先住民運動からみた日本の保守とリベラルの位相

Distorted Political Identities between Conservative and Liberal in post-war Japan: a cultural analysis of Indigenous movement's point of view

Spinoza,

Excommunicated by Samuel

Hirszenberg, 1907

先住民運動からみた日本の保守とリベラルの位相

Distorted Political Identities between Conservative and Liberal in post-war Japan: a cultural analysis of Indigenous movement's point of view

Spinoza,

Excommunicated by Samuel

Hirszenberg, 1907

1.政治的アイデンティティとしての「民 族」と、それに対する不審(distrust)

この発表は、先住民運動というもうひとつの「政治的立場」から、保守とリベラルという政治的位相を照射することを通して、21世紀の世界と 国民国家(日本)における政治的対立構造のダイナミズムを明らかにするものです。

先住民運動が、ある種の政治運動であることを理解していただくためには、政治学理論における文化多元主義を論じる中で、民族(または民族集 団)が政治的アイデンティティとして構築されることについての理解が必要になります。

2.政治理解のプラグマティック・オーク ショット主義(Pragmatic Oakeshottian)

マイケル・オークショット(Michael Joseph Oakeshott, 1901-1990)は、保守思想あるいは政治におけるテクノクラシーや計画経済を批判した政治学者で、とりわけ「政治における合理主義 (Rationalism in Politics)」(1947)の論文が有名です。

オークショットによると、政治は、政治的状況に対応することに関わる実践的活動であり、自然的な必然性からではなく、人間の選択や行動から 生じたと認められる物事の状態であり、かつ、政治的状況は、「私的」状況ではなく「公的」状況である。彼によると、どのような条件下でも、政治状況という ものは「観察可能」であり、社会科学者にとり「解釈」が求められるものであり、また未来にむけての「対応」をも含めてその理解には「熟議」が必要である、 と。

3.先住民運動の歴史的構築:アイヌ民族 を事例にとって

アイヌ先住民は、2007年「先住民族の権利に関する国際宣言(Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 略称:UNDRIP)」の国連総会採択以降、先住民族は当人ならびに国際社会から(どこに居住しようとも)先住の民として自認しそのアイデンティティを持 つものと理解されています。宣言は、先住民を本質的に定義すると同時に構成的にも可能な存在として認めています。

しかしながら、日本では「純粋なアイヌは存在しない」というヘイト発言に代表されるように、先住民/先住民族を人種にもとづく本質的に規定 する傾向が強いのです。言い方を変えると、アイヌを定義する時に、この国の社会的文脈では、文化人類学のいう民族(ethnie, ethnic group)よりも人種的概念が優先するようです。

アイヌ民族の運動家に公定の日本史とは異なる自民族の歴史の語りがあります、私は発表論文の脚注の中で、それは「対抗史(counter- history)」と名付けました。

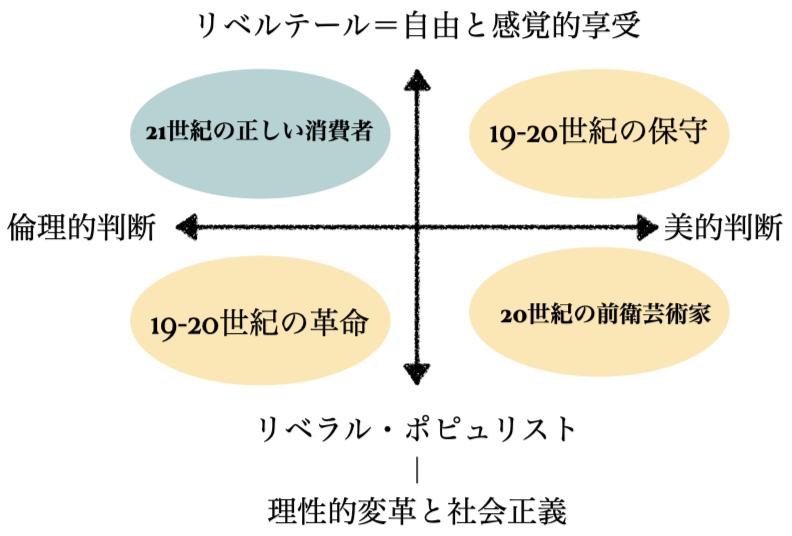

4.あべこべの、保守〈対〉革新の対立

現代日本における保守とリベラルという対立の位相を、党派政治に当てはめると奇妙な捩れがみらます。自民党はネオリベラル経済政策をとりな がら様々な改革政治をおこないます。他方、リベラル派は、五十五年体制において自民党と日本社会党が築いた国民皆保険や社会福祉政策を、今後も護持し続け ることです。また憲法改正に反対する野党の人たちは護憲つまり憲法を変えないことを、その政治主張として掲げています。つまり日本では、保守主義的政策を リベラルを自認する人たちが支持しています。

ここでオークショット論文「政治における合理主義」や「保守的であること」を思い起こしましょう。革命やテクノクラシー官僚による社会改革 は合理的に社会を改造できる進歩主義的な信念にもとづいてなされるが、それには予測不能な不確実性が生じると彼は批判します。そのような不確実な変革に委 ねるよりも、変革を避け、今ある政治的資源を活用して自分たちの生活の快適さや楽しみを追求するほうがよいとみなします。日本の現今のリベラル派は、ネオ リベラル的政策である規制緩和や(景気を下支えする[かもしれない])企業への減税には反対します。つまり、政治経済制度の法改正には関心がなく、選挙民 が喜ぶ福祉政策の拡充という改革には与党よりもさらに熱心に国民に働きかけます。

この伝統的な「保守〈対〉革新」の体制の枠組みは、日本のリベラル・ナショナリズムの通奏低音であり続けています。そのなかでは、国民統合 に棹差す先住民運動は、自民党あるいは超党派の日本会議派においては国家統合の分断分子に他ならず、その支持者たちからヘイト運動を生み出す原因になって います。またリベラル派は、LGBTを含めてあらゆるタイプのマイノリティー擁護を是とする中での先住民運動を基本的に支持しますが、国際基準のダイ ヴァーシティ容認には、保守志向の選挙民に配慮しつつ、それらのテーマの政治化には警戒しています。

