『ラモーの甥』

Rameau's Nephew, 1761-1774?[1805]

☆ 『ラモーの甥、または第二の風刺』(または『ラモーの甥』、フランス語:Le Neveu de Rameau ou La Satire seconde)は、ドニ・ディドロによる架空の哲学的対話であり、おそらく1761年から1774年の間に書かれたものである。 1805年にゲーテによるドイツ語訳が初めて出版されたが、使用されたフランス語の原稿はその後行方不明となった。ドイツ語版はド・ソーとサン=ジュニエ によってフランス語に翻訳され、1821年に出版された。フランス語原稿に基づく最初の出版版は、1823年にブリエ版ディドロ全集に収録された。現代の 版は、1890年にパリの古書店で楽譜を購入した際に、ジョルジュ・モンヴァル(Georges Monval)が発見したディドロ自身の筆による完全な原稿に基づいている。モンヴァルは1891年にその原稿の版を出版した。その後、その原稿はニュー ヨークのピアポント・モーガン図書館が購入した。 アンドリュー・S・カランによると、ディドロがその対話を生前出版しなかったのは、著名な音楽家、政治家、財政家たちを題材にしていたため、逮捕の可能性 があったからだという。

★「肝心な点は、たやすく、自由に、愉快に、どっさりと、毎晩御不浄に行くことです。「おお貴重な糞便(O stercus pretiosum!)」これこそはどんな身分にも起こる生活の偉大な結果です」——ディドロ『ラモーの甥』本田喜代治・ 平岡昇訳、岩波文庫、p.37、岩波書店、1964年。(→「うんこの哲学」)

| Rameau's Nephew, or

the Second Satire (or The Nephew of Rameau, French: Le Neveu de Rameau

ou La Satire seconde) is an imaginary philosophical conversation by

Denis Diderot, probably written between 1761 and 1774.[1][2] It was first published in 1805 in German translation by Goethe,[1] but the French manuscript used had subsequently disappeared. The German version was translated back into French by de Saur and Saint-Geniès and published in 1821. The first published version based on French manuscript appeared in 1823 in the Brière edition of Diderot's works. Modern editions are based on the complete manuscript in Diderot's own hand found by Georges Monval, the librarian at the Comédie-Française in 1890, while buying music scores from a second-hand bookshop in Paris.[3][4] Monval published his edition of the manuscript in 1891. Subsequently, the manuscript was bought by the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York. According to Andrew S. Curran, Diderot did not publish the dialogue during his lifetime because his portrayals of famous musicians, politicians and financiers would have warranted his arrest.[5] |

『ラモーの甥、または第二の風刺』(または『ラモーの甥』、フランス

語:Le Neveu de Rameau ou La Satire

seconde)は、ドニ・ディドロによる架空の哲学的対話であり、おそらく1761年から1774年の間に書かれたものである。 1805年にゲーテによるドイツ語訳が初めて出版されたが[1]、使用されたフランス語の原稿はその後行方不明となった。ドイツ語版はド・ソーとサン= ジュニエによってフランス語に翻訳され、1821年に出版された。フランス語原稿に基づく最初の出版版は、1823年にブリエ版ディドロ全集に収録され た。現代の版は、1890年にパリの古書店で楽譜を購入した際に、ジョルジュ・モンヴァル(Georges Monval)が発見したディドロ自身の筆による完全な原稿に基づいている。モンヴァルは1891年にその原稿の版を出版した。その後、その原稿はニュー ヨークのピアポント・モーガン図書館が購入した。 アンドリュー・S・カランによると、ディドロがその対話を生前出版しなかったのは、著名な音楽家、政治家、財政家たちを題材にしていたため、逮捕の可能性 があったからだという。[5] |

