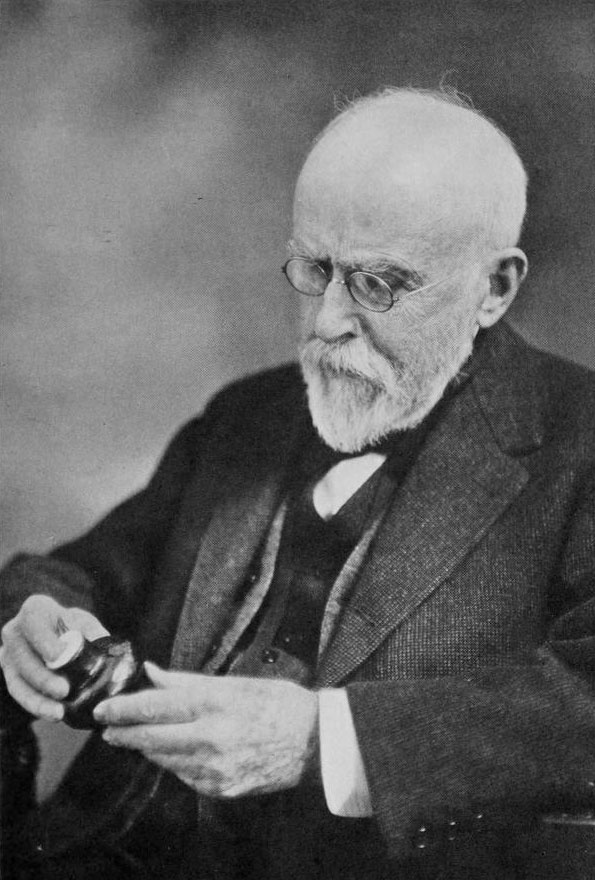

エドワード・S・モース

Edward Sylvester Morse, 1838-1925

Portrait

of American naturalist and archaeologist Edward Sylvester Morse

(1838–1925), by Frank Weston Benson.

☆ エドワード・シルベスター・モース(1838年6月18日 - 1925年12月20日)は、アメリカの動物学者、考古学者、東洋学者である。彼は「日本考古学の父」とみなされている。

