功利主義

Utilitarianism

☆

倫理学・哲学において功利主義(Utilitarianism)は、影響を受けるすべての個人の幸福と幸福を最大化する行動を規定する規範的倫理理論の一群である。様々な種類の功利主義が

異なる特徴を認めているが、全ての功利主義の背後にある基本的な考え方は、ある意味で効用を最大化することであり、それは幸福や関

連する概念で定義されることが多い。例えば、功利主義の創始者であるジェレミー・ベンサムは、効用を次のように説明する「

あらゆる対象物におけるその性質は、それによって利益、利点、快楽、善、幸福...を生み出す傾向がある。[あるいは]その利害が考慮される当事者に災い、苦痛、悪、不幸が起こるのを防ぐためである」。功利主義は帰結主義の一種であり、あらゆる行為の結果が善悪の唯一の基準であるとする。エゴイズムや利他主義のような他の形の帰結主義とは異なり、功利主

義はすべての統覚のある人の利益を平等に考える。功利主義の支持者たちは、行動はその結果に基づいて選択されるべきか(行為功利主義)、あるいはエージェントは効

用を最大化するルールに従うべきか(ルール功利主義)など、多くの問題で意見が分かれている。また、全体効用(全体功利主義)か、平均効用(平均功利主

義)か、あるいは最悪の人々[3]の効用を最大化すべきかについても意見が分かれている」(→「功利主義についての超簡単な説明」)。

★20世紀以降の功利主義の考え方(古典的功利主義はこの項目の説明のあとでおこないます)

| Ideal utilitarianism The description of ideal utilitarianism was first used by Hastings Rashdall in The Theory of Good and Evil (1907), but it is more often associated with G. E. Moore. In Ethics (1912), Moore rejects a purely hedonistic utilitarianism and argues that there is a range of values that might be maximized. Moore's strategy was to show that it is intuitively implausible that pleasure is the sole measure of what is good. He says that such an assumption:[48] involves our saying, for instance, that a world in which absolutely nothing except pleasure existed—no knowledge, no love, no enjoyment of beauty, no moral qualities—must yet be intrinsically better—better worth creating—provided only the total quantity of pleasure in it were the least bit greater, than one in which all these things existed as well as pleasure. It involves our saying that, even if the total quantity of pleasure in each was exactly equal, yet the fact that all the beings in the one possessed, in addition knowledge of many different kinds and a full appreciation of all that was beautiful or worthy of love in their world, whereas none of the beings in the other possessed any of these things, would give us no reason whatever for preferring the former to the latter. Moore admits that it is impossible to prove the case either way, but he believed that it was intuitively obvious that even if the amount of pleasure stayed the same a world that contained such things as beauty and love would be a better world. He adds that, if a person was to take the contrary view, then "I think it is self-evident that he would be wrong."[48] |

理想的功利主義 理想的功利主義の記述は、ヘイスティングス・ラッシュダルが『善悪の理論』(1907年)で初めて用いたが、より一般的にはG・E・ムーアと結びつけられ る。『倫理学』(1912年)において、ムーアは純粋快楽主義的功利主義を退け、最大化すべき価値には多様性があると論じた。ムーアの戦略は、快楽のみを 善の尺度とする考えが直観的に不合理であることを示すことにあった。彼はこう述べる: [48] 例えば、快楽以外の何もない世界―知識も愛も美の享受も道徳的資質もない世界―が、快楽の総量がほんの少しでも多いというだけで、それら全てが存在する世 界よりも本質的に優れている―創造する価値がある―と言わねばならないことになる。それはまた、たとえ両世界の快楽の総量が全く同じであっても、一方の世 界のすべての存在が、多様な知識と、その世界における美や愛すべきもののすべてを十分に享受する能力を、他方の世界の存在がまったく持たないという事実 が、前者を選ぶ理由をまったく与えないと言うことに等しい。 ムーアは、どちらの立場も証明不可能だと認めつつも、快楽の量が同じであっても、美や愛といったものを内包する世界の方がより良い世界であることは直観的 に明らかだと信じていた。彼はさらに、もし誰かが反対の見解を取るならば、「その人が間違っていることは自明である」と付け加えている[48]。 |

| Act and rule utilitarianism Main articles: Act utilitarianism and Rule utilitarianism In the mid-20th century, a number of philosophers focused on the place of rules in utilitarian thought.[49] It was already accepted that it is necessary to use rules to help you choose the right action because the problems of calculating the consequences on each and every occasion would almost certainly result in you frequently choosing something less than the best course of action. Paley had justified the use of rules and Mill says:[50] It is truly a whimsical supposition that, if mankind were agreed in considering utility to be the test of morality, they would remain without any agreement as to what is useful, and would take no measures for having their notions on the subject taught to the young, and enforced by law and opinion... to consider the rules of morality as improvable, is one thing; to pass over the intermediate generalisations entirely, and endeavour to test each individual action directly by the first principle, is another.… The proposition that happiness is the end and aim of morality, does not mean that no road ought to be laid down to that goal.… Nobody argues that the art of navigation is not founded on astronomy, because sailors cannot wait to calculate the Nautical Almanack. Being rational creatures, they go to sea with it ready calculated; and all rational creatures go out upon the sea of life with their minds made up on the common questions of right and wrong. However, rule utilitarianism proposes a more central role for rules that was thought to rescue the theory from some of its more devastating criticisms, particularly problems to do with justice and promise keeping. Smart (1956) and McCloskey (1957) initially use the terms extreme and restricted utilitarianism but eventually settled on the prefixes act and rule instead.[51][52] Likewise, throughout the 1950s and 1960s, articles were published both for and against the new form of utilitarianism, and through this debate the theory we now call rule utilitarianism was created. In an introduction to an anthology of these articles, the editor was able to say: "The development of this theory was a dialectical process of formulation, criticism, reply and reformulation; the record of this process well illustrates the co-operative development of a philosophical theory."[49]: 1 The essential difference is in what determines whether or not an action is the right action. Act utilitarianism maintains that an action is right if it maximizes utility; rule utilitarianism maintains that an action is right if it conforms to a rule that maximizes utility. In 1956, Urmson (1953) published an influential article arguing that Mill justified rules on utilitarian principles.[53] From then on, articles have debated this interpretation of Mill. In all probability, it was not a distinction that Mill was particularly trying to make and so the evidence in his writing is inevitably mixed. A collection of Mill's writing published in 1977 includes a letter that seems to tip the balance in favour of the notion that Mill is best classified as an act utilitarian. In the letter, Mill says:[54] I agree with you that the right way of testing actions by their consequences, is to test them by the natural consequences of the particular action, and not by those which would follow if everyone did the same. But, for the most part, the consideration of what would happen if everyone did the same, is the only means we have of discovering the tendency of the act in the particular case. Some school level textbooks and at least one British examination board make a further distinction between strong and weak rule utilitarianism.[55] However, it is not clear that this distinction is made in the academic literature. It has been argued that rule utilitarianism collapses into act utilitarianism, because for any given rule, in the case where breaking the rule produces more utility, the rule can be refined by the addition of a sub-rule that handles cases like the exception.[56] This process holds for all cases of exceptions, and so the "rules" have as many "sub-rules" as there are exceptional cases, which, in the end, makes an agent seek out whatever outcome produces the maximum utility.[57] |

行為功利主義と規則功利主義 主な記事:行為功利主義と規則功利主義 20世紀半ば、多くの哲学者が功利主義思想における規則の位置付けに注目した[49]。あらゆる場面で結果を計算することはほぼ確実に最適な行動選択を妨 げるため、正しい行動を選択するには規則を用いる必要があると既に認められていた。ペイリーは規則の使用を正当化し、ミルはこう述べている[50]: もし人類が「効用こそが道徳の試金石である」という点で合意したとしても、何が有用かについて合意せず、その概念を若者に教え、法律や世論によって強制す る措置を一切取らないだろうという仮定は、実に気まぐれなものである… 道徳の規則が改善可能だと考えるのは一つのことだ。中間的な一般化を完全に飛び越え、個々の行動を第一原理で直接検証しようとするのは別のことだ。…幸福 が道徳の目的であるという命題は、その目標への道筋を示す必要がないという意味ではない。…航海術が天文学に基づかないと誰も主張しない。船乗りが航海暦 を計算するのを待てないからといって。理性ある存在として、彼らは計算済みの天体暦を持って海に出る。同様に、理性ある存在は皆、善悪という普遍的な問題 について心構えを整えて人生という海に漕ぎ出すのだ。 しかし規則功利主義は、規則により中心的な役割を与えることで、特に正義や約束の履行に関する問題といった、理論に対する破壊的な批判の一部から救済でき ると考えられた。スマート(1956年)とマックロスキー(1957年)は当初「極端功利主義」と「限定功利主義」という用語を用いたが、最終的に「行為 功利主義」と「規則功利主義」という接頭辞を採用した[51][52]。同様に1950年代から1960年代にかけて、この新たな功利主義形態を支持する 論文と批判する論文が発表され、この論争を通じて現在「規則功利主義」と呼ばれる理論が形成された。これらの論文集の序文で編集者はこう述べている:「こ の理論の発展は、定式化、批判、反論、再定式化という弁証法的プロセスであった。この過程の記録は、哲学理論の協調的発展をよく示している」[49]: 1 本質的な相違点は、ある行為が正しいかどうかを決定する基準にある。行為功利主義は、行為が効用を最大化すれば正しいと主張する。規則功利主義は、行為が効用を最大化する規則に適合すれば正しいと主張する。 1956年、アームソン(1953)はミルが功利主義的原則に基づいて規則を正当化したと論じる影響力のある論文を発表した。[53] その後、ミルに対するこの解釈をめぐる論争が続いている。おそらくミル自身が特にこの区別を意図していたわけではなく、彼の著作における証拠は必然的に混 血のものとされている。1977年に刊行されたミルの著作集には、彼を行為功利主義者として分類するのが最も適切だという見解を支持する手紙が含まれてい る。その手紙でミルはこう述べている: [54] 行動の結果で行動を検証する正しい方法は、特定の行動の自然の結果で検証すべきであり、万人が同じ行動を取った場合に生じる結果で検証すべきではないとい う点では、私も君に同意する。しかし、万人が同じ行動を取った場合に何が起こるかを考慮することは、特定の事例における行動の傾向を発見する唯一の手段で ある場合がほとんどだ。 一部の学校用教科書と少なくとも一つの英国の試験委員会は、規則功利主義を強規則功利主義と弱規則功利主義にさらに区別している[55]。しかし、この区 別が学術文献でなされているかは明らかではない。規則功利主義は行為功利主義に収束すると主張されてきた。なぜなら、特定の規則において、その規則を破る ことでより多くの効用が生じる場合、例外のような事例を扱う下位規則を追加することで規則を洗練できるからである。[56] この過程は例外事例すべてに適用されるため、「規則」には例外事例の数だけ「下位規則」が生じ、結果として行為者は最大効用をもたらす結果を追求すること になる。[57] |

