Différence

et répétition, 1968

★『差異と反復』(フランス語:Différence et Répétition)は、フランスの哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズが1968年に発表した著作である。原著はフランスで出版され、1994年にポール・パット ンによって英訳された。ドゥルーズが博士号を取得するための主論文であり、副論文である歴史的論文『哲学における表現主義』——スピノザ この作品は、表象の批判を試みている——と並んで、『差異と反復』があ る。ドゥルーズは本書において、差異それ自体の概念と反復それ自体の概念、つまり、 同一性の概念に論理的・形而上学的に 先行する差異と反復の概念を構築している。ドゥルーズがカントの『純粋理性批判』(1781年)を「発生」そのものから書き直そうとしたものと 解釈する論者もいる。彼は自分の哲学的動機を「一般化された反ヘーゲル主義」(p.xix)と し、差異と反復の力がヘーゲルにおける同一性と否定の概念的代用として機能しうることを指摘している。この用語の変化の重要性は、差異と反復がともに予測 不可能な効果を持つ正の力であるということである。ドゥルーズは、ヘーゲルとは異なり、弁証法の二元論に抵抗する喜びと創造の論理から概念を作り出すこと を示唆している。「私は、私の概念を、移動する地平に沿って、常に脱中心から、それらを反復し差異化する常にずれた周縁から作り、作り変え、作り直す」 (p.xxi)。ドゥルーズは英語版の序文で、第三章(思考のイメージ)を、後のフェリックス・ガタリとの共同作業を予見させるものとして強調している。 また、「結論は最初に読むべきだ」というだけでなく、「これは本書についても言えることで、その結論があれば残りを読む必要はなくなるかもしれない」 (p.ix)とも示唆している。

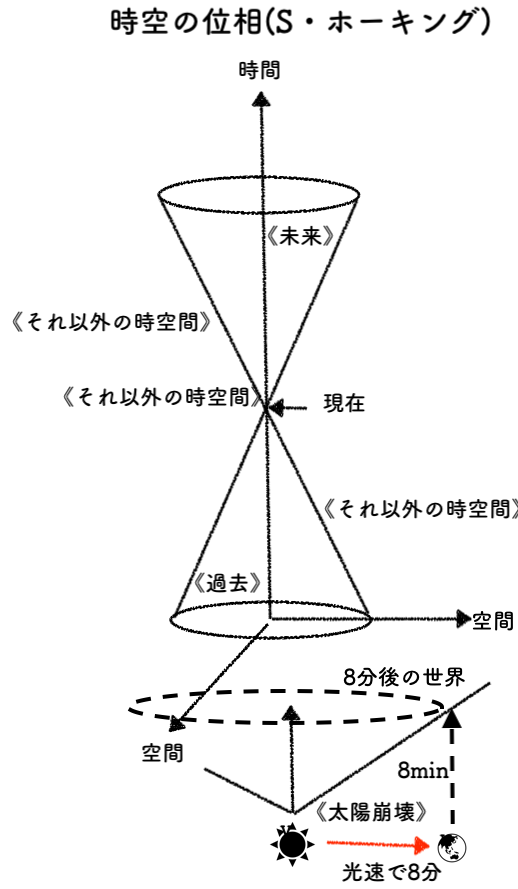

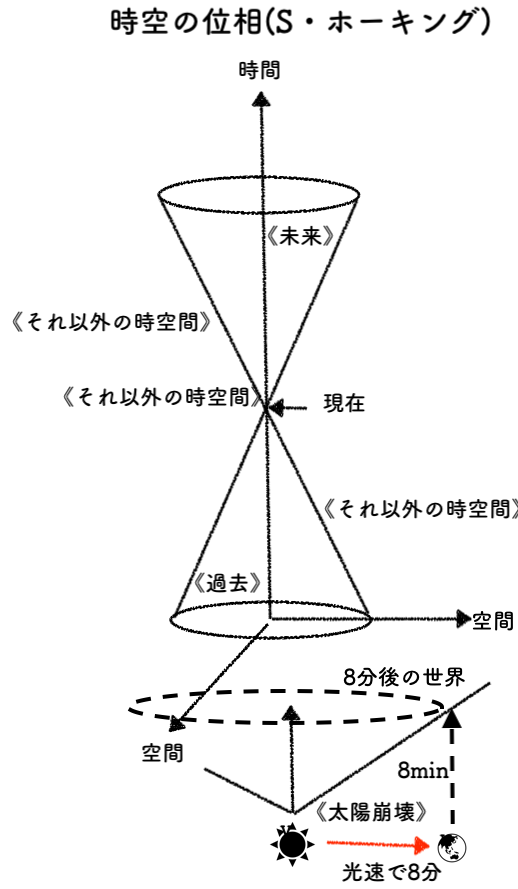

☆元祖・懐疑論者のディヴィッド・ ヒュームに 言わせれば、我々のリアル・リアリティというものは、ヴァーチャル・リアリティで あり、眼球をまぶたの側からそっと押さえつけるだけで、目に見える世界は 歪んでみえ、我々がみている情報はすべて、脳で処理された画像を感じ取っているにすぎない。手に触ったという事実ですら、脳が手の情報をそのように処理し ているにすぎない。もっとも、ヒュームの懐疑論は、哲学的省 察に必要なものであり、日常生活に懐疑論をいちいち持ち込むなという意見もある(→「理 性の綱渡り」「ヴァー チャル・リアリティ」)

***

| Différence et

Répétition est un ouvrage du philosophe français Gilles Deleuze paru

aux PUF en 1968. C'est la thèse principale de Gilles Deleuze, sous la

direction de Maurice de Gandillac, qui lui valut son doctorat en

lettres. À travers l'histoire de la philosophie, Gilles Deleuze tente de montrer les différentes potentialités et approches de la Différence et de la Répétition. Analysant la philosophie de Leibniz, Deleuze substitue le concept de multiplicité à celui de substance, d'événement à celui d'essence, et de virtualité à celui de possibilité. Ce livre propose autant une métaphysique qu'une philosophie esthétique. L'ouvrage tente une critique de la représentation. Dans le livre, Deleuze développe des concepts de différence en soi et de répétition pour soi, c'est-à-dire des concepts de différence et de répétition qui sont logiquement et métaphysiquement antérieurs à tout concept d'identité. Certains commentateurs interprètent le livre comme une tentative de Deleuze de réécrire la Critique de la raison pure d'Emmanuel Kant (1781) du point de vue de la genèse elle-même1. Il a récemment été affirmé que Deleuze a en fait recentré son orientation philosophique autour de la thèse de Gabriel Tarde selon laquelle la répétition sert la différence plutôt que l'inverse2. |

Différence et

Répétition』はフランスの哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズの著書で、1968年にPUFから出版された。モーリス・ド・ガンディラックの指導の下、ジ

ル・ドゥルーズの主要論文となり、文学博士号を取得した。 哲学史を通して、ジル・ドゥルーズは『差異と反復』のさまざまな可能性とアプローチを示そうと試みている。ライプニッツの哲学を分析し、ドゥルーズは多義 性の概念を実体の概念に、出来事の概念を本質の概念に、仮想性の概念を可能性の概念に置き換えている。本書は美学哲学であると同時に形而上学でもある。 本書は表象批判を試みている。ドゥルーズは本書の中で、それ自体における差異とそれ自体にとっての反復、すなわち同一性の概念に論理的・形而上学的に先行 する差異と反復の概念を展開している。この本を、イマヌエル・カントの『純粋理性批判』(1781年)を、発生そのものの観点から書き直そうとするドゥ ルーズの試みと解釈する論者もいる1。 最近では、ドゥルーズは実際には、反復はむしろその逆ではなく、差異に役立つというガブリエル・タルドのテーゼを中心に、哲学的方向性を再設定したのだと 論じられている2。 |

| Résumé Préface Deleuze utilise la préface pour relier l'œuvre à d'autres textes. Il décrit sa motivation philosophique comme " un anti-hégélianisme généralisé " (xix) et note que les forces de la différence et de la répétition peuvent servir de substituts conceptuels à l'identité et à la négation chez Hegel. L'importance de ce changement terminologique est que la différence et la répétition sont toutes deux des forces positives aux effets imprévisibles. Deleuze suggère que, contrairement à Hegel, il crée des concepts à partir d'une logique joyeuse et créative qui résiste au dualisme de la dialectique : " Je fais, refais et défais mes concepts le long d'un horizon mobile, à partir d'un centre toujours décentré, d'une périphérie toujours déplacée qui les répète et les différencie " (xxi). Dans la préface de l'édition anglaise, Deleuze souligne que le troisième chapitre (L'image de la pensée) préfigure son travail ultérieur avec Félix Guattari. Il suggère également non seulement que " les conclusions doivent être lues dès le début ", mais aussi que " Cela est vrai du présent livre, dont la conclusion pourrait rendre inutile la lecture du reste " (ix). |

