プラグマティズム

pragmatism

パース、ウィリアム・ジェームズ、デュー

イ

解説:池田光穂

プラグマティック・マクシム(プラグマティズムの金言) ——チャールズ・サンダー・パースの思想をウィリアム・ジェイムズ(1960:37; William James 1907:46-47)がまとめたもの。

「ある対象について私たちの考えを完全に明晰にするために、その対象が実際どんな結果をふくんでいるか、——いかなる感覚がその対象から期 待されるか、そしていかなる反応を用意しなければならないか、を考えさえすればよい。こうした結果がすぐに生じるものであろうと、ずっと後におこるもので あろうと、こうした結果について私たちの概念が、その対象に関する私たちの概念のすべてである」(魚津 2006:58)

"A glance at the history of the idea will show you still better

what pragmatism means. The term is derived from the same Greek word [pi

rho alpha gamma mu alpha], meaning action, from which our words

'practice' and 'practical' come. It was first introduced into

philosophy by Mr. Charles Peirce in 1878. In an article entitled 'How

to Make Our Ideas Clear,' in the 'Popular Science Monthly' for January

of that year [Footnote: Translated in the Revue Philosophique for

January, 1879 (vol. vii).] Mr. Peirce, after pointing out that our

beliefs are really rules for action, said that to develope a thought's

meaning, we need only determine what conduct it is fitted to produce:

that conduct is for us its sole significance. And the tangible fact at

the root of all our thought-distinctions, however subtle, is that there

is no one of them so fine as to consist in anything but a possible

difference of practice. To attain

perfect clearness in our thoughts of an object, then, we need only

consider what conceivable effects of a practical kind the object may

involve—what sensations we are to expect from it, and what reactions we

must prepare. Our conception of these effects, whether immediate or

remote, is then for us the whole of our conception of the object, so

far as that conception has positive significance at all." -

source: PRAGMATISM:

A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, By William James.

魚津郁夫(2006:13)は『プラグマ ティズムの思想』のなかで、時間を越えた3名のプラグマティストに共通する非常に「実用主義的」——プ ラグマティズムの翻訳用語 としてこのような表現があった—な発想を次のように書いている。

1)ウィリアム・ジェイムズは、それがどんな観念であっても、それを信じることが宗教的な慰めを得るのであれば「その場かぎりにおいて」こ れを心理として認めなければならない。そのような真理観を提供する。

2)リチャード・ローティは、多元主義からそれぞれの民族の人たちは自分たちの文化を基礎に生活しながら「強制なき合意」を目指した対話を めざすべきだとする。そのような実践観を提供する。

3)チャールズ・サンダー・パースは、プラグマティズムのなかに可謬主義(かびゅう・しゅぎ)の伝統を見出した。可謬(かびゅ)とは「誤り をおこす可能性」のことであるので、この考え方(=可謬主義)は、我々の認識能力には、限界があるために、誤謬(ごびゅう=誤りのこと)を可能性をもって いるという、プラグマティズム独特の認識論をもっていることを指摘した。

ここで、ジェイムズは……、ローティだ と……、パースは……と、いうふうに試験を覚えるように「プラグマティズム」を分かろうとすること自体 が、じつは「最もプラグマティックではないのだ!」ここで、プラグマティックであることは、プラグマティックに、今、ここでなんとか、理解しようとする努力のことであり、明日になれば修正 が必要になるかもしれないが、いまわかる情報から、「プラグマティズム」を暫定的に理解してしまうことなのだ。

この3人3様のプラグマティズムの指摘 は、僕たちは一見バラバラのように思えてしまう。しかし、プラグマティストならば、ここで諦めない。3つ の間に、共通しているものがある、という僕のことばを信用して、さらに思考を続けることができる。つまり、自分の理解の範囲で、整理し理解した範囲で、プ ラグマティズムをとりあえず定義しておく。そうすれば、プラグマ ティズムとは、あることをそうであると信じて、論理的にもまた経験的にも矛盾をおこさない説明体系を、その時点でのベストなものとして理解する態度の ことである。また、プラグマティズムは、別の推論や他の情報が提供されて、そのことについて自分で考え納得のいく説明が与えられたら「いつでも思考を現在持ち得る最良 の考え方にであるものに修正してよい」という考え方でもある。

このような発想の特徴は、経験主義的で、

また体系化に対する信頼をおかない発想である。『アメリカの民主政治』においてトクヴィルは、アメリカ

の哲学には体系的な思考が占めていることは僅かであると指摘しているが、アメリカで生まれたプラグマティズムには、確かに体系化に対する警戒心に満ちてい

る。

なかなか、便利な考え方だが、プラグマ ティズムにもいくつか落とし穴がある。パースの可謬主義に基づいて「いつでも修正をおこなうことに吝かで はない」というやり方は、その落とし穴を回避する一つの方法である。ただし、可謬主義も、乗り捨ててしまった考え方に対する批判的反省がないと、また再度 同じ誤りを犯す可能性がある。プラグマティズムは、いま信じているもの(n)がうまくいかなかった場合、修正(n+1)を容易に受け入れる考え方だが、他 方で、それまでの考え方(n-1)がなぜそのような誤りであったのかについて、吟味するという思考的態度がどうしても(現状肯定あるいは未来志向のため に)欠如気味になる。プラグマティズムにみられる、帰結主義(consequentialism)も、なぜ今の状態がうまくいっているのか、何も問題がな い時には、その思索の探究を現状満足に留めてしまう可能性がある——現状満足が良いか悪いかは時と場合による。帰結主義は、行為の道徳的判断において、そ の行為がうむ結果(=帰結)を考慮に入れるたちばである。先のジェイムズの「宗教的な慰め」がその帰結だからである。

また、可謬主義を思考の方法に組み込んで

いることは、このような探究をつみかさねていけば、リアルな認識に到達できるという信念が、その背景に

あるとも考えることができる。それが実在説(realism)であり、リアルなもの導かれていずれ共通した結論に到達できるという信念である。しかし、そ

れは探究によって証明できるのではなく、プラグマティズムがもつ探究の前提である。このリアリズムは、究極という想定を素朴に信じるので、揺るぎのない超

越論的なもの(=神や真理)などを容易に実在として内包してしまうという論理上の特色——Transcendentalism。このリアリズムは、先に指

摘したように体系性を持ちにくいために、プラグマティズムには「直観(intuition)」を重んじる知的伝統とも関連している。

その意味でプラグマティズムとよく似てい るが、若干異なる点で、まぎらわしいのが功利主義 (utilirarianism, ユーティリタリアニズム)で ある。後者は、歴史的にはより古くイギリスのベンサムやJ・S・ミルのことをさす。

プラグマティズムは、問題解決に取り組む 姿勢よりも、いつもどれがよいだろうかという解釈に陥る可能性を批判する立場もある。

「アメリカのプラ グマティズムは、プラトンによって開始された西洋哲学における対話でくりかえし議論された諸問題への解決を提起しようとする哲学的伝統に属するというより も、むしろ、ある特定 の歴史的瞬間におけるアメリカの自己弁明を試みるための、たえまのない文化的批評ないし解釈群なのである」——コーネル・ウェスト『哲学を回避するアメリ カ知識人』(2014:15)(→「プラグマティズム批判」)

ユタ大学で講演するコーネル・ウエスト (2008年)——"prophetic pragmatist"

| Pragmatism

is a philosophical tradition that views language and thought as tools

for prediction, problem solving, and action, rather than describing,

representing, or mirroring reality. Pragmatists contend that most

philosophical topics—such as the nature of knowledge, language,

concepts, meaning, belief, and science—are best viewed in terms of

their practical uses and successes. Pragmatism began in the United States in the 1870s. Its origins are often attributed to philosophers Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and John Dewey. In 1878, Peirce described it in his pragmatic maxim: "Consider the practical effects of the objects of your conception. Then, your conception of those effects is the whole of your conception of the object."[1] |

プラグマティズムは、言語や思考を現実を描写、表現、反映するものでは

なく、予測、問題解決、行動のための道具としてとらえる哲学の伝統である。プラグマティストは、知識の本質、言語、概念、意味、信念、科学など、ほとんど

の哲学的なトピックは、その実用的な用途や成功という観点からとらえるのが最善であると主張する。 プラグマティズムは1870年代に米国で始まった。その起源は、哲学者のチャールズ・サンダース・パース、ウィリアム・ジェームズ、ジョン・デューイに帰 されることが多い。1878年、パースは自身のプラグマティックな格言で次のように述べている。「あなたが考えた対象の実用的な効果を考慮しなさい。そう すれば、その効果に対するあなたの考えが、その対象に対するあなたの考えのすべてとなる。」[1] |

