Applied Legal Anthropology

応用_法人類学

Applied Legal Anthropology

池田光穂

応用法人類学(Applied Legal Anthropology)は、法や司法機能の社会的実装にかかわ る人類学的研究のことである(→「法人類学シラバス」)。

応用法人類学が期待される場面には、法人類学が培っ てきた法やルールの通文化的解釈や、正義概念の通文化的な相対主義という見識にもとづいて、当事者が属する文化的観点から、法の機能をチェックし、その人 の法的権利を最大限に擁護しつつ、法にまつわる紛争解決に役立てようとするものである。

ここでの学問的精神は、司法当局ではなく、当事者側

に与する共感的プラグマティズム(compassionate pragmatism)である。

具体的には、法廷や、ADRでの現場への介入や、社 会的文化的観点からの調査を通した、さまざまなオピニオン活動、犯罪学や犯罪心理学者との共同研究、などがある。

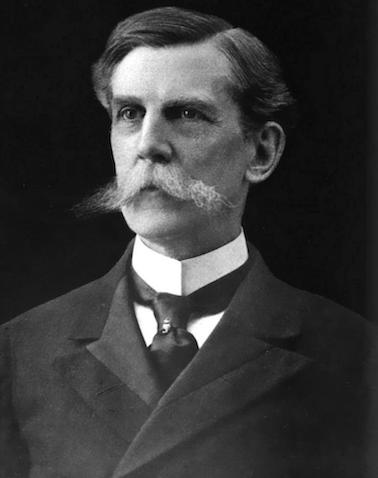

しかしながら、連邦裁判所判事だった、オリバー・ ウェンデル・ホームズ・ジュニア(Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., 1841-1935)の次のエピソードなどは、アメリカのプラグマティズムの伝統を見事の表現している。つまり、社会にとって「よいアイディア」とは、そ のアイディアを自由市場に出して、それが生き残れば(つまりビジネスとして成功すれば)それはよいアイディアなのだということだ。

オリバー・ ウェンデル・ホームズ・ジュニアの最悪の判決(→「バック対ベル訴訟」)

ADRにおいても、お互いがどれだけ理屈で勝ったか ということよりも、お互いがどれだけ、敵意を軽減することができたか、そして、類似のことが二度とおきない。均衡的和解をするための合意と補償があるのか というポイントである。

| Legal

anthropology, also known as the anthropology of laws, is a

sub-discipline of anthropology follows inter diciplinary approach which

specializes in "the cross-cultural study of social ordering".[1] The

questions that Legal Anthropologists seek to answer concern how is law

present in cultures? How does it manifest? How may anthropologists

contribute to understandings of law? Earlier legal anthropological research focused more narrowly on conflict management, crime, sanctions, or formal regulation. Bronisław Malinowski's 1926 work, Crime and Custom in Savage Society, explored law, order, crime, and punishment among the Trobriand Islanders.[2] The English lawyer Sir Henry Maine is often credited with founding the study of Legal Anthropology through his book Ancient Law (1861). An ethno-centric evolutionary perspective was pre-eminent in early Anthropological discourse on law, evident through terms applied such as ‘pre-law’ or ‘proto-law’ in describing indigenous cultures. However, though Maine’s evolutionary framework has been largely rejected within the discipline, the questions he raised have shaped the subsequent discourse of the study. Moreover, the 1926 publication of Crime and Custom in Savage Society by Malinowski based upon his time with the Trobriand Islanders, further helped establish the discipline of legal anthropology. Through emphasizing the order present in acephelous societies, Malinowski proposed the cross-cultural examining of law through its established functions as opposed to a discrete entity. This has led to multiple researchers and ethnographies examining such aspects as order, dispute, conflict management, crime, sanctions, or formal regulation, in addition (and often antagonistically) to law-centred studies, with small-societal studies leading to insightful self-reflections and better understanding of the founding concept of law. Contemporary research in legal anthropology has sought to apply its framework to issues at the intersections of law and culture, including human rights, legal pluralism, Islamophobia[3][4] and political uprisings. |

