動物行動学

Ethology

☆ 動物行動学(ethology) は、人間以外の動物の行動を研究する動物学の一分野である。その科学的ルーツは、チャールズ・ダーウィンや、チャールズ・O・ホイットマン、オスカー・ハ インロス、ウォレス・クレイグなど、19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけてのアメリカやドイツの鳥類学者の研究にある。現代の動物行動学(エソロジー)は、 1973年にノーベル生理学・医学賞を受賞したオランダの生物学者ニコラース・ティンバーゲンとオーストリアの生物学者コンラート・ローレンツ、カール・ フォン・フリッシュの研究によって1930年代に始まったと考えられている。エソロジーは実験室科学と野外科学を組み合わせたもので、神経解剖学、生態 学、進化生物学と深い関係がある。

★ 現代のethologyという言葉は、ギ リシャ語に由来する: エトス(ethos)は「性格」、ロギア(logia)は「研究」を意味する。したがって、動物行動学と倫理学(ethics)は、エトス(後者は人間のそれ)の研究をするという意味で、2つの専門用語は、 研究対象に対して、それぞれ全く異なったアプローチをするが、学問領域については隣接関係を維持したままになっている。

Honeybee workers perform the waggle dance to indicate the range and direction of food.

Great crested grebes perform a complex synchronised courtship display.

Male

impalas fighting during the rut

| Ethology

is a branch of zoology that studies the behaviour of non-human animals.

It has its scientific roots in the work of Charles Darwin and of

American and German ornithologists of the late 19th and early 20th

century, including Charles O. Whitman, Oskar Heinroth, and Wallace

Craig. The modern discipline of ethology is generally considered to

have begun during the 1930s with the work of the Dutch biologist

Nikolaas Tinbergen and the Austrian biologists Konrad Lorenz and Karl

von Frisch, the three winners of the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or

Medicine. Ethology combines laboratory and field science, with a strong

relation to neuroanatomy, ecology, and evolutionary biology. |

動

物行動学(ethology)は、人間以外の動物の行動を研究する動物学の一分野である。その科学的ルーツは、チャールズ・ダーウィンや、チャールズ・

O・ホイットマン、オスカー・ハインロス、ウォレス・クレイグなど、19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけてのアメリカやドイツの鳥類学者の研究にある。現代

の動物行動学(エソロジー)は、1973年にノーベル生理学・医学賞を受賞したオランダの生物学者ニコラース・ティンバーゲンとオーストリアの生物学者コ

ンラート・ローレンツ、カール・フォン・フリッシュの研究によって1930年代に始まったと考えられている。エソロジーは実験室科学と野外科学を組み合わ

せたもので、神経解剖学、生態学、進化生物学と深い関係がある。 |

| Etymology The modern term ethology derives from the Greek language: ἦθος, ethos meaning "character" and -λογία, -logia meaning "the study of". The term was first popularized by the American entomologist William Morton Wheeler in 1902.[1] |

語源 現代のethologyという言葉は、ギリシャ語に由来する: エトス(ethos)は「性格」、ロギア(logia)は「研究」を意味する。この用語は、1902年にアメリカの昆虫学者ウィリアム・モートン・ホイー ラー(このページの下で紹介)によって初めて一般化された[1]。 |

