ポピュリズム

Populism

出典:https://lens.monash.edu/@politics-society/2025/06/03/1387633/what-is-populism

★ポピュリズムはヒューマニズムである(落合仁司 ca.Dec. 2025)

☆ポ ピュリズム(Populism)は、議論の分かれる概念[1][2] で、「一般大衆」の考え方を重視し、多くの場合、この集団をエリートとみなす集団と対立させる、さまざまな政治的立場を指す(→「デモクラシー」)。多くの場合、反体制や反政治 の感情と関連付けられる。この用語は 19 世紀後半に生まれ、それ以来、さまざまな政治家、政党、運動に、しばしば蔑称的な意味合いで用いられてきた。政治学やその他の社会科学では、ポピュリズム についていくつかの異なる定義が用いられており、この用語を完全に排除すべきだと主張する学者もいる。「ポピュリズム」という用語は長い間誤訳の対象とな り、広範でしばしば矛盾した一連の運動や信条を表すのに使われてきた。その使われ方は大陸や文脈にまた がっており、多くの学者が「ポピュリズム」は曖昧で拡大解釈されすぎた概念であり、政治的な言説の中で広く用いられているが、その定義は一貫しておらず、 理解も不十分であるとしている[6]。このような背景から、多くの研究がメディア、政治、学術研究においてこの用語の使われ方と拡散を検証しており、これ らの領域間の相互影響に焦点を当て、この概念の進化する意味を形成してきた意味上の変遷をたどっている[7][8](→「ポピュリズムの歴史」)。

| Populism is a

contested concept,[1][2] used to refer to a variety of political

stances that emphasize the idea of the "common people" and often

position this group in opposition to a perceived elite.[3] It is

frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political

sentiment.[4] The term developed in the late 19th century and has been

applied to various politicians, parties, and movements since that time,

often assuming a pejorative tone. Within political science and other

social sciences, several different definitions of populism have been

employed, with some scholars proposing that the term be rejected

altogether.[3][5] |

ポピュリズムは、議論の分かれる概念[1][2]

で、「一般大衆」の考え方を重視し、多くの場合、この集団をエリートとみなす集団と対立させる、さまざまな政治的立場を指す。多くの場合、反体制や反政治

の感情と関連付けられる。この用語は 19

世紀後半に生まれ、それ以来、さまざまな政治家、政党、運動に、しばしば蔑称的な意味合いで用いられてきた。政治学やその他の社会科学では、ポピュリズム

についていくつかの異なる定義が用いられており、この用語を完全に排除すべきだと主張する学者もいる。 |

| Etymology and terminology The term "populism" has long been subject to mistranslation and used to describe a broad and often contradictory array of movements and beliefs. Its usage has spanned continents and contexts, leading many scholars to characterize it as a vague or overstretched concept, widely invoked in political discourse, yet inconsistently defined and poorly understood.[6] Against this backdrop, numerous studies have examined the term’s usage and diffusion across media, politics, and academic scholarship, highlighting the reciprocal influence among these spheres and tracing the semantic shifts that have shaped the evolving meaning of the concept.[7][8] |

語源と用語 「ポピュリズム」という用語は長い間誤訳の対象となり、広範でしばしば矛盾した一連の運動や信条を表すのに使われてきた。その使われ方は大陸や文脈にまた がっており、多くの学者が「ポピュリズム」は曖昧で拡大解釈されすぎた概念であり、政治的な言説の中で広く用いられているが、その定義は一貫しておらず、 理解も不十分であるとしている[6]。このような背景から、多くの研究がメディア、政治、学術研究においてこの用語の使われ方と拡散を検証しており、これ らの領域間の相互影響に焦点を当て、この概念の進化する意味を形成してきた意味上の変遷をたどっている[7][8]。 |

| Origins and early political uses The word first appeared in English in 1858, used as an antonym for “aristocratic” in a translation of a work by Alphonse de Lamartine.[9] In the Russian Empire of the 1860s and 1870s, the term was associated with the narodniki, a left-leaning agrarian movement whose name is often translated as “populists”.[10] Russian populism in the late 19th century aimed to transfer political power to the peasant communes through a radical program of agrarian reform, and would constitute a breeding ground influencing the Russian revolutions.[11] In English, however, the term gained broader prominence through its use by the U.S.-based People's Party and its predecessors, active between the 1880s and early 1900s.[12] The People's Party championed small-scale farmers, advocating for expansionist monetary policies and accessible credit, and was relatively progressive on issues concerning women’s and minority rights for its time.[13] Although both the Russian and American movements have been labeled "populist", they differed in their ideological content and historical trajectory.[14] In the early 20th century, particularly in France, the term shifted into the realm of literature, where it came to designate a genre of novel that sympathetically portrayed the lives of the lower classes.[15][16] Léon Lemonnier published a manifesto for the genre in 1929, and Antonine Coullet-Tessier established a prize for it in 1931.[17] The term entered the Latin American political lexicon in the post-war period, becoming a defining feature of the region’s political landscape.[18] It was initially associated in the media with charismatic leaders capable of mobilizing recently urbanized populations, particularly those displaced by rural migration. These new urban groups, increasingly integrated into electoral politics, were seen as escaping older systems of clientelist control such as “halter voting” (voto de cabresto or voto cantado) and began to redefine national political life. Although often viewed with suspicion and associated with manipulation or demagoguery, populism in this context frequently carried a positive connotation and was openly embraced by political actors.[19] |

起源と初期の政治的利用 この言葉は、1858年にアルフォンス・ド・ラマルティーヌの作品の翻訳で「貴族的」の反意語として初めて英語に登場した。[9] 1860年代から1870年代のロシア帝国では、この用語は、しばしば「ポピュリスト」と訳される左派農業運動「ナロードニキ」に関連付けられていた。 [10] 19 世紀後半のロシアのポピュリズムは、急進的な農地改革プログラムを通じて、政治権力を農民のコミューンに移すことを目指し、ロシア革命に影響を与える温床 となった。[11] しかし、英語では、1880 年代から 1900 年代初頭にかけて活動した、米国を拠点とする人民党とその前身によってこの用語が広く使用され、その存在感がさらに高まった。[12] 人民党は小規模農民を擁護し、拡張的な金融政策と手頃な融資を提唱し、当時の女性やマイノリティの権利に関する問題に関しては比較的進歩的だった。 [13] ロシアとアメリカの運動はどちらも「ポピュリスト」と分類されているが、そのイデオロギー的内容や歴史的経緯は異なっている。[14] 20 世紀初頭、特にフランスでは、この用語は文学の分野に移り、下層階級の生活を共感的に描いた小説のジャンルを指すようになった[15][16]。1929 年にレオン・ルモニエがこのジャンルのマニフェストを発表し、1931 年にアントニーヌ・クーレ・テシエがこのジャンルの賞を設立した[17]。 この用語は、戦後、ラテンアメリカの政治用語として定着し、この地域の政治情勢を特徴づける要素となった[18]。当初、メディアでは、都市化が進んだば かりの住民、特に農村部から移住してきた人々を動員できるカリスマ的な指導者と関連付けられていた。選挙政治にますます統合されるようになったこれらの新 しい都市部グループは、「ホルター投票」(voto de cabresto または voto cantado)などの旧来の顧客主義的支配体制から脱却したものとして見られ、国の政治生活を再定義し始めた。多くの場合、疑惑の目で見られ、操作や民 衆煽動と関連付けられていたが、この文脈におけるポピュリズムは、しばしば肯定的な意味合いを持ち、政治関係者からも公然と支持されていた[19]。 |

| Academic adoption and conceptual

drift Until the 1950s, use of the term populism in academia remained restricted largely to historians studying the People's Party. In 1954, however, two pivotal publications marked a turning point in the conceptual development of the term. In the United States, analyzing the rise of McCarthyism, sociologist Edward Shils published an article proposing populism as a term to describe anti-elite trends in US society more broadly.[20][21] Simultaneously in Brazil, political scientist Hélio Jaguaribe, responding to the country’s emerging “populist hype” in the press, published what is considered the first academic text on Latin American populism, framing it as a form of class conciliation.[22][18] Following Shils’ intervention, the 1960s saw populism gain increasing traction among US sociologists and other academics in the social sciences.[23] Notably, historian Richard Hofstadter and sociologist Daniel Bell reinterpreted the legacy of the People's Party through a critical lens, portraying it as an expression of status anxiety and irrationalism.[24][25] A parallel trend unfolded in Latin America, where scholars—often influenced by Marxist frameworks—began to investigate populism as a political phenomenon tied to modernization, mass mobilization, and developmentalist ideologies. Despite the growing interest, scholarly consensus on the definition of populism remained elusive. Notably, a 1967 conference at the London School of Economics that brought together many of the era’s leading experts failed to produce a unified theoretical framework.[26][27] The convergence of new—and often contested—academic interpretations with the use of the term by political forces critical of those labeled as populists has contributed to its increasingly negative connotation. The absence of a coherent ideological platform or consistent programmatic formulation among self-proclaimed populists, combined with the lack of a coordinated international movement, has further enabled the term to vary widely in meaning.[28] As a result, populism has come to be applied across a broad range of political contexts and figures, often without clear or consistent definition.[29] The term has often been conflated with other concepts like demagoguery,[30] and generally presented as something to be feared and discredited.[31] It has often been applied as a catchword to movements that are considered to be outside the political mainstream or a threat to democracy.[32] |