| Edward Sylvester

Morse (June 18, 1838 – December 20, 1925) was an American

zoologist, archaeologist, and orientalist. He is considered the "Father

of Japanese archaeology." |

エドワード・シルベスター・モース(1838年6月18日 -

1925年12月20日)は、アメリカの動物学者、考古学者、東洋学者である。彼は「日本考古学の父」とみなされている。 |

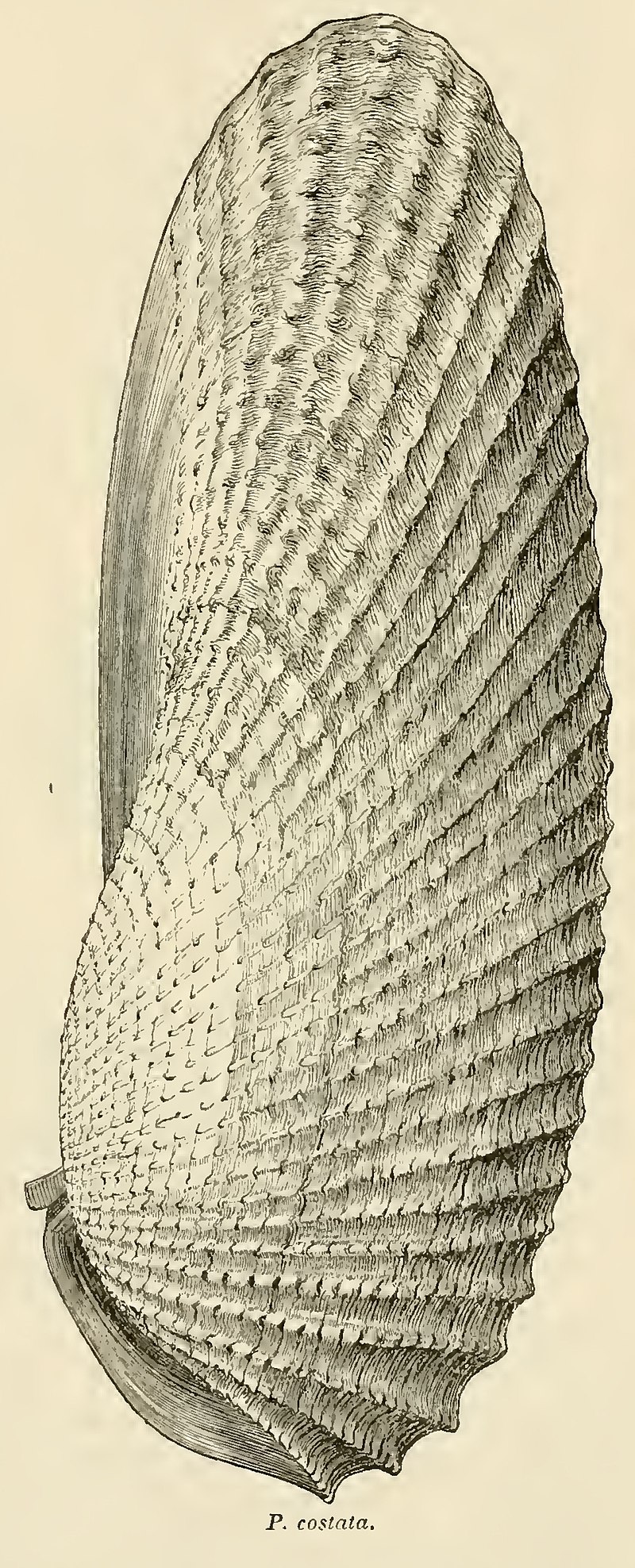

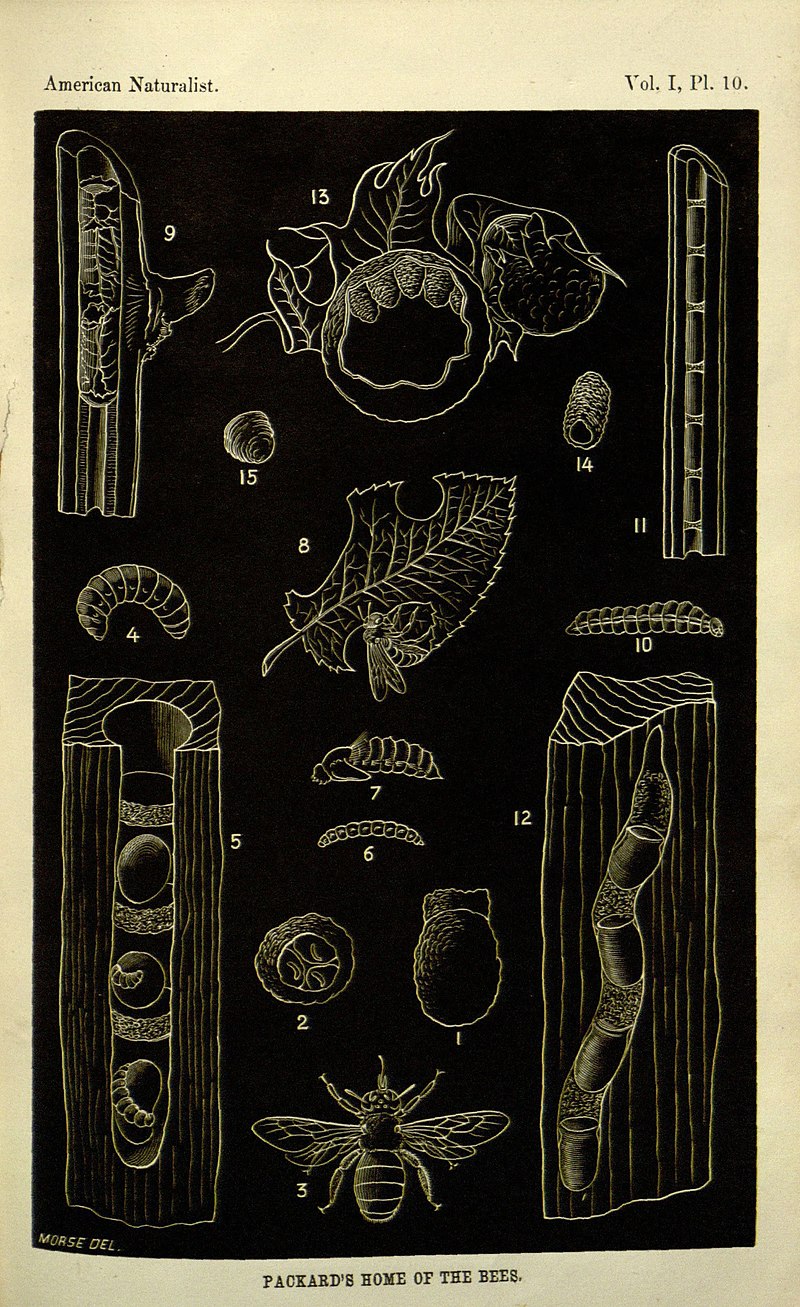

| Early life Morse was born in Portland, Maine to Jonathan Kimball Morse and Jane Seymour (Becket) Morse.[1][2] His father was a Congregationalist deacon who held strict Calvinist beliefs. His mother, who did not share her husband's religious beliefs, encouraged her son's interest in the sciences. An unruly student, Morse was expelled from all but one of the schools he attended in his youth — the Portland village school, the academy at Conway, New Hampshire, in 1851, and Bridgton Academy in 1854 (for carving on desks). He also attended Gould Academy in Bethel, Maine. At Gould Academy, Morse came under the influence of Dr. Nathaniel True who encouraged Morse to pursue his interest in the study of nature.[3] He preferred to explore the Atlantic coast in search of shells and snails, or go to the field to study the fauna and flora. By the age of thirteen he had put together an impressive collection of shells.[4] Despite his lack of formal education, his collections soon earned him the visit of eminent scientists from Boston, Washington and even the United Kingdom.[3] He was noted for his work with land snails, and discovered two new species: Helix asteriscus, now known as Planogyra asteriscus, and H. Milium, now known as Striatura milium.[5] These species were presented at meetings of the Boston Society of Natural History in 1857 and 1859.[6][7]  Pholas costata, the angel-wing clam. From Augustus Gould's Invertebrata of Massachusetts, illustrated by Morse.[8] He was a gifted draughtsman, a skill that served him well throughout his career. As a young man, it enabled him to be employed as a mechanical draughtsman at the Portland Locomotive Company and later preparing wood engravings for natural history publications. This relatively well-paid work enabled him to save enough money to support his further education. Morse was recommended by Philip Pearsall Carpenter to Louis Agassiz (1807–1873) at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University for his intellectual qualities and talent at drawing. After completing his studies he served as Agassiz's assistant in charge of conservation, documentation and drawing collections of mollusks and brachiopods until 1862.[1][3] He became especially interested in brachiopods during this time, and his first paper on the topic was published in 1862.[9][10] During the American Civil War, Morse attempted to enlist in the 25th Maine Infantry, but was turned down due to a chronic tonsil infection. On June 18, 1863, Morse married Ellen (“Nellie”) Elizabeth Owen in Portland. The couple had two children, Edith Owen Morse and John Gould Morse (named after Morse's lifelong friend Major John Mead Gould).[3] |

