はじめによんでください

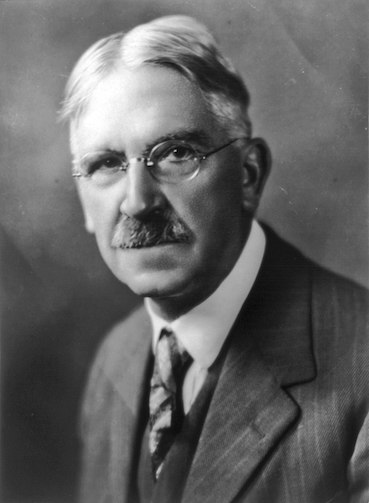

ジョン・デューイ

John Dewey (October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952)

■ジョン・デューイ(John Dewey, 1859-1952) 年譜(ウィキペディア「ジョン・デュー イ」を参照に)

|

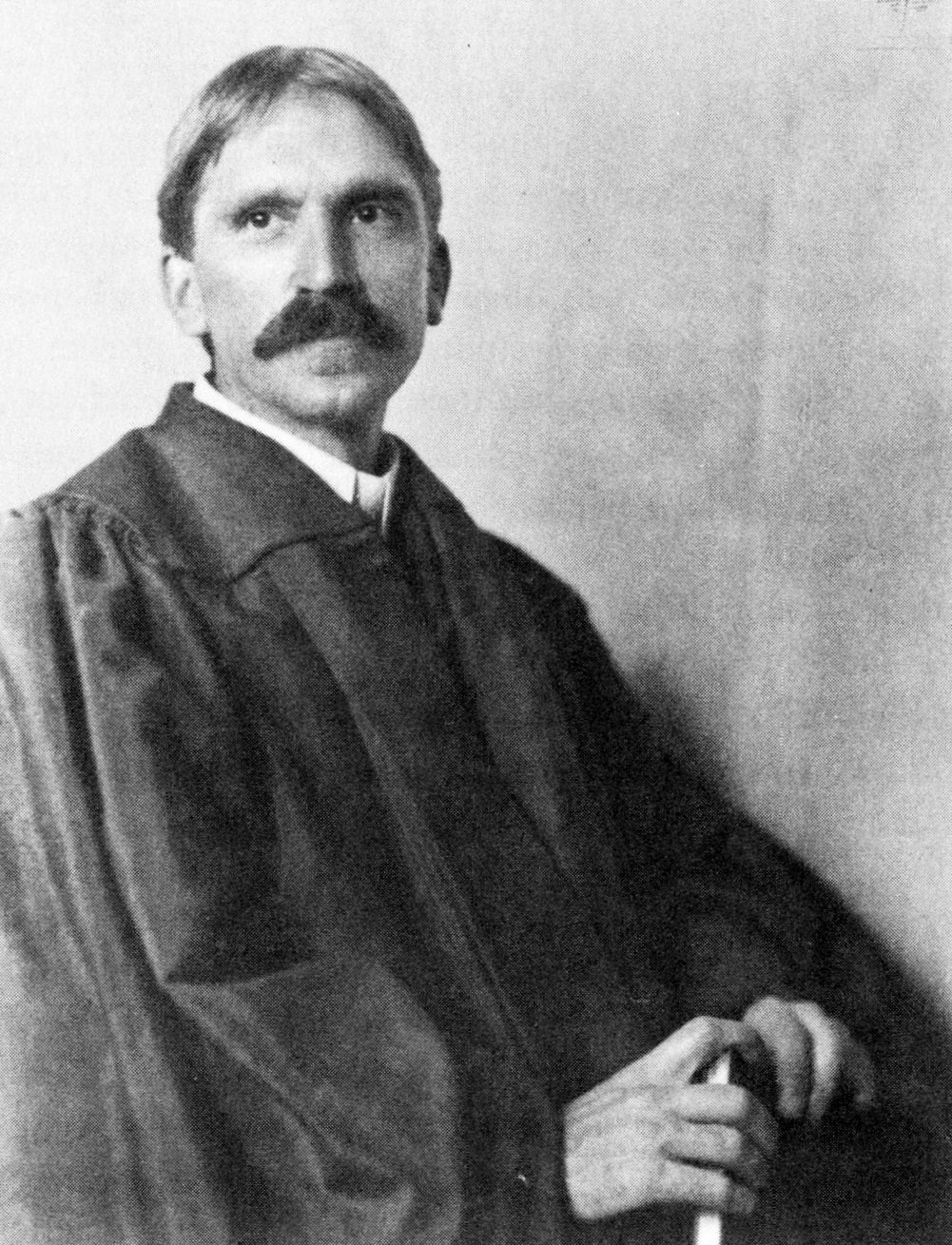

1859 生年。この年、チャールズ・ダーウィン『種の起 源』刊行 1874 バーモント大学に入学(15歳)ダーウィン進化論、コ ント実証 主義に親しむ。 1879 ペンシルバニア州のハイスクールに勤務 1881 バーモント州の小学校に勤務 1882 ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学大学院、心理学者スタンレー・ホールに師事。 1884 「カントの心理学」で哲学博士(Ph.D)。ミシガン大学哲学講師 1886 ミシガン大学准教授。ヘーゲルおよびドイツ観念論を主に研究。 1889 同大学教授。 n.d. ドイツ留学。 1891 ドイツ留学から帰国。同大学講師になったジョージ・ハーバート・ミード(George Herbert Mead, 1863-1931)[ウィリアム・ジェィムズ(William James, 1842-1910)の弟子]と交友関係をむすぶ。 1894 シカゴ大学教授としてミードと共に迎えられる。 1896 The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology. 1896 1月実験学校Laboratory School(のちシカゴ大学付属実験学校)を個人宅を借り、生徒は16人、教師は1人(他に補助教師が1人)ではじめる。1898年秋には実験室や食堂 などを敷設した校舎に移る(〜1903)。 1899 4月、関係者や生徒の親たちを前に、3年間の実験の報告を3度行う。この講演の速記をもとに出版されたのが後に教育理論 の名著と して知られることになる『学校と社会』(1899年)。 1902年のデューイ 1903 Studies in Logical Theory (1903)。アメリカ心理学会会長に選出 1904 コロンビア大学で哲学教授。 1905 アメリカ哲学会会長 1916 Democrasy and Education, Essays in Experimental Logic. 1919 ソースティン・ヴェブレン、ジェームズ・ロビンソン、チャーズ・ビアードらとニュースクールを創設。 当時、コロンビアの学生であったルース・ベネディクトは デュー イの授業を受け感銘した。のちに彼女は、個人の真偽の判断は、その人が育てられる慣習行為の中で育てられるという見解を『文化の型』(1934)の中で デューイの名を出して紹介する:"John Dewey has said in all seriousness that the part played by custom in shaping the behaviour of the individual as over against any way in which he can affect traditional custom, is as the proportion of the total vocabulary of his mother tongue over against those words of his own baby 'talk that are taken up into the vernacular' of his family." (Benedict, Patterns of Culture, 1934:2). 「ジョン・デューイは、伝統的な慣習に影響を与えることができるあらゆる方法に対して、個人の行動を形成する上で慣習が果たす

役割は、自分の母語の語彙の総量が、自分の家族の「俗語」に取り込まれる自分の赤ん坊の「話し言葉」の総量に占める割合のようなものである、と真面目に述

べている」 1919-1921 日本と中国を訪問。 1922 人間的自然と行為 1924 トルコに招へい 1925 『経験と自然』。当時、ウォルター・リップマンが『幻 の公衆(The Phantom Public)』——デモクラシー批判——を公刊したが、それに対する反論を執筆開始(2年後に公刊)。 1926 メキシコに招へい 1927 リップマン(The Phantom Public)への応答として『公衆とその問題』——デモクラシー擁護——を公刊。 1928 ソビエト訪問。 1929 世界恐慌 1931 『個人主義』 1933 チャイルズとの共著『経済状態と教育』を公刊。 1934 『経験としての芸術』『共通の信条』 1935 『自由主義と社会的行動』 1938 『論理学:探究の理論』 1939 『自由と文化』 1949 『知ることと知られたもの』 1952 没年。 |

John Dewey from Wiki.

| John Dewey John Dewey (/ˈduːi/; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the first half of the twentieth century.[6][7] The overriding theme of Dewey's works was his profound belief in democracy, be it in politics, education, or communication and journalism.[8] As Dewey himself stated in 1888, while still at the University of Michigan, "Democracy and the one, ultimate, ethical ideal of humanity are to my mind synonymous."[9] Dewey considered two fundamental elements—schools and civil society—to be major topics needing attention and reconstruction to encourage experimental intelligence and plurality. He asserted that complete democracy was to be obtained not just by extending voting rights but also by ensuring that there exists a fully formed public opinion, accomplished by communication among citizens, experts and politicians, with the latter being accountable for the policies they adopt.[citation needed] Dewey was one of the primary figures associated with the philosophy of pragmatism and is considered one of the fathers of functional psychology. His paper "The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology," published in 1896, is regarded as the first major work in the (Chicago) functionalist school of psychology.[10] A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Dewey as the 93rd-most-cited psychologist of the 20th century.[11] Dewey was also a major educational reformer for the 20th century.[6] A well-known public intellectual, he was a major voice of progressive education and liberalism.[12][13] While a professor at the University of Chicago, he founded the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, where he was able to apply and test his progressive ideas on pedagogical method.[14][15] Although Dewey is known best for his publications about education, he also wrote about many other topics, including epistemology, metaphysics, aesthetics, art, logic, social theory, and ethics. |

ジョン・デューイ ジョン・デューイ(John Dewey, /ˈdu,i, 1859年10月20日 - 1952年6月1日)は、アメリカの哲学者、心理学者、教育改革者であり、その考えは教育や社会改革に影響を及ぼしている。20世紀前半の最も著名なアメ リカ人学者の一人である[6][7]。 デューイの著作の主要なテーマは、政治、教育、コミュニケーションやジャーナリズムのいずれにおいても、民主主義に対する彼の深い信念であった[8]。 デューイ自身が1888年に、まだミシガン大学にいたときに述べたように、「民主主義と人類の一つの、究極の、倫理的理想は私の心にとって同義である」 [9] デューイは二つの基本要素、学校と市民社会は実験知性と複数性を促すために注目と再建を要する主要テーマであるとみなした。彼は完全な民主主義は投票権の 拡大だけでなく、市民、専門家、政治家の間のコミュニケーションによって達成され、後者が採用した政策に対して責任を負う、完全に形成された世論の存在を 保証することによって得られると主張した[citation needed]。 デューイはプラグマティズムの哲学に関連する主要な人物の一人であり、機能心理学の父の一人とみなされている。1896年に発表された彼の論文「心理学に おける反射弧概念」は、(シカゴ)機能主義派の心理学における最初の主要著作とみなされている[10]。 2002年に発表された『一般心理学のレビュー』の調査では、デューイは20世紀において最も引用された心理学者の93番目にランク付けされている [11]。 デューイは20世紀の主要な教育改革者でもあった[6]。 有名な公的知識人として、彼は進歩的な教育と自由主義の主要な声だった[12][13]。 シカゴ大学の教授だったとき、彼はシカゴ大学実験学校を設立し、そこで教育方法に関する彼の進歩的な考えを適用し試すことができた。14][15] デューイは教育に関する出版物で最もよく知られているが、彼は認識論、形而上学、美学、芸術、論理、社会理論、倫理など他の多くのテーマについて書いても いる。 |

| Early life and education John Dewey was born in Burlington, Vermont, to a family of modest means.[16] He was one of four boys born to Archibald Sprague Dewey and Lucina Artemisia Rich Dewey. Their second son was also named John, but he died in an accident on January 17, 1859. The second John Dewey was born October 20, 1859, forty weeks after the death of his older brother. Like his older, surviving brother, Davis Rich Dewey, he attended the University of Vermont, where he was initiated into Delta Psi, and graduated Phi Beta Kappa[17] in 1879. A significant professor of Dewey's at the University of Vermont was Henry Augustus Pearson Torrey (H. A. P. Torrey), the son-in-law and nephew of former University of Vermont president Joseph Torrey. Dewey studied privately with Torrey between his graduation from Vermont and his enrollment at Johns Hopkins University.[18][19] |

