誠実性とほんもの性

Sincerity and Authenticity

☆ 『誠実とほんもの性』は、ライオネル・トリリングが1972年に発表した著書である。1970年にハーバード大学のチャールズ・エリオット・ノートン教授 として行った一連の講義を基に執筆された[1]。 この講義では、「自己修正の過程にある道徳的生活」と表現した、西洋 の歴史における一時期(トリリングの主張によれば)を考察している。この[啓蒙時代 以前の] 時代、誠実さが道徳生活の中心的な側面となった(シェイクスピア作品などの啓蒙時代以前の文学作品に初めて見られる)。その後、20世紀には真正性が取っ て代わった。講演では、「誠実」と「真正性」という用語を定義し、説明することに多くの時間を割いているが、明確で簡潔な定義は実際には提 示されておら ず、トリリングは、これらの用語を完全に定義しないほうが良い可能性もあると考えている。しかし、彼は「自分に忠実であること」という短い公式を使って、 現代の真正性の理想を特徴づけ、道徳的に誠実な人間であることの古い理想と区別している。トリリングは、自身の論文を擁護するために幅広い 文献を参照し、 過去500年間の西洋の主要な(そして一部はそれほど知られていない)作家や思想家の多くを引用している。 トリリングの『誠実とほんもの性』は、テンプルトンや京都賞受賞者のチャールズ・テイラー(著 書『ほんもの性の倫理』)などの文学・文化評論家や哲学者に影響を与えて いる。また、カイル・マイケル・ジェームズ・シャトルワースの近著『The History and Ethics of Authenticity: Freedom, Meaning and Modernity』(2020年)や、ハンス=ゲオルク・メラーとポール・J・ダンブロシオの『You and Your Profile: Life After Authenticity』(2021年)も参照のこと。

| Sincerity

and

Authenticity is a 1972 book by Lionel Trilling, based on a series

of

lectures he delivered in 1970 as Charles Eliot Norton Professor at

Harvard University.[1] The lectures examine what Trilling described as "the moral life in process of revising itself", a period of Western history in which (argues Trilling) sincerity became the central aspect of moral life (first observed in pre–Age of Enlightenment literature such as the works of Shakespeare), later to be replaced by authenticity (in the twentieth century). The lectures take great lengths to define and explain the terms "sincerity" and "authenticity", though no clear, concise definition is ever really postulated, and Trilling even considers the possibility that such terms are best not totally defined. However, he does use the short formula "to stay true to oneself" to characterize the modern ideal of authenticity and differentiates it from the older ideal of being a morally sincere person. Trilling draws on a wide range of literature in defense of his thesis, citing many of the key (and some more obscure) Western writers and thinkers of the last 500 years. Trilling's Sincerity and Authenticity has been of influence on literary and cultural critics and philosophers, such as Templeton and Kyoto Prize winner Charles Taylor in his book The Ethics of Authenticity. See also, the more recent work of Kyle Michael James Shuttleworth in The History and Ethics of Authenticity: Freedom, Meaning and Modernity (2020), and Hans-Georg Moeller and Paul J. D’Ambrosio in You and Your Profile: Life After Authenticity (2021) |

『誠実と真正』は、ライオネル・トリリングが1972年に発表した著書

である。1970年にハーバード大学のチャールズ・エリオット・ノートン教授として行った一連の講義を基に執筆された[1]。 この講義では、「自己修正の過程にある道徳的生活」と表現した、西洋の歴史における一時期(トリリングの主張によれば)を考察している。この時代、誠実さ が 道徳生活の中心的な側面となった(シェイクスピア作品などの啓蒙時代以前の文学作品に初めて見られる)。その後、20世紀には真正性が取って代わった。講 演では、「誠実」と「真正性」という用語を定義し、説明することに多くの時間を割いているが、明確で簡潔な定義は実際には提示されておらず、トリリング は、これらの用語を完全に定義しないほうが良い可能性もあると考えている。しかし、彼は「自分に忠実であること」という短い公式を使って、現代の真正性の 理想を特徴づけ、道徳的に誠実な人間であることの古い理想と区別している。トリリングは、自身の論文を擁護するために幅広い文献を参照し、過去500年間 の西洋の主要な(そして一部はそれほど知られていない)作家や思想家の多くを引用している。 トリリングの『誠実と真正』は、テンプルトンや京都賞受賞者のチャールズ・テイラー(著 書『真正の倫理』)などの文学・文化評論家や哲学者に影響を与えて いる。また、カイル・マイケル・ジェームズ・シャトルワースの近著『The History and Ethics of Authenticity: Freedom, Meaning and Modernity』(2020年)や、ハンス=ゲオルク・メラーとポール・J・ダンブロシオの『You and Your Profile: Life After Authenticity』(2021年)も参照のこと。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sincerity_and_Authenticity |

|

| ラ

イオネル・トリリングのホットな見解【01】 ライオネル・トリリング著 2018年10月11日 ARTS & CULTURE 誰もが評論家になれるが、過去100年間でライオネル・トリリングほどの高みに到達した人物は少ない。1975年に彼が亡くなったとき、ニューヨーク・タ イムズ紙の一面に訃報が掲載された。評論という報われない分野では珍しいことだ。トリリングは『パルチザン・レビュー』誌に寄稿したエッセイや、『リベラ ルな想像力』をはじめとする著書を通じて、大きな社会変動の時代にアメリカの思想の流れを形作り、刺激を与えた。トリリング自身はかつて、自身の文章は文 学と政治の「血塗られた十字路」にあると表現したが、現実世界の関心事を文学批評の基盤とすることに専心したこの姿勢により、彼は20世紀を代表する知識 人の一人となった。トリリングはまた、手紙の執筆においても多作であった。彼自身の評価によると、毎年少なくとも600通は手紙を書いていたという。9 月、ファラー、ストラウス、ジルー社から、アダム・カークシュ編集の『Lionel Trilling: Selected Letters』が出版された。以下、トリリングの珠玉の意見の抜粋をご紹介する。彼の書簡からも、この批評家が常に執筆活動を行っていたことがわかる。 アレン・ギンズバーグの『ハウルとその他の詩』について 親愛なるアレンへ 残念ながら、私はあなたの詩をまったく好きではないと言わざるを得ない。 あなたの詩を「退屈」だと言うのはためらうが、暴力や衝撃を与えることを目的とした作品に対して「退屈」だと言うのは、周知の、そしてあまりにも安易な表 現であることは承知している。 しかし、私が「退屈」だと言うのは、おそらく誠実な気持ちからだとあなたは信じてくれるだろう。ホイットマンの詩とは違って、散文ばかりで、修辞的な表現 ばかりで、音楽性がまったくない。 あなたの詩で私が気に入っていたのは、それが良い詩か悪い詩かは別として、そこに聞こえる声だった。真実で自然で興味深い声だ。しかし、ここでは真実の声 が聞こえてこない。詩の教条的な要素については、もちろん私はそれを否定するとして、私はそれをずっと以前に聞いたことがあるように思うし、あなたはそれ を正統派のすべてで私に与え、新しいものは何も加えていない。 ユージン・オニールについて 私はオニールが人間について書いているとは決して感じない。ただ抽象化された大学生の湿っぽい魂について書いているだけだ。彼が「考える」ことができない のではなく、感じることができないのだ。彼の青年時代の素晴らしい「経験」――海や酒場、療養所――にもかかわらず、彼の人生には即時性が欠けている。彼 の言葉を見ればわかる。その恐ろしいほど、恐ろしいほど湿っぽい言葉は、まるで20年前のスラングを思わせる。触覚の喪失は、私たちの思考や文学にますま す顕著に表れている。それを表現する言葉さえ時代遅れだ。私たちは「連絡が途絶えた」と言う。オニールの手を握ろうとして手を伸ばすと、私は膨らませたゴ ム手袋を握ったような気分になる。そして、彼が何を言っているのかさっぱりわからない。それでも、罪悪感や自己欺瞞、究極的なものとの関係といった事柄 は、私が考えたり読んだりしたいものだ。聖アウグスティヌスのような真の神学的な思考と真の文学的な思考をもち、それらの事柄がいかに現実的であるか、い かに触覚的であるかを考えてみよう。人生は恐ろしいほど私たちから遠ざかっている。特に、オニールが死について語るのを聞くのが嫌いだ。あるいは、人生に ついて語るのも嫌いだ。 私が間違っているだろうか?私は鈍感で、不寛容で、意地悪だろうか?訂正してもらっても構わない。 彼のひげについて 私が口ひげを生やしていると聞いたことがあるだろうか?あまり好きではない。 偉大な小説家について 今日、D. H. ローレンスを読んだ。そして、自分でも不思議なくらい励まされた。なぜなら、私にとって、偉大な小説家は4人いるからだ。ドストエフスキー、プルースト、 セルバンテス、ディケンズ。(ラベレーは小説とは言えないので省略する。)ドストエフスキーは、ほとんど人間らしくないようで、いつも私を落ち込ませた。 ミドルトン・マーレイは、いくつかのテストによって、ドストエフスキーは小説ではなく、それ以上のものを書いていると、かなり貴重に言っている。現在、ド ストエフスキーは私にとって意味がなく、私は彼の作品を読まないが、彼の力は、二度と誰にも達成できないものであり、努力を無駄にするものであると覚えて いる。なぜなら、一時的にではあるが、私は彼を受け入れないが、彼のようなことは最も素晴らしいことのように思えるからだ。プルーストについては、私は彼 の作品を理解しており、彼について抱く感情をコントロールできる。しかし、彼の豊かさ、強さは、私を落胆させることもある。(彼の方法における途方もない 独創性と勇気を、私たちは決して十分に理解できない。) 【右上に続く】 |

