帝国とコミュニケーション

Empire and Communications

☆『帝国とコミュニケーション(Empire and

Communications)』は、1950年にトロント大学の教授ハロルド・イニスに

よって出版された本である。この本は、1948年にイニスがオックスフォード大学で行った6回の講義を基にしている。このシリーズは「ベイト・レク

チャー」として知られ、英国の帝国の歴史を探求することを目的としていた。しかし、イニスは、通信メディアが帝国の盛衰にどのような影響を与えてきたかに

ついて、広範囲にわたる歴史的調査を行うことを決意した。彼は、古代から現代に至るまで、石、粘土、パピルス、羊皮紙、紙といったメディアが及ぼした影響

をたどった。イニスは、各メディアが空間または時間に偏る「バイアス」が、そのメディアが支配する文明の性質を決定するのに役立つと主張した。「時

間を強調するメディアは、羊皮紙、粘土、石といった耐久性のある性質を持つものだ」と、彼は序文で書いている。これらのメディアは分散化を好む傾向があ

る。「空間を強調するメディアは、パピルスや紙のように耐久性が低く軽い性質のものが多い」。これらのメディアは一般的に、大規模で中央集権的な行政を好

む。イニスは、時間を維持し、空間を占領するために、帝国は時間重視のメディアと空間重視のメディアのバランスを取る必要があると信じてい

た。しかし、このようなバランスは、あるメディアを他のメディアよりも優遇する知識の独占が存在する場合、脅かされる可能性が高い。『帝国とコミュニケー

ション』では、エジプトとバビロニアの帝国における、石、粘土、パピルス、アルファベットなどのメディアの影響について検証している。また、古代ギリシャ

における口承の伝統、書かれた伝統とローマ帝国、中世ヨーロッパにおける羊皮紙と紙の影響、そして近代における紙と印刷機の影響についても考察している

(→「社会意識の審級としてのメディア」)。

| Empire and

Communications Empire and Communications is a book published in 1950 by University of Toronto professor Harold Innis. It is based on six lectures Innis delivered at Oxford University in 1948.[1] The series, known as the Beit Lectures, was dedicated to exploring British imperial history. Innis, however, decided to undertake a sweeping historical survey of how communications media influence the rise and fall of empires. He traced the effects of media such as stone, clay, papyrus, parchment and paper from ancient to modern times.[2] Innis argued that the "bias" of each medium toward space or toward time helps to determine the nature of the civilization in which that medium dominates. "Media that emphasize time are those that are durable in character such as parchment, clay and stone," he writes in his introduction.[3] These media tend to favour decentralization. "Media that emphasize space are apt to be less durable and light in character, such as papyrus and paper."[3] These media generally favour large, centralized administrations. Innis believed that to persist in time and to occupy space, empires needed to strike a balance between time-biased and space-biased media.[4] Such a balance is likely to be threatened, however, when monopolies of knowledge exist favouring some media over others.[5] Empire and Communications examines the impact of media such as stone, clay, papyrus and the alphabet on the empires of Egypt and Babylonia. It also looks at the oral tradition in ancient Greece; the written tradition and the Roman Empire; the influence of parchment and paper in medieval Europe and the effects of paper and the printing press in modern times. |

『帝国とコミュニケーション(Empire and

Communications)』 『帝国とコミュニケーション(Empire and Communications)』は、1950年にトロント大学の教授ハロ ルド・イニスによって出版された本である。この本は、1948年にイニスがオックスフォード大学で行った6回の講義を基にしている。[1] このシリーズは「ベイト・レクチャー」として知られ、英国の帝国の歴史を探求することを目的としていた。しかし、イニスは、通信メディアが帝国の盛衰にど のような影響を与えてきたかについて、広範囲にわたる歴史的調査を行うことを決意した。彼は、古代から現代に至るまで、石、粘土、パピルス、羊皮紙、紙と いったメディアが及ぼした影響をたどった。[2] イニスは、各メディアが空間または時間に偏る「バイアス」が、そのメディアが支配する文明の性質を決定するのに役立つと主張した。「時間を強調するメディ アは、羊皮紙、粘土、石といった耐久性のある性質を持つものだ」と、彼は序文で書いている。[3] これらのメディアは分散化を好む傾向がある。「空間を強調するメディアは、パピルスや紙のように耐久性が低く軽い性質のものが多い」[3]。これらのメ ディアは一般的に、大規模で中央集権的な行政を好む。イニスは、時間を維持し、空間を占領するために、帝国は時間重視のメディアと空間重視のメディアのバ ランスを取る必要があると信じていた。[4] しかし、このようなバランスは、あるメディアを他のメディアよりも優遇する知識の独占が存在する場合、脅かされる可能性が高い。[5] 『帝国とコミュニケーション』では、エジプトとバビロニアの帝国における、石、粘土、パピルス、アルファベットなどのメディアの影響について検証してい る。また、古代ギリシャにおける口承の伝統、書かれた伝統とローマ帝国、中世ヨーロッパにおける羊皮紙と紙の影響、そして近代における紙と印刷機の影響に ついても考察している。 |

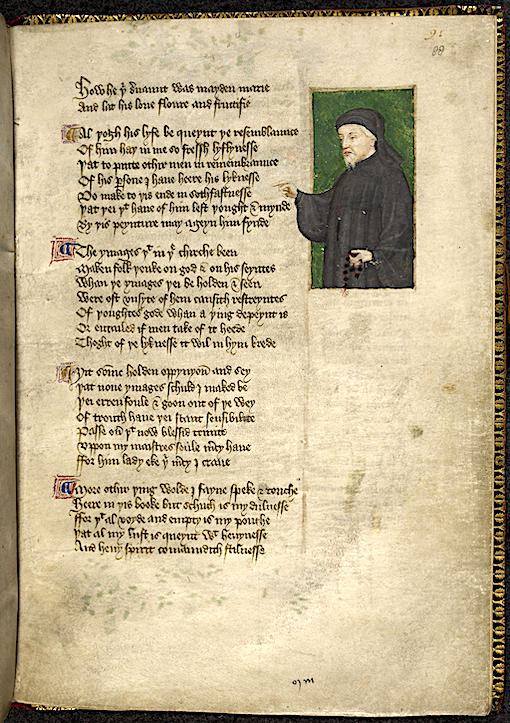

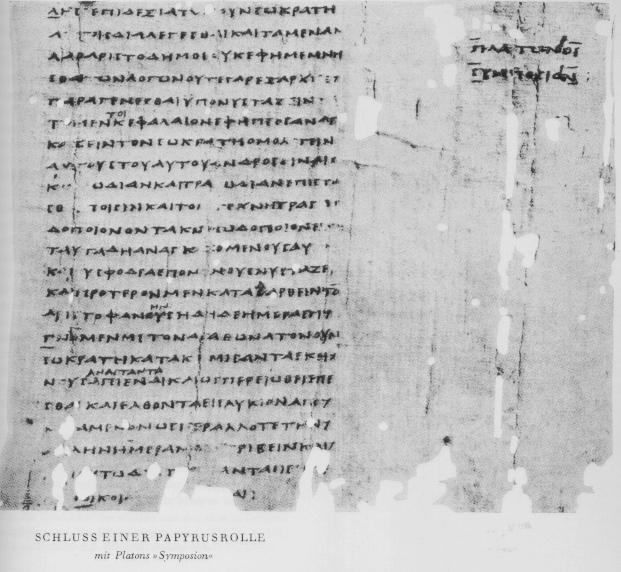

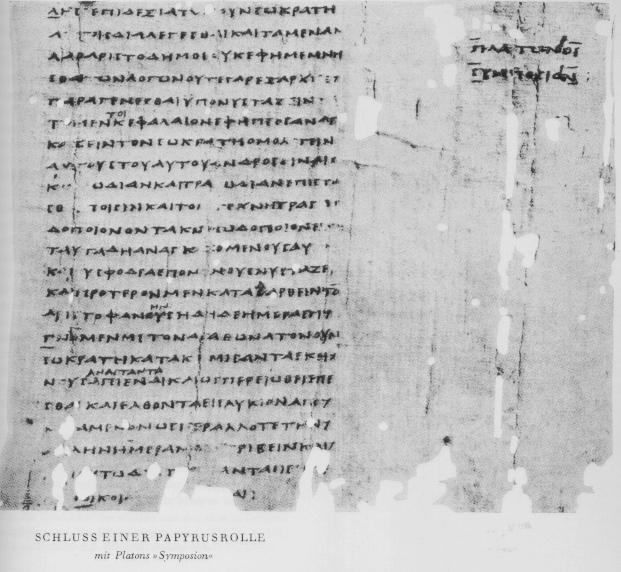

| Chapter 1. Introduction Harold Innis's highly condensed prose style, which frequently ranges over many centuries and several key ideas in one or two sentences, can make his writing in Empire and Communications difficult to understand. Biographer Paul Heyer recommends that readers use Innis's introduction as a helpful guide.[6]  Harold Innis noted that papyrus documents enabled Rome to administer its huge empire. Empire, bias and balance In his introduction, Innis promises to examine the significance of communications in a small number of empires. "The effective government of large areas," he writes, "depends to a very important extent on the efficiency of communication."[3] He argues for example, that light and easily transported papyrus enabled Rome to govern a large, centralized empire. For Innis, papyrus is associated with the political and administrative control of space. It, therefore, is a space-biased medium. Parchment, dominant after the breakup of the Roman Empire, was a durable medium used for hand copying manuscripts in medieval monasteries. For Innis, parchment favours decentralization and is associated with the religious control of time. It, therefore, is a time-biased medium. Innis argues that in order to last, large-scale political organizations such as empires must balance biases toward time and space. "They have tended to flourish under conditions in which civilization reflects the influence of more than one medium and in which the bias of one medium towards decentralization is offset by the bias of another medium towards centralization."[7] Writing, printing, and speech Innis divides the history of the empires and civilizations he will examine into two periods, one for writing and the other for printing. "In the writing period we can note the importance of various media such as the clay tablet of Mesopotamia, the papyrus roll in the Egyptian and in the Graeco-Roman world, parchment codex in the late Graeco-Roman world and the early Middle Ages, and paper after its introduction in the Western world from China."[7] Innis notes that he will concentrate on paper as a medium in the printing period along with the introduction of paper-making machinery at the beginning of the 19th century and the use of wood pulp in the manufacture of paper after 1850.[7] He is quick to add, however, that it would be presumptuous to conclude that writing alone determined the course of civilizations. Historians naturally focus on writing because it endures. "We are apt to overlook the significance of the spoken word," he writes, "and to forget that it has left little tangible remains."[4] For Innis, that tendency poses a problem. "It is scarcely possible for generations disciplined in the written and the printed tradition to appreciate the oral tradition."[8] Therefore, the media biases of one civilization make understanding other peoples difficult, if not impossible. "A change in the type of medium implies a change in the type of appraisal and hence makes it difficult for one civilization to understand another." As an example, Innis refers to our tendency to impose a modern conception of time on past civilizations. "With the dominance of arithmetic and the decimal system, dependent apparently on the number of fingers or toes, modern students have accepted the linear measure of time," he writes. "The dangers of applying this procrustean device in the appraisal of civilizations in which it did not exist illustrate one of numerous problems."[9] Innis also contrasts the strikingly different effects of writing and speaking. He argues that "writing as compared with speaking involves an impression at the second remove and reading an impression at the third remove. The voice of a second-rate person is more impressive than the published opinion of superior ability."[10] |

第1章 序論 ハロルド・イニスの文章は非常に簡潔で、1つか2つの文で数世紀にわたる歴史や複数の主要なアイデアをカバーしているため、『帝国と通信』の文章は理解するのが難しい。伝記作家のポール・ヘイヤーは、読者に対してイニスの序文を参考にするよう勧めている。  ハロルド・イニスは、パピルス文書がローマ帝国の巨大な帝国統治を可能にしたと指摘している。 帝国、偏り、バランス 序文でイニスは、少数の帝国におけるコミュニケーションの重要性を検証することを約束している。「広大な地域の効率的な統治は、非常に重要な程度までコ ミュニケーションの効率性に依存している」と彼は書いている。[3] 例えば、彼は、光を通し、容易に運搬できるパピルスがローマ帝国の巨大な中央集権的帝国統治を可能にしたと論じている。イニスにとって、パピルスは空間を 政治的・行政的に管理するものと関連付けられる。したがって、それは空間を重視するメディアである。ローマ帝国崩壊後に主流となった羊皮紙は、中世の修道 院で写本の複製を手書きするために使用された耐久性のあるメディアであった。イニスにとって、羊皮紙は分散化を促進し、時間を宗教的に管理するものと関連 付けられる。したがって、それは時間偏重のメディアである。イニスは、帝国のような大規模な政治組織が存続するためには、時間と空間に対する偏重のバラン スを取らなければならないと主張している。「文明が複数のメディアの影響を反映する状況下で、また、分散化への偏重が中央集権化への偏重によって相殺され る状況下で、それらは繁栄する傾向にある」[7] 筆記、印刷、そして音声 イニスは、彼が研究対象とする帝国と文明の歴史を、筆記の時代と印刷の時代という2つの時代に分ける。「筆記の時代には、メソポタミアの粘土板、エジプト やギリシャ・ローマ世界におけるパピルス巻物、ギリシャ・ローマ世界末期から中世初期にかけての羊皮紙、そして中国から西洋世界に伝来した紙など、さまざ まなメディアの重要性が認められる。。イニスは、印刷の時代におけるメディアとして紙に焦点を当てることを指摘し、19世紀初頭に製紙機械が導入され、 1850年以降は木材パルプが紙の製造に使用されるようになったことを挙げている。[7] しかし、彼はすぐに、文明の進路を決定したのは文字だけだったと結論づけるのは思い上がりだと付け加えている。歴史家が文字に注目するのは当然である。な ぜなら、文字は永続するからだ。「私たちは話し言葉の重要性を軽視しがちであり、話し言葉がほとんど目に見える形では残っていないことを忘れてしまいがち である」と彼は書いている。[4] インニスにとって、この傾向は問題である。「文字や印刷物の伝統に慣れ親しんだ世代が、口頭の伝統を理解することはほとんど不可能である」[8]。した がって、ある文明のメディアの偏りが、他の人々を理解することを困難にし、不可能にさえする。 「メディアの種類が変われば評価の方法も変わり、それゆえある文明が他の文明を理解することは困難になる」と。 その例として、イニスは過去の文明に現代的な時間概念を押し付ける傾向について言及している。「算術と十進法が支配的であり、指や足指の数に依存している ように見える現代の学生は、時間の直線的な尺度を受け入れている」と彼は書いている。文明の評価に、文明には存在しなかったこの画一的な尺度を適用するこ との危険性は、数多くの問題のひとつを明らかにしている。 また、イニスは、書くことと話すことの著しく異なる効果についても対比している。彼は、「話すことと比較した場合、書くことは、2段階離れた印象を伴い、 その印象を読むことは3段階離れた印象を伴う」と主張している。「能力が劣る人物の声は、優れた能力を持つ人物が出版した意見よりも印象的である」 [10]。 |

