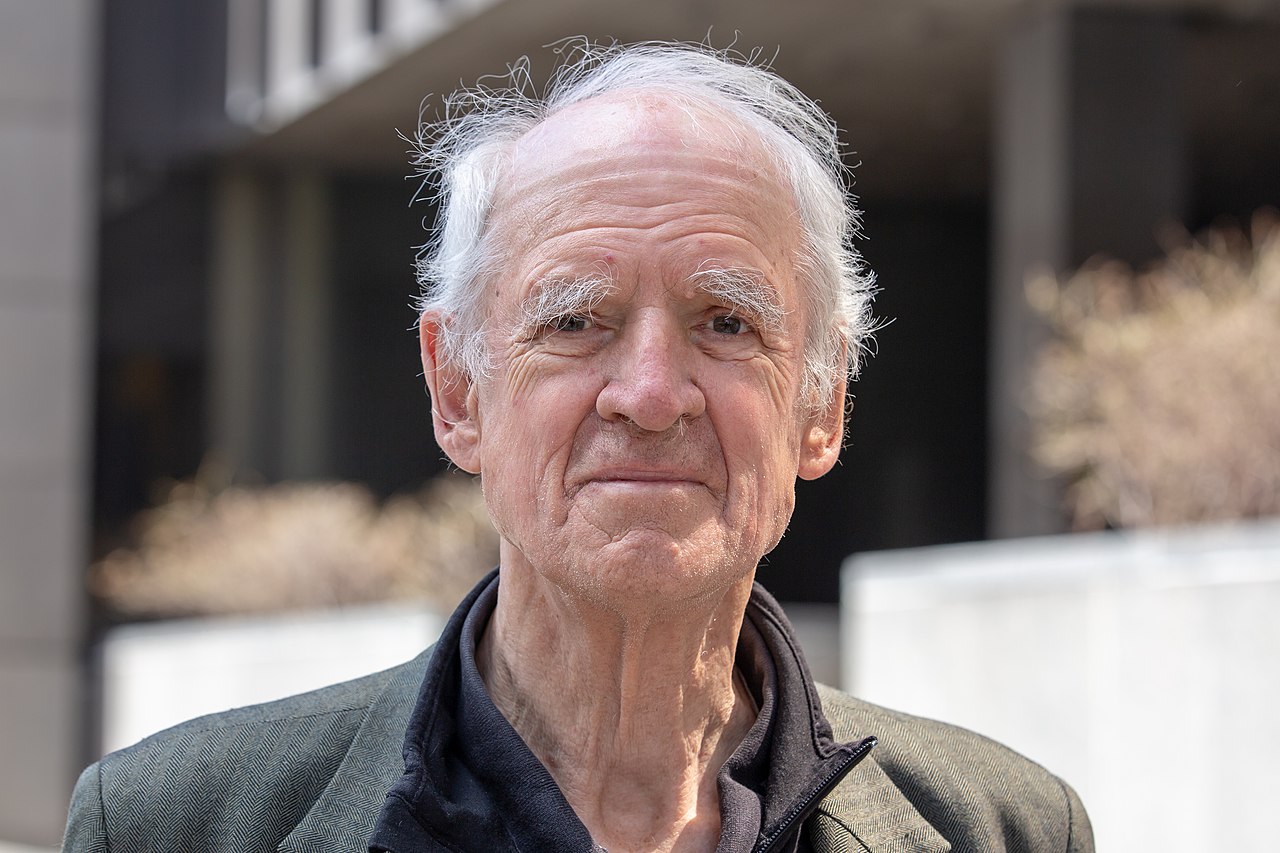

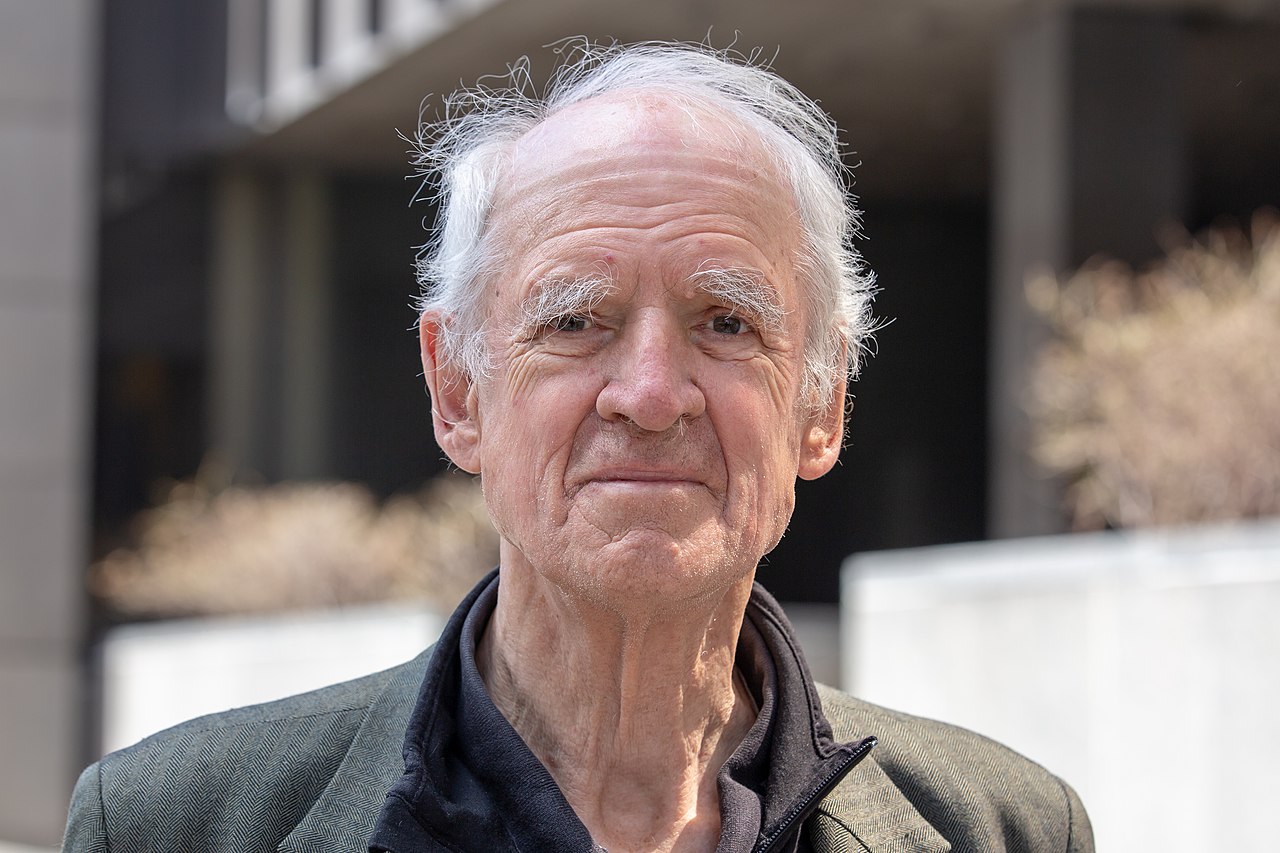

チャールズ・テイラー

Charles Taylor, b.1931

☆ ケベック州モントリオール出身のカナダ人哲学者で、政治哲学、社会科学哲学、哲学史、知的歴史学への貢献で知られるマギル大学名誉教授。2007年には、 ジェラール・ブシャールとともに、ケベック州における文化的差異に関する合理的配慮に関するブシャール=テイラー委員会の委員を務めた。また、道徳哲学、 認識論、解釈学、美学、心の哲学、言語哲学、行動哲学にも貢献している。

| Charles

Margrave Taylor

CC GOQ FRSC FBA (born November 5, 1931) is a Canadian philosopher from

Montreal, Quebec, and professor emeritus at McGill University best

known for his contributions to political philosophy, the philosophy of

social science, the history of philosophy, and intellectual history.

His work has earned him the Kyoto Prize, the Templeton Prize, the

Berggruen Prize for Philosophy, and the John W. Kluge Prize. In 2007, Taylor served with Gérard Bouchard on the Bouchard–Taylor Commission on reasonable accommodation with regard to cultural differences in the province of Quebec. He has also made contributions to moral philosophy, epistemology, hermeneutics, aesthetics, the philosophy of mind, the philosophy of language, and the philosophy of action.[49][50] |

ケベック州モントリオール出身のカナダ人哲学者で、政治哲学、社会科学

哲学、哲学史、知的歴史学への貢献で知られるマギル大学名誉教授。その業績により、京都賞、テンプルトン賞、ベルクグリューン哲学賞、ジョン・W・クルー

ジ賞を受賞。 2007年には、ジェラール・ブシャールとともに、ケベック州における文化的差異に関する合理的配慮に関するブシャール=テイラー委員会の委員を務めた。 また、道徳哲学、認識論、解釈学、美学、心の哲学、言語哲学、行動哲学にも貢献している[49][50]。 |