幼少期と教育 ジョン・デューイはバーモント州バーリントンの質素な家庭に生まれた[16]。 アーチボルト・スプラグ・デューイとルチナ・アルテミシア・リッチ・デューイとの間に生まれた4男のうちの1人であった。次男もジョンと名付けられたが、 1859年1月17日に事故で亡くなっている。次男のジョン・デューイは、兄の死から40週間後の1859年10月20日に誕生した。生き残った兄デイ ヴィス・リッチ・デューイと同じく、バーモント大学に入学し、デルタ・プシに入会し、1879年にファイ・ベータ・カッパ[17]を卒業した。 バーモント大学でデューイの重要な教授であったのは、元バーモント大学学長ジョセフ・トーレイの娘婿で甥のヘンリー・オーガスタス・ピアソン・トーレイ (H. A. P. Torrey)であった。バーモント大学を卒業してからジョンズ・ホプキンス大学に入学するまでの間、デューイはトーレイのもとで個人的に学んでいた [18][19]。 |

| Career After two years as a high-school teacher in Oil City, Pennsylvania, and one year as an elementary school teacher in the small town of Charlotte, Vermont, Dewey decided that he was unsuited for teaching primary or secondary school. After studying with George Sylvester Morris, Charles Sanders Peirce, Herbert Baxter Adams, and G. Stanley Hall, Dewey received his Ph.D. from the School of Arts & Sciences at Johns Hopkins University. In 1884, he accepted a faculty position at the University of Michigan (1884–88 and 1889–94) with the help of George Sylvester Morris. His unpublished and now lost dissertation was titled "The Psychology of Kant".[20] In 1894 Dewey joined the newly founded University of Chicago (1894–1904) where he developed his belief in Rational Empiricism, becoming associated with the newly emerging Pragmatic philosophy. His time at the University of Chicago resulted in four essays collectively entitled Thought and its Subject-Matter, which was published with collected works from his colleagues at Chicago under the collective title Studies in Logical Theory (1904).[20] During that time Dewey also initiated the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, where he was able to actualize the pedagogical beliefs that provided material for his first major work on education, The School and Society (1899). Disagreements with the administration ultimately caused his resignation from the university, and soon thereafter he relocated near the East Coast. In 1899, Dewey was elected president of the American Psychological Association (A.P.A.). From 1904 until his retirement in 1930 he was professor of philosophy at Teachers College at Columbia University.[21]  In 1905 he became president of the American Philosophical Association. He was a longtime member of the American Federation of Teachers. Along with the historians Charles A. Beard and James Harvey Robinson, and the economist Thorstein Veblen, Dewey is one of the founders of The New School. |

学歴 ペンシルベニア州オイルシティで2年間、バーモント州の小さな町シャー ロットで1年間、高校教師をした後、デューイは小中学校の教師には向かないと判断した。ジョージ・シルベスター・モリス、チャールズ・サンダース・ペアー ス、ハーバート・バクスター・アダムス、G・スタンレー・ホールに学んだ後、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学人文科学部で博士号を取得した。1884年、ジョー ジ・シルベスター・モリスの協力を得て、ミシガン大学の教員となる(1884-88年、1889-94年)。彼の未発表で今は失われている学位論文のタイ トルは「カントの心理学」であった[20]。 1894年にデューイは新しく設立されたシカゴ大学(1894-1904)に入り、そこで彼は合理的経験主義への信念を発展させ、新しく出現したプラグマ ティック哲学と関連するようになった。シカゴ大学での時間は、Thought and its Subject-Matterと総称される4つのエッセイを生み出し、これはシカゴの同僚たちの著作とともにStudies in Logical Theory (1904)という総称で出版されている[20]。 その間に、デューイはシカゴ大学のラボラトリースクールを開始し、そこで教育に関する最初の主要な著作である『学校と社会』(1899年)の素材となる教 育学的信念を実現させることができたのである。しかし、経営陣との意見の相違から、最終的には大学を辞職し、その後すぐに東海岸近くに移り住むことにな る。1899年、デューイはアメリカ心理学会(A.P.A.)の会長に選出された。1904年から1930年に引退するまで、彼はコロンビア大学のティー チャーズ・カレッジの哲学の教授であった[21]。  1905年、彼はアメリカ哲学協会の会長になった。彼はアメリカ教員連盟の長年のメンバーであった。歴史家のチャールズ・A・ビアード、ジェームズ・ハー ヴェイ・ロビンソン、経済学者のトースタイン・ヴェブレンとともに、デューイはニュースクールの創設者の一人である。 |

Dewey published more than 700 articles in 140 journals, and approximately 40 books. His most significant writings were "The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology" (1896), a critique of a standard psychological concept and the basis of all his further work; Democracy and Education (1916), his celebrated work on progressive education; Human Nature and Conduct (1922), a study of the function of habit in human behavior;[22] The Public and its Problems (1927), a defense of democracy written in response to Walter Lippmann's The Phantom Public (1925); Experience and Nature (1925), Dewey's most "metaphysical" statement; Impressions of Soviet Russia and the Revolutionary World (1929), a glowing travelogue from the nascent USSR.[23] Art as Experience (1934), was Dewey's major work on aesthetics; A Common Faith (1934), a humanistic study of religion originally delivered as the Dwight H. Terry Lectureship at Yale; Logic: The Theory of Inquiry (1938), a statement of Dewey's unusual conception of logic; Freedom and Culture (1939), a political work examining the roots of fascism; and Knowing and the Known (1949), a book written in conjunction with Arthur F. Bentley that systematically outlines the concept of trans-action, which is central to his other works (see Transactionalism). While each of these works focuses on one particular philosophical theme, Dewey included his major themes in Experience and Nature. However, dissatisfied with the response to the first (1925) edition, for the second (1929) edition he rewrote the first chapter and added a Preface in which he stated that the book presented what we would now call a new (Kuhnian) paradigm: 'I have not striven in this volume for a reconciliation between the new and the old' [E&N:4] [24]. and he asserts Kuhnian incommensurability: 'To many the associating of the two words ['experience' and 'nature'] will seem like talking of a round square' but 'I know of no route by which dialectical argument can answer such objections. They arise from association with words and cannot be dealt with argumentatively'. The following can be interpreted now as describing a Kuhnian conversion process: 'One can only hope in the course of the whole discussion to disclose the [new] meanings which are attached to "experience" and "nature," and thus insensibly produce, if one is fortunate, a change in the significations previously attached to them' [all E&N:10].[25] Reflecting his immense influence on 20th-century thought, Hilda Neatby wrote "Dewey has been to our age what Aristotle was to the later Middle Ages, not a philosopher, but the philosopher."[26] The United States Postal Service honored Dewey with a Prominent Americans series 30¢ postage stamp in 1968.[27] |

著述 デューイは140の雑誌に700以上の論文を発表し、約40冊の本を出 版した。彼の最も重要な著作は、標準的な心理学の概念に対する批判であり、その後のすべての研究の基礎となった「心理学における反射弧概念」(1896 年)、進歩的教育に関する彼の有名な著作「民主主義と教育」(1916年)、人間の行動における習慣の機能に関する研究「人間本性と行動」(1922年) であった。 22] The Public and its Problems (1927), Walter Lippmann's The Phantom Public (1925) に対抗して書かれた民主主義の擁護書; Experience and Nature (1925), デューイの最も「メタフィジカル」な声明; Impressions of Soviet Russia and the Revolutionary World (1929), 新生ソ連からの輝かしい旅行記[23]. [23] 経 験としての芸術(1934 年)、美学に関するデューイの主要な仕事であった;共通の信仰(1934年)、もともとエール大学のドワイト・H・テリー講義として行われた宗教の人文学 的研究;論理。また、アーサー・F・ベントレーと共同で執筆した『知ることと知られること』(1949年)は、彼の他の著作(トランザクション主義を参 照)の中核をなすトランスアクションの概念を体系的に概説したもので、この著作は、デューイ自身の論理学に対する珍しい概念を提示したものである。 これらの著作は、それぞれある特定の哲学的テーマに焦点を当てているが、デューイは、『経験と自然』に彼の主要なテーマを盛り込んだ。しかし、第1版 (1925年)の反響に不満だった彼は、第2版(1929年)では、第1章を書き直し、序文を加えて、この本が今でいう新しい(クーニャン)パラダイムを 提示していると述べ、「私はこの本で新しいものと古いものの間の和解に努めていない」[E&N:4][24]とクーニャン的非共有性を主張してい ます。 多くの人にとって、二つの言葉[「経験」と「自然」]の関連付けは、丸い四角を語るように見えるだろう」しかし「私は弁証法的議論がそのような反論に答え ることができる道筋を知らない」。それらは言葉の連想から生じるものであり、論証的に対処することはできない」。以下は、今となっては、クーニー的な転換 過程を述べたものと解釈できる。議論全体の過程で、「経験」と「自然」に付された[新しい]意味を開示し、それによって、もし幸運であれば、以前それらに 付されていた意味づけに変化を生じさせることを無意識に期待するしかない」[全E&N:10][25]。 20世紀の思想に対する彼の絶大な影響を反映して、ヒルダ・ニートビーは「デューイは我々の時代にとって、アリストテレスが中世後期にとってそうであった ように、哲学者ではなく、哲学者であった」と記している[26]。 アメリカ合衆国郵政公社は、1968年にデューイをプロミネント・アメリカンシリーズの30セント切手で表彰した[27]。 |

| Personal life Dewey married Alice Chipman in 1886 shortly after Chipman graduated with her Ph.D. from the University of Michigan. The two had six children: Frederick Archibald Dewey, Evelyn Riggs Dewey, Morris (who died young), Gordon Chipman Dewey, Lucy Alice Chipman Dewey, and Jane Mary Dewey.[28][29] Alice Chipman died in 1927 at the age of 68; weakened by a case of malaria contracted during a trip to Turkey in 1924 and a heart attack during a trip to Mexico City in 1926, she died from cerebral thrombosis on July 13, 1927.[30] Dewey married Estelle Roberta Lowitz Grant, "a longtime friend and companion for several years before their marriage" on December 11, 1946.[31][32] At Roberta's behest, the couple adopted two siblings, Lewis (changed to John, Jr.) and Shirley.[33] |

私生活 デューイは1886年にアリス・チップマンと結婚し、チップマンはミシガン大学から博士号を取得した。二人の間には6人の子供がいた。1924年のトルコ 旅行でマラリアにかかり、1926年のメキシコシティ旅行で心臓発作を起こして衰弱し、1927年7月13日に脳血栓症で死亡した[30]。 デューイは1946年12月11日に「結婚前の数年間、長年の友人であり仲間だった」エステル・ロバータ・ローウィズ・グラントと結婚した[31] [32]。 ロバータの希望で、夫妻はルイス(ジョン・ジュニアに変更)とシャーリーという2人の兄妹の養子となった[33]。 |

| Death John Dewey died of pneumonia on June 1, 1952, at his home in New York City after years of ill-health[34][35] and was cremated the next day.[36] |

死 ジョン・デューイは長年の不健康の末、1952年6月1日にニューヨークの自宅で肺炎のため亡くなり[34][35]、翌日火葬に付された[36]。 |

| Visits to China and Japan In 1919, Dewey and his wife traveled to Japan on sabbatical leave. Though Dewey and his wife were well received by the people of Japan during this trip, Dewey was also critical of the nation's governing system and claimed that the nation's path towards democracy was "ambitious but weak in many respects in which her competitors are strong".[37] He also warned that "the real test has not yet come. But if the nominally democratic world should go back on the professions so profusely uttered during war days, the shock will be enormous, and bureaucracy and militarism might come back."[37] During his trip to Japan, Dewey was invited by Peking University to visit China, probably at the behest of his former students, Hu Shih and Chiang Monlin. Dewey and his wife Alice arrived in Shanghai on April 30, 1919,[38] just days before student demonstrators took to the streets of Peking to protest the decision of the Allies in Paris to cede the German-held territories in Shandong province to Japan. Their demonstrations on May Fourth excited and energized Dewey, and he ended up staying in China for two years, leaving in July 1921.[39] In these two years, Dewey gave nearly 200 lectures to Chinese audiences and wrote nearly monthly articles for Americans in The New Republic and other magazines. Well aware of both Japanese expansionism into China and the attraction of Bolshevism to some Chinese, Dewey advocated that Americans support China's transformation and that Chinese base this transformation in education and social reforms, not revolution. Hundreds and sometimes thousands of people attended the lectures, which were interpreted by Hu Shih. For these audiences, Dewey represented "Mr. Democracy" and "Mr. Science," the two personifications which they thought of representing modern values and hailed him as "Second Confucius". His lectures were lost at the time, but have been rediscovered and published in 2015.[40] |

