倫理学

Ethics

★倫理学は裸の王様である(垂水源之介)——La ética es el emperador desnudo [Mitzub'ixi Qu'q Ch'ij]——Ethics is the Emperor's New Clothes.

☆倫理学または道徳哲学(Ethics or moral philosophy)は、哲学の一分野であり、「正しい行動と誤った行動の概念を体系化し、擁護し、推奨すること」を含む。倫理学の分野は、美学とともに、価値に関する事柄に関係しており、これらの分野は公理学と呼ばれる哲学の一分野を構成している。倫理学は通常、規範倫理学、応用倫理学、メタ倫理学の3つの分野に大別される。

☆倫理的な環境とは、生き方に関する考え方を取り囲んでいる風土のことです——サイモン・ブラックバーン(2025:3)

☆以下における倫理学と呼ばれているもののサブジャンルのリストと記述内容をみていると、倫理学と呼ばれるものの内容、思考法、実践的帰結はさまざまであり、《倫理学という統一体というものは存在しない》と判断しても間違いではない(→「すべての倫理学者はハンプティ・ダンプティである」)。

| Ethics or moral philosophy is

the philosophical study of moral phenomena. It investigates normative

questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally

right. It is usually divided into three major fields: normative ethics,

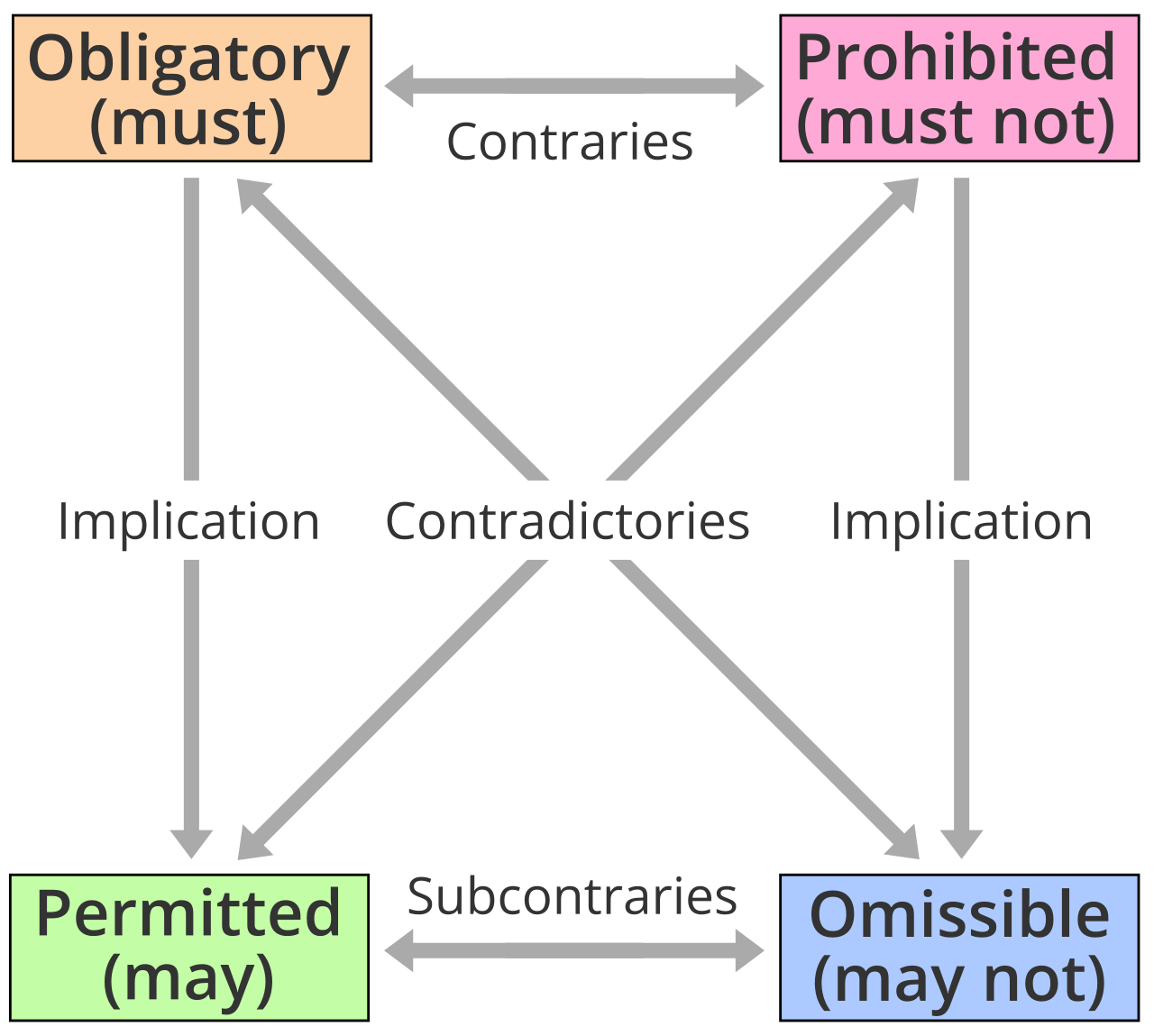

applied ethics, and metaethics. Normative ethics discovers and justifies universal principles that govern how people should act in any situation. According to consequentialists, an act is right if it leads to the best consequences. Deontologists hold that morality consists in fulfilling duties, like telling the truth and keeping promises. Virtue theorists see the manifestation of virtues, like courage and compassion, as the fundamental principle of morality. Applied ethics examines concrete ethical problems in real-life situations, for example, by exploring the moral implications of the universal principles discovered in normative ethics within a specific domain. Bioethics studies moral issues associated with living organisms including humans, animals, and plants. Business ethics investigates how ethical principles apply to corporations, while professional ethics focuses on what is morally required of members of different professions. Metaethics is a metatheory that examines the underlying assumptions and concepts of ethics. It asks whether moral facts have mind-independent existence, whether moral statements can be true, how it is possible to acquire moral knowledge, and how moral judgments motivate people. Ethics is closely connected to value theory, which studies what value is and what types of value there are. Moral psychology is a related empirical field and investigates psychological processes involved in morality, such as moral reasoning and the formation of moral character. Descriptive ethics provides value-neutral descriptions of the dominant moral codes and beliefs in different societies and considers their historical dimension. The history of ethics started in the ancient period with the development of ethical principles and theories in ancient Egypt, India, China, and Greece. This period saw the emergence of ethical teachings associated with Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, and contributions of philosophers like Socrates and Aristotle. During the medieval period, ethical thought was strongly influenced by religious teachings. In the modern period, this focus shifted to a more secular approach concerned with moral experience, practical reason, and the consequences of actions. An influential development in the 20th century was the emergence of metaethics. ++++++++++++++++++++  Ethics is concerned with the moral status of entities: for example, whether an act is obligatory or prohibited.[1] |

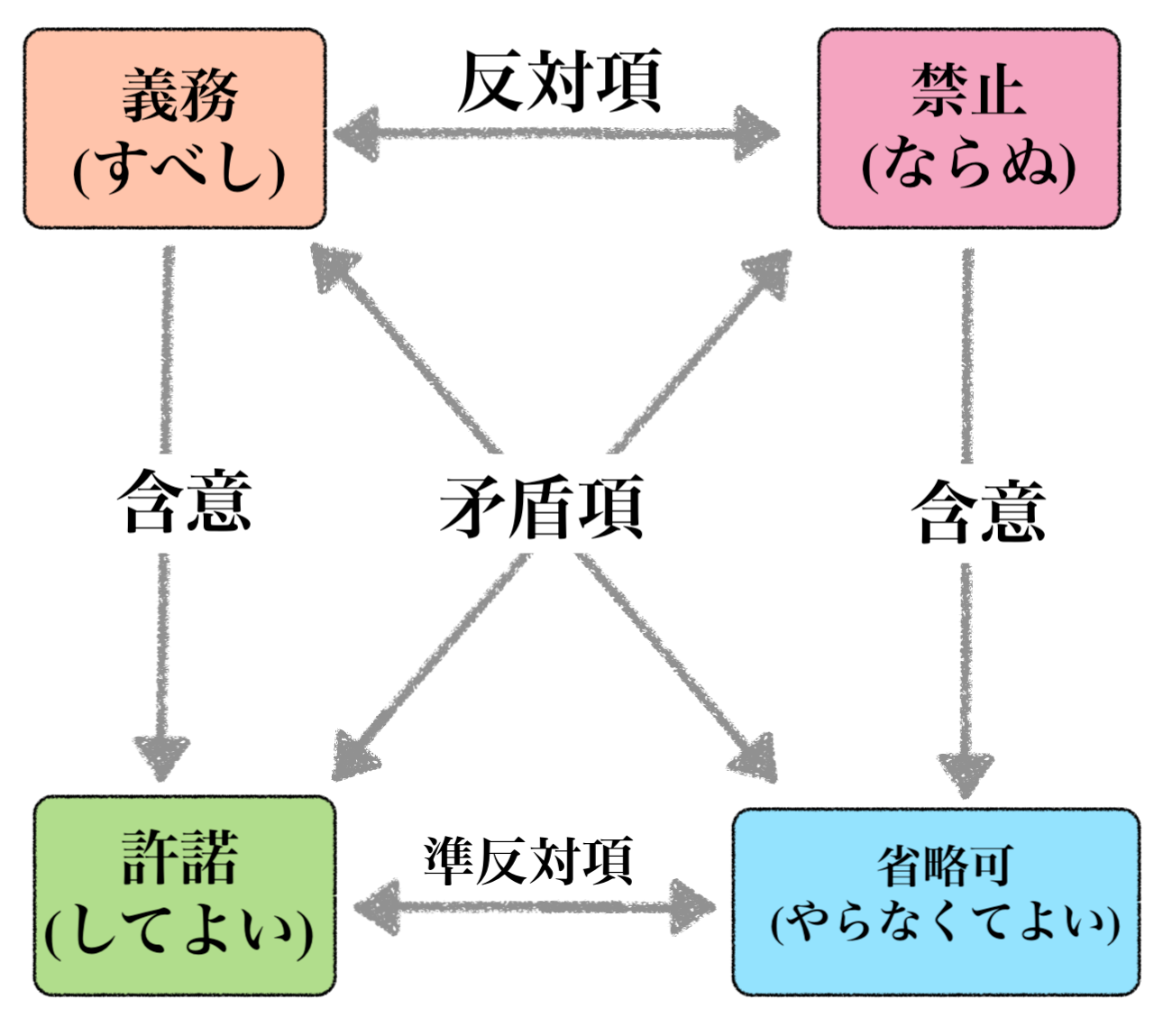

倫理学または道徳哲学は、道徳的現象についての哲学的研究である。人は何をすべきか、どの行動が道徳的に正しいか、といった規範的な問題を研究する。倫理学は通常、規範倫理学、応用倫理学、メタ倫理学の3つの分野に大別される。 規範倫理学は、どのような状況においても人がどのように行動すべきかを規定する普遍的な原則を発見し、それを正当化するものである。結果論者によれば、あ る行為が最良の結果をもたらすのであれば、その行為は正しいとされる。脱存在論者は、道徳とは真実を告げたり約束を守ったりといった義務を果たすことだと 考える。徳の理論家は、勇気や思いやりのような徳の発現を道徳の基本原理とみなす。応用倫理学は、現実の状況における具体的な倫理的問題を検討するもの で、例えば、規範倫理学で発見された普遍的原則の道徳的意味を特定の領域で探求する。生命倫理学は、人間、動物、植物などの生物に関連する道徳的問題を研 究する。ビジネス倫理学は、倫理原則が企業にどのように適用されるかを調査し、職業倫理学は、さまざまな職業のメンバーに道徳的に何が求められるかに焦点 を当てる。メタ倫理学は、倫理の基礎となる前提や概念を検討するメタ理論である。道徳的事実は心とは無関係に存在するのか、道徳的言明は真でありうるの か、道徳的知識を獲得することはどのように可能なのか、道徳的判断はどのように人々を動機づけるのか、などを問う。 倫理学は、価値とは何か、価値にはどのような種類があるかを研究する価値論と密接な関係がある。道徳心理学は関連する実証的な分野で、道徳的推論や道徳的 性格の形成など、道徳に関わる心理的プロセスを研究している。記述倫理学は、さまざまな社会で支配的な道徳規範や信条について、価値中立的な記述を提供 し、その歴史的側面を考察する。 倫理の歴史は、古代エジプト、インド、中国、ギリシャにおける倫理原則と理論の発展とともに古代に始まった。この時代には、ヒンドゥー教、仏教、儒教、道 教に関連する倫理的な教えが出現し、ソクラテスやアリストテレスのような哲学者が貢献した。中世の倫理思想は、宗教的な教えの影響を強く受けていた。近代 になると、この焦点は道徳的経験、実践的理性、行動の結果に関わる、より世俗的なアプローチへと移行した。20世紀における影響力のある発展は、メタ倫理 の出現であった。 +++++++++++++++++++  倫理学は、ある行為が義務であるか禁止であるかなど、実体の道徳的地位に関わるものである[1]。 |

