他者

Other

(philosophy)

☆

他者とは、自分とは別個の存在として、他の個人または人々を定義する際に使用される用語である。現象学では、「他者」と「構成的な他者」という用語は、自

己イ

メージにおける累積的、構成的な要因として、他の人々を自己から区別する。また、現実の存在として認識されるものでもある。したがって、

1)他者は自己、私た ち、同じものとは異なり、対極にあるものである。

2)構成的な他者とは、人間のパーソナリティ(本質的な性質)とパーソン(身体)との関係であ り、自己同一性 の本質的および表面的な特徴の関係である。自己の対極にあるが相関的な特徴の関係に対応するものである。なぜなら、その違いは自己の内側に ある違いだから である。

他者性(他者の特性)の状態と質は、その人の社会的アイデンティティや自己のアイデンティティとは異なり、疎外された状態である。哲学の議論では、「他者 性」という用語は、他者の「誰なのか?」や「何なのか?」という特徴を特定し、指し示す。これらは、象徴秩序、現実(本物で不変なもの)、美的なもの(芸 術、美しさ、趣味)、政治哲学、社会規範や社会的アイデンティティ、そして自己とは異なるものである。したがって、「他者性」の状態とは、社会の社会的規 範に適合しない、あるいは適合できない状態である。そして、「他者性」とは、国家またはそれに対応する社会政治的権限を付与された社会制度(例えば、専門 職)によってもたらされる、権利剥奪(政治的排除)の状態である。

したがって、「他者」としてレッテルを貼られた人は、他者であるがゆえに社会の中心から 疎外され、社会の周縁に追いやられる。 「他者化」または「他者化する」という用語は、ある人物をサバルタン(他者の社会的下位カテ ゴリーに属する者)としてレッテルを貼り、定義する還元的な行 為を指す。「他者化」の慣行は、自己のバージョンである社会集団の規範に適合しない人々を排除する。同様に、人文地理学では、他者化の慣行とは、他者であ るがゆえに社会集団から排除され、社会の周縁部に追いやられることを意味する。(→「サ バルタン」「ラカン的他者」「人類学における自己と他者」)。

ファ

ビアン 『時間と他者:人類学はどのようして対象を形成するか』より

★

〈他者〉とは二重の入り口をもつ母体である——ジャック・ラカン(Seminar of 21, January, 1975. in

"Feminine Sexuality", p.164)

| Other

is a term used

to define another person or people as separate from oneself. In

phenomenology, the terms the Other and the Constitutive Other

distinguish other people from the Self, as a cumulative, constituting

factor in the self-image of a person; as acknowledgement of being real;

hence, the Other is dissimilar to and the opposite of the Self, of Us,

and of the Same.[1][2] The Constitutive Other is the relation between

the personality (essential nature) and the person (body) of a human

being; the relation of essential and superficial characteristics of

personal identity that corresponds to the relationship between

opposite, but correlative, characteristics of the Self, because the

difference is inner-difference, within the Self.[3][4] The condition and quality of Otherness (the characteristics of the Other) is the state of being different from and alien to the social identity of a person and to the identity of the Self.[5] In the discourse of philosophy, the term Otherness identifies and refers to the characteristics of Who? and What? of the Other, which are distinct and separate from the Symbolic order of things; from the Real (the authentic and unchangeable); from the æsthetic (art, beauty, taste); from political philosophy; from social norms and social identity; and from the Self. Therefore, the condition of Otherness is a person's non-conformity to and with the social norms of society; and Otherness is the condition of disenfranchisement (political exclusion), effected either by the State or by the social institutions (e.g., the professions) invested with the corresponding socio-political power. Therefore, the imposition of Otherness alienates the person labelled as "the Other" from the centre of society, and places him or her at the margins of society, for being the Other.[6] The term Othering or Otherizing[7][8] describes the reductive action of labelling and defining a person as a subaltern native, as someone who belongs to the socially subordinate category of the Other. The practice of Othering excludes persons who do not fit the norm of the social group, which is a version of the Self;[9] likewise, in human geography, the practice of othering persons means to exclude and displace them from the social group to the margins of society, where mainstream social norms do not apply to them, for being the Other.[10]  The founder of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl, identified the Other as one of the conceptual bases of intersubjectivity, of the relations among people. |

他者とは、自分とは別個の存在として、他の個人または人々を定義する際

に使用される用語である。現象学では、「他者」と「構成他者」という用語は、自己イメージにおける累積的、構成的な要因として、他の人々を自己から区別す

る。また、現実の存在として認識されるものでもある。したがって、他者は自己、私たち、同じものとは異なり、対極にあるものである。構成的な他者とは、人

間のパーソナリティ(本質的な性質)とパーソン(身体)との関係であり、自己同一性の本質的および表面的な特徴の関係である。自己の対極にあるが相関的な

特徴の関係に対応するものである。なぜなら、その違いは自己の内側にある違いだからである。 他者性(他者の特性)の状態と質は、その人の社会的アイデンティティや自己のアイデンティティとは異なり、疎外された状態である。哲学の議論では、「他者 性」という用語は、他者の「誰なのか?」や「何なのか?」という特徴を特定し、指し示す。これらは、象徴秩序、現実(本物で不変なもの)、美的なもの(芸 術、美しさ、趣味)、政治哲学、社会規範や社会的アイデンティティ、そして自己とは異なるものである。したがって、「他者性」の状態とは、社会の社会的規 範に適合しない、あるいは適合できない状態である。そして、「他者性」とは、国家またはそれに対応する社会政治的権限を付与された社会制度(例えば、専門 職)によってもたらされる、権利剥奪(政治的排除)の状態である。したがって、「他者」としてレッテルを貼られた人は、他者であるがゆえに社会の中心から 疎外され、社会の周縁に追いやられる。 「他者化」または「他者化する」という用語は、ある人物をサバルタン(他者の社会的下位カテゴリーに属する者)としてレッテルを貼り、定義する還元的な行 為を指す。「他者化」の慣行は、自己のバージョンである社会集団の規範に適合しない人々を排除する。同様に、人文地理学では、他者化の慣行とは、他者であ るがゆえに社会集団から排除され、社会の周縁部に追いやられることを意味する。  現象学の創始者であるエドムント・フッサールは、他者という存在を、間主観性、つまり人と人との関係の概念的基盤のひとつとした。 |