ラ

イオネル・トリリングのホットな見解【02】 セルバンテスとディケンズの偉大な作品に関しては、それらはまさに原初的なものであり、最初から存在している。それらはただそこにあり、比較や分類を一切 許さない。しかし、ローレンスはかなり素晴らしい作家だ。ドストエフスキーほどではないにせよ、彼にも同じくらい、あるいはそれ以上の価値がある。そし て、ドストエフスキーの世界や、私が想像もできないような世界ではなく、この世界のことを扱っていることで素晴らしいのだ。 ドストエフスキーの世界であり、私には想像も及ばない世界である。彼は、この世界のことを扱うことで偉大であり、他の世界(そしてもっと重要なのは、ドス トエフスキーの世界であり、私には想像も及ばない世界である)のことを扱うことで偉大ではない。彼が偉大であることで、私も偉大になれるかもしれないとい う期待を私に抱かせる。つまり、彼は、手近にある良い方法を使い、目線を同じ高さに保ちながら物事を深く見れば、私は一流の仕事をすることができると私に 確信させている。そうだとすれば、それはまだしばらくは実現しないだろう。私が爆破されて自由になるまでは。私は良い川だと思うが、源流でない限りは全長 凍結状態であり、爆破が必要なのだ。 トム・ガンについて 詩人としての資格を持つ者にとって、ガンが本物であることに疑問の余地はないようだ。しかし、私はガンは几帳面な職人であり、よくできた詩を次々に生み出 していると考えている。 「新しいもの」について 私が知る限り、新しいものに対する敵意はない。それどころか、誰もが新しいものに対してとても親切で、成功することを望み、内心ではそれほど退屈なものに ならないことを願っている。つまり、誰もが新しいものに対して、献身的な校長や学部教授のような態度で接しているのだ。彼らは、未来は新しいものにあるこ とを知っており、それを世に出し、奨励しなければならないと考えているが、会話の相手としては他のものを探している。賭けをしよう。おいしいランチを奢る から、ここ5年間で個人的にあなたにとって意味があった本を1冊挙げてほしい。専門家としての評価ではなく、個人的な意味だ。つまり、『ウェイスト・ラン ド』や『アーティストの肖像』のような意味だ(『ユリシーズ』のような意味ではない)。『タイムズ・ブック・レビュー』では毎週のように新作が賞賛されて いるし、少なくとも受け入れられているが、その支持者たちによる歓迎の態度がすべてを物語っている。つまらない喝采だ。もちろん、私は決して新作を歓迎す る人間ではない。私は新作を探し求めるべきだと思ったことはないし、むしろ、私の抵抗をよそに、新作が私を捕らえようとするべきだと思っていた。今から2 年、3年、4年、5年後に、私の抵抗を克服し、消極的な同意を引き出す可能性のある人物が今誰で、誰が働いているのかを知ることができ、その情報を真剣に 受け止めることができるなら、私は嬉しく思うだろう。 私は、人々の心が活気を失い、ただ無気力な音を立てるような、そんな悪い時代の中にいるのだと思う。そのような時代は常に過ぎ去ってきたし、おそらく今回 もそうなるだろう。 ライオネル・トリリング(1905-1975)は、20世紀の最も重要なアメリカの文学評論家の一人である。彼はコロンビア大学で50年間教鞭をとり、 『リベラルな想像力』や小説『旅の途中』など、数多くの著作を残した。 『Life in Culture: Selected Letters of Lionel Trilling』(アダム・カークシュ編、2018年9月25日、Farrar, Straus and Giroux社刊)より抜粋。Copyright © 2018 by James Trilling and Adam Kirsch. All rights reserved. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/10/11/lionel-trillings-hottest-takes/ |