| Chapter 2. Egypt: From stone to papyrus Harold Innis traces the evolution of ancient Egyptian dynasties and kingdoms in terms of their use of stone or papyrus as dominant media of communication. His outline of Egyptian civilization is a complex and highly detailed analysis of how these media, along with several other technologies, affected the distribution of power in society. Influence of the Nile  A funerary stele from ancient Egypt's Middle Kingdom. Innis believed that hieroglyphics engraved in stone originally perpetuated the divine power of Egyptian kings. Innis begins, as other historians do, with the crucial importance of the Nile as a formative influence on Egyptian civilization. The river provided the water and fertile land needed for agricultural production in a desert region.[11] Innis writes that the Nile therefore, "acted as a principle of order and centralization, necessitated collective work, created solidarity, imposed organizations on the people, and cemented them in a society."[12] This observation is reminiscent of Innis's earlier work on the economic influence of waterways and other geographical features in his book, The Fur Trade in Canada, first published in 1930.[13] However, in Empire and Communications, Innis extends his economic analysis to explore the influence of the Nile on religion, associating the river with the sun god Ra, creator of the universe. In a series of intellectual leaps, Innis asserts that Ra's power was vested in an absolute monarch whose political authority was reinforced by specialized astronomical knowledge. Such knowledge was used to produce the calendar which could predict the Nile's yearly floods.[12] Stone, hieroglyphics and absolute monarchs As the absolute monarchy extended its influence over Egypt, a pictorial hieroglyphic writing system was invented to express the idea of royal immortality.[14] According to Innis, the idea of the divine right of autocratic monarchs was developed from 2895 BC to 2540 BC. "The pyramids," Innis writes, "carried with them the art of pictorial representation as an essential element of funerary ritual." The written word on the tomb, he asserts, perpetuated the divine power of kings.[15] Innis suggests that the decline of the absolute monarchy after 2540 BC may have been related to the need for a more accurate calendar based on the solar year. He suggests that priests may have developed such a calendar increasing their power and authority.[16] After 2000 BC, peasants, craftsmen, and scribes obtained religious and political rights. "The profound disturbances in Egyptian civilization," Innis writes "involved in the shift from absolute monarchy to more democratic organization coincided with a shift in emphasis on stone as a medium of communication or as a basis of prestige, as shown in the pyramids, to an emphasis on papyrus."[17] Papyrus and the power of scribes Innis traces the influence of the newer medium of papyrus on political power in ancient Egypt. The growing use of papyrus led to the replacement of cumbersome hieroglyphic scripts by cursive or hieratic writing. Rapid writing styles made administration more efficient and highly trained scribes became part of a privileged civil service.[18] Innis writes. however, that the replacement of one dominant medium by another led to upheaval. The shift from dependence on stone to dependence on papyrus and the changes in political and religious institutions imposed an enormous strain on Egyptian civilization. Egypt quickly succumbed to invasion from peoples equipped with new instruments of attack. Invaders with the sword and the bow and long-range weapons broke through Egyptian defence, dependent on the battle-axe and the dagger. With the use of bronze and possibly iron weapons, horses and chariots, Syrian Semitic peoples under the Hyksos or Shepherd kings captured and held Egypt from 1660 to 1580 BC.[19] Hyksos rule lasted about a century until the Egyptians drove them out.[20] Innis writes that the invaders had adopted hieroglyphic writing and Egyptian customs, "but complexity enabled the Egyptians to resist." The Egyptians may have won their victory using horses and light chariots acquired from the Libyans.[19] Empire and the one true god Innis writes that the military organization that expelled the Hyksos enabled the Egyptians to establish and expand an empire that included Syria and Palestine, and that eventually reached the Euphrates. Egyptian administrators used papyrus and a postal service to run the empire, but adopted cuneiform as a more efficient script. The pharaoh Akhnaton tried to introduce Aten, the solar disk as the one true god, a system of worship that would provide a common ideal for the whole empire. But the priests and the people resisted "a single cult in which duty to the empire was the chief consideration."[21] Priestly power, Innis writes, resulted from religious control over the complex and difficult art of writing. The monarch's attempts to maintain an empire extended in space were defeated by a priestly monopoly over knowledge systems concerned with time --- systems that began with the need for accurate predictions about when the Nile would overflow its banks.[22] Innis argues that priestly theocracy gradually cost Egypt its empire. "Monopoly over writing supported an emphasis on religion and the time concept, which defeated efforts to solve the problem of space."[23] |

第2章 エジプト:石からパピルスへ ハロルド・イニスは、古代エジプトの王朝と王国の進化を、石やパピルスを主要なコミュニケーション手段として使用したという観点から追跡している。彼のエ ジプト文明の概略は、これらの媒体が他のいくつかの技術とともに社会における権力の分布にどのような影響を与えたかという、複雑かつ非常に詳細な分析であ る。 ナイルの影響  古代エジプト中王国時代の葬祭用石碑。イニスは、もともと石に刻まれた象形文字はエジプト王の神聖な力を永遠のものとするために用いられたと考えた。 イニスは他の歴史家と同様に、エジプト文明の形成に影響を与えたナイル川の決定的な重要性をまず論じている。 ナイル川は、砂漠地帯における農業生産に必要な水と肥沃な土地を提供していた。[11] それゆえ、ナイル川は「秩序と中央集権化の原理として作用し、集団作業を必要とし、連帯感を醸成し、人々に組織を押し付け、社会を固めた」とイニスは書い ている。[12] この観察は、イニスの 水路やその他の地理的特性が経済に与える影響に関するイニスの初期の研究を彷彿とさせる。この研究は、1930年に出版された著書『カナダの毛皮貿易』に まとめられている。[13] しかし、『帝国と通信』では、イニスは経済分析をさらに発展させ、ナイル川が宗教に与えた影響を探求し、この川を宇宙の創造主である太陽神ラーと関連付け ている。一連の飛躍的な思考を経て、イニスは、ラーの力は絶対君主のものであり、その政治的権威は専門的な天文学的知識によって強化されていたと主張す る。このような知識は、ナイル川の年ごとの洪水を予測できる暦を作成するために用いられた。[12] 石、象形文字、絶対君主 絶対王政がエジプト全土に影響力を拡大するにつれ、王家の不滅性を表現するために象形文字が発明された。[14] イニスによると、専制君主の神聖な権利という概念は、紀元前2895年から紀元前2540年の間に発展した。「ピラミッドは、葬祭儀式の不可欠な要素とし て、絵画表現の技術を伴っていた」とイニスは記している。墓に書かれた文字は、王の神聖な力を永遠のものにしたと彼は主張している。[15] イニスは、紀元前2540年以降の絶対王政の衰退は、太陽年に基づくより正確な暦の必要性と関連している可能性があると示唆している。彼は、司祭たちが権 力と権威を増大させるためにそのような暦を開発した可能性があると示唆している。[16] 紀元前2000年以降、農民、職人、書記が宗教的および政治的権利を獲得した。「エジプト文明における深刻な混乱は、絶対王政からより民主的な組織への移 行に伴うものであり、ピラミッドに見られるように、コミュニケーションの媒体として、あるいは威信の基盤として石が重視されていたものが、パピルスが重視 されるようになったことと一致している」とイニスは書いている。[17] パピルスと書記官の力 イニスは、古代エジプトにおける政治権力に対するパピルスという新しい媒体の影響をたどっている。パピルスの使用が増えるにつれ、煩雑なヒエログリフの文 字は、草書体やヒエラティック文字に置き換えられていった。速記のスタイルが行政の効率化をもたらし、高度な訓練を受けた書記官は特権的な公務員となっ た。[18] しかし、イニスは、ある支配的な媒体が別のものに置き換えられることが激変につながったと書いている。 石への依存からパピルスへの依存への変化、そして政治的・宗教的機関の変化は、エジプト文明に大きな負担を強いた。エジプトは、新しい攻撃手段を備えた民 族の侵略にすぐに屈した。戦斧や短剣に頼っていたエジプトの防衛を、剣や弓、遠距離兵器を携えた侵略者たちが突破した。青銅や鉄製の武器、馬、戦車を用い て、ヒクソスまたは羊飼い王の支配下にあったシリア系セム族の人々は、紀元前1660年から1580年にかけてエジプトを占領し、支配した。 ヒクソス人の支配は、エジプト人が彼らを追い出すまで約1世紀続いた。[20] イニスは、侵略者たちはヒエログリフ文字とエジプトの慣習を取り入れたが、「複雑さによりエジプト人は抵抗することができた」と書いている。エジプト人は リビア人から入手した馬と軽戦車を用いて勝利を収めたのかもしれない。[19] 帝国と唯一神 イニスは、ヒクソスを追放した軍事組織によって、エジプト人はシリアとパレスチナを含む帝国を確立し、拡大することができたと記している。そして、その帝 国は最終的にユーフラテス川にまで達した。エジプトの行政官はパピルスと郵便制度を利用して帝国を運営したが、より効率的な文字として楔形文字を採用し た。ファラオのアメンヘテプ3世は、太陽の円盤であるアテンを唯一神として導入しようとし、帝国全体に共通の理想をもたらす崇拝体系を確立しようとした。 しかし、司祭と民衆は「帝国への義務が最優先される単一の信仰」に抵抗した。[21] インニスは、司祭の権力は、複雑で困難な文字の書き方を司祭が管理していたことから生じたと記している。空間的に拡大する帝国を維持しようとしたファラオ の試みは、時間に関する知識体系を司祭たちが独占したことによって失敗に終わった。この体系は、ナイル川がいつ氾濫するかについての正確な予測の必要性か ら始まったものである。[22] イニスは、司祭による神権政治が徐々にエジプトの帝国を衰退させた、と主張している。「文字の独占は、宗教と時間概念の重視を支え、それが空間的な問題の 解決を妨げることになった。」[23] |

