現 象 学

Phenomenology

★現象学(ギ リシャ語の φαινόμενον / phainómenon、「現れるもの」、および λόγος / lógos、「研究」から)は、哲学を経験的な学問とすることを目指してエドムント・フッサールによって創設された20世紀の思想潮流である。その名称 は、現象を通して現実をありのままに把握するというその手法に由来している。現象学は、哲学を、経験と意識[1]そのものを、自らを思考し、世界を思考す る思考の現象として体系的に研究・分析する学問としている。 この哲学の学派は、現象はそれを知覚する意識がある場合にのみ存在することを証明しようと努めている。したがって、あらゆる意識は何かに対する意識であ り、それは意識の意図性という考え方である。現象学的方法は、意識と世界との間に本質的な関係が存在することを証明しようとするものである。現象学は、本 質という概念に関する哲学的疑問を取り上げ、それを考察するアプローチとして、生きた経験、つまり現象そのものを研究する。このように、現象学は、観念論 (観念を通じて現実を捉える)と経験論(現実を通じて観念を捉える)の橋渡しをしようとしているとみなされることもある。 フッサールは、最初の主要著作『論理学研究』(1900-1901)の中で、心理主義と決別し、形而上学に対抗して、自然科学に基礎を与える科学として現 象学を確立した。彼は、自然科学は「人間と世界との関係を解明する」には不十分だと考えていた[3]。

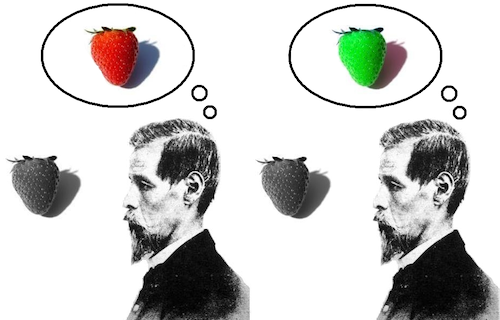

☆善の公案に似てエポケーはなかなか[分かりそうで]分かりにくい実践である.実践と書いたのは[形而上学的実践[撞着語法]]概念を自分のものにするから実践でなのであるがカントの[これまた通俗形而上学を嫌った用語としての]超越論的観念論ならぬ美学的実践だからだ.

| La phénoménologie

(du grec φαινόμενον / phainómenon, « ce qui apparaît », et λόγος /

lógos, « étude ») est un courant de pensée du xxe siècle fondé par

Edmund Husserl dans l'optique de faire de la philosophie une discipline

empirique. Elle tire son nom de sa démarche, qui est d'appréhender la

réalité telle qu'elle se donne, à travers les phénomènes. Elle fait de

la philosophie l'étude systématique et l'analyse de l’expérience vécue

et de la conscience[1] comme étant eux-mêmes des phénomènes de la

pensée qui se pense elle-même et pense le monde. Cette école de philosophie s'attache à démontrer que le phénomène n'existe que s'il y a une conscience pour le percevoir. Toute conscience serait donc conscience de quelque chose, c'est l'idée d'intentionnalité de la conscience. La méthode phénoménologique veut démontrer qu'il existe une relation essentielle entre la conscience et le monde. La phénoménologie reprend les interrogations philosophiques sur le concept d'essence, et son approche pour les aborder est d'étudier l'expérience vécue, c'est-à-dire le phénomène en tant que tel. Il est parfois considéré qu'ainsi, la phénoménologie cherche à faire le lien entre l'idéalisme (passer par l'idée pour accéder au réel) et l'empirisme (passer par le réel pour accéder à l'idée)[2]. C'est dans sa première oeuvre majeure, Recherches logiques (1900-1901), que Husserl, en rupture avec le psychologisme et en opposition à la métaphysique, fonde la phénoménologie comme science destinée à donner un fondement aux sciences de la nature, qu'il juge insuffisantes à « élucider le rapport de l'homme au monde »[3]. La phénoménologie telle qu'on la connaît aujourd'hui s'étend au sein d'un cercle de disciples dans les universités de Göttingen et de Munich en Allemagne (Edith Stein, Roman Ingarden, Martin Heidegger, Eugen Fink, Max Scheler, Nicolai Hartmann), et se propage rapidement à l'étranger, en particulier en France (grâce aux traductions et aux travaux de Paul Ricœur, d'Emmanuel Levinas, de Jean-Paul Sartre, de Maurice Merleau-Ponty) et aux États-Unis (Alfred Schütz et Eric Voegelin), souvent avec une très large prise de distance critique par rapport aux premiers travaux de Husserl, mais sans jamais que soit abandonnée sa volonté fondamentale de s'en tenir à l'expérience vécue. Il n'y a pas lieu de s'étonner de la grande variété de formulations de ce courant de pensée, qui ressortit à sa nature même, cherchant à exprimer les aspects spécifiques de chacun de ses domaines d'étude[1]. La phénoménologie constitue l'une des traditions principales de la philosophie européenne du xxe siècle. Elle a en outre inspiré de nombreux travaux hors de son champ philosophique propre, telles la philosophie des sciences, la psychiatrie, l'esthétique, la morale, la théorie de l'histoire[1], l'anthropologie existentiale[4]. |

現象学(ギリシャ語の φαινόμενον /

phainómenon、「現れるもの」、および λόγος /

lógos、「研究」から)は、哲学を経験的な学問とすることを目指してエドムント・フッサールによって創設された20世紀の思想潮流である。その名称

は、現象を通して現実をありのままに把握するというその手法に由来している。現象学は、哲学を、経験と意識[1]そのものを、自らを思考し、世界を思考す

る思考の現象として体系的に研究・分析する学問としている。 この哲学の学派は、現象はそれを知覚する意識がある場合にのみ存在することを証明しようと努めている。したがって、あらゆる意識は何かに対する意識であ り、それは意識の意図性という考え方である。現象学的方法は、意識と世界との間に本質的な関係が存在することを証明しようとするものである。現象学は、本 質という概念に関する哲学的疑問を取り上げ、それを考察するアプローチとして、生きた経験、つまり現象そのものを研究する。このように、現象学は、観念論 (観念を通じて現実を捉える)と経験論(現実を通じて観念を捉える)の橋渡しをしようとしているとみなされることもある。 フッサールは、最初の主要著作『論理学研究』(1900-1901)の中で、心理主義と決別し、形而上学に対抗して、自然科学に基礎を与える科学として現 象学を確立した。彼は、自然科学は「人間と世界との関係を解明する」には不十分だと考えていた[3]。 今日知られている現象学は、ドイツのゲッティンゲン大学とミュンヘン大学の弟子たち(エディット・シュタイン、ロマン・インガルデン、マルティン・ハイデ ガー、オイゲン・フィンク、マックス・シェラー、ニコライ・ハルトマン)の間で広まり、特にフランス (ポール・リクール、エマニュエル・レヴィナス、ジャン=ポール・サルトル、モーリス・メルロ=ポンティによる翻訳や研究のおかげで)、そしてアメリカ (アルフレッド・シュッツとエリック・ヴォーゲリン)に急速に広まった。多くの場合、フッサールの初期の研究からはかなり批判的に距離を置いていたが、経 験に忠実であり続けようという基本的な意志は決して放棄されなかった。 この思想潮流の表現が極めて多様であることは、その本質からして当然のことであり、それぞれの研究分野における特定の側面を表現しようとしている[1]。 現象学は、20世紀のヨーロッパ哲学の主要な伝統の一つだ。さらに、科学哲学、精神医学、美学、道徳、歴史理論[1]、実存的人類学[4]など、哲学の分 野以外の多くの研究にも影響を与えている。 |

| La phénoménologie avant Husserl On attribue généralement l'invention du terme « phénoménologie » à Jean-Henri Lambert (1728-1777), qui dénomme ainsi dans la quatrième partie de son Nouvel Organon (1764) la « doctrine de l'apparence »[5],[N 1]. Kant (1724-1804) Une section de la Critique de la raison pure de Kant devait s'appeler Phénoménologie ; mais Kant remplaça finalement ce nom par celui d'Esthétique transcendantale. Kant y opère la séparation entre la « chose en soi » et le phénomène (ce qui se montre), ce dernier étant donné dans le cadre transcendantal de l'espace, du temps et de la causalité[N 2]. La thèse de Kant est qu'il existe seulement un cadre a priori dans lequel les objets peuvent nous « faire encontre » et qui permet leur représentation. Ce cadre qui n'est autre que la structure de notre connaissance va ouvrir la possibilité d'une connaissance universelle[6]. Fichte (1762-1814) Cette section ne cite pas suffisamment ses sources (septembre 2024). La phénoménologie est un concept central de la philosophie de Johann Gottlieb Fichte. Elle désigne la partie de la doctrine de la science qui développe la phénoménalisation (apparition, extériorisation) du fondement et du principe du savoir. Il ne peut y avoir de savoir absolu (qui n'est pas un savoir d'un objet mais de ce qui fait qu'un savoir est effectivement un savoir) que phénoménalisé. Aussi, dès La Doctrine de la Science de 1804, oppose-t-il la doctrine du phénomène ou phénoménologie à la doctrine de l'être et de la vérité. À la fin de sa vie, Fichte identifie même la phénoménologie à la doctrine de la science, parce que, sans elle, le « savoir absolu » n'aurait pas d'existence. Hegel (1770-1831) Article détaillé : Phénoménologie de l'esprit. Des thèses kantiennes, Hegel déduit qu'avec le phénomène, la conscience découvre la structure de sa propre connaissance, s'élevant ainsi à la conscience de soi. Dans la Phénoménologie de l'esprit, « Hegel trace le parcours de cette conscience dans l'histoire de ses manifestations, de ses figures, qui sont autant d'expériences de soi dans son élan vers la science »[6],[N 3]. Schopenhauer (1788-1860) Si pour Arthur Schopenhauer, le monde est notre représentation (c'est-à-dire qu'être et être une représentation, pour le sujet, c'est tout un), il s'agit toujours pour lui de chercher plus profond que cette évidence première : comment connaître ce que le monde peut être dans son être en soi ? Il s'agit pour lui de rechercher l’essence du phénomène à partir d'une étude descriptive préalable du donné phénoménal et en particulier, de la manière dont se donne à moi mon propre corps comme « volonté »[N 4]. |

フッサール以前の現象学 「現象学」という用語の発明は、一般的にジャン=アンリ・ランベール(1728-1777)によるものとされている。彼は『新オルガノン』(1764)の第4部で、「外観の教義」[5]、[N 1]をそう呼んだ。 カント(1724-1804) カントの『純粋理性批判』の一部は、本来「現象学」という名称になる予定だったが、カントは最終的にこの名称を「超越論的美学(→邦訳では超越論的観念 論)」に変更した。カントは、この部分で「物自体」と現象(見えるもの)を区別しており、現象は空間、時間、因果関係の超越論的枠組みの中で与えられるも のであるとしている[N 2]。カントの主張は、物体が私たちに「出会う」ことができる、そしてそれらの物体を表現することを可能にする、先験的な枠組みだけが存在するというもの である。この枠組みは、私たちの知識の構造そのものであり、普遍的な知識の可能性を開くものである[6]。 フィヒテ(1762-1814) このセクションは、出典を十分に引用していない(2024年9月)。 現象学は、ヨハン・ゴットリーブ・フィヒテの哲学の中心的な概念である。それは、知識の基礎と原理の現象化(出現、外部化)を展開する科学の教義の一部を 指す。現象化されたもの以外には、絶対的な知識(対象に関する知識ではなく、知識が実際に知識である理由に関する知識)は存在しえない。そのため、 1804年の『科学の教義』以降、彼は現象の教義、すなわち現象学を、存在と真実の教義に対立させるようになった。フィヒテは、その生涯の終わりに、現象 学を科学の教義と同一視した。なぜなら、現象学がなければ、「絶対的な知識」は存在しえないからである。 ヘーゲル(1770-1831) 詳細記事:精神の現象学。 カントの説から、ヘーゲルは、現象によって意識は自らの認識の構造を発見し、それによって自己意識に到達すると結論づけた。『精神の現象学』の中で、 「ヘーゲルは、その顕現の歴史、その姿、すなわち科学への衝動における自己の経験の軌跡を、この意識の軌跡として描いている」[6]、[N 3]。 ショーペンハウアー(1788-1860) アーサー・ショーペンハウアーにとって、世界は我々の表象である(つまり、存在することと表象であることは、主体にとっては同じことである)。しかし、彼 にとっては、この第一義的な自明性よりもさらに深いところを探求することが常に重要であった。つまり、世界がそれ自体としてどのような存在であるかを、ど のように知ることができるのか?彼にとっては、現象の本質を、現象的に与えられたものを事前に記述的に研究すること、特に、自分の体が「意志」として自分 に与えられている方法を研究することである[N 4]。 |