| Biography Charles Margrave Taylor was born in Montreal, Quebec, on November 5, 1931, to a Roman Catholic Francophone mother and a Protestant Anglophone father by whom he was raised bilingually.[51][52] His father, Walter Margrave Taylor, was a steel magnate originally from Toronto while his mother, Simone Marguerite Beaubien, was a dressmaker.[53] His sister was Gretta Chambers.[54] He attended Selwyn House School from 1939 to 1946,[55][56] followed by Trinity College School from 1946 to 1949,[57] and began his undergraduate education at McGill University where he received a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree in history in 1952.[58] He continued his studies at the University of Oxford, first as a Rhodes Scholar at Balliol College, receiving a BA degree with first-class honours in philosophy, politics and economics in 1955, and then as a postgraduate student, receiving a Doctor of Philosophy degree in 1961[13][59] under the supervision of Sir Isaiah Berlin.[60] As an undergraduate student, he started one of the first campaigns to ban thermonuclear weapons in the United Kingdom in 1956,[61] serving as the first president of the Oxford Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.[62] He succeeded John Plamenatz as Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at the University of Oxford and became a fellow of All Souls College.[63] For many years, both before and after Oxford, he was Professor of Political Science and Philosophy at McGill University in Montreal, where he is now professor emeritus.[64] Taylor was also a Board of Trustees Professor of Law and Philosophy at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, for several years after his retirement from McGill. Taylor was elected a foreign honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1986.[65] In 1991, Taylor was appointed to the Conseil de la langue française in the province of Quebec, at which point he critiqued Quebec's commercial sign laws. In 1995, he was made a Companion of the Order of Canada. In 2000, he was made a Grand Officer of the National Order of Quebec. In 2003, he was awarded the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council's Gold Medal for Achievement in Research, which had been the council's highest honour.[66][67] He was awarded the 2007 Templeton Prize for progress towards research or discoveries about spiritual realities, which included a cash award of US$1.5 million. In 2007 he and Gérard Bouchard were appointed to head a one-year commission of inquiry into what would constitute reasonable accommodation for minority cultures in his home province of Quebec.[68] In June 2008, he was awarded the Kyoto Prize in the arts and philosophy category. The Kyoto Prize is sometimes referred to as the Japanese Nobel.[69] In 2015, he was awarded the John W. Kluge Prize for Achievement in the Study of Humanity, a prize he shared with philosopher Jürgen Habermas.[70] In 2016, he was awarded the inaugural $1-million Berggruen Prize for being "a thinker whose ideas are of broad significance for shaping human self-understanding and the advancement of humanity".[71] |

略歴 チャールズ・マーグレイヴ・テイラーは1931年11月5日、ケベック州モントリオールでローマ・カトリックのフランス語圏の母とプロテスタントの英語圏 の父の間に生まれた。 [1939年から1946年までセルウィン・ハウス・スクールに通い[55][56]、1946年から1949年までトリニティ・カレッジ・スクールに 通った[57]。 [最初はローズ奨学生としてバリオール・カレッジで学び、1955年に哲学、政治学、経済学の優等で学士号を取得、その後大学院生としてアイザイア・バー リン卿の指導の下、1961年に哲学博士号を取得した[13][59]。 [60] 学部生時代の1956年には、英国で熱核兵器禁止を求める最初のキャンペーンのひとつを開始し[61]、核軍縮のためのオックスフォード・キャンペーンの 初代会長を務めた[62]。 ジョン・プラメナツの後任としてオックスフォード大学社会政治理論チチェル教授に就任し、オール・ソウルズ・カレッジのフェローとなった[63]。 オックスフォード大学卒業前後の長年にわたり、モントリオールのマギル大学で政治学と哲学の教授を務め、現在は名誉教授[64]。またマギル大学退官後の 数年間は、イリノイ州エバンストンのノースウェスタン大学で法と哲学の理事会教授を務めた。 1991年、ケベック州フランス語委員会に任命され、ケベック州の商業標識法を批判。1995年、カナダ勲章コンパニオンに叙せられる。2000年、ケ ベック国家勲章グランド・オフィサー。2003年、社会科学・人文科学研究評議会(Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council)から、同評議会最高の栄誉である研究業績に対するゴールド・メダルを授与される[66][67]。2007年、スピリチュアルな現実に関 する研究や発見の進歩に対して、150万米ドルの賞金を含むテンプルトン賞を受賞。 2007年には、ジェラール・ブシャールとともに、彼の出身地であるケベック州における少数民族文化の合理的配慮とは何かについての1年間の調査委員会の 責任者に任命された[68]。 2008年6月、芸術・哲学部門で京都賞を受賞。京都賞は日本のノーベル賞と呼ばれることもある[69]。2015年、哲学者のユルゲン・ハーバーマスと 共同受賞したジョン・W・クルーゲ賞(人間性研究の業績)を受賞[70]。2016年、「人間の自己理解と人類の進歩の形成に幅広い意義を持つ思想を持つ 思想家」として、第1回100万ドルのベルクグリューエン賞を受賞[71]。 |

