アイデンティティによる政治入門

Introduction to politics of identity

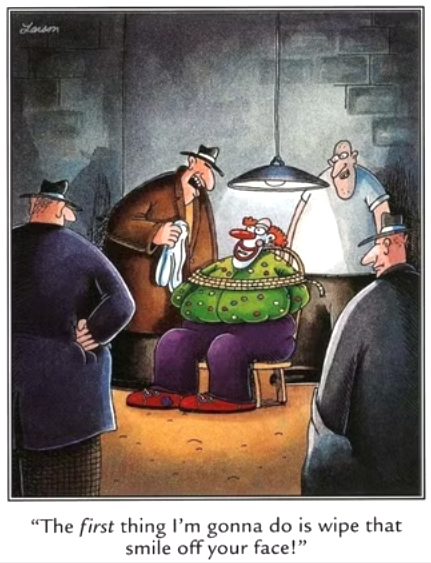

[まず最初にそのふざけたツラを拭き取ってやるぜ]

解説:池田光穂

アイデンティティによる政治入門

Introduction to politics of identity

[まず最初にそのふざけたツラを拭き取ってやるぜ]

解説:池田光穂

アイデンティティ・ポ リティクス(Identity politics)とは、民族、人種、国籍、宗教、宗派、性別、性的指向、社会背景、カースト、社会階級などの 特定のアイデンティティに基づく政治である。 この用語は、アイデンティティに基づく移動性を規制する政府の移民政策や、国家や民族の他者を排除する極右ナショナリストの政策な ど、アイデンティティ・ ポリティクスとして一般的に理解されていない他の社会現象も包含する可能性がある(→例えばポピュリズ ムは「アイデンティティポリティクス」によるかという主張には賛否両論があるが、私は「構成される帰属集団のいまここでの生成」という意味で含め たほうがいいと思う)。このため、この用語のいくつかの定義を論じているクルツウェリー、ペレ ス、シュピーゲルは、アイデンティティ政治は分析上不正確な概念であると主張している。

このページは、 マイケル・ケニー『アイデンティティの政治学』の解説を中心に、「アイデンティティによる政治」は可能か?また可能であるならば、どういった点で可能か? 不可能なら、何を克服すれば可能な条件に近づけるのかを考えてみたい。

■ マイケル・ケニー『アイデンティティの政治学』藤原孝ほか訳、日本経済評論社、2005/The politics of identity : liberal political theory and the dilemmas of difference / Michael Kenny, Cambridge : Polity , 2004

This book provides a comprehensive and critical assessment of the ways in which Anglo-American political theorists have responded to the emergence of a politics of identity in democratic society. It examines the merits and weaknesses of the ideas associated with the major schools and thinkers in contemporary philosophical liberalism. It also provides a critical exploration of the arguments of their pluralist rivals, including advocates of multiculturalism, 'difference' and recognition. Kenny illustrates how debates over such concepts as identity, difference, recognition and culture are intertwined with political theorists' characterizations of democracy, citizenship and civil society. In an analysis that juxtaposes normative political theory with the study of social movements and change, the author challenges two widely held ideas about the relationship between liberal democracy and culturally based groups. He questions the assertion that there is no place for identity based political argument in the public life of a democracy. And he challenges the pluralist conviction that the re-emergence of collective identities signals the demise of liberal culture and political thought. Written in a clear and accessible style, The Politics of Identity is intended for students, scholars and general readers interested in contemporary political and social thought, political ideologies, and political culture.

本書は、英米の政治理論家たちが民主的社会におけるアイデンティティ政治の出現にどう対応し てきたかを、包括的かつ批判的に評価するものである。現代の哲学的リベラリズムの主要な学派や思想家たちに関連する考え方の長所と短所を検証している。ま た、多文化主義、差異、承認の擁護者を含む、多元主義のライバルたちの議論についても批判的に探求している。ケニーは、アイデンティティ、差異、承認、文 化といった概念をめぐる議論が、政治理論家による民主主義、市民権、市民社会の定義とどのように絡み合っているかを明らかにしている。規範的な政治理論と 社会運動や社会変化の研究を並置する分析の中で、著者はリベラル民主主義と文化に基づく集団の関係について広く受け入れられている2つの考え方に異議を唱 えている。著者は、民主主義の公共生活においてアイデンティティに基づく政治的議論 の余地はないという主張に疑問を投げかけている。また、集団的アイデ ンティティの再出現はリベラルな文化や政治思想の終焉を意味するという多元主義者の考えにも異議を唱えている。明快で読みやすい文体で書か れた『アイデンティティの政治学』は、現代の政治思想や社会思想、政治イデオロギー、政治文化に関心のある学生、研究者、一般読者向けに書かれている。

