Political

Anthropology

Political

Anthropology

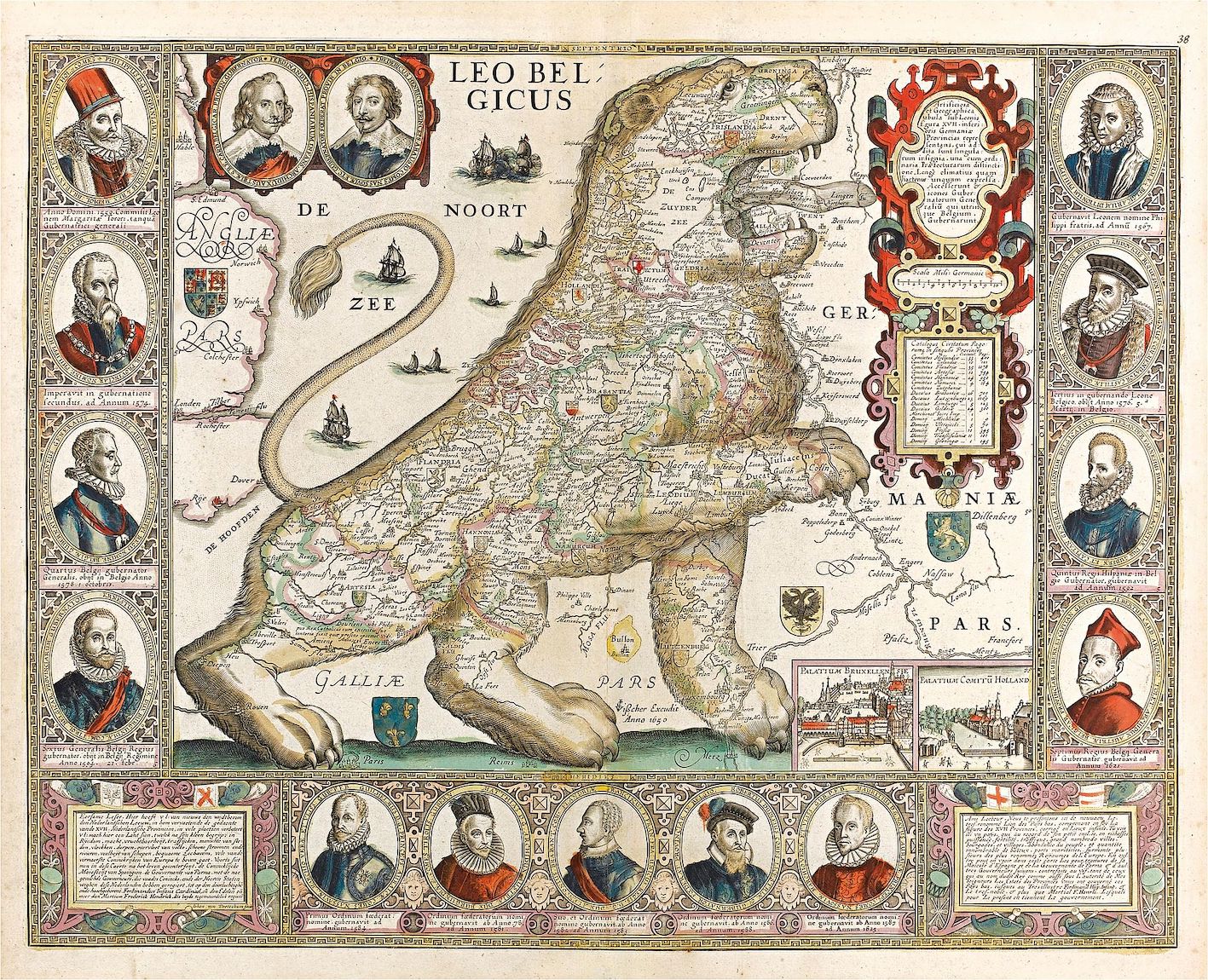

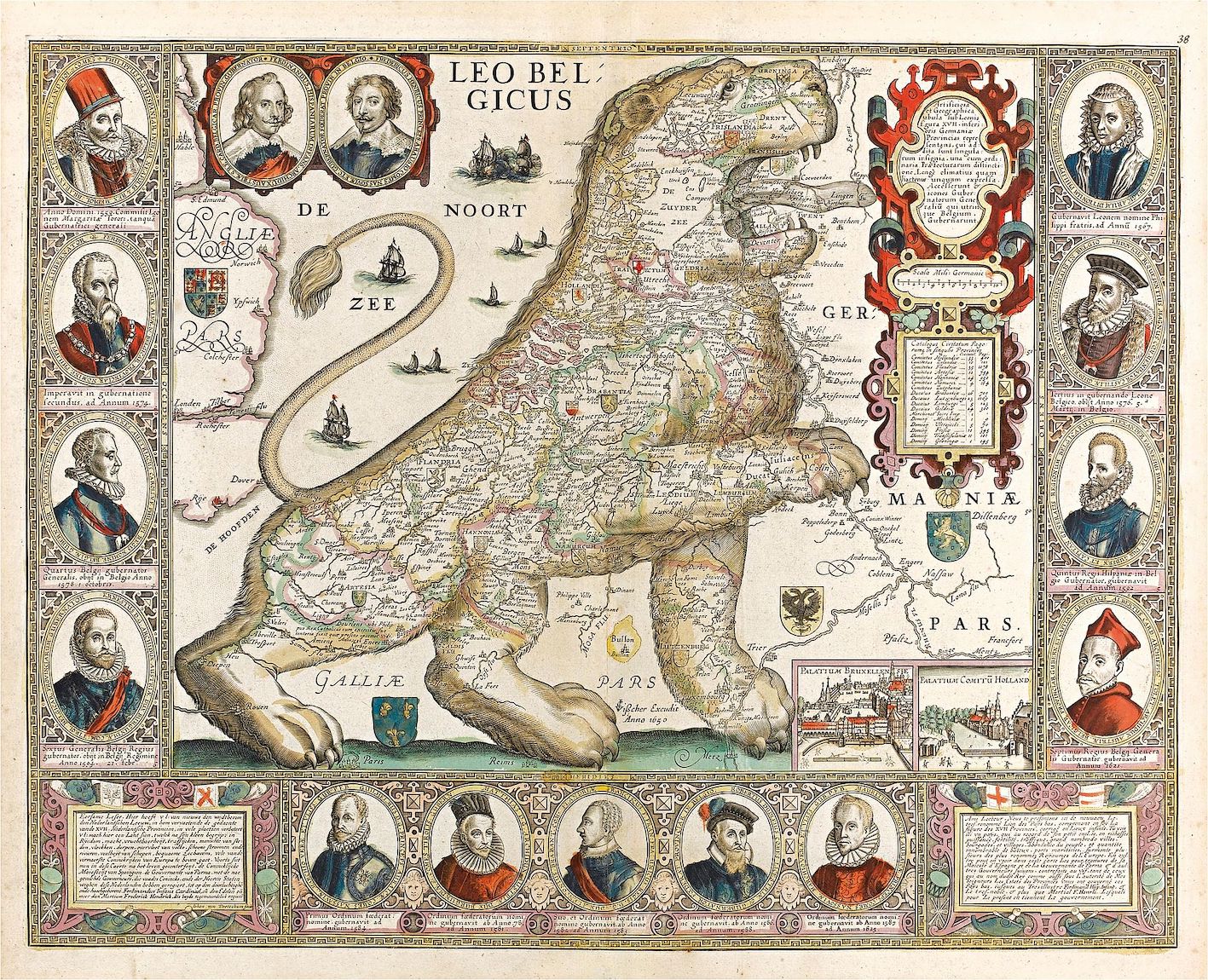

Joannes van Deutecum - Leo Belgicus 1650

政治人類学

Political

Anthropology

Political

Anthropology

解説:池田光穂

【定 義】

人間のもつ政治性、政治権力、政治体制な ど、政治(politics)に関わるもの一切を考察の対象にする人類学の分野。関連するものとして、 人類学理論:エスニシティ、植民地主義、法の人類学、宗教と儀礼、象徴の機能などがある。

人類学者と現実の政治について、主に門外 からさまざまな臆測がなされてきた。人類学者が、政治権力に対して距離をとり、相対主義的傾向がつ よい。逆に、人類学者は人間の普遍的平等性に忠誠をもつので、政治的な人が多い。フィールドワークにおいては、現地の政治体制のもとで調査をおこなうの で、政治的には保守的で、無関与の人が多い。いや、人びとと接触する機会が多いので、人類学者の多くは全体主義体制のなかで犠牲になりやすかったし、また 調査許可が下りずに長年の調査が困難な人類学者も数多くいる。

すくなくともこれらの「臆測」は個々の ケースにおいてすべてにあてはまる。しかし、それは人類学者という固有の社会的役割から来ているわけ ではなく、他の種類の多くのフィールドワーカーと同様、現地調査とその土地の政治体制と無関係に仕事ができないこと、つまりさまざまな制約を受けることを 示している。

マルセル・モース、マックス・グラックマ ン、ピエール・クラストル、ジョルジュ・バランディエ、マーシャル・サーリンズ、シドニー・ミンツ、エ リック・ウルフ、ソ ル・タックス、ヴェーナ・ダス、ナンシー・シェーパー=ヒューズ、ディビッド・グレイバー、石田英一郎、田辺繁治、清水昭俊など、歴史上、著名な人類学者 で、政治や政治理論と深く関わってき、かつその学問に多大なる影響を与えている人類学者は多い。

(1)実体主義= substantibist 的見解)

さて、政治人類学のエピソードの中で、もっとも興味深いのがクラストルのそれであろう。(政治人類学における「政治」の概念を解体する 言わ ば実体主義=substantibist 的見解)

クラストルは、それまでの政治人類学の理論が(マルクス主義流の)史的唯物論影響を受けて、人類学の政治体制の議論のなかに潜む進化主 義の 弊害に気づいていた。すなわち、彼が調査したアマゾン社会の先住民の政治体制(=国家をもたない人びと)は、歴史的な存在であったアステカやインカののよ うな王権国家体制という段階まで「進化していない」という偏見をもっているのではないかと批判した。

クラストルは考えた、アマゾンの先住民の諸社会の人びとは、国家権力がもつ暴力性によって社会を維持する制度を十全に理解した上で、自 分た ちの社会のなかに、そのような異質性(=他者性)をもちこまないように、自分たちの社会を運営していたとすれば、彼らの政治体制はどのように理解すること ができるのだろうか、と。