中国と日本への訪問 1919年、デューイ夫妻はサバティカル休暇を利用して日本へ渡った。 この旅行でデューイ夫妻は日本国民に好意的に迎えられたが、デューイは日本の統治体制にも批判的で、日本の民主主義への道は「野心的ではあるが、競争相手 が強い多くの点で弱い」と主張した[37]。 また「本当の試練はまだ来ていない」と警告している[38]。しかし、もし名目上民主的な世界が、戦時中に散々口にした公約を反故にするならば、その衝撃 は甚大であり、官僚主義と軍国主義が復活するかもしれない」[37]と警告している。 日本への旅行中、デューイは北京大学から中国訪問の招待を受け、おそらくかつての教え子である胡志明と蒋文林に頼まれたのであろう。デューイと妻のアリス が上海に到着したのは1919年4月30日で、パリで連合国が山東省のドイツ領を日本に割譲すると決定したことに抗議して、学生デモが北京の街頭で行われ る数日前であった[38]。5月4日の彼らのデモはデューイを興奮させ、活気づけ、彼は結局2年間中国に滞在し、1921年7月に帰国した[39]。 この2年間、デューイは中国の聴衆を対象に200回近い講演を行い、『ニュー・リパブリック』やその他の雑誌にアメリカ人向けの記事をほぼ毎月執筆してい た。日本の中国への進出主義と一部の中国人にとってのボルシェビズムの魅力をよく理解していたデューイは、アメリカ人が中国の変革を支援し、中国人がこの 変革を革命ではなく教育と社会改革に基づくものにすることを提唱していた。この講演には、何百人、時には何千人もの聴衆が参加し、胡志英の通訳がついた。 このような聴衆にとって、デューイは「ミスター・デモクラシー」と「ミスター・サイエンス」という、近代的価値観を代表する人物像であり、「第二の孔子」 とも称された。当時、彼の講義は失われていたが、2015年に再発見され出版された[40]。 |

| Zhixin Su states: Dewey was, for those Chinese educators who had studied under him, the great apostle of philosophic liberalism and experimental methodology, the advocate of complete freedom of thought, and the man who, above all other teachers, equated education to the practical problems of civic cooperation and useful living.[41] Dewey urged the Chinese to not import any Western educational model. He recommended to educators such as Tao Xingzhi, that they use pragmatism to devise their own model school system at the national level. However the national government was weak, and the provinces largely controlled by warlords so his suggestions were praised at the national level but not implemented. However, there were a few implementations locally.[42] Dewey's ideas did have influence in Hong Kong, and in Taiwan after the nationalist government fled there. In most of China, Confucian scholars controlled the local educational system before 1949 and they simply ignored Dewey and Western ideas. In Marxist and Maoist China, Dewey's ideas were systematically denounced.[43] |

蘇志欣はこう述べている。 デューイは、彼の下で学んだ中国の教育者たちにとって、哲学的自由主義と実験的方法論の偉大な使徒であり、思考の完全な自由を提唱し、他のどの教師より も、教育を市民的協力と有用な生活という実際的問題と同一視する人物だった[41]。 デューイは中国人に西洋の教育モデルを輸入しないように促した。彼は、タオ・シンジーのような教育者たちに、プラグマティズムを用いて、国家レベルで独自 のモデル学校システムを考案するよう勧めた[41]。しかし、国政は弱く、地方は軍閥に支配されていたため、彼の提案は国政レベルでは賞賛されたものの、 実行には移されなかった。しかし、地方ではいくつか実施された[42]。デューイの考えは、香港や、国民党政府が逃げた後の台湾でも影響を及ぼした。中国 の大部分では、1949年以前は儒学者が地域の教育制度を支配しており、彼らはデューイや西洋の考えを単に無視した。マルクス主義や毛沢東主義の中国で は、デューイの思想は組織的に糾弾されていた[43]。 |

| Visit to Southern Africa Dewey and his daughter Jane went to South Africa in July 1934, at the invitation of the World Conference of New Education Fellowship in Cape Town and Johannesburg, where he delivered several talks. The conference was opened by the South African Minister of Education Jan Hofmeyr, and Deputy Prime Minister Jan Smuts. Other speakers at the conference included Max Eiselen and Hendrik Verwoerd, who would later become prime minister of the Nationalist government that introduced apartheid.[44] Dewey's expenses were paid by the Carnegie Foundation. He also traveled to Durban, Pretoria and Victoria Falls in what was then Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and looked at schools, talked to pupils, and gave lectures to the administrators and teachers. In August 1934, Dewey accepted an honorary degree from the University of the Witwatersrand.[45] The white-only governments rejected Dewey's ideas as too secular. However black people and their white supporters were more receptive.[46] |

南部アフリカ訪問 デューイは娘のジェーンとともに1934年7月、ケープタウンとヨハネスブルグで開催された「新教育親睦世界会議」の招待を受けて南アフリカを訪れ、いく つかの講演を行った。この会議は、南アフリカのヤン・ホフマイヤー教育相とヤン・スマッツ副首相によって開かれた。会議では他にマックス・アイゼレンや、 後にアパルトヘイトを導入した国民党政権の首相となるヘンドリック・フェルヴェルトらが講演を行った[44]。 デューイの経費はカーネギー財団から支払われた。また、当時の南ローデシア(現ジンバブエ)のダーバン、プレトリア、ビクトリアフォールズを訪れ、学校を 見て、生徒と話し、管理者や教員に講義を行った。1934年8月、デューイはウィットウォータースランド大学から名誉学位を授与された[45]。白人だけ の政府はデューイの考えをあまりにも世俗的であるとして拒絶した。しかし、黒人とその白人の支持者はより受容的であった[46]。 |

| Functional psychology At the University of Michigan, Dewey published his first two books, Psychology (1887), and Leibniz's New Essays Concerning the Human Understanding (1888), both of which expressed Dewey's early commitment to British neo-Hegelianism. In Psychology, Dewey attempted a synthesis between idealism and experimental science.[1] While still professor of philosophy at Michigan, Dewey and his junior colleagues, James Hayden Tufts and George Herbert Mead, together with his student James Rowland Angell, all influenced strongly by the recent publication of William James' Principles of Psychology (1890), began to reformulate psychology, emphasizing the social environment on the activity of mind and behavior rather than the physiological psychology of Wilhelm Wundt and his followers. By 1894, Dewey had joined Tufts, with whom he would later write Ethics (1908) at the recently founded University of Chicago and invited Mead and Angell to follow him, the four men forming the basis of the so-called "Chicago group" of psychology. Their new style of psychology, later dubbed functional psychology, had a practical emphasis on action and application. In Dewey's article "The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology" which appeared in Psychological Review in 1896, he reasons against the traditional stimulus-response understanding of the reflex arc in favor of a "circular" account in which what serves as "stimulus" and what as "response" depends on how one considers the situation, and defends the unitary nature of the sensory motor circuit. While he does not deny the existence of stimulus, sensation, and response, he disagreed that they were separate, juxtaposed events happening like links in a chain. He developed the idea that there is a coordination by which the stimulation is enriched by the results of previous experiences. The response is modulated by sensorial experience. Dewey was elected president of the American Psychological Association in 1899. Dewey also expressed interest in work in the psychology of visual perception performed by Dartmouth research professor Adelbert Ames Jr. He had great trouble with listening, however, because it is known Dewey could not distinguish musical pitches—in other words was an amusic.[47] |

機能的心理学 ミシガン大学では、デューイは最初の2冊の本、Psychology (1887) とLeibniz's New Essays Concerning the Human Understanding (1888) を出版したが、これらはデューイのイギリスのネオ・ヘーゲル主義への初期の傾倒を表現するものだった。心理学』では、観念論と実験科学の間の統合を試みた [1]。 ミシガン大学の哲学教授であったデューイは、後輩のジェームズ・ヘイデン・タフツとジョージ・ハーバート・ミード、そして彼の学生のジェームズ・ローラン ド・アンジェルとともに、ウィリアム・ジェームズの『心理学原理』(1890)が最近出版されて強い影響を受け、ウィルヘルム・ヴントとその信奉者の生理 心理学よりも心と行動の活動に関する社会環境を強調した心理学を再定義しはじめた。 1894年までにデューイは、後に『倫理学』(1908年)を共に執筆することになるタフツと、設立されたばかりのシカゴ大学で合流し、ミードとアンゲル を誘い、この4人が心理学のいわゆる「シカゴグループ」の基礎を形成しました。 彼らの新しい心理学は、後に機能心理学と呼ばれ、行動と応用を重視した実践的なものであった。1896年に『心理学評論』に掲載されたデューイの論文「心 理学における反射弧概念」では、反射弧について従来の刺激-反応の理解に反対し、何が「刺激」となり何が「反応」となるかは状況をどう考えるかによるとい う「循環型」の説明を支持し、感覚運動回路の単一性を擁護している。彼は、刺激、感覚、反応の存在を否定はしないが、それらがチェーンのリンクのように並 列に起こる別々の出来事であるということには反対であった。彼は、刺激がそれまでの経験の結果によって豊かになるような調整が行われているという考えを展 開した。反応は感覚的な経験によって調節される。 デューイは1899年にアメリカ心理学会の会長に選ばれている。 デューイはまた、ダートマス大学の研究教授であるアデルバート・エイムズ・ジュニアが行った視覚知覚の心理学の研究に興味を示していた。 しかし、デューイは音楽の音程を区別できない、言い換えれば非音楽的であることが知られているため、彼は聴くことに非常に苦労していた[47]。 |

| Pragmatism, instrumentalism,

consequentialism Dewey sometimes referred to his philosophy as instrumentalism rather than pragmatism, and would have recognized the similarity of these two schools to the newer school named consequentialism. In some phrases introducing a book he wrote later in life meant to help forestay a wandering kind of criticism of the work based on the controversies due to the differences in the schools that he sometimes invoked, he defined at the same time with precise brevity the criterion of validity common to these three schools, which lack agreed-upon definitions: But in the proper interpretation of "pragmatic," namely the function of consequences as necessary tests of the validity of propositions, provided these consequences are operationally instituted and are such as to resolve the specific problem evoking the operations, the text that follows is thoroughly pragmatic.[48] His concern for precise definition led him to detailed analysis of careless word usage, reported in Knowing and the Known in 1949. |

プラグマティズム、道具主義、帰結主義 デューイは、自分の哲学をプラグマティズムではなく、道具論と呼ぶことがあり、この二つの学派が、帰結主義主義と名付けられた新しい学派と類似しているこ とを認識していたはずである。また、後年書いた本の冒頭のフレーズでは、時に持ち出す学派の違いによる論争に基づく彷徨える批判を回避するために、定義が 統一されていないこれら3学派に共通する妥当性の基準を的確かつ簡潔に定義している。 しかし「プラグマティック」の適切な解釈、すなわち命題の妥当性の必要なテストとしての結果の機能において、これらの結果が操作的に制定され、操作を呼び 起こす特定の問題を解決するようなものであれば、この後に続くテキストは徹底的にプラグマティックである[48]」と述べている。 正確な定義に対する彼の関心は、不注意な言葉の使い方の詳細な分析へと彼を導き、1949年に『Knowing and the Known』で報告されている。 |

| Epistemology The terminology problem in the fields of epistemology and logic is partially due, according to Dewey and Bentley,[49] to inefficient and imprecise use of words and concepts that reflect three historic levels of organization and presentation.[50] In the order of chronological appearance, these are: Self-Action: Prescientific concepts regarded humans, animals, and things as possessing powers of their own which initiated or caused their actions. Interaction: as described by Newton, where things, living and inorganic, are balanced against something in a system of interaction, for example, the third law of motion states that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. Transaction: where modern systems of descriptions and naming are employed to deal with multiple aspects and phases of action without any attribution to ultimate, final, or independent entities, essences, or realities. A series of characterizations of Transactions indicate the wide range of considerations involved.[51] |