1.アイデンティティの政治の性格とそ の起源

2.自由主義政治理論におけるアイデン ティティの政 治

3.シティズンシップ・公共理性・集合 的アイデン ティティ

4.市民社会とアソシエーションの道徳 性

5.アイデンティティの政治の公共面

6.運動におけるアイデンティティ:社 会運動の政治 倫理

7.自由主義と差異の政治

8.自由主義と承認の政治

9.結論 |

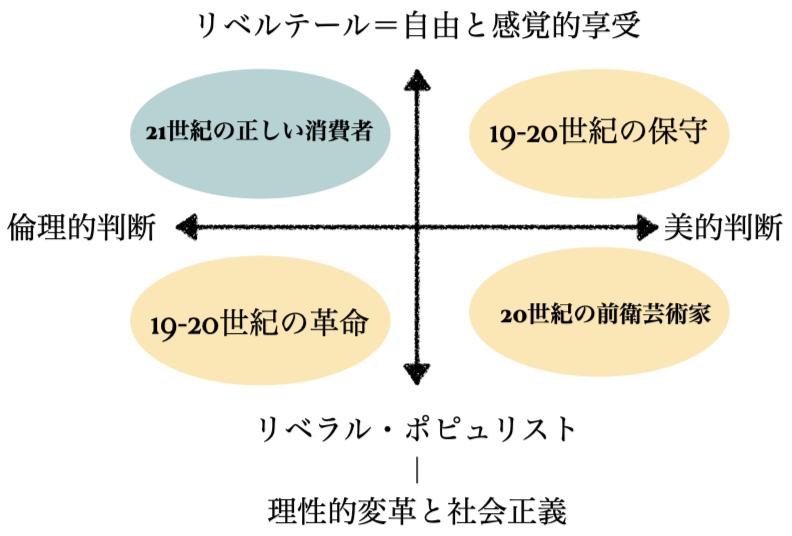

●倫理的態度の軸と、リベラル=ポピュリストとリ バータリアンの軸

| アイデンティティ・ポリティクスより(各国・各地域の事例) |

|

| Racial and ethnocultural Further information: Ethnocultural politics in the United States Ethnic, religious and racial identity politics dominated American politics in the 19th century, during the Second Party System (1830s–1850s)[33] as well as the Third Party System (1850s–1890s).[34] Racial identity has been the central theme in Southern politics since slavery was abolished.[35] Similar patterns which have appeared in the 21st century are commonly referenced in popular culture,[36] and are increasingly analyzed in media and social commentary as an interconnected part of politics and society.[37][38] Both a majority and minority group phenomenon, racial identity politics can develop as a reaction to the historical legacy of race-based oppression of a people[39] as well as a general group identity issue, as "racial identity politics utilizes racial consciousness or the group's collective memory and experiences as the essential framework for interpreting the actions and interests of all other social groups."[40] Carol M. Swain has argued that non-white ethnic pride and an "emphasis on racial identity politics" is fomenting the rise of white nationalism.[41] Anthropologist Michael Messner has suggested that the Million Man March was an example of racial identity politics in the United States.[42] |

人種および民族文化 詳細情報:米国における民族文化政治 19世紀のアメリカ政治は、第二党制(1830年代~1850年代)および第三党制(1850年代~1890年代)の時代に、民族、宗教、人種を基盤とす るアイデンティティ政治が支配的であった。[34] 人種的アイデンティティは、奴隷制度が廃止されて以来、南部の政治の中心的なテーマとなっている。[35] 21世紀に現れた同様のパターンは一般的に大衆文化で言及されており[36]、政治と社会の相互に関連する一部として、メディアや社会評論でますます分析 されるようになっている。[37][38] 人種的アイデンティティ政治は、多数派グループと少数派グループの両方に見られる現象であり、 人種に基づく抑圧の歴史的遺産に対する反応として発展する可能性がある[39]。また、一般的な集団のアイデンティティの問題として発展する可能性もあ る。「人種的アイデンティティ政治は、人種的意識や集団の集合的記憶や経験を、他のすべての社会集団の行動や利益を解釈するための本質的な枠組みとして利 用する」からである[40]。 キャロル・M・スウェインは、非白人の民族的な誇りと「人種的アイデンティティ政治の強調」が白人ナショナリズムの台頭を煽っていると主張している。 [41] 人類学者のマイケル・メスナーは、100万人行進は米国における人種的アイデンティティ政治の一例であると示唆している。[42] |

| Arab identity politics See also: Arab identity, Arab nationalism, and Pan-Arabism Arab identity politics concerns the form of identity-based politics which is derived from the racial or ethnocultural consciousness of the Arabs. In the regionalism of the Arab world and the Middle East, it has a particular meaning in relation to the national and cultural identities of the citizens of non-Arab countries, such as Turkey and Iran.[43][44] In their 2010 Being Arab: Arabism and the Politics of Recognition, academics Christopher Wise and Paul James challenged the view that, in the post-Afghanistan and Iraq invasion era, Arab identity-driven politics were ending. Refuting the view that had "drawn many analysts to conclude that the era of Arab identity politics has passed", Wise and James examined its development as a viable alternative to Islamic fundamentalism in the Arab world.[45] According to Marc Lynch, the post-Arab Spring era has seen increasing Arab identity politics, which is "marked by state-state rivalries as well as state-society conflicts". Lynch believes this is creating a new Arab Cold War, no longer characterized by Sunni-Shia sectarian divides but by a reemergent Arab identity in the region.[46] Najla Said has explored her lifelong experience with Arab identity politics in her book Looking for Palestine.[47] |

アラブのアイデンティティ政治 関連項目:アラブのアイデンティティ、アラブ民族主義、汎アラブ主義 アラブのアイデンティティ・ポリティクスは、アラブ人の人種的または民族的文化的な意識から派生したアイデンティティに基づく政治の形態を指す。アラブ世 界や中東の地域主義においては、トルコやイランなどの非アラブ諸国の国民の国家や文化的なアイデンティティとの関連において、特に意味を持つ。2010年 の著書『Being Arab: アラブ主義と承認の政治」という著書の中で、学者のクリストファー・ワイズとポール・ジェームズは、アフガニスタンとイラク侵攻後の時代において、アラブ のアイデンティティを基盤とする政治は終焉を迎えているという見解に異議を唱えた。 アラブのアイデンティティ政治の時代は過ぎ去ったと結論づける多くのアナリストの意見に反論し、ワイズとジェームズは、アラブ世界におけるイスラム原理主 義の代替案として、その発展を検証した。 マーク・リンチによると、アラブの春後の時代にはアラブのアイデンティティ・ポリティクスが増加しており、それは「国家間の対立や国家と社会の対立を特徴 とする」ものである。リンチは、これは新たなアラブの冷戦を生み出しており、それはもはやスンニ派とシーア派の宗派間の対立ではなく、地域におけるアラブ のアイデンティティの再出現によって特徴づけられると考える。ナジャ・サイードは、著書『パレスチナを求めて』で、アラブのアイデンティティ・ポリティク スに関する生涯にわたる経験を掘り下げている。 |

| Asian-American identity politics See also: Pan-Asianism, Asian American activism, Asian American movement, and Asian Americans In the political realm of the United States, according to Jane Junn and Natalie Masuoka, the possibilities which exist for an Asian American vote are built upon the assumption that those Americans who are broadly categorized as Asians share a sense of racial identity, and this group consciousness has political consequences. However, the belief in the existence of a monolithic Asian American bloc has been challenged because populations are diverse in terms of national origin and language—no one group is predominant—and scholars suggest that these many diverse groups favor groups which share their distinctive national origin over any belief in the existence of a pan-ethnic racial identity.[48] According to the 2000 Consensus, more than six national origin groups are classified collectively as Asian American, and these include: Chinese (23%), Filipino (18%), Asian Indian (17%), Vietnamese (11%), Korean (11%), and Japanese (8%), along with an "other Asian" category (12%). In addition, the definitions which are applied to racial categories in the United States are uniquely American constructs that Asian American immigrants may not adhere to upon entry to the United States. Junn and Masuoka find that in comparison to blacks, the Asian American identity is more latent, and racial group consciousness is more susceptible to the surrounding context. |