概要 序文 ドゥルーズは序文で、この作品を他のテクストと結びつけている。彼はその哲学的動機を「一般化された反ヘーゲル主義」(xix)とし、差異と反復の力が ヘーゲルにおける同一性と否定の概念的な代用品として機能しうると指摘する。この用語の転換の意義は、差異も反復も予測不可能な効果を持つ肯定的な力であ るということである。ドゥルーズは、ヘーゲルとは異なり、弁証法の二元論に抵抗する、喜びに満ちた創造的な論理から概念を創造していることを示唆してい る。 英語版への序文でドゥルーズは、第3章(思考のイメージ)が後のフェリックス・ガタリとの仕事を予見していると指摘している。 彼はまた、「結論は最初から読むべきである」だけでなく、「本書についても同様であり、その結論があれば残りを読む必要はなくなるかもしれない」(ix) とも示唆している。 |

| Introduction : Répétition et

différence Deleuze utilise l'introduction pour clarifier le terme "répétition". On peut comprendre la répétition de Deleuze en l'opposant à la généralité. Les deux mots décrivent des événements qui ont des connexions sous-jacentes. La généralité fait référence à des événements qui sont reliés par des cycles, des égalités et des lois. La plupart des phénomènes qui peuvent être directement décrits par la science sont des généralités. Des événements apparemment isolés se produiront de la même manière à maintes reprises car ils sont régis par les mêmes lois. L'eau s'écoule en pente et la lumière du soleil crée de la chaleur en raison de principes qui s'appliquent de manière générale. Dans le domaine humain, le comportement conforme aux normes et aux lois est considéré comme une généralité pour des raisons similaires. La science traite principalement des généralités parce qu'elle cherche à prédire la réalité en utilisant la réduction et l'équivalence. La répétition, pour Deleuze, ne peut décrire qu'une série unique de choses ou d'événements. L'histoire de Borges, dans laquelle Pierre Ménard reproduit le texte exact du Don Quichotte de Miguel de Cervantès, est une quintessence de la répétition : la répétition de l'œuvre de Cervantès par Ménard revêt une qualité magique en raison de sa traduction dans un temps et un lieu différents. L'art est souvent une source de répétition, car aucune utilisation artistique d'un élément n'est jamais vraiment équivalente à d'autres utilisations. (Le Pop Art pousse cette qualité jusqu'à une certaine limite en rapprochant la production du niveau du capitalisme, tandis que le Net Art s'affranchit complètement de la réplication au profit de l'identification). Pour les humains, la répétition est intrinsèquement transgressive. Comme dans Masochisme : Froideur et cruauté, Deleuze identifie l'humour et l'ironie comme des lignes d'évasion des généralités de la société. L'humour et l'ironie sont en accord avec la répétition parce qu'ils créent une distance par rapport aux lois et aux normes tout en les remettant en scène. Deleuze décrit la répétition comme une valeur partagée par un trio par ailleurs assez disparate : Kierkegaard, Nietzsche et Péguy. Il relie également cette idée à la pulsion de mort de Freud. Il définit ensuite la répétition comme "une différence sans concept" (13). La répétition s'appuie donc sur la différence plus profondément qu'elle ne s'y oppose. De plus, une répétition profonde sera caractérisée par une différence profonde. |

序論:反復と差異 ドゥルーズは序論で「反復」という言葉を明確にしている。ドゥルーズの反復は、一般性と対比させることで理解できる。どちらの言葉も、根底につながりのあ る出来事を表している。 一般性とは、周期、等式、法則によって結びついている事象を指す。科学が直接説明できる現象のほとんどは一般性である。一見孤立しているように見える事象 は、同じ法則に支配されているため、何度も同じように起こる。水は坂道を流れ、太陽光は熱を生み出すが、これは一般的に適用される原理によるものである。 人間の領域では、規範や法則に従った行動は、同様の理由で一般性とみなされる。科学は還元と等価性を用いて現実を予測しようとするため、主に一般性を扱 う。 ドゥルーズにとっての反復は、単一の物事や出来事の系列しか記述できない。ピエール・メナールがミゲル・ド・セルバンテスの『ドン・キホーテ』のテキスト を正確に再現するボルヘスの物語は、反復の典型的な例である。メナールがセルバンテスの作品を反復することで、異なる時間と場所に翻訳されることによっ て、魔法のような性質を帯びる。芸術はしばしば反復の源である。というのも、ある要素の芸術的な使用法が、他の使用法と等価であることは決してないから だ。(ポップ・アートは生産を資本主義のレベルに近づけることで、この性質をある限界まで押し上げるが、ネット・アートは複製を完全に排除して同一化を優 先する)。 人間にとって、反復は本質的に侵犯的である。マゾヒズム:冷たさと残酷さ』のように、ドゥルーズはユーモアとアイロニーを、社会の一般性から逃れるための 一線として位置づけている。ユーモアとアイロニーは反復と同調する。なぜなら、それらは法や規範から距離を置くと同時に、それらを再演するからである。 ドゥルーズは、キルケゴール、ニーチェ、ペギーという、どちらかといえば異質なトリオが共有する価値観として反復を挙げている。彼はまた、この考えをフロ イトの死の衝動と結びつけている。 さらに彼は、反復を「概念のない差異」(13)と定義する。したがって、反復は差異に対立するのではなく、差異に基づいている。しかも、深遠な反復は深遠 な差異によって特徴づけられる。 |

| . La différence en elle-même Deleuze brosse un tableau de l'histoire de la philosophie dans lequel la différence a longtemps été subordonnée à quatre piliers de la raison : l'identité, l'opposition, l'analogie et la ressemblance. Il soutient que la différence a été traitée comme une caractéristique secondaire qui émerge lorsqu'on compare des choses préexistantes ; on peut alors dire que ces choses ont des différences. Ce réseau de relations directes entre les identités recouvre grossièrement un réseau beaucoup plus subtil et involué de différences réelles : gradients, intensités, chevauchements, et ainsi de suite (50). Le chapitre contient une discussion sur la façon dont divers philosophes ont traité l'émergence de la différence au sein de l'Être. Cette section utilise Duns Scot, Spinoza et d'autres pour démontrer qu'"il n'y a jamais eu qu'une seule proposition ontologique : L'être est univoque. ... Une seule voix élève la clameur de l'être" (35). On essaie ensuite de comprendre la nature des différences qui surgissent au sein de l'être. Deleuze décrit comment Hegel a considéré la contradiction - l'opposition pure - comme le principe sous-jacent à toute différence et par conséquent comme le principe explicatif de toute la texture du monde. Il reproche à cette conception d'avoir un penchant théologique et métaphysique. Deleuze propose (en citant Leibniz) que la différence est mieux comprise par l'utilisation de dx, la différentielle. Une dérivée, dy/dx, détermine la structure d'une courbe tout en existant juste en dehors de la courbe elle-même, c'est-à-dire en décrivant une tangente virtuelle (46). Deleuze soutient que la différence devrait fondamentalement être l'objet d'une affirmation et non d'une négation. Comme pour Nietzsche, la négation devient secondaire et épiphénoménale par rapport à cette force primaire. |

I. 差異それ自体 ドゥルーズは、差異が長い間、同一性、対立、類似、相似という理性の4本の柱に従属させられてきたという哲学史の図式を描く。ドゥルーズは、差異が、既存 のものが比較されるときに現れる二次的な特徴として扱われてきたと主張する。このアイデンティティ間の直接的な関係のネットワークは、勾配、強さ、重なり といった、より微妙で複雑な現実の差異のネットワークをおおよそ覆っている(50)。 この章では、さまざまな哲学者が「存在」の内部における差異の出現をどのように扱ってきたかについて論じている。この章では、ドゥンス・スコトゥスやスピ ノザなどを用いて、「存在とは一義的である、という存在論的命題が複数存在したことはない。一つの声が存在の喧騒を高めている」(35)。その上で、私た ちは存在の中に生じる差異の本質を理解しようとする。ドゥルーズは、ヘーゲルが矛盾--純粋な対立--をすべての差異の根底にある原理として、したがって 世界の質感全体の説明原理としてとらえていたことを述べている。彼はこの概念が神学的、形而上学的な傾向を持っていると批判する。 ドゥルーズは(ライプニッツの言葉を引用して)、差異とは微分であるdxを用いることによって最もよく理解されると提唱している。微分dy/dxは、曲線 の構造を決定する一方で、曲線自体のすぐ外側に存在する、つまり仮想的な接線を記述する(46)。ドゥルーズは、差異とは否定ではなく肯定の対象であるべ きだと主張する。ニーチェと同様、否定はこの第一の力にとって二次的で表象的なものとなる。 |

| II. La répétition pour elle-même Ce chapitre décrit trois niveaux de temps différents au sein desquels la répétition se produit. Deleuze prend comme axiome la notion qu'il n'y a pas d'autre temps que le présent, qui contient le passé et le futur. Ces niveaux décrivent les différentes manières dont le passé et le futur peuvent être inscrits dans un présent. Au fur et à mesure que cette inscription se complique, le statut du présent lui-même devient plus abstrait. |

II. それ自体のための反復 この章では、反復が起こる3つの異なる時間のレベルについて説明する。ドゥルーズは、過去と未来を内包する現在以外に時間は存在しないという概念を公理と している。これらのレベルは、過去と未来が現在に刻まれうるさまざまな方法を示している。この刻み込みがより複雑になるにつれて、現在そのものの状態もよ り抽象的になる。 |

| 1. La synthèse passive Les processus fondamentaux de l'univers ont un élan qu'ils transportent dans chaque moment présent. Une "contraction" de la réalité fait référence à la collecte d'une force continue diffuse dans le présent. Avant la pensée et le comportement, toute substance effectue une contraction. " Nous sommes faits d'eau, de terre, de lumière et d'air contractés... Chaque organisme, dans ses éléments réceptifs et perceptifs, mais aussi dans ses viscères, est une somme de contractions, de rétentions et d'attentes " (73). La synthèse passive est illustrée par l'habitude. L'habitude incarne le passé (et les gestes vers le futur) dans le présent en transformant le poids de l'expérience en une urgence. L'habitude crée une multitude de "moi larvaire", dont chacun fonctionne comme un petit moi avec des désirs et des satisfactions. Dans le discours freudien, c'est le domaine des excitations liées associées au principe de plaisir. Deleuze cite Hume et Bergson comme étant pertinents pour sa compréhension de la synthèse passive. |

