パノプティコン

panopticon

『修道女と修道士』 (1591)—

コルネリス・ファン・ハールレム(Cornelis Corneliszoon van Haarlem,

1562-1638)——もしマニエリスムの時代に監視カメラがあるとこのような映像が手に入る

パノプティコン

panopticon

『修道女と修道士』 (1591)—

コルネリス・ファン・ハールレム(Cornelis Corneliszoon van Haarlem,

1562-1638)——もしマニエリスムの時代に監視カメラがあるとこのような映像が手に入る

★語の定義と紹介

パノプティコン(panopticon)=展望監視システ ムとは、ジェレ ミー・ベンサム(Jeremy Bentham, 1748-1747)が考案した、刑務所の監視システムで、展望監視装置とも呼ばれる。いわば、パノ[ラマ](展望)と視覚=オプティ、装置=コン、というベンサムによる 造語である。ミッシェル・フーコーが自著『監視と処罰:監獄の誕生』のなか で、ベンサムを引用しながら、西欧の受刑制度が、身体刑から拘禁刑に「断絶」(=認識論的切断)的に移行し、なぜ、受刑者の身体の内面からの「改 心」が求められるようになったのか、また、それがなぜ外面の監視と観察によって「証明」されるようになったのかを、同時期の啓蒙初期の軍隊や学校制度など との考察から明らかにした時に、その契機となったものである。

"The panopticon is a type of institutional building and a system of control designed by the English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century. The concept of the design is to allow all prisoners of an institution to be observed by a single security guard, without the inmates being able to tell whether they are being watched. Although it is physically impossible for the single guard to observe all the inmates' cells at once, the fact that the inmates cannot know when they are being watched means that they are motivated to act as though they are being watched at all times. Thus, the inmates are effectively compelled to regulate their own behaviour. The architecture consists of a rotunda with an inspection house at its centre. From the centre, the manager or staff of the institution are able to watch the inmates. Bentham conceived the basic plan as being equally applicable to hospitals, schools, sanatoriums, and asylums, but he devoted most of his efforts to developing a design for a panopticon prison. It is his prison that is now most widely meant by the term "panopticon."-The panopticon.

★The panopticon from Wikipedia.

| The panopticon

is a type of institutional building and a system of control designed by

the English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the 18th

century. The concept of the design is to allow all prisoners of an

institution to be observed by a single security guard, without the

inmates being able to tell whether they are being watched. Although it is physically impossible for the single guard to observe all the inmates' cells at once, the fact that the inmates cannot know when they are being watched means that they are motivated to act as though they are being watched at all times. Thus, the inmates are effectively compelled to regulate their own behaviour. The architecture consists of a rotunda with an inspection house at its centre. From the centre, the manager or staff of the institution are able to watch the inmates. Bentham conceived the basic plan as being equally applicable to hospitals, schools, sanatoriums, and asylums, but he devoted most of his efforts to developing a design for a panopticon prison. It is his prison that is now most widely meant by the term "panopticon". |

パノプティコンとは、18世紀にイギリスの哲学者・社会理論家ジェレ

ミー・ベンサムが考案した施設建築の一種であり、管理システムのこと。設計のコンセプトは、施設のすべての囚人を一人の警備員が監視し、囚人は自分が監視

されているかどうかを知ることができないようにすることである。 一人の警備員がすべての受刑者の房を一度に観察することは物理的に不可能だが、受刑者は自分がいつ監視されているのか分からないということは、常に監視さ れているかのように行動するように動機付けられるということである。このように、受刑者は事実上、自らの行動を規制せざるを得ないのである。建築は、ロタ ンダを中心にインスペクションハウスを配置したものである。その中央から、施設の管理者や職員が受刑者を監視することができる。ベンサムは、この基本計画 を病院、学校、療養所、精神病院に等しく適用できると考えていたが、パノプティコン刑務所の設計に最も力を注いでいる。現在、「パノプティコン」という言 葉で最も広く知られているのは、このベンサムの監獄である。 |

| The word panopticon derives from

the Greek word for "all seeing" – panoptes.[3] In 1785, Jeremy Bentham,

an English social reformer and founder of utilitarianism, travelled to

Krichev in Mogilev Governorate of the Russian Empire (modern Belarus)

to visit his brother, Samuel, who accompanied Prince

Potemkin.[4]: xxxviii Bentham arrived in Krichev in early 1786[5] and

stayed for almost two years. While residing with his brother in

Krichev, Bentham sketched out the concept of the panopticon in letters.

Bentham applied his brother's ideas on the constant observation of

workers to prisons. Back in England, Bentham, with the assistance of

his brother, continued to develop his theory on the

panopticon.[4]: xxxviii Prior to fleshing out his ideas of a

panopticon prison, Bentham had drafted a complete penal code and

explored fundamental legal theory. While in his lifetime Bentham was a

prolific letter writer, he published little and remained obscure to the

public until his death.[4]: 385 [4] Sprigge, Timothy L. S.; Burns, J. H., eds. (2017). Correspondence of Jeremy Bentham, Volume 1: 1752 to 1776. UCL Press. Bentham thought that the chief mechanism that would bring the manager of the panopticon prison in line with the duty to be humane would be publicity. Bentham tried to put his duty and interest junction principle into practice by encouraging a public debate on prisons. Bentham's inspection principle applied not only to the inmates of the panopticon prison, but also the manager. The unaccountable gaoler was to be observed by the general public and public officials. The apparently constant surveillance of the prison inmates by the panopticon manager and the occasional observation of the manager by the general public was to solve the age old philosophic question: "Who guards the guards?"[6] Bentham continued to develop the panopticon concept, as industrialisation advanced in England and an increasing number of workers were required to work in ever larger factories.[7] Bentham commissioned drawings from an architect, Willey Reveley. Bentham reasoned that if the prisoners of the panopticon prison could be seen but never knew when they were watched, the prisoners would need to follow the rules. Bentham also thought that Reveley's prison design could be used for factories, asylums, hospitals, and schools.[8] Bentham remained bitter throughout his later life about the rejection of the panopticon scheme, convinced that it had been thwarted by the king and an aristocratic elite. It was largely because of his sense of injustice and frustration that he developed his ideas of sinister interest – that is, of the vested interests of the powerful conspiring against a wider public interest – which underpinned many of his broader arguments for reform.[9] |

パノプティコンという言葉は、ギリシャ語で「すべてを見渡す」を意味する「パノプテス」に由来する[3]。1785年、イギリスの社会改革者であり功利主義の創始者であるジェレミー・ベンサム(Jeremy Bentham, 1847/48-1832)は、ロシア帝国モギレフ県(現在のベラルーシ)のクリチェフを訪れた。弟サミュエル(Samuel Bentham, 1757-1831)

がポチョムキン公に随行していたためである。[4]: xxxviii

ベンサムは1786年初頭にクリチェフに到着し[5]、ほぼ2年間滞在した。クリチェフで弟と同居する間、ベンサムは書簡の中でパノプティコンの概念を概

説した。ベンサムは、労働者を常に監視するという弟の考えを刑務所に適用したのである。イギリスに戻ったベンサムは、弟の協力を得てパノプティコン理論の

構築を続けた[4]: xxxviii 。パノプティコン刑務所の構想を具体化する以前、ベンサムは完全な刑法典を起草し、法理論の基礎を探求していた。

ベンサムは生涯を通じて多作な書簡作家であったが、出版物は少なく、死まで一般にはほとんど知られていなかった。[4: 385 ] [4] Sprigge, Timothy L. S.; Burns, J. H., eds. (2017). Correspondence of Jeremy Bentham, Volume 1: 1752 to 1776. UCL Press. ベンサムは、パノプティコン刑務所の管理者を人道的であるべき義務に合致させる主なメカニズムは、公表であろうと考えた。ベンサムは、刑務所に関する公開 討論を促すことによって、その義務と利益の接合原理を実践しようとした。ベンサムの検査原則は、パノプティコン刑務所の収容者だけでなく、管理者にも適用 された。責任感のない看守は、一般市民や公職者に観察されることになった。パノプティコンの看守が刑務所の囚人を常に監視し、一般市民が時折看守を観察す ることで、古くからの哲学的な疑問が解決されることになった。"誰が看守を守るのか"[6]。 ベンサムは、イギリスで工業化が進み、ますます多くの労働者が大規模な工場で働くことを求められるようになると、パノプティコンの概念を発展させ続けた [7]。ベンサムは、建築家のウィリー・レヴェリーに図面を依頼した。ベンサムは、パノプティコン監獄の囚人たちが、見られることはあっても、いつ見られ ているのか分からないとしたら、囚人たちは規則に従わなければならないだろうと推理した。また、ベンサムは、レヴェリーの刑務所の設計は、工場、精神病 院、病院、学校にも使われるだろうと考えていた[8]。 ベンサムは、パノプティコン構想が否定されたことについて、晩年も苦言を呈し、国王と貴族のエリートによって妨害されたと確信していた。彼が不吉な利益、 つまり、より広い公共の利益に対して共謀する権力者の既得権益についての考えを発展させたのは、主に彼の不正義とフラストレーションの感覚によるものであ り、改革に対する彼の幅広い議論の多くを支えた[9]。 |