アジア系アメリカ人のアイデンティティ政治 関連項目:汎アジア主義、アジア系アメリカ人の活動、アジア系アメリカ人運動、アジア系アメリカ人 ジェーン・ジュンとナタリー・マスオカによると、米国の政治領域において、アジア系アメリカ人の投票が持つ可能性は、アジア人と大まかに分類されるアメリ カ人が人種的アイデンティティの感覚を共有するという前提に基づいており、この集団意識が政治的な結果をもたらす。しかし、アジア系アメリカ人という単一 の集団の存在を信じる考え方は、人口が出身国や言語の面で多様であり、特定のグループが優勢であるわけではないことから、疑問視されている。学者たちは、 こうした多様なグループは、単一の民族としての人種的アイデンティティの存在を信じるよりも、自分たちと同じ特定の出身国を共有するグループを支持する傾 向にあると指摘している。[48] 2000年のコンセンサスによると、6つ以上の出身国グループがアジア系アメリカ人として一括りにされており、その中には、 中国系(23%)、フィリピン系(18%)、インド系(17%)、ベトナム系(11%)、韓国系(11%)、日系(8%)、「その他のアジア系」 (12%)である。さらに、米国で人種カテゴリーに適用される定義は、米国独特の概念であり、アジア系アメリカ人移民が米国に入国した際に、それに従う必 要はない。 ジュンとマスオカは、黒人と比較した場合、アジア系アメリカ人のアイデンティティはより潜在的なものであり、人種集団の意識は周囲の状況に影響されやすい ことを発見した。 |

