Introduction to

Community,

comunidad

コミュニティ入門

Introduction to

Community,

comunidad

解説:池田光穂

コミュニティ(共同体)は、人々のイメージによると、(i)おなじ空間に[一時的あるいは永続的 に]存在し、(ii)さまざまな活動を通して (iii)[仮想的にも現実的にも]紐帯を維持している(iv)集団のことを、原 義的にはさす。コミュニティのこの4つの属性からなる集団を、原初的あるいは本源的コミュニティ=primordial communityとまず名づけておこう——モデル・コミュニティ(typical community)と言ってもいいかもしれない。

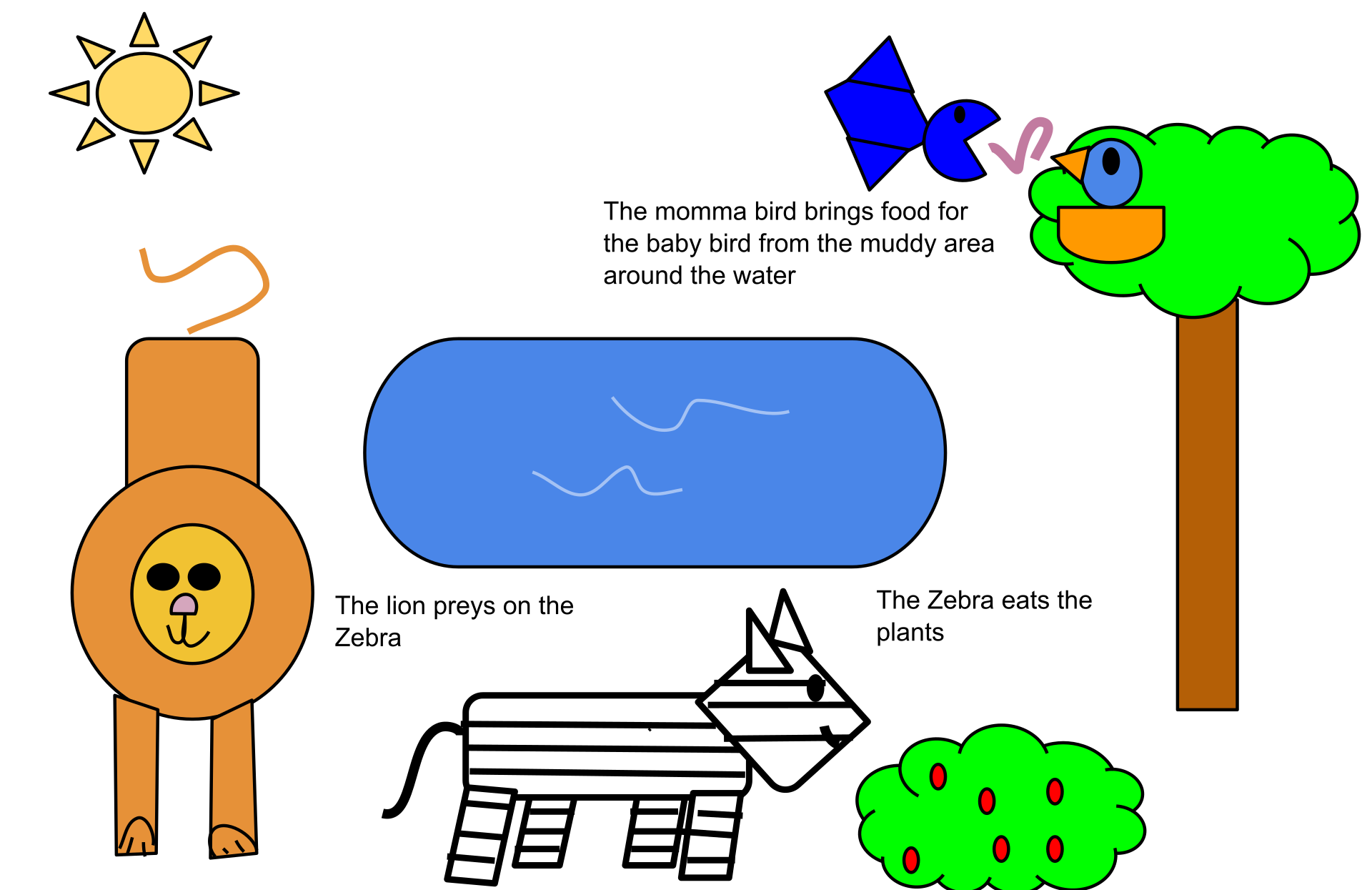

Community townhall (まちの集会所)

| A community

is a social unit (a group of people) with a shared socially-significant

characteristic, such as place, set of norms, culture, religion, values,

customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated

in a given geographical area (e.g. a country, village, town, or

neighborhood) or in virtual space through communication platforms.

Durable good relations that extend beyond immediate genealogical ties

also define a sense of community, important to people's identity,

practice, and roles in social institutions such as family, home, work,

government, society, or humanity at large.[1] Although communities are

usually small relative to personal social ties, "community" may also

refer to large-group affiliations such as national communities,

international communities, and virtual communities.[2] In terms of sociological categories, a community can seem like a sub-set of a social collectivity.[3] In developmental views, a community can emerge out of a collectivity.[4] The English-language word "community" derives from the Old French comuneté (Modern French: communauté), which comes from the Latin communitas "community", "public spirit" (from Latin communis, "common").[5] Human communities may have intent, belief, resources, preferences, needs, and risks in common, affecting the identity of the participants and their degree of cohesiveness.[6]  A community of interest gathers at Stonehenge, England, for the summer solstice. |