| Prison design The Building circular – an iron cage, glazed – a glass lantern about the size of Ranelagh – The Prisoners in their Cells, occupying the Circumference – The Officers, the Centre. By Blinds, and other contrivances, the Inspectors concealed from the observation of the Prisoners: hence the sentiment of a sort of invisible omnipresence. – The whole circuit reviewable with little, or, if necessary, without any, change of place.[10] — Jeremy Bentham (1791). Panopticon, or The Inspection House Bentham's proposal for a panopticon prison met with great interest among British government officials not only because it incorporated the pleasure-pain principle developed by the materialist philosopher Thomas Hobbes, but also because Bentham joined the emerging discussion on political economy. Bentham argued that the confinement of the prison, "which is his punishment, preventing [the prisoner from] carrying the work to another market."[clarification needed – missing verb] Key to Bentham's proposals and efforts to build a panopticon prison in Millbank at his own expense, was the "means of extracting labour" out of prisoners in the panopticon.[11] In his 1791 writing Panopticon, or The Inspection House, Bentham reasoned that those working fixed hours needed to be overseen.[12] Also, in 1791, Jean Philippe Garran de Coulon presented a paper on Bentham's panopticon prison concepts to the National Legislative Assembly in revolutionary France.[13] In 1812, persistent problems with Newgate Prison and other London prisons prompted the British government to fund the construction of a prison in Millbank at the taxpayers' expense. Based on Bentham's panopticon plans, the National Penitentiary opened in 1821. Millbank Prison, as it became known, was controversial, even blamed for causing mental illness among prisoners[citation needed]. Nevertheless, the British government placed an increasing emphasis on prisoners doing meaningful work, instead of engaging in humiliating and meaningless kill-times.[11] Bentham lived to see Millbank Prison built and did not support the approach taken by the British government. His writings had virtually no immediate effect on the architecture of taxpayer-funded prisons that were to be built. Between 1818 and 1821, a small prison for women was built in Lancaster. It has been observed that the architect Joseph Gandy modelled it very closely on Bentham's panopticon prison plans. The K-wing near Lancaster Castle prison is a semi-rotunda with a central tower for the supervisor and five storeys with nine cells on each floor.[14] It was the Pentonville prison, which was built in London after Bentham's death in 1832, that was to serve as a model for a further 54 prisons in Victorian Britain. Built between 1840 and 1842 according to the plans of Joshua Jebb, Pentonville prison had a central hall with radial prison wings.[14] It has been claimed that Bentham's panopticon influenced the radial design of 19th-century prisons built on the principles of the "separate system", including Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, which opened in 1829.[15] But the Pennsylvania–Pentonville architectural model with its radial prison wings was not designed to facilitate constant surveillance of individual prisoners. Guards had to walk from the hall along the radial corridors and could only observe prisoners in their cells by looking through the cell door's peephole.[16] In 1925, Cuba's president Gerardo Machado set out to build a modern prison, based on Bentham's concepts and employing the latest scientific theories on rehabilitation. A Cuban envoy tasked with studying US prisons in advance of the construction of Presidio Modelo had been greatly impressed with Stateville Correctional Center in Illinois and the cells in the new circular prison were too faced inwards towards a central guard tower. Because of the shuttered guard tower, the guards could see the prisoners, but the prisoners could not see the guards. Cuban officials theorised that the prisoners would "behave" if there was a probable chance that they were under surveillance, and once prisoners behaved, they could be rehabilitated. Between 1926 and 1931, the Cuban government built four such panopticons connected with tunnels to a massive central structure that served as a community centre. Each panopticon had five floors with 93 cells. In keeping with Bentham's ideas, none of the cells had doors. Prisoners were free to roam the prison and participate in workshops to learn a trade or become literate, with the hope being that they would become productive citizens. However, by the time Fidel Castro was imprisoned at Presidio Modelo, the four circulars were packed with 6,000 men, every floor was filled with trash, there was no running water, food rations were meagre, and the government supplied only the bare necessities of life.[17] In the Netherlands Breda, Arnhem and Haarlem penitentiary are cited as historic panopticon prisons. However, these circular prisons with their 400 or so cells fail as panopticons because the inwards-facing cell windows were so small that guards could not see the entire cell. The lack of surveillance that was actually possible in prisons with small cells and doors discounts many circular prison designs from being a panopticon as it had been envisaged by Bentham.[18] In 2006, one of the first digital panopticon prisons opened near Amsterdam. Every prisoner in the Lelystad Prison wears an electronic tag and by design, only six guards are needed for 150 prisoners instead of the usual 15 or more.[18] |

監獄の設計 円形の建物 - ガラス張りの鉄の檻 - ラネラーほどの大きさのガラスのランタン - 独房にいる囚人たち - 円周を占める - 中央の役人たち。ブラインドやその他の仕掛けによって、監察官は囚人の目から隠されている。それゆえ、ある種の目に見えない遍在という感情が生まれる。- 全周囲は、ほとんど、あるいは必要であれば全く場所を変えることなく、見直すことができる[10]。 - ジェレミー・ベンサム(1791)。パノプティコン,または検査所 ベンサムのパノプティコン監獄の提案は、唯物論哲学者トマス・ホッブズが開発した快楽と苦痛の原理を取り入れただけでなく、ベンサムが政治経済に関する新 しい議論に加わったことで、英国政府関係者の大きな関心を集めた。ベンサムは、刑務所の閉じ込めが「彼の罰であり、(囚人が)仕事を他の市場に運ぶことを 妨げる」[clarification needed - missing verb] と主張した。ベンサムの提案と自費でミルバンクにパノプティコン刑務所を建設する努力の鍵は、パノプティコンで囚人から「労働力を抽出する手段」であった [11]。 [11] 1791年に書いた『パノプティコン、あるいは検査所』の中で、ベンサムは、一定時間働く者は監視される必要があると推論していた[12] また、1791年にジャン・フィリップ・ガラン・ド・クーロンは、革命期のフランスの国民立法議会にベンサムのパノプティコン刑務所の構想に関する論文を 提出している[13]。 1812年、ニューゲート刑務所をはじめとするロンドンの刑務所に根強い問題があったため、英国政府はミルバンクに税金を投入して刑務所を建設することに なった。ベンサムのパノプティコン計画に基づき、1821年に開所したのが国立刑務所である。ミルバンク刑務所は、受刑者の精神疾患を引き起こすとまで非 難され、物議を醸した[citation needed]。それにもかかわらず、イギリス政府は、屈辱的で無意味な殺害時間に従事する代わりに、意味のある仕事をする囚人にますます重点を置くよう になった[11] ベンサムはミルバンク刑務所の建設を見るまで生きていたが、イギリス政府が取ったアプローチを支持しなかった。彼の著作は、税金で建設されることになった 刑務所の建築に即座に影響を与えることはほぼなかった。1818年から1821年にかけて、ランカスターに女性用の小さな刑務所が建設された。建築家ジョ セフ・ガンディが、ベンサムのパノプティコン監獄の計画に非常に近い形でモデル化したことが観察されています。ランカスター城刑務所の近くにあるK棟は、 監督官のための中央塔と、各階に9つの独房を持つ5階建ての半円形のロタンダである[14]。 1832年のベンサムの死後、ロンドンに建設されたペントンビル刑務所が、ヴィクトリア朝の英国でさらに54の刑務所のモデルとなることになった。 1829年に開所したフィラデルフィアのイースタン州立刑務所など、「分離システム」の原則に基づいて建てられた19世紀の刑務所の放射状のデザインに、 ベンサムのパノプティコンが影響を与えたと主張されている[15]。 しかし、放射状の囚人の翼を持つペンシルバニア・ペントンビル建築モデルは、個々の囚人を常に監視できるようには設計されていなかった。看守はホールから 放射状の廊下に沿って歩かなければならず、独房のドアの覗き穴から覗くことによってのみ、独房内の囚人を観察することができた[16]。 1925年、キューバ大統領ゲラルド・マチャドは、ベンサムの概念に基づき、最新のリハビリテーション科学理論を取り入れた近代的な刑務所の建設に着手し た。プレシディオ・モデルの建設に先立ち、アメリカの刑務所を調査したキューバの使節は、イリノイ州のステートビル矯正所に大きな感銘を受けたといい、新 しい円形の刑務所の独房は、中央の監視塔に向かって内側に向きすぎていた。シャッター付きの監視塔のため、看守は囚人を見ることができるが、囚人は看守を 見ることができない。キューバ政府は、監視されている可能性が高ければ囚人は「ふるまう」だろうし、囚人がふるえれば更生させることができる、と理論化し たのである。 1926年から1931年にかけて、キューバ政府はこのようなパノプティコンを4つ建設し、中央の巨大な建造物とトンネルでつないでコミュニティセンター として使用した。各パノプティコンは5階建てで、93の独房があった。ベンサムの思想に基づき、どの部屋にも扉はなかった。囚人たちは自由に刑務所を歩き 回り、職業訓練や識字のためのワークショップに参加し、生産的な市民となることを望んだ。しかし、フィデル・カストロがプレシディオ・モデロに収監される 頃には、4つの円形に6000人が詰め込まれ、どの階もゴミだらけ、水道はなく、食料配給はわずかで、政府は生活に必要な最低限のものだけを供給していた [17]。 オランダでは、ブレダ、アーネム、ハーレム刑務所が歴史的なパノプティコン刑務所として挙げられている。しかし、これらの円形の刑務所の400ほどの独房 は、内向きの独房の窓が小さく、看守が独房全体を見渡すことができなかったため、パノプティコンとしては失敗している。小さな独房とドアを持つ刑務所で実 際に可能だった監視の欠如は、多くの円形刑務所のデザインをベンサムが想定していたパノプティコンから割り引いた。 2006年、最初のデジタルパノプティコン刑務所のひとつがアムステルダム近郊に開設された[18]。レリスタッド刑務所の囚人は全員電子タグを身につけ ており、設計上、通常15人以上必要な看守が150人に対してわずか6人で済むようになっている[18]。 |