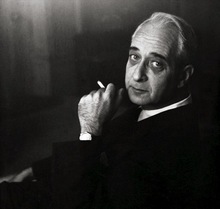

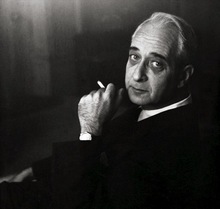

Lionel

Mordecai Trilling

(July 4, 1905 – November 5, 1975) was an American literary critic,

short story writer, essayist, and teacher. He was one of the leading

U.S. critics of the 20th century who analyzed the contemporary

cultural, social, and political implications of literature. With his

wife Diana Trilling (née Rubin), whom he married in 1929, he was a

member of the New York Intellectuals and contributor to the Partisan

Review. Lionel

Mordecai Trilling

(July 4, 1905 – November 5, 1975) was an American literary critic,

short story writer, essayist, and teacher. He was one of the leading

U.S. critics of the 20th century who analyzed the contemporary

cultural, social, and political implications of literature. With his

wife Diana Trilling (née Rubin), whom he married in 1929, he was a

member of the New York Intellectuals and contributor to the Partisan

Review.Personal and academic life Lionel Mordecai Trilling was born in Queens, New York, the son of Fannie (née Cohen), who was from London, and David Trilling, a tailor from Bialystok in Poland.[1] His family was Jewish. In 1921, he graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School, and, at age 16, entered Columbia University, thus beginning a lifelong association with the university. He joined the Boar's Head Society and wrote for the Morningside literary journal.[2] In 1925, he graduated from Columbia College, and, in 1926, earned a master's degree at the university (his master's essay was entitled Theodore Edward Hook: his life and work). He then taught at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and at Hunter College. In 1929 he married Diana Rubin, and the two began a lifelong literary partnership. In 1932 he returned to Columbia to pursue his doctoral degree in English literature and to teach literature. He earned his doctorate in 1938 with a dissertation about Matthew Arnold that he later published. He was promoted to assistant professor the following year, becoming Columbia's first tenured Jewish professor in its English department.[3] He was promoted to full professor in 1948. Trilling became the George Edward Woodberry Professor of Literature and Criticism in 1965. He was a popular instructor and for thirty years taught Columbia's Colloquium on Important Books, a course about the relationship between literature and cultural history, with Jacques Barzun. His students included Lucien Carr, Jack Kerouac, Donald M. Friedman,[4] Allen Ginsberg, Eugene Goodheart, Steven Marcus, John Hollander, Richard Howard, Cynthia Ozick, Carolyn Gold Heilbrun, George Stade, David Lehman, Leon Wieseltier, Louis Menand, Robert Leonard Moore[5] and Norman Podhoretz. Trilling was the George Eastman Visiting Professor at the University of Oxford from 1963 to 1965 and Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University for academic year 1969–70. In 1972, he was selected by the National Endowment for the Humanities to deliver the first Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, described as "the highest honor the federal government confers for distinguished intellectual achievement in the humanities."[6] Trilling was a senior Fellow of the Kenyon School of English and subsequently a senior Fellow of the Indiana School of Letters. He held honorary degrees from Trinity College, Harvard University, and Case Western Reserve University and memberships in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He also served on the boards of The Kenyon Review and Partisan Review.[7] Trilling died of pancreatic cancer in 1975.[7] He was survived by his wife and son, James Trilling, an art historian who served as a former curator at the George Washington University Museum and Textile Museum.[8] His nephew Billy Cross is a musician residing in Denmark.[9] Partisan Review and the "New York Intellectuals" In 1937, Trilling joined the recently revived magazine Partisan Review, a Marxist, but anti-Stalinist, journal founded by William Philips and Philip Rahv in 1934.[10] The Partisan Review was associated with the New York Intellectuals – Trilling, his wife Diana Trilling, Lionel Abel, Hannah Arendt, William Barrett, Daniel Bell, Saul Bellow, Richard Thomas Chase, F. W. Dupee, Leslie Fiedler, Paul Goodman, Clement Greenberg, Elizabeth Hardwick, Irving Howe, Alfred Kazin, Hilton Kramer, Steven Marcus, Mary McCarthy, Dwight Macdonald, William Phillips, Norman Podhoretz, Harold Rosenberg, Isaac Rosenfeld, Delmore Schwartz, and Susan Sontag – who emphasized the influence of history and culture upon authors and literature. The New York Intellectuals distanced themselves from the New Critics. In his preface to the essays collection, Beyond Culture (1965), Trilling defended the New York Intellectuals: "As a group, it is busy and vivacious about ideas, and, even more, about attitudes. Its assiduity constitutes an authority. The structure of our society is such that a class of this kind is bound by organic filaments to groups less culturally fluent that are susceptible to its influence." Critical and literary works Trilling wrote one novel, The Middle of the Journey (1947), about an affluent Communist couple's encounter with a Communist defector. (Trilling later acknowledged that the character was inspired by his Columbia College compatriot and contemporary Whittaker Chambers.[11][12]) His short stories include "The Other Margaret". Otherwise, he wrote essays and reviews in which he reflected on literature's ability to challenge the morality and conventions of the culture. Critic David Daiches said of Trilling, "Mr. Trilling likes to move out and consider the implications, the relevance for culture, for civilization, for the thinking man today, of each particular literary phenomenon which he contemplates, and this expansion of the context gives him both his moments of his greatest perceptions, and his moments of disconcerting generalization." Trilling published two complex studies of authors Matthew Arnold (1939) and E. M. Forster (1943), both written in response to a concern with "the tradition of humanistic thought and the intellectual middle class which believes it continues this tradition."[13] His first collection of essays, The Liberal Imagination, was published in 1950, followed by the collections The Opposing Self (1955), focusing on the conflict between self-definition and the influence of culture, Freud and the Crisis of Our Culture (1955), A Gathering of Fugitives (1956), and Beyond Culture (1965), a collection of essays concerning modern literary and cultural attitudes toward selfhood. In Sincerity and Authenticity (1972), he explores the ideas of the moral self in post-Enlightenment Western civilization. He wrote the introduction to The Selected Letters of John Keats (1951), in which he defended Keats's notion of negative capability, as well as the introduction, "George Orwell and the Politics of Truth," to the 1952 reissue of George Orwell's Homage to Catalonia. In 2008, Columbia University Press published an unfinished novel that Trilling had abandoned in the late 1940s. Scholar Geraldine Murphy discovered the half-finished novel among Trilling's papers archived at Columbia University.[14] Trilling's novel, The Journey Abandoned: The Unfinished Novel, is set in the 1930s and involves a young protagonist, Vincent Hammell, who seeks to write a biography of an older poet, Jorris Buxton. Buxton's character is loosely based on the nineteenth century Romantic poet Walter Savage Landor.[14] Writer and critic Cynthia Ozick praised the novel's "skillful narrative" and "complex characters", writing, "The Journey Abandoned is a crowded gallery of carefully delineated portraits whose innerness is divulged partly through dialogue but far more extensively in passages of cannily analyzed insight."[15] Politics Trilling's politics have been strongly debated and, like much else in his thought, may be described as "complex." An often-quoted summary of Trilling's politics is that he wished to:[16] [Remind] people who prided themselves on being liberals that liberalism was ... a political position which affirmed the value of individual existence in all its variousness, complexity, and difficulty. Of ideologies, Trilling wrote, "Ideology is not the product of thought; it is the habit or the ritual of showing respect for certain formulas to which, for various reasons having to do with emotional safety, we have very strong ties and of whose meaning and consequences in actuality we have no clear understanding."[17] Politically, Trilling was a noted member of the anti-Stalinist left, a position that he maintained to the end of his life.[18][19] Liberal In his earlier years, Trilling wrote for and in the liberal tradition, explicitly rejecting conservatism; from the preface to his 1950 essay The Liberal Imagination (emphasis added to the much-quoted last line): In the United States at this time Liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition. For it is the plain fact that nowadays there are no conservative or reactionary ideas in general circulation. This does not mean, of course, that there is no impulse to conservatism or to reaction. Such impulses are certainly very strong, perhaps even stronger than most of us know. But the conservative impulse and the reactionary impulse do not, with some isolated and some ecclesiastical exceptions, express themselves in ideas but only in action or in irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas. Neoconservative Some, both conservative and liberal, argue that Trilling's views became steadily more conservative over time. Trilling has been embraced as sympathetic to neoconservatism by neoconservatives (such as Norman Podhoretz, the former editor of Commentary). However, this embrace was unrequited; Trilling criticized the New Left (as he had the Old Left) but did not embrace neoconservativism. His wife, Diana Trilling, claimed that neoconservatives were mistaken in thinking that Trilling shared their views. “I am of the firmest belief that he would never have become a neoconservative,” she announced in her memoir of their marriage, “The Beginning of the Journey,” adding that “nothing in his thought supports the sectarianism of the neoconservative."[20] The extent to which Trilling may be identified with neoconservativism continues to be contentious, forming a point of debate.[21][page needed] Moderate Trilling has alternatively been characterized as solidly moderate, as evidenced by many statements, ranging from the very title of his novel, The Middle of the Journey, to a central passage from the novel:[22] An absolute freedom from responsibility – that much of a child none of us can be. An absolute responsibility – that much of a divine or metaphysical essence none of us is. Along the same lines, in reply to a taunt by Richard Sennett, "You have no position; you are always in between," Trilling replied, "Between is the only honest place to be."[23][page needed] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lionel_Trilling |