学術的な採用と概念の変遷 1950年代まで、学界における「ポピュリズム」という用語の使用は、主に人民党を研究する歴史家に限定されていた。しかし、1954年に2つの重要な出 版物が、この用語の概念の発展に転換点をもたらした。米国では、マッカーシズムの台頭を分析した社会学者エドワード・シルズが、米国社会における反エリー ト傾向をより広く表現する用語として「ポピュリズム」を提案する論文を発表した。[20][21] 同時期にブラジルでは、政治学者のヘリオ・ジャガーイベが、メディアで台頭していた「ポピュリズムブーム」に応えて、ラテンアメリカ・ポピュリズムに関す る最初の学術的著作を発表し、これを「階級調和の形態」として位置付けた。[22][18] シルズの提言を受けて、1960年代にはポピュリズムが米国社会学者や社会科学の他の研究者の間で徐々に注目されるようになった。[23] 特に、歴史家のリチャード・ホフスタッターと社会学者ダニエル・ベルは、人民党の遺産を批判的な視点で見直し、それを地位不安と非合理主義の表れとして描 いた。[24][25] ラテンアメリカでも同様の傾向が見られ、多くの場合、マルクス主義の枠組みに影響を受けた学者たちが、近代化、大衆動員、開発主義のイデオロギーと結びつ いた政治現象としてのポピュリズムの研究を始めた。関心の高まりにもかかわらず、ポピュリズムの定義に関する学者のコンセンサスは依然として得られていな い。特に、1967年にロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスで開催された、当時の多くの有識者が一堂に会した会議では、統一的な理論的枠組みは確立さ れなかった。[26][27] 新しい、そしてしばしば論争の的となる学術的解釈と、ポピュリストとレッテルを貼られた人々を批判する政治勢力によるこの用語の使用との融合が、その意味 のますます否定的な変化に寄与している。自己をポピュリストと称する者たち之间に一貫したイデオロギー的基盤やプログラム的な枠組みが欠如していること、 および協調的な国際運動が存在しないことは、この用語の意味の多様化をさらに助長した。[28] 結果として、ポピュリズムは明確な定義や一貫性なく、多様な政治的文脈や人物に適用されるようになった。[29] この用語は、デマゴーグ(民衆煽動)[30] などの他の概念と混同され、一般的に恐れるべきもの、信用すべきでないものとして提示されてきた。[31] また、政治的主流から外れたり、民主主義への脅威と見なされる運動に対して、キャッチフレーズとして用いられることが多かった。[32] |

| The populist hype and scholarly

debate Although scholars had already observed that populism was becoming a recurring feature of Western democracies by the early 1990s,[33][34] the term gained unprecedented global prominence following the political upheavals of 2016—most notably, the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States and the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union. Both events were widely interpreted as expressions of populist sentiment, sparking renewed public interest in the concept.[35][36] Reflecting this heightened attention, the Cambridge Dictionary selected "populism" as its Word of the Year in 2017.[37] This so-called "populist hype" also found its counterpart in academia.[38] Whereas between 1950 and 1960 roughly 160 publications on populism were recorded, that number rose to over 1,500 between 1990 and 2000.[39][40] From 2000 to 2015, an average of 95 academic papers and books annually included the term "populism" in their title or abstract as catalogued by Web of Science. In 2016, that number climbed to 266; in 2017, it reached 488; and by 2018, it had grown to 615.[41] The conceptual ambiguity surrounding the term—exacerbated by this spike in political and academic attention—has led some scholars to propose abandoning "populism" as an analytical category altogether. In particular, the frequent conflation of populism with far-right nativism has drawn criticism for misrepresenting the ethos of historical self-described populists,[13] while also providing a euphemistic gloss for racist or authoritarian political actors seeking legitimacy by claiming to represent "the people."[42][43][44] In contrast, others argue that the concept remains too integral to political analysis to be discarded. If clearly defined, they contend, "populism" could be a valuable tool for understanding a broad range of political actors, especially those operating on the margins of mainstream politics.[45] |

ポピュリズムの流行と学術的議論 1990年代初頭までに、ポピュリズムが西洋民主主義の繰り返し見られる特徴になっていることを学者たちがすでに指摘していたにもかかわらず[33] [34]、この用語は2016年の政治的混乱、特にドナルド・トランプのアメリカ合衆国大統領選挙での勝利と、イギリスの欧州連合離脱の国民投票を受け て、かつてないほど世界的に注目されるようになった。この 2 つの出来事は、ポピュリズムの感情の表れであると広く解釈され、この概念に対する世間の関心が再び高まった[35][36]。この注目度の高まりを反映し て、ケンブリッジ辞書は「ポピュリズム」を 2017 年の「今年の単語」に選んだ[37]。 このいわゆる「ポピュリズムの流行」は、学界でも見られた。[38] 1950 年から 1960 年にかけては、ポピュリズムに関する出版物はおよそ 160 件だったのに対し、1990 年から 2000 年にかけては 1,500 件以上に増加した。[39][40] 2000年から2015年にかけて、Web of Scienceでカタログ化された学術論文や書籍のうち、タイトルや要約に「ポピュリズム」という用語を含むものは、年間平均95件だった。2016年に はその数は266件に増加し、2017年には488件、2018年には615件にまで増加した[41]。 この用語をめぐる概念上の曖昧さは、政治や学界での注目度の高まりによってさらに悪化し、一部の学者は「ポピュリズム」を分析のカテゴリーとして完全に放 棄すべきだと提案している。特に、ポピュリズムと極右のナショナリズムが頻繁に混同されることは、歴史的に自らをポピュリストと自称してきた人々の精神を 誤って表現しているとして批判されている[13]。また、「人民」を代表すると主張して正当性を求める人種差別主義者や権威主義的な政治家に、婉曲的な表 現で美辞麗句を添える結果にもなっている[42][43][44]。 一方、この概念は政治分析に不可欠であり、放棄すべきではないという意見もある。正確に定義すれば、「ポピュリズム」は、幅広い政治関係者、特に主流政治 の境界で活動する政治関係者を理解するための貴重なツールとなり得る、と彼らは主張している[45]。 |

| Theories As a polysemic concept, populism has been interpreted through various theoretical lenses and given multiple definitions. Scholars differ sharply in their assessments of populism: while some define it as inherently anti-democratic, stressing its threats to liberal institutions and the rule of law,[46][47] others view it as an inherently democratic impulse aimed at empowering marginalized groups and restoring popular sovereignty.[48][49] Still others argue that populism can assume multiple and even contradictory facets depending on the context. Today, the main theoretical approaches to populism are the ideational, class-based, discursive, performative, strategic, and economic frameworks. |

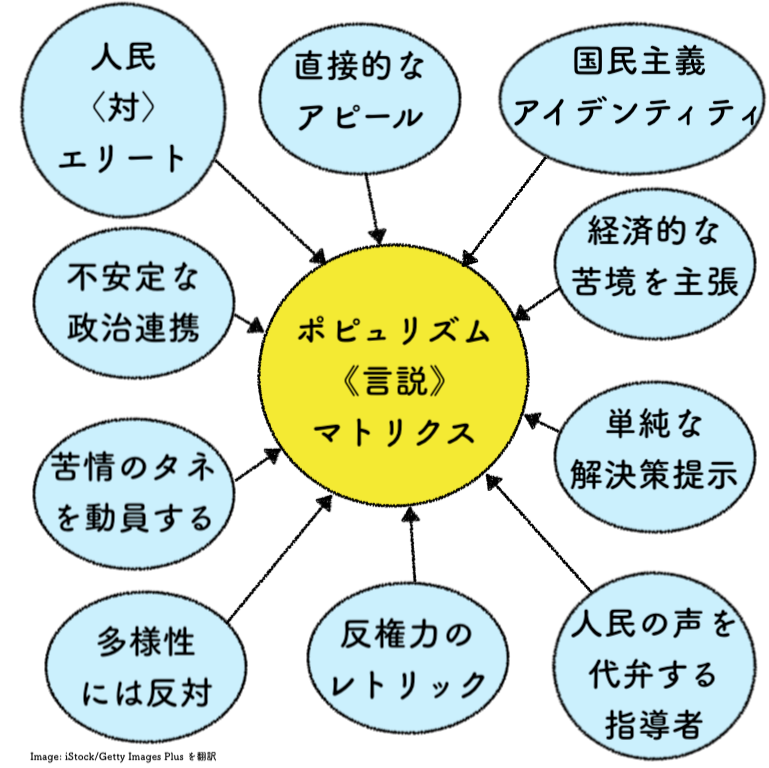

理論 多義的な概念であるポピュリズムは、さまざまな理論的観点から解釈され、複数の定義が与えられている。学者たちは、ポピュリズムの評価について大きく意見 が分かれています。ポピュリズムを本質的に反民主的と定義し、自由主義的制度や法の支配に対する脅威を強調する学者もいれば[46][47]、ポピュリズ ムを、周縁化された集団に権力を与え、民衆の主権を回復することを目的とした本質的に民主的な衝動と捉える学者もいます[48][49]。さらに、ポピュ リズムは状況に応じて複数の、あるいは矛盾した側面を併せ持つと主張する学者もいます。今日、ポピュリズムに対する主な理論的アプローチとしては、観念 的、階級的、言説的、パフォーマティビティ、戦略的、経済的な枠組みがある。 |

| Ideational approaches The ideational approach defines populism as a "thin-centred ideology" that divides society into two antagonistic groups: "the pure people" and "the corrupt elite," and sees politics as an expression of the general will (volonté générale) of the people.[50][51][52] It positions populism not as a comprehensive ideology but one that attaches itself to broader political movements like socialism, or conservatism.[53][54][55] Scholars like Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser emphasize that populism is moralistic rather than programmatic, promoting a binary worldview that resists compromise.[56] This ideology is present across diverse political systems, is not limited to charismatic leadership, and can be employed flexibly to support a range of agendas on both the left and the right.[51][57] According to ideational scholars, populism constructs "the people" as a virtuous and unified group, often with vague or shifting boundaries, allowing populist leaders to define inclusion or exclusion based on strategic goals.[53] This group is seen as sovereign and historically grounded, whose common sense is viewed as superior to elite expertise or institutional knowledge.[51] Conversely, "the elite" is portrayed as a homogeneous, corrupt force undermining the people's will. Depending on context, elites may be defined economically, politically, culturally, or even ethnically.[51] The concept of the general will is presented in the ideational approach as central to populist rhetoric, aligning with a critique of representative democracy in favor of direct forms of decision-making such as referendums.[51][53] This approach resonates with Rousseau's philosophical legacy, suggesting that only "the people" know what is best for society.[51][50] Ideational scholars emphasize the ambivalent relationship between populism and democracy.[58] While they note that not all populists are authoritarian and recognize that populism can help redeem liberal democracy from its shortcomings when operating in opposition—by mobilizing social groups who feel excluded from political decision-making processes and by raising awareness among socio-political elites of popular grievances[59]—they generally contend that populism becomes inherently detrimental to pluralism once in power.[60][61] By often claiming to represent the authentic will of the people, populists—particularly those aligned with right-wing movements—bypass or actively undermine liberal democratic institutions designed to safeguard minority rights, most notably the judiciary and the media, which are frequently portrayed as disconnected from the populace.[62][63][64] This dynamic can be especially potent in contexts where the rule of law has weak institutional foundations, creating fertile ground for democratic backsliding.[65] In such cases, populist governance may give rise to what philosopher John Stuart Mill termed the "tyranny of the majority."[66] The ideational definition is not without criticism. Some argue that it proceeds deductively, establishing a definition in advance and then applying it to cases in a way that imposes rigid assumptions—such as moral dualism and the homogeneity of "the people"—that may not hold empirically in all contexts.[67][68][69][70] Others caution that if broadly applied, the term risks becoming too vague, potentially encompassing most political discourse.[71] |