「保守〈対〉革新」の対立という枠組みが、現代日本では、本来あるべきであった「保守〈対〉革新」の対立とは「あべこべ」になっています。

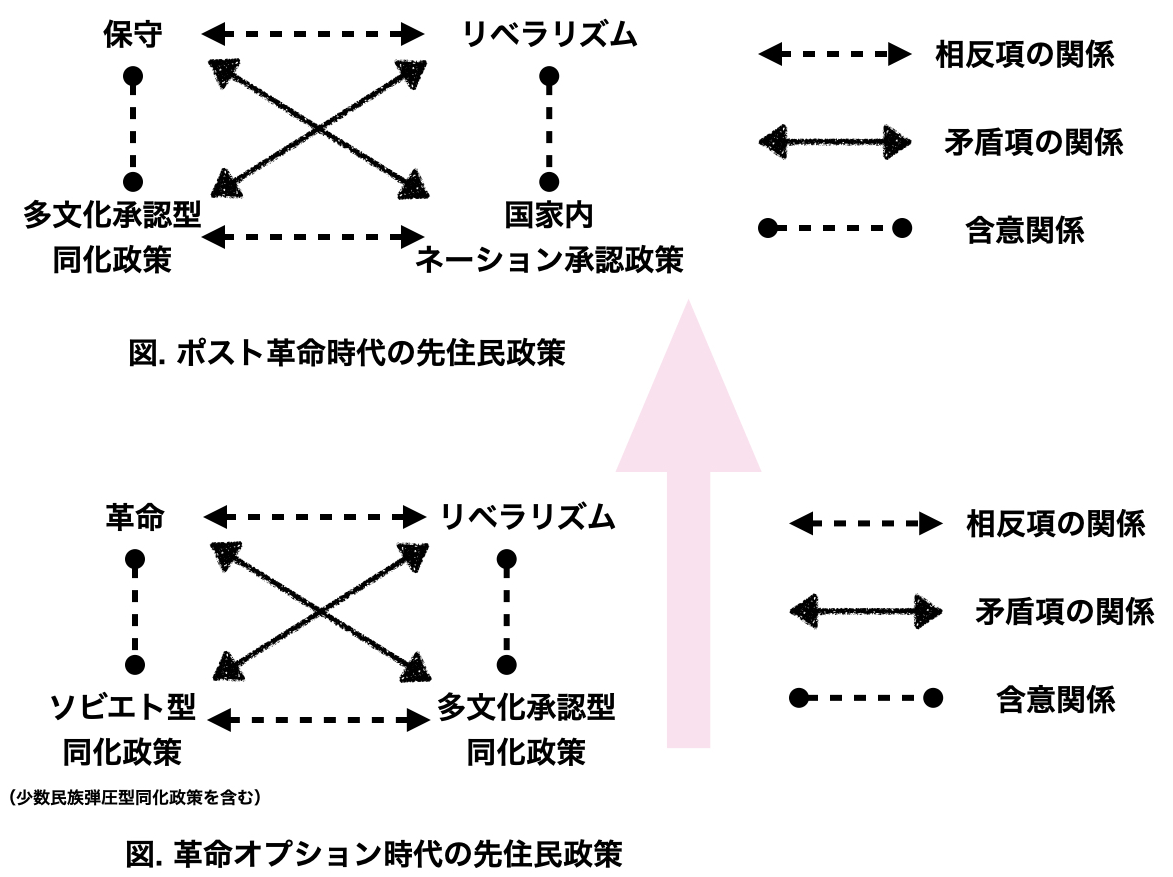

ここで、冷戦期すなわち革命〈対〉リベラリズムの対立構造があった時代における国民国家あるいは連邦国家が先住民をどのように包摂すること ができたのか、アルジダス・グレマス(1992)による「意味の四角形」 の図式で当てはめて考えてみましょう。

ロシア革命が達成されたソビエト連邦は、田中克彦(1991)先生に言わせればその名称が地名に由来しない世界初の国家だと言います。連邦 をなすそれぞれの共和国は地名ではなくエスニック・ネーション(民族分類による国民)から構成されて、それを包摂するのがソビエトすなわち「労働者・農 民・兵士の評議会」の意味です。民族と言語の多様性はソビエトではこのように担保されました。このタイプの共産主義型の多文化主義をとらなかったのが中国 共産党で「少数民族」の虐殺を含む弾圧が現在においても終わりそうにないのは衆知のとおりです。他方、冷戦期のリベラリズムの代表格であるアメリカ合衆国 は、同化主義の政策を特段改めることになく先住民の抵抗を受けながら徐々に多文化主義に転換し、採用することになりました。先住民族の国家内での歴史上の 承認が開拓時代における外交文書として保管されていたために、土地返還などの訴訟裁判でも法的権利が認定されたからです。

5.保守〈対〉リベラルの政治文化対立の 中に先住民運動を組み込む

しかしながら、冷戦構造終結後の世界では、南米のボリビアやベネズエラなどを除けば、政治革命や軍人指導の社会革命が起こりませんでした。 このような統治システムが異常あるいは破綻している地域を除くと、冷戦後は保守〈対〉リベラリズムの対立構図における先住民族政治は、近年におけるポピュ リズム政治の台頭以前には、かつてのリベラリズムが採用してした多文化承認型の同化政策を保守派がとり、リベラル派は、グローバルスタンダードと して確立 した多文化政策を推しすすめ、国家内に先住民族による独自の自治単位である国家内ネーションを認める方向にすすめてきました。リベラル国家がこのような政 策をすすめるのは、単純に国家内領域の先住民族の権利保障に真剣であるというよりも、国内融和をすすめ、先住民の分離独立運動を防ぎ国民国家の国内的安全 保障を維持しようという「治安上の理由」も考えられます。

このような国際的スキームの中で日本の先住民は不利な闘いを強いられています。それが、先に触れた先住民族側の分断・分派です。先住民運動 には、日本のマイルドな国民国家への包摂を基調とする政府と融和しようとする派が一方にあり、他方では、海外の先住民運動の影響を受けて国際社会並みの権 利獲得のためにはより積極的に政府と対峙しようとする対政府派が存在しているからです。

21世紀における保守とリベラルの対立は、直接投票による大統領選挙や国民投票が契機になり政治的分断が起こり、サイレントマジョリティが 政党をしてポピュリズム化を推し進めることが起因することが特徴としてみられます。そこでは 「合理主義による政治」というものから、真理よりも情動に訴え る政治へ、冷静よりも怒りや興奮を基調にするものが多いと言えましょう。そこで使われる政治言説もまた「情動の語彙」が多用されます。

アイヌ先住民へのヘイト活動は、政治改革に関する捻れた関係をもつ、保守派にとっても、リベラル派にとっても「扱いにくい」政治的不満の受 け皿になるというポピュリズムの流れを育成するインキュベーター(孵卵器)になっている可能性があります。あるいは、オークショット流の熟議にもとづく保 守主義の伝統も政治的合理主義(テクノクラートと政治的改革派)の伝統もいまだ定着していない日本の政治文化の貧困状況を表しているものと思われます。

このような状況を克服するためにはたくさんの可能性を模索することが社会に求められているのは言うまでもありません。そのためには、大学に おける若い世代に対して、オークショットに倣い、先生方が組する現代の政治思想についてイデオロギー的な押し付けを中断し、(言葉の正しい意味での)「政 治学」や「弁論術」の古典や基礎を学び育む必要があるように思われます。私がこの発表において提唱したプラグマティック・オークショット主義 (Pragmatic Oakeshottian)というものに何らか価値があるとすれば、性急な政治改革に期待するのではなく、すでにある多数派にとっての政治経済的資源の配 分が、社会の中のマイノリティの存在により、既存の政治枠組みを大幅に変えることなく「公正に」配分できるように働かせることにあると思われます。

|

さて、最近は僕は琉球の先住民遺骨返還運

動に関わっています。琉球の先住民性は、国連勧告などで明確で、日本政府は国内の多言語多民族性、多文化性の承認をして、国民の多様性のなかに、世界の先

端をゆく多民族共存のモデルとして前進させるべきです。その意味でも「琉球の同胞(僕はネオリベラル・コミュニストですから同志と呼びたい)」の立場も複

雑です。琉球の先住民性を後進性や原理主義とみなす沖縄のモダニストや、それを分離主義と糾弾する国民派があり、さらに辺野古移設問題や沖縄(琉球)アイ

デンティティ論が絡みとても錯綜しています。ヤマトの僕としては、その都度、私=俺(→反響としてのお前)は何者だといつも自問しています。 ●遺骨や副葬品を取り戻しつつある先住民のための試論 ●金関丈夫と琉球の人骨 ●先 住民運動からみた日本の保守とリベラルの位相 |

|

●新自由主義 ● |

★ 熟議民主主義は万能か? Is deliberative democracy a panacea?

| Deliberative

democracy

or discursive democracy is a form of democracy in which deliberation is

central to decision-making. Deliberative democracy seeks quality over

quantity by limiting decision-makers to a smaller but more

representative sample of the population that is given the time and

resources to focus on one issue.[1] It often adopts elements of both consensus decision-making and majority rule. Deliberative democracy differs from traditional democratic theory in that authentic deliberation, not mere voting, is the primary source of legitimacy for the law. Deliberative democracy is related to consultative democracy, in which public consultation with citizens is central to democratic processes. The distance between deliberative democracy and concepts like representative democracy or direct democracy is debated. While some practitioners and theorists use deliberative democracy to describe elected bodies whose members propose and enact legislation, Hélène Landemore and others increasingly use deliberative democracy to refer to decision-making by randomly-selected lay citizens with equal power.[2] Deliberative democracy has a long history of practice and theory traced back to ancient times, with an increase in academic attention in the 1990s, and growing implementations since 2010. Joseph M. Bessette has been credited with coining the term in his 1980 work Deliberative Democracy: The Majority Principle in Republican Government.[3] |

