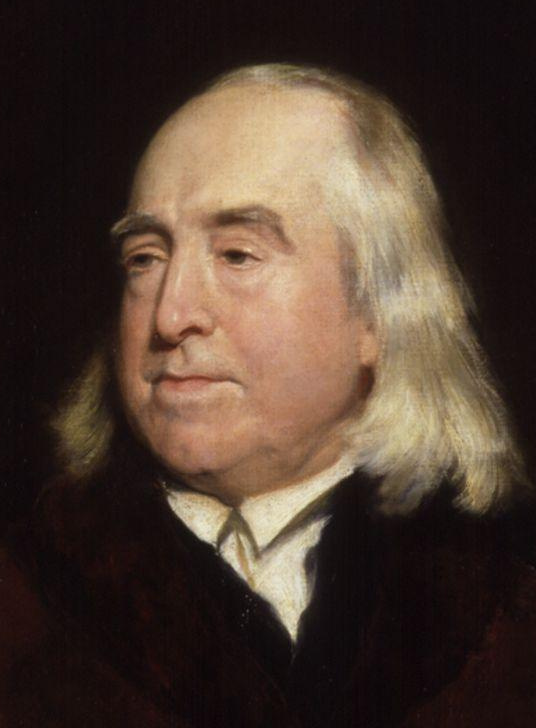

ジェレミー・ベンサム

Jeremy Bentham, 1747-1832

ベンサムのオートアイコン

☆ ジェレミー・ベンサム(Jeremy Bentham、1747年2月4日(西暦1747年2月8日)- 1832年6月6日)は、イギリスの哲学者、法学者、社会改革者で、近代功利主義の創始者とみなされている。 ベンサムは「最大多数の最大幸福こそが善悪の尺度である」という原則を彼の哲学の「基本公理」と定義した。彼は個人と経済の自由、政教分離、表現の自由、 女性の平等な権利、離婚の権利、(未発表のエッセイにおいて)同性愛行為の非犯罪化を提唱した。 また、動物の権利の初期の擁護者としても知られるようになった。個人の法的権利の拡張に強く賛成していたものの、自然法や自然権(いずれも起源が「神」ま たは「神から与えられた」と考えられている)の考え方に反対しており、それらを「竹馬の上のナンセンス」と呼んでいた。 ベンサムの弟子には、彼の秘書であり共同研究者であったジェームズ・ミル、後者の息子であるジョン・スチュアート・ミル、法哲学者のジョン・オースティ ン、アメリカの作家であり活動家であったジョン・ニールなどがいた。彼は「刑務所、学校、貧民法、法廷、議会そのものの改革に多大な影響を与えた」。 1832年に死去したベンサムは、遺体をまず解剖し、「オートアイコン」(自己像:上の写真)として永久保存するよう指示を残した。この遺体は現在、ユニ バーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドン(UCL)の学生センター入り口に展示されている。教育の一般的な利用可能性を支持する彼の主張から、彼はUCLの「精神 的創始者」と評されてきた。しかし、彼がUCLの創設に直接関与したのはごく限られたことであった。

Jeremy

Bentham

(/ˈbɛnθəm/; 4 February 1747/8 O.S. [15 February 1748 N.S.][2][3][4] – 6

June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer

regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism.[5][6] Jeremy

Bentham

(/ˈbɛnθəm/; 4 February 1747/8 O.S. [15 February 1748 N.S.][2][3][4] – 6

June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer

regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism.[5][6]Bentham defined as the "fundamental axiom" of his philosophy the principle that "it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong."[7][8] He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism. He advocated individual and economic freedoms, the separation of church and state, freedom of expression, equal rights for women, the right to divorce, and (in an unpublished essay) the decriminalising of homosexual acts.[9][10] He called for the abolition of slavery, capital punishment, and physical punishment, including that of children.[11] He has also become known as an early advocate of animal rights.[12][13][14][15] Though strongly in favour of the extension of individual legal rights, he opposed the idea of natural law and natural rights (both of which are considered "divine" or "God-given" in origin), calling them "nonsense upon stilts".[5][16] Bentham was also a sharp critic of legal fictions. Bentham's students included his secretary and collaborator James Mill, the latter's son, John Stuart Mill, the legal philosopher John Austin and American writer and activist John Neal. He "had considerable influence on the reform of prisons, schools, poor laws, law courts, and Parliament itself."[17] On his death in 1832, Bentham left instructions for his body to be first dissected, and then to be permanently preserved as an "auto-icon" (or self-image), which would be his memorial. This was done, and the auto-icon is now on public display in the entrance of the Student Centre at University College London (UCL). Because of his arguments in favour of the general availability of education, he has been described as the "spiritual founder" of UCL. However, he played only a limited direct part in its foundation.[18] |

ジェレミー・ベンサム(Jeremy Bentham、/ˈˈ;

1747年2月4日(西暦1747年2月8日)[2][3][4] -

1832年6月6日)は、イギリスの哲学者、法学者、社会改革者で、近代功利主義の創始者とみなされている[5][6]。 ジェレミー・ベンサム(Jeremy Bentham、/ˈˈ;

1747年2月4日(西暦1747年2月8日)[2][3][4] -

1832年6月6日)は、イギリスの哲学者、法学者、社会改革者で、近代功利主義の創始者とみなされている[5][6]。ベンサムは「最大多数の最大幸福こそが善悪の尺度である」という原則を彼の哲学の「基本公理」と定義した[7][8]。彼は個人と経済の自由、政教分離、 表現の自由、女性の平等な権利、離婚の権利、(未発表のエッセイにおいて)同性愛行為の非犯罪化を提唱した[9][10]。 [11]また、動物の権利の初期の擁護者としても知られるようになった[12][13][14][15]。個人の法的権利の拡張に強く賛成していたもの の、自然法や自然権(いずれも起源が「神」または「神から与えられた」と考えられている)の考え方に反対しており、それらを「竹馬の上のナンセンス」と呼 んでいた[5][16]。 ベンサムの弟子には、彼の秘書であり共同研究者であったジェームズ・ミル、後者の息子であるジョン・スチュアート・ミル、法哲学者のジョン・オースティ ン、アメリカの作家であり活動家であったジョン・ニールなどがいた。彼は「刑務所、学校、貧民法、法廷、議会そのものの改革に多大な影響を与えた」 [17]。 1832年に死去したベンサムは、遺体をまず解剖し、「オートアイコン」(自己像)として永久保存するよう指示を残した。この遺体は現在、ユニバーシ ティ・カレッジ・ロンドン(UCL)の学生センター入り口に展示されている。教育の一般的な利用可能性を支持する彼の主張から、彼はUCLの「精神的創始 者」と評されてきた。しかし、彼がUCLの創設に直接関与したのはごく限られたことであった[18]。 |

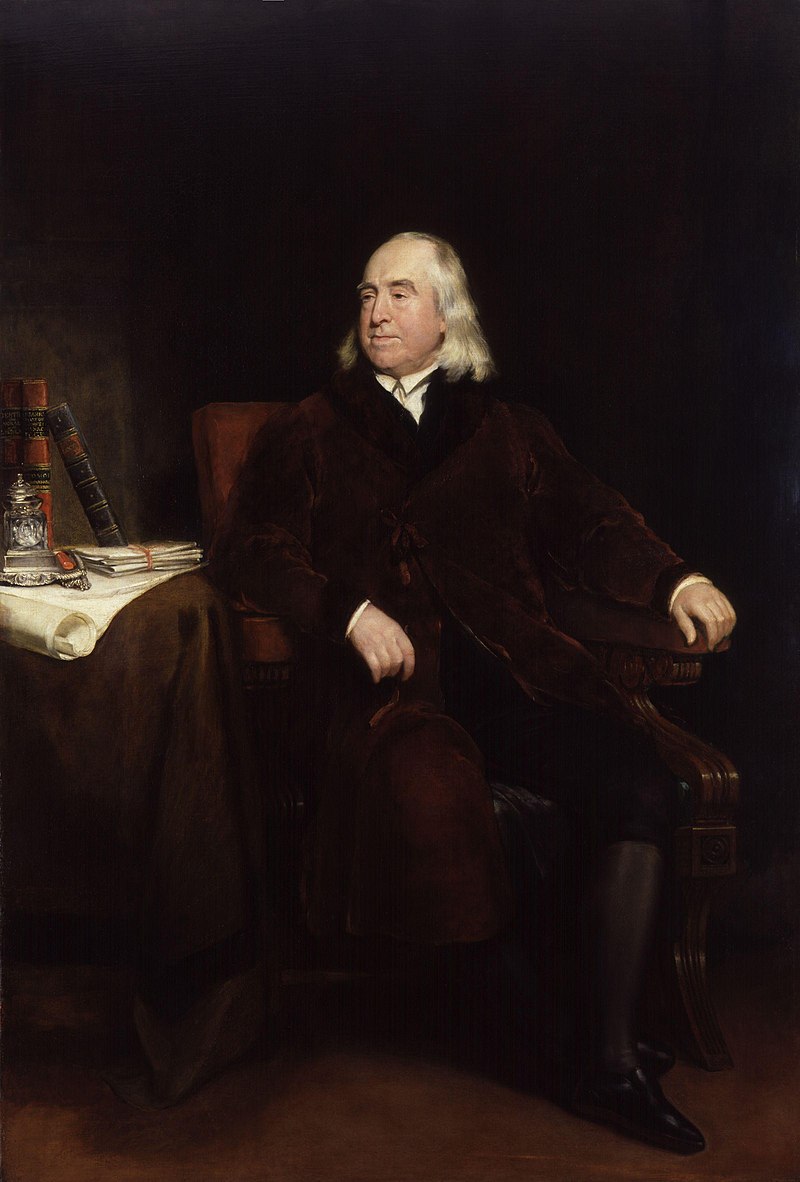

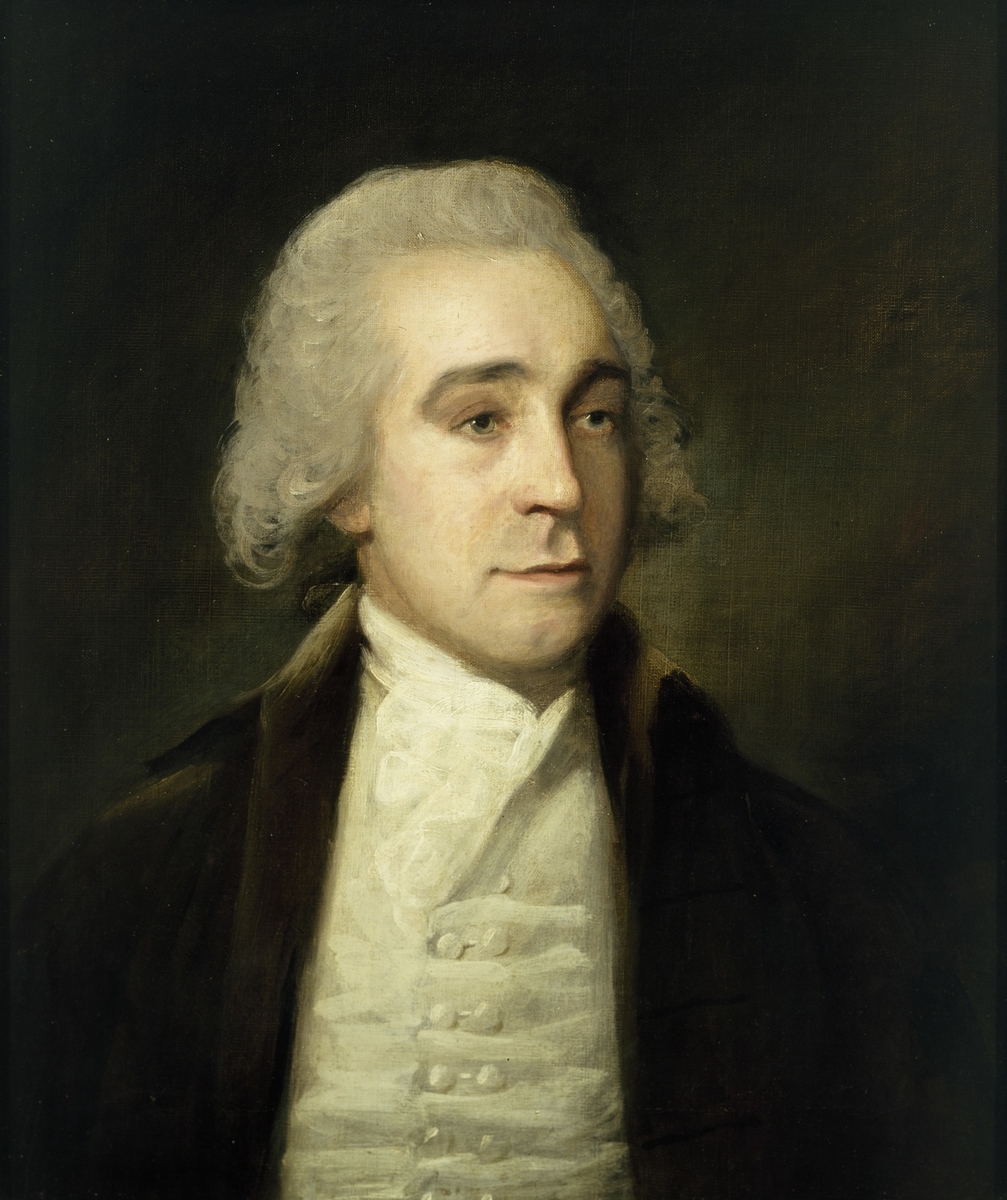

| Biography Early life  Portrait of Bentham by the studio of Thomas Frye, 1760–1762 Bentham was born on 4 February 1747/8 O.S. [15 February 1748 N.S.] in Houndsditch, London,[2] to attorney Jeremiah Bentham (1712–1792) and Alicia Woodward (died 1759), widow of a Mr Whitehorne and daughter of mercer Thomas Grove, of Andover.[19][20] His wealthy family were supporters of the Tory party. He was reportedly a child prodigy: he was found as a toddler sitting at his father's desk reading a multi-volume history of England, and he began to study Latin at the age of three.[21] He learnt to play the violin, and at the age of seven Bentham would perform sonatas by Handel during dinner parties.[22] He had one surviving sibling, Samuel Bentham (1757–1831), with whom he was close. He attended Westminster School; in 1760, at age 12, his father sent him to The Queen's College, Oxford, where he completed his bachelor's degree in 1764, receiving the title of MA in 1767.[2] He trained as a lawyer and, though he never practised, was called to the bar in 1769. He became deeply frustrated with the complexity of English law, which he termed the "Demon of Chicane".[23] When the American colonies published their Declaration of Independence in July 1776, the British government did not issue any official response but instead secretly commissioned London lawyer and pamphleteer John Lind to publish a rebuttal.[24] His 130-page tract was distributed in the colonies and contained an essay titled "Short Review of the Declaration" written by Bentham, a friend of Lind, which attacked and mocked the Americans' political philosophy.[25][26] |