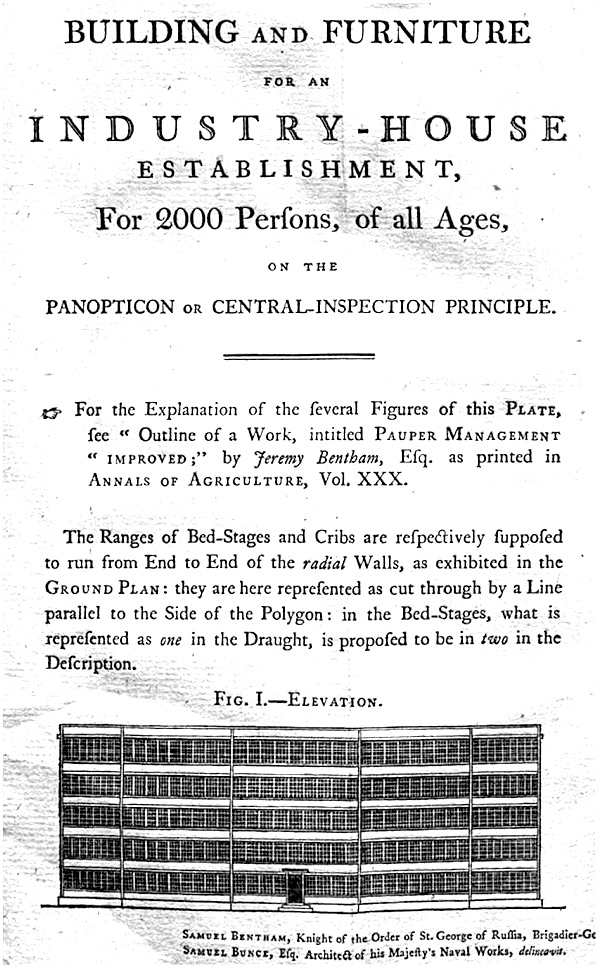

| Architecture of other

institutions Bentham's 1812 industry-house for 2000 persons Jeremy Bentham's panopticon architecture was not original, as rotundas had been used before, as for example in industrial buildings. However, Bentham turned the rotund architecture into a structure with a societal function, so that humans themselves became the object of control.[19] The idea for a panopticon had been prompted by his brother Samuel Bentham's work in Russia and had been inspired by existing architectural traditions. Samuel Bentham had studied at the Ecole Militaire in 1751, and at about 1773 the prominent French architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux had finished his designs for the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans.[20] William Strutt in cooperation with his friend Jeremy Bentham built a round mill in Belper, so that one supervisor could oversee an entire shop floor from the centre of the round mill. The mill was built between 1803 and 1813 and was used for production until the late 19th century. It was demolished in 1959.[21] In Bentham's 1812 writing Pauper management improved: particularly by means of an application of the Panopticon principle of construction, he included a building for an "industry-house establishment" that could hold 2000 persons.[22] In 1812 Samuel Bentham, who had by then risen to brigardier-general, tried to persuade the British Admiralty to construct an arsenal panopticon in Kent. Before returning home to London he had constructed a panopticon in 1807, near St Petersburg, which served as a training centre for young men wishing to work in naval manufacturing.[23] The panopticon, Bentham writes: will be found applicable, I think, without exception to all establishments whatsoever, in which within a space not too large to be covered or commanded by buildings, a number of persons are meant to be kept under inspections. No matter how different or even opposite the purpose.[24] — Jeremy Bentham (1791). Panopticon, or The Inspection House A plate by Pugin Despite the fact that no panopticon was built during Bentham's lifetime, the principles he established on the panopticon prompted considerable discussion and debate. Shortly after Jeremy Bentham's death in 1832 his ideas were criticised by Augustus Pugin, who in 1841 published the second edition of his work Contrasts in which one plate showed a "Modern Poor House". He contrasted an English medieval gothic town in 1400 with the same town in 1840 where broken spires and factory chimneys dominate the skyline, with a panopticon in the foreground replacing the Christian hospice. Pugin, who went on to become one of the most influential 19th-century writers on architecture, was influenced by Hegel and German idealism.[25] In 1835 the first annual report of the Poor Law Commission included two designs by the commission's architect Sampson Kempthorne. His Y-shape and cross-shape designs for workhouse expressed the panopticon principle by positioning the master's room as central point. The designs provided for the segregation of occupants and maximum visibility from the centre.[26] Professor David Rothman came to the conclusion that Bentham's panopticon prison did not inform the architecture of early asylums in the United States.[27] |

その他の施設の建築 ベンサムによる1812年の2000人収容の産業会館 ジェレミー・ベンサムのパノプティコン建築は、それ以前にも工業用建物などで使われていたため、独創的なものではない。しかし、ベンサムは、ロタンダ建築 を社会的機能を持つ構造に変え、人間そのものが管理の対象となった[19]。パノプティコンのアイデアは、弟のサミュエル・ベンサムのロシアでの仕事に促 されて、既存の建築の伝統に触発されたものであった。Samuel Benthamは1751年にEcole Militaireで学び、1773年頃にはフランスの著名な建築家Claude-Nicolas LedouxがArc-et-SenansのRoyal Saltworksの設計を終えていました[20] William Struttと彼の友人Jeremy Benthamはベルパーに円形の工場を建設し、1人の監督者が円形の工場の中心から工場全体を見渡すことができるようにしました。この工場は1803年 から1813年にかけて建設され、19世紀後半まで生産に使われました。ベンサムの1812年の著作では、貧困層の管理が改善され、特にパノプティコン建 築の原理を応用して、2000人を収容できる「産業施設」のための建物が含まれていた[22]。 1812年、その頃准将に昇進していたサミュエル・ベンサムは、ケントに造兵場のパノプティコン建設をイギリス提督に説得しようとした。ロンドンに帰る前 に、彼は1807年にサンクトペテルブルクの近くにパノプティコンを建設し、海軍の製造業で働くことを希望する若者のトレーニングセンターとして機能させ ていた[23]。 パノプティコンは、建物で覆われたり、指揮されたりするには大きすぎない空間の中で、多くの人が監視下に置かれることを意図している、あらゆる施設に例外 なく適用されることが見つかると思う。目的がいかに異なっていても、あるいは正反対であってもだ[24]。 - ジェレミー・ベンサム(1791年)。パノプティコン、または監察所 ピュージン作のプレート ベンサムが生きている間にパノプティコンが建設されることはなかったが、彼が確立したパノプティコンの原理は、多くの議論と討論を促した。1832年にベ ンサムが亡くなって間もなく、彼の考えを批判したのがオーガスタス・プーギンで、彼は1841年に『対比』の第2版を出版し、その中の1枚に「現代の貧し い家」が描かれている。彼は、1400年のイギリスの中世ゴシック様式の町と、1840年の同じ町を対比させ、壊れた尖塔と工場の煙突がスカイラインを支 配し、前景にはキリスト教のホスピスに代わってパノプティコンが描かれていることを指摘した。プーギンは、19世紀の最も影響力のある建築家の一人とな り、ヘーゲルとドイツ観念論の影響を受けた[25]。1835年、貧困法委員会の最初の年次報告書には、委員会の建築家サンプソン・ケンプソーンによる二 つの設計が含まれている。彼のY字型と十字型のワークハウスの設計は、主人の部屋を中心に据えることでパノプティコンの原理を表現していた。設計は、居住 者の隔離と中心からの最大限の可視性を提供した[26]。デイヴィッド・ロスマン教授は、ベンサムのパノプティコン監獄はアメリカの初期の精神病院の建築 に影響を与えていないという結論に至った[27]。 |