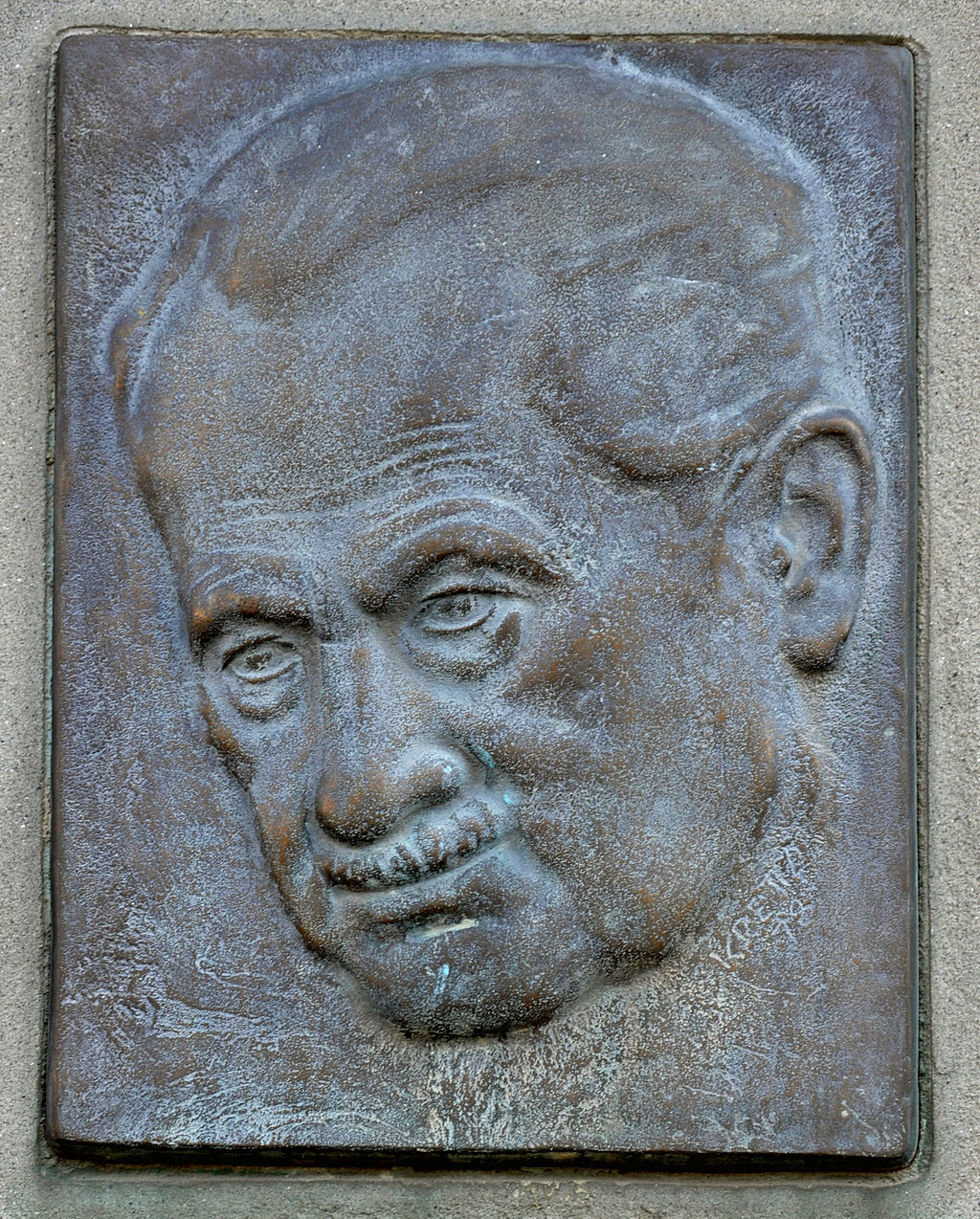

Vue d'ensemble de la phénoménologie Photographie en noir et blanc. Buste d'homme en costume. Il porte une barbe blanche fournie, des moustaches en croc et observe au-delà du spectateur. Edmund Husserl en 1900. Avec Edmund Husserl, la phénoménologie a l'ambition de se constituer en science[N 5], et elle se dote d'une problématique, d'un objet ou domaine, et d'une méthode[N 6]. Hegel encore, dans sa Phénoménologie de l'esprit donne au terme de phénoménologie le sens de méthode, qui finit avec Husserl par désigner la philosophie tout entière elle-même avec pour mot d'ordre : « revenir aux choses elles-mêmes ». La problématique L'histoire du concept de phénoménologie montre que, depuis Jean-Henri Lambert, la phénoménologie n’a cessé d’évoluer. C'est donc le contexte qui va déterminer si l'on parle de la phénoménologie au sens fichtéen, hégélien ou husserlien, même si en général, le terme de phénoménologie, pris isolément, désigne la philosophie et la méthode de Husserl ou de ses héritiers. Comprise jusqu'à lui comme science de l’« apparaître », la phénoménologie devient, chez Heidegger, la science de ce qui n’apparaît justement pas à première vue[7] ou, comme l'écrit Françoise Dastur citant Heidegger, une « phénoménologie de l'inapparent »[8]. Dans le phénomène de l'apparaître, la phénoménologie « post husserlienne », problématise la « constitution du sens » de ce qui se présente à la conscience, cela requiert une attitude qui ne se satisfait jamais de solutions définitives. Ainsi, Jean-François Courtine[9] précise que « la phénoménologie ne caractérise pas le « Was » (ce que c'est), mais le « Wie » des objets, le comment de la recherche, la modalité de leur « être-donné », la manière dont ils viennent à la rencontre »[N 7]. De telles recherches exigent de chacun qu'il refasse pour son compte l'expérience phénoménologique de celui qui l'a précédemment faite, note Alexander Schnell[10]. La phénoménologie se constitue en opposition au « néokantisme »[N 8] ; elle « consiste à décrire les phénomènes sans parti pris, en renonçant de façon méthodique à leur origine physiologico-psychologique ou à leur réduction à des principes préconçus », résume Hans-Georg Gadamer[11]. Le mot « phénomène » signifie étymologiquement « ce qui se montre », et il conserve, depuis son origine grecque un sens ambigu provenant de ce qu'il tient à la fois de l'objet et du sujet. Il est délicat de distinguer ce qui appartient à l'objet de ce qui appartient à l'interprétation propre au sujet[12] (connaissance, illusion, erreur). Cette dépendance, vis-à-vis du sujet pourrait rendre difficile, voire impossible, la constitution d'une science, à partir d'une expérience, d'où le souci grec, notamment chez Platon et Aristote, de « sauver les phénomènes »[6]. |

現象学の概要 白黒写真。スーツを着た男性の胸像。彼は豊かな白ひげと鉤鼻を生やし、観客の背後を見つめている。 1900年のエドムント・フッサール。 エドムント・フッサールにとって、現象学は科学として確立することを目指しており[N 5]、問題意識、対象または領域、そして方法論を備えている[N 6]。ヘーゲルは、その『精神の現象学』の中で、現象学という用語に方法論の意味を与え、フッサールによって、それは「物事そのものに立ち返る」というス ローガンを掲げた哲学全体そのものを指すようになった。 問題意識 現象学という概念の歴史は、ジャン=アンリ・ランベール以来、現象学が絶えず進化してきたことを示している。したがって、フィヒテ、ヘーゲル、フッサー ル、どの意味での現象論を論じるかは、文脈によって決まる。ただし、一般的に現象学という用語は、単独で使用される場合、フッサールやその継承者たちの哲 学および方法を指す。 それまでは「現れ」の科学として理解されていた現象学は、ハイデガーによって、一見しただけでは現れないものの科学[7]、あるいはフランソワーズ・ダストゥールがハイデガーを引用して書いているように、「現れないものの現象学」[8]となった。 出現という現象において、「ポストフッサール的」現象学は、意識に現れるものの「意味の構成」を問題視する。そのためには、決定的な解決に決して満足しな い姿勢が必要だ。したがって、ジャン=フランソワ・クルティーンは、「現象学は、物事の「Was」(何であるか)ではなく、物事の「Wie」(どのよう に)、つまり、研究の方法、物事の「与えられ方」、物事がどのように出会うかを特徴づける」と述べている。このような研究は、各人が、以前にそれを経験し た人の現象学的経験を、自分なりに再現することを要求する、とアレクサンダー・シュネル[10]は述べている。現象学は「新カント主義」[N 8] に対抗して成立したものであり、ハンス・ゲオルク・ガダマー[11] は「現象を偏見なく記述し、その生理学的・心理学的起源や、先入観に基づく原理への還元を体系的に放棄すること」と要約している。 「現象」という言葉は、語源的には「現れるもの」を意味し、そのギリシャ語起源以来、対象と主体の両方に由来する曖昧な意味合いを保っている。対象に属す るものと、主体固有の解釈(認識、錯覚、誤謬)に属するものを区別することは難しい。この主体への依存は、経験に基づいて科学を構築することを困難、ある いは不可能にする可能性がある。そのため、特にプラトンやアリストテレスなどのギリシャ人は、「現象を救う」[6]ことを重視した。 |

| L'objet La phénoménologie moderne, dominée par les pensées d'Edmund Husserl et de Martin Heidegger, ambitionne d'aller « droit à la chose même ». Le phénomène Husserl le répète expressément, la phénoménologie vise à se débarrasser de toute théorie préalable, de toute préconception et se soucie exclusivement de « faire droit à la chose même, [car], le voir ne se laisse pas démontrer ni déduire »[13], en s'en tenant scrupuleusement à la façon dont la chose se donne selon le principe « Zu den Sachen selbst »[N 9]. En ce sens précis, l'écoute du phénomène exige la réduction phénoménologique. « Ce n'est que par une réduction […] que j'obtiens une donnée absolue, qui n'offre plus rien d'une transcendance. Si je mets en question le moi, et le monde, et le vécu en tant que vécu du moi, alors, de la vue réflexive dirigée simplement sur ce qui est donné dans l'aperception du vécu en question, sur mon moi, résulte le phénomène de cette aperception : par exemple le phénomène perception appréhendé comme ma perception […] Mais je peux pendant que je perçois porter sur la perception le regard d'une pure vue […] laisser le rapport au moi de côté ou en faire abstraction : alors la perception saisie et délimitée dans une telle vue est une perception absolue, dépourvue de toute transcendance, donnée comme phénomène pur au sens de la phénoménologie » écrit Husserl dans L'idée de la phénoménologie[14]. En reprenant le terme de « phénoménologie », Heidegger pourrait paraître d'emblée s'inscrire dans le prolongement de la pensée de son maître Husserl, sauf qu'il en élimine une partie essentielle, en rejetant tout ce qui a succédé à ce qu'il a qualifié de « tournant non phénoménologique » de Husserl, c'est-à-dire, son penchant pour une méthodologie scientifique, qu'il discerne à partir des Ideen, et notamment l'institution du « sujet transcendantal »[15]. De plus, Martin Heidegger a pu paradoxalement avancer que l'impératif Zu den Sachen selbst (aller droit à la chose même) ne soit justement pas la chose mais « ce qui est en cause » chaque fois que nous sommes en rapport avec quoi que ce soit[16]. Pour Heidegger, ce que la phénoménologie doit finalement montrer ce n'est justement pas l'étant mais bien son « être », « or celui-ci, de prime abord, ne se montre pas, même s'il est toujours pré-compris d'une certaine manière », remarque Christian Dubois[17]. Si l'être est le phénomène par excellence […] alors la phénoménologie devrait le faire voir […] tel qu'il se montre à partir de lui-même, c'est-à-dire ne pas chercher à l'extraire de sa dissimulation, mais le montrer dans cette dissimulation même écrit Sylvaine Gourdin[18] Heidegger ambitionne ainsi, à l'encontre des évolutions contestées de son prédécesseur, de ressaisir la « phénoménologie » en sa pure possibilité d'avant ce tournant. Comme l'écrit Jean-François Courtine[19], Heidegger ne veut pas dépasser mais créer une nouvelle tendance, l'ontologie phénoménologique mise en œuvre dans Sein und Zeit, « se propose de penser plus originellement ce qu'est la phénoménologie, c'est-à-dire de prendre l'entière mesure de son importance ou de sa signification, fallût-il pour cela aller jusqu'à renoncer au titre de phénoménologie ». Cependant, les deux penseurs conviennent que le « phénomène » possède un sens phénoménologique différent de son sens dit « vulgaire », « n'étant pas immédiatement donné, ne se montre de lui-même que dans une thématisation expresse qui est l'œuvre de la phénoménologie elle-même » écrit Françoise Dastur[20]. Heidegger prend conscience que le « phénomène » a besoin pour se montrer du Logos, qu'il comprend, en revenant à la source grecque, moins comme un discours sur la chose, que d'un « faire voir » écrit Marlène Zarader[21]. Heidegger en déduit sa propre position théorique à savoir que l'ajointement des deux mots, phénomène et logos, dans celui de « phénoménologie » doit signifier « ce qui se montre à partir de lui-même »[22]. En gros, Heidegger se différencie de son maître Husserl, en ce qu'il s'intéresse moins à la relation de l'homme au monde qu'à la « pré-ouverture », autrement dit à la « dimension » qui rend possible la rencontre de ce qu'il appelle « l'étant sous la main » ; en résumé au poids ontologique du « auprès de.. » de « l'être-au-monde », préoccupé dira Paul Ricœur[23]. |