幼少期 モースは、ジョナサン・キンボール・モースとジェーン・シーモア(ベケット)・モースの間に、メイン州ポートランドで生まれた。[1][2] 父親は厳格なカルヴァン派の信仰を持つ長老派教会の執事であった。 夫の信仰とは異なっていた母親は、息子の科学への興味を奨励した。手に負えない生徒であったモースは、少年期に通った学校のうち、ポートランド村の学校 と、1851年にニューハンプシャー州コンウェイのアカデミー、1854年にブリッジトンのアカデミー(机に彫刻を施したため)を除いてはすべて退学処分 となった。また、メイン州ベセルのグールド・アカデミーにも通っていた。グールド・アカデミーでは、モースはネイサン・トゥルー博士の影響を受け、博士は モースに自然研究への興味を追求するよう勧めた。 彼は貝殻やカタツムリを求めて大西洋岸を探検したり、野に出て動植物の研究をしたりすることを好んだ。13歳までに、彼は素晴らしい貝殻のコレクションを 築き上げていた。[4] 正式な教育を受けていなかったにもかかわらず、彼のコレクションはすぐにボストンやワシントン、さらには英国から著名な科学者たちを訪ねさせることとなっ た。[3] 彼は陸産巻貝の研究で知られ、2つの新種を発見した。現在では Planogyra asteriscus として知られる Helix asteriscus、および現在では Striatura milium として知られる H. Milium の2種である。[5] これらの種は1857年と1859年にボストン自然史学会の会合で発表された。[6][7]  Pholas costata、天使の翼のようなハマグリ。モースによるイラスト付き、オーガスタス・グールド著『マサチューセッツの無脊椎動物』より。 彼は才能ある製図家であり、その技術は彼のキャリア全体を通じて役立った。若い頃、その技術によって彼はポートランド・ロコモーティブ社で機械製図家とし て採用され、後に自然史出版物の木口木版画の準備を手がけた。この比較的高給の仕事のおかげで、モースは進学に必要な資金を貯めることができた。モース は、その知性とデッサン能力を買われ、フィリップ・ピアソル・カーペンターの推薦で、ハーバード大学比較動物学博物館のルイ・アガシー(1807年- 1873年)に雇われた。研究を終えた後、1862年まで、軟体動物と腕足動物の保護、記録、収集を担当するアガシの助手を務めた。[1][3] この時期、彼は特に腕足動物に興味を抱くようになり、このテーマに関する最初の論文は1862年に発表された。[9][10] 南北戦争中、モースはメイン州第25歩兵隊に入隊しようとしたが、慢性の扁桃炎を患っていたため入隊を拒否された。1863年6月18日、モースはポート ランドでエレン・(ネリー)・エリザベス・オーウェンと結婚した。夫妻にはエディス・オーウェン・モースとジョン・グールド・モース(モースの生涯の友人 であるジョン・ミード・グールド少佐にちなんで名付けられた)の2人の子供がいた。[3] |