熟議民主主義または討議民主主義は、熟議が意思決定の中心となる民主主

義の形態である。熟議民主主義では、意思決定者をより少数ではあるがより代表的な母集団に限定し、その集団に一つの問題に集中する時間とリソースを与える

ことで、量より質を重視する。[1] また、合意に基づく意思決定と多数決の両方の要素を取り入れることが多い。熟議民主主義は、単なる投票ではなく、本物の熟議が法の正当性の主な源泉である という点で、従来の民主主義理論とは異なる。熟議民主主義は、市民との協議が民主主義のプロセスにおいて中心的な役割を果たす協議型民主主義と関連してい る。熟議民主主義と代表制民主主義や直接民主主義などの概念との距離については議論がある。一部の専門家や理論家は、熟議民主主義を、議員が立法を提案し 制定する選挙で選ばれた機関を指して用いるが、ヘレン・ランドモア(Hélène Landemore)をはじめとする一部の専門家は、熟議民主主義を、無作為に選ばれた一般市民が同等の権限を持つ意思決定を指して用いることが多くなっ ている。 熟議民主主義は古代まで遡る長い歴史を持つ実践と理論があり、1990年代に学術的な注目が高まり、2010年以降は実施例も増えている。ジョセフ・M・ ベセットは、1980年の著書『熟議民主主義:共和制政府における多数派原理』でこの用語を初めて使用した人物として知られている。[3] |

| Overview Deliberative democracy holds that, for a democratic decision to be legitimate, it must be preceded by authentic deliberation, not merely the aggregation of preferences that occurs in voting. Authentic deliberation is deliberation among decision-makers that is free from distortions of unequal political power, such as power a decision-maker obtains through economic wealth or the support of interest groups.[4][5][6] The roots of deliberative democracy can be traced back to Aristotle and his notion of politics; however, the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas' work on communicative rationality and the public sphere is often identified as a major work in this area.[7] Deliberative democracy can be practiced by decision-makers in both representative democracies and direct democracies.[8] In elitist deliberative democracy, principles of deliberative democracy apply to elite societal decision-making bodies, such as legislatures and courts; in populist deliberative democracy, principles of deliberative democracy apply to groups of lay citizens who are empowered to make decisions.[5] One purpose of populist deliberative democracy can be to use deliberation among a group of lay citizens to distill a more authentic public opinion about societal issues for other decision-makers to consider; devices such as the deliberative opinion poll have been designed to achieve this goal. Another purpose of populist deliberative democracy can, like direct democracy, result directly in binding law.[5][9] If political decisions are made by deliberation but not by the people themselves or their elected representatives, then there is no democratic element; this deliberative process is called elite deliberation.[10][11] James Fearon and Portia Pedro believe deliberative processes most often generate ideal conditions of impartiality, rationality and knowledge of the relevant facts, resulting in more morally correct outcomes.[12][13][14] Former diplomat Carne Ross contends that the processes more civil, collaborative, and evidence-based than the debates in traditional town hall meetings or in internet forums if citizens know their debates will impact society.[15] Some fear the influence of a skilled orator.[16][17] John Burnheim critiques representative democracy as requiring citizens to vote for a large package of policies and preferences bundled together, much of which a voter might not want. He argues that this does not translate voter preferences as well as deliberative groups, each of which are given the time and the ability to focus on one issue.[18] |

概要 熟議民主主義では、民主的な意思決定が正当であるためには、投票における単なる好みの集計ではなく、真正な熟議が先行されなければならないと主張する。真 正な熟議とは、意思決定者間の熟議であり、意思決定者が経済的な富や利益団体の支援を通じて得るような不平等な政治力による歪曲から自由なものである。 [4][5][6] 熟議民主主義の起源は、アリストテレスの政治観にまで遡ることができるが、この分野における主要な著作としては、ドイツの哲学者ユルゲン・ハーバーマスの コミュニケーション的理性と公共圏に関する著作が挙げられることが多い。 熟議民主主義は、代議制民主主義と直接民主主義の両方の意思決定者によって実践することができる。[8] エリート主義的な熟議民主主義では、熟議民主主義の原則は、立法府や司法府といったエリート社会の意思決定機関に適用される。大衆主義的な熟議民主主義で は、熟議民主主義の原則は、 決定権を持つ一般市民のグループに適用される。[5] ポピュリスト的討議民主主義の目的の一つは、一般市民のグループによる討議を通じて、社会問題に関するより本物の世論を抽出して他の意思決定者が考慮でき るようにすることである。また、ポピュリスト的討議民主主義のもう一つの目的は、直接民主主義と同様に、拘束力のある法律を直接的に生み出すことである。 [5][9] もし政治的意思決定が、国民やその選出された代表者ではなく、討議によってなされるのであれば、そこには民主主義的な要素は存在しない。この討議プロセス はエリート討議と呼ばれる。[10][11] ジェームズ・フィアロンとポルティア・ペドロは、熟議プロセスは公平性、合理性、関連事実の知識という理想的な条件を生み出すことが最も多く、その結果、 より道徳的に正しい結果がもたらされると考えている。[12][13][14] 元外交官のカーン・ロスは、市民が議論が社会に影響を与えることを知っている場合、このプロセスは従来のタウンホールミーティングやインターネットフォー ラムでの議論よりも、より礼儀正しく、協力的で、証拠に基づいたものになると主張している。。市民が議論が社会に影響を与えることを理解していれば、従来 のタウンホールミーティングやインターネットフォーラムでの討論よりも、より礼儀正しく、協調的で、証拠に基づくプロセスになるだろうと主張している。 [15] 熟練した演説家の影響力を懸念する声もある。[16][17] ジョン・バーンハイムは、代表制民主主義では、有権者は望んでいないかもしれない政策や希望の多くがひとまとめにされた大きなパッケージに対して投票しな ければならないと批判している。彼は、熟議グループでは、それぞれに時間を割き、一つの問題に集中する能力が与えられるため、これは有権者の好みを反映す るものではないと主張している。[18] |

| Characteristics Fishkin's model of deliberation James Fishkin, who has designed practical implementations of deliberative democracy through deliberative polling for over 15 years in various countries,[15] describes five characteristics essential for legitimate deliberation: Information: The extent to which participants are given access to reasonably accurate information that they believe to be relevant to the issue Substantive balance: The extent to which arguments offered by one side or from one perspective are answered by considerations offered by those who hold other perspectives Diversity: The extent to which the major positions in the public are represented by participants in the discussion Conscientiousness: The extent to which participants sincerely weigh the merits of the arguments Equal consideration: The extent to which arguments offered by all participants are considered on the merits regardless of which participants offer them[19] Studies by James Fishkin and others have concluded that deliberative democracy tends to produce outcomes which are superior to those in other forms of democracy.[20][21] Desirable outcomes in their research include less partisanship and more sympathy with opposing views; more respect for evidence-based reasoning rather than opinion; a greater commitment to the decisions taken by those involved; and a greater chance for widely shared consensus to emerge, thus promoting social cohesion between people from different backgrounds.[10][15] Fishkin cites extensive empirical support for the increase in public spiritedness that is often caused by participation in deliberation, and says theoretical support can be traced back to foundational democratic thinkers such as John Stuart Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville.[22][23] Cohen's outline Joshua Cohen, a student of John Rawls, argued that the five main features of deliberative democracy include:[24] An ongoing independent association with expected continuation. The citizens in the democracy structure their institutions such that deliberation is the deciding factor in the creation of the institutions and the institutions allow deliberation to continue. A commitment to the respect of a pluralism of values and aims within the polity. The citizens consider deliberative procedure as the source of legitimacy, and prefer the causal history of legitimation for each law to be transparent and easily traceable to the deliberative process. Each member recognizes and respects other members' deliberative capacity. Cohen presents deliberative democracy as more than a theory of legitimacy, and forms a body of substantive rights around it based on achieving "ideal deliberation":[24] It is free in two ways: The participants consider themselves bound solely by the results and preconditions of the deliberation. They are free from any authority of prior norms or requirements. The participants suppose that they can act on the decision made; the deliberative process is a sufficient reason to comply with the decision reached. Parties to deliberation are required to state reasons for their proposals, and proposals are accepted or rejected based on the reasons given, as the content of the very deliberation taking place. Participants are equal in two ways: Formal: anyone can put forth proposals, criticize, and support measures. There is no substantive hierarchy. Substantive: The participants are not limited or bound by certain distributions of power, resources, or pre-existing norms. "The participants…do not regard themselves as bound by the existing system of rights, except insofar as that system establishes the framework of free deliberation among equals." Deliberation aims at a rationally motivated consensus: it aims to find reasons acceptable to all who are committed to such a system of decision-making. When consensus or something near enough is not possible, majoritarian decision making is used. In Democracy and Liberty, an essay published in 1998, Cohen updated his idea of pluralism to "reasonable pluralism" – the acceptance of different, incompatible worldviews and the importance of good faith deliberative efforts to ensure that as far as possible the holders of these views can live together on terms acceptable to all.[25] Gutmann and Thompson's model Amy Gutmann and Dennis F. Thompson's definition captures the elements that are found in most conceptions of deliberative democracy. They define it as "a form of government in which free and equal citizens and their representatives justify decisions in a process in which they give one another reasons that are mutually acceptable and generally accessible, with the aim of reaching decisions that are binding on all at present but open to challenge in the future".[26] They state that deliberative democracy has four requirements, which refer to the kind of reasons that citizens and their representatives are expected to give to one another: Reciprocal. The reasons should be acceptable to free and equal persons seeking fair terms of cooperation. Accessible. The reasons must be given in public and the content must be understandable to the relevant audience. Binding. The reason-giving process leads to a decision or law that is enforced for some period of time. The participants do not deliberate just for the sake of deliberation or for individual enlightenment. Dynamic or Provisional. The participants must keep open the possibility of changing their minds, and continuing a reason-giving dialogue that can challenge previous decisions and laws. Standards of good deliberation - from first to second generation (Bächtiger et al., 2018) For Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren, the ideal standards of "good deliberation" which deliberative democracy should strive towards have changed:[6] |