| Views Despite his extensive and diverse philosophical oeuvre,[72] Taylor famously calls himself a "monomaniac,"[73] concerned with only one fundamental aspiration: to develop a convincing philosophical anthropology. In order to understand Taylor's views, it is helpful to understand his philosophical background, especially his writings on Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Taylor rejects naturalism and formalist epistemology. He is part of an influential intellectual tradition of Canadian idealism that includes John Watson, George Paxton Young, C. B. Macpherson, and George Grant.[74][dubious – discuss] In his essay "To Follow a Rule," Taylor explores why people can fail to follow rules, and what kind of knowledge it is that allows a person to successfully follow a rule, such as the arrow on a sign. The intellectualist tradition presupposes that to follow directions, we must know a set of propositions and premises about how to follow directions.[75] Taylor argues that Wittgenstein's solution is that all interpretation of rules draws upon a tacit background. This background is not more rules or premises, but what Wittgenstein calls "forms of life." More specifically, Wittgenstein says in the Philosophical Investigations that "Obeying a rule is a practice." Taylor situates the interpretation of rules within the practices that are incorporated into our bodies in the form of habits, dispositions and tendencies.[75] Following Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Michael Polanyi, and Wittgenstein, Taylor argues that it is mistaken to presuppose that our understanding of the world is primarily mediated by representations. It is only against an unarticulated background that representations can make sense to us. On occasion we do follow rules by explicitly representing them to ourselves, but Taylor reminds us that rules do not contain the principles of their own application: application requires that we draw on an unarticulated understanding or "sense of things" — the background.[75] |

見解 テイラーはその広範かつ多様な哲学的業績にもかかわらず[72]、自らを「モノマニアック」[73]と称し、ただ一つの根本的な願望、すなわち説得力のあ る哲学的人間学を発展させることだけに関心を寄せていることで有名である。 テイラーの見解を理解するためには、彼の哲学的背景、特にゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル、ルートヴィヒ・ヴィトゲンシュタイン、マル ティン・ハイデガー、モーリス・メルロ=ポンティに関する著作を理解することが有益である。テイラーは自然主義と形式主義的認識論を否定している。彼は ジョン・ワトソン、ジョージ・パクストン・ヤング、C.B.マクファーソン、ジョージ・グラントを含むカナダ観念論の影響力のある知的伝統の一部である [74][dubious - discuss]。 テイラーは彼のエッセイ「ルールに従うために」の中で、なぜ人はルールに従えないのか、標識の矢印のようなルールに人がうまく従うことができるのはどのよ うな知識があるからなのかを探求している。知識主義者の伝統は、指示に従うためには、指示に従う方法に関する一連の命題と前提を知っていなければならない と仮定している[75]。 テイラーは、ウィトゲンシュタインの解決策は、ルールの解釈はすべて暗黙の背景の上に成り立つということだと論じている。この背景とはルールや前提ではな く、ウィトゲンシュタインが "生活の形態 "と呼ぶものである。より具体的には、ウィトゲンシュタインは『哲学探究』の中で、"ルールに従うことは実践である "と述べている。テイラーはルールの解釈を、習慣、気質、傾向という形で私たちの身体に組み込まれている実践の中に位置づける[75]。 ハイデガー、メルロ=ポンティ、ハンス=ゲオルク・ガダマー、マイケル・ポランニー、ウィトゲンシュタインに続き、テイラーは世界の理解が主に表象に よって媒介されることを前提とするのは間違いであると主張する。表象が私たちに意味を与えることができるのは、明文化されていない背景があってこそであ る。しかしテイラーは、規則がそれ自身の適用原理を含んでいるわけではないことを思い出させてくれる。 |

| Taylor's critique of naturalism Taylor defines naturalism as a family of various, often quite diverse theories that all hold "the ambition to model the study of man on the natural sciences."[76] Philosophically, naturalism was largely popularized and defended by the unity of science movement that was advanced by logical positivist philosophy. In many ways, Taylor's early philosophy springs from a critical reaction against the logical positivism and naturalism that was ascendant in Oxford while he was a student. Initially, much of Taylor's philosophical work consisted of careful conceptual critiques of various naturalist research programs. This began with his 1964 dissertation The Explanation of Behaviour, which was a detailed and systematic criticism of the behaviourist psychology of B. F. Skinner[77] that was highly influential at mid-century. From there, Taylor also spread his critique to other disciplines. The essay "Interpretation and the Sciences of Man" was published in 1972 as a critique of the political science of the behavioural revolution advanced by giants of the field like David Easton, Robert Dahl, Gabriel Almond, and Sydney Verba.[78] In an essay entitled "The Significance of Significance: The Case for Cognitive Psychology", Taylor criticized the naturalism he saw distorting the major research program that had replaced B. F. Skinner's behaviourism.[79] But Taylor also detected naturalism in fields where it was not immediately apparent. For example, in 1978's "Language and Human Nature" he found naturalist distortions in various modern "designative" theories of language,[80] while in Sources of the Self (1989) he found both naturalist error and the deep moral, motivational sources for this outlook[clarification needed] in various individualist and utilitarian conceptions of selfhood.[citation needed] |