観念的アプローチ 観念的アプローチは、ポピュリズムを「薄っぺらなイデオロギー」と定義し、社会を「純粋な人民」と「腐敗したエリート」という 2 つの対立するグループに分け、政治を人民の一般意志(volonté générale)の表現とみなしている[50][51][52]。このアプローチは、ポピュリズムを包括的なイデオロギーではなく、社会主義や保守主義 などのより広範な政治運動に付随するイデオロギーと位置付けている。[53][54][55] カス・ムッデやクリストバル・ロビラ・カルタワサーのような研究者は、ポピュリズムはプログラム的ではなく道徳的であり、妥協を拒否する二元的な世界観を 促進すると強調している。[56] このイデオロギーは多様な政治システムに存在し、カリスマ的な指導者に限定されず、左派と右派の両方で多様なアジェンダを支援するために柔軟に活用され る。[51][57] 観念論的な学者によると、ポピュリズムは「人民」を、しばしば曖昧または変動的な境界を持つ、高潔で統一された集団として構築し、ポピュリストの指導者が 戦略的目標に基づいて包摂または排除を定義することを可能にする[53]。この集団は、主権的かつ歴史的に根付いた存在とみなされ、その常識はエリートの 専門知識や制度的知識よりも優れているとみなされる[51]。逆に、「エリート」は、人民の意志を損なう、均質な腐敗した勢力として描かれる。文脈に応じ て、エリートは経済的、政治的、文化的、あるいは民族的に定義される場合もある[51]。一般意志の概念は、ポピュリズムのレトリックの中心として、国民 投票などの直接的な意思決定形態を支持する代表民主主義の批判と一致して、観念論的アプローチで提示されている[51][53]。このアプローチは、社会 にとって何が最善かを知っているのは「人民」だけであるとするルソーの哲学的遺産と共鳴している。[51][50] 観念的学者たちは、ポピュリズムと民主主義の間の矛盾した関係を強調している。[58] 彼らは、すべてのポピュリストが独裁的ではないことを指摘し、ポピュリズムが対立勢力として機能する際には、政治的意思決定プロセスから排除されていると 感じる社会集団を動員し、社会政治エリートに民衆の不満を認識させることで、自由民主主義の欠点を補う役割を果たす可能性を認めている。[59] しかし、彼らは一般的に、ポピュリズムが権力を掌握すると、本質的に多元主義に有害になると主張している。[60][61] ポピュリストは、多くの場合、人民の真意を代弁すると主張することで、特に右翼運動と提携しているポピュリストは、少数派の権利を保護するために設計され た自由民主主義の制度、特に司法やメディアを、民衆から切り離されたものとして頻繁に描写し、それを回避したり、積極的に弱体化させたりしている。 [62][63][64] このような動きは、法の支配の制度的基盤が脆弱な状況において特に強力になり、民主主義の後退の温床となる。[65] そのような場合、ポピュリストの統治は、哲学者ジョン・スチュワート・ミルが「多数派の専制」と呼んだ状況を生み出す可能性がある。[66] この概念的な定義には批判もある。この定義は、あらかじめ定義を確立し、それを事例に適用する演繹的な手法を採用しており、道徳的二元論や「人民」の均質 性など、すべての状況において経験的に成り立つとは限らない厳格な仮定を課している、と主張する者もいる[67][68][69][70]。また、この用 語を広く適用すると、その意味が曖昧になり、ほとんどの政治的言説を網羅してしまうおそれがある、と警告する者もいる[71]。 |

| Class-based approaches Class-based approaches interpret populism as a phenomenon rooted in social class dynamics. Latin American scholars such as Hélio Jaguaribe and Gino Germani were among the first to interpret populism as a mass-based phenomenon of political mobilization, characteristic of societies undergoing rapid modernization.[22][72] They emphasized features such as personalist leadership, the political incorporation of previously excluded social sectors, and institutional fragility—often accompanied by authoritarian tendencies.[73] In Germani’s case, his theory of national-popular movements and the “authoritarianism of the popular classes” was developed in dialogue with American sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset.[74][75] Drawing in part on analyses of McCarthyism, Lipset argued that populism is a movement that unites various social classes, typically around a charismatic leader.[76] While noting that this characteristic also appears in fascism, Lipset emphasized a key distinction: fascism draws primarily from the middle classes, whereas populism finds its main social base among the poor. A more explicitly class-oriented interpretation comes from the Marxist tradition, particularly influential in Latin America through thinkers such as Francisco Weffort, Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Octavio Ianni.[77][78][79] Breaking with the sympathetic stance toward Russian populism found in the late writings of Karl Marx,[80] these Latin American Marxists drew instead on Marx’s reflections on Bonapartism and Antonio Gramsci's concept of Caesarism. From this perspective, populism arises in moments of equilibrium between antagonistic classes—when the bourgeoisie has lost its hegemonic capacity but the proletariat has not yet seized power.[81] In such conditions, political power gains autonomy from dominant classes and positions itself as an arbiter, drawing support from what Marx termed the “mass”: a disorganized group lacking class consciousness and vulnerable to charismatic leadership. Marxist critics in Latin America acknowledged populism’s role in integrating the popular masses into political life and fostering social and economic development. However, they argued that this integration was limited—proto-democratic in form but ultimately constrained within a bourgeois framework. Populist regimes, they contended, often demobilized collective organization by substituting social benefits and labor reforms for class struggle, while subordinating trade unions to state control and electoral interests. These critiques have been challenged by historians who argue that the so-called populist period in Latin American history was in fact marked by a growing politicization of workers—one that may have posed a challenge to established political and economic interests.[82] |

階級に基づくアプローチ 階級に基づくアプローチは、ポピュリズムを社会階級の力学に根ざした現象と解釈する。ヘリオ・ジャグアリベやジーノ・ゲルマニなどのラテンアメリカの学者 たちは、ポピュリズムを、急速な近代化が進む社会に特徴的な、大衆を基盤とする政治動員現象として最初に解釈した学者たちだ[22][72]。彼らは、個 人主義的なリーダーシップ、これまで排除されてきた社会層の政治参加、制度的脆弱性など、しばしば権威主義的傾向を伴う特徴を強調した。[73] ジェルマーニの場合、彼の国民的・大衆的運動と「大衆階級の権威主義」に関する理論は、アメリカの社会学者シーモア・マーティン・リップセットとの対話の 中で発展したものだ。[74][75] マッカーシズムの分析を一部参考にしたリップセットは、ポピュリズムは、通常、カリスマ的な指導者を軸として、さまざまな社会階級を結びつける運動である と主張した。[76] リプセットは、この特徴はファシズムにも見られると指摘しつつ、重要な違いを強調した。すなわち、ファシズムは主に中産階級を支持基盤とするのに対し、ポ ピュリズムは貧困層を中心に支持基盤を形成している。 より明確に階級志向の解釈は、マルクス主義の伝統に由来し、特にラテンアメリカでは、フランシスコ・ウェフォルト、フェルナンド・エンリケ・カルドソ、オ クタヴィオ・イアニなどの思想家を通じて影響力を持っている[77][78][79]。カール・マルクスの晩年の著作に見られるロシアのポピュリズムに対 する同情的な立場から脱却し[80]、これらのラテンアメリカのマルクス主義者は、代わりに、マルクスのボナパルティズムに関する考察とアントニオ・グラ ムシのシーザー主義の概念を参考にした。この視点から、ポピュリズムは対立する階級間の均衡状態において生じる——ブルジョアジーがヘゲモニー能力を失っ たが、プロレタリアートがまだ権力を掌握していない時期だ。[81] こうした状況下で、政治権力は支配階級から自律性を獲得し、仲裁者として位置付けられ、マルクスが「大衆」と呼んだ組織化されていない階級意識に欠け、カ リスマ的指導者に影響されやすい集団から支持を得る。 ラテンアメリカのマルクス主義批評家は、ポピュリズムが民衆を政治生活に統合し、社会経済の発展を促進する役割を認めた。しかし、彼らはこの統合は限定的 であり、形式的にはプロト民主的だが、最終的にはブルジョア的枠組み内に制約されていると主張した。ポピュリスト政権は、階級闘争の代わりに社会福祉や労 働改革を代用し、労働組合を国家の支配と選挙利益に従属させることで、集団組織の動員を阻害したと彼らは主張した。これらの批判は、ラテンアメリカ史にお けるいわゆるポピュリスト期が、実際には労働者の政治化が進んだ時期であり、既存の政治的・経済的利益に挑む可能性を秘めていたと主張する歴史家たちに よって挑戦されている。[82] |

Discursive approaches The Argentine political theorist Ernesto Laclau developed a distinctive definition of populism, viewing it as a potentially positive force for emancipatory social change. The discursive approach is most closely associated with Argentine political theorist Ernesto Laclau and other scholars of the so-called Essex School.[83] For Laclau, populism should be understood as a discursive logic in which a series of unmet demands coalesce around a symbol that names a popular movement in opposition to an elite. Although charismatic leaders are often the most common symbols of populist movements, the discursive approach maintains that populism can exist without this type of leadership. Unlike the ideational approach, the discursive tradition does not necessarily view the opposition of the "bottom" against the "top" as moralistic. In contrast to the Marxist approach, it also criticizes what it sees as the idealization of an autonomous social class, as opposed to a manipulated mass.[81] From a constructivist perspective, Laclau and his followers argue that political subjects—and particularly an entity such as "the people"—are always radically contingent discursive constructions, capable of taking on various forms.[84] Normatively, Laclau’s definition of populism refrains from judging whether populism is inherently positive or negative.[85] However, it sets itself apart from previous approaches by regarding some populist experiences in power as genuinely democratizing. Building on this perspective, some scholars influenced by Laclau argue that populism is inherently emancipatory and pluralistic, and that authoritarian and nationalist movements often labeled as populist would be more accurately described as fascist.[86] |