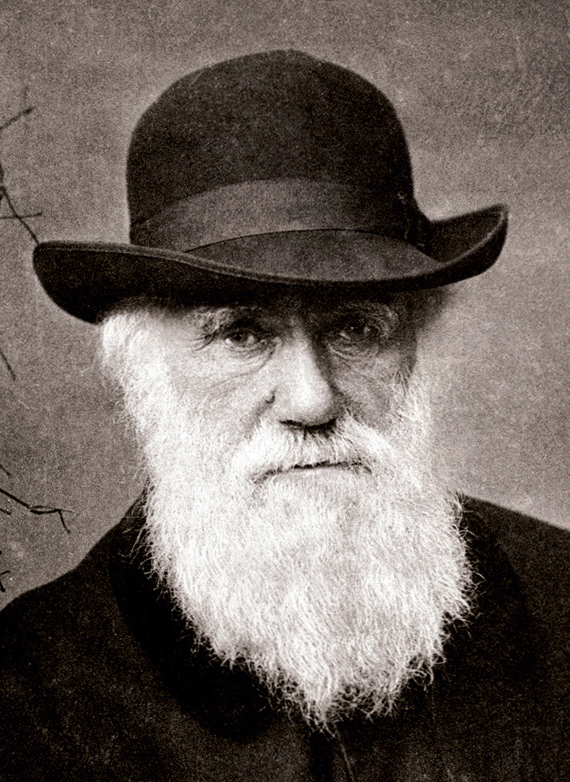

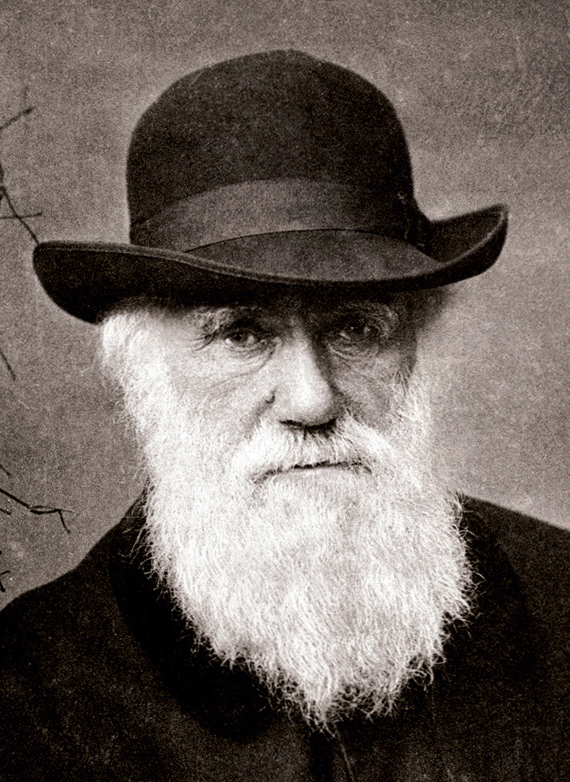

| History The beginnings of ethology  Charles Darwin (1809–1882) explored the expression of emotions in animals. Ethologists have been concerned particularly with the evolution of behaviour and its understanding in terms of natural selection. In one sense, the first modern ethologist was Charles Darwin, whose 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals influenced many ethologists. He pursued his interest in behaviour by encouraging his protégé George Romanes, who investigated animal learning and intelligence using an anthropomorphic method, anecdotal cognitivism, that did not gain scientific support.[2] Other early ethologists, such as Eugène Marais, Charles O. Whitman, Oskar Heinroth, Wallace Craig and Julian Huxley, instead concentrated on behaviours that can be called instinctive in that they occur in all members of a species under specified circumstances.[3][4][1] Their starting point for studying the behaviour of a new species was to construct an ethogram, a description of the main types of behaviour with their frequencies of occurrence. This provided an objective, cumulative database of behaviour.[1] Growth of the field Due to the work of Konrad Lorenz and Niko Tinbergen, ethology developed strongly in continental Europe during the years prior to World War II.[1] After the war, Tinbergen moved to the University of Oxford, and ethology became stronger in the UK, with the additional influence of William Thorpe, Robert Hinde, and Patrick Bateson at the University of Cambridge.[5] Lorenz, Tinbergen, and von Frisch were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973 for their work of developing ethology.[6] Ethology is now a well-recognized scientific discipline, with its own journals such as Animal Behaviour, Applied Animal Behaviour Science, Animal Cognition, Behaviour, Behavioral Ecology and Ethology. In 1972, the International Society for Human Ethology was founded along with its journal, The Human Ethology Bulletin.[citation needed] Social ethology In 1972, the English ethologist John H. Crook distinguished comparative ethology from social ethology, and argued that much of the ethology that had existed so far was really comparative ethology—examining animals as individuals—whereas, in the future, ethologists would need to concentrate on the behaviour of social groups of animals and the social structure within them.[7] E. O. Wilson's book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis appeared in 1975,[8] and since that time, the study of behaviour has been much more concerned with social aspects. It has been driven by the Darwinism associated with Wilson, Robert Trivers, and W. D. Hamilton. The related development of behavioural ecology has helped transform ethology.[9] Furthermore, a substantial rapprochement with comparative psychology has occurred, so the modern scientific study of behaviour offers a spectrum of approaches. In 2020, Tobias Starzak and Albert Newen from the Institute of Philosophy II at the Ruhr University Bochum postulated that animals may have beliefs.[10] |

歴史 動物行動学の始まり  チャールズ・ダーウィン(1809-1882)は、動物の感情表現について研究した。 動物行動学者は、特に行動の進化とその自然淘汰の観点からの理解に関心を寄せてきた。ある意味で、最初の近代的な動物行動学者はチャールズ・ダーウィンで あり、彼の1872年の著書『The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals』は多くの動物行動学学者に影響を与えた。ダーウィンは、科学的な支持を得られなかった擬人的な方法である逸話的認知主義を用いて動物の学 習と知能を調査した弟子のジョージ・ロマネスを奨励することによって、行動への関心を追求した[2]。 ウジェーヌ・マレ、チャールズ・O・ホイットマン、オスカー・ハインロス、ウォレス・クレイグ、ジュリアン・ハックスレーといった他の初期の動物行動学者 たちは、代わりに、特定の状況下で種の全メンバーに生じるという点で本能的と呼べる行動に集中した。 3][4][1] 新しい種の行動を研究するための彼らの出発点は、エトグラム(主な行動の種類とその出現頻度の記述)を構築することであった。これは行動の客観的で累積的 なデータベースを提供した[1]。 この分野の成長 コンラート・ローレンツとニコ・ティンバーゲンの研究により、動物行動学は第二次世界大戦前の数年間、ヨーロッパ大陸で力強く発展した。 ローレンツ、ティンバーゲン、フォン・フリッシュは、動物行動学を発展させた功績により、1973年にノーベル生理学・医学賞を共同受賞した[6]。 動物行動学は現在では十分に認知された科学分野であり、『動物行動学』、『応用動物行動科学』、『動物認知学』、『行動学』、『行動生態学』、『倫理学』 などの学術誌がある。1972年には国際人間倫理学会が設立され、学会誌『The Human Ethology Bulletin』も創刊された[要出典]。 社会動物行動学 1972年、イギリスの動物行動学者ジョン・H・クルックは比較動物行動学と社会動物行動学を区別し、これまで存在した動物行動学の多くは、動物を個体と して調査する比較動物行動学であり、将来的には動物行動学者は動物の社会的集団の行動とその中の社会構造に集中する必要があると主張した[7]。 E. O.ウィルソンの著書『社会生物学』: 1975年にE・O・ウィルソンの著書『社会生物学:新しい総合』が出版され[8]、それ以来行動学は社会的側面により深く関わるようになった。それは ウィルソン、ロバート・トリバース、W・D・ハミルトンに関連するダーウィニズムによって推進されてきた。さらに、比較心理学との実質的な和解が行われた ため、現代の科学的行動研究は多様なアプローチを提供している。2020年、ルール大学ボーフム哲学Ⅱ研究所のトビアス・スターザックとアルバート・ ニューエンは、動物には信念があるかもしれないと提唱した。 |