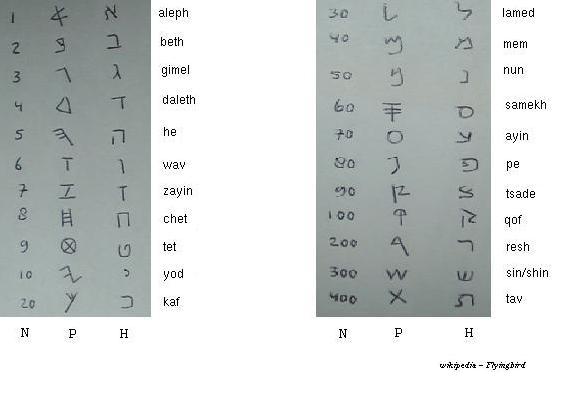

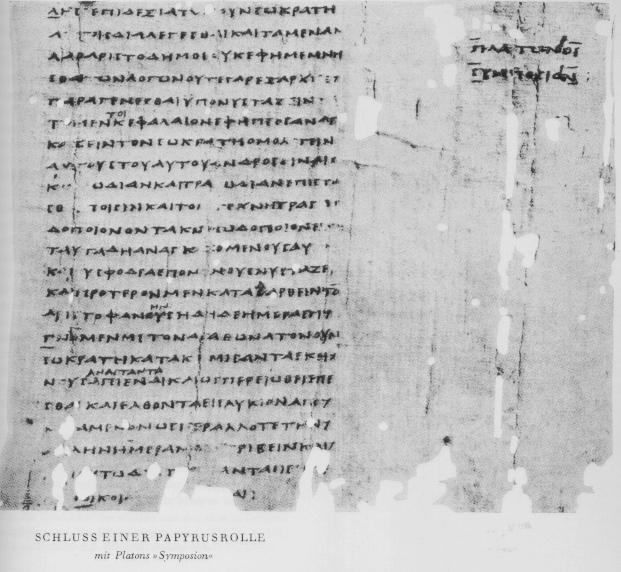

| Chapter 3. Babylonia: The origins of writing In this chapter, Innis outlines the history of the world's first civilizations in Mesopotamia. He starts with the fertile plains between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, but as the history unfolds, his discussion extends to large parts of the modern Middle East. Innis traces the origins of writing from the cuneiform script written on clay tablets to the Phoenician alphabet written on parchment and papyrus.[24] Along the way, Innis comments on many aspects of the ancient Middle Eastern empires including power struggles between priests and kings, the evolution of military technologies and the development of the Hebrew Bible. History begins at Sumer Innis begins by observing that unlike in Egypt where calculating the timing of the Nile's flooding was a source of power, along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in southern Mesopotamia the ability to measure time precisely was somewhat less critical. Nevertheless, as in Egypt, the small city-states of Sumer depended on the rivers and so the cycles of agricultural production were organized around them.[25] The rivers also provided communications materials. In Egypt, the Nile's papyrus became a medium for writing while in Mesopotamia, the rivers yielded the alluvial sediments the Sumerians used to fashion the clay tablets on which they inscribed their wedge-shaped, cuneiform script.[26] Their earliest known writing recorded agricultural accounts and economic transactions.[27] Innis points out that the tablets were not well suited to pictographic writing because making straight lines "tended to pull up the clay." Therefore, Sumerian scribes used a cylindrical reed stylus to stamp or press wedges and lines on the moist tablet. Scribes gradually developed cuneiform signs to represent syllables and the sounds of the spoken language.[28] Innis writes that as a heavy material, clay was not very portable and so was not generally suited for communication over large areas. Cuneiform inscription required years of training overseen by priests. Innis contends therefore, that as a writing medium, clay tended to favour decentralization and religious control.[29] From city-states to empires Innis suggests that religious control in Sumer became a victim of its own successes. "The accumulation of wealth and power in the hands of priests and the temple organizations," he writes, "was probably followed by ruthless warfare between city-states."[30] The time-bound priests, unskilled in technological change and the military arts, lost power to spatially oriented kings intent on territorial expansion. Around 2350 BC, the Sumerians were conquered by their northern, Semitic neighbours the Akkadians. Under Sargon the Great, the empire expanded to include extensive territories reaching northwest as far as Turkey and west to the Mediterranean.[31] Thus begins the rise and fall of a series of empires over approximately two thousand years. Innis mentions many of them, but focuses more attention on innovations that facilitated their growth. These include the advancement of civil law under Hammurabi, the development of mathematics including fixed standards of weights and measures, as well as the breeding of horses that combined speed with strength and that, along with three-man chariots, helped deliver spectacular military victories to the Assyrians.[32] Alphabet, empire and trade  The Phoenician alphabet. The Phoenicians were sailors and traders who travelled widely taking their versatile alphabet with them. In discussing the advent and spread of the alphabet, Innis refers to what he sees as the subversive relationship between those at the centre of civilizations and those on their fringes or margins. He argues that monopolies of knowledge develop at the centre only to be challenged and eventually overthrown by new ideas or techniques that take shape on the margins.[33] Thus, the Phoenician alphabet, a radically simplified writing system, undermined the elaborate hieroglyphic and cuneiform scripts overseen by priestly elites in Egypt and Babylonia. "The Phoenicians had no monopoly of knowledge," Innis writes, "[which] might hamper the development of writing."[34] As a trading people, the Phoenicians needed "a swift and concise method of recording transactions."[34] The alphabet with its limited number of visual symbols to represent the primary elements of human speech was well suited to trade. "Commerce and the alphabet were inextricably interwoven, particularly when letters of the alphabet were used as numerals."[35] The alphabet, combined with the use of parchment and papyrus, Innis argues, had a decentralizing effect favouring cities and smaller nations over centralized empires.[36] He suggests that improved communication, made possible by the alphabet, enabled the Assyrians and the Persians to administer large empires in which trading cities helped offset concentrations of power in political and religious organizations.[37] Alphabet, the Hebrews and religion Innis sketches the influence of the alphabet on the Hebrews in the marginal territory of Palestine. The Hebrews combined oral and written traditions in their scriptures.[38] Innis points out that they had previously acquired key ideas from the Egyptians. "The influence of Egypt on the Hebrews," he writes, "was suggested in the emphasis on the sacred character of writing and on the power of the word which when uttered brought about creation itself. The word is the word of wisdom. Word, wisdom, and God were almost identical theological concepts."[36] The Hebrews distrusted images. For them, words were the true source of wisdom. "The written letter replaced the graven image as an object of worship."[39] In a typically complex passage, Innis writes: "Denunciation of images and concentration on the abstract in writing opened the way for advance from blood relationship to universal ethical standards and strengthened the position of the prophets in their opposition to absolute monarchical power. The abhorrence of idolatry of graven images implied a sacred power in writing, observance of the law, and worship of the one true God."[39] The alphabet enabled the Hebrews to record their rich oral tradition in poetry and prose. "Hebrew has been described as the only Semitic language before Arabic to produce an important literature characterized by simplicity, vigour and lyric force. With other Semitic languages it was admirably adapted to the vivid, vigorous description of concrete objects and events."[40] Innis traces the influence of various strands in scriptural writing suggesting that the combination of these sources strengthened the movement toward monotheism.[40] In a summary passage, Innis explores the wide-ranging influence of the alphabet in ancient times. He argues that it enabled the Assyrians and Persians to expand their empires, allowed for the growth of trade under the Arameans and Phoenicians and invigorated religion in Palestine. As such, the alphabet provided a balance. "An alphabet became the basis of political organization through efficient control of territorial space and of religious organization through efficient control over time in the establishment of monotheism."[41] |

第3章 バビロニア:文字の起源 この章では、イニスはメソポタミアにおける世界最初の文明の歴史を概説している。彼はチグリス川とユーフラテス川の間の肥沃な平原から話を始めているが、 歴史が展開するにつれ、彼の議論は現代の中東の大部分にまで広がっている。イニスは、粘土板に書かれた楔形文字から羊皮紙やパピルスに書かれたフェニキア 文字まで、文字の起源をたどっている。[24] その過程で、イニスは古代中東の帝国のさまざまな側面について論じている。その中には、祭司と王の間の権力闘争、軍事技術の進化、ヘブライ語聖書の発展な どが含まれる。 歴史はシュメールで始まる イニスはまず、ナイル川の氾濫の時期を計算することが権力の源であったエジプトとは異なり、メソポタミア南部のチグリス川とユーフラテス川沿いでは、時間 を正確に測定する能力はそれほど重要ではなかったと指摘している。しかし、エジプトと同様に、シュメールの小さな都市国家は川に依存していたため、農業生 産のサイクルは川を中心に組織されていた。[25] 川は通信手段も提供していた。エジプトではナイル川のパピルスが文字を書くための媒体となり、メソポタミアでは川が沖積土を運び、シュメール人はそれを粘 土板に加工し、そこに楔形文字を刻み込んだ。 イニスは、粘土板は直線を書くのに適していなかったと指摘している。なぜなら、直線を書くと「粘土が引き上げられてしまう」傾向があったからだ。そのた め、シュメールの書記たちは円筒形の葦ペン先を使って、湿った粘土板に楔形文字や線を刻み込んだ。書記たちは、音節と言語音を表すために次第に楔形文字を 発達させていった。[28] インニスは、粘土は重い素材であるため持ち運びには適さず、広範囲にわたるコミュニケーションには一般的に適していなかったと記している。 楔形文字の刻印には、司祭の監督下で何年もの訓練が必要であった。 したがって、インニスは、文字媒体として、粘土は分散化と宗教的統制を好む傾向があったと主張している。[29] 都市国家から帝国へ イニスは、シュメールにおける宗教的支配は自らの成功の犠牲となったと主張している。「司祭や神殿組織が富と権力を蓄積した結果、おそらく都市国家間の非 情な戦いが続いたであろう」と彼は書いている。[30] 時間的な制約のある司祭たちは、技術革新や軍事技術に精通しておらず、領土拡大を狙う空間的な志向を持つ王たちに権力を奪われた。紀元前2350年頃、 シュメール人は北方のセム族である隣人、アッカド人に征服された。サルゴン大王の治世下で、帝国は拡大し、北西はトルコ、西は地中海にまで至る広大な領土 を包含するようになった。[31] こうして、約2000年にわたる一連の帝国の興亡が始まった。イニスは、その多くに言及しているが、それらの成長を促進した革新に特に注目している。これ には、ハムラビ法典による民法の進歩、重量や測定の固定基準を含む数学の発展、そして、スピードと強さを兼ね備えた馬の品種改良や、3人乗りの戦車ととも にアッシリア軍の目覚ましい軍事的勝利に貢献したことなどが含まれる。[32] アルファベット、帝国、貿易  フェニキア文字。フェニキア人は船乗りであり、貿易商人であり、多用途の文字を携えて広く旅をした。 イニスは、文字の誕生と普及について論じる中で、文明の中心にいる者たちと、周辺や限界にいる者たちとの間に破壊的な関係がある、と指摘している。彼は、 知識の独占は中心部で発展するが、やがて周辺部で形作られる新しいアイデアや技術によって挑戦され、最終的には打ち倒されると主張している。[33] このように、根本的に簡素化されたフェニキア文字は、エジプトやバビロニアの聖職者エリート層が管理していた精巧な象形文字や楔形文字を脅かすものとなっ た。「フェニキア人は知識を独占していたわけではない」とイニスは記している。「それは文字の発展を妨げる可能性がある」[34] 交易民族であったフェニキア人には、「取引を迅速かつ簡潔に記録する方法」が必要であった。[34] 人間の言語の主要な要素を表す視覚記号の数が限られているアルファベットは、交易に適していた。「商業とアルファベットは切っても切り離せない関係にあ り、特にアルファベットの文字が数字として使われた場合にはその傾向が強かった」[35]とイニスは述べている。アルファベットは、羊皮紙やパピルスの使 用と組み合わさることで、 アルファベットの使用により可能となったコミュニケーションの改善が、アッシリア人やペルシア人が広大な帝国を統治することを可能にし、貿易都市が政治 的・宗教的組織における権力の集中を相殺するのに役立ったと彼は示唆している。 アルファベット、ヘブライ人、宗教 イニスは、パレスチナの辺境地域におけるヘブライ人へのアルファベットの影響について概説している。ヘブライ人は、聖典において口頭伝承と書面伝承を融合 させていた。[38] イニスは、ヘブライ人は以前にエジプト人から主要な考え方を学んでいたと指摘している。「エジプトがヘブライ人に与えた影響は、文字の神聖な性格と、発せ られた言葉が創造そのものを生み出す力に重点が置かれていることから示唆されている。言葉は知恵の言葉である。言葉、知恵、神はほとんど同一の神学的概念 であった」[36] ヘブライ人は偶像を信用していなかった。彼らにとって、言葉こそが真の知恵の源であった。「刻まれた像は、崇拝の対象として文字に取って代わられた」 [39] 典型的な複雑な文章で、イニスは次のように書いている。 「偶像の非難と、抽象的なものへの執着が、血縁関係から普遍的な倫理基準への前進への道を開き、絶対的な君主権力への反対を唱える預言者の立場を強化した。偶像崇拝への嫌悪は、文字に神聖な力があること、法の遵守、唯一の真の神への崇拝を意味していた」[39] ヘブライ人は、アルファベットによって、豊かな口頭伝承を詩や散文として記録することが可能になった。「ヘブライ語は、簡潔さ、力強さ、叙情的な力強さと いう特徴を持つ重要な文学作品を生み出した唯一のセム語であると評されている。他のセム語と比較すると、具体的な物や出来事を生き生きと力強く描写するこ とに非常に適していた」[40] イニスは、聖典の記述におけるさまざまな要素の影響をたどり、それらの要素が組み合わさることで一神教への動きが強まったと示唆している。[40] 要約の文章で、イニスは古代におけるアルファベットの広範な影響について探求している。彼は、アルファベットによってアッシリア人とペルシア人が帝国を拡 大することが可能になり、アラム人とフェニキア人の下で貿易が成長し、パレスチナの宗教が活性化されたと論じている。このように、アルファベットは均衡を もたらした。「アルファベットは、領土の効率的な管理を通じて政治組織の基盤となり、一神教の確立を通じて時間の効率的な管理を通じて宗教組織の基盤と なった。」[41] |