コミュニティとは、場所、規範、文化、宗教、価値観、習慣、アイデン

ティティなど、社会的に重要な特徴を共有する社会的単位(人民の集団)である。コミュニティは、特定の地理的地域(国、村、町、近隣など)、またはコミュ

ニケーション・プラットフォームを通じて仮想空間内に位置する場所の感覚を共有することがある。コミュニティは通常、人格的な社会的結びつきに比べれば小

規模であるが、「コミュニティ」は国民コミュニティ、国際コミュニティ、仮想コミュニティなどの大規模な集団の結びつきを指すこともある[2]。 社会学的な分類の観点からは、コミュニティは社会的集団のサブセットのように見えることがある[3]。発達論的な見解では、コミュニティは集団から出現することがある[4]。 コミュニティ」という英語の語源は古フランス語のcomuneté(現代フランス語ではcommunauté)であり、ラテン語のcommunitas「共同体」、「公共の精神」(ラテン語のcommunis「共通の」)に由来する[5]。 人間の共同体は、意図主義、信念、資源、嗜好、ニーズ、リスクなどを共通に持つことがあり、参加者のアイデンティティや凝集性の程度に影響を与える[6]。  夏至の日、イギリスのストーンヘンジに 興味深いコミュニティーが集まる。 |

| Perspectives of various disciplines Archaeology Archaeological studies of social communities use the term "community" in two ways, mirroring usage in other areas. The first meaning is an informal definition of community as a place where people used to live. In this literal sense it is synonymous with the concept of an ancient settlement—whether a hamlet, village, town, or city. The second meaning resembles the usage of the term in other social sciences: a community is a group of people living near one another who interact socially. Social interaction on a small scale can be difficult to identify with archaeological data. Most reconstructions of social communities by archaeologists rely on the principle that social interaction in the past was conditioned by physical distance. Therefore, a small village settlement likely constituted a social community and spatial subdivisions of cities and other large settlements may have formed communities. Archaeologists typically use similarities in material culture—from house types to styles of pottery—to reconstruct communities in the past. This classification method relies on the assumption that people or households will share more similarities in the types and styles of their material goods with other members of a social community than they will with outsiders.[7] |

様々な分野の視点 考古学 社会共同体に関する考古学的研究では、他の分野での用法と同じように、「共同体」という用語を2つの意味で用いている。第一の意味は、コミュニティとは人 々がかつて住んでいた場所であるという非公式な定義である。この文字通りの意味では、集落、村、町、都市など、古代の定住地の概念と同義である。第二の意 味は、他の社会科学におけるこの用語の用法に似ている。コミュニティとは、社会的に相互作用する、近くに住む人々の集団である。小規模な社会的相互作用 は、考古学的データでは特定が難しい。考古学者による社会共同体の再構築のほとんどは、過去の社会的相互作用は物理的距離によって条件づけられていたとい う原則に依拠している。したがって、小さな村落集落が社会共同体を構成していた可能性が高く、都市やその他の大規模集落の空間的細分化が共同体を形成して いた可能性もある。考古学者は通常、家屋のタイプから陶器のスタイルに至るまで、物質文化の類似性を利用して過去の共同体を復元する。この分類法は、人民 や世帯は、その物的財の種類や様式において、部外者よりも社会共同体の他の構成員とより多くの共通点を持つという仮定に依拠している[7]。 |

| Sociology Early sociological studies identified communities as fringe groups at the behest of local power elites. Such early academic studies include Who Governs? by Robert Dahl as well as the papers by Floyd Hunter on Atlanta. At the turn of the 21st century the concept of community was rediscovered by academics, politicians, and activists. Politicians hoping for a democratic election started to realign with community interests.[8] |

社会学 初期の社会学的研究では、地域社会は地域の権力エリートの意向を受けたフリンジ・グループであると見なされていた。そのような初期の学術研究には、ロバー ト・ダールの『誰が統治するのか』や、アトランタに関するフロイド・ハンターの論文などがある。21世紀に入り、コミュニティという概念は学者、政治家、 活動家によって再発見された。民主的な選挙を望む政治家たちは、地域社会の利益と再調整し始めた[8]。 |

| Ecology Main article: Community (ecology) In ecology, a community is an assemblage of populations—potentially of different species—interacting with one another. Community ecology is the branch of ecology that studies interactions between and among species. It considers how such interactions, along with interactions between species and the abiotic environment, affect social structure and species richness, diversity and patterns of abundance.[9] Species interact in three ways: competition, predation and mutualism: Competition typically results in a double negative—that is both species lose in the interaction. Predation involves a win/lose situation, with one species winning. Mutualism sees both species co-operating in some way, with both winning. The two main types of ecological communities are major communities, which are self-sustaining and self-regulating (such as a forest or a lake), and minor communities, which rely on other communities (like fungi decomposing a log) and are the building blocks of major communities. Moreover, we can establish other non-taxonomic subdivisions of biocenosis, such as guilds. |

エコロジー 主な記事 群集(生態学) 生態学において、群集とは互いに影響し合う異なる種の個体群の集合体である。群集生態学は、生物種間や生物種間の相互作用を研究する生態学の一分野であ る。このような相互作用が、種と生物環境との相互作用とともに、社会構造や種の豊かさ、多様性、存在量のパターンにどのような影響を与えるかを考察する: 競争は通常、二重のマイナスとなる-つまり、相互作用によって両方の種が損をする。 捕食は勝つか負けるかの状況で、一方の種が勝つ。 相互主義では、両方の種が何らかの形で協力し、両方の種が勝利する。 生態学的共同体には大きく分けて2つのタイプがあり、森林や湖のような自立的で自制的な「大共同体」と、丸太を分解する菌類のように他の共同体に依存し、大共同体の構成要素となる「小共同体」がある。さらに、ギルドのような分類学上ではない細分化も可能である。 |