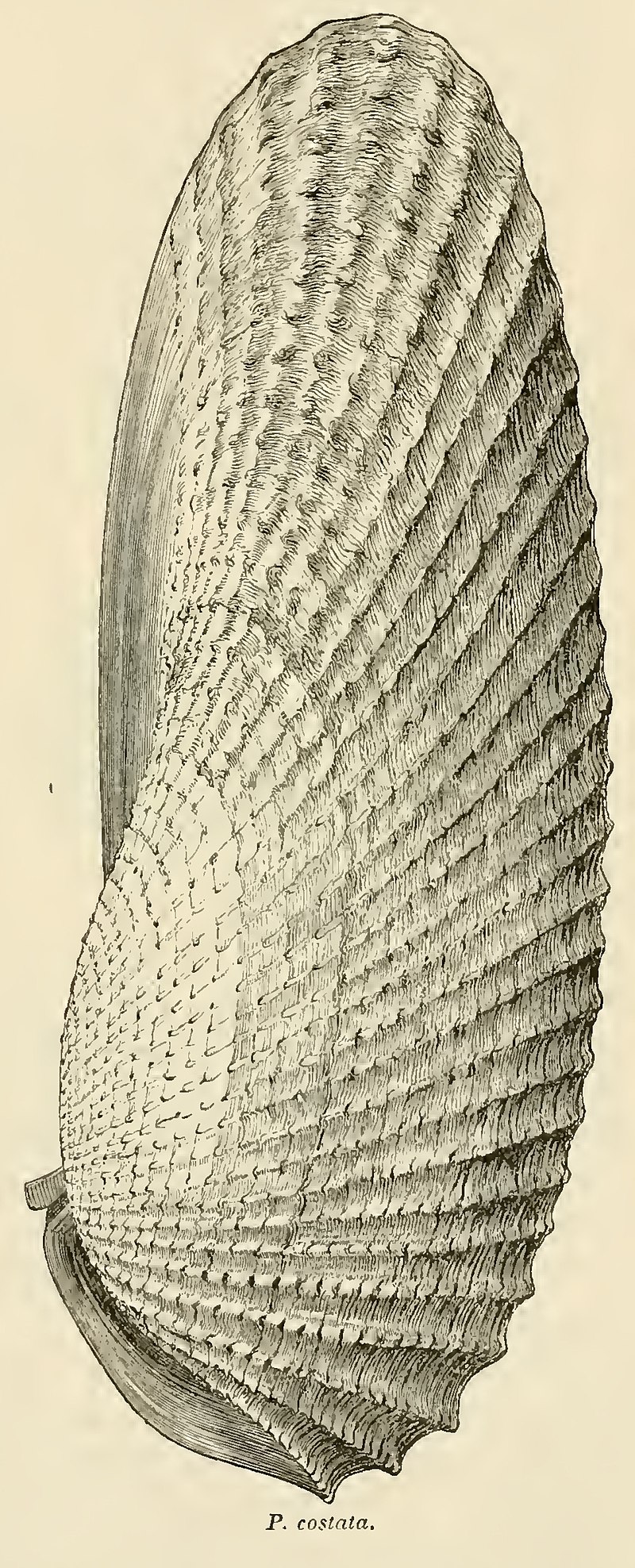

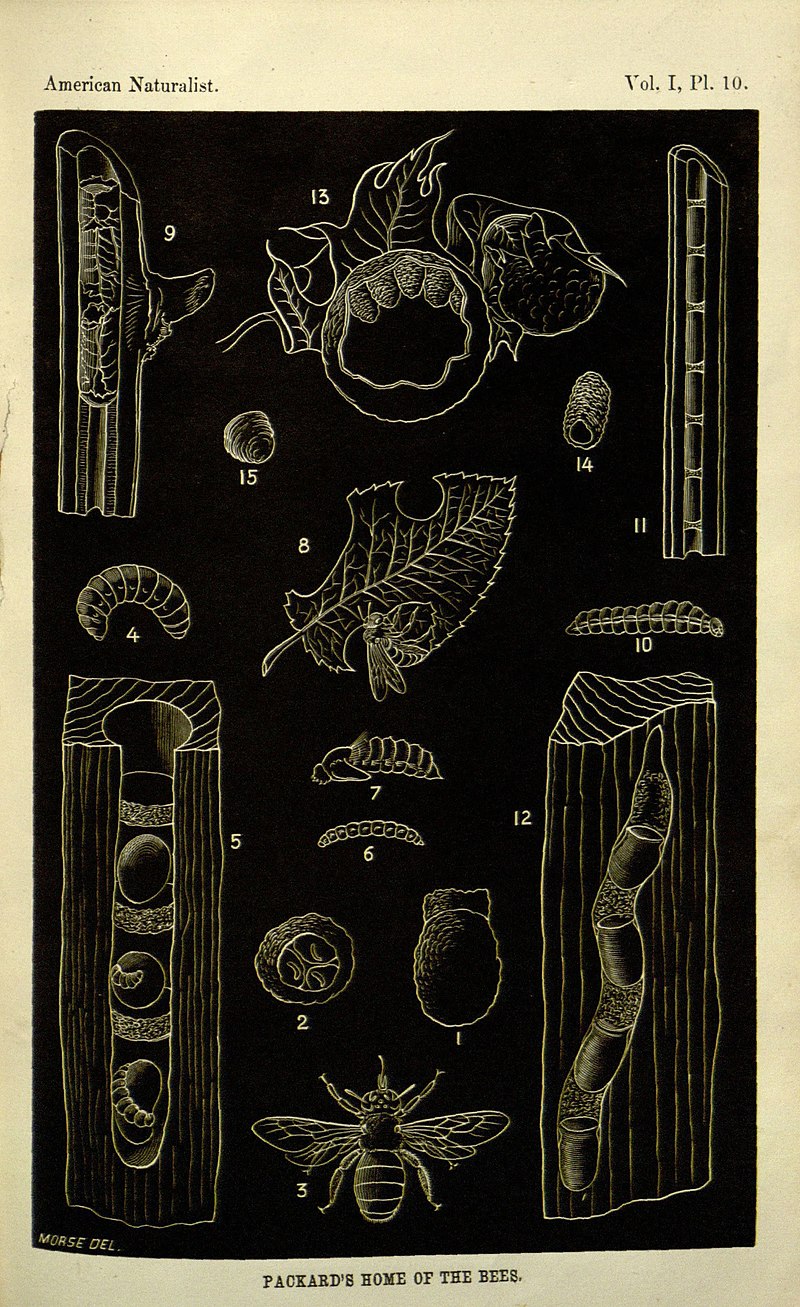

Career Zoogenetes harpa, from Morse (1864).[11] Much enlarged - the snail is about 3-4mm long. Morse rapidly became successful in the field of zoology, specializing in malacology or the study of molluscs. In 1864, he published his first work devoted to molluscs under the title Observations On The Terrestrial Pulmonifera of Maine.[11] Morse had been elected to the position of curator of the Portland Natural History Society, a position he hoped would become permanent. But in 1866 the Great Fire destroyed the buildings of the Society, along with much of Portland, and also the chance of a salaried position.[3] An alternative opportunity arose with the foundation of the Peabody Academy of Science in Salem. Morse returned to Massachusetts to work at the academy, along with Caleb Cooke, Alpheus Hyatt, Alpheus Spring Packard and Frederic Ward Putnam (director), all former students of Agassiz.[1][3]  Morse's Illustration for Alpheus Packard's Home of the Bees. Plate 10 from the American Naturalist Volume 1. In 1867, along with Putnam, Hyatt and Packard, Morse co-founded the scientific journal The American Naturalist, and Morse became one of its editors. The establishment of the Journal was very important for American Natural History. It was written by experts in the field, but aimed to be accessible to a wide readership. This aim was greatly helped by the high quality of the illustrations, many of them provided by Morse himself.[2] Morse's desire to bring natural history to a wider audience also led him to give lectures to a variety of audiences. His combination of broad knowledge, speaking skill, and ability to draw quickly on the blackboard with both hands made him a popular presenter.[1][2] Morse continued his work on brachiopods, often considered to be his most important scientific work.[1][12] In 1869, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[13] Between 1869 and 1873 he published a series of papers on the embryology and classification of the group.[14][15][16][17][18][19] Whereas in 1865 he had accepted the majority view that placed brachiopoda within the molluscs,[20] in 1870 largely on the basis of embryological observations, he proposed that the brachiopoda should be removed from the molluscs, and placed within the annelids, a group of segmented worms.[15] Modern taxonomy agrees with the first of these propositions, but not the second, classifying molluscs, brachiopods and annelids as three separate phyla within the superphylum Lophotrochozoa.[21] Helen Muir-Wood has given an account of the history of the classification of the brachiopods that places Morse's work in its historical context.[22]  Illustration by Morse for John Mead Gould's How to camp out[23] From 1871 to 1874, Morse was appointed to the chair of comparative anatomy and zoology at Bowdoin College. In 1873 and 1874 he was a teacher at the summer school established by Agassiz on Penikese Island. Though the school only operated for a few years, several of its students went on to distinguished careers, including David Starr Jordan.[24][3] In 1874, he became a lecturer at Harvard University. In 1876, Morse was named a fellow of the National Academy of Sciences.[25] In 1877, he provided the illustrations for a book by his friend John Mead Gould, entitled How to camp out.[23][26] During this period the issue of evolution caused much discussion and controversy. Agassiz was an opponent of evolution. He argued that the persistence of animals such as Lingula (a brachiopod) over immense periods of time, from the Silurian to the present day, with little change was "a fatal objection to the theory of gradual development".[27] However all of his students subsequently adopted evolutionary theory in various forms.[28] A clear statement of Morse's position on evolution is found in his address, as vice-president (Natural History) of the American Association for the Advancement of Science at its Buffalo NY meeting in August 1876 (reprinted under the title of What American Zoologists have done for Evolution)[29][30] He adopts a clear selectionist position, in contrast, for example, to Hyatt, who was a neo-Lamarckian.[28] He addresses the issue of human origins, and finds the evidence for "the lowly origin of man", and common ancestry with apes, convincing. He did not only express these views in a western context, but was subsequently the first to bring Darwin's theory of evolution to Japan.[31] Japan In June 1877 Morse first visited Japan in search of coastal brachiopods. His visit turned into a three-year stay when he was offered a post as the first professor of Zoology at the Tokyo Imperial University. He went on to recommend several fellow Americans as o-yatoi gaikokujin (foreign advisors) to support the modernization of Japan in the Meiji Era. To collect specimens, he established a marine biological laboratory at Enoshima in Kanagawa Prefecture.[2] While looking out of a window on a train between Yokohama and Tokyo, Morse discovered the Ōmori shell mound, the excavation of which opened the study in archaeology and anthropology in Japan and shed much light on the material culture of prehistoric Japan.[32] He returned to Japan in 1882–3 to present a report of his findings to Tokyo Imperial University.[2] Morse had much interest in Japanese ceramics, making a collection of over 5,000 pieces of Japanese pottery.[33] On his 1882-3 visit to Japan he collected clay samples as well as finished ceramics. He devised the term "cord-marked" for the sherds of Stone Age pottery, decorated by impressing cords into the wet clay. The Japanese translation, "Jōmon," now gives its name to the whole Jōmon period as well as Jōmon pottery.[34] He brought back to Boston a collection amassed by government minister and amateur art collector Ōkuma Shigenobu, who donated it to Morse in recognition of his services to Japan. These now form part of the "Morse Collection" of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The catalogue[35] is a monumental work, and still the only major work of its kind in English.[3] His collection of daily artifacts of the Japanese people is kept at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. The remainder of the collection was inherited by his granddaughter, Catharine Robb Whyte via her mother Edith Morse Robb and is housed at the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Banff, Alberta, Canada. He travelled several times to the Far East which inspired several books, with his own illustrations. Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings was published in 1885; On the Older Forms of Terra-cotta Roofing Tiles in 1892; Latrines of the East in 1893; Glimpses of China and Chinese Homes in 1903; and Japan Day by Day in 1917. |