| Criticism and use as metaphor In 1965, the conservative historian Shirley Robin Letwin traced the Fabian zest for social planning to early utilitarian thinkers. She argued that Bentham's pet gadget, the panopticon prison, was a device of such monstrous efficiency that it left no room for humanity. She accused Bentham of forgetting the dangers of unrestrained power and argued that "in his ardour for reform, Bentham prepared the way for what he feared". Recent Libertarian thinkers began to regard Bentham's entire philosophy as having paved the way for totalitarian states.[28] In the late 1960s, the American historian Gertrude Himmelfarb, who had published The Haunted House of Jeremy Bentham in 1965, was at the forefront of depicting Bentham's mechanism of surveillance as a tool of oppression and social control.[29][28] David John Manning published The Mind of Jeremy Bentham in 1986, in which he reasoned that Bentham's fear of instability caused him to advocate ruthless social engineering and a society in which there could be no privacy or tolerance for the deviant.[28] In the mid-1970s, the panopticon was brought to the wider attention by the French psychoanalyst Jacques-Alain Miller and the French philosopher Michel Foucault.[30] In 1975, Foucault used the panopticon as metaphor for the modern disciplinary society in Discipline and Punish. He argued that the disciplinary society had emerged in the 18th century and that discipline are techniques for assuring the ordering of human complexities, with the ultimate aim of docility and utility in the system.[31] Foucault first came across the panopticon architecture when he studied the origins of clinical medicine and hospital architecture in the second half of the 18th century. He argued that discipline had replaced the pre-modern society of kings, and that the panopticon should not be understood as a building, but as a mechanism of power and a diagram of political technology.[31] Foucault argued that discipline had already crossed the technological threshold in the late 18th century, when the right to observe and accumulate knowledge had been extended from the prison to hospitals, schools, and later factories.[31] In his historic analysis, Foucault reasoned that with the disappearance of public executions pain had been gradually eliminated as punishment in a society ruled by reason.[31] The modern prison in the 1970s, with its corrective technology, was rooted in the changing legal powers of the state. While acceptance for corporal punishment diminished, the state gained the right to administer more subtle methods of punishment, such as to observe.[31] The French sociologist Henri Lefebvre studied urban space and Foucault's interpretation of the panopticon prison, arriving at the conclusion that spatiality is a social phenomenon. Lefebvre contended that architecture is no more than the relationship between the panopticon, people, and objects. In urban studies, academics such as Marc Schuilenburg now argue that a different self-consciousness arises among humans who live in an urban area.[32] Wall of an industrial building in Donetsk, Ukraine In 1984, Michael Radford gained international attention for the cinematographic panopticon he had staged in the film Nineteen Eighty-Four. Of the telescreens in the landmark surveillance narrative Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), George Orwell said: "there was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment ... you had to live ... in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinised".[33] In Radford's film the telescreens were bidirectional and in a world with an ever increasing number of telescreen devices the citizens of Oceania were spied on more than they thought possible.[34] In The Electronic Eye: The Rise of Surveillance Society (1994) the sociologist David Lyon concluded that "no single metaphor or model is adequate to the task of summing up what is central to contemporary surveillance, but important clues are available in Nineteen Eighty-Four and in Bentham's panopticon".[35] The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze shaped the emerging field of surveillance studies with the 1990 essay Postscript on the Societies of Control.[36]: 21 Deleuze argued that the society of control is replacing the discipline society. With regards to the panopticon, Deleuze argued that "enclosures are moulds ... but controls are a modulation". Deleuze observed that technology had allowed physical enclosures, such as schools, factories, prisons and office buildings, to be replaced by a self-governing machine, which extends surveillance in a quest to manage production and consumption. Information circulates in the control society, just like products in the modern economy, and meaningful objects of surveillance are sought out as forward-looking profiles and simulated pictures of future demands, needs and risks are drawn up.[36]: 27 In 1997, Thomas Mathiesen in turn expanded on Foucault's use of the panopticon metaphor when analysing the effects of mass media on society. He argued that mass media such as broadcast television gave many people the ability to view the few from their own homes and gaze upon the lives of reporters and celebrities. Mass media has thus turned the discipline society into a viewer society.[37] In the 1998 satirical science fiction film The Truman Show, the protagonist eventually escapes the OmniCam Ecosphere, the reality television show that, unknown to him, broadcasts his life around the clock and across the globe. But in 2002, Peter Weibel noted that the entertainment industry does not consider the panopticon as a threat or punishment, but as "amusement, liberation and pleasure". With reference to the Big Brother television shows of Endemol Entertainment, in which a group of people live in a container studio apartment and allow themselves to be recorded constantly, Weibel argued that the panopticon provides the masses with "the pleasure of power, the pleasure of sadism, voyeurism, exhibitionism, scopophilia, and narcissism". In 2006, Shoreditch TV became available to residents of the Shoreditch in London, so that they could tune in to watch CCTV footage live. The service allowed residents "to see what's happening, check out the traffic and keep an eye out for crime".[38] In their 2004 book Welcome to the Machine: Science, Surveillance, and the Culture of Control, Derrick Jensen and George Draffan called Bentham "one of the pioneers of modern surveillance" and argued that his panopticon prison design serves as the model for modern supermaximum security prisons, such as Pelican Bay State Prison in California.[39] In the 2015 book Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness, Simone Browne noted that Bentham travelled on a ship carrying slaves as cargo while drafting his panopticon proposal. She argues that the structure of chattel slavery haunts the theory of the panopticon. She proposes that the 1789 plan of the slave ship Brookes should be regarded as the paradigmatic blueprint.[40] Drawing on Didier Bigo's Banopticon, Brown argues that society is ruled by exceptionalism of power, where the state of emergency becomes permanent and certain groups are excluded on the basis of their future potential behaviour as determined through profiling.[41] |

批判と比喩としての使われ方 1965年、保守派の歴史家シャーリー・ロビン・レットウィンは、フェビアンによる社会計画への熱意を初期の功利主義思想家まで遡及させた。彼女は、ベン サムの愛用したパノプティコン監獄は、人間性の入り込む余地がないほど巨大な効率を持つ装置であると主張した。彼女は、ベンサムが無制限の権力の危険性を 忘れていると非難し、「改革への熱意が、ベンサムが恐れていたものへの道を用意した」と論じた。最近のリバタリアン思想家たちは、ベンサムの哲学全体が全 体主義国家への道を開いたとみなすようになった[28]。 1960年代後半、1965年に『ジェレミー・ベンサムの幽霊屋敷』を出版したアメリカの歴史家ガートルード・ヒメルファーブは、ベンサムの監視機構を抑 圧と社会統制の道具として描写する最前線に立っていた[29]。 [29][28] デイヴィッド・ジョン・マニングは1986年に『ジェレミー・ベンサムの心』を出版し、ベンサムの不安定さに対する恐怖が冷酷な社会工学とプライバシーや 逸脱者に対する寛容さが存在し得ない社会を提唱させたと推論している[28]。 1970年代半ばに、パノプティコンはフランスの精神分析家ジャック=アラン・ミラーとフランスの哲学者ミシェル・フーコーによって広く注目されるように なった[30]。 1975年にフーコーは『規律と罰』で現代の規律社会の隠喩としてパノプティコンを使っていた。彼は規律社会が18世紀に出現し、規律は人間の複雑な秩序 を保証するための技術であり、最終的な目的はシステムにおける従順さと有用性であると主張した[31] フーコーは18世紀後半に臨床医学と病院建築の起源を研究する際にパノプティコン建築に初めて遭遇している。彼は規律が前近代の王様の社会に取って代わっ たと主張し、パノプティコンは建築物としてではなく、権力のメカニズムや政治技術の図式として理解されるべきであるとした[31]。 フーコーは、観察し知識を蓄積する権利が刑務所から病院、学校、そして後に工場へと拡張された18世紀後半に、規律はすでに技術的な閾値を越えていたと主 張していた[31](→「監視と処罰」)。彼の歴史分析において、フーコーは公開処刑の消滅とともに痛みが理性によって支配された社会における罰として徐々に排除されたと推論 した。 1970年代の修正技術を備えた近代刑務所は国家の法的権限の変化に根差していたのだった[31]。体罰に対する容認が減少する一方で、国家は観察などの より巧妙な処罰方法を施す権利を獲得した[31]。 フランスの社会学者アンリ・ルフェーヴルは都市空間とフーコーのパノプティコン刑務所に対する解釈を研究し、空間性が社会現象であるという結論に到達して いる。ルフェーヴルは、建築とはパノプティコンと人、モノとの関係にほかならないと主張した。都市研究においては、現在、マルク・シューレンブルクのよう な学者が、都市部に住む人間の間に異なる自己意識が生じると主張している[32]。 ウクライナ、ドネツクの工業用建物の壁面 1984年、マイケル・ラドフォードは映画『Nineteen Eighty-Four』で演出した映画的パノプティコンで国際的に注目されるようになった。画期的な監視小説『Nineteen Eighty-Four』(1949年)に登場するテレスクリーンについて、ジョージ・オーウェルはこう語っている。「ラドフォードの映画ではテレスク リーンは双方向であり、テレスクリーン装置が増え続ける世界においてオセアニアの市民は想像以上に監視されていた[34]。社会学者のデヴィッド・ライオ ンは『The Rise of Surveillance Society』(1994年)で、「現代の監視の中心となるものを要約する作業に適した単一のメタファーやモデルはないが、重要な手がかりは 『Nineteen Eighty Four』やベンサムのパノプティコンにある」と結論付けている[35]。 フランスの哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズは1990年のエッセイ『管理社会についてのあとがき』[36]で監視学という新たな分野を形成していた: 21 ドゥルーズは、管理社会が規律社会に取って代わろうとしていると論じていた。パノプティコンに関して、ドゥルーズは「囲いは型であるが......統制は 変調である」と論じた。ドゥルーズは、技術によって、学校、工場、刑務所、オフィスビルなどの物理的な囲いが、生産と消費を管理するために監視を拡張する 自己管理機械に取って代わられたと観察している。情報は現代経済における製品のように管理社会で循環し、将来の需要、ニーズ、リスクに関する未来志向のプ ロファイルやシミュレーションの絵が描かれることで意味のある監視の対象が探し出される[36]: 27。 1997年、トーマス・マティーセンは、マスメディアが社会に及ぼす影響を分析する際に、フーコーがパノプティコンのメタファーを使ったことを発展させて いる。彼は、放送テレビのようなマスメディアは、多くの人々に、自分の家から少数の人々を眺め、レポーターや有名人の生活を見つめる能力を与えたと主張し た。マスメディアはこうして規律社会を視聴者社会に変えた[37]。 1998年の風刺SF映画『トゥルーマンショー』では、主人公はやがて、自分でも知らないうちに自分の生活を24時間、世界中に放送しているリアリティテ レビ番組、オムニカム・エコスフィアから逃れられるようになる。しかし、2002年、ピーター・ウェイベルは、エンターテインメント産業はパノプティコン を脅威や罰としてではなく、「娯楽、解放、快楽」として捉えていると指摘する。コンテナのワンルームマンションに集団で住み、常に録画されることを許すエ ンデモル・エンタテインメントのテレビ番組「ビッグブラザー」を引き合いに、ワイベルはパノプティコンが大衆に「権力の快楽、サディズム、覗き見、展示、 スコポフィリア、ナルシズムの快楽」を提供すると主張している。2006年、ロンドンのショーディッチの住民は、CCTVの映像を生中継で見られるよう に、ショーディッチTVを利用できるようになった。このサービスによって住民は「何が起きているかを見たり、交通状況をチェックしたり、犯罪に目を光らせ たりすることができた」[38]。 2004年に出版された「Welcome to the Machine: Science, Surveillance, and the Culture of Control, Derrick Jensen and George Draffanはベンサムを「現代の監視の先駆者の一人」と呼び、彼のパノプティコン刑務所の設計がカリフォルニアのペリカンベイ州立刑務所など、現代の 超最大セキュリティ刑務所のモデルとして機能していると主張している[39]。 2015年の著書Dark Mattersにおいて、シモーヌ・ブラウンはベンサムがパノプティコン案を起草している間、貨物として奴隷を乗せた船で旅をしたことを指摘している。 On the Surveillance of Blacknessで、シモーヌ・ブラウンはベンサムがパノプティコン案を起草している間、貨物として奴隷を運ぶ船で旅をしたことに言及している。彼女 は、動産奴隷制の構造がパノプティコンの理論につきまとう、と主張する。ディディエ・ビゴの『バノプティコン』を引きながら、ブラウンは社会が権力の例外 主義によって支配されていると主張し、そこでは非常事態が永続的になり、ある集団がプロファイリングを通して決定された将来の潜在的な行動に基づいて排除 される[41]。 |