| Determinants of behaviour Behaviour is determined by three major factors, namely inborn instincts, learning, and environmental factors. The latter include abiotic and biotic factors. Abiotic factors such as temperature or light conditions have dramatic effects on animals, especially if they are ectothermic or nocturnal. Biotic factors include members of the same species (e.g. sexual behavior), predators (fight or flight), or parasites and diseases.[citation needed] Instinct This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2023)  Kelp gull chicks peck at red spot on mother's beak to stimulate regurgitating reflex Webster's Dictionary defines instinct as "A largely inheritable and unalterable tendency of an organism to make a complex and specific response to environmental stimuli without involving reason".[11] Fixed action patterns Main article: Fixed action pattern An important development, associated with the name of Konrad Lorenz though probably due more to his teacher, Oskar Heinroth, was the identification of fixed action patterns. Lorenz popularized these as instinctive responses that would occur reliably in the presence of identifiable stimuli called sign stimuli or "releasing stimuli". Fixed action patterns are now considered to be instinctive behavioural sequences that are relatively invariant within the species and that almost inevitably run to completion.[12] One example of a releaser is the beak movements of many bird species performed by newly hatched chicks, which stimulates the mother to regurgitate food for her offspring.[13] Other examples are the classic studies by Tinbergen on the egg-retrieval behaviour and the effects of a "supernormal stimulus" on the behaviour of graylag geese.[14][15] One investigation of this kind was the study of the waggle dance ("dance language") in bee communication by Karl von Frisch.[16] Learning Habituation Main article: Habituation Habituation is a simple form of learning and occurs in many animal taxa. It is the process whereby an animal ceases responding to a stimulus. Often, the response is an innate behavior. Essentially, the animal learns not to respond to irrelevant stimuli. For example, prairie dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus) give alarm calls when predators approach, causing all individuals in the group to quickly scramble down burrows. When prairie dog towns are located near trails used by humans, giving alarm calls every time a person walks by is expensive in terms of time and energy. Habituation to humans is therefore an important behavior in this context.[17][18][19] Associative learning Main article: Association (psychology) Further information: Classical conditioning and Operant conditioning Associative learning in animal behaviour is any learning process in which a new response becomes associated with a particular stimulus.[20] The first studies of associative learning were made by the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov, who observed that dogs trained to associate food with the ringing of a bell would salivate on hearing the bell.[21] Imprinting Main article: Imprinting (psychology)  Imprinting in a moose. Imprinting enables the young to discriminate the members of their own species, vital for reproductive success. This important type of learning only takes place in a very limited period of time. Konrad Lorenz observed that the young of birds such as geese and chickens followed their mothers spontaneously from almost the first day after they were hatched, and he discovered that this response could be imitated by an arbitrary stimulus if the eggs were incubated artificially and the stimulus were presented during a critical period that continued for a few days after hatching.[22] Cultural learning Main article: Cultural transmission in animals Observational learning Main article: Observational learning Imitation Main article: Imitation Imitation is an advanced behavior whereby an animal observes and exactly replicates the behavior of another. The National Institutes of Health reported that capuchin monkeys preferred the company of researchers who imitated them to that of researchers who did not. The monkeys not only spent more time with their imitators but also preferred to engage in a simple task with them even when provided with the option of performing the same task with a non-imitator.[23] Imitation has been observed in recent research on chimpanzees; not only did these chimps copy the actions of another individual, when given a choice, the chimps preferred to imitate the actions of the higher-ranking elder chimpanzee as opposed to the lower-ranking young chimpanzee.[24] Stimulus and local enhancement Animals can learn using observational learning but without the process of imitation. One way is stimulus enhancement in which individuals become interested in an object as the result of observing others interacting with the object.[25] Increased interest in an object can result in object manipulation which allows for new object-related behaviours by trial-and-error learning. Haggerty (1909) devised an experiment in which a monkey climbed up the side of a cage, placed its arm into a wooden chute, and pulled a rope in the chute to release food. Another monkey was provided an opportunity to obtain the food after watching a monkey go through this process on four occasions. The monkey performed a different method and finally succeeded after trial-and-error.[26] Another example familiar to some cat and dog owners is the ability of their animals to open doors. The action of humans operating the handle to open the door results in the animals becoming interested in the handle and then by trial-and-error, they learn to operate the handle and open the door. In local enhancement, a demonstrator attracts an observer's attention to a particular location.[27] Local enhancement has been observed to transmit foraging information among birds, rats and pigs.[28] The stingless bee (Trigona corvina) uses local enhancement to locate other members of their colony and food resources.[29] Social transmission See also: Cultural transmission in animals A well-documented example of social transmission of a behaviour occurred in a group of macaques on Hachijojima Island, Japan. The macaques lived in the inland forest until the 1960s, when a group of researchers started giving them potatoes on the beach: soon, they started venturing onto the beach, picking the potatoes from the sand, and cleaning and eating them.[8] About one year later, an individual was observed bringing a potato to the sea, putting it into the water with one hand, and cleaning it with the other. This behaviour was soon expressed by the individuals living in contact with her; when they gave birth, this behaviour was also expressed by their young—a form of social transmission.[30] Teaching See also: Animal culture § Teaching Teaching is a highly specialized aspect of learning in which the "teacher" (demonstrator) adjusts their behaviour to increase the probability of the "pupil" (observer) achieving the desired end-result of the behaviour. For example, orcas are known to intentionally beach themselves to catch pinniped prey.[31] Mother orcas teach their young to catch pinnipeds by pushing them onto the shore and encouraging them to attack the prey. Because the mother orca is altering her behaviour to help her offspring learn to catch prey, this is evidence of teaching.[31] Teaching is not limited to mammals. Many insects, for example, have been observed demonstrating various forms of teaching to obtain food. Ants, for example, will guide each other to food sources through a process called "tandem running," in which an ant will guide a companion ant to a source of food.[32] It has been suggested that the pupil ant is able to learn this route to obtain food in the future or teach the route to other ants. This behaviour of teaching is also exemplified by crows, specifically New Caledonian crows. The adults (whether individual or in families) teach their young adolescent offspring how to construct and utilize tools. For example, Pandanus branches are used to extract insects and other larvae from holes within trees.[33] |