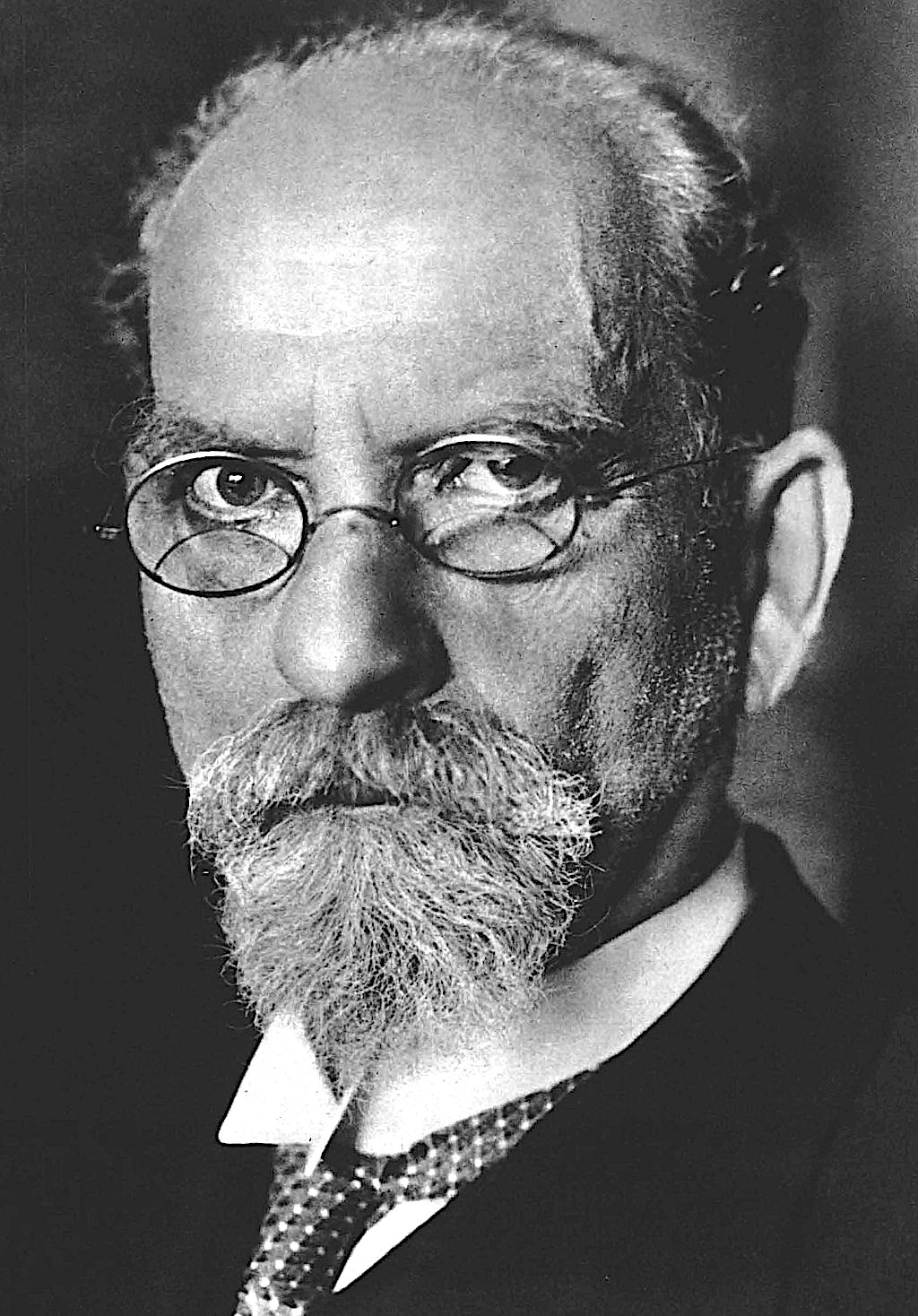

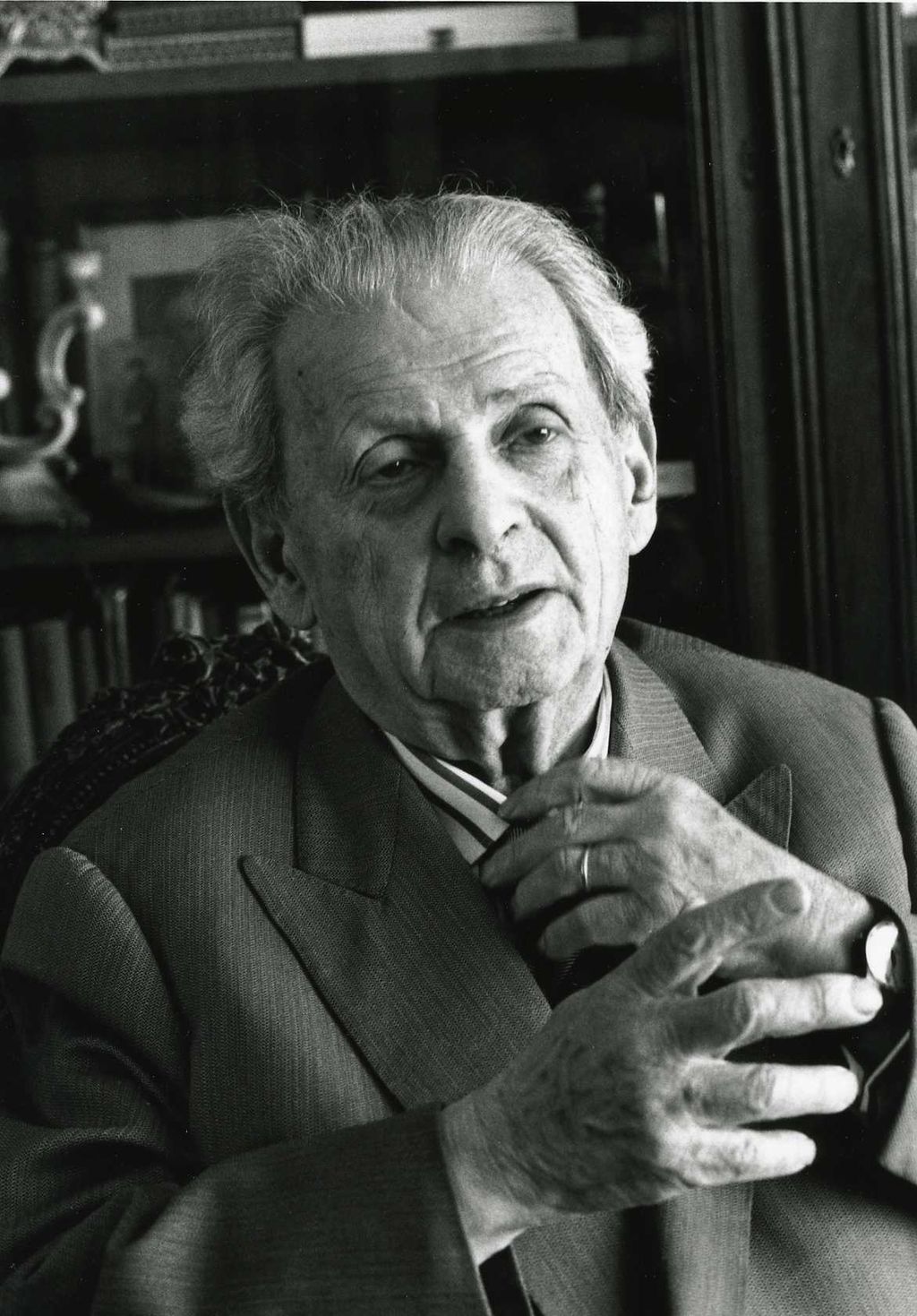

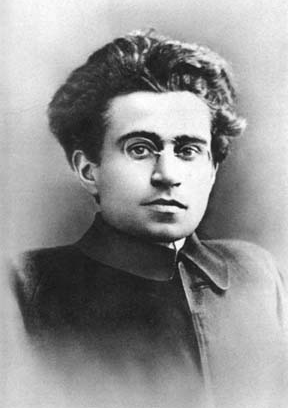

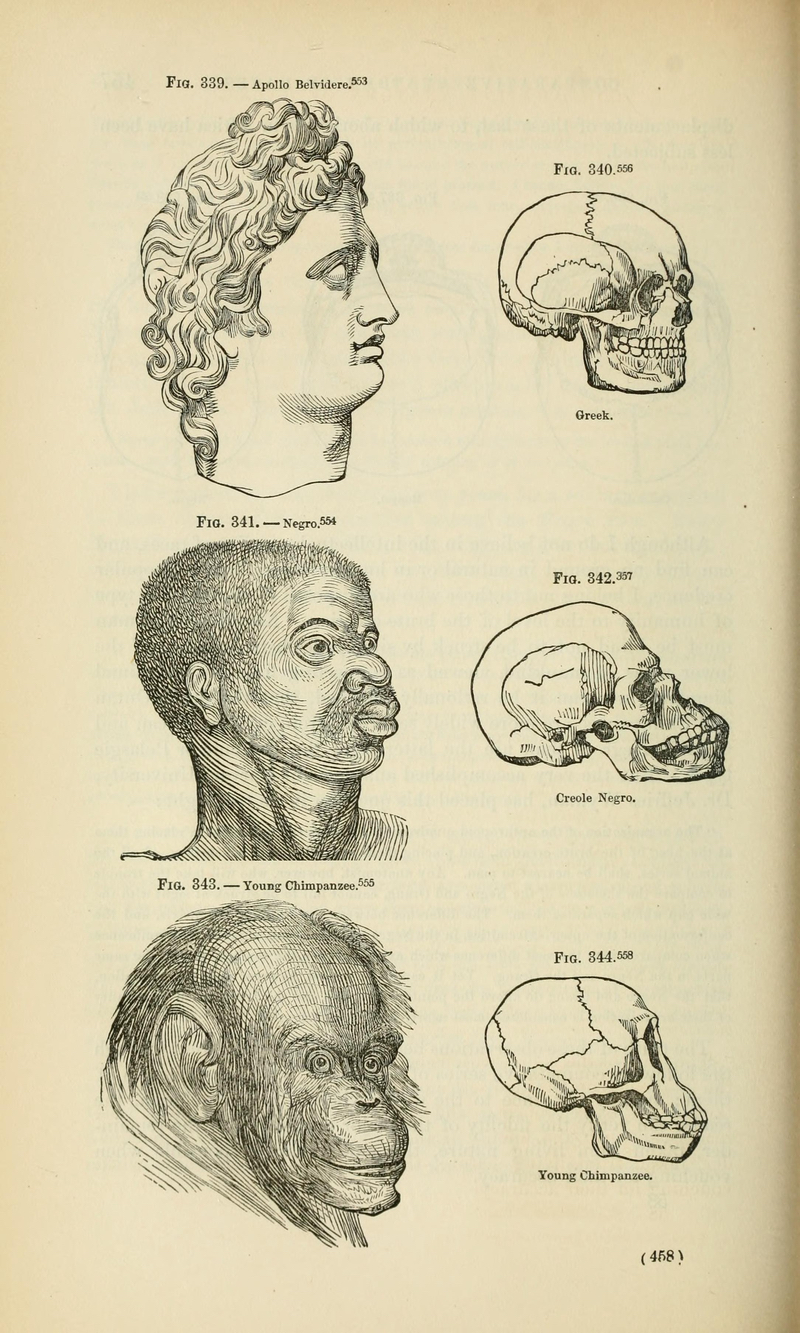

| Background Philosophy  The idealist philosopher G. W. F. Hegel introduced the concept of the Other as constituent part of human preoccupation with the Self. The concept of the Self requires the existence of the constitutive Other as the counterpart entity required for defining the Self. Accordingly, in the late 18th century, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) introduced the concept of the Other as a constituent part of self-consciousness (preoccupation with the Self),[11] which complemented the propositions about self-awareness (capacity for introspection) proffered by Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814).[12] John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) introduced the idea of the other mind in 1865 in An Examination of Sir William Hamilton's Philosophy, the first formulation of the other after René Descartes (1596–1650).[13] Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) applied the concept of the Other as the basis for intersubjectivity, the psychological relations among people. In Cartesian Meditations: An Introduction to Phenomenology (1931), Husserl said that the Other is constituted as an alter ego, as an other self. As such, the Other person posed and was an epistemological problem—of being only a perception of the consciousness of the Self.[14] In Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology (1943), Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) applied the dialectic of intersubjectivity to describe how the world is altered by the appearance of the Other, of how the world then appears to be oriented to the Other person, and not to the Self. The Other appears as a psychological phenomenon in the course of a person's life, and not as a radical threat to the existence of the Self. In that mode, in The Second Sex (1949), Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986) applied the concept of Otherness to Hegel's dialectic of the "Lord and Bondsman" (Herrschaft und Knechtschaft, 1807) and found it to be like the dialectic of the Man–Woman relationship, thus a true explanation for society's treatment and mistreatment of women. Psychology The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan (1901–1981) and the philosopher of ethics Emmanuel Levinas (1906–1995) established the contemporary definitions, usages, and applications of the constitutive Other, as the radical counterpart of the Self. Lacan associated the Other with language and with the symbolic order of things. Levinas associated the Other with the ethical metaphysics of scripture and tradition; the ethical proposition is that the Other is superior and prior to the Self. In the event, Levinas re-formulated the face-to-face encounter (wherein a person is morally responsible to the Other person) to include the propositions of Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) about the impossibility of the Other (person) being an entirely metaphysical pure-presence. That the Other could be an entity of pure Otherness (of alterity) personified in a representation created and depicted with language that identifies, describes, and classifies. The conceptual re-formulation of the nature of the Other also included Levinas's analysis of the distinction between "the saying and the said"; nonetheless, the nature of the Other retained the priority of ethics over metaphysics. In the psychology of the mind (e.g. R. D. Laing), the Other identifies and refers to the unconscious mind, to silence, to insanity, and to language ("to what is referred and to what is unsaid").[15] Nonetheless, in such psychologic and analytic usages, there might arise a tendency to relativism if the Other person (as a being of pure, abstract alterity) leads to ignoring the commonality of truth. Likewise, problems arise from unethical usages of the terms The Other, Otherness, and Othering to reinforce ontological divisions of reality: of being, of becoming, and of existence.[14] Ethics  The philosopher of ethics Emmanuel Lévinas said that the infinite demand the Other places on the Self makes ethics the foundation of human existence and philosophy. In Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority (1961), Emmanuel Lévinas said that previous philosophy had reduced the constitutive Other to an object of consciousness, by not preserving its absolute alterity—the innate condition of otherness, by which the Other radically transcends the Self and the totality of the human network, into which the Other is being placed. As a challenge to self-assurance, the existence of the Other is a matter of ethics, because the ethical priority of the Other equals the primacy of ethics over ontology in real life.[16] From that perspective, Lévinas described the nature of the Other as "insomnia and wakefulness"; an ecstasy (an exteriority) towards the Other that forever remains beyond any attempt at fully capturing the Other, whose Otherness is infinite; even in the murder of an Other, the Otherness of the person remains uncontrolled and not negated. The infinity of the Other allowed Lévinas to derive other aspects of philosophy and science as secondary to that ethic; thus: The others that obsess me in the Other do not affect me as examples of the same genus united with my neighbor, by resemblance or common nature, individuations of the human race, or chips off the old block. . . . The others concern me from the first. Here, fraternity precedes the commonness of a genus. My relationship with the Other as neighbor gives meaning to my relations with all the others.—Otherwise than Being, or Beyond Essence[17]: 232 Critical theory Jacques Derrida said that the absolute alterity of the Other is compromised, because the Other person is other than the Self and the group. The logic of alterity (otherness) is especially negative in the realm of human geography, wherein the native Other is denied ethical priority as a person with the right to participate in the geopolitical discourse with an empire who decides the colonial fate of the homeland of the Other. In that vein, the language of Otherness used in Oriental Studies perpetuates the cultural perspective of the dominantor–dominated relation, which is characteristic of hegemony; likewise, the sociologic misrepresentation of the feminine as the sexual Other to man reasserts male privilege as the primary voice in social discourse between women and men.[14] In The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine and Iraq (2004), the geographer Derek Gregory said that the US government's ideologic answers to questions about reasons for the terrorist attacks against the U.S. (i.e. 11 September 2001) reinforced the imperial purpose of the negative representations of the Middle-Eastern Other; especially when President G. W. Bush (2001–2009) rhetorically asked: "Why do they hate us?" as political prelude to the War on Terror (2001).