| Surveillance technology The metaphor of the panopticon prison has been employed to analyse the social significance of surveillance by closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras in public spaces. In 1990, Mike Davis reviewed the design and operation of a shopping mall, with its centralised control room, CCTV cameras and security guards, and came to the conclusion that it "plagiarizes brazenly from Jeremy Bentham's renowned nineteenth-century design". In their 1996 study of CCTV camera installations in British cities, Nicholas Fyfe and Jon Bannister called central and local government policies that facilitated the rapid spread of CCTV surveillance a dispersal of an "electronic panopticon". Particular attention has been drawn to the similarities of CCTV with Bentham's prison design because CCTV technology enabled, in effect, a central observation tower, staffed by an unseen observer.[42]: 249 |

監視技術 パノプティコン監獄のメタファーは、公共空間におけるCCTVカメラによる監視の社会的意義を分析するために用いられてきた。1990年、マイク・デイビ スは、集中管理室、CCTVカメラ、警備員を備えたショッピングモールの設計と運営を検討し、「ジェレミー・ベンサムの有名な19世紀の設計を堂々と盗用 している」という結論に至った。ニコラス・ファイフとジョン・バニスターは、1996年にイギリスの都市に設置されたCCTVカメラに関する研究で、 CCTV監視の急速な普及を促進した中央・地方政府の政策を「電子パノプティコン」のばらまきと呼んだ。特に,CCTVの技術が,事実上,見えない監視者 が配置された中央監視塔を可能にしたことから,ベンサムの監獄設計との類似性に注目が集まっている[42]: 249. |

| Employment and management Shoshana Zuboff used the metaphor of the panopticon in her 1988 book In the Age of the Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power to describe how computer technology makes work more visible. Zuboff examined how computer systems were used for employee monitoring to track the behavior and output of workers. She used the term 'panopticon' because the workers could not tell that they were being spied on, while the manager was able to check their work continuously. Zuboff argued that there is a collective responsibility formed by the hierarchy in the information panopticon that eliminates subjective opinions and judgements of managers on their employees. Because each employee's contribution to the production process is translated into objective data, it becomes more important for managers to be able to analyze the work rather than analyze the people.[43] Foucault's use of the panopticon metaphor shaped the debate on workplace surveillance in the 1970s. In 1981 the sociologist Anthony Giddens expressed scepticism about the ongoing surveillance debate, criticising that "Foucault's 'archaeology', in which human beings do not make their own history but are swept along by it, does not adequately acknowledge that those subject to the power ... are knowledgeable agents, who resist, blunt or actively alter the conditions of life."[42]: 39 The social alienation of workers and management in the industrialised production process had long been studied and theorised. In the 1950s and 1960s, the emerging behavioural science approach led to skills testing and recruitment processes that sought out employees that would be organisationally committed. Fordism, Taylorism and bureaucratic management of factories was still assumed to reflect a mature industrial society. The Hawthorne Plant experiments (1924–1933) and a significant number of subsequent empirical studies led to the reinterpretation of alienation: instead of being a given power relationship between the worker and management, it came to be seen as hindering progress and modernity.[44] The increasing employment in the service industries has also been re-evaluated. In Entrapped by the electronic panopticon? Worker resistance in the call centre (2000), Phil Taylor and Peter Bain argue that the large number of people employed in call centres undertake predictable and monotonous work that is badly paid and offers few prospects. As such, they argue, it is comparable to factory work.[45]: 15 The panopticon has become a symbol of the extreme measures that some companies take in the name of efficiency as well as to guard against employee theft. Time-theft by workers has become accepted as an output restriction and theft has been associated by management with all behaviour that include avoidance of work. In the past decades "unproductive behaviour" has been cited as rationale for introducing a range of surveillance techniques and the vilification of employees who resist them.[45]: x In a 2009 paper by Max Haiven and Scott Stoneman entitled Wal-Mart: The Panopticon of Time[46] and the 2014 book by Simon Head Mindless: Why Smarter Machines Are Making Dumber Humans, which describes conditions at an Amazon depot in Augsburg, it is argued that catering at all times to the desires of the customer can lead to increasingly oppressive corporate environments and quotas in which many warehouse workers can no longer keep up with demands of management.[47] |

雇用と管理 ショシャナ・ズボフは1988年の著書『スマート・マシンの時代に』でパノプティコンという比喩を使っている。コンピュータ技術がいかに仕事を可視化する かを説明するために、1988年の著書『In the Age of Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power』において、パノプティコンという比喩を使っている。ズボフは、コンピュータ・システムがどのように従業員監視に使われ、労働者の行動や生産高 を追跡しているかを調べた。彼女は「パノプティコン」という言葉を使った。労働者は自分が監視されていることを知ることができないが、管理者は彼らの仕事 を継続的にチェックすることができるからである。ズボフは、情報パノプティコンには階層によって形成される集団責任があり、管理者の従業員に対する主観的 な意見や判断を排除することができると主張した。生産プロセスに対する各従業員の貢献は客観的なデータに変換されるため、管理者は人を分析するよりも仕事 を分析できることが重要になるのである[43]。 フーコーがパノプティコンという比喩を使ったことで、1970年代の職場監視に関する議論が形成された。1981年に社会学者のアンソニー・ギデンズは現 在進行中の監視の議論について懐疑的な見方を示し、「人間が自分自身の歴史を作るのではなく、それに流されるというフーコーの『考古学』は、権力の対象と なる人々が...生活の条件に抵抗したり鈍ったり活発に変えたりする知識ある主体であることを適切に認めていない」と批判している[42]。 39 工業化された生産過程における労働者と経営者の社会的疎外は、長い間研究され理論化されてきた。1950年代と1960年代には、新興の行動科学的アプ ローチが、組織的にコミットする従業員を探し出す技能テストと採用プロセスにつながった。フォーディズム、テイラー主義、官僚主義的な工場経営は、まだ成 熟した産業社会を反映していると思われていました。ホーソン工場実験(1924-1933)とその後の相当数の実証的研究は疎外感の再解釈につながった。 労働者と経営者の間の与えられた力関係である代わりに、それは進歩と近代化を妨げるとみなされるようになった[44]。サービス産業における雇用の増加も 再評価された。電子パノプティコンに捕らわれた?Entrapped by the electronic panopticon? The Worker resistance in the call centre, 2000)において、フィル・テイラーとピーター・ベインは、コールセンターで雇用される多くの人々は、予測可能で単調な仕事を行い、賃金も低く、ほとん ど展望を提供しないと論じている。そのため、彼らは工場労働に匹敵すると主張している[45]。 15 パノプティコンは、効率性の名の下に、従業員の盗難を防ぐために一部の企業がとっている極端な措置の象徴となっています。労働者による時間泥棒は生産性の 制限として受け入れられ、盗難は経営陣によって仕事の回避を含むすべての行動と結びつけられてきた。過去数十年の間、「非生産的な行動」は様々な監視技術 を導入し、それに抵抗する従業員を中傷する根拠として引用されてきた[45]:x マックス・ハイヴンとスコット・ストーンマンによる2009年の論文では、ウォルマートと題されている。時のパノプティコン[46]とサイモン・ヘッドに よる2014年の著書「Mindless: アウグスブルクのアマゾンの倉庫での状況を描いたサイモン・ヘッドによる「Why Smarter Machines Are Making Dumber Humans」では、顧客の欲望に常に応えることは、多くの倉庫労働者がもはや経営者の要求についていくことができない、ますます抑圧的な企業環境とノル マにつながりかねないと主張されている[47]。 |