言説的アプローチ アルゼンチンの政治理論家エルネスト・ラクラウは、ポピュリズムを解放的な社会変革のための潜在的に肯定的な力として捉える、独自の定義を提唱した。 言説的アプローチは、アルゼンチンの政治理論家エルネスト・ラクラウと、いわゆるエセックス学派の他の学者たちと最も密接に関連している。[83] ラクラウにとって、ポピュリズムは、満たされていない一連の要求が、エリートに対抗する民衆運動を名指すシンボルを中心に凝集する言説的論理として理解さ れるべきだ。カリスマ的な指導者は、ポピュリズム運動の最も一般的な象徴であることが多いが、言説的アプローチは、この種の指導者がいなくてもポピュリズ ムは存在し得るとしている。 イデオロギー的アプローチとは異なり、言説的伝統は、「下」と「上」の対立を必ずしも道徳的なものと見なしていない。また、マルクス主義的アプローチとは 対照的に、操作される大衆とは対照的に、自律的な社会階級を理想化しているとして批判している[81]。構成主義的観点から、ラクラウとその追随者たち は、政治的主体、特に「人民」のような存在は、常に根本的に偶発的な言説的構築物であり、さまざまな形をとることができると主張している[84]。 規範的には、ラクラウのポピュリズムの定義は、ポピュリズムが本質的にポジティブかネガティブかを判断することを避けている。[85] しかし、権力掌握下のいくつかのポピュリズム体験を真に民主化的なものと見なす点で、以前のアプローチと一線を画している。この見解に基づいて、ラクラウ の影響を受けた一部の学者は、ポピュリズムは本質的に解放的かつ多元的であり、ポピュリストとよく呼ばれる権威主義的・ナショナリスト的な運動は、ファシ ストと表現するほうがより正確であると主張している[86]。 |

| Performative/socio-cultural

approaches The performative approach—also known as the socio-cultural approach and occasionally referred to as the stylistic approach—is often presented as a branch of the discursive approach. Its main exponents include Pierre Ostiguy, Benjamin Moffitt, and María Esperanza Casullo.[87][88][89][90] This approach views populism not as a fixed ideology but as a political style—a repertoire of symbolically mediated performances through which leaders construct and navigate power. Rather than focusing on what populists believe, this perspective highlights how they communicate and present themselves, encompassing rhetoric, gestures, body language, fashion, imagery, and staging. These aesthetic and performative elements are essential to how populism operates in practice. Critiquing what it sees as excessive formalism in Laclau’s theory, the performative approach emphasizes the theatrical and transgressive nature of populism. Populist actors often break with traditional norms and expectations of political behavior, embracing styles that are irreverent, culturally popular, and emotionally charged. Populism is thus seen as a performance that challenges the boundaries of "respectable" political discourse. While some scholars focus on the performances of charismatic leaders, others emphasize the historical and social dimension of populist transgression, noting its capacity to mobilize marginalized sectors traditionally excluded from political life. The sudden entry of these groups into the public sphere is often experienced as disruptive or shocking.[91] As with the discursive approach, advocates of the performative theory maintain that populism can, in some cases, express emancipatory potential. |

パフォーマティビティ/社会文化的なアプローチ パフォーマティビティアプローチ(社会文化的なアプローチ、時には文体的アプローチとも呼ばれる)は、しばしば談話的アプローチの一分野として紹介され る。その主な代表者は、ピエール・オスティギー、ベンジャミン・モフィット、マリア・エスペランサ・カスロなどだ[87][88][89][90]。この アプローチは、ポピュリズムを固定的なイデオロギーではなく、政治的なスタイル、つまり、指導者が権力を構築し、操るための象徴的なパフォーマンスのレ パートリーと捉えている。この視点は、ポピュリストの信念に焦点を当てるのではなく、レトリック、ジェスチャー、ボディランゲージ、ファッション、イメー ジ、演出など、ポピュリストがどのようにコミュニケーションを取り、自分自身を表現するかを強調する。こうした美的・パフォーマティビティの要素は、ポ ピュリズムが実際に機能するために不可欠なものだ。 ラクラウの理論の過度な形式主義を批判するパフォーマティビティ・アプローチは、ポピュリズムの演劇的かつ越境的な性質を強調している。ポピュリストは、 多くの場合、伝統的な規範や政治行動に対する期待を打ち破り、不遜で、文化的に人気があり、感情的なスタイルを採用している。したがって、ポピュリズム は、「立派な」政治言説の境界に挑戦するパフォーマンスとみなされる。 カリスマ的な指導者のパフォーマンスに焦点を当てる学者もいれば、ポピュリズムの越境的側面を歴史的・社会的に強調し、伝統的に政治生活から排除されてき た周縁化された層を動員するポピュリズムの能力に注目する学者もいる。こうした集団が突然公の場に登場することは、しばしば破壊的あるいは衝撃的な出来事 として受け止められる[91]。 言説的アプローチと同様、パフォーマティビティ理論の支持者は、ポピュリズムは場合によっては解放の可能性を表現することができると主張している。 |

| Strategic approaches An additional framework has been described as the "political-strategic" approach. This applies the term populism to a political strategy in which a charismatic leader seeks to govern based on direct and unmediated connection with their followers.[92] Kurt Weyland defined this conception of populism as a political strategy employed by a personalist leader who governs throught direct, unmediated, uninstitutionalized support from large numbers of mostly unorganized followers.[93] According to this perspective, a populist strategy for winning and exerting state power stands in tension with democracy and the values of pluralism, open debate, and fair competition.[94][95] A common criticism of the strategic approach is that, by focusing on leadership, this concept of populism does not allow for the existence of populist parties or populist social movements.[96] As a result, it overlooks historical cases often considered paradigmatic of populism, such as the US People's Party.[97] Furthermore, this approach may inadvertently reinforce popular perceptions of populism as a style of politics characterized by overly simplistic solutions to complex problems, delivered in an emotionally charged manner or through the promotion of short-term, unrealistic, and unsustainable policies.[98] While this usage may seem intuitively meaningful, some argue that it is difficult to apply empirically, since most political actors engage in slogans and rhetoric, and distinguishing between emotionally charged and rational arguments can be problematic. This phenomenon is more accurately described as demagogy or opportunism. |

戦略的アプローチ 追加の枠組みとして、「政治戦略的」アプローチが説明されている。これは、カリスマ的な指導者が、支持者との直接かつ仲介のない関係に基づいて統治しよう とする政治戦略に「ポピュリズム」という用語を適用したものだ。[92] カート・ウェイランドは、このポピュリズムの概念を、主に組織化されていない多数の支持者からの直接かつ仲介のない、制度化されていない支持によって統治 する、個人主義的な指導者が採用する政治戦略と定義している。[93] この観点によれば、国家の権力を獲得し、行使するためのポピュリスト戦略は、民主主義や多元主義、開かれた議論、公正な競争といった価値観と対立する。 戦略的アプローチに対する一般的な批判は、このポピュリズムの概念は、リーダーシップに焦点を当てているため、ポピュリスト政党やポピュリスト社会運動の 存在を認めないという点だ。[96] その結果、米国人民党など、ポピュリズムの典型例とよく考えられている歴史的事例を見落としている。[97] さらに、このアプローチは、複雑な問題に対して過度に単純化した解決策を、感情的な表現や、短期的で非現実的かつ持続不可能な政策の推進によって提示する 政治スタイルとしてのポピュリズムに対する一般的な認識を、意図せずに強化してしまう可能性がある。[98] この用法は直感的に意味があるように思えるが、多くの政治家はスローガンや修辞を用いるため、感情的な主張と理性的主張を区別することは困難であり、実証 的に適用するのは難しいと指摘する者もいる。この現象は、より正確にはデマゴギーや機会主義と表現すべきだ。 |

| Economic approaches Closely related to the ideas of demagogy and opportunism, the socioeconomic definition of populism refers to a pattern of irresponsible economic policymaking, in which governments implement expansive public spending—typically financed by foreign loans—followed by inflationary crises and subsequent austerity measures.[99] This understanding gained prominence in the 1980s and 1990s through economists such as Rudiger Dornbusch, Jeffrey Sachs, and Sebastián Edwards, particularly in studies of Latin American economies.[100] It builds on earlier critiques by Argentine economist Marcelo Diamand, who argued that economies like Argentina experienced cyclical swings between unsustainable populist spending and excessive austerity.[101] Although Diamand critiqued both extremes, later U.S.-based economists largely abandoned his condemnation of austerity, instead framing it as a necessary corrective for economic instability.[101][102][103] While still invoked by some economists and journalists—particularly in Latin America—this economic definition of populism remains relatively uncommon in the broader social sciences.[104] Critics argue that it reduces populism to left-wing economic mismanagement, overlooks the term’s political and ideological dimensions, and fails to account for populist leaders who implemented neoliberal policies.[105] The term "populism" is often used in this context to stigmatize heterodox economic policies, thereby narrowing space for debate. |

経済的アプローチ デマゴーグや機会主義の考えと密接に関連している、社会経済的なポピュリズムの定義は、政府が(通常は外国からの融資によって資金調達された)大規模な公 共支出を実施し、その後にインフレ危機とそれに続く緊縮政策が続く、無責任な経済政策のパターンを指す。[99] この理解は、1980年代から1990年代にかけて、ルディガー・ドーンブッシュ、ジェフリー・サックス、セバスティアン・エドワーズなどの経済学者、特 にラテンアメリカ経済の研究を通じて注目されるようになった[100]。これは、アルゼンチンの経済学者マルセロ・ディアマンドによる、アルゼンチンなど の経済は、持続不可能なポピュリスト的支出と過度の緊縮財政の循環を繰り返していると主張した以前の批判に基づいている。[101] ディアマンドは両極端を批判したが、後に米国を拠点とする経済学者たちは、彼の緊縮財政に対する非難をほぼ放棄し、代わりに、緊縮財政を経済不安定の必要 な是正措置と位置づけた。[101][102][103] 一部の経済学者やジャーナリスト、特にラテンアメリカでは依然として引用されているものの、このポピュリズムの経済学的定義は、より広範な社会科学分野で はまだあまり一般的ではない。[104] 批判者は、この定義はポピュリズムを左派の経済政策の失敗に還元し、用語の政治的・思想的な次元を無視し、新自由主義政策を実施したポピュリスト指導者を 説明できないと指摘している。[105] 「ポピュリズム」という用語は、この文脈で異端的な経済政策を非難するために使用され、議論の余地を狭めている。 |

| Possible causes Over the decades, and across various theoretical approaches, populism has been associated with massification and the dissolution of social bonds. Explanations for this process vary, pointing to economic, labor, and cultural transformations, along with their subjective consequences.[5] |