法の人類学としても知られる法人類学は、人類学の下位学問分野であり、

「社会秩序の異文化間研究」を専門とする学際的アプローチに従います[1]。

法人類学者が答えようとする質問は、法が文化にどのように存在するのかを懸念しているのでしょうか。それはどのように現れるのでしょうか。人類学者はどの

ように法の理解に貢献することができるのか。 初期の法人類学的研究は、紛争管理、犯罪、制裁、または正式な規制により狭い範囲に焦点を当てました。ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーは1926年に『未開 社会における犯罪と慣習』という著作で、トロブリアンド諸島の人々の間の法律、秩序、犯罪、刑罰について研究しました[2]。イギリスの弁護士であるヘン リー・メイン卿は、彼の著書『古代の法』(1861)によって法人類学研究を創設したとしばしば信じられています。民族中心的な進化論的視点は、初期の法 に関する人類学的言説において卓越しており、先住民の文化を説明する際に「先法」や「原法」といった言葉が適用されていることからも明らかである。しか し、メインの進化論的枠組みは、学問的にはほとんど否定されているが、彼が提起した疑問は、その後の研究の言説を形成してきた。さらに、マリノフスキーが トロブリアン島民との交流をもとに1926年に発表した『未開社会の犯罪と慣習』は、法人類学という学問分野の確立に貢献しました。マリノフスキーは、非 人道的な社会に存在する秩序を強調することで、個別の実体とは対照的に、確立された機能を通じて法を異文化間で検証することを提案した。これにより、法を 中心とした研究に加えて、秩序、紛争、紛争管理、犯罪、制裁、形式的規制などの側面を検討する多くの研究者や民族誌が生まれ(しばしば敵対的に)、小社会 の研究は、洞察に満ちた自己省察と法の創設概念のより良い理解につながりました。 現代の法人類学の研究は、人権、法的多元主義、イスラム恐怖症[3][4]、政治的暴動など、法と文化の交差点にある問題にその枠組みを適用しようとしている。 |

| What is law? Legal Anthropology provides a definition of law which differs from that found within modern legal systems. Hoebel (1954) offered the following definition of law: “A social norm is legal if its neglect or infraction is regularly met, in threat or in fact, by the application of physical force by an individual or group possessing the socially recognized privilege of so acting” Maine argued that human societies passing through three basic stages of legal development, from a group presided over by a senior agnate, through stages of territorial development and culminating in an elite forming normative laws of society, stating that “what the juristical oligarchy now claims is to monopolize the knowledge of the laws, to have the exclusive possession of the principles by which quarrels are decided” This evolutionary approach, as has been stated, was subsequently replaced within the anthropological discourse by the need to examine the manifestations of law's societal function. As according to Hoebel, law has four functions: 1) to identify socially acceptable lines of behaviour for inclusion in the culture. 2) To allocate authority and who may legitimately apply force. 3) To settle trouble cases. 4) To redefine relationships as the concepts of life change. Legal theorist H. L. A. Hart, however, stated that law is a body of rules, and is a union of two sets of rules: rules on conduct ("primary rules") [5] rules about recognizing, changing, applying, and adjudicating on rules on conduct ("secondary rules") [6] Within modern English Theory, law is a discrete and specialized topic. Predominantly positivist in character, it is closely linked to notions of a rule-making body, the judiciary and enforcement agencies. The centralized state organisation and isolates are essentials to the attributes of rules, courts and sanctions. To learn more on this view, see Hobbes. 1651 Leviathan, part 2, chapter 26 or Salmond, J. 1902 Jurisprudence. However, this view of law is not applicable everywhere. There are many acephalous societies around the world where the above control mechanisms are absent. There are no conceptualized and isolated set of normative rules – these are instead embodied in everyday life. Even when there may be a discrete set of legal norms, these are not treated similarly to the English Legal System's unequivocal power and unchallenged pre-eminence. Shamans, fighting and supernatural means are all mechanisms of superimposing rules within other societies. For example, within Rasmussen’s work of Across Arctic America (1927) he recounts Eskimo nith[check spelling]-songs being used as a public reprimand by expressing the wrongdoing of someone guilty. Thus, instead of focusing upon the explicit manifestations of law, legal anthropologists have taken to examining the functions of law and how it is expressed. A view expressed by Leopold Pospisil[7] and encapsulated by Bronislaw Malinowski: “In such primitive communities I personally believe that law ought to be defined by function and not by form, that is we ought to see what are the arrangements, the sociological realities, the cultural mechanisms which act for the enforcement of law”[8] Thus, law has been studied in ways that may be categorized by as: 1) prescriptive rules 2) observable regularities 3) Instances of dispute. |