| Description This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The recounted story takes place in the Café de la Régence, where Moi ("Me"), a narrator-like persona (often mistakenly supposed to stand for Diderot himself), describes for the reader a recent encounter he has had with the character Lui ("Him"), referring to—yet not literally meaning—Jean-François Rameau, the nephew of the famous composer,[6] who has engaged him in an intricate battle of wits, self-reflexivity, allegory and allusion. Lui defends a worldview based on cynicism, hedonism and materialism.[7] Recurring themes in the discussion include the Querelle des Bouffons (the French/Italian opera battle), education of children, the nature of genius and money. The often rambling conversation pokes fun at numerous prominent figures of the time. In the prologue that precedes the conversation, the first-person narrator frames Lui as eccentric and extravagant, full of contradictions, "a mixture of the sublime and the base, of good sense and irrationality". Effectively being a provocateur, Lui seemingly extols the virtues of crime and theft, raising love of gold to the level of a religion. Moi appears initially to have a didactic role, while the nephew (Lui) succeeds in conveying a cynical, if perhaps immoral, vision of reality. According to Andrew S. Curran, the main themes of this work are the consequences of God's non-existence for the possibility of morality and the distinction between human beings and animals.[8] Michel Foucault, in his Madness and Civilization, saw in the ridiculous figure of Rameau's nephew a kind of exemplar of a uniquely modern incarnation of the Buffoon. |

説明 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の記載がない内容は、異議申し立ておよび削除される場合があります。 (2019年10月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 語り直された物語は、カフェ・ド・ラ・レジダンスで起こる。語り手のような人物である「私」(しばしばディドロ自身と誤解される)が、読者に対して、最近 「彼」と遭遇したことを説明する。 ルイ(「彼」)は、有名な作曲家の甥であるジャン=フランソワ・ラモーを指しているが、文字通りの意味ではない。ラモーは、彼と複雑な知恵比べ、自己反 省、寓話、暗示の戦いを繰り広げた。ルイは、シニシズム、快楽主義、唯物論に基づく世界観を擁護している。 議論のテーマとして繰り返し登場するのは、道化師論争(フランス/イタリアのオペラ論争)、子供の教育、天才と金銭の本質などである。とりとめのない会話は、当時の数多くの著名人を揶揄している。 会話に先立つプロローグでは、一人称の語り手はルイを「気まぐれで贅沢、矛盾だらけの、崇高と卑俗、良識と非合理の混合体」と表現している。事実上、ルイ は挑発者であり、犯罪や窃盗の美徳を称賛しているように見える。また、モアは当初は教訓的な役割を担っているように見えるが、甥(ルイ)は、おそらくは不 道徳ではあるが、現実に対するシニカルな見方を伝えることに成功している。 アンドリュー・S・カランによると、この作品の主なテーマは、道徳の可能性に対する神の不在の影響と、人間と動物の区別である。 ミシェル・フーコーは著書『狂気と文明』の中で、ラモーの甥の滑稽な姿を、道化の現代的な化身の典型的な例として捉えている。 |