[18] Bush's rhetorical interrogation of armed resistance to empire, by the non–Western Other, produced an Us-and-Them mentality in American relations with the non-white peoples of the Middle East; hence, as foreign policy, the War on Terror is fought for control of imaginary geographies, which originated from the fetishised cultural representations of the Other invented by Orientalists; the cultural critic Edward Saïd said that: To build a conceptual framework around a notion of Us-versus-Them is, in effect, to pretend that the principal consideration is epistemological and natural—our civilization is known and accepted, theirs is different and strange—whereas, in fact, the framework separating us from them is belligerent, constructed, and situational. — The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine and Iraq (2004), p. 24.[19] Imperialism and colonialism The contemporary, post-colonial world system of nation-states (with interdependent politics and economies) was preceded by the European imperial system of economic and settler colonies in which "the creation and maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationship, usually between states, and often in the form of an empire, [was] based on domination and subordination."[20] In the imperialist world system, political and economic affairs were fragmented, and the discrete empires "provided for most of their own needs ... [and disseminated] their influence solely through conquest [empire] or the threat of conquest [hegemony]."[21] Racism  A manifestation of the Other in the form of scientific racism: In this 1857 illustration from his work Indigenous Races of the Earth, anthropologist Josiah C. Nott justified anti-Black racism by claiming that the features of African-Americans had more in common with chimpanzees than humans in comparison to white people. The racialist perspective of the Western world during the 18th and 19th centuries was invented with the Othering of non-white peoples, which also was supported with the fabrications of scientific racism, such as the pseudo-science of phrenology, which claimed that, in relation to a white-man's head, the head-size of the non-European Other indicated inferior intelligence; e.g. the apartheid-era cultural representations of coloured people in South Africa (1948–94).[22] Consequent to the Holocaust (1941–1945), with documents such as The Race Question (1950) and the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1963), the United Nations officially declared that racial differences are insignificant to anthropological likeness among human beings. Despite the United Nations' factual dismissal of racialism, institutional Othering in the United States produces the cultural misrepresentation of political refugees as illegal immigrants (from overseas) and of immigrants as illegal aliens (usually from México). Orientalism To European people, imperialism (military conquest of non-white people, annexation, and economic integration of their countries to the motherland) was intellectually justified by (among other reasons) orientalism, the study and fetishization of the Eastern world as "primitive peoples" requiring modernisation the civilising mission. Colonial empires were justified and realised with essentialist and reductive representations (of people, places, and cultures) in books and pictures and fashion, which conflated different cultures and peoples into the binary relation of the Orient and the Occident. Orientalism created the artificial existence of the Western Self and the non–western Other.[23] Orientalists rationalised the cultural artifice of a difference of essence between white and non-white peoples to fetishize (identify, classify, subordinate) the peoples and cultures of Asia into "the Oriental Other"—who exists in opposition to the Western Self.[24] As a function of imperial ideology, Orientalism fetishizes people and things in three actions of cultural imperialism: (i) Homogenization (all Oriental peoples are one folk); (ii) Feminization (the Oriental always is subordinate in the East–West relation); and (iii) Essentialization (a people possess universal characteristics); thus established by Othering, the empire's cultural hegemony reduces to inferiority the people, places, and things of the Eastern world, as measured against the West, the standard of superior civilisation.[24][25] Subaltern native  The subaltern native is a colonial identity for the Other, which conceptually derives from the Cultural hegemony work of Antonio Gramsci, an Italian Marxist intellectual. Colonial stability requires the cultural subordination of the non-white Other for transformation into the subaltern native; a colonised people who facilitate the exploitation of their labour, of their lands, and of the natural resources of their country. The practise of Othering justifies the physical domination and cultural subordination of the native people by degrading them—first from being a national-citizen to being a colonial-subject—and then by displacing them to the periphery of the colony, and of geopolitical enterprise that is imperialism.[26] Using the false dichotomy of "colonial strength" (imperial power) against "native weakness" (military, social, and economic), the coloniser invents the non-white Other in an artificial dominator-dominated relationship that can be resolved only through racialist noblesse oblige, the "moral responsibility" that psychologically allows the colonialist Self to believe that imperialism is a civilising mission to educate, convert, and then culturally assimilate the Other into the empire—thus transforming the "civilised" Other into the Self.[27] In establishing a colony, Othering a non-white people allowed the colonisers to physically subdue and "civilise" the natives to establish the hierarchies of domination (political and social) required for exploiting the subordinated natives and their country.[28] As a function of empire, a settler colony is an economic means for profitably disposing of two demographic groups: (i) the colonists (surplus population of the motherland) and (ii) the colonised (the subaltern native to be exploited) who antagonistically define and represent the Other as separate and apart from the colonial Self.[29][30] Othering establishes unequal relationships of power between the colonised natives and the colonisers, who believe themselves essentially superior to the natives whom they othered into racial inferiority, as the non-white Other.[31] That dehumanisation maintains the false binary-relations of social class, caste, and race, of sex and gender, and of nation and religion.[28] The profitable functioning of a colony (economic or settler) requires continual protection of the cultural demarcations that are basic to the unequal socio-economic relation between the "civilised man" (the colonist) and the "savage man", thus the transformation of the Other into the colonial subaltern.[31] |