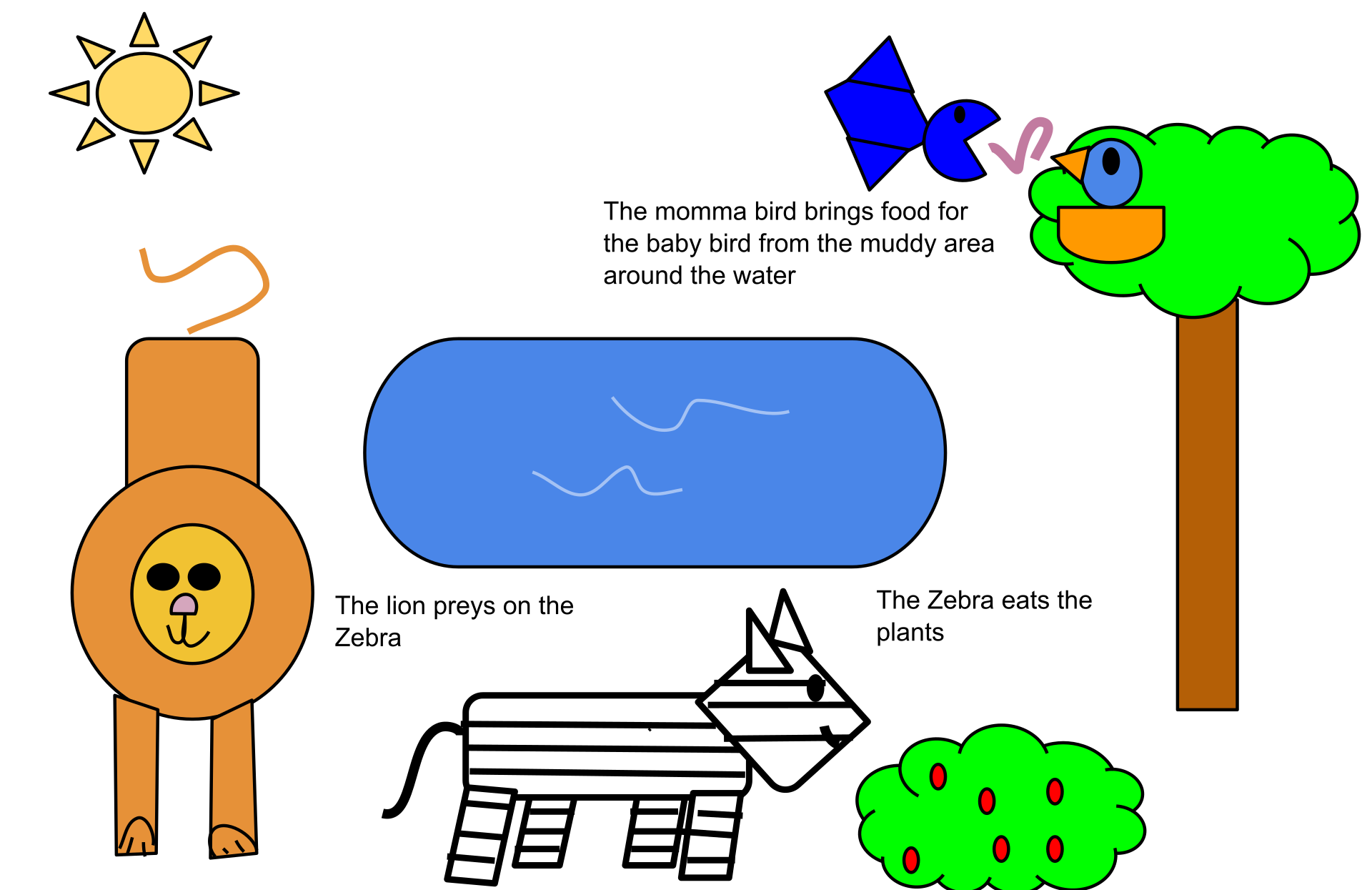

A simplified example of a community. A community includes many populations and how they interact with each other. This example shows interaction between the zebra and the bush, and between the lion and the zebra, as well as between the bird and the organisms by the water, like the worms. Semantics The concept of "community" often has a positive semantic connotation, exploited rhetorically by populist politicians and by advertisers[10] to promote feelings and associations of mutual well-being, happiness and togetherness[11]—veering towards an almost-achievable utopian community. In contrast, the epidemiological term "community transmission" can have negative implications,[12] and instead of a "criminal community"[13] one often speaks of a "criminal underworld" or of the "criminal fraternity". |

地域社会の単純化した例。共同体には多くの集団が含まれ、それらがどのように相互作用しているかがわかる。この例では、シマウマとブッシュの相互作用、ライオンとシマウマの相互作用、鳥とミミズのような水辺の生物の相互作用が示されている。 意味論 コミュニティ」という概念は、しばしば肯定的な意味合いを持ち、ポピュリストの政治家や広告主[10]によってレトリック的に利用され、相互の幸福、幸福、一体感[11]の感情や連想を促進する。 これとは対照的に、疫学用語である「コミュニティ感染」は否定的な意味合いを持つことがあり[12]、「犯罪者のコミュニティ」[13]の代わりに「犯罪者の裏社会」や「犯罪者の友愛」について語られることが多い。 |

| Key concepts Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft Main article: Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft In Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (1887), German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies described two types of human association: Gemeinschaft (usually translated as "community") and Gesellschaft ("society" or "association"). Tönnies proposed the Gemeinschaft–Gesellschaft dichotomy as a way to think about social ties. No group is exclusively one or the other. Gemeinschaft stress personal social interactions, and the roles, values, and beliefs based on such interactions. Gesellschaft stress indirect interactions, impersonal roles, formal values, and beliefs based on such interactions.[14] |

