッサールの立場では、「絶対的べき」と呼ばれた存在の情動性と受動 性を強調する動機があり、それに対する積極的な愛(「愛の価値」と「愛の共同体」)による応答、そして神学的・目的論的なものに加えて、運命、死、犠牲、 決断といったより暗い動機がある。 |

| Psychologie und Psychiatrie Die Schnittfelder der Phänomenologie mit der Psychologie und Psychiatrie stellen wohl eines der fruchtbarsten Anwendungsgebiete des von Husserl begründeten Ansatzes dar. Dies gilt insbesondere für die Psychopathologie, die, in der modernen Form von Karl Jaspers begründet, der Phänomenologie bis heute nachhaltige Impulse verdankt. Im deutschen und französischen Sprachraum übten phänomenologisch-anthropologische Konzeptionen im letzten Jahrhundert einen maßgeblichen, zeitweise sogar dominierenden Einfluss auf die Psychiatrie aus, der sich insbesondere mit den auf Heideggers Fundamentalontologie basierenden Ansätzen der „Daseinsanalyse“ verknüpfte. Nach der letzten umfassenden Synopse von Spiegelberg[87] traten phänomenologische Forschungsrichtungen jedoch in den folgenden zwei Jahrzehnten gegenüber den bis heute dominierenden experimentell-biologischen Paradigmen in den Hintergrund. Während sich die akademische Psychologie seither nur noch vereinzelt für phänomenologische Ansätze offen zeigt, ist in der Psychopathologie und Psychiatrie inzwischen wieder eine lebhafte, auch internationale Renaissance der Phänomenologie zu beobachten, die in erster Linie auf die Konzeptionen Husserls und Merleau-Pontys zurückgreift. Husserl selbst hat trotz seiner Ablehnung des Psychologismus in den Logischen Untersuchungen[88] durchaus Ansätze zu einer phänomenologischen Psychologie entwickelt, insbesondere in den gleichnamigen Vorlesungen von 1925, in denen die Konzeption einer solchen Psychologie als „apriorische[r] Wissenschaft vom Seelischen“[89] skizziert und als eine Form „regionaler Ontologie“ von der transzendentalen Phänomenologie unterschieden wird. Während die phänomenologische Psychologie sich auf dem Feld der unmittelbaren Selbst- und Fremderfahrung bewegt, deren Aufbau und Wesenstypik sie mittels der phänomenologischen Reduktion und eidetischen Variation erschließen soll, untersucht die transzendentale Phänomenologie die Konstitution alles in der subjektiven Erfahrung Gegebenen auf dem Boden der transzendentalen (absoluten) Subjektivität[90] – eine Unterscheidung, die später auch für die Psychopathologie bedeutsam wurde, da in bestimmten Formen psychotischer Erfahrung gerade diese basalen Konstitutionsleistungen gestört sind. Allerdings blieb das Projekt unausgeführt und der Beitrag der Phänomenologie zur akademischen Psychologie infolgedessen begrenzt. In der Zeit nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg entwickelte sich eine lebendige phänomenologische Bewegung in den Niederlanden, vertreten insbesondere durch Frederik Buytendijk, Johannes Linschoten und Jan van den Berg. Reichhaltige Forschungen galten dabei insbesondere der Phänomenologie der menschlichen Situation,[91] etwa in alltäglichen Erfahrungen wie der Begrüßung, dem Autofahren, der sexuellen Begegnung oder dem Einschlafen.