法とは何か? 法人類学は、現代の法制度に見られる定義とは異なる法の定義を提供している。Hoebel(1954)は、法の定義を次のように示している。「社会的規範 は、その無視や違反が、社会的に認められた特権を持つ個人または集団による物理的な力の行使によって、脅迫的にも事実上も定期的に満たされる場合、合法で ある」。 メインは、人間社会は、上級の近親者が統率する集団から、領土の発展段階を経て、社会の規範法を形成するエリートに至るまで、法的発展の3つの基本段階を 通過するとし、「法学的寡頭制が現在主張しているのは、法律の知識を独占し、論争が決定される原理を独占的に所有することだ」と述べている。 この進化論的アプローチは、先に述べたように、その後、人類学の言説の中で、法の社会的機能の発現を検討する必要性に取って代わられた。ヘーベルによれば、法には4つの機能がある。 1) 社会的に許容される行動規範を特定し、文化に取り込むこと。2) 権限を与え、誰が合法的に武力を行使できるかを決める。3) トラブルを解決する。4) 生活の概念の変化に応じて、関係を再定義すること。 しかし、法学者の H. L. A. Hart は、法とは規則の体系であり、2 つの規則の集合の連合体であると述べている。 行為に関する規則(「一次規則」)[5]。 行為に関する規則の認識、変更、適用、裁定に関する規則(「第二の規則」)[6]。 現代英国法理論の中で、法律は個別的で専門的なトピックである。実証主義的な性格が強く、規則制定機関、司法機関、執行機関といった概念と密接に結びつい ている。ルール、裁判所、制裁の属性には、中央集権的な国家組織と孤立が不可欠である。この見解について詳しく知りたい方は、ホッブズを参照されたい。 1651 『リヴァイアサン』第2部第26章やSalmond, J. 1902 『Jurisprudence』などがある。 しかし、このような法観はどこでも通用するものではない。世界には、上記のような統制機構が存在しない頭脳社会が多数存在する。概念化され孤立した規範的 なルールの集合は存在せず、それらは日常生活の中で具現化される。たとえ個別の法規範があったとしても、それらは英国の法制度の明白な権力と揺るぎない優 位性と同様に扱われることはない。シャーマン、戦闘、超自然的な手段などはすべて、他の社会にルールを押し付けるメカニズムである。例えば、ラスムッセン の『北極圏横断』(1927年)には、エスキモーのニット[スペルを確認]の歌が、罪を犯した者の悪行を表現することで公的叱責として使われたことが記さ れている。 このように、法人類学者は、法の明示的な発現に注目するのではなく、法の機能やその発現のされ方を検討するようになった。レオポルド・ポスピシル[7]によって表明され、ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーによって要約された見解。 「つまり、法の執行のために作用する取り決め、社会学的現実、文化的メカニズムが何であるかを見るべきなのだ」[8]。 このように、法は以下のように分類される方法で研究されてきた。1)規定規則 2)観察可能な規則性 3)紛争の事例。 |

| Legal pluralism Legal scholars noted that many social structures had their own rules and processes that were similar to law, which were referred to as legal orders. The viewpoint that law should be studied together with these legal orders or cannot be seens and fundamentally distinct or separate from them has been referred to as legal pluralism. Some scholars have argued that law is distinct from other law like processes, for example because of its relationship with the state.[9]: 38 |