背景 哲学  観念論哲学者G.W.F.ヘーゲルは、人間の自己へのこだわりの構成要素として他者の概念を導入した 自己の概念は、自己を定義するために必要な対となる存在として、構成的な他者の存在を必要とする。したがって、18世紀後半にゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フ リードリヒ・ヘーゲル(1770-1831)は自己意識(自己への偏執)の構成部分としての他者の概念を導入し[11]、ヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテ (1762-1814)が提示した自己認識(内省能力)に関する命題を補完していた[12]。 ジョン・スチュアート・ミル(1806-1873)は1865年に『An Examination of Sir William Hamilton's Philosophy』において、ルネ・デカルト(1596-1650)以後の他者に関する最初の定式化である他心の考えを導入している[13]。 エドムント・フッサール(Edmund Husserl, 1859-1938)は、他者という概念を相互主観性、つまり人々の間の心理的関係の基礎として適用した。デカルトの瞑想』(1859年-1938年)に おいて、フッサールは「他者」の概念を相互主観性、つまり人々の間の心理的関係の基礎として適用した: 現象学入門』(1931年)の中でフッサールは、他者は分身として、もう一人の自己として構成されると述べている。そのため、他者は自己の意識の知覚でし かないという認識論的な問題を提起し、またそうであった[14]。 存在と無』において: ジャン=ポール・サルトル(1905-1980)は、『現象学的存在論についての試論』(1943年)において、間主観性の弁証法を適用して、他者が現れ ることによって世界がどのように変化するか、世界が自己ではなく他者に向けられているように見えるかについて述べている。他者は、自己の存在に対する根本 的な脅威としてではなく、その人の人生の過程における心理現象として現れる。シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワール(1908-1986)は、『第二の性』 (1949年)の中で、他者性の概念をヘーゲルの「主と束縛者」の弁証法(Herrschaft und Knechtschaft、1807年)に当てはめ、それが男女関係の弁証法のようなものであり、したがって社会の女性に対する扱いや虐待を説明する真の ものであることを発見した。 心理学 精神分析学者ジャック・ラカン(1901-1981)と倫理哲学者エマニュエル・レヴィナス(1906-1995)は、自己の根本的な対極として、構成的 な他者の現代的な定義、用法、応用を確立した。ラカンは他者を言語や物事の象徴的秩序と結びつけた。レヴィナスは、他者を聖典や伝統の倫理的形而上学と関 連づけた。倫理的命題とは、他者が自己に優越し、それに先立つというものである。 その際、レヴィナスは(人が他者に対して道徳的責任を負う)対面的出会いを再形成し、他者(人)が完全に形而上学的な純粋存在であることの不可能性に関す るジャック・デリダ(1930-2004)の命題を盛り込んだ。他者とは、識別し、記述し、分類する言語によって創造され、描かれた表象の中で擬人化され た純粋な他者性(分身性)の実体でありうるということである。他者の本質の概念的な再定式化には、「言うことと言われること」の区別についてのレヴィナス の分析も含まれていた。それにもかかわらず、他者の本質は形而上学よりも倫理学の優先権を保持したままであった。 心の心理学(例えばR.D.レイング)では、他者は無意識の心、沈黙、狂気、言語(「言及されるもの、されないもの」)を特定し、言及する[15]。それ にもかかわらず、このような心理学的、分析的用法では、他者が(純粋で抽象的な分身の存在として)真理の共通性を無視することにつながれば、相対主義への 傾向が生じるかもしれない。同様に、「他者」、「他者性」、「他者化」という用語の非倫理的な用法が、現実の存在論的な区分、すなわち「存在すること」、 「なること」、「存在すること」を強化することから問題が生じる[14]。 倫理学  倫理学の哲学者であるエマニュエル・レヴィナスは、他者が自己に課す無限の要求が倫理学を人間の存在と哲学の基礎にしていると述べている。 全体性と無限性: エマニュエル・レヴィナスは、『外在性についての試論』(1961年)の中で、これまでの哲学は、構成的な他者を意識の対象へと貶めてきたと述べている。 それは、その絶対的な分身性--他者が自己を根本的に超越し、他者が置かれる人間のネットワークの全体性を超越するという、他者性の生得的条件--を保持 しなかったからである。自己肯定感に対する挑戦として、他者の存在は倫理の問題であり、他者の倫理的優先順位は現実の生活における存在論に対する倫理の優 先順位に等しいからである[16]。 そのような観点から、レヴィナスは他者の本質を「不眠と覚醒」と表現しており、その他者性は無限であり、他者を完全に捉えようとする試みを超えて永遠に残 る他者に対するエクスタシー(外在性)であり、他者が殺害されたときでさえ、その人物の他者性は制御されずに否定されずに残る。他者が無限であることに よって、レヴィナスは哲学や科学の他の側面をその倫理の二次的なものとして導き出すことができた: 他者において私に執着する他者は、類似性や共通性によって隣人と一体化した同属の例、人類の個性、あるいは古いブロックの欠片として私に影響を与えるので はない。. . . 他者は最初から私に関係する。ここでは、友愛が属人的な共通性に先行している。隣人としての他者との関係は、他者すべてとの関係に意味を与える。 批評理論 ジャック・デリダは、他者の絶対的な分身性は損なわれていると述べている。分身性(他者性)の論理は、特に人文地理学の領域において否定的であり、そこで は土着の他者は、他者の故郷の植民地的運命を決定する帝国との地政学的言説に参加する権利を持つ人間としての倫理的優先権を否定される。同様に、男性に対 する性的な他者としての女性性の社会学的な誤った表現は、女性と男性の間の社会的な言説における主要な発言者としての男性の特権を再確認するものである [14]。 植民地的現在』において: 地理学者のデレク・グレゴリーは、『植民地的現在:アフガニスタン、パレスチナ、イラク』(2004年)の中で、アメリカに対するテロ攻撃(すなわち 2001年9月11日)の理由についての質問に対するアメリカ政府のイデオロギー的な回答は、中東の他者に対する否定的な表象の帝国的な目的を強化したと 述べている: 非西洋的な他者による帝国への武力抵抗というブッシュの修辞的な問いかけは、中東の非白人民族とアメリカの関係において、「われわれと彼ら」というメンタ リティを生み出した。それゆえ、対テロ戦争は外交政策として、想像上の地理を支配するために戦われるのであり、それはオリエンタリストによって生み出され た、フェティッシュ化された他者の文化的表象に由来する: われわれ対彼らという概念を中心に概念的枠組みを構築することは、事実上、主要な考察が認識論的で自然なものであるかのように装うことである-われわれの 文明は既知で受け入れられており、彼らの文明は異質で奇妙である-のに対して、実際には、われわれと彼らを隔てる枠組みは好戦的であり、構築されたもので あり、状況的なものである。 - 植民地的現在: アフガニスタン、パレスチナ、イラク』(2004年)24頁[19]。 帝国主義と植民地主義 現代のポストコロニアルな国民国家の世界システム(相互依存的な政治と経済を持つ)は、「不平等な経済的、文化的、領土的関係の創出と維持が、通常は国家 間で、しばしば帝国の形態で、支配と従属に基づいていた」[20]経済植民地と入植植民地のヨーロッパ帝国システムに先行していた。[そして征服(帝国) あるいは征服の脅威(覇権)によってのみ影響力を広めた」[21]。 人種主義  科学的人種主義という形で他者を表現している: 人類学者ジョサイア・C・ノットは、彼の著作『Indigenous Races of the Earth』(1857年)に掲載されたこのイラストの中で、アフリカ系アメリカ人の特徴は白人と比較して、人間よりもチンパンジーと共通点が多いと主張 し、反黒人人種主義を正当化した。 18世紀から19世紀にかけての西欧世界における人種主義的な視点は、非白人民族の他者化とともに生み出され、それはまた、白人の頭との関係において、非 ヨーロッパ人の頭の大きさが劣った知性を示すと主張する骨相学の疑似科学のような、科学的人種主義の捏造によって支えられていた。 ホロコースト(1941年~1945年)の後、『人種問題』(1950年)や『あらゆる形態の人種差別の撤廃に関する宣言』(1963年)といった文書に よって、国連は公式に、人種差は人間同士の人類学的類似性にとって取るに足らないものであると宣言した。国連が人種主義を事実上否定しているにもかかわら ず、アメリカにおける制度的他者化は、政治難民を(海外からの)不法移民として、移民を(通常はメキシコからの)不法外国人として、文化的に誤って表現す ることを生み出している。 オリエンタリズム ヨーロッパの人々にとって、帝国主義(非白人の軍事的征服、併合、祖国への経済的統合)は、(とりわけ)オリエンタリズム、つまり文明化という近代化の使 命を必要とする「原始人」としての東洋世界の研究とフェティシズムによって知的に正当化された。植民地帝国は、異なる文化や民族を東洋と西洋という二項対 立の関係に混同した、本質主義的で還元的な表象(人、場所、文化)を本や写真やファッションに描くことで正当化され、実現された。オリエンタリズムは西洋 的な自己と非西洋的な他者という人為的な存在を作り出した[23]。オリエンタリストたちは、白人と非白人の間の本質の違いという文化的な作為を合理化 し、アジアの民族や文化を「東洋的な他者」-西洋的な自己と対立する存在-としてフェティシズム化(識別、分類、従属化)した。 [24] 帝国イデオロギーの機能として、オリエンタリズムは文化的帝国主義の3つの行為において人や物をフェティシズム化する: (i)均質化(東洋の民族はすべて一つの民族である)、(ii)女性化(東洋人は東西関係において常に従属的である)、(iii)本質化(民族は普遍的な 特徴を有している)。こうして他者化によって確立された帝国の文化的ヘゲモニーは、優れた文明の基準である西洋に対して測定される東洋世界の人々、場所、 事物を劣等なものへと還元する。 [24][25] サバルタン・ネイティヴ  サバルタン土着民は他者のための植民地的アイデンティティであり、概念的にはイタリアのマルクス主義知識人であるアントニオ・グラムシの文化的覇権主義に 由来する。 植民地の安定には、非白人である他者を文化的に従属させ、サブ・インターンの土着民へと変貌させることが必要である。他者化の実践は、先住民の物理的な支 配と文化的な従属を、彼らを劣化させることで正当化する。まず彼らを国民=市民から植民地=主体へと変質させ、次に彼らを植民地の周縁部に追いやること で、そして帝国主義という地政学的事業の周縁部に追いやることで正当化する[26]。 先住民の弱さ」(軍事的、社会的、経済的)に対する「植民地の強さ」(帝国の力)という誤った二分法を用いて、植民地支配者は非白人の他者を人為的な支配 者-被支配者の関係として作り出し、それは人種主義的なノブレス・オブリージュによってのみ解決される。 植民地を設立する際、非白人民族を他者化することで、植民者は従属する原住民とその国を搾取するために必要な支配の階層(政治的、社会的)を確立するため に原住民を物理的に服従させ、「文明化」させることができた。 [28]帝国の機能として、入植植民地は2つの人口集団、すなわち(i)植民者(祖国の余剰人口)と(ii)植民地化された人々(搾取されるべき原住民の サブアルターン)を利潤を得て処分するための経済的手段であり、彼らは他者を植民地的自己とは別個のものとして拮抗的に定義し、表象している[29] [30]。 他者化は植民地化された原住民と植民地化者の間に不平等な力関係を確立し、植民地化者は自分たちを非白人である他者として人種的に劣等な立場に追いやった 原住民よりも本質的に優れていると信じている[31]。その非人間化は社会階級、カースト、人種、セックスとジェンダー、国家と宗教の誤った二項関係を維 持する。 [28]植民地(経済的あるいは入植者)が有益に機能するためには、「文明人」(入植者)と「野蛮人」の間の不平等な社会経済的関係の基本である文化的分 界を継続的に保護することが必要であり、その結果、他者を植民地的サバルタンへと変容させるのである[31]。 |

