政治社会学

Political sociology

Protest in New York City: "All Oppression is Connected," 20 January 2018

☆政治社会学(Political

sociology)

は学際的な研究分野であり、ミクロからマクロの分析レベルにおいて、統治と社会がどのように相互作用し、影響し合っているかを探求することに関心がある。

社会全体や社会間で権力がどのように分配され、どのように変化していくのか、その社会的原因と結果に関心を持ち、政治社会学の焦点は、社会的・政治的対立

や権力争いの場として、個人の家族から国家にまで及ぶ[1][2]。

| Political

sociology is an interdisciplinary field of study concerned with

exploring how governance and society interact and influence one another

at the micro to macro levels of analysis. Interested in the social

causes and consequences of how power is distributed and changes

throughout and amongst societies, political sociology's focus ranges

across individual families to the state as sites of social and

political conflict and power contestation.[1][2] |

政

治社会学は学際的な研究分野であり、ミクロからマクロの分析レベルにおいて、統治と社会がどのように相互作用し、影響し合っているかを探求することに関心

がある。社会全体や社会間で権力がどのように分配され、どのように変化していくのか、その社会的原因と結果に関心を持ち、政治社会学の焦点は、社会的・政

治的対立や権力争いの場として、個人の家族から国家にまで及ぶ[1][2]。 |

| Introduction Political sociology was conceived as an interdisciplinary sub-field of sociology and politics in the early 1930s[2] throughout the social and political disruptions that took place through the rise of communism, fascism, and World War II.[3] This new area drawing upon works by Alexis de Tocqueville, James Bryce, Robert Michels, Max Weber, Émile Durkheim, and Karl Marx to understand an integral theme of political sociology: power.[4] Power's definition for political sociologists varies across the approaches and conceptual framework utilised within this interdisciplinary study. At its basic understanding, power can be seen as the ability to influence or control other people or processes around you. This helps to create a variety of research focuses and use of methodologies as different scholars' understanding of power differs. Alongside this, their academic disciplinary department/ institution can also flavour their research as they develop from their baseline of inquiry (e.g. political or sociological studies) into this interdisciplinary field (see § Political sociology vs sociology of politics). Although with deviation in how it is carried out, political sociology has an overall focus on understanding why power structures are the way they are in any given societal context.[5] Political sociologists, throughout its broad manifestations, propose that in order to understand power, society and politics must be studied with one another and neither treated as assumed variables. In the words of political scientist Michael Rush, "For any society to be understood, so must its politics; and if the politics of any society is to be understood, so must that society."[6] |

はじめに 政治社会学は、共産主義、ファシズム、そして第二次世界大戦を通じて起こった社会的・政治的混乱を通して、1930年代初頭に社会学と政治学の学際的なサ ブフィールドとして構想された[2]。この新しい領域は、アレクシス・ド・トクヴィル、ジェームズ・ブライス、ロバート・ミケルス、マックス・ウェー バー、エミール・デュルケム、そしてカール・マルクスの著作を引き、政治社会学の不可欠なテーマである「権力」を理解している[4]。 政治社会学者にとっての権力の定義は、この学際的研究の中で利用されるアプローチや概念的枠組みによって異なる。基本的な理解として、権力とは、他者や周 囲のプロセスに影響を与えたり、コントロールしたりする能力とみなすことができる。このことは、異なる研究者の権力に対する理解が異なるため、研究の焦点 や方法論の使い方に多様性を生み出すのに役立っている。これと並行して、彼らの学問分野 の学部や教育機関も、彼らが研究のベースライン(例 えば政治学や社会学)からこの学際的な分野へと発展す るにつれて、彼らの研究を風味づけることができる(§ 政治社会学vs政治社会学参照)。政治社会学は、その遂行方法には逸脱があるものの、社会的文脈において権力構造がなぜそのようなものであるかを理解する ことに全体的な焦点を置いている[5]。 政治社会学者は、その広範な表現を通して、権力を理解するためには、社会と政治は互いに研究されなければならず、どちらも仮定された変数として扱われるこ とはないと提唱している。政治学者マイケル・ラッシュの言葉を借りれば、「いかなる社会も理解されるためには、その政治も理解されなければならず、いかな る社会の政治も理解されるためには、その社会も理解されなければならない」[6]。 |

| Origins The development of political sociology from the 1930s onwards took place as the separating disciplines of sociology and politics explored their overlapping areas of interest.[6] Sociology can be viewed as the broad analysis of human society and the interrelationship of these societies. Predominantly focused on the relationship of human behaviour with society. Political science or politics as a study largely situates itself within this definition of sociology and is sometimes regarded as a well developed sub-field of sociology, but is seen as a stand alone disciplinary area of research due to the size of scholarly work undertaken within it. Politics offers a complex definition and is important to note that what 'politics' means is subjective to the author and context. From the study of governmental institutions, public policy, to power relations, politics has a rich disciplinary outlook.[6] The importance of studying sociology within politics, and vice versa, has had recognition across figures from Mosca to Pareto as they recognised that politicians and politics do not operate in a societal vacuum, and society does not operate outside of politics. Here, political sociology sets about to study the relationships of society and politics.[6] Numerous works account for highlighting a political sociology, from the work of Comte and Spencer to other figures such as Durkheim. Although feeding into this interdisciplinary area, the body of work by Karl Marx and Max Weber are considered foundational to its inception as a sub-field of research.[6] |

起源 1930年代以降の政治社会学の発展は、社会学と政治学という分離した学問領域が、重なり合う関心領域を探求する中で起こった。主に人間の行動と社会との 関係に焦点を当てる。政治学または政治学は、社会学のこの定義の中に位置づけられ、社会学のよく発達した下位分野とみなされることもあるが、その中で行わ れる学問的研究の規模から、独立した学問分野とみなされている。政治学は複雑な定義を提供し、「政治」が意味するものは著者や文脈によって主観的なもので あることに注意することが重要である。政府制度、公共政策、権力関係の研究に至るまで、政治学には豊かな学問的展望がある[6]。 モスカからパレートに至るまで、政治家と政治は社会的空白の中で動いているわけではなく、社会は政治の外側で動いているわけではないことを認識していた。ここで政治社会学は、社会と政治の関係を研究することに着手した[6]。 コントやスペンサーの研究からデュルケムのような他の人物に至るまで、政治社会学を強調するために数多くの著作がある。この学際的な領域に食い込んでいる が、カール・マルクスとマックス・ウェーバーによる一連の研究は、研究の下位分野としてその創始の基礎となったと考えられている[6]。 |