対象 エドムント・フッサールとマルティン・ハイデガーの思想に支配された現代現象学は、「物そのもの」に直行することを目指している。 現象 フッサールが繰り返し強調しているように、現象学はあらゆる先入観や先入観を排除し、「物事そのものを正しく捉えること」に専心する。なぜなら、物事を見 ることは、証明も演繹もできないからだ 」[13]、つまり「物事そのものへ」[N 9]という原則に従って、物事が与えられるありのままの姿を厳密に守ることにある。この厳密な意味において、現象に耳を傾けることは現象学的還元を必要と する。「還元によってのみ、私は超越性を一切持たない絶対的なデータを得る。私が自我と世界、そして自我の経験としての経験を疑問視すると、その経験の知 覚において与えられているもの、つまり私の自我に単に反射的に向けられた視線から、その知覚の現象、例えば私の知覚として把握される知覚という現象が生ま れる。しかし、知覚している間、私は純粋な視線によって知覚を観察することができる […] 自己との関係を脇に置いたり、それを抽象化したりすることができる。そうすることで、そのような視線によって捉えられ、限定された知覚は、あらゆる超越性 を欠いた、現象学の意味での純粋な現象として与えられる絶対的な知覚となる」とフッサールは『現象学の理念』[14] で述べている。 「現象学」という用語を再び取り上げたハイデガーは、一見、師である フッサールの思想の延長線上にあるように見えるかもしれない。しかし、彼はその本質的な部分を排除し、フッサールの「非現象学的転換」と彼が呼んだもの、 つまり、ハイデガーは、フッサールの『アイデア』から読み取った、科学的方法論への傾倒、特に「超越的主体」の確立を、フッサールの「非現象学的転換」と みなして、これを完全に否定したのである。さらに、マルティン・ハイデガーは、逆説的に、「物事そのものへ(Zu den Sachen selbst)」という要求は、まさに物事そのものではなく、私たちが何かと関わるときに「問題となるもの」であると主張した[16]。ハイデガーにとって、現象学が最終的に示すべきものは、まさに存在そのものではなく、その「存在」である。しかし、「それは、ある意味で常に事前に理解されているにもかかわらず、一見しただけでは見せない」とクリスチャン・デュボワは指摘している。 存在がまさに現象であるならば、現象学はそれを、それ自体から現れている姿、つまり、その隠蔽から引き出そうとするのではなく、その隠蔽そのものの中で示すべきである、とシルヴァイン・グルダンは書いている。 ハイデガーは、前任者の物議を醸した変化に反して、この転換以前の純粋な可能性としての「現象学」を取り戻そうとしている。ジャン=フランソワ・クルティ ン[19]が書いているように、 ハイデガーは、それを超えるのではなく、新しい傾向、つまり『存在と時間』で展開された現象学的オントロジーを創り出そうとしている。それは「現象学とは 何かをより独創的に考えること、つまり、たとえ現象学という名称を放棄することになっても、その重要性や意味を完全に理解すること」を提案している。 しかし、二人の思想家は、「現象」は、いわゆる「俗的な」意味とは別の現象学的な意味を持つという点で意見が一致している。フランソワーズ・ダストゥール [20]は、「現象は、すぐに与えられるものではなく、現象学そのものの仕事である、明確な主題化によってのみ自らを現す」と書いている。 ハイデガーは、「現象」が自らを現すためにはロゴスが必要であることを認識し、ギリシャ語の源流に立ち返って、それを物事に関する言説というよりも、「見 せること」と理解したと、マルレーヌ・ザラデルは述べている[21]。ハイデガーはそこから、現象学という用語における「現象」と「ロゴス」という二つの 言葉の結合は、「それ自体から現れるもの」を意味するとする、自身の理論的立場を導き出している[22]。 大まかに言えば、ハイデガーは師であるフッサールとは、人間と世界との関係よりも、「事前開放」、つまり、彼が「手元にある存在」と呼ぶものとの出会いを 可能にする「次元」に関心がある点で異なっている。つまり、ポール・リクールが言うところの、「世界における存在」の「そばにある」という存在論的重み、 つまり「傍にある」という存在論的重みに注目しているのだ。 |

| Une expérience phénoménologique : l'œuvre d'art Article détaillé : L'Origine de l'œuvre d'art.  Temple grec de Ségeste Dans l'esprit du « retour aux choses mêmes », prendre pour objets d'étude l'art et l'expérience que nous en avons montrera ce qui en fait la particularité. Le Dictionnaire des Concepts[24], distingue deux courants principaux : Pour Heidegger, l'œuvre d'art est une puissance qui ouvre et « installe un monde ». L'artiste n'a pas une claire conscience de ce qu'il veut faire, seul le « tout fera l'œuvre ». L'œuvre d'art n'est pas un outil, elle n'est pas une simple représentation mais la manifestation de la vérité profonde d'une chose : « ainsi du temple grec qui met en place un monde et révèle une terre, le matériau qui la constitue, un lieu où elle s'impose (la colline pour le temple), et le fondement secret, voilé et oublié de toute chose »[24]. . La poésie aussi va apparaître comme le dire du décèlement de l'étant à partir de l'être. Le poème, est conçu comme un « appel », appel à ce qui est éloigné à venir dans la proximité. En les nommant[N 10], la « Parole poétique » fait venir les choses en la présence, comme dans ces deux simples vers qui introduisent le poème « soir d'hiver » de Georg Trakl : « Quand il neige à la fenêtre, Que longuement sonne la cloche du soir »[25]. Le deuxième courant, représenté par Maurice Merleau-Ponty s'éloigne tout autant de la représentation idéalisée des choses pour appuyer « sur le vécu et le ressenti avant d'être nommé »[26]. « En peignant, le peintre manifeste et montre comment le monde devient sous et par ses yeux, car le peintre peint à la fois le monde et son monde. Tout en se mettant totalement dans ce qu'il peint, le peintre est le serviteur de ce qui est en face à lui »[26]. |

現象学的体験:芸術作品 詳細記事:芸術作品の起源。  ギリシャのセゲスト神殿 「物事そのものへの回帰」の精神に基づき、芸術とそれに対する我々の体験を研究対象とすることで、その特異性が明らかになる。概念辞典[24]は、主に2つの潮流を区別している。 ハイデガーにとって、芸術作品は「世界を開き、世界を構築する」力である。芸術家は自分が何をしたいのか明確に意識しているわけではない。ただ「全体が作 品を作る」だけである。芸術作品は道具でも、単なる表現でもなく、物事の深層にある真実の現れである。「ギリシャの神殿が世界を構築し、大地、それを構成 する物質、それが存在する場所(神殿にとっては丘)、そしてあらゆるものの隠された、覆い隠され、忘れられた基礎を明らかにするように」[24]。詩もま た、存在から存在を明らかにする言葉として現れる。詩は「呼びかけ」、つまり遠くにあるものを近くに呼び寄せる呼びかけとして考えられている。それらに名 前を付けることで、「詩的な言葉」は物事を現実に呼び寄せる。ゲオルク・トラクルの詩「冬の夜」の冒頭の2行は、その例だ。「窓に雪が降るとき、夕べの鐘 が長く鳴り響く」[25]。 モーリス・メルロー=ポンティに代表される第二の流れは、物事の理想化された表現から同様に距離を置き、「名付けられる前に経験し、感じる」ことを重視す る[26]。「絵を描くことで、画家は、自分の目を通して、また自分の目によって、世界がどのように変化していくかを表現し、示す。なぜなら、画家は世界 と自分の世界の両方を描くからだ。自分が描くものに完全に没頭しながら、画家は自分の目の前にあるものの僕である」[26]。 |

| La méthode Si l'on suit Levinas[27], il n'y aurait pas de méthode proprement phénoménologique, mais seulement des gestes qui révèlent un air de famille de méthodes d'approche entre tous les phénoménologues[N 11]. La « phénoménologie » n'a aucun contenu doctrinal à proposer, souligne de son côté François Doyon[28], il s'agit d'« une science qui n’en finit pas de naître et de renaître sous différentes formes », de quelque chose qui n'est même pas une méthode au sens scientifique, uniquement un « cheminement », un mode d'accès à la « chose »; c'est ce mode d'accès que Martin Heidegger va être amené à justifier dans un long paragraphe (§7) de Être et Temps en prenant appui sur le sens grec initial de ce mot, une fois celui-ci décomposé en ses deux éléments originaires, à savoir, « phénomène » et « logos » (§ 7 Être et Temps). Le philosophe Gérard Wormser[1] écrit que « la méthode distinctive (de la phénoménologie) est la « description eidétique », qui vise à rendre raison de l'essence d'un phénomène à partir de la série des variations dont est susceptible son appréhension ». Par la « réduction » le phénoménologue va chercher à isoler un noyau invariant qui permet « de rendre compte des phénomènes tels qu'ils se présentent dans leur nécessité d'essence »[1]. Levinas recense ainsi, quelques caractéristiques de la geste phénoménologique : 1. la place primordiale accordée à la sensibilité et à l'intuition. « La phénoménologie décrit les modes d'accès de la conscience à la signification, ainsi que le précise Husserl, en explorant les structures de l'intuition objectivante (noèse) et de son corrélat (noématique) en tant qu'il est inclus réellement dans l'intuition au sein de laquelle il se rapporte »[29]. 2. la disparition du concept[30], de l'objet théorique, de l'évidence, du phénomène idéalement parfait, au profit d'une attention portée à l'imperfection du vécu, de l'excédent et du surplus que le théorique laisse échapper, qui vont devenir constitutifs de la vérité du phénomène (ainsi du souvenir, toujours modifié par le présent où il revient, donc absence de souvenir absolu auquel se référer, la préférence accordée avec Kierkegaard, au dieu qui se cache, qui est le vrai dieu de la révélation). Ce qui semblait jusqu'ici un échec, une imperfection de la chose (la brumosité du souvenir), par un retournement radical du regard, devient un mode de son achèvement, sa vérité intrinsèque. 3. la réduction phénoménologique qui autorise la suspension de l'approche naturelle et la lutte contre l'abstraction[N 12]. Dans ses Problèmes fondamentaux de la phénoménologie[31], Heidegger, complète cette approche en distinguant trois éléments constitutifs de la « méthode » phénoménologique : la réduction, la construction et la « destruction », ce dernier élément constituant à la fois le socle et l’apogée de sa méthode phénoménologique selon François Doyon. |

方法 レヴィナス[27]に従えば、現象学的な方法というものは存在せず、すべての現象学者たちのアプローチ方法に共通点を見出すことができる行動があるだけだ [N 11]。フランソワ・ドヨン[28]は、「現象学」は教義的な内容を提供することはなく、「さまざまな形で生まれ、生まれ変わることを繰り返す科学」であ り、科学的な意味での方法ではなく、単に「道筋」、つまり「もの」にアクセスする方法にすぎない、と強調している。この到達方法を、マルティン・ハイデ ガーは『存在と時間』の長い段落(§7)で、この言葉のギリシャ語の本来の意味、すなわち「現象」と「ロゴス」という二つの要素に分解して、その根拠を説 明している(§ 7 『存在と時間』)。 哲学者ジェラール・ウォームサー[1]は、「(現象学の特徴的な)方法は「イデティックな記述」であり、それは、現象の理解が影響を受けうる一連の変動か ら、現象の本質を説明することを目的としている」と書いている。現象学者は「還元」によって、現象を「その本質的な必然性において表現する」[1] ことを可能にする不変の核心を分離しようとする。レヴィナスは、現象学的手法のいくつかの特徴を次のように挙げている。 1. 感受性と直感に最優先の地位を与えること。「現象学は、フッサールが指摘するように、客観化直観(ノエシス)とその相関物(ノエマティクス)の構造を探求 することにより、意識が意味にアクセスする方法を記述する。それは、直観が関連付ける直観に実際に含まれているものとしてである」[29]。 2. 概念[30]、理論上の対象、自明性、理想的に完璧な現象が消滅し、その代わりに、経験の不完全性、理論が逃してしまう過剰や余剰、つまり現象の真実を構 成する要素(したがって、現在に回帰するたびに常に変化する記憶、 つまり、参照すべき絶対的な記憶は存在せず、キルケゴールが、隠れている神、つまり啓示の真の神を優先した)。これまで失敗、つまり物事の不完全性(記憶 の曖昧さ)と思われていたものが、見方を根本的に転換することで、その完成の様式、つまりその本質的な真実となる。 3. 現象学的還元は、自然なアプローチの停止と抽象化との闘いを可能にする[N 12]。 ハイデガーは『現象学の基本問題』[31]の中で、このアプローチを補完し、現象学的「方法」を構成する3つの要素、すなわち還元、構築、そして「破壊」を区別している。フランソワ・ドヨンによれば、この最後の要素は、現象学的方法の基盤であると同時にその頂点でもある。 |

| La réduction phénoménologique Article détaillé : Réduction phénoménologique. La réduction phénoménologique ou épochè en grec (ἐποχή / epokhế) consiste pour Husserl « à suspendre radicalement l'approche naturelle du monde », posé comme objet, réduction à laquelle s'ajoute une lutte sans concession contre toutes les abstractions que la perception naturelle de l'objet présuppose[32],[N 13]. La découverte de la « réduction phénoménologique » a donc le sens d'un dépassement du cartésianisme qui se limite à combattre le doute et requiert pour sa cohésion globale, la garantie divine, note Françoise Dastur[33]. Mais si pour Husserl l'« époché », ἐποχή, ou mise entre parenthèses du monde objectif, constituait l'essentiel de la réduction phénoménologique, il n'en allait pas de même pour Heidegger selon qui le « Monde » n'ayant, par construction, aucun caractère objectif, ce type de réduction s'avérait inutile[34],[N 14]. De plus, pour Heidegger, la phénoménologie ne vaut en tant qu'instrument que pour autant que ses propres présupposés sont pris en compte dans la description elle-même. Par rapport à son maître Husserl, on note un certain nombre d'évolutions décisives telles que la recherche du domaine dit « originaire »[N 15], sis dans l'expérience concrète de la vie, par un processus de « destruction » et d'explicitation, qui vont permettre à une herméneutique de la facticité de se développer[35]. Par contre, selon Alexander Schnell[36], on peut considérer qu'on a avec la définition heideggerienne de la phénoménologie, comme reconduction du regard de l'étant à la compréhension de son être, quelque chose qui est en soi un acte de « réduction phénoménologique ». Avec Heidegger, l'« enquête phénoménologique » ne doit pas tant porter sur les vécus de conscience, comme le croyait Husserl que sur l'être pour qui on peut parler de tels vécus, et qui est par là capable de phénoménalisation, à savoir le Dasein, c'est-à-dire, l'existant. Christoph Jamme[37] écrit : « la phénoménologie doit être élaborée comme une auto-interprétation de la vie factive […]. Heidegger définit ici la phénoménologie comme science originaire de la vie en soi ». En fait, la « réduction phénoménologique » va jouer, dans Être et Temps, un rôle essentiel dans l’analytique du Dasein, notamment dans l'analyse de la quotidienneté et la mise à jour des structures existentiales du Dasein, en exigeant un regard résolument plus « authentique »[38]. La réduction dans Être et Temps, conclut François Doyon, « apparaît comme un parcours de détachement progressif à l’aveuglement de la quotidienneté du monde ambiant afin de s’exposer résolument à la finitude radicale de son être ». |