キーコンセプト ゲマインシャフトとゲゼルシャフト 主な記事 ゲマインシャフトとゲゼルシャフト ドイツの社会学者フェルディナント・テーニースは、『ゲマインシャフトとゲゼルシャフト』(Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft、1887年)の中で、人間の結びつきには2つのタイプがあると述べている: ゲマインシャフト(通常「共同体」と訳される)とゲゼルシャフト(「社会」または「協会」)である。ゲマインシャフトとゲゼルシャフトは、社会的結びつき を考える方法として提唱された。どの集団も、どちらか一方だけということはない。ゲマインシャフトは人格的な社会的相互作用と、それに基づく役割、価値 観、信念を重視する。ゲゼルシャフトは間接的な相互作用、非人間的な役割、形式的な価値観、そうした相互作用に基づく信念を強調する[14]。 |

| Sense of community Main article: Sense of community In a seminal 1986 study, McMillan and Chavis[15] identify four elements of "sense of community": membership: feeling of belonging or of sharing a sense of personal relatedness, influence: mattering, making a difference to a group and of the group mattering to its members reinforcement: integration and fulfillment of needs, shared emotional connection.  To what extent do participants in joint activities experience a sense of community? A "sense of community index" (SCI) was developed by Chavis and colleagues, and revised and adapted by others. Although originally designed to assess sense of community in neighborhoods, the index has been adapted for use in schools, the workplace, and a variety of types of communities.[16] Studies conducted by the American Psychological Association indicate that young adults who feel a sense of belonging in a community, particularly small communities, develop fewer psychiatric and depressive disorders than those who do not have the feeling of love and belonging.[17] |

共同体感覚 主な記事 共同体感覚 1986年の研究において、マクミランとチャヴィス[15]は「共同体感覚」の4つの要素を挙げている: メンバーシップ:所属しているという感覚、または人格的な関連性を共有しているという感覚、 影響力:重要であること、集団に異なる違いをもたらすこと、集団がメンバーにとって重要であること。 強化:ニーズの統合と充足、 感情的なつながりを共有する。  共同活動の参加者は、どの程度共同体感覚を経験しているのだろうか。 共同体感覚指数」(SCI)は、Chavisらによって開発され、他の人々によって改訂・適応された。もともとは近隣における共同体感覚を評価するために考案されたものであるが、この指標は学校、職場、さまざまなタイプの共同体での使用に適応されている[16]。 米国心理学会が実施した研究によると、地域社会、特に小規模な地域社会で帰属感を感じている若年成人は、愛情や帰属感を感じていない若年成人に比べて、精神疾患や抑うつ障害の発症が少ないことが示されている[17]。 |

| Socialization Main article: Socialization  Lewes Bonfire Night procession commemorating 17 Protestant martyrs burnt at the stake from 1555 to 1557 The process of learning to adopt the behavior patterns of the community is called socialization. The most fertile time of socialization is usually the early stages of life, during which individuals develop the skills and knowledge and learn the roles necessary to function within their culture and social environment.[18] For some psychologists, especially those in the psychodynamic tradition, the most important period of socialization is between the ages of one and ten. But socialization also includes adults moving into a significantly different environment where they must learn a new set of behaviors.[19] Socialization is influenced primarily by the family, through which children first learn community norms. Other important influences include schools, peer groups, people, mass media, the workplace, and government. The degree to which the norms of a particular society or community are adopted determines one's willingness to engage with others. The norms of tolerance, reciprocity, and trust are important "habits of the heart", as de Tocqueville put it, in an individual's involvement in community.[20] |

社会化 主な記事 社会化  1555年から1557年にかけて火あぶりにされた17人のプロテスタント殉教者を記念するルイスのかがり火の夜の行列 共同体の行動パターンを取り入れることを学ぶ過程は、社会化と呼ばれる。社会化の最も盛んな時期は、通常、人生の初期段階であり、この時期に個人は技能や 知識を身につけ、文化や社会環境の中で機能するために必要な役割を学ぶ。しかし社会化には、大人が新しい一連の行動を学ばなければならない、著しく異なる 環境に移ることも含まれる[19]。 社会化は主に家族から影響を受け、子どもはまず家族を通して地域社会の規範を学ぶ。その他の重要な影響としては、学校、仲間集団、人々、マスメディア、職 場、政府などがある。特定の社会や共同体の規範がどの程度採用されているかによって、他者と関わろうとする意欲が決まる。寛容、互恵、信頼といった規範 は、ド・トクヴィルが言うように、個人が地域社会に関与する上で重要な「心の習慣」である[20]。 |

| Development Main article: Community development Community development is often linked with community work or community planning, and may involve stakeholders, foundations, governments, or contracted entities including non-government organisations (NGOs), universities or government agencies to progress the social well-being of local, regional and, sometimes, national communities. More grassroots efforts, called community building or community organizing, seek to empower individuals and groups of people by providing them with the skills they need to effect change in their own communities.[21] These skills often assist in building political power through the formation of large social groups working for a common agenda. Community development practitioners understand how to work with individuals and affect communities' positions within the context of larger social institutions. Public administrators, in contrast, understand community development in the context of rural and urban development, housing and economic development, and community, organizational and business development. Formal accredited programs conducted by universities, as part of degree granting institutions, are often used to build a knowledge base to drive curricula in public administration, sociology and community studies. The General Social Survey from the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago and the Saguaro Seminar at the Harvard Kennedy School are examples of national community development in the United States. The Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University in New York State offers core courses in community and economic development, and in areas ranging from non-profit development to US budgeting (federal to local, community funds). In the United Kingdom, the University of Oxford has led in providing extensive research in the field through its Community Development Journal,[22] used worldwide by sociologists and community development practitioners. At the intersection between community development and community building are a number of programs and organizations with community development tools. One example of this is the program of the Asset Based Community Development Institute of Northwestern University. The institute makes available downloadable tools[23] to assess community assets and make connections between non-profit groups and other organizations that can help in community building. The Institute focuses on helping communities develop by "mobilizing neighborhood assets" – building from the inside out rather than the outside in.[24] In the disability field, community building was prevalent in the 1980s and 1990s with roots in John McKnight's approaches.[25][26] |

