エレナ・ポニアトウスカ

Elena Poniatowska,

b.1932

☆

エ

レーヌ・エリザベート・ルイーズ・アメリー・ポーラ・ドロレス・ポニアトウスカ・アモール(1932年5月19日生まれ)は、職業上エレナ・ポニアトウス

カ(音声ⓘ)として知られる、フランス生まれのメキシコ人ジャーナリスト兼作家である。社会問題や政治問題、特に権利を奪われた人々、とりわけ女性や貧困

層に焦点を当てた著作を専門とする。パリの上流階級の家庭に生まれた。母方の家族はメキシコ革命時にメキシコから逃れた。彼女は第二次世界大戦を逃れるた

め10歳でフランスからメキシコへ渡った。18歳の時、新聞『エクセルシオール』で取材や社交欄の執筆を始めた。1950年代から1970年代にかけて女

性が活躍する機会が乏しい中、新聞や小説・ノンフィクション書籍で社会・政治問題を書き続けた。彼女の最も有名な作品は『トラテロコの夜:口述歴史の証

言』(英語版タイトルは『メキシコ虐殺』)で、1968年にメキシコシティで起きた学生抗議運動の弾圧について書かれたものだ。左派的な思想から「赤い王

女」の異名を持つ。メキシコ文学界の重鎮とされ、現在も執筆活動を続けている。

| Hélène Elizabeth

Louise Amélie Paula Dolores Poniatowska Amor (born May 19, 1932), known

professionally as Elena Poniatowska (audioⓘ), is a French-born Mexican

journalist and author, specializing in works on social and political

issues focused on those considered disenfranchised, especially women

and the poor. She was born in Paris to upper-class parents. Her

mother's family fled Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. She left

France for Mexico when she was ten to escape World War II. When she was

18, she began writing for the newspaper Excélsior, doing interviews and

society columns. Despite the lack of opportunity for women from the

1950s to the 1970s, she wrote about social and political issues in

newspapers and both fiction and nonfiction books. Her best-known work

is La noche de Tlatelolco: Testimonios de historia oral [es] (The Night

of Tlatelolco: Testimonies of Oral History, whose English translation

was titled Massacre in Mexico), about the repression of the 1968

student protests in Mexico City. Due to her left-wing views, she has

been nicknamed "the Red Princess". She is considered "Mexico's grande

dame of letters" and is still an active writer. |

エレーヌ・エリザベート・ルイーズ・アメリー・ポーラ・ドロレス・ポニアトウスカ・アモール(1932年5月19日生まれ)は、職業上エレナ・ポニアトウスカ(音声ⓘ)として知られる、フランス生まれのメキシコ人ジャーナ

リスト兼作家である。社会問題や政治問題、特に権利を奪われた人々、とりわけ女性や貧困層に焦点を当てた著作を専門とする。パリの上流階級の家庭に生まれ

た。母方の家族はメキシコ革命時にメキシコから逃れた。彼女は第二次世界大戦を逃れるため10歳でフランスからメキシコへ渡った。18歳の時、新聞『エク

セルシオール』で取材や社交欄の執筆を始めた。1950年代から1970年代にかけて女性が活躍する機会が乏しい中、新聞や小説・ノンフィクション書籍で

社会・政治問題を書き続けた。彼女の最も有名な作品は『トラテロコの夜:口述歴史の証言』(英語版タイトルは『メキシコ虐殺』)で、1968年にメキシコ

シティで起きた学生抗議運動の弾圧について書かれたものだ。左派的な思想から「赤い王女」の異名を持つ。メキシコ文学界の重鎮とされ、現在も執筆活動を続

けている。 |

Background Princess Elena Poniatowska Poniatowska was born Helène Elizabeth Louise Amelie Paula Dolores Poniatowska Amor in Paris, France, in 1932.[1][2] Her father was Prince Jean Joseph Évremond Sperry Poniatowski (son of Prince André Poniatowski), born to a prominent family distantly related to the last king of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Stanisław August Poniatowski.[3] Her mother was French-born heiress María Dolores Paulette Amor de Yturbe, whose Mexican family lost land and fled Mexico after Porfirio Díaz was ousted during the Mexican Revolution.[2][3][4][5] Poniatowska's extended family includes an archbishop, the primate of Poland, a musician, French politicians, and several writers and statesmen, including Benjamin Franklin.[4] Her aunt was the poet Pita Amor.[6] She was raised in France by a grandfather who was a writer and a grandmother who showed her unflattering photographs of Mexico, including some in National Geographic depicting Africans, saying they were Mexican indigenes, and scared her and her siblings with stories about cannibalism there.[3][4] Although she maintained a close relationship with her mother until her death, her mother was unhappy about her being labeled a communist and refused to read Poniatowska's novel about political activist Tina Modotti.[5] World War II broke out when Poniatowska was a child. The family left Paris when she was nine, going first to the south of the country. But the deprivations of the war became too much and the southern part of France, the Zone libre, was invaded by Germany and Italy in 1942, so the family left for Mexico when she was ten years old. Her father remained in France to fight, participating later in D-Day in Normandy.[1][2][7] Poniatowska began her education in France at Vouvray on the Loire. After arriving in Mexico, she continued at the Liceo Franco-Mexicano, then at Eden Hall and the Sacred Heart Convent in the late 1940s.[4][6] In 1953, she returned to Mexico, where she learned to type, but she never went to university. Instead, she began working at the Excélsior newspaper.[1][4] Poniatowska is trilingual, speaking Spanish, English, and French. French was her primary language and was spoken the most at home. She learned Spanish from her nanny and people on the streets during her time in Mexico as a young girl.[6] Poniatowska and astronomer Guillermo Haro met in 1959 when she interviewed him, and they married in 1968.[1] She is the mother of three children, Emmanuel, Felipe, and Paula, and the grandmother of five. Poniatowska and Haro divorced in 1981, and her ex-husband died in 1988.[4] Poniatowska lives in a house near the Plaza Federico Gamboa in the Chimalistac [es] neighborhood of Mexico City's Álvaro Obregón borough. The house is filled with books. Spaces without books contain photographs of her family and paintings by Francisco Toledo.[4] She works at home.[5] |

背景 エレナ・ポニアトウスカ王女 ポニアトウスカは1932年、フランス・パリにてエレーヌ・エリザベート・ルイーズ・アメリー・ポーラ・ドロレス・ポニアトウスカ・アモールとして生まれ た[1][2]。父はジャン・ジョゼフ・エヴレモンド・スペリー・ポニャトフスキ王子(アンドレ・ポニャトフスキ王子の息子)であり、ポーランド・リトア ニア共和国の最後の国王スタニスワフ・アウグスト・ポニャトフスキと遠縁にあたる名門家系の出身であった。[3] 母親はフランス生まれの相続人マリア・ドロレス・ポーレット・アモール・デ・イトゥルベで、そのメキシコ人の家族は、メキシコ革命でポルフィリオ・ディア スが追放された後、土地を失いメキシコから逃亡した。[2][3][4][5] ポニアトウスカの親戚には、大司教、ポーランド国教会の首座司教、音楽家、フランスの政治家、そしてベンジャミン・フランクリンを含む数人の作家や政治家 がいる。[4] 彼女の叔母は詩人のピタ・アモールであった。[6] 彼女は、作家である祖父と、ナショナルジオグラフィック誌に掲載されたアフリカ人をメキシコ先住民だと偽って紹介した写真など、メキシコをあまり良くない ものに見せる写真を見せ、人食いの話で彼女や兄弟たちを怖がらせた祖母によって、フランスで育てられた。[3][4] 彼女は母親が亡くなるまで親密な関係を維持していたが、母親は彼女が共産主義者というレッテルを貼られることを嫌がり、政治活動家ティナ・モドッティに関 するポニアトフスカの小説を読むことを拒否した。[5] ポニアトフスカが子供だった頃、第二次世界大戦が勃発した。彼女が9歳のとき、家族はパリを離れ、まず南部に移った。しかし、戦争による苦難は耐え難いも のとなり、1942年にフランス南部、自由地帯がドイツとイタリアに侵攻されたため、彼女が10歳のときに家族はメキシコへと旅立った。父親はフランスに 残って戦い、後にノルマンディー上陸作戦に参加した。[1][2][7] ポニアトフスカは、フランスのロワール地方ヴーヴレで教育を受けた。メキシコに到着後、1940年代後半には、リセオ・フランコ・メヒカーノ、エデン・ ホール、サクレ・クール修道院で教育を続けた。[4][6] 1953年、彼女はメキシコに戻り、タイピングを学んだが、大学には進学しなかった。その代わりに、エクセルシオール新聞社で働き始めた。[1] [4] ポニアトウスカはスペイン語、英語、フランス語の三か国語を話す。フランス語が第一言語であり、家庭では最も頻繁に使われていた。スペイン語は幼少期にメ キシコで、乳母や街の人々から学んだものである。[6] ポニアトウスカは1959年、天文学者ギジェルモ・ハロへの取材で出会い、1968年に結婚した[1]。エマニュエル、フェリペ、パウラの3人の子の母で あり、5人の孫を持つ祖母でもある。ポニアトウスカとハロは1981年に離婚し、元夫は1988年に死去した。[4] ポニアトフスカはメキシコシティ、アルヴァロ・オブレゴン区チマリスタック[es]地区のフェデリコ・ガンボア広場近くの家に住んでいる。家は本で埋め尽 くされている。本のないスペースには家族の写真やフランシスコ・トレドの絵画が飾られている。[4]彼女は自宅で仕事をしている。[5] |