| Definition The English word ethics is derived from the Ancient Greek word ēthicas (ἠθικός), meaning "relating to one's character", which itself comes from the root word êthos (ἦθος) meaning "character, moral nature".[5] This word was transferred into Latin as ethica and then into French as éthique, from which it was transferred into English. Rushworth Kidder states that "standard definitions of ethics have typically included such phrases as 'the science of the ideal human character' or 'the science of moral duty'".[6] Richard William Paul and Linda Elder define ethics as "a set of concepts and principles that guide us in determining what behavior helps or harms sentient creatures".[7] The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy states that the word "ethics" is "commonly used interchangeably with 'morality' ... and sometimes it is used more narrowly to mean the moral principles of a particular tradition, group or individual."[8] Paul and Elder state that most people confuse ethics with behaving in accordance with social conventions, religious beliefs, the law, and do not treat ethics as a stand-alone concept.[9] The word ethics in English refers to several things.[10] It can refer to philosophical ethics or moral philosophy—a project that attempts to use reason to answer various kinds of ethical questions. As the English moral philosopher Bernard Williams writes, attempting to explain moral philosophy: "What makes an inquiry a philosophical one is reflective generality and a style of argument that claims to be rationally persuasive."[11] Williams describes the content of this area of inquiry as addressing the very broad question, "how one should live".[12] Ethics can also refer to a common human ability to think about ethical problems that is not particular to philosophy. As bioethicist Larry Churchill has written: "Ethics, understood as the capacity to think critically about moral values and direct our actions in terms of such values, is a generic human capacity."[13]  According to Aristotle, how to lead a good life is one of the central questions of ethics.[2] |

定義 英語のethicsは、古代ギリシャ語のēthicas (ἠθικός) に由来する。ēthicasは「人格に関する」という意味で、êthos (ἦθος) は「性格、道徳的性質」を意味する語源である。 ラシュワース・キダーは、「倫理学の標準的な定義には、一般的に『理想的な人間の性格の科学』や『道徳的義務の科学』といったフレーズが含まれている」と 述べている[6]。リチャード・ウィリアム・ポールとリンダ・エルダーは、倫理学を「どのような行動が知覚を持つ生き物を助け、あるいは害するかを決定す る際の指針となる一連の概念と原則」と定義している[7]。 [7]ケンブリッジ哲学辞典は、「倫理」という言葉は「一般的に『道徳』と互換的に使用され...特定の伝統、集団、個人の道徳的原則を意味するためによ り狭く使用されることもある」と述べている[8]。ポールとエルダーは、ほとんどの人は倫理を社会的慣習、宗教的信念、法律に従って行動することと混同し ており、倫理を独立した概念として扱っていないと述べている[9]。 英語における倫理学という単語は、いくつかのものを指す[10]。イギリスの道徳哲学者バーナード・ウィリアムズは、道徳哲学を説明しようとしてこう書い ている: 「探究を哲学的なものにするものは、反省的な一般性と、合理的な説得力を主張する議論のスタイルである」[11]。ウィリアムズはこの探究領域の内容を、 「人はいかに生きるべきか」という非常に広範な問いに取り組むものであると説明している[12]。生命倫理学者のラリー・チャーチルはこう書いている: 「倫理とは、道徳的価値について批判的に考え、そのような価値観の観点から私たちの行動を方向づける能力として理解され、一般的な人間の能力である」 [13]。  アリストテレスによれば、いかにして善い人生(徳のある人生)を送るかは、倫理の中心的な問題の一つである[2]。 |

| Meta-ethics Meta-ethics is the branch of philosophical ethics that asks how we understand, know about, and what we mean when we talk about what is right and what is wrong.[14] An ethical question pertaining to a particular practical situation—such as, "Should I eat this particular piece of chocolate cake?"—cannot be a meta-ethical question (rather, this is an applied ethical question). A meta-ethical question is abstract and relates to a wide range of more specific practical questions. For example, "Is it ever possible to have a secure knowledge of what is right and wrong?" is a meta-ethical question.[citation needed] Meta-ethics has always accompanied philosophical ethics. For example, Aristotle implies that less precise knowledge is possible in ethics than in other spheres of inquiry, and he regards ethical knowledge as depending upon habit and acculturation in a way that makes it distinctive from other kinds of knowledge. Meta-ethics is also important in G.E. Moore's Principia Ethica from 1903. In it he first wrote about what he called the naturalistic fallacy. Moore was seen to reject naturalism in ethics, in his open-question argument. This made thinkers look again at second order questions about ethics. Earlier, the Scottish philosopher David Hume had put forward a similar view on the difference between facts and values.[citation needed] Studies of how we know in ethics divide into cognitivism and non-cognitivism; these, respectively, take descriptive and non-descriptive approaches to moral goodness or value. Non-cognitivism is the view that when we judge something as morally right or wrong, this is neither true nor false. We may, for example, be only expressing our emotional feelings about these things.[15] Cognitivism can then be seen as the claim that when we talk about right and wrong, we are talking about matters of fact. The ontology of ethics is about value-bearing things or properties, that is, the kind of things or stuff referred to by ethical propositions. Non-descriptivists and non-cognitivists believe that ethics does not need a specific ontology since ethical propositions do not refer. This is known as an anti-realist position. Realists, on the other hand, must explain what kind of entities, properties or states are relevant for ethics, how they have value, and why they guide and motivate our actions.[16] Moral skepticism Main article: Moral skepticism Moral skepticism (or moral scepticism) is a class of metaethical theories in which all members entail that no one has any moral knowledge. Many moral skeptics also make the stronger, modal claim that moral knowledge is impossible. Moral skepticism is particularly against moral realism which holds the view that there are knowable and objective moral truths.[citation needed] Some proponents of moral skepticism include Pyrrho, Aenesidemus, Sextus Empiricus, David Hume, Max Stirner, Friedrich Nietzsche, and J.L. Mackie.[citation needed] Moral skepticism is divided into three sub-classes: Moral error theory (or moral nihilism). Epistemological moral skepticism. Non-cognitivism.[17] All of these three theories share the same conclusions, which are as follows: (a) we are never justified in believing that moral claims (claims of the form "state of affairs x is good," "action y is morally obligatory," etc.) are true and, even more so (b) we never know that any moral claim is true. However, each method arrives at (a) and (b) by different routes. Moral error theory holds that we do not know that any moral claim is true because (i) all moral claims are arguably false, and while none can be definitively proved or denied: (ii) we have reason to believe that all moral claims are false, and (iii) since we are not justified in believing any claim we have reason to deny, we are not justified in believing any moral claims. Epistemological moral skepticism is a subclass of theory, the members of which include Pyrrhonian moral skepticism and dogmatic moral skepticism. All members of epistemological moral skepticism share two things: first, they acknowledge that we are unjustified in believing any moral claim, and second, they are agnostic on whether (i) is true (i.e. on whether all moral claims are false). Pyrrhonian moral skepticism holds that the reason we are unjustified in believing any moral claim is that it is irrational for us to believe either that any moral claim is true or that any moral claim is false. Thus, in addition to being agnostic on whether (i) is true, Pyrrhonian moral skepticism denies (ii). Dogmatic moral skepticism, on the other hand, affirms (ii) and cites (ii)'s truth as the reason we are unjustified in believing any moral claim. Noncognitivism holds that we can never know that any moral claim is true because moral claims are incapable of being true or false (they are not truth-apt). Instead, moral claims are imperatives (e.g. "Don't steal babies!"), expressions of emotion (e.g. "stealing babies: Boo!"), or expressions of "pro-attitudes" ("I do not believe that babies should be stolen.") |

メタ倫理学 メタ倫理学とは、哲学倫理学の一分野であり、何が正しくて何が間違っているのかについて語るとき、私たちがどのように理解し、知り、何を意味するのかを問 うものである[14]。特定の実践的状況に関わる倫理的な問い、例えば「私はこの特定のチョコレートケーキを食べるべきか」という問いは、メタ倫理学的な 問いにはなりえない(むしろこれは応用倫理学的な問いである)。メタ倫理的な問いは抽象的であり、より具体的な現実的な問いに幅広く関連している。例え ば、「何が正しくて何が間違っているのかについて確実な知識を持つことは可能なのか」はメタ倫理的な問いである[要出典]。 メタ倫理学は常に哲学的倫理学に付随してきた。例えば、アリストテレスは、倫理学では他の探究領域よりも正確な知識が得られないことを示唆しており、倫理 学的知識は他の種類の知識とは一線を画す形で習慣や文化に依存しているとみなしている。メタ倫理学は、1903年のG.E.ムーアの『プリンキピア・エシ カ』においても重要である。その中でムーアは初めて、自然主義的誤謬と呼ばれるものについて書いた。ムーアはその公開質問状論証において、倫理学における 自然主義を否定した。これにより、思想家たちは倫理に関する二次的な問いに再び目を向けるようになった。それ以前には、スコットランドの哲学者デイヴィッ ド・ヒュームが事実と価値観の違いについて同様の見解を提唱していた[要出典]。 倫理学における「どのように知るか」についての研究は、認知主義と非認知主義に分かれる。これらはそれぞれ、道徳的善や価値に対する記述的アプローチと非 記述的アプローチをとる。非認知主義とは、私たちが何かを道徳的に正しいか間違っていると判断するとき、それは真でも偽でもないという考え方である。認知 主義とは、私たちが善悪について語るとき、事実について語っているという主張である。 倫理の存在論は、価値を持つ事物や性質、つまり倫理的命題によって言及される事物やものの種類についてである。非記述主義者や非認知主義者は、倫理的命題 が言及しない以上、倫理学に特定の存在論は必要ないと考える。これは反実在論者の立場として知られている。他方、実在論者は、どのような実体、性質、状態 が倫理に関連するのか、それらがどのように価値を持つのか、なぜそれらが私たちの行動を導き、動機づけるのかを説明しなければならない[16]。 道徳懐疑主義 主な記事 道徳懐疑主義 道徳的懐疑主義(または道徳的懐疑主義)は、メタ倫理理論の一種であり、すべてのメンバーが、誰も道徳的知識を持っていないことを含意している。道徳的懐 疑論者の多くは、道徳的知識は不可能であるという、より強い、様相的な主張も行う。道徳懐疑論は特に、知ることのできる客観的な道徳的真理が存在するとい う見解を保持する道徳的実在論に反対している[要出典]。 道徳懐疑論の支持者には、ピューロ、アエネシデムス、セクストゥス・エンピリカス、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、マックス・シュティルナー、フリードリヒ・ニーチェ、J.L.マッキーなどがいる[要出典]。 道徳懐疑論は3つのサブクラスに分けられる: 道徳エラー理論(または道徳的ニヒリズム)。 認識論的道徳懐疑主義。 非認知主義。 これら3つの理論はすべて同じ結論を共有しており、それは以下の通りである: (a) 私たちは道徳的主張(「xという状態は善である」、「yという行動は道徳的に義務である」などの形式の主張)が真であると信じることは決して正当化されない。 (b)いかなる道徳的主張も真であることを知ることはない。 しかし、それぞれの方法は異なるルートで(a)と(b)に到達する。 モラル・エラー理論では、私たちはどのような道徳的主張も真実であるとはわからないとする。 (i)すべての道徳的主張は間違いなく虚偽であり、決定的な証明も否定もできない: (ii)すべての道徳的主張が誤りであると信じる理由がある。 (iii) 否定する理由がある主張を信じることは正当化されないので、道徳的主張を信じることは正当化されない。 認識論的道徳懐疑論は、ピュロニア主義的道徳懐疑論や教条主義的道徳懐疑論を含む理論のサブクラスである。認識論的道徳懐疑論のすべてのメンバーは、2つ のことを共有している:第一に、彼らは我々がどのような道徳的主張を信じることは不当であることを認め、第二に、彼らは(i)が真であるかどうか(すなわ ち、すべての道徳的主張が偽であるかどうか)については不可知である。 ピュロン派の道徳懐疑主義は、私たちがいかなる道徳的主張も信じることが正当化されないのは、いかなる道徳的主張も真であると信じることも、いかなる道徳 的主張も偽であると信じることも、私たちにとって不合理だからであるとする。したがって、ピュロン派の道徳懐疑主義は、(i)が真であるかどうかについて 不可知であることに加えて、(ii)を否定する。 一方、教条的道徳懐疑主義は、(ii)を肯定し、(ii)の真理を、私たちがいかなる道徳的主張を信じることも正当化されない理由として挙げる。 非認知主義では、道徳的主張は真でも偽でもありえない(真理適応性がない)ので、いかなる道徳的主張も真であることを知ることはできないとする。その代わ り、道徳的主張は命令文(例:「赤ん坊を盗むな!」)、感情表現(例:「赤ん坊を盗め:ブー!」)、あるいは「肯定的態度」の表現(「私は赤ん坊が盗まれ てはいけないとは思わない」)である。 |