テイラーによる自然主義批判 テイラーは自然主義を、「人間の研究を自然科学になぞらえようとする野心」[76]を抱く、様々な、しばしば非常に多様な理論の系列と定義している。多く の点で、テイラーの初期の哲学は、彼が学生であった頃にオックスフォードで台頭していた論理実証主義と自然主義に対する批判的な反動から生まれている。 当初、テイラーの哲学的研究の多くは、さまざまな自然主義的研究プログラムに対する注意深い概念的批判から成っていた。これは1964年の学位論文『行動 の説明』から始まり、B・F・スキナー[77]の行動主義心理学に対する詳細かつ体系的な批判であり、世紀半ばに大きな影響力を持った。 そこからテイラーは他の学問分野にも批判を広めた。解釈と人間の科学」という小論は、デイヴィッド・イーストン、ロバート・ダール、ガブリエル・アーモン ド、シドニー・ヴェルバといったこの分野の巨人たちによって進められた行動革命の政治科学に対する批判として1972年に出版された[78]: 認知心理学の場合」と題されたエッセイの中で、テイラーはB・F・スキナーの行動主義に取って代わった主要な研究プログラムを歪めている自然主義を批判し ていた[79]。 しかしテイラーはまた、自然主義がすぐに明らかにならない分野でも自然主義を発見していた。例えば、1978年の『言語と人間の本性』において、彼は言語 に関する様々な現代的な「デザイン的」理論に自然主義的な歪みを見出しており[80]、一方、『自己の源泉』(1989年)において、彼は自己性について の様々な個人主義的、功利主義的な概念に自然主義的な誤りとこのような考え方の深い道徳的、動機づけの源泉[要解説]の両方を見出していた[要出典]。 |

| Taylor and hermeneutics Concurrent to Taylor's critique of naturalism was his development of an alternative. Indeed, Taylor's mature philosophy begins when as a doctoral student at Oxford he turned away, disappointed, from analytic philosophy in search of other philosophical resources which he found in French and German modern hermeneutics and phenomenology.[81] The hermeneutic tradition develops a view of human understanding and cognition as centred on the decipherment of meanings (as opposed to, say, foundational theories of brute verification or an apodictic rationalism). Taylor's own philosophical outlook can broadly and fairly be characterized as hermeneutic and has been called engaged hermeneutics.[8] This is clear in his championing of the works of major figures within the hermeneutic tradition such as Wilhelm Dilthey, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Gadamer.[82] It is also evident in his own original contributions to hermeneutic and interpretive theory.[82] |

テイラーと解釈学 テイラーが自然主義を批判するのと同時に、それに代わる哲学を発展させた。実際、テイラーの成熟した哲学は、オックスフォード大学の博士課程に在籍してい たときに、彼がフランスとドイツの近代的な解釈学と現象学に見出した他の哲学的リソースを求めて、分析哲学から失望して背を向けたときに始まる[81]。 解釈学の伝統は、意味の解読を中心とした人間の理解と認識についての見解を発展させている(例えば、ブルートな検証の基礎理論やアポディクティックな合理 主義とは対照的である)。テイラー自身の哲学的展望は広範かつ公正に解釈学として特徴づけることができ、エンゲージメント解釈学と呼ばれている[8]。こ のことはヴィルヘルム・ディルタイ、ハイデガー、メルロ=ポンティ、ガダマーといった解釈学の伝統における主要人物の著作を支持していることからも明らか である[82]。 |

| Communitarian critique of

liberalism Taylor (as well as Alasdair MacIntyre, Michael Walzer, and Michael Sandel) is associated with a communitarian critique of liberal theory's understanding of the "self". Communitarians emphasize the importance of social institutions in the development of individual meaning and identity. In his 1991 Massey Lecture The Malaise of Modernity, Taylor argued that political theorists—from John Locke and Thomas Hobbes to John Rawls and Ronald Dworkin—have neglected the way in which individuals arise within the context supplied by societies. A more realistic understanding o |

リベラリズムのコミュニタリアン批判 テイラー(およびアラスデア・マッキンタイア、マイケル・ウォルツァー、マイケル・サンデル)は、リベラル理論の「自己」理解に対するコミュニタリアン批 判と関連している。コミュニタリアンは、個人の意味やアイデンティティの発達における社会制度の重要性を強調している。 テイラーは、1991年のマッセー大学での講義『The Malaise of Modernity』において、ジョン・ロックやトマス・ホッブズからジョン・ロールズやロナルド・ドワーキンまで、政治理論家は社会が提供する文脈の中 で個人がどのように発生するかを軽視してきたと主張した。より現実的な理解とは |

| Philosophy and sociology of

religion Further information: A Secular Age and Secularity § Taylorian secularity Taylor's later work has turned to the philosophy of religion, as evident in several pieces, including the lecture "A Catholic Modernity" and the short monograph "Varieties of Religion Today: William James Revisited".[83] Taylor's most significant contribution in this field to date is his book A Secular Age which argues against the secularization thesis of Max Weber, Steve Bruce, and others.[84] In rough form, the secularization thesis holds that as modernity (a bundle of phenomena including science, technology, and rational forms of authority) progresses, religion gradually diminishes in influence. Taylor begins from the fact that the modern world has not seen the disappearance of religion but rather its diversification and in many places its growth.[85] He then develops a complex alternative notion of what secularization actually means given that the secularization thesis has not been borne out. In the process, Taylor also greatly deepens his account of moral, political, and spiritual modernity that he had begun in Sources of the Self. |