経歴 ゾーゲネテス・ハルパ(Zoogenetes harpa)、モース(1864年)による。[11] かなり拡大 - 巻貝の長さは約3-4mm。 モースは、軟体動物学すなわち軟体動物の研究を専門とする動物学の分野で急速に成功を収めた。1864年には、軟体動物に関する最初の著作『メイン州の陸 生肺類動物に関する観察』を出版した。モースは、常勤の職となることを期待して、ポートランド自然史学会の学芸員に選出されていた。しかし1866年、 ポートランドの大半の建物とともに、ポートランド自然史学会の建物も大火災で焼失し、有給の職を得るチャンスも失った。[3] 代わりにセーラムのピーボディ科学アカデミーの創設という機会が訪れた。モースはマサチューセッツに戻り、アカデミーで、かつてアガシの教え子であったカ レブ・クック、アルフィウス・ハイド、アルフィウス・スプリング・パッカード、フレデリック・ウォード・パトナム(所長)らとともに働くことになった。 [1][3]  モースによるアルフィアス・パッカード著『ミツバチの巣』の挿絵。『アメリカ自然史』第1巻のプレート10。 1867年、モースはパットナム、ハイアット、パッカードとともに科学雑誌『アメリカ自然史』を共同創刊し、編集者の一人となった。この雑誌の創刊は、ア メリカ自然史にとって非常に重要な意味を持っていた。専門家の執筆によるものだったが、幅広い読者層に親しまれることを目指していた。この目的は、モース 自身が提供した多くのイラストレーションの質の高さによって大いに助けられた。[2] 自然史をより幅広い読者層に届けるというモースの願いは、さまざまな聴衆を対象とした講演を行うことにもつながった。幅広い知識、話し上手な性格、両手を 使って黒板に素早く絵を描く能力を兼ね備えていたモースは、人気の高い講演者であった。[1][2] モースは腕足動物の研究を続け、しばしばこれが彼の最も重要な科学的業績であると考えられている。[1][12] 1869年、彼はアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーの会員に選出された。[13] 1869年から1873年の間、彼は腕足動物群の発生学と分類に関する一連の論文を発表した。[14][15][16][1 1865年には、腕足動物は軟体動物に含まれるという多数派の見解を受け入れていたが[20]、1870年には、おもに発生学的な観察に基づいて、腕足動 物を軟体動物から除外し、環形動物門(体節のある線形動物のグループ)に含めることを提案した[15] 現代の分類学では、最初の命題には同意するが、2番目の命題には同意せず、軟体動物、腕足動物、環形動物を、上綱(じょうこう) Lophotrochozoa内の3つの独立した綱として分類している。[21] ヘレン・ミューア・ウッドは、モースの研究を歴史的文脈に位置づける腕足動物の分類の歴史について説明している。[22]  モースによるジョン・ミード・グールド著『野宿の仕方』の挿絵[23] 1871年から1874年にかけて、モースはボウディン大学の比較解剖学および動物学の教授に任命された。1873年と1874年には、アガシがペニケセ 島に開設したサマースクールの教師を務めた。この学校は数年間しか運営されなかったが、その生徒の中にはデイヴィッド・スター・ジョーダンなど著名なキャ リアを歩む者もいた。[24][3] 1874年にはハーバード大学の講師となった。1876年にはモースは全米科学アカデミーの研究員に任命された。[25] 1877年には、友人のジョン・ミード・グールドの著書『野宿の仕方』にイラストを提供した。[23][26] この時期、進化論の問題は多くの議論と論争を引き起こした。アガシは進化論の反対者であった。彼は、リンゴガイ(腕足動物)のような動物がシルル紀から現 在に至るまで、ほとんど変化することなく絶え間なく存在していることは、「漸進的進化論に対する致命的な反論」であると主張した。[27] しかし、彼の教え子たちはその後、さまざまな形で進化論を採用した。[28] モースが進化論に関して明確な立場を表明したのは、1876年8月にニューヨーク州バッファローで開催されたアメリカ科学振興協会の副会長(自然史部門) としての演説においてである。1876年8月のニューヨーク州バッファローでのアメリカ科学振興協会(AAAS)の会議における彼の演説(「アメリカの動 物学者が進化論のために何をしたか」というタイトルで再版されている)[29][30] 彼は、例えばネオ・ラマルク主義者であったハイアットとは対照的に、明確な淘汰論者の立場を取っている。彼は人類の起源の問題を取り上げ、「人間の卑しい 起源」と類人猿との共通祖先という説得力のある証拠を見出している。彼はこれらの見解を西洋の文脈で表現しただけでなく、その後、ダーウィンの進化論を初 めて日本に紹介した人物となった。[31] 日本 1877年6月、モースは海岸に生息する腕足動物を求めて初めて来日した。東京帝国大学で初の動物学教授職のオファーを受けたことで、彼の滞在は3年間に 及んだ。その後、明治時代の日本の近代化を支援する外国人顧問(お雇い外国人)として、数名の同胞を推薦した。標本収集のため、神奈川県の江ノ島に海洋生 物学研究所を設立した。 モースは、横浜と東京間の列車の窓から外を眺めているときに大森貝塚を発見した。この発掘は、日本における考古学と人類学の研究に道を開き、先史時代の日 本の物質文化に多くの光を当てた。[32] 彼は1882年から1883年にかけて日本に戻り、東京帝国大学に調査結果の報告を行った。[2] モースは日本の陶磁器に強い関心を抱き、5,000点を超える日本の陶磁器のコレクションを収集した。[33] 1882年から1883年の日本訪問では、完成した陶磁器だけでなく、粘土のサンプルも収集した。彼は、濡れた粘土に紐の跡を押し付けて装飾した石器時代 の陶器の破片に「紐紋土器」という名称を考案した。日本語訳の「縄文」は、現在では縄文時代全体と縄文土器の両方に使われている。[34] 彼は、政府の大臣でありアマチュアの美術収集家でもあった大隈重信が収集したコレクションをボストンに持ち帰った。大隈は、日本への貢献を称えてモースに コレクションを寄贈した。これらのコレクションは現在、ボストン美術館の「モース・コレクション」の一部となっている。その目録[35]は記念碑的な作品 であり、現在でも英語で書かれた同種の作品としては唯一の主要な作品である。[3] 彼の収集した日本人の日常的な生活用品のコレクションは、マサチューセッツ州セーラムのピーボディ・エセックス博物館に保管されている。 コレクションの残りの部分は、彼の孫娘であるキャサリン・ロブ・ホワイトが、母親のエディス・モース・ロブを通じて相続し、カナダのアルバータ州バンフに あるカナディアン・ロッキーのホワイト博物館に収蔵されている。 彼は極東に数回旅行し、その経験から、自身のイラストを添えた複数の著書を出版した。1885年には『日本の家屋とその周辺』、1892年には『古い形式 のテラコッタ屋根瓦について』、1893年には『東洋の便所』、1903年には『中国と中国家屋の概観』、1917年には『日本の日々』を出版した。 |