現象学的還元 詳細記事:現象学的還元。 現象学的還元、あるいはギリシャ語でエポケー(ἐποχή / epokhế)とは、フッサールによれば「世界に対する自然なアプローチを根本的に停止すること」であり、対象として設定されたものに対する還元である。 この還元には、対象に対する自然な知覚が前提とするあらゆる抽象概念に対する妥協のない闘争が加わる[32]。[N 13]。したがって、「現象学的還元」の発見は、疑念と闘うことに限定され、その全体的な結束のために神の保証を必要とするデカルト主義を超越する意味を 持つと、フランソワーズ・ダストゥールは述べている[33]。 しかし、フッサールにとって「エポケー」、ἐποχή、つまり客観的世界を括弧で囲むことが現象学的還元の本質であったのに対し、ハイデガーにとってはそ うではなかった。ハイデガーによれば、「世界」は構造上、客観的性格をまったく持たないため、この種の還元は役に立たないものだった[34]、[N 14]。 さらに、ハイデガーにとって、現象学は、その前提自体が記述の中で考慮されている場合にのみ、手段としての価値がある。師であるフッサールと比較すると、 具体的な生活経験にある「原初的」領域[N 15]を「破壊」と明示のプロセスによって探求し、事実性の解釈学を発展させるという、いくつかの決定的な進化が見られる[35]。 一方、アレクサンダー・シュネルによれば、ハイデガーの現象学の定義は、存在の理解からその存在の理解へと視線を戻すものであり、それ自体が「現象学的還 元」の行為であると考えられる。ハイデガーによれば、「現象学的調査」は、フッサールが考えていたような意識の体験よりも、そのような体験について語るこ とができ、それによって現象化が可能である存在、すなわちダセイン、つまり存在者について行うべきである。クリストフ・ジャム[37]は、「現象学は、事 実上の生活に対する自己解釈として構築されなければならない[…]。ハイデガーはここで、現象学を、生活そのものに由来する科学として定義している」と書 いている。 実際、『存在と時間』において「現象学的還元」は、ダセインの分析、特に日常性の分析とダセインの実存的構造の解明において、より「真正」な視点[38] を求めることで、重要な役割を果たす。『存在と時間』における還元は、フランソワ・ドヨンが結論づけるように、「周囲の世界の日常性による盲目性から徐々 に脱却し、自らの存在の根本的な有限性に断固として直面するための道筋として現れる」のだ。 |

| La construction phénoménologique C'est à l'opération d'induction de l'« être », qui n'apparaît jamais spontanément, à partir de l'étant que Heidegger a donné le nom de « construction phénoménologique »[39], c'est une tâche, un projet, qu'il revient au Dasein de réaliser sachant « qu'il n'y a d'être que s'il y a compréhension de l'être, c'est-à-dire si le Dasein existe »[40]. Pour Heidegger, « l’interprétation existentiale du Dasein, comme souci, dans Être et Temps, est une construction ontologique qui possède un sol et une pré-esquisse élémentaire »[41]. |

現象学的構築 ハイデガーは、存在から「存在」を誘導する操作を「現象学的構築」と呼んだ。この操作は決して自発的には現れない。」と呼んだ。これは、ダセインが「存在 は、存在の理解、すなわちダセインの存在があって初めて存在する」[40]ことを認識した上で、達成すべき課題、計画である。ハイデガーにとって、「『存 在と時間』における、関心としてのダセインの実存的解釈は、基盤と基本的な下書きを持つ存在論的構築物である」[41]。 |

| La destruction phénoménologique Articles détaillés : Déconstruction (Heidegger) et Heidegger et Aristote. La « construction réductrice de l’être », en tant qu’interprétation conceptuelle de l’être et de ses structures, implique donc nécessairement une « destruction phénoménologique », c’est-à-dire une « dé-construction » ou démontage critique préalable des concepts légués par la tradition philosophique. Sophie-Jan Arrien[42] note que Heidegger délaisse très rapidement la réduction phénoménologique husserlienne pour lui préférer une méthodologie de la « déconstruction» « qui loin d'être une mise entre parenthèses du caractère facticiel des phénomènes en jeu (le soi, l'histoire, la foi), consiste plutôt à partir d'une explicitation[N 16] critique de ces concepts, en une traversée de la vie telle qu'elle se phénoménalise et se donne facticiellement »[42]. La « destruction phénoménologique » se donne pour tâche de démanteler les constructions théoriques, philosophiques ou théologiques qui recouvrent notre expérience de la vie facticielle et que nous devons faire apparaître. La tâche essentielle consistera à se rapprocher, par exemple, de l’Aristote originel, en se détournant de la scolastique médiévale qui le recouvre. De même, la destruction des présupposés de la science esthétique, qui va « permettre d'accéder à l'œuvre d'art pour la considérer en elle-même »[43], est solidaire de la destruction de l'histoire de l'ontologie. C'est surtout dans son travail sur Aristote que Heidegger a pu préciser sa propre conception de la phénoménologie. Philippe Arjakovsky[44] parle de « travail d'« anabase » que Heidegger a effectué pour dégager les soubassements tant ontologiques qu'existentiels de la Logique aristotélicienne[…] » ainsi est apparu en pleine lumière, le concept originaire de « phénomène » tel qu'il était compris par les grecs, c'est-à-dire, comme « ce qui se montre de soi-même ». Mais comme pour Heidegger les « choses mêmes » ne se donne justement pas dans une intuition immédiate, il se sépare à cette occasion définitivement de Husserl, pour s'engager résolument dans le « cercle herméneutique »[45]. Autre exercice de déconstruction, le démantèlement de la tradition théologique avec laquelle il tentera, en s'inspirant de Luther et de Paul, de retrouver la vérité première du message évangélique, qu'il considère obscurcie et voilée dans la « Scolastique » inspirée d'Aristote[46]. |

現象学的破壊 詳細記事:脱構築(ハイデガー)およびハイデガーとアリストテレス。 存在とその構造に関する概念的な解釈としての「存在の還元的な構築」は、必然的に「現象学的破壊」、すなわち哲学の伝統によって受け継がれてきた概念の 「脱構築」や事前の批判的分解を意味する。ソフィー=ジャン・アリエン[42]は、ハイデガーがフッサールの現象学的還元を非常に早く放棄し、代わりに 「脱構築」という方法論を好んだと指摘している。「これは、問題となっている現象(自己、歴史、信仰)の虚構的な性格を括弧で囲むこととは程遠く、むしろ これらの概念を批判的に明示すること[N 16] から出発し、現象として現れ、虚構的に与えられる人生を横断することである」[42] と指摘している。 「現象学的破壊」は、私たちの虚構的な人生の経験に覆い被さっている、理論的、哲学的、神学的構築物を解体し、それを明らかにすることをその任務としてい る。その本質的な任務は、例えば、中世のスコラ哲学から距離を置き、それを覆い隠しているものから離れて、原初のアリストテレスに近づくことにある。同様 に、美的科学の前提を破壊することは、「芸術作品にアクセスし、それをそれ自体として考察することを可能にする」[43]ものであり、存在論の歴史の破壊 と連帯している。ハイデガーは、とりわけアリストテレスに関する研究を通じて、現象学に関する自身の考えを明確にした。フィリップ・アルジャコフスキー [44]は、アリストテレスの論理学の「存在論的かつ実存的な基礎を明らかにするためにハイデガーが行った「アナバシス」の作業」について述べている。こ うして、ギリシャ人が理解していた「現象」という本来の概念、すなわち「自ら現れるもの」という概念が、はっきりと明らかになった。 しかし、ハイデガーにとって「物自体」は即座の直感では理解できないため、彼はこの点でフッサールと完全に決別し、「解釈学の輪」[45]に断固として取り組むことになる。 もうひとつの脱構築の試みとして、彼は、ルターやパウロに触発され、アリストテレスに触発された「スコラ哲学」によって覆い隠され、不明瞭になったと彼が考える福音のメッセージの本来の真実を見出そうとして、神学の伝統の解体に取り組んだ[46]。 |

| Le statut de la phénoménologie Dans sa volonté de saisir le sens du monde en écartant tous les préjugés comme en renonçant à se situer dans un monde prédonné ou préformé, « la phénoménologie ne rejoint pas une rationalité déjà donnée, elle l'établit par une initiative qui n'a pas de garantie dans l'être et dont le droit repose entièrement sur le pouvoir effectif qu'elle nous donne d'assumer notre histoire […] la phénoménologie comme révélation du monde repose sur elle-même se fonde sur elle-même. Car elle ne peut s'appuyer comme les autres connaissances sur un sol de présuppositions acquises. Il en résulte un redoublement infini d'elle-même. […] Elle se redoublera donc indéfiniment, elle sera comme le dit Husserl un dialogue ou une méditation infinie et dans la mesure où elle reste fidèle à son intention, elle ne saura jamais où elle va » écrit Bernhard Waldenfels dans sa contribution[47]. |

現象学の地位 あらゆる偏見を排除し、あらかじめ与えられた、あるいはあらかじめ形成された世界の中に自分の立場を置くことを放棄することで、世界の意味を理解しようと するその意志において、 「現象学は、すでに与えられた合理性に合致するものではなく、存在において保証のない、その権利が完全に、私たちの歴史を引き受ける力を私たちに与えると いう事実に基づく、独自の取り組みによってそれを確立するものである。[…] 世界を明らかにする現象学は、それ自体に基づいており、それ自体に立脚している。なぜなら、他の知識のように、既得の前提という土台に立脚することはでき ないからだ。その結果、現象学は無限に自己を倍増させることになる。[…] したがって、現象学は際限なく二重化され、フッサールが言うように、無限の対話あるいは瞑想となり、その意図に忠実であり続ける限り、その行き先を決して 知ることができない」と、ベルンハルト・ヴァルデンフェルスは自身の論文で述べている[47]。 |

| Les grandes avancées husserliennes Principaux ouvrages : Ideen, Krisis.., Méditations cartésiennes, Leçons pour une phénoménologie de la conscience intime du temps. |

フッサールの大きな進歩 主な著作:『観念』『危機』『デカルト的省察』『時間の本質に関する現象学のための講義』 |

| L'idée de phénoménologie chez Husserl La phénoménologie de Edmund Husserl se définit d'abord comme une science transcendantale qui veut mettre au jour les structures universelles de l'objectivité. Le premier objectif poursuivi fut d'assurer un fondement indubitable aux sciences et pour cela d'éclairer les conditions théoriques de toute connaissance possible[N 17]. Le projet de la phénoménologie fut d'abord de refonder la science en remontant au fondement de ce qu'elle considère comme acquis et en mettant au jour le processus de sédimentation des vérités qui peuvent être considérées comme éternelles. La phénoménologie propose une appréhension nouvelle du monde, complètement dépouillée des conceptions naturalistes. D'où ce leitmotiv des phénoménologues qu'est le retour aux choses mêmes. Les phénoménologues illustrent ainsi leur désir d'appréhender les phénomènes dans leur plus simple expression et de remonter au fondement de la relation intentionnelle[N 18]. Husserl espère ainsi échapper à la crise des sciences qui caractérise le xxe siècle. C'est avec la reprise détournée du concept d'intentionnalité, empruntée à son maître Franz Brentano, que Husserl consacre ses premiers pas en phénoménologie. Son principe est simple : toute conscience doit être conçue comme « conscience de quelque chose ». En conséquence, la phénoménologie va prendre pour point de départ la description des vécus de conscience afin d'étudier la constitution essentielle des expériences ainsi que l'essence de ce vécu[N 19]. L'intuition fondamentale de Husserl, de ce point de vue, a consisté à dégager ce qu'il appelle l’« a priori universel de corrélation », qui désigne le fait que le phénomène tel qu'il se manifeste est constitué par le sujet, que dont chaque chose a, à chaque fois, pour chaque homme une apparence différente. Husserl ne verse pas pour autant dans le relativisme bien au contraire puisqu'il affirme que cette corrélation subjective est une nécessité d'essence. Ce qui veut dire que l'étant n'est pas autrement qu'il nous apparaît, il n'y a plus de chose en soi[48],[N 20]. En ce sens, on peut donc bien dire que la phénoménologie est une science des phénomènes, mais à condition d'y entendre qu'elle a une vocation descriptive des vécus (de l'expérience subjective). Pour autant, l'activité constitutive du sujet de la corrélation ne doit pas faire croire que la phénoménologie serait un pur subjectivisme. Comme le dit Merleau-Ponty, « le réel est un tissu solide, il n'attend pas nos jugements pour s'annexer les phénomènes », et en conséquence, « la perception n'est pas une science du monde, ce n'est même pas un acte, une prise de position délibérée, elle est le fond sur lequel tous les actes se détachent et elle est présupposée par eux »[49]. La phénoménologie husserlienne se veut également une science philosophique, c'est-à-dire universelle. De ce point de vue, elle est une science apriorique, ou éidétique, à savoir une science qui énonce des lois dont les objets sont des « essences immanentes »[N 21]. Le caractère apriorique de la phénoménologie oppose la phénoménologie transcendantale de Husserl à la psychologie descriptive de son maître Franz Brentano, qui en fut néanmoins, à d'autres égards, un précurseur. La phénoménologie doit en ce sens se distinguer de l'ousiologie, laquelle, comme science philosophique, a pour but l'étude des essences indépendamment de toute subjectivité exclusivement constituante. Échappant à ces déterminations traditionnelles, on signale pour mémoire la dimension radicale de l'interprétation de cette pensée par son secrétaire particulier Eugen Fink[50] dans son ouvrage De la phénoménologie. |

