デレク・パーフィット

Derek Antony Parfit. 1942-2017

☆ デレク・アントニー・パーフィット FBA(Derek Antony Parfit、1942 年12月11日 - 2017年1月2日)は、人格の同一性、合理性、倫理学を専門とするイギリスの哲学者である。彼は20世紀後半から21世紀初頭にかけて最も 重要で影響力のある道徳哲学者の一人であると広く考えられている。 パーフィットは1971年に最初の論文「Personal Identity」を発表し、一躍注目を集めた。最初の著書『Reasons and Persons』(1984年)は、1800年代以降の道徳哲学における最も重要な著作と評されている。2冊目の著書『On What Matters』(2011年)は、出版前から広く読まれ、長年議論されていた。 パーフィットは、その学術的なキャリア全体を通じてオックスフォード大学で研究を続け、死去時にはオール・ソウルズ・カレッジの名誉上級研究員であった。 また、ハーバード大学、ニューヨーク大学、ラトガース大学では哲学の客員教授も務めた。パーフィットは、「個人のアイデンティティ、次世代への配慮、道徳 理論の構造分析に関する画期的な貢献」により、2014年のロルフ・ショック賞を受賞した。

| Derek Antony Parfit

FBA (/ˈpɑːrfɪt/; 11 December 1942 – 2 January 2017[3][4]) was a British

philosopher who specialised in personal identity, rationality, and

ethics. He is widely considered one of the most important and

influential moral philosophers of the late 20th and early 21st

centuries.[5][6][7] Parfit rose to prominence in 1971 with the publication of his first paper, "Personal Identity". His first book, Reasons and Persons (1984), has been described as the most significant work of moral philosophy since the 1800s.[6][7] His second book, On What Matters (2011), was widely circulated and discussed for many years before its publication. For his entire academic career, Parfit worked at Oxford University, where he was an Emeritus Senior Research Fellow at All Souls College at the time of his death. He was also a visiting professor of philosophy at Harvard University, New York University, and Rutgers University. He was awarded the 2014 Rolf Schock Prize "for his groundbreaking contributions concerning personal identity, regard for future generations, and analysis of the structure of moral theories."[8] |

デレク・アントニー・パーフィット

FBA(/ˈpɑːrfɪt/、1942年12月11日 -

2017年1月2日[3][4])は、人格の同一性、合理性、倫理学を専門とするイギリスの哲学者である。彼は20世紀後半から21世紀初頭にかけて最も

重要で影響力のある道徳哲学者の一人であると広く考えられている。[5][6][7] パーフィットは1971年に最初の論文「Personal Identity」を発表し、一躍注目を集めた。最初の著書『Reasons and Persons』(1984年)は、1800年代以降の道徳哲学における最も重要な著作と評されている。[6][7] 2冊目の著書『On What Matters』(2011年)は、出版前から広く読まれ、長年議論されていた。 パーフィットは、その学術的なキャリア全体を通じてオックスフォード大学で研究を続け、死去時にはオール・ソウルズ・カレッジの名誉上級研究員であった。 また、ハーバード大学、ニューヨーク大学、ラトガース大学では哲学の客員教授も務めた。パーフィットは、「個人のアイデンティティ、次世代への配慮、道徳 理論の構造分析に関する画期的な貢献」により、2014年のロルフ・ショック賞を受賞した。[8] |

| Early life and education Parfit was born in 1942 in Chengdu, China, the son of Jessie (née Browne) and Norman Parfit, medical doctors who had moved to Western China to teach preventive medicine in missionary hospitals. The family returned to the United Kingdom about a year after Parfit was born, settling in Oxford. Parfit was educated at the Dragon School and Eton College, where he was nearly always at the top of the regular rankings in every subject except maths.[9] From an early age, he endeavoured to become a poet, but he gave up poetry towards the end of his adolescence.[7] He then studied modern history at Balliol College, Oxford, graduating in 1964. In 1965–66, he was a Harkness Fellow at Columbia University and Harvard University. He abandoned historical studies for philosophy during the fellowship.[10] Career Parfit returned to Oxford to become a fellow of All Souls College, where he remained until he was 67, when the university’s mandatory retirement policy required him to leave both the college and the faculty of philosophy. He retained his appointments as regular Visiting Professor at Harvard, NYU, and Rutgers until his death. |

幼少期と教育 パーフィットは1942年、中国四川省の成都で、宣教師病院で予防医学を教えるために中国西部に移住していた医師、ジェシー(旧姓ブラウン)とノーマン・ パーフィットの間に生まれた。パーフィットが生まれてから約1年後、一家は英国に戻り、オックスフォードに定住した。パーフィットはドラゴン・スクールと イートン・カレッジで教育を受け、数学以外のすべての科目でほぼ常に成績上位者であった。[9] 幼い頃から詩人になることを目指していたが、思春期の終わり頃に詩作を断念した。[7] その後、オックスフォード大学ベリオール・カレッジで近代史を学び、1964年に卒業した。1965年から66年にかけて、ハーバード大学とコロンビア大 学でハーネスフェローを務めた。フェローシップ期間中に、歴史学から哲学へと転向した。 経歴 パーフィットはオックスフォードに戻り、オール・ソウルズ・カレッジの研究員となった。67歳になるまで同カレッジに在籍したが、この年齢に達すると、大 学が定める定年退職規定により、カレッジおよび哲学部の両方を去らなければならなかった。 パーフィットは、ハーバード大学、ニューヨーク大学、ラトガース大学の正客員教授としての職を死ぬまで維持した。 |