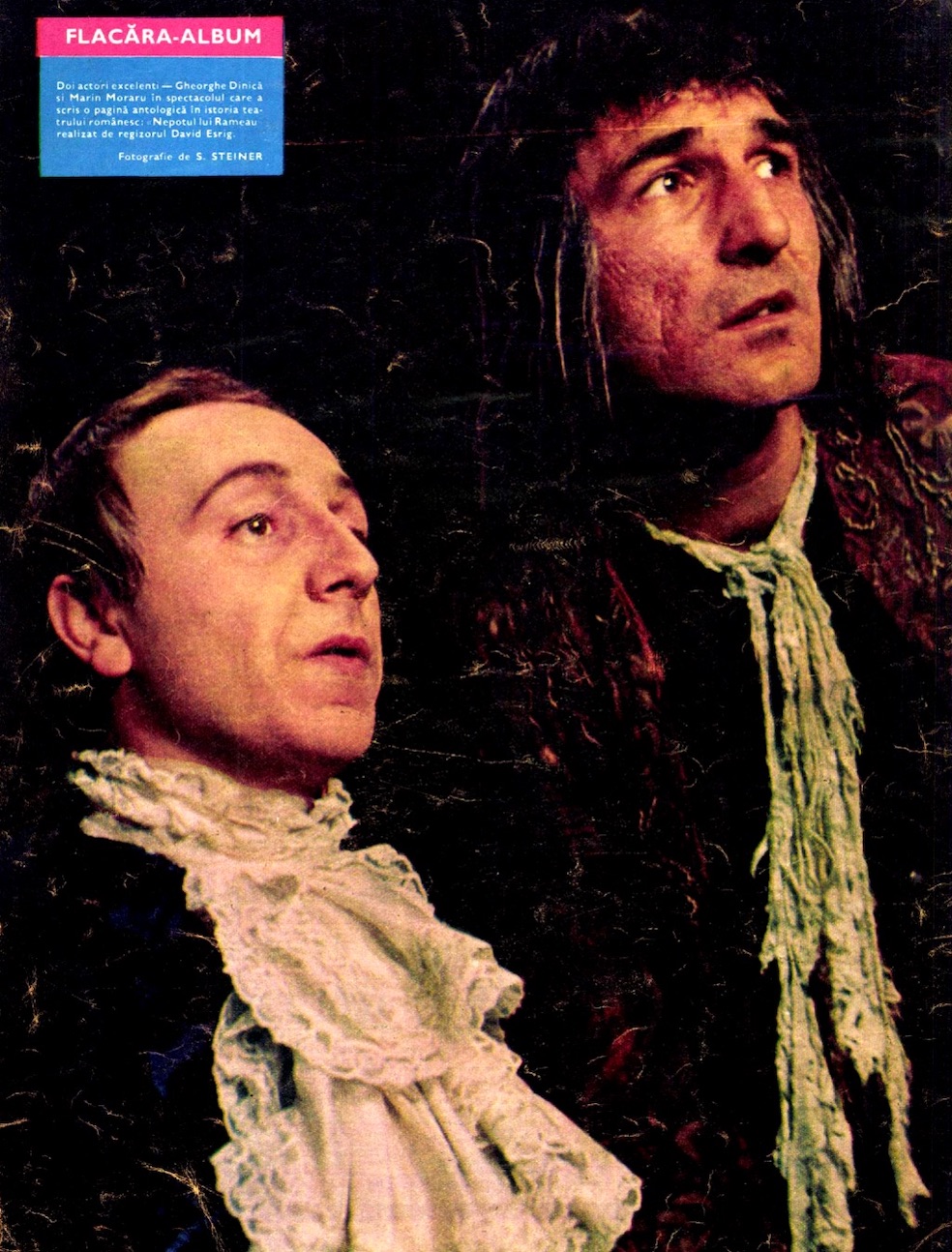

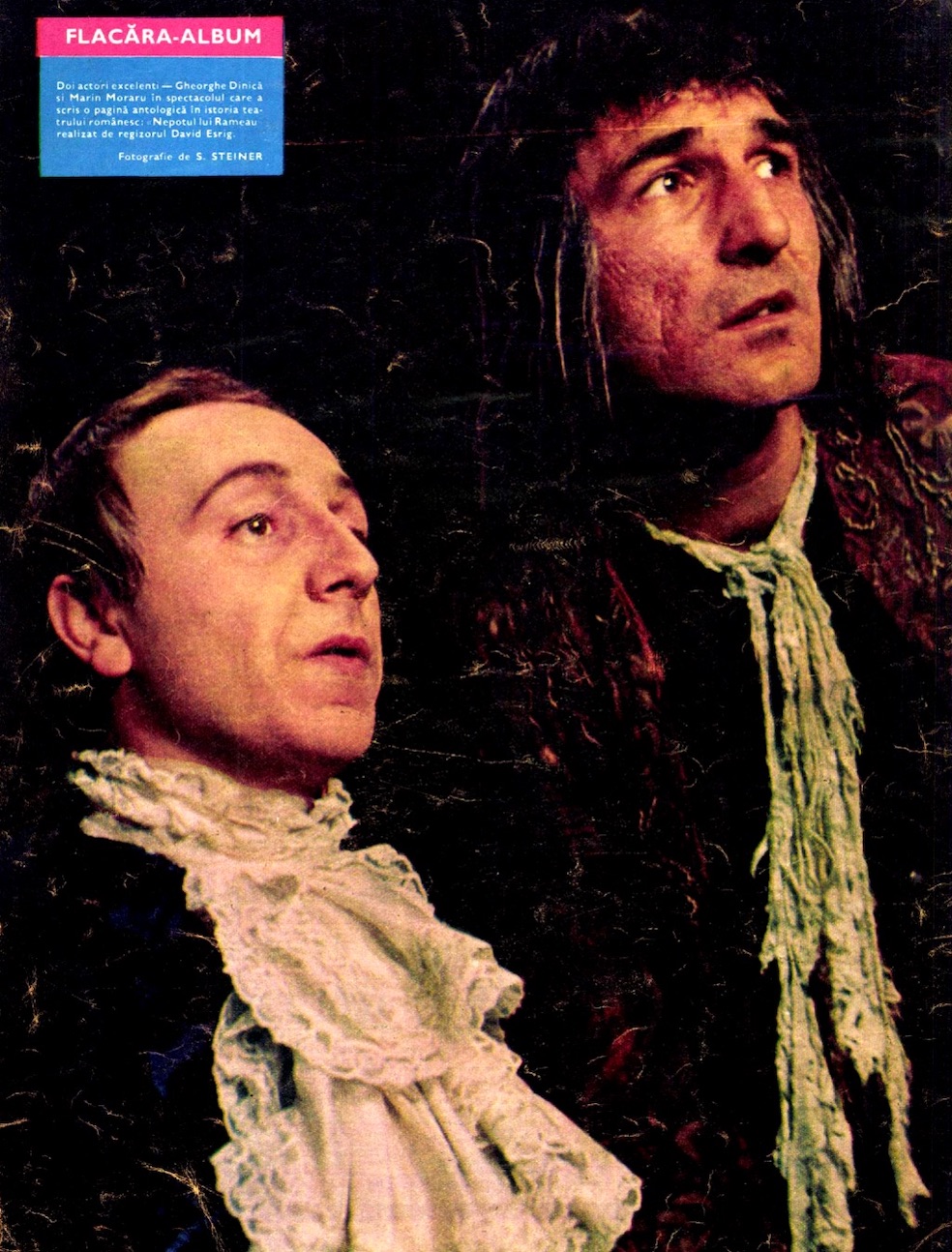

Summary Gheorghe Dinică (on the right) and Marin Moraru in David Esrig's 1968 production of the play (Nepotul lui Rameau Bulandra Theater, Bucharest); photograph by S. Steiner for Flacăra Preface The narrator has made his way to his usual haunt on a rainy day, the Café de la Régence, France's chess mecca, where he enjoys watching such masters as Philidor or Legall. He is accosted by an eccentric figure: I do not esteem such originals. Others make them their familiars, even their friends. Such a man will draw my attention perhaps once a year when I meet him because his character offers a sharp contrast with the usual run of men, and a break from the dull routine imposed by one's education, social conventions and manners. When in company, he works as a pinch of leaven, causing fermentation and restoring each to his natural bend. One feels shaken and moved; prompted to approve or blame; he causes truth to shine forth, good men to stand out, villains to unmask. Then will the wise man listen and get to know those about him.[9] Dialogue The dialogue form allows Diderot to examine issues from widely different perspectives. The character of Rameau's nephew is presented as extremely unreliable, ironical and self-contradicting, so that the reader may never know whether he is being sincere or provocative. The impression is that of nuggets of truth artfully embedded in trivia. A parasite in a well-to-do family, Rameau's nephew has recently been kicked out because he refused to compromise with the truth. Now he will not humble himself by apologizing. And yet, rather than starve, shouldn't one live at the expense of rich fools and knaves as he once did, pimping for a lord? Society does not allow the talented to support themselves because it does not value them, leaving them to beg while the rich, the powerful and stupid poke fun at men like Buffon, Duclos, Montesquieu, Rousseau, Voltaire, D'Alembert and Diderot.[9] The poor genius is left with but two options: to crawl and flatter or to dupe and cheat, either being repugnant to the sensitive mind. If virtue had led the way to fortune, I would either have been virtuous or pretended to be so like others; I was expected to play the fool, and a fool I turned myself into.[9] |