| Social media The concept of panopticon has been referenced in early discussions about the impact of social media. The notion of dataveillance was coined by Roger Clarke in 1987, since then academic researchers have used expressions such as superpanopticon (Mark Poster 1990), panoptic sort (Oscar H. Gandy Jr. 1993) and electronic panopticon (David Lyon 1994) to describe social media. Because the controlled is at the center and surrounded by those who watch, early surveillance studies treat social media as a reverse panopticon.[48] In modern academic literature on social media, terms like lateral surveillance, social searching, and social surveillance are employed to critically evaluate the effects of social media. However, the sociologist Christian Fuchs treats social media like a classical panopticon. He argues that the focus should not be on the relationship between the users of a medium, but the relationship between the users and the medium. Therefore, he argues that the relationship between the large number of users and the sociotechnical Web 2.0 platform, like Facebook, amounts to a panopticon. Fuchs draws attention to the fact that use of such platforms requires identification, classification and assessment of users by the platforms and therefore, he argues, the definition of privacy must be reassessed to incorporate stronger consumer protection and protection of citizens from corporate surveillance.[48] |

ソーシャルメディア ソーシャルメディアの影響に関する初期の議論では、パノプティコンの概念が参照されてきた。データ監視の概念は1987年にRoger Clarkeによって作られ、それ以来、学術研究者はスーパーパノプティコン(Mark Poster 1990)、パノプティックソート(Oscar H. Gandy Jr. 1993)、電子パノプティコン(David Lyon 1994)などの表現を使って、ソーシャルメディアを表現している。管理された者が中心にいて、見る者に囲まれているので、初期の監視研究はソーシャル・ メディアを逆パノプティコンとして扱っている[48]。 ソーシャルメディアに関する現代の学術文献では、横方向の監視、社会的探索、社会的監視といった用語が、ソーシャルメディアの効果を批判的に評価するため に採用されています。しかし、社会学者であるクリスチャン・フックスは、ソーシャルメディアを古典的なパノプティコンのように扱っている。彼は、メディア の利用者間の関係ではなく、利用者とメディアの関係に焦点を当てるべきだと主張しています。したがって、多数のユーザーとFacebookのような社会技 術的なWeb 2.0プラットフォームとの関係は、パノプティコンに等しいと主張するのである。フックスはこのようなプラットフォームの利用にはプラットフォームによる ユーザーの識別、分類、評価が必要であることに注目し、それゆえプライバシーの定義をより強力な消費者保護と企業の監視からの市民の保護を組み込むために 見直す必要があると主張している[48]。 |

| The arts and literature According to professor Donald Preziosi, the panopticon prison of Bentham resonates with the memory theatre of Giulio Camillo, where the sitting observer is at the centre and the phenomena are categorised in an array, which makes comparison, distinction, contrast and variation legible.[49] Among the architectural references Bentham quoted for his panopticon prison was Ranelagh Gardens, a London pleasure garden with a dome built around 1742. At the center of the rotunda beneath the dome was an elevated platform from which a 360 degrees panorama could be viewed, illuminated through skylights.[50] Professor Nicholas Mirzoeff compares the panopticon with the 19th-century diorama, because the architecture is arranged so that the seer views cells or galleries.[51] In 1854 the work on the building that was to house the Royal Panopticon of Science and Art in London was completed. The rotunda at the centre of the building was encircled with a 91 meter procession. The interior reflected the taste for religiously meaningless ornament and emerged out of the contemporary taste for recreational learning. Visitors of the Royal Panopticon of Science and Art could view changing exhibits, including vacuum flasks, a pin making machine, and a cook stove. However, a competitive entertainment industry emerged in London[52] and despite the varying music, the large fountains, interesting experiments, and opportunities for shopping,[53] two years after opening the amateur science panopticon project closed.[54] Panopticon principle lies as the central idea in the plot of We (Russian: Мы, romanized: My), a dystopian novel by Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin, written 1920–1921. Zamyatin goes beyond a concept of a single prison and projects panopticon principles to the whole society where people live in buildings with fully transparent walls. Foucault's theories positioned Bentham's panopticon prison in the social structures of 1970s Europe. This led to the widespread use of the panopticon in literature, comic books, computer games, and TV series.[55] In Doctor Who, an abandoned panopticon was featured.[56] In the 1981 the novella Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Gabriel García Márquez on the murder of Santiago Nasar, chapter four is written with a view on the characters through the panopticon of Riohacha.[57] Angela Carter, in her 1984 novel Nights at the Circus, linked the panopticon of Countes P to a "perverse honeycomb" and made the character the matriarchal queen bee.[58] In the 2011 TV series, Person of Interest, Foucault's panopticon is used to grasp the pressure under which the character Harold Finch suffers in the post-9/11 United States of America.[59] In the manga series Usogui by author Sako Toshio, an abandoned panopticon is the main setting of the Air Poker arc. |

芸術と文学 ドナルド・プレツィオージ教授によれば、ベンサムのパノプティコン監獄はジュリオ・カミッロの記憶劇場と共鳴しており、そこでは座っている観察者が中心に いて現象が配列に分類され、比較、区別、コントラスト、変化が読みやすくなる[49] ベンサムがパノプティコン監獄として引用した建築物の中には、1742年に建てられたロンドンのドーム付き遊園地のラネラージ・ガーデンというものもあっ た[50]。ドームの下のロタンダの中央には、天窓を通して照らされた360度のパノラマを見ることができる高架があった[50]。ニコラス・ミルゾエフ 教授は、パノプティコンを19世紀のジオラマと比較しているが、それは建築が監視者が細胞やギャラリーを見るように配置されているためである[51]。 1854年、ロンドンにある王立科学芸術パノプティコンが入る建物の工事が完了した。建物の中央のロタンダは91メートルの行列で囲まれていた。内装は、 宗教的に意味のない装飾を好み、娯楽的な学問を好む現代の風潮を反映して出現した。科学と芸術の王立パノプティコンでは、魔法瓶、ピンを作る機械、調理用 コンロなど、展示物の入れ替わりを見ることができた。しかし、ロンドンでは競争の激しい娯楽産業が出現し[52]、変化する音楽、大きな噴水、興味深い実 験、買い物の機会にもかかわらず、開館から2年後にアマチュア科学のパノプティコン計画は閉鎖された[53]。 パノプティコン原理は、ロシアの作家エフゲニー・ザミャーチンが1920年から1921年にかけて書いたディストピア小説『われら』(ロシア語:Мы、 ローマ字:My)の筋の中心思想として存在する。ザミャーチンは、一つの監獄という概念を超えて、壁が完全に透明な建物に人々が住むというパノプティコン の原理を社会全体に投影している。 フーコーの理論は、ベンサムのパノプティコン監獄を1970年代のヨーロッパの社会構造の中に位置づけた。ドクター・フー』では廃墟となったパノプティコ ンが登場する[56]。 1981年にガブリエル・ガルシア・マルケスがサンティアゴ・ナサールの殺害を描いた小説『Chronicle of a Death Foretold』の第4章はリオハッチャのパノプティコンを通して登場人物を見るように書かれる[57]。 アンジェラ・カーターは1984年の小説『サーカスの夜』の中で、カウンテス・Pのパノプティコンを「倒錯したハニカム」に結びつけ、そのキャラクターを 母系制の女王蜂としている[57]。 [58] 2011年のテレビシリーズ『パーソン・オブ・インタレスト』では、フーコーのパノプティコンが、登場人物のハロルド・フィンチが9/11後のアメリカ合 衆国で苦しんでいる圧力を把握するために使われている。 59] 作者の佐孝敏夫による漫画シリーズ『うそつき』では、廃墟のパノプティコンがエアポーカー編の主要舞台となる。 |

| Atrium (architecture) Architecture Consumerism Landscapes of power Mass surveillance PRISM (surveillance program) Right to privacy Social facilitation Sousveillance Urban planning Total institution Torture |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panopticon |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| 600px |