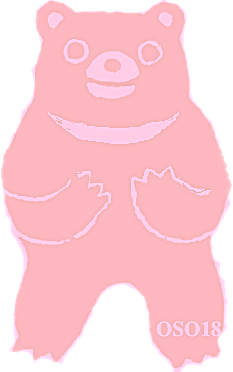

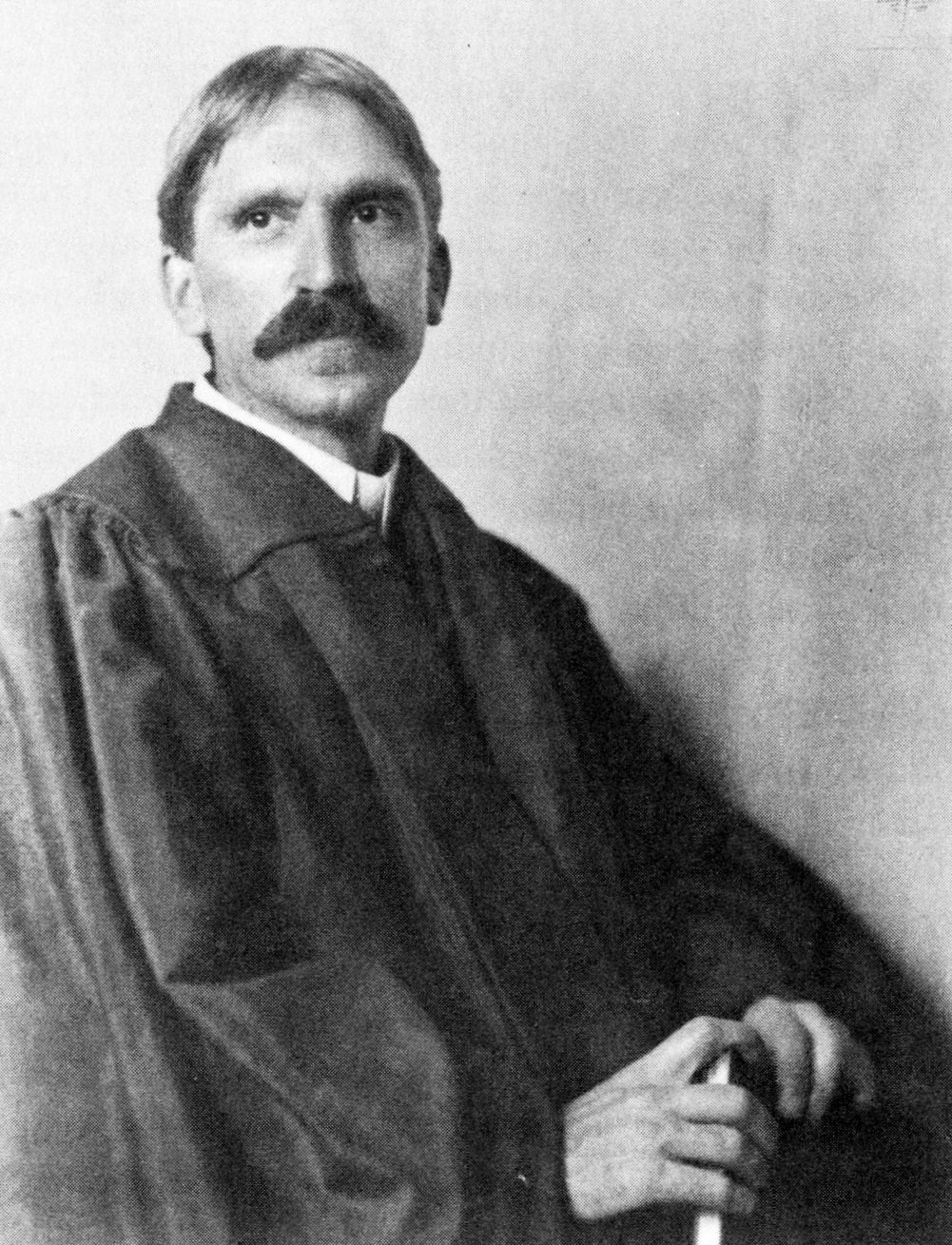

Origins Charles Peirce: the American polymath who first identified pragmatism Pragmatism as a philosophical movement began in the United States around 1870.[2] Charles Sanders Peirce (and his pragmatic maxim) is given credit for its development,[3] along with later 20th-century contributors, William James and John Dewey.[4] Its direction was determined by The Metaphysical Club members Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and Chauncey Wright as well as John Dewey and George Herbert Mead. The word "pragmatic" has existed in English since the 1500s, a word borrowed from French and ultimately derived from Greek via Latin. The Greek word pragma, meaning business, deed or act, is a noun derived from the verb prassein, to do.[5] The first use in print of the name pragmatism was in 1898 by James, who credited Peirce with coining the term during the early 1870s.[6] James regarded Peirce's "Illustrations of the Logic of Science" series—including "The Fixation of Belief" (1877), and especially "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" (1878)—as the foundation of pragmatism.[7][8] Peirce in turn wrote in 1906[9] that Nicholas St. John Green had been instrumental by emphasizing the importance of applying Alexander Bain's definition of belief, which was "that upon which a man is prepared to act". Peirce wrote that "from this definition, pragmatism is scarce more than a corollary; so that I am disposed to think of him as the grandfather of pragmatism". John Shook has said, "Chauncey Wright also deserves considerable credit, for as both Peirce and James recall, it was Wright who demanded a phenomenalist and fallibilist empiricism as an alternative to rationalistic speculation."[10] Peirce developed the idea that inquiry depends on real doubt, not mere verbal or hyperbolic doubt,[11] and said that, in order to understand a conception in a fruitful way, "Consider the practical effects of the objects of your conception. Then, your conception of those effects is the whole of your conception of the object",[1] which he later called the pragmatic maxim. It equates any conception of an object to the general extent of the conceivable implications for informed practice of that object's effects. This is the heart of his pragmatism as a method of experimentational mental reflection arriving at conceptions in terms of conceivable confirmatory and disconfirmatory circumstances—a method hospitable to the generation of explanatory hypotheses, and conducive to the employment and improvement of verification. Typical of Peirce is his concern with inference to explanatory hypotheses as outside the usual foundational alternative between deductivist rationalism and inductivist empiricism, although he was a mathematical logician and a founder of statistics.[citation needed] Peirce lectured and further wrote on pragmatism to make clear his own interpretation. While framing a conception's meaning in terms of conceivable tests, Peirce emphasized that, since a conception is general, its meaning, its intellectual purport, equates to its acceptance's implications for general practice, rather than to any definite set of real effects (or test results); a conception's clarified meaning points toward its conceivable verifications, but the outcomes are not meanings, but individual upshots. Peirce in 1905 coined the new name pragmaticism "for the precise purpose of expressing the original definition",[12] saying that "all went happily" with James's and F. C. S. Schiller's variant uses of the old name "pragmatism" and that he nonetheless coined the new name because of the old name's growing use in "literary journals, where it gets abused". Yet in a 1906 manuscript, he cited as causes his differences with James and Schiller[13] and, in a 1908 publication,[14] his differences with James as well as literary author Giovanni Papini. Peirce regarded his own views that truth is immutable and infinity is real, as being opposed by the other pragmatists, but he remained allied with them about the falsity of necessitarianism and about the reality of generals and habits understood in terms of potential concrete effects even if unactualized.[14] Pragmatism enjoyed renewed attention after Willard Van Orman Quine and Wilfrid Sellars used a revised pragmatism to criticize logical positivism in the 1960s. Inspired by the work of Quine and Sellars, a brand of pragmatism known sometimes as neopragmatism gained influence through Richard Rorty, the most influential of the late 20th century pragmatists along with Hilary Putnam and Robert Brandom. Contemporary pragmatism may be broadly divided into a strict analytic tradition and a "neo-classical" pragmatism (such as Susan Haack) that adheres to the work of Peirce, James, and Dewey.[citation needed] |

起源 チャールズ・パース:プラグマティズムを最初に認識したアメリカの多才な人物 哲学運動としてのプラグマティズムは、1870年頃にアメリカで始まった[2]。チャールズ・サンダース・パース(と彼のプラグマティックな格言)は、後 の20世紀の貢献者であるウィリアム・ジェイムズとジョン・デューイとともに、その発展の功績を認められている[3]。その方向性は、形而上学クラブのメ ンバーであるチャールズ・サンダース・パース、ウィリアム・ジェイムズ、チョーンシー・ライト、ジョン・デューイ、ジョージ・ハーバート・ミードによって 決定された[4]。 プラグマティック」という言葉は1500年代から英語に存在し、フランス語から借用したもので、最終的にはラテン語を経由してギリシャ語に由来する。ギリ シャ語で事業、行為、行動を意味するpragmaは、動詞prasseinのdoから派生した名詞である[5]。プラグマティズムという名称が印刷物で初 めて使われたのは1898年、ジェイムズによるもので、ジェイムズは1870年代初頭にパースがこの言葉を作ったと信じている。 [6]ジェイムズは、『信念の固定化』(1877年)、特に『我々の考えを明確にする方法』(1878年)を含む、パースの『科学の論理の図解』シリーズ をプラグマティズムの基礎とみなした[7][8]。パースは「この定義からすれば、プラグマティズムは従属的なものにすぎない。ジョン・シュックは「チャ ウンシー・ライトもまたかなりの称賛に値する。ペイスとジェイムズの両名が回想しているように、合理主義的な思索に代わるものとして現象論的で可謬主義的 な経験論を要求したのはライトだったからである」と述べている[10]。 パースは、探究は単なる言葉による疑いや大げさな疑いではなく、本当の疑いに依存するという考えを発展させ[11]、実りある方法で概念を理解するために は、「あなたの概念の対象の実際的な効果を考えなさい。そうすれば、それらの効果についてのあなたの観念が、その対象についてのあなたの観念の全体であ る」[1]と述べ、後にこれをプラグマティック・マキシムと呼んだ。この格言は、ある対象に関するいかなる概念も、その対象がもたらす影響の、情報に基づ いた実践にとって考えられる一般的な意味合いの範囲と等しくするものである。これは、考えられる確認可能な状況と確認不可能な状況の観点から概念に到達す る実験的な精神的反省の方法としての彼のプラグマティズムの核心であり、説明的仮説の生成に適した方法であり、検証の採用と改善に資する方法である。彼は 数理論理学者であり、統計学の創始者でもあったが、演繹主義的合理主義と帰納主義的経験主義の間の通常の基礎的選択肢の外側にある説明仮説への推論への関 心が、ペアーズの典型的なものである[要出典]。 パースは自身の解釈を明確にするためにプラグマティズムについて講義し、さらに執筆した。考えうるテストという観点から概念の意味を構成する一方で、パー スは、概念は一般的なものであるため、その意味、その知的な趣旨は、現実の効果(またはテスト結果)の明確な集合というよりも、むしろ一般的な実践に対す るその受容の意味合いと等しいことを強調した。パースは1905年にプラグマティシズムという新しい名称を「元の定義を表現する正確な目的のために」作り 出し[12]、ジェイムズとF.C.S.シラーが「プラグマティズム」という古い名称を変化させて使うことで「すべてがうまくいった」と述べ、それにもか かわらず新しい名称を作り出したのは、古い名称が「濫用される文芸誌」で使われるようになってきたからだと述べている。しかし、1906年の原稿では、 ジェイムズやシラーとの相違[13]、1908年の出版物では、ジェイムズや文学者ジョヴァンニ・パピーニとの相違[14]を原因として挙げている。ペイ スは、真理は不変であり、無限は実在するという自身の見解を他のプラグマティストたちから反対されているとみなしていたが、必然主義の偽りや、たとえ実現 されていなくても潜在的な具体的効果の観点から理解される一般性や習慣の実在性については彼らと同盟を結んでいた[14]。 1960年代にウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインとウィルフリッド・セラーズが論理実証主義を批判するために改訂されたプラグマティズムを用いた 後、プラグマティズムは再注目された。クワインとセラーズの研究に触発され、ネオプラグマティズムとして知られるプラグマティズムの一派が、ヒラリー・ パットナムやロバート・ブランダムとともに20世紀後半のプラグマティストの中で最も影響力のあったリチャード・ローティを通じて影響力を持つようになっ た。現代のプラグマティズムは、厳密な分析的伝統と、パース、ジェイムズ、デューイの仕事を信奉する「新古典派」プラグマティズム(スーザン・ハックな ど)に大別される[要出典]。 |

