リスク論における知識社会学

Sociology of

knowledge in Risk discourse

| "Risk society is the manner in which modern society organizes in response to risk. The term is closely associated with several key writers on modernity, in particular Ulrich Beck and Anthony Giddens.[1] The term was coined in the 1980s and its popularity during the 1990s was both as a consequence of its links to trends in thinking about wider modernity, and also to its links to popular discourse, in particular the growing environmental concerns during the period.[2]/ DEFINITION: According to the British sociologist Anthony Giddens, a risk society is "a society increasingly preoccupied with the future (and also with safety), which generates the notion of risk",[3] whilst the German sociologist Ulrich Beck defines it as "a systematic way of dealing with hazards and insecurities induced and introduced by modernisation itself".[4] Beck defined modernization as, "surges of technological rationalization and changes in work and organization, but beyond that includes much more: the change in societal characteristics and normal biographies, changes in lifestyle and forms of love, change in the structures of power and influence, in the forms of political repression and participation, in views of reality and in the norms of knowledge. In social science's understanding of modernity, the plough, the steam locomotive and the microchip are visible indicators of a much deeper process, which comprises and reshapes the entire social structure.[5]" | 「リスク社会とは、現代社会がリスクに対応して組織化される様態のこと

である。この用語はモダニティに関する主要な作家、特にウルリッヒ・ベックやアンソニー・ギデンズと密接に関連している[1]。この用語は1980年代に

作られ、1990年代には、より広範なモダニティに関する考え方の傾向と結びついた結果であると同時に、大衆的な言説、特にこの時期に高まりつつあった環

境問題への関心とも結びついた結果である。

[2]/定義:イギリスの社会学者アンソニー・ギデンズによれば、リスク社会とは「リスクという概念を生み出す、未来(そして安全性)にますます夢中にな

る社会」[3]であり、ドイツの社会学者ウルリッヒ・ベックは「近代化そのものによって誘発・導入された危険や不安に対処する体系的な方法」と定義してい

る。

[ベックは近代化を「技術的合理化の波と仕事と組織における変化、しかしそれ以上に多くのものを含む」と定義している。社会的特徴や通常の経歴の変化、ラ

イフスタイルや恋愛の形態の変化、権力と影響力の構造の変化、政治的抑圧と参加の形態の変化、現実の見方や知識の規範の変化などである。社会科学による近

代の理解では、耕運機、蒸気機関車、マイクロチップは、社会構造全体を構成し再構築する、より深いプロセスの目に見える指標である[5]」。 |

| Modernity and realism in science: "Beck and Giddens both approach the risk society firmly from the perspective of modernity, "a shorthand term for modern society or industrial civilization. ... [M]odernity is vastly more dynamic than any previous type of social order. It is a society ... which unlike any preceding culture lives in the future rather than the past."[6] They also draw heavily on the concept of reflexivity, the idea that as a society examines itself, it in turn changes itself in the process. In classical industrial society, the modernist view is based on assumption of realism in science creating a system in which scientists work in an exclusive, inaccessible environment of modern period." | 科学におけるモダニティとリアリズム

「ベックとギデンズはともにモダニティ(近代社会あるいは産業文明を意味する略語)の観点からリスク社会にしっかりとアプローチしている。...

[モダニティは、以前のどのタイプの社会秩序よりもはるかにダイナミックである。社会は......それまでのどの文化とも異なり、過去ではなく未来に生

きる社会である」[6]。古典的な産業社会では、モダニズムの見方は、科学者が近代という排他的で近寄りがたい環境で仕事をするシステムを作り上げる科学

における現実主義の仮定に基づいている。 |

| Environmental risks;"In 1986, right after the Chernobyl disaster, Ulrich Beck, a sociology professor at the University of Munich, published the original German text, Risikogesellschaft, of his highly influential and catalytic work (Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1986). Risikogesellschaft was published in English as Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity in 1992. The ecological crisis is central to this social analysis of the contemporary period. Beck argued that environmental risks had become the predominant product, not just an unpleasant, manageable side-effect, of industrial society. Giddens and Beck argued that whilst humans have always been subjected to a level of risk – such as natural disasters – these have usually been perceived as produced by non-human forces. Modern societies, however, are exposed to risks such as pollution, newly discovered illnesses, crime, that are the result of the modernization process itself. Giddens defines these two types of risks as external risks and manufactured risks.[7] Manufactured risks are marked by a high level of human agency involved in both producing, and mitigating such risks. As manufactured risks are the product of human activity, authors like Giddens and Beck argue that it is possible for societies to assess the level of risk that is being produced, or that is about to be produced. This sort of reflexive introspection can in turn alter the planned activities themselves. As an example, due to disasters such as Chernobyl and the Love Canal Crisis, public faith in the modern project has declined leaving public distrust in industry, government and experts.[8] Social concerns led to increased regulation of the nuclear power industry and to the abandonment of some expansion plans, altering the course of modernization itself. This increased critique of modern industrial practices is said to have resulted in a state of reflexive modernization, illustrated by concepts such as sustainability and the precautionary principle that focus on preventive measures to decrease levels of risk. There are differing opinions as to how the concept of a risk society interacts with social hierarchies and class distinctions.[9] Most agree that social relations have altered with the introduction of manufactured risks and reflexive modernization. Risks, much like wealth, are distributed unevenly in a population and will influence quality of life. Beck has argued that older forms of class structure – based mainly on the accumulation of wealth – atrophy in a modern, risk society, in which people occupy social risk positions that are achieved through risk aversion. "In some of their dimensions these follow the inequalities of class and strata positions, but they bring a fundamentally different distribution logic into play".[10] Beck contends that widespread risks contain a "boomerang effect", in that individuals producing risks will also be exposed to them. This argument suggests that wealthy individuals whose capital is largely responsible for creating pollution will also have to suffer when, for example, the contaminants seep into the water supply. This argument may seem oversimplified, as wealthy people may have the ability to mitigate risk more easily by, for example, buying bottled water. Beck, however, has argued that the distribution of this sort of risk is the result of knowledge, rather than wealth. Whilst the wealthy person may have access to resources that enable him or her to avert risk, this would not even be an option were the person unaware that the risk even existed. However, risks do not only affect those of a certain social class or place, as risk is not missed and can affect everyone regardless of societal class; no one is free from risk.[11] By contrast, Giddens has argued that older forms of class structure maintain a somewhat stronger role in a risk society, now being partly defined "in terms of differential access to forms of self-actualization and empowerment".[12] Giddens has also tended to approach the concept of a risk society more positively than Beck, suggesting that there "can be no question of merely taking a negative attitude towards risk. Risk needs to be disciplined, but active risk-taking is a core element of a dynamic economy and an innovative society."[13]"-https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_society | 環境リスク;「チェルノブイリ原発事故直後の1986年、ミュンヘン大

学の社会学教授ウルリッヒ・ベックは、大きな影響力を持ち、触媒となった著作のドイツ語原文『Risikogesellschaft』を出版した

(Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1986)。Risikogesellschaft』は英語版『Risk

Society』として出版された: Towards a New

Modernity)として1992年に出版された。エコロジーの危機は、この現代社会分析の中心である。ベックは、環境リスクは産業社会の単なる不快で

管理可能な副作用ではなく、主要な産物になっていると主張した。ギデンズとベックは、人間は常に自然災害のようなレベルのリスクにさらされてきたが、それ

らは通常、人間以外の力によって生み出されたものとして認識されてきたと主張した。しかし現代社会は、公害や新たに発見された病気、犯罪など、近代化プロ

セスそのものがもたらすリスクにさらされている。ギデンズはこれら2種類のリスクを、外部リスクと製造されたリスクと定義している。製造されたリスクは人

間の活動の産物であるため、ギデンズやベックのような著者は、社会が製造されている、あるいは製造されようとしているリスクのレベルを評価することが可能

であると主張している。このような反省的内省は、ひいては計画された活動そのものを変化させる可能性がある。一例として、チェルノブイリや「愛の運河危

機」のような災害のために、近代的プロジェクトに対する社会的信頼は低下し、産業界、政府、専門家に対する不信が残った[8]。このような近代的な産業慣

行に対する批判の高まりは、持続可能性や予防原則といった、リスクのレベルを下げるための予防措置に焦点を当てた概念によって示される、反射的な近代化の

状態をもたらしたと言われている。リスク社会という概念が、社会階層や階級差別とどのように相互作用するかについては、意見が分かれている[9]。リスク

は富と同様、集団に不均等に分布し、生活の質に影響を与える。ベックは、主に富の蓄積に基づく古い形の階級構造は、人々がリスク回避によって達成される社

会的リスクポジションを占める現代のリスク社会では萎縮すると主張している。「ベックは、広範なリスクには「ブーメラン効果」があり、リスクを生み出す個

人もまたリスクにさらされると主張している。この主張は、例えば汚染物質が水源にしみ込んだ場合、汚染を生み出す主な原因を資本に持つ裕福な個人も苦しま

なければならないことを示唆している。富裕層は、例えばボトル入りの水を買うなどして、より簡単にリスクを軽減する能力を持っているかもしれないので、こ

の議論は単純化しすぎているように見えるかもしれない。しかしベックは、この種のリスクの分布は、富よりもむしろ知識の結果であると主張している。裕福な

人はリスクを回避するための資源を利用できるかもしれないが、リスクの存在にさえ気づいていなければ、そのような選択肢はないだろう。しかし、リスクは特

定の社会階層や場所に属する人々だけに影響を与えるものではなく、リスクは見逃されるものではなく、社会階層に関係なく誰にでも影響を与える可能性があ

る。

[ギデンズはまた、ベックよりもリスク社会の概念に肯定的にアプローチする傾向があり、「リスクに対して単に否定的な態度をとることは問題ではない。リス

クは規律される必要があるが、積極的なリスクテイクはダイナミックな経済と革新的な社会の中核的要素である。 |

| -https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Risk_society | Sociology

of knowledge in Risk society |

文献:ベック、ウルリヒ第2章 危険社会 における政治的知識論『危険社会』東 廉訳、Pp.77-134、法政大学出版局

訳が悪いのか? それともベックのオツム がイマイチなのか(英語が原著の別の本を読んだけど、ベックの議論は散漫で後者の可能性が高いかもしれ ない)。ベックのリスク論とは迷信的科学論などではなく《未来に対する自分の行動性向=ヘクシスを考えるための学問的手掛かり》と認識されよ。

とりあえず、章立て。

☆ベック論

| Ulrich Beck (* 15. Mai 1944 in Stolp; † 1. Januar 2015 in München) war ein deutscher Soziologe. Weit über die Fachgrenzen hinaus bekannt wurde Beck mit seinem 1986 erschienenen und in 35 Sprachen übersetzten Buch Risikogesellschaft. Auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne. Darin beschrieb er unter anderem die „Enttraditionalisierung der industriegesellschaftlichen Lebensformen“, die „Entstandardisierung der Erwerbsarbeit“ sowie die Individualisierung von Lebenslagen und Biographiemustern. Beck kritisierte soziologische Betrachtungsweisen, die in nationalstaatlichen Aspekten und Begrifflichkeiten verharrten. Die technisch-ökonomischen Fortschritte im industriegesellschaftlichen Rahmen sah er – etwa am Beispiel der Atomkraftnutzung – von ungeplanten Nebenfolgen übernationalen und teils globalen Ausmaßes überlagert und in Frage gestellt. Bezugspunkte seiner Theoriebildung waren zunehmend die Erscheinungsformen und Folgen grenzüberschreitender Umweltprobleme und der Globalisierung. Beck war Professor für Soziologie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, an der London School of Economics and Political Science und an der FMSH (Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme) in Paris. Die Forschung und Theoriebildung Ulrich Becks war mit vielerlei aktivem politischen Engagement verbunden. Im Folgenzusammenhang der Finanzkrise ab 2007, die zu einer Staatsschuldenkrise im Euroraum führte, verfasste er 2012 gemeinsam mit dem Grünen-Politiker Daniel Cohn-Bendit das Manifest „Wir sind Europa!“, das ein Freiwilliges Europäisches Jahr für alle Altersgruppen propagierte mit dem Ziel, Europa im tätigen Miteinander seiner Bürger „von unten“ neu zu gründen. |

ウルリッヒ・ベック(1944年5月15日 - 2015年1月1日)は、ドイツの社会学者である。 ベックは、1986年に出版され35言語に翻訳された著書『リスク社会:新たな近代への道』によって、専門分野の枠を超えて広く知られるようになった。こ の著書の中で、ベックは「産業社会における生命体の脱領土化」、「有給雇用の脱標準化」、そして生活状況や伝記的パターンの個別化などを論じている。ベッ クは、国民国家の側面や概念に根ざしたままの社会学的なアプローチを批判した。彼は、産業社会の枠組みにおける技術的・経済的進歩、例えば原子力利用など は、国境を越えた、時には地球規模の予期せぬ副作用によって影が薄くなり、疑問視されるようになると見なした。国境を越えた環境問題やグローバル化の兆候 や結果は、彼の理論展開の参照点としてますます重要になっていった。 ベックはミュンヘン大学、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス、パリのFMSH(人文社会科学振興財団)で社会学の教授を務めた。ウルリッヒ・ベック の研究と理論展開は、幅広い政治的活動と結びついていた。2007年に始まり、ユーロ圏のソブリン債危機へとつながった金融危機を背景に、2012年に は、緑の党の政治家ダニエル・コーエン=ベンディット氏とともに、あらゆる年齢層を対象とした「ヨーロッパ・ボランティア・イヤー」の創設を呼びかけたマ ニフェスト「We are Europe!(我々はヨーロッパだ!)」を執筆した。このマニフェストは、市民の積極的な参加を通じて「ボトムアップ」でヨーロッパを再構築することを 目的としている。 |

| Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Leben 2 Werk 2.1 Entgrenzte Risikogesellschaft 2.2 Reflexive Modernisierung 2.3 Subpolitik 2.4 Individualisierung 2.5 Kosmopolitisierung 2.6 Europa in Theorie und Praxis 2.7 Politische Standortbestimmungen 2.8 Darstellungsmittel 3 Resonanz und Kritik 3.1 Zu Leitmotiven Becks als Forscher und Publizist 3.2 Zur Risikogesellschaft 3.3 Zur Individualisierung 3.4 Zur Kosmopolitisierung 3.5 Zur Modernisierungstheorie 3.6 Zu Beschäftigungspolitik und Grundeinkommen 3.7 Zu Ulrich Becks neuer kritischer Theorie 3.8 Zu einer anschlussfähigen Soziologie 4 Auszeichnungen 5 Schriften 5.1 Aufsätze 5.2 Interviews 5.3 Herausgeber 6 Literatur 7 Weblinks 8 Einzelnachweise und Anmerkungen |