|

| Plan of Jeremy

Bentham's panopticon prison, drawn by Willey Reveley

in 1791 |

|

| A drawing of a

panopticon prison by Willey Reveley, circa 1791. The cells are marked

with (H); a skylight (M) was to provide light and ventilation.[Bentham

Papers 119a/119. UCL Press. p. 137.] |

|

| Elevated view of

the panopticon prison, by Reveley 1791.[Bentham Papers 119a/119. UCL

Press. p. 139.] |

|

|

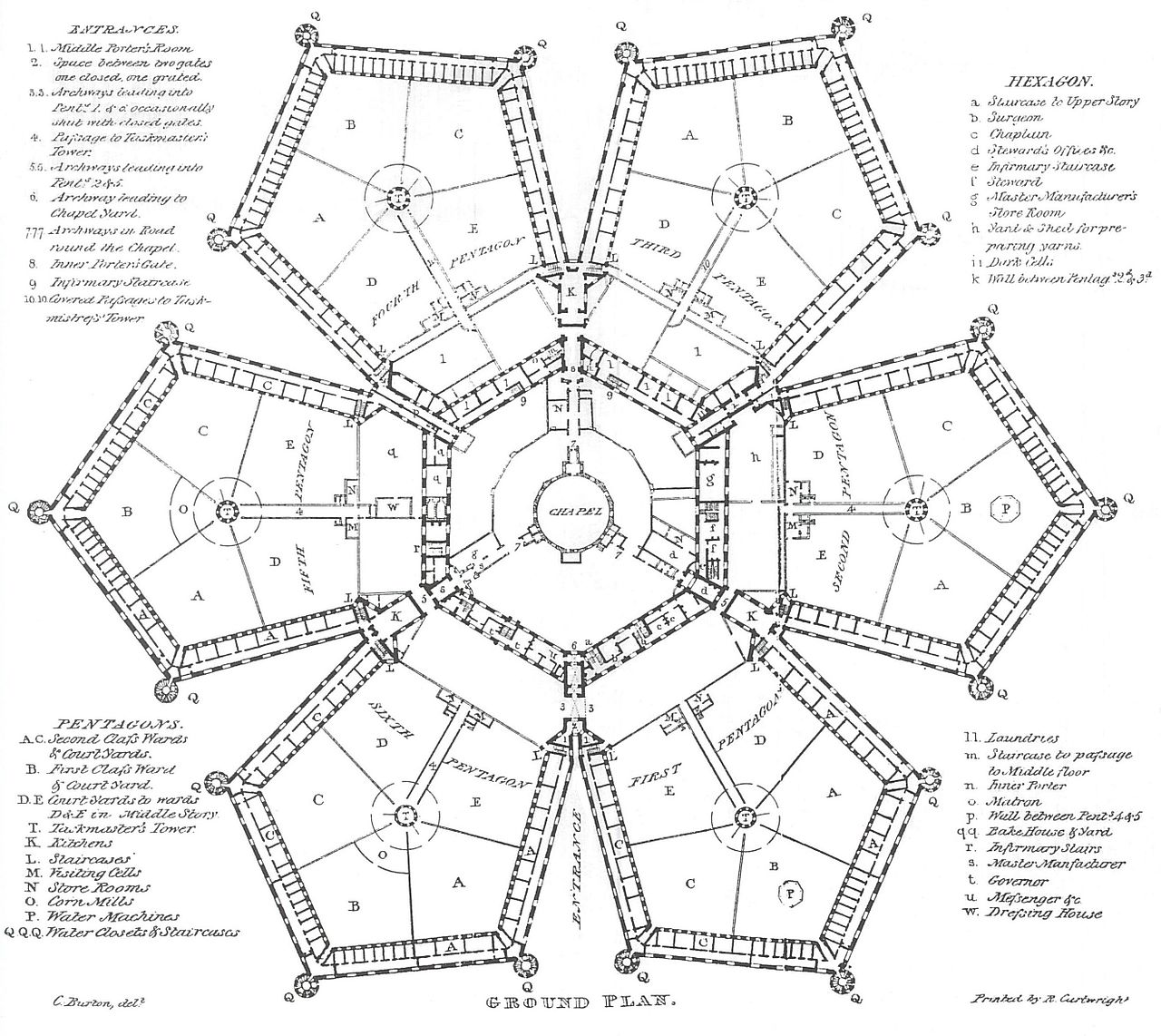

Plan of Millbank

Prison: six pentagons with a tower at the centre are arranged around a

chapel. - Millbank Prison was a prison in Millbank, Westminster,

London, originally constructed as the National Penitentiary, and which

for part of its history served as a holding facility for convicted

prisoners before they were transported to Australia. It was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890. |