| Core tenets A few of the various but often interrelated positions characteristic of philosophers working from a pragmatist approach include: Epistemology (justification): a coherentist theory of justification that rejects the claim that all knowledge and justified belief rest ultimately on a foundation of noninferential knowledge or justified belief. Coherentists hold that justification is solely a function of some relationship between beliefs, none of which are privileged beliefs in the way maintained by foundationalist theories of justification. Epistemology (truth): a deflationary or pragmatic theory of truth; the former is the epistemological claim that assertions that predicate the truth of a statement do not attribute a property called truth to such a statement while the latter is the epistemological claim that assertions that predicate the truth of a statement attribute the property of useful-to-believe to such a statement. Metaphysics: a pluralist view that there is more than one sound way to conceptualize the world and its content. Philosophy of science: an instrumentalist and scientific anti-realist view that a scientific concept or theory should be evaluated by how effectively it explains and predicts phenomena, as opposed to how accurately it describes objective reality. Philosophy of language: an anti-representationalist view that rejects analyzing the semantic meaning of propositions, mental states, and statements in terms of a correspondence or representational relationship and instead analyzes semantic meaning in terms of notions like dispositions to action, inferential relationships, and/or functional roles (e.g. behaviorism and inferentialism). Not to be confused with pragmatics, a sub-field of linguistics with no relation to philosophical pragmatism. Additionally, forms of empiricism, fallibilism, verificationism, and a Quinean naturalist metaphilosophy are all commonly elements of pragmatist philosophies. Many pragmatists are epistemological relativists and see this to be an important facet of their pragmatism (e.g. Joseph Margolis), but this is controversial and other pragmatists argue such relativism to be seriously misguided (e.g. Hilary Putnam, Susan Haack). Anti-reification of concepts and theories Dewey in The Quest for Certainty criticized what he called "the philosophical fallacy": Philosophers often take categories (such as the mental and the physical) for granted because they don't realize that these are nominal concepts that were invented to help solve specific problems.[15] This causes metaphysical and conceptual confusion. Various examples are the "ultimate Being" of Hegelian philosophers, the belief in a "realm of value", the idea that logic, because it is an abstraction from concrete thought, has nothing to do with the action of concrete thinking. David L. Hildebrand summarized the problem: "Perceptual inattention to the specific functions comprising inquiry led realists and idealists alike to formulate accounts of knowledge that project the products of extensive abstraction back onto experience."[15]: 40 Naturalism and anti-Cartesianism From the outset, pragmatists wanted to reform philosophy and bring it more in line with the scientific method as they understood it. They argued that idealist and realist philosophy had a tendency to present human knowledge as something beyond what science could grasp. They held that these philosophies then resorted either to a phenomenology inspired by Kant or to correspondence theories of knowledge and truth.[citation needed] Pragmatists criticized the former for its a priorism, and the latter because it takes correspondence as an unanalyzable fact. Pragmatism instead tries to explain the relation between knower and known. In 1868,[16] C.S. Peirce argued that there is no power of intuition in the sense of a cognition unconditioned by inference, and no power of introspection, intuitive or otherwise, and that awareness of an internal world is by hypothetical inference from external facts. Introspection and intuition were staple philosophical tools at least since Descartes. He argued that there is no absolutely first cognition in a cognitive process; such a process has its beginning but can always be analyzed into finer cognitive stages. That which we call introspection does not give privileged access to knowledge about the mind—the self is a concept that is derived from our interaction with the external world and not the other way around.[17] At the same time he held persistently that pragmatism and epistemology in general could not be derived from principles of psychology understood as a special science:[18] what we do think is too different from what we should think; in his "Illustrations of the Logic of Science" series, Peirce formulated both pragmatism and principles of statistics as aspects of scientific method in general.[19] This is an important point of disagreement with most other pragmatists, who advocate a more thorough naturalism and psychologism. Richard Rorty expanded on these and other arguments in Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature in which he criticized attempts by many philosophers of science to carve out a space for epistemology that is entirely unrelated to—and sometimes thought of as superior to—the empirical sciences. W.V. Quine, who was instrumental in bringing naturalized epistemology back into favor with his essay "Epistemology Naturalized",[20] also criticized "traditional" epistemology and its "Cartesian dream" of absolute certainty. The dream, he argued, was impossible in practice as well as misguided in theory, because it separates epistemology from scientific inquiry.  Hilary Putnam said that the combination of antiskepticism and fallibilism is a central feature of pragmatism.[21][22][23] Reconciliation of anti-skepticism and fallibilism Hilary Putnam has suggested that the reconciliation of anti-skepticism[24] and fallibilism is the central goal of American pragmatism.[21][22][23] Although all human knowledge is partial, with no ability to take a "God's-eye-view", this does not necessitate a globalized skeptical attitude, a radical philosophical skepticism (as distinguished from that which is called scientific skepticism). Peirce insisted that (1) in reasoning, there is the presupposition, and at least the hope,[25] that truth and the real are discoverable and would be discovered, sooner or later but still inevitably, by investigation taken far enough,[1] and (2) contrary to Descartes's famous and influential methodology in the Meditations on First Philosophy, doubt cannot be feigned or created by verbal fiat to motivate fruitful inquiry, and much less can philosophy begin in universal doubt.[26] Doubt, like belief, requires justification. Genuine doubt irritates and inhibits, in the sense that belief is that upon which one is prepared to act.[1] It arises from confrontation with some specific recalcitrant matter of fact (which Dewey called a "situation"), which unsettles our belief in some specific proposition. Inquiry is then the rationally self-controlled process of attempting to return to a settled state of belief about the matter. Note that anti-skepticism is a reaction to modern academic skepticism in the wake of Descartes. The pragmatist insistence that all knowledge is tentative is quite congenial to the older skeptical tradition. Theory of truth and epistemology Main article: Pragmatic theory of truth Pragmatism was not the first to apply evolution to theories of knowledge: Schopenhauer advocated a biological idealism as what's useful to an organism to believe might differ wildly from what is true. Here knowledge and action are portrayed as two separate spheres with an absolute or transcendental truth above and beyond any sort of inquiry organisms used to cope with life. Pragmatism challenges this idealism by providing an "ecological" account of knowledge: inquiry is how organisms can get a grip on their environment. Real and true are functional labels in inquiry and cannot be understood outside of this context. It is not realist in a traditionally robust sense of realism (what Hilary Putnam later called metaphysical realism), but it is realist in how it acknowledges an external world which must be dealt with.[citation needed] Many of James' best-turned phrases—"truth's cash value"[27] and "the true is only the expedient in our way of thinking" [28]—were taken out of context and caricatured in contemporary literature as representing the view where any idea with practical utility is true. William James wrote: It is high time to urge the use of a little imagination in philosophy. The unwillingness of some of our critics to read any but the silliest of possible meanings into our statements is as discreditable to their imaginations as anything I know in recent philosophic history. Schiller says the truth is that which "works." Thereupon he is treated as one who limits verification to the lowest material utilities. Dewey says truth is what gives "satisfaction"! He is treated as one who believes in calling everything true which, if it were true, would be pleasant.[29] In reality, James asserts, the theory is a great deal more subtle.[nb 1] The role of belief in representing reality is widely debated in pragmatism. Is a belief valid when it represents reality? "Copying is one (and only one) genuine mode of knowing".[30] Are beliefs dispositions which qualify as true or false depending on how helpful they prove in inquiry and in action? Is it only in the struggle of intelligent organisms with the surrounding environment that beliefs acquire meaning? Does a belief only become true when it succeeds in this struggle? In James's pragmatism nothing practical or useful is held to be necessarily true nor is anything which helps to survive merely in the short term. For example, to believe my cheating spouse is faithful may help me feel better now, but it is certainly not useful from a more long-term perspective because it doesn't accord with the facts (and is therefore not true). |