行動の決定要因 行動は3つの主要な要因、すなわち先天的本能、学習、環境要因によって決定される。後者には環境要因と生物要因が含まれる。温度や光の条件などの生物学的 要因は、特に外温性あるいは夜行性の動物に劇的な影響を与える。生物学的要因には、同じ種の仲間(性行動など)、捕食者(闘争か逃走か)、寄生虫や病気な どが含まれる[要出典]。 本能 このセクションは拡張が必要です。追加することで貢献できます。(2023年12月)  ケルプカモメの雛が母親のくちばしの赤い点をつついて嘔吐反射を促す ウェブスター辞典は本能を「理性を伴わずに環境刺激に対して複雑で特異的な反応をする、生物に主として遺伝する不変の傾向」と定義している[11]。 固定された行動パターン 主な記事 固定行動パターン コンラート・ローレンツ(Konrad Lorenz)の名前に関連しているが、おそらく彼の師であるオスカー・ハインロート(Oskar Heinroth)によるものであろう、重要な発展は、固定行動パターンの同定であった。ローレンツはこれを、標識刺激または「解放刺激」と呼ばれる識別 可能な刺激が存在する場合に確実に起こる本能的反応として広めた。固定行動パターンは現在では、種内で比較的不変であり、ほぼ必然的に完了まで実行される 本能的行動シーケンスであると考えられている[12]。 放出刺激の一例として、孵化したばかりの雛が行う多くの鳥類のくちばしの動きがあり、これは母親が子孫のために餌を吐き出すように刺激するものである。 この種の研究の1つに、カール・フォン・フリッシュによるハチのコミュニケーションにおけるワグルダンス(「ダンス言語」)の研究がある[16]。 学習 習性 主な記事 慣れの学習 慣れは単純な学習の一形態であり、多くの動物分類群で見られる。動物がある刺激に反応しなくなる過程である。多くの場合、その反応は生得的な行動である。 基本的に、動物は無関係な刺激には反応しないように学習する。例えば、プレーリードッグ(Cynomys ludovicianus)は捕食者が近づくと警戒の声を発し、群れの全個体が素早く巣穴に逃げ込む。プレーリードッグの町が人間が通る小道の近くにある 場合、人が通るたびに鳴き声を出すのは時間的にもエネルギー的にも高くつく。そのため、人間への慣れはこの文脈では重要な行動である[17][18] [19]。 連想学習 主な記事 連想(心理学) さらなる情報 古典的条件づけとオペラント条件づけ 動物の行動における連合学習とは、新しい反応が特定の刺激と関連付けられるようになる学習過程のことである[20]。連合学習の最初の研究はロシアの生理 学者イワン・パブロフによって行われた。 刷り込み 主な記事 刷り込み(心理学)  ヘラジカの刷り込み 刷り込みは、繁殖を成功させるために不可欠な、子供が同種のメンバーを識別することを可能にする。この重要な学習は、ごく限られた期間にしか行われない。 コンラート・ローレンツは、ガチョウやニワトリなどの鳥の子供が孵化後ほぼ初日から自発的に母親の後を追うことを観察し、卵を人工孵化させ、孵化後数日間 続く臨界期に刺激を与えれば、任意の刺激によってこの反応を模倣できることを発見した[22]。 文化的学習 主な記事 動物における文化伝播 観察学習 主な記事:観察学習 観察学習 模倣 主な記事 模倣 模倣とは、動物が他の動物の行動を観察し、正確に再現する高度な行動である。アメリカ国立衛生研究所の報告によると、オマキザルは真似をする研究者の仲間 を、真似をしない研究者の仲間よりも好んだという。チンパンジーの最近の研究でも模倣が観察されている。これらのチンパンジーは他の個体の行動を模倣する だけでなく、選択肢が与えられると、下位の若いチンパンジーよりも上位の年長のチンパンジーの行動を好んで模倣した[24]。 刺激と局所的強化 動物は観察学習を使って学習することができるが、模倣の過程はない。その1つの方法は刺激の増強であり、他者がその物体と相互作用しているのを観察した結 果、個体がその物体に興味を持つようになる。ハガティ(1909年)は、サルがケージの側面に登り、腕を木製のシュートに入れ、シュート内のロープを引い て餌を放出する実験を考案した。別のサルは、サルが4回このプロセスを経るのを見た後、餌を得る機会を与えられた。もうひとつの例は、犬や猫の飼い主には おなじみの、動物がドアを開ける能力である[26]。人間がドアを開けようと取っ手を操作すると、動物は取っ手に興味を持ち、試行錯誤の末に取っ手を操作 してドアを開けることを学習する。 ローカルエンハンスメントでは、実演者が観察者の注意を特 定の場所に引きつける。ローカルエンハンスメントは、鳥類、 ネズミ、ブタなどの間で採餌情報を伝達することが観察され ている。 社会的伝達 こちらも参照: 動物における文化伝播 行動の社会的伝播のよく知られた例は、日本の八丈島にいるオマキザルの群れで起こった。オマキザルは1960年代まで内陸の森で暮らしていたが、ある研究 者グループが浜辺でジャガイモを与え始めたところ、すぐに浜辺に入り、砂からジャガイモを拾い、掃除して食べるようになった。この行動は、彼女と接触して 生活している個体によってすぐに表現されるようになり、彼らが出産すると、この行動はその子供によっても表現されるようになった。 教育(教え込み) 以下も参照: 動物文化§ティーチング ティーチングとは、「教師」(実演者)が、「生徒」(観察者)がその行動の望ましい最終結果を達成する確率を高めるために、自分の行動を調整することであ る。例えば、オルカは鰭脚類の獲物を捕らえるために意図的に海岸に出ることが知られている[31]。母オルカは鰭脚類を岸に押し上げ、獲物を攻撃するよう に促すことで、鰭脚類を捕らえることを子どもに教える。母シャチは、獲物を捕らえることを子供に覚えさせるために行動を変えているのだから、これはティー チングの証拠である。例えば多くの昆虫が、餌を得るために様々な形のティーチングを行うことが観察されている。例えばアリは、「タンデムランニング」と呼 ばれる、アリが仲間のアリを餌のある場所まで誘導するプロセスを通じて、互いを餌のある場所まで誘導する[32]。この教える行動はカラス、特にニューカ レドニアのカラスにも見られる。成鳥は(個体であれ家族であれ)思春期の若い子孫に道具の作り方や使い方を教える。例えば、パンダナスの枝は木の穴から昆 虫や他の幼虫を取り出すのに使われる[33]。 |