| Two-level utilitarianism Main article: Two-level utilitarianism In Principles (1973), R. M. Hare accepts that rule utilitarianism collapses into act utilitarianism but claims that this is a result of allowing the rules to be "as specific and un-general as we please."[58] He argues that one of the main reasons for introducing rule utilitarianism was to do justice to the general rules that people need for moral education and character development and he proposes that "a difference between act-utilitarianism and rule-utilitarianism can be introduced by limiting the specificity of the rules, i.e., by increasing their generality."[58]: 14 This distinction between a "specific rule utilitarianism" (which collapses into act utilitarianism) and "general rule utilitarianism" forms the basis of Hare's two-level utilitarianism. When we are "playing God or the ideal observer", we use the specific form, and we will need to do this when we are deciding what general principles to teach and follow. When we are "inculcating" or in situations where the biases of our human nature are likely to prevent us doing the calculations properly, then we should use the more general rule utilitarianism. Hare argues that in practice, most of the time, we should be following the general principles:[58]: 17 One ought to abide by the general principles whose general inculcation is for the best; harm is more likely to come, in actual moral situations, from questioning these rules than from sticking to them, unless the situations are very extra-ordinary; the results of sophisticated felicific calculations are not likely, human nature and human ignorance being what they are, to lead to the greatest utility. In Moral Thinking (1981), Hare illustrated the two extremes. The "archangel" is the hypothetical person who has perfect knowledge of the situation and no personal biases or weaknesses and always uses critical moral thinking to decide the right thing to do. In contrast, the "prole" is the hypothetical person who is completely incapable of critical thinking and uses nothing but intuitive moral thinking and, of necessity, has to follow the general moral rules they have been taught or learned through imitation.[59] It is not that some people are archangels and others proles, but rather that "we all share the characteristics of both to limited and varying degrees and at different times."[59] Hare does not specify when we should think more like an "archangel" and more like a "prole" as this will, in any case, vary from person to person. However, the critical moral thinking underpins and informs the more intuitive moral thinking. It is responsible for formulating and, if necessary, reformulating the general moral rules. We also switch to critical thinking when trying to deal with unusual situations or in cases where the intuitive moral rules give conflicting advice. |

二段階功利主義 詳細な記事: 二段階功利主義 『原理』(1973年)において、R・M・ヘアは規則功利主義が行為功利主義に収束することを認めつつ、これは規則を「我々が望む限り具体的に、また非一 般化して」許容した結果だと主張する。[58] 彼は、規則功利主義を導入した主な理由の一つは、道徳教育や人格形成に必要な一般規則に正当性を与えるためだと論じ、「行為功利主義と規則功利主義の差異 は、規則の具体性を制限する、すなわち一般性を高めることで導入できる」と提案している。[58]: 14 この「具体的規則功利主義」(行為功利主義に帰着する)と「一般的規則功利主義」の区別が、ヘアーの二段階功利主義の基盤を成す。 我々が「神や理想的な観察者」を演じている時、すなわち具体的形態を用いる時、それは教えるべき・従うべき一般的原則を決定する際に必要となる。「教え込 む」場合や、人間の本性の偏りが適切な計算を妨げる可能性のある状況では、より一般的な規則功利主義を用いるべきである。 ヘアーは、実際にはほとんどの場合、我々は一般的な原則に従うべきだと論じる:[58]: 17 一般原則は、その普遍的な教え込みが最善をもたらす場合に遵守すべきである。実際の道徳的状況において、これらの規則を疑問視することから生じる害は、規 則に固執することから生じる害よりも大きい。状況が極めて異常でない限りは。洗練された幸福計算の結果は、人間の本性と無知がそうである以上、最大の効用 をもたらすとは考えにくい。 『道徳的思考』(1981年)において、ヘアは二つの極端な例を示した。「大天使」とは、状況を完全に把握し、個人的な偏見や弱点を持たず、常に批判的道 徳的思考を用いて正しい行動を決定する仮説上の人格である。対照的に「プロレ」とは、批判的思考が全くできず、直観的道徳思考のみを用い、必然的に教え込 まれた、あるいは模倣によって学んだ一般的な道徳規則に従わざるを得ない仮説上の人格である[59]。「一部の人々が大天使であり、他がプロレ」というわ けではなく、「我々は皆、限定的かつ様々な程度で、また異なる時期に、両者の特性を共有している」のである[59]。 ヘアは、いつ「大天使」のように、いつ「プロレ」のように考えるべきかを特定していない。いずれにせよ、それは人格によって異なるからだ。しかし、批判的 道徳思考は、より直感的な道徳思考を支え、方向付ける。それは一般的な道徳ルールを策定し、必要に応じて再構築する責任を負う。また、異常な状況に対処し ようとする時や、直感的な道徳ルールが矛盾する助言を与える場合には、批判的思考に切り替える。 |

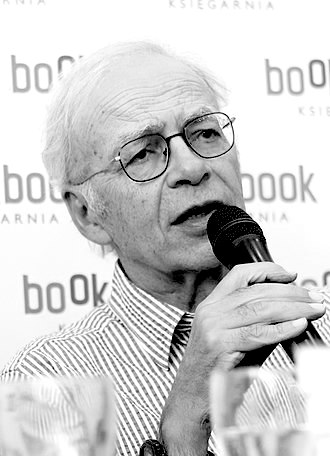

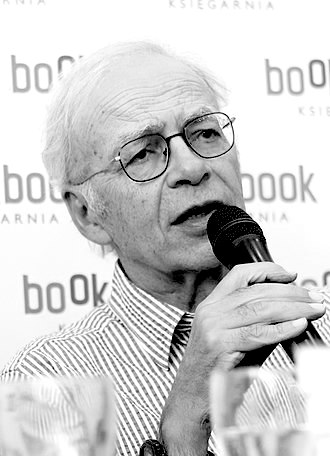

| Preference utilitarianism Main article: Preference utilitarianism Preference utilitarianism entails promoting actions that fulfil the preferences of those beings involved.[60] The concept of preference utilitarianism was first proposed in 1977 by John Harsanyi in Morality and the Theory of Rational Behaviour,[61][62] however the concept is more commonly associated with R. M. Hare,[59] Peter Singer,[63] and Richard Brandt.[64] Harsanyi claims that his theory is indebted to:[62]: 42 Adam Smith, who equated the moral point of view with that of an impartial but sympathetic observer; Immanuel Kant, who insisted on the criterion of universality, which may also be described as a criterion of reciprocity; the classical utilitarians who made maximizing social utility the basic criterion of morality; and "the modern theory of rational behaviour under risk and uncertainty, usually described as Bayesian decision theory." Harsanyi rejects hedonistic utilitarianism as being dependent on an outdated psychology saying that it is far from obvious that everything we do is motivated by a desire to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. He also rejects ideal utilitarianism because "it is certainly not true as an empirical observation that people's only purpose in life is to have 'mental states of intrinsic worth'."[62]: 54 According to Harsanyi, "preference utilitarianism is the only form of utilitarianism consistent with the important philosophical principle of preference autonomy. By this I mean the principle that, in deciding what is good and what is bad for a given individual, the ultimate criterion can only be his own wants and his own preferences."[62]: 55 Harsanyi adds two caveats. Firstly, people sometimes have irrational preferences. To deal with this, Harsanyi distinguishes between "manifest" preferences and "true" preferences. The former are those "manifested by his observed behaviour, including preferences possibly based on erroneous factual beliefs,[clarification needed] or on careless logical analysis, or on strong emotions that at the moment greatly hinder rational choice"; whereas the latter are "the preferences he would have if he had all the relevant factual information, always reasoned with the greatest possible care, and were in a state of mind most conducive to rational choice."[62]: 55 It is the latter that preference utilitarianism tries to satisfy. The second caveat is that antisocial preferences, such as sadism, envy, and resentment, have to be excluded. Harsanyi achieves this by claiming that such preferences partially exclude those people from the moral community: Utilitarian ethics makes all of us members of the same moral community. A person displaying ill will toward others does remain a member of this community, but not with his whole personality. That part of his personality that harbours these hostile antisocial feelings must be excluded from membership, and has no claim for a hearing when it comes to defining our concept of social utility.[62]: 56 |

選好功利主義(→「選好功利主義と普遍的指令主義」) 詳細な記事: 選好功利主義 選好功利主義とは、関係する存在の選好を満たす行動を促進することを意味する。[60] この概念は1977年にジョン・ハーシャニが『道徳と合理的行動の理論』で初めて提唱したが、[61][62] 一般的にはR・M・ヘア、 [59] ピーター・シンガー[63]、リチャード・ブラント[64]らと結びつけられることが多い。 ハーサニは自身の理論が以下の思想に影響を受けていると主張している[62]: 42 道徳的視点を公平でありながら共感的な観察者の視点と同一視したアダム・スミス; 普遍性の基準(相互性の基準とも表現可能)を主張したイマヌエル・カント; 社会的効用を最大化することを道徳の基本基準とした古典的功利主義者たち;そして 「通常ベイジアン意思決定理論と呼ばれる、リスクと不確実性下における合理的行動の現代理論」 ハサニは快楽主義的功利主義を、時代遅れの心理学に依存しているとして拒否する。我々の行動の全てが快楽の最大化と苦痛の最小化という欲求によって動機づ けられているとは、決して明らかではないと述べる。彼はまた、理想的功利主義も拒否する。なぜなら「人民の唯一の目的が『本質的価値を持つ精神的状態』を 得ることであるという経験的観察は、確かに真実ではない」からである。[62]:54 ハルサニによれば、「選好功利主義は、選好自律性という重要な哲学的原則と一致する唯一の功利主義形態である。ここで言うのは、ある個人にとって何が善で何が悪かを決める際、究極の基準は彼自身の欲求と選好にしかありえないという原則だ」[62]:55 ハルサニは二つの留保を加える。第一に、人間は時に非合理的な選好を持つ。これに対処するため、ハルサニは「顕在的選好」と「真の選好」を区別する。前者 は「観察された行動によって表出される選好であり、誤った事実認識に基づく可能性のある選好、あるいは不注意な論理分析に基づく選好、あるいはその時点で 合理的な選択を大きく妨げる強い感情に基づく選好」を指す。後者は「関連する事実情報を全て有し、常に最大限の注意をもって推論し、合理的な選択に最も適 した精神状態にある場合に持つであろう選好」を指す。[62]: 55 選好功利主義が満たそうとするのは後者である。 第二の注意点は、サディズム、羨望、怨恨といった反社会的選好は排除されねばならないということだ。ハルシャニは、そうした選好を持つ者は道徳共同体から部分的に排除されると主張することでこれを達成している: 功利主義倫理は我々全員を同一の道徳共同体の成員とする。他者への悪意を示す人格もこの共同体の成員ではあるが、その人格全体がそうではない。敵意ある反 社会的感情を抱く人格の部分は成員資格から除外されねばならず、社会的効用の概念を定義する際に意見を述べる権利は一切認められない。[62]:56 |