そこでは、(国家権力のもつ暴力性を自明視する)我々の政治や社会の運営の仕方が、アマゾンの先住民社会からみたら、道徳的には異様 で、こ とによれば間違っているように思えるかもしれない。

実際、アマゾンの先住民(男性なのだが)にとってリーダー(首長)になることは、メリットになることはほとんどなく、つねに監視されて い て、苦役になるほどであった。他方、暴力は、力の差異によって権力を得るためではなく、平等(男女の違いは極めて重要なので、男女間の平等はあり得なかっ たが)を維持するために——我々からみれば過剰と思えるほど——発動されるのであった。

(2)形式主義的見解

西洋社会でみられる政治現象を、文化人類学の研究対象である「現地」の人々にも見たり、その政治的要素の、土着的ないしは歴史的な「変

形」

を考えるアプローチである。

■Substantibist とformalist の違いを主張したのは、Karl Polanyi, "The Great Transformation" (1944)の中においてである。

"Substantivism is a position, first proposed by Karl

Polanyi in his work The Great Transformation (1944), which argues that

the term 'economics' has two meanings. The formal meaning, used by

today's neoclassical economists, refers to economics as the logic of

rational action and decision-making, as rational choice between the

alternative uses of limited (scarce) means, as 'economising,'

'maximizing,' or 'optimizing.'[1]/ The second, substantive meaning

presupposes neither rational decision-making nor conditions of

scarcity. It refers to how humans make a living interacting within

their social and natural environments. A society's livelihood strategy

is seen as an adaptation to its environment and material conditions, a

process which may or may not involve utility maximisation. The

substantive meaning of 'economics' is seen in the broader sense of

'provisioning.' Economics is the way society meets material needs.[1]"