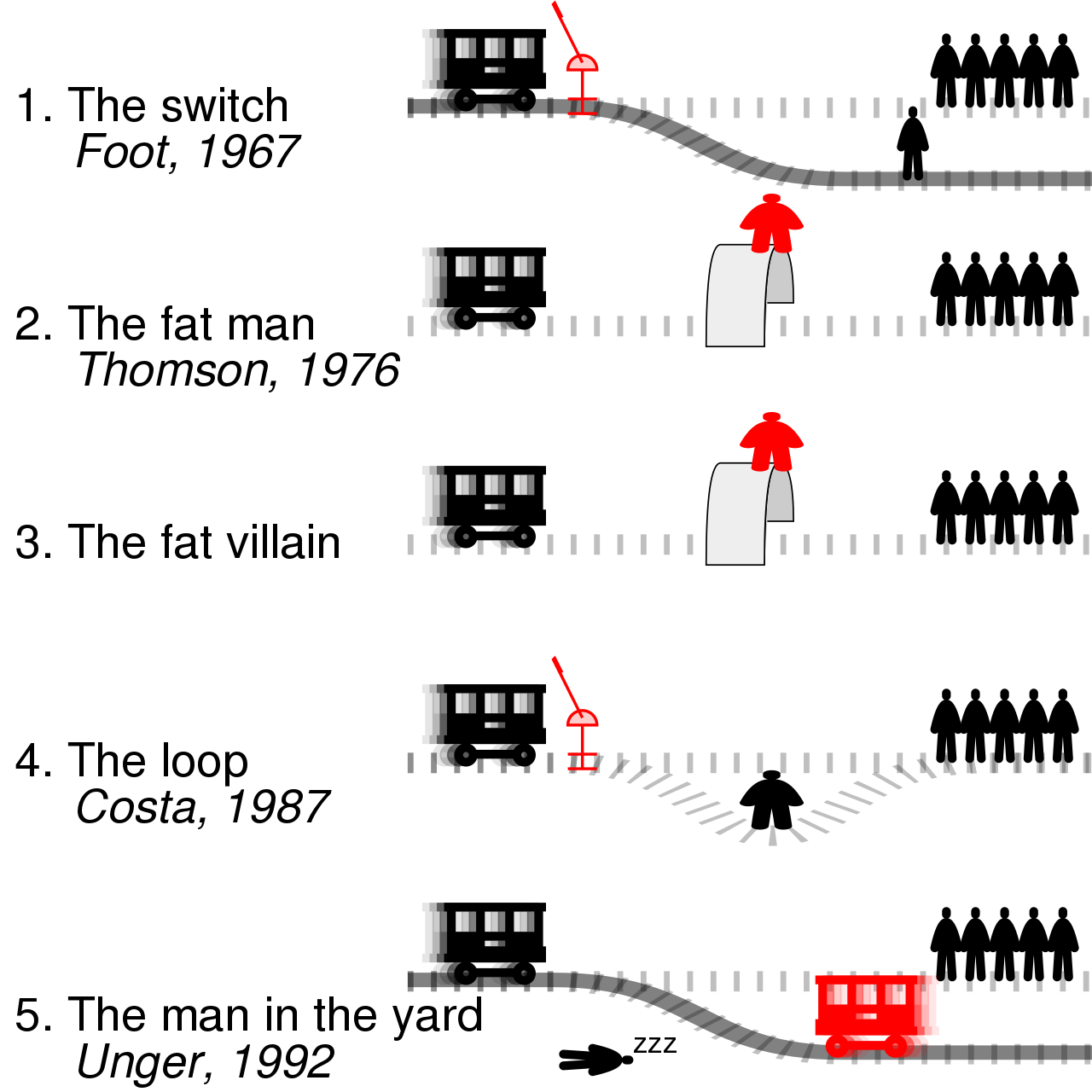

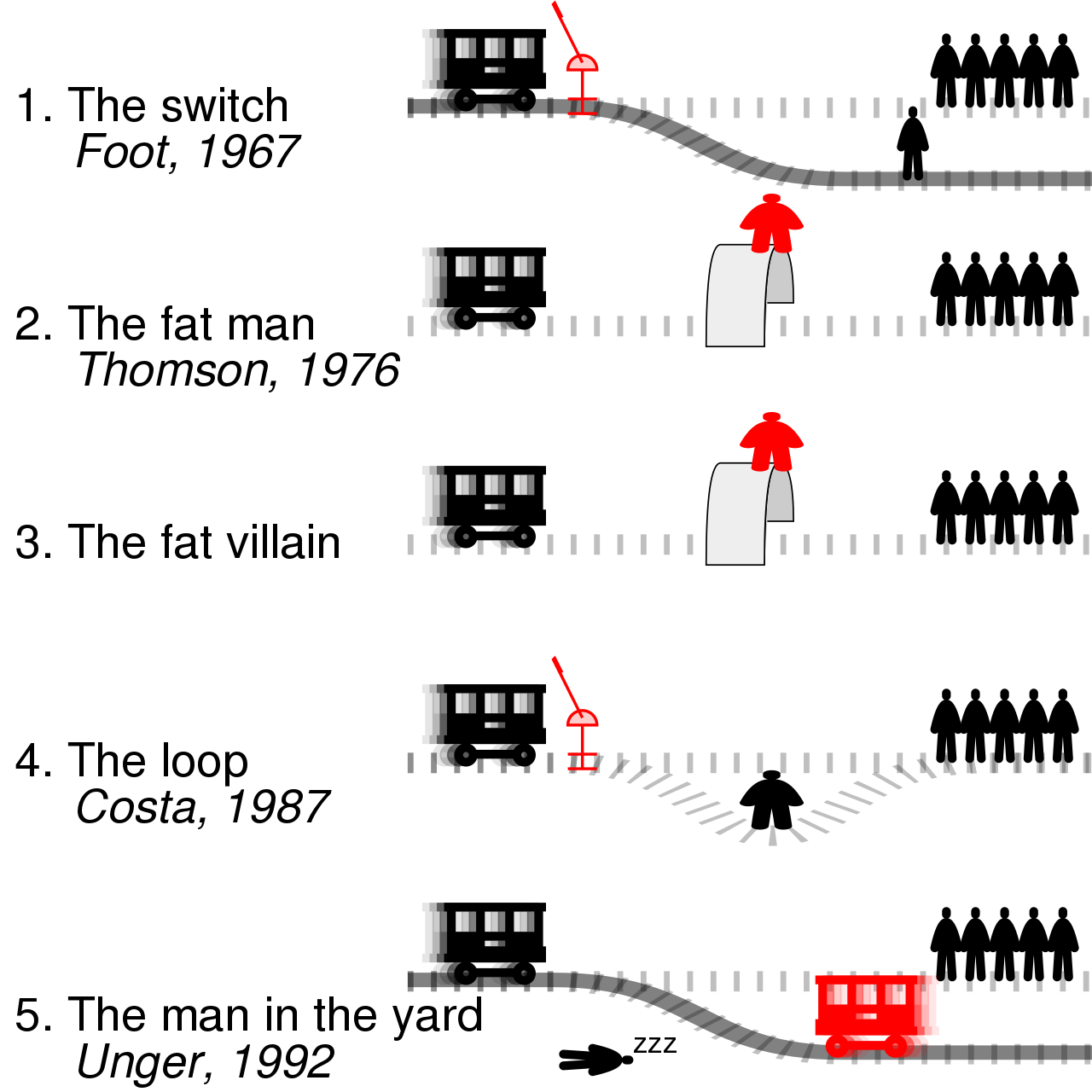

Drawing

of the trolley problem original premises and its five variants. The

trolley problem is an ethical dilemma that shows the difference between

deontological and consequentialist ethical systems. |

トロッコ問題の原前提とその5つの変形の図面。トロッコ問題は、脱自律主義的倫理体系と結果主義的倫理体系の違いを示す倫理的ジレンマである。 |

| Normative ethics Main article: Normative ethics Normative ethics is the study of ethical action. It is the branch of ethics that investigates the set of questions that arise when considering how one ought to act, morally speaking. Normative ethics is distinct from meta-ethics because normative ethics examines standards for the rightness and wrongness of actions, while meta-ethics studies the meaning of moral language and the metaphysics of moral facts.[14] Normative ethics is also distinct from descriptive ethics, as the latter is an empirical investigation of people's moral beliefs. To put it another way, descriptive ethics would be concerned with determining what proportion of people believe that killing is always wrong, while normative ethics is concerned with whether it is correct to hold such a belief. Hence, normative ethics is sometimes called prescriptive rather than descriptive. However, on certain versions of the meta-ethical view called moral realism, moral facts are both descriptive and prescriptive at the same time.[18] Traditionally, normative ethics (also known as moral theory) was the study of what makes actions right and wrong. These theories offered an overarching moral principle one could appeal to in resolving difficult moral decisions.[citation needed] At the turn of the 20th century, moral theories became more complex and were no longer concerned solely with rightness and wrongness, but were interested in many different kinds of moral status. During the middle of the century, the study of normative ethics declined as meta-ethics grew in prominence. This focus on meta-ethics was in part caused by an intense linguistic focus in analytic philosophy and by the popularity of logical positivism.[citation needed] Virtue ethics Main article: Virtue ethics Socrates Virtue ethics describes the character of a moral agent as a driving force for ethical behavior, and it is used to describe the ethics of early Greek philosophers such as Socrates and Aristotle, and ancient Indian philosophers such as Valluvar. Socrates (469–399 BC) was one of the first Greek philosophers to encourage both scholars and the common citizen to turn their attention from the outside world to the condition of humankind. In this view, knowledge bearing on human life was placed highest, while all other knowledge was secondary. Self-knowledge was considered necessary for success and inherently an essential good. A self-aware person will act completely within his capabilities to his pinnacle, while an ignorant person will flounder and encounter difficulty. To Socrates, a person must become aware of every fact (and its context) relevant to his existence, if he wishes to attain self-knowledge. He posited that people will naturally do what is good if they know what is right. Evil or bad actions are the results of ignorance. If a criminal was truly aware of the intellectual and spiritual consequences of his or her actions, he or she would neither commit nor even consider committing those actions. Any person who knows what is truly right will automatically do it, according to Socrates. While he correlated knowledge with virtue, he similarly equated virtue with joy. The truly wise man will know what is right, do what is good, and therefore be happy.[19]: 32–33 Aristotle (384–323 BC) posited an ethical system that may be termed "virtuous." In Aristotle's view, when a person acts in accordance with virtue this person will do good and be content. Unhappiness and frustration are caused by doing wrong, leading to failed goals and a poor life. Therefore, it is imperative for people to act in accordance with virtue, which is only attainable by the practice of the virtues in order to be content and complete. Happiness was held to be the ultimate goal. All other things, such as civic life or wealth, were only made worthwhile and of benefit when employed in the practice of the virtues. The practice of the virtues is the surest path to happiness. Aristotle asserted that the soul of man had three natures[citation needed]: body (physical/metabolism), animal (emotional/appetite), and rational (mental/conceptual). Physical nature can be assuaged through exercise and care; emotional nature through indulgence of instinct and urges; and mental nature through human reason and developed potential. Rational development was considered the most important, as essential to philosophical self-awareness, and as uniquely human. Moderation was encouraged, with the extremes seen as degraded and immoral. For example, courage is the moderate virtue between the extremes of cowardice and recklessness. Man should not simply live, but live well with conduct governed by virtue. This is regarded as difficult, as virtue denotes doing the right thing, in the right way, at the right time, for the right reason. Valluvar (before 5th century CE) keeps virtue, or aṟam (dharma) as he calls it, as the cornerstone throughout the writing of the Kural literature.[20] While religious scriptures generally consider aṟam as divine in nature, Valluvar describes it as a way of life rather than any spiritual observance, a way of harmonious living that leads to universal happiness.[21] Contrary to what other contemporary works say, Valluvar holds that aṟam is common for all, irrespective of whether the person is a bearer of palanquin or the rider in it. Valluvar considered justice as a facet of aṟam. While ancient Greek philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, and their descendants opined that justice cannot be defined and that it was a divine mystery, Valluvar positively suggested that a divine origin is not required to define the concept of justice. In the words of V. R. Nedunchezhiyan, justice according to Valluvar "dwells in the minds of those who have knowledge of the standard of right and wrong; so too deceit dwells in the minds which breed fraud."[21] Stoicism Main article: Stoicism Epictetus The Stoic philosopher Epictetus posited that the greatest good was contentment and serenity. Peace of mind, or apatheia, was of the highest value; self-mastery over one's desires and emotions leads to spiritual peace. The "unconquerable will" is central to this philosophy. The individual's will should be independent and inviolate. Allowing a person to disturb the mental equilibrium is, in essence, offering yourself in slavery. If a person is free to anger you at will, you have no control over your internal world, and therefore no freedom. Freedom from material attachments is also necessary. If a thing breaks, the person should not be upset, but realize it was a thing that could break. Similarly, if someone should die, those close to them should hold to their serenity because the loved one was made of flesh and blood destined to death. Stoic philosophy says to accept things that cannot be changed, resigning oneself to the existence and enduring in a rational fashion. Death is not feared. People do not "lose" their life, but instead "return", for they are returning to God (who initially gave what the person is as a person). Epictetus said difficult problems in life should not be avoided, but rather embraced. They are spiritual exercises needed for the health of the spirit, just as physical exercise is required for the health of the body. He also stated that sex and sexual desire are to be avoided as the greatest threat to the integrity and equilibrium of a man's mind. Abstinence is highly desirable. Epictetus said remaining abstinent in the face of temptation was a victory for which a man could be proud.[19]: 38–41 Contemporary virtue ethics Modern virtue ethics was popularized during the late 20th century in large part due to a revival of Aristotelianism, and as a response to G.E.M. Anscombe's "Modern Moral Philosophy". Anscombe argues that consequentialist and deontological ethics are only feasible as universal theories if the two schools ground themselves in divine law. As a deeply devoted Christian herself, Anscombe proposed that either those who do not give ethical credence to notions of divine law take up virtue ethics, which does not necessitate universal laws as agents themselves are investigated for virtue or vice and held up to "universal standards", or that those who wish to be utilitarian or consequentialist ground their theories in religious conviction.[22] Alasdair MacIntyre, who wrote the book After Virtue, was a key contributor and proponent of modern virtue ethics, although some claim that MacIntyre supports a relativistic account of virtue based on cultural norms, not objective standards.[22] Martha Nussbaum, a contemporary virtue ethicist, objects to MacIntyre's relativism, among that of others, and responds to relativist objections to form an objective account in her work "Non-Relative Virtues: An Aristotelian Approach".[23] However, Nussbaum's accusation of relativism appears to be a misreading. In Whose Justice, Whose Rationality?, MacIntyre's ambition of taking a rational path beyond relativism was quite clear when he stated "rival claims made by different traditions […] are to be evaluated […] without relativism" (p. 354) because indeed "rational debate between and rational choice among rival traditions is possible" (p. 352). Complete Conduct Principles for the 21st Century[24] blended the Eastern virtue ethics and the Western virtue ethics, with some modifications to suit the 21st Century, and formed a part of contemporary virtue ethics.[24] Mortimer J. Adler described Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics as a "unique book in the Western tradition of moral philosophy, the only ethics that is sound, practical, and undogmatic."[25]  Philippa Foot was one of the philosophers responsible for the revival of virtue ethics in the 20th century. One major trend in contemporary virtue ethics is the Modern Stoicism movement. Intuitive ethics Main article: Ethical intuitionism Ethical intuitionism (also called moral intuitionism) is a family of views in moral epistemology (and, on some definitions, metaphysics). At minimum, ethical intuitionism is the thesis that our intuitive awareness of value, or intuitive knowledge of evaluative facts, forms the foundation of our ethical knowledge. The view is at its core a foundationalism about moral knowledge: it is the view that some moral truths can be known non-inferentially (i.e., known without one needing to infer them from other truths one believes). Such an epistemological view implies that there are moral beliefs with propositional contents; so it implies cognitivism. As such, ethical intuitionism is to be contrasted with coherentist approaches to moral epistemology, such as those that depend on reflective equilibrium.[26] Throughout the philosophical literature, the term "ethical intuitionism" is frequently used with significant variation in its sense. This article's focus on foundationalism reflects the core commitments of contemporary self-identified ethical intuitionists.[26][27] Sufficiently broadly defined, ethical intuitionism can be taken to encompass cognitivist forms of moral sense theory.[28] It is usually furthermore taken as essential to ethical intuitionism that there be self-evident or a priori moral knowledge; this counts against considering moral sense theory to be a species of intuitionism.[citation needed] Ethical intuitionism was first clearly shown in use by the philosopher Francis Hutcheson. Later ethical intuitionists of influence and note include Henry Sidgwick, G.E. Moore, Harold Arthur Prichard, C.S. Lewis and, most influentially, Robert Audi.[citation needed] Objections to ethical intuitionism include whether or not there are objective moral values (an assumption which the ethical system is based upon) the question of why many disagree over ethics if they are absolute, and whether Occam's razor cancels such a theory out entirely.[citation needed] Hedonism Main article: Hedonism Hedonism posits that the principal ethic is maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain. There are several schools of Hedonist thought ranging from those advocating the indulgence of even momentary desires to those teaching a pursuit of spiritual bliss. In their consideration of consequences, they range from those advocating self-gratification regardless of the pain and expense to others, to those stating that the most ethical pursuit maximizes pleasure and happiness for the most people.[19]: 37 Cyrenaic hedonism Founded by Aristippus of Cyrene, Cyrenaics supported immediate gratification or pleasure. "Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die." Even fleeting desires should be indulged, for fear the opportunity should be forever lost. There was little to no concern with the future, the present dominating in the pursuit of immediate pleasure. Cyrenaic hedonism encouraged the pursuit of enjoyment and indulgence without hesitation, believing pleasure to be the only good.[19]: 37 Epicureanism Main article: Epicureanism Epicurean ethics is a hedonist form of virtue ethics. Epicurus "presented a sustained argument that pleasure, correctly understood, will coincide with virtue."