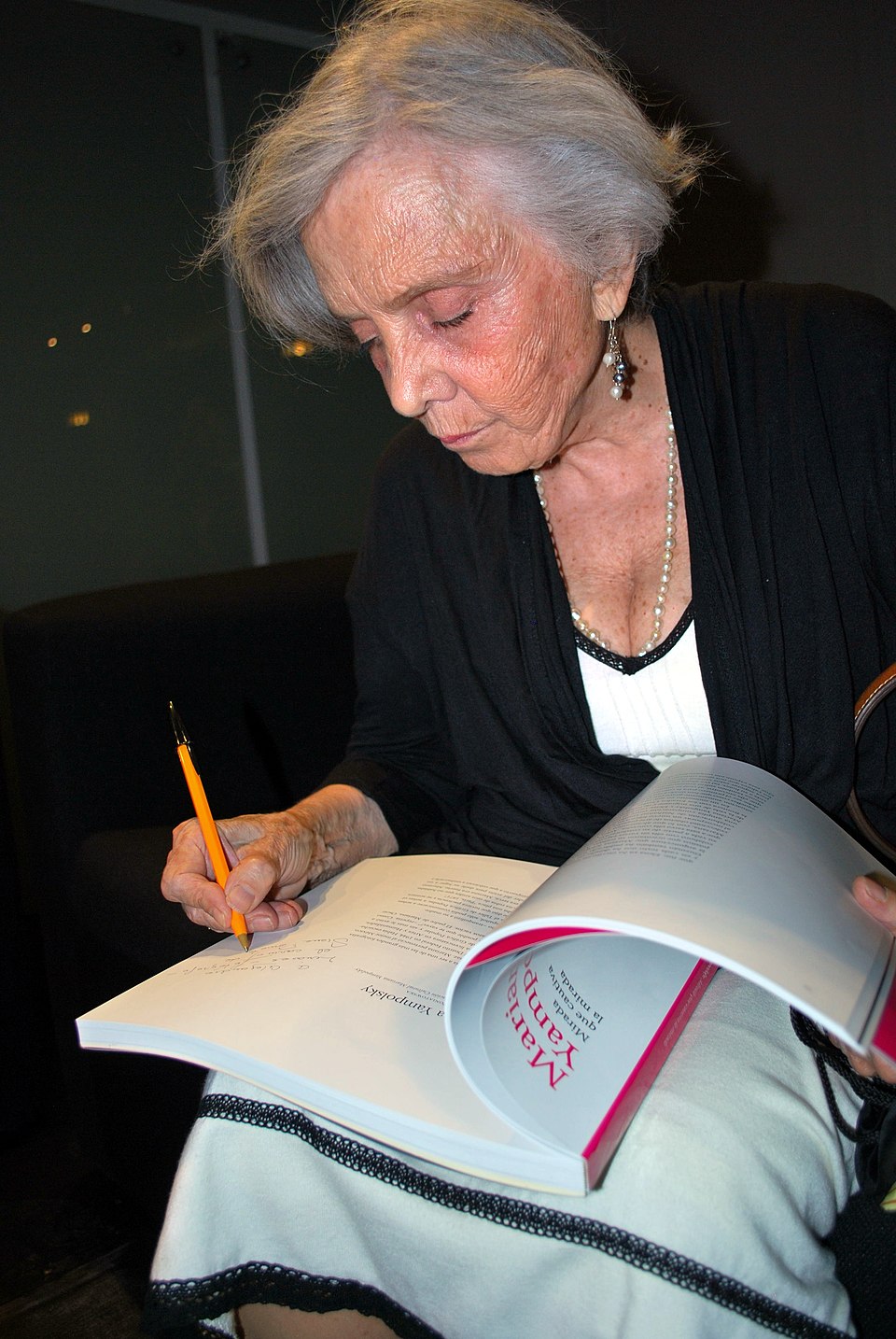

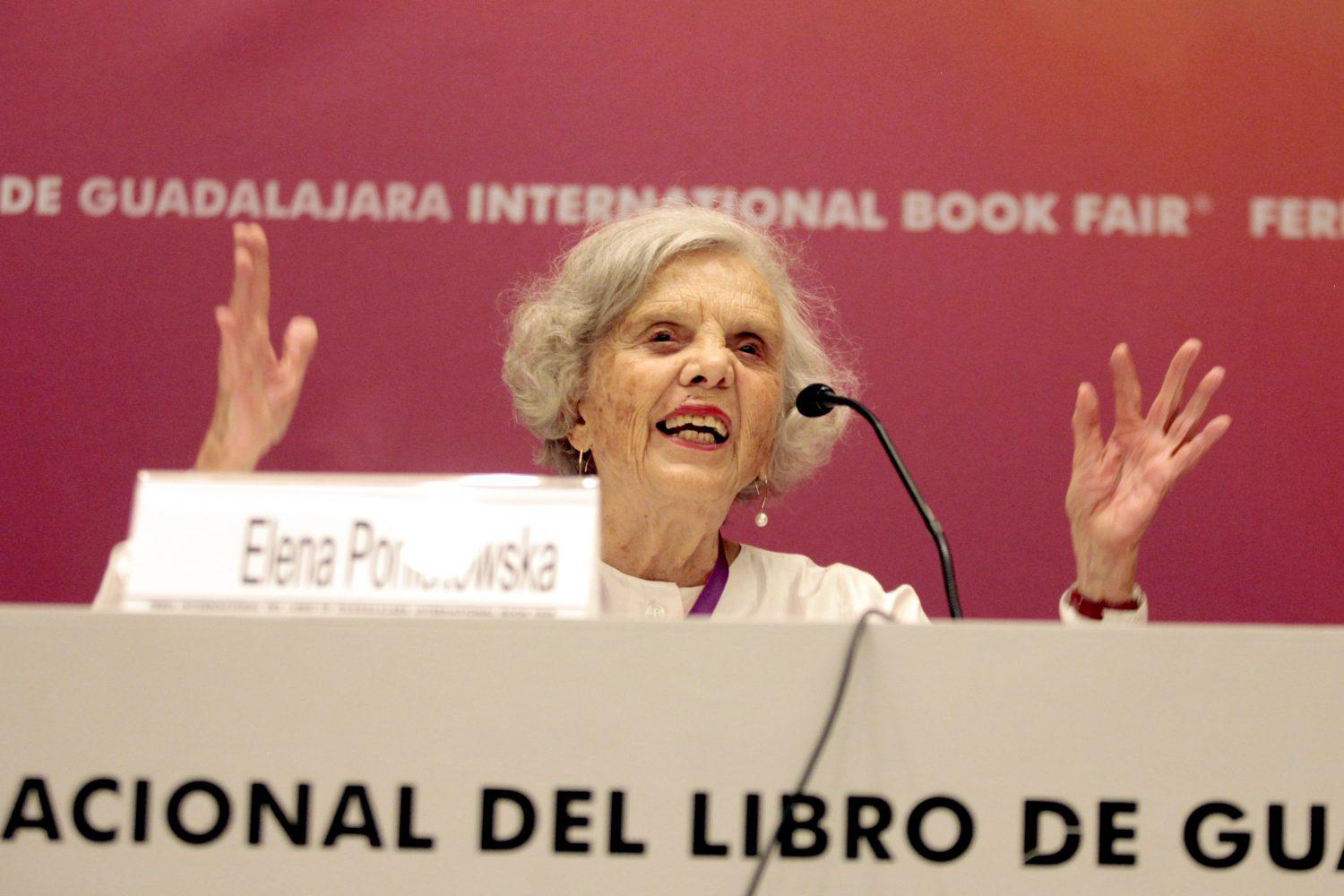

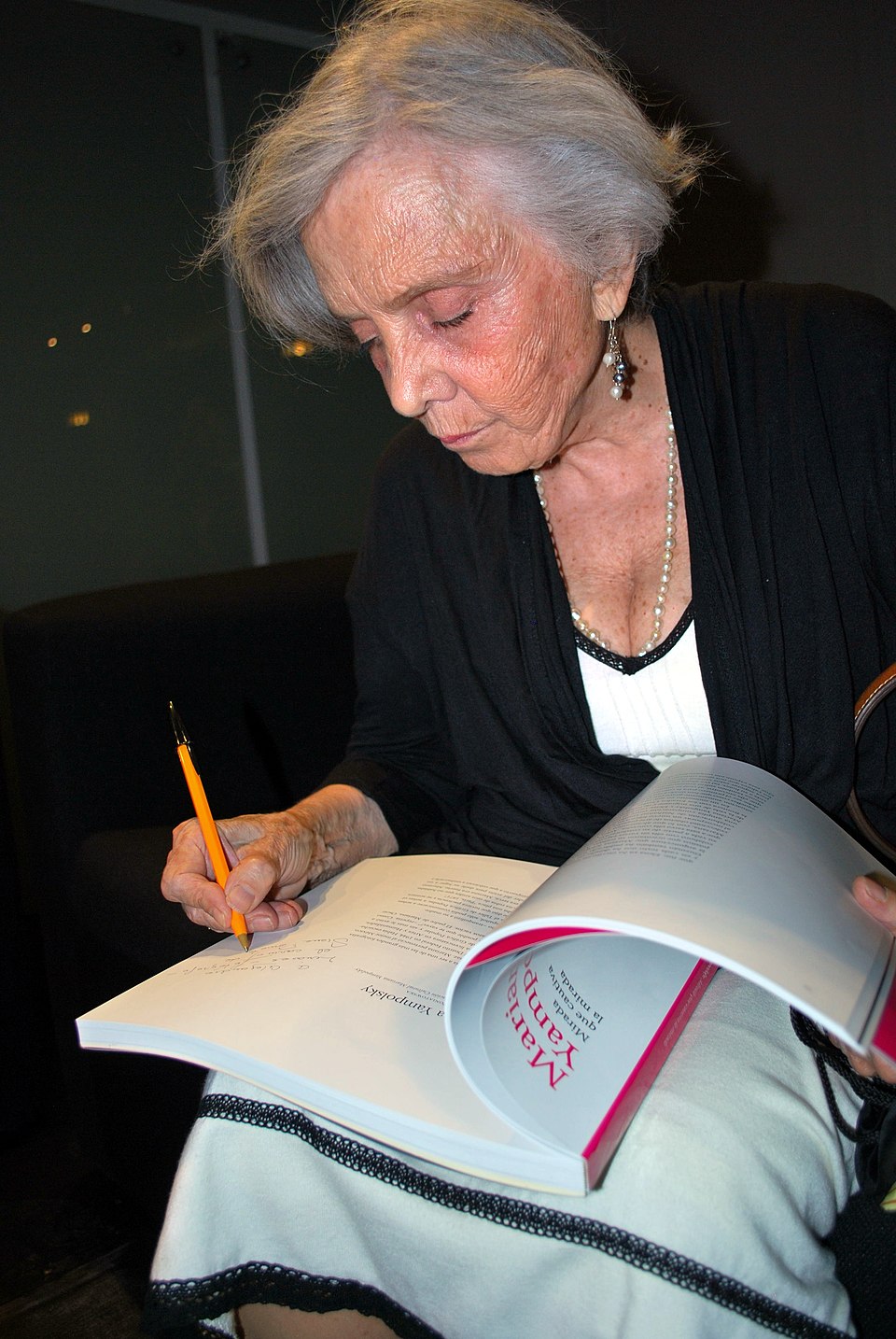

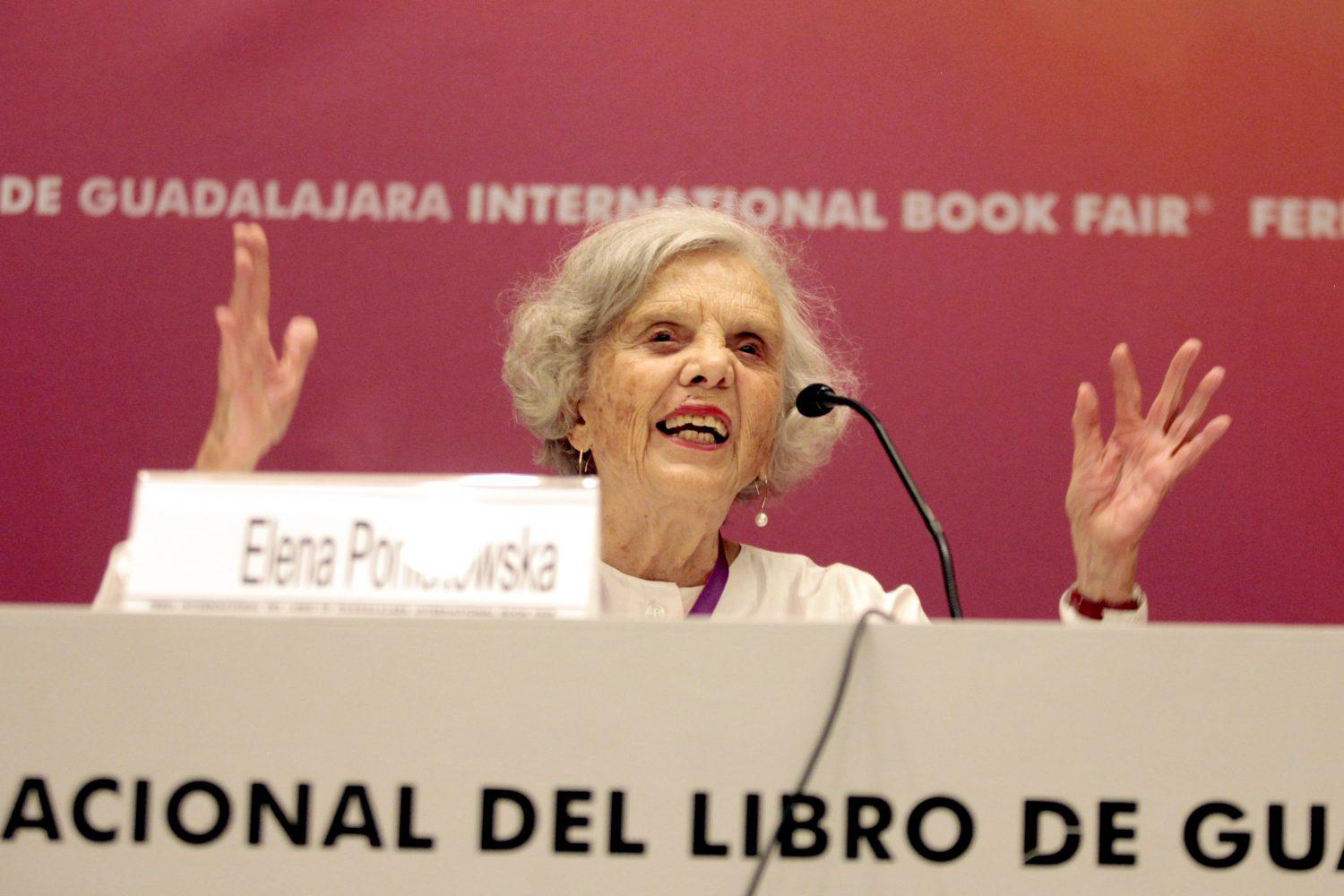

Career Poniatowska signing book on Mariana Yampolsky at the Museo de Arte Popular in 2012 Poniatowska has published novels, nonfiction books, journalistic essays, and many forewords and prologues to books on Mexican artists.[2][8] Much of her writing has focused on social and human rights issues, especially those related to women and the poor.[8] Poniatowska began her writing career in 1953 with Excélsior and the next year with the publication Novedades de México, both of which she still occasionally writes for.[4][6] Her first writing assignments were interviews of famous people and society columns related to Mexico's upper class.[4][5] Her first published interview was with the ambassador of the United States.[3] She says she began "like a donkey", knowing nothing and learning on the job.[2] She was first published under her French name, Hélene, but later changed it to Elena, and sometimes used Anel.[6] Poniatowska published her first book, Lilus Kikus, in 1954, and since then has done both journalism and creative writing.[1][8] The years from the 1950s to the '70s offered limited opportunities for women, but she eventually moved from interviews and society stories to literary profiles and stories on social issues.[5][6] She emerged as a subtly present female voice in a patriarchal society, even as she was called "Elenita" (little Elena) and her work was often dismissed as naïve interviews and children's literature. She progressed by persistence rather than direct confrontation.[5] Poniatowska most influential work has been "testimonial narratives", writings based both on historical facts and accounts by people normally not recorded by the media.[7] She began writing on social issues after a visit to Lecumberri, a prison, to interview several incarcerated railway workers who had gone on strike. She found prisoners eager to talk and share their life stories.