| Scope Overview The scope of political sociology is broad, reflecting on the wide interest in how power and oppression operate over and within social and political areas in society.[5] Although diverse, some major themes of interest for political sociology include: Understanding the dynamics of how the state and society exercise and contest power (e.g. power structures, authority, social inequality).[7] How political values and behaviours shape society and how society's values and behaviours shape politics (e.g. public opinion, ideologies, social movements). How these operate across formal and informal areas of politics and society (e.g. ministerial cabinet vs. family home).[8] How socio-political cultures and identities change over time. In other words, political sociology is concerned with how social trends, dynamics, and structures of domination affect formal political processes alongside social forces working together to create change.[9] From this perspective, we can identify three major theoretical frameworks: pluralism, elite or managerial theory, and class analysis, which overlaps with Marxist analysis.[10] Pluralism sees politics primarily as a contest among competing interest groups. Elite or managerial theory is sometimes called a state-centered approach. It explains what the state does by looking at constraints from organizational structure, semi-autonomous state managers, and interests that arise from the state as a unique, power-concentrating organization. A leading representative is Theda Skocpol. Social class theory analysis emphasizes the political power of capitalist elites.[11] It can be split into two parts: one is the "power structure" or "instrumentalist" approach, whereas another is the structuralist approach. The power structure approach focuses on the question of who rules and its most well-known representative is G. William Domhoff. The structuralist approach emphasizes the way a capitalist economy operates; only allowing and encouraging the state to do some things but not others (Nicos Poulantzas, Bob Jessop). Where a typical research question in political sociology might have been, "Why do so few American or European citizens choose to vote?"[12] or even, "What difference does it make if women get elected?",[13] political sociologists also now ask, "How is the body a site of power?",[14] "How are emotions relevant to global poverty?",[15] and "What difference does knowledge make to democracy?"[16] |

スコープ 概要 政治社会学の守備範囲は広く、権力と抑圧が社会の社会的・政治的領域において、またその内部でどのように作用しているのかという幅広い関心を反映している: 国家と社会がどのように権力を行使し、争うのか(権力構造、権威、社会的不平等など)の力学を理解すること。 政治的価値観や行動がどのように社会を形成しているのか、また社会の価値観や行動がどのように政治を形成しているのか(世論、イデオロギー、社会運動など)。 政治と社会のフォーマルな領域とインフォーマルな領域において、これらがどのように作用しているか(例:閣僚内閣と実家)[8]。 社会的・政治的文化やアイデンティティが時間とともにどのように変化するか。 言い換えれば、政治社会学は、変化を生み出すために協働する社会的な力とともに、社会的な傾向、力学、支配構造がどのように公式な政治プロセスに影響を与えるかに関心を抱いている。 多元主義は、政治を主に競合する利益集団間の争いとして捉える。エリート理論や経営理論は、国家中心のアプローチと呼ばれることもある。組織構造による制 約、半自律的な国家管理者、権力を集中する特異な組織としての国家から生じる利害に注目することで、国家が何をするのかを説明する。代表的なのはテダ・ス コッポルである。社会階級理論分析は、資本主義エリートの政治的権力を強調する[11]。それは2つの部分に分けることができる。1つは「権力構造」また は「道具主義」アプローチであり、もう1つは構造主義アプローチである。権力構造主義的アプローチは、誰が支配しているかという問題に焦点を当てており、 その最も有名な代表者はG・ウィリアム・ドムホフである。構造主義的アプローチは、資本主義経済がどのように運営されているかを重視するもので、国家があ ることをすることだけを許し、奨励するが、他のことはしないというものである(Nicos Poulantzas, Bob Jessop)。 政治社会学の典型的な研究課題は、「なぜアメリカやヨーロッ パの市民は投票に行く人が少ないのか」[12]、あるいは「女性が選挙に行くこと で何が変わるのか」[13]であったかもしれないが、政治社会学者は現在、 「身体は権力の場としてどうなのか」[14]、「感情は世界の貧困とどう関係するのか」[15]、 「知識は民主主義にどのような違いをもたらすのか」[16]とも問いかけている。 |

| Political sociology vs. sociology of politics While both are valid lines of enquiry, sociology of politics is a sociological reductionist account of politics (e.g. exploring political areas through a sociological lens), whereas political sociology is a collaborative socio-political exploration of society and its power contestation. When addressing political sociology, there is noted overlap in using sociology of politics as a synonym. Sartori outlines that sociology of politics refers specifically to a sociological analysis of politics and not an interdisciplinary area of research that political sociology works towards. This difference is made by the variables of interest that both perspectives focus upon. Sociology of politics centres on the non-political causes of oppression and power contestation in political life, whereas political sociology includes the political causes of these actions throughout commentary with non-political ones.[17] |

政治的社会学と政治の社会学の比較 どちらも有効な探求のラインではあるが、政治社会学が政治を社会学的に還元論的に説明する(例えば、社会学的レンズを通して政治領域を探求する)のに対 し、政治社会学は社会とその権力争いを社会政治的に共同で探求するものである。政治社会学を取り上げる際、政治社会学を同義語として用いることには重複が 指摘されている。Sartoriは、政治社会学は特に政治の社会学的分析を指し、政治社会学が目指す学際的な研究領域ではないと概説している。この違い は、両者の視点が注目する変数によって生じる。政治社会学は、政治生活における抑圧や権力争いの非政治的な原因に焦点を当てているのに対し、政治社会学 は、非政治的なものとの解説を通して、これらの行為の政治的な原因を含んでいる[17]。 |