| Gender and sex LGBT identities The social exclusion function of Othering a person or a social group from mainstream society to the social margins—for being essentially different from the societal norm (the plural Self)—is a socio-economic function of gender. In a society wherein man–woman heterosexuality is the sexual norm, the Other refers to and identifies lesbians (women who love women) and gays (men who love men) as people of same-sex orientation whom society has othered as "sexually deviant" from the norms of binary-gender heterosexuality.[32] In practise, sexual Othering is realised by applying the negative denotations and connotations of the terms that describe lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, in order to diminish their personal social status and political power, and so displace their LGBT communities to the legal margin of society. To neutralise such cultural Othering, LGBT communities queer a city by creating social spaces that use the spatial and temporal plans of the city to allow the LGBT communities free expression of their social identities, e.g. a boystown, a gay-pride parade, etc.; as such, queering urban spaces is a political means for the non-binary sexual Other to establish themselves as citizens integral to the reality (cultural and socio-economic) of their city's body politic.[33] Woman as identity  The philosopher of existentialism Simone de Beauvoir developed the concept of The Other to explain the workings of the Man–Woman binary gender relation, as a critical base of the Dominator–Dominated relation, which characterises sexual inequality between men and women. The philosopher of feminism, Cheshire Calhoun identified the female Other as the female-half of the binary-gender relation that is the Man and Woman relation. The deconstruction of the word Woman (the subordinate party in the Man and Woman relation) produced a conceptual reconstruction of the female Other as the Woman who exists independently of male definition, as rationalised by patriarchy. That the female Other is a self-aware Woman who is autonomous and independent of the patriarchy's formal subordination of the female sex with the institutional limitations of social convention, tradition, and customary law; the social subordination of women is communicated (denoted and connoted) in the sexist usages of the word Woman.[34] In 1949, the philosopher of existentialism, Simone de Beauvoir applied Hegel's conception of "the Other" (as a constituent part of self-awareness) to describe a male-dominated culture that represents Woman as the sexual Other to Man. In a patriarchal culture, the Man–Woman relation is society's normative binary-gender relation, wherein the sexual Other is a social minority with the least socio-political agency, usually the women of the community, because patriarchal semantics established that "a man represents both the positive and the neutral, as indicated by the common use of [the word] Man to designate human beings in general; whereas [the word] Woman represents only the negative, defined by limiting criteria, without reciprocity" from the first sex, from Man.[35] In 1957, Betty Friedan reported that a woman's social identity is formally established by the sexual politics of the Ordinate–Subordinate nature of the Man–Woman sexual relation, the social norm in the patriarchal West. When queried about their post-graduate lives, the majority of women interviewed at a university-class reunion, used binary gender language, and referred to and identified themselves by their social roles (wife, mother, lover) in the private sphere of life; and did not identify themselves by their own achievements (job, career, business) in the public sphere of life. Unawares, the women had acted conventionally, and automatically identified and referred to themselves as the social Other to men. Although the nature of the social Other is influenced by the society's social constructs (social class, sex, gender), as a human organisation, society holds the socio-political power to formally change the social relation between the male-defined Self and Woman, the sexual Other, who is not male.[36] In feminist definition, women are the Other to men (but not the Other proposed by Hegel) and are not existentially defined by masculine demands; and also are the social Other who unknowingly accepts social subjugation as part of subjectivity,[37] because the gender identity of woman is constitutionally different from the gender identity of man. The harm of Othering is in the asymmetric nature of unequal roles in sexual and gender relations; the inequality arises from the social mechanics of intersubjectivity.[38] |

ジェンダーとセックス LGBTのアイデンティティ 社会的規範(複数の自己)とは本質的に異なるという理由で、人や社会的集団を主流社会から社会的周縁へと他者化する社会的排除機能は、ジェンダーの社会経 済的機能である。男性と女性の異性愛が性的規範である社会では、他者はレズビアン(女性を愛する女性)やゲイ(男性を愛する男性)を、社会が二元的性別の 異性愛規範から「性的逸脱者」として他者化した同性指向の人々として参照し、識別する。 [32] 実際には、性的他者化は、レズビアン、ゲイ、バイセクシュアル、トランスジェンダーの人々を表す用語の否定的な意味合いや含蓄を適用することによって実現 され、彼らの個人的な社会的地位や政治的権力を低下させ、LGBTのコミュニティを社会の法的余白に追いやる。そのような文化的他者化を中和するために、 LGBTコミュニティは、都市の空間的・時間的計画を利用して、LGBTコミュニティが社会的アイデンティティを自由に表現できるような社会的空間(例え ば、ボイスタウン、ゲイ・プライド・パレードなど)を創造することによって、都市をクィア化する。このように、都市空間をクィア化することは、非二元的な 性的他者が、その都市の政治体の現実(文化的・社会経済的)に不可欠な市民として自らを確立するための政治的手段である[33]。 アイデンティティとしての女性  実存主義の哲学者シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールは、男女間の性的不平等を特徴づける支配者と被支配者の関係の批判的基盤として、男と女の二元的なジェン ダー関係の働きを説明するために「他者」の概念を発展させた。 フェミニズムの哲学者であるチェシャー・カルフーンは、女性の他者とは、男と女の関係である二元的ジェンダー関係の女性の半分であるとした。ウーマン(男 女関係における従属者)という言葉の脱構築は、家父長制によって合理化された、男性の定義とは無関係に存在するウーマンとしての女性他者という概念的再構 築を生み出した。女性の他者とは、家父長制が社会的慣習、伝統、慣習法という制度的制限によって女性の性を形式的に従属させることから自律的かつ独立して いる自意識的な女性であり、女性の社会的従属はWomanという言葉の性差別的な用法において伝達される(示され、含意される)[34]。 年、実存主義の哲学者であるシモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールは、ヘーゲルの「他者」の概念(自己認識の構成部分として)を適用し、ウーマンをマンに対する性 的な他者として表現する男性優位の文化を説明した。家父長制文化においては、男と女の関係は社会の規範的な二元的男女関係であり、そこでは性的他者とは社 会政治的主体性が最も乏しい社会的マイノリティであり、通常は共同体の女性である。家父長制の意味論では、「男は、人間一般を指定するために[男という言 葉が]一般的に使われることによって示されるように、肯定的なものと中立的なものの両方を表すのに対して、[女という言葉は]限定的な基準によって定義さ れる否定的なもののみを表し、男からの第一の性からの互恵性はない」とされているからである[35]。 1957年、ベティ・フリーダンは、女性の社会的アイデンティティは、家父長制的な西洋における社会規範である、男と女の性的関係の序列的-従属的性質の 性政治によって形式的に確立されると報告している。大学の同窓会でインタビューに応じた女性の大半は、卒業後の人生について質問されたとき、二元的なジェ ンダー言語を使い、私的な生活圏では社会的役割(妻、母、恋人)によって自らを言及し、特定した。彼女たちは知らず知らずのうちに、慣習的に行動し、自動 的に自分たちを男性にとっての社会的他者として認識し、呼んでいたのである。 社会的他者の性質は、社会の社会的構成要素(社会階級、性別、ジェンダー)に影響されるが、人間の組織として、社会は、男性によって定義された自己と、男 性ではない性的他者である女性との社会的関係を形式的に変える社会政治的権力を握っている[36]。 フェミニストの定義では、女性は男性にとっての他者(しかしヘーゲルが提唱した他者ではない)であり、男性的な要求によって実存的に定義されるものではな く、また、女性のジェンダー・アイデンティティは男性のジェンダー・アイデンティティとは体質的に異なるため、主体性の一部として社会的被支配を無自覚に 受け入れる社会的他者である[37]。他者化の弊害は、セクシュアルとジェンダーの関係における不平等な役割の非対称性にあり、不平等は相互主観性の社会 的メカニズムから生じている[38]。 |