法の多元性 法学者は、多くの社会構造が法に類似した独自のルールやプロセスを持っていることに着目し、それらを法秩序と呼んだ。法はこれらの法秩序とともに研究され るべきであり、法秩序とは基本的に異なるもの、あるいは別個のものであってはならないという視点は、法多元主義と呼ばれている。また、国家との関係などか ら、法は他の法のような過程とは区別されると主張する学者もいる[9]。 38 |

| Processual paradigm: order and conflict Order and regulatory behaviour are required if social life is to be maintained. The scale and shade of this behaviour depends on the values and beliefs held by a society deriving from implicit understandings of the norm developed through socialization. There are socially constructed norms with varying degrees of explicitness and levels of order. Conflict may not be interpreted as an extreme pathological event but as a regulatory acting force. This processual understanding of conflict and dispute became apparent and subsequently heavily theorized upon by the anthropological discipline within the latter half of the nineteenth century as a gateway to the law and order of a society. Disputes have come to be recognised as necessary and constructive over pathological whilst the stated rules of law only explain some aspects of control and compliance. The context and interactions of a dispute are more informative about a culture than the rules. Classic studies deriving theories of order from disputes include Evans-Pritchard work Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande which focused upon functional disputes surrounding sorcery and witchcraft practices, or Comaroff and Roberts (1981) work among the Tswana which examine the hierarchy of disputes, the patterns of contact and the effect norms affect the course of dispute as norms important to dispute are rarely “especially organised for jural purpose” [10] Other examples include: Leach, 1954. Political Systems of Highland Burma. Barth, 1959. Political Leadership among Swat Pathans. |

プロセス的パラダイム:秩序と対立 社会生活が維持されるためには、秩序と規制行動が必要である。この行動の規模や濃淡は、社会化を通じて培われた規範の暗黙の理解から派生する社会が持つ価 値観や信条に依存する。社会的に構築された規範には、さまざまな程度の明示性と秩序が存在する。紛争は極端な病的事象としてではなく、規制的作用力として 解釈することができる。 このような過程的な対立や紛争の理解は、19世紀後半に人類学の分野で明らかになり、その後、社会の法と秩序への入り口として重く理論化されるようになっ た。紛争は病的というよりは必要かつ建設的なものとして認識されるようになり、一方、法の規則は統制と遵守のいくつかの側面を説明するに過ぎない。紛争に おける文脈と相互作用は、ルールよりも文化についてより多くの情報を与えてくれる。 紛争から秩序の理論を導き出す古典的な研究には、魔術や呪術の実践にまつわる機能的な紛争に焦点を当てたエヴァンス=プリチャードによる『アザンド族の魔術、神託、魔法』やツワナ族のコマロフとロバーツ(1981)による研究がある。 他の例としては、以下のようなものがある。 Leach, 1954. Leach, 1954. Political Systems of Highland Burma. バース、1959. スワート・パタンにおける政治的リーダーシップ』(日本評論社、1994年 |

| Case study approach Within the history of Legal Anthropology there have been various methods of data gathering adopted; ranging from literature review of traveller/missionary accounts, consulting informants and lengthy participant observation. Furthermore, when evaluating any research it is appropriate to have a robust methodology capable of scientifically analysing the topic at hand. The broad method of study by legal anthropologists prevails upon the Case Study Approach first developed by Llewellyn and Hoebel in The Cheyenne Way (1941) not as “a philosophy but a technology” [11] This methodology is applied to situations of cross-cultural conflict and the correlating resolution, which can have sets of legal notions and jural regularities extracted from them [12] This method may be safe-guarded against accusations of imposing western ideological structures as it is often an emic sentiment: for example, “The Tiv drove me to the case method…what they were interested in. They put a lot of time and effort into cases” [13] |