目次 1 人生 2 仕事 2.1 境界のないリスク社会 2.2 反射的な近代化 2.3 サブ・ポリティクス 2.4 個人化 2.5 コスモポリタン化 2.6 理論と実践におけるヨーロッパ 2.7 政治的ポジションの確定 2.8 表現手段 3 反応と批判 3.1 研究者および広報担当者としてのベックの主題について 3.2 リスク社会について 3.3 個人化について 3.4 国際化について 3.5 近代化理論について 3.6 雇用政策とベーシックインカムについて 3.7 ウルリッヒ・ベックの新しい批判理論について 3.8 採用可能な社会学的なアプローチについて 4 受賞 5 出版物 5.1 エッセイ 5.2 インタビュー 5.3 編集 6 文献 7 ウェブリンク 8 参考文献および注釈 |

Leben Ulrich Beck und Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim (2011) auf dem Blauen Sofa Ulrich Beck wurde als Sohn des Marineoffiziers Wilhelm Beck und seiner Frau Magarete, geb. von Schulz-Hausmann, in Stolp (heute Słupsk, Polen) geboren und wuchs in Hannover auf.[1] Nach dem Abitur nahm er zunächst in Freiburg im Breisgau ein Studium der Rechtswissenschaften auf. Später erhielt er ein Stipendium der Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes[2] und studierte Soziologie, Philosophie, Psychologie und Politische Wissenschaft an der Universität München. Dort wurde er 1972 promoviert und sieben Jahre später im Fach Soziologie habilitiert. Ulrich Beck war mit der Familiensoziologin Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim verheiratet. Professuren hatte Beck von 1979 bis 1981 an der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster und von 1981 bis 1992 in Bamberg inne. Er wirkte jahrelang in Konvent und Vorstand der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie mit. Von 1999 bis 2009 war Ulrich Beck Sprecher des von der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) finanzierten Sonderforschungsbereichs 536: „Reflexive Modernisierung“, eines interdisziplinären Kooperationszusammenhangs zwischen vier Universitäten im Münchner Raum.[3] Hier wurde Becks Theorie reflexiver Modernisierung interdisziplinär anhand eines breiten Themenspektrums in entsprechenden Forschungsprojekten empirisch überprüft. Beck war Mitglied des Kuratoriums am Jüdischen Zentrum München und des deutschen PEN. Im März 2011 wurde er Mitglied der Ethikkommission für sichere Energieversorgung. Vom Europäischen Forschungsrat wurde ihm 2012 ein Projekt zum Thema „Methodologischer Kosmopolitismus am Beispiel des Klimawandels“ mit fünfjähriger Laufzeit bewilligt. Ulrich Beck starb am 1. Januar 2015 im Alter von 70 Jahren an den Folgen eines Herzinfarkts.[4] Er ist auf dem Münchner Nordfriedhof beerdigt. |

人生 ウルリッヒ・ベックとエリザベス・ベック=ゲルンスハイム著『青いソファの上で』(2011年 ウルリッヒ・ベックは、海軍士官ヴィルヘルム・ベックとその妻マグダレーテ(旧姓フォン・シュルツ=ハウスマン)の間に、ポーランドのストルプ(現スルプ スク)で生まれ、ハノーファーで育った。高校を卒業後、まずフライブルク・イム・ブライスガウで法律を学んだ。その後、ドイツ学術振興会(DAAD)から 奨学金を受け、ミュンヘン大学で社会学、哲学、心理学、政治学を学んだ。1972年に博士号を取得し、7年後に社会学の教授資格を取得した。ウルリッヒ・ ベックは家族社会学者のエリザベート・ベック=ゲルンスハイムと結婚していた。 ベックは1979年から1981年までミュンスターのヴェストファーレン・ヴィルヘルム大学、1981年から1992年までバンベルクの大学で教授職に就 いていた。また、長年にわたりドイツ社会学会の評議員および理事会のメンバーでもあった。1999年から2009年にかけて、ウルリッヒ・ベックは、ドイ ツ研究振興協会(DFG)の資金援助を受け、ミュンヘン地域の4つの大学間の学際的な協力関係である共同研究センター536「反省的近代化」のスポークス マンを務めた。3] ここでは、ベックの反省的近代化理論が、学際的な研究プロジェクトにおける幅広いトピックを題材に、実証的に検証された。 ベックはミュンヘンのユダヤセンターおよびドイツPENの評議員でもあった。2011年3月には、安全なエネルギー供給のための倫理委員会のメンバーと なった。2012年には、欧州研究会議から「気候変動を例とした方法論的コスモポリタニズム」に関する5年間のプロジェクトを授与された。 2015年1月1日、心臓発作により70歳で死去。ミュンヘンのNordfriedhof墓地に埋葬されている。 |

Werk Autograph Im Anschluss an die Erfolgspublikation „Risikogesellschaft“ von 1986 publizierte Ulrich Beck während der folgenden 25 Jahre eine Vielzahl weiterer Beiträge zu der sein Forschen bestimmenden Frage: Wie können gesellschaftliches und politisches Denken und Handeln angesichts des radikalen globalen Wandels (Umweltzerstörungen, Finanzkrise, globale Erwärmung, Krise der Demokratie und der nationalstaatlichen Institutionen) für eine historisch-neuartig verflochtene Moderne geöffnet werden?[5] Zum Gegenstand von Becks Forschungen, Publikationen und politischen Initiativen wurden hauptsächlich länderübergreifende und weltumspannende soziologische Zusammenhänge. Besonderes Augenmerk richtete er dabei auf Chancen und Probleme der europäischen Integration, auf die Globalisierungstendenzen und -herausforderungen sowie auf die Perspektiven einer Weltinnenpolitik. Entgrenzte Risikogesellschaft Im Erscheinungsjahr von Ulrich Becks Studie Risikogesellschaft. Auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne kam es am 26. April zur Nuklearkatastrophe von Tschernobyl, auf die Beck gleich eingangs Bezug nahm: „Vieles, das im Schreiben noch argumentativ erkämpft wurde – die Nichtwahrnehmbarkeit der Gefahren, ihre Wissensabhängigkeit, ihre Übernationalität, die »ökologische Enteignung«, der Umschlag von Normalität in Absurdität usw. – liest sich nach Tschernobyl wie eine platte Beschreibung der Gegenwart.“[6] Am Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts erweise sich die im Zuge der technisch-industriellen Verwandlung und weltweiten Vermarktung in das Industriesystem hereingeholte Natur als eine vernutzte und verseuchte. „Gefahren werden zu blinden Passagieren des Normalkonsums. Sie reisen mit dem Wind und mit dem Wasser, stecken in allem und in jedem und passieren mit dem Lebensnotwendigsten – der Atemluft, der Nahrung, der Kleidung, der Wohnungseinrichtung – alle sonst so streng kontrollierten Schutzzonen der Moderne.“ Dies sei das Ende der klassischen Industriegesellschaft, wie sie das 19. Jahrhundert hervorgebracht habe, sowie der herkömmlichen Vorstellungen unter anderem von nationalstaatlicher Souveränität, Fortschrittsautomatik, Klassen oder Leistungsprinzip.[7] Markantes Unterscheidungsmerkmal der Risikogesellschaft im Vergleich zu den Unsicherheiten, Bedrohungen und Katastrophen früherer Epochen – die Naturgewalten, Göttern oder Dämonen zugeschrieben wurden – sei die Bedingtheit ökologischer, chemischer oder gentechnischer Gefahren durch von Menschen getroffene Entscheidungen: „Beim Erdbeben von Lissabon im Jahre 1755 hatte die Welt aufgestöhnt. Aber die Aufklärer haben nicht, wie nach der Atomreaktor-Katastrophe von Tschernobyl, die Industriellen, die Ingenieure und Politiker, sondern Gott vor das Menschengericht zitiert.“[8] Beck stellt fest, Technologen hätten heutzutage grünes Licht, die Welt umzukrempeln, ja selbst „Verfassungsänderungen des Lebens“ voranzutreiben, die mit der Humangenetik unlegitimiert Einzug hielten. „Man wundert sich nur irgendwann später, daß es die Familie ähnlich wie die Dinosaurier und die Maikäfer nicht mehr gibt.“ Die „brave new world“ könne Wirklichkeit werden, „wenn und weil der kulturelle Horizont zerbrochen und abgestreift wurde, in dem sie noch als ‚brave new world’ erscheint und kritisierbar ist.“[9] Deutlich unterscheidet Beck zwischen Risiko und Katastrophe. Risiko schließt demnach die Antizipation zukünftiger Katastrophen in der Gegenwart ein. Daraus ergeben sich Ziel und Möglichkeiten der Katastrophenvermeidung, etwa mit Hilfe von Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnungen, Versicherungsregelungen und Prävention. Lange bevor 2008 weltweit die Finanzkrise ausbrach, prognostizierte Beck:[10] Die neuen Risiken, die eine globale Antizipation globaler Katastrophen in Gang setzen, erschüttern die institutionellen und politischen Grundlagen moderner Gesellschaften (siehe zuletzt die weltweite Kontroverse über die Risiken der Atomenergie nach der Reaktorkatastrophe von Fukushima). Der neue Typus globaler Risiken sei durch vier Merkmale gekennzeichnet: Entgrenzung, Unkontrollierbarkeit, Nicht-Kompensierbarkeit und (mehr oder weniger uneingestandenes) Nichtwissen.[11] Weil aber globale Risiken teilweise auf Nicht-Wissen beruhen, sind die Konfliktlinien der Weltrisikogesellschaft kulturell bestimmt. Wir haben es – so Beck – mit einem clash of risk cultures[12] zu tun. Ulrich Becks „Risikogesellschaft“ wurde als eines der 20 bedeutendsten soziologischen Werke des Jahrhunderts durch die International Sociological Association (ISA) ausgezeichnet.[13] |

仕事 署名(サイン) 1986年に『リスク社会』を成功裏に出版した後、ウルリッヒ・ベックは、その後の25年間にわたって自身の研究を決定づけた問題について、多数の論文を 発表した。急進的なグローバルな変化(環境破壊、金融危機、地球温暖化、民主主義と国民国家制度の危機)に直面する中で、社会および政治思想と行動を、歴 史的に前例のないほど複雑に絡み合った現代にどう適応させていくか?[5] ベックの研究、出版、政治的イニシアティブの主題は、主に国境を越えたグローバルな社会学的な文脈であった。彼は、ヨーロッパ統合の機会と問題、グローバル化の傾向と課題、そして世界的な国内政策の展望に特に注目した。 国境なきリスク社会 ウルリッヒ・ベックの研究『リスク社会』が発表されたのは、 『もう一つの近代への道』の出版に先立つ4月26日、チェルノブイリ原発事故が発生した。ベックは冒頭で次のように述べている。「本書の執筆中に議論され ていたことの多く、すなわち、危険の不可視性、知識への依存、超国家性、『生態学的収用』、正常から不条理への変容などについては、 「チェルノブイリ後の現状を平面的に描写しているようだ」[6] 20世紀の終わりに、技術的・産業的変革と世界的な商業化の過程で産業システムに取り込まれた自然は、使い尽くされ、汚染されていることが明らかになって いる。「危険は通常の消費の盲点となる。それらは風や水とともに移動し、あらゆるものや人々に存在し、私たちが呼吸する空気、口にする食物、身につける衣 類、家財道具など、生活に必要なものすべてとともに、厳格に管理された近代の保護区域をすべて通過する。」 これは、19世紀に登場した古典的な産業社会の終焉であり、国家主権、自動的な進歩、階級、あるいは成果主義といった概念の終焉でもある。 リスク社会の顕著な特徴は、それ以前の時代の不確実性、脅威、大惨事(それらは神や悪魔の仕業とされた自然の力によるもの)と比較すると、人間による決定 によって生じる生態系、化学、遺伝子工学の危険性という条件付きである。「1755年のリスボン地震では世界が悲鳴を上げた。しかし、啓蒙主義は、チェル ノブイリ原子炉事故の後にそうしたように、産業家、技術者、政治家を人間の宮廷に呼び寄せたのではなく、神を呼び寄せたのだ。」[8] ベックは、現代の科学技術者は世界をひっくり返すこと、さらには承認なしに人間の遺伝子に介入する「生命の憲法改正」さえも推し進めることを許可されてい ると指摘している。「ある時点になって、家族というものが、恐竜やコクワガタのように、もはや存在しないことに気づいて驚くだけだ。」 「もし、そして、文化的な地平線が打ち破られ、剥ぎ取られたのであれば、それは『すばらしい新世界』として依然として現れ、批判の対象となり得る。」 [9] ベックはリスクとカタストロフを明確に区別している。ベックによれば、リスクには、未来のカタストロフを現在において予期することが含まれる。その結果、 例えば確率計算や保険規制、予防措置といった手段によって、カタストロフを回避する目標と可能性が生まれる。2008年の世界金融危機が起こるはるか以前 に、ベックは、世界的な大惨事の予測が引き金となって生じる新たなリスクが、現代社会の制度や政治の基盤を揺るがすだろうと予測していた(福島原発事故後 の原子力エネルギーのリスクをめぐる世界的な論争が最近起こったことは記憶に新しい)。この新しいタイプのグローバルリスクは、境界の消滅、制御不能、補 償不能、そして(ある程度は認識されているが)無知という4つの特徴を持つ。[11] しかし、グローバルリスクは無知に部分的に基づいているため、世界リスク社会における対立の線引きは文化によって決定される。ベックによれば、私たちはリ スク文化の衝突に対処しているのだ。 ウルリッヒ・ベックの『リスク社会』は、国際社会学会(ISA)により、20世紀の社会学における最も重要な著作20冊の1つに選ばれた。[13] |