[4] She interviewed Subcomandante Marcos in 1994.[6] Much of this work has been compiled into seven volumes, including Todo México (1991–1999), Domingo siete (1982), and Palabras cruzadas (1961).[1] Her best-known book of this type is La noche de Tlatelolco, which contains testimony of the victims of the 1968 student massacre in Mexico City.[4] Poniatowska is one of the founders of La Jornada newspaper; Fem, a feminist magazine; Siglo XXI, a publishing house; and the Cineteca Nacional [es], the national film institute.[2][4]  Elena Poniatowska in the Guadalajara International Book Fair in 2017. Poniatowska's works have been translated into English, Polish, French, Danish, and German, starting in the 1990s.[4][5] She translated Sandra Cisneros's The House on Mango Street into Spanish.[2] She wrote a play, Meles y Teleo: apuntes para una comedia, a year after the birth of son Emmanuel.[1] In 1997 her novella De noche vienes (You Come by Night) was made into a feature film directed by Arturo Ripstein and starring María Rojo and Tito Vasconcelos [es].[4] She has also published biographies of the Nobel laureate Octavio Paz and artist Juan Soriano.[5] Poniatowska often gives presentations and is especially sought for talks and seminars in the United States.[5][6] She is considered to be Mexico's "grande dame" of letters[5][8] but she has not been recognized around the world like other prolific Latin American writers of her generation.[5] She has also not been fully integrated into Mexico's elite, never receiving diplomatic appointments, like Carlos Fuentes,[5] and turning down political opportunities. Nor has she spent much time in Mexico's elite literary circles. Fuentes once said that Poniatowska was too busy in the city's slums or shopping for groceries to have time for him and others. She says that such remarks show that she is considered more of a maid, a cook, or even a janitor in the "great House of Mexican Literature".[3][4] For over 30 years, Poniatowska has taught a weekly writing workshop. Through this and other efforts, she has influenced a generation of Mexican writers, including Silvia Molina and Rosa Nissán.[5] |