[29] He rejected the extremism of the Cyrenaics, believing some pleasures and indulgences to be detrimental to human beings. Epicureans observed that indiscriminate indulgence sometimes resulted in negative consequences. Some experiences were therefore rejected out of hand, and some unpleasant experiences endured in the present to ensure a better life in the future. To Epicurus, the summum bonum, or greatest good, was prudence, exercised through moderation and caution. Excessive indulgence can be destructive to pleasure and can even lead to pain. For example, eating one food too often makes a person lose a taste for it. Eating too much food at once leads to discomfort and ill-health. Pain and fear were to be avoided. Living was essentially good, barring pain and illness. Death was not to be feared. Fear was considered the source of most unhappiness. Conquering the fear of death would naturally lead to a happier life. Epicurus reasoned if there were an afterlife and immortality, the fear of death was irrational. If there was no life after death, then the person would not be alive to suffer, fear, or worry; he would be non-existent in death. It is irrational to fret over circumstances that do not exist, such as one's state of death in the absence of an afterlife.[19]: 37–38 State consequentialism Main article: State consequentialism State consequentialism, also known as Mohist consequentialism,[30] is an ethical theory that evaluates the moral worth of an action based on how much it contributes to the basic goods of a state.[30] The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy describes Mohist consequentialism, dating back to the 5th century BC, as "a remarkably sophisticated version based on a plurality of intrinsic goods taken as constitutive of human welfare".[31] Unlike utilitarianism, which views pleasure as a moral good, "the basic goods in Mohist consequentialist thinking are … order, material wealth, and increase in population".[32] During Mozi's era, war and famines were common, and population growth was seen as a moral necessity for a harmonious society. The "material wealth" of Mohist consequentialism refers to basic needs like shelter and clothing, and the "order" of Mohist consequentialism refers to Mozi's stance against warfare and violence, which he viewed as pointless and a threat to social stability.[33] Stanford sinologist David Shepherd Nivison, in The Cambridge History of Ancient China, writes that the moral goods of Mohism "are interrelated: more basic wealth, then more reproduction; more people, then more production and wealth … if people have plenty, they would be good, filial, kind, and so on unproblematically."[32] The Mohists believed that morality is based on "promoting the benefit of all under heaven and eliminating harm to all under heaven". In contrast to Bentham's views, state consequentialism is not utilitarian because it is not hedonistic or individualistic. The importance of outcomes that are good for the community outweighs the importance of individual pleasure and pain.[34] Consequentialism Main article: Consequentialism See also: Ethical egoism Consequentialism refers to moral theories that hold the consequences of a particular action form the basis for any valid moral judgment about that action (or create a structure for judgment, see rule consequentialism). Thus, from a consequentialist standpoint, morally right action is one that produces a good outcome, or consequence. This view is often expressed as the aphorism "The ends justify the means". The term "consequentialism" was coined by G.E.M. Anscombe in her essay "Modern Moral Philosophy" in 1958, to describe what she saw as the central error of certain moral theories, such as those propounded by Mill and Sidgwick.[35] Since then, the term has become common in English-language ethical theory. The defining feature of consequentialist moral theories is the weight given to the consequences in evaluating the rightness and wrongness of actions.[36] In consequentialist theories, the consequences of an action or rule generally outweigh other considerations. Apart from this basic outline, there is little else that can be unequivocally said about consequentialism as such. However, there are some questions that many consequentialist theories address: What sort of consequences count as good consequences? Who is the primary beneficiary of moral action? How are the consequences judged and who judges them? One way to divide various consequentialisms is by the many types of consequences that are taken to matter most, that is, which consequences count as good states of affairs. According to utilitarianism, a good action is one that results in an increase and positive effect, and the best action is one that results in that effect for the greatest number. Closely related is eudaimonic consequentialism, according to which a full, flourishing life, which may or may not be the same as enjoying a great deal of pleasure, is the ultimate aim. Similarly, one might adopt an aesthetic consequentialism, in which the ultimate aim is to produce beauty. However, one might fix on non-psychological goods as the relevant effect. Thus, one might pursue an increase in material equality or political liberty instead of something like the more ephemeral "pleasure". Other theories adopt a package of several goods, all to be promoted equally. Whether a particular consequentialist theory focuses on a single good or many, conflicts and tensions between different good states of affairs are to be expected and must be adjudicated.[citation needed] Utilitarianism Main article: Utilitarianism  Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that argues the proper course of action is one that maximizes a positive effect, such as "happiness", "welfare", or the ability to live according to personal preferences.[37] Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill are influential proponents of this school of thought. In A Fragment on Government Bentham says 'it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong' and describes this as a fundamental axiom. In An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation he talks of 'the principle of utility' but later prefers "the greatest happiness principle".[38][39] Utilitarianism is the paradigmatic example of a consequentialist moral theory. This form of utilitarianism holds that the morally correct action is the one that produces the best outcome for all people affected by the action. John Stuart Mill, in his exposition of utilitarianism, proposed a hierarchy of pleasures, meaning that the pursuit of certain kinds of pleasure is more highly valued than the pursuit of other pleasures.[40] Other noteworthy proponents of utilitarianism are neuroscientist Sam Harris, author of The Moral Landscape, and moral philosopher Peter Singer, author of, amongst other works, Practical Ethics. The major division within utilitarianism is between act utilitarianism and rule utilitarianism. In act utilitarianism, the principle of utility applies directly to each alternative act in a situation of choice. The right act is the one that brings about the best results (or the least bad results). In rule utilitarianism, the principle of utility determines the validity of rules of conduct (moral principles). A rule like promise-keeping is established by looking at the consequences of a world in which people break promises at will and a world in which promises are binding. Right and wrong are the following or breaking of rules that are sanctioned by their utilitarian value.[41] A proposed "middle ground" between these two types is Two-level utilitarianism, where rules are applied in ordinary circumstances, but with an allowance to choose actions outside of such rules when unusual situations call for it. Deontology Main article: Deontological ethics Deontological ethics or deontology (from Greek δέον, deon, "obligation, duty"; and -λογία, -logia) is an approach to ethics that determines goodness or rightness from examining acts, or the rules and duties that the person doing the act strove to fulfill.[42] This is in contrast to consequentialism, in which rightness is based on the consequences of an act, and not the act by itself. Under deontology, an act may be considered right even if it produces a bad consequence,[43] if it follows the rule or moral law. According to the deontological view, people have a duty to act in ways that are deemed inherently good ("truth-telling" for example), or follow an objectively obligatory rule (as in rule utilitarianism). Kantianism Immanuel Kant Main article: Kantian ethics Immanuel Kant's theory of ethics is considered deontological for several different reasons.[44][45] First, Kant argues that to act in the morally right way, people must act from duty (Pflicht).[46] Second, Kant argued that it was not the consequences of actions that make them right or wrong but the motives of the person who carries out the action. Kant's argument that to act in the morally right way one must act purely from duty begins with an argument that the highest good must be both good in itself and good without qualification.[47] Something is "good in itself" when it is intrinsically good, and "good without qualification", when the addition of that thing never makes a situation ethically worse. Kant then argues that those things that are usually thought to be good, such as intelligence, perseverance and pleasure, fail to be either intrinsically good or good without qualification. Pleasure, for example, appears not to be good without qualification, because when people take pleasure in watching someone suffer, this seems to make the situation ethically worse. He concludes that there is only one thing that is truly good: Nothing in the world—indeed nothing even beyond the world—can possibly be conceived which could be called good without qualification except a good will.[47] Kant then argues that the consequences of an act of willing cannot be used to determine that the person has a good will; good consequences could arise by accident from an action that was motivated by a desire to cause harm to an innocent person, and bad consequences could arise from an action that was well-motivated. Instead, he claims, a person has goodwill when he 'acts out of respect for the moral law'.[47] People 'act out of respect for the moral law' when they act in some way because they have a duty to do so. So, the only thing that is truly good in itself is goodwill, and goodwill is only good when the willer chooses to do something because it is that person's duty, i.e. out of "respect" for the law. He defines respect as "the concept of a worth which thwarts my self-love".[48] Kant's three significant formulations of the categorical imperative are: Act only according to that maxim by which you can also will that it would become a universal law. Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end. Every rational being must so act as if he were through his maxim always a legislating member in a universal kingdom of ends. Kant argued that the only absolutely good thing is a good will, and so the single determining factor of whether an action is morally right is the will, or motive of the person doing it. If they are acting on a bad maxim, e.g. "I will lie", then their action is wrong, even if some good consequences come of it. In his essay, On a Supposed Right to Lie Because of Philanthropic Concerns, arguing against the position of Benjamin Constant, Des réactions politiques, Kant states that "Hence a lie defined merely as an intentionally untruthful declaration to another man does not require the additional condition that it must do harm to another, as jurists require in their definition (mendacium est falsiloquium in praeiudicium alterius). For a lie always harms another; if not some human being, then it nevertheless does harm to humanity in general, inasmuch as it vitiates the very source of right [Rechtsquelle] ... All practical principles of right must contain rigorous truth ... This is because such exceptions would destroy the universality on account of which alone they bear the name of principles."[49] Divine command theory Main article: Divine command theory Although not all deontologists are religious, some believe in the 'divine command theory', which is actually a cluster of related theories which essentially state that an action is right if God has decreed that it is right.[50] According to Ralph Cudworth, an English philosopher, William of Ockham, René Descartes, and eighteenth-century Calvinists all accepted various versions of this moral theory, as they all held that moral obligations arise from God's commands.