フッサールの現象学における考え方 エドムント・フッサールの現象学は、まず第一に、客観性の普遍的な構造を明らかにしようとする超越論的科学として定義される。その第一の目的は、科学に疑 いの余地のない基礎を確立し、そのためにはあらゆる知識の理論的条件を明らかにすることだった。現象学のプロジェクトは、まず、科学が当然のことと考えて いるものの基礎に立ち返り、永遠とみなせる真理の堆積過程を明らかにすることで、科学を再構築することだった。 現象学は、自然主義的な概念を完全に排除した、世界に対する新しい理解を提案している。そこから、現象学者たちのレトモティフである「物事そのものへの回 帰」が生まれた。現象学者たちは、現象を最も単純な表現で理解し、意図的な関係の基礎に立ち返りたいという願望を、このように表現している。 フッサールは、20世紀を特徴づける科学の危機から逃れることを望んでいる。フッサールは、師であるフランツ・ブレンターノから借りた意図性の概念を間接 的に採用することで、現象学への第一歩を踏み出した。その原理は単純だ。あらゆる意識は「何かに対する意識」として理解されなければならない。その結果、 現象学は、経験の本質と、その経験の本質を研究するために、意識の体験の記述を出発点とする。 この観点から、フッサールの基本的な直感は、彼が「普遍的相関の先験的原理」と呼ぶものを明らかにすることだった。これは、現象はそれが現れる形で主体に よって構成されており、あらゆるものは、あらゆる人にとって、その都度、異なる外観を持つという事実を指している。しかし、フッサールは相対主義に陥って いるわけではない。むしろ、この主観的な相関は本質的に必要なものであると主張している。つまり、存在は私たちに現れる姿以外の姿はなく、物自体というも のはもはや存在しないということだ[48]、[N 20]。この意味で、現象学は現象の科学であると言えるが、それは、現象学が(主観的な経験という)体験を記述する役割を担っていることを理解することを 条件とする。とはいえ、相関の主体の構成的活動は、現象学が純粋な主観主義であると思わせるべきではない。メルロ=ポンティが言うように、「現実とは堅固 な織物であり、現象を併合するために我々の判断を待つことはない」ため、「知覚は世界に関する科学ではなく、行為でも、意図的な立場表明でもなく、あらゆ る行為が浮かび上がる背景であり、それらによって前提とされている」 」[49]。 フッサールの現象学は、哲学的、つまり普遍的な科学でもある。この観点から、それは先験的、つまりイデティックな科学であり、その対象が「内在的な本質」 [N 21]である法則を述べる科学である。現象学の先験的性格は、フッサールの超越論的現象学を、その師であるフランツ・ブレンターノの記述心理学と対比させ る。しかし、他の点では、ブレンターノは先駆者であった。この意味で、現象学は、哲学的科学として、あらゆる主観性を排除した本質の研究を目的とする実体 論とは区別されなければならない。 こうした伝統的な決定から逃れる形で、彼の秘書オイゲン・フィンク[50] が著書『現象学について』で示した、この思想の解釈の急進的な側面が注目される。 |

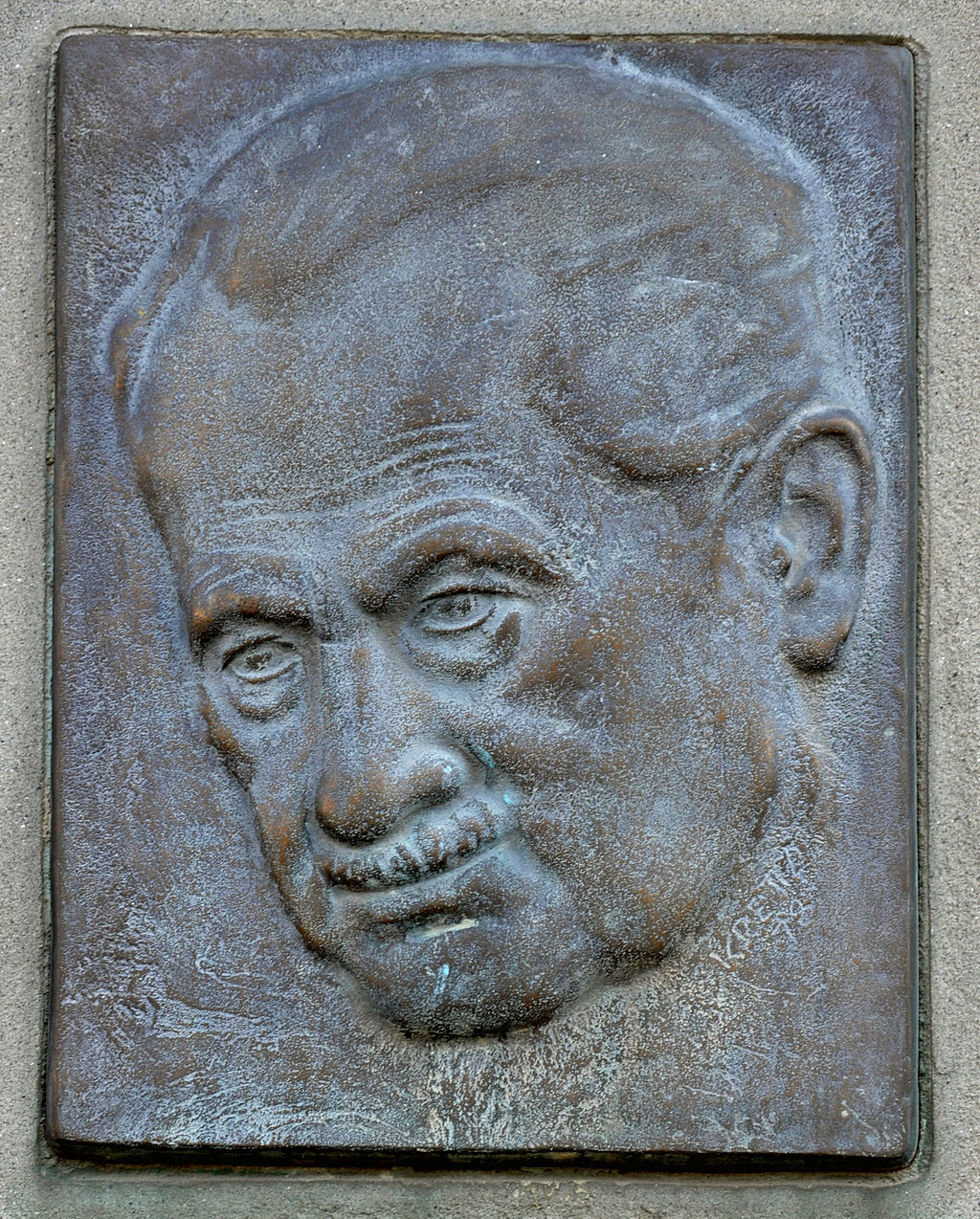

| Le concept d'Intentionnalité Article détaillé : Intentionnalité.  Franz Brentano « La phénoménologie c'est l'Intentionnalité » affirme ni plus ni moins, Levinas[51]. Heidegger donnerait son accord à cette parole, encore faut-il préciser les contours qu'il donne au concept d'« Intentionnalité », concept qu'il puise principalement dans les cinquième et sixième « Recherches logiques » de Edmund Husserl, que lui-même avait hérité de Brentano note Jean Greisch[52],[N 22]. Traits généraux du concept d'intentionnalité L'« Intentionnalité » qui est depuis Franz Brentano, un « se diriger sur », n'est plus une mise en rapport externe, mais une « structure interne à la conscience » souligne Jean Greisch[53]. Avec Husserl cette conscience ne va plus être considérée comme un simple contenant, réceptacle des images et des choses, ce qu'elle était depuis Descartes ; l'acte de conscience devient une intentionnalité visant un objet nécessairement transcendant précise Françoise Dastur[54],[N 23]. Le même raisonnement est à appliquer aux actes de représentation quels qu'ils soient, chacun tire son sens de la spécificité de l'acte intentionnel. « Tout savoir d'objet est toujours simultanément un savoir que le « Moi » a de lui-même, et ceci n'est point simplement un fait psychique, c'est bien plus une structure d'essence de la conscience » comprend de son côté Eugen Fink[55]. Le fait que l'« Intentionnalité » soit un « a priori » appartenant à « la structure du vécu et non une relation construite après coup » entraîne un sens spécifiquement phénoménologique à la notion d'acte et notamment pour ce qui concerne l'acte de représentation qui peut emprunter selon Heidegger deux directions différentes, la voie naïve qui nous dit par exemple que ce fauteuil est confortable et lourd ou l'autre qui va s'inquiéter de son poids et de ses dimensions[53]. Structure du concept C'est à Husserl que l'on doit la découverte que la connaissance implique au moins deux moments intentionnels successifs (que Heidegger portera à trois), un premier acte correspondant à une visée de sens qui se trouve ultérieurement comblé par un acte intentionnel de remplissement[56]. Heidegger saura s'en souvenir dans sa théorie du Vollzugsinn ou sens de « l'effectuation » qui domine sa compréhension de la vie facticielle et qui fait suite à deux autres moments intentionnels, le Gehaltsinn (teneur de sens), et le Bezugsinn (sens référentiel). C'est la structure intentionnelle de la vie facticielle qui nous livre ce ternaire. Pour une analyse approfondie de ces concepts voir Jean Greisch[57]. L'intuition catégoriale Dans la VIe de ses « Recherches logiques », Husserl, grâce au concept d'« intuition catégoriale »[58], « parvient à penser le catégorial comme donné, s'opposant ainsi à Kant et aux néo-kantiens qui considéraient les catégories comme des fonctions de l'entendement »[59]. Il faut comprendre cette expression d'« intuition catégoriale » comme « la simple saisie de ce qui est là en chair et en os tel que cela se montre » nous dit Jean Greisch. Appliquée jusqu'au bout cette définition autorise le dépassement de la simple intuition sensible soit par les actes de synthèse[N 24], soit par des actes d'idéation. Un exemple de l'extraordinaire fécondité de cette découverte nous est donnée dans les avancées qu'elle a permises pour délivrer Heidegger du carcan du sens attributif de la copule. Dans la proposition « le tableau est mal placé », « l'entrelacement du nom et du verbe fait que la proposition ajoute aux termes isolés, une composition qui relie et sépare donnant à voir un rapport irréductible à une relation formelle, rapport sur lequel elle se fonde plutôt qu'elle ne la fonde »[60],[N 25]. |

意図性の概念 詳細な記事:意図性。  フランツ・ブレンターノ 「現象学とは意図性である」とレヴィナスは断言している[51]。ハイデガーもこの言葉に同意するだろう。しかし、彼が「意図性」という概念に与えた輪郭 を明確にする必要がある。この概念は、エドムント・フッサールの『論理学研究』第5巻および第6巻から主に引き出されたものであり、フッサール自身がブレ ンターノから受け継いだものであると、ジャン・グレイシュは指摘している[52]、[N 22]。 意図性の概念の一般的な特徴 フランツ・ブレンターノ以来、「意図性」は「向かっていくこと」であり、もはや外的な関連付けではなく、「意識の内部構造」であるとジャン・グレイシュは 強調している[53]。フッサールによれば、この意識は、デカルト以来の、単なるイメージや事象の容器、受け皿とは見なされなくなった。意識の行為は、必 然的に超越的な対象を目指す意図性となる、とフランソワーズ・ダストゥールは述べている[54]、[N 23]。 同じ考え方は、あらゆる表現行為にも当てはまる。それぞれの行為は、意図的な行為の特殊性からその意味を引き出すのだ。「対象に関するあらゆる知識は、常 に同時に『自我』がそれ自体について持つ知識でもあり、これは単なる精神的な事実ではなく、むしろ意識の本質的な構造である」と、オイゲン・フィンクは理 解している[55]。 「意図性」が「経験の構造に属する先験的なものであり、後付けで構築された関係ではない」という事実は、行為の概念、特に表象行為に、現象学的に特有の意 味をもたらす。ハイデガーによれば、表象行為は二つの異なる方向、 例えば、この椅子は快適で重いという素朴な道と、その重さや大きさを気にする道だ。 概念の構造 知識には少なくとも2つの連続した意図的瞬間(ハイデガーはこれを3つとする)が含まれるという発見は、フッサールによるものである。最初の行為は意味の 指向に対応し、それは後に意図的な充足行為によって満たされる[56]。ハイデガーは、事実的な生活に対する理解を支配する「実行の意味」である Vollzugsinn の理論において、このことを思い出すことになる。この理論は、他の 2 つの意図的瞬間、すなわち Gehaltsinn(意味内容)と Bezugsinn(参照意味)に続くものである。事実的な生活の意図的構造が、この 3 つを私たちに提供しているのだ。これらの概念の詳細な分析については、ジャン・グレイシュを参照のこと。 カテゴリー的直観 『論理学研究』第6巻において、フッサールは「カテゴリー的直観」の概念によって [58]という概念によって、「カテゴリーを、与えられたものとして考えることに成功し、カテゴリーを理性の機能とみなしたカントや新カント派に対抗した」[59]。 この「カテゴリー的直観」という表現は、「そこにあるものを、それが現れているままの、ありのままの姿で単純に把握すること」と理解すべきだと、ジャン・ グレイシュは述べている。この定義を徹底的に適用すると、統合[N 24]の行為、あるいは観念形成の行為によって、単純な感覚的直観を超越することが可能になる。 この発見の驚くべき実り多さを示す一例は、ハイデガーを、述語の帰属的意味という束縛から解放する上で、この発見がもたらした進歩に見ることができる。 「その絵は不適切な場所に置かれている」という文では、「名詞と動詞が絡み合うことで、この文は個別の用語に加えて、結びつけ、分離する構成要素を加え、 形式的な関係に還元できない関係、つまり、その関係に基づいて成立するよりも、むしろその関係そのものを示すものとなっている」[60]、[N 25]。 |