概要 ゲオルゲ・ディニカ(右)とマリン・モラル、1968年のデビッド・エスリグ演出による同劇(ブカレスト、ブルダンドラ劇場)での様子。S. スタイナー撮影、Flacăra誌掲載 序文 語り手は雨の日にいつもの溜まり場であるフランスのチェスのメッカ、カフェ・ド・ラ・レジャンスへとやってきた。そこで彼は、フィリドールやルガルといっ た名人たちを眺めるのが好きだった。彼は風変わりな人物に話しかけられる。私はそのような変わり者を尊敬していない。他の人々は彼らを身近な存在とし、友 人とさえする。そのような人物は、その性格が通常の人間とは鋭い対照をなしており、教育や社会通念、マナーによって課せられる退屈な日常からの脱却となる ため、おそらく年に一度は彼に会うと私の注意を引く。彼と一緒のときは、彼はパン種のような働きをし、発酵を起こさせ、それぞれを本来の姿に戻す。人は揺 さぶられ、感動し、是認したり非難したりしたくなる。彼は真実を明らかにし、善良な人間を際立たせ、悪人を正体を現す。すると賢者は耳を傾け、身の回りの 人々を知ろうとする。[9] 対話 対話形式により、ディドロはさまざまな視点から問題を検証することが可能となる。ラモーの甥の性格は、極めて信頼できない人物として、皮肉で自己矛盾に満 ちた人物として描かれている。そのため、読者は彼が誠実なのか挑発的なのか、決して知ることができない。印象としては、些細な出来事の中に巧妙に埋め込ま れた真実の塊である。 裕福な家庭に寄生していたラモーの甥は、真実と妥協することを拒んだために最近追い出された。今、彼は謝罪して謙虚になるつもりはない。しかし、飢え死に するくらいなら、かつてのように、貴族の愛人となって金持ちの愚か者や悪党の犠牲になって生きるべきではないだろうか? 社会は才能ある人間を評価しないため、彼らを養うことはできない。才能ある人間は乞食になるしかないが、その一方で、富裕層や権力者、そして愚か者たち は、ビュフォン、デュクロ、モンテスキュー、ルソー、ヴォルテール、ダランベール、ディドロといった人々を嘲笑する。[9] 貧しい天才には、へつらうか、だますか、という2つの選択肢しか残されていない。どちらも繊細な心には耐えられない。もし美徳が富への道を導いていたな ら、私も美徳を実践するか、あるいはそう装っていたことだろう。私は愚か者になることを期待されていたし、実際に愚か者になったのだ。[9] |