| Negative utilitarianism Main article: Negative utilitarianism In The Open Society and its Enemies (1945), Karl Popper argues that the principle "maximize pleasure" should be replaced by "minimize pain". He believes that "it is not only impossible but very dangerous to attempt to maximize the pleasure or the happiness of the people, since such an attempt must lead to totalitarianism."[65] He claims that:[66] [T]here is, from the ethical point of view, no symmetry between suffering and happiness, or between pain and pleasure... In my opinion human suffering makes a direct moral appeal, namely, the appeal for help, while there is no similar call to increase the happiness of a man who is doing well anyway. A further criticism of the Utilitarian formula "Maximize pleasure" is that it assumes a continuous pleasure-pain scale that lets us treat degrees of pain as negative degrees of pleasure. But, from the moral point of view, pain cannot be outweighed by pleasure, and especially not one man's pain by another man's pleasure. Instead of the greatest happiness for the greatest number, one should demand, more modestly, the least amount of avoidable suffering for all... The actual term negative utilitarianism itself was introduced by R. N. Smart as the title to his 1958 reply to Popper in which he argues that the principle would entail seeking the quickest and least painful method of killing the entirety of humanity.[67] In response to Smart's argument, Simon Knutsson (2019) has argued that classical utilitarianism and similar consequentialist views are roughly equally likely to entail killing the entirety of humanity, as they would seem to imply that one should kill existing beings and replace them with happier beings if possible. Consequently, Knutsson argues: The world destruction argument is not a reason to reject negative utilitarianism in favour of these other forms of consequentialism, because there are similar arguments against such theories that are at least as persuasive as the world destruction argument is against negative utilitarianism.[68] Furthermore, Knutsson notes that one could argue that other forms of consequentialism, such as classical utilitarianism, in some cases have less plausible implications than negative utilitarianism, such as in scenarios where classical utilitarianism implies it would be right to kill everyone and replace them in a manner that creates more suffering, but also more well-being such that the sum, on the classical utilitarian calculus, is net positive. Negative utilitarianism, in contrast, would not allow such killing.[68] Some versions of negative utilitarianism include: Negative total utilitarianism: tolerates suffering that can be compensated within the same person.[69][70] Negative preference utilitarianism: avoids the problem of moral killing with reference to existing preferences that such killing would violate, while it still demands a justification for the creation of new lives.[71] A possible justification is the reduction of the average level of preference-frustration.[72] Pessimistic representatives of negative utilitarianism, which can be found in the environment of Buddhism.[73] Some see negative utilitarianism as a branch within modern hedonistic utilitarianism, which assigns a higher weight to the avoidance of suffering than to the promotion of happiness.[69] The moral weight of suffering can be increased by using a "compassionate" utilitarian metric, so that the result is the same as in prioritarianism.[74] |

否定的功利主義 詳細な記事: 否定的功利主義 カール・ポッパーは『開かれた社会とその敵』(1945年)において、「快楽を最大化せよ」という原則は「苦痛を最小化せよ」に置き換えるべきだと論じて いる。彼は「人々の快楽や幸福を最大化しようとする試みは、不可能であるばかりか非常に危険である。なぜなら、そのような試みは必ず全体主義へと導くから だ」と信じている。[65] 彼はこう主張する:[66] [T]here is, from the ethical point of view, no symmetry between苦悩 and happiness, or between pain and pleasure... In my opinion human苦悩 makes a direct moral appeal, namely, the appeal for help, while there is no similar call to increase the happiness of a man who is doing well anyway. 「快楽の最大化」という功利主義の定式に対するさらなる批判は、それが快楽と苦痛の連続的な尺度を前提としている点だ。この尺度では、苦痛の程度を快楽の 負の程度として扱える。しかし道徳的観点から言えば、苦痛は快楽によって相殺されることはなく、特に一人の人間の苦痛が別の人間の快楽によって相殺される ことはありえない。最大多数の最大幸福ではなく、より控えめに、すべての人にとって回避可能な苦悩の最小量を要求すべきだ... 「ネガティブ功利主義」という用語自体は、R・N・スマートが1958年にポッパーへの反論論文の題名として導入したものである。彼はこの原理が、人類全体を最も迅速かつ苦痛の少ない方法で殺害することを求める結果を招くと論じている。[67] スマートの主張に対し、サイモン・クヌットソン(2019)は、古典的功利主義や類似の帰結主義的見解も、人類全体を殺害することにつながる可能性がほぼ 同等だと論じている。なぜなら、それらは既存の存在を殺害し、可能ならばより幸福な存在と置き換えるべきだと示唆しているように見えるからだ。したがって クヌットソンは次のように主張する: 世界破壊論は、否定帰結主義をこれらの他の帰結主義形態に取って代わる理由にはならない。なぜなら、否定帰結主義に対する世界破壊論と同等以上に説得力のある、同様の反論が他の理論に対しても存在するからだ。[68] さらにクヌットソンは、古典的帰結主義のような他の帰結主義形態は、否定帰結主義よりも不合理な帰結を導く場合があると指摘する。例えば古典的帰結主義で は、全員を殺害し、より多くの苦悩を生み出すが同時に幸福も増加させる方法で置き換えることが正当化されるシナリオが存在する。古典的帰結主義の計算上、 その総和が正となる場合である。これに対し、否定的功利主義はそうした殺害を許容しない。[68] 否定的功利主義のいくつかの形態には以下が含まれる: 否定的総功利主義:同一の個人内で補償可能な苦悩を許容する。[69] [70] 否定的選好功利主義:殺害が侵害する既存の選好を参照することで道徳的殺害の問題を回避するが、新たな生命の創造には依然として正当化を求める。[71] 可能な正当化として、選好の挫折の平均レベルの低減が挙げられる。[72] 否定的功利主義の悲観的代表者は、仏教の思想環境に見出される。[73] 否定功利主義を、幸福の促進よりも苦悩の回避を重視する現代快楽主義功利主義の一派と見る見解もある。[69] 苦悩の道徳的重みを「慈悲的」功利主義指標を用いて増大させれば、優先主義と同様の結果が得られる。[74] |

| Motive utilitarianism See also: Virtue ethics Motive utilitarianism was first proposed by Robert Merrihew Adams in 1976.[75] Whereas act utilitarianism requires us to choose our actions by calculating which action will maximize utility and rule utilitarianism requires us to implement rules that will, on the whole, maximize utility, motive utilitarianism "has the utility calculus being used to select motives and dispositions according to their general felicific effects, and those motives and dispositions then dictate our choices of actions."[76]: 60 The arguments for moving to some form of motive utilitarianism at the personal level can be seen as mirroring the arguments for moving to some form of rule utilitarianism at the social level.[76]: 17 Adams (1976) refers to Sidgwick's observation that "Happiness (general as well as individual) is likely to be better attained if the extent to which we set ourselves consciously to aim at it be carefully restricted."[77]: 467 [78] Trying to apply the utility calculation on each and every occasion is likely to lead to a sub-optimal outcome. Applying carefully selected rules at the social level and encouraging appropriate motives at the personal level is, so it is argued, likely to lead to a better overall outcome even if on some individual occasions it leads to the wrong action when assessed according to act utilitarian standards.[77]: 471 Adams concludes that "right action, by act-utilitarian standards, and right motivation, by motive-utilitarian standards, are incompatible in some cases."[77]: 475 The necessity of this conclusion is rejected by Fred Feldman who argues that "the conflict in question results from an inadequate formulation of the utilitarian doctrines; motives play no essential role in it ... [and that] ... [p]recisely the same sort of conflict arises even when MU is left out of consideration and AU is applied by itself."[79] Instead, Feldman proposes a variant of act utilitarianism that results in there being no conflict between it and motive utilitarianism. |

動機功利主義 関連項目:徳倫理学 動機功利主義は1976年にロバート・メリヒュー・アダムズによって初めて提唱された。[75] 行為功利主義が「どの行為が効用を格律化するかを計算して行動を選択せよ」と要求し、規則功利主義が「全体として効用を格律化する規則を実施せよ」と要求 するのに対し、動機功利主義は「効用計算を用いて動機や傾向を選択し、それらの動機や傾向が行動の選択を決定する」のである。[76]: 60 個人的レベルで何らかの動機功利主義へ移行すべき論拠は、社会レベルで何らかの規則功利主義へ移行すべき論拠を反映していると見なせる。[76]: 17 アダムズ(1976)はシジウィックの観察を引用している。「幸福(一般的にも個人的にも)は、我々が意識的にそれを目指す程度を慎重に制限した場合に、 より良く達成される可能性が高い」[77]: 467 [78] あらゆる場面で効用計算を適用しようとすると、最適とは言い難い結果を招く恐れがある。社会レベルでは慎重に選定された規則を適用し、個人的レベルでは適 切な動機付けを促すことが、たとえ行為功利主義の基準で評価した際に個別の場面で誤った行動につながることがあっても、全体としてより良い結果をもたらす と主張されている。[77]: 471 アダムズは「行為功利主義の基準による正しい行動と、動機功利主義の基準による正しい動機は、場合によっては両立しない」と結論づける。[77]: 475 この結論の必然性はフレッド・フェルドマンによって否定され、彼は「問題の矛盾は功利主義学説の不十分な定式化に起因するものであり、動機は本質 的な役割を果たしていない...[そして]... [p]動機功利主義を考慮対象から外し、行為功利主義のみを適用した場合でも、まったく同じ種類の矛盾が生じる」と反論している。[79] 代わりにフェルドマンは、行為功利主義と動機功利主義の間に矛盾が生じない行為功利主義の変種を提案している。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utilitarianism |