| Ethics and rationality Reasons and Persons Main article: Reasons and Persons In Reasons and Persons, Parfit suggested that nonreligious ethics is a young and fertile field of inquiry. He asked questions about which actions are right or wrong and shied away from meta-ethics, which focuses more on logic and language. In Part I of Reasons and Persons Parfit discussed self-defeating moral theories, namely the self-interest theory of rationality ("S") and two ethical frameworks: common-sense morality and consequentialism. He posited that self-interest has been dominant in Western culture for over two millennia, often making bedfellows with religious doctrine, which united self-interest and morality. Because self-interest demands that we always make self-interest our supreme rational concern and instructs us to ensure that our whole life goes as well as possible, self-interest makes temporally neutral requirements. Thus it would be irrational to act in ways that we know we would prefer later to undo. As an example, it would be irrational for fourteen-year-olds to listen to loud music or get arrested for vandalism if they knew such actions would detract significantly from their future well-being and goals (such as having good hearing, a good job, or an academic career in philosophy). Most notably, the self-interest theory holds that it is irrational to commit any acts of self-denial or to act on desires that negatively affect our well-being. One may consider an aspiring author whose strongest desire is to write a masterpiece, but who, in doing so, suffers depression and lack of sleep. Parfit argues that it is plausible that we have such desires which conflict with our own well-being, and that it is not necessarily irrational to act to fulfill these desires. Aside from the initial appeal to plausibility of desires that do not directly contribute to one's life going well, Parfit contrived situations where self-interest is indirectly self-defeating—that is, it makes demands that it initially posits as irrational. It does not fail on its own terms, but it does recommend adoption of an alternative framework of rationality. For instance, it might be in my self-interest to become trustworthy to participate in mutually beneficial agreements, even though in maintaining the agreement I will be doing what will, other things being equal, be worse for me. In many cases self-interest instructs us precisely not to follow self-interest, thus fitting the definition of an indirectly self-defeating theory.[11]: 163–165 Parfit contended that to be indirectly individually self-defeating and directly collectively self-defeating is not fatally damaging for S. To further bury self-interest, he exploited its partial relativity, juxtaposing temporally neutral demands against agent-centred demands. The appeal to full relativity raises the question whether a theory can be consistently neutral in one sphere of actualisation but entirely partial in another. Stripped of its commonly accepted shrouds of plausibility that can be shown to be inconsistent, self-interest can be judged on its own merits. While Parfit did not offer an argument to dismiss S outright, his exposition lays self-interest bare and allows its own failings to show through.[citation needed] It is defensible, but the defender must bite so many bullets that they might lose their credibility in the process. Thus a new theory of rationality is necessary. Parfit offered the "critical present aim theory", a broad catch-all that can be formulated to accommodate any competing theory. He constructed critical present aim to exclude self-interest as our overriding rational concern and to allow the time of action to become critically important. But he left open whether it should include "to avoid acting wrongly" as our highest concern. Such an inclusion would pave the way for ethics. Henry Sidgwick longed for the fusion of ethics and rationality, and while Parfit admitted that many would avoid acting irrationally more ardently than acting immorally, he could not construct an argument that adequately united the two. Where self-interest puts too much emphasis on the separateness of persons, consequentialism fails to recognise the importance of bonds and emotional responses that come from allowing some people privileged positions in one's life. If we were all pure do-gooders, perhaps following Sidgwick, that would not constitute the outcome that would maximise happiness. It would be better if a small percentage of the population were pure do-gooders, but others acted out of love, etc. Thus consequentialism too makes demands of agents that it initially deemed immoral; it fails not on its own terms, for it still demands the outcome that maximises total happiness, but does demand that each agent not always act as an impartial happiness promoter. Consequentialism thus needs to be revised as well. Self-interest and consequentialism fail indirectly, while common-sense morality is directly collectively self-defeating. (So is self-interest, but self-interest is an individual theory.) Parfit showed, using interesting examples and borrowing from Nashian games, that it would often be better for us all if we did not put the welfare of our loved ones before all else. For example, we should care not only about our kids, but everyone's kids. ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Reasons and Persons ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Reasons and Persons is a 1984 book by the philosopher Derek Parfit, in which the author discusses ethics, rationality and personal identity. It is divided into four parts, dedicated to self-defeating theories, rationality and time, personal identity and responsibility toward future generations. Summary Self-defeating theories Part 1 argues that certain ethical theories are self-defeating. One such theory is ethical egoism, which Parfit claims is 'collectively self-defeating' due to the prisoner's dilemma, though he does not believe this is sufficient grounds to reject the theory. Ultimately, Parfit does reject "common sense morality" on similar grounds. In this section, Parfit does not explicitly endorse a particular view; rather, he shows what the problems of different theories are. His only positive endorsement is of "impersonal ethics" – impersonality being the common denominator of the different parts of the book. Rationality and time Part 2 focuses on the relationship between rationality and time, dealing with questions such as: should we take into account our past desires?, should I do something I will regret later, even if it seems a good idea now?, and so on. Parfit's main purpose in Part 2 is to make an argument against self-interest theory. Self-interest theorists consider the differences between different persons to be extremely important, but do not consider the differences between the same person at different times to be important at all. Parfit argues that this makes self-interest theory vulnerable to attack from two directions. It can be compared to morality on one side, and 'present-aim theory' on the other. Parfit argues that our present aims can sometimes conflict with our long term self-interest. Arguments that a self-interest theorist uses to explain why it is irrational to act on such aims, can be turned against the self-interest theorist, and used as arguments in favor of morality. Conversely, arguments that a self-interest theorist uses against morality could also be used as arguments in support of 'present-aim' theory. Personal identity Part 3 argues for a reductive account of personal identity; rather than accepting the claim that our existence is a deep, significant fact about the world, Parfit's account of personal identity is like this: At time 1, there is a person. At a later time 2, there is a person. These people seem to be the same person. Indeed, these people share memories and personality traits. But there are no further facts in the world that make them the same person. Parfit's argument for this position relies on our intuitions regarding thought experiments such as teleportation, the fission and fusion of persons, gradual replacement of the matter in one's brain, gradual alteration of one's psychology, and so on. For example, Parfit asks the reader to imagine entering a "teletransporter," a machine that puts you to sleep, then destroys you, breaking you down into atoms, copying the information and relaying it to Mars at the speed of light. On Mars, another machine re-creates you (from local stores of carbon, hydrogen, and so on), each atom in exactly the same relative position. Parfit poses the question of whether or not the teletransporter is a method of travel—is the person on Mars the same person as the person who entered the teletransporter on Earth? Certainly, when waking up on Mars, you would feel like being you, you would remember entering the teletransporter in order to travel to Mars, you would even feel the cut on your upper lip from shaving this morning. Then the teleporter is upgraded. The teletransporter on Earth is modified to not destroy the person who enters it, but instead it can simply make infinite replicas, all of whom would claim to remember entering the teletransporter on Earth in the first place. Using thought experiments such as these, Parfit argues that any criteria we attempt to use to determine sameness of person will be lacking, because there is no further fact. What matters, to Parfit, is simply "Relation R," psychological connectedness, including memory, personality, and so on. Parfit continues this logic to establish a new context for morality and social control. He cites that it is morally wrong for one person to harm or interfere with another person and it is incumbent on society to protect individuals from such transgressions. That accepted, it is a short extrapolation to conclude that it is also incumbent on society to protect an individual's "Future Self" from such transgressions; tobacco use could be classified as an abuse of a Future Self's right to a healthy existence. Parfit resolves the logic to reach this conclusion, which appears to justify incursion into personal freedoms, but he does not explicitly endorse such invasive control. Parfit's conclusion is similar to David Hume's bundle theory, and also to the view of the self in Buddhism's Skandha, though it does not restrict itself to a mere reformulation of them. For besides being reductive, Parfit's view is also deflationary: in the end, "what matters" is not personal identity, but rather mental continuity and connectedness. Future generations Part 4 deals with questions of our responsibility towards future generations, also known as population ethics. It raises questions about whether it can be wrong to create a life, whether environmental destruction violates the rights of future people, and so on. One question Parfit raises is this: given that the course of history drastically affects what people are actually born (since it affects which potential parents actually meet and have children; and also, a difference in the time of conception will alter the genetic makeup of the child), do future persons have a right to complain about our actions, since they likely wouldn't exist if things had been different? This is called the non-identity problem. Another problem Parfit looks at is the mere addition paradox, which supposedly shows that it is better to have a lot of people who are slightly happy, than a few people who are very happy. Parfit calls this view "repugnant", but says he has not yet found a solution. Reception Bernard Williams described Reasons and Persons as "brilliantly clever and imaginative", and commended it as part of a wave of work in analytic philosophy that deals with concrete moral problems rather than abstract meta-ethics.[1] Philip Kitcher wrote in his review of Parfit's On What Matters that Reasons and Persons "was widely viewed as an outstanding contribution to a cluster of questions in metaphysics and ethics".[2] Peter Singer included Reasons and Persons on a top ten list of favourite books in The Guardian, stating that "Parfit's penetrating thought and spare prose make this one of the most exciting, if challenging, works by a contemporary philosopher".[3] Writing for The New York Review of Books, the philosopher P.F. Strawson gave the book a positive review, stating "Very few works in the subject can compare with Parfit’s in scope, fertility, imaginative resource, and cogency of reasoning".[4] In an interview, David Chalmers said that he "loved" Reasons and Persons, saying that it gave him a "sense of how powerful analytic philosophy can be when done clearly and accessibly."[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reasons_and_Persons ++++++++++++++++++++ On What Matters ++++++++++++++++++++ Main article: On What Matters In his second book, Parfit argues for moral realism, insisting that moral questions have true and false answers. Further, he suggests that the three most prominent categories of views in moral philosophy—Kantian deontology, consequentalism, and contractarianism (or contractualism)—converge on the same answers to moral questions. In the book he argues that the affluent have strong moral obligations to the poor: "One thing that greatly matters is the failure of we rich people to prevent, as we so easily could, much of the suffering and many of the early deaths of the poorest people in the world. The money that we spend on an evening’s entertainment might instead save some poor person from death, blindness, or chronic and severe pain. If we believe that, in our treatment of these poorest people, we are not acting wrongly, we are like those who believed that they were justified in having slaves. Some of us ask how much of our wealth we rich people ought to give to these poorest people. But that question wrongly assumes that our wealth is ours to give. This wealth is legally ours. But these poorest people have much stronger moral claims to some of this wealth. We ought to transfer to these people [...] at least ten per cent of what we earn."[12] Criticism In his book On Human Nature, Roger Scruton criticised Parfit's use of moral dilemmas such as the trolley problem and lifeboat ethics to support his ethical views, writing, "These 'dilemmas' have the useful character of eliminating from the situation just about every morally relevant relationship and reducing the problem to one of arithmetic alone." Scruton believed that many of them are deceptive; for example, he does not believe one must be a consequentialist to believe that it is morally required to pull the switch in the trolley problem, as Parfit assumes. He instead suggests that more complex dilemmas, such as Anna Karenina's choice to leave her husband and child for Vronsky, are needed to fully express the differences between opposing ethical theories, and suggests that deontology is free of the problems that (in Scruton's view) beset Parfit's theory.[13] ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ On What Matters ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ On What Matters is a three-volume book of moral philosophy by Derek Parfit. The first two volumes were published in 2011 and the third in 2017. It is a follow-up to Parfit's 1984 book Reasons and Persons. It has an introduction by Samuel Scheffler. Summary Parfit defends an objective ethical theory and suggests that we have reasons to act that cannot be accounted for by subjective ethical theories. Furthermore, it attempts to present a moral theory that combines three traditional approaches in moral and political philosophy: Kantian deontology, consequentialism, and contractualism (of the sort advocated by T. M. Scanlon, and from the tradition of Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Rawls).[1] According to Parfit, these theories converge rather than disagree, "climbing the same mountain on different sides", in Parfit's metaphor.[2] Parfit labels his synthesis of these three ethical theories the "Triple Theory":[3] An act is wrong if and only if, or just when, such acts are disallowed by some principle that is 1. one of the principles whose being universal laws would make things go best, 2. one of the only principles whose being universal laws everyone could rationally will.... 3. a principle that no one could reasonably reject. On Parfit's view, these three criteria (a) represent the best versions of consequentialism, Kantian ethics, and contractualism respectively, and (b) should generally agree in their recommendations. Both claims have proven controversial. Writing The manuscript, originally titled Climbing the Mountain, circulated for many years prior to publication, and occasioned a great deal of excitement, including reading groups and a conference prior to publication.[4] Some of On What Matters is derived from lectures given at the University of California, Berkeley as part of the Tanner Lectures on Human Values in 2002. As part of that series at Berkeley, Parfit's lectures were responded to by Allen W. Wood, T. M. Scanlon and Susan Wolf.[5] Reception The economist Tyler Cowen has expressed admiration for Parfit's style ("Reading him is an unforgettable and illuminating experience") in On What Matters, but argues: I see the biggest and most central part of the book as a failure, possibly wrong but more worryingly "not even wrong" and simply missing the questions defined by where the frontier – choice theory and not just philosophic ethics – has been for some time.[6] Peter Singer was far more positive, saying that Parfit's arguments "put those who reject objectivism in ethics on the defensive".[7] Constantine Sandis raises an objection to Parfit's project: the various "theories may well converge on their recommendations, but to think that the actions that follow from them are all that matters is to already presuppose the truth of consequentialism". Sandis jokes that the significance of Parfit's work, despite his scant publication record, should cause us to question the "publish or perish" demands of the Research Excellence Framework, but "whether it will change the way we think about morality remains to be seen".[2] The sheer length of time Parfit took to write the text, and the increasing incompatibility of such extended work with the demands of academic life was raised by Nigel Thrift, vice-chancellor of the University of Warwick, in a blog post on the Chronicle of Higher Education website: Parfit's life has been able to be intellectually uncompromising because he found the infrastructure – especially All Souls College in Oxford, which does no undergraduate teaching – that allowed it to be. But I wonder how much longer that kind of infrastructure will be available in all but a few universities.[8] The philosopher Roger Scruton questioned the appropriateness of the title of the book, writing in 2015 "Nothing that really matters to human beings – their loves, responsibilities, attachments, their delights, aesthetic values, and spiritual needs – occurs in Parfit’s interminable narrative. All is swept into a corner by the great broom of utilitarian reasoning, to be left there in a heap of dust".[9] |