開発 主な記事 コミュニティ開発 コミュニティ開発とは、コミュニティ活動やコミュニティ計画と関連づけられることが多く、利害関係者、財団、政府、または非政府組織(NGO)、大学、政 府機関などの契約団体が関与して、地域社会、地域社会、場合によってはナショナリズムの社会的福利を向上させることである。コミュニティ形成やコミュニ ティ・オーガナイジングと呼ばれる、より草の根的な取り組みは、人民が自分たちのコミュニティに変化をもたらすために必要なスキルを提供することによっ て、個人や人民のグループに力を与えようとするものである[21]。これらのスキルは、共通のアジェンダのために活動する大規模な社会的グループの形成を 通じて、政治的な力を構築する助けとなることが多い。地域開発実践者は、個人とどのように協力し、より大きな社会制度という文脈の中でコミュニティの立場 に影響を与えるかを理解している。これとは対照的に、行政官は、農村部や都市の開発、住宅開発、経済開発、地域社会・組織・ビジネス開発といった文脈で、 地域開発を理解している。 行政学、社会学、コミュニティ研究のカリキュラムを推進するための知識基盤を構築するために、学位授与機関の一部として大学が実施する正式な認定プログラ ムがしばしば利用される。シカゴ大学全国世論調査センターの一般社会調査や、ハーバード大学ケネディスクールのサガロ・セミナーは、米国における国民コ ミュニティ開発の一例である。ニューヨーク州にあるシラキュース大学のマックスウェル・スクール・オブ・シチズンシップ・アンド・パブリック・アフェアー ズでは、コミュニティ開発、経済開発、そして非営利組織の発展から米国の予算編成(連邦政府から地方政府、コミュニティ基金)までの分野のコア・コースを 提供している。英国では、オックスフォード大学がコミュニティ開発ジャーナル[22]を発行し、社会学者やコミュニティ開発の実務家が世界中で利用してい る。 地域開発とコミュニティ形成の交差点には、地域開発ツールを備えたプログラムや組織が数多く存在する。その一例が、ノースウェスタン大学の資産に基づくコ ミュニティ開発研究所(Asset Based Community Development Institute)のプログラムである。この研究所では、地域社会の資産を評価し、非営利グループや地域づくりに役立つ他の組織とのつながりを作るため のダウンロード可能なツール[23]を提供している。同研究所は、「近隣の資産を動員する」ことによって地域社会が発展するのを支援すること、つまり外側 からではなく内側から構築することに重点を置いている[24]。障害分野では、1980年代から1990年代にかけて、ジョン・マックナイトのアプローチ をルーツとするコミュニティ構築が普及していた[25][26]。 |

Building and organizing The anti-war affinity group "Collateral Damage" protesting the Iraq War In The Different Drum: Community-Making and Peace (1987) Scott Peck argues that the almost accidental sense of community that exists at times of crisis can be consciously built. Peck believes that conscious community building is a process of deliberate design based on the knowledge and application of certain rules.[27] He states that this process goes through four stages:[28] Pseudocommunity: When people first come together, they try to be "nice" and present what they feel are their most personable and friendly characteristics. Chaos: People move beyond the inauthenticity of pseudo-community and feel safe enough to present their "shadow" selves. Emptiness: Moves beyond the attempts to fix, heal and convert of the chaos stage, when all people become capable of acknowledging their own woundedness and brokenness, common to human beings. True community: Deep respect and true listening for the needs of the other people in this community. In 1991, Peck remarked that building a sense of community is easy but maintaining this sense of community is difficult in the modern world.[29] An interview with M. Scott Peck by Alan Atkisson. In Context #29, p. 26. The three basic types of community organizing are grassroots organizing, coalition building, and "institution-based community organizing", (also called "broad-based community organizing", an example of which is faith-based community organizing, or Congregation-based Community Organizing).[30] Community building can use a wide variety of practices, ranging from simple events (e.g., potlucks, small book clubs) to larger-scale efforts (e.g., mass festivals, construction projects that involve local participants rather than outside contractors). Community building that is geared toward citizen action is usually termed "community organizing".[31] In these cases, organized community groups seek accountability from elected officials and increased direct representation within decision-making bodies. Where good-faith negotiations fail, these constituency-led organizations seek to pressure the decision-makers through a variety of means, including picketing, boycotting, sit-ins, petitioning, and electoral politics. Community organizing can focus on more than just resolving specific issues. Organizing often means building a widely accessible power structure, often with the end goal of distributing power equally throughout the community. Community organizers generally seek to build groups that are open and democratic in governance. Such groups facilitate and encourage consensus decision-making with a focus on the general health of the community rather than a specific interest group.[32] If communities are developed based on something they share in common, whether location or values, then one challenge for developing communities is how to incorporate individuality and differences. Rebekah Nathan suggests in her book, My Freshman Year, we are drawn to developing communities totally based on sameness, despite stated commitments to diversity, such as those found on university websites. |