★古典的功利主義

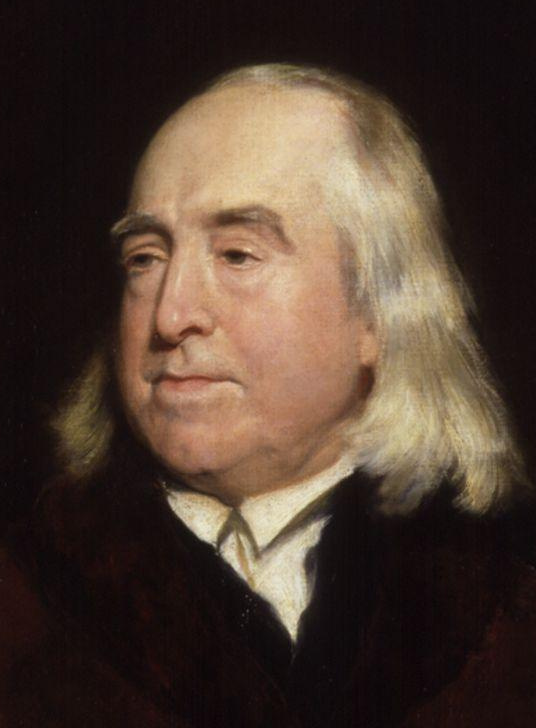

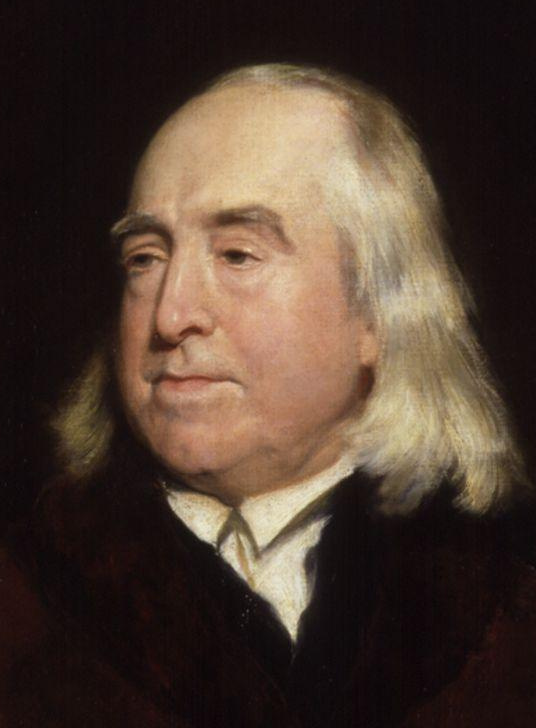

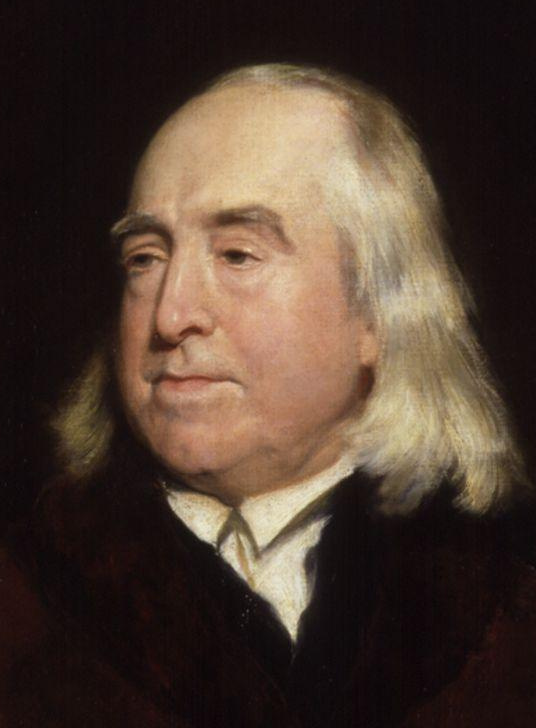

| Jeremy Bentham |

ジェレミー・ベンサム |

| Bentham's

book An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation was

printed in 1780 but not published until 1789. It is possible that

Bentham was spurred on to publish after he saw the success of Paley's

Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy.[22] Though Bentham's book

was not an immediate success,[23] his ideas were spread further when

Pierre Étienne Louis Dumont translated edited selections from a variety

of Bentham's manuscripts into French. Traité de législation civile et

pénale was published in 1802 and then later retranslated back into

English by Hildreth as The Theory of Legislation, although by this time

significant portions of Dumont's work had already been retranslated and

incorporated into Sir John Bowring's edition of Bentham's works, which

was issued in parts between 1838 and 1843. Perhaps aware that Francis Hutcheson eventually removed his algorithms for calculating the greatest happiness because they "appear'd useless, and were disagreeable to some readers,"[24] Bentham contends that there is nothing novel or unwarranted about his method, for "in all this there is nothing but what the practice of mankind, wheresoever they have a clear view of their own interest, is perfectly conformable to." Rosen (2003) warns that descriptions of utilitarianism can bear "little resemblance historically to utilitarians like Bentham and J. S. Mill" and can be more "a crude version of act utilitarianism conceived in the twentieth century as a straw man to be attacked and rejected."[25] It is a mistake to think that Bentham is not concerned with rules. His seminal work is concerned with the principles of legislation and the hedonic calculus is introduced with the words "Pleasures then, and the avoidance of pains, are the ends that the legislator has in view." In Chapter VII, Bentham says: "The business of government is to promote the happiness of the society, by punishing and rewarding.... In proportion as an act tends to disturb that happiness, in proportion as the tendency of it is pernicious, will be the demand it creates for punishment." |

ベンサム

の著書『道徳と立法の原理入門』は1780年に印刷されたが、出版されたのは1789年になってからである。ベンサムがペイリーの『道徳と政治哲学の原

理』の成功を見て出版を決意した可能性もある。[22]

ベンサムの著書は即座の成功を収めなかったが[23]、ピエール・エティエンヌ・ルイ・デュモンがベンサムの様々な原稿から選んだ部分を編集しフランス語

に翻訳したことで、彼の思想はさらに広まった。『民事及び刑事立法論』は1802年に刊行され、後にヒルドレスによって『立法論』として英訳された。ただ

しこの時点で、デュモンの翻訳作業の大部分は既に再翻訳され、1838年から1843年にかけて分冊で刊行されたジョン・ボウリング卿編ベンサム全集に組

み込まれていた。 おそらくフランシス・ハッチェソンが最終的に「無用に見え、一部の読者に不快感を与えた」[24]として最大の幸福を計算するアルゴリズムを削除した事実 を認識していたためか、ベンサムは自らの方法に新規性や根拠のない点はないと主張する。なぜなら「これら全てにおいて、人類が自らの利益を明確に認識する あらゆる場面での実践と完全に一致するもの以外は何もない」からである。 ローゼン(2003)は警告する。功利主義の記述は「ベンサムやJ・S・ミルといった功利主義者たちの歴史的実態とはほとんど似ておらず」、むしろ「20 世紀に考案された行為功利主義の粗雑な形であり、攻撃・拒絶すべき藁人形として構想されたもの」になり得ると[25]。ベンサムが規則に関心を持たなかっ たと考えるのは誤りである。彼の画期的な著作は立法の原則を扱っており、快楽計算は「したがって、立法者が目指す目的は、快楽の獲得と苦痛の回避である」 という言葉で導入されている。第7章でベンサムはこう述べている。「政府の役割は、罰と報酬によって社会の幸福を促進することである。ある行為がその幸福 を乱す傾向があるほど、その傾向が有害であるほど、その行為が引き起こす罰への要求は大きくなる」 |

| Principle of utility Bentham's work opens with a statement of the principle of utility:[26] Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do.… By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever according to the tendency it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question: or, what is the same thing in other words to promote or to oppose that happiness. I say of every action whatsoever, and therefore not only of every action of a private individual, but of every measure of government. |

効用原理 ベンサムの著作は効用原理の声明で始まる:[26] 自然は人類を二つの絶対的な支配者、苦痛と快楽の支配下に置いた。我々がなすべきことを示すのは、この二者だけである。… 効用原理とは、あらゆる行為を、それが関係者の幸福を増大させるか減少させるかの傾向によって、是認または非難する原理を意味する。言い換えれば、その幸 福を促進するか阻害するかの傾向によって判断する原理である。あらゆる行為とは、個人のあらゆる行為のみならず、政府のあらゆる施策をも含む。 |

| Hedonic calculus In Chapter IV, Bentham introduces a method of calculating the value of pleasures and pains, which has come to be known as the hedonic calculus. Bentham says that the value of a pleasure or pain, considered by itself, can be measured according to its intensity, duration, certainty/uncertainty and propinquity/remoteness. In addition, it is necessary to consider "the tendency of any act by which it is produced" and, therefore, to take account of the act's fecundity, or the chance it has of being followed by sensations of the same kind and its purity, or the chance it has of not being followed by sensations of the opposite kind. Finally, it is necessary to consider the extent, or the number of people affected by the action. |

快楽計算 第4章において、ベンサムは快楽と苦痛の価値を計算する方法を導入した。これは後に快楽計算として知られるようになった。ベンサムによれば、快楽や苦痛の 価値は、それ自体として、その強度、持続時間、確実性/不確実性、近接性/遠隔性によって測定できるという。さらに、「それを生み出す行為の傾向性」を考 慮する必要がある。つまり、その行為の「肥沃性」、すなわち同種の感覚を引き起こす可能性と、「純度」、すなわち反対の感覚を引き起こさない可能性を考慮 しなければならない。最後に、その行為の影響範囲、すなわち影響を受ける人々数を考慮する必要がある。 |

| Evils of the first and second order The question then arises as to when, if at all, it might be legitimate to break the law. This is considered in The Theory of Legislation, where Bentham distinguishes between evils of the first and second order. Those of the first order are the more immediate consequences; those of the second are when the consequences spread through the community causing "alarm" and "danger". It is true there are cases in which, if we confine ourselves to the effects of the first order, the good will have an incontestable preponderance over the evil. Were the offence considered only under this point of view, it would not be easy to assign any good reasons to justify the rigour of the laws. Every thing depends upon the evil of the second order; it is this which gives to such actions the character of crime, and which makes punishment necessary. Let us take, for example, the physical desire of satisfying hunger. Let a beggar, pressed by hunger, steal from a rich man's house a loaf, which perhaps saves him from starving, can it be possible to compare the good which the thief acquires for himself, with the evil which the rich man suffers?... It is not on account of the evil of the first order that it is necessary to erect these actions into offences, but on account of the evil of the second order.[27] |