略歴 生い立ち  トーマス・フライのスタジオによるベンサムの肖像画(1760-1762年 ベンサムは、1747年2月4日/8日(旧暦)[1748年2月15日(新暦)]、ロンドン、ハウンドスディッチで、弁護士のジェレミア・ベンサム (1712年~1792年)と、ホワイトホーン氏の未亡人で、アンドーバーの毛織物商人トーマス・グローブの娘であるアリシア・ウッドワード(1759年 没)の間に生まれた。[19][20] 彼の裕福な家族は、トーリー党の支持者だった。彼は、幼少の頃から天才児だったと伝えられている。彼は、父親の机に座って、英国の多巻からなる歴史書を読 んでいるところを発見され、3歳でラテン語を勉強し始めた[21]。バイオリンも学び、7歳の頃には、ディナーパーティーでヘンデルのソナタを演奏してい た。[22] 彼には、1757年に生まれたサミュエル・ベンサム(1831年没)という兄弟が1人おり、彼はこの兄弟と親しかった。 彼はウェストミンスター・スクールに通い、1760年に12歳で父親によってオックスフォードのクイーンズ・カレッジに送られ、1764年に学士号を取 得、1767年に文学修士号を取得した[2]。弁護士として研修を受けたが、実務には従事せず、1769年に法曹資格を取得した。彼は、イギリス法の複雑 さに深く失望し、これを「チケーン(法廷闘争)の悪魔」と呼んだ。[23] 1776年7月、アメリカ植民地が独立宣言を発表したが、イギリス政府は公式な回答を発表せず、代わりにロンドン弁護士でパンフレット作家であるジョン・ リンドに反論書の執筆を秘密裏に依頼した。[24] 彼の 130 ページにわたる小冊子は植民地に配布され、リンドの友人であるベンサムが書いた「宣言の簡潔なレビュー」というエッセイが掲載され、アメリカ人の政治哲学 を攻撃し、嘲笑した。[25][26] |

|

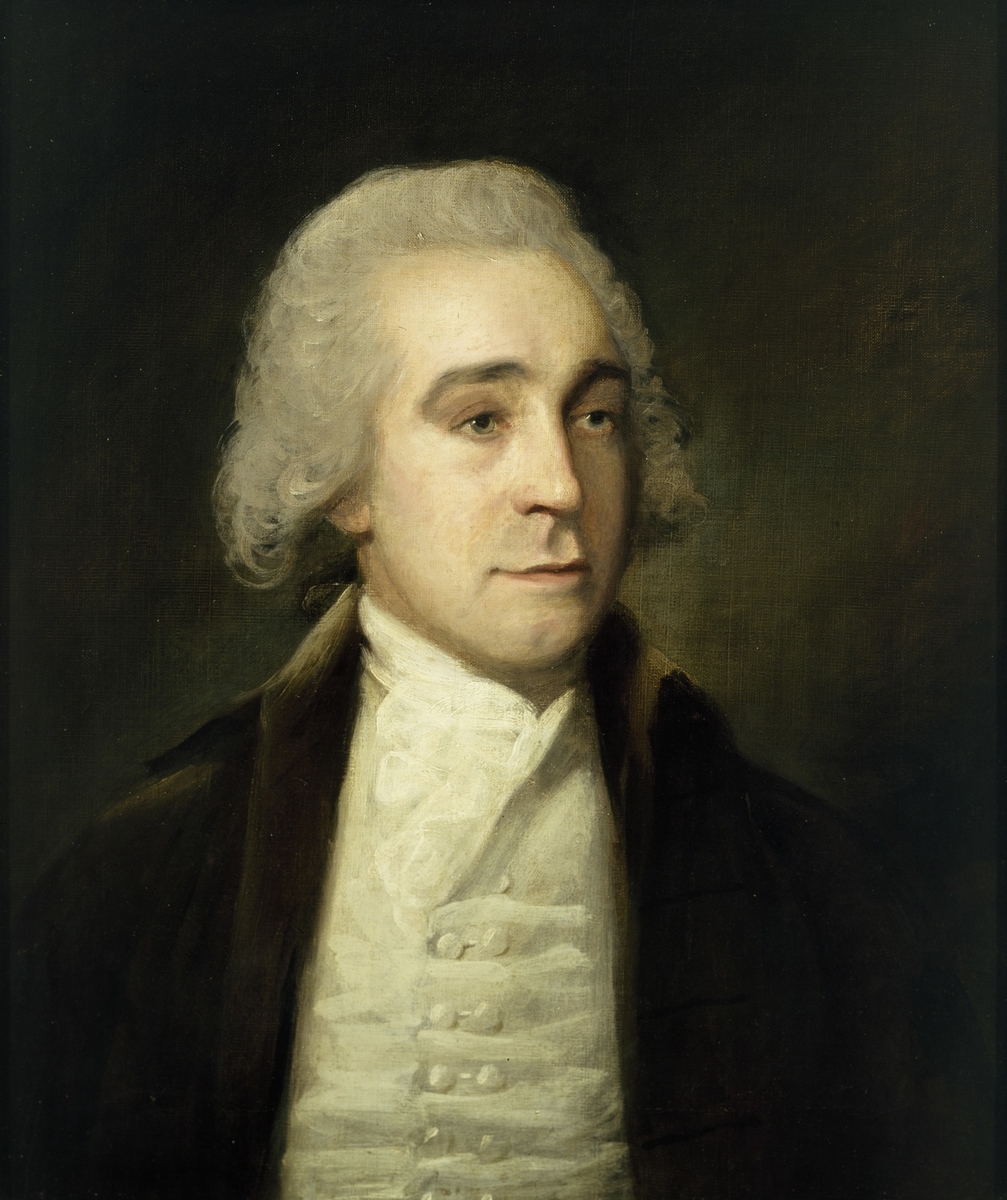

Abortive prison project and the Panopticon In 1786 and 1787, Bentham travelled to Krichev in White Russia (modern Belarus) to visit his brother, Samuel, who was engaged in managing various industrial and other projects for Prince Potemkin. It was Samuel (as Jeremy later repeatedly acknowledged) who conceived the basic idea of a circular building at the hub of a larger compound as a means of allowing a small number of managers to oversee the activities of a large and unskilled workforce.[27][28] Bentham began to develop this model, particularly as applicable to prisons, and outlined his ideas in a series of letters sent home to his father in England.[29] He supplemented the supervisory principle with the idea of contract management; that is, an administration by contract as opposed to trust, where the director would have a pecuniary interest in lowering the average rate of mortality.[30] The Panopticon was intended to be cheaper than the prisons of his time, as it required fewer staff; "Allow me to construct a prison on this model", Bentham requested to a Committee for the Reform of Criminal Law, "I will be the gaoler. You will see ... that the gaoler will have no salary—will cost nothing to the nation." As the watchmen cannot be seen, they need not be on duty at all times, effectively leaving the watching to the watched. According to Bentham's design, the prisoners would also be used as menial labour, walking on wheels to spin looms or run a water wheel. This would decrease the cost of the prison and give a possible source of income.[31] The ultimately abortive proposal for a panopticon prison to be built in England was one among his many proposals for legal and social reform.[32] But Bentham spent some sixteen years of his life developing and refining his ideas for the building and hoped that the government would adopt the plan for a National Penitentiary appointing him as contractor-governor. Although the prison was never built, the concept had an important influence on later generations of thinkers. Twentieth-century French philosopher Michel Foucault argued that the panopticon was paradigmatic of several 19th-century "disciplinary" institutions.[33] Bentham remained bitter throughout his later life about the rejection of the panopticon scheme, convinced that it had been thwarted by the King and an aristocratic elite. Philip Schofield argues that it was largely because of his sense of injustice and frustration that he developed his ideas of "sinister interest"—that is, of the vested interests of the powerful conspiring against a wider public interest—which underpinned many of his broader arguments for reform.[34] Elevation, section and plan of Bentham's panopticon prison, drawn by Willey Reveley in 1791  Bentham by an unknown artist, c. 1790. |

頓挫した監獄計画とパノプティコン 1786年と1787年、ベンサムは白ロシア(現在のベラルーシ)のクリチェフを訪れ、ポチョムキン公のためにさまざまな工業プロジェクトやその他のプロ ジェクトに携わっていた弟のサミュエルを訪ねた。少数の管理職が大規模かつ非熟練労働者の活動を監督することを可能にする手段として、大規模な敷地の中心 部に円形の建物を建てるという基本的なアイデアを思いついたのはサミュエル(ジェレミーが後に繰り返し認めている)であった[27][28]。 ベンサムはこのモデルを、特に刑務所に適用するものとして発展させ始め、イギリスの父に送った一連の手紙の中でそのアイデアを概説している[29]。 ベンサムは刑法改革委員会に「このモデルで刑務所を建設することを許可してください。私が看守になります。看守は給料をもらわず、国家に何の負担もかけな いことがおわかりでしょう」。見張り番の姿は見えないので、常時勤務する必要はなく、事実上、見張りは見張られる側に任されることになる。ベンサムの設計 によれば、囚人は下働きとしても使われ、車輪の上を歩いて織機を回したり、水車を回したりする。これによって刑務所の経費を削減し、収入源を確保すること ができる[31]。 最終的に頓挫したイギリスに建設されるパノプティコン刑務所の提案は、法律と社会改革のための彼の多くの提案のうちの一つであった[32]。 しかし、ベンサムは、彼の人生の約16年間を費やして、建物のための彼のアイデアを開発し、洗練させ、政府が彼を請負業者総督として任命する国立刑務所計 画を採用することを望んだ。刑務所が建設されることはなかったが、この構想は後世の思想家たちに重要な影響を与えた。20世紀のフランスの哲学者ミシェ ル・フーコーは、パノプティコンは19世紀のいくつかの「規律」制度の典型であると主張した[33]。ベンサムは、パノプティコン計画が国王と貴族エリー トによって阻止されたと確信し、パノプティコン計画が却下されたことについて、晩年を通じて辛辣な態度を取り続けた。フィリップ・スコフィールドは、彼が 「不吉な利益」、つまり、より広範な公共の利益に対して陰謀を企てる権力者の既得権益についての考えを発展させたのは、不公正とフラストレーションの感覚 によるところが大きかったと論じており、それが彼の改革を求める広範な主張の多くを支えていた[34]。 1791年にウィリー・レヴェリーによって描かれたベンサムのパノプティコン監獄の立面図、断面図、平面図  Bentham by an unknown artist, c. 1790. |

|

On his return to England from Russia, Bentham had commissioned drawings

from an architect, Willey Reveley.[35] In 1791, he published the

material he had written as a book, although he continued to refine his

proposals for many years to come. He had by now decided that he wanted

to see the prison built: when finished, it would be managed by himself

as contractor-governor, with the assistance of Samuel. After

unsuccessful attempts to interest the authorities in Ireland and

revolutionary France,[36] he started trying to persuade the prime

minister, William Pitt, to revive an earlier abandoned scheme for a

National Penitentiary in England, this time to be built as a

panopticon. He was eventually successful in winning over Pitt and his

advisors, and in 1794 was paid £2,000 for preliminary work on the

project.[37] The intended site was one that had been authorised (under an act of 1779[which?]) for the earlier penitentiary, at Battersea Rise; but the new proposals ran into technical legal problems and objections from the local landowner, Earl Spencer.[38] Other sites were considered, including one at Hanging Wood, near Woolwich, but all proved unsatisfactory.[39] Eventually Bentham turned to a site at Tothill Fields, near Westminster. Although this was common land, with no landowner, there were a number of parties with interests in it, including Earl Grosvenor, who owned a house on an adjacent site and objected to the idea of a prison overlooking it. Again, therefore, the scheme ground to a halt.[40] At this point, however, it became clear that a nearby site at Millbank, adjoining the Thames, was available for sale, and this time things ran more smoothly. Using government money, Bentham bought the land on behalf of the Crown for £12,000 in November 1799.[41] From his point of view, the site was far from ideal, being marshy, unhealthy, and too small. When he asked the government for more land and more money, however, the response was that he should build only a small-scale experimental prison—which he interpreted as meaning that there was little real commitment to the concept of the panopticon as a cornerstone of penal reform.[42] Negotiations continued, but in 1801 Pitt resigned from office, and in 1803 the new Addington administration decided not to proceed with the project.[43] Bentham was devastated: "They have murdered my best days."[44] Nevertheless, a few years later the government revived the idea of a National Penitentiary, and in 1811 and 1812 returned specifically to the idea of a panopticon.[45] Bentham, now aged 63, was still willing to be governor. However, as it became clear that there was still no real commitment to the proposal, he abandoned hope, and instead turned his attentions to extracting financial compensation for his years of fruitless effort. His initial claim was for the enormous sum of nearly £700,000, but he eventually settled for the more modest (but still considerable) sum of £23,000.[46] The Penitentiary House, etc. Act 1812 (52 Geo. 3. c. 44) transferred his title in the site to the Crown. More successful was his cooperation with Patrick Colquhoun in tackling the corruption in the Pool of London. This resulted in the Depredations on the Thames Act 1800 (39 & 40 Geo. 3. c. 87)[47] The Act created the Thames River Police, which was the first preventive police force in the country and was a precedent for Robert Peel's reforms 30 years later.[48]: 67–69 |