倫理と合理性 理由と人格(「理性と人格」※以下では「理由と人」とも記載) 詳細は「 理由と人格」を参照 『 理由と人格』において、パーフィットは非宗教的な倫理はまだ歴史が浅く、研究の余地が大きい分野であると示唆した。彼は、どのような行動が正しいか、ある いは間違っているかについて疑問を投げかけ、論理や言語に重点を置くメタ倫理学からは 距離を置いた。 パー フィットは『 理由と人格』の第一部で、自己矛盾した道徳理論、すなわち合理性の利己主義理論(「S」)と、2つの倫理的枠組み、すなわち常識道徳と 帰結主 義について論じている。パーフィットは、自己利益は2千年以上にわたって西洋文化において支配的であり、しばしば宗教的教義と結びついて自己利益と道徳 性を一体化させてきたと主張した。自己利益は、常に自己利益を最高の合理的な関心事とし、人生全体が可能な限りうまくいくようにすべきであると要求してい るため、自己利益は時間的に中立的な要求である。したがって、後に元に戻したいと考えるような行動を取ることは不合理である。 例えば、14歳の若者が、将来の幸福や目標(例えば、聴力が良好であること、良い仕事に就くこと、哲学の学問的キャリアなど)を著しく損なうと知りなが ら、大音量の音楽を聴いたり、破壊行為で逮捕されたりするのは不合理である。 とりわけ、利己主義理論では、自己否定行為や、幸福に悪影響を及ぼすような欲求に従うことは非合理的であると主張している。例えば、偉大な作品を書くこと を強く望む作家志望者がいるとする。しかし、そうすることで、うつ病や睡眠不足に悩まされる。パーフィットは、私たちが自身の幸福に反するような欲求を抱 くことはあり得ることであり、そうした欲求を満たすために行動することは必ずしも非合理的ではないと主張している。 自分の生活がうまくいくことに直接貢献しない欲望の妥当性という当初の主張はさておき、パーフィットは、利己主義が間接的に自己矛盾を引き起こす状況を作 り出した。つまり、当初は非合理的と想定していた要求を突きつけるのである。利己主義は、その主張自体が間違っているわけではないが、合理性の代替フレー ムワークの採用を推奨している。例えば、相互に有益な合意に参加するにあたり、信頼に足る人物となることは、私にとって利益となるかもしれない。合意を維 持するにあたり、他の条件が同じであれば、私にとって不利となることを行うことになるが。多くの場合、利己主義は、まさに利己主義に従わないよう私たちに 指示する。したがって、間接的に自己を敗北させる理論の定義に当てはまる。[11]: 163–165 パーフィットは、間接的に個人にとって自己矛盾であり、直接的に集団にとって自己矛盾であることは、Sにとって致命的なダメージではないと主張した。利己 主義をさらに葬り去るために、彼は利己主義の部分的相対性を活用し、時間的に中立的な要求とエージェント中心の要求を並置した。完全な相対性への訴えは、 理論が一つの実現の領域では一貫して中立であり、別の領域では完全に部分的であることができるかどうかという疑問を提起する。一般的に受け入れられている 妥当性の仮面を剥ぎ取り、一貫性のないことが示されれば、利己主義はそれ自身の価値で判断される。パーフィットはSを完全に否定する議論は提示していない が、彼の論述は利己主義をむき出しにし、その欠点が露わになる。それは擁護できるが、擁護者は多くの問題に直面し、その過程で信頼性を失う可能性がある。 したがって、合理性の新たな理論が必要である。パーフィットは、あらゆる競合する理論を包含できる包括的な理論として「クリティカル・プレゼント・エイム 理論」を提示した。パーフィットは、利己主義を最優先の合理的な関心事から除外し、行動のタイミングを極めて重要なものとするためにクリティカル・プレゼ ント・エイムを構築した。しかし、パーフィットは、最優先の関心事として「誤った行動を避けること」を含めるべきかどうかについては明確にしなかった。そ のような含みがあれば、倫理への道が開かれる。ヘンリー・シジウィックは倫理と合 理性の融合を切望し、パーフィットも多くの人が非道徳的な行動よりも非合 理的な行動を避けることを強く望むことを認める一方で、この2つを適切に結びつける論拠を構築することはできなかった。 利己主義が人格の分離を過度に重視するあまり、帰結主義は、人生において一部の人々に 特権的な地位を与えることによって生まれる絆や感情的な反応の重要性を認識できない。もし私たちが皆、シジウィックに従う純粋な善人であったとしても、それは幸福を最大化する結果にはなら ないだろう。人口のほんの一部が純粋な善人であり、他の人々は愛情などに基づいて行動する方が望ましい。このように、帰結主義も当初は不道徳とみなされて いた行為者に要求を課す。それは、依然として総体的な幸福を最大化する結果を要求しているため、自身の条件を満たしていないわけではないが、各行為者が常 に公平な幸福の推進者として行動することを要求している。したがって、帰結主義も修正する必要がある。 利己主義と結果主義は間接的に失敗するが、常識的な道徳は直接的に集団的に自らを破滅させる。(利己主義も同様だが、利己主義は個人の理論である。)パー フィットは興味深い例を挙げ、ナッシュのゲーム理論を援用しながら、愛する者の幸福を何よりも優先しない方が、私たち全員にとってより良い結果になる場合 が多いことを示した。例えば、私たちは自分の子供だけでなく、すべての子供たちのことを考えるべきである。 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 『理 由と人格』 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 『Reasons and Persons』は、哲学者デレク・パーフィットが1984年に発表した著書であり、著者はこの本の中で倫理、合理性、個人の同一性について論じている。 この本は4つの部分に分かれており、自己矛盾理論、合理性と時間、個人 の同一性、そして将来の世代に対する責任にそれぞれ捧げられている。 要約 1. 自己矛盾理論 第1部では、特定の倫理理論は自己矛盾をはらんでいると論じている。そ の理論のひとつに倫理的利己主義があるが、パーフィットは、これは「囚人のジレン マ」により「全体として自己矛盾をはらんでいる」と主張している。ただし、パーフィットは、これがその理論を否定するのに十分な根拠であるとは考えていな い。最終的には、パーフィットは同様の理由で「常識的な道徳」を否定している。 この章では、パーフィットは特定の見解を明確に支持することはせず、む しろ、さまざまな理論の問題点を示している。彼が唯一肯定的に支持しているのは「非人格的倫理」であり、非人格性は本書のさまざまな部分に共通する要素で ある。 2. 合理性と時間 第2部では、合理性と時間の関係に焦点を当て、次のような疑問を取り 扱っている。過去の欲望を考慮すべきか? 今良いと思えることであっても、後で後悔するようなことをすべきか? など。 パーフィットが第2部で主眼を置いているのは、利己主義理論に対する反 論である。利己主義理論の支持者たちは、異なる人々の間の相違は極めて重要であると 考えるが、同じ人物の異なる時点における相違はまったく重要ではないと考える。パーフィットは、このことが利己主義理論を2つの方向からの攻撃に対して脆 弱にしていると論じている。それは一方では道徳と比較することができ、他方では「現在志向理論」と比較することができる。パーフィットは、私たちの現在の 目的が長期的な自己利益と対立することがあると論じている。自己利益理論家が、そのような目的に基づいて行動することがなぜ非合理的であるかを説明するた めに用いる論拠は、自己利益理論家に対して向けられ、道徳を支持する論拠として用いられる可能性がある。逆に、自己利益理論家が道徳に対して用いる論拠 は、「現在の目的」理論を支持する論拠として用いられる可能性もある。 3. 個人の同一性 第3部では、個人の同一性に関する還元的な説明を主張している。すなわ ち、私たちの存在が世界に関する深い、重要な事実であるという主張を受け入れるのではなく、パーフィットの個人の同一性に関する説明は次のようである。 時間1において、ある人物がいる。 それより後の時間2において、またある人物がいる。 これらの人物は同一人物であるように見える。 実際、これらの人物は記憶や性格的特徴を共有している。 しかし、それらを同一人物とするような事実は、この世界にはこれ以上存在しない。 パーフィットのこの立場を支持する論拠は、テレポーテーション、人の分 裂と融合、脳の物質の段階的な置き換え、心理の段階的な変化など、思考実験に関する 我々の直感に基づいている。例えば、パーフィットは読者に「テレトランスポーター」に入ることを想像するように求めている。テレトランスポーターとは、乗 る人を眠らせ、その後破壊し、原子レベルに分解し、その情報をコピーして光速で火星に転送する機械である。火星では、別の機械が(炭素や水素などの現地の 資源から)乗る人を再構成し、各原子はまったく同じ相対位置に置かれる。パーフィットは、テレポーターが移動手段となりうるのかという疑問を投げかけてい る。すなわち、火星にいる人物は、地球でテレポーターに入った人物と同じ人物なのか? もちろん、火星で目覚めたとき、あなたは自分が自分であると感じ、火星に移動するためにテレポーターに入ったことを思い出し、今朝ひげを剃ったときにでき た上唇の切り傷さえ感じるだろう。 すると、テレポーターがアップグレードされる。地球のテレポーターは、 乗り込んだ人間を破壊しないように改良され、代わりに無限の複製を簡単に作り出すことができるようになる。その複製は皆、そもそも地球のテレポーターに 乗ったことを覚えていると主張するだろう。 パーフィットは、このような思考実験を用いて、同一性(アイデンティ)を決定する基準として用いるものはすべて欠如していると 主張する。なぜなら、それ以上の事実は存在しないからだ。パーフィットにとって重要なのは、単に「関係R」、すなわち記憶や性格などの心理的なつながりで ある。 パーフィットは、この論理をさらに推し進め、道徳と社会統制の新たなコ ンテクストを確立する。パーフィットは、ある人物が他の人物に危害を加えたり干渉し たりすることは道徳的に間違っており、そのような侵害から個人を守ることは社会の義務であると主張する。この考えを受け入れれば、社会には個人の「未来の 自己」をそのような侵害から守る義務があるという結論を導くのは容易である。 たばこの使用は、健康的な生活を送るという未来の自己の権利の侵害とみなすことができる。パーフィットは、この結論に達するための論理を展開しているが、 これは個人の自由への侵害を正当化しているように見える。しかし、パーフィットはこのような侵害的な管理を明確に支持しているわけではない。 パーフィットの結論は、デイヴィッド・ヒュームの束理論や仏教のスカン ダにおける自己観にも似ているが、それらを単に再定義するにとどまらない。パー フィットの見解は還元論的であるだけでなく、デフレ的でもある。つまり、結局のところ、「重要なこと」は個人の同一性ではなく、むしろ精神の連続性とつな がりなのである。 4. 未来の世代(→将来の世代に対する責任) 第4部では、人口倫理(population ethics)とも呼ばれる、未来の世代に対する私たちの責任に関する問題を取り扱う。生命を創造すること が間違っているかどうか、環境破壊が未来の人々の権利を侵害するかどうか、などといった問題が提起される。 パーフィットが提起する問題のひとつは、歴史の流れが実際に生まれる人 々に大きな影響を与える(実際に会って子供を作る可能性のある両親に影響を与えるた め、また、受胎時期の違いが子供の遺伝的構成を変えるため)ことを踏まえると、もし状況が違っていたら存在しなかったであろう未来の人々は、我々の行動に 対して不満を述べる権利があるのだろうか? これは非同一性問題と呼ばれる。 パーフィットが取り上げているもう一つの問題は、単なる足し算のパラ ドックスであり、これはおそらく、非常に幸福な少数の人々よりも、少し幸せな多くの人 々の方が望ましいことを示すものである。パーフィットはこれを「嫌悪すべき」見解と呼んでいるが、まだ解決策を見いだせていないと述べている。 評価 バーナード・ウィリアムズは『Reasons and Persons』を「見事なほどに賢く、想像力に富む」と評し、抽象的なメタ倫理学よりも具体的な道徳問題を扱う分析哲学の潮流の一部として高く評価し た。[1] フィリップ・キッチァーは、パーフィットの『On What Matters』の書評で、『Reasons and Persons』は「形而上学と倫理学における一連の問いに対する卓越した貢献として広く受け止められている」と書いた。[2] ピーター・シンガーはガーディアン紙で『Reasons and Persons』をお気に入りの本トップ10に挙げ、「パーフィットの鋭い洞察力と簡潔な文章は、この本を現代の哲学者による最も刺激的で、挑戦的な作品 のひとつにしている」と述べている。 ニューヨーク・レビュー・オブ・ブックス誌に寄稿した哲学者P.F.ス トローソンは、この本に肯定的な評価を与え、「このテーマの作品で、パーフィトの作品に匹敵するものは、その範囲、豊かさ、想像力、そして論理の説得力に おいてほとんどない」と述べた。[4] インタビューの中で、デイヴィッド・チャーマーズは『理性と人間(理由 と人)』を「愛している」と述べ、この本は「明晰かつ平易に書かれた分析哲学がどれほど強力になり得るかを感じさせてくれる」と語っている。[5] ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 重要なことについて ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 詳細は「重要なことについて」を参照 2冊目の著書で、パーフィットは道徳的リアリズムを主張し、道徳的な問いには真偽のある答えがあることを主張している。さらに、道徳哲学における最も著名 な3つの見解のカテゴリー、すなわちカント的義務論、結果論、契約論(または契約論)は、道徳的な問いに対する同じ答えに収束すると示唆している。 本書の中で、著者は富裕層には貧困層に対して強い道徳的義務があることを主張している。 「非常に重要なことのひとつは、富裕層が、そう簡単にできるにもかかわらず、世界の最貧困層が被る苦痛や早すぎる死の多くを防ぐことができなかったこと だ。私たちが夜の娯楽に費やすお金は、代わりに貧困層の人々を死や失明、慢性的な激痛から救うために使うこともできるかもしれない。もし、最貧困層の人々 への対応に誤りはないと信じるのであれば、それは奴隷を所有することが正当化されると信じていた人々と同じである。 私たちの中には、裕福な私たちがどれだけの富を最貧困層に与えるべきか、と問う人もいる。しかし、この問いは、私たちの富は私たちのものであり、与えるこ とができるという前提に立っている。この富は法的に私たちのものである。しかし、最貧困層の人々には、この富の一部を奪うことに対して、より強い道徳的権 利がある。私たちは、少なくとも収入の10%をこれらの人々に移転すべきである。」[12] 批判 ロジャー・スクラントンは著書『人間の本性について』の中で、パーフィットが自身の倫理観を支持するために用いた「トロッコ問題」や「救命ボート倫理」な どの道徳的ジレンマを批判し、「これらの『ジレンマ』は、状況から道徳的に関連する関係性をほぼすべて排除し、算術的な問題のみに還元するという有用な特 徴がある」と書いている。スクルトンは、それらの多くは欺瞞的であると考えている。例えば、彼は、パーフィットが想定しているように、トロッコ問題におけ るスイッチを引くことが道徳的に求められていると考えるのは、帰結主義者である必要はないと考えている。むしろ、例えばアンナ・カレーニナがヴロンスキー のために夫と子供を残して出て行くという選択のような、より複雑なジレンマが必要だと彼は主張している。そして、義務論は(スクラントンの見解では)パー フィットの理論を悩ませている問題を回避できると示唆している。[13] ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 『重要なことについて』 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 『On What Matters』は、デレク・パフィットによる道徳哲学の3巻本である。最初の2巻は2011年に、3巻目は2017年に出版された。これは、パフィット の1984年の著書『Reasons and Persons』の続編である。サミュエル・シェフラーによる序文がある。 概要 パフィットは客観的倫理理論を擁護し、主観的倫理理論では説明できない理由に基づいて行動すべきだと示唆している。さらに、道徳哲学および政治哲学におけ る3つの伝統的なアプローチ、すなわちカントの義務論、結果論、契約論(T. M. スキャノンの唱えるもの、およびトマス・ホッブズ、ジョン・ロック、ジャン=ジャック・ルソー、ジョン・ロールズの伝統から)を組み合わせた道徳理論を提 示しようとしている。[1] パリフィットによれば、これらの理論は対立するのではなく収束し、「異なる側面から同じ山を登る」というパリフィットの比喩で表現されている。[2] パーフィットは、これら3つの倫理理論の統合を「トリプル・セオリー」と名付けている。[3] ある行為は、それが次のいずれかの条件を満たす場合にのみ、すなわち、その行為が 1. 普遍的な法則として存在することが最善の結果をもたらす原則の1つである場合、 2. 普遍的な法則として存在することが誰もが合理的に望む唯一の原則である場合、 3. 誰もが合理的に拒絶できない原則である場合、 パーフィットの見解では、この3つの基準は、(a)それぞれ功利主義、カント主義、契約主義の最良のバージョンを表しており、(b)一般的にその提言に同 意できるはずである。両方の主張は論争を呼ぶことが証明されている。 執筆 当初『山を登る』というタイトルだった原稿は、出版される何年も前から出回っており、出版前の読書会や会議など、大きな興奮を巻き起こした。 『On What Matters』の一部は、2002年にカリフォルニア大学バークレー校で行われた「Tanner Lectures on Human Values」の一部として行われた講義から派生したものである。バークレー校での一連の講義の一部として、パーフィットの講義には、アレン・W・ウッ ド、T・M・スキャンロン、スーザン・ウォルフが応じた。 評価 経済学者のタイラー・コーエンは、『On What Matters』におけるパーフィトのスタイル(「彼の著作を読むことは忘れがたい啓発的な経験である」)に感嘆の意を表しているが、次のように論じてい る。 私はこの本の最大かつ最も中心的な部分を失敗と見なしている。おそらく間違っているが、より心配なのは「間違ってもいない」こと、そして、哲学倫理学だけ でなく選択理論というフロンティアがしばらくの間存在していた場所によって定義された問題を単純に見落としていることだ。 ピーター・シンガーは、パーフィットの主張は「倫理における客観主義を否定する人々を防戦に追い込む」と、はるかに肯定的な見方をしている。[7] コンスタンティン・サンディスは、パーフィットのプロジェクトに異議を唱えている。さまざまな「理論は推奨事項に収束する可能性が高いが、それらから導か れる行動がすべてであると考えることは、すでに結果主義の真実を前提としている」からだ。サンディスは、パフリットの業績の意義は、彼の出版実績の乏しさ にもかかわらず、研究卓越性枠組み(Research Excellence Framework)の「出版か死か」という要求に疑問を投げかけるべきであると冗談を言うが、「それが私たちの道徳観を変えるかどうかはまだわからな い」と述べている。[2] パーフィットが執筆に費やした膨大な時間、そして、このような長大な研究が学術生活の要求とますます両立しなくなっていることは、ウォーリック大学の副学 長であるナイジェル・スリフトが、Chronicle of Higher Educationのウェブサイトに掲載されたブログ記事で指摘している。 パーフィットの人生は、それを可能にするインフラ(特に学部教育を行わないオックスフォード大学オール・ソウルズ・カレッジ)を見つけたことで、知的妥協 のないものとなった。しかし、そのようなインフラが、一部の大学を除いて、今後どれほど長く利用可能であるのか疑問に思う。[8] 哲学者のロジャー・スクルートンは、2015年に「人間にとって本当に重要なもの、すなわち、愛、責任、愛着、喜び、美的価値、精神的なニーズなどは、 パーフィットの延々と続く物語の中では起こりえない。すべては功利的な推論という大きな箒によって隅に追い立てられ、埃の山となって放置される」と、この 本の題名が適切かどうか疑問を呈した。[9] |