第一の悪と第二の悪 では、法律を破ることが正当化されるのは、もしあるとすれば、いつなのかという疑問が生じる。これは『立法論』で論じられており、ベンサムは第一の悪と第 二の悪を区別している。第一の悪とはより直接的な結果であり、第二の悪とは結果が社会全体に広がり「不安」や「危険」を引き起こす場合を指す。 確かに、第一次の結果のみに限定すれば、善い意志が悪を圧倒的に上回る事例は存在する。この観点のみで犯罪を評価するなら、法の厳しさを正当化する妥当な 理由を見出すのは容易ではない。全ては第二次の悪にかかっている。この悪こそが行為に犯罪性を付与し、処罰を必要とする所以である。例えば、飢えを満たす という肉体的欲求を考えてみよう。飢えに迫られた乞食が、裕福な者の家からパンを一つ盗み、それが彼を餓死から救ったとしよう。盗人が自ら得た利益と、裕 福な者が受けた苦悩とを、果たして比較できるだろうか?... これらの行為を犯罪と定める必要性は、第一次の悪のためではなく、第二次の悪のためである。[27] |

| John Stuart Mill Main article: John Stuart Mill Mill was brought up as a Benthamite with the explicit intention that he would carry on the cause of utilitarianism.[28] Mill's book Utilitarianism first appeared as a series of three articles published in Fraser's Magazine in 1861 and was reprinted as a single book in 1863.[29][30] Higher and lower pleasures Mill rejects a purely quantitative measurement of utility and says:[31] It is quite compatible with the principle of utility to recognize the fact, that some kinds of pleasure are more desirable and more valuable than others. It would be absurd that while, in estimating all other things, quality is considered as well as quantity, the estimation of pleasures should be supposed to depend on quantity alone. The word utility is used to mean general well-being or happiness, and Mill's view is that utility is the consequence of a good action. Utility, within the context of utilitarianism, refers to people performing actions for social utility. With social utility, he means the well-being of many people. Mill's explanation of the concept of utility in his work, Utilitarianism, is that people really do desire happiness, and since each individual desires their own happiness, it must follow that all of us desire the happiness of everyone, contributing to a larger social utility. Thus, an action that results in the greatest pleasure for the utility of society is the best action, or as Jeremy Bentham, the founder of early Utilitarianism put it, as the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Mill not only viewed actions as a core part of utility, but as the directive rule of moral human conduct. The rule being that we should only be committing actions that provide pleasure to society. This view of pleasure was hedonistic, as it pursued the thought that pleasure is the highest good in life. This concept was adopted by Bentham and can be seen in his works. According to Mill, good actions result in pleasure, and that there is no higher end than pleasure. Mill says that good actions lead to pleasure and define good character. Better put, the justification of character, and whether an action is good or not, is based on how the person contributes to the concept of social utility. In the long run the best proof of a good character is good actions; and resolutely refuse to consider any mental disposition as good, of which the predominant tendency is to produce bad conduct. In the last chapter of Utilitarianism, Mill concludes that justice, as a classifying factor of our actions (being just or unjust) is one of the certain moral requirements, and when the requirements are all regarded collectively, they are viewed as greater according to this scale of "social utility" as Mill puts it. He also notes that, contrary to what its critics might say, there is "no known Epicurean theory of life which does not assign to the pleasures of the intellect ... a much higher value as pleasures than to those of mere sensation." However, he accepts that this is usually because the intellectual pleasures are thought to have circumstantial advantages, i.e. "greater permanency, safety, uncostliness, &c." Instead, Mill will argue that some pleasures are intrinsically better than others. The accusation that hedonism is a "doctrine worthy only of swine" has a long history. In Nicomachean Ethics (Book 1 Chapter 5), Aristotle says that identifying the good with pleasure is to prefer a life suitable for beasts. The theological utilitarians had the option of grounding their pursuit of happiness in the will of God; the hedonistic utilitarians needed a different defence. Mill's approach is to argue that the pleasures of the intellect are intrinsically superior to physical pleasures. Few human creatures would consent to be changed into any of the lower animals, for a promise of the fullest allowance of a beast's pleasures; no intelligent human being would consent to be a fool, no instructed person would be an ignoramus, no person of feeling and conscience would be selfish and base, even though they should be persuaded that the fool, the dunce, or the rascal is better satisfied with his lot than they are with theirs. ... A being of higher faculties requires more to make him happy, is capable probably of more acute suffering, and certainly accessible to it at more points, than one of an inferior type; but in spite of these liabilities, he can never really wish to sink into what he feels to be a lower grade of existence. ... It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, are of a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question...[32] Mill argues that if people who are "competently acquainted" with two pleasures show a decided preference for one even if it be accompanied by more discontent and "would not resign it for any quantity of the other," then it is legitimate to regard that pleasure as being superior in quality. Mill recognizes that these "competent judges" will not always agree, and states that, in cases of disagreement, the judgment of the majority is to be accepted as final. Mill also acknowledges that "many who are capable of the higher pleasures, occasionally, under the influence of temptation, postpone them to the lower. But this is quite compatible with a full appreciation of the intrinsic superiority of the higher." Mill says that this appeal to those who have experienced the relevant pleasures is no different from what must happen when assessing the quantity of pleasure, for there is no other way of measuring "the acutest of two pains, or the intensest of two pleasurable sensations." "It is indisputable that the being whose capacities of enjoyment are low, has the greatest chance of having them fully satisfied; and a highly-endowed being will always feel that any happiness which he can look for, as the world is constitute, is imperfect."[33] Mill also thinks that "intellectual pursuits have value out of proportion to the amount of contentment or pleasure (the mental state) that they produce."[34] Mill also says that people should pursue these grand ideals, because if they choose to have gratification from petty pleasures, "some displeasure will eventually creep in. We will become bored and depressed."[35] Mill claims that gratification from petty pleasures only gives short-term happiness and, subsequently, worsens the individual who may feel that his life lacks happiness, since the happiness is transient. Whereas, intellectual pursuits give long-term happiness because they provide the individual with constant opportunities throughout the years to improve his life, by benefiting from accruing knowledge. Mill views intellectual pursuits as "capable of incorporating the 'finer things' in life" while petty pursuits do not achieve this goal.[36] Mill is saying that intellectual pursuits give the individual the opportunity to escape the constant depression cycle since these pursuits allow them to achieve their ideals, while petty pleasures do not offer this. Although debate persists about the nature of Mill's view of gratification, this suggests bifurcation in his position. |

ジョン・スチュワート・ミル 主な記事:ジョン・スチュワート・ミル ミルは、功利主義の理念を継承するという明確な意図のもと、ベンサム主義者として育てられた[28]。ミルの著書『功利主義』は、1861年にフレイザー誌に3回に分けて連載され、1863年に単行本として再版された[29][30]。 高次および低次の快楽 ミルは、効用の純粋に定量的な測定を拒否し、次のように述べている[31]。 ある種の快楽は他の快楽よりも望ましく、価値が高いという事実を認めることは、効用の原則とまったく矛盾しない。他のあらゆるものを評価する際に、質も量も考慮される一方で、快楽の評価は量のみに依存すると考えるのは不合理である。 「効用」という言葉は、一般的な幸福や幸福を意味するために用いられる。ミルの見解では、効用は善い行動の結果である。功利主義の文脈における効用とは、 人々が社会的効用のために行動することを指す。ここで言う社会的効用とは、多くの人々の幸福を意味する。ミルの著書『功利主義』における効用概念の説明は こうだ。人民は真に幸福を望み、各個人が自己の幸福を望む以上、必然的に我々は皆、他者の幸福をも望み、より大きな社会的効用に寄与する。ゆえに、社会の 効用に最大の快楽をもたらす行為が最善の行為であり、初期功利主義の創始者ジェレミー・ベンサムの言葉を借りれば「最大多数の最大幸福」である。 ミルは行動を単なる効用の中核要素と見るだけでなく、道徳的人間行動の指針的規則と位置付けた。その規則とは、社会に快楽をもたらす行動のみを実行すべき だというものだ。この快楽観は快楽主義的であり、快楽こそが人生の最高の善であるという思想を追求していた。この概念はベンサムにも採用され、彼の著作に 見られる。ミルによれば、善い行動は快楽をもたらし、快楽以上に高い目的は存在しない。ミルは、善い行動が快楽をもたらし、善い人格を定義すると述べる。 より正確に言えば、人格の正当性や行動の善悪は、個人が社会効用という概念にどれだけ貢献するかに基づく。長期的には、善い人格の最も確かな証拠は善い行 動であり、悪しき行動を生み出す傾向が支配的な精神的傾向を、決して善いものとは認めない。『功利主義』の最終章でミルは、正義(行為を正義か不正義かに 分類する要素)が確固たる道徳的要件の一つであると結論づける。そしてこれらの要件を総体として見たとき、ミルが言うところの「社会的効用」という尺度に よって、それらはより大きな価値を持つと評価されるのだ。 また彼は、批判者たちの主張とは反対に、「知性の快楽に…単なる感覚の快楽よりもはるかに高い価値を認めないエピクロス派の生活理論は存在しない」と指摘 している。ただし彼は、これは通常、知的な快楽が状況的な利点、すなわち「より永続的で、安全で、費用がかからない」と考えられているためだと認めてい る。代わりにミルは、ある快楽は他の快楽よりも本質的に優れていると主張する。 快楽主義が「豚にしかふさわしくない教義」だという非難は長い歴史を持つ。『ニコマコス倫理学』(第1巻第5章)でアリストテレスは、善を快楽と同一視す ることは獣にふさわしい生活を好むことだと述べている。神学的功利主義者は幸福追求の根拠を神の意志に置く選択肢があったが、快楽主義的功利主義者は異な る弁明を必要とした。ミルのアプローチは、知性の快楽が身体的快楽よりも本質的に優れていると論じることである。 人間という人格が、たとえ獣の快楽を存分に享受できると約束されても、下等動物に変わることを承諾する者はほとんどいない。知性ある人格が愚か者になるこ とを、教養ある人格が無知者になることを、感情と良心を持つ人格が利己的で卑劣な者になることを承諾する者はいない。たとえ愚か者や無知者や卑劣な者が、 自分たちよりも自分の境遇に満足していると説得されたとしてもだ。...高次の能力を持つ存在は、より多くのものを必要として幸福を得る。おそらくより鋭 い苦悩を経験し得るし、確かに苦悩に晒される点もより多い。しかしこうした弱点にもかかわらず、自らが下等な存在だと感じるレベルに堕ちたいと心から願う ことは決してない。...満足した豚より不満な人間である方がましだ。満足した愚か者より不満なソクラテスである方がましだ。... そして愚か者や豚が異なる意見を持つのは、彼らが問題の自分側の側面しか知らないからだ...[32] ミルは、二つの快楽を「十分に熟知した」人々が、たとえより多くの不満を伴うとしても一方を明らかに好み、「いかなる量の他方とも引き換えにしない」場 合、その快楽を質的に優れていると見なすのは正当だと論じる。ミルは、こうした「有能な判断者」が常に一致するとは限らないことを認め、意見が分かれた場 合には多数派の判断を最終的なものとすべきだと述べている。ミルはまた、「より高い快楽を享受できる能力を持つ者の多くが、誘惑の影響下で時折、それをよ り低い快楽に後回しにする」ことも認めている。しかしこれは、より高次の快楽の本質的な優越性を十分に理解していることと全く矛盾しない」と述べている。 ミルは、関連する快楽を経験した者へのこの訴えは、快楽の量を評価する際に必然的に起こることに他ならないと主張する。なぜなら「二つの苦痛のうち最も鋭 いもの、あるいは二つの快楽感覚のうち最も強いもの」を測る他の方法はないからだ。「享受能力の低い存在ほど、その能力を完全に満たされる可能性が高いこ とは疑いようがない。そして高度な能力を持つ存在は、世界のあり方として期待できる幸福が常に不完全であると感じるだろう」[33] ミルはまた「知的追求は、それが生み出す満足や快楽(精神状態)の量に比例しない価値を持つ」とも考えている[34]。ミルはさらに、人々はこうした崇高 な理想を追求すべきだと述べる。なぜなら、もし人々がささいな快楽からの満足を選ぶならば、「いずれ不快感が忍び込んでくる」からだ。退屈と憂鬱に陥る」 [35]と述べている。ミルによれば、ささいな快楽からの満足は短期間の幸福しか与えず、結果的に幸福が一時的であることに気づいた個人が人生に幸福が欠 けていると感じる状態を悪化させる。一方、知的追求は蓄積された知識の恩恵によって、年月を通じて人生を向上させる絶え間ない機会を個人に提供するため、 長期的な幸福をもたらす。ミルは知的追求を「人生の『より高尚なもの』を取り込む能力を持つ」と見る一方、些細な追求はこの目標を達成できないと考える [36]。ミルは、知的追求が個人の理想達成を可能にすることで絶え間ない憂鬱のサイクルから逃れる機会を与えるが、些細な快楽にはそれが欠けていると述 べている。ミルの満足感に関する見解の本質については議論が続いているが、これは彼の立場に分岐があることを示唆している。 |