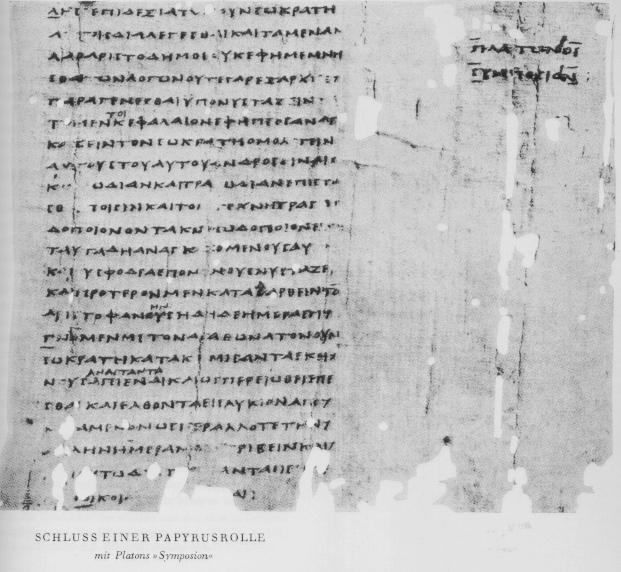

| Chapter 4. Greece and the oral tradition "Greek civilization," Innis writes, "was a reflection of the power of the spoken word."[42] In this chapter, he explores how the vitality of the spoken word helped the ancient Greeks create a civilization that profoundly influenced all of Europe. Greek civilization differed in significant ways from the empires of Egypt and Babylonia. Innis biographer John Watson notes that those preceding empires "had revolved around an uneasy alliance of absolute monarchs and scholarly theocrats."[43] The monarchs ruled by force while an elite priestly class controlled religious dogma through their monopolies of knowledge over complex writing systems. "The monarch was typically a war leader whose grasp of the concept of space allowed him to expand his territory," Watson writes, "incorporating even the most highly articulated theocracies. The priests specialized in elaborating conceptions of time and continuity."[43] Innis argues that the Greeks struck a different balance, one based on "the freshness and elasticity of an oral tradition" that left its stamp on Western poetry, drama, sculpture, architecture, philosophy, science and mathematics.[44] Socrates, Plato and the spoken word  Detail of the painting The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Louis David. Innis begins by examining Greek civilization at its height in the 5th century BC. He points out that the philosopher Socrates (c. 470 BC–399 BC) "was the last great product and exponent of the oral tradition."[45] Socrates taught using a question and answer technique that produced discussion and debate. His student, Plato (428/427 BC – 348/347 BC), elaborated on these Socratic conversations by writing dialogues in which Socrates was the central character. This dramatic device engaged readers in the debate while allowing Plato to search for truth using a dialectical method or one based on discussion.[46] "The dialogues were developed," Innis writes "as a most effective instrument for preserving [the] power of the spoken word on the written page."[47] He adds that Plato's pupil, Aristotle (384 BC – 322 BC), regarded the Platonic dialogues as "half-way between poetry and prose."[47] Innis argues that Plato's use of the flexible oral tradition in his writing enabled him to escape the confines of a rigid philosophical system. "Continuous philosophical discussion aimed at truth. The life and movement of dialectic opposed the establishment of a finished system of dogma."[47] This balance between speech and prose also contributed to the immortality of Plato's work.[47] Innis writes that the power of the oral tradition reached its height in the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides when "drama became the expression of Athenian democracy."[48] He argues that tragedy attracted the interest and participation of everyone. "To know oneself was to know man's powerlessness and to know the indestructible and conquering majesty of suffering humanity."[49] For Innis, the fall of Athens to Sparta in 404 BC and the trial and execution of Socrates for corrupting Athenian youth were symptoms of the collapse of the older oral culture. That culture had sustained a long poetic tradition, but Plato attacked poetry as a teaching device and expelled poets from his ideal republic. According to Innis, Plato and Aristotle developed prose in defence of a new culture in which gods and poets were subordinated to philosophical and scientific inquiry.[50] Innis argues that eventually, the spread of writing widened the gap between the city-states hastening the collapse of Greek civilization.[51] The Greek alphabet Innis notes that the early Mycenaean Greeks of the Bronze Age developed their own styles of communication because they escaped the cultural influence of the Minoans they had conquered on the island of Crete. "The complexity of the script of Minoan civilization and its relative restriction to Crete left the Greeks free to develop their own traditions."[52] Innis adds that the growth of a strong oral tradition reflected in Greek epic poetry also fostered resistance to the dominance of other cultures. This led the Greeks to take over and modify the Phoenician alphabet possibly around the beginning of the 7th century BC.[53] The Greeks adapted this 24-letter, Semitic alphabet which consisted only of consonants to their rich oral tradition by using some of its letters to represent vowel sounds. Innis writes that the vowels in each written word "permitted the expression of fine distinctions and light shades of meaning."[54] The classics professor, Eric Havelock, whose work influenced Innis, makes a similar point when he argues that this alphabet enabled the Greeks to record their oral literary tradition with a "wealth of detail and depth of psychological feeling" absent in other Near Eastern civilizations with more limited writing systems.[55] Innis himself quotes scholar Richard Jebb's claim that the Greek language "'responds with happy elasticity to every demand of the Greek intellect...the earliest work of art created by the spontaneous working of the Greek mind.'"[56] Poetry, politics and the oral tradition "The power of the oral tradition," Innis writes, "implied the creation of a structure suited to its needs."[54] That structure consisted of the metres and stock phrases of epic poetry which included the Homeric poems, the Iliad and Odyssey. The epics were sung by professional minstrels who pleased audiences by reshaping the poems to meet the needs of new generations. Innis points out that music was central to the oral tradition and the lyre accompanied the performance of the epic poems.[57] He argues that the Homeric poems reflected two significant developments. The first was the rise of an aristocratic civilization which valued justice and right action over the traditional ties of kinship. The second was the humanization of the Greek gods whose limited powers encouraged belief in rational explanations for the order of things.[58] "Decline of belief in the supernatural led to the explanation of nature in terms of natural causes," Innis writes. "With the independent search for truth, science was separated from myth."[59]  Head of the poet Sappho. Gradually, the flexible oral tradition gave rise to other kinds of poetry. Innis notes that these new kinds of literature "reflected the efficiency of the oral tradition in expressing the needs of social change."[59] Hesiod wrote about agricultural themes, becoming the first spokesman for common people.[60] Innis writes that his poems were produced "by an individual who made no attempt to conceal his personality."[57] In the 7th century BC, Archilochos took poetry a step further when he contributed to breaking down the heroic code of epic poetry.[57] Innis suggests he responded to a rising public opinion while historian J.B. Bury describes him as venting his feelings freely and denouncing his enemies.[61] Innis argues that these changes in poetic style and form coincided with the replacement of Greek kingdoms by republics in the 8th and 7th centuries BC.[57] Finally, he mentions the development of shorter, lyric poetry that could be intensely personal as shown in the work of Sappho. This profusion of short personal lyrics likely coincided with the spread of writing and the increasing use of papyrus from Egypt.[57] Greek science and philosophy Innis credits the oral tradition with fostering the rise of Greek science and philosophy. He argues that when combined with the simplicity of the alphabet, the oral tradition prevented the development of a highly specialized class of scribes and a priestly monopoly over education. Moreover, unlike the Hebrews, the Greeks did not develop written religious texts. "The Greeks had no Bible with a sacred literature attempting to give reasons and coherence to the scheme of things, making dogmatic assertions and strangling science in infancy."[62] Innis contends that the flexibility of the oral tradition encouraged the introduction of a new medium, mathematics. Thales of Miletus may have discovered trigonometry. He also studied geometry and astronomy, using mathematics as "a means of discarding allegory and myth and advancing universal generalizations."[63] Thus, mathematics gave rise to philosophical speculation. The map maker, Anaximander also sought universal truths becoming "the first to write down his thoughts in prose and to publish them, thus definitely addressing the public and giving up the privacy of his thought."[64] According to Innis, this use of prose "reflected a revolutionary break, an appeal to rational authority and the influence of the logic of writing."[64] |

第4章 ギリシャと口承の伝統 「ギリシャ文明は、話し言葉の力の反映であった」とイニスは書いている。[42] この章では、話し言葉の活力が古代ギリシャ人たちにヨーロッパ全体に多大な影響を与える文明を築くのにいかに役立ったかを考察している。ギリシャ文明は、 エジプトやバビロニアの帝国とは大きく異なっていた。イニスの伝記を書いたジョン・ワトソンは、それ以前の帝国は「絶対君主と学者神官の不安定な同盟関係 を中心に展開していた」と指摘している。[43] 君主は武力によって支配し、エリート神官階級は複雑な文字体系に関する知識を独占することで宗教的教義を支配した。「君主は通常、戦争の指揮官であり、空 間概念を把握することで領土を拡大し、最も高度に組織化された神権政治体制さえも取り込んだ。司祭たちは、時間と継続性に関する精巧な概念の構築を専門と していた」と書いている。[43] イニスは、ギリシア人は異なるバランスを重視し、それは「口頭伝承のフレッシュさと弾力性」に基づくもので、西洋の詩、演劇、彫刻、建築、哲学、科学、数 学にその痕跡を残したと主張している。[44] ソクラテス、プラトン、そして口頭による言葉  ジャック=ルイ・ダヴィッドによる絵画『ソクラテスの死』の細部 イニスはまず、ギリシャ文明が最盛期を迎えた紀元前5世紀について考察している。彼は、哲学者ソクラテス(紀元前470年頃 - 紀元前399年)は「口承の最後の偉大な産物であり、その代表者であった」と指摘している。[45] ソクラテスは、質問と回答の手法を用いて議論や討論を促す教育を行った。彼の弟子であるプラトン(紀元前428/427年 - 紀元前348/347年)は、ソクラテスを主人公とする対話を書き、ソクラテスの会話について詳しく述べた。この劇的な手法により、読者は議論に参加しな がら、弁証法的手法や議論に基づく手法を用いてプラトンが真理を探求するのを傍観することができた。[46] 「対話は発展し、」イニスは「口頭による言葉の力を文章として保存する最も効果的な手段となった」と記している。[47] さらに、 プラトンの弟子であるアリストテレス(前384年 - 前322年)は、プラトンの対話を「詩と散文の中間」とみなしていたとイニスは記している。[47] イニスは、プラトンが柔軟な口承の伝統を文章に取り入れたことで、硬直した哲学体系の枠組みから逃れることができたと主張している。「真理を追求する哲学 的な議論の連続。弁証法の生命と運動は、完成された教義体系の確立に反対するものであった。」[47] また、この口頭伝承と散文のバランスもプラトンの作品の不朽性に貢献した。[47] イニスは、口承の力がエウリピデス、ソフォクレス、エウリピデスの悲劇において頂点に達したと述べている。「ドラマがアテナイの民主主義の表現となった」 ときである。[48] 彼は、悲劇が人々の関心と参加を引きつけたと主張している。「自分自身を知ることは、人間の無力さを知り、苦しむ人類の不滅で征服的な威厳を知ることだっ た」[49] イニスにとって、紀元前404年のアテナイのスパルタへの陥落と、アテナイの若者を堕落させたとしてソクラテスが裁判にかけられ処刑されたことは、古い口 承文化の崩壊の兆候であった。その文化は長い詩の伝統を維持してきたが、プラトンは詩を教育手段として攻撃し、理想的な共和国から詩人を追放した。イニス によると、プラトンとアリストテレスは、神々や詩人を哲学や科学の探究に従属させる新しい文化を守るために散文を発展させた。[50] イニスは、最終的に文字の普及が都市国家間の格差を広げ、ギリシャ文明の崩壊を早めたと主張している。[51] ギリシャ文字 イニスは、青銅器時代の初期のミケーネ文明のギリシャ人は、クレタ島のミノア文明を征服したことで、ミノア文明の文化的影響を免れたため、独自のコミュニ ケーションスタイルを発展させた、と指摘している。「ミノア文明の文字の複雑さと、それがクレタ島に限定されていたことにより、ギリシア人は自分たちの伝 統を発展させる自由を手に入れた」[52]とイニスは述べている。また、ギリシアの叙事詩に見られる強力な口承伝統の成長も、他文化の支配に対する抵抗を 育んだとイニスは付け加えている。これにより、ギリシア人はおそらく紀元前7世紀の初頭頃にフェニキア文字を借用し、それを修正した。ギリシア人は、子音 のみで構成される24文字のセム文字を、母音を表すためにいくつかの文字を使用することで、豊かな口頭伝承に適応させた。イニスは、各単語の母音によって 「微妙な区別や意味の微妙な違いを表現することが可能になった」と書いている[54]。イニスに影響を与えた古典学者エリック・ハヴェロックは、このアル ファベットによってギリシア人は「細部にわたる詳細と 他の限定的な文字体系を持つ中近東の文明には見られないような、細部にわたる詳細さや心理的な深みを」ギリシア人は記録することができたと主張している。 [55] イニス自身も、ギリシア語は「ギリシア人の知性のあらゆる要求に快く弾力的に反応する...ギリシア人の心が自然に働いて作り出した最も初期の芸術作品」 であるという学者リチャード・ジェブの主張を引用している。[56] 詩、政治、口承 「口承の力は、そのニーズに適した構造の創出を暗示していた」とイニスは書いている。[54] その構造は、ホメーロスの詩である『イーリアス』や『オデュッセイア』などの叙事詩の韻律や決まり文句から構成されていた。叙事詩はプロの吟遊詩人によっ て歌われ、吟遊詩人は詩を新しい世代のニーズに合わせて作り変えることで聴衆を楽しませた。イニスは、口承の中心には音楽があり、叙事詩の演奏には竪琴が 使われたと指摘している。[57] また、ホメロスの詩は2つの重要な発展を反映していると論じている。1つ目は、伝統的な血縁関係よりも正義と正しい行動を重んじる貴族文明の台頭である。 2つ目は、ギリシャ神話の神々が人間味を帯び、その限られた力によって、物事の秩序に対する合理的な説明を信じるようになったことである。[58] 「超自然的なものの信仰の衰退は、自然の原因による自然の説明へとつながった」とイニスは記している。「真実を独自に追求する中で、科学は神話から切り離 された」[59]  詩人サッフォーの頭像。 徐々に、柔軟な口承の伝統は、他の種類の詩を生み出すようになった。イニスは、これらの新しい文学が「社会の変化のニーズを表現する口承の効率性を反映し た」と指摘している。[59] ヘシオドスは農業をテーマに詩を書き、庶民の代弁者となった。[60] イニスは、彼の詩は「個性を隠そうとしない人物によって作られた」と書いている。 」と記している。[57] 紀元前7世紀には、アルキロコスが叙事詩の英雄的規範を打破するのに貢献し、詩をさらに一歩前進させた。[57] イニスは、彼は高まりつつある世論に応えたと示唆しているが、一方で歴史家のJ.B.ベリーは、彼は自分の感情を自由に吐露し、敵対者を非難したと述べて いる。。イニスは、詩のスタイルと形式におけるこれらの変化は、ギリシャの王国が前8世紀と前7世紀に共和制へと移行した時期と一致していると主張してい る。最後に、イニスはサッフォーの作品に見られるような、より短く、より個人的な抒情詩の展開について言及している。こうした個人的な短詩の多産は、おそ らく文字の普及とエジプトからのパピルスの使用増加と一致していると考えられる。 ギリシャの科学と哲学 イニスは、ギリシャの科学と哲学の発展を口承の伝統に負うところが多いと主張している。彼は、アルファベットの簡潔さと口承の伝統が組み合わさったこと で、高度に専門化された書記階級の発生や、教育における聖職者の独占が妨げられたと論じている。さらに、ギリシア人はヘブライ人とは異なり、宗教的な文章 を書き記すことはなかった。「ギリシア人には、物事の仕組みに理由や一貫性を持たせようとする神聖な文学作品としての聖書はなく、独断的な主張を展開し、 科学の芽を摘んでいた」[62] イニスは、口承の柔軟性が新しい媒体である数学の導入を促したと主張している。ミレトスのタレスは三角法を発見したかもしれない。彼は幾何学や天文学も研 究し、数学を「寓話や神話を排除し、普遍的な一般化を進める手段」として用いた。[63] このように、数学は哲学的思索を生み出した。地図製作者のアナクシマンドロスもまた、普遍的な真理を追い求め、「散文で自分の考えを書き記し、それを出版 した最初の人物となった。これにより、彼は確実に一般大衆に訴えかけ、自分の考えの秘密を明かすことをやめた」[64]。イニスによると、散文の使用は 「革命的な変化、合理的な権威への訴え、そして文章を書くことの論理的な影響を反映した」[64]。 |