| Personal identity Parfit was singular in his meticulously rigorous and almost mathematical investigations into personal identity. In some cases, he used examples seemingly inspired by Star Trek and other science fiction, such as the teletransporter, to explore our intuitions about our identity. He was a reductionist, believing that since there is no adequate criterion of personal identity, people do not exist apart from their components. Parfit argued that reality can be fully described impersonally: there need not be a determinate answer to the question "Will I continue to exist?" We could know all the facts about a person's continued existence and not be able to say whether the person has survived. He concluded that we are mistaken in assuming that personal identity is what matters in survival; what matters is rather Relation R: psychological connectedness (namely, of memory and character) and continuity (overlapping chains of strong connectedness). On Parfit's account, individuals are nothing more than brains and bodies, but identity cannot be reduced to either. (Parfit concedes that his theories rarely conflict with rival Reductionist theories in everyday life, and that the two are only brought to blows by the introduction of extraordinary examples, but he defends the use of such examples on the grounds that they arouse strong intuitions in many of us.) Identity is not as determinate as we often suppose it is, but instead such determinacy arises mainly from the way we talk. People exist in the same way that nations or clubs exist. Following David Hume, Parfit argued that no unique entity, such as a self, unifies a person's experiences and dispositions over time. Therefore personal identity is not "what matters" in survival.[14] A key Parfitian question is: given the choice between surviving without psychological continuity and connectedness (Relation R) and dying but preserving R through someone else's future existence, which would you choose? Parfit argues the latter is preferable. Parfit described his loss of belief in a separate self as liberating:[15] My life seemed like a glass tunnel, through which I was moving faster every year, and at the end of which there was darkness... When I changed my view, the walls of my glass tunnel disappeared. I now live in the open air. There is still a difference between my life and the lives of other people. But the difference is less. Other people are closer. I am less concerned about the rest of my own life, and more concerned about the lives of others. Criticism of personal identity view Fellow reductionist Mark Johnston of Princeton rejects Parfit's constitutive notion of identity with what he calls an "Argument from Above".[16] Johnston maintains, "Even if the lower-level facts [that make up identity] do not in themselves matter, the higher-level fact may matter. If it does, the lower-level facts will have derived significance. They will matter, not in themselves, but because they constitute the higher level fact."[17] In this, Johnston moves to preserve the significance of personhood. Parfit's explanation is that it is not personhood itself that matters, but rather the facts in which personhood consists that provide it with significance. To illustrate this difference between himself and Johnston, Parfit used an illustration of a brain-damaged patient who becomes irreversibly unconscious. The patient is certainly still alive even though that fact is separate from the fact that his heart is still beating and other organs are still functioning. But the fact that the patient is alive is not an independent or separately obtaining fact. The patient's being alive, even though irreversibly unconscious, simply consists in the other facts. Parfit explains that from this so-called "Argument from Below" we can arbitrate the value of the heart and other organs still working without having to assign them derived significance, as Johnston's perspective would dictate. |