組織作りと組織化 イラク戦争に抗議する反戦アフィニティ・グループ「コラテラル・ダメージ スコット・ペックは『異なる鼓動:共同体形成と平和』(1987年)の中で、危機の時に存在するほとんど偶然的な共同体感覚は、意識的に構築することがで きると論じている。ペックは、意識的なコミュニティの構築とは、一定のルールの知識と適用に基づく意図的な設計のプロセスであると信じている[27]。 彼はこのプロセスが以下の4つの段階を経るとしている[28]。 擬似コミュニティ: 人々が初めて集まったとき、彼らは「いい人」であろうとし、最も人格的で友好的だと思われる特徴を見せようとする。 カオス: 人民は擬似共同体の不真面目さを乗り越え、「影の」自分自身を提示するのに十分な安全性を感じる。 空虚: カオスの段階での修正、癒し、改心の試みを超え、すべての人々が、人間に共通する自分自身の傷や壊れやすさを認めることができるようになる。 真のコミュニティ: この共同体における他の人々のニーズを深く尊重し、真摯に耳を傾けること。 1991年、ペックは、共同体感覚を構築するのは簡単だが、この共同体感覚を維持するのは現代社会では難しいと述べた[29]。In Context』29号、26ページ。コミュニティ・オーガナイジングの3つの基本的なタイプは、草の根オーガナイジング、連合構築、そして「組織ベース のコミュニティ・オーガナイジング」(「広範なコミュニティ・オーガナイジング」とも呼ばれ、その例として信仰ベースのコミュニティ・オーガナイジング、 あるいは信徒ベースのコミュニティ・オーガナイジングがある)である[30]。 コミュニティ形成は、単純なイベント(例:ポットラック、小規模な読書会)から大規模な取り組み(例:大規模なフェスティバル、外部の請負業者ではなく地元の参加者を巻き込んだ建設プロジェクト)まで、多種多様な実践を用いることができる。 このような場合、組織化されたコミュニティ・グループは、選挙で選ばれた役人に説明責任を求め、意思決定機関における直接的な代表者を増やす。誠実な交渉 がうまくいかない場合、こうした有権者主導の組織は、ピケッティング、ボイコット、座り込み、請願、選挙政治など、さまざまな手段を通じて意思決定者に圧 力をかけようとする。 地域社会の組織化は、特定の問題を解決することだけに焦点を当てるわけではない。組織化とは、多くの場合、広く利用しやすい権力構造を構築することであ り、その最終目標は、権力を地域社会全体に平等に分配することである。コミュニティ・オーガナイザーは一般的に、オープンで民主的なガバナンスを持つグ ループの構築を目指す。そのようなグループは、特定の利益集団よりもむしろ地域社会の全般的な保健に焦点を当て、合意による意思決定を促進し、奨励する [32]。 地域社会が、場所であれ価値観であれ、共通する何かを基盤として発展していくのであれば、地域社会を発展させるための一つの課題は、個性や異なるものをど のように取り込むかということである。レベッカ・ネイサンは、その著書『My Freshman Year』の中で、大学のウェブサイトに見られるような多様性へのコミットメントが表明されているにもかかわらず、私たちは完全に同一性に基づいたコミュ ニティの発展に引きずられている、と指摘している。 |

Types Participants in Diana Leafe Christian's "Heart of a Healthy Community" seminar circle during an afternoon session at O.U.R. Ecovillage A number of ways to categorize types of community have been proposed. One such breakdown is as follows: Location-based: range from the local neighbourhood, suburb, village, town or city, region, nation or even the planet as a whole. These are also called communities of place. Identity-based: range from the local clique, sub-culture, ethnic group, religious, multicultural or pluralistic civilisation, or the global community cultures of today. They may be included as communities of need or identity, such as disabled persons, or frail aged people. Organizationally-based: range from communities organized informally around family or network-based guilds and associations to more formal incorporated associations, political decision-making structures, economic enterprises, or professional associations at a small, national or international scale. Intentional: a mix of all three previous types, these are highly cohesive residential communities with a common social or spiritual purpose, ranging from monasteries and ashrams to modern ecovillages and housing cooperatives. The usual categorizations of community relations have a number of problems:[33] (1) they tend to give the impression that a particular community can be defined as just this kind or another; (2) they tend to conflate modern and customary community relations; (3) they tend to take sociological categories such as ethnicity or race as given, forgetting that different ethnically defined persons live in different kinds of communities—grounded, interest-based, diasporic, etc.[34] In response to these problems, Paul James and his colleagues have developed a taxonomy that maps community relations, and recognizes that actual communities can be characterized by different kinds of relations at the same time:[35] Grounded community relations. This involves enduring attachment to particular places and particular people. It is the dominant form taken by customary and tribal communities. In these kinds of communities, the land is fundamental to identity. Life-style community relations. This involves giving primacy to communities coming together around particular chosen ways of life, such as morally charged or interest-based relations or just living or working in the same location. Hence the following sub-forms: community-life as morally bounded, a form taken by many traditional faith-based communities. community-life as interest-based, including sporting, leisure-based and business communities which come together for regular moments of engagement. community-life as proximately-related, where neighbourhood or commonality of association forms a community of convenience, or a community of place (see below). Projected community relations. This is where a community is self-consciously treated as an entity to be projected and re-created. It can be projected as through thin advertising slogan, for example gated community, or can take the form of ongoing associations of people who seek political integration, communities of practice[36] based on professional projects, associative communities which seek to enhance and support individual creativity, autonomy and mutuality. A nation is one of the largest forms of projected or imagined community. In these terms, communities can be nested and/or intersecting; one community can contain another—for example a location-based community may contain a number of ethnic communities.[37] Both lists above can be used in a cross-cutting matrix in relation to each other. |