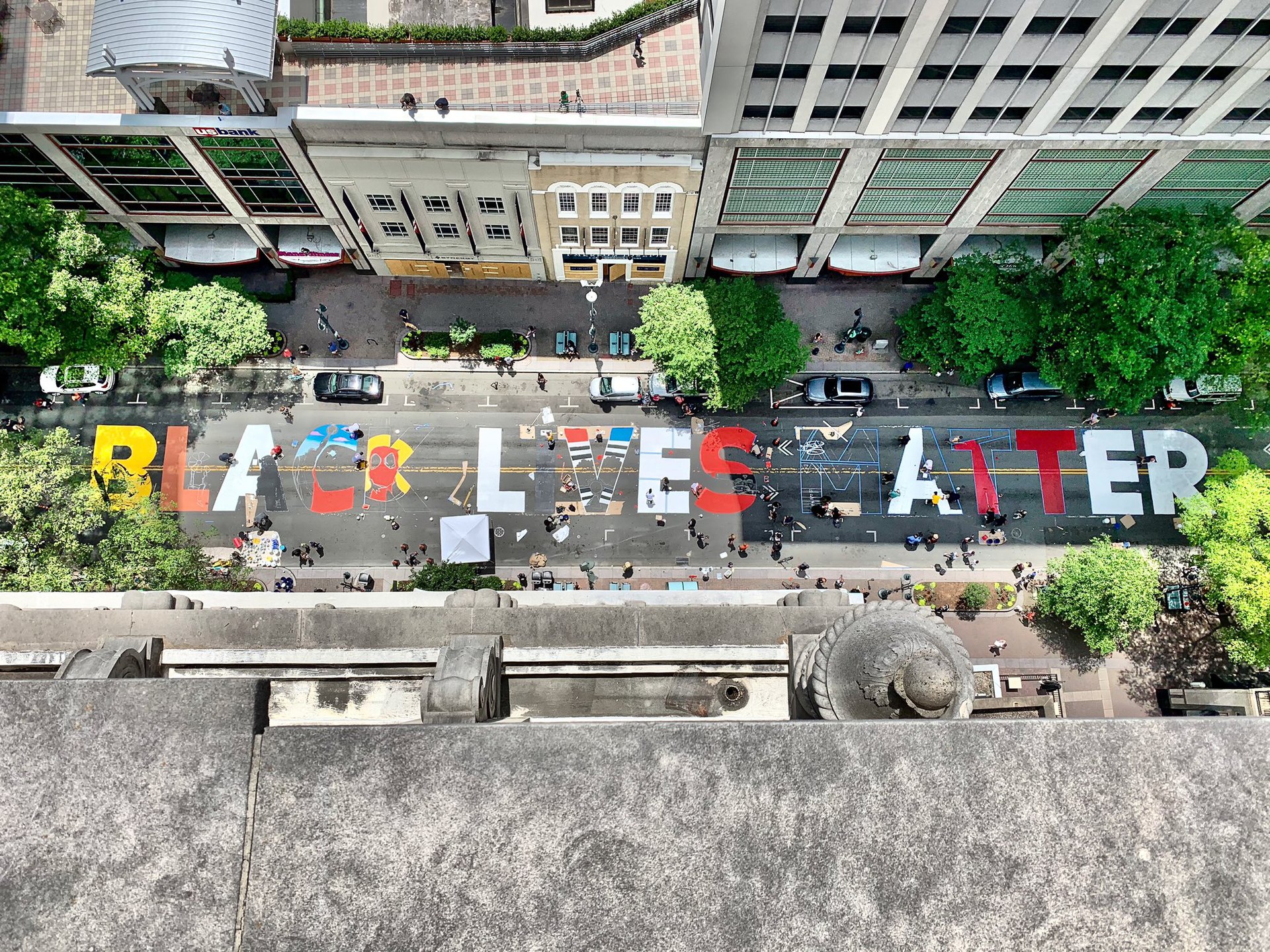

| Black and Black feminist

identity politics See also: Black nationalism, Black power, Black feminism, Combahee River Collective, and Black women in American politics Black feminist identity politics are the identity-based politics derived from the lived experiences of struggles and oppression faced by Black women. In 1977, the Combahee River Collective (CRC) argued that Black women struggled with facing their oppression due to the sexism present within the Civil Rights Movement and the racism present within second-wave feminism. The CRC coined the term "identity politics", and in their opinion, naming the unique struggle and oppression Black women faced, aided Black women in the U.S. within radical movements and at large. The term "identity politics", in the opinion of those within the CRC, gave Black women a tool, from which they could use to confront the oppression they were facing. The CRC also claimed to expand upon the prior feminist adage that "the personal is political," pointing to their own consciousness-raising sessions, centering of Black speech, and communal sharing of experiences of oppression as practices that expanded the phrase's scope. As mentioned earlier K. Crenshaw, claimed that the oppression of Black women is illustrated in two different directions: race and sex. In 1988, Deborah K. King coined the term multiple jeopardy, theory that expands on how factors of oppression are all interconnected. King suggested that the identities of gender, class, and race each have an individual prejudicial connotation, which has an incremental effect on the inequity of which one experiences. In 1991, Nancie Caraway explained from a white feminist perspective that the politics of Black women had to be comprehended by broader feminist movements in the understanding that the different forms of oppression that Black women face (via race and gender) are interconnected, presenting a compound of oppression (Intersectionality).  #BlackLivesMatter A contemporary example of Black identity politics is #BlackLivesMatter which began with a hashtag. In 2013, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi created the hashtag in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman, the officer who killed Trayvon Martin in 2012.[49] Michael Brown and Eric Garner were killed by police in 2014, which propelled the #BlackLivesMatter movement forward, first nationally, and then globally.[50] The intention of #BlackLivesMatter was to create more widespread awareness of the way law enforcement engages with the black community and individuals, including claims of excessive force and issues with accountability within law enforcement agencies.[51] The hashtag and proceeding movement garnered a lot of attention from all sides of the political sphere. A counter movement formed the hashtag, #AllLivesMatter, in response to #BlackLivesMatter.[52] |

黒人と黒人フェミニストのアイデンティティ・ポリティクス 関連項目:黒人ナショナリズム、ブラックパワー、黒人フェミニズム、コンバヒー・リバー・コレクティブ、アメリカ政治における黒人女性 黒人フェミニストのアイデンティティ・ポリティクスは、黒人女性が直面する闘争と抑圧の経験から派生したアイデンティティに基づく政治である。 1977年、コンバヒー・リバー・コレクティブ(CRC)は、黒人女性は、公民権運動における性差別と、第二波フェミニズムにおける人種差別という、2つ の差別と闘うために苦闘していると主張した。CRCは「アイデンティティ・ポリティクス」という用語を考案し、彼らの意見では、黒人女性が直面する独特の 闘争と抑圧を「アイデンティティ・ポリティクス」と呼ぶことで、米国の急進的な運動や大規模な運動における黒人女性を支援できると考えた。CRCのメン バーは、「アイデンティティ・ポリティクス」という用語は、黒人女性が直面する抑圧と立ち向かうための手段を与えるものだと考えた。また、CRCは「個人 的なことは政治的なことである」という従来のフェミニストの格言を拡大し、黒人女性のスピーチを中心とした意識向上セッションや、抑圧の経験を共有するコ ミュニティの取り組みが、この格言の適用範囲を拡大する実践であると主張した。前述の通り、K. クレンショーは、黒人女性の抑圧は人種と性別という2つの異なる方向から示されると主張した。 1988年、デボラ・K・キングは、抑圧の要因がすべて相互に結びついていることを説明する理論として、「多重の危機(multiple jeopardy)」という用語を考案した。キングは、ジェンダー、階級、人種というアイデンティティはそれぞれに偏見的な含みを持ち、それが経験する不 公平さに増幅効果をもたらすことを示唆した。 1991年、ナンシー・キャラウェイは、白人フェミニストの視点から、黒人女性が直面するさまざまな形態の抑圧(人種やジェンダーを通じて)は相互に結び ついており、複合的な抑圧(Intersectionality)を生み出しているという理解のもと、黒人女性の政治はより広範なフェミニスト運動によっ て理解されなければならないと説明した。  #BlackLivesMatter 黒人アイデンティティ政治の現代的な例としては、ハッシュタグから始まった#BlackLivesMatterがある。2013年、アリシア・ガルザ、パ トリス・カルース、オパル・トメティの3人は、2012年にトレイボン・マーティンを殺害した警官ジョージ・ジマーマンの無罪判決を受けて、このハッシュ タグを作成した。[49] 2014年にはマイケル・ブラウンとエリック・ガーナーが警察に殺害され、これが#BlackLivesM 運動はまず国内で、そして世界的に広がった。[50] #BlackLivesMatter の目的は、法執行機関が黒人コミュニティや個人と関わる方法について、より広範な認識を生み出すことであり、その中には法執行機関による過剰な力の行使や 説明責任の問題に関する主張も含まれていた。[51] このハッシュタグとそれに続く運動は、政治のあらゆる分野から多くの注目を集めた。#BlackLivesMatter への反発として、#AllLivesMatter というハッシュタグを用いたカウンター運動も起こった。[52] |

| White identity politics See also: White identity, White nationalism, White supremacy, White defensiveness, White backlash, and Identitarian movement In 1998, political scientists Jeffrey Kaplan and Leonard Weinberg predicted that, by the late 20th-century, a "Euro-American radical right" would promote a trans-national white identity politics, which would invoke populist grievance narratives and encourage hostility against non-white peoples and multiculturalism. In the United States, mainstream news has identified Donald Trump's presidency as a signal of increasing and widespread utilization of white identity politics within the Republican Party and political landscape. Journalists Michael Scherer and David Smith have reported on its development since the mid-2010s. Ron Brownstein believed that President Trump uses "White Identity Politics" to bolster his base and that this would ultimately limit his ability to reach out to non-White American voters for the 2020 United States presidential election. A four-year Reuters and Ipsos analysis concurred that "Trump's brand of white identity politics may be less effective in the 2020 election campaign." Alternatively, examining the same poll, David Smith has written that "Trump’s embrace of white identity politics may work to his advantage" in 2020. During the Democratic primaries, presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg publicly warned that the president and his administration were using white identity politics, which he said was the most divisive form of identity politics. Columnist Reihan Salam writes that he is not convinced that Trump uses "white identity politics" given the fact that he still has significant support from liberal and moderate Republicans—who are more favorable toward immigration and the legalization of undocumented immigrants—but believes that it could become a bigger issue as whites become a minority and assert their rights like other minority groups. Salam also states that an increase in "white identity" politics is far from certain given the very high rates of intermarriage and the historical example of the once Anglo-Protestant cultural majority embracing a more inclusive white cultural majority which included Jews, Italians, Poles, Arabs, and Irish.[undue weight? – discuss]  Proud Boys A contemporary example of "White identity politics" is the right-wing group Proud Boys. Proud Boys was formed by Gavin McInnes in 2016. Members are males who identify as right-wing conservatives. They take part in political protests with the most infamous being January 6, 2021, at the U.S. Capitol, which became violent and led to the arrest of their leader, Henry "Enrique" Tarrio and many others.[53] Proud Boys identify as supporters of Donald Trump for President and are outspoken supporters of Americans having unfettered access to firearms by way of the 2nd amendment of the US constitution, having expressed the belief that gun law reform is a “sinister authoritarian plot” to disarm law abiding citizens.[54] According to an article published by Southern Poverty Law Group, Proud Boys members are regularly affiliated with white nationalist extremists and are known for sharing white nationalist content across social media platforms.[55] #AllLivesMatter Another contemporary example is the hashtag movement #AllLivesMatter. #AllLivesMatter began as a counter narrative to #BlackLivesMatter. People who identify with this countermovement use this hashtag to represent what they call “anti-identity” identity politics, which is supposed to symbolize a movement against racial identities, but they've been criticized as being a white nationalist movement.[56] Created, adopted and circulated beginning in 2016, #WhiteLivesMatter exalted themselves as an anti-racist movement, while identifying #BlackLivesMatter as the opposite.[56] Columnist Ross Douthat has argued that white identity politics have been important to American politics since the Richard Nixon-era of the Republican Party. Historian Nell Irvin Painter has analyzed Eric Kaufmann's thesis that the phenomenon of white identity politics is caused by immigration-derived racial diversity, which reduces the white majority, and an "anti-majority adversary culture". Writing in Vox, political commentator Ezra Klein believes that demographic change has fueled the emergence of white identity politics. Viet Thanh Nguyen says that "to have no identity at all is the privilege of whiteness, which is the identity that pretends not to have an identity, that denies how it is tied to capitalism, to race, and to war". |