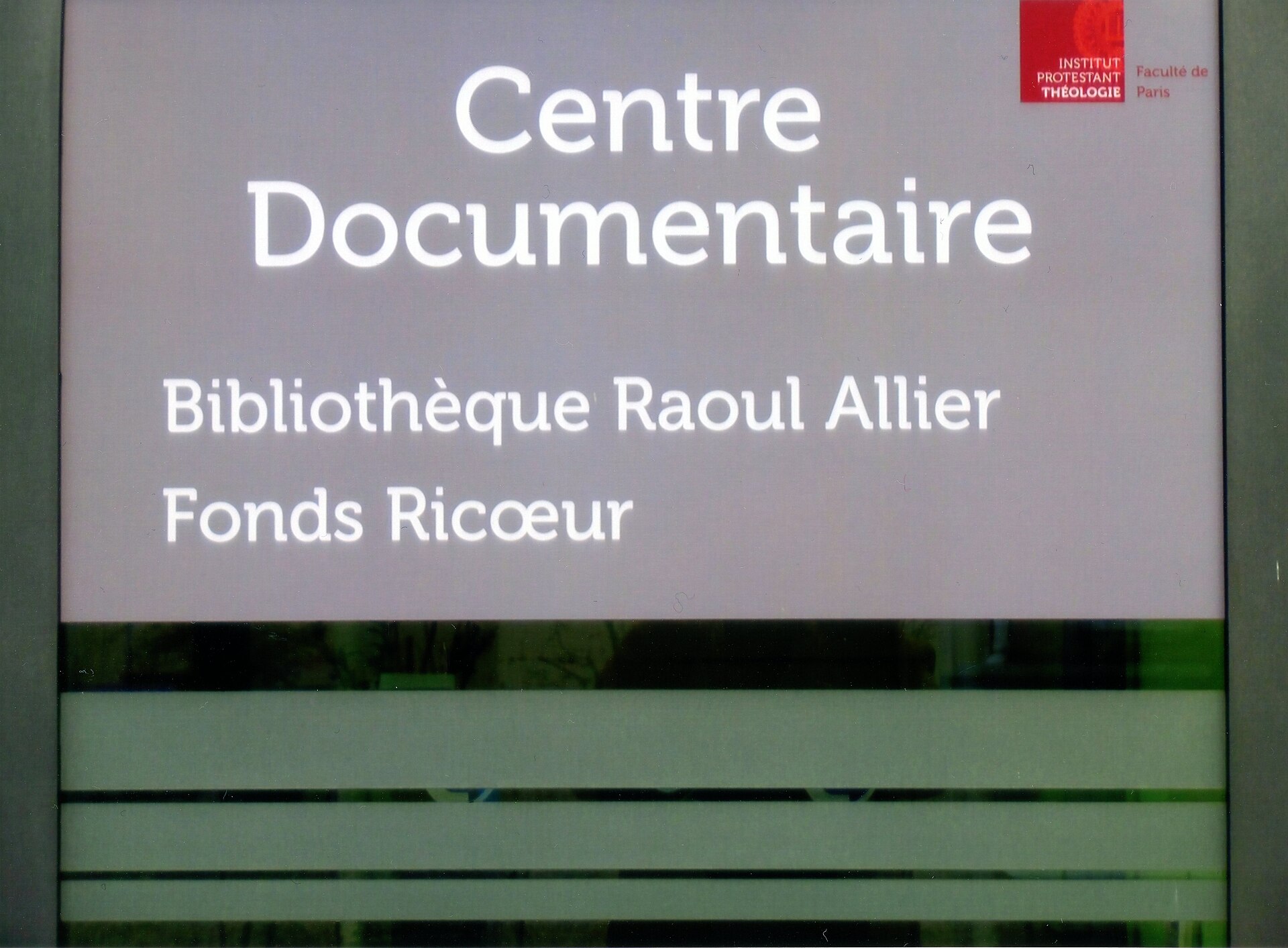

| La postérité d'Husserl Article connexe : Heidegger et la phénoménologie. Les héritiers immédiats  Centre de Recherches Phénoménologiques et Herméneutiques du CNRS, dirigé par Paul Ricœur, avenue Parmentier à Paris.  Le Fonds Ricœur à Paris. En 1933, le philosophe Eugen Fink, abandonne la carrière universitaire, pour devenir son secrétaire privé jusqu'à la mort de son maître en 1938. Il est l'auteur de trois ouvrages remarquables de commentaires et de développement à partir de l'œuvre de son mentor, traduits en français : De la phénoménologie[61], la Sixième Méditation cartésienne[62] et Autres rédactions des Méditations cartésiennes[63]. Comme élève et proche compagnon il y eut aussi, un temps, Martin Heidegger, à qui fut confié la publication de son ouvrage Leçons pour une phénoménologie de la conscience intime du temps. Hans-Georg Gadamer, un autre de ses élèves, rapporte que Husserl disait que, au moins dans la période de l'entre-deux-guerres, « la phénoménologie, c'est Heidegger et moi-même »[64]. Dans une « lettre à Husserl » d'octobre 1927, Heidegger a bien mis en évidence la question qui le séparait de son maître : « Nous sommes d'accord sur le point suivant que l'étant, au sens de ce que vous nommez "monde" ne saurait être éclairé dans sa constitution transcendantale par retour à un étant du même mode d'être. Mais cela ne signifie pas que ce qui constitue le lieu du transcendantal n'est absolument rien d'étant - au contraire le problème qui se pose immédiatement est de savoir quel est le mode d'être de l'étant dans lequel le "monde" se constitue. Tel est le problème central de Sein und Zeit - à savoir une ontologie fondamentale du Dasein »[65]. Autrement dit, l'enquête phénoménologique, pour Heidegger, ne doit pas tant porter sur les vécus de conscience, que sur l'être pour qui on peut parler de tels vécus, et qui est par là capable de phénoménalisation, à savoir le Dasein, c'est-à-dire, l'existant. Le conflit phénoménologique entre Husserl et Heidegger a influencé le développement d'une phénoménologie existentielle et de l'existentialisme : en France, avec les travaux de Jean-Paul Sartre et de Simone de Beauvoir ; en Allemagne avec la phénoménologie de Munich (Johannes Daubert, Adolf Reinach) et Alfred Schütz ; en Allemagne et aux États-Unis avec la phénoménologie herméneutique de Hans-Georg Gadamer et de Paul Ricœur[66]. La philosophie husserlienne fut ensuite développée, et en des sens souvent infléchis, par des penseurs aussi divers que Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Max Scheler, Hannah Arendt, Gaston Bachelard, Dietrich von Hildebrand, Jan Patočka, Jean-Toussaint Desanti, Guido Küng[réf. nécessaire] et Emmanuel Levinas. Emmanuel Levinas[67], se penche sur l'évolution du concept d'« intentionnalité ». En tant que compréhension d'être, c'est toute l'existence du Dasein qui se trouve concernée par l'intentionnalité. Il en est ainsi du sentiment qui lui aussi vise quelque chose, ce quelque chose qui n'est accessible que par lui. « L'intentionnalité du sentiment n'est qu'un noyau de chaleur auquel s'ajoute une intention sur un objet senti ; cette chaleur effective qui est ouverte sur quelque chose à laquelle on accède en vertu d'une nécessité essentielle que par cette chaleur effective, comme on accède par la vision seule à la couleur ». Jean Greisch[68] a cette formule étonnante « le vrai visage -vu de l'intérieur-de l'intentionnalité n'est pas le « se-diriger-vers » mais le devancement de soi du souci ». |

フッサールの後継者たち 関連項目:ハイデガーと現象学。 直接の後継者たち  CNRS(フランス国立科学研究センター)の現象学・解釈学研究センター。ポール・リクールが所長を務め、パリのパルマンティエ通りに所在。  パリのリクール基金。 1933年、哲学者オイゲン・フィンクは学界を離れ、1938年に師が亡くなるまでその私設秘書を務めた。彼は、師匠の著作に基づいて、3冊の注目すべき 解説書および発展書を執筆し、それらはフランス語に翻訳されている。それらは、『現象学について』[61]、『デカルトの第六瞑想』[62]、『デカルト の瞑想に関するその他の論文』[63]である。 弟子であり親しい仲間として、一時期、マルティン・ハイデガーもいた。彼は、フッサールの著作『時間の本質に関する現象学講義』の出版を任されていた。別 の弟子であるハンス=ゲオルク・ガダマーは、少なくとも戦間期には、フッサールが「現象学とはハイデガーと私である」[64] と語っていたと伝えている。1927年10月の「フッサールへの手紙」の中で、ハイデガーは師と自分を隔てる問題を明確に指摘している。「私たちは、あな たが『世界』と呼ぶ意味での存在は、同じ存在様式を持つ存在に立ち返ってその超越的な構成を明らかにすることはできないという点で意見が一致している。し かし、それは、超越的な場所を構成するものが、まったく存在ではないことを意味するわけではない。それどころか、すぐに生じる問題は、「世界」が構成され る存在のあり方は何か、ということだ。これが『存在と時間』の中心的な問題、すなわち、ダセインの基本的な存在論である」[65]。つまり、ハイデガーに とって、現象学的調査は、意識の体験そのものよりも、そのような体験について語ることができ、それによって現象化が可能である存在、すなわちダセイン、つ まり存在するものについて行うべきだということだ。 フッサールとハイデガーの現象学的対立は、実存的現象学と実存主義の発展に影響を与えた。フランスではジャン=ポール・サルトルとシモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォ ワールの研究、ドイツではミュンヘン現象学(ヨハネス・ダウベルト、アドルフ・ライナッハ)とアルフレート・シュッツ ドイツとアメリカでは、ハンス=ゲオルク・ガダマーとポール・リクールによる解釈学的現象学がそれにあたる[66]。 フッサールの哲学はその後、モーリス・メルロー=ポンティ、マックス・シェラー、ハンナ・アーレント、ガストン・バシュラール、ディートリッヒ・フォン・ ヒルデブランド、ヤン・パトチカ、ジャン=トゥーサン・デサンティ、グイド・キュング[要出典]、エマニュエル・レヴィナスなど、さまざまな思想家たちに よって、しばしば異なる方向へと発展していった。 エマニュエル・レヴィナス[67]は、「意図性」の概念の変遷について考察している。存在の理解として、意図性はダゼインの存在全体に関わるものである。 感情もまた、それによってのみ到達可能な何かを指し示すものであり、その点でも同様である。「感情の意図性は、感じられた対象に対する意図が加わった、熱 の核にすぎない。この実効的な熱は、本質的な必要性によってのみアクセスできる何かに開かれている。それは、視覚だけで色にアクセスするのと同じであ る」。ジャン・グレイシュ[68]は、「意図性の真の姿は、内部から見た場合、『向かっていく』ことではなく、自己の懸念を先取りすることである」という 驚くべき表現をしている。 |

| Élargissement heideggérien Délaissant l'ontologie spéculative et la phénoménologie descriptive, Heidegger considère dans Être et Temps (SZ p. 38)[N 26], « que l'ontologie et la phénoménologie devaient bel et bien partir de l'« herméneutique » du Dasein » écrit Jean Grondin[69]. S'il a été beaucoup dit que la phénoménologie de Heidegger était une herméneutique Jean Grondin[70] souligne que l'herméneutique est elle-même une phénoménologie au sens où « il s'agit de reconquérir le phénomène du Dasein contre sa propre dissimulation ». Parce qu'une chose peut se montrer en soi-même, remarque Heidegger, elle peut se montrer autre qu'elle n'est (apparence) ou indiquer autre chose (indice), note Marlène Zarader[71]. Chez Heidegger il n'y a pas d'inconnaissable en arrière-plan comme chez Kant (la chose en soi), ce qui est « phénomène » de façon privilégié selon François Vezin[72] « c'est quelque chose qui le plus souvent ne se montre justement pas, qui à la différence de ce qui se montre d'abord et le plus souvent est en retrait mais qui est quelque chose qui fait corps avec ce qui se montre de telle sorte qu'il en constitue le sens le plus profond ». Dans une opposition frontale à Husserl, Heidegger avance (SZ p. 35) que la phénoménologie a pour but de mettre en lumière ce qui justement ne se montre pas spontanément de lui-même et se trouve le plus souvent dissimulé confirme Jean Grondin[73], d'où la nécessité d'une herméneutique comme le remarque Marlène Zarader.« Si le phénomène est ce qui se montre, il sera l'objet d'une description […] ; si le phénomène est ce qui se retire dans ce qui se montre, alors il faut se livrer à un travail d'interprétation ou d'explicitation de ce qui se montre, afin de mettre en lumière ce qui ne s'y montre pas de prime abord et le plus souvent »[74]. Après Être et temps, Heidegger ne s'intéressera plus à la description du sens de l'Être à partir du Dasein « mais il tente de le faire voir tel qu'il se déploie dans et par la pensée » écrit Sylvaine Gourdain[18], qui fait par ailleurs en note la remarque suivante : « Sans doute faudrait-il préciser et dire qu'il s'agit (avec Heidegger) d'une phénoméno-logie, c'est-à-dire non d'une science descriptive et épistémologique des phénomènes tels qu'ils apparaissent à la conscience mais d'une pensée ou d'un dire du seul « phénomène », qui en réalité intéresse Heidegger, à savoir l'« Être » ». |

ハイデガーの拡張 思索的な存在論と記述的な現象学を捨て、ハイデガーは『存在と時間』(SZ p. 38)[N 26]の中で、「存在論と現象学は、まさにダセインの「解釈学」から出発すべきである」と述べている、とジャン・グロンダン[69]は記している。ハイデ ガーの現象学は解釈学であるとの見方が多くあるが、ジャン・グロンダン[70]は、解釈学自体が「実存の現象を、それ自身の隠蔽から取り戻すこと」という 意味で現象学である、と強調している。 物事はそれ自体で現れることができるため、ハイデガーは、それがそれ自体とは異なるもの(外観)として現れたり、別のものを示したり(兆候)することがで きる、と述べている[71]。ハイデガーには、カントのように(物自体という)背景にある知ることのできないものは存在しない。フランソワ・ヴェザンによ れば、それは「現象」という特権的なものである[72]。「それは、ほとんどの場合、まさに現れないものであり、最初に、そしてほとんどの場合、現れるも のとは違って、控えめであるが、現れるものと一体となって、その最も深い意味を構成するものである」。 フッサールとは正反対の立場から、ハイデガーは(SZ p. 35)、現象学の目的は、自発的には現れず、ほとんどの場合隠されているものを明らかにすることだと主張している、とジャン・グロダン[73]は述べてい る。そのため、マルレーヌ・ザラデルが指摘するように、解釈学が必要となる。現象が表れるものであるならば、それは記述の対象となるだろう […]。現象が表れるものの中に隠れているものであるならば、表れるものを解釈し、説明し、そこに表れないもの、そしてほとんどの場合、表れないものを明 らかにする作業に取り組まなければならない」[74]。 『存在と時間』以降、ハイデガーは、ダセインに基づく存在の意味の記述にはもはや関心を示さず、「思考の中で、そして思考によって展開される存在を、その まま見ようとした」とシルヴァイン・グルダンは記している[18]。また、彼女は注釈で次のように述べている。「おそらく(ハイデガーにとって)それは現 象学、つまり意識に現れる現象を記述し認識論的に研究する科学ではなく、ハイデガーが実際に興味を持っている「現象」、すなわち「存在」そのものを思考し 表現する学問である、と明確に述べるべきだろう」 」 |

| La phénoménologie sectorielle contemporaine Cette section peut contenir un travail inédit ou des déclarations non vérifiées (octobre 2021). Vous pouvez aider en ajoutant des références ou en supprimant le contenu inédit. Sergiu Celibidache : phénoménologie de la musique Gaston Bachelard : phénoménologie de l'imagination Maurice Merleau-Ponty : phénoménologie de la perception et du corps propre Jan Patočka : phénoménologie dynamique ou phénoménologie du monde naturel Hans-Georg Gadamer : phénoménologie du dialogue Michel Henry : phénoménologie de la vie (comme auto-affection) Paul Ricœur : phénoménologie de la volonté Jean-Luc Marion : phénoménologie de la donation Renaud Barbaras : phénoménologie de la vie (comme mouvement) Natalie Depraz : phénoménologie de l'attention et de la surprise Claude Romano : phénoménologie de l'événement Bruce Bégout : phénoménologie de la quotidienneté Alexander Schnell : phénoménologie constructive/générative Jean-Louis Chrétien : phénoménologie de la parole Erazim Kohák : écophénoménologie Marc Richir : phénoménologie refondue ou hyperbolique Henri Maldiney : phénoménologie de l'existence Emmanuel Falque: phénoménologie du hors-phénoménalité[75 |