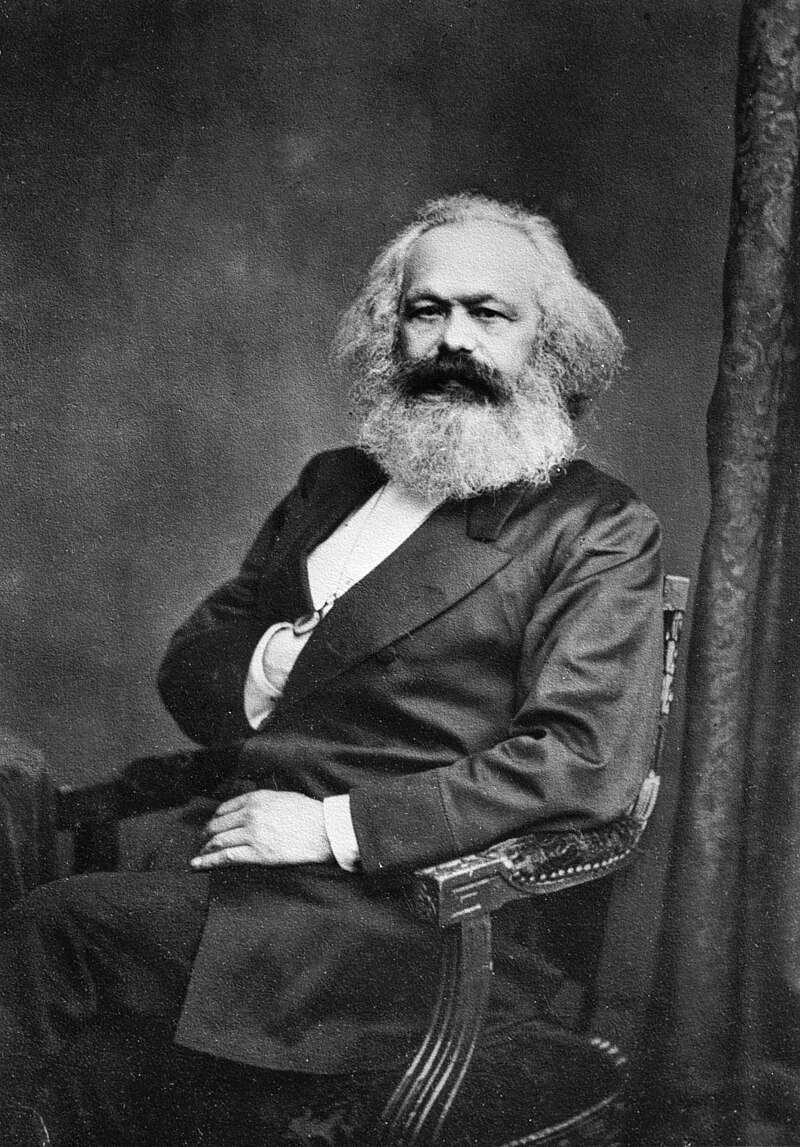

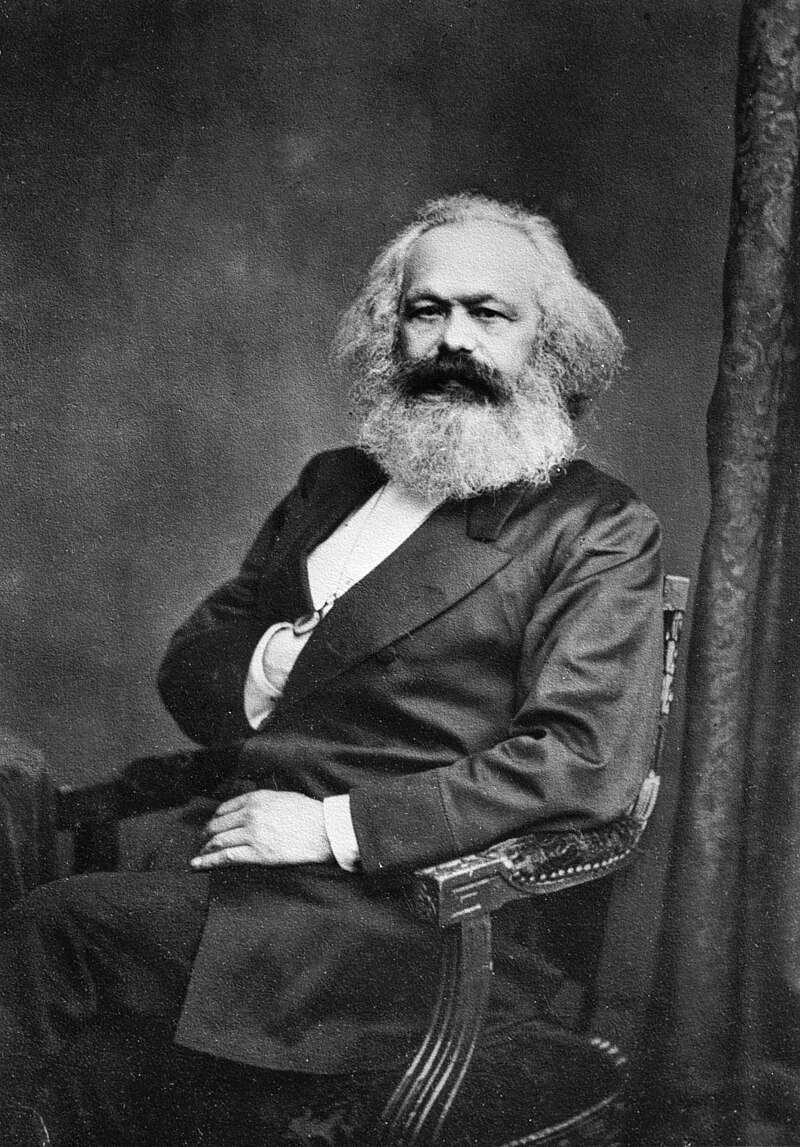

| People Karl Marx  A portrait picture of Karl Marx Marx's ideas about the state can be divided into three subject areas: pre-capitalist states, states in the capitalist (i.e. present) era and the state (or absence of one) in post-capitalist society. Overlaying this is the fact that his own ideas about the state changed as he grew older, differing in his early pre-communist phase, the young Marx phase which predates the unsuccessful 1848 uprisings in Europe and in his mature, more nuanced work. In Marx's 1843 Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right, his basic conception is that the state and civil society are separate. However, he already saw some limitations to that model, arguing: "The political state everywhere needs the guarantee of spheres lying outside it."[18][19] He added: "He as yet was saying nothing about the abolition of private property, does not express a developed theory of class, and "the solution [he offers] to the problem of the state/civil society separation is a purely political solution, namely universal suffrage".[19] By the time he wrote The German Ideology (1846), Marx viewed the state as a creature of the bourgeois economic interest. Two years later, that idea was expounded in The Communist Manifesto:[20] "The executive of the modern state is nothing but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie."[20] This represents the high point of conformance of the state theory to an economic interpretation of history in which the forces of production determine peoples' production relations and their production relations determine all other relations, including the political.[21][22] Although "determines" is the strong form of the claim, Marx also uses "conditions". Even "determination" is not causality and some reciprocity of action is admitted. The bourgeoisie control the economy, therefore they control the state. In this theory, the state is an instrument of class rule. |

人々 カール・マルクス  カール・マルクスの肖像画 国家に関するマルクスの考え方は、資本主義以前の国家、資本主義時代(すなわち現在)の国家、資本主義以後の社会における国家(あるいは国家の不在)とい う3つの主題に分けることができる。これに重なるのは、マルクス自身の国家に対する考え方が成長するにつれて変化し、初期の共産主義以前の段階、1848 年にヨーロッパで起こった蜂起が失敗に終わる以前の若いマルクスの段階、そして成熟したよりニュアンスのある仕事において異なるという事実である。 マルクスの1843年の『ヘーゲルの権利哲学批判』では、国家と市民社会は分離しているというのが基本的な考え方である。しかし、彼はすでにそのモデルに は限界があると考え、こう主張している: 「彼はさらに、「彼はまだ私有財産の廃止について何も言っておらず、階級についての発展した理論を表明しておらず、国家と市民社会の分離の問題に対する (彼の提示する)解決策は純粋に政治的な解決策、すなわち普通選挙権である」と付け加えた[18][19]。 彼が『ドイツ・イデオロギー』(1846年)を書く頃には、マルクスは国家をブルジョア経済的利益の創造物と見なしていた。その2年後、その考えは『共産 党宣言』で次のように展開された[20]。「近代国家の行政府は、全ブルジョアジーの共通の問題を管理する委員会にほかならない」[20]。 これは、生産力が人民の生産関係を決定し、その生産関係が政治を含む他のすべての関係を決定するという経済学的な歴史解釈に国家論が適合する最高点を示し ている[21][22]。「決定する」というのがこの主張の強い形だが、マルクスは「条件」も使っている。決定」であっても因果関係ではなく、ある程度の 相互作用が認められる。ブルジョアジーは経済を支配し、したがって国家を支配する。この理論では、国家は階級支配の道具である。 |