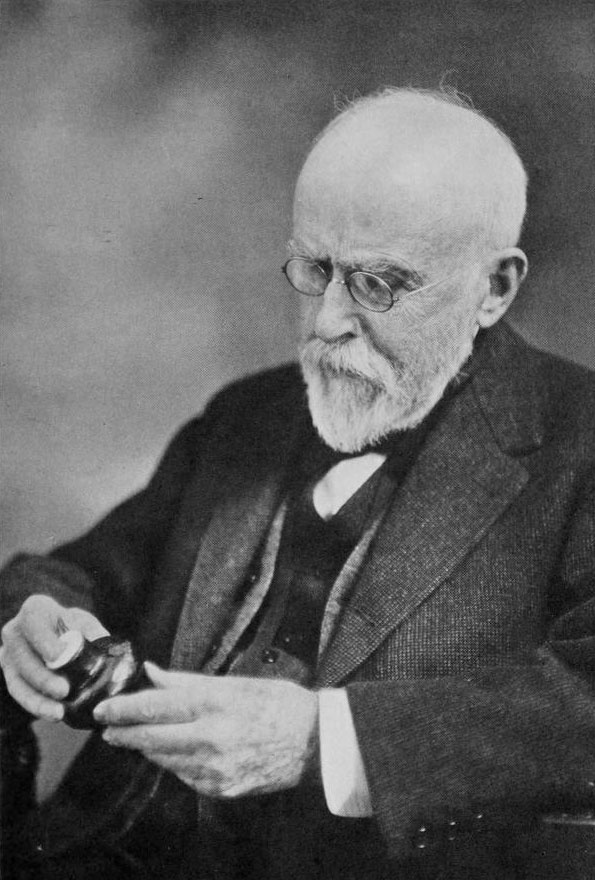

Massachusetts Morse examining pottery, circa 1920 After leaving Japan, Morse traveled to Southeast Asia and Europe. In subsequent years, he returned to Europe, and Japan in quest of pottery.[3] In 1886 Morse became president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.[4] He became Keeper of Pottery at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1890. He was also a director of the Peabody Academy of Science (now part of and succeeded by the Peabody Essex Museum) in Salem[36][1][3] from 1880 to 1914. In 1898, he was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun (3rd class) by the Japanese government.[1][26] He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1898.[37] He became chairman of the Boston Museum in 1914, and chairman of the Peabody Museum in 1915. He was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasures (2nd class) by the Japanese government in 1922.[38] Morse was a friend of astronomer Percival Lowell, who inspired interest in the planet Mars. Morse would occasionally journey to the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, during optimal viewing times to observe the planet. In 1906, Morse published Mars and Its Mystery in defense of Lowell's controversial speculations regarding the possibility of life on Mars.[3] He donated over 10,000 books from his personal collection to the Tokyo Imperial University. On learning that the library of the Tokyo Imperial University was reduced to ashes by the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, in his will he ordered that his entire remaining collection of books be donated to Tokyo Imperial University.[citation needed] Morse's last paper, on shell-mounds, was published in 1925.[39] He died at his home in Salem, Massachusetts in December of that year, of cerebral hemorrhage. He was buried at the Harmony Grove Cemetery.[3] Morse's Law In 1872, Morse noticed that mammals and reptiles with reduced fingers lose them beginning from the sides: thumb the first and little finger the second.[40] Later researchers revealed that this is a general pattern in tetrapods (except Theropoda and Urodela): digits are reduced in the order I → V → II → III → IV, the reverse order of their appearance in embryogenesis. This trend is known as Morse's Law.[41] |