- Substantivism,

by Wiki

★Political anthropology, wikiの説明

| Political

anthropology is the comparative study of politics in a broad range

of historical, social, and cultural settings.[1] |

政治人類学は、幅広い歴史的、社会的、文化的環境における政治の比較研

究である[1]。 |

| History of political anthropology Origins Political anthropology has its roots in the 19th century. At that time, thinkers such as Lewis H. Morgan and Sir Henry Maine tried to trace the evolution of human society from 'primitive' or 'savage' societies to more 'advanced' ones. These early approaches were ethnocentric, speculative, and often racist. Nevertheless, they laid the basis for political anthropology by undertaking a modern study inspired by modern science, especially the approaches espoused by Charles Darwin. In a move that would be influential for future anthropology, this early work focused on kinship as the key to understanding political organization, and emphasized the role of the 'gens' or lineage as an object of study.[2] Among the principal architects of modern social science are French sociologist Emile Durkheim, German sociologist, jurist, and political economist Max Weber, and German political philosopher, journalist, and economist Karl Marx.[3][4] Political anthropology's contemporary literature can be traced to the 1940 publication African Political Systems, edited by Meyer Fortes and E. E. Evans-Pritchard. They rejected the speculative historical reconstruction of earlier authors and argued that "a scientific study of political institutions must be inductive and comparative and aim solely at establishing and explaining the uniformities found among them and their interdependencies with other features of social organization".[5] Their goal was taxonomy: to classify societies into a small number of discrete categories, and then compare them in order to make generalizations about them. The contributors of this book were influenced by Radcliffe-Brown and structural functionalism. As a result, they assumed that all societies were well-defined entities which sought to maintain their equilibrium and social order. Although the authors recognized that "Most of these societies have been conquered or have submitted to European rule from fear of invasion. They would not acquiesce in it if the threat of force were withdrawn; and this fact determines the part now played in their political life by European administration"[6] the authors in the volume tended in practice to examine African political systems in terms of their own internal structures, and ignored the broader historical and political context of colonialism. Several authors reacted to this early work. In his work Political Systems of Highland Burma (1954) Edmund Leach argued that it was necessary to understand how societies changed through time rather than remaining static and in equilibrium. A special version of conflict oriented political anthropology was developed in the so-called 'Manchester school', started by Max Gluckman. Gluckman focused on social process and an analysis of structures and systems based on their relative stability. In his view, conflict maintained the stability of political systems through the establishment and re-establishment of crosscutting ties among social actors. Gluckman even suggested that a certain degree of conflict was necessary to uphold society, and that conflict was constitutive of social and political order. By the 1960s this transition work developed into a full-fledged subdiscipline which was canonized in volumes such as Political Anthropology (1966) edited by Victor Turner and Marc Swartz. By the late 1960s, political anthropology was a flourishing subfield: in 1969 there were two hundred anthropologists listing the subdiscipline as one of their areas of interests, and a quarter of all British anthropologists listed politics as a topic that they studied.[7] Political anthropology developed in a very different way in the United States. There, authors such as Morton Fried, Elman Service, and Eleanor Leacock took a Marxist approach and sought to understand the origins and development of inequality in human society. Marx and Engels had drawn on the ethnographic work of Morgan, and these authors now extended that tradition. In particular, they were interested in the evolution of social systems over time. From the 1960s a 'process approach' developed, stressing the role of agents (Bailey 1969; Barth 1969). It was a meaningful development as anthropologists started to work in situations where the colonial system was dismantling. The focus on conflict and social reproduction was carried over into Marxist approaches that came to dominate French political anthropology from the 1960s. Pierre Bourdieu's work on the Kabyle (1977) was strongly inspired by this development, and his early work was a marriage between French post-structuralism, Marxism and process approach. Interest in anthropology grew in the 1970s. A session on anthropology was organized at the Ninth International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences in 1973, the proceedings of which were eventually published in 1979 as Political Anthropology: The State of the Art. A newsletter was created shortly thereafter, which developed over time into the journal PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review. |

政治人類学の歴史 起源 政治人類学のルーツは19世紀にさかのぼる。当時、ルイス・H・モーガンやヘンリー・メイン卿のような思想家たちは、「原始的な」あるいは「未開の」社会 から、より「先進的な」社会への人類社会の進化を辿ろうとした。これらの初期のアプローチは、民族中心主義的で、思弁的で、しばしば人種差別的であった。 にもかかわらず、彼らは近代科学、とりわけチャールズ・ダーウィンが唱えたアプローチに触発された近代的な研究を行うことで、政治人類学の基礎を築いたの である。この初期の研究は、政治組織を理解する鍵として親族関係に焦点を当て、研究対象として「属」や血統の役割を強調したものであり、後の人類学に大き な影響を与えた[2]。 近代社会科学の主要な立役者としては、フランスの社会学者エミール・デュルケーム、ドイツの社会学者、法学者、政治経済学者マックス・ウェーバー、ドイツ の政治哲学者、ジャーナリスト、経済学者カール・マルクスが挙げられる[3][4]。 政治人類学の現代的な文献は、マイヤー・フォルテスとE・E・エバンス=プリチャードが編集した1940年の出版物『アフリカの政治制度』にまで遡ること ができる。彼らはそれ以前の著者の思索的な歴史的再構築を否定し、「政治制度の科学的研究は帰納的かつ比較的でなければならず、それらの間に見られる統一 性と、社会組織の他の特徴との相互依存関係を確立し、説明することのみを目的としなければならない」と主張した[5]。本書の寄稿者たちは、ラドクリフ= ブラウンと構造的機能主義の影響を受けていた。その結果、彼らはすべての社会がその均衡と社会秩序を維持しようとする、明確に定義された存在であると仮定 した。著者たちは、「これらの社会のほとんどは、征服されたり、侵略を恐れてヨーロッパの支配に服したりしてきた。そしてこの事実が、ヨーロッパ統治が現 在彼らの政治生活に果たしている役割を決定しているのである」[6]。この巻の著者たちは、実際にはアフリカの政治システムを、彼ら自身の内部構造という 観点から検討する傾向があり、植民地主義のより広範な歴史的・政治的背景を無視していた。 この初期の著作に対して、何人かの著者が反発している。Edmund Leachは、その著作『Political Systems of Highland Burma』(1954年)の中で、社会が静的で平衡な状態にとどまるのではなく、時代を通じてどのように変化していくのかを理解する必要があると主張し た。紛争志向の政治人類学の特別なバージョンは、マックス・グラックマンが始めたいわゆる「マンチェスター学派」で発展した。グルックマンは社会的プロセ スと、相対的な安定性に基づく構造とシステムの分析に焦点を当てた。彼の見解では、紛争は社会的アクター間の横断的な結びつきの確立と再確立を通じて政治 システムの安定性を維持していた。グルックマンは、社会を維持するためにはある程度の対立が必要であり、対立は社会秩序や政治秩序を構成するものであると さえ示唆した。 1960年代までに、この移行期の研究は本格的な学問分野へと発展し、ヴィクター・ターナーとマーク・スウォーツが編集した『政治人類学』(1966年) などの書物で正典化された。1969年には200人の人類学者がこのサブディシプリンを関心分野の一つとして挙げており、イギリスの人類学者全体の4分の 1が政治を研究テーマとして挙げていた[7]。 政治人類学はアメリカでは大きく異なる発展を遂げた。そこではモートン・フリード、エルマン・サービス、エレノア・リーコックといった著者がマルクス主義 的なアプローチをとり、人間社会における不平等の起源と発展を理解しようとした。マルクスとエンゲルスはモルガンのエスノグラファーとしての仕事を参考に していたが、これらの著者はその伝統をさらに発展させたのである。個別主義的アプローチとして、彼らは社会システムの時間的変遷に関心を寄せていた。 1960年代からは、エージェントの役割を強調する「プロセス・アプローチ」が発展した(Bailey 1969; Barth 1969)。これは、人類学者が植民地システムが解体されつつある状況で仕事をするようになったことを意味する。紛争と社会的再生産への焦点は、1960 年代からフランスの政治人類学を支配するようになったマルクス主義的アプローチに引き継がれた。ピエール・ブルデューのカビル人に関する研究(1977 年)は、この展開に強く触発されたものであり、彼の初期の研究は、フランスのポスト構造主義、マルクス主義、プロセス・アプローチとの結婚であった。 人類学への関心は1970年代に高まった。1973年の第9回国際人類学・民族学会議では人類学に関するセッションが企画され、その議事録は最終的に 1979年に『政治人類学』として出版された: The State of the Art)として出版された。その後まもなくニュースレターが創刊され、やがて雑誌『PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review』へと発展した。 |