現代の分野別現象学 このセクションには、未発表の著作や未確認の記述が含まれている可能性がある(2021年10月)。参考文献を追加したり、未発表のコンテンツを削除したりすることで、このセクションの改善に協力できる。 セルジュ・チェリビダッケ:音楽の現象学 ガストン・バシュラール:想像力の現象学 モーリス・メルロー=ポンティ:知覚と自己の身体の現象学 ヤン・パトチェカ:動的現象学または自然界の現象学 ハンス=ゲオルク・ガダマー:対話の現象学 ミシェル・アンリ:生命(自己愛着としての)の現象学 ポール・リクール:意志の現象学 ジャン=リュック・マリオン:贈与の現象学 ルノー・バルバラ:生命(運動としての)の現象学 ナタリー・デプラズ:注意と驚きの現象学 クロード・ロマーノ:出来事の現象学 ブルース・ベグー:日常性の現象学 アレクサンダー・シュネル:建設的/生成的現象学 ジャン=ルイ・クレティアン:言葉の現象学 エラジム・コハーク:エコ現象学 マルク・リシール:再構築された、あるいは双曲的な現象学 アンリ・マルディネイ:存在の現象学 エマニュエル・ファルク:現象外性の現象学[75 |

| Le tournant théologique de la phénoménologie française Dominique Janicaud[76], rappelle que dans la vision de Husserl, l'intentionnalité ne concerne que les phénomènes du monde et en aucun cas l'au-delà du monde. Renaud Barbaras[77] rappelle l'impératif explicite de Husserl : « toute intuition donatrice originaire est une source de droit pour la connaissance mais tout ce qui s'offre à nous dans cette intuition doit être simplement reçu pour ce qu'il se donne, sans outrepasser les limites dans lesquelles il se donne ». À l'occasion d'un véritable pamphlet, publié en 1990, intitulé Le tournant théologique de la phénoménologie française, Dominique Janicaud dénonce le fait qu'à « partir des années 1970, s'opère une singulière ouverture au transcendant, à l'absolu et à l'originaire qui […] scellent une alliance avec des préoccupations de type théologique ou religieux »[78]. Il situe en 1961 avec la publication de Totalité et Infini d'Emmanuel Levinas la première œuvre majeure de philosophie qui assume ce tournant de la phénoménologie vers la théologie, tendance confirmée depuis lors par toute une série d'autres philosophes (Paul Ricœur, Michel Henry, Jean-Luc Marion, Jean-Louis Chrétien). Pour Dominique Janicaud, face à ces multiples démarches, qui réintroduisent « l'absolument Autre » (Levinas), « l'Archi-Révélation de la vie »(Michel Henry), la donation pure (Jean-Luc Marion), la question devient : qu'est-ce qui reste de phénoménologique dans ces œuvres[79] ? Toutes ces tentatives restent éloignées de la neutralité scientifique dont Edmund Husserl désirait doter la phénoménologie. |

フランス現象学の神学的転換 ドミニク・ジャニコ[76]は、フッサールの見解では、意図性は世界の現象のみに関係し、決して世界の彼方に関係するものではないと指摘している。ル ノー・バルバラス[77]は、フッサールの明確な要求を次のように述べている。「あらゆる原初的な直観は、認識の権利の源泉であるが、その直観の中で我々 に提示されるものはすべて、それが与えるものとして、それが与える限界を超えずに、単に受け取られるべきである」。 1990年に出版された『フランス現象学の神学的転換』と題された、まさにパンフレットのような本の中で、 ドミニク・ジャニコーは、「1970年代以降、超越的、絶対的、原初的なものに対する特異な開放が起こり、それが神学的あるいは宗教的な関心と結びつい た」[78] ことを非難している。彼は、1961年にエマニュエル・レヴィナスが『全体性と無限』を出版したことを、現象学が神学へと転換した最初の主要な哲学作品と 位置づけており、この傾向はその後、他の多くの哲学者(ポール・リクール、ミシェル・アンリ、ジャン=リュック・マリオン、ジャン=ルイ・クレティエン) によって確認されている。ドミニク・ジャニコーは、こうした「絶対的に他者」(レヴィナス)、「生命の究極的啓示」(ミシェル・アンリ)、純粋な贈与 (ジャン=リュック・マリオン)を再導入する多様なアプローチに直面して、これらの著作に現象学的な要素は残されているのかという疑問を投げかけている [79]。これらの試みはすべて、エドムント・フッサールが現象学に与えたかった科学的客観性からは程遠いものだ。 |

| Applications pratiques La phénoménologie connaît aussi des applications pratiques. Natalie Depraz - recherches sur l'adaptation de l'attitude phénoménologique lors de pratiques d'entretiens Emmanuel Galacteros - fondateur de l'entretien phénoménologique de la vie radicale (inspiration Michel Henry) Alfonso Caycedo - pratiques de la réduction phénoménologique (Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Ludwig Binswanger) psychiatrie et prophylaxie sociale. Phénoménologie appliquée axiologos. Pierre Vermersch, technique de l'entretien d'explicitation et la psycho-phénoménologie Henri Maldiney - étude des pathologies psychiques comme fléchissement des modalités d'existence. Le Cercle herméneutique : cette revue de phénoménologie anthropologique aborde des sujets appliqués au quotidien, avec des sujets autour de l'hystérie, la paranoïa, le sentiment d'étrangeté à soi, le besoin d'événements, l'homme intérieur et le discours intérieur. Recherches qualitatives au Canada La phénoménologie a aussi eu une grande influence sur la psychologie telle qu'elle se pratique encore de nos jours et plus généralement sur l'épistémologie. Elle a donné naissance à une clinique psychiatrique particulièrement riche, à partir des travaux du psychanalyste Ludwig Binswanger. En France, elle influença le courant de la psychothérapie institutionnelle. |

実用的な応用 現象学は実用的な応用もされている。 ナタリー・デプラズ - 面接の実践における現象学的姿勢の適応に関する研究 エマニュエル・ガラクトロス - 急進的な生活に関する現象学的面接の創始者(ミシェル・アンリに触発された) アルフォンソ・カイセド - 現象学的還元の実践(エドムント・フッサール、マルティン・ハイデガー、ルートヴィヒ・ビンズワンガー)精神医学および社会予防医学。 応用現象学アクシオロゴス。 ピエール・ヴェルメルシュ、説明的面接技法および精神現象学 アンリ・マルディーネ - 存在様態の弱体化としての精神病理の研究。 解釈学サークル:この人類学的現象学の雑誌は、ヒステリー、パラノイア、自己に対する異質感、出来事への欲求、内なる人間、内なる言説など、日常生活に適用される主題を取り上げている。 カナダにおける質的調査 現象学は、今日でも実践されている心理学、そしてより一般的には認識論にも大きな影響を与えている。精神分析医ルートヴィヒ・ビンズワンガーの研究から、特に豊かな精神医学の臨床が生まれた。フランスでは、制度精神療法の流れに影響を与えた。 |

| Notes n1. « D’une façon générale, la phénoménologie s’occupe de déterminer ce qui dans chaque espèce d’apparence est réel et vrai ; à cette fin, elle fait ressortir les causes et les circonstances particulières qui produisent et modifient une apparence, afin que l’on puisse à partir de l’apparence inférer le réel et le vrai. […] La phénoménologie dans son acception la plus générale peut être qualifiée d’optique transcendante, dans la mesure où elle détermine en partant du vrai l’apparence, et inversement, en partant de l’apparence le vrai »-Lambert-Neues Organon, (§266)-« Sixième section : de la représentation sémiotique de l'apparence », dans Johann-Heinrich Lambert, Nouvel Organon : Phénoménologie (trad. Gilbert Fanfalone), Vrin, coll. « Bibliothèque des textes philosophiques », 2002 (lire en ligne [archive]), p. 193 n2. « Kant remarque que la connaissance débute avec l'expérience sensible, sans pour autant en provenir, et que l'interrogation sur le phénomène doit être menée dans le cadre d'une philosophie transcendantale. Pour cela il ne faut pas confondre la présentation des choses elles-mêmes, qui nous demeure inaccessible, et le phénomène, qui n'est autre que l'objet possible de l'intuition d'un sujet »-article Phénomène Dictionnaire des concepts philosophiques, 2013, p. 613 n3. « Dans ma Phénoménologie de l'Esprit, qui forme la première partie du système de la connaissance, j'ai pris l'Esprit à sa plus simple apparition ; je suis parti de la conscience immédiate afin de développer son mouvement dialectique jusqu'au point où commence la connaissance philosophique, dont la nécessité se trouve démontrée par ce mouvement même »-G. W. F. Hegel, Logik, §25 ; trad. fr. A. Vera : Science de la logique, Paris, Ladrange, 1859, t. 1, p. 257. n4. « La Volonté, seule, lui [sc. à l'homme] donne la clef de sa propre existence phénoménale, lui en découvre la signification, lui montre la force intérieure qui fait son être, ses actions, son mouvement. Le sujet de la connaissance, par son identité avec le corps, devient un individu ; dès lors, ce corps lui est donné de deux façons toutes différentes : d'une part comme représentation dans la connaissance phénoménale, comme objet parmi d'autres objets et comme soumis à leur loi ; et d'autre part, en même temps, comme ce principe immédiatement connu de chacun, que désigne le mot Volonté »-A. Schopenhauer, Le Monde comme volonté et comme représentation, trad. fr. A Burdeau, Paris, PUF, 1966, vol. 1, §18. n5. voir sur cette ambition la première méditation des Méditations cartésiennes, 1986, p. 6 n6. « Phénoménologie : cela désigne une science, un ensemble de disciplines scientifiques ; mais phénoménologie désigne en même temps et avant tout, une méthode et une attitude de pensée : l'attitude de pensée spécifiquement philosophique et la méthode spécifiquement philosophique »-Edmund Husserl 2010, p. 45 n7. « Heidegger ne demande jamais Was ist das Sein ?. Il met en garde au contraire contre l'absurdité d'une question ainsi formulée […] Il demande plutôt. Comment est-il signifié ? Quel est son sens ? » n8. Si pour Kant, la connaissance débute avec l'expérience sensible « ce sont les objets qui doivent se régler sur notre connaissance et non l'inverse, et les objets ne nous livrent pas la nature des choses, leur être nouménal mais les formes sous lesquelles notre connaissance les appréhende »-article Phénomène Dictionnaire des concepts philosophiques, 2013, p. 613 n9. Ce « droit aux choses mêmes », s'oppose à toutes les constructions échafaudées dans le vide, à la reprise de concepts qui n'ont rien de bien fondé que l'apparence et l'ancienneté-Martin Heidegger 1986, p. 54 n10. Nommer n'est pas simplement faire voir mais faire apparaître au sens strict insiste Jean Beaufret-Jean Beaufret 1973, p. 125 n11. par exemple c'est autour du « phénomène de la vie », que Heidegger aurait construit sa propre approche de la phénoménologie-Emmanuel Levinas 1988, p. 112 n12. voir pour l'approfondissement de tous ces points les pages lumineuses que Lévinas y consacre-Emmanuel Levinas 1988, p. 111-123 n13. À dire vrai « l'Épochè vise à faire apparaître, l'apparaître lui-même et non pas seulement telle ou telle apparition essentielle »-Dominique Janicaud 2009, p. 67 n14. « N'entre pas plus dans le débat les questions distinctes mais étroitement interdépendantes : celles de la frontière entre donné et construit, objet et sujet […] qui s'interrogent jusqu'à quel point les hommes sont prisonniers de cadres « linguistico-pragmatiques » […] à travers lesquels, ils voient le monde […] »-Dictionnaire des Concepts philosophiques, 2012, p. 614 n15. L'origine, si elle doit être autre chose qu'un flatus voci, doit correspondre au lieu d'émergence du matériau philosophique qu'est le concept et rendre compte de sa formation et de son déploiement concret-Sophie-Jan Arrien 2014, p. 38 n16. la (Auslegung ) ou explicitation est le nom que donne Heidegger à l'éclaircissement des présupposés de la compréhensionJean Grondin 1996, p. 191 n17. « L'obscurité qui enveloppe la connaissance quant à son sens ou à son essence appelle une science de la connaissance, une science qui ne veut rien d'autre qu'amener la connaissance à une clarté véritable »-Edmund Husserl 2010, p. 69 n18. Mais comme le note Jean-François Lyotard : « pour accomplir cette opération, il faut sortir de la science même et plonger dans ce dans quoi elle plonge innocemment. C'est par volonté rationaliste que Husserl s'engage dans l'anté-rationnel »-Jean-François Lyotard 2011, p. 9 n19. « Un trait distinctif des vécus qu'on peut tenir véritablement pour le thème central de la phénoménologie orientée « objectivement » : l'intentionnalité ». Cette caractéristique éidétique concerne la sphère des vécus en général, dans la mesure où tous les vécus participent en quelque manière à l'intentionnalité, quoique nous ne puissions dire de tout vécu qu'il a une intentionnalité. « C'est l'intentionnalité qui caractérise la conscience au sens fort et qui autorise en même temps de traiter tout le flux du vécu comme un flux de conscience et comme l'unité d'une conscience »-E. Husserl, Ideen I, § 84 ; trad. fr., op. cit., p. 283. n20. « L'alternative idéalisme/réalisme est dépassée (et tout aussi bien la dualité subjectif/objectif) par une corrélation préalable, ce fait irréductible qu'aucune image physique ne peut rendre : l'éclatement de la conscience dans le monde, d'emblée conscience d'« autre chose que soi ». Il n'y a pas de conscience pure. « Toute conscience est conscience de quelque chose » proclame que la pseudo pureté du cogito est toujours prélevée sur une corrélation intentionnelle préalable »-Dominique Janicaud 2009, p. 44 n21. « La phénoménologie pure ou transcendantale ne sera pas érigée en science portant sur des faits, mais portant sur des essences (en science « éidétique ») ; une telle science vise à établir uniquement des « connaissances d'essence » et nullement des faits »-E. Husserl, Ideen I, Préface ; trad. fr., op. cit., p. 7. n22. « On ne trouve dans la donnée immédiate [de la conscience] rien de ce qui, dans la psychologie traditionnelle, entre en jeu, comme si cela allait de soi, à savoir : des data-de-couleur, des data-de-son et autres data de sensation ; des data-de-sentiment, des data-de-volonté, etc. Mais on trouve ce que trouvait déjà René Descartes, le cogito, l'intentionalité, dans les formes familières qui ont reçu, comme tout le réel du monde ambiant, l'empreinte de la langue : le « je vois un arbre, qui est vert ; j'entends le bruissement de ses feuilles, je sens le parfum de ses fleurs, etc. » ; ou bien « je me souviens de l'époque où j'allais à l'école », « je suis inquiet de la maladie de mon ami », etc. Nous ne trouvons là, en fait de conscience, qu'une conscience de… »E. Husserl, Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die tanszendentale Phänomenologie, La Haye, Martinus Nijhoff, 1954, § 68 ; trad. fr. G. Granel : La crise des sciences européennes et la phénoménologie transcendantale, Paris, Gallimard, Tel, 1976, p. 262. n23. Il en découle deux conséquences : premièrement « que la perception est d'abord un commerce concret et pratique avec les choses, je ne perçois pas pour seulement percevoir mais pour m'orienter, percevoir n'est plus une simple observation neutre » et deuxièmement « que l'objet n'est plus totalement étranger au sujet, qu'il ne lui est plus absolument extérieur »Françoise Dastur 2011, p. 13 n24. L'exemple de Jean Greisch (du chat qui est sur le paillasson) et qui est autre chose qu'un paillasson plus un chat ou les exemples du troupeau de moutons ou de la foule qui manifeste, enfin encore plus simple et plus évident la forêt et pas seulement une série d'arbres, soit par des actes d' idéationJean Greisch op cité 1994 pages 56-57 n25. En effet pouvoir énoncer que « le tableau est mal placé » dans un coin de la salle suppose au préalable que soit manifeste la salle de cours en son entier, visée en tant que salle cours exigeant un emplacement déterminé du tableau et non une salle de danse exigeant un autre emplacement; le sens du « est », est plus ample que dans le simple énoncé, il opère de manière préverbale et prélogique avant tout énoncé une synthèse unifiante qui permet de rassembler les choses et de les distinguer sans les séparer (article Logique Le Dictionnaire Martin Heidegger, p. 778). n26. « La philosophie est l'ontologie phénoménologique universelle issue de l'« herméneutique » du Dasein, qui en tant qu'analytique de l'existence (l'existentialité), a fixé comme terme à la démarche de tout questionnement philosophique le point d'où il jaillit et celui auquel il remonte » |