特徴 フィッシュキンの熟議モデル ジェームズ・フィッシュキンは、15年以上にわたり、さまざまな国々で熟議投票を通じて熟議民主主義の実用的な実施方法を考案してきた人物であるが、 [15] 正当な熟議に不可欠な5つの特徴を次のように説明している。 情報:参加者が、その問題に関連していると考える妥当な正確性を持つ情報にアクセスできる程度 実質的バランス:一方の側または一方の見解から提示された議論が、他の見解を持つ人々によって提示された考察によってどの程度回答されているか 多様性:議論の参加者が、一般市民の主要な立場をどの程度代表しているか 誠実さ:参加者が議論の長所をどの程度真剣に検討しているか 平等な考察:すべての参加者が提示した議論が、どの参加者が提示したかに関わらず、その長所に基づいてどの程度検討されているか[19] ジェームズ・フィシュキン(James Fishkin)氏らの研究では、熟議民主主義は他の民主主義の形態よりも優れた成果を生み出す傾向があると結論づけている。[20][21] 彼らの研究で望ましい成果として挙げられているのは、党派性が弱まり、反対意見への共感が強まること、意見よりも証拠に基づく推論が尊重されること、関係 者による決定へのコミットメントが高まること、 異なる背景を持つ人々の間の社会的結束を促進する、広く共有された合意が生まれる可能性が高まる。[10][15] フィッシュキンは、熟議への参加によってしばしば引き起こされる公共精神の高まりについて、広範な実証的裏付けを挙げ、理論的裏付けはジョン・スチュアー ト・ミルやアレクシス・ド・トクヴィルといった民主主義の基礎を築いた思想家にまで遡ることができると述べている。[22][23] コーエンの概要 ジョン・ロールズの弟子であるジョシュア・コーエンは、熟議民主主義の主な特徴として以下の5つを挙げている。[24] 継続が期待される独立した組織。 民主主義の市民は、熟議が組織の創設における決定要因であり、組織が熟議の継続を可能にするような組織構造を構築する。 政治体制内の価値観と目標の多元主義を尊重することへのコミットメント。 市民は熟議手続きを正当性の源とみなしており、各法の正当化の経緯は透明性があり、熟議プロセスに容易に遡及できることを好む。 各メンバーは他のメンバーの熟議能力を認識し、尊重する。 コーエンは熟議民主主義を正当性の理論以上のものとして提示しており、「理想的な熟議」の達成を基盤として、実質的な権利体系を形成している。[24] それは2つの点で自由である。 参加者は、自分たちが審議の結果と前提条件のみに拘束されると考える。彼らは、過去の規範や要件の権威から自由である。 参加者は、自分たちが下した決定に従って行動できると想定する。審議プロセスは、下された決定に従うための十分な理由である。 審議の当事者は、提案の理由を述べることが求められ、提案は、審議が行われているまさにその審議の内容として、示された理由に基づいて承認または却下され る。 参加者は次の2つの点で平等である。 形式的:誰もが提案を行い、批判し、措置を支持することができる。実質的な上下関係はない。 実質的:参加者は、特定の権力、資源、または既存の規範の配分によって制限されたり拘束されたりすることはない。「参加者は…平等な者同士の自由な審議の 枠組みを確立する限りにおいて、既存の権利体系に拘束されるとはみなさない」 熟慮の目的は、合理的に導かれた合意である。すなわち、そのような意思決定システムにコミットするすべての人々が受け入れられる理由を見出すことを目的と している。合意またはそれに近いものが不可能な場合は、多数決による意思決定が用いられる。 1998年に発表された論文『民主主義と自由』の中で、コーエンは多元主義の考え方を「合理的な多元主義」へと発展させた。それは、異なる相容れない世界 観を認め、それらの世界観の保有者が可能な限りすべての人々に受け入れられる条件のもとで共存できるようにするための誠実な熟議努力の重要性を意味する。 ガットマンとトンプソンのモデル エイミー・ガットマンとデニス・F・トンプソンの定義は、熟議民主主義のほとんどの概念に見られる要素を捉えている。彼らは熟議民主主義を「自由で平等な 市民とその代表者が、お互いに受け入れ可能で、一般的にアクセス可能な理由を提示し合うプロセスにおいて、決定を正当化する政府形態である。その目的は、 現在では全員を拘束する決定を導き出すことだが、将来的には異議を申し立てることも可能にする」と定義している。[26] 彼らは、熟議民主主義には4つの要件があり、それは市民と代表者が互いに示すことが期待される理由の種類を指していると述べている。 相互的であること。その理由は、公平な協力条件を求める自由で対等な人々にとって受け入れられるものでなければならない。 アクセス可能であること。その理由は公の場で提示され、その内容は関連する聴衆にとって理解できるものでなければならない。 拘束力があること。理由提示のプロセスは、一定期間施行される決定や法律につながる。参加者は審議そのものや個人の啓発を目的として審議に参加しているわ けではない。 動的または暫定的。参加者は、考えを変える可能性を常に開いておかなければならず、以前の決定や法律に異議を唱えることができる理由説明の対話を継続しな ければならない。 熟議の基準 - 第1世代から第2世代へ(Bächtiger et al., 2018 Bächtiger、Dryzek、Mansbridge、Warrenにとって、熟議民主主義が目指すべき「熟議」の理想的な基準は変化している。 |

Standards for "good deliberation" Standards of good deliberation - from first to second generation (Bächtiger et al., 2018) For Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren, the ideal standards of "good deliberation" which deliberative democracy should strive towards have changed:[6] |