| Anthropology concerned with

states and their institutions While for a whole century (1860 to 1960 roughly) political anthropology developed as a discipline concerned primarily with politics in stateless societies,[8] a new development started from the 1960s, and is still unfolding: anthropologists started increasingly to study more "complex" social settings in which the presence of states, bureaucracies and markets entered both ethnographic[9] accounts and analysis of local phenomena. This was not the result of a sudden development or any sudden "discovery" of contextuality. From the 1950s anthropologists who studied peasant societies in Latin America and Asia, had increasingly started to incorporate their local setting (the village) into its larger context, as in Redfield's famous distinction between 'small' and 'big' traditions (Redfield 1941). The 1970s also witnessed the emergence of Europe as a category of anthropological investigation. Boissevain's essay, "towards an anthropology of Europe" (Boissevain and Friedl 1975) was perhaps the first systematic attempt to launch a comparative study of cultural forms in Europe; an anthropology not only carried out in Europe, but an anthropology of Europe. The turn toward the study of complex society made anthropology inherently more political. First, it was no longer possible to carry out fieldwork in say, Spain, Algeria or India without taking into account the way in which all aspects of local society were tied to state and market. It is true that early ethnographies in Europe had sometimes done just that: carried out fieldwork in villages of Southern Europe, as if they were isolated units or 'islands'. However, from the 1970s that tendency was openly criticised, and Jeremy Boissevain (Boissevain and Friedl 1975) said it most clearly: anthropologists had "tribalised Europe" and if they wanted to produce relevant ethnography they could no longer afford to do so. Contrary to what is often heard from colleagues in the political and social sciences, anthropologists have for nearly half a century been very careful to link their ethnographic focus to wider social, economic and political structures. This does not mean to abandon an ethnographic focus on very local phenomena, the care for detail. In a more direct way, the turn towards complex society also signified that political themes increasingly were taken up as the main focus of study, and at two main levels. First of all, anthropologists continued to study political organization and political phenomena[10] that lay outside the state-regulated sphere (as in patron-client relations or tribal political organization). Second of all, anthropologists slowly started to develop a disciplinary concern with states and their institutions (and on the relationship between formal and informal political institutions). An anthropology of the state developed, and it is a most thriving field today. Geertz's comparative work on the Balinese state is an early, famous example. There is today a rich canon of anthropological studies of the state (see for example Abeles 1990). Hastings Donnan, Thomas Wilson and others started in the early 1990s a productive subfield, an "anthropology of borders", which addresses the ways in which state borders affect local populations, and how people from border areas shape and direct state discourse and state formation (see for example Alvarez, 1996; Thomassen, 1996; Vereni, 1996; Donnan and Wilson, 1994; 1999; 2003). From the 1980s a heavy focus on ethnicity and nationalism developed. 'Identity' and 'identity politics[11]' soon became defining themes of the discipline, partially replacing earlier focus on kinship and social organization. This made anthropology even more obviously political. Nationalism is to some extent simply state-produced culture, and to be studied as such. And ethnicity is to some extent simply the political organization of cultural difference (Barth 1969). Benedict Anderson's book Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism discusses why nationalism came into being. He sees the invention of the printing press as the main spark, enabling shared national emotions, characteristics, events and history to be imagined through common readership of newspapers. The interest in cultural/political identity construction also went beyond the nation-state dimension. By now, several ethnographies have been carried out in the international organizations (like the EU) studying the fonctionnaires as a cultural group with special codes of conduct, dressing, interaction etc. (Abélès, 1992; Wright, 1994; Bellier, 1995; Zabusky, 1995; MacDonald, 1996; Rhodes, 't Hart, and Noordegraaf, 2007). Increasingly, anthropological fieldwork is today carried out inside bureaucratic structures or in companies. And bureaucracy can in fact only be studied by living in it – it is far from the rational system we and the practitioners like to think, as Weber himself had indeed pointed out long ago (Herzfeld 1992[12]). The concern with political institutions has also fostered a focus on institutionally driven political agency. There is now an anthropology of policy making (Shore and Wright 1997). This focus has been most evident in Development anthropology or the anthropology of development, which over the last decades has established as one of the discipline's largest subfields. Political actors like states, governmental institutions, NGOs, International Organizations or business corporations are here the primary subjects of analysis. In their ethnographic work anthropologists have cast a critical eye on discourses and practices produced by institutional agents of development in their encounter with 'local culture' (see for example Ferguson 1994). Development anthropology is tied to global political economy and economic anthropology as it concerns the management and redistribution of both ideational and real resources (see for example Hart 1982). In this vein, Escobar (1995) famously argued that international development largely helped to reproduce the former colonial power structures. Many other themes have over the last two decades been opened up which, taken together, are making anthropology increasingly political: post-colonialism, post-communism, gender, multiculturalism, migration, citizenship,[13][14][15] not to forget the umbrella term of globalization. It thus makes sense to say that while anthropology was always to some extent about politics, this is even more evidently the case today. |