| Antonio Gramsci Antonio Gramsci's theory of hegemony is tied to his conception of the capitalist state. Gramsci does not understand the state in the narrow sense of the government. Instead, he divides it between political society (the police, the army, legal system, etc.) – the arena of political institutions and legal constitutional control – and civil society (the family, the education system, trade unions, etc.) – commonly seen as the private or non-state sphere, which mediates between the state and the economy. However, he stresses that the division is purely conceptual and that the two often overlap in reality. [citation needed] Gramsci claims the capitalist state rules through force plus consent: political society is the realm of force and civil society is the realm of consent. Gramsci proffers that under modern capitalism the bourgeoisie can maintain its economic control by allowing certain demands made by trade unions and mass political parties within civil society to be met by the political sphere. Thus, the bourgeoisie engages in passive revolution by going beyond its immediate economic interests and allowing the forms of its hegemony to change. Gramsci posits that movements such as reformism and fascism, as well as the scientific management and assembly line methods of Frederick Taylor and Henry Ford respectively, are examples of this. [citation needed] |

アントニオ・グラムシ アントニオ・グラムシの覇権論は、資本主義国家の概念と結びついている。グラムシは国家を政府という狭い意味では理解していない。その代わりに彼は、政治 社会(警察、軍隊、法制度など)-政治制度と法的な憲法統制の場-と市民社会(家族、教育制度、労働組合など)-一般に国家と経済の間を媒介する私的領域 または非国家的領域とみなされる-に分けている。しかし彼は、この区分は純粋に概念的なものであり、現実には両者はしばしば重なり合っていると強調してい る。[政治社会は力の領域であり、市民社会は同意の領域である。政治社会は力の領域であり、市民社会は同意の領域である。グラムシは、近代資本主義の下 で、ブルジョアジーは、市民社会内の労働組合や大衆政党による特定の要求が政治領域によって満たされることを認めることによって、経済的支配を維持するこ とができると提唱する。このように、ブルジョアジーは、目先の経済的利益を超えて、その覇権の形態を変化させることを許容することによって、受動的な革命 に関与しているのである。グラムシは、改革主義やファシズムのような運動、フレデリック・テイラーやヘンリー・フォードがそれぞれ行った科学的管理や組み 立てライン方式がその例であるとする。[要出典)。 |

| Ralph Miliband English Marxist sociologist Ralph Miliband was influenced by American sociologist C. Wright Mills, of whom he had been a friend. He published The State in Capitalist Society in 1969, a study in Marxist political sociology, rejecting the idea that pluralism spread political power, and maintaining that power in Western democracies was concentrated in the hands of a dominant class.[23] |

ラルフ・ミリバンド イギリスのマルクス主義社会学者ラルフ・ミリバンドは、友人であったアメリカの社会学者C・ライト・ミルズの影響を受けていた。彼は1969年にマルクス 主義政治社会学の研究書である『資本主義社会における国家』を出版し、多元主義が政治権力を拡散させるという考えを否定し、西欧の民主主義国家における権 力は支配階級の手に集中していると主張した[23]。 |

| Nicos Poulantzas Nicos Poulantzas' theory of the state reacted to what he saw as simplistic understandings within Marxism. For him Instrumentalist Marxist accounts such as that of Miliband held that the state was simply an instrument in the hands of a particular class. Poulantzas disagreed with this because he saw the capitalist class as too focused on its individual short-term profit, rather than on maintaining the class's power as a whole, to simply exercise the whole of state power in its own interest. Poulantzas argued that the state, though relatively autonomous from the capitalist class, nonetheless functions to ensure the smooth operation of capitalist society, and therefore benefits the capitalist class. [citation needed] In particular, he focused on how an inherently divisive system such as capitalism could coexist with the social stability necessary for it to reproduce itself—looking in particular to nationalism as a means to overcome the class divisions within capitalism. Borrowing from Gramsci's notion of cultural hegemony, Poulantzas argued that repressing movements of the oppressed is not the sole function of the state. Rather, state power must also obtain the consent of the oppressed. It does this through class alliances, where the dominant group makes an "alliance" with subordinate groups as a means to obtain the consent of the subordinate group. [citation needed] |

ニコス・プーランツァス ニコス・プーランザスの国家論は、マルクス主義における単純化された理解に反発したものである。彼にとって、ミリバンドのような道具主義的なマルクス主義 者の説明は、国家は単に個別階級の手中にある道具であるとした。プーランザスは、資本家階級が、階級全体としての権力を維持することよりも、むしろ個々の 短期的な利潤に集中しすぎており、国家権力全体を単純に自分たちの利益のために行使することはできないと考えたため、これに反対した。プーランザスは、国 家は資本家階級から比較的独立しているとはいえ、資本主義社会の円滑な運営を確保するために機能しており、したがって資本家階級に利益をもたらしていると 主張した。[特に彼は、資本主義のような本質的に分裂的なシステムが、資本主義がそれ自体を再生産するために必要な社会的安定といかに共存しうるかに注目 し、資本主義内の階級的分裂を克服する手段としてナショナリズムに注目した。プーランザスは、グラムシの文化的ヘゲモニーという概念を借りて、被抑圧者の 運動を抑圧することだけが国家の機能ではないと主張した。むしろ、国家権力は被抑圧者の同意も得なければならない。それは、支配的集団が従属的集団の同意 を得る手段として、従属的集団と「同盟」を結ぶという階級同盟を通じて行われる。[要出典)。 |

| Bob Jessop Bob Jessop was influenced by Gramsci, Miliband and Poulantzas to propose that the state is not as an entity but as a social relation with differential strategic effects. [citation needed] This means that the state is not something with an essential, fixed property such as a neutral coordinator of different social interests, an autonomous corporate actor with its own bureaucratic goals and interests, or the 'executive committee of the bourgeoisie' as often described by pluralists, elitists/statists and conventional Marxists respectively. Rather, what the state is essentially determined by is the nature of the wider social relations in which it is situated, especially the balance of social forces. [citation needed] |