ロシアからイギリスに戻ったベンサムは、建築家ウィリー・レヴェリーに

図面を依頼した[35]。1791年、彼は自分が書いた資料を本として出版したが、その後も長年にわたり提案の改良を続けた。この時点で彼は、この刑務所

を建設したいとの決意を固めていた。完成後は、サミュエルの支援を受けて、自ら請負業者兼所長として刑務所を運営することになっていた。アイルランドや革

命中のフランスの当局にこの計画に興味を持ってもらう試みは失敗に終わったが[36]、彼は首相ウィリアム・ピットに、かつて放棄されたイギリス国立刑務

所の建設計画を、今回はパノプティコンとして復活させるよう説得し始めた。彼は最終的にピットとその顧問たちを説得し、1794年にこのプロジェクトの予

備作業費として 2,000 ポンドの報酬を得た。[37] 建設予定地は、以前の刑務所のために(1779年の法律[どの法律?]に基づき)認可されていたバタシー・ライズだったが、新しい提案は法的な問題や、地 元の土地所有者であるスペンサー伯爵からの反対に直面した[38]。ウールウィッチ近くのハンギング・ウッドなど、他の建設地も検討されたが、いずれも不 適格とされた。[39] 結局、ベンサムはウェストミンスター近くのトスヒル・フィールズにある敷地を候補地とした。この敷地は、土地所有者がいない共有地だったが、隣接する土地 に住宅を所有し、その住宅を見下ろす刑務所の建設に反対していたグロヴナー伯爵をはじめ、この敷地に関心を寄せる関係者が多数いた。そのため、この計画は 再び頓挫した。[40] しかし、この時点で、テムズ川に隣接するミルバンクにある近くの土地が売却可能であることが明らかになり、今回はより順調に進んだ。ベンサムは政府の資金 を用いて、1799年11月に12,000ポンドで王室に代わってこの土地を購入した[41]。 彼の観点からは、この場所は湿地帯で不衛生、かつ狭すぎるため、理想とはほど遠い場所だった。しかし、政府に追加の土地と資金を要求した際、返答は「小規 模な実験的刑務所を建設するべきだ」というものだった。ベントハムはこれを、パノプティコンを刑罰改革の柱とする概念に対する真のコミットメントが欠如し ている証拠と解釈した。[42] 交渉は続いたが、1801年にピットが辞任し、1803年に新政権のアディントン内閣はプロジェクトの継続を断念した。[43] ベンサムは打ちひしがれ、「彼らは私の最高の時代を殺した」と嘆いた[44]。 それにもかかわらず、数年後、政府は国立刑務所の構想を復活させ、1811 年と 1812 年にパノプティコンの構想に再び具体的に戻った[45]。当時 63 歳のベンサムは、依然として所長職を引き受ける意向があった。しかし、この提案に対する真摯な取り組みが依然として見られないことが明らかになったため、 彼は希望を捨て、その代わりに、長年にわたる無益な努力に対する金銭的補償の獲得に注力することにした。彼の当初の請求額は 70 万ポンドという巨額だったが、最終的にはより控えめな(しかしそれでもかなりの)23,000 ポンドで妥協した。[46] 1812 年の刑務所法(52 Geo. 3. c. 44)により、この敷地の所有権は王室に移管された。 より成功したのは、パトリック・コルクーンとの協力によるロンドン港の腐敗の撲滅だった。その結果、1800 年のテムズ川略奪防止法(39 & 40 Geo. 3. c. 87)が制定された[47]。この法律により、英国初の予防警察組織であるテムズ川警察が設立され、30 年後のロバート・ピールの改革の先例となった[48]: 67–69。 |

|

Correspondence and contemporary influences Bentham was in correspondence with many influential people. In the 1780s, for example, Bentham maintained a correspondence with the ageing Adam Smith, in an unsuccessful attempt to convince Smith that interest rates should be allowed to freely float.[49] As a result of his correspondence with Mirabeau and other leaders of the French Revolution, Bentham was declared an honorary citizen of France.[2] He was an outspoken critic of the revolutionary discourse of natural rights and of the violence that arose after the Jacobins took power (1792). Between 1808 and 1810, he held a personal friendship with Latin American revolutionary Francisco de Miranda and paid visits to Miranda's Grafton Way house in London. He also developed links with José Cecilio del Valle.[50][51] In 1821, John Cartwright proposed to Bentham that they serve as "Guardians of Constitutional Reform", seven "wise men" whose reports and observations would "concern the entire Democracy or Commons of the United Kingdom". Describing himself, among the names mentioned which also included Sir Francis Burdett, George Ensor, and Sir Matthew Wood, and as a "nonentity", Bentham declined the offer.[52] |

文通と同時代の影響 ベンサムは多くの有力者と文通をしていた。例えば1780年代、ベンサムは老齢のアダム・スミスと文通を続け、金利は自由に変動させるべきだとスミスを説 得しようとしたが失敗した[49]。1808年から1810年にかけては、ラテンアメリカの革命家フランシスコ・デ・ミランダと個人的な親交を結び、ロン ドンにあるミランダのグラフトン・ウェイの家を訪問した。また、ホセ・セシリオ・デル・バジェとも交流を深めた[50][51]。 1821年、ジョン・カートライトはベンサムに、彼らが「憲法改正の後見人」となり、「イギリスの民主主義全体またはコモンズに関わる」7人の「賢者」と して報告や観察を行うことを提案した。ベンサムは、サー・フランシス・バーデット、ジョージ・アンソール、サー・マシュー・ウッドらが名を連ねる中で、自 分自身を「無名」と表現し、この申し出を断った[52]。 |

|

South Australian colony proposal On 3 August 1831 the Committee of the National Colonization Society approved the printing of its proposal to establish a free colony on the south coast of Australia, funded by the sale of appropriated colonial lands, overseen by a joint-stock company, and which would be granted powers of self-government as soon as was practicable. Contrary to assumptions, Bentham had no hand in the preparation of the 'Proposal to His Majesty's Government for founding a colony on the Southern Coast of Australia, which was prepared under the auspices of Robert Gouger, Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, and Anthony Bacon. Bentham did, however, in August 1831, draft an unpublished work entitled 'Colonization Company Proposal', which constitutes his commentary upon the National Colonization Society's 'Proposal'.[53] |

南オーストラリア植民地の提案 1831年8月3日、全国植民地化協会委員会は、オーストラリア南岸に自由植民地を建設し、充当された植民地用地の売却によって資金を調達し、株式会社が 監督し、可能な限り早期に自治権を付与するという提案の印刷を承認した。ベンサムは、ロバート・グージャー、チャールズ・グレイ(第2伯爵)、アンソ ニー・ベーコンが中心となって作成された「オーストラリア南海岸に植民地を建設するための陛下政府への提案」の作成には関与していない。しかし、ベンサム は1831年8月に「植民地化会社の提案」と題する未発表の著作を起草しており、これは全国植民地化協会の「提案」に対する彼のコメントである[53]。 |

|

Westminster Review In 1823, he co-founded The Westminster Review with James Mill as a journal for the "Philosophical Radicals"—a group of younger disciples through whom Bentham exerted considerable influence in British public life.[54][55] One was John Bowring, to whom Bentham became devoted, describing their relationship as "son and father": he appointed Bowring political editor of The Westminster Review and eventually his literary executor.[56] Another was Edwin Chadwick, who wrote on hygiene, sanitation, and policing and was a major contributor to the Poor Law Amendment Act: Bentham employed Chadwick as a secretary and bequeathed him a large legacy.[48]: 94 |

ウェストミンスター評論 1823年、彼はジェームズ・ミルとともに、ベンサムが英国の公共の生活に多大な影響力を持った若い弟子たちによる「哲学的急進派」の雑誌『ウェストミン スター・レビュー』を創刊した[54][55]。その一人、ジョン・ボウリングはベンサムが「息子と父親」と表現するほど親しく、ベンサムは彼を『ウェス トミンスター・レビュー』の政治編集者に任命し、最終的には自分の文学的遺言執行者に指名した。[56] もう1人は、衛生、公衆衛生、警察について執筆し、貧困法改正法案に大きく貢献したエドウィン・チャドウィックだった。ベンサムはチャドウィックを秘書と して採用し、多額の遺産を遺した。[48]: 94 |

| Personal life Bentham had several infatuations with women, and wrote on sex.[57] He never married.[58] |

私生活 ベンサムは何度か女性に夢中になり、セックスについて執筆した[57]。 |

|

An insight into his character is given in Michael St. John Packe's The

Life of John Stuart Mill: During his youthful visits to Bowood House, the country seat of his patron Lord Lansdowne, he had passed his time at falling unsuccessfully in love with all the ladies of the house, whom he courted with a clumsy jocularity, while playing chess with them or giving them lessons on the harpsichord. Hopeful to the last, at the age of eighty he wrote again to one of them, recalling to her memory the far-off days when she had "presented him, in ceremony, with the flower in the green lane" [citing Bentham's memoirs]. To the end of his life he could not hear of Bowood without tears swimming in his eyes, and he was forced to exclaim, "Take me forward, I entreat you, to the future—do not let me go back to the past."[59] A psychobiographical study by Philip Lucas and Anne Sheeran argues that he may have had Asperger's syndrome.[60] Bentham's daily pattern was to rise at 6 am, walk for 2 hours or more, and then work until 4 pm.[61] |

彼の性格についての洞察は、マイケル・セント・ジョン・パックの『ジョン・スチュアート・ミルの生涯』で与えられている: 若かりし頃、パトロンであったランズダウン卿の別荘であるボウード・ハウスを訪れていたとき、彼はその屋敷の女性たち全員とうまくいかずに恋に落ち、彼ら とチェスをしたり、チェンバロのレッスンをしたりしながら、不器用な冗談まじりに求愛し、時間を過ごしていた。80歳になったとき、彼はそのうちの一人に 再び手紙を書き、彼女が「緑の小径に咲く花を、儀式として彼に贈った」[ベンサムの回想録を引用]遠い日のことを思い出していた。彼は生涯の終わりまで、 目に涙を浮かべずにボウッドの話を聞くことはできず、「私を未来に連れて行ってください。 フィリップ・ルーカスとアン・シーランによる心理伝記的研究は、彼がアスペルガー症候群であった可能性を主張している[60]。 ベンサムの1日のパターンは、午前6時に起床し、2時間以上歩き、午後4時まで働くというものであった[61]。 |

|

Legacy The Faculty of Laws at University College London occupies Bentham House, next to the main UCL campus.[62] Bentham's name was adopted by the Australian litigation funder IMF Limited to become Bentham IMF Limited on 28 November 2013, in recognition of Bentham being "among the first to support the utility of litigation funding".[63] |

遺産 ユニバーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンの法学部は、UCLのメインキャンパスに隣接するベンサム・ハウスを使用している[62]。 ベンサムの名前は、2013年11月28日、オーストラリアの訴訟資金提供会社IMFリミテッドに採用され、ベンサムが「訴訟資金提供の有用性を最初に支 援した」ことを認められ、ベンサムIMFリミテッドとなった[63]。 |