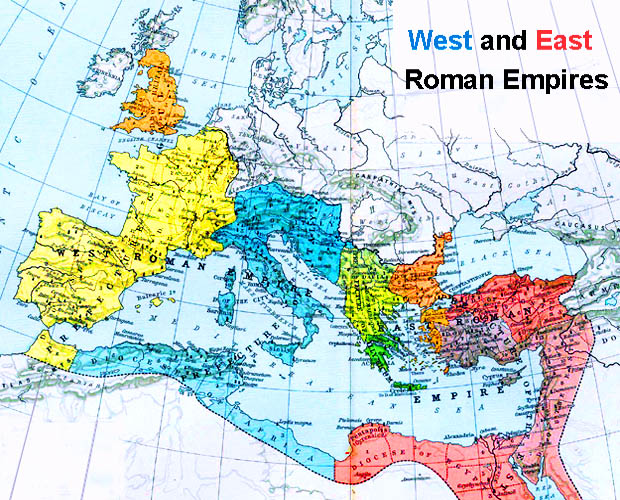

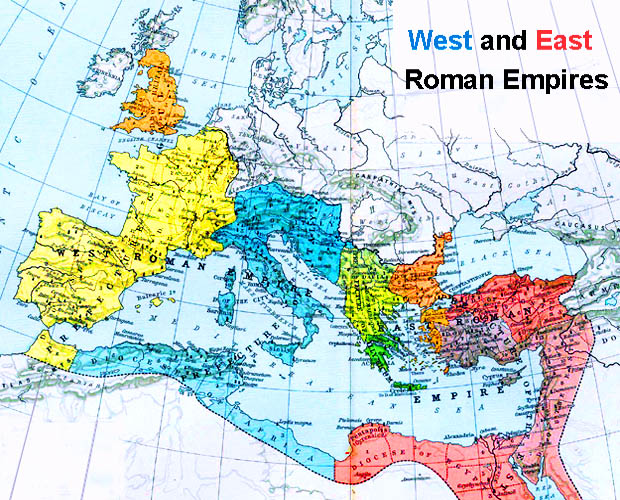

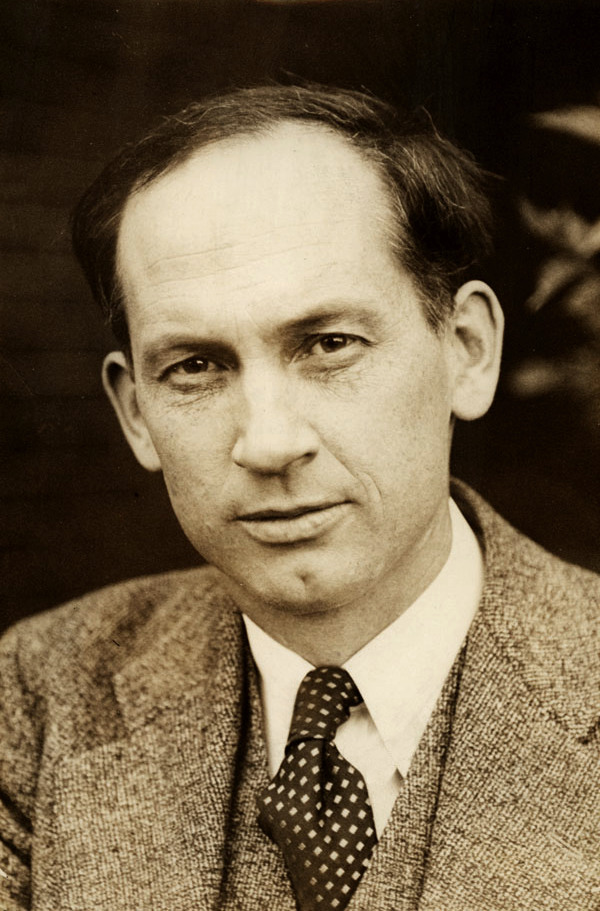

| Chapter 5. Rome and the written tradition In this chapter, Harold Innis focuses on the gradual displacement of oral communication by written media during the long history of the Roman Empire. The spread of writing hastened the downfall of the Roman Republic, he argues, facilitating the emergence of a Roman Empire stretching from Britain to Mesopotamia.[65] To administer such a vast empire, the Romans were forced to establish centralized bureaucracies.[66] These bureaucracies depended on supplies of cheap papyrus from the Nile Delta for the long-distance transmission of written rules, orders and procedures.[67] The bureaucratic Roman state backed by the influence of writing, in turn, fostered absolutism, the form of government in which power is vested in a single ruler.[68] Innis adds that Roman bureaucracy destroyed the balance between oral and written law giving rise to fixed, written decrees. The torture of Roman citizens and the imposition of capital punishment for relatively minor crimes became common as living law "was replaced by the dead letter."[69] Finally, Innis discusses the rise of Christianity, a religion which spread through the use of scripture inscribed on parchment.[70] He writes that the Byzantine Empire in the east eventually flourished because of a balance in media biases. Papyrus enabled the governing of a large spatial empire, while parchment contributed to the development of a religious hierarchy concerned with time.[71] Rome and Greece  The initials SPQR stood for Senātus Populusque Rōmānus ("The Senate and the People of Rome"). They were emblazoned on the banners of Roman legions. "The achievements of a rich oral tradition in Greek civilization," Innis writes, "became the basis of Western culture."[72] He asserts that Greek culture had the power "to awaken the special forces of each people by whom it was adopted" and the Romans were no exception.[72] According to Innis, it appears Greek colonies in Sicily and Italy along with Greek traders introduced the Greek alphabet to Rome in the 7th century BC. The alphabet was developed into a Graeco-Etruscan script when Rome was governed by an Etruscan king. The Etruscans also introduced Greek gods in the 6th century BC apparently to reinforce their own rule.[72] Rome became isolated from Greece in the 5th and 4th centuries BC and overthrew the monarchy. A patrician aristocracy took control, but after prolonged class warfare, gradually shared power with the plebeians.[73] Innis suggests that Roman law flourished at this time because of its oral tradition. A priestly class, "equipped with trained memories," made and administered the laws, their power strengthened because there was no body of written law.[74] Although plebeian pressure eventually resulted in the adoption of the Twelve Tables—a written constitution—interpretation remained in the hands of priests in the College of Pontiffs.[74] One of Roman law's greatest achievements, Innis writes, lay in the development of civil laws governing families, property and contracts. Paternal rights were limited, women became independent and individual initiative was given the greatest possible scope.[75] Innis seems to suggest that political stability coupled with strong oral traditions in law and religion contributed to the unity of the Roman Republic.[76] He warns however, that the growing influence of written laws, treaties and decrees in contrast to the oral tradition of civil law "boded ill for the history of the republic and the empire."[77] Innis quickly sketches the Roman conquest of Italy and its three wars with the North African city of Carthage. The Punic Wars ended with the destruction of Carthage in 146 BC. At the same time, Rome pursued military expansion in the eastern Mediterranean eventually conquering Macedonia and Greece as well as extending Roman rule to Pergamum in modern-day Turkey. Rome and the problems of Greek empire Innis interrupts his account of Roman military expansion to discuss earlier problems that had arisen from the Greek conquests undertaken by Philip of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. Philip and Alexander had established a Macedonian Empire which controlled the Persian Empire as well as territory as far east as India. Innis suggests Rome would inherit the problems that faced Philip and Alexander including strong separatist tendencies. After Alexander's death, four separate Hellenistic dynasties arose. The Seleucids controlled the former Persian Empire; the Ptolemies ruled in Egypt; the Attalids in Pergamum and the Antigonids in Macedonia.[78] Seleucid dynasty The Seleucid rulers attempted to dominate Persian, Babylonian and Hebrew religions but failed to establish the concept of the Greek city-state. Their kingdom eventually collapsed. Innis concludes that monarchies that lack the binding powers of nationality and religion and that depend on force were inherently insecure, unable to resolve dynastic problems.[79] Ptolemaic dynasty Innis discusses various aspects of Ptolemaic rule over Egypt including the founding of the ancient library and university at Alexandria made possible by access to abundant supplies of papyrus. "By 285 BC the library established by Ptolemy I had 20,000 manuscripts," Innis writes, "and by the middle of the first century 700,000, while a smaller library established by Ptolemy II...possibly for duplicates had 42,800."[80] He points out that the power of the written tradition in library and university gave rise to specialists, not poets and scholars — drudges who corrected proofs and those who indulged in the mania of book collecting. "Literature was divorced from life, thought from action, poetry from philosophy."[81] Innis quotes the epic poet Apollonius's claim that "a great book was a great evil."[81] Cheap papyrus also facilitated the rise of an extensive administrative system eventually rife with nepotism and other forms of bureaucratic corruption. "An Egyptian theocratic state," Innis notes, "compelled its conquerors to establish similar institutions designed to reduce its power."[82] Attalid dynasty Innis contrasts the scholarly pursuits of the Attalid dynasty at Pergamum with what he sees as the dilettantism of Alexandria. He writes that Eumenes II who ruled from 197 to 159 BC established a library, but was forced to rely on parchment because Egypt had prohibited the export of papyrus to Pergamum. Innis suggests that the Attalids probably preserved the masterpieces of ancient Greek prose. He notes that Pergamum had shielded a number of cities from attacks by the Gauls. "Its art reflected the influence of the meeting of civilization and barbarism, a conflict of good and evil, in the attempt at unfamiliar ways of expression."[83] Antigonid dynasty Innis writes that the Antigonids "gradually transformed the small city-states of Greece into municipalities."[83] They captured Athens in 261 BC and Sparta in 222 BC. The Greek cities of this period developed common interests. "With supplies of papyrus and parchment and the employment of educated slaves," Innis writes, "books were produced on an unprecedented scale. Hellenistic capitals provided a large reading public."[84] Most of the books, however, were "third-hand compendia of snippets and textbooks, short cuts to knowledge, quantities of tragedies, and an active comedy of manners in Athens. Literary men wrote books about other books and became bibliophiles."[84] Innis reports that by the 2nd century "everything had been swamped by the growth of rhetoric."[84] He argues that once classical Greek philosophy "became crystallized in writing," it was superseded by an emphasis on philosophical teaching.[84] He mentions Stoicism, the Cynics and Epicurean teachings all of which emphasized the priority of reason over popular religion. "The Olympian religion and the city-state were replaced by philosophy and science for the educated and by Eastern religions for the common man."[85] As communication between these two groups became increasingly difficult, cultural division stimulated the rise of a class structure. Innis concludes that the increasing emphasis on writing also created divisions among Athens, Alexandria and Pergamum weakening science and philosophy and opening "the way to religions from the East and force from Rome in the West."[86] Greek influence and Roman prose Innis returns to his account of Roman history by noting that Rome's military successes in the eastern Mediterranean brought it under the direct influence of Greek culture. He quotes the Roman poet Horace: "Captive Greece took captive her proud conqueror."[85] Innis gives various examples of Greek influence in Rome. They include the introduction of Greek tragedies and comedies at Roman festivals to satisfy the demands of soldiers who had served in Greek settlements as well as the translation of the Odyssey into Latin.[87] Innis mentions there was strong opposition to this spread of Greek culture. He reports for example, that Cato the Elder deplored what he saw as the corrupting effects of Greek literature. Cato responded by laying the foundations for a dignified and versatile Latin prose.[88] In the meantime, the Roman Senate empowered officials to expel those who taught rhetoric and philosophy and in 154 BC, two disciples of Epicurus were banished from Rome. Nevertheless, Innis points out that Greek influence continued as "Greek teachers and grammarians enhanced the popularity of Hellenistic ideals in literature."[88] Meantime, Innis asserts, Roman prose "gained fresh power in attempts to meet problems of the Republic."[88] He is apparently referring to the vast enrichment of the Roman aristocracy and upper middle class as wealth poured in from newly conquered provinces. "The plunder from the provinces provided the funds for that orgy of corrupt and selfish wealth which was to consume the Republic in revolution," writes Will Durant in his series of volumes called The Story of Civilization.[89] Innis mentions that the large-scale farms owned by aristocrats brought protests presumably from small farmers forced off the land and into the cities as part of a growing urban proletariat.[90] The Gracchi brothers were among the first, Innis writes, "to use the weapon of Greek rhetoric" in their failed attempts to secure democratic reforms. Gaius Gracchus made Latin prose more vivid and powerful. Innis adds that political speeches such as his "were given wider publicity through an enlarged circle of readers."[88] As political oratory shaped Latin prose style, written speech almost equaled the power of oral speech.[91] Writing, empire and religion Rome's dominance of Egypt, Innis writes, gave it access to papyrus which supported a chain of interrelated developments that would eventually lead to the decline and fall of Rome. Papyrus facilitated the spread of writing which in turn, permitted the growth of bureaucratic administration needed to govern territories that would eventually stretch from Britain to Mesopotamia.[92] "The spread of writing contributed to the downfall of the Republic and the emergence of the empire," Innis writes.[66]  Roman Colosseum, symbol of permanence. Centralized administrative bureaucracy helped create the conditions for the emergence of absolute rulers such as the Caesars which, in turn, led to emperor worship.[93] According to Innis, the increased power of writing touched every aspect of Roman culture including law which became rigidly codified and increasingly reliant on such harsh measures as torture and capital punishment even for relatively trivial crimes.[94] "The written tradition dependent on papyrus and the roll supported an emphasis on centralized bureaucratic administration," Innis writes. "Rome became dependent on the army, territorial expansion, and law at the expense of trade and an international economy."[95] Innis notes that Rome attempted to increase its imperial prestige by founding libraries.[96] And, with the discovery of cement about 180 BC, the Romans constructed magnificent buildings featuring arch, vault and dome. "Vaulted architecture became an expression of equilibrium, stability, and permanence, monuments which persisted through centuries of neglect."[97] Innis argues that the gradual rise of Christianity from its origins as a Jewish sect among lower social strata on the margins of empire was propelled by the development of the parchment codex, a much more convenient medium than cumbersome papyrus rolls.[70] "The oral tradition of Christianity was crystallized in books which became sacred," Innis writes.[98] He adds that after breaking away from Judaism, Christianity was forced to reach out to other religions, its position strengthened further by scholars who attempted to synthesize Jewish religion and Greek philosophy in the organization of the Church.[98] Constantine ended official persecution of Christianity and moved the imperial capital to Constantinople eventually creating a religious split between the declining Western Roman Empire and believers in the East. "As the power of empire was weakened in the West that of the Church of Rome increased and difficulties with heresies in the East became more acute."[99] Innis contends the Eastern or Byzantine Empire survived after the fall of Rome because it struck a balance between time and space-biased media. "The Byzantine empire developed on the basis of a compromise between organization reflecting the bias of different media: that of papyrus in the development of an imperial bureaucracy in relation to a vast area and that of parchment in the development of an ecclesiastical hierarchy in relation to time."[71] |