[51] The Divine Command Theory is a form of deontology because, according to it, the rightness of any action depends upon that action being performed because it is a duty, not because of any good consequences arising from that action. If God commands people not to work on Sabbath, then people act rightly if they do not work on Sabbath because God has commanded that they do not do so. If they do not work on Sabbath because they are lazy, then their action is not truly speaking "right", even though the actual physical action performed is the same. If God commands not to covet a neighbor's goods, this theory holds that it would be immoral to do so, even if coveting provides the beneficial outcome of a drive to succeed or do well. One thing that clearly distinguishes Kantian deontologism from divine command deontology is that Kantianism maintains that man, as a rational being, makes the moral law universal, whereas divine command maintains that God makes the moral law universal. Discourse ethics  Photograph of Jurgen Habermas, whose theory of discourse ethics was influenced by Kantian ethics Main article: Discourse ethics German philosopher Jürgen Habermas has proposed a theory of discourse ethics that he states is a descendant of Kantian ethics.[52] He proposes that action should be based on communication between those involved, in which their interests and intentions are discussed so they can be understood by all. Rejecting any form of coercion or manipulation, Habermas believes that agreement between the parties is crucial for a moral decision to be reached.[53] Like Kantian ethics, discourse ethics is a cognitive ethical theory, in that it supposes that truth and falsity can be attributed to ethical propositions. It also formulates a rule by which ethical actions can be determined and proposes that ethical actions should be universalizable, in a similar way to Kant's ethics.[54] Habermas argues that his ethical theory is an improvement on Kant's ethics.[54] He rejects the dualistic framework of Kant's ethics. Kant distinguished between the phenomena world, which can be sensed and experienced by humans, and the noumena, or spiritual world, which is inaccessible to humans. This dichotomy was necessary for Kant because it could explain the autonomy of a human agent: although a human is bound in the phenomenal world, their actions are free in the noumenal world. For Habermas, morality arises from discourse, which is made necessary by their rationality and needs, rather than their freedom.[55] Pragmatic ethics Main article: Pragmatic ethics Associated with the pragmatists Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and especially John Dewey, pragmatic ethics holds that moral correctness evolves similarly to scientific knowledge: socially over the course of many lifetimes. Thus, we should prioritize social reform over attempts to account for consequences, individual virtue or duty (although these may be worthwhile attempts, if social reform is provided for).[56] Ethics of care Main article: Ethics of care Care ethics contrasts with more well-known ethical models, such as consequentialist theories (e.g. utilitarianism) and deontological theories (e.g., Kantian ethics) in that it seeks to incorporate traditionally feminized virtues and values that—proponents of care ethics contend—are absent in such traditional models of ethics. These values include the importance of empathetic relationships and compassion. Care-focused feminism is a branch of feminist thought, informed primarily by ethics of care as developed by Carol Gilligan[57] and Nel Noddings.[58] This body of theory is critical of how caring is socially assigned to women, and consequently devalued. They write, "Care-focused feminists regard women's capacity for care as a human strength," that should be taught to and expected of men as well as women. Noddings proposes that ethical caring has the potential to be a more concrete evaluative model of moral dilemma than an ethic of justice.[59] Noddings’ care-focused feminism requires practical application of relational ethics, predicated on an ethic of care.[60] Feminist matrixial ethics Main article: Feminist ethics The 'metafeminist' theory of the matrixial gaze and the matrixial[61][62] time-space, coined and developed Bracha L. Ettinger since 1985,[63][64][65][66] articulates a revolutionary philosophical approach that, in "daring to approach", to use Griselda Pollock's description of Ettinger's ethical turn,[67][68] "the prenatal with the pre-maternal encounter", violence toward women at war, and the Shoah, has philosophically established the rights of each female subject over her own reproductive body, and offered a language to relate to human experiences which escape the phallic domain.[69][70] The matrixial sphere is a psychic and symbolic dimension that the 'phallic' language and regulations cannot control. In Ettinger's model, the relations between self and other are of neither assimilation nor rejection but 'coemergence'. In her conversation with Emmanuel Levinas, 1991, Ettinger prooses that the source of human Ethics is feminine-maternal and feminine-pre-maternal matrixial encounter-event. Sexuality and maternality coexist and are not in contradiction (the contradiction established by Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan), and the feminine is not an absolute alterity (the alterity established by Jacques Lacan and Emmanuel Levinas). With the 'originary response-ability', 'wit(h)nessing', 'borderlinking', 'communicaring', 'com-passion', 'seduction into life'[71][72] and other processes invested by affects that occur in the Ettingerian matrixial time-space, the feminine is presented as the source of humanized Ethics in all genders. Compassion and Seduction into life occurs earlier than the primary seduction which passes through enigmatic signals from the maternal sexuality according to Jean Laplanche, since it is active in 'coemergence' in 'withnessing' for any born subject, earlier to its birth. Ettinger suggests to Emanuel Levinas in their conversations in 1991, that the feminine understood via the matrixial perspective is the heart and the source of Ethics.[73][74] At the beginning of life, an originary 'fascinance' felt by the infant[75] is related to the passage from response-ability to responsibility, from com-passion to compassion, and from wit(h)nessing to witnessing operated and transmitted by the m/Other. The 'differentiation in jointness' that is at the heart of the matrixial borderspace has deep implications in the relational field[76] and for the ethics of care.[77] The matrixial theory that proposes new ways to rethink sexual difference through the fluidity of boundaries informs aesthetics and ethics of compassion, carrying and non-abandonment in 'subjectivity as encounter-event'.[78][79] It has become significant in Psychoanalysis and in transgender studies.[80] Role ethics Main article: Role ethics Role ethics is an ethical theory based on family roles.[81] Unlike virtue ethics, role ethics is not individualistic. Morality is derived from a person's relationship with their community.[82] Confucian ethics is an example of role ethics[81] though this is not straightforwardly uncontested.[83] Confucian roles center around the concept of filial piety or xiao, a respect for family members.[84] According to Roger T. Ames and Henry Rosemont, "Confucian normativity is defined by living one's family roles to maximum effect." Morality is determined through a person's fulfillment of a role, such as that of a parent or a child. Confucian roles are not rational, and originate through the xin, or human emotions.[82] Anarchist ethics Main article: Anarchism Anarchist ethics is an ethical theory based on the studies of anarchist thinkers. The biggest contributor to anarchist ethics is Peter Kropotkin. Starting from the premise that the goal of ethical philosophy should be to help humans adapt and thrive in evolutionary terms, Kropotkin's ethical framework uses biology and anthropology as a basis – in order to scientifically establish what will best enable a given social order to thrive biologically and socially – and advocates certain behavioural practices to enhance humanity's capacity for freedom and well-being, namely practices which emphasise solidarity, equality, and justice. Kropotkin argues that ethics itself is evolutionary, and is inherited as a sort of a social instinct through cultural history, and by so, he rejects any religious and transcendental explanation of morality. The origin of ethical feeling in both animals and humans can be found, he claims, in the natural fact of "sociality" (mutualistic symbiosis), which humans can then combine with the instinct for justice (i.e. equality) and then with the practice of reason to construct a non-supernatural and anarchistic system of ethics.[85] Kropotkin suggests that the principle of equality at the core of anarchism is the same as the Golden rule: This principle of treating others as one wishes to be treated oneself, what is it but the very same principle as equality, the fundamental principle of anarchism? And how can any one manage to believe himself an anarchist unless he practices it? We do not wish to be ruled. And by this very fact, do we not declare that we ourselves wish to rule nobody? We do not wish to be deceived, we wish always to be told nothing but the truth. And by this very fact, do we not declare that we ourselves do not wish to deceive anybody, that we promise to always tell the truth, nothing but the truth, the whole truth? We do not wish to have the fruits of our labor stolen from us. And by that very fact, do we not declare that we respect the fruits of others' labor? By what right indeed can we demand that we should be treated in one fashion, reserving it to ourselves to treat others in a fashion entirely different? Our sense of equality revolts at such an idea.[86] Postmodern ethics Main article: Postmodernism This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. (July 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Antihumanists such as Louis Althusser, Michel Foucault and structuralists such as Roland Barthes challenged the possibilities of individual agency and the coherence of the notion of the 'individual' itself. This was on the basis that personal identity was, in the most part, a social construction. As critical theory developed in the later 20th century, post-structuralism sought to problematize human relationships to knowledge and 'objective' reality. Jacques Derrida argued that access to meaning and the 'real' was always deferred, and sought to demonstrate via recourse to the linguistic realm that "there is no outside-text/non-text" ("il n'y a pas de hors-texte" is often mistranslated as "there is nothing outside the text"); at the same time, Jean Baudrillard theorised that signs and symbols or simulacra mask reality (and eventually the absence of reality itself), particularly in the consumer world. Post-structuralism and postmodernism argue that ethics must study the complex and relational conditions of actions. A simple alignment of ideas of right and particular acts is not possible. There will always be an ethical remainder that cannot be taken into account or often even recognized. Such theorists find narrative (or, following Nietzsche and Foucault, genealogy) to be a helpful tool for understanding ethics because narrative is always about particular lived experiences in all their complexity rather than the assignment of an idea or norm to separate and individual actions. Zygmunt Bauman says postmodernity is best described as modernity without illusion, the illusion being the belief that humanity can be repaired by some ethic principle. Postmodernity can be seen in this light as accepting the messy nature of humanity as unchangeable. In this postmodern world, the means to act collectively and globally to solve large-scale problems have been all but discredited, dismantled or lost. Problems can be handled only locally and each on its own. All problem-handling means building a mini-order at the expense of order elsewhere, and at the cost of rising global disorder as well as depleting the shrinking supplies of resources which make ordering possible. He considers Emmanuel Levinas's ethics as postmodern. Unlike the modern ethical philosophy which leaves the Other on the outside of the self as an ambivalent presence, Levinas's philosophy readmits her as a neighbor and as a crucial character in the process through which the moral self comes into its own.[87] David Couzens Hoy states that Emmanuel Levinas's writings on the face of the Other and Derrida's meditations on the relevance of death to ethics are signs of the "ethical turn" in Continental philosophy that occurred in the 1980s and 1990s. Hoy describes post-critique ethics as the "obligations that present themselves as necessarily to be fulfilled but are neither forced on one or are enforceable".[88] Hoy's post-critique model uses the term ethical resistance. Examples of this would be an individual's resistance to consumerism in a retreat to a simpler but perhaps harder lifestyle, or an individual's resistance to a terminal illness. Hoy describes Levinas's account as "not the attempt to use power against itself, or to mobilize sectors of the population to exert their political power; the ethical resistance is instead the resistance of the powerless".[89] Hoy concludes that The ethical resistance of the powerless others to our capacity to exert power over them is therefore what imposes unenforceable obligations on us. The obligations are unenforceable precisely because of the other's lack of power. That actions are at once obligatory and at the same time unenforceable is what put them in the category of the ethical. Obligations that were enforced would, by the virtue of the force behind them, not be freely undertaken and would not be in the realm of the ethical.[90] |