国家とその制度に関わる人類学 政治人類学は、丸1世紀(1860年から1960年まで)の間、主に無国籍社会における政治に関わる学問として発展してきたが[8]、1960年代から新 たな展開が始まり、現在もなお続いている。これは突発的な発展の結果でもなければ、文脈性の突然の「発見」でもなかった。1950年代からラテンアメリカ やアジアの農民社会を研究していた人類学者たちは、レッドフィールドの有名な「小さな」伝統と「大きな」伝統の区別(Redfield 1941)に見られるように、そのローカルな設定(村)をより大きな文脈に組み込むことを次第に始めていた。1970 年代には、人類学的調査のカテゴリーとしてのヨーロッパも出現した。ボワセヴァンの小論「ヨーロッパの人類学に向けて」(Boissevain and Friedl 1975)は、おそらくヨーロッパにおける文化形態の比較研究を開始する最初の体系的な試みであった。 複雑な社会を研究する方向への転換は、人類学を本質的に政治的なものにした。第一に、スペイン、アルジェリア、インドなどにおいて、地域社会のあらゆる側 面が国家や市場と結びついていることを考慮に入れずにフィールドワークを行うことは、もはや不可能となった。たしかに、ヨーロッパの初期の民族誌は、南 ヨーロッパの村落を孤立した単位や「島」であるかのようにフィールドワークしていた。しかし、1970年代からその傾向は公然と批判されるようになり、 ジェレミー・ボワセヴァン(Jeremy Boissevain)(Boissevain and Friedl 1975)は、「人類学者はヨーロッパを 「部族化 」してしまった。政治・社会科学の仲間からよく聞かれる話とは逆に、エスノグラファーは半世紀近く、民族誌の焦点をより広い社会・経済・政治構造と結びつ けることに細心の注意を払ってきた。これは、非常にローカルな現象に対するエスノグラファーとしての焦点や、細部への配慮を放棄することを意味するもので はない。 より直接的な言い方をすれば、複雑な社会への転換は、政治的なテーマがますます研究の主要な焦点として取り上げられるようになったことを意味し、主に2つ のレベルで行われた。まず第一に、人類学者は(パトロンとクライアントの関係や部族の政治組織のように)国家が規制する領域の外にある政治組織や政治現象 [10]を研究し続けた。第二に、人類学者は徐々に国家とその制度(そして公式と非公式の政治制度の関係)に関心を持ち始めた。国家の人類学は発展し、今 日最も盛んな分野となっている。バリ国家に関するギアーツの比較研究は、初期の有名な例である。今日、国家に関する人類学的研究の典拠は豊富にある(例え ば、アベレス1990を参照)。ヘイスティングス・ドナン(Hastings Donnan)、トーマス・ウィルソン(Thomas Wilson)らは、1990年代初頭に「国境の人類学」という生産的なサブフィールドを立ち上げ、国家の国境が地域住民にどのような影響を与えるのか、 また国境地域の人々が国家の言説や国家形成をどのように形成し、方向づけるのかを取り上げた(Alvarez, 1996; Thomassen, 1996; Vereni, 1996; Donnan and Wilson, 1994; 1999; 2003などを参照)。 1980年代からは、民族とナショナリズムに大きな焦点が当てられるようになった。アイデンティティ」と「アイデンティティ・ポリティクス[11]」はす ぐにこの学問分野を定義するテーマとなり、親族関係や社会組織に対するそれ以前の焦点に部分的に取って代わった。これによって人類学はより政治的なものと なった。ナショナリズムはある程度、単に国家が生み出した文化であり、そのようなものとして研究されるべきものである。そしてエスニシティとは、文化的差 異を政治的に組織化したものである(Barth 1969)。ベネディクト・アンダーソンの著書『想像された共同体』(Imagined Communities)である: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism)では、ナショナリズムがなぜ生まれたのかについて論じている。彼は、印刷機の発明が主な火付け役となり、新聞という共通の読者を 通じて、国民が共有する感情、特徴、出来事、歴史を想像できるようになったと見ている。 文化的/政治的アイデンティティの構築への関心は、国民国家の次元を超えた。現在までに、(EUのような)国際機関では、特別な行動規範、服装、交流など を持つ文化的集団として、ファンクショナリーを研究する民族誌がいくつか実施されている(Abelès, 1992; Wright, 1994; Bellier, 1995; Zabusky, 1995; MacDonald, 1996; Rhodes, 't Hart, and Noordegraaf, 2007)。今日、人類学のフィールドワークは官僚機構内部や企業内で行われることが増えている。そして官僚制は実際、その中で生活することでしか研究で きない。ウェーバー自身がずっと以前に指摘していたように(Herzfeld 1992[12])、官僚制は私たちや実務家が考えたがるような合理的なシステムからはほど遠いのである。 政治制度への関心はまた、制度主導の政治的主体性に焦点を当てることを助長してきた。現在では、政策決定の人類学が存在する(Shore and Wright 1997)。この焦点は開発人類学(Development Anthropology)において最も顕著であり、ここ数十年でこの学問分野最大のサブフィールドの一つとして確立された。ここでは、国家、政府機関、 NGO、国際機関、企業といった政治的アクターが主な分析対象である。人類学者はエスノグラファーとして、「地域文化」との出会いにおいて、制度的な開発 主体によって生み出される言説や実践に批判的な目を向けてきた(ファーガソン1994などを参照)。開発人類学はグローバルな政治経済学や経済人類学と結 びついており、イデオロギーと現実の資源の管理と再分配に関係している(例えば、Hart 1982を参照)。この流れの中で、エスコバル(Escobar 1995)は、国際開発がかつての植民地権力構造の再生産に大きく寄与していると論じた。 ポストコロニアリズム、ポスト共産主義、ジェンダー、多文化主義、移民、シティズンシップ、[13][14][15]グローバリゼーションという包括的な 用語も忘れてはならない。このように、人類学は常にある程度政治的なものであったが、今日その傾向はさらに顕著になっている。 |

| Notable political anthropologists Some notable political anthropologists include: Marc Abélès F. G. Bailey Georges Balandier Jeremy Boissevain John Borneman Robert L. Carneiro Pierre Clastres E. E. Evans-Pritchard Meyer Fortes David Graeber Dolly Kikon Ted C. Lewellen Carolyn Nordstrom James C. Scott Audra Simpson Joan Vincent |