ボブ・ジェソップ ボブ・ジェソップはグラムシ、ミリバンド、プーランザスの影響を受け、国家は実体としてではなく、戦略的効果の差異を持つ社会的関係として存在すると提唱 した。[これは、国家が、異なる社会的利害の中立的な調整役、独自の官僚的目標と利害を持つ自律的な企業行為者、あるいは多元主義者、エリート主義者/国 家主義者、従来のマルクス主義者がそれぞれしばしば述べるような「ブルジョアジーの執行委員会」のような、本質的で固定された性質を持つものではないこと を意味する。むしろ、国家が本質的に決定されるのは、国家が置かれているより広範な社会関係の性質、とりわけ社会的諸力のバランスである。[要出典)。 |

| Max Weber In political sociology, one of Weber's most influential contributions is his "Politics as a Vocation" (Politik als Beruf) essay. Therein, Weber unveils the definition of the state as that entity that possesses a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force.[24][25][26] Weber wrote that politics is the sharing of state's power between various groups, and political leaders are those who wield this power.[25] Weber distinguished three ideal types of political leadership (alternatively referred to as three types of domination, legitimisation or authority):[24][27] charismatic authority (familial and religious), traditional authority (patriarchs, patrimonialism, feudalism) and legal authority (modern law and state, bureaucracy).[28] In his view, every historical relation between rulers and ruled contained such elements and they can be analysed on the basis of this tripartite distinction.[29] He notes that the instability of charismatic authority forces it to "routinise" into a more structured form of authority.[30] In a pure type of traditional rule, sufficient resistance to a ruler can lead to a "traditional revolution". The move towards a rational-legal structure of authority, utilising a bureaucratic structure, is inevitable in the end.[29] Thus this theory can be sometimes viewed as part of the social evolutionism theory. This ties to his broader concept of rationalisation by suggesting the inevitability of a move in this direction,[30] in which "Bureaucratic administration means fundamentally domination through knowledge."[31] Weber described many ideal types of public administration and government in Economy and Society (1922). His critical study of the bureaucratisation of society became one of the most enduring parts of his work.[30][31] It was Weber who began the studies of bureaucracy and whose works led to the popularisation of this term.[32] Many aspects of modern public administration go back to him and a classic, hierarchically organised civil service of the Continental type is called "Weberian civil service".[33] As the most efficient and rational way of organising, bureaucratisation for Weber was the key part of the rational-legal authority and furthermore, he saw it as the key process in the ongoing rationalisation of the Western society.[30][31] Weber's ideal bureaucracy is characterised by hierarchical organisation, by delineated lines of authority in a fixed area of activity, by action taken (and recorded) on the basis of written rules, by bureaucratic officials needing expert training, by rules being implemented neutrally and by career advancement depending on technical qualifications judged by organisations, not by individuals.[31][34] |

マックス・ウェーバー 政治社会学において、ウェーバーの最も影響力のある貢献のひとつは、彼の「職業としての政治」(Politik als Beruf)というエッセイである。そこでヴェーバーは、国家とは物理的な力の合法的な行使を独占する存在であると定義している[24][25] [26]。ヴェーバーは、政治とは様々な集団の間で国家の権力を共有することであり、政治的指導者とはこの権力を行使する者であると書いている[25]。 カリスマ的権威(家族的権威、宗教的権威)、 伝統的権威(家父長制、家父長制、封建制)、および 法的権威(近代法と国家、官僚制)である[28]。 彼の見解によれば、支配者と被支配者の間のあらゆる歴史的関係はこのような要素を含んでおり、それらはこの三者区分に基づいて分析することができる [29]。 彼は、カリスマ的権威の不安定性は、それをより構造化された権威の形態へと「日常化」させることになると指摘している[30]。官僚的構造を利用した合理 的な法的構造の権威への移行は、最終的には避けられないものである。これは「官僚的な行政とは基本的に知識による支配を意味する」[31]というこの方向 への動きの必然性を示唆することによって、彼のより広範な合理化の概念と結びついている[30]。 ヴェーバーは『経済と社会』(1922年)において多くの理想的なタイプの行政や政府を記述していた。社会の官僚化に関する彼の批判的な研究は、彼の著作 の中で最も永続的な部分のひとつとなった[30][31]。 [最も効率的で合理的な組織化の方法として、ヴェーバーにとっての官僚化は合理的な法的権威の重要な部分であり、さらに彼はそれを西洋社会の進行中の合理 化における重要なプロセスであると考えていた。 [30][31]ヴェーバーの理想的な官僚制は、階層的な組織、一定の活動領域における明確な権限線、文書化された規則に基づいてとられる(そして記録さ れる)行動、専門的な訓練を必要とする官僚的職員、中立的に実施される規則、個人ではなく組織によって判断される技術的資格に依存する出世によって特徴づ けられる[31][34]。 |

| Approaches Italian school of elite theory Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923), Gaetano Mosca (1858–1941), and Robert Michels (1876–1936), were cofounders of the Italian school of elitism which influenced subsequent elite theory in the Western tradition.[35][36] The outlook of the Italian school of elitism is based on two ideas: Power lies in position of authority in key economic and political institutions. The psychological difference that sets elites apart is that they have personal resources, for instance intelligence and skills, and a vested interest in the government; while the rest are incompetent and do not have the capabilities of governing themselves, the elite are resourceful and strive to make the government work. For in reality, the elite would have the most to lose in a failed state. Pareto emphasized the psychological and intellectual superiority of elites, believing that they were the highest achievers in any field. He discussed the existence of two types of elites: Governing elites and Non-governing elites. He also extended the idea that a whole elite can be replaced by a new one and how one can circulate from being elite to non-elite. Mosca emphasized the sociological and personal characteristics of elites. He said elites are an organized minority and that the masses are an unorganized majority. The ruling class is composed of the ruling elite and the sub-elites. He divides the world into two group: Political class and Non-Political class. Mosca asserts that elites have intellectual, moral, and material superiority that is highly esteemed and influential. Sociologist Michels developed the iron law of oligarchy where, he asserts, social and political organizations are run by few individuals, and social organization and labor division are key. He believed that all organizations were elitist and that elites have three basic principles that help in the bureaucratic structure of political organization: Need for leaders, specialized staff and facilities Utilization of facilities by leaders within their organization The importance of the psychological attributes of the leaders |