ラ

イオネル・モルデカイ・トリリング(Lionel Mordecai Trilling、1905年7月4日 -

1975年11月5日)は、アメリカの文学評論家、短編小説家、随筆家、教師。20世紀を代表するアメリカの批評家の一人であり、文学の持つ現代的文化、

社会、政治的な意味合いを分析した。1929年に結婚した妻ダイアナ・トリリング(旧姓ルービン)とともに、ニューヨーク・インテリゲンツの一員であり、

パーティザン・レヴューに寄稿していた。 ラ

イオネル・モルデカイ・トリリング(Lionel Mordecai Trilling、1905年7月4日 -

1975年11月5日)は、アメリカの文学評論家、短編小説家、随筆家、教師。20世紀を代表するアメリカの批評家の一人であり、文学の持つ現代的文化、

社会、政治的な意味合いを分析した。1929年に結婚した妻ダイアナ・トリリング(旧姓ルービン)とともに、ニューヨーク・インテリゲンツの一員であり、

パーティザン・レヴューに寄稿していた。私生活と学問 ライオネル・モルデカイ・トリリングは、ロンドン出身のファニー(旧姓コーエン)と、ポーランドのビャウィストク出身の仕立て屋デビッド・トリリングの息 子として、ニューヨークのクイーンズで生まれた[1]。彼の家族はユダヤ人であった。1921年、彼はディウィット・クリントン高校を卒業し、16歳でコ ロンビア大学に入学した。彼は「Boar's Head Society」に入会し、文学誌「Morningside」に執筆した[2]。1925年にコロンビア大学を卒業し、1926年には同大学で修士号を取 得した(修士論文のタイトルは「Theodore Edward Hook: his life and work」)。その後、ウィスコンシン大学マディソン校とハンターカレッジで教鞭をとった。 1929年にダイアナ・ルービンと結婚し、2人は生涯にわたる文学パートナーシップを築く。1932年にコロンビア大学に戻り、英文学の博士号取得と文学 の教鞭をとる。1938年にマシュー・アーノルドに関する論文で博士号を取得し、後に出版した。翌年には助教授に昇進し、コロンビア大学英語学科初のユダ ヤ人終身在職教授となった[3]。1948年には正教授に昇進した。 トリリングは1965年にジョージ・エドワード・ウッドベリー文学・批評教授に就任した。彼は人気のある講師であり、30年にわたってジャック・バルズン とともに文学と文化史の関係について学ぶコロンビア大学の「重要な書籍に関するコロキウム」の講師を務めた。彼の教え子には、ルシアン・カー、ジャック・ ケルアック、ドナルド・M・フリードマン、アレン・ギンズバーグ、ユージン・グッドハート、スティーブン・マーカス、ジョン・ホランダー、リチャード・ハ ワード、シンシア・オジック、キャロリン・ゴールド・ハイルブラン、ジョージ・ステイド、デヴィッド・レーマン、レオン・ワイゼルタイアー、ルイ・メナ ン、ロバート・レナード・ムーア、ノーマン・ポドロッツらがいる。 トリリングは、1963年から1965年までオックスフォード大学のジョージ・イーストマン客員教授、1969年から1970年の学年度にはハーバード大 学のチャールズ・エリオット・ノートン詩学教授を務めた。1972年、トリリングは全米人文科学基金から、人文科学における傑出した知的業績に対して連邦 政府から授与される最高の栄誉とされるジェファーソン・レクチャーの第1回講演者に選ばれた[6]。トリリングは、ケニオン・スクール・オブ・イングリッ シュの上級研究員、その後インディアナ・スクール・オブ・レターズの上級研究員を務めた。彼は、ハーバード大学トリニティカレッジ、ケース・ウェスタン・ リザーブ大学から名誉学位を授与され、アメリカ芸術科学アカデミーおよびアメリカ芸術文学アカデミーの会員でもあった。また、ケニオン・レビューとパー ティザン・レビューの編集委員も務めた[7]。 トリリングは1975年にすい臓癌で死去した[7]。妻と息子のジェームズ・トリリング(ジョージ・ワシントン大学博物館およびテキスタイル博物館の元学 芸員を務めた美術史家)が残された[8]。甥のビリー・クロスはデンマーク在住のミュージシャンである[9]。 パーティザン・レビューと「ニューヨーク・インテレクチュアルズ」 ニューヨーク・インテレクチュアルズ」 1937年、トリリングは、ウィリアム・フィリップスとフィリップ・ラフが1934年に創刊したマルクス主義者だが反スターリン主義の雑誌『パーティザ ン・レビュー』に最近復活したばかりだった。 パ ルチザン・レビューはニューヨークの知識人たち-トリリング、妻のダイアナ・トリリング、ライオネル・アベル、ハンナ・アーレント、ウィリアム・バレッ ト、ダニエル・ベル、ソール・ベロー、リチャード・トーマス・チェイス、F. デュピー、レスリー・フィードラー、ポール・グッドマン、クレメント・グリーンバーグ、エリザベス・ハードウィック、アーヴィング・ハウ、アルフレッド・ カズン、ヒルトン・クレイマー、スティーヴン・マーカス、メアリー・マッカーシー、ドワイト・マクドナルド、ウィリアム・フィリップス、ノーマン・ポドホ レッツ、ハロルド・ローゼンバーグ、アイザック・ローゼンフェルド、デルモア・シュワルツ、スーザン・ソンタグ-彼らは作家や文学に歴史や文化が与える影 響を強調した。ニューヨークの知識人たちは、新評論とは距離を置いていた。 トリリングは、エッセイ集『Beyond Culture』(1965年)の序文で、ニューヨーク・インテレクチュアルズを擁護した。「グループとして、彼らはアイデア、さらに言えば態度につい て、多忙で活発である。彼らの熱心さは権威を構成している。私たちの社会の構造は、このような階級が、文化的流動性が低く、その影響を受けやすいグループ に有機的な糸でつながれているようなものである。」 批評と文学作品 トリリングは、裕福な共産主義者の夫婦が共産主義の亡命者と遭遇する小説『The Middle of the Journey』(1947)を1作執筆した。 (トリリングは後に、この作品の登場人物はコロンビア大学の同級生であり同時代のウィテカー・チェンバースから着想を得たことを認めた[11] [12])。彼の短編小説には『The Other Margaret』がある。それ以外には、文学が文化の道徳や慣習に挑む力を考察したエッセイや評論を執筆した。批評家のデイヴィッド・ダイチェスは、ト リリングについて次のように述べている。「トリリング氏は、特定の文学現象について熟考する際、その意味合いや文化、文明、現代人の思考との関連性を考察 することを好む。このような文脈の拡大により、彼は最も優れた洞察力を示す瞬間と、不安を覚えるような一般化を示す瞬間の両方を手に入れるのだ」。 トリリングは、作家マシュー・アーノルド(1939年)とE.M.フォースター(1943年)に関する2つの複雑な研究を発表したが、いずれも「人文主義 思想の伝統と、その伝統を継承していると信じる知識層」への懸念に応える形で書かれたものである[13]。彼の最初のエッセイ集『The Liberal Imagination』は1950年に出版され、 0、続いて『The Opposing Self』(1955年)、自己定義と文化の影響の間の葛藤に焦点を当てた『Freud and the Crisis of Our Culture』(1955年)、『A Gathering of Fugitives』(1956年)、そして自己性に対する現代文学と文化の態度をテーマにしたエッセイ集『Beyond Culture』(1965年)が出版された。『Sincerity and Authenticity』(1972)では、啓蒙主義以降の西洋文明における道徳的自己の概念を探求している。また、ジョン・キーツの『The Selected Letters of John Keats』(1951)の序文では、キーツの「消極的能力」の概念を擁護し、1952年に再版されたジョージ・オーウェルの『Homage to Catalonia』の序文「George Orwell and the Politics of Truth」も執筆している。 2008年、コロンビア大学出版局は、トリリングが1940年代後半に執筆を断念した未完の小説を出版した。学者ジェラルディン・マーフィーは、コロンビ ア大学に保管されていたトリリングの論文の中から、半分書きかけの小説を発見した[14]。トリリングの小説『The Journey Abandoned: 1930年代を舞台とし、年上の詩人ジョリス・バクストンの伝記を書こうとする主人公の青年ヴィンセント・ハメルが主人公である。ブクストンのキャラク ターは、19世紀のロマン派詩人ウォルター・サベージ・ランダーをモデルとしている[14]。作家であり批評家でもあるシンシア・オジックは、この小説の 「巧みな語り口」と「複雑なキャラクター」を賞賛し、「『The Journey Abandoned』は、 内面が、一部は対話を通して、そしてはるかに広範囲にわたって、巧みに分析された洞察の文章を通して明らかにされている、入念に描写された肖像画の密集し たギャラリーである」[15]。 政治 トリリングの政治思想は激しく議論されてきたが、彼の思想の他の多くの部分と同様に、「複雑」と表現できるかもしれない。トリリングの政治思想についてよ く引用される要約は、彼が次のように望んでいたというものである[16]。 リベラルであることを誇りに思う人々に思い起こさせること、すなわち、リベラリズムとは...、その多様性、複雑性、困難性において、個人の存在価値を肯 定する政治的な立場であるということ。 トリリングは、イデオロギーについて次のように書いている。「イデオロギーは思考の産物ではなく、感情的な安全に関わるさまざまな理由から、非常に強い絆 があり、その意味や実際の帰結について明確な理解がない特定の公式に対して敬意を示す習慣や儀式である」[17]。 政治的には、トリリングは反スターリン主義左派の著名な 反スターリン主義の左派の一員であり、生涯その立場を貫いた[18][19]。 リベラル トリリングは若い頃、保守主義を明確に否定し、リベラルな伝統の中で執筆していた。1950年のエッセイ『The Liberal Imagination』の序文(引用が多い最後の行に強調表示)から引用する。 この時代のアメリカにおいて、リベラリズムは支配的であるばかりでなく、唯一の知的伝統である。なぜなら、今日では保守的あるいは反動的な考え方が一般に 流通していないのは明白な事実だからである。もちろん、これは保守や反動への衝動が全くないという意味ではない。そのような衝動は確かに非常に強く、おそ らく私たちが知っているものよりも強いかもしれない。しかし、保守的な衝動や反動的な衝動は、孤立した例や教会的な例を除けば、思想としてではなく、行動 や、思想に似せようとする過敏な精神的な身振りとしてしか表現されない。 新保守主義 保守派とリベラル派の両方から、トリリングの考え方は時間の経過とともに次第に保守的になったという意見がある。トリリングは、新保守主義者(『コメンタ リー』誌の元編集者ノーマン・ポドロッツなど)から新保守主義に共感的な人物として受け入れられてきた。しかし、この受け入れは一方的であった。トリリン グはニューレフトを批判したが(オールドレフトを批判したように)、ネオコンを受け入れたわけではなかった。 彼の妻ダイアナ・トリリングは、トリリングが彼らの見解を共有しているとネオコンが考えるのは誤りであると主張した。「私は、彼が決して新保守主義者にな ることはなかったと固く信じている」と、彼女は結婚生活についての回顧録『旅の始まり』の中で述べている。「彼の思想には、新保守主義の宗派主義を裏付け るものは何もない」とも付け加えている[20]。 トリリングがどの程度新保守主義と結びつけられるかは、現在も議論の的であり 、議論の的となっている[21][ページ番号が必要] 穏健派 トリリングは、小説『旅の途中』というタイトルから、小説の重要な一節に至るまで、多くの発言から明らかなように、穏健派であると特徴づけられることもあ る。 責任から完全に解放される―それほど子供でいられる者はいない。絶対的な責任 - それほど神聖で形而上学的な本質は、私たちの中には誰もいない。 同じ考えに沿って、リチャード・セネットの「あなたは立場がない。常に中間にある」という嘲笑に対して、トリリングは「中間にあることが唯一誠実な場所 だ」と答えた[23][ページ番号が必要] |