1. 受動的な統合 宇宙の基本的なプロセスには勢いがあり、その勢いはそれぞれの現在に持ち込まれる。現実の「収縮」とは、拡散した連続的な力が現在に集まることを指す。思 考や行動の前に、あらゆる物質は収縮を受ける。「私たちは収縮した水、土、光、空気でできている。私たちは水、土、光、空気からできている......す べての生物は、受容と知覚の要素において、また内臓においても、収縮、保持、期待の総体である」(73)。 受動的統合は習慣によって説明される。習慣は過去(そして未来への身振り)を現在に具体化し、経験の重みを緊急性に変える。習慣は多数の「幼い自己」を生 み出し、それぞれが欲望と満足を持つ小さな自己として機能する。フロイトの言説では、これは快楽原則に関連する興奮の領域である。 ドゥルーズは受動的総合の理解に関連するものとして、ヒュームとベルクソンを挙げている。 |

| 2. La synthèse active Le deuxième niveau de temps est organisé par la force active de la mémoire, qui introduit une discontinuité dans le passage du temps en entretenant des relations entre des événements plus éloignés. Une discussion sur le destin montre clairement comment la mémoire transforme le temps et met en œuvre une forme plus profonde de répétition : Le destin ne consiste jamais en des relations déterministes étape par étape entre des présents qui se succèdent selon l'ordre d'un temps représenté. Elle implique plutôt entre des présents successifs des connexions non localisables, des actions à distance, des systèmes de relecture, de résonance et d'échos, des chances objectives, des signes, des signaux et des rôles qui transcendent les lieux spatiaux et les successions temporelles. (83) Par rapport à la synthèse passive de l'habitude, la mémoire est virtuelle et verticale. Elle traite les événements dans leur profondeur et leur structure plutôt que dans leur contiguïté dans le temps. Là où les synthèses passives créaient un champ de "moi", la synthèse active est réalisée par "je". Dans le registre freudien, cette synthèse décrit l'énergie déplacée d'Eros, qui devient une force de recherche et de problématisation plutôt qu'un simple stimulus de gratification. Proust et Lacan sont des auteurs clés pour cette couche. |

2. 能動的な統合 時間の第二段階は、記憶の能動的な力によって組織化される。記憶とは、より遠い出来事同士の関係を維持することによって、時間の流れに不連続性をもたらす ものである。運命について論じれば、記憶がいかに時間を変容させ、より深い反復の形を実現するかがよくわかる: 運命は決して、表象された時間の順序に従って互いに続く、決定論的な段階的関係からなるものではない。そうではなく、連続する提示の間に、非局所的なつな がり、離れた場所での行為、再読のシステム、共鳴と反響、客観的なチャンス、空間的な位置や時間的な連続性を超越するしるし、信号、役割が含まれるのであ る。(83) 習慣の受動的な統合に比べ、記憶は仮想的で垂直的である。記憶とは、出来事を時間的な連続性ではなく、その深さと構造において扱うものである。受動的な総 合が「私」の場を作り出したのに対して、能動的な総合は「私」 によって達成される。フロイト的な解釈では、この統合は、単純な満足のための刺激ではなく、研究と問題化のための力となるエロスの変位したエネルギーを描 写する。 プルーストとラカンは、この層にとって重要な作家である。 |

| 3. Le temps vide La troisième couche de temps existe toujours dans le présent, mais elle le fait d'une manière qui s'affranchit de la simple répétition du temps. Ce niveau fait référence à un événement ultime si puissant qu'il en devient omniprésent. Il s'agit d'un grand événement symbolique, comme le meurtre que doit commettre Œdipe ou Hamlet. En s'élevant à ce niveau, l'acteur s'efface en tant que tel et rejoint le royaume abstrait de l'éternel retour. Le moi et le je cèdent la place à "l'homme sans nom, sans famille, sans qualités, sans moi ou je... le déjà-surhomme dont les membres épars gravitent autour de l'image sublime" (90). Le temps vide est associé à Thanatos, une énergie désexualisée qui traverse toute la matière et supplante la particularité d'un système psychique individuel. Deleuze prend soin de souligner qu'il n'y a aucune raison pour que Thanatos produise une impulsion spécifiquement destructrice ou un " instinct de mort " chez le sujet ; il conçoit Thanatos comme simplement indifférent. Nietzsche, Borges et Joyce sont les auteurs de Deleuze pour la troisième fois. |

3. 空の時間 時間の第3層はまだ現在に存在しているが、単純な時間の繰り返しから脱却した形でそうなっている。このレベルは、遍在するほど強力な究極の出来事を指す。 オイディプスやハムレットが犯さなければならない殺人のような、偉大な象徴的出来事である。このレベルに到達することで、俳優はそのような存在から消え去 り、永遠回帰の抽象的な領域に加わる。私」と「私」は、「名もなく、家族もなく、資質もなく、私でも私でもない男......その散り散りになったメン バーが崇高なイメージの周りに引き寄せられるデジャ・シュルホルム」(90)へと道を譲る。 空虚な時間は、すべての物質を貫き、個々の心的システムの特殊性に取って代わる脱性的なエネルギーであるタナトスと結びついている。ドゥルーズは、タナト スが特に破壊的な衝動や「死の本能」を主体に生じさせる理由がないことを注意深く指摘している。 ニーチェ、ボルヘス、ジョイスが3度目のドゥルーズである。 |

| III. L'image de la pensée Ce chapitre s'attaque à une " image de la pensée " qui imprègne le discours populaire et philosophique. Selon cette image, la pensée gravite naturellement vers la vérité. La pensée se divise facilement en catégories de vérité et d'erreur. Le modèle de la pensée provient de l'institution scolaire, dans laquelle un maître pose un problème et l'élève produit une solution qui est soit vraie, soit fausse. Cette image du sujet suppose qu'il existe différentes facultés, chacune d'entre elles saisissant idéalement le domaine particulier de la réalité auquel elle est le plus adaptée. En philosophie, cette conception donne lieu à des discours fondés sur l'argument selon lequel "Tout le monde sait..." la vérité d'une idée fondamentale. Descartes, par exemple, fait appel à l'idée que tout le monde peut au moins penser et donc exister. Deleuze fait remarquer que la philosophie de ce type tente d'éliminer tous les présupposés objectifs tout en maintenant les présupposés subjectifs. Deleuze soutient, avec Artaud, que la véritable pensée est l'un des défis les plus difficiles qui soient. La pensée exige une confrontation avec la stupidité, l'état d'être humain sans forme, sans s'engager dans de vrais problèmes. On découvre que le véritable chemin vers la vérité passe par la production de sens : la création d'une texture pour la pensée qui la relie à son objet. Le sens est la membrane qui relie la pensée à son autre. Par conséquent, l'apprentissage n'est pas la mémorisation de faits, mais la coordination de la pensée avec une réalité. "Par conséquent, l'apprentissage a toujours lieu dans et par l'inconscient, établissant ainsi le lien d'une profonde complicité entre la nature et l'esprit " (165). L'image alternative que Deleuze donne de la pensée est fondée sur la différence, qui crée un dynamisme qui traverse les facultés et les conceptions individuelles. Cette pensée est fondamentalement énergique et asignifiante : si elle produit des propositions, celles-ci sont tout à fait secondaires à son développement. À la fin du chapitre, Deleuze résume l'image de la pensée qu'il critique par huit attributs : (1) le postulat du principe, ou de la Cogitatio natural universalis (bonne volonté du penseur et bonne nature de la pensée) ; (2) le postulat de l'idéal, ou du sens commun (le sens commun comme concordia facultatum et le bon sens comme la distribution qui garantit cette concorde) ; (3) le postulat du modèle, ou de la reconnaissance (la reconnaissance invitant toutes les facultés à s'exercer sur un objet supposé identique, et la possibilité conséquente d'erreur dans la distribution lorsqu'une faculté confond un de ses objets avec un objet différent d'une autre faculté) ; (4) le postulat de l'élément ou de la représentation (lorsque la différence est subordonnée aux dimensions complémentaires du Même et du Semblable, de l'Analogue et de l'Opposé) ; (5) le postulat du négatif, ou de l'erreur (dans lequel l'erreur exprime tout ce qui peut aller mal dans la pensée, mais seulement comme le produit de mécanismes externes) ; (6) le postulat de la fonction logique, ou de la proposition (la désignation est prise comme le lieu de la vérité, le sens n'étant que le double neutralisé ou le doublement infini de la proposition) ; (7) le postulat de la modalité, ou des solutions (les problèmes étant matériellement tracés à partir des propositions ou même, formellement définis par la possibilité de leur résolution) ; (8) le postulat de la fin, ou du résultat, le postulat de la connaissance (la subordination de l'apprentissage à la connaissance, et de la culture à la méthode). (167) |