「良質な熟議」の基準 熟議の基準 - 第一世代から第二世代へ(Bächtiger et al., 2018) Bächtiger、Dryzek、Mansbridge、Warrenにとって、熟議民主主義が目指すべき「熟議」の理想的な基準は変化した。[6] |

| History Early examples Main article: Sortition Consensus-based decision making similar to deliberative democracy has been found in different degrees and variations throughout the world going back millennia.[27] The most discussed early example of deliberative democracy arose in Greece as Athenian democracy during the sixth century BC. Athenian democracy was both deliberative and largely direct: some decisions were made by representatives but most were made by "the people" directly. Athenian democracy came to an end in 322 BC. Even some 18th century leaders advocating for representative democracy mention the importance of deliberation among elected representatives.[28][29][30] Recent scholarship  Call for the establishment of deliberative democracy seen at the Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear The deliberative element of democracy was not widely studied by academics until the late 20th century. According to Professor Stephen Tierney, perhaps the earliest notable example of academic interest in the deliberative aspects of democracy occurred in John Rawls 1971 work A Theory of Justice.[31] Joseph M. Bessette has been credited with coining the term "deliberative democracy" in his 1980 work Deliberative Democracy: The Majority Principle in Republican Government,[32][33] and went on to elaborate and defend the notion in "The Mild Voice of Reason" (1994). In the 1990s, deliberative democracy began to attract substantial attention from political scientists.[33] According to Professor John Dryzek, early work on deliberative democracy was part of efforts to develop a theory of democratic legitimacy.[34] Theorists such as Carne Ross advocate deliberative democracy as a complete alternative to representative democracy. The more common view, held by contributors such as James Fishkin, is that direct deliberative democracy can be complementary to traditional representative democracy. Others contributing to the notion of deliberative democracy include Carlos Nino, Jon Elster, Roberto Gargarella, John Gastil, Jürgen Habermas, David Held, Joshua Cohen, Amy Gutmann, Noëlle McAfee, Rense Bos, Jane Mansbridge, Jose Luis Marti, Dennis Thompson, Benny Hjern, Hal Koch, Seyla Benhabib, Ethan Leib, Charles Sabel, Jeffrey K. Tulis, David Estlund, Mariah Zeisberg, Jeffrey L. McNairn, Iris Marion Young, Robert B. Talisse, and Hélène Landemore.[citation needed] Although political theorists took the lead in the study of deliberative democracy, political scientists have in recent years begun to investigate its processes. One of the main challenges currently is to discover more about the actual conditions under which the ideals of deliberative democracy are more or less likely to be realized.[35] Drawing on the work of Hannah Arendt, Shmuel Lederman laments the fact that "deliberation and agonism have become almost two different schools of thought" that are discussed as "mutually exclusive conceptions of politics"[36] as seen in the works of Chantal Mouffe,[37] Ernesto Laclau, and William E. Connolly. Giuseppe Ballacci argues that agonism and deliberation are not only compatible but mutually dependent:[38] "a properly understood agonism requires the use of deliberative skills but also that even a strongly deliberative politics could not be completely exempt from some of the consequences of agonism". Most recently, scholarship has focused on the emergence of a 'systemic approach' to the study of deliberation. This suggests that the deliberative capacity of a democratic system needs to be understood through the interconnection of the variety of sites of deliberation which exist, rather than any single setting.[39] Some studies have conducted experiments to examine how deliberative democracy addresses the problems of sustainability and underrepresentation of future generations.[40] Although not always the case, participation in deliberation has been found to shift participants opinions in favour of environmental positions.[41][42][43] Platforms and algorithms Aviv Ovadya also argues for implementing bridging-based algorithms in major platforms by empowering deliberative groups that are representative of the platform's users to control the design and implementation of the algorithm.[44] He argues this would reduce sensationalism, political polarization and democratic backsliding.[45] Jamie Susskind likewise calls for deliberative groups to make these kind of decisions.[46] Meta commissioned a representative deliberative process in 2022 to advise the company on how to deal with climate misinformation on its platforms.[47] Modern examples Main article: Citizens'_assembly § Modern_examples The OECD documented hundreds of examples and finds their use increasing since 2010.[48][49] For example, a representative sample of 4000 lay citizens used a 'Citizens' congress' to coalesce around a plan on how to rebuild New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.[50][15] |

歴史 初期の例 詳細は「無作為抽出」を参照 熟議民主主義に類似したコンセンサスに基づく意思決定は、数千年も前から世界中で様々な程度とバリエーションで存在していたことが確認されている。 [27] 熟議民主主義の最もよく知られた初期の例は、紀元前6世紀のギリシャのアテナイの民主政である。アテナイの民主政は熟議的であり、かつ大部分が直接民主制 であった。一部の決定は代表者によって行われたが、ほとんどの決定は「人民」によって直接行われた。アテナイの民主政は紀元前322年に終焉を迎えた。 18世紀の指導者の中にも、代表制民主主義を擁護する者の中には、選出された代表者による熟議の重要性を指摘する者もいる。[28][29][30] 最近の研究  正気と恐怖を取り戻す集会」に見られる熟議民主主義の確立を求める声 民主主義における熟議の要素は、20世紀後半まで学術的に広く研究されることはなかった。スティーブン・ティアニー教授によると、おそらく民主主義の熟議 の側面に対する学術的な関心として最も早い注目すべき例は、ジョン・ロールズの1971年の著書『正義論』において見られるという。[31] ジョセフ・M・ベセットは、1980年の著書『熟議民主主義: 多数派原理に基づく共和制」で、[32][33] さらに1994年の著書『理性の穏やかな声』でこの概念を詳しく説明し、擁護した。1990年代には、熟議民主主義は政治学者の間で大きな注目を集めるよ うになった。[33] ジョン・ドライゼク教授によると、熟議民主主義に関する初期の研究は、民主的正統性の理論を開発する取り組みの一環であった。[34] カーネ・ロスなどの理論家は、熟議民主主義を代表民主制の完全な代替案として提唱している。より一般的な見解は、ジェームズ・フィシュキンなどの寄稿者が 支持するもので、直接的な熟議民主主義は従来の代表制民主主義を補完し得るというものである。熟議民主主義の概念に寄与しているその他の人物には、カルロ ス・ニーニョ、ジョン・エルスター、ロベルト・ガルガレッラ、ジョン・ガスティル、ユルゲン・ハーバーマス、デビッド・ヘルド、ジョシュア・コーエン、エ イミー・ガットマン、ノエル・マカフィー、レンセ・ボス、ジェーン・マンズブリッジ、ホセ・ルイス・マルティ、デニス・トンプソン 、Benny Hjern、Hal Koch、Seyla Benhabib、Ethan Leib、Charles Sabel、Jeffrey K. Tulis、David Estlund、Mariah Zeisberg、Jeffrey L. McNairn、Iris Marion Young、Robert B. Talisse、Hélène Landemoreなどがいる。 熟議民主主義の研究では政治理論家が主導的役割を果たしてきたが、近年、政治学者もそのプロセスを調査し始めている。現在、主な課題のひとつとなっている のは、熟議民主主義の理念がどの程度実現される可能性があるのか、その実態をさらに解明することである。 シュムエル・レダーマンはハンナ・アレントの研究を引用しながら、シャンタル・ムッフ、エルネスト・ラクラウ、ウィリアム・E・コノリーの著作に見られる ように、「熟議とアゴニズムがほぼ2つの異なる学派となり」、「政治に関する相互に排他的な概念」として論じられていることを嘆いている。ジュゼッペ・バ ラッチは、アゴニズムと熟議は両立するだけでなく相互に依存していると主張している。「アゴニズムを正しく理解するには熟議のスキルが必要であるが、熟議 を重視する政治であっても、アゴニズムの帰結から完全に免れることはできない」[38]。 最近では、熟議の研究における「システム的アプローチ」の台頭に注目が集まっている。これは、民主主義システムの熟議能力は、単一の場ではなく、存在する さまざまな熟議の場の相互関係を通じて理解される必要があることを示唆している。[39] いくつかの研究では、熟議民主主義が持続可能性の問題や将来世代の代表不足の問題にどのように取り組むかを検証する実験が行われている。[40] 常にそうであるとは限らないが、熟議への参加は参加者の意見を環境保護の立場に有利に変えることが分かっている。[41][42][43] プラットフォームとアルゴリズム アヴィヴ・オヴァディアは、プラットフォームのユーザーを代表する熟議グループにアルゴリズムの設計と実装を管理する権限を与えることで、主要なプラット フォームにブリッジングに基づくアルゴリズムを導入すべきだと主張している。[44] 彼は、これによりセンセーショナリズム、政治の二極化、民主主義の後退が減少すると主張している 。ジェイミー・サスキンも同様に、熟議グループがこのような決定を行うことを求めている。 現代の例 詳細は「市民会議」を参照 OECDは数百の事例を文書化しており、2010年以降、その利用が増加していると指摘している。[48][49] 例えば、4000人の一般市民の代表サンプルが「市民会議」を利用して、ハリケーン・カトリーナ後のニューオーリンズの再建計画をまとめるのに利用した。 [50][15] |

| Deliberative assembly Deliberative referendum Group decision making Jury Informed consent Liquid democracy Mediated deliberation Open source governance Participatory democracy Political equality Public reason |