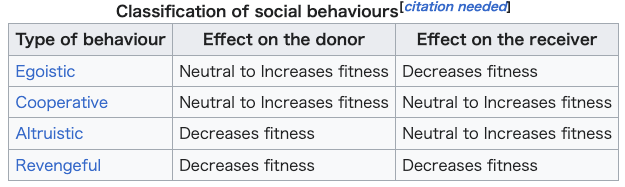

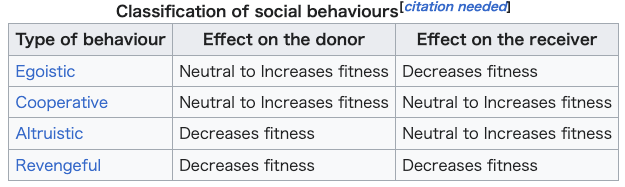

Mating and the fight for

supremacy Courtship display of a sarus crane Individual reproduction is the most important phase in the proliferation of individuals or genes within a species: for this reason, there exist complex mating rituals, which can be very complex even if they are often regarded as fixed action patterns. The stickleback's complex mating ritual, studied by Tinbergen, is regarded as a notable example.[34] Often in social life, animals fight for the right to reproduce, as well as social supremacy. A common example of fighting for social and sexual supremacy is the so-called pecking order among poultry. Every time a group of poultry cohabitate for a certain time length, they establish a pecking order. In these groups, one chicken dominates the others and can peck without being pecked. A second chicken can peck all the others except the first, and so on. Chickens higher in the pecking order may at times be distinguished by their healthier appearance when compared to lower level chickens.[citation needed] While the pecking order is establishing, frequent and violent fights can happen, but once established, it is broken only when other individuals enter the group, in which case the pecking order re-establishes from scratch.[35] Social behaviour Several animal species, including humans, tend to live in groups. Group size is a major aspect of their social environment. Social life is probably a complex and effective survival strategy. It may be regarded as a sort of symbiosis among individuals of the same species: a society is composed of a group of individuals belonging to the same species living within well-defined rules on food management, role assignments and reciprocal dependence.[citation needed] When biologists interested in evolution theory first started examining social behaviour, some apparently unanswerable questions arose, such as how the birth of sterile castes, like in bees, could be explained through an evolving mechanism that emphasizes the reproductive success of as many individuals as possible, or why, amongst animals living in small groups like squirrels, an individual would risk its own life to save the rest of the group. These behaviours may be examples of altruism.[36] Not all behaviours are altruistic, as indicated by the table below. For example, revengeful behaviour was at one point claimed to have been observed exclusively in Homo sapiens. However, other species have been reported to be vengeful including chimpanzees,[37] as well as anecdotal reports of vengeful camels.[38] Altruistic behaviour has been explained by the gene-centred view of evolution.[39][40]  Benefits and costs of group living One advantage of group living is decreased predation. If the number of predator attacks stays the same despite increasing prey group size, each prey has a reduced risk of predator attacks through the dilution effect.[9][page needed] Further, according to the selfish herd theory, the fitness benefits associated with group living vary depending on the location of an individual within the group. The theory suggests that conspecifics positioned at the centre of a group will reduce the likelihood predations while those at the periphery will become more vulnerable to attack.[41] In groups, prey can also actively reduce their predation risk through more effective defence tactics, or through earlier detection of predators through increased vigilance.[9] Another advantage of group living is an increased ability to forage for food. Group members may exchange information about food sources, facilitating the process of resource location.[9][page needed] Honeybees are a notable example of this, using the waggle dance to communicate the location of flowers to the rest of their hive.[42] Predators also receive benefits from hunting in groups, through using better strategies and being able to take down larger prey.[9][page needed] Some disadvantages accompany living in groups. Living in close proximity to other animals can facilitate the transmission of parasites and disease, and groups that are too large may also experience greater competition for resources and mates.[43] Group size Theoretically, social animals should have optimal group sizes that maximize the benefits and minimize the costs of group living. However, in nature, most groups are stable at slightly larger than optimal sizes.[9][page needed] Because it generally benefits an individual to join an optimally-sized group, despite slightly decreasing the advantage for all members, groups may continue to increase in size until it is more advantageous to remain alone than to join an overly full group.[44] |

交尾と覇権争い サルジロヅルの求愛ディスプレイ 個体の繁殖は、種内の個体や遺伝子の増殖において最も重要な段階である。このため、複雑な交尾儀式が存在し、それらはしばしば固定された行動パターンとみ なされることがあっても、非常に複雑であることがある。ティンバーゲンによって研究されたトゲウオの複雑な交尾儀式は、その顕著な例とみなされている [34]。 社会生活ではしばしば、動物は社会的覇権だけでなく、繁殖の権利のために争う。社会的・性的覇権を争う一般的な例として、家禽の間のいわゆる序列がある。 ある家禽のグループが一定期間同居するたびに、彼らは序列を確立する。このような集団では、1羽の鶏が他の鶏を支配し、つつかれることなくつつくことがで きる。2番目のニワトリは1番目のニワトリ以外のニワトリをつつくことができる。序列の上位のニワトリは、下位のニワトリに比べて健康的な外見で区別され ることもある[要出典]。序列が確立している間は、頻繁に激しい喧嘩が起こることもあるが、一度確立された序列は、他の個体がグループに入ってきたときに のみ破られ、その場合は序列はゼロから再確立される[35]。 社会的行動 ヒトを含むいくつかの動物種は、集団で生活する傾向がある。集団の大きさは彼らの社会環境の主要な側面である。社会生活はおそらく複雑で効果的な生存戦略 である。社会は、同じ種に属する個体が、食料管理、役割分担、相互依存に関する明確なルールの中で生活する集団から構成される。 進化論に関心を持つ生物学者が社会的行動を最初に調べ始めたとき、ハチのように不妊の種が生まれるのは、できるだけ多くの個体が繁殖に成功することを重視 する進化的メカニズムで説明できるのか、リスのように小さな集団で生活する動物の中で、なぜ個体が自分の命を危険にさらしてまで他の集団を救うのか、と いった一見答えのない疑問が生じた。これらの行動は利他主義の一例かもしれない[36]。以下の表が示すように、すべての行動が利他的というわけではな い。例えば、復讐的行動は一時期ホモ・サピエンスにのみ観察されると主張された。しかし、チンパンジー[37]や復讐心の強いラクダ[38]など、他の種 も復讐心が強いと報告されている。 利他的行動は、遺伝子を中心とした進化論によって説明されてきた[39][40]。  集団生活の利点とコスト 集団生活の利点の一つは捕食の減少である。群れのサイズが大きくなっても捕食者の攻撃回数が変わらない場合、希釈効果によって各被食者は捕食者の攻撃を受 けるリスクが減少する[9][要出典]。さらに、利己的群れ理論によれば、群れ生活に伴う体力的利益は群れ内の個体の位置によって異なる。この理論によれ ば、集団の中心に位置する同種の個体は捕食される可能性を減少させるが、周辺に位置する個体は攻撃を受けやすくなる[41]。 集団生活のもう一つの利点は、餌を探す能力が高まることである。ミツバチはこの顕著な例で、花の場所を巣の残りの部分に伝えるためにワッグル・ダンスを使 用する[42]。捕食者もまた、より良い戦略を使用し、より大きな獲物を倒すことができることによって、集団での狩猟から利益を受ける[9][page needed]。 集団生活にはデメリットもある。他の動物に近接して生活することは寄生虫や病気の感染を促進する可能性があり、大きすぎる集団は資源や仲間をめぐる競争が 激しくなる可能性もある[43]。 集団の大きさ 理論的には、社会的動物は集団生活の便益を最大化し、費用を最小化する最適な集団サイズを持つはずである。しかし自然界では、ほとんどの集団は最適な大き さよりもわずかに大きい程度で安定している。[9][要出典]最適な大きさの集団に加わることは、全メンバーにとっての利点をわずかに減少させるにもかか わらず、一般的に個体にとって有益であるため、集団は、過度に充実した集団に加わるよりも単独でいる方が有利になるまで、その大きさを増やし続ける可能性 がある[44]。 |