III. 思考のイメージ この章では、大衆や哲学者の言説に浸透している「思考のイメージ」に取り組む。このイメージによれば、思考は自然に真理に引き寄せられる。思考は真理と誤 謬のカテゴリーに簡単に分けられる。この思考モデルは、教師が問題を出し、生徒が真か偽かのどちらかの解答を出すという学校制度に由来する。このような主 体のイメージは、さまざまな能力があり、それぞれが最も適した現実の特定の領域を理想的に把握していると仮定している。 哲学では、このような考え方は、基本的な考え方の真理を「誰もが知っている」という議論に基づく言説を生む。例えばデカルトは、誰もが少なくとも考えるこ とができ、したがって存在することができるという考えに訴えた。ドゥルーズは、この種の哲学は、主観的な前提を維持しながら、客観的な前提をすべて排除し ようとしていると指摘する。 ドゥルーズはアルトーとともに、真の思考とは最も困難な挑戦のひとつであると主張する。思考は、愚かさ、つまり、現実の問題に関与することなく、形のない 人間である状態との対決を必要とする。私たちは、真理への真の道は意味を生み出すことにあることを発見する。つまり、思考とその対象を結びつける思考のテ クスチャーの創造である。意味とは、思考を他のものと結びつける膜である。 その結果、学習とは事実を暗記することではなく、思考を現実と結びつけることなのである。「その結果、学習は常に無意識の中で、無意識を通して行われ、自 然と心との間に深遠な共犯関係の結びつきを確立する」(165)。 ドゥルーズの代替的な思考イメージは差異に基づいており、個々の能力や概念を横断するダイナミズムを生み出している。この思考は基本的にエネルギッシュで あり、重要ではない。もしそれが命題を生み出すとしても、それはその発展にとってまったく二次的なものである。 この章の最後で、ドゥルーズは批判している思考像を8つの属性でまとめている: (1) 原理の仮定、すなわち自然普遍性(思考者の善意と思考の善性)、(2) 理想の仮定、すなわちコモン・センス(concordia facultatumとしてのコモン・センスと、このコンコーディアを保証する配分としてのコモン・センス)、(3) 理想の仮定、すなわちコモン・センス(concordia facultatumとしてのコモン・センスと、このコンコーディアを保証する配分としてのコモン・センス); (3) 模範の仮定、すなわち認識の仮定(認識は、すべての諸能力を、本来同一であるはずの対象に対して行使させるものであり、その結果、ある諸能力がその対象の ひとつを他の諸能力の異なる対象と混同したときに、分配に誤りが生じる可能性がある); (5) 否定、あるいは誤謬の仮定(この仮定において誤謬は、思考において誤る可能性のあるすべて のものを表現するが、それは外的なメカニズムの産物としてのみ表現される) (6) 論理的機能、あるいは命題の仮定(命題の中和された二重、あるいは無限の二重を意味し、指定は真理の場とされる); (7) モダリティの仮定、すなわち解決法の仮定(問題は命題から物質的に追跡され、あるいはその解決の可能性によって形式的に定義される) (8) 終わりの仮定、すなわち結果の仮定、すなわち知識の仮定(学習の知識への従属、文化の方法への従属)。(167) |

| IV. Synthèse idéelle de la

différence Ce chapitre développe l'argument selon lequel la différence sous-tend la pensée en proposant une conception des Idées fondée sur la différence. Deleuze revient sur sa substitution de la différentielle (dx) à la négation (-x), soutenant que les Idées peuvent être conçues comme " un système de relations différentielles entre des éléments génétiques déterminés réciproquement " (173-4). Les idées sont des multiplicités, c'est-à-dire qu'elles ne sont ni nombreuses ni uniques, mais une forme d'organisation entre des éléments abstraits qui peuvent être actualisés dans différents domaines. Un exemple est celui des organismes. Un organisme s'actualise selon un schéma qui peut être varié mais qui définit néanmoins les relations entre ses composants. Sa complexité est obtenue par des ruptures progressives de symétrie qui commencent par de petites distinctions dans une masse embryonnaire. Le terme "virtuel" est utilisé pour décrire ce type d'entité (néanmoins réelle). La notion de virtualité souligne la manière dont l'ensemble des relations elles-mêmes sont antérieures aux instances de ces relations, appelées actualisations. |

IV. 差異の理想的統合 本章では、差異に基づくイデアの概念を提案することで、差異が思考の根底にあるという議論を展開する。 ドゥルーズは否定(-x)に対する差延(dx)の置き換えに立ち戻り、イデアを「相互に決定される遺伝的要素間の差延的関係の体系」(173-4)として 構想することができると主張する。イデアは多重性であり、それは多数でも一意でもなく、異なる領域で現実化できる抽象的要素間の組織形態であることを意味 する。その一例が生物である。生物は、多様であっても、構成要素間の関係を定義するパターンに従って現実化される。その複雑さは、胚の塊の小さな区別から 始まる対称性の漸進的な破れによって達成される。 ヴァーチャル」という用語は、この種の(それにもかかわらず実在する)実体を表現するために使われる。仮想性という概念は、関係の集合そのものが、アク チュアリゼーションと呼ばれるこれらの関係のインスタンスに先行する方法を強調するものである。 |

| V. Synthèse asymétrique du

sensible Ce chapitre poursuit la discussion sur le jeu de la différence et explique comment le sens peut en découler. Pour ce faire, il s'appuie sur des concepts scientifiques et mathématiques liés à la différence, en particulier la théorie thermodynamique classique. Intensif et extensif Un thème majeur est l'intensif, qui s'oppose (et pour Deleuze, précède) l'extensif. L'extensité renvoie aux dimensions actualisées d'un phénomène : sa hauteur, ses composantes spécifiques. En science, les propriétés intensives d'un objet sont celles, comme la densité et la chaleur spécifique, qui ne changent pas avec la quantité. De même, alors que les propriétés extensives peuvent être divisées (l'objet peut être coupé en deux), les qualités intensives ne peuvent être simplement réduites ou divisées sans transformer entièrement leur porteur. Il existe un espace intensif, appelé spatium, qui est virtuel et dont les implications régissent la production éventuelle d'un espace extensif. Ce spatium est l'analogue cosmique de l'Idée ; le mécanisme d'actualisation des relations abstraites est le même. L'intensité régit les processus fondamentaux par lesquels les différences interagissent et façonnent le monde. "C'est l'intensité qui s'exprime immédiatement dans les dynamismes spatio-temporels de base et qui détermine une relation différentielle "indistincte" dans l'Idée à s'incarner dans une qualité distincte et une extensité distinguée" (245). Les modes de pensée Deleuze s'attaque au bon sens et au sens commun. Le bon sens traite l'univers de manière statistique et tente de l'optimiser pour produire le meilleur résultat. Le bon sens peut être rationaliste, mais il n'affirme pas le destin ou la différence ; il a intérêt à réduire plutôt qu'à amplifier la puissance de la différence. Il adopte le point de vue économique selon lequel la valeur est une moyenne des valeurs attendues et le présent et le futur peuvent être intervertis sur la base d'un taux d'actualisation spécifique. Le bon sens est la capacité de reconnaître des catégories d'objets et d'y réagir. Le bon sens complète le bon sens et lui permet de fonctionner ; la "reconnaissance" de l'objet permet la "prédiction" et l'annulation du danger (ainsi que d'autres possibilités de différence). Au sens commun et au bon sens, Deleuze oppose le paradoxe. Le paradoxe sert de stimulus à la pensée réelle et à la philosophie car il oblige la pensée à se confronter à ses limites. Individuation La coalescence des "individus" à partir du flux cosmique de la matière est un processus lent et incomplet. " L'individuation est mobile, étrangement souple, fortuite et dotée de franges et de marges ; tout cela parce que les intensités qui y contribuent communiquent entre elles, enveloppent d'autres intensités, et sont à leur tour enveloppées " (254). En d'autres termes, même après l'individuation, le monde ne devient pas un arrière-plan passif ou une scène sur laquelle des acteurs nouvellement autonomes entrent en relation les uns avec les autres. Les individus restent liés aux forces sous-jacentes qui les constituent tous, et ces forces peuvent interagir et se développer sans l'approbation de l'individu. L'embryon met en scène le drame de l'individuation. Au cours de ce processus, il se soumet à des dynamiques qui mettraient en pièces un organisme pleinement individué. Le pouvoir de l'individuation ne réside pas dans le développement d'un moi final, mais dans la capacité des dynamiques profondes à s'incarner dans un être qui acquiert des pouvoirs supplémentaires en vertu de sa matérialité. L'individuation rend possible un drame décrit comme une confrontation avec le visage de l'Autre. Distincte de la forme singulière de l'éthique lévinassienne, cette scène est importante pour Deleuze car elle représente la possibilité et l'ouverture associées à un inconnu individué. |

V. 感覚の非対称的統合 この章では、差異の相互作用についての議論を続け、そこからどのように意味を導き出すことができるかを説明する。そのために、差異に関連する科学的・数学 的概念、特に古典的な熱力学理論を利用する。 インテンシブとエクステンシブ 主要なテーマは、広範なものに対立する(ドゥルーズにとっては広範なものに先行する)集中的なものである。エクステンシヴとは、ある現象の現実化された次 元、つまりその高さや特定の構成要素を指す。科学において、物体の集中的な性質とは、密度や比熱など、量によって変化しない性質を指す。同様に、広範な性 質は分割することができるが(物体を半分にすることができる)、集中的な性質は、そのキャリアを完全に変容させることなく、単純に縮小したり分割したりす ることはできない。 スパティウムと呼ばれる集中的な空間があり、それは仮想的なもので、その意味合いが最終的に広範な空間の生成を支配する。このスパティウムはイデアの宇宙 的アナログであり、抽象的関係を現実化するメカニズムは同じである。 強度は、差異が相互作用し、世界を形作る基本的なプロセスを支配する。「基本的な時空間ダイナミズムの中で即座に自らを表現し、イデアにおける「不明瞭 な」差異関係を、明瞭な質と際立った広がりとして具現化することを決定するのは強度である」(245)。 思考の様態 ドゥルーズは常識や通念を攻撃する。常識は宇宙を統計的に扱い、最高の結果を生むように最適化しようとする。常識は合理主義的かもしれないが、運命や差異 を肯定するものではなく、差異の力を増幅させるのではなく、むしろ減少させることに関心がある。価値とは期待値の平均であり、現在と未来は特定の割引率に 基づいて交換できるという経済学的見解を採用する。 コモンセンスとは、対象のカテゴリーを認識し、それに対応する能力のことである。コモン・センスはコモン・センスを補完し、機能させるものである。対象を 「認識」することで、危険を「予測」し、キャンセルすることが可能になる(その他の差異の可能性も同様である)。 ドゥルーズは常識とコモンセンスをパラドックスと対比させる。パラドックスは、思考にその限界に立ち向かわせるので、現実の思考や哲学に刺激を与える役割 を果たす。 個体化 物質の宇宙的な流れから「個体」が合体するのは、ゆっくりとした不完全なプロセスである。「個体化は可動的であり、奇妙なほど柔軟であり、偶然的であり、 縁と余白を備えている。言い換えれば、個体化した後でも、世界は受動的な背景や、新しく自律した行為者が互いに関係を結ぶ舞台にはならない。個人は、それ らすべてを構成する根底にある力と結びついたままであり、これらの力は個人の承認なしに相互作用し、発展することができる。 胚は個体化のドラマを演出する。その過程で、胚は完全に個体化した有機体を引き裂くような力学にさらされる。個体化の力は、最終的な自己を開発することに あるのではなく、その物質性によってさらなる力を獲得する存在に、深いダイナミクスを具現化する能力にある。個性化は、他者の顔との対決と表現されるドラ マを可能にする。レヴィナス倫理学の特異な形式とは異なるこの場面は、ドゥルーズにとって重要であり、それは個体化された未知の存在に関連する可能性と開 放性を表しているからである。 |