熟議の集会 熟議の住民投票 集団による意思決定 陪審 インフォームドコンセント 液体民主主義 仲介された熟議 オープンソースのガバナンス 参加型民主主義 政治的平等 公共の理由 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deliberative_democracy |

|

| Sources Bessette, Joseph (1980). "Deliberative Democracy: The Majority Principle in Republican Government". In Goldwin, Robert A; Schambra, William A. (eds.). How Democratic is the Constitution?. Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research. pp. 102–116. ISBN 9780844734002. OCLC 6816158. Bessette, Joseph (1994). The Mild Voice of Reason: Deliberative Democracy & American National Government. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226044231. OCLC 28677011. Blattberg, C. (2003) "Patriotic, Not Deliberative, Democracy" Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 6, no. 1, pp. 155–74. Reprinted as ch. 2 of Blattberg, C. (2009) Patriotic Elaborations: Essays in Practical Philosophy. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. Burke, Edmund (1854). The Works of the Right Honourable Edmund Burke. London: Henry G. Bohn. Cohen, Joshua (1989). "Deliberative Democracy and Democratic Legitimacy". In Hamlin, Alan P; Pettit, Philip (eds.). The Good Polity : Normative Analysis of the State. Oxford, UK: B. Blackwell. pp. 17–34. ISBN 9780631158042. OCLC 18321533. Cohen, Joshua (1997). "Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy". In Bohman, James; Rehg, William (eds.). Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262024341. OCLC 36649504. Dryzek, John (2010). Foundations and Frontiers of Deliberative Governance. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956294-7. Elster, Jon, ed. (1998). Deliberative Democracy (Cambridge Studies in the Theory of Democracy). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59696-1. Fishkin, James (2011). When the People Speak. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960443-2. Fishkin, James; Laslett, Peter (2003). Debating Deliberative Democracy. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405100434. OCLC 49875309. Fishkin, James S.; Luskin, Robert C. (September 2005). "Experimenting with a democratic ideal: deliberative polling and public opinion". Acta Politica. 40 (3): 284–298. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500121. S2CID 144393786. Gutmann, Amy; Thompson, Dennis F. (1996). Democracy and Disagreement. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780674197664. OCLC 34472979. Gutmann, Amy; Thompson, Dennis F. (2004). Why Deliberative Democracy?. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691120188. OCLC 54066447. Leib, Ethan J. "Can Direct Democracy Be Made Deliberative?", Buffalo Law Review, Vol. 54, 2006 Mansbridge, Jane J.; Parkinson, John; et al. (2012), "A systematic approach to deliberative democracy", in Mansbridge, Jane J.; Parkinson, John (eds.), Deliberative systems, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–26, ISBN 9781107025394 Nino, C. S. (1996). The Constitution of Deliberative Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07727-0. Owen, D. and Smith, G. (2015). "Survey article: Deliberation, democracy, and the systemic turn." Journal of Political Philosophy 23.2: 213-234 Painter, Kimberly, (2013) "Deliberative Democracy in Action: Exploring the 2012 City of Austin Bond Development Process" Applied Research Project Texas State University. Ross, Carne (2011). The Leaderless Revolution: How Ordinary People Can Take Power and Change Politics in the 21st Century. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84737-534-6. Smith, Graham (2003). Deliberative Democracy and the Environment (Environmental Politics). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30940-0. Steenhuis, Quinten. (2004) "The Deliberative Opinion Poll: Promises and Challenges". Carnegie Mellon University. Unpublished thesis. Available Online Archived 2005-03-08 at the Wayback Machine Talisse, Robert B (2004). Democracy after Liberalism Pragmatism and Deliberative Politics. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9786610106332. OCLC 1264786012. Thompson, Dennis F (2008). "Deliberative Democratic Theory and Empirical Political Science," Annual Review of Political Science 11: 497-520. ISBN 978-0824333119 Tulis, Jeffrey K., (1988) The Rhetorical Presidency Publisher: Princeton University Press (ISBN 0-691-07751-7) Tulis, Jeffrey K., (2003) "Deliberation Between Institutions," in Debating Deliberative Democracy, eds. James Fishkin and Peter Laslett. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1405100434 Uhr, J. (1998) Deliberative Democracy in Australia: The Changing Place of Parliament, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-62465-7 |

出典 ベセット、ジョセフ(1980年)。「審議民主主義:共和制政府における多数決の原則」。ゴールドウィン、ロバート・A;シャンブラ、ウィリアム・A (編)。『憲法はどれほど民主的か?』ワシントンD.C.:アメリカン・エンタープライズ公共政策研究所。102–116頁。ISBN 9780844734002. OCLC 6816158. ベセット, ジョセフ (1994). 『理性の穏やかな声:審議民主主義とアメリカ連邦政府』. シカゴ: シカゴ大学出版局. ISBN 9780226044231. OCLC 28677011. ブラットバーグ, C. (2003) 「審議的ではなく愛国的民主主義」『国際社会政治哲学批評』6巻1号, pp. 155–74. ブラットバーグ, C. (2009) 『愛国的展開:実践哲学論集』第2章として再録. モントリオール・キングストン: マギル・クイーンズ大学出版局. バーク、エドマンド(1854)。『エドマンド・バーク著作集』。ロンドン:ヘンリー・G・ボーン。 コーエン、ジョシュア(1989)。「審議民主主義と民主的正当性」。ハムリン、アラン・P;ペティット、フィリップ(編)。『良き政治体制:国家の規範 的分析』。英国オックスフォード:B. ブラックウェル。pp. 17–34. ISBN 9780631158042. OCLC 18321533. コーエン、ジョシュア(1997)。「審議と民主的正当性」。ボーマン、ジェームズ;レグ、ウィリアム(編)。『審議的民主主義:理性と政治に関する論 考』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MITプレス。ISBN 9780262024341。OCLC 36649504。 ドリーゼック、ジョン(2010)。『審議的ガバナンスの基礎とフロンティア』。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-956294-7。 エルスター、ジョン編(1998)。『審議民主主義(ケンブリッジ民主主義理論研究)』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-521-59696-1。 フィシュキン、ジェームズ(2011)。『民衆が語る時』。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-960443-2。 フィシュキン、ジェームズ; ラスレット、ピーター (2003). 『審議民主主義を論じる』. ワイリー・ブラックウェル. ISBN 9781405100434. OCLC 49875309. フィシュキン、ジェームズ・S.; ラスキン、ロバート・C. (2005年9月). 「民主主義の理想を実験する:審議型世論調査と世論」『アクタ・ポリティカ』40巻3号、284-298頁。doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500121。S2CID 144393786。 ガットマン、エイミー;トンプソン、デニス・F.(1996)。『民主主義と意見の相違』プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 9780674197664。OCLC 34472979。 ガットマン、エイミー;トンプソン、デニス・F. (2004). 『なぜ審議民主主義か?』プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 9780691120188。OCLC 54066447。 ライプ、イーサン・J.「直接民主制は審議制と化せるか?」、『バッファロー・ロー・レビュー』第54巻、2006年 マンスブリッジ、ジェーン・J.;パーキンソン、ジョン;他(2012)、「審議民主制への体系的アプローチ」、マンスブリッジ、ジェーン・J.;パーキ ンソン、ジョン(編)、『審議システム』、ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、 pp. 1–26, ISBN 9781107025394 ニーノ, C. S. (1996). 『審議民主主義の憲法』. ニューヘイブン: イエール大学出版局. ISBN 0-300-07727-0. オーウェン, D. と スミス, G. (2015). 「概説記事:審議、民主主義、そしてシステム的転換」『政治哲学ジャーナル』23巻2号:213-234頁 ペインター、キンバリー(2013)『実践における審議民主主義:2012年オースティン市債券開発プロセスの検証』応用研究プロジェクト、テキサス州立 大学。 ロス、カーン(2011)。『指導者なき革命:21世紀において普通の人々が権力を掌握し政治を変える方法』サイモン&シュスター刊。ISBN 978-1-84737-534-6。 スミス、グラハム(2003)。『審議民主主義と環境(環境政治)』ラウトレッジ刊。ISBN 978-0-415-30940-0。 スティーンフイス、クインテン(2004)『審議型世論調査:可能性と課題』カーネギーメロン大学。未発表論文。オンラインで閲覧可能(2005年3月8 日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ) タリス、ロバート・B(2004)『自由主義後の民主主義:実用主義と審議型政治』ニューヨーク:ラウトレッジ。ISBN 9786610106332。OCLC 1264786012。 トンプソン、デニス・F(2008)。「審議的民主主義理論と実証的政治学」、『政治学年次レビュー』11: 497-520。ISBN 978-0824333119 トゥリス、ジェフリー・K.(1988)『修辞的な大統領職』プリンストン大学出版局(ISBN 0-691-07751-7) トゥリス、ジェフリー・K.(2003)「制度間の審議」『審議民主主義をめぐる論争』ジェームズ・フィシュキン、ピーター・ラスレット編。ワイリー・ブ ラックウェル。ISBN 978-1405100434 アワー、J.(1998)『オーストラリアにおける審議民主主義:議会という場の変容』ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局 ISBN 0-521-62465-7 |

| Further reading Bächtiger, André; Dryzek, John S. (2024). Deliberative Democracy for Diabolical Times : Confronting Populism, Extremism, Denial, and Authoritarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781009261821. OCLC 1406828978. |