白人アイデンティティ政治 関連項目:白人アイデンティティ、白人ナショナリズム、白人至上主義、白人防衛、白人逆襲、アイデンティタリアン運動 1998年、政治学者のジェフリー・カプランとレナード・ワインバーグは、20世紀後半までに「欧米の急進右派」が超国家的な白人アイデンティティ政治を 推進し、大衆の不満を煽り、非白人や多文化主義に対する敵意を助長するだろうと予測した。米国では、主流のニュースはドナルド・トランプの大統領就任を、 共和党や政治情勢における白人アイデンティティ政治の増加と広範な利用の兆候として捉えている。ジャーナリストのマイケル・シェア氏とデビッド・スミス氏 は、2010年代半ば以降のその発展について報告している。 ロン・ブラウンスタインは、トランプ大統領が「白人アイデンティティ政治」を自らの支持基盤を強化するために利用しており、それが2020年の米国大統領 選挙において白人以外の米国人有権者にアピールする能力を最終的に制限することになると考えていた。ロイターとイプソスによる4年間の分析でも、「トラン プ大統領の白人アイデンティティ政治は、2020年の選挙キャンペーンでは効果が薄い可能性がある」という見解で一致した。また、同じ世論調査を分析した デイビッド・スミスは、「トランプ大統領が白人アイデンティティ政治を受け入れることは、2020年の選挙戦で有利に働く可能性がある」と書いている。民 主党予備選挙中、大統領候補のピート・ブティジェッジは、大統領とその政権が白人アイデンティティ政治を利用していると公に警告した。同氏は、白人アイデ ンティティ政治はアイデンティティ政治の中でも最も分裂的な形態であると述べた。コラムニストのレイハン・サラムは、トランプが「白人アイデンティティ政 治」を利用しているとは確信できないと述べている。なぜなら、移民や不法移民の合法化に好意的なリベラル派や穏健派の共和党員から今でも多くの支持を得て いるからだ。しかし、白人人口が少数派となり、他のマイノリティグループと同様に権利を主張するようになれば、より大きな問題となる可能性があるとサラム は考えている。また、サラームは、異人種間の結婚率が非常に高いことや、かつてはアングロ・プロテスタント文化が多数派であったが、ユダヤ人、イタリア 人、ポーランド人、アラブ人、アイルランド人などを含むより包括的な白人文化が多数派となった歴史的事例を踏まえると、「白人アイデンティティ」政治の増 加は確実とは言えないと述べている。[不当な重み? – 議論する]  プラウド・ボーイズ 「白人アイデンティティ政治」の現代の例としては、右翼グループのプラウド・ボーイズがある。プラウド・ボーイズは2016年にギャビン・マクネスによっ て結成された。メンバーは右翼保守派を自認する男性である。彼らは政治的な抗議活動に参加しており、最も悪名高いのは2021年1月6日に米国議会議事堂 で発生したもので、暴力的な抗議活動となり、リーダーのヘンリー・「エンリケ」・タリオをはじめ、多数が逮捕された。[53] プラウドボーイズはドナルド・トランプ大統領の支持者であり、米国憲法修正第2条に基づき、アメリカ人が自由に銃器を所持することを公然と支持している 合衆国憲法修正第2条により、銃器に自由なアクセスを持つことを支持しており、銃規制改革は「悪意のある権威主義的な陰謀」であり、法律を遵守する市民の 武装解除を狙ったものであるという信念を表明している。[54] 南部貧困法律グループが発表した記事によると、プラウドボーイズのメンバーは白人ナショナリストの過激派と定期的に連携しており、白人ナショナリストのコ ンテンツをソーシャルメディアプラットフォームで共有することで知られている。[55] #AllLivesMatter もう一つの現代的な例として、ハッシュタグ運動 #AllLivesMatter がある。#AllLivesMatter は、#BlackLivesMatter に対するカウンター・ナラティブとして始まった。この反対運動に共感する人々は、このハッシュタグを使用して「反アイデンティティ」アイデンティティ政治 を表現している。これは人種的アイデンティティに対する運動を象徴するものと考えられているが、白人至上主義の運動であるとの批判を受けている。[56] 2016年から作成、採用、拡散されている#WhiteLivesMatterは、反人種差別運動であると主張し、#BlackLivesMatterと は対極にあると位置づけている。[56] コラムニストのロス・ドゥーサットは、白人アイデンティティ・ポリティクスは共和党のリチャード・ニクソン時代以来、アメリカの政治にとって重要であった と主張している。歴史家のネル・アーヴィン・ペインターは、白人アイデンティティ・ポリティクスの現象は移民による人種的多様性によって引き起こされ、白 人多数派を減少させ、「反多数派の敵対的文化」によって引き起こされるというエリック・カウフマンの論文を分析している。政治評論家のエズラ・クライン は、Voxに寄稿した記事で、人口動態の変化が白人アイデンティティ・ポリティクスの出現を煽ったと信じている。 ベト・タイン・ニュエンは、「アイデンティティをまったく持たないことは、白人の特権である。白人は、アイデンティティを持たないふりをし、資本主義や人 種、戦争とどう結びついているかを否定するアイデンティティである」と述べている。 |