個人の同一性 パーフィットは、個人の同一性に関する綿密で厳密、かつ数学的な調査において、他に類を見ない存在であった。 パーフィットは、テレポーテーション装置など、テレビドラマ『スタートレック』やその他のSFにインスパイアされたと思われる例を挙げ、私たちの同一性に 関する直観を探求した。 パーフィットは還元論者であり、個人の同一性を適切に判断する基準は存在しないため、人はその構成要素から切り離されて存在しているわけではないと信じて いた。パーフィットは、現実とは非人格的に完全に記述できると主張した。「私は存在し続けるのか?」という問いに対する明確な答えは必要ない。私たちは、ある人物が存続していることに関するすべての事実を知ることがで きても、その人物が存続しているかどうかを言い当てることができない。パーフィットは、生存において重要なのは個人の同一性であると考える のは誤りであり、重要なのはむしろ関係R、すなわち心理的なつながり(記憶や性格)と連続性(強いつながりの連鎖)であると結論づけた。 パーフィットによれば、個人は脳と身体にすぎず、同一性もこれらに還元することはできない。(パーフィットは、彼の理論が日常生活においてライバルの還元 主義理論とほとんど対立しないことを認めている。また、両者が対立するのは、異常な例が持ち出された場合のみであるが、そのような例を挙げるのは、多くの 人々に強い直観を呼び起こすからだという理由による。)アイデンティティは、私たちがしばしば考えるほど決定論的ではなく、むしろ、そうした決定論性は主 に私たちがどのように語るかによって生じる。人々は、国民やクラブが存在するのと同じ方法で存在する。 デイヴィッド・ヒュームにならって、パーフィット は、自己のような唯一の存在が、人の経験や性質を時を超えて統合しているわけではないと論じた。したがって、個人の同一性は生存にとって「重要」なもので はない。[14] パーフィットの重要な問いは、心理的な連続性やつながり(関係R)を伴わない生存と、他者の未来の生存を通じてRを維持したまま死ぬことの選択を迫られた 場合、どちらを選ぶか?というものである。パーフィットは後者の方が望ましいと論じている。 パーフィットは、独立した自己という概念への信頼を失うことは解放的であると述べている。[15] 私の人生はガラスのトンネルのようで、年々その中を速く進んでいき、その先には闇があるように思えた。しかし、見方を変えたとき、ガラスのトンネルの壁は 消えた。私は今、外気に触れて生きている。私の人生と他の人々の人生との間には依然として違いがある。しかし、その違いは少なくなっている。他の人々はよ り身近に感じられる。私は自分の残りの人生についてそれほど心配しなくなり、他人の人生についてより心配するようになった。 パーフィットの個人アイデンティティ観に対する批判 プリンストン大学の還元主義者マーク・ジョンストンは、パーフィットのアイデンティティの構成概念を「上からの論証」と呼んで否定している。[16] ジョンストンは、「アイデンティティを構成する下位レベルの事実自体には重要性がなくても、上位レベルの事実は重要である可能性がある。もし重要であるな らば、下位レベルの事実は派生的に重要となる。それらはそれ自体で重要なのではなく、上位レベルの事実を構成しているから重要なのである」と主張してい る。[17] ジョンストンは、この点において、人格の重要性を維持しようとしている。パーフィットの説明によると、重要となるのは人格そのものではなく、人格を構成す る事実が重要性を与えるのだという。パーフィットは、自身とジョンストンのこの相違点を説明するために、不可逆的に意識不明となった脳障害患者の例を挙げ た。患者は確かにまだ生きているが、その事実は心臓が鼓動し、他の臓器が機能しているという事実とは別である。しかし、患者が生きているという事実は、独 立したものでも、別個に得られる事実でもない。患者が生きているということは、不可逆的な意識不明の状態にあっても、他の事実によって成り立っているにす ぎない。パーフィットは、このいわゆる「下からの論証」から、ジョンストンが主張するように派生的な意義を割り当てることなく、依然として機能している心 臓や他の臓器の価値を裁定できると説明している。 |

| The future In part four of Reasons and Persons, Parfit discusses possible futures for the world.[11]: 349–441 Parfit discusses possible futures and population growth in Chapter 17 of Reasons and Persons. He shows that both average and total utilitarianism result in unwelcome conclusions when applied to population.[11]: 388 In the section titled "Overpopulation," Parfit distinguishes between average utilitarianism and total utilitarianism. He formulates average utilitarianism in two ways. One is what Parfit calls the "Impersonal Average Principle", which he formulates as "If other things are equal, the best outcome is the one in which people's lives go, on average, best."[11]: 386 The other is what he calls the "Hedonistic version"; he formulates this as "If other things are equal, the best outcome is the one in which there is the greatest average net sum of happiness, per life lived."[11]: 386 Parfit then gives two formulations of the total utilitarianism view. The first formulation Parfit calls the "Hedonistic version of the Impersonal Total Principle": "If other things are equal, the best outcome is the one in which there would be the greatest quantity of happiness—the greatest net sum of happiness minus misery."[11]: 387 He then describes the other formulation, the "non-Hedonistic Impersonal Total Principle": "If other things are equal, the best outcome is the one in which there would be the greatest quantity of whatever makes life worth living.[11]: 387 Applying total utilitarian standards (absolute total happiness) to possible population growth and welfare leads to what he calls the repugnant conclusion: "For any possible population of at least ten billion people, all with a very high quality of life, there must be some much larger imaginable population whose existence, if other things are equal, would be better, even though its members have lives that are barely worth living."[11]: 388 Parfit illustrates this with a simple thought experiment: imagine a choice between two possible futures. In A, 10 billion people would live during the next generation, all with extremely happy lives, lives far happier than anyone's today. In B, there are 20 billion people all living lives that, while slightly less happy than those in A, are still very happy. Under total utility maximisation we should prefer B to A. Therefore, through a regressive process of population increases and happiness decreases (in each pair of cases the happiness decrease is outweighed by the population increase) we are forced to prefer Z, a world of hundreds of billions of people all living lives barely worth living, to A. Even if we do not hold that coming to exist can benefit someone, we still must at least admit that Z is no worse than A. There have been a number of responses to Parfit's utilitarian calculus and his conclusion regarding future lives, including challenges to what life in the A-world would be like and whether life in the Z-world would differ very much from a normal privileged life; that movement from the A-world to the Z-world can be blocked by discontinuity; that rather than accepting the utilitarian premise of maximizing happiness, emphasis should be placed on the converse, minimizing suffering; challenging Parfit's teleological framework by arguing that "better than" is a transitive relation and removing the transitive axiom of the all-things-considered-better-than relation; proposing a minimal threshold of liberties and primary social goods to be distributed; and taking a deontological approach that looks to values and their transmission through time.[18] Parfit makes a similar argument against average utilitarian standards. If all we care about is average happiness, we are forced to conclude that an extremely small population, say ten people, over the course of human history is the best outcome if we assume that these ten people (Adam and Eve et al.) had lives happier than we could ever imagine.[11]: 420 Then consider the case of American immigration. Presumably alien welfare is less than American, but the would-be alien benefits tremendously from leaving his homeland. Assume also that Americans benefit from immigration (at least in small amounts) because they get cheap labour, etc. Under immigration both groups are better off, but if this increase is offset by increase in the population, then average welfare is lower. Thus although everyone is better off, this is not the preferred outcome. Parfit asserts that this is simply absurd. Parfit then discusses the identity of future generations. In Chapter 16 of Reasons and Persons he posits that one's existence is intimately related to the time and conditions of one's conception.[11]: 351 He calls this "The Time-Dependence Claim": "If any particular person had not been conceived when he was in fact conceived, it is in fact true that he would never have existed".[11]: 351 Study of weather patterns and other physical phenomena in the 20th century has shown that very minor changes in conditions at time T have drastic effects at all times after T. Compare this to the romantic involvement of future childbearing partners. Any actions taken today, at time T, will affect who exists after only a few generations. For instance, a significant change in global environmental policy would shift the conditions of the conception process so much that after 300 years none of the same people that would have been born are in fact born. Different couples meet each other and conceive at different times, and so different people come into existence. This is known as the 'non-identity problem'. We could thus craft disastrous policies that would be worse for nobody, because none of the same people would exist under the different policies. If we consider the moral ramifications of potential policies in person-affecting terms, we will have no reason to prefer a sound policy over an unsound one provided that its effects are not felt for a few generations. This is the non-identity problem in its purest form: the identity of future generations is causally dependent, in a very sensitive way, on the actions of the present generations. |