★ベンサムの業績

★ベンサムの業績(続き)

|

Imperialism Bentham's writings in the early 1790s onwards expressed an opposition to imperialism. His 1793 pamphlet Emancipate Your Colonies! critiqued French colonialism. In the early 1820s, he argued that the liberal government in Spain should emancipate its New World colonies. In the essay Plan for an Universal and Perpetual Peace, Bentham argued that Britain should emancipate its New World colonies and abandon its colonial ambitions. He argued that empire was bad for the greatest number in the metropole and the colonies. According to Bentham, empire was financially unsound, entailed taxation on the poor in the metropole, caused unnecessary expansion in the military apparatus, undermined the security of the metropole, and were ultimately motivated by misguided ideas of honour and glory.[91] |

帝国主義 1790年代初頭以降のベンサムの著作は、帝国主義への反対を表明していた。1793年の小冊子『植民地を解放せよ!』はフランスの植民地主義を批判し た。1820年代初頭には、スペインの自由主義政府は新世界の植民地を解放すべきだと主張した。ベンサムは、エッセイ『普遍的かつ恒久的な平和のための計 画』の中で、イギリスは新世界の植民地を解放し、植民地としての野心を捨てるべきだと主張した。彼は、帝国はメトロポールと植民地の最大多数のために悪い と主張した。ベンサムによれば、帝国は財政的に不健全であり、首都圏の貧困層への課税を伴い、軍事組織の不必要な拡張を引き起こし、首都圏の安全を損な い、最終的には名誉と栄光という誤った考えに突き動かされていた[91]。 |

|

Privacy For Bentham, transparency had moral value. For example, journalism puts power-holders under moral scrutiny. However, Bentham wanted such transparency to apply to everyone. This he describes by picturing the world as a gymnasium in which each "gesture, every turn of limb or feature, in those whose motions have a visible impact on the general happiness, will be noticed and marked down".[92] He considered both surveillance and transparency to be useful ways of generating understanding and improvements for people's lives.[93] |

プライバシー ベンサムにとって、透明性には道徳的価値があった。例えば、ジャーナリズムは権力者を道徳的な監視下に置く。しかし、ベンサムはそのような透明性がすべて の人に適用されることを望んでいた。ベンサムは、監視と透明性の両方が、人々の生活に対する理解と改善を生み出す有用な方法であると考えていた[93]。 |

| Fictional entities Bentham distinguished among fictional entities what he called "fabulous entities" like Prince Hamlet or a centaur, from what he termed "fictitious entities", or necessary objects of discourse, similar to Kant's categories,[94] such as nature, custom, or the social contract.[95] |

架空の存在 ベンサムは、ハムレット王子やケンタウロスのような「素晴らしい実体」と呼ばれる架空の実体を、自然、慣習、社会契約といったカントのカテゴリー[94] に類似した「架空の実体」、すなわち言説の必要な対象と呼んで区別していた[95]。 |

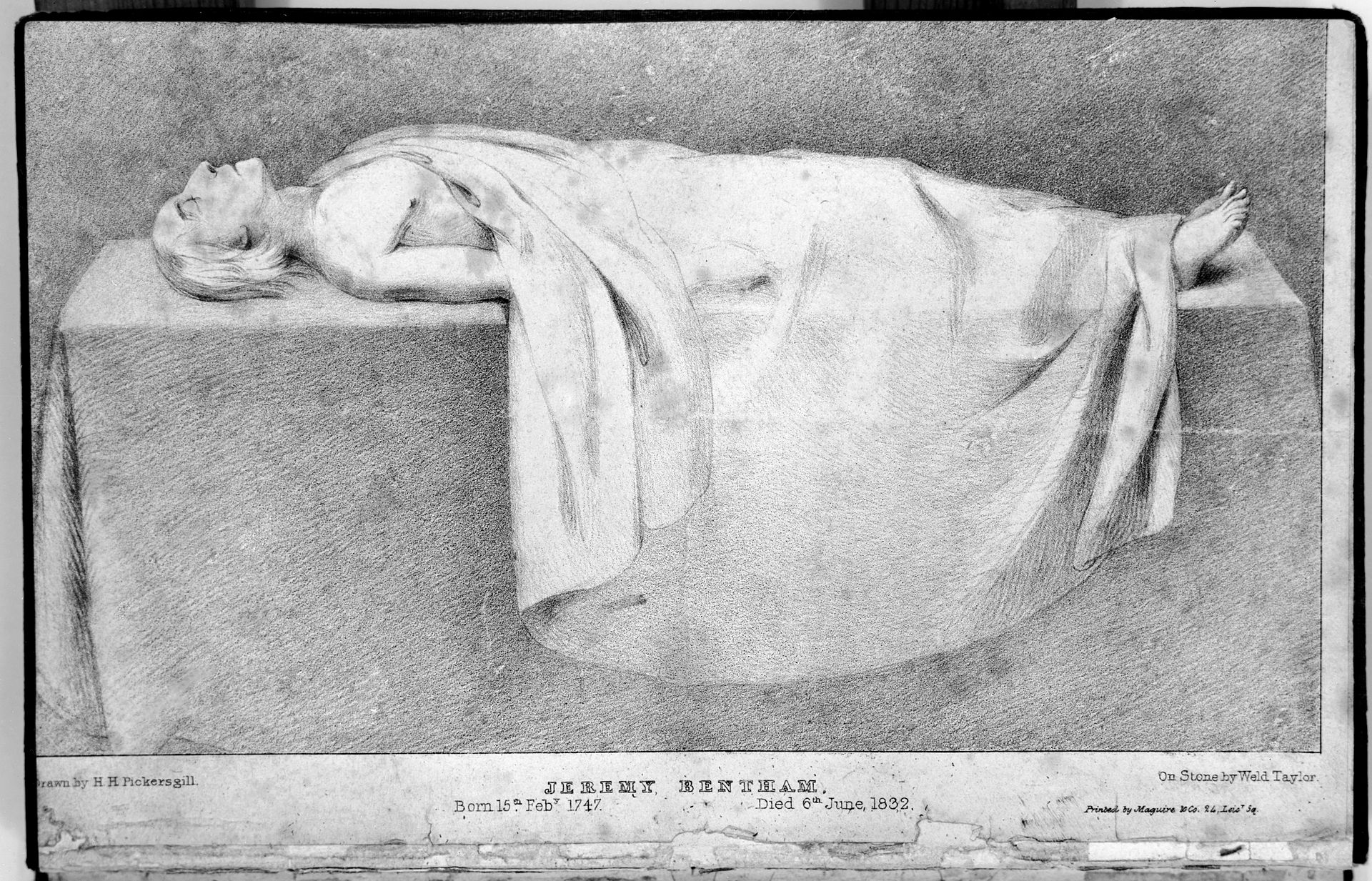

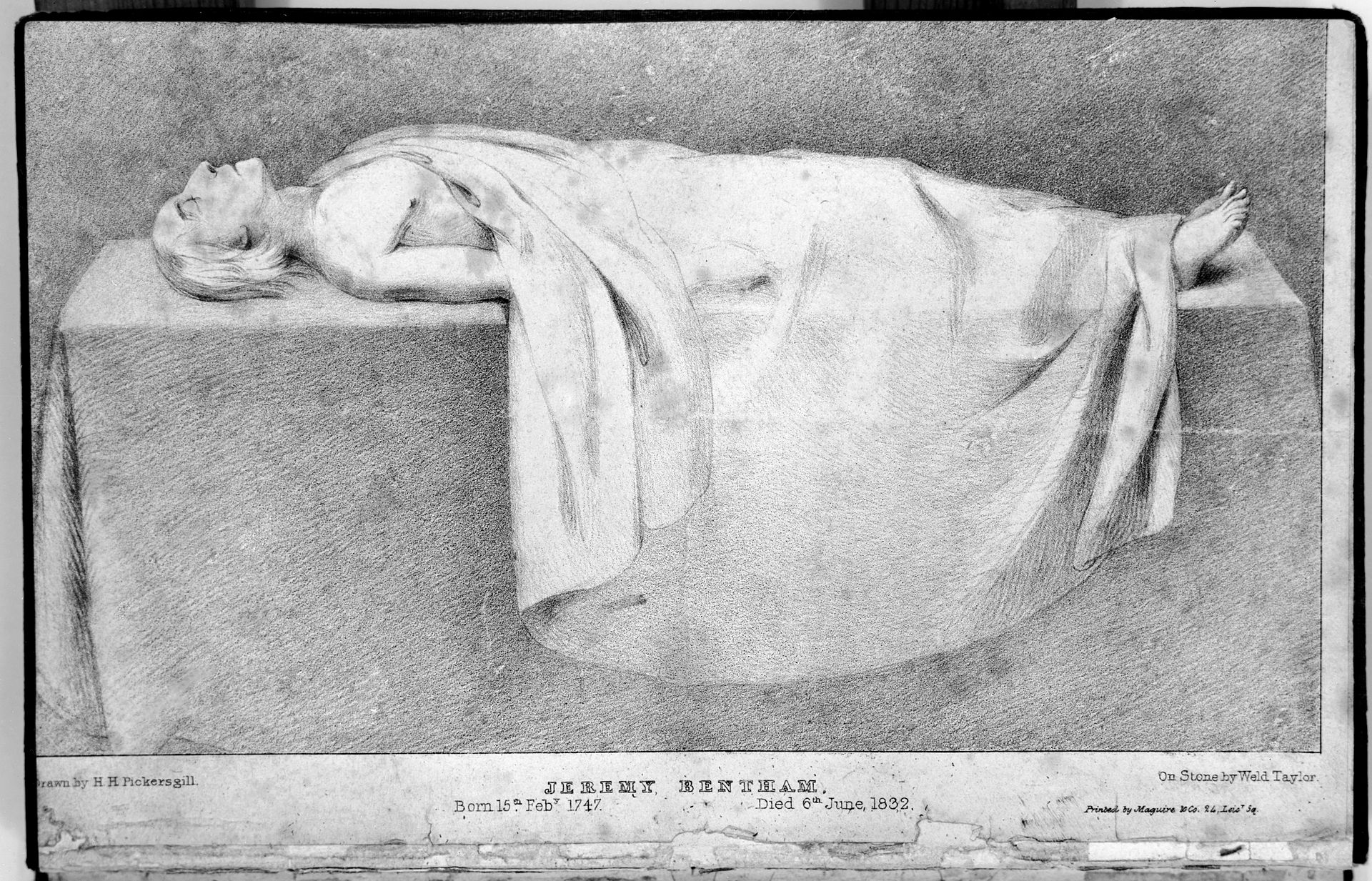

Death and the auto-icon Bentham's public dissection Bentham's auto-icon in a new display case at University College London's Student Centre in 2020 Bentham died on 6 June 1832, aged 84, at his residence in Queen Square Place in Westminster, London. He had continued to write up to a month before his death, and had made careful preparations for the dissection of his body after death and its preservation as an auto-icon. As early as 1769, when Bentham was 21 years old, he made a will leaving his body for dissection to a family friend, the physician and chemist George Fordyce, whose daughter, Maria Sophia (1765–1858), married Jeremy's brother Samuel Bentham.[2] A paper written in 1830, instructing Thomas Southwood Smith to create the auto-icon, was attached to his last will, dated 30 May 1832.[2] It stated: My body I give to my dear friend Dr Southwood Smith to be disposed of in a manner hereinafter mentioned, and I direct ... he will take my body under his charge and take the requisite and appropriate measures for the disposal and preservation of the several parts of my bodily frame in the manner in the paper annexed to this my will and at the top of which I have written Auto Icon. The skeleton he will cause to be put together in such a manner that the whole figure may be seated in a chair usually occupied by me when living, in the attitude in which I am sitting while engaged in thought in the course of time occupied in writing. I direct that the body thus prepared shall be transferred to my executor. He will cause the skeleton to be clad in one of the suits of black occasionally worn by me. The body so clothed, together with the chair and the staff in my later years borne by me, he will take charge of, and for containing the whole apparatus he will cause to be prepared an appropriate box or case, and will cause to be engraved in conspicuous characters on a plate to be affixed thereon and also on the labels on the glass case in which the preparations of the soft parts of my body shall be contained, ... my name at length with the letters ob: followed by the day of my decease. If it should so happen that my personal friends and other disciples should be disposed to meet together on some day or days of the year for the purpose of commemorating the founder of the greatest happiness system of morals and legislation, my executor will from time to time cause to be conveyed in the room in which they meet the said box or case with the contents therein, to be stationed in such part of the room as to the assembled company shall seem meet. — Queen's Square Place, Westminster, Wednesday 30 May 1832.[96] Bentham's wish to preserve his dead body was consistent with his philosophy of utilitarianism. In his essay Auto-Icon, or the Uses of the Dead to the Living, Bentham wrote, "If a country gentleman has rows of trees leading to his dwelling, the auto-icons of his family might alternate with the trees; copal varnish would protect the face from the effects of rain."[97] On 8 June 1832, two days after his death, invitations were distributed to a select group of friends, and on the following day at 3 p.m., Southwood Smith delivered a lengthy oration over Bentham's remains in the Webb Street School of Anatomy & Medicine in Southwark, London. The printed oration contains a frontispiece with an engraving of Bentham's body partly covered by a sheet.[2] Afterward, the skeleton and head were preserved and stored in a wooden cabinet called the "auto-icon", with the skeleton padded out with hay and dressed in Bentham's clothes. From 1833, it stood in Southwood Smith's Finsbury Square consulting rooms until he abandoned private practice in the winter of 1849–50, when it was moved to 36 Percy Street, the studio of his unofficial partner, painter Margaret Gillies, who made studies of it. In March 1850, Southwood Smith offered the auto-icon to Henry Brougham, who readily accepted it for UCL.[98] It is currently kept on public display at the main entrance of the UCL Student Centre. It was previously displayed at the end of the South Cloisters in the main building of the college until it was moved in 2020. Upon the retirement of Sir Malcolm Grant as provost of the college in 2013, however, the body was present at Grant's final council meeting. As of 2013, this was the only time that the body of Bentham has been taken to a UCL council meeting.[99][100] (There is a persistent myth that the body of Bentham is present at all council meetings.)[99][101] Bentham had intended the auto-icon to incorporate his actual head, mummified to resemble its appearance in life. Southwood Smith's experimental efforts at mummification, based on practices of the indigenous peoples of New Zealand and involving placing the head under an air pump over sulfuric acid and drawing off the fluids, although technically successful, left the head looking distastefully macabre, with dried and darkened skin stretched tautly over the skull.[2]  Jeremy Bentham's severed head, on temporary display at UCL The auto-icon was therefore given a wax head, fitted with some of Bentham's own hair. The real head was displayed in the same case as the auto-icon for many years, but became the target of repeated student pranks. It was later locked away.[101] In 2020, the auto-icon was put into a new glass display case and moved to the entrance of UCL's new Student Centre on Gordon Square.[102] |