著名な政治人類学者 著名な政治人類学者には以下のような人物がいる: マルク・アベレス F. G.ベイリー ジョルジュ・バランディエ ジェレミー・ボワセヴァン ジョン・ボーンマン ロバート・L・カルネイロ ピエール・クラストル E. E・エバンス=プリチャード マイヤー・フォルテス グレイバー ドリー・キコン テッド・C・ルーウェレン キャロライン・ノードストローム ジェームズ・C・スコット オードラ・シンプソン ジョーン・ヴィンセント |

| Political

sociology Legal anthropology |

政治社会学 法人類学 |

| References Journal of International Political Anthropology Abélès, Marc (1990) Anthropologie de l'État, Paris: Armand Colin. Abélès, Marc (1992) La vie quotidienne au Parlement européen, Paris: Hachette. Abélès, Marc (2010) "State" in Alan Barnard and Jonathan Spencer (eds.), The Routledge Encyclopedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology, 2nd. ed., London and New York: Routledge, pp. 666–670. ISBN 978-0-415-40978-0 Alvarez, Robert R. (1995) "The Mexican-US Border: The Making of an Anthropology of Borderlands", Annual Review of Anthropology, 24: 447–70. Bailey, Frederick G. (1969) Strategems and Spoils: A Social Anthropology of Politics, New York: Schocken Books, Inc. Barth, Fredrik (1959) Political Leadership among the Swat Pathans, London: Athlone Press. Bellier, Irene (1995). "Moralité, langues et pouvoirs dans les institutions européennes", Social Anthropology, 3 (3): 235–250. Boissevain, Jeremy and John Friedl (1975) Beyond the Community: Social Process in Europe, The Hague: University of Amsterdam. Bourdieu, Pierre. (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Brachet, Julien and Scheele, Judith. (2019) The Value of Disorder : Autonomy, Prosperity, and Plunder in the Chadian Sahara, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Donnan, Hastings and Thomas M. Wilson (eds.) (1994) Border Approaches: Anthropological Perspectives on Frontiers, Lanham, MD: University Press of America. Donnan, Hasting and Thomas M. Wilson (1999) Borders: Frontiers of Identity, Nation and State, Oxford: Berg. Donnan, Hasting and Thomas M. Wilson (eds.) (2003) "European States at Their Borderlands", Focaal: European Journal of Anthropology, Special Issue, 41 (3). Escobar, Arturo (1995) Encountering Development, the making and unmaking of the Third World, Princeton: Princeton University Press. Ferguson, James (1994) The Antipolitics Machine: "Development". Depoliticization and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Fortes, Meyer and E. E. Evans-Pritchard (eds.) (1940) African Political Systems, Oxford: The Clarendon Press. Hart, Keith (1982) The Political Economy of West African Agriculture, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Herzfeld, Michael (1992). The Social Production of Indifference. Exploring the Symbolic Roots of Western Bureaucracy, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Horvath, A. & B. Thomassen (2008) 'Mimetic errors in liminal schismogenesis: on the political anthropology of the trickster', International Political Anthropology 1, 1: 3 – 24. Leach, Edmund (1954) Political Systems of Highland Burma. A Study of Kachin Social Structure, London, LSE and Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. McDonald, Maryon (1996). "Unity and Diversity: Some tensions in the construction of Europe", in: Social Anthropology 4-1: 47–60. Redfield, Robert (1941) The Folk Culture of Yucutan, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Rhodes, Rod, A.W Paul 't Hart and Mirko Noordegraaf (eds.) (2002) Observing Government Elites, Basingstoke: Palgrave. Sharma, Aradhana and Akhil Gupta (eds.) (2006) The Anthropology of the State: A Reader, Malden, MA; Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-1468-4 Shore, Chris and Susan Wright (eds.) (1997) Anthropology of Policy: Critical Perspectives on Governance and Power, London, Routledge. Spencer, Jonathan (2007) Anthropology, Politics, and the State. Democracy and Violence in South Asia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Thomassen, Bjørn (1996) "Border Studies in Europe: Symbolic and Political Boundaries, Anthropological Perspectives", Europaea. Journal of the Europeanists, 2 (1): 37–48. Vereni, Pietro (1996) "Boundaries, Frontiers, Persons, Individuals: Questioning 'Identity' at National Borders", Europaea, 2 (1): 77–89. Wright, Susan (ed.) (1994) The Anthropology of Organizations, London: Routledge. Zabusky, Stacia E. (1995) Launching Europe. An Ethnography of European Cooperation in Space Science, Princeton: Princeton University Press. |

参考文献 国際政治人類学雑誌 Abélès, Marc (1990) Anthropologie de l'État, Paris: Armand Colin. Abélès, Marc (1992) La vie quotidienne au Parlement européen, Paris: Hachette. Abélès, Marc (2010) 「State」 in Alan Barnard and Jonathan Spencer (eds.), The Routledge Encyclopedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology, 2nd: Routledge, pp. ISBN 978-0-415-40978-0 Alvarez, Robert R. (1995) "The Mexican-US Border: The Making of an Anthropology of Borderlands」, Annual Review of Anthropology, 24: 447-70. Bailey, Frederick G. (1969) Strategems and Spoils: A Social Anthropology of Politics, New York: Schocken Books, Inc. Barth, Fredrik (1959) Political Leadership among the Swat Pathans, London: Athlone Press. Bellier, Irene (1995). 「Moralité, langues et pouvoirs dans les institutions européennes」, Social Anthropology, 3 (3): 235-250. Boissevain, Jeremy and John Friedl (1975) Beyond the Community: ヨーロッパにおける社会過程, The Hague: アムステルダム大学。 Bourdieu, Pierre. (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge: ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 Brachet, Julien and Scheele, Judith. (2019) The Value of Disorder : The Value of Disorder : The Autonomy, Prosperity, and Plunder in the Chadian Sahara, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Donnan, Hastings and Thomas M. Wilson (eds.) (1994) Border Approaches: Anthropological Perspectives on Frontiers, Lanham, MD: University Press of America. Donnan, Hasting and Thomas M. Wilson (1999) Borders: Identity, Nation and State, Oxford: Berg. Donnan, Hasting and Thomas M. Wilson (eds.) (2003) 「European States at Their Borderlands」, Focaal: European Journal of Anthropology, Special Issue, 41 (3). Escobar, Arturo (1995) Encountering Development, the making and unmaking of the Third World, Princeton: Princeton University Press. Ferguson, James (1994) The Antipolitics Machine: 「開発」。レソトにおける脱政治化と官僚権力』ミネアポリス: University of Minnesota Press. Fortes, Meyer and E. E. Evans-Pritchard (eds.) (1940) African Political Systems, Oxford: The Clarendon Press. Hart, Keith (1982) The Political Economy of West African Agriculture, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Herzfeld, Michael (1992). The Social Production of Indifference. The Social Production of Indifference. 西洋官僚制の象徴的ルーツを探る, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Horvath, A. & B. Thomassen (2008) 'Mimetic errors in liminal schismogenesis: on the political anthropology of the trickster', International Political Anthropology 1, 1: 3 - 24. Leach, Edmund (1954) Political Systems of Highland Burma. A Study of Kachin Social Structure, London, LSE and Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. McDonald, Maryon (1996). 「統一性と多様性: ヨーロッパ構築におけるいくつかの緊張」, in: Social Anthropology 4-1: 47-60. Redfield, Robert (1941) The Folk Culture of Yucutan, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Rhodes, Rod, A.W Paul 't Hart and Mirko Noordegraaf (eds.) (2002) Observing Government Elites, Basingstoke: Palgrave. Sharma, Aradhana and Akhil Gupta (eds.) (2006) The Anthropology of the State: A Reader, Malden, MA; Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-1468-4 Shore, Chris and Susan Wright (eds.) (1997) Anthropology of Policy: Critical Perspectives on Governance and Power, London, Routledge. Spencer, Jonathan (2007) Anthropology, Politics, and the State. Democracy and Violence in South Asia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Thomassen, Bjørn (1996) 「Border Studies in Europe: Symbolic and Political Boundaries, Anthropological Perspectives」, Europaea. Journal of the Europeanists, 2 (1): 37-48. Vereni, Pietro (1996) "Boundaries, Frontiers, Persons, Individuals: 国境における「アイデンティティ」を問う」, Europaea, 2 (1): 77-89. Wright, Susan (ed.) (1994) The Anthropology of Organizations, London: Routledge. Zabusky, Stacia E. (1995) Launching Europe. An Ethnography of European Cooperation in Space Science, Princeton: Princeton University Press. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_anthropology |