未来 『理由と人』の第4部において、パーフィットは世界のあり得る未来について論じている。[11]:349-441 パーフィットは『理由と人』の第17章で、あり得る未来と人口増加について論じている。 彼は、平均効用主義と全体効用主義のいずれも、人口に適用すると望ましくない結論を導くことを示している。[11]:388 「人口過剰」と題されたセクションで、パーフィットは平均効用主義と全体効用主義を区別している。 彼は平均効用主義を2つの方法で定式化している。 1つはパーフィットが「非人格的平均原理」と呼ぶもので、彼はそれを「他の条件が同じであれば、人々の生活が平均的に最もよくなるような結果が最善であ る」と定式化している[11]: 386。もう1つは彼が「 快楽主義バージョン」と呼ぶもの。彼はこれを「他の条件が等しい場合、最善の結果とは、平均的な幸福の正味総和が最も大きいものとなることである」と定式 化している[11]: 386。 パーフィットは次に、全体的功利主義の見解を2つの定式化で示している。 パーフィットは最初の定式化を「非人格的全体主義の快楽主義バージョン」と呼んでいる。「他の条件が同じであれば、最大量の幸福、すなわち最大幸福総和か ら最大不幸総和を差し引いたものが最善の結果である」[11]: 387 そして、もうひとつの「非快楽主義的非人格的全体主義」の定式化について説明している。「他の条件が同じであれば、人生を生きがいのあるものにするものす べてが最大量存在するものが最善の結果である」[11]: 387 全体的な功利主義の基準(絶対的な全体的な幸福)を人口増加と福祉の可能性に適用すると、彼が「嫌悪すべき結論」と呼ぶものにつながる。「少なくとも 100億人の人々が、非常に質の高い生活を送っていると仮定すると、他の条件が同じであれば、その人々の生活はかろうじて生きるに値するものではあって も、より良い生活を送ることができるはずである。」[11]: 388 パーフィットは、このことを簡単な思考実験で説明している。2つの未来の可能性から選択することを想像してみよう。Aでは、次の世代に100億人が生き、 誰もが現在よりもはるかに幸福な生活を送る。Bでは、200億人が生活し、Aよりも幸福度はやや劣るものの、それでも非常に幸福な生活を送る。効用最大化 の観点から、私たちはAよりもBを好むべきである。したがって、人口増加と幸福度の減少という逆行プロセス(各ケースにおいて、幸福度の減少は人口増加に よって相殺される)により、私たちはAよりも、数百億人の人々が皆、生きている価値がほとんどないような生活を送っている世界であるZを好むことを強いら れる。たとえ、存在することによって誰かが恩恵を受けるという考えを受け入れないとしても、少なくとも、 Zの世界はAの世界より悪いものではない。パーフィットの功利主義的計算と来世に関する結論に対しては、Aの世界での生活がどのようなものになるかという 疑問や、Zの世界での生活が通常の特権的な生活とそれほど変わらないのではないかという疑問、Aの世界からZの世界への移動は不連続性によって妨げられる 可能性があるという疑問、 幸福の最大化という功利主義的前提を受け入れるのではなく、その逆である苦痛の最小化に重点を置くべきであること、「~より良い」は推移的関係であり、あ らゆることを考慮した上で「~より良い」という推移的公理を排除すること、分配されるべき自由と主要な社会的財の最小限の基準を提案すること、そして、価 値とそれを時代を超えて伝達することに注目する義務論的アプローチを取ることである。 パーフィットは平均的な功利主義の基準に対しても同様の反論を行っている。もし平均的な幸福だけを気にかけるのであれば、人類の歴史上、10人という極め て少ない人口が、もしその10人(アダムとイブなど)が我々の想像を絶するほど幸福な人生を送っていたと仮定するならば、最良の結果であると結論せざるを 得ない。[11]:420 では、アメリカの移民のケースを考えてみよう。おそらく外国人の福祉はアメリカ人よりも低いだろうが、外国人は自国を離れることで多大な恩恵を受ける。ま た、アメリカ人は移民によって利益を得る(少なくとも少額ではあるが)と仮定しよう。なぜなら、彼らは安価な労働力を手に入れることができるからだ。移民 によって両グループともがより豊かになるが、この増加が人口増加によって相殺されるのであれば、平均的な福祉は低下する。このように、誰もがより豊かにな るが、これは望ましい結果ではない。パーフィットは、これは単純に不合理であると主張する。 パーフィットは、次いで将来世代の同一性について論じている。『理由と人』の第16章で、パーフィットは、個人の存在はその受胎の時期と条件に密接に関連 していると主張している。[11]:351 パーフィットはこれを「時間依存の主張」と呼んでいる。「もし特定の人物が、実際には受胎されたにもかかわらず、受胎されていなかったとしたら、その人物 は実際には存在しなかったことになる」[11]:351 20世紀の気象パターンやその他の物理現象の研究により、時刻Tにおける状況の非常に小さな変化が、時刻T以降のすべての時間に劇的な影響を及ぼすことが 示されている。これを、将来の出産パートナーとなる人々の恋愛関係に例えてみよう。今日、時間Tにおいてとられる行動は、ほんの数世代後に存在する人々に 影響を与えることになる。例えば、地球環境政策に大幅な変更が加えられた場合、妊娠のプロセスにおける条件が大きく変化し、300年後には、同じ人種で同 じ人々が生まれることは実際にはなくなる。異なるカップルが異なる時期に出会い、妊娠する。その結果、異なる人々が誕生する。これが「非同一性問題」とし て知られているものである。 したがって、異なる政策の下では同じ人々は存在しないため、誰にとっても悪い結果をもたらす悲惨な政策を策定することも可能である。個々人に影響を与える 政策の道徳的な影響を考慮した場合、その影響が数世代にわたって現れないのであれば、健全な政策よりも不健全な政策を好む理由はない。これが非同一性問題 の最も純粋な形である。つまり、将来の世代の同一性は、現在の世代の行動に非常に敏感な形で因果的に依存している。 |