ケーススタディのアプローチ 法人類学の歴史において、旅人や宣教師の記録、文献調査、インフォーマントへのインタビュー、長時間の参加型観察など、様々なデータ収集方法が採用されてきた。 また、どのような研究であっても、それを評価する際には、そのテーマを科学的に分析できる確固たる方法論を持つことが適切である。 法人類学者による広範な研究方法は、ルウェリンとホーベルがThe Cheyenne Way(1941)で初めて開発した事例研究アプローチを「哲学ではなく技術」として重用している[11]。 この方法論は異文化間の紛争とそれに関連する解決の状況に適用され、そこから抽出された一連の法的概念とジュラルな規則性を持つことができる[12]。 この方法は、しばしば叙情的な感情であるため、西洋のイデオロギー構造の押し付けという非難から守られているかもしれない:例えば、以下のように。 「ティヴは私をケースメソッドに駆り立てた...彼らが興味を抱いたのは、そのことだった。彼らはケースに多くの時間と労力を費やしていた」[13]。 |

| Law as a system of knowledge Scholars of the sociology of knowledge note that social and power relations can both be created by the definition of knowledge, and influence how knowledge is created. Scholars have argued that law provides a set of categories and relations through which to see the social world.[9]: 54 [14]: 8 Individuals themselves (rather than legal professionals) will try to frame their problems in legalistic terms to resolve them.[14]: 130 Boaventura de Sousa Santos argues that these legal categories can distort reality, Yngvesson argues that the definitions themselves can create power imbalances.[9]: 64 |

知識の体系としての法 知識社会学の研究者たちは、社会的・権力的関係が知識の定義によって生み出され、知識がどのように創造されるかに影響を与えることができると指摘している。 研究者たちは、法が社会的世界を見るためのカテゴリーと関係のセットを提供すると主張している[9]。 54 [14]: 8 個人自身は(法律の専門家ではなく)、自分の問題を解決するために法律的な用語でフレームを作ろうとするだろう[14]。 130 Boaventura de Sousa Santosは、これらの法的なカテゴリーが現実を歪めることができると主張し、Yngvessonは、定義自体が権力の不均衡を生み出すことができると 主張している[9]: 64。 |

| Issues of terminology and ethnology Regarding law, in Anthropology's characteristically self-conscious manner, the comparative analysis inherent to Legal Anthropology has been speculated upon and most famously debated by Paul Bohannan and Max Gluckman. The discourse highlights one of the primary differences between British and American Anthropology regarding fieldwork approaches and concerns the imposition of Western terminology as ethnological categories of differing societies.[15] Each author's uses the Case Study Approach, however, the data's presentation in terms of achieving comparativeness is a point of contention between them. Paul Bohannan promotes the use of native terminology presented with ethnographic meaning as opposed to any Universal categories, which act as barriers to understanding the true nature of a culture's legal system. Advocating that it is better to appreciate native terms in their own medium, Bohannan critiques Gluckman's work for its inherent bias. Gluckman has argued that Bohannan's excessive use of native terminology creates barriers when attempting to achieve comparative analysis. He in turn has suggested that in order to further the cross-cultural comparative study of law, we should use English terms and concepts of law which will aid in the refinement of dispute facts and interrelations [16] Thus, all native terms should be described and translated into an Anglo-American conceptual equivalent for the purpose of comparison. |

用語と民族学の問題 法に関しては、人類学の特徴である自意識過剰な態度で、法人類学に固有の比較分析について、ポール・ボハンとマックス・グラックマンが推測し、最も有名な 議論を展開している。この言説は、フィールドワークのアプローチに関するイギリスとアメリカの人類学の主要な違いの1つを強調し、異なる社会の民族学的カ テゴリーとして西洋の専門用語の押し付けを懸念している[15]。 それぞれの著者は事例研究アプローチを用いているが、比較可能性を達成するためのデータの提示が両者の間で論点となっている。 ポール・ボハナンは、ある文化の法制度の本質を理解する上で障壁となる普遍的なカテゴリーとは対照的に、民族誌的な意味を持つネイティブな用語の使用を推奨している。 Bohannanは、先住民の用語をその媒体で評価する方が良いと主張し、Gluckmanの著作をその固有の偏見から批判している。 Gluckmanは、Bohannanがネイティブの専門用語を多用することは、比較分析を行う上で障害になると主張している。そして、法学の異文化間比 較研究を促進するために、紛争事実と相互関係の洗練を助ける英語の用語と法学の概念を使用すべきであると提案している[16]。したがって、比較の目的の ために、すべてのネイティブ用語は、英米の概念的同等物に記述・翻訳されるべきである。 |