注 n1. 「一般的に、現象学は、あらゆる種類の現象において、何が現実であり、真実であるかを決定することに取り組んでいる。その目的のために、現象を生み出し、 変化させる特定の要因や状況を明らかにし、現象から現実と真実を推測できるようにする。[…] 現象学は、その最も一般的な意味において、超越的な視点と表現することができる。なぜなら、それは真実から外観を決定し、逆に、外観から真実を決定するか らだ」-ランバート『新オルガノン』 (§266)-「 第六節:外観の記号的表現について」ヨハン・ハインリッヒ・ランベルト著『新オルガノン:現象学』(ギルバート・ファンファローン訳)、ヴリン社、「哲学 テキスト文庫」シリーズ、2002年(オンラインで読む [アーカイブ])、193ページ n2. 「カントは、認識は感覚的経験から始まるが、そこから生じるわけではないこと、そして現象に関する探求は超越論的哲学の枠組みの中で行わなければならない ことを指摘している。そのためには、私たちには理解できない物事そのものの提示と、主体の直観の対象となりうる現象とを混同してはならない」-「現象」の 項目、哲学概念辞典、2013年、613ページ n3. 「私の『精神の現象学』では、認識体系の第一部を構成する部分において、精神をその最も単純な出現形態で捉えた。私は、即座の意識から出発し、その弁証法 的運動を、哲学的認識が始まる地点まで発展させた。その必要性は、この運動そのものによって実証されている」―G. W. F. ヘーゲル、『論理学』§25 仏訳 A. ベラ:『論理学』パリ、ラドランジュ、1859年、第1巻、257ページ。 n4. 「意志だけが、彼(人間)に、彼自身の現象的存在の鍵を与え、その意味を明らかにし、彼の存在、行動、運動を構成する内なる力を示す。認識の主体は、身体 との同一性によって、個人となる。それゆえ、この身体は二つのまったく異なる形で与えられる。一方では、現象的認識における表象として、他の物体の一つと して、そしてそれらの法則に従属するものとして。他方では、同時に、各人が直ちに認識する原理として、それは「意志」という言葉で表されるものである。」 -A. ショーペンハウアー、『意志として、また表象としての世界』、仏訳 A Burdeau、パリ、PUF、 1966年、第1巻、§18。 n5. この野望については、『デカルトの瞑想』の最初の瞑想、1986年、6ページを参照のこと。 n6. 「現象学:それは科学、一連の科学分野を指す。しかし現象学は同時に、そして何よりもまず、方法と思考の姿勢、すなわち、特に哲学的な思考の姿勢と特に哲学的な方法を指す」―エドムント・フッサール 2010年、p. 45 n7. 「ハイデガーは決して Was ist das Sein ? と問うことはない。それどころか、そのような形で問うことの不条理さを警告している […] むしろ彼はこう問う。それはどのように意味づけられているのか?その意味は何か?」 n8. カントにとって、認識は感覚的な経験から始まる。「私たちの認識に合わせて調整すべきは対象であり、その逆ではない。そして対象は、物事の性質、つまりそ の nouménal(実体)を私たちに伝えるのではなく、私たちの認識がそれを理解する形を伝えるのだ」-記事「現象」哲学概念辞典、2013年、613 ページ n9. この「物そのものに対する権利」は、空虚に構築されたあらゆる概念、外見と歴史性以外に根拠のない概念の流用とは対立する。- マルティン・ハイデガー 1986年、54ページ n10. 名付けることは、単に「見せる」ことではなく、厳密な意味で「現す」ことだとジャン・ボーフレは主張している。ジャン・ボーフレ 1973年、125ページ n11. 例えば、ハイデガーは「生命の現象」を中心に、独自の現象学のアプローチを構築したとされる。エマニュエル・レヴィナス 1988年、112ページ n12. これらの点についてさらに詳しく知りたい場合は、レヴィナスがこれについて書いた素晴らしいページを参照のこと。エマニュエル・レヴィナス 1988、111-123 ページ n13。実を言えば、「エポケーは、ある特定の重要な出現だけでなく、出現そのものを現出させることを目指している」とドミニク・ジャニコーは述べている。ドミニク・ジャニコー 2009、 p. 67 n14. 「与えられたものと構築されたもの、対象と主体の境界といった、別個でありながら密接に相互依存する問題も、この議論には含まれない。これらの問題は、人 間が「言語的・実用的な」枠組みにどの程度囚われているか、そして人間がその枠組みを通して世界を見ているのかどうかを問うものである。」-哲学概念辞 典、2012年、p. 614 n15. 起源は、単なる空虚な言葉(flatus voci)ではないならば、哲学的素材である概念が出現した場所に対応し、その形成と具体的な展開を説明しなければならない。-ソフィー・ジャン・アリエン 2014年、p. 38 n16. 解釈(Auslegung)とは、ハイデガーが理解の前提を明らかにすることを指す言葉だ。ジャン・グロンダン 1996年、191ページ n17. 「知識の意味や本質を覆い隠す曖昧さは、知識の科学、つまり知識を真に明確なものにすることを唯一の目的とする科学を必要とする」―エドムント・フッサール 2010年、69ページ n18。しかし、ジャン=フランソワ・リオタールが指摘しているように、「この作業を達成するには、科学そのものを離れ、科学が無邪気に飛び込むものに飛 び込む必要がある。フッサールは、合理主義的な意志によって、前合理的領域に取り組んでいる」―ジャン=フランソワ・リオタール 2011年、9ページ n19。「客観的に」指向された現象学の中心的なテーマと真に考えうる、経験の特徴的な側面:意図性」。このイデイティックな特徴は、すべての経験が何ら かの形で意図性に関与している限り、一般的な経験の領域に関わるものである。ただし、すべての経験が意図性を持っているとは言い切れない。「意識を強い意 味で特徴づけ、同時に経験の流れ全体を意識の流れとして、また意識の統一性として扱うことを可能にするのは、意図性である」―E. フッサール、Ideen I、§ 84、仏訳、前掲書、283 ページ。 n20. 「理想主義/現実主義という二分法(そして主観/客観という二分法も同様)は、それ以前の相関関係、すなわち、いかなる物理的イメージも表現できないとい う還元不可能な事実、すなわち、世界における意識の分裂、つまり、最初から「自分以外の何か」に対する意識によって、すでに克服されている。純粋な意識な ど存在しない。「あらゆる意識は何かに対する意識である」ということは、コギトの偽りの純粋性は、常に先行する意図的な相関関係から引き出されていること を示している」-ドミニク・ジャニコー 2009年、44ページ n21. 「純粋あるいは超越的な現象学は、事実に関する科学ではなく、本質に関する科学(「イデイティック」科学)として確立される。そのような科学は、「本質に 関する知識」のみを確立することを目的とし、事実を確立することを目的とはしない」―E. フッサール、Ideen I、序文、仏訳、前掲書、p. 7。 n22. 「(意識の)直接的なデータには、伝統的な心理学で当然のこととして扱われてきたもの、すなわち、色彩データ、音データ、その他の感覚データ、感情デー タ、意志データなどは一切見られない。しかし、ルネ・デカルトがすでに発見したもの、すなわちコギト、意図性が、周囲の世界の現実のすべてと同様に、言語 の痕跡を受けた身近な形で発見される。すなわち、「私は緑色の木を見る。その葉のざわめきを聞く、その花の香りを感じる」といったもの、あるいは「学校に 通っていた頃を覚えている」、「友人の病気のことが心配だ」といったものなどである。ここで意識として見出されるのは、実際には…の意識にすぎない。E. フッサール、Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die tanszendentale Phänomenologie、ハーグ、Martinus Nijhoff、1954年、§ 68、フランス語訳 G. Granel:La crise des sciences européennes et la phénoménologie transcendantale、パリ、Gallimard、Tel、1976年、262ページ。 n23。そこから二つの結論が導かれる。第一に、「知覚とはまず第一に、物事との具体的かつ実践的な関わりである。私は知覚するだけでは知覚しない。方向 を見定めるために知覚する。知覚はもはや単なる中立的な観察ではない」ということ。第二に、「対象はもはや主体にとって完全に異質なものではなく、主体に とって完全に外部のものでもない」ということである。Françoise Dastur 2011, p. 13 n24。ジャン・グレイシュの例(玄関マットの上にいる猫)は、玄関マットと猫を足した以上のもの、あるいは羊の群れやデモを行う群衆の例、さらに単純で 明白な例としては、単なる一連の樹木ではなく、森そのものである。つまり、観念化という行為によってジャン・グレイシュ、前掲書 1994年、56-57ページ n25. 実際、「黒板が部屋の隅に置かれている」と言うには、まず教室全体が教室として認識されていることが前提となる。つまり、黒板は教室として特定の場所に置 かれるべきであり、別の場所に置かれるべきダンススタジオではないということだ。「ある」の意味は、単純な発言よりも広範であり、あらゆる発言に先立っ て、言語的・論理的以前の段階で、物事をまとめ、分離することなく区別することを可能にする統一的な統合を行う(記事「論理」『マルティン・ハイデガー辞 典』778ページ)。 n26. 「哲学とは、ダーザイン(存在)の「解釈学」から生まれた普遍的な現象学的存在論であり、存在(実存性)の分析として、あらゆる哲学的探求の出発点と帰着点をその終着点として定めている」 |

| Références | Références(省略) |

| Articles connexes Edmund Husserl Idées directrices pour une phénoménologie et une philosophie phénoménologique pures La Crise des sciences européennes et la phénoménologie transcendantale Méditations cartésiennes Maurice Merleau-Ponty Hector de Saint-Denys Garneau Glossaire de phénoménologie Réduction phénoménologique La Voix et le Phénomène Intentionnalité Intersubjectivité (phénoménologie) Perception (phénoménologie) Phénoménologie de la perception Ontologie Dasein Martin Heidegger et la phénoménologie Maine de Biran De la phénoménologie Leçons pour une phénoménologie de la conscience intime du temps Sixième Méditation cartésienne . Catégories Concepts phénoménologiques Œuvres de phénoménologie Phénoménologues |

関連項目 エドムント・フッサール 純粋現象学および現象学的哲学のための指導的観念 ヨーロッパ科学の危機と超越論的現象学 デカルト的瞑想 モーリス・メルロー=ポンティ エクトール・ド・サン=ドニ・ガルノー 現象学用語集 現象学的還元 声と現象 意図性 相互主観性(現象学) 知覚(現象学) 知覚の現象学 存在論 ダセイン マルティン・ハイデガーと現象学 メイン・ド・ビラン 現象学について 時間の内的な意識の現象学のための教訓 第六のデカルト的瞑想 。 カテゴリー 現象学的概念 現象学の著作 現象学者 |