| Commentaire social et politique Deleuze s'écarte occasionnellement du domaine de la philosophie pure pour faire des déclarations explicitement sociopolitiques. En voici quelques exemples : " Nous prétendons qu'il y a deux manières de faire appel aux "destructions nécessaires" : celle du poète, qui parle au nom d'une puissance créatrice, capable de renverser tous les ordres et toutes les représentations pour affirmer la Différence dans l'état de révolution permanente qui caractérise l'éternel retour ; et celle du politique, qui s'attache avant tout à nier ce qui "diffère", afin de conserver ou de prolonger un ordre historique établi " (53). " Les vraies révolutions ont l'atmosphère des fêtes. La contradiction n'est pas l'arme du prolétariat, mais plutôt la manière dont la bourgeoisie se défend et se préserve, l'ombre derrière laquelle elle maintient sa prétention à décider des problèmes" (268). "Plus notre vie quotidienne apparaît standardisée, stéréotypée, soumise à une reproduction accélérée d'objets de consommation, plus il faut y injecter de l'art pour en extraire le peu de différence qui joue simultanément entre d'autres niveaux de répétition, et même pour faire résonner les deux extrêmes, à savoir la série habituelle de la consommation et la série instinctive de la destruction et de la mort" (293). |

社会的・政治的論評 ドゥルーズは時折、純粋な哲学の領域から離れ、社会政治的な発言をすることがある。以下はその例である: 「それは、永遠の回帰を特徴づける永続的な革命の状態における差異を肯定するために、あらゆる秩序と表象を覆すことのできる創造的な力の名において語る詩 人の方法と、確立された歴史的秩序を維持または延命するために、「差延」するものを否定することに主眼を置く政治家の方法である」(53)。 「本当の革命は、祝祭のような雰囲気を持っている。矛盾はプロレタリアートの武器ではなく、むしろブルジョアジーが自らを防衛し、維持する方法であり、問 題を決定するという主張を維持する背後にある影である」(268)。 「私たちの日常生活が標準化され、ステレオタイプ化され、消費財の加速度的な再生産にさらされるようになればなるほど、芸術は、他のレベルの反復の間で同 時に作用するわずかな差異をそこから引き出し、さらには、二つの極端なもの、すなわち、習慣的な消費の系列と本能的な破壊と死の系列を共鳴させるために、 そこに注入されなければならない」(293)。 |

| Ansell-Pearson, Keith. Germinal

Life: The Repetition and Difference of Deleuze. New York and London:

Routledge, 1999. Bryant, Levi R. Difference and Givenness: Deleuze's Transcendental Empiricism and the Ontology of Immanence. Evanston, Ill. : Northwestern University Press, 2008. Foucault, Michel. "Theatrum Philosophicum." Trans. Donald F. Brouchard and Sherry Simon. In Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology: Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984, Vol. 2. Ed. James D. Faubion. London: Penguin, 2000. 343-368. Hughes, Joe. Deleuze's 'Difference and Repetition': A Reader's Guide. New York and London: Continuum, 2009. Somers-Hall, Henry. Deleuze's 'Difference and Repetition: An Edinburgh Philosophical Guide. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013 Williams, James. Gilles Deleuze’s 'Difference and Repetition': A Critical Introduction and Guide. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003. |

アンセル=ピアソン、キース著『胚芽の生命:ドゥルーズの反復と差異』

ニューヨークおよびロンドン:ルートレッジ、1999年 ブライアント、レヴィ・R著『差異と与えられもの:ドゥルーズの超越論的経験論と内在性の存在論』イリノイ州エバンストン:ノースウェスタン大学出版、 2008年 フーコー、ミシェル。「Theatrum Philosophicum(哲学の劇場)」ドナルド・F・ブルチャードとシェリー・サイモン訳。『美学・方法・認識論:フーコーの主要著作 1954-1984』第2巻。ジェームズ・D・フォービオン編。ロンドン:ペンギン、2000年。343-368ページ。 Hughes, Joe. Deleuze's 'Difference and Repetition': A Reader's Guide. New York and London: Continuum, 2009. Somers-Hall, Henry. Deleuze's 'Difference and Repetition: An Edinburgh Philosophical Guide. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013 ウィリアムズ、ジェームズ。ジル・ドゥルーズ著『差異と反復』:批判的序論とガイド。エディンバラ:エディンバラ大学出版局、2003年。 |

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diff%C3%A9rence_et_R%C3%A9p%C3%A9tition |

リンク

***

| 『差異と反復』(Différence et répétition)

は、1968年にフランスの

哲学者・ジル・ドゥルーズによって発表された哲学の研究をさす。本書において、ドゥルーズは同一

性の問題に焦点を当てている。例えば「ソクラテスは人間で

ある」という言明において、ソクラテスという個別的、具体的な歴史的人物を指すものであるために排他的に用いられるものと、人間という諸々の差異を持った

存在を共通して指し示すものが等しい事態が表されている。 |

Différence

et Répétition est un ouvrage du philosophe français Gilles Deleuze paru

aux PUF en 1968. C'est la thèse principale de Gilles Deleuze, sous la

direction de Maurice de Gandillac, qui lui valut son doctorat en

lettres.

À travers l'histoire de la philosophie, Gilles Deleuze tente de montrer

les différentes potentialités et approches de la Différence et de la

Répétition. Analysant la philosophie de Leibniz, Deleuze substitue le

concept de multiplicité à celui de substance, d'événement à celui

d'essence, et de virtualité à celui de possibilité. Ce livre propose

autant une métaphysique qu'une philosophie esthétique. |

| 同

一性について、ディヴィッド・ヒュームは個々人の経験から一般的に正

しいことを導き出せるか、またそれはどのように正しいと言えるかを問題とした。本書は、このような同一性の問題に対して、(1)多種多様で

あるはずの存在がどの

ようにして同一の存在と見なせるのかを検討し、(2)同一性で処理できない差異性とその反復の過程を明らかにした。 |

(1)多種多様であるはずの存在がどの

ようにして同一の存在と見なせるのか? (2)同一性で処理できない差異性とその反復の過程を明らかにする |

| ドゥルーズは、連続する「ABABAB…」という列が「AB」の反復と

して認識されることを指摘し、そのような認識が、(3)認識の対象が持つ本質ではなく認識者の想像によると論じる。そして(4)そのような同一性の認識

は、認識者の受

動的総合から発生するため、精神による意識的な作用ではないと考える。まず(5)精神の作用が及ばない領域で認識者の過去の経験は現在に「処女的な反復」

が行な

われる。これにより、(6)それ自身では同一性を持たなかった存在が理想化され、縮

約される。ドゥルーズは、このようにあらゆる存在の同一性が過去に得られた経

験とその受動的総合、処女的な反復によって決定されることを踏まえて、哲学という活動の同一性を見直すことを主張している。(7)存在が過去に規定される

ことは

将来において連続される事態であり、過去は現在における別の反復を準備し、それゆえに将来における行為の条件となる。ドゥルーズは(8)ここから脱却する

ために

は一度も反復されていない過去を見出すことによって、新しい存在のあり方を志向できると論じる。 |

(3)認識の対象が持つ本質ではなく認識者の想像によるのだ (4)そのような同一性の認識は、認識者の受 動的総合から発生するため、精神による意識的な作用ではない。 (5)精神の作用が及ばない領域で認識者の過去の経験は現在に「処女的な反復」が行な われる (6)それ自身では同一性を持たなかった存在が理想化され、縮約される (7)存在が過去に規定されることは 将来において連続される事態であり、過去は現在における別の反復を準備し、それゆえに将来における行為の条件となっている——ただし、ドゥルーズはその事 態に承服していない。 (8)ここから脱却するために は一度も反復されていない過去を見出すことによって、新しい存在のあり方を志向できる→これは概念の創出が哲学の仕事だというドゥルーズの人生を通した主 張に合致する。 |

ウィキペディア"Difference and Repetition"より。

| Difference

and

Repetition Difference and Repetition (French: Différence et Répétition) is a 1968 book by the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze. Originally published in France, it was translated into English by Paul Patton in 1994. Difference and Repetition was Deleuze's principal thesis for the Doctorat D'Etat alongside his secondary, historical thesis, Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza. The work attempts a critique of representation. In the book, Deleuze develops concepts of difference in itself and repetition for itself, that is, concepts of difference and repetition that are logically and metaphysically prior to any concept of identity. Some commentators interpret the book as Deleuze's attempt to rewrite Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (1781) from the viewpoint of genesis itself.[1] |