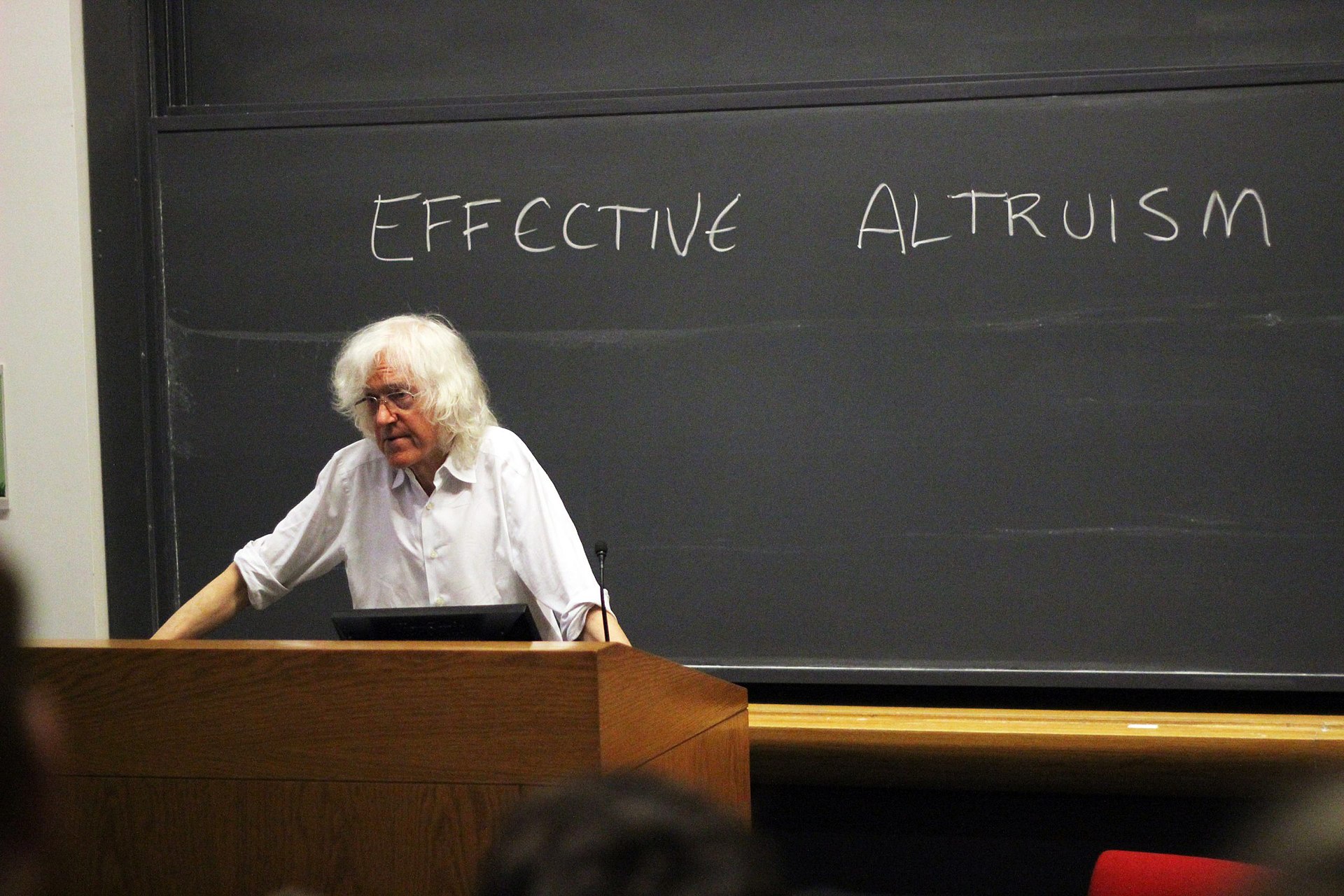

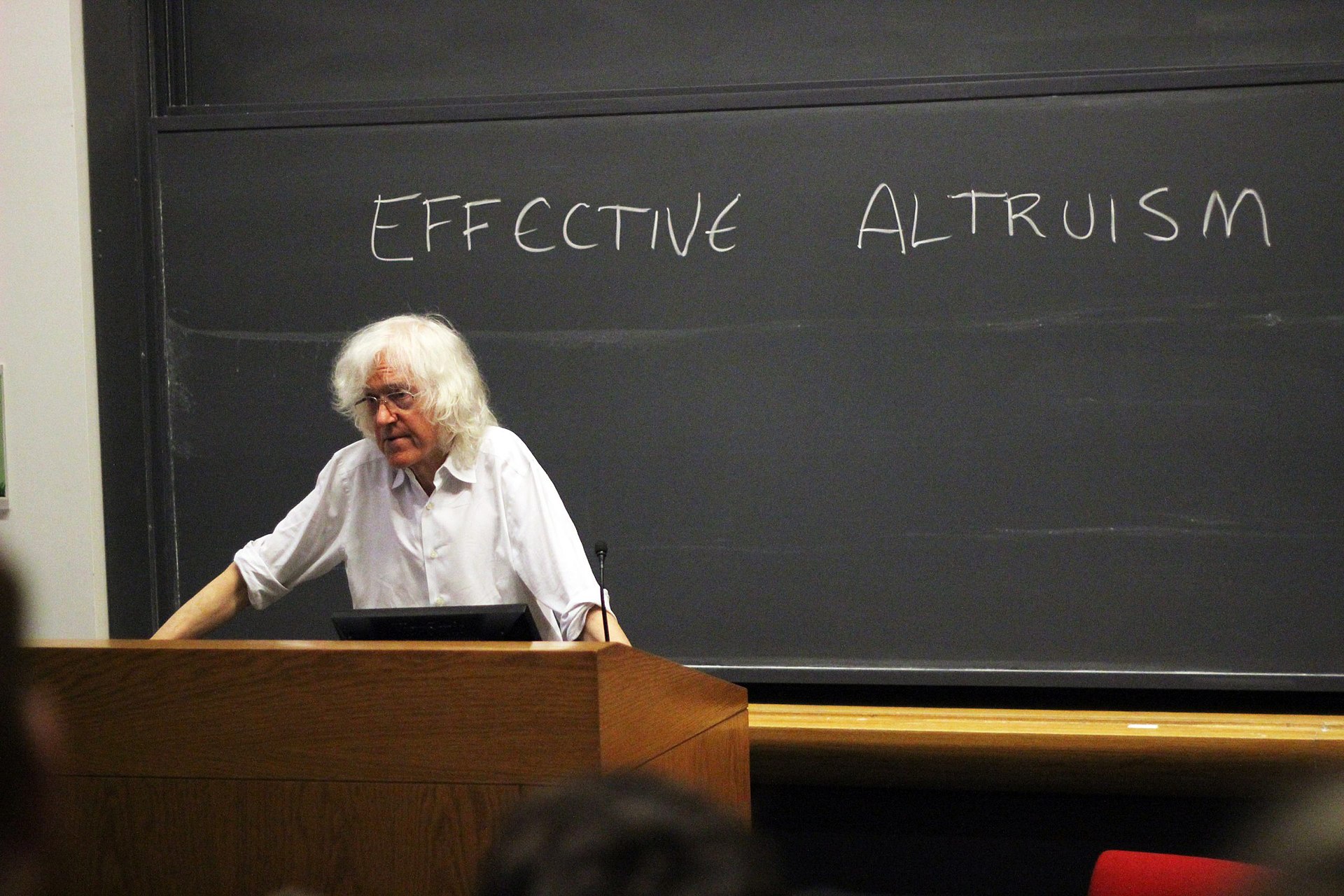

Personal life Parfit at Harvard University in April 2015 Parfit met Janet Radcliffe Richards in 1982,[5] and they then began a relationship that lasted until his death.[19] They married in 2010.[7] Richards believes Parfit had Asperger syndrome.[19][20] Parfit supported effective altruism.[20] He was a member of Giving What We Can and pledged to donate at least 10% of his income to effective charities.[21][22] Parfit was an avid photographer who regularly traveled to Venice and St. Petersburg to photograph architecture.[7] |

私生活 パーフィットは2015年4月にハーバード大学にて パーフィットは1982年にジャネット・ラドクリフ・リチャーズと出会い、[5] その後、彼の死まで続いた関係を始めた。[19] 2人は2010年に結婚した。[7] リチャーズはパーフィットがアスペルガー症候群であったと考えている。[19][20] パーフィットは効果的な利他主義を支持していた。[20] 彼は「Giving What We Can」のメンバーであり、効果的な慈善事業に対して少なくとも収入の10%を寄付することを誓っていた。[21][22] パーフィットは熱心な写真家であり、建築物の撮影のために定期的にヴェネツィアとサンクトペテルブルクを訪れていた。[7] |

| Selected works 1964: Eton Microcosm. Edited by Anthony Cheetham and Derek Parfit. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. 1971: "Personal Identity". Philosophical Review. vol. 80: 3–27. JSTOR 2184309 1979: "Is Common-Sense Morality Self-Defeating?". The Journal of Philosophy, vol. 76, pp. 533–545, October. JSTOR 2025548 1984: Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-824615-3 1992: "Against the social discount rate" (with Tyler Cowen), in Peter Laslett & James S. Fishkin (eds.) Justice between age groups and generations, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 144–161. 1997: "Reasons and Motivation". The Aristotelian Soc. Supp., vol. 77: 99–130. JSTOR 4106956 2003: Parfit, Derek (2003). "Justifiability to each person". Ratio. 16 (4): 368–390. doi:10.1046/j.1467-9329.2003.00229.x. 2006: "Normativity", in Russ Shafer-Landau (ed.). Oxford Studies in Metaethics, vol. I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 2011: On What Matters, vols. 1 and 2. Oxford University Press. 2017: On What Matters, vol. 3. Oxford University Press. |

主な著作 1964年:『Eton Microcosm』アンソニー・チータム、デレク・パーフィット編。ロンドン:Sidgwick & Jackson。 1971年:「Personal Identity(人格同一性)」。Philosophical Review。第80巻:3-27。 JSTOR 2184309 1979年:「常識的な道徳は自己否定か?」『哲学ジャーナル』第76巻、533-545ページ、10月。 JSTOR 2025548 1984年:『理由と人』オックスフォード:Clarendon Press。ISBN 0-19-824615-3 1992年:「社会的割引率に反対して」(タイラー・コーエンとの共著)、ピーター・ラスレットおよびジェームズ・S・フィッシュキン編『世代間の正義』 ニューヘイブン:イェール大学出版、144-161ページ。 1997年:「理由と動機」。『アリストテレス協会』補遺、第77巻:99-130ページ。 JSTOR 4106956 2003: パーフィット、デレク (2003年). 「各人にとっての正当性」。『比率』。16 (4): 368–390. doi:10.1046/j.1467-9329.2003.00229.x. 2006年:「規範性」Russ Shafer-Landau(編)『Oxford Studies in Metaethics』第1巻、オックスフォード:Clarendon Press。 2011年:『On What Matters』第1巻および第2巻。オックスフォード大学出版局。 2017年:『On What Matters』第3巻。オックスフォード大学出版局。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derek_Parfit |