| Works by Trilling Fiction The Middle of the Journey. New York: Viking Press. 1947. LCCN 47031472. Of This Time, of That Place and Other Stories. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. 1979. ISBN 015168054X. (Selected by Diana Trilling and published posthumously.) Geraldine Murphy, ed. (2008). The Journey Abandoned: The Unfinished Novel. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231144506. (Published posthumously) Non-fiction and essays Matthew Arnold. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 1939. LCCN 39027057. (Based on Trilling's Ph.D. thesis.) E.M. Forster. Norfolk, Conn.: New Directions Books. 1943. LCCN 43011336. The Liberal Imagination: Essays on Literature and Society. New York: Viking Press. 1950. LCCN 50006914. The Opposing Self: Nine Essays in Criticism. New York: Viking Press. 1955. LCCN 55005871. Freud and the Crisis of Our Culture. Boston: Beacon Press. 1955. LCCN 55011594. Gathering of Fugitives. Boston: Beacon Press. 1956. Beyond Culture: Essays on Literature and Learning. New York: Viking Press. 1965. LCCN 65024276. Sincerity and Authenticity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 1972. ISBN 0674808606. (A collection of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures given at Harvard in 1970.) Mind in the Modern World: The 1972 Thomas Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities. New York: Viking Press. 1973. ISBN 0670003778. Diana Trilling, ed. (1979). The Last Decade: Essays and Reviews, 1965–75. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 015148421X. (Published posthumously) Diana Trilling, ed. (1980). Speaking of Literature and Society. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 015184710X. (Published posthumously.) Leon Wieseltier, ed. (2000). The Moral Obligation to Be Intelligent: Selected Essays. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0374257949. (Published posthumously.) Arthur Krystal, ed. (2001). A Company of Readers: Uncollected Writings of W.H. Auden, Jacques Barzun, and Lionel Trilling from The Readers' Subscription and Mid-Century Book Clubs. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0743202627. Adam Kirsch, ed. (2018). Life in Culture: Selected Letters of Lionel Trilling. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 9780374185152. (Published posthumously.) Prefaces, afterwords, and commentaries Introduction to The Portable Matthew Arnold. New York: Viking Press. 1949. LCCN 49009982. Introduction to Selected Letters of John Keats. New York: Farrar, Straus and Young. 1951. Introduction to 'Collected Stories of Isaac Babel. New York: Criterion Books. 1955. Introduction to Austen, Jane (1957). Emma. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. (Riverside edition of Jane Austen's 1815 novel) Introduction to Pawel Mayewski, ed. (1958). The Broken Mirror: A Collection of Writings from Contemporary Poland. New York: Random House. LCCN 58010948. Introduction to Jones, Ernest (1961). The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465097005. LCCN 61-1950. Afterword to Slesinger, Tess (1966). The Unpossessed. New York: Avon Books. (Reprint of Tess Slesinger's 1934 novel.) Preface and commentaries to The Experience of Literature: A Reader with Commentaries. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. 1967. LCCN 67020030. Introduction to Trilling, Lionel (1970). Literary Criticism: An Introductory Reader. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN 0030795656. Introduction to James, Henry, The Princess Casamassima. New York, The Macmillan Company. 1948 Bibliography Alexander, Edward. Lionel Trilling and Irving Howe: And Other Stories of Literary Friendship. Transaction, 2009. ISBN 978-1-4128-1014-2.[24] Ariano, Raffaele. Filosofia dell'individuo e romanzo moderno. Lionel Trilling tra critica letteraria e storia delle idee, Edizioni Storia e letteratura, 2019. Bloom, Alexander. Prodigal Sons: The New York Intellectuals & Their World, Oxford University Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0-19-505177-3 Chace, William M. “Lionel Trilling”, Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism. Kimmage, Michael. The Conservative Turn: Lionel Trilling, Whittaker Chambers, and the Lessons of Anti-Communism. Harvard University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-674-03258-3.[24] Kirsch, Adam. Why Trilling Matters. Yale University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-300-15269-2. Krupnick, Mark. Lionel Trilling and the Fate of Cultural Criticism. Northwestern University Press, Evanston, 1986. ISBN 978-0-8101-0712-0 Lask, Thomas. “Lionel Trilling, 70, Critic, Teacher and Writer, Dies”, The New York Times, November 5, 1975 Leitch, Thomas M. Lionel Trilling: An Annotated Bibliography. New York: Garland, 1992 Longstaff, S. A. “New York Intellectuals”, Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism. O'Hara, Daniel T. Lionel Trilling: The Work of Liberation. U. of Wisconsin P, 1988. Shoben, Edward Joseph Jr. Lionel Trilling Mind and Character, Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1981, ISBN 0-8044-2815-8 Trilling, Diana. The Beginning of the Journey: The Marriage of Diana and Lionel Trilling. Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1993. ISBN 0-15-111685-7. Trilling, Lionel. Beyond Culture: Essays on Literature and Learning. Trilling, Lionel et al., The Situation in American Writing: A Symposium Partisan Review, Volume 6 5 (1939) Wald, Alan M. (1987). The New York Intellectuals: The Rise and Decline of the Anti-Stalinist Left from the 1930s to the 1980s. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4169-2. |