『差

異と反復』 『差 異と反復』(フランス語:Différence et Répétition)は、フランスの哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズが1968年に発表した著作である。原著はフランスで出版され、1994年にポール・パット ンによって英訳された。ドゥルーズが博士号を取得するための主論文であり、副論文である歴史的論文『哲学における表現主義』と並んで、『差異と反復』であ る。スピノザ この作品は、表象の批判を試みている。ドゥルーズは本書において、差異それ自体の概念と反復それ自体の概念、つまり、同一性の概念に論理的・形而上学的に 先行する差異と反復の概念を構築している。ドゥルーズがカントの『純粋理性批判』(1781年)を「発生」そのものから書き直そうとしたものと 解釈する論者もいる。 |

| Preface

Deleuze uses the preface to relate the work to other texts. He describes his philosophical motivation as "a generalized anti-Hegelianism" (xix) and notes that the forces of difference and repetition can serve as conceptual substitutes for identity and negation in Hegel. The importance of this terminological change is that difference and repetition are both positive forces with unpredictable effects. Deleuze suggests that, unlike Hegel, he creates concepts out of a joyful and creative logic that resists the dualism of dialectic: "I make, remake and unmake my concepts along a moving horizon, from an always decentered centre, from an always displaced periphery which repeats and differentiates them" (xxi). In the preface to the English edition, Deleuze highlights the third chapter (The Image of Thought) as foreshadowing his later work with Félix Guattari. He also suggests not only that "conclusions should be read at the outset," but also that "This is true of the present book, the conclusion of which could make reading the rest unnecessary" (ix). |

序文 ドゥルーズは序文で、この作品を他のテキストと関連づけるために使われている。彼は自分の哲学的動機を「一般化された反ヘーゲル主義」(p.xix)と し、差異と反復の力がヘーゲルにおける同一性と否定の概念的代用として機能しうることを指摘している。この用語の変化の重要性は、差異と反復がともに予測 不可能な効果を持つ正の力であるということである。ドゥルーズは、ヘーゲルとは異なり、弁証法の二元論に抵抗する喜びと創造の論理から概念を作り出すこと を示唆している。「私は、私の概念を、移動する地平に沿って、常に脱中心から、それらを反復し差異化する常にずれた周縁から作り、作り変え、作り直す」 (p.xxi)。ドゥルーズは英語版の序文で、第三章(思考のイメージ)を、後のフェリックス・ガタリとの共同作業を予見させるものとして強調している。 また、「結論は最初に読むべきだ」というだけでなく、「これは本書についても言えることで、その結論があれば残りを読む必要はなくなるかもしれない」 (p.ix)とも示唆している。 |

| Introduction:

Repetition and Difference Deleuze uses the introduction to clarify the term "repetition." Deleuze's repetition can be understood by contrasting it to generality. Both words describe events that have some underlying connections. Generality refers to events that are connected through cycles, equalities, and laws. Most phenomena that can be directly described by science are generalities. Seemingly isolated events will occur in the same way over and over again because they are governed by the same laws. Water will flow downhill and sunlight will create warmth because of principles that apply broadly. In the human realm, behavior that accords with norms and laws counts as generality for similar reasons. Science deals mostly with generalities because it seeks to predict reality using reduction and equivalence. Repetition, for Deleuze, can only describe a unique series of things or events. The Borges story, in which Pierre Menard reproduces the exact text of Miguel de Cervantes's Don Quixote, is a quintessential repetition: the repetition of Cervantes' work by Menard takes on a magical quality by virtue of its translation into a different time and place. Art is often a source of repetition because no artistic use of an element is ever truly equivalent to other uses. (Pop Art pushes this quality to a certain limit by bringing production near the level of capitalism, while Net Art does away with replication altogether in favor of identification.) For humans, repetition is inherently transgressive. As in Masochism: Coldness and Cruelty, Deleuze identifies humor and irony as lines of escape from the generalities of society. Humor and irony are in league with repetition because they create distance from laws and norms even while re-enacting them. Deleuze describes repetition as a shared value of an otherwise rather disparate trio: Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Péguy. He also connects the idea to Freud's death drive. He goes on to define repetition as "difference without a concept" (13). Repetition is thus reliant on difference more deeply than it is opposed. Further, profound repetition will be characterized by profound difference. |

イントロダクション 反復と差異 ドゥルーズは序論を使って、"反復 "という言葉を明確にしている。ドゥルーズの反復は、一般性と対比させることで理解 することができる。どちらの言葉も、何らかの根底にあるつながりを持つ 事象を表現している。一般性とは、サイクルやイコール、法則によってつながっている事象のことである。科学で直接記述できる現象のほとんど は一般性であ る。一見、孤立しているように見える事象は、同じ法則に支配されているため、何度も同じように起こります。水が流れ落ちるのも、太陽の光が暖かさを生み出 すのも、広範に適用される原理があるからだ。人間の世界でも、規範や法則に従った行動が一般性としてカウントされるのは、同様の理由からである。科学が一 般性を使われるのは、還元と等価性を使って現実を予測しようとするためである。ドゥ ルーズにとって、繰り返しは、物事や出来事のユニークなシリーズを記述 することしかできない。ピエール・メナールがミゲル・デ・セルバンテスの『ドン・キホーテ』のテキストを正確に再現するボルヘスの物語は、反復の典型であ る。メナードによるセルバンテスの作品の反復は、異なる時間と場所への翻訳によって、魔法の性質を帯びているのである。芸術はしばしば繰り返しの源であ る。なぜなら、ある要素を芸術的に使うとき、他の使い方と本当に同等であることはないからだ。(ポップ・アートは生産を資本主義のレベルに近づけること で、この性質をある限界まで押し上げるが、ネット・アートは複製を完全に排除し、識別を優先させる)。人間にとって、繰り返しは本質的に侵 犯的なものであ る。マゾヒズムのように。ドゥルーズは「冷たさと残酷さ」と同様に、ユーモアとアイロニーを社会の一般性から逃れるための線として位置づけている。ユーモ アやアイロニーは、法や規範を再演しながらも、それとの距離を作り出すものであり、反復と同列に扱われるものである。ドゥルーズは、反復を、どちらかとい えば異質なトリオが共有する価値観と表現している。キルケゴール、ニーチェ、ペギーという異質なトリオに共通する価値観として、ドゥルーズは反復を挙げて いる。彼はまた、この考えをフロイトの死の衝動と結びつけている。さらに彼は、反復を「概念なき差異」(13)と定義している。このように、反復は対立す るものよりも深く差異に依存している。さらに、深遠な反復は深遠な差異によって特徴づけられることになる。 |

| I.

Difference in Itself Deleuze paints a picture of philosophical history in which difference has long been subordinated to four pillars of reason: identity, opposition, analogy, and resemblance. He argues that difference has been treated as a secondary characteristic which emerges when one compares pre-existing things; these things can then be said to have differences. This network of direct relations between identities roughly overlays a much more subtle and involuted network of real differences: gradients, intensities, overlaps, and so forth (50). The chapter contains a discussion of how various philosophers have treated the emergence of difference within Being. This section uses Duns Scotus, Spinoza, and others to make the case that "there has only ever been one ontological proposition: Being is univocal. ... A single voice raises the clamor of being" (35). One then tries to understand the nature of differences that arise within Being. Deleuze describes how Hegel took contradiction—pure opposition—to be the principle underlying all difference and consequently to be the explanatory principle of all the world's texture. He accuses this conception of having a theological and metaphysical slant. Deleuze proposes (citing Leibniz) that difference is better understood through the use of dx, the differential. A derivative, dy/dx, determines the structure of a curve while nonetheless existing just outside the curve itself; that is, by describing a virtual tangent (46). Deleuze argues that difference should fundamentally be the object of affirmation and not negation. As per Nietzsche, negation becomes secondary and epiphenomenal in relation to this primary force. |

I. 差異それ自身 ドゥルーズは、哲学の歴史において、差異が長い間、同一性、対立、類似、類似という理性の四つの柱に従属させられてきたという構図を描いている。ドゥルー ズは、差異が、既存のものを比較したときに現れる二次的な特性として扱われてきたと主張し、これらのものは差異を持っていると言うことができるとしてい る。このような同一性間の直接的な関係のネットワークは、グラデーション、強さ、重なりといった、より微妙で複雑な現実の差異のネットワークにおおよそ重 なっている(50)。この章では、様々な哲学者が存在における差異の出現をどのように扱ってきたかについての議論が展開される。この章では、ドゥンス・ス コトゥスやスピノザなどが使われ、「存在論的命題はこれまで一つしかなかった」という主張をしている。存在とは一義的なものである......。一つの声 が存在という叫びを上げるのだ」(35)。そして、人は存在の中に生じる差異の本質を理解しようとする。ドゥルーズは、ヘーゲルが矛盾-純粋対立-を、す べての差異の根底にある原理であり、その結果、世界のすべての質感の説明原理であると考えたことを説明する。彼はこの考え方が神学的、形而上学的な傾斜を 持っていると非難している。ドゥルーズは(ライプニッツを引用して)、差はdx、微分の使用によってよりよく理解されることを提案する。微分、dy/dx は、曲線の構造を決定する一方で、曲線のすぐ外側に存在し、つまり、仮想的な接線を記述することである(46)。ドゥルーズは、差は基本的に否定の対象で はなく、肯定の対象であるべきだと主張する。ニーチェのように、否定はこの第一の力との関係で、二次的で表象的なものになる。 |

II.

Repetition for Itself II.