|

| Rational egoism (self-interest theory) Rational egoism (self-interest theory) Rational egoism (also called rational selfishness) is the principle that an action is rational if and only if it maximizes one's self-interest.[1][2] As such, it is considered a normative form of egoism,[3] though historically has been associated with both positive and normative forms.[4] In its strong form, rational egoism holds that to not pursue one's own interest is unequivocally irrational. Its weaker form, however, holds that while it is rational to pursue self-interest, failing to pursue self-interest is not always irrational.[5] Originally an element of nihilist philosophy in Russia, it was later popularised in English-speaking countries by Russian-American author Ayn Rand. Origins Rational egoism (Russian: разумный эгоизм) emerged as the dominant social philosophy of the Russian nihilist movement, having developed in the works of nihilist philosophers Nikolay Chernyshevsky and Dmitry Pisarev. However, their terminology was largely obfuscated to avoid government censorship and the name rational egoism explicitly is unmentioned in the writings of both philosophers.[4][6] Rational egoism was further embodied in Chernyshevsky's 1863 novel What Is to Be Done?,[7] and was criticised in response by Fyodor Dostoyevsky in his 1864 work Notes from Underground. For Chernyshevsky, rational egoism served as the basis for the socialist development of human society.[4][8] English philosopher Henry Sidgwick discussed rational egoism in his book The Methods of Ethics, first published in 1872.[9] A method of ethics is "any rational procedure by which we determine what individual human beings 'ought'—or what it is 'right' for them—to do, or seek to realize by voluntary action".[10] Sidgwick considers three such procedures, namely, rational egoism, dogmatic intuitionism, and utilitarianism. Rational egoism is the view that, if rational, "an agent regards quantity of consequent pleasure and pain to himself alone important in choosing between alternatives of action; and seeks always the greatest attainable surplus of pleasure over pain".[11] Sidgwick found it difficult to find any persuasive reason for preferring rational egoism over utilitarianism. Although utilitarianism can be provided with a rational basis and reconciled with the morality of common sense, rational egoism appears to be an equally plausible doctrine regarding what we have most reason to do. Thus we must "admit an ultimate and fundamental contradiction in our apparent intuitions of what is Reasonable in conduct; and from this admission it would seem to follow that the apparently intuitive operation of Practical Reason, manifested in these contradictory judgments, is after all illusory".[12] Ayn Rand The author and philosopher Ayn Rand also discusses a theory that she called rational egoism. She holds that it is both irrational and immoral to act against one's self-interest.[13] Thus, her view is a conjunction of both rational egoism (in the standard sense) and ethical egoism, because according to Objectivist philosophy, egoism cannot be properly justified without an epistemology based on reason. Her book The Virtue of Selfishness (1964) explains the concept of rational egoism in depth. According to Rand, a rational man holds his own life as his highest value, rationality as his highest virtue, and his happiness as the final purpose of his life. Conversely, Rand was sharply critical of the ethical doctrine of altruism: Do not confuse altruism with kindness, good will or respect for the rights of others. These are not primaries, but consequences, which, in fact, altruism makes impossible. The irreducible primary of altruism, the basic absolute is self-sacrifice—which means self-immolation, self-abnegation, self-denial self-destruction—which means the self as a standard of evil, the selfless as a standard of the good. Do not hide behind such superficialities as whether you should or should not give a dime to a beggar. This is not the issue. The issue is whether you do or do not have the right to exist without giving him that dime. The issue is whether you must keep buying your life, dime by dime, from any beggar who might choose to approach you. The issue is whether the need of others is the first mortgage on your life and the moral purpose of your existence. The issue is whether man is to be regarded as a sacrificial animal. Any man of self-esteem will answer: No. Altruism says: Yes.[14] Criticism Two objections to rational egoism are given by the English philosopher Derek Parfit, who discusses the theory at length in Reasons and Persons (1984). First, from the rational egoist point of view, it is rational to contribute to a pension scheme now, even though this is detrimental to one's present interests (which are to spend the money now). But it seems equally reasonable to maximize one's interests now, given that one's reasons are not only relative to him, but to him as he is now (and not his future self, who is argued to be a "different" person). Parfit also argues that since the connections between the present mental state and the mental state of one's future self may decrease, it is not plausible to claim that one should be indifferent between one's present and future self.[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rational_egoism |

合

理的エゴイズム(合理的利己主義とも呼ばれる) 合 理的エゴイズム(合理的利己主義とも呼ばれる)とは、ある行為が自己の利益を最大化 する場合にのみ合理的であるとする原則である[1][2]。そのため、 エゴイズムの規範的な形態と考えられているが[3]、歴史的には肯定的な形態と規範的な形態の両方と関連付けられてきた[4]。強い形態では、合理的エゴ イズムは、自己の利益を追求しないことは明白に非合理的であるとする。しかし、その弱い形態では、自己の利益を追求することは合理的であるが、自己の利益 を追求しないことは必ずしも非合理的ではないとする[5]。 もともとはロシアにおける虚無主義哲学の一要素であったが、後にロシア系アメリカ人の作家アイン・ランドによって英語圏に広められた。 起源 合理的エゴイズム(ロシア語:разумный эгоизм)は、ニヒリズム哲学者ニコライ・チェルヌィシェフスキーとドミトリー・ピサレフの著作の中で発展し、ロシアのニヒリズム運動の支配的な社会 哲学として登場した。合理的エゴイズムは、チェルヌイシェフスキーが1863年に発表した小説『何をなすべきか』[7]でさらに具現化され、フョードル・ ドストエフスキーは1864年に発表した『地下からの覚書』でこれを批判している。チェルヌイシェフスキーにとって、合理的エゴイズムは人間社会の社会主 義的発展の基礎となるものであった[4][8]。 イギリスの哲学者であるヘンリー・シジウィックは、1872年に出版された著書 『倫理学の方法』(The Methods of Ethics)の中で合理的エゴイズムについて論じている[9]。 倫理学の方法とは、「個々の人間が『なすべきこと』、すなわち人間にとって『正しいこと』、あるいは自発的な行動によって実現しようとすることを決定する あ らゆる合理的な手続き」のことである[10]。シジウィックはこのような手続きと して、(1)合理的エゴイズム、(2)教条的直観主義、功(3)利主義の3つを考えている。 合理的エゴイズムとは、合理的であれば、「行為者は行為の選択肢を選択する際に、自分自身にとっての結果としての快楽と苦痛の量のみを重要視し、苦痛に対 する快楽の達成可能な最大の余剰を常に求める」という考え方である[11]。 シジウィックは、合理的エゴイズムを功利主義よりも好む説得力のある 理由を見出すことは困難であると考えた。功利主義は合理的な根拠を提供し、常識的な道 徳と調和させることができるが、合理的エゴイズムは、私たちが何をなすべきかについて、同様にもっともらしい教義であるように見える。したがって、我々は 「行為において何が合理的であるかという我々の見かけ上の直観には、究極的かつ根本 的な矛盾があることを認めなければならない。このことを認めることか ら、これらの矛盾した判断に現れている実践理性の見かけ上の直観的な作用は、結局のところ幻想的なものであることが導かれるように思われる」[12]。 アイン・ランド 作家であり哲学者でもあるアイン・ランドもまた、合理的エゴイズムと呼ばれる理論を論じている。客観主義哲学によれば、エゴイズムは理性に基づく認識論な しには正しく正当化されないからである。 彼女の著書『利己主義の美徳』(1964年)は、合理的エゴイズムの概念を深く説明している。ランドによれば、理性的な人間は自分の人生を最高の価値と し、合理性を最高の美徳とし、自分の幸福を人生の最終目的とする。 逆に、ランドは利他主義の倫理的教義を鋭く批判した: 利他主義を親切心、善意、他人の権利の尊重と混同してはならない。これらは一次的なものではなく、結果的なものであり、実際、利他主義はそれを不可能にし ている。利他主義の不可逆的な原初、基本的な絶対は自己犠牲であり、それは自己犠牲、自己否定、自己破壊を意味する。乞食に一銭でも与えるべきか否かなど という表面的なことに隠れてはならない。これは問題ではない。問題は、その10円を与えなくても存在する権利があるかないかだ。問題は、自分に近づいてく るかもしれないどんな乞食からも、10セントずつ自分の命を買い続けなければならないかどうかだ。問題は、他人のニーズが自分の人生の第一抵当であり、自 分の存在の道徳的目的であるかどうかである。問題は、人間が生け贄のような動物とみなされるかどうかである。自尊心のある人間なら、こう答えるだろう: 利他主義は言う: そうだ」と言うだろう[14]。 批判 イギリスの哲学者デレク・パーフィットは、『理由と人格』 Reasons and Persons (1984)の中でこの理論を詳しく論じている。第一に、合理的エゴイズムの観点からは、たとえ自分の現在の利益(今すぐお金を使うこと)にとって不利益 であっても、今すぐ年金制度に拠出することは合理的である。しかし、自分の理由は自分にとって相対的なものであるだけでなく、現在の自分(「別人」である と主張される未来の自分ではない)にとって相対的なものであることを考えれば、現在の自分の利益を最大化することも同様に合理的であるように思われる。 パーフィットはまた、現在の精神状態と将来の自己の精神状態との間のつながりは減少するかもしれないので、現在の自己と将来の自己との間で無関心(→無頓 着、中立的)であるべきだと主張するのは妥当ではないと主張している[15]。 |

| デレク・パーフィット : 哲学者が愛した哲学者

(上・下)/ デイヴィッド・エドモンズ著 ; 森村進, 森村たまき訳、勁草書房 , 2024 |

|

| デレク・パーフィット :

哲学者が愛した哲学者

(上)/ デイヴィッド・エドモンズ はじめに 重要なこと 1 メイド・イン・チャイナ Made in China 2 人生の予行演習 Prepping for Life 3 イートンの巨人 Eton Titan 4 ヒストリー・ボーイ History Boy 5 オックスフォード文芸録 Oxford Words 6 アメリカン・ドリーム An American Dream 7 ソウル・マン Soul Man 8 遠隔転送機 The Teletransporter 9 大西洋を越えて A Transatlantic Affair 10 パーフィット・スキャンダル The Parfit Scandal 11 仕事、仕事、仕事、そしてジャネット Work, Work, Work, and Janet 12 道徳数学 Moral Mathematics 注 |

|

| デレク・パーフィット : 哲学者が愛した哲学者

(下)/ デイヴィッド・エドモンズ 13 霧と雪のなかの心の目 The Mind’s Eye in Mist and Snow 14 やった!昇任だ! Glory! Promotion! 15 ブルースとブルーベルの森 The Blues and the Bluebell Woods 16 優先説 The Priority View 17 デレカルニア Derekarnia 18 アルファ・ガンマのカント Alpha Gamma Kant 19 同じ山に登る Climbing the Mountain 20 救命艇とトンネルと陸橋 Lifeboats, Tunnels, and Bridges 21 結婚とピザ Marriage and Pizza 22 生命と両立できない Incompatible with Life 23 パーフィットの賭け Parfit’s Gamble 謝辞 注 パーフィット先生の思い出[森村たまき] 訳者あとがき[森村進] デレク・アントニー・パーフィット 年譜 参考文献 索引 |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆

"Black

Cat Dance" by Mr. Links