種類 O.U.R.エコビレッジでの午後のセッションで、ダイアナ・リーフ・クリスチャンの「健全なコミュニティの心」セミナーの参加者が輪になる。 コミュニティの種類を分類する方法は数多く提案されている。そのひとつに、以下のような分類がある: ロケーション・ベース:近隣地域、郊外、村、町、都市、地域、国民、あるいは地球全体など、さまざまな範囲を指す。これらは「場所のコミュニティ」とも呼ばれる。 アイデンティティに基づくもの:地域の徒党、サブカルチャー、民族集団、宗教、多文化、多元的文明、あるいは今日のグローバルなコミュニティ文化などである。障害者や虚弱高齢者など、ニーズやアイデンティティのコミュニティとして含まれることもある。 組織的なもの:家族やネットワークを基盤としたギルドやアソシエーションを中心にインフォーマルに組織されたコミュニティから、よりフォーマルな社団法人、政治的意思決定機構、経済企業、小規模・国民的・国際的規模の専門職団体まで、さまざまなものがある。 意図主義:先の3つのタイプをミックスしたもので、修道院やアシュラムから近代的なエコビレッジや住宅協同組合に至るまで、共通の社会的または精神的な目的を持つ、結束力の強い居住型コミュニティである。 33)(2)近代的なコミュニティ関係と慣習的なコミュニティ関係を混同しがちである。(3)民族や人種といった社会学的なカテゴリーを所与のものとして 捉えがちであり、異なる民族的に定義された人格が異なる種類のコミュニティ(地縁的、利益主義的、ディアスポラ的など)に居住していることを忘れている [34]。 このような問題に対して、ポール・ジェームズと彼の同僚たちは、コミュニティ関係をマッピングする分類法を開発し、実際のコミュニティが同時に異なる種類の関係によって特徴づけられることを認識している。 根拠あるコミュニティ関係。これは、特定の場所や特定の人々に対する永続的な愛着を伴う。慣習的共同体や部族的共同体において支配的な形態である。この種の共同体では、土地はアイデンティティの基本である。 生活様式のコミュニティ関係。これは、道徳的な関係や利害に基づく関係、あるいは単に同じ場所に住んだり働いたりするといった、選択された特定の生活様式を中心に集まる共同体に個別主義を与えるものである。したがって、次のような下位形式がある: 伝統的な信仰に基づく共同体の多くがとる形態である。 スポーツ、レジャー、ビジネスなど、定期的な交流のために集まるコミュニティを含む。 近所付き合いや共通の付き合いによって、便宜的な共同体や場所の共同体が形成される(下記参照)。 投影されたコミュニティ関係。これは、コミュニティが投影され、再創造される存在として自覚的に扱われる場合である。それは、たとえばゲーテッド・コミュ ニティといった薄っぺらな広告スローガンによって投影されることもあれば、政治的統合を求める人々による継続的な団体、専門的なプロジェクトに基づく実践 共同体[36]、個人の創造性、自律性、相互性を高め、支援しようとする結社的共同体といった形をとることもある。国民は、投影された、あるいは想像され た共同体の最大の形態のひとつである。 これらの用語では、コミュニティは入れ子になったり、交差したりすることがあり、あるコミュニティが別のコミュニティを内包することもある-たとえば、場所に基づくコミュニティがいくつもの民族コミュニティを内包することもある[37]。 |

| Internet communities Main article: Virtual community In general, virtual communities value knowledge and information as currency or social resource.[38][39][40][41] What differentiates virtual communities from their physical counterparts is the extent and impact of "weak ties", which are the relationships acquaintances or strangers form to acquire information through online networks.[42] Relationships among members in a virtual community tend to focus on information exchange about specific topics.[43][44] A survey conducted by Pew Internet and The American Life Project in 2001 found those involved in entertainment, professional, and sports virtual-groups focused their activities on obtaining information.[45] An epidemic of bullying and harassment has arisen from the exchange of information between strangers, especially among teenagers,[46] in virtual communities. Despite attempts to implement anti-bullying policies, Sheri Bauman, professor of counselling at the University of Arizona, claims the "most effective strategies to prevent bullying" may cost companies revenue.[47] Virtual Internet-mediated communities can interact with offline real-life activity, potentially forming strong and tight-knit groups such as QAnon.[48] |

インターネット・コミュニティ 主な記事 仮想コミュニティ 一般的に、バーチャル・コミュニティは知識や情報を通貨や社会的資源として重視する[38][39][40][41]。バーチャル・コミュニティが物理的 なコミュニティと異なるのは、オンライン・ネットワークを通じて情報を得るために形成される知人や見知らぬ人との関係である「弱い絆」の程度と影響である [42]。[ピュー・インターネットとアメリカン・ライフ・プロジェクトが2001年に実施した調査によると、エンターテインメント、プロフェッショナ ル、スポーツのバーチャル・グループに参加している人々は、情報を得ることに活動の重点を置いていることがわかった[45]。 特にティーンエイジャーの間で、バーチャル・コミュニティにおける見知らぬ人同士の情報交換から、いじめや嫌がらせが蔓延している[46]。いじめ防止政 策を実施しようとする試みにもかかわらず、アリゾナ大学のカウンセリング教授であるシェリ・バウマンは、「いじめを防止するための最も効果的な戦略」は企 業の収益を犠牲にする可能性があると主張している[47]。 インターネットを媒介とした仮想コミュニティは、オフラインの現実の活動と相互作用する可能性があり、QAnonのような強固で緊密なグループを形成する可能性がある[48]。 |

| Circles of Sustainability Communitarianism Community theatre Community wind energy Engaged theory Outline of community Wikipedia community |