死とオートアイコン ベンサムの公開解剖 2020年、ユニバーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンのスチューデント・センターの新しい展示ケースに収められたベンサムのオートアイコン ベンサムは1832年6月6日、ロンドンのウェストミンスターにあるクイーン・スクエア・プレイスの自邸で84歳で死去した。彼は死の1ヶ月前まで執筆を 続け、死後の遺体の解剖とオートアイコンとしての保存のために入念な準備をしていた。ベンサムが21歳だった1769年には、解剖のために自分の遺体を家 族の友人である医師で化学者のジョージ・フォーダイスに託すという遺言書を作成しており、その娘マリア・ソフィア(1765-1858)はジェレミーの弟 サミュエル・ベンサムと結婚した[2]。1832年5月30日付の遺言書には、トーマス・サウスウッド・スミスにオートアイコンの作成を指示する1830 年に書かれた紙が添付されていた[2]: 私の遺体を親愛なる友人であるサウスウッド・スミス博士に与え、後述の方法で処分する。 その骨格は、私が生きているときに普段使っていた椅子に、私が執筆中に思索にふけっているときに座っているような姿勢で座ることができるように、全体が組 み合わされるようにする。 私は、このように準備された遺体を私の遺言執行者に引き渡すよう指示する。彼は骨格に、私が時折着用していた黒のスーツを着せるだろう。そうして着せられ た遺体は、私が晩年に負担していた椅子と杖とともに、彼が管理し、装置全体を収納するために、適切な箱かケースを用意させ、そこに貼付するプレートと、私 の遺体の柔らかい部分の調製品が収納されるガラスケースのラベルに、目立つ文字で、......私の名前を長めにob:の文字で、続いて私の死亡日を刻印 させる。 万一、私の個人的な友人やその他の弟子たちが、道徳と立法に関する最も偉大な幸福体系の創始者を記念する目的で、1年のうち何日かに集うことになった場 合、私の遺言執行者は、彼らが集う部屋に、その箱またはケースとその中身を随時運搬させ、集まった一団にとってふさわしいと思われる部屋の一部に配置させ る。- 1832年5月30日水曜日、ウェストミンスター、クイーンズ・スクエア・プレイス[96]。 ベンサムの死体保存の願いは、彼の功利主義の哲学と一致していた。彼のエッセイ『オートアイコン、あるいは生者にとっての死者の用途』の中で、ベンサムは 「田舎の紳士が自分の住居に続く並木道を持っているならば、彼の家族のオートアイコンを並木道と交互に並べるかもしれない、 サウスウッド・スミスは、ロンドンのサザークにあるウェッブ・ストリート解剖医学学校で、ベンサムの遺影を囲んで長い演説を行った。印刷された説教には、 ベンサムの遺体の一部がシーツで覆われたエングレーヴィングが扉絵として使われている[2]。 その後、骸骨と頭部は「オートアイコン」と呼ばれる木製のキャビネットに保存・保管され、骸骨は干し草で水増しされ、ベンサムの服を着せられた。1833 年から1849-50年の冬に彼が個人診療をやめるまで、それはサウスウッド・スミスのフィンズベリー・スクエアの診察室に置かれ、彼の非公式なパート ナーであった画家マーガレット・ギリーズのアトリエ、パーシー・ストリート36番地に移された。1850年3月、サウスウッド・スミスはオートアイコンを ヘンリー・ブローアムに提供し、彼はUCLのためにそれを快諾した[98]。 現在、UCL学生センターの正面玄関に展示されている。以前は、2020年に移設されるまで、大学本館の南回廊の端に展示されていた。しかし、2013年 にマルコム・グラント卿が同カレッジの学長を退任すると、この遺体はグラント卿の最後の評議会に出席した。2013年の時点で、ベンサムの遺体がUCLの 評議会に持ち込まれたのはこのときだけである[99][100](ベンサムの本体はすべての評議会に出席しているという根強い俗説がある)[99] [101]。 ベンサムは、生前の姿に似せてミイラ化させた実際の頭部をオートアイコンに組み込むことを意図していた。サウスウッド・スミスは、ニュージーランドの先住 民の慣習に基づき、硫酸の上にエアポンプで頭部を置いて体液を抜き取るという実験的なミイラ化の試みを行ったが、技術的には成功したものの、乾燥して黒ず んだ皮膚が頭蓋骨の上にぴんと張ったような、不快なほど不気味な外観の頭部を残した[2]。  UCLで一時的に展示されているジェレミー・ベンサムの切断された頭部 そのため、オートアイコンには、ベンサム自身の毛髪を取り付けた蝋製の頭部が与えられた。本物の頭部は長年オートアイコンと同じケースに展示されていた が、学生たちの度重なるいたずらのターゲットとなった。後に鍵がかけられた[101]。 2020年、オートアイコンは新しいガラスの展示ケースに入れられ、ゴードン・スクエアにあるUCLの新しい学生センターの入り口に移された[102]。 |

University College London Henry Tonks' imaginary scene of Bentham approving the building plans of London University Bentham is widely associated with the foundation in 1826 of London University (the institution that, in 1836, became University College London), though he was 78 years old when the university opened and played only an indirect role in its establishment. His direct involvement was limited to his buying a single £100 share in the new university, making him just one of over a thousand shareholders.[103] Bentham and his ideas can nonetheless be seen as having inspired several of the actual founders of the university. He strongly believed that education should be more widely available, particularly to those who were not wealthy or who did not belong to the established church; in Bentham's time, membership of the Church of England and the capacity to bear considerable expenses were required of students entering the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. As the University of London was the first in England to admit all, regardless of race, creed or political belief, it was largely consistent with Bentham's vision. There is some evidence that, from the sidelines, he played a "more than passive part" in the planning discussions for the new institution, although it is also apparent that "his interest was greater than his influence".[103] He failed in his efforts to see his disciple John Bowring appointed professor of English or History, but he did oversee the appointment of another pupil, John Austin, as the first professor of Jurisprudence in 1829. The more direct associations between Bentham and UCL—the college's custody of his Auto-icon (see above) and of the majority of his surviving papers—postdate his death by some years: the papers were donated in 1849, and the Auto-icon in 1850. A large painting by Henry Tonks hanging in UCL's Flaxman Gallery depicts Bentham approving the plans of the new university, but it was executed in 1922 and the scene is entirely imaginary. Since 1959 (when the Bentham Committee was first established), UCL has hosted the Bentham Project, which is progressively publishing a definitive edition of Bentham's writings. UCL now endeavours to acknowledge Bentham's influence on its foundation, while avoiding any suggestion of direct involvement, by describing him as its "spiritual founder".[18] |

ユニバーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドン ベンサムがロンドン大学の建設計画を承認する様子を描いたヘンリー・トンクスの想像図 ベンサムは、1826年のロンドン大学(1836年にユニバーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンとなった機関)の創立に広く関係しているが、大学が開校した時、 彼は78歳であり、その設立には間接的な役割しか果たしていない。彼が直接関与したのは、新大学の株を100ポンドで購入したことに限られ、1000人を 超える株主の一人に過ぎなかった[103]。 それでもなお、ベンサムとその思想は、大学の実際の創設者の何人かにインスピレーションを与えたと見ることができる。ベンサムは、特に裕福でない人々や既 成の教会に属していない人々に対して、教育をより広く提供すべきであると強く信じていた。ベンサムの時代には、オックスフォード大学やケンブリッジ大学に 入学する学生には、英国国教会の会員であることと、多額の費用を負担する能力が求められていた。ロンドン大学は、人種、信条、政治的信条に関係なく、すべ ての人を入学させたイングランド初の大学であり、ベンサムの構想にほぼ一致するものであった。ベンサムは、傍観者的な立場から、新しい教育機関の計画に関 する議論に「受動的な役割以上のもの」を果たしたという証拠もあるが、「彼の関心は彼の影響力よりも大きかった」ことも明らかである[103]。彼は、弟 子のジョン・ボウリングが英語または歴史学の教授に任命されるのを見届ける努力には失敗したが、1829年にもう一人の弟子であるジョン・オースティンが 法律学の初代教授に任命されるのを監督した。 ベンサムとUCLのより直接的な関係は、彼のオートアイコン(上記参照)と現存する論文の大部分をカレッジが保管していることで、彼の死後何年か経ってい る。UCLのフラックスマン・ギャラリーに飾られているヘンリー・トンクスの大きな絵は、ベンサムが新大学の計画を承認している様子を描いているが、 1922年に描かれたもので、この場面はまったくの想像である。ベンサム委員会が設立された1959年以来、UCLはベンサム・プロジェクトを主催し、ベ ンサムの著作の決定版を順次出版している。 UCLは現在、ベンサムを「精神的創始者」と表現することで、直接的な関与の示唆を避けつつも、その創立に与えたベンサムの影響を認めようとしている [18]。 |