| Tinbergen's four questions for

ethologists Main article: Tinbergen's four questions Niko Tinbergen argued that ethology needed to include four kinds of explanation in any instance of behaviour:[45][46] Function – How does the behaviour affect the animal's chances of survival and reproduction? Why does the animal respond that way instead of some other way? Causation – What are the stimuli that elicit the response, and how has it been modified by recent learning? Development – How does the behaviour change with age, and what early experiences are necessary for the animal to display the behaviour? Evolutionary history – How does the behaviour compare with similar behaviour in related species, and how might it have begun through the process of phylogeny? These explanations are complementary rather than mutually exclusive—all instances of behaviour require an explanation at each of these four levels. For example, the function of eating is to acquire nutrients (which ultimately aids survival and reproduction), but the immediate cause of eating is hunger (causation). Hunger and eating are evolutionarily ancient and are found in many species (evolutionary history), and develop early within an organism's lifespan (development). It is easy to confuse such questions—for example, to argue that people eat because they are hungry and not to acquire nutrients—without realizing that the reason people experience hunger is because it causes them to acquire nutrients.[47] |

ティンバーゲンが動物行動学者に投げかけた4つの質問 主な記事 ティンバーゲンの4つの質問 ニコ・ティンバーゲンは、倫理学は行動のどのような事例にも4種類の説明を含める必要があると主張した:[45][46]。 1)機能-その行動は動物の生存と繁殖の可能性にどのように影響するのか?なぜその動物は他の方法ではなくそのように反応するのか? 2)原因-その反応を引き起こす刺激とは何か、またその反応は最近の学習によってどのように変化したのか。 3)発達-その行動は年齢とともにどのように変化するのか、またその動物がその行動を示すためには、どのような初期の経験が必要なのか。 4)進化の歴史 - その行動は近縁種の同様の行動と比較してどうなのか、系統発生 の過程でどのように始まったのか。 これらの説明は相互に排他的なものではなく、補完的なものである。例えば、食べるという機能は栄養を得ること(これは最終的に生存と繁殖を助ける)である が、食べる直接的な原因は空腹である(因果関係)。空腹と摂食は進化的に古く、多くの種に見られ(進化の歴史)、生物の寿命の初期に発達する(発達)。こ のような問題を混同することは簡単である。例えば、人が食べるのは空腹だからであり、栄養を得るためではないと主張することは、人が空腹を経験するのは栄 養を得るためであることに気づかないままである[47]。 |

| Animal behavior consultant Anthrozoology Behavioral ecology Cognitive ethology Deception in animals Human ethology List of abnormal behaviours in animals Tool use by non-human animals |

動物行動コンサルタント 人類動物学 行動生態学 認知倫理学 動物の欺瞞 人間倫理学 動物の異常行動リスト 人間以外の動物の道具使用 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethology |

|

| Burkhardt, Richard W. Jr. "On

the Emergence of Ethology as a Scientific Discipline." Conspectus of

History 1.7 (1981). |

Burkhardt, Richard W. Jr. "On

the Emergence of Ethology as a Scientific Discipline." Conspectus of

History 1.7 (1981). |

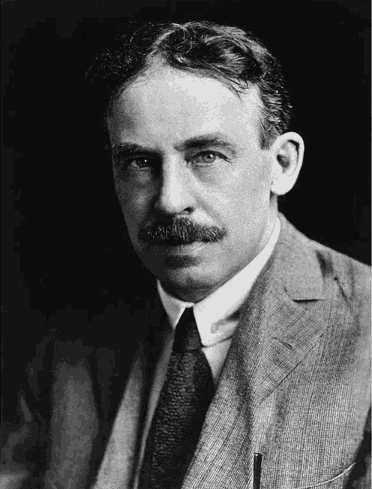

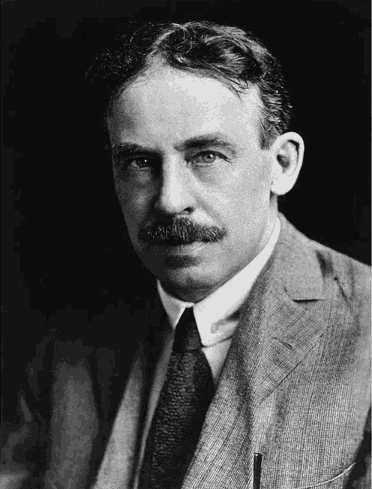

★ エソロジーの命名者としてのウィリアム・モートン・ホイーラー(1865年3月19日 - 1937年4月19日)

William Morton Wheeler (March 19,

1865 – April 19, 1937) was an American entomologist, myrmecologist and

professor at Harvard University. William Morton Wheeler (March 19,

1865 – April 19, 1937) was an American entomologist, myrmecologist and

professor at Harvard University.Biography Early life and education William Morton Wheeler was born on March 19, 1865, to parents Julius Morton Wheeler and Caroline Georgiana Wheeler (née Anderson) in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[2] At a young age, Wheeler had an interest in natural history, first being when he observed a moth ensnared in a spiders web; such observation interested Wheeler that he became importunate for more nature lore.[3] Wheeler attended public school, but, due to "persistently bad behavior", he was transferred to a local German academy which was known for its extreme discipline.[a] After he completed his courses in the German academy, he attended a German normal school. In both institutions, Wheeler was trained in a variety of subjects: he was given training in languages, philosophy and science. By this time, he could read fluently in French, German, Greek, Italian, Latin and Spanish.[2][3] While he was a student at the German academy, Wheeler would frequently observe the old museum of natural history at the institution.[4] |