第5章 ローマと文字による伝承 この章で、ハロルド・イニスは、ローマ帝国の長い歴史の中で、口頭によるコミュニケーションが徐々に書面によるメディアに置き換えられていったことに焦点 を当てている。 彼は、文字の普及がローマ共和国の崩壊を早め、ブリテン島からメソポタミアにまで広がるローマ帝国の出現を容易にしたと主張している。[65] このような広大な帝国を統治するために、ローマ人は中央集権的な官僚制度を確立せざるを得なかった。[66] これらの官僚制度は、遠距離での 書面による規則、命令、手続きの伝達。[67] 官僚的なローマ国家は、文字による影響力を背景に、権力が単独の支配者に集中する専制政治を助長した。[68] また、イニスは、ローマの官僚主義が口頭法と書面法のバランスを崩壊させ、固定化された書面による法令を生み出したと付け加えている。ローマ市民に対する 拷問や、比較的軽微な犯罪に対する死刑の適用が一般的になったのは、生きた法律が「死文化」に取って代わられたからである。[69] ついに、イニスは、羊皮紙に刻まれた聖典の使用によって広まったキリスト教の台頭について論じている。[70] 彼は、東のビザンチン帝国が最終的に繁栄したのは、メディアの偏りのバランスが取れていたからだと書いている。パピルスは広大な空間帝国の統治を可能に し、一方で羊皮紙は時間に関わる宗教的階層の形成に貢献した。[71] ローマとギリシャ  SPQRの頭文字は、元老院とローマ市民(Senātus Populusque Rōmānus)を意味した。この文字はローマ軍団の旗に描かれた。 「ギリシャ文明における豊かな口承伝統の功績は、西洋文化の基礎となった」とイニスは記している。[72] また、ギリシャ文化には「それが取り入れられた各民族の特別な力を呼び覚ます」力があり、ローマ人も例外ではなかったと主張している。[72] イニスによると、ギリシャの植民地がシチリアとイタリアにあったこと、そしてギリシャの商人たちが、紀元前7世紀にギリシャ文字をローマに伝えたようだ。 ローマがエトルリア人の王によって統治されていた時代に、このアルファベットはギリシャ・エトルリア文字へと発展した。エトルリア人は紀元前6世紀にギリ シアの神々を導入したが、これはおそらく自分たちの支配を強化するためであった。[72] ローマは紀元前5世紀と4世紀にギリシアから孤立し、君主制を廃止した。貴族階級が支配権を握ったが、長期にわたる階級闘争の後、平民と徐々に権力を共有 するようになった。[73] イニスは、口頭伝承があったため、この時代にローマ法が栄えたと示唆している。「訓練された記憶力を持つ」聖職者階級が法律を制定し、管理していたが、成 文法が存在しなかったため、彼らの権力は強化された。[74] 平民の圧力により、最終的には成文憲法である十二表が採択されたが、解釈は教皇会議の聖職者の手に委ねられたままであった。[74] ローマ法の最大の功績のひとつは、家族、財産、契約を管理する民法の発展にあるとイニスは記している。父権は制限され、女性は自立し、個人の自主性は最大 限に尊重された。[75] イニスは、政治的安定と、法律と宗教における強力な口頭伝承が、ローマ共和国の統一に貢献したと示唆しているようだ。[76] しかし、彼は、口頭伝承の市民法に対して、書面による法律、条約、布告が影響力を強めたことは、「共和国と帝国の歴史にとって不吉な兆し」であると警告し ている。[77] イニスはローマによるイタリア征服と、北アフリカの都市カルタゴとの3度にわたる戦争を簡単に概説している。 ポエニ戦争は紀元前146年のカルタゴの滅亡によって終結した。 同じ時期、ローマは地中海東部で軍事的拡大を推し進め、最終的にはマケドニアとギリシャを征服し、ローマの支配を現在のトルコにあるペルガモンにまで拡大 した。 ローマとギリシャ帝国の問題 イニスはローマの軍事的拡大について語るのを中断し、フィリッポス2世と息子のアレクサンドロス大王によるギリシャ征服から生じた初期の問題について論じ ている。フィリッポスとアレクサンドロスはマケドニア帝国を樹立し、ペルシャ帝国だけでなくインドの東方地域までを支配下に置いた。イニスは、ローマは フィリップやアレクサンダーが直面した問題、すなわち強い分離独立の傾向を含む問題を継承することになるだろうと示唆している。アレクサンダーの死後、4 つのヘレニズム王朝が誕生した。セレウコス朝はかつてのペルシア帝国を支配し、プトレマイオス朝はエジプトを支配し、アッタロス朝はペルガモンを支配し、 アンティゴノス朝はマケドニアを支配した。 セレウコス朝 セレウコス朝の支配者は、ペルシア、バビロニア、ヘブライの宗教を支配下に置こうとしたが、ギリシャの都市国家の概念を確立することはできなかった。 彼らの王国は最終的に崩壊した。 イニスは、国民性や宗教の結束力を欠き、武力に頼る君主制は本質的に不安定であり、王朝の問題を解決できないと結論づけている。 プトレマイオス朝 イニスは、豊富なパピルスが入手可能であったことから実現したアレクサンドリアにおける古代の図書館および大学の創設など、プトレマイオス朝によるエジプ ト統治のさまざまな側面について論じている。「紀元前285年までに、プトレマイオス1世が創設した図書館には2万点の写本が所蔵されていた。また、1世 紀半ばには70万点に達したが、プトレマイオス2世が創設した小規模な図書館には... おそらく重複分を保管するために作られた小規模な図書館には42,800冊が保管されていた」と指摘している。[80] 彼は、図書館や大学における書物の伝統が、詩人や学者ではなく、校正係や書物収集に熱中する人々といった専門家を生み出したと指摘している。「文学は生活 から、思想は行動から、詩は哲学から乖離した」[81] イニスは叙事詩詩人アポロニウスの主張を引用している。「偉大な書物は偉大な悪であった」[81] 安価なパピルスは、やがて縁故主義やその他の官僚腐敗の蔓延する広範な行政システムの台頭も促した。「エジプトの神権政治国家は、征服者たちに自らの権力 を弱めるための同様の制度を確立することを余儀なくさせた」とイニスは指摘している。 アッタロス朝 イニスは、ペルガモンにあったアッタロス朝の学術的探求と、彼がアレクサンドリアのディレッタント主義とみなすものとを対比させている。彼は、紀元前 197年から159年まで統治したエウメネス2世が図書館を設立したが、エジプトがパピルスのペルガモンへの輸出を禁止したため、羊皮紙に頼らざるを得な かったと書いている。イニスは、アッタロス朝は古代ギリシャの散文の名作を保存していた可能性が高いと示唆している。また、ペルガモンはガリア人の攻撃か ら多くの都市を守ったと指摘している。「その芸術は、文明と野蛮の出会い、善と悪の対立、そして未知の表現方法への試みによる影響を反映していた」 [83]。 アンティゴノス朝 イニスは、アンティゴノス朝が「ギリシャの小規模な都市国家を徐々に自治体に変えていった」と記している。[83] 彼らは紀元前261年にアテネ、紀元前222年にスパルタを征服した。この時代のギリシャの都市は共通の利益を発展させていった。「パピルスや羊皮紙の供 給と、教育を受けた奴隷の雇用により、前例のない規模で書籍が生産された。ヘレニズムの首都は、多くの読書家を生み出した」とイニスは記している。 [84] しかし、そのほとんどは「断片や教科書の三流の要約、知識への近道、大量の悲劇、アテネの活気ある風俗喜劇であった。文学者は他の本についての本を書き、 愛書家となった」[84]。イニスは、2世紀までに「すべてが修辞学の成長によって圧倒された」と報告している[84]。彼は、古典ギリシャ哲学が「文章 として結晶化」すると、哲学の教えが強調されるようになったと主張している[84]。彼は、ストア主義、キニク派、エピクロス派の教えについて言及してい るが、これらはすべて、一般の宗教よりも理性を優先することを強調していた。「オリンポスの宗教と都市国家は、教養ある人々にとっては哲学と科学に、一般 の人々にとっては東方の宗教にとって代わられた」[85]。この2つのグループ間のコミュニケーションがますます難しくなるにつれ、文化的な分裂が階級構 造の台頭を促した。イニスは、文章を書くことへの重点がますます強まったことで、アテネ、アレキサンドリア、ペルガモン間の分裂が生まれ、科学と哲学が弱 体化し、「東方の宗教と西ローマの武力」への道が開かれたと結論づけている[86]。 ギリシャの影響とローマの散文 イニスは、ローマが地中海東部で軍事的成功を収めたことにより、ギリシャ文化の直接的な影響下に入ったと指摘し、ローマの歴史に関する自身の説明に戻って いる。彼はローマの詩人ホラティウスの言葉を引用している。「捕虜となったギリシャは、誇り高き征服者を捕虜とした」[85]と。イニスは、ギリシャが ローマに与えた影響のさまざまな例を挙げている。ギリシャの植民地で従軍した兵士たちの要望に応えて、ローマの祭りでギリシャの悲劇や喜劇が上演されたこ とや、『オデュッセイア』がラテン語に翻訳されたことなどが含まれる[87]。 イニスは、ギリシャ文化の広まりに対して強い反対があったと述べている。例えば、ギリシャ文学の腐敗的影響力と見なしたカトー・ミノルが嘆いたことを報告 している。カトーは、威厳のある多才なラテン語散文の基礎を築くことでこれに応えた。[88] 一方、ローマ元老院は、修辞学や哲学を教える者たちを追放する権限を役人に与え、紀元前154年にはエピクロス派の2人の弟子がローマから追放された。し かし、イニスは「ギリシャの教師や文法学者が、文学におけるヘレニズムの理想の人気を高めた」ため、ギリシャの影響は続いたと指摘している。[88] 一方、イニスはローマの散文が「『共和国』の問題に対処する試みにおいて、新たな力を得た」と主張している。[88] 彼は明らかに、新たに征服した地方から富が流入したことによる、ローマの貴族階級と上流中流階級の大幅な豊かさの向上について言及している。「地方からの 略奪品は、腐敗と利己主義に満ちた富の乱痴気騒ぎの資金となり、それが革命によって共和国を崩壊させることになった」と、ウィル・デュラントは『文明の歴 史』シリーズで書いている。[89] イニスは、貴族が所有する大規模農場が 都市に流入した小作農民から抗議を受けた。これは、都市のプロレタリアートが増加する中で起こったことである。[90] グラックス兄弟は、民主的改革を確保しようとして失敗した最初の人物であり、「ギリシャの修辞学の武器を使用した」とイニスは書いている。ガイウス・グ ラックスはラテン語の散文をより生き生きとした力強いものにした。イニスは、彼の政治演説のようなものは「読者層の拡大により、より広く知られるように なった」と付け加えている。[88] 政治演説がラテン語散文のスタイルを形作ったため、書かれた言葉は口頭での言葉の力とほぼ同等となった。[91] 執筆、帝国、宗教 ローマによるエジプトの支配は、パピルスへのアクセスをローマにもたらし、それは最終的にローマの衰退と滅亡につながる一連の相互関連した発展を支えた。 パピルスは文字の普及を促進し、それがまた、やがてはブリテン島からメソポタミアにまで広がる領土を統治するために必要な官僚的行政の成長を可能にした。 [92] 「文字の普及は、共和国の崩壊と帝国の誕生に貢献した」とイニスは書いている。[66]  ローマのコロッセオ、永遠の象徴。 中央集権的な行政官僚制は、シーザーのような絶対的支配者の出現を促す条件を作り出し、それが皇帝崇拝につながった。[93] イニスによると、文字の普及によりローマ文化のあらゆる側面が影響を受け、 法律は厳格に成文化され、比較的些細な犯罪に対しても拷問や死刑などの過酷な手段にますます依存するようになった。[94] 「パピルスや巻物に依存する書面による伝統は、中央集権的な官僚行政を重視するようになった」とイニスは記している。「ローマは、貿易や国際経済を犠牲に して、軍隊、領土拡大、法律に依存するようになった」[95] イニスは、ローマが図書館を設立することで帝国の威信を高めようとしたと指摘している。[96] また、紀元前180年頃にセメントが発見されたことで、ローマ人はアーチ、ヴォールト、ドームを特徴とする壮麗な建造物を建設した。「ヴォールト建築は、 均衡、安定、永続性の表現となり、何世紀もの放置にも耐え抜く記念碑となった。」[97] イニスは、キリスト教が帝国の周辺に位置する社会下層階級のユダヤ教の一派として始まり、徐々に台頭していったのは、扱いにくいパピルス巻物よりもはるか に便利な羊皮紙の写本が開発されたことが推進力となったためだと主張している。[70] 「キリスト教の口頭伝承は 書物として結晶化し、神聖なものとなった」とイニスは書いている。[98] また、ユダヤ教から離脱したキリスト教は、他の宗教に手を差し伸べざるを得なくなり、ユダヤ教とギリシャ哲学を教会の組織の中で統合しようとした学者たち によって、その立場はさらに強化されたと付け加えている。[98] コンスタンティヌスはキリスト教への公式の迫害を終結させ、帝都をコンスタンティノープルに移した。これにより、衰退しつつあった西ローマ帝国と東方の信 者との間に宗教的な分裂が生じた。「西ローマ帝国の力が弱まるにつれ、ローマ教会の力は強まり、東方の異端との対立はより深刻化した。」[99] イニスは、ローマの滅亡後も東方またはビザンチン帝国が存続したのは、時間と空間を重視するメディアのバランスを取っていたからだと主張している。「ビザ ンチン帝国は、広大な地域に関連する帝国官僚機構の発展におけるパピルス、時間に関連する教会のヒエラルキーの発展における羊皮紙という、異なるメディア の偏りを反映する組織間の妥協を基盤として発展した」[71]。 |

| Chapter 6. Middle Ages: Parchment and paper In Chapter 6, Innis tries to show how the medium of parchment supported the power of churches, clergy and monasteries in medieval Europe after the breakdown of the Roman empire. Rome's centralized administration had depended on papyrus, a fragile medium produced in the Nile Delta. Innis notes that parchment, on the other hand, is a durable medium that can be produced wherever farm animals are raised. He argues, therefore, that parchment is suited to the decentralized administration of a wide network of local religious institutions.[100] However, the arrival of paper via China and the Arab world, challenged the power of religion and its preoccupation with time. "A monopoly of knowledge based on parchment," Innis writes, "invited competition from a new medium such as paper which emphasized the significance of space as reflected in the growth of nationalist monarchies."[101] He notes that paper also facilitated the growth of commerce and trade in the 13th century.[102] Monasteries and books Innis writes that monasticism originated in Egypt and spread rapidly partly in protest against Caesaropapism or the worldly domination of the early Christian church by emperors.[103] He credits St. Benedict with adapting monasticism to the needs of the Western church. The Rule of St. Benedict required monks to engage in spiritual reading. Copying books and storing them in monastery libraries soon became sacred duties.[104] Innis notes that copying texts on parchment required strength and effort: Working six hours a day the scribe produced from two to four pages and required from ten months to a year and a quarter to copy a Bible. The size of the scriptures absorbed the energies of monasteries. Libraries were slowly built up and uniform rules in the care of books were generally adopted in the 13th century. Demands for space led to the standing of books upright on the shelves in the 14th and 15th centuries and to the rush of library construction in the 15th century.[105] Innis points out that Western monasteries preserved and transmitted the classics of the ancient world.[104] Islam, images, and Christianity Innis writes that Islam (which he sometimes refers to as Mohammedanism) gathered strength by emphasizing the sacredness of the written word. He notes that the Caliph Iezid II ordered the destruction of pictures in Christian churches within the Umayyad Empire.[106] The banning of icons within churches was also sanctioned by Byzantine Emperor Leo III in 730 while Emperor Constantine V issued a decree in 753–754 condemning image worship.[106] Innis writes that this proscription of images was designed to strengthen the empire partly by curbing the power of monks, who relied on images to sanction their authority. Monasteries, he notes, had amassed large properties through their exemption from taxation and competed with the state for labour. Byzantine emperors reacted by secularizing large monastic properties, restricting the number of monks, and causing persecution, which drove large numbers of them to Italy.[106] The Western church, on the other hand, saw images as useful especially for reaching the illiterate. Innis adds that by 731, iconoclasts were excluded from the Church and Charles Martel's defeat of the Arabs in 732 ended Muslim expansion in western Europe. The Synod of Gentilly (767), the Lateran Council (769), and the Second Council of Nicea (787), sanctioned the use of images although Charlemagne prohibited image veneration or worship.[107] |