認識論 認識論と論理学の分野における用語の問題は、DeweyとBentleyによれば、組織と提示の3つの歴史的レベルを反映する単語と概念の非効率的で不正 確な使用による部分的なものである[49]。 時系列的に現れる順序では、これらは以下のとおりである。 自己行動。先史時代の概念では、人間、動物、そして事物はそれ自身の力を持っており、それが彼らの行動を開始させたり引き起こしたりするとみなされてい た。 相互作用:ニュートンが述べたように、生物、無機物を問わず、物事は相互作用のシステムの中で何かに対してバランスをとっている。例えば、運動の第三法則 では、すべての作用には等しく反対の反作用があるとしている。 トランザクション:近代的な記述と命名のシステムが、究極的、最終的、または独立した実体、本質、または現実への帰属なしに、作用の複数の側面と段階を扱 うために採用されるところ。 トランザクションの一連の特徴付けは、関与する考察の幅の広さを示している[51]。 |

| Logic and method Dewey sees paradox in contemporary logical theory. Proximate subject matter garners general agreement and advancement, while the ultimate subject matter of logic generates unremitting controversy. In other words, he challenges confident logicians to answer the question of the truth of logical operators. Do they function merely as abstractions (e.g., pure mathematics) or do they connect in some essential way with their objects, and therefore alter or bring them to light?[52] Logical positivism also figured in Dewey's thought. About the movement he wrote that it "eschews the use of 'propositions' and 'terms', substituting 'sentences' and 'words'." ("General Theory of Propositions", in Logic: The Theory of Inquiry) He welcomes this changing of referents "in as far as it fixes attention upon the symbolic structure and content of propositions." However, he registers a small complaint against the use of "sentence" and "words" in that without careful interpretation the act or process of transposition "narrows unduly the scope of symbols and language, since it is not customary to treat gestures and diagrams (maps, blueprints, etc.) as words or sentences." In other words, sentences and words, considered in isolation, do not disclose intent, which may be inferred or "adjudged only by means of context."[52] Yet Dewey was not entirely opposed to modern logical trends; indeed, the deficiencies in traditional logic he expressed hope for the trends to solve occupies the whole first part of same book. Concerning traditional logic, he states there: Aristotelian logic, which still passes current nominally, is a logic based upon the idea that qualitative objects are existential in the fullest sense. To retain logical principles based on this conception along with the acceptance of theories of existence and knowledge based on an opposite conception is not, to say the least, conductive to clearness—a consideration that has a good deal to do with existing dualism between traditional and the newer relational logics. Louis Menand argues in The Metaphysical Club that Jane Addams had been critical of Dewey's emphasis on antagonism in the context of a discussion of the Pullman strike of 1894. In a later letter to his wife, Dewey confessed that Addams' argument was: ... the most magnificent exhibition of intellectual & moral faith I ever saw. She converted me internally, but not really, I fear. ... When you think that Miss Addams does not think this as a philosophy, but believes it in all her senses & muscles—Great God ... I guess I'll have to give it [all] up & start over again. He went on to add: I can see that I have always been interpreting dialectic wrong end up, the unity as the reconciliation of opposites, instead of the opposites as the unity in its growth, and thus translated the physical tension into a moral thing ... I don't know as I give the reality of this at all, ... it seems so natural & commonplace now, but I never had anything take hold of me so.[53] In a letter to Addams, clearly influenced by his conversation with her, Dewey wrote: Not only is actual antagonizing bad, but the assumption that there is or may be antagonism is bad—in fact, the real first antagonism always comes back to the assumption. |

論理と方法 デューイは現代の論理学理論にパラドックスを見出している。近接した主題は一般的な同意と発展を集めるが、論理学の究極的な主題は絶え間ない論争を生むの である。つまり、論理演算子の真偽の問いに対して、自信満々の論理学者が答えを出すことを挑んでいるのだ。それらは単に抽象的なもの(例えば純粋数学)と して機能するのか、それとも何らかの本質的な方法でその対象とつながり、それゆえそれらを変化させたり、明るみに出したりするのか[52]。 論理実証主義もデューイの思想に影響を及ぼしていた。この運動について彼は「『命題』や『用語』の使用を避け、『文』や『言葉』を代用する」と書いている [52]。(命題の一般理論」、『論理学-探究の理論』所収)彼は、この参照語の変更を「命題の象徴的構造と内容に注意を向ける限りにおいて」歓迎してい る。しかし、彼は「文」と「言葉」の使用に対して、注意深い解釈なしに転置の行為やプロセスが「身振りや図(地図、青写真など)を言葉や文として扱うこと は慣例ではないので、記号や言語の範囲を不当に狭めてしまう」という小さな苦情を登録している。言い換えれば、文や言葉を単独で考えても意図は開示され ず、文脈によってのみ推論されるか「裁定される」ものである[52]。 しかしデューイは現代の論理的傾向に完全に反対していたわけではなく、実際、彼が傾向によって解決されることを期待して表明した伝統的な論理の欠陥は、同 じ本の最初の部分全体を占めている。伝統的な論理学について、彼はそこでこう述べている。 アリストテレス論理学は、名目上、現在でも通用するが、質的対象が完全な意味で実在的であるという考えに基づいている論理学である。この考え方に基づく論 理原理を維持したまま、反対の考え方に基づく存在論や知識論を受け入れることは、少なくとも明晰さにはつながらない。 ルイ・メナンドは『形而上学クラブ』の中で、ジェーン・アダムスが1894年のプルマン・ストライキの議論の中でデューイが拮抗作用論を強調したことに批 判的であったと論じている。後に妻に宛てた手紙の中で、デューイは、アダムスの主張はこう告白している。 私がこれまでに見た中で、知的・道徳的信仰の最も壮大な展示会でした。彼女は私を内面的には改心させたが、実際にはそうではなかったと思う。... アダムス嬢は、これを哲学として考えているのではなく、彼女のすべての感覚と筋肉でそれを信じていることを考えるとき、偉大な神...... 私はそれを諦めて、もう一度やり直さなければならないようだ。 そして、こう付け加えた。 私はいつも弁証法が間違って終わる解釈されていることを見ることができる、反対語の和解として統一、その成長の統一として反対語の代わりに、こうして道徳 的なものに物理的な緊張を翻訳した... 私は全くこの現実を与えるように知りません、...それは今とても自然で当たり前のように見えますが、私は何かが私をそうつかまえたことがありません [53]。 アダムスへの手紙の中で、明らかに彼女との会話に影響されて、デューイはこう書いている。 実際に敵対することが悪いというだけでなく、敵対がある、あるいはあるかもしれないという仮定も悪い-実際、本当の最初の敵対は常に仮定に立ち戻るのだ。 |

| Aesthetics Art as Experience (1934) is Dewey's major writing on aesthetics.[54] It is, in accordance with his place in the Pragmatist tradition that emphasizes community, a study of the individual art object as embedded in (and inextricable from) the experiences of a local culture. In the original illustrated edition, Dewey drew on the modern art and world cultures collection assembled by Albert C. Barnes at the Barnes Foundation, whose own ideas on the application of art to one's way of life was influenced by Dewey's writing. Dewey made art through writing poetry, but he considered himself deeply unmusical: one of his students described Dewey as "allergic to music."[55] Barnes was particularly influenced by Democracy and Education (1916) and then attended Dewey's seminar on political philosophy at Columbia University in the fall semester of 1918.[56] |

美学 『経 験としての芸術』(1934年)は美学に関するデューイの主要な著作である[54]。 それは共同体を強調するプラグマティストの伝統における彼の位置づけに従って、地域文化の経験に埋め込まれた(そしてそこから切り離せない)個々の美術品 の研究である。図版版では、バーンズ財団のアルバート・C・バーンズが収集した現代美術と世界文化のコレクションを利用し、芸術を自分の生き方に生かすという彼自身の考え方はデューイの著作に影響を受け ている。バーンズは『民主主義と教育』(1916年)に特に影響を受け、1918年の秋学期にコロンビア大学で行われたデューイの政治哲学のセミナーに出 席している[56]。 |

| On philanthropy, women and

democracy Dewey founded the University of Chicago laboratory school, supported educational organizations, and supported settlement houses especially Jane Addams' Hull House.[57] Through his work at the Hull House serving on its first board of trustees, Dewey was not only an activist for the cause but also a partner working to serve the large immigrant community of Chicago and women's suffrage. Dewey experienced the lack of children's education while contributing in the classroom at the Hull House. There he also experienced the lack of education and skills of immigrant women.[58] Stengel argues: Addams is unquestionably a maker of democratic community and pragmatic education; Dewey is just as unquestionably a reflector. Through her work at Hull House, Addams discerned the shape of democracy as a mode of associated living and uncovered the outlines of an experimental approach to knowledge and understanding; Dewey analyzed and classified the social, psychological and educational processes Addams lived.[57] His leading views on democracy included: First, Dewey believed that democracy is an ethical ideal rather than merely a political arrangement. Second, he considered participation, not representation, the essence of democracy. Third, he insisted on the harmony between democracy and the scientific method: ever-expanding and self-critical communities of inquiry, operating on pragmatic principles and constantly revising their beliefs in light of new evidence, provided Dewey with a model for democratic decision making ... Finally, Dewey called for extending democracy, conceived as an ethical project, from politics to industry and society.[59] This helped to shape his understanding of human action and the unity of human experience. |

慈善事業、女性、民主主義について デューイは、シカゴ大学の実験学校を設立し、教育組織を支援し、セツルメントハウス、特にジェーン・アダムスのハル・ハウスを支援した[57]。 ハル・ハウスでの活動を通じて、デューイはその活動家であるだけでなく、シカゴの大規模な移民コミュニティと女性参政権のために働くパートナーであった。 デューイは、ハルハウスの教室で貢献しながら、子どもたちの教育の欠如を体験した。またそこで彼は、移民女性の教育やスキルの欠如を体験している [58]。 ステンゲルはこう論じている。 アダムスは疑いなく民主的なコミュニティと実践的な教育の作り手であり、デューイは同様に疑いなく反省者である」[58]。ハルハウスでの仕事を通して、 アダムスは関連した生活の様式としての民主主義の形を見分け、知識と理解への実験的アプローチの輪郭を明らかにし、デューイはアダムスが生きた社会的、心 理的、教育的プロセスを分析し分類していた[57]。 民主主義に関する彼の代表的な見解には以下のようなものがあった。 第1に、デューイは民主主義が単に政治的な取り決めではなく、倫理的な理想であると 信じていた。第2に、彼は民主主義の本質を代表ではなく参加であると 考えた。第三に、彼は民主主義と科学的方法の調和を主張した。 常に拡大し、自己批判する探究の共同体は、実際的な原則に基づいて活動し、新しい証拠に照らして常に自分たちの信念を修正するものであり、民主的な意思決 定のモデルをデューイに提供した......。最後に、デューイは倫理的なプロジェクトとして構想された民主主義を政治から産業や社会へと拡張することを 求めていた[59]。 このことは人間の行動と人間の経験の統一性についての彼の理解を形成するのに役立った。 |

| Woman's

place Dewey believed that a woman's place in society was determined by her environment and not just her biology. On women he says, "You think too much of women in terms of sex. Think of them as human individuals for a while, dropping out the sex qualification, and you won't be so sure of some of your generalizations about what they should and shouldn't do".[58] John Dewey's support helped to increase the support and popularity of Jane Addams' Hull House and other settlement houses as well. With growing support, involvement of the community grew as well as the support for the women's suffrage movement. As commonly argued by Dewey's greatest critics, he was not able to come up with strategies in order to fulfill his ideas that would lead to a successful democracy, educational system, and a successful women's suffrage movement. While knowing that traditional beliefs, customs, and practices needed to be examined in order to find out what worked and what needed improved upon, it was never done in a systematic way.[58] "Dewey became increasingly aware of the obstacles presented by entrenched power and alert to the intricacy of the problems facing modern cultures".[59] With the complex of society at the time, Dewey was criticized for his lack of effort in fixing the problems. With respect to technological developments in a democracy: Persons do not become a society by living in physical proximity any more than a man ceases to be socially influenced by being so many feet or miles removed from others. His work on democracy influenced B.R. Ambedkar, one of his students, who later became one of the founding fathers of independent India.[60][61][62][63] |