|

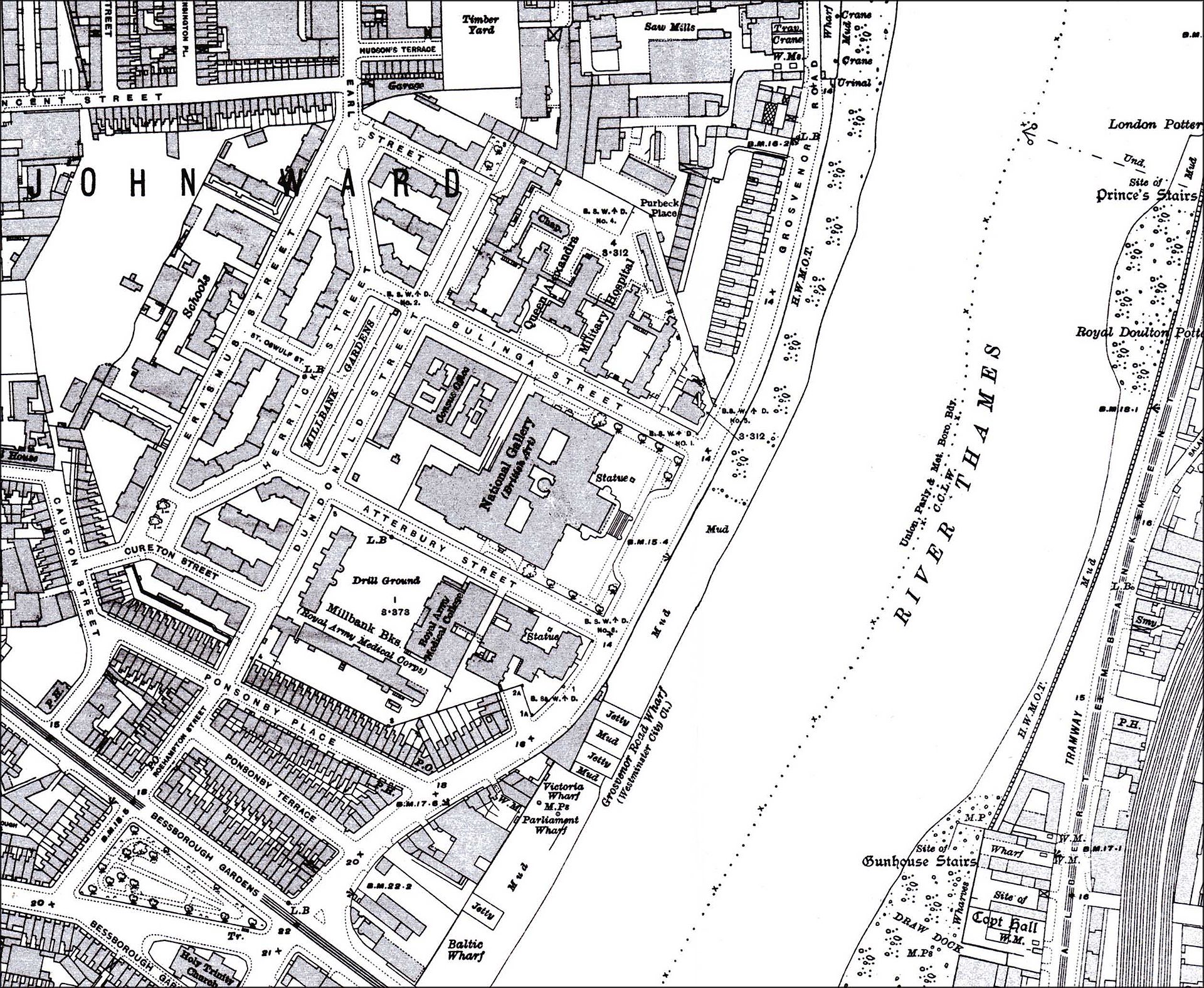

上掲の獄舎は1890年に閉鎖されて以

降、1916年の地図には、上掲のような獄舎のプランは見受けられない:The site of the prison in 1916, after

redevelopment. Its outline is still visible in the pattern of streets

and buildings. |

|

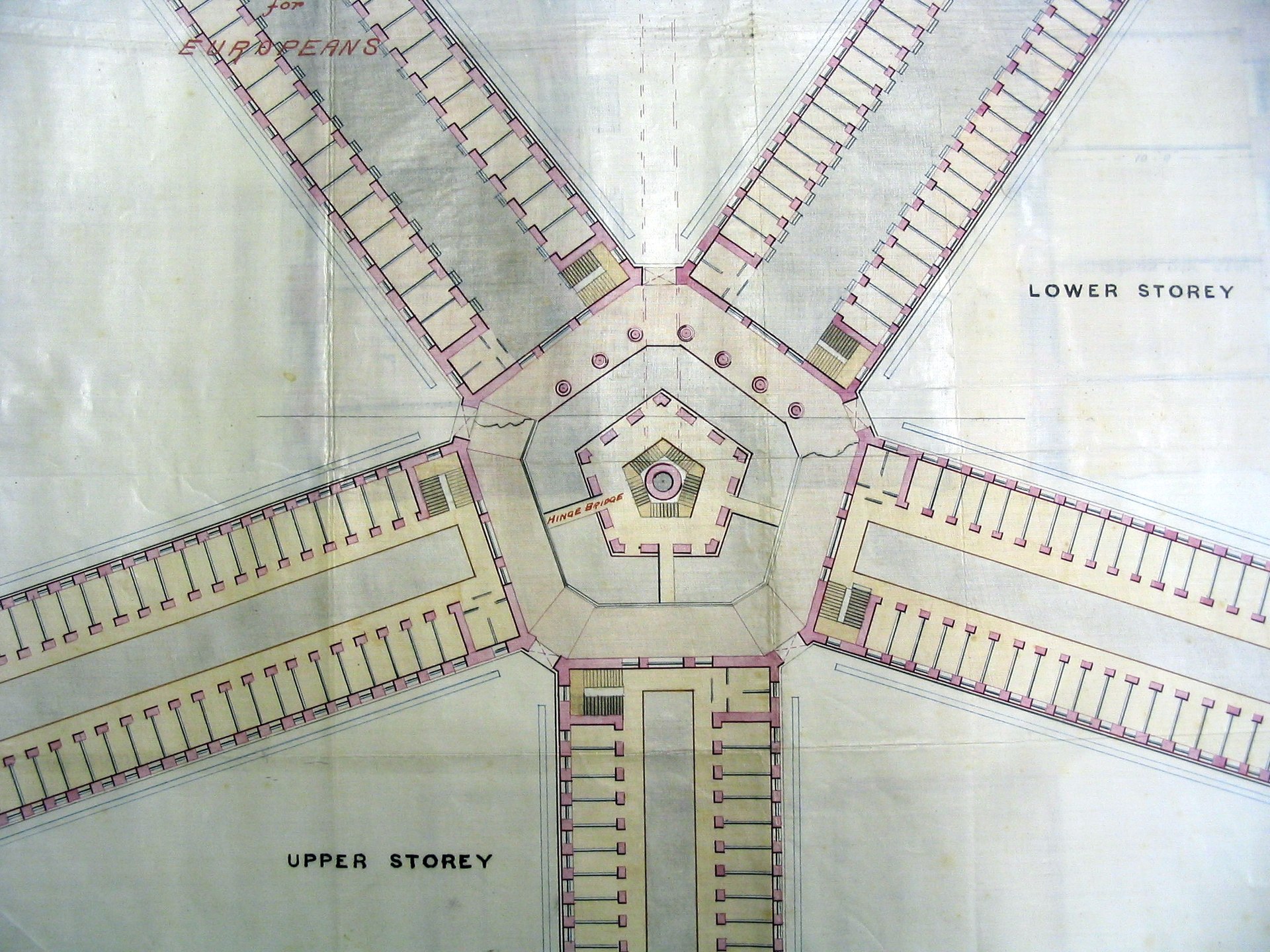

An 1880s architectural drawing by John Frederick Adolphus McNair depicting a proposed prison at Outram, Singapore that was never built.(設計図のみ) |

|

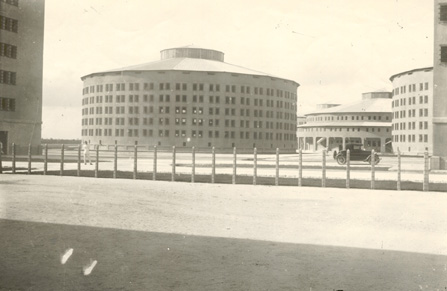

The Presidio

Modelo was a "model prison" with panopticon design, built on Isla

de Pinos (now the Isla de

la Juventud) in Cuba. It is located in the suburban quarter of

Chacón, Nueva Gerona. The prison was built under the President-turned-dictator Gerardo Machado between 1926 and 1928.[1] The five circular blocks, with cells constructed in tiers around central observation posts, were built with the capacity to house up to 2,500 prisoners in humane conditions. |

|

The Presidio

Modelo was a "model prison" with panopticon design, built on Isla

de Pinos (now the Isla de

la Juventud) in Cuba. It is located in the suburban quarter of

Chacón, Nueva Gerona. フィデル・カストロや弟のラウルもモンカダ・バラック襲撃の罪で服役したが、革命後も使われ、1967年に閉鎖されたという:"After Fidel Castro's revolutionary triumph in 1959, Presidio Modelo remained in operation. By 1961, due to the overcrowded conditions (up to 4000 prisoners at one time), it was the site of various riots and hunger strikes, especially just before the Bay of Pigs invasion, when orders were given to line the tunnels underneath the entire prison with several tons of TNT.[4] Prominent Cuban political prisoners such as Armando Valladares,[5] Roberto Martín Pérez,[6] and Pedro Luis Boitel[7] were held there at one point or another during their respective incarcerations. It was permanently closed by the government in 1967.[1]" |

|

The Presidio Modeloの内景 |

| Illinois State

Penitentiary at Stateville, ner Joliet, Illinosis |

|

|

Bentham's 1812 industry-house for 2000 persons. |

|

Closed circuit TV monitoring at the Central Police Control Station, Munich, 1973. |

|

Modern scenery of

a Chinese town in image(社会全体のパノプティコン化) 日本語の監視カメラの英訳は、CCTV(Closed-circuit television)あるいはビデオ監視システム(video surveillance)といわれる。 その歴史は古く、ソビエトにおけるテレビシステムの開発にまで、遡れるという。またナチスドイツのV-2ロケットの発射のモニター監視としてジーメンスも のが使われたという。米国ではベリコンというシステムが1949年から商用として発売されるようになる。 "An early mechanical CCTV system was developed in June 1927 by Russian physicist Léon Theremin[12] (cf. Television in the Soviet Union). Originally requested by the Soviet of Labor and Defense, the system consisted of a manually-operated scanning-transmitting camera and wireless shortwave transmitter and receiver, with a resolution of a hundred lines. Having been commandeered by Kliment Voroshilov, Theremin's CCTV system was demonstrated to Joseph Stalin, Semyon Budyonny, and Sergo Ordzhonikidze, and subsequently installed in the courtyard of the Moscow Kremlin to monitor approaching visitors.[12] Another early CCTV system was installed by Siemens AG at Test Stand VII in Peenemünde, Nazi Germany in 1942, for observing the launch of V-2 rockets.[13] In the U.S. the first commercial closed-circuit television system became available in 1949, called Vericon. Very little is known about Vericon except it was advertised as not requiring a government permit.[14]" 現在は、インターネットに接続するIPカメラの存在がある;"A growing branch in CCTV is internet protocol cameras (IP cameras). It is estimated that 2014 was the first year that IP cameras outsold analog cameras.[127] IP cameras use the Internet Protocol (IP) used by most Local Area Networks (LANs) to transmit video across data networks in digital form. IP can optionally be transmitted across the public internet, allowing users to view their cameras remotely on a computer or phone via an internet connection. For professional or public infrastructure security applications, IP video is restricted to within a private network or VPN.[128] IP cameras are considered part of the Internet of Things (IoT) and have many of the same benefits and security risks as other IP-enabled devices.[129]" |

|

小菅にある、東京拘置所(上空から) |

|

小菅にある、東京拘置所(地上から) |

| 現代のパノプティコン、東海道山陽新幹

線(N700S)——車内の監視カメラ(JRの用語では「防犯カメラ」という)- Closed-circuit

television. |

|

|

『修道女と修道士』 (1591)—

コルネリス・ファン・ハールレム(Cornelis

Corneliszoon van Haarlem,

1562-1638)——もしマニエリスムの時代に監視カメラがあるとこのような映像も手に入るかも。「16世紀のヨーロッパは、宗教や科学、政治や経済

など、社会や思想のあらゆる面から大きな動揺と不安の時代を迎え、精神的危機に直面していた。とくに前世紀以来、文芸復興の主導的役割を果たしたイタリア

では、それらを典型的に美術発展に反映している。調和・均衡・安定を重んじる規範的理想美に対する反発から、自然の模倣を無視して主知的ともいえる主観主

義の傾向を強めていく。ラファエッロの晩年やミケランジェロの後期作品の影響も受けて、その様式は、洗練された技巧に加え、錯綜(さくそう)した空間構

成、ゆがんだ遠近法、強い調子の明暗法を駆使して、幻想的な寓意(ぐうい)的表現、異常なまでにゆがめられたプロポーションや激越な運動感の描出、幻惑す

るような非現実的色彩法などをその特色とする」ニッポニカ)参照文献:若桑みどり『マニエリスム芸術論』

筑摩書房,1994年 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panopticon |

|

| A drawing of the interior design, when The Royal Panopticon of Science and Art opened in 1854 |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