Bibliography The back of No. 19, York Street (1848). In 1651 John Milton moved into a "pretty garden-house" in Petty France. He lived there until the Restoration. Later it became No. 19 York Street, belonged to Jeremy Bentham (who for a time lived next door), was occupied successively by James Mill and William Hazlitt, and finally demolished in 1877.[104][105]  Jeremy Bentham House in Bethnal Green, East London; a modernist apartment block named after the philosopher Bentham was an obsessive writer and reviser, but was only able on rare occasions of bringing his work to completion and publication.[60] Most of what appeared in print in his lifetime[106] was prepared for publication by others. Several of his works first appeared in French translation, prepared for the press by Étienne Dumont, for example, Theory of Legislation, Volume 2 (Principles of the Penal Code) 1840, Weeks, Jordan, & Company. Boston. Some made their first appearance in English in the 1820s as a result of back-translation from Dumont's 1802 collection (and redaction) of Bentham's writing on civil and penal legislation. Publications 1776. A fragment on government. This was an unsparing criticism of some introductory passages relating to political theory in William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England. The book, published anonymously, was well received and credited to some of the greatest minds of the time. Bentham disagreed with Blackstone's defence of judge-made law, his defence of legal fictions, his theological formulation of the doctrine of mixed government, his appeal to a social contract and his use of the vocabulary of natural law. Bentham's "Fragment" was only a small part of a Commentary on the Commentaries, which remained unpublished until the twentieth century. 1776. Short Review of the Declaration – via Wikisource. An attack on the United States Declaration of Independence. 1780. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. London: T. Payne and Sons.[107] 1785 (publ. 1978). "Offences Against One's Self", edited by L. Crompton. Journal of Homosexuality 3(4)389–405. Continued in vol. 4(1). doi:10.1300/J082v03n04_07. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 353189.[108] 1787. Panopticon or the Inspection-House – via Wikisource. 1787. Defence of Usury.[109] A series of thirteen "Letters" addressed to Adam Smith. 1791. "Essay on Political Tactics" (1st ed.). London: T. Payne.[110] 1796. Anarchical Fallacies; Being an examination of the Declaration of Rights issued during the French Revolution.[111] An attack on the Declaration of the Rights of Man decreed by the French Revolution, and critique of the natural rights philosophy underlying it.[112] 1802. Traités de législation civile et pénale, 3 vols, edited by Étienne Dumont. 1811. Punishments and Rewards. 1812. Panopticon versus New South Wales: or, the Panopticon Penitentiary System, Compared. Includes: Two Letters to Lord Pelham, Secretary of State, Comparing the two Systems on the Ground of Expediency. "Plea for the Constitution: Representing the Illegalities involved in the Penal Colonization System (1803, first publ. 1812) 1816. Defence of Usury; shewing the impolicy of the present legal restraints on the terms of pecuniary bargains in a letters to a friend to which is added a letter to Adam Smith, Esq. LL.D. on the discouragement opposed by the above restraints to the progress of inventive industry (3rd ed.). London: Payne & Foss. Bentham wrote a series of thirteen "Letters" addressed to Adam Smith, published in 1787 as Defence of Usury. Bentham's main argument against the restriction is that "projectors" generate positive externalities. G. K. Chesterton identified Bentham's essay on usury as the very beginning of the "modern world". Bentham's arguments were very influential. "Writers of eminence" moved to abolish the restriction, and repeal was achieved in stages and fully achieved in England in 1854. There is little evidence as to Smith's reaction. He did not revise the offending passages in The Wealth of Nations (1776), but Smith made little or no substantial revisions after the third edition of 1784. 1817. A Table of the Springs of Action. London: sold by R. Hunter. 1817. "Swear Not At All" 1817. Plan of Parliamentary Reform, in the form of Catechism with Reasons for Each Article, with An Introduction shewing the Necessity and the Inadequacy of Moderate Reform. London: R. Hunter. 1818. Church-of-Englandism and its Catechism Examined. London: Effingham Wilson.[113] 1821. The Elements of the Art of Packing, as applied to special juries particularly in cases of libel law. London: Effingham Wilson. 1821. On the Liberty of the Press, and Public Discussion. London: Hone. 1822. The Influence of Natural Religion upon the Temporal Happiness of Mankind, written with George Grote Published under the pseudonym Philip Beauchamp. 1823. Not Paul But Jesus Published under the pseudonym Gamaliel Smith. 1824. The Book of Fallacies from Unfinished Papers of Jeremy Bentham (1st ed.). London: John and H. L. Hunt. 1825. A Treatise on Judicial Evidence Extracted from the Manuscripts of Jeremy Bentham, Esq (1st ed.), edited by M. Dumont. London: Baldwin, Cradock, & Joy. 1827. Rationale of Judicial Evidence, specially applied to English Practice, Extracted from the Manuscripts of Jeremy Bentham, Esq. I (1st ed.). London: Hunt & Clarke. 1830. Emancipate Your Colonies! Addressed to the National Convention of France A° 1793, shewing the uselessness and mischievousness of distant dependencies to a European state . London: Robert Heward – via Wikisource. 1834. Deontology or, The science of morality 1, edited by J. Bowring. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green and Longman. Posthumous publications On his death, Bentham left manuscripts amounting to an estimated 30 million words, which are now largely held by University College London's Special Collections (c. 60,000 manuscript folios) and the British Library (c. 15,000 folios). Bowring (1838–1843) John Bowring, the young radical writer who had been Bentham's intimate friend and disciple, was appointed his literary executor and charged with the task of preparing a collected edition of his works. This appeared in 11 volumes in 1838–1843. Bowring based much of his edition on previously published texts (including those of Dumont) rather than Bentham's own manuscripts, and elected not to publish Bentham's works on religion at all. The edition was described by the Edinburgh Review on first publication as "incomplete, incorrect and ill-arranged", and has since been repeatedly criticised both for its omissions and for errors of detail; while Bowring's memoir of Bentham's life included in volumes 10 and 11 was described by Sir Leslie Stephen as "one of the worst biographies in the language".[114] Nevertheless, Bowring's remained the standard edition of most of Bentham's writings for over a century, and is still only partially superseded: it includes such interesting writings on international[a] relations as Bentham's A Plan for an Universal and Perpetual Peace written 1786–89, which forms part IV of the Principles of International Law. Stark (1952–1954) In 1952–1954, Werner Stark published a three-volume set, Jeremy Bentham's Economic Writings, in which he attempted to bring together all of Bentham's writings on economic matters, including both published and unpublished material. Although a significant achievement, the work is considered by scholars to be flawed in many points of detail,[115] and a new edition of the economic writings (retitled Writings on Political Economy) is currently in course of publication by the Bentham Project. Bentham Project (1968–present) Further information: The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham and Transcribe Bentham In 1959, the Bentham Committee was established under the auspices of University College London with the aim of producing a definitive edition of Bentham's writings. It set up the Bentham Project[116] to undertake the task, and the first volume in The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham was published in 1968. The Collected Works are providing many unpublished works, as well as much-improved texts of works already published. To date, 38 volumes have appeared; the complete edition is projected to total 80.[117] The volume Of Laws in General (1970) was found to contain many errors and has been replaced by Of the Limits of the Penal Branch of Jurisprudence (2010)[118] In 2017, Volumes 1–5 were re-published in open access by UCL Press.[citation needed] To assist in this task, the Bentham papers at UCL are being digitised by crowdsourcing their transcription. Transcribe Bentham is a crowdsourced manuscript transcription project, run by University College London's Bentham Project,[119] in partnership with UCL's UCL Centre for Digital Humanities, UCL Library Services, UCL Learning and Media Services, the University of London Computer Centre, and the online community. The project was launched in September 2010 and is making freely available, via a specially designed transcription interface, digital images of UCL's vast Bentham Papers collection—which runs to some 60,000 manuscript folios—to engage the public and recruit volunteers to help transcribe the material. Volunteer-produced transcripts will contribute to the Bentham Project's production of the new edition of The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham, and will be uploaded to UCL's digital Bentham Papers repository,[120] widening access to the collection for all and ensuring its long-term preservation. Manuscripts can be viewed and transcribed by signing-up for a transcriber account at the Transcription Desk,[121] via the Transcribe Bentham website.[122] Free, flexible textual search of the full collection of Bentham Papers is now possible through an experimental handwritten text image indexing and search system,[123] developed by the PRHLT research center in the framework of the READ project. |

書誌 ヨーク・ストリート19番裏(1848年)。1651年、ジョン・ミルトンはペティ・フランスの「かわいい庭の家」に引っ越した。彼は大政奉還までそこに 住んだ。その後、ヨーク・ストリート19番となり、ジェレミー・ベンサム(一時期隣に住んでいた)の所有となり、ジェームズ・ミルとウィリアム・ヘイズ リットが相次いで住み、最終的に1877年に取り壊された[103][104]。  イースト・ロンドン、ベスナル・グリーンのジェレミー・ベンサム・ハウス。哲学者の名を冠したモダニズムの集合住宅。 ベンサムは執拗なまでの著述家であり、校訂者であったが、自分の著作を完成させ、出版することができたのはごく稀であった[59]。彼の著作のいくつか は、エティエンヌ・デュモンが出版社向けに準備したフランス語訳が初出であった。例えば、『法制論』第2巻(刑法典の原理)1840年、Weeks, Jordan, & Company. ボストン。1820年代には、デュモンが1802年にベンサムの民法および刑法に関する著作を収集(および再編集)したものを逆翻訳した結果、初めて英語 で出版されたものもある。 出版物 1776. 政府に関する断片。 これは、ウィリアム・ブラックストーンの『イングランド法の解説』にある政治理論に関する序章の一部を辛辣に批判したものである。匿名で出版された本書は 好評を博し、当時の最も偉大な頭脳の何人かに信用された。ベンサムは、ブラックストーンの裁判官による法の擁護、法的虚構の擁護、混合政府の教義の神学的 定式化、社会契約への訴え、自然法の語彙の使用に反対した。ベンサムの「断片」は、20世紀まで未発表のままであった『注解』のごく一部に過ぎなかった。 1776. 宣言の短評 - ウィキソース経由。 アメリカ合衆国独立宣言に対する攻撃。 1780. 道徳と立法の原理入門』。ロンドン: T. Payne and Sons. 1785年(1978年出版)。L.クロンプトン編『自己に対する罪』。Journal of Homosexuality 3(4)389-405. vol.4(1)に続く。doi:10.1300/J082v03n04_07。issn 0091-8369. pmid 353189. 1787. パノプティコンまたは監察所 - Wikisource経由。 1787. 高利貸しの擁護[108]。 アダム・スミス宛の13通の「書簡」シリーズ。 1791. 「政治戦術論』(第1版). ロンドン: T・ペイン[109]。 1796. 無政府主義の誤謬;フランス革命中に発表された権利宣言の検討である[110]。 フランス革命によって布告された人間の権利宣言に対する攻撃と、その根底にある自然権哲学に対する批判[111]。 1802. エティエンヌ・デュモン編『市民法・刑事法研究』全3巻。 1811. 刑罰と報償 1812. パノプティコン対ニューサウスウェールズ:あるいはパノプティコン刑罰制度の比較。以下を含む: 国務長官ペラム卿に宛てた2通の書簡。 「憲法への嘆願: 刑殖制度に関わる違法性を代表するもの(1803年、初版は1812年) 1816. 友人への手紙に、アダム・スミス(Adam Smith, Esq. LL.D.に宛てた手紙(第3版)も加えている。ロンドン: Payne & Foss. ベンサムはアダム・スミス宛に13通の「書簡」を書き、1787年に『利潤の擁護』として出版した。規制に対するベンサムの主な反論は、「事業者」が正の 外部性を生み出すというものである。G.K.チェスタートンは、ベンサムの高利貸しに関するエッセイを、まさに「近代世界」の始まりと位置づけた。ベンサ ムの議論は大きな影響力を持った。「高名な作家たち」は規制撤廃に動き、撤廃は段階的に達成され、1854年にイングランドで完全に達成された。スミスの 反応についてはほとんど証拠がない。彼は『国富論』(1776年)の問題となった箇所を改訂しなかったが、1784年の第3版以降、スミスはほとんど、あ るいはまったく実質的な改訂を行っていない。 1817. 作用泉表』。ロンドン:R.ハンター販売。 1817. "誓わないこと" 1817. 議会改革案、各条に理由を付したカテキズムの形式で、中庸な改革の必要性と不十分さを示す序文を付す。ロンドン R.ハンター 1818. 英国国教会とそのカテキズムを検証する。London: エフィンガム・ウィルソン[112]。 1821. 荷造り術の要素、特に名誉毀損法における特別陪審に適用されるもの。London: エフィンガム・ウィルソン 1821. 報道の自由と公論について. ロンドン:ホーン 1822. 自然宗教が人類の一時的幸福に及ぼす影響」ジョージ・グローテとの共著。 フィリップ・ボーシャンプのペンネームで出版。 1823. パウロではなくイエス ガマリエル・スミスというペンネームで出版。 1824. The Book of Fallacies from Unfinished Papers of Jeremy Bentham (1st ed.). ロンドン: John and H. L. Hunt. 1825. A Treatise on Judicial Evidence Extracted from the Manuscripts of Jeremy Bentham, Esq (1st ed.), edited by M. Dumont. London: Baldwin, Cradock, & Joy. 1827. Rationale of Judicial Evidence, specially applied to English Practice, Extracted from the Manuscripts of Jeremy Bentham, Esq. I (1st ed.). London: Hunt & Clarke. 1830. 植民地を解放せよ!1793年フランス国民大会に宛てたもので、ヨーロッパ国家にとって遠くの属領は無用であり、いたずらであることを示す。ロンドン: Robert Heward - via Wikisource. 1834. 道徳の科学1、J.ボウリング編、"Deontology or, The science of morality 1". ロンドン: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green and Longman. 死後の出版物 ベンサムは死後、推定3,000万語にのぼる手稿を残したが、その大部分はユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンのスペシャル・コレクション(手稿 60,000葉)と大英図書館(手稿15,000葉)に所蔵されている。また、ユニバーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンには、ジェレミー・ベンサムによる、ま たはジェレミー・ベンサムについて書かれた、もしくはジェレミー・ベンサムが所有していた約500冊の蔵書がある[113]。 ボウリング(1838年-1843年) ベンサムの親しい友人であり弟子であった若き急進派作家ジョン・ボウリングは、ベンサムの文学的遺言執行人に任命され、ベンサムの著作集を作成する仕事を 任された。これは1838年から1843年にかけて全11巻で刊行された。ボーリングは、ベンサム自身の手稿ではなく、(デュモンの手稿を含む)既刊のテ キストをもとにした版を作成し、ベンサムの宗教に関する著作をまったく出版しないことを選択した。この版は、初版発行時に『エジンバラ・レヴュー』誌に よって「不完全で、不正確で、整理されていない」と評され、それ以来、その脱落と細部の誤りの両方について繰り返し批判されている。一方、第10巻と第 11巻に収録されているボウリングのベンサムの生涯についての回想録は、サー・レスリー・スティーヴンによって「言語上最悪の伝記のひとつ」と評された。 [114]にもかかわらず、ボウリングの本は1世紀以上にわたってベンサムの著作の大半の標準的な版であり続け、現在でも部分的に取って代わられているに 過ぎない。この本には、1786年から89年にかけて書かれたベンサムの『普遍的かつ永続的な平和のための計画』(A Plan for an Universal and Perpetual Peace)のような国際[a]関係に関する興味深い著作が含まれており、これは『国際法の原理』の第4部を形成している。 シュタルク(1952-1954) 1952年から1954年にかけて、ヴェルナー・シュタルクは3巻からなる『ジェレミー・ベンサムの経済著作集』を出版し、経済問題に関するベンサムの著 作のすべてを、出版されたものと未発表のものを含めてまとめようとした。重要な業績ではあるが、この著作は細部において多くの点で欠陥があると学者たちに 考えられており[115]、現在ベンサム・プロジェクトによって経済著作の新版(Writings on Political Economyと改題)が出版中である。 ベンサム・プロジェクト(1968年~現在) さらなる情報 ジェレミー・ベンサム著作集(The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham)とベンサム転写(Transcribe Bentham 1959年、ロンドン大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジの後援のもと、ベンサムの著作の決定版を作成することを目的としたベンサム委員会が設立された。ベンサ ム・プロジェクト[116]が設立され、ジェレミー・ベンサム著作集(The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham)の第1巻が1968年に出版された。Collected Worksは、未発表の著作を多数提供するとともに、すでに出版された著作のテキストを大幅に改良している。現在までに38巻が刊行されており、完全版は 80巻になると予測されている[117]。Of Laws in General (1970)の巻は多くの誤りを含んでいることが判明し、Of the Limits of the Penal Branch of Jurisprudence (2010)に置き換えられた[118]。2017年、UCL Pressによって1巻から5巻がオープンアクセスで再出版された[要出典]。 この作業を支援するために、UCLにあるベンサム論文はクラウドソーシングによって転写され、デジタル化されている。Transcribe Benthamは、University College LondonのBentham Project[119]が、UCLのUCL Centre for Digital Humanities、UCL Library Services、UCL Learning and Media Services、University of London Computer Centre、およびオンラインコミュニティと協力して運営する、クラウドソーシングによる写本転写プロジェクトである。このプロジェクトは2010年9 月に開始され、UCLが所蔵する膨大なBentham Papersコレクション(写本約6万葉)のデジタル画像を、特別に設計された書き起こしインターフェースを通じて自由に利用できるようにすることで、一 般市民の関心を高め、資料の書き起こしを手伝ってくれるボランティアを募集している。ボランティアによって作成された写本は、Bentham Projectによる『The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham』の新版作成に貢献し、UCLのデジタルBentham Papersリポジトリ[120]にアップロードされる。写本は、Transcribe Benthamウェブサイト[122]を通して、写本デスクで写本者アカウント[121]にサインアップすることで閲覧・写本することができる。 PRHLT研究センターがREADプロジェクトの枠組みで開発した実験的な手書きテキスト画像索引付け検索システム[123]により、ベンサム文書の全コレクションの自由で柔軟なテキスト検索が可能になった。 |