参考文献 ベーヒター、アンドレ;ドライゼック、ジョン・S. (2024). 『悪魔的な時代のための審議民主主義:ポピュリズム、過激主義、否定主義、権威主義への対峙』. ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 9781009261821. OCLC 1406828978. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deliberative_democracy | |

| Deliberation

is a process of thoughtfully weighing options, for example prior to

voting. Deliberation emphasizes the use of logic and reason as opposed

to power-struggle, creativity, or dialogue. Group decisions are

generally made after deliberation through a vote or consensus of those

involved. In legal settings a jury famously uses deliberation because it is given specific options, like guilty or not guilty, along with information and arguments to evaluate. In "deliberative democracy", the aim is for both elected officials and the general public to use deliberation rather than power-struggle as the basis for their vote. Individual deliberation is also a description of day-to-day rational decision-making, and as such is an epistemic virtue.  The city council of The Hague deliberating in 1636 |

熟議と

は、例えば投票前に選択肢を慎重に検討する思考プロセスである。

熟議は力関係や創造性、対話ではなく、論理と理性の活用を重視する。集団の決定は通常、熟議を経て投票や関係者の合意によって下される。 法廷では陪審員が熟議を行うことで有名だ。陪審員には有罪か無罪かといった特定の選択肢と、評価のための情報・論拠が与えられるからだ。「熟議民主主義」 では、選出された公職者と一般市民の双方が、投票の根拠として権力闘争ではなく熟議を用いることを目指す。 個人の熟議とは、日常的な合理的な意思決定の過程を指す言葉でもある。その意味で、これは認識論的な美徳と言える。  1636年に審議中のハーグ市議会 |

| Trial juries A jury In countries with a jury system, the jury's deliberation in criminal matters can involve both rendering a verdict and determining the appropriate sentence. In civil cases, the jury decision is whether to agree with the plaintiff or the defendant and rendering a resolution binding actions by the parties based on the results of the trial. Typically, a jury must come to a unanimous decision before it delivers a verdict; however, there are exceptions. When a jury does not reach a unanimous decision and does not feel it is possible to do so, they declare themselves a "hung jury", a mistrial is declared, and the trial will have to be redone at the discretion of the plaintiff or prosecutor. One of the most famous dramatic depictions of this phase of a trial in practice is the film 12 Angry Men. |

陪審員 陪審 陪審制度を採用する国では、刑事事件における陪審の熟議は、評決を下すことと適切な刑罰を決定することの両方を含む場合がある。民事事件では、陪審の決定 は原告または被告の主張を認めるか否かであり、裁判の結果に基づいて当事者の行動を拘束する解決策を提示する。 通常、陪審は評決を下す前に全員一致の決定に達しなければならない。ただし例外もある。陪審員が全員一致の決定に至らず、かつその可能性がないと判断した 場合、彼らは「陪審員が意見一致に至らない状態(hung jury)」を宣言する。これにより裁判は無効となり、原告または検察官の裁量で裁判をやり直す必要がある。 この裁判段階の実情を描いた最も有名な劇的作品の一つが、映画『十二人の怒れる男』である。 |

In political philosophy Shimer College Assembly deliberation In political philosophy, there is a wide range of views regarding how political deliberation becomes possible within particular governmental regimes. Political philosophy embraces deliberation alternatively as a crucial component or as the death-knell of democratic systems. Contemporary democratic theory contrasts democracy with authoritarian regimes. This leads to differing definitions of deliberation within political philosophy. In a broad sense, deliberation involves interaction guided by specific norms, rules, or boundaries. Deliberative ideals often include "face-to-face discussion, the implementation of good public policy, decision making competence, and critical mass."[1]: 970 The origins of philosophical interest in deliberation can be traced to Aristotle's concept of phronesis, understood as "prudence" or "practical wisdom", and its exercise by individuals who deliberate in order to discern the positive or negative consequences of potential actions.[2] Many modern political philosophers believe that strict norms, rules, or fixed boundaries either in how subjects eligible for political deliberation are formed (John Rawls) or in the types of qualifying arguments (Jürgen Habermas) can hinder deliberation and render it unfeasible. "Existential deliberation" is a term introduced by emotional public sphere theorists. They argue that political deliberation is an inherent state, not a deployable process. Therefore, deliberation is infrequent and possibly occurs only in face-to-face interactions. This concept aligns with radical deliberation insights, suggesting that politics emerges sporadically as potential within an otherwise inert social environment.[citation needed] "Pragmatic deliberation" represents the epistemic variation of existential deliberation, focusing on assisting groups in achieving positive outcomes that both aggregate and reshape the perspectives of the affected public.[citation needed] Advocates of "public deliberation" as an essential democratic practice focus on processes of inclusiveness and interaction in making political decisions. The validity and reliability of public opinion improve with the development of "public judgment" as citizens consider multiple perspectives, weigh possible options, and accept the outcomes of decisions made together.[3] |

政治哲学において シマー・カレッジ議会における熟議 政治哲学においては、特定の政府体制内で政治的熟議がどのように可能となるかについて、幅広い見解が存在する。政治哲学は熟議を、民主主義体制の重要な構 成要素として捉えるか、あるいはその終焉を告げるものとして捉えるかのいずれかである。現代の民主主義理論は民主主義と権威主義体制を対比させる。これに より政治哲学内での熟議の定義は異なるものとなる。広義において、熟議とは特定の規範・規則・境界線に導かれた相互作用を意味する。熟議の理想には「対面 での議論、良質な公共政策の実施、意思決定能力、そして臨界質量」が含まれることが多い[1]: 970 熟議に対する哲学的関心の起源は、アリストテレスの「フロンエシス」概念に遡る。これは「慎重さ」あるいは「実践的知恵」と解釈され、潜在的な行動の肯定 的・否定的な結果を見極めるために熟議を行う個人による実践を指す[2]。 多くの現代政治哲学者は、厳格な規範・規則・固定境界が、政治的熟議の対象形成(ジョン・ロールズ)あるいは適格な議論の種類(ユルゲン・ハーバーマス) のいずれにおいても、熟議を阻害し実行不可能にすると考える。 「実存的熟議」は感情的公共圏理論家によって導入された用語である。彼らは政治的熟議は展開可能なプロセスではなく、内在的な状態だと主張する。したがっ て、熟議は稀であり、おそらく対面での相互作用においてのみ発生する。この概念は急進的熟議の洞察と一致し、政治はそれ以外では不活性な社会環境の中で潜 在性として散発的に出現すると示唆している。[出典が必要] 「実用的な熟議」は実存的熟議の認識論的変種を表し、影響を受ける公衆の視点を集約し再形成する肯定的成果をグループが達成することを支援することに焦点 を当てる。[出典が必要] 「公共的熟議」を民主主義の本質的実践と位置付ける支持者は、政治的意思決定における包摂性と相互作用のプロセスを重視する。市民が複数の視点を検討し、 可能な選択肢を比較衡量し、共同で下した決定の結果を受け入れることで「公共的判断」が形成され、世論の妥当性と信頼性は向上する。[3] |