ウィリアム・モートン・ホイーラー(1865

年3月19日 - 1937年4月19日)はアメリカの昆虫学者、蟻類学者、ハーバード大学教授。 ウィリアム・モートン・ホイーラー(1865

年3月19日 - 1937年4月19日)はアメリカの昆虫学者、蟻類学者、ハーバード大学教授。略歴 生い立ちと教育 ウィリアム・モートン・ホイーラーは1865年3月19日、ミルウォーキーでジュリアス・モートン・ウィーラーとキャロライン・ジョージアーナ・ウィー ラー(旧姓アンダーソン)の両親のもとに生まれた[2]。幼い頃、ホイーラーは自然史に興味を持ち、クモの巣にかかった蛾を観察したのが最初だった。 [3] ウィーラーはパブリック・スクールに通ったが、「素行不良が続いた」ため、厳しい規律で知られる地元のドイツ人アカデミーに編入された[a] 。どちらの学校でも、ウィーラーは語学、哲学、科学などさまざまな分野の訓練を受けた。この頃には、フランス語、ドイツ語、ギリシア語、イタリア語、ラテ ン語、スペイン語を流暢に読むことができるようになっていた[2][3]。ドイツ・アカデミーの学生であった頃、ウィーラーは同校の古い自然史博物館を頻 繁に見学していた[4]。 |

| In 1884, Henry August Ward,

proprietor of the Ward's Natural Science

Establishment, brought a collection of stuffed and skeletonized

mammals, birds and reptiles, and also a series of marine invertebrates

to the academy. This was to persuade the city fathers to purchase them

and combine them with the present collection at the academy, in which

it would lay the foundation for a free municipal museum of natural

history.[5] Wheeler, who had familiarized himself with the museum since

childhood, volunteered to spend the nights in helping to unpack and

install the specimens.[4][5] Impressed by his enthusiasm, Ward offered

Wheeler a job in his Rochester, New York establishment. His first

duties were to identify and list birds and mammals and the preparation

of catalogues.[4][5] He was later made as a foreman and spent most of

his time identifying and arranging the collection of shells,

echinoderms, and sponges, as well as preparing catalogues and price

lists of these specimens for publication.[5] In 1885, Wheeler returned to Milwaukee to teach German and physiology at a high school.[4][6] At the time, George W. Peckham was the principal of the school, in which Wheeler and Peckham formed a close working relationship.[4] Wheeler collaborated with some of Peckham's published papers by illustrating the palpi and epigynes of spiders, and by assisting him and his wife with their field work on wasps.[6] Wheeler was also under the influence of C.O. Whitman and William Patten, who were embryologists at the Allis Lake Laboratory in Milwaukee. He was inspired by Patten to study insect embryology and did so for several years. During this time, Wheeler left the high school in 1887 and become a custodian at Milwaukee Public Museum, a position he held until 1890. He studied embryology at home and after work hours, in which he had set up a small laboratory.[4] He left Milwaukee after leaving the museum to assist Whitman at Clark University, and, by 1892, secured a doctorate in philosophy; his dissertation was "Contribution to Insect Embryology".[4][7] At the same time, Wheeler commenced his work on insects and published around 10 entomological papers, which presented himself as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D.[8] After receiving a call from the University of Chicago, Whitman subsequently accepted their offer, followed by Wheeler who was appointed under him as instructor in embryology in 1892. He held this position until 1897, where he became the assistant professor in his chosen field.[8] Before he began his duties at Chicago, Wheeler was given a year's absence, allowing him to study in Europe between 1893 and 1894. There, he first spent time at the Zoological Institute at the University of Würzburg as a student, and also at the Naples Zoological Station. Enamoured by the fauna of Naples, Wheeler studied the sex life of Myzostoma, a subject he further studied at the Institut Zoologique at Liege, Belgium. His monograph on Myzostoma was published in 1897 by professor E. Van Beneden in the Archives de Biologie.[9] |

1884年、ウォード自然科学研究所の経営者であったヘンリー・オーガ

スト・ウォードが、剥製や骨格標本にされた哺乳類、鳥類、爬虫類、さらに一連の海洋

無脊椎動物のコレクションをアカデミーに持ち込んだ。幼い頃から博物館に親しんでいたウィーラーは、自ら志願して夜通し標本の開梱と設置を手伝った[4]

[5]。彼の熱意に感銘を受けたウォードは、ウィーラーにニューヨーク州ロチェスターの施設での仕事を依頼した。彼の最初の仕事は、鳥類と哺乳類の同定と

リストアップ、そしてカタログの作成であった[4][5]。後に彼は主任となり、ほとんどの時間を貝殻、棘皮動物、海綿動物のコレクションの同定と整理、

そしてこれらの標本のカタログと出版用の価格リストの作成に費やした[5]。 1885年、ウィーラーは高校でドイツ語と生理学を教えるためにミルウォーキーに戻った[4][6]。当時、ジョージ・W・ペッカムが校長を務めており、 ウィーラーとペッカムは緊密な協力関係を築いていた。 [ウィーラーはまた、ミルウォーキーのアリス湖研究所の発生学者であったC.O.ホイットマンとウィリアム・パッテンの影響下にあった。ウィーラーはパッ テンに触発され、昆虫の発生学を研究するようになり、数年間そうした。この間、ウィーラーは1887年に高校を去り、ミルウォーキー公立博物館の管理人と なり、1890年までその職に就いた。彼は自宅や勤務時間外に小さな研究室を設けて発生学を研究した[4]。博物館を辞めた後ミルウォーキーを離れ、ク ラーク大学でホイットマンの助手を務め、1892年には哲学博士号を取得した。 [同時にウィーラーは昆虫の研究を始め、昆虫学の論文を10編ほど発表し、博士号候補となった[8]。シカゴでの職務に就く前に、ウィーラーには1年間の 休暇が与えられ、1893年から1894年にかけてヨーロッパで研究することが許された[8]。そこで彼はまず、学生としてヴュルツブルク大学の動物学研 究所で過ごし、またナポリ動物学ステーションでも過ごした。ナポリの動物相に魅了されたウィーラーは、ミゾストマの性生活を研究し、ベルギーのリエージュ 動物学研究所でさらに研究を進めた。Myzostomaに関する彼のモノグラフは、1897年にE.ヴァン・ベネデン教授によってArchives de Biologieに掲載された[9]。 |