核となる考え方 プラグマティズム的アプローチで活動する哲学者に特徴的な、様々な、しかししばしば相互に関連する立場のいくつかを以下に挙げる: 認識論(正当化):正当化に関する首尾一貫主義的な理論で、すべての知識や正当な信念は最終的に非推論的な知識や正当な信念という土台の上に成り立ってい るという主張を否定する。首尾一貫主義者は、正当化とは信念の間にある何らかの関 係の機能のみであり、正当化の基礎づけ論が維持するような特権的な信念は一つも ないと主張する。 認識論(真理):真理に関するデフレーション理論またはプラグマティック理論。前者は、ある文の真理を述 べるアサーションは、そのような文に真理と呼ばれる性質を帰属させないとする認識論的主張であり、後者は、ある文の真理を述 べるアサーションは、そのような文に信じるに値するという性質を帰属させるとする認識論的主張である。 形而上学:世界とその内容を概念化する健全な方法は1つではないとする多元主義的見解。 科学哲学:科学的概念や理論は、客観的現実をどれだけ正確に記述しているかとは対照的に、現象をどれだけ効果的に説明・予測しているかによって評価される べきだという道具論的・科学的反現実主義的な考え方。 言語哲学:命題、心的状態、陳述の意味的意味を対応関係や表象関係で分析することを否定し、代わりに行動への気質、推論関係、機能的役割のような概念で意 味的意味を分析する反表象主義の考え方(行動主義や推論主義など)。哲学的語用論とは無関係な言語学の下位分野である語用論と混同しないように。 また、経験主義、可謬主義、検証主義、クワイン的自然主義的形而上学などの形態は、すべてプラグマティズム哲学の一般的な要素である。多くのプラグマティ ストは認識論的相対主義者であり、これをプラグマティズムの重要な側面とみなしている(例:ジョセフ・マーゴリス)が、これには論争があり、他のプラグマ ティストはこのような相対主義は重大な見当違いであると主張している(例:ヒラリー・パットナム、スーザン・ハーク)。 概念と理論の再定義に反対する デューイは『確実性の探求』の中で、彼が「哲学的誤謬」と呼ぶものを批判した: 哲学者はしばしば、(精神的なものや物理的なものなどの)カテゴリーを当然のものと考えてしまうが、それはそれらが特定の問題を解決するために考案された 名目的な概念であることに気づいていないからである。様々な例として、ヘーゲル哲学者の「究極的存在」、「価値の領域」への信仰、論理は具体的思考からの 抽象であるため具体的思考の作用とは無関係であるという考えなどが挙げられる。 デイヴィッド・L・ヒルデブランドはこの問題を次のように要約している:「探究を構成する具体的な機能に対する知覚的不注意が、実在論者と観念論者を同じ ように、広範な抽象化の産物を経験に投影し直すような知識の説明を定式化することになった」[15]: 40 自然主義と反カルテジアニズム(=反デカルト主義) 当初からプラグマティストは哲学を改革し、彼らが理解する科学的方法とより一致させることを望んでいた。彼らは、観念論的哲学や実在論的哲学には、人間の 知識を科学が把握しうるものを超えたものとして提示する傾向があると主張した。プラグマティストたちは、前者についてはその先行主義を、後者については対 応関係を分析不可能な事実とみなすことを批判した。プラグマティズムはその代わりに、知る者と知られる者の関係を説明しようとする。 1868年[16]、C.S.パイスは、推論によって無条件に認識されるという意味での直観の力は存在せず、直観的であろうとなかろうと内観の力は存在せ ず、内的世界の認識は外的事実からの仮説的推論によるものであると主張した。内観と直観は、少なくともデカルト以来の哲学の定番である。デカルトは、認知 過程には絶対的に最初の認知は存在せず、そのような過程には始まりがあるが、常により細かい認知段階に分析することができると主張した。私たちが内観と呼 ぶものは、心についての知識への特権的なアクセスを与えるものではない-自己は外界との相互作用から導かれる概念であり、その逆ではないのである。 [17]同時に彼は、プラグマティズムと認識論一般が、特別な科学として理解される心理学の原理から導き出されることはあり得ないと主張し続けた [18]。 リチャード・ローティは『Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature(哲学と自然の鏡)』において、これらの議論やその他の議論を発展させ、多くの科学哲学者が経験科学とは全く無関係で、時には経験科学よりも 優れていると考えられている認識論のための空間を切り開こうとしていることを批判している。W.V.クワインは、「自然化された認識論 (Epistemology Naturalized)」というエッセイで、自然化された認識論が再び支持されるようになった立役者であるが[20]、「伝統的な」認識論とその絶対確 実性という「デカルトの夢」も批判していた。この夢は、認識論を科学的探究から切り離すものであるため、理論的に誤っているばかりでなく、実践的にも不可 能であると彼は主張した。  ヒラリー・パットナムは、反懐疑主義と可謬主義の組み合わせがプラグマティズムの中心的な特徴であると述べている[21][22][23]。 反懐疑主義と可謬主義の和解 ヒラリー・パットナムは、反懐疑主義[24]と可謬主義の和解がアメリカのプラグマティズムの中心的な目標であることを示唆している[21][22] [23]。人間の知識はすべて部分的であり、「神の目から見た視点」を持つことはできないが、このことはグローバル化された懐疑的態度、(科学的懐疑主義 と呼ばれるものとは区別される)急進的な哲学的懐疑主義を必要とするものではない。ペイスは、(1)推論においては、真理と実在は発見可能であり、十分に 踏み込んだ調査によって遅かれ早かれ、しかし必然的に発見されるであろうという前提があり、少なくとも希望がある[25]、(2)『第一哲学の瞑想録』に おけるデカルトの有名で影響力のある方法論に反して、疑念は、実りある探求の動機付けとなるような見せかけのものでも、言葉による気の迷いによって作り出 されるものでもなく、ましてや哲学が普遍的な疑念から始まるものでもない[26]と主張した。本物の疑念は、信念とは人が行動する用意のあるものであると いう意味で、人を苛立たせ、抑制する[1]。疑念は、ある特定の命題に対する私たちの信念を揺るがす、ある特定の不従順な事実(デューイはこれを「状況」 と呼んだ)に直面することによって生じる。そして探究とは、その問題についての信念を落ち着いた状態に戻そうとする、合理的に自制されたプロセスなのであ る。反懐疑主義は、デカルトに続く近代的な学問的懐疑主義への反動であることに注意しよう。すべての知識は暫定的なものであるというプラグマティストの主 張は、古い懐疑主義の伝統と非常に親和的である。 真理論と認識論 主な記事 プラグマティズムの真理論 進化論を知識論に応用したのはプラグマティズムが最初ではない: ショーペンハウアーは、生物にとって信じることが有益なことは、何が真実であるかとは大きく異なるかもしれないとして、生物学的観念論を提唱した。ショー ペンハウアーは生物学的観念論を提唱した。知識と行動は、生物が生命に対処するために用いるあらゆる種類の探究を超えた、絶対的または超越的な真理を持つ 2つの別々の領域として描かれている。プラグマティズムは、知識の「生態学的」説明を提供することによって、この観念論に挑戦する。現実と真実は探究にお ける機能的なラベルであり、この文脈の外では理解できない。それは伝統的に強固な意味での実在論(後にヒラリー・パットナムが形而上学的実在論と呼ぶも の)ではないが、対処しなければならない外界をどのように認めているかという点では実在論者である[要出典]。 ジェイムズの最も有名なフレーズである「真実の現金価値」[27]や「真実とは我々の思考方法における便宜的なものに過ぎない」[28]の多くは、文脈か ら取り出され、実用的な有用性を持つあらゆる考えが真実であるという見解を表すものとして、現代の文献で戯画化されている。ウィリアム・ジェームズはこう 書いている: 哲学の世界でも、少しは想像力を働かせるべきだ。批評家たちの中には、われわれの発言にあり得る限り最も愚かな意味しか読み取ろうとしない者がいるが、こ れは最近の哲学史の中で私が知る限り、彼らの想像力の信用を失墜させるものである。シラーは、真実とは 「機能する 」ものだと言った。そこで彼は、検証を最低の物質的効用に限定する者として扱われる。デューイは、真理とは「満足」を与えるものだと言う!彼は、もしそれ が真実であれば、快楽であろうものをすべて真実と呼ぶことを信じる者として扱われる[29]。 現実には、理論はもっと微妙なものだとジェイムズは主張する[nb 1]。 現実を表現する上での信念の役割は、プラグマティズムにおいて広く議論さ れている。信念は現実を表すときに有効なのだろうか?「コピーすることは、知ることの一つの(そして唯一の)真正な様式である」[30] 。信念は、探究や行動においてどれだけ役に立つかによって、真である か偽であるかを決める性質なのだろうか。信念が意味を獲得するのは、知的生物が周囲の環境と闘うときだけなのだろ うか。信念が真実になるのは、この闘争に成功したときだけなのだろうか?ジェイムズのプラグマティズムでは、実用的で有用なものは必 ずしも真実ではなく、単に短期的に生き残るのに役立つものも真実で はないとされている。例えば、浮気している配偶者が誠実であると信じることは、今は気分を楽にして くれるかもしれないが、より長期的な視点からは、事実と一致しない(したがって真 実ではない)ので、確かに役に立たない。 |

| In other fields While pragmatism started simply as a criterion of meaning, it quickly expanded to become a full-fledged epistemology with wide-ranging implications for the entire philosophical field. Pragmatists who work in these fields share a common inspiration, but their work is diverse and there are no received views. Philosophy of science In the philosophy of science, instrumentalism is the view that concepts and theories are merely useful instruments and progress in science cannot be couched in terms of concepts and theories somehow mirroring reality. Instrumentalist philosophers often define scientific progress as nothing more than an improvement in explaining and predicting phenomena. Instrumentalism does not state that truth does not matter, but rather provides a specific answer to the question of what truth and falsity mean and how they function in science. One of C. I. Lewis' main arguments in Mind and the World Order: Outline of a Theory of Knowledge (1929) was that science does not merely provide a copy of reality but must work with conceptual systems and that those are chosen for pragmatic reasons, that is, because they aid inquiry. Lewis' own development of multiple modal logics is a case in point. Lewis is sometimes called a proponent of conceptual pragmatism because of this.[31] Another development is the cooperation of logical positivism and pragmatism in the works of Charles W. Morris and Rudolf Carnap. The influence of pragmatism on these writers is mostly limited to the incorporation of the pragmatic maxim into their epistemology. Pragmatists with a broader conception of the movement do not often refer to them. W. V. Quine's paper "Two Dogmas of Empiricism", published in 1951, is one of the most celebrated papers of 20th-century philosophy in the analytic tradition. The paper is an attack on two central tenets of the logical positivists' philosophy. One is the distinction between analytic statements (tautologies and contradictions) whose truth (or falsehood) is a function of the meanings of the words in the statement ('all bachelors are unmarried'), and synthetic statements, whose truth (or falsehood) is a function of (contingent) states of affairs. The other is reductionism, the theory that each meaningful statement gets its meaning from some logical construction of terms which refers exclusively to immediate experience. Quine's argument brings to mind Peirce's insistence that axioms are not a priori truths but synthetic statements. Logic Later in his life Schiller became famous for his attacks on logic in his textbook, Formal Logic. By then, Schiller's pragmatism had become the nearest of any of the classical pragmatists to an ordinary language philosophy. Schiller sought to undermine the very possibility of formal logic, by showing that words only had meaning when used in context. The least famous of Schiller's main works was the constructive sequel to his destructive book Formal Logic. In this sequel, Logic for Use, Schiller attempted to construct a new logic to replace the formal logic that he had criticized in Formal Logic. What he offers is something philosophers would recognize today as a logic covering the context of discovery and the hypothetico-deductive method. Whereas Schiller dismissed the possibility of formal logic, most pragmatists are critical rather of its pretension to ultimate validity and see logic as one logical tool among others—or perhaps, considering the multitude of formal logics, one set of tools among others. This is the view of C. I. Lewis. C. S. Peirce developed multiple methods for doing formal logic. Stephen Toulmin's The Uses of Argument inspired scholars in informal logic and rhetoric studies (although it is an epistemological work). Metaphysics James and Dewey were empirical thinkers in the most straightforward fashion: experience is the ultimate test and experience is what needs to be explained. They were dissatisfied with ordinary empiricism because, in the tradition dating from Hume, empiricists had a tendency to think of experience as nothing more than individual sensations. To the pragmatists, this went against the spirit of empiricism: we should try to explain all that is given in experience including connections and meaning, instead of explaining them away and positing sense data as the ultimate reality. Radical empiricism, or Immediate Empiricism in Dewey's words, wants to give a place to meaning and value instead of explaining them away as subjective additions to a world of whizzing atoms.  The "Chicago Club" including Mead, Dewey, Angell, and Moore. Pragmatism is sometimes called American pragmatism because so many of its proponents were and are Americans. William James gives an interesting example of this philosophical shortcoming: [A young graduate] began by saying that he had always taken for granted that when you entered a philosophic classroom you had to open relations with a universe entirely distinct from the one you left behind you in the street. The two were supposed, he said, to have so little to do with each other, that you could not possibly occupy your mind with them at the same time. The world of concrete personal experiences to which the street belongs is multitudinous beyond imagination, tangled, muddy, painful and perplexed. The world to which your philosophy-professor introduces you is simple, clean and noble. The contradictions of real life are absent from it. ... In point of fact it is far less an account of this actual world than a clear addition built upon it ... It is no explanation of our concrete universe[32] F. C. S. Schiller's first book Riddles of the Sphinx was published before he became aware of the growing pragmatist movement taking place in America. In it, Schiller argues for a middle ground between materialism and absolute metaphysics. These opposites are comparable to what William James called tough-minded empiricism and tender-minded rationalism. Schiller contends on the one hand that mechanistic naturalism cannot make sense of the "higher" aspects of our world. These include free will, consciousness, purpose, universals and some would add God. On the other hand, abstract metaphysics cannot make sense of the "lower" aspects of our world (e.g. the imperfect, change, physicality). While Schiller is vague about the exact sort of middle ground he is trying to establish, he suggests that metaphysics is a tool that can aid inquiry, but that it is valuable only insofar as it does help in explanation. In the second half of the 20th century, Stephen Toulmin argued that the need to distinguish between reality and appearance only arises within an explanatory scheme and therefore that there is no point in asking what "ultimate reality" consists of. More recently, a similar idea has been suggested by the postanalytic philosopher Daniel Dennett, who argues that anyone who wants to understand the world has to acknowledge both the "syntactical" aspects of reality (i.e., whizzing atoms) and its emergent or "semantic" properties (i.e., meaning and value).[citation needed] Radical empiricism gives answers to questions about the limits of science, the nature of meaning and value and the workability of reductionism. These questions feature prominently in current debates about the relationship between religion and science, where it is often assumed—most pragmatists would disagree—that science degrades everything that is meaningful into "merely" physical phenomena. Philosophy of mind Both John Dewey in Experience and Nature (1929) and, half a century later, Richard Rorty in his Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979) argued that much of the debate about the relation of the mind to the body results from conceptual confusions. They argue instead that there is no need to posit the mind or mindstuff as an ontological category. Pragmatists disagree over whether philosophers ought to adopt a quietist or a naturalist stance toward the mind-body problem. The former, including Rorty, want to do away with the problem because they believe it's a pseudo-problem, whereas the latter believe that it is a meaningful empirical question. [citation needed] Ethics Main article: Pragmatic ethics Pragmatism sees no fundamental difference between practical and theoretical reason, nor any ontological difference between facts and values. Pragmatist ethics is broadly humanist because it sees no ultimate test of morality beyond what matters for us as humans. Good values are those for which we have good reasons, viz. the good reasons approach. The pragmatist formulation pre-dates those of other philosophers who have stressed important similarities between values and facts such as Jerome Schneewind and John Searle.  William James tried to show the meaningfulness of (some kinds of) spirituality but, like other pragmatists, did not see religion as the basis of meaning or morality. William James' contribution to ethics, as laid out in his essay The Will to Believe has often been misunderstood as a plea for relativism or irrationality. On its own terms it argues that ethics always involves a certain degree of trust or faith and that we cannot always wait for adequate proof when making moral decisions. Moral questions immediately present themselves as questions whose solution cannot wait for sensible proof. A moral question is a question not of what sensibly exists, but of what is good, or would be good if it did exist. ... A social organism of any sort whatever, large or small, is what it is because each member proceeds to his own duty with a trust that the other members will simultaneously do theirs. Wherever a desired result is achieved by the co-operation of many independent persons, its existence as a fact is a pure consequence of the precursive faith in one another of those immediately concerned. A government, an army, a commercial system, a ship, a college, an athletic team, all exist on this condition, without which not only is nothing achieved, but nothing is even attempted.[33] Of the classical pragmatists, John Dewey wrote most extensively about morality and democracy.[34] In his classic article "Three Independent Factors in Morals",[35] he tried to integrate three basic philosophical perspectives on morality: the right, the virtuous and the good. He held that while all three provide meaningful ways to think about moral questions, the possibility of conflict among the three elements cannot always be easily solved.[36] Dewey also criticized the dichotomy between means and ends which he saw as responsible for the degradation of our everyday working lives and education, both conceived as merely a means to an end. He stressed the need for meaningful labor and a conception of education that viewed it not as a preparation for life but as life itself.[37] Dewey was opposed to other ethical philosophies of his time, notably the emotivism of Alfred Ayer. Dewey envisioned the possibility of ethics as an experimental discipline, and thought values could best be characterized not as feelings or imperatives, but as hypotheses about what actions will lead to satisfactory results or what he termed consummatory experience. An additional implication of this view is that ethics is a fallible undertaking because human beings are frequently unable to know what would satisfy them. During the late 1900s and first decade of 2000, pragmatism was embraced by many in the field of bioethics led by the philosophers John Lachs and his student Glenn McGee, whose 1997 book The Perfect Baby: A Pragmatic Approach to Genetic Engineering (see designer baby) garnered praise from within classical American philosophy and criticism from bioethics for its development of a theory of pragmatic bioethics and its rejection of the principalism theory then in vogue in medical ethics. An anthology published by the MIT Press titled Pragmatic Bioethics included the responses of philosophers to that debate, including Micah Hester, Griffin Trotter and others many of whom developed their own theories based on the work of Dewey, Peirce, Royce and others. Lachs developed several applications of pragmatism to bioethics independent of but extending from the work of Dewey and James. A recent pragmatist contribution to meta-ethics is Todd Lekan's Making Morality.[38] Lekan argues that morality is a fallible but rational practice and that it has traditionally been misconceived as based on theory or principles. Instead, he argues, theory and rules arise as tools to make practice more intelligent. Aesthetics John Dewey's Art as Experience, based on the William James lectures he delivered at Harvard University, was an attempt to show the integrity of art, culture and everyday experience (IEP). Art, for Dewey, is or should be a part of everyone's creative lives and not just the privilege of a select group of artists. He also emphasizes that the audience is more than a passive recipient. Dewey's treatment of art was a move away from the transcendental approach to aesthetics in the wake of Immanuel Kant who emphasized the unique character of art and the disinterested nature of aesthetic appreciation. A notable contemporary pragmatist aesthetician is Joseph Margolis. He defines a work of art as "a physically embodied, culturally emergent entity", a human "utterance" that isn't an ontological quirk but in line with other human activity and culture in general. He emphasizes that works of art are complex and difficult to fathom, and that no determinate interpretation can be given. Philosophy of religion Both Dewey and James investigated the role that religion can still play in contemporary society, the former in A Common Faith and the latter in The Varieties of Religious Experience. From a general point of view, for William James, something is true only insofar as it works. Thus, the statement, for example, that prayer is heard may work on a psychological level but (a) may not help to bring about the things you pray for (b) may be better explained by referring to its soothing effect than by claiming prayers are heard. As such, pragmatism is not antithetical to religion but it is not an apologetic for faith either. James' metaphysical position however, leaves open the possibility that the ontological claims of religions may be true. As he observed in the end of the Varieties, his position does not amount to a denial of the existence of transcendent realities. Quite the contrary, he argued for the legitimate epistemic right to believe in such realities, since such beliefs do make a difference in an individual's life and refer to claims that cannot be verified or falsified either on intellectual or common sensorial grounds. Joseph Margolis in Historied Thought, Constructed World (California, 1995) makes a distinction between "existence" and "reality". He suggests using the term "exists" only for those things which adequately exhibit Peirce's Secondness: things which offer brute physical resistance to our movements. In this way, such things which affect us, like numbers, may be said to be "real", although they do not "exist". Margolis suggests that God, in such a linguistic usage, might very well be "real", causing believers to act in such and such a way, but might not "exist". Education [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2023) Pragmatic pedagogy is an educational philosophy that emphasizes teaching students knowledge that is practical for life and encourages them to grow into better people. American philosopher John Dewey is considered one of the main thinkers of the pragmatist educational approach. |