規範倫理 主な記事 規範倫理学 規範倫理学とは、倫理的行為に関する学問である。倫理学の一分野であり、道徳的にどのように行動すべきかを考える際に生じる一連の問題を研究する。規範倫 理学がメタ倫理学と異なるのは、規範倫理学が行為の正しさと間違っていることの基準を検討するのに対し、メタ倫理学は道徳的言語の意味や道徳的事実の形而 上学を研究するからである[14]。規範倫理学は記述倫理学とも異なるが、後者は人々の道徳的信念を経験的に調査するものである。別の言い方をすれば、記 述倫理学は「殺人は常に悪いことである」と信じている人の割合を決定することに関心があるが、規範倫理学はそのような信念を持つことが正しいかどうかに関 心がある。それゆえ、規範倫理学は記述的というよりむしろ規定的と呼ばれることがある。しかしながら、道徳的実在論と呼ばれるメタ倫理観のあるバージョン では、道徳的事実は記述的であると同時に規定的でもある[18]。 伝統的に、規範倫理学(道徳理論としても知られている)は、何が行為を正し、そして間違っているのかを研究するものであった。これらの理論は、困難な道徳的決定を解決する際に訴えることができる包括的な道徳原理を提供した[要出典]。 20世紀に入ると、道徳理論はより複雑なものとなり、もはや正しさと間違っていることのみに関心を持つのではなく、様々な種類の道徳的状態に関心を持つよ うになった。世紀半ばには、メタ倫理学が注目されるようになり、規範倫理学の研究は衰退した。このメタ倫理学への注目は、分析哲学における強烈な言語的焦 点と論理実証主義の流行によって引き起こされた面もある[要出典]。 徳倫理学 主な記事 徳倫理学 ソクラテス 徳倫理学は、倫理的行動の原動力としての道徳的行為者の人格を説明するものであり、ソクラテスやアリストテレスなどの初期ギリシア哲学者やヴァルヴァルな どの古代インド哲学者の倫理学を説明するのに用いられる。ソクラテス(紀元前469~399年)は、学者と一般市民の両方に、外界から人類の状態に目を向 けるよう促した最初のギリシャ哲学者の一人である。この考え方では、人間の生活に関わる知識が最も重要視され、それ以外の知識は二の次とされた。自己認識 は成功のために必要であり、本質的に本質的な善であると考えられていた。自己認識のある人は、自分の能力の範囲内で頂点に達するまで完全に行動するが、無 知な人は困難に遭遇し、低迷する。ソクラテスにとって、人は自己認識を得たいのであれば、自分の存在に関連するあらゆる事実(とその背景)を認識しなけれ ばならない。ソクラテスは、人は何が正しいかを知れば、自然に善いことをするようになると説いた。悪や悪い行いは無知の結果である。もし犯罪者が自分の行 為が知的、精神的にどのような結果をもたらすかを本当に知っていれば、そのような行為を犯すことはもちろん、犯そうとも思わないだろう。ソクラテスによれ ば、何が本当に正しいかを知っている人は、自動的にそれを実行する。ソクラテスは知識を徳と結びつけたが、同様に徳と喜びも結びつけた。真に賢明な人は、 何が正しいかを知り、善いことを行い、それゆえに幸福である[19]: 32-33 アリストテレス(紀元前384~323年)は、"徳 "と呼べる倫理体系を提唱した。アリストテレスの考えでは、人が徳に従って行動するとき、その人は善を行い、満足する。不幸やフラストレーションは間違っ たことをすることによって引き起こされ、目標の失敗や貧しい人生につながる。したがって、人は徳に従って行動することが不可欠であり、それは満足し、完全 であるためには、徳の実践によってのみ達成可能である。幸福は究極の目標である。市民生活や富のような他のすべてのものは、徳の実践に用いられて初めて価 値があり、有益なものとなる。徳の実践こそが、幸福への最も確かな道なのである。アリストテレスは、人間の魂には身体(肉体/代謝)、動物(感情/食 欲)、理性(精神/概念)の3つの性質があると主張した。肉体的な性質は運動とケアによって、感情的な性質は本能と衝動の放縦によって、精神的な性質は人 間の理性と発達した潜在能力によって、それぞれ和らげることができる。理性的な発達は、哲学的な自己認識に不可欠であり、人間特有のものとして、最も重要 であると考えられていた。中庸が奨励され、極端なものは品位を落とし、不道徳とみなされた。例えば、勇気は臆病と無謀という両極端の間の中庸の美徳であ る。人間はただ生きるだけでなく、徳に支配された行為によってよく生きるべきである。徳とは、正しいことを、正しい方法で、正しい時に、正しい理由のため に行うことである。 ヴァルヴァル(紀元5世紀以前)は、クラル文献の執筆を通じて、徳、あるいは彼が言うところのa_1am(ダルマ)を礎石としている[20]。宗教的な聖 典は一般にa_1amを神的なものとみなすが、ヴァルヴァルはそれを、精神的な遵守というよりはむしろ、普遍的な幸福につながる調和のとれた生き方として いる。 [21] ヴァルヴァルは、他の現代的な著作に書かれていることとは逆に、輿の担ぎ手であろうと輿に乗る者であろうと、アファムは万人に共通するものであるとしてい る。ヴァルヴァーは、正義をアファムの一面と考えた。プラトン、アリストテレスやその子孫のような古代ギリシャの哲学者たちは、正義を定義することはでき ず、正義は神の神秘であるという見解を示したが、ヴァルーヴァルは、正義の概念を定義するために神の起源を必要としないことを積極的に示唆した。V.R. ネドゥンチェジヤンの言葉を借りれば、ヴァルヴァルによれば正義は「善悪の基準を知る者の心に宿る。 ストイシズム 主な記事 ストア派 エピクテトス ストア派の哲学者エピクテトスは、最大の善は満足と平穏であるとした。心の平和、すなわちアパテイアは最高の価値であり、欲望や感情を自己制御することが 精神的な平和につながる。征服できない意志」がこの哲学の中心である。個人の意志は独立し、侵すことのできないものでなければならない。人が精神の均衡を 乱すのを許すことは、要するに自分自身を奴隷として差し出すことだ。もし人が自由にあなたを怒らせるなら、あなたは自分の内的世界をコントロールできず、 したがって自由もない。物質的な執着からの解放も必要だ。モノが壊れたとしても、その人は動揺するのではなく、壊れる可能性のあるモノであったことを理解 すべきである。同じように、もし誰かが死んだとしても、愛する人は死を運命づけられた生身の人間なのだから、親しい人は平静を保たなければならない。スト イック哲学は、変えられないものを受け入れ、その存在に身を任せ、理性的に耐えろという。死は恐れない。人は自分の命を「失う」のではなく、(その人とい う存在を最初に与えた)神に帰るのだから、「帰る」のである。エピクテトスは、人生における困難な問題は避けるべきものではなく、むしろ受け入れるべきだ と言った。肉体的な運動が肉体の健康のために必要であるように、それらは精神の健康のために必要な精神的な訓練なのである。彼はまた、セックスと性的欲望 は、人の心の完全性と均衡を脅かす最大の脅威として避けるべきだと述べた。禁欲は非常に望ましい。エピクテトスは、誘惑に直面しても禁欲を貫くことは、男 が誇るべき勝利であると述べている[19]: 38-41 現代の徳倫理学 現代の徳倫理学は、20世紀後半にアリストテレス主義の復活とG.E.M.アンスコムの『現代道徳哲学』への応答として普及した。アンスコムは、結果論的 倫理学と脱存在論的倫理学が普遍的な理論として実現可能なのは、この2つの学派が神の法則に立脚している場合に限られると主張している。アンスコムはキリ スト教徒(カソリック)であったため、神の法則の概念を倫理的に信用しない者は、行為者自身が徳や悪を調査し、「普遍的な基準」に拘束されるため、普遍的な法則を必要と しない徳倫理を取るか、あるいは功利主義や結果主義を望む者は、宗教的な信念にその理論の根拠を置くことを提案した。 [22]『徳の後に』を著したアラスデア・マッキンタイアは、現代の徳倫理学の主要な貢献者であり提唱者であったが、マッキンタイアは客観的基準ではな く、文化的規範に基づく相対主義的な徳の説明を支持していると主張する者もいる[22]。現代の徳倫理学者であるマーサ・ヌスバウムは、とりわけマッキン タイアの相対主義に異議を唱えており、自身の著作『非相対的徳』において、客観的な説明を形成するために相対主義者の反論に反論している: しかし、ヌスバウムの相対主義に対する非難は誤読であるようだ。誰の正義か、誰の合理性か』において、マッキンタイアが相対主義を超えた合理的な道を歩も うとしたのは、「異なる伝統によってなされる対立する主張は、相対主義なしに評価されるべきものである」(354頁)と述べていることからも明らかであ り、それは実際に「対立する伝統の間での合理的な議論と合理的な選択が可能である」(352頁)からである。モーティマー・J・アドラーは、アリストテレ スの『ニコマコス倫理学』を「西洋の道徳哲学の伝統の中で唯一無二の書物であり、健全で実践的で、独断的でない唯一の倫理学である」と評している [25]。  フィリッパ・フットは、20世紀に徳倫理学を復活させた哲学者の一人である。 現代の徳倫理学における一つの大きな潮流は、現代ストア主義運動である。 直観倫理学 主な記事 倫理的直観主義 倫理的直観主義(道徳的直観主義とも呼ばれる)は、道徳認識論(および定義によっては形而上学)における見解の一群である。最低限、倫理的直観主義とは、価値に対する直観的な認識、あるいは評価事実に対する直観的な知識が、倫理的知識の基礎を形成するというテーゼである。 この見解は、その核心は道徳的知識に関する基礎論であり、いくつかの道徳的真理は非推論的に知ることができる(すなわち、自分が信じている他の真理から推 論する必要なく知ることができる)という見解である。このような認識論的見解は、命題的内容を持つ道徳的信念が存在することを意味し、認知主義を意味す る。そのため、倫理的直観主義は、道徳的認識論に対するコヒーレント主義的アプローチ(反省的均衡に依拠するアプローチなど)と対比されるべきものである [26]。 哲学文献を通して、「倫理的直観主義」という用語は、その意味において大きな差異を伴いながら頻繁に使用されている。本稿が基礎主義に焦点を当てているのは、現代の自称倫理的直観主義者の中核的なコミットメントを反映している[26][27]。 倫理的直観主義は十分に広義に定義され、認知主義的な形態の道徳的センス理論を包含しているとみなすことができる[28]。さらに通常、倫理的直観主義にとって、自明の、あるいは先験的な道徳的知識が存在することが不可欠であるとみなされる。 倫理的直観主義は、哲学者フランシス・ハッチソンによって初めて明確に使用されていることが示された。その後、影響力を持ち注目されるようになった倫理的 直観主義者には、ヘンリー・シドウィック、G.E.ムーア、ハロルド・アーサー・プリチャード、C.S.ルイス、そして最も影響力のあったロバート・アウ ディなどがいる[要出典]。 倫理的直観主義に対する反論には、客観的な道徳的価値観が存在するかどうか(倫理体系が基づいている前提)、倫理が絶対的なものであるならばなぜ多くの人 が倫理をめぐって意見を異にするのかという疑問、オッカムの剃刀がこのような理論を完全に打ち消すかどうかなどがある[要出典]。 ヘドニズム 主な記事 ヘドニズム ヘドニズムは、快楽を最大化し苦痛を最小化することを主要な倫理とする。ヘドニズムの思想には、刹那的な欲望さえも甘受することを主張するものから、精神 的な至福の追求を説くものまで、いくつかの学派がある。結果についての考察では、他者への苦痛や出費に関係なく自己満足を擁護するものから、最も倫理的な 追求は最も多くの人々にとっての快楽と幸福を最大化するものであるとするものまで様々である[19]: 37 キレネーの快楽主義 キュレネのアリスティッポスによって創始されたキュレネ派は、即時的な満足や快楽を支持した。"食べて、飲んで、陽気になれ、明日は死ぬのだから"。つか の間の欲望でさえ、その機会が永遠に失われることを恐れて、甘やかされるべきであった。未来への関心はほとんどなく、目先の快楽を追求することで現在が支 配された。キレネーの快楽主義は、快楽が唯一の善であると信じ、ためらうことなく楽しみと放縦を追求することを奨励した[19]: 37 エピクロス主義 主な記事 エピクロス主義 エピクロス倫理学は徳倫理学の快楽主義的形態である。