トリリングの作品 フィクション The Middle of the Journey. New York: Viking Press. 1947. LCCN 47031472. Of This Time, of That Place and Other Stories. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. 1979. ISBN 015168054X. (ダイアナ・トリリングが選び、死後に出版された。) ジェラルディン・マーフィー編 (2008). The Journey Abandoned: The Unfinished Novel. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231144506. (死後に出版) ノンフィクションおよびエッセイ Matthew Arnold. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 1939. LCCN 39027057. (トリリングの博士論文に基づく。) E.M. Forster. コネチカット州ノーフォーク:New Directions Books. 1943. LCCN 43011336. The Liberal Imagination: Essays on Literature and Society. ニューヨーク:Viking Press. 1950. LCCN 50006914. The Opposing Self: Nine Essays in Criticism. ニューヨーク:Viking Press. 1955. LCCN 55005871. フロイトと私たちの文化の危機。ボストン:ビーコンプレス。1955年。LCCN 55011594。 逃亡者の集い。ボストン:ビーコンプレス。1956年。 文化の彼方:文学と学問に関するエッセイ。ニューヨーク:ビーコンプレス。1965年。LCCN 65024276。 誠実さと真正性。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版。1972年。ISBN 0674808606。 (1970年にハーバード大学で行われたチャールズ・エリオット・ノートン講演会の講演録) ダイアナ・トリリング編(1979年)。『The Last Decade: エッセイと評論、1965-75年。ニューヨーク:Harcourt Brace Jovanovich。ISBN 015148421X。死後出版 ダイアナ・トリリング編(1980年)。文学と社会について。ニューヨーク:Harcourt Brace Jovanovich。ISBN 015184710X。死後出版 レオン・ワイズリター編 (2000). The Moral Obligation to Be Intelligent: Selected Essays. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0374257949. (死後出版) Arthur Krystal, ed. (2001). A Company of Readers: Uncollected Writings of W.H. Auden, Jacques Barzun, and Lionel Trilling from The Readers' Subscription and Mid-Century Book Clubs. New York: フリープレス。ISBN 0743202627。 アダム・カークシュ編(2018年)。『文化の中の生活:ライオネル・トリリングの手紙選集』。ニューヨーク:ファラー、ストラウス、アンド・ジルー。 ISBN 9780374185152。(死後出版) 序文、あとがき、解説 『ポータブル』への序文 マシュー・アーノルド。ニューヨーク:バイキング・プレス。1949 年。LCCN 49009982。 Introduction to Selected Letters of John Keats. New York: Farrar, Straus and Young. 1951. Introduction to 'Collected Stories of Isaac Babel. New York: Criterion Books. 1955. Introduction to Austen, Jane (1957). Emma. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. (ジェーン・オースティンの1815年の小説のリバーサイド版) パウエル・メイェフスキ編(1958年)『The Broken Mirror: A Collection of Writings from Contemporary Poland(壊れた鏡:現代ポーランドからの文章集)』。ニューヨーク:ランダムハウス。LCCN 58010948。 ジョーンズ、アーネスト(1961年)『The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud(ジークムント・フロイトの生涯と業績)』。ニューヨーク:ベーシック・ブックス。ISBN 9780465097005. LCCN 61-1950. Slesinger, Tess (1966). The Unpossessed. New York: Avon Books. (Tess Slesinger の 1934 年の小説の再版) のあとがき The Experience of Literature: A Reader with Commentaries. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. 1967年。LCCN 67020030。 トリリング、ライオネル(1970年)『文学批評:入門用リーディング』ニューヨーク:ホルト、ラインハート、ウィンストン。ISBN 0030795656。 ジェームズ、ヘンリー『カスアミッサ姫』ニューヨーク、マクミラン社。1948年 参考文献 アレクサンダー、エドワード。ライオネル・トリリングとアーヴィング・ハウ: そして、その他の文学的友情の物語。Transaction、2009年。ISBN 978-1-4128-1014-2。 Ariano, Raffaele. Filosofia dell'individuo e romanzo moderno. Lionel Trilling tra critica letteraria e storia delle idee, Edizioni Storia e letteratura, 2019年。 Bloom, Alexander. Prodigal Sons: 『放蕩息子たち:ニューヨーク知識人と彼らの世界』オックスフォード大学出版、1986年。ISBN 978-0-19-505177-3 ウィリアム・M・チェイス著「ライオネル・トリリング」『ジョンズ・ホプキンス文学理論・批評ガイド』。 マイケル・キンメージ著『保守派の転換:ライオネル・トリリング、ウィテカー・チェンバーズ、反共産主義の教訓』。ハーバード大学出版、2009年。 ISBN 978-0-674-03258-3。 Kirsch, Adam. Why Trilling Matters. Yale University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-300-15269-2. Krupnick, Mark. Lionel Trilling and the Fate of Cultural Criticism. Northwestern University Press, Evanston, 1986. ISBN 978-0-8101-0712-0 Lask, Thomas. “Lionel Trilling, 70, Critic, Teacher and Writer, Dies”, The New York Times, November 5, 1975 Leitch, Thomas M. Lionel Trilling: An Annotated Bibliography. New York: ガーランド、1992年 ロングスタッフ、S. A. 「ニューヨークのインテリ」、『ジョンズ・ホプキンス文学理論・批評ガイド』。 オハラ、ダニエル T. 『ライオネル・トリリング:解放の業』。ウィスコンシン大学出版、1988年。 ショベン、エドワード・ジョセフ・ジュニア著『ライオネル・トリリングの思想と性格』フレデリック・ウンガー出版、1981年、ISBN 0-8044-2815-8 トリリング、ダイアナ著『旅の始まり:ダイアナとライオネル・トリリングの結婚』ハーコート・ブレス・アンド・カンパニー、1993年、ISBN 0-15-111685-7 トリリング、ライオネル著『文化を超えて: 文学と学問に関するエッセイ ライオネル・トリリングほか『アメリカ文学の状況:シンポジウム』『パーティザン・レビュー』第6巻第5号(1939年) アラン・M・ウォルド(1987年)『ニューヨーク知識人:1930年代から1980年代における反スターリン主義左派の台頭と衰退』ノースカロライナ大 学出版。ISBN 0-8078-4169-2。 |

| 1)誠実——その起源と発生 2)正直な魂と崩壊した意識 3)存在感と芸術感情 4)英雄的なもの、美的なものと、《ほんもの》と 5)社会とほんものの自我 6)ほんものの無意識 |

|

| 1)誠実——その起源と発生 ・誠実が英語のなかに登場するのは16世紀の3分の1あたり(23) ・16世紀の晩期、17世紀の初期に、人間の理想的な価値基準が《誠実》から《ほんもの》に変わる?(33) |

・誠実さとは、自分の感情、信念、思考、欲求のすべてに従って、正直か

つ真正直に伝え、行動する人の美徳である。コミュニケーションとは対照的に)行動における誠実さは、「真摯さ」と呼ばれることもある。(→誠実) |

| 2)正直な魂と崩壊した意識 ・ラモーの甥が、啓蒙思想がもたらした誠実概念の崩壊を予兆する? ・フロイトが気に入っていた。ラモーの甥が、エディブス・コンプレックスまがいの話を開陳する対話がある(44) ・精神現象学とラモーの甥(51-) ・カルチャーとは、ヘーゲルによれば「卑劣な自我に独特の経験の場である」(63) ・ヘーゲルは、ラモーの甥をかなり我田引水式に読んでいる(67) |

・「読者は彼=ラモーの甥が誠実なのか挑発的なのか、決して知ることが

できない。印象としては、些細な出来事の中に巧妙に埋め込まれた真実の塊である」『ラモー

の甥』 ・ラモーの甥は、社会批判。それは、不誠実の原理のうえに社会がなりたっているから(49) ・この場合の不誠実は「自己疎外」のことのようである。 ・【これは翻訳者の注解文】Much of Hegel's analysis of the first stage of this spiritual movement has also directly in view the character of Rameau in Diderot's Le neveu de Rameau. This remarkable work was written in 1760, but was first brought to the notice of the literary public by Goethe, who translated and published the work in 1805. It thus came into Hegel's hands while he was writing the Phenomenology: and this perhaps accounts the repeated references to it in the argument. The term "self−estranged spirit" with which he heads this section occurs in Goethe's translation. Rameau is an extreme type of such a spirit. (ヘーゲルのこの精神運動の第一段階に関する分析の多くは、ディドロの『ラモーの甥』におけるラモーの性格を直接的に視野に入れている。この注目すべき作 品は1760年に書かれたが、文学界で注目されるようになったのは、ゲーテが1805年に翻訳して出版してからである。ヘーゲルが『現象学』を執筆中に、 この作品が彼の目に留まった。おそらく、このことが、議論の中で繰り返し言及されている理由であろう。ヘーゲルがこのセクションのタイトルに用いた「自己 疎外の精神」という用語は、ゲーテの翻訳に登場する。ラモーは、そのような精神の極端なタイプである。)《出典》 |