他の分野 プラグマティズムは単に意味の基準として始まったが、急速に拡大し、哲学分野全体に広範な影響を及ぼす本格的な認識論となった。これらの分野で活動するプ ラグマティストたちは、共通のインスピレーションを共有しているが、彼らの仕事は多様であり、定説はない。 科学哲学 科学哲学において道具主義とは、概念や理論は単なる便利な道具に過ぎず、科学の進歩は、概念や理論が現実を反映したものであるという観点からは語れないと いう考え方である。道具主義の哲学者はしばしば、科学の進歩とは現象の説明や予測における改善以外の何ものでもないと定義する。道具論は、真理が重要でな いと述べているのではなく、真理と虚偽が何を意味し、科学においてどのように機能するのかという疑問に対する具体的な答えを提示しているのである。 C.I.ルイスの『心と世界秩序』における主な主張の一つである: Outline of a Theory of Knowledge』(1929年)におけるC.I.ルイスの主な主張のひとつは、科学は単に現実のコピーを提供するのではなく、概念体系を用いなければ ならないこと、そしてそれらは実用的な理由、つまり探究を助けるものであるからこそ選択される、というものであった。ルイス自身が開発した多重様相論理 は、その一例である。ルイスはこのことから概念的プラグマティズムの提唱者と呼ばれることもある[31]。 もう一つの発展は、チャールズ・W・モリスとルドルフ・カルナップの著作における論理実証主義とプラグマティズムの協力である。これらの作家に対するプラ グマティズムの影響は、彼らの認識論にプラグマティックな格言を取り入れたことに限定される。この運動についてより広い概念を持つプラグマティストは、彼 らに言及することはあまりない。 W. 1951年に発表されたW.V.クワインの論文「経験論の二つの教義」は、分析主義の伝統に基づく20世紀の哲学の中で最も有名な論文の一つである。この 論文は、論理実証主義者の哲学の2つの中心的な信条に対する攻撃である。ひとつは、真理(または偽り)が文中の単語の意味の関数である分析的記述(同語反 復と矛盾)(「独身者はみな未婚である」)と、真理(または偽り)が(偶発的な)状態の関数である合成的記述との区別である。もうひとつは還元主義であ り、意味のある文はそれぞれ、目の前の経験のみを参照する用語の論理的構成からその意味を得るという理論である。クワインの議論は、公理はアプリオリな真 理ではなく、合成的な記述であるというピアースの主張を思い起こさせる。 論理学 シラーは後年、教科書『形式論理学』における論理学への攻撃で有名になった。その頃までに、シラーのプラグマティズムは、古典的プラグマティストの中で最 も普通の言語哲学に近いものとなっていた。シラーは、言葉は文脈の中で使われて初めて意味を持つことを示すことで、形式論理学の可能性を根底から覆そうと したのである。シラーの主著の中で最も有名でないのは、彼の破壊的な著書『形式論理学』の建設的な続編である。この続編『使用のための論理学』において、 シラーは『形式論理学』で批判した形式論理学に代わる新しい論理学の構築を試みた。彼が提示したのは、今日哲学者たちが認めるような、発見の文脈と仮説演 繹法をカバーする論理である。 シラーが形式論理学の可能性を否定したのに対し、プラグマティストの多くは、むしろその究極的な妥当性を気取ることに批判的であり、論理学を他の論理学の 中の一つの論理的道具として、いや、多数の形式論理学を考慮すれば、他の道具の中の一つの道具セットとしてとらえている。これはC.I.ルイスの見解であ る。C.S.パースは、形式論理を行うための複数の方法を開発した。 スティーブン・トゥールミンの『The Uses of Argument』は、(認識論的な著作ではあるが)非公式論理学や修辞学の研究者たちにインスピレーションを与えた。 形而上学 ジェイムズとデューイは、経験こそが究極のテストであり、経験こそが説明されるべきものであるという、最も端的な形で経験的な思想家であった。なぜなら、 ヒューム以来の伝統において、経験主義者は経験を個々の感覚としてしか考えない傾向があったからである。プラグマティストにとって、これは経験主義の精神 に反するものであった。私たちは、経験において与えられるすべてのものを説明しようとすべきであり、その中にはつながりや意味も含まれている。急進的経験 主義、デューイの言葉を借りれば即時的経験主義は、意味や価値を、めまぐるしく変化する原子の世界への主観的な付加物として説明するのではなく、そこに居 場所を与えようとするものである。  ミード、デューイ、アンゲル、ムーアを含む「シカゴ・クラブ」である。プラグマティズムは、その支持者の多くがアメリカ人であり、またアメリカ人であるこ とから、アメリカン・プラグマティズムと呼ばれることもある。 ウィリアム・ジェームズは、この哲学的欠点について興味深い例を挙げている: [ある若い大学院生が、哲学の教室に入ったら、道ばたに置き去りにしてきた宇宙とはまったく別の宇宙との関係を開かなければならないのは当然だと思ってい た、と言い始めた。この2つは互いにほとんど関係がなく、同時に両者のことで頭をいっぱいにすることはできないと彼は言った。街路が属する具体的な個人的 経験の世界は、想像を絶するほど膨大で、もつれ、泥沼化し、痛みを伴い、当惑する。哲学の教授が紹介してくれる世界は、単純で、清らかで、気高い。実生活 の矛盾はそこにはない。... 実のところ、それはこの現実世界の説明というよりも、その上に構築された明確な付加である.具体的な宇宙の説明にはなっていない[32]。 F. C.S.シラーの最初の著書『スフィンクスの謎』は、彼がアメリカで起こっているプラグマティズム運動の高まりに気づく前に出版された。その中でシラー は、唯物論と絶対形而上学の中間を主張している。この対極にあるものは、ウィリアム・ジェイムズが強靭な経験主義と柔和な合理主義と呼んだものに匹敵す る。シラーは一方で、機械論的自然主義では我々の世界の「より高次の」側面を理解できないと主張する。これには、自由意志、意識、目的、普遍性、そして神 も含まれる。一方、抽象的な形而上学では、私たちの世界の「低次の」側面(不完全性、変化、物理性など)を理解することはできない。シラーは、自分が確立 しようとしている中間地点の正確な種類については曖昧であるが、形而上学は探究を助ける道具であるが、説明に役立つ限りにおいてのみ価値があることを示唆 している。 20世紀後半、スティーヴン・トゥールミンは、現実と外観を区別する必要性は説明スキームの中でしか生じず、したがって「究極の現実」が何からなるかを問 うことには意味がないと主張した。より最近では、ポスト分析哲学者ダニエル・デネットによって同様の考えが提案されており、世界を理解しようとする者は、 現実の「統語的」側面(すなわち、原子の疾走)と、その創発的または「意味的」特性(すなわち、意味と価値)の両方を認めなければならないと主張している [要出典]。 急進的経験主義は、科学の限界、意味と価値の本質、還元主義の実行可能性についての疑問に答えを与える。このような疑問は、宗教と科学の関係をめぐる現在 の論争で顕著に取り上げられている。そこでは、科学は意味のあるものすべてを「単なる」物理現象に貶めるものだとされることが多いが、プラグマティストの 多くはこれに同意しないであろう。 心の哲学 ジョン・デューイは『経験と自然』(1929年)の中で、リチャード・ローティはその半世紀後、『哲学と自然の鏡』(1979年)の中で、心と身体の関係 についての議論の多くは、概念的な混乱から生じていると主張している。彼らはその代わりに、存在論的カテゴリーとして心やマインドスタッフを措定する必要 はないと主張している。 プラグマティストは、哲学者が心身問題に対して静寂主義的なスタンスをとるべきか、自然主義的なスタンスをとるべきかをめぐって意見が分かれる。ローティ を含む前者は、この問題を擬似的な問題だと考えているため、この問題を取り去りたいと考えているのに対し、後者は、この問題は意味のある経験的な問題だと 考えている。[要出典]。 倫理学 主な記事 プラグマティック倫理学 プラグマティズムは、実践的理性と理論的理性の間に根本的な違いはなく、事実と価値の間に存在論的な違いはないと考えている。プラグマティズムの倫理学 は、人間として重要なことを超えた道徳の究極的なテストはないと考えているため、広くヒューマニズム的である。良い価値とは、私たちが良い理由を持ってい るものである。プラグマティストの定式化は、ジェローム・シュネーウィンドやジョン・サールのような、価値と事実の間の重要な類似性を強調した他の哲学者 の定式化よりも古い。  ウィリアム・ジェームズは、(ある種の)精神性の意味性を示そうとしたが、他のプラグマティストと同様に、意味や道徳の基礎として宗教を見ていなかった。 ウィリアム・ジェームズの倫理学への貢献は、彼のエッセイ『The Will to Believe(信じる意志)』で述べられているが、しばしば相対主義や非合理性の主張として誤解されている。このエッセイは、倫理は常にある程度の信頼 や信仰を伴うものであり、道徳的な決定を下す際に常に十分な証拠を待つことはできないと主張している。 道徳的な疑問は、その解決が賢明な証明を待つことができない疑問として即座に提示される。道徳的な問いとは、感覚的に存在するものについての問いではな く、何が善であるか、あるいはそれが存在するならば善であるかについての問いなのである。... 大なり小なり、どのような種類の社会的組織であれ、それがあるのは、各構成員が、他の構成員も同時に義務を果たすという信頼のもとに、自分の義務を果たす からである。多くの独立した人物の協力によって望ましい結果が達成される場合、その事実としての存在は、直ちに関係する人々の互いに対する信頼の純粋な結 果である。政府も、軍隊も、商業システムも、船も、大学も、運動チームも、すべてこの条件の上に存在するのであり、この条件なしには何も達成されないばか りか、何も試みられないのである[33]。 古典的なプラグマティストの中で、ジョン・デューイは道徳と民主主義について最も幅広く執筆している[34]。彼の古典的な論文「道徳における3つの独立 した要素」[35]において、彼は道徳に関する3つの基本的な哲学的視点、すなわち正しいこと、高潔なこと、善いことを統合しようとした。彼は、3つすべ てが道徳的な問題について考えるための有意義な方法を提供する一方で、3つの要素の間に対立が生じる可能性は常に容易に解決することはできないとした [36]。 デューイはまた、手段と目的という二項対立を批判し、それが日常的な労働生活や教育を劣化させる原因となっていると考えていた。彼は意味のある労働の必要 性と、教育を人生の準備としてではなく、人生そのものとみなす教育の概念の必要性を強調した[37]。 デューイは当時の他の倫理哲学、特にアルフレッド・エアの感情主義に反対していた。デューイは実験的学問としての倫理学の可能性を構想し、価値観は感情や 命令としてではなく、どのような行動が満足のいく結果をもたらすか、あるいは彼が消費的経験と呼ぶものについての仮説として特徴づけるのが最善であると考 えた。この見解のもう一つの意味は、倫理学は誤りやすい事業であるということである。なぜなら、人間は何が自分を満足させるかを知ることができないことが 多いからである。 1900年代後半から2000年の最初の10年間、プラグマティズムは、哲学者ジョン・ラックスとその弟子であるグレン・マッギーが率いる生命倫理の分野 で多くの人々に受け入れられた: A Pragmatic Approach to Genetic Engineering」(デザイナーベイビーを参照)は、プラグマティックな生命倫理の理論を発展させ、当時医療倫理で流行していたプリンシパリズム理 論を否定したことで、古典的アメリカ哲学の内部から賞賛を集め、生命倫理学からは批判を浴びた。MIT Pressから出版されたPragmatic Bioethicsと題されたアンソロジーには、Micah Hester、Griffin Trotterをはじめとする哲学者たちのこの議論への応答が収録されており、その多くはデューイ、ペアーズ、ロイスなどの研究に基づいた独自の理論を展 開していた。ラックスはプラグマティズムを生命倫理に応用し、デューイやジェイムズの研究から発展させた。 レカンは、道徳とは誤りやすいが合理的な実践であり、伝統的に理論や原理に基づいていると誤解されてきたと論じている。その代わりに、理論やルールは実践 をより知的にするための道具として生まれるのだと彼は主張する。 美学 ジョン・デューイの『経験としての芸術』は、彼がハーバード大学で行ったウィリアム・ジェームズの講義に基づくもので、芸術、文化、日常的経験(IEP) の完全性を示す試みであった。デューイにとって、芸術とはすべての人の創造的な生活の一部であり、一部の芸術家だけの特権ではない。また、観客は受動的な 受け手以上の存在であることも強調している。デューイの芸術の扱いは、芸術の独自性と美的鑑賞の無関心性を強調したイマヌエル・カントの流れを汲む、美学 への超越論的アプローチからの脱却であった。現代のプラグマティストの美学者として注目すべきは、ジョセフ・マーゴリスである。彼は、芸術作品を「物理的 に具現化され、文化的に創発された実体」であり、存在論的な奇抜さではなく、他の人間の活動や文化一般に沿った人間の「発話」であると定義している。彼 は、芸術作品は複雑で理解するのが難しく、確定的な解釈を与えることはできないと強調している。 宗教哲学 デューイとジェイムズはともに、宗教が現代社会において果たしうる役割について、前者は『共通の信仰』において、後者は『宗教的経験の多様性』において研 究している。 一般的な観点から言えば、ウィリアム・ジェイムズにとって、何かが真実であるのは、それが機能する限りにおいてのみである。したがって、例えば、祈りは聞 かれるという声明は、心理的なレベルでは機能するかもしれないが、(a)祈ったことを実現する助けにはならないかもしれない(b)祈りは聞かれると主張す るよりも、なだめる効果に言及した方がうまく説明できるかもしれない。このように、プラグマティズムは宗教に対するアンチテーゼではないが、信仰に対する 弁明でもない。しかし、ジェイムズの形而上学的立場は、宗教の存在論的主張が真実である可能性を残している。ジェイムズは『変奏曲』の最後で述べているよ うに、彼の立場は超越的実在の存在を否定するものではない。それどころか、そのような実在を信じる正当な認識論的権利を主張したのである。なぜなら、その ような信念は個人の人生に違いをもたらすものであり、知的根拠でも一般的感覚的根拠でも検証も反証もできない主張に言及しているからである。 ジョセフ・マーゴリスは『Historied Thought, Constructed World』(カリフォルニア、1995年)の中で、「存在」と「現実」を区別している。彼は、「存在する」という言葉を、ピアースの「第二性」を十分に 示すもの、つまり、われわれの動きに物理的な抵抗を与えるものだけに使うことを提案している。このようにして、数字のように私たちに影響を与えるものは、 「存在」しないが「実在」すると言うことができる。マーゴリスは、このような言語的用法では、神は「実在」し、信者にそのような行動を起こさせるかもしれ ないが、「実在」しないかもしれないと示唆している。 教育 [アイコン] このセクションは拡張が必要である。追加することで手助けができる。(2023年10月) プラグマティズム教育学とは、生徒がよりよい人間に成長するよう促し、生活に役立つ知識を教えることを重視する教育哲学である。アメリカの哲学者ジョン・ デューイは、プラグマティズム教育法の主要な思想家の一人とされている。 |