経歴 2012年、ポニアトウスカがマリアナ・ヤンポルスキーに関する書籍に署名する様子(メキシコ民芸美術館にて) ポニアトウスカは小説、ノンフィクション、ジャーナリスティックなエッセイ、そしてメキシコ人芸術家に関する書籍の序文やプロローグを数多く発表している[2][8]。彼女の著作の多くは、特に女性や貧困層に関連する社会問題や人権問題に焦点を当てている。[8] ポニアトウスカは1953年に『エクセルシオール』誌で執筆活動を始め、翌年には『ノベダデス・デ・メヒコ』誌の創刊に携わった。現在も両誌に時折寄稿し ている。[4][6] 最初の仕事は著名人へのインタビューや、メキシコ上流階級に関する社交欄記事だった。[4][5] 初掲載のインタビュー相手はアメリカ大使であった。[3] 彼女は「ロバのように」始めたと語る。何も知らず、仕事をしながら学んだのだ。[2] 最初の出版ではフランス語名のエレーヌ(Hélene)を使用したが、後にエレナ(Elena)に変更し、時にはアネル(Anel)も用いた。[6] ポニアトウスカは1954年に初の著作『リルス・キクス(Lilus Kikus)』を出版し、それ以来ジャーナリズムと創作の両方を続けている。[1] [8] 1950年代から70年代にかけては女性にとって機会が限られていたが、彼女はインタビューや社交記事から次第に文学的プロフィールや社会問題に関する記 事へと移行した。[5][6] 父権社会の中で「エレニータ」(小さなエレナ)と呼ばれ、その作品は素朴なインタビューや児童文学として軽視されることも多かったが、彼女は繊細な存在感 を放つ女性の声として台頭した。彼女は直接対決ではなく、粘り強さで前進した。[5] ポニアトウスカの最も影響力ある作品は「証言的叙述」であり、歴史的事実と、通常メディアに記録されない人々の証言に基づく著作である。[7] 彼女は、ストライキを起こした収監中の鉄道労働者数名をインタビューするためレクンベルリ刑務所を訪問した後、社会問題について書き始めた。囚人たちが熱 心に語り、自らの人生の物語を共有したがっていることに気づいたのだ。[4] 1994年には副司令官マルコスへのインタビューも行った。[6] このような作品は『トド・メヒコ』(1991-1999年)、『ドミンゴ・シエテ』(1982年)、『パラブラス・クルザダス』(1961年)など7巻に まとめられている。[1] この種の著作で最も有名なのは『トラテロコの夜』だ。メキシコシティで起きた1968年の学生虐殺事件の犠牲者たちの証言を収録している。[4] ポニアトウスカは『ラ・ホルナダ』新聞、フェミニスト雑誌『フェム』、出版社シグロXXI、国立映画研究所シネテカ・ナシオナルの創設者の一人だ。[2] [4]  2017年のグアダラハラ国際ブックフェアでのエレナ・ポニアトスカ。 ポニアトスカの作品は、1990年代から英語、ポーランド語、フランス語、デンマーク語、ドイツ語に翻訳されている。[4][5] 彼女はサンドラ・シスネロスの『マンゴー通りの家』をスペイン語に翻訳した。[2] 息子エマニュエルの誕生から 1 年後に、戯曲『Meles y Teleo: apuntes para una comedia』を書いた。[1] 1997 年、彼女の小説『De noche vienes(夜、あなたはやってくる)』が、アルトゥーロ・リプスタイン監督、マリア・ロホとティト・バスコンセロス [es] 主演の長編映画化された。[4] 彼女はまた、ノーベル賞受賞者のオクタヴィオ・パスと芸術家フアン・ソリアーノの伝記も出版している。[5] ポニアトスカは頻繁に講演を行い、特に米国での講演やセミナーで引っ張りだこである。[5][6] 彼女はメキシコ文学界の「大御所」と見なされているが[5][8]、同世代の他の多作なラテンアメリカ作家たちのように世界的に認知されているわけではな い。[5] また、カルロス・フエンテスのように外交官職に任命されることもなく、政治的な機会も断ってきたため、メキシコのエリート層に完全に組み込まれていない。 メキシコのエリート文学界にもほとんど関わっていない。フエンテスはかつて、ポニアトフスカは都市のスラム街で忙しすぎたり、食料品の買い出しに追われた りして、自分や他の作家と過ごす時間がないと述べたことがある。彼女はこうした発言こそが、自身が「偉大なるメキシコ文学の家」において、むしろメイドや 料理人、あるいは用務員と見なされている証だと語る。[3][4] 30年以上にわたり、ポニアトウスカは週1回の創作ワークショップを指導してきた。こうした活動を通じて、シルビア・モリーナやローサ・ニッサンを含むメキシコ作家の一世代に影響を与えてきた。[5] |