| Processes and methodologies As disputes and order began to be recognised as categories worthy of study, interest in the inherent aspects of conflicts emerged within legal anthropology. The processes and actors involved within the events became an object of study for ethnographers as they embraced conflict as a data-rich source. One example of such an interest is expressed by Philip Gulliver, 1963, Social Control in an African Society in which the intimate relations between disputes are postulated as being important. He examines the patterns of alliance between actors of a dispute and the strategies that develop as a result, the roles of mediators and the typologies for intervention. Another is Sara Ross, whose work Law and Intangible Cultural Heritage in the City focuses the rubric of legal anthropology specifically onto the urban context through an "urban legal anthropology", that includes the use of virtual ethnography, institutional ethnography, and participant observation in urban public and private spaces.[17] |

プロセスと方法論 紛争と秩序が研究に値するカテゴリーとして認識され始めると、紛争に内在する側面への関心が法人類学に現れるようになった。エスノグラファーは紛争を豊富なデータ源として受け入れ、その事象に関わるプロセスやアクターを研究対象とするようになった。 このような関心の一例として、フィリップ・ガリバー(1963)『アフリカ社会の社会統制』では、紛争間の親密な関係が重要であると想定している。彼は、 紛争のアクター間の提携のパターンとその結果展開される戦略、調停者の役割、介入のための類型を検証している。もう一人はサラ・ロスで、彼の著作『Law and Intangible Cultural Heritage in the City』は、「都市の法人類学」を通じて、特に都市の文脈に法人類学のルーブリックを集中させている。 |

| The legitimacy of Universal Human Rights. Political anthropologists have had much to say about the UDHR(Universal Declaration of Human Rights). Original critiques, most notably by the AAA(American Anthropological Association), argued that cultural ideas of rights and entitlement differ between societies. They warned that any attempt to endorse one set of values above all others amounted to a new western imperialism, and would be counter to ideas of cultural relativism. Most anthropologists now agree that universal human rights have a useful place in today's world. Zechenter (1997) argues there are practices, such as Indian 'sati' (the burning of a widow on her husband's funeral pyre) that can be said to be wrong, despite justifications of tradition. This is because such practices are about much more than a culturally established world view, and frequently develop or revive as a result of socio-economic conditions and the balance of power within a community. As culture is not bounded and unchanging, there are multiple discourses and moral viewpoints within any community and among the various actors in such events (Merry 2003). Cultural relativists risk supporting the most powerfully asserted position at the expense of those who are subjugated under it. More recent contributions to the question of universal human rights include analysis of their use in practice, and how global discourses are translated into local contexts (Merry 2003). Anthropologists such as Merry (2006) note how the legal framework of the UNDHR is not static but is actively used by communities around the globe to construct meaning. As much as the document is a product of western Enlightenment thinking, communities have the capacity to shape its meaning to suit their own agendas, incorporating its principles in ways that empower them to tackle their own local and national discontents. Female genital cutting (FGC), also known as female circumcision or female genital mutilation remains a hotly debated, controversial issue contested particularly among legal anthropologists and human rights activists. Through her ethnography (1989) on the practice of pharonic circumcision among the Hofriyat of Sudan (1989) Boddy maintains that understanding local cultural norms is of crucial importance when considering intervention to prevent the practice. Human rights activists attempting to eradicate FGC using the legal framework of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UNDHR) as their justification, run the risk of imposing a set of ideological principles, alien to the culture attempting to be helped, potentially facing hostile reactions. Moreover, the UNDHR as a legal document, is contested by some as being restrictive in its prescription of what is and is not deemed a violation of a human right (Ross 2003) and overlooks local customary justifications which operate outside of an international legalistic framework (Ross 2003). Increasingly (FGC) is becoming a global issue due to increased mobility. What was once deemed a largely African practice has seen a steady increase in European countries such as Britain. Although made illegal in 1985 there have as yet been no convictions and girls as old as nine continue to have the procedure. Legislation has now also been passed in Sweden, the United States and France where there have been convictions. Black, J. A. and Debelle, G. D. (1995) "Female Genital Mutilation in Britain" British Medical Journal. |