宗教哲学と宗教社会学 さらなる情報 世俗の時代』と『世俗性』§テイラー的世俗性 テイラーの晩年の仕事は宗教哲学に傾倒しており、それは講演「A Catholic Modernity」や短編モノグラフ「Varieties of Religion Today」を含むいくつかの作品に明らかである: William James Revisited "などである[83]。 テイラーのこの分野における今日までの最も重要な貢献は、マックス・ウェーバーやスティーヴ・ブルースらの世俗化テーゼに反論した著書『A Secular Age』である[84]。大まかな形では、世俗化テーゼは、近代(科学、テクノロジー、合理的な権威の形態を含む現象の束)が進展するにつれて、宗教の影 響力が徐々に低下していくというものである。テイラーはまず、近代世界は宗教が消滅したのではなく、むしろ多様化し、多くの場所で成長してきたという事実 から出発し[85]、世俗化テーゼが実証されていないことを踏まえて、世俗化が実際に何を意味するのかについて複雑な代替概念を展開している。その過程で テイラーは、『自己の源泉』で始めた道徳的、政治的、精神的近代性に関する説明も大幅に深めている。 |

| Politics Taylor was a candidate for the social democratic New Democratic Party (NDP) in Mount Royal on three occasions in the 1960s, beginning with the 1962 federal election when he came in third behind Liberal Alan MacNaughton. He improved his standing in 1963, coming in second. Most famously, he also lost in the 1965 election to newcomer and future prime minister, Pierre Trudeau. This campaign garnered national attention. Taylor's fourth and final attempt to enter the House of Commons of Canada was in the 1968 federal election, when he came in second as an NDP candidate in the riding of Dollard. In 1994 he coedited a paper on human rights with Vitit Muntarbhorn in Thailand.[86] In 2008, he endorsed the NDP candidate in Westmount—Ville-Marie, Anne Lagacé Dowson. He was also a professor to Canadian politician and former leader of the New Democratic Party Jack Layton. Taylor served as a vice president of the federal NDP (beginning c. 1965)[62] and was president of its Quebec section.[87] In 2010, Taylor said multiculturalism was a work in progress that faced challenges. He identified tackling Islamophobia in Canada as the next challenge.[88] In his 2020 book Reconstructing Democracy he, together with Patrizia Nanz and Madeleine Beaubien Taylor, uses local examples to describe how democracies in transformation might be revitalized by involving citizenship.[89] |

政治 1962年の連邦選挙では、リベラルのアラン・マクノートンに次ぐ3位だった。1963年には順位を上げ、2位となった。最も有名なのは、1965年の選 挙で新人で後に首相となるピエール・トルドーに敗れたことだ。この選挙戦は全米の注目を集めた。テイラーの4回目、そして最後の下院議員への挑戦は 1968年の連邦選挙で、ダラード選挙区のNDP候補として2位になった。1994年にはタイのヴィティット・ムンタルボーンと人権に関する論文を共同編 集した[86]。2008年にはウェストマウント=ヴィル=マリーのNDP候補アン・ラガセ・ダウソンを支持した。また、カナダの政治家で新民主党の ジャック・レイトン前党首の教授でもあった。 テイラーは連邦NDPの副総裁(1965年ごろから)[62]を務め、ケベック支部長も務めた[87]。 2010年、テイラーは多文化主義は課題に直面した進行中の作業であると述べた。彼は次の課題として、カナダにおけるイスラム恐怖症への取り組みを挙げた [88]。 2020年に出版された『Reconstructing Democracy(民主主義の再構築)』では、パトリツィア・ナンツとマドレーヌ・ボービアン・テイラーとともに、変革期にある民主主義が市民権を巻き 込むことによってどのように活性化されるかを、地域の事例を用いて説明している[89]。 |

| Interlocutors Himani Bannerji: "Charles Taylor's Politics of Recognition: A Critique" (2000) Richard Rorty Bernard Williams Alasdair MacIntyre: critique of liberalism Will Kymlicka Martha Nussbaum Kwame Appiah Hubert Dreyfus: co-author Quentin Skinner Talal Asad |

対談者 ヒマニ・バナジー:「チャールズ・テイラーの認識の政治学: 批評」(2000年) リチャード・ローティ バーナード・ウィリアムズ アラスデア・マッキンタイア:自由主義批判 ウィル・キムリッカ マーサ・ヌスバウム クワメ・アピア ユベール・ドレフュス:共著 クエンティン・スキナー タラル・アサド |