Advocacy and writing style Poniatowska at the 30 year commemoration of the 1985 Mexico City earthquake. Her work is a cross between literary fiction and historical construction.[9] She began to produce major works in the 1960s and her work matured in the 1970s, when she turned to producing works in put herself in solidarity with those who are oppressed politically and economically against those in power. Her work can be compared to that of Antonio Skármeta, Luis Rafael Sánchez, Marta Traba, Sergio Ramírez, Rosario Ferré, Manuel Puig and Fernando del Paso.[9] Although most of her fame is as a journalist, she prefers creative writing. Her creative writings are philosophic meditations and assessments of society and the disenfranchised within it.[5] Her writing style is free, lacking solemnity, colloquial and close.[6] Many of her works deconstruct societal and political myths, but they also work to create new ones. For example, while she heavily criticizes the national institutions which evolved after the Mexican Revolution, she promotes a kind of "popular heroism" of the common person without name. Her works are also impregnated with a sense of fatalism.[9] Like many intellectuals in Mexico, her focus is on human rights issues and defending various social groups, especially those she considers to be oppressed by those in power, which include women, the poor and others. She speaks and writes about them even though she herself is a member of Mexico's elite, using her contacts as such on others’ behalf.[6][8][10] She is not an impartial writer as she acts as an advocate for those who she feels have no voice. She feels that a personal relationship with her subjects is vital.[10] She stated to La Jornada that the student movement of 1968 left a profound mark on her life and caused her consciousness to change as students were murdered by their own police. It was after this that she was clear that the purpose of her writing was to change Mexico.[3] She has visited political and other prisoners in jail, especially strikers and the student protestors of 1968.[2] According to one biography, her house was watched around the clock. She was arrested twice (one in jail for twelve hours and once detained for two) when observing demonstrations. However, she has never written about this.[5] She has involved herself in the causes of her protagonists which are generally women, farm workers and laborers, and also include the indigenous, such as the Zapatistas in Chiapas in the 1990s.[3][10] She puts many in touch with those on the left side of Mexico's and the world's political spectrum although she is not officially affiliated with any of them.[10] She considers herself a feminist to the bone and looks upon civil movements with sympathy and enthusiasm.[3] However, she has resisted offers to become formally involved in political positions.[3] She became involved in Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s 2005 presidential campaign. She wrote about the seven-week occupation of the Zócalo that followed López Obrador's loss in 2006. She blames Mexico's businessmen and the United States for his loss as well as López Obrador's naivete.[2] |

主張と文体 ポニアトウスカは1985年のメキシコシティ地震30周年記念式典に出席した。 彼女の作品は文学小説と歴史構築の融合である。[9] 彼女は 1960 年代に主要な作品の制作を開始し、1970 年代にその作品は成熟した。この時代、彼女は権力者に対して政治的、経済的に抑圧されている人々に連帯する作品の制作に転向した。彼女の作品は、アントニ オ・スカルメタ、ルイス・ラファエル・サンチェス、マルタ・トラバ、セルジオ・ラミレス、ロサリオ・フェレ、マヌエル・プイグ、フェルナンド・デル・パソ の作品と比較することができる。[9] 彼女の名声は主にジャーナリストとしてのものだが、彼女自身は創作活動を好んでいる。彼女の創作は、社会と、その社会の中で権利を剥奪された人々に対する 哲学的な考察と評価である。[5] 彼女の文章スタイルは自由で、厳粛さを欠き、口語的で親しみやすい。[6] 彼女の作品の多くは、社会や政治に関する神話を解体する一方で、新しい神話を創り出す役割も果たしている。例えば、メキシコ革命後に発展した国家機関を厳 しく批判する一方で、名もなき一般市民の「民衆的英雄主義」を称揚する。また、彼女の作品には宿命論的な感覚が染み込んでいる。[9] メキシコの多くの知識人と同様に、彼女の関心は人権問題と様々な社会的集団の擁護、特に権力者によって抑圧されていると彼女が考える女性や貧困層などに注 がれている。自身はメキシコの上流階級に属しながら、そうした人脈を他者のために活用し、彼らについて語り書き続けている[6][8][10]。声なき者 たちの代弁者として行動するため、彼女は中立的な作家ではない。取材対象との個人的な関係を極めて重要視している。[10] 彼女はラ・ホルナダ紙に対し、1968年の学生運動が自らの人生に深い刻印を残し、学生が自国の警察によって殺害されたことで意識が変化したと述べてい る。この事件を経て、自身の執筆目的がメキシコを変えることだと明確に認識したのだ[3]。彼女は政治犯やその他の囚人、特にストライキ参加者や1968 年の学生抗議者らを刑務所で面会している。[2] ある伝記によれば、彼女の自宅は24時間監視されていた。デモを観察中に2度逮捕されている(1度は12時間、もう1度は2時間の拘留)。しかし彼女はこ れについて書いたことはない。[5] 彼女は主人公たちの運動に関与してきた。主人公は主に女性、農場労働者、労働者であり、1990年代のチアパス州のサパティスタのような先住民も含まれ る。[3][10] 彼女はメキシコや世界の政治スペクトルにおいて左派に位置する者たちと多くの人々をつなぐ存在だが、公式にはいずれの組織にも所属していない。[10] 自らを骨の髄までフェミニストと位置づけ、市民運動に共感と熱意をもって接する。[3] しかし、政治的立場に正式に関与するよう提案されることには抵抗してきた。[3] 彼女は2005年のアンドレス・マヌエル・ロペス・オブラドール大統領選挙運動に関与した。2006年のロペス・オブラドール敗北後に続いた7週間にわた るソカロ占拠について執筆している。彼の敗因について、メキシコの企業家層とアメリカ合衆国、そしてロペス・オブラドール自身の純真さを非難している。 [2] |

| Major works Her major investigative works include La noche de Tlatelolco (Massacre in Mexico) (1971), Fuerte es el silencio (Strong is Silence) (1975) and Nada nadie. Las voces del temblor (Nothing No one: The Voices of the Earthquake) (1988).[9] The best known of these is La noche de Tlatelolco about the 1968 repression of student protests in Mexico City.[2][7] She found out about the massacre on the evening of October 2, 1968, when her son was only four months old.[5] Afterwards, Poniatowska went out on the streets in the neighborhood and began interviewing people while there was still blood on the streets and shoes strewn about and women searching for the children who had not come home. The book contains interviews with informants, eyewitnesses, former prisoners which are interspersed with poems by Octavio Paz and Rosario Castellanos, excerpts from pre Hispanic texts and newspaper, as well as political slogans.[2][5][7] Massacre in Mexico was the only book published on the subject for twenty years, contradicting the government's account of the events and the number dead. The government offered her the Xavier Villaurrutia Award in 1970 for the work but she refused it.[2][5] She did the same after the 1985 Mexico City earthquake. Her book about this event Nada, nadie, las voces del temblor was a compilation of eyewitness accounts not only to the destruction of the earthquake, but also to the incompetence and corruption of the government afterwards.[2][5] Fuerte es el silencio is about several themes, especially the families of disappeared political prisoners, the leaders of workers’ movements, another look at the massacre in Tlatelolco and others who have defied the government.[5][9][10] Her first novel was Lilus Kikusy from 1954. It is a coming-of-age story about Mexican women before feminism. It centers on an inquisitive girl who is carefully molded by society to become an obedient bride.[5][9] Tinísima is a fictionalized biography of Italian photographer and political activist Tina Modotti.[2] This book was the result of ten years of researching the life of the photographer and political activist.[5] Querido Diego (Dear Diego) is an epistolary recreation of Diego Rivera’s relationship with his first wife, Russian painter Angelina Beloff with the aim of "de-iconize" him.[4][5] Hasta no verte Jesús mío (Here's to You, Jesusa) from 1969 tells the story of Jesusa Palancares, a poor woman who fought in the Mexican Revolution and who later became a washerwoman in Mexico City.[2] Based on interviews conducted with the woman who was the model for the main character over a period of some ten years,[5] the book is considered to be a breakthrough in testimonial literature. Las Soldaderas: Women of the Mexican Revolution is about the women who were in combat accompanied by photographs from the era.[2] Las siete cabritas (The Seven Little Goats) is about seven women in Mexican society in the 20th century, only one of whom, Frida Kahlo, is well known outside Mexico. The others are Pita Amor, Nahui Olín, María Izquierdo, Elena Garro, Rosario Castellanos and Nellie Campobello.[8] La piel del cielo (The Skin of the Sky) provides moving descriptions of various regions of Mexico, as well as the inner workings of politics and government.[5] |