| Neopragmatism Main article: Neopragmatism Neopragmatism is a broad contemporary category used for various thinkers that incorporate important insights of, and yet significantly diverge from, the classical pragmatists. This divergence may occur either in their philosophical methodology (many of them are loyal to the analytic tradition) or in conceptual formation: for example, conceptual pragmatist C. I. Lewis was very critical of Dewey; neopragmatist Richard Rorty disliked Peirce. Important analytic pragmatists include early Richard Rorty (who was the first to develop neopragmatist philosophy in his Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979),[39] Hilary Putnam, W. V. O. Quine, and Donald Davidson. Brazilian social thinker Roberto Unger advocates for a radical pragmatism, one that "de-naturalizes" society and culture, and thus insists that we can "transform the character of our relation to social and cultural worlds we inhabit rather than just to change, little by little, the content of the arrangements and beliefs that comprise them".[40] Late Rorty and Jürgen Habermas are closer to Continental thought. Neopragmatist thinkers who are more loyal to classical pragmatism include Sidney Hook and Susan Haack (known for the theory of foundherentism). Many pragmatist ideas (especially those of Peirce) find a natural expression in the decision-theoretic reconstruction of epistemology pursued in the work of Isaac Levi. Nicholas Rescher advocates his version of methodological pragmatism, based on construing pragmatic efficacy not as a replacement for truths but as a means to its evidentiation.[41] Rescher is also a proponent of pragmatic idealism. Not all pragmatists are easily characterized. With the advent of postanalytic philosophy and the diversification of Anglo-American philosophy, many philosophers were influenced by pragmatist thought without necessarily publicly committing themselves to that philosophical school. Daniel Dennett, a student of Quine's, falls into this category, as does Stephen Toulmin, who arrived at his philosophical position via Wittgenstein, whom he calls "a pragmatist of a sophisticated kind".[42] Another example is Mark Johnson whose embodied philosophy[43] shares its psychologism, direct realism and anti-cartesianism with pragmatism. Conceptual pragmatism is a theory of knowledge originating with the work of the philosopher and logician Clarence Irving Lewis. The epistemology of conceptual pragmatism was first formulated in the 1929 book Mind and the World Order: Outline of a Theory of Knowledge. French pragmatism is attended with theorists such as Michel Callon, Bruno Latour, Michel Crozier, Luc Boltanski, and Laurent Thévenot. It often is seen as opposed to structural problems connected to the French critical theory of Pierre Bourdieu. French pragmatism has more recently made inroads into American sociology and anthropology as well.[44][45][46] Philosophers John R. Shook and Tibor Solymosi said that "each new generation rediscovers and reinvents its own versions of pragmatism by applying the best available practical and scientific methods to philosophical problems of contemporary concern".[47] |