マサチューセッツ モースが陶磁器を調査している様子、1920年頃 日本を離れたモースは、その後東南アジアとヨーロッパを訪れた。その後、陶磁器を求めてヨーロッパと日本に戻った。 1886年、モースはアメリカ科学振興協会の会長に就任した。[4] 1890年にはボストン美術館の陶磁器保管係となった。また、1880年から1914年まで、セーラムのピーボディ科学アカデミー(現在はピーボディ・エ セックス博物館の一部)の理事も務めた。1898年、日本政府から勲三等旭日中綬章を授与された。[1][26] 1898年にはアメリカ古物協会の会員に選出された。[37] 1914年にはボストン美術館の館長に、1915年にはピーボディ博物館の館長に就任した。1922年には日本政府から勲二等瑞宝章を授与された。 モースは天文学者パーシバル・ローウェルの友人であり、ローウェルは火星への関心を喚起した。モースは最適な観測時期にアリゾナ州フラッグスタッフのロー ウェル天文台を訪れ、火星を観測した。1906年、モースは火星に生命体が存在する可能性に関するローウェルの物議を醸した推測を擁護する『火星とその 謎』を出版した。 彼は、自身の蔵書1万冊以上を東京帝国大学に寄贈した。1923年の関東大震災で東京帝国大学の図書館が焼失したことを知った彼は、遺言で自身の蔵書すべ てを東京帝国大学に寄贈するよう指示した。 モースの最後の論文は貝塚に関するもので、1925年に発表された。[39] 同年12月、マサチューセッツ州セーラムの自宅で脳溢血により死去した。ハーモニーグローブ墓地に埋葬された。[3] モースの法則 1872年、モースは指の数が減少した哺乳類や爬虫類では、側面から順に指が失われていくことに気づいた。最初は親指、次に小指である。[40] 後の研究により、これは四肢動物(獣弓類と有尾類を除く)における一般的なパターンであることが明らかになった。指は、胚発生における出現順序とは逆の順 序で減少する。I → V → II → III → IVである。この傾向はモースの法則として知られている。[41] |

| Published works 1875. First Book of Zoölogy New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1, 3, and 5 Bond Street. Second Edition, 1886 1885. Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings. New York: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 3050569 1892 On the Older Forms of Terra-cotta Roofing Tiles Bulletin of the Essex Institute 24: 1-72 1893 Latrines of the East The American Architect and Building News 39: 170-174 1901. Catalogue of the Morse collection of Japanese pottery. Cambridge, Printed at the Riverside Press. 1902. Glimpses of China and Chinese Homes. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 1116550 1917. Japan Day by Day, 1877, 1878-79, 1882-83. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 412843. Volume I.; Volume II. |

出版作品 1875年 『動物学入門』ニューヨーク:D. Appleton and Company、1、3、5ボンドストリート。第2版、1886年 1885年 『日本の家屋とその周辺』ニューヨーク:Harper & Brothers。OCLC 3050569 1892年 テラコッタ屋根瓦の古い形式について Essex Institute紀要 24: 1-72 1893年 東洋の便所 The American Architect and Building News 39: 170-174 1901年 日本陶器のモース・コレクション目録 ケンブリッジ、リバーサイドプレス印刷所 1902年 『中国と中国家庭の概観』 ボストン:リトル・ブラウン社。OCLC 1116550 1917年 『日々の日本』 1877年、1878-79年、1882-83年。ボストン:ホートン・ミフリン社。OCLC 412843。第1巻;第2巻。 |

| American Association of Museums Takamine Hideo Hiram M. Hiller, Jr. |

アメリカ博物館協会 高嶺 秀夫 Hiram M. Hiller, Jr. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_S._Morse |

|

| 文明化の尺度(1878) 「もし、文明の指標の中にお互いを親切に取り扱うこと、子供達に対してつねに親切を示すこと、自分より下等の動物達をやさしく扱うこと、父 母を敬うこと、体を申し分なく清潔に保つこと、衣食住の習慣に関して、質素で節度ある暮らしをすることなどなどが数えられるならば、もしこういったことが 文明的ということだと認められるならば、この国民がこれらの点で我々をはるかに越えているものは、我々がフエゴ諸島民にまさっているのと同じである」 (1878, Nov. Health-Matters in Japan.)[太田雄三訳:一部訳語を変えた、pp.83-4]。 |