女性の地位 デューイは、女性の社会的地位は生物学的なものだけでなく、環境によっ て決まると考えていた。女性について、彼はこう言っている。「あなたは女性を性の面から考えすぎている。そうすれば、彼女たちが何をすべきで、何をすべき でないかという一般論について、それほど確信が持てなくなるだろう」[58]と述べている。支援の高まりとともに、コミュニティへの関与が高まり、女性参 政権運動への支援も高まっていった。 デューイの最大の批判者がよく主張するように、デューイは、民主主義、教育システム、女性参政権運動の成功につながる彼のアイデアを実現するための戦略を 打ち出すことができなかった。伝統的な信念、慣習、慣行は、何が機能し、何が改善される必要があるかを見つけるために検討される必要があることを知ってい ながら、それは決して体系的に行われなかった[58] 「デューイは定着した権力によって示される障害にますます気づき、現代文化が直面している問題の複雑さに注意を払うようになった」[59] 当時の社会の複雑さに、デューイは問題解決への努力が不足していると批判された。 民主主義における技術的発展に関して。 人は物理的な近さで生活することによって社会になるのではなく、人が他者から何フィート、何マイルも離れることによって社会的な影響を受けなくなるのと同 じことである」。 民主主義に関する彼の研究は、後に独立インドの建国の父の一人となった彼の弟子の一人であるB.R.アンベードカルに影響を与えている[60][61] [62][63]。 |

| On education and teacher

education Dewey's educational theories were presented in My Pedagogic Creed (1897), The Primary-Education Fetich (1898), The School and Society (1900), The Child and the Curriculum (1902), Democracy and Education (1916), Schools of To-morrow (1915) with Evelyn Dewey, and Experience and Education (1938). Several themes recur throughout these writings. Dewey continually argues that education and learning are social and interactive processes, and thus the school itself is a social institution through which social reform can and should take place. In addition, he believed that students thrive in an environment where they are allowed to experience and interact with the curriculum, and all students should have the opportunity to take part in their own learning. The ideas of democracy and social reform are continually discussed in Dewey's writings on education. Dewey makes a strong case for the importance of education not only as a place to gain content knowledge, but also as a place to learn how to live. In his eyes, the purpose of education should not revolve around the acquisition of a pre-determined set of skills, but rather the realization of one's full potential and the ability to use those skills for the greater good. He notes that "to prepare him for the future life means to give him command of himself; it means so to train him that he will have the full and ready use of all his capacities" (My Pedagogic Creed, Dewey, 1897). In addition to helping students realize their full potential, Dewey goes on to acknowledge that education and schooling are instrumental in creating social change and reform. He notes that "education is a regulation of the process of coming to share in the social consciousness; and that the adjustment of individual activity on the basis of this social consciousness is the only sure method of social reconstruction". In addition to his ideas regarding what education is and what effect it should have on society, Dewey also had specific notions regarding how education should take place within the classroom. In The Child and the Curriculum (1902), Dewey discusses two major conflicting schools of thought regarding educational pedagogy. The first is centered on the curriculum and focuses almost solely on the subject matter to be taught. Dewey argues that the major flaw in this methodology is the inactivity of the student; within this particular framework, "the child is simply the immature being who is to be matured; he is the superficial being who is to be deepened" (1902, p. 13).[64] He argues that in order for education to be most effective, content must be presented in a way that allows the student to relate the information to prior experiences, thus deepening the connection with this new knowledge. |

教育・教師教育について デューイの教育論は、『私の教育学信条』(1897)、『初等教育のフェティッシュ』(1898)、『学校と社会』(1900)、『子どもとカリキュラ ム』(1902)、『民主主義と教育』(1916)、エヴリン・デューイとの『明日の学校』(1915)、『体験と教育』(1938)などに示されていま す。これらの著作には、いくつかのテーマが繰り返し登場する。デューイは、教育や学習は社会的かつ相互作用的なプロセスであり、したがって学校そのもの が、社会改革を行うことができる、また行うべき社会制度であると主張し続けた。さらに彼は、生徒がカリキュラムを体験し、相互作用することが許される環境 で生徒が成長し、すべての生徒が自分自身の学習に参加する機会を持つべきであると考えた。 デューイの教育に関する著作では、民主主義と社会改革という考え方が絶えず議論されている。デューイは、教育が単に内容的な知識を得る場としてだけでな く、生き方を学ぶ場としても重要であることを強く訴えている。教育の目的は、決められたスキルを身につけることではなく、自分の可能性を最大限に引き出 し、そのスキルをより大きな利益のために活用できるようにすることである、と彼は考えている。彼は、「将来の生活のために彼を準備させることは、彼に自分 自身を支配させることを意味し、それは、彼がすべての能力を完全に、そしてすぐに使えるように訓練することを意味する」(『私の教育学信条』デューイ、 1897年)と述べている。 デューイは、生徒が自分の可能性を十分に発揮できるようにすることに加えて、教育や学校教育が社会の変化や改革を生み出すのに役立つことを認めている。そ して、「教育とは、社会意識を共有するようになる過程を調整することであり、この社会意識に基づいて個人の活動を調整することが、社会再建の唯一の確実な 方法である」と述べている。 教育とは何か、教育が社会にどのような影響を与えるべきかについての考え方に加え、デューイは教室の中でどのように教育が行われるべきかについても具体的 な考えを持っていた。デューイは『子どもとカリキュラム』(1902年)の中で、教育学に関して対立する2つの主要な学派を論じている。ひとつはカリキュ ラムを中心としたもので、教えるべき教科にほぼ一点集中するものである。デューイは、この方法論の大きな欠点は生徒の不活性さにあると主張し、この特定の 枠組みの中で、「子どもは単に成熟されるべき未熟な存在であり、彼は深められるべき表面的存在である」(1902、13ページ)。 64] 彼は、教育を最も有効にするためには、内容が、学生が情報を以前の経験に関連付けることができ、したがってこの新しい知識との関係を深めることができる方 法で示されなければならないと主張している。 |

| Ideas on education At the same time, Dewey was alarmed by many of the "child-centered" excesses of educational-school pedagogues who claimed to be his followers, and he argued that too much reliance on the child could be equally detrimental to the learning process. In this second school of thought, "we must take our stand with the child and our departure from him. It is he and not the subject-matter which determines both quality and quantity of learning" (Dewey, 1902, pp. 13–14). According to Dewey, the potential flaw in this line of thinking is that it minimizes the importance of the content as well as the role of the teacher. In order to rectify this dilemma, Dewey advocated an educational structure that strikes a balance between delivering knowledge while also taking into account the interests and experiences of the student. He notes that "the child and the curriculum are simply two limits which define a single process. Just as two points define a straight line, so the present standpoint of the child and the facts and truths of studies define instruction" (Dewey, 1902, p. 16). It is through this reasoning that Dewey became one of the most famous proponents of hands-on learning or experiential education, which is related to, but not synonymous with experiential learning. He argued that "if knowledge comes from the impressions made upon us by natural objects, it is impossible to procure knowledge without the use of objects which impress the mind" (Dewey, 1916/2009, pp. 217–18).[65] Dewey's ideas went on to influence many other influential experiential models and advocates. Problem-Based Learning (PBL), for example, a method used widely in education today, incorporates Dewey's ideas pertaining to learning through active inquiry.[66] Dewey not only re-imagined the way that the learning process should take place, but also the role that the teacher should play within that process. Throughout the history of American schooling, education's purpose has been to train students for work by providing the student with a limited set of skills and information to do a particular job. The works of John Dewey provide the most prolific examples of how this limited vocational view of education has been applied to both the K–12 public education system and to the teacher training schools who attempted to quickly produce proficient and practical teachers with a limited set of instructional and discipline-specific skills needed to meet the needs of the employer and demands of the workforce. In The School and Society (Dewey, 1899) and Democracy of Education (Dewey, 1916), Dewey claims that rather than preparing citizens for ethical participation in society, schools cultivate passive pupils via insistence upon mastery of facts and disciplining of bodies. Rather than preparing students to be reflective, autonomous and ethical beings capable of arriving at social truths through critical and intersubjective discourse, schools prepare students for docile compliance with authoritarian work and political structures, discourage the pursuit of individual and communal inquiry, and perceive higher learning as a monopoly of the institution of education (Dewey, 1899; 1916). For Dewey and his philosophical followers, education stifles individual autonomy when learners are taught that knowledge is transmitted in one direction, from the expert to the learner. Dewey not only re-imagined the way that the learning process should take place, but also the role that the teacher should play within that process. For Dewey, "The thing needful is improvement of education, not simply by turning out teachers who can do better the things that are not necessary to do, but rather by changing the conception of what constitutes education" (Dewey, 1904, p. 18). Dewey's qualifications for teaching—a natural love for working with young children, a natural propensity to inquire about the subjects, methods and other social issues related to the profession, and a desire to share this acquired knowledge with others—are not a set of outwardly displayed mechanical skills. Rather, they may be viewed as internalized principles or habits which "work automatically, unconsciously" (Dewey, 1904, p. 15). Turning to Dewey's essays and public addresses regarding the teaching profession, followed by his analysis of the teacher as a person and a professional, as well as his beliefs regarding the responsibilities of teacher education programs to cultivate the attributes addressed, teacher educators can begin to reimagine the successful classroom teacher Dewey envisioned. |

教育の理念 同時にデューイは、自分の信奉者を名乗る教育学派の「子ども中心」の行 き過ぎの多くに警鐘を鳴らし、子どもへの過度の依存は学習過程にとって同様に有害であると主張した。この第二の思想家は、「われわれは子どもとともに立 ち、子どもから離れなければならない。学習の質と量の両方を決定するのは彼であり、主題ではない」(Dewey, 1902, pp.13-14)のである。デューイによれば、この考え方の潜在的な欠陥は、教師の役割と同様に内容の重要性を最小限に抑えてしまうことである。 このジレンマを解消するために、デューイは、知識を与える一方で、生徒の興味や経験を考慮したバランスの取れた教育構造を提唱した。彼は、「子供とカリ キュラムは、一つのプロセスを規定する二つの限界にすぎない」と指摘している。2つの点が直線を定義するように、子どもの現在の立場と勉強の事実と真理が 指導を定義する」(Dewey, 1902, p.16)。 このような推論を通じて、デューイは体験学習や体験型教育の最も有名な提唱者の一人となったのである。体験型教育は体験学習と関連はあるが、同義ではな い。彼は、「もし知識が自然物によって私たちに与えられた印象から来るのであれば、心に印象を与える物を使用せずに知識を得ることは不可能である」 (Dewey, 1916/2009, pp.217-18)[65] と主張した。デューイの考えは、他の多くの影響力のある経験的モデルや支持者に影響を与えることになった。例えば、今日教育で広く用いられている問題にもとづく学習(PBL)は、能動的な探究を通じた学習に関するデューイの考えを取り入れたものである[66]。 デューイは学習プロセスが行われるべき方法だけでなく、そのプロセスの中で教師が果たすべき役割も再想像していた。アメリカの学校教育の歴史を通して、教 育の目的は、特定の仕事をするための限られたスキルと情報のセットを学生に提供することによって、仕事のために学生を訓練することであった。ジョン・ デューイの著作は、この限定的な職業教育観が、幼稚園から高校までの公教育制度と、雇用者のニーズと労働力の需要に応えるために必要な限られた指導力と分 野固有のスキルを持った熟練した実践的教師を迅速に育成しようとした教員養成学校の両方に適用されてきたことを示す最も多くの例を示している。 デューイは、『学校と社会』(Dewey, 1899)と『教育の民主主義』(Dewey, 1916)の中で、学校は、市民が倫理的に社会に参加できるようにするのではなく、事実を習得し身体を鍛錬することに固執して、受動的な生徒を育成してい ると主張している。学校は、生徒を、批判的で間主観的な言説を通じて社会的真理に到達できる内省的で自律した倫理的存在に育てるのではなく、権威主義的な 仕事や政治構造に従順に従うように生徒を育て、個人や共同体の探求を抑制し、高等教育を教育機関の独占的なものとして認識している(デューイ、1899、 1916年)。 デューイと彼の哲学的信奉者たちにとって、知識は専門家から学習者への 一方向に伝達されるものだと学習者が教えられると、教育は個人の自律性を抑圧することになる。デューイは、学習プロセスのあり方だけでなく、その中で教師 が果たすべき役割についても再定義した。デューイにとって、「必要なことは教育の改善であり、それは単に、しなくてもよいことをよりよくできる教師を輩出 することではなく、むしろ、教育を構成するものの概念を変えることである」(デューイ、1904、p.18)。 デューイのいう教師としての資質とは、幼い子どもたちと一緒に仕事をすることに対する自然な愛情、職業に関連するテーマや方法、その他の社会問題について 探究する自然な傾向、そして獲得した知識を他の人々と共有したいという願望であり、外見的に示される一連の機械的スキルとは異なるものである。むしろ、 「自動的に、無意識に働く」(Dewey, 1904, p.15)内面化された原理や習慣としてとらえることができるだろう。教職に関するデューイのエッセイや講演に目を向けると、人間としての教師、職業人と しての教師、そして、これらの特性を育むための教師教育プログラムの責任に関するデューイの信念を分析し、教師教育者はデューイが思い描いた成功するクラ ス担任を再想像し始めることができるのである。 |