Repetition for Itself The chapter describes three different levels of time within which repetition occurs. Deleuze takes as axiomatic the notion that there is no time but the present, which contains past and future. These layers describe different ways in which past and future can be inscribed in a present. As this inscription grows more complicated, the status of the present itself becomes more abstract. 1. Passive synthesis Basic processes of the universe have a momentum that they carry into each present moment. A 'contraction' of reality refers to the collection of a diffuse ongoing force into the present. Prior thought and behavior, all substance performs contraction. "We are made of contracted water, earth, light, and air...Every organism, in its receptive and perceptual elements, but also in its viscera, is a sum of contractions, of retentions and expectations" (73). Passive synthesis is exemplified by habit. Habit incarnates the past (and gestures to the future) in the present by transforming the weight of experience into an urgency. Habit creates a multitude of "larval selves," each of which functions like a small ego with desires and satisfactions. In Freudian discourse, this is the domain of bound excitations associated with the pleasure principle. Deleuze cites Hume and Bergson as relevant to his understanding of the passive synthesis. 2. Active synthesis The second level of time is organized by the active force of memory, which introduces discontinuity into the passage of time by sustaining relationships between more distant events. A discussion of destiny makes clear how memory transforms time and enacts a more profound form of repetition: Destiny never consists in step-by-step deterministic relations between presents which succeed one another according to the order of a represented time. Rather, it implies between successive presents non-localisable connections, actions at a distance, systems of replay, resonance and echoes, objective chances, signs, signals, and roles which transcend spatial locations and temporal successions. (83) Relative to the passive synthesis of habit, memory is virtual and vertical. It deals with events in their depth and structure rather than in their contiguity in time. Where passive syntheses created a field of 'me's,' active synthesis is performed by 'I.' In the Freudian register, this synthesis describes the displaced energy of Eros, which becomes a searching and problematizing force rather than a simple stimulus to gratification. Proust and Lacan are key authors for this layer. 3. Empty time The third layer of time still exists in the present, but it does so in a way that breaks free from the simple repetition of time. This level refers to an ultimate event so powerful that it becomes omnipresent. It is a great symbolic event, like the murder to be committed by Oedipus or Hamlet. Upon rising to this level, an actor effaces herself as such and joins the abstract realm of eternal return. The me and the I give way to "the man without name, without family, without qualities, without self or I...the already-Overman whose scattered members gravitate around the sublime image" (90). Empty time is associated with Thanatos, a desexualized energy that runs through all matter and supersedes the particularity of an individual psychic system. Deleuze is careful to point out that there is no reason for Thanatos to produce a specifically destructive impulse or 'death instinct' in the subject; he conceives of Thanatos as simply indifferent. Nietzsche, Borges, and Joyce are Deleuze's authors for the third time. |

II. 自己のための反復 II. 自己のための反復 この章では、反復が発生する3つの異なるレベルの時間について説明する。ドゥルーズは、過去と未来を含む現在以外に時間は存在しないという概念を公理とし ている。これらの層は、過去と未来が現在に刻み込まれるさまざまな方法を説明する。この刻み込みがより複雑化するにつれて、現在の状態そのものがより抽象 的になっていくのである。1. 受動的な合成 宇宙の基本的なプロセスは、現在の各瞬間に持ち込まれる勢いがある。現実の「収縮」とは、拡散した進行中の力が現在に集められることを指す。思考と行動の 前に、すべての物質が収縮を行う。「私たちは収縮した水、土、光、空気でできている...あらゆる生物は、その受容的、知覚的要素において、またその内臓 においても、収縮、保持、期待の総体である」(73)。受動的な統合は習慣によって例証される。習慣は、経験の重みを緊急性に変えることで、過去(と未来 への身振り)を現在に受肉させる。習慣は多数の「幼年期の自分」を作り出し、そのそれぞれが欲望と満足を持つ小さな自我のように機能する。フロイトの言説 では、これは快楽原則に関連する束縛された興奮の領域である。ドゥルーズは、受動的総合の理解に関連するものとして、ヒュームとベルクソンを挙げている。 2. 能動的な合成 時間の第二のレベルは、記憶の能動的な力によって組織され、より遠い出来事の間の関係を維持することで、時間の経過に不連続性を導入するものである。運命 について考察することで、記憶がいかに時間を変容させ、より深遠な反復を実現するかが明らかになる。運命は決して、表象された時間の順序に従って互いに継 承される提示物の間の段階的な決定論的関係で成り立っているのではない。むしろ、運命は、空間的な位置や時間的な連続性を超越した、非局所的な接続、距離 のある行為、再生のシステム、共鳴と反響、客観的な機会、記号、信号、役割などを連続する提示の間に含意している。(83)習慣の受動的な合成に比べ、記 憶は仮想的で垂直的である。時間的な連続性よりも、むしろその深さと構造において出来事を扱う。受動的合成が「私」のフィールドを作り出したのに対し、能 動的合成は「私」によって行われる。フロイトのレジスターでは、この合成は、満足への単純な刺激ではなく、探索と問題提起の力となるエロスの変位したエネ ルギーを記述している。 プルーストとラカンは、この層の重要な作家である。3. 空の時間 時間の第三の層は依然として現在に存在するが、それは時間の単純な反復から脱却した形で行われる。この層は、遍在するほど強力な究極の出来事を指してい る。それは、オイディプスやハムレットが犯すべき殺人のような、偉大な象徴的な出来事である。このレベルに達すると、俳優は自分自身を消し去り、永遠の帰 結の抽象的な領域に加わる。私」と「私」は、「名もなく、家族もなく、資質もなく、自分も自分もない人間...その散らばったメンバーが崇高なイメージの 周りに引き寄せられるすでにオーバーマン」(90)へと道を譲るのである。空虚な時間はタナトスと関連しており、すべての物質を貫き、個々の心的システム の特殊性に取って代わる脱俗的なエネルギーである。ドゥルーズは、タナトスが特に破壊的な衝動や「死の本能」を主体に生み出す理由はないと注意深く指摘 し、タナトスを単に無関心であると見なしている。ニーチェ、ボルヘス、ジョイスは、ドゥルーズの三度目の作家である。 |

| III. The Image of Thought This chapter takes aim at an "image of thought" that permeates both popular and philosophical discourse. According to this image, thinking naturally gravitates towards truth. Thought is divided easily into categories of truth and error. The model for thought comes from the educational institution, in which a master sets a problem and the pupil produces a solution which is either true or false. This image of the subject supposes that there are different faculties, each of which ideally grasps the particular domain of reality to which it is most suited. In philosophy, this conception results in discourses predicated on the argument that "Everybody knows..." the truth of some basic idea. Descartes, for example, appeals to the idea that everyone can at least think and therefore exists. Deleuze points out that philosophy of this type attempts to eliminate all objective presuppositions while maintaining subjective ones. Deleuze maintains, with Artaud, that real thinking is one of the most difficult challenges there is. Thinking requires a confrontation with stupidity, the state of being formlessly human without engaging any real problems. One discovers that the real path to truth is through the production of sense: the creation of a texture for thought that relates it to its object. Sense is the membrane that relates thought to its other. Accordingly, learning is not the memorization of facts but the coordination of thought with a reality. "As a result, 'learning' always takes place in and through the unconscious, thereby establishing the bond of a profound complicity between nature and mind" (165). Deleuze's alternate image of thought is based on difference, which creates a dynamism that traverses individual faculties and conceptions. This thought is fundamentally energetic and asignifying: if it produces propositions, these are wholly secondary to its development. At the end of the chapter, Deleuze sums up the image of thought he critiques with eight attributes: (1) the postulate of the principle, or the Cogitatio natural universalis (good will of the thinker and good nature of thought); (2) the postulate of the ideal, or common sense (common sense as the concordia facultatum and good sense as the distribution which guarantees this concord); (3) the postulate of the model, or of recognition (recognition inviting all the faculties to exercise themselves upon an object supposedly the same, and the consequent possibility of error in the distribution when one faculty confuses one of its objects with a different object of another faculty); (4) the postulate of the element or of representation (when difference is subordinated to the complementary dimensions of the Same and the Similar, the Analogous and the Opposed); (5) the postulate of the negative, or of error (in which error expresses everything which can go wrong in thought, but only as the product of external mechanisms); (6) the postulate of logical function, or the proposition (designation is taken to be the locus of truth, sense being no more than the neutralized double or the infinite doubling of the proposition); (7) the postulate of modality, or solutions (problems being materially traced from propositions or indeed, formally defined by the possibility of their being solved); (8) the postulate of the end, or result, the postulate of knowledge (the subordination of learning to knowledge, and of culture to method). (167) |