エピクロスは「正しく理解された快楽は美徳と一致するという持続的な議論を提示した」[29]。彼は キレネ派の極端主義を否定し、一部の快楽や耽溺は人間にとって有害であると考えた。エピクロスは、無差別な耽溺が時に否定的な結果をもたらすことを観察し ていた。それゆえ、ある体験は頭から拒絶され、ある不快な体験は将来のよりよい生活を保証するために現在我慢することになった。エピクロスにとって、 sumum bonum(最大の善)とは、節度と注意によって行使される慎重さであった。過度の耽溺は快楽を破壊し、苦痛をもたらすことさえある。例えば、ある食べ物 を頻繁に食べ過ぎると、人はその味を感じなくなる。一度にたくさん食べると、不快感や不健康につながる。痛みや恐怖は避けるべきものだった。痛みや病気を 除けば、生きることは本質的に良いことだった。死は恐れるべきものではなかった。恐怖は不幸の元凶と考えられていた。死への恐怖を克服すれば、自ずと人生 は幸福になる。エピクロスは、死後の世界と不死があるならば、死を恐れるのは不合理だと考えた。死後の生がないのであれば、人は苦しみ、恐れ、心配するた めに生きているのではない。死後の世界が存在しないのに、自分の死の状態のような、存在しない状況について思い悩むのは不合理である[19]: 37- 38 国家結果主義 主な記事 国家結果主義 スタンフォード哲学百科事典(Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)は、紀元前5世紀まで遡る墨家による結果主義を「人間の福利を構成するものとして捉えられた複数の本質的財に基づく著しく洗練された バージョン」と説明している。 [31]快楽を道徳的善とみなす功利主義とは異なり、「墨家主義的帰結主義における基本的な財とは、...秩序、物質的豊かさ、人口の増加である」 [32]。墨家的帰結主義の「物質的豊かさ」とは、シェルターや衣服のような基本的なニーズのことであり、墨家的帰結主義の「秩序」とは、無意味であ り社会の安定を脅かすと見なした戦争や暴力に対する茂木のスタンスのことである[33]。 スタンフォード大学の中国学者デイヴィッド・シェパード・ニヴィソンは『The Cambridge History of Ancient China(ケンブリッジ古代中国史)』の中で、墨家主義の道徳的財は「相互に関連している:基本的な富が多ければ繁殖も多くなり、人が多ければ生産も 富も多くなる......もし人々が豊かであれば、善良で、孝行で、親切で、そういったことが問題なく行われるだろう」[32]と書いている。ベンサムの 見解とは対照的に、墨家結果主義は快楽主義でも個人主義でもないため、功利主義ではない。共同体にとって良い結果の重要性は、個人の快楽や苦痛の重要性を 凌駕する[34]。 帰結主義 主な記事 帰結主義 以下も参照: 倫理的エゴイズム 帰結主義とは、特定の行為の結果が、その行為に関する有効な道徳的判断の基礎を形成する(あるいは判断のための構造を形成する)とする道徳理論を指す (ルール結果主義を参照)。従って、帰結主義の立場からは、道徳的に正しい行為とは、良い結果(帰結)をもたらす行為である。この見解は、しばしば「目的 は手段を正当化する」という格言として表現される。 「帰結主義」という用語は、1958年にG.E.M.アンスコムが「現代の道徳哲学」というエッセイの中で、ミルやシドウィックによって提唱されたようなある種の道徳理論の中心的な誤りであると彼女が考えたものを説明するために作ったものである。 帰結主義道徳理論の特徴は、行為の正誤を評価する際に結果に重きを置くことである[36]。結果主義理論では、行為や規則の結果は一般的に他の考慮事項よ りも優先される。この基本的なアウトラインを除けば、結果主義について明確に言えることはほとんどない。しかし、多くの結果主義理論が扱ういくつかの疑問 がある: 良い結果とはどのような結果を指すのか? 道徳的行為の主な受益者は誰か? 結果はどのように判断され、誰がそれを判断するのか? 様々な帰結主義を分ける一つの方法は、最も重要であるとされる多くの種類の結果、つまりどの結果が良い状態としてカウントされるかによって分けられる。功 利主義によれば、善い行為とは増大する肯定的な効果をもたらす行為であり、最良の行為とは最大多数のためにその効果をもたらす行為である。これと密接に関 連するのが幸福帰結主義(eudaimonic consequentialism)であり、これによれば、多くの喜びを享受することと同じかどうかは別として、満ち足りた豊かな生活が究極の目的であ る。同様に、美を生み出すことを究極の目的とする美的帰結主義を採用することもできる。しかし、関連する効果として非心理的な財に焦点を当てるかもしれな い。例えば、刹那的な「快楽」ではなく、物質的平等や政治的自由の向上を追求する。他の理論では、複数の財のパッケージを採用し、すべてを等しく促進す る。特定の帰結主義理論が単一の財に焦点を当てるにせよ、多くの財に焦点を当てるにせよ、異なる財の状態間の対立や緊張は予想されることであり、裁定され なければならない[要出典]。 功利主義 主な記事 功利主義  ジェレミー・ベンサムと ジョン・スチュアート・ミル ジェレミー・ベンサムとジョン・スチュアート・ミルはこの学派の有力な支持者である[37]。ベンサムは『政府についての断片』の中で、「善悪の尺度であ るのは最大多数の最大幸福である」と述べ、これを基本公理としている。道徳と立法の原理序説』では「効用の原理」と述べているが、後に「最大の幸福の原 理」の方が好まれる[38][39]。 功利主義は結果主義の道徳理論の典型的な例である。この形態の功利主義は、道徳的に正しい行為とは、その行為によって影響を受けるすべての人々にとって最 良の結果をもたらす行為であるとする。ジョン・スチュアート・ミルは功利主義の説明の中で、ある種の快楽の追求が他の快楽の追求よりも高く評価されること を意味する快楽のヒエラルキーを提唱した[40]。功利主義の他の注目すべき支持者には、『The Moral Landscape』の著者である神経科学者のサム・ハリスや、『Practical Ethics』などの著者である道徳哲学者のピーター・シンガーがいる。 功利主義における大きな区分は、行為功利主義とルール功利主義である。行為功利主義では、選択状況における各代替行為に効用の原理が直接適用される。正し い行為とは、最良の結果(または最も悪い結果)をもたらす行為である。ルール功利主義では、効用原理が行動のルール(道徳原理)の妥当性を決定する。約束 を守るようなルールは、人々が勝手に約束を破る世界と、約束を拘束する世界の結果を見ることによって確立される。これら2つのタイプの間の「中間地点」と して提案されているのが、2レベル功利主義であり、通常の状況ではルールが適用されるが、異常な状況がそれを必要とする場合には、そのようなルールの範囲 外の行動を選択することができる。 義務論 詳細は「義務論的倫理」を参照 義務論的倫理または義務論(ギリシャ語の「義務、責務」を意味する「δέον(デオン)」および「-λογία(-ロギア)」に由来)は、行為や、その行 為を行う者が遂行しようとした規則や義務を調査することによって、善や正しさを判断する倫理へのアプローチである。これは、正しさが行為の結果のみに基づ いており、行為自体に基づかない功利主義とは対照的である。デオントロジーでは、たとえ悪い結果を招いたとしても、その行為が規則や道徳律に従っている場 合は正しいとみなされる可能性がある。[43] デオントロジーの観点では、人々は本質的に良いとみなされる方法で行動する義務(例えば「真実を語る」など)がある、または客観的に義務付けられている規 則に従う義務がある(規則功利主義の場合のように)。 カント主義 インマヌエル・カント 主な記事 カント倫理学 カントは、道徳的に正しい行動をとるためには、人は義務(Pflicht)から行動しなければならないと主張している。 道徳的に正しい方法で行動するためには、純粋に義務から行動しなければならないというカントの議論は、最高の善はそれ自体が善であり、かつ無条件に善でな ければならないという議論から始まる[47]。何かが「それ自体が善」であるのは、それが本質的に善であるときであり、「無条件に善」であるのは、その何 かが加わることによって状況が倫理的に悪化することがないときである。そしてカントは、知性、忍耐、快楽など、通常善であると考えられているものは、本質 的に善でもなければ、無条件に善でもないと主張する。例えば、快楽は無条件に善であるとは言えない。なぜなら、人が苦しむのを見て快楽を感じるとき、その 状況は倫理的に悪化するように思われるからである。彼は、真に善いものはひとつしかないと結論づける: 善なる意志を除いて、無条件に善と呼べるようなものは、この世界には、いや、この世界を超えるものでさえも、考えつくことはできない」[47]。 善い結果は、罪のない人に危害を加えたいという欲望に突き動かされた行為から偶然生じる可能性があり、悪い結果は、十分に動機づけられた行為から生じる可 能性があるからである。そうではなく、「道徳律を尊重して行動する」ときに、人は善意を持つのだと彼は主張する[47]。つまり、それ自体が真に善である ものは善意だけであり、善意が善であるのは、意志を持つ人が、それがその人の義務であるから、つまり法に対する「敬意」から何かをすることを選択したとき だけである。彼は尊重を「私の自己愛を妨げる価値の概念」と定義している[48]。 カントの定言命法の3つの重要な定式化は以下の通りである: 普遍的な法則となるような格言に従ってのみ行動しなさい。 自分自身であれ、他の人であれ、常に人間性を単なる手段としてではなく、常に同時に目的として扱うように行動しなさい。 すべての理性的存在は、あたかも自分がその格言を通じて、普遍的な目的の王国の立法メンバーであるかのように行動しなければならない。 カントは、唯一絶対的に善いものは善い意志であり、ある行為が道徳的に正しいかどうかを決定する唯一の要因は、それを行う人の意志、すなわち動機であると 主張した。例えば「私は嘘をつく」というような悪い最大公約数に基づいて行動しているのであれば、たとえ良い結果がもたらされたとしても、その行動は間 違っている。ベンジャミン・コンスタン(Benjamin Constant)の『政治的反応(Des réactions politiques)』に反論する小論『慈善的関心から嘘をつく権利について(On a Supposed Right to Lie because of Philanthropic Concerns)』の中で、カントは次のように述べている。「それゆえ、単に他者に対する意図的な真実でない宣言として定義される嘘は、法学者がその定 義で要求するような、他者に害を与えるという追加条件を必要としない(mendacium est falsiloquium in praeudicium alterius)。なぜなら、嘘は常に他者に害を及ぼすからである。ある人間でなくとも、権利の根源[Rechtsquelle]を冒涜する以上、それ は人類一般に害を及ぼすからである......。すべての権利の実践的原則は、厳格な真理を含んでいなければならない.というのも、そのような例外は、原 理が原理という名を冠するゆえんである普遍性を破壊してしまうからである」[49]。 神聖命令説 主な記事 神聖命令説 ラルフ・カドワース(イギリスの哲学者)によれば、オッカムのウィリアム、ルネ・デカルト、18世紀のカルヴァン主義者たちは皆、道徳的義務は神の命令か ら生じるとし、この道徳理論の様々なバージョンを受け入れていた。 [51] 神の命令説は脱ontologyの一形態であり、それによれば、あらゆる行為の正しさは、その行為から生じる善い結果のためではなく、その行為が義務であ るために実行されることに依存する。神が安息日に働くなと命じたのであれば、安息日に働かないことは正しい行為である。怠け者だから安息日に働かないので あれば、実際に行われる物理的な行動は同じであっても、その行動は本当の意味で「正しい」とは言えない。神が隣人の財を貪るなと命じているのであれば、た とえ貪ることが成功や成功への意欲という有益な結果をもたらすとしても、そうすることは不道徳であるというのがこの理論である。 