| Reflexive Modernisierung Die Theorie reflexiver Modernisierung (siehe auch die Unterscheidung von Erster und Zweiter Moderne) arbeitet den Grundgedanken aus, dass der Siegeszug der industriellen Moderne über den Erdball Nebenfolgen erzeugt, die die institutionellen Grundlagen und Koordinaten der nationalstaatlichen Moderne infrage stellen, verändern, für politisches Handeln öffnen.[14] Für Beck handelt es sich im Kern um die Selbstkonfrontation von Modernisierungsfolgen mit den Modernisierungsgrundlagen: „Die Konstellationen der Risikogesellschaft werden erzeugt, weil im Denken und Handeln der Menschen und der Institutionen die Selbstverständlichkeiten der Industriegesellschaft (der Fortschrittskonsens, die Abstraktion von ökologischen Folgen und Gefahren, der Kontrolloptimismus) dominieren. Die Risikogesellschaft ist keine Option, die im Zuge politischer Auseinandersetzungen gewählt oder verworfen werden könnte. Sie entsteht im Selbstlauf verselbständigter, folgenblinder, gefahrentauber Modernisierungsprozesse. Diese erzeugen in der Summe und Latenz Selbstgefährdungen, die die Grundlagen der Industriegesellschaft in Frage stellen, aufheben, verändern.“[15] Reflexive Modernisierung geht laut Beck einher mit Formen der Individualisierung sozialer Ungleichheit. Die kulturellen Voraussetzungen sozialer Klassen schwinden, wobei es zu einer Verschärfung sozialer Ungleichheit kommt, „die nun nicht mehr in lebenslang lebensweltlich identifizierbaren Großlagen verläuft, sondern (lebens)zeitlich, räumlich und sozial zersplittert wird.“[16] Wolfgang Bonß und Christoph Lau sehen reflexive Modernisierung als einen Prozess des Grundlagenwandels, bei dem die alten Gegebenheiten und Lösungsansätze neben neuen anderen weiterbestehen. Zur alten Form der Kernfamilie gesellten sich diverse neue Formen; neben der klassischen Form des fordistischen Unternehmens etablierten sich die neuen Formen der Netzwerkorganisation; zum klassischen „Normalarbeitsverhältnis“ kämen neue, flexibilisierte Arbeitsformen hinzu; und neben die herkömmlichen Formen disziplinärer Grundlagenforschung träten nun diverse Formen transdisziplinärer Forschung. „Gerade diese Gleichzeitigkeit von Altem und Neuem macht es so schwierig, den Wandel eindeutig zu diagnostizieren oder gar als klaren Bruch zu beschreiben.“[17] Becks Theorie reflexiver Modernisierung zielt auf übergreifende Wechselwirkungen und Zusammenhänge, auch in wissenschaftstheoretischer Hinsicht. So heißt es in Risikogesellschaft: „Rationalität und Irrationalität sind nie nur eine Frage der Gegenwart und Vergangenheit, sondern auch der möglichen Zukunft. Wir können aus unseren Fehlern lernen – das heißt auch: eine andere Wissenschaft ist immer möglich. Nicht nur eine andere Theorie, sondern eine andere Erkenntnistheorie, ein anderes Verhältnis von Theorie und Praxis dieses Verhältnisses.“[18] Über die Soziologie hinaus trat Beck dafür ein, nicht in den herkömmlichen Forschungsansätzen und -theorien zu verharren. So monierte er etwa in der Geschichtswissenschaft einen Mangel an Sorge um „eine theoretisch umfassende Auseinandersetzung mit den Grundfragen der Historiographie“ und plädierte dafür, historischen Wandel auch im Lichte geeigneter soziologischer Theorieaspekte zu erforschen. Anlass dazu gab ihm die Untersuchung von Benjamin Steiner Nebenfolgen in der Geschichte. Eine historische Soziologie reflexiver Modernisierung, für die Beck das Geleitwort schrieb.[19] Steiner selbst, nachdem er sein Thema der historischen Nebenfolgen an vier Untersuchungsgegenständen von der Attischen Demokratie bis zur Krise des Historismus exemplifiziert hat, gelangt zu dem Schluss: „Die Rolle, die unintendierte Nebenfolgen in der Geschichte spielen, sollte auch aus dem Grunde stärker anerkannt werden, dass unsere Zeit mehr denn je eines Verständnisses der tieferen Strukturen bedarf, die dem historischen Geschehen zugrunde liegen.“[20] |

再帰的近代化 再帰的近代化の理論(第1近代と第2近代の区別も参照)は、世界的な産業近代の勝利が、国家近代の制度的基盤や調整を問い直し、変化させる副作用を生み出 し、政治的行動へと開放するという基本的な考え方を詳しく説明している。14] ベックにとって、これは本質的には、近代化の結果と近代化の基盤との自己対峙の問題である。 「リスク社会の星座は、産業社会の自明の前提(進歩のコンセンサス、生態学的結果と危険性の抽象化、制御の楽観主義)が人々や組織の思考や行動を支配して いるために生み出される。リスク社会は、政治的議論の過程で選択または拒否できる選択肢ではない。それは、結果に盲目で危険に耳を傾けない近代化プロセス が自己増殖することによって生じる。これらのプロセスは、総体として、また潜在的に自己を危険にさらすものであり、産業社会の基盤を問い直し、一時停止 し、変化させるものである。 ベックによれば、再帰的近代化は、社会的不平等の個人化の形と表裏一体である。社会階級の文化的前提条件が衰退し、その結果、社会的不平等の激化が起こ る。「それはもはや、生涯を通じて生活世界で識別可能なマクロな状況で起こるのではなく、(生活)時間、空間、社会の観点から断片化されている」 [16] ヴォルフガング・ボンツとクリストフ・ラウは、再帰的近代化を、古い状況と解決策が新しい状況と共存する根本的な変化のプロセスと捉えている。核家族の古 い形態はさまざまな新しい形態と混在し、古典的なフォード主義的企業の形態と並んで、新しいネットワーク組織の形態が確立された。古典的な「正規雇用関 係」は、より柔軟な新しい雇用形態と混在し、規律的な基礎研究の伝統的な形態は、さまざまな学際的研究の形態と混在した。「まさにこの新旧の同時進行こそ が、変化を明確に診断することを非常に困難にしている。ましてや、それを明確な断絶として表現することはなおさらである」[17] ベックの再帰的近代化論は、科学哲学の観点からも、包括的な相互作用と相互関係に焦点を当てている。『リスク社会』の中で、彼は次のように書いている。 「合理性と非合理性の問題は、決して現在と過去の問題だけではなく、将来の可能性の問題でもある。私たちは過ちから学ぶことができる。これはまた、異なる 科学が常に可能であることを意味する。異なる理論だけでなく、異なる認識論、理論と実践の関係における異なる関係である」[18] 社会学の領域を超えて、ベックは従来の研究アプローチや理論に固執しないことを提唱した。例えば、歴史学における「歴史叙述の根本的な問題に対する理論的 な包括的な検証」への関心の欠如を批判し、歴史的変化を適切な社会学的な理論的観点から研究することを提唱した。このきっかけとなったのは、ベンヤミン・ シュタイナーによる研究であり、ベックは『歴史の余波。再帰的近代化の歴史社会学』(Nebenfolgen in der Geschichte. Eine historische Soziologie reflexiver Moderne)の序文を執筆した。 [19] シュタイナー自身は、アッティカ民主政から歴史主義の危機に至るまでの4つのテーマを例に挙げた上で、次のような結論に達している。「歴史において予期せ ぬ副作用が果たす役割は、より十分に認識されるべきである。また、現代はこれまで以上に、歴史的事件の根底にあるより深い構造の理解を必要としているとい う理由からも、である。」[20] |

| Subpolitik Reflexive Modernisierung, die auf die Bedingungen „hochentwickelter Demokratie und durchgesetzter Wissenschaftlichkeit“ trifft, so Ulrich Beck bereits 1986 in Risikogesellschaft, „führt zu charakteristischen Entgrenzungen von Wissenschaft und Politik. Erkenntnis- und Veränderungsmonopole werden ausdifferenziert, wandern aus den vorgesehenen Orten ab und werden in einem bestimmten, veränderbaren Sinn allgemein verfügbar.“[21] Die Wissenschaften kämen in der Zweiten Moderne nicht mehr nur für Problemlösungen in Betracht, sondern auch als Problemverursacher; denn wissenschaftliche Lösungen und Befreiungsversprechen hätten im Zuge der praktischen Umsetzung unterdessen ihre fragwürdigen Seiten offenbart. Dies und die aus der Ausdifferenzierung von Wissenschaft sich ergebende unüberschaubare Flut zweifelhafter, unzusammenhängender Detailergebnisse erzeugten eine Unsicherheit auch im Außenverhältnis; so würden Adressaten und Verwender wissenschaftlicher Ergebnisse in Politik, Wirtschaft, und Öffentlichkeit „zu aktiven Mitproduzenten im gesellschaftlichen Prozeß der Erkenntnisdefinition“ – eine Entwicklung von „hochgradiger Ambivalenz“:[22] „Sie enthält die Chance der Emanzipation gesellschaftlicher Praxis von Wissenschaft durch Wissenschaft; andererseits immunisiert sie gesellschaftlich geltende Ideologien und Interessenstandpunkte gegen wissenschaftliche Aufklärungsansprüche und öffnet einer Feudalisierung wissenschaftlicher Erkenntnispraxis durch ökonomisch-politische Interessen und »neue Glaubensmächte« Tor und Tür.“[23] Im Sinne einer reflexiven Verwissenschaftlichung und subpolitischen Kontrolle setzte Beck u. a. auf institutionell abgesicherte Gegenexpertise und alternative Berufspraxis. „Nur dort, wo Medizin gegen Medizin, Atomphysik gegen Atomphysik, Humangenetik gegen Humangenetik, Informationstechnik gegen Informationstechnik steht, kann nach außen hin übersehbar und beurteilbar werden, welche Zukunft hier in der Retorte ist. Die Ermöglichung von Selbstkritik in allen Formen ist nicht etwa eine Gefährdung, sondern der wahrscheinlich einzige Weg, auf dem der Irrtum, der uns sonst früher oder noch früher die Welt um die Ohren fliegen läßt, vorweg entdeckt werden könnte.“[24] Für die Zukunft der Demokratie aber gehe es um die Alternative, ob die Bürgerschaft „in allen Einzelheiten der Überlebensfragen“ vom Urteil der Experten und Gegenexperten abhänge oder ob man mit der kulturell hergestellten Wahrnehmbarkeit der Gefahren die individuelle Urteilskompetenz zurückgewinne.[25] Seit den 1980er Jahren wurden laut Beck wichtige politische Themen von Bürgerinitiativen gesetzt – gegen den Widerstand der etablierten Parteien im Westen, gegen den Spitzel- und Überwachungsapparat der Staatsmacht durch die seinerzeitigen Widerstandsformen und Straßendemonstrationen im Osten Europas.[26] Solche Ansätze und Formen der Gesellschaftsgestaltung von unten bezeichnet er als Subpolitik. Zu ihren Merkmalen gehöre die direkte punktuelle Teilhabe von Bürgern an politischen Entscheidungen, vorbei an Parteien und Parlamenten als den Institutionen repräsentativer Willensbildung. Wirtschaft, Wissenschaft, Beruf und privater Alltag gerieten so in die Stürme politischer Auseinandersetzung. Zu den besonders auffälligen und effektiven Mitteln von Subpolitik zählt Beck massenhafte, auch transnationale Boykottbewegungen.[27] |