主要作品 彼女の主要な調査報道作品には、『トラテロコの夜』(メキシコ虐殺事件、1971年)、『沈黙は強い』(1975年)、『何もない、誰もいない。地震の 声』(1988年)がある。[9] これらの中で最も有名なのは、1968年にメキシコシティで起きた学生抗議運動の弾圧を描いた『トラテロコの夜』である。[2][7] 彼女は1968年10月2日の夜、生後4ヶ月の息子を抱えながら虐殺を知った。[5] その後、ポニアトウスカは近隣の路上に飛び出し、路上に血が残り、靴が散乱し、帰宅しない子供を探す女性たちがいる中で、人々に聞き取りを始めた。本書に は情報提供者、目撃者、元囚人へのインタビューが収録され、オクタビオ・パスとロサリオ・カステジャノスの詩、先コロンブス期の文献や新聞からの抜粋、政 治スローガンが散りばめられている。[2][5][7] この虐殺事件について出版されたのは、この本が二十年間で唯一だった。政府の事件説明や死者数とは矛盾する内容だった。政府は1970年、この著作に対し て彼女にサビエル・ビジャウルティア賞を授与したが、彼女はこれを拒否した。[2][5] 彼女は1985年のメキシコシティ地震の後も同様の行動を取った。この事件に関する彼女の著作『ナダ、ナディエ、ラス・ボセス・デル・テンブロ(地震の声)』は、地震の破壊だけでなく、その後の政府の無能さと腐敗についての目撃証言を集めたものだった。[2][5] 『フエルテ・エス・エル・シレンシオ(沈黙は強い)』はいくつかのテーマを扱っている。特に、失踪した政治犯の家族、労働者運動の指導者たち、トラテロルコ虐殺の再考、そして政府に反抗した人々についてだ。[5][9][10] 彼女の最初の小説は1954年の『リルス・キクスィ』だ。フェミニズム以前のメキシコ女性を描いた成長物語である。好奇心旺盛な少女が、従順な花嫁へと社 会によって慎重に形作られていく過程が中心だ。[5][9]『ティニシマ』はイタリア人写真家兼政治活動家ティナ・モドッティの伝記小説化作品である。 [2] この本は写真家兼政治活動家の生涯を十年かけて調査した成果である。[5] 『親愛なるディエゴへ』はディエゴ・リベラと最初の妻であるロシア人画家アンジェリーナ・ベロフの関係を手紙形式で再現した作品で、彼を「偶像から解き放 つ」ことを目的としている。[4][5] 『ハスタ・ノ・ベルテ・ヘスース・ミオ(君に捧ぐ、ヘスースア)』は1969年の作品で、メキシコ革命で戦い、後にメキシコシティで洗濯婦となった貧しい 女性ヘスースア・パランカレスの物語だ。[2] 主人公のモデルとなった女性への約10年にわたるインタビューを基にしており、[5] 証言文学における画期的な作品と見なされている。 『ラス・ソルダデラス:メキシコ革命の女たち』は、当時の写真と共に戦闘に参加した女性たちについて書かれている。[2] 『ラス・セイト・カブリタス(七匹の子山羊)』は、20世紀メキシコ社会に生きた七人の女性たちについて書かれている。その中ではフリーダ・カーロだけが メキシコ国外で広く知られている。他の6人はピタ・アモール、ナウイ・オリン、マリア・イスキエルド、エレナ・ガロ、ロサリオ・カステジャノス、ネリー・ カンポベッロである[8]。 『空の皮』はメキシコの様々な地域描写に加え、政治や政府の内部事情を感動的に描いている[5]。 |

| Awards Poniatowska's first literature award was the Mazatlan Literature Prize (Premio Mazatlán de Literatura)[11] in 1971 for the novel Hasta no verte Jesús mío.[1] She received this award again in 1992 with her novel Tinísima. The Mazatlan Literature Prize was founded by writer, journalist, and National Journalism Prize Antonio Haas, a close lifelong friend of Elena, and editorial columnist and collaborator next to her in Siempre! weekly news magazine and the national Mexican newspaper Excélsior. Poniatowska was nominated for the coveted Villarrutia Award in the 1970s, but refused it by saying to the Mexican president, "Who is going to award a prize to those who fell at Tlatelolco in 1968?"[4] In 1978, Poniatowska was the first woman to win Mexico's National Journalism Prize of Mexico [es][12] for her contributions to the dissemination of Mexican cultural and political expression.[1][4] In 2000, the nations of Colombia and Chile each awarded Poniatowska with their highest writing awards.[5] In 2001, Poniatowska received the José Fuentes Mares National Prize for Literature in 2001[5] as well as the annual prize for best novel by Spanish book publishing house Alfaguara, Alfaguara Novel Prize for her novel La piel del cielo (Heaven's Skin).[8] The International Women's Media Foundation gave Poniatowska the Lifetime Achievement Award in 2006, in recognition for her work.[2] Poniatowska won the Rómulo Gallegos Prize in 2007 with her book El Tren pasa primero (The Train Passes First).[6] In the same year, she received the Premio Iberoamericano by the government of the Mexico City mayor.[1] Poniatowska has received honorary doctorates from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (2001), the Autonomous University of Sinaloa (1979), the New School of Social Research (1994), the Metropolitan Autonomous University (2000) and the University of Puerto Rico (2010).[1][5] Other awards include the Premio Biblioteca Breve for the novel Leonora, awards from the Club de Periodistas (Journalists Club), the Manuel Buendia Journalism Prize, and the Radio UNAM Prize for her book of interviews with Mexican authors entitled Palabras Cruzadas ("Crossed Words"). She was selected to receive Mexico's National Literary Prize, but she declined it, insisting that it should instead go to Elena Garro, although neither woman ultimately received it.[4] In 2013, Poniatowska won Spain's Premio Cervantes Literature Award, the most prestigious Spanish-language literary award for an author's lifetime works, becoming the fourth woman to receive such recognition, following María Zambrano (1988), Dulce María Loynaz (1992), and Ana María Matute (2010). Elena Poniatowska was awarded the Premio Cervantes for her "brilliant literary trajectory in diverse genera, her special style in narrative and her exemplary dedication to journalism, her outstanding work and her firm commitment to contemporary history."[citation needed] In April 2023, the Senate voted unanimously to award her its Belisario Domínguez Medal of Honor, Mexico's highest active civilian award.[13] |