第6章 中世:羊皮紙と紙 第6章でイニスは、ローマ帝国の崩壊後の中世ヨーロッパにおいて、羊皮紙という媒体が教会、聖職者、修道院の権力をいかに支えていたかを示そうとしてい る。ローマの中央集権的な行政は、ナイル川デルタで生産される壊れやすい媒体であるパピルスに依存していた。一方、羊皮紙は耐久性のある媒体であり、家畜 が飼育されている場所であればどこでも生産できるとイニスは指摘している。したがって、パーチメントは地方の宗教施設が広くネットワーク化された分散型の 行政形態に適していると主張している。[100] しかし、中国やアラブ世界を経由して紙が伝来したことにより、宗教の権力と時間への固執が試されることとなった。「羊皮紙に基づく知識の独占は、国家主義 的な君主制の成長に反映されているように、空間的な重要性を強調する紙のような新しい媒体との競争を招いた」とイニスは記している。[101] また、13世紀には紙が商業と貿易の成長を促進したとも指摘している。[102] 修道院と書籍 イニスは、修道院制度はエジプトで始まり、皇帝による初期キリスト教会の世俗支配に対する抗議運動として急速に広まったと記している。[103] 彼は、修道院制度を西方教会のニーズに適応させたのは聖ベネディクトであると評価している。聖ベネディクトの規則では、修道士は精神的な読書に従事するこ とが求められた。本の写本を書き写して修道院の図書館に保管することは、すぐに神聖な義務となった。[104] イニスは、羊皮紙に文章を書き写すには力と努力が必要だったと指摘している。 1日に6時間作業しても、書き写しは2ページから4ページで、聖書の写本には10ヶ月から1年4ヶ月を要した。聖典のサイズは修道院のエネルギーを吸収し た。図書館は徐々に整備され、13世紀には書籍の管理に関する統一規則が概ね採用された。スペースの需要により、14世紀と15世紀には書架に本を縦に並 べるようになり、15世紀には図書館の建設ラッシュが起こった。[105] イニスは、西洋の修道院が古代世界の古典を保存し、伝えてきたと指摘している。[104] イスラム教、画像、キリスト教 イニスは、イスラム教(彼が「モハメッド教」と呼ぶこともある)は、文字の神聖さを強調することで勢力を拡大したと書いている。彼は、ウマイヤ朝のカリ フ、イェジド2世が、ウマイヤ朝内のキリスト教教会の絵画の破棄を命じたことを指摘している。[106] 教会内のイコンの禁止は、730年にビザンチン皇帝レオ3世によっても承認され、コンスタンティノス5世は 753年から754年にかけて、画像崇拝を非難する法令を発布した。イニスは、この画像の禁止は、画像を権威の承認に頼っていた修道士たちの力を抑制する ことで、帝国を強化することを目的としていたと記している。修道院は、免税措置により広大な土地を所有し、労働力をめぐって国家と競合していた。ビザンチ ン皇帝はこれに対して、修道院の広大な財産を世俗化し、修道士の数を制限し、迫害を引き起こした。これにより、多くの修道士がイタリアへと逃れた。 [106] 一方、西方教会では、特に文盲の人々への伝道に画像が役立つと見なされていた。イニスは、731年には偶像破壊派が教会から排除され、732年にはシャル ル・マルテルがアラブ軍を破り、西ヨーロッパにおけるイスラム教徒の拡大に終止符を打った、と付け加えている。ゲントの公会議(767年)、ラテラン公会 議(769年)、ニカイア公会議(787年)では、画像の使用が許可されたが、シャルルマーニュは画像崇拝や礼拝を禁止していた。[107] |

| Chapter 7. Mass media, from print to radio In his final chapter, Harold Innis traces the rise of mass media beginning with the printing press in 15th century Europe and ending with mass circulation newspapers, magazines, books, movies and radio in the 19th and 20th centuries. He argues that such media gradually undermined the authority of religion and enabled the rise of science, facilitating Reformation, Renaissance and Revolution, political, industrial and commercial. For Innis, space-biased and mechanized mass media helped create modern empires, European and American, bent on territorial expansion and obsessed with present-mindedness. "Mass production and standardization are the enemies of the West," he warned. "The limitations of mechanization of the printed and the spoken word must be emphasized and determined efforts to recapture the vitality of the oral tradition must be made."[108] Bibles and the print revolution Innis notes that the expense of producing hand-copied, manuscript Bibles on parchment invited lower-cost competition, especially in countries where the copyists' guild did not hold a strong monopoly. "In 1470 it was estimated in Paris that a printed Bible cost about one-fifth that of a manuscript Bible," Innis writes. He adds that the sheer size of the scriptures hastened the introduction of printing and that the flexibility of setting the limited number of alphabetic letters in type permitted small-scale, privately-owned printing enterprises.[109] "By the end of the fifteenth century presses had been established in the larger centres of Europe," Innis writes. This led to a growing book trade as commercially minded printers reproduced various kinds of books including religious ones for the Church, medical and legal texts and translations from Latin and Greek. The Greek New Testament that Erasmus produced in 1516 became the basis for Martin Luther's German translation (1522) and William Tyndale's English version (1526). The rise in the numbers of Bibles and other books printed in native or vernacular languages contributed to the growth in the size or printing establishments and further undermined the influence of hand-copied, religious manuscripts. The printed word gained authority over the written one. Innis quotes historian W.E.H. Lecky: "The age of cathedrals had passed. The age of the printing press had begun."[110] Innis notes that Luther "took full advantage of an established book trade and large numbers of the New and later the Old Testament were widely distributed at low prices." Luther's attacks on the Catholic Church including his protests against the sale of indulgences, Canon law and the authority of the priesthood were widely distributed as pamphlets along with Luther's emphasis on St. Paul's doctrine of salvation through faith alone.[111] Monopolies of knowledge had developed and declined partly in relation to the medium of communication on which they were built, and tended to alternate as they emphasized religion, decentralization and time; or force, centralization, and space. Sumerian culture based on the medium of clay was fused with Semitic culture based on the medium of stone to produce the Babylonian empires. Egyptian civilization, based on a fusion of dependence on stone and dependence on papyrus, produced an unstable empire which eventually succumbed to religion. The Assyrian and Persian empires attempted to combine Egyptian and Babylonian civilization, and the latter succeeded with its appeal to toleration. Hebrew civilization emphasized the sacred character of writing in opposition to political organizations that emphasized the graven image. Greek civilization based on the oral tradition produced the powerful leaven that destroyed political empires. Rome assumed control over the medium on which Egyptian civilization had been based, and built up an extensive bureaucracy, but the latter survived in a fusion in the Byzantine Empire with Christianity based on the parchment codex.[112] In the United States the dominance of the newspaper led to large-scale developments of monopolies of communication in terms of space and implied a neglect of problems of time...The bias of paper towards an emphasis on space and its monopolies of knowledge has been checked by the development of a new medium, the radio. The results have been evident in an increasing concern with problems of time, reflected in the growth of planning and the socialized state. The instability involved in dependence on the newspaper in the United States and the Western world has facilitated an appeal to force as a possible stabilizing factor. The ability to develop a system of government in which the bias of communication can be checked and an appraisal of the significance of space and time can be reached remains a problem of empire and of the Western world.[113] |

第7章 印刷からラジオまでのマスメディア 最後の章で、ハロルド・イニスは、15世紀のヨーロッパにおける印刷機から始まり、19世紀と20世紀における大量発行の新聞、雑誌、書籍、映画、ラジオ で終わるマスメディアの台頭をたどっている。彼は、このようなメディアが徐々に宗教の権威を弱体化させ、科学の台頭を可能にし、宗教改革、ルネサンス、革 命、政治、産業、商業を促進したと論じている。イニスにとって、空間的偏重と機械化されたマスメディアは、領土拡張に固執し、目先のことに気を取られた欧 米の近代帝国の形成を助けた。「大量生産と標準化は西洋の敵である」と彼は警告した。「印刷された言葉と話し言葉の機械化の限界は強調され、口承の伝統の 活力を取り戻すための努力が決定されなければならない」[108] 聖書と印刷革命 イニスは、羊皮紙に手書きで写された写本の聖書は、写本のギルドが独占力を強く持っていない国々では、特に低価格競争を招いたと指摘している。「1470 年、パリでは印刷された聖書は写本の聖書の約5分の1の価格であると見積もられていた」とイニスは書いている。また、聖書の分量の多さが印刷技術の導入を 早めたこと、アルファベット文字を限られた数だけ活字に設定できる柔軟性により、小規模な個人所有の印刷事業が可能になったことを付け加えている。 「15世紀末までに、ヨーロッパの主要都市には印刷所が設立されていた」とイニスは書いている。商業的な印刷業者が、教会向けの宗教書、医学や法律のテキ スト、ラテン語やギリシャ語からの翻訳など、さまざまな書籍を複製したことで、書籍の取引が拡大した。エラスムスが1516年に制作したギリシャ語の新約 聖書は、マルティン・ルターによるドイツ語訳(1522年)とウィリアム・タイラーによる英語版(1526年)の基礎となった。聖書やその他の書籍が、現 地語や方言で印刷される数が増えたことで、印刷所の規模が拡大し、手書きの宗教的写本の影響力がさらに弱まった。活字印刷された文字は、手書きの文字より も権威を持つようになった。イニスは、歴史家W.E.H.レッキーの言葉を引用している。「大聖堂の時代は過ぎ去った。印刷機の時代が始まったのだ」 [110] イニスは、ルターが「確立された書籍取引を最大限に活用し、新約聖書やのちに旧約聖書も低価格で広く流通させた」と指摘している。ルターによる贖宥状販売 への抗議、教会法、聖職者の権威に対する攻撃など、カトリック教会への攻撃は、ルターが信仰のみによる救済という聖パウロの教義を強調したパンフレットと して広く配布された。 知識の独占は、それが築かれたコミュニケーションの媒体と部分的に関連して発展し衰退し、宗教、分散化、時間、あるいは力、集中化、空間を強調するものと して交互に現れる傾向があった。粘土を媒体とするシュメール文化は、石を媒体とするセム文化と融合し、バビロニア帝国を生み出した。石への依存とパピルス への依存の融合を基盤とするエジプト文明は、不安定な帝国を生み出し、最終的には宗教に屈した。アッシリア帝国とペルシア帝国はエジプト文明とバビロニア 文明を融合しようとし、後者は寛容さをアピールすることで成功した。ヘブライ文明は、刻まれた像を強調する政治組織に反対して、文字の神聖な性格を強調し た。口頭伝承に基づくギリシャ文明は、政治的帝国を破壊する強力な原動力を生み出した。ローマはエジプト文明が基盤としていた媒体を支配し、広範な官僚機 構を構築したが、エジプト文明は羊皮紙の写本に基づくキリスト教と融合したビザンチン帝国で生き残った。[112] アメリカ合衆国では、 新聞の支配は、空間におけるコミュニケーションの独占を大規模に発展させ、時間の問題の軽視を暗示した。... 紙が空間を強調し、知識を独占する傾向は、ラジオという新しいメディアの発展によって抑制された。その結果、時間の問題への関心が高まり、計画の成長や社 会主義国家の誕生に反映されている。米国や西洋世界における新聞への依存に伴う不安定さは、安定化要因として力への訴えを促すこととなった。コミュニケー ションの偏りを是正し、空間と時間の重要性を評価できるような統治システムを開発する能力は、帝国や西洋世界の問題として残っている。[113] |

| Recent critical opinion Innis's research findings, however dubiously achieved, put him far ahead of his time. Consider a paragraph written in 1948: "Formerly it required time to influence public opinion in favour of war. We have now reached the position in which opinion is systematically aroused and kept near boiling point.... [The] attitude [of the U.S.] reminds one of the stories of the fanatic fear of mice shown by elephants." Innis's was a dark vision because he saw the "mechanized" media as replacing ordinary face-to-face conversation. Such conversations since Socrates had helped equip free individuals to build free societies by examining many points of view. Instead we were to be increasingly dominated by a single point of view in print and electronic media: the view of the imperial centre. Would Innis have been cheered by the rise of the Internet and its millions of online conversations? Probably not. As Watson observes, the advent of the web is eradicating margins. The blogosphere simply multiplies the number of outlets for the same few messages. If we are to hope for new insights and criticism of the imperial centre, Watson says, we will have to turn to marginal groups: immigrants, women, gays, First Nations, francophones and Hispanics. They are as trapped in the imperial centre as the rest of us, but they still maintain a healthy alienation from the centre's self-referential follies. — Crawford Kilian[114] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Empire_and_Communications |

最近の批判的な意見 イニスの研究結果は、その信憑性には疑問が残るものの、彼を時代をはるかに先取りした存在にした。1948年に書かれた文章を考えてみよう。「かつては戦 争を支持する世論に影響を与えるには時間がかかった。しかし、今では世論が組織的に喚起され、沸点近くに保たれる状況にまで至っている。米国の)態度は、 ネズミに対する象の狂信的な恐怖の話を思い起こさせる」 イニスが悲観的な見方をしたのは、「機械化」されたメディアが通常の対面式の会話に取って代わることを予見していたからである。ソクラテス以来、そうした 会話は、さまざまな視点の検討を通じて、自由な個人が自由な社会を築くのに役立ってきた。しかし、私たちは印刷メディアや電子メディアを通じて、帝国の中 心部の視点という単一の視点にますます支配されるようになっていた。イニスはインターネットの台頭と、その数百万件に上るオンラインでの会話に喝采を送っ ただろうか?おそらくそうではないだろう。ワトソンが指摘するように、ウェブの出現 は余白を根絶しつつある。 ブロガーは、同じ少数のメッセージを単に発信する数を増やすだけである。帝国の中心に対する新たな洞察や批判を期待するのであれば、ワトソンは言う、私た ちは周縁的なグループに目を向けなければならない。移民、女性、同性愛者、先住民、フランス語話者、ヒスパニックなどである。彼らは私たちと同様に帝国の 中心に閉じ込められているが、中心の自己言及的な愚行に対しては依然として健全な疎外感を維持している。— クローフォード・キリアン[114] |