アプローチ イタリアのエリート理論学派 ヴィルフレド・パレート(1848年-1923年)、ガエタノ・モスカ(1858年-1941年)、ロバート・ミケルス(1876年-1936年)は、西洋の伝統におけるその後のエリート理論に影響を与えたイタリア学派の共同創設者である[35][36]。 イタリア学派のエリート主義の展望は2つの考えに基づいている: 権力は主要な経済的・政治的制度における権威の地位にある。エリートを際立たせる心理的な違いは、エリートが人格的な資源、たとえば知性や技能を持ち、政 府に対して既得権益を持っていることであり、それ以外の人々は無能であり、自ら統治する能力を持っていないが、エリートは機知に富み、政府を機能させよう と努力する。現実には、エリート層が国家破綻で最も失うものが大きいからだ。 パレートはエリートの心理的・知的優位性を強調し、エリートはどの分野でも最高の業績を上げると考えた。彼は2種類のエリートの存在を論じた: 統治エリートと非統治エリートである。彼はまた、エリート全体が新しいエリートに取って代わられる可能性があること、そしてエリートから非エリートへと循 環する可能性があることについても考えを広げた。モスカはエリートの社会学的、人格的特徴を強調した。彼は、エリートは組織化された少数派であり、大衆は 組織化されていない多数派であると述べた。支配階級は支配エリートとサブエリートで構成される。彼は世界を2つのグループに分けた: 政治階級と非政治階級である。モスカは、エリートは知的、道徳的、物質的な優越性を持ち、高く評価され影響力があると主張する。 社会学者ミケルスは寡頭政治の鉄則を展開し、社会的・政治的組織は少数の個人によって運営され、社会組織と分業が鍵を握ると主張した。彼は、すべての組織はエリート主義であり、エリートには政治組織の官僚主義的構造に役立つ3つの基本原則があると考えた: リーダー、専門スタッフ、施設の必要性 リーダーによる組織内での施設の利用 リーダーの心理的属性の重要性 |

| Pluralism and power relations Contemporary political sociology takes these questions seriously, but it is concerned with the play of power and politics across societies, which includes, but is not restricted to, relations between the state and society. In part, this is a product of the growing complexity of social relations, the impact of social movement organizing, and the relative weakening of the state as a result of globalization. To a significant part, however, it is due to the radical rethinking of social theory. This is as much focused now on micro questions (such as the formation of identity through social interaction, the politics of knowledge, and the effects of the contestation of meaning on structures), as it is on macro questions (such as how to capture and use state power). Chief influences here include cultural studies (Stuart Hall), post-structuralism (Michel Foucault, Judith Butler), pragmatism (Luc Boltanski), structuration theory (Anthony Giddens), and cultural sociology (Jeffrey C. Alexander). Political sociology attempts to explore the dynamics between the two institutional systems introduced by the advent of Western capitalist system that are the democratic constitutional liberal state and the capitalist economy. While democracy promises impartiality and legal equality before all citizens, the capitalist system results in unequal economic power and thus possible political inequality as well. For pluralists,[37] the distribution of political power is not determined by economic interests but by multiple social divisions and political agendas. The diverse political interests and beliefs of different factions work together through collective organizations to create a flexible and fair representation that in turn influences political parties which make the decisions. The distribution of power is then achieved through the interplay of contending interest groups. The government in this model functions just as a mediating broker and is free from control by any economic power. This pluralistic democracy however requires the existence of an underlying framework that would offer mechanisms for citizenship and expression and the opportunity to organize representations through social and industrial organizations, such as trade unions. Ultimately, decisions are reached through the complex process of bargaining and compromise between various groups pushing for their interests. Many factors, pluralists believe, have ended the domination of the political sphere by an economic elite. The power of organized labour and the increasingly interventionist state have placed restrictions on the power of capital to manipulate and control the state. Additionally, capital is no longer owned by a dominant class, but by an expanding managerial sector and diversified shareholders, none of whom can exert their will upon another. The pluralist emphasis on fair representation however overshadows the constraints imposed on the extent of choice offered. Bachrauch and Baratz (1963) examined the deliberate withdrawal of certain policies from the political arena. For example, organized movements that express what might seem as radical change in a society can often by portrayed as illegitimate.[38] |

多元主義と権力関係 現代の政治社会学は、このような問いを真摯に受け止めているが、社会全体における権力と政治の戯れに関心を抱いており、これには国家と社会の関係も含まれ るが、それに限定されるものではない。これは社会関係の複雑化、社会運動組織化の影響、グローバリゼーションの結果としての国家の相対的弱体化の産物であ る。しかし、かなりの部分において、それは社会理論の根本的な再考によるものである。これは現在、マクロな問題(国家権力をいかに獲得し利用するかなど) と同様に、ミクロな問題(社会的相互作用によるアイデンティティの形成、知識の政治学、意味の争いが構造に及ぼす影響など)にも焦点が当てられている。こ こでの主な影響には、カルチュラル・スタディーズ(スチュアート・ホール)、ポスト構造主義(ミシェル・フーコー、ジュディス・バトラー)、プラグマティ ズム(リュック・ボルタンスキー)、構造化理論(アンソニー・ギデンズ)、文化社会学(ジェフリー・C・アレクサンダー)などがある。 政治社会学は、西欧資本主義システムの出現によって導入された2つの制度システム、すなわち民主的立憲自由主義国家と資本主義経済の間の力学を探求しよう とするものである。民主主義がすべての市民の前で公平性と法的平等を約束する一方で、資本主義システムは不平等な経済力をもたらし、その結果、政治的不平 等も起こりうる。 多元主義者にとって[37]、政治権力の分配は経済的利益によって決まるのではなく、複数の社会的分裂と政治的課題によって決まる。異なる派閥の異なる政 治的関心や信条は、集団的組織を通じて協力し合い、柔軟で公正な代表を生み出し、それが今度は決定を下す政党に影響を与える。権力の分配は、対立する利益 集団の相互作用によって達成される。このモデルでは、政府は単なる仲介役として機能し、いかなる経済力による支配からも自由である。しかし、この多元的民 主主義には、市民権や表現のメカニズムを提供し、労働組合のような社会的・産業的組織を通じて代表を組織する機会を提供するような基本的枠組みの存在が必 要である。最終的には、自分たちの利益を追求するさまざまな集団間の複雑な交渉と妥協のプロセスを通じて、意思決定がなされる。多くの要因が、経済エリー トによる政治領域の支配に終止符を打ったと多元主義者は考えている。組織化された労働者の力と、介入主義を強める国家が、国家を操作し支配する資本の力に 制限を加えている。さらに、資本はもはや支配的な階級によって所有されているのではなく、拡大する経営部門と多様化する株主によって所有されている。 しかし、公正な代表を強調する多元主義的な考え方は、提供される選択の範囲に課される制約を覆い隠してしまう。Bachrauch and Baratz (1963)は、特定の政策が政治の場から意図的に撤退することを検討した。例えば、社会における急進的な変化と思われるような組織的な運動は、しばしば 非合法なものとして描かれることがある[38]。 |