|

| 現

在、この仮説を積極的に支持するような民族誌学上の証拠

はありません。また、用語や訳語の選択には、現在では人種主義的偏見にもとづいている見解もあります。この資料引用は、そのような推断の歴史的ならびに人

類学的な分析の資料のための提示で、モースの説を無批判に紹介するものではありません。 食人の風習(1879) 「大森貝塚に関連して最も興味のある発見の一つは、そこでみられた食人風習の証拠である。それは日本に人喰い人種[ママ] (cannibals―引用者)がいたことを、初めてしめる資料である。人骨は、イノシシ・シカその他の獣骨と混在した状況でみいだされている。これら は、獣骨と同様、すべて割れていた。これは、髄を得る目的か、その長さのままで煮るには土器が小さすぎるため、煮るに便利なように割ったのである。人骨各 部分は発見された際に、まったくばらばらであった。この場所が埋葬の目的で使われたという期待もいだかれた。しかし、とくに注意して一体分にまもとまる骨 を探したければこの仮定をささえる証拠はなにもなかった。骨のこの状況は、世界の他の場所で同種の貝塚(shell mounds―引用者)を調査した研究者の経験と一致する。人骨は、他の獣骨と識別できない状況に混在していた。ひっかいたり切りこんだりした傷がいちじ るしい骨もある。これはことに、筋肉の付着面、すなわち苦労して骨から筋肉をとり離さなければならない個所に著しい。割れ方自体が、はっきり人為的とわか るものもあり、筋肉の付着面に深く切りこみをいれてあるものもある。食人の風習を証明するこれらの事項は、フロリダの貝塚にかんする報告で、ワイマン教授 が推断したことに完全に一致している」(『大森貝塚』近藤・佐原訳、1983:49)。 「ニューイングランドおよびフロリダの貝塚における食人風習の事実は、当然予期されたものであった。なぜなら北米インディアンの多くの種族 は、人肉を食べたという記録があり、また南北両アメリカには、この風習をのこす種族が現存するからである。ところが、日本における食人風習の証拠は、別な 意義をもっている。なぜならば、日本の歴史著述者[ママ]による詳細かつ苦心の年代記は、かなりの正確さをもって一五〇〇年ないしはそれ以上もさかのぼる ことができるが、こうした奇異な習慣の形跡などうかがえない。日本人が人喰人種[ママ]でなかっただけではない。/彼らがが、こうした習慣をもった種族に 遭遇したという記録もない。このようないちじるしい習俗があれば、彼らの記録に何か言及されていてしかるべきだ。初期の歴史著述家[ママ]は、アイヌがひ じょうに温厚かつおだやかな気質であって、彼らの間では人を殺す術が知られていないとのべている。たとえ最も高い文明のしゅぞくであろうと、食物がじゅう ぶんに供給されなければ、必然的に人を食べるという極限状況においこまれる。しかし、大森貝塚時代の人々を、このようにショッキングな選択に追いこむ必然 性はなかった。これに関連して、緊急の状況においこまれ、人肉で命をつないだという記録が日本にあるかどうか判れば興味深い」(『大森貝塚』近藤・佐原 訳、1983:51-2)。 「なお最近、帝国の南部にある貝塚[熊本県下益城郡松橋町大野の当尾貝塚―引用者]を調査して、食人風習の明白な証拠をひじょうに多く発見 した」(『大森貝塚』近藤・佐原訳、1983:54)。 「私は肥後の国の巨大な一貝塚[上掲―引用者]を調査した。……人骨はすべて割れており、堆積層のあちこちに無秩序に散乱していた」(『大 森貝塚』近藤・佐原訳、1983:56)。 【出典】 E.S.モース『大森貝塚』近藤義郎・佐原真 編訳、岩波文庫、岩波書店、1983年 |

|

| 文化相対主義的な視点(1886) 「他の国民を研究する場合、望ましいのは色メガネをかけずに対象を見ることである。しかしながら、もしそれが出来ないならば偏見のススでよ ごれたメガネをかけるよりもバラ色のメガネをかける方がましである。民族学の研究者は自分がこれからその風俗習慣を調べようとする国民に対しては、まちが うなら好意的に見すぎるという方向でまちがう方が単に損得ということから言っても賢明であろう。世界中どこにいっても、批判のされることをいやがるのが人 情である。そして、研究者が自国中心的な偏見でこりかたまった目で多民族の風俗習慣を調査しようとするときは、彼はどこに行っても歓迎されない。彼は何も 見せてもらえない。したがって、彼の観察はまず皮相なものにとどまらざるをえない。逆に、研究者が他民族の長所をさぐろうと正直につとめるときには、彼が それがどんな調査であれ、自分の調査をすすめる際に進んで協力してもらうことができるのである。そして人々は不快に思えるような風習でさえも隠さずに自由 に見せてくれる。それはその研究者がはじめからみんなが悪習と認めているものをことさらゆがめて伝えて、不快さをつのらせるようなことを彼らが知っている からである」「序論」『日本の家とその周辺(Japanese House and their Surroundings)』(太田雄三訳、pp.155-6) |

★東京都品川区大森貝塚遺跡庭園内にあるエドワード・モース(1838-1925)の胸像/京浜東北線・大森駅(東京都大田区)構内にある「日本考古学発祥地」のモニュメント:2012年7月 14日撮影

1938 アメリカ合衆国メーン州ポートランドに生まれる。

ハーバード大学博物館の動物学者L・アガシーに師事(1859-62)。ピーボディ・アカデ ミー主事を経て、メーン州立大学、ボードウィン大学、ハーバード大学(比較解剖学、動物学)教授。

1875 First Book of Zoology

1877(明治10)来日(6月~11月):腕足類研究のため私費で来日。大森貝塚発見(Nature,

1877年12月19日号に、同年9月21日付として自身の大森貝塚発見の記事を投稿。Heinrich von Siebold,

1852-1908が、同誌に1878年1月31日号に寄稿し発見の先行を主張し、モースの激怒を買う。ウィキペディア日本語)(→「日本文化人類学

史」)

1878年4月より79年9月まで東京大学で教鞭をとる。

[東京開成学校が改称、Apr. 1877-1886、その後、東京帝国大学:ただし英語名は常にImperial University]動物学生理学教授(Shell Mounds of Omori, Aug.1879)。

ダーウィンの進化論の日本への紹介をする最初の科学者となる。

1878, Nov. Health-Matters in Japan.

1880-1914 Peabody museum 館長

1882-1883 日本に滞在(3度目)

1886-87 The American Association for the Advancement of Science 会長

1886 Japanese House and their Surroundings

1890 日本陶器のコレクションをボストン美術館に売却(借財より解放される)。(→「物神化する文化」)

1917 Japan Day by Day

1922 勲二等瑞宝章

1923 関東大震災の報道を聞き、死後蔵書を東京帝国大学に寄贈を決意

1925 死亡(87歳)

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