サブポリティクス ウルリッヒ・ベックは、1986年の著書『リスク社会』で早くも指摘しているが、「高度に発達した民主主義と確立された科学」という条件に直面する再帰的 近代化は、「科学と政治の境界を特徴的に曖昧にする」ことになる。知識と変化の独占は分化し、意図された場所から移動し、特定の変化可能な意味において一 般的に利用可能になる。」[21] 第二の近代において、科学はもはや問題解決のみを目的とするのではなく、問題を生み出すものともみなされるようになる。なぜなら、科学的解決策や解放の約 束は、その実用化の過程で、その疑わしい側面を露呈しているからだ。また、科学の分化によって生じた疑わしく、支離滅裂な詳細な結果の制御不能な洪水も、 外部関係に不安を生じさせた。このようにして、政治、ビジネス、公共の場における科学結果の受容者や利用者は、「知識を定義する社会的プロセスにおける能 動的な共同制作者」となった。これは「非常に両義的な」性質を持つ発展である。[22] 「これは、科学によって社会実践を科学から解放する可能性を含んでいる。その一方で、社会的に有効なイデオロギーや利害に基づく視点が科学的啓蒙主義の主 張に対して免疫力を持ち、経済的・政治的利益や『新たな信念の力』によって科学的知識の実践が封建化される可能性を開くことになる」[23] 再帰的サイエンスと政治的支配という意味において、ベックは、制度的に保護されたカウンター・エクスパート(専門的知識に対抗する専門家)や代替的専門的実践などを提唱した。 「医学が医学に、原子物理学が原子物理学に、人間遺伝学が人間遺伝学に、情報技術が情報技術に立ち向かう場所においてのみ、この試験管内の未来が外部から 見られ、判断される。あらゆる形での自己批判を可能にすることは脅威ではなく、おそらく、さもなければ遅かれ早かれ我々の周囲の世界を吹き飛ばすような過 ちを事前に発見できる唯一の方法である。」[24] しかし、民主主義の未来にとって重要なのは、市民権が「生存に関する問題のあらゆる細部にわたって」専門家と反専門家の判断に依存するのか、それとも文化的に構築された危険に対する感受性によって、個々人の判断能力が回復するのか、という選択である。 ベックによれば、1980年代以降、西欧諸国の既成政党の抵抗や、東欧諸国における抵抗運動や街頭デモの形をとった国家の密告・監視機構に反対する形で、 重要な政治問題は市民のイニシアティブによって決定されるようになってきた。その特徴としては、代表制の意思決定機関である政党や議会を迂回して、市民が 政治的意思決定に直接かつ選択的に参加することが挙げられる。こうして、経済、科学、労働、そして個人の日常生活が政治的議論の嵐に巻き込まれることに なった。ベックは、大規模な国境を越えた不買運動を、サブポリティクスの手段の中でも特に印象的で効果的なものとして挙げている。 |

| Individualisierung Individualisierung im Sinne Ulrich Becks meint nicht Individualismus, auch nicht Emanzipation, Autonomie, Individuation (Personenwerdung). Vielmehr gehe es um Prozesse erstens der Auflösung, zweitens der Ablösung industriegesellschaftlicher Lebensformen (Klasse, Schicht, Geschlechterverhältnisse, Normalfamilie, lebenslanger Beruf), unter anderem hervorgerufen durch institutionellen Wandel in Form von an das Individuum adressierten sozialen und politischen Grundrechten, in Gestalt veränderter Ausbildungsgänge und ausgreifender Mobilität der Arbeit. Es komme zu Verhältnissen, in denen die Individuen ihre Biographie selbst herstellen, inszenieren, zusammenschustern müssen. Die „Normalbiographie“ wird laut Beck zur „Wahlbiographie“, zur „Bastelbiographie“, zur „Bruchbiographie“. Die Menschen seien – in Anlehnung an Sartre – zur Individualisierung verdammt.[28] Diese Entwicklung gehe nicht nur in den klassischen Industrieländern vor sich, sondern betreffe zeitversetzt und in anderen Formen z. B. auch China, Japan und Südkorea.[29] |

個人化 ウルリッヒ・ベックのいう個人化とは、個人主義でもなく、解放でも、自律でも、個体化(個人になること)でもない。むしろ、それは、産業社会の生活様式 (階級、階層、ジェンダー関係、標準的な家族、終身雇用)からの離脱と断絶のプロセスであり、とりわけ、個人を対象とした社会および政治的権利の形での制 度変更、訓練プログラムの変更や労働力の流動化の形によってもたらされるものである。その結果、個々人が自らの伝記を創造し、演出し、つぎはぎしていかな ければならない状況が生じている。ベックによれば、「標準的な伝記」は「選択伝記」、「ごちゃ混ぜ伝記」、「断片化伝記」となる。 人々はサルトルの言葉を借りれば、個人化という運命を背負わされているのだ。[28] この変化は、典型的な工業国だけでなく、時間差を伴いながらも、異なる形態で中国、日本、韓国などでも起こっている。[29] |

| Kosmopolitisierung Die zweite Moderne, so besagt eine Kernthese Becks, hebt ihre eigenen Grundlagen auf. Basisinstitutionen wie der Nationalstaat und die traditionale Familie werden von innen her globalisiert. Ein gravierendes Ausrichtungsdefizit in Forschung und Praxis ist für ihn der methodologische Nationalismus des politischen Denkens, der Soziologie und anderer Sozialwissenschaften.[30] Methodologischer Nationalismus soll heißen: Die Sozialwissenschaften sind in ihrem Denken und Forschen Gefangene des Nationalstaats. Sie definieren Gesellschaft und Politik in nationalen Begriffen, sie wählen den Nationalstaat als Einheit ihrer Forschungen, als sei das die natürlichste Sache der Welt. All ihre Schlüsselbegriffe (Demokratie, Klasse, Familie, Kultur, Herrschaft, Politik usw.) basieren laut Beck auf nationalstaatlichen Grundannahmen. Das mag historisch angemessen gewesen sein im Europa des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, werde aber in der Epoche der Globalisierung und Weltrisikogesellschaft zunehmend falsch, weil transnationale Abhängigkeiten und Interdependenzen, eben globale Risiken nahezu alle Probleme und Phänomene von innen her durchdrängen und tiefgreifend veränderten. Der methodologische Nationalismus aber mache blind für diesen globalen Wandel, der sich in nationalen Gesellschaften vollziehe.[31] Deshalb entwarf Beck seit 2000 eine kosmopolitische Soziologie, um die Soziologie als Wirklichkeitswissenschaft im 21. Jahrhundert zu fundieren.[32] Denn nur so könnten die Sozialwissenschaften den globalen Wandel überhaupt beobachten, der sich nicht „da draußen“, sondern „hier drinnen“ – in Familien, Haushalten, Liebesbeziehungen,[33] Organisationen, Berufen, Schulen, sozialen Klassen,[34] Gemeinden, Religionsgemeinschaften,[35] Nationalstaaten[36] – vollziehe. Kosmopolitisierung meint den Wandel von einer Gesellschaftsform, die in Politik, Kultur, Wirtschaft, Familie und Arbeitsmarkt wesentlich durch den Nationalstaat geprägt ist, hin zu einer Gesellschaftsform, in der die Nationalstaaten sich von innen globalisieren (Internet und soziale Netzwerke; Export von Arbeitsplätzen; Migration; globale Probleme, die national nicht mehr zu lösen sind). Damit ist nach Beck kein Weltbürgertum, kein Kosmopolitismus im klassischen Sinne gemeint, kein normativer Aufruf zu einer „Welt ohne Grenzen“. Vielmehr erzeugen seiner Auffassung nach Großrisiken eine neue nationenübergreifende Zwangsgemeinschaft, weil das Überleben aller davon abhängig ist, ob sie zu gemeinsamem Handeln zusammenfinden.[37] Kosmopolitismus handelt von Normen, Kosmopolitisierung von Fakten. Kosmopolitismus im philosophischen Sinne, bei Immanuel Kant wie bei Jürgen Habermas, beinhaltet eine weltpolitische Aufgabe, die der Elite zugewiesen ist und von oben durchgesetzt wird, oder aber von unten durch zivilgesellschaftliche Bewegungen. Kosmopolitisierung dagegen vollzieht sich von unten und von innen, im alltäglichen Geschehen, oft ungewollt, unbemerkt, auch wenn weiterhin Nationalflaggen geschwenkt werden, die nationale Leitkultur ausgerufen und der Tod des Multikulturalismus verkündet wird. Kosmopolitisierung meint die Erosion eindeutiger Grenzen, die einst Märkte, Staaten, Zivilisationen, Kulturen, Lebenswelten und Menschen trennten; meint die damit entstehenden, existentiellen, globalen Verstrickungen und Konfrontationen, aber eben auch Begegnungen mit dem Anderen im eigenen Leben.[38] Becks sozialwissenschaftlicher Kosmopolitismus zielt auf drei Komponenten: eine empirische Forschungsperspektive, eine gesellschaftliche Realität und eine normative Theorie. Diese drei Aspekte zusammengenommen machen den sozialwissenschaftlichen Kosmopolitismus zur Kritischen Theorie unserer Zeit, indem die tradierten Wahrheiten infrage gestellt werden, die das Denken und Handeln heute bestimmen: die nationalen Wahrheiten. Beck hat – oft in Koautorenschaft mit anderen – den empirischen Gehalt seiner Theorie des sozialwissenschaftlichen Kosmopolitismus an folgenden Themen bzw. Phänomen erprobt, überprüft und weiterentwickelt: Macht und Herrschaft,[39] Europa,[40] Religion,[41] soziale Ungleichheit[42] sowie Liebe und Familie.[43] |

コスモポリタニゼーション ベックの主要な主張のひとつによると、第二の近代は、その基盤を自ら打ち消す。国家や伝統的な家族といった基本的な制度は、内側からグローバル化される。 彼にとって、研究と実践の深刻な不整合とは、政治思想、社会学、その他の社会科学における方法論的ナショナリズムである。 方法論的ナショナリズムとは、社会科学が思考や研究において国民国家の囚人となっていることを意味する。社会科学は社会や政治を国家の観点から定義し、あ たかもそれが世界で最も自然なことであるかのように、国民国家を研究の単位として選択している。ベックによると、社会科学の主要概念(民主主義、階級、家 族、文化、支配、政治など)はすべて、国民国家の基本的な前提に基づいている。これは19世紀および20世紀のヨーロッパにおいては歴史的に妥当であった かもしれないが、グローバル化と世界リスク社会の時代においてはますます誤りとなりつつある。なぜなら、国家間の依存関係や相互依存関係、すなわちグロー バルリスクが、ほぼすべての問題や現象を内側から浸透し、それらを深く変化させているからである。しかし、方法論的ナショナリズムは、国民社会の中で起 こっているこのグローバルな変化から私たちを盲目にさせる。 だからこそ、ベックは2000年にコスモポリタン社会学の構築に着手し、21世紀における現実の科学としての社会学を確立しようとしたのだ。 [32] 社会科学がグローバルな変化を観察できるのは、それが「外」ではなく「内」、すなわち家族、世帯、恋愛関係[33]、組織、職業、学校、社会階級 [34]、コミュニティ、宗教コミュニティ[35]、国民国家[36]において生じているからである。 コスモポリタニゼーションとは、政治、文化、経済、家族、労働市場の観点から、本質的に国家によって特徴づけられる社会形態から、国家が内側からグローバ ル化する社会形態への変化を指す。(インターネットやソーシャルネットワーク、雇用の海外移転、移民、国家レベルではもはや解決できないグローバルな問題 など) ベックによれば、これは世界市民、古典的な意味でのコスモポリタニズム、あるいは「国境のない世界」という規範的な呼びかけを意味するものではない。むし ろ、彼の考えでは、生存のすべてが、人々を団結させて共に活動させることができるかどうかにかかっているため、大きなリスクが国家を超越する新たな強制共 同体を生み出すことになる。 コスモポリタニズムは規範に関するものであり、コスモポリタン化は事実に関するものである。イマニュエル・カントやユルゲン・ハーバーマスが理解するよう な哲学的な意味でのコスモポリタニズムは、エリート層に課せられ、上から、あるいは市民社会運動によって下から強制されるグローバルな政治的課題を伴う。 一方、コスモポリタン化は、日常生活の中で、下から、内側から、しばしば意図せず、気づかれないままに起こる。たとえ人々が国旗を振り続け、自国の文化を 指針として宣言し、多文化主義の死を宣言したとしてもである。コスモポリタニズムとは、かつて市場、国家、文明、文化、生活世界、そして人々を隔てていた 明確な境界の浸食を指す。また、それによって生じる実存的なグローバルな絡み合いや対立、そして自身の生活における他者との遭遇をも指す。 ベックの社会科学的なコスモポリタニズムには、経験的研究の視点、社会的な現実、規範理論という3つの要素がある。これら3つの側面を総合すると、社会科 学的なコスモポリタニズムは、今日の私たちの思考や行動を決定する伝統的な真実、すなわち「国家の真実」を問い直すことで、現代の批判理論となる。ベック は、他の研究者との共著も含め、社会科学的コスモポリタニズムの理論の実証的内容を、権力と支配[39]、ヨーロッパ[40]、宗教[41]、社会的不平 等[42]、そして愛と家族[43]といったトピックや現象において検証し、見直し、さらに発展させてきた。 |