| List of animal rights advocates List of civil rights leaders List of liberal theorists Philosophy of happiness – Philosophical theory Rule according to higher law – Belief that universal principles of morality override unjust laws Rule of law – Political situation in which every citizen is subject to the law |

動物権利擁護者一覧 公民権運動家一覧 自由主義理論家一覧 幸福の哲学 – 哲学的理論 高次の法による支配 – 不公正な法律よりも普遍的な道徳原則が優先されるという信念 法の支配 – すべての市民が法律に従う政治状況 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeremy_Bentham |

Bentham, Jeremy, 『道徳および立法の諸原理序説』(上/下)中山元訳、ちくま文庫 |

| イ

ギリス近代を代表する思想家にして法学者ジェレミー・ベンサム(1748-1832)。本書は、近体功利主義の創始者として知られる彼の代表作と目される

記念碑的著作である。ここでベンサムは、人間の快と苦痛のみに基礎づけられた功利性の原理をもとに個人と共同体のありようを徹底的に解析し、そこから真に

普遍的な法体系を導出しようと試みる。その挑戦はわれわれをどこに導くのか?刊行より200年以上経てもなお倫理学、法哲学、政治思想など広範な分野に圧

倒的な影響を与え続けている名著を、このうえなく清新かつ平明な訳文で送る。上巻は「第13章 罰すべきでない場合」まで。文庫オリジナル。 https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BC16322671 「政治と道徳の学問の土台をなす真理は、数学のような厳密な学問的な調査によらなければ、そして比較を絶するほど複雑で広範な調査によらなければ、見いだ すことはできない」。序文に記されたこの言葉通り、本書全体の三分の一を占める長大な「第16章 不法行為の分類」においてベンサムは人間の不法行為のあ りようを執拗に追跡し、精緻な考察を繰り広げていく。そこに映し出されるのは、科学に立脚して立法と道徳を問いなおし、完全なる法体系を打ち立てんとする ベンサムの強靱な意志である。幸福とは、人間の道徳とは、そして法の目的とは—。哲学史に燦然と輝く重要古典、待望の完訳。 https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BC16322423 |

第1章 功利性の原理について 第2章 功利性の原理に反するさまざまな原理について 第3章 快と苦痛の四つの源泉および制裁 第4章 さまざまな快と苦痛の価値ならびにその測定方法 第5章 快と苦痛について、その種類 第6章 感受性に影響を与える状況について 第7章 人間の行動一般について 第8章 意図について 第9章 意識について 第10章 動機について 第11章 人間の気質一般について 第12章 有害な行為の結果について 第13章 罰すべきでない場合 第14章 刑罰と不法行為の均衡関係について 第15章 刑罰に与えるべき特性 第16章 不法行為の分類 第17章 法理学の刑法分野の境界について 結語としての覚書 |

| Sources Armitage, David (2007). The Declaration of Independence: A Global History. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674022829. Bartle, G. F. (1963). "Jeremy Bentham and John Bowring: a study of the relationship between Bentham and the editor of his Collected Works". Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. 36 (93): 27–35. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1963.tb00620.x. Bedau, Hugo Adam (1983). "Bentham's Utilitarian Critique of the Death Penalty". The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 74 (3): 1033–1065. doi:10.2307/1143143. JSTOR 1143143. Benthall, Jonathan (2007). "Animal liberation and rights". Anthropology Today. 23 (2): 1–3. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8322.2007.00494.x. ISSN 0268-540X. Burns, J. H. (2005). "Happiness and Utility: Jeremy Bentham's Equation". Utilitas. 17 (1): 46–61. doi:10.1017/S0953820804001396. ISSN 0953-8208. S2CID 146209080. Burns, J. H. (1989). "Bentham and Blackstone: A Lifetime's Dialectic". Utilitas. 1: 22. doi:10.1017/S0953820800000042. S2CID 144397742. Campos Boralevi, Lea (2012). Bentham and the Oppressed. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110869835. Crimmins, James E. (1986). "Bentham on Religion: Atheism and the Secular Society". Journal of the History of Ideas. 47 (1). University of Pennsylvania Press: 95–110. doi:10.2307/2709597. JSTOR 2709597. Crimmins, James E. (1990). Secular Utilitarianism: Social Science and the Critique of Religion in the Thought of Jeremy Bentham. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198277415. Cutrofello, Andrew (2014). All for Nothing: Hamlet's Negativity. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262526340. Daggett, Windsor (1920). A Down-East Yankee From the District of Maine. Portland: A.J. Huston. Dinwiddy, John (2004). Bentham: selected writings of John Dinwiddy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804745208. Dupont, Christian Y.; Onuf, Peter S., eds. (2008). Declaring Independence: The Origin and Influence of America's Founding Document : Featuring the Albert H. Small Declaration of Independence Collection. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Library. ISBN 978-0979999703. Everett, Charles Warren (1969). Jeremy Bentham. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0297179845. OCLC 157781. Follett, R. (2000). Evangelicalism, Penal Theory and the Politics of Criminal Law: Reform in England, 1808–30. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403932761. Foucault, Michel (1977). Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 978-0140137224. Francione, Gary (2004). "Animals: Property or Persons". In Sunstein, Cass R.; Nussbaum, Martha C. (eds.). Animal Rights: Current Debates and New Directions. Oxford University Press, US. ISBN 978-0195152173. González, Ana Marta (2012). Contemporary Perspectives on Natural Law: Natural Law as a Limiting Concept. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1409485667. Grayling, A. C. (2013). "19 York Street". The Quarrel of the Age: The Life and Times Of William Hazlitt. Orion. ISBN 978-1780226798. Gruen, Lori (1 July 2003). "The Moral Status of Animals". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Gunn, J. A. W. (1989). "Jeremy Bentham and the Public Interest". In Lively, J.; Reeve, A. (eds.). Modern Political Theory from Hobbes to Marx: Key Debates. London: Routledge. pp. 199–219. ISBN 978-0415013512. Hamburger, Joseph (1965). Intellectuals in Politics: John Stuart Mill and the Philosophic Radicals. Yale University Press. Harris, Jonathan (1998). "Bernardino Rivadavia and Benthamite 'discipleship'". Latin American Research Review. 33: 129–149. doi:10.1017/S0023879100035780. S2CID 252743662. Harrison, Ross (1983). Bentham. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0710095260. Harrison, Ross (1995). "Jeremy Bentham". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. pp. 85–88. Archived from the original on 29 January 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2007. Hart, Jenifer (July 1965). "Nineteenth-Century Social Reform: A Tory Interpretation of History". Past & Present (31): 39–61. doi:10.1093/past/31.1.39. JSTOR 650101. Harte, Negley (1998). "The owner of share no. 633: Jeremy Bentham and University College London". In Fuller, Catherine (ed.). The Old Radical: representations of Jeremy Bentham. London: University College London. Himmelfarb, Gertrude (1968). Victorian Minds. New York: Knopf. Kelly, Paul J. (1990). Utilitarianism and distributive justice: Jeremy Bentham and the civil law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198254188. King, Peter J. (March 1966). "John Neal as a Benthamite". The New England Quarterly. 39 (1): 47–65. doi:10.2307/363641. JSTOR 363641. Anonymous (1776). An Answer to the Declaration of the American Congress. London: T. Cadell. Lease, Benjamin (1972). That Wild Fellow John Neal and the American Literary Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226469697. Lucas, Philip; Sheeran, Anne (2006). "Asperger's Syndrome and the Eccentricity and Genius of Jeremy Bentham" (PDF). Journal of Bentham Studies. 8. doi:10.14324/111.2045-757X.027. S2CID 58729643. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 April 2012. Morriss, Andrew P. (1999). "Codification and Right Answers". Chic.-Kent L. Rev. 74: 355. McStay, Andrew (2014). Privacy and Philosophy: New Media and Affective Protocol. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1433118982. Murphy, James Bernard (2014). The Philosophy of Customary Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199370627. Packe, Michael St. John (1954). The Life of John Stuart Mill. London: Secker and Warburg. Persky, Joseph (1 January 2007). "Retrospectives: From Usury to Interest". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 21 (1): 228. doi:10.1257/jep.21.1.227. JSTOR 30033709. Postema, Gerald J. (1986). Bentham and the Common Law Tradition. Oxford U. P. ISBN 978-0198255055. Priestley, Joseph (1771). An Essay on the First Principles of Government: And on the Nature of Political, Civil, and Religious Liberty. London: J. Johnson. Roberts, Clayton; Roberts, David F.; Bisson, Douglas (2016). A History of England. Vol. II: 1688 to the Present (6th ed.). London and New York: Routledge. p. 307. ISBN 978-1315509600. Robinson, Dave; Groves, Judy (2003). Introducing Political Philosophy. Cambridge: Icon Books. ISBN 184046450X. Rosen, F. (1983). Jeremy Bentham and Representative Democracy: A Study of the "Constitutional Code". Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 019822656X. Rosen, Frederick (1990). "The Origins of Liberal Utilitarianism: Jeremy Bentham and Liberty". In Bellamy, R. (ed.). Victorian Liberalism: Nineteenth-century Political Thought and Practice. London: Routledge. p. 5870. Rosen, Frederick (1992). Bentham, Byron, and Greece: constitutionalism, nationalism, and early liberal political thought. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198200781. Rosen, Frederick, ed. (2007). Jeremy Bentham. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0754625667. Schofield, Philip (2006). Utility and Democracy: The Political Thought of Jeremy Bentham. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198208563. Schofield, Philip (2009). Bentham: a guide for the perplexed. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-0826495891. Schofield, Philip (2009a). "Werner Stark and Jeremy Bentham's Economic Writings". History of European Ideas. 35 (4): 475–494. doi:10.1016/j.histeuroideas.2009.05.003. S2CID 144165469. Schofield, Philip (2013). "The Legal and Political Legacy of Jeremy Bentham". Annual Review of Law and Social Science. 9 (1): 51–70. doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102612-134101. Semple, Janet (1993). Bentham's Prison: a Study of the Panopticon Penitentiary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198273878. Spiegel, Henry William (1991). The Growth of Economic Thought (3rd ed.). Duke University Press. ISBN 08223-09734. Stephen, Leslie (1894). "Milton, John (1608–1674)" . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 38. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 32. Stephen, Leslie (2011). The English Utilitarians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108041003. Sunstein, Cass R. (2004). "Animal Rights". In Sunstein, Cass R.; Nussbaum, Martha C. (eds.). Animal Rights: Current Debates and New Directions. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195152173. Thomas, William (1979). The Philosophic Radicals: Nine Studies in Theory and Practice, 1817–1841. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198224907. Twining, William (1985). Theories of Evidence: Bentham and Wigmore. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804712859. Vergara, Francisco (1998). "A Critique of Elie Halévy; refutation of an important distortion of British moral philosophy" (PDF). Philosophy. 73 (1). London: Royal Institute of Philosophy: 97–111. doi:10.1017/s0031819197000144. S2CID 170370954. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2016. Vergara, Francisco (2011). "Bentham and Mill on the "Quality" of Pleasures". Revue d'études benthamiennes (9). Paris. doi:10.4000/etudes-benthamiennes.422. ISSN 1760-7507. Weiss, Gunther A. (2000). "The Enchantment of Codification in the Common-Law World". The Yale Journal of International Law. 25 (2): 435–532. Retrieved 3 September 2021. Williford, Miriam (1975). "Bentham on the Rights of Women". Journal of the History of Ideas. 36 (1): 167–176. doi:10.2307/2709019. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2709019. |