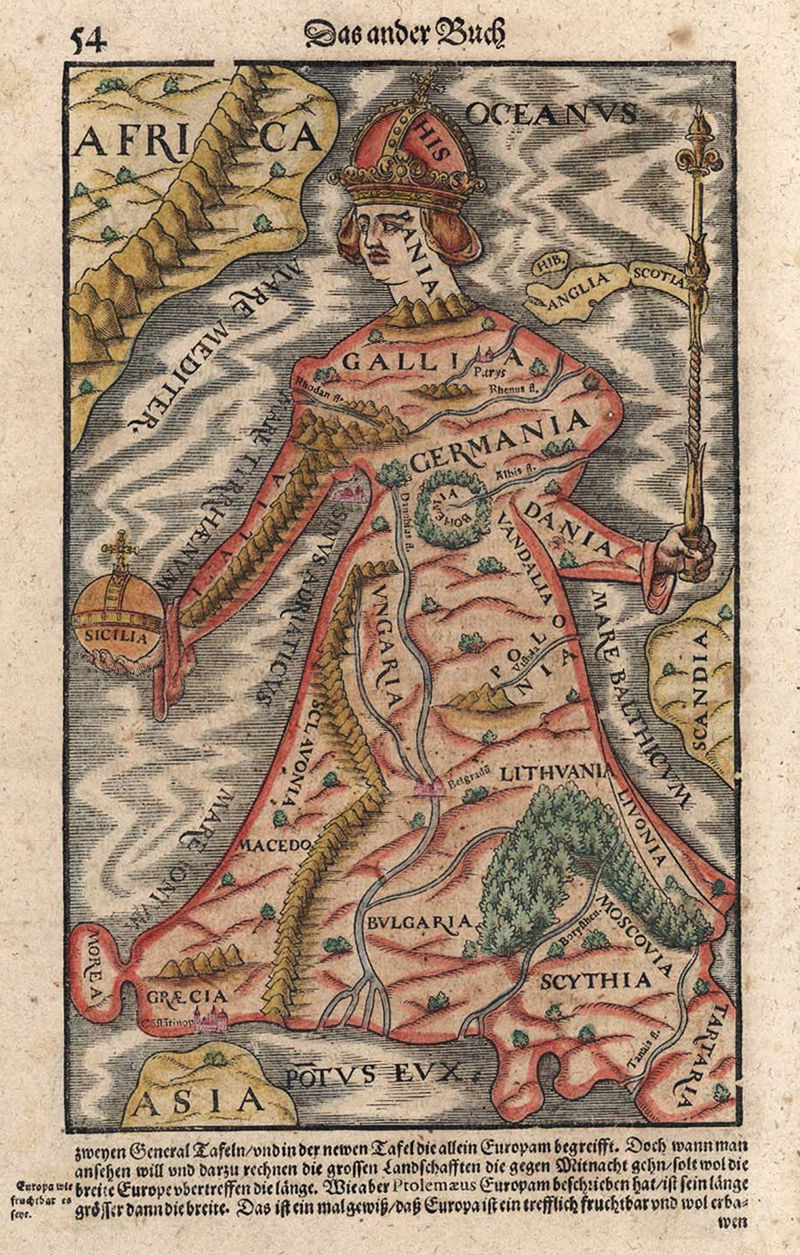

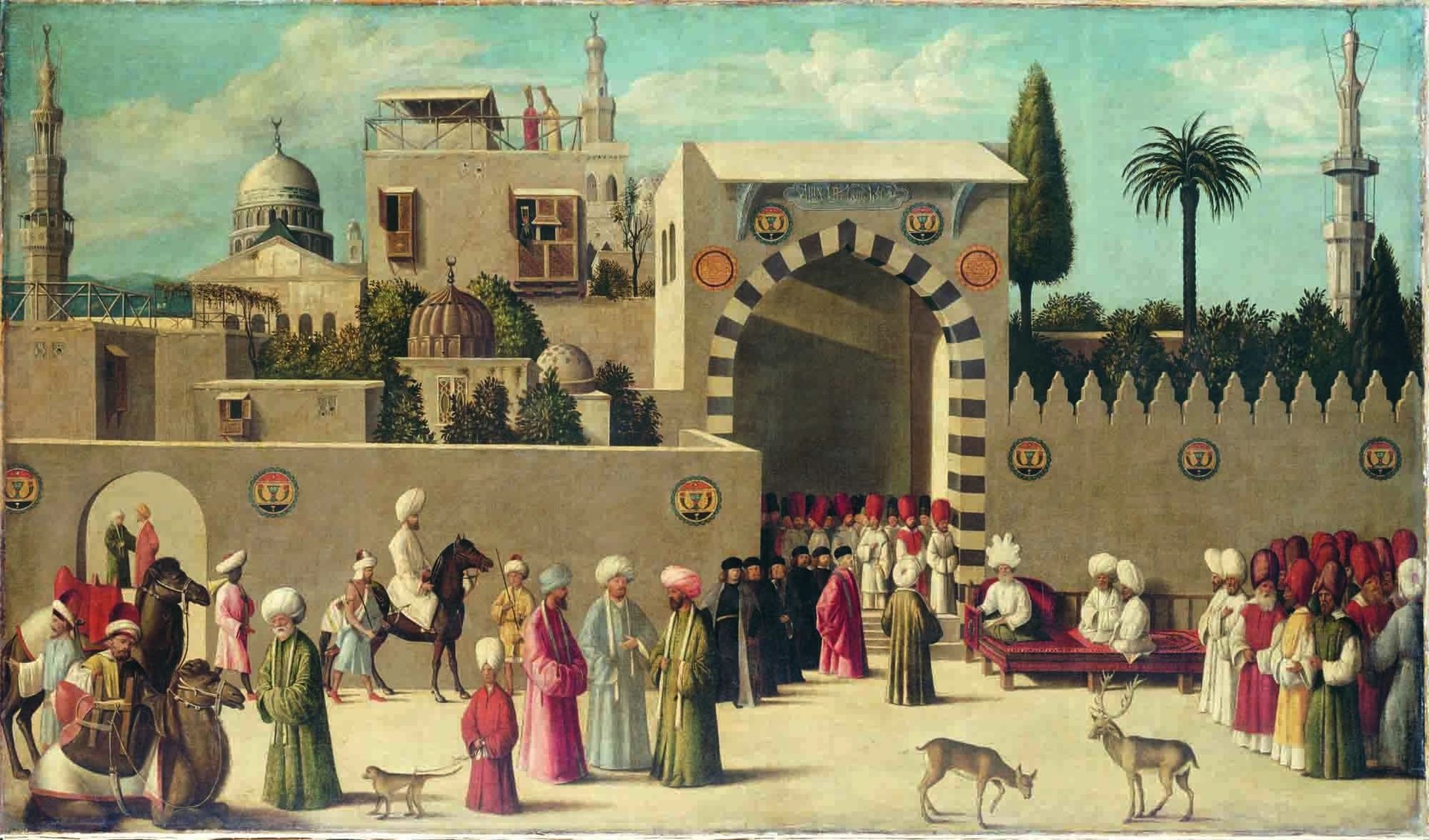

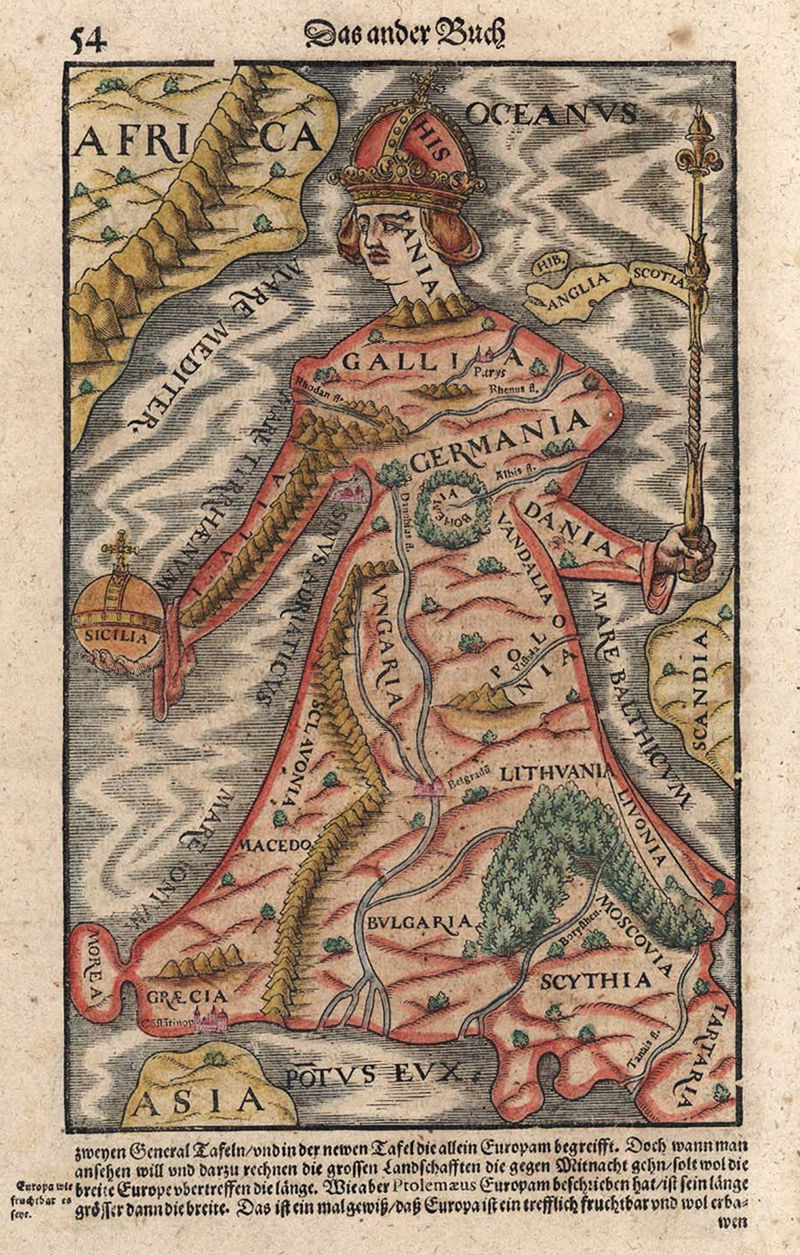

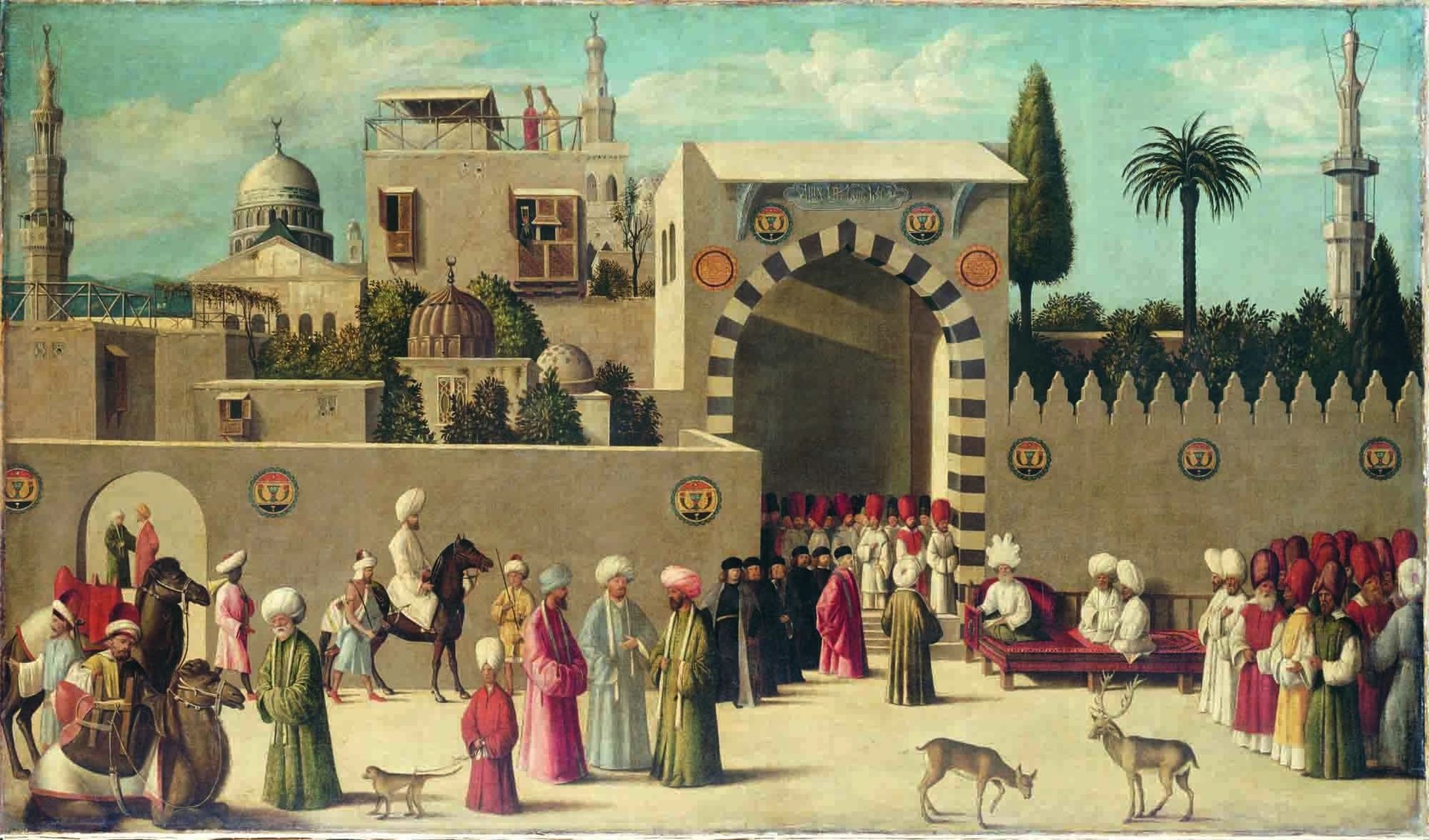

| Knowledge Cultural representations  The Yellow Terror in all His Glory, an 1899 editorial cartoon depicting a Chinese man standing over a fallen white woman. The Chinese man, the "other", represents the Boxer movement and the woman represents Christian Europeans.[39] About the production of knowledge of the Other who is not the Self, the philosopher Michel Foucault said that Othering is the creation and maintenance of imaginary "knowledge of the Other"—which comprises cultural representations in service to socio-political power and the establishment of hierarchies of domination. That cultural representations of the Other (as a metaphor, as a metonym, and as an anthropomorphism) are manifestations of the xenophobia inherent to the European historiographies that defined and labelled non–European peoples as the Other who is not the European Self. Supported by the reductive discourses (academic and commercial, geopolitical and military) of the empire's dominant ideology, the colonialist misrepresentations of the Other explain the Eastern world to the Western world as a binary relation of native weakness against colonial strength.[40] In the 19th-century historiographies of the Orient as a cultural region, the Orientalists studied only what they said was the high culture (languages and literatures, arts and philologies) of the Middle East, but did not study that geographic space as a place inhabited by different nations and societies.[41] About that Western version of the Orient, Edward Saïd said that: the Orient that appears in Orientalism, then, is a system of representations framed by a whole set of forces that brought the Orient into Western learning, Western consciousness, and later, Western empire. If this definition of Orientalism seems more political than not, that is simply because I think Orientalism was, itself, a product of certain political forces and activities. Orientalism is a school of interpretation whose material happens to be the Orient, its civilisations, peoples, and localities. Its objective discoveries – the work of innumerable devoted scholars who edited texts and translated them, codified grammars, wrote dictionaries, reconstructed dead epochs, produced positivistically verifiable learning – are and always have been conditioned by the fact that its truths, like any truths delivered by language, are embodied in language, and, what is the truth of language?, Nietzsche once said, but "a mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms – in short, a sum of human relations, which have been enhanced, transposed, and embellished poetically and rhetorically, and which, after long use, seem firm, canonical, and obligatory to a people: truths are illusions about which one has forgotten that this is what they are." — Orientalism (1978) pp. 202–203.[42]: 202 In so far as the Orient occurred in the existential awareness of the Western world, as a term, The Orient later accrued many meanings and associations, denotations, and connotations that did not refer to the real peoples, cultures, and geography of the Eastern world, but to Oriental studies, the academic field about the Orient as a word.[43] Academia  In "Cosmographia" (1570), by Sebastian Münster, "Europa regina" is the cartographic centre of the world. In the Eastern world, the field of Occidentalism, the investigation programme and academic curriculum of and about the essence of the West—Europe as a culturally homogeneous place—did not exist as a counterpart to Orientalism.