| Power elite A main rival to pluralist theory in the United States was the theory of the "power elite" by sociologist C. Wright Mills. According to Mills, the eponymous "power elite" are those that occupy the dominant positions, in the dominant institutions (military, economic and political) of a dominant country, and their decisions (or lack of decisions) have enormous consequences, not only for the U.S. population but, "the underlying populations of the world." The institutions which they head, Mills posits, are a triumvirate of groups that have succeeded weaker predecessors: (1) "two or three hundred giant corporations" which have replaced the traditional agrarian and craft economy, (2) a strong federal political order that has inherited power from "a decentralized set of several dozen states" and "now enters into each and every cranny of the social structure", and (3) the military establishment, formerly an object of "distrust fed by state militia," but now an entity with "all the grim and clumsy efficiency of a sprawling bureaucratic domain." Importantly, and in distinction from modern American conspiracy theory, Mills explains that the elite themselves may not be aware of their status as an elite, noting that "often they are uncertain about their roles" and "without conscious effort, they absorb the aspiration to be ... The Onecide." Nonetheless, he sees them as a quasi-hereditary caste. The members of the power elite, according to Mills, often enter into positions of societal prominence through educations obtained at establishment universities. The resulting elites, who control the three dominant institutions (military, economy and political system) can be generally grouped into one of six types, according to Mills: the "Metropolitan 400", members of historically notable local families in the principal American cities, generally represented on the Social Register "Celebrities", prominent entertainers and media personalities the "Chief Executives", presidents and CEOs of the most important companies within each industrial sector the "Corporate Rich", major landowners and corporate shareholders the "Warlords", senior military officers, most importantly the Joint Chiefs of Staff the "Political Directorate", "fifty-odd men of the executive branch" of the U.S. federal government, including the senior leadership in the Executive Office of the President, sometimes variously drawn from elected officials of the Democratic and Republican parties but usually professional government bureaucrats Mills formulated a very short summary of his book: "Who, after all, runs America? No one runs it altogether, but in so far as any group does, the power elite."[39] Who Rules America? is a book by research psychologist and sociologist, G. William Domhoff, first published in 1967 as a best-seller (#12), with six subsequent editions.[40] Domhoff argues in the book that a power elite wields power in America through its support of think-tanks, foundations, commissions, and academic departments.[41] Additionally, he argues that the elite control institutions through overt authority, not through covert influence.[42] In his introduction, Domhoff writes that the book was inspired by the work of four men: sociologists E. Digby Baltzell, C. Wright Mills, economist Paul Sweezy, and political scientist Robert A. Dahl.[7] |

パワーエリート アメリカにおける多元主義理論の主なライバルは、社会学者C・ライト・ミルズによる「パワーエリート」の理論であった。ミルズによれば、「パワーエリー ト」とは、支配的な国の支配的な制度(軍事、経済、政治)において支配的な地位を占める人々のことであり、彼らの決定(あるいは決定の欠如)は、米国の人 々だけでなく、「世界の根底にある人々」にも甚大な影響を及ぼす。彼らが率いる組織は、弱い前任者の後を継いだ三すくみのグループであるとミルズ氏は仮定 する: (1)伝統的な農耕経済と工芸経済に取って代わった「200から300の巨大企業」、(2)「数十の州からなる分散型」から権力を受け継ぎ、「今や社会構 造の隅々にまで入り込んでいる」強力な連邦政治秩序、(3)かつては「州の民兵によって養われている不信」の対象であったが、今では「広大な官僚制領域の あらゆる重苦しさと不器用な効率性」を持つ存在となった軍事組織、である。 」 重要なのは、現代アメリカの陰謀論とは一線を画し、エリート自身がエリートとしての地位を自覚していない場合があるということだ。エリートであることを自 覚していないかもしれない。それにもかかわらず、彼は彼らを準世襲的なカーストと見ている。ミルズ氏によれば、パワーエリートの構成員は、多くの場合、既 成の大学で得た教育によって社会的に著名な地位に就く。その結果、3つの支配的な制度(軍事、経済、政治システム)を支配するエリートは、ミルズ曰く、一 般的に6つのタイプのいずれかに分類される: メトロポリタン400」:アメリカの主要都市に住む、歴史的に著名な地方家族のメンバーであり、一般に社会登録簿に記載されている。 「セレブリティ」:著名な芸能人やメディア人格者 最高経営責任者(Chief Executives)」は、各産業部門における最も重要な企業の社長やCEOである。 企業富裕層」:主要な地主や企業の株主 軍閥」、軍幹部、特に統合参謀本部 政治理事会」、大統領府の上級指導部を含むアメリカ連邦政府の「行政府の50人余り」、民主党や共和党の選挙で選ばれた議員から選ばれることもあるが、たいていはプロの政府官僚である。 ミルズ氏は自著を非常に短くまとめた: 「結局のところ、誰がアメリカを動かしているのか?結局のところ、アメリカを動かしているのは誰なのか?完全に動かしているのは誰もいないが、ある集団が動かしている限りにおいて、パワーエリートである」[39]。 誰がアメリカを支配しているのか」は、研究心理学者であり社会学者であるG・ウィリアム・ドムホフによる著書であり、1967年に出版されベストセラー (第12位)となり、その後6版が出版された。 [さらに彼は、エリートは隠然たる影響力によってではなく、あからさまな権威によって制度をコントロールしていると論じている[42]。序文でドムホフ は、この本が4人の人物、すなわち社会学者のE・ディグビー・バルツェル、C・ライト・ミルズ、経済学者のポール・スウィージー、政治学者のロバート・ A・ダールの研究に触発されたと書いている[7]。 |

| Concepts T. H. Marshall on citizenship T. H. Marshall's Social Citizenship is a political concept first highlighted in his essay, Citizenship and Social Class in 1949. Marshall's concept defines the social responsibilities the state has to its citizens or, as Marshall puts it, "from [granting] the right to a modicum of economic welfare and security to the right to share to the full in the social heritage and to live the life of a civilized being according to the standards prevailing in the society".[43] One of the key points made by Marshall is his belief in an evolution of rights in England acquired via citizenship, from "civil rights in the eighteenth [century], political in the nineteenth, and social in the twentieth".[43] This evolution however, has been criticized by many for only being from the perspective of the white working man. Marshall concludes his essay with three major factors for the evolution of social rights and for their further evolution, listed below: The lessening of the income gap "The great extension of the area of common culture and common experience"[43] An enlargement of citizenship and more rights granted to these citizens. Many of the social responsibilities of a state have since become a major part of many state's policies (see United States Social Security). However, these have also become controversial issues as there is a debate over whether a citizen truly has the right to education and even more so, to social welfare. |