カント主義的脱ontologismと神的命令的脱ontologismを明確に区別する一つの点は、カント主義が理性的存在である人間が道徳法則を普遍的なものにすると主張するのに対し、神的命令は神が道徳法則を普遍的なものにすると主張することである。 言説倫理学  カント倫理学の影響を受けた言説倫理学の理論を持つユルゲン・ハーバーマスの写真。 主な記事 言説倫理学 ドイツの哲学者ユルゲン・ハーバーマスは、カント倫理学の流れを汲む言説倫理学の理論を提唱している[52]。カント倫理学と同様に、言説倫理学は認知倫 理理論であり、倫理的命題に真理と偽りを帰属させることができると仮定している。またカントの倫理学と同様に、倫理的行為を決定することができるルールを 定式化し、倫理的行為が普遍化可能であるべきであると提唱している[54]。 ハーバーマスは自身の倫理理論がカントの倫理学の改善であると主張している[54]。カントは、人間が知覚し経験することができる現象世界と、人間にはア クセスできないヌーメナ(精神世界)とを区別していた。この二分法はカントにとって必要なものであり、人間の主体性を説明することができるからである。人 間は現象界では束縛されているが、根源界では行動は自由である。ハーバーマスにとっては、道徳は言説から生じるものであり、言説は人間の自由というよりも むしろ合理性とニーズによって必要とされるものである[55]。 プラグマティック倫理学 主な記事 プラグマティック倫理学 プラグマティストのチャールズ・サンダーズ・ピアース、ウィリアム・ジェイムズ、そして特にジョン・デューイに関連するプラグマティック倫理学は、道徳的 正しさは科学的知識と同様に、何度も人生をかけて社会的に進化していくものだと考えている。したがって、結果や個人の美徳や義務を説明する試みよりも、社 会改革を優先すべきである(社会改革が提供されるのであれば、これらは価値のある試みかもしれないが)[56]。 ケアの倫理 主な記事 ケアの倫理 ケア倫理学は、結果論的理論(例えば功利主義)や脱自律論的理論(例えばカント倫理学)といった、よりよく知られた倫理モデルとは対照的に、伝統的に女性化された美徳や価値を取り入れようとするものである。こうした価値観には、共感的な関係や思いやりの重要性が含まれる。 ケア重視のフェミニズムはフェミニズム思想の一分野であり、主にキャロル・ギリガン[57]とネル・ノディングズ[58]によって展開されたケアの倫理学 に影響を受けている。ケアを重視するフェミニストたちは、女性のケア能力を人間的な強さとみなしており、それは女性だけでなく男性にも教えられ、期待され るべきものである」と彼らは書いている。ノディングスのケア重視のフェミニズムは、ケアの倫理を前提とした関係倫理の実践的な適用を要求している [60]。 フェミニスト的母系倫理学 主な記事 フェミニスト倫理学 1985年以来、ブラチャ・L・エッティンガーの造語であり、発展させた、母系的まなざしと母系的[61][62]時間空間に関する「メタフェミニズム」 理論[61][62]。この革命的な哲学的アプローチは、エッティンガーの倫理的転回をグリゼルダ・ポロックが表現した[67][68]「母性以前の出会 いを伴う出生前」、戦争における女性への暴力、そしてショアーに「あえて接近する」ことで、自らの生殖可能な身体に対する各女性主体の権利を哲学的に確立 し、男根の領域から逃れた人間の経験に関係する言語を提供してきた。 [69][70]マトリクス領域は、「男根」的な言語や規制では制御できない精神的・象徴的な次元である。エッティンガーのモデルでは、自己と他者との関 係は同化でも拒絶でもなく、「合体」である。エマニュエル・レヴィナスとの対話(1991年)の中で、エッティンガーは、人間の倫理の源泉は、女性性-母 性、女性性-母性以前の母性的な出会いの出来事であると提唱している。セクシュアリティと母性は共存し、矛盾するものではなく(ジークムント・フロイトと ジャック・ラカンが確立した矛盾)、女性性は絶対的な変質性ではない(ジャック・ラカンとエマニュエル・レヴィナスが確立した変質性)。エッティンガー的 なマトリックス的時間空間において起こる「起源的な反応能力」、「ウィット(h)ネッシング」、「ボーダーリンキング」、「コミュニケアリング」、「コム パッション」、「生への誘惑」[71][72]などの影響によって投資されるプロセスによって、女性性はすべてのジェンダーにおいて人間化された倫理性の 源泉として提示される。慈愛と生への誘惑は、ジャン・ラプランシュによれば、母性的なセクシュアリティからの謎めいたシグナルを通過する一次的な誘惑より も早く起こる。エッティンガーは1991年のエマニュエル・レヴィナスとの対談の中で、母性的な視点を通して理解される女性性は倫理学の中心であり源泉で あることを示唆している[73][74]。生命の始まりにおいて、幼児によって感じられる起源的な「ファシナンス」[75]は、m/Otherによって操 作され伝達される、応答可能性から責任へ、com-passionからcompassionへ、with(h)nessingからwitnessingへ の通過に関連している。境界の流動性を通して性的差異を再考する新たな方法を提案するマトリクス理論は、「出会い-出来事としての主観性」[78] [79]における慈愛、運搬、非放棄の美学と倫理に影響を与えるものであり、精神分析やトランスジェンダー研究において重要な意味を持っている[80]。 役割倫理 主な記事 役割倫理 役割倫理は家族の役割に基づく倫理理論である[81]。美徳倫理とは異なり、役割倫理は個人主義的ではない。ロジャー・T・エイムズとヘンリー・ローズモ ントによれば、"儒教の規範性は家族の役割を最大限効果的に生きることによって定義される"。道徳は、親や子といった役割を果たすことによって決まる。儒 教的な役割は合理的なものではなく、心、つまり人間の感情を通じて発生するものである[82]。 アナキズム倫理学 主な記事 アナキズム アナーキスト倫理学は、アナーキスト思想家の研究に基づいた倫理理論である。無政府主義倫理学の最大の貢献者はピーター・クロポトキンである。 クロポトキンの倫理的枠組みは、生物学と人類学を基礎として、ある社会秩序が生物学的・社会的に繁栄するために何が最適かを科学的に立証するものであり、人類の自由と幸福の能力を高めるための特定の行動実践、すなわち連帯、平等、正義を強調する実践を提唱している。 クロポトキンは、倫理そのものが進化論的なものであり、文化的な歴史を通じて一種の社会的本能として受け継がれるものであると主張し、それによって道徳に 関する宗教的で超越論的な説明を一切否定している。動物と人間の両方における倫理的感情の起源は、「社会性」(相互主義的共生)という自然的事実の中に見 出すことができると彼は主張し、人間はそれを正義(すなわち平等)の本能と結合させ、さらに理性の実践と結合させることで、超自然的でない無政府主義的な 倫理体系を構築することができる[85]。クロポトキンは、無政府主義の核心にある平等の原理は黄金律と同じであると示唆している: 自分がされたいと思うように他者を扱うというこの原則は、無政府主義の基本原理である平等とまったく同じ原理以外の何ものなのだろうか。この原則を実践し ない限り、どうして自分をアナーキストだと信じることができようか。私たちは支配されることを望まない。そして、まさにこの事実によって、われわれ自身が 誰も支配したくないと宣言しているではないか。われわれは欺かれることを望まず、常に真実のみを告げられることを望む。そして、まさにこの事実によって、 私たち自身が誰も欺くことを望まず、私たちは常に真実を、真実以外の何ものでもなく、完全な真実を語ることを約束すると宣言しないでしょうか?私たちは労 働の成果を奪われることを望まない。そして、その事実によって、私たちは他人の労働の成果を尊重すると宣言するのではないだろうか?他人をまったく異なる やり方で扱うことを自分たちに留保しておきながら、自分があるやり方で扱われることを要求できる権利があるだろうか?私たちの平等意識は、そのような考え に反旗を翻す[86]。 ポストモダンの倫理 主な記事 ポストモダニズム この記事またはセクションには、本トピックへの言及や関連性が確認できない資料の統合が含まれている可能性がある。関連する議論はトークページにあります。(2009年7月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) ルイ・アルチュセール、ミシェル・フーコー、ロラン・バルトのような構造主義者のような反人間主義者は、個人の主体性の可能性と「個人」という概念自体の 一貫性に異議を唱えた。これは、個人のアイデンティティは、その大部分が社会的な構築物であるという根拠に基づいていた。20世紀後半に批評理論が発展す るにつれ、ポスト構造主義は知識と「客観的」現実との人間関係を問題化しようとした。ジャック・デリダは、意味や「現実」へのアクセスは常に後回しにされ ると主張し、「テキストの外/非テキストは存在しない」("il n'y a pas de hors-texte "はしばしば「テキストの外には何もない」と誤訳される)ことを、言語的領域に依拠することで実証しようとした。同時に、ジャン・ボードリヤールは、特に 消費社会においては、記号やシンボル、あるいはシミュラクラが現実(ひいては現実そのものの不在)を覆い隠すと理論化した。 ポスト構造主義とポストモダニズムは、倫理は行為の複雑で関係的な条件を研究しなければならないと主張する。正しいという考え方と特定の行為を単純に一致 させることは不可能である。考慮することができない、あるいはしばしば認識することさえできない倫理的な残余が常に存在する。このような理論家は、ナラ ティヴ(あるいはニーチェやフーコーに倣って系譜学)が倫理を理解するための有用なツールであると考える。なぜなら、ナラティヴは常に、個別的で個別の行 為に観念や規範を割り当てるのではなく、あらゆる複雑さの中で特定の生きた経験について語るものだからである。 ジグムント・バウマンは、ポストモダンは幻想のないモダンと表現するのが最も適切であり、幻想とは、人類が何らかの倫理原則によって修復されると信じるこ とである、と述べている。このように考えると、ポストモダンは、人間の厄介な性質を変えられないものとして受け入れることだと言える。このポストモダンの 世界では、大規模な問題を解決するために集団的かつグローバルに行動する手段は、すべて信用されなくなり、解体され、あるいは失われている。問題は局所的 で、それぞれが独自にしか対処できない。すべての問題処理は、他の場所の秩序を犠牲にしてミニ秩序を構築することを意味し、その代償として世界的な無秩序 が増大し、秩序を可能にする資源の供給が枯渇する。彼はエマニュエル・レヴィナスの倫理学をポストモダンとみなしている。他者を両義的な存在として自己の 外側に置いておく近代の倫理哲学とは異なり、レヴィナスの哲学は他者を隣人として、また道徳的な自己がそれ自身を獲得していく過程における重要な登場人物 として再認識させる[87]。 デイヴィッド・クーゼンス・ホイは、エマニュエル・レヴィナスの他者の顔に関する著作とデリダの倫理と死の関連性に関する考察は、1980年代と1990 年代に起こった大陸哲学における「倫理的転回」の兆候であると述べている。ホイはポスト批評倫理を「必然的に果たさなければならないものとして自らを提示 するが、人に強制されるものでも強制可能なものでもない義務」と表現している[88]。 ホイのポスト批判モデルは倫理的抵抗という用語を使用している。この例としては、よりシンプルだがおそらくは困難なライフスタイルへの後退における消費主 義に対する個人の抵抗や、末期的な病気に対する個人の抵抗が挙げられる。ホイはレヴィナスの説明を「それ自身に対して権力を行使する試みでもなく、政治的 権力を行使するために人口の一部を動員する試みでもない。 ホイは次のように結論づけている。 それゆえ、われわれが他者に対して権力を行使する能力に対する無力な他者の倫理的抵抗は、われわれに強制力のない義務を課すものである。その義務は、まさ に他者に力がないからこそ、強制不可能なのである。行為が義務的であると同時に強制不可能であることが、倫理的な範疇に入る理由なのである。強制される義 務は、その背後にある力によって、自由に引き受けられるものではなく、倫理的な領域にはないだろう[90]。 |