[44] In the postmodern era, the Orientalist practices of historical negationism, the writing of distorted histories about the places and peoples of "The East", continues in contemporary journalism; e.g. in the Third World, political parties practice Othering with fabricated facts about threat-reports and non-existent threats (political, social, military) that are meant to politically delegitimise opponent political parties composed of people from the social and ethnic groups designated as the Other in that society.[45] The Othering of a person or of a social group—by means of an ideal ethnocentricity (the ethnic group of the Self) that evaluates and assigns negative, cultural meaning to the ethnic Other—is realised through cartography;[46]: 179 hence, the maps of Western cartographers emphasised and bolstered artificial representations of the national-identities, the natural resources, and the cultures of the native inhabitants, as culturally inferior to the West. Historically, Western cartography often featured distortions (proportionate, proximate, and commercial) of places and true distances by placing the cartographer's homeland in the centre of the mapamundi; these ideas were often utilized to support imperialistic expansion. In contemporary cartography, the polar-perspective maps of the northern hemisphere, drawn by U.S. cartographers, also frequently feature distorted spatial relations (distance, size, mass) of and between the U.S. and Russia which according to historian Jerome D. Fellman emphasise the perceived inferiority (military, cultural, geopolitical) of the Russian Other.[46]: 10 Practical perspectives  Orientalist art: The Reception of the Ambassadors in Damascus (1511) features wildlife (the deer in the foreground) that is not native to Syria. In Key Concepts in Political Geography (2009), Alison Mountz proposed concrete definitions of the Other as a philosophic concept and as a term within phenomenology; as a noun, the Other identifies and refers to a person and to a group of persons; as a verb, the Other identifies and refers to a category and a label for persons and things. Post-colonial scholarship demonstrated that, in pursuit of empire, "the colonizing powers narrated an 'Other' whom they set out to save, dominate, control, [and] civilize . . . [in order to] extract resources through colonization" of the country whose people the colonial power designated as the Other.[32] As facilitated by Orientalist representations of the non–Western Other, colonization—the economic exploitation of a people and their land—is misrepresented as a civilizing mission launched for the material, cultural, and spiritual benefit of the colonized peoples.[32] Counter to the post-colonial perspective of the Other as part of a Dominator–Dominated binary relationship, postmodern philosophy presents the Other and Otherness as phenomenological and ontological progress for Man and Society. Public knowledge of the social identity of peoples classified as "Outsiders" is de facto acknowledgement of their being real, thus they are part of the body politic, especially in the cities. As such, "the post-modern city is a geographical celebration of difference that moves sites once conceived of as 'marginal' to the [social] centre of discussion and analysis" of the human relations between the Outsiders and the Establishment.[32] See also |