| Professionalization of teaching

as a social service For many, education's purpose is to train students for work by providing the student with a limited set of skills and information to do a particular job. As Dewey notes, this limited vocational view is also applied to teacher training schools who attempt to quickly produce proficient and practical teachers with a limited set of instructional and discipline skills needed to meet the needs of the employer and demands of the workforce (Dewey, 1904). For Dewey, the school and the classroom teacher, as a workforce and provider of social service, have a unique responsibility to produce psychological and social goods that will lead to both present and future social progress. As Dewey notes, "The business of the teacher is to produce a higher standard of intelligence in the community, and the object of the public school system is to make as large as possible the number of those who possess this intelligence. Skill, the ability to act wisely and effectively in a great variety of occupations and situations, is a sign and a criterion of the degree of civilization that a society has reached. It is the business of teachers to help in producing the many kinds of skills needed in contemporary life. If teachers are up to their work, they also aid in the production of character."(Dewey, TAP, 2010, pp. 241–42). According to Dewey, the emphasis is placed on producing these attributes in children for use in their contemporary life because it is "impossible to foretell definitely just what civilization will be twenty years from now" (Dewey, MPC, 2010, p. 25). However, although Dewey is steadfast in his beliefs that education serves an immediate purpose (Dewey, DRT, 2010; Dewey, MPC, 2010; Dewey, TTP, 2010), he is not ignorant of the impact imparting these qualities of intelligence, skill, and character on young children in their present life will have on the future society. While addressing the state of educative and economic affairs during a 1935 radio broadcast, Dewey linked the ensuing economic depression to a "lack of sufficient production of intelligence, skill, and character" (Dewey, TAP, 2010, p. 242) of the nation's workforce. As Dewey notes, there is a lack of these goods in the present society and teachers have a responsibility to create them in their students, who, we can assume, will grow into the adults who will ultimately go on to participate in whatever industrial or economic civilization awaits them. According to Dewey, the profession of the classroom teacher is to produce the intelligence, skill, and character within each student so that the democratic community is composed of citizens who can think, do and act intelligently and morally. |

社会サービスとしての教育の専門化 多くの人にとって、教育の目的は、特定の仕事をするための限られたスキルや情報を学生に与えることによって、仕事のために学生を訓練することである。 デューイが指摘するように、この限定された職業観は、雇用者のニーズや労働力の需要に応えるために必要な限られた指導・規律スキルを持つ熟練した実践的教 師を迅速に育成しようとする教員養成学校にも適用されている(デューイ、1904年)。デューイにとって、学校と教室の教師は、労働力として、また社会 サービスの提供者として、現在と未来の両方の社会の進歩につながる心理的・社会的財を生み出すという独自の責任を負っているのである。 デューイは「教師の仕事は、より高い水準の知性を地域社会に生み出すことであり、公立学校制度の目的は、この知性を持つ人々の数をできるだけ多くすること である」と述べている。さまざまな職業や状況において賢明かつ効果的に行動する能力である技能は、その社会が到達した文明の程度を示すしるしであり、基準 である。現代の生活で必要とされるさまざまなスキルを身につける手助けをするのが教師の仕事である。もし教師がその仕事に従事しているならば、人格の生産 を助けることにもなる」(Dewey, TAP, 2010, pp. 241-42)と述べている。 デューイによれば、「20年後の文明がどうなっているかを確実に予言することは不可能である」(Dewey, MPC, 2010, p.25)ため、現代生活に役立つこれらの特性を子どもたちに作り出すことに重きが置かれているのである。しかし、デューイは、教育が当面の目的にかなう という信念を堅持しているが(Dewey, DRT, 2010; Dewey, MPC, 2010; Dewey, TTP, 2010)、現在の生活の中で幼児に知性や技能、人格といった資質を与えることが将来の社会に対して与える影響を知らないわけでもないだろう。デューイ は、1935年のラジオ放送で教育や経済の現状を訴えながら、その後の経済恐慌を、国の労働力の「知性、技能、人格の十分な生産の欠如」(Dewey, TAP, 2010, p.242)に結びつけている。 デューイが指摘するように、現在の社会ではこれらの財が不足しており、教師は生徒の中にそれらを作り出す責任がある。生徒は、最終的にどのような産業文明 や経済文明が待っていようと、それに参加する大人へと成長すると考えることができるのである。デューイによれば、教室の教師の職業は、民主的な共同体が知 的かつ道徳的に考え、実行し、行動できる市民で構成されるように、各生徒の中に知性、技能、人格を作り出すことである。 |

| A teacher's knowledge Dewey believed that successful classroom teacher possesses a passion for knowledge and intellectual curiosity in the materials and methods they teach. For Dewey, this propensity is an inherent curiosity and love for learning that differs from one's ability to acquire, recite and reproduce textbook knowledge. "No one," according to Dewey, "can be really successful in performing the duties and meeting these demands [of teaching] who does not retain [her] intellectual curiosity intact throughout [her] entire career" (Dewey, APT, 2010, p. 34). According to Dewey, it is not that the "teacher ought to strive to be a high-class scholar in all the subjects he or she has to teach," rather, "a teacher ought to have an unusual love and aptitude in some one subject: history, mathematics, literature, science, a fine art, or whatever" (Dewey, APT, 2010, p. 35). The classroom teacher does not have to be a scholar in all subjects; rather, genuine love in one will elicit a feel for genuine information and insight in all subjects taught. In addition to this propensity for study into the subjects taught, the classroom teacher "is possessed by a recognition of the responsibility for the constant study of school room work, the constant study of children, of methods, of subject matter in its various adaptations to pupils" (Dewey, PST, 2010, p. 37). For Dewey, this desire for the lifelong pursuit of learning is inherent in other professions (e.g. the architectural, legal and medical fields; Dewey, 1904 & Dewey, PST, 2010), and has particular importance for the field of teaching. As Dewey notes, "this further study is not a sideline but something which fits directly into the demands and opportunities of the vocation" (Dewey, APT, 2010, p. 34). According to Dewey, this propensity and passion for intellectual growth in the profession must be accompanied by a natural desire to communicate one's knowledge with others. "There are scholars who have [the knowledge] in a marked degree but who lack enthusiasm for imparting it. To the 'natural born' teacher learning is incomplete unless it is shared" (Dewey, APT, 2010, p. 35). For Dewey, it is not enough for the classroom teacher to be a lifelong learner of the techniques and subject-matter of education; she must aspire to share what she knows with others in her learning community. |

教師の知識 デューイは、教室で成功する教師は、教える教材や方法に対して、知識への情熱と知的好奇心を持っていると考えた。デューイにとってこの性向は、教科書の知 識を習得し、暗唱し、再現する能力とは異なる、学習に対する先天的な好奇心と愛情である。「デューイによれば、「キャリア全体を通じて知的好奇心を維持で きない者は、(教育という)任務を遂行し、これらの要求を満たす上で本当に成功することはできない」(Dewey, APT, 2010, p.34)のである。 デューイによれば、「教師は、自分が教えなければならないすべての科目において高級な学者になるよう努力しなければならない」のではなく、「教師は、歴 史、数学、文学、科学、美術など、何か一つの科目において並外れた愛情と適性を持たなければならない」(Dewey, APT, 2010, p.35)のである。クラス担任は、すべての教科の研究者である必要はない。むしろ、ある教科を心から愛していれば、教えるすべての教科において、真の情 報と洞察力を感じることができるのである。 このように教える教科を研究する傾向に加えて、学級担任は「学校の教室での仕事を常に研究する責任、子どもや方法、生徒への様々な適応における教科を常に 研究する責任を認識している」(Dewey, PST, 2010, p.37)のである。デューイにとって、この生涯学習の追求の欲求は、他の職業(例えば、建築、法律、医療分野;Dewey, 1904 & Dewey, PST, 2010)にも内在しており、教育の分野では特に重要であると言える。デューイによれば、「このさらなる研究は副業ではなく、職業の要求と機会に直接適合 するものである」(Dewey, APT, 2010, p.34)。 デューイによれば、職業における知的成長に対するこのような傾向や情熱は、自分の知識を他者に伝えたいという自然な欲求を伴うものでなければならない。 「知識を)顕著な程度で持っていても、それを伝えようとする熱意に欠ける学者がいる。生まれつきの』教師にとって、学習は共有されなければ不完全である」 (デューイ、APT, 2010, p.35)。デューイにとって、教室の教師は、生涯にわたって教育の技術や題材を学び続けるだけでは十分ではなく、自分が知っていることを学習コミュニ ティの他の人々と共有することを熱望しなければならないのである。 |

| A teacher's skill The best indicator of teacher quality, according to Dewey, is the ability to watch and respond to the movement of the mind with keen awareness of the signs and quality of the responses he or her students exhibit with regard to the subject-matter presented (Dewey, APT, 2010; Dewey, 1904). As Dewey notes, "I have often been asked how it was that some teachers who have never studied the art of teaching are still extraordinarily good teachers. The explanation is simple. They have a quick, sure and unflagging sympathy with the operations and process of the minds they are in contact with. Their own minds move in harmony with those of others, appreciating their difficulties, entering into their problems, sharing their intellectual victories" (Dewey, APT, 2010, p. 36). Such a teacher is genuinely aware of the complexities of this mind to mind transfer, and she has the intellectual fortitude to identify the successes and failures of this process, as well as how to appropriately reproduce or correct it in the future. |

教師の技量 デューイによれば、教師の質の最も優れた指標は、提示された主題に関して生徒が示す反応の兆しと質を鋭敏に認識しながら、心の動きを観察し対応する能力で ある(Dewey, APT, 2010; Dewey, 1904)。デューイによれば、「私はしばしば、教授法を学んだことのない教師が、それでも非常に優れた教師であるのはなぜかと聞かれた。その説明は簡単 である。彼らは、自分が接している人々の心の動きやプロセスに、素早く、確実に、たゆまぬ共感を持っている。自分の心が他者の心と調和して動き、他者の困 難を理解し、他者の問題に入り込み、他者の知的勝利を共有する」(デューイ、APT, 2010, p.36)のである。 このような教師は、心と心の交流の複雑さを真に理解し、このプロセスの成功と失敗を見極め、今後どのように適切に再現し、修正していくかという知的強靭さ を持っているのである。 |

| A teacher's disposition As a result of the direct influence teachers have in shaping the mental, moral and spiritual lives of children during their most formative years, Dewey holds the profession of teaching in high esteem, often equating its social value to that of the ministry and to parenting (Dewey, APT, 2010; Dewey, DRT, 2010; Dewey, MPC, 2010; Dewey, PST, 2010; Dewey, TTC, 2010; Dewey, TTP, 2010). Perhaps the most important attributes, according to Dewey, are those personal inherent qualities that the teacher brings to the classroom. As Dewey notes, "no amount of learning or even of acquired pedagogical skill makes up for the deficiency" (Dewey, TLS, p. 25) of the personal traits needed to be most successful in the profession. According to Dewey, the successful classroom teacher occupies an indispensable passion for promoting the intellectual growth of young children. In addition, they know that their career, in comparison to other professions, entails stressful situations, long hours, and limited financial reward; all of which have the potential to overcome their genuine love and sympathy for their students. For Dewey, "One of the most depressing phases of the vocation is the number of careworn teachers one sees, with anxiety depicted on the lines of their faces, reflected in their strained high pitched voices and sharp manners. While contact with the young is a privilege for some temperaments, it is a tax on others and a tax which they do not bear up under very well. And in some schools, there are too many pupils to a teacher, too many subjects to teach, and adjustments to pupils are made in a mechanical rather than a human way. Human nature reacts against such unnatural conditions" (Dewey, APT, 2010, p. 35). It is essential, according to Dewey, that the classroom teacher has the mental propensity to overcome the demands and stressors placed on them because the students can sense when their teacher is not genuinely invested in promoting their learning (Dewey, PST, 2010). Such negative demeanors, according to Dewey, prevent children from pursuing their own propensities for learning and intellectual growth. It can therefore be assumed that if teachers want their students to engage with the educational process and employ their natural curiosities for knowledge, teachers must be aware of how their reactions to young children and the stresses of teaching influence this process. |