| Career In 1894 Wheeler returned to the University of Chicago where he was a teacher of embryology for five years. He continued to publish papers, half of which involved insects. In 1898, Wheeler married Dora Bay Emerson in Chicago, where they had met earlier.[9] In 1899, he was offered the "Professorship In Zoology" following the death of professor Norman of the University of Texas. There, he took the opportunity to reorganize the department as professor of zoology. He remained there until 1903, but during this period was when Wheeler developed an interest in the behavior and classification of ants. The ants would eventually become the predominant group of insects he studied.[10][11] His two children were also born in Rockford, Illinois while he was staying in Texas.[12] A number of students sought to study under Wheeler; notable entomologists such as C. T. Brues and A. L. Melander made their way to Austin and spent several years studying there in his laboratory. This began an influx of young students, both who were pupils and scientific associates, to study and research for long periods of time under his guidance.[12] Other students include C. L. Metcalf, T. B. Mitchell, O. E. Plath, George Salt, Alfred C. Kinsey, George C. Wheeler, Frank M. Carpenter, William S. Creighton, Neal A. Weber, J. G. Myers, William M. Mann, Marston Bates and Philip J. Darlington.[13] In 1903, Wheeler resigned from his position at the University of Texas and accepted the position "Curator of Invertebrate Zoology" at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.[11][13] Wheeler was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1909 and the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1912.[14][15] A close contact of the British myrmecologist and coleopterist Horace Donisthorpe, it was to Wheeler whom Donisthorpe dedicated his first major book on ants in 1915. Donisthorpe and Wheeler also frequently exchanged specimens, leading the latter to first develop the idea that the Formicinae subfamily had its origins in North America. Wheeler was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1916.[16] For his work, Ants of the American Museum Congo Expedition, Wheeler was awarded the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academy of Sciences in 1922.[17] He was professor of applied biology at Harvard University's Bussey Institute, which had one of the most highly regarded biology programs in the United States. In 1924 he spent about two months in Panama with Dr. Nathan Banks, collecting invertebrates around Barro Colorado and along the railroad in the vicinity of Panama City. Wheeler led the Harvard Australian Expedition (1931–1932) on behalf of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, a six-man venture sent for the dual purpose of procuring specimens - the museum being "weak in Australian animals and...desires[ing] to complete its series" - and to engage in "the study of the animals of the region when alive."[18][19] The mission was success with over 300 mammal and thousands of insect specimens returning to the United States.[20][21] Wheeler was elected in 1901 a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science[22] and in 1906 a fellow of the Entomological Society of America.[23] A species of gecko, Nephrurus wheeleri, is named in his honor.[24] His work includes 467 titles.[25] |

経歴 1894年、ウィーラーはシカゴ大学に戻り、5年間発生学の教師を務めた。彼は論文を発表し続け、そのうちの半分は昆虫に関するものであった。1898 年、ウィーラーは以前から出会っていたドーラ・ベイ・エマーソンとシカゴで結婚した[9]。1899年、テキサス大学のノーマン教授の死去に伴い、「動物 学教授職」のオファーを受ける。そこで彼は、動物学教授として学部を再編成する機会を得た。彼は1903年までそこに留まったが、この時期にウィーラーは アリの行動と分類に興味を持つようになった。アリはやがて彼が研究する昆虫の主要なグループとなる[10][11]。彼がテキサスに滞在していた間に、彼 の2人の子供もイリノイ州ロックフォードで生まれた[12]。 C.T.ブルースやA.L.メランダーといった著名な昆虫学者たちがオースティンを訪れ、彼の研究室で数年間学んだ。これによって、ウィーラーの指導の下 で、弟子や科学仲間として、若い学生たちが長期にわたって研究・勉学に励むようになった[12]。 1903年、ウィーラーはテキサス大学の職を辞し、ニューヨークのアメリカ自然史博物館の「無脊椎動物学キュレーター」の職に就いた[11][13]。 ウィーラーは1909年にアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーに、1912年にはアメリカ合衆国科学アカデミーに選出された[14][15]。 イギリスの蟻類学者で鞘翅類学者のホレス・ドニストホープと親交が深く、ドニストホープが1915年にアリに関する最初の主著をウィーラーに献呈した。ド ニストホープとウィーラーは頻繁に標本の交換も行い、ドニストホープがタイワンアリ亜科の起源が北アメリカにあるという考えを初めて打ち立てた。 ウィーラーは1916年にアメリカ哲学協会に選出された[16]。 1922年、『Ants of the American Museum Congo Expedition(アメリカ博物館コンゴ探検隊のアリ)』により、ウィーラーは全米科学アカデミーからダニエル・ジロー・エリオット・メダルを授与さ れる。 1924年にはネイサン・バンクス博士とともにパナマに約2ヶ月滞在し、バロ・コロラド周辺やパナマ・シティ近郊の鉄道沿いで無脊椎動物を採集した。 ウィーラーは、ハーバード大学比較動物学博物館を代表して、ハーバード・オーストラリア探検隊(1931~1932年)を率いた。この6人組の探検隊は、 標本の調達と、「この地域の動物を生きたまま研究する」という2つの目的のために派遣されたもので、同博物館は「オーストラリアの動物に弱く、そのシリー ズを完成させたい」と望んでいた[18][19]。 ウィーラーは1901年にアメリカ科学振興協会のフェローに選出され[22]、1906年にはアメリカ昆虫学会のフェローに選出された[23]。 ヤモリの一種であるNephrurus wheeleriは彼にちなんで命名された[24]。 彼の著作には467のタイトルが含まれる[25]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Morton_Wheeler |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