| 4)英雄的なもの、美的なものと、《ほんもの》と | |

| 5)社会とほんものの自我 | |

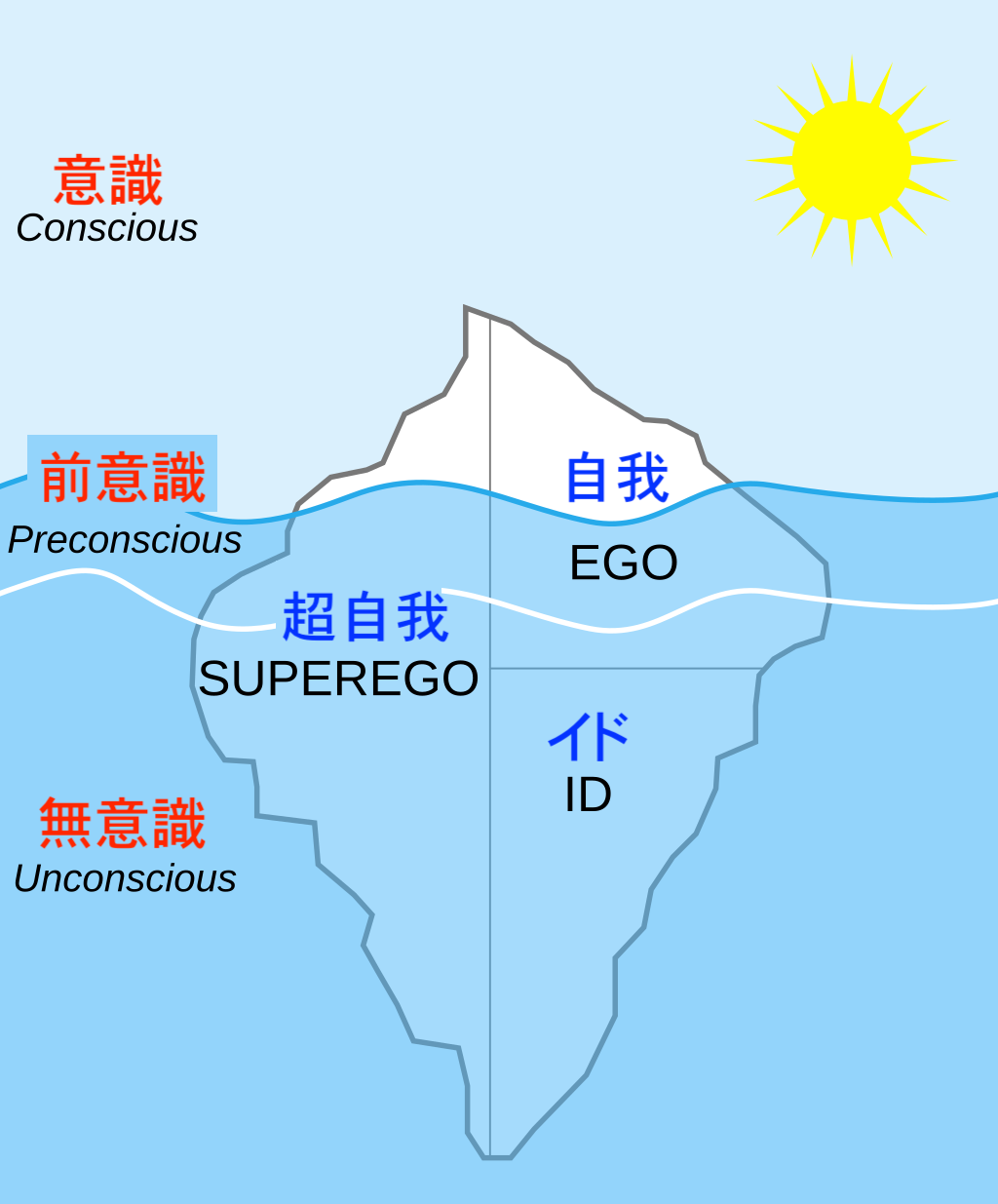

6)ほんものの無意識(→「ジークムント・フロイト」) ・フロイトの弁「意識の拠点たるエゴとは無意識である『イドの正面』である」(193) ・フロイトは、1919年(彼が63歳の時点)以降、無意識の理論とくにエゴについての理論に徹底的に修正を加えはじめる(199)→エゴにも無意識の部分がある。1923年 『自我(エゴ)とイド』 ・無意識のなかにも規則性(意図性)がある(202) ・フロイトもとうとう「ニセモノの自我(エゴ)」を認めざるをえなくなる。そのニセモノの自我が、社会と葛藤をおこす(→「文明とその不安」の視点につづく) ・社会と個人の対立とそのジレンマ(「文明とその不安」は社会が個人の本能を抑圧するという視点で描く) ・抑圧に反発するエゴと無意識のダイナミズムも想定していただろう(か?)(204) ・罪悪感ではなく「責任の負債?=苛責(かせき)」(205-206) |

・「わたしたちは、みな病気」(13, 194)——精神分析入門 ・ 【患者による否認の例?】"This is all very nice and interesting. And I would be glad to continue it. It would affect my malady considerably if it were true. But I don't believe that it is true and as long as I don't believe it, it has nothing to do with my sickness." a-general-introduction-to-psychoanalysis, p.256(「これはとても素晴らしいことだし、興味深いことだ。ぜひ続けてほしい。もしそれが本当なら、私の病気にかなり影響するだろう。しかし、私は それが真実だとは信じていないし、信じていない限り、私の病気とは何の関係もない。」) ・"But if you take a theoretical standpoint and disregard these quantitative relations, you can readily say that we are all sick, or rather neurotic, since the conditions favorable to the development of symptoms are demonstrable also among normal persons." p.315. (しかし、理論的な立場に立ち、このような量的な関係を無視するならば、私たちはみな病気であり、むしろ神経症なのだ) |

★

ヘーゲル『精神現象学』における自己疎外 - The Phenomenology of Mind, C: Free Concrete Mind:

(BB) Spirit, B: The Spirit in Self-Estrangement — The Discipline of

Culture and Civilisation (2)

| Φ 484. The ethical

substance preserved and kept opposition enclosed within its simple

conscious life; and this consciousness was in immediate unity with its

own essential nature. That nature has therefore the simple

characteristic of something merely existing for the consciousness which

is directed immediately upon it, and whose “custom” (Sitte) it is.

Consciousness does not take itself to be particular excluding self, nor

does the substance mean for it an existence shut out from it, with

which it would have to establish its identity only through estranging

itself and thus at the same time have to produce that substance. But

that spirit, whose self is absolutely insular, absolutely discrete,

finds its content over against itself in the form of a reality that is

just as impenetrable as itself, and the world here gets the

characteristic of being something external, negative to

self-consciousness. Yet this world is a spiritual reality, it is

essentially the fusion of individuality with being. This its existence

is the work of self-consciousness, but likewise an actuality

immediately present and alien to it, which has a peculiar being of its

own, and in which it does not know itself. This reality is the external

element and the free content(1) of the sphere of legal right. But this

external reality, which the lord of the world of legal right takes

control of, is not merely this elementary external entity casually

lying before the self; it is his work, but not in a positive sense,

rather negatively so. It acquires its existence by self-consciousness

of its own accord relinquishing itself and giving up its essentiality,

the condition which, in that waste and ruin which prevail in the sphere

of right, the external force of the elements let loose seems to bring

upon self-consciousness. These elements by themselves are sheer ruin

and destruction, and cause their own overthrow. This overthrow,

however, this their negative nature, is just the self; it is their

subject, their action, and their process. Such process and activity

again, through which the substance becomes actual, are the estrangement

of personality, for the immediate self, i.e. the self without

estrangement and holding good as it stands, is without substantial

content, and the sport of these raging elements. Its substance is thus

just its relinquishment, and the relinquishment is the substance, i.e.

the spiritual powers forming themselves into a coherent world and

thereby securing their subsistence. |

Φ 484.

倫理的な実体は、その単純な意識的生命の中に反対勢力を保持し、封じ込めたままであり、この意識はそれ自身の本質的な性質と即座に一体であった。それゆ

え、その本性は、それに直ちに向けられ、その「習慣」(Sitte)である意識のために単に存在するものという単純な特徴を持っている。意識は、それ自身

を、自己を排除した特殊なものだとは考えず、また、物質が、そこから締め出された存在を意味するわけでもない。しかし、自己が絶対的に孤立し、絶対的に分

離しているその精神は、自己と同じように不可解な現実という形で、自己と対立する内容を見出す。しかし、この世界は精神的現実であり、本質的に個性と存在

の融合である。その存在は自意識の仕事であるが、同様に、自意識に即座に存在し、自意識とは異質な実在であり、その実在はそれ自身の独特な存在を持ち、そ

の中で自意識を知らない。この現実は、法的権利の領域の外的要素であり、自由な内容(1)である。しかし、法的権利の世界の領主が支配するこの外的実在

は、単に自己の前に何気なく横たわっているこの素朴な外的実体ではなく、それは彼の作品であるが、肯定的な意味においてではなく、むしろ否定的な意味にお

いてである。それは、権利の領域に蔓延する浪費と破滅の中で、放たれた諸要素の外的な力が自己意識にもたらすと思われる条件である本質性を、自己意識が自

らの意志で放棄し、手放すことによって、その存在を獲得するのである。これらの要素はそれ自体、まったくの破滅であり、破壊であり、自らの転覆を引き起こ

す。しかし、この転覆、つまり彼らの否定的な性質は、まさに自己であり、

彼らの主体であり、活動であり、その過程である。このような過程と活動は、物質が現実になることを通して、再び人格の疎外となる。なぜなら、直接的な自

己、すなわち疎外のない自己であり、そのまま善を保持する自己は、実質的な内容を持たず、これらの荒れ狂う要素のスポーツだからである。それゆえ、その実

体は単にその放棄であり、放棄は実体、すなわち霊的な力がそれ自身を首尾一貫した世界に形成し、それによってその存続を確保することなのである。 |

| Φ 485. The substance in this way

is spirit, self-conscious unity of the self and the essential nature;

but both also take each other to mean and to imply alienation. Spirit

is consciousness of an objective reality which exists independently on

its own account. Over against this consciousness stands, however, that

unity of the self with the essential nature, consciousness pure and

simple over against actual consciousness. On the one side actual

self-consciousness by its self-relinquishment passes over into the real

world, and the latter back again into the former. On the other side,

however, this very actuality, both person and objectivity, is cancelled

and superseded; they are purely universal. This their alienation is

pure consciousness, or the essential nature. The “present” has directly

its opposite in its “beyond”, which is its thinking and its being

thought; just as this again has its opposite in what is here in the

“present”, which is the actuality of the “beyond” but alienated from it. |

Φ 485. このような意味での実体とは精神であり、自己と本質的な性質との自己意識的な一体性であるが、両者はまた、互いに疎外を意味し、意味するものでもある。精 神とは、それ自身の責任において独立して存在する客観的現実の意識である。しかし、この意識の向こう側には、自己と本質的自然との一体性、つまり、現実の 意識に対する純粋で単純な意識が立っている。一方では、現実の自己意識は、その自己放棄によって現実世界に入り込み、後者は再び前者に戻る。しかし、他方 では、この現実性そのものが、人格も客観性も、打ち消され、取って代わられる。この疎外は純粋意識、すなわち本質である。現在」は、その「彼方」にその対 極を直接持っている。それは「彼方」の思考であり、思考されることである。 |