教師の気質 教師は、最も形成期にある子どもたちの精神的、道徳的、霊的生活を形成する上で直接的な影響力を持つことから、デューイは教師という職業を高く評価し、し ばしばその社会的価値を聖職や子育てと同等に扱っている(Dewey, APT, 2010;Dewey, DRT, 2010;Dewey, MPC, 2010;Dewey, PST, 2010;Dewey, TTC, 2010;Dewey, TTP, 2010)。デューイによれば、おそらく最も重要な属性は、教師が教室に持ち込む個人的な固有の資質である。デューイによれば、「いくら学習しても、ま た、教育的技術を習得しても、専門職として最も成功するために必要な個人的特性の不足を補うことはできない」(デューイ、TLS、p.25)のである。 デューイによれば、成功するクラス担任は、幼児の知的成長を促進するために不可欠な情熱を持っている。また、他の職業と比較して、ストレスの多い状況、長 時間労働、限られた経済的報酬など、生徒に対する純粋な愛情や同情心に打ち勝つことができる職業であることもわかっている。 デューイにとって、「この職業で最も憂鬱な局面は、顔のしわに不安を描き、緊張した高い声と鋭い態度に反映された、疲れ切った教師の数々を目にすることで ある」。若者と接することは、ある種の気質にとっては特権であるが、ある種の気質にとっては負担であり、その負担にうまく耐えられないのである。また、学 校によっては、教師1人に対して生徒が多すぎ、教える科目が多すぎ、生徒の調整が人間的というより機械的に行われているところもある。人間の本性は、この ような不自然な状況に対して反応する」(デューイ、APT、2010年、35頁)。 生徒たちは、教師が自分たちの学習を促進させるために純粋に投資していないことを感じ取ることができるため、クラス担任が自分たちに課された要求やストレ スに打ち勝つ精神的傾向を持つことが重要であるとデューイは述べている(Dewey,PST,2010)。デューイによれば、このような否定的な態度は、 子どもたちが学習や知的成長のために自らの性向を追求することを妨げてしまう。したがって、もし教師が生徒を教育プロセスに参加させ、知識に対する自然な 好奇心を働かせることを望むなら、教師は幼児に対する自分の反応や教えることのストレスがこのプロセスにどのように影響するかを意識しなければならないと 考えることができるのである。 |

| The role of teacher education to

cultivate the professional classroom teacher Dewey's passions for teaching—a natural love for working with young children, a natural propensity to inquire about the subjects, methods and other social issues related to the profession, and a desire to share this acquired knowledge with others—are not a set of outwardly displayed mechanical skills. Rather, they may be viewed as internalized principles or habits which "work automatically, unconsciously" (Dewey, 1904, p. 15). According to Dewey, teacher-education programs must turn away from focusing on producing proficient practitioners because such practical skills related to instruction and discipline (e.g. creating and delivering lesson plans, classroom management, implementation of an assortment of content-specific methods) can be learned over time during their everyday school work with their students (Dewey, PST, 2010). As Dewey notes, "The teacher who leaves the professional school with power in managing a class of children may appear to superior advantage the first day, the first week, the first month, or even the first year, as compared with some other teacher who has a much more vital command of the psychology, logic and ethics of development. But later 'progress' may consist only in perfecting and refining skill already possessed. Such persons seem to know how to teach, but they are not students of teaching. Even though they go on studying books of pedagogy, reading teachers' journals, attending teachers' institutes, etc., yet the root of the matter is not in them, unless they continue to be students of subject-matter, and students of mind-activity. Unless a teacher is such a student, he may continue to improve in the mechanics of school management, but he cannot grow as a teacher, an inspirer and director of soul-life" (Dewey, 1904, p. 15). For Dewey, teacher education should focus not on producing persons who know how to teach as soon as they leave the program; rather, teacher education should be concerned with producing professional students of education who have the propensity to inquire about the subjects they teach, the methods used, and the activity of the mind as it gives and receives knowledge. According to Dewey, such a student is not superficially engaging with these materials, rather, the professional student of education has a genuine passion to inquire about the subjects of education, knowing that doing so ultimately leads to acquisitions of the skills related to teaching. Such students of education aspire for the intellectual growth within the profession that can only be achieved by immersing one's self in the lifelong pursuit of the intelligence, skills and character Dewey linked to the profession. |

プロフェッショナルなクラス担任を育成するための教師教育の役割 デューイの教えることへの情熱-幼い子どもたちと一緒に働くことへの自然な愛情、専門職に関連する科目や方法、その他の社会問題について探究する自然な傾 向、そして獲得した知識を他の人々と共有したいという願望-は、外側に現れる一連の機械的スキルではない。むしろ、「自動的に、無意識のうちに働く」 (Dewey, 1904, p.15)内面化された原理や習慣とみなすことができるだろう。なぜなら、指導や規律に関する実践的な技能(例えば、授業計画の作成と実施、教室管理、様 々な内容別の方法の実施など)は、生徒との日々の学校生活の中で時間をかけて学ぶことができるからである(Dewey, PST, 2010)と述べている。 デューイは、「子どもたちのクラスを管理する力をもって専門学校を去る教師は、発達の心理、論理、倫理についてはるかに重要な指揮をとっている他の教師と 比較して、最初の日、最初の週、最初の月、あるいは最初の年には、優位に立っているように見えるかもしれない」と指摘している。しかし、その後の「進歩」 は、すでに持っている技術を完璧にし、洗練させることにしかならないかもしれない。このような人は、教え方を知っているように見えるが、教えることを学ん でいるわけではない。たとえ彼らが教育学の本を研究し、教師の雑誌を読み、教師の研究所などに通い続けたとしても、主題の生徒であり、心の活動の生徒であ り続けない限り、問題の根本は彼らの中にないのである。教師がそのような生徒でない限り、学校運営の機械的な面では向上し続けるかもしれないが、教師とし て、魂生活の鼓舞者、指導者として成長することはできない」(デューイ、1904年、15頁)。 デューイにとって、教師教育は、プログラムを修了してすぐに教え方のわかる人間を育てることではなく、むしろ、教える対象、用いられる方法、知識を授受す る心の動きについて探求する性質を持った、教育の専門家である学生を育てることに関心を向けるべきであるというのである。デューイによれば、このような学 生は、表面的に教材に触れているのではなく、むしろ、教育専門学生は、教育対象を探究する純粋な情熱を持っており、そうすることが最終的に教育に関する技 術の習得につながると知っているのである。このような教育専門学生は、デューイが職業と結びつけた知性、技能、人格を生涯にわたって追求することによって のみ達成できる、職業における知的成長を志しているのである。 |

| Professional As Dewey notes, other professional fields, such as law and medicine cultivate a professional spirit in their fields to constantly study their work, their methods of their work, and a perpetual need for intellectual growth and concern for issues related to their profession. Teacher education, as a profession, has these same obligations (Dewey, 1904; Dewey, PST, 2010). As Dewey notes, "An intellectual responsibility has got to be distributed to every human being who is concerned in carrying out the work in question, and to attempt to concentrate intellectual responsibility for a work that has to be done, with their brains and their hearts, by hundreds or thousands of people in a dozen or so at the top, no matter how wise and skillful they are, is not to concentrate responsibility—it is to diffuse irresponsibility" (Dewey, PST, 2010, p. 39). For Dewey, the professional spirit of teacher education requires of its students a constant study of school room work, constant study of children, of methods, of subject matter in its various adaptations to pupils. Such study will lead to professional enlightenment with regard to the daily operations of classroom teaching. As well as his very active and direct involvement in setting up educational institutions such as the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools (1896) and The New School for Social Research (1919), many of Dewey's ideas influenced the founding of Bennington College and Goddard College in Vermont, where he served on the board of trustees. Dewey's works and philosophy also held great influence in the creation of the short-lived Black Mountain College in North Carolina, an experimental college focused on interdisciplinary study, and whose faculty included Buckminster Fuller, Willem de Kooning, Charles Olson, Franz Kline, Robert Duncan, Robert Creeley, and Paul Goodman, among others. Black Mountain College was the locus of the "Black Mountain Poets" a group of avant-garde poets closely linked with the Beat Generation and the San Francisco Renaissance. |

専門職 デューイが述べているように、法律や医学などの他の専門分野では、自分 の仕事や仕事の方法を常に研究し、知的な成長と自分の職業に関連する問題への関心を永続的に必要とする専門家精神が培われている。教師教育も専門職とし て、これらと同じ義務を負っている(Dewey, 1904; Dewey, PST, 2010)。 そして、何百人、何千人もの人々が頭脳と心を駆使して行うべき仕事を、いかに賢明で巧みであっても、トップの十数人に知的責任を集中させようとすること は、責任の集中ではなく、無責任の拡散である」(Dewey, PST, 2010, p.39)と述べている。デューイにとって、教師教育の専門的精神は、学生に対して、学校での仕事を常に研究すること、子どもについて、方法について、生 徒への様々な適応における主題について、常に研究することを要求しているのである。このような研究は、教室での指導の日常業務に関する専門的な啓発につな がるものである。 また、シカゴ大学ラボラトリースクール(1896年)やニュースクール社会調査研究所(1919年)などの教育機関の設立に非常に積極的かつ直接的に関わ り、デューイの思想の多くは、ベニントン大学やバーモント州のゴダード大学の設立に影響を与え、彼は理事を務めていた。また、ノースカロライナ州に短期間 だけ開校したブラック・マウンテン・カレッジは、学際的な研究に焦点を当てた実験的な大学で、バックミンスター・フラー、ウィレム・デ・クーニング、 チャールズ・オルソン、フランツ・クライン、ロバート・ダンカン、ロバート・クレーリー、ポール・グッドマンなどが教授として名を連ねていたこともデュー イの作品や哲学に大きな影響を与えた。ブラック・マウンテン・カレッジは、ビート・ジェネレーションやサンフランシスコ・ルネッサンスと密接に結びついた 前衛詩人のグループ「ブラック・マウンテン・ポエッツ」の拠点となった。 |

| On journalism Since the mid-1980s, Dewey's ideas have experienced revival as a major source of inspiration for the public journalism movement[citation needed]. Dewey's definition of "public," as described in The Public and its Problems, has profound implications for the significance of journalism in society. As suggested by the title of the book, his concern was of the transactional relationship between publics and problems. Also implicit in its name, public journalism seeks to orient communication away from elite, corporate hegemony toward a civic public sphere. "The 'public' of public journalists is Dewey's public." Dewey gives a concrete definition to the formation of a public. Publics are spontaneous groups of citizens who share the indirect effects of a particular action. Anyone affected by the indirect consequences of a specific action will automatically share a common interest in controlling those consequences, i.e., solving a common problem.[67] Since every action generates unintended consequences, publics continuously emerge, overlap, and disintegrate. In The Public and its Problems, Dewey presents a rebuttal to Walter Lippmann's treatise on the role of journalism in democracy. Lippmann's model was a basic transmission model in which journalists took information given to them by experts and elites, repackaged that information in simple terms, and transmitted the information to the public, whose role was to react emotionally to the news. In his model, Lippmann supposed that the public was incapable of thought or action, and that all thought and action should be left to the experts and elites. Dewey refutes this model by assuming that politics is the work and duty of each individual in the course of his daily routine. The knowledge needed to be involved in politics, in this model, was to be generated by the interaction of citizens, elites, experts, through the mediation and facilitation of journalism. In this model, not just the government is accountable, but the citizens, experts, and other actors as well. Dewey also said that journalism should conform to this ideal by changing its emphasis from actions or happenings (choosing a winner of a given situation) to alternatives, choices, consequences, and conditions,[68] in order to foster conversation and improve the generation of knowledge. Journalism would not just produce a static product that told what had already happened, but the news would be in a constant state of evolution as the public added value by generating knowledge. The "audience" would end, to be replaced by citizens and collaborators who would essentially be users, doing more with the news than simply reading it. Concerning his effort to change journalism, he wrote in The Public and Its Problems: "Till the Great Society is converted in to a Great Community, the Public will remain in eclipse. Communication can alone create a great community" (Dewey, p. 142). Dewey believed that communication creates a great community, and citizens who participate actively with public life contribute to that community. "The clear consciousness of a communal life, in all its implications, constitutes the idea of democracy." (The Public and its Problems, p. 149). This Great Community can only occur with "free and full intercommunication." (p. 211) Communication can be understood as journalism. |