| Hispanic/Latino identity politics See also: Hispanic and Latino Americans in politics According to Leonie Huddy, Lilliana Mason, and S. Nechama Horwitz, the majority of Latinos in the United States identity with the Democratic Party.[57] Latinos' Democratic proclivities can be explained by: ideological policy preferences and an expressive identity based on the defense of Latino identity and status, with a strong support for the latter explanation hinged on an analysis of the 2012 Latino Immigrant National Election Study and American National Election Study focused on Latino immigrants and citizens respectively. When perceiving pervasive discrimination against Latinos and animosity from the Republican party, a strong partisanship preference further intensified, and in return, increased Latino political campaign engagement. |

ヒスパニック系/ラテン系アメリカ人のアイデンティティ政治 参照:政治におけるヒスパニック系およびラテン系アメリカ人 レオニー・ハディ、リリアナ・メイソン、S・ネチャマ・ホーウィッツによると、米国のラテン系住民の大半は民主党にアイデンティティを見出している。 [57] ラテン系住民の民主党への傾倒は、次のように説明できる。傾向と、ラテン系の人々のアイデンティティと地位の擁護に基づく表現力豊かなアイデンティティで ある。後者の説明については、それぞれラテン系移民と市民に焦点を当てた2012年のラテン系移民全国選挙調査とアメリカ全国選挙調査の分析に強く依存し ている。ラテン系の人々に対する広範な差別と共和党からの敵意を認識すると、党派性への強い支持がさらに強まり、それに応じてラテン系の人々の政治キャン ペーンへの関与も増加した。 |

| Hispanic/Latino identity politics See also: Hispanic and Latino Americans in politics According to Leonie Huddy, Lilliana Mason, and S. Nechama Horwitz, the majority of Latinos in the United States identity with the Democratic Party.[57] Latinos' Democratic proclivities can be explained by: ideological policy preferences and an expressive identity based on the defense of Latino identity and status, with a strong support for the latter explanation hinged on an analysis of the 2012 Latino Immigrant National Election Study and American National Election Study focused on Latino immigrants and citizens respectively. When perceiving pervasive discrimination against Latinos and animosity from the Republican party, a strong partisanship preference further intensified, and in return, increased Latino political campaign engagement. |

ヒスパニック系/ラテン系アメリカ人のアイデンティティ政治 参照:政治におけるヒスパニック系およびラテン系アメリカ人 レオニー・ハディ、リリアナ・メイソン、S・ネチャマ・ホーウィッツによると、米国のラテン系住民の大半は民主党にアイデンティティを見出している。 [57] ラテン系住民の民主党への傾倒は、次のように説明できる。傾向と、ラテン系の人々のアイデンティティと地位の擁護に基づく表現力豊かなアイデンティティで ある。後者の説明については、それぞれラテン系移民と市民に焦点を当てた2012年のラテン系移民全国選挙調査とアメリカ全国選挙調査の分析に強く依存し ている。ラテン系の人々に対する広範な差別と共和党からの敵意を認識すると、党派性への強い支持がさらに強まり、それに応じてラテン系の人々の政治キャン ペーンへの関与も増加した。 |

| Indian politics In India, caste, religion, tribe, ethnicity play a role in electoral politics, government jobs and affirmative actions, development projects.[58] |

インドの政治 インドでは、カースト、宗教、部族、民族が選挙政治、政府の仕事、積極的差別是正措置、開発プロジェクトに影響を与えている。[58] |

| Māori identity politics See also: Māori identity and Māori nationalism Due to somewhat competing tribe-based versus pan-Māori concepts, there is both an internal and external utilization of Māori identity politics in New Zealand.[59] Projected outwards, Māori identity politics has been a disrupting force in the politics of New Zealand and post-colonial conceptions of nationhood.[60] Its development has also been explored as causing parallel ethnic identity developments in non-Māori populations.[61] Academic Alison Jones, in her co-written Tuai: A Traveller in Two Worlds, suggests that a form of Māori identity politics, directly oppositional to Pākehā (white New Zealanders), has helped provide a "basis for internal collaboration and a politics of strength".[62] A 2009, Ministry of Social Development journal identified Māori identity politics, and societal reactions to it, as the most prominent factor behind significant changes in self-identification from the 2006 New Zealand census.[63] |

マオリ族のアイデンティティ政治 関連情報:マオリ族のアイデンティティとマオリ族ナショナリズム 部族ベースの概念と全マオリ族ベースの概念が競合しているため、ニュージーランドではマオリ族のアイデンティティ政治が内部および外部で利用されている。 [59] 外に向かって展開されるマオリ族のアイデンティティ政治は、 ニュージーランドの政治や、ポストコロニアルの国家観に混乱をもたらしてきた。[60] また、その発展は、マオリ族以外の民族における並行する民族アイデンティティの発展の原因ともなっている。[61] アリソン・ジョーンズ教授は、共著『トゥアイ: 2つの世界の旅人』の中で、マオリのアイデンティティ政治の一形態が、パケハ(白人ニュージーランド人)と直接対立する形で、「内部の協力と強さの政治の 基盤」を提供してきたと示唆している。[62] 2009年の社会開発省の機関誌は、2006年のニュージーランド国勢調査における自己認識の大幅な変化の背景には、マオリのアイデンティティ政治とそれ に対する社会の反応が最も顕著な要因であったと指摘している。[63] |

| Muslim identity politics Since the 1970s, the interaction of religion and politics has been associated with the rise of Islamist movements in the Middle East. Salwa Ismail posits that the Muslim identity is related to social dimensions such as gender, class, and lifestyles (Intersectionality), thus, different Muslims occupy different social positions in relation to the processes of globalization. Not all uniformly engage in the construction of Muslim identity, and they do not all apply to a monolithic Muslim identity. The construction of British Muslim identity politics is marked with Islamophobia; Jonathan Brit suggests that political hostility toward the Muslim "other" and the reification of an overarching identity that obscures and denies cross-cutting collective identities or existential individuality are charges made against an assertive Muslim identity politics in Britain.[64] In addition, because Muslim identity politics is seen as internally/externally divisive and therefore counterproductive, as well as the result of manipulation by religious conservatives and local/national politicians, the progressive policies of the anti-racist left have been outflanked. Brit sees the segmentation that divided British Muslims amongst themselves and with the anti-racist alliance in Britain as a consequence of patriarchal, conservative mosque-centered leadership. A Le Monde/IFOP poll in January 2011 conducted in France and Germany found that a majority felt Muslims are "scattered improperly"; an analyst for IFOP said the results indicated something "beyond linking immigration with security or immigration with unemployment, to linking Islam with a threat to identity".[65] |