考えられる原因 何十年にもわたり、さまざまな理論的アプローチにおいて、ポピュリズムは、大衆化と社会的絆の崩壊と関連付けられてきた。この過程の説明はさまざまで、経 済、労働、文化の変容、およびそれらの主観的な影響が指摘されている。[5] |

| Economic grievance The economic grievance thesis argues that economic factors have contributed to the formation of a 'left-behind' precariat marked by low job security, high inequality, and wage stagnation. On this account, the group would be more inclined to support populism.[106][107][108] Reasons for precarity vary: in the Global North, it has often been linked to a decline in living standards due to deindustrialization, economic liberalization, and deregulation, whereas in the Global South, it tends to follow a truncated process of upward mobility, in which workers emerge from extreme poverty but remain in unstable, low-quality employment and living conditions.[109] To account for these dynamics, some theories focus specifically on the effects of economic crises,[110][111] or inequality,[112] while others emphasize globalization’s role in disrupting established labor markets and fueling economic dislocation. Macro-level evidence suggests that resentment toward outgroups tends to rise during periods of economic hardship,[5][113] and economic crises have been associated with gains for far-right parties—entities frequently conflated with populist movements, though not necessarily synonymous.[114][115] However, micro-level studies have found only limited evidence linking individual economic grievances directly to support for populist candidates or parties.[5][107] |

経済的不満 経済的不満説は、経済要因が、雇用不安、高い不平等、賃金停滞を特徴とする「取り残された」プレカリアートの形成に寄与したと主張している。この説によれ ば、このグループはポピュリズムを支持する傾向が強いとされている。[106][107][108] 不安定化の要因は多様です:グローバル・ノースでは、産業の空洞化、経済自由化、規制緩和による生活水準の低下と関連付けられることが多く、一方、グロー バル・サウスでは、極端な貧困から脱却した労働者が不安定で低品質な雇用と生活条件に留まるという、上昇移動のプロセスが不完全な形で進行する傾向があり ます。[109] これらの動向を説明するため、一部の理論は経済危機[110][111]や不平等[112]の影響に焦点を当てている一方、他の理論はグローバル化が既存 の労働市場を混乱させ、経済的混乱を助長する役割を強調している。 マクロレベルの証拠は、経済的困難期にアウトグループに対する不満が高まる傾向があることを示しており[5][113]、経済危機は極右政党の支持拡大と 関連していることが指摘されている。これらの政党はしばしばポピュリスト運動と混同されるが、必ずしも同義ではない[114][115]。しかし、ミクロ レベルの研究では、個人の経済的不満とポピュリスト候補者や政党への支持を直接結びつける証拠は限定的だ。[5][107] |

| Modernization The modernization losers theory argues that certain aspects of transition to modernity have caused demand for populism. This argument was advanced in the 1950s by Hofstadter and other early revisionist scholars who examined the People’s Party, interpreting their populism as a response to deep-seated cultural anxieties in the face of modern economic and social transformations. This anxiety manifested in a partial rejection of modernity—not against technology or progress itself, but against the perceived social and moral effects of modern capitalism and urbanization.[24] More recently, scholars have pointed to the anomie that followed industrialization, resulting in dissolution, fragmentation, and differentiation, which weakened the traditional ties of civil society and increased individualization.[116] Some analysts argue that such conditions—marked by fragmented identities and weak collective structures—now resemble the dynamics long observed in the Global South, where class fluidity, economic insecurity, and limited institutional integration have historically shaped populist politics.[117] Populism appeals to déclassé elements across all social strata,[77] offering a broad identity which gives sovereignty to the previously marginalized masses as "the people".[118] |

近代化 近代化の敗者理論は、近代化への移行の特定の側面がポピュリズムの需要を引き起こしたと主張している。この主張は、1950年代にホフスタッターをはじめ とする初期の修正主義学者たちによって提唱され、人民党を分析し、そのポピュリズムを、近代的な経済・社会変革に直面した根深い文化的不安に対する反応と 解釈した。この不安は、技術や進歩そのものではなく、現代資本主義と都市化がもたらすとされる社会的・道徳的影響に対する部分的な拒否として現れた。 [24] 近年では、産業化に続くアノミーが、伝統的な市民社会の絆を弱め、個人化を促進する解体、分断、分化をもたらしたと指摘されている。[116] 一部の分析者は、アイデンティティの断片化と集団構造の弱体化というこうした状況は、階級流動性、経済不安、制度統合の限界が歴史的にポピュリスト政治を 形成してきたグローバル・サウスで長い間見られた動態と似ている、と主張している[117]。ポピュリズムは、あらゆる社会階層における脱階級層[77] にアピールし、これまで周縁化されていた大衆を「人民」として主権を与える幅広いアイデンティティを提供している[118]。 |

| Cultural backlash Another theory that connects the emergence of populism to transformations associated with modernity—though from a different angle—is the cultural backlash thesis.[5] Focusing specifically on the rise of far-right populism, Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart argue that such movements are a reaction to the growing prominence of postmaterialism in many developed countries, including the spread of feminism, multiculturalism, and environmentalism.[119] According to this view, the diffusion of new ideas and values gradually challenges established norms, eventually reaching a "tipping point" that provokes a backlash from segments of the population who previously held dominant social positions—particularly older, white, less-educated men—expressed through support for right-wing populism.[119] Some theories limit this argument to being a reaction to just the increase of ethnic diversity from immigration.[120] Such theories are particularly popular with sociologists and with political scientists studying industrial world and American politics.[5] Empirical studies testing the cultural backlash thesis have produced mixed results.[120] While individual-level research shows strong links between sociocultural attitudes—such as views on immigration or racial resentment—and support for right-wing populist parties, macro-level analyses have not consistently found correlations between aggregate populist sentiment and electoral outcomes.[5] Nonetheless, political science and psychology research point to the significant role of group-based identity threats: individuals who feel their social group is under threat are more likely to back political actors who promise to protect its status and identity.[121][122] Although much of this work has focused on white identity politics, similar patterns are observed among other groups that perceive themselves as marginalized.[123][124] |

文化的反発 ポピュリズムの台頭と現代性に伴う変化を結びつけるもう一つの理論は、異なる角度から見たものの、文化的反発説である[5]。極右ポピュリズムの台頭に特 に焦点を当て、ピッパ・ノリスとロナルド・イングルハートは、こうした運動は、フェミニズム、多文化主義、環境保護主義の広がりなど、多くの先進国で見ら れるポストマテリアリズムの台頭に対する反応であると主張している。[119] この見解によれば、新しい思想や価値観の拡散は、徐々に既存の規範に挑み、最終的には「転換点」に達し、これまで社会で支配的な地位を占めていた層、特に 高齢の白人、教育水準の低い男性から、右翼ポピュリズムへの支持という形で反発を引き起こすという。[119] 一部の理論は、この議論を、移民による民族の多様化の進展に対する反応に限定している。[120] このような理論は、社会学者や、工業化世界やアメリカの政治を研究する政治学者たちに特に人気がある[5]。 文化的な反発説を検証した実証研究では、さまざまな結果が出ています[120]。個人レベルの研究では、移民に対する見方や人種的嫌悪感などの社会文化的 態度と、右翼ポピュリスト政党への支持との間に強い関連性があることが示されていますが、マクロレベルの分析では、ポピュリストの感情の集計と選挙結果と の間に一貫した相関関係は確認されていません[5]。それにもかかわらず、政治学や心理学の研究は、集団に基づくアイデンティティの脅威が重要な役割を果 たしていることを指摘しています。自分の社会集団が脅威にさらされていると感じる個人は、その地位やアイデンティティを保護することを約束する政治家を支 持する傾向が強い[121][122]。これらの研究の多くは白人のアイデンティティ政治に焦点を当てたものだが、自分たちを周縁化していると認識する他 の集団でも同様のパターンが見られる[123][124]。 |

| Post-democracy Various authors have presented populism as a response, reaction, or symptom of post-democracy.[125] Post-democracy refers to a condition in which the formal institutions of liberal democracy—elections, parties, and representative government—continue to exist, but their functioning is increasingly dominated by elites, technocratic decision-making, and market forces. In this context, populism is seen as a reaction to the narrowing of political choice and the decline of responsive, representative governance. Scholars offer various explanations for this development. One perspective holds that these dynamics are especially pronounced in societies where civil society is weak or in decline—a condition that some scholars view as historically characteristic of the Global South, where populism has been more recurrent, but which is increasingly visible in the Global North as well.[117] Others emphasize the role of globalization, which is seen as having seriously limited the powers of national elites and constrained their capacity to respond to popular demands.[126] Another commonly cited factor is the convergence of mainstream parties, particularly those on the center-left and center-right, which often avoid addressing contentious or pressing public concerns.[5][127][128] Authors have pointed out that the design of political systems can also influence the perception of distance between representatives and represented, and shape the conditions under which populism emerges. Low levels of political efficacy and high proportions of wasted votes are associated with increased support for populist alternatives.[129] In the United States, mechanisms such as gerrymandering, special-interest lobbying, and opaque campaign financing contribute to the perception that government is unresponsive to the majority. In the European Union, the transfer of policy authority to technocratic and supranational bodies—such as the European Central Bank—can distance decision-making from voters, further intensifying democratic disaffection.[130] Likewise, widespread corruption scandals can deepen the sense that political elites are self-serving and out of touch with ordinary citizens, which can increase support for populist movements.[111] |