| History In Rameau's Nephew, Diderot attacked and ridiculed the critics of the Enlightenment, but he knew from past experience that some of his enemies were sufficiently powerful to have him arrested or the work banned. Diderot had been imprisoned in 1749 after publishing his Lettre sur les aveugles (Letter about the Blind) and his Encyclopédie had been banned in 1759. Prudence, therefore, may have dictated that he showed it only to a select few. After the death of Diderot, a copy of the manuscript was sent to Russia, along with Diderot's other works.[10] In 1765, Diderot had faced financial difficulties, and the Empress Catherine the Great of Russia had come to his help by buying out his library. The arrangement was quite a profitable one for both parties, Diderot becoming the paid librarian of his own book collection, with the task of adding to it as he saw fit, while the Russians enjoyed the prospect of one day being in possession of one of the most selectively stocked European libraries, not to mention Diderot's papers.[11][12] An appreciative Russian reader communicated the work to Schiller, who shared it with Goethe who translated it into German in 1805.[1] The first published French version was actually a translation back into French from Goethe's German version. This motivated Diderot's daughter to publish a doctored version of the manuscript. In 1890, the librarian Georges Monval found a copy of Rameau's Nephew by Diderot's own hand while browsing the bouquinistes along the Seine. This complete version is now in a vault in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York City.[13] Hegel quotes Rameau's Nephew in §522 and §545 of his Phenomenology of Spirit. |

歴史 『ラモーの甥』において、ディドロは啓蒙主義の批判者たちを攻撃し、嘲笑したが、過去の経験から、敵の中には彼を逮捕したり、作品を禁止するほどの権力を 持つ者もいることを知っていた。ディドロは1749年に『盲人についての手紙』を出版した後に投獄され、1759年には『百科全書』が発禁処分となった。 そのため、彼はそれを厳選された少数の人々だけに公開したのかもしれない。 ディドロの死後、原稿の写しが、ディドロの他の作品とともにロシアに送られた。[10] 1765年、ディドロは経済的に困窮していたが、ロシア女帝エカチェリーナ2世が彼の蔵書を買い取ることで彼を救った。この取り決めは双方にとって非常に 有益なもので、ディドロは自身の蔵書の有償司書となり、必要に応じて蔵書を充実させるという任務を負った。一方、ロシア側は、ディドロの蔵書はもちろんの こと、ヨーロッパでも最も厳選された蔵書の一つを手に入れるという見通しを喜んだ。[11][12] 感謝したロシアの読者は、その作品をシラーに伝え、シラーはそれをゲーテに紹介した。ゲーテは1805年にそれをドイツ語に翻訳した。[1] 最初に出版されたフランス語版は、実際にはゲーテのドイツ語版をフランス語に翻訳したものだった。これに刺激されたディドロの娘は、原稿の改ざん版を出版 した。1890年、図書館司書のジョルジュ・モンヴァルがセーヌ川沿いの古書商を物色している際に、ディドロ自身の手による『ラモーの甥』の写本を発見し た。この完全版は現在、ニューヨーク市のピアポント・モーガン図書館の金庫に保管されている。[13] ヘーゲルは『精神現象学』の§522と§545でラモーの『ラモーの甥』を引用している。 |

| English translations Jacques Barzun and Ralph H. Bowen: Rameau's Nephew and Other Works (The Library of Liberal Arts, 1964) Leonard Tancock: Rameau's Nephew and D'Alembert's Dream (Penguin, 1966) Ian C. Johnston: Rameau's Nephew (2002) Margaret Mauldon: Rameau's Nephew and First Satire (Oxford, 2006) Kate E. Tunstall and Caroline Warman: Denis Diderot's 'Rameau's Nephew': A Multi-Media Edition (Open Book Publishers, 2014; revised 2015)[14] |

英語訳 ジャック・バルゾン、ラルフ・H・ボーエン著:『ラモーの甥とその他の作品』(リベラルアーツ文庫、1964年 レナード・タンコック著:『ラモーの甥とダランベールの夢』(ペンギン、1966年 イアン・C・ジョンストン著:『ラモーの甥』(2002年 マーガレット・モールドン:『ラモーの甥』と『第一風刺』(オックスフォード、2006年) ケイト・E・タンスターとキャロライン・ウォーマン:『ラモーの甥』:マルチメディア版(オープン・ブック・パブリッシャーズ、2014年;改訂版2015年)[14] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rameau%27s_Nephew |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