[92] Abschließend sei noch auf die für die Zukunft der Forschungsrichtung bedeutsame Frage der phänomenologischen Methode hingewiesen, die sich gerade in der Psychologie gegenüber der dominanten empirisch-experimentellen Orientierung zu behaupten hat. Eine elaborierte Methodik deskriptiver Phänomenologie wurde unter anderem von Giorgi seit den 1960er Jahren an der Duquesne University entwickelt.[93] Basierend auf der phänomenologischen Epoché und eidetischen Variation, soll die subjektive Erfahrung in empathischer Intuition erfasst und so als Basis für weitere qualitative Analysen genutzt werden. Ähnliche Ansätze zur Praxis phänomenologischer Introspektion und Erfahrungsanalyse finden sich heute in der französischen Phänomenologie.[94] Als systematisches Projekt der Untersuchung der Strukturen subjektiver Erfahrung eignete sich die Phänomenologie naturgemäß auch als Grundlagenwissenschaft für die Psychopathologie. Karl Jaspers und Ludwig Binswanger, der über diesen hinausgehend eine phänomenologisch-anthropologische Richtung der Psychiatrie entwickelte, sind hier zu erwähnen. Zu den Hauptvertretern der von Binswanger ausgehenden phänomenologisch-anthropologischen Psychiatrie gehören Erwin Straus, Emil von Gebsattel, Eugen Minkowski, Jürg Zutt, Roland Kuhn, Hubertus Tellenbach, Wolfgang Blankenburg, Bin Kimura und Arthur Tatossian. Phänomenologische Ansätze in Psychologie und Psychiatrie untersuchen die Phänomene, Strukturen und Aufbauelemente der bewussten Erfahrung, insbesondere hinsichtlich Leiblichkeit, Zeitlichkeit, Intentionalität und Intersubjektivität, um so auch ihre Abwandlungen in psychischer Krankheit zu erfassen. Für die Erforschung dieser Erfahrungsschichten stellt die Phänomenologie ein reichhaltiges Instrumentarium zur Verfügung, das von der phänomenologischen Deskription über die Erfassung von eidetischen Typologien bis zur transzendentalen Phänomenologie, zur Konstitutions- und Lebensweltanalyse reicht. Die damit sich bietenden Forschungsmöglichkeiten sind bei weitem noch nicht ausgeschöpft. Gerade in den letzten zwei Jahrzehnten ist vielmehr eine internationale Renaissance der besonders an Husserl und Merleau-Ponty orientierten phänomenologischen Psychiatrie zu beobachten, die die Bedeutung der präreflexiven und affektiven Erfahrung, der „passiven Synthesen“ in der Erfahrungskonstitution und nicht zuletzt der transzendentalen Intersubjektivität für das Verständnis psychischer Erkrankungen aufweisen kann.[95] Obgleich sie methodisch nach wie vor jegliche Annahmen zu kausalen Erklärungen einklammert, liefert die Phänomenologie damit einen Rahmen für die Analyse der Subjektivität und ihrer Störungen, die auch zu empirisch testbaren Hypothesen über zugrundeliegende ätiologische Prozesse führen. Die phänomenologisch-anthropologische Psychiatrie versteht sich dabei nicht als eine unbeteiligte Beobachtung von außen. Ihre Analysen der Intersubjektivität schließen auch die Beziehung zwischen Patient und Therapeut ein, und ihre besondere Aufmerksamkeit gilt der Phänomenologie des diagnostischen und therapeutischen Prozesses selbst: etwa den Phänomenen der Intuition, der Zwischenleiblichkeit, des empathischen Verstehens und der existenziellen Begegnung:[96] Damit trägt sie nicht zuletzt auch zur philosophischen Grundlegung der Psychotherapie bei.