ネオ・プラグマティズム 主な記事 ネオプラグマティズム ネオプラグマティズムとは、古典的プラグマティストの重要な洞察を取り入れつつも、それとは大きく乖離した様々な思想家を指す、現代における広範なカテゴ リーである。例えば、概念的プラグマティストのC.I.ルイスはデューイを非常に批判しており、ネオプラグマティストのリチャード・ローティはパースを 嫌っている。 重要な分析的プラグマティストには、初期のリチャード・ローティ(『哲学と自然の鏡』(1979年)でネオ・プラグマティズム哲学を最初に発展させた)、 ヒラリー・パットナム、W・V・O・クワイン、ドナルド・デイヴィッドソンなどがいる[39]。ブラジルの社会思想家であるロベルト・アンガーは、社会と 文化を「脱自然化」するラディカルなプラグマティズムを提唱しており、その結果、私たちは「それらを構成する取り決めや信念の内容を少しずつ変えるのでは なく、私たちが住む社会的・文化的世界との関係の性格を変革する」ことができると主張している[40]。 古典的なプラグマティズムにより忠実なネオプラグマティズムの思想家には、シドニー・フックやスーザン・ハーク(ファウンドヒーレント主義理論で知られ る)などがいる。多くのプラグマティストの思想(特にペイスの思想)は、アイザック・レヴィの研究において追求された認識論の決定論的再構成において自然 な表現を見出す。ニコラス・レシャーは方法論的プラグマティズムを提唱しているが、これはプラグマティズムの有効性を真理に取って代わるものとしてではな く、それを証明するための手段として解釈することに基づいている[41]。 すべてのプラグマティストが簡単に特徴づけられるわけではない。ポスト分析哲学の登場と英米哲学の多様化によって、多くの哲学者がプラグマティスト思想の 影響を受けたが、必ずしもその哲学学派に公的にコミットする必要はなかった。クワインの弟子であるダニエル・デネットはこの範疇に入るし、スティーヴン・ トゥールミンは、彼が「洗練された種類のプラグマティスト」と呼ぶウィトゲンシュタインを経由して自身の哲学的立場に到達している[42]。もう一人の例 はマーク・ジョンソンであり、彼の具現化哲学[43]はプラグマティズムと心理学主義、直接実在論、反カルテジアニズムを共有している。概念的プラグマ ティズムは哲学者であり論理学者であるクラレンス・アーヴィング・ルイスの研究に端を発する知識論である。概念的プラグマティズムの認識論は、1929年 の著書『心と世界秩序』で初めて定式化された: Outline of a Theory of Knowledge)で初めて定式化された。 フランスのプラグマティズムには、ミシェル・カロン、ブルーノ・ラトゥール、ミシェル・クロジエ、リュック・ボルタンスキー(Luc Boltanski)、ローラン・テヴノといった理 論家が参加している。ピエール・ブルデューのフランス批評理論と結びついた構造的問題と対立しているとみなされることも多い。フレンチ・プラグマティズム は、最近ではアメリカの社会学や人類学にも浸透している[44][45][46]。 哲学者のジョン・R・シュックとティボール・ソリモシは、「それぞれの新しい世代は、現代の関心事である哲学的問題に利用可能な最善の実践的・科学的方法 を適用することによって、プラグマティズムの独自のバージョンを再発見し、再発明している」と述べている[47]。 |

| Legacy and contemporary relevance In the 20th century, the movements of logical positivism and ordinary language philosophy have similarities with pragmatism. Like pragmatism, logical positivism provides a verification criterion of meaning that is supposed to rid us of nonsense metaphysics; however, logical positivism doesn't stress action as pragmatism does. The pragmatists rarely used their maxim of meaning to rule out all metaphysics as nonsense. Usually, pragmatism was put forth to correct metaphysical doctrines or to construct empirically verifiable ones rather than to provide a wholesale rejection. Ordinary language philosophy is closer to pragmatism than other philosophy of language because of its nominalist character (although Peirce's pragmatism is not nominalist[14]) and because it takes the broader functioning of language in an environment as its focus instead of investigating abstract relations between language and world. Pragmatism has ties to process philosophy. Much of the classical pragmatists' work developed in dialogue with process philosophers such as Henri Bergson and Alfred North Whitehead, who aren't usually considered pragmatists because they differ so much on other points.[48] Nonetheless, philosopher Donovan Irven argues there's a strong connection between Henri Bergson, pragmatist William James, and the existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre regarding their theories of truth.[49] Behaviorism and functionalism in psychology and sociology also have ties to pragmatism, which is not surprising considering that James and Dewey were both scholars of psychology and that Mead became a sociologist. Pragmatism emphasizes the connection between thought and action. Applied fields like public administration,[50] political science,[51] leadership studies,[52] international relations,[53] conflict resolution,[54] and research methodology[55] have incorporated the tenets of pragmatism in their field. Often this connection is made using Dewey and Addams's expansive notion of democracy. Effects on social sciences In the early 20th century, Symbolic interactionism, a major perspective within sociological social psychology, was derived from pragmatism, especially the work of George Herbert Mead and Charles Cooley, as well as that of Peirce and William James.[56][57] Increasing attention is being given to pragmatist epistemology in other branches of the social sciences, which have struggled with divisive debates over the status of social scientific knowledge.[4][58] Enthusiasts suggest that pragmatism offers an approach that is both pluralist and practical.[59] Effects on public administration The classical pragmatism of John Dewey, William James, and Charles Sanders Peirce has influenced research in the field of public administration. Scholars claim classical pragmatism had a profound influence on the origin of the field of public administration.[60][61] At the most basic level, public administrators are responsible for making programs "work" in a pluralistic, problems-oriented environment. Public administrators are also responsible for the day-to-day work with citizens. Dewey's participatory democracy can be applied in this environment. Dewey and James' notion of theory as a tool, helps administrators craft theories to resolve policy and administrative problems. Further, the birth of American public administration coincides closely with the period of greatest influence of the classical pragmatists. Which pragmatism (classical pragmatism or neo-pragmatism) makes the most sense in public administration has been the source of debate. The debate began when Patricia M. Shields introduced Dewey's notion of the Community of Inquiry.[62] Hugh Miller objected to one element of the community of inquiry (problematic situation, scientific attitude, participatory democracy): scientific attitude.[63] A debate that included responses from a practitioner,[64] an economist,[65] a planner,[66] other public administration scholars,[67][68] and noted philosophers[69][70] followed. Miller[71] and Shields[72][73] also responded. In addition, applied scholarship of public administration that assesses charter schools,[74] contracting out or outsourcing,[75] financial management,[76] performance measurement,[77] urban quality of life initiatives,[78] and urban planning[79] in part draws on the ideas of classical pragmatism in the development of the conceptual framework and focus of analysis.[80][81][82] The health sector's administrators' use of pragmatism has been criticized as incomplete in its pragmatism, however,[83] according to the classical pragmatists, knowledge is always shaped by human interests. The administrator's focus on "outcomes" simply advances their own interest, and this focus on outcomes often undermines their citizen's interests, which often are more concerned with process. On the other hand, David Brendel argues that pragmatism's ability to bridge dualisms, focus on practical problems, include multiple perspectives, incorporate participation from interested parties (patient, family, health team), and provisional nature makes it well suited to address problems in this area.[84] Effects on feminism Since the mid 1990s, feminist philosophers have re-discovered classical pragmatism as a source of feminist theories. Works by Seigfried,[85] Duran,[86] Keith,[87] and Whipps[88] explore the historic and philosophic links between feminism and pragmatism. The connection between pragmatism and feminism took so long to be rediscovered because pragmatism itself was eclipsed by logical positivism during the middle decades of the twentieth century. As a result, it was lost from feminist discourse. Feminists now consider pragmatism's greatest strength to be the very features that led to its decline. These are "persistent and early criticisms of positivist interpretations of scientific methodology; disclosure of value dimension of factual claims"; viewing aesthetics as informing everyday experience; subordinating logical analysis to political, cultural, and social issues; linking the dominant discourses with domination; "realigning theory with praxis; and resisting the turn to epistemology and instead emphasizing concrete experience".[89] Feminist philosophers point to Jane Addams as a founder of classical pragmatism. Mary Parker Follett was also an important feminist pragmatist concerned with organizational operation during the early decades of the 20th century.[90][91] In addition, the ideas of Dewey, Mead, and James are consistent with many feminist tenets. Jane Addams, John Dewey, and George Herbert Mead developed their philosophies as all three became friends, influenced each other, and were engaged in the Hull House experience and women's rights causes. |