受賞歴 ポニアトウスカが初めて受賞した文学賞は、1971年に小説『愛しきイエスよ、君に会うまで』で受賞したマサトラン文学賞(Premio Mazatlán de Literatura)である[11]。彼女は1992年にも小説『ティニシマ』で同賞を再び受賞した。マサトラン文学賞は、作家・ジャーナリストであ り、エレーナの生涯の親友でもあったアントニオ・ハース(国家ジャーナリズム賞受賞者)によって創設された。ハースは週刊ニュース誌『シエンプレ!』や全 国紙『エクセルシオール』で、エレーナの隣のコラムニスト兼協力者として活動していた。 ポニアトウスカは1970年代に権威あるビジャルティア賞の候補となったが、メキシコ大統領に対し「1968年にトラテロルコで倒れた者たちに、いったい誰が賞を授けるというのか?」と述べて受賞を辞退した[4]。 1978年、ポニアトウスカはメキシコ文化・政治表現の普及への貢献が認められ、メキシコ国家ジャーナリズム賞[es][12]を女性として初めて受賞した[1][4]。 2000年には、コロンビアとチリの両国民がそれぞれ最高位の文学賞をポニアトウスカに授与した。[5] 2001年、ポニアトウスカはホセ・フエンテス・マレス国家文学賞[5]、およびスペインの出版社アルファグアラが授与する年間最優秀小説賞、アルファグアラ小説賞を、小説『La piel del cielo(天国の肌)』で受賞した。[8] 国際女性メディア財団は、ポニアトウスカの功績を称え、2006年に彼女に生涯功労賞を授与した。 ポニアトウスカは、2007年に著書『El Tren pasa primero(列車は先を行く)』でロムロ・ガリエーゴス賞を受賞した。同年、メキシコシティ市長からイベロアメリカン賞も授与された。[1] ポニアトウスカは、メキシコ国立自治大学(2001年)、シナロア自治大学(1979年)、ニュー・スクール・オブ・ソーシャル・リサーチ(1994 年)、メトロポリタン自治大学(2000年)、プエルトリコ大学(2010年)から名誉博士号を授与されている。[1] [5] その他の受賞歴には、小説『レオノーラ』によるプレミオ・ビブリオテカ・ブレベ賞、クラブ・デ・ペリオディスタス(ジャーナリストクラブ)賞、マヌエル・ ブエンディア・ジャーナリズム賞、メキシコ人作家へのインタビュー集『交差する言葉(Palabras Cruzadas)』によるラジオUNAM賞がある。彼女はメキシコ国家文学賞の受賞者に選ばれたが、その栄誉はエレナ・ガロに与えられるべきだと主張し て辞退した。結局、どちらの女性も受賞することはなかった。[4] 2013年、ポニアトウスカはスペインのセルバンテス文学賞を受賞した。これはスペイン語圏で最も権威ある文学賞であり、作家の一生をかけた業績に対して 贈られるものである。彼女はこの栄誉を受けた4人目の女性となり、マリア・サンブラノ(1988年)、ドゥルセ・マリア・ロイナズ(1992年)、アナ・ マリア・マトゥテ(2010年)に続く受賞者となった。エレナ・ポニアトウスカは「多様なジャンルにおける輝かしい文学的軌跡、物語における独特のスタイ ル、ジャーナリズムへの模範的な献身、卓越した業績、そして現代史への揺るぎない取り組み」が評価され、セルバンテス賞を受賞した。[出典必要] 2023年4月、上院は満場一致で彼女にベリサリオ・ドミンゲス名誉勲章を授与することを決定した。これはメキシコで現役の民間人に対して授与される最高の勲章である。[13] |

| List of works 1954 – Lilus Kikus (collection of short stories) 1956 – "Melés y Teleo" (short story, in Panoramas Magazine) 1961 – Palabras cruzadas (chronicle)[clarification needed] 1963 – Todo empezó el Domingo (chronicle) 1969 – Hasta no verte, Jesus mío (novel) 1971 – La noche de Tlatelolco: Testimonios de historia oral [es], about the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre (historical account) [The Night of Tlatelolco] 1978 – Querido Diego, te abraza Quiela (collection of fictional letters from Angelina Beloff to Diego Rivera) 1979 – Gaby Brimmer, co-written autobiography of Mexican-born author and disability rights activist Gabriela Brimmer 1979 – De noche vienes (collection of short stories) 1980 – Fuerte es el silencio (historical account) 1982 – Domingo Siete (chronicle) 1982 – El último Guajolote (chronicle) [The Last Turkey] 1985 – ¡Ay vida, no me mereces! Carlos Fuentes, Rosario Castellanos, Juan Rulfo, la literatura de la Onda México (essay) 1988 – La flor de lis (novel) 1988 – Nada, nadie. Las voces del temblor, about the 1985 Mexico City earthquake (historical account) [Nothing, Nobody: The Voices of the Earthquake] 1991 – Tinísima (novel) 1992 - Frida Kahlo: la cámara seducida (in Spanish. Co-written with Carla Stellweg also in English as Frida Kahlo: The Camera Seduced) 1994 – Luz y luna, las lunitas (essay) 1997 – Guerrero Viejo (photos and oral histories of the town of Guerrero, Coahuila, flooded by damming of the Rio Grande) ISBN 978-0-9655268-0-7 1997 – Paseo de la Reforma (novel) [Paseo de la Reforma] 1998 – Octavio Paz, las palabras del árbol (essay) 1999 – Las soldaderas (photographic archive) [The Soldier Women] 2000 – Las mil y una... La herida de Paulina (chronicle) 2000 – Juan Soriano, niño de mil años (essay) 2000 – Las siete cabritas (essay) 2001 – Mariana Yampolsky y la buganvillia 2001 – La piel del cielo (novel, Winner of the Premio Alfaguara de Novela 2001) 2003 – Tlapalería (collection of short stories) [Translated into English as The Heart of the Artichoke] 2005 – Obras reunidas (complete works) 2006 – El tren pasa primero (novel, Winner of the Rómulo Gallegos Prize) 2006 – La Adelita (children's book) 2007 – Amanecer en el Zócalo. Los 50 días que confrontaron a México (historical account) 2008 – El burro que metió la pata (children's book) 2008 – Rondas de la niña mala (poetry, songs) 2008 – Jardín de Francia (interviews) 2008 – Boda en Chimalistac (children's book) 2009 – No den las gracias. La colonia Rubén Jaramillo y el Güero Medrano (chronicle) 2009 – La vendedora de nubes (children's book) [The Seller of Clouds] 2011 – Leonora (historical novel on the surrealist painter Leonora Carrington, Seix Barral Biblioteca Breve Prize) 2012 – The Heart of the Artichoke. Trans. George Henson. Miami: Alligator Press (collection of short stories) [In Spanish Tlapalería] |

作品一覧 1954年 – 『リルス・キクス』(短編集) 1956年 – 「メレスとテレオ」(短編小説、『パノラマ』誌掲載) 1961年 – 『クロスワード』(クロニクル)[注釈が必要] 1963年 – 『すべては日曜日に始まった』(クロニクル) 1969年 – 『イエスよ、君に会うまで』(小説) 1971年 – 『トラテロコの夜:口述歴史の証言』[スペイン語]、1968年トラテロコ虐殺に関する歴史的記録[原題:La noche de Tlatelolco] 1978年 – 『愛しきディエゴへ、キエラより』(アンヘリーナ・ベロフからディエゴ・リベラへの架空の手紙集) 1979年 – 『ギャビー・ブリマー』(メキシコ生まれの作家で障害者権利活動家、ガブリエラ・ブリマーとの共著自伝) 1979年 – 『夜、君は来る』(短編集) 1980年 – 『沈黙は強い』(歴史的記録) 1982年 – 『日曜日の七時』(クロニクル) 1982年 – 『最後の七面鳥』(クロニクル) 1985年 – 『ああ人生よ、お前は俺にふさわしくない!カルロス・フエンテス、ロサリオ・カステジャノス、フアン・ルルフォ、メキシコ・オンダの文学』(エッセイ) 1988年 – 『ユリの花』(小説) 1988年 – 『何もない、誰もいない。地震の声』(1985年メキシコシティ地震に関する歴史的記録) 1991年 – 『ティニシマ』(小説) 1992年 – 『フリーダ・カーロ:魅せられたカメラ』(スペイン語。カーラ・ステルヴェグとの共著。英語版は『Frida Kahlo: The Camera Seduced』) 1994年 – 『光と月、小さな月たち』(エッセイ) 1997年 – 『ゲレーロ・ビエホ』(リオ・グランデ川ダム建設により水没したコアウイラ州ゲレーロ町の写真と口述歴史)ISBN 978-0-9655268-0-7 1997年 – 『パセオ・デ・ラ・レフォルマ』(小説) 1998年 – 『オクタビオ・パス、樹の言葉』(エッセイ) 1999年 – 『ラス・ソルダデラス』(写真アーカイブ) 2000年 – 『千一夜…パウリーナの傷』(クロニクル) 2000年 – 『千年の少年フアン・ソリアーノ』(エッセイ) 2000年 – 『七匹の子山羊』(エッセイ) 2001年 – 『マリアナ・ヤンポルスキーとブーゲンビリア』 2001年 – 『空の皮』(小説、2001年アルファグアラ小説賞受賞作) 2003年 – 『トラパレリア』(短編集) [英語版は『The Heart of the Artichoke』として翻訳 2005年 – 『Obras reunidas』(全集 2006年 – 『El tren pasa primero』(小説、ロムロ・ガリエーゴ賞受賞 2006年 – 『La Adelita』(児童書 2007年 - 『ソカロの夜明け。メキシコを揺るがした50日間』(歴史書) 2008年 - 『足を踏み外したロバ』(児童書) 2008年 - 『悪い女の子の歌』(詩、歌) 2008年 - 『フランスの庭 (インタビュー) 2008年 – 『チマリストックの結婚式』(児童書) 2009年 – 『感謝するな。ルベン・ハラミージョとゲロ・メドラノのコロニー』(記録) 2009年 – 『雲の売り子』(児童書) 2011年 – 『レオノーラ』(シュルレアリスト画家レオノーラ・キャリントンを題材とした歴史小説、セイシュ・バラル・ビブリオテカ・ブレベ賞受賞作) 2012年 – 『アーティチョークの心臓』(ジョージ・ヘンソン訳、マイアミ:アリゲーター・プレス刊)[スペイン語原題:トラパレリア] |