イスラム教徒のアイデンティティ政治 1970年代以降、宗教と政治の相互作用は中東におけるイスラム主義運動の高まりと関連付けられてきた。サルワ・イスマイルは、イスラム教徒としてのアイ デンティティはジェンダー、階級、ライフスタイルといった社会的次元(交差性)と関連していると主張している。そのため、グローバル化のプロセスに関連し て、異なるイスラム教徒は異なる社会的立場を占めることになる。 すべてのイスラム教徒が均一にイスラム教徒としてのアイデンティティの構築に関与しているわけではなく、また、そのアイデンティティは一枚岩的なものでは ない。 英国のイスラム教徒のアイデンティティ政治の構築は、イスラム恐怖症の傾向が顕著である。ジョナサン・ブリットは、イスラム教徒という「他者」に対する政 治的な敵意と、横断的な集団的アイデンティティや実存的な個性を覆い隠し否定する包括的なアイデンティティの固定化が、英国における主張の強いイスラム教 徒のアイデンティティ政治に対する非難であると指摘している。 64] さらに、イスラム系アイデンティティ政治は、内部または外部で不和を生み出し、非生産的であると見なされている。また、宗教保守派や地方・中央の政治家に よる操作の結果であるとも考えられているため、反人種差別左派の進歩的政策は後手に回っている。ブリットは、英国のイスラム教徒を分裂させ、反人種差別同 盟との間に亀裂を生じさせた分断は、家父長的で保守的なモスク中心の指導体制の結果であると見ている。 2011年1月にフランスとドイツで実施されたルモンド紙とIFOPの世論調査では、大多数が「ムスリムは不適切に散らばっている」と感じていることが判 明した。IFOPのアナリストは、この結果は「移民と安全、移民と失業の関連性を超え、イスラム教とアイデンティティの脅威の関連性を示すもの」であると 述べた。[65] |

| Gender Gender identity politics is an approach that views politics, both in practice and as an academic discipline, as having a gendered nature and that gender is an identity that influences how people think.[66] Politics has become increasingly gender political as formal structures and informal 'rules of the game' have become gendered. How institutions affect men and women differently are starting to be analysed in more depth as gender will affect institutional innovation.[67] A key element of studying electoral behavior in all democracies is political partisanship. In 1996, Eric Plutzer and John F. Zipp examined the election of 1992 election, also commonly referred to as "Year of the Woman", where a then-record- breaking fourteen women ran for governor or U.S. senator, four of whom were successfully elected into office. In analyzing the possibility that male and female voters react differently to the opportunity to cast a vote for a woman, the study provided lent support to the idea that women tend to vote for women and men tend to vote against them.[68] For example, among Republican voters in California, Barbara Boxer ran 10 points behind Bill Clinton among men and about even among women, while Dianne Feinstein ran about 6 points among men but 11 points ahead among women. This gender effect was further amplified for Democratic female candidates who were rated as feminist. These results demonstrate that gender identity has and can function as a cue for voting behavior. |

ジェンダー ジェンダー・アイデンティティ政治とは、政治を実践面でも学問分野としてもジェンダーの性質を持つものと見なし、ジェンダーは人々の考え方に影響を与える アイデンティティであるとするアプローチである。[66] 政治は、公式の構造と非公式の「ゲームのルール」がジェンダー化されるにつれ、ますますジェンダー政治化している。ジェンダーが制度の革新に影響を与える ため、制度が男性と女性に異なる影響を与える仕組みがより深く分析され始めている。[67] すべての民主主義国家における選挙行動を研究する上で重要な要素は、政治的党派性である。1996年、エリック・プルッツァーとジョン・F・ジップは、一 般的に「女性の年」とも呼ばれる1992年の選挙を調査した。この年は、当時記録を塗り替える14人の女性が州知事や連邦上院議員に立候補し、そのうち4 人が当選を果たした。女性候補に投票する機会に対して、男性有権者と女性有権者が異なる反応を示す可能性を分析したこの研究は、女性は女性候補に投票し、 男性は女性候補に反対票を投じる傾向にあるという考えを裏付けるものとなった。[68] 例えば、カリフォルニア州の共和党有権者では、ビル・クリントン候補に対して、バーバラ・ボクサー候補は男性では10ポイント、女性ではほぼ同数という結 果であった。一方、ダイアン・ファインスタイン候補は、男性では6ポイント、女性では11ポイントの差をつけた。この性差は、フェミニストと評価された民 主党の女性候補者においてはさらに拡大した。これらの結果は、性自認が投票行動の指標として機能していること、また、機能しうることを示している。 |

| Women's identity politics in the

United States Scholars of social movements and democratic theorists disagree on whether identity politics weaken women's social movements and undermine their influence on public policy or have reverse effects. S. Laurel Weldon argues that when marginalized groups organize around an intersectional social location, knowledge about the social group is generated, feelings of affiliation between group members are strengthened, and the movement's agenda becomes more representative. Specifically for the United States, Weldon suggests that organizing women by race strengthens these movements and improves government responsiveness to both violence against women of color and women in general.[69] |