世界人権の正統性 政治人類学者はUDHR(世界人権宣言)について多くのことを語ってきました。特にAAA(アメリカ人類学会)による最初の批評は、権利や資格に関する文 化的な考え方は社会によって異なると主張しました。彼らは、一つの価値観を他のすべての価値観よりも優先して支持する試みは、新たな西洋帝国主義に相当 し、文化相対主義の考え方に反すると警告した。現在、ほとんどの人類学者は、普遍的人権が今日の世界において有用な位置を占めていることに同意している。 Zechenter(1997)は、インドの「サティ」(未亡人を夫の葬儀の火葬場で焼くこと)のように、伝統の正当化にもかかわらず、間違っていると言 える慣習があると論じている。なぜなら、こうした慣習は、文化的に確立された世界観以上のものであり、社会経済状況やコミュニティ内のパワーバランスの結 果として発展したり復活したりすることが多いからである。文化は束縛されず不変のものではないことから、どのようなコミュニティにおいても、またそのよう な出来事に関わる様々なアクターの間でも、複数の言説や道徳的視点が存在する(Merry 2003)。文化相対主義者は、最も強力に主張される立場を支持し、その下で服従する人々を犠牲にする危険を冒すことになる。 普遍的人権の問題に対するより最近の貢献としては、その実践における使用や、グローバルな言説がどのようにローカルな文脈に翻訳されるのかについての分析 がある(Merry 2003)。Merry(2006)のような人類学者は、UNDHRの法的枠組みが静的なものではなく、意味を構築するために世界中のコミュニティによっ て積極的に利用されていることを指摘している。この文書が西洋の啓蒙思想の産物であるのと同様に、コミュニティは自分たちの課題に合うようにその意味を形 成する能力を持っており、自分たちの地域や国の不満に取り組む力を与える方法でその原則を組み込んでいるのである。 女性性器切除(FGC)は、女性割礼や女性性器切除としても知られ、特に法人類学者や人権活動家の間で、いまだに熱い議論が交わされている問題である。ボ ディーは、スーダンのホフリヤート族における割礼の実践に関する民族誌(1989年)を通じて、この実践を防ぐための介入を考える際に、地域の文化規範を 理解することが極めて重要であると主張している。世界人権宣言(UNDHR)の法的枠組みを正当化するためにFGCを撲滅しようとする人権活動家は、支援 しようとする文化とは異なるイデオロギー的原則を押し付ける危険性があり、潜在的に敵対的反応に直面する可能性がある。さらに、法的文書としての UNDHRは、人権の侵害と見なされるものと見なされないものの規定が制限的であり(Ross 2003)、国際的な法的枠組みの外で運用される地域の慣習的正当性を見落としているとして、一部の人々から異論を唱えられています(Ross 2003)。移動の増加により、(FGC)はますます世界的な問題となりつつある。かつては主にアフリカの習慣とみなされていたものが、イギリスなどの ヨーロッパ諸国では着実に増加しています。1985年に違法とされたものの、いまだ有罪判決を受けておらず、9歳の少女がこの処置を受け続けています。現 在、スウェーデン、アメリカ、フランスでも法律が制定され、有罪判決が下されている。Black, J. A. and Debelle, G. D. (1995) "Female Genital Mutilation in Britain" British Medical Journal. |