ジャーナリズムについて 1980年代半ば以降、デューイの思想はパブリック・ジャーナリズム運動の主要な源泉として復活を遂げている[citation needed]。デューイが『公共とその問題』で述べた「公共」の定義は、社会におけるジャーナリズムの意義に深い示唆を与えている。本のタイトルが示唆 するように、彼の関心は公共と問題の間の取引関係であった。また、その名前にもあるように、パブリック・ジャーナリズムは、コミュニケーションをエリート や企業のヘゲモニーから市民的な公共圏に向かわせようとするものである。パブリック・ジャーナリストの "パブリック "はデューイのパブリックである」。 デューイは、パブリックの形成に具体的な定義を与えている。公共とは、ある行為の間接的な影響を共有する市民の自発的な集団である。特定の行為の間接的な 結果によって影響を受ける者は、自動的にそれらの結果を制御すること、すなわち共通の問題を解決することに共通の関心を持つようになる[67]。 あらゆる行為が意図しない結果を生み出すので、公共は絶えず出現し、重なり合い、そして崩壊する。 デューイは『公共とその問題』の中で、民主主義におけるジャーナリズムの役割に関するウォルター・リップマンの論文に対する反証を提示している。リップマ ンのモデルは、専門家やエリートから与えられた情報を、ジャーナリストが簡単な言葉でまとめ直し、その情報を大衆に伝え、大衆はそのニュースに対して感情 的に反応するのが役割であるという基本的な伝達モデルであった。リップマンは、一般大衆は思考も行動もできず、思考も行動もすべて専門家やエリートに委ね られるべきであるとした。 デューイはこのモデルに反論し、政治は各個人が日常生活の中で行う仕事であり、義務であるとした。このモデルでは、政治に関わるために必要な知識は、市 民、エリート、専門家の相互作用によって、ジャーナリズムの仲介と促進によって生み出されるものであるとされた。このモデルでは、政府だけでなく、市民、 専門家、その他のアクターも説明責任を負っているのである。 デューイはまた、ジャーナリズムは会話を促進し、知識の生成を改善するために、行動や出来事(与えられた状況の勝者を選ぶ)から代替案、選択、結果、条件 へとその重点を変えることによってこの理想に適合するべきだと述べている[68]。ジャーナリズムはすでに起こったことを伝える静的な製品を生み出すだけ でなく、大衆が知識を生み出すことによって価値を付加することによって、ニュースは常に進化している状態になるであろう。視聴者 "は終わり、市民や協力者がユーザーとなり、単にニュースを読むだけでなく、より多くのことを行うようになる。ジャーナリズムを変えようとする努力につい て、彼は『公共とその問題』の中でこう書いている。「偉大な社会が偉大な共同体に変わるまで、大衆は日食されたままだろう。コミュニケーションだけが偉大 な共同体をつくることができる」(デューイ、p.142)。 デューイは、コミュニケーションは偉大な共同体を創り出し、公共生活に積極的に参加する市民はその共同体に貢献すると考えた。"共同生活の明確な意識は、 そのすべての意味において、民主主義の思想を構成する。" (『公共とその問題』149頁)。この大共同体は、"自由で完全な相互コミュニケーション "によってのみ発生することができる。(p.211)コミュニケーションはジャーナリズムと理解することができる。 |

| On humanism As an atheist[69] and a secular humanist in his later life, Dewey participated with a variety of humanistic activities from the 1930s into the 1950s, which included sitting on the advisory board of Charles Francis Potter's First Humanist Society of New York (1929); being one of the original 34 signatories of the first Humanist Manifesto (1933) and being elected an honorary member of the Humanist Press Association (1936).[70] His opinion of humanism is summarized in his own words from an article titled "What Humanism Means to Me", published in the June 1930 edition of Thinker 2: What Humanism means to me is an expansion, not a contraction, of human life, an expansion in which nature and the science of nature are made the willing servants of human good.[71] |

ヒューマニズムについて 無神論者[69]であり、晩年は世俗的なヒューマニストとして、デューイは1930年代から1950年代にかけて、チャールズ・フランシス・ポッターの ニューヨークの第一ヒューマニスト協会の諮問委員会に参加し(1929年)、第一ヒューマニスト宣言の最初の34人の署名者の一人(1933年)、ヒュー マニストプレス協会の名誉会員に選ばれた(1936年)等様々なヒューマニズム活動に参加している[70]。 ヒューマニズムに対する彼の意見は、『思想家2』1930年6月号に掲載された「私にとってヒューマニズムとは」と題する記事から彼自身の言葉で要約され ている。 私にとってヒューマニズムが意味するのは、人間の生活の縮小ではなく拡大であり、その拡大においては、自然と自然科学が人間の善の自発的な奉仕者にされる のである[71]。 |

| 1894 Pullman Strike While Dewey was at the University of Chicago, his letters to his wife Alice and his colleague Jane Addams reveal that he closely followed the 1894 Pullman Strike, in which the employees of the Pullman Palace Car Factory in Chicago decided to go on strike after industrialist George Pullman refused to lower rents in his company town after cutting his workers’ wages by nearly 30 percent. On May 11, 1894, the strike became official, later gaining the support of the members of the American Railway Union, whose leader Eugene V. Debs called for a nationwide boycott of all trains including Pullman sleeping cars.[72] Considering most trains had Pullman cars, the main 24 lines out of Chicago were halted and the mail was stopped as the workers destroyed trains all over the United States. President Grover Cleveland used the mail as a justification to send in the National Guard, and ARU leader Eugene Debs was arrested.[72] Dewey wrote to Alice: "The only wonder is that when the 'higher classes' – damn them – take such views there aren't more downright socialists. [...] [T]hat a representative journal of the upper classes – damn them again – can take the attitude of that harper's weekly", referring to headlines such as "Monopoly" and "Repress the Rebellion", which claimed, in Dewey's words, to support the sensational belief that Debs was a "criminal" inspiring hate and violence in the equally "criminal" working classes. He concluded: "It shows what it is to be a higher class. And I fear Chicago Univ. is a capitalistic institution – that is, it too belongs to the higher classes".[72] Dewey was not a socialist like Debs,[citation needed] but he believed that Pullman and the workers must strive toward a community of shared ends following the work of Jane Addams and George Herbert Mead. |

1894年プルマンストライキ 実業家ジョージ・プルマンが、労働者の賃金を30%近くカットした後、自分の会社のある町の家賃を下げることを拒否したため、シカゴのプルマン・パレス カー工場の従業員がストライキに踏み切ったのである。1894年5月11日、ストライキは公式になり、後にアメリカ鉄道組合のメンバーの支持を得た。その リーダーであるユージン・V・デブスは、プルマン寝台車を含む全ての列車の全国的なボイコットを呼び掛けた[72]。 ほとんどの列車がプルマンカーであったことを考えると、シカゴからの主要24路線は停止し、労働者がアメリカ中の列車を破壊したため、郵便も停止させられ た。グローバー・クリーブランド大統領は、郵便物を正当化して州兵を送り込み、ARUのリーダーであるユージン・デブスは逮捕された[72]。 デューイはアリスにこう書いている。「唯一の不思議は、"上流階級 "が、畜生どもが、そのような見解を示すとき、もっと真っ当な社会主義者がいないことだ。[上流階級の代表的な雑誌が-また彼らを呪うが-あのハーパー週 刊誌のような態度をとることができるなんて」、「独占」や「反乱を抑圧せよ」といった見出しに言及し、デューイの言葉では、デブスは「犯罪者」であり、同 様に「犯罪者」の労働者階級に嫌悪と暴力を鼓舞するという扇動的信念を支持するものであったとしている。彼はこう結論づけた。「これは、上流階級になると はどういうことかを示している。そして、シカゴ大学は資本主義的な機関であり、つまり、それも上流階級に属していることを恐れている」[72]。デューイ はデブスのような社会主義者ではなかったが[引用者註]、ジェーン・アダムスとジョージ・ハーバート・ミードの仕事に従ってプルマンと労働者は目的を共有 する共同体に向かい努力しなければならないと信じていた。 |

| Pro-war stance in First World War Dewey was an advocate of US participation in the First World War. For this he was criticised by Randolph Bourne, a former student whose essay "Twilight of Idols", was published in the literary journal Seven Arts in October 1917. Bourne criticised Dewey's instrumental pragmatist philosophy.[73] International League for Academic Freedom As a major advocate of academic freedom, in 1935 Dewey, together with Albert Einstein and Alvin Johnson, became a member of the United States section of the International League for Academic Freedom,[74] and in 1940, together with Horace M Kallen, edited a series of articles related to the Bertrand Russell Case. Dewey Commission He directed the famous Dewey Commission held in Mexico in 1937, which cleared Leon Trotsky of the charges made against him by Joseph Stalin,[75] and marched for women's rights, among many other causes. League for Industrial Democracy In 1939, Dewey was elected President of the League for Industrial Democracy, an organization with the goal of educating college students about the labor movement. The Student Branch of the L.I.D. would later become Students for a Democratic Society.[76] As well as defending the independence of teachers and opposing a communist takeover of the New York Teachers' Union,[77] Dewey was involved in the organization that eventually became the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, sitting as an executive on the NAACP's early executive board.[78] He was an avid supporter of Henry George's proposal for taxing land values. Of George, he wrote, "No man, no graduate of a higher educational institution, has a right to regard himself as an educated man in social thought unless he has some first-hand acquaintance with the theoretical contribution of this great American thinker."[79] As honorary president of the Henry George School of Social Science, he wrote a letter to Henry Ford urging him to support the school.[80] |

第一次世界大戦での戦争推進姿勢 デューイは、アメリカの第一次世界大戦への参戦を支持する立場であった。このため、かつての教え子であるランドルフ・ボーンのエッセイ「偶像の黄昏」が 1917年10月に文芸誌『セブンアーツ』に掲載され、批判を受けた。ボーンはデューイの道具的プラグマティズムの哲学を批判していた[73]。 学問の自由を求める国際連盟 学問の自由の主唱者として、1935年にデューイはアルバート・アインシュタインやアルヴィン・ジョンソンとともに、国際学問の自由連盟のアメリカ支部の メンバーとなり[74]、1940年にはホレス・M・カレンとともに、バートランド・ラッセル事件に関連した一連の記事を編集した。 デューイ委員会 1937年にメキシコで開催された有名なデューイ委員会を指揮し、ジョセフ・スターリンによるレオン・トロツキーの容疑を晴らし[75]、女性の権利のた めの行進など、多くの活動を行った。 産業民主化同盟 1939年、デューイは大学生に労働運動について教育することを目的とした組織である産業民主化連盟の会長に選出された。L.I.D.の学生支部は、後に 『民主社会のための学生同盟』となる[76]。 教師の独立を擁護し、ニューヨーク教員組合の共産主義者の買収に反対するだけでなく、デューイは、最終的にNational Association for the Advancement of Colored Peopleとなった組織に関与し、NAACPの初期の執行委員会の役員として座っていた[78]。 彼はヘンリージョージの土地価値に課税する提案を熱心に支持した。ジョージについては、「高等教育機関の卒業生であっても、この偉大なアメリカの思想家の 理論的貢献について直接知らなければ、自分を社会思想の教養人とみなす権利はない」と書いている[79]。ヘンリー・ジョージ社会科学大学院の名誉学長と して、ヘンリー・フォードに手紙を書き、この学校を支援するように促している[80]。 |

| Other interests Dewey's interests and writings included many topics, and according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "a substantial part of his published output consisted of commentary on current domestic and international politics, and public statements on behalf of many causes. (He is probably the only philosopher in this encyclopedia to have published both on the Treaty of Versailles and on the value of displaying art in post offices.)"[81] In 1917, Dewey met F. M. Alexander in New York City and later wrote introductions to Alexander's Man's Supreme Inheritance (1918), Constructive Conscious Control of the Individual (1923) and The Use of the Self (1932). Alexander's influence is referenced in "Human Nature and Conduct" and "Experience and Nature."[82] As well as his contacts with people mentioned elsewhere in the article, he also maintained correspondence with Henri Bergson, William M. Brown, Martin Buber, George S. Counts, William Rainey Harper, Sidney Hook, and George Santayana. |

その他の関心事 スタンフォード哲学百科事典によると、「彼の出版物のかなりの部分は、現在の国内および国際政治に関する解説と、多くの大義を代弁する公的声明から成って いた。(彼はおそらくこの百科事典の中で、ベルサイユ条約と郵便局に美術品を展示することの価値についての両方を発表した唯一の哲学者である)」 [81]。 1917年、デューイはニューヨークでF・M・アレクサンダーと出会い、後にアレクサンダーの『人間の最高の遺産』(1918)、『個人の建設的意識的制 御』(1923)、『自己の使用』(1932)の序文を執筆している。アレクサンダーの影響は、「人間の本性と行動」と「経験と自然」の中で言及されてい る[82]。 記事の他の場所で言及された人々との接触だけでなく、アンリ・ベルクソン、ウィリアム・M・ブラウン、マーティン・ブーバー、ジョージ・S・カウンツ、 ウィリアム・レイニー・ハーパー、シドニー・フック、ジョージ・サンタヤナとも文通を続けていた。 |