| Europa in Theorie und Praxis Im Jahr der Osterweiterung der Europäischen Union 2004 legte Ulrich Beck gemeinsam mit Edgar Grande die Buchveröffentlichung Das kosmopolitische Europa vor. Darin werden Modellvorstellungen und Szenarien einer europäischen Zukunft im Zeichen der reflexiven Modernisierung entwickelt. Das Kosmopolitische und das Nationale bilden dabei keine sich ausschließenden Gegensätze. „Vielmehr muß das Kosmopolitische als Integral des Nationalen begriffen, entfaltet und empirisch untersucht werden. Mit anderen Worten: Das Kosmopolitische verändert und bewahrt, es öffnet die Geschichte, Gegenwart und Zukunft einzelner Nationalgesellschaften und das Verhältnis der Nationalgesellschaften zueinander.“[44] Als theoretisches Konstrukt und politische Vision in einem sei die Formel vom kosmopolitischen Europa zu verstehen. Dabei gelte, dass Nationalität, Transnationalität und Supranationalität sich positiv zu einem Sowohl-als-auch ergänzten.[45] Im Sinne einer neuen Kritischen Theorie der Europäischen Integration komme es darauf an, von einer binnenfixierten Gestaltung der europäischen Integration wegzukommen, die darauf beruht habe, außereuropäische Bedrohungs- oder Herausforderungsszenarien hochzuspielen, um Widerstände auf nationalstaatlicher Ebene gegen europäische Integrationsfortschritte zu neutralisieren. Ausgehend von einem kosmopolitischen Europa könnten darüber hinaus multiple Kosmopolitismen begünstigt werden.[46] Dabei gehe es letztlich um die Organisation von Widersprüchen und Ambivalenzen; „diese müssen ausgehalten und politisch ausgetragen werden, auflösen lassen sie sich nicht.“[47] Eigendynamik und Nebenfolgen als konstitutive Merkmale der reflexiven Moderne zeigen sich für Beck und Grande auch in der nur bedingt zu steuernden Fortentwicklung Europas, die auf ein „Doing Europe“ angelegt sei. Der Geist des zeitgemäßen europäischen Handelns entstehe aus dem erinnerten Blick in die Abgründe europäischer Zivilisation. Doing Europe sei das tatgewordene Nie-Wieder.[48] „Das kosmopolitische Europa ist das in seiner Geschichte verwurzelte, mit seiner Geschichte brechende und die Kraft dafür aus seiner Geschichte gewinnende, selbstkritische Experimentaleuropa.“[49] Eine europäische Zivilgesellschaft und ein kosmopolitisches Europa sind den Autoren nur solidarisch vorstellbar. Es gelte, das Selbstverständnis aller beteiligten Gruppen im Sinne eines kosmopolitischen Common sense zu verändern in Richtung auf ein europäisches Gesellschaftsbewusstsein, das die positive Einstellung zur Andersheit der Anderen favorisiere.[50] Als gravierende und nötig zu bearbeitende Fehlentwicklung sehen Beck und Grande die seit der Gründung der Europäischen Gemeinschaften dominierende Verstaatlichung der Europapolitik, die die europäischen Bürger entmündigt habe. Als Gegenmittel empfehlen sie ergänzend zu den bestehenden Institutionen parlamentarischer Demokratie die Einführung eigenständiger Artikulations- und Interventionsmöglichkeiten für die Bürger, speziell in Form europaweiter Referenden zu jedem Thema, initiiert von einer qualifizierten Anzahl europäischer Bürger, mit bindender Wirkung für die supranationalen Institutionen.[51] Im Außenverhältnis solle Europa im Sinne des eigenen Modells das Prinzip der regionalen Kosmopolitisierung voranbringen und regionale Staatenbündnisse mit Einbeziehung nichtstaatlicher globaler Akteure wie NGOs fördern. Dabei sei eine einseitige Ausrichtung zu vermeiden, seien alternative Entwicklungspfade der Moderne zu akzeptieren. Auch dürfe es nicht länger bei entwicklungspolitischen Almosen bleiben; vielmehr müssten die europäischen Märkte für Produkte und Initiativen der Anderen partnerschaftlich geöffnet werden.[52] Mit Blick auf den für die Anfangsphase des 21. Jahrhunderts vorherrschenden Befund wachsender sozialer Ungleichheit, der sich im globalen wie vielfach auch im nationalen Rahmen aus zunehmendem Reichtum einerseits und vermehrter Armut andererseits ergibt, haben sich Ulrich Beck und Angelika Poferl 2010 mit den diesbezüglichen Verhältnissen in der EU auseinandergesetzt. Zur Anwendung kommt dabei Max Webers Unterscheidung zwischen einer zwar womöglich sehr drastischen, aber als legitim hingenommenen sozialen Ungleichheit und einer, die zu einem politischen Problem wird. So werde nationale Ungleichheit durch das Leistungsprinzip, globale Ungleichheit durch das Nationalstaatsprinzip (in der Form „institutionalisierten Wegsehens“) legitimiert.[53] Doch je mehr Schranken und Grenzen innerhalb des EU-Binnenraums abgebaut und Gleichheitsnormen durchgesetzt würden, desto stärker würden fortbestehende oder neu sich ergebende Ungleichheiten zum Politikum, wie in der Eurokrise markant deutlich werde: „Man denke nur an die Gegensätze zwischen Defizit- und Überschußländern, das Risiko des Staatsbankrotts, das einerseits bestimmte Länder trifft, andererseits die Eurozone insgesamt gefährdet; aber auch an die Bemühungen um europapolitische Antworten, die nicht nur die Regierungen der »leeren Kassen« gegeneinander aufstacheln, sondern nationalistische Atavismen in den Bevölkerungen wachrufen. Auf diese Weise entstehen neue Ungleichheits- und Herrschaftsverhältnisse zwischen Ländern und Staaten innerhalb der EU. […] An den Unruhen, die sich daran entzünden, wird exemplarisch deutlich: Im Erfahrungshorizont der europäischen Ungleichheitsdynamik hat sich eine gewaltige Wut aufgestaut, die in eine Destabilisierung einzelner Länder oder sogar der EU münden könnte.“[54] Im September 2010 war Ulrich Beck an der Gründung der Spinelli-Gruppe beteiligt, die sich für den europäischen Föderalismus einsetzt. In dem gemeinsam mit Daniel-Cohn Bendit verfassten Wir sind Europa! Manifest zur Neugründung der EU von unten setzte er sich im Jahr 2012 unter anderem für die Schaffung eines Freiwilligen Europäischen Jahres ein. Hintergrund der Initiative, die nicht nur an die Brüsseler EU-Organe gerichtet war, sondern auch an die nationalen Parlamente und die Unionsbürger, waren speziell die in den südeuropäischen Ländern grassierende Jugendarbeitslosigkeit und die aufklaffende Schere zwischen Armut und Reichtum.[55] |

理論と実践におけるヨーロッパ 2004年、EUの東方拡大の年、ウルリッヒ・ベックとエドガー・グランデは『コスモポリタンなヨーロッパ』を出版した。この本では、再帰的近代化の兆し が見られるヨーロッパの未来のモデルとシナリオが展開されている。コスモポリタンとナショナルは、互いに相容れない対立概念ではない。 むしろ、コスモポリタニズムは、ナショナルなものの不可欠な一部として理解され、発展させられ、経験的に検証されなければならない。言い換えれば、コスモ ポリタニズムは変化をもたらし、維持するものであり、個々のナショナルな社会の歴史、現在、未来、そしてナショナルな社会間の関係を開拓するものである。 [44] コスモポリタンなヨーロッパの公式は、理論的構築と政治的ビジョンを併せ持つものと理解されるべきである。この文脈において、国籍、超国家性、国際性は 「~だけでなく/~も」という形で互いに補完し合う。 [45] 欧州統合に関する新たな批判理論の観点から言えば、欧州統合の固定的な内部設計から離れることが重要である。この設計は、欧州統合に対する国家レベルでの 抵抗を無効化するために、非欧州的な脅威や挑戦シナリオを強調することに基づいている。さらに、コスモポリタンなヨーロッパを基盤として、複数のコスモポ リタニズムが育まれる可能性もある。46] 究極的には、これは矛盾や相反するものの組織化の問題である。「これらは容認され、政治的に解決されなければならない。しかし、解決することはできな い。」47] ベックとグランデにとって、再帰的近代の構成要素としての勢いと副作用は、ヨーロッパのさらなる発展においても明白であり、それは限定的にしか制御でき ず、「ヨーロッパの実現」に向かっている。現代のヨーロッパの行動の精神は、ヨーロッパ文明の深淵を振り返る視点から生じている。ヨーロッパの実現は、行 動となった「二度と繰り返さない」ことである。 「コスモポリタン的なヨーロッパは、自己批判的な実験的なヨーロッパであり、その歴史に根ざし、その歴史を断ち切り、その歴史から力を引き出すものである」[49] 著者らは、連帯し合うヨーロッパ市民社会とコスモポリタン的なヨーロッパを想像することしかできない。他者の他者性に対して肯定的な態度をとるヨーロッパ的社会意識の方向に、関与するすべてのグループの自己理解を変える必要がある。 ベックとグランデは、欧州共同体の創設以来支配的であり、ヨーロッパ市民の権利を奪ってきたヨーロッパ政策の国家化を、深刻かつ必要な逸脱と見なしてい る。その解決策として、彼らは、議会制民主主義の既存の制度に加えて、市民が独自の主張や介入を行う手段を導入することを提案している。具体的には、一定 数の欧州市民が発議し、超国家機関に拘束力を持つ効果をもたらす、あらゆるテーマに関する欧州全域での国民投票という形での導入である。 対外的には、ヨーロッパは自らのモデルに沿って地域コスモポリタニゼーションの原則を推進し、NGOなどの国家以外のグローバルアクターを含む国家間の地 域同盟を支援すべきである。その際、一方的な志向を避け、近代化の代替的な発展経路を受け入れるべきである。また、単なる施しを与えるというものであって はならない。むしろ、パートナーシップの精神に基づき、欧州市場を「その他」の国々の製品や取り組みに開放すべきである。 21世紀初頭に蔓延している社会的不平等が拡大しているという事実を踏まえ、ウルリッヒ・ベックとアンゲリカ・ポフェルは2010年にEUの状況を調査し た。その際、彼らは、たとえそれが極端なものであっても正当なものとして受け入れられる社会的不平等と、政治的な問題となる社会的不平等とを区別したマッ クス・ウェーバーの考え方を適用している。したがって、国内における不平等は「成果主義」の原則によって、またグローバルな不平等は国民国家の原則(「制 度化された見て見ぬふり」という形)によって正当化される。[53] しかしながら、EU域内の障壁や国境が取り払われ、平等性の規範が強化されるにつれ、既存の、あるいは新たに生じる不平等が政治問題となる。ユーロ危機に おいて、そのことが顕著に示されている。 「赤字国と黒字国の対照的な状況、国家破産のリスクを考えてみるだけで、それは一方では特定の国々に影響を及ぼす一方で、ユーロ圏全体を危険にさらす。ま た、ヨーロッパの政策対応を見つけるための努力についても考えてみる。それは、財源が空っぽの政府同士を互いにけしかけるだけでなく、国民の間に民族主義 的な先祖返りを引き起こす。このようにして、EU内の国と国との間に、新たな不平等と支配の関係が生まれている。[...] この状況を招いた暴動は、その典型的な例である。ヨーロッパにおける不平等構造には、膨大な量の鬱積した怒りが存在しており、それは個々の国家、さらには EUの不安定化につながる可能性がある。」[54] 2010年9月、ウルリッヒ・ベックは欧州の連邦制を提唱するスピネッリ・グループの創設に関与した。ダニエル・コーン・ベンディットとの共著である 2012年のマニフェスト『We are Europe!』では、ベックは自主的な欧州の年の創設を提唱した。このイニシアティブの背景には、ブリュッセルのEU機関だけでなく、各国議会やEU市 民に向けたものだったが、南ヨーロッパ諸国における若年層の失業の蔓延と、貧困と富裕の格差の拡大があった。 |

| Politische Standortbestimmungen Beck plädierte volkswirtschaftspolitisch dafür, neue Prioritäten zu setzen. Vollbeschäftigung sei angesichts der Automatisierung und der Flexibilisierung der Erwerbsarbeit[56] nicht mehr erreichbar, nationale Lösungen seien unrealistisch, „neoliberale Medizin“ wirke nicht. Stattdessen müsste der Staat ein bedingungsloses Grundeinkommen garantieren und dadurch mehr Bürgerarbeit ermöglichen.[57] Eine solche Lösung sei nur realisierbar, wenn auf europäischer Ebene bzw. – im besten Fall – auf diversen transnationalen Ebenen einheitliche wirtschaftliche und soziale Standards gelten würden. Nur so sei es möglich, die transnational agierenden Unternehmen zu kontrollieren. Zur Eindämmung der Macht transnationaler Konzerne (TNKs) plädiert er daher für die Errichtung Transnationaler Staaten als Gegenpol.[58] So würde auch die Durchsetzung einer Finanztransaktionssteuer möglich, die Handlungsspielräume für ein soziales und ökologisches Europa eröffnet.[59] Auf rechtlicher Ebene war Beck der Ansicht, dass ohne den Auf- und Ausbau des internationalen Rechts und demgemäßer rechtsprechender Instanzen die Beilegung transnationaler Konflikte mit friedlichen Mitteln ausgeschlossen sei. Dafür prägte er den Begriff Rechtspazifismus.[60] Beck veröffentlichte kontinuierlich Beiträge in großen europäischen Zeitungen: Der Spiegel, Die Zeit, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Frankfurter Rundschau, La Repubblica, El País, Le Monde, The Guardian u. a. m. Als Mitglied der Ethikkommission der deutschen Bundesregierung für eine sichere Energieversorgung warnte Beck 2011 davor, dass Katastrophen wie die in Fukushima zu einer Erosion des Demokratieverständnisses führen könnten: „Die Politik hat sich durch die Zustimmung zur Kernenergie an das Schicksal dieser Technologie gebunden. Mit dem Eintritt des Unvorstellbaren geht das Vertrauen der Bürger gegenüber den Politikern verloren.“[61] |