| Φ 486. Spirit in this case,

therefore, constructs not merely one world, but a twofold world,

divided and self-opposed. The world of the ethical spirit is its own

proper present; and hence every power it possesses is found in this

unity of the present, and, so far as each separates itself from the

other, each is still in equilibrium with the whole. Nothing has the

significance of a negative of self-consciousness; even the spirit of

the departed is in the life-blood of his relative, is present in the

self of the family, and the universal power of government is the will,

the self of the nation. Here, however, what is present means merely

objective actuality, which has its consciousness in the beyond; each

single moment, as an essential entity, receives this, and thereby

actuality, from an other, and so far as it is actual, its essential

being is something other than its own actuality. Nothing has a spirit

self-established and indwelling within it; rather, each is outside

itself in what is alien to it. The equilibrium of the whole is not the

unity which abides by itself, nor its inwardly secured tranquillity,

but rests on the estrangement of its opposite. The whole is, therefore,

like each single moment, a self-estranged reality. It breaks up into

two spheres: in one kingdom self-consciousness is actually both the

self and its object, and in another we have the kingdom of pure

consciousness, which, being beyond the former, has no actual present,

but exists for Faith, is matter of Belief. Now just as the ethical

world passes from the separation of divine and human law, with its

various forms, and its consciousness gets away from the division into

knowledge and the absence of knowledge, and returns into the principle

which is its destiny, into the self which is the power to destroy and

negate this opposition, so, too, both these kingdoms of self-alienated

spirit will return into the self. But if the former, the first self

holding good directly, was the single person, this second, which

returns into itself from its self-relinquishment, will be the universal

self, the consciousness grasping the conception; and these spiritual

worlds, all of whose moments insist on having a fixed reality and an

un-spiritual subsistence, will be dissolved in the light of pure

Insight. This insight, being the self grasping itself, completes the

stage of culture. It takes up nothing but the self, and everything as

the self, i.e. it comprehends everything, extinguishes all

objectiveness, and converts everything implicit into something

explicit, everything which has a being in itself into what is for

itself. When turned against belief, against faith, as the alien realm

of inner being lying in the distant beyond, it is Enlightenment

(Aufklärung). This enlightenment completes spirit's self-estrangement

in this realm too, whither spirit in self-alienation turns to seek its

safety as to a region where it becomes conscious of the peace of

self-equipoise. Enlightenment upsets the household arrangements, which

spirit carries out in the house of faith, by bringing in the goods and

furnishings belonging to the world of the Here and Now, a world which

that spirit cannot refuse to accept as its own property, for its

conscious life likewise belongs to that world. In this negative task

pure insight realizes itself at the same time, and brings to light its

own proper object, the “unknowable absolute Being” and utility.(2)

Since in this way actuality has lost all substantiality, and there is

nothing more implicit in it, the kingdom of faith, as also that of the

real world, is overthrown; and this revolution brings about absolute

freedom,, the stage at which the spirit formerly estranged has gone

back completely into itself, leaves behind this sphere of culture, and

passes over into another region, the land of the inner or subjective

moral consciousness (moralischen Bewusstsein). https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/ph/phc2b.htm |

Φ 486.

それゆえ、この場合の精神は、単に一つの世界を構築するのではなく、分割され自己対立する二重の世界を構築するのである。倫理的精神の世界は、それ自身の

適切な現在であり、それゆえ、それが持つあらゆる力は、この現在の統一性の中に見出され、それぞれが他から分離する限りにおいて、それぞれは依然として全

体と均衡を保っている。亡くなった人の魂でさえ、その親族の生き血の中にあり、家族の自己の中に存在し、政府の普遍的な権力は国家の意志であり、自己であ

る。しかし、ここでいう「現在」とは、単に客観的な実在性を意味するのであって、それは彼方にその意識を持つものである。何ものも、その内側に自らを確立

し内在する精神を持ってはいない。むしろ、それぞれが、それとは異質なものにおいて、自らの外側にあるのである。全体の均衡は、それ自体によって存在する

統一でもなく、内的に確保された平穏でもなく、その対極にあるものの疎遠の上に成り立っている。それゆえ、全体は一瞬一瞬と同じように、自らを離れた現実

なのである。一つの王国では、自己意識は実際に自己であると同時にその対象でもあり、もう一つの王国では、純粋意識の王国があり、それは前者を超えている

ため、実際の現在を持たず、信仰のために存在し、信念の問題である。さて、倫理的世界が、さまざまな形態を持つ神と人間の法則の分離から抜け出し、その意

識が、知識と知識の不在への分裂から離れ、その運命である原理の中、この対立を破壊し否定する力である自己の中に戻っていくように、自己を疎外した精神の

これらの王国もまた、自己の中に戻っていくのである。しかし、前者、善を直接保持する第一の自己が一人の人間であったとすれば、自己放棄から自己の中に戻

るこの第二の自己は、普遍的な自己、観念を把握する意識となる。この洞察は、それ自身を把握する自己であり、文化の段階を完成させる。つまり、すべてを理

解し、すべての客観性を消し去り、すべての暗黙的なものを明示的なものに変え、それ自体に存在するものをそれ自体のためにあるものに変える。遠い彼方に横

たわる内なる存在の異質な領域としての信念、信仰に対して向けられるとき、それは悟り(Aufklärung)である。この悟りは、この領域においても精

神の自己疎外を完成させる。自己疎外に陥った精神は、自己平等の平安を意識するようになる領域へと、その安全を求めるために向かうのである。悟りは、

「今、ここ」の世界に属する品物や調度品を持ち込むことによって、精神が信仰の家で行っている家庭の取り決めを混乱させる。この否定的な作業において、純

粋な洞察は同時に自らを実現し、自らの本来の対象である「知ることのできない絶対的存在」と効用を明るみに出すのである。

(2)このようにして、現実性はすべての実質性を失い、それ以上何も暗示されなくなったので、信仰の王国は、現実世界の王国と同様に、打倒される。この革

命は絶対的自由をもたらし、以前は疎遠であった精神が完全に自己の中に戻り、この文化の領域を離れ、別の領域、内的または主観的な道徳的意識

(moralischen Bewusstsein)の土地に渡る段階である。 |

| Φ 487. THE sphere of spirit at

this stage breaks up into two regions. The one is the actual world,

that of self-estrangement, the other is that which spirit constructs

for itself in the ether of pure consciousness raising itself above the

first. This second world, being constructed in opposition and contrast

to that estrangement, is just on that account not free from it; on the

contrary, it is only the other form of that very estrangement, which

consists precisely in having a conscious existence in two sorts of

worlds, and embraces both. Hence it is not self-consciousness of

Absolute Being in and for itself, not Religion, which is here dealt

with: it is Belief, Faith, in so far as faith is a flight from the

actual world, and thus is not a self-complete experience (an und für

sich). Such flight from the realm of the present is, therefore,

directly in its very nature a dual state of mind. Pure consciousness is

the sphere into which spirit rises: but it is not only the element of

faith, but of the notion as well. Consequently both appear on the scene

together at the same time, and the former comes before us only in

antithesis to the latter. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/ph/phc2b1.htm |

Φ 487.

この段階での精神の領域は2つの領域に分かれる。ひとつは現実の世界、すなわち自己疎外の世界であり、もうひとつは精神が純粋意識のエーテルの中で、第一

の世界の上に自らを高めて構築する世界である。この第二の世界は、その疎外と対立し、対照的に構築されているが、それだけに、疎外から自由ではない。それ

どころか、それはまさにその疎外のもう一つの形態にすぎず、二つの種類の世界に意識的存在を持つことで、まさに成り立っており、その両方を包含している。

信仰が現実世界からの逃避である限りにおいて、それは信仰であり、自己完結した経験(an und für

sich)ではない。したがって、このような現実世界からの逃避は、その本質において、直接的には二重の心の状態である。純粋意識は精神が上昇する領域で

あるが、それは信仰の要素であるだけでなく、観念の要素でもある。その結果、両者は同時に登場し、前者は後者に対するアンチテーゼとしてのみ私たちの前に

現れる。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