★感情の政治学/感情の政治(→「アフェクト」より)

| 感情政治学/感情の政治(Affective

politics) |

(→「アフェクト」 より) |

| Affective politics explores how

emotions, feelings, and moods shape political behavior, power, and

identity, moving beyond purely rational views to show how politicians

strategically use emotions (like fear, hope, outrage) to influence

citizens, and how citizens' collective feelings (affective

polarization, solidarity) create political realities, especially in

digital spaces. It studies how emotional appeals in media,

policy-making, and discourse create shared "feeling rules," influence

governance, and build or challenge social bonds, impacting everything

from voting to national security. Affective politics is a field of study and a political practice that recognizes emotions—such as fear, anger, joy, and hope—not as distractions from rational thought, but as the primary drivers of political views, actions, and collective identities. |

感 情政治学(Affective

politics)は、感情や気分が政治行動、権力、アイデンティティをどう形作るかを研究する。純粋に合理的な見解を超え、政治家が恐怖や希望、怒りと

いった感情を戦略的に利用して市民に影響を与える方法、そして市民の集合的感情(感情的分極化や連帯感)が特にデジタル空間において政治的現実をどう生み

出すかを示す。メディアや政策決定、言説における感情的訴求が、いかに共有された「感情ルール」を生み出し、統治に影響を与え、社会的絆を構築あるいは挑

戦するのかを研究する。投票行動から国家安全保障に至るまで、あらゆる事象に影響を及ぼすのである。 感情政治学とは、恐怖や怒り、喜び、希望といった感情を、理性的な思考の妨げではなく、政治的見解や行動、集団的アイデンティティの主要な原動力として認 識する研究分野であり、政治的実践である。 |

| Key Aspects of Affective

Politics: Emotional Appeals: Politicians and actors deliberately use emotional rhetoric (e.g., inciting outrage, fostering compassion) to persuade and mobilize people, often by framing issues to trigger specific reactions. Digital Media's Role: Social media amplifies affective dynamics, making it crucial for understanding modern political communication, misinformation, and polarization. Affective Polarization: A key concept where partisans strongly dislike and distrust opponents, creating deep emotional divides rather than just policy disagreements. Emotions as Social Practices: Drawing from scholars like Sara Ahmed, it sees emotions not just as individual feelings but as social practices that produce political realities, power structures, and subjectivities. Ontological Security: How collective emotions (grief, solidarity) help communities cope with trauma and rebuild stability, with political leaders playing a role in restoring trust. Reciprocal Relationship: A two-way street where politicians use voters, but voters also "use" politicians to experience certain feelings, and shared feelings create collective political identities. |

感情政治の主要な側面: 感情的訴求:政治家や関係者は、意図的に感情的なレトリック(例:怒りを煽る、同情を育む)を用いて人々を説得し動員する。多くの場合、特定の反応を引き 起こすよう問題を設定する。 デジタルメディアの役割:ソーシャルメディアは感情的な力学を増幅させる。現代の政治コミュニケーション、誤情報、分極化を理解する上で極めて重要だ。 感情的分極化: 支持者が対立する陣営を強く嫌悪し不信感を抱く核心概念であり、単なる政策上の意見の相違ではなく深い感情的な断絶を生む。社会的実践としての感情: サラ・アーメドら研究者の見解に基づき、感情を単なる個人の感情ではなく、政治的現実・権力構造・主体性を生み出す社会的実践と捉える。 存在論的安心感:集団的感情(悲嘆、連帯感)が、コミュニティがトラウマに対処し安定を再構築するのをどう助けるか。政治指導者は信頼回復に役割を果た す。 相互関係:双方向の関係性。政治家が有権者を利用する一方で、有権者も特定の感情を経験するために政治家を「利用」する。共有された感情が集団的政治的ア イデンティティを形成する。 |

| Examples in Action: Bismarck's Doctored Telegram: A historical example of manipulating emotions (French outrage) to instigate war. Neoliberalism: How dependency discourses evoke emotions (shame, undeservingness) to enforce particular social values and identities. Post-Truth Era: How feelings of being unheard, rather than just facts, drive political belief and action. |

実例: ビスマルクの改ざん電報:戦争を煽るために感情(フランスの怒り)を操作した歴史的事例。 新自由主義:依存関係に関する言説が感情(恥、不適格感)を喚起し、特定の社会的価値観やアイデンティティを強要する仕組み。 ポスト・トゥルース時代:単なる事実ではなく、声を聞いてもらえないという感情が政治的信念と行動を駆り立てる仕組み。 |

| In essence, affective politics

argues that emotions are not just background noise but a central,

dynamic force in politics, shaping how we understand the world and act

within it. |

本質的に、感情政治学は、感情は単なる背景の雑音ではなく、政治におけ

る中心的で動的な力であり、私たちが世界をどう理解し、その中でどう行動するかを形作るものであると主張する |

| (→「アフェクト」 より) |

ことば

「ヌアー族における最大の政治単位は部族である」(向井元子訳、1978年岩波版、p.7)The largest political

segment among the Nuer is the tribe. (Evans-Pritchard 1940:5)——エヴァンズ=プリチャード

リンク集

● A companion to the anthropology of politics, edited by David Nugent and Joan Vincent, Blackwell, 2007

"This Companion offers an unprecedented overview of anthropology's unique contribution to the study of politics. * Explores the key concepts and issues of our time - from AIDS, globalization, displacement, and militarization, to identity politics and beyond * Each chapter reflects on concepts and issues that have shaped the anthropology of politics and concludes with thoughts on and challenges for the way ahead * Anthropology's distinctive genre, ethnography, lies at the heart of this volume" - Nielsen BookData

Synopsis of Contents.