III. 思想のイメージ 本章では、一般社会と哲学的言説の両方に浸透している「思想のイメージ」を取り上 げる。このイメージによれば、思考は自然に真理に引き寄せられる。思考は真理と誤りのカテゴリーに簡単に分けられる。思考のモデルは教育機関に由来し、師 匠が問題を出し、弟子が真か偽のどちらかの解を出すというものである。このような主体のイメージは、異なる能力が存在し、それぞれが最も適した現実の特定 の領域を理想的に把握することを想定している。哲学では、このような考え方の結果、ある基本的な考え方の真偽を「誰もが知っている」とい う論証を前提とした言説が生まれる。例えばデカルトは、誰もが少なくとも考えることができ、したがって存在する、という考えを訴えた。ドゥルーズは、この 種の哲学が、主観的な前提を維持したまま、客観的な前提をすべて排除しようとすることを指摘している。ドゥルーズはアルトーとともに、真の意味での思考は 最も困難な課題の一つであると主張する。考えることは、愚かさ、つまり、現実の問題に関与することなく、形もなく人間である状態との対決を必要とする。真 理に至る真の道は、センスの生産、つまり思考をその対象と関連づけるテクスチャーの創造にあることを発見する。センスとは、思考と他者とを結びつける膜で ある。したがって、学習とは、事実の暗記ではなく、思考と現実との調整なのである。その結果、「学習」は常に無意識の中で、また無意識を通じて行われ、そ れによって自然と心の間の深遠な共犯関係の絆が確立される」(165)。ドゥルーズの代替的な思考のイメージは差異に基づくものであり、それが個々の能力 と概念を横断するダイナミズムを生み出している。この思考は、基本的にエネルギッシュであり、寓意的である。もしそれが命題を生み出すとしても、それはそ の発展にとって完全に二次的なものである。 本章の最後でドゥルーズは、批判する思考像を8つの属性で総括している。(1)原理の仮定、すなわち Cogitatio natural universalis(思考者の善意、思考の善い性質) (2)理想の仮定、すなわち常識(common sense as the concordia facultatum、この一致を保証する分配としての善意) (3)模範の仮定、すなわち認識の仮定(recognition of model)。(3)モデルの仮定、または認識の仮定(認識は、すべての能力が同じであるはずの対象に対して行使するよう要求し、その結果、ある能力がそ の対象のひとつを他の能力の異なる対象と混同するとき、分配に誤りが生じる可能性がある)(4)要素の仮定または表現の仮定(差が、同一と類似、類似と反 対という相補的次元に従属させられる場合)。(5)否定の仮定、または誤りの仮定(この中で、誤りは、思考においてうまくいかない可能性のあるすべてのも のを表現するが、それは外部機構の産物としてのみである);(6)論理的機能の仮定、または命題(指定は真実の場所とされ、感覚は命題の中和した二重また は無限二重以外のものではない);(7)修飾の仮定、または表現の仮定(この中で、意味は命題の無限の倍化以外のものではない)。(7)モダリティの仮 定、すなわち解決策(問題は命題から物質的に追跡され、実際、解決される可能性によって形式的に定義される)、(8)目的の仮定、すなわち結果、知識の仮 定(学習の知識への従属、教養の方法への従属)である。(167) |

| IV.

Ideas and the Synthesis of

Difference This chapter expands on the argument that difference underlies thought by proposing a conception of Ideas based on difference. Deleuze returns to his substitution of the differential (dx) for negation (-x), arguing that Ideas can be conceived as "a system of differential relations between reciprocally determined genetic elements" (173-4). Ideas are multiplicities—that is, they are neither many nor one, but a form of organization between abstract elements that can be actualized in different domains. One example is of organisms. An organism actualizes itself according to a schema that can be varied but nevertheless defines relations between its components. Its complexity is achieved by progressive breaks in symmetry that begin with small distinctions in an embryonic mass. The term 'virtual' is used to describe this type of (nevertheless real) entity. The notion of virtuality emphasizes the way in which the set of relations themselves are prior to instances of these relations, called actualizations. |

IV.

イデアと差異の合成 本章では、差異に基づくイデアの概念を提案することによって、思考の根底にあるのは差異であるという議論を展開する。ドゥルーズは、否定(- x)に対する 差延(dx)の置き換えに戻り、イデアを「相互に決定される遺伝的要素間の差延関係のシステム」(173-4)として概念化することができると主張する。 イデアは多重性である-つまり、多でも一でもなく、抽象的な要素間の組織化の形態であり、異なる領域で現実化しうるものである。その一例が生物である。生 物は、多様でありながら、構成要素間の関係を定義するスキーマに従って自己を実現する。その複雑さは、胚の塊の中の小さな区別から始まる対称性の漸進的な 破れによって達成される。このような(にもかかわらず実在する)実体を表現するために、「ヴァーチャル」という言葉が使われる。仮想性という概念は、一連 の関係そのものが、現実化と呼ばれるこれらの関係のインスタンスに先行する方法を強調するものである。 |

| V.

Asymmetrical Synthesis of the Sensible This chapter continues the discussion of the play of difference and explains how sense can arise from it. To do so, it engages with scientific and mathematical concepts that relate to difference, in particular, classical thermodynamic theory. Intensive and Extensive One major theme is the intensive, which opposes (and for Deleuze, precedes) the extensive. Extensity refers to the actualized dimensions of a phenomenon: its height, its specific components. In science, an object's intensive properties are those, like density and specific heat, that do not change with quantity. Correspondingly, while extensive properties can be subject to division (the object can be cut in half), intensive qualities cannot be simply reduced or divided without transforming their bearer entirely. There is an intensive space, called spatium, which is virtual and whose implications govern the eventual production of extensive space. This spatium is the cosmic analogue of the Idea; the mechanism of abstract relations becoming actualized is the same. Intensity governs the basic processes through which differences interact and shape the world. "It is intensity which is immediately expressed in the basic spatio-temporal dynamisms and determines an 'indistinct' differential relation in the Idea to incarnate itself in a distinct quality and a distinguished extensity" (245). Modes of Thought Deleuze attacks good sense and common sense. Good sense treats the universe statistically and attempts to optimize it to produce the best outcome. Good sense may be rationalist, but it does not affirm fate or difference; it has an interest in reducing rather than amplifying the power of difference. It takes the economic view in which value is an average of expected values and present and future can be interchanged on the basis of a specific discount rate. Common sense is the ability to recognize and react to categories of objects. Common sense complements good sense and allows it to function; 'recognition' of the object enables 'prediction' and the cancellation of danger (along with other possibilities of difference). To both common sense and good sense, Deleuze opposes paradox. Paradox serves as the stimulus to real thought and to philosophy because it forces thought to confront its limits. Individuation The coalescence of 'individuals' out of the cosmic flow of matter is a slow and incomplete process. "Individuation is mobile, strangely supple, fortuitous and endowed with fringes and margins; all because the intensities which contribute to it communicate with each other, envelop other intensities, and are in turn enveloped" (254). That is, even after individuation takes place, the world does not become passive background or stage on which newly autonomous actors relate to each other. Individuals remain bound to the underlying forces that constitute them all, and these forces can interact and develop without individual approval. The embryo enacts the drama of individuation. In the process, it subjects itself to dynamics that would tear apart a fully individuated organism. The power of individuation lies not in the development of a final I or self, but in the ability of the deeper dynamics to incarnate themselves in a being that gains additional powers by virtue of its materiality. Individuation makes possible a drama described as a confrontation with the face of the Other. Distinct from the singular form of Levinasian ethics, this scene is important for Deleuze because it represents the possibility and openness associated with an individuated unknown. |

V. 感覚的なものの非対称的合成 この章では、差の戯れについての議論を続け、そこからいかに感覚が生じるかを説明する。そのために、差異に関連する科学的・数学的概念、特に古典的な熱力 学的理論に関わる。インテンシブとエクステンシブ 一つの大きなテーマは、エクステンシブと対立する(そしてドゥルーズにとっては先行する)インテンシブである。インテンシブとは、ある現象の現実化した次 元、すなわちその高さや具体的な構成要素を指す。科学では、密度や比熱のように、量によって変化しないものを集中的性質と呼ぶ。このため、広範な性質は分 割することができるが(物体を半分にすることができる)、集中的な性質は、その担い手を完全に変容させずに単純に縮小したり分割したりすることができな い。スパティウムと呼ばれる集中的な空間があり、これは仮想的なもので、その意味合いが最終的に広範な空間を生み出すことを支配する。このスパティウムは イデアの宇宙的アナログであり、抽象的な関係が現実化されるメカニズムは同じである。強度は、差異が相互作用し、世界を形成する基本的なプロセスを支配し ている。基本的な時空間ダイナミズムの中で即座に表現されるのは強度であり、イデアにおける「不明瞭な」差異関係を、明確な質と際立った伸張性の中に具現 化するよう決定する」(245)。 思想の様態 ドゥルーズは良識と常識を攻撃する。良識は宇宙を統計的に扱い、最良の結果を生むように最適化しようとする。良識は合理主義的かもしれないが、運命や差異 を肯定するものではなく、差異の力を増幅するのではなく、むしろ減少させることに関心を抱いている。価値とは期待値の平均であり、現在と未来は特定の割引 率に基づいて交換されるという経済学的な考え方をとる。常識とは、対象のカテゴリーを認識し、それに反応する能力である。常識は良識を補完し、機能させ る。対象物の「認識」は「予測」を可能にし、危険を(他の違いの可能性とともに)キャンセルすることができる。常識と良識の両方に対して、ドゥルーズはパ ラドックスに対抗する。パラドックスは、思考にその限界を直視させるので、真の思考と哲学への刺激として機能する。 個体化 物質の宇宙的な流れから「個」が生まれるのは、遅く、不完全なプロセスである。「個体化は可動的で、奇妙にしなやかで、偶然性があり、縁と余白を備えてい る。すべて、それに寄与する強度が互いに通じ合い、他の強度を包み込み、今度は包まれるからだ」(254)。つまり、個性化が起こった後でも、世界は受動 的な背景や舞台にはならず、そこで新たに自律した行為者が互いに関係し合うのである。個人は、それらすべてを構成する根源的な力に縛られたままであり、こ れらの力は個人の承認なしに相互作用し、発展することができるのである。 胚は個体化のドラマを演じている。 その過程で、胚は、完全に個体化された有機体を引き裂くような力学に身をさらすことになる。個体化の力は、最終的な私や自己の形成にあるので はなく、より深い原動力が、 物質的であることによってさらなる力を獲得した存在として具現化する能力にあるのです。個体化は、他者の顔との対決と表現されるドラマを可能にする。レ ヴィナス倫理学の特異な形式とは異なり、この場面はドゥルーズにとって重要であり、それは個性化された未知の存在に関連する可能性と開放性を象徴している からである。 |

| Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Difference_and_Repetition |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

- 感覚与件︎▶virtual reality︎▶ヴァーチャル・ツーリズム︎︎▶︎Brain-machine Interface : BMI▶︎︎ジル・ドゥルーズ▶︎▶︎︎▶︎

- 同一性(アイデンティティ)▶︎︎リゾーム▶︎▶︎

文献

- 医 学界新聞(特集号:BCI)3451,2022

- 『差異と反復』財津理訳、河出書房新社、1992年

その他の情報

☆

☆