| Published works Books The Explanation of Behaviour. Routledge Kegan Paul. 1964. The Pattern of Politics. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. 1970. Erklärung und Interpretation in den Wissenschaften vom Menschen (in German). Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. 1975. Hegel. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 1975. Hegel and Modern Society. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 1979. Social Theory as Practice. Delhi: Oxford University Press. 1983.[a] Human Agency and Language. Philosophical Papers. Vol. 1. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 1985. Philosophy and the Human Sciences. Philosophical Papers. Vol. 2. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 1985. Sources of the Self: The Making of Modern Identity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 1989. The Malaise of Modernity. Concord, Ontario: House of Anansi Press. 1991.[b] The Ethics of Authenticity. Harvard University Press. 1991. Multiculturalism and "The Politics of Recognition". Edited by Gutmann, Amy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1992.[c] Rapprocher les solitudes: écrits sur le fédéralisme et le nationalisme au Canada [Reconciling the Solitudes: Writings on Canadian Federalism and Nationalism] (in French). Edited by Laforest, Guy. Sainte-Foy, Quebec: Les Presses de l'Université Laval. 1992. English translation: Reconciling the Solitudes: Essays on Canadian Federalism and Nationalism. Edited by Laforest, Guy. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. 1993. Road to Democracy: Human Rights and Human Development in Thailand. With Muntarbhorn, Vitit. Montreal: International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development. 1994. Philosophical Arguments. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 1995. Identitet, Frihet och Gemenskap: Politisk-Filosofiska Texter (in Swedish). Edited by Grimen, Harald. Gothenburg, Sweden: Daidalos. 1995. De politieke Cultuur van de Moderniteit (in Dutch). The Hague, Netherlands: Kok Agora. 1996. La liberté des modernes (in French). Translated by de Lara, Philippe. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. 1997. A Catholic Modernity? Edited by Heft, James L. New York: Oxford University Press. 1999. Prizivanje gradjanskog drustva [Invoking Civil Society] (in Serbo-Croatian). Edited by Savic, Obrad. Wieviel Gemeinschaft braucht die Demokratie? Aufsätze zur politische Philosophie (in German). Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. 2002. Varieties of Religion Today: William James Revisited. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 2002. Modern Social Imaginaries. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. 2004. A Secular Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 2007. Laïcité et liberté de conscience (in French). With Maclure, Jocelyn. Montreal: Boréal. 2010. English translation: Secularism and Freedom of Conscience. With Maclure, Jocelyn. Translated by Todd, Jane Marie. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 2011. Dilemmas and Connections: Selected Essays. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 2011. Church and People: Disjunctions in a Secular Age. Edited with Casanova, José; McLean, George F. Washington: Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. 2012. Democracia Republicana / Republican Democracy. Edited by Cristi, Renato; Tranjan, J. Ricardo. Santiago: LOM Ediciones. 2012. Boundaries of Toleration. Edited with Stepan, Alfred C. New York: Columbia University Press. 2014. Incanto e Disincanto. Secolarità e Laicità in Occidente (in Italian). Edited and translated by Costa, Paolo. Bologna, Italy: EDB. 2014. La Democrazia e i Suoi Dilemmi (in Italian). Edited and translated by Costa, Paolo. Parma, Italy: Diabasis. 2014. Les avenues de la foi : Entretiens avec Jonathan Guilbault (in French). Montreal: Novalis. 2015. English translation: Avenues of Faith: Conversations with Jonathan Guilbault. Translated by Shalter, Yanette. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press. 2020. Retrieving Realism. With Dreyfus, Hubert. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 2015. The Language Animal: The Full Shape of the Human Linguistic Capacity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 2016. Reconstructing Democracy. How Citizens Are Building from the Ground Up. With Nanz, Patrizia; Beaubien Taylor, Madeleine. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 2020 Selected book chapters Taylor, Charles (1982). "The Diversity of Goods". In Sen, Amartya; Williams, Bernard (eds.). Utilitarianism and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–144. ISBN 9780511611964. |