| 'Proving' the principle of utility In Chapter Four of Utilitarianism, Mill considers what proof can be given for the principle of utility:[37] The only proof capable of being given that an object is visible, is that people actually see it. The only proof that a sound is audible, is that people hear it.… In like manner, I apprehend, the sole evidence it is possible to produce that anything is desirable, is that people do actually desire it.… No reason can be given why the general happiness is desirable, except that each person, so far as he believes it to be attainable, desires his own happiness…we have not only all the proof which the case admits of, but all which it is possible to require, that happiness is a good: that each person's happiness is a good to that person, and the general happiness, therefore, a good to the aggregate of all persons. It is usual to say that Mill is committing a number of fallacies:[38] naturalistic fallacy: Mill is trying to deduce what people ought to do from what they in fact do; equivocation fallacy: Mill moves from the fact that (1) something is desirable, i.e. is capable of being desired, to the claim that (2) it is desirable, i.e. that it ought to be desired; and the fallacy of composition: the fact that people desire their own happiness does not imply that the aggregate of all persons will desire the general happiness. Such allegations began to emerge in Mill's lifetime, shortly after the publication of Utilitarianism, and persisted for well over a century, though the tide has been turning in recent discussions. Nonetheless, a defence of Mill against all three charges, with a chapter devoted to each, can be found in Necip Fikri Alican's Mill's Principle of Utility: A Defense of John Stuart Mill's Notorious Proof (1994). This is the first, and remains[when?] the only, book-length treatment of the subject matter. Yet the alleged fallacies in the proof continue to attract scholarly attention in journal articles and book chapters. Hall (1949) and Popkin (1950) defend Mill against this accusation pointing out that he begins Chapter Four by asserting that "questions of ultimate ends do not admit of proof, in the ordinary acceptation of the term" and that this is "common to all first principles".[39][38] Therefore, according to Hall and Popkin, Mill does not attempt to "establish that what people do desire is desirable but merely attempts to make the principles acceptable."[38] The type of "proof" Mill is offering "consists only of some considerations which, Mill thought, might induce an honest and reasonable man to accept utilitarianism."[38] Having claimed that people do, in fact, desire happiness, Mill now has to show that it is the only thing they desire. Mill anticipates the objection that people desire other things such as virtue. He argues that whilst people might start desiring virtue as a means to happiness, eventually, it becomes part of someone's happiness and is then desired as an end in itself. The principle of utility does not mean that any given pleasure, as music, for instance, or any given exemption from pain, as for example health, are to be looked upon as means to a collective something termed happiness, and to be desired on that account. They are desired and desirable in and for themselves; besides being means, they are a part of the end. Virtue, according to the utilitarian doctrine, is not naturally and originally part of the end, but it is capable of becoming so; and in those who love it disinterestedly it has become so, and is desired and cherished, not as a means to happiness, but as a part of their happiness.[40] We may give what explanation we please of this unwillingness; we may attribute it to pride, a name which is given indiscriminately to some of the most and to some of the least estimable feelings of which is mankind are capable; we may refer it to the love of liberty and personal independence, an appeal to which was with the Stoics one of the most effective means for the inculcation of it; to the love of power, or the love of excitement, both of which do really enter into and contribute to it: but its most appropriate appellation is a sense of dignity, which all humans beings possess in one form or other, and in some, though by no means in exact, proportion to their higher faculties, and which is so essential a part of the happiness of those in whom it is strong, that nothing which conflicts with it could be, otherwise than momentarily, an object of desire to them.[41] |

効用原理の「証明」 『功利主義』第四章において、ミルは効用原理に対してどのような証明が可能かを考察する:[37] ある物体が視認可能であることの唯一の証明は、人々が実際にそれを見ていることである。ある音が聴取可能であることの唯一の証明は、人々がそれを聞いてい ることである。…同様に、何かが望ましいものであることの唯一の証拠は、人々が実際にそれを望んでいることだと私は考える。… 一般の幸福が望ましい理由として挙げられるのは、各人格が達成可能と信じる限りにおいて自らの幸福を望むという事実以外にはない…我々は幸福が善であるこ と、すなわち各人格の幸福がその人格にとって善であり、したがって一般の幸福は全人の集合にとって善であることについて、この事例が許容するあらゆる証明 だけでなく、要求しうるあらゆる証明をも得ているのである。 ミルはいくつかの誤謬を犯しているとよく言われる:[38] 自然主義的誤謬:ミルは人々が実際にしていることから、人々がすべきことを導き出そうとしている 曖昧語法による誤謬:ミルは(1)何かが望ましい(すなわち、望まれる可能性がある)という事実から、(2)それが望ましい(すなわち、望まれるべきである)という主張へと飛躍している。 構成の誤謬:個人が自らの幸福を望むという事実が、全ての人の総体が一般の幸福を望むことを意味しない。 このような主張は、ミルの存命中に、『功利主義』の出版直後に現れ始め、1世紀以上にわたって続いた。とはいえ、最近の議論では流れが変わってきている。 とはいえ、3つの非難すべてに対するミルの弁護は、それぞれ1章を割いて、ネジップ・フィクリ・アリカンの『ミルの効用原理:ジョン・スチュワート・ミル の悪名高い証明の弁護』(1994年)に見ることができる。これは、この主題について初めて、そして(いつまで?)唯一の書籍として扱ったものである。し かし、この証明における誤謬の指摘は、学術雑誌の記事や書籍の章で、今もなお学者の関心を集め続けている。 ホール(1949)とポプキン(1950)は、ミルが「究極の目的に関する問題は、その用語の通常の意味において証明を認めない」と主張して第 4 章を開始しており、これは「すべての第一原理に共通」であると指摘して、この非難に対してミルを擁護している。[39][38] したがってホールとポプキンによれば、ミルは「人々が実際に望むものが望ましいと立証しようとしたのではなく、単にその原理を受け入れられるようにしよう とした」のである。[38] ミルが提示する「証明」とは「ミルが誠実で合理的な人間に功利主義を受け入れさせるかもしれないと考えた、いくつかの考察に過ぎない」のだ。[38] 人民が実際に幸福を欲すると主張したミルは、次にそれが唯一欲するものであることを示さねばならない。人民が徳のような他のものを欲するという反論を予見 している。彼は、人民が幸福への手段として徳を欲し始めるかもしれないが、最終的にはそれが個人の幸福の一部となり、それ自体が目的として欲されるように なると論じる。 効用原理は、例えば音楽のような特定の快楽や、健康のような特定の苦痛からの免除が、幸福という集合的な何かの手段として見なされ、その理由で望まれるべ きだという意味ではない。それらはそれ自体において、それ自体のために望まれ、望ましいものである。手段であることに加え、それらは目的の一部でもあるの だ。功利主義の教義によれば、徳は本来的に目的の一部ではないが、そうなり得る。そして無私無欲に徳を愛する者においては、すでに目的の一部となり、幸福 への手段としてではなく、彼らの幸福の一部として求められ、大切にされているのだ。[40] この不本意さについて、我々は好きなように説明できる。誇りという名のもとに帰することもできる。この言葉は、人類が持つ最も尊い感情から最も卑しい感情 まで、無差別に用いられる。あるいは自由と個人的独立への愛に帰することもできる。ストア派がこれを説く際に用いた最も効果的な手段の一つが、この愛への 訴えであった。権力への愛や興奮への愛に帰することもできる。これら二つの感情は実際にこの感情に入り込み、それを助長する。しかし最も適切な呼称は尊厳 感である。これはあらゆる人間が何らかの形で持ち、より高い能力に比例して(決して正確ではないが)強くなる。そしてこの感覚が強い者にとって、幸福の不 可欠な要素であるため、それと矛盾するものは、たとえ一瞬であっても、彼らの欲望の対象となり得ないのだ。[41] |