[97] Vor allem in den Konzepten humanistischer und existenzieller Orientierung wie Gestalttherapie, Gesprächstherapie, Daseins- und Existenzanalyse steht sie vielfach als methodisches Werkzeug im Vordergrund. Nicht zuletzt kann die Phänomenologie heute als die maßgebliche Richtung in den Wissenschaften von der Psyche gelten, die die Wirklichkeit und Bedeutsamkeit von Subjektivität und Intersubjektivität gegenüber reduktionistisch-naturalistischen Ansätzen verteidigt. |

心理学と精神医学 現象学と心理学および精神医学の交差は、おそらくフッサールが創始したアプローチの最も実りある応用分野のひとつである。これは特に精神病理学に当てはま り、カール・ヤスパースによって現代的な形に確立された精神病理学は、今日に至るまで現象学から持続的な刺激を受けている。ドイツ語圏やフランス語圏で は、現象学的人間学の概念は、前世紀の精神医学に決定的な影響を与え、時には支配的な影響力さえも及ぼした。特に、ハイデガーの基本的な存在論に基づく 「存在分析」のアプローチと関連していた。しかし、シュピーゲルバーグによる最新の包括的な概説[87]によると、今日まで支配的な立場を維持している実 験生物学のパラダイムに直面し、現象学的研究の方向性は、その後の20年間で後景へと退いた。それ以来、学術心理学は現象学的なアプローチに対して散発的 にしか門戸を開いてこなかったが、現在では、フッサールやメルロ=ポンティの概念を主に参照する現象学の活気のある国際的なルネサンスが精神病理学や精神 医学の分野で観察されるようになっている。 『論理的研究』において心理主義を否定したにもかかわらず[88]、フッサール自身は現象学心理学へのアプローチを展開し、特に1925年の同名の講義で は、そのような心理学の概念が「魂のアプリオリな科学」[89]として概説され、「局所存在論」の一形態として、 。現象学心理学は自己と他者の直接経験の領域に関わるものであるが、現象学的還元とエイドス的変異によってその構造と本質を明らかにしようとするものであ る。一方、 超越論的現象学は、超越論的(絶対的)主観性に基づいて主観的経験において与えられるあらゆるものの構成を調査する。この区別は、後に精神病理学において も重要となった。なぜなら、精神病的な経験の特定の形式において混乱しているのは、まさにこれらの基本的構成プロセスだからである。しかし、この計画は実 現されることはなく、結果として、学術心理学における現象学の貢献は限定的なものにとどまった。 第二次世界大戦後の時期には、オランダで活発な現象学運動が展開され、特にフレデリック・ブイトェンダイク、ヨハネス・リンショテン、ヤン・ファン・デ ン・ベルクらが代表的な存在であった。特に、人間の状況の現象学に関する広範な研究が行われた。[91] 例えば、挨拶、車の運転、セックス、入眠などの日常的な経験である。 最後に、研究分野の将来にとって重要な現象学的方法の問題について言及しておくべきである。特に心理学では、支配的な経験的・実験的志向に対して、自らを 主張しなければならない。記述的現象学の精巧な方法論は、とりわけジョルジによって、1960年代以降、デュケイン大学で開発されてきた。93] 現象学的エポケーとエイドス的変異に基づいて、主観的経験は共感的直観によって把握され、それによってさらなる質的分析の基礎として用いられる。現象学的 内省と経験分析の実践に対する同様のアプローチは、今日のフランス現象学にも見られる。 主観的経験の構造の調査という体系的なプロジェクトとして、現象学は当然、精神病理学の基礎科学としても適していた。カール・ヤスパースとルートヴィヒ・ ビンスワンガーは、ヤスパースよりもさらに踏み込んで、精神医学における現象学的・人類学的方向性を発展させた。ビンズワンガーに端を発する現象学的・人 類学的精神医学の主な代表者には、エルヴィン・ストラウス、エミール・フォン・ゲプサッテル、オイゲン・ミンコフスキー、ユルク・ズット、ローランド・ クーン、フーベルトゥス・テレンバッハ、ヴォルフガング・ブランケンブルク、ビン・キムラ、アーサー・タトシアンなどがいる。 心理学や精神医学における現象学的アプローチでは、意識経験の現象、構造、要素を、特に身体性、時間性、志向性、相互主観性との関連で調査し、精神疾患に おけるそれらの変化も把握しようとする。これらの経験の層を研究するために、現象学は現象学的記述から、エイドス的類型の記録、超越論的現象学から、構成 と生活世界の分析に至るまで、豊富なツールセットを提供している。これらのツールによって提供される研究の可能性は、まだまだ尽きることはない。それどこ ろか、特にフッサールとメルロ=ポンティに重点を置く現象学的精神医学の国際的なルネサンスが、この20年間で観察されている。それは、精神疾患の理解に とって、前反射的および情動的な経験、経験の構成における「受動的統合」、そしてとりわけ超越論的間主観性の重要性を示すことができる。 因果関係の説明に関する仮定を排除し続けているが、現象学は主観性とその障害を分析する枠組みを提供しており、その枠組みは、根本的な病因プロセスに関す る経験的に検証可能な仮説にもつながっている。現象学的・人類学的精神医学は、外部から関与しない観察者として自分自身を捉えてはいない。その相互主観性 の分析には、患者とセラピストの関係も含まれ、診断および治療プロセス自体の現象学、例えば直観、中間的身体性、共感的理解、実存的遭遇などの現象に特に 注意が払われる。 [97] 現象学は、ゲシュタルト療法、クライエント中心療法、実存分析などの人間中心主義的および実存主義的な志向の概念において、特に方法論的なツールとして顕 著である。 現象学は、還元論的・自然主義的なアプローチに対して主観性および間主観性の現実性と重要性を擁護するものであり、今日の精神科学において最も影響力のあ るアプローチであると考えられる。 |