| References 1. "Elena Poniatowska, un clásico de la literatura mexicana ampliamente premiada: BIBLIOTECA BREVE (Biografía)" [Elena Poniatowska, a well-rewarded classic of Mexican literature: Biblioteca Breve (biography)]. EFE News Service (in Spanish). Madrid. February 7, 2011. 2. DiNovella, Elizabeth (May 2007). "Elena Poniatowska". The Progressive. 71 (5): 35–38. 3. Juan Rodríguez Flores (November 5, 2006). "Elena Poniatowska: escritura con sentido social" [Elena Poniatowska: writer with social sensibility]. La Opinión (in Spanish). Los Angeles. pp. 1B, 3B. 4. Schuessler, Michael K (June 1997). "Elenita Says". Business Mexico. 7 (6): 53–55. 5. Coonrod Martinez, Elizabeth (March–April 2005). "ELENA PONIATOWSKA: Between the Lines of the Forgotten". Americas. 57 (2): 46–51. 6. Alonso, María Del Rosario (2008). "Elena Poniatowska, Una biografía íntima, una biografía literaria". Bulletin of Hispanic Studies. 85 (5): 733–737. doi:10.3828/bhs.85.5.9. 7. "Elena Poniatowska". London: BBC. Retrieved May 6, 2012. 8. Coonrod Martinez, Elizabeth (February 25, 2012). "Avant-Garde Mexican Women Artists: Groundbreakers Get Long Overdue Tribute". The Hispanic Outlook in Higher Education. 12 (10): 20. 9. Perilli, Carmen (1995–1996). "Elena Poniatowska: Palabra y Silencio" [Elena Poniatowska: Word and Silence]. Kipus: Revista Andina de Letras. Quito: 63–72. 10. Ela Molina Morelock (2004). Cultural Memory in Elena Poniatowskas' "Tinisma" (Thesis). Miami University. Docket 1425071. 11. "Premio Nacional de Periodismo". periodismo.org.mx (in Spanish). August 29, 2011. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2025. 12. Mexico National Journalism Award "Premio Nacional de Periodismo de México" Spanish Wikipedia 13. Robles de la Rosa, Leticia (April 12, 2023). "Senado galardona a Elena Poniatowska con Medalla de Honor Belisario Domínguez 2022". Excélsior. Retrieved April 13, 2023. |

参考文献 1. 「エレナ・ポニアトウスカ、数々の賞を受賞したメキシコ文学の古典:ビブリオテカ・ブレベ(伝記)」[Elena Poniatowska, a well-rewarded classic of Mexican literature: Biblioteca Breve (biography)]。EFE通信社(スペイン語)。マドリード。2011年2月7日。 2. ディノベラ、エリザベス (2007年5月)。「エレナ・ポニアトウスカ」。ザ・プログレッシブ。71巻5号:35–38頁。 3. フアン・ロドリゲス・フローレス(2006年11月5日)。「エレナ・ポニアトウスカ:社会意識を持った作家」。ラ・オピニオン(スペイン語)。ロサンゼルス。pp. 1B, 3B. 4. Schuessler, Michael K (1997年6月). 「エレニータは言う」. Business Mexico. 7 (6): 53–55. 5. Coonrod Martinez, Elizabeth (2005年3月–4月). 「エレナ・ポニアトウスカ:忘れられた行間」. アメリカ大陸。57 (2): 46–51。 6. アロンソ、マリア・デル・ロサリオ (2008)。「エレナ・ポニアトウスカ、親密な伝記、文学的伝記」。ヒスパニック研究紀要。85 (5): 733–737。doi:10.3828/bhs.85.5.9。 7. 「エレナ・ポニアトウスカ」。ロンドン:BBC。2012年5月6日取得。 8. クーロン・マルティネス、エリザベス(2012年2月25日)。「前衛的なメキシコ人女性芸術家たち:先駆者たちに遅ればせながらの賛辞が贈られる」。高等教育におけるヒスパニックの展望。12 (10): 20。 9. ペリリ、カルメン (1995–1996). 「エレナ・ポニアトウスカ:言葉と沈黙」. Kipus: Revista Andina de Letras. キト: 63–72. 10. エラ・モリーナ・モレロック(2004)。『エレナ・ポニアトウスカの「ティニスマ」における文化的記憶』(学位論文)。マイアミ大学。ドケット番号1425071。 11. 「全国ジャーナリズム賞」periodismo.org.mx(スペイン語)。2011年8月29日。2011年6月29日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2025年3月8日に閲覧。 12. メキシコ国民ジャーナリズム賞「Premio Nacional de Periodismo de México」スペイン語版ウィキペディア 13. ロブレス・デ・ラ・ロサ、レティシア(2023年4月12日)。「上院、エレナ・ポニアトウスカに2022年ベリサリオ・ドミンゲス名誉勲章を授与」。エクセルシオール。2023年4月13日閲覧。 |

| Further reading English Stories That Make History: Mexico through Elena Poniatowska's Crónicas, Lynn Stephen, 2021 Elena Poniatowska: an intimate biography, Michael Karl Schuessler, 2007 Through their eyes: marginality in the works of Elena Poniatowska, Silvia Molina and Rosa Nissán, Nathanial Eli Gardner, 2007 Reading the feminine voice in Latin American women's fiction: from Teresa de la Parra to Elena Poniatowska and Luisa Valenzuela, María Teresa Medeiros-Lichem, 2002 The writing of Elena Poniatowska: engaging dialogues, Beth Ellen Jorgensen, 1994 Spanish Viento, galope de agua; entre palabras: Elena Poniatowska, Sara Poot Herrera, 2014 La palabra contra el silencio, Elena Poniatowska ante la crítica, Nora Erro-Peralta y Magdalena Maiz-Peña (eds.), 2013 Catálogo de ángeles mexicanos : Elena Poniatowska, Carmen Perilli, 2006 Elenísima : ingenio y figura de Elena Poniatowska, Michael Karl Schuessler, 2003 Me lo dijo Elena Poniatowska : su vida, obra y pasiones, Esteban Ascencio, 1997 Elena Poniatowska, Margarita García Flores, 1983 |

追加文献(さらに読む) 英語 歴史を紡ぐ物語:エレナ・ポニアトウスカの『クロニカス』から見るメキシコ、リン・スティーブン、2021年 エレナ・ポニアトウスカ:親密な伝記、マイケル・カール・シューラー、2007年 彼らの眼を通して:エレナ・ポニアトウスカ、シルビア・モリーナ、ローザ・ニッサン作品における周縁性、ナサニエル・イーライ・ガードナー、2007年 ラテンアメリカ女性小説における女性的な声の読み解き:テレサ・デ・ラ・パラからエレナ・ポニアトウスカ、ルイーサ・バレンズエラまで、マリア・テレサ・メデイロス=リケム、2002年 エレナ・ポニアトウスカの創作:対話による考察、ベス・エレン・ヨルゲンセン、1994年 スペイン語 風よ、水の疾走よ;言葉の狭間で:エレナ・ポニアトウスカ、サラ・プート・エレラ、2014年 沈黙への言葉:批評に直面するエレナ・ポニアトウスカ、ノラ・エロ=ペラルタとマグダレナ・マイズ=ペニャ(編)、2013年 『メキシコの天使たちカタログ:エレナ・ポニアトウスカ』カルメン・ペリリ著、2006年 『エレナ・ポニアトウスカの才気と風格』マイケル・カール・シュエッサー著、2003年 『エレナ・ポニアトウスカが語った:その生涯、作品、情熱』エステバン・アセンシオ著、1997年 『エレナ・ポニアトウスカ』マルガリータ・ガルシア・フローレス著、1983年 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elena_Poniatowska |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099