米国における女性のアイデンティティ・ポリティクス 社会運動の研究者や民主主義理論家は、アイデンティティ・ポリティクスが女性の社会運動を弱体化させ、公共政策への影響力を損なうか、あるいは逆の効果を もたらすかについて意見が分かれている。S. Laurel Weldonは、周縁化された集団が交差する社会的立場を中心に組織化されると、その社会的集団に関する知識が生まれ、集団メンバー間の帰属意識が強ま り、運動の議題がより代表的なものになる、と主張している。特に米国に関して、ウェルドンは、人種別に女性を組織化することがこれらの運動を強化し、有色 人女性に対する暴力や女性一般に対する政府の対応を改善すると提案している。[69] |

| LGBT See also: LGBT social movements, Anti-LGBT rhetoric, Violence against LGBT people, Queer nationalism, Political lesbianism, and Bisexual politics  A man in a blue shirt wearing glasses and a flower garland waves to a crowd. Frank Kameny By the early-1960s, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people in the United States were forming more visible communities, and this was reflected in the political strategies of American homophile groups. Frank Kameny, an American astronomer and gay rights activist, had co-founded the Mattachine Society of Washington in 1961. While the society did not take much political activism to the streets at first, Kameny and several members attended the 1963 March on Washington, where having seen the methods used by Black civil rights activists, they then applied them to the homophile movement. Kameny had also been inspired by the black power movements slogan "Black is Beautiful", coining his own term "Gay is Good".[70] The gay liberation movement of the late-1960s urged lesbians and gay men to engage in radical direct action, and to counter societal shame with gay pride.[71] In the feminist spirit of the personal being political, the most basic form of activism was an emphasis on coming out to family, friends and colleagues, and living life as an openly lesbian or gay person.[71] By the mid-1970s, an "ethnic model of identity" had surpassed the popularity of both the homophile movement and gay liberation.[72] Proponents operated through a sexual minority framework and advocated either reformism or separatism (notably lesbian separatism).[72] While the 1970s were the peak of "gay liberation" in New York City and other urban areas in the United States, "gay liberation" was the term still used instead of "gay pride" in more oppressive areas into the mid-1980s, with some organizations opting for the more inclusive "lesbian and gay liberation".[71][73] Women and transgender activists had lobbied for more inclusive names from the beginning of the movement, but the initialism LGBT, or "queer" as a counterculture shorthand for LGBT, did not gain much acceptance as an umbrella term until much later in the 1980s, and in some areas not until the '90s or even '00s.[71][73][74] During this period in the United States, identity politics were largely seen in these communities in the definitions espoused by writers such as self-identified, "black, dyke, feminist, poet, mother" Audre Lorde's view, that lived experience matters, defines us, and is the only thing that grants authority to speak on these topics; that, "If I didn't define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people's fantasies for me and eaten alive."[75][76][77] |

LGBT 関連項目:LGBT社会運動、反LGBT的レトリック、LGBTに対する暴力、クィア・ナショナリズム、政治的レズビアニズム、両性愛者の政治  青いシャツを着て眼鏡をかけ花輪をつけた男性が群衆に手を振っている。 フランク・カメン 1960年代初頭までに、米国のレズビアン、ゲイ、バイセクシュアル、トランスジェンダーの人々は、より目に見えるコミュニティを形成するようになってお り、それは米国の同性愛者グループの政治戦略にも反映されていた。米国の天文学者でゲイの権利活動家であるフランク・カメンイは、1961年にワシント ン・マタチネ協会を共同設立した。当初はあまり政治的な活動は行なっていなかったが、1963年のワシントン大行進にはカメンと数人の会員が参加し、そこ で黒人公民権運動の活動家たちが用いていた方法を目の当たりにしたことで、それを同性愛者運動に適用するようになった。カメンは黒人解放運動のスローガン 「ブラック・イズ・ビューティフル」に触発され、自身の造語「ゲイ・イズ・グッド」を考案した。 1960年代後半のゲイ解放運動は、レズビアンやゲイ男性に急進的な直接行動を促し、社会的な恥をゲイプライドで打ち消すことを求めた。[71] フェミニズムの「個人的なことは政治的なこと」という精神に基づき、最も基本的な活動形態は、家族や友人、同僚にカミングアウトし、オープンなレズビアン またはゲイとして生活することに重点を置いたものだった。[71] 1970年代半ばには、「民族的アイデンティティ」がホモフォイル運動とゲイ解放運動の両方の人気を上回っていた。[72] 推進派は性的少数派の枠組みで活動し、改革主義または分離主義(特にレズビアン分離主義)を提唱した。[72] 1970年代は、ニューヨーク市や米国の他の都市部では「ゲイ解放」のピークであったが、1980年代半ばまでは、より抑圧的な地域では「ゲイ解放」とい う用語が依然として「ゲイ・プライド」の代わりに使用されていた。一部の団体は、より包括的な「レズビアンおよびゲイ解放」という用語を選んでいた。 [71][73] 女性やトランスジェンダーの活動家は、運動の初期からより包括的な名称を求めてロビー活動を行っていたが、 運動の初期から女性やトランスジェンダーの活動家たちはより包括的な名称を求めていたが、LGBTの頭文字をとったLGBTや、カウンターカルチャーの略 語として使われた「クィア」が包括的な用語として広く受け入れられるようになったのは、1980年代もかなり経ってからであり、地域によっては1990年 代、あるいは2000年代に入ってからであった。[71][73][74] この時期の米国では、アイデンティティ・ポリティクスは主にこれらのコミュニティにおいて 作家のオードラ・ローデが提唱した定義、すなわち「黒人、レズビアン、フェミニスト、詩人、母親」という自己認識、生きている経験こそが重要であり、それ が私たちを定義し、これらのトピックについて発言する権限を付与する唯一のものであるという見解が、これらのコミュニティで広く受け入れられた。「もし私 が自分自身のために自分を定義しなければ、私は他人の私に対する空想に押しつぶされて、生きながら食い殺されてしまうだろう」[75][76][77] |

| 参照先:アイデンティティ・ポリティクス | |

リンク

文献

その他の情報:【出典】インディオ・メスティソ・ラサ:ラテンアメリカにおける人種的

カテゴリー再考(研究ノート)

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

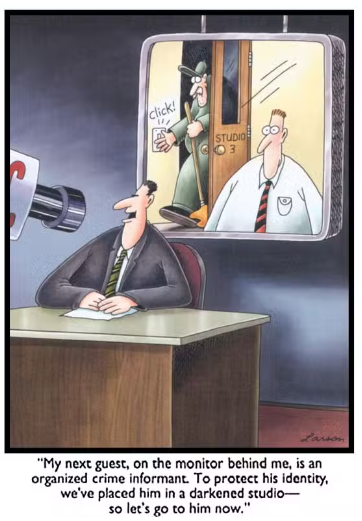

さあ私の次のゲストはモニターにみえる組織犯罪に関する情報提供者です

彼のアイデンティティを保護するために彼には暗いスタジオのなかで答えていただきます。さあ、彼の登場です!!