出版作品 書籍 『行動の説明』。Routledge Kegan Paul。1964年。 『政治のパターン』。トロント:McClelland and Stewart。1970年。 『人間科学における説明と解釈』(ドイツ語)。フランクフルト:Suhrkamp。1975年。 『ヘーゲル』。ケンブリッジ、イングランド:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。1975年。 ヘーゲルと近代社会。ケンブリッジ、イングランド:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。1979年。 社会理論としての実践。デリー:オックスフォード大学出版局。1983年。 人間の行動と言語。『哲学論文集』第1巻。ケンブリッジ、イングランド:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。1985年。 哲学と人間科学。『哲学論文集』第2巻。ケンブリッジ、イングランド:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。1985年。 自己の源泉:近代的アイデンティティの形成。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。1989年。 近代の不安。オンタリオ州コンコード:ハウス・オブ・アナンシ・プレス。1991年。 真正性の倫理。ハーバード大学出版局。1991年。 多文化主義と「承認の政治」。編集:グットマン、エイミー。ニュージャージー州プリンストン: 1992年[c] 『孤独の和解:カナダの連邦主義とナショナリズムに関する著作』(フランス語)。ガイ・ラフォレスト編。ケベック州サントフォイ、ラヴァル大学出版。 1992年。 英語訳:『孤独の和解:カナダの連邦制とナショナリズムに関する論文』。ガイ・ラフォレスト編。モントリオール:マギル・クイーンズ大学出版。1993年 『民主主義への道:タイにおける人権と人間開発』。ヴィティット・ムンターブホーンとの共著。モントリオール:国際人権・民主主義開発センター。1994 年 『哲学的論争』ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ:ハーバード大学出版局。1995年 『アイデンティティ、自由、共同体:政治哲学テキスト』(スウェーデン語)編集:Grimen, Harald。スウェーデン、ヨーテボリ:Daidalos。1995年 『近代の政治文化』(オランダ語)オランダ、ハーグ:Kok Agora。1996年 La liberté des modernes (フランス語). 翻訳:de Lara, Philippe. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. 1997. A Catholic Modernity? 編集:Heft, James L. New York: Oxford University Press. 1999. Prizivanje gradjanskog drustva [Invoking Civil Society] (セルビア・クロアチア語). 編集:Savic, Obrad. Wieviel Gemeinschaft braucht die Demokratie? Aufsätze zur politische Philosophie (ドイツ語). Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. 2002. 現代の宗教の諸相:ウィリアム・ジェームズ再訪. ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ州:ハーバード大学出版局. 2002. 現代の社会的想像力. ダーラム、ノースカロライナ州:デューク大学出版局. 2004. A Secular Age. ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ州:Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 2007. Laïcité et liberté de conscience(フランス語)。ジョスリン・マクルアとの共著。モントリオール:Boréal. 2010. 英語訳:Secularism and Freedom of Conscience. ジョスリン・マクルアとの共著。トッド、ジェーン・マリー訳。ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ州:Harvard University Press. 2011. ジレンマとつながり:選集エッセイ。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局Belknap Press。2011年。 教会と人々:世俗時代の断絶。カサノヴァ、ホセ、マクリーン、ジョージ F. ワシントン:価値と哲学の研究協議会。2012年。 『民主共和制/共和党民主制』編集:クリスティ、レナート、トランジャン、J. リカルド。サンチアゴ:LOM Ediciones。2012年 『寛容の境界』編集:ステパン、アルフレッド C. ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版。2014年 Incanto e Disincanto. Secolarità e Laicità in Occidente (in Italian). Edited and translated by Costa, Paolo. Bologna, Italy: EDB. 2014. La Democrazia e i Suoi Dilemmi (in Italian). Edited and translated by Costa, Paolo. Parma, Italy: Diabasis. 2014. Les avenues de la foi : Entretiens avec Jonathan Guilbault (フランス語). Montreal: Novalis. 2015. 英語訳:Avenues of Faith: Conversations with Jonathan Guilbault. Translated by Shalter, Yanette. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press. 2020. Retrieving Realism. With Dreyfus, Hubert. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 2015. 『ことばの動物:人間の言語能力の全容』ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ:ハーバード大学出版局。2016年 『民主主義の再構築:市民がゼロから作り上げる』ナンツ、パトリツィア、ボービアン・テイラー、マドレーヌとの共著。ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ: ハーバード大学出版局。2020年 書籍の章の抜粋 テイラー、チャールズ(1982年)。「財の多様性」。セン、アマルティア、ウィリアムズ、バーナード(編)。『功利主義とその先』ケンブリッジ大学出版 局、ケンブリッジ。129-144ページ。ISBN 9780511611964。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Taylor_(philosopher) |

|

| 近代社会に特有の、三つの不安がある。第一に、個人主義により道徳の地

平が消失すること。第二に、費用対効果の最大化を目的とする道具的理

性が社会の隅々にまで浸透すること。第三に、「穏やかな専制」が訪れ

て人々が自由を喪失し、政治的に無力になること。著者はこれらの不安の由来と根拠をあらためて問い質し、近代の道徳的理想、すなわち「“ほんもの”という倫理」の回復こそが、よりよい生と未来を切り拓くための闘争

を可能にすると説く。現代を代表する政治哲学者が、その思考のエッセンスを凝縮した名講義。 第1章 三つの不安 第2章 かみ合わない論争 第3章 ほんものという理想の源泉 第4章 逃れられない地平 第5章 承認のニード 第6章 主観主義へのすべり坂 第7章 闘争は続く 第8章 より繊細な言語 第9章 鉄の檻? 第10章 断片化に抗して https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BD01223367 |

マルチカルチュラリズム / チャールズ・テイラー [ほか] 著 ; エイミー・ガットマン編 ; 佐々木毅, 辻康夫, 向山恭一訳, 東京 : 岩波書店 , 1996.10 民族・宗教・性差等の境界が揺れ動く現代において、複合的なアイデンティティ形成は可能だろうか。チャールズ・テイラーの問題提起にハーバーマス、ウォルツァーらが応答を試みた、マルチカルチュラリズムの基本文献。 緒論 承認をめぐる政治 コメント(多文化主義と教育;自由主義と承認をめぐる政治;二つの自由主義) 民主的立憲国家における承認への闘争 アイデンティティ、真正さ、文化の存続—多文化社会と社会的再生産 https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA83751081 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