| Radical deliberation This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Radical deliberation refers to a philosophical view of deliberation inspired by the events of the student revolution in May 1968. It aligns with political theories of radical democracy from figures like Michel Foucault, Ernesto Laclau, Chantal Mouffe, Jacques Rancière, and Alain Badiou. These theories emphasize political deliberation as a means of engaging diverse perspectives, setting the stage for political possibilities. In their view, radical democracy remains open-ended and susceptible to changes beyond individual influence. Instead, it's shaped by the discourse resulting from contingent gatherings within larger political entities. Michel Foucault employs "technologies of discourse" and "mechanisms of power" to explain how deliberation can be hindered or emerge through discourse technologies that give a semblance of agency by reproducing power dynamics among individuals. The concept of "mechanisms" or "technologies" presents a paradox. On one hand, these technologies are intertwined with the subjects who utilize them. On the other, discussing the coordinating machine or technology implies an infrastructure organizing society collectively. This notion suggests distancing individuals from the means of their organization, offering a god's-eye view of the social that is coordinated by the movement of its parts. Chantal Mouffe employs "the democratic paradox" to establish a self-sustaining political model founded on inherent contradictions. These unresolved contradictions fuel productive tensions among subjects who acknowledge each other's right to speak. According to Mouffe, the only stable political foundation is the configuration of the social and the certainty of a penultimate articulation's deferral[clarification needed]. This signifies that societal re-articulations will persist. Here, process prevails over content: the liberal/popular sovereignty paradox propels radical democracy. The rhetorical gesture of the foundational paradox[clarification needed] functions as a mechanism—an interface connecting human and language machinery, fostering the conditions for ongoing reconfiguration: a positive feedback loop within politics. Chantal Mouffe and Jacques Rancière hold contrasting views regarding the conditions of politics. For Mouffe, it involves internal rearrangements of existing social structures through "articulations". Conversely, Rancière sees it as the intrusion of an unaccounted-for externality. In the realm of political "arithmetical/geometric" distinctions, there's a clear nod to mechanics or mathematics. Politics endures by perpetuating a dynamic between homeostasis and reconfiguration, akin to what N. Katherine Hayles terms "pattern" and "randomness". This cycle relies on counting what's within the police order. The political mechanism facilitates future reconfigurations by adding new elements, reshaping the social fabric, and then returning to equilibrium, ensuring the perpetuity of an incomplete "whole". Once more, it's a rhetorical paradox driving politics—a foundational arbitrariness in determining who can speak and who can't. |

急進的熟議 この節は出典を一切示していない。信頼できる出典を引用してこの節を改善してほしい。出典のない記述は削除される可能性がある。(2023年7月)(この メッセージの削除方法と時期について) 急進的熟議とは、1968年5月の学生革命の出来事から着想を得た熟議に関する哲学的見解を指す。これはミシェル・フーコー、エルネスト・ラクラウ、シャ ンタル・ムフ、ジャック・ランシエール、アラン・バディウらによる急進的民主主義の政治理論と一致する。これらの理論は、多様な視点を交わす手段としての 政治的熟議を重視し、政治的可能性の基盤を築く。彼らの見解では、急進的民主主義は開放的なままであり、個人の影響を超えた変化を受けやすい。むしろ、よ り大きな政治的実体内の偶発的な集まりから生じる言説によって形作られる。 ミシェル・フーコーは「言説の技術」と「権力機構」を用いて、個人間の力学を再生産することで主体性の幻影を与える言説技術が、いかに熟議を阻害し、ある いは生み出すかを説明する。「機構」あるいは「技術」という概念は逆説を呈する。一方で、これらの技術はそれを利用する主体と密接に絡み合っている。他方 で、調整装置や技術について論じることは、社会を集団的に組織化する基盤を暗示する。この概念は、個人が自らの組織化手段から距離を置くことを示唆し、そ の構成要素の動きによって調整される社会を神の目線で捉える視座を提供する。 シャンタル・ムフは「民主主義のパラドックス」を用いて、内在的な矛盾に基づく自律的な政治モデルを確立する。これらの未解決の矛盾は、相互の発話権を認 める主体間の生産的な緊張を促進する。ムフによれば、唯一の安定した政治的基盤は、社会構成と「最終的な明確化」の延期[注釈必要]の確実性である。これ は社会的再構築が持続することを意味する。ここでは内容がプロセスに優先せず、リベラル/大衆主権のパラドックスが急進的民主主義を推進する。基礎的パラ ドックス[説明が必要]という修辞的ジェスチャーは、メカニズムとして機能する。人間と言語の機械を繋ぐインターフェースであり、継続的な再構成の条件を 育む。政治内部の正のフィードバックループである。 シャンタル・ムフとジャック・ランシエールは、政治の条件に関して対照的な見解を持つ。ムフにとってそれは、「言説化」を通じた既存社会構造の内部再編を 意味する。一方ランシエールは、説明不能な外部性の侵入と見る。政治的「算術的/幾何学的」区別の領域には、明らかに力学や数学への言及がある。政治は恒 常性と再構成の間の動的均衡を永続させることで存続する。これはN・キャサリン・ヘイルズが「パターン」と「ランダムネス」と呼ぶものに類似している。こ の循環は、警察秩序内の要素を数えることに依存する。政治的メカニズムは新たな要素を加え、社会構造を再形成し、均衡状態へ回帰することで将来の再構成を 可能にし、不完全な「全体」の永続性を保証する。ここでもまた、政治を駆動する修辞的パラドックス——誰が発言権を持ち誰が持たないかを決定する根源的な 恣意性——が存在する。 |

| Other theorists Giorgio Agamben – Italian philosopher (born 1942) Hannah Arendt – German-American historian and philosopher (1906–1975) Lauren Berlant – American academic and author (1957–2021) Bonnie Honig – American political theorist (born 1959) Bruno Latour – French philosopher, anthropologist and sociologist (1947–2022) |

その他の理論家 ジョルジョ・アガンベン – イタリアの哲学者(1942年生まれ) ハンナ・アーレント – ドイツ系アメリカ人の歴史家・哲学者(1906–1975) ローレン・バーラント – アメリカの学者・作家(1957–2021) ボニー・ホーニグ – アメリカの政治理論家(1959年生まれ) ブルーノ・ラトゥール – フランスの哲学者、人類学者、社会学者(1947–2022) |

| Argument map – Visual

representation of the structure of an argument Blank pad rule – American legal doctrine and metaphor Dialogue mapping – Argumentation scheme Low-information rationality – Psychological problem-solving tendency Online deliberation |

議論マップ – 議論の構造を視覚的に表現したもの ブランクパッドの法則 – アメリカの法理論と隠喩 対話マッピング – 議論の枠組み 低情報合理性 – 心理的な問題解決傾向 オンライン熟議 |

| 1. Pedro, Portia (2010-02-01).

"Note, Making Ballot Initiatives Work: Some Assembly Required". Harvard

Law Review. 123 (4): 959. 2. Aristotle (2004-03-30). Tredennick, Hugh (ed.). The Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Thomson, J.A.K. Penguin Classics. p. 209. ISBN 9780140449495. 3. Yankelovich, Daniel (1991-05-01). Coming to Public Judgment: Making Democracy Work in a Complex World (1st ed.). Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815602545. |

1.

ペドロ、ポーシャ(2010年2月1日)。「注記:住民発議を機能させるために:組み立てが必要」。ハーバード・ロー・レビュー。123巻4号:959

頁。 2. アリストテレス (2004-03-30). トレデンニック, ヒュー (編). 『ニコマコス倫理学』. トムソン, J.A.K. 訳. ペンギン・クラシックス. p. 209. ISBN 9780140449495. 3. ヤンケロヴィッチ、ダニエル(1991-05-01)。『公共判断の形成:複雑な世界における民主主義の機能』(初版)。シラキュース大学出版局。 ISBN 9780815602545。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deliberation |

|

◎クレジット:第93回日本社会学会 大会11月1日09:30-12:30AM)権力・政治(司会:中澤秀雄・中央大学)フルペーパー(JSSA20201101mikeda.pdf)パスワードなし

リンク(先住民と政治について)

リンク(政治について)

文献

その他

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

先住民の視点からグローバル・スタディーズを再構築する領域横断研究研究課題(基盤研究(B), 18KT0005)

先住民族研究形成に向けた人類学と批判的社会運動を連携する理論の構築(基盤研究(A),

20H00048)

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099