出典 アーミテージ、デビッド(2007)。『独立宣言:グローバルな歴史』ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0674022829。 バートル、G. F. (1963). 「ジェレミー・ベンサムとジョン・バウリング:ベンサムと彼の全集の編集者との関係に関する研究」. 歴史研究所紀要. 36 (93): 27–35. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1963.tb00620.x. ベダウ、ウーゴ・アダム (1983). 「ベンサムの死刑に対する功利主義的批判」 『刑事法および犯罪学ジャーナル』 74 (3): 1033–1065. doi:10.2307/1143143. JSTOR 1143143. ベンタル、ジョナサン (2007). 「動物解放と権利」. Anthropology Today. 23 (2): 1–3. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8322.2007.00494.x. ISSN 0268-540X. バーンズ、J. H. (2005). 「幸福と効用:ジェレミー・ベンサムの方程式」。Utilitas. 17 (1): 46–61. doi:10.1017/S0953820804001396. ISSN 0953-8208. S2CID 146209080. Burns, J. H. (1989). 「ベンサムとブラックストーン:生涯の弁証法」 Utilitas. 1: 22. doi:10.1017/S0953820800000042. S2CID 144397742. Campos Boralevi, Lea (2012). Bentham and the Oppressed. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110869835. Crimmins, James E. (1986). 「宗教に関するベンサム:無神論と世俗社会」 『Journal of the History of Ideas』 47 (1). ペンシルベニア大学出版局: 95–110. doi:10.2307/2709597. JSTOR 2709597. Crimmins, James E. (1990). 世俗的功利主義: ジェレミー・ベンサムの思想における社会科学と宗教批判. クラレンドン・プレス. ISBN 978-0198277415。 カットロフェロ、アンドルー (2014)。すべては無駄:ハムレットの否定性。MIT プレス。ISBN 978-0262526340。 ダゲット、ウィンザー (1920)。メイン州出身のダウンイースト・ヤンキー。ポートランド:A.J. ヒューストン。 ディンウィディ、ジョン (2004)。ベンサム:ジョン・ディンウィディの選集。カリフォルニア州スタンフォード:スタンフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0804745208。 デュポン、クリスチャン・Y.、オヌフ、ピーター・S.(編)(2008)。『独立宣言:アメリカの建国文書の起源と影響:アルバート・H・スモール独立宣言コレクションを特集』。シャーロッツビル:バージニア大学図書館。ISBN 978-0979999703。 エベレット、チャールズ・ウォーレン(1969)。ジェレミー・ベンサム。ロンドン:Weidenfeld & Nicolson。ISBN 0297179845。OCLC 157781。 フォレット、R. (2000)。福音主義、刑罰論、刑法政治:1808年から1830年のイギリスの改革。パームグレイブ・マクミラン。ISBN 978-1403932761。 フーコー、ミシェル (1977)。規律と罰:刑務所の誕生。アラン・シェリダン訳。ハーモンズワース:ペンギン。ISBN 978-0140137224。 フランシオーネ、ゲイリー (2004)。「動物:財産か人格か」。サンスティーン、キャス R.、ヌスバウム、マーサ C. (編)。動物の権利:現在の議論と新たな方向性。オックスフォード大学出版局、米国。ISBN 978-0195152173。 ゴンサレス、アナ・マルタ(2012)。自然法に関する現代的視点:制限概念としての自然法。アッシュゲート出版。ISBN 978-1409485667。 グレイリング、A. C. (2013)。「19 ヨークストリート」。The Quarrel of the Age: The Life and Times Of William Hazlitt。オリオン。ISBN 978-1780226798。 Gruen, Lori (2003年7月1日). 「動物の道徳的地位」. スタンフォード哲学百科事典. ガン、J. A. W. (1989). 「ジェレミー・ベンサムと公共の利益」 『ホッブズからマルクスまでの現代政治理論:重要な議論』 Lively, J.; Reeve, A. (eds.). ロンドン:Routledge. pp. 199–219. ISBN 978-0415013512. ハンバーガー、ジョセフ (1965)。『政治における知識人:ジョン・スチュワート・ミルと哲学的急進派』。エール大学出版局。 ハリス、ジョナサン (1998)。「ベルナルディーノ・リバダビアとベントハムの『弟子たち』」。『ラテンアメリカ研究レビュー』。33: 129–149。doi:10.1017/S0023879100035780. S2CID 252743662. ハリソン、ロス (1983). ベンサム. ロンドン: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0710095260. ハリソン、ロス (1995)。「ジェレミー・ベンサム」。ホンデリッチ、テッド (編)。『オックスフォード哲学事典』。オックスフォード大学出版局。85-88 ページ。2017年1月29日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2007年11月23日取得。 ハート、ジェニファー(1965年7月)。「19世紀の社会改革:歴史のトーリー派解釈」。『過去と現在』 (31): 39–61。doi:10.1093/past/31.1.39。JSTOR 650101。 Harte, Negley (1998). 「株式番号 633 の所有者:ジェレミー・ベンサムとロンドン大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジ」 Fuller, Catherine (編). The Old Radical: representations of Jeremy Bentham. ロンドン:ロンドン大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジ。 Himmelfarb, Gertrude (1968). Victorian Minds. ニューヨーク:Knopf。 ケリー、ポール J. (1990)。功利主義と分配の正義:ジェレミー・ベンサムと民法。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0198254188。 キング、ピーター J. (1966年3月)。「ベンサム主義者としてのジョン・ニール」。ニューイングランド・クォータリー。39 (1): 47–65。doi:10.2307/363641. JSTOR 363641. 匿名 (1776). An Answer to the Declaration of the American Congress. ロンドン: T. Cadell. リース、ベンジャミン (1972). That Wild Fellow John Neal and the American Literary Revolution. シカゴ: シカゴ大学出版局. ISBN 0226469697. ルカーチ、フィリップ; シーラン、アン (2006). 「アスペルガー症候群とジェレミー・ベンサムの偏屈さと天才性」 (PDF). ベンサム研究ジャーナル. 8. doi:10.14324/111.2045-757X.027. S2CID 58729643. 2012年4月3日にオリジナルからアーカイブ (PDF)。 モリス、アンドリュー P. (1999). 「成文化と正しい答え」. Chic.-Kent L. Rev. 74: 355. マクステイ、アンドリュー (2014). プライバシーと哲学:新しいメディアと感情的プロトコル. ピーター・ラング. ISBN 978-1433118982。 マーフィー、ジェームズ・バーナード (2014)。慣習法の哲学。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0199370627。 パック、マイケル・セント・ジョン (1954)。ジョン・スチュアート・ミルの生涯。ロンドン:セッカー・アンド・ウォーバーグ。 パースキー、ジョセフ (2007年1月1日)。「回顧:高利貸しから利息へ」。The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 21 (1): 228. doi:10.1257/jep.21.1.227. JSTOR 30033709. ポステマ、ジェラルド J. (1986)。ベンサムとコモンローの伝統。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0198255055。 プリーストリー、ジョセフ (1771)。政府の第一原理に関するエッセイ:そして政治的、市民的、宗教的自由の性質について。ロンドン:J. ジョンソン。 ロバーツ、クレイトン、ロバーツ、デビッド F.、ビッソン、ダグラス (2016)。『イングランドの歴史』 第 II 巻:1688 年から現在まで (第 6 版)。ロンドンおよびニューヨーク:Routledge。307 ページ。ISBN 978-1315509600。 ロビンソン、デイブ、グローブス、ジュディ (2003)。『政治哲学入門』。ケンブリッジ:アイコン・ブックス。ISBN 184046450X。 ローゼン、F. (1983)。『ジェレミー・ベンサムと代表民主制:「憲法」の研究』。オックスフォード:クレアンドン・プレス。ISBN 019822656X。 ローゼン、フレデリック (1990)。「自由主義的功利主義の起源:ジェレミー・ベンサムと自由」。ベラミー、R. (編)『ビクトリア朝の自由主義:19 世紀の政治思想と実践』。ロンドン:Routledge。5870 ページ。 ローゼン、フレデリック (1992)。ベンサム、バイロン、そしてギリシャ:憲法主義、ナショナリズム、そして初期の自由主義政治思想。オックスフォード:クラレンドン・プレス。ISBN 0198200781。 ローゼン、フレデリック編 (2007)。ジェレミー・ベンサム。アルダーショット:アッシュゲート。ISBN 978-0754625667。 スコフィールド、フィリップ (2006)。『効用と民主主義:ジェレミー・ベンサムの政治思想』。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0198208563。 スコフィールド、フィリップ (2009)。『ベンサム:困惑する者のためのガイド』。ロンドン:Continuum。ISBN 978-0826495891。 スコフィールド、フィリップ (2009a). 「ヴェルナー・スタークとジェレミー・ベンサムの経済著作」 『ヨーロッパ思想史』 35 (4): 475–494. doi:10.1016/j.histeuroideas.2009.05.003. S2CID 144165469. スコフィールド、フィリップ (2013)。「ジェレミー・ベンサムの法的・政治的遺産」。法律と社会科学の年次レビュー。9 (1): 51–70. doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102612-134101. センプル、ジャネット (1993)。 |

| Further reading Public Domain Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Benthamism". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bentham, Jeremy" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. Macdonell, John (1885). "Bentham, Jeremy" . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 4. London: Smith, Elder & Co. Jeremy Bentham, "Critique of the Doctrine of Inalienable, Natural Rights", in Anarchical Fallacies, vol. 2 of Bowring (ed.), Works, 1843. Jeremy Bentham, "Offences Against One's Self: Paederasty", c. 1785, free audiobook from LibriVox. |

さらに詳しく パブリックドメイン ハーバーマン、チャールズ編(1913)。「ベンサム主義」。カトリック百科事典。ニューヨーク:ロバート・アップルトン社。 チザム、ヒュー編(1911)。「ベンサム、ジェレミー」。ブリタニカ国際大百科事典。第 3 巻(第 11 版)。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 マクドネル、ジョン (1885)。「ベンサム、ジェレミー」 スティーブン、レスリー (編)。国民伝記大辞典。第 4 巻。ロンドン:スミス、エルダー社。 ジェレミー・ベンサム、「不可侵の自然権に関する批判」、Anarchical Fallacies、第 2 巻、Bowring (編)、Works、1843 年。 ジェレミー・ベンサム、「自己に対する犯罪:小児性愛」、1785 年頃、LibriVox の無料オーディオブック。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeremy_Bentham |

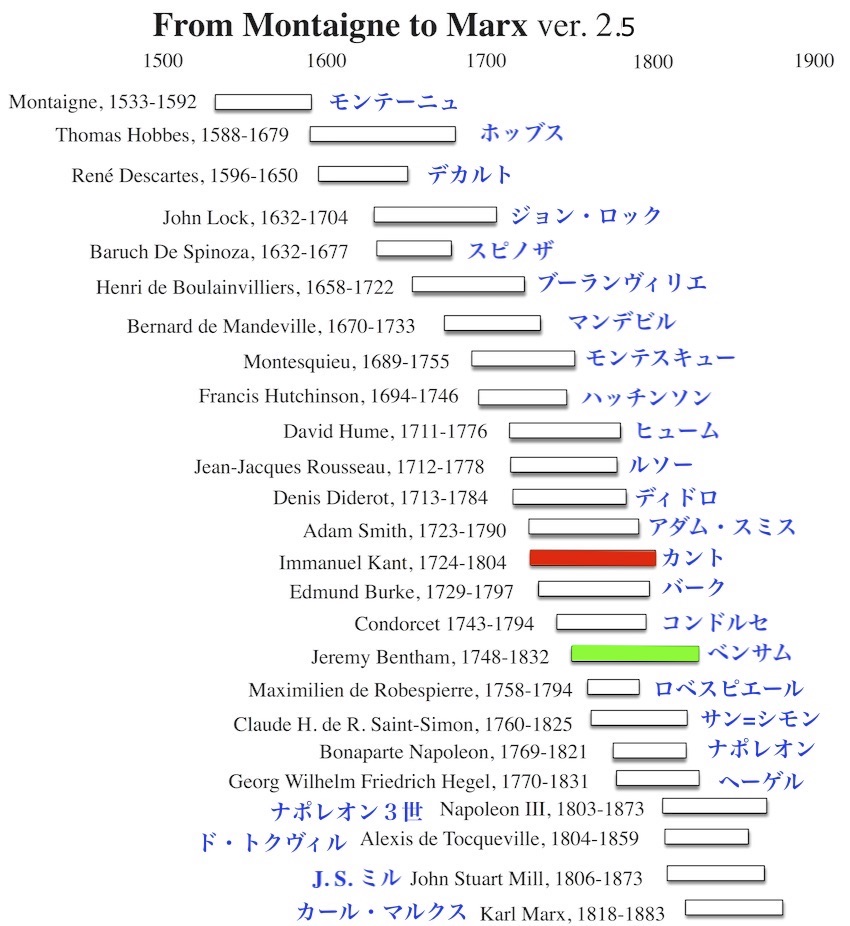

★ベンサムが生きた時代

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