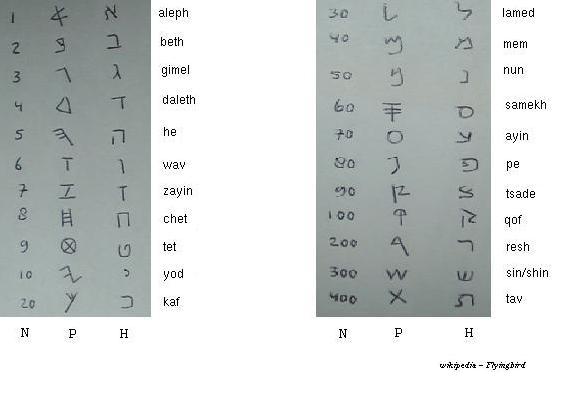

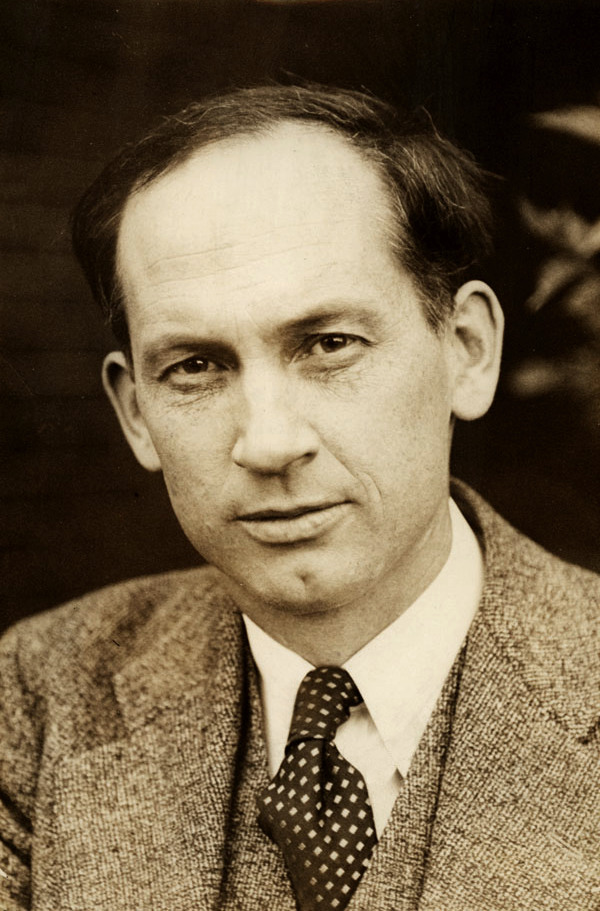

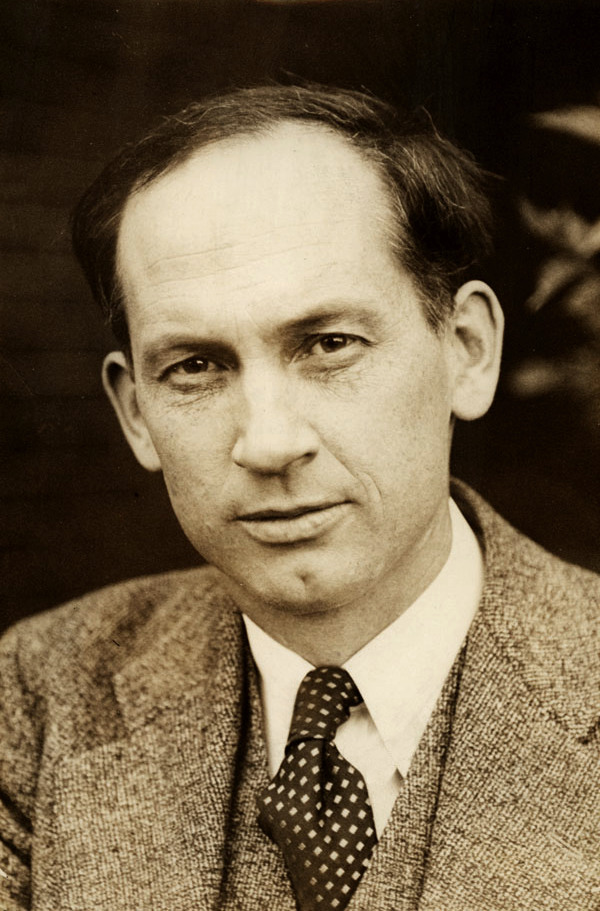

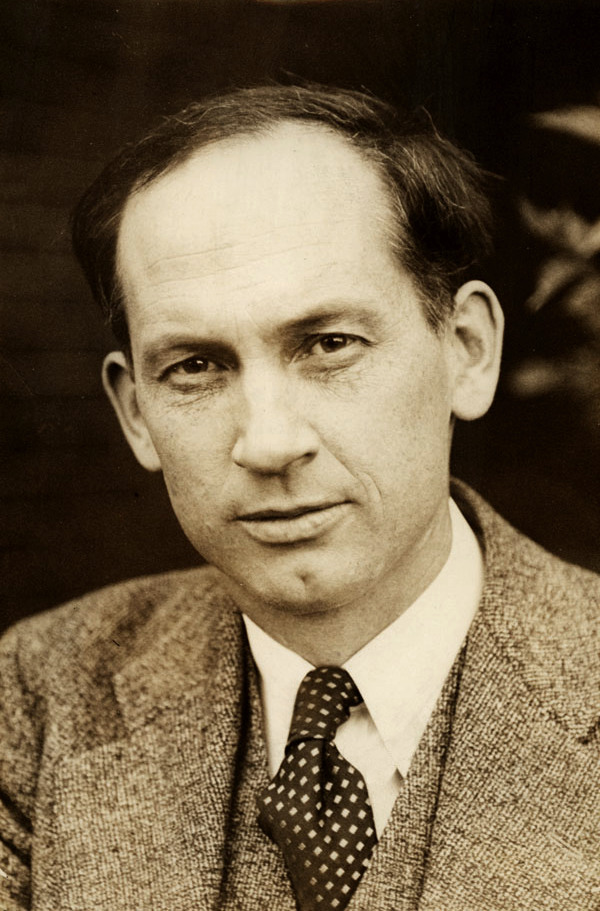

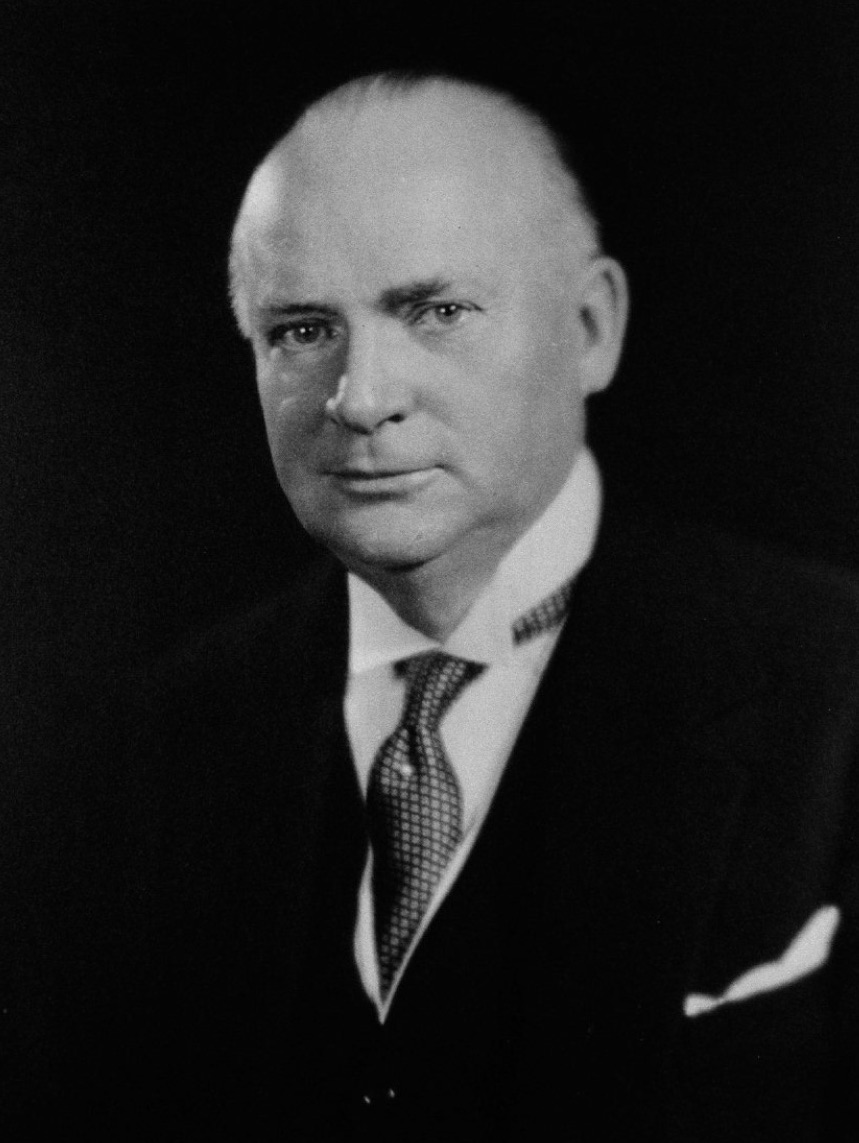

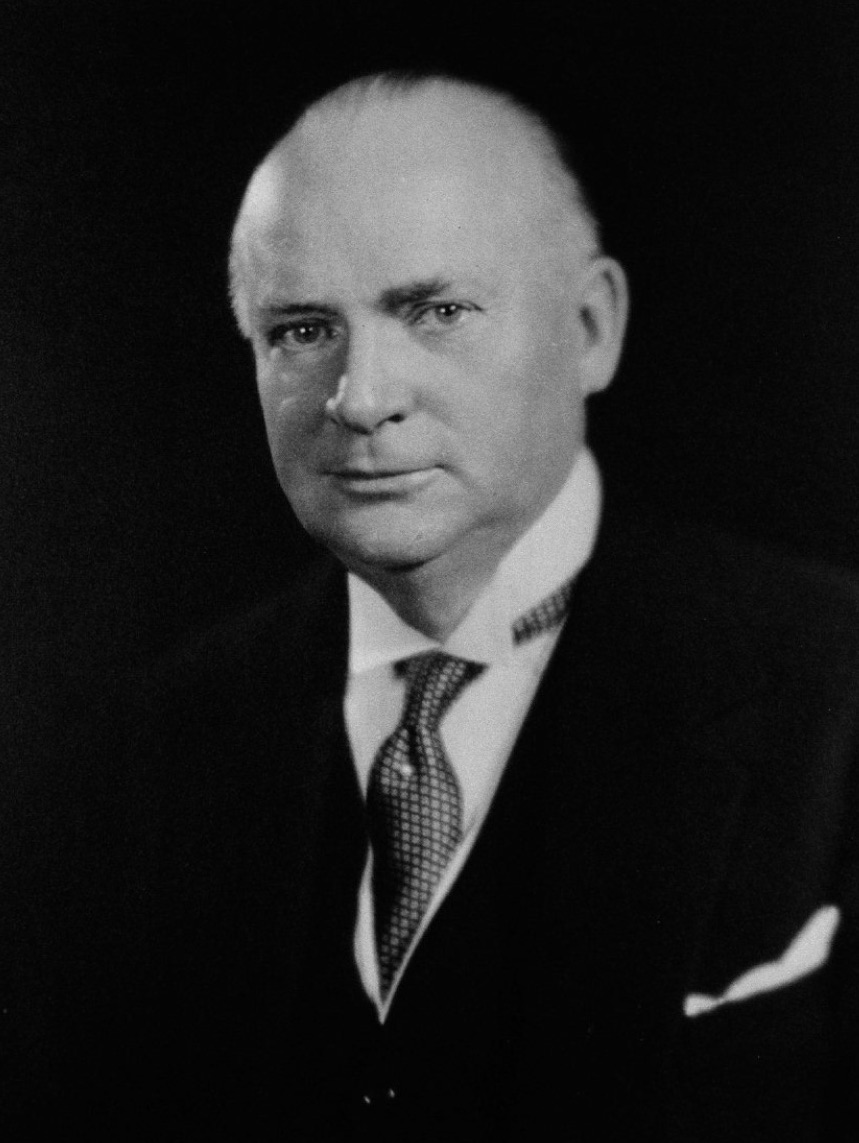

Harold

Adams Innis (November 5, 1894 – November 8, 1952) was a professor of

political economy at the University of Toronto and the author of

seminal works on Canadian economic history and on media and

communication theory. He helped develop the staples thesis, which holds

that Canada's culture, political history and economy have been

decisively influenced by the exploitation and export of a series of

staples such as fur, fish, wood, wheat, mined metals and fossil

fuels.[1] Innis's communications writings explore the role of media in

shaping the culture and development of civilizations.[2] He argued, for

example, that a balance between oral and written forms of communication

contributed to the flourishing of Greek civilization in the 5th century

BC.[3] But he warned that Western civilization is now imperiled by

powerful, advertising-driven media obsessed by "present-mindedness" and

the "continuous, systematic, ruthless destruction of elements of

permanence essential to cultural activity."[4] Harold

Adams Innis (November 5, 1894 – November 8, 1952) was a professor of

political economy at the University of Toronto and the author of

seminal works on Canadian economic history and on media and

communication theory. He helped develop the staples thesis, which holds

that Canada's culture, political history and economy have been

decisively influenced by the exploitation and export of a series of

staples such as fur, fish, wood, wheat, mined metals and fossil

fuels.[1] Innis's communications writings explore the role of media in

shaping the culture and development of civilizations.[2] He argued, for

example, that a balance between oral and written forms of communication

contributed to the flourishing of Greek civilization in the 5th century

BC.[3] But he warned that Western civilization is now imperiled by

powerful, advertising-driven media obsessed by "present-mindedness" and

the "continuous, systematic, ruthless destruction of elements of