政治的立場 経済政策に関して、ベックは新たな優先事項の設定を提唱した。オートメーション化や柔軟な雇用形態を考慮すると、完全雇用はもはや達成不可能であり、国家 レベルでの解決策は非現実的であり、「新自由主義的処方」は機能していない。代わりに、国家は無条件の基本所得を保証し、それによってより多くの市民が働 くことを可能にすべきである。57] このような解決策は、ヨーロッパレベル、あるいは最良のケースではさまざまな超国家レベルで均一な経済・社会基準が適用された場合にのみ実現可能である。 そうして初めて、多国籍企業を統制することが可能になる。多国籍企業の力を抑制するために、彼は対抗勢力として多国籍国家の設立を提唱した。[58] また、これは金融取引税の導入も可能にし、社会と環境に配慮したヨーロッパの実現への道を開くことになる。[59] 法的レベルでは、ベックは、国際法とそれに対応する司法機関の確立と拡大なしには、平和的手段による超国家的な紛争の解決は不可能であるという意見であった。彼はこの考えを「法的な平和主義」という言葉で表現した。 ベックは、ドイツの主要紙だけでなく、ヨーロッパの主要紙にも継続的に寄稿している。寄稿先には、『シュピーゲル』、『ツァイト』、『南ドイツ新聞』、 『フランクフルト・ルンドシャウ』、『ラ・レプブリカ』、『エル・パイス』、『ル・モンド』、『ガーディアン』などが含まれる。ドイツ政府の「安全なエネ ルギー供給に関する倫理委員会」のメンバーであるベックは、2011年に福島第一原発のような大惨事は民主主義の理解を損なう可能性があると警告した。 「政治は原子力エネルギーに同意することで、この技術の運命に自らを縛り付けた。想像を絶する事態の発生により、市民の政治家に対する信頼は失われた」 [61] |

| Darstellungsmittel Angetrieben von „seiner enzyklopädischen Bildung und einer schier unerschöpflichen Fülle der Interessen“[62] haben Becks soziologische und politische Publikationen oft die Form des Großessays angenommen. In ihnen gelang es Beck wiederholt, für gesellschaftliche Sachverhalte und Entwicklungen eingängige Kurzformeln zu entwickeln. So prägte er zahlreiche Begriffe, darunter fallen: Risikogesellschaft, reflexive Modernisierung, Fahrstuhleffekt, methodologischer Nationalismus, sozialwissenschaftlicher Kosmopolitismus, Individualisierung, Deinstitutionalisierung, Enttraditionalisierung sowie in Bezug auf die Globalisierung die Begriffe Zweite Moderne, Globalismus, Globalität, Brasilianisierung sowie Transnationalstaat und kosmopolitisches Europa. Der Umgang mit Sprache war für Beck ein besonderes Thema. „Die Soziologie, die im Container des Nationalstaats angesiedelt ist, und ihr Selbstverständnis, ihre Wahrnehmungsformen, ihre Begriffe in diesem Horizont entwickelt hat, gerät methodisch unter den Verdacht, mit Zombie-Kategorien zu arbeiten. Zombie-Kategorien sind lebend-tote Kategorien, die in unseren Köpfen herumspuken, und unser Sehen auf Realitäten einstellen, die immer mehr verschwinden.“[63] Dagegen setzte Beck die Suche nach einer neuen Beobachtungssprache der Sozialwissenschaften für eine globalisierte Welt. |

発表の手段 「彼の博識な教育と尽きることのない幅広い関心」[62]に突き動かされ、ベックの社会学および政治学に関する出版物は、多くの場合、主要な論文という形 を取っていた。 それらの論文において、ベックは社会問題や社会の変化を端的に表現するキャッチーな短い公式を繰り返し開発することに成功した。彼は、リスク社会、再帰的 近代化、「リフト効果」、方法論的ナショナリズム、社会科学コスモポリタニズム、個人化、脱施設化、脱伝統化など、数多くの用語を考案した。また、グロー バル化に関連して、「第二の近代」、「グローバリズム」、「グローバリティ」、「ブラジル化」、「トランスナショナル国家」、「コスモポリタンなヨーロッ パ」といった用語も考案した。ベックにとって、言語の使用法は特に重要なテーマであった。「国民国家という枠組みの中で自己理解、認識の形式、概念を発展 させてきた社会学は、その地平の中で、ゾンビカテゴリーを使用しているのではないかと、組織的に疑われている。ゾンビカテゴリーとは、生と死の間をさまよ い、私たちの心に潜み、ますます消えゆく現実に対して私たちの視点を調整するカテゴリーである。」[63] これに対して、ベックはグローバル化した世界における社会科学のための新たな観察言語の探求を提唱した。 |

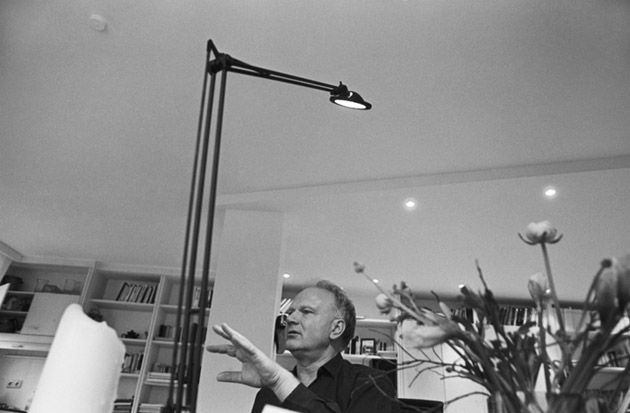

Resonanz und Kritik Ulrich Beck in seiner Wohnung in München 1999 Ulrich Beck war einer der bekanntesten deutschen Soziologen der Gegenwart, dessen Begriffe und Thesen weit über das Fachpublikum hinaus auf Resonanz zielen und stoßen. Er gehört zu den meistzitierten und anerkanntesten Sozialwissenschaftlern der Welt.[64] Seine Werke wurden und werden in mehr als 35 Sprachen übersetzt. Eva Illouz sieht in Beck nicht nur den international erfolgreichen Wissenschaftler, sondern die Verkörperung europäischer Bürgerschaft, für die er mit seinem politischen Engagement und seinen soziologischen Arbeiten eingestanden habe. Das sei für ihn aber nur ein Zwischenschritt hin auf eine Weltinnenpolitik mit verschwimmenden nationalen Grenzen gewesen.[65] „Beck wäre in jedem Land der Welt ein origineller Soziologe gewesen“, meint Illouz, „im Zusammenhang der deutschen Soziologie aber war er besonders originell und einzigartig.“[66] Auch aus der Sicht von Rainer Erd nimmt Beck innerhalb der deutschen Soziologie eine „herausragende Position“ ein. In einer Situation versteinerter Theorieverhältnisse (betreffend etwa die Entwicklung der Soziologie im Nachkriegsdeutschland, den Werturteilsstreit in der Soziologie, die marxistische Theorie, die Rollentheorie oder die Luhmannsche Systemtheorie) sei Beck 1986 mit seinem Buch Risikogesellschaft. hervorgetreten. „Was andere sich wünschten, Beck gelang es. Er brachte die Verhältnisse zum Tanzen, die Wissenschaftsverhältnisse freilich nur. Kaum über ein anderes Buch der deutschen Nachkriegssoziologie ist so erbittert gestritten worden, kaum ein anderer Autor hat soviel Lob gehört, aber auch soviel Schimpf über sich ergehen lassen müssen. Beck hat die wohl eingerichteten Verhältnisse der Sozialwissenschaften heftig durchgerüttelt. Da er sich keiner großen Theorietradition systemtheoretischer oder marxistischer Provenienz zuordnen ließ, waren Verblüffung und Ärger um so größer.“[67] Im Unterschied zu den Gesellschaftstheorien von Niklas Luhmann und Jürgen Habermas hat Becks diagnostische Gesellschaftstheorie[68] empirische Konsequenzen, die den Mainstream in den speziellen Soziologien der sozialen Ungleichheit, Familie, Liebe, Erwerbsarbeit, Industrie, Politik, des Staates usw. herausfordern und insofern bis heute anhaltend international und interdisziplinär lebhafte Kontroversen auslösen. In diesem Sinne kann man von einer internationalen/interdisziplinären Individualisierungs-Debatte,[69] Risikogesellschafts-Debatte[70] sowie Kosmopolitismus-Debatte[71] sprechen. „Es steckte viel Dialektik in diesem Soziologen“, heißt es im Nachruf auf Ulrich Beck in der Neuen Zürcher Zeitung, „einiges von Hegels ‚List der Vernunft’ und eine Portion von Ernst Blochs ‚Prinzip Hoffnung’.“ Mit Zuversicht habe Beck wahrgenommen, dass die Antizipation von Katastrophen Gegenkräfte mobilisieren könne: „Bürgerbewegungen entstehen, und aufs Weiterwursteln abonnierte Politiker fangen an, sich Gedanken zu machen.“[72] Mehrere Arten von kritischen Einwänden werden gegen Beck vorgebracht, darunter solche, die auf oberflächlichen Kenntnissen und pauschalen Urteilen beruhen. So wird beispielsweise immer wieder behauptet, es handele sich bei Becks Schriften eher um politische Philosophie als um handfeste, empirisch gehaltvolle Soziologie. Dabei werden weder die thematisch breitgefächerten, zehnjährigen, interdisziplinären, empirischen Arbeiten des von der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) finanzierten Sonderforschungsbereichs 536 „Reflexive Modernisierung“ (1999–2009)[73][74] noch die zahlreichen empirischen Studien zur Kenntnis genommen, die national[75] und international[76] inzwischen vorliegen. Tatsächlich gibt es aber auch international eine umfangreiche Kritik, die aus der intensiven Auseinandersetzung mit Beck erwächst. |

反応と批判 1999年、ミュンヘンの自宅アパートにて ウルリッヒ・ベックは、その概念やテーゼが専門家の枠をはるかに超えた反応を引き起こし、またそれに応えることを目指す、現代ドイツで最も著名な社会学者 の一人であった。彼は世界で最も引用され、最も認められた社会科学者の一人である。64] 彼の作品はこれまでに35以上の言語に翻訳され、現在も翻訳され続けている。エヴァ・イローズは、ベックを国際的に成功した科学者であるだけでなく、政治 的関与と社会学的業績によって擁護してきたヨーロッパ市民権の体現者でもあると見ている。しかし、彼にとってこれは、国境の曖昧な世界的な国内政策に向け た中間的なステップに過ぎなかった。 「世界のどの国においても、ベックは独創的な社会学者であっただろう」とイロウスは言う。「しかし、ドイツ社会学の文脈においては、彼はとりわけ独創的で ユニークであった」[66] ライナー・アースもまた、ベックがドイツ社会学のなかで「際立った地位」を占めていると考えている。理論的な関係が固定化された状況(例えば、戦後ドイツ における社会学の発展、社会学における価値判断の論争、マルクス主義理論、役割理論、あるいはルーマンのシステム理論など)において、ベックは1986年 に『リスク社会』を著して登場した。「他の人々が望んでいたことを、ベックは成し遂げた。彼は状況を踊らせた。ただし、それは科学の状況だけである。ドイ ツの戦後社会学において、これほどまでに激しい論争の的となった書籍は他にない。また、これほどまでに賞賛を受けながらも、これほどまでに酷評に耐えなけ ればならなかった著者は他にいない。ベックは、社会科学の確立された状況を激しく揺さぶった。システム理論やマルクス主義といった主要な理論的伝統のいず れにも分類されないため、動揺と怒りはより大きなものとなった。」[67] ニクラス・ルーマンやユルゲン・ハーバーマスの社会理論とは対照的に、ベックの診断的社会理論[68]は、社会的不平等、家族、愛、有償雇用、産業、政 治、国家などに関する特定の社会学の主流派に異議を唱える実証的な帰結をもたらし、今日に至るまで活発な国際的・学際的な論争を引き起こし続けている。こ の意味において、国際的/学際的な個別化論争[69]、リスク社会論争[70]、コスモポリタニズム論争について語ることができる。 「この社会学者には弁証法が満ち溢れていた」と、ウルリッヒ・ベックの訃報記事で『ノイエ・チュルヒャー・ツァイトゥング』は書いた。「ヘーゲルの『理性 のリスト』とエルンスト・ブロッホの『希望の原理』の要素が混在していた」と。ベックは、惨事を予期することで対抗勢力が結集できると確信していた。「市 民運動が台頭し、これまで『何とかなるだろう』と考えていた政治家たちも考え直すようになった」[72] ベックに対しては、表面的な知識や一面的な判断に基づくものも含め、いくつかの批判が寄せられている。例えば、ベックの著作は、確固とした実証的社会学と いうよりも政治哲学であるという主張が繰り返しなされている。その際、彼らはドイツ研究振興会(DFG)の資金提供を受けた共同研究センター536「再帰 的近代化」(1999年~2009年)のテーマが幅広く、10年間にわたる学際的な実証的研究[73][74]や、現在では国内[75]および国際的に数 多くの実証的研究が利用可能になっていることにも注目していない。実際、ベックとの集中的な関わりから生じた広範な国際的な批判もある。 |

| Zu Leitmotiven Becks als Forscher und Publizist In dem Bestreben, Leitmotive und Kontinuitäten in den über mehrere Jahrzehnte verteilten Publikationen Ulrich Becks zu ermitteln, konstatiert Elmar J. Koenen, dass es für Beck – beginnend bereits 1971 in der mit Elisabeth Gernsheim verfassten Studie „Zu einer Theorie der Studentenunruhen in fortgeschrittenen Industriegesellschaften“ – angesichts konträrer Standpunkte in politischen Auseinandersetzungen keinen „richtigen“ Standpunkt der (soziologischen) Beobachtung gegeben habe. Der theoretische und politische Pluralismus zwängen zum ständigen Reagieren auf Veränderungen, sodass mit der geforderten Stellungnahme nicht die Festlegung auf eine politische oder theoretische Position einhergehe. „Allenfalls ginge es um das Projekt“, so Koenen, „sich selbst zu einer politischen und/oder theoretischen Position zu machen, und zu dieser allerdings mit äußerster Konsequenz zu stehen.“[77] Durch die Forschenden nicht fixierbar stelle sich für Beck andererseits auch die Verwendung sozialwissenschaftlichen Wissens in der gegenwärtigen politischen Praxis dar. Das Angebotene werde eher als „Steinbruch“ genutzt, „wo man sich bei Bedarf und Gelegenheit bedient. Ohne Rücksicht auf seine Intention oder seine Form findet es seine unkontrollierte praktische Verwendung. Sie kann vom Sozialwissenschaftler weder antizipiert noch gesteuert werden. […] Eine dergestalt entinstitutionalisierte Verwendung des Wissens muss darauf hoffen, dass sich seine ‚gesellschaftliche Nützlichkeit’ – in bester liberaler Tradition – gleichsam hinter ihrem Rücken herstellt.“[78] Unter dem ihn stark beunruhigenden Eindruck der globalen ökologischen Risiken habe Ulrich Beck die häufigen Wechsel der Beobachtungspositionen diesbezüglich erheblich eingeschränkt. Mit der Publikation zur Risikogesellschaft habe er sich „für eine Praxis der Theorie“ entschieden, die auf ein breites Publikum zielte. Die Abfassung von Texten allein für Fachkollegen habe ihm fortan nicht mehr genügt; und die auf Verbreitung von Neuigkeitseffekten eingestellten Medien hätten seine Wirkung gefördert und das Verdienst, „die Stichworte der Beckschen Textproduktion (Individualisierung, zweite Moderne, Industriemoderne, Risiko, reflexive Moderne etc.) in Form semantischen Kleingelds unter die gebildeten Leute gebracht zu haben.“[79] |