Preface.

Notes on Contributors.

Introduction. (Joan Vincent).

1. Affective States. (Ann Laura Stoler).

2. After Socialism. (Katherine Verdery).

3. AIDS. (Brooke Grundfest Schoepf).

4. Citizenship. (Aihwa Ong).

5. Cosmopolitanism. (Ulf Hannerz).

6. Development. (Marc Edelman and Angelique).

7. Displacement. (Elizabeth Colson).

8. Feminism. (Malathi de Alwis).

9. Gender, Race, and Class. (Micaela di Leonardo).

10. Genetic Citizenship. (Deborah Heath, Rayna Rapp, and

Karen-Sue Taussig).

11. The Global City. (Saskia Sassen).

12. Globalization. (Jonathan Friedman).

13. Governing States. (David Nugent).

14. Hegemony. (Gavin Smith).

15. Human Rights. (Richard Ashby Wilson).

16. Identity. (Arturo Escobar).

17. Imagining Nations. (Akhil Gupta).

18. Infrapolitics. (Steven Gregory).

19. "Mafias". (Jane C. and Peter T. Schneider).

20. Militarization. (Catherine Lutz).

21. Neoliberalism. (John Gledhill).

22. Popular Justice. (Robert Gordon).

23. Postcolonialism. (K. Sivaramakrishnan).

24. Power Topographies. (James Ferguson).

25. Race Technologies. (Thomas Biolsi).

26. Sovereignty. (Caroline Humphrey).

27. Transnational Civil Society. (June Nash).

28. Transnationality. (Nina Glick-Schiller).

Index

● The anthropology of politics : a reader in

ethnography, theory, and critique, 2002

The anthropology of politics : a reader in ethnography, theory, and critique, edited by Joan Vincent, Blackwell Publishers, 2002

"Political anthropology has long been among the most vibrant subdisciplines within anthropology, and work done in this area has been instrumental in exploring some of the most significant issues of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, including (post)colonialism, development and underdevelopment, identity politics, nationalism/transnationalism, and political violence. In The Anthropology of Politics: A Reader in Ethnography, Theory, and Critique readers will find a remarkable collection of classic and contemporary articles on the subject. Following on from her landmark book on politics and anthropology, in this volume Joan Vincent provides a sweeping historical and theoretical introduction to the field. Selected readings from figures such as E. E. Evans-Pritchard, Edmund Leach, Victor Turner, Eric Wolf, Benedict Anderson, Talal Asad, Michael Taussig, Jean and John Comaroff, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak are enriched by Vincent's headnotes and suggestions for further reading. The Anthropology of Politics will prove an indispensable resource for students, scholars, and instructors alike." - Nielsen BookData.

Acknowledgements.

Introduction (Joan Vincent).

Part I: Prelude:

The Enlightenment and its

Challenges. Introduction. Adam Ferguson, Civil Society (1767).

Adam Smith, Free-Market Policies

(1776).

Immanuel Kant, Perpetual Peace

(1795),

Universal History with

Cosmopolitan Purpose (1784), and Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of

View (1797).

Henry Sumner Maine, The Effects

of the Observation of India on European Thought (1887).

Lewis Henry Morgan, The Property

Career of Mankind (1877).

Karl Marx, Spectres outside the

Domain of Political Economy (1844).

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels,

The World Market (1847).

James Mooney,

The Dream of a Redeemer (1896).

Part II: Classics

and Classics Revisited. Introduction.

1. Nuer Politics: Structure and

System (1940) (E.E. Evans-Pritchard).

2. Nuer Ethnicity Militarized

(Sharon Elaine Hutchinson).

3. "The Bridge":Analysis of a

Social Situation in Zululand (Max Gluckman).

4. "The Bridge" Revisited

(Ronald Frankenberg).

5. Market Model, Class Structure

and Consent: A Reconsideration of Swat Political Organization (Talal

Asad).

6. The Troubles of Ranhamy Ge

Punchirala (E. R. Leach).

7. Stratagems and Spoils (F. G.

Bailey).

8. Passages, Margins, and

Poverty: Religious Symbols of Communitas (Victor W. Turner).

9. Political Anthropology (Marc

J. Swartz, Victor W. Turner, and Arthur Tuden).

10. New Proposals for

Anthropologists (Kathleen Gough).

11. National Liberation

(Eric R. Wolf).

Part III: Imperial

Times, Colonial Places. Introduction.

12. From the History of Colonial

Anthropology to the Anthropology of Western Hegemony (Talal Asad).

13. East of Said (Richard G.

Fox).

14. Perceptions of Protest:

Defining the Dangerous in Colonial Sumatra (Ann Stoler).

15. Culture of Terror - Space of

Death (Michael Taussig).

16. Images of the Peasant in the

Consciousness of the Venezuelan Proletariat (William Roseberry).

17. Of Revelation and Revolution

(Jean and John Comaroff).

18. Between Speech and Silence

(Susan Gal).

19. Facing Power - Old Insights,

New Questions (Eric R. Wolf).

20. Ethnographic Aspects

of The World Capitalist System (June Nash).

Part IV:

Cosmopolitics: Confronting a New Millennium.

Introduction.

21. The New World Disorder: (Benedict Anderson).

22. Grassroots Globalization and the Research Imagination

(Arjun Appadurai).

23. Transnationalization, Socio-political Disorder, and

Ethnification as Expressions of Declining Global Hegemony (Jonathan

Friedman).

24. Deadly Developments and Phantasmagoric Representations

(S. P. Reyna).

25. Modernity at the Edge of Empire (David Nugent).

26. Politics on the Periphery (Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing).

27. Flexible Citizenship among Chinese Cosmopolitans (Aihwa

Ong).

28. Long-distance Nationalism Defined (Nina Glick Schiller

and Georges Fouron).

29. Theorizing Socialism: A Prologue to the "Transition"

(Katherine Verdery).

30. Marx Went Away but Karl Stayed Behind (Caroline

Humphrey).

31. The Anti-politics Machine (James Ferguson).

32. Peasants against Globalization (Marc Edelman).

33. On Suffering and Structural Violence: A View from Below

(Paul Farmer).

34. Anthropology and Politics: Commitment, Responsibility

and the Academy (John Gledhill).

35. Thinking Academic Freedom in Gendered Post-coloniality (Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak). I

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