| Further information There are a number of useful introductions to the field of legal anthropology,[18] Sally Falk Moore, a leading legal anthropologist, held both a law degree and a PhD in anthropology. An increasing number of legal anthropologists hold both JDs and advanced degrees in anthropology, and some teach in law schools while maintaining scholarly connections within the field of legal anthropology; examples include Rebecca French, John Conley, Elizabeth Mertz, and Annelise Riles. Such combined expertise has also been turned to more applied anthropological pursuits such as tribal advocacy and forensic ethnography by practitioners. There is a growing interest in the intersection of legal and linguistic anthropology. If looking for anthropology departments with faculty specializing in legal anthropology in North America, try the following schools and professors: University of California, Berkeley (Laura Nader), University of California, Irvine (Susan Bibler Coutin, Bill Maurer, Justin B. Richland), Duke University (William M. O'Barr), Princeton University (Lawrence Rosen, Carol J. Greenhouse), State University of New York at Buffalo (Rebecca French), New York University (Sally Engle Merry), Harvard University (Jean Comaroff ), and George Mason University (Susan Hirsch).[19] In Europe, the following scholars and schools will be good resources: Vanja Hamzić (SOAS University of London), Jane Cowan (University of Sussex), Ann Griffiths and Toby Kelly (University of Edinburgh), Sari Wastell (Goldsmiths, University of London), Harri Englund and Yael Navaro (University of Cambridge), and Richard Rottenburg (Martin-Luther Universität). The Association for Political and Legal Anthropology (APLA), a section of the American Anthropological Association, is the primary professional association in the U.S. for legal anthropologists and also has many overseas members. It publishes PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review, the leading U.S. journal in the field of legal anthropology, which is accessible via http://polarjournal.org/ or http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1555-2934 'Allegra: a Virtual Laboratory of Legal Anthropology' is an online experiment by a new generation of legal anthropologists designated to facilitate scholarly collaboration and awareness of the sub-discipline. |

さらに詳しい情報 法人類学の分野では多くの有用な入門書があり[18]、法人類学の第一人者であるサリー・フォーク・ムーアは法学士と人類学の博士号を併せ持つ。法人類学 者の中には、法学博士と人類学の上級学位を併せ持つ者も増えており、法人類学の分野で学術的なつながりを保ちながら、法科大学院で教鞭をとる者もいる。こ のような複合的な専門性は、実務家による部族擁護や法医学的民族誌など、より応用的な人類学の追及にも向けられています。法律人類学と言語人類学の交差点 への関心も高まっています。 北米で法人類学を専門とする教員のいる人類学教室を探すなら、以下の学校と教授を試してみてください。カリフォルニア大学バークレー校(Laura Nader)、カリフォルニア大学アーバイン校(Susan Bibler Coutin, Bill Maurer, Justin B. Richland)、デューク大学(William M. O'Barr)、プリンストン大学(Lawrence Rosen, Carol J. Greenhouse)、ニューヨーク州立大学バッファロー校(Rebecca French)、ニューヨーク大学(Sally Engle Merry)、ハーバード大学(Jean Comaroff )、ジョージメイソン大学(Susan Hirsch)です [19]. ヨーロッパでは、以下の学者や学校が良いリソースとなる。ヴァンヤ・ハムジッチ(ロンドン大学SOAS)、ジェーン・コーワン(サセックス大学)、アン・ グリフィスとトビー・ケリー(エディンバラ大学)、サリ・ワステル(ロンドン大学ゴールドスミス)、ハーリ・エングルンドとヤエル・ナバロ(ケンブリッジ 大学)、リチャード・ロッテンブルグ(マルティン・ルター大学)。 APLA(Association for Political and Legal Anthropology)は、米国人類学会の一部で、法人類学者のための米国における主要な専門家団体であり、海外にも多くの会員を擁しています。法人 類学分野における米国の代表的な学術誌「PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review」を発行しており、http://polarjournal.org/ または http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1555-2934 でアクセス可能。 アレグラ:法人類学のバーチャルラボラトリー」は、法人類学の新しい世代によるオンライン実験で、学術的なコラボレーションとサブディシプリンの認知を促進するために指定されています。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legal_anthropology |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

関連リンク(このリンクは、北米における応用=法人 類学に関連するサイトを紹介するものです)

サイト内リンク

文献