ポスト民主主義 さまざまな著者が、ポピュリズムをポスト民主主義の反応、反動、または症状として提示している[125]。ポスト民主主義とは、選挙、政党、代表制政府と いった自由民主主義の形式的な制度は存続しているものの、その機能はエリート、テクノクラートによる意思決定、市場原理によってますます支配されている状 態を指す。 この文脈において、ポピュリズムは政治的選択肢の狭まりと、応答性のある代表制統治の衰退に対する反応と見なされている。学者たちはこの動向について多様 な説明を提示している。一つの見方は、これらの動向は市民社会が弱体化または衰退している社会で特に顕著だとするもので、一部の研究者はこれをグローバ ル・サウス(南半球の途上国)の歴史的特徴と見なし、ポピュリズムがより頻繁に現れる傾向があるが、最近ではグローバル・ノース(先進国)でも目立つよう になっていると指摘している。[117] 他の人々は、グローバル化が国民エリートの権力を著しく制限し、国民の要求に対応する能力を制約していると指摘し、その役割を強調している[126]。も う一つのよく引用される要因は、主流政党、特に中道左派と中道右派の政党が、論争の的となる問題や差し迫った国民的課題への対応をしばしば回避しているこ とであり[5][127][128]、 研究者は、政治制度の設計が代表者と被代表者の間の距離の認識に影響を与え、ポピュリズムが台頭する条件を形作る可能性を指摘している。政治的効力感の低 下と無駄票の割合の高さは、ポピュリスト的な選択肢への支持増加と関連している。[129] アメリカ合衆国では、選挙区画定操作、特殊利益団体のロビイング、不透明な選挙資金調達などのメカニズムが、政府が多数派の要求に反応しないという認識を 強化している。欧州連合(EU)では、政策決定権が技術官僚や超国家機関(例えば欧州中央銀行)に移譲されることで、意思決定が有権者から遠ざかり、民主 主義への不満がさらに深刻化している。[130] 同様に、広範な腐敗スキャンダルは、政治エリートが自己利益追求的で一般市民の現実から乖離しているという認識を深化させ、ポピュリズム運動への支持を高 める可能性がある。[111] |

| Media transformation Further information on the role of the mass media in the emergence of populism: Mediatization (media) Several scholars have linked the rise of populism to transformations in media and communication dynamics. Since the late 1960s, the spread of television has contributed to the personalization of politics, favoring charismatic leadership over party-centered politics—an approach frequently associated with populism.[131] Populist leaders have often made strategic use of mass media to cultivate a sense of direct connection with their audiences, relying on unfiltered communication to strengthen their legitimacy. In various regions, broadcast formats have historically been used to bypass intermediaries and appeal to constituencies traditionally marginalized by elite discourse.[132] Some scholars argue that media ownership and market dynamics have further accentuated these trends. As private media companies competed for audiences, they increasingly prioritized sensationalism and political scandal, fostering anti-establishment sentiment and public cynicism toward government institutions. Media outlets, driven by commercial imperatives, have also been said to contribute to the dissemination of populist rhetoric by providing disproportionate coverage to controversial figures, thereby amplifying their visibility and normalizing transgressive discourse. This dynamic has been observed across a range of media systems, including tabloids and even elements of the quality press.[133][134] In the digital era, scholars have argued that social media platforms have further reshaped political communication in ways that favor populist discourse.[135] These platforms have been described as having "elective affinities" with populism, as they bypass traditional gatekeeping mechanisms and foster the impression that political authority and legitimacy now rest directly with the people.[136] Furthermore, political communication on these platforms tends to rely on fragmentation and conflict-driven narratives, which may amplify populist messages.[137] |

メディアの変容 ポピュリズムの台頭におけるマスメディアの役割に関する詳細情報:メディア化(メディア) 複数の学者は、ポピュリズムの台頭をメディアとコミュニケーションのダイナミクスの変容と関連付けている。1960年代後半以降、テレビの普及は政治の個 人化に貢献し、政党中心の政治よりもカリスマ的なリーダーシップを好む傾向が強まった。この傾向は、ポピュリズムとよく関連している。[131] ポピュリストの指導者は、大衆との直接的なつながりを育むためにマスメディアを戦略的に活用し、フィルタリングされていないコミュニケーションによって自 らの正当性を強化することが多い。さまざまな地域において、放送形式は、仲介者を回避し、エリートの言説によって伝統的に疎外されてきた有権者にアピール するために、歴史的に利用されてきた[132]。 一部の学者は、メディアの所有形態や市場力学が、こうした傾向をさらに強めていると主張している。民間メディア企業が視聴者争奪戦を展開する中、センセー ショナルな報道や政治スキャンダルをますます優先するようになり、反体制感情や政府機関に対する国民の皮肉的な見方が助長されている。商業的要請に駆り立 てられたメディアは、物議を醸す人物に過大な報道をすることで、ポピュリスト的な言説の拡散に寄与し、その可視性を高め、規範を逸脱した言説を正常化して いると指摘されている。この動態は、タブロイド紙や品質重視のメディアの一部を含む多様なメディアシステムで観察されている。[133][134] デジタル時代において、研究者はソーシャルメディアプラットフォームがポピュリスト的言説を有利にする形で政治コミュニケーションを再構築したと主張して いる。[135] これらのプラットフォームは、従来のゲートキーピングのメカニズムを迂回し、政治的権威と正当性は今や直接人民にあるという印象を助長するため、ポピュリ ズムと「選択的親和性」があるとの説明がある[136]。さらに、これらのプラットフォームにおける政治コミュニケーションは、断片化と対立を煽る物語に 依存する傾向があり、ポピュリストのメッセージを増幅させる可能性がある[137]。 |

| Mobilization Several authors have examined populism as a form of political mobilization that incorporates previously invisible or marginalized sectors into the political arena.[138][139][91] However, the specific forms that this mobilization takes remain a subject of debate in the literature. While some scholars argue that populism is inherently tied to the figure of a charismatic leader,[140] others contend that it can manifest in three distinct but sometimes coexisting forms: the populist leader, the populist political party, and the populist social movement.[141] |

動員 複数の著者は、これまで目に見えなかった、あるいは周縁に追いやられていた層を政治の舞台に取り込む政治動員の一形態として、ポピュリズムを分析している [138][139][91]。しかし、この動員が具体的にどのような形をとるのかについては、文献でも議論が分かれている。一部の研究者は、ポピュリズ ムは本質的にカリスマ的な指導者の存在と不可分であると主張している[140]一方、他の研究者は、ポピュリズムは3つの異なる形態(ポピュリスト指導 者、ポピュリスト政党、ポピュリスト社会運動)で現れるが、これらの形態は時に共存すると主張している[141]。 |

| Leaders See also: Demagogue Populism is frequently associated with charismatic leadership.[142][143] In an era of increasingly personalized politics, populist leaders tend to build support through their individual appeal.[144] Such leaders claim to represent “the people” and, in many cases, portray themselves as the embodiment of the people—as the vox populi, or “voice of the people.”[145] Drawing on Margaret Canovan’s insight that populists often employ undiplomatic rhetoric and a tabloid style that contrasts with institutional norms,[146] scholars from sociocultural and performative approaches have emphasized the theatrical and stylistic dimensions of populist leadership.[147] While genuine political outsiders are relatively rare,[148] populist leaders often perform a form of outsiderness to construct authenticity and distinguish themselves from “suited elites” and professional politicians.[149] The literature highlights the transgressive nature of this performance, noting that it can take multiple, overlapping forms: interactional, rhetorical, and theatrical.[150] Interactional transgressions refer to the ways populist leaders violate conventional norms of interpersonal conduct—employing personal insults, invading personal space, using provocative gestures, or making suggestive innuendos—to create a confrontational political presence.[151] Scholars from the ideational approach link such behavior to populism’s underlying moral framework, which constructs politics as a struggle between a virtuous people and corrupt elites, framing critics and opponents as “enemies of the people.”[152] Rhetorical transgressions include a rejection of the polished, technocratic language typical of establishment politicians. Populist speech often favors simplicity, directness, or even vulgarity—aligning with the populist emphasis on authenticity. Populist figures may adopt the persona of the “uomo qualunque” (common man), using informal or crude speech.[153] Ethnic identity can likewise be mobilized: leaders such as Evo Morales and Alberto Fujimori used their non-white heritage to position themselves in contrast to historically white-dominated elites.[154] Others have drawn on indigenous or vernacular languages in public speech, symbolically rejecting elite or colonial norms.[149] Gendered performances also shape populist transgressive rhetoric. Male populists may emphasize virility or dominance—Umberto Bossi’s obscene gestures or Silvio Berlusconi’s sexual boasts are emblematic—while female populists often present themselves as protective maternal figures, such as Sarah Palin’s “mama grizzly” persona or Pauline Hanson’s claim to care for Australia “like a mother.”[155] Performative scholars such as Casullo have argued that this transgressive style not only affirms ordinariness but also incorporates performances of extraordinariness.[156] For instance, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and Eva Perón used glamorous fashion not to signal simplicity but to project aspirational ideals and popular empowerment.[157] Theatrical transgressions involve a refusal to conceal the performative nature of political life. While mainstream politicians typically mask the staged aspects of their public appearances, populist leaders often foreground them. Donald Trump, for example, frequently made metapolitical asides during U.S. presidential debates, mocking rhetorical conventions and drawing attention to their formulaic nature.[158] |

指導者 関連項目:デマゴーグ ポピュリズムは、カリスマ的な指導者と関連付けられることが多い[142][143]。政治の個人化が進む時代において、ポピュリストの指導者は、個人の 魅力によって支持基盤を築く傾向がある[144]。こうした指導者は、「人民」を代表すると主張し、多くの場合、人民の代弁者、すなわち「人民の声」とし て自らを演出する[145]。 ポピュリストは、多くの場合、外交的ではないレトリックや、制度的規範とは対照的なタブロイド紙的なスタイルを採用するというマーガレット・カノヴァンの 見解[146] を参考にし、社会文化学的およびパフォーマティビティ的アプローチの学者たちは、ポピュリストのリーダーシップの演劇的かつ文体的な側面を強調している。 [147] 真の政治のアウトサイダーは比較的まれであるが[148]、ポピュリストの指導者は、多くの場合、アウトサイダーとしての側面を演じて、その真正性を強調 し、「スーツを着たエリート」や職業政治家との差別化を図っている[149]。文献では、この演技の越境的な性質が強調されており、その形態は、相互作用 的、修辞的、演劇的など、複数の形態が重複して現れることがあると指摘されている[150]。 相互作用の越境とは、ポピュリストの指導者が、対人関係の慣習的な規範に違反し(個人への侮辱、個人のスペースへの侵入、挑発的なジェスチャー、暗示的な 発言など)、対立的な政治的存在感を演出することを指します。[151] 観念的アプローチの学者は、このような行動を、政治を「高潔な人民と腐敗したエリートとの闘争」と捉え、批判者や反対者を「人民の敵」と位置付ける、ポ ピュリズムの根底にある道徳的枠組みと関連付けている[152]。 修辞的な規範違反には、確立された政治家特有の洗練された技術官僚的な言語の拒否が含まれる。ポピュリストの言説は、シンプルさ、直接性、あるいは下品さ さえも好む傾向があり、ポピュリズムの「本物さ」への強調と一致している。ポピュリストの指導者は、「uomo qualunque」 (普通の人)のペルソナを採用し、非公式で粗野な言葉遣いを好む[153]。同様に、民族のアイデンティティも動員される。エボ・モラレスやアルベルト・ フジモリなどの指導者は、白人以外の祖先を持つことを利用して、歴史的に白人が支配してきたエリート層とは対照的な立場を確立した[154]。また、公の 演説で先住民語や方言を使用し、エリート層や植民地時代の規範を象徴的に拒絶する者もいる[149]。ジェンダーによる表現も、ポピュリストの規範違反的 なレトリックを形作っている。男性ポピュリストは、ウベルト・ボッシの卑猥なジェスチャーやシルヴィオ・ベルルスコーニの性的自慢など、男性らしさや支配 性を強調する傾向がある一方、女性ポピュリストは、サラ・ペイリンの「ママ・グリズリー」のキャラクターやポーリン・ハソンの「オーストラリアを母親のよ うに守る」という主張のように、保護的な母親像を呈することが多い。[155] カズッロなどのパフォーマティビティの研究者は、この越境的なスタイルは、平凡さを肯定するだけでなく、非平凡さのパフォーマンスも取り入れている、と主 張している[156]。例えば、クリスティーナ・フェルナンデス・デ・キルチネルやエバ・ペロンは、華やかなファッションを、質素さを示すためではなく、 願望的な理想や民衆のエンパワーメントを投影するために用いた[157]。 演劇的な越境には、政治生活のパフォーマティビティを隠そうとしない姿勢がある。主流の政治家は通常、公の場での演出的な側面を隠すが、ポピュリストの指 導者はしばしばそれを前面に出す。例えば、ドナルド・トランプは、米国大統領候補討論会で、レトリックの慣習を嘲笑し、その定式的な性質に注目を集めるよ うな、メタ政治的な発言を頻繁に繰り返した[158]。 |