| Henry Sidgwick Main article: Henry Sidgwick Sidgwick's book The Methods of Ethics has been referred to as the peak or culmination of classical utilitarianism.[42][43][44] His main goal in this book is to ground utilitarianism in the principles of common-sense morality and thereby dispense with the doubts of his predecessors that these two are at odds with each other.[43] For Sidgwick, ethics is about which actions are objectively right.[42] Our knowledge of right and wrong arises from common-sense morality, which lacks a coherent principle at its core.[45] The task of philosophy in general and ethics in particular is not so much to create new knowledge but to systematize existing knowledge.[46] Sidgwick tries to achieve this by formulating methods of ethics, which he defines as rational procedures "for determining right conduct in any particular case".[43] He identifies three methods: intuitionism, which involves various independently valid moral principles to determine what ought to be done, and two forms of hedonism, in which rightness only depends on the pleasure and pain following from the action. Hedonism is subdivided into egoistic hedonism, which only takes the agent's own well-being into account, and universal hedonism or utilitarianism, which is concerned with everyone's well-being.[46][43] Intuitionism holds that we have intuitive, i.e. non-inferential, knowledge of moral principles, which are self-evident to the knower.[46] The criteria for this type of knowledge include that they are expressed in clear terms, that the different principles are mutually consistent with each other and that there is expert consensus on them. According to Sidgwick, commonsense moral principles fail to pass this test, but there are some more abstract principles that pass it, like that "what is right for me must be right for all persons in precisely similar circumstances" or that "one should be equally concerned with all temporal parts of one's life".[43][46] The most general principles arrived at this way are all compatible with utilitarianism, which is why Sidgwick sees a harmony between intuitionism and utilitarianism.[44] There are also less general intuitive principles, like the duty to keep one's promises or to be just, but these principles are not universal and there are cases where different duties stand in conflict with each other. Sidgwick suggests that we resolve such conflicts in a utilitarian fashion by considering the consequences of the conflicting actions.[43][47] The harmony between intuitionism and utilitarianism is a partial success in Sidgwick's overall project, but he sees full success impossible since egoism, which he considers as equally rational, cannot be reconciled with utilitarianism unless religious assumptions are introduced.[43] Such assumptions, for example, the existence of a personal God who rewards and punishes the agent in the afterlife, could reconcile egoism and utilitarianism.[46] But without them, we have to admit a "dualism of practical reason" that constitutes a "fundamental contradiction" in our moral consciousness.[42] |

ヘンリー・シジウィック メイン記事: ヘンリー・シジウィック シジウィックの著書『倫理学の方法』は、古典的功利主義の頂点あるいは集大成と評されている。[42][43][44] この書における彼の主目的は、功利主義を常識的道徳の原理に根差すことであり、それによって両者が対立するという先人たちの疑念を払拭することにある。 [43] シジウィックにとって倫理とは、どの行為が客観的に正しいかについてのものである。[42] 正誤に関する我々の知識は常識的道徳から生じるが、その核心には一貫した原理が欠けている。[45] 哲学全般、特に倫理学の任務は、新たな知識を創造することよりも、既存の知識を体系化することにある。[46] シジウィックは倫理学の方法論を構築することでこれを達成しようとする。彼は倫理学の方法論を「個々の事例において正しい行動を決定する合理的手続き」と 定義する。[43] 彼は三つの方法を特定する:直観主義(様々な独立して有効な道徳原理を用いて「なすべきこと」を決定する)と、快楽主義の二形態(正しさは行動から生じる 快楽と苦痛のみに依存する)。快楽主義はさらに細分化される。行為者自身の幸福のみを考慮する利己的快楽主義と、全ての者の幸福を扱う普遍的快楽主義(功 利主義)である。[46] [43] 直観主義は、道徳原理について直観的(推論を必要としない)知識が我々にあると主張する。この知識は認識者にとって自明である。[46] この種の知識の基準には、明確な言葉で表現されていること、異なる原理が互いに矛盾しないこと、専門家による合意が存在することが含まれる。シジウィック によれば、常識的な道徳原理はこのテストを通過しないが、「私にとって正しいことは、全く同じ状況にある全ての人格にとって正しいに違いない」とか、「人 は自分の人生の全ての時間的側面を等しく気にかけるべきだ」といった、より抽象的な原理の中には通過するものがある。[43][46] この方法で導かれる最も一般的な原理はすべて功利主義と両立する。ゆえにシジウィックは直観主義と功利主義の調和を見出すのである。[44] 約束を守る義務や公正であるべき義務といった、より一般的でない直観的原理も存在するが、これらは普遍的ではなく、異なる義務が衝突する事例も存在する。 シジウィックは、対立する行動の結果を考慮することで、功利主義的な方法でこうした矛盾を解決すべきだと提案している。[43][47] 直観主義と功利主義の調和は、シジウィックの全体的な計画における部分的な成功である。しかし彼は、宗教的な前提を導入しない限り、同等に合理的と見なす 利己主義を功利主義と調和させることは不可能だと見ている。[43] 例えば、死後の世界で行為者を報い罰する個人的神の存在といった前提は、利己主義と功利主義を調和させ得る。[46] しかしそれらなしでは、我々は道徳的意識における「根本的矛盾」を構成する「実践的理性の二元論」を認めざるを得ない。[42] |

★功利主義一般の解説(上掲の「20世紀以降の功利主義の考え方」と「古典的功利主義」の記述と重複があります)

目次

| In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism

is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that

maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.[1][2] Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different characterizations, the basic idea behind all of them is, in some sense, to maximize utility, which is often defined in terms of well-being or related concepts. For instance, Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism, described utility as: That property in any object, whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness ... [or] to prevent the happening of mischief, pain, evil, or unhappiness to the party whose interest is considered. Utilitarianism is a version of consequentialism, which states that the consequences of any action are the only standard of right and wrong. Unlike other forms of consequentialism, such as egoism and altruism, utilitarianism considers the interests of all sentient beings equally. Proponents of utilitarianism have disagreed on a number of issues, such as whether actions should be chosen based on their likely results (act utilitarianism), or whether agents should conform to rules that maximize utility (rule utilitarianism). There is also disagreement as to whether total utility (total utilitarianism), average utility (average utilitarianism) or the utility of the people worst-off[3] should be maximized. Though the seeds of the theory can be found in the hedonists Aristippus and Epicurus, who viewed happiness as the only good, and in the work of the medieval Indian philosopher Śāntideva, the tradition of modern utilitarianism began with Jeremy Bentham, and continued with such philosophers as John Stuart Mill, Henry Sidgwick, R. M. Hare, and Peter Singer. The concept has been applied towards social welfare economics, questions of justice, the crisis of global poverty, the ethics of raising animals for food, and the importance of avoiding existential risks to humanity. |

倫理哲学において功利主義は、影響を受けるすべての個人の幸福と幸福を最大化する行動を規定する規範的倫理理論の一群である[1][2]。 様々な種類の功利主義が異なる特徴を認めているが、全ての功利主義の背後にある基本的な考え方は、ある意味で効用を最大化することであり、それは幸福や関 連する概念で定義されることが多い。例えば、功利主義の創始者であるジェレミー・ベンサムは、効用を次のように説明する: あらゆる対象物におけるその性質は、それによって利益、利点、快楽、善、幸福...を生み出す傾向がある。[あるいは]その利害が考慮される当事者に災い、苦痛、悪、不幸が起こるのを防ぐためである。 功利主義は帰結主義の一種であり、あらゆる行為の結果が善悪の唯一の基準であるとする。エゴイズムや利他主義のような他の形の帰結主義とは異なり、功利主 義はすべての統覚のある人の利益を平等に考える。功利主義の支持者たちは、行動はその結果に基づいて選択されるべきか(行為功利主義)、あるいはエージェントは効 用を最大化するルールに従うべきか(ルール功利主義)など、多くの問題で意見が分かれている。また、全体効用(全体功利主義)か、平均効用(平均功利主 義)か、あるいは最悪の人々[3]の効用を最大化すべきかについても意見が分かれている。 この理論の種は、幸福を唯一の善と見なした快楽主義者アリスティッポスとエピクロス、および中世インドの哲学者シュアンティデーヴァの研究に見出すことが できるが、近代功利主義の伝統はジェレミー・ベンサムから始まり、ジョン・スチュアート・ミル、ヘンリー・シドウィック、R・M・ヘアー、ピーター・シン ガーなどの哲学者に受け継がれている。この概念は、社会福祉経済学、正義の問題、世界的貧困の危機、食用動物の飼育倫理、人類存亡の危機を回避することの 重要性などに応用されてきた。 |

| Etymology Benthamism, the utilitarian philosophy founded by Jeremy Bentham, was substantially modified by his successor John Stuart Mill, who popularized the term utilitarianism.[4] In 1861, Mill acknowledged in a footnote that, though Bentham believed "himself to be the first person who brought the word 'utilitarian' into use, he did not invent it. Rather, he adopted it from a passing expression" in John Galt's 1821 novel Annals of the Parish.[5] However, Mill seems to have been unaware that Bentham had used the term utilitarian in his 1781 letter to George Wilson and his 1802 letter to Étienne Dumont.[4] |