遺産と現代の関連性 20世紀において、論理実証主義と通常の言語哲学の動きはプラグマティズムと類似している。プラグマティズムと同様に、論理実証主義は無意味な形而上学を 排除するはずの意味の検証基準を提供するが、論理実証主義はプラグマティズムのように行動を強調しない。プラグマティストたちは、意味の格言を用いて形而 上学をすべてナンセンスなものとして排除することはほとんどなかった。通常、プラグマティズムは、形而上学の教義を修正したり、経験的に検証可能な教義を 構築したりするために提唱されたのであって、全面的な否定を行うために提唱されたわけではない。 通常の言語哲学が他の言語哲学よりもプラグマティズムに近いのは、その名辞主義的な性格(ただし、パースのプラグマティズムは名辞主義ではない[14]) と、言語と世界の間の抽象的な関係を調査するのではなく、環境における言語のより広範な機能をその焦点としているからである。 プラグマティズムはプロセス哲学と結びついている。古典的なプラグマティストの研究の多くは、アンリ・ベルクソンやアルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッド といったプロセス哲学者との対話の中で発展していったが、彼らは他の点で大きく異なるため、通常はプラグマティストとは考えられていない[48]。それに もかかわらず、哲学者のドノヴァン・アーヴェンは、アンリ・ベルクソン、プラグマティストのウィリアム・ジェームズ、実存主義者のジャン=ポール・サルト ルの間には、真理論に関して強いつながりがあると主張している[49]。 心理学や社会学における行動主義や機能主義もプラグマティズムとつながりがあるが、ジェイムズとデューイがともに心理学の研究者であり、ミードが社会学者 になったことを考えれば驚くことではない。 プラグマティズムは思考と行動の結びつきを強調する。行政学、[50]政治学、[51]リーダーシップ研究、[52]国際関係、[53]紛争解決、 [54]研究方法論[55]などの応用分野は、プラグマティズムの信条をその分野に取り入れてきた。多くの場合、この関連はデューイとアダムスの民主主義 の拡大概念を用いてなされる。 社会科学への影響 20世紀初頭において、社会学的社会心理学の主要な視点である象徴的相互作用論はプラグマティズム、特にジョージ・ハーバート・ミードやチャールズ・クー リー、そしてペイスやウィリアム・ジェームズの研究に由来していた[56][57]。 社会科学的知識の地位をめぐる分裂的な議論に苦慮してきた社会科学の他の分野においても、プラグマティズム的認識論への注目が高まっている[4] [58]。 プラグマティズムの熱狂的な支持者は、プラグマティズムが多元主義的かつ実践的なアプローチを提供することを示唆している[59]。 行政への影響 ジョン・デューイ、ウィリアム・ジェイムズ、チャールズ・サンダース・パースの古典的プラグマティズムは、行政学分野の研究に影響を与えてきた。最も基本 的なレベルでは、行政官は多元的で問題志向の環境においてプログラムを「機能」させる責任を負っている。行政官はまた、市民との日々の仕事にも責任を負っ ている。デューイの参加型民主主義は、このような環境において適用することができる。デューイとジェイムズの「道具としての理論」という概念は、行政官が 政策や行政の問題を解決するための理論を構築するのに役立つ。さらに、アメリカの行政学の誕生は、古典的プラグマティストの影響が最も大きかった時期と密 接に一致している。 どちらのプラグマティズム(古典的プラグマティズムとネオ・プラグマティズム)が行政学において最も理にかなっているかは、議論の種となってきた。この議 論は、パトリシア・M・シールズがデューイの「探求の共同体」という概念を紹介したときに始まった[62]。ヒュー・ミラーは、探求の共同体の1つの要素 (問題状況、科学的態度、参加民主主義)である科学的態度に異議を唱えた[63]。ミラー[71]やシールズ[72][73]もこれに応じた。 加えて、チャータースクール[74]、契約やアウトソーシング[75]、財務管理[76]、業績測定[77]、都市のクオリティ・オブ・ライフ・イニシア チブ[78]、都市計画[79]を評価する行政学の応用研究は、概念的枠組みや分析の焦点の開発において、部分的に古典的プラグマティズムの考え方を利用 している[80][81][82]。 医療部門の管理者によるプラグマティズムの使用は、そのプラグマティズムが不完全であると批判されているが[83]、古典的プラグマティストによれば、知 識は常に人間の利益によって形成される。管理者が「結果」に重点を置くことは、単に彼ら自身の利益を前進させるだけであり、この結果に重点を置くことは、 多くの場合プロセスに重点を置く市民の利益を損なうことが多い。他方、デイヴィッド・ブレンデルは、プラグマティズムの二元論を橋渡しする能力、実際的な 問題に焦点を当てる能力、複数の視点を含む能力、利害関係者(患者、家族、医療チーム)の参加を取り入れる能力、暫定的な性質が、この分野の問題に取り組 むのに適していると論じている[84]。 フェミニズムへの影響 1990年代半ば以降、フェミニストの哲学者たちは、フェミニズム理論の源泉として古典的プラグマティズムを再発見している。Seigfried、 [85]Duran、[86]Keith、[87]Whipps[88]による著作は、フェミニズムとプラグマティズムの間の歴史的かつ哲学的なつながり を探求している。プラグマティズムとフェミニズムの結びつきが再発見されるまでにこれほど長い時間を要したのは、プラグマティズム自体が20世紀半ばの数 十年間、論理実証主義に駆逐されてしまったからである。その結果、プラグマティズムはフェミニストの言説から失われてしまった。フェミニストたちは現在、 プラグマティズムの最大の強みは、その衰退を招いた特徴そのものであると考えている。すなわち、「科学的方法論の実証主義的解釈に対する執拗かつ初期の批 判、事実の主張の価値次元の開示」、美学を日常的経験に情報を与えるものとみなすこと、論理的分析を政治的・文化的・社会的問題に従属させること、支配的 言説を支配と結びつけること、「理論を実践と再調整すること、認識論への転向に抵抗し、代わりに具体的経験を強調すること」である[89]。 フェミニスト哲学者たちは、古典的プラグマティズムの創始者としてジェーン・アダムスを挙げている。メアリー・パーカー・フォレットもまた、20世紀初頭 の数十年間、組織運営に関わる重要なフェミニスト・プラグマティストであった[90][91]。さらに、デューイ、ミード、ジェイムズの考え方は多くの フェミニストの信条と一致している。ジェーン・アダムス、ジョン・デューイ、ジョージ・ハーバート・ミードは、3人とも友人となり、互いに影響を与え合 い、ハル・ハウスの経験や女性の権利運動に従事する中で、それぞれの哲学を発展させていった。 |

| Criticisms In the 1908 essay "The Thirteen Pragmatisms", Arthur Oncken Lovejoy argued that there's significant ambiguity in the notion of the effects of the truth of a proposition and those of belief in a proposition in order to highlight that many pragmatists had failed to recognize that distinction.[92] He identified 13 different philosophical positions that were each labeled pragmatism.[92] The Franciscan friar Celestine Bittle presented multiple criticisms of pragmatism in his 1936 book Reality and the Mind: Epistemology.[93] He argued that, in William James's pragmatism, truth is entirely subjective and is not the widely accepted definition of truth, which is correspondence to reality. For Bittle, defining truth as what is useful is a "perversion of language".[93] With truth reduced essentially to what is good, it is no longer an object of the intellect. Therefore, the problem of knowledge posed by the intellect is not solved, but rather renamed. Renaming truth as a product of the will cannot help it solve the problems of the intellect, according to Bittle. Bittle cited what he saw as contradictions in pragmatism, such as using objective facts to prove that truth does not emerge from objective fact; this reveals that pragmatists do recognize truth as objective fact, and not, as they claim, what is useful. Bittle argued there are also some statements that cannot be judged on human welfare at all. Such statements (for example the assertion that "a car is passing") are matters of "truth and error" and do not affect human welfare.[93] British philosopher Bertrand Russell devoted a chapter each to James and Dewey in his 1945 book A History of Western Philosophy; Russell pointed out areas in which he agreed with them but also ridiculed James's views on truth and Dewey's views on inquiry.[94]: 17 [95]: 120–124 Hilary Putnam later argued that Russell "presented a mere caricature" of James's views[94]: 17 and a "misreading of James",[94]: 20 while Tom Burke argued at length that Russell presented "a skewed characterization of Dewey's point of view".[95]: 121 Elsewhere, in Russell's book The Analysis of Mind, Russell praised James's radical empiricism, to which Russell's own account of neutral monism was indebted.[94]: 17 [96] Dewey, in The Bertrand Russell Case, defended Russell against an attempt to remove Russell from his chair at the College of the City of New York in 1940.[97] Neopragmatism as represented by Richard Rorty has been criticized as relativistic both by other neopragmatists such as Susan Haack[98] and by many analytic philosophers.[99] Rorty's early analytic work, however, differs notably from his later work which some, including Rorty, consider to be closer to literary criticism than to philosophy, and which attracts the brunt of criticism from his detractors. |

批判 アーサー・オンケン・ラヴジョイは1908年のエッセイ「13のプラグマティズム」において、多くのプラグマティストがその区別を認識できていないことを 強調するために、命題の真理の効果と命題を信じることの効果という概念には重大な曖昧さがあると主張していた[92]。彼はそれぞれプラグマティズムとラ ベル付けされた13の異なる哲学的立場を特定していた[92]。 フランシスコ会の修道士であるセレスティン・ビトルは1936年の著書『現実と心』においてプラグマティズムに対する複数の批判を提示していた: 彼は、ウィリアム・ジェームズのプラグマティズムにおいては、真理は完全に主観的なものであり、広く受け入れられている真理の定義である現実との対応関係 ではないと主張した[93]。ビトルにとって、真理を有用なものとして定義することは「言語の倒錯」である[93]。真理が本質的に善いものへと還元され ることで、それはもはや知性の対象ではなくなる。したがって、知性によって提起された知の問題は解決されるのではなく、むしろ改名されるのである。バイト ルによれば、真理を意志の産物として改名しても、知性の問題を解決することはできない。バトルは、プラグマティズムの矛盾と思われる点として、客観的事実 から真理は生まれないことを証明するために客観的事実を用いることなどを挙げた。これは、プラグマティストが真理を客観的事実として認識していることを明 らかにするものであり、彼らが主張するように、有用なものとして認識しているわけではない。ビトルは、人間の福祉を判断することができない記述も存在する と主張した。そのような言明(例えば「車が通り過ぎる」という主張)は「真理と誤り」の問題であり、人間の福祉には影響しない[93]。 イギリスの哲学者であるバートランド・ラッセルは1945年に出版した『西洋哲学史』の中でジェイムズとデューイにそれぞれ1章を割いており、ラッセルは 彼らに同意する部分を指摘する一方で、ジェイムズの真理に関する見解とデューイの探究に関する見解を嘲笑していた[94]: 17 [95]: 120-124 ヒラリー・パットナムは後に、ラッセルはジェイムズの見解[94]を「単なる戯画として提示した」と論じている: 17 と「ジェイムズの誤読」[94]: 20を、トム・バークはラッセルが「デューイの視点の歪んだ特徴付け」を提示したと長々と論じている[95]: 121 また、ラッセルの著書『心の分析』において、ラッセルはジェイムズの急進的な経験主義を賞賛しており、ラッセル自身の中立的一元論の説明はそれに依拠して いた[94]: 17 [96] デューイは『バートランド・ラッセル事件』の中で、1940年にラッセルをニューヨーク市立大学の彼の椅子から解任しようとした試みに対してラッセルを擁 護している[97]。 リチャード・ローティに代表されるネオプラグマティズムは、スーザン・ハック[98]のような他のネオプラグマティストからも、多くの分析哲学者からも相 対主義的であると批判されている[99]。しかしローティの初期の分析的研究は、ローティを含む何人かが哲学よりも文芸批評に近いと考え、彼を非難する人 々から批判の矢面に立たされている後期の研究とは著しく異なっている。 |

| List of pragmatists |

省略 |

| American philosophy – Activity,

corpus, and tradition of philosophers affiliated with the United States Charles Sanders Peirce bibliography Communication Theory as a Field § Russill, pragmatism as an eighth tradition Doctrine of internal relations – Philosophical doctrine that relations are internal to their bearers Morton White – American philosopher and historian of ideas New legal realism |

アメリカ哲学 - アメリカに属する哲学者の活動、コーパス、伝統 チャールズ・サンダース・パース書誌 分野としてのコミュニケーション論§ラッシル、第八の伝統としてのプラグマティズム 内的関係の教義 - 関係はその担い手の内的なものであるという哲学的教義 モートン・ホワイト - アメリカの哲学者、思想史家 新しい法的実在論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pragmatism |

リンク

文献

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099