| Political parties Populism does not oppose party-based parliamentary representation outright, but seeks to redefine it by privileging figures who claim to speak authentically for "the people."[159] Populist political parties often emerge around a charismatic leader, adopting top-down structures that concentrate decision-making and symbolic authority in a single figure.[159] These parties function as vehicles for personal leadership, reinforcing the central role of the leader in mobilizing support and framing political identity. Leadership transitions can be pivotal: some parties, like Argentina’s Justicialist Party and Venezuela’s United Socialist Party (PSUV), maintained cohesion after the deaths of their founding figures, while others fractured.[160] Sometimes, rather than founding new parties, populists overtake existing ones, as seen with the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) and the Swiss People's Party (SVP).[161] In other cases, established parties undergo a gradual populist transformation. A notable example is the Greek party SYRIZA, which between 2012 and 2015 evolved from a radical left-wing party primarily appealing to “the left” and then “the youth,” to one that claimed to represent “the people.” This transformation was marked not only by changes in speeches but also by increasingly transgressive performances by its leaders, who, once in power, broke with conventional political decorum.[162] As the case of SYRIZA illustrates, the boundaries between political parties and social movements can be fluid. While SYRIZA eventually became a major institutional actor, its early trajectory was deeply intertwined with grassroots mobilizations against austerity.[163] Other populist parties have emerged even more directly from mass movements seeking to channel grassroots discontent into formal politics. The Spanish party Podemos, for example, was founded in the wake of the Indignados movement, while India's Aam Aadmi Party grew out of the India Against Corruption campaign.[164] These examples illustrate how populist energy can flow between civil society and electoral arenas—a phenomenon further explored in the context of grassroots populist movements. |

政党 ポピュリズムは、政党による議会代表制度を完全に否定するものではなく、「人民」の声を真に代弁すると主張する人物に優位性を与えることで、その制度を再 定義しようとしている[159]。ポピュリスト政党は、多くの場合、カリスマ的な指導者を軸として誕生し、意思決定と象徴的権威を 1 人の人物に集中させるトップダウン型の構造を採用している。[159] こうした政党は、個人的なリーダーシップの手段として機能し、支持の動員や政治的アイデンティティの形成において指導者の中心的な役割を強化する。指導者 の交代は極めて重要になる場合がある。アルゼンチンの正義党やベネズエラの統一社会党(PSUV)のような政党は、創設者の死後も結束を維持したが、他の 政党は分裂した[160]。 時には、新しい政党を設立するよりも、既存の政党を乗っ取る場合もある。オーストリアの自由党(FPÖ)やスイスの人民党(SVP)がその例だ。 [161] また、既存の政党が徐々にポピュリスト化する場合もある。その顕著な例が、2012 年から 2015 年にかけて、「左翼」そして「若者」を主な支持層とした急進的な左翼政党から、「人民」の代表を標榜する政党へと変貌を遂げたギリシャの政党 SYRIZA だ。この変貌は、演説の内容の変化だけでなく、政権獲得後に従来の政治の礼儀作法を破る、ますます越境的な行動を取るようになった党首たちの行動にも表れ ている[162]。 SYRIZAの事例が示すように、政治政党と社会運動の境界は流動的だ。SYRIZAは最終的に主要な制度的主体となったが、その初期の軌跡は緊縮政策に 反対する草の根運動と深く結びついていた。[163] 他のポピュリスト政党は、草の根の不満を正式な政治に導こうとする大規模な運動からさらに直接的に台頭している。例えば、スペインのポデモス党はインディ グナドス運動の後に設立され、インドのアアム・アアドミ党はインド反腐敗運動から生まれた。[164] これらの例は、ポピュリストのエネルギーが市民社会と選挙の場の間を流動的に移動する現象を明らかにしており、この現象は草の根ポピュリスト運動の文脈で さらに深く考察されている。 |

| Social movements The wave of mass protests that followed the 2008 financial crisis has often been characterized as a populist phenomenon. Although differing in context, tone, and social composition, these mobilizations shared a rejection of established political elites, emphasized the moral authority of "the people," and advanced demands for more inclusive and participatory forms of democracy. The Occupy movement in the United States, the Indignados movement in Spain, the anti-austerity protests in Greece, and the Gilets jaunes (Yellow Vests) in France all combined anti-elite rhetoric with horizontal experiments in democratic organization.[165][166] Symbolic slogans such as “We are the 99%” captured the populist framing of these protests, portraying a voiceless majority in opposition to a privileged elite. Although they shared common traits, the social base and geographical focus of these mobilizations varied: while earlier protests were often concentrated in urban hubs, the Gilets jaunes mobilized primarily rural and peri-urban populations, voicing the grievances of what was sometimes called “la France oubliée” (forgotten France).[167][168] These grassroots mobilizations, whether or not they evolved into lasting political structures, exerted a profound influence on electoral politics and public discourse. They reshaped political agendas, introduced new rhetorical styles centered on anti-elitism and citizen empowerment, and forced established actors to respond to new forms of popular expression. In Spain and Greece, protest movements reconfigured political debates around austerity and democratic renewal. In the United States, the Occupy Wall Street movement influenced the language and priorities of Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign, particularly its emphasis on economic inequality and corporate power. Conversely, right-wing populist energy found expression through the Tea Party movement, which contributed to shifting the Republican Party toward a more anti-establishment posture and paved the way for the rise of Donald Trump.[169] Scholars in the discursive tradition of populism studies have emphasized the complex and often reciprocal relationship between populist leaders and social movements—particularly in left-wing or socially oriented contexts. Rather than assuming a one-directional, top-down mobilization, this view highlights how leaders can contribute to the politicization and organization of civil society, and how movements, in turn, can shape and transform leadership. In Latin America, this dynamic has deep historical roots. Mid-twentieth-century leaders such as Juan Perón in Argentina and Getúlio Vargas in Brazil played a central role in organizing labor unions and incorporating subaltern sectors into national politics.[170] While initially aligned with the regime, these sectors often gained autonomy and began articulating demands independently.[171] More recently, Hugo Chávez in Venezuela promoted participatory structures such as Bolivarian Circles, Communal Councils, and Urban Land Committees.[172] Designed to deepen popular engagement and distribute resources, these initiatives also created new networks of mobilization. A further example, noted by political theorists Paula Biglieri and Luciana Cadahia, is the role of grassroots feminist activists in Argentina, who successfully pressured the Peronist leadership to support the legalization of abortion—despite their initial opposition to the measure.[173] |

社会運動 2008年の金融危機後に起こった大規模な抗議運動は、しばしばポピュリスト現象と特徴づけられてきた。その背景、トーン、社会的構成は異なるものの、こ れらの運動は、既存の政治エリートを拒絶し、「人民」の道徳的権威を強調し、より包括的で参加型の民主主義形態を要求するという共通点があった。アメリカ 合衆国のオキュパイ運動、スペインのインディグナドス運動、ギリシャの緊縮政策反対デモ、フランスのジレ・ジョーヌ(黄色いベスト)運動は、すべて反エ リート的な言辞と民主的組織の水平的な実験を組み合わせたものでした。[165][166] 「私たちは99%だ」といった象徴的なスローガンは、これらの抗議運動のポピュリスト的な枠組みを捉えており、特権的なエリート層に対抗する声なき多数派 を描き出していた。これらの動員は共通の特徴を共有していたものの、社会的基盤と地理的焦点には違いがあった:初期の抗議運動は都市部を中心に集中してい たのに対し、ジレ・ジョーヌは主に農村部と都市近郊の住民を動員し、「忘れられたフランス」(la France oubliée)と呼ばれる層の不満を代弁した。[167][168] これらの草の根運動は、持続的な政治構造へと発展したかどうかに関わらず、選挙政治と公共の議論に深い影響を与えた。政治アジェンダを再構築し、反エリー ト主義と市民の権限強化を軸とした新たな修辞スタイルを導入し、既成の政治勢力に新たな形態の市民の表現に対応することを迫った。スペインとギリシャで は、抗議運動が緊縮政策と民主主義の再生を巡る政治議論を再構成した。米国では、オキュパイ・ウォールストリート運動が、バーニー・サンダースの 2016 年大統領選挙のキャンペーンにおける言葉遣いや優先課題、特に経済的不平等や企業権力への重点に多大な影響を与えた。一方、右翼ポピュリストのエネルギー はティーパーティー運動を通じて表現され、共和党をより反体制的な姿勢へと転換させ、ドナルド・トランプの台頭を準備した[169]。 ポピュリズム研究における言説の伝統を継承する学者たちは、ポピュリストの指導者と社会運動、特に左翼や社会志向の文脈における両者の複雑でしばしば相互 的な関係を強調している。この見解は、一方向的なトップダウン型の動員を前提とするのではなく、指導者が市民社会の政治化と組織化にどのように貢献できる かを強調し、その一方で、運動が指導者を形成、変革する仕組みを明らかにしている。ラテンアメリカでは、このダイナミズムは歴史的に深い根を持っている。 20 世紀半ば、アルゼンチンのフアン・ペロンやブラジルのゲトゥリオ・ヴァルガスなどの指導者は、労働組合の組織化とサバルタン層(被抑圧層)の国民政治への 参加において中心的な役割を果たした[170]。当初、政権と足並みを揃えていたこれらの層は、しばしば自治権を獲得し、独立して要求を表明するように なった[171]。最近では、ベネズエラのウゴ・チャベス大統領が、ボリバル円卓会議、コミューン評議会、都市土地委員会などの参加型組織を推進した。 [172] これらのイニシアチブは、市民の参加を深化させ、資源を分配することを目的としていたが、新たな動員ネットワークも生み出した。政治理論家のパウラ・ビグ リエリとルチアナ・カディアが指摘する別の例として、アルゼンチンの草の根フェミニスト活動家が、当初反対していたペロン派指導部に中絶の合法化を支持さ せることに成功した事例がある。[173] |

| Responses to populism Debates around how to respond to populism reveal sharp divides between those who see it as a threat to be contained and those who view it as a symptom of deeper democratic failures. While many mainstream actors focus on defending liberal institutions from populist erosion, left-wing theorists have explored how populist energies might be redirected toward egalitarian or emancipatory ends. |