研究者および広報担当者としてのウルリッヒ・ベックの主要テーマについて ウルリッヒ・ベックの数十年にわたる出版物の主要テーマと継続性を特定する試みにおいて、エルマー・J・ 政治論争における相反する立場を考慮すると、ベックにとって「正しい」立場など存在しなかったと述べている。1971年にエリザベート・ゲルンスハイムと 共同執筆した研究論文「先進工業社会における学生の反乱に関する理論」において、すでに(社会学的な)観察という観点から、ベックには「正しい」立場など 存在しなかった。理論的・政治的多元主義は、絶え間なく変化に対応することを強いるため、必要な声明には政治的または理論的な立場へのコミットメントは伴 わない。「せいぜい、自分自身に政治的および/または理論的な立場を確立し、最大限の一貫性をもってそれに立ち向かうことくらいだろう」とKoenenは 述べている。[77] 一方で、ベックは、現代の政治的実践における社会科学の知識の利用は、研究者によって修正することはできないと主張している。提供されるものは、「採石 場」のように利用される。「必要に応じて、機会があるときに、自分で利用する」のである。その意図や形式に関わらず、それは制御されない実践的な方法で利 用される。これは社会科学者によって予測したり制御したりすることはできない。[...] このような脱施設化された知識の利用は、いわば陰ながら、リベラルの最良の伝統に則った「社会的有用性」が確立されることを期待せざるを得ない。」 [78] 地球規模の生態学的リスクに深く憂慮するウルリッヒ・ベックは、この点に関して、頻繁に観察位置を変えることを大幅に制限した。『リスク社会』の出版後、 彼は幅広い読者層をターゲットに「理論の実践」を選択した。それ以来、同僚の専門家だけを対象とした文章を書くだけでは彼にとって十分ではなくなり、新奇 性を広めることに重点を置くメディアが彼の影響力を高め、「ベックのテキスト生産のキーワード(個別化、第二近代、産業近代、リスク、再帰的近代など)を 意味の変化という形で教養ある人々に紹介する」という功績を残した。[79] |

| Zur Risikogesellschaft Mit seiner aufsehenerregenden und hohe Verbreitung erlangenden Veröffentlichung von Risikogesellschaft fand Ulrich Beck schon 1986 die gedankliche Mitte für eine produktive und bis heute anschlussfähige Theoriebildung.[80] Ein „brillantes Buch“ ist Risikogesellschaft für Eva Illouz, „weil es den Kapitalismus weder anklagte noch verteidigte, sondern eine Bestandsaufnahme seiner Folgen vornahm und untersuchte, wie er Institutionen umstrukturierte – wie er sie zwang, die von ihnen selbst angerichteten Zerstörungen in den Blick zu nehmen, zu bewältigen und in einer neuen Kostenrechnung abzubilden, die jene Risiken einbezog, die mit der Ausbeutung der natürlichen Ressourcen und mit den technischen Innovationen verbunden sind.“[81] Viel Kritik hat sich an der Behauptung Becks in der „Risikogesellschaft“ entzündet, dass mit der sozialen Produktion von Risiken soziale Klassen an Bedeutung verlieren – „Not ist hierarchisch, Smog ist demokratisch“.[82] Demgegenüber wurde und wird zum Teil geltend gemacht, dass Klassenungleichheiten in den Gegenwartsgesellschaften von kontinuierlicher, oft sogar wachsender Relevanz sind.[83] Die Relativierung der Klassenkategorie für die globalisierte Welt am Beginn des 21. Jahrhunderts – so wird in dieser Debatte deutlich – kann allerdings genau Entgegengesetztes bedeuten: zum einen die Abnahme, zum anderen die Zunahme, ja Radikalisierung sozialer Ungleichheiten. Beck steht der zweite Fall vor Augen, wenn er argumentiert, dass der Klassenbegriff eine zu „idyllische Beschreibung“ („too soft a category“) für die radikalisierten Ungleichheiten am Beginn des 21. Jahrhunderts liefert.[84] „Zygmunt Bauman hat darauf hingewiesen“, sagt Beck im Gespräch mit Johannes Willms, „was diese monströse, neue Armut von der alten Armut unterscheidet: Diese Menschen werden schlicht nicht mehr gebraucht. Marx’ Rede vom Proletariat oder Lumpenproletariat unterstellt immer noch aktuelle oder potenzielle Ausbeutung im Arbeitsprozess. Dort, wo die Zivilisation in ihr Gegenteil, in bewohnte Müllhalden umschlägt, ist selbst der Begriff ‚Ausbeutung‘ ein Euphemismus… Weder innerhalb von noch zwischen Nationalstaatsgesellschaften bildet der Klassenbegriff die entstandene Komplexität radikal ungleicher Lebensverhältnisse ab. Er gaukelt vielmehr eine falsche Einfachheit vor.“[85] Andernorts wurde kritisiert, dass Becks vermeintlich undifferenziertes, katastrophisches Verständnis von Risiken, das seiner Kritik der Klassenkategorie zugrunde liege, große Teile der Realität verfehle. Dagegen wird vorgeschlagen, die soziale Verteilung von Risiken in die Klassenkategorien einzubauen, um auf diese Weise eine neue Kritische Theorie der Klassen in der Risikogesellschaft zu entwickeln: Es herrsche ein verhängnisvoller Magnetismus zwischen Armut, sozialer Verwundbarkeit und Risikoakkumulation.[86] |

リスク社会について ウルリッヒ・ベックはセンセーショナルで影響力の大きい著書『リスク社会』を1986年に発表し、生産的で現在でも関連性のある理論の概念的基盤を提供し た。80] エヴァ・イロウズにとって『リスク社会』は「素晴らしい本」である。なぜなら、この本は資本主義を非難することも擁護することもなく、 しかし、その影響を評価し、資本主義が制度をどのように再編したか、すなわち、自然資源の搾取や技術革新に伴うリスクを考慮に入れ、それに対処し、新たな 原価計算に反映させることを制度に強いたかを検証した。」[81] ベックの『危険社会』における主張、「リスクの社会的生産により、社会的階級はその意義を失う」という主張は、多くの批判を呼んだ。「ニーズは階層的だ が、スモッグは民主的である」[82]。これに対して、現代社会における階級間の不平等は、継続的であり、しばしば拡大さえしているという主張も一部では なされている。 しかし、この議論が明らかにしているように、21世紀初頭のグローバル化した世界において階級というカテゴリーを相対化することは、まったく逆の結果を意 味しうる。すなわち、一方では格差の縮小、他方では格差の拡大、さらには格差の急進化である。ベックは、21世紀初頭における急進化した不平等に対して階 級概念が「牧歌的な描写」(「あまりにも甘いカテゴリー」)を提供していると主張し、2つ目のケースを指摘している。[84] ベックはヨハネス・ヴィルムスとの対談で、「ジグムント・バウマンが指摘しているように、この怪物のような新しい貧困が古い貧困と異なるのは、 これらの人々は、もはや必要とされていないのだ。マルクスのプロレタリアートやルンペンプロレタリアートに関する議論は、労働過程における現在または潜在 的な搾取を前提としている。文明がその対極である居住可能なゴミ捨て場へと変化している場所では、「搾取」という言葉さえも婉曲表現である。国家社会の内 部でも、国家社会の間でも、階級という概念は、生じた根本的な不平等な生活条件の複雑さを反映していない。むしろ、それは偽りの単純さを示唆している。 また、ベックスが階級カテゴリーを批判する根拠となっている、リスクに対する彼の想定上の区別のない、破滅的な理解は、現実の大部分を見落としているとい う批判もある。むしろ、リスク社会における階級に関する新たな批判理論を展開するためには、リスクの社会的分布を階級カテゴリーに組み込むべきであると提 案されている。貧困、社会的脆弱性、リスク蓄積の間には、運命的な磁力が存在する。 |

| Zur Individualisierung Die Individualisierungsthese (eine von drei Thesen in Becks Theorie reflexiver Modernisierung, siehe oben) hat zunehmend an Einfluss in der englischsprachigen Welt gewonnen, was zum einen an der breiten Anwendung in empirischen Forschungen abgelesen werden kann,[87] zum anderen an den einschlägigen theoretischen Debatten[88] über ihre Kernunterscheidungen und Methodologie beispielsweise in der Jugendsoziologie.[89] Um Missverständnisse zu vermeiden, hat Beck vorgeschlagen, klar zwischen Individualisierung und Individualismus zu unterscheiden, also zwischen institutionellem Wandel auf der Makroebene der Gesellschaft (des Familien-, Scheidungs-, Arbeits- und Sozialrechts) und biographischem Wandel auf der Mikroebene der Individuen: „Mit anderen Worten: Individualisierung muss klar unterschieden werden von Individualismus oder Egoismus. Während Individualismus gewöhnlich als eine persönliche Attitüde oder Präferenz verstanden wird, meint Individualisierung ein makro-soziologisches Phänomen, das sich möglicherweise – aber vielleicht eben auch nicht – in Einstellungsveränderungen individueller Personen niederschlägt. Das ist die Krux der Kontingenz: Es bleibt offen, wie die Individuen damit umgehen.“ – Ulrich Beck[90] Einige Kritiken beruhen auf dem Missverständnis, dass Individualisierung die Orientierungen und Werte des Individualismus verwirkliche. Ein besonders interessantes Beispiel dafür ist Paul de Beers empirische Überprüfung der Individualisierungstheorie.[91] Er untersucht die Frage, wie individualisiert die Holländer sind, indem er das Ausmaß der Detraditionalisierung, Emanzipation und Heterogenisierung erforscht. Dabei übersieht de Beer, dass Individualisierung tatsächlich zu einer wachsenden Abhängigkeit des Individuums von Institutionen führt[92] und zu einem paradoxen Prozess der Konformität durch Wahlentscheidungen.[93] Auch diese empirische Überprüfung der Individualisierungstheorie tappt also in die Falle, Individualisierung mit Individualismus gleichzusetzen und kommt schließlich so zu der Schlussfolgerung, dass holländische Individuen (gemäß zwei der drei Indikatoren) nicht „individualistischer“ geworden seien.[94] Der Anthropologe Yunxiang Yan, der an der UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) lehrt, kritisiert dagegen, dass die Unterscheidung zwischen der „makro-objektiven“ und der „mikro-subjektiven“ Dimensionen von Individualisierung die Frage nach der Rolle des Individuums im Prozess der Individualisierung verschleiere.[95] Sein Einwand lautet, dass Beck paradoxerweise eine „Individualisierung ohne Individuen“ behaupte.[96] |