知識 文化的表現  倒れた白人女性の上に立つ中国人を描いた1899年の社説漫画『The Yellow Terror in all His Glory』。他者」である中国人は義和団運動を、女性はキリスト教徒であるヨーロッパ人を表している[39]。 哲学者ミシェル・フーコーは、自己ではない他者に関する知識の生産について、他者化とは想像上の「他者に関する知識」の創造と維持であり、それは社会政治 的権力と支配のヒエラルキーの確立に奉仕する文化的表象で構成されると述べている。メタファーとして、メトニムとして、擬人化として)他者の文化的表象 は、非ヨーロッパ民族をヨーロッパ的自己ではない他者として定義し、レッテルを貼ったヨーロッパの歴史学に内在する外国人嫌悪の現れである。帝国の支配的 なイデオロギーの還元的な言説(学問的、商業的、地政学的、軍事的)に支えられ、植民地主義者による他者の誤った表象は、植民地の強さに対する先住民の弱 さという二項対立の関係として、東方世界を西方世界に対して説明していた[40]。 文化的地域としてのオリエントに関する19世紀の歴史学において、オリエンタリストたちは中東の高度な文化(言語と文学、芸術と言語学)と言われるものだ けを研究していたが、異なる国家や社会が居住する場所としての地理的空間については研究していなかった: オリエンタリズムに登場するオリエントとは、オリエントを西洋の学問、西洋の意識、ひいては西洋の帝国に引き入れた一連の力によって枠付けられた表象の体 系である。このオリエンタリズムの定義が政治的であるように見えるとすれば、それは単に、オリエンタリズムがそれ自体、ある種の政治的な力と活動の産物で あったと私が考えるからである。 オリエンタリズムとは、オリエント、その文明、民族、地方を素材とする解釈の学派である。その客観的発見は、テキストを編集し、翻訳し、文法を体系化し、 辞書を書き、死滅した時代を再構築し、実証的に検証可能な学問を生み出した無数の献身的な学者たちの仕事であるが、その真理は、言語によってもたらされる あらゆる真理と同様に、言語に具現化されているという事実によって、常に条件づけられてきた、 ニーチェはかつてこう言ったが、「隠喩、メトニム、擬人化の移動可能な軍隊、要するに、詩的、修辞的に強化され、転置され、装飾された人間関係の総体であ る。 - 『オリエンタリズム』(1978年)202-203頁[42]: 202 オリエントが西洋世界の実存的な意識において用語として発生した限りにおいて、オリエントは後に多くの意味や連想、呼称、含蓄を獲得したが、それは東洋世 界の実在の民族、文化、地理を指すものではなく、言葉としてのオリエントに関する学問分野であるオリエント研究を指すものであった[43]。 アカデミア  セバスチャン・ミュンスターによる『コスモグラフィア』(1570年)では、「Europa regina」が世界の地図上の中心である。 東洋世界では、オクシデンタリズムの分野、西洋の本質についての調査プログラムや学問的カリキュラム、すなわち文化的に均質な場所としてのヨーロッパは、 オリエンタリズムと対をなすものとして存在しなかった。ポストモダンの時代においても、歴史否定主義、すなわち「東洋」の場所や民族について歪曲された歴 史を書くというオリエンタリズムの実践は、現代のジャーナリズムにおいて続いている。 例えば、第三世界では、政党が、その社会で他者として指定された社会的・民族的集団の人々から構成される対立政党を政治的に委縮させることを意図して、脅 威報告や存在しない脅威(政治的、社会的、軍事的)に関する捏造された事実を用いて他者化を実践している[45]。 ある人物や社会集団の他者化は、民族的な他者に対して否定的で文化的な意味を評価し割り当てる理想的な民族中心主義(自己の民族集団)によって、地図製作 を通じて実現される[46]: 179 したがって、西洋の地図製作者の地図は、民族的アイデンティティ、天然資源、そして先住民の文化が西洋よりも文化的に劣っているという人為的な表現を強調 し、強化した。 歴史的に、西洋の地図製作は、地図製作者の祖国をマパマンディの中心に置くことで、場所や真の距離の歪曲(比例、近接、商業)をしばしば特徴とし、こうし た考え方はしばしば帝国主義的な拡張を支持するために利用された。現代の地図製作において、米国の地図製作者によって描かれた北半球の極地遠近図もまた、 米国とロシアの歪んだ空間関係(距離、大きさ、質量)を頻繁に特徴としており、歴史家ジェローム・D・フェルマンによれば、ロシアという他者の劣等感(軍 事的、文化的、地政学的)を強調している[46]: 10 実践的視点  オリエンタリズム芸術 The Reception of the Ambassadors in Damascus』(1511年)には、シリアに生息しない野生動物(手前の鹿)が描かれている。 アリソン・マウンツは『Key Concepts in Political Geography』(2009年)の中で、哲学的な概念として、また現象学における用語として、他者について具体的な定義を提唱している。名詞として、 他者は人や人のグループを特定し、それを指す。 ポストコロニアル研究は、帝国を追求するために、「植民地化する大国が、保存し、支配し、統制し、文明化するために着手した『他者』を物語った。[非西洋 の他者に対するオリエンタリズムの表象によって促進されるように、植民地化-ある民族とその土地の経済的搾取-は、植民地化された民族の物質的、文化的、 精神的な利益のために開始された文明化の使命として誤って表象されている[32]。 支配者と被支配者の二項関係の一部としての他者というポストコロニアルの視点とは反対に、ポストモダンの哲学は他者と他者性を人間と社会の現象学的、存在 論的進歩として提示している。アウトサイダー」と分類される人々の社会的アイデンティティを公に知ることは、彼らが実在することを事実上認めることであ り、したがって彼らは、特に都市においては、政治的身体の一部なのである。そのため、「ポストモダンの都市は、かつて『周縁的』と考えられていた場所を、 アウトサイダーとエスタブリッシュメントとの人間関係の[社会的な]議論と分析の中心に移動させる、地理的な差異の祭典である」[32]。 以下も参照。 |

| Allophilia Allosemitism Alterity Caste system in India Dissociative Identity Disorder Exoticism Generalized other Identity politics Kyriarchy Markedness Marx's theory of alienation Open individualism Otherness of childhood Role suction Social alienation Vertiginous question Xenocentrism Books Orientalism (1978), by Edward Saïd The Wretched of the Earth, (1961), by Frantz Fanon The Other (2006), by Ryszard Kapuściński The Other, 1972 movie based on the novel by Thomas Tryon. Sexual difference Judith Butler Julia Kristeva Luce Irigaray Sarojini Sahoo |

アロフィリア(異邦人好み) アロセミティズム 異質性 インドのカースト制度 解離性同一性障害 異国趣味 一般化された他者 アイデンティティ政治 キリアキー マーク性 マルクスの疎外論 開かれた個人主義 子供時代の他者性 役割の吸引 社会的疎外 垂直問題 異人種中心主義 著書 オリエンタリズム』(1978年)エドワード・サイード著 地の哀れ』(1961年)フランツ・ファノン著 他者』(2006年)リシャルド・カプシチスキ著 1972年、トマス・トライオンの小説を基にした映画『他者』。 性的差異 ジュディス・バトラー ジュリア・クリステヴァ ルース・イリガライ サロジニ・サフー |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Other_(philosophy) |

|

キュー バにおける、ボーヴォワール、サルトル、そしてチェ・ゲバラ.

★

「女は何を欲しているのか?」——“[Freud] said once to Marie Bonaparte: 'The great

question that has never been answered, and which I have not yet been

able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine

soul, is "What does a woman want?” ― Sigmund Freud: Life and Work

(Hogarth Press, 1953) by Ernest Jones, Vol. 2, Pt. 3, Ch. 16, p. 421.

In a footnote Jones gives the original German, "Was will das Weib?"

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