ポピュリズムへの対応 ポピュリズムへの対応をめぐる議論は、それを封じ込めるべき脅威と捉える立場と、より深刻な民主主義の失敗の兆候と捉える立場との間で、鋭い対立を露わに している。多くの主流派は、ポピュリズムによる侵食から自由主義的制度を守ることに重点を置いているが、左派の理論家たちは、ポピュリズムのエネルギー を、平等主義や解放主義的な目標に向けて転換する方法を探っている。 |

| Mainstream responses Among liberal scholars, a central concern has been the preservation of institutional safeguards. Authors like Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt argue that populist figures with authoritarian leanings often become viable only when traditional elites choose to accommodate them for strategic reasons. In their account, democratic backsliding typically occurs when political elites fail to uphold informal norms of mutual toleration and institutional forbearance.[174] Their approach aligns with aspects of elite theory, emphasizing the responsibility of established power-holders to act as gatekeepers in order to safeguard democratic norms.[175] Reflecting this logic, several European countries have adopted the strategy of a cordon sanitaire, in which mainstream parties refuse to cooperate or form coalitions with populist or extremist actors, seeking to prevent their institutional legitimation.[176] The media, too, can play a crucial role in either reinforcing or undermining these gatekeeping efforts. In some contexts, media institutions have amplified populist narratives or provided favorable coverage, while in others they have attempted to marginalize such movements. Additionally, some scholars note that when mainstream actors adopt elements of the populist style—such as anti-elitist rhetoric—they may inadvertently contribute to the normalization of populism rather than containing it.[177] Related to this is the concept of militant democracy or defensive democracy, originally articulated by Karl Loewenstein in the 1930s. Loewenstein argued that liberal democracies must sometimes take exceptional restrictive measures that might seem arbitrary and limit certain freedoms to defend themselves against actors who exploit democratic procedures to undermine democratic substance—a concern that also resonates with Karl Popper’s paradox of tolerance.[178][179] This approach has gained renewed attention in contexts such as Brazil, where the Supreme Court expanded its own procedural interpretations to investigate anti-democratic activities after the Prosecutor General's Office had been politically aligned with then-president Jair Bolsonaro. These actions were justified as necessary to uphold the rule of law in the face of institutional capture.[180] A similar logic has been invoked in Romania, where legal and institutional efforts to constrain far-right movements have prompted public controversy over how far democracies can go in defending themselves without compromising pluralism and political freedom.[181][182] Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, while critical of populism, caution against the widespread liberal impulse to disqualify populists as “irrational,” “immoral,” or “foolish.” In their view, such discursive strategies often play into the hands of populists, reinforcing the binary logic—“the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”—on which they believe populism thrives.[183] Rather than moralizing condemnation, they advocate for sustained engagement with populist supporters and arguments, alongside a principled defense of liberal democratic values.[184] |

主流の反応 リベラルな学者たちの間では、制度的保障の維持が中心的な関心事となっている。スティーブン・レヴィツキーやダニエル・ジブラットなどの著者は、権威主義 的な傾向のあるポピュリストは、伝統的なエリートが戦略的な理由から彼らを受け入れることを選択した場合にのみ、しばしば実現可能性を得るようになる、と 主張している。彼らの説明によれば、民主主義の後退は通常、政治エリートが相互の寛容と制度的寛容という非公式の規範を守れない場合に発生します [174]。彼らのアプローチは、民主主義の規範を守るためのゲートキーパーとしての既得権力者の責任を強調するエリート理論の一側面と一致しています [175]。 この論理を反映して、いくつかのヨーロッパ諸国は、主流政党がポピュリストや過激派との協力や連立を拒否し、彼らの制度的正当化を防ぐ「衛生防護線」戦略 を採用している[176]。メディアも、こうしたゲートキーピングの取り組みを強化したり、弱体化させたりする上で重要な役割を果たす。ある状況では、メ ディア機関がポピュリストの主張を誇張したり、好意的に報道したりしている一方、別の状況では、こうした運動を周縁化しようとしている。さらに、一部の学 者は、主流のアクターが反エリート主義的なレトリックなど、ポピュリストのスタイルの一部を採用すると、ポピュリズムを封じ込めるどころか、その正常化に 不本意ながら貢献してしまう可能性がある、と指摘している[177]。 これに関連するのが、カール・ローウェンシュタインが1930年代に提唱した「戦闘的民主主義」または「防御的民主主義」の概念だ。ローウェンシュタイン は、自由民主主義は、民主的手続きを悪用して民主主義の本質を損なうアクターから自身を守るため、時として恣意的に見える制限措置を講じ、特定の自由を制 限する必要があると主張した。この懸念は、カール・ポッパーの「寛容のパラドックス」とも共鳴する。[178][179] このアプローチは、ブラジルのような文脈で再注目されている。ブラジルでは、検察総長が当時の大統領ジャイル・ボルソナロと政治的に連携していた後、最高 裁判所が自らの手続き解釈を拡大して反民主的活動を調査した。これらの措置は、制度的支配に対抗して法の支配を維持するために必要だと正当化されました。 [180] 同様の論理はルーマニアでも引用されており、極右運動を制約するための法的・制度的取り組みが、民主主義が多元主義と政治的自由を損なうことなく自己防衛 のためにどこまで踏み込むことができるかについて、公の議論を巻き起こしています。[181][182] ムッデとロビラ・カルタッサーは、ポピュリズムに批判的ながらも、ポピュリストを「非合理」「不道徳」「愚か」と排除する広範なリベラルな傾向に警鐘を鳴 らしている。彼らの見解では、このような言説戦略は、ポピュリストたちが繁栄する基盤である「純粋な人民」対「腐敗したエリート」という二分法的な論理を 強化し、しばしばポピュリストたちに有利に働くからです[183]。彼らは、道徳的な非難ではなく、リベラルな民主主義の価値観を原則的に擁護するととも に、ポピュリストの支持者や主張と持続的に関わっていくことを提唱しています[184]。 |

| Left populist responses From the perspective of left populism, the rise of reactionary populist movements is often interpreted as a response to a broader anti-political sentiment—a rejection of technocratic consensus, elite detachment, and social abandonment. Thinkers such as Chantal Mouffe argue that this dissatisfaction should not be left in the hands of the right, but rather reappropriated through a left populist project that mobilizes passion for democratic and egalitarian ends.[185] However, there are strategic disagreements among left populists. Some scholars suggest that left movements must engage with national identity and reduce emphasis on minority-focused policies in order to reconnect with disaffected working-class constituencies.[186] This perspective underlies proposals for a left populism that emphasizes cultural belonging and national sovereignty alongside economic redistribution, as seen in the positions of German politician Sahra Wagenknecht, who has criticized the left for abandoning “ordinary people” in favor of urban progressive elites.[187] In contrast, other scholars warn that such strategies risk reproducing far-right framings without yielding electoral gains. They instead advocate for intersectional alliances rooted in solidarity among marginalized groups, grounded in inclusive democratic values.[citation needed] These debates are shaped by national contexts, electoral systems, and the particular forms populism takes in different settings.[citation needed] |

左派ポピュリズムの反応 左派ポピュリズムの観点からは、反動的なポピュリズム運動の台頭は、より広範な反政治感情、すなわちテクノクラート的なコンセンサス、エリートの離反、社 会的見捨てへの拒絶に対する反応として解釈されることが多い。シャンタル・ムフなどの思想家は、この不満は右派に任せるべきではなく、民主主義と平等主義 の目標のために情熱を動員する左派ポピュリストのプロジェクトを通じて再獲得すべきだと主張している[185]。 しかし、左派ポピュリストの間には戦略上の意見の相違がある。一部の学者は、左派運動は、不満を抱く労働者層とのつながりを回復するために、国民的アイデ ンティティを取り入れ、マイノリティに焦点を当てた政策の重視を弱めるべきだと主張している。[186] この見方は、経済の再分配とともに文化的帰属意識と国家主権を重視する左派ポピュリズムの提案の根底にある。これは、都市部の進歩的なエリートを優先して 「一般大衆」を見捨てたとして左派を批判しているドイツの政治家、ザーラ・ヴァゲンクネヒトの立場にも見られる。[187] 一方、他の学者たちは、このような戦略は、選挙での勝利をもたらさないまま、極右の枠組みを再現する危険性があると警告している。その代わりに、彼らは、 包括的な民主主義の価値観に基づき、周縁化された集団間の連帯に根ざした、交差的な同盟を提唱している。これらの議論は、各国の状況、選挙制度、および異 なる状況下でポピュリズムが取る特定の形態によって形作られている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Populism |

続き「ポピュリズムの歴史」 |

| Labourism Neopopulism [es] Fiscal populism Argumentum ad populum Black populism Class warfare Communitarianism Demagogue Elite theory Empire of Democracy Extremism Fanaticism Fundamentalism List of populists Iron law of oligarchy Judicial populism Ochlocracy (mob rule) Paternalism Penal populism Politainment Polite populism Political polarization Poporanism Populism in Latin America Post-democracy Radical politics Reactionism Third party (politics) Tyranny of the majority |

労働主義 ネオポピュリズム [es] 財政ポピュリズム 大衆の意見に訴える論法 黒人ポピュリズム 階級闘争 共同体主義 デマゴーグ エリート理論 民主主義の帝国 過激主義 狂信 原理主義 ポピュリストのリスト 寡頭政治の鉄則 司法ポピュリズム オクロクラシー(暴徒政治) 父権主義 刑罰ポピュリズム ポリティメント 礼儀正しいポピュリズム 政治的二極化 ポポラニズム ラテンアメリカにおけるポピュリズム ポスト民主主義 急進的政治 反動主義 第三政党(政治) 多数派の専制 |