持続可能性の輪 コミュニタリアニズム コミュニティ劇場 コミュニティ風力エネルギー エンゲージド理論 コミュニティ概要 ウィキペディア コミュニティ |

| Barzilai, Gad. 2003. Communities and Law: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Beck, U. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage: 2000. What is globalization? Cambridge: Polity Press. Chavis, D.M., Hogge, J.H., McMillan, D.W., & Wandersman, A. 1986. "Sense of community through Brunswick's lens: A first look." Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 24–40. Chipuer, H.M., & Pretty, G.M.H. (1999). A review of the Sense of Community Index: Current uses, factor structure, reliability, and further development. Journal of Community Psychology, 27(6), 643–658. Christensen, K., et al. (2003). Encyclopedia of Community. 4 volumes. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Cohen, A. P. 1985. The Symbolic Construction of Community. Routledge: New York. Durkheim, Émile. 1950 [1895] The Rules of Sociological Method. Translated by S.A. Solovay and J.H. Mueller. New York: The Free Press. Cox, F., J. Erlich, J. Rothman, and J. Tropman. 1970. Strategies of Community Organization: A Book of Readings. Itasca, IL: F.E. Peacock Publishers. Effland, R. 1998. The Cultural Evolution of Civilizations Mesa Community College. Giddens, A. 1999. "Risk and Responsibility" Modern Law Review 62(1): 1–10. James, Paul (1996). Nation Formation: Towards a Theory of Abstract Community. London: Sage Publications. Lenski, G. 1974. Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc. Long, D.A., & Perkins, D.D. (2003). Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Sense of Community Index and Development of a Brief SCI. Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 279–296. Lyall, Scott, ed. (2016). Community in Modern Scottish Literature. Brill | Rodopi: Leiden | Boston. Nancy, Jean-Luc. La Communauté désœuvrée – philosophical questioning of the concept of community and the possibility of encountering a non-subjective concept of it Muegge, Steven (2013). "Platforms, communities and business ecosystems: Lessons learned about entrepreneurship in an interconnected world". Technology Innovation Management Review. 3 (February): 5–15. doi:10.22215/timreview/655. Newman, D. 2005. Sociology: Exploring the Architecture of Everyday Life, Chapter 5. "Building Identity: Socialization" Archived 2012-01-06 at the Wayback Machine Pine Forge Press. Retrieved: 2006-08-05. Putnam, R.D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster Sarason, S.B. 1974. The psychological sense of community: Prospects for a community psychology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 1986. "Commentary: The emergence of a conceptual center." Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 405–407. Smith, M.K. 2001. Community. Encyclopedia of informal education. Last updated: January 28, 2005. Retrieved: 2006-07-15. |

Barzilai, Gad. 2003. コミュニティと法: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ベック、U. 1992. リスク社会: リスク社会:新しい近代に向けて. London: Sage: 2000. グローバリゼーションとは何か?ケンブリッジ: ポリティ・プレス Chavis, D.M., Hogge, J.H., McMillan, D.W., & Wandersman, A. 1986. 「ブランズウィックのレンズを通した共同体感覚: A first look.". Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 24-40. Chipuer, H.M., & Pretty, G.M.H. (1999). Sense of Community Indexのレビュー: 現在の使用法、因子構造、信頼性、さらなる発展。Journal of Community Psychology, 27(6), 643-658. Christensen, K., et al. コミュニティ百科事典。全4巻。Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Cohen, A. P. 1985. The Symbolic Construction of Community. Routledge: ニューヨーク。 Durkheim, Émile. 1950 [1895] 『社会学的方法の規則』. S.A.ソロヴェイ、J.H.ミューラー訳。ニューヨーク: The Free Press. Cox, F., J. Erlich, J. Rothman, and J. Tropman. 1970. コミュニティ組織の戦略: A Book of Readings. Itasca, IL: F.E. Peacock Publishers. Effland, R. 1998. The Cultural Evolution of Civilizations Mesa Community College. Giddens, A. 1999. 「リスクと責任」 Modern Law Review 62(1): 1-10. James, Paul (1996). 国民形成: Towards a Theory of Abstract Community. London: Sage Publications. Lenski, G. 1974. 人間社会: マクロ社会学入門. ニューヨーク: McGraw-Hill, Inc. Long, D.A., & Perkins, D.D. (2003). センス・オブ・コミュニティ指数の確証的因子分析と簡易SCIの開発。Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 279-296. Lyall, Scott, ed. (2016). スコットランド現代文学におけるコミュニティ. Brill | Rodopi: Leiden | Boston. Nancy, Jean-Luc. La Communauté désœuvrée - コミュニティ概念の哲学的問いかけと、非主体的概念との出会いの可能性 Muegge, Steven (2013). 「プラットフォーム、コミュニティ、ビジネス・エコシステム: 相互接続された世界における起業家精神についての教訓". Technology Innovation Management Review. 3 (February): 5–15. doi:10.22215/timreview/655. Newman, D. 2005. Sociology: Exploring the Architecture of Everyday Life, Chapter 5. 「アイデンティティを築く: Socialization" Archived 2012-01-06 at the Wayback Machine Pine Forge Press. 取得:2006-08-05. Putnam, R.D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American community. ニューヨーク: Simon & Schuster Sarason, S.B. 1974. 心理学的共同体感覚: コミュニティ心理学の展望。サンフランシスコ: Jossey-Bass. 1986. 「解説: 概念的中心の出現". Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 405-407. Smith, M.K. 2001. コミュニティ。Encyclopedia of informal education. 最終更新日:2005年1月28日: 2005年1月28日。取得:2006-07-15. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Community |

基本用語・キーワード

リンク(さまざまなコミュニティ概念の使 われ方)

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