コンセプト T. シチズンシップについて T. H.マーシャルの「社会的市民権」は、1949年の小論『市民権と社会階級』で初めて強調された政治概念である。マーシャルの概念は、国家が国民に対して 負う社会的責任を定義するものであり、マーシャルに言わせれば、「経済的な福祉と安全に対するわずかな権利から、社会的遺産を十分に共有し、社会で一般的 な基準に従って文明人としての生活を営む権利までを(付与する)」ものである。 [マーシャルの重要なポイントのひとつは、「18世紀には市民権、19世紀には政治的権利、20世紀には社会的権利」[43]と、市民権を介して獲得され たイギリスにおける権利の進化に対する彼の信念である。しかし、この進化は、白人の労働者の視点に立ったものでしかないとして、多くの人々から批判されて きた。マーシャルは、社会的権利の進化とそのさらなる進化のための3つの主要な要因を以下に列挙して、彼のエッセイを締めくくっている: 所得格差の縮小 「共通の文化と共通の経験の領域の大幅な拡大」[43]。 市民権の拡大とこれらの市民に付与される権利の拡大。 国家の社会的責任の多くは、その後、多くの国家の政策の主要な部分となった(米国の社会保障を参照)。しかし、市民が本当に教育を受ける権利があるのか、さらには社会福祉を受ける権利があるのかという議論もあり、これらは論争の的ともなっている。 |

| Seymour Martin Lipset on the social requisites of democracy In Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics political sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset provided a very influential analysis of the bases of democracy across the world. Larry Diamond and Gary Marks argue that "Lipset's assertion of a direct relationship between economic development and democracy has been subjected to extensive empirical examination, both quantitative and qualitative, in the past 30 years. And the evidence shows, with striking clarity and consistency, a strong causal relationship between economic development and democracy."[44] The book sold more than 400,000 copies and was translated into 20 languages, including: Vietnamese, Bengali, and Serbo-Croatian.[45] Lipset was one of the first proponents of Modernization theory which states that democracy is the direct result of economic growth, and that "[t]he more well-to-do a nation, the greater the chances that it will sustain democracy."[46] Lipset's modernization theory has continued to be a significant factor in academic discussions and research relating to democratic transitions.[47][48] It has been referred to as the "Lipset hypothesis",[49] as well as the "Lipset thesis".[50] |

シーモア・マーティン・リプセット:民主主義の社会的要件について 政治的人間』(Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics 政治社会学者シーモア・マーティン・リプセットは、世界中の民主主義の基盤について非常に影響力のある分析を行った。ラリー・ダイヤモンドとゲイリー・ マークスは、「経済発展と民主主義の直接的な関係というリプセットの主張は、過去30年間、量的にも質的にも広範な実証的検証を受けてきた。そしてその証 拠は、経済発展と民主主義の間に強い因果関係があることを、驚くほど明瞭かつ一貫性をもって示している」[44]: リプセットは、民主主義は経済成長の直接的な結果であり、「裕福な国民ほど民主主義を維持できる可能性が高い」とする近代化理論の最初の提唱者の一人であ る。 「リプセットの近代化理論は、民主主義の移行に関連する学術的な議論や研究において重要な要素であり続けている[47][48]。 リプセット仮説」[49]や「リプセット・テーゼ」[50]とも呼ばれている。 |

| Videos Tawnya Adkins Covert (2017), "What is Political Sociology?" (SAGE, paywall). V. Bautista (2020), "Introduction to Political Sociology" (YouTube). |

動画 Tawnya Adkins Covert (2017), 「What is Political Sociology?」. (SAGE、有料)。 V. バウティスタ(2020)「政治社会学入門」(YouTube)。 |

| Research organisations Political sociology Aalborg University: Political Sociology Research Group American Sociological Association: Section on Political Sociology European Consortium for Political Research: Political Sociology Standing Group University of Amsterdam: Political Sociology Power, Place and Difference Programme Group University of Cambridge: Political Sociology Cluster Interdisciplinary Harvard University: Political and Historical Sociology Research Cluster See also Bibliography of sociology Political anthropology Political philosophy Political spectrum Power structure Political identity |

研究組織 政治社会学 オールボー大学 政治社会学研究グループ アメリカ社会学会 政治社会学部門 ヨーロッパ政治研究コンソーシアム: 政治社会学常設グループ アムステルダム大学 政治社会学権力・場所・差異プログラムグループ ケンブリッジ大学 政治社会学クラスター 学際的 ハーバード大学 政治・歴史社会学研究クラスター 以下も参照のこと。 社会学の書誌 政治人類学 政治哲学 政治スペクトラム 権力構造 政治的アイデンティティ |

| Bibliography Introductory Dobratz, B., Waldner, L. and Buzzell, T., 2019. Power, Politics, and Society: An Introduction to Political Sociology. London: Routledge. Janoski, T., Hicks, A., Schwartz, M. and Alford,, R., 2005. The handbook of political sociology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Lachmann, R., 2010. States and Power. Oxford: Wiley. Nash, K., 2007. Readings in contemporary political sociology. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. Neuman, W., 2008. Power, state, and society. Long Grove, Ill.: Waveland Press. Orum, A. and Dale, J., 2009. Introduction to political sociology. New York: Oxford University Press. Rush, M., 1992. Politics and Society: An Introduction to Political Sociology. London: Routledge. General Amenta, E., Nash, K. and Scott, A., 2016. The Wiley-Blackwell companion to political sociology. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons. Criminology Jacobs, D. and Carmichael, J., 2002. The Political Sociology of the Death Penalty: A Pooled Time-Series Analysis. American Sociological Review, 67(1), p. 109. Jacobs, D. and Helms, R., 2001. Toward a Political Sociology of Punishment: Politics and Changes in the Incarcerated Population. Social Science Research, 30(2), pp. 171–194. Health and well-being Banks, D. and Purdy, M., 2001. The Sociology and Politics of Health. London: Routledge. Beckfield, J., 2018. Political sociology and the people's health. Abingdon: Oxford University Press. Science Frickel, S. and Moore, K., 2006. The new political sociology of science. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. |

ビブリオグラフィー 序論 Dobratz, B., Waldner, L. and Buzzell, T., 2019. Power, Politics, and Society: An Introduction to Political Sociology. ロンドン: Routledge. Janoski, T., Hicks, A., Schwartz, M. and Alford,, R., 2005. 政治社会学ハンドブック。ニューヨーク州ニューヨーク: Cambridge University Press. Lachmann, R., 2010. States and Power. オックスフォード: Wiley. Nash, K., 2007. Readings in contemporary political sociology. Malden, Mass. Neuman, W., 2008. Power, state, and society. Long Grove, Ill.: Waveland Press. Orum, A. and Dale, J., 2009. 政治社会学入門。ニューヨーク: オックスフォード大学出版局。 Rush, M., 1992. Politics and Society: 政治社会学入門. London: Routledge. 一般 Amenta, E., Nash, K. and Scott, A., 2016. The Wiley-Blackwell companion to political sociology. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons. 犯罪学 Jacobs, D. and Carmichael, J., 2002. 死刑の政治社会学: 死刑の政治社会学:プール時系列分析 American Sociological Review, 67(1), p. 109. Jacobs, D. and Helms, R., 2001. Toward a Political Sociology of Punishment: 収容人口の政治と変化。社会科学研究, 30(2), 171-194頁。 保健と幸福 Banks, D. and Purdy, M., 2001. The Sociology and Politics of Health. ロンドン: Routledge. Beckfield, J., 2018. Political sociology and the people's health. Abingdon: Oxford University Press. 科学 Frickel, S. and Moore, K., 2006. The new political sociology of science. マディソン: ウィスコンシン大学出版局。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_sociology |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099