個人化について 個人化論(ベックの再帰的近代化理論における3つの論点のうちの1つ、上記参照)は英語圏で影響力を強めているが、そのことは、経験的研究における幅広い 応用[87]と、その中核となる区別や方法論に関する関連理論の議論[88]、例えば若者社会学などから見て取れる。 誤解を避けるために、ベックは「個人化」と「個人主義」を明確に区別することを提案している。すなわち、社会のマクロレベルにおける制度の変化(家族、離 婚、労働、社会法)と、個人のミクロレベルにおける伝記の変化である。 「言い換えれば、個人化は個人主義や利己主義とは明確に区別されなければならない。個人主義は通常、個人の態度や好みとして理解されるが、個人化は個人の 態度の変化に反映される場合もされない場合もあるマクロ社会学的な現象を指す。これが偶然性の核心である。個人化にどう対処するかは依然として未解決の問 題である」 ウルリッヒ・ベック[90] 一部の批判は、個人化が個人主義の志向や価値を実現するという誤解に基づいている。この点について特に興味深い例は、ポール・デ・ビアによる個人化理論の 実証的レビューである。[91] 彼は脱伝統化、解放、異質化の度合いを調査することで、オランダ人がどの程度個人化されているかという問題を検証している。その際、デ・ビールは、個人化 が実際には個人による制度への依存を強め[92]、選択による同調という逆説的なプロセスにつながるという事実を見落としている。 93] この個人化理論の実証研究も、個人化と個人主義を同一視するという罠にはまり、最終的にはオランダ人は(3つの指標のうち2つにおいて)「個人主義的」に なっていないという結論に達している。 UCLA(カリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校)で教鞭をとる人類学者のヤン・ユンシャンは、「マクロ的客観性」と「ミクロ的主観性」という「個人化」の区 分が 個人化のプロセスにおける個人の役割という問題を曖昧にしていると批判している。[95] 彼の主張は、ベックは逆説的に「個人抜きでの個人化」を主張しているというものである。[96] |

| Zur Kosmopolitisierung Becks Kritik am methodologischen Nationalismus der Sozialwissenschaften ist Gegenstand heftiger Kontroversen.[97] Seine Kritiker wenden ein, dass bereits die Klassiker der Soziologie, beispielsweise sowohl Émile Durkheim als auch der Begründer der Soziologie Auguste Comte sich ausdrücklich mit dem Kosmopolitismus als einer möglichen Zukunft moderner Gesellschaften befassten.[98] Andere widersprechen, indem sie auf zentrale Autoren wie Immanuel Wallerstein und Niklas Luhmann hinweisen, die bereits in den 1970er Jahren die Begriffe „world system“ und Weltgesellschaft eingeführt haben.[99] Demgegenüber besteht auch hier Beck auf der Unterscheidung zwischen Kosmopolitismus als Norm und Kosmopolitisierung als Tatsache (siehe oben Werk). In diesem Sinne haben sich viele Gesellschaftstheoretiker im 19. Jahrhundert zwar mit normativem Kosmopolitismus befasst, nicht aber mit den empirischen Prozessen der Kosmopolitisierung, die das Zusammenwachsen der Welt (angesichts Internet und Facebook, globaler Risiken sowie der inneren Globalisierung von Familien, Klassen u. a. m.) ins Zentrum stellt. Autoren wiederum, die Kosmopolitisierung in diesem empirischen Sinne ernst nehmen, kritisieren, dass Kosmopolitisierung letzten Endes auf ein unkritisches Verständnis von Globalisierung hinauslaufe, sei doch strukturelle Kosmopolitisierung nicht an Reflexion und Interaktion von Individuen über Grenzen hinweg gebunden.[100] Wenn Kosmopolitisierung auch Prozesse der Renationalisierung und Reethnifizierung umfasst, dann drohe der Begriff leer zu werden. Auch wird eingewendet, dass Beck zwar behauptet, dass Kosmopolitisierung irreversibel sei, aber nicht begründet, warum dies angesichts der Renaissance von Nation und Nationalismus überall in der Welt der Fall sein soll. Yishai Blank, der International Law in Tel Aviv lehrt, kritisiert, dass empirische Verweise auf die Akteure fehlen, die die Kosmopolitisierung vorantreiben, ein Mangel, der für eine soziologische Studie erstaunlich sei. Schließlich setze Becks Idee der Kosmopolitisierung die Idee des Nationalismus voraus; er unterscheide also gewissermaßen zwischen einem guten und einem bösen Nationalismus, lasse jedoch den Leser damit allein, diese Unterscheidung in der Realität zu treffen. Bestenfalls sei Becks Theorie der Kosmopolitisierung im Ergebnis unterentwickelt, schlimmstenfalls widersprüchlich.[101] |

コスモポリタニズム化について、 ベックによる社会科学の方法論的ナショナリズム批判は激しい論争の的となっている。97] 彼の批判者たちは、例えば、社会学の創始者であるエミール・デュルケムとオーギュスト・コントの両者が、近代社会の将来の可能性として明確にコスモポリタ ニズムを論じていると反論している。 [98] これに反対する意見もある。例えば、イマニュエル・ウォーラーステインやニクラス・ルーマンといった中心的な著述家を挙げ、彼らが1970年代には早くも 「世界システム」や「世界社会」という用語を導入していたことを指摘する。 これに対し、ベックは、規範としてのコスモポリタニズムと事実としてのコスモポリタニゼーションの区別を主張している(前述の著作を参照)。この意味にお いて、19世紀の多くの社会理論家は規範的なコスモポリタニズムには関心を抱いていたが、コスモポリタニゼーションの実証的なプロセスには関心を抱いてい なかった。コスモポリタニゼーションの実証的なプロセスとは、インターネットやFacebook、グローバルリスク、家族や階級などの内部におけるグロー バル化に直面する中で、世界が融合していくことに焦点を当てている。 この経験的な意味でのコスモポリタニゼーションを真剣に捉える著者は、構造的なコスモポリタニゼーションが国境を越えた個人間の省察や相互作用と結びつい ていないため、コスモポリタニゼーションは最終的にグローバル化を無批判に理解することに帰結するという事実を批判している。[100] コスモポリタニゼーションが再国民化や再民族化のプロセスも包含するものであるならば、この用語は空虚なものとなる危険性がある。また、ベックがコスモポ リタニゼーションは不可逆的であると主張しているが、世界中で国家とナショナリズムが復活している状況を踏まえると、その理由を説明していないという異論 もある。 テルアビブで国際法を教えるイシャイ・ブランクは、コスモポリタニゼーションを推進するアクターに関する実証的な参照が欠如していることを批判しており、 これは社会学的研究としては驚くべき欠点である。結局のところ、ベックのコスモポリタニゼーションの概念はナショナリズムの概念を前提としている。そのた め、ベックはある程度まではナショナリズムの善し悪しを区別しているが、現実社会でこの区別を適用するのは読者に任せている。ベックのコスモポリタニゼー ション理論は、良くてもその成果が未熟であり、悪く言えば矛盾している。 |

| Zur Modernisierungstheorie Becks soziologische Sicht auf die Moderne war laut Eva Illouz eine doppelte: Einerseits habe sie uns jegliches Gefühl der Sicherheit, Gewissheit und Stabilität genommen; andererseits habe sie unser Leben bunter gemacht, erfindungsreicher, improvisierter, weniger festgeschrieben. „Gegen den alternativen Gassenhauer einer Foucaultschen Moderne, die auf Ordnung und Disziplin hinauslief, stellte Beck die überraschende Auffassung, dass die Moderne offen und tastend war und dem Einzelnen viel größere Kreise der Zugehörigkeit und Identifikation erschloss.“[102] Gegen die Theorie reflexiver Modernisierung wird oft eingewandt, sie sei ungeeignet eine neue Epoche zu definieren, da Moderne qua Begriff immer reflexiv sei.[103] Reflexive Modernisierung meint bei Beck jedoch Spezifischeres, nämlich „Modernisierung der Moderne“:[104] Die westliche Moderne wird sich selbst zum Thema und Problem, ihre Basisinstitutionen – Nationalstaat, Familie, Demokratie, Erwerbsarbeit usw. – lösen sich im Zuge radikalisierter Modernisierung von innen her auf; das Projekt der Moderne wird offen für politische Alternativen – ökologische Wende des Kapitalismus, Atomenergie versus erneuerbare Energien, globale Regulierung der Finanzmärkte. Die gewandelten Optionen müssten im Streit zwischen altem Zentrum und aufstrebender Peripherie, zwischen USA, China, EU, Afrika usw. neu verhandelt werden. Ein Einwand besagt, dass Becks Unterscheidung zwischen erster und zweiter Moderne beliebig sei und sprechen von den westlichen Gegenwartsgesellschaften als „dritter Moderne“.[105] Eine weitere Lesart hält dagegen: „Wir sind nie modern gewesen“.[106] |

近代化論について エヴァ・イローズによると、ベックの近代化に関する社会学的見解は2つの側面を持つ。すなわち、一方では、それは私たちからあらゆる安心感、確実性、安定 性を奪った。他方では、それは私たちの生活をよりカラフルで、独創的で、即興的で、規定の少ないものにした。「フーコー的な近代に対する一般的な考え方と は対照的に、秩序と規律を意味するものとして、ベックは驚くべき考え方を提示した。すなわち、近代は開放的で暫定的なものであり、個人にとって帰属と同一 化のより大きな輪を切り開くものである、という考え方である」[102] 近代性は常に概念として再帰的であるため、再帰的近代化の理論は新しい時代の定義には不適切であるという反論がしばしばなされる。103] しかし、ベックの著作における再帰的近代化は、より具体的な意味を持つ。すなわち、「近代性の近代化」である。104] 西洋の近代性は、その主体と問題となる。その基本的制度、すなわち国民国家、家族、民主主義、有給雇用などは、 急進的な近代化の過程で内側から崩壊し、近代主義プロジェクトは政治的な代替案を受け入れるようになる。すなわち、資本主義のエコロジー的転換、原子力エ ネルギー対再生可能エネルギー、金融市場のグローバル規制などである。変容した選択肢は、旧来の中心と台頭しつつある周辺、すなわち米国、中国、EU、ア フリカなどとの間の論争の中で再交渉されなければならないだろう。 ベックの第一近代と第二近代の区別は恣意的であり、現代の西洋社会を「第三近代」と呼んでいるという異論もある。[105] これに対しては、「我々は決して近代的ではなかった」という反論もある。[106] |

| Zu Beschäftigungspolitik und Grundeinkommen In einem Bericht der Bayerisch-Sächsischen Zukunftskommission von Kurt Biedenkopf und Meinhard Miegel stellte Beck 1996/1997 ein Konzept von Bürgerarbeit und Gemeinwohlunternehmertum für alle, für Arbeitslose und Erwerbstätige vor. Er ging in diesem Konzept davon aus, dass es in Zukunft wahrscheinlich nicht mehr für alle Arbeit geben werde. Erwerbslose sollten bei sogenannten „Gemeinwohlunternehmern“ Bürgerarbeit leisten. Beck hielt also in der Bürgerarbeit an der Arbeitsethik – an Erwerbsarbeit als Normalität – fest,[107] obwohl er Vollbeschäftigung in der Perspektive für unwahrscheinlich hielt. Kritiker haben Beck vorgeworfen, mit seiner Bürgerarbeit, die durch staatliche Stellen als gemeinwohlbezogene anzuerkennen ist und mit einer Lohnzahlung einhergehen sollte, eine gigantische Bürokratisierung und eine Kommerzialisierung des ehrenamtlichen Sektors zu propagieren. Kritik wurde sogar dergestalt geübt, die Bürgerarbeit sei das technokratische Horrorszenario eines modernen Arbeitshauses; denn die Arbeitslosen würden behördlich unter Kuratel der Arbeitsethik gestellt, indem ihnen eine staatlich kontrollierte Bürgerarbeit angeboten werde, die sie gegebenenfalls als Einkommenszuverdienst anzunehmen gezwungen seien. Von Makroökonomen, die sich auf die im angelsächsischen Raum weithin anerkannten neukeynesianischen Ansätze berufen, wurde Beck heftig für seine These kritisiert, dass eine wirksame staatliche Beschäftigungspolitik heute nicht mehr möglich sei. Kritisch vermerkt wurde auch Becks Intellektuellenbündnis mit Anthony Giddens, das die rot-grüne Politik der Agenda 2010 von Gerhard Schröder bzw. die Arbeitsmarktreformen von Tony Blair in Großbritannien mit Wohlwollen begleitete. Gemeinsame Basis dafür war das Modell des „workfare“ und des „aktivierenden Sozialstaats“. Als zu diesem Ansatz widersprüchlich wurde wahrgenommen, dass Beck sich später als Befürworter des Grundeinkommensvorschlags zu Wort meldete, obwohl er zuvor eher Gegensätzliches propagiert hatte. |

雇用政策とベーシックインカムについて クルト・ビートケンプフとマインハルト・ミーゲルのバイエルン・ザクセン未来委員会の報告書の中で、ベックは1996年から1997年にかけて、失業者と 就業者全員を対象とした市民労働と公共福祉起業の構想を提示した。彼はこの構想の中で、おそらく将来は誰もが仕事に就ける状況ではなくなると想定した。失 業者は、いわゆる「公共福祉起業家」のために市民活動を行うべきである。ベックは、長期的には完全雇用はあり得ないと考えていたが、市民活動における労働 倫理、すなわち有給雇用を正常な状態として固守したのである。ベックは、市民労働を推進することで、ボランティア部門の巨大な官僚化と商業化を促進してい ると批判されている。市民労働とは、公益に関連する労働として国家機関に認められ、賃金が支払われるべきものである。市民労働は、現代のワークハウスのテ クノクラートによる恐ろしいシナリオであるという批判さえもあった。なぜなら、失業者は、必要に応じて追加収入として受け入れを余儀なくされる、国家管理 の市民労働を公式に提供されることで、労働倫理の指導下に置かれることになるからだ。 アングロサクソン圏で広く認知されているニュー・ケインジアン・アプローチを信奉するマクロ経済学者たちは、効果的な国家雇用政策は今日ではもはや不可能 であるというベックの論文を強く批判している。また、ベックがアンソニー・ギデンズと知的同盟を結び、ゲアハルト・シュレーダーの「アジェンダ2010」 における「赤緑政策」や英国のトニー・ブレアの労働市場改革を支持したことも批判された。その共通の基盤となったのは、「ワークフェア」と「活性化社会国 家」というモデルであった。ベックが後に基本所得案を支持する発言をしたことは、このアプローチと矛盾していると受け止められた。ベックはそれまで、むし ろその反対のことを主張していたにもかかわらずである。 |