語源 ジェレミー・ベンサムによって創設された功利主義哲学であるベンサム主義は、功利主義という言葉を広めた彼の後継者であるジョン・スチュアート・ミルに よって大幅に修正された[4]。 1861年、ミルは脚注の中で、ベンサムは「『功利主義者』という言葉を最初に使ったのは自分自身であると信じていたが、彼はそれを発明したわけではな い。しかし、ミルはベンサムが1781年にジョージ・ウィルソンに宛てた書簡や1802年にエティエンヌ・デュモンに宛てた書簡で功利主義者という言葉を 使っていたことを知らなかったようである[4]。 |

| Historical background See also: Hedonism Pre-modern formulations The importance of happiness as an end for humans has long been recognized. Forms of hedonism were put forward by Aristippus and Epicurus; Aristotle argued that eudaimonia is the highest human good; and Augustine wrote that "all men agree in desiring the last end, which is happiness." Happiness was also explored in depth by Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica.[6][7][8][9][10] Meanwhile, in medieval India, the 8th-century Indian philosopher Śāntideva was one of the earliest proponents of utilitarianism, writing that we ought "to stop all the present and future pain and suffering of all sentient beings, and to bring about all present and future pleasure and happiness."[11] Different varieties of consequentialism also existed in the ancient and medieval world, like the state consequentialism of Mohism or the political philosophy of Niccolò Machiavelli. Mohist consequentialism advocated communitarian moral goods, including political stability, population growth, and wealth, but did not support the utilitarian notion of maximizing individual happiness.[12] 18th century Utilitarianism as a distinct ethical position only emerged in the 18th century, and although it is usually thought to have begun with Jeremy Bentham, there were earlier writers who presented theories that were strikingly similar. Hutcheson Francis Hutcheson first introduced a key utilitarian phrase in An Inquiry into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue (1725): when choosing the most moral action, the amount of virtue in a particular action is proportionate to the number of people such brings happiness to.[13] In the same way, moral evil, or vice, is proportionate to the number of people made to suffer. The best action is the one that procures the greatest happiness of the greatest numbers, and the worst is the one that causes the most misery. In the first three editions of the book, Hutcheson included various mathematical algorithms "to compute the Morality of any Actions." In doing so, he pre-figured the hedonic calculus of Bentham. John Gay Some claim that John Gay developed the first systematic theory of utilitarian ethics.[14] In Concerning the Fundamental Principle of Virtue or Morality (1731), Gay argues that:[15] happiness, private happiness, is the proper or ultimate end of all our actions... each particular action may be said to have its proper and peculiar end…(but)…they still tend or ought to tend to something farther; as is evident from hence, viz. that a man may ask and expect a reason why either of them are pursued: now to ask the reason of any action or pursuit, is only to enquire into the end of it: but to expect a reason, i.e. an end, to be assigned for an ultimate end, is absurd. To ask why I pursue happiness, will admit of no other answer than an explanation of the terms. This pursuit of happiness is given a theological basis:[16] Now it is evident from the nature of God, viz. his being infinitely happy in himself from all eternity, and from his goodness manifested in his works, that he could have no other design in creating mankind than their happiness; and therefore he wills their happiness; therefore the means of their happiness: therefore that my behaviour, as far as it may be a means of the happiness of mankind, should be such...thus the will of God is the immediate criterion of Virtue, and the happiness of mankind the criterion of the will of God; and therefore the happiness of mankind may be said to be the criterion of virtue, but once removed…(and)…I am to do whatever lies in my power towards promoting the happiness of mankind. Hume In An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (1751), David Hume writes:[17] In all determinations of morality, this circumstance of public utility is ever principally in view; and wherever disputes arise, either in philosophy or common life, concerning the bounds of duty, the question cannot, by any means, be decided with greater certainty, than by ascertaining, on any side, the true interests of mankind. If any false opinion, embraced from appearances, has been found to prevail; as soon as farther experience and sounder reasoning have given us juster notions of human affairs, we retract our first sentiment, and adjust anew the boundaries of moral good and evil. Paley  Modern Utilitarianism by Thomas Rawson Birks 1874 Gay's theological utilitarianism was developed and popularized by William Paley. It has been claimed that Paley was not a very original thinker and that the philosophies in his treatise on ethics is "an assemblage of ideas developed by others and is presented to be learned by students rather than debated by colleagues."[18] Nevertheless, his book The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy (1785) was a required text at Cambridge[18] and Smith (1954) says that Paley's writings were "once as well known in American colleges as were the readers and spellers of William McGuffey and Noah Webster in the elementary schools."[19] Schneewind (1977) writes that "utilitarianism first became widely known in England through the work of William Paley."[20] The now-forgotten significance of Paley can be judged from the title of Thomas Rawson Birks's 1874 work Modern Utilitarianism or the Systems of Paley, Bentham and Mill Examined and Compared. Apart from restating that happiness as an end is grounded in the nature of God, Paley also discusses the place of rules, writing:[21] [A]ctions are to be estimated by their tendency. Whatever is expedient, is right. It is the utility of any moral rule alone, which constitutes the obligation of it. But to all this there seems a plain objection, viz. that many actions are useful, which no man in his senses will allow to be right. There are occasions, in which the hand of the assassin would be very useful.… The true answer is this; that these actions, after all, are not useful, and for that reason, and that alone, are not right. To see this point perfectly, it must be observed that the bad consequences of actions are twofold, particular and general. The particular bad consequence of an action, is the mischief which that single action directly and immediately occasions. The general bad consequence is, the violation of some necessary or useful general rule.… You cannot permit one action and forbid another, without showing a difference between them. Consequently, the same sort of actions must be generally permitted or generally forbidden. Where, therefore, the general permission of them would be pernicious, it becomes necessary to lay down and support the rule which generally forbids them. |

歴史的背景 「快楽主義(Hedonism)」 近代以前の定式化 人間にとっての目的としての幸福の重要性は、長い間認識されてきた。アリストテレスはエウダイモニアが人間の最高の善であると主張し、アウグスティヌスは 「すべての人は幸福である最後の目的を望むことに同意する」と書いた。一方、中世インドでは、8世紀のインドの哲学者シュアンティデーヴァが功利主義の最 も初期の支持者の一人であり、私たちは「すべての衆生の現在と未来のすべての苦痛と苦しみを止め、現在と未来のすべての喜びと幸福をもたらすべきである」 と書いている[11]。 古代や中世の世界にも、モヒズムの国家帰結主義やニコロ・マキアヴェッリの政治哲学のように、さまざまな種類の帰結主義が存在した。モヒズムの結果主義 は、政治的安定、人口増加、富を含む共同体主義的な道徳的財を提唱したが、個人の幸福を最大化するという功利主義的な概念を支持しなかった[12]。 18世紀 功利主義が明確な倫理的立場として登場したのは18世紀になってからであり、通常はジェレミー・ベンサムによって始まったと考えられているが、それ以前にも驚くほど類似した理論を提示した作家がいた。 ハッチェソン フランシス・ハッチソンは、『An Inquiry into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue』(1725年)の中で、功利主義の重要なフレーズを初めて紹介した。最も道徳的な行為を選択するとき、特定の行為における徳の量は、その行 為が幸福をもたらす人々の数に比例する。最良の行為とは、最大多数の最大幸福をもたらすものであり、最悪の行為とは、最大不幸をもたらすものである。この 本の最初の3版では、ハッチェソンは「あらゆる行為の道徳性を計算する」さまざまな数学的アルゴリズムを盛り込んだ。そうすることで、彼はベンサムのヘド ニック計算を先取りしたのである。 ジョン・ゲイ ジョン・ゲイは功利主義倫理の最初の体系的理論を開発したと主張する者もいる[14]。 ゲイは『徳または道徳の根本原理について』(1731年)の中で次のように主張している[15]。 幸福、すなわち私的な幸福は、われわれのすべての行為の適切な、あるいは究極的な目的である......それぞれの特定の行為には、その適切で独特な目的 があると言うことができる......しかし......それでもなお、それらはより遠いものに向かう傾向があるか、あるいは向かうべきである。しかし、 究極的な目的に対して理由、すなわち目的が与えられることを期待するのは不合理である。なぜ私が幸福を追求するのかと問うことは、その用語の説明以外の答 えを認めないだろう。 この幸福の追求には神学的根拠が与えられている[16]。 神の本性、すなわち、神が永遠に無限に幸福であること、また、神の御業に示された神の善性から明らかなように、神は人間を創造するにあたって、その幸福以 外のいかなる意図も持ちえなかったのであり、それゆえ、神は人間の幸福を意志されるのであり、したがって、人間の幸福の手段なのである。 ...したがって、神の意志は徳の直接的な基準であり、人類の幸福は神の意志の基準である。したがって、人類の幸福は徳の基準であると言えるが、一旦は取 り除かれる...(そして)...私は、人類の幸福を促進するために、自分の力にあることは何でもしなければならない。 ヒューム 道徳の原理に関する探究』(1751年)の中で、デイヴィッド・ヒュームは次のように書いている[17]。 道徳のすべての決定において、この公益という状況が常に第一義的に考慮される。哲学においても一般生活においても、義務の境界に関して論争が起こる場合に は、どのような方法によっても、人類の真の利益を確認すること以上に、この問題をより確実に決定することはできない。外見から受け入れられている誤った意 見が優勢であることが判明した場合、より長い経験とより健全な推論によって、人間の問題についてより正しい見解が得られるや否や、私たちは最初の感情を撤 回し、道徳的善悪の境界を新たに調整する。 ペイリー  『近代功利主義』 トマス・ローソン・バークス著 1874年 ゲイの神学的功利主義は、ウィリアム・ペイリーによって発展・普及した。ペイリーはあまり独創的な思想家ではなく、彼の倫理学論考の中の哲学は「他の人々 によって発展させられたアイデアの集合体であり、同僚によって議論されるよりもむしろ学生によって学ばれるために提示されたものである」と主張されている [18]。 18]にもかかわらず、彼の著書『道徳政治哲学の原理』(The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy、1785年)はケンブリッジ大学の必修テキストであり[18]、スミス(Smith、1954年)は、ペイリーの著作は「かつてア メリカの大学では、ウィリアム・マクガフィー(William McGuffey)やノア・ウェブスター(Noah Webster)の読み手や綴り手が小学校にいたのと同じようによく知られていた」と述べている[19]。シュネーウィンド(Schneewind、 1977年)は、「功利主義は、ウィリアム・ペイリーの著作によって初めてイギリスで広く知られるようになった」と書いている[20]。 今では忘れ去られたペイリーの重要性は、トーマス・ローソン・バークスの1874年の著作『Modern Utilitarianism or the Systems of Paley, Bentham and Mill Examined and Compared』のタイトルから判断することができる。 ペイリーは、目的としての幸福が神の本性に根ざしていることを再確認する以外に、規則の位置づけについても論じており、次のように書いている[21]。 [行為はその傾向によって評価されるべきである。好都合なものは何でも正しい。道徳的規則の義務を構成するのは、その有用性だけである。 しかし、これには明白な反論があるように思われる。すなわち、多くの行為は有用であるが、その行為を正しいと認める人は、その感覚では誰もいないというこ とである。真の答えはこうである。結局のところ、これらの行為は有用ではなく、それゆえに、またそれゆえにのみ、正しくないのである。 この点を完璧に理解するためには、行為の悪い結果には、特殊なものと一般的なものの2つがあることを観察しなければならない。ある行為の特定の悪い結果と は、その一つの行為が直接的かつ即座に引き起こす災いのことである。一般的な悪い結果とは、必要または有用な一般的ルールに違反することである。 ある行為を許し、別の行為を禁じることは、両者の違いを示すことなしにはできない。したがって、同じ種類の行為は、一般的に許可されるか、一般的に禁止さ れなければならない。したがって、一般的に許可することが悪質である場合には、一般的に禁止する規則を定め、それを支持することが必要となる。 |